Aperture's Blog, page 13

December 13, 2024

How Tina Barney Became an Astute Observer of the Upper Class

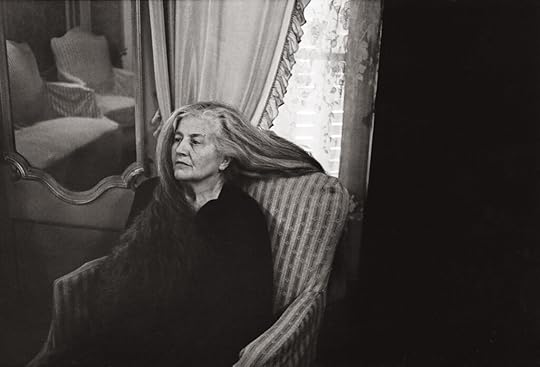

In the late 1970s, Tina Barney began a decades-long exploration of the everyday but often hidden life of the New England upper class, of which she and her family belonged. Photographing close relatives and friends, she became an astute observer of the rituals common to the intergenerational summer gatherings held in picturesque homes along the East Coast. Developing her portraiture further in the 1980s, she began directing her subjects, giving an intimate scale to her large-format photographs. These personal, often surreal, scenes present a secret world of the haute bourgeoisie—a landscape of hidden tension found in microexpressions and in, what Barney calls, the subtle gestures of “disruption” that belie the dreamlike worlds of patrician tableaux.

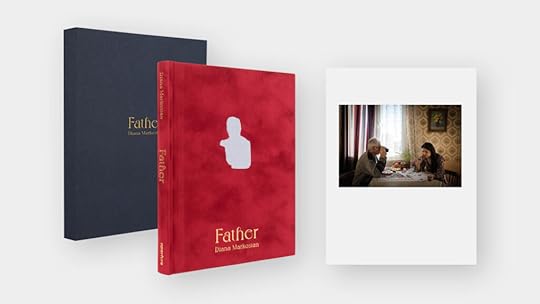

This year, Aperture published Family Ties, which collects sixty large-format portraits from the three decades that defined Barney’s career. The volume accompanies the first retrospective exhibition of the artist in Europe at the Jeu de Paume, Paris. Here, in an interview from the book, Aperture’s executive director Sarah Meister speaks with Barney on her beginnings with the medium, the transition to working in color, and her approach to large-format photography and working on assignment.

Tina Barney with her sister, Jill, and their grandfather, Sands Point, New York, 1956

Tina Barney with her sister, Jill, and their grandfather, Sands Point, New York, 1956  Lillian Fox, Tina Barney’s mother, on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, August 1940. Photomontage by Herbert Bayer

Lillian Fox, Tina Barney’s mother, on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, August 1940. Photomontage by Herbert Bayer Sarah Hermanson Meister: I thought we could begin by exploring some of your earliest connections with photography, including the fact that your grandfather was an amateur photographer.

Tina Barney: He photographed us whenever he came over with all different kinds of cameras. I have his 4-by-5 glass-plate negatives from the First World War and some of his photographs.

Meister: Your mother was a model. Do you remember seeing her modeling photographs around the house?

Barney: No, she only showed them to us when we were adults. I think she was kind of hiding them. She stopped modeling when she married my father.

Meister: Did you know she was a model?

Barney: Oh yes. She was incredibly stylish. She brought me to see the collections in Paris where I saw memorable shows, including Yves Saint Laurent’s first fashion show when I was sixteen. So, fashion has really been a part of my life.

Meister: In 1972 you joined the Junior Associates at MoMA and started volunteering there in the Department of Photography. Do you remember when you were first aware of someone who approached photography as an artist, unlike your grandfather for whom it was a hobby?

Barney: When my friend Ali Anderson suggested I become a volunteer, I had barely heard of any fine-art photographers. I knew nothing. My first memory of being at MoMA was when I saw a man showing another man a photograph: It was John Szarkowski showing someone a Ken Josephson photograph. There was a woman there that I befriended and she mentioned Ansel Adams, but I had never heard of him. She started talking about the two photo galleries in New York at the time and that’s how it all began. I went to Witkin Gallery and to Light Gallery. Marvin Heiferman was at Light. Jain Kelly, who worked at Witkin, basically started teaching me the history of photography. That is when I started buying photographs.

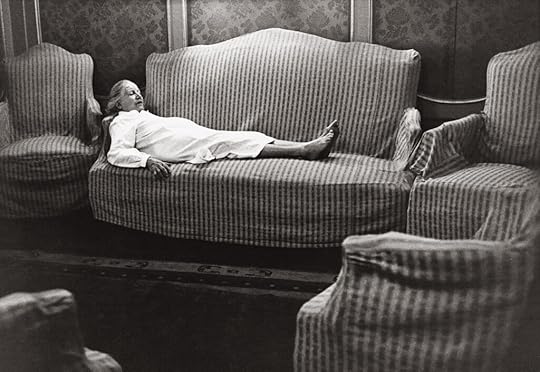

Tina Barney, Marina’s Room, 1987

Tina Barney, Marina’s Room, 1987  Tina Barney, Jill and Polly in the Bathroom, 1987

Tina Barney, Jill and Polly in the Bathroom, 1987 Meister: Do you remember what you were buying?

Barney: Imogen Cunningham, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank. Just the greatest hits. I have the bills—$150 was the most I spent.

Meister: Pretty good investments. Do you still have the pictures?

Barney: Yes. I also saw the great Friedlander, Arbus, Winogrand exhibition at MoMA in 1967 [New Documents]. It was like seeing God, let’s put it that way. I think it had a great deal to do with the subject matter of Diane Arbus, but also the way these three people were photographing in such different ways. I started looking at photographs more and more, and then I went to Sun Valley and started making my own pictures.

Meister: When you moved to Sun Valley, Idaho, in 1974, you started taking classes at the Sun Valley Center for the Arts and Humanities [now Sun Valley Museum of Art]. What was that experience like?

Barney: The director of the photo department, Cherie Hiser, who came from Aspen, was a sort of goddess—the heroine of photography at that time. She was a combination of Marilyn Monroe and Nan Goldin: a great character. Peter de Lory was my first teacher. And after Peter left, Mark Klett came in to teach color and Ellen Manchester became the director. That is when JoAnn Verburg, Ellen Manchester, and Mark Klett were making their Rephotographic Survey Project. That was very important to me, both because Mark was working with a 4-by-5 camera and because of their commitment to returning to the same place multiple times. They were great teachers.

The setup was quite primitive: you would walk in, in your shorts or ski boots, and famous photographers would come there and teach. It was an incredible environment. Not only did they talk about photography, but about literature, philosophy, and books that I had never even heard of before. So, basically, I was educating myself. I didn’t finish college. I read a lot and learned a great deal besides printing and doing my own work. My own work didn’t really develop there because there was nothing to photograph. It came very slowly after I left.

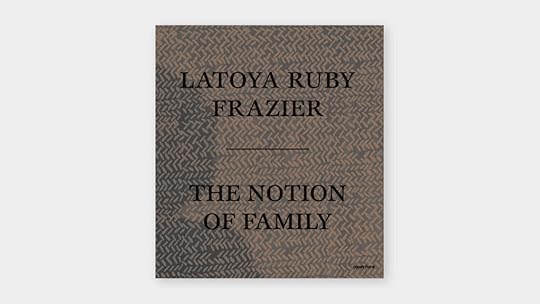

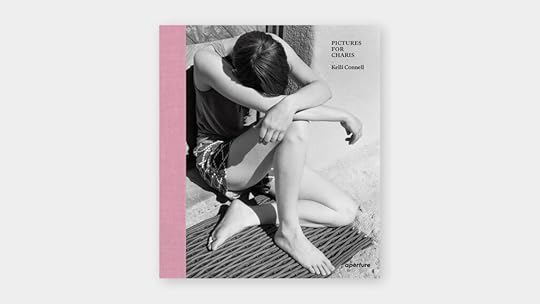

Tina Barney: Family Ties 65.00 Tina Barney’s keenly observed portraits offer a window into a rarified world of privilege with sixty large-format works imbued with a spontaneity and intimacy that remind us of what we hold in common.

Tina Barney: Family Ties 65.00 Tina Barney’s keenly observed portraits offer a window into a rarified world of privilege with sixty large-format works imbued with a spontaneity and intimacy that remind us of what we hold in common. $65.0011Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Tina Barney: Family TiesPhotographs by Tina Barney. Text by Quentin Bajac and James Welling. Interviewer Sarah Meister.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.0011Add to cart

View cart Description Tina Barney’s keenly observed portraits offer a window into a rarified world of privilege with sixty large-format works imbued with a spontaneity and intimacy that remind us of what we hold in common.

In the late 1970s, Tina Barney began a decades-long exploration of the everyday but often hidden life of the New England upper class, of which she and her family belonged. Photographing close relatives and friends, she became an astute observer of the rituals common to the intergenerational summer gatherings held in picturesque homes along the East Coast. Developing her portraiture further in the 1980s, she began directing her subjects, giving an intimate scale to her large-format photographs. These personal, often surreal, scenes present a secret world of the haute bourgeoisie—a landscape of hidden tension found in microexpressions and in, what Barney calls, the subtle gestures of “disruption” that belie the dreamlike worlds of patrician tableaux.

Family Ties collects sixty large-format portraits from the three decades that defined Barney’s career—accompanying the first retrospective exhibition of the artist in Europe at the Jeu de Paume, Paris. The book includes an essay by Quentin Bajac, the exhibition’s commissioner and director, as well as an interview with the artist by Sarah Meister, the executive director of Aperture, and a text by the artist James Welling. These texts illuminate the artist’s approach to large-format photography, her ongoing interest in the rituals of families, and her personal ideas of composition, color, and the complex relationship between photography and painting.

Tina Barney: Family Ties is copublished by Aperture and Atelier EXB.

Format: Hardback

Number of pages: 176

Number of images: 98

Publication date: 2024-11-14

Measurements: 11.3 x 9.5 x 1 inches

ISBN: 9781597115889

Tina Barney (born in New York, 1945) is an American photographer best known for her large-scale color portraits of family and close friends in New York and New England. Her books include The Europeans (2005), Players (2011), and Tina Barney: The Beginning (2023). She lives in New York and Rhode Island.

Quentin Bajac has been director of the Jeu de Paume since 2019, after having been the head of the Photography Department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 2013 to 2019 and curator for photography at the Musée National d’Art Moderne–Centre Pompidou from 2007 to 2012.

Sarah Meister is executive director of Aperture, following more than twenty-five years at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where she curated numerous exhibitions, including Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964 (2021), Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (2020), and Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction (cocurator, 2017).

James Welling has produced a continuously evolving body of images that engages the history and technical parameters of photography. He is a recipient of the Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography, New York, and teaches at Princeton University, New Jersey.

Meister: Like most photographers in the 1970s, you began working in black and white. Why was that, and how did you decide to shift to color?

Barney: I have a feeling that the change might have come from color being a fad at that time. When I was making black-and-white work, it really was like speaking another language. I would actually think about the transfer into black and white, I would imagine it in my mind. With black-and-white photography you’re dealing with tones and shadow, or light and dark, as opposed to color. I feel like color is a more natural translation of reality.

Meister: So you don’t make that translation when you’re working in color?

Barney: No. Actually, it’s something I don’t think about. This is what it might be like: English is my native language and when I speak it, I don’t do a translation. But if I speak French or Italian, there’s a translation going on in this section of my brain, which fascinates me. I think that is what happens when I’m photographing in black and white.

Meister: Let’s turn to the question of format. What camera do you use?

Barney: Well, for almost as long as I can remember, I have photographed with a large-format camera. Those earliest pictures were 35mm, and I don’t think that I’ve gone back since 1982, except in moving imagery, which is a whole other topic. Large format is really my native tongue. It’s so much a part of me, it’s automatic for me now. One of the best parts about it is that it slows me down. I have a very fast- moving personality, which might sound great, but it’s not: I badly need to slow down. Those view cameras really do slow you down, which means thinking. I love the 8-by-10 because when I go under that dark cloth, it’s like a meditative process, which is just not part of my personality. Even though there might be other people around me, I concentrate when I’m under that dark cloth.

Tina Barney, The Magician, 2002

Tina Barney, The Magician, 2002Meister: How did you learn to work with a 4-by-5 camera?

Barney: I must have gone out and bought one right as I was leaving Sun Valley. When I left, I knew nothing about that format, and I had no teachers and nobody to ask. I don’t even know how I learned to use it—the same Toyo camera I have today—when I got to New York. In the beginning, I had the rail of the camera showing in the picture because I didn’t even know how to open it up. I really did it by trial and error. I don’t remember how I got the film developed or where it was printed or any of those things.

Meister: You have spoken about learning to make larger prints in Sun Valley . . .

Barney: Peter de Lory taught us how to do that in black and white and Wanda Hammerbeck came in and talked about a lab in Berkeley that Richard Misrach used to make 30-by-40-inch color prints. Around that time, I went to Houston and met Anne Tucker [then photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts]. She told me about a place where they could make an even bigger print—48-by-60 inches. It was a really big deal to do that. Before that I don’t think the paper had been invented. That’s when everything started happening.

Meister: Tell me more about meeting Anne Tucker.

Barney: I went to Houston [from Sun Valley] with another friend who was a painter. She wanted to become famous, too. When we saw Anne, we rolled the prints out on the floor. She said, “Wait a minute,” and then ran out in the hallway and started getting everybody in the department to come in and said, “You’ve got to see these pictures.” Then she phoned her friend Marti Mayo who was working at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston and said, “Marti, you’ve got to come over and see these.” I sat there and said, “OK, I think I’m dreaming,” because that is what every artist in the universe dreams of.

Anne said, “You’ve got to call this guy John Pultz at MoMA. He’s having a show about big pictures.” I called MoMA and said, “Hi, I have a picture I’d like to show to you.” I don’t know how I even found the phone number. While I was on vacation with my kids, the phone rang and it was John Pultz. He said, “We’d like to show your picture [Sunday New York Times] at the Museum of Modern Art.”

I didn’t even go to the opening because I was in Sun Valley. I never saw it hanging there. That’s how it happened.

Tina Barney, Sunday New York Times, 1982

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Meister: Let’s talk about Sunday New York Times, which you made less than a year before it appeared in that exhibition.

Barney: You know, when I look at that picture—I just looked at it the other day, I don’t see it often—the resolution is so incredible. That’s what is amazing. I don’t know how I did it because there are ten people in the picture and they’re all running around like crazy idiots. I asked the father to sit at the head of the table, I counted one thousand, two thousand, three thousand . . . and he held still. That was just enough. I had no idea what I was doing counting those seconds. I was so untechnical: I just guessed.

Meister: About the gallerist Janet Borden . . .

Barney: I have to mention Janet because she is definitely the most important person in my career. You know how people say someone made them? She made me. She had the imagination and the personality to put me in a context I think I could have totally missed. She knew the most far-out people. She went to Smith College, she was friends with actors that worked in The Wooster Group, she went to Rochester Institute of Technology. Every person she introduced me to was cool and happening. I think that was very important because I could have been put in this category of “nice little portraiture,” you know?

Meister: How did you meet her?

Barney: She worked for Robert Freidus, and I must have heard about his gallery somehow. I bought a couple of pictures from her. Then, when I had the big pictures, I think I called her and said, “Would you like to look at these?” It took her a long time to get her own gallery, so at first she showed them out of her little apartment. One show was in a restaurant of a friend of hers, tacked up on the wall. Another was in a gallery, and you had to walk through another show that was so terrible to get to my show. I went to the opening and thought, Oh my God, I’m going to die. She introduced me to everyone. She knew all the curators and everybody in the photo world.

Meister: So, when your work was included in the Whitney Biennial in 1987, you had been working with Janet for a while?

Barney: I was very lucky because I was in quite a few shows in the 1980s, but the Whitney Museum was a big deal. My best friend in Sun Valley, Mary Rolland, who ran a gallery there, said, “You’ve got to show your work at the Boise Gallery of Art” [now Boise Art Museum]. I replied, “Oh, don’t be ridiculous,” but I sent Beverly, Jill and Polly and Sunday New York Times and they took them both. Patterson Sims was the judge and he gave me first prize. He was then a curator at the Whitney, and Lisa Phillips was also there. They took three of my pictures for that Whitney Biennial. The Starn twins [Doug and Mike] were in it too; it was an interesting show.

Tina Barney, Two Sisters, 2019

Tina Barney, Two Sisters, 2019  Tina Barney, spread of Connoisseur, March 1988, from “Issey Miyake Is Changing the Way Men View Clothes”

Tina Barney, spread of Connoisseur, March 1988, from “Issey Miyake Is Changing the Way Men View Clothes” Meister: Shortly after the Biennial you did your first editorial assignment.

Barney: I think that was with Connoisseur magazine, which was fantastic. That came from Janet too. She knew the guy who was on the cover of it with Polly, my niece. The photograph was taken in my sister’s apartment. It was terrific. Issey Miyake clothes. I used my son in another picture. We had a blast. That was the first shoot I ever did and I was really nervous, but I loved it. In 1990 Michael Collins, one of my dearest friends who is now a photographer, was the picture editor of the Daily Telegraph magazine. He hired Larry Sultan, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, me, and many others to do editorial jobs all over the United States. I worked for him for a long time and it branched out into many more things. That was when I really started doing editorial work and I loved it. He sent me on the weirdest jobs you could ever imagine.

Meister: Bill Brandt once observed: “I hardly ever take photographs except on an assignment. It’s not that I do not get pleasure from the actual taking of photographs, but rather that the necessity of fulfilling a contract—the sheer having to do a job—supplies an incentive, without which the taking of photographs just for fun seems to leave the fun rather flat.” I feel as if I’ve heard you say something similar.

Barney: Well, that’s exactly how I feel. It’s almost like having an assignment in school that you enjoy and really want to do. Anyone who’s not an artist does not realize what it’s like to be an artist. You don’t jump out of bed every day and think, Oh boy, I have a lot of great ideas and I can’t wait to get out there. I always think you have to make inspiration come. You really sit around and start to think, What should I do every day?—which is not the most fun part of making art. The longer you keep doing it, the harder it gets to reinvent yourself each time. I’ve been lucky enough to do what I want and I really do enjoy it. Some of the pictures have ended up being really strong and some haven’t. But most of the time, because I’ve had such good choices, I’ve really enjoyed them.

Meister: Is it important to you that someone can tell whether a photograph was made on an editorial assignment?

Barney: No. To me they fit right in. The fact that they are from an assignment is like having an extra-spicy sauce on top of dinner. They’re a fun added attraction.

Meister: I’d like to ask you about the decision to shoot analog or digital.

Barney: When I first started using a digital camera in 2014, I did it because I thought, OK, this is what’s happening in the world and I sure don’t want to be out of it. I’d better damn well figure out what this is all about. I struggled with it. I made pictures, most of which were not successful at all. Now, when I do a fashion or commercial job, I struggle with my assistants, my agent, and the clients because they all want me to use film! This just started happening four or five years ago. I thought everybody was crazy: They don’t know the difference. Now it’s the first thing people ask, “Will she use film?” They don’t know the pain in the neck it is—let alone the cost—all the other equipment, plus a lot of other things, including finding an assistant who knows about view cameras.

I love the 8-by-10 because when I go under that dark cloth, it’s like a meditative process.

Meister: What do you think they’re after?

Barney: The main thing is they want my pictures that I’m doing for them to look like my own work. They think what defines my own work is the camera and film I’m using. I still think they’re crazy, but sometimes, I think they’re right. There are a couple of things you’re not going to get if you digitize that 4-by-5 or 8-by-10 negative. You’re not going to get that sort of edge—edges that are so sharp and fine and sort of false-looking. The other thing is that I think people don’t realize how much is out of focus in my view-camera work—and has been for the last forty years.

Meister: When you’re working with a digital camera, that kind of thing is not possible?

Barney: Right. There’s a softness to it. There’s also a color difference. There’s a pastel look to analog film. But it’s very hard to explain without actually looking at the image in front of you.

Meister: Could we talk about moving images for a moment?

Barney: Super 8 films are my really great love; they are very close to my heart. I always feel like a beginner and I’ll never get past that. If I had my way, I would just take the film and say, “Here, take it. This is what I love. We don’t need to make any sense out of it. There doesn’t have to be a story. I just love the way this looks.” This kind of vintage look is what I really love. I’ve tried to make many little films and I don’t think they’re successful or important, but I love the fact that they might be shown. Actually, one film that’s going to be shown at the Jeu de Paume is a VHS. So much time has gone by that it actually looks great. I mean, it’s just a mess. Forget about focus. I had this prehistoric sound system. I had no idea what I was doing, but I did it.

Tina Barney, The Lipstick, 1999

Tina Barney, The Lipstick, 1999  Tina Barney, Family Commission with Snake, 2007

Tina Barney, Family Commission with Snake, 2007 Meister: What did working with a moving image offer?

Barney: Because I just love looking at film. It’s like when you see something you like you say, “I want that too. I want to have that dress or make a cake that tastes like that.” It was basically that I wanted to try it. I also thought about recording the people I was photographing: imagine if you could hear what they were saying—not only because I’m so in love with anthropology and sociology—their accents, the intonation, the way they treat each other. That is all part of it.

Meister: You’ve also made digital videos. What interests you about those?

Barney: I have one film called Youth [2016–18] in which I filmed the same identical twin boys, following them year after year. That film is a combination of digital, Super 8, and some stills, even an 8-by-10. When you look at the same subject matter with a different medium, do you feel differently about that subject? That’s what interests me.

Meister: In 1990, seven years after you showed your first picture at MoMA, Catherine Evans did a solo exhibition of your work there. Do you remember how that came about?

Barney: I don’t, but it was pretty unusual. I felt like it was pretty early to give me a show. It was very much the greatest hits of what I had done up to that point. After that, other museums in the United States gave me shows. This all has to do with Janet and her connections because she knew so many people in all those museums: Columbus, Cleveland, Denver. They all bought my work and gave me shows, mostly Theater of Manners work.

Meister: I love capturing what a great dealer can do for an artist’s career.

Barney: This was it, especially at that time. A lot was happening, very, very, quickly.

Meister: Were you there for that MoMA opening?

Barney: Oh yes, I was. I remember getting my hair done and the hairdresser did the worst kind of Toulouse-Lautrec [updo]. I remember Janet’s face when I walked in. When I look at the snapshots, I think, Why didn’t I take it down? Luckily, I was so young and thin and I had a beautiful dress on. But I don’t know why I didn’t just tear it down.

Meister: Let’s jump forward a bit, to your next major body of work. What made you decide to go to the American Academy in Rome?

Barney: That’s very simple: Chuck Close and Dorothea Rockburne. Both said, “Tina, you’ve got to go and apply.” I kept thinking about it but thought it was too crazy. Then, by chance, a friend of mine, who is also from Sun Valley, had an Italian friend who lived in Rome. I met her as she also lived on the East Coast here and traveled back and forth. It was love at first sight. I knew that I had a friend there that was going to help—that woman really was the beginning, the creator. I couldn’t have done The Europeans without her. Bob [Liebreich, Tina’s partner] and I went together and lived at the Academy. We went three different falls [1996, 1997, 1998], but she supplied the friends. What I had not realized is that sometimes Italians marry different nationalities. They would say, “Oh, I have a cousin in this country, I have a nephew in that country,” and that is how it dominoes into other countries.

Tina Barney, The Two Students, 2001

Tina Barney, The Two Students, 2001  Tina Barney, Nuevo Mexico, 2003

Tina Barney, Nuevo Mexico, 2003 Meister: Will you talk a little bit about The Europeans?

Barney: As with all my projects, at first I never thought something would come of it. Bob was my assistant. When I got to the first location, it was so beyond anything I could have ever imagined in fifty-thousand million years, I thought, Oh my God. For the picture Father and Sons, it was really like central casting had come in and done a set for me. Every time I met another person, they introduced me to another person, and it would just get better and better. It was eight years of bliss. In some countries, it was more difficult finding people—I don’t speak German, for instance. It makes a big difference to speak the language.

Meister: Do you think that that would have been different if you had been approaching American strangers?

Barney: Gosh, I never thought of that. But, you know, you can’t even compare because quite a few of these people were nobility. Some Americans think they’re nobility but boy, there’s a difference. I’ll tell you what it is. The act of having your portrait made was so much a part of their culture and their heritage that it was a very normal thing for someone to come in and make their portrait without knowing them. The beautiful part—and I noticed this on that first picture—was that I could not direct these people or tell them what to do. Not because of the language, but just because of the way they were. They held poses that I think are subconsciously handed down from generation to generation, for the sake of the portrait. I don’t know if I’m making that up, but I felt it, and right away the pictures became more formal, or static. The resolution was so beautiful, because for once people weren’t moving around, out of the plane of focus. When I started printing, they were better than any picture I’d ever made in the sense of quality of focus and color and eventually lighting—the lighting was just like a joke in the beginning.

Meister: You resist characterizing the subjects of your portraits in your titles, yet you once said, “I know now that before I take a picture, I have to be sure how I feel about the subjects.” Do you still feel this way today?

Barney: That depends so much on the situation. It has to do with whether it’s a job and because I don’t really photograph people I know well anymore. Youth is probably the last time I photographed people I knew well, although not as well as the pictures in Theater of Manners, because they weren’t my children, brothers, or sisters.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Meister: Did photographing The Europeans change the way you would approach that statement?

Barney: Absolutely. That project was so very different. It was people I didn’t know at all. Sometimes I didn’t speak their language. I was in a foreign place, thinking about portraiture in a different way than ever before. Most of the time it was formal or visual in The Europeans.

Meister: To the question of artistic communities, do you feel that you’re a part of one?

Barney: I don’t ever feel like I was part of a photo or art group. I was in Sun Valley because we were all stuck in that little place, but since I came back here [to the East Coast] I’ve really been on my own. Larry Sultan was a really, really good friend. I met him through Janet Borden because we both showed there. We had the most in common of any photographer I’ll ever meet. We just knew that what we were doing was deep down the same thing, and we were tortured by the difficulty of what we were doing. But most of the time, I didn’t really hang out with other photographers.

Meister: What about Mitch Epstein? How did you become friends?

Barney: My friend Judith Freeman said, “You should meet Mitch Epstein,” and I called him up and said, “Let’s meet.” I actually introduced him to his wife, so yes, we’re very good friends. He is the kindest, most generous person you could ever find. Some artists are very protective of what they do in many different ways, and Mitch just isn’t. He’s always the person I call.

Tina Barney, Graham Cracker Box, 1983

Tina Barney, Graham Cracker Box, 1983  Tina Barney, Ada’s Interior, 1981

Tina Barney, Ada’s Interior, 1981All photographs © the artist and courtesy Kasmin, New York

Meister: You are not a big self-promoter. You are, dare I say, a little shy. And yet for Theater of Manners, you appear in more than twenty photographs. That was a pretty big chunk of your first book.

Barney: I can’t remember why I thought that was important. You’re right, because that was sort of unlike me. But I think that book had a lot to do with the editor Walter Keller, who kept on saying, “More, more, more.” He was brilliant, absolutely brilliant. I’m so glad I did it.

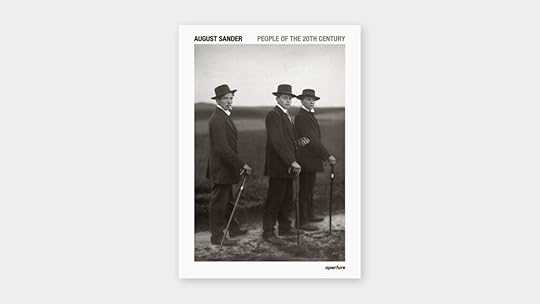

Meister: You and I got to know each other better through August Sander: you were the first person to speak at the five-year research initiative Noam Elcott and I convened. You set the tone in such an unexpected and moving way because you mused about August Sander as a human, noting that “every word you say, every move you make, reflects on that photograph.” I’d like to ask you to think about August Sander in the context of this exhibition of your portraits.

Barney: I love his work: the purity of it, the simplicity. Really, portraiture is my great love. When I say portraiture, I mean someone just standing there with nothing around, doing nothing, just looking straight into the camera. About as simple a picture as you could take. The complexity of that, the investigation into a human being by using that machine—those two things together, to me, are the ultimate, and the most difficult.

Meister: Hearing this brings to mind some of your self-portraits, where it’s just you and the camera, almost wrestling with one another.

Barney: I think if we look through the history of art, self-portraits are probably the most important works an artist makes. Probably because you know yourself the best. I think photography is the most difficult medium to use to do this. Of course, others that use other mediums would probably say their medium is the most difficult. The camera has the problem of focusing. How do you focus on yourself? Well, there are different tricks, but it’s damn hard to do. Also, what you’re thinking about when you take the picture. To me, that’s probably the most important thing of all, what you decide to think about.

Meister: Because you think you can see that?

Barney: Well, you should be able to. You hope you can. And then can you answer that question yourself, too? Who am I? What am I?

Meister: I’m curious to hear what you think of “environmental” portraits, which I consider an important piece of your oeuvre. I’m surprised to hear you say that somebody without anything around them is the purest form of portraiture.

Barney: That is because it’s the most difficult.

Meister: But it doesn’t seem to me like you’re taking the easy way out with the other ones . . .

Barney: The more stuff in a space or a room for me, the easier it is. The more minimalistic a space is, the more difficult it is, because then you have to work harder. You’ve got to think about that figure and what to do with it.

Meister: I’d like to conclude by asking how you feel about being an artist, despite your not-so-bohemian upbringing?

Barney: I actually really struggle to say that I’m an artist. Well, first of all, I feel like that’s such a phony thing to say. Then again, it’s just so much a part of me that I don’t feel like it’s a separate thing.

This interview originally appeared in Tina Barney: Family Ties (Aperture/Atelier EXB, 2024).

Charlie Engman Transforms the Internet’s Murk into Art

All photographs come from somewhere—are of something. At least that’s still the premise, even as AI-generated pictures suffuse the world. A cursed image, then, is one without context: someone slicing sausage with a bootleg Windows XP disc, a motorcycle tucked into a bed, so much wayward spaghetti. From nowhere, going nowhere; a scratch in the feed.

“They feel like products of the deep internet that have this authorless, golem-like quality,” Charlie Engman says of his recent work. “Images that have taken on a life of their own, that seem to have been created from the murk of the internet rather than by any one real scenario.” His new photobook is duly titled Cursed (2024).

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Engman is typically a camera-using, straight-ahead photographer, perhaps best known for a lengthy series of revealing, bare portraits of his photogenic mother. In the last two years, though, he’s become something of an AI whisperer, employing Midjourney, DALL·E, and their ilk of generative AI programs to dredge the internet. He plumbs the mushy, statistically average but practically unreal quality that makes AI-generated pictures derivative and bad until he finds something compelling: Body horror. Misbegotten hugs. Ceramic or part-human swans wading knee-deep in impossibly shallow parking lot puddles. Waxen human-approximates crumpled on bedcovers. The interface—where people touch objects and one another, where light touches an object—is the place in which AI miscarries.

Drawing on reservoirs of sleazy hard flash, incidental still lifes, and pickling Polaroids, Engman leans into these pictures being photographs, assembled from whatever clots of photographic data float through the internet’s sewer. “I feel like, weirdly, this work is the most photographic work that I’ve ever made,” he states. In his previous output, he was trying to push and bend photography’s conventions, its history. With the AI images, “I actually felt like I was running toward photography to see how close I could get,” he says, “and what that kind of closeness would mean in this new context.”

Charlie Engman, A Cliff Overlooking Water, 2024

Charlie Engman, A Cliff Overlooking Water, 2024  Charlie Engman, Boy Glint, 2024

Charlie Engman, Boy Glint, 2024 Are his pictures technically photographs? It’s hard to say, but their source images are, or, somewhere down the line, were. Engman’s pictures draw on a latent, ghostly indexicality, the sense that light touched something, a piece of something, bounced into a lens, and now the software is doing its best impression of that light.

The images in Cursed derive primarily from Midjourney, although a few incorporate Engman’s custom models or photographs he made. It was important to him to use accessible technology. In the spirit of the “cursed” genre—popularized on Tumblr in 2015 to describe certain lo-fi photographs with an unintentional creep factor—you don’t need special training (though maybe a taste for the uncanny) to pull the most haunted accidents. This sifting is part of Engman’s process. From a slough of trawled pictures, the software replies to each prompt with four composites. He’ll feed in his own images, add both language and image prompts, and process the pictures again and again until they eke that cursed look.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

The square format, the nostalgic default of Instagram via the Polaroid instant camera, is also the standard for text-to-image models. Photobook aficionados, perhaps allergic to social media’s rigid conventions, “really balked at the fact that I was making a square book,” Engman tells me. The square is too basic, too accessible—which, he continued, illuminates a tacit line of critique of AI: that it is undermining the rarefied conventions of fine art (as well as scraping images without permission). The availability of cursed images is part of their threat: Simply by dipping into the mainline, you can find something that surpasses the most studied fine-art photograph for punchy strangeness.

Engman grants that there’s something a bit perverse to having made a photobook out of this material. A binding elevates and fixes the content it contains, marking a particular state of the art even as technology rushes on. It is all the more contrarian to pause images that might have had no destiny. Engman is standing in rushing waters. He described perusing images he’d generated not two years ago and finding them outdated, the quirks of early AI (extra fingers, mismatched eyes) already digested by pop culture.

“I became excited by this idea that you could be nostalgic for the present,” he says. “There’s an experience of things moving at such a scale that you couldn’t even be present with what you were making because you are already anticipating it becoming valueless or irrelevant.” The project, of course, also pokes at the notion that AI itself is a cursed invention, rushing to the world’s end. “Does interaction with the technology curse the user?” he muses. “Does it curse the author? Does it curse the viewer?” Engman’s recent pictures ooze from our AI-crazed moment but also float free of it. Consider yourself cursed.

Charlie Engman, Watermelon, 2024

Charlie Engman, Watermelon, 2024  Charlie Engman, Swan III, 2024

Charlie Engman, Swan III, 2024  Charlie Engman, Leaves, 2024

Charlie Engman, Leaves, 2024  Charlie Engman, Ants, 2024

Charlie Engman, Ants, 2024  Charlie Engman, Bedroom Animal II, 2024

Charlie Engman, Bedroom Animal II, 2024  Charlie Engman, Hand to Chest, 2024

Charlie Engman, Hand to Chest, 2024All images courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257, “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”

December 6, 2024

A Photographer Captures the Experience of Dispossession in Turkey

Cansu Yıldıran was born in 1996 and spent the first seven years of their life in Çaykara, a town in the Kuşmer Highlands, in northern Turkey, on the Black Sea. As a teenager, they found photography, and began taking self-portraits on a smartphone, posing for androgynous images, savoring the medium’s genderqueer potential. They enrolled in photography school in Istanbul and purchased a digital SLR, a Fujifilm, using their mother’s credit card without her knowledge. (This caused a fuss, but their mother said she’s glad they stole the card.) At age seventeen, Yıldıran began shooting the images that would form two ongoing series, The Dispossessed and The Shelter.

Yıldıran’s images are polyphonic; their projects overlap. Many photographs are rich with autoethnographic elements. The Dispossessed contains dimly lit scenes captured in the Black Sea mountains and valleys of their ancestry. In darkness, a flashlight exposes a rural woman or a detail in the landscape with such brightness that it turns them into surfaces with newborn vitality. Yıldıran uses flashlights extensively “because this is what women who work and live in those mountains do.” In one image, a woman appears faceless against a dark background. Yıldıran had instructed her to point the flashlight to her face. “I cherish the performative aspect of photography,” they told me.

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016Yıldıran spent many summers returning to and taking pictures of Çaykara, or “lower village,” which lies in a V-shaped valley in the Pontic Mountains. Nomadic Turkish tribes, Armenians, and Greek-speaking Christians populated the region for centuries. Traces of its history as part of the Byzantine, Trebizond, and Ottoman Empires remain. In 1915, during the Caucasus Campaign of World War I, the Russian Army invaded. The ensuing decade saw the Ottoman extermination of some three hundred and fifty thousand Pontic Greeks. Today, Çaykara has a population of about twelve thousand.

On their visits, Yıldıran tried to embrace and understand the place. Portraying women and animals that for centuries formed “an alliance of mountain creatures,” they said, was a means of announcing, “We’re here to ponder the memory of our homeland.” Yıldıran joined their mother, aunt, and other relatives as they picked nuts. Taking pictures, walking around, and trying to be helpful proved therapeutic. The fog that covered the view created sublime landscapes. A woman burns fallen leaves; four women pray before lunch; a goat is milked in a barn.

In this fairy-tale land, Yıldıran’s dreamy images capture a historical process of dispossession. Yıldıran’s mother, who studied dentistry before returning to her hometown, couldn’t own a house because of an old custom that says only men could buy property there. “I realized my work was about being guests for life. About the desire to belong to a place but being rejected by it.” (The Kuşmer Highland is deeded to 373 households residing in Çaykara, which prevents people who emigrated from the village from acquiring property.) “For some reason, I’m taking all these depressive, dark, uncanny images amidst so much natural beauty,” they said. “When I looked at my photos, I noticed they’re all sad because of this cloud of dispossession.”

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016As Yıldıran frequented Çaykara in the mid-2010s, social protests were rocking Turkey and testing the patience of its authoritarian leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Yıldıran skipped class to join protests at Cerattepe, where thousands marched against planned mining activities by cronies of Erdoğan; eventually, because they were failing her coursework, they left college. Women led the charge in these protests against mining: blowing whistles, playing accordions and drums, banging pots and pans. They inspired Yıldıran to spend a month in 2015 tracking, climbing mountains, and photographing local activists, with an eye to “preserve these things and to act as their memory,” they said. “To help me recall how they felt like at the time.”

In 2016, Yıldıran won a photography contest, Foto Istanbul. The winning image shows Burçak, a trans woman walking down a street. Her back naked and straight, she stands tall against several people, primarily men, who consider her from a judging distance. Taken during Trans Pride in Istanbul, Yıldıran’s photograph, part of their Shelter series, distills the Turkish government’s intensifying assault on queer communities, known locally as lubunyalar. As efforts to marginalize and criminalize lubunyalar increased, Yıldıran’s interest in documenting the “self-exploration” of Generation Y grew: One man places his head on another’s naked body, where he takes refuge. Shaving each other’s heads, sharing lights for cigarettes, cruising, and dancing, Istanbul’s lubunyalar opened their bodies and hearts to the photographer. Yıldıran shared those images on Instagram, where they had seventeen thousand followers. Then, in 2022, Instagram closed the account. “It was because of the nudes,” said Yıldıran. “That day I learned not to trust Instagram.” Now, they are focused on maintaining an archive and not relying on social media.

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2019

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2019For years Yıldıran mainly used a Canon AE-1 and shot their projects on 35mm film. Pressing the shutter once, instead of fifty times, felt right, and they savored “this serenity of waiting for the right image.” The technique empowered hallucinatory frames where characters seem unaware of being filmed but also act out. One example is Yıldıran’s work on Eleni Çavuş, a rifle-wielding Pontic guerrilla, who spent a year in the Nebiyan mountains in Samsun in 1924, before Turkish soldiers captured her in a cave there. Yıldıran’s mother Ayşe Durgun played the role of Eleni. According to legend, a Turkish sergeant had killed Eleni’s child, so she killed him, wore his jacket and gun, and climbed the mountain, from whence her dead body returned. “What happened to the Pontus people is rarely talked about. It’s a really dark history,” said Yıldıran. “It’s not part of the public conversation, and that pisses me off.”

Installation views of Cansu Yıldıran: Haunt the Present, the Arts Center at Governors Island, New York, 2024. Photographs by Yi Hsuan Lai

Installation views of Cansu Yıldıran: Haunt the Present, the Arts Center at Governors Island, New York, 2024. Photographs by Yi Hsuan LaiCourtesy Protocinema and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council

Haunt the Present, Yıldıran’s first exhibition in the US—recently presented at the Arts Center at Governors Island in New York—riffs on previous series, adding new layers. The photographic-sculptural installation tells a semifictional immigration story, imagining a scenario in which Yıldıran’s mother immigrates to the US from the Black Sea. The show includes images of both places, and for the images of America, Yıldıran spent weeks road-tripping from Michigan to the Pacific Ocean, driving up to ten hours daily, visiting national parks. Istanbul’s lubunyalar were an inspiration: Yıldıran observed how they began immigrating outside Turkey in large volumes over the past decade. “I felt oppressed in Istanbul, and to get away and see all the vast vistas opened me up.” The superimposed images explore the possibility of meshing the Anatolian plateau and the American landscapes and ask whether they can converse.

The intermingled fragments of Yıldıran’s vision will endure: the faces of their mother and aunt in costume, details from historic Pontus photographs, and images of Black Sea women who continue to live under the oppression of a patriarchal regime. Their multilayered compositions create new geographies. “This is why I add volume, cut, and shape my images,” they said. “I build my dreamlands.”

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2023

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2023 Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2016 Cansu Yıldıran, from The Shelter, 2022

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Shelter, 2022 Cansu Yıldıran, Ahsen and AkışKa, 2022, from The Shelter

Cansu Yıldıran, Ahsen and AkışKa, 2022, from The Shelter Cansu Yıldıran, from The Shelter, 2017

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Shelter, 2017 Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2017

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2017  Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2018

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2018  Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2023

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2023  Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2017

Cansu Yıldıran, from The Dispossessed, 2017All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

December 5, 2024

Trevor Paglen on Artificial Intelligence, UFOs, and Mind Control

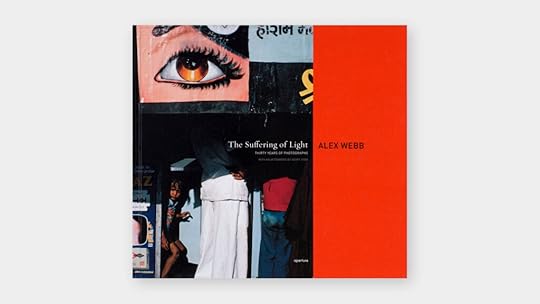

Long before the torrent of attention unleashed by ChatGPT’s public release in November 2022, the artist Trevor Paglen was patiently teaching us about the underlying technologies and training sets of artificial intelligence. He not only demonstrated how they interpret images—rendering them into data whose applications have severe social and moral consequences—but also unveiled what they are made of. Paglen’s art is about surveillance, technology, and hidden forms of power. But one could also say his work is about faith and doubt: It bolsters our faith that certain things we can’t see really do exist, and sows doubt about whether we consented to live in a society where certain things exist. CIA black sites and rendition programs. Spy satellites. Secret military bases. Machine-hallucinated images. Racist classification schemes fueling facial recognition systems. The surveillance of our everyday behaviors. UFOs.

Paglen deploys the camera less for depictive purposes than as an analogy for the extraordinary labor of making something visible—whether the thing to be seen is a surveillance drone, the computational analysis routinely performed on photographs of our faces, or a strategy of psychological warfare shaping our media consumption. Photography is neither his sole medium nor his raison d’être, but it’s indispensable to a practice that examines how belief is compelled.

Trevor Paglen, Tornado (Corpus: Spheres of Hell) Adversarially Evolved Hallucination, 2017

Trevor Paglen, Tornado (Corpus: Spheres of Hell) Adversarially Evolved Hallucination, 2017Sarah M. Miller: You’ve interrogated the history, tools, and implications of AI for about twelve years, focusing particularly on systems that interpret images. How does it feel that the rest of the world is catching up to this topic—and is it too late?

Trevor Paglen: It’s not too late. I’m happy that the rest of the world is catching up, because it’s important to have other voices in these conversations. For a very long time, these conversations have been happening in computer science departments, in tech companies, and I think a lot of people from the humanities didn’t even know that there was this whole other mode of vision—seeing with machines—being developed and becoming a part of our everyday infrastructures. The theory of perception underlying so much of AI and computer vision is shockingly bad from a humanities perspective. It’s crucial for people with backgrounds outside the tech industry to look at these systems critically.

Miller: You often use the terms “computer vision” or “machine learning”—as opposed to “artificial intelligence”—to describe the subject of your research. What’s the difference?

Paglen: Computer vision has a long history, going back to the 1950s and ’60s, that overlaps with the development of digital photography, digital imaging, image processing, et cetera. And there are a bunch of pre–machine learning algorithms that are still in common use in computer vision. I generally try to use “computer vision” because I’m bracketing out stuff about language, and chatbots, and other kinds of optimization algorithms that fall under AI more generally.

The machine learning moment really starts around 2012, and it’s when people figure out that you can use neural networks, which had been invented a long time ago, to actually do stuff—as long as you have a whole bunch of training data and a whole bunch of computing power. Machine learning is the stuff that what we now call AI is made out of. But there have been different approaches to AI in the past that had nothing to do with machine learning at all—the dominance of the machine learning approach is relatively new, whereas AI has been around for a long time.

“Artificial intelligence” also doesn’t really mean anything, and it has a lot of ideological associations. It’s a term that lends itself to mystification.

Trevor Paglen, Image Operations. Op. 10, 2018. Single channel video projection, sound, 23 minutes

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { const fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); const fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); const watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { const containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace('px', '')); const containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace('px', '')); const bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace('px', '')); const marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); const observer = new MutationObserver(function(mutationsList, observer) { for(var mutation of mutationsList) { if (mutation.type == 'childList') { watchFullWidthImage();//necessary because images dont load all at once } } }); const observerConfig = { childList: true, subtree: true }; observer.observe(document, observerConfig); }Miller: A lot of your work related to AI functions as tutorial—teaching viewers how computer vision works and what it’s built on. One of my favorites is Image Operations. Op. 10 (2018). Could you describe how you made that piece?

Paglen: It’s a video of musicians performing Debussy’s String Quartet in G minor, Op. 10. You’re watching the string quartet playing, you’re hearing the music, and your visual perspective gradually shifts from that of a camera to that of various computer vision and AI algorithms, which are interpreting the performers and their actions—the machinic eyes of algorithms that are designed to estimate age, gender, ethnicity, emotional states, gestures. So you’re getting a sense of the different ways that humans have developed to try to have computers make sense of images.

We built a programming language in my studio to work with computer vision tools, and to turn their algorithmic abstractions back into images. I looked at different kinds of media and images to find the thing that I felt contrasted most with the machinic ways of seeing. Instrumental music performance—that’s almost pure affective excess, fundamentally not quantifiable. So that’s the juxtaposition I set up in that piece.

Miller: It’s amazing to watch the analytics take place in real time. It makes you understand that the calculations about who these people are, what they’re doing and expressing, are constantly changing and often confounding. If these algorithms were being applied in a situation like analyzing surveillance footage, they’d be unreliable and—at least sometimes—totally out of sync with what a human would be perceiving.

Paglen: I also made a series of images of clouds. You’re seeing the cloud in a photograph I made, but you’re also seeing the cloud as it’s being seen through computer vision algorithms—including some used by drone and missile systems, facial recognition systems, and self-driving cars. It’s kind of a contemporary take on Stieglitz’s photographs of clouds. When you think about computer vision, what it’s essentially doing is taking an image, or some kind of visual sensory input, and creating a mathematical abstraction out of it.

Miller: A critic writing for Forbes, Jonathon Keats, said that you are to artificial intelligence “what Upton Sinclair was to meatpacking.” It’s a great comparison.

Paglen: Well, that’s a very high compliment, because it took me a long time to develop an understanding of how these tools work, and a feeling for it, and then to find language to talk about it. It’s a different paradigm, a fundamentally different way of thinking about images than I was taught in art school.

Trevor Paglen, ImageNet Roulette (detail), 2019

Trevor Paglen, ImageNet Roulette (detail), 2019Miller: Your work on training sets has exposed the perils of simplistic image labeling that equates picture with thing, type, or identity. ImageNet Roulette (2019), for example, demonstrates that the prevailing attitudes underlying our foundational facial image recognition tools are equal parts absurd, crass, stereotypical, racist, and misogynist, not to mention culturally and historically bound.

Paglen: ImageNet is the most widely used dataset in computer vision research, created between 2009 and 2011. The people who created it said they wanted to make a database of “the entire world of objects.” So how do you do that? They took WordNet, a specific kind of dictionary where synonyms are clustered according to concept, in a hierarchical structure, under high-level categories like plant, person, and artifact. They only kept the nouns; the theory was that a noun is an object you can take a picture of. Each synonym became a slot. Then they scraped the whole internet, pulling in as many images as they could, and hired clickworkers to organize those images into the slots. In other words, the process required workers to decide what each image meant, and label it from a pre-given classification scheme.

It was kind of quaint, in retrospect. They were thinking, It’s so big, who could possibly ever look at the whole thing? Well, you can look at twenty thousand words, and the images to which they’ve been correlated, in an afternoon. The fundamental approach is terrible. There are tons of misogynistic nouns, tons of racist nouns, cruel nouns—nouns that are at once abstract and terrible. There are also plenty of nouns that aren’t visual at all.

When projects like ImageNet Roulette came out, and other people started looking at these datasets and realizing how terrible they were, the industry response was: “Let’s just remove anything that could be controversial.” There was no fundamental rethinking of the architecture, or of that relationship between images and concepts.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Miller: In an article coauthored with Kate Crawford, you wrote: “Images are remarkably slippery things, laden with multiple potential meanings, irresolvable questions, and contradictions. Entire subfields of philosophy, art history, and media theory are dedicated to teasing out all the nuances of the unstable relationship between images and meanings.” And yet here we are: subject to vastly powerful systems built by people who never seem to question the relationship between representation and reality, pictures and meaning.

Paglen: Where these correspondences are most obviously “useful” is in industrial processes and in policing. Computer vision systems built to monitor truck drivers are a good example. Right now, you’re seeing the truck drivers as the canaries in coal mines, in terms of what the future AI-assisted labor surveillance looks like. The company that owns the truck will install a smart camera in the truck that watches the driver, and if—according to an algorithm—the driver is smoking a cigarette, or eating, or takes their eyes off the road, or looks drowsy, they’ll get pinged. They’ll get fined, or their supervisors will be contacted. So there’s an automation of surveillance of this kind of labor.

You’re seeing something similar emerge now in normal cars, where insurance companies want data about how you’re driving, and to modulate your insurance premiums in real time based on how a computer vision system is evaluating your driving. Philosophically and morally, there are huge problems with this way of thinking about images. But if you want to extract value from a domestic or previously private space, these tools are very good at doing that.

“Artificial intelligence” doesn’t really mean anything. It’s a term that lends itself to mystification.

Miller: I think you’re saying that the work of extracting value from labeled images via artificial intelligence gets more sophisticated—but the approach to images themselves is not getting any more nuanced.

Paglen: I want to say something more precise, which is that literalness and the economics of extraction go hand in hand. If a company wants to extract value by putting a computer vision system in your kitchen to watch what you eat, what they don’t want to do is say, “Oh, the meaning of that food is variable . . . it’s all contextual, it’s relational.” What they want to be able to say is, “You ate the doughnut, your health insurance is going to go up.” So the quantification is part of the process of value extraction. The quantification of an image is where I think we agree there’s a massive philosophical problem, as well as a human rights problem. But that moment of quantification is the precondition for being able to extract value. These very rigid ways of seeing are a feature of the system, not a bug.

Miller: You regularly talk to people who work in AI, and specifically in the area of training sets for machine learning. What do they say when you raise the idea that images don’t have transparent, consistent meanings?

Paglen: It’s very rare, I’ve found, among people who come from an engineering background, or mathematics or computer science, to be able to conceptualize the world in a way that does not reduce it to computation. I have yet to have a nuanced discussion with somebody coming out of that technical background who is able to really engage with the idea that there is a deep, irresolvable philosophical problem here—one that is not just a thought experiment but that has genuine and often deadly consequences for real life.

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead … (SD18), 2020. Mug shots of accused criminals and incarcerated people served as a common source for facial recognition algorithms in the early 1990s.

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead … (SD18), 2020. Mug shots of accused criminals and incarcerated people served as a common source for facial recognition algorithms in the early 1990s.  Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . . (#00638_1_F), 2019

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . . (#00638_1_F), 2019 Miller: Your work is dedicated, in large part, to exposing the infrastructures of analytical and predictive systems that we can’t see. Do you think that the recent shift in popular attention to generative AI—this widely available power to order up an image, or generate text—is a distraction from the underlying technologies? Or does it inspire you to pursue a new set of questions?

Paglen: The work I’ve done in response to the generative turn doesn’t use AI machine vision at all. I’m thinking about the history and practice of the manipulation of perception, in relation to media that’s increasingly self-optimized to produce a specific response in an individual—to make them believe something that you want them to believe, to make them perceive something that you want them to perceive, or to make them do what you want them to do.

I’m looking at things like CIA mind-control experiments, stage magic, military psychological operations. These are all examples of some kind of authority using techniques that take advantage of the quirks in your perception, in order to make you perceive the world in a particular way. That is not only what generative AI is doing under the hood, so to speak, but where I think it will go culturally.

Miller: What accounts for your shift in approach? Much of the work you did about computer vision was openly didactic, whereas the more recent work on psyops and mind control seems more oblique.

Paglen: I think about my history as an artist as characterized by different ways of looking at technology. One mode is looking at infrastructure: Let’s go look at data centers, undersea cables, spy satellites in the sky. Let’s see all the stuff around us that is part of planetary computation systems, or surveillance systems, or sensing systems. In mode two, I’m looking at things that are also looking at me. How do these machines see? That encompasses computer vision, AI, that sort of thing.

I think the third phase I’m heading into now is: How are they currently able to make us see things, and images, that we didn’t see before? What are the politics of that? In other words, how did these technologies that are able to see us create the possibility of a media landscape in which not only are we being surveilled, but that surveillance is being used to create new kinds of visual culture for humans, in order to extract value from us?

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Miller: Could you describe one of the newer works that addresses the media you’re describing—media that is tailored to make us see, or react to, or believe something?

Paglen: One of the central works so far is a video installation of a guy talking, Doty (2023). The guy is Richard Doty, who did psyops for the Air Force in the 1970s and 1980s. He talks about the technique and the trainings: “This is how you conduct influence operations.” “These are the elements that you need to make a good one.” He’s breaking down how you do it. Then he talks about influence operations that he ran against different people, mostly using UFOs as a kind of mimetic device to get people to see things or to believe things that he wanted them to believe. But then, there’s also a flip in the film, where he says, “Yes, I created a ton of disinformation and ran a bunch of psyops using the UFO as a mimetic device. But also, UFOs are real. And I’m going to tell you about them now.”

I find this guy’s tactics a, for lack of a better word, mind fuck. I also think it points to an emerging media environment where the distinction between reality and unreality, or between hallucination and fidelity, is irrelevant.

I have a new project of UFO photography, which is something I’ve always been super interested in. I often think about UFO photography as the paradigm of photography. Something like, all photos are UFO photos. It’s very much in line with the recent work on psyops.

Trevor Paglen, Near Windy Hill (undated), 2024

Trevor Paglen, Near Windy Hill (undated), 2024  Trevor Paglen, UNKNOWN #89161 (Unclassified object near The Revenant of the Swan), 2023

Trevor Paglen, UNKNOWN #89161 (Unclassified object near The Revenant of the Swan), 2023All images courtesy the artist; Altman Siegel, San Francisco; and Pace Gallery

Miller: Photography historians like me, of course, love to point out that it’s always been possible to manipulate or stage or alter an image to present a deceptive or partisan view of reality. But with generative AI, we’re way beyond Stalin removing his political rivals from official photographs, both in terms of reach and potential consequences. How do you think we might deal with the problem of propagandistic deep fakes, for example, without reinforcing the notion that a real photograph is, or ever was, a necessarily truthful witness?

Paglen: As people who think about photographs, we know that they’re staged, they’re decontextualized, et cetera. However, I think that both of us would say it is a good thing that we got the images from Abu Ghraib, for example, in the sense that they did political work. Or at least, they prompted discussion by making something visible. Even though photographs don’t tell the Truth, they have a kind of aesthetics of truth that can take you pretty far in terms of putting things on a cultural agenda.

AI breaks the idea that somebody took the picture. I worry that even though we’re suspicious of concepts like indexicality, they still do cultural work in terms of how we read photographs collectively. When that breaks, I don’t know what happens. It does break a shared reality, which didn’t exist in the first place, that was always manufactured. That’s a depressing question to have to ask: Is manufacturing consent the precondition of a certain kind of democracy?

Miller: Is this the end of photography as we knew it then?

Paglen: Well, I think how we understand photography is more important than ever. People who study photographs or make photographs or work with photographs are highly relevant to a world in which everything is photography. I think about self-driving cars as photography and spy satellites and drones as photography. I think about any facial recognition system as photography. Photography is the paradigm of human-technology interfaces, and at this point, it’s basically synonymous with a huge amount of the infrastructure we interact with. People who think critically about photographs have a great deal to contribute, in terms of trying to conceive of and implement the kind of world that we want to live in, because the world is increasingly hard to distinguish from photography.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 257, “Image Worlds to Come: Photography & AI.”

November 22, 2024

How Can Photography Shape our Relationship to the Environment?

Edra Soto’s El Destino (Destination) (2024)—a wall-sized structure installed in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh—is filled with snapshots of San Juan, Puerto Rico: bright bougainvillea, neighborhood street views, a house glimpsed through a hole in a fence. Except, you wouldn’t know it. The images can only be accessed by bending down to peer through the little holes in the structure, as you would look through the viewfinders or keyholes of a different time. It’s a piece that sets the tone for Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape, an exhibition that proposes expansive and multidimensional responses to human-environmental relationships as mediated through photography. The nineteen artists in the exhibition engage with land and place through the sensorial and the political, proposing possible answers to scholar Eva Díaz’s question, “How can we overturn the historical bias of experiencing site primarily through vision?”

Edra Soto, El Destino (Destination), 2024. Paint, sintra, aluminum, viewfinders, inkjet prints

Edra Soto, El Destino (Destination), 2024. Paint, sintra, aluminum, viewfinders, inkjet prints David Hartt, The Histories (Crépuscule), 2021. Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, radio, tapestry. Installation views in Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 2024

David Hartt, The Histories (Crépuscule), 2021. Single-channel 4K video, color, sound, radio, tapestry. Installation views in Widening the Lens: Photography, Ecology, and the Contemporary Landscape, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, 2024Photographs by Zachary Riggleman

Near El Destino, David Hartt’s The Histories (Crépuscule) (2021) presents a fabricated experience of the sublime. A broad, woven vista of the Jamaican coastline recalls nineteenth-century paintings, while a blue-hued video of icebergs conjures a sense of impending doom. Graphically rendered palm trees on the far side of the tapestry situate the viewer in the tropics. All is set to lo-fi electronic music. The effect of peering at Soto’s small pictures fosters curiosity at the same time that it negates and obfuscates the type of broad views that Hartt’s work references and re-presents, offering two alternatives to, and critiques of, the visual language of colonial landscapes that has long characterized views of Latin America and other Global South territories. In contrast to Hartt’s monumental images, only one person at a time can see a particular view in Soto’s structure; landscape is construed as a slow, private experience.

Chanell Stone, Silt, 2022

Chanell Stone, Silt, 2022Courtesy the artist

Chanell Stone, River Wading, 2022

Chanell Stone, River Wading, 2022 Widening the Lens succeeds in foregrounding realms beyond the visual and in centering artists who address fraught histories of slavery and forced labor, indigenous dispossession, and ongoing structural inequity and exclusion inscribed in landscape. They contend directly with the imperial origins of photography, as per theorist Ariella Azoulay. Through performative gestures, Xaviera Simmons, Dionne Lee, and Chanell Stone present various photographic approaches for grappling with the history of landscape in relation to the Black female body. In her Sundown series (2018–23), Simmons appears in brightly patterned clothing, holding up objects that refer to the history of Sundown towns, municipalities or neighborhoods that excluded Black people after sunset, a widespread form of Jim Crow–era discrimination. In Sundown (Number Two) (2018), the artist wears a purple patterned dress and stands with her back to the camera, facing a dense, green hedge. She holds across her back a photograph of a group of Black agriculture laborers and white overseers, all leaning against the back of a truck. These are sharecroppers, not enslaved workers, but the photograph still makes explicit a racial hierarchy that descends from chattel slavery.

The connection between Black bodies and the land is also front and center in Dionne Lee’s poetic photographs, which reflect on strategies and skills for wilderness survival and on the construction of the outdoors as intended for white leisure. Lee’s images of tender gestures also reflect on the medium-specificity of photography: Breaking the Fall (2016) closely frames the artist’s brown hands as they move across a color photograph of natural vegetation, tearing into it, as if making room for darkness and absent histories.

Victoria Sambunaris, Untitled (jump), Glamis, CA, 2020

Victoria Sambunaris, Untitled (jump), Glamis, CA, 2020Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Justine Kurland, Broadway (Joy), 2001

Justine Kurland, Broadway (Joy), 2001Courtesy the artist

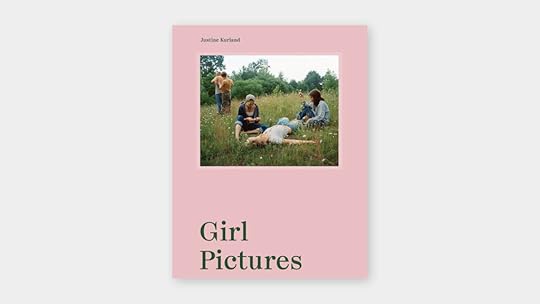

Stone’s dark, large self-portraits in agricultural fields allude to the perils of the outdoors that Black individuals and Maroon communities faced; other pictures focus on the place of Black bodies in urban, public spaces. With their somber, silvery hues, Stone’s photographs recall the deep darkness of Dawoud Bey’s and Roy DeCarava’s photographs, but frame an emphatically female gaze and presence in the landscape. The outdoors as a place for women and queer individuals is also foregrounded in Justine Kurland’s joyous Girls series (1997–2002), and in more somber, striking tones in Mark Armijo’s McKnight’s high-contrast, black-and-white series Hunger for the Absolute, which depicts queer male bodies languorously embedded within the Southern California desert. Sam Contis’s delicate black-and-white views of walls and fences in the British countryside, from the series Overpass (2020–22), home in on the modifications that render them porous and traversable, while veteran landscape photographer Victoria Sambunaris’s expansive views of sand dunes reveal the dirt bikers in their midst only to those who step up close.

David Alekhuogie, Borrowed Recipe 1, 2021

David Alekhuogie, Borrowed Recipe 1, 2021Courtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Dionne Lee, A Plot that Also Grounds, 2016

Dionne Lee, A Plot that Also Grounds, 2016Courtesy the artist