Aperture's Blog, page 48

November 23, 2021

The Unexpected Photographs Ansel Adams Made before Becoming a Household Name

It is difficult to associate Ansel Adams with anything other than sublime, silver-print vistas. You picture him alone beneath majestic mountains, in the shadow of Half Dome at Yosemite, and looking up at billowy clouds through which light streams down to the rocky terrain of California’s Central Valley. There are rarely any humans visible in Adams’s most famous photographs, and so, by extension, it’s easy to think of him simply as a quiet man who communed attentively with nature.

Mike Mandel met Adams in 1975 when the former photographed the latter for Untitled (Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards), Mandel’s witty commentary on the rising status of well-known photographers of the time. This was just a couple of years before Mandel collaborated with Larry Sultan on Evidence, which was published in 1977. That book (and exhibition), composed of found photographic oddities culled from governmental and corporate archives, forged an approach to looking at vernacular pictures that wryly reveal commentary when taken out of their official context. Mandel had the idea for Zone Eleven, a new book that culls out-of-character Adams pictures, back then, while Adams was still alive (he died in 1984).

Ansel Adams, Freshmen Reception, University of California, Berkeley, 1966

Ansel Adams, Freshmen Reception, University of California, Berkeley, 1966Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

Ansel Adams, Dr. Benson Roe, Open Heart Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, 1965

Ansel Adams, Dr. Benson Roe, Open Heart Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, 1965Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

The size and horizontal orientation of Zone Eleven echoes that of Evidence, as if they are siblings born forty-four years apart, with divergent personalities. Evidence has an ominous, black dust jacket with the title in white, like a heading on a dossier. There is dark humor to that design that runs counter to the cover of Zone Eleven. A crisp, clean white, this new cover features a title in the same serif font in roughly the same position as Evidence’s, only with letters that move through a spectrum of full black to gentle gray.

This range of shades refers to the famous ten-zone system, which Adams codeveloped. The system goes from zero to ten, black to white, as a means of creating optimal black and white exposure and printing. As a title, Zone Eleven (itself containing ten letters!) suggests Spinal Tap’s pumping up the volume to that next level, though the degree of comedic energy to this project is moderate. Ten is the pure white side of Adams’s tonal spectrum; eleven could be something beyond recognition.

Ansel Adams, C.T. Hibino, artist, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, 1943

Ansel Adams, C.T. Hibino, artist, Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, 1943Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

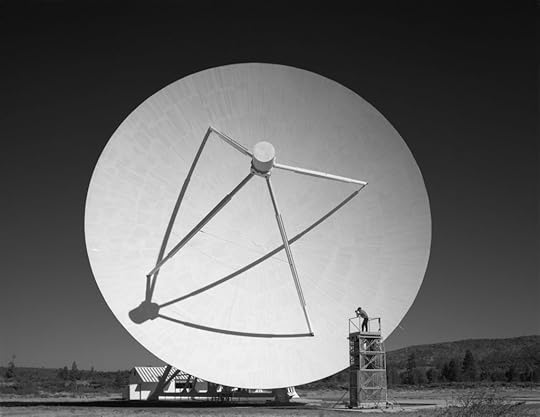

Ansel Adams, Hat Creek Radio Astronomy Station, Shasta County, California, 1964

Ansel Adams, Hat Creek Radio Astronomy Station, Shasta County, California, 1964Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

The eighty-three images in Zone Eleven are not masterworks but pictures Adams took for commercial clients before he could survive on sales of his artwork. “These are essentially vernacular pictures that happen to be made by Ansel Adams—totally unlike Adams’s best-known photographs,” writes Erin O’Toole in the book’s contextualizing essay. The latter, she adds, “Mandel terms ‘unitary,’ meaning singular pictures that don’t depend on what comes before and after.” Adams’s name is on the spine (just like Sultan’s is on Evidence), and Mandel, in this quasi-collaboration, is responsible for adding the “canny selection and juxtaposition,” as O’Toole describes it. Mandel, in a no-longer-revolutionary strategy, had combed through archives of some 50,000 images at the Center for Creative Photography and the California Museum of Photography at UC Riverside, most dating from the 1940s through the 1960s.

He chose some outdoor shots of beaches, hillsides, prairies—though these, countering the sublime, seem more like sites of recreation, of beach wading and guided treks up snow-covered peaks. Because these settings are in Adams’s wheelhouse, they’re less surprising than pictures that depict social situations—you realize just how few of his known photos include people.

There are crowds, and there is frolic, as in Recreation Center: University of California Los Angeles (1966), a series of six images that capture divers hovering above an expansive swimming pool with smoggy views of Los Angeles in the background. There is wit and magic to the illusion of levitation, to the figures floating, expectantly, forever captured on film.

Ansel Adams, Drama Rehearsal, Misty Morning, University of California, Irvine, 1966Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

Ansel Adams, Drama Rehearsal, Misty Morning, University of California, Irvine, 1966Sweeney/Rubin Ansel Adams Fiat Lux Collection, California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside Ansel Adams, Cole and Dorothy Weston at Home, ca. 1940

Ansel Adams, Cole and Dorothy Weston at Home, ca. 1940Fortune Magazine Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

There is a 1928 photograph of a man in diaphanous drag, titled Fun in Camp—the Premier Danseuse, Ernest Arnold, Canadian Rockies. There’s no information provided on the subject, though bearded Ernest looks rather like a demure member of the Cockettes, that infamous San Francisco hippie drag troupe, with his makeshift costume of cheesecloth and wildflowers. Another college scene, Drama Rehearsal, Misty Morning, University of California, Irvine (1966), shows youthful hipsters emoting and reclining on a rock, and while dressed, they seem like precursors to the desert orgy in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point. You just don’t equate youthquake energy with Adams, and it’s heartening to be able to.

Cole and Dorothy Weston at Home (ca. 1940) shows an ardent kiss framed behind a front-door screen—it’s an amorous winter embrace, and which, surprisingly, comes from the Fortune Magazine Collection archives. Mandel pairs it with Building Through Window Screen (undated), a hazy view of a barn-like structure as seen through a wire mesh panel. The two pictures are linked by domesticity. Other sequences depict shadows on walls, modernist architecture, and scientific equipment.

There was a time when Adams was the most famous photographer working, a household name, and a staple of college dorm room posters.

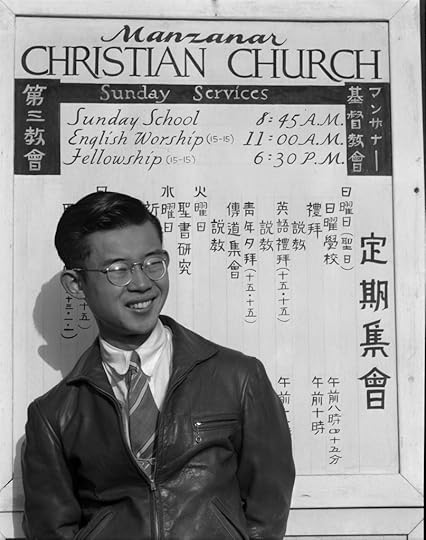

The center of the book features a few portraits of Japanese Americans at the Manzanar internment camp. These are grounded, humanizing images that focus on individuality over strife. Tatsuo Miyake (student of divinity), Manzanar War Relocation Center, California (1943) shows the subject posing in front of a rectangular sign for camp church services. The composition, however, reads something like an identification photo, even though Miyake leans left and smiles broadly. These, along with a few exteriors of the Manzanar Relocation Center, have a more documentary feel, as they offer an on-the-ground view of a politicized site that Adams famously photographed from an aesthetic distance. This sequence also hints at a social conscience that isn’t as visible elsewhere in the book.

Ansel Adams, Tatsuo Miyake (student of divinity), Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, 1943

Ansel Adams, Tatsuo Miyake (student of divinity), Manzanar War Relocation Center, California, 1943Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Unlike the anonymous photographers in Evidence, here the photographer is an extremely known entity. The images in Zone Eleven are commercial works attributed to Adams, but are they essentially found images that have little to do with his artistic vision? Outside of the Manzanar pictures, they don’t tell us much about the man other than the fact that he actually had ties to civilization.

There was a time when Adams was the most famous photographer working, a household name, and a staple of college dorm room posters. His role in popularizing the medium cannot be underestimated. His focus on glorious natural subjects and his reverence and advocacy for careful darkroom printing and photo education now seem quaint in a world saturated with digital filters and phone cameras, and when instances of environmental catastrophe are the new sublime. There’s a nostalgic sweetness to this project, both in the images and in Mandel’s form of homage. But there isn’t much urgency. Which is to say, if Zone Eleven is meant to provide evidence for reevaluating Adams, it lands pleasantly in zone five.

Mike Mandel: Zone Eleven was published by Damiani in October 2021.

November 19, 2021

Aperture’s 2021 Holiday Gift Guide

From best-selling Aperture books The New Black Vanguard and Photo No-Nos; to iconic monographs by Nan Goldin, Deana Lawson, and Philip Montgomery; to essay and activity books for all-ages—we’ve rounded up titles for everyone on your list.

Must-Haves for Photography Lovers

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic

As We Rise looks at multifaceted ideas of Black life through the lenses of community, identity, and power. Drawn from Dr. Kenneth Montague’s Wedge Collection, the book features works by Black artists from Canada, the Caribbean, Great Britain, the US, South America, and Africa—providing a timely exploration of Black identity on both sides of the Atlantic.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Goldin’s candid, visceral photographs captured a world seething with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis. Over thirty years after it was first published, the influence of The Ballad on photography and other aesthetic realms can still be felt, firmly establishing it as a contemporary classic.

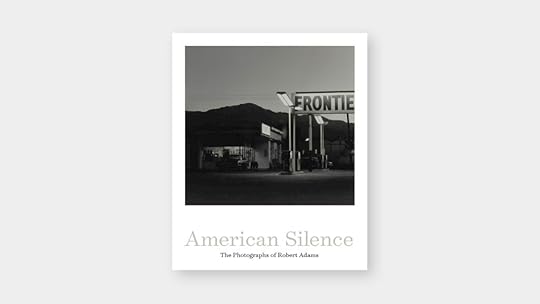

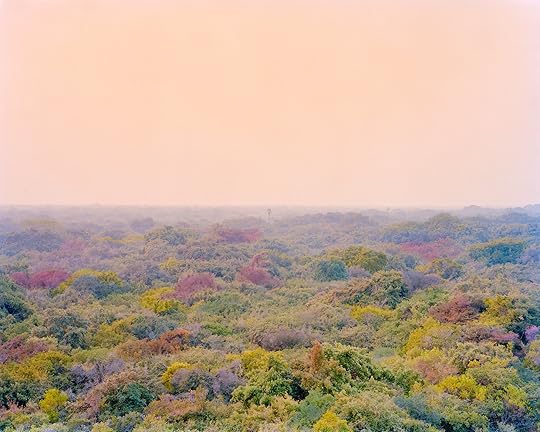

American Silence: The Photographs of Robert Adams

For fifty years, Robert Adams has made compelling, provocative, and highly influential photographs that show us the wonder and fragility of the American landscape, its inherent beauty, and the inadequacy of our response to it. American Silence features over 175 works from Adams’s career photographing throughout Colorado, California, and Oregon—capturing suburban sprawl, strip malls, highways, homes, and the land—examining the artist’s act of looking at the world around him and the almost palpable silence of his photographs.

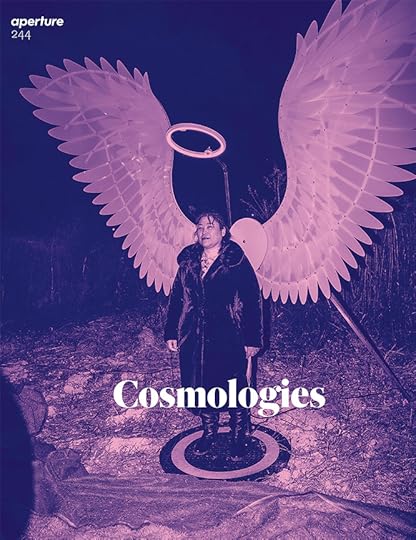

Aperture magazine subscription

Leading the conversation on contemporary photography with thought-provoking commentary and visually immersive portfolios, Aperture is required reading for everyone seriously interested in photography. With thematic issues ranging from “Vision & Justice” to “Native America,” “New York,” and more, Aperture has been the essential guide to photography since 1952.

Give the Gift of Inspiration

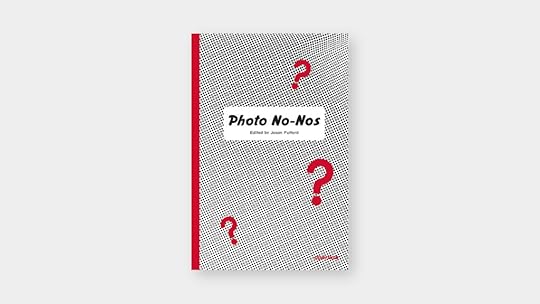

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph

What is a “photo no-no”? Photographers often have unwritten lists of subjects they tell themselves not to shoot—things that are cliché, exploitative, derivative, sometimes even arbitrary. Edited by Jason Fulford, this volume brings together ideas, stories, and anecdotes from over two hundred photographers and photography professionals. Not a strict guide, but a series of meditations on “bad” pictures, Photo No-Nos covers a wide range of topics, from sunsets and roses to issues of colonialism, stereotypes, and social responsibility—offering a timely and thoughtful resource on what photographers consider to be off-limits, and how they have contended with their own self-imposed rules without being paralyzed by them.

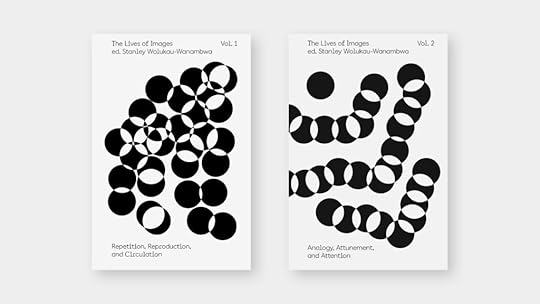

The Lives of Images, Volumes 1 & 2

The Lives of Images, edited by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, is a set of contemporary thematic readers designed for educators, students, practicing photographers, and others interested in the ways images function within a wider set of cultural practices. The first volume, Repetition, Reproduction, and Circulation, addresses the multiple life cycles of the image and the significance of technological reproduction for contemporary forms of social, cultural, and political life. Meanwhile, Vol. 2: Analogy, Attunement, and Attention addresses the complex relationships that the reproducible image creates with its viewers, and their bodies, minds, and identities.

PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice

How does a photographic project or series evolve? How important are “style” and “genre”? What comes first—the photographs or a concept? PhotoWork is a collection of interviews by forty photographers about their approaches to making photographs and a sustained a body of work. Structured as a Proust-like questionnaire, editor Sasha Wolf’s interviews provide essential insights and advice from both emerging and established photographers—including LaToya Ruby Frazier, Todd Hido, Rinko Kawauchi, Alec Soth, and more—while also revealing that there is no single path in photography.

The Photography Workshop Series Bundle

In our Photography Workshop Series, Aperture works with the world’s top photographers to distill their creative approaches to, teachings on, and insights into photography, offering the workshop experience in a book. From Richard Misrach on landscape photography and meaning, to Dawoud Bey on photographing people and community, to Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb on the poetic image, these books offer inspiration to photographers at all levels who wish to improve their work, as well as readers interested in deepening their understanding of the art of photography.

Contemporary Classics

Philip Montgomery: American Mirror

Through his intimate, powerful reporting and signature black-and-white style, Philip Montgomery reveals the fault lines of American society—from police violence and the opioid addiction crisis, to the COVID-19 pandemic and demonstrations in support of Black lives. American Mirror is the first monograph by the award-winning photographer, distilling his vision through seventy-one iconic images. Like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans before him, Montgomery has made an unforgettable testament of a nation at a crossroads.

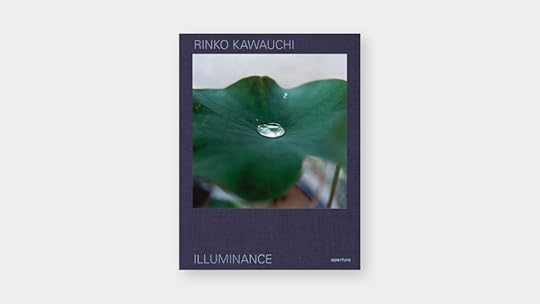

Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance (Tenth Anniversary Edition)

Ten years after its original publication, Aperture republishes Rinko Kawauchi’s beloved volume Illuminance. Through her images of keenly observed gestures and details, Kawauchi reveals the mysterious and beautiful realm at the edge of the everyday world. As Kawauchi describes, “I want imagination in the photographs—a photograph is like a prologue. You wonder, ‘What’s going on?’ You feel something is going to happen.” This new edition of Illuminance retains the Japanese photographer’s original sequence, alongside texts by David Chandler, Lesley A. Martin, and Masatake Shinohara.

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph

Over the last ten years, Deana Lawson has portrayed the personal and the powerful in her large-scale, dramatic portraits of people in the US, Caribbean, and Africa. One of the most compelling photographers working today, Lawson’s Aperture Monograph is the long-awaited first photobook by the visionary artist. “Outside a Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in the book’s essay. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

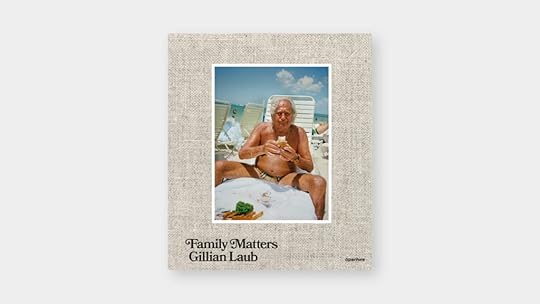

For over twenty years, Gillian Laub has photographed her family in an exploration of the ways society’s most complex questions are revealed in our most intimate relationships. For Laub, this became all the more tangible when she found herself on the opposing side from her family during the 2016 US presidential election—and further in the lead-up to the 2020 election, the COVID-19 pandemic, and protests in support of Black Lives Matter. Family Matters combines Laub’s subversively funny and often gut-wrenchingly familiar photographs alongside personal reflections, offering a compelling picture of the fractures in contemporary American society through the artist’s own family.

Ethan James Green: Young New York

Ethan James Green’s first monograph presents a selection of striking portraits of New York’s Millennial scene-makers, a gloriously diverse cast of models, artists, nightlife icons, queer youth, and gender binary–flouting muses of the fashion world and beyond. Young New York showcases a bright young talent who is redefining beauty and identity for a new generation.

Photobooks Celebrating Black Artists

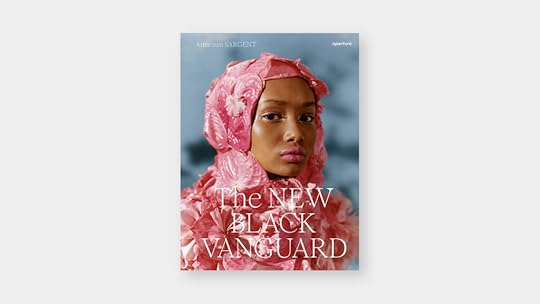

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in art and fashion today, highlighting the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation.

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the ’50s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color. Born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite and his brother Elombe were responsible for creating the African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. Until now, Brathwaite has been underrecognized, and Black Is Beautiful is the first-ever monograph dedicated to his remarkable career.

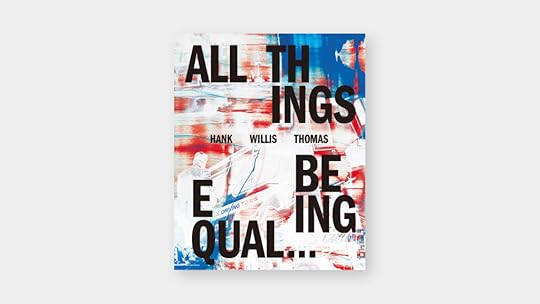

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal

Throughout his prolific and interdisciplinary career, Hank Willis Thomas’s work has explored issues of representation, perception, and American history. At the core of his practice is the ability to parse and critically dissect the flow of images that comprise American culture, with particular attention to race, gender, and cultural identity. All Things Being Equal is the first in-depth overview of Thomas’s extensive career, highlighting the artist’s diverse range of visual approaches and mediums—from advertising and branding, archival Civil Rights and apartheid-era photography, and sculpture, to public art projects and more.

For the Armchair Traveler

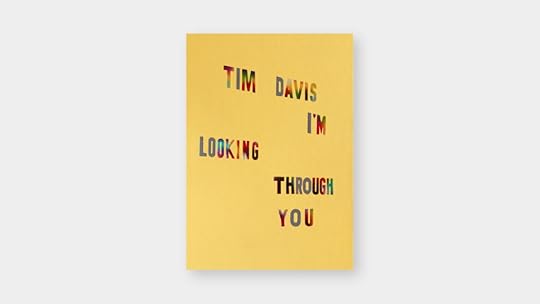

Tim Davis: I’m Looking Through You

Since 2017, Tim Davis has photographed throughout Los Angeles, creating an expansive visual poem celebrating the city’s glamorous surface. From closely observed details of LA’s social landscape to a host of absurd and otherworldly street encounters, Davis captures the surreal beauty, fierce energy, and hidden messages harbored in the streets of the City of Angels. “The camera is a machine that can see only surfaces,” Davis writes. “The world casts its spell, and the camera gobbles up its glamour, uncritically, with pure certainty, assuming there is nothing underneath.”

Gail Albert Halaban: Italian Views

Through Gail Albert Halaban’s lens, the viewer is welcomed into the private lives of ordinary Italians. Her photographs explore the conventions and tensions of urban lifestyles, feelings of isolation in the city, and the intimacies of home and daily life. Francine Prose’s wonderful essay discusses the curious thrill of being a viewer. This invitation to imagine the lives of neighbors across windows renders the characters and settings personal and mysterious.

In the winter of 1958, Sergio Larrain traveled to London. He spent just a few months there, photographing subjects that interested him and embracing the shadows of the city. In the cold and damp, his images captured a tangible darkness in which he could “materialize that world of phantoms.” This new edition of Larrain’s original and poetic visual volume London features previously unpublished photographs alongside texts by Agnès Sire and the late Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño.

Caspian: The Elements by Chloe Dewe Mathews

Between 2010 and 2015, Chloe Dewe Mathews traveled through the beguiling region surrounding the Caspian Sea, creating a record of the ways materials such as oil, fire, uranium, and water are integral to the mystical, economic, religious, and therapeutic aspects of daily life. In photographs that range from stark and primordial to lush and mysterious, Dewe Mathews’s Caspian: The Elements is a powerful document of the ways humans are inextricably linked to this enigmatic and much-coveted land.

Children’s Activity and Educational Books

The Colors We Share by Angélica Dass

Inspired by her family tree, Angélica Dass—a Brazilian artist of African, European, and Native American descent—began creating portraits of people from all over the world against backgrounds that match their skin tones. Brought together in a book made for young readers, The Colors We Share celebrates the diverse beauty of human skin, while also considering concepts of race and the limited categories we use to describe each other.

Eyes Open: 23 Photography Projects for Curious Kids

Compiled by Susan Meiselas, Eyes Open is a sourcebook of photography ideas for kids to engage with the world through the camera. Broken into chapters ranging from “Alphabetography” to “Light,” “Movement,” “Neighborhood,” and more, each idea starts with a prompt, illustrated with pictures by students from around the world, and followed by the words and images of artists who share their ways of seeing. Playful and meaningful, this book is for young would-be photographers and those interested in expressing themselves creatively.

Seeing Things by Joel Meyerowitz

Seeing Things is a wonderful introduction to photography that asks how photographers transform ordinary things into meaningful moments. Joel Meyerowitz introduces young readers to the power and magic of photography, exploring key concepts in the medium—from light and gesture to composition—through the work of famous photographers such as William Eggleston, Helen Levitt, Mary Ellen Mark, and Martin Parr.

Go Photo! An Activity Book for Kids

Go Photo! features twenty-five hands-on and creative activities inspired by photography. Aimed at children between eight and twelve years old, this playful and fun collection of projects encourages young readers to experiment with their imaginations and build their own visual language. Indoors or outdoors, from a half hour to a whole day, there is a photo activity for all occasions—and some don’t even require a camera!

For the Collector

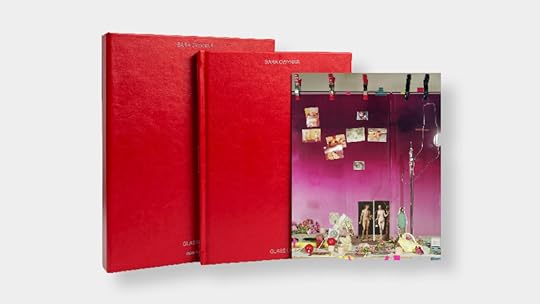

Sara Cwynar: Glass Life (Limited-Edition Box Set)

Sara Cwynar’s multilayered portraits are an investigation of color and image-driven consumer culture. Working in her studio, Cwynar collects, arranges, and archives eBay purchases into her visually complex photographs that examine how images circulate online, as well as how the lives and purposes of both physical objects and their likenesses change over time. This special limited-edition box set features a differentiated version of Cwynar’s debut monograph, Glass Life, accompanied by a signed print from the artist.

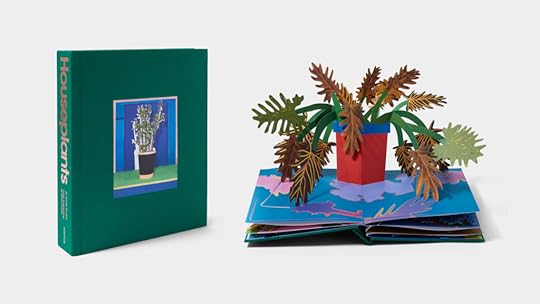

This highly collectible, limited-edition pop-up book is a work of art in itself, rendering Daniel Gordon’s sculptural forms into a new layer of materiality and animating them in a pop-up performance. The book consists of six works in pop-up form, some featuring simple plants, others unfolding more elaborate tableaux.

Vik Muniz: Postcards from Nowhere

Vik Muniz’s two-volume Postcards from Nowhere grapples with how, through photographs, we have come to “see” and understand distant yet iconic sites we may never actually view with our own eyes, while also serving as an homage to the quasi-obsolete artifact of the picture postcard. Volume I includes thirty-two single postcards displaying each of the images in the series; Volume II presents a series of thirty-six postcards that, when assembled, can be viewed as a single, large-scale work of thirty by forty inches.

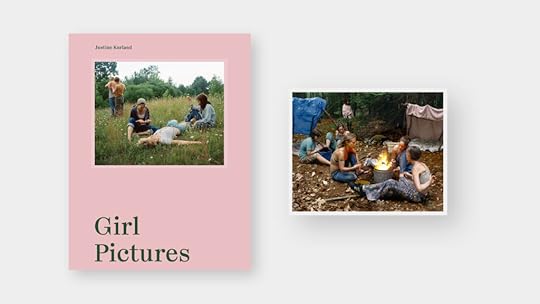

Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures (Signed Book and Limited-Edition Print Bundle)

Between 1997 and 2002, Justine Kurland photographed teenage girls as imagined runaways, offering a radical vision of community and feminism against the masculine myth of the American landscape. Kurland portrays these girls as fearless and free, tender yet fierce—imagining a world at once lawless and utopian, an Eden in the wild. This bundle features a signed edition of her now-iconic series Girl Pictures and a signed and numbered limited-edition print from the book.

Shop Aperture’s Holiday Sale for 30% off photobooks, magazines, and prints.

November 18, 2021

A New Delhi Photographer’s Searching Look at Fathers and Sons

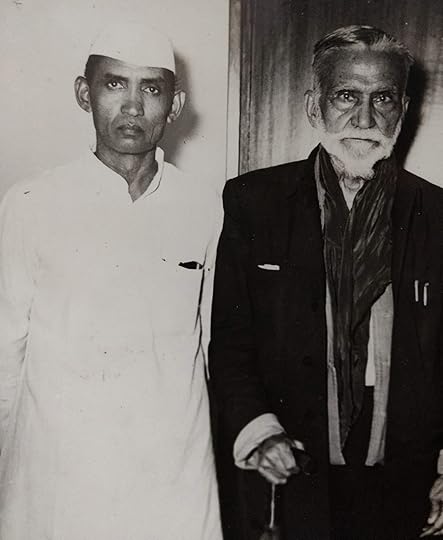

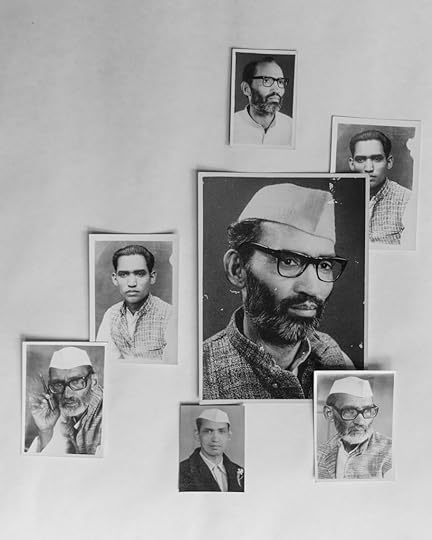

The New Delhi–based photographer Devashish Gaur’s series This Is the Closest We Will Get (2019–ongoing) was sparked by the chance discovery of photographs of his grandfather during the renovation of their family home. “The title is derived from the limitations around knowing someone who doesn’t exist anymore,” Gaur says. “There will always be a certain distance. The gap between generations is one that can’t be altogether diminished.” Arising partly out of his curiosity about the life and persona of his grandfather, and partly from his urge to better understand his own somewhat strained relationship with his father, the series poses an intergenerational dialogue between individuals, objects, and beliefs. This Is the Closest We Will Get is among the winners of the Vantage Point Sharjah prize from the Sharjah Art Foundation, where the series is currently on view through December 18, 2021.

Devashish Gaur, Last treat. Home, 2019

Devashish Gaur, Grandpa. Archives, 2019

Gaur curates his narratives by combining old photographs requisitioned from family albums, archives, and vintage shops onto which the by-lanes of Delhi abruptly descend, with fresh documentation from his research. A number of his past projects are steeped in nostalgia, excavating material memory to reconstruct the notion of home and coalescing intimacies of different kinds—corporeal, social, or spatial. The slow-evolving continuities of domestic dispositions betray traces of the rapidly shifting backdrop of public life. One gets the uncanny sense that Gaur’s mundane and somewhat outmoded subjects—like the last glass of homemade ice cream waiting in the freezer—are holding still for a time-lapse as the world around them streaks forth at the speed of technology.

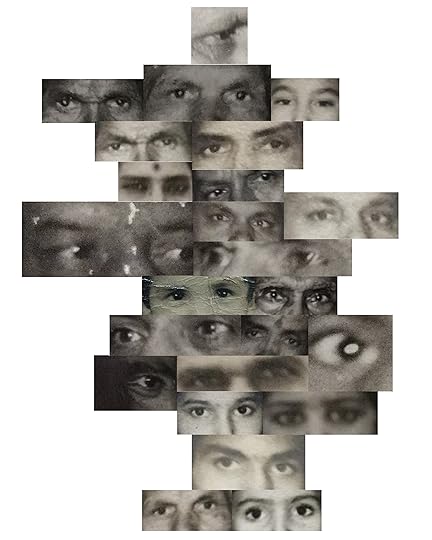

This is the Closest We Will Get assumes an ambiguous attitude toward surveillance. The many-eyed collage Witness of Existence (2019) exhibits Gaur’s desire to retro-vicariously surveil and inhabit the bodily dispositions of his grandfather, much like how the state surveils and inhabits the public behavior of its citizenry through CCTV cameras. Composed of multiple images cropped to eyes that once must have touched his grandfather, the work positions longing as a mode of “both belonging and ‘being long,’ or persisting over time,” to borrow Elizabeth Freeman’s words from her book Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (2010).

Devashish Gaur, Witness of Existence, 2019

Devashish Gaur, Dad dressing up as Grandpa. Home, 2020

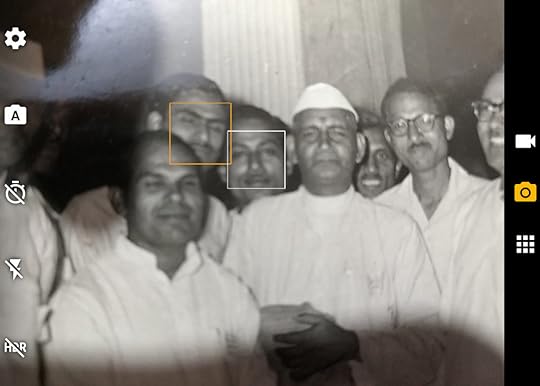

Gaur’s act of pointing a smartphone camera to these pre-smartphone pictures produces the curious anachronism of an AI trying to recognize faces that were never territorialized in this manner. The AI’s confused attempt at back-tracing these sovereign faces to nonexistent data-bodies prompts the following set of questions, encapsulated in the work’s title: How much can the software know? How much meaning is lost in face detection? And how many memories are forever gone? In addition to resurrecting modes of parenting and past traumas, Gaur’s ghosting-in-reverse critiques the recent bids by the Indian government for greater biopolitical control through state-run registers of citizen data. In the most surveilled city in the world, pointing a smartphone camera to an unyielding picture becomes a symbolic act of defiance.

Devashish Gaur, How much can the software know? How much meaning is lost in face detection and how many memories are forever gone?, 2019

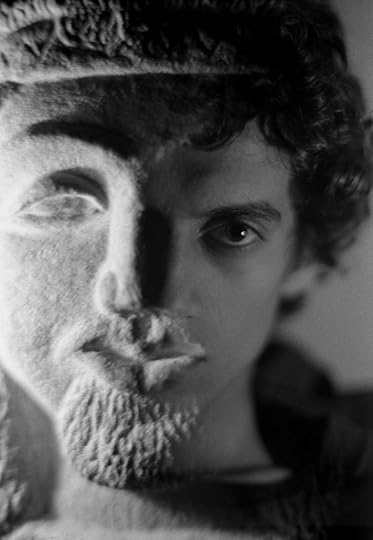

Devashish Gaur, How much can the software know? How much meaning is lost in face detection and how many memories are forever gone?, 2019The subjects of This is the Closest We Will Get tease oedipal dialectics. In Dad dressing up as Grandpa (2020) the uncharacteristic desire of Gaur’s camera-shy father to be photographed for his social media intersects with his late grandfather’s habit of posing regularly for his friends’ cameras. We don’t know whether or not the choice of donning the white Gandhi cap, like Gaur’s grandfather used to, is conscious, but the correspondence is tantalizing. If these framings help the artist imagine what kind of relationship existed between his father and his grandfather, collages like Me and Dad (2019) hit closer to home. Composed of bits of Gaur’s own portrait overlaid with that of his father’s, the work speculates, queerly, about the commingling of personalities from the standpoint of prolonged proximity, not genealogy.

Elsewhere, the tamrapatra (copper plate) awarded to Gaur’s grandfather for his contributions to India’s struggle for independence, photographed from behind, seems to gently mock the precious freedom that was fought for. “I was told that my grandfather wasn’t a religious person,” Gaur says. Referring to the chance discovery of a forsaken image of the popular saint, Sai Baba, in a riverbed, he adds: “A religious icon that was once worshipped and took up space in someone’s house is now left behind. I think my grandfather would laugh at the absurdity of this cycle from adoration to obsolescence and abandonment.” This fate is echoed by a small votive of Shani Dev (Saturn) that Gaur’s father once worshipped and now lies neglected somewhere in the house, gesturing toward the rising tide of right-wing conservatism in a country that no longer sees faith as innocent.

The black-and-white photograph of a splotchy old pillow beckons with the knowledge of untold mysteries. Titled after a Dean Martin song, Pillow that you dream on (2020), the photograph not only expresses a wish for a more intimate relation with a reticent father but also delineates a broader search for softness within masculinist cultures. As Gaur observes, “details about how people held each other, sat with a certain elegance—placing hands on their legs while sitting—signal rare beauty and delicateness sanctioned to masculinity.” When lips are silent, pillows can talk a great deal.

Devashish Gaur, Portraits of Grandpa; he enjoyed being in front of the camera and would often have photo-sessions with friends. From the archives, 2019

Devashish Gaur, Portraits of Grandpa; he enjoyed being in front of the camera and would often have photo-sessions with friends. From the archives, 2019

Devashish Gaur, Dad grooming to look like his father. Home, 2021

Devashish Gaur, Untitled. Home, 2020

Devashish Gaur, Pillow that you dream on. Home, 2020

Devashish Gaur, Pillow that you dream on. Home, 2020

Devashish Gaur, Untitled. Home, 2019

All photographs from the series This Is the Closest We Will Get, 2019–ongoing. Courtesy the artist

Devashish Gaur, Tapmrapatra: An award for outstanding contribution to freedom struggle during the British rule by the Indian Government, 2020

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

November 17, 2021

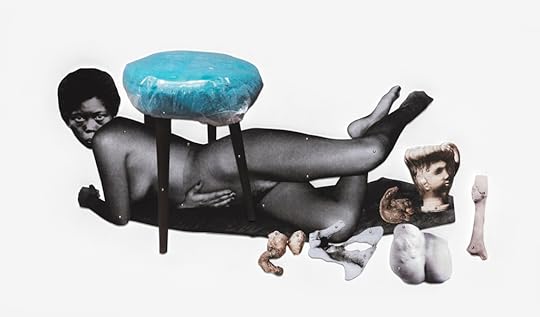

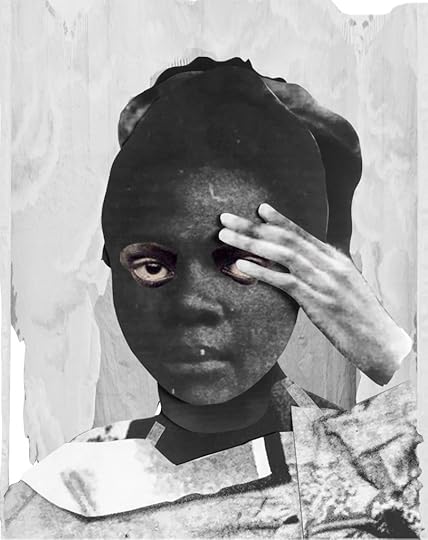

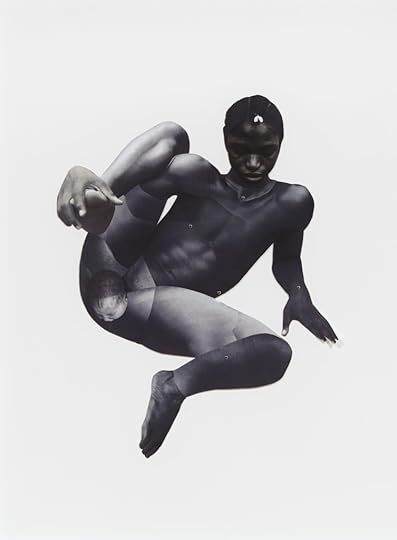

In Frida Orupabo’s Collages, the Black Feminine Figure Is a Rich Expressive Force

Frida Orupabo is a sociologist and artist whose practice spans photography, collage, sculpture, and video. Her artistic work fashions new objects, images, and moving-image sequences from extant images sourced from a variety of common sources, like the internet, as well as from various institutional and parainstitutional archives. The history and presence of the Black woman and the symbolic and material force of Black gender nonconformity sit at the center of Orupabo’s artist work, and these factors surface through collaged figures which she (re)assembles in digital space and (re)produces as sculptural aggregates. In Orupabo’s collages, the Black feminine figure is both a site for reparative work and an agent of rich expressive force: she is taped and riveted together from historical fragments, but possessed of an irreducible scopic power to look back at our looking—from her stance on the margins of history, but at the center of Orupabo’s image world.

Frida Orupabo, Lying with Objects, 2020. Collage with paper pins

Frida Orupabo, Lying with Objects, 2020. Collage with paper pinsCourtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Amsterdam, Cape Town, and Johannesburg. Photograph by Mario Todeschini

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: I’m curious to better understand how images accumulate in your personal archives, both digital and physical, and then how they might slowly or suddenly be transformed into the scaled prints and sculptural objects out of which you make your collages. How are you encountering images, and accumulating, assessing, and exploring them in digital and physical form?

Frida Orupabo: Most of the images I accumulate and work with are digital. I use different platforms (like Tumblr, Pinterest, Instagram, eBay, Etsy, and Google, among others). Google is often used when I’m already tracking something, when I am actively looking for very specific things; this is often the case when I’m working on a digital collage and need things along the way—a shoe, a pregnant belly, etc. While other times I am more in “research” mode, where one finding leads to another.

It’s hard to speak to how I encounter images or how I am exploring them in digital and physical form, because the whole process (of searching, finding, accumulating, and making use of them) is very intuitive. Some images just make me stop. It can be a person’s face or something about the whole composition or arrangement of objects in a room. Or it can just be something I haven’t seen before—a twist on something that is familiar.

When starting on a digital collage, I will begin with something I really like and then go back and forth—testing different parts that will accompany the first piece. The selection of the different parts is done based on how they or it feel(s). It’s like a silent knowledge and a big trust of one’s own eye.

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2019. Collage

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2019. CollageCourtesy the artist

Wolukau-Wanambwa: How do you begin to work out a physical scale for the collages? Do they come together digitally first, before becoming scaled objects in space?

Orupabo: Yes, the digital collage is always the starting point, the base for the physical collage. I enlarge it (in Photoshop) and then print it, stitching together all of the layers (first by using tape, then pins). Usually, the collages will be close to human size or bigger. It depends on the project and the space, and how I would like to organize the images (individually or grouped together). The space I am working in—which is my apartment—naturally also sets a limit to how big I can make them.

The first time I enlarged and printed out a digital collage, I was so delighted and a bit startled to experience how present she (the collage) felt in the room, and I immediately knew that this was how they should be presented. Before, I had looked at the digital collages as done; but after this, I started to see them more as sketches.

When it comes to the sculptures, I will use more time finding the right scale. I will make a physical test where I use paper or cardboard. Then all of the info and sometimes even the tests and mock-up will be sent to the company that is going to realize it.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: How do you think about the gesture or grammar of creating Black figures—principally Black female figures, although arguably also Black gender-nonconforming figures—through the language of collage?

Orupabo: I think of it as something liberating, and as something very closely linked to creating and sustaining one’s own self. I see collage as an effective way of questioning and recreating narratives and identities, by combining images that originally were not meant to stand together; to take apart, leave out, bring together. I feel that the layering reveals complexities and contradictions—things that makes us human, but which often are denied Black people within Western discourses.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can I ask if you’re thinking principally of the liberation of the depicted figures? (And I guess we’d center here on the faces of the figures.) This idea of liberation through archival practices of reassembly brings to mind a broader set of intellectual, theoretical, and artistic practices of fabulation. But is the liberation yours personally, as well as that of the depicted figure, as you construe the effects of collage?

Orupabo: Liberation might be a strong word, but it is how it feels when working on something. I feel totally free. Just like bell hooks has described her relationship with theory—seeing it as a place of belonging, and healing—I would describe my relationship to my own work the same way.

I am not only speaking about the finished collage (what it addresses or questions), but the whole process of getting there. It’s about my own lived experience and truth, which of course cannot be separated from the political. Or, as Grada Kilomba has said, “My biography theorizes something.”

I don’t think I would say that I am liberating the depicted figures. I would rather say I am trying to recontextualize the images.

Frida Orupabo, Baby in belly, 2020. Collage with paper pins

Frida Orupabo, Baby in belly, 2020. Collage with paper pinsCourtesy the artist and Stevenson Gallery, Amsterdam, Cape Town, and Johannesburg. Photograph by Mario Todeschinini

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I’m drawn to the hybridity of your figures, whom I would tentatively describe as Black women—tentatively, because it’s clear that your figures are assemblages of multiple bodies, and that there’s an element of gender nonconformity at play that exceeds the cisgender frame of womanhood. But in thinking about Kilomba and also a kind of hybridity of personhood grounded in Blackness and Black histories, I hear echoes of Hortense Spillers from her essay “Interstices: A Small Drama of Words ” [2003], in which she writes:

A feminist critique in the specific instance of sexuality would encourage a counter-narrative in pursuit of the provenance and career of word- and image-structures in order that agent, agency, act, scene, and purpose regain their differentiated responsiveness. The aim, though obvious, might be restated: to restore to women’s historical movement its complexity of issues and supply the right verb to the subject searching for it, feminists are called upon to initiate a corrected and revised view of women of color on the frontiers of symbolic action.

It seems to me that you’re also actively engaged in the field of symbolic action, and concerned with Black grammars of personhood, so I wonder if you could talk more about how you think about figuration, agency, the “scene” your work constructs—perhaps in relation to the work’s exhibited forms.

Orupabo: The gaze is important to me, and I see it as linked to agency. I am, for the most part, working with images where the subject gazes directly at the spectator, which (hopefully) makes possible an internal dialogue—engaging people to pose questions like “What do I see?” and “Why?”

You mentioning Spillers made me think of something bell hooks wrote concerning the white feminist movement—that they made woman synonymous with white women and Black synonymous with Black men. Black women were made invisible (or hypervisible). To be white is to be neutral—it defines normality—while everything else is othered and racialized.

I revisited hooks’s writings recently and came across a conversation she had with Carrie Mae Weems [in Art On My Mind: Visual Politics (1995)], where Weems posed the question of whether it is possible to use Black subjects to represent universal concerns, which is something I think about often. I think this question has a strong presence in the process of making, shaping, and also placing my work within a gallery context—like, how to create complex narratives and identities that oppose and break with stereotypical ideas of what it means to be a Black woman.

And so, the twisting of limbs, the gaze, the different bodies and body parts is, for me, an attempt to escape these really narrow and violent understandings or discourses of who I am or who we are.

Related Items

The Lives of Images, Vol. 1: Repetition, Reproduction, and Circulation

Shop Now[image error]

Paul Pfeiffer on the Transformative Effects of the Pop Culture Image

Learn More[image error]

The Lives of Images, Vol. 2: Analogy, Attunement, and Attention

Shop Now[image error]Wolukau-Wanambwa: Right. Weems says that “Black images can only stand for themselves and nothing more,” implying that they are unable to “create a cultural terrain that we watch and walk on and move through,” as she puts it—that they cannot be universalized as a or our general field. hooks then goes on to distinguish between confrontation and contestation, which reminds me of the level gazes of your figures, gazes I’m considering in this context as a contestation of the programmatic invisibility of Black femininity.

But I imagine that for you, the figures, and Black femininity, cannot ultimately only be grounded in negation—that a whole rich spectrum of Black life lies on the other side of this erasure. I sense that in Untitled [2018], which develops a theatrical scene on which Black women at once attend to small white children in one section of the image, but also wrestle among themselves in leotards behind tree trunks at the other end of the stage.

Can you talk about the visual dramas you create in this context of creating “a cultural terrain that we watch and walk on and move through”?

Orupabo: I like this image. It still interests me—probably because of the composition, as well as the different subjects involved. In a way, they are recognizable (as far as being linked to a specific time and place), but because they are all thrown into the same frame, things are getting more interesting or complex. Past and present are intertwined. The same can be said about their lives. It’s a quiet image, but also very violent. It’s as if they are all there trying to convey their own lived experiences and truths.

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2019. Collage with paper pins mounted on aluminum

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2019. Collage with paper pins mounted on aluminumCourtesy the artist and the Maxi and Christian Broecking collection. Photograph by Gerhard Kassner

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can you talk a little more about how you approach making these images, where collaged figures are embedded on top of continuous background scenes? Do you think of or approach these images differently?

Orupabo: Yes, absolutely. I do think about them differently. For instance, they differ from the collages which are, more often than not, portraits of people alone in a frame with a white background or alone floating on a wall (usually a white wall). It adds a narrative or an emotion that I am interested in exploring. For instance, it can be used to say something about belonging—who belongs where and why. That further can speak to not only misrepresentation but also the erasure of Black people’s presence in paintings, photographs, films, etc. And with that, they can be seen as a more direct way of “writing oneself in,” as Octavia Butler and so many others have stressed—to write oneself into a history that has mainly been male, white, and heteronormative.

But they also differ in that I usually make them when I am not working toward something specific. In a way, they are more for me, and therefore a bigger liberty is involved when making them, because I don’t spend time fixing the resolution and so on. They are, in a way, meant to stay small and live inside my computer.

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2017. Collage with paper pins

Frida Orupabo, Untitled, 2017. Collage with paper pinsCourtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin, Stockholm, and Mexico City

Wolukau-Wanambwa: That’s intriguing. I wonder if you could say something about how your Instagram account, @nemiepeba , fits within your artistic practice, but also outside of or unrelated to it. What does the platform afford you, and how do you interact with those that follow you there?

Orupabo: I started my account out of a need to find a space where I could just post images and be quiet and anonymous. It was the perfect “working” environment—a small group of friends and family applauding me quietly from the sidelines, plus some people I didn’t know. It made the platform safe, and I didn’t feel too watched—considering my profile was public.

I have always interacted with people in some way or another on Instagram—mostly with people I already know. But most of the time when I’m there, I am just looking for things, grabbing, downloading, screenshotting, liking, and posting. It used to be a platform where you could also see what other accounts liked and commented on, so IG was (more then than now) a resource to find material for my collages. Though I will say, it is both a medium used to create something apart from it and an artistic practice in itself. It’s hard to draw a line or to separate the two.

This interview was originally published in The Lives of Images, Volume 2: Analogy, Attunement, and Attention (Aperture, 2021), the second in a six-volume set of contemporary thematic readers.

Register for The Lives of Images Symposium Series (November 30–December 2, 2021), presented by Aperture and ICP, featuring conversations with Ariella Azoulay, David Campany, Sarah Cervenak, Saidiya Hartman, Tom Holert, Thomas Keenan, and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa.

November 12, 2021

Announcing the Winners of the 2021 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of the 2021 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. From the thirty-five shortlisted, a final jury in Paris selected this year’s winners. The jury included Aurélien Arbet, founder and creative director, Études; Daniel Blaufuks, visual artist; Taous R. Dahmani, art historian and author; Fannie Escoulen, head of the photographic department, Ministry of Culture, France; and Tatyana Franck; director, Photo Elysée.

Final juror Taous R. Dahmani commented that the jury chose “books with strong narratives that were able to find the right forms for the stories they were telling; up-and-coming image makers surprising us with transatlantic stories, highlighting the things we have all been missing over these last few difficult years—families and communities, parties, traveling, and being able to connect with each other. Importantly, the selected winners present strong individual investigations and artists whose stories have been untold, using the book form to disseminate those voices more widely.”

All shortlisted and winning titles are profiled in The PhotoBook Review, a newsprint publication that accompanies the Winter 2021 issue of Aperture magazine. As well, an exhibition of the thirty-five books shortlisted for the 2021 PhotoBook Awards is currently on view at Paris Photo and will travel to Printed Matter in New York City, January 20–February 27, 2022.

Below, read more about this year’s winning titles.

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year

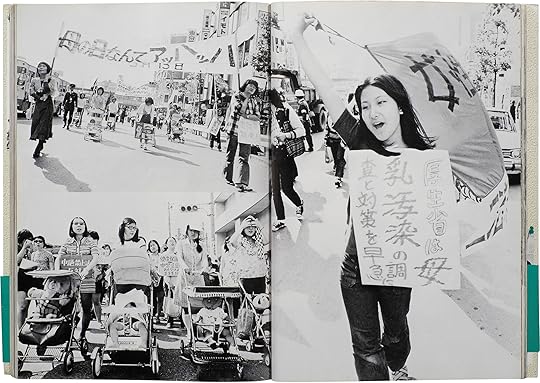

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999

Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, eds.

10×10 Photobooks, New York

The winner of the Photography Catalogue of the Year, What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999 by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, features a selection of 250 photobooks, including traditional publications (from landmark titles to largely unknown works), as well as items not generally considered “books”—portfolios, personal albums, scrapbooks, and zines. Final juror Fannie Escoulen commented that this project is important to recognize for its “extensive, original research and the contributions it makes to the history of photography,” noting that the photobook is historically grounded in the production of a female photographer, Anna Atkins. “In What They Saw, the design, the research and discoveries come together to make a great book,” Escoulen concluded.

From What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999 by Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, eds (10×10 Photobooks, New York)

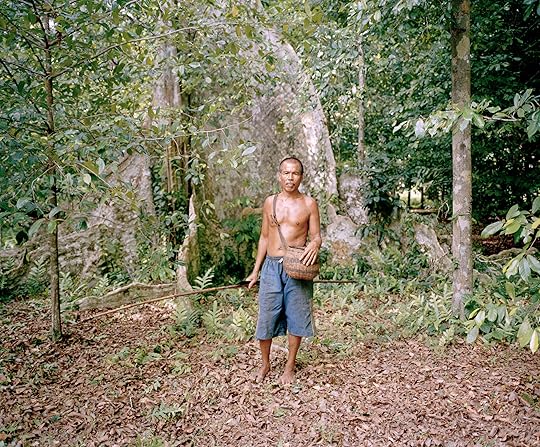

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year

Muhammad Faldi and Fatris MF

The Banda Journal

Jordan, jordan Édition, Jakarta Indonesia

The winner of the PhotoBook of the Year Award, The Banda Journal, by photographer Muhammad Fadli and writer and folklore enthusiast Fatris MF, presents the little-known story of the Indonesian Banda Islands, a tiny archipelago that has served an outsize role in global trade and the modern economy. Through incisive and engaging storytelling, the book connects a seemingly distant and brutal past with its contemporary consequences on the islands today.Final juror Daniel Blaufuks noted that, “The Banda Journal is very well-designed; very engaging—a book in which text and image are expertly intertwined, inviting return viewing and reading—and that offers us new perspectives from a region we don’t often have the opportunity to hear from artistically.”

Muhammad Fadli from The Banda Journal

Courtesy the artist

Winner of First PhotoBook

Sasha Phyars-Burgess

Untitled

Capricious Publishing, New York

The winner of the First PhotoBook Award, Untitled by Sasha Phyars-Burgess, was selected by the jury as a prime example of the fresh perspective mentioned by Dahmani. As a first-generation American born to Trinidadian parents, Phyars-Burgess explores her heritage and its complicated history through photography. Her images are by turns gentle and meditative, expressive and energetically vibrant. Shortlist juror Darius Himes noted that this book “takes a position, states an opinion, and doesn’t pull any punches.”

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, from Untitled

Courtesy the artist and Capricious Publishing

Juror’s Special Mention

Vasantha Yogananthan

Amma

Chose Commune, Marseille, France

The final jury also chose to award a Jurors’ Special Mention to Amma by Vasantha Yogananthan, the final volume of A Myth of Two Souls, a seven-book series the artist started in 2016. In the series, Yogananthan intervenes and reinterprets the Ramayana, creating his own modern retelling of this classic Hindu epic tale. Final juror Tatyana Franck highlighted the overall project as “a very persuasive, visionary, and committed journey by the artist; one which employed a wide range of materials, formats, and approaches to storytelling over the life of the book series”—all of which is clearly manifest in this latest offering, Amma.

Vasantha Yogananthan, The Fishermen, Danushkodi, Tamil Nadu, India, 2013, from Amma

Courtesy the artist

Vasantha Yogananthan, Sea Of Trees, Valmiki Nagar, Bihar, India, 2014, from Amma

The 2021 Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Exhibition opens on January 20, 2022 at Printed Matter, New York.

November 9, 2021

Aperture Establishes First-Ever Endowment through $1 Million Matching Grant from the Andrea Frank Foundation

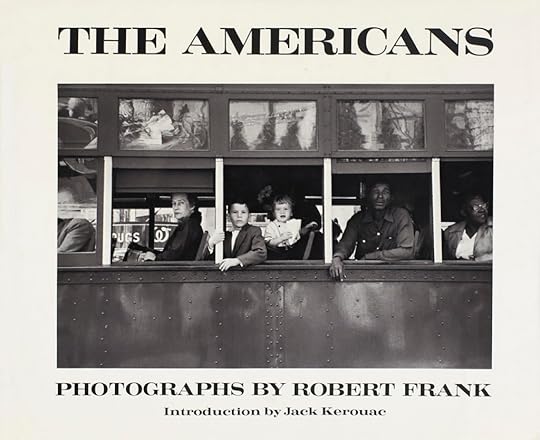

On November 9, the birthday of the late artist Robert Frank, Aperture announces the establishment of its first-ever publications endowment through a landmark $1 million matching grant from the Andrea Frank Foundation (AFF), dedicated to continuing Aperture’s nearly seventy-year history of supporting photographers and expanding conversations around the medium of photography. The grant is one of the biggest donations in Aperture’s history, one that will further and significantly strengthen Aperture’s position at the forefront of photobook publishing in the United States and internationally.

In conjunction with the grant, AFF and Aperture will collaborate on a new edition of Robert Frank’s formative photobook The Americans, to be published in 2024, the centennial of Frank’s birth. The new edition will be created in close collaboration with AFF, using scans made from a complete set of Robert Frank’s own prints. The new edition extends Aperture’s longstanding history with the series, most notably its 1968 edition of The Americans, copublished with the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and a subsequent edition released in 1978.

“We are humbled and inspired by this signal of confidence in Aperture’s future,” said Sarah Meister, executive director of Aperture. “This transformative gift will allow us to expand the ways in which we are able to elevate emerging voices in the field. In assuming responsibility for the publication of The Americans, we are able to foster connections between this landmark achievement and similarly original, ambitious photobooks for generations to come. It is equally pivotal that the impact of AFF’s support is amplified by challenging the rest of our donor community to match this level of funding. We are honored that AFF has entrusted us with the incredible responsibility of publishing The Americans for the centennial of Frank’s birth, and for AFF’s confidence in the future and enduring impact of Aperture for decades to come.”

Cover of The Americans (Aperture/MoMA, 1968)

Cover of The Americans (Aperture/MoMA, 1968)First published by Delpire in France in 1958, The Americans was released in English a year later by Grove Press, with an introduction by Jack Kerouac. In his characteristically spontaneous prose, Kerouac compared Frank’s photographs to an epic poem, and presciently suggested its effect on the culture: “What a poem this is, what poems can be written about this book of pictures some day by some young new writer high by candlelight bending over them describing every gray mysterious detail.”

The Americans has influenced generations of photographers around the world and became the subject of a major exhibition, Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans, presented in 2009 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and traveling to New York and San Francisco. Aperture honored Robert Frank in 2014 at the foundation’s gala celebrating The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip, a best-selling photobook about journeys and the freedom of the road in US photography, from Frank to Justine Kurland, Stephen Shore, and Alec Soth.

Frank’s revelatory sequence of eighty-three photographs, made with the support of a Guggenheim Fellowship throughout his ten-thousand-mile road trip across the United States, has become a touchstone. “The Americans challenged the presiding midcentury formula for photojournalism, defined by sharp, well-lighted, classically composed pictures, whether of the battlefront, the homespun American heartland or movie stars at leisure,” Philip Gefter noted in the New York Times in 2019. “Mr. Frank’s photographs—of lone individuals, teenage couples, groups at funerals and odd spoors of cultural life—were cinematic, immediate, off-kilter and grainy, like early television transmissions of the period. They would secure his place in photography’s pantheon.”

November 4, 2021

Awol Erizku’s Surreal Visions of Africa and Its Diaspora

In Awol Erizku’s Jaheem (2020), an African mask is engulfed by fire, an orange-white burn so totalizing that the lapping flames light the steel-mesh fence against which the object is set. Energizing in every sense, Jaheem is a singular image, but the picture also coheres many of the aesthetics and subjects characteristic of Erizku’s multivalent conceptual photographic practice: Africa and its diaspora; the mystical, the spiritual, and the surreal; creation both natural and cultural. High saturate color. Luminosity. Heat.

Awol Erizku, Fit it, critic, get it, hit it, run it, drill it, wet it, I’m in it, really. Split it fifty-fifty. Ball, Reggie. Ready, set, go!, 2021

Awol Erizku, Jaheem, 2020

Fire is not seen but implied in Quotidian Drip (2018–20), the scene bathed in a warm orange, near-red, glow. A still life, the work demonstrates Erizku’s open yet refined embrace of wide-ranging cultural reference points. Leather loafers—one shoe propped up on bricks—meet a Stanley-brand measuring tape, stacks of crisp Benjamins, a single rose stem in a clear vase, alongside a half dozen other dissimilar items. In one art-historical sense, this assemblage can be understood as purposefully nonsensical, engaging traditions of Dadaism and Surrealism. A photographic scrim that a C-clamp would conventionally clasp gets enigmatically replaced by an Ashanti “Akuaba” fertility doll. Behind it, a maneki neko, “lucky cat,” peeks out from behind a jar. To stop at the absurd, however, would risk occluding the ways that Erizku’s arrangements are constructed with intentions toward meaning-making of a kind. The unconventional construction visualizes the syncretism and multiplicity characteristic of contemporary global life, and, perhaps, especially Black creative life: leather, flowers, dollars, labor. At the same time, through selection, placement, and staging, these stable (and ofttimes staid) referents and symbols are cracked open and made anew both ontologically and aesthetically. There is no single reading of any object or juxtaposition, each unfurling along unending chains of signification. A bumblebee is a sartorial flourish . . . an ecological touchstone . . . a simple flash of gold.

Awol Erizku, Quotidian Drip, 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Quotidian Drip, 2018–20This persistent signification is especially true in the case of Erizku’s treatment of cultural objects from the continent. In Quotidian Drip, the faint profile of the Queen Nefertiti bust—ubiquitous within the Western imaging of African cultural import—is enclosed within a semitransparent jeweled cube. Barely visible but resolute, she is both familiar cultural referent and distanced glistening form. In Love Is Bond (Young Queens) (2018–20), Nefertiti is again present, with a quintet of young Black girls encircling a pedestaled bust of the royalty, while playing ring-around-the-rosy. In Erizku’s imaginings, Africa is not only ancient but also mythical, technical, experimental, futurist, innovative, (e)strange(d).

Awol Erizku, Moon Voyage (Keep Me in Mind), 2018–20

All photographs courtesy the artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts, London

Awol Erizku, Untitled (Orchid #9), 2021

It is also cosmic. In Moon Voyage (Keep Me in Mind) (2018–20), a picture that features two individuals in a ballroom- like embrace, a female figure wears what appears to be a stylized African mask pigmented in blue. Her silk dress and arm-length gloves bring tradition to the image, while the mask presents an electrifying portal to the mythological alien. The energy powering Moon Voyage is not solar but lunar, a green celestial light under which the two dance. But even without fire, the same sensibility that guides work such as Jaheem is present here, as it is in all of Erizku’s still lifes, portraits, and tableaux. It is an approach marked by intuition, style, history, and opacity. A reverence and a confidence. Heat.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “Awol Erizku: Mystic Parallax.”

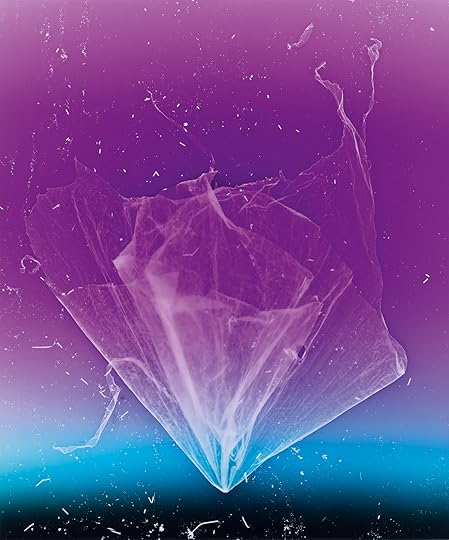

The Artist Creating Ethereal Photograms from the River Thames

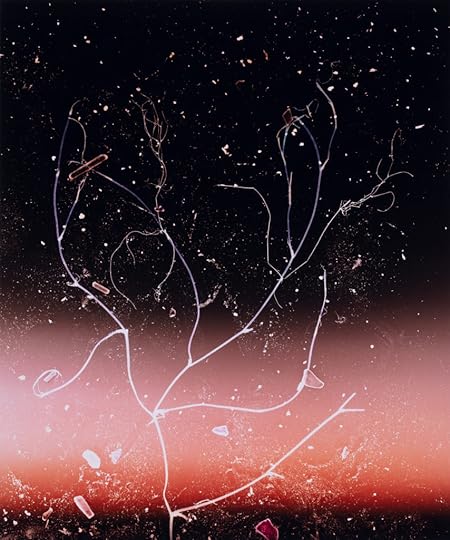

Soft color fields, obscure chemical compositions, hazy space photographs—Anne Hardy’s recent work presents us with evocative photograms that oscillate between the concrete and abstract, between the real and the fantastical. The hard-to-define images move gradually from an inky black to bright hues. Their color palette ranges from cool blue and turquoise tones to warm reds and orange tints, conveying an alternation between coolness and heat, or—as the title of one image suggests—the “rising of heat.”

Anne Hardy, Simultaneous Reality, 2020

Anne Hardy, Simultaneous Reality, 2020The photograms are based on encounters with light and small objects that Hardy gathered from the foreshore of the River Thames while she was working on her 2019 commission for Tate Britain, The Depth of Darkness, the Return of the Light. The large-scale, dystopian installation transformed the museum’s neoclassical façade into an abandoned building decorated with fairy lights, ripped banners, and a rhythmical cascade of objects. The dark, mystical aesthetic was accompanied by a soundscape that used elements recorded at the river.

Anne Hardy, Descent, 2020

Anne Hardy, Call Sign, 2020

Hardy’s first photograms came into existence in 2015, when she was working on an exhibition at Modern Art Oxford. Using leftover materials and dusty debris swept up from the studio floor, she made a series titled Process Photograms that is comparable to the photograms of The Depth of Darkness, the Return of the Light in its atmospheric aesthetic. Through intuitive as well as highly controlled alchemical darkroom processes, Hardy composed her recent photograms during lockdown. London, usually bustling and busy, showed its vulnerability and was forced to stand still. Against this background, the link of the photograms to Hardy’s immersive Tate work seems particularly fitting, as the installation was essentially, according to Hardy, “about a point of collapse and fragility and what might spring from that as a result.” The Thames debris can be viewed as a sad representation of the extreme threat we humans cause the planet, which is gradually heating up. It symbolizes countless untraceable people and their long-lasting impacts on the earth, linking different times and spaces.

Related Items

Aperture 244

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Awol Erizku’s Surreal Visions of Africa and Its Diaspora

Learn More[image error]However, The Depth of Darkness, the Return of the Light is a multilayered photogram series that references the micro as much as the macro, the tangible outside as much as the intimate inside, physical space as much as perception, the conscious as much as the unconscious. The fragments from the river convey an infinite planetary aesthetic, and real objects suggest fantastical images. Asked about these relationships and transformations, Hardy has stated: “I’m interested in the ‘gap’ between what you call the concrete and the abstract as a productive space of reencounter and imagination, in which knowledge or certainty becomes more tenuous. . . . The micro and infinite seem interchangeable to me. It’s all about your perception and what scale of measurement you decide to apply—the same systems and energies are at work.”

Anne Hardy, Rising Heat, 2020. All works from the series The Depth of Darkness, the Return of the Light

Anne Hardy, Rising Heat, 2020. All works from the series The Depth of Darkness, the Return of the LightCourtesy the artist and Maureen Paley, London

Whether the atmospheric photograms are viewed as depictions of tiny river objects or as fantastical space images, the series draws attention to time and its endless cycles of transformation, as reflected in titles such as Rising Heat or Into Darkness. Hardy herself stresses the potential of change. In the soft forms and bright colors of her photograms, there is a sense of postapocalyptic magic that turns old waste into new, beautiful art.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the title “Anne Hardy: Return of the Light.”

October 28, 2021

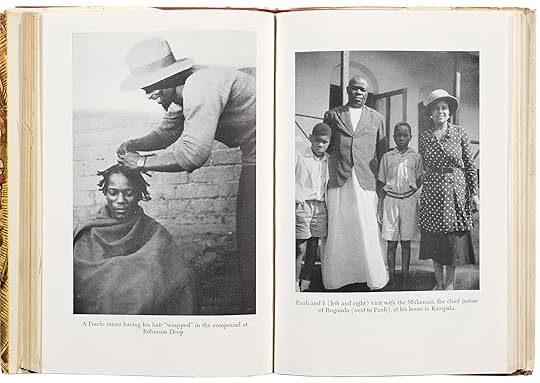

How Autograph’s Photobooks Champion Black British Photography

If you step out of the tube station at Old Street, in London’s East End, and wander the narrow lanes of Shoreditch, with their chic gastropubs and boutique hotels, you might suddenly find yourself in front of an inviting yet commanding building, its slate gray and glass distinct from the nineteenth-century stock brick of the neighborhood. Rivington Place, as it’s known, was built by David Adjaye in 2007, and it’s the home to Autograph, the influential organization that supports Black photographers through exhibitions and publishing. Founded as an agency in 1988, Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers) intended to advocate for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) artists by commissioning new work and producing traveling exhibitions. Publications, especially artists’ monographs, were central. “The model was massively ambitious,” Mark Sealy, the longtime director of Autograph, recalled this spring, speaking over Zoom from his house in South London. “The aspiration for publishing was always on the table.”

Among Autograph’s most influential titles are monographs by the late Rotimi Fani-Kayode (an Autograph founder), Omar D, Joy Gregory, Youssef Nabil, Yto Barrada, Syd Shelton, and Sunil Gupta. Autograph has collaborated with the Power Plant and the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto, and the Photographers’ Gallery in London, on major group exhibitions and studies of historical archives. One measure of Autograph’s sustained, thirty-year commitment to the visibility of Black artists, and the centering of identity and human rights, is its reverberation in establishment British art museums. A decade before Zanele Muholi’s solo show at Tate Modern and James Barnor’s at the Serpentine Galleries, Autograph presented exhibitions by both photographers; before Barrada and Gupta were renowned internationally, they worked with Autograph. Sealy knows about the long game: he spent much of his career, as a scholar, curator, and arts leader, trying to convince cultural institutions of the importance of diversity. It’s why Autograph’s elegant gallery and offices on Rivington Street—which represent the manifestation, in the form of a publicly funded arts building, of the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s ideals about difference and belonging—will welcome you, and challenge you.

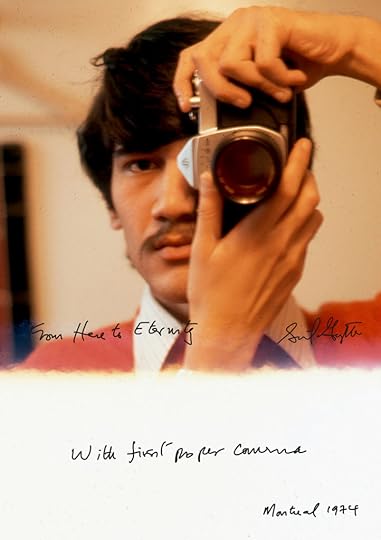

Cover of Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity (Autograph ABP, 2020)

Cover of Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity (Autograph ABP, 2020)Brendan Embser: In the 1980s, when the people who started Autograph were getting going, were there any publishers in the UK who were regularly putting out monographs or studies of Black image makers?

Mark Sealy: There were one or two. Some photographers had got their act together to self-publish. Armet Francis, for example, had published his book The Black Triangle [Seed, 1985]. And Clement Cooper had been published by Cornerhouse Publications. Rotimi Fani-Kayode published his monograph Black Male/White Male [1988] with Gay Men’s Press. But there was certainly a gap there to be filled.

Embser: Was there a culture around photobooks? For example, for Black American photographers, specifically, there is an iconography that emanates from The Sweet Flypaper of Life [Simon & Schuster, 1955]. In the UK, were there any similar books that held the same power for Black British artists?

Sealy: For me, it was Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage [Random House, 1967]. In the UK, we were much more focused on what was happening in South Africa, especially in the ’80s, with the ANC, the demonstrations in Trafalgar Square every day, with the popular culture being really aligned with the ideas of people like Steve Biko and Nelson Mandela, who was still in jail. Sweet Flypaper was in the conversation, absolutely. But to actually see it, to get hold of it, I don’t think I actually saw an original copy in the flesh until I knew what I was looking for—it was not something you could find with ease.

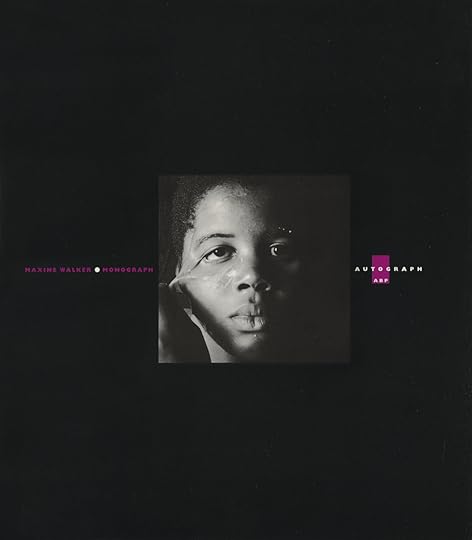

Covers of Eileen Perrier and Maxine Walker (Autograph ABP, 1999)

Embser: Autograph began publishing books soon after the organization was founded. Were books a way to allow projects to travel beyond the space of an exhibition?

Sealy: The most important thing that we did was publish. I always thought that publishing was kind of the cherry, the golden fleece of a cultural organization—if we could get there, in a meaningful way. I was very keen to make sure that everything had an ISBN, because if they have an ISBN, you legally have to register them with the British Library: it lives forever, rather than the ephemeral nature of an exhibition coming up and down and being left with an invite card and the memory of people, or a review.

It was very difficult to go out into the world and sell exhibitions in London, Manchester, or Liverpool, of Black photographers’ works, because the answer would be, “It’s not very good,” or, “We don’t have an audience for that,” or “Why would we do it?” It was very, very derogatory in terms of the reception of the work. So the book was a way of at least, then, syndicating their work—get them out there, and then they’ll become alive in the world.

Embser: It’s interesting that you emphasize the ISBN, because I was able to find Autograph’s books on WorldCat and Amazon because of that—they exist in the tentacles of the internet as a result of this data that you entered early on.

Sealy: Yeah, thank God.

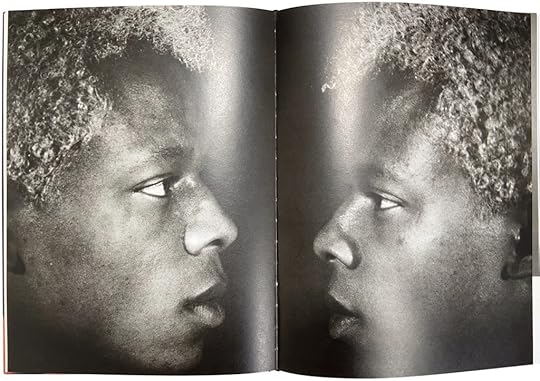

Maxine Walker, Cleansing, 1991, from the series Black Beauty

Maxine Walker, Cleansing, 1991, from the series Black BeautyCourtesy the artist and Autograph, London

Embser: In the late ’90s, Autograph did a number of small monographs that were between twenty or thirty pages each, for example, by Eileen Perrier and Maxine Walker [both 1999]. Were those small books among their first artist publications?

Sealy: Absolutely. In many instances, that monograph series, I think, is really important. I think that is one of the first monograph series dedicated to Black photographers.

Embser: And did those publications often arise on the occasion of an exhibition that Autograph had organized, or were they separate initiatives?

Sealy: Often it was just, “You’ve got enough work, let’s do it.” Or we would commission a new body of work and find a permanent way to record it.

Yto Barrada, Ceuta Border, Illegally Crossing the Border into the Spanish Enclave of Ceuta, Tangier, 1999

Yto Barrada, Ceuta Border, Illegally Crossing the Border into the Spanish Enclave of Ceuta, Tangier, 1999Courtesy the artist and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Embser: Can you talk about the range and aesthetic of Autograph’s books? You have exquisite artists’ books, for example—I have a copy of Yto Barrada’s A Life Full of Holes / The Strait Project [2005].

Sealy: Oh, yeah, keep that.

Embser: Apparently it’s five hundred dollars on Amazon!

Sealy: I thought Yto’s look at the whole issue of migration in the Maghreb, in Morocco, of “the burnt ones,” was such a powerful project. But also, done through a lens of ennui, a nation’s depression. And in many ways, the book launched that body of work.

Spread from Rotimi Fani-Kayode & Alex Hirst: Photographs (Autograph ABP and Revue Noire, 1996)

Spread from Rotimi Fani-Kayode & Alex Hirst: Photographs (Autograph ABP and Revue Noire, 1996)Embser: Rotimi Fani-Kayode and Alex Hirst: Photographs [1996] was copublished by Revue Noire in Paris. How did this book come about?

Sealy: Rotimi died in ’89. Alex, his partner, was looking after the estate, but he died of AIDS in 1992. I made a solemn pledge that I would advocate for the work and try and bring it into the public sphere, in the best possible way we could. I was lucky enough to meet the guys at Revue Noire—Simon Njami and Jean Loup Pivin—who also appreciated the work. They saw Rotimi’s radicality as a queer African guy, and they really appreciated that. And that was good. They wanted to invest in the politics of that transgressive relationship. Which, of course, they identified with as well, for personal, cultural, and political reasons. You know, what’s interesting for me, when we talk about diversity in our institutions and all that stuff? It really is just to do with the people in the room. If people get it, then we get it.

Embser: Absolutely.

Sealy: If they’re not in the room, then we have to sell so much and work so hard just to try and have the conversation, right? The moments of success for Autograph happened because sometimes the people in the room kind of got it, you didn’t have to work so hard. When you literally fight for visibility, what are you doing? That sense of urgency gets interpreted as anger, and it’s wrong, because it’s not. It’s to do with, do you get the urgency of what we’re trying to talk about here? And it’s thirty years of that sense of urgency, and we go round in circles. And we’re in another cycle now, which is interesting. I’m hoping that with each turn, the turn gets easier, or a bit faster, so that things can change. I think publishing is part of that, helping people. That’s why Sweet Flypaper is so important, that’s why House of Bondage is so important. That’s why Rotimi’s book is so important.

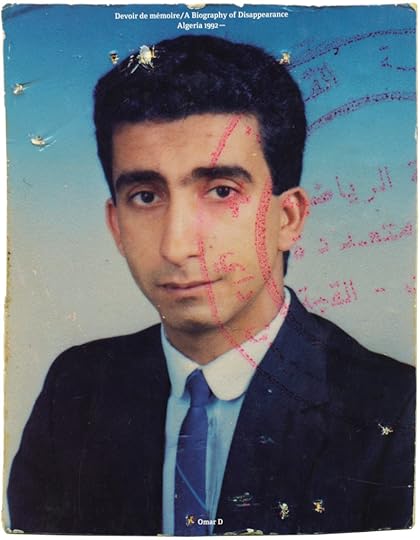

Cover of Omar D, Devoir de mémoire / A Biography of Disappearance, Algeria 1992– (Autograph ABP, 2007)

Cover of Omar D, Devoir de mémoire / A Biography of Disappearance, Algeria 1992– (Autograph ABP, 2007)Embser: In addition to artist monographs, Autograph has also published compendia on really difficult, hard-hitting issues around human rights. Why is copublishing important for these kinds of research-based projects, where you bring together lots of ideas, some of which will be challenging for audiences?

Sealy: Human Rights, Human Wrongs [2013] was the result of three years working in the Black Star Collection at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto. I wanted to try and make a case for how awkward the archive is, in terms of documentary photography concerning the image of the Black subject. Always framed, always debased. And it was great that a university gallery could try and understand that conversation, which was nuanced and difficult. As we develop a project, the ideas do need to be encapsulated beyond the show.

With a copublishing project, you share the risk in terms of the investment. You can do much more in partnership. You can take a thirty-thousand-pound production, and it’s fifteen each. Sammy Baloji and Filip De Boeck’s book Suturing the City [2016], for example, has about four or five different stakeholders in there. There’s his gallery, there’s the Power Plant, and the dealers; they invest in it, they get their amount of copies. But Autograph was the publisher, and we thank them very much for supporting it. And sharing that, sharing that risk means things can happen.

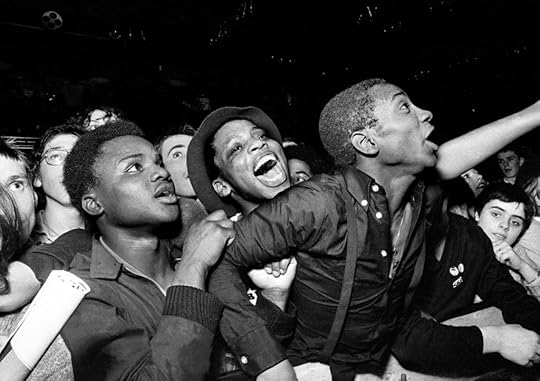

Syd Shelton, Specials Fans, RAR Carnival Against the Nazis, Leeds, 1981

Syd Shelton, Specials Fans, RAR Carnival Against the Nazis, Leeds, 1981Courtesy Autograph, London

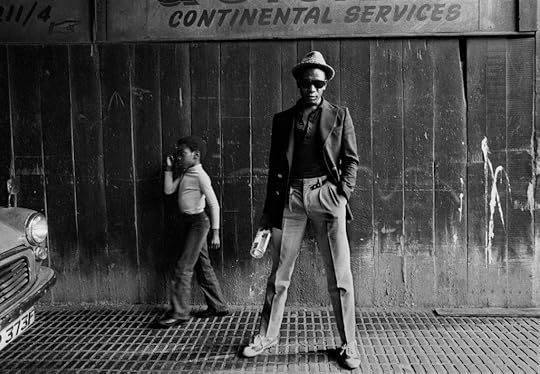

Syd Shelton, Bagga, vocalist with Matumbi, Hackney, London, 1978

Syd Shelton, Bagga, vocalist with Matumbi, Hackney, London, 1978Courtesy Autograph, London

Embser: There’s a sense of idealism with Autograph’s publishing, but also perseverance, trying to get stories into the world. How does this extend to marketing?

Sealy: We sell things directly. We don’t distribute in a really aggressive way. We often do around about a thousand copies of a book, and the idea is that they’re not really made to make money. If they make money, that’s great, and they often do. Like, for example, Lina Iris Viktor’s book Some Are Born to Endless Night—Dark Matter [2020] is sold out. Syd Shelton’s Rock Against Racism [2015]—off, gone. We could reprint them, but that’s not the purpose. The idea is to just get them circulated, get them out there. And they’re great success stories, you know?

Lina Iris Viktor, We are the Night—The Keepers of Light, 2015–19

Lina Iris Viktor, We are the Night—The Keepers of Light, 2015–19Commissioned by Autograph. Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London

Embser: What are a few of your favorite Autograph titles, either because they’re really beautiful, or because you know that they’ve had a lasting impact—you see them on your shelf, and it just fills you with joy or pride?

Sealy: I enjoyed watching the impact of Yto’s book; that was very nice. Sunil Gupta’s recent book on his ephemera From Here to Eternity [2020] is beautiful. But I don’t think there’s any particular one that I would champion. In that series, the artists do such different kinds of work. One of the things I try and do at Autograph is to talk about Blackness as a politically conscious space. I can’t help but think how divisive racial politics are, and the labeling of BAME (Black, Asian, and minority ethnic), and how things get segregated. I always wanted to build an inclusive conversation around consciousness and thinking, and I still think that one of the few frames by which I can join the dots across that thinking is the lens of human rights.

This piece originally was published in Issue 019 of The PhotoBook Review.

October 27, 2021

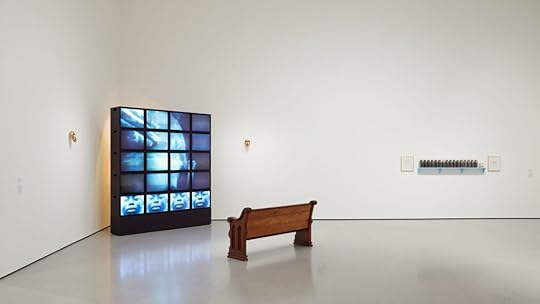

A Prolific Video Artist’s Infinite Screens

The opening to the mirror box is a gilded frame through which viewers can watch a kaleidoscopic film. Titled Brave New World (1999)—versions of which have been installed in exhibitions in Washington, D.C., Rome, and New York—the film is “a very simple idea but very effective,” as one viewer says to Theo Eshetu, its creator. You poke your head into the mirror box where the film is playing, and where, given the continuous loop of bisymmetrical clips, you get the illusion of being surrounded by seemingly endless reflections of yourself as you watch. Filmed with a Super 8 camera, the footage is looped together from a thrilling array of sources, including a ceremony of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, a commercial for an Italian insurance company, and enchanting images of dancers in Bali. “The idea is that it sort of creates an image of the world, no?” Eshetu asks a mesmerized viewer as they both stand in front of the mirror box, observing its fantastical twists. He is proposing an image of the world tripled or quadrupled many times over, so that what is seen is not simply illusory but infinite and indeterminate, as though gathering the entirety of the world’s faces into a single orb.

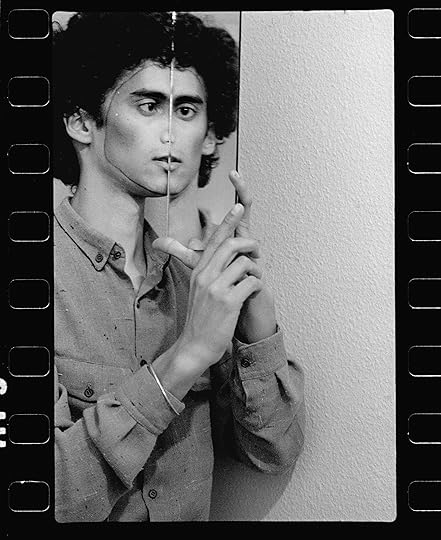

Theo Eshetu, Self-Portrait, 1975