Aperture's Blog, page 45

March 4, 2022

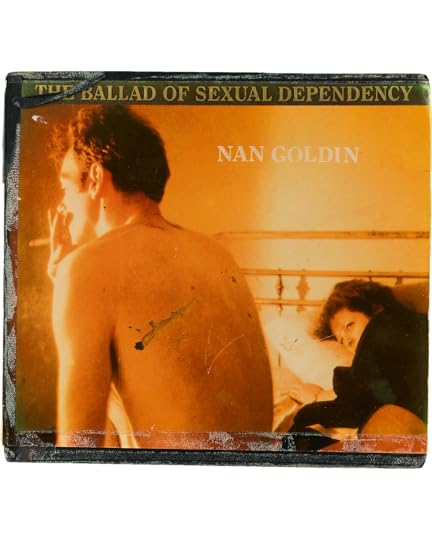

Why “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” Endures in the Twenty-First Century

It’s thirty-five years later and the twenty-first printing of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. I love this book, it’s why I’m here now. It amazes me that it still resonates in the world. I’ve lived many lives since then. That was perhaps the lifetime that formed me the most, the years of the Ballad. I still believe these photos tell the truth of that time. It’s important, for me, to recontextualize the afterword every ten years. The foreword is forever, that’s the real narrative of this work. Just like I constantly re-edit my slideshows, I want to continue updating the record of my life.

I grew up in a period in which the glue of suburbia was denial. It maintained the culture, the mentality, the outer face. I didn’t accept the myths that families tell themselves and present to the world. I saw very early that my experience could be negated. That I never said that, I never did that, that never happened. I needed to get away.

Nan Goldin, Flaming Car, Salisbury Beach, N.H., 1979

Nan Goldin, Flaming Car, Salisbury Beach, N.H., 1979I took the pictures in this book so that nostalgia could never color my past. I wanted to make a record of my life that nobody could revise: not a safe, clean version, but instead, an account of what things really looked like and felt like and smelled like. I don’t think I could, at this age and in this body now, live the life that I lived then. It took a certain level of fearlessness, a wildness, quick changes—of clothes, of friends, of lovers, of cities.

When I wonder what people are talking about when they say that the Ballad helped them, I guess that it showed young people there was another way to live, that they didn’t have to swallow the version of the norm that hurt them, that they didn’t feel part of, that was destroying them. The book gave a mirror to kids who had no reflection of themselves in the world around them. They knew that they weren’t alone.

In the old days, people told me they moved to New York because of the Ballad. They were introduced to other great artists, other great personalities, and a whole other world of brilliance and beauty. They found a world where friends could replace family, where the people who kept you alive were the ones you chose. Relationships weren’t based on toxic expectations of who you were. You were free to be anyone you wanted. Somebody told me recently my work averted their suicide. If I can help one person survive, that’s the ultimate purpose of my work.

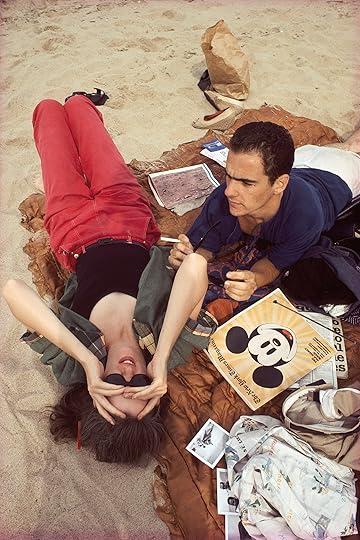

Nan Goldin, C.Z. and Max on the beach, Truro, Massachusetts, 1976

Nan Goldin, The Hug, New York City, 1980

It’s commonly said that this book is about “marginalized” people. We were never marginalized. We were the world. We were our own world, and we could have cared less about what “straight” people thought of us. I made my people into superstars, and the Ballad maintains their legacy.

In the ’80s, there was a certain freedom, and a sense of immortality, that ended with that decade. AIDS cracked the earth. With everyone dying, everything shifted. Our history got cut off. We lost a whole generation. We lost a culture. We didn’t just lose the actors, we lost the audience. There are few people left with that kind of intensity. There was an attitude towards life that doesn’t exist any- more, everything’s been so cleaned up.

Lately when I’m working with the photos of my missing friends, it’s as if they are frozen in amber. For long periods of time I forget they’re not on this planet. But the pictures show me how much I’ve lost; the people who knew me the best, the people who carried my history, the people I grew up with and I was planning to get old with are gone. They took my memory with them. The pictures in the Ballad haven’t changed. But Cookie is dead. David is dead. Greer is dead. Kenny is dead. I talk to them all the time, but they don’t talk back anymore. Mourning doesn’t end, it continues and it transmutes. This book is now a volume of loss, as well as a ballad of love.

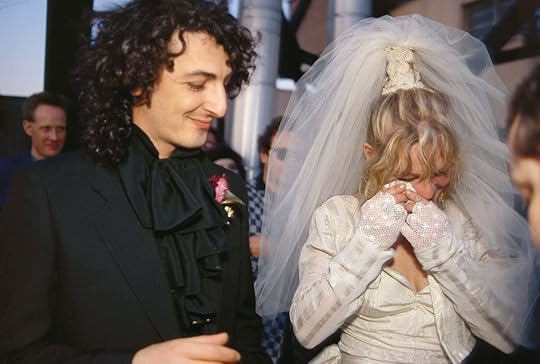

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City, 1986

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City, 1986In spite of everyone dying around me, there is that sense in your youth that you’re immortal. Death isn’t relevant to you directly. I went from being young to being old, I didn’t experience the transition. In your sixties, it’s a much different awareness of death, of seeing how limited your time is and how quickly it goes. After fifty a woman is invisible in this country, which is sort of a relief, it gives you a freedom that I like. Americans are not conditioned to respect their elders. Young people are really dismissive, you lose your credibility. They treat me like a crazy old lady because I look like a punk grandma. I’ve talked to other women over fifty and many of them feel the same. I would like to just not give a fuck.

The world has changed so much as to be unrecognizable. These are dark days. Everybody has to find their way to fight back, because that’s all we have. We don’t have elected officials that are going to fight for us. We don’t have leaders that will save us. We don’t have courts that will give us justice. We have the media but it’s been jeopardized. The people in the streets are the only chance we have.

When I got sober in 1988 and came out of my self-imposed isolation, I realized the extent of the AIDS epidemic and how many of my friends were dying. I curated the first show about AIDS in New York, Witnesses Against Our Vanishing. The catalogue was censored because of the brilliant and furious words of David Wojnarowicz, which provoked outrage and brought people to the streets. Witnesses helped lay the foundation for the art world to start organizing around AIDS.

Related Items

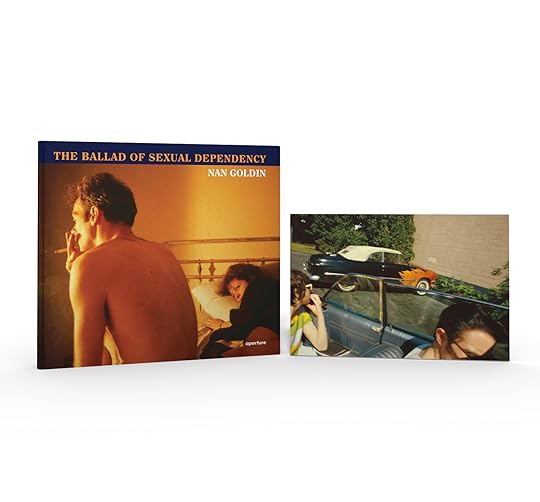

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency: Book and Print Set

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 239

Shop Now[image error]

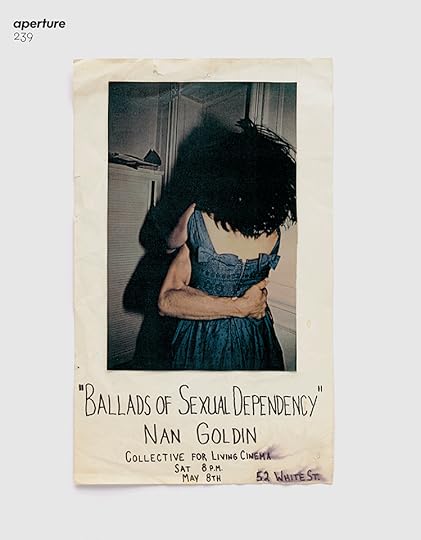

The Original Ballad

Learn More[image error]When I got sober in 2017, I needed to find my fight again. As always, I did what I know in my body. For three years, I’d been lost in a deadly addiction to Oxycontin. I came out of my own opioid crisis and realized that America was in the throes of a terrible overdose crisis. I couldn’t stand by to watch another generation disappear.

I decided to make the personal political. I organized a group of artists and activists called P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). Our first mission was to , the family behind Oxycontin. Their private Pharma company ignited the opioid overdose epidemic, profiting off the addiction and death of five hundred thousand Americans. To get their ear we called them out on the stage where their name was most celebrated––the museum world. Through their toxic philanthropy they created a myth, but we succeeded in changing their legacy.

My work is in the permanent collections of these museums and at the risk of ruining my career I confronted them as an artist. P.A.I.N. is a small group but we make a lot of noise through direct action. We started by throwing thousands of fake Oxy bottles into the Nile at The Met in 2018 and since then we’ve acted up in museums across the world. We’ve been successful in pushing institutions to live up to their ethical mandate by cutting ties with the family and taking down their name.

Nan Goldin, Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979

Nan Goldin, Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979By giving a public face to the opioid epidemic we’re helping to destigmatize drug use and over- dose. P.A.I.N. is not anti-opioid, we’re anti-opioid profiteers. We’re working with other activists to create a safe world for drug users.

One thing I haven’t talked about all these years is my sex work in the late ’70s and early ’80s. That’s how I could afford to buy the film and to develop the photos in this book. I’ve always needed to protect this secret. Many people already write about the Ballad in a very reductive way, that it’s only about drugs and sex. I worried that this would become the voyeuristic filter through which all of the work would be viewed. That who I am and everything I do would be discredited by that role.

A sex worker is a hard worker, and it’s a term that shows due respect. Words matter. The same evolution of language applies to people with substance-use disorder, those of us who used to be called junkies. I feel it’s important to share my last secret, the one I’ve held onto since the ’70s, in order to combat stigma. If it gives a voice to somebody else to feel less shame, then it’s worth it.

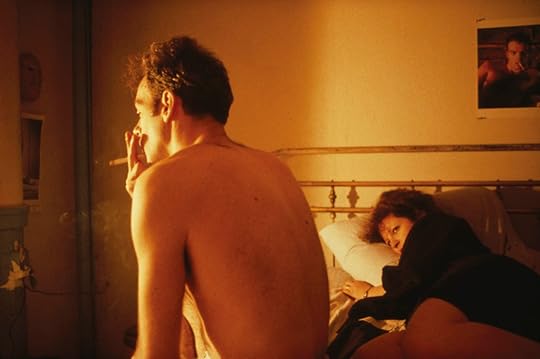

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983All photographs courtesy the artist

My thoughts about relationships and interdependency have changed over the decades. I still make no emotional distinction between my friends and my lovers. But I don’t want the same kind of stranglehold intimacy that I needed in the past. I don’t need somebody else to prove I exist. There’s no Nan Goldin in my house, there’s only Nan.

Photography has been redemptive for me, it’s helped me chart my descents and my reconstruction. For many years, I didn’t pick up a camera except to photograph the sky. I lost the need to photo- graph my life or the people in it. My photos were no longer my diary, my paintings were. Then during the COVID-19 quarantine, I started photographing a new friend for the first time in years. I wanted to show my friend her beauty. It’s fascinating to see how much a face can change over a year when you look at someone deeply enough and how the degree of intimacy colors a photo.

When I was a kid I thought, What a waste if I don’t leave a mark on the world. Through the Ballad I found a way to make a mark.

This essay originally appeared in Aperture’s 2021 edition of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

February 25, 2022

The Designer Translating Photographers’ Visions into Inventive Books

Session Press was founded in 2012 in response to the ongoing demand for photobooks and my belief in the book as a perfect platform for photography. We also recognized a role for independent publishers to play in meeting and satisfying collector demands. In particular, Session Press has worked hard to support Japanese and Chinese voices through our publishing program, which is focused on introducing these photographers to English-language audiences.

Working with printers, lithographers, and designers that I trust is key for successful book making. If I gain critical acclaim for my publications, it’s in large part thanks to the world-class collaborators with whom I work. Alex Lin is one of my favorite designers in NYC. I’ve worked with his studio for Mao Ishikawa’s Red Flower (2017) and Ren Hang’s Athens Love (2016) and New Love (2015). In my time as the manager at Dashwood Books, we have carried many publications that Studio Lin designed, including Hello Future by Farah Al Qasimi (Capricious, 2021), Tyler Mitchell’s I Can Make You Feel Good (Prestel, 2020), David Brandon Geeting’s Neighborhood Stroll (Same Paper, 2019), Mark Ghuneim’s Surveillance Index Edition One (self-published, 2016), John Edmonds’s Higher (Capricious, 2018), and Naoya Hatakeyama’s Excavating the Future City (Aperture, 2018), among others.

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Park Frivolity), 2019, from I Can Make You Feel Good (Prestel, 2020)

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Park Frivolity), 2019, from I Can Make You Feel Good (Prestel, 2020)Courtesy the artist

As a New York–based publisher, Session Press wants to create books with a team that understands both Western and Eastern aesthetic traditions. I don’t want to make books that feel like those published by Japanese designers or publishers. But it’s also important for me to team up with a designer who understands and respects Eastern design philosophies. Alex has this and melds his understanding with a strong, rigorously trained design practice based in contemporary Western theories. For example, he studied traditional Chinese calligraphy as a child, and it’s important for me that he has a capacity to see Asian language in a creative and intellectual sense, not just as typefaces available on a computer. I appreciate working with Studio Lin because they always contribute unique ideas that are respectful to the photographer’s work, even in very difficult circumstances. I am excited to interview Alex Lin of Studio Lin and share his ideas about design here.

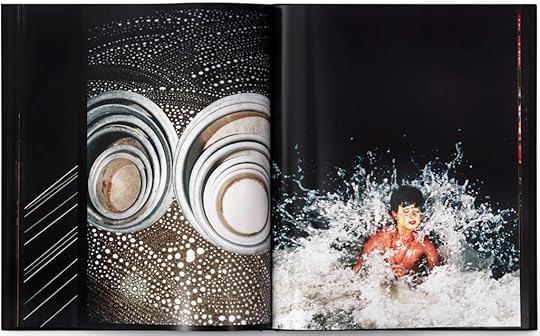

Interior spread of Red Flower by Mao Ishikawa (Session Press, 2017)

Interior spread of Red Flower by Mao Ishikawa (Session Press, 2017)Miwa Susuda: One of my favorite books you’ve done with Session Press is Mao Ishikawa’s Red Flower. Can you tell me how you arrived at the final design?

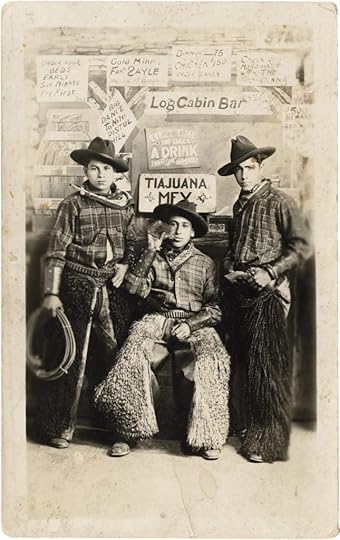

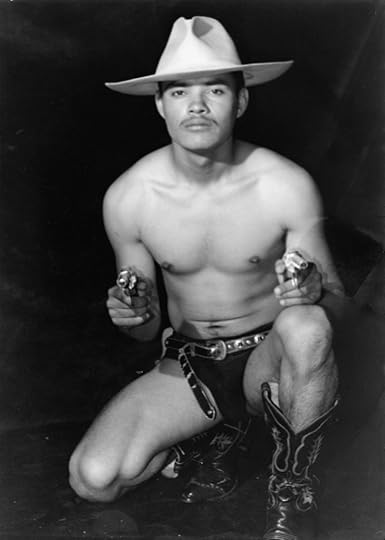

Alex Lin: Red Flower is a collection of photos Mao Ishikawa took from 1975 to 1977. The photos capture intimate relationships between Japanese bar women and soldiers stationed in Okinawa, Japan. We started with poor quality scans of physical prints; in fact, we weren’t even sure we could work with these scans since they had dust all over them. Thankfully, our frequent collaborator Sebastiaan Hanekroot was able to remove all the dust and duotone the images for printing.

The photos were printed full bleed in a chronological sequence in five undivided chapters. We chose Munken Print as the interior paper stock because of its rough texture and high ink absorption. The wood content in the paper causes a beautiful yellow patina when pages are exposed to light. We were after a design that felt timeless, so you wouldn’t necessarily know when the book came out. Typography is often the element that dates a book, so we intentionally left that off the cover. Instead, we silkscreened a primary character from the book in fluorescent red for the cover. The exact color came from a parking sign in Manhattan that I walked by every day; it felt like the perfect supercharged red. We sent a piece of the sign to the printer, who was able to mix a custom silkscreen ink to match. A statement from Ishikawa is printed on the opening spread in the same fluorescent ink, directly on top of an image. The tactile and imperfect quality of the silkscreen ink gives the book a special feeling when held.

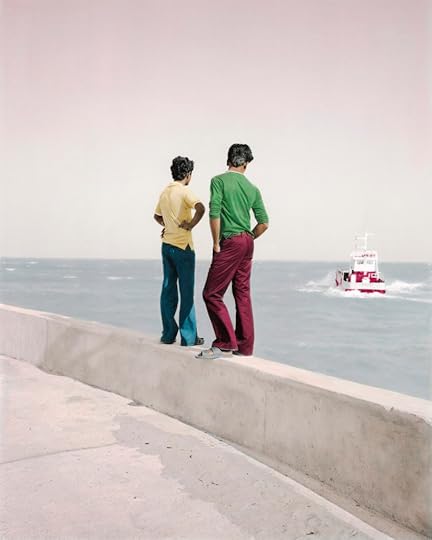

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Boys of Walthamstow), 2018, from I Can Make You Feel Good (Prestel, 2020)

Tyler Mitchell, Untitled (Boys of Walthamstow), 2018, from I Can Make You Feel Good (Prestel, 2020)Courtesy the artist

Susuda: You’ve worked with many young photographers, often on their first monographs. I’m thinking about Tyler Mitchell’s I Can Make You Feel Good and Farah Al Qasimi’s Hello Future. Can you talk about that?

Lin: I feel fortunate to have been trusted with the design of many young photographers’ first books. It is a humbling experience, as I’m often in awe of the work that I’ve been charged with giving physical form to. In each case, I try hard to incorporate as much from the photographer as possible.

Tyler wanted to create a special object within the constraints of a large commercial publishing house (Prestel). We achieved this through various tweaks in the binding and cover design. The cover is a printed book cloth that wraps onto the front and back cover boards. Since there are no endpapers, you can see exactly how the cover image folds over, giving the book a handmade quality. The cloth adheres directly to the book block along the spine, allowing the book to be exceptionally limber despite being a hardcover. All surfaces of the interior are printed full bleed on uncoated paper; there is no white space. And lastly, we printed the title of the book on a ribbon that is attached to the inside back cover instead of along the spine.

Hello Future is published by Capricious, a small independent publisher. Farah Al Qasimi was the winner of the third annual Capricious photo prize (previously, John Edmonds and Sasha Phyars-Burgess). Her work is incredibly playful and references things ranging from SpongeBob to postcolonial structures of power, gender, and aesthetics in the Gulf Arab states.

Interior spread of Hello Future by Farah Al Qasimi (Capricious, 2021)

Interior spread of Higher by John Edmonds (Capricious, 2018)

The primary body of photos is presented one per spread. Occasionally, the sequence is interrupted by research images that are printed with only the cyan channel, giving them clear separation from the main body of photos and also referencing how printed images often fade in UV light. For the cover, we looked at an exhibition Farah had at Helena Anrather gallery (New York). The frames around her prints were a reflective chrome metal, which we thought worked incredibly well with her work. We sourced a similar material for the cover and endpapers. Farah wanted to do something with stickers from the very beginning, but we were struggling to find a way to incorporate these that didn’t feel too gimmicky or separate from the book itself. We thought a book jacket would be the perfect place for this. The book jacket features four large images and a series of thumbnails on the spine. Each image is kiss cut around elements within the photo, allowing Farah’s work to live in any place you can adhere a sticker. We also left the chrome hardcover under the sticker jacket blank to encourage each book owner to create their own cover image.

Susuda: What do you think has changed in the last five years in the world of photobooks?

Lin: Prior to Instagram, once you designed the book, you didn’t really have any insight into how it lived in the world. Now you can literally follow it into the hands of the people who have purchased it through images posted. My favorite is seeing people’s photos of the object; you can see the book in ways and places that you’d never imagine.

Mark Ghuneim, who we worked with on his Surveillance Index (Mediaeater, 2016) book, told me that unless something is printed, it doesn’t exist. Paradoxically, I believe this is even more true with the rise of digital media and social networks.

Naoya Hatakeyama, #02607, Loos-en-Gohelle, Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, France, 2009, from the series Terrils, from Excavating the Future City (Aperture, 2018)

Naoya Hatakeyama, #02607, Loos-en-Gohelle, Pas-de-Calais, Hauts-de-France, France, 2009, from the series Terrils, from Excavating the Future City (Aperture, 2018)Susuda: Can you give a brief summary of your design philosophy when it comes to photobooks? What, in your mind, makes a great photobook stand out from the many competing titles that get published every year?

Lin: Books are an obsession for me. My favorite place to be is where the best books are, like Dashwood, the Strand, or McNally Jackson. I’m always on the hunt for old books that still feel contemporary or fresh, despite being twenty, forty, or even sixty years old. Sometimes it is the layout or typography, sometimes the material, binding . . . you never know. Quite often, I literally decide which books to pull out of the rows and rows of shelves by what the typography on the spine looks like. The way the type looks on the spine supersedes anything else, so it doesn’t even matter to me what the book is about!

I strive to design books that have lasting value. I want to capture the idiosyncrasies of each photographer. I seek to make decisions that are meaningful in some way. Sometimes when faced with an important decision like binding method or paper choice, I’ll ask myself how I’d tell the design story when the book is done. That often helps me make a more meaningful decision.

This interview originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review, issue 019, under the title “Designer Spotlight: Studio Lin.”

February 22, 2022

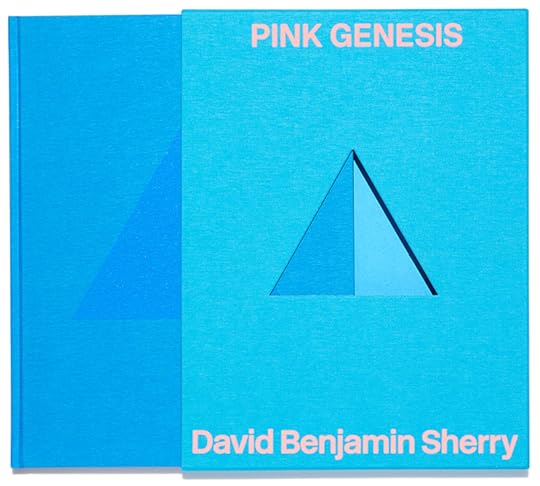

A Photographer Conjures the Hypnotic Power of Extreme Color

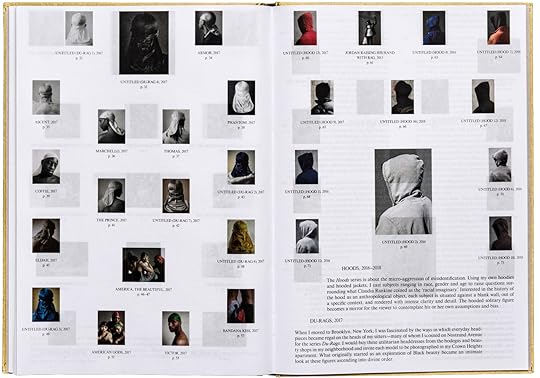

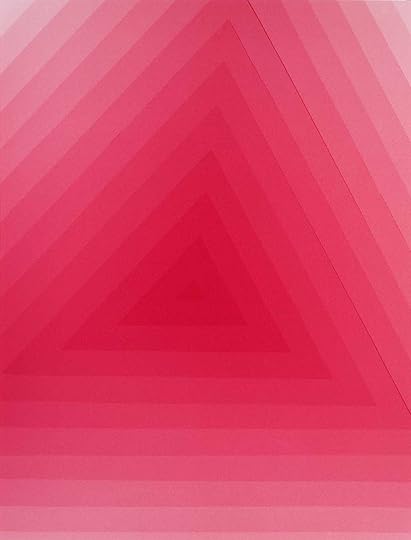

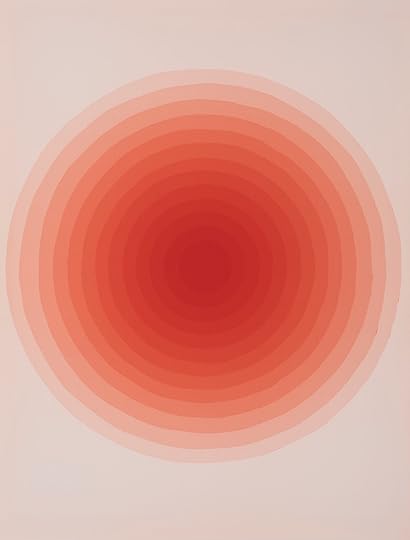

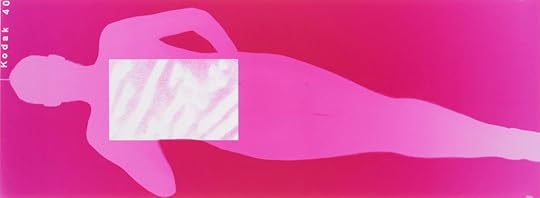

Pink Genesis, David Benjamin Sherry’s 2017 series of photograms, was born out of what the artist has called “the transformative potential of the darkroom.” The series title was inspired by James Bidgood’s 1971 film Pink Narcissus, which explores the fantasies imagined and enacted by a male prostitute played by Bobby Kendall. Kendall’s character realizes multiple roles in a created world of spectacular costumes and intense colors, not unlike the vivid colors that Sherry uses in his work. (The film was made over the course of eight years and shot almost solely in Bidgood’s New York apartment.) Amid the shock and horror Sherry felt at the end of 2016, following the US presidential election, he was also energized by the example of Bidgood’s film, in which a small interior space—specifically, a space of queer imagination—can be a site of fantasy and possibility. In his own artistic practice, Sherry also hopes to find a place of alternative possibilities, and in Pink Genesis, the photographic darkroom becomes that place. Following the election, Sherry found himself making pictures while attending protests, documenting the immediate responses of his and others’ communities. But he also felt the urge to turn toward something elemental, in an effort to investigate a new path in his own work, and to find a way forward during a difficult period. It was a time to start from the beginning. As he later reflected, photograms are “the most primal form of the analog photographic process.”

David Benjamin Sherry, Submission, 2017

David Benjamin Sherry, Submission, 2017Sherry first experimented with color darkroom photograms in an earlier series, Astral Desert (2011–12). In fact, eleven of the plates in this book are drawn from that body of work, while the rest are from Pink Genesis. In those earlier works, Sherry also used stencils to create areas of color, but the overall compositions of each work were based on the monochrome landscape photographs that were part of the series. Sherry has long been committed to interrogating and reinvigorating a tradition of American landscape photography. In much of his work, he uses a large-format film camera to capture the beautiful wilderness of North America, much like his photographic predecessors. Yet rather than considering an “untouched” sublime that is seemingly immune to human exploitation, Sherry highlights the rapid environmental change of our time, often utilizing saturated monochromatic color.

David Benjamin Sherry, Sailing on Solar Winds (Self-Portrait), 2017

David Benjamin Sherry, Sailing on Solar Winds (Self-Portrait), 2017Prior to initiating the Pink Genesis series, he was already investigating the ways landscape photography could be edged toward abstraction by removing horizon lines and “pushing color to its extremes to evoke an emotional experience.” He spent 2015 capturing the devastating effects of climate change across the country, and had recently completed the series Paradise Fire, a body of work titled after the massive fire in Olympic National Park, in Washington State, that burned almost three thousand acres that year. The series title pairs those two seemingly contradictory words, paradise and fire—an amalgam that attempts to articulate the incomprehensible toll of humankind’s impact on the natural world.

Related Items

David Benjamin Sherry: Pink Genesis

Shop Now[image error]

Death Valley, California, 2012

Shop Now[image error]As a queer photographer on the road, Sherry struggled with understanding his own position in relation to that of recognized heterosexual white male forebears, but he found particular inspiration in the work of Minor White, a founder and longtime editor of Aperture magazine. White approached photography with a uniquely personal vision, striving to achieve a kind of spiritual practice, including through sequences in which a poignant portrait might follow a series of abstracted landscapes. “White’s work has been an endless road map of encouragement, power, and comfort on some of my darkest nights while alone on the road,” Sherry has noted. “His work is proof to me that magic is real in the world; queerness is power and the camera can be a tool used to harness the energy.” In the book Minor White: Rites and Passages, which was conceived with White’s participation and published posthumously by Aperture in 1978, passages from White’s diaries and letters are interspersed with what Sherry has called his “empathetic abstractions.” One passage reads, “The spring-tight line between reality and photograph has been stretched relentlessly, but it has not been broken. These abstractions of nature have not left the world of appearances; for to do so is to break the camera’s strongest point—its authenticity.” For Sherry, stripping things down further—rendering images as fields of color, produced through chemicals, light, and time, but without the camera itself—was an opportunity to go back to the beginnings of photography at such a fraught moment.

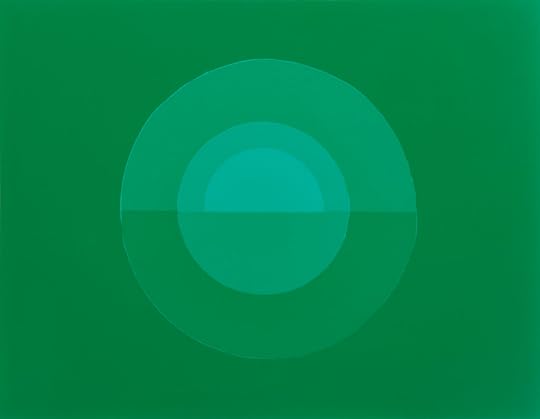

David Benjamin Sherry, Winter, 2017

David Benjamin Sherry, Winter, 2017The first photogram made for the Pink Genesis series, Winter, consists of a rich green field with a circular motif at its center. Sherry later realized that this shape, with its round depth augmented by multiple shades of green, approximates the hollow form of a pipeline, an object that was the subject of some of his recent landscape photographs shot in different areas of the United States, inspired by the #NODAPL (No Dakota Access Pipeline) movement. But Sherry understood that he had not just reimagined, in the darkroom, a form that he had encountered in the landscape; the circles held other meanings too: “The work became not only a pipeline but also an escape tunnel, an evacuation route, and a portal to another place.” Other works, such as the pink-hued Sublime Bottom II, further link this motif to the potential of queer transcendence. In this way, at a time when Sherry was acutely aware of himself as a witness to the struggles, environmental and otherwise, within the world around him, the darkroom became a refuge and a place to realize new possibilities.

David Benjamin Sherry, Sublime Bottom II, 2017

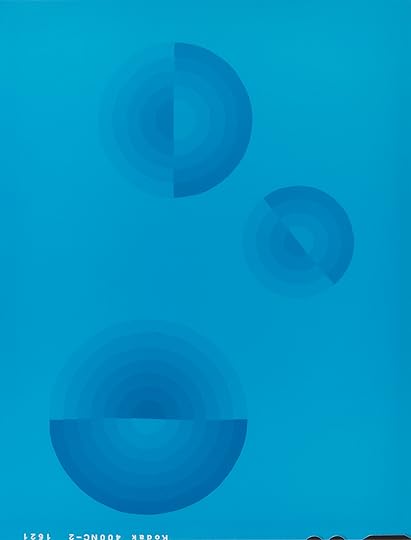

David Benjamin Sherry, Revolution, 2017

The depth of this portal is intentional. Sherry wanted to find a way to counter the “two-dimensional” quality he had normally associated with photograms. He embraced moments of texture: the imperfect edges of the spheres were the result of hand-cutting his stencils from board. Though the exposure process itself required a great degree of control and precision—carefully counting down seconds, completing multiple steps in a specific order—the handmade character of Sherry’s works is immediately apparent. He has cited the influence of Francis Picabia’s Dada explorations of the 1920s, in which the artist painted depictions of mechanical tools and technical operations; these works left a strong impression when Sherry experienced them in the artist’s 2016 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In Sherry’s photogram Revolution, three circles of different sizes float on a blue ground. Each has been halved and built through concentric semicircles of gradually changing intensity. These pulsating targets might recall the interchanging black and white rings of Picabia’s Optophone [I] (1922), which was titled after an instrument that could read variations in light as variations in sound. Likewise in Sherry’s Revolution, an image rendered from light can be understood through aural tones.

David Benjamin Sherry, Metamorphosis (Self-Portrait with Wizard), 2017

David Benjamin Sherry, Metamorphosis (Self-Portrait with Wizard), 2017Picabia’s Optophone depicts a human silhouette at its center, and in a number of major works in Pink Genesis, Sherry also incorporates the human form—his own body—by literally climbing onto the enlarger table and putting himself in direct contact with the paper. In Sailing on Solar Winds (Self-Portrait), Sherry overlays an undulating wave pattern onto his own silhouette, playing with notions of space and depth while conjuring the impact of the buzzing energy of those vibrations on the self. In another self-portrait, Metamorphosis (Self-Portrait with Wizard), Sherry achieves a different kind of symbiosis by bringing his dog, Wizard, into the darkroom with him. Sherry has pointed to Robert Gober’s Death Mask (2008) as an important predecessor to his own portrait. Gober’s plaster sculpture combines a cast of his own face with the sculpted snout of his dog Paco, who had recently died, in the tradition of death masks made to keep the image of loved ones in memory. Sherry’s medium also invokes Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg’s collaborative cyanotypes from about 1950, which were largely made on the floor of the New York apartment they shared and which therefore inherently picture their domestic life, just as Sherry pictures himself with his chosen family member Wizard.

David Benjamin Sherry, Pink Genesis (Self-Portrait with Mars), 2017

David Benjamin Sherry, Pink Genesis (Self-Portrait with Mars), 2017All photographs courtesy the artist

“Let the subject generate its own photograph. Become a camera,” Minor White wrote in another excerpt quoted in Rites and Passages. Of course, Sherry typically photographs outdoors with a large-format camera, a process that requires a physical relationship with the apparatus. But to make his photograms, that tool is put aside and the process is pared down to the essentials; he works with only the paper and chemicals in the darkroom itself. In the titular work from the series, Pink Genesis (Self-Portrait with Mars), Sherry’s long figure stands out against a deep pink background. His arms are positioned such that he appears to hold a rectangle of light in front of his chest, a white shape filled with a texture that he appropriated from a NASA photograph of sand dunes on Mars. Sherry is holding in his hands the fantasy space of another world and harnessing the possibilities of emerging anew.

This essay and photographs originally appeared in David Benjamin Sherry: Pink Genesis (Aperture, 2021).

How Pictures Can Shape an Essential History of Queer Life

“There’s no place like home,” Dorothy famously chanted. Queer people find themselves still under that spell, wrapped in its ambivalent multivalence: longing for a safe space of our own, relieved to leave childhood trauma behind, settled into the uncertainty of our place in the world. “They say that home is where the heart is,” mourned troubadour of the demimonde Marc Almond, “but home is only where the hurt is.”

Curator and historian Stephen Vider seeks to complicate all that in his new book The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II. The work assembles material records and cultural meanings of “home”: from pictures of weddings and other domestic/clandestine gatherings in the 1950s, through 1965’s blockbuster, camp culinary guide The Gay Cookbook; from lesbian feminist architect Phyllis Birkby’s 1970s multiple relationship “domes,” to contemporary queer and trans elder housing. Vider recently Zoomed from his own home to discuss with Jesse Dorris how the work of Samuel Steward, Susan Kuklin, Bruce Pavlow, and countless anonymous others should broaden our understanding of what homemaking looks like.

Photograph from the albums of a Philadelphia lesbian couple, ca. 1953

Photograph from the albums of a Philadelphia lesbian couple, ca. 1953Human Sexuality Collection, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Jesse Dorris: What is the origin story of this book?

Stephen Vider: It was at a moment when the same-sex marriage cases were beginning to make their way through the courts. A lot of the critiques were that same-sex marriage was going to be a kind of normalizing project that was going to strip queer culture of everything that made it different. What intrigued me was the ways that domesticity, or home, seemed to be made synonymous with marriage—which meant that “home” was a normalizing project. And I got interested in thinking about the ways that queer people had, in fact, used home spaces in ways that challenged gender and sexual norms. We are always in the practice of opening our homes to other people. Feminist scholars have pointed to the labor of home; we should think about that as part of a political project also. And so, home is a kind of portal to public life. If we disentangled home from marriage, what else would we see?

Mark Haldane’s illustration for ONE magazine’s cover story, “Let’s Push Homophile Marriage,” June 1963

Mark Haldane’s illustration for ONE magazine’s cover story, “Let’s Push Homophile Marriage,” June 1963Courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Dorris: Home can be protection from the state. But it can also be a site of the state’s power. Queer people have always been present in the creation of these spaces: the interior decorator, the butch handyperson—they’re acting as boundaries for what heteronormative homes look like. They pose a threat. But there’s the idea that gay men began to decorate as a way to assert themselves in the home, to convince people their presence is valuable.

Vider: One starting point for the stereotype is a 1917 piece Dorothy Parker wrote for Vogue, about a fictional decorator named Alistair St. Cloud. Everywhere you look in this house he decorated, there were tassels. Off of the curtains, off of the furniture. And he’s also wearing a robe with tassels coming off of it. So there’s a way that his queer body inhabits this space. In the 1940s and ’50s, this image of the gay decorator really takes off. It’s partly this idea of an alignment of gay men, especially, with a kind of expert taste—only as a visitor, someone who’s creating all the conditions for the heterosexual home and then going to depart it. And who knows where he goes after that, because he often doesn’t seem to have a home of his own. There’s also a profound anxiety about gay men corrupting the home.

Bruce Pavlow, Resident at Survival House, 1977

Bruce Pavlow, Resident at Survival House, 1977Courtesy the artist

Dorris: Meanwhile, some forms of photography require a private space, an actual darkroom, a home or space of your own. Artists like Samuel Steward and James Bidgood made their homes projection screens of their own fantasies.

Vider: Well, George Platt Lynes developed his own photography. But Steward is using Polaroids, and so he doesn’t have to worry about going to a drugstore to have them developed. There’s a photo of his in the book where he has one of his lovers sitting on his Murphy bed, and behind him are these drawings he had painted of two men, naked, smoking. There’s a strange kind of mirroring, of fantasy becoming reality and then fantasy again, in the frame of the photograph. There’s a quote I love from anthropologist Mary Douglas, “The home is the realization of ideas”—home is the process of making a fantasy real. And that complicates our ideas about gay men in the ’50s: we think of a lot of sex happening in public—in bathrooms, in parks. But what happens when you pick someone up and bring them back to your apartment? What happens in that space, after?

Dorris: And how to hold onto the memories.

Vider: There’s a series of photographs in the book of a gay wedding in Philadelphia around 1953. There’s cutting the cake, there’s doing the ceremony, there’s kissing after the ceremony, there’s dancing. It looks like any other wedding album. We know what the poses are supposed to be. And they perform them. The difference is that this is happening at home, because it can’t happen in public. And so that raises, again, the larger question about what it is that home made possible.

Philadelphia couple cutting their wedding cake, 1957

Philadelphia couple cutting their wedding cake, 1957Courtesy the ONE Archives at the USC Libraries

Dorris: There’s a tenderness and sadness in thinking about these gay designers telling women how to organize their houses, their living rooms, with a wedding photograph in a lovely frame in pride of place over the mantel or whatever.

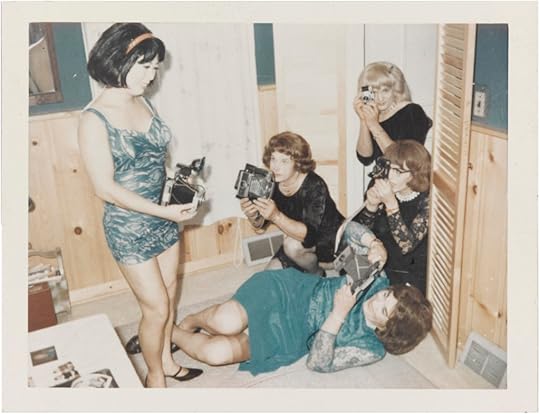

Vider: In places like Casa Susanna, the mid-century retreat in the Catskills for trans women, taking photographs was really important. This was a space where people could go and be themselves, express themselves as they wanted to, as they felt, without fear. Photographs were part of preserving that, but also mirroring it back. To take a photograph of a moment is to affirm it.

Dorris: These photographs must have been so treasured. But also, perhaps, hidden. Because they’re evidence of their subjects’ existence, but also of the kind of gender crimes the people in them are committing. Their existence creates danger.

Vider: The early trans leader Virginia Prince, who published the magazine Transvestia, wrote about her first time at Casa Susanna. Going to the house was a way of having life the way you always wanted it to be. If home is about the realization of ideas, photographs help hold onto those ideas and that reality, even as time is passing, and even when that life isn’t always possible.

Photo shoot, 1964-69. Attributed to Andrea Susan

Photo shoot, 1964-69. Attributed to Andrea SusanCollection of the Art Gallery of Ontario

Dorris: Home was also the place where one could receive Transvestia. Which gets to this idea of privacy. We’re at this extraordinary moment where we have this infinite and encouraged ability to represent ourselves, to represent our homes, mediated through companies who make money off it. At the same time, the US Supreme Court is poised, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, to more or less overturn Roe, and thus, let’s say, complicate our current idea that we have a right to privacy within our own bodies. And, so many of us have been stuck in our homes for so long, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vider: Even though privacy is often thought about as a right, the way that home actually mediates privacy is always a kind of privilege.

Video still from Two Men and a Baby, 1992, dir. Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski for Living With AIDS

Video still from Two Men and a Baby, 1992, dir. Juanita Mohammed Szczepanski for Living With AIDSCourtesy Juanita Szczepanski, Jean Carlomusto, and GMHC

Dorris: The right to privacy might be a right, but the right to a home has never been established.

Vider: In the book, I write about attempts to set up the earliest group homes and shelters for queer and transgender youth in the 1970s. What does it mean when privacy at home cannot be taken for granted? What does it mean to try to create that space for people whose lives are very precarious? It is a particular class of queer people who are able to take their privacy for granted. The link between privacy and home really becomes clear in the case of unhoused youth. These group homes, they are not private: there are a lot of people coming in and out. They’re being talked about in funding reports. They’re being photographed. It’s a mediated privacy.

But also, home can be isolating. For people living with AIDS in the 1980s and ’90s, home became a space that could keep them invisible. It reinforces silence and shame and stigma when people are too sick to go and do grocery shopping for themselves. How do we think of who is reaching into these spaces, volunteers going into these spaces to care for people? If you think of home as simply private, you can miss those stories. If you think of home as porous, you start to think about it as a space of connection, people making connections across different types of racial or gender or sexual difference in ways that are meaningful and powerful.

Dorris: It’s also a space in which technology comes through and changes. For Samuel Steward, and for the makers of documentaries you write about including the TV series Living with AIDS (1987), their work was possible because of a relative democratization of the machinery. Home is a site of creation.

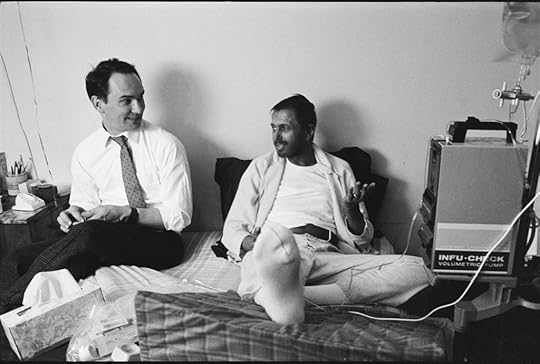

Vider: There was a recognition by artists and activists that the ways HIV and AIDS were playing out in people’s home lives actually needed to be made more public. Because to make everyday home life with illness more public is to destigmatize it and restore humanity to people who are often disavowed by the culture at large. A photograph that’s really been important to me is one by Susan Kuklin of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis volunteer Kachin Fry and Michael, her buddy or client, as GMHC would have called him.

Susan Kuklin, Kachin and Michael at Michael’s Apartment, 1987

Susan Kuklin, Kachin and Michael at Michael’s Apartment, 1987Courtesy of the artist

Dorris: How did you come across this photograph?

Vider: I was curating an exhibition called AIDS at Home for the Museum of the City of New York, doing research on GMHC’s Buddy Program. And I stumbled on Kuklin’s book, Fighting Back: What Some People Are Doing about AIDS (1989), for which she had followed a Buddy team in the East Village for a year to create this mixture of photographs and writing. I spent a lot of time talking to her about her photographs. There’s so much happening in this one. First, there’s this surface level of a kind of unlikely pairing of people. Then, Michael is wearing a T-shirt with the “Silence=Death” emblem, and the photo is from 1987, just as that emblem is being introduced as activism. So the photo is raising questions about what happens when activists go home. The photograph itself is a form of activism.

Susan Kuklin, Ed and Steven at Steven’s Apartment, ca. 1987

Susan Kuklin, Ed and Steven at Steven’s Apartment, ca. 1987Courtesy the artist

Dorris: The caregiving is activism.

Vider: And we don’t always think of caregiving that way. Susan captures their emotional intimacy so well, but also their physical intimacy. It’s really important to remember that this is a moment when people had a lot of misconceptions about how HIV was transmitted. The idea of somebody coming into your home, lying on your bed and talking with you—it’s really powerful.

Bruce Pavlow, Residents at Survival House, 1977

Bruce Pavlow, Residents at Survival House, 1977Courtesy of the artist

Dorris: There’s another photo I can’t stop thinking of, by Bruce Pavlow of a resident at the group home Survival House in 1977. What was the background here?

Vider: Pavlow self-published a book of the photographs he had taken as part of a class at Berkeley, where he was an undergraduate—and this would have been very new for 1977, a class on gay space. This is a moment where there’s so much growing of queer commercial space; this is the moment of Harvey Milk. The fact that Bruce thought to go to a queer group home is really fascinating in itself. He also created a two-hour documentary film about Survival House with all of his interviews, which we’ve worked together to preserve and digitize. But the photographs convey a sense of the range of people who were living in Survival House. The photo on the cover of the book is of the group of residents playing Monopoly. It has this sweetness of playing a board game, which we think of as so much of a family activity, to claim their household as a new kind of queer family. And then there’s the irony that Monopoly is a game that’s entirely about buying property being played by a group of unhoused youth.

The photo you pointed out is of one of the unnamed residents, who’s not interviewed in the film. There’s something really classic about the pose in the photograph, and of this floral armchair taking up the full frame. The curtain behind her, the cup of coffee next her. And the way that she inhabits the space, looking off. It conveys a kind of privacy, a boundary about how much we can know.

Bruce Pavlow, Janis, a resident at Survival House, 1977

Bruce Pavlow, Janis, a resident at Survival House, 1977 Courtesy the artist

Dorris: Because we don’t know the story, we project all kinds of things over the image. I don’t know the subject’s pronouns, I don’t know if they consented to having the photograph taken, and I don’t know the stakes of the photograph’s existence. As we were talking about life at Casa Susanna, this is proof that a certain life was being lived in a certain way. And that proof can be weaponized, right?

Vider: Survival House closes in 1978 because they can’t maintain the funding. But other queer and trans group homes for unhoused youth come after. The Buddy Program continues from 1982 into the early 2000s. So I guess I’m looking at moments of emergence. By the Clinton years, home was starting to be political in a new way, when you saw domestic-partnership legislation and the early debates around same-sex marriage. Domesticity takes on a different meaning once you start really seeking legal recognition of queer couples and families. And now, there are these new group homes for queer and trans elders. That’s striking, because it seems like another iteration of the way queer people use home: recognizing the importance of having an affirming home and its precarity.

Dorris: Home has changed again, as a result of COVID.

Vider: There was a sense, at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, that people felt driven to preserve the moment, because it felt so exceptional. COVID archives emerged very quickly, and those are archives of domestic life. And I’m thinking of all those moments of people clapping for health care workers, which was a profoundly public moment of people in their private spaces performing together. That challenges what home is.

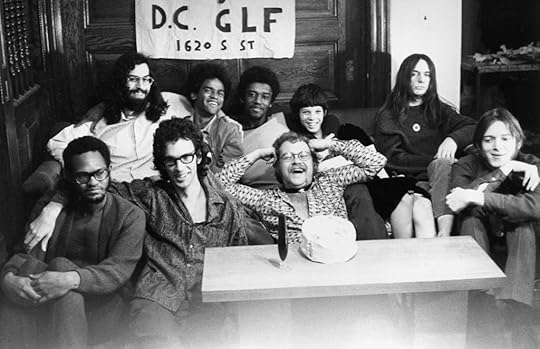

Gay Liberation House, Washington, D.C., ca. 1970

Gay Liberation House, Washington, D.C., ca. 1970Courtesy the Rainbow History Project

Dorris: And we see it all instantly. Whereas there’s much less information around queer pasts. It’s meaningful to see that, yes, these people lived, and their homes looked very different than ours, and just like ours. There’s a continuity and a difference.

Vider: What I hope the book shows is a method for thinking about everyday life. The photographs give us emotional access in ways other types of material culture don’t, because they are representations of moments, but also because a lot of care goes into taking a photograph. A lot of care went into making the decision to take a photograph. When you see one of someone’s home life, you see a desire to preserve that moment. They make real to us a moment in space and time. But they’re also a kind of willed testimony of people in the past who wanted this story to be preserved. Maybe they didn’t imagine it being preserved for us.

Dorris: But they saw themselves as valuable in a way that’s deeply moving. It’s maybe easy to take it for granted, like taking privacy for granted. But the proof that they saw themselves as valuable enough to make these little monuments to themselves is deeply moving.

Vider: And there’s a tension in them. Some of it’s moving, some of it’s challenging. And that’s why it’s powerful.

The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality, and the Politics of Domesticity after World War II was published by the University of Chicago Press in December 2021.

February 15, 2022

A Collaborative Photobook Makes the Case for Radical Democracy

“Our book was supposed to be published in the summer of 2020. Then the virus came. What’s your take on the last year?”

So begins one of the several conversations in Politics & Passions (MACK, 2021), a stunningly multifaceted collaborative book in which the artist Anna Ostoya revisits a 2002 essay of the same name by the political theorist Chantal Mouffe, and repurposes her own artistic archive to create a dialogue in images and words. It’s a complex revisiting—and a manifest reminder that all art and theory is inherently collaborative. It’s also an exchange of image and text, as Ostoya finds in Mouffe’s work the “inspiration to make things differently.” The “experience of looking,” Ostoya notes, “has been always connected with a political, historical, and personal reflection. It immediately raises the questions ‘what was?’ and ‘what is?’.”

In her 2002 essay “Politics and Passions: The Stakes of Democracy,” Mouffe offers a bold critique of the abiding politics of neoliberalism and a warning about what it enables: the upsurge of right-wing populism. She attributes the effectiveness of the right to the appeal of the stories it tells about itself. Worrying and wondering about how the left might radicalize democracy, about how to resist the status quo and prevent violence, Mouffe asserts the need for equally passionate counternarratives that move beyond moral condemnation of the “other” side. She convincingly argues for the futility of such condemnation, however emotionally satisfying it might feel; historically, shouting “capitalism is bad” has proved a losing strategy.

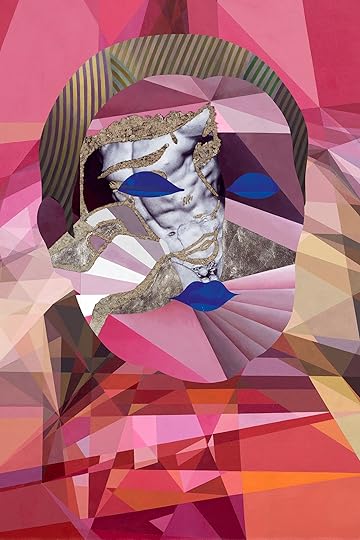

In 2009, Ostoya made of Mouffe’s essay a booklet of textual collages. Compelled and convinced by Mouffe’s ideas—and struck by Mouffe’s uncanny prescience—Ostoya revisits the original essay, her 2009 booklet adaptation of it, and a decade’s worth of her own artwork to create a new Politics & Passions (or, to render “Politics and Passions” anew). In this 2021 version, Ostoya reproduces her 2009 textual intervention and composes for it a series of twenty-five composite portraits.

Ostoya’s portraits are based on sketches she made of fellow citizens riding the J line of the New York City Subway system. “It was striking how the demographic changed along the route,” she muses, “since the train went from Wall Street through Chinatown and the Lower East Side in Manhattan to Williamsburg, Bushwick, all the way to JFK Airport and the Jamaica stop in Brooklyn.” Ostoya liked the energy of her drawings and the variety of people represented—a microcosm of our larger common life—but wanted to do something more with them. She decided “to follow the sketches’ outlines to compose photomontages,” using reproductions of her own paintings and collages from the preceding decade. They are, in effect, fragmented forms of Mouffe’s ideas. Each image foregrounds a central but abstracted figure and constitutes a moving testament to the ways Ostoya is moved by Mouffe’s words and aspires, in turn, to move us.

Conventional in form, Mouffe’s original essay is a succinct sixteen pages. Ostoya cuts it up, spreads it out, and extends it, making it a book-length piece, leaving scanner shadows intact. In other words, the copy is a self-consciously lo-fi reproduction—Ostoya’s translation rendered visual. In her hands, the theoretical essay becomes a veritable conceptual poem (what she calls “vertical compositions”), replete with enjambments and caesuras, offering it a different tone and tenor. She “followed an imaginary reader’s voice” to decide just how to truncate and separate Mouffe’s prose lines, giving them more time and space—breathing room that encourages heightened attention and intimacy. It’s a taking apart that builds anew.

Here, most lines are a mere word or two long, and some pages contain only a line or two, variously spaced. In places, full pages remain blank. Still others reproduce one simple line—not a line made up of words, but the black horizontal line that in Mouffe’s original appears under the essay’s page numbers or above her footnotes. Ostoya isolates such lines and turns them, too, refusing to play it straight. The slant becomes a rich visual pun, the manifestation of a different perspective, a new angle. It’s a reminder to look again and askance. The verbal and visual play radiates in multiple directions. It asks questions.

Intriguingly, while Ostoya arranges Mouffe’s essay otherwise, she omits nothing but page numbers, frustrating traditional citational methods in the process. She leaves Mouffe’s original word order and thus the overall argument intact. That said, the very act of formally translating Mouffe’s text is inherently interpretive. Ostoya alters our experience of it, its affect, by transforming the look, feel, and rhythm of the words and adding her visually dense portraits throughout. She asserts that the “only rule I followed was to put the ‘I’ and its derivatives on top of a page. These are the pages with colorful images.”

Every portrait and textual collage is an exploration of “the stakes of democracy,” and an invitation to consider their implications and revelations.

The first colorful image we encounter (it’s also the book’s cover image) appears on the left-hand side of a spread with a radically enjambed line on the right: “I / have / been / concerned / with / what.” Next to Ostoya’s portrait, we might read this line and its exaggerated caesuras as a question: who is “I” (Mouffe? Ostoya? both? neither?) and with what is “I” concerned? We might well read this line as I have been concerned with what is happening on the political left—arguably the animating concern of this project. (Notably, all the portraits appear on the left-hand side of page spreads.) Looking to the left, there’s a subtle yet discernible interrogative in the portrait itself, a curved line around the primary subject punctuated at its collar. In the background, there are archival photographs of quite serious people (all men, save one), but the most powerful photographic impression is that central eye (coded female) with its direct stare. The homonymic relation between visual “eye” and textual “I” remains a question of perspective.

The “eye” is ripe with interpretative potential. We might read it as a kind of disturbing surveillance or, instead, as an invitation to connect—to be in relation, to look more intimately and more deeply. It might also function as confrontation or challenge: Can you see and acknowledge the “other”? What separates and connects “I” and “you”? Can you resist turning away, despite potential antagonism and discomfort? In conjunction with Ostoya’s spatial extension of the original essay, such visual motifs prolong readerly attention and engagement. It’s also a testament to the care, respect, and intimacy necessary for political engagement.

Every portrait and textual collage is an exploration of, among other things, “the stakes of democracy,” and an invitation to consider their implications and revelations. Ostoya’s portrait collages are made up of many things—including images of others—in various configurations. No two look alike. Her subjects are not sovereign, necessarily existing in relation with others. There is a constant interplay—or irreducible tension—between the individual and collective, self and other, women and men, friend and enemy, mind and body, visible and invisible, literal and figurative, (photo)realism and abstractionism, past and present, presence and absence, interior and exterior, black-and-white versus color, hard lines and supple curves, access and denial, political left and right, “us” and “them.” The portraits are Mouffe’s ideal of an anti-essentialist “agonistic pluralism” aestheticized, illustrations of a “multiplicity of positions in society, some of which can never be reconciled,” and a strong assertion that they can “coexist without violence.”

All works by Anna Ostoya from the book Politics & Passions (MACK, 2021)

All works by Anna Ostoya from the book Politics & Passions (MACK, 2021)Words and images are in dynamic dialogue throughout Politics & Passions; fittingly, the book’s concluding section comprises a substantive, sustained conversation between Mouffe and Ostoya marked by energy, curiosity and, it must be said, passion. It’s a welcome coda. Each is against apathy, easy answers, and consensus politics; each believes in resistance rather than resignation, and the abiding potential of change—there are always ways to fight against the hierarchical and hegemonic powers that be. They wonder, wander, and riff with each other on topics ranging from the past forty years of political terrain (in various countries) to our current contexts (including the pandemic), to the value and purpose of art, to the need for “more experimental thinking.”

Mouffe describes herself as an “intellectual activist,” and we might likewise consider Ostoya an artistic activist. When Mouffe asks Ostoya how she would like her art to impact people, Ostoya identifies the dignity and power we embody, if only we can see clearly and passionately enough to use them. She hopes her art might make us “imagine other possibilities,” she says. “And when I say my art is a tool, I mean I hope it could help diminish violence and suffering, since I do believe that art can inspire people to realize who they are and who they want to be.” They agree this is especially crucial in the profound “social, economic and ecological” crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. As Mouffe asserts, we need “to awaken positive feelings and mobilise affects” as “a step towards the radicalisation of democracy.”

Politics & Passions was published by MACK in July 2021.

February 8, 2022

The Black Photographers Rethinking What History Is All About

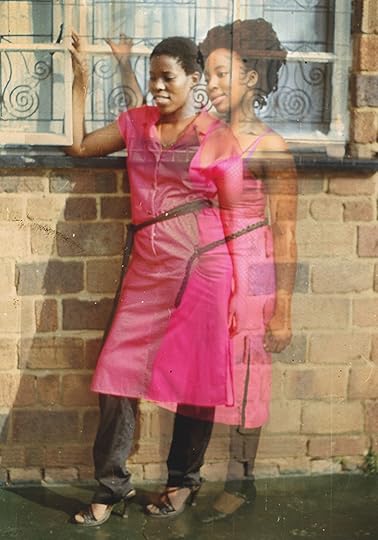

Lebohang Kganye, Re shapa setepe sa lenyalo II, 2013

Courtesy the artist

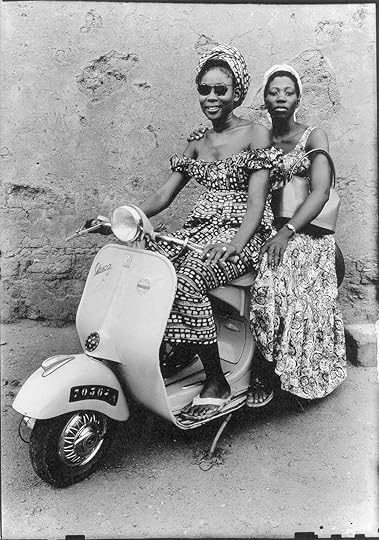

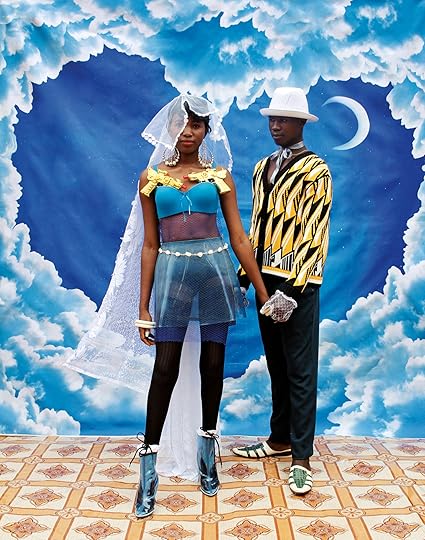

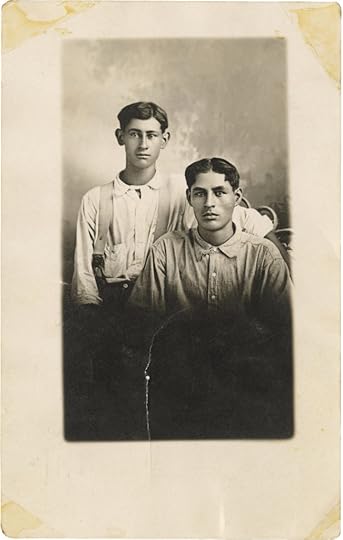

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1952–55

Courtesy the artist and SKPEAC

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (2021)

In 1997, Dr. Kenneth Montague founded the Wedge Collection in Toronto in an effort to acquire and exhibit work by artists of African descent. As We Rise features over one hundred works from the collection, bringing together artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa in a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

From Jamel Shabazz’s definitive street portraits; to Lebohang Kganye’s blurring of self, mother, and family history in South Africa; to J. D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s landmark series documenting Nigeria’s rich hairstyle traditions, As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. As Teju Cole describes in his preface, “Too often in the larger culture, we see images of Black people in attitudes of despair, pain, or brutal isolation. As We Rise gently refuses that. It is not that people are always in an attitude of celebration—no, that would be a reverse but corresponding falsehood—but rather that they are present as human beings, credible, fully engaged in their world.”

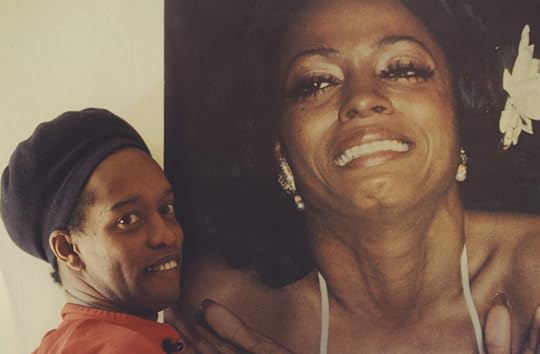

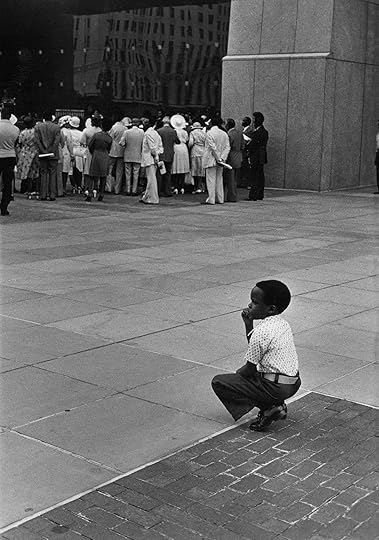

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976

Ming Smith, What’s It All About?, Harlem, New York, 1976 Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (2020)

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1975, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem, to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

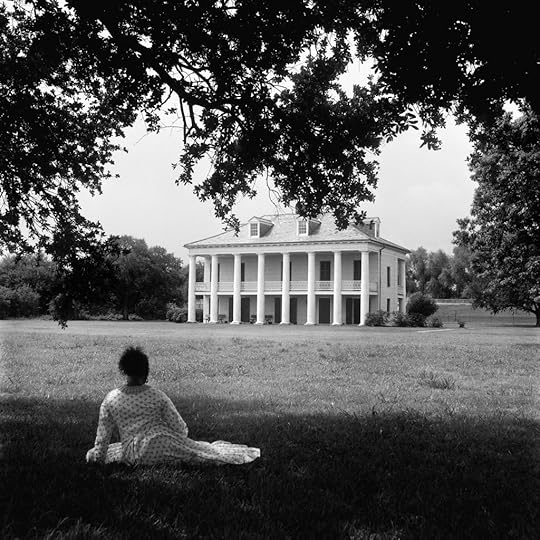

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (2020)

To Make Their Own Way in the World is a profound consideration of some of the most challenging images in the history of photography: fifteen daguerreotypes of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty—men and women of African descent who were enslaved in South Carolina. Photographed by Joseph T. Zealy for Harvard University professor Louis Agassiz in 1850, the images were rediscovered at Harvard’s Peabody Museum in 1976.

Throughout the volume, essays by prominent scholars explore topics such as the identities and experiences of those depicted in the daguerreotypes, the close relationship between photography and race in the nineteenth century, and visual narratives of slavery and its lasting effects, as well as the ways contemporary artists have used the daguerreotypes to critique institutional racism today. With over two hundred illustrations, including new photography by Carrie Mae Weems, this book frames the Zealy daguerreotypes as works of urgent engagement.

To Make Their Own Way in the World is firmly grounded in events still shaping American lives today. Instead of supporting Agassiz’s pseudoscientific notions about white supremacy and racial hierarchies (as was their original intent), the daguerreotypes now provoke wide-ranging interpretations and raise critical questions about representation and identity. “At this moment and in these divided states of America, perhaps more than at any time since their rediscovery in 1976,” Molly Rogers writes, “the daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, George Fassena, Drana, and Jack command our attention, demanding that we look closely, listen intently, and speak out—however difficult this may be—giving voice to all that we have learned.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2070386), 2017

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2070386), 2017Courtesy the artist and DOCUMENT, Chicago, team (gallery inc.), New York, and Vielmetter, Los Angeles

Paul Mpagi Sepuya (2020)

Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s studio portraits challenge and deconstruct traditional portraiture by way of collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, all through the perspective of a Black, queer gaze. Although the creation of artist books has been a long-standing part of his practice, this 2020 volume is the first widely released publication of Sepuya’s work.

For Sepuya, photography is a tactile and communal enterprise, with his multilayered scenes coming together through groups of the artist’s friends, fellow artists, collaborators, and himself. Moving away from the slick artifice of contemporary portraiture, Sepuya’s frames are filled with the human elements of picture-taking, from fingerprints and smudges to dust on mirrored surfaces. Sepuya pushes this even further by directly inviting us to look inside the studio setting—while also considering the construction of subjectivity.

Nadine Ijewere, The Art of Renaissance, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Ruth Ossai, Miu Miu Babes, 2018

Courtesy the artist

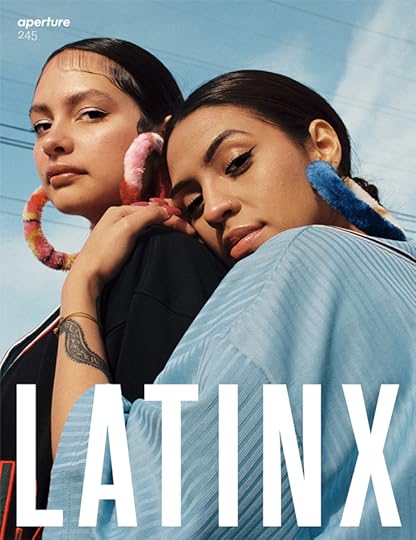

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (2019)

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in fashion and art today. The book highlights the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation—including Tyler Mitchell, the first Black photographer to shoot a cover story for Vogue; Campbell Addy and Jamal Nxedlana, who have founded digital platforms celebrating Black photographers; and Nadine Ijewere, whose early series title The Misrepresentation of Representation says it all.

From the role of the Black body in media; to cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture; to the institutional barriers that have historically been an impediment to Black photographers, The New Black Vanguard opens up critical conversations while simultaneously proposing a brilliantly reenvisioned future. “Often in this culture, when we think about the work of Black artists, we almost never think about, How do we celebrate young Black artists? And I wanted to change that,” Sargent states. “I wanted to say that what was happening right now with these very young artists is significant. It has shifted our culture, it has shifted how we think about photography, and it has shifted who gets to shoot images.”

Kwame Brathwaite, Sikolo Brathwaite wearing a headpiece designed by Carolee Prince, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1968

Kwame Brathwaite, Sikolo Brathwaite wearing a headpiece designed by Carolee Prince, African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Harlem, ca. 1968Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the ’50s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color. Born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling agency for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Until recent years, Brathwaite has been under-recognized. This is the first-ever monograph of his work. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation . . . . [They] were the woke set of their generation.”

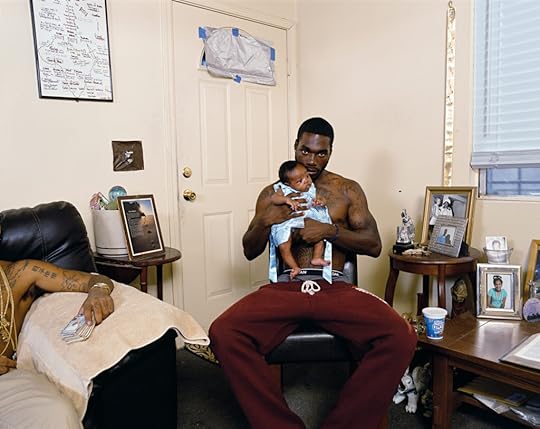

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Over the last decade, Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors, to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s landmark first publication, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson’s images portray the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Zanele Muholi, Zithulele, Worcester, South Africa, 2016

Zanele Muholi, Zithulele, Worcester, South Africa, 2016Courtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg, and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Zanele Muholi: Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (2018)

Zanele Muholi first gained recognition for their 2006 series Faces and Phases, documenting the LGBTI+ community, creating ambitiously bold portraits in an attempt to build a visual history and remedy Black queer erasure. Muholi then started to turn the camera inward, beginning a series of evocative self-portraits brought together in this 2018 monograph.

Using props and materials found in their immediate environment, Muholi crafts starkly contrasted frames that directly respond to contemporary and historical racisms—while also providing a platform for self-discovery. “I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces—brave enough to create without the fear of being vilified,” Muholi states. “To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is all about, to reclaim it for ourselves—to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.” One of the most powerful visual activists of our time, Muholi’s self-portraits remain radical statements of identity, race, and resistance.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Iké Udé and Lyle, Los Angeles, 1995

Lyle Ashton Harris, Iké Udé and Lyle, Los Angeles, 1995Courtesy the artist

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs (2017)

In the late 1980s and ’90s, a radical cultural scene emerged in cities across the globe, finding expression in the galleries, nightclubs, and bedrooms of New York, London, Los Angeles, and Rome. As a young artist experimenting with different mediums at the time, Lyle Ashton Harris began obsessively photographing his friends, lovers, and individuals who were, or would become, figures of influence, including Nan Goldin, Stuart Hall, bell hooks, Catherine Opie, and Marlon Riggs. Harris’s photographs offer a raw, authentic portrait of the cultural and political communities that defined an era and continue to resonate to this day.

In this 2017 volume, the artist’s archive of 35 mm Ektachrome images is presented alongside personal journal entries and recollections from artistic and cultural figures. It offers a unique document of what Harris has described as “ephemeral moments and emblematic figures shot in the ’80s and ’90s, against a backdrop of seismic shifts in the art world, the emergence of multiculturalism, the second wave of AIDS activism, and incipient globalization.” Together, Harris’s photographs and journals not only sketch his personal history and journey as an artist, but also provide an intimate look into this groundbreaking period of art and culture.

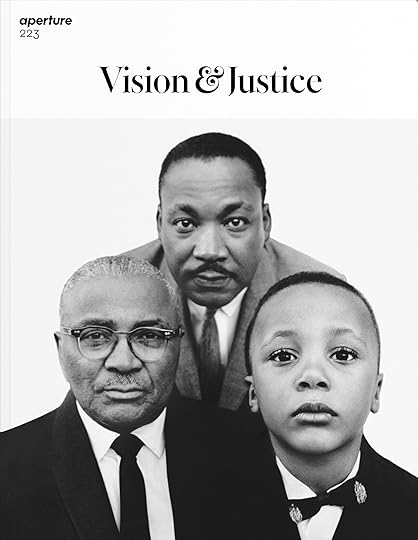

Richard Avedon, Martin Luther King, Jr., civil rights leader, with his father, Martin Luther King, Baptist minister, and his son, Martin Luther King III, Atlanta, Georgia, March 22, 1963

Courtesy The Richard Avedon Foundation

Awol Erizku, Untitled (forces of Nature #1), 2014

Courtesy the artist and Condé Nast/Vogue.com

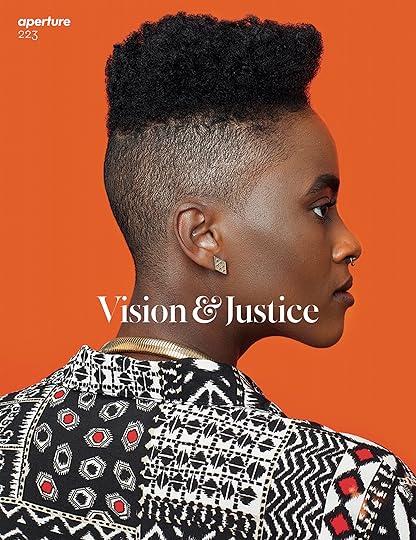

Aperture 223: “Vision & Justice ” (Summer 2016)

In 2016, art historian, curator, and writer Sarah Elizabeth Lewis guest edited Aperture’s summer issue, “Vision & Justice,” a monumental edition of the magazine that sparked a national conversation on the role of photography in constructions of citizenship, race, and justice. The issue features a wide span of photographic projects by artists such as Awol Erizku, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Deana Lawson, Jamel Shabazz, Hank Willis Thomas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deborah Willis; alongside essays by some of the most influential voices in American culture, including Vince Aletti, Teju Cole, and Claudia Rankine. “Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil,” writes Lewis, “but America’s progress would require pictures because of the images they conjure in one’s imagination.”

In 2019, Aperture worked with Lewis to create a free civic curriculum to accompany the issue, featuring thirty-one texts on topics ranging from civic space and memorials to the intersections of race, technology, and justice. Taking its conceptual inspiration from Frederick Douglass’s landmark Civil War speech “Pictures and Progress” (1861)—about the transformative power of pictures to create a new vision for the nation—the curriculum addresses both the historical roots and contemporary realities of visual literacy for race and justice in American civic life.

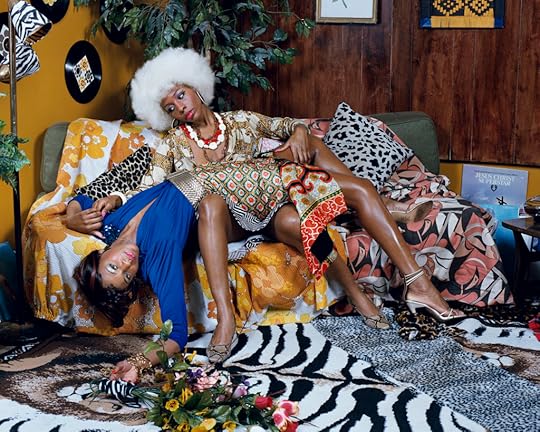

Mickalene Thomas, Le leçon d’amour, 2008

Mickalene Thomas, Le leçon d’amour, 2008Courtesy the artist and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Muse by Mickalene Thomas (2015)

Mickalene Thomas’s large-scale, multitextured tableaux of domestic interiors and portraits subvert the male gaze and assert new definitions of beauty. Thomas first began to photograph herself and her mother as a student at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut—which became a pivotal experience in her creative expression as an artist.

Since then, throughout her practice, Thomas’s images have functioned as personal acts of deconstruction and reappropriation. Many of her photographs draw from a wide range of cultural icons, from 1970s “Black Is Beautiful” images of women, to Édouard Manet’s odalique figures, to the mise-en-scène studio portraiture of James Van Der Zee and Malick Sidibé. Perhaps of greatest importance, however, Thomas’s collection of portraits and staged scenes reflect a very personal community of inspiration—a collection of muses that includes herself, her mother, her friends and lovers—emphasizing the communal and social aspects of art-making and creativity that pervade her work.

Sign-up for Aperture’s newsletters for updates on new releases, magazine and online-exclusive content, events, and more.

February 7, 2022

A Young Photographer’s Intimate Chronicle of Family in El Salvador and the United States

I don’t have any pictures of my family in my home. My spouse has a photograph of us and our dog, on our bookcase, I think. I don’t keep images of my parents or brother on my phone. Pictures of family are a source of terror for me because they remind me of the people I love too much, and the people I love are the most vulnerable beings I know. I am an artist and can only ease their suffering so much.

Adelante (2018–ongoing), a series by Steven Molina Contreras, who was born in El Salvador in 1999 and grew up on Long Island, chronicles his jumping-bean dynamics with his family—his mother, father, stepfather, grandparents, sisters. The images are hard to look at because so much is familiar in them. His father’s and stepfather’s hands look like mine—dark brown, thick fingers, neatly trimmed fingernails. But Molina Contreras doesn’t make hands his focus, unlike many photographers who document migrant men. He is curious about the men in his life, he asks them to reveal everything they have to show. As always, our parents tell us some things, lie out of love or self-preservation.

Steven Molina Contreras, Las Flores de Dios (The flowers of God), Mother Carmen and Mother Alma, United States, 2021

Steven Molina Contreras, Las Flores de Dios (The flowers of God), Mother Carmen and Mother Alma, United States, 2021His mother, Alma, is a fantastic source of theater. She recently got her degree in ministry at a school on Long Island, Molina Contreras tells me. Sometimes she puts on her blazer and preaches on Instagram Live, even to an audience of three. Women in evangelical traditions have a familiar stage presence—a straight back, a straightening of the spine they inspire in others—and she has it in Nuestro Corazón and Abigail’s Portrait. Alma is the matriarch, posing like Tina Knowles, accepting our gratitude for giving us the artist, acknowledging her own artistic direction. She picked out her clothing, she focuses her gaze, meeting our own. Our moms’ image is always picked out. When they are working hard to make a living, they pick out clothes to feel themselves fully to be working hard to make a living. Molina Contreras’s photographs don’t pretend to return dignity to his family, or to restore broken bonds, none of that. They reveal a family’s theater of family, and a loving family’s meticulousness in their love for each other, how that fussiness is sometimes embodied in artifice or even clutter.

Steven Molina Contreras, We meet at the Ocean, Amy, El Salvador, 2021

Steven Molina Contreras, We meet at the Ocean, Amy, El Salvador, 2021A certain romance of the subject is inherent to portraiture. In Adelante, Molina Contreras showcases a family I love the way you can only love a family you encounter solely through image or text. These photographs are beautiful to me. They don’t cause me pain. But they do give me hope because they all seem to be taken in the tender moment of ongoing forgiveness. In one picture from El Salvador, the artist’s younger sister Amy, whom he has only seen for a total of three weeks in their lives, looks at him searchingly, hungrily, angrily, and her portrait seems like an offering. Molina Contreras is immortalizing her with his gift, and maybe that counts for something. We see the exaltation of generations of sacrifice in Mujeres Celestiales, a portrait of the women in his family—his older sister, little sister, mother, and grandmother. Matriarchy is important to the artist. The women sit in a white bed with a frilly white frame against a white wall, daring the viewer, or anybody, to divide them again.

Photographs we take on our phones might be too much to bear, the texts we send to our families gnaw at immediate needs. But these photographs, made with patience and taken as part of an ongoing collection of curated images of family, borders, possessions, and belonging, are art. Those of us with hurt and gifts know what it is to bring them to the table to capture something that would otherwise be forgotten. The lucky ones can save what’s lost.

Steven Molina Contreras, Mujeres Celestiales (Celestial women), United States, 2021

Steven Molina Contreras, Mujeres Celestiales (Celestial women), United States, 2021 Steven Molina Contreras, To have and to hold, Tío y Tía (Uncle and aunt), El Salvador, 2021

Steven Molina Contreras, To have and to hold, Tío y Tía (Uncle and aunt), El Salvador, 2021 Steven Molina Contreras, Abigail’s Portrait, United States, 2019

Steven Molina Contreras, Abigail’s Portrait, United States, 2019 Steven Molina Contreras, Las Flores de mi Abuelita Carmen (My Grandma Carmen’s flowers), El Salvador, 2019

Steven Molina Contreras, Las Flores de mi Abuelita Carmen (My Grandma Carmen’s flowers), El Salvador, 2019 Steven Molina Contreras, Mother Alma #3, She’ll hold you for a lifetime, United States, 2019

Steven Molina Contreras, Mother Alma #3, She’ll hold you for a lifetime, United States, 2019All photographs courtesy the artist

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “Adelante.”

January 28, 2022

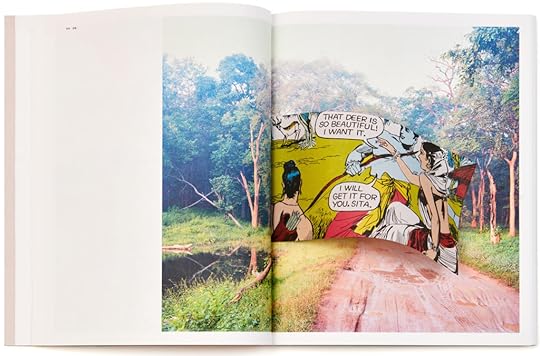

A Seven-Volume Photobook Retells the Story of an Ancient Hindu Epic

“The Ramayana’s over and they want to know whose father Sita is.”