Aperture's Blog, page 24

November 6, 2023

How John Akomfrah’s Videos Tell a Story of Migration and Belonging

For more than four decades, John Akomfrah has sought to tell myriad tales of migration and belonging. Akomfrah left Ghana for the UK as a young child after the country’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, was overthrown in the 1966 coup, which put his activist mother’s life in danger. In a 2012 interview for The Guardian, Akomfrah stated that his father’s death was due in part to the turmoil and “struggle leading up to the coup.” In 1982, he and a group of peers cofounded the organization Black Audio Film Collective. Inspired and energized by the work of theorists such as Paul Gilroy and Stuart Hall, the collective addressed landmark moments in British history with an astute critical gaze, connecting the discrimination that migrants to England faced to the malaise and postindustrial decline of the country.

After the collective dissolved in 1998, Akomfrah continued to write and direct films and video essays, including the three-screen installation The Unfinished Conversation (2012) and The Stuart Hall Project (2013), both based on the life and work of the pioneering postcolonial scholar. In 2019, Akomfrah was one of six artists invited to show at Ghana’s first-ever pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and in 2024 he will represent Great Britain at the international event. Akomfrah’s practice and oeuvre is testament to the notion of hybridity: his project is to name the political ghosts and specters that haunt the present day, to confront complex histories—no matter how violent or gruesome—and tackle the bad spirits. Last spring, Akomfrah spoke from London with the writer Vanessa Peterson and the artist Lyle Ashton Harris about the dialogues between Ghana and its diaspora.

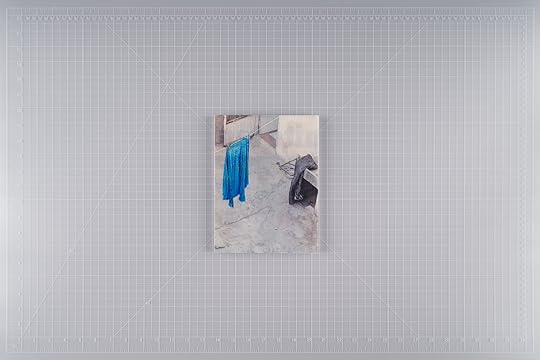

Installation view of Five Murmurations, 2021, Lisson Gallery, New York. Video, 45 minutes, black and white, sound

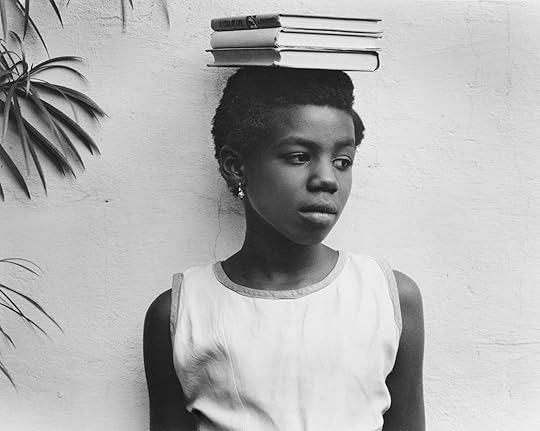

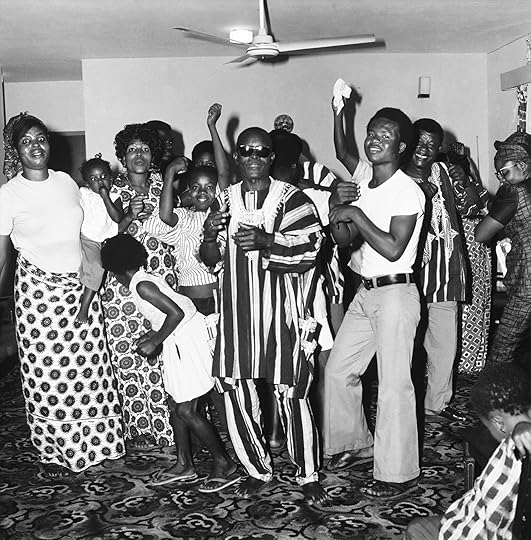

Installation view of Five Murmurations, 2021, Lisson Gallery, New York. Video, 45 minutes, black and white, sound  Still from Testament, 1988. Video, 79 minutes, color, sound

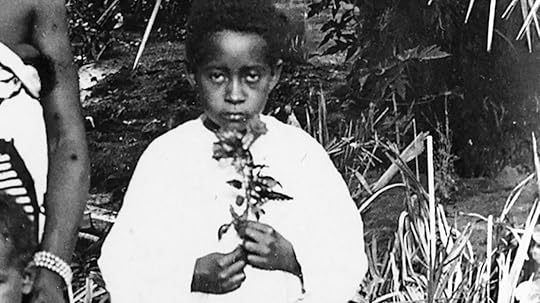

Still from Testament, 1988. Video, 79 minutes, color, sound Vanessa Peterson: An interesting place to start would be to talk about your first narrative feature film, Testament (1988), which was shot in Ghana and England. The film follows Abena, a political exile who returns to Ghana after the overthrow of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, to interview the German director Werner Herzog, who is also in the country, shooting Cobra Verde. Abena also seeks to reunite with her former political colleagues. I’d be curious to know what led you to making Testament, and the origins of the film.

John Akomfrah: The paradox of the film was that even though I am the most Ghanaian of Ghanaians—born in the year of independence, parents were anticolonial activists completely committed to that project of the transfer of power, both political and cultural—even though all of that was me, and continues to be me, I hadn’t really thought about making that film. I, like the character, was in flight from that subject, for all kinds of emotional and psychic reasons. But it was inescapable at a certain point. Even though you might suppose that the reluctance to engage with Ghana was a reluctance to engage with Africa in general, that was the very opposite of the case. I had been tracking and following African cinema and its histories for many years.

I was in Ouagadougou for the Pan African Film Festival when a number of other filmmakers, Haile Gerima being one of them, said to me: “Did you know that Werner Herzog is in Ghana making a film? What are you doing sitting here? Why don’t you go and make one, rather than allowing that guy to do your story?” I was like, “Okay. I’m not sure he’s going to do my story, but I get the point.” It was really via Pan-Africanism that I returned to the nation, and very specifically, it was the urgings of other filmmakers who were all part of that Pan-African movement that took me there.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Lyle Ashton Harris: I saw Testament when you showed it at CalArts. It seems prescient, if you think about the book White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa (2021) by Susan Williams, who writes about the Cold War–era involvement of the United States in assassinations and coups in newly independent African states. You address a lot of similar themes.

Akomfrah: One of the reasons for avoiding the subject was precisely to do with the terrain that White Malice covers. There were a number of living rooms in that African revolution, and I happened to be in probably the epicenter of the living rooms, because both my parents were involved with it, working for the Convention People’s Party, founded by Nkrumah in 1944. My mother was at the university, the ideological institute that the film deals with. Many of the subjects later covered by Susan Williams were ones I was intimately familiar with. For instance, I remember having a conversation with my mom in the ’70s when I first read Malcolm X’s autobiography. She must have seen it on my desk. She said, “Oh, you’re reading Malcolm X?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “Oh, I knew him.” That blew me away.

Since the ’70s, I had known that there were these forces at play on our continent, and specifically in Ghana. I didn’t want to go there.

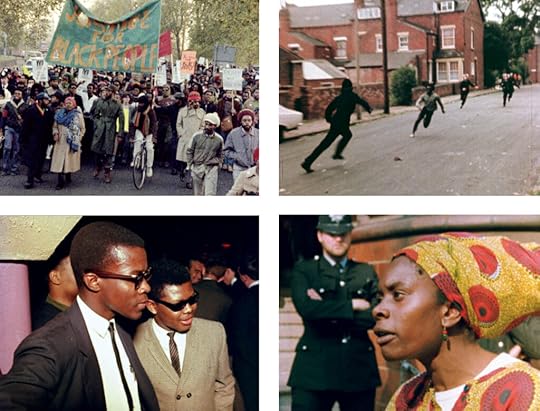

Black Audio Film Collective (John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and Trevor Mathison), Stills from Handsworth Songs, 1986. Video, 58 minutes, 33 seconds, color, sound

Black Audio Film Collective (John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and Trevor Mathison), Stills from Handsworth Songs, 1986. Video, 58 minutes, 33 seconds, color, soundPeterson: Testament makes me think of autofiction—it’s fictional, but it’s also playing on deeply biographical elements. Sometimes it’s the only way to tell a story, especially one filled with pain and dislocation. To me, that is what writing and directing Testament was for you. Did you feel it was a way for you to reckon with your familial circumstances, as well as the legacies of Ghana’s turbulent politics? To guard against a sense of amnesia that comes with the passing of time?

Akomfrah: Yes, of course. What’s been odd for me since we made it in 1987 is that it became a kind of subgenre of African filmmaking. This “returning” film. There were so many films afterward of people returning for one reason or another.

Ashton Harris: Such as Sankofa by Haile Gerima. In actuality, you anticipated his film.

Akomfrah: Yes. That’s very odd. I hadn’t even thought about that. But it is true. Including the grandmaster Haile himself. Basically, this primal scene of African suffering with its tragedies and its accidents. It was almost Greek in profile, in the sense that there were forces at play that seemed bigger than individuals. One of the ways in which I think many of us exilic kids came to deal with this was via fiction and filmmaking. Many people seemed committed to the idea that there was this hidden country that they felt—a country of ghosts, if you like—where they felt brave enough to go only through cinema or the moving image. That was an extraordinary thing.

Ashton Harris: With regard to returning-to-Ghana narratives in literature, we can also look at travelogues by Richard Wright, Saidiya Hartman, and Ekow Eshun.

Akomfrah: Certainly. There was a period when very many people who had either left as children or came of age and were old enough to begin to chart their connections with the continent—for them the moving image was a very good source, as well as literature. I think in the “war zone of memories” here, as Testament very clearly says. And in that war zone, the politics of location and identities is crucial. Malcolm was prophetic in all kinds of ways, not just for himself but for my mother and our institute. A year after he died, the military coup happened in Ghana, on March 6, 1966. Everything that that moment stood for was wiped away. You can say that, had Malcolm been alive in ’66, and had he wanted to be in Ghana, none of the conditions that made it possible for him to be there would have existed. He wouldn’t have been allowed in because the military would have seen him as a troublemaker. Many Pan-African institutions had been shut down for being communist and Marxist. He was prophetic in a way that he hadn’t anticipated, because when he spoke about his end, he was actually speaking about the end of a lot more than that.

Installation view of The Unfinished Conversation, 2012, Museum of Modern Art, NewYork. Video,

45 minutes, color, sound

Courtesy Art Resource, NY

Peterson: And then your life suddenly changed.

Akomfrah: Yes. Following my father’s death, we were quite literally in flight, and through a circuitous route via the US, we arrived in this country, begging for shelter, which is so bizarre to me, then and now. The thing that was bizarre to me was the fear of being in Ghana. The fear that something terrible was about to happen to us was palpable. I was very young, but I knew it. I could feel it. Let no one tell you fear does not have a personality, an ontology. It really does. Ghosts do fucking exist, and they do stuff. I was aware, palpably, that we were being stalked by something. I mean, phantom is too innocent a word. A kind of ogre. And nothing but flight would save us. I was absolutely relieved when we arrived here, in a way that I think people who now go on boats to leave, to come to this country, would know, would understand. The palpable sense of relief was extraordinary for me.

We arrived here in the late ’60s and continued to try to make this place a home. At the time, we consciously tried to create an Accra in London, in our house, which would stand for the Accra that I left. In this weird Faustian bargain that I think most exilic figures make with the historical, you slice a piece of it, a manageable piece, you construct a tableau either in your bedroom or your house or your new town, and that becomes your version of where you’ve left.

Having been brought up in a Pan-African environment, a lot of things were easier for me to navigate than they might appear at first.

Peterson: Did you speak about Ghana?

Akomfrah: We spoke about narratives. I remember my mother being obsessed with the narratives of betrayal—who did what, when; how this happened; who was responsible. And it wasn’t just a regional thing. It wasn’t just a local thing. It was a continental thing. We were in the space of every defeated, every vanquished, every political uprising that didn’t happen. I’m including in this all of the ones that were to be, whether it’s Angola or South Africa or Zimbabwe—it was just all these places of defeat and the vanquished, which became our country and our continent. In London, you met other people who’d lost their home and were running from violence. There is this incredible, ironic reversal in that period, where you meet all of these folks who had left to go and throw out the British, coming, begging, cap in hand to the British to take them on.

Ashton Harris: I’ve used a quote of yours many times, and it has been a guiding force to me: “The problem with the Black avant-garde is that we’re constantly having to reproduce itself, because we don’t actually protect it. We don’t give a citation. We don’t acknowledge it.” Starting with Testament, there’s a thread through all of your work in terms of its radical project of, to Vanessa’s point, anti-amnesia. How did you emerge? Why were you chosen by Stuart to be the architect of The Unfinished Conversation or The Stuart Hall Project?

Akomfrah: Growing up in a house of the vanquished, of the dismissed, I am aware of what I would call the thing to come, which is the thing that stalks all powerless lives. It’s the coming of the disaster, really. All of that made me comfortable with the unpopular. I never had a problem with the avant-garde because many of its conceits had organized my life: asymmetry, bricolage, nonlinearity.

Stuart was one of the few who made generational sense to us. I think it’s to do with his purchase on this place, because he got here when he was young and had worked his way into many institutions. He became a product of all of those. When he spoke, we could feel that he inhabited several living rooms at the same time. I wasn’t born here, but I always felt more connected with people of my generation here. I didn’t see what I was doing as being something from a Ghanaian kid. I knew that I had to make the transition from a Ghanaian kid to a Black British one. But at the same time (and this is the important thing that the people who usually call me Ghanaian are not aware of ), most of my generation were doing exactly the same thing. Because their parents had come from somewhere else. It fell on them, as the children, to deliver on the promise of post-migrancy. Sometimes people say to me, “Oh, it’s so interesting that you understood Caribbean culture so well that you’d make Handsworth Songs.” What do you mean? It became clear that Black Britishness was going to be arrived at by a mélange of Caribbean and West African culture.

Having been husbanded, schooled, brought up, and nurtured in a Pan-African environment, a lot of things were easier for me to navigate than they might appear at first. And the navigation wasn’t at the expense of being Ghanaian, because no one could remove that. Even as a seven- year-old, I knew that I was forever marked by that place. I knew things that everyone who lives abroad has to contend with. It’s typical to meet somebody from the Caribbean who goes back to where they grew up and realizes that they embody everything that that place has lost. The place itself has moved on and doesn’t cherish anymore the kinds of fruit that were there that you liked. All that’s gone. You have, in a very real sense, become a custodian for that lost life.

Still from Four Nocturnes, 2019. Video, 50 minutes, color, sound

Still from Four Nocturnes, 2019. Video, 50 minutes, color, sound  Still from Vertigo Sea, 2015. Video, 48 minutes, 30 seconds, color, sound

Still from Vertigo Sea, 2015. Video, 48 minutes, 30 seconds, color, sound Peterson: In relation to being a custodian, there are specific references to being Ga—an ethnic group from the Greater Accra region—throughout Testament. You reference rivers in relation to memory, for instance. Can you speak more to your relationship with your Ga heritage, and how memory and legacy appear in your work?

Akomfrah: I am aware of huge strands of Ghanaian life that only people like me embody, because it’s gone. I remember a time when it was common knowledge that as Ga people, people of the rivers, that our gods were the rivers. I realized that once you lose your memories, everything else will be gone. One of the things I was certain about as a grandson of a Ga elder was what those things mean—what it is to be the high priest of a river, what it means to be an herbalist in a certain kind of tradition. Testament was trying to make an oblique reference to a familial past that may not make sense to everybody else. I think there was all kinds of what would now be called ecological consciousness that being Ga entailed. There was an ascetic, frugal relationship with our environment. Quite a lot of it disappears, because the frugality of it was one of the reasons people wanted independence—they were sick of living these frugal lives.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Peterson: I’m also Ga. My family are from La and Jamestown, where various colonial administrations, such as the British, were based. We’ve been speaking about anti-amnesia, and now initiatives, such as Year of the Return—when in 2019 Ghana invited African diasporans to return to the country and commemorate four centuries since the beginning of transatlantic slavery—have been put in place to regather and bring those in the United States back to the continent.

Akomfrah: One of my relations with the country at the moment is via a morbid symptom, which is that I go to Ghana frequently, usually to bury someone or to attend memorials. My father had six sisters, five of whom have now passed away in the last fifteen years. I’ve returned to La every two years or so to bury someone. I flew into Accra a few years ago, and it happened to coincide with the Year of the Return project. The airport was full of hundreds of people—it was the most extraordinary thing. It reminded me of something that I’ve always felt. We talk about ghosting, phantoms, and unseen guests. There’s a real sense in which these figures and apparitions have a right to that landscape. Many generations of people may not necessarily be from Accra but passed through Accra on their journey elsewhere. We’re one of these strange spaces where I think our sense of sovereignty needs to be a postmodern one. Our sovereignty cannot simply lie with the living any more than it can lie with just the dead of that place—we have several millions of dead elsewhere who are of that place.

Akufo-Addo, Ghana’s president, may have just had economic logic with Year of the Return. Whatever reasons they have, cynical or otherwise, fine. The important thing was that it happened, because someone needed to swing that door of no return the other way. It reduced me to tears because I knew that there would be a day when it wasn’t just Maya Angelou and a few friends or Malcolm X who visited—there’d be thousands of people of African origin who feel connected to the place and feel it is indebted to them. And that’s right. Because it is. It’s indebted to them, in a sense that it has to open the door of memory.

Stills from Five Murmurations, 2021. Video, 45 minutes, black and white, sound

Stills from Five Murmurations, 2021. Video, 45 minutes, black and white, soundAll works courtesy Smoking Dogs Films and Lisson Gallery

Peterson: On a granular note, I’d like to think about hybridity. This is a term that is often used to describe your work and practice. With your relative distance to the country, alongside your project of anti-amnesia, I would love to know what representing Ghana in 2019 at the Venice Biennale brought forth for you.

Akomfrah: The strange thing is that by 2019, a lot had been ironed out for me. Some of the creases of discomfort are gone. One is also aware of this question of temporality. Just about everybody who was involved in my being turfed out is gone. There’s no one alive who was an architect of the 1966 coup. So you’re aware of being slowly moved to the front of the queue. That seems to me to come with certain obligations. If you’ve known Nana Oforiatta Ayim, who curated the pavilion; David Adjaye, who designed it; or Okwui Enwezor, an advisor on the project, for as long as I had, and they ask, then you’re not just saying yes to a country; you’re also saying yes to an ambition of theirs to do something.

Nana made it clear that she was interested in this conversation between Ghana and its diaspora, the old and the young, midcareer and emerging artists. I am, too. I might not live in Ghana, but I am Ghanaian in one very important sense, which is that its future matters to me. I’ve got relatives who still live there, cousins and aunties. I have very real connections that are ongoing, which make demands on me. For those reasons alone, when someone decides to pull me into a space called the Ghana Pavilion, I thought, Well, I’m not officially, but I’m sort of already there.

If you’d told the younger me that there would be a time when I’d be happy with this, I would have shot you. There was just no way that I wanted to be owned by that place, because it had disowned us in a very violent way, and for me, that was the end of the story. I was quite happy for it to be that. The disavowal of the place or people, it was a disavowal of the connection—the presumed connection between me and it. Providing it didn’t try to acknowledge or claim me, I was quite happy for it to be there, doing its own thing. I’d even go there, but when I left, that was it. It’s like, Okay, you’re there and I’m here. Finished. It’s only recently that I’ve started to understand it. That places don’t let you go so easily.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”

November 3, 2023

Tyler Mitchell Stages a Homecoming in Georgia

The SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia, is a former depot building of the Central of Georgia Railway, a line that once transported cotton and drove the state’s economy in the nineteenth century. One of the museum’s galleries, at nearly three hundred feet long, retains the heritage of the building, constructed in 1853, with its archways and original Savannah-gray brick. This is the setting for Tyler Mitchell’s latest exhibition, Domestic Imaginaries, which marks the debut of new fabric prints by the photographer and sculptural pieces inspired by vintage furniture. “I started imagining the cargo that came through here, the people that came through here, that maybe worked here, what this exact site was hundreds of years ago,” Mitchell, who grew up in Atlanta, told me, when the exhibition opened in September. The light-filled gallery’s unconventional shape presented an opportunity for him to move photographs off the wall, to play with the idea of the home and the backyard as an art space, and to pursue a form of storytelling based on gesture and memory—a “collective memory,” Mitchell says, “of what nature and the South and the Southern landscape means for Black people now and then.”

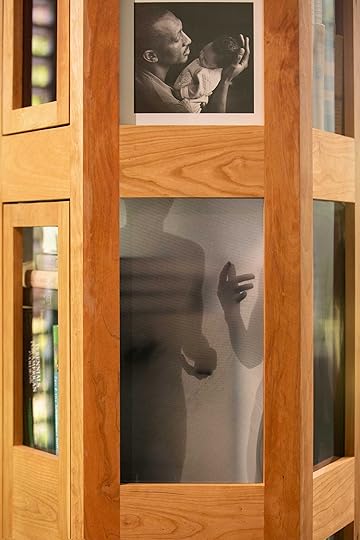

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023. Installation views of Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, 2023

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023. Installation views of Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, 2023

At the center of Domestic Imaginaries, a laundry line zigzags from a brick wall to a row of tall windows. Numerous photographs, dye-sublimation prints on silk, jersey, linen, or cotton and clipped with clothespins, sway gently as visitors move about. The pictures retain the signature pastel color palette of Mitchell’s well-known fashion and editorial work, but the figures are elusive: many are only partially visible, obscured by sheets of fabric within the original image, which offers a surreal, mise en abyme quality. “I wanted to push further into loosening the boundaries of photographic presentation,” Mitchell says. “It’s not just about pushing against what a photograph can do, it’s also expanding into what stories a photograph can tell through gesture, through poetic shape.” Other fabric-based photographs are draped over open frames and installed on the wall, an homage to David Hammons’s mixed-media paintings that stage a refusal by blocking visual elements, thereby inciting all the more intrigue.

Domestic Imaginaries also contains several works, commissioned by the SCAD Museum of Art, fabricated in Georgia cherry and walnut, and modeled after objects Mitchell found in antique shops or through his research about midcentury Black domestic life. Some of these “altars” contain books of literature, sociology, poetry, and photography by artists including William Eggleston and Baldwin Lee. The spines or covers are visible through glass windows, in the way that precious heirlooms might be displayed in a home, while some panes are covered by Mitchell’s own photographs, printed on glass. One altar, a hexagonal tower, seems to ask the viewer to move continuously round and round, absorbing all the words and references at new vantage points. And as the seasons change, the arc of the sun will cast varying degrees of light throughout the exhibition, making each encounter a new one. In the conversation that follows, Mitchell speaks about these themes with Daniel S. Palmer, chief curator at the SCAD Museum of Art, and how Domestic Imaginaries is an exhibition that should be experienced “holistically.” —Brendan Embser

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023Daniel S. Palmer: Domestic Imaginaries is your most ambitious exhibition to date and your first solo exhibition in your home state. Maybe we should start off talking a bit about your upbringing—and the influence of Georgia on your artistic outlook?

Tyler Mitchell: My work has been informed by narratives of how Black life connects to nature and to the outdoors. This exhibition heightens that to a new degree, I would say. Being from suburban Atlanta, I reflect a lot on the sheer amount of nature that surrounded me in my upbringing. Atlanta has the most amount of nature in any American city. I like the idea of making images that offer an expanded lens of where Black life can reside. I don’t think that we immediately, in terms of the wider culture of images of Black people, think of Black life as being tied to nature in a deeply leisurely way. I think we’re constantly bombarded with other kinds of images. So, my work tries to center that as a place for meditative repose and leisure, as well as joy.

Domestic Imaginaries frames these ideas as an installation and invites the viewer to go on a journey through proverbial domestic space, from the outdoors, which is signified by laundry lines—the photographs hung on diaphanous fabrics in the gallery—to the altar sculptures, which reference historical furniture and place. I situate my own photography inside the sculptures.

Palmer: That leads perfectly to a discussion about the gallery within the museum where your work is exhibited, which we call the Pamela Elaine Poetter Gallery. It is a unique and large-scale space that is about three hundred feet long. One side is all windows out to the museum’s courtyard, and the other side is a wall of historic Savannah-gray brick. It’s a very impressive space but also a challenging space for a lot of artists. I think you approached it so brilliantly. What did you think about the space when you first came to the SCAD Museum of Art to consider doing a show?

Mitchell: I visited SCAD a little over a year and a half ago, initially for an “in conversation” with Antwaun Sargent. And then I saw the museum, and I was very impressed with the spaces. The Poetter Gallery is the only daylit space in the museum. When you told me that the museum is situated in what was the oldest train station in Savannah, Georgia, and in that gallery you could see the arches of the Savannah-gray brick, where the train would pull up and where cargo was moved, immediately there was this flood of historical imagery that came into my mind. It became a space I was inspired by physically but also historically. And the idea of situating my work against that backdrop created for a really powerful conversation. You think about the idea that the bricks were themselves laid by formerly enslaved people, that Savannah is a city that is still alive with its complicated and sometimes horrible history—all of that plays a role in this work. In many different ways, my work is about striving for self-determination, for agency, for empowerment and joy against the backdrop of history.

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory (detail), 2023

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory (detail), 2023Palmer: Then the question of what we would do in this space arose. You approached that by making your most ambitious laundry-line work to date. How did the laundry line as a series begin? And how did it evolve for this installation?

Mitchell: The initial idea started over three years ago, when I was invited to do an exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York, which was curated by Isolde Brielmaier. There was a very unique space that I was given, which was a long and very narrow hallway, about sixty feet long. It suddenly felt inappropriate to hang framed works in that hallway. The viewer might breeze past them or might not be able to properly engage with them at different distances. It was actually an idea borne out of a need, a very functional need for what was going to happen in that space. I’ve always been interested in playing with ideas of photographic presentation in a gallery space, but it was there that I thought to make my first laundry-line installation. It included six years of my portraits across both commissioned and personal work.

This iteration, expanded for Domestic Imaginaries, is a marriage of form and content. These new images in the laundry line think more deeply about textile and fabric not just as a presentation or aesthetic choice, but as a formal and conceptual choice. I’m thinking about how textile contains cultural and material significance. I’m thinking about how fabric plays a role within the home, how it can contain memory, physically and literally, by being worn, by being engaged with as lives, as sheets, as towels—how those things play a functional role in our everyday lives. In the images themselves there are figures silhouetted or masked or partially hidden by fabrics blowing in the wind. Fabric is literally in motion and interacting with the young Black men and women that I photographed.

Related Items

The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 241

Shop Now[image error]Palmer: Since the gallery space can be navigated in two directions—there is not a formal front or back—the exhibition has created an environment for people to navigate and explore. Then your images have this trompe l’oeil dimension to them, where you see a picture of somebody behind fabric as well as laundry lines and clothespins in the image, but you also see the physical laundry lines and clothespins that are actually hanging the work in the gallery. Can you share a bit about the kinds of scenes you were setting—and how you chose the different types of fabric that certain images were printed and displayed on?

Mitchell: It was a very intuitive process. I’m interested in wanting to disrupt the formality of the framed photograph. I’m interested in making dynamic experiences with my work, which comes about through sculpture and installation. And that while I’m committed to the photographic image as an object, I’m also committed to expanding on notions of what that can be. The photographs themselves continue a lot of the scene-making that I do in my other work, my portrait work, which features young Black men and women, who I usually cast, whether they’re young artists, whether they’re friends of friends, whether they are models that have appeared in fashion projects that I’ve done before. They are the “protagonists,” as I call them. We have a day together, in which we make these images, in which real moments of leisure are experienced, real moments of community are experienced, and real moments of togetherness are had. Usually, when I’m making my work, I allow for a looseness and collaboration with my sitters. In one image you see two young men silhouetted lifting up or unveiling or revealing or concealing themselves behind fabric. You see a young girl posing in front of a fabric that’s blowing up against her back in the wind. And you almost feel the wind or that joy yourself as the viewer. And that’s the goal of the work.

Tyler Mitchell, Longing for a Future, 2023. Dye-sublimation print on fabric with walnut frame

Tyler Mitchell, Longing for a Future, 2023. Dye-sublimation print on fabric with walnut frame  Tyler Mitchell, Altar VI (Urn) (detail), 2023. Cherry wood, UV print on glass, glass, ephemera

Tyler Mitchell, Altar VI (Urn) (detail), 2023. Cherry wood, UV print on glass, glass, ephemera Palmer: The other central aspect of this exhibition is the series of altar works that you made—the sculptural pieces that reference historic furniture and evoke domestic spaces. This feels like another point of connection. How did these altar works come about for you? Why did you think it was an important element to incorporate?

Mitchell: Throughout the past few years, I’ve been thinking about the essential power in how we dress everyday spaces like our homes. The gesture of framing and displaying a photograph of a loved one can be a very simple or ordinary act, but one that shows true and high admiration. The home is the most important public-private gallery in the world. It’s where you invite those close to you, or guests, to come and see how you live, and oftentimes at the center of that is photography.

In 2019 I was named a Gordon Parks Foundation Fellow, which culminated in a solo exhibition at the Foundation’s gallery space in upstate New York in 2021. At that point in time, I don’t think I had been home to Atlanta in over eighteen months due to the various COVID-19 lockdowns, and having been distanced from my roots for so long, only then was I starting to think about making work that really considered how those years were formative to me. So I made, first, a work that’s called The Grand Sofa, which is a custom-fabricated sofa which features my photographs of a Haitian family in New York embedded into the upholstery. I started to think about these domestic objects as containing within themselves very important visual memories and moments. That’s where these altar sculptures emerged from. And they also fused my own love and compulsive obsession with collecting photobooks. Some of the works include books from my own personal library and studio—Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life; Robin Coste Lewis’s To the Realization of Perfect Helplessness; and even Blu-ray DVDs like To Sleep with Anger, directed by Charles Burnett. Those books and DVDs are repositories of knowledge, and they come together to string a sentence about the makeup of my own artistic practice, and about image-makers, writers, and thinkers that have come before me that I would like to keep with me.

Installation view of Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, 2023

Installation view of Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, 2023Palmer: You’ve also embedded images in these altar works. Your own images that you’ve taken and printed on metal or glass, but you’ve also included smaller, postcard-like reference images. Between those tipped-in images, the books, and the DVDs, I feel like this is a wonderful annotation of all your artistic inspiration.

Mitchell: Exactly.

Palmer: To many people, you’re known as a commercial photographer whose images grace the covers of magazines or fashion photography spreads. But, I think that this exhibition is so important in showing that you are an art photographer too. Not just an art photographer, but also a major innovator in the field of fine art, that you are pushing photography beyond the bounds of the printed, framed photograph. The final element in the show is the group of three “relief” works which each have a walnut frame mounted on the wall with an image printed on fabric draped over them. This really feels to me like a thesis in innovation in photography.

Mitchell: That’s a very high compliment. And I can only hope to continue to push in all those ways. I like to think of myself as someone who is pushing the boundaries of categorization in general, be it fashion or art. I’m thankful to have done that with this exhibition. It has been such a beautiful journey to find a community initially as solely a fashion photographer, to find, I would say, a purpose. I enjoy communicating visually about personhood by way of style and by way of clothing. And I was also a student under the tutelage of Deborah Willis, taking classes like Black Body and the Lens at NYU, where I found a way to marry my own concerns, questions, explorations about identity—my own identity and the identity of other young Black people around me, my contemporaries—into this work.

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023

Tyler Mitchell, Threads of Memory, 2023All images courtesy the artist, SCAD, and Jack Shainman Gallery

Palmer: Domestic Imaginaries is on view here at SCAD, at a teaching museum. I wonder if we could wrap by asking if you have any advice for the students here at the university, and young artists generally. What do you hope to impart with this exhibition?

Mitchell: One element that I really enjoy talking about with this exhibition, and what I hope could potentially inspire others, is the emphasis of humanism in the work. The word humanism has been thrown around quite a lot in wider discourse, but to me it’s really a certain striving for moments of personal and unencumbered joy or happiness and whatever that may look like, especially, I have to say, in these anxiety-ridden times. Hopefully the work encourages young people in general, but especially young artists, to make work that is about their own interiority, and their own visualizations of joy.

Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries is on view at the SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, through December 31, 2023.

November 2, 2023

What Was the NFT?

In the winter of 2021, it was hard not to suspect that the world had produced a wholly novel lament. That December, the art dealer Todd Kramer took to Twitter and cried out: “All my apes gone.”

The apes in question—for those who were not terminally online during that phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, were not the majestic beasts that have fascinated primatologists like Jane Goodall and Frans de Waal (though those, too, are in danger of being gone). Rather, Kramer was referring to his collection of Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) non-fungible tokens, or NFTs, which had been stolen from him by an enterprising hacker. (NFTs are unique digital objects that have been indelibly recorded on the blockchain, a decentralized ledger that is the backbone of all cryptocurrency and digital collectible transactions.) Part of a collection of ten thousand unique cartoon chimps, whose faces sport lackadaisical pouts and yawns, smug grimaces and manic grins, and who come with a dizzying array of clothes and accessories that are randomly combined to create a chucked-in-a-blender mélange of looks, Kramer’s band of apes were then worth an eye-watering $2.2 million.

This was during the heady days of the 2021 NFT frenzy, when fortunes were made and lost and sometimes made again in mere days. Everyone, it seemed—celebrities, fly-by-night financial wizards, credulous day traders—was thirsting for a piece of the lucrative market in monkey JPEGs. (Collectors are currently suing several bold-faced names, including the late-night host Jimmy Fallon and the pop star Justin Bieber, along with the auction house Sotheby’s, for allegedly promoting the project “misleadingly” and colluding with BAYC creator Yuga Labs to artificially inflate prices.)

It wasn’t just Bored Apes. People clamored for CryptoPunks, Doodles, Cool Cats, Azukis, Pudgy Penguins, and more. Buyers snapped up so-called “generative-art” projects—collections of related yet subtly unique images made by creatively coded algorithms—like Tyler Hobbs’s Fidenza and Erick Calderon’s Chromie Squiggles. Blue-chip artists like Jeff Koons, Urs Fisher, Takashi Murakami, and Damien Hirst jumped on the bandwagon. New collectors flush with crypto cash swooped in and transformed the lives of previously unknown artists with the click of a button. Who could forget the meteoric rise of Beeple (aka Mike Winkelmann), whose massive NFT collage Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021) sold at Christie’s for $69 million? Once the fire hose of money got turned on, it seemed like anyone could have a drink.

During the hype, photographers were eager to join the NFT circus too. Outside of digitally native art like Bored Apes, whose commercialization and monetization via NFTs was something of a no-brainer, photography was the medium most ripe for an NFT crossover. After all, most photographs are consumed through screens now. Why not sell them that way too?

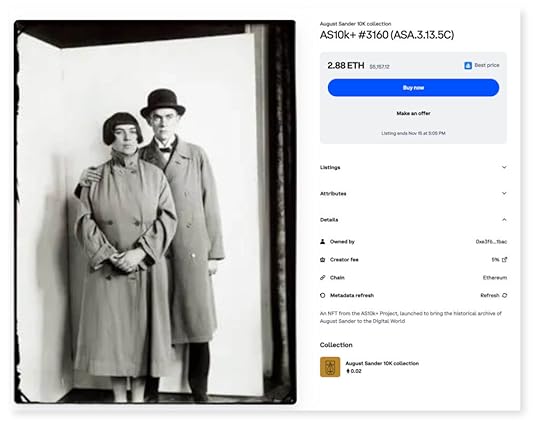

Screenshot of the Coinbase page hosting the “August Sander 10K” collection. “By engaging in the collection of Contact Sheets of Sander’s work,” the marketing copy reads, “you become a part of the history of this groundbreaking body of photography.”

Screenshot of the Coinbase page hosting the “August Sander 10K” collection. “By engaging in the collection of Contact Sheets of Sander’s work,” the marketing copy reads, “you become a part of the history of this groundbreaking body of photography.”Photography’s push into the cryptosphere saw prominent artists—Joel Sternfeld, Gregory Crewdson, Alec Soth, Joel Meyerowitz, and others—dig into their archives to unearth unseen pictures, whether to tokenize ephemera such as production stills or release older projects in NFT form. There was even an attempt by Julian Sander, the great-grandson of August Sander, to enshrine the entirety of the eminent photographer’s output—over ten thousand photographs in all—as a collection of NFTs, which has resulted in an ongoing legal battle. Others, like Justin Aversano, whose lackluster project Twin Flames (2017–18) gained a baffling amount of market momentum, became overnight sensations. Perhaps these photographers were motivated by a true interest in the blockchain’s brave new world. But most, I suspect, were seduced by the opportunity for a quick cash injection.

Unlike the market for painting and sculpture, which has come roaring back after the 2008 crash, the market for photography has recently been in a bit of a slump. (This remains the case despite the notable efforts of the fledgling photography-focused art fair Photofairs New York, and a smattering of recent expectation-defying auction prices fetched by significant historical works like Man Ray’s 1924 Le Violon d’Ingres, which sold last year for a record-breaking $12.4 million at Christie’s.) Collectors, it seems, have lost some of their taste for photographic prints. At the same time, economic headwinds for photographers have been picking up: the cost of producing and framing a photograph, which has always taken a bite out of photographers’ comparatively thin profit margins, has been pushed ever higher; teaching jobs have become simultaneously more competitive and lower paid; lucrative commercial work looks increasingly threatened by artificial intelligence. No wonder so many photographers jumped at the chance to make NFTs. It was one of the few places where the money was.

The mere idea of photography being bought and sold as an NFT is likely to raise the hackles of connoisseurs of fine photographic prints and other members of the photo world’s old guard.

The crypto crowd is fond of pithy mantras. Those who didn’t believe the hype were told to “have fun staying poor.” When speculators are asked about the rationale for purchasing a particular NFT or altcoin (the catchall term for non-Bitcoin cryptocurrency), they might respond simply, “Because number go up”—a line that provided the journalist Zeke Faux with the title for his recent book Number Go Up: Inside Crypto’s Wild Rise and Staggering Fall. But numbers can’t go up forever. In 2022, the prices of both cryptocurrencies and NFTs spectacularly collapsed, immolating untold amounts of wealth and leading most sane people to strongly question the wisdom of spending sums more commonly associated with the purchase of, say, a Learjet or a chalet in Gstaad.

Now, as we survey the rubble, the landscape appears bleak. At the market’s peak in January 2022, global sales of NFTs reached $5.7 billion dollars, according to DappRadar; by May 2023, that number had dwindled to $675 million, a decrease just shy of ninety percent. The biggest NFT sales event of this year so far, a Sotheby’s auction entitled “Grails: Property from an Iconic Digital Art Collection Part II,” pulled in a respectable haul just under $11 million. But it was tainted by the fact that it was organized by an advisory firm handling the liquidation of disgraced crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, which made the event feel less like a white-glove evening sale than like a police auction. Recent analysis by dappGambl, a crypto-gambling and gaming-analysis website, concluded that 95 percent of all NFT collections are now effectively worthless.

Related Items

How Will AI Transform Photography?

Learn More[image error]

Do Blue-Chip Photographers Prop up Global Capitalism?

Learn More[image error]Galleries that had dived headfirst into the NFT space, like Galerie Nagel Draxler in Germany, appear to have either stopped their crypto-based programming entirely, or radically throttled it. Last summer, Takashi Murakami issued a public apology after his Murakami.Flowers NFT collection experienced a spectacular peak-to-trough price collapse of 99.2 percent. And after the bottle-popping, Lambo-flexing, NFT hypefest that was Art Basel Miami Beach 2021 and the calculated pomp of Art Dubai Digital 2022—during the boom, the UAE emerged as the premier tax haven for the crypto rich—the new art-market trend seems to be a reversion to the safest bet for minting money: painting, painting, painting.

Nevertheless, some have kept the hope alive. Kenny Schachter, an artist, collector, and prolific arts journalist, has emerged as one of the foremost cheerleaders of NFTs. During the boom, he wrote incessantly about them in his regular column in Artnet and extolled their virtues to his legions of Instagram followers. He also made and sold them, both through traditional galleries and online NFT marketplaces like Nifty Gateway. (His first round of sales, he tells me, netted him three hundred thousand dollars.) Famously, he even had the name of his one-man art movement, “NFTism,” tattooed on his arm. After the market crashed, he amended it to read “post-NFTism.”

Schachter believes that the NFT space is “in the healthiest, most beautiful place it’s ever been.” Indeed, he sees this moment in NFT history as an echo of the art world of the 1990s. “When I started out in the art world, there was a recession where the market didn’t constrict, it all but evaporated,” he tells me. In his mind, the implosion of the market brought with it a kind of cleansing fire, burning away the dross. “A lot of the adult population, when it comes to making money in crypto, is reduced to infants,” he says. “They’re like limited-edition tchotchke thingies that you can buy and sell with your friends, like baseball cards for rich people.”

Absent this kind of speculative buffoonery, real creativity and community will be allowed to flourish, he assures me. Schachter and others I talked to were particularly keen to emphasize the communal aspect of the NFT scene, where virtual camaraderie on Discord has taken the place of boozy exhibition openings, and direct access to artists is assumed to be part of the package, rather than the exclusive privilege of, say, those who get invited to the gallery dinner. “Art is a means of self-expression, and a crucial conduit to relate to other people,” Schachter says. “I can’t imagine anyone who ever made art with a digital inclination before the collapse stopped doing so then.”

Installation view of Collecting the Future: Photography and Generative Art on the Blockchain, Assembly, Houston, 2023. Left to right: works by Klea McKenna, Matt DesLauriers, Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Penelope Umbrico, Daniel Gordon, and ArandaLasch. Photograph by Peter Molick

Installation view of Collecting the Future: Photography and Generative Art on the Blockchain, Assembly, Houston, 2023. Left to right: works by Klea McKenna, Matt DesLauriers, Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs, Penelope Umbrico, Daniel Gordon, and ArandaLasch. Photograph by Peter MolickCourtesy Assembly

Shane Lavalette, a photographer who is also the former director of Light Work and founding director of Assembly, a gallery focused primarily on photography and video in Houston, and Assembly Curated, which he calls the “first curated fine-art photography NFT platform,” would tend to agree. “In terms of a longer timeline, I feel like we are still very early in the emergence of a technology,” he tells me. “Digital collecting is not going to be something that’s less a part of our lives as we go forward, it’s going to be more a part of our lives. And the technology that was introduced makes that very easy when it comes to the things that we need to create and collect digitally, which is authenticity and ownership and provenance.” Notably, Lavalette also points to the usefulness of NFTs for securing royalties for artists when their work, whether digital or physical, is resold on the secondary market, a transaction that can be coded into an NFT’s smart contract, which is a computer program written into the blockchain that is designed to execute automatically. (After a 2018 ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco struck down the California Resale Royalty Act, artists are no longer entitled to receive royalties on the resale of their artwork anywhere in the US.)

The mere idea of photography being bought and sold as an NFT is likely to raise the hackles of connoisseurs of fine photographic prints and other members of the photo world’s old guard, but Lavalette sees the development as part of a continuum that stretches back to the medium’s origins. “I think the medium of photography has been intrinsically linked to technology since its beginnings,” he says. “And we’ve seen all of these moments with, you know, the emergence of digital photography, people rejecting that as actually being photography, and then ten or fifteen years later, those same people shooting with a digital camera and it not being a question.” But Lavalette doesn’t assume that NFTs will supplant old modes of photographic distribution and display. “Yeah, I definitely think of it more as an addition,” he says. “And photography is a medium that is well suited to existing in many forms.” As for the question of the NFT’s appeal over more traditional forms of collecting photography, Lavalette admits that sometimes it’s the draw of a hot new technology, while other times it comes down to more practical concerns: “As a collector, you can, in a way that’s actually very efficient, kind of have a stake in an artist’s cultural capital. And, that’s something that’s not going to appeal to everyone, right? For people who it does appeal to, it’s extremely exciting, because you don’t need storage space.”

It seems clear that even after the market apocalypse, artists will continue to mint NFTs and collectors will keep collecting them (though in what quantities is still anyone’s guess). But a fundamental question, which seemed to be lost on everyone during the hype cycle, remained unanswered for me: Is the NFT actually a medium, or merely a medium of exchange?

Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #11, 2011–12. Cartagena’s photograph was later issued as an NFT.

Alejandro Cartagena, Carpoolers #11, 2011–12. Cartagena’s photograph was later issued as an NFT.Courtesy the artist

For an answer on the photography front, I turned to Alejandro Cartagena, an artist, publisher, and infectiously enthusiastic NFT advocate who has cofounded two photography NFT platforms: Obscura, where he is currently an advisor, and Fellowship, where he now works full time. Cartagena began by turning my question around, asserting that photography is a medium that has an ambivalent relationship to its materiality in the first place. “As a commissioned artist,” he tells me, “I get sent by the New York Times to do pictures, and I send them back ten JPEGs. They send me digital money for those JPEGs. So in in essence, I’ve been selling NFTs for quite a while. It’s just that we didn’t call them NFTs.” There is nothing inherent in a photograph that dictates the fine-art print must be its final—collectible—form. Once a photograph is taken, it becomes a kind of wandering image, in search of a home. So, in a digital world, why couldn’t that home be the blockchain? “Maybe we’re ready to think of photography as this unsettling medium that doesn’t have a native thing for it,” Cartagena says.

Cartagena did acknowledge, however, that photographers were not taking advantage of the expanded possibilities of digital distribution nearly enough. This is something he and his cofounders at Fellowship are looking to remedy. One project he described, which strikes me as truly novel, is a collaboration with the photographer Joel Meyerowitz, called Sequels. To make it, Meyerowitz arranged 3,650 previously unseen images from his six-decade archive into a preposterously long, playfully associative sequence. With the help of a custom smart contract, Fellowship is currently in the process of minting one of the images in this sequence per day and putting it up for auction, so that collectors can, it is hoped, not buy only individual images but smaller subsequences of photographs from the larger whole. The minting process of the entire sequence will take a decade, making it something like the miniature visual equivalent of a concept-driven long-haul composition like John Cage’s Organ2/ASLSP (As Slow as Possible), a performance of which is currently underway in Germany and is slated to last another six centuries.

But such projects are still few and far between. When I talked to Brian Droitcour, the editor in chief of the high-toned fine-art NFT platform Outland, he described a few NFT projects for which custom-designed smart contracts were fundamental to the work itself but generally took a more utilitarian view. “I think their main use is just as an editioning technology for digital art,” he tells me. “A lot of people in the art world say they hate the phrase ‘NFT art,’” he adds, “because it doesn’t really refer to the medium in the way that talking about, like, video art does. But it’s about the social and economic environment in which that art circulates. Think of it as an analog to, say, something like ‘contemporary art,’ which doesn’t really say a lot about the work, but it does put it in this field of museums and galleries, and art magazines and art schools, and sets it apart from people who are just painting landscapes.” In other words, NFT art is not a medium, it’s a milieu.

How, then, can we sum up the NFT milieu, at this point in its young life? It was, on the whole, a reflection of the culture at large, which increasingly rests on the cornerstones of greed and grift. (It is not a coincidence that quadruply indicted former president Donald Trump, avatar of these particular vices, issued his own collection of NFTs after leaving office.) It was also, like the crypto boom more generally, fueled by desperation. Vast numbers of people hoped that they, too, could flip enough monkey JPEGs or Dogecoin or what have you to have a chance at a comfortable, dignified life, as the writer Sarah Resnick brilliantly chronicled last year in an essay for n+1, entitled “Walk Away like a Boss.”

For all its unseemliness, excitement generated by NFTs produced a little bit of good too. “Regardless of what happens to the market,” Tina Rivers Ryan, a curator at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum who specializes in digital art, tells me, “it’s gratifying to know that at the very least, NFTs appear to have helped broaden the audience for digital art within the mainstream contemporary art world in the long term, and that some artists were able to reap benefits in the short term.” As for the great mass of people who were convinced that they were buying into the next great revolution in art? Well, most of them got stuck holding the bag.

October 30, 2023

How Can Photobooks Expand the Canon?

Gregory and Rachel Barker founded their photobook publishing house, Stanley/Barker, based in Shropshire in the West Midlands of England, in 2014. Their first publication, Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 (2014), sequenced the photographer’s unpublished portfolio as a one-night journey into the depths of perhaps the most mythical nightclub ever. Stanley and Barker, who studied photography and art in London, and who are now both in their midthirties, have since published monographs by lesser-known but nonetheless formidable photographers, reviving interest in Mimi Plumb, Judith Black, and Jack Lueders-Booth. Superb black-and-white reproductions and narrative structure have become hallmarks of the Stanley/Barker approach, as well as a sensitivity to the look and feel of a publication held in the hand.

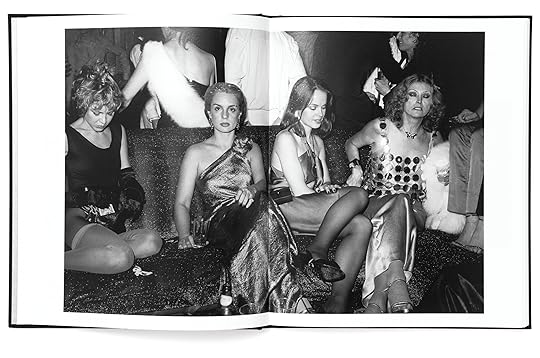

Spread from Tod Papageorge, Studio 54, 2014

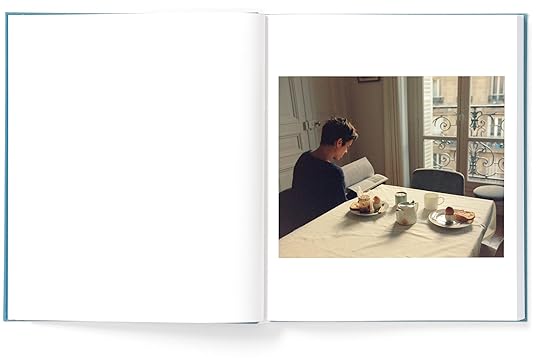

Spread from Tod Papageorge, Studio 54, 2014  Spread from Christopher Anderson, Marion, 2022

Spread from Christopher Anderson, Marion, 2022 Alistair: First off, could you tell me how you both got into publishing?

Rachel Barker: Greg studied photography, and I studied fine art. Then we met at Blurb, the print-on-demand book company.

Gregory Barker: It was quite fortuitous. We had both graduated and gone to work at probably the worst place to work when you’re interested in publishing. But it was 2009, the very start of the golden age of photobooks. We ran a book fair together called Photo Book London, which was the first photobook event in London. But we did it only once. Then, we spent the next three years looking for our first project, because we had a very clear idea of what we thought a photobook could be.

In 2013, we went to Paris Photo and saw Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 images as a wall at Galerie Thomas Zander, and then we spent the next six months convincing Tod and Thomas to let two twenty-five-year-olds who had no prior experience publish a book about it.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Alistair: And now, a decade later, following the pandemic and other changes, how would you describe the photobook market in 2023?

Gregory: It’s returning.

Rachel: It can change rapidly, and we keep our eye on it constantly. With the decisions we make and the books we choose to publish, we have to be sure that in the current market there is an audience for a book and that we are going to be able to sell it. We’re just gearing up for the spring 2023 release of Trent Parke’s new book, Monument, and it’s one of our biggest presellers ever. People are really excited about it. So, that’s a signifier that there is still a real energy around photography and photobooks and buying them and printing them.

Gregory: We’ve always seen our role in the publishing community as righting the wrongs of our forebears in terms of finding these projects that should have been books, but they didn’t quite get the attention they deserved. We’ve always thought that we need to make books that people actually want to buy and are important books that need to exist.

Trent Parke, from Monument, 2023

Trent Parke, from Monument, 2023  Trent Parke, from Monument, 2023

Trent Parke, from Monument, 2023 Alistair: So as much as they are reassessments, they are also contributions to the canon?

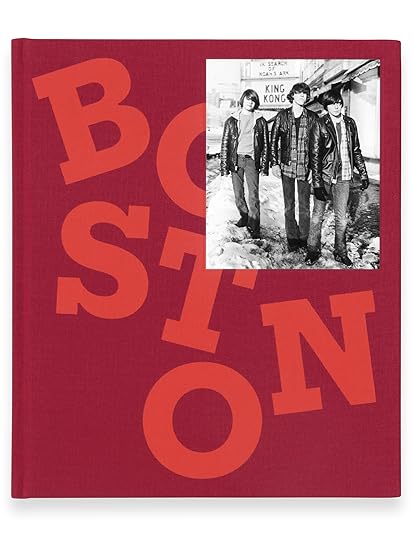

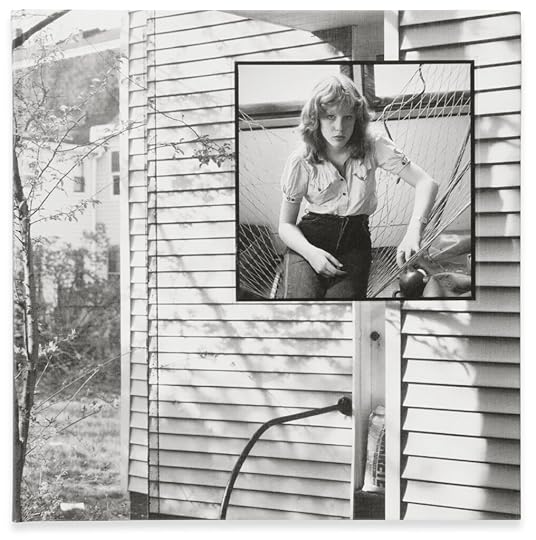

Gregory: Yes, finding where those holes are that shouldn’t exist. We do a lot of work with people who were in Massachusetts and the surrounding states in the 1970s, such as Sage Sohier, Mark Steinmetz, Sergio Purtell, Susan Kandel, Paul McDonough, Mike Smith, Joan Albert, Henry Horenstein, Jack Lueders-Booth, and Katherine Turczan. There was such a movement of female artists making incredible images. And for some reason, it didn’t quite take off at that time. It’s really bizarre. We’ve been quite fortunate to be able, as you say, to reassess the canon and put that important moment back in place.

Alistair: How do you conceive a photobook?

Gregory: For us, the bookmaking process is always about being as collaborative as possible. It’s definitely a three-way collaboration between the artist, us, and the designer. We’re always trying to take the artist’s work and present it in a way that allows the viewer to have the greatest depth of understanding. We don’t want the book to be our taste. We want it to be an extension of the content.

Photographers spent so long making these bodies of photographs—they devoted twenty to thirty years of their lives. So, it’s important that the physical object have as much attention to craft and design as possible. But having said that, we keep the insides of our books very simple. Once you get past the title page, what follows are clear, beautifully rendered prints of the photographer’s work, because at that point, we’re in their headspace. Everything coming before is trying to put the reader in the space where they can appreciate the photographs to the best, fullest extent.

Mimi Plumb, from Megalith Still, 2023

Mimi Plumb, from Megalith Still, 2023

Alistair: You mentioned that you’re very motivated by the principle of narrative.

Rachel: Yeah. Probably the book that really inspired what we do was Watabe Yukichi’s A Criminal Investigation from 2011. When we both looked through it, we were just so blown away—it is so elegant and simply done. But the detail in it is just amazing, in terms of the points at which it makes you think about the journey you’re going on, and the references, such as the typewriter font and the band around it, make the book feel like a criminal dossier.

Gregory: The sequencing.

Rachel: The sequencing, yes. You’re following this sort of investigation. It’s a story. It’s like a novel but visual.

We took a lot from that book and put those ideas into our publications. Looking at the Mark Steinmetz books that we publish; Carnival (2019) follows a day at the carnival. When you’re looking through its sequence, we take you right from the start, arriving at the carnival, through enjoying the carnival, to the end, when the daylight fades, and the lights of the carnival come on. It’s really simple, but it’s a pleasurable experience, hopefully, for whoever buys the book and looks through it. They’re taken on that journey.

Gregory: There’s nothing more boring than “this looks like that.” In sequencing, people so often think, Oh, there’s a picture of a ball. And then on the next page, There’s a picture of a moon. That really takes you out of experiencing the pictures. Instead, it puts you into a space of trying to find how someone has linked things visually. Whereas we’re always trying to get back to—no one talks about it in reviews or anything anymore—the emotional experience of looking through a body of work. We’re trying to get people away from looking at pictures and toward experiencing looking at pictures. If we can give them something very direct, like a journey that they’re going to go on, once the brain cops on to this very simple idea, you’re no longer looking at the sequence. You’re experiencing the pictures and the flow of pictures. That’s not to say we don’t do conceptual editing. We’ve just edited a Mimi Plumb book, and it’s sequenced to the Zen story of the ten ox-herding pictures, like the journey to enlightenment. It was a really interesting way for us to edit a book.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

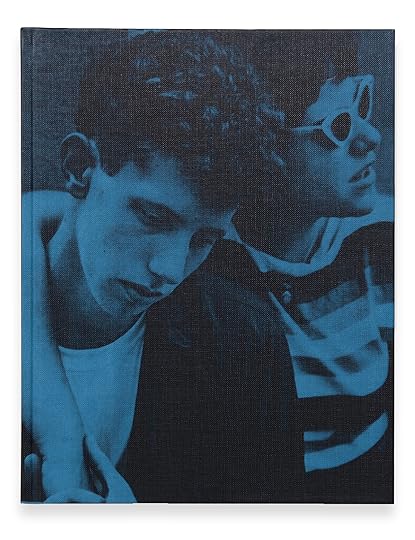

Cover of Dave Heath, Washington Square, 2016

Cover of Dave Heath, Washington Square, 2016  Cover of Mike Smith, Streets of Boston, 2021

Cover of Mike Smith, Streets of Boston, 2021 Alistair: Journey is a really good word to describe it, because it’s almost as if the journey you take the reader on is slightly different from, perhaps, the journey that the photographer’s portfolio established. Do you think that’s a fair distinction?

Rachel: Yeah, I guess. Sometimes the photographer trusts us with their work, and the sequence we put together perhaps isn’t what they brought to us in the first place. I mean, even looking at Studio 54, I’m not sure Tod Papageorge ever thought about those images in that sequence—of coming to the nightclub, and then in the middle of the book, you’ve got the buildup to the real crescendo of the party in full swing, and then you see, as it kind of peters out in the last pages, people lying around on the floor, they’ve had too much to drink, they’re too tired, and then it ends.

Gregory: He didn’t have the idea, but he did do forty PDFs of the sequence. We were incredibly fortunate that with the early photographers we published—Tod Papageorge, Bill Henson, Larry Fink, Karen Knorr—it’s like having a master class every time you work with one of these people.

Cover of Judith Black, Pleasant Street, 2020

Cover of Judith Black, Pleasant Street, 2020Alistair: Why do you think sequencing is not up for discussion in the critique of photobooks? What do you think the critique is more attentive to?

Gregory: I think it’s because it’s harder to talk about your emotional response to art. It’s a really difficult thing to do well in any way that means anything to anyone else. Ten people can look at a book and have ten different emotional responses.

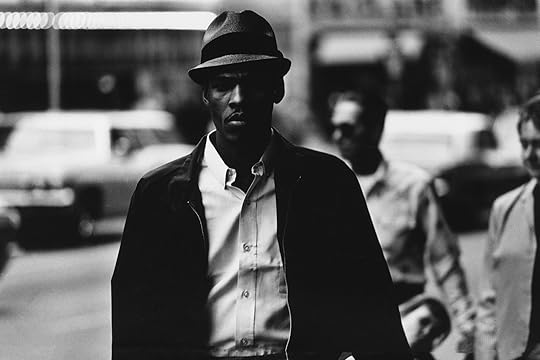

Dave Heath’s work—we’ve published two of his books, One Brief Moment (2022) and Washington Square (2016)—is people walking along a street, and there’s nothing inherently emotionally driven about a street scene. But the way he captures skin and light has such an emotional resonance; it’s almost impossible to say how that works. It’s like the Minor White quote about looking at photographs to see what else they are, which is difficult and kind of nonsensical at the same time. But that’s what’s special about it. We always look for books that are two things. So, to one extent, Dave Heath’s books show street scenes; someone who’s not interested in photography can totally understand these are pictures on the East Coast in 1967. But someone who’s interested in our world can look at them and see unfathomable depths of beauty and sadness.

Dave Heath, from One Brief Moment, 2023

Dave Heath, from One Brief Moment, 2023  Dave Heath, from One Brief Moment, 2023

Dave Heath, from One Brief Moment, 2023All photographs courtesy Stanley/Barker

Alistair: It’s also about a kind of metropolitan life, a kind of interaction with other human beings that doesn’t really exist anymore. It’s gone. Washington Square is not like that anymore. As we see in some of these portfolios, there is a sense of loss articulated in the act of looking back and trying to reappraise the canon.

One last question. You’ve got a lot of books piled behind you, and I don’t think they’re all published by you. So, you enjoy collecting books yourself, I presume? How do you buy books today?

Gregory: More often than not, the books we buy now are bad books of good photography. Because the type of photography that we love generally wasn’t made into beautiful books, since it’s from an earlier time period. We tend to buy a lot, just because you see one picture by someone, maybe scrolling through a museum’s archive pages, and you think, I bet there’s more there, there’s got to be more, there’s a whole series there. So you buy the book to see, and then you realize there is just that one picture. But then, you’ve got the book.

Rachel: We come back with a lot of books from events as well. We’ll always go in and have a look at other book stands and end up buying more than we need.

Gregory: Yeah, and the bookshelves fill up, and then other rooms get filled with books.

Alistair: It’s a terrible problem of modern life. It’s not the bookcases you have, it’s the book towers at the side of them.

Gregory: If a fire marshal came in, they’d just say, “Oh, what are you doing? There’s kindling everywhere.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra,” in The PhotoBook Review.

October 27, 2023

The Creative Power of Barbara Ess

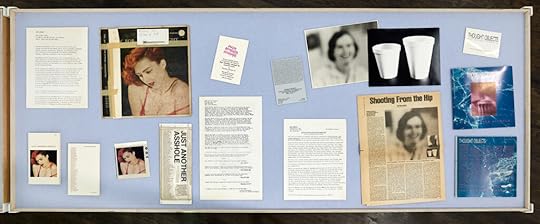

Toward the back of White Columns’s outstanding recent exhibition Barbara Ess – Archives—past the photo of a baby whose chimerical eyes interrupt an otherwise glazed expression, past flyers advertising outrageously stacked lineups of bands at legendary New York City clubs—two typed white pages hang on a wall. Each is undated. Each is titled, in capital letters, STATEMENT. The one on the right begins with a one-line paragraph: “The natural subject of photography is voyeurism.” The one on the left repeats the same thing. Except, in Ess’s red pencil, a spiral almost closes itself around the word voyeurism. A circle fully traps the word natural, which Ess also pencils within quotation marks. Another red line leashes it to a large question mark.

Installation view of Barbara Ess – Archive, White Columns, New York, 2023

Installation view of Barbara Ess – Archive, White Columns, New York, 2023Words like natural and voyeurism seem germane to the life and work of Barbara Ess. Before her death in 2021, she played a crucial role in establishing downtown Manhattan as both scene and a style. In an ecosystem of big lofts, low rent, and high ambitions, Ess blossomed. That’s her in those band posters; in the feminist trio Y Pants, she and the artist Virginia Piersol and the filmmaker Gail Vachon played Mickey Mouse drum kits and kiddie-size pianos for what was fittingly advertised as “amplified toy rock,” at CBGB and the epochal 1981 Noise Fest—a nine-day marathon at White Columns’s previous location on Spring Street, organized by Thurston Moore in part to debut his new band, Sonic Youth. Ess kept excellent binders of this ephemera and asked the writer and curator Kirby Gookin to hold a parallel, backup archive.

Detail of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023

Detail of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023The Archives exhibition pins the contents of those binders to the gallery’s walls, which, after all, are flyers’ natural habitat. Certain kinds of people built certain kinds of lives assessing these kinds of layered invitations; the walls of bars were social calendars. Walking past their recreations, I wonder if I would have been invited, would have gone, would have met someone and lost them. At the entrances of the kind of record store that would sell Y Pants’ music, flyers used to pile up like Félix González-Torres mounds, never seeming to lose their mass as if they were themselves alive. All this ephemeral is melancholic. I’m grateful it survived. And I feel I’m somehow eavesdropping.

Details of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023

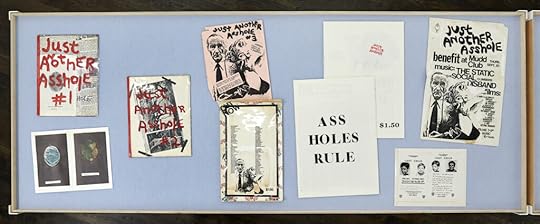

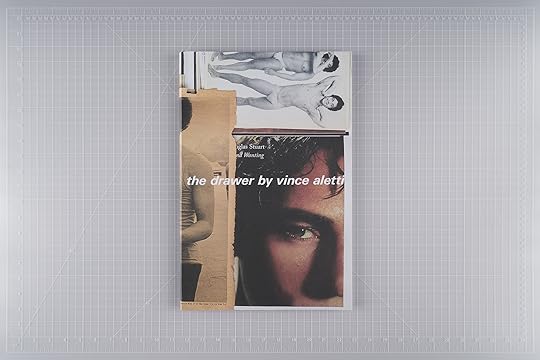

Details of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023Ess made things of what she saw people doing on all those nights out: a publication called Just Another Asshole (JAA). Edited with her longtime partner, the experimental-music linchpin Glenn Branca, JAA quickly became a who’s who of the downtown scene. The pair invited artists—among them Kathy Acker, Barbara Kruger, David Wojnarowicz, Lynne Tillman—to do whatever the hell they wanted on its newsprint pages or within a cassette tape. JAA was a mixed-media zine that could take most any format. In terms of chronology, ambition, and result, you could slip it between publications such as File and Visionaire. At White Columns, a display table offers a 1987 Village Voice review of issue seven by Vince Aletti, which quotes Ess saying that the zines “aren’t about craft, they’re about sensibility.” Aletti eyes the issue’s photographic contributions by Louise Lawler and Laurie Simmons, writing, “The new portraitists use the medium as a distancing device, subverting the notion of sympathetic portraiture by refusing to pierce the façade.” Today, that kind of po-faced posing seems like the birth of a New York style, one that has sympathy for the notion that a facade is as close to the truth as you can get.

Barbara Ess, Portrait of Cookie Mueller, n.d.

Barbara Ess, Portrait of Cookie Mueller, n.d.Courtesy the estate of Barbara Ess and Magenta Plains, New York

The exhibition presents just one example of the pinhole photography Ess later became known for, as Aperture published a monograph of this work in 2001, and, more recently, Magenta Plains gallery has begun exhibiting the pictures. But this example is a doozy: The undated Portrait of Cookie Mueller centers the writer and actor in a circle of light like a Renaissance saint. Mueller turns over tarot cards for an unseen subject. The inquisitive light of the pinhole makes it all but impossible to look away. Mueller couldn’t have known how soon her own life would be extinguished nor how subsequent generations would take her up as a role model and icon. Perhaps in this pinhole, Mueller is peeping into a similar cult-hero future for Ess.

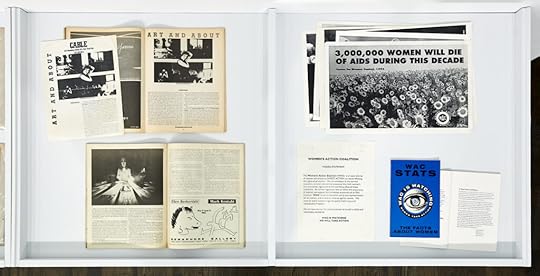

Detail of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023. All installation views courtesy the estate of Barbara Ess and White Columns, New York. Photographs by Marc Tatti

Detail of Barbara Ess – Archive, 2023. All installation views courtesy the estate of Barbara Ess and White Columns, New York. Photographs by Marc TattiAnd it came true: as AIDS and gentrification ravaged the downtown scene, Ess joined the radical feminist group Women’s Action Coalition (WAC) in 1992. Its mission statement, displayed on a table next to a pamphlet emblazoned with WAC’s eye-catching logo of an eye with the acronym arranged into an iris, reads, in part, “We will exercise our full creative power to launch a visible and remarkable resistance.” WAC taught women and other feminists that what matters isn’t only that you organize, but how you organize. Sensibility is political. Ess spent the next two decades as a professor in the photography program at Bard College. A sample classroom assignment in the show is titled “Tell Us Something About Yourself.” Twenty-six prompts follow, including “Use the photograph to bring us closer. Use the photograph as your mother. Use the photograph as your lover. Use the photograph to keep us away.” Barbara Ess – Archives uses her photographs, uses what she made, to tell us about herself, and how all the playing around downtown became a posture, then a politic, then a pedagogy. She made it feel like a natural progression, and it deserves a look.

Barbara Ess – Archives was on view at White Columns, New York, from September 12 through October 21, 2023.

October 26, 2023

Sally Mann, Edmund de Waal, and a Dialogue about Formalism

To light, and then return—, an exhibition of photographs by Sally Mann and sculptures by Edmund de Waal at Gagosian’s bookstore gallery on Madison Avenue, is a formalist pas de deux between two old friends. The pair are also both Gagosian artists; they met after a third, Cy Twombly, gave Mann a copy of de Waal’s memoir, The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010). Perhaps nudged by their dealer (Gagosian previously paired Mann with Deana Lawson), each artist presents work specifically inspired by the other’s: Mann has produced gauzy still lifes of small, often indistinct objects, while de Waal, a self-described potter, has emphasized the pictorial presentation of his grisaille porcelain works.

Although the objects Mann photographs aren’t literally de Waal’s pieces, her compositions often hang on ambiguous, shadowy cylinders and paper-thin rectangles, echoing his vocabulary of forms. De Waal has composed groups of upright tubes roughly the size of candle holders, small sheets and blocks of various porcelains and metals, in wall-mounted shadowboxes or on plinths pushed to the wall to limit your view to a “front”—as if anticipating the sculptures’ lives as images.

Left: Edmund de Waal, untitled (an exchange of territory, or world) (detail), 2023. Photograph by Alzbeta Jaresova; right: Sally Mann, Platinum, Stone #10 (detail), 2022. Photograph by Rob McKeever

Left: Edmund de Waal, untitled (an exchange of territory, or world) (detail), 2023. Photograph by Alzbeta Jaresova; right: Sally Mann, Platinum, Stone #10 (detail), 2022. Photograph by Rob McKeever The two artists also echo one another materially. De Waal has incorporated slivers of platinum and silver, the elements that make Mann’s prints possible, into his arrangements (as well as Corten steel, the stuff of Richard Serra). Mann, through the positive tintype process, invokes a kind of sculptural imperfection: no two tintypes will ever be exactly alike, and where the collodion and silver nitrate have been unevenly applied, the images bear an extra layer of materiality—scratches, blotches, and blooms. Mann approached photo processes with the eye of an object maker; De Waal approached sculpture like an image maker.

For Mann’s part, a career of technical exploration manifests here in two distinct modes: eight still lifes are platinum prints, a remarkably detailed process; another eighteen are tintypes, dim and roughshod. Mann’s early portraits of her children (1984–1992) often used shallow depth of field to highlight details, a stain or a lock of hair, but the glass plate collodion process she employed beginning in 1997 can’t help but evoke death. If you don’t know already, you eventually learn that what looks like a simple wood or clearing or hill is a Civil War battlefield or a graveyard or a waystation for escaped enslaved people. As a reinvigoration of the genre of landscape photography, the misty necromancy of hand-coated negatives and, in the Blackwater series (2008–12), tintypes, is surprisingly effective for Mann’s gothic style of conceptualism.

Crudely speaking, these latest and most abstract, murky pictures of objects complete entwined career arcs of aging and abstraction, from childhood to the grave. Not that Mann is done making images—or objects—but she has moved through the search for subject matter into a search for space within the mediums that constitute classical photography. It almost doesn’t matter what objects Mann’s photographs depict—only that there are in fact objects, bits of marble or a cracked cup, light gilding a broken ring or a swooping edge, variegating the final composition.

Sally Mann, Tintype, Still Life #43, 2020. Photograph by Rob McKeever