Aperture's Blog, page 19

April 25, 2024

A Biennial in Houston Explores the Politics of Visibility

In the waning decades of Soviet rule in Czechoslovakia, Prague’s T-Club was an open secret. The clandestine gay nightclub had claimed its own gravitational force, tucked into a basement behind Wenceslas Square, where much of the drama of the 1968 Prague Spring and the subsequent “normalization” period were playing out. It was an anxious time, and the country was quickly sliding back into autocratic rule; there were widespread crackdowns on pro-democracy reformists and state eyes were everywhere. For patrons who were marginalized by the sitting regime for their sexuality and politics, T-Club was a space of possibility and freedom—however precarious—but also one where the presence of plainclothes police was routine.

The photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková came of age in this Prague. She was still a teenager when Soviet tanks rolled into the city in the late 1960s, and over the years, she charted a private geography that ultimately led her to T-Club in the early ’80s. It was here that Jarcovjáková learned to see with the intimacy and intensity that define her vibrant, monochrome images. People draped over chairs, tables, and one another in a drunken stupor; glimmers of leather, sequin, and metal, all shining against Jarcovjáková’s totalizing flash, which was both a practical necessity and form of permission. She wanted to get as close as possible—and perhaps to even try and bridge that impossible gap the camera creates. “I am trying to document the world . . . without describing it,” she writes in a diary entry. At a time when the camera invited suspicion, Jarcovjáková’s photographs freeze the club in opposition to the political reality aboveground. Her subjects stare directly into her lens, insisting on their presence.

Libuše Jarcovjáková, from the series T-Club (1983–85), 2024

Libuše Jarcovjáková, from the series T-Club (1983–85), 2024Courtesy FotoFest

Photographs from T-Club—now the subject of a photobook and documentary—fill a quiet hallway at downtown Houston’s Sawyer Yards, the sprawling rail-yard-turned-arts-complex that has been the longtime home of the FotoFest Biennial, now in its twentieth edition. Jarcovjáková is one of many entry points into the biennial’s larger theme, Critical Geography, which explores photography’s role in constructing and critiquing our conception of place. These ideas aren’t new to the medium, but in the context of FotoFest’s wide and notably international program—featuring more than twenty artists and collectives across a central exhibition curated by executive director Steven Evans—they spark intriguing connections and contrasts.

Siu Wai Hang, 2019.6.16-II, from the series Clean Hong Kong Action, 2019–21

Siu Wai Hang, 2019.6.16-II, from the series Clean Hong Kong Action, 2019–21Courtesy FotoFest

If Jarcovjáková’s work recovers a sense of spontaneity and visibility against the regimenting of public life, Siu Wai Hang’s series Clean Hong Kong Action (2019) suggests that absence can be a viable strategy for survival too. In his images of Hong Kong’s anti-extradition demonstrations, Siu obscures protestors’ faces by punching holes into his prints. The careful, repetitive omissions, and ironic series title, reframe anonymity as an active position rather than a retreat from authority, with the camera as accomplice. Houston-based artist Phillip Pyle II similarly uses strategic erasure in his series Forgotten Struggle (2011–ongoing), for which he removes all text from the picket signs of civil-rights protest photographs, provoking a reflection on the gradual dilution and removal of Black revolutionary thought and history from Texas school curricula.

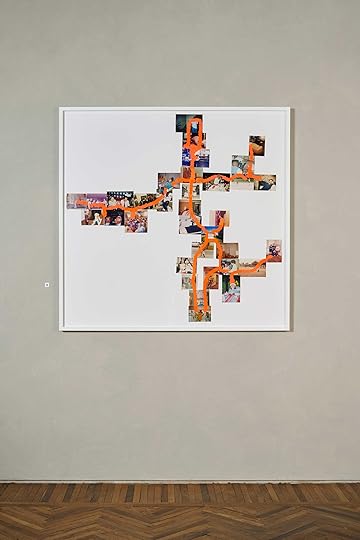

Stephanie Syjuco, Block Out the Sun (Shield), 2022

Stephanie Syjuco, Block Out the Sun (Shield), 2022Courtesy FotoFest

The politics of visibility, a motif across the biennial, gains further meaning in the work of Stephanie Syjuco. Her series Block Out the Sun (2022) asks how one might talk back to an archive, drawing on images from the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, for which the United States government forcibly brought over a thousand people from the Philippines, then a new colony, to populate staged ethnographic scenes for American audiences. To Syjuco—who thinks deeply about how institutions and archives legitimize imperial histories—the very act of seeing these faux arrangements reinforces racist hierarchies and colonial narratives. She uses her hands to partially block the archival images and rephotographs them, evidencing the medium’s violence while denying it historical power.

Binh Danh’s daguerreotypes from All I Asking for Is My Body (2024), which sit in vitrines at the far end of an adjacent corridor, engage a related history of imperialism and enslavement. Danh, who often uses early photographic processes, impresses archival images of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Portuguese, and African laborers who worked across America’s plantations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries onto silver tableware (“a symbol of sustained American colonial power and status,” as the exhibition text reads). His intervention—like Syjuco’s—wrests these images from their presumed archival facticity and questions the kinds of knowledge produced from their preservation.

Binh Danh, All I Asking for is My Body, 2024. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan Hawk

Binh Danh, All I Asking for is My Body, 2024. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan HawkCourtesy FotoFest

C. Rose Smith, Scenes of Self: Redressing Patriarchy, 2022–ongoing. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan Hawk

C. Rose Smith, Scenes of Self: Redressing Patriarchy, 2022–ongoing. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan HawkCourtesy FotoFest

C. Rose Smith’s series Scenes of Self: Redressing Patriarchy (2022–ongoing) likewise responds to the visual legacy of transatlantic enslavement through a subtle but sharp juxtaposition. Dressed in a white cotton shirt and code-switching between distinct gendered postures, Smith photographs themself at former American plantation sites, drawing an association between identity, fashion, place, and the performance of whiteness in the antebellum South. Presented as dye-sublimation prints on translucent white polyester, Smith’s images hang like ghostly curtains down a wide hallway, culminating in a video-performance piece. The series, a highlight of the biennial, will also be on display at Autograph ABP, London, this summer.

Linarejos Moreno, On the Geography of Green I-I, 2016–21

Linarejos Moreno, On the Geography of Green I-I, 2016–21Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery

In addition to its core programming, every edition of FotoFest involves several partner institutions, which mine their collections to create a dialogue with the biennial theme, spilling across Houston and its suburbs. Madrid-based artist Linarejos Moreno’s subseries On the Geography of Green, installed at Inman Gallery, is a standout. Moreno’s large-format images mimic the organizational logic of German geographer Alexander von Humboldt, who traveled and mapped American landscapes in the nineteenth century. Her photographs feature abandoned drive-in theaters in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, and include a central image bracketed by an index of data, from the scientific to the subjective: numbers on geography, weather, vegetation, and, in one instance, ratings of films out during the years the theaters were active, in order of popularity. The overabundance of information reinforces Moreno’s broader point about how data’s supposed objectivity—like photography’s—both catalogs and produces specific social realities and hierarchies.

Lou Peralta, Disassemble #41, 2019

Lou Peralta, Disassemble #41, 2019Courtesy the artist and Koslov Larsen Gallery

Nearby, at Koslov Larsen gallery, Mexican photographer Lou Peralta experiments with the limits of portraiture and sculpture for her series Disassemble (2022), introducing both contemporary local and pre-Hispanic materials and foliage into her photographic compositions. Along a similar vein, at Anya Tish Gallery, Dallas-based Vietnamese artist Han Cao hand-embroiders colorful botanical motifs onto found photographs, using her interventions to play with new ways of engaging and connecting with old images. “I am always trying to change the story of the photo,” Cao says.

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vlad Krasnoshckok, from the series Documentation of War, 2022–ongoing

Sergiy Lebedynskyy and Vlad Krasnoshckok, from the series Documentation of War, 2022–ongoingCourtesy FotoFest

Walking the corridors of the central exhibition, one feels the weight of history—and a palpable energy among artists to reconsider its terms. Two notable works, however, bring us directly into the present day, where the relationship between the camera and the politics of place is tense and unresolved. The war-stained photographs of the series Documentation of War (2022–ongoing), by Ukrainian collective the Shilo group, chronicle the destruction of several cities, including Kharkiv, home to the group’s founding members, Sergei Lebedinsky and Vlad Krasnoshchok. Made from expired Soviet-era papers and homemade developer chemicals, the images are charged with the imprints of wartime. They constitute what artist and researcher Susan Schuppli would call a “material witness” to the conflict. The hazy, impressionistic dispatches have the effect of wet-plate prints, subverting our expectations of modern conflict imagery and the photojournalist as a detached observer. They’re reminiscent of the relationship between process and place in Blackwater, Sally Mann’s haunting, Prix Pictet–winning series from southeastern Virginia.

Shona Illingworth, Topologies of Air, 2021. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan Hawk

Shona Illingworth, Topologies of Air, 2021. Installation view at FotoFest, Houston, 2024. Photograph by Ryan HawkCourtesy FotoFest

“Images do not have an innate truth,” argues Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, writing about the Israeli government’s weaponization of images to further its occupation of Gaza. “They live in community with or against those who are involved in them.” The idea resonates throughout Critical Geography—from Jarcovjáková’s covert paradise to Siu’s public protests; from Syjuco’s belated interventions to Smith’s reclamation. Danish Scottish artist and filmmaker Shona Illingworth’s video Topologies of Air (2021) engages with this idea directly. Using precisely arranged footage, photography, and interviews across a three-channel installation, Illingworth explores our evolving relationship to the sky and how airspace has been increasingly exploited and territorialized by global corporations and governing structures. The video draws from the Airspace Tribunal, a public forum founded by Illingworth and human rights lawyer Nick Grief to advocate for a “new human right to live without physical or psychological threat from above.”

Against the larger context of increased aerial surveillance and warfare, as well as the biennial’s broader interest in placemaking as socially, politically, historically, and environmentally bound, Illingworth’s work suggests one strategy for re-narrating our historical assumptions. The broader argument proposed by Critical Geography rests on the power of such strategies, and their ability to create room for disruptions, reorientations, close readings, and—crucially—dialogue.

The 2024 FotoFest Biennial, Critical Geography, was on view at the Silver Street Studios and Winter Street Studios in Houston March 9–April 21, 2024.

April 22, 2024

8 Photobooks that Consider How Artists Engage with the Environment

Robert Adams, New Housing, Reche Canyon, San Bernardino County, California, 1983

Robert Adams, New Housing, Reche Canyon, San Bernardino County, California, 1983American Silence: The Photographs of Robert Adams (2021)

For fifty years, Robert Adams has made compelling, provocative, and highly influential photographs that show us the wonder and fragility of the American landscape, its inherent beauty, and the inadequacy of our response to it. Photographing what Adams calls “the silence of light” of the American West, his images capture the sense of peace and harmony that nature can instill in us while questioning the desecration of that beauty by consumerism, industrialization, and lack of environmental stewardship.

American Silence features over 175 works from Adams’s career photographing throughout Colorado, California, and Oregon—capturing suburban sprawl, strip malls, highways, homes, and the land. By examining the artist’s act of looking at the world around him, this volume showcases the almost palpable silence of his photographs.

Lieko Shiga, from the series Human Spring, 2018–19

Lieko Shiga, from the series Human Spring, 2018–19Courtesy the artist

Aperture, issue 234, “Earth,” Spring 2019

In the age of climate change, how are photographers and artists envisioning dramatically politicized landscapes? Aperture’s “Earth” issue focuses on our relationship with the natural world as the vulnerability of our environment is underscored each day.

Throughout the “Earth” issue, photographers, artists, and writers including Carolyn Drake, Eva Díaz, William Finnegan, Gideon Mendel, and Lieko Shiga grapple with the reality of our climate crisis and the age of the “Anthropocene,” in which human actions determine the factors shaping Earth’s geology and ecosystems.

Sam Contis, Untitled (from the series Overpass), 2020-2022

Sam Contis, Untitled (from the series Overpass), 2020-2022Courtesy the artist

In Overpass, Sam Contis explores what it means to move through the landscape. Walking along a vast network of centuries-old footpaths through the English countryside, Contis focuses on stiles, the simple structures that offer a means of passage over walls and fences and allow public access through privately owned land. In immersive sequences of black-and-white photographs, they become repeating sculptural forms in the landscape, invitations to free movement on one hand and a reminder of the history of enclosure on the other.

In an age of rising nationalism and a renewed insistence on borders, Overpass invites us to reflect on how we cross boundaries, who owns space, and the ways we have shaped the natural environment and how we might shape it in the future.

Naoya Hatakeyama, #02607, Loos-en-Gohelle, Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, France, 2009, from the series Terrils

Naoya Hatakeyama, #02607, Loos-en-Gohelle, Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, France, 2009, from the series TerrilsCourtesy the artist

Naoya Hatakeyama: Excavating the Future City (2018)

For over thirty years, Naoya Hatakeyama has undertaken a photographic examination of the life of cities and the environment. Throughout his work, Hatakeyama focuses on different facets of growth and transformations of the urban landscape, from his photographs on the quarrying of limestone via explosive blasts to images of Hatakeyama’s hometown of Rikuzentakata, which was almost completely destroyed by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Excavating the Future City considers forms of human intervention with the landscape and natural resources and intersections between geology, architecture, and time—offering an evocative rumination of the death and rebirth of the city.

Justine Kurland, Like a Black Snake, 2008

Justine Kurland, Like a Black Snake, 2008Courtesy the artist

Justine Kurland: Highway Kind (2021 Edition)

Following the photographic lineage of Robert Frank, Stephen Shore, and Joel Sternfeld, Justine Kurland’s Highway Kind contrasts the fantasy of the American dream with the nation’s reality. In the early 2000s, Kurland and her young son, Casper, traveled in their customized van through the United States. Balancing her life as an artist and mother, Kurland’s photographs reveal her fascinations in concepts of the road, the western frontier, escapism, and ways of living outside mainstream values. Casper’s interests—particularly in trains, and later cars—and the people he befriends along the way weave throughout Kurland’s images. From images of open vistas and epic landscapes, to the communities and subcultures they depict, Kurland’s work is equal parts raw and romantic, idyllic and dystopian.

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2005

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake, Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, 2005Courtesy the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution

Kimowan Metchewais: A Kind of Prayer (2023)

Kimowan Metchewais’s exquisitely layered works explore Indigenous identity, community, and colonial memory. After his untimely death at the age of forty-seven, in 2011, Metchewais left behind an expansive body of photographic and mixed-media work—including an extensive Polaroid archive that addresses a range of themes, including self-portraiture, the body, language, and landscapes.

In 2020, Aperture featured Metchewais’s work in the “Native America” issue, guest edited by Wendy Red Star, before going on to publish A Kind of Prayer (2023), the first-ever survey dedicated to the late Cree artist, showcasing Metchewais’s singular artistic vision. “His work explores the ground, aesthetic and territorial, on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand,” writes Christopher Green in an essay on the artist from Aperture’s Fall 2020 issue, “and his images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotype.”

Richard Misrach, Hazardous Waste Containment Site, Dow Chemical Corporation, Mississippi River, Plaquemine, Louisiana, 1998

Richard Misrach, Hazardous Waste Containment Site, Dow Chemical Corporation, Mississippi River, Plaquemine, Louisiana, 1998Courtesy the artist and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, and Marc Selwyn Gallery, Los Angeles

Richard Misrach: Petrochemical America (2014)

Throughout his career, Richard Misrach has created expansive bodies of work that focus on the relationship between humans and their environment. In Petrochemical America, Misrach’s haunting photographic record of Louisiana’s Chemical Corridor investigates decades of environmental abuse along the largest river system in North America.

Featured alongside Misrach’s photographs is landscape architect Kate Orff’s Ecological Atlas, a series of “speculative drawings” developed through research and mapping of data by the region. Together, these bodies of work unpack the complex cultural, physical, and economic ecologies along the 150 miles of the Mississippi River, from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, an area of intense chemical production that first garnered public attention as “Cancer Alley” when unusual occurrences of cancer were discovered in the region. The resulting volume offers an in-depth exploration of the ways in which the petrochemical industry has permeated every facet of contemporary life.

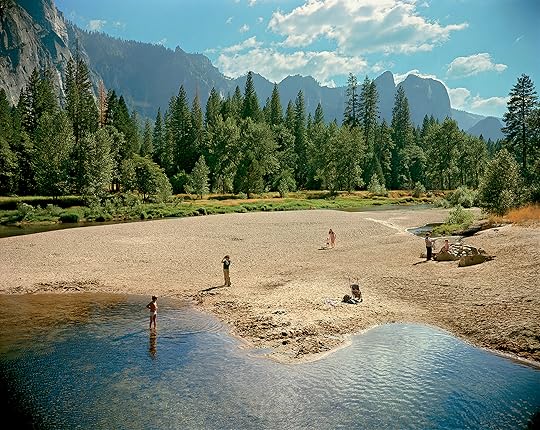

Stephen Shore, Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California, August 13, 1979

Stephen Shore, Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California, August 13, 1979Courtesy the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

Picturing America’s National Parks (2018)

Photography has played an integral role in both the formation of United States National Parks and in the depiction of the country itself. Picturing America’s National Parks traces the symbiotic relationship that the parks and photography have developed over 150 years.

From Ansel Adams’s iconic photographs of Yosemite Valley in the 1930s and ’40s, to David Benjamin Sherry’s hyper-saturated queering of the American West, the volume examines how photography has shaped the parks throughout their history and helped ensure their survival.

See here to browse the full collection of featured titles

April 19, 2024

Picturing Britain’s Working Class after the “End of History”

To get to Herbert Art Gallery from Coventry station, you must follow a series of pedestrian tunnels under an overpass toward the old city center, which was razed by the German Luftwaffe. What bombs didn’t flatten, postwar developers buried, sinking much of Coventry—like so many other towns in the Midlands—in a tangle of highways and footpaths incongruous with pedestrian habit. This was back in the 1950s, when the UK actually had a social welfare policy; even then, master-planning politicians and architects preferred to regard working-class life from an aerial view.

Rob Clayton, Lin, Careers Advisor and Mother, Wilson House, 1990–91

Rob Clayton, Lin, Careers Advisor and Mother, Wilson House, 1990–91 Half a century later, that postwar infrastructure has fallen into disrepair, supplemented only by a mean, bootstrapping ideology which leaves the poor to fend for themselves. Income inequality is its highest in modern British history, and the country faces a dire cost of living crisis. It’s the topic on everybody’s lips, yet when working-class solidarity is mentioned, the mind’s eye turns to black and white: marches against Margaret Thatcher, miners and Bobbies facing off in coal-dusted trenches. It’s in this context that After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024 seeks a corrective. Thirty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall—a moment that might be considered “peak Thatcherism”—the exhibition asks how a younger generation of blue-collar British photographers have responded to the rising tide of neoliberalism, shifting their lens from the sociological skies to the streets.

Eddie Otchere, Junglist, Ah London Sumting, Samantha’s NightClub, Soho, 1995

Eddie Otchere, Junglist, Ah London Sumting, Samantha’s NightClub, Soho, 1995Bookending the show are photographs of the 1990s and early 2000s London jungle scene by Eddie Otchere and Ewen Spencer, respectively. Just to the right of the entrance, Otchere’s C-prints, taken with a slow shutter speed, catch young Black men on nightclub dancefloors in a fiery orange blur. Spencer’s photographs of sweat-slicked dancers and snogging couples, frozen in suspended animation, are printed on blueback paper and pasted as a panorama along the gallery’s back wall, where two lovers’ bodies, collapsing into each other against the sharp glare of Spencer’s flash, reminded me distinctly of Nan Goldin’s The Hug (1980).

Ewen Spencer, Necking, Twice as Nice, Ayia Napa, 2001

Ewen Spencer, Necking, Twice as Nice, Ayia Napa, 2001Those late days of film, before digital became dominant, seemed to produce an efflorescence of photographic production in the UK, much of it for cultish magazines like i-D and The Face, where Elaine Constantine was a regular. Her pictures from the 100 Club, a long-running London spot for Northern Soul music, are infectiously energetic but almost too sartorial; the clubbers on a parquet floor might as well be wearing Grace Wales Bonner. Other highlights get out of the boroughs and into the ’burbs, like Tom Wood’s views from inside Merseyside buses or Rob Clayton’s Estate series from the West Midlands, both shot in the early ’90s. Clayton’s richly saturated photograph of an elderly dogwalker outside the checkered tile exterior of The Phoenix Pub, M&B or a bottle of milk and sugar bowl next to an Early “Bush” Transistor Radio (both 1990–91) recall the work of William Eggleston. Curator Johny Pitts claims that these images raise “questions about the still high demand for public housing and public health crisis, and [shed] light on the neglected environment after construction,” though like Eggleston’s American still lifes and landscapes, they mostly find notes of sublimity in the mundane. The exhibition’s urgent political prerogatives notwithstanding, such analysis views these images through an unwarranted, condescending filter.

Serena Brown, Bollo Bridge, 2018

Serena Brown, Bollo Bridge, 2018 More recent contributions to the show mostly follow the same old formats to lesser effect. Serena Brown’s portraits of young women in London, dressed by the artist in knockoff designer tracksuits, fall victim to their own stiff over-staging. In Igoris Taran’s council estate landscapes, annotated with handwritten notes like “community is important,” flat images and flatter text do little to amplify a sense of depth. Then there are Rene Matic’s lusciously shot photographs of bus upholstery and shuttered discount store exteriors, in which working-class people feel eerily, conspicuously absent.

Sam Blackwood, Rat Palace, 2013–ongoing

Sam Blackwood, Rat Palace, 2013–ongoing

After the End of History takes its title from American political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 declaration of the triumph of the neoliberal order. With the benefit of hindsight—and thirty-five years of corporate oppression—we can say that history has not so much ended as been made to endlessly repeat its past mistakes. Call it self-immolation by design; an elite few profit while the world burns. In this sense, the exhibition contributes inadvertently to the impression that there’s been nothing new since New Labour came to power in 1997—and a malaise, now prevalent in British society, that the country has been foundering in what the late theorist Mark Fisher called an economic and cultural “cul-de-sac.” Missing are images of working-class resistance—the 2010 protests against austerity or the 2011 London riots—and practices that adopt the most popular image production and circulation technologies of our age, from phone cameras to TikTok. Such images, which surely exist in abundance, would serve as a better weathervane than photography employing means virtually unchanged since the days of social reformer Adolphe Smith (1846–1924).

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, May 2022

Hannah Starkey, Untitled, May 2022All photographs courtesy the artists

Of course, the exhibition has some notable exceptions. Sam Blackwood’s Rat Palace series of grainy risograph prints (2013–ongoing), in which detritus feels like readymade art installations (accidental or intentional, it’s difficult to tell), bring the show a welcome dose of deadpan humor: I found his orange traffic cone thrown through a plate glass window and two melted ice pops flaccid on a chain-link fence inexplicably funny. Most extraordinary of all is Hannah Starkey’s untitled photograph from a Belfast street corner in 2022. A girl with cherry-red hair and a bubblegum Harajuku costume—pink pleats, fur trim, and chunky heels—faces down the gales of a coming storm, her candy-bright look a shocking effrontery to the dark gray sky. Her Louis Vuitton monogrammed handbag feels perverse alongside a Royalist mural of red roses from the pro-Union South Ulster Brigade. Taken shortly after Brexit tossed out the Good Friday Agreement and drew a new border in the Irish Sea, the photograph invokes the recursiveness of history as a grim joke. It’s precisely this kind of view, in which local struggles meet the pressures of global capitalism like the twin fronts of a hurricane, that really takes today’s working-class temperature—and indicates which way the wind may be blowing.

After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989–2024 is on view at the Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry, England, through June 16, 2024.

April 16, 2024

Announcing the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Aperture’s support of emerging photographers and other lens-based artists is a vital part of our mission. The annual Aperture Portfolio Prize aims to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography—identifying contemporary trends in the field and highlighting artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Aperture’s editors reviewed an outstanding number of submissions, and we are thrilled to announce the shortlisted artists for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize:

River Claure

Janna Ireland

Abhishek Khedekar

Avion Pearce

Laila Stevens

These artists join the ranks of illustrious winners and runners-up artists for the Portfolio Prize in past years, including Felipe Romero Beltrán, Dannielle Bowman, Alejandro Cartagena, Jessica Chou, Eli Durst, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Natalie Krick, Daniel Jack Lyons, Mark McKnight, Vân-Nhi Nguyễn, Drew Nikonowicz, Sarah Palmer, RaMell Ross, Bryan Schutmaat, Donavon Smallwood, Ka-Man Tse, and Guanyu Xu.

The 2024 Portfolio Prize winner, to be announced on Tuesday, May 14, will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize and a $1,000 gift card for gear at mpb.com, and present an exhibition at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York. The four runners-up will each receive an online feature.

Alongside the shortlisted artists, Aperture’s editors also selected a longlist of twenty outstanding artists to recognize:

Shavon Aja Morris, Andrés Barón, Robin Bernstein, Jo Ann Chaus, Jesse Clark, Leah DeVun, Jenna Garrett, S*an D. Henry-Smith, Khashayar Javanmardi, Alexander Komenda, Gabriel Lopez, Max Miechowski, Nathalie Mohadjer, Kriss Munsya, Adali Schell, Aaryan Sinha, Val Souza, Gilleam Trapenberg, Balázs Turós, Stan De Zoysa

All twenty-five artists will each receive a virtual portfolio review session with an Aperture editor, who will provide thoughtful and constructive feedback on their work.

River Claure, Don Raymundo, 2023, from the series MITA

River Claure, Don Raymundo, 2023, from the series MITA Janna Ireland, Untitled, 2023, from the series Pauline

Janna Ireland, Untitled, 2023, from the series Pauline Abhishek Khedekar, Church, 2018, from the series DAPOLI, Lost and Found

Abhishek Khedekar, Church, 2018, from the series DAPOLI, Lost and Found Avion Pearce, Container, 2022, from the series In the Hours Between Dawn

Avion Pearce, Container, 2022, from the series In the Hours Between Dawn Laila Stevens, Lineage, 2022, from the series The Clayton Sisterhood Project

Laila Stevens, Lineage, 2022, from the series The Clayton Sisterhood Project

April 11, 2024

The Musicians Who Energized a Revolution in Nepal

When the People’s War began in Nepal, in 1996, eight-year-old Prasiit Sthapit noticed that his great-grandfather’s portrait had suddenly disappeared from the living-room wall. Later, as an adult, he realized that the picture of the mustachioed man he had assumed to be his great-grandfather was, in fact, a framed poster of Joseph Stalin. Sthapit’s grandfather, an ardent Communist, looked up to Stalin. In the decade-long, violent armed conflict between the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN-Maoist) and the state, anyone left-leaning was seen as a Maoist sympathizer, and many were arrested or, worse, disappeared. During Sthapit’s teen years, his family’s political leanings, as well as his own youthful romanticization of what a revolution symbolizes, made him curious about the bloody rebellion that shook Nepal.

His interest in this history deepened in 2006 when, at age eighteen, he took a spontaneous trip with friends, a month after the war had ended, through the western Nepali districts of Rukum and Rolpa—the heartland of the revolution. These areas had been a war zone just weeks before. “We saw bullet holes on bridges and houses. I met many Maoists; some were curious and kind, others not so much. I realized how sheltered we were in Kathmandu, and how the war was not over in the minds and lives of many people,” Sthapit told me over coffee one morning last fall in Kathmandu. Many in the capital initially experienced the war as something that would never reach them—just some hooligans making noise with pressure-cooker bombs that would surely die down in no time.

Prasiit Sthapit, Pradeep Dewan playing the harmonium in his home, Kathmandu, 2022

Prasiit Sthapit, Pradeep Dewan playing the harmonium in his home, Kathmandu, 2022

But the war lasted ten years, and in that time, many brothers, sisters, friends, and relatives, fighting on opposing sides—with the Maoist-led People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or the Nepal Police—brutally killed one another. When the war ended, at least thirteen thousand Nepali men, women, and children had been killed, thirteen hundred disappeared, and thousands were left displaced and disabled. Although the war started in February 1996, the seeds of the revolt had been sown back in the 1960s. At the time, Nepal was brought under Panchayat rule, wherein the country’s leader, King Mahendra, instated an autocratic regime that saw the dissolution of parliamentary democracy, a ban on political parties, the imprisonment and exile of elected leaders, and the curtailment of freedom of expression and many civil rights. The Panchayat era was notorious also for instituting the erasure of the country’s diverse peoples, cultures, and languages under the slogan “one king, one nation, one language, one costume.” It was under this system that many Maoist leaders, then in their twenties, became radicalized.

Inspired by Peru’s far-left group Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), the Maoists waged guerrilla warfare, attacking police stations, acquiring weapons, using different aliases while living and working underground among the people, and recruiting new members through song, speeches, and stories. They gained momentum and support in the rural areas of western and midwestern Nepal. As the war progressed, news of casualties increased. Reports of bomb blasts became frequent. In 2001, the government declared a state of emergency. Even urban areas such as Kathmandu saw army patrols and barbed-wire checkpoints. Freedom of expression, movement, and assembly were curtailed; state crackdowns and raids in search of Maoists increased, as did countrywide shutdowns and curfews. The government declared the Maoists “terrorists,” violent revolutionaries whose image— in camouflage, a red bandana with a star tied across the forehead, guns in hand—became feared.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

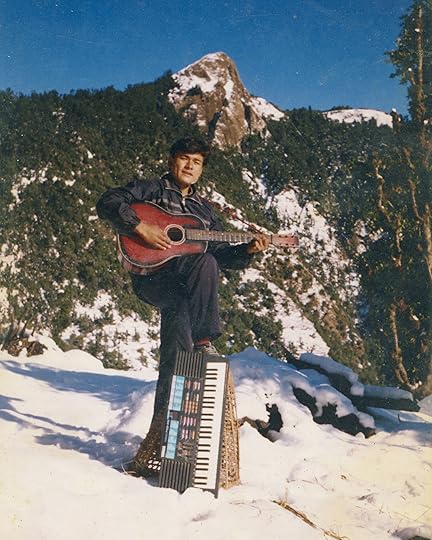

It is this one-dimensional view that Sthapit complicates in his project Moonsongs for Earth (2022–ongoing), a studied look at the musicians who energized the Maoist movement through song. “There was the PLA, who carried guns and bombs, and then there were musicians, who carried guitars and harmoniums,” Sthapit said as he scrolled through images from the series, which includes a mix of his own contemporary portraits, archival imagery, videos, interviews, and songs. Many of the archival photographs feature musicians posing in nature with their instruments, showing the world what they love and how they want to be seen. Group photographs depict them practicing and performing. “We had seen plenty of war images in the media, but I wanted to see the war through the eyes of the musicians,” Sthapit explained. “These intimate musical sessions too were a part of the war. These musicians held and spread the dream of the revolution through their songs.”

Prasiit Sthapit, The stage for a concert by musicians, many affiliated with the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN-Maoist), World Music Day, 2022

Prasiit Sthapit, The stage for a concert by musicians, many affiliated with the Communist Party of Nepal (CPN-Maoist), World Music Day, 2022  Prasiit Sthapit, Magar’s sarangi, Chunbang, Rukum, 2020

Prasiit Sthapit, Magar’s sarangi, Chunbang, Rukum, 2020 In 2019, Sthapit traveled to what is marketed as the Guerrilla Trail, a path the PLA used during the war that cuts across the spine of the country and branches out like a tree. He initially had begun working on a multimedia project to uncover stories of the war along the trail, until he met the former Maoist Jhankar Budha Magar, who sang for Sthapit a popular war song: “You must fight and win this final battle. Torn hearts and drenched bodies are waiting for a new day.” The song is part of an opera, Returning from the Battlefield, by the late Khusiram Pakhrin, a musician and cultural leader of the revolution. The opera was commissioned for the 2005 central committee meeting of the Maoist party in the village of Chunbang. This meeting would prove historic, as it opened a path for two feuding Maoist leaders—Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Baburam Bhattarai—to reconcile their differences. A video from the gathering captures the two visibly sobbing as they watch the opera, which presents the story of a soldier’s death, his willingness to sacrifice himself for the larger cause, and his wife’s plea to continue fighting to fulfill the dream of the revolution. The Chunbang meeting would be followed by the formation of an antimonarchy alliance with mainstream political parties and a 2006 peace accord marking the end of the war. In 2006, the second People’s Movement began, and by 2008, the country’s 240-year-old monarchy was brought to an end. The new, secular Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal was born, with the Maoist party elected to office. Dahal became the republic’s first prime minister. Since then, the Maoists have come into power four times, and Dahal is currently the country’s prime minister.

The music was medicine, a balm, and also a reminder for fighters who were alive to continue the mission of building a just world.

Would the outcome in Chunbang have been different had there been no musicians, no opera, no tears? “Our duty was to sing encouraging farewell songs to our friends going into battle,” the musician Laxmi Gurung told Sthapit during an interview from her home in Kathmandu. In 1999, the twenty-two-year-old Gurung joined the Maoist party after the state killed her father. “Everyone used to think of me as the daughter of a Maoist who would amount to nothing. I didn’t join the party only for revenge, but I wanted to show that I could change the world and make it beautiful,” she said. Later, Gurung lost her daughter during the conflict. And it has been more than twenty-four years since her husband went missing. Today, Gurung, now forty-six, doesn’t want violence: “If there has to be another war again, I hope it will be a war led by love, and a war where we fight with our ideas to change society, not guns and bombs.” During their conversation, she broke into a popular war song: “In the battlefield, my friend, in the battlefield. The lives of the brave will flower in the battlefield.” Midway through, she stopped singing and let out a sharp laugh. “How can life flower if you’re dead? But that song would get everyone riled up. Everyone would be ready to kill, ready to give their lives.”

A section of the cultural wing of the Maoist party, Salyan, late 1990s

A section of the cultural wing of the Maoist party, Salyan, late 1990s  Magar, Mohit Shrestha, and others performing during People’s Liberation Army training, Ot, Rolpa, 2000

Magar, Mohit Shrestha, and others performing during People’s Liberation Army training, Ot, Rolpa, 2000Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

The musician and educator Pradeep Dewan, who calls himself “the people’s artist,” described music as the salt of the revolution. Like many Maoist musicians, Dewan was influenced by the progressive songs of the 1960s and ’70s, most composed by left-leaning Nepali writers and musicians whose lyrics brought people to the streets to protest against Panchayat rule. But even with a movement toward democracy in the early 1990s, Dewan saw little change. “Everyone had a feudal mindset that they couldn’t seem to shake,” he explained to Sthapit. In 1997, Dewan joined the Maoists. Like many on the movement’s cultural front, he traveled around the nation, training other musicians and convincing people to “walk the path of revolution.” They wrote and performed hundreds of songs to excite, educate, and capture the hearts and minds of various oppressed groups: the poor, women, Dalits, and farmers.

The musicians were also healers. After battles, they sang songs to not only memorialize the dead but console their families and friends, as well as the many who were wounded. The music was medicine, a balm, and also a reminder for fighters who were alive to continue the mission of building a just world. Today, some musicians express frustration that the goals of the revolution—equality across caste and class lines, health care, good schools, security—were never fully realized. The popular musician and writer Mohit Shrestha expressed anger and betrayal. “I’ve thrown away all my diaries with lyrics and unrecorded songs. They did not feel important. I didn’t know that someone like you would come looking for them one day,” he told Sthapit. “These songs painted a dream of a revolution, but they didn’t bring the change we wanted.”

Watch Now: Prasiit Sthapit on Moonsongs for EarthIn “Counter Histories,” Aperture’s latest issue produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation, the artist investigates the complex role of musicians in Nepal’s Maoist insurrection.

Moonsongs for Earth not only shows us a different aspect of the war but also illustrates what hope can look and sound like. “I am not trying to glorify war,” Sthapit told me. “The war was not only gruesome, it was a disastrous failure in many ways, but I think the motivation behind any revolution has to be considered. These artists, these humans, really believed that their singing and their music would bring change not only to Nepal but to the entire world.” Today, many of them are invited to perform original and cover songs on radio or television, or they find audiences on social media and YouTube. While some are still affiliated with the Maoist party, others have moved away from politics altogether.

As an image maker and a storyteller, Sthapit is an expert at revealing and concealing, nudging viewers to understand that things are not always as they appear. When I asked what surprised him most while making Moonsongs for Earth, he said that it was Laxmi Gurung’s vulnerability. He hadn’t expected a “steely Maoist fighter” to be this soft. “She thinks there is no one in the world who cries as much as she does,” he explained. “During the war, she would go into the forest, or lock herself in her room, and just cry. Even today, she cries when she composes music. Everything touches her.”

Prasiit Sthapit, Laxmi Gurung at her apartment, Kathmandu, 2022

Prasiit Sthapit, Laxmi Gurung at her apartment, Kathmandu, 2022  Gurung in her performance uniform, Solukhumbu, 2003

Gurung in her performance uniform, Solukhumbu, 2003Courtesy Laxmi Gurung Collection

Prasiit Sthapit, Mahesh Arohee at home, Ghorahi, Dang, 2023

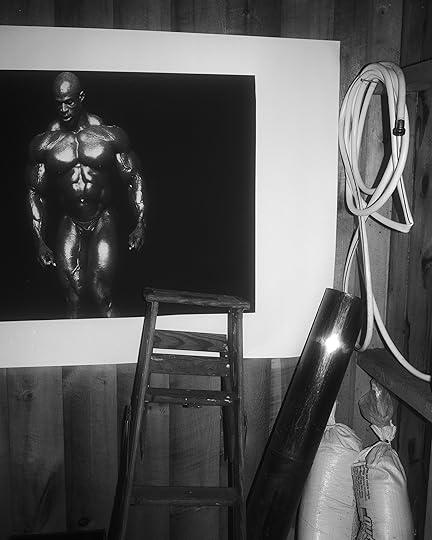

Prasiit Sthapit, Mahesh Arohee at home, Ghorahi, Dang, 2023  Prasiit Sthapit, Arohee’s room with a photograph of him taken during the war, Ghorahi, Dang, 2023

Prasiit Sthapit, Arohee’s room with a photograph of him taken during the war, Ghorahi, Dang, 2023  Arohee (right) and comrade Ritesh, both from Magarat Cultural Family, clad in combat gear, Palpa, 2004

Arohee (right) and comrade Ritesh, both from Magarat Cultural Family, clad in combat gear, Palpa, 2004Courtesy Mahesh Arohee Collection

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Prasiit Sthapit, Mohit Shrestha outside his apartment, Kathmandu, 2022

Prasiit Sthapit, Mohit Shrestha outside his apartment, Kathmandu, 2022  Shrestha during a training session for new musicians of the party, Arkha, Pyuthan, 2002

Shrestha during a training session for new musicians of the party, Arkha, Pyuthan, 2002Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

Comrades recording Shrestha’s latest song, Salyan, 2001

Comrades recording Shrestha’s latest song, Salyan, 2001Courtesy Mohit Shrestha Collection

Prasiit Sthapit, Shrestha’s harmonium and diary of songs, Kathmandu, 2022

Prasiit Sthapit, Shrestha’s harmonium and diary of songs, Kathmandu, 2022Photographs by Prasiit Sthapit © the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation.

April 5, 2024

Close Encounters with Miranda July

On the day the world shut down, Miranda July received a strange phone call. It was Friday, March 13, 2020, and July was on her way to a café when she learned that her child’s school was going to close “indefinitely.” As she waited for a friend, stunned by the news that the pandemic scare was all too real, a telemarketer from the Philippines called with an offer for “services,” which July learned were related to promotional strategies for self-published authors. An artist and filmmaker whose breakout indie film, Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), retains an enduring fanbase, July is also the author of the short-story collection No One Belongs Here More Than You (2007) and the novel The First Bad Man (2015), both New York Times bestsellers. But she humored her caller, who was following a script. At the end, July could have hung up. Instead, she said, “Can I ask you some questions now?”

Installation view of Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024

Installation view of Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024July has a knack for spinning an otherwise forgettable encounter into a beguiling narrative—visual, literary, or cinematic. At age seventeen, she staged a performance at a Berkeley, California, punk club based on her pen-pal correspondence with a man in prison for murder. She collaborated with Oumarou Idrissa, an Uber driver from Niger, on the conceptual, time-based sculpture I’m the President, Baby (2018), which concerned his insomnia and anxiety about getting a visa in the United States. For seven years, some eight thousand people participated in Learning to Love You More (2002–9), a web project July initiated with Harrell Fletcher, in which participants completed various assignments: “Make an encouraging banner”; “Write a press release about an everyday event”; “Recreate 3 minutes of a Fresh Air interview.”

Installation view of Services, 2020, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024

Installation view of Services, 2020, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024After July began asking questions to Richie Jay Benedicto, the Filipino telemarketer, they struck up a six-month dialogue, exchanging ideas and performance-based images. July asked Benedicto, a trans woman, to respond to various prompts, such as acting out a dream or naming “5 people you love and 1 you hate.” (Benedicto loves Jesus and Jamie Dornan, but confesses that she hates herself.) July was impressed by Benedicto’s openness and honesty; she paid her correspondent for her services and gave her directions, “like an actress on one of my sets.” Five images from of the resulting coauthored project, Services (2020)—first published in Germany by Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, followed by a deluxe, concertina-style book sculpture produced by the London publisher MACK—are now on view in New Society, July’s solo exhibition at the Fondazione Prada in Milan. The low-resolution camera-phone images, enlarged as prints and set in pale pink frames, amplify the pandemic’s mood of dislocation and intangibility: so close, yet so far away.

Miranda July, Audience participants in New Society, 2015, Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York

Miranda July, Audience participants in New Society, 2015, Brooklyn Academy of Music, New YorkPhotograph by Julieta Cervantes

Installation view of Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024

Installation view of Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024New Society is curated by Mia Locks and spans July’s career, from video documentation of her performances to her newest work, an Instagram-based participatory experiment called F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) (2024). The exhibition is presented in the Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio galleries, on the fifth and sixth floors of Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, in the beating heart of Milan’s upscale shopping district. Posters, tickets, scripts, and cassettes are presented reverently in vitrines, while costumes—the wig from July’s short film The Amateurist (1997), the swimsuit from The Love Diamond (1998), the multiple iterations of an emerald-green blouse that audiences cut strips from during live productions of New Society (2015)—are affixed to the walls.

July is attuned to interpersonal dynamics, and the possibility of failure, especially when it comes to social interactions, animates her work.

The effect, at the outset, is to historicize July’s multimedia productions and feminist, punk sensibility, which Locks places in a lineage with Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke, and Cindy Sherman. (Sherman contributed a conversation with July for the Fondazione Prada publication; characteristically, July returns Sherman’s questions with perceptive questions of her own.) Early in her career, July believed in the “radical” power of archives, as she recounted in the preview for the exhibition: “I realized that what is saved is remembered, and what is remembered becomes history, and history creates reality.” Power itself is both a theme and a tool throughout July’s work, given her collaborations with strangers and audience members. “Power, in July’s world, is not an object of possession, nor a zero-sum game,” Locks writes in the exhibition publication, noting the feminist preference for power sharing. “It is not something you own or wield; it is something to play with.”

Installation view of Two Things Are Sure, 1993/2024, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024

Installation view of Two Things Are Sure, 1993/2024, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024  Miranda July, Two Things Are Sure (detail), 1993/2024. Collage with found photographs, stickers

Miranda July, Two Things Are Sure (detail), 1993/2024. Collage with found photographs, stickers Photography and image making emerge in New Society as central to July’s art. For Two Things Are Sure (1993/2024), July collaged numerous small photographs salvaged from Urban Ore, a recycling center in Berkeley, where she grew up. She didn’t know any of the people in the images, but because the pictures were culled from Bay Area photo albums, occasionally she would recognize someone and have a hunch about where they went to high school. July deftly sequenced the pictures into a captivating network of associations and visual gestures, applying a circuit of Day-Glo orange stickers of the kind viewers will recall from Me and You and Everyone We Know, in which July plays Christine, an aspiring video artist who delivers a videocassette decked out with neon-pink stickers to an imperious contemporary art curator. The work’s title comes from a church sign—those vernacular prophesies seen in so much American deadpan photography—placed at the center of the composition, reading “Two Things Are Sure in Life: There Is a God and You Are Not Him,” a line July could have written herself. The piece, July said, is about the “energy that connects people, a sort of spirituality, almost.”

Miranda July, Video still of July, @craigmontyjames (C.M. James), and @thongria (Zoë Ligon) in F.A.M.I.L.Y. Ceiling, 2024

Miranda July, Video still of July, @craigmontyjames (C.M. James), and @thongria (Zoë Ligon) in F.A.M.I.L.Y. Ceiling, 2024  Miranda July, Video still of July, @enter_laughing (Augusta Dayton), @thongria (Zoë Ligon), and @goatzfoot (Lisa Ziegenfuss) in F.A.M.I.L.Y. Cloud, 2024

Miranda July, Video still of July, @enter_laughing (Augusta Dayton), @thongria (Zoë Ligon), and @goatzfoot (Lisa Ziegenfuss) in F.A.M.I.L.Y. Cloud, 2024 July made F.A.M.I.L.Y., a nine-channel video installation, by recruiting participants through a private Instagram channel. She asked seven strangers to film themselves making gestures that would leave room for July, who then used a cut-out tool to merge videos of herself with her various cast members. She would give briefs, such as “You show me how you want to be touched, and I will figure out how to fit us together.” The results are a series of low-fi pas-de-deux, with July enacting often intimate movements with people of various body types, genders, and abilities. “I tried to create an image that gave us perhaps what we had wanted from the technology in the first place, from social media, from Instagram in particular, which I think we wanted to be looked at so lovingly that we felt OK,” July said, “like a new kind of sex or birth, like what you imagined sex would be like when you were a child, that would just merge. This perfect togetherness.” Yet the result is strangely cold and distancing. Though made this year, well post-pandemic, F.A.M.I.L.Y. seems to be a response to the problem of seeking intimacy at a time of separation. In an exhibition where July shows how early performance work led to feature films, F.A.M.I.L.Y. (which will continue to evolve as new video clips are added) feels like a sketch for a bigger idea.

Installation view of F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You), 2024, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024

Installation view of F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You), 2024, in Miranda July: New Society, Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2024All works courtesy Miranda July Studio. Installation photographs by Valentina Sommariva. Courtesy Fondazione Prada

In 2020, Prestel published a monograph lining up all of July’s projects chronologically, complete with images of her sketchbooks, zines, press clippings, letters, video stills, installation views from the Venice Biennale, a collaboration with Roe Ethridge, wardrobe tests for The Future, and behind-the-scenes content from her film sets. Tellingly, her short-story collection and her novel were photographed as objects, and therefore appear as artworks. A copy of No One Belongs Here More Than You is open to a critical scene in the collection’s finest story, “Something That Needs Nothing,” about a young woman who, short on cash, takes up work as a peep-show performer. There’s a glass barrier between the narrator and her client, who speak over the phone. It’s a metaphor for July’s singular method of building a performance from the simplest of materials: the glass like the lens of a camera, the words spoken through the phone like lines from a script. July is highly attuned to interpersonal dynamics, and the possibility of failure, especially when it comes to social interactions, animates her work. New Society shows a sui generis artist taking risks in every direction. Risk can feel almost “devotional,” July tells Cindy Sherman in their conversation. “Risking and letting go.”

Miranda July: New Society is on view at the Fondazione Prada Osservatorio, Milan, through October 14, 2024.

Mariko Mori’s Anime-Inspired Critique of Gender in Japan

It is 1994 in Tokyo and Mariko Mori is angry. She has just come out of a business meeting, and is appalled to find that intelligent women, with degrees from leading universities, are being made to serve tea while working at the office. She has recently returned from five years overseas, studying art in London at the Chelsea College of Art and Design, followed by two years in New York at the Whitney Museum’s rigorous Independent Study Program. “I was exposed to seeing the position of women in the West,” she recalled in a recent conversation with me, speaking from her home in New York. “I was shocked. I wanted to demonstrate, as a social criticism, the lack of equality for women in Japan.”

Dressed in a silver bodysuit with pointy ears, Mori sets out to Shinjuku, Tokyo’s busiest business district. She clacks along the sidewalk in her patent heels and pinafore, carrying a tray of green tea in porcelain cups and saucers. She smiles and serves dutifully, as businessmen rush by on their morning commutes. The scene is at once comical and unsettling. Guised as a cyborg in a setting that epitomizes economic prosperity and power, Mori critiques the antiquated gender roles of corporate Japan and illustrates how women are alienated and othered in these spaces.

Mariko Mori, Tea Ceremony II, 1994

Mariko Mori, Tea Ceremony II, 1994The performance culminated in a trilogy of still photographs, Tea Ceremony I, II, and III (1994). They are part of a wider body of work in which Mori adopts futuristic personas inspired by Japanese anime and pop culture. These images propelled Mori into the international spotlight. In 1995, at age twenty-eight, she held her first solo show at American Fine Arts, Co., New York, and two years later exhibited at the 47th Venice Biennale. Today, Mori’s multidisciplinary art, characterized by a fascination with futurism, technology, and spirituality, is exhibited and collected by museums worldwide. Although now recognized as one of Japan’s leading contemporary artists, she describes being ignored around the time the Tea Ceremony images were made. Not only was she disregarded by passersby during the performance, the series remained unexhibited in Japan until 2002, when it was shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. “Japanese society is collective,” Mori explains. “We don’t have such a strong culture of criticism. I don’t think this work ever received a reaction from Japanese society. The reaction was mostly from the West.”

Today, there are more opportunities for women, but the behavioral expectations illustrated by Mori—of modesty, tidiness, courtesy, and compliance—remain firmly embedded in the national psyche.

Feminism has existed in Japan since the Meiji Restoration in the nineteenth century. However, its progression has been comparatively slow. In the United States, women’s suffrage was achieved in 1920; in Japan, women did not gain the right to vote until 1947. A similar pattern can be seen in the art world. Women artists in the postwar era, such as Atsuko Tanaka of the Gutai group, Yuki Katsura, and Yoshiko Shimada, actively responded to feminist thought, but it was not until the 1990s that their work was recognized, when Japanese critics and curators began to consider art from a feminist perspective.

In that context, Mori’s Tea Ceremony was radical in its overt criticism of gender inequality. This critique is, sadly, still relevant: in government, women make up just 8 percent of the ruling party. “It really was worse,” Mori reflects on the moment she made this work. “But the fundamental structure is still there today. We need to deconstruct that concept that has been inherited through history; otherwise, it’s not going to change.”

Mariko Mori, Tea Ceremony, III, 1994

Mariko Mori, Tea Ceremony, III, 1994© the artist and courtesy Sean Kelly, New York

Over the last few decades, working women in Japan have experienced, paradoxically, liberation and oppression. The pay gap has shrunk by a third, and while policies to diversify leadership positions have been put in place, women continue to face discriminatory hiring practices. A closer look at Mori’s costume, inspired by her favorite childhood anime character, Astro Boy, reveals an interrogation of persistent gendered dress codes. Her button-up pinafore and high heels signal the cultural icon of the “office lady”: a female employee of corporate Japan, colloquially abbreviated to OL (o-eru). Japanese companies are notorious for standards of dress that have been reported to include guidelines on the height of heels and a requirement to wear makeup. Back in the 1990s, women were treated as low-skilled clerical workers, despite their being equally educated in comparison to their male counterparts. They were paid substantially less, and their jobs consisted mainly of answering phones, entering data, and making tea. Today, there are more opportunities for women, but the behavioral expectations illustrated by Mori—of modesty, tidiness, courtesy, and compliance—remain firmly embedded in the national psyche.

In Japan, feminism has not flooded the collective consciousness in the same way it has in the West. Perhaps artists offer some hope. Feminist photographers such as Yurie Nagashima, Ishiuchi Miyako, and Tomoko Sawada are receiving renewed recognition for their work, and a younger generation of artists, such as the collective Tomorrow Girls Troop, is speaking out. “Artists have the ability to project a future vision,” says Mori. “We have a responsibility to imagine a better future, because if we can’t imagine it, we will never make it.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” under the column Viewfinder.

The World Is Martin Parr’s Runway

The British documentary photographer Martin Parr has long chronicled how people experience leisure and pleasure by interacting with the trappings of consumerism. His depictions of shoppers in Laura Ashley, tourists in beach cafes, and Tupperware parties scrutinized late twentieth-century British life in new ways. His more recent, cropped-in, color-saturated pictures are graphic commentaries on the glorious and hollow nature of manufactured delights. Sometimes, they are discreet commissions by fashion magazines and fashion brands. The Martin Parr Foundation, an exhibition space, library, and archive focused on photographers from Britain and Ireland, opened in Bristol, England, in 2017. I met him there earlier this year to talk about his new book project.

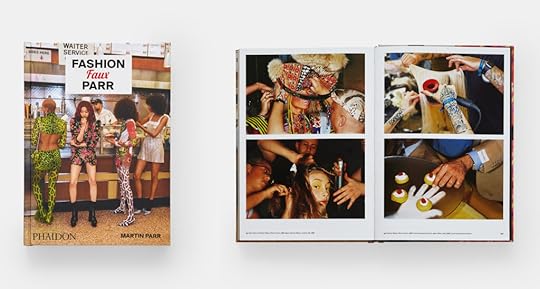

Cover and interior spread of Fashion Faux Parr by Martin Parr (Phaidon, 2024)

Cover and interior spread of Fashion Faux Parr by Martin Parr (Phaidon, 2024)Alistair O’Neill: Good afternoon, Martin. I’d like to talk to you about your forthcoming publication with Phaidon, Fashion Faux Parr, which is the first book dedicated to your fashion photography. How did the book project come about and why now?

Martin Parr: I guess I started fashion in 1999, when I was invited by Amica magazine from Italy to do something, and I thought, “Oh, why not? I’ll just do a fashion shoot.” That turned out fine. Since then I’ve continued to do fashion, more editorial than commercial. In the last five years I’ve had an extra spurt of doing fashion for brands like Vogue and Gucci. It’s been quite a productive period, so it struck me as the right time to show what I’ve done in the fashion world. I think most people would associate me more with documentary, so it’s nice to have this opportunity to show another side of my work. We run the foundation here and the income from fashion assignments, both editorial and commercial, helps to keep this place alive and well, really, because it is twelve people working here and they’ve all got to be paid. And I enjoy doing fashion, it’s fun. I like the idea that you can use photography to solve the problem. You’ve got to basically make an interesting picture. And obviously, people employ me because I’m Martin Parr and I have to make Martin Parr pictures, which is no problem. That’s it in a nutshell.

O’Neill: It is funny though, because that kind of economic model that you just described, where the fashion work helps to support the work of the foundation, it’s not that dissimilar from the way that say, postwar photographers who wanted to be photographers in their own right took on fashion work in order to get the money to produce their personal portfolio.

Parr: I’m not saying this is a highly original way of working. There are a lot of people now in the documentary world who do fashion—Jack Pierson, Harley Weir, and Juergen Teller—to support their own work. And in fact, they try and make it into their own work. That’s the question, whether it does become that. And I guess I look through this and I think, “Oh, this is not bad and I’m happy I’ve done it.” But when I go to the pearly gates, it won’t be the first book I get out.

O’Neill: I can well imagine.

Parr: That doesn’t mean I don’t like it. I’m very happy to have this published.

Martin Parr, Cannes, France, 2018. Commissioned by Gucci

Martin Parr, Cannes, France, 2018. Commissioned by GucciO’Neill: Let me ask you about the title, it’s a play on words. Rather than faux pas, P-A-S, it uses your surname.

Parr: With Phaidon, we sat down, looked at different titles. In the end, everyone liked it and off we went. So it didn’t take much effort to come up with this. It was there in the first instance, and it survived, and all the others fell away.

O’Neill: But the idea of the faux pas as a kind of misstep or an indiscretion, or something that’s socially embarrassing, when you connect it to fashion it’s very potent.

Parr: Absolutely, all the implications of the phrase really work. I think you’re right, it’s a critique and yet it’s not at the same time.

O’Neill: I think what’s interesting about fashion is that it’s very revealing of us—in that it allows us to project something of ourselves, but it also reveals how that projection sometimes is out of line; or says something that perhaps we didn’t really want to reveal. Do you think that’s something that’s particular to fashion?

Parr: I don’t think so particularly. I mean, I like to go outside into the real world. And when I look through the books of contemporary fashion photographers, they basically seem to stick to the studio. And for me, getting out in the real world, trying to make a real plausible picture that works, that looks interesting is the challenge and that’s what I’ve basically done. I don’t think there’s any shots in the studio at all here. It’s all in the outside world.

Martin Parr, London, UK, 2017. Commissioned by Chaos 69

Martin Parr, London, UK, 2017. Commissioned by Chaos 69  Martin Parr, Dakar, Senegal, 2001. Commissioned by Rebel

Martin Parr, Dakar, Senegal, 2001. Commissioned by Rebel O’Neill: In 2005, you published your own fashion magazine, which followed the format of a conventional consumer title, but all the pictures were yours. It even had an editor’s letter, where you said that the boundaries between what’s a fashion editorial and what’s documentary has become blurred, and that there’s something pleasurable about that.

Parr: I still think that’s the case. For example, when I do a fashion shoot, I get twelve pages. If I do an editorial shoot or just submit pictures to do with a recent book, if I get four, it’s a miracle. So this is amazing that you can actually have this work where you can make interesting pictures and get a big spread and get well paid as well. What’s not to like?

O’Neill: So is it about a kind of control that you are able to exercise?

Parr: Well, in the end, you don’t have control. I don’t talk to the art director about which images to use. I’ll make a selection, they’ll go through them and then they’ll request the high-res. And it’s up to them after that, I’m not involved.

O’Neill: But can you ascertain a difference in terms of working with art directors and editors in fashion, as opposed to photography or design?

Parr: Well, they’re more enthusiastic, basically. Fashion people are generally enthusiastic and they all wear black. I mean, that’s two things I can tell you about them that you probably know already.

O’Neill: Well, yes, they do have a tendency to dress in a quasi-uniform.

Parr: Exactly.

Martin Parr, New York, USA, 2019. Commissioned by Vogue USA

Martin Parr, New York, USA, 2019. Commissioned by Vogue USAO’Neill: And you’re not averse to wearing fashion yourself in some of your pictures. There’s a great picture in that magazine of you wearing a black CP Company jacket.

Parr: What happened was I did this book called Autoportrait, and there was a very good guy at W Magazine, what was he called? Dennis something or other.

O’Neill: Dennis Freedman.

Parr: But I remember Dennis was a really inspirational guy and I did a great spread for him, editorially for W. And then he saw this Autoportrait book that I’d done and he commissioned me. Maybe the one you mentioned isn’t part of that shoot, but he commissioned me to go. He says, “I’m sending you ten pairs of trousers, ten jumpers or whatever, go and have your portrait taken.” So that’s just what I did. That’s a pretty inspired sort of editorial request, I guess.

Martin Parr, London, UK, 2023. Commissioned by Amina Muaddi

Martin Parr, London, UK, 2023. Commissioned by Amina MuaddiO’Neill: Well, Freedman was an important editor. He was responsible for commissioning art photographers like Tina Barney and Philip-Lorca diCorcia to take fashion pictures for W. And it’s considered a real high point of fashion imagery in that moment.

I wanted to ask you about an observation you made about going to the Paris shows in 2011, when you were shooting for Madame Figaro and you saw the Dior show just after John Galliano had exited, and a Celine show by Phoebe Philo. You made this really interesting point of comparison between the two shows about lighting. You said the Dior show looked like a poorly lit disco, and that the Celine show was so clean and consistently lit, you could see everything in one glance. And it made me think that some photographers are very much more focused on the smoke and mirrors of fashion as opposed to say, the clothes themselves.

Parr: I hadn’t considered that, but certainly when I go to these fashion shows, the first thing I’m hoping is that where the show’s going to take place is not black because you just can’t really work that.

Martin Parr, Katz’s Delicatessen, New York, USA, 2018. Commissioned by Vogue USA

Martin Parr, Katz’s Delicatessen, New York, USA, 2018. Commissioned by Vogue USAO’Neill: The other thing about fashion shows is that photography is really zoned. So, you have people at the front of the catwalk who are there to get the catwalk shots—total head-to-toe front looks—and then you’ve got the people backstage who are doing beauty and prep shots. And sometimes you have a roving photographer as a kind of journalist, who might be someone like you. Is it something you try to fight against when you’re in those environments?

Parr: Well, obviously you go to backstage and it’s crawling with photographers, though sometimes less because they’re more picky. And it depends how good your access is, really. It’s a real hierarchical business. I remember when I went with the editor of Stiletto magazine, Laurence Benaïm, she knew everybody. And just sticking with her meant I got in everywhere. But if I go on my own, it wouldn’t be as easy, the access would be limited.

O’Neill: A pass sometimes is not enough, it’s better to be visually recognizable. When were you first introduced to fashion?

Parr: Well, I sort of vaguely knew about people in the fashion world before I started doing it myself, but I haven’t taken it that seriously, really. I noticed in auctions that fashion pictures always got the best prices, which I always thought was interesting. And then I started, and of course I didn’t know much at the beginning, I know a bit more now. But of course, I still say I’m not a fashion photographer, which is really the case. I’m a documentary photographer that does fashion from time to time. And I think that’s the best way to present it.

Martin Parr, Versailles, France, 2023. Commissioned by Jacquemus

Martin Parr, Versailles, France, 2023. Commissioned by JacquemusAll photographs courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

O’Neill: I think what you’ve just said—that you are not a fashion photographer, you are a documentary photographer, standing on the outside, let’s say, pointing your camera in to this system, this world. But what this book demonstrates is that you’ve developed quite a prolific body of work in this area. Do you still see yourself as sitting outside of it?

Parr: I think so, yes.

O’Neill: Do you think the boundary has become even fuzzier?

Parr: Absolutely. Same with me and with many other photographers. And the whole business now of how these documentary photographers get drawn into fashion. I think it’s a healthy thing, basically. It’s always good to see a shake-up of the market.

O’Neill: Of course. But it’s interesting that it does only seem to be fashion that has the economic propensity to allow documentary photographers, artist photographers, or others to work in a certain way and still be able to retain a degree of creative freedom.

Parr: Yes, especially editorial. Once you do a commercial, it’s much stricter in terms of they’ve got it all planned out, they know exactly what they want. But with editorial, you do get a lot of freedom.

O’Neill: You have photographed a lot of food in your career. And yet you haven’t had the same inroads in terms of producing food editorial or commercial.

Parr: No, because it always looks too grim, basically.

O’Neill: So you think you make food look bad and you make fashion look good?

Parr: Well, obviously I like junk food, it makes the best pictures. Posh food doesn’t work as well.

Martin Parr’s Fashion Faux Parr was published by Phaidon in April 2024.

March 29, 2024

What Christopher Gregory-Rivera Discovered in Puerto Rico’s State Secrets

As a high school student in Puerto Rico, around 2005, Christopher Gregory-Rivera grew active in student movements that fought university tuition hikes. His mother wasn’t happy about it. “She would say, ‘Cuidado, te van a carpetear,’ which meant that the police were going to open a file on me,” Gregory-Rivera told me recently. “That was my first exposure to the idea that the police were opening files, or carpetas, on dissidents. I was like, ‘Mom’s crazy, she’s paranoid,’ but it turned out to be something that’s super present in Puerto Rican protest culture and the Puerto Rican imaginary in general.”

Gregory-Rivera’s mother’s warnings prompted questions about his homeland, and he soon learned the violent history of carpetas (“folders”). Since the early 1900s, an active independence movement sought to wrest Puerto Rican sovereignty from the United States, while the Puerto Rican government and high-ranking US officials such as J. Edgar Hoover sought to suppress activists through tactics that ranged from monitoring to murder. By 1978, pressures came to a head when an undercover police agent named Alejandro González Malavé led the independence activist Arnaldo Darío Rosado and his teenage associate Carlos Soto Arriví to Cerro Maravilla, a mountain at the center of the island. The young men allegedly planned to set fire to or bomb television towers positioned there but were met by officers who killed them in a barrage of gunfire.

Christopher Gregory- Rivera, Intelligence Division surveillance manual with a secret compartment, 2022

Christopher Gregory- Rivera, Intelligence Division surveillance manual with a secret compartment, 2022  Arnaldo Darío Rosado, identified with a faint number fourteen on the print, 1975

Arnaldo Darío Rosado, identified with a faint number fourteen on the print, 1975 The island’s governor at the time, Carlos Antonio Romero Barceló, later called the police officers “heroes,” in accord with the official story—that the victims had been terrorists and the police acted in self-defense. But in 1983, the Judiciary Committee of the Senate of Puerto Rico determined the youths had been executed by the police to intimidate the independentistas. (It also turned out that the FBI had advance knowledge of the ambush.) During the prosecutions that followed, a former agent of the Intelligence Division, William Colón Berríos, admitted the police kept files on activists. The whispered fears of being “foldered” had circulated through Puerto Rico for decades but, until that time, were often chalked up to rumor. Now people learned the stories were real. Since the 1930s, the police had investigated at least 135,000 individuals (about 3 percent of the island) suspected of favoring independence. Moreover, they’d used informants—suspects’ associates, friends, and sometimes even family members.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

These revelations gave way to litigation, and in 1988 the Puerto Rican Supreme Court declared that the police’s dossier practice violated the constitutional rights to speech, association, and privacy, while also insulting “the dignity of the human being.” The court required that the files be returned to their subjects, a measure the legal scholar Marc-Tizoc González describes as “habeas data.” Instead of instituting a formal protocol that would help give citizens some emotional closure, people were simply told to come to the Center to Arrange Confidential Records and pick up their unredacted papers. There was no reconciliation process, no truth commission. Beginning in September 1989, people grabbed their files from the Center, took them home, read them, and then stored them in their bureaus or cupboards. If no one showed up to claim a carpeta, it was stored in the National Archives, where many remain today.

Twenty-four years after this process began, Gregory-Rivera was in Washington, DC, striving toward his dream of becoming a photojournalist. Posted to the White House and on Capitol Hill while working as an intern for the New York Times, he began to reimagine his career when he heard about Edward Snowden’s 2013 data leaks, which revealed that the National Security Agency had collected the phone records of millions of Verizon customers. “Everyone was like, ‘It’s not important, I have nothing to hide,’” Gregory-Rivera says. “But I knew that in Puerto Rico, everyone is afraid to express themselves politically because they think that the government is watching them. I had this crisis. So, I went back to Puerto Rico and started this project.”

Christopher Gregory- Rivera, A confiscated copy of William J. Pomeroy, Guerrilla Warfare & Marxism, 2022