Aperture's Blog, page 31

April 7, 2023

Remembering the Life and Work of Kwame Brathwaite

Aperture is deeply saddened by the loss of Kwame Brathwaite, who passed away on April 1, 2023, at the age of eighty-five. Brathwaite (1938–2023) was a visionary Harlem-based photographer who used his images to advance the Black Is Beautiful message throughout the 1960s. From his photographs of jazz icons to his indelible images featuring the Grandassa Models, Brathwaite blended art, music, fashion, and community activism to spread a powerful message of social, economic, and representational justice.

At Aperture, we were honored to feature Brathwaite’s work in the pages of our magazine, to publish his first monograph (Black Is Beautiful, 2019), and to collaborate with him and his son, Kwame S. Brathwaite, to organize a traveling exhibition dedicated to his work. As we consider Kwame Brathwaite’s incredible legacy and how his work continues to move audiences globally, we asked a group of Aperture contributors to offer their reflections.

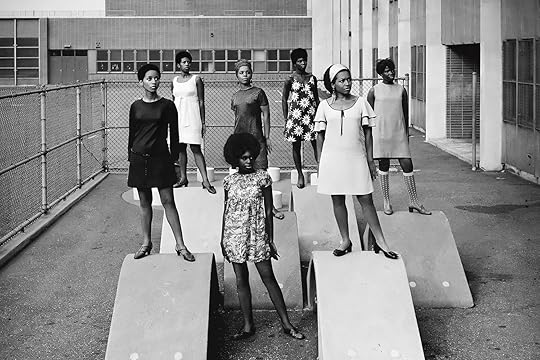

Kwame Brathwaite, A school for one of the many modeling groups that had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s, ca. 1966

Kwame Brathwaite, A school for one of the many modeling groups that had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s, ca. 1966  Kwame Brathwaite, Priscilla Bardonille, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1962

Kwame Brathwaite, Priscilla Bardonille, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1962 Antwaun Sargent

Kwame Brathwaite’s influence on the world of Black image production has been felt across the culture. Brathwaite gave visual power to the now common belief that Black is beautiful. This has resulted in generations of Black image makers making photographs that have further defined and celebrated our collective humanity. Without Brathwaite’s considerable contribution I don’t know where photography would be today. His rich image archive is a testament to a people who took control of their own representations.

Antwaun Sargent is author of The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion (Aperture, 2019) and Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists (2020).

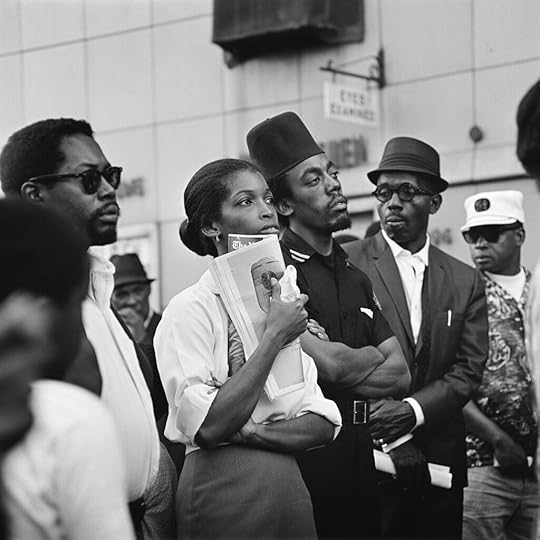

Kwame Brathwaite, Marcus Garvey Day Parade, Harlem, ca. 1967

Kwame Brathwaite, Marcus Garvey Day Parade, Harlem, ca. 1967Tanisha C. Ford

Much has been said about the power and boldness of Kwame Brathwaite’s photography. It is true, he chronicled the Black radical spirit of the 1950s and 1960s in ways unparalleled. But his sensitivity was his greatest asset. The way he adjusted the aperture of his lens, the way he positioned himself in relation to his subjects: these artistic choices gave his photographs complexity, layers. You can see softness and vulnerability, not just righteous anger, in the facial expressions of the freedom fighters whom Brathwaite captured on celluloid. And you can’t help but to linger in this nuance, to grapple with how the images force you to reconsider everything you think you know about Black Power, about beautiful Blackness. Sensitivity. I immediately discerned the depth and dimensionality of Kwame Brathwaite’s emotional register when I interviewed him for the first time. His sincerity, his humility, informed his commitment to depicting the full humanity of Black people around the globe. I hope we will always recognize his sensitivity as the vital element of his artistic and political legacy.

Tanisha C. Ford is a regular contributor to Aperture, and author of Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (Aperture, 2019), and Dressed in Dreams: A Black Girl’s Love Letter to the Power of Fashion (2019).

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970Tyler Mitchell

From the moment I first saw Kwame Brathwaite’s work I was transfixed. There’s a clarity and power to his portraits, which remind me that conversations around photography, representation, and equity have always been and will always be vital. I’m saddened to hear of his loss. I thank him for his timeless images and I thank his son Kwame Jr. for his commitment to the upkeep of his father’s archive.

Tyler Mitchell is a photographer based in New York. His work appeared in Aperture’s Winter 2020 issue, “Utopia,” and his book I Can Make You Feel Good was published in 2020.

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa Models and AJASS members posing for a Naturally ’67 poster outside the Apollo Theater, Harlem, ca. 1967

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa Models and AJASS members posing for a Naturally ’67 poster outside the Apollo Theater, Harlem, ca. 1967 All photographs courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa Models at the Merton Simpson Gallery, New York, ca. 1967

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa Models at the Merton Simpson Gallery, New York, ca. 1967 Ekow Eshun

Kwame Brathwaite said his goal was to show “the greatness of our people” and that’s what he did with his work. He understood that for Black people in the 1960s, a commitment to style and elegance and self-fashioning was not a superficial preoccupation. That’s why the slogan he popularized, “Black Is Beautiful,” was so resonant. It represented a personal politics of visibility and assertion. It was about resisting the white gaze and defining how you were seen on your own terms. It meant liberation. Black aliveness. This is what his photographs stand for.

Ekow Eshun is a curator, writer, and regular contributor to Aperture. His latest book is In the Black Fantastic (2022).

Related Items

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Shop Now[image error]

Black Is Beautiful

Learn More[image error]April 6, 2023

Janet Malcolm’s Life in Snapshots

“Taking a picture is a transformative act,” Janet Malcolm once wrote. As photography critic for the New Yorker from 1975 to 1981, she developed an understanding of the camera not as a mirror—that naïve, and now passé belief that photographs simply reflect reality—but instead as a light source: illuminating, even coloring, and leaving plenty in the shadows. “The images our eyes take in and the images the camera delivers are not the same,” she reasoned. An artist herself, with collages and photographs exhibited and published, she was practiced in the ways the lens can transform.

Malcolm’s critical view is not Susan Sontag’s charge of photography as aggression; nor is it Roland Barthes’s dirge for what is no longer. Malcolm, who died in 2021, was drawn to the form for its confounding potency and evasive, expansive nature, particularly in quotidian images like the snapshot. She was interested in the chasm, not only between the eye and the camera, but between the images our eyes take in and what we later recall. Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory, published posthumously at the beginning of this year, shows a writer drawn to the photo as it relates to memory, the ultimate object of Malcolm’s suspicion.

Malcolm’s grandmother, Klara, with Malcolm’s mother Hanna (left), and Malcolm’s aunt Jiřina (right), date unknown

Malcolm’s grandmother, Klara, with Malcolm’s mother Hanna (left), and Malcolm’s aunt Jiřina (right), date unknownFamily photographs are a way into personal writing for Malcolm. Through the twenty-six vignettes that form Still Pictures, she follows almost as many images toward memories and associations that together form a life in snapshots. A portrait of Malcolm’s mother as a girl; neighbors and friends of her parents; “my bad-girl friend Francine”; a scene from Camp Happyacres; a family trip to Atlantic City; Malcolm grinning with her husband; Malcolm looking writerly in the 1990s, around the time she saw a speech coach to prepare for a libel lawsuit against her—these are just some of the images that “stir” Malcolm to remember.

Born Jana Klara Wienerova to a Jewish family in Prague in 1934, Malcolm and her family fled Nazism in 1939, and by the next year were living in a Czech neighborhood in Yorkville on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Still Pictures includes tender moments and instances of Malcolm’s love of the absurd, a humor inherited especially from her father. One of two opening pictures shows a tiny Malcolm, age two or three, sitting on a step, her hands on her knees in an “assertive pose” that she finds interesting but that she cannot identify with. “If I were writing an autobiography, it would have to begin after the time of that photograph,” Malcolm writes. “My first memory dates from several years later.”

Malcolm at 2 or 3 years old, ca. 1936

Malcolm at 2 or 3 years old, ca. 1936Consummate eye-narrower and precise observer, Malcolm is perhaps best known in her writing for her authoritative persona and interrogation of the official narrative. Throughout a long career, she drew attention to the ways in which writing and reporting can be not only acts of transformation, but hostility. The opening of The Journalist and the Murderer—“Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible”—is one of the better-known sentences in literary nonfiction (and though at first one of the more controversial, many now consider it conventional wisdom). And while Still Pictures treads some of this familiar territory (“Do we ever write about our parents without perpetuating a fraud?”), in her last book Malcolm flirts with the possibility of doing what she vowed she never would: autobiography.

“I cannot write about myself as I write about the people I have written about as a journalist,” Malcolm explained in 2010. “No one is dictating to me or posing for me now.” Through old family photos, Malcolm finds many a willing model, most of them conveniently dead. It is an appropriately oblique way in for a writer who saw autobiography as “an exercise in self-forgiveness,” as opposed to her unforgiving—and, according to Malcolm, unforgivable—work as a journalist. Photos allow Malcolm to make her way toward personal writing, but at times she still cheekily refuses to play. Recalling an ornate Italian plate she bought long ago to use in an apartment where she met the lover who would later become her husband, Malcolm writes: “What did it mean to me? Why did it come to mind after so many years? I know the answer, but—like a balky child—I find myself reluctant to give it. I would rather flunk a writing test than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart.”

Malcolm (middle) with her parents as they depart from Prague in 1939, date unknown

Malcolm (middle) with her parents as they depart from Prague in 1939, date unknownThe creation of an honest former self always gave Malcolm serious pause. “Not only have I failed to make my young self as interesting as the strangers I have written about, but I have withheld my affection,” she noted in 2010. Critics have appraised the efficacy of Still Pictures as memoir (though apparently Malcolm did not characterize the essays as such), including Vivian Gornick, who wrote in the Nation, “After reading the collection, I felt obliged to agree with her. Malcolm does withhold affection from her long-ago self, and as a result the most important element in memoir writing—a satisfying persona—is missing.”

And yet, despite or because of this, in Still Pictures Malcolm follows memory’s lead—as if “simply by going with the camera instead of against it,” as she wrote in 1978 to describe when “photography went modernist.” The book could be said to mimic memory’s natural, often unsatisfying rhythms, embodying its inconsistencies, whims, repetitions, and blind spots. If Malcolm is a memoirist at once seduced and repulsed by memory, Still Pictures is a memoir that takes memory’s artistry as both muse and captor.

From left: Malcolm’s father, Malcolm’s sister Marie, 15-year-old Malcolm, and Malcolm’s mother, Atlantic City Boardwalk, June 12, 1949

From left: Malcolm’s father, Malcolm’s sister Marie, 15-year-old Malcolm, and Malcolm’s mother, Atlantic City Boardwalk, June 12, 1949Photography finds itself a partner to this reluctant but inspired tango with the past. “Most of what happens to us goes unremembered,” she writes. “The events of our lives are like photographic negatives. The few that make it into the developing solution and become photographs are what we call our memories.” And yet, “Occasionally… like memory itself, one of these inert pictures will suddenly stir and come alive.” A memoir-in-snapshots may be the only form up to the task of “memory’s perversity.”

Though she never fully trusts memory to tell a good story, the sharp-eyed critic and journalist manages a memoir-in-snapshots by looking.

The book’s formal conceit could seem an apt conclusion to a fifty-five-year, career-long preoccupation. “People tell journalists their stories as characters in dreams deliver their elliptical messages,” Malcolm wrote in The Journalist and the Murderer, “without warning, without context, without concern for how odd they will sound when the dreamer awakens and repeats them.” In Still Pictures: “as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.” At the end of her writing life, Malcolm was as skeptical as ever about our ability to interpret our own lives. And yet, as both dreamer and journalist, she attempts to parse hers.

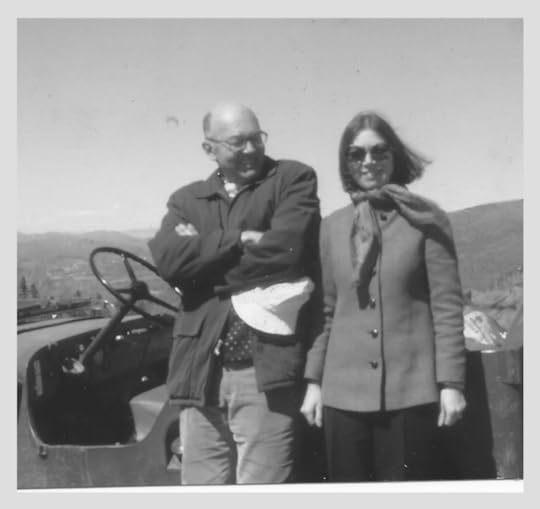

Malcolm with her second husband, Gardner Botsford, date unknown

Malcolm with her second husband, Gardner Botsford, date unknownOne vignette, titled “Lovesick,” was stirred by an image of a group of high-schoolers found in a box in Malcolm’s apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” The number of times throughout the book Malcolm refers to love as a sickness, a virus “for which there is no vaccine,” a habit, a contagion, is striking. Letting her narratorial guard down briefly, she revels, almost childlike and at times approaching cliché, in life’s inexplicable timing and force, the elusiveness of what remains. Though she reports boredom at the randomness of what’s lost and what’s retained by memory, Malcolm was also clearly fascinated by the mystery, the art of it. Of her own collages, she once wrote to a colleague, “There does seem to be something occult going on here, and I don’t think I believe in the occult.” This tension is felt throughout Still Pictures.

In the introduction to Diana & Nikon, a 1980 collection of her photography criticism rich with literary reference, Malcolm describes the medium as at once fascinating and baffling—“Defying anyone to say what exactly its place in the arts is. The force of this singular orneriness is felt by every critic of photography and gives writing about photography its own peculiar atmosphere of unease and uncertainty.” Photography’s reputation as untrustworthy—elusive, even suspicious, implicated—would congeal during and after Malcolm’s days as a photo critic. (The title’s “Diana” refers to a plastic camera meant for hobbyists but taken up by artists such as Nancy Rexroth and Jo Ractliffe.) Decades later, in Still Pictures, Malcolm seems to trust the famously compromised medium to explore something more spacious than fact, some greater truth about time, subjectivity, and memory.

Gardner Botsford, Untitled, 1971

Gardner Botsford, Untitled, 1971 All photographs courtesy Janet Malcolm

Malcolm’s reliance on pictures from everyday personal collections allows for an intimate excavation of the chief concern of her photography criticism, after the medium’s relation to painting: how the artform was influenced by utilitarian uses of the camera like the snapshot. This was long before democratization via the smart phone, but around the time of the invention of the digital camera, a boon for amateur photographers. In the final vignette of Still Pictures, “A Work of Art,” Malcolm reveals that alongside her title essay in Diana & Nikon, which discusses the “deliberately artless photography” collected in Aperture’s Fall 1974 issue, “The Snapshot,” she snuck in an “outstandingly terrible snapshot” of a couple on a tennis court that her husband kept as a joke. That this random photo was printed without question alongside photographs by Rexroth, Joel Meyerowitz, and Robert Frank, inspired great delight in Malcolm.

A playful yet serious interest in authenticity animates Still Pictures. Who is the authority on our own lives? Malcolm had her answers and, daring finally to turn the lens on herself, she answers anew. Though she never fully trusts memory to tell a good story, the sharp-eyed critic and journalist manages a memoir-in-snapshots by looking, a skill long honed; then she follows memory, the ultimate absurdist artist.

Janet Malcolm’s Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory was published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2023.

April 5, 2023

Aperture and Google’s Creator Labs Launch Second Season of Creator Labs Photo Fund

Today, Google’s Creator Labs and Aperture announce the second season of the Creator Labs Photo Fund—an initiative to support image makers.

The fund, made possible by Google Pixel in partnership with Aperture, will be distributed through a national open call, starting April 5 and running through May 1, 2023. Submissions will be free and open to any photographer or lens-based artist living in the United States, and thirty selected artists will be awarded a prize of $6,000 each.

Aperture serves as an essential platform for artists, fostering critical dialogue within the photographic community—in print, in person, and online. “Partnering with Google on the second iteration of the Creator Labs Photo Fund embodies Aperture’s longstanding mission to surface and support new voices in photography,” says Aperture’s creative director, Lesley A. Martin. “We recognize the impact of images within our shared world and actively encourage and cultivate the creative exchange around this work.”

To apply to the Creator Labs Photo Fund, all entrants will need to submit eight to ten images from one body of work, showing a commitment to making a cohesive and compelling series or project. The project can be but does not need to be finished in order to enter. Entrants will not be evaluated on the basis of prior experience, publications, or exhibition history, but instead on the strength and originality of their visions.

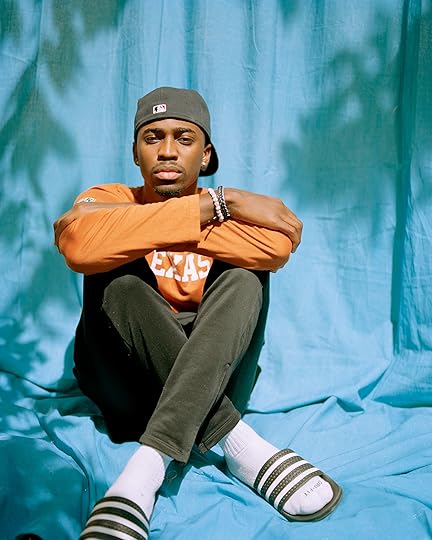

To kick off season two, Aperture, Google’s Creator Labs, and SN37 are hosting a conversation on April 5. Senior managing editor of Aperture magazine, Brendan Embser, and associate editor at the Atlantic, Nicole Acheampong, will be in conversation with artists Adraint Bereal, Daveed Baptiste, and Sydney Mieko King. Each artist will share insight into their practice as recipients of the inaugural Creator Labs Photo Fund grant in 2021.

Submit now to the Creator Labs Photo Fund, open from April 5–May 1, 2023.

About the Creator Labs Photo Fund

Google’s Creator Labs Photo Fund was created out of a desire to extend the mission and message of Creator Labs to the wider creative community. It is increasingly important and vital to provide support to the creative community—to continue their practice, and have their narratives reverberate, for years to come. In 2021, twenty artists were selected by Aperture’s editors for the inaugural season of this fund, in recognition of the strength and originality of their portfolios. Each artist was awarded a prize of $5,000 to sustain their work and practice.

About the Creator Labs

Creator Labs is a partnership between Google and SN37 to support artists in the production of important personal work. Participating photographers and filmmakers are selected for their ability to author distinct, concentrated visual narratives with an authentic point of view. All work made through this program is created using Google Pixel.

March 31, 2023

A Celebratory Chronicle of Black College Life

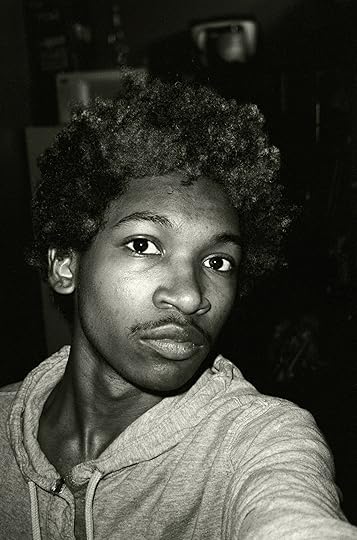

Adraint Bereal is in a tight spot.

He spent much of 2021 on the road, taking more than a dozen flights, plus Amtraks, buses, and rental cars. He lived out of his suitcase for months, lugging along eight cameras—point-and-shoot, Polaroid, medium-format, “everything you could think of”—until the weight of all that gear wore him down. He shipped all but two home and kept going.

Bereal’s mission was heavy enough: to meet at least one hundred Black college students across the country, capture their lives in images and words—preferably their own—and compile this material in The Black Yearbook, the second iteration of a project Bereal birthed in his senior year at the University of Texas at Austin. Returning from his travels, he faced another, more challenging task: meet a book deadline. He needed to pare down hundreds of hours of conversation, toss aside thousands of images, and cull from intimate human stories to produce a selection that his publisher, Penguin Random House, could present for mass consumption. The tightest spot of all is how to tell his and his peers’ stories “without cutting away so much of ourselves,” he told me recently.

Bereal’s first photography endeavors occurred when he was a teenager in Waco, Texas, taking iPhone pictures of his mother’s outfits before she went out. “It sounds so silly,” he says, “but that was practice for me. I was learning about composition, learning how to have a conversation with not only the camera but the person in front of it as well.” The Black Yearbook, in a sense, is an evolution of his earliest image making, equal parts archive and affirmation.

Bereal’s project started from a desire to help his classmates see themselves and celebrate one another.

Photography wasn’t much more than a pastime until one of his college professors suggested Bereal check out the work of Wolfgang Tillmans. “I went to the Austin Public Library,” he remembers, “and there was one image in particular.” Bereal later shared the image, Forever Fortresses (1997), which captures Tillmans holding the hand of his late partner, Jochen Klein, just hours before Klein died of AIDS-related pneumonia. “Seeing that image, photography as an art form, the power of images, finally clicked for me.” Aside from their demonstration of technical mastery, Tillmans’s photographs gave Bereal a portal through which to explore his own queerness, to see and understand himself.

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington Featuring a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington Featuring a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.” $200.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington $ 200.00 –1+$200.00Add to cart

View cart Description This print will be available for sale from March 28 through April 6 only. The number of prints acquired will be the number produced.This Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition features a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live” for only $200.

This issue of the magazine explores the relationship between photography and storytelling across generations and geographies. Featuring stories that illuminate daily life, this issue evokes the late, celebrated writer Joan Didion, who declared, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” and features a portfolio of Waplington’s work that includes this image. Aperture first published work from the Living Room project as a book in 1991. Spending years documenting the daily lives of two working-class families on a council estate in Nottingham, England, Waplington photographing in saturated color, weaved together a document of the lives of these families, capturing these often poignant intimate narratives, often with unexpected glimpses of humor.

“The Living Room project is one of my most well-known photographic works; the pictures were taken in Nottingham, England, roughly between 1986 and 1997, and two books from the project, Living Room and The Weddings were published in the 1990s by Aperture. The work deals with the daily existence of a group of families who lived in public housing in the city during the Thatcher years when the United Kingdom went through a series of radical social and political changes. Throughout this period, I would repeatedly return to the public housing projects where the families lived to stay with my grandfather, who had a house there. By 1992, when this picture was taken, some of my subjects had left the housing project and were living in Victorian housing near Nottingham city center. On a warm, sunny June afternoon, Dawn, the woman in the photograph, climbed on her boyfriend’s car roof and posed for me. Because it was so unique to the pictures I was making, I disregarded it at the time, but I came across it again recently as I reevaluated the work some thirty years later. Like the project as a whole, this image shows the fun and happy time we had back then, ‘mucking around in the street,’ as we say in England.”

—Nick Waplington

NOTE: Prints will begin to ship by April 26, 2023 Details

Radford, 1992

Pigment Print

Paper Size: 5 x 7 inches

Signed by the artist

Available for sale March 28—April 6

For additional information on international shipping quotes email prints@aperture.org

The Black Yearbook project started from a similar desire: to help his classmates see themselves and celebrate one another on a campus where Black students comprise around 5 percent of the fifty-thousand-plus student body. The resulting crowdfunded 2020 publication resonated widely enough to spur him on his current journey to chronicle students’ lives beyond Texas. “This is the first time anybody has ever just sat down, shut up, and listened to what they had to say,” he states. He’s found striking, if sobering, similarities across the country. “Many of these students haven’t been taken care of on these campuses,” he tells me. Some don’t have proper housing, or a place to go back to for the holidays. Many students are struggling with mental health issues. Perhaps most obvious is the devastating effect of the pandemic. Bereal, who graduated in 2020—the first in his family to do so—participated in a virtual ceremony in lieu of a physical graduation. This is only one example of the ways in which he and his peers “had the rug pulled completely from underneath us.” Yet, he’s found much more than gloom. “Whether it be through a state of escapism or delusion, there are some students who are absolutely enjoying themselves,” Bereal observes.

Related Stories Essays Nick Waplington’s Histories from Below

Essays Nick Waplington’s Histories from Below

Images from homecoming at the University of Texas embody Bereal’s approach and illuminate the lives that fill The Black Yearbook. There’s one of the homecoming queen herself—flash galore, from the camera to her smile, her makeup highlights, her red nails, her glittering tiara. Echoes of the fit pic, with the patina of a 1990s family photograph. “I’m having a really voyeuristic moment,” Bereal says, “but I’m also participating in it, hanging out with my friends and just dancing with everyone.”

In Bereal’s practice, the photographer is comrade and chronicler, griot and visual artist. He walks the tightrope that stretches between the I and the we, engaging in the noble struggle to get the balance right and, most of all, to tell the truth, to capture the agony and ecstasy and in-between of what it is to be a Black college student today.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

This kaleidoscopic hunger helps explain the variety in Bereal’s images. Starting from a foundation of portraits, he seems as drawn to the disposable-camera-esque candid as he is to the high-gloss, highly staged ad. He is a poet of the party scene—some of Bereal’s photographs call to mind the crowded, joyful abandon of Ernie Barnes’s iconic 1976 painting The Sugar Shack—as well as the selfie, which he considers “an affirmation of self,” recalling one of the positive things to come out of the COVID-19 lockdown. “When the pandemic happened, I spent a lot of time with myself. And it forced me to look in the mirror and say, ‘All right, this is who I am. I don’t always feel good. I don’t always feel pretty. I don’t always feel handsome. But I still love myself.’”

For Bereal, this love includes kindness toward himself and toward his fellow artists, whose development, he fears, might be stifled by the paralyzing effects of too-early criticism and the capitalist pressure to build a “brand,” if only because one has to pay rent and student loans, et cetera. “I’m still so young,” the twenty-four-year-old says, “and I really hope that people I respect give me the grace to grow and learn as an artist.”

All photographs by Adraint Bereal from the series The Black Yearbook, 2020–21

All photographs by Adraint Bereal from the series The Black Yearbook, 2020–21Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

March 28, 2023

Nick Waplington’s Histories from Below

In 1996, the British photographer Nick Waplington wrote out a handwritten slogan that states: “EVERYTHING THAT HAS HAPPENED BEFORE IS HAPPENING NOW.” Published in Safety in Numbers (1997), his account of a year on the road in New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Johannesburg, and London, it’s a line that might also describe Waplington’s methods, as he often makes photographic series without a sense of his final intention. “I keep work when I am not really sure why I am making it at the time. I build up an archive to use in the future, and then I’ll come back to it,” Waplington says. “For example, I took a lot of pictures from the age of fourteen to twenty that I only started publishing in 2014.”

Waplington is committed to the idea of entering communities in order to understand them and, in turn, himself. When I visited his East London studio last summer, he told me, “I have an ability to seek out weird, subcultural groups that I find interesting, and I kind of submerge myself. It becomes my world, and I make work about it. Then, I present the work to the world.”

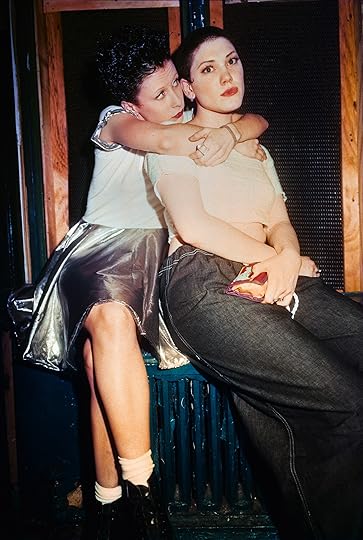

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series New York Club, 1994

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series New York Club, 1994  Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Surf Riot, 1996

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Surf Riot, 1996 With a career spanning more than thirty years, Waplington, who was born in 1965, has dedicated himself to extended periods of fieldwork in the United Kingdom, the United States, Europe, and Japan. He has produced photobooks that deal with subjects as diverse as the inhabitants of a housing estate in the East Midlands of Britain, a beach riot in Southern California, Jewish settlers in the West Bank, river swimmers in East London, and club kids in New York. His is a wandering existence, connected to the level of the everyday in the community in which he is immersed, but not to a place he can necessarily call home.

It’s a way of working that the social sciences identify as participant observation. But Waplington’s photographs are not academic; they lack critical distance from their subjects, and their objectivity is not as detached as it could be. His time-consuming, personal involvement enables a pictorial command of how people function in such groups: his pictures hum as scenes of life.

Waplington is committed to the idea of entering communities in order to understand them and, in turn, himself.

The writer Joan Didion’s description (in 1979’s The White Album) of how she saw her life at the end of the 1960s in Los Angeles is evocative of what Waplington’s photography looks like: “I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience.” Waplington takes a subjective viewpoint, like Didion’s, and turns it into an image the viewer can recognize through visual cues. In sequence his photographs might look like a set of snapshots, yet the flashes and fragments amass until meaning is strung across them. His work confirms that photography is no longer about the nonfictional single image, but neither is his work about the staged moment.

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington Featuring a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington Featuring a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.” $200.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Nick Waplington $ 200.00 –1+$200.00Add to cart

View cart Description This print will be available for sale from March 28 through April 6 only. The number of prints acquired will be the number produced.This Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition features a signed print by Nick Waplington, accompanied by a copy of Aperture 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live” for only $200.

This issue of the magazine explores the relationship between photography and storytelling across generations and geographies. Featuring stories that illuminate daily life, this issue evokes the late, celebrated writer Joan Didion, who declared, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” and features a portfolio of Waplington’s work that includes this image. Aperture first published work from the Living Room project as a book in 1991. Spending years documenting the daily lives of two working-class families on a council estate in Nottingham, England, Waplington photographing in saturated color, weaved together a document of the lives of these families, capturing these often poignant intimate narratives, often with unexpected glimpses of humor.

“The Living Room project is one of my most well-known photographic works; the pictures were taken in Nottingham, England, roughly between 1986 and 1997, and two books from the project, Living Room and The Weddings were published in the 1990s by Aperture. The work deals with the daily existence of a group of families who lived in public housing in the city during the Thatcher years when the United Kingdom went through a series of radical social and political changes. Throughout this period, I would repeatedly return to the public housing projects where the families lived to stay with my grandfather, who had a house there. By 1992, when this picture was taken, some of my subjects had left the housing project and were living in Victorian housing near Nottingham city center. On a warm, sunny June afternoon, Dawn, the woman in the photograph, climbed on her boyfriend’s car roof and posed for me. Because it was so unique to the pictures I was making, I disregarded it at the time, but I came across it again recently as I reevaluated the work some thirty years later. Like the project as a whole, this image shows the fun and happy time we had back then, ‘mucking around in the street,’ as we say in England.”

—Nick Waplington

NOTE: Prints will begin to ship by April 26, 2023 Details

Radford, 1992

Pigment Print

Paper Size: 5 x 7 inches

Signed by the artist

Available for sale March 28—April 6

Waplington currently lives in New York and London. The pandemic’s ban on travel and social interaction arrested his embedded style of photography, but he made use of the time it granted him by taking stock of his archive in preparation for a survey publication, Comprehensive (to be published this fall). “I’ve had a trajectory where I make work all the time, and I don’t exhibit very much,” he says. “All I’ve done for the last thirty-five to forty years is make work, and then make books, and, very occasionally, do a show. This means that the amount of images is kind of crazy. Rather than use a bit of everything, what I am trying to do in Comprehensive is illustrate between five and eight projects in a bit more depth. When you open the book, you’ll see a lot of pictures that you’ve never seen before.”

Related Stories Essays The Afterimage of Joan Didion

Essays The Afterimage of Joan Didion This approach provides a refreshing opportunity to reconsider previously published series, destabilizing the narrative threaded through the sequencing of images in previous photobooks. What Waplington proposes with this method is the showing of a new hand by reshuffling and adding to the deck. For example, Living Room (Aperture, 1991), his first publication, has fifty-nine plates, but they are drawn from five years’ worth of photographs. So in Comprehensive, the tightly edited, linear narrative of the original photobook will be exchanged for a more circuitous route, offering fresh intersections and insights.

This strategy also makes the work engage with the concerns of the here and now. In discussing with Waplington which portfolios will appear in Comprehensive, it becomes apparent that the historical trajectory behind the production of the bodies of images weaves them together in ways that aren’t pictorially evident. The book not only reveals Waplington as a prolific image maker, focused on more than one project at any one time, but shows how he networked across distinct creative cultures in Nottingham, London, and New York from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s.

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Living Room, 1994

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Living Room, 1994  Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Living Room, 1994

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Living Room, 1994 Living Room deals with life in the Broxtowe housing estate in Aspley, Nottingham, a predominantly working-class development in which Waplington’s grandfather lived from the time it was built in the 1930s. Waplington’s upbringing, in Surrey, was markedly different; his father had gone to university and was a nuclear scientist. Waplington started to take photographs, at age fourteen, of anti-apartheid marches and his friends skateboarding or partying; by the age of eighteen, he had become drawn to documenting life around his grandfather’s house, and he would eventually apply for a degree in photography at Trent Polytechnic, enabling him to live and make work in Nottingham. It was during this formative time that Waplington honed his signature style, described in jest by the photographer himself as “that kind of Nick Waplington, 6-by-9 Fuji with the big flash gun of bounced flash, where things are happening in the corner, and the middle’s kind of empty, or things are cut off.”

Living Room is ostensibly about domestic life, but, as the pictures weave and sway from one house into another in fully saturated color, there is no clear-cut sense of where one family ends and the other begins. Babies gurgle, fists fly, ice creams are bought, and humanity rolls on. “I really enjoyed being around those families, and the kind of looseness and fun and camaraderie that was going on in the estate. The ridiculous things that we would get up to were very different from the extremely rigid world of the Surrey stockbroker belt that I had grown up in, where my father, having come from that, was very keen that it was forgotten.”

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series New York Club, 1994

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series New York Club, 1994In 1988, at an interview for a place in the MA Photography program at the Royal College of Art, Waplington learned that Richard Avedon would be visiting the following spring to accept an honorary doctorate—and would give a master class. Waplington asked if he could attend, even though he would not yet have enrolled in the course; afterward Avedon raved about his photographs. When Waplington was in Connecticut in the summer of 1989, a few months before starting his MA, a note from Avedon arrived back home for him, saying, “I really was impressed, moved by the work you brought to my class.” Avedon asked about acquiring a set of prints. Soon after, Waplington was hanging out in Avedon’s New York studio.

Having recognized Waplington’s talents, Avedon primed him to follow in his footsteps and become a commercial photographer. He introduced Waplington to the fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi, for whom he took photographs backstage and pictures of fittings from the late ’80s to 1994, at the rate of $250 per day. At night Waplington was out in clubs, taking photographs at the Sound Factory, Limelight, Save the Robots, and various after-hours parties. “Mizrahi paid for the film and processing for those pictures, not that he knew it at the time,” Waplington says. “It was very nice of him that he never questioned it.”

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series New York Club, 1994

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }It’s hard to see a relationship between the two bodies of images, or to correlate how the days might have connected to the nights: one looks like the last days of Versailles (before grunge hits), the other, the start of Fellini Satyricon (but with everyone in Lycra). Waplington says he always wanted to make art, and the experience only underscored that he had no interest in commercial photography. “What I wanted was to just make projects the way I wanted to do them,” he says. “I came back to London and got a studio space on Brick Lane, with the Chapman Brothers and Sam Taylor-Wood. Even though there wasn’t the money in it, there was an excitement.” Soon, the print room at the Photographers’ Gallery, London, was selling his pictures for £150 each; a small exhibition followed, and word spread quickly. In 1990, Living Room won an Eastman Kodak Award.

Waplington’s work might best be served not by the ideas of social documentary photography—as a means of raising awareness or a tool for social change—but by the idea of “history from below.” Developed by the British historian E. P. Thompson and typified in his book The Making of the English Working Class (1963), history from below rejects the focus on “the great and the good” of traditional political history in favor of the study of ordinary people and everyday life. Waplington’s photography honors this recalibration’s acknowledgment of class but destabilizes powers of division and exclusion by inverting the social hierarchy. Waplington’s own needs align with this viewpoint. At the time that Living Room was being turned into an Aperture publication in New York, in the early ’90s, Waplington was meeting photographers, including Sally Mann and Nan Goldin, who were bringing new meanings to the concept of belonging, in both nuclear and nontraditional families. Goldin was the first to tell Waplington that, maybe, he was looking for the family he never had.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

The remarkable and unique quality of Waplington’s approach to taking photographs is his command not only of what is included within the frame but of what is missing. Ursula K. Le Guin calls what is left in and out in storytelling “crowding” and “leaping”: “By crowding I mean also keeping the story full, always full of what’s happening in it; keeping it moving, not slacking and wandering into irrelevancies; keeping it interconnected with itself, rich with echoes forward and backward. . . . But leaping is just as important. What you leap over is what you leave out. And what you leave out is infinitely more than what you leave in. There’s got to be white space around the word, silence around the voice.” Le Guin is addressing a writer employing words, but it is no great leap to observe how well these ideas apply to Waplington’s craft, especially the sheer physicality of what he pushes and pulls with his eye.

“The excitement never ends,” Waplington says. “There isn’t a day when I don’t wake up excited to be getting on with it again. As New Order sings, ‘There is no end to this.’ I love it.”

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Safety in Numbers, 1996

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Safety in Numbers, 1996  Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Safety in Numbers, 1996

Nick Waplington, Untitled, from the series Safety in Numbers, 1996All photographs courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 250, “We Make Pictures in Order to Live.”

March 24, 2023

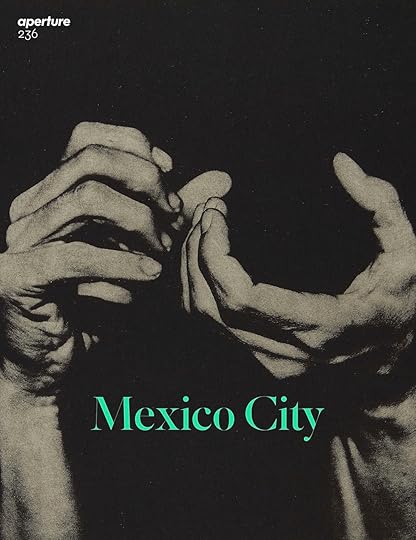

Miguel Calderón Journeys into the Soul of Mexico

Miguel Calderón is a hunter of good stories. Once, he traveled by taxi from Mexico City to Tijuana—a journey of more than 1,700 miles—only to end up with one photograph, an image of a man whom we see from a distance, with his back to the camera, urinating. It’s a testament to an adventure that began when Calderón asked various taxi drivers if they would be willing, at that very moment, to take him to the Mexico-US border, a drive of more than thirty hours traversing extremely rough regions of the country—controlled by drug cartels—so that he could produce a piece for a festival on borderland art. After a few attempts, one brave driver decided to accompany him on the adventure, from which that extraordinary image emerged. This is Calderón: an artist whose work extends from a photo of himself vomiting upon leaving a party when he was twenty-something years old, to a complex video installation wherein a panther approaches the spectator in total darkness, revealing itself solely by the glint of a pair of alert eyes and some sounds.

Calderón works in video, installation, painting, and drawing, but his photography, in particular, is sui generis. It isn’t the image per se that matters, but the story behind it. I recently spoke with Calderón at the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, where his exhibition Materia estética disponible (Aesthetic material available) was on view—a small but carefully curated survey that covers his trajectory from the 1990s to the present.

Miguel Calderón, Taxímetro, 2017

Miguel Calderón, Taxímetro, 2017María Minera: What is your relationship to photography? Perhaps you wouldn’t define yourself as a photographer because you use so many different mediums, but it’s clear you have an important relationship to photography.

Miguel Calderón: Without a doubt. Throughout my career there’s been a lot of back and forth between considering myself a photographer or not. These days I consider myself a photographer, but one who has renounced technique and decided to grab a camera and take snapshots. Of course, there are cases in which I work with a professional team to achieve certain effects that are more difficult to attain, but that’s dependent on the work.

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #58, 1987–1991

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #58, 1987–1991My history with photography is strange. When my parents separated, my mother married a photographer who had a darkroom, various cameras, and all the photographic paraphernalia, and this really interested me. He also had an enormous collection of National Geographic. My parents’ separation was incredibly painful for me, but in the midst of distress, I found very valuable things, as much thanks to my mother’s husband as to my father’s wife, who was interested in art. My parents had no interest in art; they never took us to museums. So these new presences, with all their associated problems, were tremendously enriching. I remember my mother’s house was robbed and they took the better part of her husband’s photography equipment, including his favorite camera. This had a major impact on me, and to this day, when someone says Nikon, it’s like hearing Ferrari.

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #24, 1987–1991

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #24, 1987–1991  Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #11, 1987–1991

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #11, 1987–1991 Because of the disillusionment of having lost everything in the robbery, my mother’s husband quit photography, but, interestingly enough, my father’s wife decided to buy the few things that remained off him—filters and light—and put up her own darkroom. She enrolled in the Escuela Activa de Fotografía (a photography school in Mexico City), and I remember her returning with her assignments for class and that making a significant impression on me. So when I had the opportunity, I decided to study photography. And of course, my early attempts were incredibly pretentious, they strove to imitate the work I admired: Nacho López, Tina Modotti, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Ansel Adams.

For this exhibit, we decided to show some of what I created during that period, between the ages of sixteen and nineteen. They’re photographs that perhaps never had any intention of being works of art, but in which I nevertheless found a certain value for their attempts at imitating other photographers. I think they contain some salvageable moments while also being a way for me to see a different me: the Miguel at fifty looking at an enthusiastic teenager eager to document his surroundings, to immerse himself in situations that call his attention, and an obsessive thirst for life.

Miguel Calderón, Vómito posmoderno, 1998

Miguel Calderón, Vómito posmoderno, 1998Minera: We’re standing in front of two photographs from very different periods, and what seems incredible to me, in a certain sense, is that your work hasn’t changed that much over time. There are still many aspects of that initial spirit of searching that persist, of trying to understand the world that surrounds you, and trying to find yourself in that world. This is a constant in your work. I’m thinking, for example, of the piece from 1998 that’s called Vómito postmoderno (Postmodern vomit).

Calderón: For me, the nineties in Mexico City are like a cloud of memory and forgetting. We lived in tremendous chaos and amid a lot of uncertainty, because what we did wasn’t accepted. People would ask you: “What kind of protest is this? Are you an artist? What are you?” And being really young, that makes you question yourself.

Related Items

Aperture 236

Shop Now[image error]

Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Imagination

Shop Now[image error]During that time, I lived in a warehouse and lots of people stayed in my house. I remember that the most fun wasn’t going to a party, because by the time you got there everyone had already left, there were plastic cups thrown all over, an empty bottle of Bacardi. What was most fun was the journey in search of the party, roaming all over the city with your friends. And it was pretty typical at that age to end up vomiting. So I started to compile an archive of photos of my friends vomiting. And one day, after developing material that I’d taken with a 35 mm Olympus, I found that there was a photo of me that of course I couldn’t have taken myself, but I also couldn’t remember who had taken it. But when I saw it, it immediately brought me back to Bruce Nauman and his Self-Portrait as a Fountain; this was my own uncomfortable version, my self-portrait as an adolescent fountain. I mounted it in a lightbox because that was the exact size of the illuminated images that they used to put up in bus stops.

Miguel Calderón, Espacio abierto 1, 2012

Miguel Calderón, Espacio abierto 1, 2012Minera: And alongside it, we see Espacio abierto (Open space), a more recent work, from 2013, a diptych, of two birds of prey.

Calderón: It’s a white hawk that was in a refuge for injured animals. The story comes from long before—when I moved with my mother and her husband to Balcones de la Herradura, a kind of American-type suburb. My mom’s husband had a dog, and one time when I went to pick him up from the veterinarian’s office, where they were bathing him, there was a hawk there and I fell madly in love with it. I wanted to connect with nature in a different way than what was taught in school, where you were just taught to repeat exactly what was in the book. At that time, I had bicycles that I built myself—maybe that was my first introduction to making art unconsciously, off the page. So I became friends with the veterinarian, Pedro, who lived in a nearby town. I would go to his house and we would talk. In reality, I wanted to buy his hawk, but I didn’t have enough money. But one day, he saw my bike and he said: “I’ll bet you the bike for the hawk if you do one hundred sit-ups while hanging from the van where I transport the dogs.” And so I did the hundred sit-ups and when I got to the ninety-ninth he shouted: “110! 110!”; and I cried and looked up at the sky while thinking: “The hawk, the hawk.” And I won it—I had it in my house and I learned to take care of it. That’s where my interest in them began. Now I’m making a documentary, not so much about the hawks, but about people like me, who find a kind of anxiolytic through their relationships with hawks.

The piece you see here has to do with the nictitating membrane that all hawks have. It isn’t an eyelid, it’s a layer that protects the eye, for example, when the blood of their prey splashes into it when they hunt. What’s incredible is that they don’t lose their field of vision. And what I wanted to do was put myself in the place of the prey; feel what they feel when they confront a bird like this one, right at the moment before being attacked.

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #7, 1987–1991

Miguel Calderón, Triple exposure #7, 1987–1991Minera: I’m drawn to the fact that each photograph has a distinct size and quality. There is a myriad of photographic decisions involved.

Calderón: A fundamental shift occurred in my life when I saw one of Cindy Sherman’s photographs in the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo. It had a tremendous impact on me. For one thing, the scale. Second, her colors. Third, the question of the artist’s multiple personalities, of exploring the self by virtue of various physical manifestations. And it was something that I felt: I am many different selves in different situations and with different people. It made such an impression on me that I began taking large-format photographs. Time passed and I understood that not all photographs require that. It was something intuitive.

Miguel Calderón, Taxímetro, 2017. Installation view at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, 2023

Miguel Calderón, Taxímetro, 2017. Installation view at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, 2023Minera: We’re now standing in front of Taxímetro (Taximeter), a piece from 1997 comprised of a single image and a running taximeter. Tell me the story of this piece, which is the one you presented at InSite that same year.

Calderón: This story is a little long, it involves two trips to the border and a failed art piece. But in the end, the piece emerged from a trip that I made by taxi to Tijuana from Daniel Garza, the neighborhood where I was living in Mexico City. I stopped various taxi drivers and everyone told me: “No, you’re crazy, that’s terrifying.” Until one of them said: “Yes, come to my house with me.” We went to get his things and we left at sunrise. The trip took four days, and we went to bars, we drank, got drunk, and just saw everything. And, in the midst of all that, it was incredibly interesting to try to convince him of the validity of my work—which I never managed to do. We ended up striking up a deep, though passing, friendship, as I never saw him again. I took lots of photos—of cities, of him and I cohabitating in the hotel, drunk in our underwear. In the end I chose the image that most called my attention, where he’s seen urinating, completely out of his element, alongside the taxi, which was allegedly ecological, though the only remotely ecological thing about it was that it was painted green.

We were in La Rumorosa, an extremely dangerous highway. He wanted to stop, although it was a total risk, to urinate. After the trip, he gifted me the taximeter and I decided to show it alongside the image. I liked adding this element of running time and money. How do you do the accounting for something as endearing as this trip we undertook together? I felt the influence of an artist like Félix González-Torres here, whose work always interested me.

Miguel Calderón, Chapultepec #11, 2003

Miguel Calderón, Chapultepec #11, 2003All works courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City and New York

Minera: Your series Chapultepec (2003) also has an interesting backstory, right?

Calderón: The Daniel Garza neighborhood was a pretty dangerous place, and going out into the street was a whole adventure; there were always run-ins with people, lots of drinking, violence. The mere exercise of going to Chapultepec Park, which was right next to it, was like a border crossing, because of the cars and buses giving off tons of smoke, and the amount of trash to get through. This gave me a sense for human fragility. And then in the park I’d come across dead animals or see fish, and I had no idea how they survived in this filthy lake. I’ve always been interested in studying chaos. And unconsciously I started to make a connection with the disasters depicted by Goya in his series The Disasters of War. We often think of the disasters of war, but what about the disasters of peace—an incredibly precarious peace, like the kind here in Mexico—which also exist.

So, I started to go to the park without really knowing exactly what it was I wanted to do, and more as an exercise for calming my distress. As a child, I celebrated all my birthdays in this park with my family. It’s the quintessential place for celebrating whatever the occasion might be with elaborate picnics. And that’s where it occurred to me to ask these families to let me take a photo of them pretending that a disaster had just occurred. Of course, they refused. So, I asked a friend of mine who’s a curator to accompany me, and I imagine a female presence changed the dynamic because people started to agree and even invited us to eat with them. And so, I became obsessed and over the course of ten weekends in a row, I went to document these scenes. I thought a lot about La jetée, Chris Marker’s film, about something that could be but isn’t, but once you do it, it becomes a reality. Of course, there’s a lot of humor in this work, even though it also speaks to the fragility in which we can all collapse at any given moment. When COVID-19 emerged and I looked at these photos, I felt a tremendous resonance.

Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.

March 23, 2023

A Visit to Kunié Sugiura’s New York Studio

This article originally appeared in Aperture’s spring 2022 issue, “Celebrations.”

In 1811, when the Commissioners’ Plan established the map that was to dictate Manhattan’s development north of Houston Street, city fathers settled on the gridiron as the ideal form not for its Euclidean elegance but for the sake of rank commerce: “Right angled houses are the most cheap to build,” they declared.

Meanwhile, in the city that already existed, streets slouched and coiled like vagabonds, their winding shapes defined by rivers, shorelines, swamps, and large rocks. Among these vintage arteries, Doyers Street, a narrow, two-hundred-foot dogleg angling between the Bowery and Pell Street, is unlike any other. The crime journalist Herbert Asbury, who covered downtown New York, once called it “a crazy street” and said “there has never been any excuse for it.” Turning onto it feels like stumbling into Venice or Kowloon and makes me think of Walter Benjamin’s sentiment in One-Way Street that as soon as we gain our bearings in a city, habit erodes our sense of wonder about it. Somehow, visiting Doyers never stops feeling like the first time because it never stops feeling like being lost.

Recently, I went to the old gray brick building at number 7 and rang the buzzer of Kunié Sugiura, who has lived and worked there in a rough, roomy, fourth- floor loft since 1974, making art that combines photography and painting in ways that confound conventions of both (often involving cameraless photographs and paintings that function more as sculptural objects than as canvases).

Sugiura, seventy-nine, born in Nagoya and raised in Tokyo, moved to the United States in 1963 to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she fell under the sway of one of her professors, Kenneth Josephson, who was at work establishing the terms of what would come to be known as Conceptual photography.

In the early 1970s, Sugiura began layering photographic emulsion, exposed with her Minimalist images of the city.

Sitting at a long worktable in the front of her loft, framed by tall windows overlooking Doyers, Sugiura told me: “I liked photography because photography was not really what it looked like. It’s such a subconscious thing, and you can experiment. Of course, all the other art students at that time completely looked down on us.” She moved to New York in 1967, partly because she sensed it was on the verge of generational upheaval. “And I knew that great social change is when culture happens,” she says. “But mostly, I just thought New York City was a lot of fun. Even going to a deli here was entertainment.”

In the early 1970s, Sugiura began layering photographic emulsion, exposed with her Minimalist images of the city—a storefront, high-rise windows, approaching headlights, the hull of the Staten Island Ferry—on surfaces such as aluminum, wood, and ceramics, until settling on canvas, a nod to the influences of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, though her work had a quiet poise that resembled neither. As the process developed, she incorporated monochrome or striped painted canvases along with the emulsions, sometimes grouped in wooden armatures that suggested frames but seemed more like elegantly deconstructed Shaker furniture. (The critic Karen Rosenberg once said that Sugiura’s early pieces appeared as if “Walker Evans had teamed up with Anne Truitt.”) Over subsequent decades, she has continued to press restlessly at photography’s boundaries, experimenting with collage, painterly photogram techniques, and landscape-like pigment prints.

Sugiura was featured early on in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1972 Annual Exhibition, curated by James Monte, and her work has appeared in exhibitions over the years at OK Harris, White Columns, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, among many others.

In the early 1970s, after the breakup of a marriage, she met the pioneering dealer Richard Bellamy “who told me he would be my agent—whatever that meant—but he really began to help my career and introduced me to other downtown artists like Neil Jenney.” She began hunting downtown for a space to live and work and chanced on the Doyers Street building, which had once housed the city’s first Chinese-language theater and later became a flophouse before being virtually abandoned in the 1960s. In 1971, the sculptor John Duff claimed the building for artists, making a loft on the top floor, where he remains today, and Sugiura moved in with two artist friends three years later, sharing the building with a Buddhist temple and, for a while, a loft of rowdy Cajuns with connections to Philip Glass’s musical circle and the artist-run restaurant Food, founded by Gordon Matta-Clark.

“This was where I really was first able to have the life of an artist,” she says. “It has sometimes been crazy or hard, but Doyers still feels like a sort of hidden place in the city, even in Chinatown, and the light that comes in my windows is north-east light, which is always beautiful. It’s my home.”

Related Items

Aperture 246

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]March 22, 2023

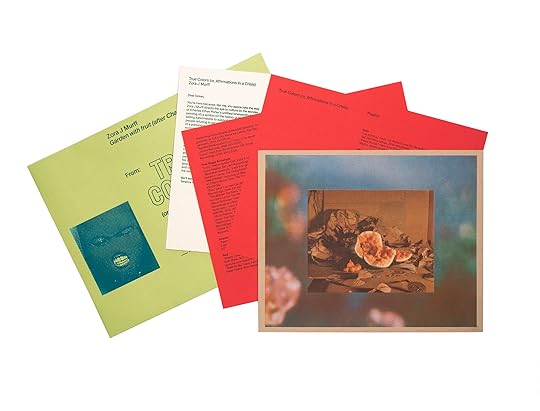

Aperture Salutes Ming Smith and Zora J Murff on the Occasion of the International Center of Photography Annual Gala

On March 28, the International Center of Photography in New York will honor artists Ming Smith for Lifetime Achievement and Zora J Murff for Documentary Practice and Visual Journalism at ICP’s annual Infinity Awards. Aperture is proud to have published first major monographs by Smith and Murff—and we join ICP in celebrating their extraordinary artistic visions and contributions to photography.

Ming Smith, Jump, Harlem, New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020)

Ming Smith, Jump, Harlem, New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020)Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Ming Smith, Amen Corner Sisters, Harlem, New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020)

Ming Smith, Amen Corner Sisters, Harlem, New York, 1976, from Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2020) When Ming Smith was a young photographer and newly arrived in 1970s New York, she passed by the Museum of Modern Art and said to herself, “I’m going to be in there one day.” She was right. In 1979, Smith became the first Black woman whose photographs were collected by the museum. Over the next four decades, she made images of astonishing range: cover art for jazz albums, spectral silhouettes of city streets, iconic portraits of Sun Ra and Grace Jones, and a series made in response to the plays of August Wilson. Smith’s first major monograph was published by Aperture in fall 2020 and includes a range of essays and interviews from artists, curators, and writers such as Emmanuel Iduma, Arthur Jafa, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Namwali Serpell, and Greg Tate.

This season, Smith returns to MoMA for the exhibition Projects: Ming Smith, and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston presents the career survey Ming Smith: Feeling the Future. With a technical mastery that underscores her improvisational energy, Smith has made an evocative, sometimes surreal chronicle of Black life and culture. Belated but timely, both exhibitions stand to reintroduce Smith as a major figure in American art who creates poetic images of rare distinction—a photographer who uses light to affirm self-determination and freedom.

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013 from True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) (Aperture, 2021)

Zora J Murff, Kenny at 19, 2013 from True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis) (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist and Webber Gallery, London

Zora J Murff constructs a manual for coming to terms with the historical and contemporary realities of America’s divisive structures of privilege and caste. Since leaving social work to pursue photography over a decade ago, Murff’s work has consistently grappled with the complicit entanglement of the medium in the histories of spectacle, commodification, and race, often contextualizing his own photographs with found and appropriated images and commissioned texts. Murff’s work is included in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where he was included in New Photography 2020: Companion Pieces.

True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis), published by Aperture in 2022, continues that work, expanding to address the act of remembering and the politics of self, which Murff identifies as “the duality of Black patriotism and the challenges of finding belonging in places not made for me—of creating an affirmation in a moment of crisis as I learn to remake myself in my own image.” Nuanced, challenging, and inspiring, True Colors is a must-have monograph by a rising and standout artist.

Related Items

Zora J Murff: True Colors (or, Affirmations in a Crisis)

Shop Now[image error]

Garden with fruit (after Charles Ethan Porter), 2020

Shop Now[image error]March 16, 2023

How Will AI Transform Photography?

Earlier this year, when I asked the photographer Laurie Simmons why she started using artificial intelligence as a creative tool, she said: “Because it exists!” Simmons’s initial interest in AI emerged as the COVID-19 pandemic limited excursions or gatherings for photo shoots, and she has recently used DALL-E, a popular text-to-image generator launched in 2021, to make new work. Amid debates about copyright and originality that AI sparked throughout 2022, she’s among a growing number of photographers exploring the potential and problems inherent in the technology.

Many concerns around AI and photography stem from the lack of structure or accountability for image-to-text generators, which scrape the internet for billions of images with associated text—captions, tags, and so on—to feed their databases. A group of artists recently filed a class-action suit against Stability AI for copyright infringement, as has the stock photography service Getty Images. Anxiety about the death of art seems to accompany contemporary art with every new development, even as artists adopt and adapt new tools in their practice. Simmons recently featured some of her new work in the online collection In and Around the House II, organized by the Web3 platform Fellowship.

Laurie Simmons, (In and Around The House II #32), 2022

Laurie Simmons, (In and Around The House II #32), 2022 Laurie Simmons, (In and Around The House II #13), 2022

Laurie Simmons, (In and Around The House II #13), 2022In many ways, AI is too broad a term, encompassing everything from self-driving cars to email phrasing prompts to personalized medical recommendations. It’s supporting your Google searches as well as the object-selection tool in Photoshop. For many artists, AI has meant a radical expansion of possibilities, but the technology also foreshadows the automation of much creative labor. People worry about their jobs.

Artists were initially intrigued by an early form of AI known as GANs, or generative adversarial networks, which created composite visuals from existing data, including images. GANs allow artists to compile personalized data sets; for instance, photographers may use their own archive of images to create novel work. In contrast, text-to-image generators depend on massive data sets that no single artist can compile. Until recently, they also needed invitations from developers to access these generators. But, by 2022, with the proliferation of the technology, a growing number of artists began sharing their experiments, and people saw firsthand what these systems could create from a simple string of words.

Simmons compares the experience of using DALL-E to watching an analog photograph appear in the developer solution. Almost immediately, the artist was able to make images that reproduce the domestic and psychological interiority for which her work is known, including doll-like figures in familial settings, extending the feminist discourse pervasive in her practice. Even when her AI figures are outdoors—strolling in fields or sitting on patios—her compositions suggest vignettes, creating a sense of the figures being contained or constrained by objects and environments. One “self-portrait” depicts a woman walking a dog along a country lane, and bears a startling resemblance to Simmons, her own dog, and even the roads near her home.

Shortly after her early encounters with DALL-E, she became more deliberate about her process and began identifying features and attributes to carefully construct more accurate and effective text prompts. For Simmons, these prompts feel like secrets—at least for now—and also full of surprises. “Some days I feel like an AI whisperer, other days like a flop,” she says.

Our physical gestures are expressive of internal, psychological states, but AI struggles to process the aesthetic of emotions.

Due to the range of sources from which these image generators pull data—online images ranging from stock photography, news imagery, social media posts, and personal websites—the results can range from the real to the uncanny. New York–based photographer Charlie Engman believes that AI’s limited understanding of bodies stems from perceiving them through images, not lived experiences. Informed by a background in dance and performance, Engman’s work spans fashion imagery as well as collaborative portraits of his mother. His AI experiments push some of these ideas further, exploring how the technology is able and unable to articulate bodily movement.

Our physical gestures are expressive of internal, psychological states, but AI struggles to process the aesthetic of emotions. Grief or pleasure may appear on AI-generated faces but isn’t replicated in those figures’ postures or gestures. Engman has observed that the body language of performers includes subtle movement choices cultivated over time to express thoughts and feelings, but these are rarely read accurately across AI data sets. Tags associated with images don’t typically specify a relationship between affect and a particular gesture. For instance, an emotion might be determined as happy because many images with smiles are tagged “happy,” but the AI might not be prompted to discern other subtle postures or stances, such as relaxed shoulders. For Engman, this gap is a compelling reason to explore the technology.

Charlie Engman, Parking Lot I, 2023

Charlie Engman, Parking Lot I, 2023 Charlie Engman, Sweetcheeks, 2023

Charlie Engman, Sweetcheeks, 2023The works he’s made using Midjourney, another text-to-image generator, depict strange and impossible contortions, many that bend the laws of physics and physical proximity. He’s been able to use the tool to create situations that he would never request of a subject, for ethical reasons as well as physiological limitations. His images of bodies merged into chairs, for example, playfully satirize modern office life. Other experiments have yielded images that mimic the visual language of fashion spreads, with his version featuring elongated models that appear both familiar and unnatural. Anyone interested in making images “must be curious at the very least,” Engman says.

Charlie Engman, Fashion Design V, 2023

Charlie Engman, Fashion Design V, 2023When DALL-E and Midjourney became widely available, many were also curious about how these data sets might interpret various identities and lifestyles. The interdisciplinary artist and researcher Minne Atairu developed an interest in AI in 2020, as part of her ongoing examination of creative technologies as a PhD student at Columbia University. Atairu’s work has primarily focused on the ways that technologies can reproduce or alter absences in cultural histories, particularly those of postcolonial Nigeria.

Initially, she trained a GAN data set to produce portraits based on images of Black models she downloaded from Instagram. When she turned to Midjourney, she discovered that the system’s ability to image Black identity produced recurring stereotypes, despite her efforts to push past them. Typing specific descriptions into the generator—such as a lime-green color for clothing—produced an image of a Black person in a cityscape with details she found remarkably similar to those of her neighborhood in Harlem. After some trial and error, Atairu inferred that Midjourney presumes a set of socioeconomic conditions by associating bright colors and Blackness.

Like the data sets that form them, these systems are not neutral. Midjourney’s limitations further spurred Atairu’s investigation into how text-to-image generators depict certain features on a Black person. Her series Blonde Braids (2023–ongoing) tackles this problem and the corrective work required. Requesting “blonde” hair as a part of her text prompt generated a suburban, middle-class environment, reproducing broad cultural stereotypes that reinforce racist imaginaries. The generators likely also struggled due to limited information in the data sets about people. Atairu explained how Melanesians—the Indigenous inhabitants of Fiji, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea—have naturally light hair, but the generator’s struggle to depict this suggested that it was unfamiliar with this identity. When she requested to prompt to generate an image of two people and specified melanin tones, the request for blonde hair would appear on both figures, but the generator seemed incapable of making them the same skin tone; one was always lighter than the other.

“Coded biases and stereotypes cannot be eradicated by tweaking text prompts and curated selections,” she says. “Instead, to address such inference problems, the developers need to review the underlying data structures used for training the model.” Atairu’s photographs may not represent actual people, but they reflect a significant and enduring information bias. “No matter how hyperrealistic,” she adds, “there will always be a glitch.”

Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study IV, 2023

Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study IV, 2023 Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study V, 2023

Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study V, 2023 Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study II, 2023

Minne Atairu, Blonde Braids Study II, 2023 All photographs courtesy the artists

These are still early days, and many feel this is a special, even fragile, time for AI-generated imagery. To discredit these representations based on image quality or veracity alone is to miss the larger point about the inequality of the culture from which they emerge—both in terms of social mores and online data. Experimenting with these systems is a first step toward demanding they be made better and more inclusive. While Engman and Simmons push their work in new aesthetic directions, Atairu alerts us of the assumptions and imbalances that underlie AI databases.