Aperture's Blog, page 43

April 19, 2022

Announcing the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Aperture’s support of emerging photographers and other lens-based artists is a vital part of our mission. The annual Aperture Portfolio Prize aims to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography—identifying contemporary trends in the field and highlighting artists whose work deserves greater recognition. This year, Aperture’s editors reviewed over one thousand submissions, and we are thrilled to announce the shortlisted artists for the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize:

Felipe Romero Beltrán

Juan Brenner

Margo Ovcharenko

Adrien Selbert

Allie Tsubota

These artists join the ranks of illustrious winners and artists shortlisted for the Portfolio Prize in past years, including Dannielle Bowman, Alejandro Cartagena, Jessica Chou, Eli Durst, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Natalie Krick, Daniel Jack Lyons, Mark McKnight, Drew Nikonowicz, Sarah Palmer, RaMell Ross, Bryan Schutmaat, Donavon Smallwood, Ka-Man Tse, and Guanyu Xu.

The 2022 Portfolio Prize winner, to be announced on Friday, May 13, will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York. Each runner-up will receive an online feature.

Alongside the five shortlisted artists, twenty finalists were selected by Aperture’s editors. The finalists and shortlisted artists will each receive a virtual portfolio review session with an Aperture editor, who will provide thoughtful and constructive feedback on their work.

The twenty finalists are:

Aparna Aji, Morgan Ashcom, Steven Baboun, Adraint Bereal, Robert Andy Coombs, Luis Corzo, Mateo Ruiz Gonzalez, Arielle Gray, Pang Hai, Maen Hammad, Sarah Mei Herman, Abdulhamid Kircher, Alan Nakkash, Clyde Nichols, Marc Ohrem-Leclef, Louie Palu, José Ibarra Rizo, Muhammad Salah, Yvonne Venegas, and Patricia Voulgaris

Felipe Romero Beltrán, Fight between Hamza and Aziz, 2020, from the series Dialect

Felipe Romero Beltrán, Fight between Hamza and Aziz, 2020, from the series Dialect Juan Brenner, Untitled, 2021, from the series B’OKO’, City of Walls

Juan Brenner, Untitled, 2021, from the series B’OKO’, City of Walls Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021, from the series Overtime

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021, from the series Overtime Adrien Selbert, The Lovers, 2020, from the series The Real Edges

Adrien Selbert, The Lovers, 2020, from the series The Real Edges Allie Tsubota, Unidentified Bunker from USSBS General Photographic File, 2021, from the series The Magician’s Bombardier

Allie Tsubota, Unidentified Bunker from USSBS General Photographic File, 2021, from the series The Magician’s Bombardier

April 17, 2022

The Elusive Gaze in Chanell Stone’s Self-Portraits

Even as a technology of seeing, photography can be used to orchestrate optic negation or refusal. Present and historical forms of visibility are especially treacherous for Black women, who are pinned between the extremes of surveillance and erasure. Chanell Stone’s elegant formulation of herself as “sitter and seer,” as she said in a recent conversation, illuminates the self-circuitry of a photographic practice that reckons with this predicament through methods of withholding.

Stone’s new series, Umbra (2022), is comprised mostly of diptychs, made in Southern California, where she is currently based, and during her travels to Guadalajara and Mexico City. The establishing shots, taken in Mexico, are bereft of people and distinguishing features, giving them the vaguely familiar air of any place whatsoever. Stone appears as a solitary presence within these unmarked environments; her images are a conversation with herself. The artist has said that this flattening aspect is a way to avoid the photographic grammars of tourism, which invade the lives of daily residents and are hyperfocused on evidence of local particularity. Several of her contextualizing photographs have a kind of sfumato effect—as if they’ve been softened by a smoky haze—which accents the somnambular quality of the series. A voluminous white sheet drying on a clothesline is the one recurring object, shot alone and with Stone, and contributing to the sleepy impression of a comforting, mundane intimacy.

Stone conceived of Umbra as a conversation with images by Tony Gleaton, a Black American photographer who worked extensively in Mexico in the 1980s and 1990s, and who was known for his sensitive, dignified black-and-white portraiture of diasporic Africans in Central and South America. Another geographic connection creates a miniconstellation of global Black cultural practices: in 1969, at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the Martinican poet and theorist Édouard Glissant claimed a “right to opacity” in the face of violently totalizing and racialized demands for transparency, particularly by “the West” towards “the Other.” Thinking alongside Glissant accentuates the shared stakes of Gleaton’s and Stone’s work in Mexico. Gleaton’s foregrounding of Black people became a way of confronting histories of colonialism and expressing his interest in cultural hybridity. Similarly, Stone’s intricate adjustments of the levers of sight in her images are a rejection of colonially inflected demands for absolute exposure.

In her previous series Natura Negra (2018–19), Stone crafted a quietly expressive visual language for her study of Black urban ecologies, situating her mesmerizing self-portraits amidst eruptions of greenery fringed by concrete. Umbra fuses this attentiveness to her self-presentation inside controlled environments with a method inclined towards opacity. Four diptychs include portraits of Stone facing away from the camera. In three of these, she is wearing an open-backed black leotard and standing almost pressed against a grainy, unevenly textured wall. She sees these images, she says, as extending her investigations into “how much you can access a photograph.” The wall, which takes up the entirety of the background, acts as a limit to sight. Stone’s proximity to the wall means that the viewer’s gaze stops where she stops.

There are echoes between Stone’s work and that of Carrie Mae Weems, who has engaged in Black feminist refusals to meet the gaze throughout her oeuvre. In The Louisiana Project (2003), Weems positions herself with her back firmly turned to the camera. Stone’s corporeal choreography is more oblique—she sometimes places herself at a slight angle rather than facing directly away—yet has a similar effect of making the self-portraits an exercise in balancing visual autonomy and personal withholding. In one diptych, Stone turns her back, possibly in a position of vulnerability: her arms are pushed back, almost as if she were manacled. This is paired with a close-up of a floral embroidered fabric, split not quite in half by the shadow created by a sharp crease, which accents the severe verticality of the work. A key difference between Weems’s and Stone’s setups is that while Weems frequently looks out at spacious expanses, Stone’s placement of herself is almost claustrophobic. She could also be turning inwards, creating a small space of refuge.

In addition to Gleaton and Glissant, Stone crafted her images in dialogue with bell hooks, particularly the late Black feminist theorist’s 1992 essay “The Oppositional Gaze.” In that piece, hooks considers the specificity of Black women’s practices of critical looking, as well as the broader potential for the act of looking to be recuperated by those marginalized by the dominant visual order: “The ‘gaze’ has been and is a site of resistance for colonized black people globally. Subordinates in relations of power learn experientially that there is a critical gaze, one that ‘looks’ to document, one that is oppositional.” Hooks assigns a particular capacity for oppositional gazing to Black women because of the ways they are positioned to consider the collusions of race and gender (as well as class) in shaping “looking relations”—the structures of power marked in the acts of seeing and being seen.

Through the mode of self-portraiture in Umbra, Stone not only claims autonomy over how she appears photographically but also safeguards herself from looking relations that would demand otherwise. Gaze averted, Stone’s interiority in these images is beautifully self-contained and unknowable. As hooks writes, “We come home to ourselves.”

Chanell Stone’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX100S with a FUJINON GF80mm F1.7 R WR lens.

All photographs by Chanell Stone from the series Umbra, 2022, for Aperture

All photographs by Chanell Stone from the series Umbra, 2022, for ApertureCourtesy the artist

April 14, 2022

A Ukrainian Photography Duo’s Fantastical World

Roman Noven and Tania Shcheglova’s story begins far from photography and far from each other. Noven studied automated processing at university; Shcheglova attended a school dedicated to oil and gas research. Noven lived in Lutsk and Shcheglova in Ivano-Frankivsk, cities in Ukraine that are eight hours apart by train. But they both found themselves drawn to art—and then to each other, after meeting in 2008 through a website for photographers. They soon began an artistic collaboration, dubbing themselves Synchrodogs, a name that reflected how they paralleled each other in taste, perception, and thought. (They were also fond of dogs, as storied, reliable companions to humans.)

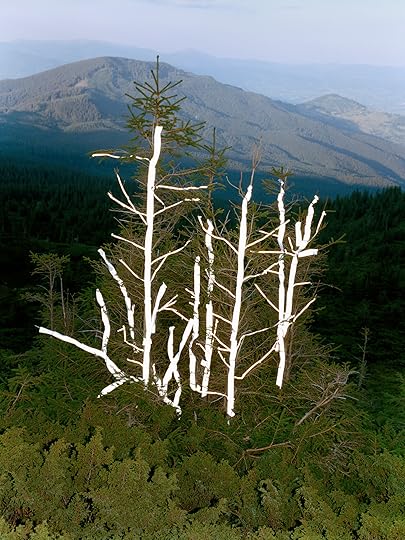

Synchrodogs, 2011

Synchrodogs, Slightly Altered, 2017

Starting out, they took a diaristic approach to photographing their own lives, but gradually they embraced the fantastic, shifting toward a highly stylized approach that plays with tropes of futurism, science fiction, and their own idiosyncratic brand of psychedelia. They have set out to beguile audiences with a blend of visual effects, play, and consideration of the body in relationship to the lansdscape. The series Supernatural (2015), shown at Dallas Contemporary in 2015, is the result of a four-thousand-mile drive around the United States; its photographs, made in the sunbaked, arid landscapes of the American Southwest, at times resemble scenes from Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point.

Another series, Reverie Sleep (2013), delves into the liminal state between being awake and asleep, restaging the contents of the duo’s dreams. The earlier series Ukraina (2011) is more straightforwardly documentary and playfully homes in on the rhythms of daily life. “The project is a visual portrait of [the] country that brought us up,” they write on their website. “Life here has always been slow and calm, people doing ordinary things. . . . The project strives to convey Ukraine’s solitary nature showing the paradox of being in the center of events [but] still isolated, being the biggest European country [but] still somehow forceless concerning its own future.” It is self-evident that recent catastrophic events, following Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine, have altered the meaning of these words and images. Ordinary life in Ukraine is now shattered, the country’s future uncertain at best.

Over the years, Synchrodogs has found an international audience through commissions for fashion magazines, such as Dazed and Harper’s Bazaar, and for brands including Kenzo. Last February, the duo was on location for a job abroad when the war in Ukraine plunged the country into chaos, making it impossible for them to return home. Currently in limbo in Central America, they are looking to relocate to the United States, and now spend their days strategizing about how to support relief efforts for the Ukrainian people.

Synchrodogs, Reverie Sleep, 2013

Synchrodogs, Reverie Sleep, 2013Michael Famighetti: You are in a specific location that you cannot disclose. What kind of photography project were you working on there when the war in Ukraine began?

Roman Noven and Tania Shcheglova: We were shooting an advertising campaign, but we can tell no details, as we signed a nondisclosure agreement. Usually, we get contacted by clients that want something interesting, that request an artistic approach; those that do not expect a classic outcome but strive for innovation. It was one of those projects where we could take our time to experiment. Also, a big part of the proceeds from it was donated to help people of Ukraine.

Synchrodogs, Ukraine, 2011

Synchrodogs, Ukraine, 2011Famighetti: You both now live in Ivano-Frankivsk, a city near Lviv. What was the art and photography scene like there before the war?

Noven and Shcheglova: We can’t divide artistic scene by cities and regions in Ukraine; it is a big country, but the community knows each other and is quite tight, as a lot of artists either move to Kiev or go there from time to time. All artists, musicians, fashion designers, publishers intersect, making for quite multidisciplinary groups of friends. Before the full-scale war, we all used to have what people call “plans”; now we skipped to another kind of life. Day by day, small victory after small victory, we are on our way to freedom and peace. Many artistic people we know (including us) created their own initiatives to support Ukraine or work as volunteers. The part of our life that deals with creating new works is currently suspended, as there are a lot of other important and urgent things to do connected with war and overcoming its consequences.

Synchrodogs, Ukraine, 2011

Synchrodogs, Ukraine, 2011

Famighetti: Your 2011 series Ukraina has a different poignancy today. What was the original impulse behind this series?

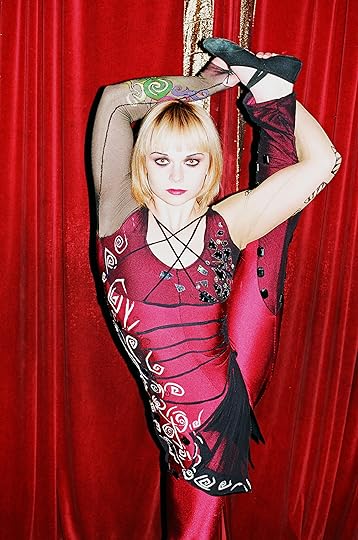

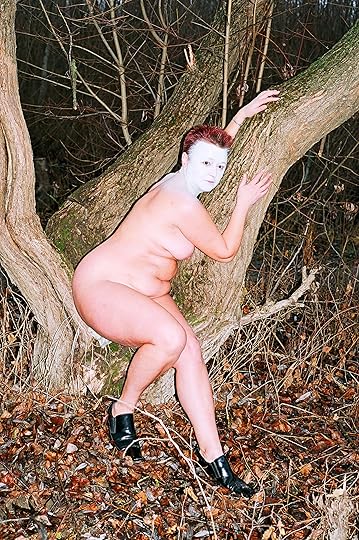

Noven and Shcheglova: Our goal was to make a slightly surrealistic documentary project. Ukraine at that time had a lot of kitsch, especially in villages. The project is raw and sincere, just like the people in every picture. All portraits are accompanied with interesting stories, like a portrait of a naked woman with a painted face whom we found via a newspaper ad that said, “Looking for a friend,” or forty-two-year-old Orlando, who liked dancing on trees, using them for pole dancing. There are also a lot of kids in the series. With all of them, we had a touching first meeting and deep conversations. That was totally another country twelve years ago. Ukraine grew up and became much more cosmopolitan.

Famighetti: There is a quiet sense of theatricality in that series, an element that becomes more pronounced in later series, which are more clearly directed. How do you negotiate constructing artifice in an image while trying to represent what’s before you in the world?

Noven and Shcheglova: We always try to balance between real and surreal, natural and artificial; it is a big part of our recognizable style. We know that documentary photography has some kind of unwritten rules, but we wanted to show soul more than the body, to convey the spirit, vibe, mood of that time more than the actual mundane life. So we broke the rules and made things how we saw them. We have a big archive of photographs of that time, and one day we will make a book out of them.

Synchrodogs, Slightly Altered, 2017

Synchrodogs, Slightly Altered, 2017Famighetti: Your work has also expanded into moving images recently.

Noven and Shcheglova: For the last nine months, we were working on our first short movie, consisting of eleven scenes shot in Ukraine, Norway, France, and Italy. The movie is going to be on the edge of classic theater and opera and innovative technologies, like contemporary digital art, and should show how science and art can harmoniously coexist. We were in the process of shooting when the war started, so we had to freeze it. We really hope we can find funding to resume the film in the future.

Famighetti: Environmental phenomena and playing with futuristic tropes are currents throughout your work. How did these interests and aesthetic form?

Noven and Shcheglova: Weird and paranormal things have been haunting us since the beginning of Synchrodogs. We have plenty of stories about how we heard UFO sounds in Marfa, Texas, or saw a unicorn in Colorado after a lightning bolt hit the ground right in front of our car during a big storm. Once, we were shooting Tania on Icelandic lava, and it was impossible to stand on the very sharp stones and not get cut, so we put some clothes under Tania’s legs. When we finished, the clothes were gone. After, we scanned the film, and they were also not there in the shots. In the evening, locals asked us if some of our things disappeared, as there are elves living in that district that steal things all the time. In other words, these situations happen—they are part of the process.

Synchrodogs, Slightly Altered, 2017

Synchrodogs, Inner Garden, 2021

Famighetti: Sounds like the universe delivers hallucinatory magic for you, as a third collaborator. Some of your photography is also based on another unpredictable element, dream states.

Noven and Shcheglova: Dreams have a straight connection with our art. Over the years, we developed our own nighttime meditation technique, which deals with catching a subtle moment between wakefulness and sleep. It involves trying to fall asleep and move into non-rapid eye movement sleep, a stage during which some people might experience hypnagogic hallucinations. We usually wake ourselves up in the middle of the night to make a note of what we have just seen, in order to recreate those visions via photography and mixed-media art afterward. That’s how many of our projects begin.

Famighetti: What can the international art and photography community do now to support Ukrainian artists?

Noven and Shcheglova: Many of us are in difficult or unstable life situations, so we appreciate any support. We feel now is the time to concentrate on supporting Ukraine overall. The situation is really difficult, especially for cities that are under Russian siege (like Mariupol, Bucha, Chernigiv, Kharkiv, and many more). People have lost their families, homes; whole cities have been erased by Russian bombs. We made our own charitable initiative where we sell our prints and donate money to urgent causes. We also are selling NFT art now on SuperRare and Foundation, which has helped fund medical operations and refugee evacuation.

Synchrodogs, Supernatural, 2015

Synchrodogs, Supernatural, 2015Famighetti: How are you staying up to date and getting information on the evolving situation?

Noven and Shcheglova: We don’t only read big newspaper articles; we are subscribed to trusted Telegram and Instagram channels run by small groups of volunteers that are updating news every twenty minutes. A huge amount of information is being processed, and we try to react where help is needed most. For instance, yesterday we helped collect money for a Jeep that was needed, for buying medicine, and to create new homes for refugee families who have lost everything.

Ukrainians are united as never before, like a big family. There is endless love, pride, and warmth toward one another. We are grateful for the tremendous support of other countries. We radiate gratitude to all the kind people helping us withstand these days. Please keep doing so: address your governments, state your position against the invasion, request a Russian gas embargo, help us by providing air defense systems. This is the battle for our freedom from Russia, which has terrorized us for centuries. We believe our brave people will defeat evil with the help of the democratic world. Truth and justice have to win.

April 7, 2022

How a Japanese Card Game Inspired Will Matsuda’s Pictures of the Pacific Northwest

Will Matsuda grew up in Oregon, a state famed for its environmental extremes—dense forest, volcanoes, desert, and Crater Lake, the deepest such body in the United States. Matsuda began to be interested in making images about place when he left home for college and experienced a longing for visual materials that reflect the complexity of the American landscape, with its ambivalent histories of theft, loss, and reinvention.

As Susuki #2, an image from his series Hanafuda (2020–21), reveals, Matsuda works with a distinct vocabulary, seeming to construct his photographs piece by piece, using simple tools such as on-camera flash to create resonant, nearly aphoristic effects. Similar to vanitas paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Matsuda’s pictures manipulate elements of the natural world in order to comment on the ultimate artificiality and fleetingness of human mastery. Susuki #2, for example, might ask that we question our overly celebratory, frequently acquisitive, Instagram-abetted relationship to images. The hand of the mirror holder, who would appear to have successfully captured the face of the moon and its delicate maria, has, ironically, begun to fade away.

But the vanitas connection is merely one reading. Hanafuda, or “flower cards,” are a Japanese style of playing card developed from Portuguese decks that entered the Asian nation in the seventeenth century. These cards were banned by the Japanese government and then constantly redesigned and recirculated by enterprising gamblers to circumvent the rulings. Matsuda encountered modern-day hanafuda during New Year’s gatherings in Hawaii with extended family. His paternal grandmother, Amy Matsuda, encouraged him to play. The cards are organized into twelve suits corresponding to the twelve months of the year; their imagery is simple—landscapes, flora, and fauna printed primarily in black, red, and white—yet striking, memorable.

Will Matsuda, Momiji #1, 2021

Will Matsuda, Ume #1, 2021

Matsuda’s work in this series is, in part, derived from hanafuda illustrations. He sometimes titles the photographs after the plants that correspond to the suits—susuki (grass), kiku (chrysanthemum), ume (plum blossom)—or after special cards that bear figures, such as the phoenix. Yet the cards’ calendrical structure does not absolutely determine the content of Matsuda’s images, which are rather loosely inspired by memories of time spent with family and questions related to place. As he explains, the Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock tradition has also been a primary influence. Matsuda is drawn to the stylized flatness of ukiyo-e (literally, “floating-world pictures”) as well as the virtuosic manipulation of colored ink seen in these patently commercial images, which became popular in urban centers during the Edo period. The term uki (浮) refers to a “floating” lifestyle of consumerist hedonism that grew up in the context of sumptuary laws that prevented wealthy nonaristocratic city dwellers from purchasing some items, including but not limited to land.

According to the photographer Ricardo Nagaoka, a friend of Matsuda’s who is depicted in Ricardo (2021), even Matsuda’s portraits “feel connected to the landscape”—human figures seem intimately mingled with, rather than set above or against, natural elements. Given present-day environmental disasters, along with housing shortages and astronomical real-estate prices in the United States and beyond, Matsuda’s hanafuda are a reminder that, although we may all be experiencing a certain floating feeling, it is possible to come back down to Earth. Just follow the stark and strangely joyful outline of a chicken held aloft, for example. Viewed in a particular light, it is, in fact, a phoenix being reborn.

Will Matsuda,

Susuki #3

, 2020

Will Matsuda,

Susuki #3

, 2020 Will Matsuda,

Ricardo

, 2020

Will Matsuda,

Ricardo

, 2020 Will Matsuda,

Untitled

, 2020

Will Matsuda,

Untitled

, 2020 Will Matsuda,

Kiku #3

, 2021

Will Matsuda,

Kiku #3

, 2021 Will Matsuda,

Pheonix

, 2021

Will Matsuda,

Pheonix

, 2021 Will Matsuda,

Ume #2

, 2020. All photographs from the series Hanafuda

Will Matsuda,

Ume #2

, 2020. All photographs from the series HanafudaCourtesy the artist

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “Hanafuda.”

April 6, 2022

Mine Dal’s Nationwide Search for the Father of the Turks

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, “the father of the Turks” (1881–1938), was a soldier-turned-politician who cut a stylish figure in his fashionable suits. Thinker, teacher, trailblazer, he soon became a role model for a fledgling Republic of Turkey. Critics of Atatürk’s modernizing legacy have long viewed him skeptically as a symbol of forced Westernization. Regardless, Atatürk’s photographs are everywhere in Turkey. Since 2002, when Islamists first ascended to power, his iconography flourished, and the image of Atatürk gained fresh significance. Nowadays, his portraits furnish teahouses, classrooms, airports, greengrocers, bakeries, and indoor swimming pools: you can find his likeness while queuing in a butcher shop or waiting for a haircut in the barbershop. Tourists who treat themselves to Turkish cuisine may notice the leader’s gimlet gaze on the walls. At night clubs, photographs that depict Atatürk dancing with Turkish women at state balls abound. Dead since 1938, Atatürk remains perennially alive.

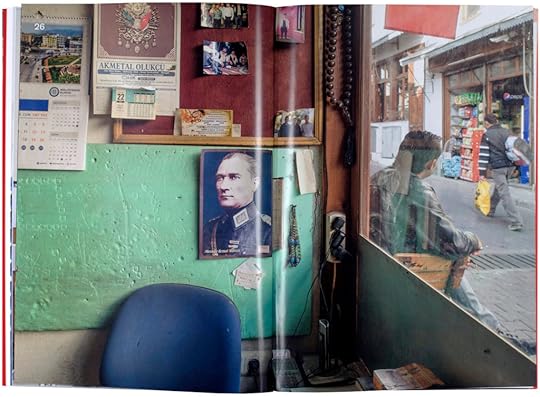

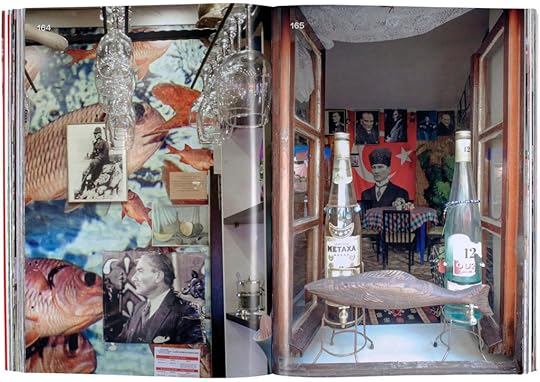

Spread from Mine Dal, Everybody’s Atatürk (Edition Patrick Frey, 2020)

Spread from Mine Dal, Everybody’s Atatürk (Edition Patrick Frey, 2020)In 2013, Mine Dal, a Turkish photographer based in Switzerland since 1999, set out to capture this phenomenon and answer a question: why have so many people put up Atatürk pictures when nobody asked them to? Everybody’s Atatürk (Edition Patrick Frey, 2020) comprises fruits of her labors. “For seven years, I’ve searched Atatürk photographs wherever I went in Turkey,” Dal tells me on a recent Zoom call. “When I entered a florist, or a tailor, or a butcher, my eyes would automatically locate him.” But after two years of documentation, she decided Istanbul was too narrow a focus for this memory archive. She would travel through Turkey: from the Black Sea to the Aegean, from the Mediterranean to eastern Anatolian, no region would remain unexplored. “It began as a curiosity and turned into an obsession.”

Dal’s initial strategy was a protracted one: locate Atatürk imagery, decide how to frame them, step outside, work on her Canon EOS 6D’s settings, reenter the space, and ask for inhabitants’ permission to photograph. “I was trying to be sympathetic, but my camera unnerved people,” she says. That Atatürk stands in the ambivalent intersection between private and public in Turkey is a discovery Dal made the hard way one day when a shopkeeper told her to “immediately leave” his shop. “How can I make sure you’re not an agent?” he inquired.

Mine Dal, Karacaahmet, Istanbul, 2019

Mine Dal, Karacaahmet, Istanbul, 2019With people growing anxious about her presence, Dal changed tactics. She began using a tiny camera—a Sony DSC-RX100M3. Taking advantage of its mobility, she operated guerrilla-style but faced novel challenges. One day in 2015, three policemen detained Dal after noticing her camera. “When they asked what I was doing, I told them there was an Atatürk picture next to the WC which I wanted to photograph,” she recalls. “They took me into a room in the police station for interrogation. I was convinced I’d be arrested.” They let her go.

Dal’s work appreciates the ingenious ways that Turkish people integrate Atatürk into their daily lives.

Turning the pages of her bulky book, which features 364 images on its 652 pages, and essays by Turkish musician and novelist Zülfü Livaneli and the former politician Altan Öymen, is a perplexing experience. Dal’s gaze is capacious, one that captures manifold ways in which Atatürk is commodified in contemporary Turkey. There he is, sitting beneath packs of cigarette packs in a grocery store; and there Atatürk appears in a poster, glued next to Frida Kahlo and the Joker. The military genius is placed near jars of pickles in another picture. His face adjacent to loo paper and detergent in a tiny shop may puzzle outsiders. For Dal, though, his all-encompassing presence is a cause for celebration: her work appreciates the ingenious ways that Turkish people integrate Atatürk into their daily lives.

Mine Dal, Dalyan, 2017, from Everybody’s Atatürk

Mine Dal, Dalyan, 2017, from Everybody’s AtatürkFor the seller of Chivas Regal bottles that Dal photographs in a bourgeois Istanbul neighborhood, Atatürk’s image hung in his shop may serve as a reminder that the Westernizing founders of the Turkish republic also consumed alcohol—that there is no shame in enjoying life a bit. Elsewhere, Dal captures a man with an arm in a cast posing for a photograph in front of an Atatürk statute. How does that make him feel? A Syriac Orthodox abbot at the Mor Hananyo monastery in southeastern Anatolia points reverently toward Atatürk in another image. (“If it weren’t for him, I wouldn’t be here,” he told Dal.)

Among the most striking images is a view of the Buca district in the coastal city of Izmir, where a giant concrete bust of Atatürk has been carved into the side of a mountain. And furnishing the back cover is an image of a man baring his chest to reveal an Atatürk tattoo. For him, and numerous others, Atatürk is a sacred figure, almost a deity. He masterminded the secularist project. He abolished the caliphate and the sultanate. He changed the Turkish script from Arabic to Latin. He asked citizens to dress like Europeans and assured them that they belonged to the “modern world.” For a nation used to living under a sultan’s reign, he became a Republican sultan whose every move and speech were treated as sacred. No wonder Atatürk appears in one of Dal’s pictures in the form of an angelic icon placed next to verses from the Qur’an. But for the majority of people, Atatürk belongs, above all, to the mundane. Swimming in the sea, entertaining a kid, fishing, roaring with laughter, promenading with his colleagues, he’s fallible, human.

Mine Dal, Çanakkale, 2018, from Everybody’s Atatürk

Mine Dal, Çanakkale, 2018, from Everybody’s AtatürkThere is a strong sense of spontaneity in Dal’s compositions. Her Atatürk photographs in domestic settings have an exceptionally tender air. We find him next to a hoover in a house, beneath a chair. Elsewhere, Atatürk is attached to an evil eye, a deterrent to those who mean harm. “People who read my book say, ‘We notice Atatürk pictures everywhere now, thanks to you,’” Dal says. But she adds that she intended to “reflect Atatürk’s multilayered personality; I’m by no means idolizing him.” Instead, she is interested in how his images and spaces in Turkey intersect to tell stories. “In researching for the book, I’ve looked into other examples, like Mao and Lenin. Neither is as popular a figure today. There is no other country whose founder is as deeply embedded in the texture of every day.”

Spread from Mine Dal, Everybody‘s Atatürk (Edition Patrick Frey, 2020)

Spread from Mine Dal, Everybody‘s Atatürk (Edition Patrick Frey, 2020)Yet, when Dal proposed the project to Turkish publishers specializing in “Atatürk books,” she received the cold shoulder. “They found my book weird,” she recalls. “They prefer publishing fancy coffee-table books with Atatürk images. I was more interested in investigating how people interacted with Atatürk’s images. They said such a book wouldn’t sell.” A Swiss publisher disagreed, and Everybody’s Atatürk was shortlisted for the Rencontres d’Arles Book Awards in 2021. Each copy contains two standalone Atatürk pictures. “The idea was that you could place your own Atatürk picture in your setting, just like those people did in my pictures,” Dal explains. The book compiles her archive in mostly chronological order, and its penultimate image was taken in 2019. A photo of two clocks that have stopped at the time of Atatürk’s death, 9:05 a.m., it is a poignant double-reflection on the chronological aspect of the book’s sequence and the pre-pandemic nature of this catalogue of images.

Mine Dal, Maltepe, Istanbul, 2019, from Everybody’s Atatürk

Mine Dal, Maltepe, Istanbul, 2019, from Everybody’s AtatürkAll images courtesy Edition Patrick Frey

Dal’s images carry the scars of recent history. They bear witness to seven traumatic years for Turkey. In 2013, four weeks after Dal took the earliest photo in the book, environmentalists filled Istanbul’s Gezi Park, unleashing the most momentous protest movement in modern Turkey’s history. At Gezi, protesters used Atatürk posters, appropriating the image of Turkey’s westernizing founder as a symbol of their struggle. The government reacted by calling them “degenerates” and “foreign agents.”

Nevertheless, in the autocratic atmosphere that has suffocated Turkey since 2013 and in the wake of the failed coup attempt of 2016, instigated by a shadowy religious sect, Atatürk remains a guiding figure for the liberal, westward-looking part of Turkey. Meanwhile, Dal’s book, produced thanks to so many visits to public spaces, seems like a relic just a year and a half after its publication. I tried to imagine all its documented interiors as they remained vacant during lockdowns: dark, empty, and yet connected by countless images of their common occupant.

Everybody’s Atatürk was published by Edition Patrick Frey in 2020.

April 5, 2022

A Photographer’s Unflinching Portrait of America in Crisis

American Mirror is the award-winning photographer Philip Montgomery’s dramatic chronicle of the United States at a time of profound change. Through his intimate and powerful reporting and a signature black-and-white style, Montgomery reveals the fault lines in American society, from police violence and the opioid addiction crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic and the demonstrations in support of Black lives. Yet in his unflinching images, we also see moments of grace and sacrifice, glimmers of solidarity and tireless advocates for democracy. Like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans before him, Montgomery has made an unforgettable testament of a nation at a crossroads. As Patrick Radden Keefe writes in American Mirror, “Montgomery’s photographs capture the reality of Americans in crisis, in all our flawed, tragic, ridiculous glory.” Here, we look at the stories behind nine of Montgomery’s iconic photographs.

Philip Montgomery, A family mourns the loss of their son, Brian Malmsbury, who died of an opioid overdose in the basement of their home, Miamisburg, Ohio, September 2017

Philip Montgomery, A family mourns the loss of their son, Brian Malmsbury, who died of an opioid overdose in the basement of their home, Miamisburg, Ohio, September 2017Saying Goodbye to Brian

A family mourns the loss of their son, Brian Malmsbury, who died of an opioid overdose in the basement of their home. Brian’s death was an especially quiet one. He was thirty-three and had been working toward sobriety after years of addiction. Opioid-related overdoses are the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of fifty, killing more individuals each year than car accidents or gun violence.

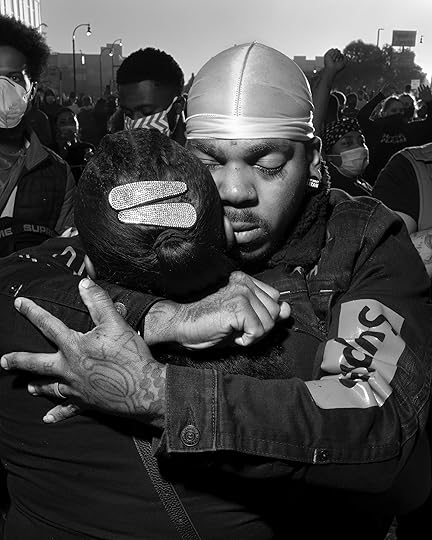

Philip Montgomery, Demonstrators embrace ahead of curfew in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 2020

Philip Montgomery, Demonstrators embrace ahead of curfew in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police, Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 2020Minutes to Curfew

Tony Clark embraces a fellow protester shortly before a citywide curfew in Minneapolis. Minutes later, protesters were attacked with impact munitions and tear gas. The murder of George Floyd renewed a sense of urgency for the Black Lives Matter movement in the US—and galvanized protests around the world. Within days, as both peaceful protests and violence erupted in the city, state officials imposed an overnight curfew, and Minnesota National Guard troops were deployed to the streets.

Philip Montgomery, Members of Milwaukee Ironworkers Local 8 on a break, Kenosha, Wisconsin, 2015

Philip Montgomery, Members of Milwaukee Ironworkers Local 8 on a break, Kenosha, Wisconsin, 2015Union Break

Facing single-digit temperatures, members of Milwaukee Ironworkers Local take a break at a job site near Kenosha, Wisconsin. A state with a longstanding history of labor activism, Wisconsin has become a crucible in a nationwide Conservative effort to destroy America’s labor unions. Its right-to-work law, signed by Governor Scott Walker in 2015, eliminates the requirement for private sector workers represented by a union to pay dues.

Philip Montgomery, Members of the Texas congressional delegation chant “Trump” during the third night of the 2016 Republican National Convention, Cleveland, Ohio, July 2016

Philip Montgomery, Members of the Texas congressional delegation chant “Trump” during the third night of the 2016 Republican National Convention, Cleveland, Ohio, July 2016Texas for Trump

Members of the Texas congressional delegation chant “Trump” during the third night of the 2016 Republican National Convention. Trump carried Texas in the 2016 election, but only by nine points—the smallest margin of victory for a Republican in the state since Bob Dole’s five-point win twenty years earlier.

Philip Montgomery, Queens Hospital Center, Queens, 2020

Philip Montgomery, Queens Hospital Center, Queens, 2020The Onset

Prior to entering the emergency department, a health care worker at the Queens Hospital Center puts on personal protective equipment, known familiarly as PPE. At the onset of the pandemic, PPE was in such short supply at New York City’s public hospitals that workers were forced to improvise, reusing single-use surgical masks designed to be worn once and fashioning hospital gowns out of their own foot coverings.

Philip Montgomery, The People’s Way, George Floyd Square, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June, 2020

Philip Montgomery, The People’s Way, George Floyd Square, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June, 2020The People’s Way

The intersection of East 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis, the site of George Floyd’s arrest and murder, became a gathering place for protesters, a site of mourning, and the center of a movement. Demonstrators perched on rooftops and filled the parking lot of the Speedway gas station across the street, which kept a running tally of each day that passed after Floyd’s death. The intersection, eventually named George Floyd Square, remained a meeting place throughout the trial of Derek Chauvin, who in April 2021 was found guilty on all three charges he faced in the murder of Floyd.

Philip Montgomery, Lauren Gundlach returns to her childhood home after it was destroyed by floodwater from Hurricane Harvey, Houston, Texas, September 2017

Philip Montgomery, Lauren Gundlach returns to her childhood home after it was destroyed by floodwater from Hurricane Harvey, Houston, Texas, September 2017Lauren Returns Home

Lauren Gundlach returns to her childhood home after it was destroyed by floodwater from Hurricane Harvey. Along with her father, she set out to retrieve an original 1936 lithograph by Henri Matisse. Once inside, she and her father realized that they also needed to rescue a work by Edgar Degas. They waded out of the neighborhood with these and other artworks propped atop a small kayak.

Philip Montgomery, A Christmas eviction, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, December, 2015

Philip Montgomery, A Christmas eviction, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, December, 2015A Christmas Eviction

Housing is intertwined with the persistence of poverty in the US. Some low-income families, facing impossible rent demands, become used to moving between shelters and the streets in the aftermath of an eviction order. Shortly before Christmas Day in 2015, an eviction notice was served to a family in north Milwaukee, where one management company advertises evictions for $395, providing a “hassle-free way to deal with problem ten- ants.” Today, the majority of poor renting families spends more than half their income on housing, and millions of Americans are evicted every year.

Philip Montgomery, After viewing the body of Brian Malmsbury, who died of an opioid overdose, his family members gathered at a funeral home, Kettering, Ohio, September 2017

Philip Montgomery, After viewing the body of Brian Malmsbury, who died of an opioid overdose, his family members gathered at a funeral home, Kettering, Ohio, September 2017All photographs courtesy the artist

The Viewing

After viewing Brian Malmsbury’s body, his family members gathered at a funeral home in Kettering, Ohio. Eight days earlier, Brian had been found dead from a heroin overdose in the basement of his mother’s home. Brian had struggled with depression and addiction for many years. “He’d always just been a sad kid,” said Patty Neff, Brian’s mother.

These photographs and texts originally appeared in Philip Montgomery: American Mirror (Aperture, 2021).

March 31, 2022

How a Hmong Photographer Creates a Striking Narrative about Laos

Our Hmong elders often narrate stories about Laos. In one, they carry bamboo baskets on their backs as they leisurely walk barefoot along the rugged mountainsides toward the rice paddy fields. Idiosyncratically shaped hills embellish the landscape, providing a panoramic view of steep valleys as green as dragon skin. Gibbons frolicking atop banana trees serenade passersby with their melodies, while Asian unicorns prance behind the emerald timbers. In another story, the elders transport us to wartime Laos, where mountains are set ablaze by cluster bombs. Rotting carcasses of water buffalos litter the bomb-stricken landscape. Bloodstained trails zigzag through the compressed jungles as the eyes of trees surveil lost wanderers. In this account, dead men become tigers, the most malevolent of all creatures. The tigers lurk behind bamboo huts, roaring through crevices exposed in the dead of night.

Pao Houa Her, Three Bachelors at the Elder Center, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Three Bachelors at the Elder Center, 2017Pao Houa Her, a Hmong photographer born in Laos and raised in the United States, takes these conflicting geographies of Laos as frameworks for the series My Grandfather Turned into a Tiger (2017) to ask: How do Hmong in the United States imagine Laos when they do not have a direct connection to it? Which of these scenes—literal or allegorical—resonates with Hmong? After the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, Indigenous Hmong who served as American proxy soldiers in Laos were displaced into the West as political refugees. Many Hmong refugees resettled in Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Minnesota, where Her’s family has lived since the mid-1980s.

Her’s photographic repertoire draws on the fragmented temporalities and uneven geographies of worlds past to perform a visual narrative of how these disconnected histories unfold in the present. She always carries a camera with her in order to stage a photograph or capture an accidental moment with family and community members, both in Laos and Minnesota. Her imbues her photographs with lust and desire—for her subjects and for the homeland—with the need to grieve for the dead, now specters in our splintered memories.

Pao Houa Her, Maroon Backdrop, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Maroon Backdrop, 2017“One challenge of my photography is to create a narrative that does not require a beginning or an end,” Her told me recently. A circuitous trajectory of Her’s work formulates a complex metaphorical dialectic: the blurriness of both prewar and war-torn Laos narrated by her elders. The country’s distance—both geographically and metaphorically—seems closer than it appears. This circular vision materializes through a sequence of illusions that are simultaneously mundane, absurd, and chaotic.

Faux flora epitomizes a major hallucinogen in Her’s work. “The floral makes something hard to look at beautiful to look at,” Her says. The paradoxical pain and pleasure in looking requires a psychic reconciliation to disentangle the various oppositional elements within Her’s photographs. How do we resolve the antagonistic impressions of Laos? Her does not claim to fulfill the expectations of our imagined geographies, but rather to draw from our contradictory archives of knowledge to adjust our gaze—and mind—beyond the visual medium.

Pao Houa Her, Cave in Laos, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Cave in Laos, 2017 Pao Houa Her, Two Red Chairs inside Western Union, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Two Red Chairs inside Western Union, 2017 Pao Houa Her, Prince Charming, 2016

Pao Houa Her, Prince Charming, 2016 Pao Houa Her, Vince Crying, 2017. All photographs from the series My Grandfather Turned into a Tiger

Pao Houa Her, Vince Crying, 2017. All photographs from the series My Grandfather Turned into a TigerCourtesy the artist and Bockley Gallery, Minneapolis

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “My Grandfather Turned into a Tiger.”

An Artist’s Book Grapples with the Consequences of the US Prison System

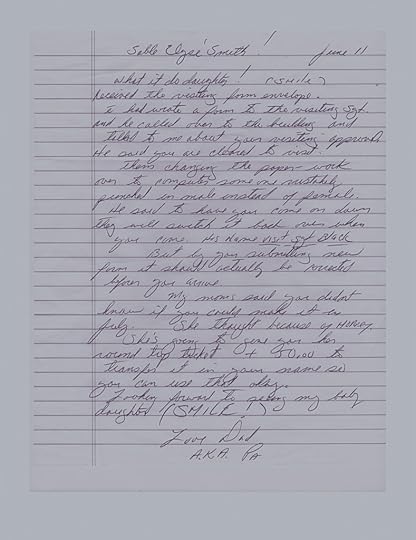

Landscapes & Playgrounds (2017), Sable Elyse Smith’s recent artist’s book, from which a sequence of pages is excerpted here, is a meditation on two sites of the prison environment after which the book takes its name. Within it, we encounter a world through the eyes of a young protagonist grappling with the prison system.

Smith, an artist working across video, poetry, and performance, is not merely interested in the cataclysmic consequences of mass incarceration that tend to be the focus of our justice dialogues in the United States. Landscapes & Playgrounds contains aerial images of prison architecture, surrounding land, and recreational areas such as basketball courts. But we also glimpse, through handwritten letters, the intimacy between an incarcerated father and a daughter that is not theirs alone, but one embedded in surveillance. Not all of the texts from these letters, written on crinkled lined paper, is visible, but the handwritten notes that we can read evoke a gentleness in their direct address. They often begin with a cheerful greeting like “What it do daughter!” and close with an equally heartfelt “Love you, Miss You. Pops. A.K.A. Pa.”

Still, the reader should resist a purely autobiographical read of Smith’s work. As she stated in the introduction to her recent exhibition Ordinary Violence (2017–18) at the Queens Museum, New York, “I am haunted by Trauma. We are woven into this kaleidoscopic memoir by our desires to consume pain, to blur fact and fiction, to escape.” Language becomes essential to Smith’s cartographical process, to her move away from the fact of her father’s incarceration while also drawing upon the truth of that experience. Amid a series of small photographs that are never quite center-aligned, some awash in hues of turquoise and beige, or overlaid with blocks of solid color, a refrain appears in white letters on a black ground, beginning: “We are a weird triangle of silence and smiles and pauses, of stepping backwards one foot after another after another until we’ve found the cold corner of a wall.” Here we, the readers, must also reckon with the interiority of the sentiment—the feel—that moves us closer to the minutiae of the protagonist’s visit.

Smith wades in the slippages between poetic language and family letters, between forensic photographic documents and tender snapshots. Rejecting concretized form, she probes the possibilities of the feel so that we might better understand the tactility of syntax and what it signifies through its materials and visions. “The images are made so that I can see the people in them,” Smith says of her practice. “So that I can see me.”

All works by Sable Elyse Smith from Landscapes & Playgrounds (San Francisco: Sming Sming Books, 2017)

All works by Sable Elyse Smith from Landscapes & Playgrounds (San Francisco: Sming Sming Books, 2017)Courtesy the artist

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation.”

March 30, 2022

A Photographer’s Canny Investigation of American Privilege

For Buck Ellison, a California-based photographer who stages deadpan, meticulously stylized pictures of people in elite, banal-seeming scenarios, privilege is defined in minute details and practically unseen movements. Elise Silver, a model cast in Oh (2015), a study of innocuous teenage expression, will be recognizable to those who have seen her as a glamorous figure in luxury car advertisements. In Untitled (Cars) (2008), when Ellison ventures into the world of automobiles, two Land Rovers are parked at ridiculously steep angles. It captures a dealership’s demonstration of the vehicles’ rugged capabilities—cartoonishly tough, masculine, expensive. At closer glance, one of the cars bears a vanity license plate reading MARIN, the name of the Northern California county where Ellison was raised, one of the most affluent in the country.

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Cars), 2008

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Cars), 2008Growing up, Ellison says, “I felt guilty that I was attracted to symbols of wealth, because they are often facilitated by things I find reprehensible.” When he was fifteen, Ellison saw an editorial campaign for the brand Kate Spade that he later learned had been photographed by Larry Sultan. It depicts, in staged scenes, an upper-middle-class family’s tourist trip to New York to visit their daughter, with their accompanying forays into consumerism. A photographer himself since 2008, Ellison sets about re-creating deliberately artificial depictions of the kind of life he was born into, crafted with the precision of commercial shoots.

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017For a commission by Arena Homme +, Ellison cast agency models to portray members of his own family, approximating the idea of a traditional, seated portrait. (“It was always my dream to do a portrait of my family,” he says, “but they didn’t share my enthusiasm.”) Working with the stylist Charlotte Collet, Ellison shot nearly four thousand frames, purposefully exhausting his subjects until they stopped acting. Embedded are subtle codes and imperfections: the stiffened smiles, the wrinkles and rumples in the carefully dressed-down clothing, the silver tray of cocktail tumblers, the child with his face in a phone.

Ellison’s stage-managed casualness brings to mind Tina Barney’s complex, intimate photographs of her family; they share Barney’s rarefied milieu and immersive feeling without being documentary. “It’s not about capturing a moment before it disappears, but finding something that’s almost invisible or illegible to the rest of us,” he says. His pictures are an investigation of small gestures—a frank, off-kilter conversation between advertised and unspoken wealth, somewhere between aspiration, imagination, and projected reality.

Buck Ellison, Hilda, 2014

Buck Ellison, Anxious Avoidant, 2016

The similarity between the minimalism of Hilda (2014) and the cool detachment of Thomas Ruff and the photographers of the Düsseldorf School—in particular the painterly, late 1980s and early ’90s family portraits of Thomas Struth—isn’t a coincidence. Ellison studied German literature at college in New York before relocating to Germany for graduate school, a move that added another dimension of distance from which to view the visual projections of privilege in the United States. At the Städelschule Frankfurt, Ellison collected advertisements for Deutsche Bank and luxury watches—“images of prudent investment,” he says a little wryly. He looked at early U.S. colonial portraits, particularly those by less technically skilled painters: “There was so much insecurity about who we were as a country.” In his studio, he pinned Bruce Weber’s photographs from Ralph Lauren campaigns to his wall: contemporary, idealized renderings of the American West as envisioned by the Bronx-born fashion designer who changed his name from the Belarusian Ralph Lifshitz to create a global brand.

Buck Ellison, Oh, 2015

Buck Ellison, Oh, 2015In their own way, Ellison’s photographs lift the taboo that still protects the upper echelons of American life. “It’s like, ‘don’t talk about money,’” Ellison says from Los Angeles, where he lives and works now. Instead, he borrows that attitude of reserve to provoke dialogue, allowing complicated social dynamics to play out beneath the exterior of clean, formal arrangements. Using the inner vocabulary of privilege, Ellison shows the fissures that seep through its idealized surfaces.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style.”

Lucy Raven’s Sonic Journeys Near and Far

Lucy Raven wanted to get wired. Searching for the networks of power that hold up global communications and commerce, she traveled from a pit mine in Nevada to a smelter in China to trace the transformation of raw ore into copper wire, the conduit for transmitting energy. China Town (2009), the resulting photographic animation, combines thousands of still images with on-location ambient sounds, locked together by wild sync—sounds that correspond to an image, but are not actually synchronized. For Raven, a New York–based artist whose practice incorporates photography, video, installation, and performance, the research becomes the work itself. Following China Town, Raven used test patterns for film and sound as both raw material and subject matter, turning the spotlight on standards for picture and audio quality developed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. Her experiments in 3D filmmaking yielded video installations that place stereoscopic photographs within immersive surround-sound environments. Connecting all of these disparate strands is the artist’s continuing exploration into the effects of technology and labor in the production of movies, as well as the poetic relationship between sound and image. In advance of the New York debut of her major installation Tales of Love and Fear (2015) at the Park Avenue Armory, in September 2016, Raven spoke with curator Drew Sawyer about sonic journeys near and far.

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015Stereoscopic photograph, custom-built projection rig, and sound, Installation view, Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York

Drew Sawyer: Thinking about sound and its relationship to images, let’s start with your work China Town, which consists of thousands of still photographs and a sound track, and explores the production of copper from a pit in Nevada to a smelter in China. It’s not a typical film. I’m curious about your choice to use still images with a separate sound track rather than working in a more traditional video format.

Lucy Raven: The choice to use stills came first. I’d been working on stop-action animations and exploring ideas of work and exhaustion. When I had the initial ideas that led to China Town, I was still thinking about those questions. I had a residency with the Center for Land Use Interpretation at their site in Wendover, Utah, in the middle of the Great Basin. I became interested in a copper mine called Bingham Pit, where Robert Smithson had proposed, but never completed, a reclamation project.

The other impetus comes from Paul Valéry, who suggested that just as we receive water and gas and electricity into the home from far off with a very minimal effort, one day we’ll be receiving images and sounds into the home, appearing and disappearing with barely a signal of the hand, hardly more than a sign. Now that Valéry’s idea has become commonplace, and wireless technology has made images and sounds coming into the home ubiquitous, the part of his construction that I found more abstract was how water, gas, and, in this case, electricity get into the home.

So I had an idea from the beginning that the images and sounds would “appear and disappear” using some form of animation. As I began to work on the edit, with my editor Mike Olenick, it started to become clear that the sound would need to be continuous alongside the disjunctive imagery. It becomes a means of orientation. Each recording was made at the same location where I took the images.

Lucy Raven, 29Hz, 2012. Randomized audio samples from optical and magnetic film sound track test material

Lucy Raven, 29Hz, 2012. Randomized audio samples from optical and magnetic film sound track test materialSawyer: How did you go about recording? Obviously, when you were going to these different locations, you were taking the still photographs. Were you simultaneously recording sound?

Raven: I couldn’t do both at the same time, because my camera made an audible shutter sound, so I had to switch between the two modes. Luckily, most every process I recorded in the film happens twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, so even though it sometimes required revisiting a site I hadn’t intended to return to, I was able to rerecord when necessary. I became very interested in experimenting with wild sync, which is when the sound corresponds to the image, but is not actually synchronized.

Since I was taking still photographs and animating them later, the process precluded the possibility of recording synchronous sound. So sound, at the beginning, was unhinged completely from the images. It could maintain a sort of loose association with what you were watching, or could be attached more precisely to actions depicted in images so the two correspond, or seem to. When you see a sequence of photographs of a truck dumping copper ore, you hear the sound of ore being dumped, but it might be from a trip I made months later to the same location. Of course, some places were more difficult to access, like the wire factory in Shenzhen, or the furnace in Tongling, both in China. At those times I was just trying my best to do both in quick succession.

Lucy Raven, RP31, 2012. 35mm film (Installation view), Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Lucy Raven, RP31, 2012. 35mm film (Installation view), Hammer Museum, Los AngelesSawyer: In the tradition of documentary film, sound or text usually provides some sort of narrative that frames what one is seeing. It seems your use of sound doesn’t do that in a typical way.

Raven: My process involves figuring out how to strip down both the visuals and the sounds to what’s essential. You bring up the documentary tradition. As I assembled all the parts that eventually became China Town, I came to think of both the images and the sounds as records, or documents, of particular places and processes. That’s one reason I decided to record sound on location rather than use industrial sounds recorded elsewhere, or archival recordings. It was important to me to document the very particular production line I was following, and that neither the process nor the sites come to operate on the level of metaphor. Rather than explaining, or even understanding, this global commodity flow, I was more interested in how the form of the movie could relate to the gaps, inequalities, and intervals inherent in such a system. Nothing really comes together in the movie—the many parts of the production remain disjointed, as do the images. The sound becomes a through line.

Related Items

Aperture 224

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Sawyer: Which is why your term animation makes so much sense, because in a way the sound is animating the images. That film makes me think of this idea of the “disassembled movie,” which Allan Sekula used to describe his piece Aerospace Folktales, from 1973. The work consisted of 142 photographs installed in a gallery like a filmstrip, and then four audio tracks played separately. This idea of the disassembled movie also relates to your work in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, RP47 (2012), and projects you’ve done at the Hammer Museum, like RP31 (2012), using test patterns, as well as purely audio works that are related, like 29Hz (2012). What led you in the direction of looking into cinema?

Raven: Working on China Town prompted a number of questions having to do with the relationship between still and moving images, and, more basically, how movies are made today.

The works you’re referring to started with an interest in motion capture that I saw as related to—in some ways the inverse of—how I’d shot China Town. I had a research residency at the Hammer, and I visited one of the motion capture studios used for big Hollywood films. The day I showed up, everyone had just found out that a huge amount of the work they were doing would be outsourced to India, specifically the backdrops and landscapes for the figures developed through motion capture. They would also be sending over films shot in 2D to be converted into 3D through a very elaborate process that involves the digital creation of a synthetic second-eye view for every frame in the film. I found myself confronted with what seemed like a twenty-first-century version of China Town. Here, though, the raw materials being exported from the American West to overseas were images— literally raw files, one for every frame of film. In the case of 3D conversion, what was being outsourced was actually the labor to produce the illusion of spatial depth.

I began trying to understand how 3D film works, and how it has developed technologically since its quite early invention. I found myself looking at 3D calibration charts, used to align dual 35mm projectors for 3D projection. The images were beautiful—the first ones I saw were clearly photographed from handmade paper maquettes that read “See with Left Eye” and “See with Right Eye.” I searched out more of these charts, and soon realized that there were charts used to calibrate and test most every type and gauge of film projector. This then led me to their sonic equivalent—test tones meant to play in an empty theater before showtime to calibrate the theater’s sound.

While I was researching and beginning production on the works having to do with Hollywood’s outsourcing of its images— the pieces that later became Curtains (2014) and then Tales of Love and Fear (2015)—I became interested in these charts as logging a history of the standardization of perception that was developed for optimal viewing and listening standards, yet born of economic, cultural, and technological conditions as much as for some notion of pristine image or sound.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009Sawyer: So 29Hz is the audio for test sounds.

Raven: Yes. I used twenty-nine different test tones in the work, and Hz is the abbreviation for hertz, which is the unit of frequency for sound. The RP in the filmic work titles is borrowed from the most common test pattern for 35mm film, RP40, where RP stands for recommended practices. In RP47, I included forty-seven different test patterns, and in RP31 there are thirty-one.

Sawyer: Does RP31 also have a sound track?

Raven: For RP31, you hear the sound of the 35mm projector that is running constantly, in tandem with a film looper, in the room. The presence and the sound of the projector is an important part of the installation. For RP47, I asked two genius friends, Jesse Stiles and Rob Ray, to design a software program for the work that would also enable me to add more images and sounds as I continued to find and archive them. The pairing of images and sounds in that piece is randomized, and the image stays up for as long as the duration of the sound file.

Sawyer: But they wouldn’t be related otherwise?

Raven: No, they are two different types of tests—one for sound, one for images.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009Sawyer: So those projects led to Curtains, and then Tales of Love and Fear the following year, which both involve 3D images and surround sound.

Raven: Curtains consists of ten different scenes, each of which animates a stereoscopic photograph that I took in one of ten different postproduction facilities around the globe—from cities in Asia with very low labor costs to some of the most expensive cities in the world, such as London and Vancouver, where local governments offer studios massive tax breaks and incentives— that convert Hollywood films from 2D to 3D. In the piece, the stereoscopic image is split into left- and right-eye images using old-school anaglyph red-cyan separations. The two images come together from offscreen, briefly converge, then diverge again, passing through some strange intermediate zones of overlap that the eyes struggle, nearly involuntarily, to resolve. I recorded the sound in much the same way I approached it in China Town. The sound for each section is based on field recordings from each facility. They’re all office spaces, but the subtle differences between them register substantial differences in location, culture, and activity.

Tales of Love and Fear is a piece I worked on through a residency at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute up in Troy, New York. The idea was to make a cinema for a stereoscopic photograph. In collaboration with EMPAC’s amazing production team, we built a rig that enables 360-degree rotation of two projectors over the forty-minute duration of the work. The rig acts as both 3D film projection apparatus and as a kinetic sculpture performing the architecture of the space.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009All works courtesy the artist

Sawyer: How are the image and sound related?

Raven: The image comes from a stereo photograph I took of bas- relief carvings at a site in India. One of the first sounds you hear in the piece is from a field recording I’d made while seeing a Bollywood horror film with a few friends. One of them, an actress, was translating to me in real time from Hindi to English—the film’s sound was pulpy and totally overblown.

So my friend is doing different voices while whispering the translations, people are screaming, and we’re eating popcorn and laughing. Paul Corley, a composer and sound engineer, worked with me to shape a score, a sonic journey from the Mumbai movie theater, into the film itself, and out the other side into a very different, nearly meditative drone state.

Sawyer: Your most recent project, Fatal Act (2016), involves, in part, the history of one sound in particular.

Raven: Yes, sound is an important aspect of Fatal Act, a new moving- image work I’m currently at work on with my research and production collective Thirteen Black Cats. The eventual film centers on the difficulty of imaging and recording the atomic. One scene includes the description of a CBS sound engineer tasked with providing sound for a nuclear-bomb test detonation in Frenchman Flat, Nevada, in 1951. Camera crews had been invited to film the explosion for television broadcast, but to escape fallout, they were necessarily positioned too far away to record sound. Given three turntables, twenty minutes, and the CBS sound library, the engineer improvised, using the slowed-down roar of an African waterfall to make the now iconic sound of an atomic chemical fireball.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 224, “Sounds,” under the title “Wild Sync.”

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers