Aperture's Blog, page 54

June 26, 2021

Family Fun Day at Fotografiska NY

Fotografiska NY

281 Park Ave S

New York

Family Fun Days at Fotografiska NY

Fotografiska NY

281 Park Ave S

New York

Book Signing with Tim Davis at Outside Space NYC

Outside Space NYC

216 Classon Ave

Brooklyn

Tim Davis Book Signing at Artbook in Los Angeles

Artbook at Hauser & Wirth

917 East 3rd Street

Los Angeles

Book Signing with Ming Smith

Nicola Vassell Gallery

138 Tenth Avenue

New York

June 23, 2021

Why Lynn Hershman Leeson Is Always Ahead of Her Time

In a 1978 film called Lynn Turning into Roberta, the artist Lynn Hershman Leeson applies makeup to her face, sets a wig on her head, and gradually eases into the role of her fictitious persona and multiyear performance piece Roberta Breitmore (1972–79). Roberta rode buses around San Francisco, went to a psychiatrist, and had her own credit card. “Several times I left my house as Roberta, forgot something, and had to return in Roberta costume and makeup,” Hershman Leeson recalled of the years she spent enacting her alternate self, “which was a continual annoyance to my then eleven-year-old daughter.”

To say that Hershman Leeson was ahead of her time would be an understatement. A pioneer in performance, video, and multimedia art who throughout her life has probed the connections between technology and society, she recently converted her collected works into synthetic DNA. As early as 1980, in an interview with Nam June Paik, Hershman Leeson asked, “How long will it be before ordinary people supersede movie stars, and intercommunicative TV and computers supplant fictional film?”

During the 1970s and ’80s, while Hershman Leeson was redefining contemporary art, Eileen Myles was writing the stories that would be celebrated in her iconic 1994 book, Chelsea Girls, in which life becomes art and the body becomes poetry. “Nothing I said was forgettable,” Myles, who is also a photographer, has noted. “It was all designed to be remembered.” Here, for Aperture magazine’s “Orlando” issue, Hershman Leeson and Myles speak about past glories, present fame, and the long life of an artist.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Exorcism (Roberta Multiple, Michelle Larson, Being Transformed), 1978

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Exorcism (Roberta Multiple, Michelle Larson, Being Transformed), 1978Eileen Myles: Well, what should we talk about?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: I don’t know. It’s up to you.

Myles: I was thinking you would know.

Hershman Leeson: What they told me was that you were going to interview me, so I didn’t prepare anything.

Myles: This is very funny. See, I think they told me the same thing.

Hershman Leeson: [Laughs] Well, that makes sense. We could start with doubles.

Myles: What does “doubles” mean?

Hershman Leeson: Well, I once lived as another person for close to seven years. In the 1970s, I was trying to focus on the blurriness between fiction and reality, so I created a kind of fictional person. Her name, and the name of the project, was Roberta Breitmore. She had real artifacts, though, and a documented physical presence in the world. She saw a psychiatrist. She had an apartment. She had a driver’s license and checking accounts. And she put ads in the newspaper. I lived as this other character for almost a decade.

Myles: When you say she went to the psychiatrist, does that mean you went to the psychiatrist under her name?

Hershman Leeson: Yeah, as her. She was blonde; I wasn’t. She had a particular taste. She had a certain way of walking and speaking; she had her own language—it was English, but it was her language, not mine.

Myles: Did you create a different psyche?

Hershman Leeson: I did. She had a different background. She was younger than I was. She went to therapy because she was broke and lonely and kept having negative experiences. I have her psychiatric record from the psychiatrist who treated her.

I didn’t know it would last seven years, but when you start to define how you make somebody real, she needs to be fleshed out and have a history. In fact, she’s more real than I am, because I couldn’t get credit cards, and I couldn’t get other artifacts of life and the records that she easily acquired. So for me, it was kind of just living her life.

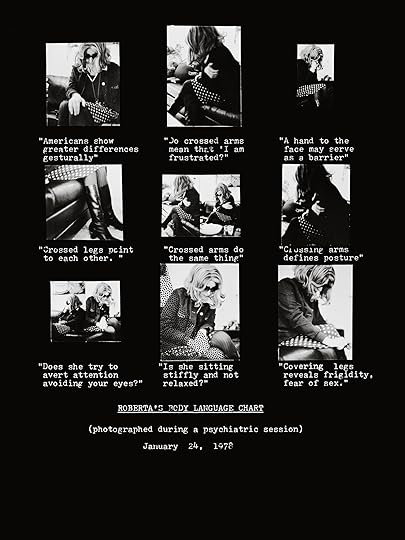

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roberta’s Body Language Chart, 1976

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roberta’s Body Language Chart, 1976Myles: How did you choose a therapist for her?

Hershman Leeson: I found somebody who was an expert in schizophrenia; he was also an art collector.

Myles: So he knew what was going on?

Hershman Leeson: Not really, because nobody had ever done anything like that. I told him that a friend of mine needed to see him, and I didn’t explain what it was, because I didn’t really know. In the early 1970s, nobody used the words performance or endurance performance or anything like that, so everything was kind of a test.

Myles: How did the performance end? Why did it end? And how did you feel afterward?

Hershman Leeson: This character, Roberta, kept having very negative experiences. I wanted to invert that. At the end of nearly a decade, I felt that she had enough substance of reality to prove that she actually was a fiction that became real. I ended her with an exorcism in Lucrezia Borgia’s crypt in Ferrara, Italy. There were dancers who could move like her; I brought one of them to Ferrara, and she did a performance at the Palazzo dei Diamanti where she took Roberta Construction Chart #1 (1975) and an effigy off the museum wall and set them on fire. She—the Roberta multiple—lay in state for twenty-four hours while the museum filled with smoke from the burning ashes of Roberta’s history. I felt that she was kind of like a phoenix, and when she surfaced again, she wouldn’t be such a victim.

Myles: Does she surface?

Hershman Leeson: She does. But she doesn’t surface as the original Roberta, rather as a mutation. For instance, CYBEROBERTA (1993–95) was born. She was a telerobotic doll with two eyes that were cameras. One captured what she saw in the room she was in, the other captured images and posted them on the Internet, and from the Internet you could turn her head 180 degrees. It was like a nanny cam, but about a decade pre–nanny cam. The doll is a miniature replica of Roberta. I resized Roberta’s clothes with a seamstress so they would fit the doll, I sent photographs to the doll maker to make her look like Roberta, and I had little glasses and all the artifacts that were hers replicated, but in miniature. And then, in 2018, I made an antibody with a scientist, Dr. Thomas Huber at Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research in Basel, that had Roberta’s name on it and was called erta. There’s also a lynn hershman antibody, and there’s a roberta breitmore antibody— because I thought it was appropriate, since she no longer had a body.

Roberta was/is a mirror of her culture. The images are the remains of her life, in nonhierarchical form, with surveillance photographs, her replacement at work, the button she lost from her coat, all of which comprise the varying series she endured becoming herself. Almost two hundred images and documents. She was meant not only to demolish the barriers of definitions of theater, literature, and photography, but was also meant to blur the very nature of reality set as a simulation in real time. When one looks through the artifacts and remains of her life now, some forty years later, it is as if they are reperforming or re-embodying her.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roberta Getting Ready to Go to Work, 1975

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roberta Getting Ready to Go to Work, 1975Myles: When you stopped, what was the effect on you?

Hershman Leeson: I think that it was a beginning of my own journey toward nonvictimization and healing. It was a vehicle through which I understood that there’s more than one victim in our culture. People can revive themselves into a new dimension or perceptions by looking at new choices, so that when they become seventy-two, they might finally get discovered, because their options aren’t so constrained. And that’s exactly what happened to me.

Myles: So tell me about your discovery at seventy-two.

Hershman Leeson: All my life people said that what I did wasn’t art. Then about four years ago, a curator in Germany, Peter Weibel, offered to do a show and a book of my work, not realizing how much of it had never been shown. The exhibition was at ZKM, in Karlsruhe, and was called Civic Radar (2014); it included eight hundred artworks. People realized that the previously unexhibited work anticipated many ideas from 1966 on, and that many other people had been credited for doing the work I originated. Finally, my work was noticed—or you could say “discovered.” It absolutely changed my life’s trajectory. The unintended consequences of that show were that it got me out of debt and it gave me a kind of recognition that had always eluded me.

Myles: How does the “double” play out in the series Hero Sandwich (1981–84)?

Hershman Leeson: Those photographs were created by crossing negatives of easily obtainable publicity photographs of media heroes in a way in which either the male or female dominated. The male/female images of stars were cross-pollinated, so to speak, by “sandwiching” the negatives, manipulating the outcome, and reprinting the result several times. Each work from Hero Sandwich is generally composed of a male and female pair, not necessarily from the same time period. The overlapping imagery focuses on common gestures or intentions that reflect media strategies responsible for producing these “heroes.” Individual identities surrender to artificial personas. During the process of creating these photographs, I felt like I was working in Gregor Mendel’s garden, seeing what would emerge from shifting domination, a kind of image genetics that created varying strains of recombination.

Myles: Photographs feel like a double in a way writing never does, unless it’s simply how writing a story makes the person themself— the author, I mean—kind of redundant. Since I use my own life frequently in my work, I sometimes get that glazed-over look from people because the “I” of my book has already told them “that” before. It’s like I’m in a long-term relationship with everybody. But photographs just kind of hang out there in the world.

When my show poems (2018–19) was up at Bridget Donahue, in New York, I didn’t know where to put my body. I missed my opening because I was on a book tour for my new poetry collection, Evolution (2018), and we kept going back and forth about whether we should tell people through the press release that I wouldn’t be at the opening. How much am I a part of the work? Writing is all about the body, to my mind. As long as you’re not dead, people want to see the author.

Years ago, I gave a talk with a slideshow in Germany. Well, actually, I missed that too, but that’s another story. But my intention was to give a talk with all these pictures flashing behind me. The lecture was called “The Poet’s Body.” I was feeling very sad at the time I was putting that piece together, and the last line of the talk was, “My tears have turned into pictures, my tears have turned into pictures.” The show that you saw in New York was like all these flickers, like you were passing things on a train: purple drink, view from bed in my apartment, the line of the train in Marfa.

Hershman Leeson: Who published Chelsea Girls (1994)?

Related Items

Aperture 235

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Spirit of the Age

Learn More[image error]Myles: Ha. I did not count on you knowing my work. Black Sparrow Press did; then HarperCollins published it the second time around, in 2015. That’s how I got “famous.” The line was, “Underground dyke poet makes big.” The thing that’s funny is that it was always my plan—to be mainstream at this point in my life.

I meant it as a film. I also thought of it as all these ways of being female. I was in a new life; I come from a long line of alcoholics and addicts, and I had stopped all that. I was a clear- eyed poet. So my capacity to project myself into a place where I had been at some other point in my life—tales of my own drunkenness, young memories before I could articulate them— became interesting and desirable. The chapters were like little movies, because I always wanted to make films. The book itself was me transitioning from being a poet into being a fiction writer—and back, of course. I don’t trust staying away from poetry too long. It’s my water.

Interestingly, I just made my first actual film in Marfa, called The Trip (2019), with David Fenster; he shot it on Super 8. It’s a road film with puppets, but the puppets aren’t just any puppets—I made them when I was nine. We took them on this glorious road trip between Marfa and Alpine, Texas. Yet the narrative that arose wound up being very emotional. The same old alcoholic family was suddenly also along for the ride.

Chelsea Girls went out of print someplace in the aughts when Black Sparrow ceased, and I just decided that I was going to let it stay out of print until I could do it with someone good. And when it did come out again, I had a boom. It was almost a joke. In the fall of 2015, I think the New York Times wrote about me four or five times. People were like, “Again?” Poets were pretty great about it, like I was taking one for the team. But by now, since I am female and queer, I sort of get the feeling I’m supposed to vanish into my fame in some way. In 2016, I was even in that part of The New York Times Magazine where they ask you twenty questions. Then it was how Eileen spends her Sunday night. What’s great about publicity is the self you build out there. I told them I masturbate on Sunday night—doesn’t everybody? I thought the point of a public body is to say what the public body never says. Especially a female.

Actually, I wanted the show at Bridget’s to invisibilize my book release. Books are so heavy, and photographs are so quick and light. Like a film. Passing.

Eileen Myles, –, 2018

Eileen Myles, –, 2018Courtesy the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

Hershman Leeson: Do you see any correlation between your writing and your photographs?

Myles: They are the same. I’ve always thought of my writing as visual art, so photography is just making something manifest that was already there in another form. I’ve been taking pictures since I was a kid. Earliest was trick photography. I staged crimes at home and caught them on film. Mostly I was interested in making legends; now I like things trapped in time, dazzling in some way. I think the best you can do is create discomfort. It’s so real. I suppose that is why I like taking photographs. My career is so unrelentingly queer, but my photographs are not queer … though the world is queer. Get out there and walk around; it’s undeniable. It’s queer and falling apart.

I’m sixty-nine—it’s such a joke, a dirty joke before seventy. The thing that’s great about aging is that something is retiring. My forties were a struggle. I was doing performance art; I was writing art reviews; I was writing poems. And I was writing the stories that would become Chelsea Girls. It was a very constructive decade. I ran for president in my forties, and an enormous part of it was an enormous construction of self and feeling. If at thirty-nine I felt like an exhausted old poet, I would nonetheless at forty and forty-one be a young presidential candidate. It was truly endurance performance art. If you want to endure something, run for president. It’s horrible. Honestly, before I ran for president, I was famous for being poor; running for president really blew my life out of scale entirely. I was a wreck after that. I was always a figure in my poems, but now I was a figure in the world. Big in the way you could be big in the 1990s—on MTV, written up in art magazines, touring in twenty- eight states. For years people were stopping me at ATMs.

Didn’t you run for president?

Hershman Leeson: I created a virtual character that ran for president in 2004. Her name was DiNA, and she ran for tele-president. She was running against George W. Bush, and her platform was “Artificial intelligence is better than no intelligence.” But alas, she also didn’t win.

Myles: That’s a very good platform. Mine was “Total disclosure.”

Hershman Leeson: That’s why you didn’t win.

Myles: I know. A presidential candidate is supposedly creating an other self, and I was using my actual self, which was kind of like used material. I think they prefer it if you come up with something new.

A couple of years ago, Amazon optioned Chelsea Girls for a movie. I was hired as the screenwriter. When I was a young poet and imagining what my life later on would be, I had this idea that writers, if they were lucky, would all go and sell out to Hollywood and become rich, and that was my plan. Back in the 1970s, when I was deliberately being dramatic and sick of shitty jobs, I went and sold my blood one day for, like, six dollars. It was an awful experience, and I freaked out; they told me never to come back there because I truly had a panic attack. There were these two old maroon plastic couches you laid down on, and they hooked me up, and I could see my blood pouring out of my body into this big sack. There was this old street guy next to me, lying there, who clearly did this every week. He was lying there very calmly, and I was just freaking the fuck out. I just couldn’t handle it. And they were so mad at me. I took my six dollars, and I remember going next door and buying a ginger ale—and then it was down to around two dollars—and I was writing a poem on a napkin about how when I was a rich screenwriter in LA I would think about this day when I sold my blood.

Eileen Myles, it’s absinthe, 2018

Eileen Myles, it’s absinthe, 2018Courtesy the artist and Bridget Donahue, New York

Hershman Leeson: Anyway, we fulfilled our dreams.

Myles: Exactly. This kind of hard touring, which probably both of us have been doing for the past years, is very literally selling your blood. Right?

Hershman Leeson: Yeah.

Myles: I mean, that’s why I want to stop. It’s like my body is like a candle and I am burning it, and this is not what I want to do.

Hershman Leeson: Like the world becomes a vampire, and you have to endure this bloodletting to survive. And it seems, in a particular way, too, about being female. It might be that men seem to understand boundaries better and don’t let this systemic leakage happen. I think as a female artist, and also as an artist who has gotten more attention later in life, I am like a broken machine that says yes to any opportunity. I am only now realizing that there is another machine inside of me that finally is learning how to say no. Once you jump-start the second machine, it becomes kind of addictive. Saying no gives you a lot more power than saying yes.

Myles: Totally.

Hershman Leeson: Just being able to hear things in a different way than you do when you’re overcommitted, as luxurious as being overcommitted is. Wasn’t it Tennessee Williams who, when his play opened on Broadway and was a big success, wasn’t able to write because they were putting him up at a fancy hotel with room service? Eventually, he moved down to Mexico to some little dumpy place so that he could find out who he was again and start to write. The same thing happened to Francis Bacon. They actually destroyed his studio and got him a nice, clean, new one, and he couldn’t paint in it. They had to rebuild the old one so that he could work again.

Myles: That’s hysterical. My whole life on Instagram is just documenting my studio, which is mostly my apartment. But also walking down the street, collecting stuff. It’s like the inside of the head, whether it’s inside the apartment or inside the subway or inside the airport.

We’re in such a funny moment technologically, because we can share all those in-between stages, or the permanently present one of where we are, with so many people so swiftly. It’s this very godly feeling. It’s disgusting, and then very beautiful. It’s a little bit like dying all the time.

Hershman Leeson: Yes. That’s sort of what I was trying to find out with Roberta’s psychiatrist. I wanted to know more about collective trauma, or a connective trauma that we’re all dealing with, because we are all connected through DNA and just from being alive at this time. I recently completed a project, The Infinity Engine (2006–18), that was modeled after a genetics lab, and I was able to convert all the work and research I had done for the last thirty-four years, including some of my films, into DNA itself.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Room #8 – Lynn Hershman DNA and Lynn Hershman Antibody (detail), 2018

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Room #8 – Lynn Hershman DNA and Lynn Hershman Antibody (detail), 2018All photographs by Hershman Leeson courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York, and Anglim Gilbert Gallery, San Francisco

Myles: Wow.

Hershman Leeson: It wouldn’t have been possible before this year, because they just developed this technique. George Church, a professor of genetics at Harvard and an expert on synthetic biology, worked with Technicolor and Microsoft to create technology that enabled this process. I look at it as a kind of expanded cinema, because you have to put all of the information on a time line, one frame at a time, and they convert it to zeros and ones at the micromolecular level and store it as synthetic DNA, which has a life span of a million years, rather than fifty, which is what most films have.

Myles: The very gesture itself is so anti-storage. How big is it?

Hershman Leeson: They put it in a tiny test tube. It’s about two inches by a half inch. My entire life fits in this tiny thing that’s practically invisible. I carry it in my wallet.

Myles: It’s so beautiful. It’s like a crazy, insane, microscopic retrospective.

Hershman Leeson: Exactly. A simmering essence. A haiku of being. Myles: Right? Or a fossil.

Hershman Leeson: [Laughs] Exactly.

This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 235, “Orlando,” under the title “The Double.”

June 18, 2021

Family Fun Days at Fotografiska NY

Fotografiska NY

281 Park Ave S

New York

Celebrating "I’m Looking Through You" with Tim Davis and Sarah Bay Gachot

Family Fun Day at Fotografiska NY

Fotografiska NY

281 Park Ave S

New York

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers