Aperture's Blog, page 25

October 4, 2023

The Women Behind Accra’s Storied Makola Market

It is often said that if you are unable to locate a particular item in Makola Market, or get assistance from a trader who knows where to find it, then the product does not exist—or it’s not available in Ghana. But only when you go to Makola does this image of a one-stop shop become apparent. Though chaotic at first glance, the market is clearly structured, so you may wind through hawkers and petty traders to lanes of vendors selling imported fabrics and wax prints, or wigs, hair creams, relaxers, and conditioners—sometimes all at the same table. There are stalls, kiosks, and tabletop shops in the market and open-air areas. You may stumble on wholesalers of beauty products, candy, combs, and spare parts, among other goods that reflect the ingenuity of the traders and a complex system of wholesale, retail, and distribution services.

Misper Apawu, Hannah Korkor, tomato seller, 2023

Misper Apawu, Hannah Korkor, tomato seller, 2023  Misper Apawu, Hannah Korkor, tomato seller, 2023

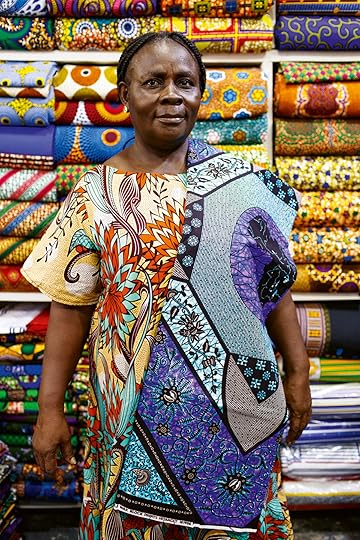

Misper Apawu, Hannah Korkor, tomato seller, 2023 Makola is located in Accra’s central business district, and since being built in 1924 it has been dominated by women. Historically, women from Accra’s indigenous Ga ethnic group, who had been trading since the sixteenth century, made Makola a thriving market. Makola is now a much more diverse place, with women from all over Ghana participating in the trading business. Many, including Winnifred Aku Tetteh, a smoked-fish seller, have been working in Makola for more than thirty years. They supply Accra’s five million residents with fresh produce, household supplies, clothing, and everything else for their daily needs. The women’s success depends on their ability to read cultural shifts and use of a range of marketing techniques while keeping up with global trends. For example, wax print sellers, such as Veronica Agbozo, who source their fabrics and lace from the United States, China, Nigeria, and Togo, among other places, rely on their storytelling skills—beginning with the naming of new patterns to reflect Ghanaian sociocultural realities—to help sell their products.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Last spring, the Accra-based photographer Misper Apawu made repeated trips to Makola to produce a series of portraits of women traders. Apawu, whose work has often focused on the lives of women in Ghana, claims that her first encounter with photography occurred in a market in Dambai, a town in the Oti region of Ghana, an experience that changed her life. In her childhood, when she used to sell iced water in the market, she watched the women’s faces light up whenever tourists pointed their cameras at them. And when tourists showed the women their pictures, they would beam with delight. The joy Apawu witnessed between the women and the camera inspired her to take up photography as a young adult.

Misper Apawu, Makola Market, 2023

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Women in Ghana’s markets have built and expanded their businesses on centuries-old systems, including apprenticeships. Alberta Koshie Lamptey, a bead seller, and Lydia Owusu, an avocado seller, learned the trade from their mothers. Makola has changed since they took over their stalls more than a decade ago, with an increased number of traders, higher costs of goods, and the lack of a credit system. Like women in markets throughout Ghana, they are grateful for their jobs, financial independence, and the ability to provide for their families. For women such as Elizabeth Darkwa Mensah, Makola has given her not only financial freedom but the opportunity to lead. As president of a wax print sellers’ association in Makola, she is part of a team of market queens who manage market facilities, enforce rules, provide financial support, respond to emergencies, and create networking opportunities. Makola, like other markets, is underfunded and underresourced, but its leaders ensure that it runs smoothly.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

As influential and visible players in the economy, market women bear the brunt of rising prices, which are often caused by inflation and poor fiscal management. During the 1979 economic crisis, both the government and Ghana’s citizens blamed Makola’s sellers for rising prices and shortages of essential goods, and for that the market was demolished by soldiers. Elizabeth Darkwa Mensah still remembers the trauma and the challenges that followed when trading resumed in 1987, and she is thankful that Makola has transitioned into a thriving commercial hub in Accra.

Misper Apawu, Winnifred Aku Tetteh, smoked-fish seller, 2023

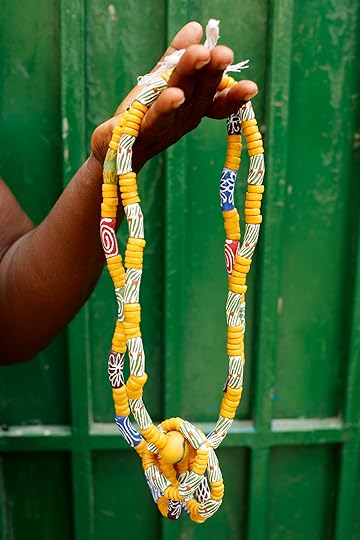

Misper Apawu, Winnifred Aku Tetteh, smoked-fish seller, 2023  Misper Apawu, Alberta Koshie Lamptey, bead seller, 2023

Misper Apawu, Alberta Koshie Lamptey, bead seller, 2023  Misper Apawu, Veronica Agbozo, textile seller, 2023

Misper Apawu, Veronica Agbozo, textile seller, 2023  Misper Apawu, Lydia Owusu, avocado seller, 2023

Misper Apawu, Lydia Owusu, avocado seller, 2023 This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”

Aperture Honors Dawoud Bey for 2023 Gala

On October 3, Aperture celebrated the 2023 Gala, its most prominent annual benefit supporting Aperture’s mission and belief that photography can inspire a more curious, creative, and equitable world. The evening signaled a transformational moment for Aperture, with an upcoming move to the Upper West Side, expanding visibility and reach for the seventy-one-year-old nonprofit organization. The Gala also marked a joyous occasion for Aperture supporters and artists to gather in tribute to a beloved force in the field—photographer, educator, and MacArthur Fellow Dawoud Bey. In remarks at the event, Aperture Executive Director Sarah Meister described Bey, who is also an Aperture Trustee, as “a North Star for the organization.” She continued, “If Aperture is dedicated to creating insight, community, and understanding through photography, then there is no one who exemplifies that more than Dawoud.”

Sarah Meister, Dawoud Bey, and LaToya Ruby Frazier

Sarah Meister, Dawoud Bey, and LaToya Ruby FrazierThe Gala was graciously cochaired by Agnes Gund and Aperture Trustees Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, Dr. Kenneth Montague, Bob Rennie, and Lisa Rosenblum. Guests arriving at the Ertegun Atrium at Jazz at Lincoln Center were greeted by the cochairs, served sparkling drinks, and had the opportunity to view and bid on works in an auction.

Live music by the Harlem Renaissance Orchestra welcomed guests into the Appel Room for a seated dinner with an early autumnal menu. Aperture Board Chair and Gala Cochair Cathy Kaplan thanked the many friends and colleagues for their ongoing support and alliance with Aperture, which was followed by a spirited tribute to Dawoud Bey’s legacy as an artist and activist.

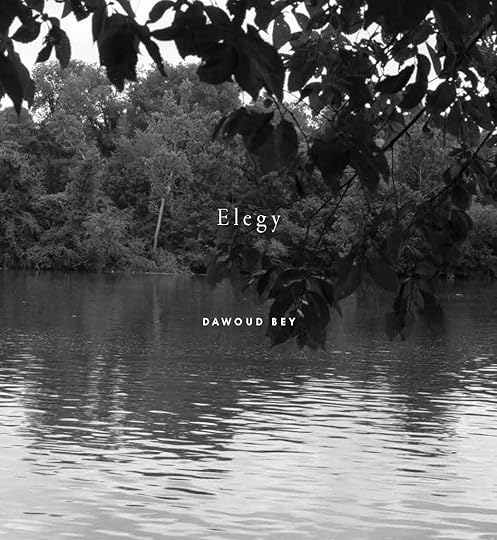

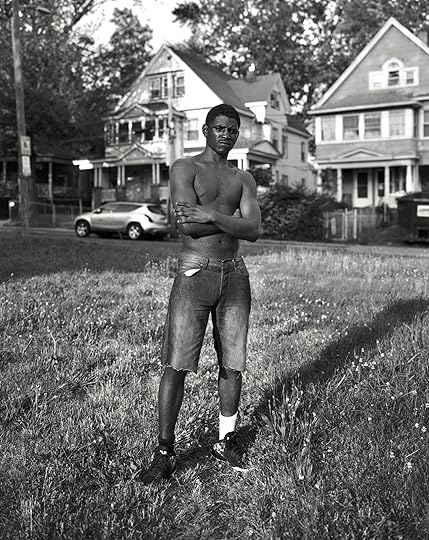

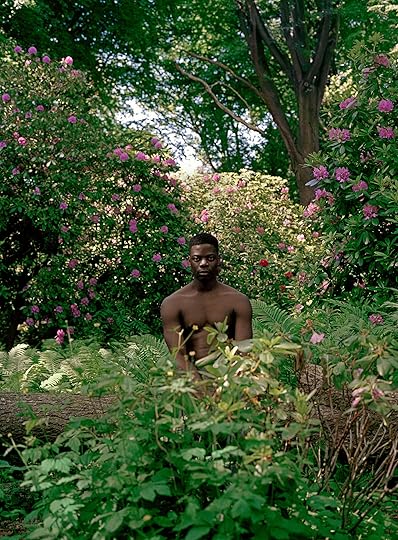

For decades, Dawoud Bey (born in Queens, 1953) has made evocative photographs that mine the histories of marginalized Black communities, with works ranging from the side streets and thoroughfares of Harlem, the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, and the dense, unmarked trails of the Underground Railroad. His forthcoming Aperture publication, Elegy (copublished with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts), assembles the history projects and landscape-based work Bey has made since 2012, and is being published in conjunction with a new exhibition. In admiration ofBey’s impact on modern visual culture, his friend, artist Carrie Mae Weems contributed for the video program: “Thank you for the way in which you’ve brought other photographers forward. You’ve made space for others. You’ve given us something special through your life’s work, and for that I am deeply grateful.”

Gala cochairs: Lisa Rosenblum, Elizabeth Kahane, Bob Rennie, Dawoud Bey, Agnes Gund, Kenneth Montague, Cathy Kaplan, and Sarah Meister

Kwame S. Brathwaite, Colette-Veasey Cullors, Laurie Cumbo, Dawoud Bey, Hank Willis Thomas, Kenneth Montague, and Sarah Meister

Lyle Ashton Harris, Gale Brewer, Dawoud Bey, and Sarah Meister

Natasha Egan, Sarah Meister, Dawoud Bey, An-My Lê, and Lesley A. Martin

Pamela and Lennell Myricks, Sarah Meister, Dawoud Bey, and Tom Schiff

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Dawoud Bey, Carrie Mae Weems, and Sarah Meister

Elizabeth Kahane, Dawoud Bey, and Stuart Cooper

Previous NextAdditionally in the video tribute, artist Tyler Mitchell and Elisabeth Sherman, curator at International Center of Photography, shared experiences that illustrate Bey’s dedication and practice. On stage, fellow artist LaToya Ruby Frazier admired her colleague’s virtuosic ability to capture both the historic and everyday rhythms of Black life. During her introduction of Bey, Frazier remarked, “To encounter you, is to elevate in confidence, rigor, and thought what it means to be a photographer, what it means to be an artist, the discipline and commitment it takes.”

With performances from the Harlem Renaissance Orchestra, the evening included powerful remarks from Laurie Cumbo, New York City Commissioner of Cultural Affairs, and Gale A. Brewer, New York City Councilmember representing the Upper West Side neighborhood where Aperture will soon establish a new permanent home. Also joining were many artists who have collaborated with Aperture on publications and programs in support of their work over the years, such as Kelli Connell, Sara Cwynar, Angélica Dass, John Edmonds, Awol Erizku, Adam Fuss, Phyllis Galembo, Gail Albert Halaban, Lyle Ashton Harris, Tommy Kha, Justine Kurland, Gillian Laub, An-My Lê, Jarod Lew, Missy O’Shaughnessy, Ari Marcopoulos, Ryan McGinley, Susan Meiselas, Joel Meyerowitz, Philip Montgomery, Matthew Pillsbury, Stephen Shore, Paul Anthony Smith, Rosalind Fox Solomon, Joel Sternfeld, Hank Willis Thomas, Alex Webb, Rebecca Norris Webb, author and curator Nicole R. Fleetwood, and writer Rebecca Bengal.

Dawoud Bey and Elizabeth Sherman

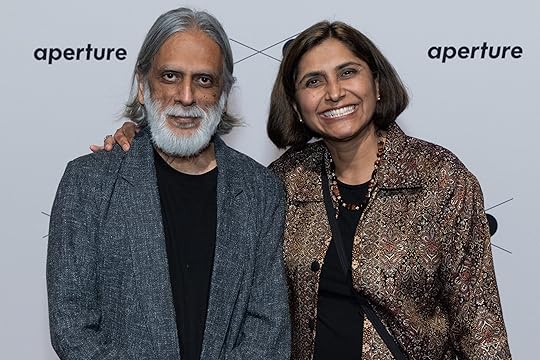

Dawoud Bey and Elizabeth Sherman Vasant Nayak and Sheela Murthy

Vasant Nayak and Sheela Murthy Harlem Renaissance Orchestra

Harlem Renaissance Orchestra Ryan McGinley, Marc Domingo, and Awol Erizku

Ryan McGinley, Marc Domingo, and Awol Erizku Jarod Lew and Sunny You

Jarod Lew and Sunny You Remi Onabanjo, Leigh Raiford, and Lucy Gallun

Remi Onabanjo, Leigh Raiford, and Lucy Gallun Jon Stryker, Biljana Simic, and Slobodan Randjelović

Jon Stryker, Biljana Simic, and Slobodan Randjelović  Cathy Kaplan

Cathy Kaplan Rebecca Bengal, Tommy Kha, and Michael Famighetti

Rebecca Bengal, Tommy Kha, and Michael Famighetti Ari Marcopoulos and Kara Walker

Ari Marcopoulos and Kara WalkerThe night also featured a live auction, animated by Sarah Krueger, Head of Photographs at Phillips, with an impressive lot of works by Dawoud Bey, Kwame Brathwaite, Gordon Parks, Gregory Crewdson, and Justine Kurland. A silent auction, hosted on Artsy through noon on October 4, included work by Jamel Shabazz, Joel Meyerowitz, Gail Albert Halaban, Garry Winogrand, An-My Lê, Lillian Bassman, Shirin Neshat, Erwin Olaf, Vik Muniz, and Robert Polidori. A paddle raise to benefit Aperture’s work scholar program which offers invaluable career development and experience in arts and publishing, inspired a swell of contributions from Gala attendees. Proceeds from the Gala and auction support Aperture’s work as a nonprofit leader in the field, including its award-winning publications, educational initiatives, exhibitions, and public programming. Those attending the Gala as well as those reading along in support are encouraged to make a donation of any amount here.

Commissioner Laurie Cumbo

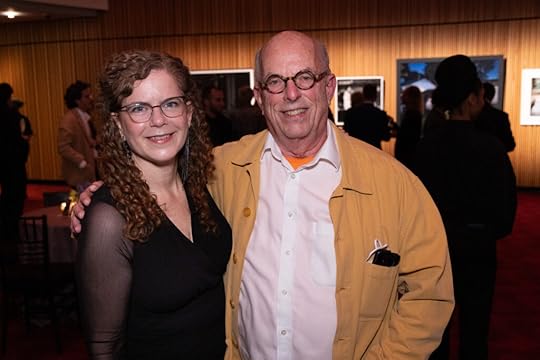

Commissioner Laurie Cumbo Joel Meyerowitz and Clark Winter

Joel Meyerowitz and Clark Winter Elizabeth Gregory Gruen, Kellie McLaughlin, Bob Gruen

Elizabeth Gregory Gruen, Kellie McLaughlin, Bob Gruen Denise Wolff and Marvin Heifernan

Denise Wolff and Marvin Heifernan

Aperture’s 2023 Gala thanks Founders Agnes Gund, Judy and Leonard Lauder, Lisa Rosenblum, Thomas R. Schiff and Mary Ellen Goeke; Gala Leaders Dawoud Bey, Allan Chapin and Anna Nilsson, Emerson Collective, Goldman-Sonnenfeldt Foundation, Elizabeth and William Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan and Renwick D. Martin, Melissa and James O’Shaughnessy, and Sean Kelly Gallery. Thanks to those who made the auction possible, including Dawoud Bey, Sean Kelly Gallery, The Gordon Parks Foundation, Kwame S. Brathwaite and the Brathwaite Archive, Michael Hoeh, Gregory Crewdson, and Justine Kurland and Higher Pictures.

Related Items

Dawoud Bey: Elegy

Shop Now[image error]

Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities

Shop Now[image error]September 29, 2023

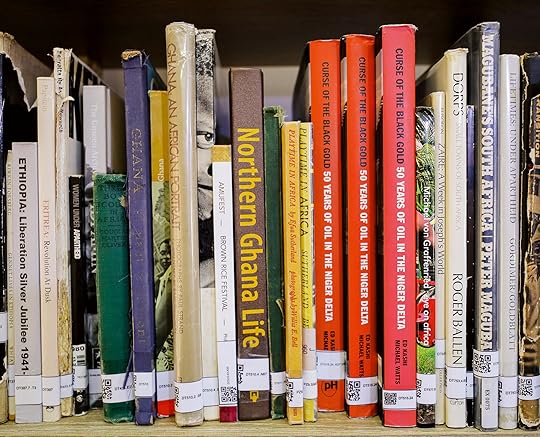

How Archives Illuminate the History and Culture of Ghana

The first time I heard of a photographic archive in Ghana was in 2009 after returning to Accra following studies in London. I was the editor of Dust, a quarterly love letter to Accra that documented the city’s (then) nascent cultural scene. We were drafting an article about one of our inspirations—the iconic South African magazine Drum (which published photography by the likes of Ernest Cole and James Barnor in the 1950s and 1960s)—when my photo-editor, Seton Nicholas, mentioned the Willis Bell Archive.

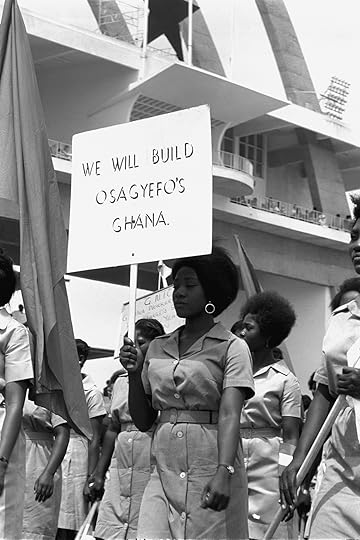

Bell, an American photographer who died in 1999, snapped thousands of images during a long residence in postindependence Ghana, including commissioned photographs of Ghana’s first leader, Kwame Nkrumah. Those photographs are currently being restored and digitized by the Mmofra Foundation, a nonprofit organization continuing the work of Bell’s close friend Efua Sutherland, a playwright who was one of Ghana’s first and most prominent cultural activists and advocates for children. Mmofra (which means “children” in Akan) runs a beautiful park on the Sutherland compound, where Bell once lived, and is dedicated to the cultural and intellectual enrichment of Ghana’s children.

Deo Gratias studio, Accra, 2023

Deo Gratias studio, Accra, 2023Photograph by Francis Kokoroko for Aperture

Photographic City, Agbozume, Group of friends photographed at the beach, Volta Region, 2000s

Photographic City, Agbozume, Group of friends photographed at the beach, Volta Region, 2000s© and courtesy the artist and Saman Archive

There are, of course, other archives in a land as visually compelling as Ghana. Photographs were once a marker of social status here, and many elite Ghanaian families have flocked to places such as Accra’s Deo Gratias, one of Ghana’s oldest photographic studios, to immortalize themselves. Deo Gratias (Latin for “thanks to God”) was founded by the photographer J. K. Bruce-Vanderpuije in 1922. Born to a wealthy family in 1899, he opened the studio after a three-year apprenticeship under the photographer J. A. C. Holm. The firm made portraits of British and Indian families as well as Black professionals, then expanded to cover corporate events. Bruce-Vanderpuije was later joined by one of his sons, Isaac, also a gifted photographer. Deo Gratias, situated in a graceful old building in the heart of Jamestown, one of the city’s first districts, is surrounded by history: it is walking distance from a lighthouse, two colonial-era forts, and a palace. It is run today by Kate Tamakloe, who builds on her father’s and grandfather’s work by scanning and digitizing pictures from old film and glass plates.

Tamakloe considers archives such as Deo Gratias to be vitally important in Africa, where history is often ignored, forgotten, or obscured. The introduction of photography in West Africa in the mid-nineteenth century would ultimately give Ghanaians a better appreciation of the landmark events of independence a hundred years later. The photographs housed at Deo Gratias “prove history, occasion, and even lifestyle,” she says, and, in turn, inspire books, films, and documentaries. One might think that this would make the archiving of photography a national priority, but Tamakloe explains that individual Ghanaians have always been more supportive of photography than any of Ghana’s myriad political administrations.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

That said, one of Ghana’s most important repositories, the J. H. Kwabena Nketia Archives, part of the University of Ghana, benefits, at least indirectly, from government support. Currently run by Judith Opoku-Boateng, the archive is named after Joseph Hanson Nketia, Africa’s foremost ethnomusicologist until his passing in 2019, at the age of ninety-seven. Its contents include music from all over Africa—priceless recordings of vanishing traditions—as well as the Institute of African Studies’ historical records dating as far back as the 1960s, and a large photographic collection of postcolonial Ghana. It is the largest and most systematic set of recordings of any African ethnomusicologist, initially spanning forty years of field research by Nketia and his colleagues, and documents sounds, stories, and songs across the length and breadth of Ghana, along with oral and performance traditions of the numerous peoples within (and sometimes beyond) its borders. Recent initiatives to grow the collection have included the gathering of special historical papers, photographs, and other audiovisual materials from the families of other deceased scholars. Nketia was the first to capture practices passed down for generations through oral tradition. While his association with music means that the archive may be known primarily for its traditional and highlife recordings, it also houses thousands of negatives and prints that capture the lives of Ghanaians of all walks of life at a crucial time in our history.

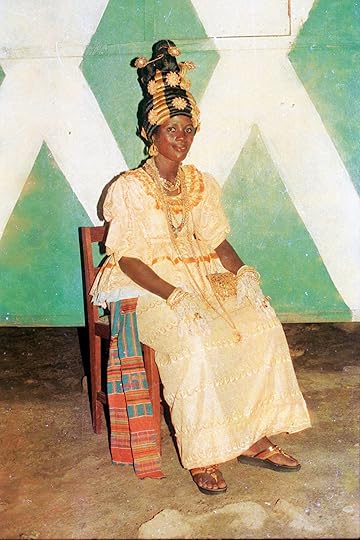

Jacob Quaye Mensah, Woman photographed at a wedding, Apam, Ghana, ca. 1990s

Jacob Quaye Mensah, Woman photographed at a wedding, Apam, Ghana, ca. 1990s© and courtesy the artist and Saman Archive

Independence Day Parade, Accra, early 1960s

Independence Day Parade, Accra, early 1960s© Mmofra Foundation, Accra, and courtesy Willis Bell Photographic Archive

Although it feeds from the budget allocated to the Institute of African Studies by the University of Ghana, Opoku-Boateng explains that funding is still barely sufficient for the smooth running of the complex equipment and logistics required by the archive. Another challenge is understaffing: besides Opoku-Boateng and two senior research assistants, one of whom is part time, the archive relies on interns. There is also the problem of obsolescence, with much of the information being stored on analog media formats and requiring playback equipment unavailable in Ghana, “leaving the value of these materials totally locked up.”

Photographs are no longer exclusive to high Ghanaian society. I remember how hard it was to get one’s photograph taken while growing up in 1990s Cape Coast, Ghana’s former capital. My boarding-school mates and I would pool together pocket money, and one of us would make a beeline to the nearby photo studio to book an appointment for the following weekend, when we would pose in our best school uniforms. Then we would wait—for as long as a month—for our pictures to be developed and printed. Unlike for today’s middle-class Ghanaians, who grow up capturing their entire lives on mobile phones to share on social media, there are reasons why many in my generation lack the millennial impulse to document the mundane.

Deo Gratias studio, Accra, 2023

Photograph by Francis Kokoroko for Aperture

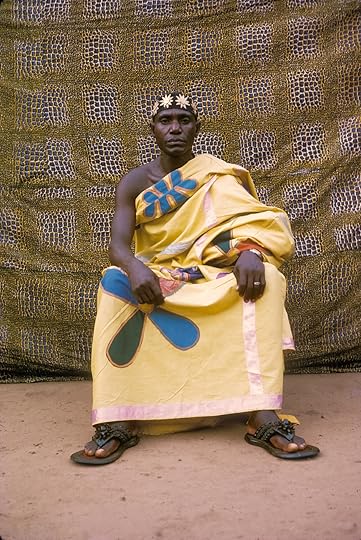

Tamakloe expresses skepticism for online platforms such as Instagram and the dominance of digital. “We have lost all the technicalities of a beautiful photograph, even knowledge of the long process of using chemicals in the darkroom,” she says. “Today, it’s plug and play. Once the photo is not blurry, it’s considered ‘a good shot.’” Nevertheless, some do attempt to harness the power of these platforms for the greater good. One such entity is Si Hene—a reference in Akan to the enstoolment of royalty—which was founded in 2020 as a website and Instagram account by Rita Mawuena Benissan, a Ghanaian American interdisciplinary artist who describes Si Hene as “an archive-based collection of images of Ghanaian chieftaincy.” Such work is important in the context of a continent whose royals were reduced from kings and queens to “chiefs” by colonizers whose worldview stopped them from seeing Africans as equals.

When I visited Benissan at Gallery 1957, a contemporary art space and commercial gallery housed in Accra’s Kempinski Hotel, she was preparing for an exhibition at the gallery on the elaborately designed umbrellas that provide more than mere cover from sun and rain to Ghanaian chiefs during royal durbars and festivals. (In Ghana, such umbrellas, as much symbols of royalty as any crown or scepter, are used during sacred traditional ceremonies and festivals.) Benissan tells me that she sees her exhibition and online archiving as extensions of the same work. “People say ‘chieftaincy is dead,’ but it’s not. Literally everything we do is derived from chieftaincy: from our stools to our names to the kente we wear to how we style our hair and present ourselves. It all comes from the chieftaincy. The photos are a way to bridge that heritage.”

Photography has changed from focusing on members of high society to becoming a people’s visual history.

She has been inspired by others including Amy Sall, founder of SUNU Journal—an independent, Pan-African, postdisciplinary multimedia platform that publishes works dealing with Africa and its diaspora—as well as by Nana Oforiatta Ayim, a Ghanaian art historian, and Deborah Willis, the African American historian of photography who once invited Benissan to a “life-changing” conference on Black portraiture at New York University. Benissan was struggling to find images of royal umbrellas for her US graduate-school research. Out of this frustration Si Hene was born. “Even though I had a lot of books,” Benissan explains, “there were no old images, only pictures of recent chiefs, or images from Benin and Nigeria but not Ghana.” Wanting to find out more about how these umbrellas were designed in the early 1800s and 1900s, she scoured archives at museums, institutions, and universities; family albums; and YouTube and internet resources, including Tumblr, to find the answer. It was hard work. “Sometimes, I could spend five hours looking for a photo and not find anything. But then you change a keyword, an image pops up, and you spend six more hours from that one connection,” Benissan tells me.

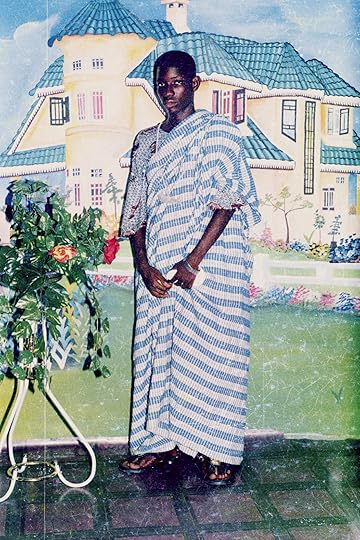

Perseverance Photo Studio, Teenage boy photographed with studio backdrop, Anloga, Ghana, 2000s

Perseverance Photo Studio, Teenage boy photographed with studio backdrop, Anloga, Ghana, 2000s© the artist and courtesy Saman Archive

Portrait of Nana Kofi Yeboah, the Akrofromhene, 1970

Portrait of Nana Kofi Yeboah, the Akrofromhene, 1970Courtesy D. Michael Warren Papers, University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections and Archives, and Si Hene

After the COVID lockdowns lifted, Benissan returned to Ghana and gained access to chieftaincy meetings, where she was guided toward reference materials and archival collections that included pictures, postcards, stamps, and stills. She is seeing a slow rise of chiefs building their own museums, but she wonders whether these are aimed at Ghanaians or visitors from Africa’s diaspora trying to better understand the ancient nations and cultures out of which their ancestors were stolen. It is an important question: Africans in the diaspora have access to museums, universities, and other institutions their cousins in Africa lack. In Ghana, Benissan explains, you have to ask “a hundred people” for that kind of information, you have to wait and seek approval. Accessibility afforded by social media is key, but Benissan also notes that many parents, grandparents, and chiefs are not on Instagram. She describes being introduced to chiefs who appreciate her idea but ask an important question: “How do I see it?” She also faces copyright issues, as Si Hene does not own any of these images. She nevertheless tries to contact as many institutions, curators, and families as she can. Even if some do not respond, others, Benissan says, “seem happy we are providing another accessible way to see their collections.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Similar in digital form to Si Hene stands Saman Archive, named after an Akan word that simultaneously means “ghost” and “photographic negative.” Founded in 2015 by the artist and writer Adjoa Armah, Saman began as a repository for the thirty thousand negatives dating from 1963 to 2010 that Armah collected from studios and photographers across Ghana as part of her practice-led doctoral research at the University of Oxford. She considers Saman to be more than just a collection of negatives, stating that the project is a place for “my own photographs and those of my collaborators across the country, recorded conversations with photographers, ephemera, and the research conducted as negatives are being collected.”

Album covers, clockwise from top left: Kelenkye Band, Moving World, 1974; Ogyatanaa Show Band, Yerefrefre, 1975; African Brothers Band (International), Afrohili Soundz, 1973; Canadoes Super Stars of Ghana led by Big Boy Dansoh, Afaa Boatemah, 1985

Album covers, clockwise from top left: Kelenkye Band, Moving World, 1974; Ogyatanaa Show Band, Yerefrefre, 1975; African Brothers Band (International), Afrohili Soundz, 1973; Canadoes Super Stars of Ghana led by Big Boy Dansoh, Afaa Boatemah, 1985Images courtesy Bokoor African Popular Music Archives Foundation (BAPMAF) and J. H. Kwabena Nketia Archives

The archives at Deo Gratias studio, Accra, 2023

The archives at Deo Gratias studio, Accra, 2023Photograph by Francis Kokoroko for Aperture

Saman stands on the shoulders of giants. As Armah explains, “We never start from zero. The best we can do is honor those who came before us.” She values Deo Gratias and holds particular appreciation for the Nketia Archives’ custodianship of Ghanaian sonic histories, saying, “It’s their work and the work that families do, in which the stories around photographs are central, that really influence me.” In contrast to Si Hene, Saman’s areas of collecting go beyond chieftaincy, and its public face is a website. Noting the way photography has changed from focusing on members of high society to becoming a people’s visual history, Saman is, she says, “interested in what lives looked like beyond the grand narratives that cater toward middle-to-upper-class people.”

Armah surprises me with a “two-hundred-year plan” that includes eventually housing Saman in a physical space. Benissan also dreams of museum and research institutions, where physical images can be better preserved, in all sixteen regions of Ghana. She points out that chieftaincy palaces are ultimately homes and, as such, cannot offer visitors the same levels of exposure as museums. The goal is to balance access to the physical images housed in these spaces with respect for royal privacy. While Deo Gratias already serves as a physical museum, it, too, encounters problems of scaling up, a process that involves, as Tamakloe explains to me, “maintaining the glass plates, digitizing them totally, and making it available virtually to the world to tell the Ghanaian story.” Ghana’s archives are invaluable resources for understanding the nation’s past. Ongoing efforts to preserve and digitize such records—both physical objects and data—are essential for future generations. This work is shaping a collective understanding of history and identity that may otherwise be lost in the maelstrom of modern culture: a thing that is never static.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra.”

Carrie Schneider Unspools a Riddle about Photography and Cinema

In the vast former-factory space of MASS MoCA, a singular, inscrutable, sculptural photograph, titled Madame Psychosis (Joelle van Dyne) (2023) and measuring an astonishing forty inches by eight hundred feet, unfurled in a seemingly endless scroll, pitched in a roof formation at its peak and rippling out over a large plinth. Another work (Infinite Kill, 2023) cascaded across the gallery’s walls. In the adjacent spaces, one room displayed more than a hundred dreamlike, abstract photographs—multiple exposures of images sourced from a litany of artists, films, and social-media feeds of the artist’s friends, layered onto personal images. Lurid with color, all were photographed and rephotographed in dark, transitory, predawn hours. Here, they were installed with little wall space separating each of them, emphasizing their shared connection. And projected in the back room is a 16mm film that exudes a Warholian Screen Tests energy. Composed of stills showing the actor Romy Schneider, the work flickers on the walls so that Romy seems to watch her own image scatter around.

The film is Carrie Schneider’s Sphinx (the answer isn’t man) (2023). Sphinx is also the title of her solo exhibition at MASS MoCA, which was on view from March to September 2023, and featured work that the Brooklyn and Hudson, New York–based artist made beginning in the spring of 2020. All Schneider’s vivid, sometimes gigantically large photographs were made with a room-size camera that she built herself out of industrial plastic and outfitted with a Rodenstock lens. (Some of the pieces have been shown at Candice Madey and Chart galleries in New York.) As in previous series that incorporate self-portraiture, personal traces of and references to the artist were present in Sphinx too. There’s Romy Schneider, who shares the artist’s surname, in the film, and in Infinite Kill, where she appears on a phone screen that the artist cradles in one hand, nails painted bright red, and holds up to the camera. Revenge Body (2022), a floor-to-ceiling photograph of a repeated abstracted still from the 1976 film Carrie, depicts Sissy Spacek’s title character, who shares the artist’s first name, her face dripping with blood.

Installation view of Carrie Schneider: Sphinx at MASS MoCA, 2023. Photograph by Jon Verney

Installation view of Carrie Schneider: Sphinx at MASS MoCA, 2023. Photograph by Jon VerneyOn the surface, the pieces that made up Sphinx represent a radical and monumental shift in scale, material, and conception within Schneider’s practice, but also in thinking about photography itself. This is work that particularly invites and rewards close looking, revealing subtle and surprising connections with many of Schneider’s previous series of photographs and videos, from Burning House (2012–13)—for which she built to scale a small house on a tiny island, set it aflame, and filmed its burning—to her numerous collaborations, including those with the choreographer and dancer Kyle Abraham, artist Abigail DeVille, and composer and musician Cecilia Lopez.

I first met Schneider in 2009, when we were both in residence (in visual arts and fiction, respectively) at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, where Rineke Dijkstra was a visiting master artist. A few years later, I participated in Reading Women (2012–14), comprising immersive photographic and video portraits of a hundred of her women-identifying friends and peers reading books by other women in their homes or studios. There’s a clear path, it seems to me, from Reading Women to Sphinx. As artist and filmmaker Cauleen Smith (who also participated in the former project) wrote in a 2014 essay titled “Carrie Schneider’s Grown-Ass Women: You Better Recognize”: “She sits with her. She lets her be. Like a thermal current on a cool day the condensation of a woman into a being of pure thought, silent and in violent motion at the atomic level offers mad quotients of marvel. A woman reading is not accessible or controllable. We cannot know what she might do. We are left to wonder.”

Unraveling and unfurling their inner selves, reclaiming how they are seen, the works in Schneider’s Sphinx similarly unspool their riddles before us. Recently, Schneider and I spoke about the process of making Sphinx and discussed its influences, ranging from Imogen Cunningham to renowned film theorist Laura Mulvey, author of the landmark essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” and creator of films including Riddles of the Sphinx (1977).

Carrie Schneider, Sphinx (the answer is man), 2023

Carrie Schneider, Sphinx (the answer is man), 2023Rebecca Bengal: Congratulations again on such a brilliant exhibition and catalog—which has stayed so much on my mind since I got to visit earlier this summer. I’m curious how the exhibition changed for you during the span of its run.

Carrie Schneider: Thank you! It was so fresh when I installed the work. My studio is a renovated one-car garage, so there was no way for me to test out these large sculptures. I had been making them in this camera that I built, exposing hundreds and hundreds of feet of this color chromogenic paper—there’s something like 4,600 feet of paper in all in the show—but until we installed, they existed as a plan in my mind of what I wanted to make.

I installed for two weeks straight with a crew of twelve people, and it really extended the way that I thought about the work immediately. It just exploded my brain. I felt like suddenly I had twenty-four arms, and it also really made me think of the next six projects I’ll make. I’m still unpacking what it was like for me to finally see it in this space: I feel like, when it opened, it was so new on the walls, that I really saw it as other people saw it. I’m still in a state of semi-confusion. It still feels very new to me, even though the show itself is almost over.

Installation view of Carrie Schneider: Sphinx, MASS MoCA, 2023

Installation view of Carrie Schneider: Sphinx, MASS MoCA, 2023Bengal: It’s true, even some of the first works in the exhibition feel so new in this context. I’m thinking of Deep Like (2020–21), your series of 105 pictures, all around twenty by twenty-five inches, which take up an entire room in the show. How did that work lead to the larger pieces?

Schneider: Those were the earliest kind of experiments. I think of them as being my alphabet for the language that I then develop in the larger works in the adjacent galleries. I was exposing this chromogenic paper through the lens of this camera that I built in my studio in the pandemic, and then I decided I wanted to scale up. So I made larger prints, I built my camera a little bit larger, just further exhausting the motifs. And then I really leaned into using an image that started in Deep Like: really looking at the face of the actress Romy Schneider.

There was a certain moment where I realized that didn’t need to cut the paper. It was coming in these long rolls, shipped to my home during the early pandemic. And instead of cutting the paper in the dark and putting it into my camera, it just dawned on me: I’ll just continue to advance the paper kind of frame by frame or bit by bit, exposing a continuous roll. That was, maybe about a year into making the work, when I had that realization that I wanted to just use the material in this way that was really structural, expanded into hundreds of feet-long photographs. And then I had to figure out how I would show them, how they would become became installations or sculptures, kind of coming off the wall.

Carrie Schneider, Infinite Kill, 2022

Carrie Schneider, Infinite Kill, 2022Bengal: When and why did you decide to build your own camera?

Schneider: Before the pandemic I’d also been doing a side project where I was figuring out how to expose chromogenic paper through the camera’s lens, and filter it so that if I were to reshoot it as a paper negative, it would faithfully invert—achieving a kind of black-and-white and a neutral tone. And I had been making tests for years using a large-format Deardorff camera that I bought from a mentor.

I was ready for it to move to the next level. I really knew I wanted to scale up, and I’d been shopping around how to get a custom camera built. But the quotes I was getting felt prohibitively expensive, and of course it’s the pandemic, and everything was so demoralizing. One day I’m out on a run and I thought, suddenly, Oh my god, I know how to make a fucking camera! It’s just a light-tight box. It’s just a dark box. It doesn’t have to be beautiful. And that same day, I went to Home Depot with a mask on and bought all that stuff . . . I think it was something like $110 total. And I went home and I made it, and it completely worked, first try. What I’m working with now is maybe the sixth generation of it. It’s slightly bigger now. I call it my Frankencamera.

Carrie Schneider, Still from Burning House, 2012–13. HD film, 12 minutes, color, sound

Carrie Schneider, Still from Burning House, 2012–13. HD film, 12 minutes, color, sound Carrie Schneider, Still from Burning House, 2012–13. HD film, 12 minutes, color, sound

Carrie Schneider, Still from Burning House, 2012–13. HD film, 12 minutes, color, soundBengal: It makes me think about the sculptural aspect of your work, especially projects like Burning House: the idea of a camera as a house.

Schneider: Exactly. They’re actually about the same size. And of course, camera means “room” in Latin.

Bengal: Your approach to this work is so intuitive and original, but I also know there’s some important inspirations for you lurking in its backstory.

Schneider: I really love everything about Imogen Cunningham’s work, but there are these two negative images in particular: one is of a snake, and one is of her friend Roberta. When I first saw that one, Roberta (Negative) (1961), about fifteen years ago, I thought, What is this? I immediately printed it out and put it on my studio wall. I think what she did is she just used a paper negative, kind of like a contact sheet in reverse. I just wanted more things like that to exist in the world.

Bengal: It’s such a cool and incredible picture. What else about it, specifically, drew you in?

Schneider: What I took from it as a kind of a stepping-off point is seeing how an image of a familiar thing in negative produces this really uncanny effect. I think the image of Roberta is just some textures, like plants and her face. It’s just that simple, but when they’re inverted and negative and kind of superimposed on one another, the results are so surprising. So what I took from that is that the magic didn’t really need to be made with much, but to just be open to experimenting with everyday things floating around. I didn’t feel like I had to go too far to find something that might produce something satisfying to me in a similar way.

I don’t know if I’ve made my Roberta (Negative) yet, but I feel it gave me permission to start really simply, just shooting from within a dark room out of a window. Just seeing how the world outside looked in negative. I think it was very, very simple at first, and then pretty soon after that I started getting a little more weird.

Carrie Schneider, Jacob F, 2021

Carrie Schneider, Jacob F, 2021Bengal: With Deep Like, you sourced images from friends’ and others’ social-media feeds, starting when we were all a bit isolated in early pandemic days. Were you actively looking for images at first, or was it born out of mindlessly doomscrolling in that doomy era?

Schneider: I don’t think it was so conscious at first. When I’m teaching, I try to remind my students that it’s okay to work intuitively because you have this whole armature of theory, or the art history you’ve absorbed. In early pandemic no one was watching. I didn’t have any shows lined up. So, in a way, I was totally liberated.

I was working at this really fast clip. I had to work in complete darkness because I’m working with the chromogenic paper, which is totally light sensitive. I wasn’t able to totally black out my studio, and of course I couldn’t even have a safe light, so I had to work at night when there was no sunlight. I’d had some insomnia in the pandemic, and I was going to sleep when my then five-year-old son was, at eight p.m., and then I was waking up at three or four in the morning. This became my prime time. I think it’s really kind of a famous time of day for, like, mother-artists’ work. I think Sylvia Plath called it the blue hour—you know, before anyone wakes up, where you actually have time to yourself. I felt that really viscerally.

Related Items

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

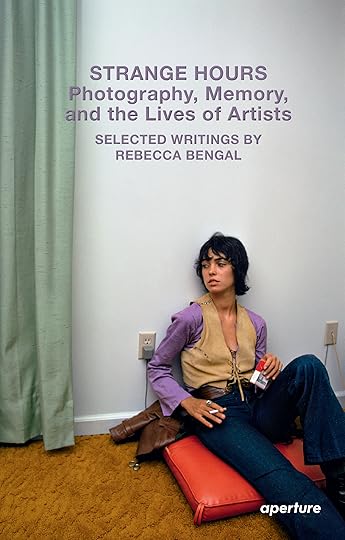

Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists

Shop Now[image error]Bengal: I love those times. They can be super generative and freeing when the rest of the world is turned off. You have a beautiful artistic relationship to night, too, that’s there in your 2015 series Moon Drawings. Were there other discoveries you made from working these hours?

Schneider: Before I was a photographer, I was a painter, and so when I started this work, I was thinking about Sigmar Polke and the way he just exhausted motifs. He would appropriate something from somewhere and just make hundreds of photocopies of it, and they’d show up in paintings, these serigraphic images. It’s this different sort of engagement with Polke. It’s not like Warhol; it wasn’t a commentary on mass media or anything. It was just the weirdest, most idiosyncratic stuff. It emboldened me to do the same thing, and then there was this moment where I realized, Oh, these images that I’m reproducing, what if I then rephotographed those and those kind of invert yet again, and then I invert them again. I was really immersed in it.

Carrie Schneider, Choose Well, 2022

Carrie Schneider, Choose Well, 2022  Carrie Schneider, tfw, 2022

Carrie Schneider, tfw, 2022 Bengal: So much of your work is cinematic in feeling and in origin, embodying these ideas that go back to Laura Mulvey, who introduced this idea of the male gaze—viewing a woman’s image as sexual object or giant threat.

Schneider: I’d had a Zoom studio visit with my friend Sarah, she had also studied with Laura, like I did at the Whitney Independent Study Program. And as we were talking, she said, “Have you read Laura recently? Maybe you should read her again.” And it was like, Oh my god, you’re so right. I mean, I hadn’t, like, in a decade. I went back, and I saw that the new work was illustrating this. It was so bizarre. Obviously, this was part of the armature upon which I’m building this work when I’m working intuitively, but it wasn’t conscious at all. When I reread her texts, I was just smacking myself on the forehead. You couldn’t do that, in a sincere way, to illustrate theory, but it felt so unbelievably parallel that I reached out to Laura and asked her if she’d meet with me on Zoom. We’ve had an ongoing conversation since then. She’s so sharp, and she’s writing about so many other things, too, and also updating texts she wrote that are now, like, forty-five years old.

She was telling me the other day how she was screening Citizen Kane for some people and when she was loading the film, it unspooled. It just spilled everywhere—but it also retained this form of the coil. There’s chaos, but it also somehow retains its form.

Carrie Schneider, Eve of the Future, 2023. Installation view at MASS MoCA. Photograph by Jon Verney

Carrie Schneider, Eve of the Future, 2023. Installation view at MASS MoCA. Photograph by Jon VerneyBengal: Which was surely messy and maybe a little horrifying in the moment. But, as I also see it in the unspooling of your Sphinx, so vulnerable and exciting, to just lay it all bare and be. I think there’s a power in that. I also wanted to go back to something you said earlier, where you described your “alphabet of imagery.”

Schneider: I call it a seed-library impulse. At the start of making this work I was reading Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, as so many people were. So, just the idea of preserving these creative influences, whether they were my peers or mentors or just different canonical works in the history of art, like this very idiosyncratic collection, but kind of preserving them in an analog form, just in case the digital technology could fail. There was something doomsdayish about it.

I also thought about it as, maybe that Mariah Carey clip [present in Schneider’s recent exhibition at Chart, I don’t know her] is, like, the golden record. To preserve some aspect of human culture and make this analog, as if we were sending it out into space. Putting it into a tangible form was a way of making a big statement about wanting to possess it or preserve it in a way.

Bengal: It feels to me also like a reclamation. To make your own camera. To articulate your own language. To take that all into your hands. To repossess those images and retranslate how they are seen. The immense space that the sphinx and Romy Schneider and Spacek-as-Carrie and all these women occupy in these rooms.

Schneider: When I kind of scaled up my camera, I started working in a way that felt much more loose. But also, sourcing these original images, it felt like it was something that could spin outwardly forever into these infinite possibilities, like in the way Agnes Martin could infinitely source a grid. For her the grid was so innocent and pure, like a tree. I felt like there was this really beautiful thing where I thought: I don’t have to go any further. I have it all right here, in this cache of images.

But also: if it is autobiographical, I think about the way Lauren Berlant said that the autobiographical impulse is inherently anxious and ambivalent. I think that’s kind of what drives it, that tension. There’s an element of possession and homage, but also theft.

Carrie Schneider, Madame Psychosis (Joelle van Dyne) (detail), 2023

Carrie Schneider, Madame Psychosis (Joelle van Dyne) (detail), 2023All photographs courtesy MASS MoCA

Bengal: How did the physical process of making those giant prints affect the way you felt about and understood your own work?

Schneider: The owner of My Own Color Lab, where I printed all of it, and all of the employees—they went out of their way, stayed late, would help me run these massive things through. And just seeing, you know, that they even allowed me to do that is so rad. But also, their excitement about it was so motivating. I think it goes back to using all these technologies that require a lot of material knowledge but then using them in a way that they’re not meant to be used. That spirit of experimentation just made it all possible. The fact that they were even game to let me try to do it and were so psyched about it.

Bengal: There’s this inherent spirit of rebelliousness about that. How far can you extend this idea?

Schneider: What if this could just go on to infinity?

Carrie Schneider: Sphinx was on view at Mass MoCA through September 17. The accompanying catalog was published in 2023 by Hassla.

September 26, 2023

What It Means to Make Photographs as a Young Artist in Iran

Over the last century, photography in Iran has often been overshadowed by the country’s social and political conditions and historic flash points—among them the transition from the Qajar to the Pahlavi era in the 1920s, the Islamic Revolution in the late 1970s, and the Iran–Iraq War the following decade. As a result, many photographers, particularly those from the new generation who transcend geographical confines, have received relatively little recognition.

In countries where the art scene has attained a certain level of prosperity, there is a dynamic relationship between artists, curators, historians, and institutions. These elements collaborate to set the cycle in motion: the artist generates a piece of work, and curators exhibit these works in galleries and museums to explore new ideas. As a result, the artist’s work garners visibility, curators unearth innovative concepts, history advances, and ultimately, museums and galleries manage the economic aspects of this process. But young Iranian photographers encounter a distinct set of issues once they progress beyond the political imaginary.

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2021, from the series Disorders

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2021, from the series Disorders  Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2023, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2023, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot While the significance of photography has only recently grown due to the establishment of photography faculties within Iran’s universities, the absence of curators is a notable void. The lack of curators renders the interaction between artists and galleries both more challenging and complicated. This poses a significant issue for those striving to display and showcase their artworks. Consequently, we are observing a static environment wherein photographers’ most fundamental requirements, namely sales and exposure, remain unfulfilled.

I recently spoke with three young photographers about their practices: Zahra Motallebi, a twenty-five-year-old photography student at Tehran University of Art who focuses on gender minorities in Iran and who has been documenting her personal journey after the loss of her mother; Ehsan Noortaqani, twenty-six, who studied at Art University of Isfahan and finds photographic inspiration in his family, particularly after the passing of his father; and Zhoobin Abdiani, a twenty-eight-year-old photography student at the University of Tehran whose work draws on his birthplace in Kurdistan.

Ehsan Noortaqani, Last Day of Summer, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23

Ehsan Noortaqani, Last Day of Summer, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23Amin Yousefi: During the late 1990s and early 2000s, being an Iranian photographer required a series of visual elements that functioned as legitimizing indicators when emerging in the art scene. Those components, such as explorations of identity, masculinity, the evolving role of contemporary Iranian women in a male-dominated society, and depictions of the country’s social conditions, were prominent in most visual depictions . Recently, they have become more implicit, requiring some decoding at times. Do you believe that these elements exist in your work? Would you like to incorporate these elements intentionally?

Zhoobin Abdiani: I believe it should be present. Speaking from my own project, let’s consider the landscape in Kurdistan, Iran, compared to the landscape around London. As a landscape photographer working in Kurdistan, I cannot simply overlook its Iranian essence. However, I don’t approach it from an exotic perspective. In my work, I capture concepts and objects that have undergone a historical process within the landscape, yet they hold their own distinct identity within Iran. From this perspective, I strongly believe that these elements should exist, be given priority, and be emphasized.

Zahra Motallebi: I find myself unintentionally engaged in this matter, even if I may not be particularly interested in being labeled solely as an Iranian photographer. However, others argue that it is important to acknowledge that these images were captured within a specific geographic context like Iran. For instance, when I photograph gender minorities, the appeal stems from my connection with those individuals. Yet, I soon find that I am being criticized for focusing on what was considered an exotic subject matter! Despite this, the project holds great personal significance for me, as my curiosity lies with these minority groups.

Ehsan Noortaqani: Perhaps I’m not the best person to answer this question, as those observing me and my work from an external perspective can make that judgment. However, personally, I don’t dwell on whether I should be classified as an Iranian photographer while creating my projects and shaping the photos. What truly concerns me is that the artistic aspect of Iranian photographers’ works is often overlooked. There always seem to be other factors at play when interpreting the works of Iranian artists, which I find bothersome.

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2021, from the series Disorders

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, 2021, from the series DisordersYousefi: Where do your projects begin and how does photography enable you to explore and expand your ideas?

Abdiani: I have always had a curious and research-based mindset, and I found that snapshot photography wasn’t quite suitable for me. While I do some experiments with photography at the start of a project, the point of my work has consistently revolved around the themes of identity and the Kurdistan region. These aspects are clearly reflected in my works. For me, photography is nothing more than a medium to execute my projects, and I am not always faithful to it. I prefer to follow conceptual artists and utilize photography as a documentation tool.

Noortaqani: My projects are deeply personal and originate from my memories and the insecurities that make me feel vulnerable. The catalyst for my photography journey was actually the passing of my father. The criticisms directed toward me, suggesting that I lacked responsibility, served as a starting point for me to prove the opposite through photography.

Motallebi: For me, it stems from curiosity and the desire to immerse myself in and understand the subjects that intrigue me. However, this process manifests in different ways across various projects. Take, for instance, photographing my mother before she passed away. I harbored a profound fear that she might have an incurable illness, and that she might not be alive for much longer—each photo I took of her could potentially be the last. Emotionally, I felt compelled to capture countless images of my mother, ensuring I wouldn’t forget her face once she was gone. But as the project progressed, and this sentiment intensified, I began approaching the subject of my mother with a more raw and unflinching perspective. She had become, in a way, my own personal subject (thing) till she passed away.

Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Stone section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23

Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Stone section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23 Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Zrêbar section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23

Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Zrêbar section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23Yousefi: And what are these pictures for? I’m curious to understand the intention behind your photography.

Abdiani: I try to research my topic before starting the project. From reading books and articles to field research, I try to understand my topic and diagnose it for myself. These aspects may not be directly visible in my project, but they are definitely tangible. In the project I am currently working on, on the Zrêbar Lake, I even had to speak with a geologist to find out the reasons for the presence of rocks that are foreign to this geography. Zrêbar Lake is one of the largest freshwater lakes in the world. No water enters it, and its water is supplied from the springs at its bottom. Additionally, it supports 151 species of animals in its wildlife. However, this lake has been destroyed in recent decades due to the accumulation of a significant amount of garbage at its bottom. I must admit that this part of the research is much more enjoyable for me than the production of photographs itself because, more than anything else, it increases my knowledge of my surroundings. In general, these things in the landscape are very interesting to me, and I strive to learn more about them even if I’m not working on a project related to them.

Motallebi: Photography serves as a reliable friend and companion for me to explore my curiosities. What photography provides me with is precisely that fleeting sense of satisfaction or jouissance, as mentioned by Lacan. It allows me to immerse myself in spaces that evoke this feeling within me, offering that momentary sense of gratification.

Noortaqani: You know, photography just makes me feel good at times. I believe there’s both an internal and external aspect to it. Unlike Zahra, I turned to photography when I was eighteen, following my father’s passing. Experiencing the sudden loss of my father, who I saw in the morning and who was gone by the afternoon, made me value our time even more. While Zahra discovered the significance of capturing moments before her mother’s death, I had a similar realization after my father’s passing. This has gradually emphasized the importance of the people around me in my life, day by day.

Ehsan Noortaqani, Holidays, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23

Ehsan Noortaqani, Holidays, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23  Ehsan Noortaqani, After Midnight, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23

Ehsan Noortaqani, After Midnight, from the series Monochrome Days, 2019–23 Yousefi: Has the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran inspired you to create a project in response, even though you are not a photojournalist? I think you have the potential to respond to the situation around you through your practice.

Abdiani: No. While it is a concern shared by many, creating a project directly addressing such events is not my preferred style. Even though tackling these subjects may bring fame, I still prefer to maintain my own political approach in my work. Moreover, it surprises me that some say that addressing the landscape is not political. I think that dealing with land and landscape is quite political nowadays because humans are trying to destroy it more than ever. Art history serves as a guiding framework for me. For example, the painting The Third of May 1808 (1814) by Goya, in my opinion, is as much about the killing as it is about the land where these events take place, and it is present in the painting.

Noortaqani: I never engage in [political movements], especially during times of crisis. While there may be implicit criticisms within my work, I believe that making accurate judgments in such moments is difficult. I see it as a form of exploiting the situation, and I prefer not to partake in it directly.

Motallebi: Well, as a woman in Iran, I have always experienced these conditions firsthand. However, I have always detested the idea of exploiting these circumstances or using them directly in my work for personal gain. Directly engaging with them would seem to imply that I have accepted these dreadful conditions, which is something I am not willing to do.

Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Zrêbar section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23

Zhoobin Abdiani, Untitled (from Zrêbar section), from the series Remains of a Body, 2017–23Yousefi: As representatives from three esteemed art institutions in Iran, I am curious to know what influences you, beyond your academic backgrounds. What things or individuals have had an impact on your artistic journey?

Abdiani: There are several photographers I could mention, such as Mehran Mohajer in Iran and Dusseldorf-based photographers like Bernd and Hilla Becher or Thomas Ruff. However, apart from them, the Minimalists and their straightforward approach to materials have had a significant influence on me.

Noortaqani: I have also been influenced by filmmakers like Nuri Bilge Ceylan and artists such as Julian Schnabel. Additionally, Iranian artists like Mohammad Shirvani and even Khosrow Hassanzadeh, who we recently lost, have left a lasting impact on me. And, of course, I cannot forget the influence of Japanese photographers as well.

Motallebi: Antoine d’Agata helped me to think about collaboration with the models in my photographs. I aim to capture their facial expressions, body language, and poses according to my vision. It is about creating a belief in the person being photographed that I possess the ability to depict them as sad, in a bad mood, infatuated, defeated, or weak. I want to portray them as if they were observing themselves from a distance during unfortunate moments of their lives, like in solitary moments, when they are sitting alone in their house or room, and their dark side is revealed. This realization was further reinforced by the works of filmmakers such as Gaspar Noé, Lars von Trier, and Yorgos Lanthimos. Recently, while I was writing down all my thoughts on photography for my MA thesis, I became interested in the works of Sadegh Tirafkan. In fact, he had the courage and audacity to showcase something that no one could do at that time. To me, he was confronting himself. The symbolic identity apparent in his works remains a mystery to me. When I observe his self-portraits, it is not easy to understand his approach. It seems he explores masculinity from a feminine perspective, or perhaps the other way around. It’s as if his identity, sexuality, and history are intricately intertwined in his works.

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot, 2022

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot, 2022  Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot, 2023

Zahra Motallebi, Untitled, from the series The Self-Taught Parrot, 2023 Yousefi: How do you typically showcase your works? What options are available in Iran, and what are your aspirations or ideals in terms of presenting your art?

Abdiani: It varies depending on the project, but personally, I have a keen interest in exhibitions, whether they take place within gallery spaces or outside of them. Unfortunately, organizing an exhibition in Iran can be quite challenging, particularly for our generation. Galleries do not readily provide exhibition opportunities for the younger generation who aspires to have their first solo exhibition, and this poses a significant problem. I totally support and agree with alternative methods of presentation, but this also has challenges in Iran due to economic and sociopolitical conditions.

I am interested in exhibiting because I believe it is the way projects are seen in Iran. While alternative methods may have their audience in Europe or the United States, in Iran, they are still in their early stages. For me, showcasing a project in a gallery holds greater importance than anything else, as it provides an opportunity for critique and discussion.

Ehsan Noortaqani, Locked in Heaven, 2023, from the series Locked in Heaven

Ehsan Noortaqani, Locked in Heaven, 2023, from the series Locked in HeavenAll photographs courtesy the artists

Ehsan Noortaqani, Hanna and Celine, 2023, from the series Locked in Heaven

Ehsan Noortaqani, Hanna and Celine, 2023, from the series Locked in Heaven Noortaqani: Most of my projects have been created with the desire to be featured in a photobook due to the timeline or sequence that has always been present in my work. When you look at my work, you notice the passage of time, the growth of people, and the changes in things and my family. I have been photographing them for many years, and this timeline is what interests me in creating a photobook. I believe photobooks can effectively depict the progression of time. In the end, my ideal is to make money from what I’m doing. However, I’m facing a dilemma due to the economic aspects of photography. Making money as a photographer poses challenges that I’m currently dealing with. The balance between pursuing passion and making a sustainable income requires careful consideration. For instance, I must admit that in recent years, due to being focused on my project, I haven’t tried to exhibit or sell my work, either in a gallery or as a photobook. This hesitance has also resulted from a combination of reasons, including lack of self-confidence and uncertainty about the right approach.

Yousefi: Yes, I have experienced the same issues, and I fully understand how challenging these situations can be.

Motallebi: I believe the role of photography curators is highly significant, particularly for artists like me whose works are made based on their practice, not on a specific project. While I have a certain awareness of my role in creating work, I think there should be individuals like curators who can effectively manage the presentation of works. Their absence is deeply felt in Iran.

Announcing the Winners of the 2023 Creator Labs Photo Fund

Google’s Creator Labs and Aperture are thrilled to announce the recipients of the second season of The Creator Labs Photo Fund—an initiative providing financial support to encourage artists at formative moments in their careers. Started in 2021 and made possible by Google Devices and Services in partnership with Aperture, the second season of the Creator Labs Photo Fund supports thirty artists working in photography and lens-based practices with a one-time $6,000 grant.

The winning artists of this year’s Creator Labs Photo Fund are:

Ramie Ahmed, Wesaam Al-Badry, Devin Blaskovich, Kierra Branker, Luis Corzo, Daniel Diasgranados, Lisa Elmaleh, Ryan Frigillana, Golden, Jeremy Grier, Avijit Halder, Oji Haynes, Jenica Heintzelman, Ramona Jingru Wang, Natalie Keyssar, Ryan Patrick Krueger, Xi Li, Ira Lupu, Yael Malka, Ashley Markle, Ashley McLean, Arlene Mejorado, Shala Miller, Clara Mokri, Colton Rothwell, Keisha Scarville, Tam Stockton, Jennifer Teresa Villanueva, Isaiah Winters, and Zhidong Zhang.

Aperture serves as an essential platform for artists, fostering critical dialogue within the photographic community. “Partnering with Google on the second edition of the Creator Labs Photo Fund embodies Aperture’s longstanding mission to support new voices in photography,” states Brendan Embser, senior editor of Aperture magazine. “The thirty selected artists bring us projects with a dynamic and wide range of approaches, including commentaries on photography’s documentary and archival potential, and intimate explorations of identity and community. Aperture’s editorial team recognizes critical rigor animating the work by each of these artists, reaffirming the role that images play in creating a dialogue with the past and envisioning new possibilities for the future.”

Ramie Ahmed, Batty Boi, 2022, from the series Beauty and Its Time Has Come

Ramie Ahmed, Batty Boi, 2022, from the series Beauty and Its Time Has ComeRamie Ahmed

How can portraiture illustrate the potential of protest without crossing into exploitation? With Beauty and Its Time Has Come, Ramie Ahmed seeks an answer. “I don’t think people realize how powerful a weapon a camera is,” he says. While protest is often seen from a documentary angle, Ahmed removes the activists from that setting, instead photographing them as individuals in their own spaces. This is his community, a group of Black, queer individuals grown over the past three years as protesters have forayed into the streets of cities across the US. Ahmed rarely makes just one portrait of his sitters. Rather, he shows the viewer multiple angles. One subject lies on top of bedsheets, looking inquisitively at the camera, then holds their hands in front of their face; another faces the camera directly, then looks away at her shadow on the wall. “The quiet moments mean so much to me,” says Ahmed. These are protest portraits, make no mistake—but protest as afterimage, reflection as opposed to reaction.

Wesaam Al-Badry, Amirah Al-Badry, 11, 2022, from the series From Which I Came

Wesaam Al-Badry, Amirah Al-Badry, 11, 2022, from the series From Which I CameWesaam Al-Badry

In his series From Which I Came, Wesaam Al-Badry seeks a correction to the narrative, created through decades of media coverage and cultural stereotyping, of the violent Arab Other. Born in Nasiriyah, Iraq, Al-Badry is a refugee of the first Gulf War. His life in the United States is a symbol of a cultural and political coalescence that pervades his work. “It’s impossible to say there is one type of Arab,” he says. “So the project came to be, ‘I’m just going to photograph people as they are.’” The resulting photographs depict what one might imagine to be a quintessentially American family with the familiar marks of Al-Badry’s Iraqi heritage. In one photograph, two women wearing abayas sit in plastic chairs on a lawn, the house creeping into the edge of the picture; in another, a young girl in a leotard stretches in the same spot. The Midwestern backdrop underscores a transgressive goal, the statement that Al-Badry’s community needs no introduction and no excuse. “These people don’t see themselves as the Other, they see themselves as them,” Al-Badry says.

Devin Blaskovich, Untitled, 2022, from the series Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying

Devin Blaskovich, Untitled, 2022, from the series Don’t Let the Sun Catch You CryingDevin Blaskovich

In 2021, in his hometown of San Diego, editorial and fashion photographer Devin Blaskovich worked occasionally as a day laborer on construction projects. In time, he began to bring his camera along, photographing the physical objects surrounding him. As he continued the physical work, class consciousness drove creatively to complicate further depictions of building and landscape. “How do you separate it from those symbols that are very mixed with American photographic culture,” he asks, “and still make something that is about human infrastructure?” Though at first glance, the photographs in Blaskovich’s Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying appear as a collection of stark black-and-white sculptural still lifes divorced from their material reality, upon closer examination, a second, vastly different visual vocabulary emerges. While a formal reading of the photographs provides enough for an art historian to latch onto, these images are intended for a different audience: working-class viewers, many of whom may recognize Blaskovich’s scenes and the unique labor behind his constructions.

Kierra D. Branker, Brave New World, 2018, from the series Get It and Come Back

Kierra D. Branker, Brave New World, 2018, from the series Get It and Come BackKierra Branker

In Get It and Come Back, Kierra Branker’s colorful photographs give off a sense of discovery, as if the artist had simply happened upon her subjects. Shades of pink, blue, and brown find common ground across the images, as the scenes of community in south Florida cohere into a narrative of Black Caribbean diaspora (Branker herself is Trinidadian American). In one still life, the thesis is clear: a globe, rotated to show the Americas, with two dark figurines next to it, a set of dominoes in front. The project “has been building more into looking into these objects,” says Branker, “things like carnival headdresses and feathers, music, and dominoes, all of those little details that tell the bigger picture of how we’re moving and passing on legacy from our family members.” Mirrors too recur in the portraits; paired with the domestic settings of other photographs, these works serve to confirm an identity, creating a new home in an unfamiliar place and continuing the memory making of diaspora.

Luis Corzo, Mardo, 2023, from the series Money Transfer

Luis Corzo, Mardo, 2023, from the series Money TransferLuis Corzo

Mixing portraiture, still life, and an indexical sort of architectural photography, Luis Corzo, in his project Money Transfer, follows the homeward path of foreign workers’ remittances to their families abroad. The photographs are clear-sighted and often unsentimental, but Corzo’s diligence brings an emotional touch to an extensive international monetary network. The network itself sometimes plays a role—Corzo describes seeing the storefronts that facilitate remittances in all kinds of settings, first in New York with the delivery workers. “On another occasion, I’m in this little village in the Andes Mountains and Western Union is there,” he says. “I’d like to have an abnormal amount of documentation of these storefronts.” While the individual characters in Money Transfer could get lost in the expanse, Corzo keeps their lives and stories at center stage. By not only focusing on the workers he meets in the United States, Corzo pulls back the curtain on the entire global system, photographing the objects they carry and, eventually, their homes abroad at the other end of the cycle.

Daniel Diasgranados, Alejandro, 2021, from the series Voyager II

Daniel Diasgranados, Alejandro, 2021, from the series Voyager IIDaniel Diasgranados

For Daniel Diasgranados, suburbia becomes fiction and landscape becomes the universe. Diasgranados spent most of his life in the DMV, the area comprising Washington, DC, and parts of Maryland and Virginia, which he takes as a starting point for his series, Voyager II. “I wanted to make fictional stories through photobooks,” he says, “and really inform them from my life experiences.” The other origin point for the work is the titular NASA spacecraft, launched in 1977 carrying what was known as the “Golden Record,” containing a sampling of sounds from Earth (a greeting from the UN, wind and rain, Mozart and Chuck Berry) as a guide for extraterrestrial life. The settings in Diasgranados’s photographs are hyperlocal—a long stretch of road used for drag racing, a parking lot connected to a space station nearby that first led him to make the Voyager connection—and his collaborators are close friends and siblings. This is his Golden Record: the DMV and its inhabitants take on a universal role, “not necessarily canonizing images, but leaving remnants,” as he puts it.

Lisa Elmaleh, Hermanas Misioneras de la Eucaristia, 2022, from the series Promised Land

Lisa Elmaleh, Hermanas Misioneras de la Eucaristia, 2022, from the series Promised LandLisa Elmaleh

Around three years ago, Lisa Elmaleh began volunteering with humanitarian aid groups at the US-Mexico border, returning over time to make photographs of the landscape, aid workers, and migrants along the border. Unlike much of the photojournalism documenting the border—often characterized by quick snapshots of action or dramatic newspaper front pages—Elmaleh’s photographs, made with her 8×10 camera, operate with a different approach. “The whole process is slow,” she says. “I get to know each person that I’m photographing. I get to know the landscape in which I’m traveling.” Collectively, the photographs entangle the vast, harsh landscape—where Elmaleh has joined aid groups in search parties for migrants who have gone missing—with the soft portraits of those affected by a history of US policies. The result complicates a narrative often told in short, distinctly presented stories; in lengthening everything from the time spent on a single picture to the long-term goals of her work and activism, Elmaleh tells a story, years in the making, of empathy in a time of migratory crisis.

Ryan Frigillana, Phantom Limb, 2023, from the series Manong

Ryan Frigillana, Phantom Limb, 2023, from the series ManongRyan Frigillana

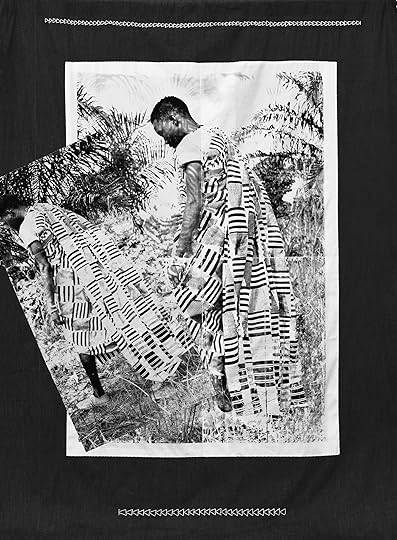

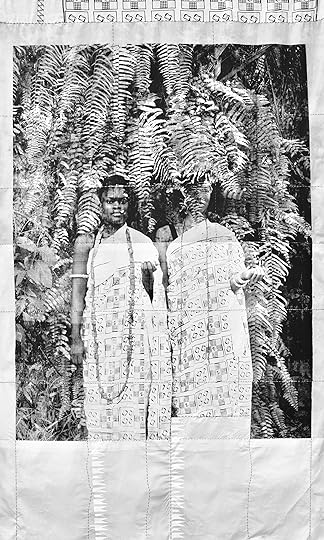

In Manong, Ryan Frigillana expertly agitates and bends the archive to navigate a personal and collective history of Filipino migrants in the United States, centered on his family. “Combing through visual history is my attempt to exhume those hidden parts of myself, the parts that live in my body but can’t be seen,” he says. The photographs are presented in physical entanglement, with archival images placed within and on top of Frigillana’s own photographs, or vice versa. Past and present are one and the same, acknowledging history, as he explains, “not as an inert relic, but as a living, breathing, and speaking presence.” Frigillana primarily focuses on his parents, and his closeness to this collective history is apparent in his portraits of his mother and the material details of their life in America. In total, Manong provides a formally distinct addition to photography’s ability to tell an asynchronous history of oneself and one’s community.

Golden, I am home in the arms of the armed, 2022, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum/Dutch Room, from the series On Learning How to Live

Golden, I am home in the arms of the armed, 2022, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum/Dutch Room, from the series On Learning How to LiveGolden