Aperture's Blog, page 21

February 23, 2024

A Harrowing Meditation on Documenting Life in Gaza

Taysir Batniji’s gift as an artist may well be his restlessness. He paints, he draws, he takes photographs and does performances. He has never settled on one mode of art-making or another. Some of his most memorable projects involve, for example, mounds of sand piled like seaside dunes on either side of an opened suitcase (Untitled, 1998–2021); bars of olive-oil soap engraved with an Arabic proverb and stacked onto a wooden palette (No Condition Is Permanent, 2014); a set of keys on a key ring, all rendered in delicate glass (Untitled, 2014); and molded pieces of Swiss chocolate, neatly arranged on a tabletop, that spell out article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (Man Does Not Live on Bread Alone, 2007).

Batniji’s images and object-based installations often depend on the presence of documents, texts, and symbols whose meanings are immediately clear. His best works, however, delve into more complicated material, where the arguments, by necessity, head into the unknown and take unexpected twists and turns. In those works, Batniji asks serious, often difficult questions (usually philosophical, ethical ones), and he leaves them wide open. Among them: Can documentary images expose events occurring in the world—namely, acts of violence, destruction, and dispossession happening in places where power is brutally contested—and call them facts? Or is it possible that abstract forms can be more effective in channeling the terrible consequences of such events, in part because they sidestep the issue of accepting images as truth and make viewers feel, or at least approximate, what it means to be suddenly thrown into confusion, disconnection, and horror?

Batniji was born in Gaza. He left, against his family’s wishes, to study art in Europe in 1994. Those were the heady days of the Oslo Accords, when it seemed like a real peace deal between Israel and Palestine might be possible, before the assassination of Israel’s then Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and, soon after, the ascension of Benjamin Netanyahu, who has now held office in Israel longer than anyone and has become, in the words of New York Times columnist and pundit Thomas Friedman, “the worst leader in [Israel’s] history—maybe in all of Jewish history.” For ten years, Batniji was able to go back and forth between Gaza and France. The trip was often terrible.

In 2003, Batniji was detained for three days at Rafah, on the border crossing between Egypt and Gaza, which was occupied by Israel at the time (in mid-February, Israel was poised to launch an aggressive ground invasion of Rafah despite international outcry). Due to the security and surveillance regime, Batniji was unable to document his detention in Rafah with his camera, but he replicated the listlessness and anger of being there, the intimidation and exhaustion, and the fights and desperation that broke out among men in a cinematic series of pencil drawings on paper titled Transit #2 (2003). Two years later, Israel abruptly withdrew from Gaza. A power struggle between Fatah and Hamas ensued. Hamas took over the local government, at which point Israel imposed a punishing blockade. Although Batniji harbors a dream of returning to Palestine permanently, it has been impossible for him to enter Gaza since 2006. In the intervening years, he has turned the experience of exile into a kaleidoscopic practice, venturing as far as to the Palestinian diaspora in the United States, the subject of his 2018 Aperture book and exhibition Home Away from Home, to consider the complicated relationship of racism and colonialism to national-liberation struggles.

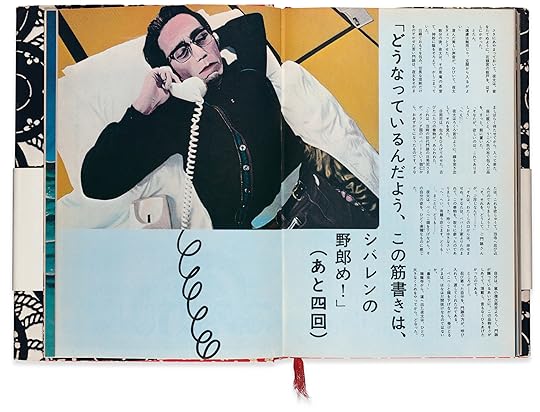

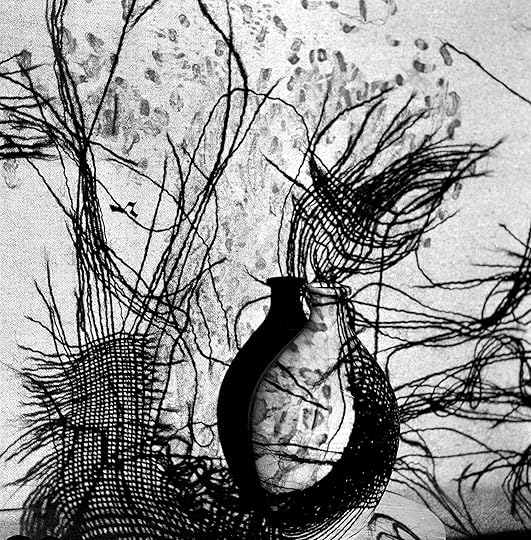

Cover and interior spread from Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024

Cover and interior spread from Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024Batniji’s most recent publication, Disruptions (2024), published by Loose Joints this winter, offers a harrowing meditation on the tensions between the impulse to document reality and the potential for abstraction to communicate something more. The book is only 128 pages long, with a short, evocative text at the back written in French by the writer and photography historian Taous R. Dahmani and translated into Arabic and English. A nervy watercolor from Batniji’s 2022 series Fading Roses appears on the front cover, laid over what appears to be a beautiful blue sky but is more likely, and effectively, an error screen on the artist’s mobile phone.

These images cannot but appear achingly beautiful, if for no other reason than for how they capture a refusal to die.

Disruptions follows a sequence of around seventy images, divided by dates ranging from April 2015 to December 2016. All of these images are screenshots that Batniji took during WhatsApp calls to his mother and family in Gaza. The screenshots capture moments of communications breakdown. They show the glitches, frozen pictures, and dropped signals of video calls failing in their promise to connect in real time. Page after page of Batniji’s book reveals eruptions of wild pixelation, accidental grids, and intense waves of blue and green, which might have suggested verdant landscapes and dazzling seas if they weren’t so obviously the colors of broken tech. Every so often a face appears, or parts of a face, showing a sudden smile, a look of uncertainty, palpable fear, distress, or expressions of soul-sucking fatigue. As soon as one begins to recognize buildings and street scenes, it looks as though the very same buildings and street scenes are exploding on the following pages.

The images that make up Disruptions are therefore already a consolation, with the video call as the next best thing to meeting his loved ones face to face, embracing them, and feeling their warmth. But given everything that has happened in Gaza since Israel’s withdrawal in 2006, including several major bombing campaigns by Israel and countless smaller attacks and skirmishes—and more broadly in Palestine since the eruption of wars, dislocations, and displacements that accompanied the creation of the state of Israel in 1948—Batniji’s work here, in Dahmani’s words, “acts as a repository of grief.” His images visualize the compulsive violence and terror from which Gazans have been unable to escape. Blasted by bad connections, these images cannot but appear achingly beautiful, if for no other reason than for how they capture a refusal to die, a refusal to stop calling your mom, a refusal to stop loving and needing and reaching out to friends, relatives, and colleagues.

All images by Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024

All images by Taysir Batniji, Disruptions, 2024© the artist and courtesy Loose Joints

And this is to say nothing, yet, of the unconscionable damage that Israel has done to Gaza since October 7, 2023, when Hamas launched an attack on Israeli military sites and kibbutzim, killing, among others, some of the most ardent peace activists in Israel. Disruptions begins with a shattering dedication to his family. Batniji lost his mother in 2017. Then, during Israel’s retaliatory war on Gaza (funded like all of Israel’s military campaigns by massive amounts of US aid), fifty-two members of Batniji’s family were killed in the month of November alone. His sister was killed, and a few days after that, his brother died for lack of medical care. That Batniji could produce a book under such circumstances is remarkable. That he could direct all of the proceeds from Disruptions to Medical Aid for Palestinians is heartening. That his images could create a language for addressing the cataclysmic violence that we are witnessing from near and far, a language both abstract and evidentiary, is an audacious sign that life persists.

Disruptions was published by Loose Joints in February 2024.

February 16, 2024

What Does It Mean to Collaborate in Photography?

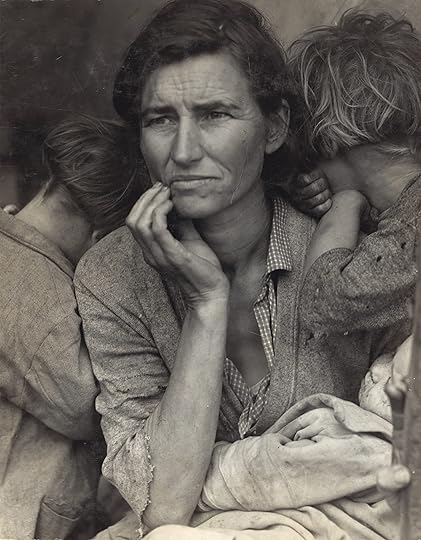

Consider the origin stories of two famous photographs. In 1936, Dorothea Lange photographed a white woman displaced by the Dust Bowl who was staring into the distance. In the image, the woman’s two children cling to her but turn away from Lange’s camera so we see only their tousled hair. The photo’s protagonist—whom we now know to be Florence Owens Thompson—gingerly touches the corner of her mouth and looks as if she wants to disappear. Migrant Mother became an icon of the Great Depression, and Lange was apparently eager to cast Thompson as a consensual so-called subject. Even though Lange never asked Thompson for permission to snap her, she once told an interviewer that the sitting dynamic had “a sort of equality about it.” For her part, Thompson felt affronted. “I’m tired of being a symbol of human misery,” she later said. “I didn’t get anything out of it. I wish she hadn’t taken my picture.”

Dorothea Lange, Destitute Peapickers in California, a 32-year-old Mother of Seven Children, February 1936

Dorothea Lange, Destitute Peapickers in California, a 32-year-old Mother of Seven Children, February 1936Courtesy the Library of Congress

Pierre-Louis Pierson, Scherzo di Follia, 1863–1866. Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione

Pierre-Louis Pierson, Scherzo di Follia, 1863–1866. Virginia Oldoini, Countess of CastiglioneCourtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In a far more exuberant exchange, Virginia Oldoini, better known as the Countess of Castiglione, orchestrated more than seven hundred self-portraits down to the last detail: the dress, the shawls, the hairdo. In 1863, she commissioned a representative tableau vivant titled Scherzo di Follia from the French court photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson. The masterpiece reveals the countess wearing a tasseled robe, with her salt-and pepper hair swept away from her forehead like spindrift floating up from the ocean. In her bejeweled hand, she presses a surreal monocle made of cardstock up to her eye. “I equal the highest-born ladies with my birth, I surpass them with my beauty, and I judge them with my mind,” she once bragged, in a testament to her amour propre.

One woman was exploited; the other was affirmed. What links Thompson and the countess? In a new book, Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography (2024), Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Wendy Ewald, Susan Meiselas, Leigh Raiford, and Laura Wexler show us that the women were both photography collaborators—and that the term itself is due a reconsideration. “Collaboration is the condition of photography in the most basic sense,” the authors explain in their introduction. Yet too often participation is “disregarded or unnoticed.” Collaboration offers the stories of Thompson and Castiglione along with 113 other examples from the history of photography (each accompanied by short essays written by art-world luminaries) that should be understood as products of community action—not as rarities birthed from solitary genius. In cases like Thompson’s, collaboration issues from a photographer’s usurpation, which jostles against the photographed person’s manifestations of discomfort or protest; in cases like the countess’, it can be a joyous co-creation made possible by resources and willpower. Regardless, photography is often a group undertaking shaped by power, race, and wealth.

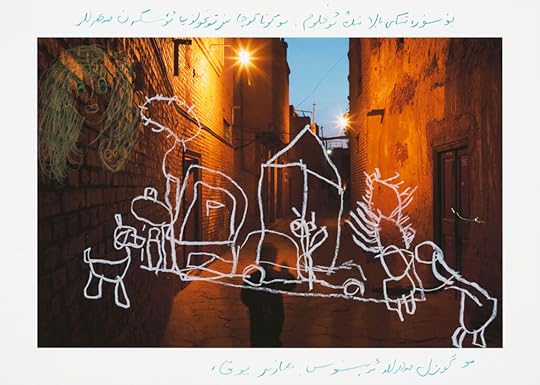

Carolyn Drake, Uyghur Community, 2007–2013

Carolyn Drake, Uyghur Community, 2007–2013Courtesy the artist

Some of the most important revelations in Collaboration reinterpret important photographs as imperialist-subaltern composites. One example is Nick Ut’s “shooting” of Phan Thi Kim Phúc, the child in Napalm Girl (1972). A ubiquitous figure in Nixon-era reporting on the Vietnam War, and a shorthand for US barbarity, Phúc flees a bombing while nude, screaming, and flayed alive by napalm. How did she “collaborate”? First by suffering, and then by dissenting. “I didn’t like that picture at all. I feel like why he took my picture when I was in agony, naked,” Phúc subsequently asserted. Another case is Marc Garanger’s images of Algerian women, whom he snapped in the 1960s at the orders of a military commander who had stripped them of their veils. Collaboration reproduces three of these images, which show the incensed faces of the captives. In the aftermath, Garanger admitted that “the women had no choice in the matter. Their only way of protesting was through their look.”

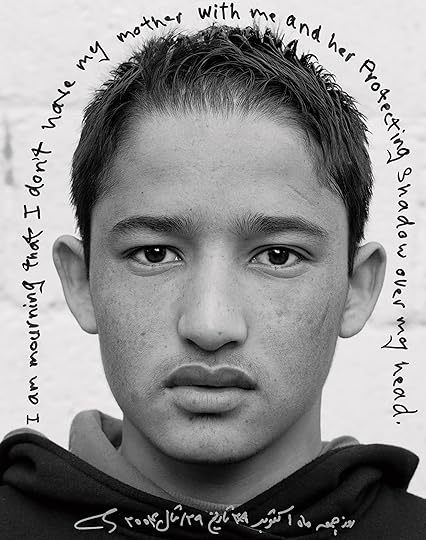

Wendy Ewald, Reza, 2003–5

Wendy Ewald, Reza, 2003–5Courtesy the artist

Beyond these instances of forced entanglement, Collaboration’s authors also assess that photographic co-action can be generative, such as when community members work together to unearth new narratives. Such hopeful forms of participatory photography are exemplified by Wendy Ewald, who in the 1970s asked her students in rural Kentucky to “photograph themselves, their families, their animals and their community.” Radiant results are found in Denise Dixon’s Self-Portrait Reaching for the Red Star Sky (1976–82), which reveals a young girl jubilantly raising her arms to the empyrean with her eyes closed, and Janet Stallard’s I Took a Picture with the Statue in My Backyard (1980), showing Stallard’s awestruck face as she gazes into her own lens.

Denise Dixon, Self-Portrait Reaching for the Red Star Sky, 1976–82

Denise Dixon, Self-Portrait Reaching for the Red Star Sky, 1976–82Courtesy the artists

Janet Stallard, I Took A Picture with the Statue in my Backyard, 1980

Janet Stallard, I Took A Picture with the Statue in my Backyard, 1980 Participatory photography can also take on more expressly activist incarnations. In the 2000s, LaToya Ruby Frazier recorded the effects of environmental racism on her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Since the late 1800s, many Black Americans have worked at a local steel mill once owned by Andrew Carnegie, and now by US Steel. The mill has polluted the environment with soot, volatile organic compounds, and carbon monoxide to the extent that, in 2022, US Steel had to pay the government a $1.5-million-dollar penalty for “longstanding” air-pollution violations. Frazier and her mother suffered the effects of the toxins and have “battled cancer and autoimmune disorders like lupus,” the artist said. To document these ills, Frazier took pictures of her mom, who then took pictures of her. “It’s irritating when you put that camera in my face,” her mother told her. But the results are striking: Momme (2008) shows Frazier facing the camera and fronted by her mother. Both women’s facial expressions convey the weight of their love and the health problems they carry.

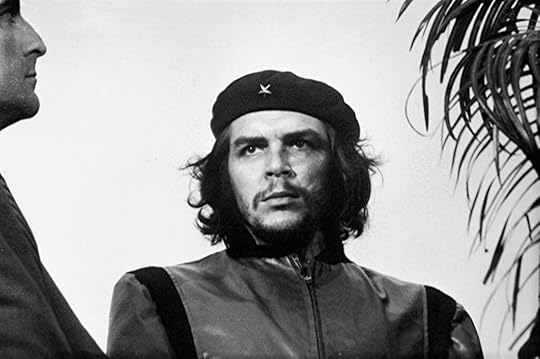

Alberto Korda, Guerrillero Heroico, Havana, March 5, 1960

Alberto Korda, Guerrillero Heroico, Havana, March 5, 1960 Cuban Ministry of the Interior, featuring Che Guevara and his slogan that translates as “Until Victory, Always,” 2008

Cuban Ministry of the Interior, featuring Che Guevara and his slogan that translates as “Until Victory, Always,” 2008Courtesy GM Photo Images/Alamy

Another photographic collaboration driven by similar environmental and ethical concerns comes from the DIY, opensource nonprofit Public Lab. Since 2019, Public Lab has partnered with communities across the Gulf South to track the health effects of petrochemical plants on nearby Black communities. Public Lab provides local “grassroots mappers” with helium balloons, kites, and digital cameras, which they send skyward to take images that are later stitched together into atlases used to pursue interventions. In an adjoining essay, the artist-activist Imani Jacqueline Brown observes that the endeavor allows locals to “surveil the corporate-state and reclaim both their sense of place and their place in the struggle.”

Eugene Richards, Final Treatment, Boston Hospital for Women, Boston, 1979

Eugene Richards, Final Treatment, Boston Hospital for Women, Boston, 1979Courtesy the artist

As Collaboration reveals, photography is a wide-ranging practice of joint creation. This discipline ranges from the felicitous exchanges between the Countess of Castiglione and Pierre-Louis Pierson to the dominance and opposition that activates Migrant Mother, Napalm Girl, and Marc Garanger’s arrogations; to the communal imaginings of Ewald, Dixon, Stallard, the Fraziers, Public Lab, and Southern Gulf community members—and also to the viewers and writers who insist on cocreating photographs with their perceptions and critique.

In an age when conflict and disaster photography transfixes audiences with scenes of individuals’ experiences of violence, grief, abandonment, famine, and terror (consider, for example, the current coverage of the crisis in Gaza and the 2023 Libyan floods), we would do well to practice Collaboration’s brand of consciousness-raising. By viewing these images as collaborations, we can pivot from easy narratives about solo photographers who “capture” their “subjects” toward an understanding that the pictures we consume are community-created artifacts whose most important participants often lack full voice and choice.

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography was published by Thames & Hudson in 2024.

The Sweetened Reality of Marcelo Gomes’s Photographs

The remarkable story of the photographer Marcelo Gomes begins in northern Brazil, near the equator. It was wet there. When he was twelve, his parents took him to a concert by the Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso, a cofounder of the avant-pop psychedelic movement Tropicália, who had been exiled from his home country during its military dictatorship. For Gomes, who grew up in a smaller city, it was a transformative, visceral experience, an introduction to how art could move people. As an adult, in 2016, he took Veloso’s picture at a concert at the Inhotim art gallery in Minas Gerais. I asked Gomes in a recent conversation what he wanted from such portraits of his heroes. “To preserve them,” he says. “There’s a dream where I’m from, a dream of Brazil that sort of dies with him, in a sense, which will be very sad.”

Gomes, who now lives in Paris after years in New York, came to the United States to attend the University of Iowa on a full basketball scholarship. Team sports resonated, he explains, because of the surrender, the subsuming of one’s self into a composite. “There’s something really beautiful about the fact that you’re a collective of very disparate upbringings and cultures and geographies,” he says. “There’s something really nice about just sticking these people together and letting them figure it out. And if they do figure it out, the odds are that they will be much better than the individual.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Photography is an individual pursuit that often relies on team collaboration. Gomes makes evocative work entirely for himself but also dips into the fashion world. Lately, he says, the two are blending further, as he’s permitted to use personal work in commercial contexts. His images for Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle feature red rectangular forms, like an olfactory Rothko canvas. He trades traditional advertising’s aspirational charge—buy this so you can be this—for expressions of beauty that are expansive yet found mostly in closely observed moments and things.

A bubble becomes, in its bursting, a portal. A fig beads with ooze. In the end, natural splendor depends on submission. An image from Hydra is all cerulean swoon, but accessible only because someone built a ladder of bent metal and stuck it in the sea. The water is still, but we know those waves. They can pool like the wooden beard Gomes cropped from a large statue he saw in Paris, its ostentatious masculinity virile and swirling. The image is grainy; it could almost be chewed. Gomes calls his world of texture a “sweetened reality.” It’s bigger and beautiful. What more could one want?

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (After Durer, New York), 2017

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (After Durer, New York), 2017  Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Fig, Paris), 2017

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Fig, Paris), 2017  Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Hydra), 2020

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Hydra), 2020  Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Marrakesh), 2020

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Marrakesh), 2020 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Milan), 2016

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Milan), 2016  Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Paris), 2022

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Paris), 2022  Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Flower Study, Paris), 2020

Marcelo Gomes, Untitled (Flower Study, Paris), 2020

All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”

February 15, 2024

In Sierra Leone, a Photographer Finds Beauty in Everyday Encounters

One afternoon last March, while he was walking along Lumley Beach in Freetown, Sierra Leone, Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr. decided to pray. The photographer set his equipment down, and as he reached for water to start his ablution, he was approached by three boys selling water in plastic sachets. Could they join him in prayer? Yes, Kanu replied. But first, with his camera, he immortalized a moment of the boys squatting by the unending ocean, vigorously wiping their faces with water. A folded cloth—for cushioning a vending pan—still sat on one boy’s head. Kanu led them in prayer. When they finished, he shared words of encouragement: he had fasted for the first time when he was about their age, so they could do it too; they should focus on school and do their best. “That was a really beautiful encounter for me,” Kanu told me.

The photographer has a knack for having beautiful encounters. He runs into fishermen, boxers, street cyclists, hooligans, vagrant kids. In his almost minimalist black-and-white images, Sierra Leone’s capital becomes its own universe that is poetic, even mythical. Everyday people are seen marching on valiantly on epic quests. Kanu’s images are ostensibly of the obvious things one might encounter in a city. But they also give a glimpse of a richer architecture of human relations, desires, and preoccupations that lurk just beneath the obvious. “We Sierra Leoneans are storytellers by nature,” he said. “You ask someone today how [their] day went, and they’ll tell you how they slept, what happened overnight, if they had mosquitoes, if it was really hot, but [it] turned out fine.”

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys performing abultion before Asr prayers, Lumley Beach, Freetown, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys performing abultion before Asr prayers, Lumley Beach, Freetown, 2023  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man walking on Lumley Beach, Freetown, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man walking on Lumley Beach, Freetown, 2022 Kanu was exposed to photography from a young age. His father would carry around a camera and take photos of his sister and him all the time. His mother worked as a cashier at one of the first digital-photography studios in the area, on Rawdon Street. A peaceful childhood was cut short: for him and many of his peers, the decades-long civil war in the country threw life as they knew it into disarray. Kanu’s family sought refuge in Guinea, until their return to Freetown in the early aughts. The image of Salone had by then become one of destruction and disorder, desolation, chaos, and fear—all the negative stereotypes of Africa that feed the Western imagination.

Photography took a back seat for Kanu until a stint as a student in Turkey rekindled his love for the art. In 2015 he moved to Sakarya, a town by the Black Sea just northeast of Istanbul, to pursue a degree in information-systems engineering, but he struggled and felt isolated. “I knew Turkish and was fluent in it,” he said, “but it was quite different when it came to the academics.” He also wasn’t truly passionate about his topic of study. “At some point, I got good at coding and building programs, but it wasn’t as interesting as photography.” The province is full of traditional and historical Ottoman sites and natural scenery like lakes, rivers, and springs. He ventured around town with a camera, interacting with people and breaking the bubble of loneliness that sometimes engulfed him. But the real thrill was during breaks when he traveled to Istanbul. There, he met and learned from other street photographers as he tried to explore every corner of this legendary city that charmed him.

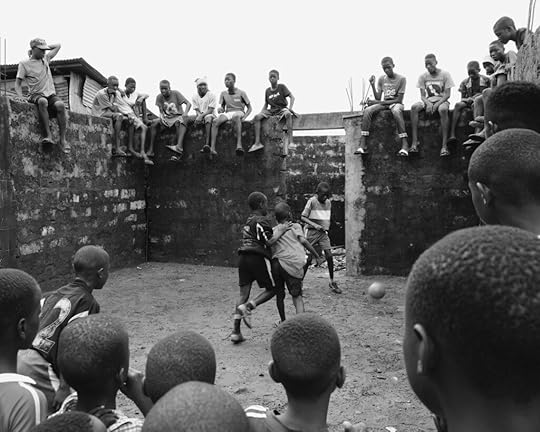

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys playing a football tournament inside an unfinished building, Brookfields, Freetown, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys playing a football tournament inside an unfinished building, Brookfields, Freetown, 2023Kanu’s photographs display a preternatural ability to be in the right place at the right time. He knows the city’s cadences, and time seems to slow down for him to observe his surroundings, so that his viewers may peer into a brief but more detailed view of things. One day, while running an errand for his dad, he came across a soccer gala organized by some neighborhood kids in the sitting room of an unfinished building. Abandoning his bike, he raced to the scene to take a photo; through his eyes, the viewer becomes part of the throng of ecstatic spectators who consume the action in the arena.

Kanu’s major influences range from old-school photographers such as Gordon Parks and James Barnor to the young, self-taught New Yorker Steve Sweatpants. He finds particular resonance in Parks’s documentation of segregation across the United States, famously portrayed in the series Segregation Story. Several of Kanu’s own photographs have echoes of Parks’s. Take one photograph of a man in a kufi and billowy caftan. The photograph captures him mid-step, neck strained as he looks in the direction of a house; in Parks’s from 1948, Leonard “Red” Jackson, seen from behind, is also mid-step, his slightly baggy suit billowing in the wind. In Parks’s photo, the tall buildings tower over the man, suggesting the scale of what a Black man has to contend with in America. In Kanu’s, the more modest building is made of zinc and wooden parts. It reminds the photographer of the Freetown of old: “Twenty years ago after the war, when you look around, you’d see places like this,” he said. “People just rebuild slowly using zinc, wood, and whatever materials they can find.” In their adornments, the men in both photographs communicate dignity in the face of a reality that looms large.

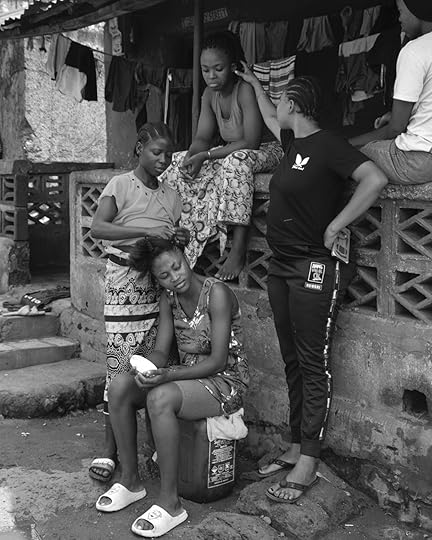

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., My aunts at my late grandpa’s house, Rogbin Village, Northern Province, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., My aunts at my late grandpa’s house, Rogbin Village, Northern Province, 2022  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man looking at a zinc house, Freetown, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man looking at a zinc house, Freetown, 2022 The work of Kanu and his generation represents a continuation of attempts to establish new relationships to the image and image-making in Sierra Leone. During and immediately after the war, Sierra Leoneans were subjected to the exploitative Western gaze of international journalists and organizations in search of what we now term poverty or disaster porn. Some people, tired after years of cameras being pointed at them, coined the phrase “you click you pay,” demanding recompense.

Today most people smile at Kanu and ask him to make more photos. Once, he was photographing a street celebration when a little girl waved him down. “Snap me, I’m fine,” she demanded. Recalling this beautiful encounter, he told me: “I literally just burst into tears of, like, Oh my god, the confidence. I’m always grateful to be able to capture these little moments of time, and the people.” Kanu sees his work as a way of documenting life and being in community. “Initially, one of the top goals of my work was to counter some of the narratives that were around about Sierra Leone not being safe,” he said. “And one way I feel like you can answer that is by showing daily life.”

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys leaning on a coconut tree to get a view of a drone, Moyamba, Southern Province, 2021

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys leaning on a coconut tree to get a view of a drone, Moyamba, Southern Province, 2021  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A boy stands by a bicycle, Lunsar, Northern Province, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A boy stands by a bicycle, Lunsar, Northern Province, 2023  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Siaka Stevens Street at sunrise, Freetown, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Siaka Stevens Street at sunrise, Freetown, 2023  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A rollerblade club, Freetown, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A rollerblade club, Freetown, 2023 Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A young lady and a bubu player at a political rally, Lunsar, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A young lady and a bubu player at a political rally, Lunsar, 2023  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man talking about livestock, Malontho Village, Northern Sierra Leone, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man talking about livestock, Malontho Village, Northern Sierra Leone, 2022  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A girl getting braids for school, Calaba Town, Freetown, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A girl getting braids for school, Calaba Town, Freetown, 2022  Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man walks through a hazy street, Freetown, 2022

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., A man walks through a hazy street, Freetown, 2022 Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys after Eid Prayers, Goderich, Freetown, 2023

Abdul Hamid Kanu Jr., Boys after Eid Prayers, Goderich, Freetown, 2023All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

February 9, 2024

What Photobooks Does the Metropolitan Museum of Art Collect?

An experimental collaboration between a legendary Japanese graphic artist and novelist, a book of decorative glass panes, and another with a slipcase in the shape of a cigarette pack. The diversity of books at the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art reveals the flexibility of the form, one that can accommodate endlessly inventive designs and meanings. Home to more than a million objects—which span centuries and include historically significant volumes, contemporary photobooks, and inventive artists’ books—the library’s shelves are full of surprises. As collections librarian, Jared Ash oversees its encyclopedic holdings and works with his team, online and offline, to create a wider appreciation for what a book can be.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Russet Lederman: The Watson Library has a rich assortment of artists’ books. How was the collection formed?

Jared Ash: The Watson Library is as comprehensive as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, maybe even more so, because it’s a lot easier to acquire a book than it is a work of art—and storage is a lot less expensive! For a long time, individual departments, like Drawings and Prints, selectively collected artists’ books, but twentieth-century and contemporary examples weren’t well represented. About eight years ago, a defined collection of artists’ books was formalized to fill this gap.

Lederman: You often share books on your Instagram feed, @MetLibrary. Can you discuss some of the treasures you have highlighted?

Ash: Instagram is an exceptional calling card for us. Our account features unusual materials, especially photobooks and artists’ books that don’t fall squarely within a specific curatorial department’s range, such as object-like books that have inventive formats or include atypical elements made from textiles or glass. By the Piece (2016), by the artist, typographer, and researcher Tabea Nixdorff, is a good example. Printed in a limited edition of twenty copies, it evolved from her research at the Chicago Historical Society and is centered on Agnes Nestor, an early twentieth-century glove-maker and suffragette, who was also a labor rights activist.

Spread from Clarissa Sligh, What’s Happening with Momma? (Women’s Studio Workshop, 1988)

Spread from Clarissa Sligh, What’s Happening with Momma? (Women’s Studio Workshop, 1988)  Slipcase for Thomas Sauvin, Until Death Do Us Part (Jiazazhi, 2015)

Slipcase for Thomas Sauvin, Until Death Do Us Part (Jiazazhi, 2015) Lederman: How does a book like Nixdorff ’s come into the collection?

Ash: We acquire works through different means: about a third are gifts and two-thirds are purchases. Nixdorff and her fellow students were in the city for Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair, and we invited them to visit the Watson Library. We shared some books from our collection, and they showed us some of the works they were exhibiting at the fair. When objects stand out, like Nixdorff ’s book, we see an opportunity.

Lederman: What are some other acquisitions that cross boundaries?

Ash: Sandra C. Davis’s Queen Anne’s Lace (2006) is a small-scale book composed of cyanotypes on handmade Japanese paper, overlaid with hand stitching. A play on words, it tells the history of the wildflower, embellished with lace thread and a real bloom. Clarissa Sligh’s What’s Happening with Momma? (1988), published by the Women’s Studio Workshop, is cut in the shape of a house and illustrated with screenprinted photographic images from a family album. Sligh is an exceptional artist whose biography includes work at NASA and Goldman Sachs alongside her social- justice-focused art practice. In this volume, she explores notions of domesticity and class, elucidating childhood memories through texts printed on folded sheets of paper that drop down like sets of stairs.

Lederman: More recently you acquired the Beijing-based photographer Thomas Sauvin’s Until Death Do Us Part (2015), which is distinctive for its slipcase that looks like a cigarette pack.

Ash: Yes, I believe you could buy this book either individually or by the carton! Inside is a board book of found photographs, sourced from the Beijing Silvermine archive of salvaged negatives from a Chinese recycling plant, celebrating a Chinese wedding tradition where the bride lights a cigarette for each male guest and the couple plays smoking games that include stuffing as many cigarettes in one’s mouth as possible and then lighting them all at once. We value books that challenge people’s perceptions of what a book is.

We value books that challenge people’s perceptions of what a book is.

Lederman: Some of the books in your collection did not start as fine-art objects, such as a trade catalog of cast-glass samples that is nearly one hundred years old.

Ash: As part of the twenty-one departmental libraries that are centralized through the Watson Library, we have a substantial collection of trade catalogs. They show how art movements like Art Deco, Art Nouveau, and Constructivism found their way into everyday life, whether on wallpaper patterns or baby carriage designs. This notion of art into life and life into art is important for us.

The Album des principaux modeles de verres: produits spéciaux en verre coulé (1913), a.k.a. “The Glass Book,” is a trade catalog from a French firm, Manufactures des glaces & produits chimiques de Saint-Gobain, Chauny & Cirey, that has made glass for centuries, including for the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles. From the outside, the book doesn’t look like much, but inside are pages filled with more than a hundred samples of multicolored decorative glass panes, including the glass that Hector Guimard used for the Paris Métro. It’s a good example of how ordinary materials can be beautiful and inspire wonder. I also really like the backstory of how this book came to us. It was delivered to the library on New Year’s Eve by a book dealer who transported it on his bicycle!

Irina Popova, If You Have a Secret (Dostoevsky Publishing, 2017)

Irina Popova, If You Have a Secret (Dostoevsky Publishing, 2017)  Spread from Tadanori Yokoo and Renzaburo Shibata, Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata (Yata, the Vagabond; Shueisha, 1975)

Spread from Tadanori Yokoo and Renzaburo Shibata, Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata (Yata, the Vagabond; Shueisha, 1975)All photographs by Elizabeth Legere. Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Lederman: More contemporary yet equally inspiring is Irina Popova’s If You Have a Secret (2017). What is its design and concept?

Ash: This book’s inventive design requires activation to discover its message. In this second printing of If You Have a Secret, Popova, a Russian photographer now living in the Netherlands, interweaves personal and public images taken in her former homeland with poems and vignettes printed on semitranslucent, half-cut sheets to reflect on her past life. Most of the text appears on the front of each page, but in several instances, words or lines of type are printed on the reverse side of the sheet— forcing the viewer to hold the book up to the light to read the full text and understand its deeper meaning.

Lederman: Radically different, but just as inventive, is Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata (Yata, the Vagabond; 1975), a collaboration between the designer Tadanori Yokoo and the novelist Renzaburo Shibata.

Ash: I think our Yokoo holdings are a good example of how the Watson Library is a study collection. In this case, we’ve collected an artist in-depth, providing a comprehensive collection for research. During the New York Art Book Fair, a dealer from Japan had nearly an entire booth filled with books by Yokoo, which made us realize our lack. We wound up buying about fifteen books from the dealer, Ezoshi Urotsuki Yata among them. Even without knowing its fablelike narrative, the work can be appreciated for its experimental visual elements and dynamism alone. It never fails to wow people.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Lederman: With so many to choose from, I imagine it is hard to have a favorite book, but if you had to pick one, which would it be?

Ash: The collection that I feel closest to is a series of zines that evolved from Teens Take The Met!, a free, museum-wide public program that we co-organize every year with community partners. For several of these events, the Watson Library partnered with Endless Editions, who brought a Risograph machine that the teens used to make zines. We had a group of Russian teens from Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, this past May, right before Mother’s Day, and one of them made a zine about piroshki that is a tribute to his babushka. Every year, program participants include kids from all over the city, many speaking different languages. These are our future visitors, and this event lets them know that this space exists for everyone.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire,” in The PhotoBook Review.

Young Photographers in Myanmar Express a Nation’s Anxiety

In the early hours of February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military began knocking on the doors of dissidents. The Tatmadaw, as they are officially known, had launched a brutal coup that swiftly overthrew the democratically elected government. Within weeks, the military transformed the country into a full-fledged dictatorship, suppressing peaceful protests with lethal force and arresting anticoup activists. The move was reminiscent of the junta that had ruled Myanmar in various forms from 1962 to 2011, evoking a familiar horror for those who had lived through previous takeovers. For the younger generation, which had come of age in a relatively democratic and free Myanmar, the coup represented an existential crisis. Due to the junta’s ongoing efforts to repress citizens’ freedom—including enforced disappearances, long prison sentences, and executions—the majority of Myanmar’s population remains opposed to the military regime.

Sai, from the series Trails of Absence, 2021–ongoing

Sai, from the series Trails of Absence, 2021–ongoing

Sai [Redacted], a multidisciplinary artist who works under a partially redacted pseudonym (sai means “mister” in a Shan dialect) for his family’s safety and to highlight Myanmar’s censorship of its citizens, was in the former capital, Yangon, when the military arrived at his family home in the country’s Shan State. His father—a chief minister and senior member of the National League for Democracy party—was promptly arrested, forcing Sai into hiding. In May 2021, the artist secretly returned to his home, where his mother had been placed under house arrest. After a brief reunion, he fled again to avoid possible arrest, as military intelligence was keeping the family members of detained leaders under close watch.

His series Trails of Absence (2021–ongoing) uses a physical gap to portray family trauma, fear, and the void left by his father’s imprisonment. The artist stages portraits where he and his mother appear with a string running between them. Their faces are obscured by pieces of fabric woven in the style of a traditional Shan carpet. These fabrics, originally worn by those being held—and effectively disappeared—in Myanmar’s notorious prisons after the February 2021 coup, were given to Sai through personal connections. “I asked to get some sort of evidence that can represent their existence,” he told me recently. “They gave me their clothes.”

For those in Myanmar who oppose the coup, there has been a lot of frustration over the Western media’s coverage. Despite the fact that ordinary citizens are subjected to daily armed violence and arbitrary detentions, the focus has seemed to remain on high-profile political figures. In 2022, Sai’s father was sentenced to twenty years of imprisonment and hard labor. “The series is a call to action for the world to take notice of political prisoners in Myanmar,” the artist says. “Can the world still sweep us under the carpet if we become the carpet?”

Ri, Statues on a large monument that represents the three branches of the military; Army, Navy, and Air Forces, Nay Pyi Taw, 2019, from the series Soulless City, 2019

Ri, Statues on a large monument that represents the three branches of the military; Army, Navy, and Air Forces, Nay Pyi Taw, 2019, from the series Soulless City, 2019 Ri, A replica of Hkakabo Razi mountain from Kachin state, an armed conflict prone area in Northern part of Myanmar, Nay Pyi Taw, 2019, from the series Soulless City, 2019

Ri, A replica of Hkakabo Razi mountain from Kachin state, an armed conflict prone area in Northern part of Myanmar, Nay Pyi Taw, 2019, from the series Soulless City, 2019For the photographer Ri—who also works under a pseudonym—Myanmar’s political present is both deeply personal and historically bound. While her previous images focused on community, queer relationships, and Myanmar’s landscape, after that February’s events, she felt the need for a change. While photographing anticoup demonstrations in Yangon in 2021, Ri wanted to move beyond a documentary approach and instead explore the historical power structures perpetuating oppression. “I felt like I had a responsibility to do something when the coup happened,” she tells me. “It was partly because of survivor’s guilt.”

In her multimedia piece What We Remember, When We Remember (2021–ongoing), Ri uses archival imagery, original photographs, and collage to explore the impact of nearly half a century of military rule on the country’s collective psyche. She spoke with a range of subjects—those who have embraced the Tatmadaw along with those who fear and despise them—asking, “When did you learn to hate or be afraid of the military?” One issue that came up often was money. The previous military, led by the dictator General Ne Win, instituted a swathe of policies, including the devaluing of select banknotes from Myanmar’s currency, ultimately weakening the cash-based national economy. Ri’s mother, who worked in a state-owned factory then, was affected by these changes, losing all of her life savings. In one piece from the series, two defunct coins cover the former dictator’s eyes, a commentary on the economic stresses placed on ordinary people.

Zicky Le, Late Pyar (Butterfly), Yangon 2021

Zicky Le, Late Pyar (Butterfly), Yangon 2021  Zicky Le, from the series I Don’t Trust These Dreams, 2021

Zicky Le, from the series I Don’t Trust These Dreams, 2021  Zicky Le, from the series We Are Who We Are, 2022

Zicky Le, from the series We Are Who We Are, 2022All photographs courtesy the artists

Despite broad national resistance to the coup, Myanmar’s population is far from a monolith, with more than 135 ethnic groups across several states. Currently living between Bangkok and Yangon, the photographer Zicky Le is half Burmese and half Karen, an ethnic minority with a long history of conflict with Myanmar’s governments that dates back to the country’s independence from British rule in 1948. Zicky has been a fashion and editorial photographer for nearly a decade, with work published in Vogue Italia and the Madrid-based Sicky magazine. The series We Are Who We Are (2022) expresses his frustration with how queer people are portrayed—often, with mockery—in Myanmar’s popular culture and mainstream media. In response, Zicky photographs his queer friends with vibrant color and lighting to celebrate their beauty, diversity, and truth. “I want to contribute to a cultural revolution that overthrows sexism, transphobia, and homophobia,” Zicky says. “Representation is not the end of liberation but a means.”

Young artists such as Sai, Ri, and Zicky have grown up in the shadow of two Myanmars, belonging to a generation that has experienced both partial democracy and dictatorship. Like them, many artists in the country have begun to self-censor their endeavours under a junta-ruled Myanmar. Some, also using pseudonyms, have worked exclusively with foreign institutions or exiled outlets. Several photographers have fled to neighboring countries, including Thailand, while others have joined the armed revolt. In their own context, each has contributed to the creation of informal communities of support that challenge the political systems and ideologies inherited from decades of military rule. For these artists, photography is a crucial tool for solidarity, resistance, and visibility—and it is one of many.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 252, “Accra,” under the column Dispatches.

February 6, 2024

A Photographer’s Record of New Year Celebrations in Northern China

In 2018, the Chinese photographer Zhang Xiao received the Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography, which supports an artist’s photographic project about the “human condition anywhere in the world.” Past winners have included Yto Barrada, Chloe Dewe Mathews, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Dayanita Singh, and Guy Tillim, some of whom have published a monograph or presented an exhibition at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

For his project Community Fire, Zhang takes a local, hometown look at Shehuo (社火), a Chinese Spring Festival tradition celebrated in rural Northern Chinese communities that includes temple fairs, dragon dances, and storytelling. Shehuo—literally, “community fire”—is devoted to the worship of land and fire, and boasts a history of many thousands of years. During the festival, people hold ceremonies, pray for the next year’s good harvest, and confer blessings of peace and safety on all family members. However, what was once a heterogeneous cultural tradition with myriad regional variations has largely become a tourist-facing, consumption-oriented enterprise.

Zhang Xiao, A girl waits, in the early morning, to change into her costume, Huanghuayu Village, Shaanxi Province (Shaanxi series, No. 1), 2007

Zhang Xiao, A girl waits, in the early morning, to change into her costume, Huanghuayu Village, Shaanxi Province (Shaanxi series, No. 1), 2007  Zhang Xiao, Shehuo performers walk in procession, Huanghuayu Village, Shaanxi Province (Shaanxi series, No. 3), 2007

Zhang Xiao, Shehuo performers walk in procession, Huanghuayu Village, Shaanxi Province (Shaanxi series, No. 3), 2007 Zhang’s extraordinary exploration of Shehuo documents the changes this ancient tradition has undergone over the course of a decade of modernization. Taken during a series of visits to the Shaanxi and Henan provinces from 2007 to 2019, his photographs ask us to consider how the medium of photography—in its ready availability for the straightforward documentation of singular moments—can evoke not only the vestiges of other times, but also the political and economic forces that bridge the past and the present. The painterly tones and muted focus in his early photographs of Shaanxi, beginning in 2007, offer insight into the several millennia of history upon which Shehuo rituals have been built. Participants costumed in traditional clothing passed down across centuries blend with the misty, mystical aura of the artist’s compositions, scenes that gesture to the piety and gravity of their ancestors through the makeup, facial expressions, and performance styles inherited from previous generations. Zhang’s method of “sleepwalking”—as he calls it—alongside the performers suggests an empathetic connection with the practitioners of this tradition.

In contrast, Zhang’s photographs taken one decade later illustrate the popularization and commercialization of a new, tourist-facing Shehuo performance, one that nonetheless converses with the histories of performance and belief that endure in villages across Northern China. He composes sharply focused, portrait-like images of the new mass-produced costumes and props, highlighting their disconnect from historically accurate portrayals of the rituals they will be used for. With a touch of humor, Zhang reveals the almost absurd-looking elements of mass production: stacks of plaster faces piled high in a desolate room; masks in plastic shopping bags hanging off tree branches; a multitude of identical, ill-fitting costumes the performers’ ancestors could never have imagined.

Zhang Xiao: Community Fire 65.00 In his project Community Fire, the photographer Zhang Xiao takes a local, hometown look at Shehuo (社火), a Chinese Spring Festival tradition celebrated in rural Northern Chinese communities that includes temple fairs, dragon dances, and storytelling.

Zhang Xiao: Community Fire 65.00 In his project Community Fire, the photographer Zhang Xiao takes a local, hometown look at Shehuo (社火), a Chinese Spring Festival tradition celebrated in rural Northern Chinese communities that includes temple fairs, dragon dances, and storytelling. $65.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Zhang Xiao: Community FirePhotographs by Zhang Xiao. Text by Ilisa Barbash and Zhang Xiao.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.00Add to cart

View cart Description In his project Community Fire, the photographer Zhang Xiao takes a local, hometown look at Shehuo (社火), a Chinese Spring Festival tradition celebrated in rural Northern Chinese communities that includes temple fairs, dragon dances, and storytelling.Shehuo— literally, “community fire”—is devoted to the worship of land and fire, and boasts a history of many thousands of years. During the festival, people hold ceremonies, pray for the next year’s good harvest, and confer blessings of peace and safety on all family members. However, what was once a heterogeneous cultural tradition with myriad regional variations has largely become a tourist-facing, consumption-oriented enterprise. In the early 2000s, Shehuo received an “intangible cultural heritage” designation from the People’s Republic of China, resulting in increased funding in exchange for greater government involvement. While altering the practitioners’ relation to Shehuo, this change expresses itself most visually in the way costumes and props have been replaced with newer, cheaper products from online shopping websites.

Zhang’s colorful and fantastical photographs capture how these mass-produced substitutions have transformed the practice of Shehuo. Community Fire—with essays in English and Chinese—is a dynamic visual exploration of one of China’s oldest traditions.

Copublished by Aperture and Peabody Museum Press Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 192

Number of images: 150

Publication date: 2023-08-08

Measurements: 7.1 x 9.25 x 1 inches

ISBN: 9781597115452

“Zhang’s work explores the extent to which ancient folk beliefs and rural society can sustain themselves amid modernization, and how they can weather the effects of an industrialized and digitalized economy.”—Faith Sutter, The Harvard Gazette

“Captured in sepia tones and darkened vignettes, theatre performers wander through a drab winter village in flamboyant makeup and fantastic costumes, looking like deities from ancient folklore.”—Yuwen Jiang, ArtReview Asia

ContributorsZhang Xiao (born in Yantai city, Shandong Province, China, 1981) graduated from the department of architecture and design at Yantai University in 2005. He was a photojournalist for Chongqing Morning Post from 2005 to 2009. He won the Prix HSBC pour la Photographie in 2011, the Three Shadows Photography Award in 2010, and the Hou Dengke Photography Award in 2009. Zhang has participated in several solo and group exhibitions, including at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing; Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur, Switzerland; Lianzhou Photography Museum, Guangdong Province, China; Shanghai Center of Photography; Musée du Quai Branly, Paris; and A4 Art Museum in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. His books include Shanxi (2013), Coastline (2014), They (2014), The River (2017) and A Hometown (2021). Zhang currently lives and works in Chengdu. He is the 2018 winner of the Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography from the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

Ou Ning (born in Suixi, Guangdong province, China, 1969) is the director of the documentaries San Yuan Li (2003) and Meishi Street (2006). He was chief curator of the Shenzhen and Hong Kong Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture (2009); jury member of 8th Benesse Prize at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009); member of the Asian Art Council at the Guggenheim, New York (2011); founding chief editor of the literary journal Chutzpah! (2010–2014); founder of the Bishan Project (2011–2016); visiting professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation (2016–2017); and senior research fellow of the Center for Arts, Design, and Social Research, Boston (2019–2022). His most recent book is Utopia in Practice: Bishan Project and Rural Reconstruction (2020).

Ilisa Barbash is curator of visual anthropology at Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. She is codirector of the films In and Out of Africa (1992) and Sweetgrass (2009). Barbash is the author of Where the Roads All End: Photography and Anthropology in the Kalahari (2016), which was awarded the John Collier Jr. Award for Still Photography.

In his most recent photographs, shot between 2018 and 2019, we discern traces of alienation and hints of ennui in some of the performers, as they casually rest, or take a smoke break. We see an array of whimsical festive lanterns once illuminated by candles and now with electricity. The newfound commerciality of Shehuo is brightly revealed through the flatness of a selection of online web advertisements, which present an overwhelming variety of products, all available, anywhere, for any purpose, and out of their original context.

Zhang’s response to Robert Gardner’s call for fellows to “document the human condition” is a portrait of a rapidly changing rural Chinese society. His work explores the extent to which the ancient folk beliefs and self-organization of folk society will sustain itself amid the advancements of modernization, and how it will weather the government-mandated changes to tradition, as brought on by “intangible cultural heritage” designations and the effects of an industrialized and digitalized economy. It is human nature to change and adapt. Through his photography, Zhang shows how a tradition that was once heterogeneous in its practice and individually expressive can undergo homogenization and mechanization, illuminating the effects of modernity upon rural life. Further, it inspires us to contemplate the essence of performance and the visual expressions of communal belief, to ponder their origins and notice how they have been transformed, in so many places, at an accelerating speed.

Zhang Xiao, Ensemble of Blood Shehuo performers, Yanjiaan Village, Shaanxi Province, 2018

Zhang Xiao, Ensemble of Blood Shehuo performers, Yanjiaan Village, Shaanxi Province, 2018  Zhang Xiao, Villagers wearing a lion dance costume for two performers, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018

Zhang Xiao, Villagers wearing a lion dance costume for two performers, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018  Zhang Xiao, Unfinished dragon head props, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018

Zhang Xiao, Unfinished dragon head props, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018  Zhang Xiao, Partly finished dragon heads, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2019

Zhang Xiao, Partly finished dragon heads, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2019 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Zhang Xiao, Shehuo performer riding a donkey, Xunxian County, Henan Province, 2019

Zhang Xiao, Shehuo performer riding a donkey, Xunxian County, Henan Province, 2019  Zhang Xiao, Two red lion performers in costume, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018

Zhang Xiao, Two red lion performers in costume, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018  Zhang Xiao, Huo Guanghui in his office, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2019

Zhang Xiao, Huo Guanghui in his office, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2019  Zhang Xiao, A luminous dragon dance prop lies in the grass on the outskirts of the village, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018

Zhang Xiao, A luminous dragon dance prop lies in the grass on the outskirts of the village, Huozhuang Village, Henan Province, 2018All photographs courtesy the artist

This piece is adapted from Zhang Xiao: Community Fire (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2023). Shehuo: Community Fire is on view at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, through April 14, 2024.

February 2, 2024

13 Photobooks that Highlight Black Lives and Artistic Visions

Samuel Fosso, ‘70s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Samuel Fosso, ‘70s Lifestyle, 1975–78Courtesy the artist and JM.PATRAS/PARIS

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

Collect a special vinyl LP, As We Rise: Sounds from the Black Atlantic , featuring a celebratory collection of classic and contemporary Black music made throughout the Diaspora.

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019

Dawoud Bey, Irrigation Ditch, 2019Courtesy the artist

Dawoud Bey: Elegy (2023)

In the artist’s most recent volume, Elegy, Dawoud Bey focuses on the landscape to create a portrait of the early African American presence in the United States. Renowned for his Harlem street scenes and expressive portraits, Bey continues his ongoing work exploring African American history. Copublished by Aperture and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Elegy focuses on three of Bey’s landscape series—Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017); In This Here Place (2021); and Stony the Road (2023)—shedding a light on the deep historical memory still embedded in the geography of the US.

Bey takes viewers to the historic Richmond Slave Trail in Virginia, where Africans were marched onto auction blocks; to the plantations of Louisiana, where they labored; and along the last stages of the Underground Railroad in Ohio, where fugitives sought self-emancipation. By interweaving these bodies of work into an elegy in three movements, Bey not only evokes history but retells it through historically grounded images that challenge viewers to go beyond seeing and imagine lived experiences. “This is ancestor work,” Bey tells the New York Times. “Stepping outside the art context, the project context, this is the work of keeping our ancestors present in the contemporary conversation.”

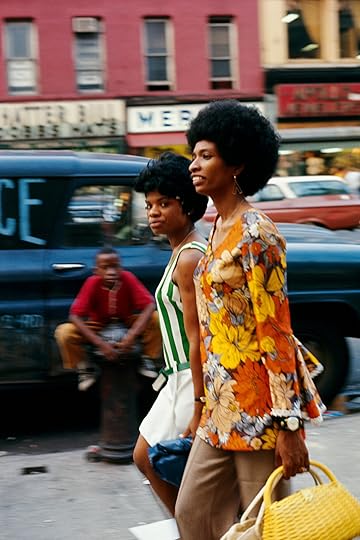

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the 1950s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color.

Brathwaite, who passed away in 2023, was born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance. Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling agency for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Black Is Beautiful is is the first-ever monograph of his work, showcasing Brathwaite’s riveting message about Black culture and freedom. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation. . . . [They] were the woke set of their generation.”

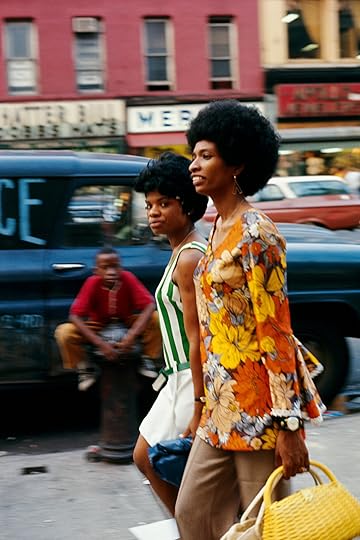

Ernest Cole, Untitled 1968–71

Ernest Cole, Untitled 1968–71Courtesy the Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole, Untitled 1968–71

Ernest Cole, Untitled 1968–71 Ernest Cole: The True America (2024)

After fleeing South Africa to publish his landmark book House of Bondage in 1967 (reissued by Aperture in 2022) on the horrors of apartheid, Ernest Cole became a “banned person” and resettled in New York. Supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cole photographed the city’s streets extensively, chronicling daily life in Harlem and around Manhattan. In 1968 he traveled across the country to cities including Chicago, Cleveland, Memphis, Atlanta, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, as well as to rural areas of the South, capturing the activism and emotional tenor in the months leading up to and just after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. These photographs reflect both the newfound freedom Cole experienced in the US and the photographer’s incisive eye for inequality as he became increasingly disillusioned by the systemic racism he witnessed.

Cole released very few images from this body of work while he was alive. Thought to be lost entirely, the negatives of Cole’s American pictures resurfaced in Sweden in 2017 and were returned to the Ernest Cole Family Trust. The True America marks the first time these photographs have been brought together in a major publication. With more than 260 previously unpublished images, this compilation redefines the scope of Cole’s work.

Awol Erizku, Moon Voyage (Keep Me in Mind), 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Moon Voyage (Keep Me in Mind), 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax (2023)

Awol Erizku’s interdisciplinary practice references and reimagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism. Mystic Parallax is the first major monograph to trace the rising artist’s career. Spanning over ten years, the volume blends together his studio practice with his work as an in-demand editorial photographer, including his conceptual portraits of Black culture icons such as Solange, Amanda Gorman, and Michael B. Jordan.

Throughout his work, Erizku consistently questions and reimagines Western art, often by casting Black subjects in his contemporary reconstructions of canonical artworks. “I always think about my work as a constellation, and a new piece is just another star within the universe,” he asserts in his wide-ranging conversation with curator Antwaun Sargent, included in the book. “This goes back to the idea of a continuum of the Black imagination. When it’s my turn, as an image maker, a visual griot, it is up to me to redefine a concept, give it a new tone, a new look, a new visual form.”

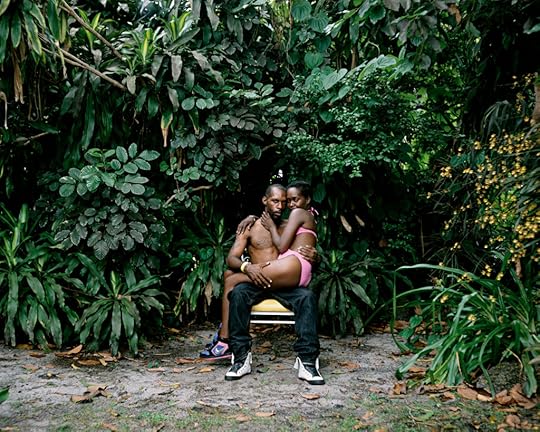

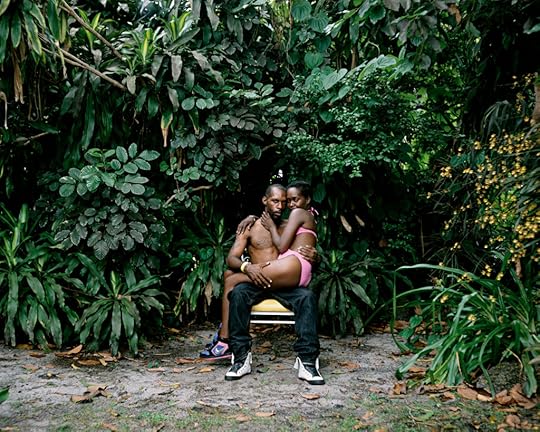

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013Courtesy the artist

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s first book, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in an essay for the book. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-on C-print.

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Twins II), New York, 2017

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Twins II), New York, 2017Courtesy the artist

Quil Lemons, South Philadelphia, 2018

Quil Lemons, South Philadelphia, 2018Courtesy the artist

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019)

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in fashion and art today. The book highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation—including Tyler Mitchell, the first Black photographer to shoot a cover story for Vogue; Campbell Addy and Jamal Nxedlana, who have founded digital platforms celebrating Black photographers; and Nadine Ijewere, whose early series title The Misrepresentation of Representation says it all.

From the role of the Black body in media to cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture, and to the institutional barriers that have historically been an impediment to Black photographers, The New Black Vanguard opens up critical conversations while simultaneously proposing a brilliantly reenvisioned future. “Often in this culture, when we think about the work of Black artists, we almost never think about, How do we celebrate young Black artists? And I wanted to change that,” Sargent states. “I wanted to say that what was happening right now with these very young artists is significant. It has shifted our culture, it has shifted how we think about photography, and it has shifted who gets to shoot images.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

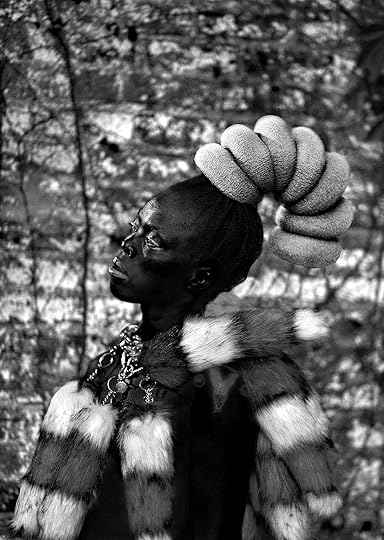

Zanele Muholi, Senzekile II, Cincinnati, 2016

Zanele Muholi, Senzekile II, Cincinnati, 2016Courtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (2018)

South African artist Zanele Muholi is one of the most powerful visual activists of our time. Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases that documents the LGBTIA+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. From there, Muholi began to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits brought together in their 2018 monograph Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness.

Muholi’s self-portraits are radical statements of identity, race, and resistance. Using props and materials found in their immediate environment, Muholi crafts starkly contrasted frames that directly respond to contemporary and historical racisms—while also providing a platform for self-discovery. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without fear of being vilified,” Muholi states. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.”

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013Courtesy the artist and Webber Gallery, London

Zora J Murff: True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) (2022)

Zora J Murff’s photographs construct an incisive, autobiographic retelling of the struggles and epiphanies of a young Black artist working to make space for himself and his community.

Since Murff left social work to pursue photography over a decade ago, his work has consistently grappled with the complicit entanglement of the medium in the histories of spectacle, commodification, and race, often contextualizing his own photographs with found and appropriated images and commissioned texts.

True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) continues this conversation, examining the act of remembering and the politics of self, which Murff describes as “the duality of Black patriotism and the challenges of finding belonging in places not made for me—of creating an affirmation in a moment of crisis as I learn to remake myself in my own image.”

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978

Ming Smith, Sun Ra Space II, New York, 1978Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes for the New Yorker, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

Hank Willis Thomas, The Cotton Bowl, 2011, from the series Strange Fruit

Hank Willis Thomas, The Cotton Bowl, 2011, from the series Strange FruitCourtesy the artist

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal (2018)

Throughout Hank Willis Thomas’s prolific and interdisciplinary career, his work has explored issues of representation, perception, and American history. At the core of his practice is the ability to parse and critically dissect the flow of images that comprise American culture, with particular attention to race, gender, and cultural identity.

Since his first publication, Pitch Blackness (Aperture, 2008), Thomas has established himself as a significant voice in contemporary art. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge, a transmedia project that uses video to facilitate conversations among Black men, and the artist collective For Freedoms.

In 2018, Aperture and the Portland Art Museum copublished All Things Being Equal, the first in-depth overview of the artist’s extensive career. Featuring over 250 images from his oeuvre, the volume highlights Thomas’s diverse range of visual approaches and mediums—from advertising and branding, civil-rights and apartheid-era photography, and sculpture, to public-art projects and more.

Mickalene Thomas, Le leçon d’amour, 2008

Mickalene Thomas, Le leçon d’amour, 2008Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Muse by Mickalene Thomas (2015)

Mickalene Thomas’s large-scale, multitextured tableaux of domestic interiors and portraits subvert the male gaze and assert new definitions of beauty. Thomas first began to photograph herself and her mother as a student at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut—which became a pivotal experience in her creative expression as an artist.

Since then, throughout her practice, Thomas’s images have functioned as personal acts of deconstruction and reappropriation. Many of her photographs draw from a wide range of cultural icons, from 1970s “Black Is Beautiful” images of women to Édouard Manet’s odalisque figures, to the mise-en-scène studio portraiture of James Van Der Zee and Malick Sidibé. Perhaps of greatest importance, however, is that Thomas’s collection of portraits and staged scenes reflect a very personal community of inspiration—a collection of muses that includes herself, her mother, her friends and lovers—emphasizing the communal and social aspects of art-making and creativity that pervade her work.

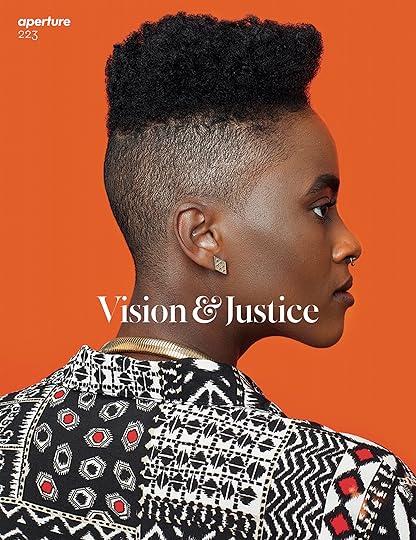

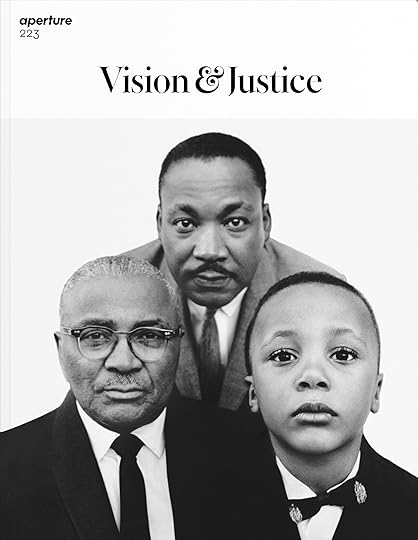

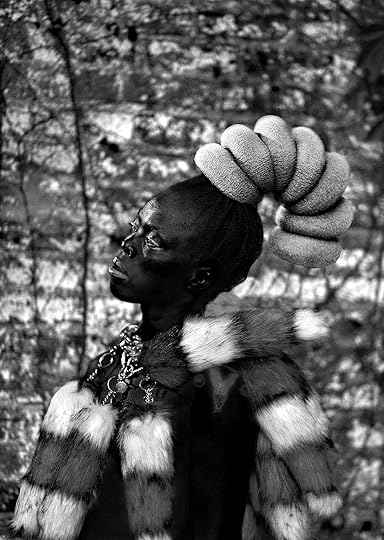

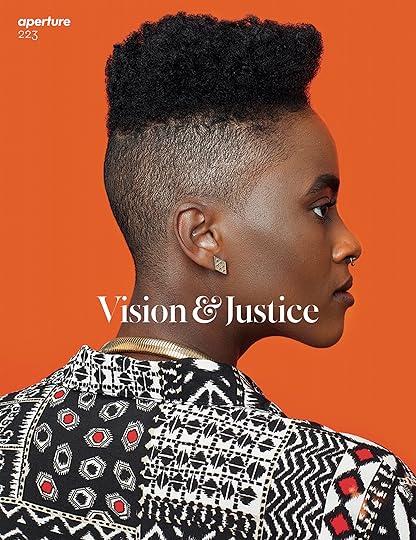

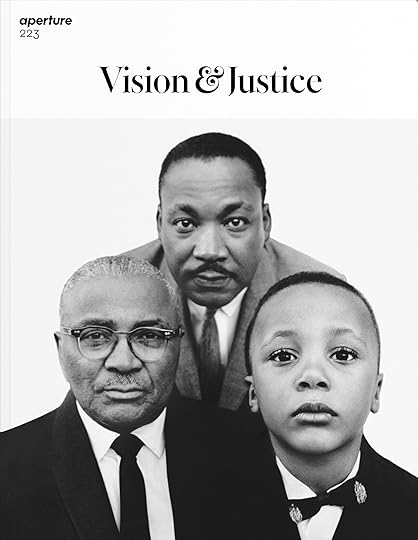

Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice ” (Summer 2016)

The art historian, curator, and writer Sarah Elizabeth Lewis guest edited Aperture’s summer 2016 issue, “Vision & Justice,” a monumental edition of the magazine that sparked a national conversation on the role of photography in constructions of citizenship, race, and justice. The issue features a wide range of photographic projects by artists such as Awol Erizku, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Deana Lawson, Jamel Shabazz, Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis; alongside essays by some of the most influential voices in American culture, including Vince Aletti, Teju Cole, and Claudia Rankine. “Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil,” writes Lewis. “It is the artist who knows what images need to be seen to affect change and alter history, to shine a spotlight in ways that will result in sustained attention.” In 2019, Aperture worked with Lewis to create a free civic curriculum to accompany the issue, featuring thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice. Taking its conceptual inspiration from Frederick Douglass’s landmark Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress” (1861)—about the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation—the curriculum addresses both the historical roots and contemporary realities of visual literacy for race and justice in American civic life.