Aperture's Blog, page 51

September 7, 2021

The New Era of South Asian Photography Festivals

On February 12, 2021, Chobi Mela, a biennial photography festival in Dhaka, Bangladesh, launched its Shunno or Zero edition. The statement accompanying the title read that it “raises essential questions about its own purpose.” Mounted amid a global pandemic, via this “self-reflective edition,” the festival asked a pertinent question: “Is art in any way relevant any more to a time of endless loss of life and livelihood?”

Since last year, an invisible force—one that has raged and ravaged through lives and communities—connected individuals across the world. While the manner in which we have been impacted and the protections that we have been afforded have been a reflection, to an extent, of our independent privileges, the virus, at different times, has managed to bring the entire world to a standstill. As I spoke with the founders and directors of three photography festivals in South Asia, a sentiment that emerged was the need to slow down and reflect. In this time of overwhelming personal as well as collective grief, the forced pause on our trajectories has sprouted reckonings—some that had been in a slow churn before and others that responded intuitively to this moment.

Salma Abedin Prithi, Untitled, from the series Torn, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. The artist’s work was featured in Chobi Mela, 2021

Salma Abedin Prithi, Untitled, from the series Torn, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. The artist’s work was featured in Chobi Mela, 2021Courtesy the artist

Tanzim Wahab of the Bengal Foundation, who took over as Chobi Mela’s festival director from photographer-activist Shahidul Alam in February 2019, spoke to me about this pause, while elaborating on the title for their latest edition. He sees Shunno as a vacuum that is both “philosophical and spiritual,” essential to “restarting from ground zero,” allowing a space to rethink, unlearn, and recalibrate. For the longest-running major photography festival in South Asia, founded in 2000, this would have been its eleventh edition. However, the festival team decided to position it as a bonus edition, one which was “baggage-free” from the expectations that a legacy of two decades may impose on it in a pandemic year. “We just wanted down-to-earth engagement of people, where people can freely experiment with the form, with the medium, and also with their content. Where they can strategize. They can also make some mistakes,” Wahab said, terming this edition “a star in the sky,” one that would “contextualize time” but will not be counted as the eleventh iteration.

This reconfigured thinking about the form of a festival resonated with others in the region. NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati, festival director of the biennial Photo Kathmandu, Nepal’s first and only international photography festival, has been thinking through the relevance of a festival format since its inception. Photo Kathmandu launched in 2015, the year Nepal was struck by a devastating earthquake, and Kakshapati was conscious of the timing of the festival in that critical year, and of the dilemma of spending resources on an arts-based event when over nine thousand Nepalis had lost their lives and thousands of others had their homes destroyed. Kakshapati, along with members of photo.circle, a self-described “platform for photography” based in Kathmandu that she cofounded, were themselves involved in relief efforts in the aftermath of the earthquake. “That year we were also responding to a very specific set of needs,” she told me. At a time when the economy of the country was significantly impacted, especially the tourism sector that sustained many livelihoods, Kakshapati saw the festival as a way to contribute to its rebuilding by attracting visitors and boosting tourism. Five years on, she was once again attuned to the need of the festival to evolve with changing circumstances and realities.

Prasiit Sthapiit, Hemp weaving, Rachibang, Rolpa, 2019. The artist’s work was featured in Photo Kathmandu, 2020

Prasiit Sthapiit, Hemp weaving, Rachibang, Rolpa, 2019. The artist’s work was featured in Photo Kathmandu, 2020Courtesy the artist

On December 3, 2020, Photo Kathmandu launched its fourth edition, with a week’s lineup of online artist talks and panel discussions, and an informal virtual “mixer”—an online version of Photo Kathmandu’s infamous “speed dating,” in which attendees networked and introduced themselves to others in rapid succession. In the introductory note, Kakshapati, on behalf of the festival team, proposed to shift from the five-week-long festival schedule to a yearlong form. “The festival is part of a larger continuum of image-making, research and civic engagements for us,” Kakshapati wrote, referencing the non-public facing work that photo.circle and Nepal Picture Library (a digital photo archive run by photo.circle) do throughout the year. Reflecting further on this continuum, she posited, “What might be possible if we were to take the resources and energy we commit to a 5-week festival, and stretch it out over a longer period? Would we be able to foster deeper, less frenzied connections and dialogue? This feels like a good time to shift gears and find out.”

This need for deeper engagement is a sentiment that reverberates across festivals, including Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB), a public arts initiative based in Chennai, India. Founded in 2016, CPB was meant to have its third edition in December 2020. Imagined as a “city’s biennale,” CPB intended to follow the lead of its counterparts in Dhaka and Kathmandu in extending beyond traditional exhibition spaces to include, as noted in their mission statement, “public spaces and those parts of Chennai that have remained outside the realm and remit of contemporary cultural activities.” With their heavy focus on engaging the city’s public, and the restrictions the pandemic posed to this endeavor, cofounders Varun Gupta and Shuchi Kapoor spoke about shifting the festival to a later date. With the change in timeline, amid an ongoing pandemic, came a shift in the festival’s imagined shape. “If we’re unable to bring people to the biennale,” Kapoor reflected, “aren’t there ways that the biennale can go to them?” Gupta returned to the emphasis on public spaces, calling it a “biennale without walls,” and referred to some of the sites that have been used for exhibitions in prior editions: “the train station, the park, the beach—these are the places we love to work in. So how do we not lose that?”

Angela Grauherholz, Privation, installation view at the Madras Literary Society, Chennai Photo Biennale, 2019. Photograph by Charles & Dhina

Courtesy the artists

Sheba Chhachhi and Sonia Jabba, When the gun is raised, the dialogue stops, installation view at the Senate House, Chennai Photo Biennale, 2019

Courtesy CPB Foundation

The pandemic has presented a unique conundrum for these three festivals. While public engagement and building community have been at the core of their missions, the isolation forced by the spread of COVID-19 across the world has meant a complete overhaul in conceptualizing how these engagements take place. Chobi Mela, with its two-decade history of civic engagement with a local audience in Dhaka, has always valued this as much as curating contemporary photography for industry professionals. While previous editions have taken photography to the streets and to local residents, by mounting mobile exhibitions on rickshaws or showing photography in public theaters and libraries in the old city, the pandemic year of 2021 was the first that did not include this in its programming. However, the emphasis on the local was not missing, only remapped. Shunno was a South Asia–specific edition, including works from India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka in addition to the host country, Bangladesh. Many participating artists were alumni of Pathshala, a school for photography in Dhaka recognized as one of the key institutions for photography education in the region (alongside others such as NID in Ahmedabad), and also one of the parent organizations of the festival. “I think we have this fluid network of artists, and we are used to calling it ‘community.’ The community we have built is quite intimate. Intimacy is really important to us,” Wahab said.

Speaking about the festival’s definition of local, Wahab added, “South Asia is our local regional collaborator in every sense.” This cross-pollination was reflected in Chobi Mela’s cultural partnership with Colomboscope, a contemporary art festival based in Sri Lanka, for this year’s edition. “I think we are answerable for this ecology and ecosystem in South Asia. We always try to see how we can share not only ideas but tangible resources,” Wahab told me, “but our resource is also the community itself, idea-sharing and sometimes courage-sharing in a difficult time.”

With the curatorial focus on regional narratives and collaboration, the festival opened its exhibitions in the newly constructed media space DrikPath Bhobon, using not just the gallery, but the stairways, parking lot, and classrooms as innovative sites of display. The building—designed by Bangladeshi architect Bashirul Huq—resembles a film strip and offered Chobi Mela a dynamic venue, one where the works were in constant conversation with the architecture. While the physical edition ran for ten days, the entire site and all the exhibitions in it were converted into a virtual viewing experience, which continued through August 31. In this new avatar, the festival garnered a worldwide audience, bigger than ever before. I asked Wahab if he missed being on the street with the festival. “Of course. But it was intentional, we don’t regret it,” he said, emphasizing that there was no rush to go back to the physical rendition since, being an integral part of the ethos of Chobi Mela, it will inevitably return as part of regular programming post pandemic.

[Off] Limits exhibition, installation view at DrikPath Bhobon, Chobi Mela, 2021. Photograph by Farhad Rahman

[Off] Limits exhibition, installation view at DrikPath Bhobon, Chobi Mela, 2021. Photograph by Farhad RahmanCourtesy Chobi Mela

At their very core, festivals are events that bring people together, and our present circumstances raise many questions about the sustainability of pre-existing formats. Kakshapati, who has been thinking through these questions about the festival form, stressed that each edition should respond to the needs and reality of the community it builds from, as well as the one it serves. She says this adaptation is continuous, “because it is not like the community is a monolithic or permanent entity. It is evolving.” Recognizing the demands—mental, physical, emotional, financial—that the pandemic imposes both on those who attend and host the festival, Photo Kathmandu has laid low after its first week of programming. True to the spirit of malleability that Kakshapati espoused, she said that the festival has somewhat “gone into hibernation,” allowing for a larger reflection on its purpose and position within a broader institutional framework.

The CPB team has also grappled with the unpredictability of the present moment. While Gupta admitted that the pandemic, by disrupting the biennale schedule, opened up room for them to “catch their breath,” up until early 2021, they were moving ahead, as planned, with a largely physical edition of the festival. However, as the second wave of COVID-19 devastated India in April, their plans changed. The team felt a strong impulse to respond to the urgency of the crisis and launched a print sale titled PhotoSolidarity, in which 137 artists came together to sell prints to raise money for COVID relief.

It was at this juncture that CPB decided to pivot the majority of the upcoming festival edition online. Having already shifted their interim year programming online in 2020, and, like Chobi Mela, significantly expanded their audience engagement, they had some preparation for the new venture. However, unlike Chobi Mela, CPB does not plan on converting physical exhibition spaces into virtual reality, but rather intends to build “a virtual exhibit that is purely looking at the art works being presented,” Gupta told me. Kapoor echoes this sentiment, adding, “Not everything that was imagined as physical can be translated into the virtual,” challenging the curatorial team to construct a novel exhibition experience in the digital space. While this idea may cater to professional photography audiences, Gupta and Kapoor continue to stress ways to “travel the festival to the public.” To this end, the curatorial team is working on a broadsheet that can make its way into local neighborhoods as well as across the country, and potentially lead to some “home-spun” shows. The team is also planning an e-journal as a precursor to the latest festival edition, which will preview some works and carry critical texts, podcasts, and interviews, all opening up interpretations of their theme, Maps of Disquiet.

Nida Mehboob, Get Indoors When The Mullah Roars, from the series Shadow Lives, 2017–ongoing. The artist’s work was featured in Chobi Mela, 2021

Nida Mehboob, Get Indoors When The Mullah Roars, from the series Shadow Lives, 2017–ongoing. The artist’s work was featured in Chobi Mela, 2021Courtesy the artist

While the pandemic has emerged as the single most consistent disruptor of our lives, it is important to recognize that it has also served as a smoke screen for other injustices that have swiftly been taking place under authoritarian regimes in South Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh, during this period. As we grapple with the impact of a virus as a “visible” crisis, what is more insidious is the erosion of civil liberties and fundamental rights, especially in vulnerable communities. CPB addresses this directly through their festival theme, and their curatorial statement, with plans to build a collection of lens-based works that respond to today’s political volatility. This tactic of mediating sociopolitical issues through the arts is not new to this edition. Gayatri Nair, the third cofounder of the biennale, has been doing so via CPB Prism, an arts learning program she runs for adolescents and young adults. (Nair is currently working on a curriculum on masculinity that is communicated primarily through image-based learning tools.) The festival, and its spillovers, can then be seen as interventions into civil society, with a hope to influence public opinion and thought.

A need to respond to ongoing societal realities was also reflected in Photo Kathmandu’s 2018 edition, which hosted filmmaker Amar Kanwar’s The Lightning Testimonies, a multiscreen video projection focusing on the experiences of survivors of sexual violence, especially in environments of conflict in India. With the #MeToo movement erupting in South Asia in the month prior, the exhibition was particularly relevant and programming around it continued for six months, well beyond the five-week festival schedule. “We were reaching out to young law students, young journalists, and practicing lawyers, because the role that law plays in addressing sexual violence was something we were very specifically trying to tease out,” Kakshapati explained, speaking about how the festival and its exhibitions can become prompts for conversations that do not happen elsewhere. Wahab, from Chobi Mela, echoed this sentiment of the festival as a “safe space,” and the need to come together under one roof. He sees this as not only necessary to strategize, but also to “build courage through each other.”

The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project exhibition, installation view at Photo Kathmandu, 2018. Photograph by Chemi Dorje

The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project exhibition, installation view at Photo Kathmandu, 2018. Photograph by Chemi Dorje Courtesy the artist

What became increasingly evident through my conversations with these festival directors and curators was the need to focus on intellectual as well as community involvement in the time between festival editions. While the event itself may be a trigger, or a starting point, many engagements really take shape and form after the frenzy of the opening week subsides. The day The Lightning Testimonies closed after its six-month run at Photo Kathmandu, a new initiative called Imperfect Solidarities (IMSOL) was launched. Unwilling to give it a binding definition, and aligning with its fluid nature, Kakshapati described IMSOL as a methodology that relies on narrative psychotherapy tools to cultivate “nonjudgmental conversations” and an “opportunity to create time and space with people who you feel some kind of community with.” As an example of how an image-based work can serve as a prompt for larger, time-intensive conversations on issues that are plaguing society, this initiative helped foster knowledge-sharing beyond the presence of the work itself.

Chobi Mela perhaps has the longest experience with this kind of interdisciplinary exchange with photography, as well as with extending the concerns raised by the festival into the interim period between two editions. Two of the festival’s parent organizations—Drik and Pathshala—engage with civil society throughout the year, as in November 2019, when Drik organized an event on the necessity of prison reform, marking the anniversary of the release of its managing director, Shahidul Alam. Alam, who had been abducted and then jailed for criticizing the Bangladeshi government, shared his experience along with other previously incarcerated individuals. Wahab, when speaking about the future, emphatically says, “Shahidul is our logo, Shahidul is our flag,” while also admitting that the way forward for the medium is to “embrace its transformation.” With Chobi Mela, as well as other initiatives in the region, opening up their doors to cross-disciplinary practice as well as new forms of visual culture, Wahab’s words help root this transition to a purposeful intent—“the medium is only the tool or voice with which we want to question power.”

Read more about South Asian photography communities in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In” (Summer 2021).

August 24, 2021

Gregory Halpern on the Impossibility of Documentary Photography

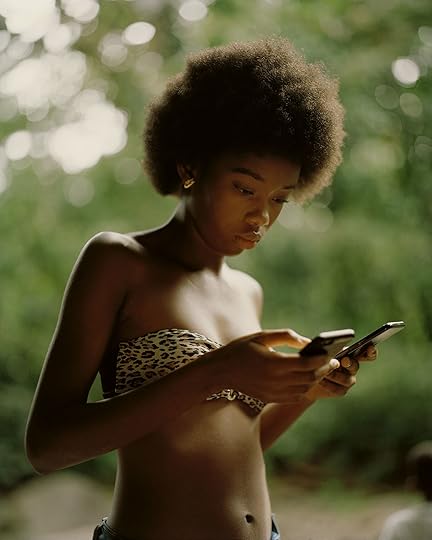

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa: This new work you’ve made is a little unusual relative to your earlier work, in that you’re making photographs in a place that’s distant from you and relatively unknown to you. Up to now, you’ve only made work in the US, and yet here, you’re making work on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. How does your relative distance from it all inform the way you’ve approached the project?

Gregory Halpern: It’s true—a lot of my work is about the American experiment, its promises, its failures, and trying to look at that in new ways. But in Guadeloupe, I felt overwhelmed at times by the sense that I was such an interloper. The constant awareness of being a white, American man with a camera in the Caribbean, the relationship between photography and colonialism, the fear that I was no more than a glorified tourist—all of that was creatively paralyzing at times.

For the Immersion commission, I was asked to propose a project based in France. I spent a lot of time thinking about how and where I could work in “mainland” France. I struggled with that question until I realized that it might be interesting to think about France through the experience of a former French colony and landed on Guadeloupe, a modern-day “overseas region” of France.

The barriers were much larger than in previous projects, and my French is pretty poor. Plus, the weight of history there felt immense; it felt unknowable to me in a way that I wasn’t used to. So I felt much less confident at first editorializing in Guadeloupe than I did in, say, Los Angeles—which by comparison I knew quite well, and where I felt more comfortable imposing my vision on the place.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: What was notable to me in looking at the first and then especially the second edit of the book, was the extent to which you’ve found a means to address concerns that I’d argue are integral to your ongoing project as an artist, but from Guadeloupe. I see you looking at death and violence as they’re figured in the earth, in symbols, and on bodies; I see you working across an epic register of forms of light: that seems to me very consonant with your ongoing work.

Halpern: I’ve never been one to make quick photographic visits, especially to foreign countries, so making this work in less than three months was a challenge. I like to sit with the work, show people, figure out what’s working and what’s not, and then return to making pictures with a more informed vision. Both ZZYZX [2016] and A [2011] took five years to finish, and Omaha Sketchbook [2009/2019] was made over fifteen years. But I think you’re right that almost whatever I photograph, I tend to think about the same sets of issues, and want similar ideas and feelings to drive the pictures.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Do you worry at all that there might have been a different story to be told, but that you were incapable of telling it, whether in this accelerated time frame, or perhaps at all?

Halpern: I worried about both. The time constraint forced me to be productive, but the fear was that I would be desperate to come back with images, without having the time to consider if they were the right images. And yes, a story I couldn’t tell was a story from the perspective of an insider. I worried whether that story would be more compelling than mine could ever be.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: For me, from your vantage point as an outsider, the photograph that most powerfully forces us to reckon with the continuities and discontinuities pursuant to slavery, colonialism, and their aftermath is the one of a dark black male figure with the fisherman’s hat, who stands in the water, carefully carrying the recumbent figure of a white woman. It’s incredibly beautiful, and it’s suffused with the explosively uneven nature of racialized difference, which is as central to the United States as it is to colonial France. I imagine, or I hypothesize, that your way “in” to making work in Guadeloupe might have been to look at it as someone who is an inheritor of settler-colonial violence, and to make work from that standpoint.

Halpern: You’re right that the histories of the two places are not entirely dissimilar, but the trauma of slavery and colonialism somehow feels so much more raw there than in the US. Perhaps the contemporary, semicolonial relationship with France continues to irritate those wounds? But also, the vast majority of the population of Guadeloupe is black, which helps ensure that that history is not relegated to the margins. There’s an incredible number of slavery-related memorials, for example, and there’s nothing like that in the US. They address very directly the violence and trauma of the past, and picturing them was simply one way of trying to visualize that history.

As for the photograph you mention, I liked how that moment was hard to read. Who is playing what role? Are the arms of the dark figure protective or menacing, loving or servile, a reference to the “utility” of colonialism’s past—or present, for that matter, because it’s the labor of locals that carries tourists, as if they were weightless, through their island vacations.

For a picture to work there has to be something that defies expectation, that surprises or unsettles or nags at you, something that doesn’t just reaffirm what you already know or feel. For me, that picture did that.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Did you try to photograph regular forms of labor and activity? Were you thinking about work specifically? Did you make a choice to more or less avoid the tourist trade?

Halpern: I tried photographing the tourist trade at points, but the pictures were caricatures or one-liners. I couldn’t seem to get past the sort of ridiculous look or “character” of the tourist. There’s a clichéd or clownish image of tourists we all know—bad style, pasty skin, camera, English spoken with an air of loud entitlement—it’s an image we know, true or not, and my pictures sometimes couldn’t get beyond that reference. Or if they did, they functioned within the book to suggest two polarized worlds—tourists and locals— which is a legitimate way of viewing the island, but it made for a more reductionist reading of the book. The individuals pictured became symbols of one group or another, and it felt somehow an injustice to everyone.

In relation to labor, I have recently gone back to Guadeloupe to make a video, which touches on it. There’s a market in downtown Pointe-à-Pitre near the harbor, and when the cruise ships dock, hundreds of tourists flood downtown for a few hours. They stroll into the market and inevitably photograph the women working there, usually without asking permission. The women sometimes respond by yelling “no photo” at the tourists, annoyed that they haven’t asked permission, or bought fruit, or even said hello first.

I sat there one day and watched the dynamic, mesmerized. It was unsettling. I was shocked by some of the tourists’ brazenness and disrespect, shooting as if on a safari, not talking or making eye contact. I found myself sympathizing squarely with the workers as they yelled at the tourists, and yet I also couldn’t help but recognize myself, at least to a degree, in the tourists. There was something quite powerful and instructive in that dynamic being laid so bare.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I can certainly see how heavily the images you excluded would skew the balance of symbolism in the book toward fundamentally external concerns. They sound a loud, interrupting note. Are there other images in the book that emerge from you trying to look outward from a Guadeloupean perspective, or from following an island dweller’s instructions or invitations as to where to go, or where to look?

Halpern: Maybe half of the images are the result of advice from a Guadeloupean. I tend to wander and talk to a lot of people. I’m sort of a sponge when I have the camera, accepting just about any invitation, picking up hitchhikers, following stray cats down alleys, et cetera. I often start the day with a vague plan, maybe choosing a spot on a map or returning to a place where the light was poor previously. I rarely stick to the plan, but the plan is an important starting point, because it gets me out the door.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can you describe a few of the conversations you had with people in Guadeloupe as you made the work, and perhaps speak to the extent that they’ve varied from or mirrored conversations you had in Los Angeles or Omaha, Nebraska, or Buffalo, New York?

Halpern: I think my conversations are pretty similar no matter where I am, but it was definitely more of a challenge to connect with people, because my French is mediocre and very few people are fluent in English there. There were a lot of photographs I couldn’t wind up making well because of language, and perhaps because of my timidity as an outsider, but nonetheless, I occasionally still made strong connections, and that’s always amazing when that happens. Twice in my life, I’ve made portraits of people where the only communication was with hand gestures and facial expressions—once there was a lot of smiling and laughing at ourselves, and once it was just really silent and peaceful, but both times were intense and beautiful experiences.

It’s always hard photographing people, though, even when you speak the same language. I’m pretty introverted, and I usually still have to work up the nerve. I tend to approach people in a sort of formal way—respectful, positive, honest, and direct about what I’m doing. I’m always aware of what a huge ask I’m making. I’m aware of the skepticism I’d feel if a stranger approached me on the street asking for a portrait, and that’s always in the back of my mind. And I carry a little laser-printed card that I hand to people, so they know how to reach me if they want copies of pictures. A lot of people don’t follow up, but I think the gesture is appreciated nonetheless.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: Can you speak about the ways in which your Jewishness informs your sensitivity to ethnic and racial difference? I’m thinking about the ways that certain racial and ethnic differences can go unobserved, and the ways your own personal experiences might attune you to the different, but related, inequities that others suffer.

Halpern: I’ve generally been uninterested in making work about myself or my identity, but increasingly, I’ve come to think my Jewishness is a powerful reality in the background that has deeply shaped how I see. My brother and I were the only Jews in our high school in Buffalo, and there was the sense that it was wise to just “pass.” Oddly that sentiment has lingered, and I sometimes still find myself wondering whether or not to “out” myself in conversations. My grandfather fled Hungary just before the outbreak of the Second World War and snuck into the US illegally because of anti-Semitic immigration laws. I am alive because he made that journey. The family who stayed in Hungary was almost entirely killed in extermination camps by the Nazis, although my great-aunts Olga and Goldie somewhat miraculously survived Auschwitz.

When I was a kid, usually at Thanksgiving, my dad would almost ritually ask my grandfather to tell the story of coming to the US—two weeks hidden in the bottom of a boat, going to the bathroom in the corner. And so this became our family’s origin story—fleeing genocide and sneaking into a country that did not want us. I have a complicated relationship to this story, and over the years have felt various combinations of pain, shame, strength, and pride in relation to it. And then there is the history of those who did not escape—the photographs of the piles of pale, malnourished bodies I somehow saw as a child, and which became, and perhaps remain, the primary association I have with the word Jewish. It’s such an overwhelming experience to see those pictures for the first time, especially as a child, that that becomes your people and your history.

Of course, whether or not Jews came to this country legally, they came of their own volition, not as enslaved people. Whether or not it’s useful to compare griefs, I don’t know, but there is something quite dark and not often talked about in the inherited trauma of Jews. I think it manifests itself in strange ways. It may be present, if latent, in the pictures, which is not to say that viewers need to know any of that when looking at the pictures, but I do think perhaps it’s there. Narratives and traumas across cultures are obviously different, and I don’t make this point to overlook or discredit the singular experience of any one narrative, but I do feel that through art there is the potential for shared experience, for some form of transcendence.

A family photo was taken before the Nazis invaded in 1944. My grandfather had already left Europe, so he is not pictured. Of the rest, all but three were killed in Auschwitz. Of those three, my great-aunt Olga is the only one still alive, at age ninety-two.

All this makes me think of a 2019 New York Review of Books piece by Zadie Smith called “Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction.” It’s a remarkable piece, running counter to the current mood, that argues for the potential value of portraying the “other” as a possible form of connection:

[W]hat insults my soul is the idea—popular in the culture just now, and presented in widely variant degrees of complexity—that we can and should write only about people who are fundamentally “like” us: racially, sexually, genetically, nationally, politically, personally.

She goes on to argue that in our own deeply personal, unique experiences of grief, there is the potential for us to know each other:

I was fascinated to presume that some of the feelings of these imaginary people—feelings of loss of homeland, the anxiety of assimilation, battles with faith and its opposite—had some passing relation to feelings I have had or could imagine. That our griefs were not entirely unrelated. . . .

What do I have in common with Olive Kitteridge, a salty old white woman who has spent her entire life in Maine? And yet, as it turns out, her griefs are like my own. Not all of them. It’s not a perfect mapping of self onto book—I’ve never met a book that did that, least of all my own. But some of Olive’s grief weighed like mine.

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I think that you’ve often made photographs that engage with the production of difference, or the individuated experience of racial difference particularly. I’d argue that your sensitivity to, and your compulsive interest in the forces that shape how we might articulate our inchoate selves, and the forces that might limit our capacity to be receptive to others, are central to much of the work you’ve made. One thread that runs through some portraits is a powerfully reflexive figuration of difference. You make photographs that point to the activity of picturing in complex and expressly racial ways. Do you think that your sensitivity to the reduction of Jewishness to images of emaciated corpses, or the reduction of Jewishness to anti-Semitic tropes that are expressly visual, might inform your relationship to imaging more broadly? I think about this as a black photographer too: I know how the power of looking can shift suddenly, radically, and all too often dangerously, and that has a meaningful effect on the ways I think about seeing and about images.

Halpern: That’s a great question. I don’t know the answer. But I think there’s something fascinating there—especially when I think about the ability of images to work powerfully on our unconscious mind, and how susceptible we are to being manipulated visually, be it through propaganda or advertising.

At the same time, I’m pretty skeptical of the power of images to transform reality or to create change. More and more, I’ve come to feel that change happens almost exclusively through protest and direct political action, when enough people come together to create a tipping point. I think that the art world is driven too much by capitalism to have any teeth as a political tool. I’m not sure any highly collectible commodity can ever really bite its owner, so to speak.

On the other hand, making art is a way of participating in a conversation, and conversation is perhaps the starting point for all change. The images of the [extermination] camps, for example, transformed reality for me. As did a book by Milton Rogovin, which I also saw when I was a boy. Rogovin lived and photographed not far from where I grew up in Buffalo. He made portraits of the same people over the course of twenty-five years, and when I first saw his work, as a teenager, I was shaken to the core.

I remember feeling confused, almost ashamed, that these pictures of strangers had moved me to tears. I hadn’t known art could do that. That book changed the course of my life, and so in that sense, I can’t deny the power of images to create change.

The impact of images is so hard to quantify. It’s so internal, like they skip past the cerebrum and get deep inside, into the body. It’s like they have the power to bypass the conscious mind and infiltrate without us knowing how, or what they’re doing once they’re inside. We think we know what we’re seeing, at least we tell ourselves that. But it’s more like we never really know what we’re seeing.

What about you? Are you ever discouraged to think that what we make are “just pictures”?

Related Items

Gregory Halpern: Let the Sun Beheaded Be

Shop Now[image error]

Let The Sun Beheaded Be: Limited Edition

Shop Now[image error]

Gregory Halpern’s Lyrical Chronicle of a Rust Belt City

Learn More[image error]Wolukau-Wanambwa: I recognize precisely the quandary you’re describing, if that’s the right word. How can making objects that circulate in relatively or absolutely small numbers for middle-class people, or infinitesimally in even smaller numbers for wealthy collectors and institutions, be considered a form of radical political action? I get that, and I’d agree that it’s not. I think that there’s a very good case to be made that says that these activities are not inherently radical forms of political action, and that they cannot be divorced from normative politics either.

I think we’ve also certainly seen meaningful social and political mobilizations in physical space as a response to both art images (Dana Schutz) and to the terrible realities approximated by nonart images (Michael Brown, Eric Garner). The circulation of those images does have real-world consequences, even though we need to be careful in those cases not to mistake the image for the real.

Do you think that a viewer of your work would respond differently if they viewed your photographs as fiction rather than as indexical fact? Would adopting the stance of storyteller—à la Zadie Smith—rather than documentarian, alleviate any of the contemporary concerns we’ve been discussing around difference and the structural violences meted out against the marginalized? I have this sense from so many discussions in the contemporary American classroom, that the identity position of the author matters far more than genre today.

Halpern: I agree with you about the emphasis on the author’s identity position, especially in the American classroom. After centuries of (mis)representation, there’s a need for marginalized groups to take ownership of their own narratives. And increasingly that’s being celebrated, and that’s essential. But in my eyes, it doesn’t eliminate the need to connect, to try to create something transcendent, or to look for the shared weight of experience across those lines that separate us.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Marina Abramovic ́’s The Artist Is Present—when over the course of nearly three months in 2010, for eight hours a day, Abramovic ́ sat in a chair at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and stared into the eyes of one person at a time, often for longer than five minutes each—and thinking about how so many of those sessions ended in tears. As children we’re taught not to stare, especially at strangers, and among adults, staring is often considered offensive or threatening. I’ve always been fascinated by how, through portraiture, the face of a stranger can take on meaning for another stranger, how an anonymous viewer can look at that person—a person who should mean nothing to them—and feel something. In an evolutionary sense, there’s no logical reason why one stranger should feel something for another. To me, there is something deeply mysterious and hopeful knowing that we can react to each other that way.

But to get to your question, I see fiction and nonfiction as existing on a spectrum. If science fiction represents one end of the spectrum and journalism represents the other, the middle might be occupied by things like lyric documentary, creative nonfiction, and perhaps, photography itself. I definitely borrow from a documentary tradition and aesthetic, but I have difficulty with the term documentary. It carries so much baggage, and is too often misunderstood as implying indexical fact. Once you claim the authority to understand and represent another’s reality, you’re sort of on shakey ground, as far as I see it. In that sense, to call the work fiction seems more honest.

But it can be both liberating and unsettling to not know how to classify work. When you pick up a book of literature, it’s usually categorized right on the back cover (fiction or nonfiction), and that can be helpful in knowing how to read and process the work. That doesn’t exist in photography, which is interesting.

What about your work—One Wall a Web [2018], for example —how would you classify it in terms of traditional genres?

All photographs Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2019, from Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Aperture and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2020)

All photographs Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2019, from Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Aperture and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2020)Courtesy the artist

Wolukau-Wanambwa: I think that to some extent (but by no means universally) in this identitarian moment, and especially in the (white) liberal art world, who you’re perceived to be as an artist can often dictate what your pictures can say, which then handily relieves a viewer of working that out for themselves. For me, the term documentary is one that I would want to reclaim in all its inherent complexity, rather than abandon it. I think that what I sought to document in One Wall a Web—far beyond a specific place or person—was the enervated psychic states from which white-supremacist, white-heteronormative violence flows. I wanted to document that violence as a real but also importantly intangible force. I tried, through the structure of the book, to trace its presence and effects on the landscape, in and on and around differing people, and through a history of appropriated photographic images and texts that extended into those images and texts I made in the present tense. In that sense, a lot of my “subject matter” is ethereal, immaterial, and inherently fantasist. So the forms of realism I needed varied over time, and those variances (hopefully) help to break up any notion that there’s one stable, transparent, objective lens through which what’s on offer can be reliably seen and understood.

To come back to your earlier points about the perils and virtues of categories like documentary, I think that maybe we’re focused on a symptom rather than the cause. I think that many of us in the Western world are exhausted, overstimulated and undercooked, overworked and undereducated, full of sensations and terrified of feeling, full of thoughts and uncertain how to think. I think that veridical statements and notionally credible documents (“real” news vs. “fake” news; “documentary” images vs. “fake” images) help to alleviate some of our interpretive anxiety. Simplifying our sense of the world by outsourcing interpretive responsibility for understanding it is appealing, precisely because we’re drowning in false choices all day long. I think that we sometimes need to believe that facts are simple, and that documents are true.

Halpern: I think you’re right, and in a way, that’s what concerns me about photography—that at times we all want to be fed facts, that we want to trust what we see. It’s unsettling to think of photography as fiction, but I think it can be useful.

Earlier, when you critiqued the notion of art being “reliably seen and understood,” I was struck by the idea of reliability and found myself thinking about the unreliable narrator in literature. I love the idea that a reader can’t trust an author/artist even when they appear to be telling the reader what to think. It forces the reader/viewer into the uncomfortable, but important, position of having to decide for themselves.

I am thinking here of the way William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury [1929] might get at the messy truth of a single family more than any traditional documentary about a family might. As a narrative strategy/structure, it’s just such a beautiful way of speaking to the impossibility of “telling the story” of a single family, in all its inconsistencies and contradicting truths. In that sense, I find the deliberately fractured nature of One Wall a Web, with its multiple “narrators” or “voices,” similarly beautiful and a fitting way of documenting, as you say, the “enervated psychic states from which white-supremacist, white-heteronormative violence flows.” That is an impossible thing to “document,” as I see it, but the dilemma of that impossibility is one of the things I find compelling about the work, and I like that you don’t shy away from the word. Maybe for documentary to be reclaimed, it needs to be embraced in that way, by artists who are working in profoundly innovative and experimental ways, who celebrate not only its potentials but its pitfalls as well.

This interview and images were originally published in Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Aperture and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2020).

Aperture at Photoville!

Brooklyn Bridge Park, Pier 1

2 Furman St

Brooklyn

August 22, 2021

Celebrating "The Colors We Share" with Angélica Dass

Creator House

35 E 21st St

New York

August 18, 2021

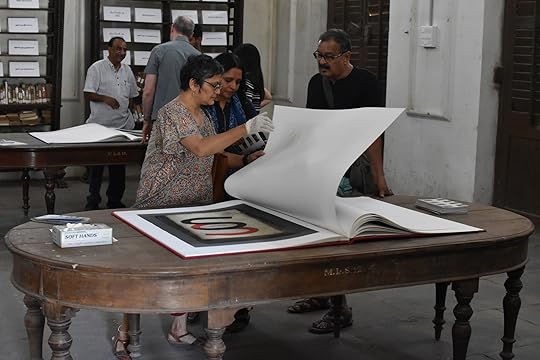

How Women Artists in South Asia Are Reinventing the Photobook

Photobooks force us to think outside and beyond the photograph. They serve as activist tools and sites for introspection. In South Asia, photobooks have experienced remarkable growth in recent years, instigated by artists’ urges to tell personal stories related to their social, political, and cultural situations. This gesture carries the belief that these stories are worth telling, that they can act as connective tissue between people in a global nervous system. The photobook experience—understood as the compilation of skillfully produced pictures and texts, held in one’s hand and savored, attentive to aesthetic and intellectual pleasures—can arguably be traced in India to the Islamic book, especially Mughal-era muraqqa, which contain painted images and writings. In the nineteenth century, the Indian photographer Raja Deen Dayal’s albums, with their careful arrangements of texts and images documenting architectural heritage, military maneuvers, and VIP visits to princely territories, and assembled by hand as multiples, can be considered photobooks in today’s terms.

Through the late twentieth century, the cost of publishing in India was prohibitive, despite the diversification of photographic practices. Those who found ways did so outside the country, such as Raghubir Singh, whose photobooks captured a sense of geographic and cultural contemporaneity. Dayanita Singh has been recognized for rethinking the photobook by playing with scale, materiality, and the nonstatic sequencing of images. The economic liberalization of the 1990s in India led to better quality and more affordable publishing opportunities with specialized printers in tune with photobook and self-publishing cultures. Initiatives such as BIND, the Alkazi Collection of Photography photobook grant, and the Delhi-based Offset have encouraged a new generation of image practitioners.

From her home in Toronto, the curator Deepali Dewan recently spoke by video with two compelling makers of photobooks: Indu Antony, a Bangalore-based artist, and Kaamna Patel, a Mumbai-based photographer and founder of JOJO Books. Together, they discussed new works made just before and during the pandemic lockdown, and how photobooks can give visibility to women’s experiences.

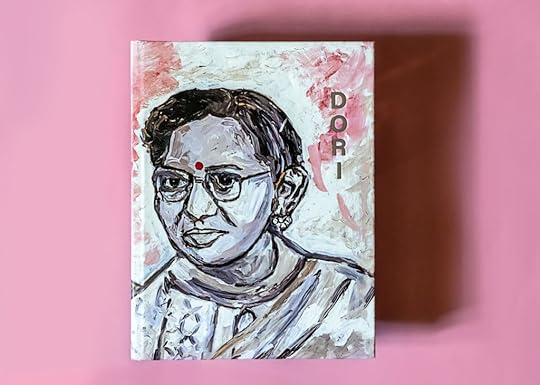

Kaamna Patel, cover of Dori, 2021

Kaamna Patel, cover of Dori, 2021Deepali Dewan: In India, the energy around photobooks and self-publishing that’s going on, is so relevant to the larger global practice of photobook making. Both of you are at the forefront of that energy and creating some of the most exciting examples. Kaamna, photography is the main aspect of your visual practice, and through that, you’ve come to photobooks. What led you to making books? And Indu, you have a varied artistic practice of which photobooks have been a more recent aspect. At what point did you turn to photobooks as a part of your practice?

Kaamna Patel: I discovered photobooks through a friend who was already working with them. It was actually thanks to him that I really understood what it means to publish, or even self-publish. In my head, I said, Wow, you can self-publish? Why have I been knocking on the doors of galleries all this time? That’s the reason I decided to self-publish. Then the risk is mine, the loss is mine, and if there’s any success in reaching out to people through this, well, then, I will have done it, and I will know for sure whether my voice is worth amplifying or not.

Indu Antony: I did my first-ever photobook project in 2008. Surprisingly, I found it the other day, and I thought, Wow, I didn’t even know this was a photobook. At the time, I had attended a book-making workshop, and I was really excited about the idea of making books by hand.

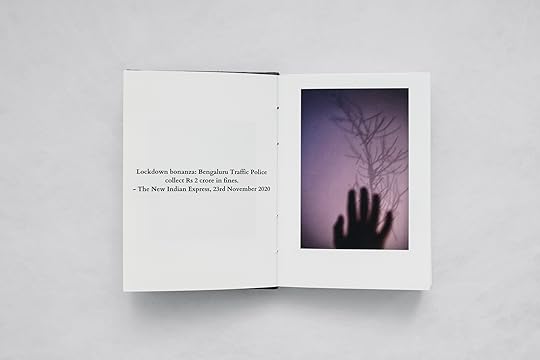

I am part of a collective called Kanike. We are four artists who get together, share a space, and also make work collaboratively. Jolly Bird (2020) is the first piece that we did together, reflecting on what we went through during COVID, when the lockdown happened from March onward. The book comes with a small note describing our lockdown experiences. The title Jolly Bird is after a song by S. P. Balasubrahmanyam, who we lost during COVID, and the work opens with his lyrics. It’s a small dedication to him.

The book follows the different things that we did during the lockdown period. For example, for the forty days of the lockdown, which were quite intense, every day at 5:20 PM, I would record ten words that describe how I felt that day, such as lonely, love, sex, I, no, scooter, eraser, isolation, me, and off. It was a way to relieve my anxiety. We also used a lot of the news headlines and images from the lockdown: “Bengaluru police is using drones trying to find lockdown violators.” “Sales for sex toys rise 65 percent in post-COVID-19 lockdown: Karnataka stands second.” We made just fifty copies of the book, and it was so surprising that within twenty hours all fifty copies were sold out. We were quite shocked to see how people were responding to this collective book.

Spreads from Indu Antony and Kanike collective, Jolly Bird, 2020

All works courtesy the artists

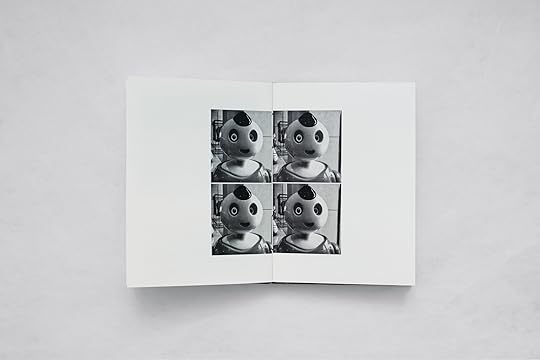

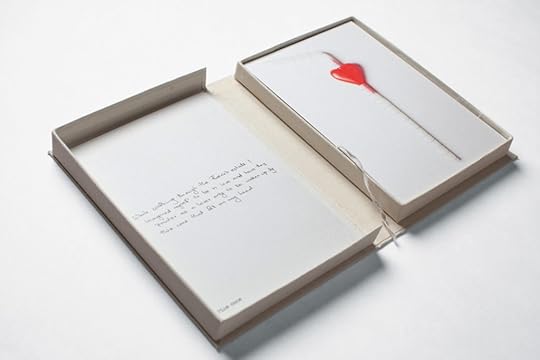

Dewan: Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons (2021), rather than a bound book, has loose pages collected in a box that opens up, and each page has a photographic image on it with text on the back corresponding to that image. How did this come about?

Antony: During the lockdown, everybody went into an extensive cleaning of their homes as I did. I found mountains of boxes that I’ve collected with objects from my life. I wanted to slow down. Though everything around was still, my mind was not still. So I started taking out each of these objects, and, at that point, I had only watercolor papers. So I was like, Okay, let me stitch each of these objects onto the paper using a strand of my hair and see what happens. The idea of having the book in the form of a box, where you open it with a tiny window, indicates a small window into my life—who I am. The box is made of Kora cloth. I went hunting for Kora cloth, which are rejects from the railways in Bangalore, and got someone to actually make those boxes. And then the box actually went into another Kora cloth bag stitched by me.

Dewan: Kaamna, your most recent projects are In Today’s News: Alpha Males and Women Power (2019) and Dori (2020). Can you describe these projects and give a sense of their materiality?

Patel: Dori means thread in Gujarati. I was playing on the idea of a “thread” that joins me to my grandparents, the focus of the book, and eventually that will join their story to future generations. I put everyone to work, and it became a family project, in a way. My aunt, who is their daughter, did the painted portraits of my grandparents reproduced on the front and back on paper that feels like canvas. She’s a dentist and also an artist. Actually, this book was a collaboration between all of their kids and me. At the end, there is a text in Gujarati and in English. One text is my voice, and the other text is a foreword by Veeranganakumari Solanki, who is a curator and a writer. My other aunt, who lives in LA, helped with the translations of both texts.

In Today’s News was made with yotsume toji, a type of Japanese binding, and with unbleached, uncoated paper that gives it a yellow tint. Essentially, the book opens with an image from the newspaper. And the title as well comes from a headline that I found in the newspaper. This project basically started as Instagram stories.

It was also a response to the fact that the #MeToo movement was still strong in India. I realized that through the exercise of making those Instagram stories, I had a lot of concerns cropping up in my mind, and I thought maybe I should put them down and see what comes through. The themes for me were primarily women’s sexuality; the evolving role of women in society, whether as a moral support system for men or as more independent, working individuals; and issues related to victims of domestic abuse. It was just kind of an outpour. I had this whole collection of images on my phone, and then, when I decided to actually explore it a little more, I started scanning and using a better camera.

Kaamna Patel, spread from Dori, 2021

Kaamna Patel, spread from Dori, 2021Dewan: Has this past year in the lockdown been, in some ways, a generative and creative space for producing photobooks?

Antony: I don’t think either Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons or Jolly Bird would have happened if not for the lockdown. Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons developed because I was so craving touch. Looking at those objects in my memory boxes was like a certain kind of calmness. Not only were there good memories, but there were also heavy memories in them. But at least I had the tactility of touching them. So it came out of that space.

Jolly Bird, also, is a result of 2020’s events because all four of us were looking at how to survive the pandemic: What are we doing with our surroundings? What were we making and reflecting on? We put all of that together and then made the book.

Even though we find ourselves in a place where you can receive threats just for expressing yourself in your photobook, I hope that in a couple of years that will change. I think that’s a risk you take if you’re going to bare your soul in your work.

Patel: Actually, I wasn’t even thinking about making books that year. I took to writing, working on grant projects, proposals, residency applications, things like that. It was toward the end of 2020 when I realized Dori was almost there. It had been in the making for five years. I had done many different versions of it and many different edits, and I finally had come to this almost final stage. It was just about picking the format and getting the design elements together. So it was quite an impulsive decision. I said, Okay, it’s ready.

Dewan: To what extent do you find the photobook a space that is a good platform to bring forward a landscape of the personal? What does the photobook allow you to do that another format doesn’t?

Patel: Because books are small, for the most part, and intimate, you hold them close to you. As a reader, once I have the book, once I open it, I choose how much time I spend with the images, how I go back and forth through the pages, where I read it, whether I read it in my personal space, whether I read it in a public space. All of this allows you to experience somebody else’s story as if it were your own. That’s why it’s so conducive to communicating, honestly and candidly, a story that maybe you wouldn’t otherwise want to put up on the wall.

Indu Antony, Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons, 2021

Indu Antony, Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons, 2021Antony: Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons is a project in itself, and none of it would ever exist in any other format than this particular book. It’s a great format for people to express their personal narratives.

Dewan: Your work gives a certain attention to women’s lives that doesn’t often get seen in a public sphere. How do you feel the photobook allows you to do that? Kaamna, In Today’s News is as personal as Dori, because these are your selections from newspapers. I recall hearing you say that decontextualizing a newspaper image from its context and putting it together with something else creates a different kind of narrative that is very much about your reading of the popular press. But both works also occupy the space of giving visibility to women’s experiences and women’s lives in a different way than is often represented in the public sphere. Can you talk about that?

Patel: You are absolutely right. That is exactly what I was thinking of when I was taking these images out of their context and putting them into diptychs that made sense to me as diptychs—so basically putting them straight into another chronology. That’s because I really believe that images are very, very powerful in the sense that they show truth, but they can also show lies and make you believe they’re true. And somewhere in that middle ground is where you can arrive at a subjective truth, which reveals to you something not only about yourself but about what you understand about the world, your perspective on life, and everything else. So in that sense, yes, it’s deeply personal.

But as far as using photobooks to create a feminist space, I wouldn’t say that I am doing this actively. It’s definitely not an agenda that I am chasing. It just so happens that I am a woman who has been raised to be independent in a country like India. So the feminist message is really just a part of my story and a part of my life. It’s just natural to me. So it’s only natural that it comes out within the work I make because that’s the lens with which I view the world.

Antony: Why Can’t Bras Have Buttons, even though it’s about me, also talks about some form of abuse, some form of what my body has gone through, my own identity. Which is why it’s not all beautiful memories, but it is also about my existence, and my gender, and what I as a person have gone through.

Related Items

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Arundhati Roy Sees Delhi as a Novel

Learn More[image error]Dewan: It feels like a very raw and honest representation of female life, and at the same time something that, I imagine, is very relatable for many of us. Do you feel there’s risk in that, in putting out this aspect of women’s lives in a space like India, or even in the world?

Antony: Since my book was released, someone wrote to me through Instagram, and he started threatening me. It’s still not an easy thing, because it took a lot for me to be as vulnerable as possible, to put out a book such as this one, to talk about things that my closest friends would not know. But I felt it was, in some way, important to do so. So, yes, it’s not easy.

Patel: Being a woman in India, and generally a woman in a man’s playground, at some point in your life, you are going to have to face abuse. Speaking out in a country like India is difficult because of this sense of the self-appointed moral police that encourages repression in our society, which eventually leads to us not being able to talk about our sexuality, or our needs, or things that are happening to us. It’s the shame culture that we live in—that’s probably where it’s coming from.

But I feel like it’s definitely changing. And the support systems for artists who speak out are growing. So even though we find ourselves in a place where you can receive threats just for expressing yourself in your photobook, I hope that in a couple of years that will change. I think that’s a risk you take if you’re going to bare your soul in your work, because you are speaking things that either nobody wants to hear or everyone wishes they could say, and so you find solidarity in it. Either way, it has to be done.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “The Photobook as Public Space.”

August 16, 2021

The Photographer Confronting the Restlessness of Lockdowns

Tirtha Lawati was born in Nepal and raised in Britain. He grew up across a number of counties—Kent, North Yorkshire, and Warwickshire—before studying photography at Warwickshire College, and then fashion photography at London College of Fashion. His editorials published in Vogue Italia and Dazed narrate fashion collections designed by his peers, of models at ease in clothes worn with confidence; but his own portfolio documents the tentative experience of first-generation Asian youth in the UK, suspended between the worldview of their parents and the accommodation of British values. For Lawati, the boundaries of the home also express this tension: “I have been exposed to two identities, one being inside the home, and one being outside,” he tells me. He describes his ongoing project Nyauli as a call for home. It refers to the Great Barbet (Nyauli), a bird native to Nepal whose song, according to folklore, is that of a lost lover.

The UK’s COVID-19 lockdowns forced Lawati to confront his own conception of home over an extended period of time spent in close confines with his extended family. What started as practical exercises to stem his restlessness—teaching himself the qualities of natural light by shooting in the garden at dawn, trying his hand at nature photography, or taking portraits of his nieces during breaks between home-schooling lessons—soon developed into a studied depiction of domestic life based on his own compositions. Lawati works by first drawing his portraits and then staging them. This process lends the images a somewhat studied sense, as though they are vignettes in which his family are the protagonists.

“I wanted to do something to transform bleak times into something playful, something like a reality,” Lawati says. His project was produced partly out of the prevailing restrictions, so he had to use a postal lab service to develop the analog film. Despite the pandemic’s varied obstacles, this new body of work, published here for the first time, is finely observed and supplies the distraction of small details.

The photographs are strangely familiar. They speak of roles and responsibilities in family relations but in unlikely terms. A blanket drying on a clothesline envelops a matriarch, fists raised, a smile on her lips, and a beanie pulled over the crown of a wide-brimmed summer hat; an older man rests the fullness of his palm on his head in a gesture of self-possession; a girl dozes as she inhales the hair of the younger sister in her arms. They are tender likenesses that radiate with a sense of security in being held.

Lawati’s nieces became a particular focus, as they were the same age that Lawati and his sister were when they first arrived in Britain to confront a new life and a new language. The struggles of Lawati’s assimilation is lost on the two young girls, who speak English as their mother tongue. Lawati captures the desire to overcome a generational divide in a portrait of his nieces with their hair plaited with lacha, a traditional red hair accessory worn by Nepali women with floral appendages made from raw jute fiber, yarn, beads and threads. Like most young girls, Lawati’s nieces wear the braids their own way, studded with chrysanthemums picked from the garden. One of them raises a hand to the sky, as a plastic dragonfly rests on her fingertip.

The image is inspired by a memory of Lawati’s early childhood in Nepal, when he was fascinated by the dragonfly, attracted by the whirring of its wings as it hovers almost still in midair. Trying to connect experience across a generation’s worth of difference, Lawati depicts the dragonfly as symbolic of living freely, and in the photograph, it is gifted benevolently to his nieces. He intends to continue to photograph them, he says, to follow “how they cope and how they find the answer to their identity or sense of belonging.”

All photographs by Tirtha Lawati from the series Nyauli, 2020–ongoing

All photographs by Tirtha Lawati from the series Nyauli, 2020–ongoingCourtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

August 12, 2021

A Sweeping Reconsideration of Photography and Land Use in America

When Sandra S. Phillips was named curator emerita of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016, after three very busy decades leading the department, she had no intention of slowing down. In fact, she was actively at work on what fairly can be called the most ambitious project of her career to date: American Geography: Photographs of Land Use from 1840 to the Present, an exhibition scheduled to appear at SFMOMA in 2020. Lamentably, the exhibition itself was a casualty of the coronavirus pandemic, but the accompanying publication—much more than a catalogue—was published earlier this year by Radius Books in Santa Fe.

Lucas Foglia, George Chasing Wildfires, Eureka, Nevada, 2012

Lucas Foglia, George Chasing Wildfires, Eureka, Nevada, 2012Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake, from Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack 04.21.06, 2006

Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake, from Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack 04.21.06, 2006Courtesy the artist

The book has ninety-four beautifully printed full-page plates plus an illustrated catalogue of the 165 photographs selected by Phillips with Sally Martin Katz, curatorial assistant at SFMOMA. The main text by Phillips is followed by essays by Richard B. Woodward, Hilary N. Green, Jenny Reardon, Layli Long Soldier, and Richard White, and a poem by Beverly Dahlen. A concluding chapter highlights twenty-three photobooks illustrating American land use that “were, until quite recently, the principal resource for understanding the subject.”

An extended preface by the late writer and environmental activist Barry Lopez sets the tone. Before he began discussing the project with Phillips, he notes, she had already assembled extensive photographic evidence of “clearcuts, toxic settling ponds, transmission towers, contrails, open pit mines, stalled traffic, sprawling feed lots, and the rest of humanity’s infrastructure.” At first he urged her to include, in addition, “other, perhaps more welcoming photographs . . . of unmanipulated land. . . . But,” he writes, “I came around to her point of view.” The selection of photographs squarely faces what Lopez calls “the boot prints, if you will, of the colonial invader.”

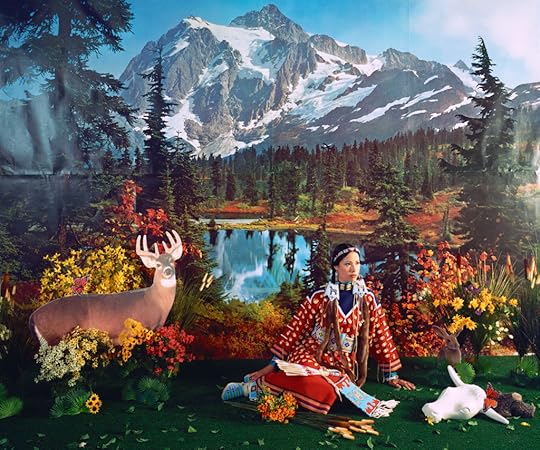

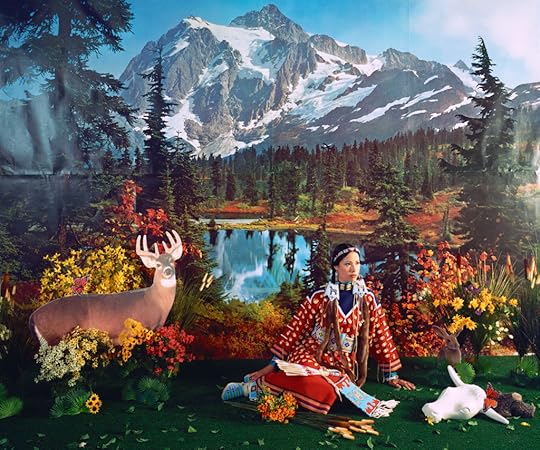

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

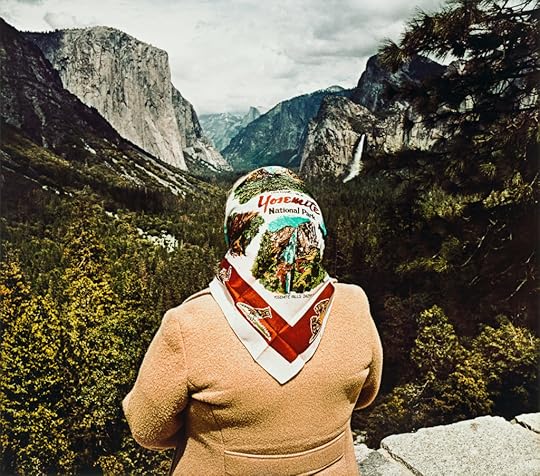

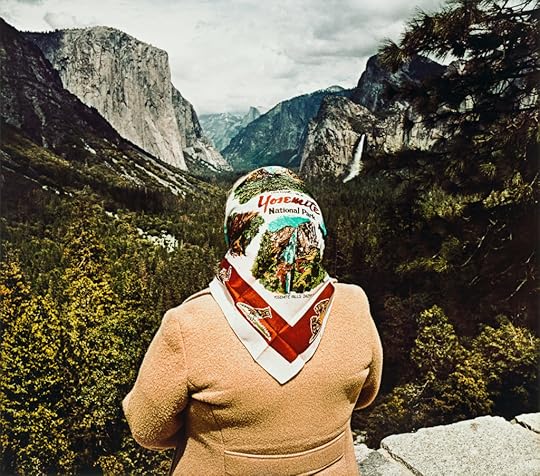

Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, CA, 1980

Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, CA, 1980Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Phillips’s essay skillfully traces the intertwined histories of American photography and land use in America, together with what might be called their metahistories: not just what humans were doing on and to the land, but what they thought about what they were doing; not just what pictures photographers were making but how those pictures reached their audiences and how they were interpreted. She persuasively treats the various threads as aspects of a single story, with the result that many familiar elements are seen in a fresh light.

Amani Willett, “Hiding Place,” Cambridge, MA, from the series The Underground Railroad, 2010

Amani Willett, “Hiding Place,” Cambridge, MA, from the series The Underground Railroad, 2010Courtesy the artist

The same is true of the selection and presentation of the photographs. Phillips explains that American Geography expands on the groundwork of an exhibition and catalogue titled Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West, 1849 to the Present, which she presented at SFMOMA in 1996. Nineteenth-century photographs of the American West have been a staple of photographic history from the beginning, and comparable attention has been lavished upon both the romantic idealism of Western landscape photography in the twentieth century and the critical view of the human footprint that followed: the pictures that rigorously cropped out cars and telephone wires, then the pictures that went the extra mile to include them. Nineteenth-century landscape photography in the eastern US was largely ignored, however. As Woodward points out, that changed dramatically with East of the Mississippi, Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography, a major exhibition organized by Diane Waggoner at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in 2017 and, now, with American Geography.

Alec Soth, Cemetery, Fountain City, Wisconsin, 2002

Alec Soth, Cemetery, Fountain City, Wisconsin, 2002Courtesy the artist

Sheron Rupp, St. Albans, Vermont, 1991

Sheron Rupp, St. Albans, Vermont, 1991Courtesy the artist and Robert Klein Gallery

Dramatic as it is, the inclusion of the eastern US is only one aspect of the originality of Phillips’s exhibition. (Partly because the great majority of the original prints belong to SFMOMA or to San Francisco’s Sack Photographic Trust—Phillips played a key role in building both collections—it is not unreasonable to hope that the museum may mount the actual exhibition in the not terribly distant future.) Given the centrality of the theme to American photography as a whole, it is not surprising that the selection includes dozens of familiar, even famous photographs by celebrated photographers. They need to be here, but they sing with a new resonance in concert with an equal number of marvelous but unfamiliar images, some of them by photographers whose names are unknown even to specialists. Many pictures bring the project right up to date, such as Stanley Greenberg’s Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York (2020); other contemporary pictures explicitly point at the past, such as one made in 2017 by Dawoud Bey for his beautifully somber series retracing the Underground Railroad. More than one in ten of the photographs in the book were made within the past decade, which says a good deal about a project of such historical breadth.

Stanley Greenberg, Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York, 2020

Stanley Greenberg, Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York, 2020Courtesy the artist

Like the work of Phillips’s longtime friend Robert Adams (rightly featured here), her book is distinguished by its equanimity. It addresses without flinching what we Europeans have done to the land and the Native peoples of what we now call America, as well as to the people we brought here forcibly. It is not a pretty picture, and there is no escaping that this painful past and alarming present are contributing to a still more alarming global reality. And yet the book is, if not exactly beautiful, then richly eloquent—a powerful testament to photography’s uncanny capacity to reward the act of looking clearly at something that matters.

American Geography: Photographs of Land Use from 1840 to the Present was published by Radius Books in May 2021.

A Sweeping Look at American Landscape Photography

When Sandra S. Phillips was named curator emerita of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2016, after three very busy decades leading the department, she had no intention of slowing down. In fact, she was actively at work on what fairly can be called the most ambitious project of her career to date: American Geography: Photographs of Land Use from 1840 to the Present, an exhibition scheduled to appear at SFMOMA in 2020. Lamentably, the exhibition itself was a casualty of the coronavirus pandemic, but the accompanying publication—much more than a catalogue—was published earlier this year by Radius Books in Santa Fe.

Lucas Foglia, George Chasing Wildfires, Eureka, Nevada, 2012

Lucas Foglia, George Chasing Wildfires, Eureka, Nevada, 2012Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake, from Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack 04.21.06, 2006

Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake, from Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack 04.21.06, 2006Courtesy the artist

The book has ninety-four beautifully printed full-page plates plus an illustrated catalogue of the 165 photographs selected by Phillips with Sally Martin Katz, curatorial assistant at SFMOMA. The main text by Phillips is followed by essays by Richard B. Woodward, Hilary N. Green, Jenny Reardon, Layli Long Soldier, and Richard White, and a poem by Beverly Dahlen. A concluding chapter highlights twenty-three photobooks illustrating American land use that “were, until quite recently, the principal resource for understanding the subject.”

An extended preface by the late writer and environmental activist Barry Lopez sets the tone. Before he began discussing the project with Phillips, he notes, she had already assembled extensive photographic evidence of “clearcuts, toxic settling ponds, transmission towers, contrails, open pit mines, stalled traffic, sprawling feed lots, and the rest of humanity’s infrastructure.” At first he urged her to include, in addition, “other, perhaps more welcoming photographs . . . of unmanipulated land. . . . But,” he writes, “I came around to her point of view.” The selection of photographs squarely faces what Lopez calls “the boot prints, if you will, of the colonial invader.”

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006

Wendy Red Star, Indian Summer, from the series Four Seasons, 2006Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, CA, 1980

Roger Minick, Woman with Scarf at Inspiration Point, Yosemite National Park, CA, 1980Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Phillips’s essay skillfully traces the intertwined histories of American photography and land use in America, together with what might be called their metahistories: not just what humans were doing on and to the land, but what they thought about what they were doing; not just what pictures photographers were making but how those pictures reached their audiences and how they were interpreted. She persuasively treats the various threads as aspects of a single story, with the result that many familiar elements are seen in a fresh light.

Amani Willett, “Hiding Place,” Cambridge, MA, from the series The Underground Railroad, 2010

Amani Willett, “Hiding Place,” Cambridge, MA, from the series The Underground Railroad, 2010Courtesy the artist

The same is true of the selection and presentation of the photographs. Phillips explains that American Geography expands on the groundwork of an exhibition and catalogue titled Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West, 1849 to the Present, which she presented at SFMOMA in 1996. Nineteenth-century photographs of the American West have been a staple of photographic history from the beginning, and comparable attention has been lavished upon both the romantic idealism of Western landscape photography in the twentieth century and the critical view of the human footprint that followed: the pictures that rigorously cropped out cars and telephone wires, then the pictures that went the extra mile to include them. Nineteenth-century landscape photography in the eastern US was largely ignored, however. As Woodward points out, that changed dramatically with East of the Mississippi, Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography, a major exhibition organized by Diane Waggoner at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, in 2017 and, now, with American Geography.

Alec Soth, Cemetery, Fountain City, Wisconsin, 2002

Alec Soth, Cemetery, Fountain City, Wisconsin, 2002Courtesy the artist

Sheron Rupp, St. Albans, Vermont, 1991

Sheron Rupp, St. Albans, Vermont, 1991Courtesy the artist and Robert Klein Gallery

Dramatic as it is, the inclusion of the eastern US is only one aspect of the originality of Phillips’s exhibition. (Partly because the great majority of the original prints belong to SFMOMA or to San Francisco’s Sack Photographic Trust—Phillips played a key role in building both collections—it is not unreasonable to hope that the museum may mount the actual exhibition in the not terribly distant future.) Given the centrality of the theme to American photography as a whole, it is not surprising that the selection includes dozens of familiar, even famous photographs by celebrated photographers. They need to be here, but they sing with a new resonance in concert with an equal number of marvelous but unfamiliar images, some of them by photographers whose names are unknown even to specialists. Many pictures bring the project right up to date, such as Stanley Greenberg’s Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York (2020); other contemporary pictures explicitly point at the past, such as one made in 2017 by Dawoud Bey for his beautifully somber series retracing the Underground Railroad. More than one in ten of the photographs in the book were made within the past decade, which says a good deal about a project of such historical breadth.

Stanley Greenberg, Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York, 2020

Stanley Greenberg, Coronavirus Shelter, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York, 2020Courtesy the artist

Like the work of Phillips’s longtime friend Robert Adams (rightly featured here), her book is distinguished by its equanimity. It addresses without flinching what we Europeans have done to the land and the Native peoples of what we now call America, as well as to the people we brought here forcibly. It is not a pretty picture, and there is no escaping that this painful past and alarming present are contributing to a still more alarming global reality. And yet the book is, if not exactly beautiful, then richly eloquent—a powerful testament to photography’s uncanny capacity to reward the act of looking clearly at something that matters.

American Geography: Photographs of Land Use from 1840 to the Present was published by Radius Books in May 2021.

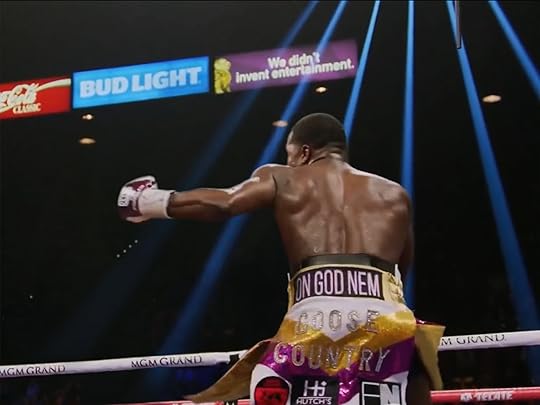

Paul Pfeiffer on the Transformative Effects of the Pop Culture Image

Paul Pfeiffer’s practice spans sculpture, video, installation, and photography. His central material and concern over more than twenty years has been the photographic, televisual, and filmic image in the context of our mainstream habits of image consumption. Much of Pfeiffer’s work has centered on forms of racialized performance in sporting events like boxing matches and basketball and football games—sites of mass spectacle with deep and widespread cultural appeal. He has also made work in response to concert performances, and to iconic films or physical sites that have acquired a ubiquity for their connections to the visual vernacular of social life. Pfeiffer’s work has focused on the transformative effects of popular cultural images on our embodied and psychic experiences of the world. That work has developed in the context of his ongoing interest in the histories of globalized labor and racialized violence.