Aperture's Blog, page 41

June 8, 2022

How the Architect Frida Escobedo Thinks About Art and Design

In March 2022, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, announced the selection of the architect Frida Escobedo to design the museum’s new modern and contemporary art wing. Here, we revisit an interview with Escobedo in the magazine’s “House & Home” issue, originally published in spring 2020.

When she landed the commission to design London’s Serpentine Pavilion in 2018, Frida Escobedo established herself as a young architect with a compelling vision. By that time, she already had a number of accomplished projects under her belt, from the renovation of La Tallera, the former studio of the painter David Alfaro Siqueiros turned public art gallery, to Casa Negra, a house featuring wide-screen views of her native Mexico City, designed for a photographer and inspired by the concept of a camera obscura. Escobedo’s works—often made with raw materials like perforated concrete blocks—opt for flexibility and a restrained yet daring form to create simple visual gestures.

Though Escobedo says she was too intimidated to apply to art school, deciding on an architecture path instead, her creative process is close to that of a visual artist who lets her pieces speak for themselves. But she also has an eye on the cultural landscape in which her work exists—Mexico’s social divisions and class dynamics have often been a concern in her investigations of buildings and housing—as well as on the storied history of built environments in her home country. “Mexican architecture is informed by its context,” she has remarked. “I think it’s more like a spirit rather than a style.” Here, she speaks about transforming lives through design and space, and her own spirit of invention.

Frida Escobedo, Casa Negra, Mexico City, 2006

Frida Escobedo, Casa Negra, Mexico City, 2006Photograph by José Fernando Sánchez. Courtesy the artist

Alejandra González Romo: One of your first projects was the Casa Negra (2006) on the outskirts of Mexico City, which resembles a dark camera. Is there any connection between the concept for that house and that of an old camera?

Frida Escobedo: The first two projects I worked on were house renovations, so this was indeed the first one I developed from scratch. I was twenty-three back then, fresh out of college, and a small, very simple house had to be built with limited resources. The idea was to build a one room studio with a mezzanine as a quick solution. The owner, who is a photographer, had inherited that plot on the outskirts of Mexico City, on the road to Cuernavaca. A small space, it had to be made permeable to light, and the solution was to build a huge window looking out onto the city, which frames the view. It is a black box standing on columns. One enters by a bridge. When entering the box, one immediately sees the landscape, a mixture of forest and city. At night, especially, the box creates a camera-obscura effect with the city lights visible in the distance.

González Romo: How would you describe the way natural light comes into the space?

Escobedo: The light comes in from the north. Therefore, the house works perfectly as a studio. The only risk was that the house turns out to be very cold. For this reason, we installed an L shaped skylight, so it has an additional light inlet from the south, thus warming it a bit. We painted it dark gray—almost black—so that it attracts more light and heat. It also has a ramp that goes from the kitchen up to a terrace. Therefore, the social space is doubled, the peripheral view from the roof offering a whole different experience. It is indeed a type of camera aiming at the city, but, at the same time, it’s spatially functional. Also, its position and angle resemble the way any photographer would choose to set a tripod.

A photograph by Frida Escobedo’s sister, Ana Gómez de León, at Escobedo’s home, Mexico City, 2019

A photograph by Frida Escobedo’s sister, Ana Gómez de León, at Escobedo’s home, Mexico City, 2019Photographs by Yvonne Venegas for Aperture

Frida Escobedo’s home, Mexico City, 2019

Frida Escobedo’s home, Mexico City, 2019 González Romo: Looking at the documentation of your projects, I can see the signature of the photographer Rafael Gamo is on practically every single piece. What is the role of photography in your creative process?

Escobedo: The process behind architecture is overflowing with images. But if we talk of photography’s recording value, my interest is in having documentation done on more than one occasion. I like working with Rafael, because he always comes back to the sites to capture the way a project evolves. Neither of us is interested in the perfect picture. All we want is a living record. Even though, in many cases, owners make it difficult to keep that record, I am interested in capturing how each construction ages.

González Romo: What other photographers have influenced your way of seeing?

Escobedo: Josef Koudelka, Sebastião Salgado, Graciela Iturbide, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Gerhard Richter—their interventions with photographs. My sister Ana Gómez de León is also a photographer. A photograph of hers sits by the entrance of my house. I forced her to give it to me as a present. She took the photograph from a plane, where you can see a river crossing the mountains. When I saw it, I thought of Salgado and his endless journeys to shoot such images. This one was taken through a filthy window using an iPhone. I love it. It is my favorite photograph. Here, in my office, I have a postcard taken by the architect Mauricio Rocha, in 1988. It is an image of a wooden wagon with glass doors reflecting a lake. It is a photograph he took at a very young age, and I interpreted it as some sort of acknowledgment of what I was doing in my first years as an architect.

I recently saw Hans Haacke’s exhibition at the New Museum, in which he analyzes the relationships between power, real-estate value, and built space in New York. His research draws lines between the Shapolsky family and 142 buildings across the city, while keeping a record of each property’s square meters, its conditions, its owner, et cetera. It is well known that power concentrates in very few families around the world; yet, visualizing it in such a clear way takes the subject out of the abstract. A similar analysis, but one made indoors, is Daniela Rossell’s series Ricas y famosas (Rich and famous, 1994–2001), where she shows the interiors of immense mansions in Mexico, unveiling the tastes and personalities of women who may lack anything but money. It is a portrait of society through space and architecture from an intimate perspective.

Carlos Somonte, Still of Yalitza Aparicio in Roma (Alfonso Curarón, dir.), 2018

Carlos Somonte, Still of Yalitza Aparicio in Roma (Alfonso Curarón, dir.), 2018Courtesy Netflix

González Romo: Haacke’s piece sounds similar to what you achieved with your research project and book Domestic Orbits (2019), based on the fact that there are more than 2.4 million domestic workers in Mexico and that 90 percent of them are women. It is a cartographical analysis of the way the domestic sphere is configured around race, class, and gender. What triggered your interest in this subject?

Escobedo: Few people know that Luis Barragán’s domestic worker still lives in his house, more than thirty years after Barragán’s death. As part of his will, he decided she could continue living there for the rest of her life. We are talking about an iconic house built by a Pritzker Prize winner, which currently functions as a museum but has a hidden configuration: a house within a house that no one knows about and that is designed not to be discovered by visitors. Nonetheless, if you pay attention, there are hints of that invisibility everywhere. There are bells under the tables to communicate with that other zone, and there are secondary routes that allow staff to pass through the main areas without being seen.

This analysis of Casa Barragán was the first exercise. Three years later, we decided to expand our research, as these signs of invisibility can be seen in architecture on different scales. In the building where I live, there are also rooms for the service staff that are completely invisible. Walking around the city, we see massive apartment buildings with wonderful views, built by renowned architects. But what invisible architecture lies behind?

I don’t think there should only be one concept of home. I think the actual problem is the will to standardize.

We also analyzed the house where Alfonso Cuarón’s 2018 movie Roma was filmed, which has a little tower where the character Cleo [the family’s domestic worker] lives. Another very interesting case is a building from 1957 in Polanco [a neighborhood in Mexico City], where the service staff rooms are in a separate building a few blocks away. These are very small dwellings built around a main courtyard, where the service staff can have a private life and bring visitors if they so wish, in addition to having a spatial separation between work and leisure. That possibility has almost completely disappeared within one generation, and current domestic workers often commute up to four hours every day from the outskirts of the city to their workplaces.

Frida Escobedo, Mar Tirreno, Mexico City, 2016–19

Frida Escobedo, Mar Tirreno, Mexico City, 2016–19Photograph by Rafael Gamo. Courtesy the artist

González Romo: You live in a building designed by Mario Pani, one of the most widely renowned architects in Mexican history, and a representative of what was perhaps the golden age of architecture in the country. What reflections do you have from living in a space like that?

Escobedo: Two years ago, I went through a separation and moved into this apartment, although it was rather by chance. This is a building from 1956, a time when many buildings full of two-hundred-square-meter apartments were built. It is a space with a history, which means it has been modified before. In the past, it was divided, but now it consists of rather open spaces. I have very few pieces of furniture: one Wassily chair that my father gave me when I first went to live by myself, and another we made at the office, which is a reinterpretation of the Donald Judd chairs, but made of volcanic rock. It’s more of a joke. The table is attached to the wall, as was Barragán’s, and the bookshelves surrounding the space are very low, so they can be used as seats when throwing a party. There are very few things, but I like the space to look empty, more like a dance floor. My walls are also clear. I do not like hanging pictures on the wall, as it looks way too formal to me. I prefer to lean them against bookshelves or other objects and move them around from time to time.

Objects in Frida Escobedo’s home, including concrete panel research and design models, Mexico City, 2019

Objects in Frida Escobedo’s home, including concrete panel research and design models, Mexico City, 2019Photographs by Yvonne Venegas for Aperture

González Romo: From an architectural point of view, what is your idea of a home?

Escobedo: I don’t think there should only be one concept of home. I think the actual problem is the will to standardize. There are many configurations of housing and family that are not considered when developing real-estate projects. They insist on selling us as many labels as possible in spaces that are increasingly small: a living room, a dining room, a kitchen, two bedrooms, two and a half bathrooms … and that nonsense walk-in closet, as if that were indeed going to increase our quality of life. Why doesn’t anyone go for, say, large, flexible areas for people to transform freely?

Related Items

Aperture 238

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]González Romo: You built a house for the Ordos 100 project (2008), organized by Ai Weiwei and Herzog & de Meuron. For this, one hundred architects from twenty-seven countries were invited to build a thousand-square-meter luxury villa in the Mongolian desert. You also designed a small house as part of a program for the Mexican government that sought low-cost housing alternatives for disadvantaged people. How did you respond to such opposite concepts?

Escobedo: For the Ordos 100 project, the challenge was to rethink housing and come up with an experimental proposal to be developed in a rather inhospitable territory. There were guidelines to be followed—some interesting, some obvious. The idea was to create weekend houses. Each one had to have a safe, a cellar, a pool, et cetera. What caught my attention was the fact that they asked for two kitchens: one closed with storage space and the other open, like an island. After talking to the organizers, I understood that the first kitchen was for the service staff, and I realized that they would live there full-time. Therefore, in the remaining space, I designed an independent house for the cleaning staff, cooks, gardeners, et cetera, where they would have their own courtyards, linked to the main construction. For that project, enormous, outrageous houses were designed. I was the youngest among a hundred architects, and my house was the smallest one.

Objects in Frida Escobedo’s home, including concrete panel research and design models, Mexico City, 2019

Objects in Frida Escobedo’s home, including concrete panel research and design models, Mexico City, 2019Photographs by Yvonne Venegas for Aperture

For the INFONAVIT (Institute of the National Fund for Workers’ Housing) project (2019), the challenge was quite the opposite: designing with minimal resources and in a reduced area. I was invited, together with other architects, to design a social housing prototype. We created one that would adapt both to a rural area and to an urban context. It is a very flexible vaulted house, which in a rural context can also be adapted as a barn. As for an urban environment, these arches integrate very well with the local architecture, as they are part of the architectural language of that city, Taxco. On a certain level, it is similar to the Casa Negra, which we discussed at the beginning, because it was an open space with a mezzanine offering easy and economical possibilities of expansion without the need for skilled labor. The idea is that instead of repeating that design ad nauseam—as has been the case with many social-housing projects, and I think it is a big mistake to believe that this configuration should be massive and standardized—families living in contiguous houses would have common, adaptable courtyards and spaces that would contribute to building communities.

Frida Escobedo, From Territory to Inhabitant, INFONAVIT, Vivienda Rural, Apan, Hidalgo, Mexico, 2019

Frida Escobedo, From Territory to Inhabitant, INFONAVIT, Vivienda Rural, Apan, Hidalgo, Mexico, 2019Photograph by Rafael Gamo. Courtesy the artist

González Romo: However, the housing project remained in limbo, making evident the government’s lack of commitment to address the precarious condition in which a large part of the Mexican population lives.

Escobedo: As soon as we completed the project for INFONAVIT, we were told that all those prototypes, designed for different contexts, would be exhibited together in a plot intended to become a housing lab for researchers. Thus, instead of giving those houses to people who actually need them, they are in some kind of showroom. That project ended up being tremendously frustrating for me. It was a waste of resources that we cannot afford.

González Romo: Many of your projects transcend the boundaries of architecture and could be read as similar to those of a visual artist. How do your references to other forms of art come into play in projects like the pavilion you created for the Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City, or in your installation for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London?

Escobedo: In the case of El Eco, I was dealing with very high-level architecture—a work by Mathias Goeritz. Thus, profiting from the flexibility offered by loose bricks, I proposed guidelines to build a different space configuration for every event taking place in that courtyard: a stage for concerts, seats for a film projection, or simply a brick sculpture that kids could play with or destroy to build something new. In this case, one of my references was the concrete poetry of Ferreira Gullar, who seeks the maximum expression with a minimal amount of words. At first glance, a brick is a rigid industrial piece. It looks like an object that does not allow much expression. Yet, when people appropriate it, the expressions are infinite.

The project for the Victoria and Albert Museum was developed in the context of the Year of Mexico in England, so the challenge was to make a pavilion in the central courtyard that made reference to Mexico. Nowadays a national pavilion is a somewhat forced idea, because everyone has windows to other countries and cultures, so we intended to enable an exchange, which seemed more interesting. We started from an investigation on land appropriations and decided to allude to the first appropriation that took place in Mexico City after the [Spanish] conquest, to recall the original city, which was a lake city full of reflections. This lake city is literally buried under the urban history of the country’s capital. It is fascinating, even surreal. How did anyone come up with building a city on water? The idea involves high doses of magical realism, but somehow they managed.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home.” Translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles.

June 7, 2022

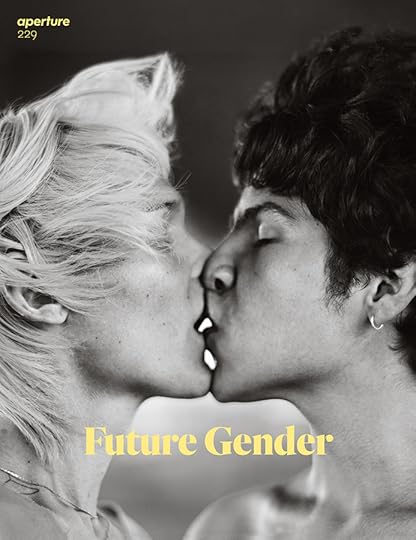

Alec Soth Guest Edits Aperture’s Summer 2022 Issue

It is easy to imagine Alec Soth daydreaming in pictures. As an acclaimed photographer, teacher, publisher, YouTuber, and one-time blogger, he is as dedicated to thinking about what pictures mean as he is to making them. Since his 2004 debut, Sleeping by the Mississippi, a series he described not as a chronicle of place but an excuse to wander, Soth has made lyrical bodies of work—modest meditations on consciousness—that parse the surfaces of the everyday. “In my projects, I allow myself to change course and follow my nose,” he notes of his process, which is decidedly driven by a search for serendipity.

As guest editor, Soth pursued a theme that wouldn’t constrain him. “This ‘Sleepwalking’ issue,” he says, “is one in which I’m always surprised on turning the page, where good old descriptive photographs of the real world tap into the logic of dreams. I want the reader to feel like they are sleepwalking.” We hope you enjoy the journey with eyes wide open, or shut.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition: Alec Soth

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Read more from Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking.”

June 3, 2022

An Artist’s Video Choir Tells a Story about Black and Queer Visibility

Bad singer? Check. Queer female masc? Check. Game to explore both? Check.

On July 15, 2021, I was scrolling through Facebook when I saw a post by Toronto artist Michèle Pearson Clarke announcing a new project about learning to sing. She needed three game participants who fit the above criteria. I stopped in my tracks and immediately answered her invitation because, yes, that’s me.

I am indeed both a bad singer and on the spectrum of queer female masculinity, so I was fully confident in my fit for Michèle’s Quantum Choir. I was also thoroughly discomfited by what it would ask of me. I’m an objectively awful singer: memories of being instructed to lip-sync in my elementary-school choir still haunt me. And this is precisely why I responded to Michèle with lightning speed: I worried that if I had time to think about it, I’d back out. I had a strong desire to embrace what terrified me and reminded myself that I had nothing to lose but face. And in my forty-eight years I’ve learned that saving facing is overrated, anyway.

There were other reasons for my yes. I admire and respect Michèle’s work, so I welcomed the opportunity to create something with her. And as a writer and photographer who asks people to say yes to sharing parts of themselves with me, I want to offer my own yeses in turn. I also learned that our professional vocal coach would be Teiya Kasahara—not only a supremely talented soprano (and currently a Disrupter-in-Residence at the Canadian Opera Company) but also a former soccer teammate. In short, I knew that despite my trepidation (okay, terror), this would be a unique and compelling learning experience, no matter the outcome.

There was joy in being a complete amateur, in playing around in the sonic sandbox, in letting go, or attempting to let go, of my perfectionism, in having no control over the final product. I knew that, with Michèle and Teiya, I was putting myself—and my voice—in safe hands. My work was the process of learning to sing one song over the span of a few months. The process was the thing, not the product, not perfection.

I spent a few months learning John Grant’s “Queen of Denmark,” which is an incredibly challenging song to sing because it’s quiet, it’s loud, it’s low, and it’s long. I learned that I’m an alto (no matter how much I’d love to be a tenor). I learned new vocabulary as I worked with Teiya to train my voice as a muscle. I also learned new ways of thinking about my body. I can now utter such phrases as “I’m working on my diaphragmatic breathing” and “inviting resonance from my nasal cavity and occipital bones” and “projecting sound at a forward angle” and know what they mean (sort of).

For Quantum Choir, part of Michèle’s first major solo exhibition, Muscle Memory, currently at the Art Gallery of Hamilton in Ontario, success meant showing up, being curious about the work, and, in the end, performing for her camera. Getting through the song was the goal. There was a freedom in not needing to be good, in not needing to be attached to outcomes. At the same time, I wanted, desperately, to not entirely embarrass myself in the final piece. There wasn’t enough time to excel, but I wanted to sound less bad in the end. Between weekly lessons with Teiya and daily solo practices (including recording my solo renditions of the song so I could hear myself in playback), I did get better.

Now that the practicing is over, the recording is behind me, and the video installation is live, I look at the performance with some pride. There are moments when I don’t cringe at the sound of my own voice. Seeing Michèle’s final edit, her making the four of us a choir on massive screens, was unlike anything I’ve experienced. My partner watched it multiple times, from different angles, and said (through her femme tears) that it was “hugely moving to be with butch fierceness and vulnerability.” Other members of our queer community thanked us for offering a reflection of themselves on screen. It has been a telling reminder that butch representation matters, and that despite our legibility, there is a continued erasure of us in the culture at large.

I began this project confident in who I am as a masculine-of-center woman with deep awareness of myself as a terrible singer. But one of the biggest takeaways for me is that I sound better if I act like I’m good at it: if I really give it in performance and pretend I’m a superstar. Not holding back meant simultaneously carrying confidence and vulnerability, singing badly with shoulders back, head high, lungs full, voice loud.

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022Kerry Manders: Where did the idea for Quantum Choir come from?

Michèle Pearson Clarke: Quantum Choir arose from me thinking about my process and coming to understand that I’m not a good judge of what other people are willing to do in and for my artwork. I’ve made this repeated artistic gesture of asking community members to be vulnerable before the camera, but then a few projects fell apart or needed to be changed quite significantly because nobody was willing to do what I was asking.

Quantum Choir emerged from this question: What is my line in the sand? What would push my limits? How do I lean into discomfort? What would it look like to make a project addressing my greatest source of vulnerability? It was clear immediately that this meant singing because I’ve had this lifelong shame about my singing voice.

Manders: How do you feel about your singing voice?

Clarke: Until Quantum Choir, I’d never sung publicly in my entire life. I’ve always avoided it in every single situation that required it—whether it was “Happy Birthday” or the national anthem. I would mouth the words to appear as though I’m participating. A few years ago, I thought about taking singing lessons to overcome my fear, but even the idea of singing in front of a teacher felt daunting and embarrassing. And I started thinking about this in relation to queer female-bodied masculinity. Is the vulnerability that I was feeling about singing just personal, or was it rooted in something larger? I wanted to combine the personal and the cultural context—to invite us to think about these issues more broadly.

Because part of the shame I feel about singing is rooted in a gendered childhood memory: I went to an all-girls school where choir was very popular—a very “cool girl” thing to do. But I couldn’t sing, so I couldn’t join. There is a very real feeling of failure tied to this girlhood memory that steered Quantum Choir.

Manders: That’s a visceral memory of being a girl who failed and, in a way, a failed girl.

Clarke: That’s the link for me to notions of queer failure and its relationship to female masculinity. But that memory is also linked to being shaped by a Trinidadian culture of performance and wit, of natural entertainers, of enthusiastic dancers, of loud voices, of engaging storytellers. So, it’s interesting for me to feel like a failure at this particular performance thing—singing. So many of us understand what it feels like to be a failure at singing. I hope people can tap into that when they watch us try to do it. I hope I’m touching on both individual and larger cultural narratives around what it means not to be “good.”

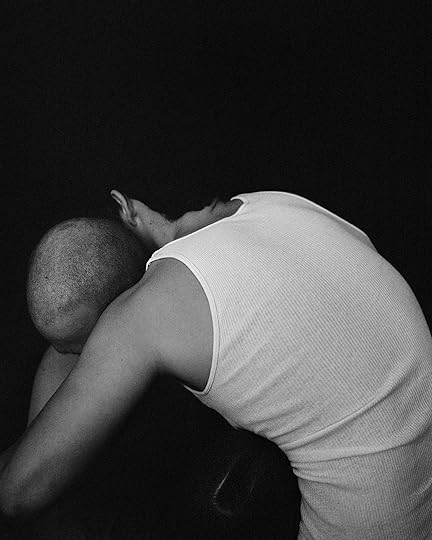

Manders: The tensions and intersections between individual and larger cultural narratives are a big part of your work, which brings me to The Animal Seems to Be Moving (2018–23)—a striking title for a series of still images.

Clarke: Like several of my titles, it was inspired by something I was reading. I was thinking about the ways in which the Black male body is often seen as beastly, animal-like; and I was thinking of how my self-portraits are documenting a transition period in my life. There’s a sense of motion and movement over time in them.

This project is about aging, the shift in my appearance, and the shift in responses to my appearance. I’ve always been read as younger than I am, and now, whatever threat I present to some people seems to be increasing as I physically get older. I was also thinking about my own relationship to masculinity and the complex pleasure that has given me throughout my life. There’s something kind of primal in my sense of my own masculinity, particularly in the yearning. There’s a desire for certain experiences that I will never be able to have. As a female-bodied person, there’s a gap that can’t be bridged.

Manders: I’m thinking about your use of the words primal and animal and associating it with something forceful and fundamental. Often the human relationship to animals is one of paternalism, hierarchy, ownership.

Clarke: I’m always contending with those power relations given the history of visual representations of Blackness—the ways that photography has been complicit in constructing certain ideas of Blackness, and teaching us to see Blackness in certain ways, including seeing it as something to be conquered and owned. That history continues to provide violent and damaging assumptions about cis Black men, and those beliefs affect me as well, because of my masculinity.

No matter what your race is, we’ve all been fed certain visual representations of Black lives, and these continue to shape and influence the ways we make images.

Black masculinity is often deemed to be dangerous, brute, animalistic. And connected to these ideas is the assumption that we feel less pain. These dehumanizing stereotypes had specific and purposeful effects: to justify enslavement, to justify segregation, to justify torture, and they continue to be deployed to justify the disproportionate amount of force we face when we’re arrested.

Manders: That these ideas and stereotypes are still very current is a crucial aspect of your work.

Clarke: As a Black artist, I have to grapple with that representational history. I think of it as a thick filter that anyone looking at a contemporary image is necessarily looking through. That filter comprises nearly two centuries of negative images that we’ve all been exposed to. Those perceptions and representations get layered on top of contemporary images, and I question whether it’s possible to see a contemporary image of Blackness without these older ideas present. No matter what your race is, we’ve all been fed certain visual representations of Black lives, and these continue to shape and influence the ways we make images.

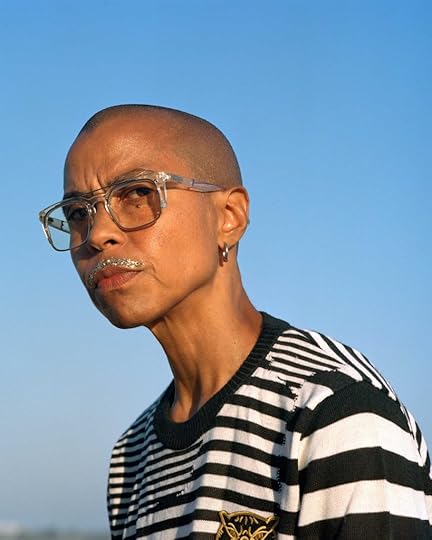

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Glitter Stache, 2021

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Glitter Stache, 2021Manders: How do you contend with that racist history?

Clarke: To date, for me, the most effective strategy has been performance. I read Nicole R. Fleetwood’s Troubling Vision (2011) during my MFA studies, and her analyses of the relationship between performance, visuality, and Blackness were very compelling.

Also indispensable was Tina Campt’s Listening to Images (2017), in which she invites us to tune into the frequencies that affect how we see Blackness when we look. So, what we feel shapes what we see. Taking my lead from these scholars, I try to harness the affective qualities of performance—to shape a particular relationship to the visual content of the photograph.

I’m not necessarily trying to speak back to or against the history—to resist it. I don’t even use resistance anymore in descriptions of my work because that really frames what I’m doing in a binary relationship to an external anti-Black gaze. Instead, performance becomes a pathway to foreground my own pleasure and agency, to address my communities and to both reveal and withhold my experiences of being queer, being Black, being masculine. I’m good with being all those things. Any issues I have emerge from other peoples’ ideas about them.

With these self-portraits, I am really embracing humor and play as I perform for the camera. They are my attempt to speak to the absurdity of the way my Black masculinity is framed through those racist historical visual lenses.

Installation view of Michèle Pearson Clarke: Muscle Memory, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2022. Photograph by Yuula Benivolski

Installation view of Michèle Pearson Clarke: Muscle Memory, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2022. Photograph by Yuula BenivolskiManders: At the Art Gallery of Hamilton, the self-portraits are in a room adjacent to our Quantum Choir video installation. Are there connections between these two parts of the show you call Muscle Memory? Did Quantum Choir grow out of the self-portrait work, as an extension of it?

Clarke: They’re connected to my rebuilding of self as I grieved my mother’s death over the past decade. As anyone who has been through the grief process knows, you can become unrecognizable to yourself along the way. Thankfully, I’ve recovered most of myself, I think, and part of that rebuilding has involved both my gender and my aging self.

This happened during a time of increasingly fraught cultural conversations about masculinities. About toxic masculinity. About trans masculinity and increasing visibility. About white masculine privilege. About Black masculinity and police violence. All these masculinities act upon my own masculinity and shape others’ ideas about me. Both The Animal Seems to Be Moving and Quantum Choir emerged from these broader reflections.

Manders: I’m curious about why you crafted a choir out of the idea of learning to sing.

Clarke: When I started to think about this project, I knew I wanted multiple people in it. All my work involves collectivity and kinship. I come from a community engagement background, and that always influences the way I work. And speaking against oppression, addressing difficult issues, doing hard things—all of these things are easier when you can do them with other people.

I’m also trying to say something about systemic issues rather than individual ones. Oppression is not a personal problem, it’s not unique to me. Taking an autoethnographic approach—making projects derived from my own experiences—but including other people who share those experiences is a strategic choice to avoid that reduction.

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022Manders: Four of us comprise Quantum Choir, but we didn’t actually sing the song together. We’re a bit of a paradox: a choir made up of solo performances. You say that doing a hard thing with others is easier, but we did most of the actual work separately. Can you talk about the balance between the individual and the collective aspects of this work?

Clarke: Practicing and filming individually was always the plan, because I wanted each of you to have your own experience of doing this very hard thing—your own vocal lessons, your own performance in front of the camera. I didn’t want you to have to worry about what anyone else was doing or to have to try to perform in any particular way.

Through my edit and the design and layout of the video installation, I was then able to construct and communicate collectivity—that’s in the very structure of the work. We become a choir in the way we address the viewer. But it felt important to keep the vocal lessons mostly private so that you would have your own relationships with our vocal coach, and we could learn the song in our own time and as we wanted, needed, and were able to.

We were all dealing with our own shame around our “bad” singing voices—I thought about what I was asking of you and what I’d want as a participant, and it wasn’t to feel shame in front of others all the way through. That would be adding another layer of difficulty.

Manders: It was difficult! When I first saw the artist statement for your exhibition, I had a very visceral reaction to the title, Muscle Memory. It felt incongruous to my experience: I have absolutely no muscle memory when it comes to singing!

Clarke: But you built some over the course of two months of lessons, right? The title Muscle Memory really ties both parts of the show together. Both look at female masculinity. One is about my own Black aging body, and the other is about the four of us learning to sing as a way to reflect on the vulnerability of visibly queer female masculinity.

The vulnerability in both projects has to do with the external gaze—the way people see me, see us. For any one of us who deals with hypervisibility in our culture, muscle memory develops as a response. Every time I leave my house, I adjust automatically to make myself as least threatening as possible. I’m always aware of others’ eyes on me. This lifetime of hypervisibility means that we’re used to being looked at and to being judged for how we look. Like, we walk into the women’s washroom and automatically code-switch—adjust ourselves, our bodies, to that space and what’s expected there.

Manders: Ah, yes, butch bodies in bathrooms. I find myself pushing out my chest a bit, so others can see that I have breasts and I might avoid the dreaded bathroom battle. When we were all at the AGH for that donor reception, I went to the washroom down the hall from Quantum Choir and got the familiar, “You’re in the wrong washroom, sir.” As soon as I spoke, the woman apologized. My speaking voice is a tell.

Clarke: Your body knows to expect that surveillance and has engrained reactions to it. It’s that automatic and repeated response: muscle memory as coping mechanism. And it’s so often a spatial thing for us. A lot of what I experience as a queer masculine person is about spatial discrimination—I’m not “supposed” to be in a women’s washroom, or I’m not “supposed” to move in a certain kind of way in a certain kind of place.

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022Manders: Like how we walk. Apparently, I have a sort of swagger when I walk, and I take long strides. I’ve been told my whole life that I don’t walk in a “ladylike” or feminine manner. I’m not a “proper” woman.

Clarke: As I mentioned earlier, the exhibition overall addresses that notion of queer failure. If models of success in our society involve heterosexual, white, able bodies, then Muscle Memory addresses the queer, female, masculine body as a subsequent failure. Queer theorists have invited us to think about this failure not as a space of deficit or negativity, but as a generative space that produces other ways of knowing, thinking, and feeling.

I accept that invitation in reframing the “failure” of my singing as an opportunity to generate something meaningful for me, for the three of you, and then hopefully for our audiences. I wanted to explicitly address the homophobia and the shame that the four of us experience by opening up our failure as something playful and productive. Rather than be reduced by it, I wanted to expand—to just allow us a little bit more breathing room.

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022

Michèle Pearson Clarke, Still from Quantum Choir, 2022Manders: Speaking of breathing room—that chorus!—why did you choose John Grant’s “Queen of Denmark” for us to perform?

Clarke: It’s the title track from one of my favorite albums. The lyrics resonate, and I enjoy their ambiguity too. The chorus is clearly an address, but to whom? There’s a slippage there that works as both an invitation and provocation. And there’s that drastic change in tempo where the song goes from the melancholic to the soaring. I wanted that drama for us! I also wanted to sing a song by a queer artist, and I’ve appreciated the way that Grant has spoken about gender and queerness in the past. Grant and I might come at the issues in different ways from different lived experiences, but we meet in the song.

Manders: “We meet in the song” is a wonderful and evocative way to describe the individual and collective experience of making Quantum Choir itself, and perhaps the experience of the audience who listens to us. We all meet in the song. That’s part of the experience for the spectators’ bodies, too, how you set up the exhibition space to orient those bodies in certain ways that are maybe uncomfortable and confusing. Many people don’t know where to stand or how to look or listen when they encounter the installation.

Clarke: I’ve been really struggling with the power dynamics of the exhibition space itself. What does it mean to position queer or Black vulnerability in an art gallery for public consumption? There’s a long history of our suffering bodies being used for pure spectacle and entertainment. While I can’t free myself from that history, I don’t want simply to replicate it.

In galleries, a lot of video installations are projected on a wall, and a spectator sits on a bench in front of it and passively consumes the content. For Quantum Choir, I wanted to construct a more active relationship with the spectator—I wanted to ask the spectator to think consciously about their own body in a spatial way while looking at us. I wanted active versus passive viewership. I also wanted to find ways to introduce more opacity into my work. In this case, all four of us are always on screen, but because of the set up, you can never look at all four of us at the same time.

It’s like: I’m going to share my vulnerability with you. I’m going to give you all of this but I’m also going to hold something back. There are moments, too, when auditorily, each of us is holding something back because only three voices or two voices or one voice can be heard. You can never see or hear all of us all at once.

Installation view of Michèle Pearson Clarke: Muscle Memory, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2022. Photograph by Yuula Benivolski

Installation view of Michèle Pearson Clarke: Muscle Memory, Art Gallery of Hamilton, Ontario, 2022. Photograph by Yuula BenivolskiAll images courtesy the artist

Manders: It’s a different performance depending on where your body is positioned in the space. Move your body and you necessarily see and hear our bodies differently. And speaking of bodies in space, tell me about the soccer balls and practice pylons on the gallery floor.

Clarke: I wanted to have some kind of intervention in the gallery to support this experiment around asking the viewer to be active. I want the viewers to have to do a little navigational work, to actively orient their own bodies in the gallery space and in relation to us. Not a lot of work, but a little bit of effort in this exchange.

Conceptually, I chose the soccer balls and cones because, for all four of us, sports has been the only consistent place in our lives where our masculinity has been encouraged and supported. While the four of us are in the very center of this gallery doing this hard, vulnerable thing, we’re literally surrounded by these symbols of a safe space for our masculinities.

Manders: Have there been responses to the exhibition that have surprised you?

Clarke: Kids are loving it! I don’t think that I ever considered kids as spectators when I was making this work. They love the soccer balls but are a bit frustrated that they can’t kick them. But the balls are objects that kids run through and by. They are interacting with those aspects of the show in ways that adults don’t.

I think kids like the sonic experience of the song too. Formally, Quantum Choir builds on strategies of intentional repetition, and children respond to that. And I think they respond to the buildup to the song—us doing our different vocal warm-ups.

I also didn’t expect that so many people would cry while watching it. I thought that might happen for people who know us and love us, but it seems to offer a more general sense of release amidst the tension and stress of ongoing pandemic life. After all of this time of being isolated from one another, I can only hope that our collectivity provides some solace.

Michèle Pearson Clarke: Muscle Memory is on view at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, in Hamilton, Ontario, through September 5, 2022.

June 2, 2022

How to Produce a Photobook

What does it truly take to make a photobook? Making a photobook is like playing a puzzle or a game, one with plenty of room for creativity within certain rules or parameters. As Christina Labey, cofounder and creative director of publisher and bespoke production house Conveyor Studio, puts it: “One thing I love about the book format is that it inherently has limitations.” There are many possible permutations in book design, which is perhaps why Labey and other publishers and designers often get involved early on. This can mean coming on board when the project exists solely as a folder of images—or even before the photographer has started shooting.

Designer Hans Gremmen is the founder of Fw:Books, the respected Dutch publisher behind award-winning titles such as Andres Gonzalez’s American Origami (2019) and Lora Webb Nichols’s Encampment, Wyoming (2021), as well as designing a number of Aperture publications, including Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance (2011; reissued 2021), Ametsuchi (2013), and Halo (2017). Gremmen, who has worked during the concept stage and while the photographer was still making the series, explains how getting involved early can allow for a holistic approach, for thinking of the book and the project together. The approach also helps to prevent issues such as realizing too late that something is missing.

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi, director of French publishing house Chose Commune, always approaches the artists she wants to work with so she can broach the possibility of a book before they’ve even thought of it. And for Cemre Yeşil Gönenli, the artist, publisher, and brains behind Istanbul’s FiLBooks, the first step is to question whether a project should be a book at all. “I get involved when I really think that the book as a format adds to the narrative of the story,” she explains. “I feel I need to justify the reason behind why that specific work has to be in a book form.”

If a book makes sense, these makers typically get involved in editing and sequencing the images. This can be done digitally—with Poimboeuf-Koizumi using Adobe Bridge to edit images before sliding them onto InDesign—but will usually also involve physically printing the images and laying them out. Making a photobook will always involve making a dummy or prototype at some stage, though this may be without the images. As Poimboeuf-Koizumi points out: “The act of flipping through pages is definitely not the same as clicking on a PDF.”

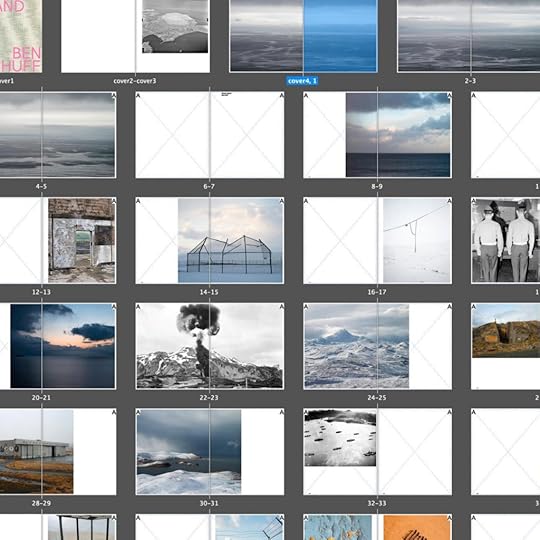

Working on the edit and layout of Atomic Island by Ben Huff (FW: Books, 2021)

Working on the edit and layout of Atomic Island by Ben Huff (FW: Books, 2021)Courtesy Hans Gremmen

That physical aspect is important when thinking through the edit and sequence, because both can be affected by the choice of papers and binding. As Gremmen explains, books are typically made in sections of eight or sixteen pages, which means any special group of images will ideally be gathered in multiples of those numbers; once that set is assembled, it can’t be added just anywhere in the rest of the pages.

The paper—or papers—is a key factor in the book’s tactile impact, but it can also affect the images. Coated or glossy papers typically hold the inks better than uncoated pages, which means the photographs will look sharper, more detailed, and more contrasted. On the other hand, the glossy papers will also reflect light more, making the images harder to see. Uncoated papers feel softer between the fingers but may result in images that are slightly less crisp. If the book is being bound with a spiral ring, the paper will also need to have a minimum thickness to withstand being punctured.

The image and paper combination can also affect a photobook’s size, because one must strike a delicate balance between maintaining creative freedom and keeping within budget. Making the book at one size mean printing thirty-two pages per printing sheet, for example; making the book just one inch bigger might mean cutting that to sixteen pages per printing sheet, which instantly doubles the paper cost.

Factory Visit: Conveyor Studio from Conveyor Studio on Vimeo.

Going large will add weight and therefore transportation costs, which Labey points out can have a significant impact when shipping books long distance for book fairs or distribution. “There is an added pressure to sell heavy books at a fair, or correctly predict how many to bring, otherwise you have to ship them home, and you might end up losing money on that edition,” she says. “When you print in smaller editions the production price per book is notably higher—an important factor if you hope to profit, or honestly, just break even.”

Size and weight are also critical to the reading experience. A big book may work well for very detailed images, for example, which call to be printed at a substantial size; on the other hand, going large can create a monster volume that is unwieldy to hold or move. “In addition to practical considerations for the book maker or publisher, you need to consider how the reader gets physical with your work,” Gönenli says. “The size of the book is a very fundamental element which directly influences the intimacy between the book and the reader.”

“The basic things I always try to get down very quickly are the size of the book and the amount of pages,” Gremmen adds. “When you know about those two things, then the paper choice follows quite quickly afterwards. But also with those two things, you determine what kind of book you are making. You can calculate budget based on those two specifications, but you also decide on the kind of book.”

Cover and interior spread of American Origami by Andres Gonzalez (FW: Books, 2019)

Cover and interior spread of American Origami by Andres Gonzalez (FW: Books, 2019)A text—or texts—may also be included, though the publishers included here are wary of thoughtless or overly didactic writing. If a text is going in, a typeface will also have to be chosen. Fonts can be used multiple times by a designer, who may already have some available at minimal cost, but if not, a new font can be bought in or, to go the whole hog, created bespoke for the project.

Printing essentially comes down to two choices: offset or digital. Put simply, offset is the traditional option that involves aluminum plates with a silicon base for each sheet; the inked image is transferred from a plate to a rubber blanket and then to the printing surface. Since each plate comes at a price, offset is typically used for print runs of a minimum of five hundred copies, allowing the initial outlay to be spread over more units. Though digital printing is often regarded as lower quality, it can work best for smaller prints runs, as the price per book remains the same.

The choice between offset or digital printing also depends on the capabilities of the printer, because digital offset can be used for bulk jobs to more average ends, or by skilled operators to a very high level. “We print on an HP Indigo, which is considered a digital-offset press,” says Labey. “It combines the electrophotographic process of a copy machine with the architecture and liquid ink of a traditional offset press. In short, the printing plate is wiped clean, and a new image is etched with each rotation. This removes the time and cost of creating physical plates and allows us to print very small quantities with high-quality results.”

Printing the cover of Laissez-Faire by Cristiano Volk (FW: Books, 2022)

Printing the cover of Laissez-Faire by Cristiano Volk (FW: Books, 2022)Courtesy Hans Gremmen

Whether it’s traditional or digital offset, books are printed with the CMYK color model (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black), which means the images must be converted from the RGB color values (red, green, blue) generated by digital cameras and scans. The CMYK gamut contains a much smaller range of colors than the RGB color space, and although the conversion can theoretically be done by anyone with access to Photoshop, it’s a complex art best approached by an expert. In skilled hands, this, too, can become a creative process that might even involve alternative inks. Labey has worked with artists who replaced the magenta ink with fluorescent pink, for example, “which makes the images pop.”

Before pressing play on the print run, it’s advisable to print off some test images (which can cost over five hundred dollars per sheet of test paper, but that’s much cheaper than having to scrap an entire edition). Perhaps surprisingly, it’s unusual to test print all the images when using offset, because of the cost of the plates. Instead, a few key photographs are typically selected and printed on the paper to be used in the book, creating what’s known as a “wet proof.” An upside to printing digital offset is that it is possible to proof the full book on the same press and paper stock, trimmed to the same size as the final version.

There’s no one right way or recipe or formula. A book should always listen to its own rules.

Alternatively, a publisher can make digital proofs, which can represent every image in the book because they are cheaper per print. However, these tests are only simulations of the final result, and Gremmen takes a dim view of them. “To me those things are useless,” he says. “If you make a test print, it’s not about simulating, it’s seeing one on one how things will be.” Gremmen is often willing to oversee and sign off on the printing and production of books himself, but he says he prefers to work with companies he knows. Similarly, Gönenli works with only one printer: “Ofset Yapımevi, and they are perfectionists.”

The final step is putting everything together and binding the book—and, as with everything else in photobook-making, there are many options and lots of creative potential. Binding basically involves stacking the pages and combining them in a durable way, but books can be stapled, screwed together, or even folded together, if in handmade territory. In larger print runs, books are typically glued or sewn together.

Related Items

Aperture 246

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Gluing, considered “perfect binding,” involves adding glue along the spine and simply affixing the cover. It can be efficient and very affordable, but it’s less dependable in the long term—a fact familiar to anyone who’s seen a book spine crack in the cold or melt in the heat. Sewing is more complicated because it involves folding and collating the separate sections, or signatures, of paper, then stitching them all together. There are many different approaches to this stitching, and it’s sometimes left exposed as a design feature.

The technical difference means that sewn books typically open and lie flat more easily than glued ones, though again, that’s not a hard-and-fast rule. The degree of flexibility depends on factors as (seemingly) obscure as the direction of the fibers in the end paper or the quality of the glue, making bookbinding another expert field. “It’s getting more tricky to find really good binders—they all go bankrupt, or retire, or whatever, and the knowledge is lost,” Gremmen says.

“But the most important thing for me is that the book opens very well,” he adds. “I see a lot of photobooks and, with almost half of them, I think, ‘This is horribly bound.’ It’s such a pity. You spend all this money on printing perfectly, and then you don’t care if this book opens well or not? I don’t understand it at all.”

Alec Soth, Two Towels, 2004, from Niagara (Steidl, 2008)

Alec Soth, Two Towels, 2004, from Niagara (Steidl, 2008)Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

With all these variables at work, making a photobook can be tricky to get right—but it’s not impossible. When asked, all four designers and publishers easily named outstanding photobooks that they believe pull off everything mentioned above and more. For Gremmen, it’s Elasticity by Aglaia Konrad (NAi Publishers, 2002), which he describes as “perfect on a technical level” but also remarkable because of its interplay of image and design. “They push one another to another level,” he explains. “The photography makes the design better and the other way around.”

Gönenli reflects on Niagara by Alec Soth (Steidl, 2008) for many reasons, but partly for little details, such as the fact that “you have to tilt the book to be able to read the text on the back cover, as if it were a daguerreotype.” Poimboeuf-Koizumi says she was immediately struck by Rinko Kawauchi’s Utatane (Little More, 2001), explaining: “It’s literally when I understood the power of sequencing.”

For Labey, Misplaced Fortunes by Ross Mantle (Sleeper Studio, 2021) is a special book. Mantle cofounded Sleeper Studio with fellow photographers Ben Alper and Peter Hoffman, and his book is a good example of why this model can be beneficial, according to Labey. “It’s clear he was able to choreograph and control all of the elements from concept to design to production,” she says. “Thus, it really feels like a work in its own right.”

“There’s no one right way or recipe or formula,” Gremmen says. “A book should always listen to its own rules.”

May 27, 2022

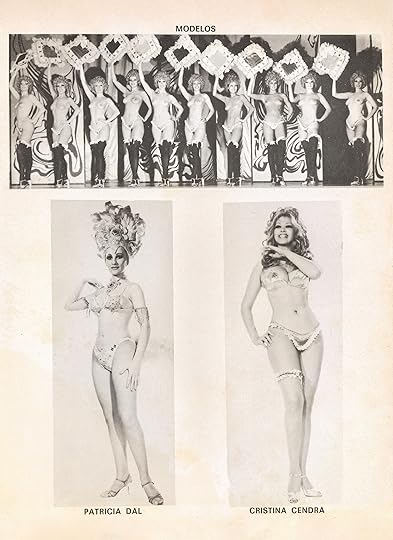

Heinkuhn Oh’s Vivacious Portrait of Seoul in the 1990s

Behind the gleaming Namsan Tower that stands imposingly at the center of Seoul rests Itaewon, a compact quarter in which locals, artists, U.S. soldiers, drag performers, Muslims, gay men, transgender people, sex workers, and expats from around the world have long coexisted. The district’s history is thorny: when the U.S. army established a base in the area in the years following the Korean War, it garnered a reputation as an untamed, foreign terrain where GIs and Americana ruled. Soon after, the neighborhood became a territory for outsiders of all kinds, offering refuge for those who did not belong anywhere else in the city. Seoul’s inadvertent dip into multiculturalism thus began under the mythical, Cold War–inspired pretext of U.S. armed forces safeguarding democracy in South Korea—a nation that remains largely ethnically and culturally homogeneous to this day.

That gritty, crude version of Itaewon is extinct now for the most part, as relentless gentrification replaced small businesses with shiny but sterile coffee shops and restaurants. A glimpse into its past is nonetheless possible in the images of Heinkuhn Oh, who ventured out into the streets of Itaewon in 1993, shortly after studying photography in the U.S. at the Brooks Institute and Ohio University. As with his preceding series Americans Them (1990–91), which captures the raw, unglamorous lives of lay protagonists across Louisiana, Ohio, and Kentucky, Itaewon Story is tinted with a documentary outlook, curiously tapping into the disparate lives of individuals unfamiliar to the photographer. But if the earlier project portrayed rural America from the perspective of an outlander from the Far East, Itaewon Story locates the feeling of estrangement within the bounds of Oh’s hometown. Its impetus perhaps originates with the mavericks who meandered the cramped streets between brothels and the nearby Seoul Central Mosque as well as Oh’s own experience encountering his offbeat childhood neighborhood as a returnee from the United States.

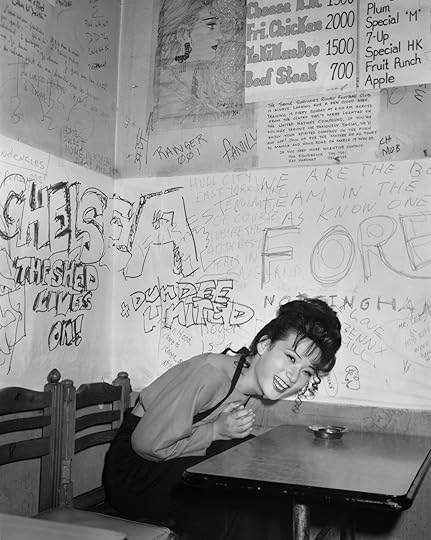

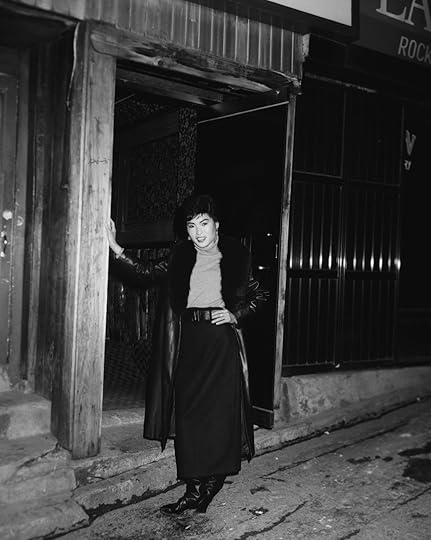

Heinkuhn Oh, Jiyoung in the Itaewon Barbecue Ramen House, February 1993

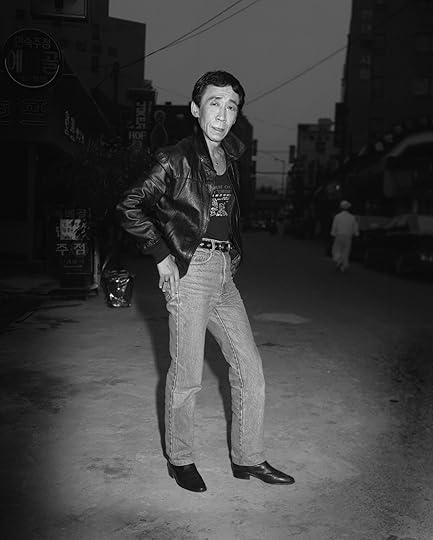

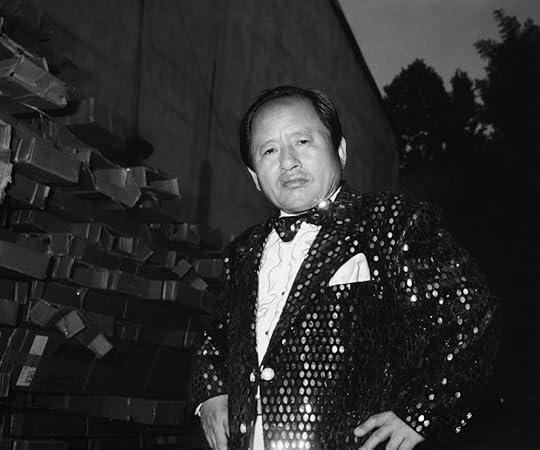

Heinkuhn Oh, Jiyoung in the Itaewon Barbecue Ramen House, February 1993Yet there is little distance between Oh and his protagonists in Itaewon Story. Theatrical as they might be, the characters of the series are photographed, in black and white, at moments of candor with minimal pretension, producing an unapologetic take on the traits of the locale. One image, Jiyoung in the Itaewon Barbecue Ramen House, features a young trans woman immaculately made-up, wearing a dark dress and a light-colored off-the-shoulder crop top, chuckling in the corner of a run-down restaurant whose walls are filled with graffiti. In another, Twist Kim, a forgotten movie star who made a living performing late-night shows in local bars and clubs, stands cheekily on the street with enough flair to land him on the cover of a fashion magazine. Astutely but affectionately, Oh’s camera seizes these releases of fleeting freedom, only made possible in the corners of seedy Itaewon.

Oh’s series thus resonates with other artistic endeavors to represent the marginalized and the vulnerable, including contemporaneous projects from the United States, such as Hustlers (1990–92) by Philip-Lorca diCorcia, that were shaped in the wake of the culture wars in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. Nonetheless, unlike counterparts across the Pacific, with Itaewon Story, Oh resists the temptation to politicize the identities of the individuals depicted—almost naively so, perhaps because there was no public sphere to accommodate discourses on identity at the time in South Korea. The series instead serves as a tender reminder of these Itaewon denizens’ existence, capturing a certain childlike sensibility of the young artist. Oh’s images demand that we remain curious about those strangers, foreigners, and outsiders around us, that we let them freely roam, showing us who they are.

Heinkuhn Oh, Twist Kim, Actor and Singer, March 1993

Heinkuhn Oh, Twist Kim, Actor and Singer, March 1993 Heinkuhn Oh, Background Actress, June 1993

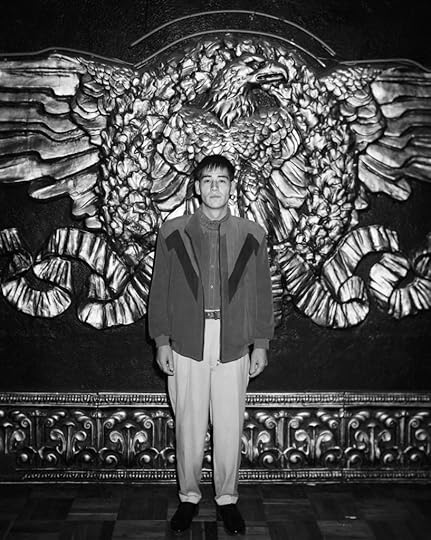

Heinkuhn Oh, Background Actress, June 1993 Heinkuhn Oh, Youngbok Han, GI Club Waiter, on the Dance Floor of King Club in Itaewon, February 1993

Heinkuhn Oh, Youngbok Han, GI Club Waiter, on the Dance Floor of King Club in Itaewon, February 1993 Heinkuhn Oh, Bulyi Kim, Actor, in a Backyard behind Tae-pyoung Theater, March 1993

Heinkuhn Oh, Bulyi Kim, Actor, in a Backyard behind Tae-pyoung Theater, March 1993 Heinkuhn Oh, Some Lady on the Hill of Lucky Club, January 1993

Heinkuhn Oh, Some Lady on the Hill of Lucky Club, January 1993All photographs from the series Itaewon Story and courtesy the artist

Related Items

Aperture 246

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “Itaewon Story.”

May 26, 2022

What Is a Feminist Picture?

In her book Girlhood (2021), Melissa Febos describes what it felt like as a child to be a body, before she learned to see herself as a body from without: “I would read or think or feel myself into a brimming state—not joy or sorrow, but some apex of their intersection . . . body vibrating, heart thudding, mind foaming.” This overpowering sense of sublimity—absent from the “composure and linearity” of “school bus routes and homework and gender and bedtimes and taxes”—feels connected to her young body. The feeling is a comfort in the face of such dissonance between her inner world and the imposing outer world.

It is a familiar story well told: this inner-outer dissonance, both universal and particular to the challenges a girl faces, to stay close to herself through adolescence and into adulthood in a world determined to will us from subject to object. We might resist by refusing to be seen, by looking back—or, as Febos does, by returning our gaze to our selves.

Justine Kurland, Bathers, 1998

Justine Kurland, Bathers, 1998© the artist

Gazing as both refusal and becoming informs Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum, an exhibition on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Kornblum, a psychotherapist, began collecting the work of women photographers at a time when photography was first being institutionally recognized as a fine art and “maleness was the norm,” as she writes in her catalogue essay. In 2021, she gifted the archive to MoMA in honor of the museum’s senior curator of photography Roxana Marcoci. Ninety of these collected works and a handful of photobooks fill a small room on the fifth floor of the museum, one effort of many made by art institutions over the last half-century to correct the art historical canon. The works were given in friendship, a fact that is unusually highlighted in both the provenance labels and the catalogue. The curator Kathy Halbreich, who introduced Kornblum to Marcoci, writes: “No one talks much about the meaning and impact of friendship on institutions. . . . It’s as if we are afraid of being accused of a lack of critical disinterest or distance if something as subjective and sentimental as affective attachment is broached.”

The show begins with Justine Kurland’s Bathers (1998), an image in which teen girls embody the titular art historical trope, swimming and lounging on rocks in a dappled pond. Febos’s sensory-dizzy narrator might be among them, their freedom exultant, collective yet private—and still, we might sense, threatened. The photo is mounted on a floor-to-ceiling clouded, wavering mirror, beside introductory wall text that asks, “How have women artists used photography as a tool of resistance? As a way of unsettling established narratives? As a means of unfixing the canon?”

Susan Meiselas, A Funeral Procession in Jinotepe for Assassinated Student Leaders. Demonstrators Carry a Photograph of Arlen Siu, an FSLN Guerilla Fighter Killed in the Mountains Three Years Earlier, 1978

Susan Meiselas, A Funeral Procession in Jinotepe for Assassinated Student Leaders. Demonstrators Carry a Photograph of Arlen Siu, an FSLN Guerilla Fighter Killed in the Mountains Three Years Earlier, 1978© the artist

“The male gaze” has become so commonly referenced as to approach cliché—the sign of a powerful idea. Laura Mulvey’s term—which came out of 1970s feminist film theory—has led to further consideration of what a “female gaze” might entail. One intervention, posed by bell hooks, considers the “oppositional gaze” of Black female spectatorial interrogation; others question the heterosexual female gaze. Some of the work included in Our Selves arguably engages with the notion of a female gaze, but the show does not offer a chronological history or comprehensive account of feminist photography. The wall text explains that instead, “specific constellations of works and ideas” present “an invitation to look at pictures through a contemporary feminist lens.”

“What is a feminist picture?” The question, offered as the title of an online panel held in conjunction with the exhibition, knowingly invites infinitude. Many of the event’s fourteen speakers—including artists in the show such as Susan Meiselas and Cara Romero—wisely did not attempt an explicit answer, in part because feminism itself might be defined as variously as one might picture it.

Documentary photography throughout the show—by Susan Meiselas, Mary Ellen Mark, and others—emphasizes subjectivity, collaboration, and power rather than claiming objectivity or authority.

In her book Living a Feminist Life (2017), Sara Ahmed describes feminism as a collective movement, adding, “A collective is what does not stand still but creates and is created by movement.” Multiplicitous and relational, equally informed by intersectionality and phenomenology, Ahmed’s feminism is about how we move through the world together as bodies. Feminism is often an “experience that begins with sensation.” What is sensed might not immediately be named. But by bringing into the foreground what is so often in the background—things generally assumed unremarkable and therefore unremarked upon, like gender or taxes—a shift in perception can sustain the movement of infinite interpretation. In Our Selves, the camera frames these moments of the invisible made visible to picture feminism—static as an image, ever in flux as a project.

The “constellations” of Our Selves vary between thematic and more associative or conversational clusters. Some images are abstract or conceptual; others are of the natural world. One grouping features mostly early twentieth-century European photographers, including Dora Maar, Grete Stern, Ilse Bing, and Kati Horna. (Many were also present in the exhibition The New Woman Behind the Camera (2021–22), organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.) Here their photos explore the literal and figurative mask, in some cases to anti-capitalist or anti-fascist ends, with mirrors and mannequins, dolls and double exposures, obscured faces and the faceless.

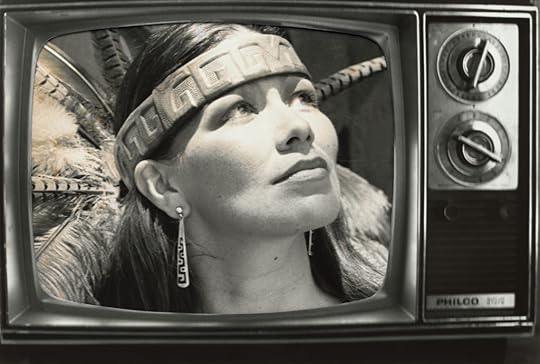

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, Vanna Brown, Azteca Style, 1990

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, Vanna Brown, Azteca Style, 1990© the artist

Many women photographing in this era straddled commercial and experimental worlds, smudging the boundaries or exploring opportunities for critique from within. Germaine Krull’s The Hands of the Actress Jenny Burnay (about 1930) might have been an advertisement for the delicate ring Burnay wears. Her hands are otherwise unadorned: bare-nailed and crossed in a way that obscures a finger on each, giving the impression of abstraction and a more intimate subject. Across the room, Lorna Simpson’s Details (1996) consists of twenty-one images of close-cropped hands from found studio portraits of Black Americans, each paired with words or phrases. Half learned and carried a gun underline the making of racist stereotypes, while separated and stopped speaking to each other seem to comment on the relationality of all knowledge, including that of ourselves.

Documentary photography throughout the show—by Meiselas, Mary Ellen Mark, and others—emphasizes subjectivity, collaboration, and power rather than claiming objectivity or authority. The images grouped in the catalogue’s chapter “Performance as Ethnography” subvert colonial-patriarchal control even more explicitly. Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (whose beautiful essay “When Is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words?” argues for an Indigenous “photographic sovereignty”), created a photocollage as part of her Native Programming series. Titled Vanna Brown, Azteca Style (1990), the image nods to the Wheel of Fortune personality and the dearth of Native representation in media.

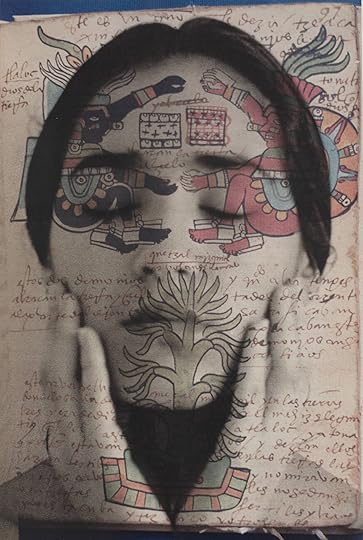

Tatiana Parcero, Interior Cartography #35, 1996

Tatiana Parcero, Interior Cartography #35, 1996© the artist

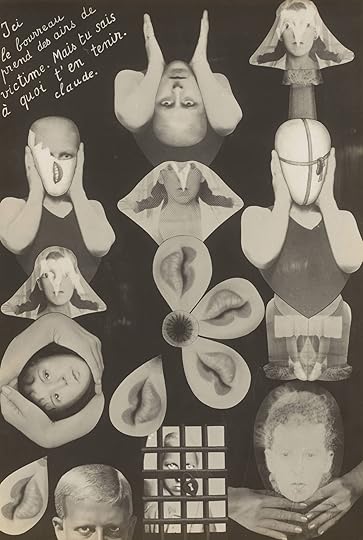

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob), M.R.M (Sex), ca. 1929–30

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob), M.R.M (Sex), ca. 1929–30 Structural inequality—sexual violence, policed bodily autonomy, pay disparity—may seem difficult to picture. Our Selves includes a variety of approaches. In Tatiana Parcero’s captivating Interior Cartography #35 (1996), the artist’s face is overlaid with the sixteenth-century Tudela Codex that details Mexico’s precolonial Aztec culture. The image shows her with eyes closed, fingers resting on cheeks, an illustration of a cacao tree meeting her closed lips. Nearby, Ruth Orkin’s American Girl in Italy (1951) is a straightforward and strikingly composed portrait of street harassment.

But moving through Our Selves, one might begin to see the structural—the background, coming into foregrounded focus—everywhere. An image from Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series (1990) shows the artist’s alter ego sitting with a daughter figure at the table, both applying lipstick before their own vanity. It is a moment of private ritual and maternal care, the performance of gender, an assertion of Black female beauty in relation to the gaze, and more. The series came out of Weems’s search for her own voice. In the audio guide she reflects on using her own domestic space: “What I’m suggesting really is that the battle around the family, the battle around monogamy, the battle around polygamy, the social dynamics that happen between men and women—that war gets carried on in that space.”

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman and daughter with makeup), 1990© the artist

In her work, Ahmed often invokes phenomenologist Edmund Husserl’s “writing table” to queer it. She considers the kitchen or dining table, recalling A Room of One’s Own and Kitchen Table press to reflect on how long women have understood, by necessity, how tables are multiuse. Women have also understood the work that goes on behind them, out of view. Of the Kitchen Table Series, curator Adrienne Edwards has written: “There are moments when Weems clearly resists the ordering device that is the table—lying across it, leaning against a wall—and through serial images and a polyphonic voice we come to see how the figure comes to know and feel herself, affirming or countering our impressions of her.”

We are often made responsible for coming to our seat at the table. But we might demand that the table change if we are to sit, or we might change the table by sitting. Perhaps we ourselves are the site—or sight—of change. Catherine Opie’s Angela Scheirl (1993), of Scheirl against a rich red background, in a dapper suit, bright socks, and long shoes that command our attention, is a “portrait of becoming,” writes Dana Ostrander, a curatorial assistant at MoMA, in the catalogue.

Installation view of Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022

Installation view of Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022Photograph by Robert Gerhardt

Queerness, in all the fullness of its meaning and possibility, also grants an understanding of the self with the permission to change—to become. Opie’s portrait of the Austrian artist and filmmaker, who would later go by Hans and now Ashley Hans, is a testament to the temporality and fluidity of self. Claude Cahun, whose work was largely overlooked until the 1990s, made complex Surrealist collages in collaboration with their lover and stepsister Marcel Moore. Cahun famously wrote in their 1930 “anti-memoir” Disavowels: “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” Their acute work playfully and presciently explores the multiplicity of the self, anticipating later feminist theory including, Marcoci writes in the catalogue, Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990).

The sheer physicality of two pieces on the back wall is memorable. In Jeanne Dunning’s Leaking (1994), what seems to be tomato flesh appears—joyously, erotically—in the place of a woman’s tongue. The portrait is framed beside that same wet red in close-up, both images ovular, like giant locket portraits. Amanda Ross-Ho’s Invisible Ink (2010) is a ghostly imprint of the artist’s body, first made accidentally and then embellished, including with cut-out eyes that hauntingly penetrate.

Jeanne Dunning, Leaking, 1994

Jeanne Dunning, Leaking, 1994© the artist

All works courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Helen Kornblum in honor of Roxana Marcoci

As the narrator’s body in Febos’s Girlhood begins to change, bumping up against the world’s expectations and desires of her (“My hips went purple from crashing them into table corners,” those unyielding ordering devices), she begins to experience shame more than that exhilarating embodiment of the sublime. She learns to fit herself, over time and to painful consequence, around such obstacles and demands. She learns to see from another’s eyes rather than her own. Febos finds her way back to herself, just as in Our Selves, women and gender-nonconforming photographers make their way through seeing, unseeing, and seeing anew. One woman’s life’s work—a collection of the labor of many, given to another in friendship—is a gift of sight seeking self and of self seeking sight.

Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through October 2, 2022.

At the Venice Biennale, a Surreal and Intimate Showing for Photography

The 2022 Venice Biennale opens, in the Giardini, with an image of a green elephant: life-size, atop a white pedestal, radiating in the magnificence of its unnatural being. A surreal apparition, it recalls certain scenes shot by Paolo Sorrentino, in which a silent gorilla may pervade, with enigmatic mystery, the carefree tranquility of the Vatican gardens. Time stands still and the viewer cannot help but wonder: Why? An answer does not necessarily exist. The green elephant is a 1987 work by Katharina Fritsch, winner of this year’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award, along with Cecilia Vicuña. Standing at the beginning of the international exhibition, titled The Milk of Dreams and curated by Cecilia Alemani, director of High Line Art in New York, the sculpture is a sort of declaration of intent: the dream will be the main dimension of the art presented in this Biennale.

Installation view of The Milk of Dreams. Photograph by Gus Powell

Installation view of The Milk of Dreams. Photograph by Gus Powell  Central Pavilion of The Milk of Dreams, with sculpture by Katharina Fritsch. Photograph by Gus Powell

Central Pavilion of The Milk of Dreams, with sculpture by Katharina Fritsch. Photograph by Gus Powell Another animal-symbol present in the Biennale is the giraffe. In fact, there are eight white giraffes that drag a large anatomical model of the male reproductive system on wheels, to which are affixed tags bearing the names of illnesses that can afflict individual body parts. This work by German artist Raphaela Vogel, titled Ability and Necessity (2022), resembles an ancient Roman triumphal procession and positions the male organ as the definitive war trophy for the patriarchy. The Milk of Dreams is a feminist exhibition not only in terms of numbers (it is very difficult to recall a male artist among the 213 participants) but also, and readily, in its contents. The feminist and surrealist imprint will be why this Biennale will make history, no matter what you think of it.

If instead observed from the perspective of photography, which occupies a marginal presence at the Venice Biennale, Alemani’s exhibition does not seem capable of being a watershed moment. We see no true shake-up regarding the medium’s reflections or evolutions, only excellent choices that enrich the exhibition’s collective effect, which is another of its great virtues.

Nan Goldin, Sirens, 2019–2021. Photograph by Ela Bialkowska

Nan Goldin, Sirens, 2019–2021. Photograph by Ela BialkowskaCourtesy the artist and La Biennale di Venezia

Let us begin our examination with the well-deserved tribute to Nan Goldin, who is exhibiting for the first time in the Venice Biennale. The work she presents is not a series of photographs but a sixteen-minute video, Sirens (2019–20), that is dedicated to Donyale Luna, considered the first top Black model and who died from an overdose in 1979. The video, a collage of clips taken from works by Kenneth Anger, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Federico Fellini, and Lynne Ramsay, as well as screen tests by Andy Warhol, attempts to convey the glamourous atmosphere associated with drug use. Its title refers to mythological characters who are both seductive and lethal.