Aperture's Blog, page 37

October 5, 2022

Hannah Whitaker’s Images About Technology and Anxiety at the Turn of the Millennium

For Aperture‘s “70th Anniversary” issue, seven photographers were invited to consider a single issue, an article, an idea, or even an omission, from a decade of the magazine’s history. In an original commission, Hannah Whitaker reflects on the 2000s.

The language of technological innovation is tinged with anxiety and awe. Its vision recasts us as beneficiaries of a more connected humanity—somehow both more human and more than human—yet its promise often feels suspect. In a review of William A. Ewing’s 2004 exhibition About Face, which proclaimed the death of the photographic portrait, Vince Aletti writes in the pages of Aperture’s Winter 2004 issue: “Even before photography’s documentary credibility was deliberately and irrevocably eroded from within, pictures of our fellow humans had been stripped of virtually all pretense to revelation, insight, or any but the most superficial emotional content.”

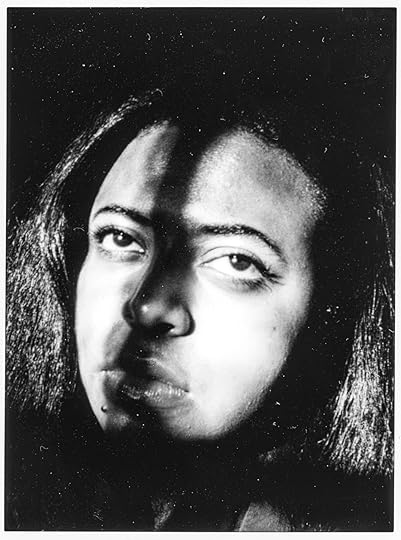

This skepticism frames Hannah Whitaker’s silhouetted portraits and still lifes, which address an unease, pervasive in the twenty-first century, about how technology relates to our humanity.

Seemingly familiar human figures are obscured and manipulated into dark, synthetic forms. “I wanted to make photographs that center around a particular face, without actually depicting it,” Whitaker states. Using mirrors, long exposures, reflective materials, special lighting, and anthropomorphized arrangements, her work treats technology as a medium as well as an aesthetic position. Many images employ digital interventions to conceal, dislocate, or duplicate human appendages, a response to technology’s tendency to fragment our everyday experiences and evacuate meaning in the service of data. In their stark contrasts, these “portraits” carry a menacing subtext within their outlines and an all-too-human trepidation in the face of disorienting change—a feeling as relevant today as it was decades ago.

All photographs by Hannah Whitaker from the series Millennium Pictures, 2022, for Aperture

All photographs by Hannah Whitaker from the series Millennium Pictures, 2022, for Aperture Courtesy the artist

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue.”

Hannah Whitaker’s Images About Technology at the Turn of the Millennium

For Aperture‘s “70th Anniversary” issue, seven photographers were invited to consider a single issue, an article, an idea, or even an omission, from a decade of the magazine’s history. In an original commission, Hannah Whitaker reflects on the 2000s.

The language of technological innovation is tinged with anxiety and awe. Its vision recasts us as beneficiaries of a more connected humanity—somehow both more human and more than human—yet its promise often feels suspect. In a review of William A. Ewing’s 2004 exhibition About Face, which proclaimed the death of the photographic portrait, Vince Aletti writes in the pages of Aperture’s Winter 2004 issue: “Even before photography’s documentary credibility was deliberately and irrevocably eroded from within, pictures of our fellow humans had been stripped of virtually all pretense to revelation, insight, or any but the most superficial emotional content.”

This skepticism frames Hannah Whitaker’s silhouetted portraits and still lifes, which address an unease, pervasive in the twenty-first century, about how technology relates to our humanity.

Seemingly familiar human figures are obscured and manipulated into dark, synthetic forms. “I wanted to make photographs that center around a particular face, without actually depicting it,” Whitaker states. Using mirrors, long exposures, reflective materials, special lighting, and anthropomorphized arrangements, her work treats technology as a medium as well as an aesthetic position. Many images employ digital interventions to conceal, dislocate, or duplicate human appendages, a response to technology’s tendency to fragment our everyday experiences and evacuate meaning in the service of data. In their stark contrasts, these “portraits” carry a menacing subtext within their outlines and an all-too-human trepidation in the face of disorienting change—a feeling as relevant today as it was decades ago.

All photographs by Hannah Whitaker from the series Millennium Pictures, 2022, for Aperture

All photographs by Hannah Whitaker from the series Millennium Pictures, 2022, for Aperture Courtesy the artist

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue.”

October 3, 2022

Announcing the 2022 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

This year marks the tenth anniversary of the Paris Photo–Aperture PhotoBook Awards—a celebration of the photobook’s contributions to the evolving narrative of photography. The award recognizes excellence in three major categories of photobook publishing: First PhotoBook, PhotoBook of the Year, and Photography Catalogue of the Year.

“We are very proud to celebrate ten years of the PhotoBook Awards on this twenty-fifth anniversary of Paris Photo and the seventieth anniversary of Aperture,” comments Florence Bourgeois, director of Paris Photo. “It is a delight to witness each year what this award means to the photography community, through the number and quality of entries received, but also through the ongoing enthusiasm around this medium that remains a central part of the Fair, bringing together so many artists, publishers, collectors, and enthusiasts alike.”

This year’s shortlist selection was made by a jury comprising: Clinton Cargill, visual editor, the New York Times; Lesley A. Martin, creative director, Aperture; Miwa Susuda, Dashwood Books; publisher, Session Press; Brian Wallis, executive director, Center for Photography at Woodstock; and Leslie M. Wilson, associate director for Academic Engagement and Research, Art Institute of Chicago.

Wilson observed about the process, “The shortlist jury is an opportunity to see what kind of books are being made today. With so many books to consider, one gets a strong sense that you’re in touch with the pulse of what photography can be in this moment.”

The total number of books received this year was a robust tally of 1,026, a remarkable increase in entries from the initial years of the awards (a little more than six hundred titles were entered in 2012). Jurying the PhotoBook Awards takes part in two stages. The first took place at Aperture in New York, September 19–21, 2022, a process that involved the initial review of submissions in order to select the thirty-five shortlisted books in all categories.

A final jury will gather at Paris Photo this November to select and announce the winners for all three prizes. From there, shortlisted and winning titles will be profiled in a printed catalogue, to be released and distributed for free during Paris Photo fair, along with the Winter 2022 issue of Aperture magazine. The shortlisted books will be exhibited at the Grand Palais Éphémère during Paris Photo, and will tour internationally thereafter.

Below, see the thirty-five selected titles for the 2022 PhotoBook Awards shortlist.

First PhotoBook

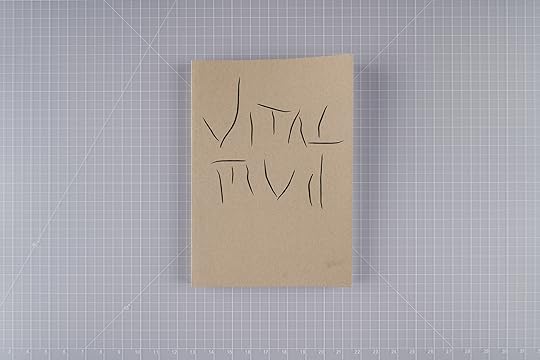

Hiske Altena, Vital Mud, Self-published, Amsterdam

Gabriella Angotti-Jones, I Just Wanna Surf, Mass Books, New York

Florian Bachmeier, In Limbo, Buchkunst Berlin

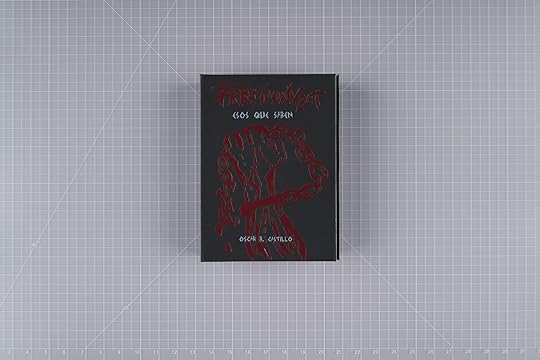

Oscar B. Castillo, ESOS QUE SABEN (Those who know), Raya Editorial, Manizales, Colombia

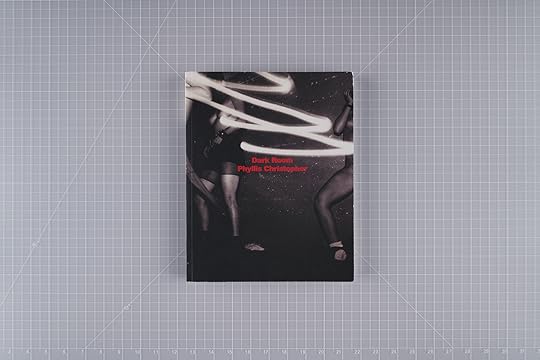

Phyllis Christopher, Dark Room, Book Works, London

Sabiha Çimen, HAFIZ, Red Hook Editions, New York

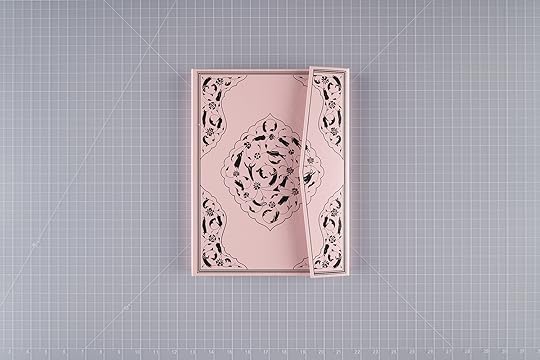

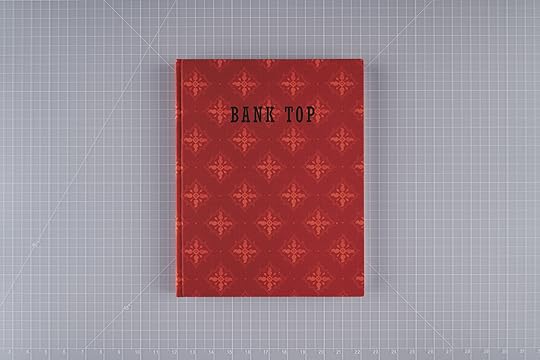

Craig Easton, Bank Top, GOST Books, London

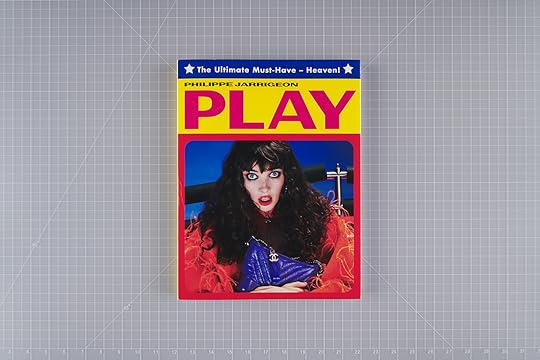

Philippe Jarrigeon, PLAY, RVB Books, Paris

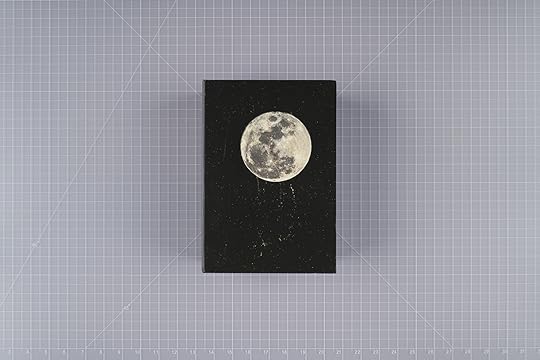

Hari Katragadda and Shweta Upadhyay, I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you, Self-published in association with Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi

Stacy Kranitz, As It Was Give(n) to Me, Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Youqine Lefèvre, The Land of Promises, The Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Carla Liesching, Good Hope, MACK, London

Sabelo Mlangeni, Isivumelwano, Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Marilyn Nance, Marilyn Nance: Last Day in Lagos, CARA, New York, and Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg

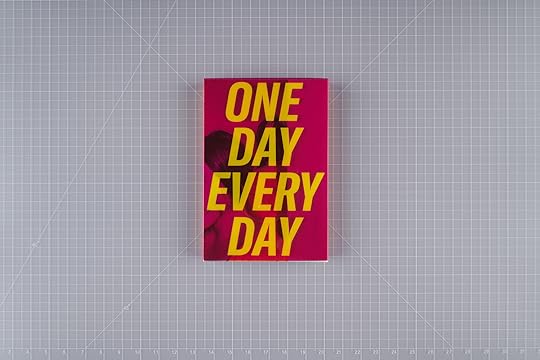

Zuzana Pustaiova, One Day Every Day, Reflektor (self-published), Vienna / Slovakia

Paola Jiménez Quispe, Rules for Fighting (Reglas para pelear), Images Vevey, Switzerland, and Witty Books, Turin, Italy

Yoshinori Saito, After the Snowstorm, the(M) éditions, Paris, and IBASHO, Antwerp, Belgium

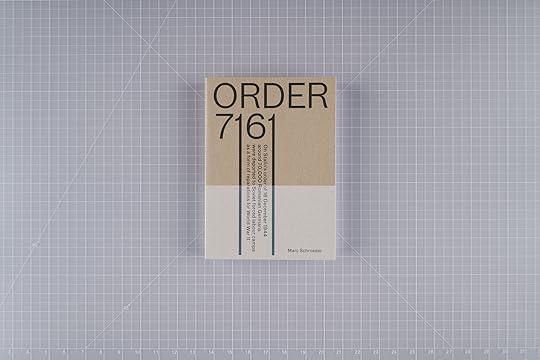

Marc Schroeder, Order 7161, The Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

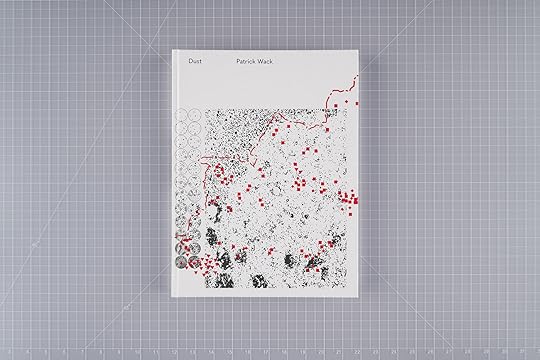

Patrick Wack, Dust, André Frère Éditions, Marseille, France

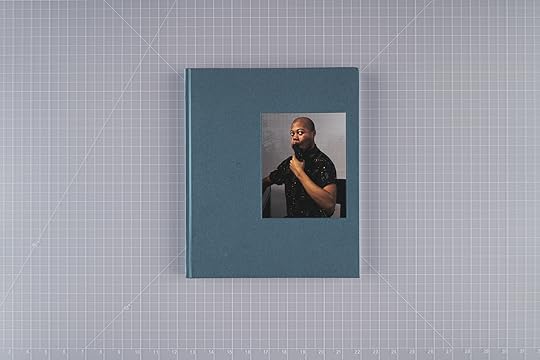

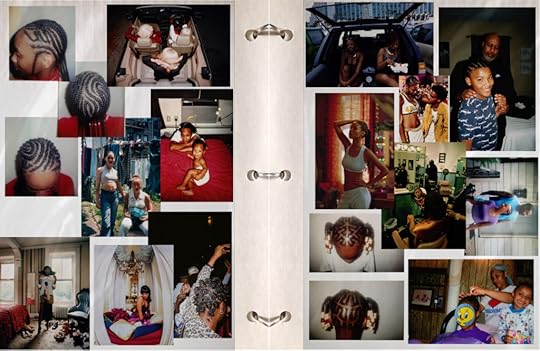

D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Contact High, MACK, London

Previous NextHiske Altena

Vital Mud

Self-published, Amsterdam

Gabriella Angotti-Jones

I Just Wanna Surf

Mass Books, New York

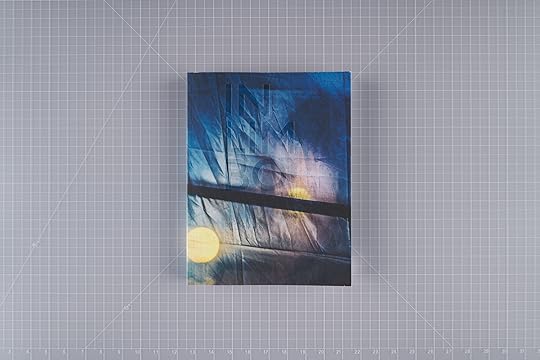

Florian Bachmeier

In Limbo

Buchkunst Berlin

Oscar B. Castillo

ESOS QUE SABEN (Those who know)

Raya Editorial, Manizales, Colombia

Phyllis Christopher

Dark Room

Book Works, London

Sabiha Çimen

HAFIZ

Red Hook Editions, New York

Craig Easton

Bank Top

GOST Books, London

Philippe Jarrigeon

PLAY

RVB Books, Paris

Hari Katragadda and Shweta Upadhyay

I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you

Self-published in association with Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi

Stacy Kranitz

As It Was Give(n) to Me

Twin Palms Publishers, Santa Fe, New Mexico

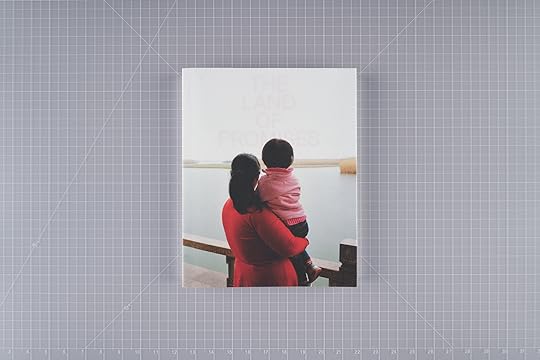

Youqine Lefèvre

The Land of Promises

The Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Carla Liesching

Good Hope

MACK, London

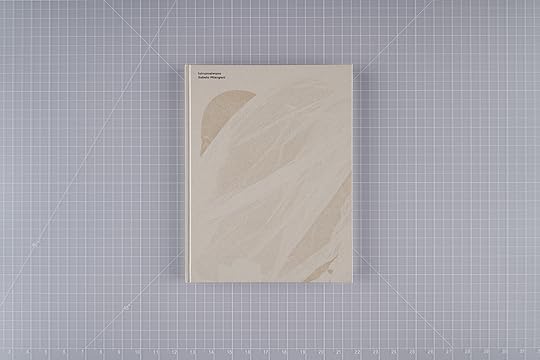

Sabelo Mlangeni

Isivumelwano

Fw:Books, Amsterdam

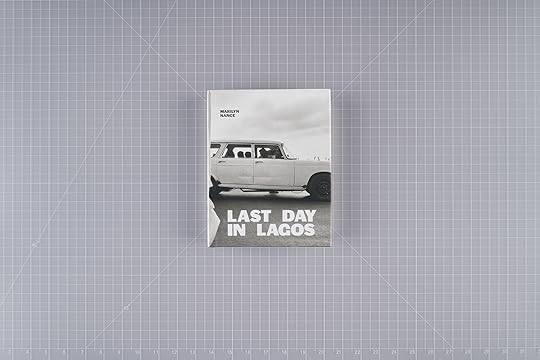

Marilyn Nance

Marilyn Nance: Last Day in Lagos

CARA, New York, and Fourthwall Books, Johannesburg

Zuzana Pustaiova

One Day Every Day

Reflektor (self-published), Vienna / Slovakia

Paola Jiménez Quispe

Rules for Fighting (Reglas para pelear)

Images Vevey, Switzerland, and Witty Books, Turin, Italy

Yoshinori Saito

After the Snowstorm

the(M) éditions, Paris, and IBASHO, Antwerp, Belgium

Marc Schroeder

Order 7161

The Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Patrick Wack

Dust

André Frère Éditions, Marseille, France

D’Angelo Lovell Williams

Contact High

MACK, London

PhotoBook of the Year

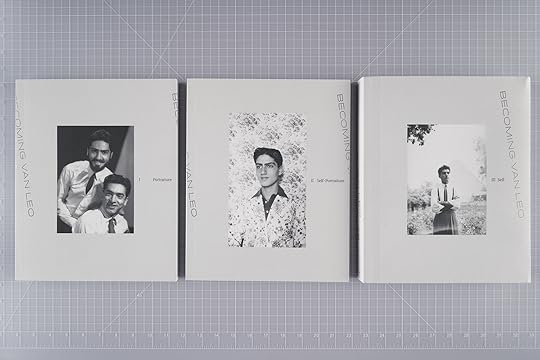

Karl Bassil, in collaboration with Negar Azimi and Katia Boyadjian, Becoming Van Leo, Arab Image Foundation, Beirut, and Archive Books, Berlin

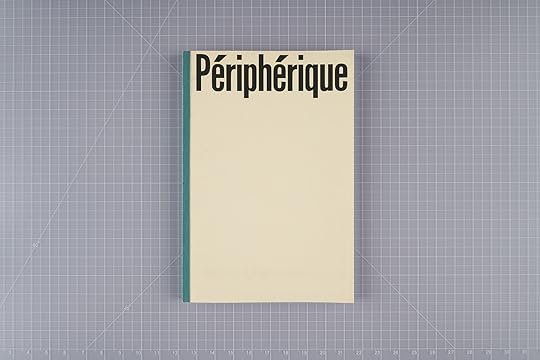

Mohamed Bourouissa, Périphérique, Loose Joints, Marseille, France

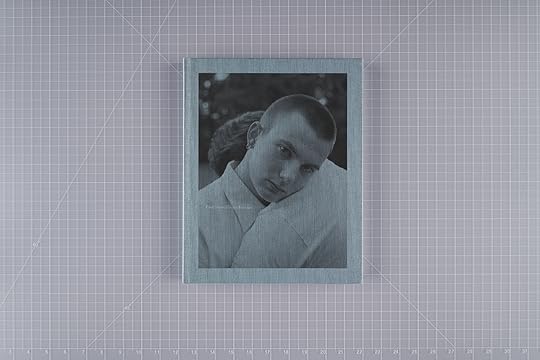

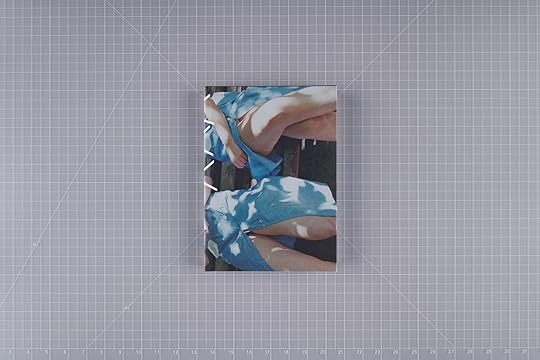

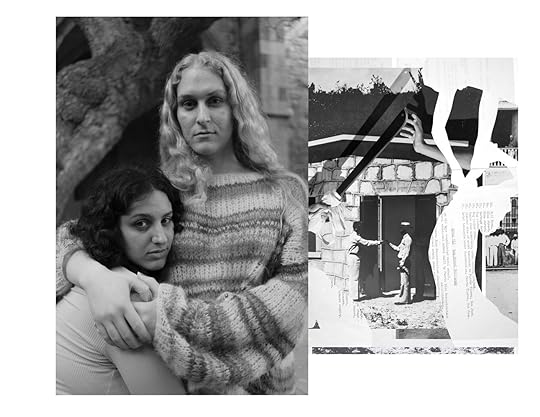

Jess T. Dugan, Look at me like you love me, MACK, London

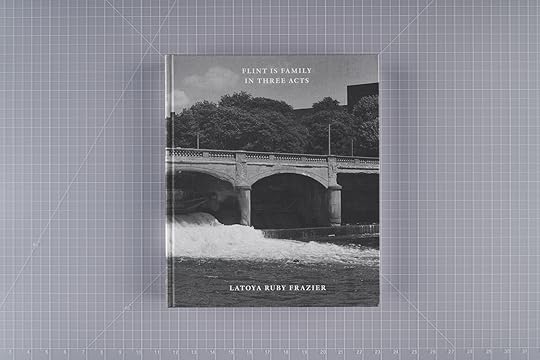

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Flint Is Family in Three Acts, Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, and The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, New York

Curran Hatleberg, River’s Dream, TBW Books, Oakland, California

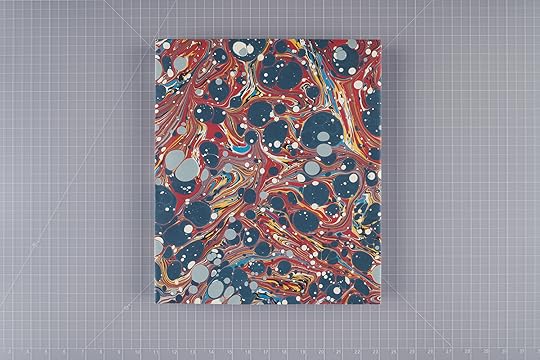

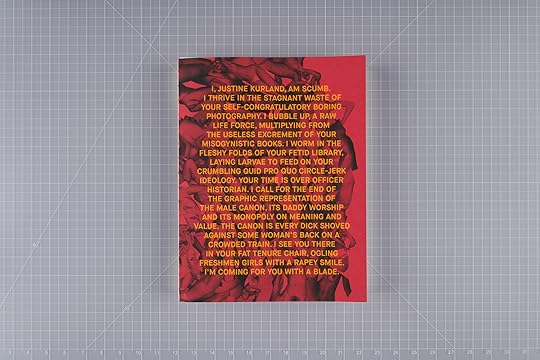

Justine Kurland, SCUMB Manifesto, MACK, London

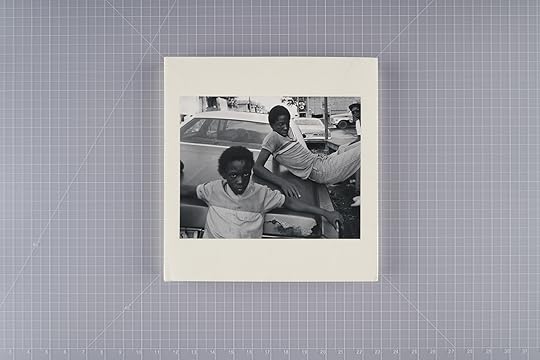

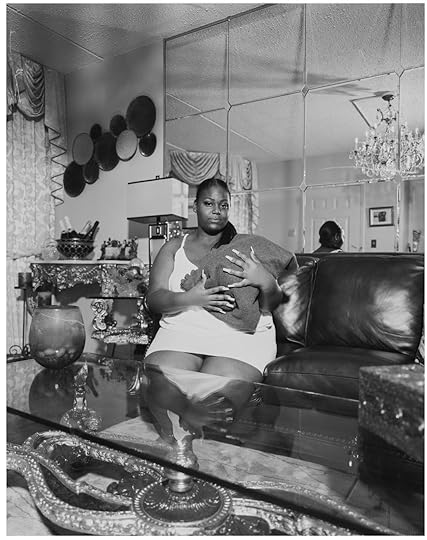

Baldwin Lee, Baldwin Lee, Hunters Point Press, New York

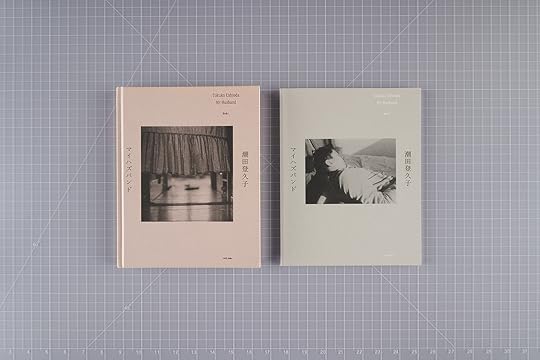

Tokuko Ushioda, My Husband, torch press, Tokyo

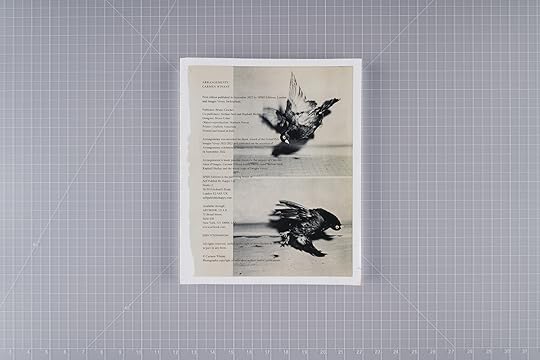

Carmen Winant, Arrangements, SPBH Editions, London, and Images Vevey, Switzerland

Yelena Yemchuk, УYY, Départ Pour l’Image, Milan

Previous NextKarl Bassil, in collaboration with Negar Azimi and Katia Boyadjian

Becoming Van Leo

Arab Image Foundation, Beirut, and Archive Books, Berlin

Mohamed Bourouissa

Périphérique

Loose Joints, Marseille, France

Jess T. Dugan

Look at me like you love me

MACK, London

LaToya Ruby Frazier

Flint Is Family in Three Acts

Steidl, Göttingen, Germany, and The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, New York

Curran Hatleberg

River’s Dream

TBW Books, Oakland, California

Justine Kurland

SCUMB Manifesto

MACK, London

Baldwin Lee

Baldwin Lee

Hunters Point Press, New York

Tokuko Ushioda

My Husband

torch press, Tokyo

Carmen Winant

Arrangements

SPBH Editions, London, and Images Vevey, Switzerland

Yelena Yemchuk

УYY

Départ Pour l’Image, Milan

Photography Catalogue of the Year

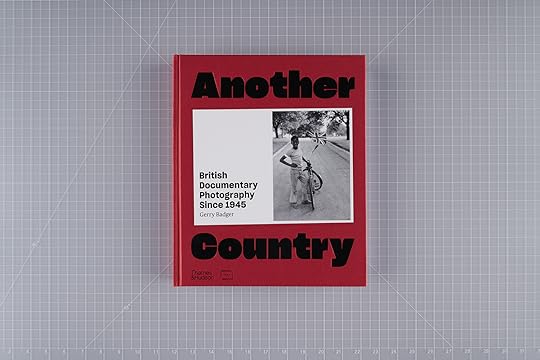

Another Country: British Documentary Photography since 1945, Gerry Badger, Thames & Hudson, London

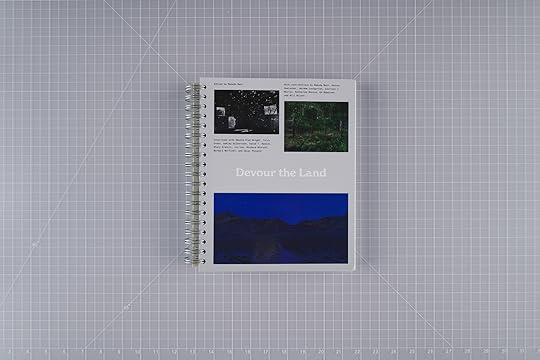

Devour the Land: War and American Landscape Photography since 1970, Makeda Best, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

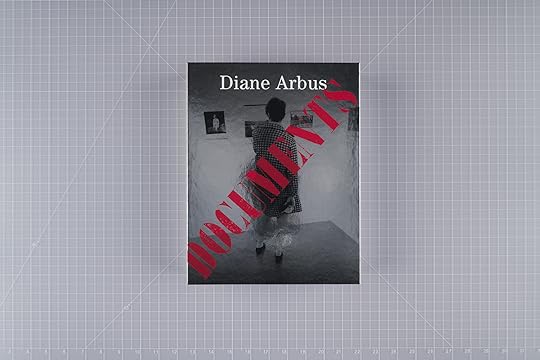

Diane Arbus Documents, Max Rosenberg, ed., David Zwirner Books, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

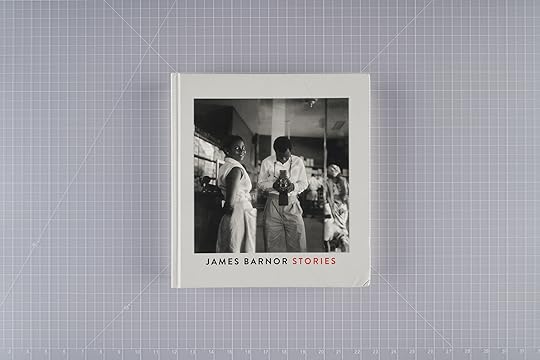

James Barnor: Stories. Pictures from the Archive (1947–1987) , LUMA Foundation, Arles, and Maison CF, Paris

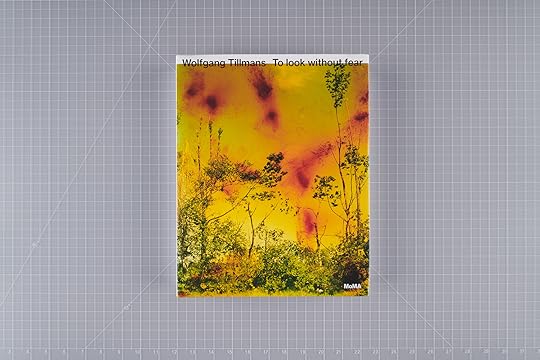

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, Roxana Marcoci, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Previous NextAnother Country: British Documentary Photography since 1945

Gerry Badger

Thames & Hudson, London

Devour the Land: War and American Landscape Photography since 1970

Makeda Best

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Diane Arbus Documents

Max Rosenberg, ed.

David Zwirner Books, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

James Barnor: Stories. Pictures from the Archive (1947–1987)

LUMA Foundation, Arles, and Maison CF, Paris

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear

Roxana Marcoci

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Special Juror’s Mention: PhotoBooks for Ukraine

Jim Goldberg and Iryna Tsilyk, Another Life, STANLEY/BARKER, London

Katya Lesiv, I Love You, IST Publishing, Kyiv

Émeric Lhuisset, Ukraine — Hundred Hidden Faces, Paradox, Edam, Netherlands, and André Frère Éditions, Marseille, France

Katerina Motylova, Loss, Self-published, Kyiv, Ukraine

Mark Neville, Stop Tanks with Books, Nazraeli Press, Paso Robles, California

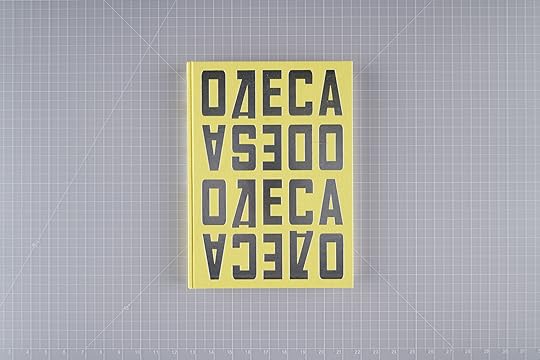

Yelena Yemchuk, Odesa, GOST Books, London

Previous NextJim Goldberg and Iryna Tsilyk

Another Life

STANLEY/BARKER, London

Katya Lesiv

I Love You

IST Publishing, Kyiv

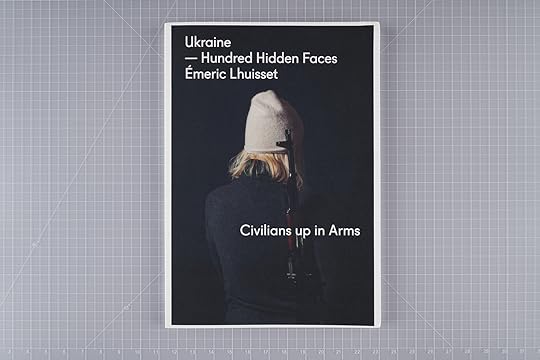

Émeric Lhuisset

Ukraine — Hundred Hidden Faces

Paradox, Edam, Netherlands, and André Frère Éditions, Marseille, France

Katerina Motylova

Loss

Self-published, Kyiv

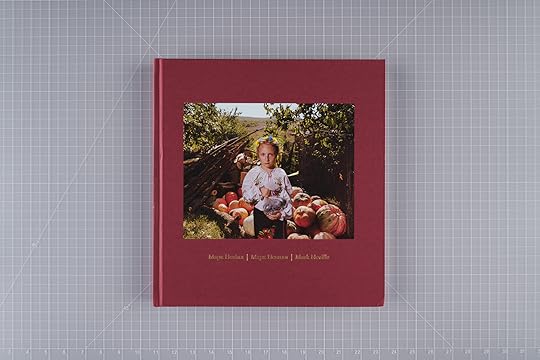

Mark Neville

Stop Tanks with Books

Nazraeli Press, Paso Robles, California

Yelena Yemchuk

Odesa

GOST Books, London

The 2022 PhotoBook Award winners will be announced during Paris Photo on Friday, November 11, 2022.

September 30, 2022

Dr. Kenneth Montague Joins Aperture Board of Trustees

Aperture announces the appointment of Dr. Kenneth Montague to its board of trustees, effective September 15, 2022, joining the range of community advocates, philanthropists, business leaders, educators, artists, and collectors that lead and support the esteemed photography nonprofit.

“Ken is an incredibly committed advocate for artists and underrepresented voices, who brings with him extensive leadership experience in the arts, nonprofit institutions, medicine, and business,” said Cathy M. Kaplan, Chair of Aperture’s board. “We are thrilled to welcome him to Aperture’s leadership as we celebrate our 70th anniversary this year and look ahead to the opening of our new permanent home in summer 2024.”

An avid art collector, community leader, nonprofit founder, and advocate for African and Diasporic artists, Dr. Montague comes to Aperture with a breadth of expertise in championing underrecognized achievements and a long-standing commitment to the medium of photography. Montague started the Wedge Collection in 1997 to acquire and exhibit art that explores Black identity and subsequently founded Wedge Curatorial Projects, a nonprofit arts organization that helps to support emerging Black artists. The organization mounts exhibitions and lectures that explore Diasporic narratives, identity, and issues of representation.

Based in Toronto, Montague is a successful business leader who founded the group practice Word of Mouth Dentistry. He has served on the boards and acquisition committees of major institutions internationally, including the Art Gallery of Ontario’s board of trustees since 2015, and as a member of the African acquisitions committee at Tate Modern, London. He is also an advisor to the Department of Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Dr. Montague’s book, As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (Aperture, 2021), serves as a testament to the support provided to artists by collecting and amplifying their work. As Teju Cole writes in “Letter to a Friend,” Montague “hews closely to his father’s mantra, ‘lifting as we rise,’ in his collecting, elevating the experiences of Black lives, the artists who capture them and, in turn, viewers who identify with them. As a result of this dynamic, Montague’s collection of photographs—made through the lens of the African and African diasporic experience—is a rare, insightful, radical, and bold act of deliverance.”

Dr. Montague joins Aperture’s existing board members with a shared dedication to the medium of photography: Peter Barbur, Julie Bédard, Dawoud Bey, Kwame Samori Brathwaite, Allan Chapin, Stuart B. Cooper, Kate Cordsen, Elaine Goldman, Lyle Ashton Harris, Michael Hoeh, Julia Joern, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, Philippe E. Laumont, Andrew E. Lewin, Lindsay McCrum, Joel Meyerowitz, Vasant Nayak, Dr. Stephen W. Nicholas, Helen Nitkin, Melissa O’Shaughnessy, Lisa Rosenblum, Thomas R. Schiff, Colette Veasey-Cullors, Casey Taylor Weyand, and Deborah Willis.

September 28, 2022

How Photographers in the 1970s Redefined the Medium

I was born in 1958, and now, all these donkey’s years later, am more conscious than ever of how my consciousness was shaped by the world as it existed before I became a part of it: by the England of just-passed austerity, of rationing (which only came to a complete end in Britain in 1954), of World War II, and, going further back, of my parents’ experiences of growing up in the 1930s. So? What on earth has that got to do with Aperture and photography?

William Eggleston, Untitled, 1975

William Eggleston, Untitled, 1975© Eggleston Artistic Trust and courtesy David Zwirner

I became interested in photography in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and looking at these old issues of Aperture, I see how much my sense of photography was a direct consequence of what was happening before then, in the 1970s. Photographers were busy taking photographs, making work, but interesting photographs are always being taken, great work is always being made, whatever the decade. In the ’70s, though, photography was being examined and defined in a way that harked back to Alfred Stieglitz’s pioneering inquiries into—and tireless lobbying on behalf of—the “idea photography” at the beginning of the century.

Books by Susan Sontag, John Berger, and Roland Barthes (whose Camera Lucida was published in French in 1980) were intended for the intellectually curious general reader rather than the specialist, and certainly not for practicing photographers. As Tod Papageorge later remarked, “Garry Winogrand never read Roland Barthes, and found whatever he’d seen of [Janet] Malcolm’s and Sontag’s original articles about photography in the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books grimly laughable.” (How about photography curators? Well, there weren’t many back then, a point we’ll return to shortly.) These back issues of Aperture show the cultural texture and grain of the times, the work being done at the coal face of photographic life. As revealed in discussions and portfolios of documentary photography, color photography (as exemplified by William Eggleston), snapshot aesthetics, and so on, what we see, close-up and from a distance (of forty to fifty years), is a landscape of awareness.

William Gedney, Cornett Girls, Kentucky, 1964, from Aperture, Spring 1978

William Gedney, Cornett Girls, Kentucky, 1964, from Aperture, Spring 1978Courtesy the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

The Spring 1978 issue features a review of Mirrors and Windows, an exhibition organized by John Szarkowski, head of the Museum of Modern Art’s department of photography. It was not until I went to the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University to work on William Gedney, in the mid-’90s, that I began to understand who—and how influential a figure—Szarkowski was. But I had been unconsciously in thrall to him before then. I think of my idea of photography as having been shaped by Berger and Sontag, but behind the scenes, it was Szarkowski who promoted certain photographers (including Gedney, for a while), and certain kinds of photography, at the expense of others. While Berger and Sontag were writing about the act of looking, they were also passive recipients of prior choices, or, as Marx famously put it, they did not make their choices “under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances already existing, given and transmitted from the past.” The kind of photographs they were looking at had, to a large extent, been actively determined by Szarkowski. It was Szarkowski, more than anyone else, who had assembled the material or evidence on which crucial parts of their cases would rest. (Barthes was less susceptible.)

There was, of course, a certain amount of “conceptual” photography around in the ’70s, a somewhat redundant formulation since photography is such an interesting concept in itself.

Broadly speaking, and at the risk of relying on an instructively unsustainable distinction, Szarkowski favored photographers who saw themselves as photographers rather than as artists using a camera (to employ the currently preferred job description). The paradox, embodied by Eugène Atget, is that if they were artists, that was because of their single-minded dedication to photography.

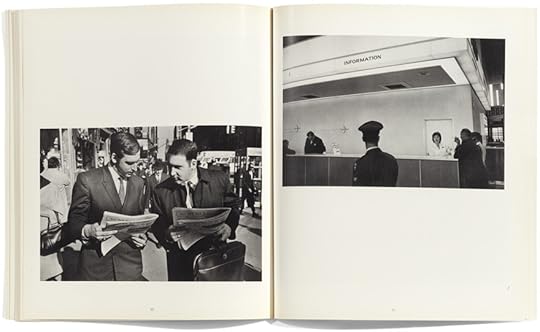

Spread from Aperture, Fall 1974, with photographs by Garry Winogrand

Spread from Aperture, Fall 1974, with photographs by Garry WinograndThere was, of course, a certain amount of “conceptual” photography around in the ’70s, a somewhat redundant formulation since photography is such an interesting concept in itself. Winogrand, ostensibly the least conceptual of photographers, showed enough philosophical nous to keep any seminar room awake—the best one can hope for in such airless environs when he said that if you photograph in Texas a lot then your pictures are going to look a lot like Texas. It was in the ’70s, also, that prints started to become valuable, an unexpected source of revenue for photographers and another factor in the tilt—steeper now than it’s ever been away from journalism or documentary and toward art. In this way, the ’70s point to the future, when Enrique Metinides’s pictures of car crashes and other catastrophic mishaps, originally taken to satisfy the sensational hunger of mass-market Mexican tabloids, would be shown in galleries for the more refined, scarcely less rapacious market of collectors’ homes. But the decade of the ’70s was also a time when there was a concerted looking back in the other direction: a strongly felt, vigorously articulated, carefully navigated exploration of tradition, not as mausoleum but in the process of constant formation.

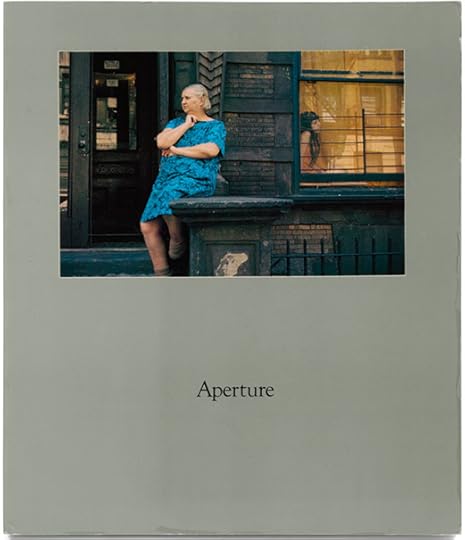

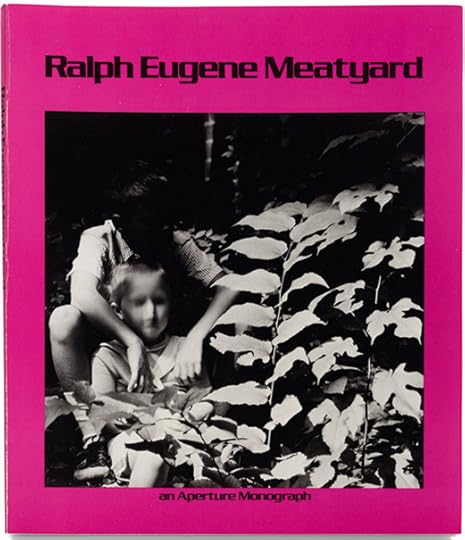

Covers of Aperture from Summer 1975, with photograph by Helen Levitt, and Summer 1974, a monographic issue on Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Covers of Aperture from Summer 1975, with photograph by Helen Levitt, and Summer 1974, a monographic issue on Ralph Eugene Meatyard

Viewed in this light, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the subject of Aperture’s Summer 1974 issue, is an entirely distinctive figure, simultaneously pivotal and enduringly marginal. An optician by trade, Meatyard conducted experiments in seeing that were consistently at odds with any ideal of twenty-twenty vision. The lenses he prescribed—and dispensed in the form of prints—had the unusual and pleasantly disturbing effect of articulating a form of spooky night vision in the broad daylight of Kentucky. To us now, his work seems, in equal measure, haunted by future ghosts (Francesca Woodman’s, most obviously) and blurrily indebted to the interior metaphysics of Walker Evans: “It’s as though there’s a wonderful secret in a certain place and I can capture it,” Evans said. “Only I, at this moment, can capture it, and only this moment and only me.”

While Meatyard insists on being seen, quite literally, as an eccentric, Evans’s centrality in any account of American photography is indisputable. On the occasion of the photographer’s 1971 retrospective at MoMA, Szarkowski wrote that “Evans’ work is rooted in the photography of the earlier past, and constitutes a reaffirmation of what had been photography’s central sense of purpose and aesthetic: the precise and lucid description of significant fact.” This statement has the force of an archaeological discovery, a Rosetta stone that was never hidden or lost, merely taken for granted and, thereby, easily overlooked. It is also a yardstick by which to assess what is going on in photography now. A single axiom can never be relied on to determine value in any medium, but Szarkowski’s has proved more reliable than anything else written about photography. It could help us today, saving a lot of time, sparing our eyes unnecessary exposure to all manner of visual froth and nonsense.

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue,” under the title “The Idea of Photography.”

September 22, 2022

“To Show Our World Now”: The Midcentury Photographers Who Balanced Reportage with Artistry

If the eye has a focal distance for any particular scene, might it also have a focal period, a time span in which an image can be apprehended in perfect focus? The idea occurs to me because of a possibility floated in the last Aperture of the 1960s, a monograph dedicated to W. Eugene Smith that gathers together his sublime expressionist images of atrocity, deprivation, and ordinary pleasure, from the invasion of Iwo Jima to Charlie Chaplin, Haiti, and the KKK.

Cover and spread of Aperture, Winter 1969, with photographs by W. Eugene Smith

In an afterword on Smith’s work, subtitled “Success or Failure: Art or History,” the critic, collector, and all-around polymath Lincoln Kirstein chews over the contested status of the photograph, coolly disparaging both its elevation to fetishized art object and its capacity for intercession in the realm of realpolitik. Nope and nope. A photograph can’t stop a war. The notion that war causes injury and horror is news to no one, from Homer on. The evidence a photograph brings home has long since been preceded by maimed veterans and body bags unloaded from military vessels. But one thing Kirstein thinks a photograph might do is address the future, specifically the new world order of the twenty-first century: “They may have their small if solid use by that world then to show our world now.”

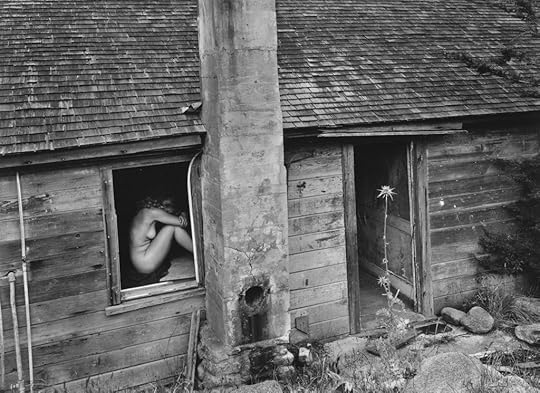

Wynn Bullock, Woman and Thistle, 1953, from Aperture, Fall 1961

Wynn Bullock, Woman and Thistle, 1953, from Aperture, Fall 1961© Bullock Family Photography LLC

In the same essay, Kirstein says of the photographer, “His greatest service is the seizure of the metaphorical moment.” That’s a great, if weirdly organized, sentence. You might more typically be inclined to write it as verb, not noun: “to seize,” as in snatch or secure, rather than “the seizure,” which carries with it simultaneous meanings of possessing and going into spasm. Seizure is not so dissimilar to Roland Barthes’s punctum, with its suggestion of an image that arrests the heart.

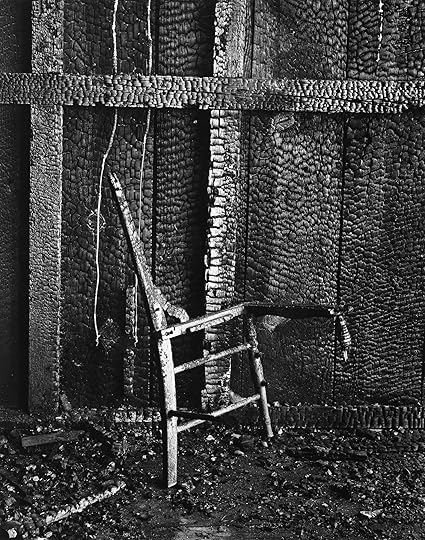

Wynn Bullock, Burnt Chair, 1954, from Aperture, Fall 1961

Wynn Bullock, Burnt Chair, 1954, from Aperture, Fall 1961© Bullock Family Photography LLC

I want to take Kirstein at his word, to see what the world of the ’60s looks like from the platform of now, seen by way of a few seizures of the metaphorical moment that caught my eye. Let’s start in Fall 1961, with a sequence by Wynn Bullock that seems, at first glance, concerned with natural surface textures, especially where they offer stark contrasts. Redwoods, abandoned cabins, a collapsing bank. The standout picture is of a burned chair against a burned wooden wall. It’s an account of aesthetic process, a fascinated investigation into the sheeny, scaly properties of charcoal. But hasn’t something unpleasant happened here, to folk unknown? One of the costs of seizing the metaphorical moment is that it necessitates severing the threads of narrative.

Bullock’s burnt chair exemplifies a tension that runs right through the ’60s issues, made under the ardent stewardship of Minor White, between what a photograph can be and what a photograph can show, which is to say the artistic impulse versus that of documentary. Take Bad Trouble over the Weekend (1964) by Dorothea Lange, from the Fall 1969 issue. The down-home phrasing serves as an additional button of veracity on this portrait of devastation, testimony to a dire sociopolitical situation. Yet the surfaces are as finely recorded as Bullock’s: knitted collar, worn wedding band, thin hair, thin hands covering the face, the black stub of a cigarette. It’s a Raymond Carver story condensed to a single frame, a universal semaphore for distress. And the cause of the trouble? Long gone, along with the subject’s name.

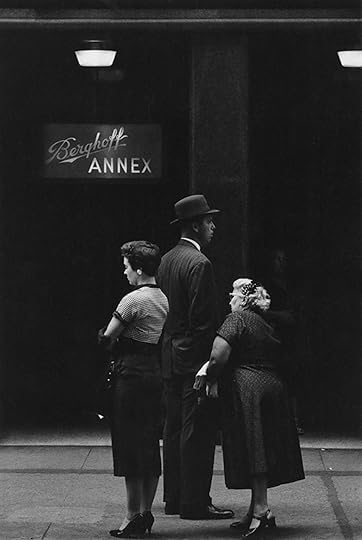

Ray K. Metzker, 58 EM-33, Chicago – Loop, 1958, from Aperture, Summer 1961

Ray K. Metzker, 58 EM-33, Chicago – Loop, 1958, from Aperture, Summer 1961© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Ray K. Metzker, whose sequence “My Camera and I in the Loop” appears in the Summer 1961 issue, is particularly articulate about the slippage between image and record. A choreography of solid bodies—cuffed/shirted/skirted/shod in white—emerges from slabs of urban dark, as theatrical in their composition as anything by Edward Hopper or Fritz Lang. Hardly reportage, except it is. “I began shooting,” Metzker explains, “in accord with my socioliteral viewpoint. The resulting pictures could not stand alone; they needed the propping of verbal explanation to exist.” Gradually, over the course of a painful winter, he saw that a photograph wasn’t anything save a “composition of light.” What it communicated or recorded was not as important to Metzker as the encounter between camera and eye: “To photograph is to be involved with form in its primal state.”

Even the most fantastical image betrays something about the world, not to mention about the person making it.

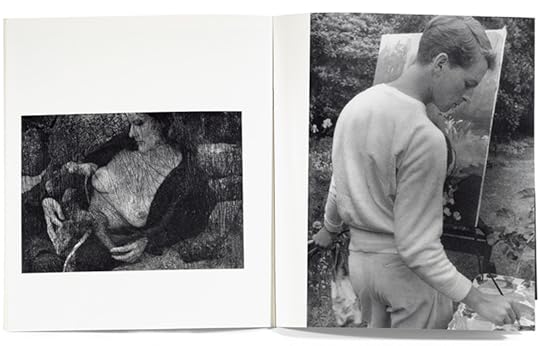

But is pure form any more attainable than pure reportage? Even the most fantastical image betrays something about the world, not to mention about the person making it. The Summer 1965 issue includes a series of dream scenes constructed by Edmund Teske. They’re layered, pictorial, artificial, melancholic, wistful, fey. Toward the end of the run, there’s a portrait of a man painting, his cold hawk’s face in profile. The eye travels down a lovely ogee: nape, shoulder, buttock. Something unsaid here, a secret pulse.

Spreads from Aperture: Summer 1965, with photographs by Edmund Teske

Spreads from Aperture: Summer 1965, with photographs by Edmund TeskeThis curve reminds me of another story Kirstein told. His essay on Smith culminates with a little epilogue, the story of an anonymous journalist friend he calls Jerry. It’s 1942, and Jerry doesn’t want to be drafted. Finally, one hard-drinking night, he admits he’ll say he’s queer rather than risk being shot up. Kirstein needs to use the bathroom; Jerry doesn’t want to let him. When Kirstein does finally enter, he discovers the room is pasted floor to ceiling with Smith’s photographs of the Pacific landings, stolen from the Time magazine offices. Dead boys in Eden. “Did Jerry sit there and amuse himself by shots of Tarawa?” Kirstein wonders cruelly. “Now you know,” Jerry says as Kirstein reemerges. “I can’t take it. I’m scared. Did you see those pictures?” When Kirstein comments mockingly on their beautiful composition, poor Jerry cries out: “They’re real.”

I wonder, was Jerry a good reader of photography or not? He refused to accept the photograph as a composition of light. For him, it was a memo from the future: watch out. Everything extraneous had been scraped away, until there was just the moment, a seizure that could stop the heart. Who knows what the boys were called, or even what they’d done. It was the pictures that were real now.

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue,” under the title “Did You See Those Pictures?”

When the Party Came to Lagos

Marilyn Nance can’t find Stokely Carmichael. She is compiling a bibliography for her forthcoming book, Last Day in Lagos, which documents her time as a photographer at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, or FESTAC ’77, as it is popularly known. Nance has a lingering, unshakeable, urge to include a book by Carmichael. His life’s work “sprung from being a young intellect to a civil rights worker to a Pan-Africanist,” she told me recently. “My life, while much more humble, follows a similar trajectory.” The Pan-African revolutionary, later known as Kwame Ture, attended the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers, Algeria, where Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Panther Party also held court. Combing through photographic archives, books, and his own writings, Nance believes that the radical lover of Black music and culture should have been at FESTAC ’77. But it has never been easy to tell who was actually there, especially among revolutionaries always on the move.

Nance’s and Ture’s paths had crossed a couple of times before. The first time, in the late 1960s, Nance was a member of the Black Cultural Society at the Bronx High School of Science and the group invited Ture, an alumnus, to speak. The second time, about a decade later, was in West Virginia at the John Henry Memorial Blues and Gospel Jubilee. Then, there was an All-African People’s Revolutionary Party event at Syracuse University, in the late 1980s. “If our paths crossed three times, then, why not at FESTAC?” she asks.

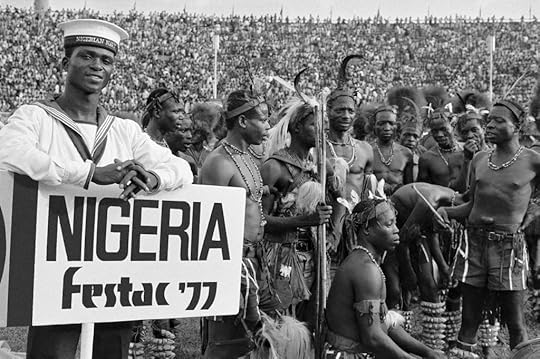

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77, 1977

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77, 1977Over fifteen thousand artists, dancers, actors, musicians, scholars, activists, photographers, filmmakers, and other cultural workers from the extended Black family came together for a month in 1977 for FESTAC. Officially, it sought to “provide a forum for the focusing of attention on the enormous richness and diversity of African contributions to world culture.” What makes one look back at FESTAC ’77 with wonder is the sense that it was an extraordinary representation of arrival—a high point of exchanges, conversations, and overtures Black people had been making with and toward each other in response to the historic rupture of slavery. As early as 1859, Black abolitionists such as Martin Delany were scoping out possible sites on the African continent for free Blacks to return to. In 1900, W. E. B. Du Bois closed the first Pan-African Conference, held in London, by declaring “the color line” as the problem of the twentieth century. At the 1956 Conference of Negro-African Writers and Artists in Paris, Richard Wright declared that African Americans were in “the technological vanguard” among Black people and “would prove of inestimable value to the developing African sovereignties.” These initiatives pulled together the creative and political energies of Black people all over the world to harmonize efforts in a collective liberation. Ten years later, Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes, and Alvin Ailey joined Wole Soyinka and Nelson Mandela at the 1966 First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.

FESTAC ’77 was bigger. Nance, who attended and photographed this historic event, describes it as the Olympics, a biennial, and Woodstock combined. Ebony magazine declared that “for the first time in 500 years, the black family was together again.” This was possibly the largest group of African American artists, over four hundred of them, to have traveled to the African continent together. Those on this “symbolic reversal of the transatlantic slave trade,” as Nance has described the 1977 moment, included Stevie Wonder, Jayne Cortez, Betye Saar, Faith Ringgold, Paule Marshall, and Jeff Donaldson.

Marilyn Nance, Miriam Makeba performing in Tafawa Balewa Square (one of many wardrobe changes), 1977

Marilyn Nance, Miriam Makeba performing in Tafawa Balewa Square (one of many wardrobe changes), 1977A photographer for the U.S. contingent, Nance made images of the great diversity of people at FESTAC. Getting there hadn’t been easy. In 1974, she submitted her portfolio to the festival organizers to participate as an artist, sending, among other things, a photograph of her grandmother sitting at a lunch table in Alabama. In 1975, Nance heard back that her work was accepted. But the next year, she was informed that the number of attendants from the United States—herself included—had been cut. Discovering that there was a need for a photo-technician, she made a case to be chosen, especially since the photograph of her grandmother had been lost by the organizers. Nance called the offices of the festival’s North American headquarters, housed in Howard University’s art department, every day until they relented. There was no pay, or camera, or film. Just a ticket on Capitol International Airlines to Lagos and back.

With a similar spirit of persistence, Nance stayed for the full length of the festival rather than the two weeks she was allotted by the organizers, allowing her to see and document it in a comprehensive way. The resulting photographic archive remains one of the largest visual records of this monumental occasion, where the poet Audre Lorde “felt the earth move.” A selection from Nance’s approximately 1,500 FESTAC images will be collected in Last Day in Lagos.

Marilyn Nance, David Stephens, Oghenero Akpomuje, Frank Smith, and Valerie Maynard at U.S. Ambassador’s reception for FESTAC artists, 1977

Marilyn Nance, David Stephens, Oghenero Akpomuje, Frank Smith, and Valerie Maynard at U.S. Ambassador’s reception for FESTAC artists, 1977At FESTAC, Nance was less interested in the contentious academic arguments around a definition of Blackness that had carried over from previous international gatherings. (The words Black and African in the festival’s name were used to allow for the inclusion of North Africans who might not consider themselves Black.) Instead, Nance was busy in the streets and arenas, at cafeterias and parties, interacting with people and collecting on-the-scene photographic representations of the joy of recognition among participants from around the globe, of spontaneous relations being formed through identified commonalities, and of the forging of communities and collaborations. This trip was Nance’s first time traveling outside of the United States, and, as the spirits of the ancestors would have it, all of Africa had come to meet her.

Seeing the faces of friendly folks from the other side of the world, Nance thought she recognized characteristics of her U.S. relatives and acquaintances—in the cadence of speech, in the pitch of laughter, in facial expressions. She had a desire to visually investigate Africanisms—the shared habits, tendencies, and proclivities observed wherever Blacks had been sprinkled. Nance had long thought of herself, although born in the United States, as African. Here, in Africa, she was seen as an American. She began to grapple with her place, and that of African Americans in general, in the larger Black diasporic family. “I got an understanding of the history of how we became African Americans,” she says. “I knew it. But at FESTAC, you could feel it.” Feeling complemented a political awareness of Blackness drawn equally from her African ancestry as from her political education and knowledge of history informed by the civil rights and the Black Arts movements. “I feel connected to other people,” she says, “and my photographs document that connection.”

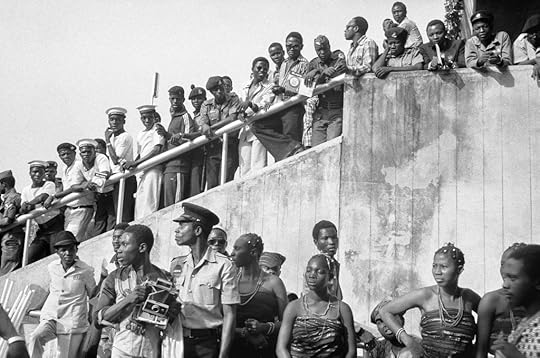

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77 Opening Day Ceremony onlookers, 1977

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77 Opening Day Ceremony onlookers, 1977Nance was born in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 1953. Her father and mother had left Wadesboro, North Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama, respectively, as part of the Great Migration north. Her grandmother (who thought of herself as African and was most excited about Nance’s “return” to Africa) was born in 1886. “Her father would have been born in the time of enslavement,” Nance states, “meaning our family is only two generations removed from having been enslaved and one generation removed from sharecropping.” As a child, Nance came to know family members primarily through photographs. Her mother would point out people and tell her their stories. At age eight, she received her first camera, a gift from her cousin that is still in her possession. Nance would graduate from New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, study graphic design at Pratt Institute, train in audio and film production at the Institute for New Cinema Artists, and earn a master of fine arts degree in photography from the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Nance’s archive remains one of the largest visual records of this monumental occasion, where the poet Audre Lorde “felt the earth move.”

Arriving at FESTAC, at age twenty-three, with a wide multimedia skill set was beneficial. But a more important foundation for her work, then and later, is the political education on which Nance’s craft is erected. Her mother’s father was a labor organizer and only in adulthood did she realize that never crossing a picket line isn’t a commandment everyone’s parents held them to. From middle-school days, she remembers conversations with her sister about demonstrations demanding summer jobs for Black teens. In 1968, the year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, she attended her first Black Power rally while in high school. Her formative years were suffused with the political energies of the civil rights movement and the creative energies of the Black Arts movement, which encouraged art with the purpose of awakening consciousness, forming community, and striving for liberation. “I really believed in all African people,” she says, “because that had been my training, my political education.” Nance immersed herself in the recordings of the musician and activist Rahsaan Roland Kirk and the teachings of Malcolm X, participated in Black cultural rallies, and went to see plays by Amiri Baraka and Ed Bullins, who served as the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party. “FESTAC was a triumph of the Black Arts movement,” Nance explains, “because in the Black Arts movement, there was always a reference to Africa.”

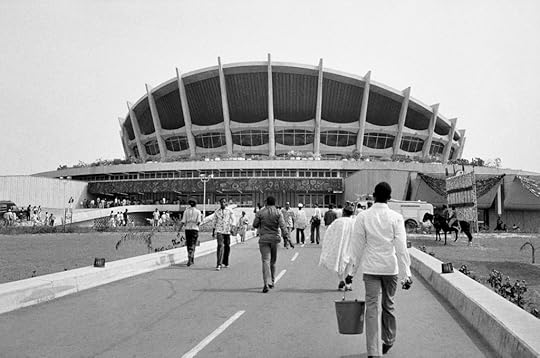

Marilyn Nance, The National Theater, Lagos, Nigeria, 1977

Marilyn Nance, The National Theater, Lagos, Nigeria, 1977In Lagos, and in true Pan-African style, Nance roamed from one contingent to the next. Language could be a big barrier. Nance recalls a lot of smiling, staring, and dancing as ways of communicating. At the lunch table, you might find Indigenous Australians across from you, musicians from Burundi to your left, and North African intellectuals to your right. “‘Who are you?’ and ‘Oh, look at you!’ were the ethos,” she says; physical presence was the currency of exchange. Tagging along with Nance through her photographic archive is a wild ride. We see not just Lagos but journey also to Ile-Ife and Benin City. We feel the blistering afternoon sun; squeeze into a rehearsal of Sun Ra and his Arkestra; and dance with Stevie Wonder and Miriam Makeba at Fela Kuti’s nightclub the Shrine.

With either her Canonet point-and-shoot or Miranda Sensomat cameras ever present, Nance navigated this month of encounters by quite literally being in people’s faces. This immediate nearness and proximity, almost making her invisible to her subjects, gives the viewer a strong illusion of being present on the scene. In one image from the opening day ceremony, the frame includes no action from the festival but is zoned in on the crowd. Standing on the ground level is an eclectic collection of observers—women wrapped in their traditional cloths, beads draped gently around their necks; a fedora-wearing man with a tailored shirt and trousers; a young photographer with a pinkie ring, firmly holding his folding camera; above, on a staircase and landing, facing the photographer, are naval men in white shirts and sailor caps, assorted security men in their starched uniforms, and a group of general onlookers. The photograph is filled with people, yet there is a sense that you are interacting with each person on their own terms, sharing their perspective—wondering what has caught their attention as the rich and active atmosphere of the festival has drawn everyone’s gaze toward a different direction.

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77 Opening Ceremony, Duro Ladipo flanked by two men holding talking drums, 1977

Marilyn Nance, FESTAC ’77 Opening Ceremony, Duro Ladipo flanked by two men holding talking drums, 1977“While her images of FESTAC ’77 have left an indelible mark on how we understand the festival visually,” Oluremi C. Onabanjo, an associate curator in the department of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, says, “I feel FESTAC ’77 also left its own mark on her, as a formative experience in her life as a photographer and adult.” Onabanjo, who is the editor of Nance’s photobook on FESTAC, traces a special attention and interest in bodily expression in Nance’s later work—of the intimate, the sensual, the quiet—back to FESTAC. As Nance states, “It is what is in your heart and in your mind that makes the images.”

Related Items

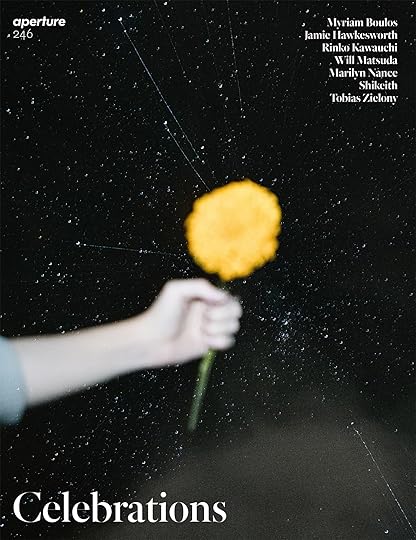

Aperture 246

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]An “undying love for the people,” a phrase Nance borrowed from Kwame Ture, is the spirit that inspires her photographs. Attending FESTAC intensified Nance’s commitments to the principles and values of the Black Arts movement. In her coverage of anti-apartheid activism in New York and the vulnerable, ecstatic scenes at the Oyotunji African village in South Carolina, there remains that interest in interchanges of ideas, people, and events found at FESTAC. As Onabanjo explains, Nance’s photography after 1977 “witnesses an amplified scope of vision as to the various transnational spiritual, cultural, and political experiences . . . while showing a finely attuned sensitivity of the place of African Americans within this global context.” She points to Nance’s 1980 images of the Black Indians in New Orleans; her work as a producer on the 1985 film Voices of the Gods, directed by her husband, Al Santana; her image Three Placards from 1986, with the faces of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Elijah Muhammad on placards at an anti-apartheid rally in Central Park; and the place of Yoruba culture in her installation Egungun Work (1994).

Nance is a self-described “digital elder” who seems to bring her archival practice to all her interactions. Perhaps this approach reflects back to her childhood of “meeting” family through photo- albums. In a wider sense, her focus on connecting people and histories corresponds to the African practices of festivals, where it is believed that all generations—the living and the dead—come together. Last Day in Lagos, then, is a festival of its own, a feast for the creative imagination that introduces today’s generation to their artistic ancestors.

Marilyn Nance, Stevie Wonder performing on the drums, 1977

Marilyn Nance, Stevie Wonder performing on the drums, 1977All photographs © the artist and courtesy Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

For Nance, the images are “visual medicine,” a reminder of mutual joy preserved for the future. The making of Last Day in Lagos led Nance to rediscover other FESTAC goers. In the process of creating the book, Nance found mementos—address books, cloths, notes, letters—that fueled her desire to bring together what she refers to as the FESTAC ’77 fellowship. Despite the event’s historic nature, on returning, participants found little interest in telling others about their time in Lagos. In March 1977, Kay Brown, of the Black women artists collective Where We At, organized an open house in Brooklyn for participants to share photographs and stories. The following month, the Studio Museum in Harlem hosted a reception honoring U.S. participants. But there was no organization or space created to hold FESTAC archival materials or oral histories. Until relatively recently, interest in the work and experiences of the Black artists who were there has been relegated to a handful of academic articles and discussions. Memories of the festival, outside of the participants and their personal archives, persist in some memoirs and biographies. In 2017, the curator Dominique Malaquais organized the panel “FESTAC ’77 and Other Pan-African Festivals” where participants, including Nance, spoke. Nance’s images are also found in the 2019 book Festac ’77: 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. In 2021, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, acquired twenty of Nance’s photographs. When I ask Nance why the sudden uptick in interest in FESTAC, she throws the question back to me. “I was ready in 1977 but there was no interest, so we had to go on living,” Nance says. “My job was to make the images. I did the work. I kept the work. I respected the work. I just had to live long enough and wait until the right time came around.”

These days, Nance is occupied with “deep sleuthing” online. She’s tracked down, connected with, and even spoken to some of the people she’s identified in the photographs. Whether or not she finds Kwame Ture in her archive, she is determined that the legacy of the Black Arts movement is not lost to history. U.S. participants at FESTAC spanned generations, from members of the Harlem Renaissance to their creative descendants. For Nance, this is American history, Black history, world history, and art history that she won’t allow to be forgotten. “I’m interested in making sure that someone knew that I was here,” she says. “To be a Black person in America is to always be disregarded, to never be thought of as an intellectual, or an artist, or a collector.” If FESTAC, in the shadow of a civil war, military coups, and political instability, and lacking the technology and degree of connectedness we have in the world today, could be planned and executed successfully in the 1970s, imagine—Nance’s archive seems to tell us what the future could hold.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “When the Party Came to Lagos.”

September 16, 2022

Announcing the Winners of Google’s 2022 Image Equity Fellowship

Today, in partnership with Google, For Freedoms, and FREE THE WORK, Aperture is pleased to announce the twenty recipients of the 2022 Image Equity Fellowship.

The winners of the 2022 Image Equity Fellowship are:

Jamil Baldwin, Miranda Barnes, McKayla Chandler, Maneesha Chaudhary, Nykelle DeVivo, Emanuel Hahn, Eric Hart Jr., Vikesh Kapoor, Adeline Lulo, Tiffany Luong, Maya June Mansour, Da’Shaunae Marisa, Xavier Scott Marshall, Ricardo Nagaoka, Nasrah Omar, David López Osuna, Walé Oyéjidé, Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola, C.T. Robert, Giancarlo Montes Santangelo

Google’s first-ever Image Equity Fellowship is a six-month, application-based Fellowship awarded to twenty early-career image-based creators of color in the US. This year’s selection involved the review of more than a thousand submissions by a jury comprised of Lebanese filmmaker and photographer Ahmed Klink; American artist and 2016 Guggenheim Fellow Lyle Ashton Harris; photographer and documentarian Bee Walker; multi-hyphenate creative Mahaneela; and Rujeko Hockley, Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The Fellows will each receive $20,000 in unrestricted funds to create an image-based project that explores and uplifts communities of color. Throughout their six-month fellowships, they will be supported by Google and three industry-celebrated nonprofit partners—Aperture, For Freedoms, & FREE THE WORK—in the form of dedicated mentorship, workshops, funding, and publication of and press for their completed projects.

Bee Walker, a mentor and reviewer, noted how much she is looking forward to working with the fellows, “Each of their portfolios personally moved, inspired, and challenged me, but more importantly, made me curious about what else they have to say visually… I’m certain that it will be a creatively enriching process for me as well.” Ahmed Klink also reflected on the review process, “I was thoroughly impressed by the quality and thoughtfulness of all the portfolios we got to look at. I cannot speak highly enough about the level of craft and the visual storytelling all the photographers brought to the table. It truly made an impact on me and it made the selection all the more difficult.”

Photograph by Jamil Baldwin

Photograph by Jamil Baldwin Photograph by Miranda Barnes

Photograph by Miranda Barnes Photograph by McKayla Chandler

Photograph by McKayla Chandler Photograph by Maneesha Chaudhary

Photograph by Maneesha Chaudhary Photograph by Nykelle DeVivo

Photograph by Nykelle DeVivo Photograph by Emanuel Hahn

Photograph by Emanuel Hahn Photograph by Eric Hart Jr.

Photograph by Eric Hart Jr. Photograph by Vikesh Kapoor

Photograph by Vikesh Kapoor Photograph by Adeline Lulo

Photograph by Adeline Lulo Photograph by Tiffany Luong

Photograph by Tiffany Luong Photograph by Maya June Mansour

Photograph by Maya June Mansour Photograph by Da’Shaunae Marisa

Photograph by Da’Shaunae Marisa Photograph by Xavier Scott Marshall

Photograph by Xavier Scott Marshall Photograph by Ricardo Nagaoka

Photograph by Ricardo Nagaoka Photograph by Nasrah Omar

Photograph by Nasrah Omar Photograph by David López Osuna

Photograph by David López Osuna Photograph by Walé Oyéjidé

Photograph by Walé Oyéjidé Photograph by Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola

Photograph by Oluwatosin “Tosin” Popoola Photograph by C.T. Robert

Photograph by C.T. Robert Photograph by Giancarlo Montes Santangelo

Photograph by Giancarlo Montes Santangelo

September 15, 2022

Historic Building in New York’s Upper West Side to Become New Permanent Home for Aperture

Aperture’s Board of Trustees today announced plans for two floors of a historic building in the heart of New York’s Upper West Side to become the organization’s new permanent home. Located at 380 Columbus Avenue, the building situates Aperture at the nexus of a vibrant residential neighborhood and bustling tourist destination—across from the American Museum of Natural History and blocks from the New-York Historical Society and Central Park—providing access to a wider spectrum of local and international audiences than ever in the organization’s history.

Featuring a new ground floor entrance and expansive street presence, the building enables Aperture to expand its reach and strengthen the impact of its initiatives, which demonstrate the power of photography to spark curiosity and enhance understanding of the world and each other. Two floors, encompassing 10,000 square feet of the 1886 building, will be repurposed as a hub for collaboration and convening, and a site for public engagement with Aperture’s quarterly magazine, books, and prints.

Aperture has engaged award-winning architecture practice LEVENBETTS to design flexible spaces for public programming and small-scale installations, the Aperture bookstore, and re-imagined office and production spaces for Aperture’s robust publishing program, while retaining the building’s historic character. Visitors will be able to see directly into several of Aperture’s work spaces, fostering transparency and giving audiences a window into the organization’s activities.

380 Columbus Avenue c. 1930

380 Columbus Avenue c. 1930Courtesy Landmark West

Marking its 70th anniversary this year, Aperture has been located for nearly two decades in a fourth-floor space in Chelsea, where the organization has mounted exhibitions and public programs; published Aperture magazine and countless acclaimed photobooks; and hosted its bookstore and limited-edition print program. The acquisition and design of its new ground floor home is funded in part through the early phase of a capital campaign which laid the groundwork for phase two of the campaign, set to launch in the coming months. The acquisition was spearheaded by Cathy Kaplan, Chair of Aperture’s Board, Helen Nitkin, Chair of the Board’s Real Estate Committee, and Sarah Meister, who was named Executive Director of Aperture in 2021.

The announcement comes on the eve of Aperture’s 70th anniversary celebration this fall, marked by the release of a special 70th anniversary issue of Aperture magazine; 70 different limited-edition photographs available to collectors by some of the most celebrated and influential photographers in the history of the medium, each with a special tie to Aperture; and Aperture’s fall gala on Monday, October 17, in New York, to be hosted by Board Chair Cathy Kaplan, Executive Director Sarah Meister, and Gala Co-chairs Helen Nitkin, Aperture Trustee, Yesim Philip, CEO & Creative Director at L’Etoile Sport, Kara Ross, award-winning jewelry designer, and Antwaun Sargent, independent writer, curator, and critic.

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

17 Photographers Reflect on Key Images for Aperture’s Seventieth Anniversary

Learn More[image error]“As we celebrate Aperture’s 70th anniversary, our new permanent home provides a rock-solid foundation for the next 70 years,” said Cathy Kaplan, Chair of Aperture’s Board of Trustees. “I am grateful to the leadership and vision of Helen Nitkin, our entire Board of Trustees, and Sarah Meister in cementing Aperture’s distinct position as a convenor, community builder, and publisher that has advanced the medium of photography for seven decades.”

Kwame S. Brathwaite, Aperture Trustee, adds: “Aperture has been absolutely pivotal over its long history in nurturing artists and creating visible platforms for their practices that broaden understanding of their work and of photography more broadly. I’ve seen this first hand through my father Kwame Brathwaite and his own practice. This new permanent home for Aperture strengthens its ability to advance this important work for many more decades.”

“Aperture has long been an anchor for the photography community, not just in New York but globally. Our permanent commitment to the Upper West Side and a highly visible ground floor space signals a renewed, long-term vision for Aperture’s future as we move into our eighth decade—one that recognizes Aperture’s critical role in fostering collaboration and bringing together the array of artists, writers, institutions, and enthusiasts that are transformed by photography every day,” said Sarah Meister, Aperture executive director. “In addition to serving as a hub for the photography community in New York, Aperture will continue to engage audiences around the world through collaborative programming outside of our space—an approach we see as key to the ongoing impact of the organization.”

In its new home, Aperture’s exhibition program will be comprised of focused presentations. Extending the organization’s reach beyond its New York space, Aperture will also continue its recent history of collaborations with major institutional partners to mount large-scale exhibitions and programming. Recent partnerships include the Aperture-organized exhibitions Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, currently on view at the New-York Historical Society; As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic on view at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto; The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, curated by Antwaun Sargent and on view at Fotografiska, Sweden; Prison Nation, curated by Nicole Fleetwood and Michael Famighetti, on view at the Albin O. Kuhn Gallery, University of Maryland, Baltimore County; and Orlando, curated by Tilda Swinton, expanding on her role as guest editor for an issue of Aperture magazine, opening at C/O Berlin on September 17.

Read more about Aperture’s new permanent home on the New York Times.

Historic Building in New York’s Upper West Side To Become New Permanent Home for Aperture

Aperture’s Board of Trustees today announced plans for two floors of a historic building in the heart of New York’s Upper West Side to become the organization’s new permanent home. Located at 380 Columbus Avenue, the building situates Aperture at the nexus of a vibrant residential neighborhood and bustling tourist destination—across from the American Museum of Natural History and blocks from the New-York Historical Society and Central Park—providing access to a wider spectrum of local and international audiences than ever in the organization’s history.

Featuring a new ground floor entrance and expansive street presence, the building enables Aperture to expand its reach and strengthen the impact of its initiatives, which demonstrate the power of photography to spark curiosity and enhance understanding of the world and each other. Two floors, encompassing 10,000 square feet of the 1886 building, will be repurposed as a hub for collaboration and convening, and a site for public engagement with Aperture’s quarterly magazine, books, and prints.

Aperture has engaged award-winning architecture practice LEVENBETTS to design flexible spaces for public programming and small-scale installations, the Aperture bookstore, and re-imagined office and production spaces for Aperture’s robust publishing program, while retaining the building’s historic character. Visitors will be able to see directly into several of Aperture’s work spaces, fostering transparency and giving audiences a window into the organization’s activities.

380 Columbus Avenue c. 1930

380 Columbus Avenue c. 1930Courtesy Landmark West

Marking its 70th anniversary this year, Aperture has been located for nearly two decades in a fourth-floor space in Chelsea, where the organization has mounted exhibitions and public programs; published Aperture magazine and countless acclaimed photobooks; and hosted its bookstore and limited-edition print program. The acquisition and design of its new ground floor home is funded in part through the early phase of a capital campaign which laid the groundwork for phase two of the campaign, set to launch in the coming months. The acquisition was spearheaded by Cathy Kaplan, Chair of Aperture’s Board, Helen Nitkin, Chair of the Board’s Real Estate Committee, and Sarah Meister, who was named Executive Director of Aperture in 2021.

The announcement comes on the eve of Aperture’s 70th anniversary celebration this fall, marked by the release of a special 70th anniversary issue of Aperture magazine; 70 different limited-edition photographs available to collectors by some of the most celebrated and influential photographers in the history of the medium, each with a special tie to Aperture; and Aperture’s fall gala on Monday, October 17, in New York, to be hosted by Board Chair Cathy Kaplan, Executive Director Sarah Meister, and Gala Co-chairs Helen Nitkin, Aperture Trustee, Yesim Philip, CEO & Creative Director at L’Etoile Sport, Kara Ross, award-winning jewelry designer, and Antwaun Sargent, independent writer, curator, and critic.

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

17 Photographers Reflect on Key Images for Aperture’s Seventieth Anniversary

Learn More[image error]“As we celebrate Aperture’s 70th anniversary, our new permanent home provides a rock-solid foundation for the next 70 years,” said Cathy Kaplan, Chair of Aperture’s Board of Trustees. “I am grateful to the leadership and vision of Helen Nitkin, our entire Board of Trustees, and Sarah Meister in cementing Aperture’s distinct position as a convenor, community builder, and publisher that has advanced the medium of photography for seven decades.”

Kwame S. Brathwaite, Aperture Trustee, adds: “Aperture has been absolutely pivotal over its long history in nurturing artists and creating visible platforms for their practices that broaden understanding of their work and of photography more broadly. I’ve seen this first hand through my father Kwame Brathwaite and his own practice. This new permanent home for Aperture strengthens its ability to advance this important work for many more decades.”

“Aperture has long been an anchor for the photography community, not just in New York but globally. Our permanent commitment to the Upper West Side and a highly visible ground floor space signals a renewed, long-term vision for Aperture’s future as we move into our eighth decade—one that recognizes Aperture’s critical role in fostering collaboration and bringing together the array of artists, writers, institutions, and enthusiasts that are transformed by photography every day,” said Sarah Meister, Aperture executive director. “In addition to serving as a hub for the photography community in New York, Aperture will continue to engage audiences around the world through collaborative programming outside of our space—an approach we see as key to the ongoing impact of the organization.”

In its new home, Aperture’s exhibition program will be comprised of focused presentations. Extending the organization’s reach beyond its New York space, Aperture will also continue its recent history of collaborations with major institutional partners to mount large-scale exhibitions and programming. Recent partnerships include the Aperture-organized exhibitions Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, currently on view at the New-York Historical Society; As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic on view at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto; The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, curated by Antwaun Sargent and on view at Fotografiska, Sweden; Prison Nation, curated by Nicole Fleetwood and Michael Famighetti, on view at the Albin O. Kuhn Gallery, University of Maryland, Baltimore County; and Orlando, curated by Tilda Swinton, expanding on her role as guest editor for an issue of Aperture magazine, opening at C/O Berlin on September 17.

Read more about Aperture’s new permanent home on the New York Times.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers