Aperture's Blog, page 16

August 29, 2024

The Exhibitions That Transformed African Photography

“The history of Europe in the past few centuries is an African history, whether one likes it or not,” the curator Simon Njami writes in the catalog for Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent. The landmark exhibition opened in Düsseldorf, Germany, in 2004, before traveling to London, Paris, Tokyo, Stockholm, and—amazingly, given the rarity of exhibitions about Africa originating in the global north ever travelling to the continent—Johannesburg. “Just as African history,” he adds, “is resolutely European.”

Implicit in Njami’s proposal about the continents’ entangled histories is an understanding that curatorial work is also history, that curators are also historians; like West Africa’s griots, custodians of oral histories, the curator-historian uses eccentric methods to reach provocative conclusions. Twenty years later, Africa Remix stands as a record of an era’s preoccupations and artistic statements. But does it hold up?

The catalog arrived amid a groundswell of Euro-American interest in contemporary African photography, spurred by the 1990s-era Bamako and Dakar biennials and the invaluable archival work of Revue Noire, the quarterly magazine Njami cofounded and edited. Collectively, these projects contributed to the wider reception of West African photographers like Mama Casset, Seydou Keïta, and Malick Sidibé, who were active between the 1950s and ’70s, as well as Cameroonian-born Nigerian photographer Samuel Fosso, who developed an inventive artistic practice of staged self-portraiture, beginning in the mid-’70s.

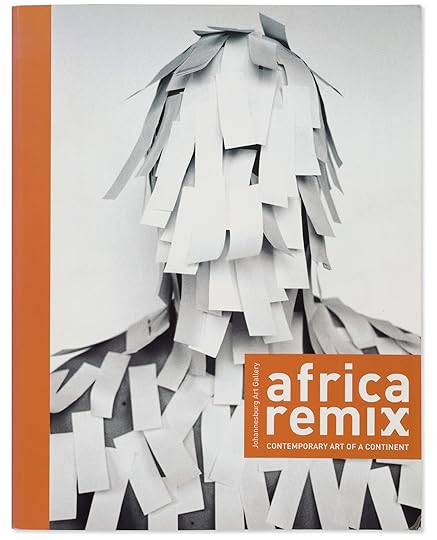

Cover of Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Jacana Media, 2007)

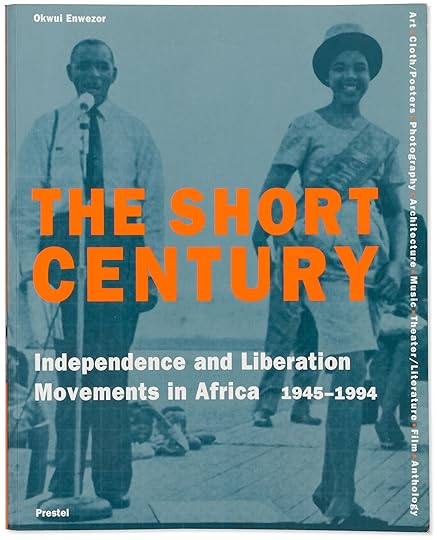

Cover of Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Jacana Media, 2007)  Cover of The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (Prestel, 2001)

Cover of The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (Prestel, 2001) Whereas painting is now at the vanguard of African creativity, both in the art market and in museums, photography was the zeitgeist medium across Africa in the early 2000s. As in Africa Remix, it featured prominently in two similarly photo-interested traveling exhibitions, both overseen by the late Nigerian American curator Okwui Enwezor: The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994, which opened in Munich in 2001, and Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, which launched in New York in 2006.

Less experimental and more obviously anthropological than Njami’s exhibition, The Short Century presented an overdue engagement with African modernity through work by fifty artists from twenty-two African countries. A ranging and analytical curator, Enwezor organized the historical objects around seven subject areas: modern and contemporary art, film, photography, graphics, architecture/space, music/recorded sound, and literature and theater, all linked to an historical framework. Snap Judgments was a less dialectical affair—only just. Composed of recent conceptual, documentary, and fashion photography, the show proposed that the “rigorous analytical perspective” of the thirty-four artists and one collective featured was expanding the lexicon of African art.

Installation view of Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, International Center of Photography, New York, 2006, with photographs by Kay Hassan and Allan deSouza

Installation view of Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, International Center of Photography, New York, 2006, with photographs by Kay Hassan and Allan deSouza© International Center of Photography

Exhibitions, especially large group exhibitions, typically open with great fanfare, and then begin to weaken and atrophy, in varying increments depending on the strength of their visual arguments, until their memory can appear hazy, imprecise, in need of recall—arguably a key labor of the catalog.

Africa Remix, The Short Century, and Snap Judgments are all memorialized with doorstoppers. When they first appeared, these hefty and increasingly hard-to-find books represented important contributions to knowledge about African photography. They also updated the arguments that had been staged in two vital 1990s publications: the Guggenheim Museum’s In/Sight: African Photographers 1940 to the Present (1996), which includes a compass-setting essay by Enwezor, and Revue Noire’s Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (1999), which features multiple contributions on individual photographers by Njami.

Enwezor’s and Njami’s focus on photography in the early 2000s was guided by their activism, yet their perspectives on photography and rhetorical styles also reflect their respective apprenticeships in New York and Paris. After studying politics at Jersey City State College in the early 1980s, Enwezor dove headlong into poetry (notably performing at the Nuyorican Poets Café), before emerging as an outspoken art critic interested in postcolonial identity, plurality, whiteness, and the endurance of western cultural hegemony. Njami too had literary ambitions, publishing four novels in the 1980s, before establishing himself as a rambunctious critic, who in 1991 told Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambety, “I hate photography.”

Explaining Africa in the museums of the global north is a longstanding activity, freighted by a history of colonial encounter and subjugation.

As a writer, Njami is temperamentally and attitudinally very different from Enwezor. His rhetorical mode in Africa Remix is provocative (“Africa is a scandal . . . a continent in constant mutation . . . without doubt the kingdom of immateriality”) and philosophical (“Different forms of contemporaneity coexist without necessarily echoing each other). To resist the homogenizing tendencies of European exhibitions on Africa art, Njami organized the sculpture, video, installation, and painting into three thematic groupings: identity and history, body and soul, city and land. A quarter of the artists on view used photography as their primary medium; yet, strangely, Njami barely discusses photography in his essay.

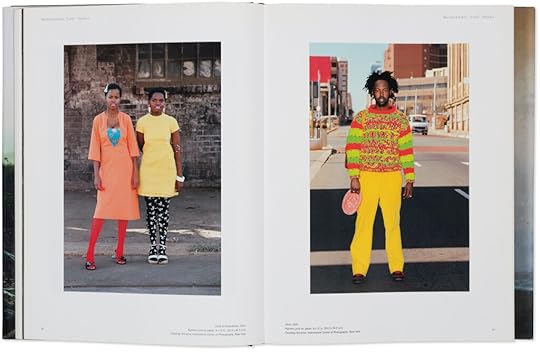

Spread from Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (ICP/Steidl, 2006), with photographs by Nontsikelelo Veleko

Spread from Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography (ICP/Steidl, 2006), with photographs by Nontsikelelo VelekoEnwezor, particularly in Snap Judgments, is far more persuasive about the evolution and arc of African photography at the start of the new century. Noting the increasingly analytical mode of recent work, he writes, “the new position the artists adopt engages broader spheres of interest such as landscape, urban studies, performance, portraiture, and documentary, differing from earlier approaches.”

History informs the thinking of both Njami and Enwezor as curators, and an historical perspective is ever-present in their work as writers (“To broach contemporaneity in Africa,” writes Njami in his Africa Remix essay, “inevitably leads to a re-reading of history”). Their cosmopolitan ethos and genre-spanning approaches were shaped by the presentation of Africa in Paris and New York, in particular “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (1984), a controversial New York exhibition pairing classical African art with examples of high modernist European painting and sculpture, and Magiciens de la terre (1989), an equally charged Paris exhibition that juxtaposed established Western artists such as John Baldessari and Louis Bourgeois with a broad constituency of non-Western folk artists, crafters, shamans, priests, and hard-to-classify visionaries like Frédéric Bruly Bouabré and Bodys Isek Kingelez (each of whom would have posthumous solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, New York).

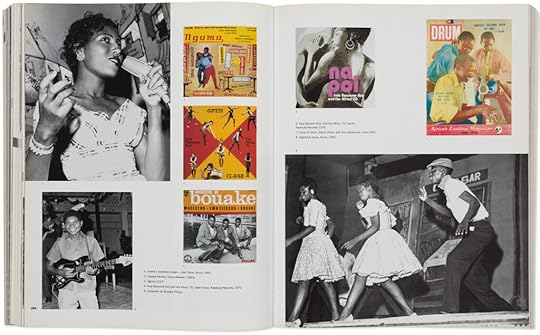

Spread from The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (Prestel, 2001), with a cover of Drum magazine, photographs, and album covers from the 1950s–70s

Spread from The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 (Prestel, 2001), with a cover of Drum magazine, photographs, and album covers from the 1950s–70sShowcasing and explaining Africa in the museums of the global north is, of course, a longstanding activity, freighted by a history of colonial encounter and subjugation, but also informed by different traditions of art scholarship and literary style. Njami, who was born in Lausanne, Switzerland, thinks and writes in the intellectual mode of Baldwin, Sartre, and Senghor, balancing activism and rhetoric with an acute literary style, while Enwezor—a refugee of the Biafran War, a circumstance mentioned in his Snap Judgments essay—was a quintessential New York intellectual gripped by the ideas of Agamben, Derrida, and Glissant, philosophers who informed his logical precision and ethical ambition as a writer.

Njami is far more playful and epigrammatic than Enwezor, who jettisoned his argumentative style of the early 1990s in favor of method, reason, and flashes of lyrical brilliance that connected his practice to the history work of griots. In his essay in Short Century, for instance, he quotes a passage from Martinican writer and politician Aimé Césaire’s epic poem, Notebook of a Return to a Native Land (1939), when a mutiny on a slave ship causes it to crack apart and reveal the “ghastly tapeworm of its cargo.” In response, he writes: “Like the cracking of the slave ship, the relationship of African modernity to Europe’s construction of the universal subject is both a critique and modification, a rip in the body of the colonial text.”

Catalogues are opportunities not only to read but also to look. Snap Judgments features an untitled 2003 portrait of a cane worker by Zwelethu Mthethwa on its cover. A leading figure in South Africa’s early post-apartheid photography scene (evidenced by his appearance in Africa Remix and The Short Century, too) Mthethwa was incarcerated in 2017 for a violent murder committed four years earlier. By then, African photography’s critical moment had also seemingly passed, although the Rencontres de Bamako, the biennial of African photography established in Mali in 1994, continued intermittently to present exhibitions of photography, as did spaces such as the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos and RAW Material in Dakar. Still, figurative painters like Marlene Dumas and Kerry James Marshall, who appeared in Enwezor’s 2015 Venice Biennale, defined the new zeitgeist.

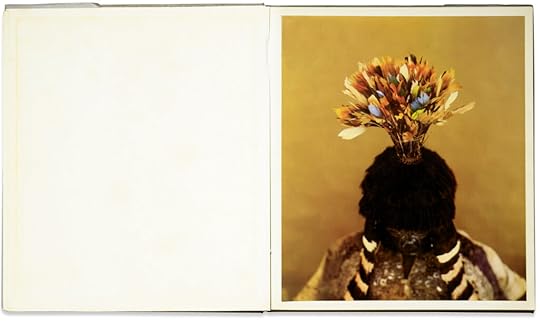

Moshekwa Langa, Untitled XXI, 2005

Moshekwa Langa, Untitled XXI, 2005Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

Moshekwa Langa, Untitled XII, 2005

Moshekwa Langa, Untitled XII, 2005 Only two other artists appeared in all three exhibitions: Moshekwa Langa and Zarina Bhimji, who like Mthethwa were South African. For a period in the 1990s and early 2000s, South Africa was a site for ambitious exhibition making. Africa Remix opened at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, a century-old municipal museum, in 2007. The date is at the midpoint between Enwezor’s stellar curatorship of the second Johannesburg Biennale, in 1997, and the 2015 presentation in Johannesburg of his exhibition Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, which, like Snap Judgments, originated at the International Center of Photography.

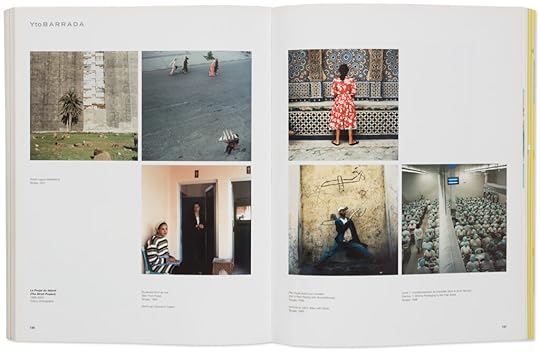

For South Africans, Africa Remix presented a rare opportunity to see the work of local photographers in conversation with works by the likes of Akinbode Akinbiyi, Yto Barrada, Hicham Benohoud, and Jellel Gasteli. It also provided an opportunity to test the veracity of the negative reviews Africa Remix generated in London in 2005. Brian Sewell, a neoconservative critic in the tradition of Hilton Kramer, described Njami’s exhibition as a “wretched assembly of post tribal artifacts”—and much worse. Perplexed by Njami’s thematic focus on urban Africa and strong preference for lens-based media, Jonathan Jones told Guardian readers, “Africa Remix misdescribes the continent.” The exhibition represented the view of “city-dwelling elites” Jones reported back to his constituency of, yes, city-dwelling elites.

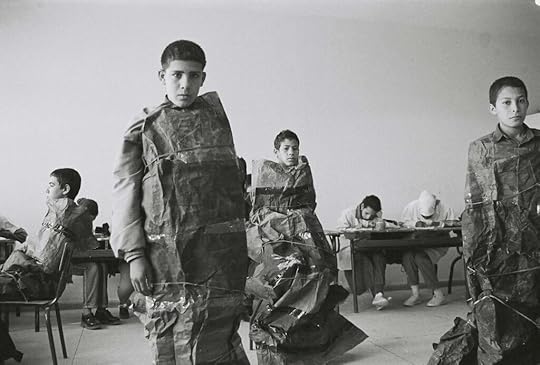

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe (The classroom), 1994–2001

Hicham Benohoud, La salle de classe (The classroom), 1994–2001Courtesy the artist

Although it remains the least urbanized continent on the planet, in 2005, Africa had forty-three cities with more than one million inhabitants. Writing a year earlier in his magnum opus, For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities (2004), urban theorist AddouMaliq Simone argued: “In city after city, one can witness an incessant throbbing produced by the intense proximity of hundreds of activities: cooking, reciting, selling, loading and unloading, fighting, praying, relaxing, pounding.”

Both Enwezor and Njami were keen to show this proximity. In his introduction to the section of photos grouped under “city and land” in Africa Remix, Njami leans into this cliché of a rural continent (“The city is a recent concept in Africa”), and then promptly detonates it by emphasizing the extraordinary volume of work about African cities (“Showing the city is never gratuitous”). Enwezor too was interested in the metropolitan subjectivity and focus of new African photography. “A large selection of Snap Judgments brings together studies of urban sites,” writes Enwezor, who was interested in how the work of Barrada, Kay Hassan, and the collective Depth of Field (founded in 2001 by Nigerians Kelechi Amadi-Obi, Uchechukwa James-Iroha, Toyin Sokefun and Amaize Ojeikere, the son of studio photographer J.D. Okhai Ojeikere), among others, addressed “modes or urban living and the changes that shape the postcolonial metropolis.”

Spread from Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Jacana Media, 2007), with photographs by Yto Barrada

Spread from Africa Remix: Contemporary Art of a Continent (Jacana Media, 2007), with photographs by Yto BarradaAll book photographs by Mia Thom

Africa Remix’s arrival in Johannesburg inspired the production of an updated (and also more affordable) edition of the original 2005 catalog. Both editions prominently foreground photography: Samuel Fosso’s vibrant color self-portrait, The Chief Who Sold Africa to the Settlers (1997), features on the cover of the first edition, while a black-and-white self-portrait from Moroccan photographer Hicham Benohoud’s series Version Soft (2003) adorns the later version, which includes new essays by philosopher Achille Mbembe and JAG director Clive Kellner. “This is the first time a major exhibition of contemporary African art will be held in Africa,” writes Kellner in a preface. This is not true. What he meant to say was that it was one of the first times a major Western exhibition of any art, let alone African art, visited the continent.

“There have been many, in recent years almost too many, great exhibitions of African art in Europe and in America,” writes Frank McEwen, the charismatic and worldly director of Rhodes National Gallery (now National Gallery of Zimbabwe), in the catalog accompanying the First International Congress of African Culture in 1962. Held in Harare, the accompanying exhibition explored ideas rehearsed in “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art and Magiciens de la terre, more than two decades later. It was high time, ventured McEwen, “that African art were shown more often in Africa, and reclaimed culturally by its creators.”

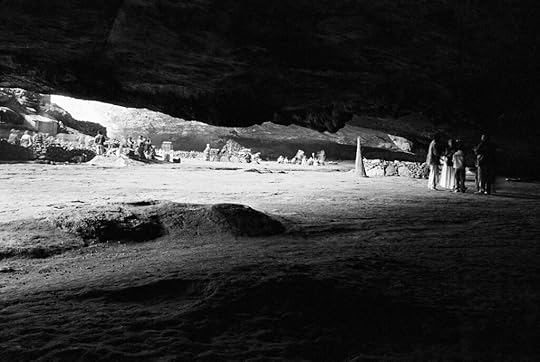

Santu Mofokeng, Inside Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 1996

Santu Mofokeng, Inside Motouleng Cave, Clarens, 1996© Santu Mofokeng Foundation and courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

That possibility was not an abstraction. In 1958, Edward Steichen’s large-scale photo exhibition, The Family of Man, was presented in Johannesburg. Photographer Peter Magubane, whose early Drum-era work is illustrated in the catalogue for The Short Century, attended the exhibition. “I began working very, very hard to try and reach the standard of those pictures that I saw,” Magubane told photographer Ken Light. Magubane’s statement is a caution against lionizing the role of curators simply or only as historians involved in the production of revisionist texts. Exhibitions are embodied and experiential; seeing an exhibition in person, more so than reading about its ambitions after the fact, is a privileged occasion to pause, think, maybe learn, possibly even aspire.

August 22, 2024

An Ardent Observer of Beirut

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Winter 2023, “Desire,” under the column Dispatches.

Tanya Traboulsi is an ardent observer of the Lebanese coastline. Her photographs probe the ways in which clay tennis courts and fake grass playing fields are tucked into the hills sliding down to the sea in Ras Beirut, on the western side of the city’s promontory. She is also a dedicated student of vernacular architecture. She details vestibules, awnings, bougainvillea peeking through tactical breeze-blocks, and the elegant arches of a derelict Ottoman mansion. She returns again and again to the playfulness with which shopkeepers in the Lebanese capital use language to advertise the Renaissance Sporting Club, New Fashion, or Dalida, a tiny chocolatier downgraded under financial duress to an all-purpose dekaneh, or grocery store, named for a pop music sensation.

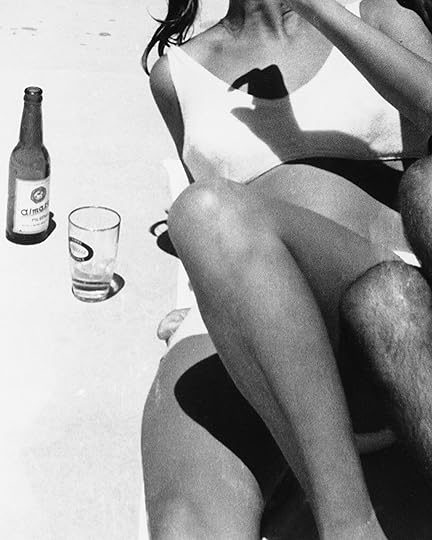

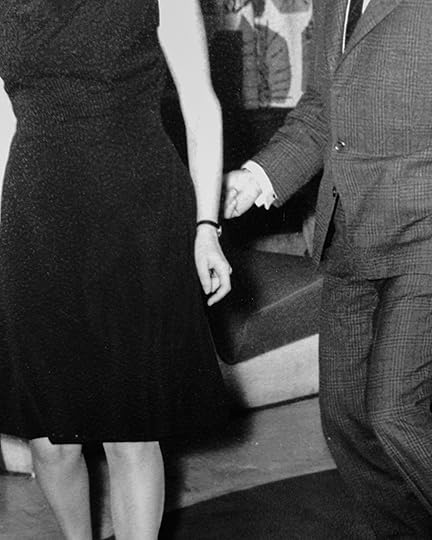

Traboulsi’s series Beirut, Recurring Dream (2021–ongoing) pairs photographs she has taken in the last two years with images from her personal archive: six large boxes of material, including family albums and pictures she took during her childhood and adolescence. Traboulsi’s diptychs are fluid and unfixed. They appear in different configurations, depending on their context. They are also matched by intuition. By placing a photograph of a couple lounging on a beach in the 1960s next to an image of a woman standing alone, her back to the viewer, on the corner of a low wall jutting into the sea, as she gazes toward a blurry horizon and ambivalent skies, Traboulsi isn’t suggesting narrative so much as time travel or a flash of inherited memory.

Traboulsi was seven years old when she left Beirut with her family on a boat crossing the Mediterranean Sea. It was 1983. Lebanon’s civil war was lurching through its first decade. The center of the capital had been destroyed in the first round of fighting, starting in 1975. Beirut was split in half and the armed forces had fractured. The government was about to collapse. Massacres had occurred all over the country, and there was shelling in densely residential neighborhoods. Syria had intervened, and in 1982, Israel had invaded and besieged the country, which, among other things, closed the airport for months at a time. Fleeing residents had to risk dangerous mountain roads or the ferry lines connecting Beirut to Cyprus.

As a city, Beirut has been photographed with a prodigiousness disproportionate to its size, even its history.

Traboulsi’s parents met before the civil war began. Her mother had moved to Lebanon from Vienna to work as a ski instructor, and Traboulsi’s father cut the line to sit with her on the lift. An enduring romance ensued. Traboulsi was born in Austria but spent her early years in Beirut, taking pictures of the city using an Instamatic camera and 110 film. Her family left and stayed away for more than a decade, in part because the civil war lasted so long and in part because it ended with such uncertainty. A general amnesty was announced in 1991, although some argue the conflict continued by other means.

“The moment I left, I wanted to go back,” Traboulsi told me this past summer. “The image of how Beirut looked from the sea stuck with me for thirteen years.” She was separated from her two best friends in Lebanon and saw them constantly in her dreams. She didn’t return until 1996. From that point, she shuttled back and forth between Austria and Lebanon until she finished university. She settled in Beirut in 2003.

As a city, Beirut has been photographed with a prodigiousness disproportionate to its size, even its history. The so-called photographic mission of 1991 invited six leading photographers—Gabriele Basilico, Raymond Depardon, Fouad Elkoury, René Burri, Josef Koudelka, and Robert Frank—to document the tremendous violence done to the heart of Beirut’s city center by fifteen years of civil war. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, artists and filmmakers such as Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic, and Akram Zaatari responded to the conditions of postwar and reconstruction-era Beirut with their own trenchant questions. In their wake, Traboulsi has emerged as one of the city’s most thoughtful and affectionate chroniclers.

Related Items

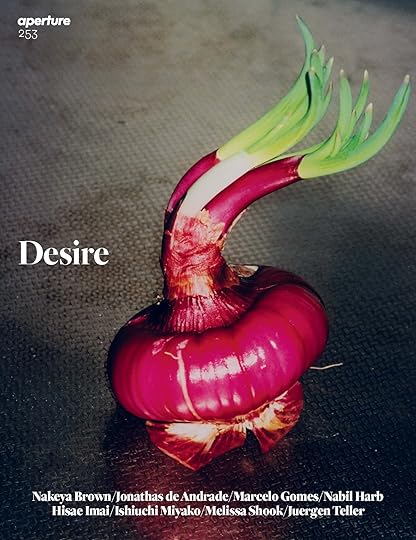

Aperture 253

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Traboulsi and I are nearly the same age and came to live in Beirut at the same time. In many ways, her photographs narrate my own relationship to the city. She has photographed buildings I have lived in, corners I have loved, places I have walked by and wondered about daily. I vividly remember my first encounter with her work, in a group show called Be-Sides: How Young Lebanese Photographers See Present-Day Lebanon, organized by the Goethe-Institut in 2007.

Beirut’s photographic history can make the city feel trapped in the past, forever in the rubble of the civil war. But Traboulsi has stayed with the story and followed the city through more recent upheavals. With great subtlety and sensitivity, in Beirut, Recurring Dream she gathers traces of the revolution that erupted in 2019, followed by the economic collapse that devalued the local currency by 90 percent and plunged more than half the country into poverty. She captures the afterlives of the catastrophic explosion that ripped through the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020, killing hundreds, injuring thousands, and displacing three hundred thousand people from their damaged homes.

All photographs by Tanya Traboulsi, from the series Beirut, Recurring Dream, 2021–ongoing

All photographs by Tanya Traboulsi, from the series Beirut, Recurring Dream, 2021–ongoingCourtesy the artist

“The explosion changed everything,” Traboulsi told me. “It changed me, my friendships, my relationships, my view of love, what I accept and what I can give to other people.” Seeing the city so damaged compelled her to admit that Beirut was and always had been her subject.

The Lebanese poet Etel Adnan described a mountain in California as her best friend. She painted it every day, in all kinds of light and weather, for more than a year. This was in the mid-1980s, after Adnan, the ultimate chronicler of Beirut, had made her own exit from the city and Lebanon’s civil war. In 2021, Traboulsi made a film with the writer Ibrahim Nehme, unrelated to Beirut, Recurring Dream, called Son of the Sun. Nehme’s voiceover offers a visceral response to the port explosion (he was seriously injured in the blast), but Traboulsi’s images are long, steady shots of the sun rising and falling on the coastline, waves lapping the shore. Adnan had her mountain, Traboulsi has her city on the sea.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, Winter 2023, “Desire.”

August 16, 2024

When Luigi Ghirri Photographed the Ferrari Factory

Luigi Ghirri did not preoccupy himself with cars, but he did enjoy driving. He owned a number of Volkswagen Beetles that were constantly breaking down. In the 1980s, he switched to a Volvo station wagon, paragon of Swedish vehicular functionality and safety. An accumulation of unpaid traffic fines suggests he may not have been a great driver, or that he was blasé about traffic rules. Nonetheless, he crisscrossed Italy and Europe taking the photographs for which he is now celebrated: unpeopled landscapes that rush toward a vanishing point, architectural details, found images within images pasted around a town. All are realized in soft washes of warm color that cushion reality, making it feel ever so distant and dreamlike. Adele Ghirri, his daughter, who now manages his estate and archive from his former home and studio in Reggio Emilia, recalls that her father’s cars were unwashed, neglected. His focus, one can assume, was on looking out the window for pictures. As Ghirri wrote, he sought to “observe the outside world in order to represent it.”

For anyone growing up in and around Reggio, the mythic car manufacturer Ferrari, based in nearby Maranello, loomed large. The company, in a crowded field of contenders, is an apex of Italian style, industrial design, and brilliant ingenuity. Michael Mann’s recent film Ferrari dramatizes the origins of the firm and the personal travails of its founder, Enzo Ferrari. Even so, on-screen, the cherry-red cars throbbing along twisting roads emerge as the indefatigable protagonists.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

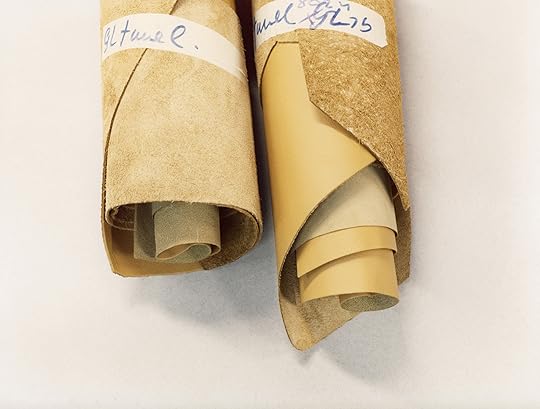

In the mid-1980s, Ghirri was invited to photograph at the Ferrari factory. The pictures feel like a laboratory record. Workers don elegant lab coats emblazoned with the company logo—that rearing horse. Interior leather samples are arranged in Ellsworth Kelly–like compositions. There is little sense of mechanical noise or grease. Even an image of molten steel being poured is quiet. By contrast, Chris Killip’s noirish pictures from the Pirelli tire factory, stylish as they are, and made around the same time, hint at noisier manufacturing underway. Ghirri’s Ferrari images haven’t been widely published or exhibited. Not made for the public, they were used in a promotional publication, designed by the influential architect Pierluigi Cerri, that also included photographs by Walter Iscra, Gianni Rogliatti, Wolfgang Wilhelm, and a selection from the Ferrari archives.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Ghirri’s interest in clean lines, perspective, and landscape can be traced back to his earlier job as a land surveyor. He was passionate about architecture and design, reading—and sometimes collaborating with—magazines such as Ottagono, Lotus, and Domus. He photographed many buildings by Aldo Rossi, an architect Ghirri admired for how the colors of his exteriors resonated with their surroundings. Like most photographers scratching out a living, Ghirri worked on commission from time to time, often merging image making with a story about design. In the 1980s the jewelry brand Bulgari hired him to take photographs of its newly minted Fifth Avenue store in New York. From 1975 to 1985, he worked with Marazzi, an Italian heritage tile company, using the opportunity of a commercial commission to create exquisite images of trompe l’oeil play and clever meditations on the act of picture making itself. The simple colored tiles presented a stage on which to work and arrange miniatures of a camera on a tripod, a baby grand piano, or, in a nod to Fra Angelico, an egg resting in a stand. A recently published book of Ghirri’s work, Italia in Miniatura (2024), explores his interest in the detailed facsimiles of famous sites and landscapes at a theme park in Rimini. Ghirri’s writings—his essays are prolific—ruminate on representations that shrink reality: postcards, atlases, Lilliputian worlds.

In the Ferrari images, too, there is a sense of making things small. As with his famous picture taken through a window at Versailles, deflating the ostentatious grandeur of the palace gardens, Ghirri’s photographs for Ferrari bring the company down to earth from the upper stratosphere of luxury. This is seen on the factory floor and in a 1990 photoshoot staged on a hilltop overlooking Florence. A group of cars selected to celebrate the company’s history was displayed and framed in an installation of cubes designed by Cerri. The Duomo is visible in the background. The cars look like toys. Describing the experience of being inside a Rossi building, Ghirri wrote: “There is also a joyous sense of wandering, magically, inside a wonderful toy, getting lost and finding one’s way amid the gears and little wheels.” The same might be said of his pictures for Ferrari. The pleasure of design is fully on display, and the glitz of a storied brand takes a backseat to a careful study of its component parts.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

All photographs by Luigi Ghirri, from the series Ferrari, 1985–90

All photographs by Luigi Ghirri, from the series Ferrari, 1985–90© Estate of Luigi Ghirri

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”

August 9, 2024

12 Graphic Designers on Their Favorite Books

There are proper photobooks, showcasing the work of a single photographer’s accomplishments, and then there are books that use photography in the service of something else, as a manual, guide, illustration, or history lesson. For Aperture’s “Design Issue,” we invited a group of graphic designers to select some of their favorite books that use photographs to delve into a range of ideas related to design.

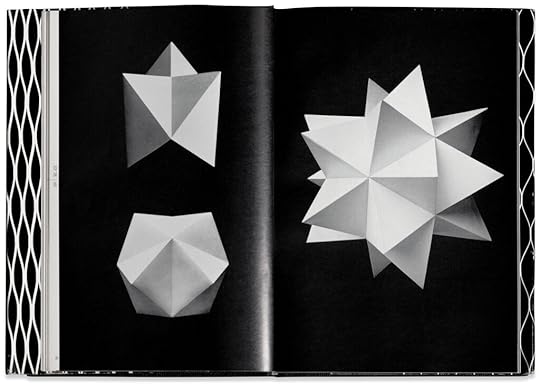

Interior spread of The Art of Papercraft (B. T. Batsford, 1971)

Interior spread of The Art of Papercraft (B. T. Batsford, 1971)Sonya Dyakova

The Art of Papercraft (B. T. Batsford, 1971) by Hiroshi Ogawa is a comprehensive guide to the Japanese art of paper sculpture. It contains more than 110 photographs, with great attention to detail. The images are dramatic and atmospheric, as if the sculptures are suspended in space and time. The black background and soft shadows enhance the beauty of the shapes. Ogawa provides not only general instructions and suggestions but also explanatory illustrations and notes to accompany the photographs, making this book a practical resource for anyone interested in paper sculpture. It’s special to see the way humble materials and simple techniques can come together to create something so powerful.

Sonya Dyakova is the founder of Atelier Dyakova, a design studio in London.

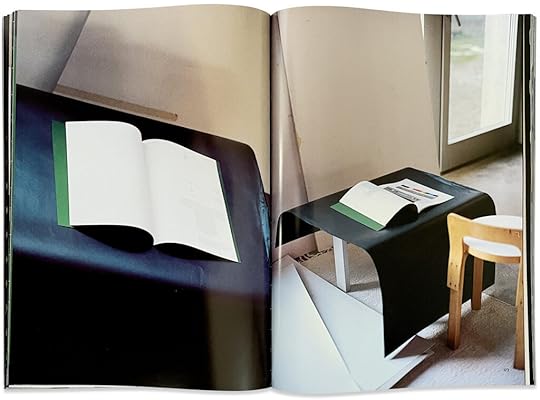

Interior spread of The Most Beautiful Swiss Books (Federal Office of Culture, Bern)

Interior spread of The Most Beautiful Swiss Books (Federal Office of Culture, Bern)Duncan Whyte

The Most Beautiful Swiss Books (Federal Office of Culture, Bern) is an annual publication documenting a yearly competition. The volumes are always fascinating, with a Swiss budget for epic reproduction. The two volumes with the best photographs are from 2016 and 2022: 2016 is devoted to “examination,” with spreads comparing all the nominated books through thirty or so different criteria, including spine, strength, and pagination; 2022 features a moody fashion shoot for each book.

Duncan Whyte is an independent art book designer living and working in France.

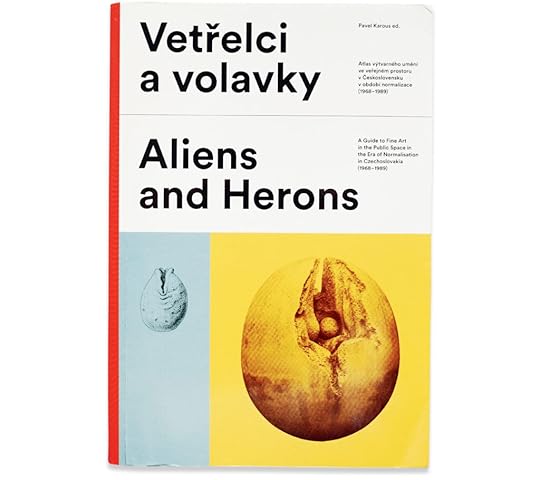

Cover of Aliens and Herons (Arbor Vitae, 2016)

Cover of Aliens and Herons (Arbor Vitae, 2016)Jordan Marzuki

Aliens and Herons (Arbor Vitae, 2016) by Pavel Karous is a guidebook documenting postcommunist public art throughout the Czech Republic. The book employs its own taxonomy—class, order, family, genus, and species—to identify each artwork, along with beautifully structured typography and colorful pages. Cheeky illustrations contribute to an unconventional and hilarious narrative, in stark contrast to the serious, often dark history of the region.

Jordan Marzuki is a designer based in Jakarta, Indonesia, and the founder of Jordan, jordan Édition.

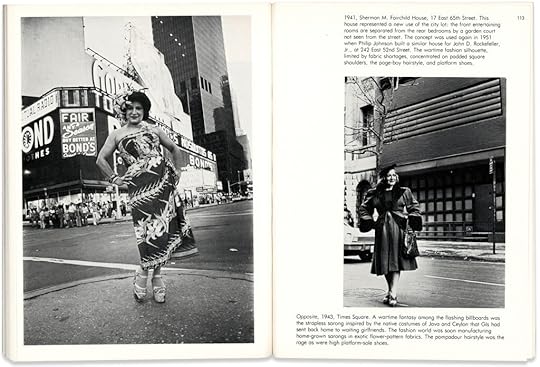

Interior spread of Facades by Bill Cunningham (Penguin, 1978)

Interior spread of Facades by Bill Cunningham (Penguin, 1978)Other Means

Bill Cunningham’s Facades (Penguin, 1978) features 128 photographs of his neighbor Editta Sherman posing in front of buildings in New York City, wearing period-correct outfits Bill collected over ten years. In most cases the buildings and clothing are in harmony, with the exception of the Twin Towers—Bill contrasts the clean, austere modernism of the towers with the “raunchy” blue jeans culture of the time. Our favorite photographs show Editta next to a graffiti-covered subway, illustrating the book’s core concept of the city as a collage of design spanning two hundred years. The cover, designed by Quentin Fiore, is printed in brilliant red and blue spot colors on metallic paper, evoking Midtown Manhattan’s reflective facades.

Other Means, a design studio in New York, was founded by Ryan Waller, Gary Fogelson, and Phil Lubliner.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Cover of Ghetto Gastro Presents Black Power Kitchen (Artisan, 2022)

Cover of Ghetto Gastro Presents Black Power Kitchen (Artisan, 2022)WORK/PLAY

For us, Ghetto Gastro Presents Black Power Kitchen (Artisan, 2022) is more than just a cookbook. We love how the chefs incorporate experimental recipes along with new takes on traditional recipes and the histories behind these meals. The pages are culturally immersed in who we are as Black people and are showcased through a Black cultural lens. From the Bronx to destinations all across the globe, Ghetto Gastro is bringing “food for freedom, fuel for thought.”

WORK/PLAY is an interdisciplinary design studio cofounded by Danielle and Kevin McCoy and based in St. Louis, Missouri.

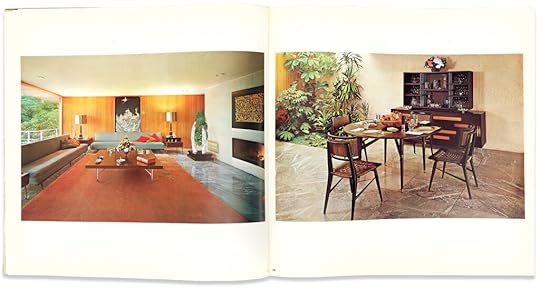

Interior spread of Francisco Artigas (Tlaloc, 1972)

Interior spread of Francisco Artigas (Tlaloc, 1972)Maricris Herrera

Roberto Luna’s photographs of the architect Francisco Artigas’s houses published in Francisco Artigas (Tlaloc, 1972) are distinguished by their challenging of traditional visual conventions and their exploration of new forms of architectural expression. With remarkable boldness, Luna constructs insightful narratives for utopian scenarios, revealing his unique ability to fuse modern aesthetics with functionality. Beyond his architecture, Artigas’s distinctive style of self-presentation stands out for its innovation and, above all, its provocative character.

Maricris Herrera established the Mexico City–based design practice Estudio Herrera in 2016.

Interior spread of Puruchuco (Editorial Organización de Promociones Culturales, Lima, ca. 1981)

Interior spread of Puruchuco (Editorial Organización de Promociones Culturales, Lima, ca. 1981)Vera Lucía Jiménez

I first learned about Puruchuco (Editorial Organización de Promociones Culturales, Lima, ca. 1981) from a beautiful piece written by the Peruvian poet Jorge Eduardo Eielson. Illustrated with photographs by José Casals, Puruchuco shows, with words and images, the attempt to rethink an architectural complex on the coast of Peru that belonged to the Inca Empire from the thirteenth century and served as an administrative center and house of the curaca, an elite official. Casals’s images detail the precision and sensitivity of pre-Hispanic architecture: places connected to the corporality of the inhabitant and the uses they gave to the spaces.

Vera Lucía Jiménez is a publication designer who works between Lima, Peru, and Porto, Portugal.

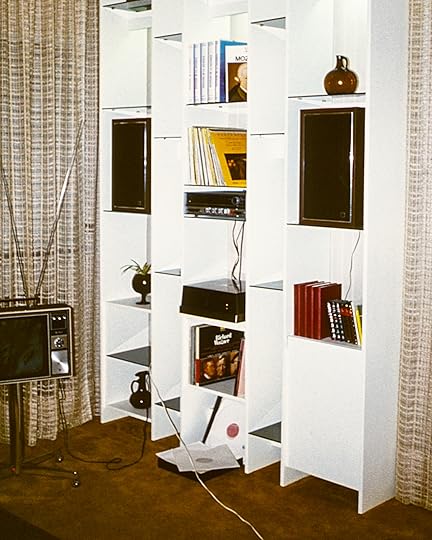

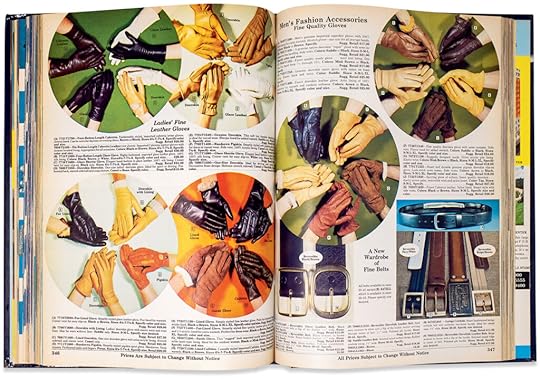

Interior spread of Blue Book of Quality Merchandise 1980 (Bennett Brothers, 1980)

Interior spread of Blue Book of Quality Merchandise 1980 (Bennett Brothers, 1980)Adam Turnbull

I was drawn to this publication—the Blue Book of Quality Merchandise 1980 (Bennett Brothers, 1980)—because of the product imagery. I love how the photographs are art directed and the products styled: the hands wearing the gloves, the staged still lifes, the radios with the dark gradient background. The repetition of the products laid out on the page creates a beautiful rhythm. It’s an amazing relic of a piece of marketing material that was both functional and pleasing.

Adam Turnbull is the cofounder, with Elizabeth Karp-Evans, of Pacific, a creative studio in New York.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Interior spread of UP UP: Stories of Johannesburg’s Highrises (Fourthwall, 2016)

Interior spread of UP UP: Stories of Johannesburg’s Highrises (Fourthwall, 2016)Gabrielle Guy

I happened to be living in Johannesburg at the time that UP UP: Stories of Johannesburg’s Highrises (Fourthwall, 2016) came out. I found the city fascinating—so different from Cape Town, where I’m from. The city center is big and run-down, and so much more ambitious architecturally. I remember going to the book launch, held in a cool space in Braamfontein on the outskirts of the Central Business District. I love how the book manages to incorporate old and new photographs, architectural illustrations, and archival documents. It’s difficult to deal with such a range of visual material in layout, yet UP UP, with its solid grid, strong typeface, and rigid approach to sections and binding manages to create a strong aesthetic.

Gabrielle Guy is an art book designer and artist based in Cape Town, South Africa.

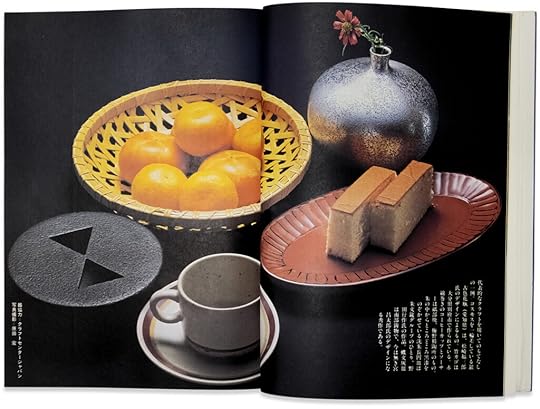

Interior spread of Kurashi no souzou, no. 7 (Sogei Shuppan, 1978)

Interior spread of Kurashi no souzou, no. 7 (Sogei Shuppan, 1978)Akiko Wakabayashi

Kurashi no souzou, no. 7 (Sogei Shuppan, 1978) is the design magazine’s special issue on Japanese craft. For me, the most attractive element is the cover image. The still life on the front is mirrored and then layered twice on the back. One section is treated with a distortion effect. Was this a mistake, a conscious experiment with technique, or is there a hidden conceptual message? The result is puzzling, but this mysterious outcome raises a lot of questions, which I love.

Akiko Wakabayashi is an independent designer based in the Netherlands.

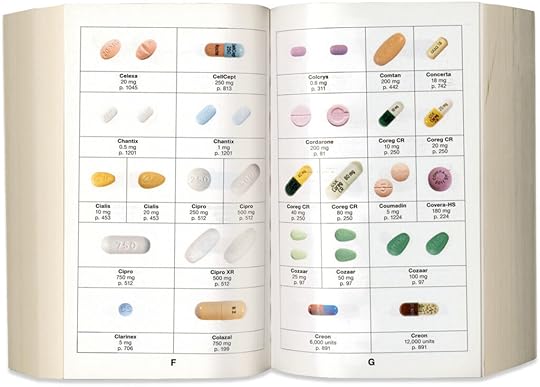

Interior spread of The Pill Book (Bantam, 2012)

Interior spread of The Pill Book (Bantam, 2012)Alex Lin

I found The Pill Book (Bantam, 2012), which covers more than 1,800 of the most regularly prescribed drugs in the United States, to be an effective use of photography as a reference for people. It’s a really beautiful and practical book, which runs more than 1,200 pages. I think it’s also great that the pills are printed to scale.

Alex Lin established Studio Lin, a Brooklyn-based graphic design practice, in 2012.

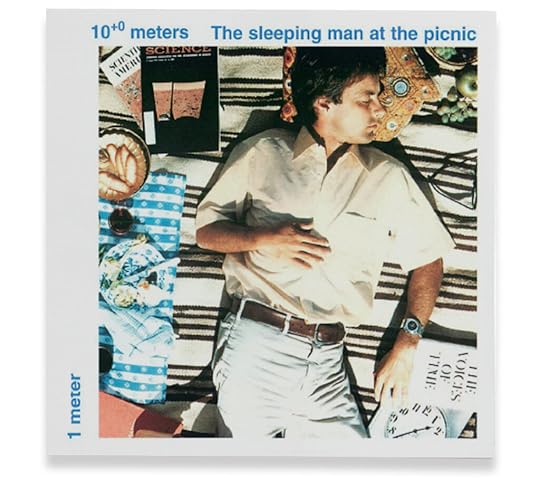

Interior spread of The Powers of Ten (W. H. Freeman & Co., 1998)

Interior spread of The Powers of Ten (W. H. Freeman & Co., 1998)Scott Williams

The Powers of Ten (W. H. Freeman & Co., 1998) is a flipbook depicting stills from a film of the same name, created by the office of Charles and Ray Eames in 1977. The book is a conceptual and pictorial journey that starts at the edge of the universe and hurtles down to Earth, at tenfold steps, with a photograph depicting each interval along the way. The camera descends rapidly to Earth until the lens eventually enters the hand of a man lounging at a picnic at a park on Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, down into his cells, his DNA, and finally to a single proton. It’s a small book with a big idea.

Scott Williams is cofounder, with Henrik Kubel, of A2/SW/HK, a design studio in London.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 255, “The Design Issue,” in The Photobook Review.

August 1, 2024

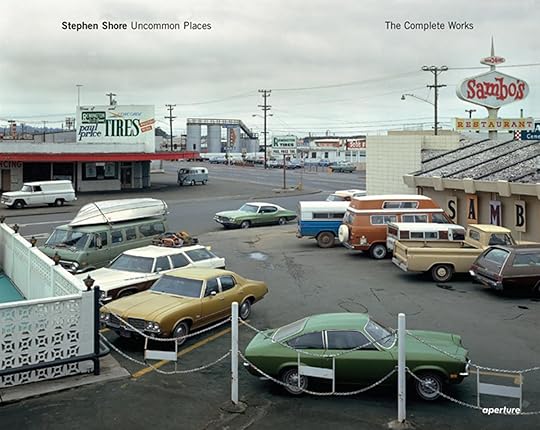

Stephen Shore’s American Beauty

Stephen Shore makes remarkable pictures of seemingly unremarkable things: a freeway seen from above, a Texaco gas station, runners on a paved road. His work is consistently a pleasure to look at, especially because it can subvert the conventions of what a photographic composition is, or use a vernacular form uncommon in the art world. Vehicular & Vernacular, an exhibition this summer at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation, Paris, reveals these qualities and also offers a moment to reconsider Shore’s output in relation to Pop and Conceptual art.

In 1965, Andy Warhol hired Shore. Instead of pursuing school, the young photographer stayed at the Factory until 1967. In a discussion with Lynne Tillman, Shore once remarked on two things he learned from Warhol: to focus on concepts and to work serially. He took something else from him, too, a certain vulgarity—that is to say, an embrace of common or vernacular forms. If Warhol used silkscreen and film, for example, Shore would use postcards and color photography, then later print-on-demand books and drones.

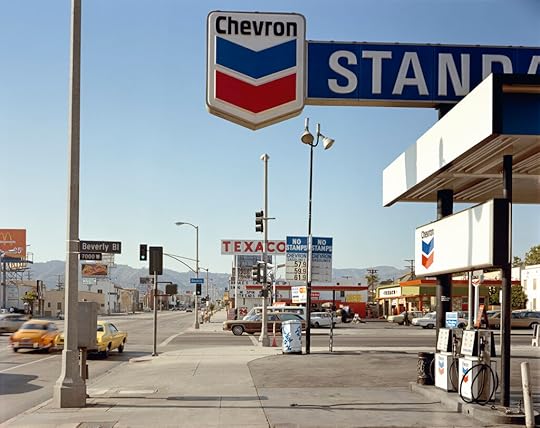

Stephen Shore, Beverly Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, June 21, 1975, from the series Uncommon Places, 1973–86

Stephen Shore, Beverly Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, June 21, 1975, from the series Uncommon Places, 1973–86 Stephen Shore, Los Angeles, California, February 4, 1969, from the series Los Angeles, 1969

Stephen Shore, Los Angeles, California, February 4, 1969, from the series Los Angeles, 1969The earliest work in the exhibition dates from 1969, not long after those so-called Velvet Years in New York. By then, Shore was taking what he had learned at the Factory and applying it to one of his recurring subjects: the complexity of American ways of seeing. One year after he had acquired a copy of Ed Ruscha’s 1966 accordion-format photobook Every Building on the Sunset Strip (and in the same year that Jeff Wall, an artist with whom he shares affinities, was producing Landscape Manual), Shore shot from the backseat window of a car hired by his businessman father as it went from meeting to meeting across Los Angeles. The artist was twenty-one. When he exhibited these photographs, instead of presenting the selection he thought best, he showed all of them in a row. The work was as much about the idea of how to see a city like Los Angeles as it was about any individual image’s value as a picture. The photographs themselves are raw, observational, sometimes cropped at odd angles, sometimes blurry, almost always compelling.

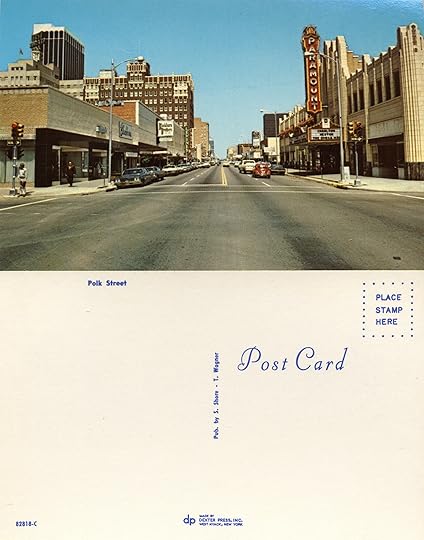

Stephen Shore, Polk Street. 1971, from the series Greetings from Amarillo, 1971

Stephen Shore, Polk Street. 1971, from the series Greetings from Amarillo, 1971Among other early works on display is Greetings from Amarillo (1971), a playful series of postcards Shore produced of banal buildings and intersections in the eponymous Texas city. On the road the following year, using a simple 33mm camera, he started American Surfaces: quotidian snapshots of people, ads, cars, horizons, a hotel toilet bowl—the sort of thing more likely found in a scrapbook, not a gallery. At nearly the same time as Luigi Ghirri in Italy and William Eggleston in the American South, he decided to print in color, which was then associated with advertising, fashion photography, or family photo albums, not serious art. Perhaps in homage to Warhol, he displayed small-format “drugstore prints” on the wall in grids.

Related Items

Stephen Shore: Uncommon Places

Shop Now[image error]

Stephen Shore: Selected Works, 1973-1981

Shop Now[image error]In 1973, Shore switched to a bulky view camera, setting his tripod in front of movie theaters in small towns, motels in the middle of nowhere, gas stations in the heart of Los Angeles. Uncommon Places, which he continued for over a decade, depicts the vastness of North America, from formally sophisticated photographs of a vegetable truck unloading goods in Idaho, to a Hopperesque street in Massachusetts, to a small white chapel against big sky and high mountains in Alberta. American Surfaces and Uncommon Places were both informed, to some degree, by the Factory—curious but detached, conceptual but sensual. Both series, which often included representations of everyday American architecture, led to a collaboration with Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and Robert Venturi on Signs of Life (1976), an installation recreated in the exhibition, in which floor-to-ceiling images pasted on three walls, complete with a fire hydrant and parking sign, replicate the space of a street.

Stephen Shore, U.S 89, Arizona, June 1972, from the series American Surfaces, 1972–73

Stephen Shore, U.S 89, Arizona, June 1972, from the series American Surfaces, 1972–73 Stephen Shore, Meagher County, Montana, July 26, 2020, 46°11.409946N 110°44.018901W, from the series Topographies, 2020–21

Stephen Shore, Meagher County, Montana, July 26, 2020, 46°11.409946N 110°44.018901W, from the series Topographies, 2020–21While Vehicular & Vernacular also exhibits Shore’s commercial work for Nike and his print-on-demand photobooks of the early 2000s, both noteworthy inclusions, the next significant series here is the recent one produced with remote-controlled drones. Made during the pandemic, in 2020, these prints present wide horizons, high up from the sky: rows of two-story houses in Hudson, New York; a single white horse dwarfed by perspective in a verdant field in Bozeman, Montana. It’s almost as if Shore is bringing us back, even if only in buried allusion, to that early moment in photographic history when Nadar made his aerial views of Paris from a hot-air balloon. Whether on the ground or from above, Shore’s insistence on using vernacular forms of photography make his work vulgar in the best possible way.

Stephen Shore: Vehicular & Vernacular is on view at Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris, through September 15, 2024.

July 23, 2024

How Alex Webb Sees in Color

In 1975, I reached a kind of dead end in my photography. I had been photographing in black and white, then my chosen medium, taking pictures of the American social landscape in New England and around New York—desolate parking lots inhabited by elusive human figures, lost-looking children strapped in car seats, and dogs slouching by on the street. The photographs were a little alienated, sometimes ironic, occasionally amusing, perhaps a bit surreal, and emotionally detached. Somehow I sensed that the work wasn’t taking me anywhere new. I seemed to be exploring territory that other photographers—such as Lee Friedlander and Charles Harbutt—had already discovered. I happened to pick up Graham Greene’s novel, The Comedians, a work set in the turbulent world of Papa Doc’s Haiti, and read about a world that fascinated and scared me. Within months, I was on a plane to Port-au-Prince.

That first three-week trip to Haiti transformed me—both as a photographer and as a human being. I photographed a kind of world I had never experienced before, a world of emotional vibrancy and intensity: raw, disjointed, often tragic. I began to explore other places—in the Caribbean, along the U.S.-Mexico border—places, like Haiti, where life seemed to be lived on the stoop and in the street. Three years after my first trip to Haiti, I realized there was another emotional note that had to be reckoned with: the intense, vibrant color of these worlds. Searing light and intense color seemed somehow embedded in the cultures that I had begun working in, so utterly different than the gray-brown reticence of my New England background. Since then, I have worked predominantly in color.

Alex Webb: The Suffering of Light 65.00

Alex Webb: The Suffering of Light 65.00 $65.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Alex Webb: The Suffering of LightPhotographs by Alex Webb. Text by Geoff Dyer.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.00Add to cart

View cart Description The Suffering of Light is the first comprehensive monograph charting the career of acclaimed American photographer Alex Webb. Gathering some of his most iconic images, many of which were taken in the far corners of the earth, this exquisite book brings a fresh perspective to his extensive catalog. Recognized as a pioneer of American color photography since the 1970s, Webb has consistently created photographs characterized by intense color and light. His work, with its richly layered and complex composition, touches on multiple genres, including street photography, photojournalism, and fine art, but as Webb claims, “to me it all is photography. You have to go out and explore the world with a camera.” Webb’s ability to distill gesture, color and contrasting cultural tensions into single, beguiling frames results in evocative images that convey a sense of enigma, irony and humor. Featuring key works alongside previously unpublished photographs, The Suffering of Light provides the most thorough examination to date of this modern master’s prolific, 30-year career.Alex Webb (born in San Francisco, 1952) has published more than fifteen books, including Aperture titles Brooklyn: The City Within (2019, with Rebecca Norris Webb), La Calle: Photographs from Mexico (2016), On Street Photography and the Poetic Image (2014, with Rebecca Norris Webb), and a survey of his color work, The Suffering of Light (2011). Webb has been a full member of Magnum Photos since 1979. His work has been shown widely, and he has received numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007. Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 204

Publication date: 2011-05-31

Measurements: 13.2 x 12.2 x 0.9 inches

ISBN: 9781597111737

The images – rich in color and visual rhythm – span 30 years and several continents. Of course, Haiti and the Mexican border are well represented, locales that opened up a new way to see.He has been able to render Haiti – a place often depicted for its chaos – with a precise eye, finding personal moments that are as still as they are complex. He can use shadows as skillfully as a be-bop musician to set the tempo. The people in his frames can look like dwarfs being stomped on by giant, disembodied feet. He can make an American street seem far more foreboding than any Third World slum.–David Gonzalez”The New York Times” (12/18/2011)

ContributorsAlex Webb was born in San Francisco in 1952. His photographs have been featured in The New York Times Magazine, Life, Stern, and National Geographic and exhibited at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, and the International Center of Photography and Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. He is a recipient of the Leica Medal of Excellence (2000) and a member of Magnum Photos.

Geoff Dyer is the author of “Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi, “among other novels, and several nonfiction books, including “Out of Sheer Rage”. He won a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2012 for “Otherwise Known as the Human Condition”. He lives in Los Angeles.

Not a typical documentary photographer or photojournalist, I’ve worked essentially as a street photographer, exploring the world with the camera, allowing the rhythm and the life of the street to guide and inform the work. For me, everything comes, first and foremost, from the street. Whatever insights—sociopolitical, cultural, or aesthetic—I may have into the societies I have photographed over the years come not from preconception, but from the process of wandering the street. At times, I feel the street can sometimes be a kind of bellwether, hinting at sociopolitical changes to come.

Over the years, my way of seeing in color, which first emerged in the tropics, has expanded into various projects, leading me not just to other parts of Latin America and to Africa, but also to Florida and to Istanbul. I have been consistently drawn to places of cultural and often political uncertainty—borders, islands, edges of societies—where cultures merge, sometimes clashing, sometimes fusing. Some of my projects have taken years to complete. Others have been briefer. Many have overlapped. Sequenced more or less chronologically, this book reflects the sometimes chaotic, sometimes mysterious process of creation, interweaving projects and obsessions, themes and passions, cultural tensions and offbeat moments, into one continuous chronicle of the street, from 1979 to the present.

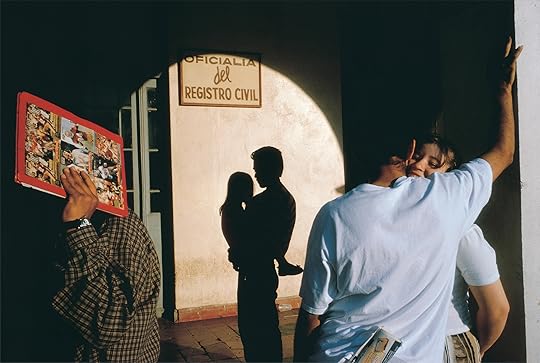

Alex Webb, Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, 1996

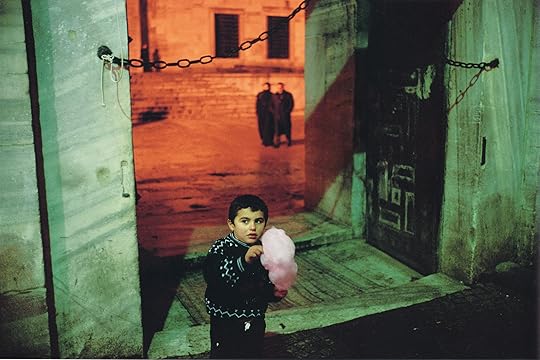

Alex Webb, Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, 1996  Alex Webb, Istanbul, Turkey, 2001

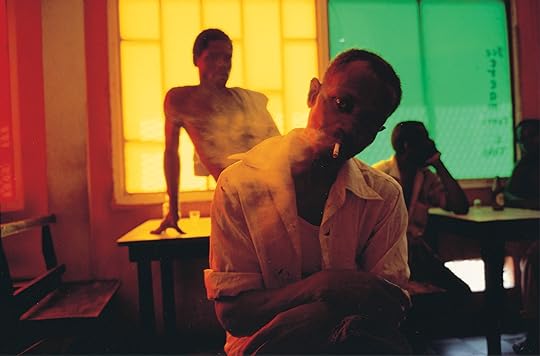

Alex Webb, Istanbul, Turkey, 2001  Alex Webb, Bombardopolis, Haiti, 1986

Alex Webb, Bombardopolis, Haiti, 1986  Alex Webb, León, Mexico, 1987

Alex Webb, León, Mexico, 1987 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Alex Webb, San Ysidro, California, 1979

Alex Webb, San Ysidro, California, 1979  Alex Webb, Munich, 1991

Alex Webb, Munich, 1991  Alex Webb, Ethiopia, 1997

Alex Webb, Ethiopia, 1997  Alex Webb, Alto Paraguay, Paraguay, 1990

Alex Webb, Alto Paraguay, Paraguay, 1990  Alex Webb, Havana, 2000

Alex Webb, Havana, 2000  Alex Webb, Gouyave, Grenada, 1979

Alex Webb, Gouyave, Grenada, 1979All photographs courtesy the artist and Magnum Photos

Related Items

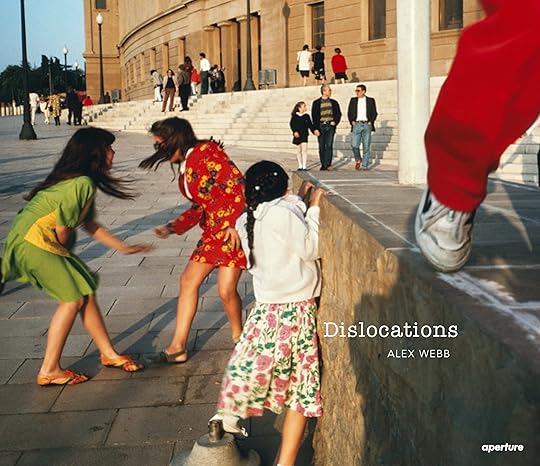

Alex Webb: Dislocations

Shop Now[image error]

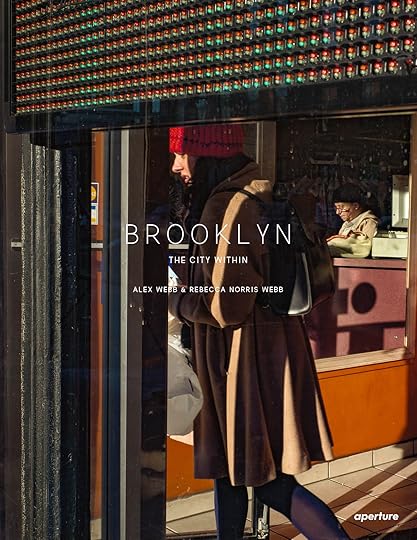

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb: Brooklyn, The City Within

Shop Now[image error]This text originally appeared in Suffering of Light (Aperture, 2011).

July 18, 2024

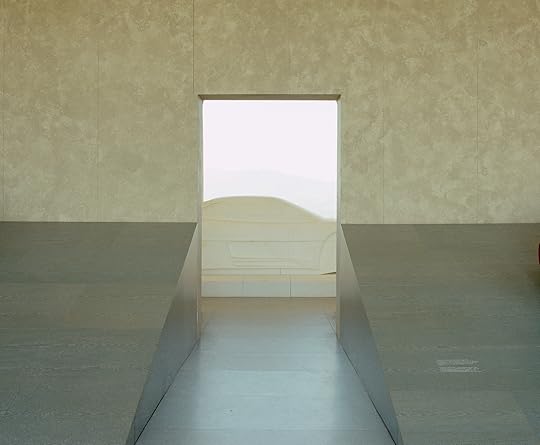

Dayanita Singh Finds Common Ground in the Work of Two Architects

Architecture and photography have always been intimately connected. These media share a few fundamentals: impacts of light and air, the balance of surface and depth, interiority and exteriority, and how these relations are mediated by the human body. Attending to such concerns has guided the expansive, fluid artistic practice of Dayanita Singh, whose open-ended approach to the photographic image has led to distinctive architectural modes of display. Encased in teak frames, screens, and boxes that often double as display cases which can be placed on walls and bookshelves, Singh’s photographs circulate in modular forms that are adjustable to individual taste. They underscore how images accrue meaning over time, as people live and grow alongside them.

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing  Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing “To me, a photograph is something you touch and you move and it warps and it gets dented: it’s alive,” Singh remarked in a recent interview. Recounting her upbringing in India, she notes how her family’s many photographs extended beyond stuffed albums and were wedged under the glass tabletop in their living space, where they seemed to vibrate with their own physicality, like another form of furniture. Her long-term engagement with the architects Geoffrey Bawa and Bijoy Jain draws from this personal history and aligns with a longer arc of modernist photography and its fascination with portraying surface, depth, and environment to extend the capacity of human vision. In her corpus of photographs made in conversation with Bawa’s and Jain’s respective designs, Singh’s ever-curious photographic eye reveals shared principles between the two architects—commitment to the use of local materials, respect for craftspeople and traditions, seamless integration with the surrounding environment—while allowing their practices to remain fully distinct.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Born in 1919 in colonial Ceylon, Geoffrey Bawa traveled extensively throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe in the years after World War II before returning home, where he purchased a former rubber plantation in the southern coastal town of Bentota. He hoped to turn it into a garden villa like the ones he had seen in Italy. Realizing the complexity of the task, Bawa apprenticed with the local architect H. H. Reid and went on to complete studies in architecture in England between 1953 and 1956. Bawa became a partner in Reid’s firm in Ceylon in 1957, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s designed private homes, hotels, and schools across the island—renamed Sri Lanka in 1972—and later in Indonesia, Singapore, and Fiji.

Singh recalls her first visit to the Kandalama Hotel—designed by Bawa on the outskirts of Dambulla, in 1994—as a kind of déjà vu experience. Her arrival at the Lunuganga estate in Bentota felt similarly fated. For her Bawa Series (2016– ongoing), Singh photographed the interiors of Bawa’s estate, as well as a modernist domicile he designed for the artist Ena de Silva in 1960, which was moved brick by brick from Colombo to Lunuganga.

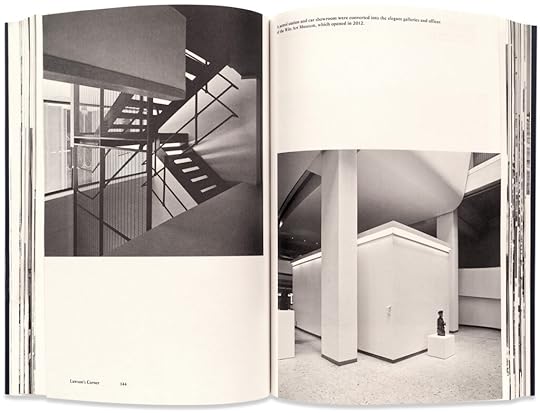

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing  Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Bawa Series, 2016–ongoing Singh’s photographs highlight Bawa’s meticulous selection of materials to create contrast, a hallmark of the so-called tropical modernism associated with his legacy. Consider how the rough, jagged surface of an outside portico’s tear-shaped stone pillar harmonizes with the whitewashed walls and glass windows, or the way the curves of the molded chairs in Bawa’s living room balance its wide floor-to-ceiling windows, shaded by reed screens.

Singh’s photographs highlight Bawa’s meticulous selection of materials to create contrast, a hallmark of the so-called tropical modernism associated with his legacy.

Harmony with the local environment is also central to the practice of Mumbai-based Bijoy Jain, whose studio work was recently the subject of an exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. Born in 1965, Jain studied architecture in the United States and worked for Richard Meier before founding an eponymous firm in 1995, later renamed Studio Mumbai. For Studio Mumbai (2019–ongoing), Singh made a series of images at the former tobacco warehouse in the south Mumbai enclave of Byculla that serves as Jain’s studio space. “There is something I am seeking when I am photographing architecture,” she says. “It’s not the architects, but this exhalation that I find again and again in Studio Mumbai’s work.” Singh trained her camera on surface textures of concrete and wood to draw out formal homologies within the studio: a large overstuffed spherical form rhymes with a nearby wall hanging, the folds of the fabric creating further associations. In one image, a trio of folding chairs hangs on a wall above a low wooden daybed.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Jain, who acknowledged his respect for Bawa’s precision and dogged devotion to local material and craft in his 2012 Geoffrey Bawa Memorial Lecture, illustrates here that a pared-down approach can open up new possibilities. That ethos is not unlike Singh’s, whose spare, monochromatic images of domestic space highlight how constraint offers a way to channel creative energies and draw new connections across different forms and media. Metabolizing the elemental principles shared by photography and architecture, and allowing these connections to take center stage, Singh’s images offer a world in which the loftiest aspirations of modernism—to create better living conditions through careful design—are realized.

Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoing  Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoing  Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoing

Dayanita Singh, Studio Mumbai, 2019–ongoingAll photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”

July 12, 2024

Confronting the Legacy of Photography’s Anti-Blackness

Photography and death are tied, inextricably, in a knot. Art historians, critics, poets, and theorists have covered this extensively: Post-mortem photography began alongside the medium’s invention. The American Civil War is recalled primarily through photographs of dead or dying soldiers and civilians. Even fake death, as in Hippolyte Bayard’s Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840), attests to its presence in photography.

Roland Barthes wrote that a photograph is “the living image of a dead thing.” Susan Sontag said that photography “converts the whole world into a cemetery.” But what kinds of death have been, and still are, imaged—and how are they imaged? What separates the imaging of various cultures and races and how are these images disseminated?

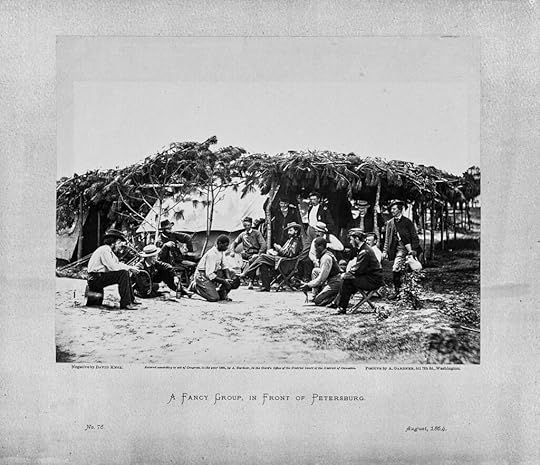

Alexander Gardner, A Fancy Group, in Front of Petersburg, 1864

Alexander Gardner, A Fancy Group, in Front of Petersburg, 1864Getty Images

Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual (2024), by Kimberly Juanita Brown, examines these questions through Black death—the imaging of the death of Black people—and shows the legacy of anti-Blackness to be characteristic of the photographic enterprise. The inaugural volume of On Seeing, a new series from MIT Press, Mortevivum is a necessary addition to the archive of photographic thought. It will change the way readers look at images of all kinds. It shows how the scaffolding that structures the photographic enterprise is laid out before us in the everyday onslaught of images.

Photography grew up with the United States, flourishing along the path of empire as it advanced westward. The medium was instrumental to the national project, as seen in the many nineteenth-century surveys designed to scout exploitable land for settling and mineral mining. Intentionally and unintentionally, it promoted the white supremacy of colonial conquest. “Because the nation’s history is intertwined with black enslavement, indigenous slaughter and removal, theft and unacknowledged violence, the land is haunted and so are its people,” Brown writes. “Photographs reinforce a national ‘we’ that never was and never will be.”

Peter Magubane, Soweto Riots, South Africa, 1976

Peter Magubane, Soweto Riots, South Africa, 1976Courtesy the International Center of Photography

Mortevivum lays out an array of exhibits: the Civil War, lynching, Jim Crow, the civil rights movement, apartheid and the Soweto uprising in South Africa, the Rwandan genocide, Rodney King, and George Floyd, among many others. As Brown writes, “antiblackness blankets this history like a cloak with no beginning and no end, offering only momentary exercises of reprieve. And almost never on purpose.” The latent effects are as treacherous as the obvious. Film stock, for example, was tested specifically to flatter white and lighter skin tones. Despite years of complaints from Black mothers concerned by the faces of their children looking like “ink blots,” Kodak changed its film only when furniture and chocolate manufacturers claimed that their formulations discriminated against dark hues. In 2012, the artist duo Broomberg & Chanarin explored this history in their series To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light. The project’s title phrase had been used by Kodak to signal that its new film stock could render dark skin. Today, the legacy of this bias continues, as the researcher Joy Buolamwini discovered, with flawed facial recognition programs and artificial intelligence.

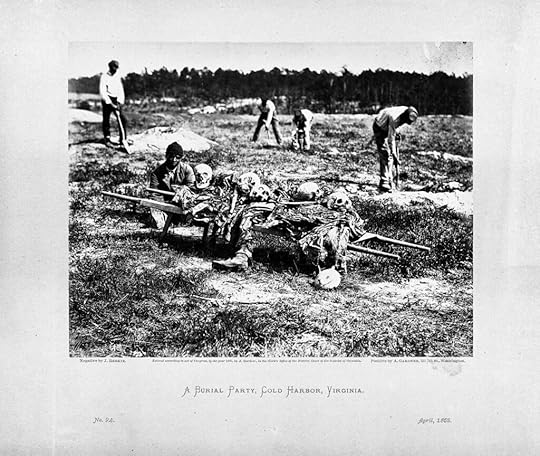

John Reekie, A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1865

John Reekie, A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia, 1865Getty Images

Brown offers the term mortevivum—“the living dead” in Latin—in order “to understand this particular photographic phenomenon: the hyperavailability of images in the media that traffic in tropes of impending black death. These tropes cohere around an ocular logic steeped in racial violence (and the nostalgia engendered therein), and they make any tragedy, any crisis, an opportunity for viewers to find pleasure in black peoples’ pain.” Thus, the history of photography is shadowed by the aestheticization of Black death.

Mortevivum is a shock to the system delivered with incendiary grace. Brown makes visible the latency—or veiling—of the Black experience of photography and the disseminated image through media. Her critical perspective moves across the shared history of postcolonial Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. She writes about these moments and their reverberations in a way that conjures today’s realities. The book feels present, even when the photographs and histories tell us of well-trod pasts. The reader is to use history to reckon with the present, as in a Civil War–era photograph Brown examines early in the book: John Reekie’s A Burial Party, Cold Harbor, Virginia (1865), wherein five Black soldiers bury the bodies of their slain comrades. One of these men sits just behind a cart piled with skeletal remains and five skulls; five skulls and five Black men. The seated man gazes into the lens, to the living.

Bill Hudson, Police Dog Attack, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963

Bill Hudson, Police Dog Attack, Birmingham, Alabama, 1963Courtesy MIT Press

Nearly 150 years later, in The Birmingham Project (2013), photographer Dawoud Bey made a series of striking diptychs addressing the human toll of the civil rights movement. He paired a Black child who, at the time of the portrait, was the same age as the victims of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, and an adult fifty years older—the age the child would have been in 2013. The series has become one of Bey’s most stirring reflections on the Black experience of violence, hate, and resiliency in America—here the sitting figures confronting the viewer through a gaze suffused with this history.

In Mortevivum, essays on white paper with black text are interrupted with black pages that broadcast pull quotes set in white type, a design strategy that reflects the binary Brown examines throughout. It reinforces the ideas between the pages: Blackness relegated to punctual interlocution. The three main chapters—The Empire, The Viewer, and The Sentiment—cover historical epochs or pinpoint significant moments in time and examine a few photographs selected for their representative potency, such as Bill Hudson’s Police Dog Attack, Birmingham, Alabama (1963), and Peter Magubane’s photobook Magubane’s South Africa (1978). The text is dense with references to photographic thought, theory, and social history, from Frantz Fanon and Aimé Cesaire’s anticolonial discourse to Achille Mbembe’s and Giorgio Agamben’s work on biopower, sovereignty, enmity, and killing. For some, this may feel impenetrable, a wall put up by the author. Instead, the strategy braids together photographic relevance and truth to testify that anti-Blackness is characteristic of the photographic enterprise. “Imperial dispossession is a photographic practice, an existing archive of destruction, enslavement, and scopic control,” Brown writes.

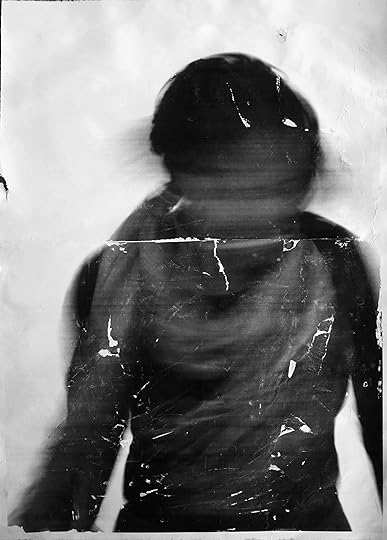

Sandra Brewster, Blur 1, 2/3, 2016–17

Sandra Brewster, Blur 1, 2/3, 2016–17Courtesy the artist

There are the power structures between photographer, subject, and viewer—and there are also the circumstances of dissemination, the observer-reporter who interferes in what has transpired and what will transpire. This is why Brown reproduces newspaper images of Black death with the bodies omitted, not as a form of censorship, but as an act of resistance. These altered newspaper images force the viewer to reckon with the reactions of witnesses. “I contend that black death is such a naturalized photographic documentary position,” Brown writes, “that most white viewers do not notice how ubiquitous it is.”

And yet, Brown shows us life as well—the life of those reacting to death but more importantly the work of artists who are resisting this ubiquity through creation. Sandra Brewster’s series It’s all a blur (2017) embodies this resistance through works that refuse or evade the detail of the documentary position. Her photographs depict subjects as ghostly silhouettes that are, in Brown’s words, “bathed in the protective submersion of anonymity.” Inspired by Brewster’s parents, who immigrated from Guyana to Canada in the 1960s, the images depict the facelessness of migrancy. We know the figures are moving, shaking their heads during a long exposure as if rejecting the constraints of the fixated moment. The flecking of emulsion (a product of the gel transfer process) from the surface of the works becomes a Black-like skin falling away from the hard, evidentiary white surface. “We will continue to exceed the frame of the photograph so that it will not be the only way to define us,” Brown writes. “We will have beauty without terror and without violence.”

Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual was published by MIT Press in February 2024.

July 11, 2024

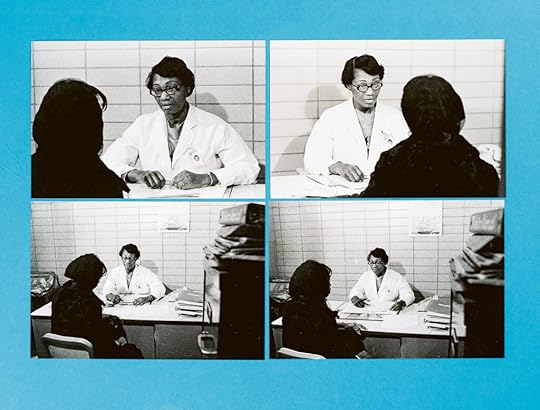

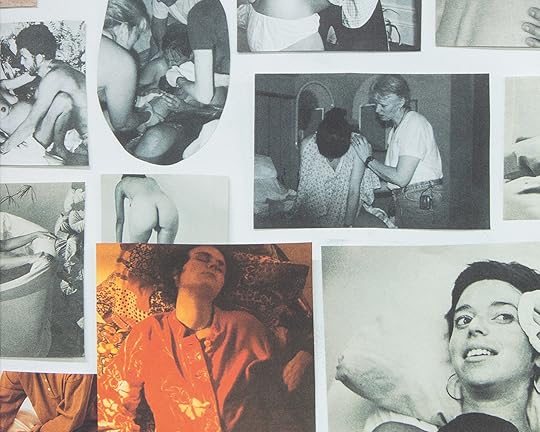

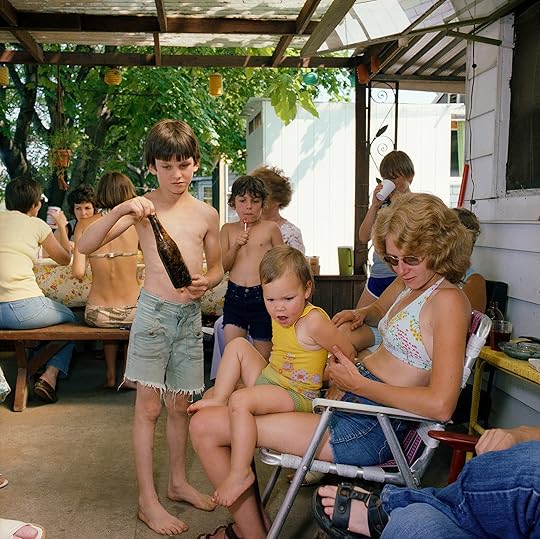

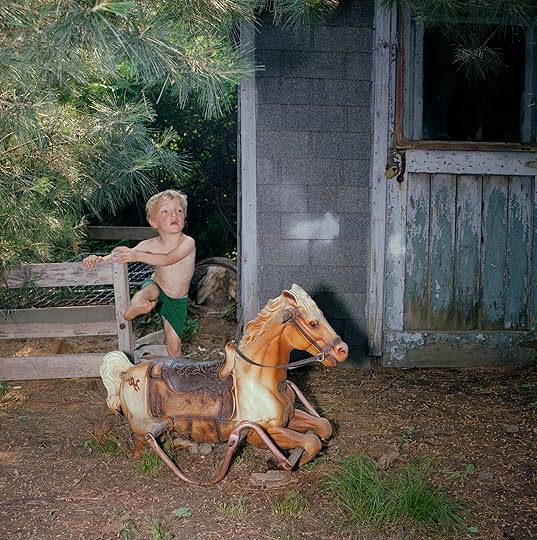

Carmen Winant’s Powerful Homage to Abortion Care Workers

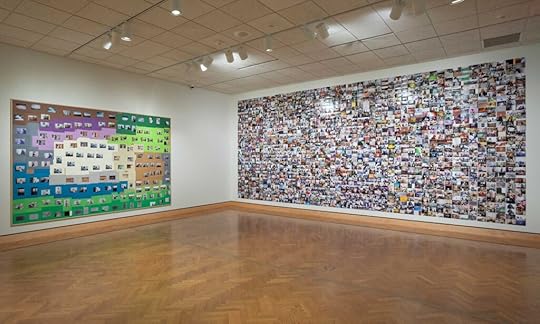

Carmen Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion claims an entire wall at the 2024 Whitney Biennial, a floor-to-ceiling sweep of images gathered and created in partnership with the health care workers it honors. Composed of nearly 2,500 individual photographs, each capturing the daily routines of abortion care workers, The Last Safe Abortion is a monumental homage to feminist health care. Striking in scale and precise in its ordering of each 4-by-6 color print, The Last Safe Abortion compels viewers to move closer and walk alongside it to absorb the smallest elements of the assemblage. The conceptual meticulousness of the whole belies the everydayness of the images within the grid, and that is the point: Each snapshot is, as Winant puts it, “an ordinary drugstore print” of the office work performed in clinics across the midwestern United States. These seemingly unremarkable images of people answering phones, entering data, filing paperwork, and completing mandatory trainings are a deliberate de-escalation of the visuals associated with abortion care by its opponents; instead, Winant places our attention upon the routine, even mundane, labor performed by providers as they care for their clients and each other.

For the better part of the last decade, Winant has drawn inspiration from and within networks of care, considering their associations with radical social movements. When her landmark installation My Birth opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2018, Winant put feminist health care at the forefront of the museum world’s public conversation; in many ways, The Last Safe Abortion continues that work, albeit in a newly charged political and cultural landscape. (Winant’s book about the project, published by SPBH Editions and MACK, was recently honored by Les Rencontres d’Arles, the French photography festival.) With recent United States Supreme Court decisions impacting the lives of millions of Americans—including Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which dismantled federal rights to abortion care in June 2022, and the decision in June 2024 to uphold national access to mifepristone, a pill used in medication abortion—Winant’s project is ever more resonant. We recently spoke together about the origins of The Last Safe Abortion, a project conceived during the pandemic for presentation at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in the fall of 2023, and how she wants the work to continue in the months and years ahead.

Carmen Winant installing The Last Safe Abortion at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Photograph by Charles Walbridge

Carmen Winant installing The Last Safe Abortion at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Photograph by Charles WalbridgeCasey Riley: Why don’t we begin by talking about the origins of the project and maybe sharing a little bit about its evolution. We first started our conversation early in 2019.

Carmen Winant: Another lifetime ago! Initially, we had just a series of open-ended phone conversations. It never felt like you had an agenda; we were just getting to know one another. We had so much affinity. Not just our shared political commitments, but also the way we held conversations, remember? We talked that way on and off for at least six or eight months before surfacing the idea of doing a project together. Do I have that timeline right?

Riley: Absolutely. The overall process for us was about four years.

Winant: There were different iterations of what the show was going to be during that extended period. We had the luxury of time, and to be responsive to the world as it was shifting around us.

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018. Installation view of Being: New Photography 2018, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018. Photograph by Kurt Heumiller

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018. Installation view of Being: New Photography 2018, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2018. Photograph by Kurt HeumillerRiley: It really was an iterative process. You started off thinking that you wanted to use the feminist obituaries you were collecting, to experiment with them materially in the studio.

Winant: In 2019, I was still coming off the experience of showing My Birth (2018) at MoMA, an installation curated by Lucy Gallun. That had been such a profound experience. But, based on the kinds of invitations that followed, I was worried about being pigeonholed as an artist who exclusively made work about biological birth. In fact, I considered My Birth to be a part of a larger project that engaged the sociality of feminist healthcare coalitions—of how feminists build kin networks. Centering my obituary collection felt like a new way to do that. I had hundreds of them then; I must have thousands now.

Riley: I’m sure Luke [Stettner, Winant’s partner] loves that.

Winant: Yes, especially when they spill over from my studio, which is in the attached garage, to the house and onto the dining room table.

Riley: “What’s that?” “That’s just mommy’s death pile.”

Winant: I can’t help myself! You and I talked through that process for months. You were so generous in your time and openness, especially as it wasn’t coming together as I’d hoped. We tried to wrestle with it together, and I never felt like I had to hide anything that wasn’t working from you. In the end I didn’t work with those obits, but the process yielded the project that we did work on together that centered abortion care workers and advocates, as so many of the feminist obituaries were about women who crusaded for reproductive justice. It was a matter of trusting the process, and its sort of unexpected evolution.

Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion, 2023. Installation view, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Photograph by Charles Walbridge

Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion, 2023. Installation view, Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2023. Photograph by Charles WalbridgeRiley: Why don’t you describe the work that resulted for folks who have not attended the Whitney Biennial or seen the show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art?