Aperture's Blog, page 35

December 14, 2022

Jimmy DeSana’s Transgressive Vision of Life and Desire

In the early 1970s, those in the know of the mail-art network might have found their lucky boxes stuffed with an image of a handsome young man. He had a throbbing dick and his neck in a noose. The man went by Jimmy, or Jim, DeSana, or de Sana, or De Sana—what’s in a name? The photograph was by him too. DeSana got around; he seemed to know everybody who was or would be anybody in American downtown culture, and so if you were one of them you might have gotten it from him directly. Mail art was amazing that way: if you were connected, your postal carrier might deliver a minor masterpiece or intriguing experiment, sent by an artist on the other side of the world or a few blocks away, as frequently as you might stumble upon one in a gallery.

If not, you might have seen the photograph in the February 1974 issue of File, the Torontonian queer collective General Idea’s ground- and boundary-breaking magazine. Or, on the cover of Vile, Anna Banana’s baiting File lampoon. If you didn’t know the face, you could grok the aesthetic: The noir rubbernecking of Weegee, in content. Its tone was Arbus. Its form, the way his arms pulled back like Hermes and chest stretched like Christ, evoked the life-and-death magic of Kenneth Anger. Its refusal to remain as a single ownable object, with a singular meaning, pulled in strategies of Surrealism, Fluxus, and punk, while its instant appeal was pure Pop. It was abject, funny, and oddly abstract. It should be unforgettable.

Jimmy DeSana, Sofa, 1977–78

Jimmy DeSana, Sofa, 1977–78 Photograph by Allen Phillips

Submission, the Brooklyn Museum’s welcome retrospective of DeSana’s photography and video, is overdue in the sense that the COVID-19 pandemic delayed it by almost two years and also because it should have happened decades ago. The artist Laurie Simmons, DeSana’s friend and collaborator, has been working for years to archive and protect his work—and champion his legacy. At the show’s long-awaited opening in November 2022, she gave a toast to its curator Drew Sawyer, noting that the work was waiting for him. We should be glad they found each other.

DeSana’s vision feels as much of its own moment as it does ours; a photo like Sink (1979), in which a corseted figure bobs for something in a sink full of bubbles is so smart, and stupid, that it achieves timelessness. At a moment in which queer visibility is once again increasingly life-threatening, it’s admirable that the museum mounted this show on the ground floor—in a space near the entrance that was formerly the gift shop—for all the world to see. Sawyer’s nimble installation sidesteps prurience and preciousness, moving viewers through rooms of insouciant early 1970s photos to the hallucinatory, dignified work DeSana made before dying of AIDS-related complications in 1990. Without succumbing to the self-congratulatory drama of a rescue mission, Submission recoups what may have otherwise been lost.

Installation views of Jimmy DeSana: Submission, Brooklyn Museum, 2022

Installation views of Jimmy DeSana: Submission, Brooklyn Museum, 2022 Photographs by Danny Perez

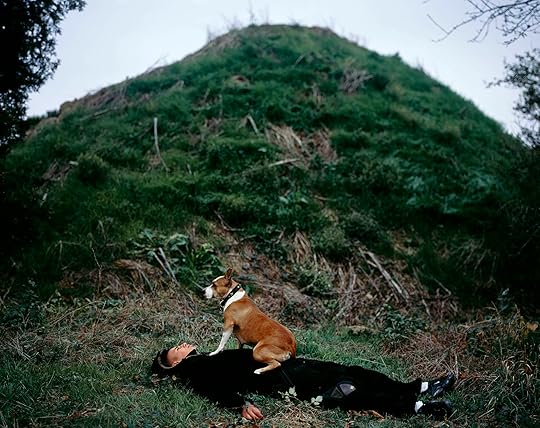

DeSana was born in Detroit in 1949 to middle-class suburbanites, who raised him and his brother in Atlanta. His mother was a strict Methodist; his father abandoned the family as DeSana entered adulthood. While studying art at Georgia State University, DeSana began making precocious, conceptual photography of suburban houses, generally banal, and of his friends, often naked. But his final thesis, 101 Nudes (1972), is a landmark. Likely taken with a Leica IIIf and lit by a flash, as Sawyer notes in his catalog essay, the portraits form a kind of fanzine of queer friends. DeSana shows off their muscles like he’s making Physique Pictorial, or crouches and crops their bodies like a funnier Man Ray. A drag queen looks right into the camera, bold; a man shoves his face into a pillow, ass beckoning. Bodies are unstable, and DeSana captures how funny, and how frightening, that can be, and how those two emotions comprise desire. Sawyer hangs these prints on the wall like Teen Beat posters in a teenage bedroom. It’s hard not to be a fan.

Jimmy DeSana, Stephen Varble, 1975

Jimmy DeSana, Stephen Varble, 1975Photograph by Allen Phillips

Evidence and expression in hand, DeSana moved to New York in 1973 and spent the 1970s hanging out at the nightclubs downtown, enjoying the spectacular squalor of Times Square, and working rooms further uptown, like Robert Stefanotti’s gallery on 59th Street. He took early portraits of the Talking Heads and Laurie Anderson and Debbie Harry that quickly established their personae. His non-star subjects also seem like them. Submission positions these images like family portraits. Often, they are black and white, stark as his earlier autoerotic provocation, sometimes lit by a single bulb on the sideline. The lighting doubles their bodies into an architecture for their charisma, or a shadow they couldn’t shake off. When he worked in color, it was those of candy wrappers, neon, the camp saturation of advertising. Recognizable but not realism.

With a wink to the commonalities of darkrooms and backrooms, Sawyer built a red-light district for DeSana’s extensive investigations of BDSM, in which piss is expelled and enjoyed, and gimp-masked figures kneel in toilets or near dog bowls. In Party Picks (1981), toothpicks stuck into gums between teeth make a crown of thorns around a gasping mouth, or maybe make that mouth St. Sebastian’s wound. Cardboard (1985) offers a room with a single, lurid red band of light and corrugated carboard that slices a bending body. In such a place, you might think of Samuel Steward’s card catalog of his conquests, or if Flavin’s work is really about its shadows, or what to do with that butt. DeSana’s frisky, familiar portraits reject the po-faced posing of Mapplethorpe and the social-climbing sadism of Helmut Newton. He gets that such proclivities are mind games played with bodies and bets you might want to play them too.

Jimmy DeSana, Storage Boxes, 1980

Jimmy DeSana, Storage Boxes, 1980 Jimmy DeSana, Marker Cones, 1982

Jimmy DeSana, Marker Cones, 1982 All photographs © Estate of Jimmy DeSana and courtesy the Jimmy DeSana Trust and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York

Toward the end of his life, DeSana went monumental. Soft Ball (1985) puts a toy on a plinth and conjures an awe somewhere between Ansel Adams and Kubrick. Grill (1985), captures its titular forger of suburban masculinity bent over in blue. It looks like a mammoth cage. It might be about his childhood. Sawyer provocatively asks viewers to return to the beginning when exiting the show, refusing to let death have the last word. Now, it’s almost impossible to resist the sense that DeSana was just getting started. But we must. He did so much, and it was enough.

A decade after DeSana photographed himself hung in a noose, he made Stitches (1984). The self-portrait shows off his sexy Calvin Klein briefs, and also the thick, roping scar he earned when HIV infection (and celiac disease) ruptured his spleen. The sutures are both evidence and prophesy, but really, they’re just a part of him and his art—what he made from mortality. I’m thinking as I write this of the selfie Daniel Davis Aston posted just before he was shot dead at Club Q in Colorado, in which he caresses the stitches of his top surgery. DeSana claimed the right to make bodies as he saw fit. Submission demands we now also have that right. His work is immortal in its unabashed mortality. We might live that way too.

Jimmy DeSana: Submission is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through April 16, 2023.

December 13, 2022

Nan Goldin Reflects on Art, Addiction, and Activism

This interview originally appeared in Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” summer 2020.

Nan Goldin moved from Boston in 1978 to Manhattan’s Lower East Side. She was twenty-five years old. New Wave was starting to happen, and so was she. Nan went everywhere with her camera. She was part of the Times Square Show in 1980, on her way, it would turn out, to the Whitney Biennial in 1985 and beyond. She was creating The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1983–2008) as a slide-show during this time, when the underground, of which she was a star, suddenly riveted the attention of a larger culture. This new youth vanguard was urban and music-driven, as into film as it was into books.

Stylistically, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency claimed descent from Weimar (the echo of a song title from The Threepenny Opera in Nan’s title is deliberate), from the women as well as the men of the Beat generation, and from Andy Warhol. But the toughness was a front. Nan’s early images survive a time of sexual life before AIDS and a love of drugs before the wages of addiction had to be paid. Nan is the witness of a passing American innocence, watching her community as it became decimated by AIDS.

Cover of the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Cover of the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985Courtesy Nan Goldin

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency was first published as a book in 1986. Its more than one hundred photographs show the drive of Nan’s aesthetic—her intimacy with her subjects, her decision not to photograph anyone doing something she herself would not be willing to be photographed doing, her theatrical sense of place, her mastery of visual narrative. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is a story about love and desire, loneliness and friendship, men and women. The people we see are her friends, her lovers, and the family she had made for herself. Nan has called it “the diary I let people read.” It is a work that evolved as a slideshow from performance to performance. The installation of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in the 2016–17 season featured 690 images.

“It was photography as the sublimation of sex,” Nan wrote in 2017, “a means of seduction, and a way to remain a crucial part of my subjects’ lives.” Her story goes a long way toward explaining her work, seen in numerous books. The Other Side (1993), an homage, in part, to drag, followed The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. Then came A Double Life (1994) and the catalog of her spectacular retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, I’ll Be Your Mirror (1996). The Devil’s Playground (2003) encompassed much of her new work at the time. The Beautiful Smile (2007) marked the occasion of Nan receiving the Hasselblad Award. Eden and After (2014) is a touching work about childhood. In Diving for Pearls (2016), Nan engages with art in the collection of the Louvre through her photography. Her work constitutes an autobiography in several volumes, her life as an episodic tale.

The range of subjects, the sheer amount of published photographs, speaks of Nan being always at work, immersed in her purpose to document the movement of a life. Just as her subjects have changed, so has her practice. Her projects, such as Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls (2004) and Memory Lost (2019), take to an unprecedented level the slideshow form she has made her own. Her unique, unforgettable installations have been exhibited in museums and galleries throughout the world. Nan is one of the most critically acclaimed and inspiring photographers working today. The courage she has shown in her work is fueled by a social bravery that makes her formidable as an activist for marginal communities. Luc Sante once called Goldin a “portraitist of souls.”

New York’s Lower East Side, Berlin, Naples, London, Bangkok, Tokyo, Paris—she’s laid her head down in a good many places. The other day it rained when I went to see her where she now lives in Brooklyn. Everything about her place was quiet, tranquil. —Darryl Pinckney

Nan Goldin, Ivy on the way to Newbury St., Boston Garden, Boston, 1973

Nan Goldin, Ivy on the way to Newbury St., Boston Garden, Boston, 1973Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Nan Goldin: Do you mind if I smoke a cigarette? Thanks. I discovered art photography when I took my first photography course. I was nineteen, and it was Diane Arbus, Larry Clark, Weegee, and August Sander. But before then, I was entirely influenced by the glamour of black-and-white Hollywood film and fashion photography, like Guy Bourdin and Louise Dahl-Wolfe. I had already seen Flaming Creatures (1963) by Jack Smith and Warhol’s early films. I saw Trash (1970) many times. We always went to the movies. And not just Hollywood. Truffaut, Fellini, Antonioni. I realized that I wanted to be a photographer from a scene in Blow-Up (1966).

Darryl Pinckney: We can see Hollywood in some of the work. And you were already doing the slideshows in Boston, right? Were those the sort of glamorous, black- and-white photographs of the queens?

Goldin: No, they were terrible pictures of a lesbian community in Provincetown. Because in art school, you had to show what you were doing, but there was no darkroom, so I couldn’t show prints. That’s why I had to show them as a slideshow. Bruce Balboni had shown a slideshow in our apartment in Provincetown with my pictures of Cookie [Mueller] and Sharon [Niesp], and he invited them. We wanted them to like us. There are gorgeous pictures of Cookie and Sharon. I looked at these images recently, but aside from those, the work is banal, boring, and brown.

Pinckney: Are you a very harsh judge of your own work?

Goldin: I imagine so. But I think I’m right about my own work. Anyway, the lesbian community in Provincetown at the time was very small, and all the women were fucking each other, which made it interesting. I fell in love with a woman and obsessively photographed and filmed her for a long time, even after she broke up with me. I guess that was the beginning of what drove me to photograph people.

Then I left Provincetown and found the community at the Other Side [a Boston club]. I was attracted to the glamour and the fact that it was underground.

Pinckney: There’s an edge in the drag queen photographs.

Goldin: Right. They were living something that was so taboo then that they couldn’t even leave the house in the daytime. We went to the Other Side every night. It was our haven and our headquarters. I moved in with Bea and Kenny, who were the most beautiful. I was standing in New York on Second Street and Second Avenue two years ago, and I suddenly heard the name Nancy being called out. I didn’t recognize that name at all. It was Bea from Boston.

We hadn’t seen each other in forty-five years, and she recognized me. She’s just the same—funny and dry. She was still married to the same guy. I went to Boston to have tea with her. It was lovely. And she told me that everyone else in my pictures is dead.

Poster for The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, with Desperate Living, a film by John Waters, OP Screening Room, New York, March 29, 1982; Artwork by Janet Stein

Poster for The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, with Desperate Living, a film by John Waters, OP Screening Room, New York, March 29, 1982; Artwork by Janet SteinCourtesy Nan Goldin and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: You had left Boston in the late ’70s for New York.

Goldin: Yes. I used to hitchhike down to New York to fuck my boyfriend while living in this separatist lesbian community. I’ve always been able to live with ambivalence.

I moved to New York, and I worked as a go-go dancer, like all the girls did, like a lot of women in the art world were doing at the time to have money to do their work. Until I met Maggie Smith [co-owner of the bar Tin Pan Alley in Times Square]. She rescued me. That’s when the work changed. That’s when my view of life changed. That’s when I felt that I was secure in saying that I was political. She gave me that frame. She saw the slideshow at the Times Square Show, and she said, “You’re a very political artist.” That was huge for me. She analyzed it within a gender framework—of politics around gender, the sex trade, and male violence. Working at Tin Pan Alley at the beginning was a liberation for me. I hadn’t known anyone quite like Maggie. She opened big doors for me.

Maggie was so many different people at once. She was involved with that bar and the people who worked behind that bar. And then she was involved with the radical Puerto Rican Liberation Front. And then she had her Women Against Pornography. She was one of the essential people in that. And then also, she loved ballet. Not many people can sustain that much, be so multifaceted.

The first slideshows were constructed in the context of parties, and then underground movie theaters and performance spaces. Maggie used to attend every single one. Editing and reediting is a big part of the story that I like thinking about, and sometimes I would be editing while I was doing the show. And the projector would break down at OP Screening Room, and I would have to leave and go back home and get a bulb and bring it back. And people would still be there. But the audience would be everybody who was in the slideshow. Afterward, they’d be furious about some picture they looked ugly in, and I would take it out. I never had that again, that the slideshow was for the people in the room. Except it did happen in the ’90s. I did a slideshow every week in Bruce Fuller’s apartment for the people in the pictures. They had editorial control.

Pinckney: J. Hoberman had a nice expression about the early slideshows in New York. He said, “Part of the excitement was the sheer brinkmanship of them.”

Goldin: In what way?

Pinckney: Well, would Nan show up?

Goldin: Oh, I thought you meant the content of the work.

Pinckney: No, of the performance.

Goldin: And whether you had to wait five hours.

Pinckney: I can remember your light tables and the hundreds of slides as you would—

Goldin: Edit and reedit. And then, there was this time when I was showing in a gay club on Second Avenue, and the place was packed. Rene Ricard was with me, and there was coke on all the slides. Marvin Heiferman was representing me all those years, and he was ready to drop me. The owner accused us of all being junkies. At the time, I didn’t want to accept that analysis. So, it was brinkmanship of whether I would show up. That’s true.

Pinckney: You always showed up.

Goldin: Eventually.

Pinckney: No, you did.

Goldin: And then J. Hoberman was the first to contextualize it as a film. I was thrilled. It became one of those underground phenomena, like Todd Haynes’s Barbie film [Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, 1988], that people had to see. And, as we said in those years, in the ’80s and ’90s, there was no way to see anything unless you were present.

Pinckney: Yes. That’s what gave, I think, the call-and-response with the work.

Goldin: Yes. Exactly.

Nan Goldin, Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 2022)

Nan Goldin, Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Pinckney: It was kind of like going to church. I remember it as very vocal.

Goldin: Cookie and I would stand in the back and crack jokes all the time. Now I sit in the back and count how many people are dead, and speak to them through the slideshow. That’s my contact with them. My deep visceral contact with loss. The slideshow’s very much about loss. It was at the time. The loss of my sister, which permeated it. But also, the potential loss in relationships. And, it’s a lot about violence, also, which people don’t talk about much. People write about drugs and parties.

Pinckney: Yes. Or they focus on the moment of violence when you were in Berlin, the battery.

Goldin: The battering, yes, which is essential to the slideshow and to the book. That kind of imagery was not seen at the time. A lot of women came to me and told me their stories, from all over the world, all over Europe and America. I traveled through Europe for a couple of years showing the slideshow.

Pinckney: This is when?

Goldin: 1984. It was never the same show. Every time was different. For one thing, when I was first doing it, I had people read to the images. I later added music, especially after seeing the films of Vivienne Dick. She had an enormous influence on me, the way she handled music. Her segues. Start, stop, go.

Pinckney: I still see a lot of … I won’t call it innocence, but fragility.

Goldin: Well, there’s always been fragility in my work.

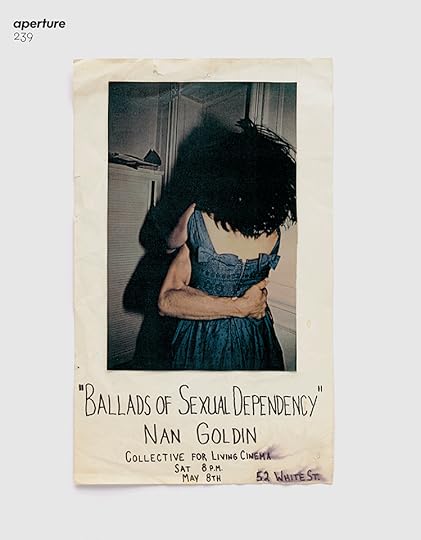

Poster for Ballads of Sexual Dependency, Collective for Living Cinema, New York, May 8, 1983

Poster for Ballads of Sexual Dependency, Collective for Living Cinema, New York, May 8, 1983Courtesy Nan Goldin and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: But so much strength in the aesthetic behind it. I think especially about Tin Pan Alley and Maggie and this women’s collective, however informal it was, supporting the work and feeding into this work, starting with how much Vivienne Dick’s films meant to you.

Goldin: When I started working at Tin Pan, I thought it was an escape from the art world. I wasn’t really in the art world, so I don’t know what I was escaping from. I retracted from that world and went to Times Square. It also permeated my sensibility, not my artistic sensibility, but my life and my sense of self.

Pinckney: Were drugs a part of that?

Goldin: I was taking coke. I wasn’t doing dope then. My first drug during the ’70s was quaaludes, at art school with the queens. I lived on quaaludes for about seven years. Loved them. They gave me a big social personality.

Pinckney: Looking at these photographs again, I was very moved. Well, first, everyone’s youth. Maybe that’s …

Goldin: Envy.

Pinckney: … where I feel the fragility. And their beauty. But, also, the photographs now seem to me so much more composed than they did at the time. They’re not loose. The composition is very strong in each.

Goldin: That’s interesting.

I have often been able to show people how beautiful they are, when they don’t know it.

Pinckney: And also, they have a documentary impact beyond the relationships you were recording and talking about. There’s so much social history in a red telephone. Who knew?

Goldin: It’s ethnography, right?

Pinckney: The light is extraordinary.

Goldin: This is my eye. I wanted to get close to people. But, also, I was very interested in where people were situated in a room, and what was in the room. But it was often just to feel close to people. I couldn’t have been taught this eye. You don’t teach someone an art.

Pinckney: No. There is something called the mystery of talent. There is one photograph in there of a woman in her slip, and her boyfriend in a slip. I think of that as a very androgynous moment, that old-fashioned word.

Goldin: I still love that word. They weren’t androgynous. That was more a sort of playing with sexual games.

Pinckney: We don’t know who they are. It’s a guy and a girl, and they’re both wearing slips. That’s another thing about The Ballad. The eroticism of it is stronger than ever. But it’s never been pornographic.

Goldin: I love that it’s erotic, people with dirty feet. You can smell the people, and you can’t smell photography, usually. It’s very tender.

Nan Goldin, Brian on the Bowery roof, New York City, 1982

Nan Goldin, Brian on the Bowery roof, New York City, 1982Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: Or the photograph of Brian, your then boyfriend, on a Bowery rooftop.

Goldin: That’s a story that doesn’t exist anymore. Even the skyline is completely destroyed. I didn’t photograph people I didn’t love. I had to feel a connection.

Pinckney: Maggie provided a venue for downtown artists at Tin Pan. We could connect.

Goldin: I miss Maggie. She also took you to things. Besides politicizing me, she introduced me to theater and ballet and skin care. That was the big one. No, she loved my work. She loved me.

Pinckney: Most of the junkies we met when we thought—

Goldin: You’re not allowed to use that word anymore.

Pinckney: You’re not?

Goldin: Substance use disorder. That’s important, politically. But we can call each other junkies.

Pinckney: Oh. I always think of the William Burroughs title.

Goldin: Yes. But it’s about respect and destigmatizing.

Pinckney: You and I speak the language of our time.

Goldin: Exactly.

Pinckney: There was a time when we didn’t think cocaine was addictive.

Goldin: I know. We grew up on that note. I believed that all through the ’80s when I was totally strung out on coke. I didn’t know what was happening because it wasn’t addictive.

Pinckney: An addict was a heroin addict, and most addicts weren’t nodding on the stoop. They were going to work and coming home.

Goldin: It’s still true. It’s still true.

Related Items

Aperture 239

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Shop Now[image error]Pinckney: That’s the world of addiction, of old-fashioned addiction.

Goldin: But it’s so important to take the onus off. And those words are stigmatizing. I referred to myself as a junkie at the VOCAL [Voices of Community Activists & Leaders] office one day, and the old-time junkies jumped on me. “We don’t use that word. It’s really important.” But I wanted to be a junkie. I grew up wanting to be a junkie. I got the [Velvet Underground & Nico] album with Warhol’s banana on the cover when I was thirteen, and I was in a situation where I was very isolated, and that album was my attachment to life. It framed my view of the world.

And because I shot dope when I was eighteen, for a year, and then put the needle down and met quaaludes, I thought I wasn’t an addict because I put the needle down.

Pinckney: I was going to say that with the passage of time, I feel the drugs much less in the photographs than I did.

Goldin: Good. My new piece Memory Lost is about drugs. I just came out of a huge addiction three years ago. Enormous. My dealer called me and said that the OxyContin that I was addicted to had been thirty dollars each, and he was having a sale. He called me at the hospital. I think he’d lost his biggest customer.

Pinckney: He was having a sale?

Goldin: Twenty-five each. Somehow, it didn’t grab me. But soon after, he died. If he hadn’t died, I would have a really hard time staying clean because he came 24/7. And he was constantly freebasing. He used to try to get me to freebase. He would kiss me, although he was ugly, and it was nothing romantic, just to blow the freebase into my mouth. And that’s all I would do. I never picked it up. I’m so lucky because that would’ve been the end.

Nan Goldin, Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983

Nan Goldin, Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: Talk about something that isolates you.

Goldin: I was so isolated. There’s a lot of sadness. That has to do with looking back on the images now.

Pinckney: The photographs capture the complexity of then, the sadness within the late nights and parties. The one of Cookie in Tin Pan is really so striking in every way.

Goldin: That’s because it’s lit by movie lights. It was taken during the filming of Variety.

Pinckney: But it’s also the moment you capture. There’s a drink. There’s a cigarette. And her arms are folded as though she’s disinterested.

I remember Luc Sante writing once that one of the surprises in your work is that there you were, in the same scene with all this, and yet, you could take these pictures.

Goldin: I had to take these pictures. They gave me a reason to be there. I think the whole reason that I write about in The Ballad, about my sister’s death and the need to record everything, was predominant. It wasn’t an act of will or very much about pursuing art. It was out of need. All my work, I think, is out of need.

Pinckney: So the photography leads you to something else, even if it’s another city or another person?

Goldin: The photography took me traveling, in many different ways. And, most of the time, the relationships came first and then the pictures. Sometimes the pictures came first and then the relationship. The pictures became a way to introduce myself to someone or to become important in somebody’s life. I have often been able to show people how beautiful they are, when they don’t know it.

Pinckney: Was this the feeling behind your book The Other Side?

Goldin: Yes. Very much. Starting with the early black-and-white work.

Pinckney: Then, after The Other Side, you get these terrific photographs using natural light.

Goldin: Yes. I stopped using the flash fifteen years ago. And I don’t photograph much anymore. What I’m working with is existing footage. My piece Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, for instance—it’s almost entirely archival footage, including snapshots from my childhood. And for Memory Lost, I didn’t shoot anything. But I photograph the sky. I have a relationship with the sky. For me, it’s magic. It gives us our sense of space and size in the world. I try to photograph people, but it doesn’t work anymore.

Pinckney: Why is that do you think?

Goldin: I don’t know. I don’t have it anymore. But there are very few instances in which I feel the desire to photograph someone. It’s not my life anymore. People are more self-conscious as they get older. My world isn’t quite so free. We’re not so free. Not so off the grid. It’s on the grid.

Pinckney: Is it age?

Goldin: And lifestyle.

Pinckney: We ask different things of a city, the older we get.

Goldin: Well, I ask different things of my friends. I have different types of relationships. I don’t party. The relationships are much quieter and calmer, and I spend a lot of time alone. But I also spend time with people, working with them. I was bemoaning that to my therapist, and she said, “Well, you love to work.” So it’s a fun and loving thing to do.

Pinckney: Is it also that you have reached a time in life when to reflect and look back is natural?

Goldin: No. I analyze less, and I really don’t look back much unless I see something like Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, and then it’s very scary to go back there.

There are a lot of broken relationships, there’s a lot of death, an enormous amount of death in my community. And there are a lot of relationships that, at some point, I wish I could fix, but I’m not sure I can. I would like to.

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 2022)

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Pinckney: Memory Lost is certainly really the whole story in a way.

Goldin: It’s about being addicted and the darkness of life.

Pinckney: And then the priory photographs [taken in a London hospital] are very touching, but the self-portraits in Memory Lost are chilling.

Goldin: I used mostly myself and my friend Guido [Costa], whose idea it was to make the piece. And a few other people. But most of the other people are dead. There are a few people still alive, but I tried to make them more or less anonymous.

Pinckney: But the beautiful dancing frame—you know, the black-and-white frame?

Goldin: Oh, you mean the old Super-8 at the beginning and the end?

Pinckney: Your things are very consciously constructed.

Goldin: Yes. Very. I would say that my work is editing. I’ve always said that primarily the art is not photography, the art is editing. I’ve always said that if anyone would have taken as many pictures as me they could be considered a good photographer.

But that’s not the point. The point is what I’ve done with the pictures. The point is about making cinematic work out of still images, and the editing is where I feel my intelligence lies.

Pinckney: The recent work is much closer to what you were talking about when you say you think of yourself in the way of a filmmaker. It’s moved much more in that direction than The Ballad.

Goldin: I think so. The Ballad is a pretty straightforward form. There are slides, and there’s music. These other two pieces have a lot more elements. In Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, it goes from archival, to film, to stills, and from music, to narration, to voices. And then with Memory Lost, there’s the old Super-8 film, and then there are the old answering machine tapes, which I think this generation won’t even recognize what they are because they’ve never seen an answering machine. It’s crazy.

Pinckney: The dial tone.

Goldin: Exactly. They won’t know what that is.

Pinckney: There are a lot of cries for help coming through.

Goldin: And I sound so coked up. The Ballad for me now is about loss. And while Memory Lost does not feel like a hopeful piece, there is some hope that’s essential to it. I wouldn’t have made it if I didn’t have some hope.

Pinckney: Well, the sky makes its appearance.

Goldin: And it ends with [Franz] Schubert and Gabor Maté, a philosopher, psychiatrist, and writer who I respect so much, saying that it’s only human to do drugs.

Pinckney: And then, the woman falls back into the water. It’s beautiful.

Goldin: Thank you. I felt it was very important to use that text by Gabor to destigmatize drugs. It could have been at the beginning, but then it would have been a little heavy-handed. But I want people to leave with some relief of the stigma of what they’ve just seen.

Pinckney: It’s in the right place. Actually, it kind of deglamorizes it.

Goldin: Well, that’s not a glamorous piece.

Pinckney: No. Whereas Ballad—

Goldin: Ballad is glamorous.

Pinckney: Yes, the youth, and the subject is desire and love.

Goldin: And passion and sensuality. Memory Lost is not a sensual piece.

Pinckney: The colors are super saturated. And each became a memory as soon as it was photographed.

Goldin: That saturation is how I see the world, but I don’t see memory that way.

Pinckney: No?

Goldin: For me, I don’t have that same relationship to memory. I don’t see photographs as freezing life because of the way that I use them. I never believed in the decisive moment. I never believed that one photograph encapsulates the whole of one person. Of course, published, there are single images on a page, but the whole way that I frame my work is in multiple images. Now I use grids when I show pieces on the wall, which I’ve wanted to do since the ’80s, but I couldn’t afford it then. They are like storyboards. I show a lot of grids and triptychs and diptychs.

In the late 1990s and the 2000s, I was influenced by color-field painting. It doesn’t relate to my work, but I like art that’s very far away from me. And I started making grids that were just colors. Black, red, a kind of homage to the color field painters.

Pinckney: Are some of the paintings in Memory Lost yours?

Goldin: They are mine.

Pinckney: Well, it is the kind of stuff that comes with the price. Not to sound romantic.

Goldin: It’s not romantic, and it has a price. As I realized going back into Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, it’s a high price. It’s a high price to make it, and it’s a high price for me to look at it.

Pinckney: Nothing is casual.

Goldin: Unfortunately not. Yet there are images in The Ballad that are very casual, that don’t have that same weight of self.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Mark Mahoney in Bruce’s car, Boston, 1977

Nan Goldin, Nan and Mark Mahoney in Bruce’s car, Boston, 1977Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: Well, because a lot of what’s in The Ballad is celebratory.

Goldin: In Sisters, Saints, and Sibyls, it’s an accusation against American suburbia—what a toxic life suburban America was in the ’60s. It’s also very angry toward my family and the family structure.

Pinckney: You talk about how you didn’t like Julia Margaret Cameron’s work at first, and then, after a while, you began to appreciate how she took an accident and made it her kind of aesthetic.

Goldin: Yes, slightly out of focus and like spirit photographs almost. The best pictures of mine are accidents. Memory Lost is entirely accidents. It was so much fun to find the worst photographs. The less that was in the photograph, the better it was. The darker it was, the better it was for that piece. But the voices are really important.

Pinckney: And the voices add a completely different theme. It made me think about your writing. You don’t do that anymore either?

Goldin: I needed to write. I needed to draw. To keep myself alive in both those situations, both times. So when you don’t need it, it’s too painful. It’s too difficult. You are a writer—you know how difficult and horrible it is. The empty page is the nastiest thing in the world. And I think the mark, the pencil mark, is the truest sign of mankind. I needed a disinhibitor to do that.

Pinckney: But has all of your work shared this sense that I must do it in order to survive?

Goldin: I don’t know that I thought in those terms, but I knew I had to do it. So you know my diaries, of which there are thousands—I have to make sure they’re destroyed when I die because they weren’t written for anyone except for me to stay alive, and basically it’s thirty years of: “I’m so depressed.” “I’m so fat.” Kenny once stole them, and read them, and said they were so boring. And they are. There’s nothing in them that other people should read. It will completely destroy the myth of Nan Goldin. They’re just about me, and my pain, and nothing else. There are no great observations about New York in the ’80s. They’re not Warhol’s diaries. They’re just about being depressed.

Pinckney: People turn to diaries for different reasons.

Goldin: And mine were not witty observations.

Pinckney: The work you’re doing now, though, it’s important.

Goldin: We are really survivors.

Pinckney: I’m afraid so.

Goldin: It’s a miracle that I’m alive. Doesn’t make any sense that I should be.

Pinckney: Some of the things I did, some of the places I was, some of the chances I took as though nothing bad could ever happen.

Goldin: Falling into that swimming pool, falling, falling, falling. A lot of falling, a lot of hospitals. It’s hard for me to own that period of my life. I feel there is a big separation. Oh, and there’s also the myth of Nan Goldin. Nan Goldin is not in this house. Nan Goldin’s external, and I have very little to do with her. Only when I’m giving a talk, then I’m Nan Goldin. At my opening, I’m Nan Goldin. But otherwise in my life, I’m Nan, and that’s really important to me. If you believe your own myth, it’ll destroy you.

Nan Goldin, Sunny at the spa, distortion, L’Hôtel, Paris, 2009, from the series Memory Lost

Nan Goldin, Sunny at the spa, distortion, L’Hôtel, Paris, 2009, from the series Memory LostCourtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Pinckney: Your own experience was a part of this from-the-inside feel of your work about women and desire. However you feel about the period now, you weren’t separate from your subjects then. Maybe that is why the sense of distance is so strong now. But how vivid and real the images are. And maybe that’s part of what gives the work its freshness today, because it is still transgressive, though that’s an overused word.

Goldin: I like it.

Pinckney: Unexpected.

Goldin: Transgressive is better. I love it. I mean, let’s hope to be transgressive.

Pinckney: Okay. Well, it certainly was, even just a pregnant girl—

Goldin: Naked. Nowadays that’s even more transgressive. People are much more conservative. These images are more shocking now. Nudity is more shocking now.

Pinckney: It’s strange to think that these images, which, as we were saying, are not pornographic, are so threatening in 2020. At one point, they were so liberating.

Goldin: They’re taboo almost. Which is really scary. The old taboos were lifted, and now they’ve been recycled. When it’s shown, there are thousands of young people who go to see it, and I wonder what it says to them.

Pinckney: First thing it says is: You weren’t there.

Goldin: True. Everyone’s obsessed with the ’80s. They think they know the ’70s and ’80s from watching The Ballad. They don’t. But it must mean more to the kids than just that. They must be able to see themselves in The Ballad. Not just the clothes, but on some emotional level.

Pinckney: There’s a line through the work, the drag queens, The Ballad, The Other Side. Do you think that some of the changes of setting have to do with what used to be called geographics?

Goldin: Well, I skipped America for a long time, and I didn’t go back at all in the 2000s. But it’s not like I really experienced Berlin or Paris. I just hid for about ten years. I want to be careful not to do that again. It’s easy for me to do that. I have to make myself engage with the world. I’m so shy. That was what drugs did for me—they took away that terrible binding shyness. And I thought that they were giving me a social personality.

Pinckney: This is an irony the work and the activism share—bold public confrontation from the most private experiences, a confessional aesthetic from a vulnerable and therefore carefully recessed personality.

Goldin: So I have to try to find other ways to get over it. I’ve made my life an open book, which, nowadays, has served me well in this online culture of digging up people’s pasts and canceling them. It has served me well that I had this need to make the private public. There are secrets, but secrets before there was the Internet. The Sackler family, or someone, sent a private investigator here. He parked outside the house, following my assistant home, taking pictures. It’s been very surprising that they’ve not tried to out me about anything. Though basically, there’s nothing to out me about because I made everything public. They can’t exactly announce that I was addicted to drugs. I mean, deep scandal on that.

Pinckney: What could he do?

Goldin: Nothing. Megan and Harry, the two lieutenants of PAIN [Prescription Addiction Intervention Now], went down and confronted him, took a picture of him, and then he disappeared.

Nan Goldin staging a “die-in” at the Harvard Art Museums, 2018

Nan Goldin staging a “die-in” at the Harvard Art Museums, 2018Photograph by TW Collins

Pinckney: When did PAIN begin?

Goldin: In 2017, after I read an article in The New Yorker by Patrick Radden Keefe called “The Family That Built an Empire of Pain.” He exposed the Sackler family of multibillionaires who ignited the opioid crisis through their cynical greed. Their family business developed and marketed OxyContin, the most powerful narcotic painkiller on the market. They pushed it like the best drug dealers. Supposedly, the company made thirty-five billion dollars off it. They fed on the stigma of addiction and blamed the drug users. I always thought of them as philanthropists, but they were using museums to wash their reputation.

PAIN started with a focus on pressuring museums to stop taking their money. It also shamed members of the Sackler family who cared about their social status. We staged sexy actions that got a lot of media attention at the Guggenheim, and at the Metropolitan in New York, the Victoria & Albert in London, and the Louvre in Paris. The actions succeeded in helping us to win our demand that museums stop accepting their funding. The Louvre actually took their name down.

Pinckney: Has your activism had an adverse effect on your working life?

Goldin: People warned me at the beginning that this could be very dangerous. They were talking more about my career and how it could affect that. And the actual physical danger was an issue at the beginning, but nothing happened. Nobody made up the crisis. It’s really out there and was underacknowledged for a long time. People didn’t do the shocking arithmetic.

Pinckney: You and your group put the conversation in the mainstream.

Goldin: It’s gotten out and stayed out, and it’s stayed out there because of the support of the press.

Pinckney: You’ve always had an activist side.

Goldin: It wasn’t focused until I got sober three years ago, and I realized what was going on in the world and felt I had to do something. So, I chose what I know best, which is drugs, something I understand in my body. I didn’t know the tragedy of what was going on, and I became enraged. That rage is what provoked me to start the group.

I have to say that being in the public with PAIN, with the group that I started, has kept me sober.

Pinckney: You know how we say you have to get sober for yourself ? But now yourself includes a vast number of people.

Goldin: I think there’s the whole ideology that you need something bigger than yourself to stay sober. For me, that is being political in the world.

Pinckney: They are your higher power, other sufferers?

Goldin: No, not them. The idea of taking a political stance and making it public is my higher power. It’s something much larger than me.

Pinckney: Like the Artists Space show in ’89, the AIDS show [Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing]?

Goldin: I was newly sober then, too. I talk about the Artists Space show as part of my political growth, but I can also associate it with sobriety.

Pinckney: It was very important at the time. Two of the most important unifying elements that I think of when I think of you are an uncompromising sort of intelligence governing the work, but also this will to beauty.

Goldin: I think beauty is very important in art, because, after all, it’s an aesthetic experience.

Pinckney: These works, some of them, are very raw but never ugly.

Goldin: Yes, exactly. I have a very big aversion to ugly. I still think beauty is another level that we need. It’s a rest, it’s a caress, beauty. You know Arthur Jafa’s work? He makes these incredible videos about race. Brilliant. They are a condemnation and a provocation. One was just shown at the Museum of Modern Art [APEX, 2013]. And, you know, it can be about the ugliest things in the world and still be beautiful, if you consider honesty a form of beauty.

Pinckney: That’s Nan. You’re always beautiful, Nan.

Goldin: Thank you.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

December 7, 2022

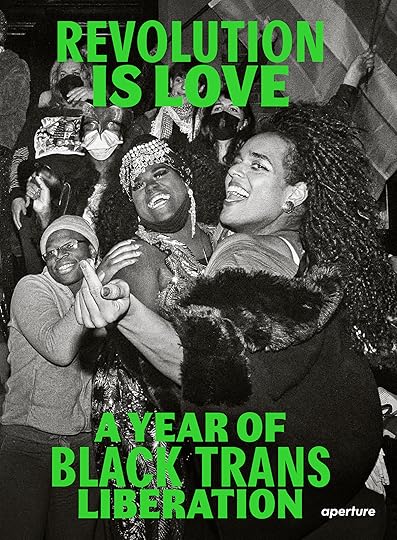

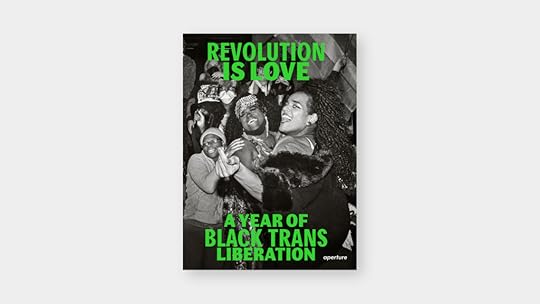

Inside the Revolution Is Love Book Launch Extravaganza

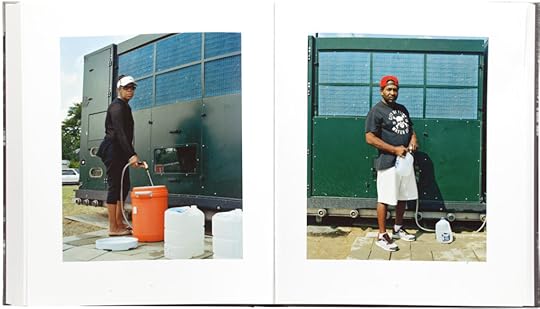

On Thursday, November 17, guests gathered at 99 Scott Studio in Bushwick, New York for a book launch extravaganza hosted by B. Hawk Snipes and Qween Jean in honor of Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation. The night featured DJ sets and dancing from a joyful crowd ready to celebrate the recently released publication and revel in community.

The activist, artist, and organizer behind Revolution Is Love, Qween Jean said of the evening, “To me, tonight is what Revolution Is Love symbolizes: we are beautiful people, we are brave people, we are talented people, and we deserve to live. Tonight, we unleash all of the power, the music, the vibrancy, because we are owed it.”

Qween Jean makes opening remarks to crowd, November 17, 2022.

Qween Jean makes opening remarks to crowd, November 17, 2022.Photo by Laura Randall.

The publication is a powerful visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City, and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community. Twenty-four photographers were gathered to share images and words on the contemporary Stonewall Protests started in June 2020. Through photographs, interviews, and text, Revolution Is Love celebrates the power of shared joy and struggle in trans community and liberation. Many of the book’s contributors were in attendance at the November launch event including Ramie Ahmed, Brandon English, Deb Fong, Stas Ginzburg, Chae Kihn, Erica Lansner, Daniel Lehrhaupt, Caroline Mardok, Ryan McGinley, Josh Pacheco, Jarrett Robertson, Cindy Trinh, Sean Waltrous, and Ruvan Wijesooriya.

The night’s guests were treated to performances from Linda La, Mariyea, Basit, Lady Jasmin Van Wales, Vuyo Sotashe, and others. DJ sets from Byrell the Great, Bronz3 Godd3ss, and Rajah Rah energized the party late into the night.

In a moving speech, Qween Jean said, “Revolution Is Love is a love letter to the Queer and Trans folks who are fighting desperately to be seen, to not only have their rights validated, but to have them protected. It is an honor to fight for liberation, it is an honor to show up and fight for Black Trans Women each and every day.”

Guests dancing at 99 Scott.

Guests dancing at 99 Scott.Photo by Ye Fan.

Book Launch made possible, in part, by Yola Mezcal. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Book Launch made possible, in part, by Yola Mezcal. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Guests enjoy the night. Photo by Ye Fan.

Guests enjoy the night. Photo by Ye Fan.

Keith Scott, Victor Rodrigues, Nick Varaguez, Aziz Osko, Laurent Claquin, Jacob Sparling, and Fataah Dihaan. Photo by Laura Randall.

Cindy Trinh. Photo by Laura Randall.

Dallas Diaz and Lori Ro. Photo by Laura Randall.

Alex Schlecter, Emily Patten, and Taia Kwinter. Photo by Laura Randall.

Max Battle and Alex Galan. Photo by Laura Randall.

Lizzie Soufleris, Scott Semler, Sam Kang, Adrian Ababovic, Emily Patten, and Maggie DiMarco. Photo by Laura Randall.

Keith Scott, Laurent Claquin, Jacob Sparling, and Fataah Diham. Photo by Laura Randall.

Jarrett Key and Jon Key. Photo by Laura Randall.

Nick Haby, Daniel Lehrhaupt, and Andrew DeMio. Photo by Laura Randall.

Antonio Vascual, Bryan Russel Smith, and Fabian Bernal. Photo by Laura Randall.

Previous Next Qween Jean and Laurent Claquin. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Qween Jean and Laurent Claquin. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Book Launch made possible, in part, by Jack’d App. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Book Launch made possible, in part, by Jack’d App. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Book Launch made possible, in part, by MAC Cosmetics. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Book Launch made possible, in part, by MAC Cosmetics. Photo by Serena Nappa.  ALONE. Photo by Serena Nappa.

ALONE. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Brandon English and Josh Pacheco. Photo by Ye Fan.

Brandon English and Josh Pacheco. Photo by Ye Fan.  Jasmin Van Wales. Photo by Laura Randall.

Jasmin Van Wales. Photo by Laura Randall.  Maya Margarita and Ceyenne Doroshow. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Maya Margarita and Ceyenne Doroshow. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Linda La. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Linda La. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Sara Ramirez. Photo by Ye Fan.

Sara Ramirez. Photo by Ye Fan.  Qween Jean. Photo by Ye Fan.

Qween Jean. Photo by Ye Fan.  Arewa Basit and party guest. Photo by Ye Fan.

Arewa Basit and party guest. Photo by Ye Fan.  Photo by Serena Nappa.

Photo by Serena Nappa.  Kamyo (K.K De La Transcendence) and party guest. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Kamyo (K.K De La Transcendence) and party guest. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Qween Jean, Ora Wise, and B. Hawk Snipes. Photo by Serena Nappa.

Qween Jean, Ora Wise, and B. Hawk Snipes. Photo by Serena Nappa.  Sinn Chhin. Photo by Abi Benitez.

Sinn Chhin. Photo by Abi Benitez.  Adam Eli. Photo by Abi Benitez.

Adam Eli. Photo by Abi Benitez.  Photo by Serena Nappa.

Photo by Serena Nappa. Related Items

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]Book Launch made possible, in part, by Black Trans Liberation, ALL, MAC Cosmetics, J&K’s Soul Food, Trans Equity, Jack’d App, Yola Mezcal, and Perrier.

For a pro-account on Jack’d use promo code “APFDN2022.”

This project was made possible, in part, with generous support from David Dechman and Michel Mercure, in honor of Slobodan Randjelović; Elaine Goldman; and Michael Hoeh.

December 6, 2022

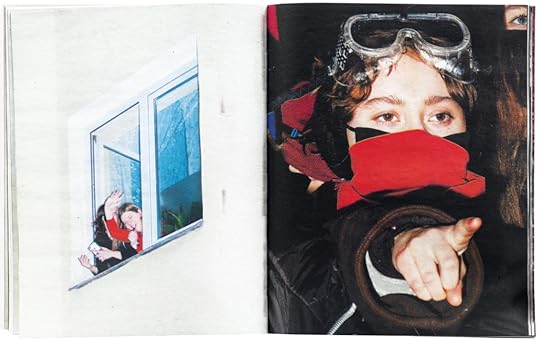

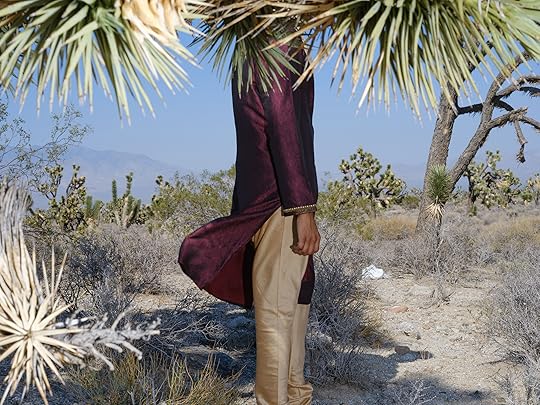

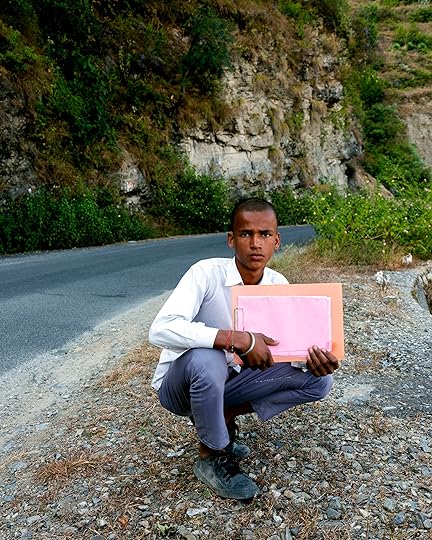

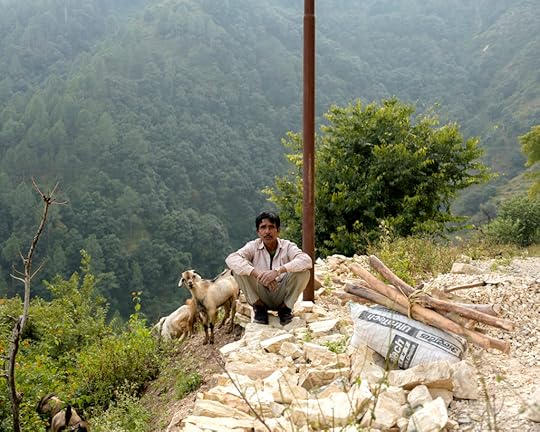

Grace Wales Bonner on the Photographers That Inspire Her Visionary Fashion Design

Fashion’s constant churn may mean that nods to the past come and go without much fanfare. But for the celebrated London-based designer Grace Wales Bonner, cultural references are conjured with careful intention. They become a form of reckoning and homage, a way to center Black artists and thinkers within a generous, ever-growing constellation of ideas. One clothing collection from 2019 was named Mumbo Jumbo, after Ishmael Reed’s 1972 novel.

Writing on Wales Bonner in The New Yorker, the critic Hilton Als reflects that she “aims to make the broken history of the Black artist and intellectual in African, European, and American culture whole.” She does this through her diligent research, an eponymous label, and high-profile collaborations with other companies, such as Christian Dior and Adidas, that expand her reach.

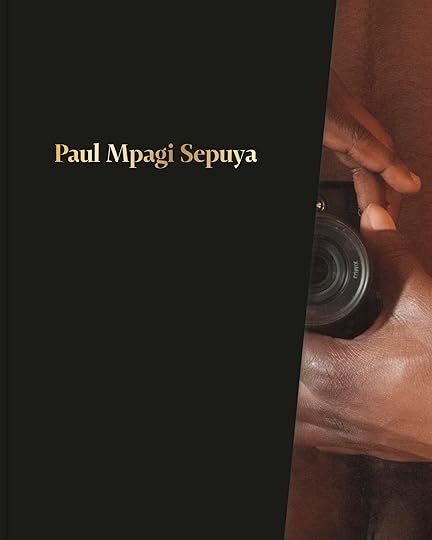

Photography is central to this project. Past collections have been inspired by John Goto’s 1970s-era portraits of British Caribbeans of African descent and Sanlé Sory’s stylish studio images from Burkina Faso. Wales Bonner has recently collaborated with Liz Johnson Artur, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, and Tyler Mitchell. Her interest in working with artists extended further in 2019, when she presented a multimedia exhibition at London’s Serpentine Galleries that explored relationships between visual art, spirituality, and mysticism. Last August, the curator Ekow Eshun spoke with Wales Bonner about how she uses design to salute the past and imagine the future.

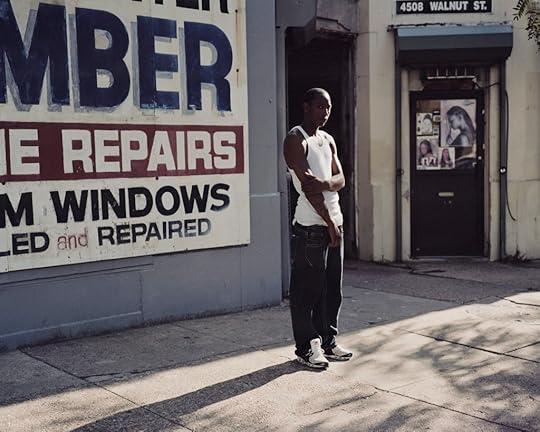

Spreads from Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Fundi (Billy Abernathy), In Our Terribleness (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1970)

Spreads from Imamu Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Fundi (Billy Abernathy), In Our Terribleness (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1970)Ekow Eshun: When you graduated from Central Saint Martins, in 2014, you bought a copy of In Our Terribleness, the 1970 Amiri Baraka and Billy Abernathy book that combines poetry and photography. Why that book?

Grace Wales Bonner: I remember it was quite an investment after I’d graduated. I got a copy signed by Baraka. I guess it shows my priorities and what I wanted to spend significant money on at a time when I probably didn’t have any money. There was the poetry, or the Ebonics, the sound of Blackness, and then also a visual record and the poetry and photography mirroring each other. The intonation of Baraka’s writing informing the rhythm of the book and the layout. Such incredible photographs, but the poetry has equal strength. It merged a lot of things.

Eshun: Yes, it’s a really striking synthesis of image, text, and design.

Wales Bonner: When I was leaving school, I wasn’t sure if I would be a designer. I thought I could be an art director. I was interested in a holistic way of representing fashion. It wasn’t just about clothing but about clothing in context. There’s a lot that can go into that, whether it’s thinking about the sounds that you’re hearing at the time, or the literature that you may be exposed to. I was also drawn to unselfconscious portraiture and photography that gives you a record of style at a certain time. Images that weren’t consciously fashion images. Another book that has that kind of format is Roy DeCarava’s The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), with poems by Langston Hughes. I picked up on the lineage of that book, where photography and poetry have some relationship, which is something I explored with Rhapsody in the Street, a magazine I curated. It’s not about images in isolation, but it’s about the freedom to interpret with poetry using a more abstract or romantic imagining around these images, not necessarily in a contextual or historical approach.

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled, 2022, for the Kerry James Marshall and Wales Bonner capsule collection

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled, 2022, for the Kerry James Marshall and Wales Bonner capsule collection© the artist

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Mirror Study for Grace (0X5A2018), 2017

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Mirror Study for Grace (0X5A2018), 2017Courtesy the artist; DOCUMENT, Chicago; Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich; and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Eshun: Let’s discuss the photographers you’ve chosen to collaborate with: Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Liz Johnson Artur, and Tyler Mitchell. What led you to them?

Wales Bonner: There is a sense of curation around the people I work with, but there’s often a natural and emotional relationship that is a starting point. For example, Paul Sepuya—I saw his exhibition in New York. This was 2017 or 2018. I was really moved by it, by the attention to detail in the aesthetics, the frames, the space around the images. I could tell that he had incredible taste. I just emailed him and said, “I’m a really big fan, and I’d love to meet.” I ended up going to his studio in LA. He’s so informed in everything he does. I do think about photographic archives, and he’s someone who engages with archives. He told me that he used to archive older Black artists’ work for them.

Eshun: In your office, which I’ve been to, you have a lot of books that you’re looking at and thinking about. What is compelling to you about that process of archiving?

Wales Bonner: For me, researching is an artistic practice for myself—or even a spiritual practice. That’s the art form that I feel like I connect with most naturally. But I also like the fact that it doesn’t need to result in something for Wales Bonner clothing.

I want to create more space for that practice. Within fashion, there is a specific cycle, an output and a pace to it. I’ve been looking at how to safeguard my process. Actually, I now have a grant for the next four years to focus on research.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.Eshun: Every one of your collection shows comes with texts and also some of your visual references. It’s a very particular approach—this insistence that some of these influences that you’re drawing from, or are in conversation with, are made explicit.

Related Stories Essays Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

Essays Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

Photobooks For Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Books Are a Way to Think About Time

Photobooks For Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Books Are a Way to Think About Time Wales Bonner: What I do is connected to a lineage of artists and writers, and so informed by that history that it’s about transparency— revealing that process and documenting it quite methodically so that people can follow those threads. That was an intention at the 2019 Serpentine exhibition [Grace Wales Bonner: A Time for New Dreams], to show how different artists have informed a development of thinking. I want to point to those things. And it’s more for my own process really, to mark certain moments. It is often fragments: a memory of a text or an isolated image. There’s a lot of space to fill in gaps and to create worlds around these references.

The way I think about references is that they’re a library. Everything that’s in there is important.

Eshun: Can you talk about some of the visual decisions you made for the Serpentine show in terms of working as an artist and a curator rather than as Grace Wales Bonner, the fashion designer?

Wales Bonner: There’s definitely a different process. The actual making connections between artists crosses over, but with that exhibition, I wanted to transform the gallery space into a place for reflection and meditation. I was thinking a lot about the idea of a portal, whether that’s a spiritual assemblage, like, say, a shrine, that allows you to interact or have communion, or whether that’s a musical meditation that transports you. Ben Okri wrote invocations for the shrines, which is how I loosely thought about the collection of objects and artworks. He also wrote these interruptions within the space that were on the ceiling or in places you wouldn’t expect they would be. There was a sound shrine that I made, which would come on only at certain times. There was this element of the unexpected, for things not to be perfectly neat, for there to be space to be subtly disruptive. More than anything, it was about an emotional quality and how people would feel in that space.

Installation view of work by Liz Johnson Artur in A Time for New Dreams, Serpentine Galleries, London, 2019. Photograph by and courtesy the artist

Installation view of work by Liz Johnson Artur in A Time for New Dreams, Serpentine Galleries, London, 2019. Photograph by and courtesy the artist Eshun: The photographer Liz Johnson Artur made a kind of shrine, too, for the exhibition. What did you see in her work?

Wales Bonner: I think she’s an exceptional artist and someone who has archived history. For me, it’s also about a level of excellence in her photography. That’s probably a connection among the people I tend to drive to, that they are mastering their craft. Sometimes I feel out of my depth with the talents of the artists I’m working with, and maybe that’s good and motivating. With Liz, photography is almost a material to make art from. The way that she presents her imagery is elaborate.

John Goto, Lovers’ Rock 02, Lewisham, London, 1977

John Goto, Lovers’ Rock 02, Lewisham, London, 1977Courtesy the artist

Sanlé Sory, L’Équilibriste, 1973

Sanlé Sory, L’Équilibriste, 1973© the artist and courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Eshun: Some of your collection shows have directly referenced historical photographers: John Goto in your Lovers Rock Autumn Winter 2020 collection and Sanlé Sory in Volta Jazz for Spring Summer 2022. You were looking at their projects from the 1970s. Why select a particular moment in time?

Wales Bonner: Certain photographic records are timeless—like Goto’s pictures. Actually, his Lovers’ Rock series from 1977 is so influential because it records a moment in time, and it’s connected to a community. You start to see these different characters and a very clear record of what people were wearing and what people were listening to. Certain times, it might be inspirational, but for me it’s not really seasonal. It’s a kind of timeless reference.

Sanlé Sory, in the fashion context, has been very influential as well, but he might not always be given visibility in a direct manner. The way I think about references is that they’re a library. Everything that’s in there is important. All these things become quite embodied.

Advertisement googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-4'); }); Advertisement googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-3'); });Eshun: And there’s also photography as collaboration, as with someone such as Tyler Mitchell, whom you invited to photograph a collection. What might lead you to collaborate with a certain photographer?

Wales Bonner: I prefer continuity. Liz was part of the Serpentine exhibition, but she’d been photographing my designs since 2019 in an informal setting. It’s critical for me to have that continued dialogue with people over time. With Tyler Mitchell as well. It’s never a one-off, really. I want to have relationships with people. We’re developing together; there’s an evolution in real time. I do have a long view in that sense, whether that’s a view on the past and how it is influencing the present or it’s creating something that has longevity.

Jeano Edwards, Untitled, 2022, from the series Sunlight Reverie

Jeano Edwards, Untitled, 2022, from the series Sunlight Reverie Courtesy Wales Bonner

Eshun: We’ve talked about your role as an archivist, researcher, historian, artist, curator, and fashion designer. How do you think of yourself?

Wales Bonner: I would say researcher, as a grounding practice—and research being an artistic practice. And then, I want to consider how that can inform different outcomes, whether that becomes a musical experience or a fashion show or a garment or a publication. That’s the starting point.

Eshun: You recently collaborated with the painter Kerry James Marshall.

Wales Bonner: I would say Kerry James Marshall is probably the artist who has influenced me most, even my wanting to create Wales Bonner.

Related Items

Aperture 249

Shop Now[image error]

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Shop Now[image error]Eshun: Let’s dwell on that for a moment. Why?

Wales Bonner: He has seen within art history the absence of Black presence. And he has been strategic in order to influence and infiltrate and be part of something at a very high level. Even the way that he makes his paintings large in scale so that in an exhibition space there’s a physical Black presence. He’s understood exactly what knowledge and what resources are needed to have such a position. I saw a similar lack within the fashion space. I wanted to create a fashion brand that could represent a highly sophisticated image of a Black cultural perspective. So, yeah, he’s been really influential to my work and my understanding of beauty.

Samuel Fosso, Autoportraits II (Fosso Fashion), 2021, for A Magazine Curated by Grace Wales Bonner

Samuel Fosso, Autoportraits II (Fosso Fashion), 2021, for A Magazine Curated by Grace Wales BonnerCourtesy Jean Marc Patras, Paris

Liz Johnson Artur, Photograph for the Wales Bonner campaign Lovers Rock, 2020

Liz Johnson Artur, Photograph for the Wales Bonner campaign Lovers Rock, 2020Courtesy Wales Bonner

Eshun: Is there a strategy on your part in terms of making visible the kind of references that we talked about but also of honoring those partnerships that you continue to develop over a number of years?

Wales Bonner: I wouldn’t necessarily say that’s really strategic, because I feel like it’s a quite natural part of my process. It’s part of how I think about time probably, and connecting past, present, future.

Eshun: There is an insistence on inscribing a Black presence and asserting the significance of those photographers or those other image makers and artists as figures whose work changes the culture as a whole.

Wales Bonner: I’m very interested in beauty, or in having a specific representation of beauty, but it’s also important to show that this is not at all new. There’s so much evidence, so many records. There’s a vast body of work over history. That’s the frame I’m exposed to. For me, there is a sense of thinking about history and just revealing what’s there—what’s always been there.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

December 2, 2022

6 New and Notable Photobooks

From The PhotoBook Review in Aperture magazine’s fall issue, “The 70th Anniversary Issue,” six writers consider a selection of recent photobooks.

Covers of Mame-Diarra Niang, The Citadel: a trilogy (MACK, 2022)

Covers of Mame-Diarra Niang, The Citadel: a trilogy (MACK, 2022)The Citadel: a trilogy by Mame-Diarra Niang

Grief estranges the bereaved from the mourned and clarifies that certain emotional distances are unbridgeable. When the French artist Mame-Diarra Niang first returned to Dakar, Senegal, in 2007, it was to bury her father. Niang’s book The Citadel: a trilogy (MACK, 2022) combines these facts of loss and image making to propose an idea larger than the sum of biography and composition. This is perhaps best represented by the spectral presence of Anchises from Virgil’s Aeneid—a figure moving through epochs, outside time and place, who points his son Aeneas to the world as it will yet become. As Niang has said, it doesn’t matter that her photographs were made in Africa: “I want to express a simple idea that my body is always somewhere else; it is always connected to somewhere else in the world.”

The Citadel constitutes a three-part examination of place. It begins with Sahel Gris, an assortment of ocher-toned images that show construction sites, stray beasts of burden, and a jumble of bricks on weedy earth. At the Wall is a closer look at what is formed on the surface: buildings incomplete yet inhabited, unattended to, or hastily finished; walls weathered by time and neglect; the occasional presence of pedestrians or laborers, who flit into view as though the city were made mostly of concrete. In Metropolis, the conclusion, no building is under construction; the photographs are glimpses of a panorama, views of a city at once grand and impossible to behold.

Portions of the Aeneid are interspersed throughout Metropolis, as though establishing the mythological parameters of Niang’s work. In the final excerpt, the following is said of Anchises and Aeneas: “So they wander here and there through the whole region, over the wide city plain, and gaze at everything.” Wandering, the wide city, a gaze at everything: this is the triangular basis of The Citadel. The vision belongs to a wanderer, whose sights, as in Sahel Gris, are lone and hurried. Yet it is a hurry that doesn’t dispense with compressed attention, in which walls of a storied city can seem like meditations on how much a surface can hold, and how much is kept from view.

The trilogy, collected in an embossed slipcase, is serialized in the order of conceptualization: a movement across three volumes, from the wide-angled imagery of Dakar and Abidjan to a further tightening of the frame in Johannesburg. Each book is treated to its own idiosyncratic format and papers—accordion fold, hardcover, and Japanese fold—making The Citadel throb with melancholy and conscientiousness.

Niang grew up between France and West Africa, “in a state of constant metamorphosis,” as she describes her childhood. She incorporates that experience into her artistic journey, formulating the fragmentary as an ethos. Her photographs are never about what is whole or total or fully seen but, rather, what is angular, oblique, halved, seen sideways, and knowable only in part—a vision of tensions that occur on the exterior, as though to present the viewer with a background fit for introspection. —Emmanuel Iduma

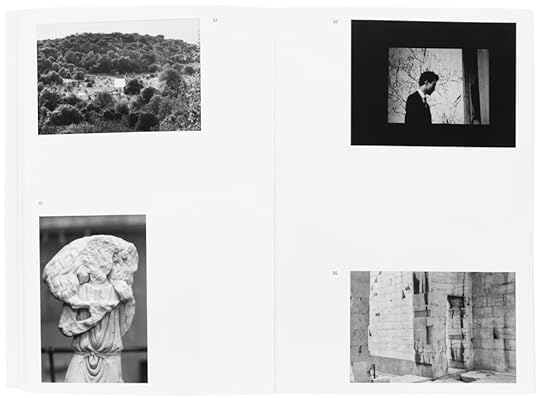

Spread from Jeff Weber, Serial Grey (Roma Publications, 2021)

Spread from Jeff Weber, Serial Grey (Roma Publications, 2021)Serial Grey by Jeff Weber

In recent years, a small but growing cohort of information-obsessed knowledge workers have tried to build “second brains.” By this, they mean the organization of their thoughts with digital archives and note files that will, they hope, help them to find connections between their ideas and “unlock [their] creative potential.” One patron saint of this group is the late German sociologist Niklas Luhmann, whose own repository involved thousands of intricately annotated index cards housed in cabinets.

The fifteen-year practice of the Belgian artist Jeff Weber is characterized, in part, by a search for tools and methods of “unlocking creative potential”—to devise systems that produce photographic images and films. Early in his career, Weber established his own Luhmann-style archive, which he sardonically termed An Attempt at a Personal Epistemology with the Help of a Cardfile as Generative Mechanism (2009–10). “It was meant to form an interactive tool that could mirror the self and that I could work with—or, rather, rely on to create art,” he says. The frustrations of that project put Weber on the path he has followed since. Serial Grey (Roma Publications, 2021), his new book, documents both an exhibition at Carré d’Art–Musée d’art contemporain, Nîmes, and the evolution of his art.

The book is initially forbidding in its seeming austerity: the cover depicts an unprepossessing grid of small squares in varying shades of gray, an image seen in six more variations before you arrive at the table of contents. But persistence is rewarded with the slow disclosure of an idiosyncratic and all-too-human search for connection (it’s a “personal” epistemology, after all).

The heart of Serial Grey is a collection of casual-seeming snapshots in a rich range of moody grays. In them, some figures recur, such as a young woman with short dark hair, alternately posed and unposed as she interacts with others, travels through sunny landscapes, and visits museums. Those galleries provide another theme: snapshots of artworks and objects from ancient cultures, mute testaments to human creativity. Yet other pictures focus on doorways and portals, or render a city roofscape, suggesting untold stories.

Weber made many of these photographs in relation to Kunsthalle Leipzig, an institution-as-artwork he ran out of an apartment from 2014 to 2017. By entering into extended creative dialogue with those he invited to exhibit at the space, Weber made images that are simultaneously records of his subjective experience, of creative processes (his and theirs), and of fulfilling relationships.

After Kunsthalle Leipzig closed, Weber returned to impersonal generative technologies: the patterned grids in the early pages of this book are, in fact, recent photograms resulting from a hacked-together combination of artificial neural networks, torn-open LCD displays, and a traditional photographic enlarger. Such oblique strategies require explanation for their impact to be fully felt. But, as hermetic and aloof as the book can seem, it is both intellectually fertile and, surprisingly, emotional. Serial Grey makes plain that Weber derives meaning from reciprocity, whether the relationship in question is with another person, with a tool, or, above all, with art. —Brian Sholis

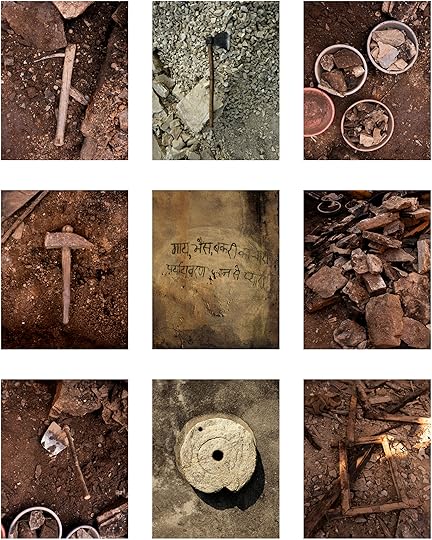

Spread from Arko Datto, Snake Fire (L’Artiere Edizioni, 2021)

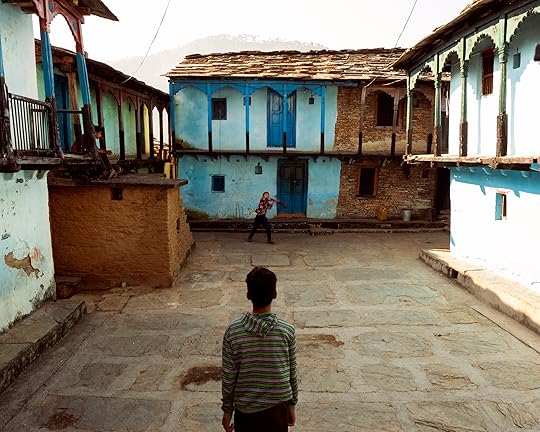

Spread from Arko Datto, Snake Fire (L’Artiere Edizioni, 2021)Snake Fire by Arko Datto

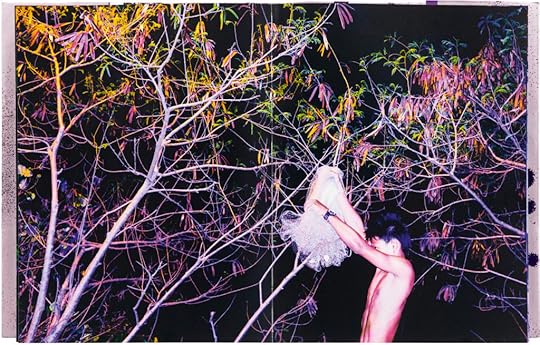

Although Arko Datto’s journalistic photographs are firmly grounded in the lived encounters in his native India and other countries across Southeast Asia, his artistic practice is not solely tethered to a truthful representation of his subjects. Reimagined in filters and tints that infuse the frames with striking, saturated hues, Datto’s portraits and landscapes verge on dreamscapes, where illusory, chimerical combinations of light and color come into tangible focus.

In his new book, Snake Fire (L’Artiere Edizioni, 2021), Datto, who is based in Kolkata, continues to expand his constructed world, where reality is reconfigured to generate a trance vision. A compilation of arresting, and at times unsettling, photographs that portray anonymous creatures of the night, derelict urban landscapes of Southeast Asia, and inadvertent collisions between nature and human civilization, the publication features a hundred or so images, taken in Malaysia and Indonesia, printed in full bleed from one page to the next. Here, we see an old man treading along a deserted road with a cadaver of a pig cut in half; a crocodile floating in muddied water; a riverbank inundated with heaps of trash and rubber tires where a dilapidated boat is parked; and a pair of godlike figures carved in stone, on which pieces of fabric and other paraphernalia are attached.

Resisting the grammar of photobooks built around the narrative potential created by the pacing of images with empty spaces in between, Snake Fire opts to submerge the reader in a succession of frames with such acute, rich colors that the images are rendered ethereal. A coat of silver and fluorescent ink sprayed atop numerous pages heightens the surreal aesthetics of Datto’s photographs, allowing each scene to appear differently according to the amount of light on the spread. Perhaps counterintuitively, these postproduction effects dissociate the images from the palette one typically associates with the region, despite the iconography of snake and moth that firmly root the frames in the natural environments of Southeast Asia. Instead, they invoke a fantastical parallel world produced by the layering of a colored filter onto a reality in which Datto’s eerie images could be conjoined to create an ecosystem.

Datto’s documentary work, featured by Time and National Geographic, seeks to inform the spectator of such pressing issues as migration and urbanization as they unfold in South and Southeast Asia. But Snake Fire takes a psychedelic direction, as if in opposition to reportage. Instead of flattening its images into an orderly assortment of discrete moments, Snake Fire offers a collection of hypnotic encounters that simultaneously activate the reader’s sense of sight and touch. In doing so, it disputes the status of photobooks as incomplete, albeit decent, alternatives to prints. As a satisfying counterexample of the genre, Snake Fire lets itself drift as a site of handheld dreams. —Harry C. H. Choi

Spread from Nigel Shafran, The Well (Loose Joints, 2022)

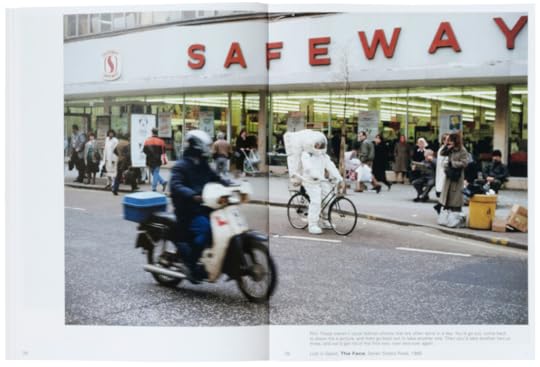

Spread from Nigel Shafran, The Well (Loose Joints, 2022)The Well by Nigel Shafran

The British historian Raphael Samuel once noted that consumer society sees the world as a shop window display. Nigel Shafran is a photographer who has lingered long around high street plate glass. It’s easy to call him a fashion photographer, but his engagement with the urban vernacular and his disinterestedness in seeking commercial jobs placed him for many years on the margins of the industry. Yet The Well (Loose Joints, 2022), a newly published survey of Shafran’s work to date, notes the quiet revolution his photography has ushered in. Threaded through a chronological selection of published editorials, portfolio pieces, and outtakes is a conversation—like a series of interconnected captions—between the photographer and his collaborators, including stylists, models, editors, and art directors, recounting projects across a more than thirty-year period.