Aperture's Blog, page 27

July 18, 2023

An Artist Sees the Potential for Healing in the Aftermath of War

On the third floor of the New Museum in New York, the elevator doors part to reveal a series of framed photographs in which uniformed soldiers stare stoically at the camera, a groom wraps an arm around his smiling bride on their wedding day, women and children pose for formal studio portraits, and extended families gather around dining tables eating and laughing. It’s easy to imagine the mix of black-and-white, sepia, and color prints in the background of someone’s living room, rather than hanging on a gallery wall. These moments, spanning several decades, represent generations of the Vietnamese Senegalese community in Dakar, whose stories have often gone untold or have been deliberately suppressed.

Installation view of Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance, New Museum, New York, 2023. Photograph by Dario Lasagni

Installation view of Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance, New Museum, New York, 2023. Photograph by Dario LasagniIn Radiant Remembrance, Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s first solo exhibition in a US museum, the Vietnamese artist expands the possibilities of collective memory and storytelling through film and video installations, as well as archival material and sculptures. While research remains integral to Nguyen’s practice, he also understands its limits. “I would go out on a limb and say that the archive is quite useless,” he tells the exhibition’s curator Vivian Crockett in a conversation for the accompanying catalog. He clarifies that he’s referring to official records, which often preserve only one side or a partial version of history. Nguyen explains, “I use the archive as a counterpoint to what I’m doing, creating a counternarrative and working with people that are marginalized or have been disregarded in the dominant narrative to bring their stories to the forefront.”

Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019

Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019  Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019

Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Specter of Ancestors Becoming, 2019 In addition to connecting with families in Senegal who sent him the archival photographs installed at the exhibition’s entrance, Nguyen collaborated with the descendants of the Senegalese soldiers who, during the 1940s and ’50s, were sent by the French to fight anticolonial uprisings in Southeast Asia, and the Vietnamese wives they brought back home with them. He captures their complicated legacies in The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), a “metafictional” project, first shown at the Dakar Biennale in 2022, that features imagined conversations narrated over four video channels. In one of three stories, a woman silhouetted in profile, speaking into a microphone, recounts a memory in French; the English subtitle reads, “I remember you stood in front of a rifle in Indochina to save a black man.” Timeworn portraits flash across an adjacent screen, showing a younger version of the grandmother whom the speaker is addressing and the Black man in question, her grandfather. The reenactment of a granddaughter combing her grandmother’s hair appears on a different screen, while on another a woman faces the camera directly and mouths the words heard in the narration: “Did the black soldier return?” The immersive approach brings to life the anecdotes hidden within family photos while simultaneously acknowledging the gaps for what may never be known.

Installation view of Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance, New Museum, New York, 2023. Photograph by Dario Lasagni

Installation view of Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance, New Museum, New York, 2023. Photograph by Dario LasagniBecause No One Living Will Listen / Người Sống Chẳng Ai Nghe (2023), Nguyen’s most recent film to examine Vietnam’s postcolonial history, takes an even greater speculative turn. As with the previous project, the two-channel video relies on an imagined conversation, this time by way of a woman’s letter to her father who died after defecting from the French army during the same anticolonial uprisings fought by Senegalese soldiers. In this case, her father was one of many Moroccans sent to Vietnam, who left behind a monument: the Moroccan Gate in Hanoi. The structure appears throughout the film, ultimately becoming a surreal portal that connects father and daughter, who says to him: “If I find you, I’ll bring you back to Morocco. But if I can’t find you, I’ll bring Morocco to you.” On the second screen, the portal erupts into flames as the woman fades away. Accompanying the film is Letters from the Other Side (2023), two wall hangings embroidered with text lifted from propaganda leaflets, which were intended to persuade the North African colonial soldiers to the Vietnamese cause.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Moroccan Gate, Ba Vì, Viet Nam, 2023

Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Moroccan Gate, Ba Vì, Viet Nam, 2023Found objects and sculptures become physical embodiments of the traumas explored in the single-channel video The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon (2022). The film, a work of fiction grounded in historical events, follows a character named Nguyệt who makes art out of junkyard scraps and weapons leftover from when the US bombed the Vietnamese province of Quảng Trị. Those pieces take the form of Alexander Calder–inspired mobiles, which Nguyen cast from a brass artillery shells and unexploded ordnances. A Rising Moon through the Smoke (2022) reflects fragments of the video projection on its hanging mirrored surfaces, emphasizing the relationship between the film and the “testimonial object”—a concept Nguyen borrows from scholar Marianne Hirsch. Another sculpture, Unexploded Resonance (2022), reconfigures an M117 bomb, previously dropped from an American B-52 plane, into a temple bell. Further drawing upon the film’s Buddhist imagery, Shattered Arms (2022) features a found Quan Yin carving whose missing hand and fingers Nguyen replaced with new appendages also cast from brass artillery shells. This act of restoration and transformation echoes the real-life stories depicted in the film, such as that of Hồ Văn Lai, whose encounter with an unexploded landmine as a child resulted in the loss of his limbs and an eye.

Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon, 2022

Still from Tuan Andrew Nguyen, The Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon, 2022All works courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York

Together, Nguyen’s multimedia works consider the potential for healing in the aftermath of colonial violence and war. By incorporating pieces of historical “evidence” alongside first-person accounts, the artist reminds us how large-scale events reverberate through interpersonal stories and vice versa. The process of remembrance similarly unlocks the complex lives captured in those family photographs. Even then, Nguyen’s art only begins to scratch the surface of the many entangled global histories that have been overlooked, perhaps, but not forgotten.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Radiant Remembrance is on view at the New Museum, New York, through September 17, 2023.

Rineke Dijkstra’s Captivating Videos Portray the Gestures of Youth

A young ballerina attempts to perfect a dance routine, a schoolgirl draws an artwork, gymnasts practice exercises: the Dutch artist Rineke Dijkstra is masterful at filming her models so the viewer never forgets that her sitters know they are being watched. In Dijkstra’s well-known photographic portraits, this is obvious because her subjects look directly at the camera. In her videos, though, they rarely do—unless their gaze crosses it because of their movements. Still, the models in Dijkstra’s videos act as if they are keenly aware of the camera’s presence, without ever being theatrical. I See You, Dijkstra’s current exhibition at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris, highlights this aspect of her work, displaying four video projections alongside a few supplementary photographs, all of which depict the actions of mostly girls: ballerinas, gymnasts, and schoolchildren. Each work is a study of self-presentation where the camera is an interlocutor. In these videos, Dijkstra’s models command attention by showing the viewer what they are capable of, whether it is a particular skill, the completion of a task, or an opinion of an artwork. Their absorption possesses the same presence that the outward-looking subjects of Dijkstra’s photographs have.

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Ruth Drawing Picasso, 2009

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Ruth Drawing Picasso, 2009Known for her portraits of adolescents and young adults, Dijkstra, who has exhibited for over thirty years, has been the subject of major solo retrospectives at museums such as Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Unlike in the works of other contemporary photographers such as Collier Schorr or Roe Ethridge that incorporate the language of advertising, Dijkstra’s synthesis, a result of her starting out as a commercial photographer, is at first less easy to spot. Her best-known work is a series of teenagers at beaches (in Poland, Ukraine, Croatia, and the US), in which she merges two different approaches to portraiture: traditional studies of specific individuals with the more sociological samples of populations. Influenced equally by August Sander and Diane Arbus, her work exhibits a productive tension between her early commercial training and the fine-art documentary tradition.

Dijkstra simultaneously makes the camera feel neutral and active, a tool through which her subjects are encouraged to present themselves.

Dijkstra has stated on many occasions that she gives her models minimal direction, wanting to let them present themselves naturally. And yet, not everyone could manage to elicit such personality or ease out of her models. In the video Ruth Drawing Picasso (2009), for example, a nine-year-old girl sits on a museum floor sketching the modernist painter’s infamous The Weeping Woman (1937). For all six minutes, the camera remains at floor level, focused on Ruth as she attempts to recreate the painting. She concentrates, she sketches, she hums and haws, she passes a crayon to a classmate sitting on the floor just outside of the frame. Much of this young girl’s willful character comes through in the faces she makes while she works; as the video began to cycle through one complete screening, I found myself smiling because of how charming she is. At a certain point, though, I wondered if her completely natural-looking concentration came from knowing she was being filmed. “Life,” writes the French filmmaker Robert Bresson, “cannot be rendered by photographic recopying of life, but by secret laws in the midst of which you can feel your models moving.” Instead of making a portrait feel less natural, awareness from the model becomes a vessel through which their character is transmitted. In a playful gesture, Ruth’s drawing of The Weeping Woman is displayed in a vitrine in the museum’s hallway adjacent to the screening room. It is titled, dated, signed, and dedicated: “For Rineke.”

Installation view of Rineke Dijkstra, I See a Woman Crying (Weeping Woman), 2009, MEP, Paris, 2023. Photograph by Quentin Chevrier

Installation view of Rineke Dijkstra, I See a Woman Crying (Weeping Woman), 2009, MEP, Paris, 2023. Photograph by Quentin ChevrierIn I See a Woman Crying (Weeping Woman) (2009), a three-channel video that forms a sort of diptych with Ruth, a mixed group of schoolchildren wearing the same uniforms look at Picasso’s Weeping Woman, which is again outside of Dijkstra’s frame. The children describe the painting and discuss what they think it is about: what has happened to her, why she is crying. The responses, which range from projections of trouble at home to fantasies about video games and money, are charming, hilarious, and sometimes heartbreaking. It becomes a sort of collective work of criticism on the infamous portrait of Dora Maar from the perspective of children from northern England, and they clearly enjoy giving their opinions.

Their ease seems to come from Dijkstra’s filming method. She simultaneously makes the camera feel neutral and active, a tool through which her subjects are encouraged to present themselves. She creates an awareness, a certain visual reciprocity, between the viewer and model. There are little to no religious connotations in Dijkstra’s work, particularly non-Western ones, but while watching the videos, I couldn’t help but think of the Sanskrit word darshan. The word can translate very simply as “worship.” More literally, it means “glimpse” or “view,” implying visual interrelatedness between the human and the divine, and a sense of simultaneously seeing and being seen. Dijkstra’s models hold themselves in a way that manifests a secular version of this concept. Each model behaves as if they believe they can transmit themselves through the camera, not simply be captured by it.

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Marianna (The Fairy Doll), 2014

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Marianna (The Fairy Doll), 2014The final two of the works that visitors encounter in I See You, Marianna (The Fairy Doll) and The Gymschool, were originally produced for Manifesta in 2014, the year the biennial took place in St. Petersburg. (Watching these works within the context of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces feels both unsettling and poignant, particularly because Dijkstra also shot in Ukraine in the 1990s.) In Marianna, a young ballerina practices The Fairy Doll, taking instructions from her off-camera teacher. As the instructor drills her further and further, for nearly twenty minutes, the girl maintains her resolve and concentration, although as the video reaches its end, she clearly attempts to ward off strain or even frustration from appearing on her face. In the accompanying photograph, the only large-scale one in the exhibition, Marianna and Sasha, Kingisepp, Russia, November 2, 2014, the ballerina and her instructor look directly at the camera, the former maintaining her poise and determination. This leads to a hallway with smaller-scale photographs of gymnasts, which introduce a video in the next room. Each figure is in mid-pose, their eyes capturing those of the viewer.

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Eva, The Gymschool, 2014

Still from Rineke Dijkstra, Eva, The Gymschool, 2014All works courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris and New York

In Gymschool, the final three-channel video, a cohort of young girls at the Zhemchuzhina Olympic School in St. Petersburg practice a particularly Russian form of training that combines gymnastics, body contortion, and ballet. The girls, ages eight to twelve, present a range of accomplishment. At the beginning of the video, the younger ones learn some of the routines, at times with an aid, such as a ball, while the older ones have mastered each of the body contortions and practice them effortlessly. While none of them look at the camera (as they do in the preceding photographs), they seem proud to display their accomplishments. As the video ends, the eldest gymnast completes a seemingly impossible contortion. Her gaze passes the camera and lands somewhere just beyond it. She smiles lightly.

Rineke Dijkstra — I See You is on view at MEP, Paris, through October 1, 2023.

July 11, 2023

An Asian American Family’s Public History and Private Rituals

Context is rarely tidy. Even as it clarifies, it confounds. Consider this: in 1982, Vincent Chin was beaten to death by two Detroit autoworkers on the night of his bachelor party. In the aftermath, he became an enduring icon of the Asian American civil rights movement. Thirty years after Chin’s murder, the photographer Jarod Lew discovered that his mother had been the one engaged to him. If this is context, I wondered, viewing Lew’s family portraits in his series In Between You and Your Shadow (2021–ongoing), what to do with it?

In one photograph, Lew’s mother hides her face behind a bouquet of bright spring flowers. In another, two vacant chairs sit against the wall of his aunt’s Chinese restaurant in Metro Detroit. I admit I tried to make such images carry the loss of a man the photographer never knew, could never know, his absence making it possible (though who knows) for Lew to be here in the first place. Forking paths and multiverses, they’re in the air, imbuing our traumas and silences with the infinite weight of context—not just the past, present, and future but the what if. Yet if conveying such weight is a maximalist project, Lew’s portraits interest me because they’re deliberately uncluttered.

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Cutting Flowers), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Cutting Flowers), 2023  Jarod Lew, Untitled (Yellow Chairs), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Yellow Chairs), 2023 Still figures are neatly framed between window shutters, an open car door, shadows, light. In the restaurant, plastic tulips take the spotlight next to a Michigan Chinese mainstay, almond boneless chicken. At home, Lew’s now retired father sits in his socks and his old work uniform. One can draw a straight line from the lamp in the background, to the United States Postal Service logo, to the floor vase in the foreground—the symbol of an American institution floating between two objects that could have been acquired by googling “oriental decor.”

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Not so, Lew tells me. He grew up in this house, with that lamp and vase. After coming home from the post office, his father would sit at that ottoman to decompress and chat. Lew has his family reenact everyday rituals, from the trimming of flowers to his mother slipping food to his brother before he drives off. There’s a private intimacy here, from which the photographs also provoke a more public meaning. The lamp, the vase, the logo, the father, the socks—are the relationships among these elements complementary? Contradictory? Depends who’s looking.

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Dad the Mail Carrier), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Dad the Mail Carrier), 2023  Jarod Lew, Untitled (Red Flower), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Red Flower), 2023 Set mid-meal, mid-chat, some of the images also indicate an interruption. The subjects look back, as if aware of our looking. But these, too, are replicated scenes, the usual motion of spontaneity channeled into the stillness of control. To be aware of such control is to question the very connections that you can’t help but make.

“The connection I have for Vincent Chin was through the documentaries that I watched, based on so much pain. I can’t fully embed myself into that,” Lew explains. I question, too, the line that we feel compelled to draw from Chin to more recent incidents of violence toward Asians, from the Atlanta spa shootings, to the assaults on Asian elders, to the Monterey Park and Half Moon Bay shootings, committed by Asian male elders. As though a line would make all this tragedy more meaningful. As though there were such a thing as more meaningful.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Lew’s work resists this pressure: control is also a means to build a protective structure around the living. When posing for the camera, Lew’s mother felt, at first, as though she were playing a character; now she’s happy playing herself. Afterward, Lew shows her the pictures on his camera, a method of instant collaboration that was one of the reasons he switched to digital from his usual film. If these photographs obscure a larger context, they do so as an act of care. I think of Grace Paley’s short story “A Conversation with My Father,” in which a writer tells her dying father different versions of a sad tale, to mixed results. “How long will it be?” he finally asks her. “Tragedy! You too. When will you look it in the face?”

The story ends on that question. But perhaps Lew’s portraits pick up the thread. Look or don’t look, they say. I’ll listen all the same.

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Mom and Jake), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Mom and Jake), 2023  Jarod Lew, Untitled (Family Restaurant), 2023

Jarod Lew, Untitled (Family Restaurant), 2023All photographs from the series In Between You and Your Shadow (2021–ongoing). Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.” Jarod Lew’s photographs are a continuation of his commission for Creating Stories for Tomorrow, a series produced in partnership with FUJIFILM.

July 7, 2023

Madame Yevonde’s Color Revolution

In the early 1910s, while looking through the suffragette newspaper Votes for Women, Yevonde Philone Cumbers came across an advertisement seeking a photography assistant. Her curiosity was piqued: she had been determined to find a career, believing it would aid the women’s movement, and photography was an important tool in creating suffragette propaganda. Soon, Cumbers (or Madame Yevonde, as she was called) was studying under the tutelage of Lallie Charles, at the time Britain’s most commercially successful woman portraitist. In 1914, she set up her own studio in London, in a building shared with the Women’s Institute, thus beginning a photography practice that would span over six decades.

Initially motivated by the women’s movement to pursue photography as a profession, Madame Yevonde became enamored with the craft. The first color photograph was created in 1861, but it didn’t take a foothold until much later in the twentieth century. Thus, while compositionally Madame Yevonde is an adept photographer, it’s her unconventional use of color and fantastical sets with dreamlike, mythological themes in the 1930s that makes her work so distinctive. This summer, the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in London reopened its doors, after three years of renovations and with a new initiative to spotlight women artists, with Yevonde: Life and Colour. The exhibition serves as both a retrospective of Madame Yevonde’s work and a broader exploration of the origins of fine art color photography.

Madame Yevonde, Self-Portrait with Vivex One-shot Camera, 1937

Madame Yevonde, Self-Portrait with Vivex One-shot Camera, 1937  Madame Yevonde, Margaret Sweeny (Whigham, later Duchess of Argyll), 1938

Madame Yevonde, Margaret Sweeny (Whigham, later Duchess of Argyll), 1938  Madame Yevonde, Dorothy Gisborne as Psyche, 1935

Madame Yevonde, Dorothy Gisborne as Psyche, 1935 Color photography was “vilely expensive” and “very complicated,” Madame Yevonde wrote in her 1940 autobiography, In Camera. Nonetheless, she became a pioneer of the Vivex process, a trichrome-printing technique developed in the late 1920s that required three color-pigment sheets, eighty steps, and twelve hours to complete. Soon after, in 1935, Kodachrome hit the market, making color photography much more accessible. This development prompted Madame Yevonde to push against the tedium of infinite blacks, grays, and whites. “‘Be original or die’ would be a good motto for photographers to adopt,” she said in an address to the Royal Photographic Society in 1936. “Let them put life and color into their work.”

Many photographers of that era held a disparaging view of color, considering it unartistic and relegating it to the realm of advertising. “It didn’t provide the lovely rich blacks and the chalky whites that artistic photography could,” says the NPG’s associate curator of photographs Clare Freestone, who organized the exhibition. William Eggleston, a proponent of color photography whose 1976 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York helped permanently shift color into the photography world, said that Henri Cartier-Bresson once dismissively told him that “color is bullshit.” (Cartier-Bresson himself did shoot in color, albeit rarely.) Madame Yevonde wasn’t deterred by the negative perceptions and forged ahead with Vivex prints. The resulting work is so vividly hued that it’s hard to believe it was made almost a century ago.

Despite the successes in her time, Madame Yevonde’s pioneering work has been overshadowed in history by her male compatriots—as is often the case for many women artists.

The exhibition will undoubtedly serve as an introduction to Madame Yevonde’s work for most visitors, but she wasn’t unknown during her time. In 1932, she had her first solo exhibition at the Albany Gallery in Mayfair, London, which was met with warm reception. Five years later, MoMA included two of her images in a photography survey: color pictures documenting the construction and interior decoration of the ocean liner RMS Queen Mary. The composition of one of these works, RMS Queen Mary, Funnel (1936), is strikingly modernist, with geometric lines and forms reminiscent of Alfred Stieglitz’s The Steerage (1907)—if The Steerage were richly saturated with shades of red.

Madamde Yevonde, RMS Queen Mary, Funnel, 1936

Madamde Yevonde, RMS Queen Mary, Funnel, 1936  Madame Yevonde, Mask (Rosemary Chance), 1938

Madame Yevonde, Mask (Rosemary Chance), 1938Some of the most striking images on view at the NPG hail from Madame Yevonde’s series Goddesses (1935), in which she portrays society women as figures from classical mythology. One portrait features Lady Campbell as Niobe—who, as the legend goes, wept for the deaths of her fourteen children at the cruel hands of Apollo and Artemis. Foregoing the elaborate sets she created for some of her other “goddesses,” Madame Yevonde photographed her sitter so closely that the entirety of her face isn’t in frame, just the pearlescent tears streaming down her cheeks, her agony palpable.

Madame Yevonde, Lady Dorothy (‘Dolly’) Campbell as Niobe, 1935

Madame Yevonde, Lady Dorothy (‘Dolly’) Campbell as Niobe, 1935A particularly fascinating image in the exhibition is a portrait of the actor Joan Maude, photographed in color and later inverted into a negative image, in which Maude’s skin is rendered a shimmering cobalt blue and her hair a blinding white. “She was experimenting still,” says Freestone, who chose to present the inverted print as well as separation negatives and solarizations to demonstrate the breadth of Madame Yevonde’s work. These brilliantly-hued experimentations are the stars of the show: her black-and-white imagery, taken after the war when color film was less available, misses some of the magic that those Vivex prints hold.

Madame Yevonde, Joan Maude, 1940s

Madame Yevonde, Joan Maude, 1940s All photographs © and courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Despite the successes in her time, Madame Yevonde’s pioneering work has been overshadowed in history by her male compatriots—as is often the case for many women artists. The auction and museum worlds have historically played a part in diminishing the contributions of women artists: a 2019 study showed that between 2008 and 2018, women artists accounted for only 11 percent of major museum acquisitions in the United States, and even fewer have received exhibitions dedicated solely to their work.

Yevonde: Life and Colour seems to signal a shifting tide. After acquiring her negatives in 2021, the National Portrait Gallery pulled Madame Yevonde’s existing prints from its archive, where they have mostly laid dormant since the artist herself donated them in 1971, and dedicated a show to her. It’s a clear response to a growing desire among audiences to see more historically underrecognized artists, and with this ethos, the National Portrait Gallery has reopened with a bang—and, as Madame Yevonde put it, a “riot of color.”

Yevonde: Life and Colour is on view at the National Portrait Gallery, London, through October 15, 2023.

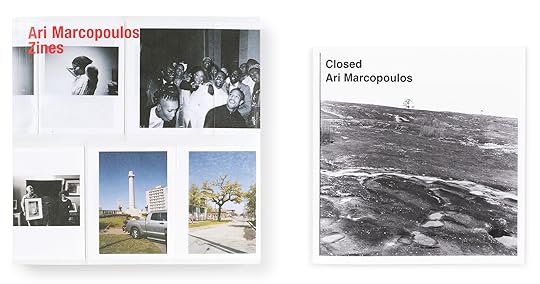

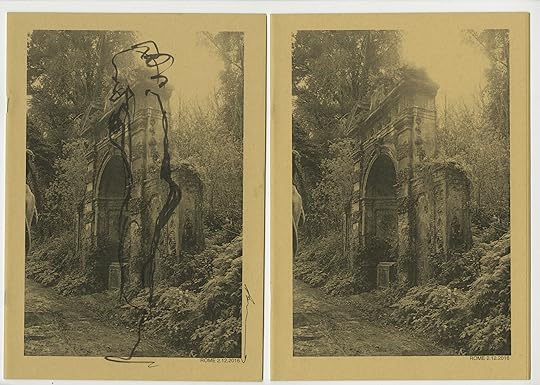

Ari Marcopoulos on the Essential Art of Zines

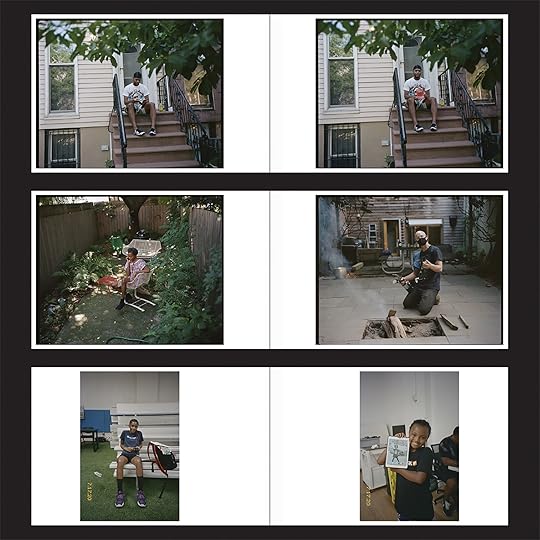

Ari Marcopoulos is an inveterate maker of zines. Often self-published or created in collaboration with independent publishers, his DIY-aesthetic creations function as sketchbooks, diaries, installation spaces, and means of processing daily life. Marcopoulos’s latest volume, Zines, is the first overview of his publications. Beginning in 2015 and presented chronologically by year, the book features key zines—including previously unpublished works and some made during the pandemic, when Marcopoulos worked primarily on the screen to make PDF zines. Marcopoulos recently spoke with Hamza Walker about the role of zines as an essential part of his artistic practice.

Hamza Walker: Could you speak about the difference between the printed zine and the PDFs? What’s their relationship? Don’t the PDFs go through the same process of making them, whether they’re printed or not?

Ari Marcopoulos: Yes. The PDFs really started because of thinking about the vertical or landscape book. Usually when you make a zine, you have an 8.5-by-11-inch paper, and you fold it in half, and then you have 8.5-by-5.5-inch. It’s a vertical format. I wanted to work against that. I started by creating the container for the images, and that container was a 9-by-11-inch landscape format, sideways. So, I made a PDF, which I thought I could print myself, but the 9-by-11-inch format was too big to print at home. And the copy shops were all closed. After I made the first one on my computer, which was too big to print, I was like, Okay, so, what do I do with it now? I decided to email it to a few friends, because everything had ended once the pandemic began. You weren’t seeing other people anymore. I figured, Well, instead of writing a letter, why don’t I just send them these images, this PDF that I put together? I got really beautiful responses. I sent some to Pierre Huyghe, who had moved to Chile. He had been living in Brooklyn, and they moved right before the pandemic, he and his wife and child. He replied, “Oh, I really miss Brooklyn. Thank you for sending this. It makes me think about my walks in town.” Actually, a lot of the zines featured in this book are made as a gift, like the ones I sent to Pierre. Usually, it’s people around the neighborhood that I photograph, like at the barber shop, or my neighbors, and then I give them a print. One weekend, there were two men that I didn’t recognize sitting on the steps down the street, but they looked related.

My neighbor Gary had told me it was his brother’s birthday party. I asked, “Are you guys here for the birthday party?” And they said yeah. I asked, “Do you mind if I take your picture? I’m a friend of Gary’s.” And they’re like, Yeah, take our picture. I took it, and then went on my way. When I came back, there was a third guy, so I stopped again and said, Oh, there’s another person, I should take another picture. All through the weekend, as I passed by, there were different people, different characters. I photographed them whenever I saw someone different. When I got the film back, I looked at the faces, and there were fourteen different people. So, I put together a zine. I printed something like twenty copies, and slipped fourteen of them into the mailbox for Gary. When I went to the barbershop next to get my hair cut—this is pre-pandemic—they said, “Gary brought in the book that you made for him.” He had brought it in to show to them. Now all the guys, when I see them, they’re like, Oh, you made that book for us! That exchange is part of my practice.

Walker: Which is a very beautiful ethos, to think of the relationship to the sitter, however casual. The sitter as recipient—the sitter as the audience for the work. It completes a full circuit. If you take the picture and put it on the wall of a gallery, it’s a very different means of distribution or circulation.

Marcopoulos: You make the work, you have your ideas about it, and it can live like that, but it’s really only finished if it’s circulating outside of yourself and there’s a viewer involved. Because the viewer finishes the work. Just recently, I bumped into Gary, and I hadn’t seen him for a while. I said hi to him, and I took his photograph, because whenever I bump into him, I take his photograph. Then he told me, “Oh, I have to go to the funeral of my brother.” I said, “Oh, your brother? I’m sorry. I’m glad I took his picture.” And he says, “Yeah, I am too.” Every relative that was on the stoop that day has a copy of that zine.

I always believe that the images that I work with are shared experiences, where the viewer might recognize something in their own life.

Walker: It’s a zine, but …

Marcopoulos: It is a book. And it can be a very beautiful book.

Walker: The nature in which a zine is a book, in terms of how it is handled and its reception and how it is held, formally, is interesting. Photography’s always had this promise of being able to make multiple prints and then distribute them. It seems like you’re fulfilling that process through the zine rather than the print itself. You could give somebody a photographic print, which perhaps goes in an album or could be framed and put on a wall. But that’s something different. The book or a zine is cinematic, is in sequence. It’s another kind of intimacy. The wall is public, the book is private.

Marcopoulos: Oh, it’s definitely a private experience. A book is basically just held at arm’s length. It’s why I often believe some books are too big. To have a photobook that holds and reads like a novel is really quite intimate, you know? Of course, I do exhibitions. I put things on the wall—large things on the wall. Although most of the installations that I’ve done in the last ten years or so have been often lots of photographs, quite small and also sequenced quite tightly together. But it’s still very different. When you have a sequence of photographs on the wall, you have an overview right away. With a book, you can look at it backwards, start in the middle, anywhere. But still, you’re always dealing with the page—where the page is open, that’s what you’re dealing with.

Walker: Right, one spread at a time.

Marcopoulos: And to share it with someone, you actually have to sit quite close together. So often in photography, one thinks about the single image. I started to think more cinematically, about how a sequence of images becomes a more layered way of looking at something.

Walker: I guess the bigger question is, how much does the zine structure inform your photographic output? In other words, when you work and you’re taking pictures, are zines the logical destination for your work?

Marcopoulos: I believe that any image I make can potentially end up in a zine. There are certain images in this book which might not have ever made it into print otherwise. The content might be a bit more personal, but I always believe that the images that I work with are shared experiences, where the viewer might recognize something in their own life. And then maybe, in the zines, there are things that might shed new light on something that is very particular. I have very particular interests that weave through. For forty years, these things come back through the work. When am I going to stop photographing ’70s muscle cars? Probably never. Or when am I going to stop photographing trees? When am I going to stop photographing people? Those are my recurring themes. And then there’s also the struggle to get away from that. Opening up new roads for yourself. I’m just saying, Look, here. Not because every photograph I’ve published is a masterwork. They’re just things that I saw.

Walker: I like what you were saying about how your interests are woven throughout. At any given instant, a muscle car could appear. You’re always making pictures. That’s a given. So, you wouldn’t make a zine of ’70s muscle cars. But they will recur.

Marcopoulos: I would have to go through my archive and look for every muscle car picture and then start putting them all in a row. That’s just not how I work. The way I work is more about, if I go for a walk today, am I going to see a muscle car? Possibly not. Now, what I might do is maybe I would go now and photograph the car and I would make a zine of that. There’s a zine in the book called September/October/November, and it’s just pictures I took in that period of time. And it happens to be that in those months, I went to Paris and to Beirut. And I was in New York in between. I don’t take a lot of pictures every day, so all of those cities might be on one roll. That is kind of how zines are. I don’t very often work chronologically. But the zines are marked by a start date and an end date. I started using a camera that has a date stamp that you see in a lot of these photos.

Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (“Closed” zine/launch edition) 65.00

Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (“Closed” zine/launch edition) 65.00 $65.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (“Closed” zine/launch edition)Photographs by Ari Marcopoulos. Text by Maggie Nelson. Interviewer Hamza Walker.

$ 65.00 –1+$65.00Add to cart

View cart DescriptionTo celebrate the launch of Ari Marcopoulos: Zines, the first 250 copies ordered will include a limited edition zine.

Ari Marcopoulos is an inveterate maker of zines. This project collects in one volume for the first time a selection of zines by Marcopoulos, many never before released, providing a unique insight and overview into an essential part of this influential artist’s daily practice. Often self-published or created in collaboration with boutique and independent publishers like ROMA, Dashwood Books, and PPP Editions, these informal, DIY-aesthetic creations function as sketchbook, diary, installation space, and a means of processing Marcopoulos’s daily practice of photographing his life, his family, his neighborhood, and the rarified cultural milieu in which he operates.

This collection showcases an impressive array of printed zines, exploring each as an artistic object through an engaging layout. Beginning in 2015 and presented chronologically per year, key zines are featured—including some made during the pandemic, when Marcopoulos worked primarily on the screen, making PDF zines—and punctuated by individual images presented full scale. An interview with Hamza Walker underscores the role of zines as an essential part of Marcopoulos’s artistic practice, emphasizing the personal, diaristic element within the work, while an essay from Maggie Nelson meditates on the work’s position within a wider social and cultural context. Ari Marcopoulos: Zines is a must-have for anyone interested in this prolific artist’s personal practice and zine culture.

This publication was made possible, in part, by the generous support of Gucci. Additional support for the publication was made possible by Philip and Shelley Aarons; Galerie Frank Elbaz, and Supreme.

Details

Format: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 336

Number of images: 385

Publication date: 2023-06-13

Measurements: 8.7 x 8.7 x 1.25 inches

ISBN: 9781683952558

Ari Marcopoulos (born in Amsterdam, 1957) is a photographer and filmmaker known for documenting the American subculture scenes of skateboarding and hip-hop. In 1980, he emigrated from the Netherlands to the US, settling in New York and working as an assistant to Andy Warhol. Marcopoulos is a prolific author and creator of photobooks, zines, and other printed matter, such as posters. In 2020, Polaroids 92–95 (CA) and Polaroids 92–95 (NY) were published. He has shown his work in solo exhibitions at Foam, Amsterdam; Berkeley Art Museum, California; and MoMA PS1, New York, and his work has been included twice in the Whitney Biennial.

Maggie Nelson is the author of the national bestseller On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (2021), the National Book Critics Circle Award winner The Argonauts (2015), The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (2011), Bluets (2009), and Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (2007). She writes frequently on art, and in 2016 received a MacArthur “genius” Fellowship. She currently teaches at the University of Southern California and lives in Los Angeles.

Hamza Walker is the director of LAXART, an independent nonprofit art space in Los Angeles. Previously, he served as the director of education and associate curator at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago.

Walker: What’s beautiful is that the few thematic zines that are very discrete do not feel anomalous. They feel like, Oh, yeah, it’s a possibility. But they’re not the drive. I like that you brought up the issue of the personal. It’s personal but it’s not personal. There needs to be something to which the viewer can relate. The viewer can relate to a picture, not necessarily because of what it discloses, but because of their own experiences. There are also some individuals in the photographs that are recurring. And those pictures come out of friendship and love.

I’m also curious about the role of Robert Frank and June Leaf, for you. Could you talk a little bit, maybe, about that relationship and those pictures?

Marcopoulos: I met Robert a long time ago, but I always felt that going up to ring the doorbell or hanging out wasn’t something I could do, because he’s this icon, of course. But one day a friend of mine went over to drop a sandwich off for them. And said, “Come with me.” And I said, “No, it’s okay. I’m not coming.” He said, “No, Robert knows you.” That was in 2018 or something.

Walker: So, you struck up a friendship with Robert Frank rather late.

Marcopoulos: Well, I’d met him before, but didn’t really hang out. I went to his opening at the National Gallery in Washington, but the reconnection happened much later. I took a picture of June’s arm and showed it to her. She loved it. And then Kara came up, and June said she admired Kara’s work. And so I told Kara, “Come by and meet June and Robert.” And Kara was a little bit [sighs] “Okay.” But June and Kara hit it off pretty well, as you can imagine. Both are unique, out-there thinkers. So, we started seeing them more often. We had a ritual that we would go every Sunday evening and we would have dinner. Sometimes I’d talk to Robert about photography, but more about his life. His memory was somewhat fading. I would ask him questions about his youth. He would tell me some good stories. Robert and I both moved to New York around the same age. That was something that we had in common that we sometimes talked about, leaving the comfort of a country where you know everything, to a place where you’re new and that is distinctly more exciting than where you came from [laughs]. New York City, you know.

Walker: When you first came to New York, you spent two years printing for Andy Warhol. How did you get that job?

Marcopoulos: I moved to New York in 1980. I thought that in order to make money with photography you had to be a fashion photographer. I had to find a job as an assistant or something. I did some freelance assisting, but the first job I landed was printing 8-by- 10-inch photographs for Warhol, black-and-white prints. I worked in a darkroom off-site, not at the Factory. I printed, on average, seventy 8-by-10-inch pictures a day, 350 prints a week of his pictures. He was incessantly taking pictures. He would mark the contact sheets, and I would print those. Thousands of them. I did that for almost two years. I saw all the pictures that he took. I saw all that he saw when he was traveling. I would see pictures of Joseph Beuys, of Berlin, of Beijing, of whatever. Wherever the fuck he went, I saw pictures of it. You know, he would go to some rich person’s house and he would photograph the table with the family photos on there. It was like a diary. He just photographed everything. He loved celebrities and got to hang with them. Signs, people, people’s houses. Before I moved to New York, I had worked at a camera store, where people would bring their film to be developed. So, I also had the experience of seeing everybody’s pictures from the town I grew up in every morning when they came in. And that was kind of like Warhol’s pictures. I saw all the pictures.

Walker: What influence do you think that had on you?

Marcopoulos: Andy Warhol had an influence on me even before that, via his films and his artwork. But yes, working and printing Warhol’s pictures had a profound influence on me, although my camera shop job was maybe equally profound. I learned that everything is worth photographing. I learned that you should never say, Why would I take a picture of this? After I stopped working for Warhol, I worked for Irving Penn for two years. Then, I worked for the most restricted, anal-retentive photographer that you can imagine. Everything was controlled.

There’s no spontaneity in Irving Penn’s photographs. It was very technical. The influence of working with Penn was that I started to understand how light works, what you can do with light—what you can do with artificial light, but also what you can do with daylight. I started understanding how composition can emphasize a shape or can steer the eye. When I look at my work, I can see that even when I take a quick image of something, I’ve placed myself so that the subject stands out; it’s well delineated. It’s not blending into the background. But it’s all very intuitive.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Walker: But with Warhol, it wasn’t just the experience of printing his photos that impacted you, right? It was an entrée to the art world.

Marcopoulos: Oh yeah. It plugged me in. Warhol’s painting assistant became one of my best friends. He and I would go see all these rap and hip-hop shows that started coming downtown. I knew I wanted to do something. I wanted to also make work. I just started taking pictures in the street, walking around. I started taking portraits of artists, because I had a certain amount of access. I photographed Andy. I photographed Richard Serra. You know, different artists from that time. Ashley Bickerton. And the way I photographed them is very casual. I was working Monday to Friday, nine to six, you know? Every day. But I found time to go take these pictures. At that time, you had people like Annie Leibovitz putting Whoopi Goldberg in a bath of milk and I was like, What the fuck? That’s the photography you would see in the magazines, so that’s how you start to think you have to shoot to make money, because for sure, I wasn’t going to make money in the art world with my prints on the wall.

But I could never do that. I would go meet Poor Righteous Teachers to take a picture, and I just took them just standing in the street somewhere. When I got the pictures back, I always thought, God, these are so boring. But now when I look at them, I think, Wow, these pictures are incredible because it’s just them and me, and we’re not trying to be anything other than that. I’m not lying on my knees. I’m not climbing on a ladder. My camera is up in my eye, and I click the shutter, and that’s it. And that’s the picture.

All photographs from Ari Marcopoulos: Zines(Aperture, 2023)

All photographs from Ari Marcopoulos: Zines(Aperture, 2023)Courtesy the artist

Walker: You have a healthy bibliography of traditional, offset books, but obviously it doesn’t compare to zines. How do you think people know your work, primarily? Is there a singular way that people get to know the work? What place do the zines hold in getting your work out in the world?

Marcopoulos: The zines have been a huge aspect of getting it out into the world. The funny thing about zines is that when you make 150 zines with Nieves—Nieves might sell ten, five, eight copies to a bookstore in Berlin; a bookstore in Frankfurt, in Amsterdam, in London, in Tokyo, in Rio, in LA. So maybe five people in Berlin have this Nieves zine. But because there’s only five people that have it, they go to their friends and say, Check it out, I got this Ari Marcopoulos zine. And they go, Oh yeah. I think that’s how people have come to know me.

Walker: So are zines an integral aspect of your identity as a photographer?

Marcopoulos: Oh, yeah. I think they are, for sure.

Walker: I like that you’re making a distinction between the five people in Berlin who bought the zine, who are different than the five people who buy your book, don’t you think?

Marcopoulos: Yeah. Well, yeah, for sure. Because I think the zine is cheaper, one, and they’re also—

Walker: It’s more accessible, but at the same time, rarer.

Marcopoulos: Yeah. You have to be a bit more of a connoisseur, in a weird way. You’ve got to want to chase down all the zines; and you gotta be on top of it. You’ve got to have your finger on the pulse to know that it’s coming, and that you’re getting it.

Walker: So that appeals to you, in terms of the notion of the zine being more for the fans only.

Marcopoulos: The fact that it’s rarefied doesn’t really appeal to me. What appeals to me mostly is that the zine will find its way into the hands of somebody that will never buy a book. Maybe because it’s too expensive, or maybe because they’re really not into books.

But what happened, I think, through zines—and not just my own—is that some kids became book collectors. It’s like how the Printed Matter Art Book Fair has become like the hippest thing to go to for kids? I’m like, who are all these people? [laughs] I worked at the table at Roma Publications, because the publisher, Roger, is my friend, and people come up to the table, and they talk to you, and while they talk to you, they flip through a book, and they don’t even look up. It’s like a scene. It’s like a club. They have the whole zine section. When I go there, people come up to me and say, I want you to have my zine, my book, my records, my this, my that.

Walker: And that’s very nice in terms of the ethos of distribution, accessibility, and sharing.

Marcopoulos: A zine you can give away very easily. You make it, you give it.

This interview is an excerpt from Ari Marcopoulos: Zines (Aperture, 2023).

July 6, 2023

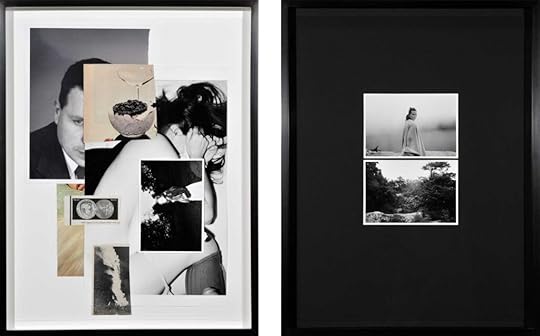

The Photographers Who Captured Love and Longing

The logical way into Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy, at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York, is to turn right at the doors from the building’s dramatic stairwell (left from the elevator) and wind your way counterclockwise through the space. Thematically, the exhibition moves around Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1973–86) and the pairing of Nobuyoshi Araki’s Sentimental Journey (1971) and Winter Journey (1989–90), which are judiciously placed at even intervals within the sequence of works by twelve artists on ICP’s second floor (an additional four bodies of work are arranged on the third). Turn the other way, however, and you’ll find yourself in the middle of the messy set of relationships that constitute the setup of Leigh Ledare’s incredible Double Bind (2010).

Leigh Ledare, Diptych from the series Double Bind, 2010

Leigh Ledare, Diptych from the series Double Bind, 2010Courtesy the artist

Five years after Ledare and his wife Meghan divorced, he asked her to accompany him to a remote cabin in upstate New York, where he wanted to photograph her over the course of four days. Meghan agreed, but in the time between Ledare’s invitation and their departure, she remarried. To complicate things further, her new husband is also a photographer, Adam Fedderly. Still, Ledare and Meghan stuck to their itinerary. They traveled together but slept in separate beds. Ledare took five hundred pictures of Meghan smiling, glowering, strutting through morning shadows and wildflowers. Then he arranged for Meghan and Fedderly to repeat the trip two months later, going to the same cabin for the same duration and taking the same number of pictures, returning them to Ledare as unprocessed rolls of film.

Double Bind takes shape as a room-size installation. The images by Ledare are placed on black backgrounds; the images by Fedderly are placed on white backgrounds. Smaller prints are stacked in a glass vitrine. The installation features beguiling collages, another vitrine filled with pictures cut from magazines, and a framed piece of paper on which the artist has scrawled the “conceptual script” of the piece. Does Meghan Ledare-Fedderly appear happier, more hopeful, more seductive in one set of images? Is she angry, resentful, rueful in the other? Where does her love run deepest? The genius of Ledare’s installation is that he scrambles expectations and gives no easy answers. Intimacy is, above all, complicated.

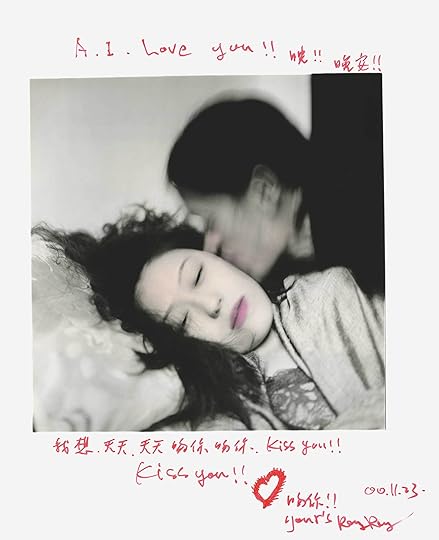

Rong Rong&inri, from Personal Letters, 2000

Rong Rong&inri, from Personal Letters, 2000Courtesy the artists

Love Songs has arrived at ICP from Paris, where it was originally organized by Simon Baker and exhibited last summer at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) under the title Love Songs: Photographies de l’intime. Goldin’s Ballad, presented here as a series of nine prints rather than a slideshow, as originally shown, captures a wholly interior world thick with lust, loss, and longing. Atmospheric and diaristic, Goldin’s images are as much about the intensity of friendships as a bulwark against trauma as they are about sex or drugs. By contrast, the two series by Araki delve into the photographer’s marriage to Yoko Aoki—from their wedding and honeymoon in 1971 to her illness and death in 1990—and follow a narrative line that is tender, episodic, and tragic, with none (or little) of the abjection and domination that make much of Araki’s other work so dubious today.

Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971

Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Journey, 1971Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery

The series by Goldin and Araki are landmarks in the late twentieth-century history of photography. With an emotional rawness that was unprecedented in their day, they turn the outward gaze of traditional documentary photography inside out. Their influence reverberates throughout the New York iteration of Love Songs, particularly in projects such as Fouad Elkoury’s On War and Love (2006), a literal diary about a relationship falling apart against a backdrop of Beirut being bombed and besieged; Ergin Çavuşoğlu’s Silent Glide (2008), a highly scripted three-screen video installation about lovers calling it quits amid the industrial devastation of an old Ottoman town east of Istanbul; Collier Schorr’s extended rumination on gendered looking, titled Angel Z (2020–21); and the delicate structure of annotation and exchange defining RongRong & inri’s Personal Letters (2000).

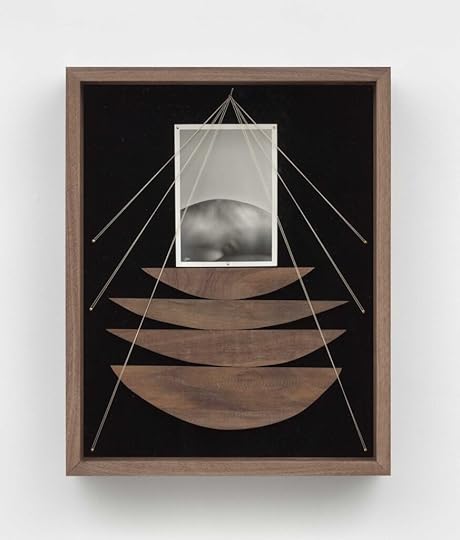

Sheree Hovsepian, Euclidean space, 2022

Sheree Hovsepian, Euclidean space, 2022Courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery

Love Songs has undergone a radical transformation in the move to New York. The ICP iteration, organized by the perspicacious and resourceful independent curator Sara Raza, has dispensed with the works of Emmet Gowin, Hideka Tonomura, and Larry Clark, whose grittiness is excessive in combination with Goldin and Araki. Gone, too, is the pretense of using intimacy to reconfigure the history of photography. Instead, Love Songs offers a subtler, more expansive take on how photography can be used to create, sustain, and destroy intimacy in its many forms.

Love isn’t synonymous with intimacy. Each can exist without the other, and intimacy is just as often fraught, messy, and conflicted.

Raza’s additions are stellar. Of the sixteen artists who span seven decades and three continents, five are completely new to the show. Raza splices old and new together. The flirtatiousness of René Groebli’s high-contrast black-and-white photographs of his wife on their Parisian honeymoon creates a fascinating dialogue with the blended-family chaos in Motoyuki Daifu’s Lovesody (2008), chronicling the photographer’s infatuation with a single mother about to give birth to her second child, and the explosion of laundry, dishes, trash, breast milk, and snot that follows.

Karla Hiraldo Voleau, from the series Another Love Story, 2022

Karla Hiraldo Voleau, from the series Another Love Story, 2022© the artist

Karla Hiraldo Voleau’s immersive account of her discovery of a lover’s double lives and infidelities (Another Love Story, 2022) is expertly installed, replete with a maze of hanging ribbons and flowers, and utterly engrossing. Sheree Hovsepian’s mesmeric constructions made from ceramics, nails, string, photograms, and wood combined with images of her sister’s body add a necessary element of abstraction to the show.

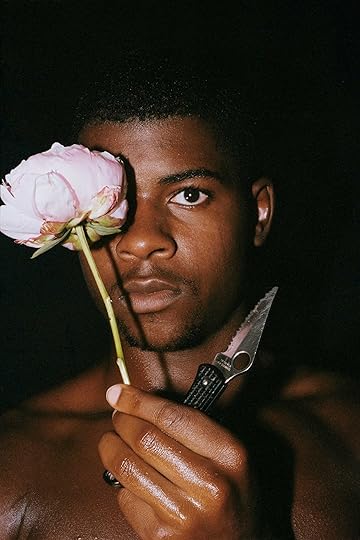

The real highlight of the exhibition, however, is the lush and dramatic portraiture of Clifford Prince King, whose work is featured on the cover of the catalog and best embodies the idea of intimacy as a form of complexity. In Conditions (2018), a young man’s face is half hidden by the bloom of a pink peony and a paring knife. In Poster Boys (2019), two sets of Black men’s limbs, a tangle of soft feet and denim, stretch beneath a benevolent portrait of Martin Luther King Jr., tilted just so. It’s an image that pulls together all the exhibition’s strands of atmosphere, narrative, and entanglement, and adds threads of glinting beauty and vulnerability.

Clifford Prince King, Conditions, 2018

Clifford Prince King, Conditions, 2018Courtesy STARS, Los Angeles

King’s portraits, like Ledare’s installation, create a compelling framework for Love Songs based on knots and entanglements rather than strict binaries. In his text for the new Love Songs catalog, David E. Little, ICP’s executive director since 2021, asks whether pictures of love aren’t a greater, more complex challenge than those showing conflict and struggle. But love isn’t synonymous with intimacy. Each can exist without the other, and intimacy is just as often fraught, messy, and conflicted. Love and war partake of the same tools. Photography is one of them.

Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through September 11, 2023.

5 New and Notable Photobooks

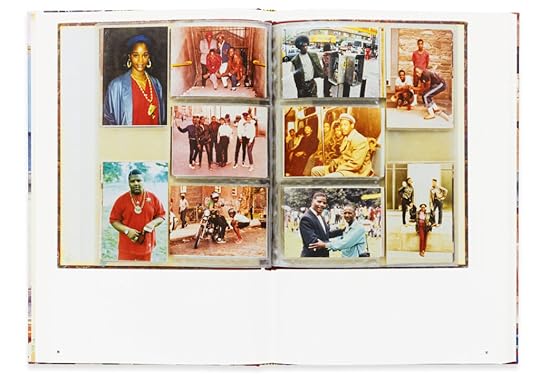

Spread from Jamel Shabazz: Albums (Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, 2022)

Spread from Jamel Shabazz: Albums (Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, 2022)Jamel Shabazz

If you want to understand the look of life on the streets of New York City in the 1980s, turn to Jamel Shabazz and his singular record of Black joy and sartorial flair. After a stint in the US Army, stationed in Germany, Shabazz returned to his home of New York. He worked on Wards Island and as a corrections officer on Rikers Island, the city’s notorious jail, at the height of the crack epidemic and the “war on drugs,” which devastated communities of color. On the weekends, he traversed the city, making portraits of individuals and collective portraits of friends and families in collaboratively choreographed poses. In an era of take-and-run street photography, Shabazz worked slowly. He spoke with people. “When I look at you, I see greatness,” he’d say when approaching a potential subject. “If you don’t mind, I’d like to take a photograph of you and your crew.” The sidewalks and subway platforms of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx were his studio.

The long-anticipated book Jamel Shabazz: Albums (Steidl and the Gordon Parks Foundation, 2022; 320 pages, $50) is not simply a record of how he archived his prints. Rather, it is a journey into his process. When he photographed, he carried an album of photographs, to earn the trust of those he wanted to picture by showing them the style, generosity, and care he brought to making a portrait. This smartly designed book reproduces these albums—conduits of human connection—at scale, in facsimile form, in their original arrangements. Spread by spread, we see couples embracing on graffiti-covered subway cars, friends posing in Kangol hats and fresh Cazal eyewear, loving fathers and mothers, children pausing from play to strike a pose. The cumulative effect is something between a yearbook, a lookbook, and a family album—it is a reminder that no one transmits the vitality of Black life and community in New York quite like Jamel Shabazz. —Michael Famighetti

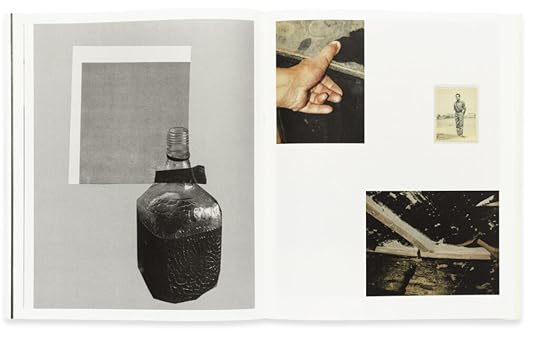

Spread from Bharat Sikka, The Sapper (Fw:Books, 2022)

Spread from Bharat Sikka, The Sapper (Fw:Books, 2022) Bharat Sikka

Bharat Sikka’s long-term project about his father in The Sapper (Fw:Books, 2022; 192 pages, €40) is composed of fragments: a still life of his father’s tools glinting in the sun; a portrait of his desk left unattended. Other images depict the impression of the elastic of his socks on his calves and shins, the constellation of age spots on his back. These oblique but telling observations leaven a series of studies of his father’s face, of his figure in the landscape or caught up close in the burst of an off-camera flash. In The Sapper, Sikka’s approach to portraiture resonates with The Great Unreal (Patrick Frey, 2015), the Swiss photographers Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs’s American road-trip book.

Sikka was born in New Delhi and studied photography at Parsons School of Design in New York. He has frequently focused on the subject of masculinity, and his intervention with the artifacts of his father’s career as a member of the Indian Army Corps of Engineers pays tribute to a man’s life outside of traditional familial roles—in the book’s evocative presentation of sharply observed elements there is a puzzle to be worked out. His construction and deconstruction of photographs as a means of teasing answers out of these otherwise mute details is effectively underwritten by the book’s deft pairing and sequencing of images—patterns emerge and subside, only to return again. We remember, or think we do, but each moment of recall has been slightly altered from the last.

One segment in particular—an eight-page suite of full-bleed, black-and-white images reproduced to emulate cheap, Xerox-style copies—creates an enigmatic rupture in the otherwise gentle flow of images, confirming that something has been knocked asunder. An easy summation of Sikka’s subject of consideration lies tantalizingly just beyond reach. Instead, The Sapper offers an affecting negotiation of meaning and understanding of a father by his son, and a bittersweet confirmation of the fragility of memory. —Lesley A. Martin

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

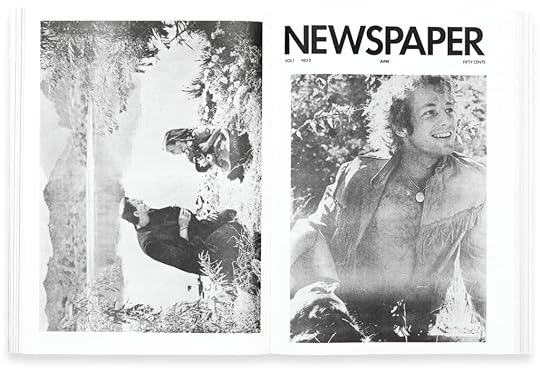

Spread from Steve Lawrence, Peter Hujar, Andrew Ullrick, Newspaper (Primary Information, 2023)

Spread from Steve Lawrence, Peter Hujar, Andrew Ullrick, Newspaper (Primary Information, 2023) Newspaper

In 1968, Peter Hujar, Steve Lawrence, and Andrew Ullrick began printing and distributing Newspaper, a short-form, image-only, black-and-white newsprint publication. Over its brief three-year lifespan, Newspaper compiled a star-studded list of contributors—Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and Andy Warhol, among many others—and provided a platform for artists to exhibit different kinds of work from what was shown at galleries at the time. Unfortunately, scholarship about and recognition of Newspaper has been limited; the ephemeral nature of newsprint (which resists archiving) and the original publication’s limited distribution and print run meant that after its end in 1971 it quickly faded into obscurity.

More than fifty years later, the Brooklyn-based publisher Primary Information has compiled the complete fourteen-issue set of Newspaper for the first time. While, for practical considerations, Primary Information’s publication doesn’t replicate the original’s format and material, the issues are presented in their entirety, giving light to the boundary-pushing publication that Hujar, Lawrence, and Ullrick smartly edited. The content of Newspaper (Primary Information, 2023; 416 pages, $40), edited by Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez, is kaleidoscopic. The book forces the reader to consider connections between and create meaning across multiple visual registers. Photographs, drawings, collages, imagery from high and low culture—all chaotically coexist within the pages. The effect is befuddling, cerebral, and provocative. Reproduced in Primary Information’s volume, the content of Newspaper can at times feel dense and indecipherable.

However, once primed to imagine the work within its earlier form and context, one can sense the underlying dynamism between the riotous arrangement of imagery, the casual and disposable form of the original tabloid, and the larger ecosystem of artist publications and queer periodicals of the late 1960s and early ’70s. In his preface to a detailed timeline of Newspaper’s history included in the back of the book, Yáñez clearly states his intentions: “to make the periodical accessible as a document. My hope is that by doing so, further information and scholarship about Steve Lawrence and Newspaper will arise.” —Noa Lin

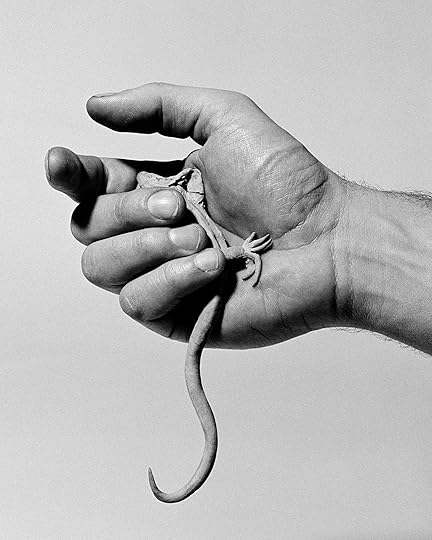

Giulia Parlato, Lizard, 2019

Giulia Parlato, Lizard, 2019  Giulia Parlato, Gap, 2020

Giulia Parlato, Gap, 2020 Giulia Parlato

Giulia Parlato is drawn to false accounts and fictional retellings, to the tension between museums and cultural objects—particularly how each endows the other with historical meaning. The Italian photographer conceived of her debut photobook, Diachronicles (Witty Books, 2023; 120 pages, €35), while researching forgeries and counterfeits at the Warburg Institute in London, and she argues that this meaning is first and foremost a construct, unstable and often the result of numerous interventions. Photographs play a split role in this equation, sometimes as displayed object and other times as document. For Parlato, they also offer a clever form of investigation and play as she appropriates the visual language of archaeological excavations, forensics, dioramas, and museum archives and displays to stage her own constructions, which are somewhere between evidence and fiction. Parlato’s photographs—which she made between her London studio, Sicily, and several European museums—appear stark and direct, almost instructional. A gap in the painted ceiling of an eighteenth-century palace in Palermo reveals innards of wood, stone, and rubber piping. Gloved hands confer archaeological meaning to an object concealed in tarp, seemingly exhumed from a dig. “Indeed, it is almost as if the more straightforward the imagery seems, the less straightforward it really is,” writes David Campany in his introduction. A curious reader might equally wonder whether the lack of context, and the book’s rather austere layout, limits its overall effect. One must invariably work backward and reconstruct the story; must look, and look again. By developing fictional histories from fragments and fakes, Diachronicles is both about what is said and what is withheld, positioning the photographer as both chronicler and unreliable narrator. —Varun Nayar

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Spread from Roe Ethridge, American Polychronic (MACK, 2022)

Spread from Roe Ethridge, American Polychronic (MACK, 2022) Roe Ethridge

A refrigerator, a black eye, a tennis player, a highway. Chloë Sevigny, Willem Dafoe, Weebleville, and then—wait, an ad? For Hermès? Oh, this is a Roe Ethridge book! Ethridge being the American photographer who has unlocked that little velvet rope between art and commerce to delirious and delightful effect, who has compiled four hundred “and something” images into a massive book, American Polychronic (MACK, 2022; 480 pages, $70), “some of which were for art exhibitions and some which were made for magazines and advertising,” as he notes in an addendum. “A healthy portion are both and a lesser portion neither.” So, anything goes, from a babe in a bikini to Telfar Clemens naked on a sofa to a screenshot of a conversation about a twenty-year-old Lexus. It all feels like a decadent European magazine (there’s even a French-fold dust jacket protecting the paperback covers), the kind you buy when you’re hungover and dreaming of a life in fashion. You certainly wouldn’t throw American Polychronic in the recycling bin, but is it a masterpiece for the bookshelf? Maybe! Jamieson Webster compares Ethridge’s photography to psychoanalysis—“symptom and repression are attacked through evoking an assemblage of fantasy, memory, and reality that shakes the frame”—in an essay printed in small type at the end of our photographer’s elliptical journey through his archive, from 1999 to 2022. (At first glance, the text appears quite literally like an afterthought.) Still, you didn’t come to American Polychronic, a production of staggering charm and shrewd editing, a monument to one of the most successful image makers of our era, to learn something new about fugue states or “hysterical flowers.” You came for the Chanel tennis balls, the beach umbrellas, the winsome smiles, the paper towels. You came for Anna, Karl, Hans Ulrich, Thanksgiving, laughter, tears, birds, sunsets, and “pure beauty” (as one chic cannabis brand would have it), beauty so pure and sweet you might need to take an aspirin and turn on Cat Power’s Moon Pix. —Brendan Embser

These reviews originally appeared in Aperture, issue 251, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America,” in The PhotoBook Review.

June 28, 2023

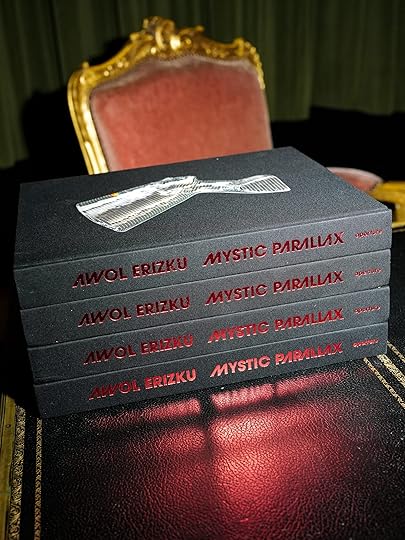

A Look Inside the Book Launch for Awol Erizku’s Long-Awaited First Monograph

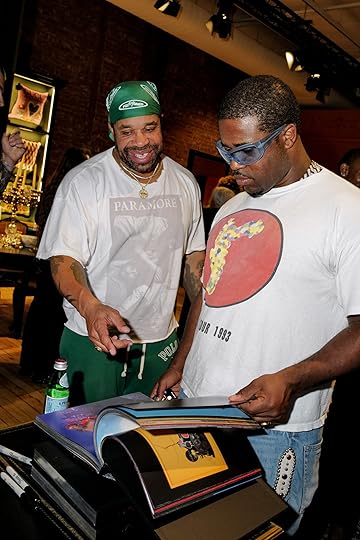

On Tuesday, June 27, at the Gucci Wooster Bookstore in SoHo, Aperture and Gucci celebrated the launch of Mystic Parallax, the long-awaited first major monograph dedicated to artist Awol Erizku’s expansive vision.

The intimate evening offered lively conversation and celebratory cocktails, including an Ethiopian honey wine as a tribute to Erizku’s heritage. Guests had the opportunity to have their copy of Mystic Parallax signed by the artist, who graciously autographed books throughout the evening.

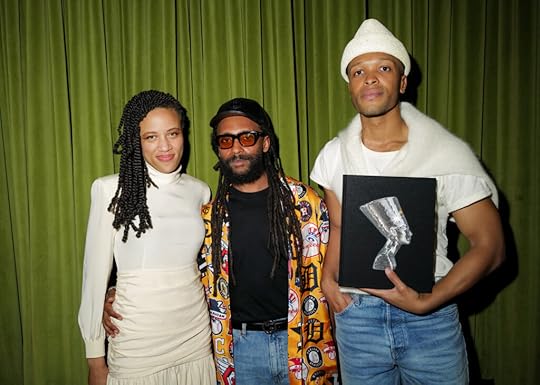

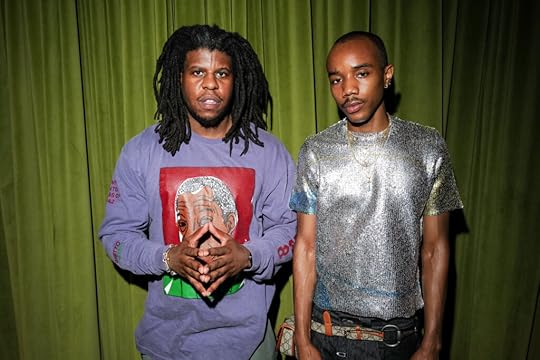

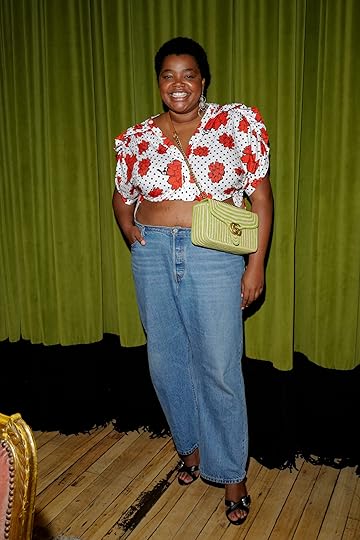

Ashley James, Awol Erizku, Antwaun Sargent

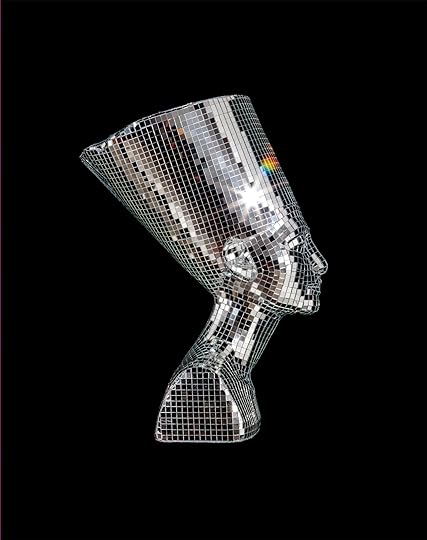

Ashley James, Awol Erizku, Antwaun SargentPublished by Aperture, Mystic Parallax showcases over ten years of Erizku’s multivalent practice that critically engages art history, personal experience, and Pan-African thought and symbolism. Working across photography, film, video, painting, and installation, his work references and re-imagines African American and African visual culture, from hip-hop vernacular to Nefertiti, while nodding to traditions of spirituality and Surrealism.

Joining to toast Awol Erizku and Aperture were many of the project’s contributors and supporters, including curator and book contributor Antwaun Sargent, curator Ashley James, Aperture Executive Director Sarah Meister, Aperture Editor Michael Famighetti, Aperture Trustees Lyle Ashton Harris, Deb Willis, and Cathy Caplan, as well as Adam Eli, ASAP Ferg, Chase Hall, Hank Willis Thomas, Isolde Brielmaier, Jane Holzer, Kathleen Lynch, Kathy Paciello, Lisa Sutcliffe, Quil Lemons, Rachel Tashjian, Ryan McGinley, Whitney Mallett, Willa Bennett, and many more.

Awol Erizku

Awol Erizku  Hank Willis Thomas, Sanford Biggers, Awol Erizku, Lyle Ashton Harris

Hank Willis Thomas, Sanford Biggers, Awol Erizku, Lyle Ashton Harris  Awol Erizku, ASAP Ferg

Awol Erizku, ASAP Ferg  Book Launch in partnership with Gucci

Book Launch in partnership with Gucci  Janine Cirincione, Awol Erizku, Cecile Panzieri, Jeffrey Grove

Janine Cirincione, Awol Erizku, Cecile Panzieri, Jeffrey Grove  Michael Famighetti, Awol Erizku

Michael Famighetti, Awol Erizku  Cathy Kaplan, Awol Erizku

Cathy Kaplan, Awol Erizku  Sarah Meister, Darla Vaughn

Sarah Meister, Darla Vaughn  Ghetto Gastro, Quil Lemons

Ghetto Gastro, Quil Lemons  Steven Chaiken, Whitney Mallett

Steven Chaiken, Whitney Mallett  Feruz Erizku, Awol Erizku

Feruz Erizku, Awol Erizku  Lovia Gyarkye, Brendan Embser, Lesley Martin, Nicole Acheampong

Lovia Gyarkye, Brendan Embser, Lesley Martin, Nicole Acheampong  Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

Gabriella Karefa-Johnson  Terry Ferguson, ASAP Ferg

Terry Ferguson, ASAP Ferg  Lauren Kelly, ASAP Ferg, Elphin Murren, Adrian Phillips

Lauren Kelly, ASAP Ferg, Elphin Murren, Adrian Phillips Cameron Welch, Chase Hall, Ashley James, Antwaun Sargent, Antoine Gregory, Awol Erizku

Cameron Welch, Chase Hall, Ashley James, Antwaun Sargent, Antoine Gregory, Awol ErizkuAll photographs by Ben Rosser for BFA.com, June 27, 2023

Related Items

Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax

Shop Now[image error]

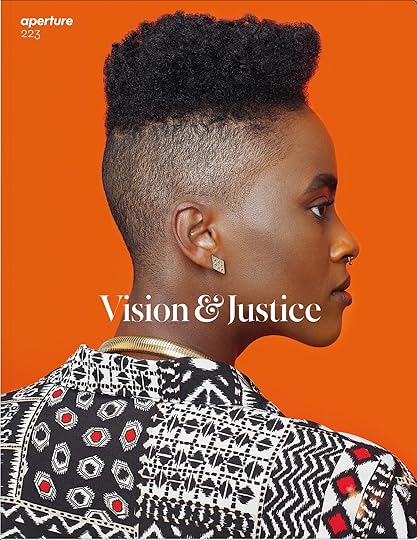

Aperture 223

Shop Now[image error]Book launch made possible by Gucci.

This project was made possible, in part, with generous support from the Momentary and the Aperture Artist Book Committee, including Founding Members Peter Barbur and Tim Doody, Jeff Gutterman and Russet Lederman, and Frank Arisman, Joe Baio and Anne Griffin, Frédérique Destribats, Michael Hoeh, Loring and Diana Knoblauch, Andrew and Marina Lewin, David Solo, and Alice Sachs Zimet. Special thanks to Sean Kelly Gallery and Ben Brown Fine Arts.

June 23, 2023

An Artist’s Collages about Memory and Migration

When she was four or five years old, Priya Suresh Kambli watched her mother cut out her own face from family photographs. Kambli’s mother left the pictures of her daughters, Priya and her elder sister, Sona, intact. This act of simultaneous erasure and preservation fascinated Kambli. Decades later, she brings the same dialectic into play when creating her own artworks drawn from family photo-albums.

Kambli was born in 1975, in the Indian city of Mumbai, then called Bombay, and came to the United States at the age of eighteen. A few years earlier, Kambli’s mother had died from cancer, and just six months later, her father had suffered a fatal heart attack. In the period that followed, Kambli was adrift. One of her aunts, a pediatrician in Louisiana, sponsored Kambli’s move. Art hadn’t, so far, been a part of her repertoire, and photography was even less attractive to her. Kambli’s father, however, a trained pastry chef, had been an avid amateur photographer. As a child, her father’s fussiness over his pictures, and the time he took arranging his family’s poses, felt like punishment. But, as an undergrad, Kambli enjoyed her photography class. She didn’t have her father’s Minolta, so she borrowed a camera from her aunt’s husband.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the summer 2023 issue, “Being & Becoming: Asian in America.”

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

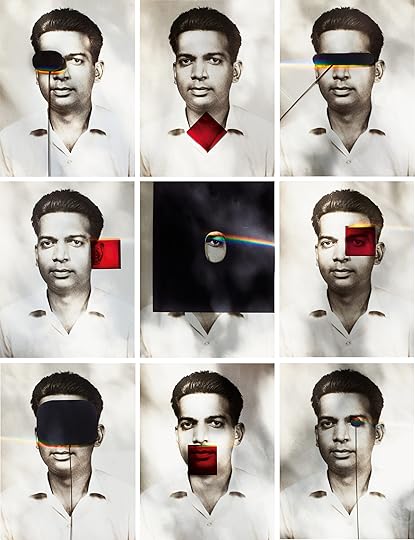

By graduate school she had discovered the excitement of creating art. She was learning from the work of artists such as Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson, who were interested in issues of identity, but she also experienced a sense of dissatisfaction with Western image making. In 2003, Kambli traveled to New York to see an exhibition from the Alkazi Collection of Photography. The pictures were mostly taken in India, and Kambli remembers being “blown away” by the hand-painted portraits showing some parts of the figure in black and white while other parts, particularly clothing and jewelry, were rendered in glittering color. These vernacular images in the pristine white gallery space, Kambli says, were very much like those in the two albums of family photographs she had brought in her suitcase from India. She began to work with those familial pictures, embellishing them in different ways, making connections between her present and her past.

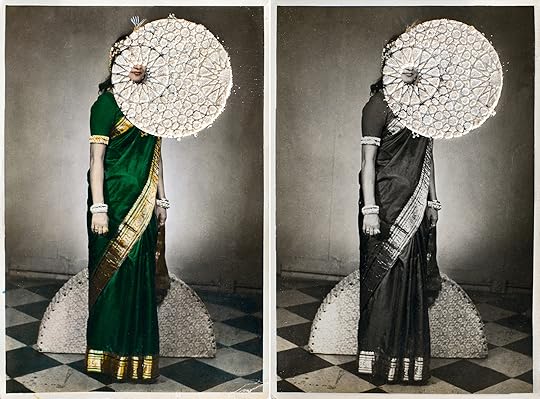

Priya Suresh Kambli, Mama and Muma, 2019

Priya Suresh Kambli, Mama and Muma, 2019  Priya Suresh Kambli, Mami, 2016

Priya Suresh Kambli, Mami, 2016 As Kambli was telling me all this over Zoom from her home in Kirksville, Missouri, I was thinking about her images in which faces are obscured—in one depicting her maternal aunt, Mami (2016), the face is left only partially visible under a decorative arrangement of flour. Flour was always at hand in the home of a pastry chef, and the patterns are borrowed from the traditional Indian practice of rangoli drawings, which are used during festivals or seen printed on textiles. It is difficult not to think of Kambli’s practice as therapeutic: the artist returns to a disquieting memory of her mother disfiguring photographs and then produces a transformed object that bears traces of its past but is altogether new and beautiful.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

In his book Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographs (1997), a classic study of the role of portraiture in India, Christopher Pinney describes a photography studio as a “chamber of dreams.” Pinney observes that in the small town in India where he was conducting his anthropological study, the creativity of the studio photographer as well as his subjects lay in their envisioning fluid selves that defied any narrow, realistic self-representation. In Kambli’s images, we are no longer in small-town India, but the impulse is the same. There is imaginative storytelling about possible selves, among them a cosmopolitan iteration stretching across continents. What we see over and over again, in collagelike constructions, are numerous selves tied to different temporalities and identities.