Aperture's Blog, page 62

January 14, 2021

The Counterculture Collective Who Wanted to Save the Earth

For more than a decade, the filmmaker Matt Wolf has won acclaim for his meticulously crafted documentaries that reveal lost histories through deep dives into media archives. His focus is often on radical outsiders whose projects range from the quixotic to the paranoiac. His first film, Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell (2008), is an exploration of the life and work of an avant-garde cellist and disco producer, while Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (2019) examines the fascinating obsession of its subject, who recorded live television news continuously from 1979 until her death in 2012.

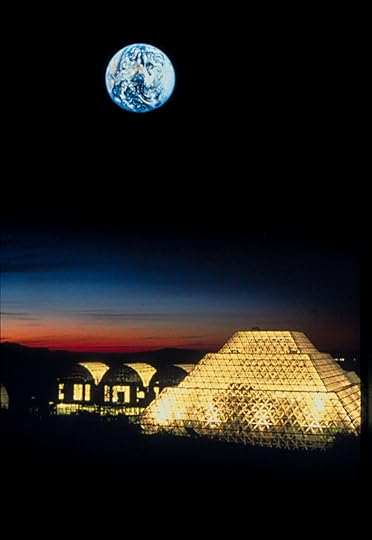

Wolf’s latest film, Spaceship Earth (2020), traces the activities of a counterculture collective known as the Synergists from the 1969 founding of a sustainable ranch in New Mexico through the 1991 launch of Biosphere 2, a staggeringly ambitious attempt to pave the way for human life on Mars and to learn about how to live more sustainably on Earth by building a completely self-enclosed ecosystem inside a glass pyramid in the Arizona desert. Last summer, Wolf spoke to the architect and critic Julian Rose about the uncanny resonance of the Synergists’ efforts to give form to the future.

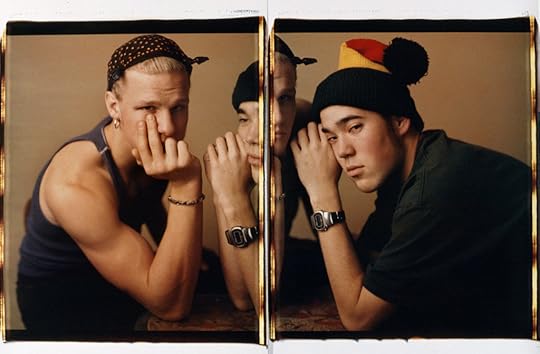

Biospherian candidates, 1990

Biospherian candidates, 1990Julian Rose: One of the fascinating things about Spaceship Earth is that the protagonists were obsessively documenting their own work as it progressed, producing countless hours of film and video that captured the projects they pursued. How did you first become aware of all that archival material, and how did your film evolve out of it?

Matt Wolf: My creative process involves searching for archives because I’m drawn toward hidden histories. Most of the preliminary research I do begins on the Internet. In this case, I came across these striking images of eight people in bright-red jumpsuits, looking like the band Devo, standing in front of a glowing glass pyramid, and I genuinely thought they were stills from a ’90s science-fiction film. But I quickly realized that, in fact, this structure was real—it was Biosphere 2—and that those people lived sealed inside of it for two years. And the more I looked into the history of the project, the more byzantine the story became. I learned that it had been the brainchild of this countercultural group called the Synergists, and I went to their commune-ranch in New Mexico called Synergia Ranch. When I arrived, I was brought into this temperature-controlled closet that had hundreds of 16mm films and analog videotapes and thousands of images. I learned that this group had been documenting their activity for nearly half a century, and that the material had never been used or seen.

Rose: The term archival usually suggests material that’s raw or unprocessed, but when I watched the film, I was struck by how highly authored, even artistic, much of the footage is—some of it looks like it could be experimental film or video art. Did that level of authorship complicate your own role as a filmmaker?

Wolf: My filmmaking involves working with personal archives—personal in the sense that they are outside established institutions or are even anti-institutional. I’m often looking at people who pursued complex and multifaceted projects, and they didn’t necessarily represent and explain those projects in ways that were accessible. I want to reappraise their legacies and act as a translator, helping to find the logic and coherence and vision behind this idiosyncratic activity, and to explore how it is often incredibly relevant to the broader world. For this film, the archival footage was literally shot from the perspective of my subjects, so I had a unique opportunity to visually translate their story beyond the flattened coverage in the news media.

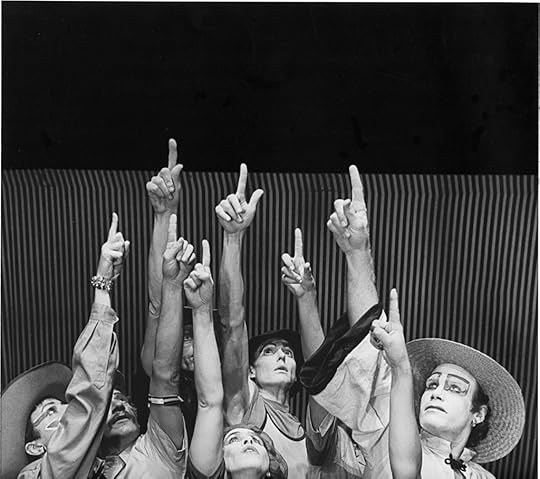

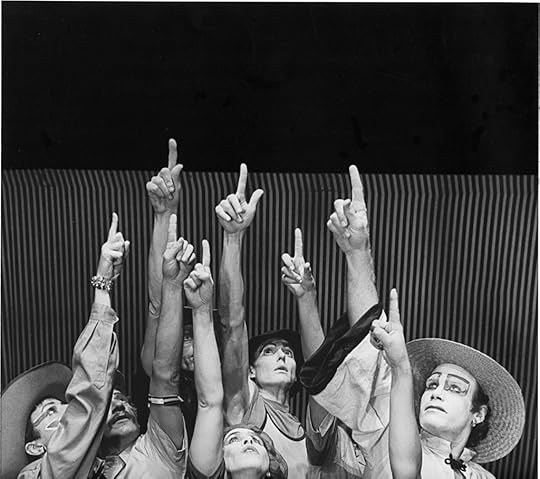

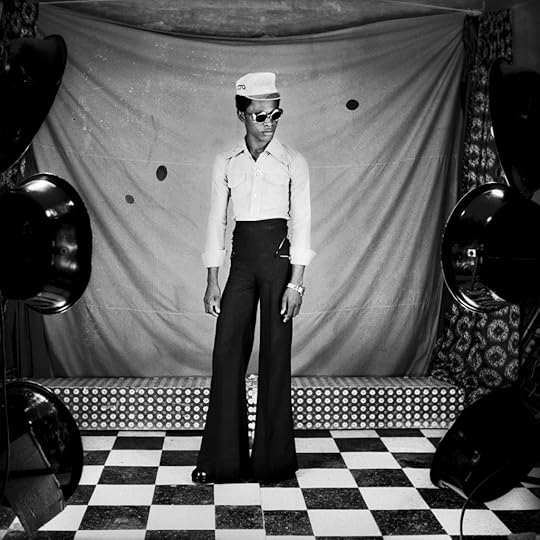

Performance still, Theater of All Possibilities of Synergia Ranch, featuring Biospherians Mark Nelson and Jane Poynter, ca. 1990

Performance still, Theater of All Possibilities of Synergia Ranch, featuring Biospherians Mark Nelson and Jane Poynter, ca. 1990Rose: There’s a fascinating tension that emerges between the footage shot by the subjects themselves and all the contemporary media coverage that you have woven into the film. At the time of the original experiment, Biosphere 2 was widely regarded as a spectacular failure, largely because of the way it was covered in the media. There were tremendous controversies about various technical problems and the ways they were solved—questions about secretly bringing materials into the structure and even pumping oxygen inside.

Do you think the project was seen as a failure because the vision it presented was too radical, too utopian, or simply because the Synergists couldn’t navigate the transition from their own personal documentation of the project to its depiction in the mass media?

Wolf: Well, there are two prongs to that question, one dealing with utopia and one dealing with the media’s impact on the project. The Synergists actually rejected the idea of utopia, primarily because it has historically been so associated with the imaginary and the impractical with failure. In his autobiography, John Allen, who coalesced the group, expresses how, in so many senses, the Synergists tried to create a place that doesn’t yet exist. So what I would say is that the underlying impulse behind this group was futurist rather than utopian.

Rose: But then that vision of the future couldn’t handle all the attention it attracted? The ethos of the project didn’t seem to survive translation into a kind of media spectacle.

Wolf: The title Spaceship Earth is a nod to the theatricality of the project as well as its ambitions. It’s obviously a reference to Buckminster Fuller’s seminal counterculture book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969). Fuller was hugely influential for the Synergists. But it is also a nod to the Epcot amusement-park ride called Spaceship Earth, which is a kind of cartoonish sci-fi architecture with animatronic vignettes that depict progress and the future. Biosphere 2 was really this potent mix of countercultural sustainability and theme-park theatrics.

When you pursue a project as ambitious and big as Biosphere 2, it’s inevitable that it is going to attract attention. It became a real mainstream, pop-culture phenomenon. I don’t think this group was equipped with the public-relations skills to manage that. And the experimental dimension of the project, with the eight inhabitants, called the Biospherians, sealed inside of the structure for two years, also stoked the voyeuristic tendencies of the public that later found their expression in reality television shows such as Big Brother and The Real World, and ultimately, of course, Survivor. You can’t separate the way Biosphere 2 was treated in the media from those broader cultural trends. In fact, when The Real World was released, in 1992, the New York Times even called it something like “MTV’s answer to Biosphere 2.”

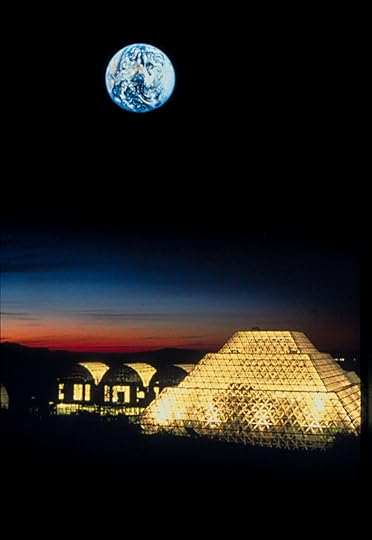

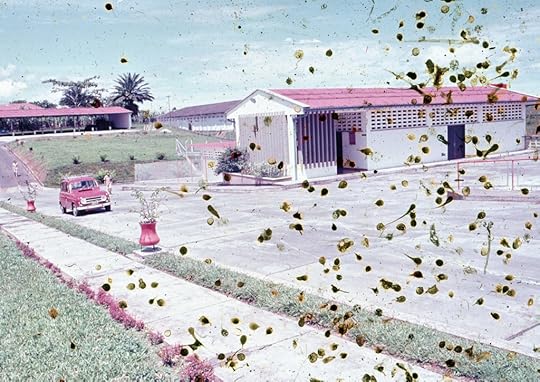

Biosphere 2, 1991

Biosphere 2, 1991Rose: Visually, the physical structure of Biosphere 2 is absolutely stunning— this vast, futuristic complex of crystalline glass prisms rising up out of the empty desert. But was the architecture part of the problem precisely because it was so spectacular, so monumental, and so symbolic? You have some beautiful passages in your interviews with the Synergists where they talk about Fuller’s key architectural invention, the geodesic dome, as a perfect model for their group because the struts individually are very light and not very strong, but you put them together and they become incredibly powerful—the sum is greater than the parts. The symbolism is almost too good.

Wolf: That’s like the motto of this film: the symbolism is almost too good.

Rose: A great subtitle if it’s not too late! But you see where I’m going. Did the architecture place an impossible burden on the project?

Wolf: There is a kind of Emerald City aspect to the complex, but I don’t think it’s all theatrical, or that it’s responsible for the demise of the project. I find the architecture to be inspiring and bizarre and futuristic and speculative in terms of science fiction. To me, the aesthetics of it is what makes the project magnificent. That’s one of the words that Linda Leigh, one of the Biospherians, uses. Part of the Biospherians’ perspective is that they fell in love with the biosphere that they had created. There is an intoxicating appeal to the architecture as well as the ecological design inside, and if they fall in love with Biosphere 2, it’s instructive in the sense that we all have to fall in love with the biosphere. That’s what needs to happen for us to create a sustainable future.

Rose: I like the rejoinder that an aesthetic dimension is ultimately what makes it an inspiring project, which might suggest a way of rethinking the fate of utopia as a concept in architecture, where it has almost become a bad word. The thinking goes that modernism did not succeed in large part because it had utopian aspirations that were utterly misguided, and that because of those misguided aspirations, the movement has to be rejected wholesale. Modernism set out to transform the world for the better, and instead it left many things the same and made some things much worse. So when you hear someone describe modernism as utopian, that’s almost a coded reference to its failure. But, as your film shows, there is still so much that can be learned from a subtle, contradictory, and complex project—these projects are still worth studying, and we shouldn’t collapse our understanding of them into a binary of success or failure.

Wolf: The kernel of utopian aspiration is meaningful, and we shouldn’t shut down that aspiration because it is an engine of change. I think it’s quite cynical to dismiss the project of utopia wholesale even if it’s historically proven to fail in empirical terms. And again, I think that the architecture of Biosphere 2 did constitute an achievement in many ways. From a technical perspective, it was incredibly sophisticated—it was perhaps the most airtight structure ever built at that time. The architecture of Biosphere 2 is really the ultimate expression of ecotechnics—to use the Synergists’ term for the combination of ecology and technology— because to make it, engineers and ecologists and architects and experts from a wide variety of fields had to work together to create a system that could support life.

Related Items

Aperture 241

Shop Now[image error]

How Photographers Responded to the Arab Spring

Learn More[image error]

Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

Learn More[image error]Rose: When you mention technology, it makes me think of the uneasy, even paradoxical, relationship between capitalism and utopia. One of the most surprising moments in the film is when you reveal that this massively ambitious ecological research station was funded by a Texas oil billionaire.

Wolf: They were doing a self-financed project that was trying to change the world for the better and make money at the same time. It’s 100 percent the model of Silicon Valley—of “disruption.” It’s the ethos of Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg, of breaking things to make them better. They were doing it before that model existed and was viable.

I can’t tell you whether that was why the project failed; I can only speak to my point of view as the filmmaker. I wanted the film to be a parable about the limitations of this model, of private venture environmentalism. As much as the film honors and celebrates the vision and aspirations of this group, it is a cautionary tale about how radical environmentalism and corporate interests aren’t the best bedfellows. And speaking of symbolism that’s too good to be true—Steve Bannon is the person who facilitated the corporate takeover of Biosphere 2.

Rose: What a twist in the story! When I saw the footage of Bannon giving a press conference outside of the Biosphere 2 building, it certainly did throw the project’s connections with the present into stark relief. And speaking of these contemporary resonances, I have to ask about the idea of colonization. The Synergists and the Biospherians you interview are totally open about the fact that it was originally envisioned as a step toward colonizing Mars. It’s clear that this seemed harmless to them—after all, they’re talking about an uninhabited planet—but we’re in a moment of fundamentally questioning colonial projects of all kinds. Do you think that there is something about the desire to start over by conquering new territory that is inherently flawed? Is the link between utopias and colonies unavoidable, and is that another dark side of the utopian project?

Wolf: I do think there is a postcolonial analysis of Biosphere 2 that needs to be carried out. The project was conceived of and executed by an entirely white crew. This group said that they were undertaking an ecological project or a scientific project, but in so many ways Biosphere 2 ended up replicating certain dynamics of society. It became a model of society in which there were no established politics about decision-making. So John Allen and Margaret Augustine, the Biosphere 2 CEO, sort of de facto became these totalitarian leaders. The whole question of power spiraled out of control.

Rose: There’s a very powerful moment in the film when you’re cutting between footage of tourists visiting the facility soon after the mission began, when the Biospherians were still inside. We see a group of African American students, one of whom looks into the camera and says, “I would like to know what a young Black woman from Brooklyn would do in a biosphere!” I imagine that by this point in the film most contemporary viewers have registered the lack of diversity in the project, but you made an editorial decision to explicitly call it out.

Wolf: In the past few months, as we’re looking really critically at systemic racism, I’ve recognized that ideas about sustainability are intrinsically connected to the need for equity. Racial justice and environmentalism aren’t always seen as intersecting. We can’t sustain a just society unless we restructure things to enhance equity. I think a lot of utopian projects didn’t do that. Even if they aim to live sustainably on Earth or to create sustainable models of design, these projects reify structural power dynamics that are ultimately oppressive.

Biospherians Mark Nelson and Linda Leigh measuring trees, 1991

Biospherians Mark Nelson and Linda Leigh measuring trees, 1991All images from the documentary Spaceship Earth, 2020. Courtesy Matt Wolf

Rose: You could never have planned this, but your film is reaching audiences at a moment when we all feel a little bit like Biospherians. We’ve spent months isolated in these little microcosmic worlds of our homes, where some of us are experiencing the strains of undergoing that experience with small groups of other people, and some of us are experiencing the strains of going through that in isolation and only seeing other people in a mediated way on screens. Has this changed how you see the film? Has it changed your hopes for its impact?

Wolf: It changed the reality of how the film has reached its audience and how it was distributed in the world. In some ways, that’s disappointing to me. I really miss showing films for audiences, communicating with people in real life. In other ways, it was a kind of uncanny opportunity to reach people who were captive at home. As a documentary filmmaker, you’re obviously cognizant of the unexpected, and you always realize that a film you make that’s about the real world can take on an intense new meaning in the future. That’s part of the excitement.

It was quite unusual to make a film that I thought was already prescient because it dealt with issues of ecological catastrophe but then became hyperprescient in the sense that it spoke to the experience we are all going through in quarantine. I don’t necessarily think the film is directly instructive for people about the quarantine, but I do think we can learn from the experience of the Biospherians. The Biospherians, when they left Biosphere 2, all spoke about a feeling of personal transformation. One of them, Mark Nelson, said at the reentry ceremony, “To live in a small world … changes who you are.” They could no longer take anything for granted when they reentered the larger system of planet Earth.

Rose: And you were thinking about how quarantine might have similar lessons about our relationship to the world outside?

Wolf: When the film first came out, at the height of the quarantine, I hoped that the experience would shift people’s consciousness about the environment, would show how we could start thinking about creating lower levels of pollution, about eating food in more sustainable ways—maybe that the transformations we underwent during quarantine would affect how we continue living. But now, thinking about it, perhaps the real transformation is that people are no longer willing to accept the injustices that have existed around us for all of our lives. As a result of being isolated, injustice became intolerable, and this realization broke through the barrier of quarantine so that people went back out into the world to protest. What ended up happening, a month or two after the film came out, was the largest series of civil rights protests in American history. I do think, without a doubt, there’s a correlation between the quarantine and the protests. Because people seem to have gone through an experience of personal transformation in which the way they engage in the outside world had shifted.

Rose: The estrangement of quarantine created enough distance for people to start reevaluating social structures that they might have previously taken for granted.

Wolf: When the world is fucked up by a pandemic, and that actually intervenes in your day-to day life, your consciousness about the fucked-up-ness of the world is really thrown into focus. People are realizing: We don’t want to go back to normal because normal was unjust. So how do we define the new normal? And now, in a way, we’re talking about futurism. And how we’re choosing to reimagine this world is as a new normal that’s more just. That sense of equity is often the missing link in these utopian projects.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Spaceship Earth.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The Counterculture Collective Who Wanted Save the Earth

For more than a decade, the filmmaker Matt Wolf has won acclaim for his meticulously crafted documentaries that reveal lost histories through deep dives into media archives. His focus is often on radical outsiders whose projects range from the quixotic to the paranoiac. His first film, Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell (2008), is an exploration of the life and work of an avant-garde cellist and disco producer, while Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (2019) examines the fascinating obsession of its subject, who recorded live television news continuously from 1979 until her death in 2012.

Wolf’s latest film, Spaceship Earth (2020), traces the activities of a counterculture collective known as the Synergists from the 1969 founding of a sustainable ranch in New Mexico through the 1991 launch of Biosphere 2, a staggeringly ambitious attempt to pave the way for human life on Mars and to learn about how to live more sustainably on Earth by building a completely self-enclosed ecosystem inside a glass pyramid in the Arizona desert. Last summer, Wolf spoke to the architect and critic Julian Rose about the uncanny resonance of the Synergists’ efforts to give form to the future.

Biospherian candidates, 1990

Biospherian candidates, 1990Julian Rose: One of the fascinating things about Spaceship Earth is that the protagonists were obsessively documenting their own work as it progressed, producing countless hours of film and video that captured the projects they pursued. How did you first become aware of all that archival material, and how did your film evolve out of it?

Matt Wolf: My creative process involves searching for archives because I’m drawn toward hidden histories. Most of the preliminary research I do begins on the Internet. In this case, I came across these striking images of eight people in bright-red jumpsuits, looking like the band Devo, standing in front of a glowing glass pyramid, and I genuinely thought they were stills from a ’90s science-fiction film. But I quickly realized that, in fact, this structure was real—it was Biosphere 2—and that those people lived sealed inside of it for two years. And the more I looked into the history of the project, the more byzantine the story became. I learned that it had been the brainchild of this countercultural group called the Synergists, and I went to their commune-ranch in New Mexico called Synergia Ranch. When I arrived, I was brought into this temperature-controlled closet that had hundreds of 16mm films and analog videotapes and thousands of images. I learned that this group had been documenting their activity for nearly half a century, and that the material had never been used or seen.

Rose: The term archival usually suggests material that’s raw or unprocessed, but when I watched the film, I was struck by how highly authored, even artistic, much of the footage is—some of it looks like it could be experimental film or video art. Did that level of authorship complicate your own role as a filmmaker?

Wolf: My filmmaking involves working with personal archives—personal in the sense that they are outside established institutions or are even anti-institutional. I’m often looking at people who pursued complex and multifaceted projects, and they didn’t necessarily represent and explain those projects in ways that were accessible. I want to reappraise their legacies and act as a translator, helping to find the logic and coherence and vision behind this idiosyncratic activity, and to explore how it is often incredibly relevant to the broader world. For this film, the archival footage was literally shot from the perspective of my subjects, so I had a unique opportunity to visually translate their story beyond the flattened coverage in the news media.

Performance still, Theater of All Possibilities of Synergia Ranch, featuring Biospherians Mark Nelson and Jane Poynter, ca. 1990

Performance still, Theater of All Possibilities of Synergia Ranch, featuring Biospherians Mark Nelson and Jane Poynter, ca. 1990Rose: There’s a fascinating tension that emerges between the footage shot by the subjects themselves and all the contemporary media coverage that you have woven into the film. At the time of the original experiment, Biosphere 2 was widely regarded as a spectacular failure, largely because of the way it was covered in the media. There were tremendous controversies about various technical problems and the ways they were solved—questions about secretly bringing materials into the structure and even pumping oxygen inside.

Do you think the project was seen as a failure because the vision it presented was too radical, too utopian, or simply because the Synergists couldn’t navigate the transition from their own personal documentation of the project to its depiction in the mass media?

Wolf: Well, there are two prongs to that question, one dealing with utopia and one dealing with the media’s impact on the project. The Synergists actually rejected the idea of utopia, primarily because it has historically been so associated with the imaginary and the impractical with failure. In his autobiography, John Allen, who coalesced the group, expresses how, in so many senses, the Synergists tried to create a place that doesn’t yet exist. So what I would say is that the underlying impulse behind this group was futurist rather than utopian.

Rose: But then that vision of the future couldn’t handle all the attention it attracted? The ethos of the project didn’t seem to survive translation into a kind of media spectacle.

Wolf: The title Spaceship Earth is a nod to the theatricality of the project as well as its ambitions. It’s obviously a reference to Buckminster Fuller’s seminal counterculture book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969). Fuller was hugely influential for the Synergists. But it is also a nod to the Epcot amusement-park ride called Spaceship Earth, which is a kind of cartoonish sci-fi architecture with animatronic vignettes that depict progress and the future. Biosphere 2 was really this potent mix of countercultural sustainability and theme-park theatrics.

When you pursue a project as ambitious and big as Biosphere 2, it’s inevitable that it is going to attract attention. It became a real mainstream, pop-culture phenomenon. I don’t think this group was equipped with the public-relations skills to manage that. And the experimental dimension of the project, with the eight inhabitants, called the Biospherians, sealed inside of the structure for two years, also stoked the voyeuristic tendencies of the public that later found their expression in reality television shows such as Big Brother and The Real World, and ultimately, of course, Survivor. You can’t separate the way Biosphere 2 was treated in the media from those broader cultural trends. In fact, when The Real World was released, in 1992, the New York Times even called it something like “MTV’s answer to Biosphere 2.”

Biosphere 2, 1991

Biosphere 2, 1991Rose: Visually, the physical structure of Biosphere 2 is absolutely stunning— this vast, futuristic complex of crystalline glass prisms rising up out of the empty desert. But was the architecture part of the problem precisely because it was so spectacular, so monumental, and so symbolic? You have some beautiful passages in your interviews with the Synergists where they talk about Fuller’s key architectural invention, the geodesic dome, as a perfect model for their group because the struts individually are very light and not very strong, but you put them together and they become incredibly powerful—the sum is greater than the parts. The symbolism is almost too good.

Wolf: That’s like the motto of this film: the symbolism is almost too good.

Rose: A great subtitle if it’s not too late! But you see where I’m going. Did the architecture place an impossible burden on the project?

Wolf: There is a kind of Emerald City aspect to the complex, but I don’t think it’s all theatrical, or that it’s responsible for the demise of the project. I find the architecture to be inspiring and bizarre and futuristic and speculative in terms of science fiction. To me, the aesthetics of it is what makes the project magnificent. That’s one of the words that Linda Leigh, one of the Biospherians, uses. Part of the Biospherians’ perspective is that they fell in love with the biosphere that they had created. There is an intoxicating appeal to the architecture as well as the ecological design inside, and if they fall in love with Biosphere 2, it’s instructive in the sense that we all have to fall in love with the biosphere. That’s what needs to happen for us to create a sustainable future.

Rose: I like the rejoinder that an aesthetic dimension is ultimately what makes it an inspiring project, which might suggest a way of rethinking the fate of utopia as a concept in architecture, where it has almost become a bad word. The thinking goes that modernism did not succeed in large part because it had utopian aspirations that were utterly misguided, and that because of those misguided aspirations, the movement has to be rejected wholesale. Modernism set out to transform the world for the better, and instead it left many things the same and made some things much worse. So when you hear someone describe modernism as utopian, that’s almost a coded reference to its failure. But, as your film shows, there is still so much that can be learned from a subtle, contradictory, and complex project—these projects are still worth studying, and we shouldn’t collapse our understanding of them into a binary of success or failure.

Wolf: The kernel of utopian aspiration is meaningful, and we shouldn’t shut down that aspiration because it is an engine of change. I think it’s quite cynical to dismiss the project of utopia wholesale even if it’s historically proven to fail in empirical terms. And again, I think that the architecture of Biosphere 2 did constitute an achievement in many ways. From a technical perspective, it was incredibly sophisticated—it was perhaps the most airtight structure ever built at that time. The architecture of Biosphere 2 is really the ultimate expression of ecotechnics—to use the Synergists’ term for the combination of ecology and technology— because to make it, engineers and ecologists and architects and experts from a wide variety of fields had to work together to create a system that could support life.

Related Items

Aperture 241

Shop Now[image error]

How Photographers Responded to the Arab Spring

Learn More[image error]

Tyler Mitchell’s Love for a Common Way of Life

Learn More[image error]Rose: When you mention technology, it makes me think of the uneasy, even paradoxical, relationship between capitalism and utopia. One of the most surprising moments in the film is when you reveal that this massively ambitious ecological research station was funded by a Texas oil billionaire.

Wolf: They were doing a self-financed project that was trying to change the world for the better and make money at the same time. It’s 100 percent the model of Silicon Valley—of “disruption.” It’s the ethos of Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg, of breaking things to make them better. They were doing it before that model existed and was viable.

I can’t tell you whether that was why the project failed; I can only speak to my point of view as the filmmaker. I wanted the film to be a parable about the limitations of this model, of private venture environmentalism. As much as the film honors and celebrates the vision and aspirations of this group, it is a cautionary tale about how radical environmentalism and corporate interests aren’t the best bedfellows. And speaking of symbolism that’s too good to be true—Steve Bannon is the person who facilitated the corporate takeover of Biosphere 2.

Rose: What a twist in the story! When I saw the footage of Bannon giving a press conference outside of the Biosphere 2 building, it certainly did throw the project’s connections with the present into stark relief. And speaking of these contemporary resonances, I have to ask about the idea of colonization. The Synergists and the Biospherians you interview are totally open about the fact that it was originally envisioned as a step toward colonizing Mars. It’s clear that this seemed harmless to them—after all, they’re talking about an uninhabited planet—but we’re in a moment of fundamentally questioning colonial projects of all kinds. Do you think that there is something about the desire to start over by conquering new territory that is inherently flawed? Is the link between utopias and colonies unavoidable, and is that another dark side of the utopian project?

Wolf: I do think there is a postcolonial analysis of Biosphere 2 that needs to be carried out. The project was conceived of and executed by an entirely white crew. This group said that they were undertaking an ecological project or a scientific project, but in so many ways Biosphere 2 ended up replicating certain dynamics of society. It became a model of society in which there were no established politics about decision-making. So John Allen and Margaret Augustine, the Biosphere 2 CEO, sort of de facto became these totalitarian leaders. The whole question of power spiraled out of control.

Rose: There’s a very powerful moment in the film when you’re cutting between footage of tourists visiting the facility soon after the mission began, when the Biospherians were still inside. We see a group of African American students, one of whom looks into the camera and says, “I would like to know what a young Black woman from Brooklyn would do in a biosphere!” I imagine that by this point in the film most contemporary viewers have registered the lack of diversity in the project, but you made an editorial decision to explicitly call it out.

Wolf: In the past few months, as we’re looking really critically at systemic racism, I’ve recognized that ideas about sustainability are intrinsically connected to the need for equity. Racial justice and environmentalism aren’t always seen as intersecting. We can’t sustain a just society unless we restructure things to enhance equity. I think a lot of utopian projects didn’t do that. Even if they aim to live sustainably on Earth or to create sustainable models of design, these projects reify structural power dynamics that are ultimately oppressive.

Biospherians Mark Nelson and Linda Leigh measuring trees, 1991

Biospherians Mark Nelson and Linda Leigh measuring trees, 1991All images from the documentary Spaceship Earth, 2020. Courtesy Matt Wolf

Rose: You could never have planned this, but your film is reaching audiences at a moment when we all feel a little bit like Biospherians. We’ve spent months isolated in these little microcosmic worlds of our homes, where some of us are experiencing the strains of undergoing that experience with small groups of other people, and some of us are experiencing the strains of going through that in isolation and only seeing other people in a mediated way on screens. Has this changed how you see the film? Has it changed your hopes for its impact?

Wolf: It changed the reality of how the film has reached its audience and how it was distributed in the world. In some ways, that’s disappointing to me. I really miss showing films for audiences, communicating with people in real life. In other ways, it was a kind of uncanny opportunity to reach people who were captive at home. As a documentary filmmaker, you’re obviously cognizant of the unexpected, and you always realize that a film you make that’s about the real world can take on an intense new meaning in the future. That’s part of the excitement.

It was quite unusual to make a film that I thought was already prescient because it dealt with issues of ecological catastrophe but then became hyperprescient in the sense that it spoke to the experience we are all going through in quarantine. I don’t necessarily think the film is directly instructive for people about the quarantine, but I do think we can learn from the experience of the Biospherians. The Biospherians, when they left Biosphere 2, all spoke about a feeling of personal transformation. One of them, Mark Nelson, said at the reentry ceremony, “To live in a small world … changes who you are.” They could no longer take anything for granted when they reentered the larger system of planet Earth.

Rose: And you were thinking about how quarantine might have similar lessons about our relationship to the world outside?

Wolf: When the film first came out, at the height of the quarantine, I hoped that the experience would shift people’s consciousness about the environment, would show how we could start thinking about creating lower levels of pollution, about eating food in more sustainable ways—maybe that the transformations we underwent during quarantine would affect how we continue living. But now, thinking about it, perhaps the real transformation is that people are no longer willing to accept the injustices that have existed around us for all of our lives. As a result of being isolated, injustice became intolerable, and this realization broke through the barrier of quarantine so that people went back out into the world to protest. What ended up happening, a month or two after the film came out, was the largest series of civil rights protests in American history. I do think, without a doubt, there’s a correlation between the quarantine and the protests. Because people seem to have gone through an experience of personal transformation in which the way they engage in the outside world had shifted.

Rose: The estrangement of quarantine created enough distance for people to start reevaluating social structures that they might have previously taken for granted.

Wolf: When the world is fucked up by a pandemic, and that actually intervenes in your day-to day life, your consciousness about the fucked-up-ness of the world is really thrown into focus. People are realizing: We don’t want to go back to normal because normal was unjust. So how do we define the new normal? And now, in a way, we’re talking about futurism. And how we’re choosing to reimagine this world is as a new normal that’s more just. That sense of equity is often the missing link in these utopian projects.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Spaceship Earth.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

January 12, 2021

Finding Trance and Transcendence in Vasantha Yogananthan’s Photographic Epic

Vasantha Yogananthan trails the horizon of counterparts, the thin line of contact between allegory and anecdote, forethought and spontaneity, the end and the beginning. In his eight-year photography project A Myth of Two Souls, the French photographer of half Sri Lankan descent retraces the Ramayana through contemporary India and Sri Lanka, evoking each chapter of the ancient Indian epic through an exploration of the daily and the eternal of both local life and myth. Across a range of cities and ever-evolving techniques, including hand-painting and mixed media, Yogananthan’s first five books—Early Times (2016), The Promise (2017), Exile (2017), Dandaka (2018), and Howling Winds (2019)—transpose the journey of the exiled Prince Rama, which reaches its apex with the great war between Rama and the evil Ravana in Yogananthan’s newest installment, Afterlife (2020).

In chapter six, Yogananthan takes us to the modern-day Dussehra festival, an annual Hindu autumnal rite celebrating Rama’s victory over evil. Yogananthan’s images from night-long attempts to reach trance and transcendence are coupled with a text adaptation by the lyrically outspoken Indian author Meena Kandasamy, whose poem becomes the footpath on the seam of nighttime: “Walk with me as we walk past ourselves.”

I spoke with Yogananthan over Skype on the cusp of the new year about the episodic night vision of this unique chapter, where gravity is reversed, eyelids never fully meet, the body glides outside of its own lines, and darkness shines the way.

Vasantha Yogananthan, The Dark Knight, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

Vasantha Yogananthan, The Dark Knight, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019Yelena Moskovich: When did you first encounter the story of the Ramayana?

Vasantha Yogananthan: I read a comic-book version when I was a kid. My dad used to have them at home. But then, I completely forgot about it for many years, until I traveled to India in 2013. I was looking for a story that would allow me to explore India and Sri Lanka, as well as photography as a medium and the space between documentary and fiction. The Ramayana was just the perfect fit. Although it’s an Indian story and very specific to South Asia, the main events could have taken place in an epic from the West. There’s a prince and a princess, the princess is abducted, and there’s a big war. You don’t need to be particularly versed in Indian mythology to relate to the feelings in the story. It brings up questions about family and love, the concept of purity, relationships, things that could speak to anyone.

Vasantha Yogananthan, CMYK, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018

Vasantha Yogananthan, CMYK, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018Moskovich: For this chapter, the darkest of the story, what drew you to choose the Dussehra festival as your visual landscape?

Yogananthan: This was the most challenging chapter, because I had to find a visual response to war. I knew from the start that I was not going to witness any real-life battles, so the festival was a really good way for me to enter the story. Before I experienced the festival, I had imagined it more like a carnival. But when I did the first trip to Rajasthan, then the subsequent trips to the south, I saw there was a very different vibe. Most people were staying up till daylight, sometimes getting really drunk, not eating or sleeping, men dressing as women, painting their faces in black or blue, trying to reach this state of trance. War can be photographed or documented, like in photojournalism, but there’s a visual response to war that can be, not at a physical level, but rather in the mind.

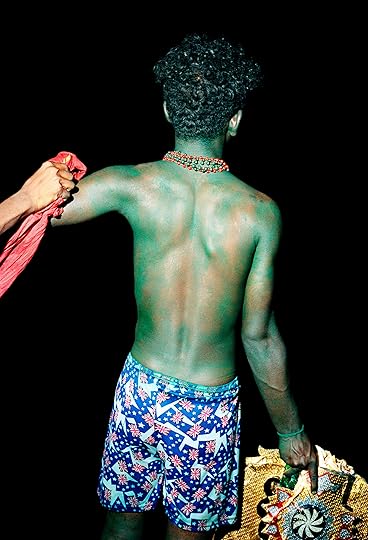

Vasantha Yogananthan, Green Soldier, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

Vasantha Yogananthan, Green Soldier, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019Moskovich: This is so telling of our modern sense of war, actually. We aren’t necessarily going to be exposed to a battlefield, but we all know the terrain of psychological or internal struggle.

Yogananthan: Absolutely. And the thing is, no one goes to war alone. War is a collective experience. This is what was so striking for me in the festival, how all these people express this struggle with their bodies—without fighting each other. You have to imagine thousands and thousands of people. In the photos in the book, you don’t necessarily see that, because I made the choice of using the flash to have this black background where the figure stands out over the darkness.

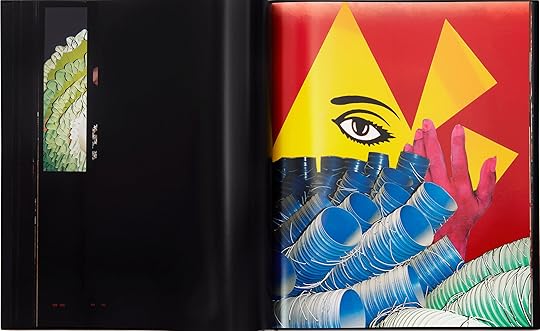

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)Moskovich: Darkness is an experience in itself in Afterlife. The utter black backgrounds you describe, or even the sequence of images that are punctuated with these glossy pages of pure or near-pure blackout.

Yogananthan: Well, book number six of the Ramayana is known as the “Black Book.” Integrating the void that someone can’t help but feel when they face the darkness was very important. At some points, I wanted there to be almost nothing to look at but black. It’s really the relationship of the reader with this void that becomes the thing that’s happening.

Moskovich: There’s quite a shift in density and color palette in general in this book from your earlier work.

Yogananthan: Yes, my natural color palette is very soft, pastel colors. It’s true that this book is drastically different than the previous ones. This part of the story, the war, was calling for a more vivid palette, higher saturation, deep reds, deep blues, deep black. It was the first time I shot with a flash, which made for harsher photos with stark contrast.

Vasantha Yogananthan, Tear Gas, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

Vasantha Yogananthan, Tear Gas, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019Moskovich: The images you gather from the festival are uncanny, but not for the reasons one would expect. Dussehra is so full of “photogenic” rituals, so to speak—carrying clay statues of certain gods or goddesses to be dissolved in the water, or the burning of effigies of Ravana (the symbolic evil), yet you’ve sidestepped the depiction of fanfare to take us into the energy of the experience.

Yogananthan: These festivals have been so widely photographed. The idea, for me, was to use the space of the festival not to show what was happening, but what emotions were happening. What the people were feeling. For example, the last night of the festival, they burn the big Ravana statues in the middle of the night. Visually, it’s a very powerful sight. I took so many pictures of them burning Ravana, but in the end, I didn’t use a single photo of this moment in the book, because I didn’t want to fall into illustration.

Moskovich: The burning comes across in other ways. The one that stuck out for me was the couple of shots where a person is entering the sea, and the water is splashing in midair as if bursting into flames. The surprising alchemy of the sea on fire.

Yogananthan: It’s funny, because I didn’t notice that the water is always going upward. But yes, when the people are going into the sea, we see the water up in the air, we don’t know if it’s falling or rising—and the people themselves, we don’t know if they are falling or rising.

Vasantha Yogananthan, Ghost Dog, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018

Vasantha Yogananthan, Ghost Dog, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018Moskovich: Throughout the book as a whole, there’s an otherworldly gravity at play. Can you tell me a little more about the distinct movement of this chapter of your project?

Yogananthan: I shot most of the previous chapters with a large-format camera, in a slow process, where everything was carefully framed and constructed over many one- or two-month trips. For Afterlife, each festival was only a few nights, so I had a very tight time frame. I was often in the middle of a crowd of thousands, and there was no room or time to look into the viewfinder. Everything was in movement. I was holding the camera with the flash and shooting in complete blindness. We don’t often speak about the physicality of photography. As a photographer, your body, how you relate to the landscape and the people, how close you get to the people, especially in portraits, it’s a very physical experience. I was using a 50 mm lens, so if I wanted to get up close, like a crop shot, I had to almost get in the face of the person.

Vasantha Yogananthan, Watching The Dead Go, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018

Vasantha Yogananthan, Watching The Dead Go, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018Moskovich: The eyes in these portraits are so fascinating. Many are half-open or just barely closed, almost stuck between two realms. Or else, the iris is stretched to the very corner of the eye, as if sliding into a different consciousness.

Yogananthan: I’m really glad that you noticed that. In a way, these are the kinds of photos a photographer would generally dismiss, because you either shoot someone with their eyes open or closed. Even the shots with the most direct eye contact are disorientating. One of the strongest ones for me in the book is where we don’t really know if it’s a man or a girl, but they’re washing their face and wiping it with a piece of fabric that covers one eye, and with the other, they look directly at us.

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)Moskovich: It almost implicates us into their experience of the trance. Looking in to look out, a way of pulling out of their bodies. You emphasize this pursuit of dislocation by introducing collage work into the project with this book. Was that method envisioned from the beginning?

Yogananthan: The collage part was a discovery for me. When I got back from the second trip, I laid out the prints, and I could see so many of them had something in the background that didn’t work. I decided to start cutting things out of the prints and gluing them together, then scanning the collage. This was quite a revelation. It allowed me to mix the physical space of the festival in various cities—the pictures I shot in Kota with the ones I shot in Tamil Nadu, for example—and create a third space. If you look closely, you can see the trace of the cutter. Also, the different sizes of the pages layered with each other, so that you can turn one smaller page and it reveals the full photo underneath it. There was a lot more work put into the editing and sequencing of this book than any of my other ones. I’ve come to realize that studio practice is as important as being in the field and research prior to travel.

Moskovich: What brought you to invest so heavily in studio work this time around?

Yogananthan: Afterlife was shot in ten, twelve days, but put together over many months. When I started developing the photos and putting them together for the book, the pandemic hit and France went into lockdown. All the assignments and projects for photographers were canceled. I was by myself, confined at home, going to the studio every day, just facing myself, my work, what I could do, what I could not do.

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)Moskovich: That really speaks to, not only our global situation, but the Ramayana as well, the journey of confronting oneself.

I’d like to talk about the text in this book, which is another sort of confrontation. You’ve collaborated with various contemporary authors for the text in these chapters. What made you think of Meena Kandasamy, an Indian poet, fiction writer, and activist who’s quite emotionally courageous on the topic of intimacy, to render this chapter’s adaptation?

Yogananthan: Meena’s strength as a feminist, a woman, and a storyteller really made sense for this chapter. She received the pdf of the book and had carte blanche. You know, with this sort of collaboration, some writers want me to explain the photos or my process. But Meena didn’t ask one single question. She just emotionally responded to the photos.

The original epic has a patriarchal perspective, the princess waiting to be saved. In Meena’s poem, she twists the epic in an unusual and disturbing way. It becomes a long walk into the night and into the darkness of the soul, where the princess, Sita, is the one leading the way, walking with Ravana, who abducted her.

Vasantha Yogananthan, Dragonfly, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018

Vasantha Yogananthan, Dragonfly, Kota, Rajasthan, India, 2018Moskovich: Both the text and images complement each other’s sensuality.

Yogananthan: Yes, there is sensuality in the photos, these bodies, painted or half-naked, on the black background. But there was also a specific sensuality to the festivals.

In India, men are more comfortable with their bodies and with closeness. The festival would happen in these small villages where there weren’t enough accommodations for the thousands of people who came, so come nighttime, many would sleep outside, together in the street. And when it was cold, the men would sort of cuddle each other, so at like three or four in the morning, you’d be walking over all these bodies in the street hugging each other. It was very powerful to see.

Moskovich: It’s interesting that in this book, it’s a woman’s voice narrating images of mainly men’s bodies. We’re so used to seeing women’s bodies being narrated by a man’s voice.

Yogananthan: It’s like a woman in the darkness, on the battlefield, and she’s the one taking you through, from the first page to the last.

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)

Spread from Vasantha Yogananthan, Afterlife (Chose Commune, 2020)All photographs © the artist

Moskovich: The last line of Meena’s poem, “Walk with me until it is time to walk away,” is an eerie sort of promise. Till forever and only now. It’s so resonant with the treatment of time in this book, one night between mortality and the everlasting.

Yogananthan: I wanted to find a way to condense time, so that the book can feel like just one night, one single, very long walk from light to darkness, and perhaps back to light again—but it’s very open at the end. You don’t really know if you are finally getting out of the darkness and walking toward the light, or if the darkness will be there always. The end of the chapter is really terrifying. Though Rama rescues Sita, it isn’t just a typical happy ending. They are together again, but they will never be together again.

Moskovich: This long walk is also about walking with the contradictions.

Yogananthan: Yes, the whole walk is asking this big question: what, if anything, comes after?

Vasantha Yogananthan’s Afterlife was published by Chose Commune in September 2020.

January 8, 2021

How Photographers Responded to the Arab Spring

Hrair Sarkissian traced the flight path of a migratory bird and found it looked exactly like a noose. He constructed a small model of the building where he spent most of his life in Damascus, then, over seven hours, bashed it to bits with a sledgehammer, pausing after every strike to take a picture. Maha Maamoun used literary fiction, cinematic history, and a cache of YouTube videos documenting the nighttime break-ins at state security buildings in Cairo (and elsewhere in Egypt) to convey the weird inner fantasies let loose by periods of political unrest. She made works based on the stories of a man haunted by visions and a drug dealer who turned into an animal hybrid of zebra and goat. Samar Al Summary scoured Beirut for signs of survival and resistance at a time of imminent economic collapse. In that blighted city, heaving with protest, she captured not a single suffering body but the deep layers and delicate textures of material poverty, an ethos of improvisation hovering just above ruin.

A decade has passed since the start of the so-called Arab Spring, when a movement for radical change erupted in Tunisia and Egypt, rolled across North Africa and the Middle East, and spilled down into the Gulf. People were fed up with corrupt and autocratic rulers, unemployment, lack of opportunity and mobility, hunger, and the increasingly threadbare quality of their lives. From the beginning, young protesters and their ideological elders spoke of their movement in terms of revolution. The demonstrations were first sparked by ugly events: the Tunisian street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi burning himself to death in the interior town of Sidi Bouzid, and the Egyptian millennial Khaled Said dragged out of an internet café and beaten lifeless by police in the coastal city of Alexandria. The protests grew, in part, because images of young people demonstrating in public and jostling for change circulated widely on social media and in the press. Exuberant crowds on Tunis’s Avenue Habib Bourguiba and in Cairo’s Tahrir Square forced the regimes of Zine al Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak to fall. No matter what happened after, much of the initial footage, like the electrifying physical experience of being in those crowds, was beautiful and exhilarating and brave.

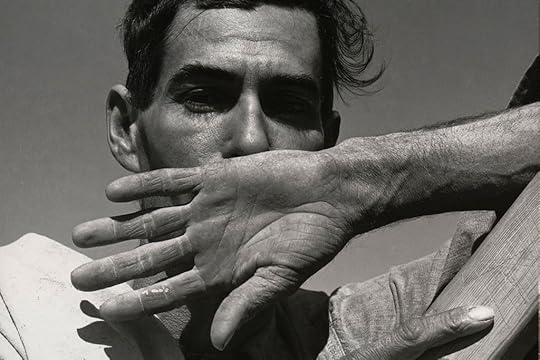

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008Courtesy the artist

But the outcomes for almost every country where protests took place—from the end of 2010, throughout 2011 and after, and into the periodic resurgences occurring to this day in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Sudan—have been terrible. Syria descended into civil war. Yemen and Libya were left in total disarray (both countries are currently deemed failed states). Egypt is now more authoritarian than ever. The trajectory of the Arab Spring has been so dismal that many participants and observers disavow the notion that it was ever a movement at all, that the narrative of disparate events strung together into a single story had any coherence beyond useless generalities. That shift has put artists and image makers in a curious bind. On one hand, there was tremendous hunger for work addressing the events of the Arab Spring, particularly from the art market and from museums in the years after 2011. On the other, any serious attempt to make sense of what happened seems delusional and as doomed to fail as the revolutions themselves.

Perhaps for those ostensibly paradoxical reasons, some of the most thoughtful bodies of work to arise from this long and painful decade are also the subtlest. They come at the Arab Spring from odd angles. Works by Sarkissian, Maamoun, and Al Summary, and others by Omar Imam, Kamel Moussa, Fethi Sahraoui, and Katia Kameli, give shape and meaning to the fleeting possibility, to the crack in the way things were, to the sense of an opening that was present in the early protests. If there was anything utopian in the impulses of the Arab Spring, then it can be found in the notion of a “suspended space,” Al Summary’s description of what she looks for in the scenes she photographs. It applies to the art of a handful of artists who, like her, address difficult circumstances with integrity, nuance, and immovable specificity. In their work, they hold on to that suspended space for future reference, maybe even for eventual use. In doing so, they use new forms and imaging technologies to address a sadly familiar story without resorting to cliché.

Omar Imam, Untitled 12, 2009

Omar Imam, Untitled 12, 2009Courtesy the artist and Catherine Edelman Gallery

Sarkissian left Damascus for Europe in 2008, the same year he made an unforgettable body of work called Execution Squares, a series of fourteen lush, eerie images of the sites of public hangings in Aleppo, Damascus, and Latakia. Each picture shows an urban area packed with history but completely emptied of people, taken in the exquisite pale-orange light of early morning. Sarkissian hasn’t returned to Syria since 2011. In 2014, I asked him if he ever thought about addressing the conflict in his work. Emphatically, he told me, “No.” And, moreover, he wouldn’t allow Execution Squares to be shown in a context where it would be misunderstood—where it would be mistaken for an illustration of events in Syria after the start of the uprising there. Earlier this year, I asked Sarkissian the same question. Again, he said, “No.” He hesitated before continuing, “At least not directly. When it comes to doing something about Syria, I really don’t want to make a work about people who are suffering. Because then it will be hung on a wall and people will say it’s beautiful, or they will say it’s horrible.” He paused, then added, “But I do tell the story of Syria through the story of a bird.”

Hrair Sarkissian Final Flight, 2018–19. Photograph by Oak Taylor Smith

Hrair Sarkissian Final Flight, 2018–19. Photograph by Oak Taylor SmithCourtesy the artist

Final Flight (2018–19) is unusual in Sarkissian’s oeuvre in that it doesn’t feature any of his own photography. Instead, it consists of a nine-hour video he recorded from Google Earth; a print of a photograph borrowed from an Italian diplomat; a map in relief on aluminum; and nine hand-painted sculptures, all cast in resin and bone from the 3-D scan of a skull from the northern bald ibis in a Spanish zoo. The story of the northern bald ibis, one of the rarest bird species in the Middle East, is epic and multifaceted. For Sarkissian, “It’s exactly what the Syrians have gone through,” without being obvious or in your face. The story of a bird that has been endangered, rediscovered, and disappeared makes for a profound metaphor for migration and freedom of movement.

At a time when hundreds of her colleagues have left Egypt for a better life in Europe or North America, Maamoun still lives in the same Cairo neighborhood where she grew up. A cofounder of the Contemporary Image Collective and of the upstart publishing house Kayfa ta, meaning “how-to” in Arabic, Maamoun has developed a singular style combining popular materials and high literary forms. Like Sarkissian’s Execution Squares, one of her best-known works, the nine-minute video 2026 (2010), is often cast, and probably misunderstood, as a work of prophecy. It reenacts an iconic scene from Chris Marker’s landmark film La Jetée (1962), pairing it with an excerpt from an Egyptian sci-fi novel, Mahmoud Osman’s Revolution of 2053: The Beginning (2007), in which a time traveler describes a nightmarish tableau at the pyramids in the aftermath of a revolution far into the future.

Maha Maamoun, Still from 2026, 2010. Single-channel video, 9 minutes

Maha Maamoun, Still from 2026, 2010. Single-channel video, 9 minutesCourtesy the artist

Maha Maamoun, Still from Dear Animal, 2016. Single-channel video, 25 minutes, 30 seconds

Maha Maamoun, Still from Dear Animal, 2016. Single-channel video, 25 minutes, 30 secondsCourtesy the artist

For the eight-and-a-half-minute video Night Visitor: The Night of Counting the Years (2011), Maamoun pieced together a riveting sequence excerpted from YouTube clips uploaded by Tahrir Square protesters. Soon after the start of the revolution, they broke into various state security buildings, which had been totally inaccessible during the Mubarak regime. Maamoun deleted all of the accompanying commentary and focused on signs of wealth and leisure that protesters found stashed in the forbidding structures of the state. Even where the footage pauses on the letters of political prisoners, Maamoun emphasizes poetic language over any explosive revelations of fact. Her twenty-five-minute video Dear Animal (2016) interweaves a short story by the writer Haytham el-Wardany, about a drug dealer who turns into a goat with zebra stripes, with the seemingly guileless dispatches of Azza Shaaban, an activist who left Egypt to find spiritual healing in India. Longer and more capacious than her previous works, Dear Animal is Maamoun’s clearest expression to date of a suspended space, which she creates from the disjunction between wildly different source materials.

Fethi Sahraoui, Youngsters in a large irrigation channel, Relizane, Algeria, 2016, from the series Escaping the Heatwave

Fethi Sahraoui, Youngsters in a large irrigation channel, Relizane, Algeria, 2016, from the series Escaping the HeatwaveCourtesy the artist and Collective 220

What’s striking about these evocative works emanating from the Arab world in the decade since the Arab Spring is how little they show the protests themselves. One of Omar Imam’s surreal images, from an untitled series that spans the years before and after the uprising in Syria, shows a young couple seated in two suitcases. They seem to have dropped from the sky into a graveled landscape, the devastating conditions in Syria envisioned only through the extreme tensions they have created among people in love, who are perhaps planning a future and therefore struggling with the decision to stay, separate, or abandon their country. Since 2014, Fethi Sahraoui has been documenting a group of teenage boys in northwestern Algeria, whom he links to the generation now orchestrating the country’s popular uprising in the streets. But Sahraoui’s pictures, in the series Stadiumphilia and Escaping the Heatwave (both 2014–18), never go there. They linger instead in the sports stadiums where his subjects have developed their political consciousness, through the songs and banners of football matches, which are some of the only events where young men in Algeria can gather for entertainment in large numbers. Or they escape to the various locales, including water towers and irrigation channels in addition to the sea, where the boys seek relief from the extreme summer heat.

One of the reasons Samar Al Summary moved to Beirut was to learn a certain method of care and sensitivity from the artists and thinkers of the well-established art scene there (specifically the practitioners associated with Ashkal Alwan’s Home Workspace Program, where Al Summary was a fellow), who had for generations worked through the problems and dangers of photographing in public and on the street. Born and raised in Jeddah, Al Summary grew up poor in Saudi Arabia, a country both renowned and reviled for its riches. She also came of age with the understanding that “being an artist was basically on the edge of criminality.” When she moved to the United States as a teenager, Al Summary was visually overwhelmed. She started taking pictures “as a way to live and be at peace” with the overabundance of detail in the world around her. By the time she left the American Southwest (she studied in Arizona and New Mexico) and returned to the Arab world, she had started to develop her own visual language.

Samar Al Summary, Pegasus Corporate Logo, Casting Shell of Saint, and a Floral Love Seat, Lebanon, 2020

Samar Al Summary, Pegasus Corporate Logo, Casting Shell of Saint, and a Floral Love Seat, Lebanon, 2020Courtesy the artist

The protests that broke out in Lebanon in 2019, and the horrific explosion in Beirut in August, transformed many things. However, none of the pictures in Al Summary’s ruminative series Trust Beauty Bank and Secure the Door (both 2019–20) focus on the actuality of those events. Instead, Al Summary turns to textures, remnants, and pileups of competing imagery, from advertisements and forgotten campaign posters to cobbled-together homes and businesses stripped of signage. One of the things she looks for is vibrant color, which doesn’t last in the hot, humid climate of the Levantine coast. “Color in a hot climate is a sign of being contemporary,” Al Summary told me. “A place may look like a ruin, but if the color is bright, then it’s still lived in. We have so many images of death— I’m looking for a certain vivacity, a sense of balance and assembled beauty that goes beyond description.” She continued, “In the visual arts, we’re forced to contemplate without drawing conclusions, to be in a suspended space. For artists in the Middle East, when art is dealing with these hot-button issues, when formulas come to mind, it’s difficult to find the poetry of that moment while also being realistic.” The fact that she does so in her photographs may be one of the more important lessons of the last ten years—that even when political actions falter and movements for change fall short, works of art can hold on to the spaces they opened up for memory and for debate, even if the future remains uncertain.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Remains of the Day.” Read more from the issue, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

December 28, 2020

Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2020

This year, we revisited Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, considered how Native artists challenge the story of America today, and asked what it means to be a photographer in the age of COVID-19. Here are some of this year’s highlights in photography and ideas.

The Many Faces of Home in Japanese Photography

Messy, minimal, or melancholic? From Aperture magazine’s “House & Home” issue, these images show the myriad forms of longing for home.

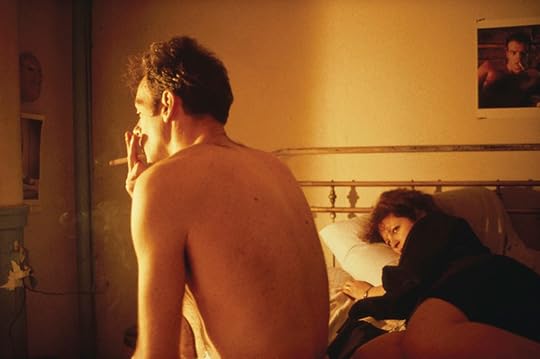

The Inside Story of How Nan Goldin Edited “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency”

From Aperture magazine’s “Ballads” issue, Elle Pérez speaks with Marvin Heiferman about the making of an iconic photobook.

11 Photographers on How to Finish a Body of Work

When should you bring a photographic project to an end? LaToya Ruby Frazier, Justine Kurland, Alec Soth, and more reflect on how to know when a series of work is complete.

Dorothea Lange and the Afterlife of Photographs

An exhibition reveals how Lange’s concern for the dispossessed has never been more relevant.

A Portrait of an Iranian Surfer Reveals Western Fantasies of the Middle East

The Italian photographer Giulia Frigieri wanted to profile a young Iranian surfer. But there was more to the story than her images revealed.

What “Greater New York” Got Right about Photography in the Age of Instagram

In 2010, photography was at a turning point. How did an ambitious survey at MoMA PS1 anticipate a generation of artists who define the field today?

How to Be a Photographer Right Now

Three artists confront how COVID-19 has changed their lives and work—and how they see the world.

The Queer Black Artists Building Worlds of Desire

From Aperture magazine’s “Utopia” issue, in these photographs, queer acts and communal yearning flourish beyond the confines of mainstream gay culture.

Deborah Willis Thinks the Photobook Can Be Transformative

In Issue #018 of The PhotoBook Review, the renowned scholar speaks about her early career in photography, confronting racism in publishing, and why books about Black life are vital.

What Can Artists and Communities Learn from Historic Collections of Native Photography?

From Aperture magazine’s “Native America” issue, Wendy Red Star and Emily Moazami on images, ancestors, and the archives of the National Museum of the American Indian.

Yurie Nagashima’s Self-Portraits Interrogate the Male Gaze

In her latest photobook, the Japanese photographer discusses self-portraiture as a radical feminist gesture.

Why Photo Editors Need to Hire Black Photographers Every Day

How can we commit to making photography more Black, far into the future?

Subscribe to Aperture magazine and never miss an issue.

December 22, 2020

The Queens Photographer Building a Legacy for His Friends

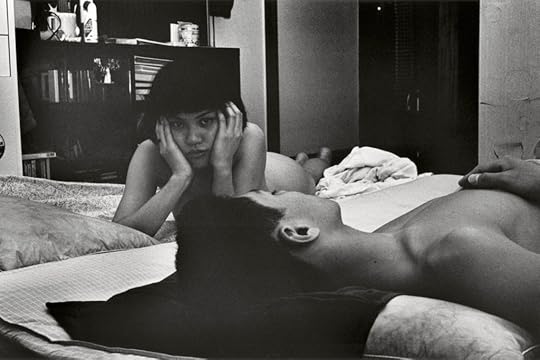

In one of Dean Majd’s photographs, a young man slowly spits into an empty film cannister. The photograph is drenched in ruby red. The shot is close, close enough to make you squirm at the sight of the gob unspooling. The spit makes the photo harsh, but the red makes it soft, bleeding the subject into the surrounding environment in a hazy wash of neon light. It’s an image that is crude, an image that is beautiful. Majd’s ongoing series Hard Feelings doggedly walks this line between two sensations.

Majd started Hard Feelings in 2016. The arena is the skateboarding and graffiti scene in Queens, and the photographs are mostly of men. Men sprawled on cluttered beds or clutching a bloodied hand; men who have hurt themselves; men softening into a pool of water or a pool of light. “There’s something about the men that I photograph—there’s both a sensitivity and a hardness,” Majd tells me during a call over FaceTime. “As men, we’re not supposed to express our feelings, we’re not supposed to act a certain way.” But he and his friends are the opposite, they “do all that.” Majd’s friends cry with their faces in full view of the camera.

Dean Majd, karim (reborn), 2018

Dean Majd, karim (reborn), 2018He met many of these men several years ago, after he had become disconnected from the skateboarding scene, focusing on his studies in international relations and creative writing at City College of New York, in Upper Manhattan. He’d reunited with an old friend, James, at his local skatepark in Astoria. A week later, James suddenly passed away. Majd was the last person to photograph him. In the wake of this loss, Majd met James’s friends, a tightknit community of skaters and artists. “It just happened naturally that we all became super close,” he says. “And they were willing to be photographed.”

Traces of loss flit through Hard Feelings. James, he says, is always “hovering over the images.” In the ruby-drenched portrait spit (2017), the subject is shirtless. On his lower abdomen is a just-visible tattoo of the letters “DE” in bubbled graffiti styling. The full word is “DECE,” in homage to James’s nickname and graffiti tag, the art he used to mark his place.

Majd used his father’s hand-me-down Olympus point-and-shoot as a kid, photographing parties and concerts. But he didn’t think of becoming a professional photographer. His parents are immigrants from Palestine, and Majd’s imagined career choices were shaped by the classic first-gen decree: doctor, lawyer, or engineer. Still, his passion for photography persisted, and at around age eighteen, he came across Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 1986). “That was the book for me,” he said. “That opened everything.” Majd fell in love with Goldin’s breathtakingly unguarded shots of her New York community. Spending time with Goldin’s work has sharpened his own artistic purpose: “to build a legacy for my friends, for Queens.”

Dean Majd, bohemian rhapsody, 2017

Dean Majd, bohemian rhapsody, 2017Since then, Majd has stayed steady with his photographic origins: his camera, almost always, is a point-and-shoot. Compact, fast, discrete. “If someone is off guard,” he says, “in order to keep it as authentic as possible, I need to be quick with it.” Unmediated moments are critical, and Majd catches his friends in visceral, vulnerable flashes. In bobby and caleb (bear hug) (2018), one young man clutches another, his expression riveted by private sadness. A glaze of green tones covers the photograph, underscoring the unease that likely prompted the embrace. rissa (2018) is an arresting departure, in which Majd turns his lens on one of the women in his friend group; her black eye is painful to witness, but the camera’s gaze is one of care, and her own is both candid and trusting. self-mutilation (2018), a photograph of a friend’s arm lined with self-inflicted cuts, is bathed in warm hues. Majd’s documentation is uncensored and frank, but never cold or stark.

As with those early rolls, Majd seldom appears in the frame, but self-portraiture is a difficult muscle he is committed to working. “There are instances where I’ve been with people in the darkest times of their lives,” he tells me. “It would be disingenuous to not do the same. If someone is offering themselves, in every aspect, to be photographed, I can only counter that by saying, I’m doing the same with myself.”

In one such self-portrait, the ruby-red lighting returns. Majd photographs his face from below, framed against graffiti-covered interior walls—perhaps he’s at a concert. Blurred, out-of-focus, his silhouette appears ghostly, intentionally indistinct from the constellation of graffiti tags that, one can imagine, different members of Majd’s community have inscribed over different seasons.

“This work began with a death,” Majd says. At the end of October, another loss: one of Majd’s close friends died unexpectedly. “He was someone that I photographed all the time.” Majd photographed him less than a week before his passing, just like he had James. Now, when Majd looks through Hard Feelings, he greets griefs past and present. “It’s hard to even call the people in my images ‘subjects,’ because this goes beyond a photographic relationship,” Majd says. “The people in my images are my family, my blood. I don’t know what my life would be without them. I love them deeply, and through that love, these images are made.” Born of hurt, laden with tenderness, Hard Feelings is a remembrance, a gathering place, a legacy for those he loves.

Dean Majd, freddy (hyper dark), 2019

Dean Majd, freddy (hyper dark), 2019 Dean Majd, rissa, 2018

Dean Majd, rissa, 2018 Dean Majd, dylan (baptism), 2019

Dean Majd, dylan (baptism), 2019 Dean Majd, self-portrait (hard feelings), 2017

Dean Majd, self-portrait (hard feelings), 2017 Dean Majd, blowout (zeke’s birthday), 2019

Dean Majd, blowout (zeke’s birthday), 2019 Dean Majd, spit, 2017

Dean Majd, spit, 2017 Dean Majd, self-mutilation, 2018

Dean Majd, self-mutilation, 2018 Dean Majd, dylan and eli (silhouette kiss), 2017

Dean Majd, dylan and eli (silhouette kiss), 2017 Dean Majd, self-portrait (acid tongue), 2019

Dean Majd, self-portrait (acid tongue), 2019 Dean Majd, jacob (red ecstasy), 2019

Dean Majd, jacob (red ecstasy), 2019All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

An Exhibition in Tucson Looks at the Things We Leave Behind

Where one artist collects, another deliberately erases and alters. On Halloween in downtown Tucson, Arizona, Etherton Gallery’s opening of El Sueño, an exhibition of Tom Kiefer’s photographs of migrants’ seized belongings and Alejandro Cartagena’s reconfigured found prints, was extended for seven hours—ten people at a time, maximum, a COVID-era measure that prompted small waves of drifting viewers. The exhibition takes its title from a larger presentation of Kiefer’s work earlier this year at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles (El Sueño Americano/The American Dream); it is given new context here, in the company of Cartagena’s work and a small selection of Mexican folk retablos, vernacular paintings on tin representing the trials of Catholic saints. Perhaps particularly for a visitor to the city—I was working just outside Tucson for several weeks, close to the Sonoran Desert, hyperaware of my own temporary existence there—the exhibition felt attuned to the paths we travel, the things we carry, the impressions we leave behind.

Cartagena’s slashed, cutout, altered, and recollaged found photographs suggest the images we discard, and those that remain. In other series of works, Cartagena—born in the Dominican Republic and based in Monterrey, Mexico—has often focused on hidden and unseen lives and the wide disparity between reality and myth. In Carpoolers (2011–12), he photographed workers riding in the backs of trucks to and from work. In A Small Guide to Homeownership (2005–20; featured in the “House and Home” issue of Aperture magazine and recently published as a photobook by The Velvet Cell), he placed images from previous series, including Carpoolers and Suburbia Mexicana: Fragmented Cities (2005–10), with found texts from guidebooks for potential homeowners, highlighting the profound gap between blithe propaganda and reality.

Alejandro Cartagena, Dismembered #30, 2019

Alejandro Cartagena, Dismembered #30, 2019In Cartagena’s Dismembered and Faces series, from his larger project Photographic Structures (2017–19), rather than compounding images, he removes and alters them. He mines landfills and flea markets in Mexico City for snapshots and family photographs, which he then transforms with a sharp blade, slicing and discarding crucial elements of the picture. Faces become empty voids; entire bodies disappear from group photos. Elsewhere, white oval-shaped space hovers above groups of well-dressed people, impressions of souls. Sometimes, he manipulates the cut fragments, juxtaposing an outline of a face against a larger silhouette, like an eclipse.

We are in a world now where many of us have become somewhat accustomed to seeing only aspects of each other, whether on Zoom calls, or out in the world, faces partially obscured by masks. Cartagena’s reconfigurations remove what we think of as the most definitive physical identifiers (eyes, nose, and mouth, for instance); his rearranged leftovers resemble a dissection model of all the empty pieces that exist within us. In one reconstruction, a jaggedly cut-out head leaves a comet-like trail. Cartagena’s restructured photographs call into question their original constructs: how much a picture can tell us, and how lasting are the impressions we leave. As with all found photographs, part of the fascination is the mystery of why they ended up in a stranger’s hands. Why do we hold onto images? Why do we let them go? Seeing them torn apart and remade again, defaced and reincarnated, endows them with a mystic quality. Cartagena renders their absence visible.

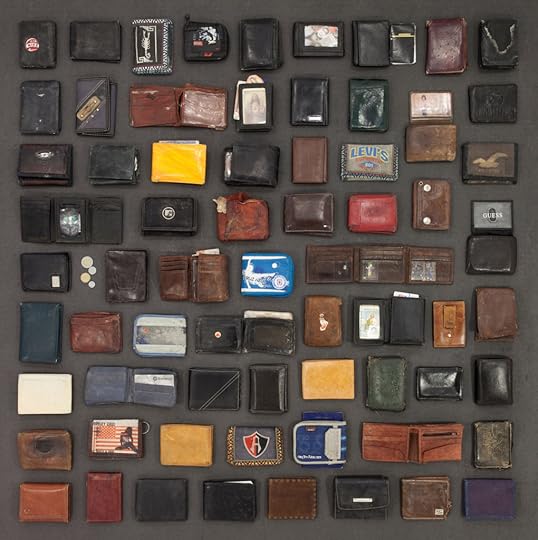

Tom Kiefer, Billfolds and Wallets, 2014