Aperture's Blog, page 23

December 6, 2023

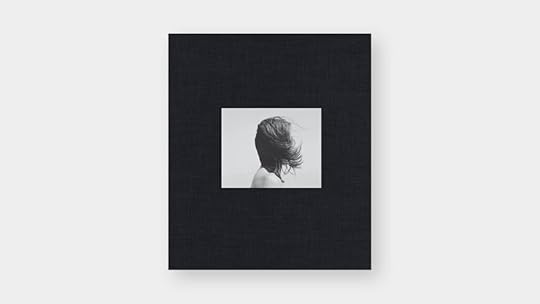

Sam Contis Asks What It Means to Move through the Landscape

This essay originally appeared in Sam Contis: Overpass (Aperture, 2022) under the title “H.”

A desire line is a path made to cut corners. You’ll have seen them—in a field, tracing the most concise route between two gateways, or in an urban park in places where the paving winds the long way around the grass. Many people follow the same shortcut, and eventually a path becomes visible where the vegetation is worn away. Even when there is nobody there, you can see the physical traces of all those people and something they were aiming for, written plainly on the bared ground.

There are similar traces visible in Sam Contis’s photographs of stiles, tracks, and fences, images of human passage in which the human form is notably absent. A stile is a crossing point: a step or narrow gap in a fence, wall, or hedge, designed so that people can pass through but sheep and cattle can’t. It’s an old form: simple and variable. Anything that allows a person to pass over or through a barrier, but which is too narrow or fiddly for livestock, works. Two steps made of cobbles, breezeblocks, or pieces of wood nailed together; a slim gap let into a low stone wall; plastic sacking tied around a barbed-wire fence. All in and around these stiles there are traces of human activity, desire lines in an extended sense: people ’s desires and needs pressed into the places where they’ve been. There are trodden grasses and plants that have been crushed or bent around the worn paths. Cinder blocks, placed in front of one stile to help small legs make it up to the first step. A broken fence has been mended in a makeshift way, a short length of wire looped and twisted to hold a closure, it looks like a bad impression of a cobweb. Elsewhere, vertical posts are cut with a tapering droplet form at the top, narrowing to give the human hand something to hold. There’s a place where three empty lager cans have been dropped on the ground, below a stile at the meeting of a footpath and a road: not long ago, somebody sat on the fence here, drinking. They crumpled the cans and then they moved on.

Looking at these images, I thought of the histories of the English countryside told by Oliver Rackham, an ecologist whose books describe how layers of history materialize in a landscape. Rackham reads terrain as though it was an archive and he finds everything, everywhere crowded with evidence of past lives. Roads commemorate encounters, desires, and obstructions: the route bends here, where a farmer once dumped a pile of trash, and here where a group of kids lit a bonfire, and here, where a woman abandoned her dead horse. Travelers continued to pursue these diversions even after the obstruction was removed, so that the road, as it moved across a landscape, became a “series of wobbles,” each wobble the mark of an event. Barriers have stories too: there are hedges that stand as “the ghosts of woods that have been grubbed out,” a line of trees from the original edge making a lasting boundary between new fields. Perhaps every mark in any landscape is somehow a sign of drive, force, want, or need.

If we were to read the story of one of these stiles, in one of these images, what desires would it document? The stile seen here looks ordinary. A thin plank supported by two greenish posts: a single wooden step, bridging a fence between two sheep pastures in the north of England. A large, flat-faced cobble from the nearby river has been placed on the ground at one side to steady the feet. This stile is almost identical to the stile in the next field … but this one is messier, slightly asymmetrical, because this one began with a bad mood. It was the product of a poor repair job, knocked together one October day in 2004, a little past midday. The farmer who made it would, ordinarily, have been eating, but that day the telephone rang and he left his plate on the table, still half full. He talked, and listened, and the food cooled. It was his sister on the phone. She wanted to discuss their elderly mother’s care. They ended up arguing.

After the conversation, the farmer didn’t feel like finishing his meal. He left the house with his toolkit and went out across the fields to mend the broken stile. He took down the collapsed plank, and tested the posts to check that they were still sound. Then he knelt on the makeshift paving slab to hammer in the new step. One hand gripped the stile, the other pounded in the nails rapidly and hard. As he worked, he was running back over the argument in his mind, thinking of what he should have said to his sister, and the hammer went down on his thumb. Abruptly, he had to stop. Black blood pooled under the nail. He stood and stepped back, folding the fingers of his other hand protectively around the damaged thumb, to look at his work. The stile was unbalanced, the plank extending too far on one side, leaving only a narrow ledge on the other.

There had been stiles like this on his land for centuries, wherever people needed to pass. His parents and grandparents had tended to some, neglected others. Throughout the country are tens of thousands of miles of public footpaths, running across private land. Historically, landowners would see to the upkeep of stiles and gateways along these paths, when it was in their interests to do so. But relatively recently this upkeep was made a legal obligation. Since the Countryside Act of 1968, landowners have been required to maintain the stiles that made free movement possible, and this particular repair was long overdue. Over the years, the stile had taken many forms: its stakes and poles had been erected and knocked over; the stone slabs at its base used, worn, cracked, and carried away; the horizontal planks had been replaced many times.

The new plank that our farmer hammered in that day has its own story. It was Scots pine, swift-grown on timberland in western Scotland in the late 1990s. Tree by regularly spaced tree, the forest was being infiltrated by a poisonous fungus. The fungus didn’t look like much (fingernail-sized, pearly umbrellas growing on the ground below each sick tree), but it could rot live wood before the tree matured. Two square miles of pine were felled young to stop the spread and the timber from these trees, which couldn’t be sold through the usual channels, went cheap. Our farmer purchased green posts and thin planks from the lot, roughly cut and still wet.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

But none of this explains the path. It doesn’t tell us why people were passing through right here, in this place—why they needed a crossing-point here, at this corner of this field, and why there was a stile that our farmer was now legally bound to maintain. We need to travel back again to make sense of it, to see the stories that caused it to materialize here.

Long before the 1968 Act, the English countryside was occupied and worked in common. Landowners held legal and political power, but commoners had the right to grow food, raise animals, or gather fuel from the fields and forests that they lived near. This was no Arcadia: landowners couldn’t have maintained their power without giving the peasants who worked for them some means to feed themselves. But the rights were real and honored. They were written down and lived out for centuries, during which peasants were able to make a living off their local land, right up to the point at which those rights were eroded and in some places eradicated between the seventeenth and the nineteenth centuries, during a series of movements known as enclosures. Parish by parish, commoners were decisively deprived of this long-held tenancy of the landscape. Small plots farmed in rotation were ploughed up in favor of rationalized growing systems, with long straight hedgerows dividing large, regular fields. Straight roads, which ran from town to town, were expanded, and the tracks that mazed across fields, connecting every cottage or farmstead, woodland, or pond, faded into the grass. The pathway on which our stile stands was once a highway: a practical route rather than a recreational footpath. It had its deliveries and its commuters. Its placement, right here, made the neatest cut-through for the milkmaid in the early eighteenth century who used to take a pail from the dairy farm to the big house every other day; passing, in the other direction, children sent out by their parents to gather sticks for the fire. Already, then, this crossing had been in use for hundreds of years. Medieval peasants were here, going between their cottages and their strips of land, and occasional travelers exported materials across longer distances, moving stone and timber, lime and metals and chalk and charcoal, from forests and mines, to cities, building sites, shipyards. The crossing had been used for years, decades, centuries before that. Back when the lightly worn path was barely visible on the ground, humans walked here, taking hazels and hawthorn with them when they passed.

Perhaps, looking at the histories that materialize in this ordinary stile, we have to push its beginning even earlier. The environmental activist and writer George Monbiot, among others, has propagated a theory that the British landscape is one that evolved in response to threats that have long since disappeared. The blackthorn spines we see in our hedge evolved to deter rhinoceros tongues. Birch bark, glowing white with dark striations on the edge of this wood, would confuse an ancient elephant’s limited color vision. Monbiot mentions the hippopotamus bones discovered in central London, below Trafalgar Square, and pictures a vision of the whole of Britain as a place adapted to species that no longer live there, “a ghost ecosystem.”

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Perhaps our stile began, then, before the human, and even before other mammals made the earliest desire paths here, into and out of the wood. Perhaps we need to explore the stories of the mycorrhiza, evolving in symbiosis with aquatic plant life, which enabled plants to colonize dry land, which enabled trees to emerge, which enabled our Scots pine, which created this green fencepost.

Or, looking at the river stone that’s used as a rudimentary step, we need to rewind to its moment of creation: boiling seas; molten rock in a volatile atmosphere; eons inside the earth’s crust, millennia on a mountainside, decades of rolling underwater before it was stranded on the riverbank during a late-summer drought when our farmer took it away.

But, no. None of that is early enough. We need to move back further. Thousands and millions and billions of years; the origins of life. Meteors were seeding the planet with lively microscopic forms. Electrified molecules were merging and splitting in a primordial soup. The precise sequence of events is uncertain. The only thing we can say for sure is that things were volatile. Something unstable stuck, and set into being this sequence of events that leads us here, to this crossing-point, in the present.

You can look at any landscape like that, seeing all these things that happened in this place in the past. They’re layered into every tiny area. A fencepost, a cobble, and a footprint in the mud, where ground has been worn bare below the stile, contains the story of last weekend’s rambler, and the evergreen that was cut down thirty years ago, and the primal molecule. You can look at a Peruvian mountainside, its trees and torn ruins, and see the signs of an industrious city. Or stand in Trafalgar Square to see ancient hippopotami wallowing where the waters used to meet. Or watch a harvester mechanically progressing through a soy crop in Kentucky and hear voices singing somewhere inside the field.

All these histories are live, shaping landscapes and affecting bodies in the present, and determining what’s possible in the future. Maybe this is a photography of speculation, rather than documentary, not an archive but a forecast: these images are not testaments to the past, they’re pictures of a future in which alternative forms of experience have a greater force and presence. The term stile comes from a diminutive form of an earlier word for “climb.” You look out with a slight deviation in your perspective. The landscape opens. You step up, placing your foot on the horizontal—the stone step, the wooden cross-beam—and then you see something else.

These images are not testaments to the past, they’re pictures of a future in which alternative forms of experience have a greater force and presence.

When you step down from the stile the ground comes up fast. There are these trippy images of movement, interspersed with the wide, still spaces. The perspective has been shifted, as though the subject is on the move. They give the feeling of descending to finding the ground slightly closer and harder than you’d expected, stumbling. All forms are dappled and blurred, meshed with light that moves unstably in water, earth, branches, or bark. These images are preoccupied with shadows and reflections, the places where branches and walls allow light to pass. Water rushes through the teeth of a barrier that catches flotsam. Barbed wire runs right up to the place where the fence can be crossed, then runs on at the side. Many of these pictures spell out the shape of the letter H: a horizon-line, seen between vertical strokes of trees or fences or walls. Planks, stones, wires, gates, stiles, fences, walls, all arrange a horizontal barrier or bridge that spans two uprights. I typed the lone letter into a search engine and discovered that my inference ran in the wrong direction: it’s not the landscape that recalls the letter, but the letter that depicts a landscape: “H” is derived from a Levantine hieroglyph for fence. A stile is a means of access but it is also a barrier technology, like a subway gate. It selects. It discriminates. It filters bodies.

Looking at these contemporary images, seen through fences and barriers, it’s difficult to ignore what the English landscape leaves out. If we were to follow the story of this stile horizontally, rather than vertically—not moving back through the past, but staying in the present and reaching out across the landscape and the world—what would we see? Starting right here, to watch a couple help one another over the stile one winter afternoon. They’re gray-haired, married, able-bodied, white; dressed, expensively, in Scandinavian waterproofs. Any time you go out for a hike in the English countryside, a gap opens up between the historical and legal fact of the right of access, and the political and geographical realities that determine who actually visits or inhabits any given landscape. The barriers that exist now, through which access to a landscape is granted or denied, have become more sinister because they are concealed. Ancient privileges and dispossessions have gone into hiding but they’re still around. Rural England is overwhelmingly white and right-leaning, and it’s poorly served by public transport. If you live in London or Manchester it’s easier and often cheaper to travel to Amsterdam or Mallorca, than to reach some closer part of rural East Anglia or the Lake District, without private transport. Barriers that sustain inequality in the contemporary world are no longer as simple as the wooden posts and lengths of wire that pen the sheep. Perhaps this is why there was a powerful dreaminess and longing in the way Trump used to fantasize about his wall. The thing that was remarkable, in the way he described it, was that his imagination was so literal—the height and dimensions, the building materials he would use, the itemized bills and who would pay them. The wall manifested a desire that ’s felt by many—not only those who wanted it—to go back into a world in which material force is the first currency, there are none of the receded or virtual barriers and passageways that shape realities now.

Sam Contis: Overpass 60.00

Sam Contis: Overpass 60.00 $60.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Sam Contis: OverpassPhotographs by Sam Contis. Text by Daisy Hildyard. Designed by Julian Bittiner.

$ 60.00 –1+$60.00Add to cart

View cart Description Overpass is about what it means to move through the landscape. Walking along a vast network of centuries-old footpaths through the English countryside, artist Sam Contis focuses on stiles, the simple structures that offer a means of passage over walls and fences and allow public access through privately owned land. In her immersive sequences of black-and-white photographs, they become repeating sculptural forms in the landscape, invitations to free movement on one hand and a reminder of the history of enclosure on the other. Made from wood and stone, each unique, they appear as markers pointing the way forward, or decaying and half-hidden by the undergrowth. An essay by writer Daisy Hildyard contextualizes this body of work within histories of the British landscape and contemporary ecological discourses. In an age of rising nationalism and a renewed insistence on borders, Overpass invites us to reflect on how we cross boundaries, who owns space, and the ways we have shaped the natural environment and how we might shape it in the future. DetailsFormat: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 224

Number of images: 122

Publication date: 2022-11-15

Measurements: 6.75 x 9.75 x 0.94 inches

ISBN: 9781597115391

“The work reveals something subtly subversive about our access to the countryside”—Josh Lustig, The Financial Times

ContributorsSam Contis (b. 1982) lives in California. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at the Barbican Centre, London; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Carré d’Art, Nîmes; and MoMA, New York. She is the recipient of a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship and the author of Deep Springs (2017) and Day Sleeper (2020).

Daisy Hildyard (b. 1984) is author of two novels—Emergency (2022) and Hunters in the Snow (2013)—and one work of nonfiction, The Second Body (2017). She lives in North Yorkshire.

Moving along the hedgerow and into the fields and woods, we track away from the couple and they disappear on the other side of the stile. A new set of subjects gains presence: small, shadowy, all nonhuman, some barely corporeal. The fencepost to one side of the stile is a growing pole for wild carrot plants, which lean on it as they move towards the light. The stile ’s wet, soft plank is food to the fungus that cover its surface in orange spots. The stake in the fence offers delicious relief for a cow’s itchy back on a hot afternoon. Moss and lichen creep over dank areas on a stone ’s surface. Spaces between loose stones in the wall are tunnels used by field mice and a weasel. A kestrel sometimes lands on the telegraph wire that runs above the stile, where it can see things moving through the opening below. A hole in the wire, low down in the fence, is the place where a lamb tried to climb through; got stuck and struggled, tangling his wool tighter until the barbed edge tore his skin. An elm sapling cranes over the gap in the hedge, its branches extended to catch spare light. Around the stile there ’s a patch of mud where feet have worn away the grass, and this is the fragile place where the rare, specialized, increasingly endangered flora of the footpath thrive in mud, shade, and the pressure of feet. The area below the stile is an underpass for badgers and foxes. The tall stone wall is a barrier to an extended family of rabbits, who make room and clear passage for their exploding population by undermining it.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Contis’s subjects are small but tough: stalks, seeds, pieces of grit, thorns, hairs tangled into the wire fence. I thought of Albrecht Dürer’s Great Piece of Turf, a modest sixteenth-century watercolor of a clump of weeds and grasses. Dürer’s image could easily be described as photographic realism, but his attention amplifies his subject, so that the spent dandelion buds and thin blades of grass become spectacular, hyperreal. Contis’s images are like that: her subjects gain force when seen with this intensity. These are quiet places, but their quietness is suggestive. The worn paths and spaces between walls trace presence. The vegetation is lush, tangled, profuse. Everything leans into everything else, germinating, growing, subsiding, collapsing, and then regenerating. A landscape comes into being through encounters between soils and microbes, birds and chemicals, lichens and moisture, plants and mammals. A million different infrastructures, created by many species and successive climates, all built and perpetually building up into and against one another. You can look at any landscape like that, too: to find the many living storylines that come together in the present. Some are apparent, some are hidden, but they all make it what it is. Between your feet on the sidewalk there is a small basement where young men sleep on rotating shifts. From the top deck of the bus you might glimpse a lonely woman inside the state palace, sitting out long days behind drawn curtains, or the gulls on the palace kitchen roof, waiting for the food waste to be put out. Sunbathing on a suburban lawn on a hot afternoon you can feel, behind the back of your head, disturbed earth where a fox was clawing the ground for worms last night. The stile draws many different environments and experiences together, in the same place: it’s a stile, a scratching post, a gate, and a barrier. It’s a place to find something to eat, a hiding place and an escape route. It’s a gap, brought into sharp focus—emptiness, tended for a human body to pass.

All photographs Sam Contis, Untitled (from the series Overpass), 2020-2022, from Overpass (Aperture 2022)

All photographs Sam Contis, Untitled (from the series Overpass), 2020-2022, from Overpass (Aperture 2022)Courtesy the artist

The landscapes themselves, spacious and closely inhabited, pass on too: they extend over the edge of the photograph and beyond the horizon. The plastic bag caught in the hedge here blows into a stream and floats downriver, out into the North Sea, drawn by circulating currents into the Atlantic and then the Pacific, where it joins other plastic bags all floating in an island together through turquoise waters. This tuft of reedy grasses is closely related to the marsh plants that emerge through the snowmelt in southern Siberia each spring. The wire fence that runs on either side of the stile runs on between the posts and away into the distance. The same wire fencing cross-hatches the moors and crosses down into the Dales. It runs through fields. It runs around a prison and a livestock market and runs on through more fields. It runs around migrant detention facilities and gated residential communities. It guards the train tracks at the entrance to the channel tunnel in Kent and resurfaces at its exit in Normandy. The fencing runs, intermittently, across Europe. Where the land meets the ocean there is a gap in the fence, and on the other side of the ocean, right there at the water’s edge, the fencing begins again. This same material—thick, square-hatched wire—runs riot around the freeways and border kiosks where El Paso meets Ciudad Juárez, it divides Syria from Turkey, Ukraine from Russia, Pakistan from Afghanistan, it has a field day on the Gaza Strip and runs on, circumnavigating the planet.

This essay originally appeared in Sam Contis: Overpass (Aperture, 2022).

Sam Contis: Overpass is on view at Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York, October 27–December 16, 2023

December 1, 2023

An-My Lê on Vietnam, the Chaos of War, and the Tangibility of Memory

This interview was originally published in An-My Lê: Small Wars (Aperture, 2005).

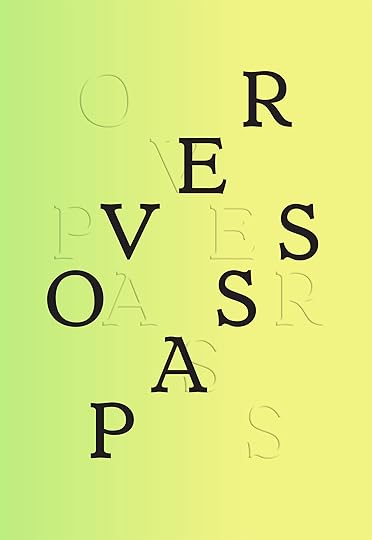

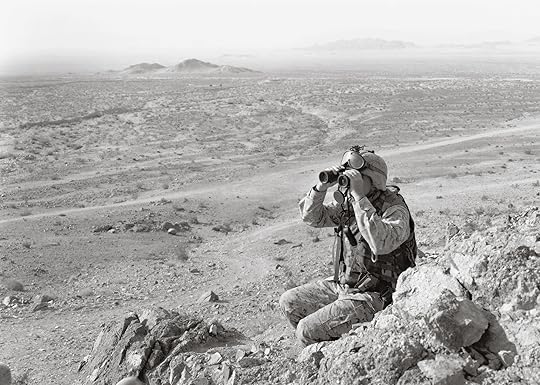

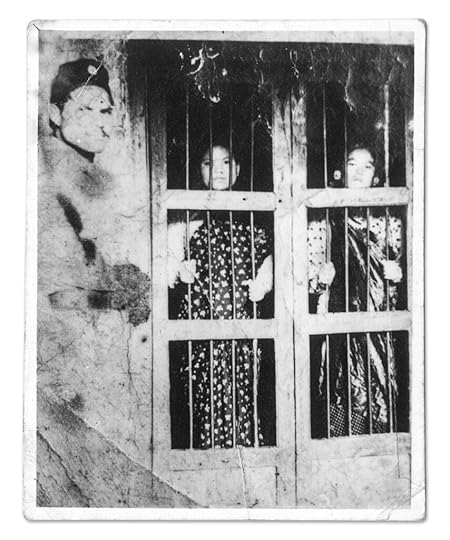

An-My Lê was born in Vietnam in 1960 and came to the United States as a political refugee at age fifteen. She received a grant to return to her homeland just after US Vietnamese relations were formally restored. Lê went back several times between 1994 and 1997, creating stunning large-format, black-and-white photographs, expertly printed in a middle-gray scale reminiscent of Robert Adams. These images do not address the war specifically, but rather represent Lê’s attempt to reconcile memories of her childhood home with the contemporary landscape that now confronted her. The war haunts the images in eerie metaphors: dozens of kites double as dive-bombing planes; crop fires and construction sites recall napalm and mass graves.

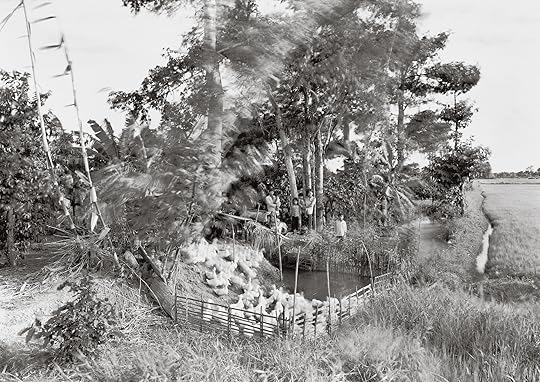

In 1999 Lê began working with Vietnam War reenactors in North Carolina who restage battles as well as the training and daily life of soldiers—both Viet Cong and American GIs. For four summers, she not only photographed but also participated in battles of the Vietnam War restaged on her adopted American soil. Relating to both documentary and staged photography, the work is aesthetically rigorous and conceptually challenging. Soldiers at rest give themselves up to portraiture, while battle compositions recognizable from classic war photojournalism possess the qualities of a dream. Most recently, Lê has photographed exercises performed by the US military in the American desert in preparation for maneuvers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Lê’s works elucidate the complicated nature of the aesthetics and spectacle of war. But perhaps the most intriguing conceptual component is Lê’s own relationship to the subjects and the landscapes she presents. —The Editors, from Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018)

Hilton Als: For Americans born in the 1960s, Vietnam, or, rather, the “issue” of Vietnam—the “problem” of Vietnam—was something that we always lived with: on television, in newspapers, and the rest. But we did not necessarily understand what “the war” in Vietnam was about. Can you provide a thumbnail sketch of the historical and political background of your country, and the effect its invasions—by the French, by Americans—had on you, your family, and your environs?

An-My Lê: My mother’s family—much more dominant in my life than my father’s—was from Thai Binh, a small town near Hanoi. They lived through the Japanese occupation and under Communist rule. My mother grew up in Hanoi but for higher education traveled to Paris in the 1950s. In 1954, while she was still in Paris, my grandmother moved to Saigon when the country was divided at the 17th parallel and the Communists took over the North. My mother met my father and married him in Paris, where my older brother was born. They eventually returned to Saigon, where I was born.

We lived through many political coups, years of fear and uncertainty, as the Viet Cong would shell the city randomly every night. War became a routine, something we accepted as part of our lives, until 1968 when the Communists attacked Saigon during the Tet celebrations. They took over the American embassy and the radio station behind our house. This offensive sent shock waves through the community. We all felt vulnerable. My parents decided we had to leave Vietnam to find shelter, even if it was for a short while. Fortunately my mother received a scholarship to work on a Ph.D. at the Sorbonne. We were able to move to Paris (my father stayed behind) and lived there for five years while she completed her Ph.D. We returned to Saigon in 1973, only to see the country fall to the Communists in 1975. We were fortunate to be evacuated by the Americans that April. In spite of our ties to France, my parents decided to remain in the United States because it seemed to offer more opportunities at that time. For better or for worse, my life and those of the last three generations of my family have been underscored by the complicated political history of Vietnam.

An-My Lê, Untitled, Ho Chi Minh City, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Untitled, Ho Chi Minh City, 1995, from the series Viêt Nam  An-My Lê, Untitled, Son Tay, 1998, from the series Viêt Nam

An-My Lê, Untitled, Son Tay, 1998, from the series Viêt Nam Als : Your photographs deal so specifically with ideas of landscape; do you work from your memory of the Vietnamese landscape to examine your feelings about it, or to imagine what its colonizers might have felt about it?

Lê: Over the years, disconnected from the place and with only a handful of family pictures available, I had come to construct my own notions of a Vietnam drawn mostly from memories, but also from photojournalism and Hollywood films. In 1994 when I returned for the first time, I realized that I was not particularly interested in reexamining contemporary Vietnam. Instead of seeking the real, I began

making photographs that use the real to ground the imaginary. The landscape genre or the description of people’s activities in the landscape lent itself well to this way of thinking.

My attachment to the idea of landscape is a direct extension of a life in exile. The sense of home has to do with the importance of food and location, and it is all connected to the land. Vietnam has always been (and still is somewhat) an agricultural society. Its culture and history are deeply rooted in its land. Growing up I did not know much of the country, actually not much outside of the capital and a few other large cities in the South, since it was difficult and unsafe to travel to the countryside during wartime. Especially when we lived in Paris and later in the U.S., I came to fantasize about this traditional agricultural way of life. Through folktales, legends, and many stories I heard from my mother and grandmother, I imagined a life that was truly magical but at the same time real and grounded—a life of hardship, working the land, with threats of war and disease but also the joys of living close to nature in a large, close-knit family.

Vietnamese society and in a way its people (especially in the North but partly in the South as well) have also been deeply scarred by years of immobilization and deprivation during the war and during the earlier part of the reunification. In the meantime, in spite of the destruction, the landscape seems to have recovered and, to someone living in exile, has managed to retain and exude that sense of culture and history that can signal that one has arrived home.

The idea of the landscape and its climate was also such an important topic when the Vietnam War was covered in military analyses, news reports, and Hollywood films. The word terrain was often mentioned: how treacherous it was, how the enemy was better prepared for it and had a greater advantage. Working with the Vietnam War reenactors I became fascinated by the significance of the landscape in terms of its strategic meaning. Every hilltop, bend in the road, group of trees, and open field became a possibility for an ambush, an escape route, a landing zone, or a campsite.

In spite of the influence of Vietnamese culture on my life, I am also a product of colonial attitude, having grown up in a Francophile home and then later having lived in France. Eugène Atget has been a great inspiration—not only his work, which brilliantly captures the notions of change and transition in a place and a culture, but his entire life and working process.

An-My Lê, Untitled, Mekong Delta, 1994, from the series Viêt Nam

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Als : When did you begin your career in photography? And why?

Lê: It began by chance. I never felt I had a calling for anything in particular but was fairly good in the sciences, so I chose to study biology in college in preparation for a career in medicine. I was not accepted to any of the medical schools I applied to in my senior year, and it was suggested that I do biomedical research, publish, pursue a master’s degree in biology, and reapply. While completing a master’s at Stanford University, I wanted to take a drawing class to fulfill a nonscience requirement. It was full, so I chose photography instead. To my surprise, the class completely took over my life. If I was not photographing, I was in the darkroom printing until late. I loved every minute of it.

What drew me at first was simply how the camera gave me license to go out and discover more of the world; it taught me about people and places and about myself as well. The immediacy of responding to a situation when you snap your photo, the opportunity to be more analytical later when you edit the pictures, and the blend of the intuitive and the cerebral was very satisfying. Whatever a calling could be, it seemed to me that this was it.

In 1986 I moved back to Paris, where I floundered for a few months until Laura Volkerding, my teacher from Stanford, arrived. She came to document the casting of Rodin’s Gates of Hell that had been donated to Stanford by Gerald Cantor. It was to be cast using the lost wax method at a foundry that belongs to a guild of craftsmen called the Compagnons du Devoir du Tour de France. The guild dates back to the Middle Ages and is comprised of various métiers: metalwork, masonry, stone-cutting, and carpentry/woodwork. These craftsmen were responsible for the construction of most churches and cathedrals in France. Now they do a lot of restoration work.

It turned out that the guild needed a staff photographer, and Laura referred me. I spent the next four years touring France and working for them. I was completely unprepared for the demands of this job; I quickly learned how to use a view camera on my own, how to use color film, how to light a space. I underwent a lot of trial and error. It was a great opportunity for me to travel and learn about the art and architecture of France, but more importantly, working for the guild deeply affected the way I saw things and represented them photographically. It was always about seeing clearly: showing the curve of a stairwell in an unencumbered way, the texture of this marble or that wood, drawing the volume of a vault in the most readable way. I also learned to respect the materiality of things (the nobility of stone, metal, and wood). I developed an appreciation of all things well made and a love for everything about the tradition of the craftsman and his work.

I moved back to the U.S., to New York City, in 1990. I finally realized that I did not want to be a commercial photographer and applied to graduate school. I then went to the Yale School of Art for my MFA. That’s when I began to grapple with the scope of a possible life as a visual artist.

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain 52.00 The first comprehensive survey of the Vietnamese American artist, featuring works from Lê’s series inlcuding Viêt Nam, Small Wars, 29 Palms, Events Ashore, and more.

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain 52.00 The first comprehensive survey of the Vietnamese American artist, featuring works from Lê’s series inlcuding Viêt Nam, Small Wars, 29 Palms, Events Ashore, and more. $65.00 $52.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

An-My Lê: On Contested TerrainPhotographs by An-My Lê. By Dan Leers. Text by Lisa Sutcliffe and David Finkel. Interviewer Viet Thanh Nguyen. Interviewee An-My Lê.

$ 52.00 –1+$65.00 $52.00Add to cart

View cart Description An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain is the first comprehensive survey of the Vietnamese American artist, published on the occasion of a major exhibition organized by Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.Drawing, in part, from her own experiences of the Vietnam War, Lê has created a body of work committed to expanding and complicating our understanding of the activities and motivations behind conflict and war. Throughout her thirty-year career, Lê has photographed noncombatant roles of active-duty service members, often on the sites of former battlefields, including those reserved for training or the reenactment of war, and those created as film sets.

This publication includes selections from her well-known series Viêt Nam, Small Wars, 29 Palms, and Events Ashore, in addition to never-before-seen images, including recent photographs from the US-Mexico border, formative early work, and lesser-known projects. Essays by the organizing curator Dan Leers and curator Lisa J. Sutcliffe, as well as a dialogue between Lê and Pulitzer Prize–winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen, address the ways in which Lê’s quiet, nuanced work complicates the landscapes of conflict that have long informed American identity.

Copublished by Aperture and Carnegie Museum of Art Details

Format: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 204

Number of images: 128

Publication date: 2020-06-16

Measurements: 9.25 x 10.5 x 0.8 inches

ISBN: 9781597114813

An-My Lê’s work has been exhibited at such venues as the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Lê has received many awards, including fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts (1996), John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (1997), and MacArthur Foundation (2012). She is a professor in the Department of Photography at Bard College.

Dan Leers is a curator of photography at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, and organized the traveling exhibition An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain. Previously, Leers was the Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, and an independent curator and consultant to the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art (New Paltz, New York), Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, and 2013 Venice Biennale.

Lisa Sutcliffe is the Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts at the Milwaukee Art Museum. From 2007 to 2012, she served as assistant curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Prior exhibitions include Marking Time in Photography and Film (2013), The Provoke Era: Postwar Japanese Photography, and Photography Now: China, Japan, Korea (both 2009).

David Finkel is a journalist and author whose honors include a MacArthur fellowship and a Pulitzer Prize.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is author of The Sympathizer (2015), which received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, among other awards. He is a recipient of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and MacArthur Foundation. Nguyen is a professor and the Aerol Arnold Chair of English at the University of Southern California.

Als : After you began photographing, did you immediately establish long-range plans in terms of what you wanted to accomplish with it, such as your studies of the reenactors in “their” recreated Vietnam, or is it all a process of discovery?

Lê: It was all subconscious. I am rather amazed at how the three projects have come together as a sort of trilogy. Going into a project, I never know the photographs I will end up making. It is a process of discovery, and I try to stay as open-minded as possible. For me it is first about learning something about the world, about myself. It is a little frightening starting a project in such a way and not feeling prepared, but so much of it is about problem solving. I am always asking myself what it is I am trying to find out about the situation, about the people: What does it all mean in terms of a cultural and historical context? What are my personal issues here? What is the point? Is it worthwhile? What kind of photographs could attempt to broach and perhaps begin to answer those questions?

The Vietnam project happened in 1993 after graduation from Yale, where I had been encouraged to do work that was more personal and autobiographical. The U.S. was loosening its diplomatic and economic relations with Vietnam. I saw the opportunity to return to Vietnam, which is something we never thought we could do when we left in 1975. The question of war was not central to the photographs I made in Vietnam. Only at the conclusion of this project did I feel ready to tackle that issue head-on. I had to also ask myself: how do you address something that has happened so long ago? I felt stumped; other than working with press images or trying to memorialize the event, what could I do?

Some of what I did in Vietnam, where I learned how to place people in the landscape, prepared me for the subsequent series. I learned that it is all about scale. How far back can you go to get a great drawing of the land, while still being able to suggest the activity of the people?

Als : How did you find out about the “reenactments”? And what was your first response to them? Did you have to go through a great deal of bureaucratic rigmarole to gain access to photograph?

Lê: I had heard about these small, low-key groups of men who reenact the Vietnam War. After some research on the Internet, I found one group based in Virginia and contacted them. It was smaller and more exclusive when I first worked with them than it is now. Gaining an invitation to the first event involved a lot of back and forth emailing with the founder. Once I was there, it became a lot easier because it was clear I wanted to help contribute to the event as best as I could while making my photographs.

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Lesson, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars  An-My Lê, Explosion, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars

An-My Lê, Explosion, 1999–2002, from the series Small Wars Als : Did you actually become involved in any of the war games that you documented?

Lê: Yes, that’s the requirement for attending the events, which last three days. The reenactors are obsessed with re-creating a situation that is seamless. So it is crucial that everything—from the erection of Viet Cong villages and GI firebases to a haircut and the smallest details in a uniform—be of the period. To fit in I often played a VC guerilla or North Vietnamese army soldier. I did what I needed to do to find the right VC uniform, sandals, rucksacks, and hammock. To go on the GI side, I would become a “Kit Carson” scout, a turncoat who would inform the Americans.

The reenactors truly enjoyed having me there. I added to the authenticity of the event, and they would often concoct elaborate scenarios around my character. I have played the sniper girl (my favorite—it felt perversely empowering to control something that I never had any say in). I have been the lone guerilla left over in a booby-trapped village to spring out of a hut and ambush the GI platoon. I have played the captured prisoner.

Initially I was terrified at the prospect of spending three days with these unknown men on a hundred- acre private property ten hours from New York City. My friend Lois Connor accompanied me. It turns out the reenactors are straightforward, conservative men who are so dedicated to this hobby. It’s an obsession for many of them—an obsession with collecting and trading all the paraphernalia, meshed with an interest in military history. Reenacting events are an opportunity for them to put their stuff to use, meet other men who share their interest, and live in a kind of virtual reality or travel back in time, all while having an adventure with their buddies.

From many conversations, I also learned that their interest in the military and in Vietnam stemmed from complicated personal histories. These men came from all sorts of professions. A few had been in the military, but rarely did they have experience in a combat situation. Some had missed their calling for the military and were steered by their parents toward law school or business school; some had

lost a brother in Vietnam. I met at least two men whose fathers had distinguished themselves in combat in Vietnam. It seemed that many of them had complicated personal issues they were trying to resolve, but then I was also trying to resolve mine. In a way, we were all artists trying to make sense of our own personal baggage.

Als : How did you develop the topic of the third series?

Lê: In 2002 and 2003 the U.S. was gearing up for the war in Iraq and Afghanistan just as I finished working with the reenactors. I was extremely distressed the day the war began in March 2003. Strangely enough, my heart did not go out immediately to the Iraqi civilians, but to our troops. I first thought of the scope and impact of war on them and their extended families. I am not categorically against war, but I feel the decision makers and policy makers have no idea how devastating the effects of war can be. Remembering my own experience, I also felt completely vulnerable. War just seemed unreasonable and unjustified in this case.

Trying to make sense of all this, I decided I had to find a way to go to Iraq. It was, unfortunately, too late to become embedded. I came across a photograph of the Marines training in the California desert in 29 Palms that looked just like parts of Afghanistan and Iraq. I immediately knew this place held great potential for a new project. Working there would follow with the idea of the reenactment and training for something. I was also drawn by the concept of simulations that are once removed but allow one to see and understand the real thing with clarity and perhaps more objectivity.

Once I began photographing at the Marine Air Ground Combat Center in 29 Palms, it became obvious that my pictures stand in complete opposition to combat photography. We are dealing with parallel subjects, but the outcome—the meaning—is completely different. In the case of combat photography, the die is cast. The photographer is thrown into a conflict where his work is about capturing the action or the aftermath. Chaos, he horrific violence of the moment, and the obvious risk incurred by the photographer in this situation all play into producing an image with a brutal if not blinding immediacy. Conversely, working with the military in training allows for breathing room. What jumps out for me is the way in which the magnitude of the firepower used—from artillery weapons to mortars, C-4 explosives, and air-delivered bombs—and its destructive potential, becomes muted and transformed as it is photographed in these exercises in the middle of a tranquil desert. One can then step back and ponder the larger issues of war. For me the question is not only are we militarily ready, but also are we politically, morally, and philosophically prepared? No, we are not. This project is an impassioned plea for a much-needed consideration of the consequences of war.

An-My Lê, Mechanized Assault, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Mechanized Assault, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms  An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Colonel Greenwood, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms Als : Have you looked at a great many war photographs? And do you agree with many photography critics when they say that photographs of war “depersonalize” pain? By working with “staged” coups and so on, does that distance Vietnam for you?

Lê: I am a great admirer of the nineteenth-century war photographers, but I also respect the more contemporary ones: Robert Capa, Larry Burrows, James Nachtwey, Gilles Peress, Tyler Hicks. I have studied the work of many North Vietnamese combat photographers. In a way I feel closer to them and the nineteenth-century European photographers because of the importance they give the landscape in their work.

I do think the current photos of war from Iraq and Afghanistan (except for the Abu Ghraib pictures, which were not made by professional photographers) are a lot more tame and feel more glossy than anything ever made in Vietnam, but it’s also true that our hearts are colder these days from having been bombarded with one agonizing and horrific picture after another. In the end I think it is the cumulative effect of the images over time that will have as much effect on us as the single image of the young Vietnamese girl burned by a napalm bomb.

What are the effects of war on the landscape, on people’s lives? How is war imprinted in our collective memory and in our culture?

The more contemporary photographs that capture the immediate moment certainly convey the devastation and pain, but they are usually so horrific one has to turn away in shock—they go more to your gut than to your head. In the end these photographs certainly remind us we are at war, but how thought provoking are they?

I am more interested in the precursor to war and its psychic aftermath. There is something about addressing the preparation for war or the memory of war itself that allows one to think about the larger issues of war and devastation. Again, how prepared are we? And what are the effects of war on the landscape, on people’s lives? How is war imprinted in our collective memory and in our culture? How does it become enmeshed with romance and myth over time (i.e., for Hollywood and for the reenactors)? My concern is to make photographs that are provocative in response to the reality of war while challenging its context.

Als : Of course, all photographs lie. I consider pictures to be metaphors for actual events and the people in them. For me, photographs capture something — an essence — of an event or a person, but selectively. Given the pictorial and emotional scope of your work, how do you set about capturing such a large portion of our collective political history?

Lê: Great landscape photography has a literal but also a metaphorical scope to it (Atget, Robert Adams, etc.). There is something about seeing people’s lives (or the suggestion of it) splayed across a landscape that can be breathtaking and unforgettable. There is no escaping the specificity of photography, but I aspire to achieve a certain lyrical objectivity. It is more about patterns of behavior than the specificity of it, which perhaps allows for a larger understanding of history and culture. August Sander and Judith Joy Ross manage to do this through portraiture. Here it is landscape photography that gives me that opportunity. It allows for descriptive possibilities. You can ascribe character to a landscape; you can suggest its usage. It is like a stage and, most importantly, I try to not let the people and their activities completely take over.

Related Items

Night Operations, 2003-4

Shop Now[image error]

Untitled, Thanh-Hoa, 1998

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 251

Shop Now[image error]Als : Why do you shoot in black and white? And what kind of camera do you use?

Lê: I always consider all possible tools at the beginning of a project (color or black-and-white film; small-, medium-, or large-format cameras). But so far, the 5-by-7-view camera has been my tool of choice, in spite of its inconveniences. It provides a great large negative full of details. It allows for a certain clarity and descriptive sharpness. Above all, in an image from 5-by-7 negatives or larger, one can sense the volumes of air moving between things and inside spaces. I tend to prefer black and white because I am very interested in the way things are “drawn.” This is much more apparent in black and white, where the palette is reduced simply to black, white, and various shades of gray. The world as seen in black and white also feels one step removed from its reality, so it seems fitting as a way to conjure up memory or to blur fact and fiction. Most of my memories of the Vietnam War, aside from what I witnessed firsthand, derive from black-and-white television news footage and black-and-white newspaper images.

The 5-by-7 view camera is very clunky because of its size, weight, numerous accessories, and the need for a tripod. You can’t work that spontaneously. All shots have to be somewhat premeditated and directed, especially those involving people, because of slow shutter speeds and delay between framing the image and closing the shutter/cocking the lens/exposing the film. A lot of this accounts for the pictures in all my projects seeming staged. There were situations where I had to photograph what was in front of me, but there were also times when I had an idea and went about constructing the scene from scratch (using the setting and prop of choice, choosing the people, and directing them). Working this way—either planning something from scratch or anticipating something before it happens—feels much more cerebral. We often say that photographers hide behind their cameras. In a way the view camera has provided me with multiple shields from the painful memory of war, while allowing me to come as close as possible to try to understand it.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Als : Some of your pictures look like film stills; have you looked at a lot of narrative and documentary films about Vietnam in preparation for your work?

Lê: If they resemble film stills, most are more in the vein of the establishing shots—those that situate everything. I have always looked at Vietnam War films. (Well, only starting in the mid-eighties—it was too soon and still somewhat too traumatic before then.) I was interested in seeing how something that I knew so well, something that affected me so deeply, was portrayed on screen. Watching these movies was also the only opportunity to get a glimpse of “Vietnam.” Even when another country or Chinese actors were used as stand-ins, any suggestion of the country, its life, and its people satisfied my curiosity (and tempered my homesickness and yearning). The Anderson Platoon, a documentary by Pierre Schoendorffer, and of course Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Casualties of War, Platoon—the first three are my favorites. More recently, I have seen these movies with a completely different interest in mind. I am interested in the Vietnam of the mind. It’s fascinating to me how all these other countries (Thailand and the Philippines mostly) are stand-ins for Vietnam and how the landscape has become a character.

I have been paying attention to how the cinematography is used to conjure up the past. The idea of the period piece is an interesting conceit. Many people find the activities of the Vietnam War reenactors very disturbing. Comparatively, Hollywood’s obsession with the Vietnam War and its numerous, painstaking “reenactments” on film seem completely reasonable. For me the fascination lies in the dialogue these two worlds establish between experience and chaos versus memory and storytelling.

These days, young Americans are first introduced to the subject of Vietnam, the Holocaust, or World War II by movies like Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, or Apocalypse Now, and only later (or maybe never) will they learn the hard historical facts in textbooks in a classroom situation. From the start, there is a blurring of fact and fiction that’s fascinating.

I draw my motivations for these projects from personal memories and from both a fascination and an aversion for anything that has to do with war and destruction, for the military, paramilitary fringe groups. Mix into that an interest in mediated images in popular culture—all of these influence the way my pictures look: they could be as much about my memory of GIs walking down Tu Do street in Saigon as an echo of the depiction of the Air Cavalry machos in Apocalypse Now. I consider my work an inquiry into the literal representation of things vs. depictions that live in popular imagination.

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Infantry Platoon, Alpha Company, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms  An-My Lê, Night Operations VII, 2003–4, from the series 29 Palms

An-My Lê, Night Operations VII, 2003–4, from the series 29 PalmsAll photographs courtesy the artist

Als : How did you feel at the end of these various projects? Did you feel as if you had “come home” in a sense? Has this work helped you deal with your origins?

Lê: It’s interesting that you ask about “coming home.” I’ve been obsessed with that idea because it applies to the type of fieldwork I do as a photographer as much as it is relevant to the experiences of the refugee and the soldier. Ambiguity and contradictions—the conflict between expectations and memories—these are all built into the experience of coming home for a refugee, for a soldier (whether from a real or virtual battle), or even for a photographer. Whether it is a childhood abruptly ended or a violently murderous week-long siege during the battle of Khe Sanh, some of us are confronted with these intense life experiences. They’re defining experiences that echo throughout one’s life. Whether coming home, returning to the country of origin for the refugee, going back to civilian life for the soldier, one is compelled to construct a story for oneself and hopefully come to terms with what happened. In attempting to construct a coherent narrative, one must negotiate a contentious and sometimes contradictory terrain, reconciling one’s own experience with other people’s ideas of it and against general expectations. It’s about understanding how one’s experience fits into the larger scheme of things and finding a personal equilibrium within that.

And as a photographer, there’s another layer—I have a different relationship to memories than the refugee or the soldier because through the work, there is potential for tangibility. I am the type of photographer who is interested in the way things look and in letting that be my major story-telling device. In that pointed moment it allows one to raise pertinent questions and to ponder the larger issues involved.

Crudely, my work is about reconciling what I thought I was getting myself into and what is actually revealed to me in the field. It’s not about taking a specific stand, or dignifying something that is important to me—nor is it about exalting a specific cause I’m committed to or exploring a subculture in depth. I’m satisfied in simply addressing these subjects: Vietnam, the military and the glamour of war, cultural and political history, and small subcultures. Photography becomes the perfect medium for conjuring up a sense of clarity (if not necessarily the truth) in the midst of chaotic and polarizing subjects.

This interview was originally published in An-My Lê: Small Wars (Aperture, 2005) and anthologized in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).

An-My Lê: Between Two Rivers/Giua hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, November 5, 2023–March 16, 2024.

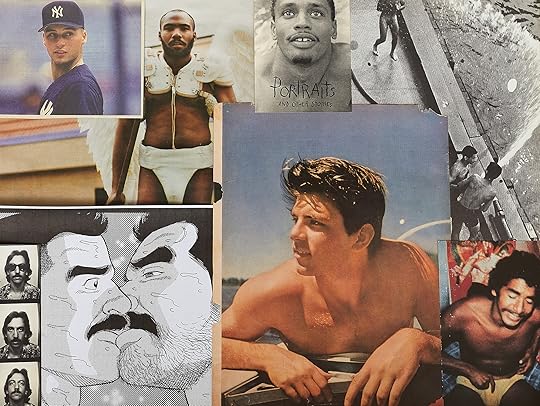

Remembering the Energy, Emotion, and Sensuality of Larry Fink’s Photography

Larry Fink, who passed away at the age of eighty-two on November 25, 2023, was a man of contradictions in the best possible way; he contained multitudes. He was as much an artist and a seer, as a teacher and mentor, a musician, a farmer, Martha Posner’s husband, among many other lives. His work is in the top museum collections, yet he regularly entered the annual juried show for Pennsylvania photographers at the Allentown Art Museum. He was game to be part of the mix. The contrasts suited him. He moved easily between the formal society galas and gatherings of Manhattan’s social elite and the farm life of the Sabatine family, his neighbors in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania. The body of work combining the two, Social Graces, was first published by Aperture in 1984 in an unassuming nine-by-ten-and-a-quarter-inch hardcover for $25. It was his first book, and in the short text—the sole accompaniment to sixty-nine pictures—he mused, “When I walk around in a tuxedo and tap my toes, I’m a fancy dude. When I walk around Martins Creek, I’m a rolling country belly.” Social Graces would go on to become an icon among photobooks and the work that most defined him.

Larry Fink, Oslin’s Graduation Party, Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, June 1977

Larry Fink, Oslin’s Graduation Party, Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, June 1977  Larry Fink, Pat Sabatine’s Eighth Birthday Party, Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, April 1977

Larry Fink, Pat Sabatine’s Eighth Birthday Party, Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, April 1977  Larry Fink, Studio 54, New York City, May 1977

Larry Fink, Studio 54, New York City, May 1977Looking at it again now, in the week after his passing, I’m struck by the gorgeousness of these pictures. All of the things that make a Larry Fink photograph are here: that framing with its push and pull at the edges and vigorous cropping, the flash illuminating and exaggerating the energy, emotion, and sensuality. There’s a real roundness to the printing (produced at the legendary Meriden Gravure) and the physicality that pervades every one of Fink’s pictures comes forward—every wrinkled hand grasping, pursed-lipped smile, rolling country belly. The book begins each sequence in the middle of the party—Peter Beard’s ICP opening and Pat Sabatine’s eighth birthday (both 1977)—and then moves around the edges of the merriment with searing precision. It’s easy to get drawn in. Each picture is captioned simply with the event and year, even the family photos of birthdays and graduations. You can’t escape the truth that the camera stopped time to mark this moment, or the sense of what’s to come when the party’s over or when John and Jeannie Sabatine, already getting on in years in the pictures, pass away. Larry’s daughter, Molly, also appears in the sequence with the Sabatines, as a baby and then a toddler—a visual reminder that time is passing in a personal way for the photographer as well. It’s not that he is thinking of the idea of memory or death, so often touted in relationship to photography. It’s that he’s seeing they’re alive and that photography’s ability to capture this life is miraculous.

Larry Fink, New York Magazine Party, New York City, October, 1977

Larry Fink, New York Magazine Party, New York City, October, 1977  Larry Fink, Harlem, New York City, July 1964

Larry Fink, Harlem, New York City, July 1964All photographs from Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation (Aperture, 2014). Courtesy the artist

Larry Fink, Women on 5th Avenue, New York City, 1961

Larry Fink, Women on 5th Avenue, New York City, 1961 We worked together on his book for Aperture’s workshop series (Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation, 2014), which is based on interviews and audio of his insights and teachings. Each visit, Larry would pick me and former colleague Robyn Taylor up from the bus station and drive us to the farm, crossing over the creek and up the winding driveway. And then he would promptly disappear. Where was Larry? He was out talking to a neighbor about a bulldozer or goofing off or in the sauna on the property. When we finally did get to work that first day, we had a magical conversation, talking about the impossibility of using the cold instrument of the camera to convey emotion. But, just as we were both starting to congratulate ourselves on such sparkling, high-minded prose, we realized we had forgotten to hit record. We spent the rest of our time trying to recreate that conversation. It was impossible, but led to other turns and tangents. How good pictures unfold as a question, how the edges of the frame can both enclose and leave open the picture, how to take a picture of water in a way that feels wet or cold, how you had to have a life outside the camera to make meaningful work.

In his singular and elliptical voice, “The goal, I suspect, through harmonies and edges and everything that we have in our command, is to take a dumb two-dimensional picture and make it something that a viewer enters and doesn’t want to leave.” The same could be said about a good book. When a book has been a pleasure to work on, I find myself reluctant to finish it. Even though it is the beginning of the book’s life in the world when it goes to the printer, the process of making it comes to a close. On the workshop book, we were beyond late, and Larry was nowhere to be found when I called the farm to push him again to get through the final layouts. I left a message saying I would give him a prize if he could return it within forty-eight hours—an impossible deadline, but it worked! I wasn’t ready to let the book go then, and I’m not ready to say goodbye now. But I know what Larry would say. We ended the workshop book with: “Photography is not all that there is. You gotta live.”

November 29, 2023

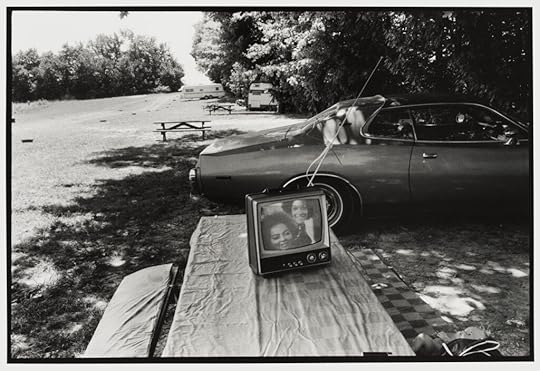

Alex Webb on Reimagining a Photobook, Twenty-Five Years Later

About twenty-five years ago, I was looking at a group of photographs that intrigued and somewhat puzzled me. None of these rather curious stray images had yet found their way into any of my books. It wasn’t just that the photographs didn’t fit the geographic parameters of the recent books I had published on Florida and the Amazon River, but also that they seemed almost placeless. As I selected and sequenced the images—seeing visual links, trying to understand the nature of the work—I began to realize that many of them struck a note of dislocation: inevitably geographically, as they were taken all over the world, but also sometimes emotionally, visually, psychologically, culturally. There was often something just a little odd, a little strange. As I shaped and expanded the sequence, it became clear that they belonged together as a single body of work.

In 1998, I was invited to publish a limited edition artist book of this work by Harvard’s Film Study Center. Dislocations was an experiment in alternative bookmaking—a notion that seems a bit quaint these days, what with the vast variety of photographic books now being produced. Dislocations was printed in an edition of forty with four artist proofs. It was an accordion book with Canon laser prints (then considered state of the art) of some fifty photographs tipped in on debossed pages, with titles that I handwrote. And, it came in a unique collapsible box.

Alex Webb: Dislocations 50.00 Newly reimagined edition of Alex Webb’s now-classic and long out-of-print Dislocations.

Alex Webb: Dislocations 50.00 Newly reimagined edition of Alex Webb’s now-classic and long out-of-print Dislocations. $50.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Alex Webb: DislocationsPhotographs by Alex Webb. Text by Alex Webb. Designed by David Chickey.

$ 50.00 –1+$50.00Add to cart

View cart Description Newly reimagined edition of Alex Webb’s now-classic and long out-of-print Dislocations.Dislocations presents a contemporary update of Alex Webb’s long out-of-print 1998 book by the same name, which was first published by Harvard’s Film Study Center as an experiment in alternative book making. The book brought together pictures from the many disparate locations over Webb’s oeuvre, meditating on the act of photography as a form of dislocation in itself. Dislocations was instantly collectable and continues to be sought after today.

Webb returned to the idea of dislocation during the pandemic, looking at images produced in the twenty years since the original publication—as well as looking back at that first edition. Dislocations expands a beloved limited edition with unpublished images that speak to today’s sense of displacement. As a series of pictures that would have been impossible to create in a world dominated by closed borders and disrupted travel, it continues to resonate as the world resets. Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 128

Number of images: 80

Publication date: 2023-11-28

Measurements: 11.8 x 10.2 inches

ISBN: 9781597115445

Alex Webb (born in San Francisco, 1952) has published more than fifteen books, including Aperture titles Brooklyn: The City Within (2019, with Rebecca Norris Webb), La Calle: Photographs from Mexico (2016), On Street Photography and the Poetic Image (2014, with Rebecca Norris Webb), and a survey of his color work, The Suffering of Light (2011). Webb has been a full member of Magnum Photos since 1979. His work has been shown widely, and he has received numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007.

Featured Content Featured Alex Webb's La Calle Gives Voice to Mexico's Streets

Featured Alex Webb's La Calle Gives Voice to Mexico's Streets Since creating the first version, I’ve continued to produce other dislocated images. Three years ago, during another kind of dislocation—in sequestration for the coronavirus in the spring of 2020 in Wellfleet, Massachusetts—I started putting together this new, expanded edition on the magnetic walls of my Cape Cod studio. I began selecting images from the more than twenty years since the original publication, as well as work from the first edition and a few earlier unpublished images. This new version of Dislocations—with some eighty photographs made on five continents—incorporates nearly half of the original photographs from the first edition, with the lion’s share comprised of later images.

Related Event Alex Webb and Denise Wolff Discuss “Dislocations”

Alex Webb and Denise Wolff Discuss “Dislocations”Looking back, perhaps I was drawn to reimagining and enlarging this series during the pandemic in part because it was impossible to create such images in a world dominated by closed borders and disrupted travel.

Alex Webb, Tokyo, 1985

Alex Webb, Tokyo, 1985  Alex Webb, Genoa, Italy, 2019

Alex Webb, Genoa, Italy, 2019  Alex Webb, Chongqing, China, 2017

Alex Webb, Chongqing, China, 2017  Alex Webb, Lunéville, France, 2000

Alex Webb, Lunéville, France, 2000  Alex Webb, Porto Cervo, Sardinia, 1998

Alex Webb, Porto Cervo, Sardinia, 1998  Alex Webb, Madrid, 1992

Alex Webb, Madrid, 1992  Alex Webb, Milan, 2016

Alex Webb, Milan, 2016  Alex Webb, Dallas, 1981

Alex Webb, Dallas, 1981  Alex Webb, Madrid, 1992

Alex Webb, Madrid, 1992  Alex Webb, Atlanta, 1996

Alex Webb, Atlanta, 1996All photographs courtesy the artist

This text originally appeared in Dislocations (Aperture, 2023).

November 22, 2023

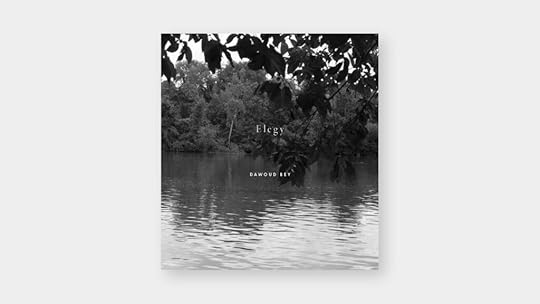

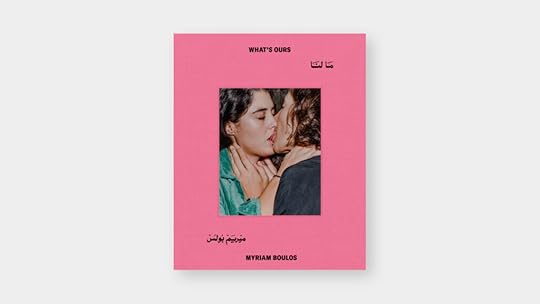

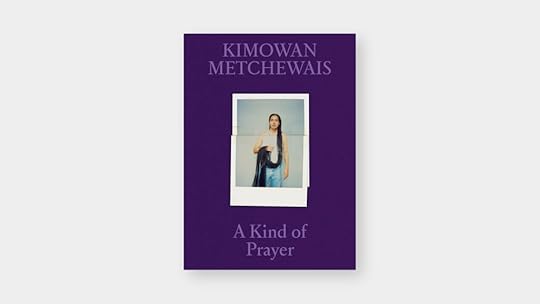

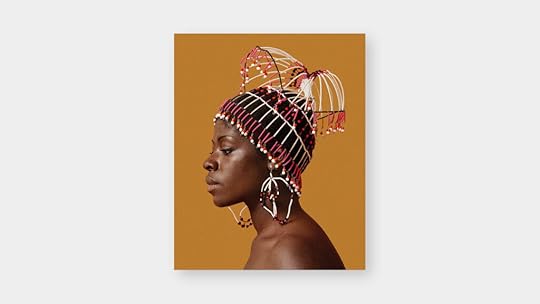

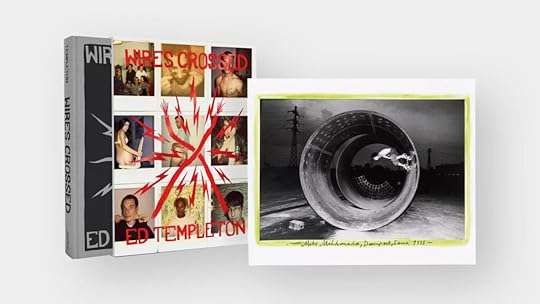

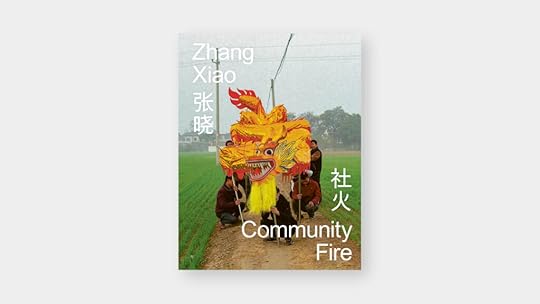

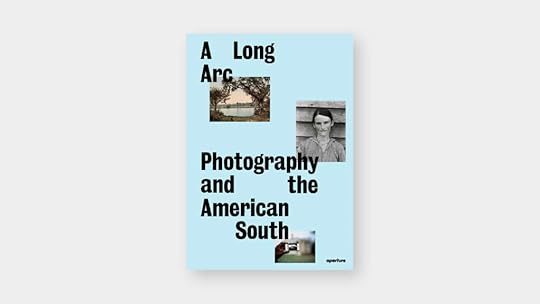

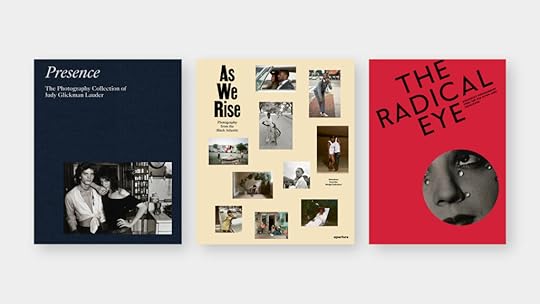

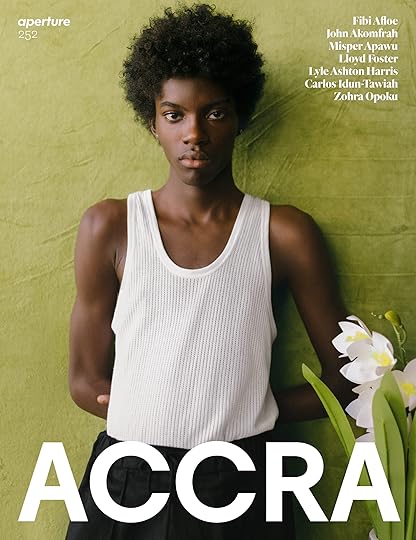

31 Photobooks for Everyone on Your Holiday Gift List

Looking for the perfect holiday gift? From a gift subscription to Aperture magazine, major debut monographs, newly released book bundles, engaging photography reads, and so much more—we’ve rounded up titles for everyone on your list.

Must-Haves for Photo Lovers

Aperture Magazine Subscription

The source for photography since 1952, Aperture features immersive portfolios, in-depth writing, and must-read interviews with today’s leading artists. Numerous luminaries have guest edited issues, including Wolfgang Tillmans, Tilda Swinton, Alec Soth, Sarah Lewis, Nicole R. Fleetwood, and Wendy Red Star, making the magazine essential reading for anyone interested in photography and contemporary culture.

Josef Koudelka: Next is an intimate portrait of the life and work of one of photography’s most renowned and celebrated artists. Drawn from extensive interviews conducted over nearly a decade with the artist and his friends, family, colleagues, and collaborations from around the globe, author Melissa Harris offers an unprecedented glimpse into the mind and world of this notoriously private photographer. Richly illustrated with hundreds of photographs, this visual biography includes personal and behind-the-scenes images from Koudelka’s life, alongside iconic images from his extensive body of work spanning the 1950s to the present.

Looking for more inspiring photography reads? Bundle and save with our Reader Book Bundle featuring Josef Koudelka: Next, Strange Hours by Rebecca Bengal, and We Were Here by Sunil Gupta.

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in art and fashion today, highlighting the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation.