Aperture's Blog, page 22

January 26, 2024

A Photographer Recasts the Secret Lives of Teenage Girls

In Elizabeth Renstrom’s studio, there are shelves filled with pink goodies: a can of Aqua Net, a fluffy leopard blanket, perfume bottles, pencils, faux fur, the pretty princess phone of 1980s teen-movie bedrooms we wanted to live in as young girls. They’re props, it turns out, in both the literal and metaphorical senses of the word: objects Renstrom uses to stage her images, but also visual representations of narratives we’re given of femininity, consumerism, and bodily autonomy.

Over the years, Renstrom, a photographer and photo editor, has produced significant editorial work for the New Yorker, the New York Times, VICE, and TIME, among others. She’s shot portfolios for TIME and the New York Times, made covers for Salty and Numéro Berlin, campaigns for Dice and Vimeo, and photographed for the book Carnal Knowledge: Sex Education You Didn’t Get in School (2020). For both her editorial and personal work, she arranges her props to illustrate richly complex ideas using vibrant color, nostalgia, and humor.

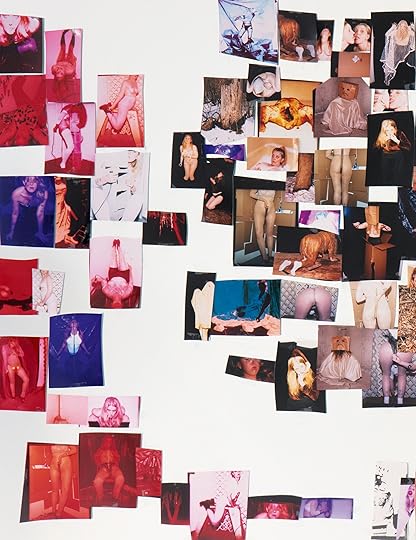

In her recent series Yummy (2023), now on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY, Renstrom combines still-life photography and AI-generated imagery inspired by the world that women of a certain age inherited—a world women are still inheriting, whether they’re teens now or millennials witnessing the aesthetics of our teen years making a comeback; who were raised on magazines like Seventeen, CosmoGirl, and others; who were sold butterfly clips and low-rise jeans by their Claire’s and Wet Seal ad pages; who listened when they told us how to lose the zits and gain a beach body, or how to be fifteen, flirty, and thriving.

Elizabeth Renstrom, Flirty Fun, 2023

Elizabeth Renstrom, Flirty Fun, 2023  Elizabeth Renstrom, Beauty Under $10, 2023

Elizabeth Renstrom, Beauty Under $10, 2023 Teen magazines from the early 2000s are what initially got Renstrom into photography; she read them growing up in Connecticut. These magazines brimmed with bright, airbrushed, catalog-esque shots of teen models with flowing hair and glossy lips in power poses. Happy, smiling young women leaned with hands on hips, flitted on beaches, washed flawless skin in a bathroom mirror, did crunches for summer in the magazines’ pages, their frosted eyeshadow twinkling as they got into limos for prom.

For Yummy, Renstrom concentrated on this aesthetic, liberally sprinkled with the glory of neon graphics, to remember and comment on their impact. When I visited her studio, she pulled out an issue of the now-defunct magazine YM from October 2002 to show me some of her inspiration for the project. Avril Lavigne is on the hot-pink cover, fake growling in a white button-down shirt, black tie askew. It’s an issue I vividly remember owning.

A child of this era like myself, Renstrom was excited by the possibility of generating her own images using Midjourney, prompting it to reproduce visuals in the style of teen magazines like YM. These appear in three separate branches across the exhibition. The first is a series of three print magazines featuring AI-generated cover stars, advertisements, and editorials. The magazine was designed by art director Elena Foraker, who combed Renstrom’s AI images with editorial sections constructed by the writer Coralie Kraft, also using AI. Stylized with a darkly humorous undercurrent, the publication is called Yummy Teen!—as much a diminutive as a critique of the way young women have often been sexualized within dominant cultural narratives.

Installation view of Yummy, Baxter St, New York, 2023

Installation view of Yummy, Baxter St, New York, 2023 Elizabeth Renstrom, Yummy (Teen Edition), 2023

Elizabeth Renstrom, Yummy (Teen Edition), 2023The second aspect of the project features actual photographs, which Renstrom staged at a friend’s childhood home in Pennsylvania. She cast teen girls to interact with Yummy Teen! magazines at a fictional sleepover, cut and collaged Yummy Teen! onto their walls, and wove the magazines into these girls’ fictional lives. Nail polish drips onto the carpet, rogue Cheetos find their way out of bags, feathery pens wait to be used. A series of brightly shadowed eyes are cut from a pile of faces on the floor and stuck onto a mirror. “We’re remixing these things, but we’re also being really violent with this image,” Renstrom says, referring to the way women’s faces and bodies have been cut apart to create another idealized image. “It reflects how we feel about ourselves when we’re reading it.”

The third aspect is a physical installation in Baxter St of furry, pink beanbags on top of a bright lavender carpet, in front of a wall painted pink. The installation invites visitors to apply custom stickers and images from Yummy Teen! to the wall, just like the girls in the photographs do. For a few moments, Renstrom wants us all to be teen girls, to understand a life even if we never had the occasion to remember it.

Much about being a teen girl is about longing—having a crush, wishing to lose weight, wanting to fit in with great clothes and beautiful hair. Renstrom captures that by flashing images from the past back to us: the heartthrobs, the perfume ads, the stars we loved and wanted to be. The cover of the June issue of Yummy Teen!, for example, features the AI-generated star Sierra Knight, her blond hair glistening and teeth pearly white, not unlike teens on the Laguna Beach of our youth who were paired with headlines promising to teach us how to “tone up and slim down,” “make HIM ask you out,” and “radiate with confidence!”

Installation view of Yummy, Baxter St, New York, 2023

Installation view of Yummy, Baxter St, New York, 2023Yummy lives in the uncanny valley of 2000s girlhood, where all its images and text are just slightly familiar in ways enlightening and jarring. Teen magazines were so prolific in their time and of such a specific style and tone; that AI images and text may be generated from them in the first place is a comment on their ubiquity and uniformity. They look and feel exactly as they did when they were first published, and with such accuracy that I wonder if I’ve seen them before. And, of course, I have. Yummy is as much about nostalgia as it is satire, as much commentary as memory. There’s a certain absurd hilarity to the phrase “Hot Bod!” independent of any context, and especially as it appears on stickers Renstrom made for the exhibition opening.

Renstrom’s experiences with AI reflected the problems in the images that proliferated mainstream print culture during this time period. Her project features a multitude of ethnicities, for example, but she found she had to ask for that specifically when prompting Midjourney; otherwise, a thin white woman was the norm. “I didn’t have to prompt for it to feed me a woman of a certain size,” Renstrom says. “A white woman is often what will be popped out unless you prompt it to give you a different race. There’s lots of aspects of it that are so fucked up and interesting.”

In bold pinks, yellows, purples, and greens, Renstrom tells the story of what it’s like to be a teen receiving these messages—and then an adult woman dealing with their aftermath. “I think we all indulged in these magazines in a really insecure time of our lives, where we’re looking for guidance and advice,” she says. “This project is a tribute to that, but also a critical eye at the way that these magazines play off those insecurities. It’s a lot about the way we talked to women during this time.”

Elizabeth Renstrom, Eye Magic, 2023

Elizabeth Renstrom, Eye Magic, 2023 All photographs courtesy the artist and Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY

Renstrom’s work is always asking audiences to query what they’re seeing. As Coralie Kraft tells me, Renstrom is “trojan horse-ing” commentary into her work about gender, about femininity, about the way we talk, and have talked, about women, the way we have understood or not understood our relationship to consumerism. There were times, Renstrom says, when her work was dismissed for being too nostalgic, frivolous, glossy, feminine. But those who write it off for its aesthetics are missing the point. “I feel really strongly about my palette and the kind of textures and softness that I bring in,” she continues. “I want it to feel inviting, so that you spend time and look at what I’m trying to say or the media I’m trying to put in front of you.”

The return of Y2K aesthetics has coincided with a cultural reconsideration of how we look at stories of the pop icons whose public lives defined the decade, including Janet Jackson, Britney Spears, and Pamela Anderson. Renstrom’s work lives here, too, in its own reconsiderations of “ordinary teenage girls,” as she says. I think of the writer Olivia Gatwood’s poem “When I Say That We Are All Teen Girls”: Even the men who laugh their condescending laughs / when a teen girl faints at the sight of her / favorite pop star, even those men are teen girls, / the way they want so badly to be so big / and important and worshipped by someone.

Renstrom shows us that the state of the teen girl is more universal than we think, that similar experiences color generations of people confronted by comparison, self-doubt, and fear. What we find in her work is that maybe we’re all hoping for a way out, all hoping to be loved, zits and all.

Yummy is on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of NY through February 2, 2024.

January 19, 2024

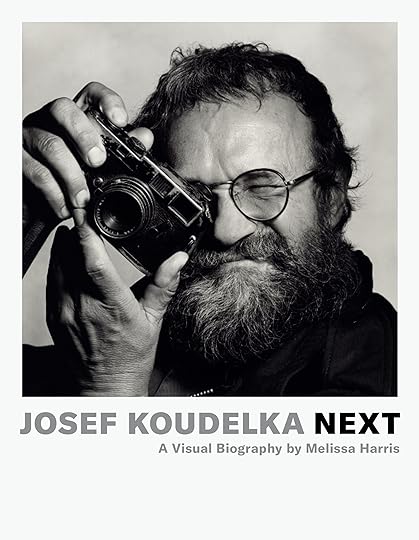

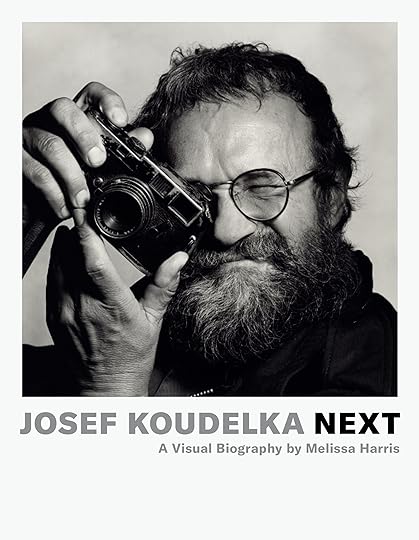

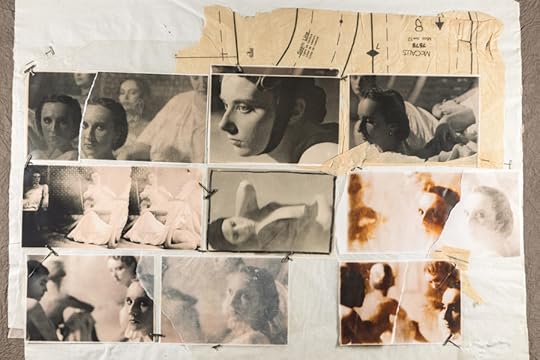

The Inside Story of Josef Koudelka’s Groundbreaking Career

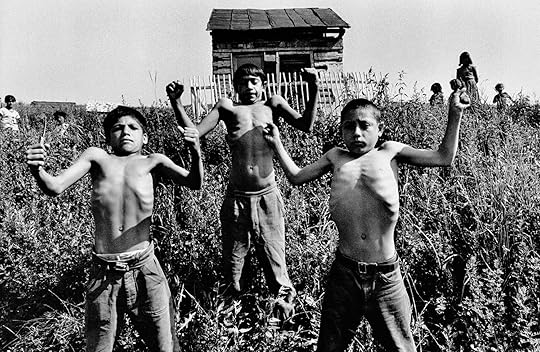

Born in 1938, the year of the German occupation of his native Czechoslovakia, Josef Koudelka has lived through seminal events in the twentieth century. He grew up under communism, experienced the Prague Spring, saw the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of the Czech Republic, and ultimately the Russian invasion that persists in Ukraine. In Josef Koudelka: Next, Melissa Harris considers his sixty-year-long obsession with photography, from his early interpretation of Czech theater to his expansive project on the Roma culture in Eastern Europe; from his legendary coverage of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague to the solitude of exile and the often-devastating impact humans have had on the landscape.

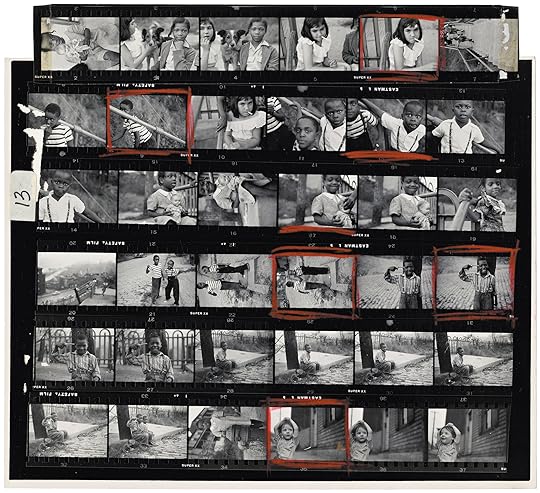

Over the course of nearly a decade, Harris conducted hundreds of hours of interviews with the artist at his home and studio spaces in Prague and Ivry-sur-Seine, outside of Paris, and led ongoing conversations with his friends, family, colleagues, and collaborators worldwide. The deftly told, richly illustrated biography shares stories on Koudelka’s early years as a touring musician and engineering student, his ritualistic repeated visits to favored places and festivals, and his thoughts around adapting to the panoramic format used in his later work. Anecdotes offer new insight into some of his most renowned images, such as accounts of smuggling Koudelka’s film out of the Prague Spring conflict zone, or of a London friend facilitating a membership card to the Gypsy and Travellers’ Council, an organization that advocated for the rights of the Roma, to help Koudelka ease frequent suspicions by police during his limitless itineraries. Last year, Lesley A. Martin spoke with Harris about the process of writing and editing Koudelka’s story.

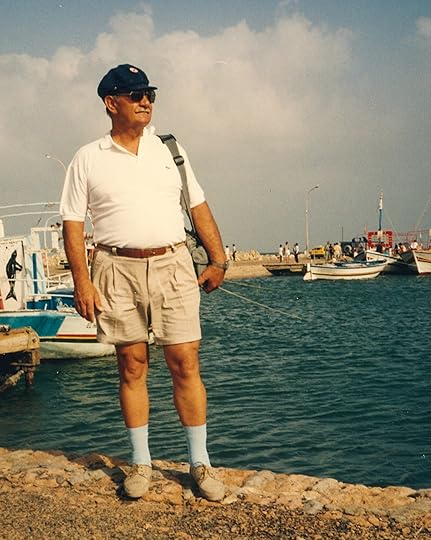

Josef Koudelka and Melissa Harris on the train to Boskovice, 2014. Photograph by Lucina Hartley Koudelka

Josef Koudelka and Melissa Harris on the train to Boskovice, 2014. Photograph by Lucina Hartley Koudelka  Hervé Hughes, Olympus OM-2, Josef Koudelka, 1984. Koudelka notes his concerns about camera 5 (“Serge”) to his camera repairer, Hughes, in French; Hughes’s response is in English

Hervé Hughes, Olympus OM-2, Josef Koudelka, 1984. Koudelka notes his concerns about camera 5 (“Serge”) to his camera repairer, Hughes, in French; Hughes’s response is in English Lesley A. Martin: Melissa, tell us a little bit about the genesis of this project. How did you get involved in writing this biography? What was it that appealed to you in particular?

Harris: Susan Meiselas called me up one day and asked me if I would be interested in writing Josef’s biography for a Magnum Foundation biography series conceived by Andy Lewin, who served as its managing editor. I was still working on the first biography I had written about Nick Nichols, and I really didn’t think Josef would say yes. I knew he didn’t like to answer personal questions and said no to almost all interviews. I remember saying to Susan, “Sure, but I don’t think he’ll agree.” And then he did. I think what convinced him was a dear friend of his, Hervé Tardy, teasingly told him that he should do it because if he didn’t do it now, while he was alive, it would happen when he was dead, and people could say whatever they wanted to, and he wouldn’t be there to help get the facts precise. So, if he wanted to have any input whatsoever, and make sure the rest of us didn’t make up things, he should do it now.

Martin: What was interesting to you about taking this on? Was it the work? His life story? What was the most compelling element?

Harris: Josef is fascinating to me. I’d worked with him enough before to know that this was going to mean a big commitment of time and energy on my part, but I also knew that if he agreed to do it, that he’d be all in—that he would totally commit himself. When he says he’s going to do something, he does it. I didn’t know a lot about his life story, but what I knew was compelling to me. And I think the work is superb. I’d worked with him previously on an exhibition of Invasion 68: Prague, his coverage of the Soviet invasion, which Aperture hosted in the gallery in 2008, but it was mostly just about realizing its presentation. I also worked with him on his book Wall (2013).

I knew I would learn so much from speaking with Josef, and I knew that it would be a real challenge. I wanted the challenge, not just in terms of information or content, but the writing as well. Telling his kind of story is complicated, in part because he goes back to projects so often that there’s no way to stick strictly to chronology. For example, his work on the Roma, published as Gypsies (1975; reissued by Aperture, 2011), comes up early on in the book, and then comes up again at different points throughout his career as he returns to that work in different ways. So how do you figure that out? Do you have a chapter on Gypsies and do the whole shebang in one place, or do you allow it to unfold the way his life has unfolded? There were just a lot of puzzles to work out—the kind of structural puzzles that I thought would be interesting for me because I’ve never done anything like that before.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Martin: It is a real puzzle. How do you prepare to take a project like this, in which you have to understand the entirety of a life—or at least try to? What is the process of research?

Harris: We just started talking. I wasn’t really sure where to start with him, and so I thought I would start personally. He really did not know what he’d gotten himself into. It was brutal, our first meeting: Nobody was unpleasant or anything, but it was just really hard for him to talk about his parents or to talk about certain things about his childhood. Not because he had bad relationships or had been unhappy, but because he is very private, and in his own way, quite shy. At the start, it was mostly about figuring out the pacing and just going slowly, letting him formulate responses to questions he hadn’t been asked before or that he had stealthily evaded.

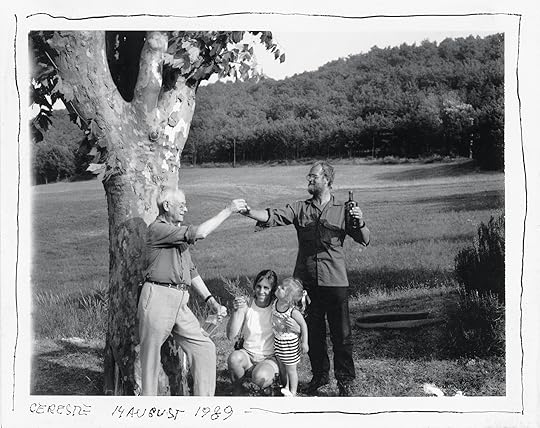

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jill Hartley, Lucina Hartley Koudelka, and Josef Koudelka at the home of Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck, under the tree by which bottles of slivovitz are buried, Céreste, France, 1989. Photograph by Marthe Cartier-Bresson

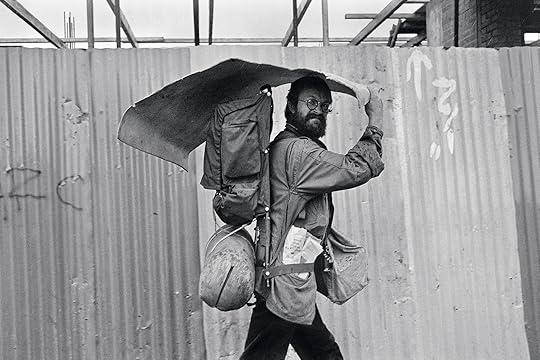

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Jill Hartley, Lucina Hartley Koudelka, and Josef Koudelka at the home of Cartier-Bresson and Martine Franck, under the tree by which bottles of slivovitz are buried, Céreste, France, 1989. Photograph by Marthe Cartier-Bresson  Paul Trevor, Brick Lane, London E1, 1980

Paul Trevor, Brick Lane, London E1, 1980 Martin: You spoke to so many people in putting the book together—people who knew Josef at different stages in his life, and who weigh in on his life and his work. As a reader, you really develop a sense of the author as a detective in this book, reassembling the story as Josef tells it, but also confirming or adding nuance to it through other perspectives.

Harris: Yes. This is a real reported biography. People think you’re nuts when you tell them you’re working on a biography of a living person, but for me, it’s a pleasure because I don’t really consider myself a historian. Of course, you have to do a lot of historical research for a book like this, when you are writing about somebody who was born in 1938. You have to present and contextualize the very rich history of Central Europe. But for me, the pleasure of the research was the reporting and interviewing process. Not just the interviews with Josef but pretty much everybody who played a key role in his life—those who were still living, obviously. When I started, everybody except for major figures like Anna Fárová, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Martine Franck were still alive.

Josef loves a challenge, a visual challenge. He had not really worked in this way before, where there had to be a clear relationship between text and image.

Writing about Josef’s relationship with those who were deceased was greatly facilitated by Viktor Stoilov, the founder of the Czech publishing house Torst, who kindly made all of the correspondence between Josef and Anna (that Anna had given to him) available to me, as well as all of her texts on Josef for magazines, catalogs, et cetera. It wasn’t the same as talking to her, but it was almost like talking to her. For Martine and Henri—I had known them, which helped—and Josef had kept all of their correspondence, plus there were his diary entries. So between what Josef had and Henri’s own writing, I was able to build certain things. Sheila Hicks, who I spoke with, who is a very dear friend of Josef’s, had very strong memories of Martine, and Hervé and others had memories of Josef and Henri, so there many ways in.

Martin: I do love the idea of a “reported history”—an oral history of sorts. It’s really a portrait of Josef in relation to his community, of the network of people who supported him in different ways, but also of the photo community itself, and especially in Europe at a particular time. Was that a conscious storyline that you pursued, or did it happen organically?

Harris: It was bound to happen because of what happened with Josef and Magnum. I knew that Magnum had helped distribute the Invasion 68: Prague work early on before he was a member, and that was a win-win for everybody: they had this remarkable body of work that nobody else had, and he became connected to this community. And then Elliott Erwitt, Marc Riboud, and Charles Harbutt and others helped Josef enormously. Henri Cartier-Bresson and David Hurn were like brothers to him. That sense of community at Magnum then, and in the photo community at large, was extraordinary.

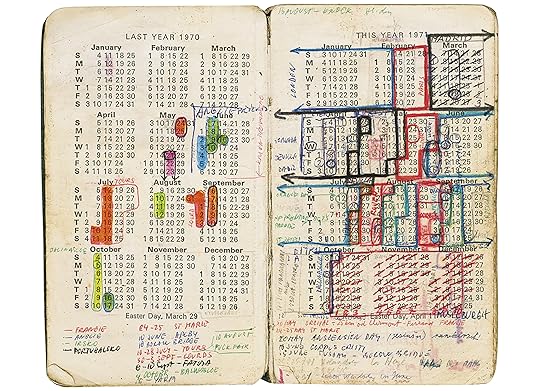

Pages of Koudelka’s 1971 agenda noting travel schedules, color-coded by country

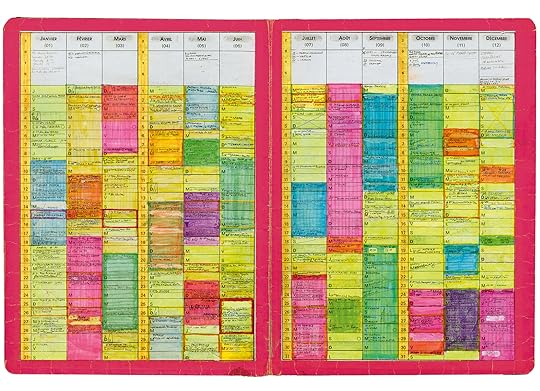

Pages of Koudelka’s 1971 agenda noting travel schedules, color-coded by country  Koudelka’s 2015 agenda

Koudelka’s 2015 agenda Martin: As you’re describing this process, it also underscores your own engagement and history with the field and with this community of people. You’re very clear in your positioning of yourself as the invested author, and that impacts the structure of the book to some degree. You’ve described how this is not a series-by-series retelling of an artist’s practice—because Josef is digressive in his approach to his own work. But can you talk a little bit more about the different structural approach that you wanted to bring to writing this as a nontraditional biography?

Harris: One thing that I thought, journalistically, is that I had to be completely transparent. In other words, it had to be clear that I had worked with Josef before, that I knew him. That’s why I write in the first person. I also wanted it to be clear when I entered his story. I am transparent about my own work with Josef previously—and also about his daughter Lucina’s presence throughout the book. Right from the start, Lucina was filming our conversations. I used her as a foil of sorts, both to help convey Josef’s emotionality, as well as to establish some chronological anchors.

At some point I also realized that I needed a breath every once in a while throughout the book. I needed a way catch the reader up or say where we were in time, because I wasn’t writing linearly. This is why there are sections I refer to as a “Pause.” It was a way to stop, step back, and say, “Okay, here we are. This is what we’re looking at.” For example, I had to jump ahead a little bit at the beginning, so the reader has an idea of who Josef is and what he’s known for, and then go back, and then move forward again, and then continue, back and forth. It’s like a cha-cha or something. The prologue and the epilogue function the same way.

Then there was my editor Diana Stoll’s suggestion that I write about some of Josef’s key work right at the beginning and just describe it. I preferred to get to the work gradually, but I understood her reasoning. Instead, I talked to Josef about the idea of an overture, where we show a selection of his signature images so that anybody who knows photography is going to immediately understand: “Oh, it’s this guy. The one who made that picture.” Josef called these his “icons.”

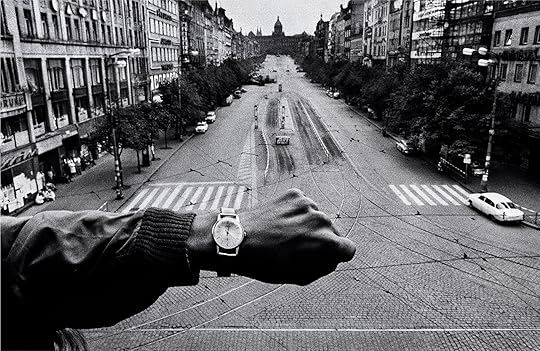

Josef Koudelka, Hand and wristwatch, Prague, August 1968

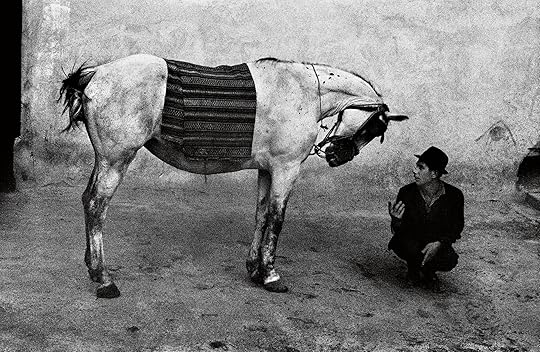

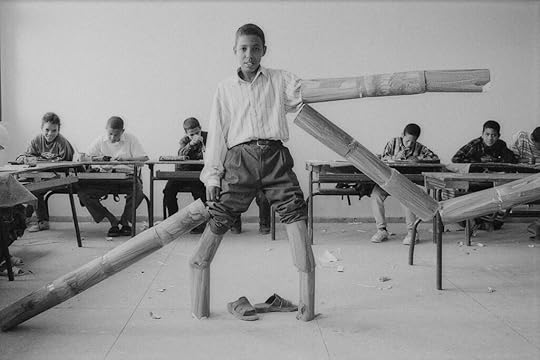

Josef Koudelka, Hand and wristwatch, Prague, August 1968  Josef Koudelka, Romania, 1968

Josef Koudelka, Romania, 1968 Martin: Speaking of the iconography and the mythos of Josef as a figure, were there particular stories, apocryphal or otherwise, that you felt you wanted to really puncture, or bust?

Harris: I just wanted him to be human. The book isn’t a press release for Josef. I think it was Elliott Erwitt who told me that early on at Magnum they called him St. Josef for a while, in part because of the way he lived, and that he didn’t care about money. Josef has always and only cared about having the work the way he wants it, in terms of how it’s published, how it’s presented, how it’s contextualized, all of that.

But I didn’t want him to be godlike. In fact, at some point I got tired of the love fest I heard from people—and I say this with enormous fondness for Josef. For Josef to be interesting, he has to be human, and all of us humans are flawed. I needed to allow for his flaws, along with all the amazing things about him, to really write honestly, as best as I could, about who he is. Josef is difficult sometimes. He’s not the perfect partner for a woman, or the perfect father. He tries very hard to be a good friend. All of these things matter to him, and they’ve mattered more and more as he’s gotten older.

Martin: Was there anything that surprised you as the book evolved, or did your thinking change in any way about Josef or his work?

Harris: It wasn’t even that my thinking changed as much that I came to have an even greater appreciation of his work as I saw more, and understood it better. Projects like Gypsies and Exiles and the 1968 invasion and theater images work beautifully in a book: they’re immediate and intimate. I had found many of the Black Triangle and Ruins photos stunning, but I hadn’t yet wrapped my head around the panoramas as a whole. As I spent the time with them, they became formidable to me. For example, I saw a show in Bologna that François Hébel did at MAST, and I understood so much more; I thought they were so powerful. In Josef’s work, the images often inform or play off each other. They build to something. When you start seeing them together, you get something intense and profound.

Josef Koudelka, Black Triangle region (Ore Mountains), Czechoslovakia, 1991

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Martin: That’s another aspect of the book that I appreciated—how you make these connections by showing some of the panoramic images together in a way that emphasized the geometry and the construction of them, but that is also informed by the context and understanding you build into the narration. We learn about his background as an engineer, and how precise he is, along with all of the other details of what he cares about over time, which leads to a better understanding of the work.

Harris: Exactly. When I started really learning about his work, and especially the Black Triangle, but also his other panoramic commissions, I realized that a lot of what he’s looking at is “the hand of man” on the landscape, and its huge ecological implications. I hadn’t previously thought about it that way in part because a lot of the earliest panoramic projects had been collected and published in a very poetic way, but not really in terms of specific content—by Delpire in Chaos—which is sequenced formally. Looking at the images, you get a sense that at this moment in our Earth’s history, everything is a little out of alignment or out of balance. It’s tremendously evocative. But then to actually go through every project and see all the work that was done in each—no matter what the commission was—you realize that Josef’s not just capturing a changing landscape through industrialization, or a historical rupture, or urbanization, or whatever it might be. I came to understand that he is most often thinking about the ecological or environmental implications of these issues, which was interesting to me. I didn’t expect to go there in my thinking.

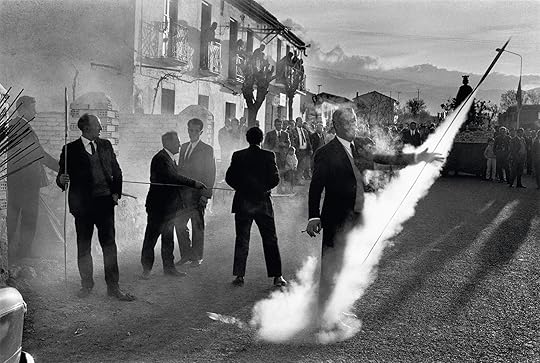

Josef Koudelka, Moravia (Strážnice), 1966

Josef Koudelka, Moravia (Strážnice), 1966  Josef Koudelka, Spain, 1971

Josef Koudelka, Spain, 1971 Martin: Yes—by looking at the long arc of his practice, one really starts to get a sense of an ongoing set of concerns that he returns to time and time again, even if the work seems quite different on the surface.

Harris: I looked at his book Chaos, and I looked at the captions which are in the back. There are, for example, images made in Beirut and Auschwitz, and of the Berlin Wall. They had been organized via their formal composition, which is very much how Josef thinks, and how Delpire thought. The sequence of that book is spectacular. It’s wonderful. But it’s not about content; it’s about form. I needed to think more about content, because in a biography, you have to think about content. You’re thinking about where this guy is, what he’s looking at, and what are the consequences of what he is seeing and considering.

To pull out the picture of the Berlin Wall in what was East Berlin, and to think about him being there, after all these years of not being able to be in that part of Europe—and then to know that he also went to Auschwitz—you can’t help but think about how that would play into his perception of the Wall in Israel when he later photographed there. The benefit of going back into his work from a content-driven perspective was finding certain images that I had only looked at formally before, because that’s how they had been presented to me, then suddenly knowing, “Oh, this is what I am looking at” and understanding the relationship to where he was in time and what he’s photographing now.

Josef Koudelka: Next 50.00 The definitive and only authorized biography of Josef Koudelka—an intimate portrait of the life and work of one of photography’s most renowned and celebrated artists.

Josef Koudelka: Next 50.00 The definitive and only authorized biography of Josef Koudelka—an intimate portrait of the life and work of one of photography’s most renowned and celebrated artists. $50.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Josef Koudelka: NextBy Melissa Harris. Photographs by Josef Koudelka. Designed by Aleš Najbrt.

$ 50.00 –1+$50.00Add to cart

View cart Description The definitive and only authorized biography of Josef Koudelka—an intimate portrait of the life and work of one of photography’s most renowned and celebrated artists.Throughout his more than sixty-year-long obsession with the medium, Josef Koudelka considers a remarkable range of photographic subjects—from his early theater work, to his seminal project on the Roma and his legendary coverage of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague, to the solitariness of exile and the often-devastating impact humans have had on the landscape. Josef Koudelka: Next embraces all of Koudelka’s projects and his evolution as an artist in the context of his life story and working process. Based on hundreds of hours of interviews conducted over the course of almost a decade with Koudelka—as well as ongoing conversations with his friends, family, colleagues, and collaborators worldwide—this deftly told, richly illustrated biography offers an unprecedented glimpse into the mind of this notoriously private photographer. Writer, editor, and curator Melissa Harris has independently crafted a unique, in-depth, and revelatory personal history of both the man and his photography.

Josef Koudelka: Next is richly illustrated with hundreds of photographs, including many biographical and behind-the-scenes images from Koudelka’s life, as well as iconic images from his work, from the 1950s to the present. The visual presentation is conceived in collaboration with Koudelka himself, as well as his longtime collaborator, Czech designer Aleš Najbrt.

Copublished by Aperture and Magnum Foundation Details

Format: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 352

Number of images: 282

Publication date: 2023-11-21

Measurements: 7.25 x 9.5 inches

ISBN: 9781597114653

“Melissa Harris’s visual biography, intriguingly titled Next, was written with his cooperation, and is a thorough and informative overview of his life and work. Rich in personal ephemera – family portraits, snapshots and glimpses of his many journals – it traces his trajectory from Boskovice, a small town in Moravia, where he had dreams of becoming an engineer, to his status as one of the world’s most revered photographers.”

ContributorsMelissa Harris is editor at large of Aperture and served as editor in chief of Aperture magazine from 2000 to 2012. Since 1990, she has also edited more than forty books for Aperture. Harris curates exhibitions worldwide, and teaches at New York University at the Tisch School of the Arts, in the department of Photography and Imaging / Emerging Media. She served on New York City’s Community Board 5 for several years, is a trustee of the John Cage Trust, and author of A Wild Life: A Visual Biography of Photographer Michael Nichols (Aperture, 2017).

Josef Koudelka (born in Moravia, Czech Republic, 1938) is a member of Magnum Photos and has received the Prix Nadar, Grand Prix National de la Photographie, HCB Award, and Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography. His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and International Center of Photography, New York; Hayward Gallery, London; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; and Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

Aleš Najbrt studied typography and book design with Jan Solpera at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design, Prague. He was an art director of the influential Czech weekly Reflex and founder of his own magazine, Raut. With Pavel Lev, he cofounded Studio Najbrt.

Interviews Koudelka's Prague, Fifty Years Later

Interviews Koudelka's Prague, Fifty Years Later  Featured Revisiting Josef Koudelka’s Photographs of Europe’s Roma Communities

Featured Revisiting Josef Koudelka’s Photographs of Europe’s Roma Communities Martin: Working with a living subject as a biographer is difficult. Did you have to establish some kind of ground rules going into it—as much as I understand you were interested in working with Josef and a collaborative approach?

Harris: The text was mine. He knew that. The rules were, at the beginning, I told him he cannot tell people what to say or what to think, and he can’t tell me not to use something because he doesn’t like it, because it was absolutely clear that he was going to be reading as we went along, and that he was going to be very involved in checking the facts. But he understood he couldn’t be censorious at all, and he was not inclined to be. Given the oppressiveness of the period in which he grew up, he does not want to tell people what they can and cannot express. And he was a man of his word. There were times he didn’t like what was said, and there are things he doesn’t like that are in the book, but he never tried to get me to take anything out.

Figuring out the visuals, however, was always going to be a real collaboration in terms of both the picture research and the layout. For that, we were also working with Aleš Najbrt, his longtime Czech designer and collaborator. I knew this was going to be another type of challenge because I also had discussed with Josef early on that the book wasn’t conceived as a retrospective. He originally thought it would be structured more classically—like one of his retrospective publications: that there’d be an essay and the work would appear more in the order in which he had made it. I told him that, to the contrary, it was going to be text-driven and not always chronological, and that also there would be biographical images. He got excited, because Josef loves a challenge, a visual challenge. Once he understood what I meant, he was very engaged. He had not really worked in this way before, where there had to be a clear relationship between text and image.

Koudelka photographing atop a Soviet tank, Prague, August 1968. Photographer unknown

Koudelka photographing atop a Soviet tank, Prague, August 1968. Photographer unknownAll photographs by Koudelka courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

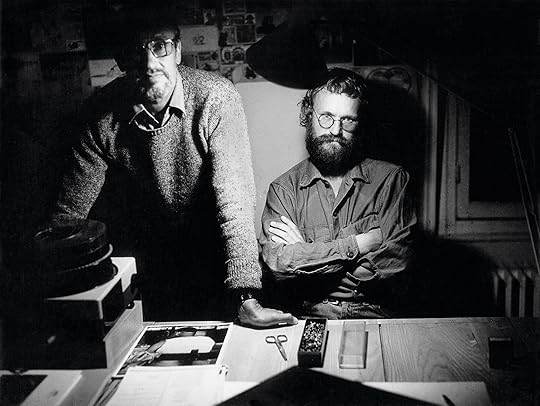

Robert Delpire and Koudelka, 1978. Photograph by Sarah Moon

Robert Delpire and Koudelka, 1978. Photograph by Sarah Moon© the artist

Martin: I want to go back to that process of building trust with Josef. Just to mention that one of the other things that no doubt encouraged him to see you as a good collaborator was your prior work with Robert Delpire and his legacy. Can you tell us a little bit about that and if you think that was important?

Harris: With Josef, he likes it when people do what they say they’re going to do—when they’re very clear about what they can do and what they can’t do and why. I learned early on through other people I worked with, too, but especially with Josef, it’s better not to sugarcoat anything. What happened with me and Josef was that he came into Aperture one day. We hardly knew each other. He had done an interview with some magazine in English, and he wanted me to read it and correct it because he’d heard I was “smart.” At that time, he didn’t have a cell phone, and he wouldn’t give me his phone number where he was staying because he didn’t give it to anyone. He didn’t want anybody to call him. I couldn’t reach him. I remember finally saying to Josef, “If I have questions, if I can’t reach you, I can’t help you.” I told him I’d help him, and I did it, finally, and it worked.

After that interview, we were coming up to the anniversary of the Soviet invasion of Prague in 2008. I knew he was doing a book, gathering all of his work from that period for the first time, so I asked him if we could do an interview in the magazine—at that time, I was the editor of Aperture magazine—which he agreed to do. I also asked Josef if we could do a show at Aperture Gallery. At first, he said no. But after we had done the interview, I asked him again, and he said, “Well, maybe.” He’d already curated the show, basically. He’d selected the work, he had a sequence for it, so it became my role to figure out how to present it, install it—to produce it. We pulled certain texts from the book, which were original source materials just from what was going on in Prague at that time, radio reports and all that, and we used the same fonts and typefaces as the book, so there was a clear visual relationship. The installation was very cinematic. Aperture was kind enough to let me paint all the walls black; Josef let me blow up two or three of the works into big murals, which he had never done before, and he just really liked it. And because I kept him in the loop the entire time—showing him a mock-up, samples of the wall text, and everything else—I think we had some trust built up from that.

After that, he decided that I had to meet Robert Delpire. Bob was having this comprehensive show at Arles, which told the story of his work with publishing, exhibitions, advertising, films, and design—everything. Josef felt that that show should come to New York and thought I was the one to do it. So that was the next big thing, which I was able to deliver. I think that also helped with the trust. And then, through working on this book, we got to the point that as much as Josef will trust anyone, I think he trusts me now. At least I hope so.

Josef Koudelka: Next was published by Aperture in 2023.

January 17, 2024

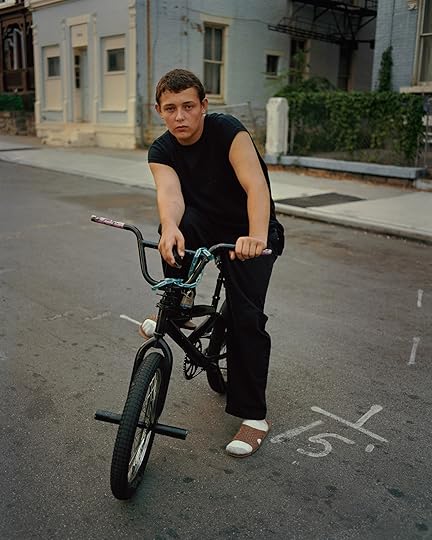

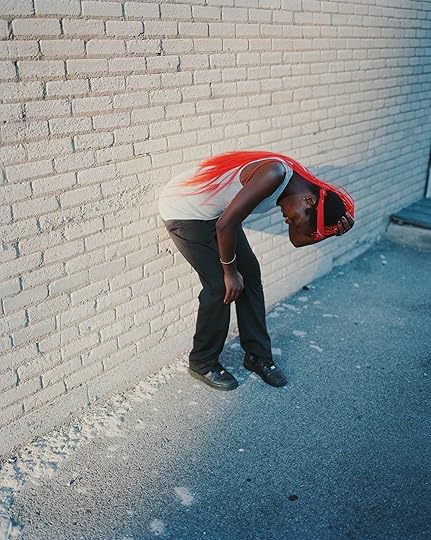

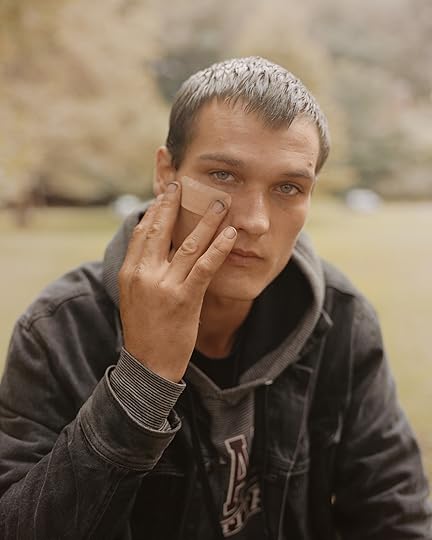

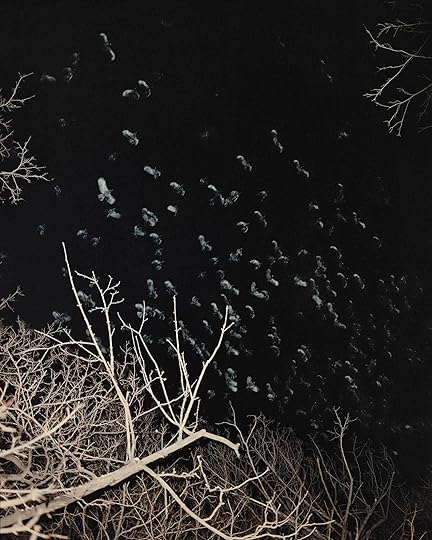

How Gregory Halpern Found His Voice in Buffalo

Gregory Halpern has been making photographs in Buffalo, New York, the city where he grew up, for the last twenty years. You could say that Buffalo has been his muse. It’s also been his crucible. It’s a place known for pummeling blizzards and buffalo wings (invented at the Anchor Bar), the Erie Canal and the Martin House (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright), and, of course, the Buffalo Bills. (“Where else would you rather be,” the legendary Bills coach Marv Levy chanted back in 1986, “than right here, right now?”) For Gregory, Buffalo has been a fecund site for childhood exploration, and in his photographs, it is a vast stage across which finely etched characters cross for their cameos: bundled up, making out, climbing up a sledding hill, or lying naked in a silty stream. As the introduction to his solo exhibition 19 winters / 7 springs, curated by Phil Taylor and currently on view at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, puts it, Buffalo is where “the appearance of everyday reality becomes both volatile and marvelous.”

Gregory’s brother, the journalist Jake Halpern, knows something about Buffalo characters too. He can give you a man’s profile in fifty-one words: “Adrian Paisley spends his days hunting for scrap metal: aluminum, brass and (holy of holies) copper. At 42, Paisley, who weighs just 135 pounds, is wiry and muscular. I once saw him move an old refrigerator by himself, hurling it onto his pickup truck as if it were made of Styrofoam.” That’s from Jake’s story for the New York Times Magazine about the scrap-metal industry. Gregory made the photographs. They’ve teamed up a few times, including for Jake’s rollicking Times Magazine article about freegan squatters. Jake has written about a safe house in Buffalo where refugees from around the world await passage to Canada. Welcome to the New World (2020), his twenty-part graphic series about a Syrian family establishing a new life in the US, with illustrations by Michael Sloan, won a Pulitzer Prize.

Installation view of Gregory Halpern: 19 winters / 7 springs, George Eastman Museum, 2023

Installation view of Gregory Halpern: 19 winters / 7 springs, George Eastman Museum, 2023Gregory and Jake left Buffalo as young men. There was a sense that in order to succeed, you had to leave. Gregory studied with the photographer Larry Sultan at the California College of the Arts. Jake wrote a book about debt collectors and was a Fulbright Scholar in India. Gregory’s photobook ZZYZX (2016)—about a desert town east of Los Angeles—heralded a new vogue for contemporary photography’s lyrical documentary style and won the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award in 2016. It’s since become one of the most important photobooks of the last decade; the “Halpern effect” is evident in a generation of young photographers who have studied ZZYZX as though it were gospel. But ZZYZX, Gregory says, wouldn’t have been possible without Buffalo and the time he spent there—nineteen winters, to be exact—honing his voice. Selections from the Buffalo work were first published in Aperture’s “American Destiny” issue in 2017 (he also made the issue’s cover). In his interview with the magazine, Gregory notes that “certain people would say the city is dying, but it’s also continually being born.”

19 winters / 7 springs was presented at the Transformer Station in Cleveland before traveling to Rochester, where Gregory now lives and teaches. Last year, just before Christmas, I spoke with Gregory and Jake about the exhibition. They were together at a cabin in the Adirondacks. “It’s kind of like a guys’ trip this time,” Gregory said. They looked at Gregory’s pictures and spoke about Buffalo with both the fondness and distanced critique that comes from being away for so long. “There are things about your home that you feel forever bound to,” Jake, who now lives in New Haven, said. Yet the city calls them back, continually. As I listened to the Halpern brothers speak about their lives and work in Buffalo, I thought perhaps they never really left.

Brendan Embser: I grew up south of Buffalo, on the border of New York and Pennsylvania, but I haven’t actually been to Buffalo in years, so the key images in my mind are probably the most obvious ones, like the Galleria Mall or the Anchor Bar—or Canisius High School, where we used to go for debate tournaments. So, just to start off, I wonder if you could talk about your upbringing in Buffalo and how the city shaped your worldview.

Gregory Halpern: I’ve always found Buffalo kind of magical, which I realize to some people might sound like a ridiculous statement. I often think about when we were kids, exploring buildings. There were some key amazing buildings that I often think about as the source of my interest in where “realism” and “surrealism” come together. When we were teenagers, we would go to the old psychiatric center where you used to be able to just wander into the building. It was abandoned, but you could go in. Or the old central train terminal. They almost felt like pilgrimages to me. We made little documentaries of our explorations, with this old VHS camcorder. Jake, I don’t know if you have the same sort of feeling about those memories?

Jake Halpern: I totally remember that. I feel like we would get a little crew of friends together and then organize a visit.

Gregory: Were those impactful?

Jake: Yeah. To me, it felt like a version of Dungeons & Dragons. The premise of Dungeons & Dragons is that a group of explorers goes to the outskirts of the town where the ruins are and looks for treasures. One time we were in the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, and a sudden rainstorm came overhead, and because the roof was out, the stairwell was turned into roaring rapids. It was crazy. I think that if you’re growing up in a Midwestern town, and all of a sudden you can go to a place that feels like you’re on the set of Stranger Things—even though Stranger Things didn’t exist then—that was the feeling.

Brendan: Did you grow up in Buffalo proper, or the suburbs?

Gregory: We grew up in an area called North Buffalo. It was near Delaware Park, and there were a lot of beautiful old houses. It was definitely a far cry from the kind of places we’re describing. There weren’t like, ruins around us. It took a while to even kind of know that part of the city existed. I don’t think it was until we were teenagers that we could start to find these places that felt on the periphery of our maps.

Brendan: What is your relationship to Buffalo, now that you no longer live there?

Gregory: Growing up, I feel like there was this notion that if you’re going to “succeed,” you should leave. That’s less so now, because the city is having a bit of a renaissance. But I also remember being sort of pulled back there continually—photographically. I felt like I had something to share, or that I knew something about this place. The further away I got from it, the more unique I realized it felt.

Jake: To be honest, my relationship with Buffalo is complicated in the way that people’s relationships with home often are. There are things about your home that you’re eager to get away from, and there are things about your home that you feel forever bound to. I think it’s taken me much of my adult life to sift through those two opposing dynamics.

We moved there as transplants, because my dad got a job at the university there, and so we didn’t have deep roots in the city. We didn’t have any family there. We had friends, but they were friends that we made as we were growing up, and I never felt a deep connectedness when I was younger in the way that maybe some of our friends did. I think that when I left, like many young people who leave their homes, there was a kind of exhilaration and being out in the great world and thinking, Oh, where I come from is very small, and isn’t it great to see the wideness of the world?

I don’t ever feel like a total insider or a total outsider in Buffalo. But I think that’s been key to me—to have both insider knowledge, but also a little bit of distance.

Yet, as I’ve gotten older, I’m often surprised by the fact that the place has more meaning to me than I even admitted to myself, and like Greg, I’ve come back for stories. Many of the stories I’ve written are Buffalo-based stories: my book Bad Paper (2014), about the debt-collection industry; pieces I’ve written in the New Yorker about the refugees coming through Buffalo; the scrap-metal industry written for the New York Times Magazine. I think, in part, as a writer, the world of stories that are New York–based or LA-based or Chicago-based or Miami-based is just overpopulated, and Buffalo is this greatly overlooked place, but one that I think people are also curious about. It’s a place now that I both know and don’t know. But the older I get, the more I realize that it’s not just someplace in my rearview mirror that I left at eighteen and has nothing to do with me.

Brendan: Where did your family move from?

Jake: My dad and my mom were New Yorkers. Even though I was born in Buffalo, I just didn’t feel of that place. Another layer here is that we are Jews. There is a Jewish population in Buffalo, but it’s in the suburbs. I often say at our high school, City Honors, of one thousand people, I would bet there were maybe no more than ten Jews?

Gregory: Oh, I don’t think it was that many.

Jake: Yeah. Not that we were super-religious or anything. But that also added, for me, a slight otherness feeling.

Gregory: Totally.

Jake: We’ve both become tellers of stories, in a way, whose lives are dependent on being able to talk to people from very different walks of life. Greg had that at a much younger age than I did. He had a very easy time crossing barriers of race, class, clique, in a way that’s pretty unusual for high school. I found my small group of people where I felt I belonged in high school, and I didn’t venture out of that. It wasn’t until later on in my life—maybe even the era when I started returning to Buffalo as a storyteller—when I learned both the ability and also the joy of crossing those divides and telling other people’s stories.

Brendan: Did your parents end up feeling rooted in Buffalo?

Gregory: Our parents split up when I left for college. I’m the younger one. Our mom moved back to New York City, and our dad stayed in Buffalo. He’s totally fallen in love head over heels with Buffalo.

Jake: Our mom kept our house that we grew up in on Woodbridge Avenue for many years. Initially, it was nice to have that house, because there was a place to come home to. But she eventually sold it and built another house in western Massachusetts with Paul, our stepdad. Home is a weird idea. You can hold on to the shell of the house, even when it no longer serves a purpose because you’re tethered by all the memories that exist there. Sometimes you hold on to it so tightly because you want it, but it’s not home anymore, and you really need it to be someplace else. I relate to that kind of tug and pull.

Installation views of Gregory Halpern: 19 winters / 7 springs, George Eastman Museum, 2023

Installation views of Gregory Halpern: 19 winters / 7 springs, George Eastman Museum, 2023

Brendan: That presents a fascinating reading of the three-dimensional work in Greg’s exhibition—the houses with the photographs of the solar eclipses on the interior. Greg, do you feel there’s a psychological aspect to this idea of home as both a shelter, but also as a place from which to look out—to dream of other ways of living?

Gregory: I like that reading. A home is where you sleep, and also where you dream. It’s one of those aspects of life that photography sometimes can’t get to. I was also just thinking about the very simple fact that photographs record the surface of things, literally—like light bouncing off the surface of a thing. Metaphorically, sometimes they only do that, and then sometimes they go deeper. I was thinking about those internal worlds, like the inside of a house that you want to know about, or inside of a person’s dream world that you can’t see with photographs.

Brendan: At what point along the many years of this project did you begin making those 3D works?

Gregory: I made the first house, a little tiny one, over ten years ago now. But it was all four sides. It looked cool, but it looked like a miniature, like a toy or a model, and it didn’t really feel like a work of art. Then, somewhere along the line—I don’t know if I was building it or taking it apart—I had to build two walls at a time. I saw a huge gaping hole in the middle of this house. That’s when this idea occurred to me that seeing the inside was maybe more interesting than just replicating the thing around all four sides.

Jake: To a child, your physical house is your world. It is your universe. On the outside, it may just look like clapboard, but inside, the memories of all the things you’ve explored and discovered for the first time, all the holidays, all the foods you’ve tasted—it’s this kind of wondrous space. It is the universe. I thought your sculptures captured that feeling.

Brendan: The exhibition is called 19 winters / 7 springs. Did you sense at the outset that this would be a long-term endeavor?

Gregory: I started the work when I was in graduate school in California. I was really struggling. Larry Sultan was my advisor, and he pulled me aside and he said, “I think you might need a third year.” It was a two-year program, and I wasn’t going to graduate because I couldn’t find anything in California to photograph. I had nothing to say. I had no idea what to do. But the one thing I feel like I’ve got to offer, or to say that I can claim as my own, was going back to Buffalo in winter. So I took a month in between the semesters, sort of in a panic, and I went back and I photographed every day in winter. That was nineteen years ago. That’s what inspired the title. But the oldest pictures in the book came from that winter.

Brendan: And that’s what pushed you over the finish line for graduate school?

Gregory: Yeah. I was able to get my diploma. Although in retrospect, I feel like a third year with Larry would have been great.

Related Items

Aperture 226

Shop Now[image error]

Gregory Halpern: Let the Sun Beheaded Be

Shop Now[image error]Brendan: As someone from Western New York, my first interpretation of the title was that there were only seven springs, meaning it was so cold for those nineteen years that you only got seven warm seasons.

Gregory: I mean, in a way, yeah, it kind of is that! I first thought of the project as being about Buffalo and winter, because to me, that’s when the city earns its identity, and there’s a really unique feeling there in winter. But then I realized that it was more interesting to mix the other seasons, to create more dynamism in the work.

Jake: I never actually heard you say that, Greg. I didn’t know that when you were out in California, you were struggling to find what your work would be, and you went back to Buffalo. I feel like I’ve done that same thing many times. You want to tell a story, but you ask yourself, What story am I qualified to tell? What story hasn’t been told? When you’re going home to a place, even if you haven’t been there in a long time, there’s some sense of, well, this is my home. I’m not a stranger. When you tell a story, whether it’s through pictures or words, you’re basically an interpreter of place, but you also need to have left that place. I think that’s the commonality between my brother and I—we’re both, in our own ways, interpreters of Buffalo. Which is not to say that we know it better than anyone else. I haven’t lived there in almost thirty years. But maybe what gives me the sense is that I can—or that we can do that.

Brendan: Thanks for saying that. I was also thinking, Jake, about your reporting for the New Yorker on Vive, a shelter in Buffalo that supports asylum seekers. Can you talk about that experience?

Jake: The Vive story came to me through a mutual friend of Greg and ours from high school, Tara Lynch. I was visiting Tara in Austin, Texas, and she said that Vive was almost like an Underground Railroad for refugees. Again, you see the similarity between me and Greg in our worldviews. It felt mysterious and kind of magical, this idea that there’s a secret network that goes through Buffalo into Canada.

Gregory: Jake, you should say a word about who the refugees are. And our family connection to the refugee experience. It’s not related to Buffalo, our family history, but I think it’s related to how we both see the world.

Jake: At the time, Vive was inhabiting an old school building that had been in a significantly abandoned part of Buffalo. These migrants, some of whom were refugees, were hoping to continue to Canada and claim political asylum.

Gregory: Where were they coming from?

Jake: Their paths were incredible. Some could fly to the US on a tourist visa, and they would show up at Vive and get asylum. Others were coming from Eritrea, then ending up in South America, going overland via South America through Central America, showing up at the Mexican border, asking for asylum there, and then coming to Buffalo—all because when they were back in their native land of Eritrea or Mongolia or wherever, someone had told them they could get to this house in Buffalo. That was the part of the story that just blew my mind. But to Greg’s point: Our families were very much immigrants. My great-grandfather stowed away in a boat to come to America. So I think there’s a sense of connectedness to the Vive story, to the sense that an immigrant could end up in a far-flung outpost like Buffalo.

Gregory: Totally.

Brendan: Greg, I’m so intrigued to hear this story about your time in graduate school and your impulse to return to Buffalo. You made a photographic essay over many years about your hometown, but I don’t see it as autobiographical. It’s not full of snapshots or excavations of your family’s past. There’s a lot of restraint in the scenes you chose, and in your decision not to deal with very specific family memories, but to look at Buffalo in the widest possible way. Can you talk about that approach?

Gregory: That’s a great question. I was just looking at the pictures with Jake. There were two pictures that were made, actually, on our high-school playground, that are up now at Eastman, and there are some places and people that we have connections to. But I never wanted to make it specific or personal that way. It just never interested me, and I didn’t think that it would be interesting to others to make it too much about me. I guess it’s about a way of seeing. It’s about feeling my way through the city. In that sense, I feel it’s deeply personal. Somehow, I don’t fully see it until I actually go make pictures of it.

Brendan: It’s like what you said, Jake, about coming back to a place and having a perspective simply because now you’re an outsider.

Jake: There’s one picture in particular that stood out, of a house that’s surrounded by a red-brick building. It’s winter, and the street looks kind of desolate, and there’s snow on the roof. I looked at the photograph, and I did, like, a shiver, like, “Ooh!” It reminded me of this feeling of childhood and Buffalo. There could be, in the depths of winter, this kind of barrenness that not just made you feel cold, didn’t just chill your bones, but made you feel a kind of deep loneliness of trudging through a place that is a little bit forgotten by time.

Brendan: There is something poignant about the way that house seems to be crowded by a school or a municipal building of some sort, but it’s also very clearly a two-family house, because the staircase that’s covered in snow going up to the second floor appears to be the entry to the upstairs apartment. And no one has shoveled out the snow yet, which is a very familiar feeling for Western New York. The other one that struck me is a very modest but lovely little house where there are tulips in front, but also snow on the grass. To me, that’s quintessential Buffalo.

Gregory: I’m so glad you noticed the tulips because I always worry that they get missed. But yeah, that was an amazing moment.

Brendan: Greg, did you feel that the Buffalo work began to give you your photographic language that you later brought to your projects in California and elsewhere? It’s so interesting that you said that you didn’t have anything to say about California, and then you then went on to make XXYZX, an iconic project about a very specific place in California.

Gregory: XXYZX was the project where I finally found my voice. In a way, I’ve kind of continued in that tradition since. That took seven or eight years after I moved to California to figure out that I had something to say, and that’s where ZZYZX came from. I was living back in the East Coast when I did that ZZYZX work, and I was living in California when I started the Buffalo work. I think this gets back to what you were saying, Jake: there’s something really helpful about being both an insider and an outsider. I don’t know if the writing world is like this, but the photography world sometimes has this, I think, oversimplified language. Are you a photojournalist outsider? Or are you an insider making work about an identity or an experience that you can claim as your own? There’s a lot of fascinating and important work that sits somewhere in the middle. I don’t ever feel like a total insider or a total outsider in Buffalo. But I think that’s been key to me—to have both insider knowledge, but also a little bit of distance.

All photographs by Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from the series 19 winters / 7 springs, 2003–2023

All photographs by Gregory Halpern, Untitled, from the series 19 winters / 7 springs, 2003–2023Courtesy the artist

Jake: When I saw ZZYZX, I was absolutely blown away because I felt it was a quantum leap forward in your vision and your craft. You basically, to my mind, found a sun-drenched version of Buffalo in Los Angeles. All those themes that were there in Buffalo—the surrealness; the hints of the apocalypse; the biblical, wandering characters with their beards; all this stuff—you found it in this other place. And I had been to LA a lot, but I had never seen it through that lens. This is the lens of Buffalo being trained on some other world, creating some incredible original projection. I think that we both owe Buffalo a lot, in our own ways. It has taught us about the kind of characters and the stories that appeal to us. And it’s really powerful to see what that lens looks like when it’s moved somewhere else.

Gregory Halpern: 19 Winters / 7 Springs is on view at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York, through March 3, 2024.

January 12, 2024

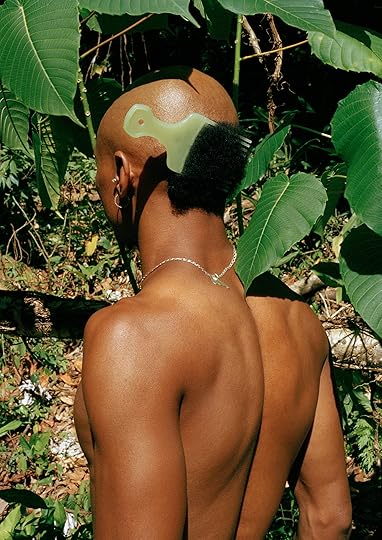

Nabil Harb Seeks Mystery and Community in Central Florida

In Polk County, Florida, Nabil Harb arranges his calendar around nights when the light turns green at dusk, how the shadows look blue in spring, or how the cicadas start to hum as the temperature reaches a hundred degrees. To live here is to know the feeling of humidity enveloping you like a duvet in July. To know in what oak hammocks you’ll find butterfly orchids blooming by May. And to count the seconds between lightning strikes and thunder in August. More than five and you’ll be fine.

Then, come September, Polk County’s creeks, rivers, and trickling branches of sweet water swell. The Green Swamp at the northern edge of the county collects the remnants of the afternoon storms before that water moves south into the Peace River as it wends its way into the Gulf of Mexico. For Harb, those veins of water that course through Polk County, alongside 554 lakes, form a map he’s been tracing all his life. With a camera, he’s started to draw his own maps, as did William Faulkner in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, William Christenberry in Hale County, or Zora Neale Hurston next door in Orange County.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Harb left his hometown three times, living in Boston, New York, and New Haven. And like many Southerners, he returned home three times—putting stakes down between the urban sprawl of Tampa Bay and the edge of the Everglades’ headwaters just south of Orlando. “I moved back because I don’t like being that far from my concerns,” he tells me. Often, folks told him, “You’re gay. You need to move to New York,” as if he couldn’t be himself at home. “I hate that,” he says.

Here, everything is growing, green as ever, always. The live oaks are ancient, the sites of treaties, lynchings, and produce stands. Bends in the river call up Indigenous history, archaeology, and colonialism. In making a photograph, Harb wants you to feel how wet it is, the fog of mosquitoes, the mist rising off the ground. He wants people to better understand what rural places once were and are becoming, to know there’s good and bad in Bartow, taciturn and queer in Eloise, this and that in Frostproof. He wants others “to actually see this place, rather than the stereotypes or easy metaphors.” Beneath the headlines generated by lawmakers’ political ambitions, past the policies that target the most vulnerable and most vital minorities in Florida, Harb gives a nod to the deep well of mystery here, to a place full of people as hopeful as they are complicated.

Nabil Harb, Allegra, 2019

Nabil Harb, Allegra, 2019  Nabil Harb, Pulse Exterior (Lakeland), 2019

Nabil Harb, Pulse Exterior (Lakeland), 2019 His parents, both Palestinians who left Nazareth, made lives together in Lakeland, Florida, but for Harb, who was raised there, the roads and rivers now seem bound up in his bones. Growing up brown, Muslim, and queer in central Florida set him apart from the good ole boys, but, he states softly, “I am just as much a part of this place.”

A year after the 2016 murder of forty-nine people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Harb started photographing his local gay bar in Lakeland. The work he made there was the product of questions, or a way to ask them. But as he explains, you arrive with one set of questions and leave haunted by another. These photographs, which began in earnest six years ago, have become inextricably, although not deliberately, engaged with what’s happening in Florida and throughout America today.

And as in the photographs he was making all around Polk County—say, the bugs at dusk in the Green Swamp, or his friend Clay in the cab of a truck painted in mud—he focused on the quieter details inside the bar, capturing gestures, the sense that life was being lived and celebrated. His life. Here were the queens who formed the heart of the performances, but here, also, were the people sitting at the back of the bar, his friends, the ones who lent this building and this part of America its character. As he tells me, “You should see the people.”

Nabil Harb, Dani, 2018

Nabil Harb, Dani, 2018  Nabil Harb, J & J, 2019

Nabil Harb, J & J, 2019 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Nabil Harb, Vape, 2021

Nabil Harb, Vape, 2021  Nabil Harb, Northside, 2020

Nabil Harb, Northside, 2020  Nabil Harb, Python, 2022

Nabil Harb, Python, 2022All photographs courtesy the artist

Nabil Harb, Carter Road, 2019

Nabil Harb, Carter Road, 2019 This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”

January 3, 2024

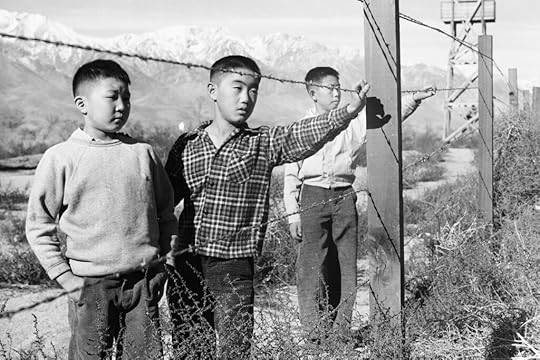

The Women Photographers Who Consider the Dynamics of Being Seen

Sometime around 1987, at the age of seven, I got caught looking. I was curled up on the sofa after school, watching MTV with the volume down low. The channel was all but verboten in our house at the time. At some point, the video for Madonna’s “Open Your Heart” came on, featuring the singer herself as an exotic dancer who—spoiler alert!—ultimately escapes from the peep-show theater in which she performs. I was immediately entranced. I turned the volume lower still, ashamed but unable to avert my eyes. And then, just as Madonna pranced across the screen clad in a black satin bustier complete with gold nipple caps and tassels, my mother walked into the living room. “What are you watching?” she asked, somewhat dismayed to find me mesmerized by the sexualized performance playing out before us. Before I could change the channel, she turned off the TV and proceeded to the kitchen.

Decades later, I still love this music video, which seems rather tame in hindsight. Released amid the Reagan administration’s antiporn campaign, the video was banned by a few channels and became a lightning rod for feminist debate. Some critics viewed Madonna’s portrayal of a sexualized woman subjected to the male gaze as retrograde. Others believed the video helped to destabilize the hierarchy of the gaze, with Madonna unafraid to return the lascivious stare of unsightly, sleazy male patrons. Perhaps the divided opinions in my house mirrored this split among critics. Looking back now, I wonder about my mother’s response. Did she believe I was too young to view anything with an erotic charge or subtext? Should a child not be allowed to conceive of a woman as a sexualized figure, or even as an object of desire? And why had I felt ashamed? Was there some corollary between me and the innocent “presexual” boy in the video, who lingers outside the theater and plays one-way peekaboo with a nude female on a pinup poster until Madonna emerges and skips off with him into the sunset?

This line of inquiry ultimately invites a larger question: Who gets permission to look?

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

I found myself asking this same question in 2016, upon my first encounter with the New York–based artist Talia Chetrit’s work. Shown as part of the AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), in Toronto, the opening wall displayed a provocative diptych: at left, an image of Chetrit’s camera on a tripod held between her bare legs, suggestively angled toward her crotch (which was presumably exposed, but not included in the frame); at right, an image of her lower body, naked from the waist down except for a pair of “invisible” jeans (effectively a waistband with the seams of the excised denim pant legs still attached). I watched the room to see how other visitors were engaging with her photographs, feeling as if I’d unwittingly stumbled into a video store that only stocked adult films. No one else appeared fazed.

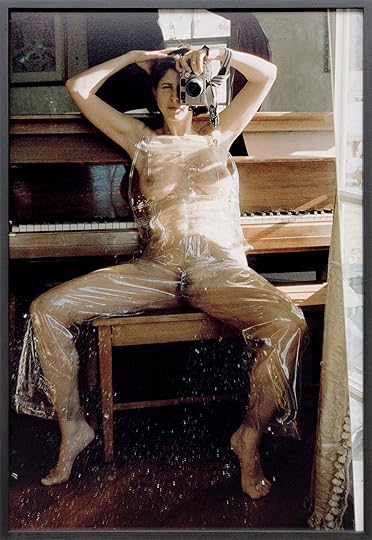

Another photograph by Chetrit, Plastic Nude (2016), which I came across later in her 2019 book Showcaller, further complicates the question at hand. In this image, Chetrit photographed herself from head to toe with the aid of a mirror—which, in its reflection, reveals that she is dressed in transparent overalls. While Chetrit’s see-through garment leaves virtually nothing to the imagination, it’s not exactly titillating by default. Perhaps this image is an evocation of the striptease, which, as Roland Barthes characterized it, “is based on a contradiction: Woman is desexualized at the very moment when she is stripped naked.” Then again, is Chetrit nude? As she leans back against a piano, her plastic-wrapped torso and legs all but open to be viewed, I can’t help but be reminded of the beguiling woman dressed deceptively in a flesh-colored body stocking that E. J. Bellocq photographed a century earlier. In each case, the viewer must look closely to determine if the nudity is an illusion.

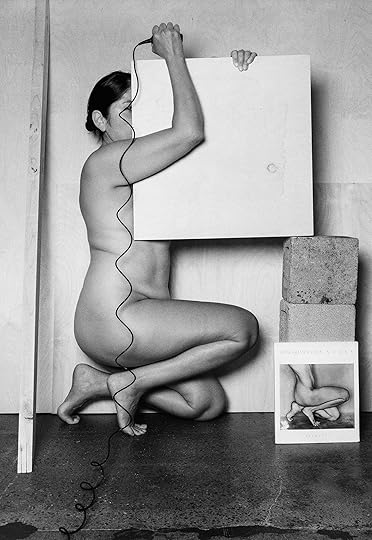

Tarrah Krajnak, Self- Portrait as Weston/as Bertha Wardell, 1927/2020, from the series Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, 2020

Tarrah Krajnak, Self- Portrait as Weston/as Bertha Wardell, 1927/2020, from the series Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, 2020© the artist and courtesy Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

Talia Chetrit, Plastic Nude, 2016

Talia Chetrit, Plastic Nude, 2016Courtesy the artist; kaufmann repetto, New York; Hannah Hoffmann Gallery, Los Angeles; and Sies + Höke, Düsseldorf

In Plastic Nude, Chetrit’s body remains encased in some kind of PVC layer, akin to a work of art displayed behind glass. Her outfit ultimately says: You can look, but you can’t touch. With this work Chetrit embodies the oft-cited idea that the film theorist Laura Mulvey described in her groundbreaking 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”: “The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.” And yet, holding a camera in front of her face, she simultaneously reminds the viewer that she—the artist and the sitter—participates in the act of looking while presenting herself as the sight to be looked at.

Since my visit to the AGO, I have noticed something of a vogue among a small but sharp crop of contemporary photographers—all of them women born within a decade of forty-one-year-old Chetrit—for whom self-representation functions as an exercise in “to-be-looked-at-ness.” On the face of things, this is not new. Within the history of photography, there is a rich tradition, particularly in the West, of women photographers’ work disrupting the structures of looking. As the noted art historian Griselda Pollock wrote in 1982, arguing for feminist rethinkings of art history, “creativity has been appropriated as an ideological component of masculinity while femininity has been constructed as man’s and, therefore, the artist’s negative.” Looking across the twentieth century, one can find interwar women photographers such as Gertrud Arndt and Claude Cahun, who made pictures of themselves that countered conventional and patriarchal ways of seeing women. In the 1970s, a particularly fertile moment in this history, feminist practitioners like Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke generated self-representational work that further complicated the objectification of women and addressed what Pollock referred to as “the signification of woman as body and as sexual.” Emerging in their wake in the 1980s, another wave of groundbreaking women photographers—Laura Aguilar, Jeanne Dunning, and Catherine Opie among them—made work depicting bodies (their own) that further deviated from art-historical norms and contemporary conventions of beauty and femininity.

Just as there’s often a need for women to talk to one another for their voices to be heard, there’s an enduring need for us to see each other, too, in all our multiple, complicated selves.

Chetrit and other midcareer photographers consciously deploying self-representational forms today are certainly inspired and informed by this history. Some were even formally educated by women who helped to shape it. But beyond their placement, chronologically speaking, as part of its continuum, how do they relate to the tradition of female photographic self-representation? And how does this seeming trend of soliciting, welcoming, and approving “to-be-looked-at-ness” relate to the present moment in which it unfolds?

By the 1980s, several decades before this latest wave of practitioners began their careers, feminist issues and theory had reached the mainstream, and criticism had strengthened its focus on the problem of “woman-as-image,” as identified by the art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau. With discussion around the representational politics of gender and the power relations of looking already well underway, younger contemporary photographers have entered into the conversation midstream, arriving with different agendas.

For some, inclusion in the canon of photography and the visibility it brings—the understanding that their bodies will most certainly be looked at—is part and parcel of the impulse to photograph oneself. The Peru-born, Oregon-based photographer Tarrah Krajnak models this approach in her 2020 series Master Rituals II: Weston’s Nudes, wherein she poses in the guise of Edward Weston’s female sitters but, given her Latin American background, challenges what she describes as “the ideal of white female beauty central to Weston’s work and its historical appreciation.” Krajnak incorporates direct references to her predecessors, such as Weston’s one-time wife and model Charis Wilson, by including Weston’s images of them within the scenes she stages, ultimately generating distorted mise en abymes.

Nydia Blas, My Body Has Been Colonized, 2022

Nydia Blas, My Body Has Been Colonized, 2022Courtesy the artist

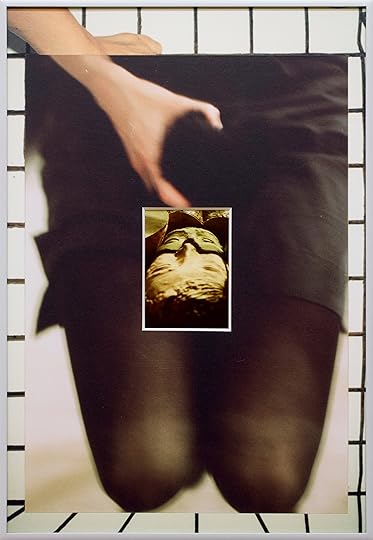

B. Ingrid Olson, Shuttle, 2015–16

B. Ingrid Olson, Shuttle, 2015–16Courtesy the artist

Nydia Blas, raised in the predominantly white city of Ithaca, New York, employs photography as a means for creating spaces that celebrate multiracial bodies like hers, which historically have been discouraged if not prevented from representing themselves. In a photograph of her midsection and upper thighs, titled My Body Has Been Colonized (2022), Blas reveals a tattoo in Spanish—the language of her father, which she can’t speak fluently—and stretch marks. She subtly obscures the latter while maintaining her modesty with a handkerchief covered in flowers native to Panama, her father’s birthplace. “Is it possible to reclaim something like sexuality in a photograph where you don’t have clothes on?” Blas asked when I spoke with her recently. “How can you still maintain power?” She admits that while she doesn’t have an answer, there is strength in reclaiming something for oneself in self-representation, in part because, as any photographer knows, it’s devilishly difficult to photograph yourself.

Two other photographers, Iiu Susiraja and Whitney Hubbs, despite the marked differences in their work, both mobilize the trope of the feminine pinup and its associative baggage, employing humor to neutralize it. Hubbs, born in 1977 and based in Syracuse, New York, mocks her own ability to adapt this fetish, partly given her age. Wearing protective knee pads while balancing a watermelon on her back or reclining topless while supported by a chair pad, Hubbs’s stagings evoke something like the grotesque or carnivalesque. In the case of Susiraja, absurd props, occasional bruises, and a deadpan style confound conventional expectations around viewing an image of a seminude body, if not to simply desire, consume, or covet it. According to Susiraja, who lives and works in Turku, Finland, the prospect of acceptance partly fuels the public dissemination of her photographs. In a 2022 interview, she likened her interest in seeking approval through self-representation to how people utilize social media: “I believe when you put self-portraits to Instagram, you look for acceptance and love.”

Iiu Susiraja, Lovely Wife (Ihastuttava vaimo), 2018

Iiu Susiraja, Lovely Wife (Ihastuttava vaimo), 2018© and courtesy the artist