Aperture's Blog, page 58

April 19, 2021

How One Photographer Covered the Unfolding of the Pandemic

In March 2020, within weeks of the first diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in New York, Philip Montgomery began documenting the health-care workers and staff in nine of the city’s hospitals. On his first day, 1,162 new patients had been hospitalized with the disease, and 349 had died. By April 6, his last day, 19,177 people had been hospitalized with the virus in New York, and 3,202 had died. As the story shifted to how New Yorkers would mourn an unimaginable loss, Montgomery chronicled a funeral home in the Bronx, where two undertakers strove to provide services with dignity in a time of isolation. Montgomery hoped his images would “galvanize” the country—and testify to the scale of the tragedy.

One of the most accomplished photojournalists of his generation, Montgomery has covered major U.S. stories from the aftermath of Michael Brown’s killing in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, to the flooding after Hurricane Harvey in Houston, in 2017. Faces of an Epidemic, his account of the devastating effects of the opioid-addiction crisis in Ohio, earned a 2018 National Magazine Award. Last fall, Montgomery spoke with Kathy Ryan about covering New York as the city became the global epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, publishing powerful photographic essays in The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine, where Ryan is the director of photography. As Montgomery recalls, “It was like a movie being played out in front of me in real life.”

Philip Montgomery, Manhattan’s financial district as New York began its shutdown at the start of the global pandemic, March 2020, for The New Yorker

Philip Montgomery, Manhattan’s financial district as New York began its shutdown at the start of the global pandemic, March 2020, for The New YorkerKathy Ryan: What was it like to be in the epicenter of the pandemic, photographing in New York’s hospitals during this crisis? How do you prepare for something like that?

Philip Montgomery: I’m not sure there was a way to really prepare. I wasn’t necessarily in panic mode, but it was a feeling of all-hands-on-deck in thinking about how we were going to cover this in the city. You and I had discussed it: “Well, let’s do ride-alongs with paramedics.” “Let’s look at the USNS Comfort.” But I think we both knew that this story was best told inside the hospitals. That was priority number one.

Ryan: Yes.

Montgomery: When we ended up getting access to nine of the eleven of New York’s public hospitals, which was a breakthrough moment, I don’t think we really knew what to expect. We were following the statistics, but you have no way of knowing how that’s going to look. So in terms of preparation, I didn’t really know what to prepare for, emotionally or visually. On the safety front, we were so terrified that we went above and beyond with the PPE, and I’m happy we did, but thinking back on it, maybe some things were a little bit unnecessary.

But what we weren’t prepared for was the sheer volume of patients at the peak of the pandemic in New York. As I talk to you now, I have the contact sheet of the shoot at Queens Hospital Center in front of me, and I’m looking through the images, frame by frame, of walking in there, from the first picture to the middle of the take. I remember feeling completely overwhelmed by what we were seeing. I remember feeling really emotional and, at times, was even in tears.

Philip Montgomery, A passenger on an uptown F train wears a makeshift mask, New York, March 2020, for The New Yorker

Philip Montgomery, EMT Atma Degeyndt after treating a patient who was suffering from symptoms of COVID-19 in an apartment complex in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, March 2020, for The New York Times Magazine

Ryan: Why did you choose to use a handheld strobe to illuminate the scenes you were documenting?

Montgomery: It was pretty immediately clear that was what needed to be done. The light within hospitals is really clinical and flat, and there is so much going on in the space, so the way that I used the light was to enable me to isolate certain scenes and moments. I had to set up parameters within the hospital. HIPAA law dictates that only individuals who had consented to photography could be photographed. And using that light actually helped me to isolate those individuals and frame out the other elements that weren’t supposed to be seen in the photographs—unconsenting patients, or patients who were on ventilators, or patients who were being admitted into the ER.

Ryan: The light is obviously part of your signature. In our editing, we also spent a lot of time dealing with privacy issues. It was an overwhelming part of this particular project. It’s so unusual to have that kind of access in a hospital, and we wanted to be respectful of patient privacy.

At one point, you photographed fire department paramedics who were resuscitating a coronavirus patient who had gone into cardiac arrest when he stopped breathing. What was that like for you? There you are, you’re making pictures, and now you’re seeing a life-and-death moment.

Montgomery: It was like a movie being played out in front of me in real life. There were beds and beds and beds. There was barely any walking space within the emergency department at that time, and the room was already high-intensity. Much like you’d see in a television show like ER, these paramedics rushed in with the gurney and didn’t really have time to station a man in a specific spot, and they were working to save his life in the middle of the unit. It had to be done right there. I watched the two paramedics taking turns, administering chest compressions to the point where I’m pretty sure they had broken the man’s chest plate. It was this profound, cinematic moment—you just couldn’t believe it was really happening. But for those working in the ER, this sort of thing happened all day, especially in the time of COVID.

Philip Montgomery, Dr. Sherry Melton (center) moves a gurney after transferring a COVID-19 patient from the emergency department to the intensive care unit, Lincoln Medical Center, Bronx, New York, April, 2020, for The New York Times Magazine

Philip Montgomery, Dr. Sherry Melton (center) moves a gurney after transferring a COVID-19 patient from the emergency department to the intensive care unit, Lincoln Medical Center, Bronx, New York, April, 2020, for The New York Times MagazineRyan: What was your interaction like with the health-care workers? How do you communicate when there’s that kind of chaos unfolding?

Montgomery: I would try to read the room. Everybody was in N95 masks and face shields. I could see through the shield, and so if someone’s eyes locked on me, I could nod. I could sense how they were feeling, and how busy they were. A lot of the time, I was just trying to stay the hell out of the way.

The set of questions I always asked was: “What do you want us to see? What is important for the public to see?” Given the moment with COVID, a lot of doctors were pretty clear about what they wanted to convey to the world, and they largely wanted to reinforce how serious the situation was.

Ryan: In addition to documenting the news and capturing the first visual draft of history unfolding, many photojournalists hope and think and believe that the work they do will provoke some kind of change. What were you hoping the photographs in the hospitals would do in terms of provoking change?

Montgomery: After all that I had seen, I was hoping they would terrify and galvanize the public into taking preventive measures recommended by scientists, namely social distancing and mask wearing. I was hoping the photographs would spark a collective show of respect for the severity of the disease and the sacrifices by the frontline workers combating it.

How did you feel, as the director of photography at the magazine, receiving those pictures?

Related Items

How a Museum’s Photographic Archive Honors Generations of Chinese American Lives

Learn More[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]Ryan: I was shocked. When the pictures came in, it was worse than I could even have imagined—the amount of people crowded into the rooms in the hospital, and the number of health-care workers who were there. It was literally like nothing I’d seen. The project was so emotionally wrenching, partly because of what we were seeing in the hospitals, the speed we were working at, the risks you were taking, and the fact that it was in our own city. Honestly, that did make it different.

We had all just left our lives as we knew them. We’ve vacated our offices. We’re working from home. And we’re producing this photo-essay that’s going to be extremely important, and hopefully have exactly the impact you were hoping for—which would be to get people to change their behavior and wear masks. This was in March, when there was still a lot of trying to convince people how serious COVID was and how important it was to wear masks and social distance. I felt acutely the unusual experience of producing and editing the photographs while, at the same time, living through this heartrending moment in our city’s history. When this issue came out, the response was huge. It was the first, I think, really major moment when a photo essay kind of showed what it was like, showed everything.

As you were working in the hospitals, it sadly became clear that the next part of your coverage of the pandemic in New York would be to photograph how New Yorkers are mourning their dead. In April, we arranged for you to spend time at the Farenga Brothers Funeral Home in the Bronx. The idea was that you would photograph the Farenga brothers as they guided families through the mourning process, and you would photograph the families mourning their lost loved ones. One of the first things you did was photograph Nick Farenga retrieving one of those bodies out of a trailer outside a hospital. How did you find the strength to make pictures witnessing that?

Philip Montgomery, Gurmit Kaur, left, with her five daughters at the small service held for Paramjit Singh Purewal at the Farenga Brothers Funeral Home, Bronx, New York, April 2020, for The New York Times Magazine

Philip Montgomery, Gurmit Kaur, left, with her five daughters at the small service held for Paramjit Singh Purewal at the Farenga Brothers Funeral Home, Bronx, New York, April 2020, for The New York Times MagazineMontgomery: I never quite know how to answer that question. The responsibility of the task at hand far outweighs any sort of internal conflict I may have. When I’m working on stories of this significance, there’s not much consideration for myself. There’s no question of, Can I do this or can I not? I absolutely must.

When I was photographing in the hospitals, the refrigerated trucks being used as temporary morgues were a dark reality, but they were also a mystery. In order to convey the urgency of the pandemic, the public needed to see inside these hidden places. So when we gained access to a funeral home, I thought it was an imperative piece of the story.

The scene inside the funeral home was the evidence. There were bodies stacked on top of bodies. Nick, one of the funeral directors, had to retrieve a body for a family, and he had to move multiple bodies from the shelves to do so. It was completely surreal. He was professional, and at that point he’d done this countless times. For him, it was just work. For me, being there was work as well, but it required another level of focus and sensitivity.

Ryan: I felt you showed a tenderness on the part of Nick and Sal Farenga. That is difficult, harsh stuff, lifting a body bag off the shelf. The moment that you captured, there’s a tenderness to the way that he’s holding it, and his head is bent down. I only wanted to mention that because you’ve got to make pictures that people can bear to look at.

At the time, New York was becoming totally unbearable for everyone—for the people who were losing people, for the people who were trying desperately to save lives. It was just a difficult, difficult time. And you want people to be able to look at this picture. And a lot of people think, Oh, I can’t look at that picture inside that trailer, with all the bodies stacked up on the shelves. We never would have thought we’d see something like that in the city.

I felt something similar in your photograph of Sal preparing a body for the embalming procedure, a close-up of his gloved hand as he’s washing the hand of the body. There’s something about it that feels almost religious. What is your memory of that one?

Montgomery: Sal and Nick are tough men. But when they were doing their work, they implemented a sensitivity that was really surprising and beautiful. I say surprising just because of their demeanors. They’re from the Bronx. They’re a little rough around the edges. So that juxtaposition was striking.

In the photograph that you’re describing, while Sal’s embalming a body, he’s carrying on a conversation with one of his staff members, and it’s like how you or I would talk to a colleague in the office, but he’s also still, at the same time, displaying this great respect for the process. I think that’s why the picture presented itself to me. His hands were so delicate in handling the hands of the deceased.

I’m sure, in your job at the magazine, you have to ask, How do you show bodies of the deceased? Does that change if they are Americans or foreigners? You must have had this conversation many times throughout your career. It’s harder for an American readership to see stories close to home. What were the internal discussions around that, especially considering this story was in our backyard?

Philip Montgomery, Gurmit Kaur at a viewing for her husband, Paramjit Singh Purewal, Farenga Brothers Funeral Home, Bronx, New York, April 2020, for The New York Times Magazine

Philip Montgomery, Gurmit Kaur at a viewing for her husband, Paramjit Singh Purewal, Farenga Brothers Funeral Home, Bronx, New York, April 2020, for The New York Times MagazineRyan: We approached it with tremendous care, and every step of the way we were extremely careful to protect the privacy of the patients. It was hard to do the story without showing bodies, and we were committed to making sure that with every picture we showed one could see that the body was being treated with dignity.

The Purewal family agreed to give you full access to document the funeral service of Paramjit Singh Purewal. Mr. Purewal’s wife had just recovered from COVID herself and been released from the hospital in time to mourn her husband. For the cover of that issue, we decided to go with the picture of Mr. Purewal lying in the casket, and his wife is stroking his head, and her hand is gloved. So the gloved hand indicates this moment in time, this year of 2020, with COVID, and the fact that she had to wear gloves to touch her deceased husband one of the last times she’s going to see his body.

Right up until the end, I was very nervous and concerned and hopeful that the Purewal family would be okay with this decision. We don’t seek approval for how we’re going to use the pictures in the magazine. It’s understood that they know they’re being photographed for The New York Times Magazine and that, ultimately, we’ll decide which images to use. But in this particular photo-essay, I remember wanting to be confident that the family members would feel good about the picture because it was very courageous of the Purewal family to agree to this project. You managed to make brutally honest documentary pictures of the horrendous loss of lives and, at the same time, incredibly honest pictures of tender love, just gentle enough that the people who were pictured in them were accepting of the images.

Montgomery: In each of those scenes, and in other stories I’ve worked on where I’m meeting someone on arguably the toughest day of their life, whether that’s an opioid overdose or a funeral in the wake of COVID, I ask myself, What if that were my father or my mother?

I thought that cover image spoke to how our process of mourning, and our process of engaging death in the time of COVID, has dramatically changed, and how traumatic that could be for a family, from New York, where the funeral homes were completely overwhelmed, funerals were limited and socially distanced, and a lot of New Yorkers were begging funeral homes to help them retrieve loved ones whose bodies had been stored in these trailers for days or weeks.

Ryan: Being denied the chance to even attend the funerals of their loved ones.

Montgomery: Exactly.

Ryan: I also think the cover image, because of the light that you brought to it, gave it a little bit of a celestial feel. Without that deft lighting, the picture might not have transcended to the degree that it does, where it feels spiritual.

Montgomery: At the magazine, news moves at a different cadence. But when you have these moments, 9/11, or the peak of the pandemic in New York, where does your mind go as a photography director, when a story is dominating the whole world? What was your headspace at the beginning of the pandemic?

Philip Montgomery, Members of the Sharks in director Ivo van Hove’s reimagining of West Side Story, Manhattan, New York, December 2019, for The New York Times Magazine

Philip Montgomery, Members of the Sharks in director Ivo van Hove’s reimagining of West Side Story, Manhattan, New York, December 2019, for The New York Times MagazineRyan: I would say it all started with Jake Silverstein, the editor in chief of The New York Times Magazine, literally on the night before we vacated the New York Times building for what’s now turned out to be at least a year. Who knew? We thought we’d be back in weeks. The COVID crisis was huge at that point in Italy, and it was really just starting to become the issue that it became in New York. Jake said that the story was going to be huge, and be with us for months, and that he wanted to cover it in a big way photographically.

So I knew what I needed to do. I said we should put you on assignment for a month. When I first reached out to you, we didn’t even know what we were going to be covering. The likelihood was it would be the hospitals. Clearly that was at the top of the list. But at that point, we didn’t have an actual assignment, to say, “We’d like you to go to the hospitals tomorrow and the day after.” We weren’t there yet. But it was very clear that major things were happening, and happening in our city, and I desperately wanted us to be able to document it.

Your pictures make people slow down. They make me think of the sort of golden era of Life magazine, when people really stared at a picture. It’s so hard now, with everybody looking on their phones, and pictures go by so quickly. Before the COVID crisis took hold, the last assignment you had done for us, in January, was to go into the studio on a big theatrical shoot. We were doing a cover story coming up on the remake of West Side Story on Broadway, and literally the weekend before it was due to go into previews, we got permission and access for you to photograph the whole cast of dancers and singers in the studio. The producer of West Side Story arranged for them to go there on a Sunday, and theyspent a long day with you.

You got them dancing, singing, reenacting scenes from the musical, doing their own thing—a little bit of everything. It was an extraordinarily joyous day. The youthful energy and enthusiasm and excitement was bouncing off the walls, because for the majority, I think about thirty of these actors, it was their first Broadway role. It just was magical.

In a way, it’s almost like I still cannot believe that none of us that day, none of us, could have anticipated that within two months all Broadway shows would be shut down, theaters would go dark. These poor actors are out of a job. This iconic picture of them, which I thought just defined youth and vitality, ends up being ancient history within two months.

Montgomery: I don’t know about you, but that was the last time I had fun with the craft of photography. The last photographs I made before the pandemic were during a studio shoot with Matthew McConaughey in LA. Since then, I’ve photographed New York’s empty streets, COVID testing sites, Wall Street as the stock market crashed, John F. Kennedy Airport as it shuttered. Last year, two days before Thanksgiving, I photographed the Rainbow Room on top of Rockefeller Center. The initial excitement at seeing the skyline quickly gave way to sadness. Being up there, I began to unpack the profound transformation both our city and our nation had experienced.

Philip Montgomery, The Rainbow Room, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, two days before Thanksgiving, November 2020, for Aperture

Philip Montgomery, The Rainbow Room, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, two days before Thanksgiving, November 2020, for ApertureAll photographs courtesy the artist

Ryan: The first couple of months of the pandemic, when I would look at this picture of the West Side Story cast, so happy and full of excitement about their future, it would make me sad. Now, I look at it and have a different reaction—it’s a picture about faith. You’ve got to have faith in New York.

Montgomery: Absolutely. What I’m so proud of in this city is the collective understanding of what we all experience as one. Since those photoshoots, I’ve traveled a bit throughout the country, and nowhere else is operating like New York in terms of being cautious and considering thy neighbor. That gives me optimism in our path forward. At the beginning, we would see people flee the city—at the first sign of trouble, folks were out. For you and me, people who are over the-top in our love for New York, it’s like, What? Are you crazy? We go down with the ship.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Life and Death in an American City.”

Philip Montgomery’s first monograph, American Mirror, will be published by Aperture in fall 2021.

April 16, 2021

Picturing One Brooklyn Family’s Life and Love

Too much weight is often placed on the value of an outsider’s vision, presumed to be clear and unfettered. But what of the insider? He who can witness more intimately what the outsider cannot. That has long been Rafael Rios’s prerogative. The New York–based photographer’s images center on his extended Puerto Rican family, many of whom have lived in the same Fort Greene house since his aunt and uncle bought it in the early 1980s. Growing up, he and his parents lived on the top floor, his cousins on the second, and his aunt and uncle on the ground floor. His work tells the story of this house as much as it does that of his family members. And both are memorialized in his aptly titled 2018 book, Family, which contains images taken over an eight-year period, from 1999 to 2007.

Multigenerational living is common among Latinx and other immigrant families in New York, driven by economic necessity and tight-knit family values. In the mountainside village, in the Dominican Republic, where my family is from, relatives often live in clusters—small, multihued houses built near enough to each other that one can easily pop in for coffee or make lunch a neighborhood affair.

Rafael Rios, Getting ready for the party, 2004

Rafael Rios, Getting ready for the party, 2004In New York, driven by necessity, my extended family replicated that communal living. We grew up in two- or three-bedroom apartments where every second at home was a shared one, every space communal. My father bought his own home when I was a teenager, and we all moved in there, separated only by wooden beams and drywall. This sort of setup is becoming more common in the United States. A 2016 analysis of census data indicated that 20 percent of the population, or sixty-four million people, were living with multiple generations in a home—particularly in Latinx and Asian households. Rios documents the intimacy of this arrangement in his photographs.

Rafael Rios, Marcus on Thanksgiving, 2002

Rafael Rios, Marcus on Thanksgiving, 2002Over the years, Rios has captured his family at play and at rest, braiding one another’s hair or lying twisted in an embrace. When his aunt got sick, he took his camera to the hospital and photographed her cackling into a ventilator and later, at home, family members crowding into bed with her. “Families gather for parties, or when something bad is happening,” Rios says. He shows his family in various states of gathering, for both quotidian and special occasions. Rios also presents the same people in different contexts, and across time.

Rafael Rios, Mom sanitizing her hands, 2020

Rafael Rios, Mom sanitizing her hands, 2020Gathering is much more difficult and dangerous now, during the pandemic, and the focus of Rios’s camera has necessarily narrowed, homing in on his partner, Jassine, and his daughter, René, who was born in June of 2020. “All of René’s life has been in quarantine,” Rios tells me. He returned to the family home and took a photograph of his mother standing in front of a framed portrait of herself from Family, wearing a mask and sanitizer in hand, seemingly mid-pump. She held René for the first time only recently. In another image, Jassine sits on a park bench with René, a black mask pulled down underneath her chin.

Rafael Rios, Mom in her room, 2003. All 2020 photographs for Aperture

Rafael Rios, Mom in her room, 2003. All 2020 photographs for Aperture Courtesy the artist

These photographs reflect how the pandemic is forcing us all into isolation, testing our bonds. When I got COVID 19 in late November, many family members dropped medicinal teas and food at my doorstep. One night, my aunt came by. She left tearfully saying, “I love you,” and “I can’t be with you.” As if trying to reconcile the two statements. There is joy in gathering, but perhaps there is a different sort of connection to be found in our new reality, a renegotiation of family love—an air kiss rather than a physical one, a delayed reunion rather than a tragic one.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Family.”

In New York’s Parks, Images That Make Us Long for Connection

I happened to be reading Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse (1977) when these photographs by Widline Cadet landed in my in-box. Although, Cadet’s photographs might have a more likely kinship with Barthes’s Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1980), his highly personal study, in which he writes that “in order to see a photograph well, it is best to look away or close your eyes.”

Eyes closed, I tried to re-create my own version of these images, which would remain with me long after they were out of sight. What persisted was their coupling and twinning, what in a mix of Haitian Creole and English (Crenglish) one might call their marasa-ness.

In a section on “figures” in A Lover’s Discourse, Barthes writes, “A figure is established if at least someone can say: ‘That’s so true! I recognize that scene of language.’” It is those types of scenes and unspoken languages that keep bringing me back to Cadet’s photographs.

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Marsha and Tashae), 2020

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Marsha and Tashae), 2020Here is an unseen hand offering a blessing to an openly receptive face peacefully receiving it, with eyes closed. The hand might belong to a healer, and the gesture a type of prayer. Here is the elder who’s accepting her own blessing, through embrace, while both she and the person embracing her are out in the cold. Here they are, these same two Black women of different generations meeting, or reuniting. Was one lost and is now found? Here are two young women, near mirror images of each other, almost, but not quite, marasa, or twins. Are they sisters? Lovers? Friends? Sister friends?

These scenes, made in New York parks and collected in a series Cadet calls Soft (2017–20), capture figures who also seem like memories or dreams. Here I can’t help but see my mother and me, my daughters and me. Among a series of recollections that these photographs sparked, this particular memory lingers.

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Ebony and Gail), 2017

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Ebony and Gail), 2017When my oldest daughter was six years old, we took my mother to the airport so she could return to her home in Brooklyn, after a long visit with us in Miami. We waited for Manman, as I called her—my daughter called her Grann—to clear security and wave goodbye to us before disappearing into a crowd of other travelers. As an adult, taking Manman to the airport and watching her leave was one of the most recurrently painful moments involving my mother and me. Each time we had to experience this particular ritual, I wanted to scream because these moments reminded me of my first concrete childhood memory, which was of being separated from my mother on the day she left Haiti for the United States when I was four years old. No one had told me that she was leaving without me, and that we would only be reunited in Brooklyn when I was twelve. When it came time for her to walk toward the plane, my body had to be peeled off of hers. Mysteriously, or perhaps not mysteriously, that day, as my six-year-old daughter and I watched my mother merge into the crowd heading toward her gate at the airport in Miami, my daughter screamed, “Manman!” I was too concerned with consoling her to ask her why she let out that particular cry, at that particular moment—years later she does not remember this at all—but it felt as though the part of me that was inside of my daughter had gone back in time to help me scream.

“Absence persists—I must endure it,” Barthes writes in A Lover’s Discourse. This cross-generational absence persisted in my daughter, and persists, too, in these striking and moving photographs by my fellow Haitian, who moved to New York in 2002, when she was ten years old. I felt somewhat vindicated in what seemed like an overreach in imposing my own absences on Cadet’s photographs when I read some words she shared in a 2019 interview with Zora J Murff of the Strange Fire artist collective. “My mother’s parents, for example, died before I was born and there aren’t any pictures of them anywhere that I could find. The same thing could be said about my siblings and I, of when we were growing up in Haiti,” Cadet stated. “I feel more desperate to have an image of them as a point of reference and remembrance when memories start to fail. In addition to that, I honestly just get fed up with the way people produce and distribute images of Black bodies.”

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Nene and Beryl), 2020. All photographs from the series Soft

Widline Cadet, Untitled (Nene and Beryl), 2020. All photographs from the series SoftCourtesy the artist

Entering Cadet’s world makes me long for a type of physical contact and familial intimacy that for now has been put on hold. Here are Black bodies that have not yet become the battlefields of a deadly virus. Here are maskless people lovingly touching one another, intergenerationally. “Here we are,” Cadet’s subjects seem to be telling us with their tender gazes and gestures. Absence persists, but we will endure. Nou la toujou. Each photograph is an amulet and a memorial, and a welcome breath of fresh air.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Absence Persists.”

April 15, 2021

Zoe Leonard’s Elegiac Images of Downtown New York

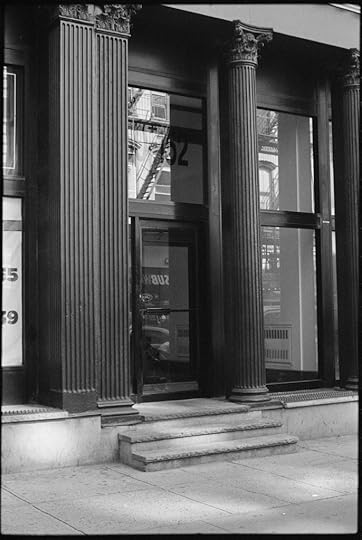

Zoe Leonard made the twenty-one photographs that compose her series Downtown (for Douglas) on the occasion of her friend, the late art critic and curator Douglas Crimp’s much-loved publication Before Pictures (2016). Leonard’s photographs depict the various residences and neighborhoods Crimp called his own during his first decade in New York City—between 1967, the year he moved from his home state of Idaho to an apartment in Manhattan’s Spanish Harlem, and 1976, the year before he curated the groundbreaking Pictures exhibition, moving downtown into a loft apartment in the landmark Bennett Building, “pretending,” he writes in the book, “to be an office tenant.”

Leonard’s series appears as double-page spreads before each discrete section of Crimp’s book, as would establishing shots in the sequence of frames that constitute the narrative flow of film, introducing Crimp’s readers to the writer by taking us to his doorstep—where Crimp would go before and after work, or ballet class, or a night dancing at Crisco Disco or the Cock Ring. If being queer, as Crimp defines in the preface, “is a matter of a world you inhabit, not something you simply are,” then we might read Leonard’s unpeopled, site-specific photographs as queer, in that they only indirectly suggest the various possibilities of what they define: not the sex, for instance, but the temporality of fantasy that leads up to it—the erotic activity we could call “waiting.”

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016One image depicts a waiting area near a turnstile in Fulton Street station (a central transit hub in Manhattan’s Financial District, recently refashioned as a food hall and mini-mall). Leonard provides a layered composite of surfaces—grimy tiles, placards, and serif fonts; light fixtures and floors—emblematic to the subway system’s design and the elements of our peripheral attention that are likely to linger in the short-term memory of an actively commuting New Yorker, as Crimp once was. In framing this leitmotif, Leonard’s photograph asks the viewer to reinterpret the principles that organize our sense of the familiar. I find something similar at work in Crimp’s memoir, which resurfaces primary documents from the writer’s past—for example, a “cringe-worthy” notation from a Moroccan cookbook he cowrote, or the lengthy excerpts of art criticism reproduced across the volume—without too much hand-holding. As in Leonard’s photograph, Crimp captures the amalgam of discourses imminent to the emergence of “downtown” as it gained purchase as a cultural touchstone. What did downtown mean before 1977? What does it mean now—and for whom?

In her 4Columns review of Survey, Leonard’s 2018 retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, the critic Johanna Fateman points out the “poetic measure of time” one may glean from Leonard’s sculptural works, as from her photographs; their framing of the quotidian having the powerful effect, Fateman writes, of an “impersonal particularity.” The photographs in Downtown (for Douglas), for example—of the exteriors of apartment buildings and interiors of subway stations—are all of spaces that are public; their crisp registration in Leonard’s photographs details the striking features of the banal spaces we share. I’m reminded of fellow downtowner Joe Brainard’s incantatory memoir from the same era, I Remember (1975), in which a procedural conceit (to reconstruct a memory in writing starting with the phrase “I remember”) is used to catalogue impressions, encounters, and misapprehensions. Personality is sieved out as pithy insight or charm, and readers get a sense of the various social systems to which Brainard belonged.“[I Remember] is about everybody else as much as it is about me,” writes Brainard in a letter to the poet Anne Waldman. “And that pleases me. I mean, I feel like I am everybody. And it’s a nice feeling. It won’t last. But I am enjoying it while I can.”

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016As part of Before Pictures: New York City 1967–1977 at Galerie Buccholz in New York, curated by Crimp in 2016, Leonard’s Downtown prints hung at eye level in the front corridor alongside photos from Alvin Baltrop’s striking piers series and archival prints made for George Balanchine’s production of Igor Stravinsky’s Agon (1957). The only contemporary artist included in the show, Leonard’s images of New York produced, if memory serves, a kind of strobing effect. When hung in a row, the dark canals of the subway stations interspersed with reflective abstractions that appear in the windows of Crimp’s homes (in one window is the reflection of a Subway fast-food restaurant) generate a visual equivalent to the glamorous nightlife Crimp writes about.

Looking at Leonard’s photographs now, more than four harrowing years after this exhibition, they seem to ask other questions about how mobility works within, and beyond, the art world. I’ve always read Before Pictures as a book that is not only about jobs but also the kinds of access and mobility—both geographic and social—a job in the arts afforded one specific writer. But what happens next?

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016

Zoe Leonard, Downtown (for Douglas), 2016All photographs courtesy the artist; Galerie Capitain, Cologne; and Hauser & Wirth, New York

Leonard’s black-and-white images of empty subway stations reflect an underfunded and mismanaged municipal institution whose ridership dropped catastrophically in the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020. Its passengers were essential workers only, for the first few months—until the summer came, and the George Floyd uprisings found the city’s populous rioting on foot, across the streets of every borough; we learned how to move again. As the artist and writer Hannah Black wrote in her adieu to 2020 for Artforum, “A riot can’t resurrect the dead, but it can resurrect the dead spaces of cities.” New York City had, meanwhile, responded with perverse enthusiasm to the conditions brought about by the public health crisis, repopulating the vacant subways with a battery of newly hired, idling, armed police officers to persecute the thousands of New Yorkers left homeless by their attempt to survive winter in a pandemic. I see in Leonard’s images the curious, uncompromising qualifier one must accept if one wants to survive in America: get to work, or else.

Read more about New York City in Aperture, issue 242, “New York.”

April 13, 2021

How James Barnor’s Photographs Became Symbols of Black Glamour

James Barnor’s deeply personal artistic practice has traversed cities, continents, and genres over six decades, all in reverence of the African diaspora. Barnor is a newsman, studio photographer, and fashion image maker. But the too common neglect of Black artists in the art world means his genteel images have been presented only on a handful of grandstand stages, beginning with exhibitions in London, in 2010, and Ghana, in 2012. Now, art history is finally catching up. Barnor, who was born in Ghana in 1929, was pronounced a 2020 recipient of the Royal Photographic Society Awards, and his work will be the subject of a solo exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries this year.

James Barnor, Drum cover model Marie Hallowi at Charing Cross Station, London, 1966

James Barnor, Drum cover model Marie Hallowi at Charing Cross Station, London, 1966Courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

The result of cataloging tens of thousands of photographs, the exhibition James Barnor: Accra/London will be the most comprehensive survey of Barnor’s work. Originally scheduled to open in June 2020 on the event of his ninety-first birthday, the exhibition was delayed until 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A second national lockdown in the U.K. last autumn meant that I could only speak with Barnor by phone. Barnor is forthcoming and earnest despite not being able to travel home to Ghana for the burial of his sister Ivy Barnor, who modeled for him, or his close friend Jerry John Rawlings, Ghana’s former president, both of whom passed away in quick succession in November 2020. Rawlings once said, “I’m just an ordinary, hungry, screaming Ghanaian who wants to realize his creative potential. Who wants to contribute.” Barnor began making his own contributions in 1950, as the first appointed photojournalist for Accra’s Daily Graphic, a state-owned newspaper. Self-motivated and eager, Barnor captured a nation remaking itself. Twenty-eight years after Barnor’s birth, Ghana would gain independence from Britain in 1957.

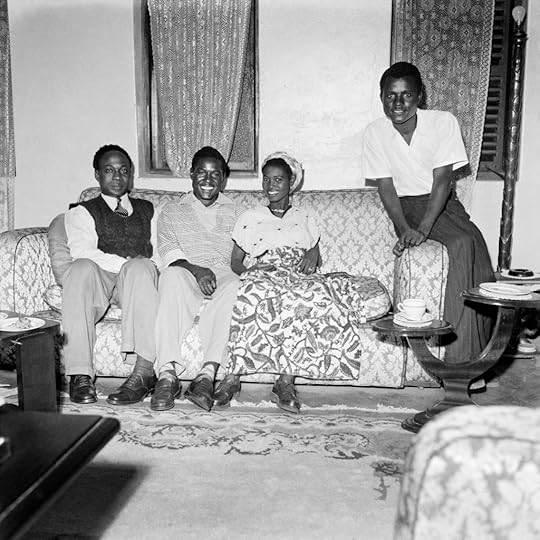

James Barnor, Self-portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah, and his wife, Rebecca, Accra, ca. 1952

James Barnor, Self-portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, Roy Ankrah, and his wife, Rebecca, Accra, ca. 1952 Courtesy Autograph ABP, London

Whispered news spread that Ghana was planning to introduce color television, and it was impressed on Barnor how invaluable it would be for him to travel and learn new imaging techniques to bring back home to Ghana. Taking heed, Barnor left behind his first, and successful, portrait studio, Ever Young, in Jamestown, a neighborhood of Accra, frequented by young couples, artists, and government officials, and arrived in London on December 1, 1959. Looking at a 1952 self-portrait with Kwame Nkrumah, who would become the first prime minister and president of Ghana, it’s easy to imagine the kind-eyed young man who arrived in the London metropolis curiously enchanted, unaware of the literal and figurative cold challenges ahead.

James Barnor, A group of friends photographed during Mr. and Mrs Sackey’s wedding, London, ca. 1966

James Barnor, A group of friends photographed during Mr. and Mrs Sackey’s wedding, London, ca. 1966Courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

In the 1960s, Black photographers were not actively employed in the United Kingdom, and only on occasion would some be assigned to jobs in darkrooms, out of sight. In his first years in London, Barnor worked multiple jobs to generate enough income. He attended Medway College of Art, in Kent, for two years (despite not having a general certificate of education), learning how to take photographs, process film, and print in color. He also worked at the Colour Processing Laboratory, where he was eventually promoted to an assistant technician.

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl, Erlin Ibreck, at Trafalgar Square, London, ca. 1966

James Barnor, Drum Cover Girl, Erlin Ibreck, at Trafalgar Square, London, ca. 1966Courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

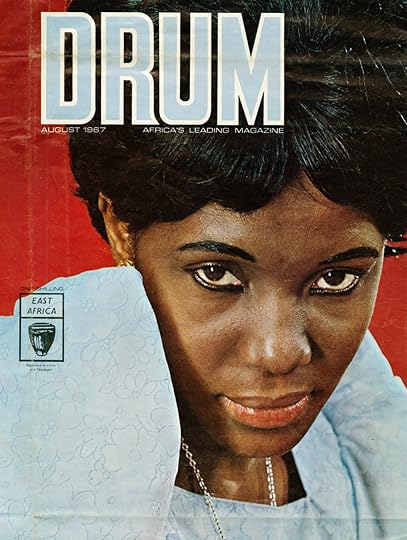

During this time, when fashion was limited to very specific European ideals of beauty, Black women would become symbolic repositories of glamour, style, and Black social life in Barnor’s photography. Erlin Ibreck and the Jamaican-born Rosemary “Funflower” Thompson frequented his editorials for Drum, the anti-apartheid South African lifestyle and politics magazine, which had offices and editions in various African cities and was distributed internationally. Drum’s London office on Fleet Street became a personal and professional safe home for Barnor. His sitters were aspiring models, passersby, and, in one case, a London bus driver, but all were effortlessly alluring and a much-needed counterimage to the esteemed British swinging ’60s model Twiggy. On a trip to London, the Ugandan musician and singer Constance Mulondo was photographed for the August 1967 Drum cover. Her oval eyes are framed with thick black eyeliner and her chin is angled downward, nestled into the powder-blue collar of her dress.

James Barnor, Cover of Drum magazine with Constance Mulondo, East Africa Edition, August 1967

Courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris

James Barnor, Constance Mulondo at London University with the band The Millionaires, published inc Drum magazine, London, 1967

Barnor returned to Ghana in 1969, as a representative for Agfa-Gevaert, to introduce color processing facilities in Accra; soon after, he established a new portrait studio, Studio X23, which ran from 1973 to 1992. But in 1994, Barnor chose to adopt London as his permanent home. There, he developed a brotherhood with the younger Black British photographers Neil Kenlock and Charlie Phillips that continues through the pandemic. That sense of community has been visible in Barnor’s work all along. “What unites all the images is Barnor’s extraordinary ability to make visible his personal connection to his sitters,” says Lizzie Carey-Thomas, the chief curator of the Serpentine Galleries. “As he has stated: ‘People are more important than places.’”

James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective will be on view at the Serpentine Galleries, London, from May 19–October 22, 2021.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the column “Backstory.”

April 9, 2021

Carrie Mae Weems Confronts the Fraught History of American Photography

I sliced a watermelon open across its belly last summer and gasped, as the red flesh and black seeds resembled bodies inside the barracoon. When I go to the nation’s edge and put my feet into the shore of the Atlantic, I think of women throwing their babies overboard to be set free by the water, and the crashing waves turn to screams. When I ask my grandmother about her time on the cotton plantations of Louisiana, she rolls her eyes: “Here she go remembering again.”

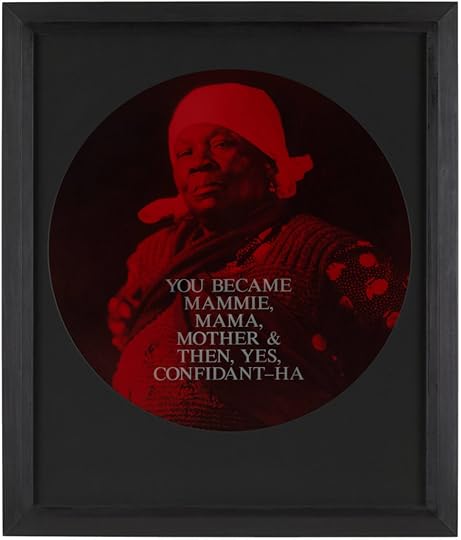

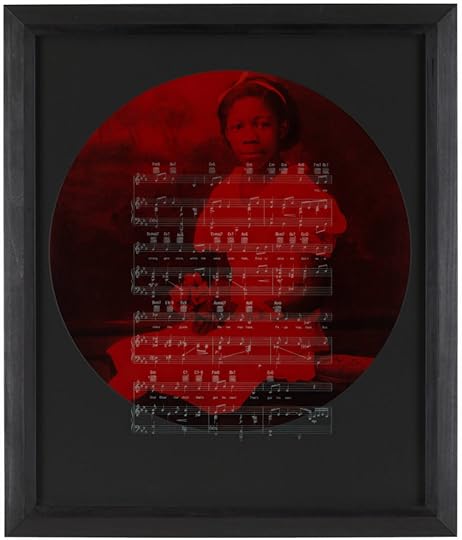

Carrie Mae Weems, You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother & Then, Yes, Confidant–Ha, 1995–96

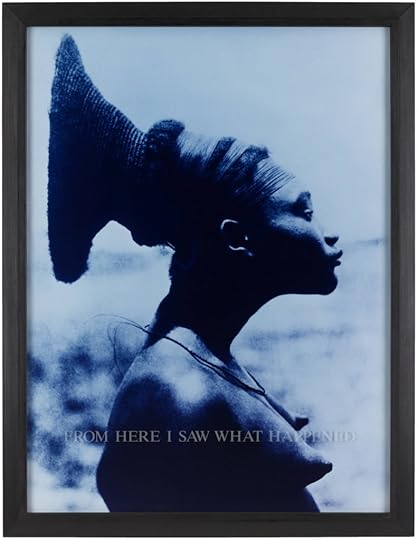

Carrie Mae Weems, You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother & Then, Yes, Confidant–Ha, 1995–96A “land condemned to forgetfulness” is what the writer Eduardo Galeano once called America. Forget where you come from, forget your languages, forget your rituals, religions, homeland. Forget centuries of enslaved labor. But it’s all I can think about. To be Black in America often means that your history has been deliberately withheld, and the fragments that remain have been reframed to veil the unconscionable terrors that built the foundation of this nation. Conceptual artist Carrie Mae Weems has taken these fragments to construct a narrative that reckons with this somber history and draws a straight line to contemporary racialized norms in her photographic series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96), currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Installation view of Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2020

Installation view of Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2020Photograph by Denis Doorly

Thirty-three images, a divine number—including four enlarged daguerreotypes of enslaved men and women captured in 1850 by Joseph T. Zealy, produced in the name of eugenics by Harvard University scientist Louis Agassiz, and archived at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. Weems’s series was originally commissioned in 1994 by the J. Paul Getty Museum for an exhibition called . The Zealy daguerreotypes and other portraits of unnamed souls from the 1850s are situated alongside more contemporary images, like Garry Winogrand’s Central Park Zoo (1967), depicting a white woman and a Black man holding monkeys (the presumed outcome of miscegenation’s one-drop rule) and, furthermore, just how insignificant progress has been. But what of the Black woman whose hair is tied down, but her legs lie wide open on the bed, her hand and the lens positioned in between? In the way she holds her mouth, slightly turned up but not quite a smile, you can see that the subject has subverted her oppression to power as Black Venus, both despised and hypersexualized: You Became Playmate to the Patriarch. Weems’s prose bites and stings. I look away quickly, in fear of further demeaning Black Venus, in fear of seeing myself in her.

Carrie Mae Weems, Some Laughed Long & Hard & Loud, 1995–96

Carrie Mae Weems, Some Laughed Long & Hard & Loud, 1995–96Weems, the sixty-seven-year-old Portland, Oregon–born artist-curator, has long been a genius—even before she was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2013, and before she became the first Black woman artist to have a retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2014. She has been most notably characterized by the care and complexity that she extends to her subjects, and also to her peers and colleagues, such as the photographer, curator, and historian Deborah Willis, whom Weems invited to Los Angeles for her first professional exhibition. HBO’s recent documentary film Black Art: In the Absence of Light (2021), directed by Sam Pollard, highlights the dynamic community formed with the Studio Museum in Harlem as its nucleus and home base, and the insistence on Black artists to reshape the ways that the world sees. To reclaim and expand the limiting views projected onto the Black body. Weems is featured saying what many have recognized: “Most of the primary cultural institutions have been behind.”

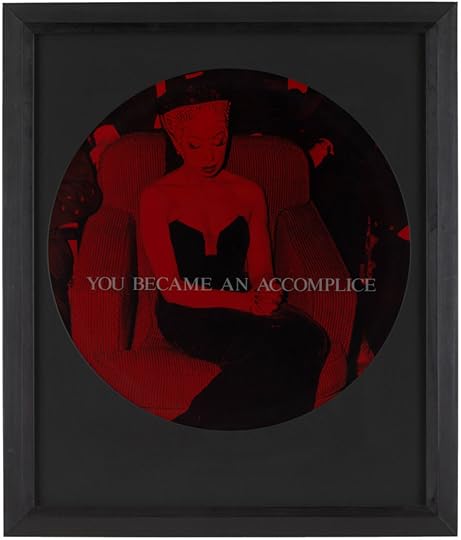

Carrie Mae Weems, You Became an Accomplice, 1995–96

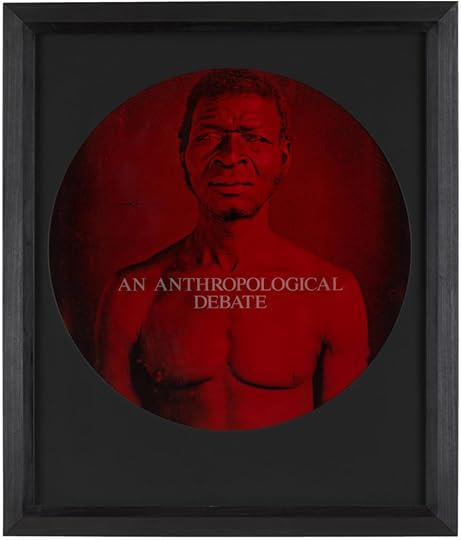

Carrie Mae Weems, You Became an Accomplice, 1995–96In From Here I Saw What Happened, the images Weems draws from are cropped, tinted red, like the bloodshed that is not immediately present, placed in circular mattes that emulate the lens of the camera, and covered by glass sandblasted with Weems’s famously poetic prose; that circular lens, like a spotlight or crosshair, focuses on the subjects, but exposes the intent of the shooter. As well as the oppositional gaze of the subjects. Even in physical captivity, their eyes express dignity and dissent. The subjects captured by Zealy are mostly positioned naked and profiled, much like mug shots or anthropological specimens, revealing a race so eager to demean another in support of theories of superiority that it renders those responsible pathetic, and yet more, deeply ill.

Carrie Mae Weems, An Anthropological Debate, 1995–96

Carrie Mae Weems, An Anthropological Debate, 1995–96Science has a long, dark history that includes the mistreatment of darker-skinned individuals: from J. Marion Sims’s establishment of modern gynecology on enslaved women, whom he made addicted to morphine to perform nonconsensual procedures, to the Tuskegee syphilis study. In Harriet A. Washington’s Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (2007), the author is in conversation with Weems’s work when she draws a direct line between the images captured by Zealy and today’s Black infant mortality rates and a life expectancy that is six years less than that of white people. Weems and Washington are in unison with a chorus that sings the song of reckoning. In 1996, Harvard threatened to sue Weems for her use of Zealy’s images, as she had originally agreed not to appropriate them without permission, but then changed her mind. Instead, as Weems later recounted to Willis, she summoned the university, saying, “I think that your suing me would be a really good thing. You should, and we should have this conversation in court.” The question of ownership shows itself again. Who is entitled to images of enslaved humans who were captured by Europeans? Harvard backed down and simply acquired Weems’s collection. Capitalism is but a white sheet.

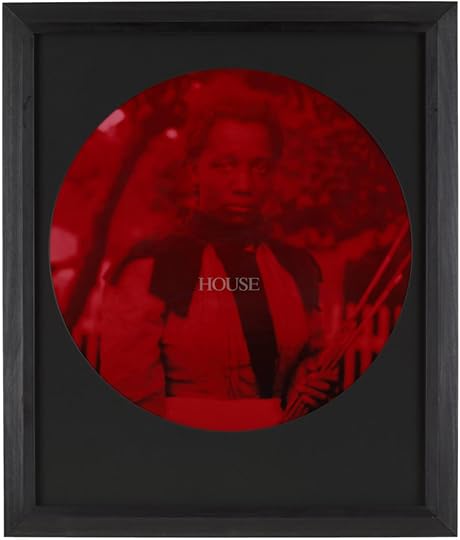

Carrie Mae Weems, House, 1995–96

Carrie Mae Weems, House, 1995–96Entering the gallery at MoMA where From Here I Saw What Happened is displayed is a bit like entering a time portal. Inside the dreamy grey room in the David Geffen Wing, the viewer is made to feel completely immersed in the throes of a history we often try to escape. Bookended by blue-tinted images of a royal Mangbetu woman named Nobosodrou, positioned to bear witness to her lineage—much like Janus, the ancient Roman god of beginnings and passages. Weems’s commitment to history and memory has reached into popular culture, as Nobosodrou’s style has been reimagined in films like Beyoncé’s Black Is King (2020) and Lemonade’s “Sorry” music video (2016), as well as Angela Bassett’s character, Ramonda, in Black Panther (2018). With narrow context, these films have been viewed as a form of cultural appropriation, just as scholars and critics accused Weems’s series of being sarcastic and nothing more than a revictimization of the subjects.

Carrie Mae Weems, From Here I Saw What Happened, 1995–96

Carrie Mae Weems, From Here I Saw What Happened, 1995–96But to dispose of and forget the reality of this cruel history is another form of violence, of erasure. As the Nigerian proverb states, “Don’t let the lion tell the giraffe’s story.” Is Weems not entitled to a history that lives inside her bones? A history that beckons her? She was called to the South in her Sea Islands Series (1991–92) and The Louisiana Project (2003), in which she explored the landscapes and land built and tilled with Black hands in South Carolina, Georgia, and New Orleans. One can imagine the tremors that exist inside her as she works to bridge the gaps between the memories of the land and waters that betrayed the enslaved in their journeys across the Atlantic, yet also provided a means of escape and sustainability, proving that water is a body too.

Carrie Mae Weems, (Musical Score to “God Bless the Child”), 1995–96

Carrie Mae Weems, (Musical Score to “God Bless the Child”), 1995–96All works from the series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995–96. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Weems, who studied dance and folklore, is able to identify the silences present in the appropriated photographs and read the gestures of the bodies like a poem. The musical notes of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child” (1941) lay over the frame of a young girl holding sadness in her eyes, perhaps her only inheritance. Each of Weems’s rhythmic syllables lands with impact, taking us deeper into a past that we have been taught to avoid. Weems dissects the messages communicated through their limp limbs, forced smiles, and slouched welted backs. And we see that, sometimes, a camera is a gun.

Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through spring 2021.

March 30, 2021

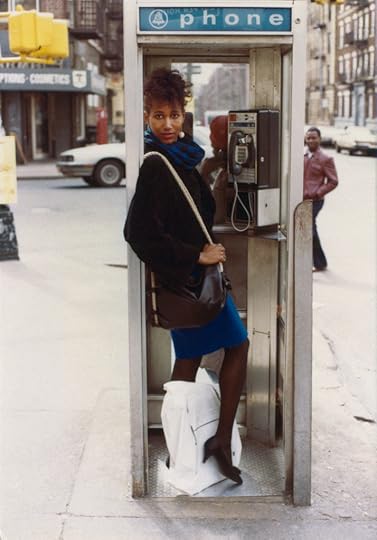

Why Jamel Shabazz Is New York’s Most Vital Street Photographer

New York is a ghost town. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the metropolis to a standstill. Many are scared to even leave their apartments to buy groceries. The globe-trotting photographer Jamel Shabazz is tucked away in his Long Island home, his “sanctuary.” Shabazz’s world is rocked daily by yet another phone call announcing the death of a loved one. It is a calendar of loss with which he is intimately familiar. He survived the 1980s crack era and the AIDS crisis, when so many friends from his Brooklyn neighborhoods—Red Hook and then East Flatbush—did not.

Every morning, while living under quarantine, Shabazz saunters into one of the several closets in his home and picks up a heavy archive box. Hundreds of identical boxes line every available space in his home. They are organized chronologically and then subdivided by type: black and white, color, medium format, and so forth. One box, just like the others, holds bits of time frozen on negatives, slides, and photographic prints. It is an archive so vast (which even contains the negatives belonging to his father, who was also a photographer) that when asked about the quantity, Shabazz replies, “I just can’t give a count.” He carries the box into the center of his work-space floor. This is a new routine that has become the only consistent thing in uncertain times. Shabazz will spend the next eight hours meticulously sifting through the box, rediscovering faces and city landscapes that he had forgotten even photographing. He scans some of his faves. Then he posts them on his Instagram, sometimes with an accompanying music track, sometimes not. Within seconds, likes and comments from his one-hundred-thousand-plus followers of all ages, from around the world, start flooding in. Those frozen bits of time still elicit the same delight, pride, and awe as they did in the ’80s and ’90s.

Jamel Shabazz, Rolling Partners, Downtown Brooklyn, 1982

Jamel Shabazz, Rolling Partners, Downtown Brooklyn, 1982“I think I’m an alchemist,” Shabazz tells me. “I freeze time and motion.” It is as if this moniker were a new revelation, the result of now having the time and space to reflect on his odyssey into professional photography. When examined as a whole, Shabazz’s brand of portraiture cannot, and perhaps should not, be characterized simply as street photography or fashion photography. He says he is an alchemist. I believe him.

In the early ’70s, the Shabazz home in Red Hook was alive and buzzing with the funky sounds of Marvin Gaye, the Jackson 5, and Earth, Wind & Fire. And books. There were tons of books. Books on politics, photography, and culture were neatly organized on a massive wall of shelves. “My father had a really vast library of books, and I would go through every single book he had in the house,” he remembers. “National Geographic, Life magazine—all those publications informed me.” Shabazz, who had developed a serious speech impediment when he was quite young, discovered that while he struggled to communicate verbally, he could get lost in the worlds of his father’s books and album covers. Leonard Freed’s Black in White America (1968) was among Shabazz’s favorites. He flipped through it so often during his adolescent years that the book had fallen apart by the time Shabazz reached high school.

Jamel Shabazz, Harlem Week, Harlem, 1988

Jamel Shabazz, Harlem Week, Harlem, 1988To escape the brewing trouble that was ensnaring many Black boys in Brooklyn in the waning years of the Black Power movement, Shabazz made the decision to enlist in the army as soon as he could. In 1977, a seventeen-year-old Jamel Shabazz was assigned to a post just outside Stuttgart, Germany. He followed the lead of an older Black soldier who carried his camera with him everywhere he went. “For practically everybody who was in the military, a camera was the biggest thing to have. Because for them, they were getting away for the very first time. So it’s through that experience that they brought home photographs.” Shabazz’s Canon AE-1 became his closest companion. He snapped pictures of everything he saw and tasted as he moved through Germany. He became something of an ethnographer, translating the subversive spirit of the Black poets he was discovering—Sonia Sanchez, Nikki Giovanni, and Amiri Baraka—as he manipulated the camera’s aperture and shutter settings.

After one tour in the army, Shabazz returned home to Brooklyn, in 1980, a changed man. “I came home a revolutionary,” he recalls. No longer enticed by the lures of street life, Shabazz wanted to create real change in his community. The 35mm camera that he had learned to use in the army would be key to his revolutionary arts ministry. Shabazz proclaims, “My journey has never been about wanting to be a photographer. The primary vision was to save our people.” His mission was to mobilize those the Black Panthers referred to as the “lumpen proletariat”—gangsters, pimps, and sex workers—who were most vulnerable to labor exploitation, drug addiction, and homelessness. Many of Shabazz’s childhood friends made up this underground economy. And now, the man who had once struggled to speak was committed to using his camera to initiate conversations with these old friends, and even strangers, across Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Jamel Shabazz, Styling & Profiling, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1980

Jamel Shabazz, Styling & Profiling, Flatbush, Brooklyn, 1980Those early years were less about following some industry craft standards and more about using the special relationship between photographer and subject to establish a deeper spiritual connection. Shabazz was channeling James VanDerZee’s ability to capture pure human emotion and Gordon Parks’s versatility, allowing him to blend different genres of photography. He quickly learned that one could not approach Black Americans, particularly the street-oriented folks he wanted to reach, dressed like a slouch. “I think that some might view me as sort of dapper,” he says. “And it made people more open to me when they saw me.” They could instantly see that Shabazz understood the style economy of the block, that he spoke a common language. He was an insider. This insider status granted Shabazz access to their inner selves—an intimacy reflected in his subjects’ body postures and poses—and gave him a chance to lovingly prophesy alternative possibilities for their futures.

Photography was also saving Shabazz’s life, especially once he was hired, in 1983, as a corrections officer at the infamous Rikers Island prison. Long shifts “witnessing the inhumanity that men would inflict on other men,” as he describes it, were a daily part of this job. Shabazz says of his frequent after-work photoshoots, “I had to go out on the streets and gain my balance by tapping joy, tapping into brotherhood and unity.” He would photograph around East Flatbush, often using his 28mm wide-angle lens. Then maybe he would head to the Lower East Side, where he would switch to his 50mm lens while chatting with and photographing sex workers dressed in their ’80s fly-girl fashions: gold bangles and bamboo earrings, leggings and heels. Other times, he might spend a Sunday in Harlem, catching the Masons, Eastern Stars, and church-going folk in their finery, before heading to Central Park, to Midtown, then Delancey Street. “I would cover a lot of areas. I’d even get on the train and just look at neighborhoods that were interesting, and get off, and go photograph them.” He walked so much that he repeatedly wore holes in the soles of his designer shoes. The more he photographed, the more he could distance himself from the horrors of the prison.

Related Items

Aperture 242

Shop Now[image error]

How a Museum’s Photographic Archive Honors Generations of Chinese American Lives

Learn More[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]The subtle shift from dance music to something that sounded and looked much grittier might have been imperceptible if Shabazz had not been there to record it on film. “Can I capture your legacy?” Shabazz’s simple prompt would offer later viewers of his work a window into the burgeoning hip-hop culture of the early ’80s. To live on film was a promise of immortality that the tumultuous street life could not guarantee. One of his most iconic photographs of that era, Rude Boy (1982), is symbolic of this early hip-hop style ethos. “Kerral was a hustler,” Shabazz says of the photograph’s subject. “He was a really smooth, debonair guy who I thought had a lot of potential.” Decked out in his pinstripe suit and tons of gold jewelry, Kerral slyly posed for Shabazz’s camera—bent over slightly, hand on chin. Kerral was murdered only a couple of years after that photograph was taken. But his legacy lives on in the National Museum of African American History and Culture and on social media. That image also represents Shabazz’s pioneering approach to street-style photography. It was not about stealthily capturing a candid portrait of an unknowing subject; it was about collaborating with the person. Shabazz wanted to photograph Black and Latinx youth in a way that allowed them to shape how they wanted to be seen and understood by posterity.

Jamel Shabazz, Too Fly, Downtown Brooklyn, 1982

Jamel Shabazz, Too Fly, Downtown Brooklyn, 1982In the late ’90s, Shabazz’s pictures, which had been circulating around the hood and in prisons for nearly two decades, started catching the eye of hip-hop magazine editors. Vibe, The Source, and Trace were helping to translate hip-hop culture for a global audience. Their staffs of writers, editors, and creative directors—most of whom were under thirty were always looking for something that screamed “fresh,” “authentic,” “of the culture.” During his lunch breaks, Shabazz—then on the cusp of forty and working in Lower Manhattan—would make his way over to the magazines’ nearby offices to show editors his portfolio. By then, he had upgraded his equipment to a Nikon N6006 SLR. But the editors especially loved the photographs taken in the ’80s, on his old Canon. “He captured a pureness, an essence of hip-hop culture at its rawest and its best. One that was not at all negotiating its relationship to the mainstream or the white gaze,” says Joan Morgan, the program director of New York University’s Center for Black Visual Culture, who was a Vibe staff writer in the mid-’90s. The Source ran a multipage spread of Shabazz’s photography in its 1998 anniversary issue featuring the greatest moments of hip-hop. “That put me on the map, and that started my fan base,” Shabazz remembers.

Seemingly overnight, Shabazz went from a modest-wage-earning city employee to a recognized professional photographer. “I started to make a transition from working in a very negative, hateful atmosphere to now doing solo art shows.” Antwaun Sargent, an art critic and the author of The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion (Aperture, 2019), believes Shabazz’s images connect viewers to a familiar Black vernacular in ways that redefine portraiture: the street slang, the body postures, the sartorial politics, the photographs hanging on grandma’s wall. “The way that we think about Black portraiture comes through the vernacular, the local. It comes through the neighborhood photographer,” says Sargent. Some of Shabazz’s biggest influences were the family photo-albums in his childhood home, which had been passed down from generation to generation: “Those personal, intimate photo-albums really allowed me to see the power of photography.” Shabazz has exhibited this homegrown approach to Black portraiture everywhere from the Studio Museum in Harlem to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London to the Addis Foto Fest in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Three of his books published by powerHouse—Back in the Days (2001), The Last Sunday in June (2003), and A Time Before Crack (2005)—are considered classics for their articulation of a Black visual vernacular.

Jamel Shabazz, The X Men, West Village, 1985

Jamel Shabazz, The X Men, West Village, 1985All photographs courtesy the artist

Despite now being heralded as a king of the culture by folks in the know, Shabazz has never received the same acclaim as lauded photographers who chronicled New York’s vibrant street life. “I don’t think there has been a real reckoning with these images,” says Sargent, although he believes we would not have Tyler Mitchell, Stephen Tayo, Tommy Ton, or Scott Schuman without Shabazz’s pioneering work. The truth is Shabazz was never into it for the fame and institutional recognition. It was always about building community. “You see me through my subjects. Through the eyes of my subjects, you’re seeing me,” Shabazz says. For years, he could not completely explain why he sought to establish a connective bond with the people he photographed. But now, as a veteran photographer—an alchemist—he is able to powerfully voice just how frozen bits of time can transform a community.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “The Alchemist.”

March 29, 2021

What Is the Future of Photography at MoMA?

In February 2020, New York’s Museum of Modern Art announced that Clément Chéroux would step into the shoes vacated by his compatriot Quentin Bajac two years earlier, assuming the role of the museum’s Joel and Anne Ehrenkranz Chief Curator of Photography. At the time of the announcement, Chéroux was senior curator of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Pritzker Center for Photography, a position he held for three productive years, producing two major thematic exhibitions that explored the intersection of vernacular and traditional “art” photography, including snap+share: transmitting photographs from mail art to social networks (2019) and Don’t! Photography and the Art of Mistakes (2019), as well as a series of solo exhibitions by artists like Louis Stettner (2018), Carolyn Drake (2018), and Walker Evans (2017). (The latter, in fact, had been originated by Chéroux while he was still serving as chief curator of photography at the Centre Pompidou, Paris.)

In the year since Chéroux’s MoMA appointment, the social and cultural landscape of New York has been incalculably transformed by the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic; the shock waves of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police in Minneapolis; the ascendant Black Lives Matters movement; and the 2020 US presidential election and its aftermath. Aperture’s creative director, Lesley A. Martin, spoke with Chéroux by phone in January 2021, just days prior to the announcement that his colleague at MoMA, , had been named incoming executive director of Aperture Foundation. Martin and Chéroux’s conversation ranges from the radical changes on the streets of New York to the equally urgent new demands placed on institutions, artists, and curators, and their approaches to the photographic image.

Clément Chéroux. Photograph by Frederic Neema

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by Iwan Baan

Lesley A. Martin: Could you narrate your arrival to New York? In what must have been quite a surreal time!

Clément Chéroux: I started working remotely for MoMA in July, and I came to New York in the beginning of September. It was a very strange time to settle in in the US. New York was not the New York that I was expecting. The city that never sleeps seems to be under a very strong narcotic. I was really looking forward to being in New York and meeting with so many artists that I appreciate and follow. So one thing that I miss the most is not being able to do artist studio visits.

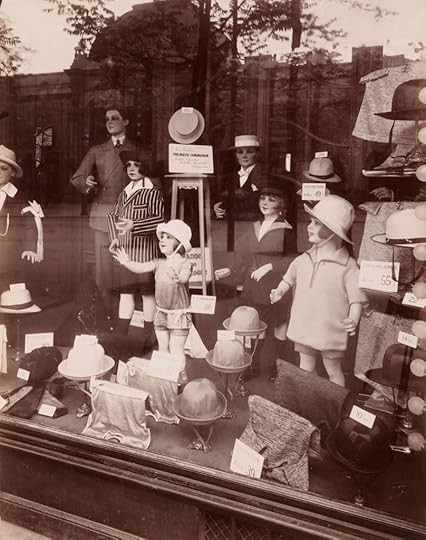

Visually, what struck me during these first months in New York were the storefronts covered with plywood. In the 1920s, exactly a century ago, Eugène Atget photographed the large glass window panels, which were relatively new at the time in modern cities. Atget took these photographs in Paris, not in New York, but for a whole century, the store window was the visible face of capitalism. Something has changed in the past years thanks to the internet, with merchandise mostly stored in large warehouses in the suburbs and out of sight. Now, with all of these windows covered with plywood in recent months, and especially during election week, it’s as if we’re clearly witnessing the end of something, a kind of symbolic death of this very visible and aggressive form of capitalism.

Martin: That phenomenon seems to be in tandem with the process of our entire lives now being lived through the screen.

Chéroux: Exactly. We have very different access to objects.

Eugène Atget, Magasin, avenue des Gobelins, 1925

Eugène Atget, Magasin, avenue des Gobelins, 1925Martin: Your arrival also coincided with a particularly unique time politically—not just the ongoing pandemic, but Black Lives Matters protests, the election and its aftermath, and general soul-searching in relation to the nature of the American project. What are the obligations of an institution like MoMA to reflect on current events, and how do you feel this stance will impact your work?

Chéroux: This is something that my colleagues and I talk about almost every day. Personally, I was really shocked by what happened in Washington, DC, on January 6. That was a traumatizing moment. It’s important for a museum like MoMA to reflect on moments like this. Of course, we are working much more in the long term of history than in the immediacy of current events, but there is no doubt that what happened in the recent days or in the recent months will have a long-term impact on our future projects. I fully believe that an institution like MoMA must be a place where democratic principles are defended and reflected on. I also believe that photography has something to say in this debate around democracy. Photography is a democratic medium: everyone can take a photo, and everyone can have their own photo taken with the same level of detail. And of course, at the same time, you also have to understand that photography has been the tool of profoundly undemocratic systems. Photography has been used, for example, in the service of colonial power and as an instrument of domination. It’s not the medium of photography in itself that is discriminatory or racist; that responsibility lies with the individual using the photograph in a racist or an antidemocratic way. Photography is just a tool.

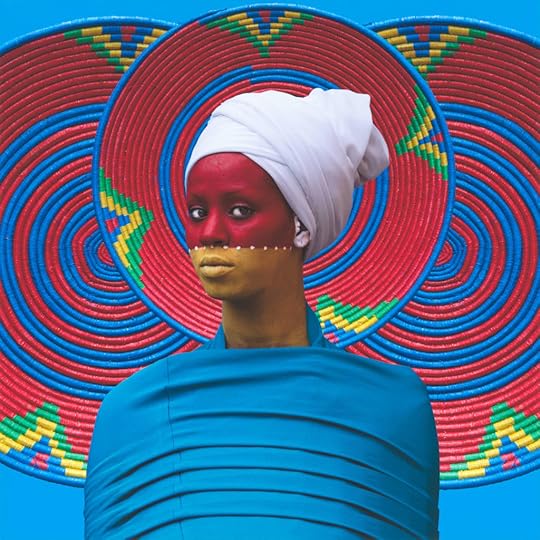

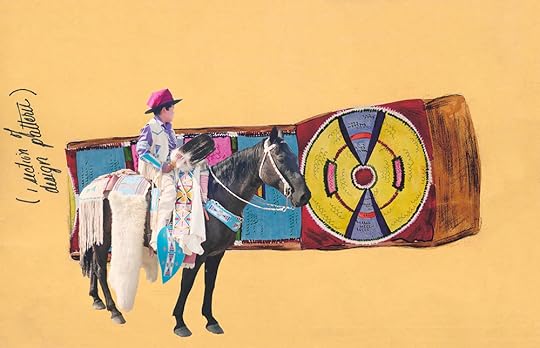

Aïda Muluneh, City Life, 2016. Muluneh’s work was featured in Being: New Photography 2018

Aïda Muluneh, City Life, 2016. Muluneh’s work was featured in Being: New Photography 2018Martin: In your research and your writing, you are often drawn to popular forms of photography—the postcard, paparazzi, and spirit photography, among others. I’m curious how you see the tensions between “high art,” which traditionally has not recognized those forms of photography, and your notion of photography as a democratic medium.

Chéroux: Photography is a vernacular medium, and I’ve never been able to think about photography exclusively as an art. There has always been a tension between high and low, between this democratic aspect of photography and art-making. This is what interests me about the medium. In the context of what we are living through today, this issue of photography as a democratic tool is extremely important.

We are living in a world which is marked by violence: the violence of the pandemic; the violence of climate change; the violence of civil and political unrest, which includes the violence behind building walls; the violence of systemic racism; police violence and the refusal to condemn those responsible. I’m talking about the violence that denies equal rights to members of the LGBTQ community, the violence of refusing to accept the results of a democratic election, as well as the violence that stormed the Capitol.

In this context, for me, it’s more important than ever to strengthen what is at the heart of the democratic principle, which is the plurality of different voices. We have to reaffirm the democratic principle: the necessity of plurality, equality, and diversity. This is the conversation I’ve been having with my colleagues Roxana Marcoci, Sarah Meister, and Lucy Gallun. We have made a commitment to focus on questions of diversity. This is going to be at the heart of our program for the coming years.

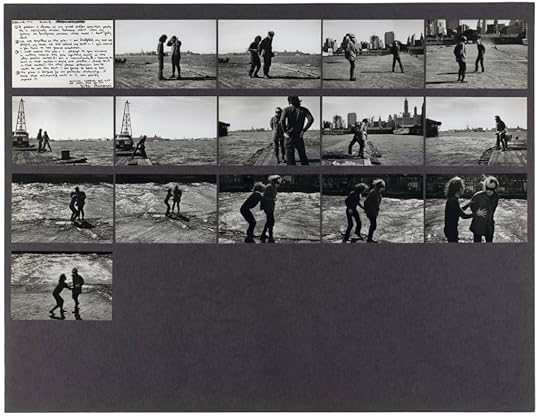

Vito Acconci, Security Zone, 1971. Photograph by Shunk‑Kender. Acconci’s work will be part of Artist’s Choice: Yto Barrada—A Raft

Vito Acconci, Security Zone, 1971. Photograph by Shunk‑Kender. Acconci’s work will be part of Artist’s Choice: Yto Barrada—A Raft© J. Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Martin: I wonder if you could give some concrete examples of how you’re enacting those commitments, both for the photo department and museum-wide.

Chéroux: We have three tools as museum curators: You make acquisitions and build a collection. You make exhibitions. And you create public debates and conversations. In each of these, we will address diversity in terms of which photographers we work with and collect, but also diversity in the modes of photography.

The MoMA collection has long defined itself through the canon of the white Western male. Things had already started to change before I arrived, but we will continue to amplify diverse voices in the coming years—it will be at the heart of our acquisition program. This also goes back to my own interests: the diversification of the photographers we collect must go hand in hand with the diversification of photographic forms. MoMA’s acquisition history has had a particular emphasis on the photographic print as defined by photographers like Ansel Adams, who believed that the print was the final expression of the photographer’s visualization—Adams worked closely with Beaumont Newhall when the photography department at MoMA was founded in 1940.

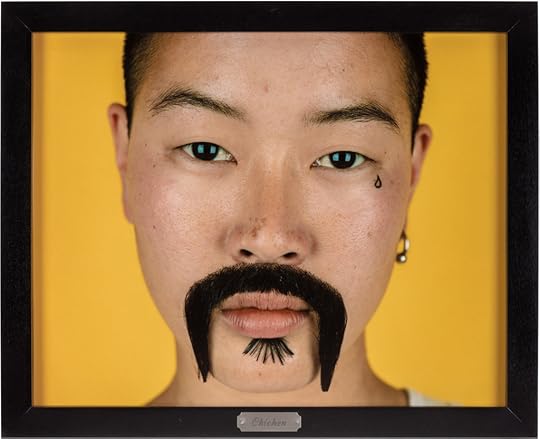

Catherine Opie, Being and Having, 1991. Opie’s work was acquired for MoMA’s collection in 2020

Catherine Opie, Being and Having, 1991. Opie’s work was acquired for MoMA’s collection in 2020Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong and Seoul

But of course, photography exists in many other forms than just the beautiful framed print. Photography exists in public space, on screens, as installation; and photography also exists, very importantly, as books. We have to deal with that. We are into what the art historian George Baker defined in 2005 as the “expanded field” of photography. We want to do more around these questions. We want to do more in terms of public debate, acquisition, and exhibition.

In terms of exhibitions, in the spring, the French Moroccan artist Yto Barrada is working with Lucy Gallun on an “artist’s choice” exhibition—in which the artist is looking at the collection, working closely with the curator to create a selection in response to a theme chosen by the artist. Barrada’s thematic focus is the French filmmaker and ethologist Fernand Deligny, and she’s creating a fascinating program around the show. Also, in May, we will open an exhibition titled Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964, curated by Sarah Meister, focusing on São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Club Bandeirante—an amazing movement with important photographers such as Geraldo de Barros, Thomaz Farkas, and Gertrudes Altschul. The exhibition highlights the extraordinary dynamism of this Brazilian modernist scene between the forties and the sixties, and rewrites an entire chapter of the history of modernism and photography.

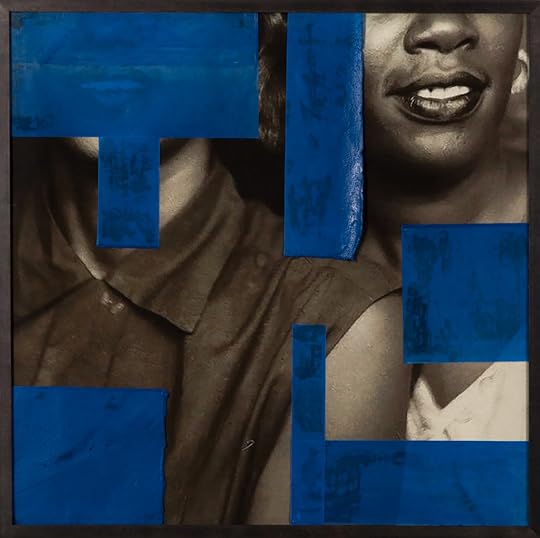

André Carneiro, Rails (Trilhos), 1951. Carneiro’s work will be included in Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964

André Carneiro, Rails (Trilhos), 1951. Carneiro’s work will be included in Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964© Estate of André Carneiro

Martin: Do you see this interest in amateurism as important to your concerns as well?

Chéroux: Yes—it’s another way to rethink modernism. Usually, we talk about modernism through the great white masters, like László Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, and Aleksandr Rodchenko. This is a way to rethink that notion of modernism as taking place in European avant-garde circles; it also circulated in hobbyist photo clubs and other sites.

Martin: I think this all sounds very much in line with this proposition that you set for us at the beginning, that this is a time for thinking about plurality of both voice and form. As you know, the MoMA chief curator of photography has a reputation for having been “the judgment seat of photography”—a single perspective defining what is of importance in and to photography. Are you interested in deconstructing that idea?