Aperture's Blog, page 17

July 2, 2024

The Uncanny Worlds of Nhu Xuan Hua

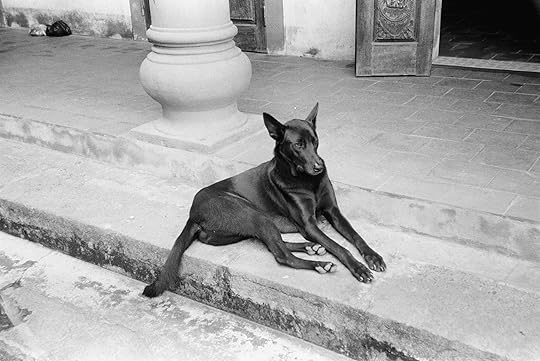

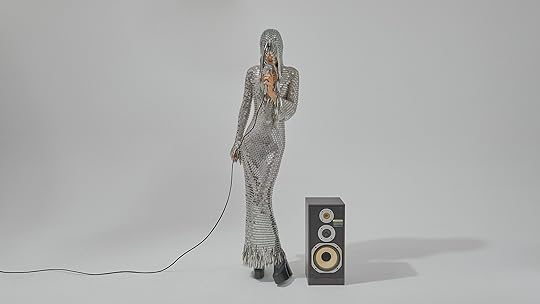

Nhu Xuan Hua’s photographs defy easy interpretation. A woman sings karaoke in a shining, armored gown. An archival wedding photograph is beguilingly redacted, dress and suit visible but the bodies of husband and wife absent contours. A black dog gazes out the entrance of a temple—whom, or what, is it guarding? Even the simplest image is limned with story; we sense it the way we remember our dreams upon waking. Hua’s powerful narrative vision shines through in the clarity of her photographs, which unfold like time passing in slow motion.

Born in Paris to Vietnamese immigrant parents, Hua grew up within a French culture that prized assimilation as a mode of survival. It wasn’t until after finishing her studies in photography at the Lycée Auguste Renoir Paris in 2011 and moving to London that Hua was confronted with the question of her origins. “Not enough answers were given by my family,” she tells me. “Because when you start asking questions, they say, ‘Why, why are you asking, the past belongs to the past.’” In 2016, Hua traveled to Vietnam, beginning an ongoing process of reconnection that has shaped her body of work.

Nhu Xuan Hua, Gardienne du Temple, 2020

Nhu Xuan Hua, Gardienne du Temple, 2020  Nhu Xuan Hua, The Wedding – Archive from 1985, 2016–21

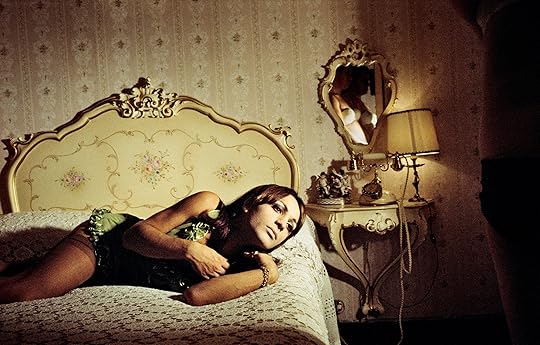

Nhu Xuan Hua, The Wedding – Archive from 1985, 2016–21 These personal interests seamlessly flow into Hua’s commissioned photography. Though she’s shot for clients as diverse as Maison Margiela, Time, and British Vogue, when asked about balancing expectations from brands and publications with her own perspective, she declares: “I take them on board with my vision, along the way with me.” Hua’s aesthetic propels every assignment, her exhaustive preparation and detailed mood boards merging art and design in the process. For Hua, an editorial campaign can function in two ways: as a stylized fashion shoot and as an exploration of her own references—the femmes fatales of Taiwanese cinema, her relationship with her deaf father, or her mother’s loneliness, for example.

In these shoots, Hua often constructs sets made of paper, a medium to which she was originally drawn for its accessibility; now she uses its inherent fragility to explore the constructed nature of memory. Truth, Hua knows, is only ever approximated: we create narratives in its stead. “Designing an object or a landscape as an extension of reality always comes with a story,” she says. Her use of construction as metaphor rhymes with her interest in Vietnamese modernist architecture, particularly as described in the architect Phu Vinh Pham’s 2021 book Poetic Significance, which argues that the style makes use of available modes and materials, blending rationalist function with spirituality and imagination.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Hua sees photography as a means to represent emotional truth without relying on the belief in the camera as sole witness. For her series Tropism, Consequences of a Displaced Memory (2016–21), Hua began by gathering archival photographs from her family’s time in Vietnam and their early years in France. Using a simple algorithmic tool that fills a shape with the information around it, she then digitally manipulated these images, working without a plan, allowing the process and the feelings it evoked to guide her. “It was a sensation you can hardly materialize—so I had to find it by working on the pictures,” Hua says.

Reworking the surface of the images, which Hua likens to the act of painting, mirrored her experience of filling the lacunae in her understanding of her family and Vietnamese identity. “Nothing is random,” she says. “Each image is a statement that took me a while to reflect on. When the image is done, it’s a way of saying that my reflection is done.”

Nhu Xuan Hua, Singer: “How much love can be repeated?,” 2022

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); } Nhu Xuan Hua, ILU, 2017

Nhu Xuan Hua, ILU, 2017  Nhu Xuan Hua, The Distorted Bench, 2019

Nhu Xuan Hua, The Distorted Bench, 2019 Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Nhu Xuan Hua, We walked in the forest at night, 2018

Nhu Xuan Hua, We walked in the forest at night, 2018  Nhu Xuan Hua, Sharp Tongue, Round Fingers, 2017

Nhu Xuan Hua, Sharp Tongue, Round Fingers, 2017All photographs courtesy the artist

Nhu Xuan Hua, Feeding, 2018

Nhu Xuan Hua, Feeding, 2018 This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue.”

June 26, 2024

Akihiko Okamura’s Outsider View of Northern Ireland

Early in the BBC documentary series Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland (2023), a powerful collection of personal testimonies on the Troubles, one speaker recalls his childhood excitement during the first waves of civil unrest. “It was mad . . . it was like a movie,” he reminisces, thinking back on the innocent elation he experienced as mass protests, running street battles, and military patrols became regular features of everyday life. Inevitably, as the daily drama intensified, with bombings, shootings, and funerals dominating the headlines, the desperate gravity of the situation became clear. Even to kids playing with pretend guns on the backstreets of Derry and Belfast, as the BBC interviewee remembers, “this was serious . . . it wasn’t like a movie anymore.”

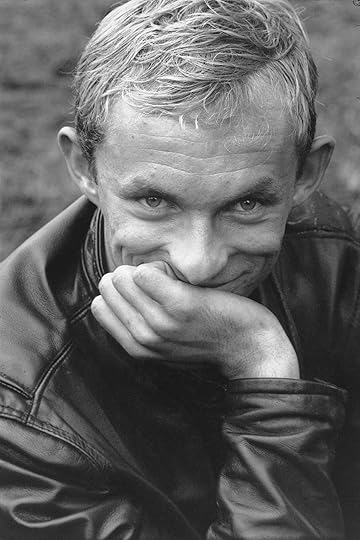

The Japanese photographer Akihiko Okamura first visited Northern Ireland during this formative phase of the thirty-year conflict, and his images capture, with understated eloquence, a sense of reality as shifting and unstable, both not quite real and all too real. In 1968, Okamura moved to Dublin with his family, prompted by a plan to explore the Irish roots of President John F. Kennedy. From there he made numerous trips north of the border, documenting occasions of historic significance, such as landmark civil rights marches, while also attending to people and places on the margins of the era’s main events.

Akihiko Okamura, Women crossing through British Army barricade, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1969

Akihiko Okamura, Women crossing through British Army barricade, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1969Okamura was unfamiliar with the specific circumstances of Northern Ireland’s political divisions but no stranger to societies upturned by warfare, struggle, and suffering. Before settling in Ireland, he had photographed the chaos and cruelty of the Vietnam War, gaining extraordinary access to Viet Cong camps, and traveled to Cambodia, Malaysia, and Korea, documenting life in nations coping with the corrosive, long-term effects of colonialism. (Later, he also reported on the Nigerian Civil War and journeyed through Ethiopia, photographing victims of famine.) Tracking political developments and, more routinely, everyday existence in Ireland during the late 1960s and early ’70s, Okamura brought a worldly outsider’s capacity to find surprising new angles and the patience and sensitivity of someone willing to stick around, to look beyond the breaking news.

Okamura singles out low-key moments, discovering worlds within worlds.

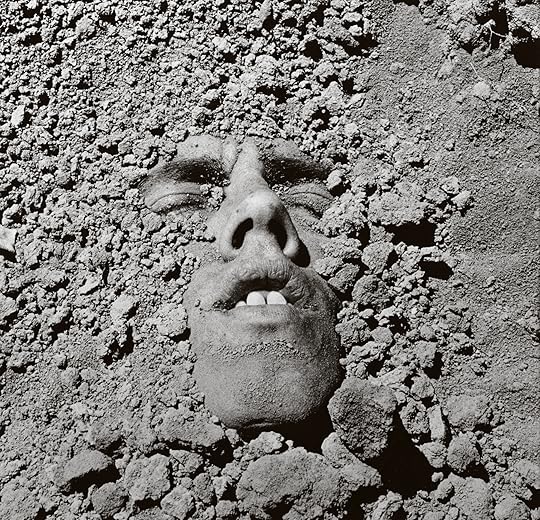

The pictures selected for Atelier EXB’s publication Akihiko Okamura: Les Souvenirs des autres (The Memories of Others, 2024) and an associated exhibition at the Photo Museum Ireland, Dublin, showcase Okamura’s subtly modulating stylistic range, combining moments of big-picture photojournalistic storytelling, gently surrealistic black comedy, and hazily dreamlike glimpses of communities or individuals in states of fearful transition or uneasy stasis. Some images have orthodox historical value. There are, for instance, valuable shots of key characters in early episodes of the Troubles. Okamura catches the stern vanity of the firebrand sectarian preacher Ian Paisley as he lays a wreath at the culmination of an Ulster Loyalist parade, his hair slicked and quiffed like a ’50s rock-and-roll star. The civil rights activist Bernadette Devlin, Paisley’s left-wing, nonsectarian rival for the most dynamic public speaker of the era, is memorably pictured in a typical pose: megaphone in hand, leading the action from a barricade during Derry’s Battle of the Bogside in 1969. The most resonant of the photographs, however, are those with more unassuming, antiheroic attributes. They stir feelings of unusual intimacy with characters living through the strange convulsions of their times.

Akihiko Okamura, Street memorial on Lecky Road, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1971

Akihiko Okamura, Street memorial on Lecky Road, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1971Okamura singles out low-key moments, discovering worlds within worlds. He seems to be, as W. G. Sebald once said of his fellow writer Robert Walser, a “clairvoyant of the small,” looking for what we might learn of desire, sadness, loneliness, or dreaming among the dispersed, matter-of-fact materials of daily life. Two women clamber through a makeshift army barricade; one wears a bright red coat, its cheerful design an incidental affront to the surrounding gloom. Two little girls, prim and dainty in their Sunday best, pay their respects at an improvised memorial to a shooting victim on a Derry street. Behind the shadowy presence of an armed soldier in heavy fatigues, a pair of pristine white wedding dresses appear in the window of a bridal shop. Another lone figure, a young man in a slim-fitting suit, leans against a lamppost reading a newspaper; above him, street and shop signs declare “No Entry” and “Eclipse.”

Akihiko Okamura, Preparations for the Twelfth of July celebrations in the Fountain area, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1969

Akihiko Okamura, Preparations for the Twelfth of July celebrations in the Fountain area, Derry city, Northern Ireland, ca. 1969All photographs © Estate of Akihiko Okamura/Junko Sato

There are quite a few signs in Okamura’s Irish oeuvre: street names, traffic directions, advertising posters. Here and there, the texts hint at hope of stable meaning—such as in one picture of a grieving woman carrying a protest banner, appealing for justice—or unbending allegiance to a political position: in another shot, showing residents gaily decorating a terraced street for the Unionist community’s Twelfth of July celebrations, we see the intransigent slogan “No Surrender” emblazoned on a wall mural. Often, words produce moments of mischievous irony: a helmeted soldier, bearing a shield and a baton, framed partially by a sign saying “caterers”; or the words “Police Enquiries” posted outside a fortified Royal Ulster Constabulary station, barely visible on the ludicrously forbidding sheet metal facade. If with such teasing image-text contradictions Okamura gestured toward satire, he did so without becoming direct or dogmatic. However dark their humor, however bleak their mood, his photographs create space to see ordinary life at the time of the Troubles a little differently: one unexpected scene, one small detail, after another.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 255, “The Design Issue,” under the column Viewfinder.

Akihiko Okamura: The Memories of Others is on view at the Photo Museum Ireland through July 6, 2024.

June 21, 2024

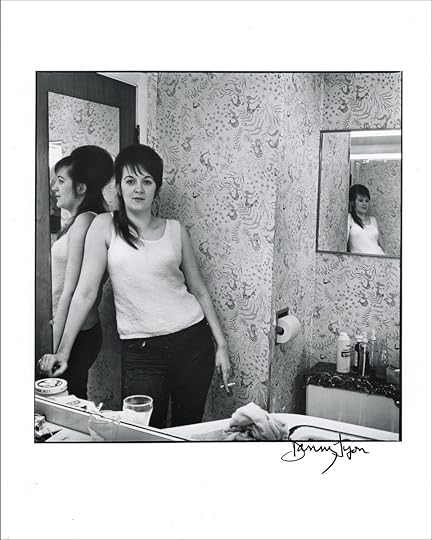

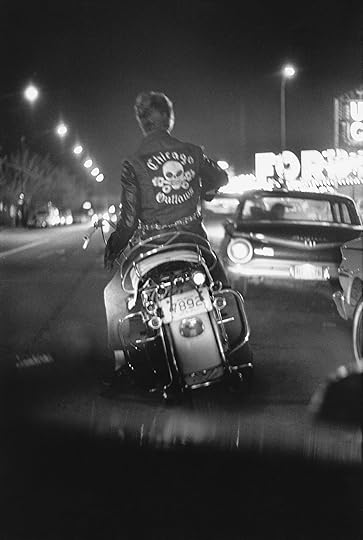

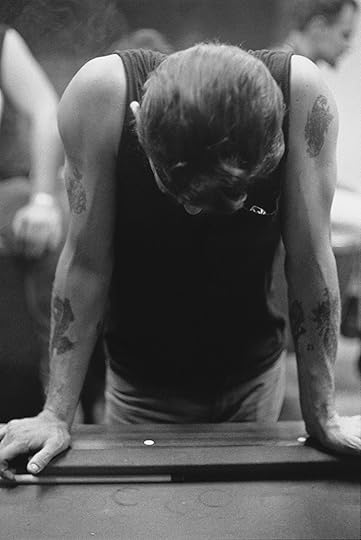

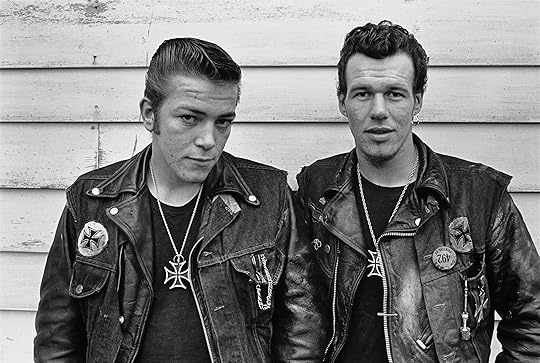

Danny Lyon on the Making of “The Bikeriders”

Danny Lyon has a story to tell—many stories, in fact. The photographer who captured a young John Lewis, then chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other moments of the early civil rights era is known for embedding himself in communities and documenting scenes with historic import and cultural specificity, including a 1960s Texas prison, a downtown New York demolition, and the Vietnam War protests. Perhaps most famously of all, Lyon photographed the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, joining the group to document it from the inside. But to say this was simply the strategic move of an artist is to elide the complex ways in which Lyon has always tended to live his work.

On the eve of his forthcoming memoir, This is My Life I’m Talking About (2024), where he tells all the best stories of his eighty years, Lyon spoke about his landmark work The Bikeriders, first published in 1968 and reissued by Aperture in 2014, and inspiration behind a new Jeff Nichols film starring Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, and Jodie Comer—and Mike Faist as Lyon—releasing this month.

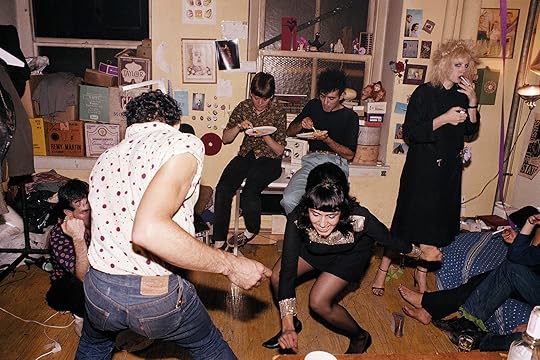

“I met Andy at the bar across the street, leaning on the juke box,” Lyon writes in the memoir. “He looked a little like a short James Dean, his hair as curly as mine. Wearing a sleeveless shirt, Andy was lame, and staggered badly with each step he took. He limped over and grabbed a man that Jack had posed with, pressed his cheek against his face, and wanted me to make a picture of that as his buddy held out the bottle of beer. By my second exposure, Andy had completely embraced his friend, his body wrapped around him, without disturbing the beer, which everyone insisted be in the picture. We went outside to stand in the doorway where Andy posed with a pretty dark-haired girl wearing a leather vest. Sometime that same night, somebody said to me, ‘Why don’t you join the club?’ I had found my subject.”

Here, Lyon speaks about his first race, why he doesn’t like the term photobook, and the desire to drive off into the sunset. This conversation has been edited and condensed.

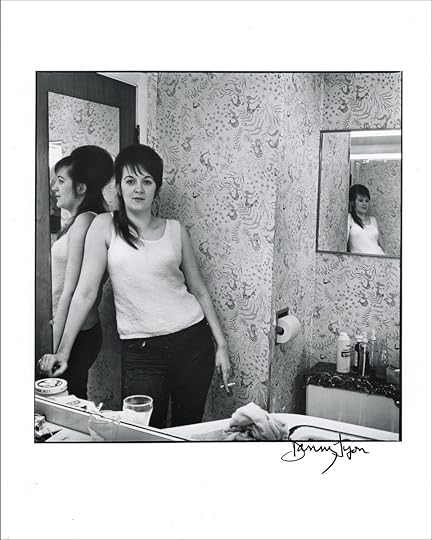

Danny Lyon, Frank Jenner, La Porte, Indiana, 1963–67

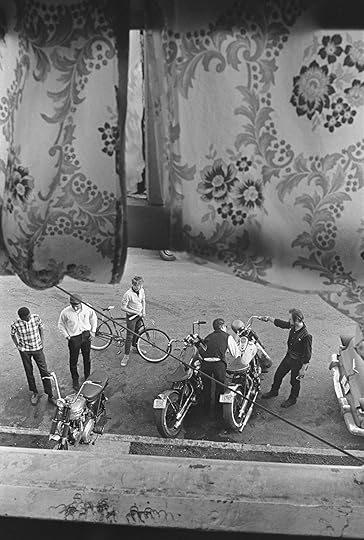

Danny Lyon, Frank Jenner, La Porte, Indiana, 1963–67  Danny Lyon, Club house during the Columbus run, Dayton, Ohio, 1965

Danny Lyon, Club house during the Columbus run, Dayton, Ohio, 1965 Lucy McKeon: Tell me a little about your introduction to this world that would become your work titled The Bikeriders.

Danny Lyon: Some of the first pictures I ever made are of motorcycles. This is years ago. I’m young. I have my first good camera, which is this East German–made single-lens reflex called an Exa. I’m a student in Chicago, and I have friends who are riding motorcycles. The very first picture on the first page of The Bikeriders is a portrait of a very handsome guy. He was from upstate New York, a University of Chicago student. His name was Frank Jenner. He had entered school, and he had been a motorcycle racer—this was as an eighteen-year-old. He’s part of our crowd, and we all look up to him, and we all want to get motorcycles. That’s the first picture in the book because it’s really through Frank that I enter this world. BSAs were popular, which I think are British, and I rode a Triumph, which is also British. Nobody rode Harley-Davidsons. I was looking at the Chicago Outlaw website, and it’s a requirement today, if you’re a member of the Chicago Outlaws, to ride a Harley-Davidson. None of us did.

McKeon: So you didn’t grow up with this culture in Queens, I’m imagining.

Lyon: I couldn’t even drive a car in Queens.

In 1963, I had a good friend named Skip Richheimer, who is a graduate student at that point. But by then, I’m close to my junior or senior year. We’re both bikeriders, and we get in his Volkswagen to go to a race. He was also a photographer, and he’s still alive. We drive off to Wisconsin to a rally. Many years later, I met Bob Dylan, who also rode a motorcycle, apparently almost got killed on one. He had seen the book, and he used to go to the same track. It was McHenry . . . or where the hell was it? I think I got it right. Let’s call it McHenry.

But I was in Wisconsin when these motorcycles pass us—I see them behind us, and Skip’s driving, and I start yelling, “Keep up with them!” I’m shooting through the front window with a 105mm lens, and I make this picture called Route 12, Wisconsin, which I think the British Museum later declared as a masterpiece of photography. I was twenty years old. It’s a pretty good picture. It’s perfectly arranged. It’s done through the front window of a moving car, and it’s very geometrical. That’s the cover of The Bikeriders.

Kathy, Chicago, from The Bikeriders, 1967–69 250.00 To celebrate the premiere of The Bikeriders, the new film inspired by Danny Lyon’s iconic book, Aperture is offering a new signed print by the artist. Available through July 4, 2024.

Kathy, Chicago, from The Bikeriders, 1967–69 250.00 To celebrate the premiere of The Bikeriders, the new film inspired by Danny Lyon’s iconic book, Aperture is offering a new signed print by the artist. Available through July 4, 2024. $250.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Kathy, Chicago, from The Bikeriders, 1967–69 $ 250.00 –1+$250.00Add to cart

View cart Description Aperture is pleased to release a second print from The Bikeriders by the renowned photographer Danny Lyon. The seminal publication of photographs and interviews that documents the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club in the 1960s, when Lyon was a member, is the inspiration behind the new film of the same title. To celebrate its premiere and the release of I’m Talking About My Life Here (2024), Lyon’s recent memoir, Lyon chose the photograph Kathy, Chicago, for his second collaboration with Aperture, in homage to Jodie Comer, whose performance as Kathy in the film has garnered critical acclaim.Lyon’s groundbreaking approach to storytelling—adapting audio recordings from interviews to form texts featured in The Bikeriders—underscores the authenticity and depth of his work. Lyon’s picture of Kathy, the girlfriend and future wife of Chicago Outlaws club member Benny (played by Austin Butler in the film), intimately captures her vulnerability and defiance, embodying the spirit of counterculture and freedom that characterized Lyon’s work from that era.

Each 8-by-10-inch pigment print is signed by Danny Lyon as an open edition and is available at this accessible price now through July 4, 2024, with proceeds supporting Aperture’s nonprofit publishing, public programs, and limited-edition prints. As a special offering, Lyon’s iconic Route 12, Wisconsin, the cover photograph of The Bikeriders , is available once again—perfect for those who missed it the first time. This signed 8-by-10-inch pigment print is available as part of a unique collector’s set that includes the newly released print of Kathy, Chicago, for a limited time only, now through July 4, 2024.

The Bikeriders, starring Jodie Comer, Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Michael Shannon, Mike Faist (as Danny Lyon), and Norman Reedus, is in theaters now. Original audio recordings of Kathy Bauer can be heard on Lyon’s blog, Bleak Beauty. Follow Danny Lyon @dannylyonphotos2. Details

Signed archival pigment print

Image Size: 5 x 7 in.

Paper Size: 8 x 10 in.

Printed by Picturehouse + thesmalldarkroom, New York, under the artist’s supervision

Open edition (as many acquired are produced)

International flat-rate shipping available. Email prints@aperture.org for all inquiries

This print is also available as part of a set that includes Route 12, Wisconsin for a limited timed only.

Danny Lyon (born in New York, 1942), regarded as one of the most influential documentary photographers, is also a filmmaker and writer. His many books include The Movement (1964), The Bikeriders (1968, reissued by Aperture, 2014), Conversations with the Dead (1971), Knave of Hearts (1999), Like a Thief ’s Dream (2007), and Deep Sea Diver (2011), and most recently his memoir Danny Lyon: This Is My Life I’m Talking About (2024). Lyon’s work is widely exhibited and collected, and he has been awarded two Guggenheim Fellowships, numerous National Endowment for the Arts grants, and a 2011 Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism. You can follow him on Instagram @dannylyonphotos2.

McKeon: Can you remember your impression of that race with Skip? Was there a sort of epiphany you had about bikeriders and photography?

Lyon: Epiphany. I love this. I’m going to try to invent one for you. It wasn’t really like that. The day was great. But did I end the day saying, I want to do bike rides? No. The light was apparently perfect, meaning it was a bright, overcast day. But I think it was being around and seeing these guys.

I shot a bunch of film, and I was all excited, and I showed them to Hugh Edwards at the Art Institute of Chicago. Hugh had the epiphany. He said this stuff’s incredible. He told me I should make a book about it. He wrote me a letter about it. I got the letter in May 1963. The letter was a result of looking at the pictures I made that bright, overcast day, and he mentioned the idea of a book, suggested all these crazy people who could write the text. I think he mentioned John Dos Passos, James Jones, and somebody else [Burroughs]. And he told me it should be in gravure. He had it all worked out.

Then, I got caught up with the civil rights movement. But I never forgot my time taking pictures of motorcycles, so I returned to Chicago, two years later.

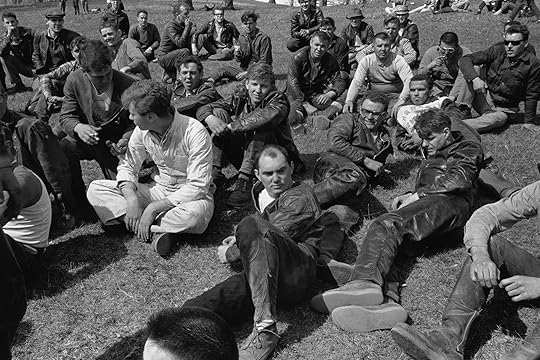

Danny Lyon, Riders’ Meeting, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1963

Danny Lyon, Riders’ Meeting, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1963  Danny Lyon, Field meet, Long Island, New York, 1965

Danny Lyon, Field meet, Long Island, New York, 1965 McKeon: Two years later. So in 1965?

Lyon: 1965, I return. At that point in my life, I’m already a photographer. I’ve also gotten better because I’ve been trying to get better. I was a street photographer in New Orleans, and once in Chicago, I go to Uptown, and I start doing better work. But I was still looking for a subject. I think I knew I wanted to do a book, and the model for me was Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, which is mostly text. I read the whole thing, and James Agee’s writing really spoke to me. The Americans had been a big flop, but it showed anyone paying attention that the way to be recognized as a photographer was to make a book. So to make a book was my big dream—and I did.

But the book was a total failure. Not only was it a failure but the printing was also horrific: Seven pictures were out of register; there was no ink on it. There weren’t any typos, but as for reproductions, they were awful. It broke my heart when I saw it. And in addition, it was a total flop. That’s the first edition. It came out in 1968.

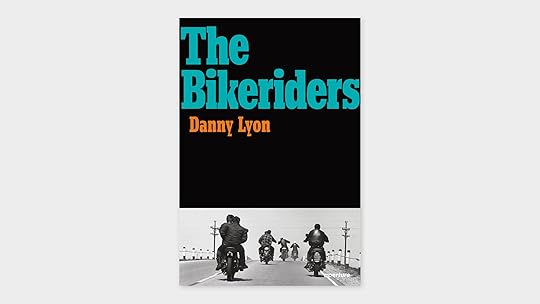

Cover of The Bikeriders (Aperture, 2014)

Cover of The Bikeriders (Aperture, 2014)Twenty years later, Jack Woody, who’s a wonderful publisher, wants to do it in gravure, and he makes it a little bigger. There are no additional pictures, but the format’s a little different, and I write a second introduction. So that’s the second edition. That’s really gorgeous.

But The Bikeriders was meant to be a popular book. It was originally in softback. You could fold it in half. You could fit it in the back pocket of a pair of jeans. It cost $2.95. In other words, it wasn’t meant to be an art book. It was meant to be a book that was based on photographs and had text and was affordable. So, with the second edition, it lost the feel, so that upset me.

Then, in another ten years, Chronicle Books offered me money to publish it again if I added pictures. This is the worst version of The Bikeriders. I added color pictures in the back, because I had made color pictures. I wrote a third introduction. And I really hated that book.

Life went on, then the people at Aperture, including Lesley A. Martin, asked if they could give it try. And this time, they did it right. It’s great. I love the new edition.

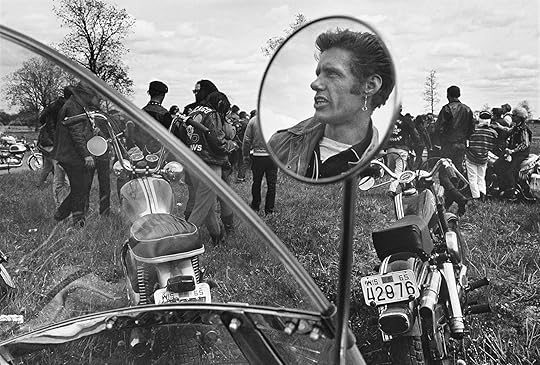

Danny Lyon, Ronnie and Cheri, La Porte, Indiana, 1962

Danny Lyon, Ronnie and Cheri, La Porte, Indiana, 1962  Danny Lyon, Cal, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1966

Danny Lyon, Cal, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1966 McKeon: A success story. Tell me more about the text in the book. You used a tape recorder when you were making it.

Lyon: So I’m making these photos. I found my subject. It’s a fabulous subject, and it’s perfect for photography and I know it. I’m cranking out all these pictures. I joined the Outlaws club. I have access to all these other guys, and I’m also protected by them, meaning I can wander in bars or at rallies, and I’m wearing a patch, so no one’s going to fuck with me. I’m one of the guys, and I make the pictures.

I go to New York, trying to publish it. Everybody was saying no to me. I go to Aaron Asher. He was at Viking and did these arty photography books. I remember sitting in an office with him. I had these boxes of pictures, and he told me this is just a box of pictures and that it’s not a book. He said I needed a text. I go back to Chicago. I got help from Lucy Montgomery, who had been a big supporter of SNCC. She was a white Southerner of wealth. I said, “Lucy, I need a tape recorder.” I needed a portable one because I rode around on my motorcycle. She gave me eight hundred dollars, and I bought a small Uher five-inch reel-to-reel tape recorder. I recorded everyone, and I made my text.

It turns out, when I got it published, The Bikeriders was the second book in the English language to use a tape recorder as a source of the text. I had the recordings typed out by a woman who worked for Studs Terkel. I picked parts of the text. I did very little editing. I simply cherrypicked the great speeches, made that the text—and then no one would publish it. In fact, I went to Michael Hoffman at Aperture. But they wouldn’t pay me any money, and I was determined to live off my work. So I said no. Then, I ran into Alan Rinzler, who I knew from the civil rights movement. We had had a big fight, and I ran into him by accident. He was at MacMillan, and he did, like, fifty books a year—trade books. He slipped the contract for my book into his pile, and it came back approved.

It’s amazing to sit in a movie theater and watch Tom Hardy and Austin Butler and Jodie Comer speak the lines that I recorded in 1966.

McKeon: There’s a wonderful scene in your forthcoming memoir about a 1966 gallery show, speaking of Hugh Edwards, who put it up at the Art Institute of Chicago. You talk about inviting the bikeriders and their families to come see the photos displayed.

Lyon: Hugh was the curator. He’s really an enormous figure in photography, really the greatest figure in the museum and curatorial worlds of the late twentieth century. I believe John Szarkowski said so when he visited the Art Institute. Hugh was a self-educated guy from Paducah, Kentucky, who loved The Bikeriders. He gave me my first show (I was twenty-five), and he showed The Bikeriders, and I think he showed prints of Uptown, Chicago (1965). I was in the Outlaws club at the time, and the whole gang came down. I have pictures of them. They got dressed up. I have one frame of them in the room: their children are in it, the women dressed up. Most of these guys never went downtown. Some of them were truck drivers. They were blue-collar people. About twenty-five of them came, and I took pictures of them in the gallery.

But the club changed. I left and then it changed. In the third edition of the book, I wrote about the change. The change happened when Vietnam vets, who were into drugs and were violent, took over the club. This didn’t happen when I was present. So the Outlaws morphed, got indicted in a RICO charge. They got into a fight with the Hells Angels. It got really grim. This is public knowledge. And to this day, the Outlaws still exist. I was talking recently to a club member. They have thousands of members. This fellow, who’s a nice guy and retired from the club, said that some people joined the club because of my photographs. Which is funny. But I created this romantic vision of being a motorcycle rider. And then there were the people I knew—one of them was an electrician; the head of the club was a long-haul truck driver; Cal was a house painter who didn’t do anything; Funny Sonny played blues.

Mike Faist as Danny and Jodie Comer as Kathy in director Jeff Nichols’s The Bikeriders, 2024

Mike Faist as Danny and Jodie Comer as Kathy in director Jeff Nichols’s The Bikeriders, 2024Courtesy Kyle Kaplan/Focus Features

Emory Cohen as Cockroach, Jodie Comer as Kathy, and Austin Butler as Benny in director Jeff Nichols’s The Bikeriders, 2024

Emory Cohen as Cockroach, Jodie Comer as Kathy, and Austin Butler as Benny in director Jeff Nichols’s The Bikeriders, 2024 McKeon: What do you think of the movie version of The Bikeriders?

Lyon: Well, Jeff Nichols made the movie. Years ago, he told me he wanted to make a movie out of my book. I’m thinking, Wow, movies are a big deal. The analog recordings I made survive. You can hear them on my blog, Bleak Beauty. You can click on them, and you can hear their voices. They’re on quarter-inch tapes. About thirty or forty tapes survive, most of which I never even used. So I gave all of it over to Jeff.

Jodie Comer, the actress who plays Kathy, and Boyd Holbrook, the actor who plays Cal, could sit down with earphones and listen to these recordings, and so as actors, they do perfect imitations of Kathy’s and Cal’s voices. While not an Outlaw, Kathy’s a woman with three children who’s married to this kind of young lunatic and who also narrates a number of stories in the book. And Cal, who is a Hells Angel, narrates another four. Zipco was an amazing guy and tells an amazing story in the book about the draft board. He’s incredibly funny, like Falstaff. I mean, he’s a drunk. He’s a fuckup. He has a Latvian accent. He’s very, very, very funny, this guy. When I interviewed him, he’d gotten drunk, crashed his bike, broke his leg, and Cal and I visited him in the hospital—and that was one of the recordings.

Anyway, these are the stories that drive the film, and it’s amazing to sit in a movie theater and watch Tom Hardy and Austin Butler and Jodie Comer speak the lines that I, as a twenty-five-year-old kid, recorded with an analog tape recorder in 1966. They’re the exact same words.

Danny Lyon, Benny, Grand Division, Chicago, 1965

Danny Lyon, Benny, Grand Division, Chicago, 1965  Danny Lyon, Benny at the Stoplight, Cicero, Illinois, 1965

Danny Lyon, Benny at the Stoplight, Cicero, Illinois, 1965 McKeon: You consulted for the movie, right? Did you visit set?

Lyon: They were filming in a small town outside of Cincinnati, a place that hasn’t changed much since the ’50s. On a street corner was a bar, and when I stepped inside, it looked exactly like my pictures of the bar sixty years ago, only it was in color. I was transported back to my youth. Outside, parked all around the bar were vintage motorcycles, mostly Harleys along with one BSA and on the corner, a Triumph. It was the very same bike I had first ridden, the 440-pound single carburetor TR6, with a worn banana seat. I went over and sat on it. Mine had a black gas tank, and this was dark brown, but otherwise it was exactly the same. And as I looked down next to the flat oil tank, I saw the key, a very small key stuck into the bike, and I reached down and turned it on. Then, I jumped up in the air and came down as best I could with my right foot on the kick-starter, and the motor sort of coughed. I jumped down again, and the bike roared to life. It was like the start of war, considering the amount of noise made from the straight pipes.

A hundred people were wandering around the set, setting up lights, and talking on radios, and every one of them turned to look at me. How badly I wanted to ride off on that bike. I was twisting the throttle in my right hand, making the engine roar, and all I had to do was push down with my foot and put it into gear, lean forward to knock it off the kickstand, and I would be riding that bike—my old bike—off into the night. I just didn’t have the guts to do it.

Danny Lyon, Crossing the Ohio, Louisville, 1966

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }McKeon: Plenty of rides to recall in your past. You’ve gone and written a memoir. Tell me about that process. What has it meant to you, and what you were trying to do with it?

Lyon: I’ve been writing for years. The memoir has been a struggle, and I’m so happy to get it out there. Like The Bikeriders, it had no one wanting to publish it. I couldn’t get an agent for it. But Damiani, an Italian publisher, who’s doing a lot of picture books—I think they’re doing something by Susan Meiselas—said they’d do it. I’m thrilled. It’s on press now.

This kind of writing began for two reasons. One, I was in New Zealand fishing. I mean, this was fifteen years ago. I thought what I did was so extraordinary. I was just trying to go fishing. But fishermen are really crazy. I mean, they really can be psychotic. I was going through the jungle, climbing trees and falling off cliffs, then crossing rivers, hoping to catch a two- or three-pound fish—which, of course, I don’t do. But later I thought, This is so crazy I should write about it. And I did. I wrote a long manuscript called “The Fisherman,” and it was really terrible. Then later, I had health problems. I started from scratch. And then, people like you helped me edit it, and now it’s done.

There’s a lot of adventure in being a photographer. When Nancy told our son Noah that I was writing a memoir, Noah said, “Again?” This is because Knave of Hearts (1999) is in fact an illustrated manuscript with a memoir within, but it’s much shorter. This new one has more writing, more words.

McKeon: Did this feel like a chance to tell a different story than you had before?

Lyon: To get even, you mean? I wish I had done that, but I didn’t. I’m eighty years old. The civil rights movement for me was sixty years ago. There are so many adventures involved in the kind of work I did.

Looking back on my life, I don’t know, maybe I did do a lot of it for the adventure. I get bored. I love doing exciting stuff. I seem to like danger involved. I even managed to make fishing dangerous.

I’m doing stuff now, and basically, I got to drive six hundred miles to do it. I love it.

McKeon: This is in New Mexico?

Lyon: Arizona. So far, I’ve done the Oklahoma Panhandle, Nebraska, and Arizona. We’re about to head to the California border. I don’t want to talk about it too much. I want to do it.

Danny Lyon, Big Barbara, Chicago, 1965

Danny Lyon, Big Barbara, Chicago, 1965  Danny Lyon, From Lindsey’s room, Louisville, 1966

Danny Lyon, From Lindsey’s room, Louisville, 1966 McKeon: Do you have a favorite picture from the book or a favorite speech?

Lyon: Well, I’m glad you asked. Because of this conversation, I decided to pick up the book. I looked through the Aperture edition of The Bikeriders, which is just beautifully reproduced. There are forty-nine pictures. When you’re a young photographer, you just want to make a great photograph. That’s all you want to do. I don’t know what painters do . . . they make sketches and they make a painting. But photography isn’t like that. You can go out and make twenty pictures in a day. You can make fifty pictures in a day. But you just want to make one good picture—one really good picture. That’s what you’re trying to do.

There are only six great pictures in The Bikeriders. Which is great for me. That’s what I was trying to do. The rest is filler. It’s about making a book and showing it to people. In the prison book, that was also my objective. The objective has always been to make great photographs and then construct a book around it using texts.

I wish photography books were more respected, you know, as literature. There’s something I call “Photo Literature,” which sounds pretentious, I know. But Nan Goldin does it. Larry Clark did it. Jim Goldberg does it. Susan Meiselas does it. They use words. They are photographers, but they make books, and they use words. It’s a really kind of a separate category of books, I think.

Danny Lyon, Sparky and Cowboy (Gary Rogues), Schererville, Indiana, 1965

Danny Lyon, Sparky and Cowboy (Gary Rogues), Schererville, Indiana, 1965  Danny Lyon, Outlaw camp, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1965

Danny Lyon, Outlaw camp, Elkhorn, Wisconsin, 1965All photographs from The Bikeriders (Aperture, 2014). Courtesy the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

McKeon: You don’t like the term photobook.

Lyon: I don’t even like the word photography. I call photographs “pictures.” I did a book with Michael Hoffman, who was the head of Aperture, and he wanted to do a collection, which I resisted because it wasn’t really a book. It was a collection that’s called Pictures from the New World. Michael told me that Aperture spent thirty years trying to educate people about photographs, and now I want to call them “pictures.”

Photography was not considered an art. Stieglitz spent a lot of time saying photography is really an art form. Robert and Mary Frank were a couple, and Mary was an artist, and Robert comes to America in the late ’40s, makes his pictures in the ’50s, and he knows all these artists. He said he wasn’t considered an artist. His wife was considered an artist because she did sculpture. But Robert wasn’t. Hugh Edwards said there were only three types of photographs—landscapes, portraits, and interiors. Think about that.

McKeon: Before we close, I just want to return to your early experiences riding a motorcycle. I would love it if you would describe the memory of a ride, what that feeling gave you.

Lyon: When I was in Lower Manhattan, I would ride around on a red Triumph. People would come to New York, I’d put them on the back of my Triumph, and then I’d get on the East Side Drive, which skirts the East River, and going south, you go under all three bridges—you go under the Brooklyn, Williamsburg, and Manhattan Bridges on a motorcycle. There’s nothing but you, the air, and the water, and you can go around the bottom, come up the other side. It’s really a thrilling ride. There was less traffic then. No more. I got old. I like boating, and I had a tractor for a few years. All that goes. But I can still make pictures.

The Bikeriders was reissued by Aperture in 2014.

In Kyoto, a Family Portrait by Two Japanese Photographers

In the late 1970s Tokuko Ushioda lived in a modest fifteen-tatami-mat apartment with her husband and their newborn daughter. They lived sparingly. A couch doubled as a guest bed; the kitchen consisted of a table in the corner; they shared a downstairs bathroom with the building’s other residents. One day, her husband arrived home with an old Swedish refrigerator that Ushioda described to be as large as a polar bear. The hulking appliance, much too big for their space, malfunctioned from the beginning. It froze vegetables solid and at night rattled like a poltergeist, stirring anxiety and fear about the future in Ushioda’s mind.

She found peace with the appliance by making it her subject. Using a six-by-six camera mounted on a tripod, she began a ritual of photographing her home invader straight on, with its door open and closed, and over time created a Becher-like typology. Closed, the appliance is an imposing, utilitarian tower, a sleek but vintage example of industrial design. With its heavy door agape, it is less imposing, even vulnerable. Anyone who has had a house guest rummage inside their fridge knows how this appliance is the kitchen’s underwear drawer, revealing a diary of culinary tastes, habits, and degrees of cleanliness. Intrigued by the process of studying her own fridge, Ushioda began to photograph those belonging to her landlord and family members, working according to the same set of formal rules.

Tokuko Ushioda, Setagaya, Tokyo, 1983, from the series Reizōko (Ice Box)

Tokuko Ushioda, Setagaya, Tokyo, 1983, from the series Reizōko (Ice Box) Tokuko Ushioda, Untitled, 1981, from the series My Husband

Tokuko Ushioda, Untitled, 1981, from the series My HusbandCourtesy the artist

For Ushioda, a mother who was often at home, the domestic realm has functioned as a site of curiosity and creative possibility. She works in a tradition of photographers who candidly observed the details of their own existence, long before social media normalized, monetized—and exhausted—doing so. A related series, My Husband, portrays ordinary scenes at home with her spouse (also a photographer) and their then newborn daughter. This is a family album that is loving without being saccharine or sanitized; the messiness of life is left intact and on display.

Both projects were recently exhibited at the Kyocera Museum of Art, Kyoto, as part of Kyotographie, the annual international photography festival that presents exhibitions across the city, often in notable architectural venues. “There is a certain quietness to the space with the ordinary scenes of the mundane being framed and displayed,” Ushioda says of the exhibition. She is an astute observer of small, everyday moments, accumulating detail upon detail, which, assembled together, decades on, unsentimentally describe the passage of time.

Installation view of Tokuko Ushioda, Ice Box + My Husband, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, 2024

Installation view of Tokuko Ushioda, Ice Box + My Husband, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, 2024Courtesy Takeshi Asano and Kyotographie

Installation view of Tokuko Ushioda, Ice Box + My Husband, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, 2024

Installation view of Tokuko Ushioda, Ice Box + My Husband, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, 2024Courtesy Takeshi Asano and Kyotographie

Her desire to archive her own life extends beyond photography. The exhibition also included vitrines filled with personal belongings, toys, children’s shoes, mannequin hands, a film canister, jewelry, among other sundry items—relics of her past. “I have a habit of keeping ridiculous things, like the umbilical cord and fingernail clippings from when my child was born, or their baby teeth,” Ushioda says. “We cherish the things that we have, things including my husband,” she laughed—her response knowingly pointing to how photography is always partly an act of objectification and preservation.

Her work from this period, 1978 to 1985, was discovered by chance. Five years ago, while cleaning a room, she came across a box of prints in the back of a wardrobe that held a time capsule of her life. My Husband was collected in a celebrated volume published by Torch Press in 2022. For the exhibition in Kyoto, she was selected by Rinko Kawauchi, a photographer of a younger generation who is also renowned for her close studies of the almost invisible phenomena animating the everyday, picturing what might be deemed mundane with absorbing reverence and attention.

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitiled, 2020, from the series as it is

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitiled, 2020, from the series as it is Rinko Kawauchi, Untitiled, 2020, from the series as it is

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitiled, 2020, from the series as it isCourtesy the artist

In an adjacent gallery in the museum, Kawauchi presented a project titled Cui Cui (2005), after a French onomatopoeia describing a sparrow’s twitter: a metaphor, in Kawauchi’s mind, for how the accumulation of minutiae forms the fabric of family life. Through her gaze, the cycle of life unfolds, image by image, charting events both large and small. Details of hands reveal the softness of youth or the leathering of age. Her young daughter, arms outstretched, reaches forward to register the novelty of a breeze. Sunshine, air, texture—everything is available for the senses. Here, in contrast to Ushioda’s more documentary, black-and-white images, life manifests within a dreamy atmosphere awash in soft pastels and diffuse, angular light. The death of Kawauchi’s grandfather, the marriage of her brother, the birth of her own daughter; time passes, cycles of life carry on. “Looking through the camera’s viewfinder feels like peering into a window,” Kawauchi notes of the commonalities of her work and Ushioda’s. “We share the world we are peering into.”

Kyotographie 2024 was on view at multiple locations in Kyoto, Japan, from April 13 to May 12, 2024.

A Brazilian Artist Finds Beauty in Hidden Revelations

It was during the last Carnival, where Tadáskía said she had truly abandoned herself to the revelry for the first time, that she was bitten on her leg by a lacraia—what certain Brazilian regions call a centipede with a long body, a flat back, and numerous pairs of legs. They may or may not be poisonous.

I wasn’t familiar with the word lacraia before hearing this story, but I was struck by how it had become key to helping me describe Tadáskía’s practice. Tadáskía is an artist based between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in the southeast of Brazil. I have been engaged in a number of extended conversations with her, especially after the inclusion of her work Ave preta mística (Mystical black bird) in the 35th São Paulo Biennial in 2023, a large-scale installation currently featured in Tadáskía’s solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. During one of our encounters, Tadáskía used the centipede episode to explain what she describes as “apparition”: a moment of revelation in which one of its principles is believing that “something is going to arise; it is already arising, it already exists,” even if the moment of creation is an inoffensive centipede.

Installation view of Projects: Tadáskía, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2024. Photograph by Jonathan Dorado

Installation view of Projects: Tadáskía, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2024. Photograph by Jonathan DoradoTadáskía—who uses drawing, sculpture, photography, installation, and performance to express the enigmatic capacity of finding beauty from her experiences as a Black trans woman—has an ability to process an event as a “hidden revelation” by reading ordinary situations beyond their obvious meanings. In the case of the centipede, for example, between its most diminutive and extreme degrees of significance, the artist launched herself into a chromatic approximation of the chilopod with the figure of Exú—a deity in Afro Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. Due to Tadáskía’s long relationship with the Pentecostal church, she had not been intimate with his figure nor experienced his festival par excellence, Carnival.

Listening to Tadáskía and reflecting deeply both on my commitment to written history and her commitment to things created to be impermanent, I thought about the French writer Annie Ernaux, whom I had read on the eve of Carnival, and Saidiya Hartman, who writes about Black women’s ordinary lives and the monumental nature of their everyday experiences. Together, the two led me to consider the overlaps in the relationships between photography and performance, and between events, permanence, and disappearance. When I ask Tadáskía about how her photographs happen, she answers, “Things show up. And what I don’t know, maybe is in the notebooks.”

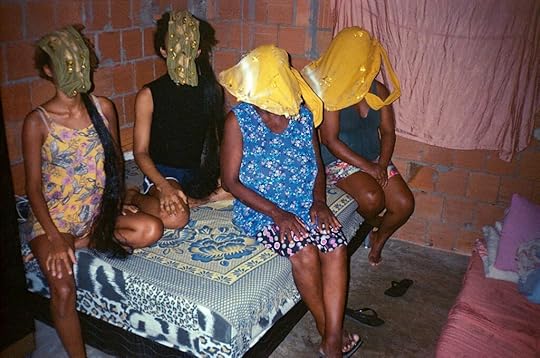

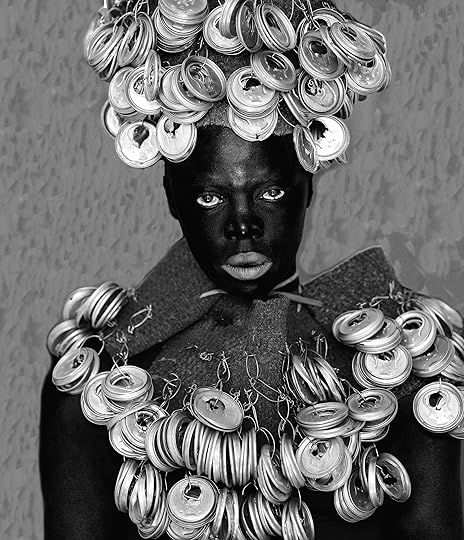

Tadáskía, to show to hide Trepadeiras em nossa casa (to show to hide Trepadeiras in our house), 2020

Tadáskía, to show to hide Trepadeiras em nossa casa (to show to hide Trepadeiras in our house), 2020Lacraia (Centipede) is the title with which she baptized her 2024 notebook. At the time I began writing this essay, that notebook didn’t exist yet, but it was nonetheless happening, and ultimately appeared within another entitled Traveler’s Tote Bag—as Tadáskía would tell me. Tadáskía has often asserted that her work is grounded in composing with her eyes closed and in the relationships between doing and not knowing, showing and hiding, drawing and not seeing. The ideas and forms appear and reappear. They arrive through different channels. And just like the many images, orientations, instructions, sketches, and observations that have already begun to take shape in Lacraia, her works to show to hide (2020), Corda dourada (Golden rope, 2019), and Hálito (Breath, 2019) sprang to life through a similar procedure performed through notebooks.

In to show to hide, the mystery of apparition tells us about facing the issue of representation. “I believe that not everything can be revealed, not everything can be delivered,” Tadáskía says. “When you think about photography of Black and low-income people, there is always something to try to represent, to document, to bring an identity, an identification.” Certainly, that’s not what the artist is aiming for. With these photographs, if on one hand she feels the need to show the reality she came from—which on its face looks like a tremendously precarious context—then on the other the photographic language provides the chance to show what it itself is hiding. “It’s the moment when you are going to find a treasure, a certain spirituality of life as well as all of the conflicts that still haven’t been resolved,” she says.

Tadáskía, to show to hide Zumbidas e Rastejantes com minha vó Maria da Graça, minha mãe Elenice Guarani e minha irmã Hellen Morais (to show to hide Zumbidas e Rastejantes with my sister Hellen Morais, my grandmother Maria da Graça, my mother Elenice Guarani), 2020

Tadáskía, to show to hide Zumbidas e Rastejantes com minha vó Maria da Graça, minha mãe Elenice Guarani e minha irmã Hellen Morais (to show to hide Zumbidas e Rastejantes with my sister Hellen Morais, my grandmother Maria da Graça, my mother Elenice Guarani), 2020Made with a Yashica 35mm camera that her father used during many childhood outings, to show to hide displays Tadáskía’s interest in the idea that something can appear in a photograph based on this belief in apparition. Because she stops looking at her notebooks after she creates them, the photographs arise from the pages of her imagination, almost like a prophecy. The apparitions aren’t rehearsed or literal. Her performative writing, which is often poetic and fantastical, plays a central role, coexisting in a syncretic way to allow the manifestation of expression to appear in different languages and converge in the construction of the apparition’s meaning. We can get even closer to this making-abstraction procedure in the work Ave preta mística (Mystical black bird), originally a book-length poem-drawing in pastel whose mystical words give wings to a multisensory world. As an installation, this world is animated with floor-to-ceiling charcoal drawings that embrace sculptures of cattails, where citric fruits, golden eggshells, sticks of bamboo, and colored powder gravitate.

Between notebooks and family albums, there is a golden thread that ties, connects, sews, stitches together and, as Tadáskía says, “redistributes the center” in many of her works.

As she performs with and against the camera, Tadáskía often invites the presence and participation of members of her family. The epistemologies of escape and the affective ancestral repertoire fill her cognitive framework. In to show to hide (2020), Tadáskía creates a family of sculptural objects that are worn and performed by her mother, Elenice Guarani, and her father, Aguinaldo Morais. Their names are Zumbidas (Buzzings), Rastejantes (Crawlers), Rabos (Tails), Trepadeiras (Creepers), and Gruda-gruda (Sticky-Sticky). These wearable sculptures end up camouflaging or masking the expected image of everyday Black life. The play and the dialogue between two families—human and sculptural—show and hide the ordinary and the alien in an interaction in which the family appears not only as a theme within the work, but also as the protagonist of a broader artistic project of redistributing abundance.

Tadáskía, to show to hide Rabos com Minha mãe Elenice Guarani (to show to hide Rabos with my mother Elenice Guarani), 2020

Tadáskía, to show to hide Rabos com Minha mãe Elenice Guarani (to show to hide Rabos with my mother Elenice Guarani), 2020Between notebooks and family albums, there is a golden thread that ties, connects, sews, stitches together and, as Tadáskía says, “redistributes the center” in many of her works. This redistribution of resources as an aesthetic methodology and ethical procedure (a perspective recurrent in the practices of many other Black and Indigenous artists) recalls Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s affirmation, in “Fade of the Black Family Photography,” an essay in the 2023 book What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life (2023), that “of all the art forms photography is the one most susceptible to a discourse of rights, for good reason. And the right it most invokes is the right to ownership.” Harney and Moten’s positioning of photography in relation to property resonates with the compulsory but generative state of dispossession, the expropriation of Black life, and the relationships between the subject and object “that resists the ends of gaze and image,” they write.

The fundamental ethics of Tadáskía’s photographic project include sharing any earnings with the family members present in the images, as well as undertaking a range of economic reparations projects. As such, the photographs seem to confirm a family pact that ironically says, “We can have some ownership, even being owned.” The artist herself has said, “On January 10, I invited my family and friends to appear at 1 p.m. to eat a golden meat and a black juice . . . I served the golden meat and the black juice into the hands of each person using a wooden spoon. After eating, we put away the towel and the objects for our second apparition. On the same day, at 4 p.m., we appeared in front of the door of Cavalariças. And so, we heard people saying olha o passarinho [watch the birdie] as they photographed us and we rolled our eyes. Each person in their own time.”

Tadáskía, Corda dourada com meus primos Lucas Moraes, Breno Moraes e Gabriel Moraes (Golden rope with my cousins Lucas Moraes, breno Moraes and Gabriel Moraes), 2020

Tadáskía, Corda dourada com meus primos Lucas Moraes, Breno Moraes e Gabriel Moraes (Golden rope with my cousins Lucas Moraes, breno Moraes and Gabriel Moraes), 2020Family pictures can fade or be abandoned—or they might not exist at all. In one group of photographs from 2020 called Corda Dourada (Golden rope), Tadáskía considers the economy of visual ownership and the relationship between owning and being owned. Here, the rope in the title is seen connecting various figures. For Tadáskía, the past is the present as well as the history of Black existence. The rope revealed itself as an apparition, she tells me; fortune can’t simply be summed up in material measurements. The performance, then, arises as a gesture that expands reality’s objective need: to realize an act in which gold is ritualized and is prophesied as an image for the future. Even if framed by the bricks of an unplastered home or by an architecture that structures poverty, family is a commodity that resists its own photographic objecthood and competes with history’s own reproducibility. Tadáskía’s photographs promote the creation of a prolific visual vocabulary in which the relationship to memory and property is remade under her own terms.

Tadáskía, Corda dourada com minha mãe Elenice Guarani, minha tia Marilúcia Moraes, minha vó Maria da Graça e minha tia Gracilene Guarani (Golden rope with my mother Elenice Guarani, my aunt Marilúcia Morais, my Grandmother Maria da Graça and my aunt Gracilene Guarani), 2020

Tadáskía, Corda dourada com minha mãe Elenice Guarani, minha tia Marilúcia Moraes, minha vó Maria da Graça e minha tia Gracilene Guarani (Golden rope with my mother Elenice Guarani, my aunt Marilúcia Morais, my Grandmother Maria da Graça and my aunt Gracilene Guarani), 2020Perhaps this change in perception and scratches of humor and irony are among the difficult gifts that Moten and Harney speak of in relation to the image of the Black family. “Existence insists upon this blur of wound and blessing,” they write. “It’s the aspiration of our dying breath, the substance of being unseen in always being seen, which, secretly, selflessly, we see with ourselves, not seeing our selves but seeing something more in seeing with, as if seeing with were all, as if all were just that practice, just how we do on Sunday evening, evidently.”

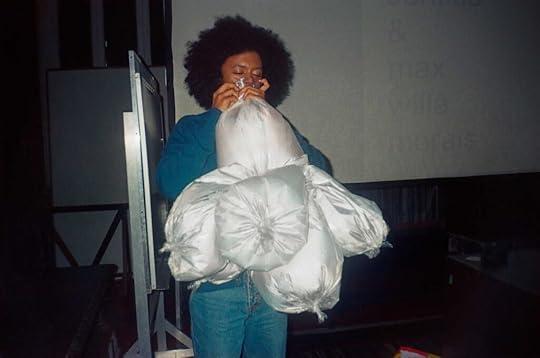

It’s also with a sigh and a breath that Tadáskía meditates on the brutal event that lit up the news in 2018: the murder of Matheusa Passarelli, a twenty-one-year-old student, artist, and LGTBQ activist, in Rio de Janeiro. After days without explanation of her disappearance, at 10 a.m. on May 30, Tadáskía built a small fortress to hide in. “I am wearing a red dress in homage to Matheusa Passareli,” the artist recalls. In her performance Atrás do muro (homenagem à Matheusa Passareli) (Behind the wall [homage to Maltheusa Passareli], 2018), Tadáskía passes a plastic bag through a hole in a wall of cement blocks that she built; she fills, empties, and breathes into the bag as it is wedged into the wall. Passareli is family, and this breath of life appears in different scenes. Tadáskía’s work becomes a photograph of a family that was destroyed, dispossessed of its self-image. Or could it be another kind, our kind, the kind considered possible for a Black family album?

Tadáskía, Hálito com minha mãe Elenice Guarani (Breath with my mother Elenice Guarani), 2019

Tadáskía, Hálito com minha mãe Elenice Guarani (Breath with my mother Elenice Guarani), 2019

Hálito (Breath, 2019), which includes a photograph of Tadáskía puffing into plastic bags melted by fire, unfolds in the kitchen of the artist’s home with her mother, her father, her grandmother, aunts, and cousins. It is the duration of a life that creates this portrait. The framing of the photograph, Harney and Moten write, “is commissioned against but also under the terms of a contract of civil butchery. Held out, held back, shard, shielded—the chemistry of stolen moments is our true and terrible and beautiful black share.” Hálito may be what the artist calls “an elementary exercise in vitality” or “a temporary meeting that wilts.” Harney and Moten continue: “This chain of viewing (looking, looking like, seeing with, seeming, unseaming) is a chain of handing. There’s violence in being held on the verge of being hidden. Being treasured is all but being lost. Nothing found in being sought. Common breath is gone and we can’t reconstruct it. And, anyway, what’s this presumption of family, and its rights and its brokenness, all of which are confirmed in the snapshot’s uncanny, untimely career? Can there be such a thing as a Black family photograph? Should there be?”

Tadáskía, com o Hálito (with the Breath), 2019

Tadáskía, com o Hálito (with the Breath), 2019All photographs courtesy the artist and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel

The breath of life of Tadáskía’s photography, as a whole itself a sweaty and hot photography, stems from her insistence on the animating power of transformation and resistance, and through her awareness that this is the language of perception that we possess in order to be possessed. Between what Harney and Moten call “the interminable flash, the undefinable moment of being stolen,” and the fact that “we are disappearing,” the Exú-like centipede renews the artist’s commitment to believing that “not all dangers are lethal,” and in our own belief that apparition is an act of faith. We need to take stock of shallow and banal images. I return to the prophecy of the artist’s notebooks: “We belong to the family of the Mystical Black Birds. We are also known as the Enchanted Chickens. Inspired by Sankofa. Friends of Magic.”

“All the images will disappear,” Ernaux writes. Will there be someone who recognizes us?

This essay was originally commissioned by ZUM magazine, published by the Moreira Salles Institute in São Paulo. Translated from the Portuguese by Zoe Sullivan.

June 18, 2024

One of Photography’s Most Enigmatic Love Triangles Finally Gets Its Due

Nick Mauss and Angela Miller’s book Body Language: The Queer Staged Photographs of George Platt Lynes and PaJaMa (2023) brings new critical discourse to representations of queerness in American modernism. Part of a series called “Defining Moments in Photography,” the book contains two richly illustrated essays with an introduction by Anthony W. Lee. Mauss appraises the wide-ranging practice of George Platt Lynes, a photographer who is known (if at all) primarily for his male nudes from the 1930s and ’40s. Miller writes about the collaborative photographs of Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret Hoening French, who worked contemporaneously to Lynes under the moniker PaJaMa, a combination of their first names. Both essays explore the social roles these images played when circulated among a coterie of queer artists as well as their relationship to mass media, and how they not only informed other artworks made by their participants but also reflected a network of queer culture in America between the two world wars.

Angela Miller’s essay, “PaJaMa Drama,” is the first published piece of in-depth scholarly writing about the work of this landmark queer photography collaborative. PaJaMa made highly staged figurative photographs on the beach in queer havens such as Fire Island and Provincetown, Massachusetts; in the apartments of friends in New York’s Greenwich Village; and later on the shores of Nantucket. Their collaboration started in 1937, and they produced thousands of negatives of staged tableaux, working as a formal collective through 1955, though they informally photographed each other for the rest of their lives, into the 1980s. The pictures were not created for exhibition but were instead “gift images” circulated among friends, sent in letters, and handed out at dinner parties. They were also used as reference images for paintings. Significantly, the label PaJaMa was applied only to the collaborative images by Cadmus, the most famous artist of the trio, when the pictures were first exhibited in the 1970s. Both Margaret and Jared hated the name.

Jared, Margaret, and Paul (in shadow, taking photograph), Nantucket, 1946

Jared, Margaret, and Paul (in shadow, taking photograph), Nantucket, 1946Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The pictures dramatize the complex dynamics between the collaborators. Paul Cadmus and Jared French had been deeply involved romantically for eight years before Jared married Margaret French in 1937, and they remained so afterward. Margaret came from a moneyed New Jersey family; she was devoted to Jared and supported him financially. Margaret and Paul had a “loving if guarded” friendship, Miller writes, because they were both in love with Jared. Today, we might describe this as polyamory, but within PaJaMa’s network of friends and lovers, a kind of freedom existed in the lack of labels and sexual categories, in the unnamed nature of things.

For Miller, the photographs, which are often foreboding in their sense of light and always statuesque in composition, provided still points of mooring amid their tempestuous and fluid personal lives. She attributes the recurring motif of a doubled, shadowed self in the photographs to Jared French’s interest in Jungian archetypes and the dual sides of anima and animus. Miller also argues that the members of PaJaMa were influenced by the aesthetics of 1940s Hollywood film noir and, in particular, melodrama. Reading Miller’s list of citations shows the new ground she is tilling. She cites auction catalogs, newspaper reviews of the relatively small number of exhibitions of PaJaMa’s work, and websites, in addition to the extensive correspondence and personal papers that Cadmus and the Frenches left to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

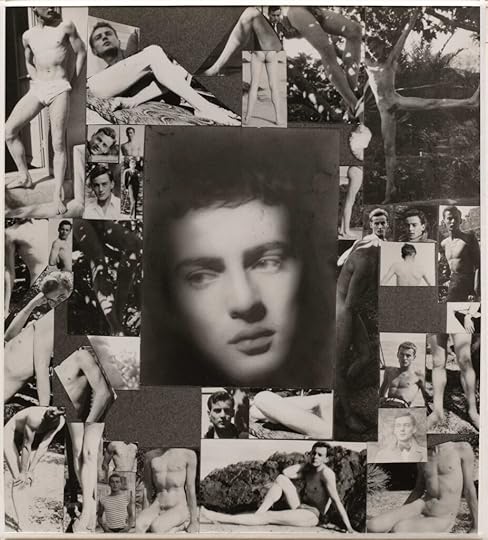

George Platt Lynes, Untitled self-portrait collage, ca. 1935

George Platt Lynes, Untitled self-portrait collage, ca. 1935Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © Estate of George Platt Lynes

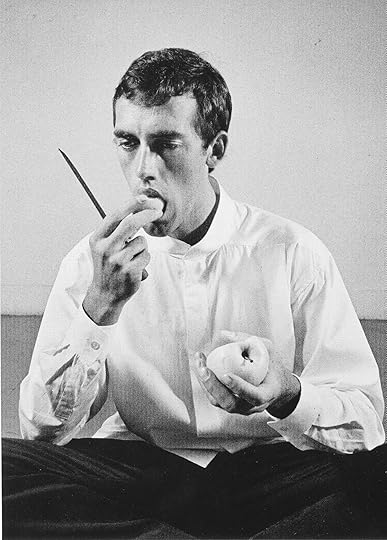

Nick Mauss is a visual artist and writer whose 2018 exhibition Transmissions at the Whitney Museum in New York featured photographs by Lynes and PaJaMa. In his essay, “The Uses of Photographs,” he discusses the multiple ways that George Platt Lynes’s photographs circulated, both publicly and privately. He maps the intertwined nature of Lynes’s practices as a portraitist, a photographer of fashion and dance, and an enthusiastic proponent of the male nude. Mauss’s research provides a counterpoint to the publications released by Twelvetrees Press between 1981 and 1994 that introduced Lynes’s work to a broad audience, but which silo his artistic production into three separate artistic genres. But Mauss’s research goes beyond these sources, examining the staggering wealth of archival material Lynes left behind in the form of correspondence, personal scrapbooks, and printed ephemera, making connections that are unique to a visual artist’s sensibility. To connect the dots, he also includes the work Lynes did not want to leave behind—his fashion photographs, which he begrudgingly made for a living and tried to destroy by burning the negatives before his death. Thankfully for Mauss, they had circulated widely in print and could not be erased.

Within PaJaMa’s network of friends and lovers, a kind of freedom existed in the lack of labels and sexual categories, in the unnamed nature of things.

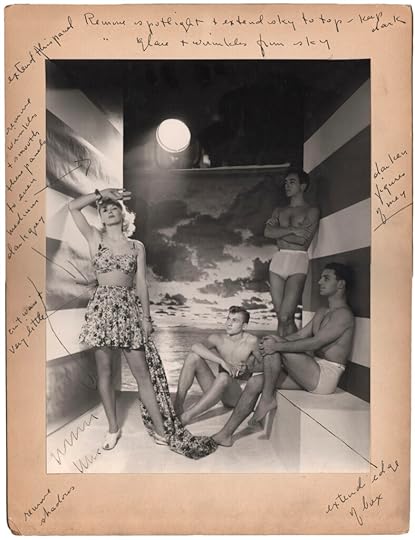

Mauss tracked down objects and models across different genres of Lynes’s artistic output, showing not only their interconnectedness but also how they fed into and fueled one other. In one example, he shows the evolution of a photograph within Lynes’s world. For a swimsuit advertisement shot in 1937, Lynes built a set that looks like a cabana, with a mural-size photograph of a beachscape as backdrop. The image captures a stiff composition of three men staring at a woman in a bathing suit. It has long been suspected that Lynes reused commercial sets after-hours for his erotic work, and Mauss provides evidence in the form of one of Lynes’s better-known photographs titled Demus, also from 1937, in which a dejected-looking nude man cradles his head in the same cabana against the same seascape. Here, Mauss writes, the setting has been transformed to evoke a well-known 1836 painting by Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin, whose figure of another “sad young man” became “an archetypal cipher for the homosexual’s isolation from society.”

George Platt Lynes, Nicholas Magallanes and Tanaquil Le Clerq in Jones Beach, 1950

George Platt Lynes, Nicholas Magallanes and Tanaquil Le Clerq in Jones Beach, 1950Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library © Estate of George Platt Lynes

George Platt Lynes, Swimsuit advertisement with notes for retouching, ca. 1937

George Platt Lynes, Swimsuit advertisement with notes for retouching, ca. 1937Courtesy Keith de Lellis Gallery © Estate of George Platt Lynes

Building on this revelation, Mauss identifies one of the male models in the fashion advertisement as the American ballet dancer Nicholas Magallanes, one of Lynes’s frequent subjects and a charter member of the New York City Ballet. A 1950 photograph Lynes made for George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins’s ballet Jones Beach uses a similar otherworldly set of a beach and features Magallanes cradling the dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq, whose pose is strikingly akin to that of the model in Demus. Finally, Mauss links this dance image to a spectacular male nude that Lynes photographed on the same set as the Jones Beach image, perhaps on the same day, in which a male model strikes this same pose but is turned upside down and rotated toward the camera in what Mauss describes as “a flagrant consecration of the rectum.”

Earlier in his text, Mauss asks: “Could Lynes’s work be seen as a new form that fused commercial imaging with vanguard aesthetics, and opened up the performative potential of the photographer’s studio? Would it not be more accurate to call Lynes an artist who used a camera rather than labeling him a studio photographer?” Though photographers may bristle at the second question, it identifies Lynes’s work as an important antecedent to the conceptual photography that prevailed at a much later period in the 1980s. As Miller writes in her essay on PaJaMa, the staging of scenes for the camera “anticipated the postmodern turn toward artists who used photography as an instrument of self-performance and role-playing.” In the staged photographs of PaJaMa, one begins to see a precursor to the far-off stares of motionless figures in Gregory Crewdson’s tableaux or, as Miller notes, artists of the Pictures Generation, including Cindy Sherman.

James Ogle, Portrait of George Platt Lynes in his studio, ca. 1940

James Ogle, Portrait of George Platt Lynes in his studio, ca. 1940Princeton University Art Museum

Body Language is part of a resurgence of interest in these mid-twentieth-century queer photographers, beginning in 2019 with two concurrent shows about queer modernism in New York: Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Young and Evil, curated by Jarrett Earnest at David Zwirner Gallery. Since then, the gay photography historian Allen Ellenzweig has published an extensive biography of Lynes, The Daring Eye (2021), and the art director Sam Shahid has released a documentary about Lynes titled Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes (2024). Artists have also depicted similar themes of love and desire, particularly through staged photography. These projects include Ian Lewandowski’s intricate and luminous contact prints of queer communities in conversation with vintage prints by PaJaMa and Lynes and the recent exhibition Communion at Brick Aux Gallery in Brooklyn of photographs by the self-taught photographer Kris Mendoza, who describes sharing a “spiritual connection” with PaJaMa.

The concept of a “gift image”—an artwork that has no immediate purpose other than to act as an expression of friendship or shared queerness—is particularly important to consider now, in a time when art and arts education have become over-professionalized. Mauss considers the function of gift images to be “not unlike love letters, or the circulation of painted portrait miniatures among friends, lovers, and family members in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England and the United States, or the exchange of painted fans inscribed with verse between nineteenth-century painters, poets, and their muses.” Artists should be trading more inscribed fans; as something to be shared among artists, this book shows the potential of such an exchange. Lynes, the authors of Body Language note, was devoted to creating a “future history of art”—a line that is also used as the book’s epigraph. In a sense a gift image itself, Body Language provides a fascinating, deeply researched background for the enigmatic works these queer artists left behind, helping to illuminate their contributions for generations to come.

Body Language: The Queer Staged Photographs of George Platt Lynes was published by the University of California Press in 2023.

How Images Make the Objects We Desire Seem Irresistible

Imagine having lost a loved one in the New England of the 1870s. Then, a knock at your door: a salesman in a suit. He pulls out a bound catalog of albumen-silver prints, with as many photographs in it as you’ve maybe seen in a lifetime, each showing a tombstone ready to memorialize your loss. The trade catalog for the Vermont Marble Companies offers a purchase for your grief, documentation that something exists in the here and now to honor those in the here-after. This is an example of what the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s research assistant Virginia McBride calls “the truth claim of photography,” a way companies used the supposed veracity of photographic images to convince customers they would deliver what they promised.

Photographer unknown, Trade Catalogue for Producers’ Marble and Vermont Marble Companies (detail), 1870s–80s

Photographer unknown, Trade Catalogue for Producers’ Marble and Vermont Marble Companies (detail), 1870s–80sCourtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It’s an early highlight of a Met show on view this summer that McBride has curated, The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography, which tracks how pictures made people familiar with objects for consumption and then, with the arrival of modernism, rendered such objects radiantly unfamiliar. The show, which features work from the nineteenth century to the late 1940s, arrives at a moment when many artists have been drawing inspiration from the long history of how photography has been used to sell all manner of commodities. It’s a moment marked by a turn from the object for sale to the meaning of the sale itself.

H. Raymond Ball, Pocket Comb, ca. 1930s

H. Raymond Ball, Pocket Comb, ca. 1930sCourtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Edward J. Steichen, “Sugar Lumps” Pattern Design for Stehli Silks, ca. 1920s

Edward J. Steichen, “Sugar Lumps” Pattern Design for Stehli Silks, ca. 1920sCourtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

But first you had to make the sale, and the best way to do that was to catch someone’s eye. A commercial photographer in Providence, Rhode Island, named H. Raymond Ball photographed a comb from an unknown manufacturer balancing mysteriously on its edge; in his Pocket Comb (ca. 1930s), the expanse of the object’s shadow somehow echoes both the architect Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch in St. Louis and the bob hairstyle favored by flappers. “It’s an object lesson in what the camera can do with the right light and the right shadow and any object at all,” McBride explained.

Corporate resources funded adventurous photographers to push things even further. Edward J. Steichen was commissioned by a Swiss textile manufacturer to lend their products a touch of the new. His “Sugar Lumps” Pattern Design for Stehli Silks, from the 1920s, staggers rows of the treat to cleverly arrange their shadows into a fresh take on a checkerboard; in 1927, Stehli made a textile with Steichen’s photograph printed upon it, and the advertisement itself became the product.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

August Sander went even further. For Osram Light Bulbs (ca. 1930) he composed a spiral of lightbulbs, creating a gelatin-silver print that seems lit vertiginously from within. If the bulbs could do that on a magazine page, what wonders they might lend to your house! In such advertisements, photography transcends its lifelike authority to become life itself, abuzz with a kind of optimism some Americans in the 1930s and ’40s might’ve found lacking in their daily lives, as they flicked through Depression-era fashion magazines and war-stricken newspapers.

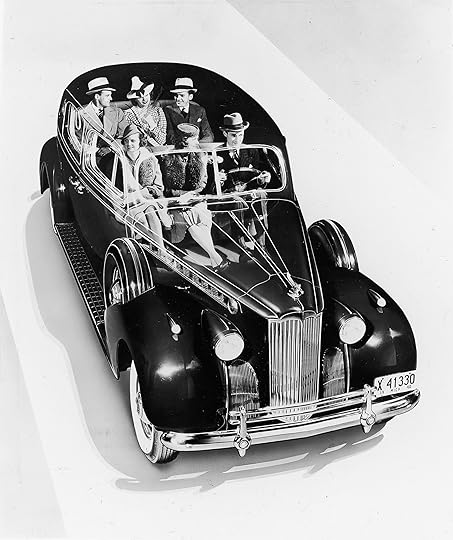

Ralph Bartholomew Jr.’s carbo print Soap Packaging (1936) erects a cityscape of candy-colored packaged soap on newsprint in a bubbly anticipation of Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie six years later. An unknown image maker gassed up a car ad with the latest editing techniques for Montage for Packard Super Eight (ca. 1940), which you can imagine zipping around that soap package city, even if that many people couldn’t possibly fit in a Packard that size. Modernism, with its emerging formal concerns of experimentation and abstraction, was an irresistible tool kit for a sales pitch.

August Sander, Osram Light Bulbs, ca. 1930

August Sander, Osram Light Bulbs, ca. 1930Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Photographer unknown, Montage for Packard Super Eight, ca. 1940