Aperture's Blog, page 20

March 22, 2024

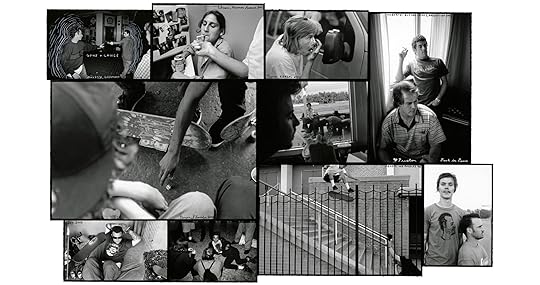

Naomieh Jovin’s Photo Collages of Haitian American Life

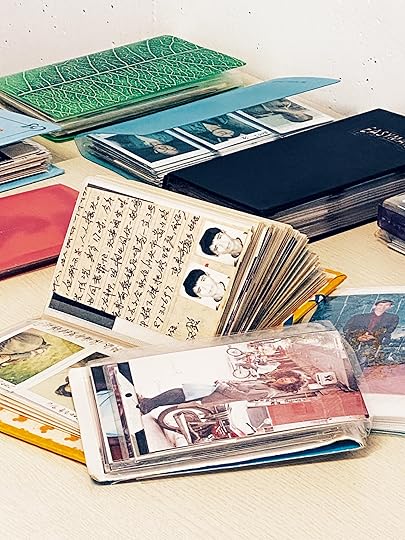

Recently, moving to New York from Miami, after living there for over two decades, with each box I packed I wrestled with what to let go and what to keep. There was no hesitation about the family photo-albums, many of which I’d inherited from my mother after she died eight years ago. Each plastic-sheathed photograph is unique, some taken in photography studios in Port-au-Prince, others with my father’s oversize camera in 1970s New York, and some Polaroids that had long faded, leaving behind only silhouettes. Those albums were a large part of my family’s history—baptisms, christenings, weddings, funerals, visits to Haiti, church celebrations, rare vacations—until cell phones came along.

That young people are now returning to film cameras and digital point-and-shoots, blending a world of old and new, makes work by the photographer Naomieh Jovin both of its time and timeless. Merging family archives with close-up and detailed photographs of body parts, Jovin employs the type of fragmentation and lacunae that the telling of intergenerational immigrant stories sometimes demands. She calls on present and past, clothed and unclothed, young and old, well and unwell, secular and religious bodies to create an arresting interconnected call-and-response visual narrative.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Migration is rarely an individual affair. Jovin was born in Philadelphia to parents who immigrated to the United States from Haiti in the early 1980s. “Since middle school, I used to bring my baby album with me and sit at lunch flipping through the pages,” Jovin has said. “I loved looking at the amazing outfits my parents put me in for my birthdays. Dressed like a true Haitian baby! I also enjoyed looking back at old photographs and trying to figure out the story behind them.”

For first- or second-generation immigrants, the stories behind the photographs in our family albums are sometimes purposefully hidden from us, because they are too painful to tell. The people whose faces we are looking at might have been wounded in some way, either before or after these photographs were taken. As demonstrated by the cutouts in some of Jovin’s images, absence is as tangible as presence. The archival materials in the pictures, including the diplomas, the unopened bills, the ceramic animals and fruit, illustrate gaps that Jovin attempts to fill, at times, with incorporeal and disembodied hands, seemingly reaching out to take hold of these stories.

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled, 2021

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Images like the ones in Jovin’s family albums are archived in many Haitian and Haitian-diaspora households, sometimes with notes scribbled on the back, often from lovers pleading from a distance not to be forgotten. With the photograph titled Madame Lucien (2021), of a young woman standing in front of a Japanese-garden backdrop, we expect that kind of sentiment. But Jovin tells us that the superimposed words are part of a breakup note from Madame Lucien: “Life is a flower and a blow. Very often, right next to joy, pleasure, and laughter, there are always tears and sorrow that bring ugliness and darkness to our existence. Because Life is made of separation, I must bend to the laws of nature.”

Often, when an older Haitian person dies, the picture chosen for the cover of their funeral program is of them in their prime, when they were at their most handsome or beautiful. We look at these faces from the present and the past and can’t help but wonder what our descendants might look like, who they will resemble, where they might live. How much of all this incidental archive might they let go of, and what might they keep? Will it be the indoor or outdoor pictures? Those portraits in the barbershop or living room? Or those out in nature, with flowing streams and rocks? Will it be the communion one or the nudes? Or will it be the fanfa, the funeral band accompanying the mourners and their massive bouquet of flowers to the cemetery?

Watch Now: Naomieh Jovin on Gwo FanmIn “Counter Histories,” Aperture’s latest issue produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation, the artist tells an intergenerational family story from Haiti to the US.

In November 2020, a photo-essay by Jovin in The Nation made its way to me via friends and family WhatsApp groups. “There Is a Name for Women Like My Mother” read the headline. The piece was mainly about Jovin’s mother, but most Haitians know someone who’s been called gwo fanm—“big woman”— in either a complimentary or derogatory way. Jovin’s mother was in the favorable category. A smart dresser and hard worker who’d sponsored many family members to come to the United States, she died of breast cancer when Jovin was ten, making it understandable that Jovin would spend so much time looking at her baby album as a girl. These images were her way of communing with her mother and tout sa n pa wè yo, a Creole expression meaning “all those who are no longer visible, those who can no longer see.” That photo-album made Jovin’s mother visible to her.

“Even in death, she took up space,” Jovin writes.

She calls her project Gwo Fanm (2017–ongoing), describing a gwo fanm as “a woman who stands out in life and stands up for the ones they love. But a Gwo Fanm is also a woman who takes more than their fair share of the slings and arrows this world throws at them, absorbs hurt and pain that could crush less resilient or determined people.”

Jovin, too, is a gwo fanm, as an aunt once told her, based partly on her success as a photographer.

“So much of the immigrant experience is one of loss, loss of the community they leave behind, loss of the history in their home country,” Jovin writes. “By creating these photos of the women in my family, and reclaiming the images they made during their lifetimes, I hope to forestall this loss, to show the purpose and honor that defined their lives, and to actively create a new narrative for my generation.”

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled, 2021

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled, 2021  Naomieh Jovin, Untitled (Daddy’s Toolbox), 2020

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled (Daddy’s Toolbox), 2020 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled, 2022

Naomieh Jovin, Untitled, 2022  Naomieh Jovin, Madame Lucien, 2021. All photographs from the series Gwo Fanm, 2017–ongoing

Naomieh Jovin, Madame Lucien, 2021. All photographs from the series Gwo Fanm, 2017–ongoingCourtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation.

March 21, 2024

How One Photographer Documented Ghana’s Transformations

Gerald Annan-Forson seeks offbeat images in routine social scenes and during spectacular events. His first job as a professional photographer was taking secret pictures for a private investigator, capturing evidence of cheating spouses and people faking injuries for insurance scams in 1970s California. This required technical precision and a bold eye for visual reportage. Traces of his reflex for catching people in the act, for freezing a moment in time to tell a complex story, permeate his photographic practice, lending it both a narrative sensibility and an ethereal character.

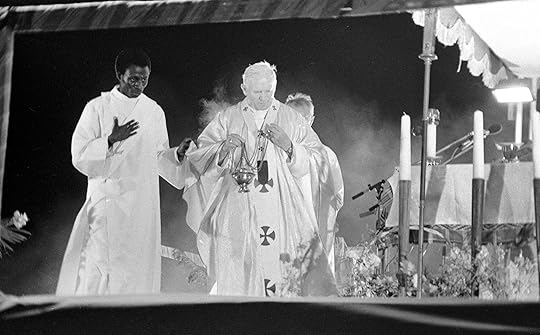

Gerald Annan-Forson, Pope John Paul II, assisted by Reverend Bobby Benson, leads an open-air mass at the Accra Sports Stadium, 1980

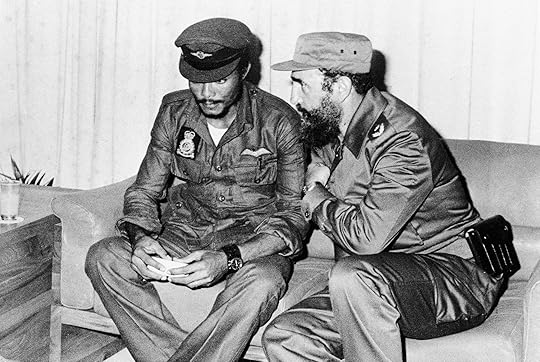

Gerald Annan-Forson, Pope John Paul II, assisted by Reverend Bobby Benson, leads an open-air mass at the Accra Sports Stadium, 1980  Gerald Annan-Forson, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings with Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba, n.d.

Gerald Annan-Forson, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings with Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba, n.d. Annan-Forson was born in London in 1947, to a mother from Kildare, Ireland, and a Fante father from the Gold Coast, an officer with the British West African Frontier Force stationed in the UK during World War II. In London, to hide his color and avoid racist attacks, Annan-Forson’s mother had to wrap him in a blanket when they traveled. The family moved to Accra in 1954 to be a part of the Gold Coast’s fight for freedom from British colonial rule. But in the passionate racial and national struggle, the young Annan- Forson was often confronted for being a foreigner, due to his mixed ancestry. In 1957, the new nation of Ghana won independence under the leadership of the Pan-African politician Kwame Nkrumah, and the capital of Accra became a cosmopolitan global center of Pan-African artistic expression and political thought.

Annan-Forson learned photography and image developing with a pinhole camera at a central Accra studio. The experience of being seen as Black and foreign in Britain and white and foreign in Ghana shaped his desire to challenge the idea that identities are singular. Like that of many artists who have multiple sociocultural fluencies, his aesthetic practice has been a response to his status as a constant outsider. Photography became his way to grapple with this double form of exclusion and seek refuge from racial violence. Taking pictures allowed him to move through the world while hiding in plain sight and sidestepping simplistic facades of public belonging by telling multilayered tales.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

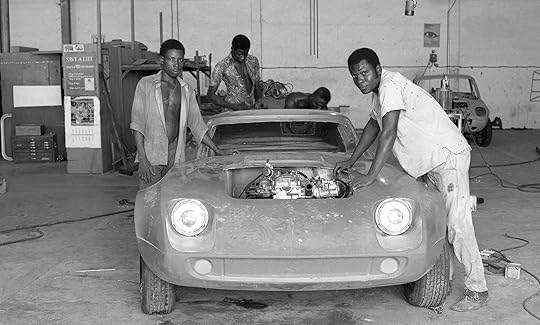

His photographic journey reflects the variegated political history of Ghana more than other image makers who have covered the same terrain. He grew up during the renaissance decade of independence-era Accra, when it became a magnetic hub for radical Black thinkers, musicians, and artists from around the world. The city evolved rapidly as Nkrumah sought to modernize the country and create a strong Pan-African socialist state. But in 1966, this revolutionary experiment ended when the government was overthrown by senior military and police officers in a US-and British-backed coup d’état. Ghana was restructured under a neoliberal capitalist regime, which in 1972 was also overthrown in a coup. Over two decades, as Ghana alternated between civilian and military regimes, the rising generation of artists and intellectuals blended Pan-Africanism, futurist aspiration, and myriad local expressive styles into a uniquely West African modernist aesthetic.

Gerald Annan-Forson, Workers at Mark Coffie Engineering build a local sports car, 1980

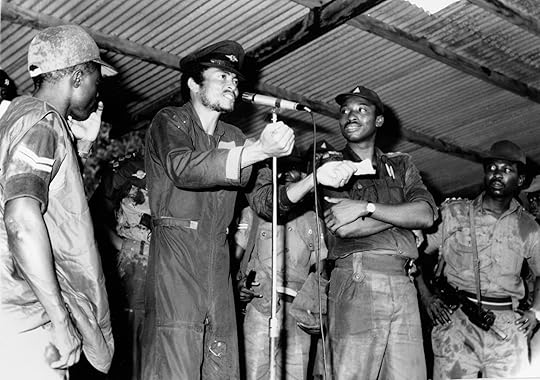

Gerald Annan-Forson, Workers at Mark Coffie Engineering build a local sports car, 1980  Gerald Annan-Forson, Jerry John Rawlings stands at attention in front of the troops after handing over power, 1979

Gerald Annan-Forson, Jerry John Rawlings stands at attention in front of the troops after handing over power, 1979 Annan-Forson returned to Accra from California in the mid-1970s and began to develop his visual approach by documenting the changing city and its eclectic, diverse inhabitants. He worked across genres and styles as a freelancer, photographing heads of state and national events and selling pictures to New African, African Business, West Africa, Essence, and international magazines and newspapers. Even as radical ideas of Pan-African political unity were diluted, Accra was alive with highlife and Afrobeat music and celebrations of global Black styles. A rising generation sought new dreams and hustles that were at once locally grounded and cosmopolitan. Two of his early major assignments were to capture the visit of Charles, the Prince of Wales, with the head of state General I. K. Acheampong, in 1977—an unusual pairing of old imperial ruler with young defiant military officer—and, in 1980, to photograph the arrival in Ghana of the pope, not long after another coup. Annan-Forson’s camera witnessed the mix of political ideologies, social pleasures, and economic struggles of 1970s and 1980s Accra, a city characterized by its easy intimacies and stark contrasts. His images highlight juxtapositions that express the contradictions of life in the coastal capital after the celebrations of independence faded.

Annan-Forson’s images challenge colonial modes for organizing a visual language of African urban social and political life.

Annan-Forson’s photographs are hard to categorize. They encompass street photography, documentary, portraiture, landscape, and abstraction. His archive organically challenges colonial modes for organizing a visual language of African urban social and political life. In his relationships with his subjects, he implicitly counters pervasive orientalist image-making practices, creating what the curator Okwui Enwezor has described in relation to postindependence African photography as a “different iconography of the African self.” In the colonial lexicon, photographs of Africa were means of objectification drawing on tourism and travel, ethnography and documentation, administrative fixity and exoticizing obsession. Instead, Annan-Forson finds vibrant, quirky uncertainties and moments of personal recognition within public events and spaces. He often uses compositional doubling, pairing contrasting figures he finds in a social scene. Annan-Forson’s image making reflects the ways Accra’s citizenry navigates the multiplicity of its dynamic landscape and shows how life in the city requires people to be many things in rapid succession.

Gerald Annan-Forson, Jerry John Rawlings sits on a golden stool crafted by artist Kofi Antubam and prepares to hand over power to the democratically elected Dr. Hilla Limann in Parliament House, 1979

Gerald Annan-Forson, Jerry John Rawlings sits on a golden stool crafted by artist Kofi Antubam and prepares to hand over power to the democratically elected Dr. Hilla Limann in Parliament House, 1979Annan-Forson was thrown into political change when a coup d’état on June 4, 1979, elevated Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings as chairman of the new ruling Armed Forces Revolutionary Council. Annan-Forson had been schoolmates with Rawlings and suddenly found himself with insider access to a revolution. Rawlings, like Annan-Forson, was of mixed European and Ghanaian ancestry, and at times the photographer was mistaken for the head of state. Annan-Forson documented key national transformations from an intimate perspective, telling the spectacular story of change through the candid eyes of major players as well as common people caught in unexpected moments of terror, joy, contemplation, and frustration. He was an observer at the center of power. As a photographer among soldiers he documented the tenuous ways power was formulated.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But the pressure of taking pictures in the midst of political upheaval took its toll, as he was constantly on call to capture everything from executions to trials to clandestine meetings. Soldiers woke him up at all hours to record secret military maneuvers and meetings, the whipping of market traders accused of hoarding commodities, and surreptitious images of the country from a military fighter jet re-creating the experience of an aerial battle. His camera followed Rawlings over several decades of transformations: rebel, populist revolutionary, authoritarian leader, and democratic president.

On one level, Annan-Forson’s work is engaged in a grand scheme of mythmaking, reimagining an African urban future. On another, his images expose cracks in the edifice of the normative and the powerful, and how they are challenged by contradiction, humor, pleasure, and pain. His work often focuses on the aesthetics and rituals of power, revealing how authority is conferred through ceremony. But his ability to find the intimate within formal portraits of leaders shows how authority is always partial, temporary, and unstable. He seizes on signs that disrupt expectations, revealing the inner lives of his subjects through unexpected downcast eyes, hidden glances, and quirky gestures. When public figures are caught off guard, we see another side of power. At its core, Annan-Forson’s work illustrates the contradictions that emerge in periods and spaces of transformation. His visual grammar, refined over a lifetime of taking pictures, provokes observers to ask what kind of mythic landscape the contemporary decolonizing city constitutes.

Gerald Annan-Forson, After the coup d’état on June 4, 1979, Rawlings, Chairman of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, speaks to soldiers while Captain Boakye Djan watches, Burma Camp, Accra, 1979

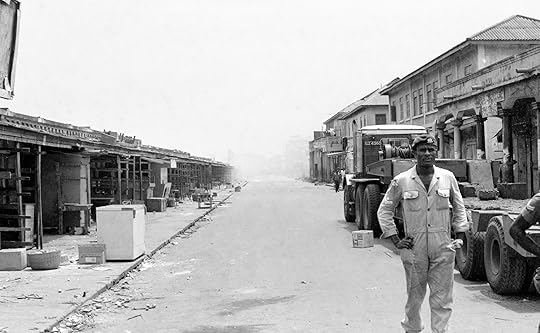

Gerald Annan-Forson, After the coup d’état on June 4, 1979, Rawlings, Chairman of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, speaks to soldiers while Captain Boakye Djan watches, Burma Camp, Accra, 1979  Gerald Annan-Forson, A soldier keeps guard after the military regime dynamited and bulldozed Makola Market in central Accra, 1979

Gerald Annan-Forson, A soldier keeps guard after the military regime dynamited and bulldozed Makola Market in central Accra, 1979All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”

In Public Spaces, Tender Photographs about Love and Friendship

Clifford Prince King is a self-taught photographer and filmmaker known for his intimate, tender, and atmospheric images of Black queer men. He revels in the possibilities of leisure time, whether picturing care and comfort—or a latent erotic charge, the sense the chemistry is right for just about anything to happen. King’s work was featured in Aperture’s “Ballads” issue, published in the summer of 2020 and inspired by the legacy of Nan Goldin’s book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. His first book, Orange Grove (2020), was shortlisted for the 2023 Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards. “A lot of the imagery I try to create is just placing Black men in scenarios or scenes that seem familiar,” King told Aperture. “And so the ultimate goal to me is creating imagery where we see these Black men—whether they’re masculine-presenting or effeminate—and give that imagery a space.”

This season, King’s photographs are on view in an exhibition organized by the Public Art Fund and presented at JCDecaux bus shelters and newsstands on the streets of New York, Chicago, and Boston. Made in various locations, from Brazil to Fire Island, the photographs in Let me know when you get home expand upon King’s generous vision of love and friendship, and present a window onto the lives of young men kissing, lounging, and just being in the world. In February, on the occasion of the exhibition’s opening, King spoke with the artist Lyle Ashton Harris at the Cooper Union in New York about ideas of sexuality and belonging. Here is their conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Clifford Prince King, guilty of love, 2023

Clifford Prince King, guilty of love, 2023  Clifford Prince King, darrius, 2023

Clifford Prince King, darrius, 2023 Lyle Ashton Harris: I want to take a moment of silence to dedicate our conversation to the memory of Brent Sikkema, and to acknowledge his vision and the gifts he gave to so many of us. To start, I want to congratulate you and Public Art Fund on your exhibition of thirteen new works created in the past year.

Clifford Prince King: Most were created over the summer, at BOFFO Residency in Fire Island and the Eighth House residency in Vermont. Then I went to Brazil for two weeks—it wasn’t technically a residency—and then I went to Light Work in Syracuse, followed by the Cayman Islands.

Harris: I grew up in the Bronx, the northeast Bronx to be exact, and I negotiate the city in varying ways. What came to mind is the level of intimacy between men in your work—two Black men, two queer men—in a public sphere, and what it meant to grow up as a Black queer in the Bronx even today, at my age and station. Maybe trauma is one way of looking at it, in terms of hypervigilance in negotiating location, space, et cetera. I am interested in how these images function as public art and their power to give agency to Black love, intimacy, and queer representation in a public space. I’m intrigued by that, the radicalness of that.

King: Yes, a lot of this work was made outdoors, but it was still private while outdoors. Seeing the photographs on display in the street now feels almost as though the behind-the-scenes is being displayed in the opposite kind of environment. Most of the work that I’ve done is a lot more interior-based, and I’ve observed that a lot of your work is as well. But even photographing people outside, there is a level of alertness of surroundings, in order to keep the people you’re shooting feeling comfortable. You don’t want people saying things while passing by. You just want to provide a safe environment for creativity to flourish.

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, Boston, 2024. Photograph by Mel Taing

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, Boston, 2024. Photograph by Mel TaingCourtesy the Public Art Fund

Harris: I think it’s going to be very beautiful to see how people from different walks of life engage with the work. I appreciate that, creating a safe space when you’re photographing. Part of the beauty here is that they will be exhibited at hundreds of sites across three cities, and we can consider what it means to have this imagery and experience in those places, which is a very powerful thing. I’m thinking of the Grand Fury campaign “Kissing Doesn’t Kill” in 1989, and what it meant at that time to critique stereotypes around HIV and AIDS, in terms of both its transmission and the power of public art, the power of using a public sphere to engage the complexities of intimacy.

Take us back to your early days in Tucson.

King: I didn’t have any sort of visual narrative of what my life could look like living in my authentic truth until I was much older. Thinking about growing up in Tucson, Arizona, not in an art household, most of my media exposure was the Disney Channel. I minimized myself a lot and stayed out of the way. I was a good kid and I just did normal things. I was on Tumblr a lot, just building a creative archive of things that I would find interesting, and I watched a lot of movies during the summer. My first love is cinematography, and that’s how I picked up a camera, by way of the moving image.

Clifford Prince King, dj and ryan, 2023

Clifford Prince King, dj and ryan, 2023  Clifford Prince King, early departure, 2023

Clifford Prince King, early departure, 2023 Harris: When did you get your first camera, and who were your subjects?

King: It was very competitive to get into photography class in my high school—and I didn’t get in. But someone who was in the program gave me an old Canon when the cameras were being thrown away due to the program ending. During my sophomore year of high school, I just started taking photos with it. Tucson was landscape, cactus, family. Eventually, I took a class in Portland intermittently for six months, but it was mostly just my friends or myself if I went out of town, and street photography.

There’s an early photo I took of a washing machine on top of a car, just random things that I found interesting. I used to get the film processed at Walgreens before I found a small camera shop in Portland. Toward the end of my time there, I started to develop a mission more clearly: I wanted to make friends that were Black and queer in the community, and I used my camera as a way to get to know people. This was at a time when Instagram was kind of coming up more and people wanted to book shoots and have content, around 2015. I would offer portrait or event photography, and I would also take my own photos, so it was kind of like a trade.

Harris: Where were you meeting people?

King: Mostly when I went out, on the street, or dating apps. And there was a small ballroom scene in Portland. How have you met the people you’ve photographed?

Clifford Prince King, alvin in the forest, 2023

Clifford Prince King, alvin in the forest, 2023Harris: Well, firstly I was influenced by my grandfather, who shot thousands of images documenting his friends, family, and the church. Also my cousin Ricky, who made the invitation card for my first show in New York and photographed our whole family in black and white, as well as my stepfather, who taught by example. There was always the presence of a camera around, the ritual of taking pictures of each other. It came naturally, and I also observed the way my grandfather would choreograph things. It was a running joke among his three daughters that he took a lot of time to compose a photograph. You know what I’m saying?

King: It’s a personality trait. My dad had a VHS camcorder, and he would narrate home-improvement projects. Looking back on the film, he’s talking to himself about what he’s going to do to our kitchen, and then I started doing that with my room reorganization. I would paint it and do all these things that I thought were really interesting at the time, and film it. Then I would also mix music videos in, so there were breaks between my interior-design quests. Things like that kept me busy: making a playlist, learning about my taste. There’s something very special about time with yourself.

Clifford Prince King, BLESSED!, 2023

Clifford Prince King, BLESSED!, 2023Harris: I love that. Looking at your work, there’s such an architecture of intimacy. Let’s talk a little bit about some of the subjects in the photographs.

King: I think they’re all friends. Going to smaller towns, I really want to connect with local people in a way that isn’t taking from the city. Oftentimes I’ll photograph in my quarters, where I’m staying, versus going out and taking photos of people in their neighborhoods. I’m not opposed to it, but careful about that. I met one subject on an app and we had coffee, then met for a meal a few days later. I was going over the idea of taking his photo because at Light Work, there’s a huge auditorium lit by this fantastic orange light. It used to be an elementary school and is now an apartment building. I remember trying to figure out what time of day the light was best, and I told him to come over at 6:30, that certain special window when the light hit, and then we took photos including morning glory.

It was very specific. When it comes to elements of time and daylight, it can be a little stressful, but if things are happening, I just surrender the technical aspects, whether the light is gone or if it’s going to be blurry. There are certain images that I’m very particular about what I want to get at, but if not, then that’s fine too. At least I tried, or if it didn’t work out, it was for a reason and the end result is what was meant to be . . . I’ve shot some people and there was no film in the camera. But then two months later I’m like, thank God, because that person ended up being not someone that I wanted to photograph. And I’m just like, look at that. You know what I mean? I kind of trust for things to happen.

Clifford Prince King, dante (capoeira), 2023

Clifford Prince King, dante (capoeira), 2023  Clifford Prince King, the fear of letting go, 2023

Clifford Prince King, the fear of letting go, 2023 Harris: Yeah, I’ve done that.

King: Do you still talk to the subjects of your photos?

Harris: Yes, in most cases, for better or for worse, I would say that I’ve had a longstanding connection with many former lovers, partners, or dear friends. I’m very much inspired by your generation, too, and by your work, in terms of my trajectory. I appreciate that it relates to me revisiting certain early moments, but also the moment of today, in my late fifties, actually recapturing the erotic charge in works I’m thinking about, which pertains to my practice overall. For me, it’s about a certain intimacy and exchange.

King: There’s something that’s built. It’s trust, it’s understanding and communication.

I think even the photos that don’t specifically feature two men, there is a layered, underlying feeling of intimacy. It can be universal, but also, if you know, then you know.

Harris: I’m allowed to come into the space and answer the call of the great Marlon Riggs, in terms of Black men loving Black men as a revolutionary act. I feel, in a way, that there’s something about the energy of the work, which feels that you are involved in creating skin or language around that erotic possibility that’s also a political possibility. I reflect upon the way that Riggs came out at the landmark Black Popular Culture conference, and what it meant at that time to claim space in such an environment, and similarly, the way your portrait of two men on the cover of your book Orange Grove (2022) engage in a level of frottage before Martin Luther King. There’s a tension and notion that one can engage with, without having to be hit over the head with a hammer. You were saying, “I can draw from a multiplicity of identities and histories, et cetera,” and that feels fresh.

King: I feel that things just take different forms. There’s always the need to be an advocate for something, but the way that happens changes forms and is regenerated throughout different times. I really try to surround myself with people who inspire me, so then the work is not to be credited entirely to me, but to those people who surround me and their existence that enlightens me. It’s a collaboration between people, creating that space that you find to be beautiful and then waiting for moments to happen within that space. You just have to be present and pay attention to watch it unfold.

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, New York, 2024. Photograph by Nicholas Knight

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, New York, 2024. Photograph by Nicholas KnightCourtesy the Public Art Fund

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, Boston, 2024. Photograph by Mel Taing

Installation view of Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home, Boston, 2024. Photograph by Mel TaingCourtesy the Public Art Fund

Harris: I understand and I appreciate that. I’m also interested in your Public Art Fund project’s inevitable afterlife, how these billboards are functioning within the community, and the reaction to them. How do you document that, because there’s the work, but there’s also how that work engages with the public. In a culture that is deeply homophobic and racist, I’m wondering how to give a space in which to document the impact of these images, thinking of the recurring incidents of violence against and vilification of trans and queer people. At fifty-nine, trauma still arises, recalling what it meant to negotiate, for example, being called a slew of derogatory names in junior high school many times a day. Part of your exhibition’s power is the visibility of these very intimate photographs in public space.

King: There are some people who will say, “These issues are no longer issues. It’s 2024, no one’s racist anymore.” But then when there are projects like this, a lot of things still continue to happen, and there’s no coverage on it. It’s sidelined almost, and I feel we have a continuous fight for ourselves.

Harris: I’m intrigued by how your photographs resonate in the global context, because you are a global citizen, as demonstrated by the varying locations where you shot this imagery.

King: Right, and I think even the photos that don’t specifically feature two men, there is a layered, underlying feeling of intimacy. It can be universal, but also, if you know, then you know.

Harris: Tell us more about the works in Let me know when you get home.

King: Two of the featured works are set at Eighth House in Vermont, where I rested for two weeks and let my body catch up with my emotions.

Harris: What does resting look like to you?

King: I watch a lot of bad TV, or I’m doing nothing, being outside, off my phone. Just kind of dissociating a little bit, if I can. How about you, living upstate?

Harris: Resting, to me, means eating well, feeding people, going for a walk every day, a little yoga and music.

Clifford Prince King, the 8th house, 2023

Clifford Prince King, the 8th house, 2023All photographs courtesy the artist; STARS Gallery, Los Angeles; and Gordon Robichaux, New York

King: Do you have a favorite photograph you’ve taken?

Harris: There’s one, a childhood friend of mine named Gasper. It was taken in ’85, and his image has appeared and reappeared over the years throughout my work. In May, my work will be the subject of an exhibition at the Queens Museum that is anchored by my Shadow Works series, which are unique assemblages that layer various imagery. This photograph of Gasper appears in several of these works. There’s something in this photograph that contains the impression this person left on me. In the photograph, he’s glancing at an athletic training guidebook with ankle weights at his feet, as he sits in front of a makeshift backdrop, smoking. So clearly, I was thinking about constructing images in my childhood bedroom. I’m wondering out of the thousands of photographs I’ve taken, why that one? Maybe because there was innocence and the erotic possibility that was never consummated in the most literal sense, but it was an exchange. It was an engagement. And only very recently as my exhibition catalog was going to print, did I find out whether Gasper was still living or not. A studio assistant helped me find that he’s a CEO, with two kids in Westchester. We spoke on the phone about a month ago.

King: That’s beautiful.

Harris: What I really love about the work is that there is a certain freedom that I feel, and it’s generative for me today as someone who, even when I was an undergrad or in grad school, had to figure out what it meant to somehow carve and open up a space to be dealing with these issues here, in those spaces. It has necessitated a certain criticality, and I feel inspired by your work, the synergy, and the connection that offers new possibilities.

King: Well, all of this is through people in photography before me. It’s kind of like I’m doing that because of y’all, so thank you.

Clifford Prince King: Let me know when you get home is on view in New York, Chicago, and Boston through May 26, 2024.

March 14, 2024

How Kishin Shinoyama Found Fame and Controversy

If the average Japanese person was asked to name a photographer, they might first answer: Kishin Shinoyama. Starting in the 1970s, Shinoyama was a constant presence in Japanese photography magazines, but by the 1990s his fame had grown and he became a public figure in Japan, known for his well-produced images of celebrities. John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Yukio Mishima, and nearly all glitterati, as well as anyone and everyone of note in the world of Japanese culture, sat before his camera.

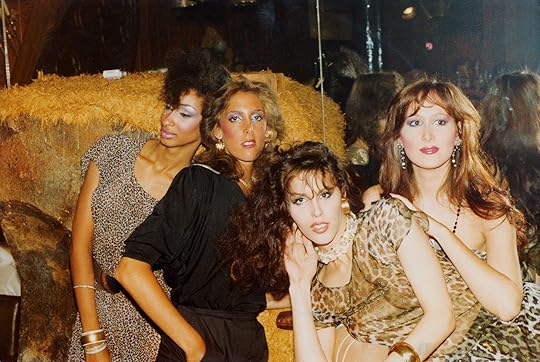

Spread from Fever by Kishin Shinoyama, Camera Mainichi, March 1965

Spread from Fever by Kishin Shinoyama, Camera Mainichi, March 1965However, what first earned his broad recognition were his nudes. Gekisha was a series featured in Goro, a weekly men’s magazine published by Shogakukan between 1974 and 1992. These images fit into the category of “gravure,” a term used in Japanese magazines for nude pinups. Shinoyama’s gravures stood out because of his selection of well-known actresses and models as subjects. The term gekisha, which Shinoyama coined, combines the kanji for intense and shoot, suggesting a photograph crafted as a spectacle. The success of the series led to the 1979 release of Gekisha: 135 Female Friends, which purportedly sold hundreds of thousands of copies. Buoyed by these impressive sales, Shogakukan debuted the monthly magazine Sharaku (1980–85), featuring Shinoyama as the principal photographer.

Despite the relatively demure nature of Shinoyama’s nudes, his work began to court controversy in 1985 after he published the photobook Pygmalionisme (Bijutsu Shuppan), which features photographs of dolls created by the artist Simon Yotsuya. Some of Yotsuya’s dolls feature pubic hair, which at the time was deemed obscene. Japan enforces laws regulating the publication of obscene material, and throughout the 1980s, what constituted “obscene” underwent an incremental revision process. Publishers regularly gambled with how far they could push the boundary between artistic expression and pornography.

Spread from Wraiths by Kishin Shinoyama, Asahi Camera, October 1969

Spread from Wraiths by Kishin Shinoyama, Asahi Camera, October 1969 Spread from Wraiths by Kishin Shinoyama, Asahi Camera, October 1969

Spread from Wraiths by Kishin Shinoyama, Asahi Camera, October 1969The year 1990 proved to be a watershed moment for Shinoyama. He released Tokyo Nude, published by Asahi Shimbun Company, one of Japan’s main newspaper companies. News of the photobook’s publication even made broadcast television. The book is comprised of cityscapes of Tokyo shot at night or in the early hours, with streets deserted save for nude models standing within the landscape, positioned like mannequins. What shocked many about the book was the presentation of the naked form against the utterly mundane views of the megalopolis. This was a prelude to the publications that would elevate Shinoyama to broad recognition.

The following year, Shinoyama published Water Fruit (Asahi Press), featuring nudes of the actress Kanako Higuchi. A few months later, the attention the book garnered was soon overshadowed by that of his next photobook, Santa Fe, which features the actress Rie Miyazawa, known for her modeling career since early adolescence. At the time of Santa Fe’s publication, she was said to have been underage during the photoshoot. Such incidents of the 1980s and 1990s have become defining elements in the public perception of Shinoyama’s oeuvre. However, it would be a disservice to his diverse oeuvre to confine it solely to this brief period. His career spanned sixty years wherein he found a balance between commercial and artistic pursuits and was deeply engaged in the discourse on photography.

Spread from Duel on Photography 8: Eventless by Kishin Shinoyama, with texts by Takuma Nakahira, Asahi Camera, August 1976

Spread from Duel on Photography 8: Eventless by Kishin Shinoyama, with texts by Takuma Nakahira, Asahi Camera, August 1976Shinoyama would not have an exhibition at the prestigious Tokyo Photographic Art Museum until 2021, because the museum maintained a hardline stance against showing the work of a “commercial” photographer. It exhibited the series Hareta no hi (A fine day), which dates from 1975 and has been published as a photobook with the same title. Upon receiving a copy of the book, the photographer Takuma Nakahira, a founding member of the influential 1960s collective Provoke, is said to have been reinvigorated about the potential of photography. In Shinoyama’s work, Nakahira saw something unique. This led to their yearlong collaboration in 1976, during which they created the twelve-part series Ketto shashinron (A duel of photography theory) for the magazine Asahi Camera, featuring photographs by Shinoyama and writings by Nakahira.

That same year, Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, and ten other photographers put together an exhibition called Shashin urimasu (Photos for sale), held at a boutique in Tokyo’s posh fashion district. At the time, there was a hardly a market for photography in Japan, so this project was planned to find meaning in the buying and selling of prints. But Shinoyama was having none of it. In response, he held the exhibition Shashin agemasu ten: Marī no natsuyasumi (Photos for free: Marie’s summer vacation), featuring a model on holiday, at the now defunct Minolta Photo Space. One camp posited photography as an object-based fine art that could have market and archival value; the other saw the photographic print simply as what was given to a publisher for mass reproduction.

Much photography in Japan has now been subsumed within the category of art, as signified by the renaming of the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography to the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2016. This shift in vision prompts reflection on what might be obscured by this type of recategorization. Historically, experiencing photography through magazines and as an element of mass media has shaped our general understanding of the medium, especially in Japan, where print culture has thrived. By redefining photography narrowly as art, we risk losing sight of its broader context, influence, and potential. Perhaps Shinoyama’s legacy—in addition to being the face of an epoch in Japan’s photographic history and his reputation as a provocateur—offers a counterpoint to prevailing norms regarding what defines a photograph’s value and significance.

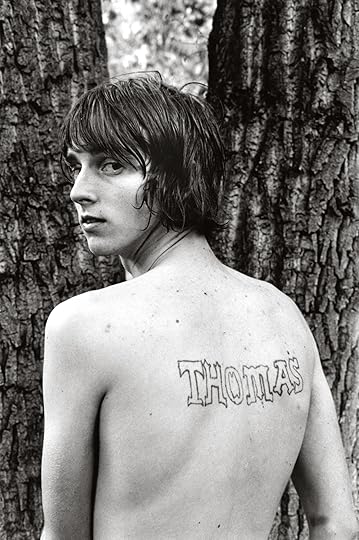

A Photographer Deconstructs Masculinity and Colonialism

Greek theater is famous for its masks. There are several, each with its own purpose, such as the neutral, the comedic, or the tragic. Actors would use them to portray different roles on stage. The photographer and artist Ibrahim Ahmed isn’t so convinced these masks are removed once the performance ends.

Born in Kuwait and raised across Egypt and the United States, Ahmed’s identity is convoluted, and that’s exactly how he thinks it should be. “I’m an amalgamation of all these things,” he tells me. His work explores the complexities of identity, history, and the performance of masculinity and citizenship—both in Egypt and globally. Central to his artistic ethos is the rejection of imposed identity categories and an inquiry into what life for men could look like beyond the confines of the status quo. He’s taken these themes to several solo exhibitions—including at the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond; Tintera Gallery, Cairo; and Primary, Nottingham—and has also participated in group shows, including at the Sharjah Art Museum and biennials in Dakar and Havana.

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #6, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #6, 2020  Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #4, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #4, 2020His series, I Never Revealed Myself to Them (2016–2021), is concerned with both the politics and the nature of visibility. What does it mean to be seen as a man, as an Arab man, as a colonial subject, as an Egyptian, as none or all of those things at once? “When we center the nation-state, we have to pick a side,” he tells me. “That in itself is still centering a colonial legacy. The idea of the annihilation of the self is very important to me because, in a world full of representation and hypervisibility, to be invisible is powerful.” Absence as presence has been a motif throughout his career, which also includes a well-established textile and sculpture practice, with work that meditates on the American dream and inherited codes of masculinity.

In the first installment of the series, You Can’t Recognize What You Don’t Know, Ahmed deliberately obfuscates his face in his self-portraits. “The idea is not about me as an individual,” he says. “It’s about the individual as representative of this performance of masculinity.” Understanding notions of “Arab masculinity” as inextricable from global patriarchy, Ahmed explains that his work invests in breaking down entrenched mythologies surrounding manhood: “the psychological aspect of it, the grotesque nature of it, and how that is deeply rooted not just in Arab culture, but in cultures around the world.” His images reimagine idealized masculinity, drawing on documentary and studio photography from across Africa and the Middle East; Greco-Roman and Pharaonic poses; and advertising aesthetics associated with men’s clothing.

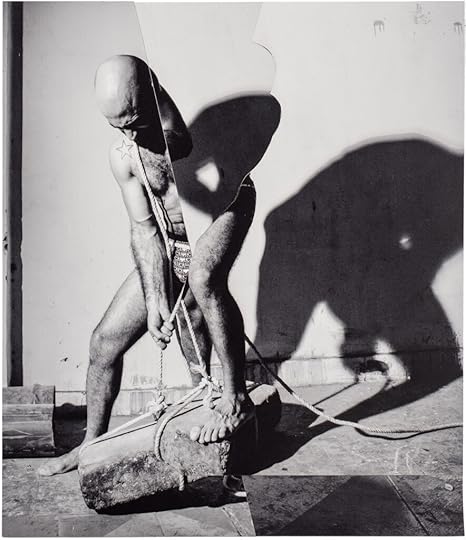

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #29, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #29, 2020 Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #26, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #26, 2020Ahmed primarily works with collage, using photographs as a material to “collapse our immediate affiliations” and construct something new “from the rubble.” He calls it an experiment. In Figure #26 (2020), Ahmed pulls a rock with rope, his muscles tensed and an enlarged shadow behind him. With a bare stone background, the composition alludes to iconic classical sculptures such as Myron’s The Discobolus, Rodin’s The Thinker, and, of course, Michelangelo’s David.

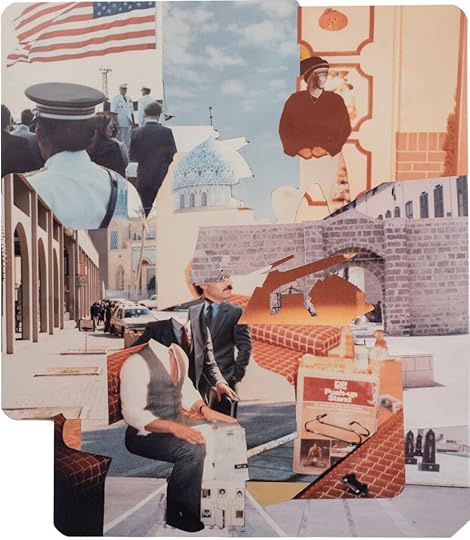

In Some Parts Seem Forgotten, the second installment, Ahmed uses archival photographs, predominantly those his father made over a fifty-year span as he was building a successful career as a businessman in the US. He situates these alongside black-and-white studio images from the previous installment to highlight a repetitive history of masculine performance within his family nucleus, as seen in Figure #2 and Figure #5 (both 2020), which show almost caricatured power stances and flexed biceps in Greek statuesque poses. Ahmed appropriates his father’s lens on the world and his belief in such constructs in order to critique the pattern manifesting within himself.

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #5, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #5, 2020 Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #3, 2020

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #3, 2020 The third installment, Quickly but Carefully Cross to the Other Side, follows a nonlinear timeline where family album images from the ’50s are spliced with those from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. These include photos of a young Ahmed standing by his father in Figure #4 (2020), the scene adorned with a US flag and a classic Western car, allusions to the “self-made American dream” that his father pursued. The work encapsulates a broader discourse on identity, colonial legacies, and the complexities of cultural affiliations. In Figure #3 (2020) we see an American flag behind a lineup of navy men on a warship alongside a classic American car, with the photographer and his father posing together in traditional Gulf attire. Through his references, Ahmed builds on the work of visual artists throughout Southwest Asia and North Africa—including M’hammed Kilito, Filwa Nazer, Huda Lutfi, and Mahmoud Talaat—as well as curators and writers Farida Youssef and Nadine Nour el Din.

When Egypt was reimagining itself into a strong, Arab nation-state, new ideas of masculinity were adopted from British colonizers, who occupied the country from 1882 to 1965. Egyptian men were disciplined away from traits considered “feminine, lazy” and instead turned into enforcers. “You are a regulator of the system,” Ahmed tells me. For him, living in an Egypt that has gone through multiple revolutions—from Nasser’s reforms to the Arab Spring—shrugging off colonial ideas of masculinity starts from deep within. “It’s not that you’re going to break free from these things because of some academic writing. That is where my spirituality comes in,” he adds.

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #11, 2020. All works from the multipart series I Never Revealed Myself to Them, 2016–2021

Ibrahim Ahmed, Figure #11, 2020. All works from the multipart series I Never Revealed Myself to Them, 2016–2021© the artist and courtesy Tintera Gallery

Ahmed’s spiritual compass guides his work and centers the idea of universality, where the philosophy of an “annihilation of the self” comes into play. He strives for accessibility, emphasizing everyday experiences in his work and deconstructing ideas of the individual. To achieve this, he attempts to democratize his art to reach beyond academic realms; hence the familiar touchstones of the family photo album and the location of his studio in Ard El Lewa, a working-class neighborhood of Cairo.

Through his collages, Ahmed dismantles the masks of societal expectations, inviting viewers to confront the intricacies of selfhood as they pertain to hypermasculinity and class, and the legacy of colonialism in enforcing them. In Figure #11 (2020), from the third installment of his series, a mosque towers above men only to be topped by a US flag, beckoning us to confront our understanding the hierarchies of power in self and in society.

March 6, 2024

12 Essential Photobooks by Women Photographers

Diane Arbus, Child in a nightgown, Wellfleet, Mass., 1957

Diane Arbus, Child in a nightgown, Wellfleet, Mass., 1957© The Estate of Diane Arbus

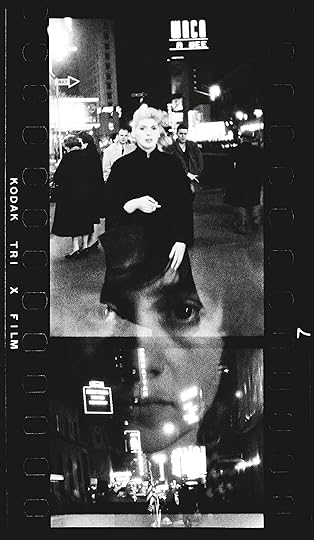

Diane Arbus, Inadvertent double exposure of a self-portrait and images from Times Square, N.Y.C., 1957

Diane Arbus, Inadvertent double exposure of a self-portrait and images from Times Square, N.Y.C., 1957 Diane Arbus Revelations (2022)

One of the best-known image makers of her generation, Diane Arbus was already a legend in the photography community when she died at the age of forty-eight, in 1971. Despite her significant influence, only a relatively small number of her pictures were widely known at the time. Diane Arbus Revelations was released on the fiftieth anniversary of Arbus’s posthumous 1972 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the simultaneous publication of Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph.

Arbus’s frank treatment of her subjects and faith in the intrinsic power of the medium have resulted in photographs that are often shocking in their purity and steadfast celebration of things as they are. Revelations explores the origins, scope, and aspirations of Arbus’s wholly original vision. Featuring two hundred full-page duotones of Arbus’s photographs spanning her entire career, the volume presents many of her lesser-known or previously unpublished photographs in the context of the iconic images—revealing a subtle yet persistent view of the world.

Myriam Boulos, Untitled, 2017–20

Myriam Boulos, Untitled, 2017–20Courtesy the artist

Myriam Boulos: What’s Ours (2023)

In her searing, diaristic account of a city and society in revolution, Myriam Boulos creates an intimate portrait of youth, queerness, and protest. What’s Ours, her debut monograph, brings together over a decade of images, casting a determined eye on the revolution that began in Lebanon in 2019 with protests against government corruption and austerity through to the aftermath of the devastating Beirut port explosion of August 2020.

Photographing her friends and family with energy and intimacy, Boulos portrays the body in public space as a powerful symbol of vulnerability and resistance against neglect and violence. “Boulos’s lens inspires and entices her subjects,” writes Mona Eltahawy in an accompanying essay. “They know they have an ally, a secret sharer in their intimacy who then shares them with the rest of us.”

Collect a special signed book and print bundle of Myriam Boulos: What’s Ours.

Kelli Connell, Doorway II, 2015

Kelli Connell, Doorway II, 2015Courtesy the artist

Kelli Connell: Pictures for Charis (2024)

In Pictures for Charis, Kelli Connell takes inspiration from the life of Charis Wilson and her collaborations with Edward Weston through the contemporary lens of a queer woman artist. Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Wilson was Weston’s partner, model, and collaborator, working with the photographer on some of his most iconic images.

Connell focuses on Wilson and Weston’s shared legacy, traveling with her own partner, Betsy Odom, to locations in the western United States where the latter couple made photographs together more than eighty years ago. In chasing Wilson’s ghost, Connell tells her own story, finding a new kinship with the collaborative duo as she navigates a cultural landscape that has changed, yet remains mired in the same mythologies about nature, the artist, desire, and inspiration. Bringing together photographs and writing by Connell alongside Weston’s classic figure studies and landscapes, Pictures for Charis raises vital questions about photography, gender, and portraiture in the twenty-first century.

Collect Kelli Connell’s limited-edition print Doorway II, 2015 from Pictures for Charis.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008Courtesy the artist

LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Notion of Family (2014)

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first photobook, The Notion of Family, offers an incisive exploration of the legacies of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Examining this impact throughout the community and her own family, Frazier intervenes in the histories and narratives of the region. Setting the story across three generations—her grandma Ruby, her mother, and herself—Frazier’s statement becomes both personal and political.

In The Notion of Family Frazier acknowledges and expands on the traditions of classic black-and-white documentary photography, enlisting the participation of her family, her mother in particular. In creating these collaborative works, Frazier reinforces the idea of art and image making as transformative, and a means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives—both those of her family and of the community at large.

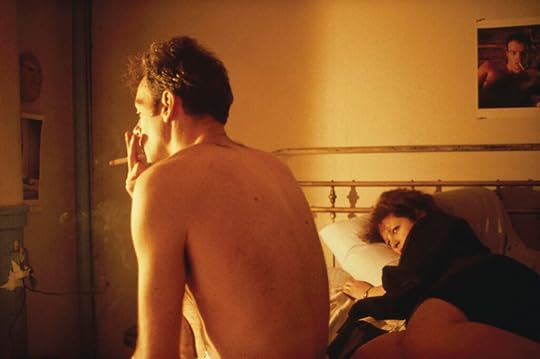

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983Courtesy the artist

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (2021 Edition)

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary The Ballad of Sexual Dependency chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Goldin’s candid, visceral photographs captured a world seething with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis.

First published by Aperture in 1986, The Ballad continues to exert a major influence on photography and other aesthetic realms, its status as a contemporary classic firmly established. As Goldin reflects in an updated afterword from Aperture’s 2021 edition: “I took the pictures in this book so that nostalgia could never color my past. I wanted to make a record of my life that nobody could revise.”

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (opium flower with pink fabric), 2019, from the series The Imaginative Landscape

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (opium flower with pink fabric), 2019, from the series The Imaginative LandscapeCourtesy the artist

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (portrait of a woman in gray by a waterfall), 2019, from the series The Imaginative Landscape

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (portrait of a woman in gray by a waterfall), 2019, from the series The Imaginative Landscape Pao Houa Her: My grandfather turned into a tiger…and other illusions (2024)

Pao Houa Her’s debut monograph presents a deeply personal exploration of the fundamental concepts of home and belonging. A recipient of the 2023–24 Next Step Award, Her creates compelling and personal narratives grounded in the traditions and contemporary metaphors of the Hmong diasporic community. Throughout her images, the artist draws from myriad sources: apocryphal family lore, portraits of the artist and her community, and reimagined landscapes in Minnesota and Northern California that stand in for Laos.

My grandfather turned into a tiger brings together four of the artist’s major series, reflecting her keen perspective on the boundary between authenticity and imitation, stating that photography is “a truth if you want it to be a truth.”

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance, 2011

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance, 2011Courtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance (2021 Edition)

In her images of keenly observed gestures and details, Rinko Kawauchi reveals the mysterious and beautiful realm at the edge of the everyday world. For Kawauchi, the act of photographing is less a way of referring to the appearance of everyday reality than it is about evoking the luminous openness that exists when the boundaries between things become blurred. As Kawauchi describes, “I want imagination in the photographs—a photograph is like a prologue. You wonder, ‘What’s going on?’ You feel something is going to happen.”

In 2021, ten years after its original publication, Aperture published a new edition of Kawauchi’s beloved photobook, retaining the artist’s original sequence alongside new texts by David Chandler, Masatake Shinohara, and Lesley A. Martin that contribute new context to and perspective on Kawauchi’s influential work.

Justine Kurland, Daisy Chain, 2000

Justine Kurland, Daisy Chain, 2000Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures (2020)

The North American frontier is an enduring symbol of romance, rebellion, escape, and freedom. At the same time, it’s a profoundly masculine myth: cowboys, outlaws, Beat poets. Photographer Justine Kurland, known for her idyllic images of American landscapes and their fringe communities, sought to reclaim this space with her now-iconic series Girl Pictures. Made between 1997 and 2002, Kurland’s photographs stage scenes of teenage girls as imagined runaways, offering a radical vision of community and feminism.

Kurland portrays these girls as fearless and free, tender yet fierce. They hunt and explore, braid each other’s hair, swim in sun-dappled watering holes. Kurland imagines a world at once lawless and utopian, an Eden in the wild. “I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls,” writes Kurland. “Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it—one of them, a girl made strong by other girls.”

Collect a special signed book and print bundle of Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures.

Deana Lawson, Binky & Tony Forever, 2009

Deana Lawson, Binky & Tony Forever, 2009Courtesy the artist

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s first book, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in an essay for the book. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-on C-print.

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Rescue, 1999–2002, from the series Small WarsCourtesy the artist

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain (2020)

Throughout her thirty-year career, An-My Lê has used photography to examine her personal history and the structures and legacies of US military power. Lê was born in Saigon in 1960 and evacuated with her family to the United States in 1975. Part of a lineage of artists who have adapted the conventions of landscape photography to explore how conflict has long informed American history and identity, Lê’s work has brought her to photograph former battlefields—spaces reserved for training for or reenacting war—and the noncombatant roles of active service members.

On Contested Terrain is the first comprehensive survey of Lê’s career, featuring her well-known series Small Wars, 29 Palms, and Events Ashore, alongside and the artist’s most recent photographs from the US-Mexico border. “Lê’s photographs are balanced, quiet, and nuanced works of art that offer the viewer an opportunity for contemplation,” Dan Leers writes. “She invites us to examine our own perception of, and involvement in, war as something that is not straightforward or clear-cut.”

Kristine Potter, Knoxville Girl, 2016

Kristine Potter, Knoxville Girl, 2016Courtesy the artist

Kristine Potter, Breakneck, 2016

Kristine Potter, Breakneck, 2016 Kristine Potter: Dark Waters (2023)

Kristine Potter’s dark and brooding photographs reflect on the Southern Gothic landscape of the American South as evoked in the popular imagination of “murder ballads” from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the American murder ballad (which has grown a cult appeal and continues to be rerecorded today), the riverscape frequently doubles as a crime scene. Places like Murder Creek, Bloody Fork, and Deadman’s Pond are haunted by both the victor and the violence in the world Potter conjures.

The artist’s seductive, richly detailed black-and-white images channel the setting and characters of these songs—capturing the landscape and creating evocative portraits that stand in the oft-unnamed women at the center of these stories. The resulting volume, Dark Waters, reflects the casual popular glamorization of violence against women that remains prevalent in today’s cultural landscape. As Potter notes, “I see a through line of violent exhibitionism from those early murder ballads, to the Wild West shows, to the contemporary landscape of cinema and television. Culturally, we seem to require it.”

Collect Kristine Potter’s limited-edition print Pearl, 2019, from Dark Waters.

Wendy Red Star, Apsáalooke Feminist #4, from the series Apsáalooke Feminist, 2016

Wendy Red Star, Apsáalooke Feminist #4, from the series Apsáalooke Feminist, 2016Courtesy the artist

Wendy Red Star: Delegation (2022)

In her dynamic photographs, Wendy Red Star recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective. Red Star (Apsáalooke/Crow) centers Native American life and material culture through her imaginative self-portraiture, vivid collages, archival interventions, and site-specific installations. Whether referencing nineteenth-century Crow leaders or 1980s pulp fiction, museum collections or family pictures, she constantly questions the role of the photographer in shaping Indigenous representation. The artist’s first major monograph, Delegation, is a spirited testament to the intricacy of Red Star’s influential practice, gleaning from elements of Native American culture to evoke a vision of today’s world and what the future might bring.

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

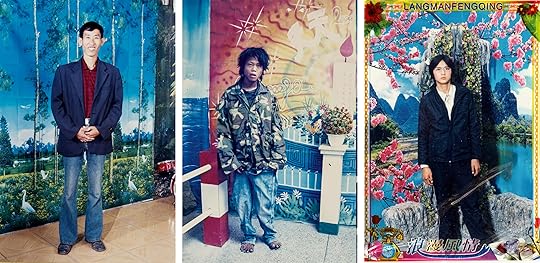

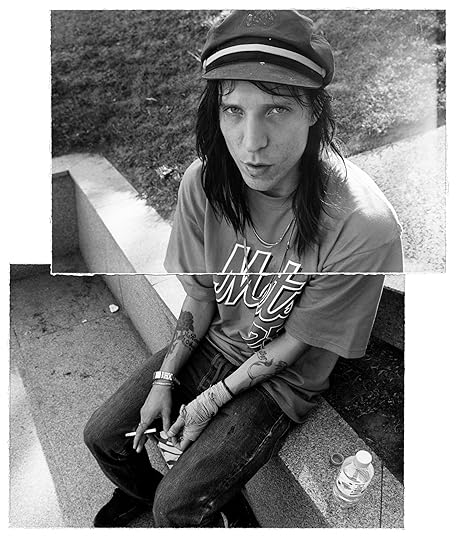

A Mother’s Relentless Quest to Find her Missing Son

The mother’s quest began on August 24, 2000. Her name was Yu Lai Wai-ling, a housewife who lived in a public-housing estate with her husband, a civil servant, and her son, an autistic teenager. Outside the walls of their small flat, a typhoon breached Hong Kong and calmed into a storm. The unsettling weather disturbed her son, so her husband suggested a diversion: lunch. After leaving a dim sum restaurant, the three huddled through the Yau Ma Tei underground station—and this was when the boy let go of her hand, sprinted into the crowd, and disappeared.

Ms. Yu was frantic. Her son, named Yu Man-hon, was a two-year-old in a fifteen-year-old’s lanky body. He couldn’t speak. How could he manage the packed underground station alone? She went to the police, whose website still displays a missing person photograph of her son: a thin boy, his eyes set slightly apart, his mouth drooping. Man-hon began a journey whose mysterious sequence we can reconstruct from a Hong Kong Immigration Department report released after his disappearance. After somehow traveling twelve miles north, he inexplicably appeared behind the Chinese border at 1:47 PM, despite lacking the permit needed to cross. At the Lo Wu border checkpoint in Shenzhen, Chinese immigration officials found the boy answered to Cantonese, not Mandarin, and returned him to Hong Kong.

Billy H.C. Kwok, A statue of Guanyin, the goddess of mercy and compassion in Chinese mythology, atop Ms. Yu’s living room cabinet, 2022

Billy H.C. Kwok, A statue of Guanyin, the goddess of mercy and compassion in Chinese mythology, atop Ms. Yu’s living room cabinet, 2022  Billy H.C. Kwok, Five roosters in Ms. Yu’s living room, 2022

Billy H.C. Kwok, Five roosters in Ms. Yu’s living room, 2022 Immigration officials there noted the boy’s disheveled state. He wore shoes from a Chinese brand. He didn’t respond when they asked him about Andy Lau, one of Hong Kong’s most famous celebrities. Panicking, the boy flailed his arms and spat at the officers, who handcuffed him to a chair. To them, he was clearly an “illegal” migrant. His poverty, the officers inferred, suggested a Chinese, rather than Hong Kong, origin, so they dragged him back into Shenzhen. That fateful last act separated Ms. Yu from her son.

In the coming days, Ms. Yu’s tearful, inconsolable cries circulated across the newspapers and TV news. A massive force of Hong Kong police officers flooded the city. Search teams scoured Shenzhen and Guangdong. Was Man-hon still alive? Had gangsters captured him? Did he become another unhoused migrant in China? The boy came to represent Hong Kong itself—a phantom languishing inside the foreign motherland that had absorbed the former British colony only three years prior.

Billy H.C. Kwok heard about Ms. Yu and her son when he was a secondary-school student in Hong Kong. Be careful at the border, his mother had told him. Now a boy not much older than him had vanished into China. Living today between Hong Kong and Taiwan, Kwok works as a photojournalist; his images for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal depict the contentious new Sinophone century: a Hong Kong protestor raises a flaming stick at riot police, steelworkers protest in Guangzhou, and a man fixes a flagpole outside a Taiwanese temple he’s taken over with Chinese flags. In the National Archives of Taiwan, Kwok uncovered letters written by those captured and later executed during the White Terror, the authoritarian wave of oppression that began in 1947. The letters were never delivered, until Kwok intervened to complete the correspondence. For his project Last Letters (2017–ongoing), he approached their authors’ families and photographed those who agreed to read them. The most fascinating part, Kwok told me, was observing the children of these victims kowtowing before statues of Chiang Kai-shek, the right-wing leader who presided over the persecution, only to gradually realize he had authored their own family tragedies. Kwok appreciated how these statues, whose removal he also documents, constituted both objects and manifestations of political ideology. Having made this archival interrogation into one alternative China, a project oriented less around visuality than the failure and persistence of ideological narratives within objects, Kwok wondered how he could investigate the story of Hong Kong.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

He recalled that lost boy he’d heard about growing up, whose story hinted at a surreptitious way to interrogate Hong Kong’s vexed status without triggering Chinese censorship. In June 2022, Kwok cold-called Ms. Yu, whose number he found in one of the many classified advertisements she’d placed looking for her son decades earlier. When he introduced himself as someone researching Man-hon, Ms. Yu told him to read the internet and the newspapers. I’ve read all the newspapers and the internet, he told her. You’re the only source. He plied Ms. Yu to meet him at a restaurant, where he encountered a woman he described as deeply saddened and driven by love and discipline. By their third meeting, she invited him to her apartment.

Kwok lived only two stations away, and he visited her every week for nine months, each time carrying his camera to acclimate her to the idea of perhaps one day being photographed. However, the photographs they focused on were not his, but hers. For one astonishing consequence of Ms. Yu’s son’s disappearance is how her search led her to deploy many of the techniques of art practice, such as object making, photography, and performance. Kwok’s ongoing project has been to curate and present her archive related to her son’s disappearance, and his initial instantiation, For So Many Years When I Close My Eyes (2022–23), combines elements of her images and records with his own maps and photographs created in locations related to her story.

Few forces in the universe are as powerful as a mother’s grief. Supported by donations from people who’d heard about her loss, Ms. Yu began creating notices asking if anyone had seen Man-hon. This media project included newspaper classified ads, text-based spots aired on TV and Hong Kong trains, and, remarkably, playing cards featuring Man-hon’s portrait. This collision of public memory and a simple deck of cards reminded Kwok of how the US military trained the soldiers invading Iraq to identify Saddam Hussein’s leadership circle by printing their faces on playing cards. Ms. Yu also posted missing person flyers in Shenzhen and elsewhere in southern China. A few of the flyers resemble zines or print art. Monochromatic enigmas, they show her son’s missing person photograph, an embellished image of him with long hair, and only the Chinese words missing person.

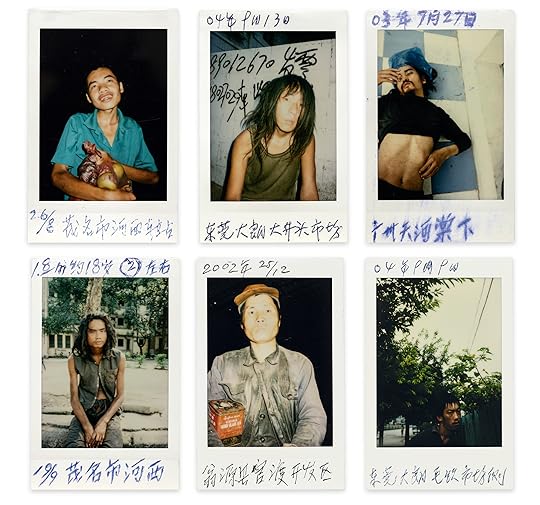

Playing cards and a transparent wallet made by Ms. Yu featuring Man-hon’s portrait, ca. 2000–2003

Playing cards and a transparent wallet made by Ms. Yu featuring Man-hon’s portrait, ca. 2000–2003  Polaroid images taken by Ms. Yu in southern Chinese cities, ca. 2000–2005

Polaroid images taken by Ms. Yu in southern Chinese cities, ca. 2000–2005 During these visits, she searched for Man-hon among the transient and disabled men she encountered. As Kwok explained to me, she would see an unhoused man, approach him, and, like some early Christian saint, brush the hair from his face. After verifying the man wasn’t Han’er (her son Han, in Chinese), she would take his portrait. The resulting Polaroids include, in her handwriting, the man’s name, the location, and the date. Your eyes fall upon the men’s shoulders, shrunken from hunger. Their necks seem too slender, their heads and often matted, overgrown hair loom over their torsos, grown tiny from want. Another man, smiling, looks comparatively nourished. His shirt and trousers are blemished with stains. His toes jut from his right boot.

“By photographing individuals who were not Man-hon, she was able to indirectly prove his existence through some method of elimination,” Kwok writes. However, these portraits did not prove he was living. They transferred his identity onto a substitute object, another man who might temporarily have contained the possibility of being Man-hon. Each portrait depicts someone not there, a vicarious memento mori. Her portraiture resembles few others because of her almost random relationship to those she photographed. Unlike a social reformer such as Jacob Riis, Ms. Yu had no investment in uplifting their plight. Their identities were almost incidental to her project, yet she documented them compulsively. Her unstudied repetition, obsessive seriality, and endless male subjects all recall efforts to index a specific population, but her portraits are not mug shots, ID cards, or a form of surveillance. She does not seek to exercise power over the “long hairs,” as Kwok called these men. Her figures look the viewer in the eye without any sense of shame, but also lack the inverted grandeur that suffuses, say, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936). Her Polaroids sometimes present young men roaming the nocturnal city, a genre whose closest Western correlative might be bohemian nightlife photographs, though the men here seem trapped in far more destitute straits.

The boy came to represent Hong Kong—a phantom languishing inside the foreign motherland.