Aperture's Blog, page 14

November 12, 2024

For Sohrab Hura, Photography Is a Way of Feeling Visible

For a period of about three years during his mid-twenties, Sohrab Hura strived to be what he called an anti-photographer. Doubt had begun seeping into his work. In particular, he felt conflicted about the ways in which documentary photography generates images from other people’s oppression. Regarding his own role, he quotes Arundhati Roy, who writes: “The trouble is that once you see it, you can’t unsee it. And once you’ve seen it, keeping quiet, saying nothing, becomes as political an act as speaking out. There’s no innocence. Either way, you’re accountable.”

In his first-ever US survey, Sohrab Hura: Mother, at MoMA PS1, the artist, who was born in Chinsurah, India, in 1981, reconsiders the possibilities of images. His body of work, spanning two decades, includes photography and film as well as drawing, painting, and writing—an astonishing range for someone who is self-taught. While the exhibition features experimentations with different media, Hura insists all of his work remains image driven.

Sohrab Hura, Self-portrait, 2024

Sohrab Hura, Self-portrait, 2024“The moment when I think of it as a survey show, suddenly I become the center of it, and then it becomes about my journey,” he told me recently. “But for me, really, it’s about the multiple lives of images, and that also allows me to look at any of these older works as being no different, in terms of there not being any kind of hierarchy compared to some of the new works.”

The curator Ruba Katrib had been following Hura’s career when he began shifting from a primarily lens-based practice to other forms of art making. She sees a continuity to his approach, saying, “For him, it’s all about what an image can do and the stories it can tell.”

When Hura first picked up a camera as a teenager, like so many aspiring photographers before him, he saw the power in making something seen. “I’d been feeling invisible,” Hura, now forty-three, recalled of his younger self. “And so, photography became a way to feel visible, to feel like I could touch someone, which I felt I wasn’t able to for a long time.”

Sohrab Hura, Details from the series Land of a Thousand Struggles, 2005–6

Sohrab Hura, Details from the series Land of a Thousand Struggles, 2005–6Initially, photography promised immediate transmission of the stories he felt were most urgent. “I started photography at a time when I believed that photography could change the world,” he said. Youthful idealism combined with a desire to travel led him to document what he was witnessing for local press. One of his earliest series, Land of a Thousand Struggles (2005–6), exposes the grim reality of impoverished rural communities in central India. Black-and-white photographs capture women, children, and older people swinging pickaxes, breaking rocks, and engaging in other physical labor. Candid and wide shots show workers gathering at a rally. The portrait of an injured man lying down, a wound healing into a scar on his bare left hip, reveals the brutal aftermath of police violence that targeted protestors. These encounters provided Hura, then a recent graduate student with a master’s degree in economics, his first introduction to grassroots politics.

Hura’s handwritten captions contextualize the images in the series, as if to acknowledge the link between the lives of the people he was recording and his own. It was an entanglement he understood from the beginning. “Right from the start,” he said, “I felt a bit of a dichotomy where, on the one hand, I wanted to do photography that would nourish my heart, and at the same time there was a voice in my head that would tell me that I had the responsibility to carry people’s stories forward.”

Sohrab Hura, Still from Bittersweet, 2019. Video, color, sound, 13 minutes, 48 seconds

Sohrab Hura, Still from Bittersweet, 2019. Video, color, sound, 13 minutes, 48 secondsTurning to video allowed Hura to expand upon the realist mode of storytelling. In Pati (2010/20), he narrates his experience revisiting the region he had photographed years earlier over still images from his previous series. Near the end of the eleven-plus-minute film, he keeps the camera rolling on a figure standing in front of a stark, barren landscape. There’s no sound except for the wind. A boy gradually comes into focus. The fifteen seconds of footage offers a glimpse of something more truthful, perhaps.

“This question of honesty was really important to me,” Hura said about what was troubling his work. As he became more technically skilled, he found himself growing increasingly cynical. “I knew exactly what photograph to make, to make someone feel what way, you know? So it started to feel performative,” he said.

Sohrab Hura, Untitled, from the series Snow, 2015–ongoing

Sohrab Hura, Untitled, from the series Snow, 2015–ongoingA series he made later in his career, Snow (2015–ongoing), pushes the visual language of documentary photography even further. The photographs allude to the conflict in Kashmir without showing explicit violence or trauma. Only a distant shot of uniformed soldiers hints at the heavy military presence. Instead, Hura observes the region through its phases of winter, directing the viewer’s gaze to the back of a person in a frayed coat holding a snowball, bright orange fruit floating in a thawing puddle, a pair of hands uprooting dandelions from the grass. These details subvert the exploitation and voyeurism often associated with photojournalists who parachute into places of conflict.

Paired with Snow, a four-channel video plays television footage from the 1980s and ’90s that includes news clips representing Kashmir as a place of “terrorism” and Bollywood movies romanticizing it as a backdrop—stereotypes Hura would have been exposed to while growing up in India. The work speaks not only to problems of representation, but also to the artist’s feelings of complicity.

Sohrab Hura, The Coast, 2013–19

Sohrab Hura, The Coast, 2013–19

Hura has long wrestled with his role as a photographer and confessed to becoming “a bit jaded” about what he was doing. “People would be really generous to me,” he said. “They would open up their lives, their stories. They would have this expectation that I would change their life by taking the stories back, and every time I had to tell them that that wasn’t the case.” Eventually, he concluded, “photography had its limitations.”

His project The Coast (2013–19), a collection of pigment prints, a single-channel video, and an artist’s book, arose as a critique of image-making. Hura describes the images as “a little intrusive, a little violent” in feeling. Indeed, an ominous mood pervades the scenes from a religious festival taking place along India’s southernmost coast. Accompanying the photographs, the seventeen-and-a-half-minute film slows down footage of people running and jumping into the surf at night, which plays over tense, droning audio that radiates into the other galleries of the exhibition. The images also appear in the book, interspersed among twelve fictional short stories by the artist. On a practical level, the photobook serves as a method for easily transporting and presenting the work. Its curation also manifests as a kind of logic. In The Coast, the photographs sometimes repeat, or “glitch”—a term Hura applies to resisting the so-called perfect image.

Sohrab Hura, Still from The Coast, 2020. Video, color, sound, 17 minutes, 27 seconds

Sohrab Hura, Still from The Coast, 2020. Video, color, sound, 17 minutes, 27 secondsThe Lost Head and the Bird (2019) rescrambles many of the same images in a ten-minute-long split-screen video. Katrib characterizes Hura’s practice as being “quite iterative,” whereby images will reappear in different bodies of work. “It’s a practice that builds upon itself,” she said. Additionally, the film, which was previously screened at the Museum of Modern Art in 2021, incorporates “appropriated material” from pop culture, current events, and media circulating on WhatsApp. The sequencing mirrors how people in India—and globally—are inundated with manipulated images and propaganda disguised as news. In conversation, Hura said he isn’t afraid of technology such as AI. He’s more concerned with structures of power and how they influence our perceptions of reality. He frequently compares the image to a “mask.”

If image-making itself is a kind of obfuscation, then Hura realized he needed to confront his truth. When he was seventeen years old, his mother was diagnosed with acute paranoid schizophrenia. As he was taking pictures of other people in their most vulnerable states, a thought stayed with him: that it was “easy for me to photograph someone else’s mother.” He continued, “But somehow I wasn’t able to photograph my own mother.” He worried that made him a hypocrite. And so, as difficult as it was, he decided to photograph his mother.

Sohrab Hura, Untitled, from the series The Songs of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer, 2013–ongoing

Sohrab Hura, Untitled, from the series The Songs of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer, 2013–ongoingAll works courtesy the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata and Mumbai

She smokes a cigarette in bed in a black-and-white photograph published in the book Life Is Elsewhere (2015), one of three that Hura made about her. In Bittersweet (2019), a video that rotates through images like a slideshow, she’s kissing her dog Elsa. Again, she’s shown smoking in a pastel drawing from the book Things Felt but Not Quite Expressed (2022–24). Along the gallery wall, dozens of drawings hang like family portraits. Hura, who began drawing and painting only recently, said he was searching for “softness” within the image.

In the installation Timelines (Delhi, Mother, Sheila, The Bus, The School, The Olive Tree, Bees, Protest, and Mail) (2024–ongoing), he asks, Where do our stories begin? Painting with acrylics on cardboard boxes, he illustrates various memories of his mother’s life, including her sleeping in bed with Elsa, as well as moments from history. “Depending on how the box is folded, you see a different combination of stories, a different combination of points of time,” he said. “In this timeline we see many different points of time, and we make our stories based on that.”

Sohrab Hura: Mother is on view at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, New York, through February 17, 2025.

November 8, 2024

Announcing the Winners of the 2024 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture are pleased to announce the winners of the 2024 Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards—an annual celebration of the photobook’s enduring role within the narrative of photography. The awards recognize excellence in three major categories of photobook publishing: First PhotoBook, PhotoBook of the Year, and Photography Catalog of the Year. A final jury met in Paris on November 7, 2024, to select this year’s winners. The jury included Kim Bourus, founder and director, Higher Pictures; Azu Nwagbogu, curator; Lisa Sutcliffe, curator, Department of Photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Jean-Baptiste Talbourdet-Napoleone, creative director, M le magazine du Monde; and Mame-Diarra Niang, artist.

This year, Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards received 940 books from fifty-nine countries around the world, including standout entries from Argentina, Japan, Indonesia, New Zealand, and elsewhere. On September 18–20, the shortlist jury met in New York for three concentrated days of review and deliberation, narrowing the entries down to a shortlist of thirty-five titles. The shortlist jury consisted of the following international team: Negar Azimi, editor in chief, Bidoun; Jacqueline Bates, photography director, Opinion, New York Times; Michael Famighetti, editor in chief, Aperture; Nontsikelelo Mutiti, director of graduate studies in graphic design, Yale School of Art; and Anna Planas, artistic director, Paris Photo.

Related Stories PhotoBook Awards A Look Inside the Titles Shortlisted for the 2024 PhotoBook Awards

PhotoBook Awards A Look Inside the Titles Shortlisted for the 2024 PhotoBook Awards A presentation of the thirty-five books shortlisted for the 2024 PhotoBook Awards is currently on view at Paris Photo through November 10 and will be on view at Printed Matter in New York, January through February 2025, and then to the Leipzig Photobook Festival, in Germany, in March, with additional venues to be announced.

Below, read about this year’s winning titles.

Photography Catalog of the Year

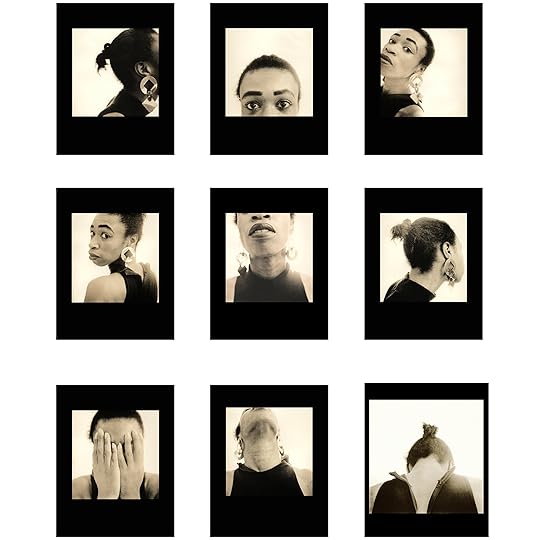

Shining Lights: Black Women Photographers in 1980s–90s Britain

Joy Gregory, editor, and Taous Dahmani, associate editor

Autograph and MACK, London, Design by Morgan Crowcroft-Brown

Shining Lights, edited by artist Joy Gregory and Taous Dahmani, is a restorative anthology that charts Black women’s essential but often overlooked contributions to Britain’s photography scene in the late twentieth century. Extensively researched and vividly illustrated, the book showcases a tremendous range of visual materials, including photographs from over fifty artists, archival images, documents, and more. This constellation of visual resources is carefully organized by theme—self-portraiture, family, and community activism—and includes scholarly essays, personal reflection, a roundtable discussion, and a detailed timeline. “I love the use of the materials; there’s a friendliness to the cardstock cover, and beautiful neon spine that carries through in how certain elements get highlighted within the running text,” remarks juror Nontsikelelo Mutiti. “For a project so comprehensive, it feels very generous and inviting. I’m so glad that this project exists.”

Maxine Walker, from the series Untitled, 1987

Maxine Walker, from the series Untitled, 1987Courtesy the artist

Joy Gregory, Autoportrait, 1990

Joy Gregory, Autoportrait, 1990Commissioned by Autograph. Courtesy the artist

First PhotoBook Award

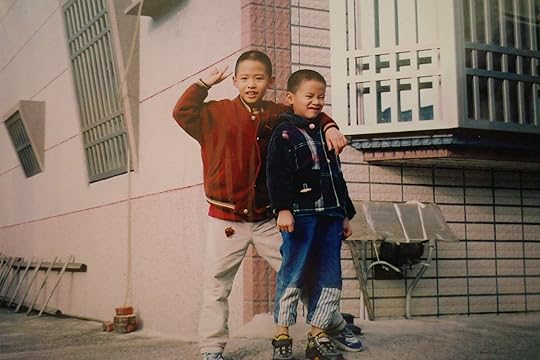

Born from the Same Root by Tsai Ting Bang

Self-published, Taipei, Design by Tsai Ting Bang and Shū Hé Zhì

Tsai Ting Bang’s Born from the Same Root forms a moving portrait of the artist’s older brother Hsien and reflects upon their shared family trauma. The boys grew up in separate homes, and as a young adult, Hsien began suffering from mental health issues and cut contact with the family for three years. Tsai uses the book to explore the estrangement, misrecognitions, and mystery at the heart of their bond, interweaving archival family photographs and his own tender portraits of Hsien and his day-to-day life. “The book tells a simple but powerful story and is full of lovely, unguarded moments,” says juror Anna Planas. The intimately sized volume involves a clever bipartite structure, forcing the reader to turn the pages of the book in opposition, as one might open a gatefold. Per Planas, “we loved how the design thoughtfully reflects both the distance and closeness of the brothers’ relationship.”

Tsai Ting Bang, from Born from the Same Root, 2024

Tsai Ting Bang, from Born from the Same Root, 2024

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

PhotoBook of the Year

Disruptions by Taysir Batniji

Loose Joints Publishing, Marseille, France / London, Design by Loose Joints Studio

Opaque, yet frighteningly urgent, Taysir Batniji’s Disruptions compiles pixelated screenshots from WhatsApp video calls to his family in Gaza, taken between April 2015 and June 2017. The fragmentary aesthetic of fragile phone connections offers a metaphor for the breakdown of the psyche in the midst of daily life compromised by conflict. This compact softcover houses about seventy images, which are accompanied by a poignant text from photo-historian Taous R. Dahmani. Amid warped portraits and pixelated landscapes, the viewer is confronted with bursts of vibrant color signaling failed communication, broken only by solid pages of green that display the date of each call. Disruptions is an oblique but essential reflection on life under occupation. “As Gaza is obliterated in real time, Batniji’s Disruptions is a timely reminder of the precarious nature of human life,” remarks juror Negar Azimi.

Taysir Batniji, from Disruptions, 2024

Taysir Batniji, from Disruptions, 2024

Jurors’ Special Mention

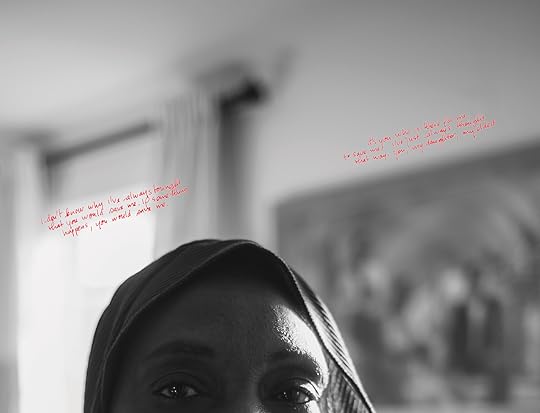

i am (not) your mother by Hady Barry

Self-published, Penumbra Foundation, New York, Design by Hady Barry

In 2002, amid a civil war, Hady Barry and her family fled Côte d’Ivoire to resettle in Senegal. As her mother left for the United States to seek asylum, and her father was mostly absent, traveling for work, Barry, age thirteen, found herself taking care of three younger siblings. Her self-published photobook i am (not) your mother interlaces portraits and documentary photographs, archival imagery, journal entries, and transcribed conversations, unpacking the trauma of an adolescence cut short by the tremendous responsibilities of parenting. The book’s imagery alternates between the vivid, nostalgic palette of rediscovered family photographs and the black-and-white of Barry’s own austere pictures of nature, people, and interiors. “There’s this parallel with her personal story and the personal way she made the publication,” says juror Anna Planas. The book’s smaller 6 ½-by-9 inch format and use of one-of-a-kind Risograph printing, befit the intimacy and rawness of Barry’s painful subject matter.

Hady Barry, from i am (not) your mother, 2024

Hady Barry, from i am (not) your mother, 2024

An exhibition of 2024 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist will be on view at Paris Photo through November 10, and will travel to Printed Matter in New York City in January 2025.

October 31, 2024

Rafael Goldchain’s Portraits of Grief and Piety in Latin America

Over the last decade, the Art Gallery of Ontario embarked on an initiative to incorporate twentieth-century photography detailing life in Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico into its collections. Beyond poetic images created by Graciela Iturbide and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, the Toronto museum also houses photographs of protests and coups. Such grim subjects might be expected in a Latin American collection: during the latter half of the century, the region was convulsed by civil wars, a genocide, dictatorship, and murderous US intervention.

One recent acquisition provides an unexpected twist: lushly colored images by Rafael Goldchain, a Chilean-born photographer of Polish Jewish heritage, who settled in Toronto in the 1970s and in the mid-1980s traveled on a grant to Mexico and Central America. There, he took pictures of residents who struggled on the sidelines of the Guatemalan civil war, CIA interference in Honduras, and Nicaragua’s revolution. Yet instead of focusing on conflict’s “decisive moments,” Goldchain showed lyrical glimpses of people’s desire, grief, repose, and piety.

Rafael Goldchain, A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua, 1986

Rafael Goldchain, A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua, 1986Such is the case in A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua (1986), which reveals a collage adorning a final resting place. The artwork frames a studio portrait of the deceased, a wide-eyed, thinly mustachioed stripling surrounded by dried flowers, clouds, and angels. The offering is saturated with intense blues. “I was in a cemetery in Matagalpa,” Goldchain told me recently, mentioning the city in west-central Nicaragua involved in the Iran–Contra conflict. “Had this young man fallen as part of that? I didn’t know. I had heard that there was a tradition where children who pass away automatically become angels. This boy was of the age that he could be both, a soldier and an angel.”

Goldchain’s ability to freeze tender, ambiguous moments against the backdrop of political violence constitutes a distinct kind of conflict photography. The 1980s “were the era of Susan Sontag and the whole Goya perception of pain,” AGO curator Marina Dumont-Gauthier explained. She referenced Sontag’s On Photography (1977), which inveighs against the power of war images to anesthetize viewers to suffering. “What Rafael is offering is so different,” she said. According to Dumont-Gauthier, back when Goldchain photographed his images, people were not ready to view complex and polysemous images of war “because it somehow felt disingenuous.” She thinks the time is now ripe for Goldchain’s approach. “The pain is still there. Once the war is over, these stories continue.”

Rafael Goldchain, Easter Procession, Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, 1986

Rafael Goldchain, Easter Procession, Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, 1986Goldchain presents the continuing story in works such as Easter Procession, Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala (1986). Depicting ten men carrying a tinseled casket that appears to contain a statue of Jesus Christ in the tradition of Santa Semana, the picture achieves a forward propulsion amplified by the undulating line created by the heads and shoulders of the pallbearers. The image’s mingling of beauty and mourning is complicated by the fact that four years after it was taken, army soldiers would open fire on an unarmed crowd of Tz’utujil Mayans in Santiago Atitlán as part of the atrocities that punctuated the country’s civil war.

“I wasn’t a war photographer,” Goldchain told me. “I sometimes took photos of bullets in walls, semi-destroyed ruins, but those pictures didn’t have any of the complexity that I was after. And I didn’t want a bullet in the heart either. My work is more elliptical.”

Related Items

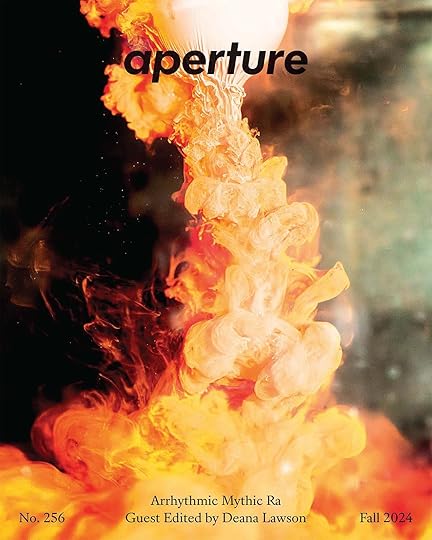

Aperture No. 256

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Goldchain’s allusive impulses led to Nocturnal Encounter, Comayagua, Honduras (1987), which initially reads like a snapshot of carefree lovers. A man wearing a striped blue shirt smiles down at a dark-haired woman who sways her hips. The innocent-looking assignation takes place in a turquoise-and-cerulean alleyway. But knowledge of the political context introduces menacing undertones of male dominance to the photograph. “During the Iran–Contra affair, there was a very large air base in Honduras called Palmerola. There were a lot of bars where American soldiers met lovely Honduran girls. This is a red-light district, a meat market.”

“Rafael’s work allows people to engage with photography that tells a fuller story,” Dumont-Gauthier said, an affirmation of Goldchain’s Mexican and Central American images that resonates with the recent institutional validation of Latinx photographers, such as Louis Carlos Bernal and Paz Errázuriz, who breathed new life into the documentary tradition in the 1970s and 1980s. The curator also noted Goldchain’s deliberate use of color, suggesting that “Blue is associated with nostalgia. The colors help us process our own emotions. If the photo were against a red backdrop, it would have a completely different meaning.”

Rafael Goldchain, A Tehuantepec Maiden, Juchitán, Oaxaca, México, 1986

Rafael Goldchain, A Tehuantepec Maiden, Juchitán, Oaxaca, México, 1986All images courtesy the artist

Goldchain’s associative palette perhaps finds its deepest expression in A Tehuantepec Maiden, Juchitán, Oaxaca, México (1986), where a girl wearing a huipil stitched with crimson-and-pink florals stands against a mural of the Virgin of Guadalupe. As in A Young Man’s Grave, Nicaragua, a painted sky forms the backdrop. The jaunty artificial flowers in the girl’s hair contrast with her stoic expression. Does her steadfast look telegraph the larger struggle of armed forces disappearing and murdering Oaxacan dissidents during this era? The girl’s gaze seems almost unnervingly grave in light of that history.

“She was fifteen years old,” Goldchain recalled, nodding his head contemplatively. “When I first showed these photos, people said I was noncommittal and too artistic and aesthetic. But I could only be who I could be.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture no. 256, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” guest edited by Deana Lawson.

October 26, 2024

What Is Street Photography Today?

The street and the camera were destined to collide. In retrospect, it seems obvious that the first photographs that managed to freeze objects in motion would be taken on the bustling streets of newly industrialized nineteenth-century cities. That era belonged to the crowd, and to the savvy navigators of the endlessly renewable theater of sidewalks and boulevards the world over, those flaneurs whom the poet Charles Baudelaire, in his essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” pegged as one of the nineteenth century’s most fertile archetypes. Baudelaire called for an art that would dive headfirst into the bracing water of the everyday. Impressionism followed, with its gauzy tableaux of bourgeois life, but in time it became clear that it was not the likes of Baudelaire’s titular, now-forgotten painter who were best suited to document the upheavals of the modern era. The pace of everything was quickening, and the newfangled camera was the perfect tool to slow things down, trapping the chaos in amber. Photographers became the ultimate flaneurs, shaping our collective vision as they wandered through the world.

Jamel Shabazz, Man & Dog on the Lower East Side, 1980

Jamel Shabazz, Man & Dog on the Lower East Side, 1980Courtesy the artist

Street pictures soon became practically synonymous with serious photography. The introduction of the fast, handheld 35mm Leica, in 1925, disencumbered roving shutterbugs from their bulky gear, allowing artists like Alexander Rodchenko to make a new kind of image that was as dynamic and spontaneous as the streets themselves. After that, it was off to the races. In 1952, inspired by the Surrealists’ obsession with chance encounters and striking juxtapositions, Henri Cartier-Bresson coined the indelible phrase “the decisive moment.” There followed Robert Frank’s Beatnik-era, dirge-like book The Americans; the epochal exhibition New Documents, featuring Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand, at MoMA, in 1967; the Pop art–adjacent work of William Eggelston carved out space for previously déclassé color photography in hallowed museum halls; and, finally, the postmodern turn in the late 1970s, which laid the groundwork for the innovative scenes by Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Jeff Wall, deploying what were by then well-worn street photography tropes in the service of creating cinematic images that blended fact and fiction or were wholly fabricated for the camera.

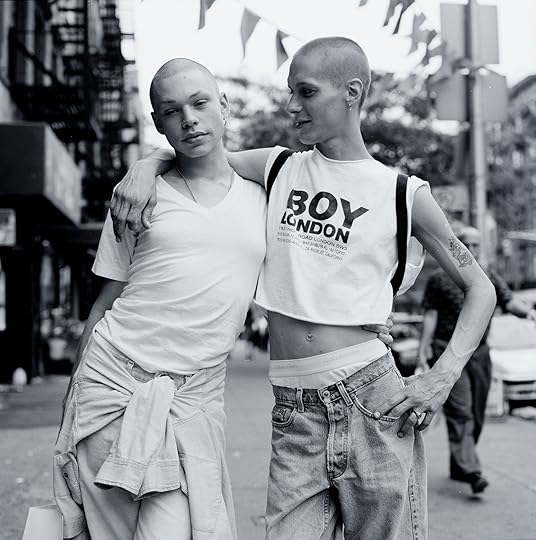

Janette Beckman, Jean and Chris, East Village, New York City, 1995

Janette Beckman, Jean and Chris, East Village, New York City, 1995Courtesy the artist

Alexey Titarenko, White Dresses, St. Petersburg, 1995

Alexey Titarenko, White Dresses, St. Petersburg, 1995© the artist and courtesy Nailya Alexander Gallery, New York

Daidō Moriyama, Pretty Woman, 2017

Daidō Moriyama, Pretty Woman, 2017© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation

Or anyway, that’s the usual history of street photography, made up of mostly white male Westerners. While I could have mentioned the work of photographic giants like Helen Levitt, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Vivian Maier, Gordon Parks, Daidō Moriyama, Mohamed Bourouissa, or others who have a rightful place in the street photography canon, this was pretty much how the story was relayed to me, as I studied photography in college. Clearly, that blinkered history needed to make room for some heterodox voices.

A sprawling new exhibition, We Are Here: Scenes from the Streets, currently on view at the International Center of Photography (ICP), in New York, has this aim. The show, curated by Isolde Brielmaier, with the assistance of Noa Wynn, features thirty-four artists working in twenty-two different countries. Some of the work stretches back as far as the 1970s (in a show-within-a-show that the curators have dubbed “On the Shoulders of Giants,” which focuses on New York street photography), but the lion’s share of the pictures on view are from the last ten years or so. Arranged in four broad categories—street style, neighborhood and community, protest and advocacy, and urban landscapes—We Are Here strives to provide a picture of the state of street photography now(ish), and to tell us something about the state of our world as a result.

Martha Cooper, Kids climbing a fence in an abandoned lot, Lower East Side, NYC, from the series Street Play, 1978

Martha Cooper, Kids climbing a fence in an abandoned lot, Lower East Side, NYC, from the series Street Play, 1978Courtesy the artist

We Are Here is admirably diverse, and many of the pictures are great. Highlights include the lush, wacky, fashion-forward work that Feng Li has been making on the streets of Chengdu, China; Romuald Hazoumè’s cheeky sculptural typologies of laden bike riders in Benin; the oneiric pictures of 1990s Saint Petersburg by Alexey Titarenko; a collection of era-defining 1990s Japanese street-style pictures that Shoichi Aoki shot for his magazine FRUiTS; and exuberant pictures of children’s play in gritty 1970s New York by graffiti documentarian Martha Cooper, which elaborate on earlier projects by Helen Levitt and Arthur Leipzig. Yet the exhibition is also dogged by a nagging question: Is twenty-first-century street photography hopelessly outmoded?

Street photographers fall into essentially three sometimes overlapping camps. First are the descendants of Cartier-Bresson, who stalk the sidewalks in the hope of catching some serendipitous urban gestalt, which is either compositionally gorgeous, weirdly poignant, funny, freighted with sociopolitical import, or some combination thereof. Second are those engaged in a long-term project of social stock-taking, like Walker Evans or Robert Frank, who use the street to a weave semi-personal narrative about the character of a time and place. (This place, historically, has been America, though there are notable exceptions to be found in projects like Paul Graham’s New Europe.) Third are those photographers who inflect their street photographs with their personal presence, whether formal or emotional, such that the line between the inner and outer world becomes hopelessly blurry: the photographic equivalent of New Journalism, with Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander at the helm rather than Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe.

Lam Yik Fei, Riot police officers fire teargas during clash with protestors outside Shum Shui Po police station in Hong Kong on 11 August, 2019

Lam Yik Fei, Riot police officers fire teargas during clash with protestors outside Shum Shui Po police station in Hong Kong on 11 August, 2019Courtesy the artist

Grace Ekpu, Protesters at the Lekki-Ikoyi tollgate calling for an end to the rogue police unit, Special Anti-robbery Squad, Lagos, Nigeria, October 2020

Grace Ekpu, Protesters at the Lekki-Ikoyi tollgate calling for an end to the rogue police unit, Special Anti-robbery Squad, Lagos, Nigeria, October 2020Courtesy the artist

Aside from the work in We Are Here that is best described as reportage—namely the pictures of protest movements grouped together under the “protest and advocacy” subheading—much of the exhibition consists of pictures that rehash previously extant styles of street photography, but in an era that can no longer be called modern. I’ll leave it to others to tell what our era could be rightly called—“postmodern” is entirely too retro—but we can be certain that the space that most exemplifies it is no longer the street. Perhaps, as the anthropologist Marc Augé argued in his 1995 book Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, it is instead one of the featureless spatial products of globalization—airports, supermarkets, shopping malls, chain hotels—that form a fractured, yet uncannily contiguous purgatory, scattered across the earth. More likely it is the space right under your nose, where you are reading this text: cyberspace.

Given the pull that the Internet has over our daily lives, it is almost shocking how little technology shows up in the pictures on view at ICP. By my count, there are only five pictures in which smartphones even appear, and just two of these show people gazing into them, perhaps the most commonplace sight in any city anywhere. Beyond that, almost none of the images contain technological tells that they were taken anytime this century. On the production end, only Michael Wolf, who made a collection of found street photographs using Google Maps, has utilized technology that would be unfamiliar to the modernists. A feeling of anachronism prevails.

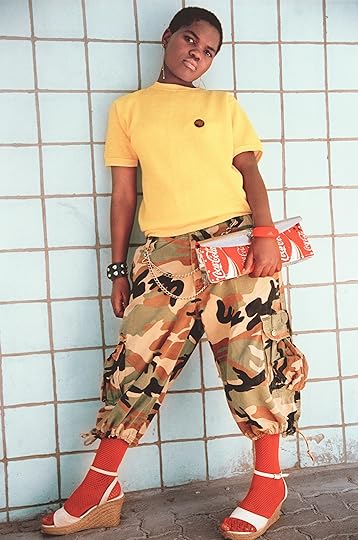

Nontsikelelo Veleko, Nonkululeko, 2003–4

Nontsikelelo Veleko, Nonkululeko, 2003–4Courtesy the artist

Shoichi Aoki, from the series FRUiTS, 1998

Shoichi Aoki, from the series FRUiTS, 1998Courtesy the artist

Even people’s manner of dress, which Baudelaire insisted was key to taking the temperature of any age, looks temporally fuzzy in the exhibition. Save for some bold, funky takes on traditional African garb captured by Trevor Stuurman in Dakar, Senegal, a few cutting-edge looks found in Feng Li’s pictures, and the presciently chic fashions captured in South African cities by Nontsikelelo Veleko twenty years ago, the clothes people wear are mostly a drab parade of generic causal wear, the fast fashion and sportswear slop that sloshes out of the globalized garment industry trough. The most futuristic looks in the bunch hail, paradoxically, from the past—Aoki’s pictures of Japanese youth taken nearly thirty years ago.

Perhaps the former sense of technological anachronism is an indication that contemporary street photographers are averse to depicting the banalizing aspects of our technological society, which have steadily made the world uglier, and the public sphere less vibrant. (Even back in the 1990s, an aging Helen Levitt lamented: “Children used to be outside. Now the streets are empty. People are indoors looking at television or something.”) Maybe, similarly, street photographers avoid photographing excessively trendy fashionistas because they fear their pictures will be defined by the clothes they capture. Or the feeling that time is out of joint in this exhibition is a telling sign of the kind of cultural stagnation that Mark Fisher, citing the Italian philosopher Franco Berardi, called the “slow cancellation of the future.” Likely all of the above. But it is also the case that as we exited the modern age and migrated the dynamos of capital and social life online, the world has begun to mostly transform off stage, becoming governed not by the life of the street, but through subtle shifts in the digital pleroma.

Farnaz Damnabi, Untitled, Birjand, Iran, 2017

Farnaz Damnabi, Untitled, Birjand, Iran, 2017Courtesy Farnaz Damnabi and 29 Arts In Progress gallery

Anthony Hernandez, Screened Pictures X #90, 2018–19

Anthony Hernandez, Screened Pictures X #90, 2018–19Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson

In some ways, this is an extension of an old problem. Walter Benjamin, in his 1931 text “A Little History of Photography,” complained that the photograph “can endow any soup can with cosmic significance but cannot grasp a single one of the human connections in which it exists.” To elaborate on this, he quotes Bertolt Brecht, who observed that “less than ever does the mere reflection of reality reveal anything about reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or the AEG tells us next to nothing about these institutions. . . . The reification of human relations—the factory, say—means that they are no longer explicit.” But, in ways that Benjamin and Brecht could scarcely have imagined, our situation has become even more abstract. If a photograph could reveal “next to nothing” about a world run by the factory system, consider how much less it must reveal about a world run by algorithms.

Youcef Krache, Climat de France, Algiers, 2016

Youcef Krache, Climat de France, Algiers, 2016Courtesy the artist and Collective 220

We now live in the era of the so-called black box, ruled by systems whose internal workings are opaque even to their creators. Our sociopolitical world is increasingly governed by social media algorithms which have sowed division and ignited civil unrest, either as the result of an unhappy accident of their flawed designs or through the malicious machinations of state actors and shady billionaires. (Even street protest movements, which We Are Here puts forward as triumphant engines of social change, have become social media–engineered phenomena, which rarely achieve their stated goals, and, conversely, give political ammunition to forces that oppose them. As the filmmaker Adam Curtis, in his BBC documentary Hypernormalisation, and the journalist Vincent Bevins, in his book If We Burn: The Mass Protest Decade and the Missing Revolution, have both pointed out, the Internet age makes it easy to get people to the streets, but has not made it easier to figure out what to do after they get there, which is the tricky part). The strings of our economy are pulled by supercomputers running high-frequency trading algorithms like BlackRock’s Aladdin, which now manages in excess of twenty-one trillion dollars in assets, likely more than the GDP of any country on earth. The truth value of images themselves, and their impact, have never been more questionable, as we are fed a constant slurry of algorithmically optimized and increasingly artificially generated “content,” managed by vast server farms that are quietly sucking our aquifers dry and rudely shoving aside the pesky carbon emissions targets that stand in the way of promised progress. Soon, it seems, the whole of our reality might be shaped by our encounter with a fundamentally alien, super powerful AI. How can we possibly hope to capture this world from street level, using as blunt and as literal a tool as a camera? Perhaps we must return to Baudelaire’s plea for the creation of a contemporary vision of contemporary times, and try to chart a new way forward.

We Are Here: Scenes from the Street is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through January 6, 2025.

October 18, 2024

Aperture Celebrates 2024 Gala

How Emmet Gowin Defines Intimacy in Photography

October 11, 2024

Behind the Scenes of Aperture Magazine’s Design Refresh

This summer, Aperture enjoyed a subtle transformation. Working closely with the magazine’s editors, the London-based studio A2/SW/HK—Scott Williams and Henrik Kubel—drew inspiration from Aperture’s rich seven-decade design history to devise a format that better reflects what readers want in a photography magazine today. We unveiled the results in June with an issue titled—what else?—“The Design Issue,” which explores photography’s relationship to design, from fashion to architecture to the printed page. Our fall issue—released in September and titled “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra”—finds guest editor Deana Lawson reimagining the magazine’s format in her own way. Here, Williams talks to designer Rob Giampietro about the details that went into perfecting Aperture’s new look. —The Editors

Details of Aperture, Summer 2024, “The Design Issue”

Details of Aperture, Summer 2024, “The Design Issue”

Rob Giampietro: How did this project begin? What was the brief?

Scott Williams: Early last year, Aperture asked how we felt about working on a design refresh of the magazine. It had been so long since we were brought on to redesign the magazine, in 2012, and it felt like time for a review. Typically, our process is to start every project afresh and to work from the ground up, exploring everything from formats to grids to printing techniques to designing typefaces. But the challenge here was to design with assets we’ve already created, with renewed criteria.

The key elements of the brief were to explore a new, smaller format, to develop a new approach to the front cover design, to explore a more prominent Aperture nameplate on the cover, and to rethink the table of contents. That said, a small change such as adjusting the format will have a knock-on effect on almost every part of the magazine.

Another early suggestion from Aperture, a brilliant one, I think, was the idea of using a single weight of the Aperture Serif font family as the primary typeface for the entire magazine. The ramifications of this are quite dramatic—previously, we were working with a palette of twenty to thirty fonts from the Aperture Sans and Serif type families. Suddenly, it’s one font with a supporting typeface.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Giampietro: It’s rare for a print redesign to have a strong focus on usability, but that seems to have been an important element of this one—and it’s a welcome change. I certainly feel the difference of the smaller trim size in handling the magazine.

Williams: Usability is absolutely key in all design. Yes, a new design should be bold, ingenious, playful, inspiring, or be able to pique a user’s curiosity, but surely not at the expense of functionality. The refresh was largely prompted by Aperture’s desire to explore a new format, one that felt more comfortable in the hand and more convenient to carry and read on the go. Ever since the original redesign, we had been very conscious of the size and proportion of the art that features in the magazine, so we decided to build around the proportions based on the traditional 8-by-10 photograph format. The rationale behind adhering to the ratio of 8-by-10 is that full-bleed images will sit perfectly within the format with minimal cropping. Interestingly, even though we’re in a fluid, digital age when it comes to image-making, many contemporary photographers featured in Aperture are using traditional formats.

The new format has an aesthetic quality, yet it was born out of very practical considerations, which I like. It’s based on a photographic format, and there’s minimal waste on the printed sheet. It’s also more economical and responsible from a sustainability point of view.

Covers of Aperture: Summer 1952, Fall 1957, and Summer 1967

Covers of Aperture: Summer 1952, Fall 1957, and Summer 1967Giampietro: Everywhere in this design, I feel typography from the past—the column lines, the historical serif, the justified text, gestures like “No. 255.” How do you think about these details in the context of the present? How do they set a different stage for us to view and learn about photography?

Williams: Some of the gestures you refer to were established for the magazine when we redesigned it in 2012. We’re certainly not trying to replicate layouts from magazines past but reacting to what a reader wants from a photography magazine today. We’re using design cues from Aperture’s rich history to help identify a design DNA, if you will, from which we can build upon.

Luckily, Aperture had recently digitized their entire archive—stretching all the way back to the first issue, in 1952. I spent a few days reviewing every issue published over their seven-decade history. It does sound a little overwhelming, but it was a fascinating journey through Aperture’s rich history and print design more generally. For example, early issues of the magazine are clearly put together by hand using primitive paste-up techniques, and then there is the transition from black-and-white to color printing, then the advent of early desktop publishing, then, finally, the era we are familiar with today.

Covers of Aperture: Spring 2013, “Hello, Photography;” Spring 2015, “Queer;” and Winter 2015, “Performance”

Covers of Aperture: Spring 2013, “Hello, Photography;” Spring 2015, “Queer;” and Winter 2015, “Performance”A key design element that’s been present since the launch of Aperture is the use of a modernist sans serif in a bold weight, variations of which have been used for the magazine’s logotype and as a magazine text font at various times. In 2012, we created a bold sans serif font, one we now use for captions, running footers, and page numbers—all the supporting architecture of the page.

Ultimately, magazines should evolve and react to the present. I do hope the refresh feels modern and contemporary and not too reminiscent of a bygone era.

Interior spreads from Aperture, Summer 2024, “The Design Issue”

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Giampietro: Some of these gestures also feel quite “newsy,” and I know it’s been an ambition of yours to do a newspaper. Did some of that desire creep in here, in the more journal-like format of the new design?

Williams: The “newsy” feel you mention is not something we intentionally set out to achieve—though I would love to design a newspaper!—but, I think, more of a byproduct of using a classical serif-style font, set in neat justified columns. This is a common device favored by most newspapers and many magazines too. We were very aware that making the magazine smaller would have a big impact on word counts, and a simple way to mitigate this is to use a justified setting for body copy.

Giampietro: You have to be quite intentional about building the grid in these projects, since the images and type are so closely interlocked. Does that start with your own typefaces in this case?

Williams: It’s been very much an iterative process of refinement with the team at Aperture. And as we started to review early sketches and to assess how the Aperture fonts performed at the smaller trim size, we had a discussion in the studio about the font weights in the Aperture Serif font family. More specifically, we felt the Light weight was too light, and the Regular weight was slightly too heavy, so we created a new cut of the serif to work on this new scale.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Luigi Ghirri, from the series Ferrari, 1985–90, in “The Design Issue”

Luigi Ghirri, from the series Ferrari, 1985–90, in “The Design Issue”Giampietro: One of the things I enjoy about all your work is the way that typographic gestures really have space to be seen and felt. And yet when they get the limelight, they often bring a kind of quiet confidence and understated elegance that I feel particularly in this format.

Williams: That’s very kind of you to say. I do believe those attributes you mention, including the quiet confidence, come with experience and with the time we’ve dedicated to our craft. Typography and typographic design have been a linchpin of our design approach since we founded our studio almost twenty-five years ago. Typography is a seamless and truly integrated aspect of how we work, from creating unique fonts for clients to working with type on a daily basis. It’s an aspect of design we continue to feel passionate about—so much so that we developed this strand of our practice and launched our type foundry in 2010 to include the full library of fonts.

Giampietro: Do you feel any particular connection to one of the features in this issue?

Williams: I’m immediately drawn to Luigi Ghirri’s photographs taken at the Ferrari factory. At first glance, it’s Ghirri’s unique eye and its rich visual vocabulary that appeals to me, but it is also the subject matter I find inspiring—a celebration of craftspeople working apart and together in the pursuit of excellence and with an incredible attention to detail. A true labor of love.

Cover and interior of Aperture, Fall 2024, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra”

Cover and interior of Aperture, Fall 2024, “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra”

Giampietro: What was issue one of the design refresh like versus issue two? How does having an artist like Deana Lawson as guest editor start to stretch and refine the design gestures from the initial redesign issue on a more applied level? Are there aspects of the initial redesign that have come more fully into focus from this collaboration?

Williams: In typical fashion, having just established a set of rules for the new-look issue No. 255, we immediately set about dismantling it with issue No. 256.

Going from the rather slow-paced first issue to the fast-paced second issue, guest edited by Deana Lawson and titled “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra,” was definitely a bit of a gear shift. Also, structurally, the issues are notably different. The customary arrangement of long- and short-form reads, including articles, interviews, and artist portfolios, was, unexpectedly, replaced with a striking series of works selected by Deana, along with a few shorter texts and poems.

Again, returning to your point about usability, poetry is unlikely to sit very well, or read or scan as it should, set justified in a narrow column. As a result, several of the original design guidelines were swiftly abandoned in service to the art. As with each issue of Aperture, some of the key design considerations are to do with flow, rhythm, use of white space, juxtaposition of images, and sequencing—this is very much front and center with “Arrhythmic Mythic Ra.”

Click here to subscribe to Aperture.

Wendy Red Star on the Power of Indigenous Art

In her dynamic photographs, the influential artist Wendy Red Star recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective. Red Star, who was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in October 2024, centers Native American life and material culture through her imaginative self-portraiture, vivid collages, archival interventions, and site-specific installations. Whether referencing nineteenth-century Crow leaders or 1980s pulp fiction, museum collections or family pictures, she constantly questions the role of the photographer in shaping Indigenous representation. In the following interview with Josh T. Franco from her book Delegation (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2022), Red Star speaks about her family history, what it was like to collaborate with her daughter, and how her multifaceted practice gleans from elements of Native American culture to evoke a vision of today’s world.

Wendy Red Star, To Have Good Vision, from the series Picture Day, 2021

Wendy Red Star, To Have Good Vision, from the series Picture Day, 2021Josh T. Franco: When and where were you born?

Wendy Red Star: I was born in 1981 in Billings, Montana.

Franco: What were your parents doing at the time?

Red Star: My mom is of Irish descent, and she grew up in Colorado. She went into nursing through the army and that took her to Korea, and she was stationed there for a while. She adopted my sister there, and then came back to the States and continued her nursing career, and decided that she wanted to work on a Native American reservation. She looked into the Crow Reservation and Pine Ridge, a Lakota reservation in South Dakota, and I think one other one, and she chose to go to the Indian Health Service in Crow Agency, which is where my reservation is.

Franco: She adopted your sister before she met your father?

Red Star: Yes. She was young. I would describe my mom as being really adventurous. I could not imagine myself at that age being in a foreign country and deciding to adopt a child. Also, her decision to work on a Native American reservation and at the Indian Health Service was very progressive.

My father is from the Crow Indian Reservation, and at that time he was working for the tribe as a game warden. And they met just because everybody ends up going to the Indian Health Service at some point. I think one of his cousins was working with my mom and then introduced them.

Franco: So was it love at first sight?

Red Star: I have no idea [laughs]. My parents never got married. And I have four half-siblings from my father—he was forty when I was born, and my mom, I think, was twenty-nine.

I have a very special bond with my father. He was able to get my grandfather’s land out of a non-Indian lease. It was leased by this white family for over fifty years. I would go with him on the weekends, all summer, while he ranched that land.

Wendy Red Star, Indian Woman Standing, from the series Indian Woman, 2005

Wendy Red Star, Indian Woman Standing, from the series Indian Woman, 2005  Wendy Red Star, Amnía (Echo), 2021

Wendy Red Star, Amnía (Echo), 2021 Franco: What does it mean to be a Red Star?

Red Star: There’s a lot of pride in it. My sister and a lot of my cousins have Red Star tattoos. The name itself has a very interesting history, and it ties into all the Crows on the reservation. Red Star is my great-grandfather. When they were allotting the land, he was of that generation where he was a head of household. All his family members in his household were then given his name as a last name. That’s how I got my last name. There’s a lot of beautiful Apsáalooke names—and it can all be traced to one individual around the allotment of the Crow reservation.

Franco: Do you have memories of making art in childhood?

Red Star: I daydreamed and I had a very vivid imagination. I was able to entertain and occupy myself, and spent a lot of time alone as a kid. I was having to fill that space with creation, or creative ideas, or fantasies. And so, now, it’s really important for me to walk out in the woods. That’s where all my ideas either come to me or, if I’m stuck, I find solutions, and it’s just so important to have that time and headspace. And when I think about it, I’ve just been doing that since I was a little kid.

I went to school in Hardin, Montana, which is just off the reservation. The reason why the white folks wanted to remove Hardin from the reservation and incorporate the town is because they wanted to sell alcohol to Crows, and that was a big profit for them. I found that to be fascinating, because my dad remembers going to Hardin. Hardin is super racist. And there would be “No Indians allowed” or “No Indians allowed in the bar” or whatever signage, and actual segregated places for them to use the bathroom and stuff. It’s just crazy to talk to somebody, you know, actually talk to my dad, who has had that experience.

Franco: Did your high school give you space for making art?

My high school art teacher focused on realistic drawing, and I just didn’t excel in that at all. This is when in the art dynamic—which you continue to see—the people who are able to realistic-draw in the art class are the art stars. I was like, I’m not a good artist. I think I took one semester, and then I was out. I never took an art class after that in high school.

Franco: What did you do the rest of high school?

Red Star: I found this other teacher who was totally wacky. She ran the computer class, and the thing she focused on was video editing. I was having a blast. And she called this whole process “graphic design.” I was like, That’s what I’m doing. I’m going to be a graphic designer. I graduated in 2000, and I ended up going to Montana State University in Bozeman, which is about a three-hour drive from the reservation, and enrolled in graphic design as my major. And that was a very rude awakening [laughs].

Wendy Red Star, iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dáanniili = we parade, 2016

Wendy Red Star, iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dáanniili = we parade, 2016  Wendy Red Star, Catalogue Number 1949.73, 2019

Wendy Red Star, Catalogue Number 1949.73, 2019 Franco: Was that more like poster design?

Red Star: Exactly. And working with different fonts and kerning. I was like, What the hell is this? I soon realized that my high school teacher was totally misusing the term graphic design.

Franco: While you were still in school in Hardin, you spent your summers in Pryor with your dad ranching?

Red Star: Yes. My dad would get me on the weekends. What bonded me and my dad was horses. I was going out to the land, and I would just ride horses all day long while my dad would be on a tractor for like eight to ten hours. I was alone, but I didn’t care, because I had my imagination, and I had my horses and bologna sandwiches. Our horses roamed free like wild horses. I would do everything that they did, and I knew when they took their nap, and I knew when they went and got their water, and then they would follow me and I would take them and say, “We’re going to eat over here.” I learned the language of the horse.

Franco: When you went to college, what did you major in?

Red Star: Well, I started out in graphic design, and then I went into a minor in Native American studies. That was super important, sort of a revelation, to take Native studies classes. At first, I thought it was a joke. It’s kind of like when somebody takes a language course and they already know how to speak the language.

Franco: You thought you were going to get an A.

Red Star: Yeah. What I soon found out was I knew nothing. I didn’t even question why there was a reservation. It was just where I grew up. You know? Then I started learning, and it just blew my mind, because that was not taught at all in my history classes. We never touched on anything near what I was learning in Native studies classes.

Wendy Red Star, Interference, 2004

Wendy Red Star, Interference, 2004Franco: Do you remember any things you made then?

Red Star: An important series I made then is called Interference [2004]. It’s a piece that is foundational for the way that I work today, in that I learned about an important chief of ours called Sits In The Middle Of The Land. He’s the one who told the US government where our territory was, basically, and he’s the one that said we had over thirty million acres. But he used this beautiful metaphor of the foundational way that we set up our tipis, which is with the four poles. And he said, “My home is where my tipi sits” and then he placed each of those four poles on the major seasonal migration stops that we would camp at. To me, that was kind of the first time of really thinking about a Crow perspective, and how beautiful that was, and how much that takes me out of Western thinking. Like, the home is where the tipi sits, and the tipi actually is a woman. The interior is the womb, and you’re being hugged by your mother, and to think the Earth is your mother.

So it’s really interesting to have him illustrate that in this way, and then to have the US government be like, Okay, let’s draw a line around thirty million acres. You know, reduce it down. That inspired me, because when I looked within that land base, Bozeman was actually Crow territory. I was shocked. My reservation was about 2.25 million acres, three hours away. I harvested lodge poles, and my dad and mom came and helped me set up tipis around campus. This research project was inspired by a photo—I saw a photo of him, and I was like, Who’s this guy? Then from that, I found out about his speeches and from there, produced a work.

Franco: How was it received on campus?

Red Star: The tipis didn’t have the canvas on them. A lot of them were just the four-pole structure. I would scout pieces of prime real estate that students used to cut across, and see if they would go through it or go around it. But what ended up happening was the tipis were being knocked down. I thought, Well, maybe it was the wind. Then I realized that somebody was knocking them down. Which then prompted me to put them on the fifty-yard line in the football field, and that was the end of the project. They’re all documented through photo. But to me, it was very much a sculpture in addition to a performance and a photo. But I was really minimizing photo. That’s just the documentation of it.

There was a visiting professor teaching sculpture at the time, and he said, “Wow, you really like to make political work.” That was our home. There was nothing political about it. It’s the truth. People tend to think a lot of my work is political, and I’m not offended by that. But really, it’s just a fact. And if that fact is political to you, then that’s interesting.

Franco: You went to UCLA for grad school and studied with Nancy Rubins. What did you learn from Nancy?

Red Star: Nancy had this solid belief in me. I was really a fish out of water because, in my undergrad, we didn’t learn anything about contemporary art. Contemporary art was Salvador Dalí [laughs]. Some of my grad peers had full-on art-monograph libraries. And I was like, I don’t know any of these artists. I was severely lacking. And going to UCLA was a very steep learning curve. One of the professors I took a seminar with was Ron Athey, and I did not know who he was or about his work. The first day of class, he said, “I’m going to show you my work.” I went from Salvador Dalí to pearls coming out of an anus with the sun tattooed around it.

After Nancy left, she invited me to be in a group show at the Cartier Foundation in Paris, France, which invited their past exhibiting artists to select a young artist who they had mentored to show in a group exhibition. The summer after my first year of grad school, I ended up flying to Paris with the photos of the tipi series. All these young students were so excited to be showing in this amazing institution. The opening was a big party, and I remember Takashi Murakami was there, and he had this entourage of young people. Nan Goldin was there. And we got to go up on the roof of the Cartier, and the Eiffel Tower was sparkling.

Franco: Magic.

Red Star: I remember sitting there with my friends, who came to support me from UCLA. Like, this is part of being an artist. You can do shit like this. I thought, I will never attain this level ever again. This is it for me. This is so incredible.

Wendy Red Star, Hawate (One), from the series A Float for the Future, 2021

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Franco: Did your time at UCLA give you any names or bodies of work that became touch-points?

Red Star: The thing that really turned me on were people doing identity-based artwork, like Fred Wilson and Adrian Piper and Kara Walker. Because there were maybe two other artists in the program focused on identity-based work. I was the only Native student. There were other artists of color there, which was awesome. But we were the only ones that were doing work based on identity. And we were, I felt, very ridiculed for it and always told that we need to just get over it, like we were being didactic. And especially the work that I made and the content I made, I think, intimidated people. Now, what I realize is that the work just made people uncomfortable, because it pointed to the missing spaces in their knowledge. I talk to other Native students who are in art programs now, and they’re still feeling the same feelings that I felt. It would be really hard to hear, you know, a studio visit in the next studio going so well with somebody who is doing abstract painting—a white student—and then to have that same professor come in and say, “Uh . . . can you, like, fill me in, give me a little history lesson?”

Franco: Was feminism part of the conversation in grad school?

Red Star: Not at all. It was even about being genderless, more like not being a woman, was kind of the goal. I had a professor, a visiting professor, who was Korean. And she said that was her goal—that when people looked at her work, they would not know her gender or her identity. So that’s kind of where I was at. Me doing work about my culture and being a Crow woman was so not the deal.

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006  Wendy Red Star, Fall, from the series Four Seasons, 2006

Wendy Red Star, Fall, from the series Four Seasons, 2006 Franco: Are things different now?

Red Star: Early this year, I got to be a visiting artist and do a lecture and studio visits virtually with UCLA grad students. They’re having such a different experience than I did.

I made one of the most important works of my career, Four Seasons [2006] in graduate school. And that was everything. I had a studio visit with Cathy Opie and Robert Gober, which was a dream. They talked about Four Seasons, and that’s the first time I heard the word tableau.

Franco: Is it fair to say that Four Seasons is a little tongue-in-cheek?

Red Star: Oh, yeah. I was watching a lot of John Waters’s movies.

Wendy Red Star: Delegation 65.00 Delegation is the first comprehensive monograph by Apsáalooke/Crow artist Wendy Red Star, whose photography recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective.

Wendy Red Star: Delegation 65.00 Delegation is the first comprehensive monograph by Apsáalooke/Crow artist Wendy Red Star, whose photography recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective.$65.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Wendy Red Star: DelegationArtworks by Wendy Red Star. Contributions by Jordan Amirkhani, Julia Bryan-Wilson, Josh T. Franco, Annika K. Johnson, Layli Long Soldier, and Tiffany Midge.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.00Add to cart

View cart Description Delegation is the first comprehensive monograph by Apsáalooke/Crow artist Wendy Red Star, whose photography recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective.Red Star centers Native American life and material culture through imaginative self-portraiture, vivid collages, archival interventions, and site-specific installations. Whether referencing nineteenth-century Crow leaders or 1980s pulp fiction, museum collections or family pictures, she constantly questions the role of the photographer in shaping Indigenous representation. Including a dynamic array of Red Star’s lens-based works from 2006 to the present, and a range of essays, stories, and poems, Delegation is a spirited testament to an influential artist’s singular vision.

Copublished by Aperture and Documentary Arts Details

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 272

Number of images: 280

Publication date: 2022-06-14

Measurements: 8 x 10.25 x 1.13 inches

ISBN: 9781597115193

Wendy Red Star (born in Billings, Montana, 1981) is an Apsáalooke artist based in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been included in numerous solo and group exhibitions and is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum; Saint Louis Art Museum; and IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe. Red Star guest edited Aperture magazine’s Fall 2020 issue, “Native America.”

Jordan Amirkhani is an art historian, educator, and critic based in Washington, DC.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is the Doris and Clarence Malo Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author, most recently, of Fray: Art and Textile Politics (2017).

Josh T. Franco is an artist and art historian from West Texas. He is national collector at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Annika K. Johnson is associate curator of Native American art at the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha.

Layli Long Soldier is an Oglala Lakota poet, writer, artist, and activist. She is author of the chapbook Chromosomory (2010) and the poetry collection Whereas (2017), which won a National Book Critics Circle award and was a finalist for the 2017 National Book Awards.

Tiffany Midge is a poet, writer, and editor. She is author of several books, including the poetry collection The Woman Who Married a Bear (2016) and the memoir Bury My Heart at Chuck E. Cheese’s (2019). She is a Hunkpapa Lakota enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux.

Franco: That makes total sense.

Red Star: I was interested in sets, and I found out that I could rent objects—that’s the way that it worked for movie sets. And then there was the influence of other grad students, especially one who had these seventies photomural backdrops, and he showed me where you get them. I was actually told by the sculpture tech, “If you can’t make it, someone in LA can.”

Franco: Did you go to Skowhegan immediately after grad school?

Red Star: I went to Skowhegan in the summer of 2006. And it was like an oasis in the sense that it was the first time that I’d been around so many artists of color who were working on identity-based artwork. And that gave me real faith that there were other artists like me out there. There was a community from all different backgrounds and cultures. And I met my ex-husband at Skowhegan. An extremely important and amazing thing is that my daughter came from that union.

I found out I was pregnant when I was at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, so I didn’t get to do the full round. I came to Portland because he is a professor at Portland State University. And that was the very first time that I’d ever been to Portland, spent time in Oregon. I had no clue what a weird little town this is. At first, I just really did not know what to make of Portland, but I’ve grown to love it for the access to quick hiking and amazing food, of being able to do a waterfall hike and eat fancy donuts. The textile community here is super strong. I love to sew. I started sewing here.

Wendy Red Star, Alaxchiiaahush / Many War, from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014

Wendy Red Star, Alaxchiiaahush / Many War, from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014  Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014 Franco: What were the significant bodies of work you made during this period?

Red Star: In 2014, I made 1880 Crow Peace Delegation [2014], and I also made a series called White Squaw [2014]. 1880 Crow Peace Delegation is a set of ten portraits that were taken of Crow chiefs in 1880 by Charles Milton Bell. They are delegation portraits from a trip that they took to Washington, DC, to meet with the president, and they went there because the US government was going to put a train through a large tract of our hunting territory. That was the first time that I investigated this very popular image of this one chief, Medicine Crow. Because his image had been used commercially a lot, like on Honest Tea. It was the first time that I actually was like, What is going on with this photo? And that body of work introduced me to archives and to museum collections, and actually looking at the Portland Art Museum’s collection of Crow objects, which then got me into the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship program.

Franco: What did you do to the photograph?

Red Star: I was just asking that question: What’s going on in this photo? What happened that day when he sat down to take that photo? I did a quick Google search, and information came pouring out. And then, I would follow the leads. They would take me to different archives, like at Montana State University in Billings—they have all these amazing drawings of circus animals that Medicine Crow drew in relation to that trip.

When I looked into who took the photo, then all the other Crow chiefs that went on that same trip and sat down during that same photo session popped up. I had no idea that they went and were photographed and had the same experience. So I started researching each of those chiefs. And through that, I was like, I want people, when they look at this photo, to actually have a sense of what is trying to be conveyed from my culture in this image. And so, I started outlining their outfits. Partly for myself to really look at all the tiny details. I started to realize that they all wore brass rings on their fingers. I started to notice the details, like the conch shells, and that one of them has an eagle-claw bracelet. And all of that was just stuff that I wasn’t picking up from looking.

I’m also marking on history. And red—I always think about school and failing papers and getting that red mark on your paper. I wanted that red mark on history.

Franco: Literally outlining in red ink on the image.

Red Star: In red ink. And then through that, I would start telling people, “Oh, this is ermine” and “This is an eagle feather that is part of a coup that he had to acquire chief status.” I would look into census records and learn more about them and try to pinpoint their age. Then, if I could find their name written in the Crow language, I would write that on there. And if they had any descendants, I would try to include interesting facts about them and, more importantly, gossip that I heard about them as well from the community. it’s the kind of document that results from an art history student studying in their textbook and writing on it. there’s something spectacular about seeing that very intimate act of study elevated to the scale and status of artwork on the wall.

That’s so great to hear. I really want to humanize, and part of that is getting to see my terrible handwriting [laughs] and my spelling errors, and relating physically to these people in the portraits. It was important to me. But I’m also marking on history. And red—I always think about school and failing papers and getting that red mark on your paper. I wanted that red mark on history.

Wendy Red Star, from the series White Squaw, 2014. From left to right: Bareback Beauty #20, Twin Peaks—Or Bust #9, Horn of Plenty #8, Virgin Territory #3

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Franco: Did you make White Squaw around the same time?