Aperture's Blog, page 18

May 23, 2024

Paolo Gasparini on How Photographs Can Help Us Learn to See

In spring 2024, nearly thirty years after he represented Venezuela at the Venice Biennale, Paolo Gasparini returned to Venice to participate in the latest edition of the international exhibition, Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa. Here, we revisit Gasparini’s conversation with Sagrario Berti in the magazine’s “Interview Issue,” originally published in fall 2015.

Although Paolo Gasparini was born in Italy, Venezuela is his adopted home. He has spent his life documenting the cities and people of Latin America, south of “the northern imperialist,” as he refers to the United States in the following interview. Born in 1934 in Gorizia, in Northeast Italy, he emigrated to Caracas in 1954 to join his mother and older brother. This was a time of oil fueled growth, prosperity, and urban expansion as well as inequality, poverty, and cramped living conditions in new housing complexes. Working alongside his architect brother Graziano, Gasparini sought to document both the transformation of the built environment and the city’s inhabitants.

In 1961, impassioned by the Cuban Revolution, Gasparini traveled there and stayed for four years. Later, in the 1970s, he was commissioned by UNESCO to photograph urban centers from Mexico to Argentina, focusing on both architecture and the stark social inequality he witnessed. The project resulted in the photobook Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America, 1972), now considered a classic.

Gasparini has continued to make work, often reinterpreting his still photographs through the use of sound and elements of performance. In 1995, he represented Venezuela at the 46th Venice Biennale. For this interview, Sagrario Berti, a Venezuelan photography curator, researcher, and longtime friend, met with Gasparini at his home and studio in the Bello Monte neighborhood in Caracas. They spoke about his recent book Karakarakas, which features six decades’ worth of Caracas work; what it means to identify as a Latin American photographer; and why, for Gasparini, photographs should still be seen as a product of ideology.

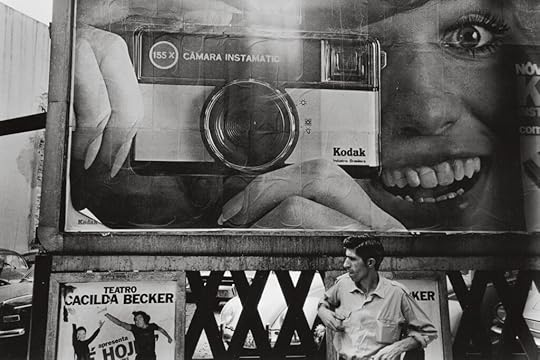

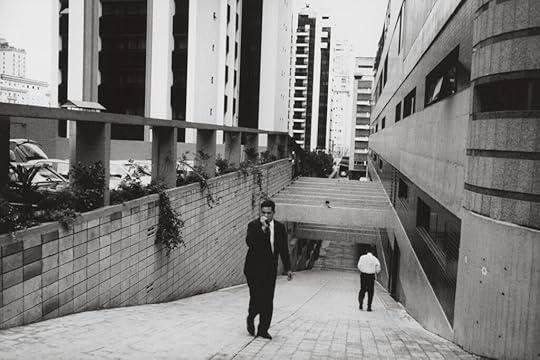

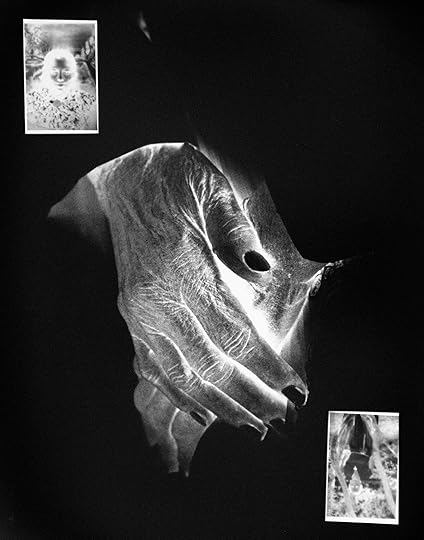

Paolo Gasparini, São Paulo, 1972, from the series Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America)

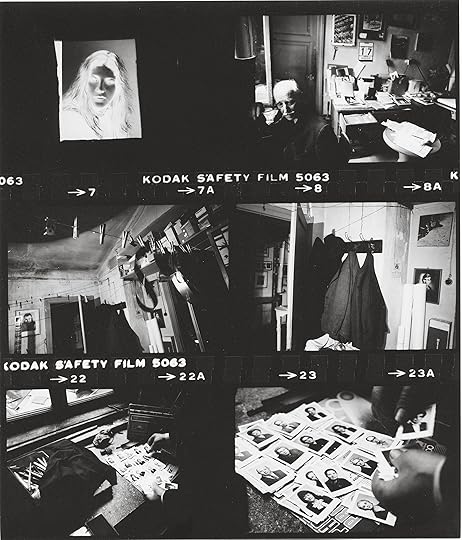

Paolo Gasparini, São Paulo, 1972, from the series Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America) Paolo Gasparini, Italian miracle, Rome, 1966

Paolo Gasparini, Italian miracle, Rome, 1966Sagrario Berti: What led you to immigrate to Latin America and settle in Venezuela?

Paolo Gasparini: In order to avoid enlisting in the army, before turning twenty-one I moved to Caracas. My father and two brothers were already living there. My mother traveled constantly to Venezuela where Graziano, one of my brothers, was working as an architect and photographer. He was conducting research on popular, indigenous, and colonial architecture of Latin America.

Berti: Were you already taking photographs?

Gasparini: Yes. After one of my mother’s trips to Caracas, she came home with a Leica camera for me as a gift from Graziano, and at seventeen I began photographing. In Gorizia, Italy, my girlfriend Franca Donda and I frequented a photography studio. That’s where we learned developing and copying techniques. I also took part in the exhibitions organized by Gorizia’s photo-club, where I showed photographs of fishermen, peasants, and circus workers.

Berti: And in Caracas?

Gasparini: Having only been in Caracas for eight days, thanks to Graziano’s architect friends, I began photographing the buildings of Carlos Raúl Villanueva, Venezuela’s great modernist architect: the Central University of Venezuela and the construction of the 23 de Enero [January 23] public housing blocks. I settled into a rich cultural world full of writers, philosophers, critics, and thinkers from the magazine Cruz del Sur (1951–61), a publication run by Violeta and Alfredo Roffé that linked cultural issues with societal problems and served as a focal point for leftist intellectuals who opposed the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952–58). I worked for Villanueva and for architects like Pedro Neuberger, Dirk Bornhorst, and Jorge Romero Gutiérrez on El Helicoide, a proposed shopping mall and industrial exposition center in Caracas built on a rock of gigantic proportions that was never finished. Now it’s a prison.

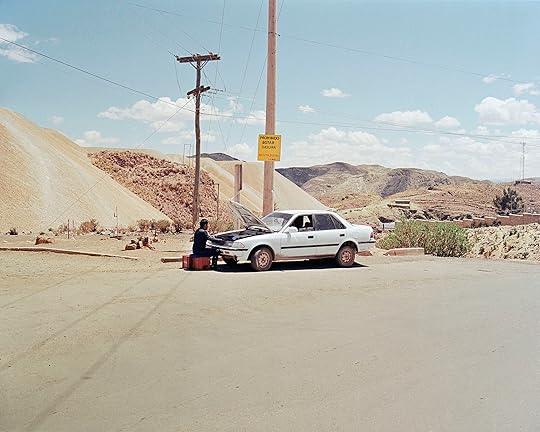

Paolo Gasparini, National Electoral Council, Caracas, 1968

Paolo Gasparini, National Electoral Council, Caracas, 1968 Paolo Gasparini, Potosí hill, Bolivia, 1991

Paolo Gasparini, Potosí hill, Bolivia, 1991Berti: You alternated between being an architectural photographer and documenting various neighborhoods. You also traveled around the interior of the country. Which work from this period do you consider most important?

Gasparini: My architectural work, without a doubt. Remember, this period marked the beginnings of publicity and advertising in Venezuela. I had offers to work in publicity that were much better paid, but I turned them all down because I was not, and am still not, interested in advertising photography used to sell products. I traveled either by myself or with Graziano. We went all over the Paraguaná. Peninsula, an arid territory, between 1954 and 1960. We traveled from Los Castillos on the Orinoco River—in the eastern part of Venezuela—and ended up enjoying ourselves and admiring the white houses of the Falcón State in the west. Then we moved onward to the market of Los Filúos in the Guajira Peninsula, on the border of Colombia, and crossed the Andes. Over the course of these travels I made two photo-essays: Las Salinas de Margarita (The salt mines/lakes of Margarita) and Bobare, el pueblo más miserable del Estado Lara (Bobare, the most miserable town in the State of Lara). Both were published in Cruz del Sur. I photographed Bobare under Paul Strand’s documentary influence. Franca, who was living in Paris at the time, contacted Strand—who was self-exiled in Paris, fleeing from McCarthyism in the U.S.—and showed him the work that had been published in the magazine, as well as other photographs that I had taken in Venezuela. Strand brutally criticized Bobare. At one point he told me, “I had to look at it under a yellow light in order to soften the unpleasant yellow hue of the print.” But he liked the other photographs. [Gasparini and Strand met later, in Orgeval, France, in 1956.]

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Ecuador, 1982

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Ecuador, 1982Berti: Aside from Strand, what were your influences?

Gasparini: When I was eleven, I saw the horrors of World War II: photographs of bodies that had been mutilated, hung, and shot. The photographs belonged to a Yugoslav partisan and guerrilla fighter. This was my first experience with photography and it caused a deep impression.

My visual imagination was also fed by magazine photography and film. During the postwar period I went to the Venice Film Festival; at the time, in the United States Information Agency offices, the American Army was projecting films in Gorizia and Trieste. In Venice I saw The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936); The River (1938), which was produced by the Farm Security Administration; [Robert] Flaherty’s film Nanook of the North (1922); The Photographer (1948), a documentary on Edward Weston; and the first images from the concentration camps. I saw films that hadn’t been screened in Italy because of the war, Gone with the Wind (1939) and Que Viva Mexico! (1930), for example, and, of course, the Italian neorealism of [Cesare] Zavattini, [Roberto] Rossellini, and [Vittorio] De Sica.

I became acquainted with the “American way of life” through magazines like Collier’s, Life, and Picture Post. I became enraptured by photography in the films of Paul Strand, such as Redes (1936), and I was especially drawn to the documentary photography, or rather the “social realism,” of his book La France de Profil [with Claude Roy, 1952].

So the basis of my imagination was the documentary propaganda disseminated by the United States army. I left Europe for South America with the war photographs that I’d seen, and with my head full of images of America—hence my constant need to represent both worlds in my photographic practice.

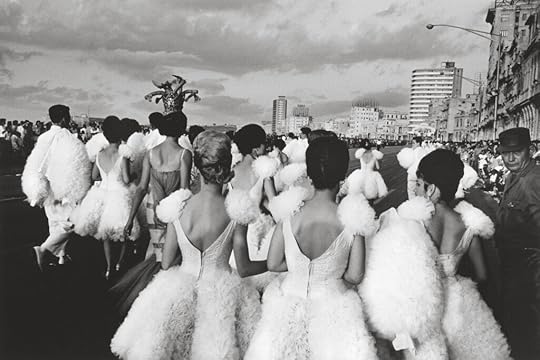

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba, 1963–64, from the series Cuba, ver para creer

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba, 1963–64, from the series Cuba, ver para creer Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Havana, 1964

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Havana, 1964Berti: You lived in Cuba between 1961 and 1965, after the revolution. You photographed with Alejo Carpentier, the renowned Cuban writer, and published the book La ciudad de las columnas (The city of columns, 1970). What drew you to Cuba?

Gasparini: On the one hand, there was an interest in modernity, beauty, folklore, and the authenticity of American life—in magical realism. In 1958, on the other hand, the Cuban Revolution had exploded as a response to the deep social problems that existed in Cuba and the rest of Latin America. The Cuban architect Ricardo Porro and Alejo Carpentier—both exiled in Venezuela—invited me to visit Cuba. I went with Franca; we were married by then. We intended to stay six months but the trip was extended to four and a half years. Carpentier wanted to write a book about Havana, an archive of baroque Cuban architecture—that’s what became La ciudad de las columnas. He liked my “walking” work, he said, because I passed through all of the city streets, registering the stained-glass windows, hallways, and gates. I also befriended many of the fervent supporters of the first revolutionary wave.

Berti: Following the parties celebrating the Cuban Revolution, you shifted the content and style of your photographs, focusing on people living in poverty.

Gasparini: Yes, the speed of the social and cultural events in Cuba made me change my camera. I switched from medium- and large-format reflex cameras (which I used thanks to Strand) to a versatile 35mm, which obviously changed my way of seeing and capturing reality with tremendous speed. I became part of the artistic and intellectual circles, which included photographers, filmmakers, and architects such as Santiago Álvarez, Alberto Korda, and Iván Espín. In Havana I also met Cartier-Bresson, René Burri, Chris Marker, and Italo Calvino, all formidable intellectuals. This amplified my desire to expand the discourse of the Cuban Revolution throughout all of Latin America.

Paolo Gasparini, Brasília, 1972, from the series Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America)

Paolo Gasparini, Brasília, 1972, from the series Para verte mejor, América Latina (The better to see you, Latin America)Berti: How did your Cuban themes differ from those in your other Latin American work?

Gasparini: In Cuba I documented the celebration, euphoria, triumph, and hope following the revolution. In the rest of Latin America, I documented social contradictions.

Berti: When did you begin to expand your travel around Latin America?

Gasparini: In 1970, UNESCO hired me to photograph pre-Columbian, colonial, and contemporary edifices. I focused on the urban building projects being erected from Mexico to the Pampas, from Brasília to Machu Picchu, designed by great modernist architects. I insisted on photographing the lives of marginalized individuals, of those who have nothing, and the huge differences that coexist beside and around these huge building projects.

Berti: In addition to the book Panorama of Latin American Architecture (1977), you published the book of photographs Para verte mejor, América Latina. How did this project materialize and where did the title come from?

Gasparini: It came from an eagerness to document Cuba once again. Edmundo Desnoes wrote the text and Humberto Peña designed the book. The title paraphrases [Charles] Perrault’s story “Little Red Riding Hood” (1967).

Paolo Gasparini, Electoral campaign, Caracas, 1968, from the series Karakarakas

Paolo Gasparini, Electoral campaign, Caracas, 1968, from the series Karakarakas Paolo Gasparini, Bite me, Paris, 1982, from the series Retromundo (Retroworld)

Paolo Gasparini, Bite me, Paris, 1982, from the series Retromundo (Retroworld)Berti: Tell me about Retromundo (Retroworld, 1986), your second book, which was about the representation of two worlds, Europe and Latin America. Here you juxtapose two ways of life: that of the inhabitants of Paris, New York, and Rome, and that of citizens in São Paulo, Mexico City, and Lima.

Gasparini: As I told you earlier, I left Europe with images of America. Later on, I returned to the first world carrying images of the Latin American reality. That’s where Retromundo came from—a book of photographs that doesn’t confront realities but rather tries to serve as evidence for what’s occurring on both continents.

Berti: And El suplicante (The supplicant, 2010)? Where did you get the idea of structuring a book according to your long travels through Mexico?

Gasparini: El suplicante was another adventure. I was invited to develop a project based on the urban culture of Mexico City. I took a photographic tour from the border of the northern imperialist to Subcomandante Marcos’s land of Chiapas.

Related Items

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Conversations

Shop Now[image error]Berti: And your most recent book, Karakarakas [wordplay on Caracas that incorporates the “ka” sound from the words Kodak and Kafka] (2014), takes the form of a political manifesto about the city.

Gasparini: That book brings together photographs taken in Caracas between 1954 and 2014. I put together these photographs with il senno di poi, “the wisdom of hindsight.” I combined images, connecting them with different themes, places, and dates, in an attempt to organize a new discourse that—by way of architecture and certain aspects of daily urban life—would offer a reinterpretation of Caracas’s past and evolution, representing its social, political, and cultural contradictions. As in the previous books, I worked with a great team. The book managed to give significant shape to a politically urgent discourse on the circumstances Venezuela currently endures, from the incongruences of the Bolivarian Revolution to the so-called socialism of the twenty-first century. I also tried to reflect, through architecture, on daily city life in this country that’s so wealthy with oil and yet so poor—a failure of modernity—and on the empty commitments of the governments preceding Chávez.

Berti: You also include images of the last sixteen years, which comprise the Chávez and post- Chávez years (1999–present). Looking at Karakarakas, it seems that the situation has not advanced. We see no changes, and the misery and poverty continue.

Gasparini: Chávez was the product, precisely, of a nonworking democracy. He wanted to put an end to the bourgeois government and built a populist state that ended up dividing the people. The result has been the destruction of modern society, economic ruin, and the collapse of basic services: health care, education, work, among others. No one knows— nor can define—the economic, political, and social chaos we’re suffering.

Paolo Gasparini, Los Ruices, Caracas, 1967–70

Paolo Gasparini, Los Ruices, Caracas, 1967–70 Paolo Gasparini, El oficio de vivir, Gorizia, Italy (The purpose of living, Gorizia, Italy), 1983, from the series Epifanías (Epiphanies)

Paolo Gasparini, El oficio de vivir, Gorizia, Italy (The purpose of living, Gorizia, Italy), 1983, from the series Epifanías (Epiphanies)Berti: In your Fotomurales (Photo-murals), which you began in the ’90s and are still working on, and in the series Epifanías (Epiphanies, 1980s–90s), you use audiovisual narratives. Why use an audiovisual component in a photography book project?

Gasparini: This allows me to incorporate spoken or written texts—poetry, music, sound, and imagery. Above all, it allows me to add a temporal shift. For me, audiovisual is the most complex and all-encompassing medium. The form helps deepen what I want to express. There I find what the photograph on its own doesn’t provide—with its claim to replace the disorder of the world with the balanced order of the composition.

Berti: Since the 1980s you’ve been presenting audiovisuals together with slide-show projections, synchronizing three carousels of slides in a cinematic way. You orchestrated the projection in museums as well, as a sort of in situ performance.

Gasparini: The performance is important because, as the author of the project, I am present. The projection allows me to establish a dialogue with the public. Before projecting the piece, I can insert or extract images and organize a loose discourse, one that’s mutable and changeable, different with every projection.

Berti: You have often framed writing in your photographs, be it publicity slogans or graffiti. Do you feel that the image is not significant in and of itself?

Gasparini: The image on its own nailed to a wall doesn’t interest me. My interest has always been to edit images in the same way as words or discourse. From a fleeting image I like to develop visual phrases.

Paolo Gasparini, Los Filúos market, Guajira Peninsula, ca. 1980

Paolo Gasparini, Los Filúos market, Guajira Peninsula, ca. 1980 Paolo Gasparini, Prontuario, Mexico City, 1993, from the series El suplicante (The supplicant)

Paolo Gasparini, Prontuario, Mexico City, 1993, from the series El suplicante (The supplicant)Berti: In the series Fotomurales, in some of the audiovisuals (early 2000s), you appropriated the revolutionary iconography of the continent, depicting Che or Tina Modotti; you uplift heroes who were dedicated to the Cuban dictatorship, as in Che’s case. Is this a way of remembering or refreshing a political position?

Gasparini: What you’re asking corresponds with a specific moment and context in recent Latin American history. In the ’60s and ’70s, there wasn’t a single place in South America that hadn’t been invaded by a political or advertising message, to the point where Coca-Cola and Che both became hypercontaminated icons in Latin America’s cultural memory.

Berti: In Modotti’s case it seems more like a romantic relationship.

Gasparini: Tina is special. She was born in Udine, a city close to Gorizia, my native city. When I was very young, Strand spoke to me of her, describing her as a great heroine of the revolution and an extraordinary photographer. In Mexico, I was a friend of [Manuel] Álvarez Bravo’s, who studied, worked, and helped Tina with her Mexican ordeal, so full of betrayals. Edward Weston’s journals speak of Tina, and for years his journals were by my bedside. In addition, Tina was beautiful and her photography was beautiful. Tina is another love in the journey of my life.

Berti: You developed your photography practice in close collaboration with the women you shared your life with.

Gasparini: I’ve been lucky. With the women I’ve loved I’ve had relationships filled with complicity and mutual interests. They were all intelligent, passionate, curious about photography, and shared my concern for social equality. Franca was a great partner; she helped me with my lab work. Duda Ferrari, an Italian architect, complemented my architecture work and designed several political publications in Caracas in the 1970s. With María Teresa Boulton I began a project of promoting photography as art in Venezuela, through the Fototeca gallery (1977–82), later the Venezuelan Council for Photography. Finally, with Marianela Figarella, an intelligent and passionate researcher, I shared ideas about photography as art and cultural product.

Paolo Gasparini, The habitat of man, Bello Monte, Caracas, 1968

Paolo Gasparini, The habitat of man, Bello Monte, Caracas, 1968 Paolo Gasparini, Mexico City, 1971–72, from the series El suplicante

Paolo Gasparini, Mexico City, 1971–72, from the series El suplicanteBerti: You still take pictures. Why?

Gasparini: In the end, after so many journeys, I believe there are some images that “bite,” or pierce you, as Barthes notes. I think photographs can help us learn how to look. How to think about and resist this world that’s consecrated to the grandiloquence of symbols that propagate lies and that, more and more, reduce and undervalue life.

Berti: How do you view the relationship between politics and photography?

Gasparini: Whether the formalists and Conceptualists like it or not, the image—the photograph—is a product of ideology. What is captured is in the mind of the person who triggers the shutter. Photography is the result of a thought process; it’s a serious subject. It’s not a click made with, say, a smartphone for uploading photographs to Instagram or Facebook.

Berti: Why take a political stance?

Gasparini: As Georges Didi-Huberman, a popular philosopher among the young Venezuelan Conceptual artists, says, “In order to know, you have to take a position. To take a position is to want, is to demand something, is to situate oneself in the present and aspire to a future.”

Berti: What do you think about being considered a Latin American photographer?

Gasparini: I’m eighty-one years old. I’ve lived for sixty years in Latin America and twenty in Italy. I’ve lived between two worlds and I travel frequently. Obviously I consider myself a Latin American photographer in the sense that my work is connected to the social and cultural events of the continent.

Paolo Gasparini, Guajira women in Maracaibo, Venezuela, 1969

Paolo Gasparini, Guajira women in Maracaibo, Venezuela, 1969 Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Quito, Ecuador, 1982, from the series La calle (The street)

Paolo Gasparini, Untitled, Quito, Ecuador, 1982, from the series La calle (The street)All photographs © and courtesy Paolo Gasparini

Berti: Is there such a thing as Latin American photography?

Gasparini: If we locate photographic practice in a given territory, evidently Latin American photography exists, in the same way people speak of North American or Japanese photography. Photography has a history here: The second half of the nineteenth century saw the rise of travel photography and its stubborn depiction of the “other.” The first decade of the twentieth century included Agustín Casasola’s extensive and unprecedented coverage of the Mexican Revolution. The Cuban Revolution expanded the drive to photograph every corner of Latin America. During the Cold War, the medium was used by those we now call the “Conceptualists of the South” as a tool for dissent against totalitarian regimes, such as Pinochet’s in Chile.

Recently, Alexis Fabry curated the exhibition América Latina: Photographs, 1960–2013 (2013) at the Fondation Cartier in Paris, and also organized Urbes Mutantes (Mutated metropolises, 2013–14), in Bogotá and New York; these were extraordinary exhibitions that covered a wide repertoire of photographs made in Latin America. Currently, many photographers work in the region, documenting diverse local realities, and they generate proposals that are comparable to those of photographers on other continents.

Berti: You’ve spent more than sixty years taking photographs. Do you have an opinion about contemporary photography?

Gasparini: Paul Strand, my teacher and friend, fought all his life for socialist ideals and for photography to be accepted in museums and purchased for its rightful commercial value. Now, in Latin America and in the rest of the world, socialism is dead or confined to museums. Photographs are sold at art fairs, veritable art supermarkets. Strand’s photographs sell for thousands at art auctions: they’ve gone for more than a hundred thousand dollars! It has all come to pass, cara Sagrario.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan and Paula Kupfer. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.”

May 16, 2024

An Unexpected Pairing of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron

This spring, the National Portrait Gallery in London has staged an unexpected pairing of Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron, whose bodies of photographic work were made a hundred years apart. The lushly titled Portraits to Dream In, the result of a thoughtful and imaginative curatorial inquiry, provides a compelling guide to their posthumous resemblances and describes a cultural arc of Romanticism from the mid-nineteenth-century to the turn of the twentieth, from luminous and pastoral to haunted and opaque. Both artists were engaged with the past, and the exhibition places them in a shared classicism of figuration and myth—a revelatory insight for Woodman. Both practiced photography for less than fifteen years. Both of their biographies often eclipse their critical reception. At times their congruence feels magnetic; at times their differences are as illuminating as their similarities.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1979

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1979Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation/DACS, London

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Dream (Mary Hillier), 1869

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Dream (Mary Hillier), 1869Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The exhibition is organized by curator Magda Keaney in tidy themes that support affinities between the two women, among them “Angels and Otherworldly Beings,” “Mythology,” “Doubling,” and “Nature and Femininity.” Much of this is informative and, indeed, suggests a universal lexicon beyond this survey of dual sensibilities. Some of the rhymes are less plausible: a section entitled “Men” fails to persuade that Cameron’s depictions of eminent male political and cultural figures mirror Woodman’s male portraits. Unclothed men make rare appearances in Woodman’s photographs, where they do little to diminish the images as self-portraits. Festooned with a seashell, egg, pomegranate, or dead bird, the men serve as playful surrogates for the photographer herself.

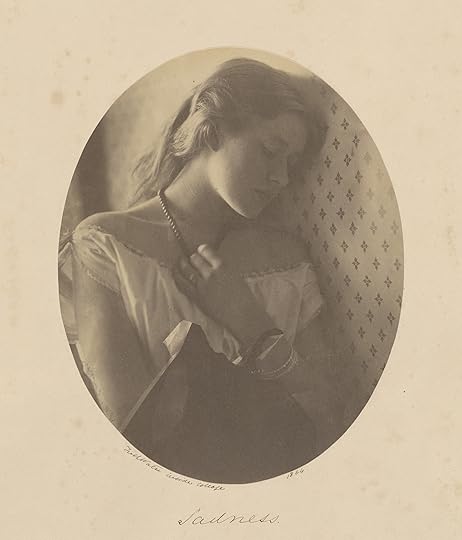

Julia Margaret Cameron, Sadness (Ellen Terry), 1864

Julia Margaret Cameron, Sadness (Ellen Terry), 1864Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Francesca Woodman, Polka Dots #5, 1976

Francesca Woodman, Polka Dots #5, 1976Courtesy Woodman Family Foundation/DACS, London

Portraits to Dream In is an occasion to revel in the sumptuous texture of the photographic print, born from technologies decades apart. For both photographers, darkroom manipulation and tactility contribute to the pictures’ emotional mood, however diametric. For Cameron, the shallow depth of field and long shutter speed of the glass plate negative and wet collodion process renders a picture that flutters as if provisional, a vision subject to light glinting off an immaterial surface. They are as ethereal and transparent as Woodman’s are submersed in shadow; a moth bounding away from flame. One body of work, despite its soft patina, feels rooted in a sense of presence, the other by absence: fraught and confessional without evident disclosure.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1977, from the series Angels

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1977, from the series AngelsCourtesy Woodman Family Foundation/DACS, London

Julia Margaret Cameron, I Wait (Rachel Gurney), 1872

Julia Margaret Cameron, I Wait (Rachel Gurney), 1872Courtesy the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

One of the pleasures of the exhibition is that it inspires thinking about the diversity of photographic narrative—here, one illustrative and the other suggestive. So too, the formal characteristics of the medium as an embodiment of the values of its era. As an act of photographic theatre, Cameron’s portraits are famously a pictorialist stagecraft: a pantomime of Christian archetypes, Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics, and the influence of contemporary poets such as Shelley, Keats and Tennyson. What would be considered as potential subject matter for this nascent thirty-year-old medium was formative and cautious, and the conventions of beauty and gender, static.

In vivid contrast to this Victorian piety and virtue, Francesca Woodman’s theater is a modern dramaturgy of emotional monologue (and the staging of Samuel Beckett), of performance art and contemporary choreography and most crucially, an assertion of the female body into the social space, aligning with feminist thinking. The work was made at a time when the subjectivity of the medium and a photographic narrative for what was felt was emerging, and particularly embraced in art school, where self-expression and identity seemed obligatory. In the 1970s, a smart photography student would be absorbing the work of Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Duane Michals, Nancy Rexroth, and Deborah Turbeville. As a student, Woodman gathered this burgeoning photographic interiority to the self-absorption of youth.

Installation view of Francesca Woodman’s Caryatid series at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 2024. Photograph by David Parry

Installation view of Francesca Woodman’s Caryatid series at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 2024. Photograph by David ParryIt’s possible to perceive both aesthetic contexts as a continuing exemplar of photography seeking its status as a high art form, contrary to its mechanical reputation. A meaningful presence in Portraits to Dream In is one of the last works of Francesca Woodman, from 1980, which departs dramatically from her more familiar small and elusive pictures. The monumental schema of the Caryatid series, an eight-foot-high construction of diazotypes—a form of blueprint—of draped female figures, referring to the carved figurative pillars in ancient Greek art: Here is a self-portrait of empowerment, of architectural strength, suggesting the future of her work with the benevolence of time. These last Untitled works connect the correspondences between the two artists—who shared a legacy of romanticism, rooted in the mythic antique—and their enduring power through their lifetimes and into our present.

Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In is on view at the National Portrait Gallery, London, through June 15, 2024.

May 14, 2024

Avion Pearce Creates a World between Reality and Dreams

In her poem “A Litany for Survival,” Audre Lorde speaks of the precarious experience of living with the knowledge that one’s survival is not only without guarantee but actively, purposefully threatened. Avion Pearce borrowed a line from Lorde for the title of their series In the Hours Between Dawn (2022–24), an ode to the possibilities of the midnight hours. The experience of the queer and trans community of color in Brooklyn that Pearce photographs is a testament to Lorde’s words. Survival—half shrouded, yet insistent—can appear in forms both soft and strong.

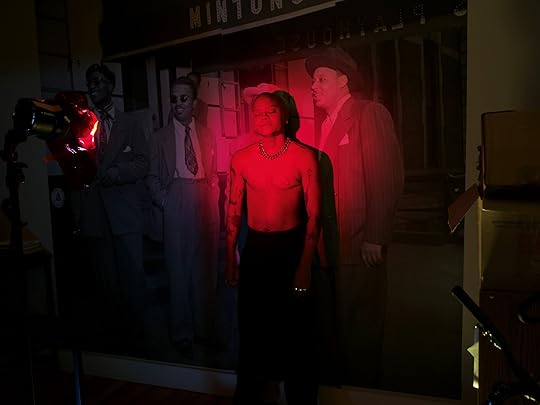

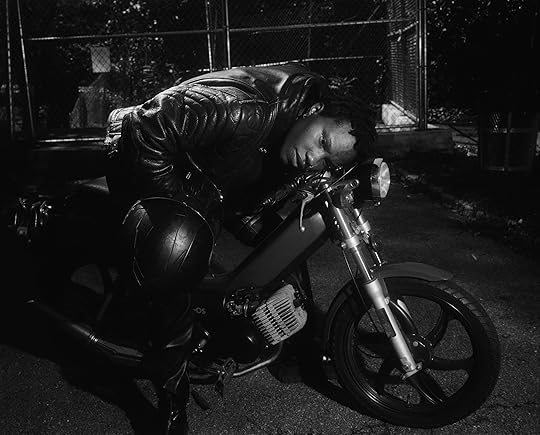

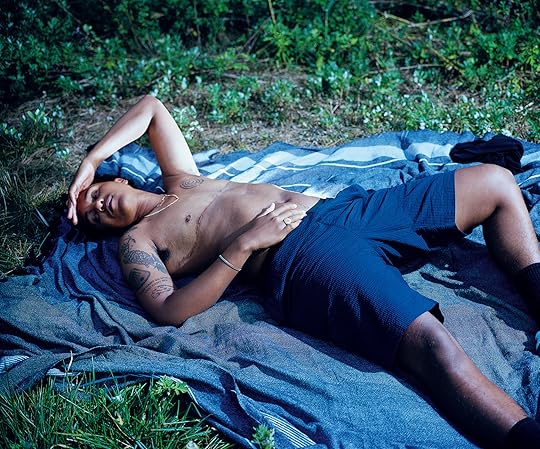

Pearce, who works with 8-by-10 and medium-format cameras, considers how photography shapes ideas about identity and history. “I was looking at some of the tools that have been used to construct these ideas,” Pearce told me recently, describing their desire to use older photographic methods to address the way the form has influenced how we see and understand the world. The presence of other photographic documents—a film still, a poster, a backdrop showing men in suits outside a Harlem jazz club—within Pearce’s pictures is also notable, and seems to speak to the power, promise, and perils of imagery.

Avion Pearce, Caravan, Clinton Hill, 2023

Avion Pearce, Caravan, Clinton Hill, 2023  Avion Pearce, Offerings, Both Ways, 2022

Avion Pearce, Offerings, Both Ways, 2022 Merging analog techniques with political purpose and a poetic sensibility, Pearce creates a visual realm that operates somewhere between reality and dreams. How to express what goes purposefully unseen? The assault on trans and queer rights, recently emboldened in this country, requires new ways of thinking about visibility, Pearce said, describing a certain aesthetic associated with queer photography: subjects pictured in a straightforward and highly perceivable way. “That work is really important and necessary, but I also feel that, in this particular moment, it’s important to think about whether or not visibility is necessary, and when it’s harmful.” For some images, Pearce photographed at night, while in others, they used a day-for-night technique that approximates night, allowing for a selective exposure within the frame while leaving the rest in darkness.

The assault on trans and queer rights, recently emboldened in this country, requires new ways of thinking about visibility.

Born in Flatbush, Brooklyn, to Guyanese parents, Pearce now lives in New Haven, Connecticut. Growing up, their parents took many family snapshots of Pearce and their brother, and the photographer remembers bringing their father’s 35mm camera to middle school to make pictures of friends. World-building and an attraction to magical realism is an inheritance from their mother, who shared an interest in beauty, detail, and the cultivation of a space.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Pearce attended Parsons School of Design for photography, and commercial photography, then advertising, before pursuing an MFA at Yale. It was there that Pearce was inspired by Abelardo Morell’s use of the camera obscura, which is deployed in one of Pearce’s particularly striking images: a figure lies in a dark bed, the Brooklyn skyline floating upside down on the wall above their head like a dream made visible. The camera obscura technique, employed for centuries by painters, recalls Pearce’s impressionistic use of light and shadow, focus and atmosphere throughout their imagery. Other influences include Ming Smith, Roy DeCarava, and Graciela Iturbide—photographers who innovated with light, motion, and ambiance—and the films of Wong Kar-wai and Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Pearce’s series also tells a story of housing insecurity and displacement, with Brooklyn, and especially Crown Heights, a character in its own right. Exploring photography’s potential to chart the interplay between time, the body, and the borough’s transformation, Pearce’s expression relies as much on feeling as on fact. In the Hours Between Dawn inhabits multiple registers, a document of what is and a vision of what could be. As in Lorde’s “A Litany for Survival,” Pearce’s sight stretches, “looking inward and outward / at once before and after / seeking a now that can breed / futures.”

Avion Pearce, Ellington, Crown Heights, 2023

Avion Pearce, Ellington, Crown Heights, 2023Beyond Lorde, there is a distinct literary quality to Pearce’s photographs. “Toni Morrison has this really beautiful way of describing light, of describing atmosphere, of describing the mundane,” said Pearce, who in a recent rereading of Beloved was particularly taken by Morrison’s depiction of the pulsing red light that fills the house at 124 Bluestone Road, where the ghost of Beloved returns to her mother.

“I just really wanted to know how that could translate to the process of making an image,” Pearce explained, considering how transcendent color might communicate feeling, sensation, even memory. “Is it possible,” they added, “to transport someone to a space or a time using something like light and color?” The luminous imprint of In the Hours Between Dawn lingers long after one’s eyes have left the artist’s world.

Avion Pearce, T, Crown Heights, 2023

Avion Pearce, T, Crown Heights, 2023  Avion Pearce, Van, Shirley Chisholm Park, 2022. All photographs from the series In the Hours Between Dawn, 2022–24

Avion Pearce, Van, Shirley Chisholm Park, 2022. All photographs from the series In the Hours Between Dawn, 2022–24Courtesy the artist

Avion Pearce is the winner of the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize. A solo exhibition of their work will be on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York in June 26–July 26, 2024.

This piece appears in Aperture, issue 255, Summer 2024.

A Playful Investigation of Community and Territory

Since the sixteenth-century, mining has been a dominant part of the Bolivian landscape and economy. During the colonial era, silver mining played a vital role in establishing the dominance of the Spanish Empire, and to this day, the region has continued to see extraction for minerals such as tin, zinc, and lithium. In his series MITA (2022–ongoing), the photographer River Claure asks: What are the repercussions of five hundred years of colonial extraction on a person’s sense of identity, history, and territory?

Photographing throughout Llallagua, Uncia, and Catavia—all former mining communities in the Bolivian Andes—Claure explores the shifting dynamics between landscape and self. “With this project, I return to these sites to think about the inherent relationship between nature and history, and how what happened in these places can be and is an analogy of the world to come,” says Claure. “These images speculate about the end of the world, the memory of my family, and our colonial relationship with the land.”

River Claure, Ocuri, 2023

River Claure, Ocuri, 2023Born in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where he is currently based, Claure studied graphic design and visual communication at Universidad Mayor de San Simón, before pursuing a master’s degree in contemporary photography at the Centro Internacional de Fotografía y Cine, in Madrid. Today, he considers his artistic practice to possess three main threads: identity, immigration, and territory. His previous series include Jinetes (2018), a body of work on identity and typology of the Bolivian Amazon, and Warawa Wawa (2019–20), a recontextualization of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s 1943 novel The Little Prince within contemporary Andean culture.

When Claure began to delve into his family’s history in Bolivia, MITA came into focus. Both of Claure’s grandfathers worked in a silver mine in the region, having emigrated to Cochabamba in the early 1970s, fleeing political conflict and seeking better living conditions. “I began to have more intentional conversations with my grandmother about what our history had been like, how they had decided to migrate to the city, and what their memories of these places were,” Claure says. “There was something already brewing.”

River Claure, Soccer Player 5, 2023

River Claure, Soccer Player 5, 2023Claure immersed himself in the communities he was photographing for three months at a time. Seeking to work collaboratively, he shared his knowledge through photography and art workshops for high school children, many of whose families became subjects in MITA. “During my time there I became friends with the local radio station, and sometimes we ran announcements on the town radio, calling for people who wanted to participate in a teatro (theater),” Claure says, “the term teatro is friendlier than photography.”

Teatro is an accurate word for Claure, who describes his process of conceptualizing images as “writing directed games. I don’t have rigid or immovable ideas, they are games that trigger images or small stories that I would like to see visually.” There is a playful, fundamentally performative quality to the images. “‘Play’ for me is a space where the emotional, rational, and visceral meet.”

Throughout MITA, Claure creates an amorphous blend of time, merging past, present, and future (or, as Claure puts it, “a post-apocalyptic future”). The resulting images feel like a mere second within a larger scene, a series of tableaux vivants inviting viewers to imagine what might transpire next. Two men, dressed in black and white, stand at odds against a bare landscape. A woman kneels with her face at the edge of a still pond disrupted by a mysterious splash, a foot ominously edging into the frame. A soccer player’s body leaps out of the image, with another player in motion on the ground, as if he’s propelled the player in the air.

River Claure, Virgen cerro 2, 2023

River Claure, Virgen cerro 2, 2023Images of the environment and towns offer rare moments of stillness throughout MITA, reminding us of the unfulfilled promises of modernity. In one of the few photographs in which a subject stares directly into the camera, a woman’s face peers out, palms open, from a large triangular sculpture made from sheepskin and adorned with metallic birds and stars. Here, Claure seems to draw from the imagery of both the eighteenth-century painting Virgin of the Mountain of Potosí and Pachamama, or Mother Earth, a revered goddess of the Indigenous people of the Andes—attending to the multiple layers that create one’s understanding of their identity.

In MITA, Claure doesn’t seek to provide a form of “truth” often associated with photography. Rather than straight representations of the people and locations he encounters, Claure’s images question our assumptions to address the multifaceted way identity can be marked by territory—and what it means when that territory is mired by centuries of colonial violence. “What happens when the landscape is exhausted? What happens when industry and modernity have consumed everything? What happens when flags and nation states define us less and less?” asks Claure. “Is it possible to identify myself more with a mountain, with a sea, with a jungle than with the nationality written in my passport?”

River Claure, Untitled 3, 2023

River Claure, Untitled 3, 2023 River Claure, Seven adults and one child in the landscape, 2023

River Claure, Seven adults and one child in the landscape, 2023 River Claure, Pianist, 2023

River Claure, Pianist, 2023 River Claure, 26, 2023. All photographs from the series MITA, 2022–ongoing

River Claure, 26, 2023. All photographs from the series MITA, 2022–ongoingCourtesy the artist

River Claure is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

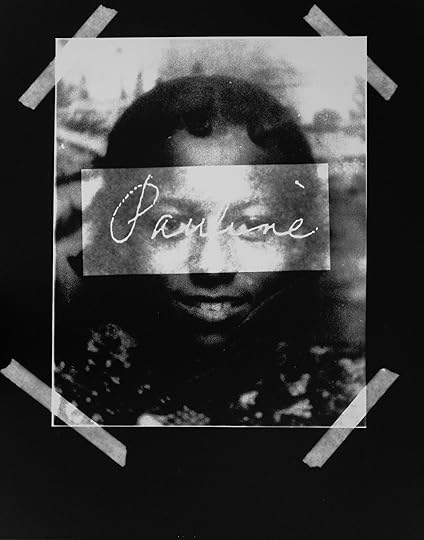

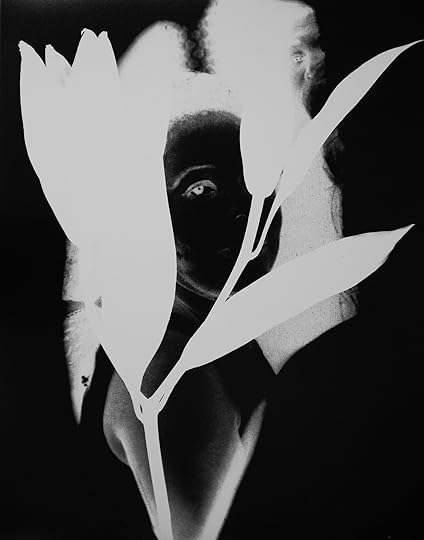

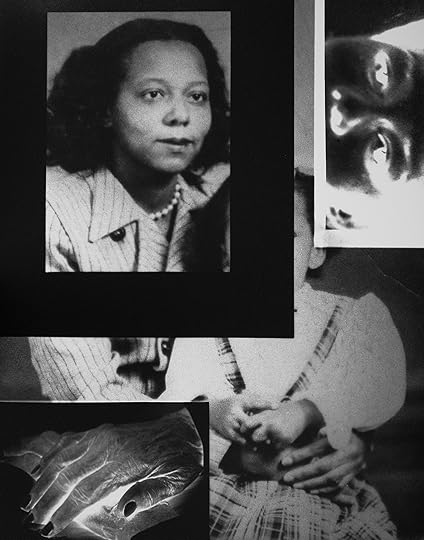

Janna Ireland’s “Pauline” Is a Passport into a Past Life

Janna Ireland takes a multifaceted approach in her artistic practice, ranging from architectural photography—such as her critically acclaimed project Regarding Paul R. Williams (2016–2020), which highlights the work of the first certified Black architect west of the Mississippi River—to darkroom experiments. In her series Pauline (2023), Ireland uses the vernacular of the family photo-album to consider the significance of the “amateur” photographer, creating what she describes as “a non-linear tribute to my grandmother.” When the eponymous Pauline died, in 2022, Ireland inherited hundreds of her photographs. The project finds her manipulating some of them in a darkroom, seeing through the images to interpret her grandmother’s lived experience as a teenager in Philadelphia during the 1930s and ’40s. The result is a collection of images that almost seem to be without author.

Born in Philadelphia, Ireland is now based in Los Angeles, where she is an assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Occidental College. She was influenced by her father, a photographer who learned the art form in the Army during the 1960s, and she became an avid collector of vintage photographs, mostly daguerreotype and ambrotype portraits from the nineteenth century. “Something I think about a lot when I look at those photographs is how disconnected they have become from their original source,” she says. “For many years, each one was an important and precious family artifact, but one day, the last person who cared for them died.”

Pauline is as a passport into a past life, visible through moments in time that live on from generation to generation. For Ireland’s grandmother, making photographs and being photographed were radical acts of self-definition and self-preservation. “Framed photographs and family albums are domestic objects that have always fascinated me. It made sense to me to explore family photographs in my work,” Ireland says. In the pivotal essay “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” the author bell hooks describes the relationship between photography and Black image production: “Cameras gave to black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images. Hence it is essential that any theoretical discussion of the relationship of black life to the visual, to art making, make photography central.” Woven alongside Ireland’s consideration of the Black experience is a sense of the celebratory nature of deconstructing her grandmother’s archive.

“Pauline is an act of transmutation, taking images that have a special, specific meaning to me and transforming them into something else,” Ireland says. In the process, she combined 35mm enlargements, contact prints, and photograms to create twenty-one different panels that comprise one complete work. Lilies (a symbol of mourning), fragments of her grandmother’s jewelry, and photograms from her funeral were incorporated to memorialize her grandmother’s complex, remarkable life.

Ireland invites viewers to witness the imperfections of her work: the fuzzy quality of duplicated photographs, overlapping edges, and handwriting she’s described as “very left-handed,” illustrating the fondly cherished flaws of family. She says the process was meditative, “day after day manipulating various elements to return to the same images of my grandmother—that felt iconic.” Ireland hopes through her work that the images will live beyond the family photo-album, where others can see and find value in them, just as she has. “They are abstracted versions of the source images, made to be shared, while the originals—in all their specificity—remain private, just for me and my family.”

All photographs by Janna Ireland, Untitled, 2023, from the series Pauline, 2023

All photographs by Janna Ireland, Untitled, 2023, from the series Pauline, 2023Courtesy the artist

Janna Ireland is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

In India, an Artist Revives the Legacy of a Small-Town Photo Studio

Abhishek Khedekar grew up by the sea. For most of his childhood, his hometown of Dapoli—which clings to India’s western coastline, about 125 miles south of Mumbai—felt like a precious secret. Flanked on either side by mountains and the Arabian Sea, the town was once a British army camp; today, it’s a beloved regional tourist destination, replete with coconut trees that tower over the graves of colonial officers. Dapoli offered a limitless canvas to a young Khedekar, who spent countless afternoons exploring its verdant expanse with his friends. He didn’t know it back then, but the images of home formed in his boyhood would inspire a search years later. The resulting series, Dapoli, Lost and Found (2018–ongoing), is a portrait of a place and time, and an attempt to reconjure the latent magic of childhood—to see more clearly what was, and what perhaps still may be.

Khedekar knew he wanted to be an artist from an early age, and also knew that he’d have to leave Dapoli to make that happen. At eighteen, he moved to the city of Pune to attend a fine arts university, where his interest in drawing and performance evolved into a fascination with photography. While cameras were still relatively expensive pieces of hardware for a student’s budget, there were more photo studios in a city like Pune than in small-town Dapoli. A friend of Khedekar’s who worked at one allowed him to pick up some work during the day and experiment with the camera and lighting equipment at night. “I started by making passport-sized photographs,” he says. It wasn’t until his senior year, when his parents gifted him his own Canon DSLR, that Khedekar finally had the freedom to push his photography forward.

Abhishek Khedekar, Friend of Mine, 2021

Abhishek Khedekar, Friend of Mine, 2021As he gained confidence in his pictures, Khedekar enrolled in one of India’s most prestigious art and design schools, the National Institute of Design (NID), in Ahmedabad, for a master’s degree in photography. “This was where I started learning more about the history of photography,” he says, “and what my notion about it could be.” If it’s true that we must leave a place to understand it better, Khedekar carried Dapoli with him wherever he went. He returned home a few times to photograph it, but it wasn’t until his thesis assignment that a framework began to emerge.

Central to the story of photography in India is the small-town photo studio, where industrious photographers, who more often saw themselves as operators rather than artists, captured generations of life—photographs for weddings, birthdays, school enrollments, job applications, matrimonial ads, and death certificates. In the clamor for iconic images and image-makers, the work of these studio photographers has largely been forgotten. NID encourages students to uncover this history, and to find previously unknown photographers, often from their own hometowns, to document. This is how Khedekar found Subhash Kolekar, who ran a beloved studio in Dapoli and, for some time in the 1960s, was its only photographer. Khedekar found traces of Kolekar’s photographic imprint across town: in family albums and on living rooms walls, in newspapers and police reports, and even as scientific illustrations still held at the local university. Kolekar rarely kept his own negatives and prints, but his archive was woven into the larger fabric of life in Dapoli.

Abhishek Khedekar, Young Boy, 2018

Abhishek Khedekar, Young Boy, 2018  Abhishek Khedekar, Archival Image, Dr. Sachin Gujar, 2018

Abhishek Khedekar, Archival Image, Dr. Sachin Gujar, 2018 While he’s still decidedly the author of Dapoli, Khedekar channels his older counterpart throughout the series (Kolekar died in 2018). One close-up portrait of a young Mallakhamb apprentice mimics an image from Kolekar’s archive of another boy of similar age, seemingly carved into the silhouette of a flame. In other instances—as with Coconut Milk (2018), Jackfruit (2018), and Dryfish (2021)—Khedekar attempts to recreate Kolekar’s scientific and instructional imagery, linking it to his own upbringing in their shared hometown. The photographs in Dapoli don’t just follow their predecessor’s visual blueprint, they embody its unrealized possibilities. What might have happened if Kolekar had the means to pursue his own artistic vision of Dapoli?

Khedekar now lives and works in Delhi, and often takes on commercial and editorial work. Most recently, Loose Joints published his debut monograph, Tamasha (2023), in which he follows a nomadic troupe of Dalit performers that he first saw as a child. The work in Dapoli is ongoing. “I’ve been photographing a lot of the old houses,” he says, “to focus on how quickly my sleepy, sensitive town is changing.” Despite their soft, temperate patina, Khedekar’s photographs are haunted by a double vision—of two photographers separated by time and circumstance, and of one separated from his own childhood by memory and distance. Homecomings are a tricky business, charged with both warmth and alienation. As the scholar Homi K. Bhabha once wrote about returning to his native Mumbai: “Your person divides, and in following the forked path you encounter yourself in a double movement . . . once as stranger, and then as friend.”

Abhishek Khedekar, Scarecrow, 2018

Abhishek Khedekar, Scarecrow, 2018  Abhishek Khedekar, Summer Afternoon, 2018

Abhishek Khedekar, Summer Afternoon, 2018  Abhishek Khedekar, Dry Fish, 2021

Abhishek Khedekar, Dry Fish, 2021  Abhishek Khedekar, Broken Bridge, 2022. All photographs from the series DAPOLI, Lost and Found, 2018–ongoing

Abhishek Khedekar, Broken Bridge, 2022. All photographs from the series DAPOLI, Lost and Found, 2018–ongoingCourtesy the artist

Abhishek Khedekar is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Laila Stevens Seeks Sisterhood in Her Portraits of Black Women

When Laila Stevens first drove from New York to North Carolina to visit her extended family on a summer trip in 2021, she was immediately struck by the historical weight of the Southern landscape. “It was my first experience with seeing swampland, plantations, trees that were reminiscent of things that I’ve seen in history books,” Stevens says. “It was very shocking and moving to me—it felt like it needed to be documented.” Shortly after arriving, she took a walk through the swamplands with her sister. Having just watched Gordon Parks’s film The Learning Tree (1969), she instantly recalled the tragic scene in which a Black man is chased into a swamp and shot by a white sheriff. “I had to be able to capture and reference how similar both of these are, this historical scene ingrained in my memory, and this contemporary one that’s right in front of me.”

Laila Stevens, Untitled (Swamp), 2021

Laila Stevens, Untitled (Swamp), 2021It was, perhaps counterintuitively, this fraught encounter with the natural landscape that spurred the first images that would evolve into The Clayton Sisterhood Project (2021–ongoing), her series of intimate, celebratory, and powerful black-and-white portraits of Black women and girls in and around the home. As Stevens spent more time with her family in their North Carolina home, ideas around landscape, history, family, and ownership began to percolate. “I eventually realized that it’s really important to have these natural references, especially as Black people have not always had the authority or the economic power to acquire land,” she says. “In contrast, all of these domestic images show people able to take economic power through the ownership of space—having the power to decorate, create safety inside, and being able to gather, speak, and tell stories.”

Stevens, who was born in Queens and now lives in Brooklyn, studied photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology, where she initially struggled to reconcile her images of her family with the images she was making back in New York. Over time, as she continued to photograph the women around her, she found that the concept of “sisterhood” was a central, unifying factor. At first, this concept had a more literal application, as Stevens staged portraits of her relatives in Queens and North Carolina. As the project progressed, the term “sister” expanded to include people who identify as femme or women, and to signify a broader sense of relational bonding between women. “A lot of my friends identify as queer or lesbian, and discovered that we were creating our own form of sisterhood and family bonding that I wanted to memorialize in portraiture,” she explains.

Laila Stevens, Ibtisam & Momma, 2023

Laila Stevens, Ibtisam & Momma, 2023Stevens cites as influences the work of Gordon Parks and Carrie Mae Weems as well as portraits of Black women writers from the 1980s. In photographs of June Jordan by Gwen Phillips or Ntozake Shange by Martin Reichenthal, Stevens found the sense of admiration, veneration, and softness that she wanted to achieve. “There’s also an image called Sister Love by Jim Alexander—a group photograph of Gwendolyn Brooks, Toni Cade Bambara, Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and others—that I love,” Stevens says. “I’m looking at both the visual aspects of positioning in collective gathering, but also the emotional sincerity of these singular moments that are all emphasized by the soft light.”

In Ibtisam & Momma (2023), a young woman in repose confronts the camera, lit softly by the ambient light of the living room, while Stevens’s mother looks on, silhouetted in the background. The authority of the subject’s gaze, the intimacy of the domestic scene, and the suggestion of intergenerational kinship codifies the wonderful sense of reverence, respect, and tenderness that is emblematic of Stevens’s work, where sisterhood is both the subject and the method of making. “I want to allow a sense of authority for the women in the images who might not otherwise have a sense of authority in the world,” Stevens says. “Despite social implications or perceptions, they’re looking into the camera, they’re looking at the person and saying, This is me, this is who I am, this is my family.”

Laila Stevens, Lineage, 2022

Laila Stevens, Lineage, 2022 Laila Stevens, Tear, 2021

Laila Stevens, Tear, 2021  Laila Stevens, Branches, 2021

Laila Stevens, Branches, 2021  Laila Stevens, We Will All Cross Paths, 2023

Laila Stevens, We Will All Cross Paths, 2023  Laila Stevens, Bike Race, 2021

Laila Stevens, Bike Race, 2021 Laila Stevens, Stevens Family Portrait, 2021. All photographs from the series The Clayton Sisterhood Project, 2021–ongoing

Laila Stevens, Stevens Family Portrait, 2021. All photographs from the series The Clayton Sisterhood Project, 2021–ongoingCourtesy the artist

Laila Stevens is a runner-up for the 2024 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

May 1, 2024

A Young Photographer Makes a Family Tree about South Africa

A vast and variegated holiday destination, a bottomless repository of cheap Black labor, and a site of bitterly fought wars of resistance against colonial dispossession—South Africa’s Eastern Cape is as beautiful as it is unknowable. The province occupies the moodiest quarter of the country’s coastline and stretches into the semiarid escarpment and the southern edge of the Drakensberg mountain range. Its landscape is at parts lush, rugged, pristine, and broken.

In the Johannesburg-based photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa’s newest series Ezilalini (The Country) (2020–ongoing), the elements guide a search for wholeness. The terrain—misty, parched, and undulating—offers more vestiges and apparitions than signposts. Sobekwa likens the segue into this project, in which he travels between the township of Thokoza, where he grew up, and his parents’ rural homesteads, to “digging a hole I’m afraid to look into.” This outsiderness is writ large over many of the photographs. It is visible in the scraps of land overused to the point of collapse, in the somnambulism of everyday routines that overburden women, and in an idleness in young men interrupted only by the gendered enactment of ceremonial roles.

Newly graduated initiates from Qumbu Black Hill village, Eastern Cape, 2021

Newly graduated initiates from Qumbu Black Hill village, Eastern Cape, 2021  Sobekwa’s aunt in Ekhwenzane village, where his maternal family lives, Tsomo, Eastern Cape, 2020

Sobekwa’s aunt in Ekhwenzane village, where his maternal family lives, Tsomo, Eastern Cape, 2020 Sobekwa began making frequent trips to the Eastern Cape for an earlier series on the troubled life of his late elder sister. Even as he mapped his family tree, an endeavor to which he gives repetitious, totemic expression throughout Ezilalini, his obsession was undergirded by a desire to think of home in less regimented ways. “It’s not only about my family, it’s a family tree about South Africa,” he explains. “The history, the migration, my family’s legacy with mines. I almost worked in the mines myself. A lot of people can relate to that.”

Sobekwa’s work provides the space for personal contemplation and the wider political reflection required in a nation as young as South Africa.

Trees, plant life, and graves anchor this trip through the countryside. One of the project’s more evocative images, made in Tsomo, depicts his mother, shoulders covered and back to the camera, paying respects to her daughter and brother. Her reverence, split between two graves, recalls Sobekwa’s struggle to reconcile the maternal and paternal branches of his family tree. Viewing the series, we flit between Tsomo, his mother’s homestead, and Qumbu, 120 miles northeast, where his father was raised. Each location holds sacred family folklore: how his grandmother went into labor on a hilly outcrop in Tsomo, earning his mother the name Nontaba, meaning “child of the mountain.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

In all these images, Sobekwa invites the harshness of rural life to stare at us in poetic ways, even as some of his subjects avert their gazes. The posed images do not mask the tensions, both personal and societal, arising in the wake of his search. In one image made in Qumbu, a church in which Sobekwa’s father married his first wife stands gutted after a fire. In another, Sobekwa photographs a woman named Gogo Lucy Zwane as she inhales the scent of hollyhocks from a garden she planted as a symbol of peace, as apartheid’s secret agents fueled political violence. On the same ground where photojournalists once recorded grim scenes, Sobekwa authors a new myth, one that recasts the killing fields of Thokoza as dreamy, fragile panoramas of serenity.

Sobekwa’s mother visiting the family’s ancestral graveyard, Tsomo, Eastern Cape, 2020

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Sobekwa was introduced to photography through Of Soul and Joy, a workshop in Johannesburg’s East Rand, in 2012, as a high school student. Given the speed at which he developed his talents, Sobekwa’s dilemma would be honing a personal style from the wide pool of influences at his disposal. “My early work says a lot about the people that inspired me, like Ernest Cole, Santu Mofokeng, Peter Magubane, David Goldblatt,” he states. “I’m lucky that I discovered that passion early on, and I took it seriously.”

He remembers being reduced to tears on his first encounter with Cole’s 1967 photobook House of Bondage, and his ego being shattered by Mofokeng, who simply told Sobekwa to read in order to frame his work on his own terms. Sobekwa’s oeuvre is fittingly laden with homage. But the vulnerability with which he approaches his subject matter reveals a generational encumberment—a fitful, perhaps sacrificial, desire to get to grips with the cumulative horrors of a society coming undone. In this pursuit, the twenty-eight-year-old Sobekwa has turned to both the rich canon of his home country and the work of others who have continued to challenge the constraints of documentary photography. The power of a work like Ezilalini is that it provides the space for both personal contemplation and the difficult, wider political reflection required in a nation as young as South Africa.

The ruins of a church where Sobekwa’s father was married, Qumbu, Eastern Cape, 2020

The ruins of a church where Sobekwa’s father was married, Qumbu, Eastern Cape, 2020  Girls from the Nala clan during a traditional ceremony called intlombe, Cofimvaba, Eastern Cape, 2021

Girls from the Nala clan during a traditional ceremony called intlombe, Cofimvaba, Eastern Cape, 2021 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Sobekwa’s father’s childhood friends from Ntabasigogo village, Qumbu, Eastern Cape, 2020

Sobekwa’s father’s childhood friends from Ntabasigogo village, Qumbu, Eastern Cape, 2020  A street food stall on Khumalo Street, Thokoza, Johannesburg, 2021

A street food stall on Khumalo Street, Thokoza, Johannesburg, 2021  Gogo Lucy Zwane in her garden, Thokoza, Johannesburg, 2021. All photographs by Lindokuhle Sobekwa from the series Ezilalini (The Country), South Africa, 2020–ongoing

Gogo Lucy Zwane in her garden, Thokoza, Johannesburg, 2021. All photographs by Lindokuhle Sobekwa from the series Ezilalini (The Country), South Africa, 2020–ongoing© the artist/Magnum Photos

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 254, “Counter Histories,” produced in collaboration with Magnum Foundation.

Kosen Ohtsubo’s Flower Planet

For nearly fifty years, Kosen Ohtsubo has run roughshod over the idea of ikebana as a stately practice of arranging flowers in a vase. He is known for using vegetables, when he sticks to plants at all, and he often sets his compositions in unconventional containers. His 1984 work I Am Taking a Bath Like This was arranged in his own bathroom. On one wall, a cobalt vase in a small alcove holds some flowering irises. But this is only an accent within the wild gaiety of the entire piece, in which iris leaves have been plastered across the tiled room and gather neatly in the tub below, next to an array of flowers including roses, yellow lilies, and hydrangeas that just cover the bare chest of a man lying in the drawn bath. That’s Ohtsubo himself, with a faint but devious smile playing across his face. Is Ohtsubo’s own body also part of the “arrangement”? His knowing gaze, which lures the viewer into the scene, is directed toward the camera, operated in this case by Koichi Taniguchi, a photographer employed by the ikebana school to which Ohtsubo belongs. Recently, Ohtsubo has exhibited his ikebana in the form of photographs. He collaborates with other photographers, most often Taniguchi, though he sometimes operates the camera himself.

Now in his mid-eighties, Ohtsubo lives in Tokorozawa, a suburb of Tokyo, in a house that also serves as his studio and classroom. The building’s exterior is clad in ruddy steel plates that call to mind Richard Serra, but, by contrast, a charming, goofy sign that reads “Flower Planet,” in colorful and playful letters, hangs above the door. When I visited Ohtsubo in late 2022, he greeted me warmly and invited me to lunch before we started speaking about his work.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Strange Callas II, 1978

Kosen Ohtsubo, Strange Callas II, 1978  Kosen Ohtsubo, Like an Umbilical Cord, 1974

Kosen Ohtsubo, Like an Umbilical Cord, 1974 Ohtsubo has taken a gleefully unorthodox approach to ikebana, a practice of flower arrangement that emerged in Japan roughly six hundred years ago. Since then, various methods of displaying plants in vessels have been developed, discarded, and revived. In its modern form, the study and exhibition of ikebana are largely administered by various schools, to which almost all artists belong. Ohtsubo is no exception; for many years, he worked as one of the top teachers of the Ryuseiha School, and even in retirement he continues to serve as a special advisor to the school’s headmaster. Ohtsubo’s having such an esteemed position is somewhat ironic: when I spoke with him, his eyes lit up as he talked about how he wanted to produce work “with the goal of destroying ikebana.” Against the more rigid aspects of ikebana, Ohtsubo sought to introduce the rambunctious energy of free jazz, which he listened to eagerly as a teenager. In 1971, he caused a stir with his contribution to the Ryuseiha’s annual exhibition: he gathered up plant clippings and trash left behind by other artists who were preparing their ikebana on-site, threw everything into a large canvas bag, and put that on display. The act drew excitement and scorn in equal measure.

Ohtsubo has taken a gleefully unorthodox approach to ikebana, a practice of flower arrangement that emerged in Japan roughly six hundred years ago.

Submitting a sack of botanical trash to an official exhibition was a deliberately provocative gesture. Since then, Ohtsubo has continued to poke at the limits of ikebana; he titled one 1988 composition Is a Vegetable Stir Fry Avant-Garde Ikebana? It is, in fact, a vegetable stir fry, not so much arranged as plated in a large dish. But Ohtsubo is no simple jester: the work forces the viewer to consider what separates plating from arranging, cooking from ikebana. To prod the discipline in this way recalls the gestures of conceptual artists from the 1970s, whom Ohtsubo watched carefully. For example, he was deeply impressed by Between Man and Matter, a large 1970 exhibition in Tokyo in which Arte Povera and Mono-ha artists were shown alongside each other. Highlighting the Greek artist Jannis Kounellis in particular, Ohtsubo tells me that he was drawn to conceptual art for the same reason that he liked free jazz—it “rejected a traditional aesthetic, and tried to take an attitude toward material itself.” In other words, these practitioners of different disciplines—music, ikebana, contemporary art—are linked by a shared desire to go beyond the accepted structures of art.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Car Crash, 1996

Kosen Ohtsubo, Car Crash, 1996  Kosen Ohtsubo, Rikka of Lotus, 1993

Kosen Ohtsubo, Rikka of Lotus, 1993 Even so, Ohtsubo is also capable of working in classical modes. Take Rikka of Lotus (1993), in which three lotus flowers run straight down the middle, while their leaves extend outward with the slight asymmetry that corresponds to classical ideals of beauty within ikebana. The entire composition curves thrillingly through space, describing a gentle arc to the left, while the top leaf returns back to the central axis. The arrangement is placed in a studio, and here the photograph seems to be more clearly about recording the plants at hand. “Photography is not able to completely grasp the content of ikebana,” Ohtsubo says. Looking at this photograph, I can only imagine the smells and spaces that the picture cannot contain.

Kosen Ohtsubo, Keloid Man, 1976

Kosen Ohtsubo, Keloid Man, 1976  Kosen Ohtsubo, Mr. O’s Breakfast, 1973

Kosen Ohtsubo, Mr. O’s Breakfast, 1973 Perhaps for this reason, the relationship between these two forms has not always been friendly. The avant-garde ikebana artist Yukio Nakagawa, a precursor to Ohtsubo, also engaged extensively with photography, using techniques gleaned from the famed Japanese photographer Ken Domon. Nakagawa also swore off traditional materials and vessels. His most famous work, Flowery Priestess (1973), shows nine hundred carnation petals stuffed into a blown-glass vase, which has been turned upside down so that the paper below is stained with a red liquid that has spilled out. This could not possibly be stored in a museum—audiences today know it only as a photograph. And yet, in an interview from 1974 that dealt specifically with the relationship between ikebana and photography, Nakagawa argued for the former’s greater importance: “The main subject is the flowers that I arrange,” he said. “I do not arrange them for the purpose of being photographed.” The interviewer pressed a bit further: Couldn’t the photographs that result from his work be shown as photographs in their own right? Nakagawa offered a terse reply: “No. This is my ikebana.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Ohtsubo is less tied to these disciplinary boundaries than Nakagawa, perhaps because of his more mischievous approach— after all, Nakagawa never jumped in the bath with his flowers. “I do believe in the power of photography,” Ohtsubo says. “It can bring out really important aspects of ikebana. In that sense, I have hopes for fantastic photographers.” Perhaps ikebana needs photography in a way that sculpture does not, for the simple reason that plants wither away. Even in I Am Taking a Bath Like This, as soon as Ohtsubo stands up he will have disturbed the carefully laid out flowers at his chest. Histories of performance are often told through still and moving images, and the ephemeral aspects of Ohtsubo’s work, which go above and beyond the simple decaying of plants, both draw him to photography and place him within a broader tradition of performance art.

Yukio Nakagawa, Flowery Priestess, 1973

Yukio Nakagawa, Flowery Priestess, 1973Photograph by Naomi Maki © the artist

Kosen Ohtsubo, Botanical Man, 1978

Kosen Ohtsubo, Botanical Man, 1978Photographs by Koichi Taniguchi. Courtesy the artist and Ikebana Ryuseiha

In Botanical Man (1978), Ohtsubo again puts himself in the arrangement, to such an extent that he seems to merge with the plants. He strikes a studied pose, looking over a series of bound magazines with a cigarette held lightly between two fingers. Purplish castor oil bean plants crawl up the table and intertwine with his own body, held in place by white fabric resembling a bandage. I try to press Ohtsubo about why he included himself in this image, but he is keen to play down his role. He tells me that the castor oil bean plants had been assigned to him by an ikebana magazine as a prompt. “I tried a few things, and they weren’t working,” he says. “In the course of putting things together, I thought that it would be better to have the plants wrapped around me than using a vase—that’s all!”

Ikebana, photography, or performance? Ohtsubo relishes in leaving such questions unresolved. His work thrills by consistently, and exuberantly, mixing disciplines, leaving them all a bit refreshed—like they just went for a bath.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 253, “Desire.”

April 30, 2024

Aperture Breaks Ground for New Home on Upper West Side of New York City

On April 30, 2024, Aperture hosted a ceremonial ground-breaking at 380 Columbus Avenue to mark the commencement of construction of its new permanent home on New York’s Upper West Side, set within two floors of a historical building. Opening in early 2025, the highly visible and welcoming space signals a renewed, long-term vision for Aperture’s future—one that recognizes Aperture’s critical role in bringing together the array of artists, writers, institutions, and enthusiasts that are transformed by photography every day.

While honoring Aperture’s legacy and enduring role in the field, the celebration heralded a new era for the seventy-two-year-old photography publisher and organization. Inspirational remarks were given by elected officials whose steadfast support and capital funding have helped Aperture embark upon this momentous project and expand its access and reach. Gale A. Brewer, New York City council member, recognized the alignment of Aperture’s vision and values with the interests of the local community; Laurie Cumbo, commissioner of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, attested to the vitality instilled by the arts and the importance of culture being widely accessible for all New Yorkers; and Keisha Sutton-James, Manhattan’s deputy borough president, addressed the economic and cultural impact of Aperture and the arts within New York City. Colette Veasey-Cullors, Aperture trustee and Education Committee member, emphasized Aperture’s commitment to education and the illumination of a range of perspectives and pointed to the variety of public programs that Aperture has developed and will continue to offer at its new home.

Along with Aperture Executive Director Sarah Meister and Board Chair Cathy M. Kaplan, additional trustees, staff, and friends joined the event, including artists, funders, representatives from the neighborhood, and colleagues from fellow arts organizations.

“Today marks the start of a new era for Aperture,” said Aperture Executive Director Sarah Meister. “By expanding our reach and enhancing access to critical conversations around photography, we further solidify Aperture’s enduring role within New York City’s cultural landscape worldwide.”

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine stated: “I’m thrilled to see Aperture expanding into their new home on the Upper West Side, and I look forward to how Aperture will grow photography’s footprint in the city and partner with the community along the way. The arts stand as indispensable pillars, crucial to both our cultural richness and economic vitality, and Aperture is a testament to the innovation and prosperity that the arts bring to New York City.”