Aperture's Blog, page 66

October 14, 2020

The Photographer Using Space Travel to Theorize about Climate Change

COVID Economy. To speak of utopia at this moment is heartrending. COVID-19 has infected more than 38 million people and upended countless lives; it has also brutally exacerbated racial, gender, and economic inequalities in the U.S. and worldwide. At this time, I don’t know who is going to care for and educate my children for the foreseeable future during the hours I need to work, and my partner’s pandemic relief unemployment benefits have ended. Many find themselves jobless without options; the economic depression the U.S. is undergoing offers precious little safety net. Consequently, many are in even worse circumstances: hungry, or facing precarious health and housing situations with scant protection in the privatized, competitive neoliberal state. The rich sequester themselves in country homes while the masses are left vulnerable; individual wealth trumps universal human welfare.

Race. And yet. In mid-2020 the largest social protests in U.S. history were mobilized in the Black Lives Matter movement, making demands for racial and economic justice and the cessation of violence by police and white people against minorities.

Air. The ambivalence over whether we can safely hold large outdoor demonstrations after months of strict social distancing comes from a (still) partial understanding of the peculiar nature of the coronavirus; it doesn’t seem to present as great a threat of contagion in fresh air, particularly with the use of individual face masks. The epidemiology of COVID-19 is still maddeningly uncertain, and that the images of hazmat suit–clad health care workers in March and April morphed into pictures of rallies of bandana- and home-made mask–wearing crowds in May and June presented a whiplash turn of events.

Breath. George Floyd’s last words as he was killed by police in Minneapolis, like Eric Garner’s when he was killed by the NYPD in Staten Island, were “I can’t breathe.” And now we mask. Or not. Breathing has become politicized, with Trumpists having believed they were invincible to a “Chinese” virus that initially hit urban areas hardest and was therefore dismissed, while Black people continue to be deprived of their lives by white officers or white vigilantes.

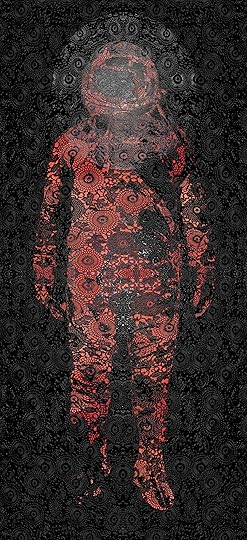

Dawn DeDeaux, Grasping Nature, 2013

Dawn DeDeaux, Grasping Nature, 2013Courtesy the artist

Outer Space. And yet. White tech billionaires continue their race to spacestead, to colonize the moon, or Mars, creating artificial ecologies that will compel the continuous techno-engineering of synthetic air. Capsule life requires some serious PPE in the inhospitable environment of outer space. Why do the privileged not protect the air on Earth, for those who currently inhabit the planet? “NewSpace” endeavors funded by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Paypal co-founder Elon Musk race to flee the planet. The so-called exit strategy of these private NewSpace exploration and colonization schemes will be limited to those who can afford a wholly simulated atmosphere shielding them from the asperity of space.

Space Clowns. From 2012 to 2016 the Louisiana-based artist Dawn DeDeaux created a series of images of astronaut-like creatures on metal panels, drawn in large part from photography sessions she conducted with first responders dressed in moderate to extreme protective equipment. DeDeaux later staged exhibitions of these digital photocollages, titled Space Clowns, in venues in New Orleans and Alabama as part of her larger MotherShip project, a work concerned with the kinship of climate change relocations and the disorientation of space travel.

Many of DeDeaux’s Space Clowns depict full-length silhouettes of figures in a kind of hybridized protective gear based on hazmat suits and diving equipment. (The original portraits were shot at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva, Florida, and the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans, where DeDeaux had art residencies.) The surfaces of the works are decorated with lace, floral, or wrought-iron patterns. According to DeDeaux, these biomorphic ornamental motifs will remind future space travelers of Earth’s lost bounty: as she writes, the explorers are adorned with “colorful curvilinear patterns belonging to our place of origin, a place called Earth. . . . It is imagined that even the most manly men now wear their flower suits like a badge of honor, a symbol of identity.” The appearances of DeDeaux’s space travelers are as important as their destinations, and, like the elaborate getups of the Sun Ra Arkestra and Parliament-Funkadelic, their costumes are a pastiche of historical references; while DeDeaux combines diving bells and radiation equipment, the Arkestra drew on the geometries of the ancient Egyptian visual canon, and Parliament-Funkadelic riffed on 1970s urban street fashion styled in futuristic metallic fabrics.

Dawn DeDeaux, Red Velvet Space Clown, 2016–17

Dawn DeDeaux, Red Velvet Space Clown, 2016–17Courtesy the artist

New Orleans. DeDeaux has discussed MotherShip as a reaction to the destruction wrought by climate change and the future potential wasteland of a human-altered ecology. Though these may seem apocalyptic musings, between the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the catastrophe of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, DeDeaux’s native Louisiana has been hammered by ecological disasters that have made parts of the Mississippi River Delta Basin uninhabitable and threaten to destroy wildlife habitats throughout the Gulf Coast. The Ebola outbreak in nearby Dallas in 2014 brought a fresh fear to the region; at the time of a residency DeDeaux conducted there, Tulane’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine was among the leading combatants against the spread of the Ebola virus.

MotherShip. DeDeaux cites the architect-engineer R. Buckminster Fuller’s warnings about population expansion and reduced resources as inspiration for the project, stating, “I was in touch with Fuller in 1981 or ’82 just prior to his death to solicit an essay from him for a book I was aiming to publish titled ‘Out There: Man’s Invasion of Space.’” DeDeaux also makes no secret of the influence of Afrofuturism on the MotherShip project—it takes its name from the P-Funk Mothership, a “funk deliverance” spacecraft used as a stage prop in Parliament-Funkadelic’s large arena shows in the 1970s. The P-Funk Mothership acted in part as a heuristic object, delivering the lessons of funk bestowed by the mother, mother Africa. The mothership metaphor in the band’s mythology is powerfully joined to that of the parliament, a legislative body of government, as forming a collective’s identity. The word parliament is derived from the French parler, “to speak.” Invoking a deliberative body of governance, a parliament in this sense takes care of the Earth in anticipation of the return of the mothership. Parliament is a collection of voices, but, in every way, it cares for the Earth understood as a singular object: we have but one Earth.

As the theorist Kodwo Eshun has explained, P-Funk’s Mothership Connection is “the link between Africa as a lost continent in the past and between Africa as an alien future.” While Ra’s call to rapture Black people to Saturn with his interplanetary Arkestra, using the metaphor of the ark fleeing Earth, contested the history of slavery and its slave ship vehicles, the metaphor of the mothership, in contrast, invokes the concept of the brood, in which the big ship transports travelers to safety upon her return. It also inverts the concept of Mother Earth to instead envision technology as feminine and maternal, comforting children upon her arrival, and nourishing them with a funky party, initially the lavish P-Funk Earth Tours of 1976 and 1977.

Dawn DeDeaux, Guardian at the Levee Gate, 2012–13

Dawn DeDeaux, Guardian at the Levee Gate, 2012–13Courtesy the artist

Mothership Earth. Metaphors are powerful, and Fuller’s use of the now famous “Spaceship Earth” formulation puts forward a vision of Earth as a technological ecology created by humans. The concept of Spaceship Earth seeks to supplant the biological codependency of humanity and nature with a vision of a human-authored, technologically administered planet that can find surrogates in or be replaced by other spaceships—Spaceship Mars or Spaceship Europa, moon of Jupiter, perhaps. To redirect us from the plurality and profligacy of the metaphor of the spaceship, I propose a new metaphor—that of Mothership Earth, combining the two singularities of the Mother and the Earth. For in P-Funk lore the mothership is a singular object; one can have but one biological mother, and there is pointedly not one mothership among many. We cannot build our mothers as we would a spaceship; rather, they make us.

Dawn DeDeaux, FALLOUT: Green First Responder in Headlights with Palms, 2013

Dawn DeDeaux, FALLOUT: Green First Responder in Headlights with Palms, 2013Courtesy the artist

Guardians. And yet. The fascination with outer space colonization, in the time of human-driven climate change, political upheaval, and a widespread health crisis, recently brought DeDeaux back to the photographic origins of Space Clowns. What initially seemed like mere source images for the baroque Space Clowns collages now appear as harbingers of a new kind of breath regulation. These first responder portraits, which DeDeaux initially shot using Rauschenberg’s own 8-by-10 camera in Captiva, she terms Guardians. The images present an eerie foreshadowing of the protections necessary to survive in the ongoing age of deadly airborne viruses. From mustard gas to nuclear radiation, from oil spills to gas leaks, from influenza (fowl or swine origin) to coronavirus (bat origin), humans have created countless situations in which air has been made toxic and unbreathable due to alterations to ecologies and encroachments on and the destruction of wildlife habitats. In Fallout (2013), one of DeDeaux’s photographs from Guardians, a man in a neon-green cloaked hazmat suit with a clear visor gazes above the viewer’s line of sight. Photographed at an extreme horizontal angle from a perspective beneath his chin, he appears reclined, and his fixed stare lends him a preternatural stillness that is almost corpse-like. Wearing a ventilator beneath his face shield, he assumes an uncanny, cyborgian quality. As he looks upward, the blur of palms and other plants around him gives the impression that he is moving in space, plunging backward in a vertiginous fall. The isolation of his stuffy, fogged-up suit keeps him from the surrounding jungle of vegetation, a habitat on Earth that humans once traversed naturally, effortlessly, without fear of whatever hazardous condition from which he is insulated. In the Guardians series, DeDeaux is reassessing the ways in which our current moment has returned to consciousness the insecurity of ever being fully protected against often invisible threats like warming oceans and disease, or of being prepared for the unpredictable effects of the depletion of life-sustaining resources on Mothership Earth. As she states, “During the [coronavirus] quarantine I have come to value equally my straightforward photography of responders. The decorative aspects of the [Space Clowns] work went extreme future tense, imagining us already exiled from the planet, when the curvilinear lines of flora and fauna superseded the straight lines of flags in terms of conveying our place of origin, Earth, as we drifted further and further away, looking for its closest replica. It is the natural world of earth and rain, the fresh water, that shaped the aesthetic of our planet and perhaps our future wardrobe signifiers. . . . [Yet] the original portrait photos offer a greater punch of evidence for our NOW. This time of alienation is REAL, and the unadorned photo seems more poignant.”

October 9, 2020

Announcing the 2020 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards welcome a new partner in DELPIRE & CO, who has joined forces with Paris Photo and Aperture to ensure the continuity of the awards in this most unusual of years. While the international photography community will not be able to gather in celebration at the Grand Palais this year, Paris Photo and Aperture are delighted to confirm that the prize continues. The exhibition of the shortlisted books will be hosted in Paris by DELPIRE & CO from November 5–28. The final jury will take place as planned, and the winner will be announced on Friday, November 13—including the announcement of the recipient of the $10,000 cash prize in the First PhotoBook category. The shortlisted books for 2020 will also be featured in Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review, co-published with DELPIRE & CO. Additional selections from this special issue of The PhotoBook Review, guest edited by Dr. Deborah Willis, will be presented alongside the exhibition of shortlisted books in Paris.

The 2020 shortlist jury took place over the course of three days at Mana Contemporary in New Jersey, and involved the review of more than seven hundred submissions. Our thanks to the shortlist jurors, including Joshua Chuang (New York Public Library), Lesley A. Martin (Aperture Foundation), Sarah Hermanson Meister (MoMA), Susan Meiselas (photographer, Magnum Foundation), and Oluremi C. Onabanjo (independent curator and historian).

“Despite the fact that the usual rhythms of book perusal and discovery have been disrupted, it’s clear that the photobook community has continued to find ways to connect, and more importantly, to keep creating,” states the jury chair, Lesley Martin. Juror Oluremi Onabanjo asserts, “In 2020, the book and catalogue in contemporary photographic practice continues to evolve and unfurl in many different directions, while offering more audiences the opportunity to get involved and fall in love with books.”

The Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards were founded in 2012 to celebrate the photobook’s contributions to the evolving narrative of photography and comprise three major categories: First PhotoBook, PhotoBook of the Year, and Photography Catalogue of the Year. Below are the 35 books selected for the 2020 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist.

First PhotoBook

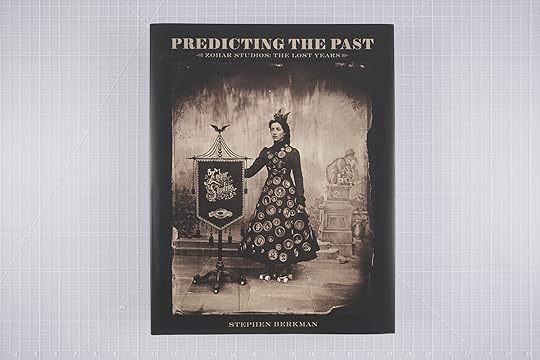

Stephen Berkman, Predicting the Past—Zohar Studios: The Lost Years, Hat & Beard Press, Los Angeles

Judith Black, Pleasant Street, STANLEY/BARKER, Shrewsbury, United Kingdom

Soumya Sankar Bose, Where the Birds Never Sing, Red Turtle Photobook (self-published), Kolkata, India

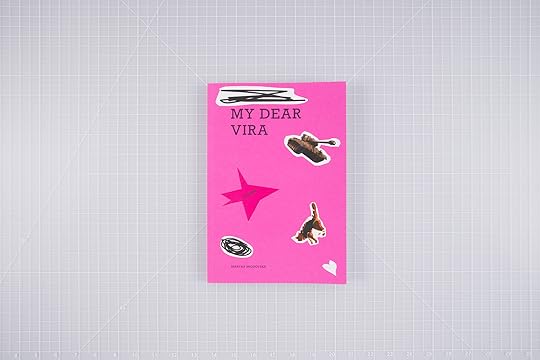

Maryna Brodovska, My Dear Vira, Self-published, Kyiv, Ukraine

June Canedo de Souza, Mara Kuya, Small Editions (self-published), Brooklyn

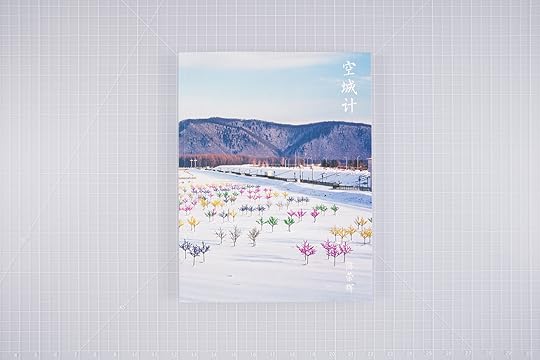

Ronghui Chen, Freezing Land, Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China

Ryan Debolski, LIKE, Gnomic Book, Brooklyn

Caroline & Cyril Desroche, Los Angeles Standards, Poursuite, Paris

Buck Ellison, Living Trust, Loose Joints Publishing, Marseille, France

Charlie Engman, MOM, Edition Patrick Frey, Zürich

Zahara Gómez Lucini, Recetario para la memoria, Self-published, Mexico City

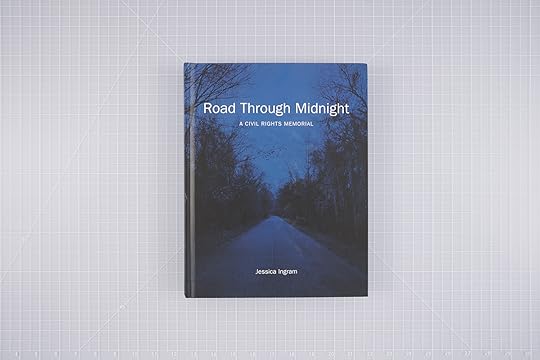

Jessica Ingram, Road through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

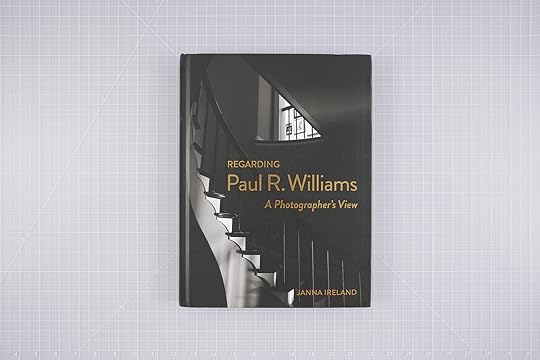

Janna Ireland, Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View, Angel City Press, Santa Monica, California

Francesca Leonardi, ’O Post Mio, Postcart Edizioni, Rome

Yael Martínez, La casa que sangra, KWY Ediciones, Lima, Peru

Sara Perovic, My Father’s Legs, J&L Books, New York

Fabio Ponzio, East of Nowhere, Thames & Hudson, London

Agnieszka Sejud, HOAX, Self-published, Wrocław, Poland

Diana Tamane, Flower Smuggler, Art Paper Editions, Ghent, Belgium

Efrem Zelony-Mindell, n e w f l e s h , Gnomic Book, Brooklyn

Previous

Next

Stephen Berkman

Predicting the Past—Zohar Studios: The Lost Years

Hat & Beard Press, Los Angeles

Judith Black

Pleasant Street

STANLEY/BARKER, Shrewsbury, United Kingdom

Soumya Sankar Bose

Where the Birds Never Sing

Red Turtle Photobook (self-published), Kolkata, India

Maryna Brodovska

My Dear Vira

Self-published, Kyiv, Ukraine

June Canedo de Souza

Mara Kuya

Small Editions (self-published), Brooklyn

Ronghui Chen

Freezing Land

Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China

Ryan Debolski

LIKE

Gnomic Book, Brooklyn

Caroline & Cyril Desroche

Los Angeles Standards

Poursuite, Paris

Buck Ellison

Living Trust

Loose Joints Publishing, Marseille, France

Charlie Engman

MOM

Edition Patrick Frey, Zürich

Zahara Gómez Lucini

Recetario para la memoria

Self-published, Mexico City

Jessica Ingram

Road through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial

University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Janna Ireland

Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View

Angel City Press, Santa Monica, California

Francesca Leonardi

’O Post Mio

Postcart Edizioni, Rome

Yael Martínez

La casa que sangra

KWY Ediciones, Lima, Peru

Sara Perovic

My Father’s Legs

J&L Books, New York

Fabio Ponzio

East of Nowhere

Thames & Hudson, London

Agnieszka Sejud

HOAX

Self-published, Wrocław, Poland

Diana Tamane

Flower Smuggler

Art Paper Editions, Ghent, Belgium

Efrem Zelony-Mindell

n e w f l e s h

Gnomic Book, Brooklyn

Photography Catalogue of the Year

Anne Turyn: Top Stories, Elena Cheprakova and Kirsten Weiss, eds., Weiss Berlin, Berlin

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other, Steven Evans, Max Fields, and Mark Sealy, eds., Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam, and FotoFest, Houston

Bill Brandt | Henry Moore, Martina Droth and Paul Messier, eds., Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

Hommage à Moï Ver, The Ghetto Lane in Wilna (Schaubücher 27): 65 Pictures by M. Vorobeichic, Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, ed., Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore, Vilnius

Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography, Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis, eds., Walther Collection, New York, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Previous

Next

Anne Turyn: Top Stories

Elena Cheprakova and Kirsten Weiss, eds.

Weiss Berlin, Berlin

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other

Steven Evans, Max Fields, and Mark Sealy, eds.

Schilt Publishing, Amsterdam, and FotoFest, Houston

Bill Brandt | Henry Moore

Martina Droth and Paul Messier, eds.

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

Hommage à Moï Ver, The Ghetto Lane in Wilna (Schaubücher 27): 65 Pictures by M. Vorobeichic

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, ed.

Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore, Vilnius

Imagining Everyday Life: Engagements with Vernacular Photography

Tina M. Campt, Marianne Hirsch, Gil Hochberg, and Brian Wallis, eds.

Walther Collection, New York, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

PhotoBook of the Year

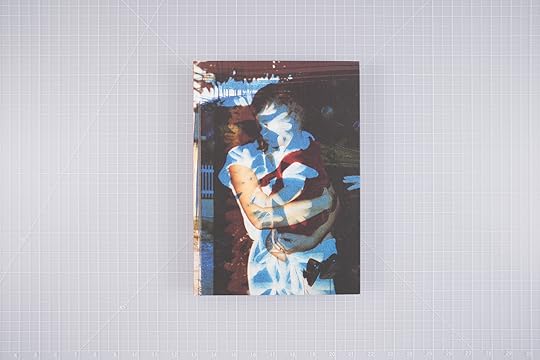

Carolyn Drake, Knit Club, TBW Books, Oakland, California

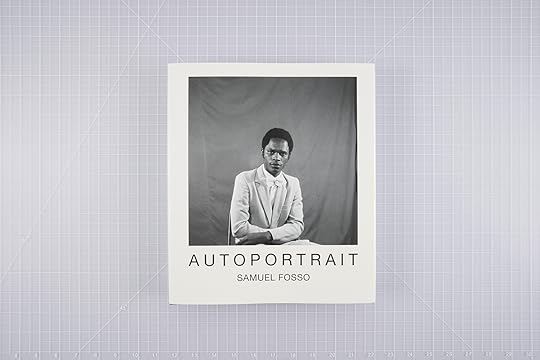

Samuel Fosso, Autoportrait, Walther Collection, New York, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

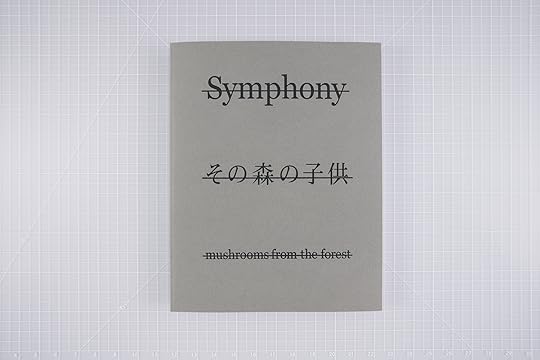

Takashi Homma, Symphony—Mushrooms from the Forest, Case Publishing, Tokyo

Thomas Kuijpers, Hoarder Order, Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Adam Lach and Dyba Lach, How to Rejuvenate an Eagle, Self-published, Warsaw

Edgar Martins, What Photography & Incarceration Have in Common with an Empty Vase, The Moth House, Bedford, United Kingdom

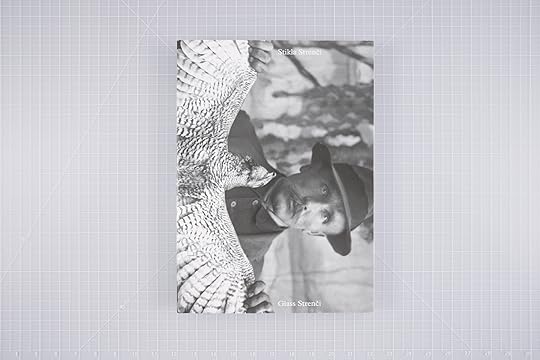

Orbita, Glass Strenči, Orbita and The Latvian Museum of Photography, Riga, Latvia

Gloria Oyarzabal, Woman Go No’Gree, Editorial RM, Barcelona, and Images Vevey, Switzerland

Luis Carlos Tovar, Jardín de mi Padre, Editorial RM, Barcelona, and Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland

Cemre Yeşil Gönenli, Hayal & Hakikat: A Handbook of Forgiveness & A Handbook of Punishment, GOST Books, London, and FiLBooks, Istanbul

Previous

Next

Carolyn Drake

Knit Club

TBW Books, Oakland, California

Samuel Fosso

Autoportrait

Walther Collection, New York, and Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Takashi Homma

Symphony—Mushrooms from the Forest

Case Publishing, Tokyo

Thomas Kuijpers

Hoarder Order

Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Adam Lach and Dyba Lach

How to Rejuvenate an Eagle

Self-published, Warsaw

Edgar Martins

What Photography & Incarceration Have in Common with an Empty Vase

The Moth House, Bedford, United Kingdom

Orbita

Glass Strenči

Orbita and The Latvian Museum of Photography, Riga, Latvia

Gloria Oyarzabal

Woman Go No’Gree

Editorial RM, Barcelona, and Images Vevey, Switzerland

Luis Carlos Tovar

Jardín de mi Padre

Editorial RM, Barcelona, and Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland

Cemre Yeşil Gönenli

Hayal & Hakikat: A Handbook of Forgiveness & A Handbook of Punishment

GOST Books, London, and FiLBooks, Istanbul

All photographs by Daniel Salemi.

Note: Given the jurors’ extensive engagement in the scholarship and production of photography books, the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBoook Awards maintain a strict policy of recusal, in which the juror in question must remove themselves from the discussion of books in which they were directly involved; those books must be unanimously voted in by the remaining jurors.

October 8, 2020

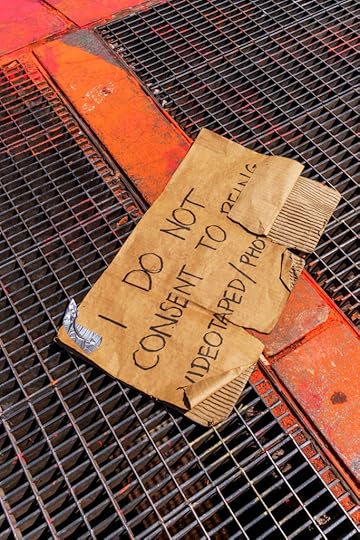

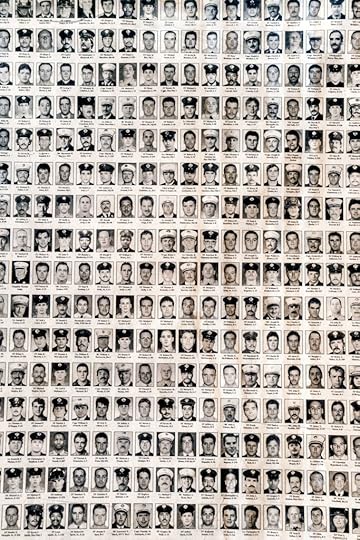

Can Photographs Provide Information When Truth Is Disrupted?

The 2020 Aperture Summer Open, Information, presents new work by fourteen photographers and lens-based artists who examine globalization, technology, and politics, and the dynamic changes to personal and social identity charted by mass media today. They consider declassified military archives and CIA conspiracy theories, stage encounters with race and memory, present evidence of incarceration and violence, and visualize the physical spaces where digital information is concealed from the public eye. While some artists interrogate the construction of images themselves, others rely on the photograph’s power to cross between dream and dystopia, fact and fable. Together, they broadcast new ways of viewing our present—and our future.

Javier Alvarez, Marco Antonio in His Room , 2016, from the series PRÉDIO

Javier Alvarez, Marco Antonio in His Room , 2016, from the series PRÉDIOJavier Alvarez is a documentary photographer who examines inequality and social justice. His project PRÉDIO (Portuguese for “building”) explores the Marconi building, a repurposed office tower in São Paulo. In the 1990s, workers and social activists broke into the building and began squatting there. In 2013, Alvarez started visiting the Marconi building regularly, living there off and on a few times per year for up to eight weeks at a time, and began compiling a series of photographs, video footage, interviews, archival material, and collages from a personal travel journal, all of which deal with themes of home and family (or lack thereof), social responsibility, and the power of visibility. Alvarez deftly adapts his work to match the improvised style of those living in the Marconi building: he layers short, emotional accounts on top of and around images; collages hand-colored pages; and tapes portraits into his small notebook. Toggling between images of entire buildings and close-cropped portraits, Alvarez portrays the Marconi building as a metaphor for the issues facing urban life and survival in contemporary Brazil. —Luke Bolster

Gus Aronson, Family Album, 2019, from the series Eurydice

Gus Aronson, Family Album, 2019, from the series EurydiceThe photographs in Gus Aronson’s series Eurydice are individual stories of engagement with obsessions and motifs found in his wanderings, yet together, they provide point and counterpoint, fact and fiction. Central to the series is an attempt to visualize the myth of Orpheus, who travels to the underworld to retrieve his wife, Eurydice, only to lose her again when, breaking the set conditions for Eurydice’s return, he turns back to see if she’s still following behind him on their way out. While the story is often interpreted as one of love and despair, Aronson prefers to center the act of looking. Photography does not have to be a record of the past but can remain in a constant present or envision a potential future. In Eurydice, pictures of hands flipping through a photo album, or of an artist painting a facsimile, break down the temporal walls that confine old theories of photographic fact. “Don’t look back,” these pictures seem to say. “Keep moving, and see what you will find.” —Eli Cohen

Widline Cadet, Kò an Kòm yon Lokal ki Baze sou Je (The Body as a Site Based on Sight), 2019, from the series Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances)

Widline Cadet, Kò an Kòm yon Lokal ki Baze sou Je (The Body as a Site Based on Sight), 2019, from the series Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances)As a Haitian-born artist now based in New York, Widline Cadet’s identity is deeply rooted in duality. At the center of this duality is the self, the subject Cadet investigates most thoroughly in her project Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances). Across her images, she considers how race, memory, migration, and specifically Haitian cultural identity function in the United States. With other women often serving as her doubles in “self-portraits”—flashes or scarves obscuring their faces—Cadet thinks of photography as “a means of disappearing into visibility,” a sentiment that arises from the fact that for immigrants, especially those who are undocumented, recognition or surveillance can be dangerous. For Cadet, a photograph can provide a form of camouflage, actively disrupting a viewer’s expectations and offering to her subjects—and herself—a sense of poetic visual presence. —Luke Bolster

Emma Cantor, Document Storage Facility, 2018, from the series The Production of Certainty

Emma Cantor, Document Storage Facility, 2018, from the series The Production of CertaintyEmma Cantor’s series The Production of Certainty investigates the material presence of information in the digital age—the flow and protection of information through data servers and fiber-optic cables, and the destruction of information in high-security facilities. “The physical presence of information is both hidden and also, with each passing year, shrinking,” she says. Storage units, the transfer of confidential documents, and a private investigator’s inventory each represent tangible forms of information otherwise invisible and transferred online, yet a blasted hard drive or an Infoshred worker vacuuming shreds of paper dramatize destruction. The facilities where Cantor photographed, what she calls “physical spaces concerned with the material reality of digital information,” are a backdrop to illustrating the spectacular erasure of information in a time when most records of our personal and professional lives would seem, paradoxically, to have a permanent digital footprint. —Zora Gandhi

Yu-Chen Chiu, America Seen: 4. Paradise Valley, Arizona, 2017, from the series America Seen

Yu-Chen Chiu, America Seen: 4. Paradise Valley, Arizona, 2017, from the series America SeenYu-Chen Chiu’s work focuses on notions of migration and belonging in the United States, her “second home,” as she puts it. In her project America Seen, Chiu brings an outsider’s perspective to the country’s tumultuous social and political moment. The project, she says, is “a visual poem about the social landscape of the United States during the Trump administration.” Rather than exacerbate the deeply personal and often volatile themes of race and patriotism, Chiu crafts subdued and contemplative images. Through the use of black and white, and somber subjects framed by buildings or train windows, Chiu creates images that border on memories or dreams, vaguely familiar, but just out of reach of comfortable nostalgia. Her work attempts to access the varied nature of America, “from the happy dreamers to the lonely wanderers.”—Luke Bolster

Ash Garwood, Folded and Faulted, 2020, from the series Common Fault

Ash Garwood, Folded and Faulted, 2020, from the series Common FaultTheory and practice intersect in Ash Garwood’s Common Fault, a series of grandiose gelatin-silver prints, where an uncanny valley of landscape photography meets digitally constructed images. The process begins in Cinema 4D, a modeling software in which Garwood pieces together photographs with generated textures to render a negative that is then developed and printed in the darkroom. Garwood does not hide the construction, deciding instead to showcase the process as a focal point in understanding the work; when the final image hangs on the wall, it performs as both photograph and digital art. Garwood’s landscapes bring together seemingly disparate ideas about queer theory, environmental studies, and quantum physics into depictions both familiar and unrecognizable: a mountain range could look like an ocean, a rocky field like the surface of the moon. In presenting digitally created works that “pass” as landscape photographs—in a confluence of the word’s meanings—Garwood reclaims the power implicit in producing landscape imagery, a field often dominated by white, male, heteronormative, settler-colonial ideas of power. Rather than evading ideals of authority and reality, her prints invite the viewer to the feeling of uncertainty. —Eli Cohen

Evan Hume, Project Oxcart (A-12), 2019, from the series Viewing Distance

Evan Hume, Project Oxcart (A-12), 2019, from the series Viewing DistanceGrowing up in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC, Evan Hume spent much of his life in close proximity to the operational center of the US government. In his work, Hume transmits a version of this early familiarity to a wider audience. Through years of research and requests through the Freedom of Information Act, Hume has amassed a collection of informational photographs from agencies such as the CIA, FBI, and NSA. Viewing Distance deals with the form of photography as much as with its content. Leaning into both deliberate redactions and unintentional distortions that occur after years of archival storage and repeated photocopying, Hume’s work evaluates the supposed authenticity of an image as well as its subject matter. Presenting what he calls “historical fragments in a state of flux,” Hume shows how incomplete, indeterminate, and fluid images can be, despite capturing a fixed moment in time. The line between past and present is often blurred—modern iPhones sitting on top of stacks of old, Polaroid-type photographs; or futuristic jets flying across black-and-white, grainy landscapes. These distortions probe the source of the image, and the time between its capture and the present. —Luke Bolster

Seunggu Kim, Globe Amaranth Festival, 2018, from the series Better Days

Seunggu Kim, Globe Amaranth Festival, 2018, from the series Better DaysBalancing natural and unnatural elements in the frame, Seunggu Kim highlights the societal ironies embedded in contemporary Korean life. In the large-scale images of his project Better Days, Kim shows people enjoying leisure activities in crowded scenes, the cityscape of Seoul looming in the background—people work so many hours and have so few vacation days that they’re unable to travel very far. “People are sincere, optimistic, and dynamic,” Kim says. Crowds enjoy their limited time off amongst one another, camp alongside each other, assist each other in taking group photos, maintain a watchful eye over children in a swimming pool. This enduring sense of community—possibly a fantasy, definitely a dream in the era of pandemic—reminds us: is there anything more important than living happily together? —Allie Monck

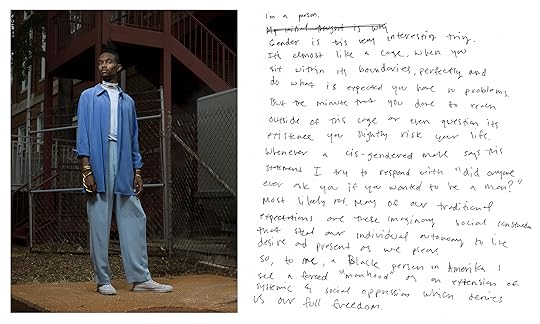

Joshua Rashaad McFadden, Avery Jackson, Morehouse College, 2017, from the series Evidence

Joshua Rashaad McFadden, Avery Jackson, Morehouse College, 2017, from the series EvidenceWho controls the conversation around Black men in the media? This question animates the artist and photojournalist Joshua Rashaad McFadden’s project Evidence, which revolves around the seven years he lived in Atlanta. His time there exposed him to the numerous and disproportionate ways violence is enacted on Black people in the US. Transcending statistics to focus on individual lives and experiences, McFadden confronts the conventional, too-often negative representations of Black men in America by including, alongside his portraits, written testimony, historical newspapers, and conversations with and texts by playwrights, actors, and historians. Evidence is a project of disruption, what McFadden calls “an archive to reframe societal views of Black masculinity and gender identity.” As an homage to Frederick Douglass’s The North Star antislavery newspaper, McFadden’s own broadsheet, Evidence, acts as both a way of transmitting information and as a pure artistic pursuit that extends beyond the museum walls. McFadden’s work is ultimately optimistic, but nuanced, as he pushes for photographs and words to recognize Black men’s lives as a “collective story you can’t ignore.” —Luke Bolster

Daniel Mebarek, Untitled, 2020, from the series La Lucha Continua (The Struggle Continues)

Daniel Mebarek, Untitled, 2020, from the series La Lucha Continua (The Struggle Continues)In October 2019, protests erupted across Bolivia after a national election resulted in claims of fraud committed by then president Evo Morales, who returned with a counterclaim calling the protests a coup. Over the next month, Morales would resign, the conservative senator Jeanine Áñez would step in as an interim leader, and a new election date would be set for 2020. In the meantime, protests turned violent. Photographs of protesters and rioters circulated worldwide as people watched the unfolding events in Bolivia. Daniel Mebarek, whose family is Bolivian and Algerian, and whose uncle and grandfather were involved in Bolivian revolutionary politics—his grandfather was killed in 1971, during Hugo Banzer Suárez’s dictatorship—converges two distinct sets of photographs in his series La Lucha Continua (The Struggle Continues). One comes from archival material—pamphlets, family photographs, and identity photographs that Mebarek collected in recent years from his family members—which he has remade as cyanotypes. He pairs these with photographs he made in January in La Paz. A direct challenge to a historically linear vision of protest and progress in Latin America, La Lucha Continua seeks to define a space between archive and news, past and present, what Mebarek refers to as “the loopholes in official memory.” —Eli Cohen

Kean O’Brien from the series Mapping a Genocide, 2015–20

Kean O’Brien from the series Mapping a Genocide, 2015–20Kean O’Brien’s interdisciplinary projects focus on masculinity, queer strategies for survival, and the construction of identity. His project Mapping a Genocide attempts to “develop a theoretical bridge between environmental and social justice” by documenting sites where transgender individuals were murdered, and noting how unexceptional many of these spaces appear. By using Google Maps to create images of intersections and neighborhoods, O’Brien co-opts a technology of surveillance in an effort to create a queer cartography of life and death. Mapping a Genocide asks viewers to imagine a world that is free of radicalized and gendered violence. Instead of prints, O’Brien presents the work as a slideshow, with images flickering in and out of presence, an evanescent quality that serves as a reminder, he says, that “trans people are verbs rather than nouns and are ever evolving and shifting. And so is the meaning of these landscape maps that we occupy and place ourselves within.” —Allie Monck

Florence Omotoyo, Choose Love, 2019, from the series Everywhere + Nowhere

Florence Omotoyo, Choose Love, 2019, from the series Everywhere + NowhereFlorence Omotoyo’s photography explores the impact of social surroundings on narratives of identity in the UK, often highlighting communal spaces and transit systems. For her series Everywhere + Nowhere, she stages photographs of seemingly mundane acts, such as commuting, gathering with one’s friends, and moments of solitude. “As much as we may present and embody a group or collective,” she says, “on a deeper level, we are ruled by a set of histories, perspectives, and tastes that can only be explored by first looking at the solo individual.” This framing of community is threaded throughout Everywhere + Nowhere, emphasizing the multitudes that exist in everyday spaces. Whether depictions of waiting for a train, joining a group of friends, or taking selfies in the bathroom, Omotoyo’s photographs consider “alternative ways to be away from the structures and systems that have continuously perpetuated the same story.” —Allie Monck

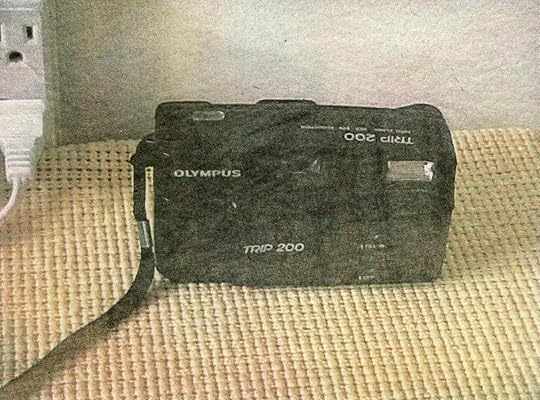

Rowan Renee, Evidence #16: Olympus Camera, 2019, from the series No Spirit For Me

Rowan Renee, Evidence #16: Olympus Camera, 2019, from the series No Spirit For MeRowan Renee is a genderqueer artist who examines the complex and restrictive relationship that law enforcement has with queer identity, addressing intergenerational trauma, gender-based violence, and the impact of the criminal justice system. Their project No Spirit For Me is a deeply personal examination of the evidence compiled by the Florida State Attorney surrounding Renee’s father’s criminal prosecution in 2008. Renee recreates the official photographs as photolithographs, adding little alteration to the cold, factual images. The transformation from digital to print mimics the transformation that these once mundane items underwent upon their father’s prosecution—VHS tapes, cameras, and computers emerge as pastel-hued ready-mades, objects of inquiry and mystery. No Spirit For Me invokes the violence inherent in the criminal justice system, pushing the limits of photography’s “burden of proof” by showing how it uses, or misuses, imagery to enforce official narratives. —Luke Bolster

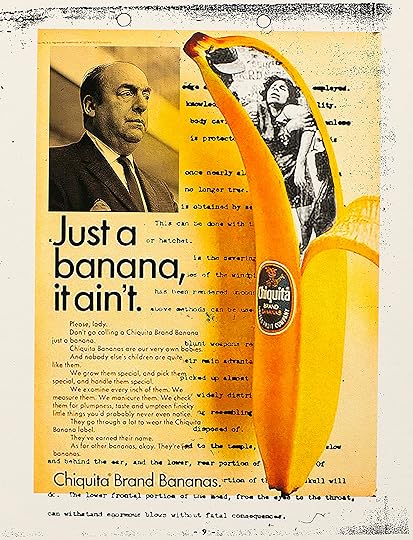

George Selley, The Simplest Local Tools. . ., 2018, from the series A Study of Assassination

George Selley, The Simplest Local Tools. . ., 2018, from the series A Study of AssassinationA Study of Assassination, declassified through the Freedom of Information Act in 1997, was a manual developed prior to the US-backed 1954 coup in Guatemala and details the CIA’s methods and standards for extrajudicial killings. The United Fruit Company, which had ties to the destabilization of multiple Latin American governments, was entangled in the violence and has settled class action lawsuits regarding its funding of paramilitary groups in Colombia as recently as 2018 under its current conglomerate, Chiquita Brands International. Alongside his photographic interpretations of A Study of Assassination, George Selley collages images of Chiquita bananas and military photographs together with pages from the manual—specifically, instructions on how to divert attention and operate covertly. He uses quotes from the manual as captions, the tense language often removing the agent from the act of killing. Selley’s reconstruction of the manual underscores the disturbing realities of American involvement in Latin America and the strategic alliance between capitalist enterprise and corrupt governance that continues to this day. —Eli Cohen

The 2020 Aperture Summer Open, Information, is curated by Brendan Embser, managing editor of Aperture magazine, with Farah Al Qasimi, artist; Amanda Hajjar, director of exhibitions at Fotografiska; Kristen Lubben, executive director of the Magnum Foundation; and Paul Moakley, editor at large for special projects at TIME. The exhibition is on view at Fotografiska New York through October 25, 2020.

Aperture’s 2020 Virtual Gala Honors Trailblazing Women in Photography

For sixty-eight years, Aperture has chronicled, reflected, and encouraged innovation in photography. Women have played a central role since Aperture began in 1952—with Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, Nancy Newhall, and Dody Weston Thompson critical to the creation of Aperture magazine—and throughout its history as a prominent thought-leader in our field. On October 20, Aperture’s first free virtual gala honors Dr. Naomi Rosenblum and Ming Smith, two legends who have played important and undersung roles in the evolution of photography.

The gala, streamed on YouTube Live, will feature entertainment and surprises by April Hunt, Kasseem “Swizz Beatz” Dean, and Cecily, alongside tributes and special guest appearances by Derrick Adams, Chris Boot, Sherry Bronfman, Darius Himes, Cathy Kaplan, Antwaun Sargent, and Deborah Willis.

Coinciding with the gala, Aperture is partnering with Christie’s for an online auction, with live bidding October 19–28 of over sixty pieces by artists such as Sharon Core, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Benjamin Sherry, Stephen Tayo and more.

Read below to learn about this year’s Aperture Gala honorees, Dr. Naomi Rosenblum and Ming Smith, and register online for free to watch the October 20, 2020 Aperture Virtual Gala: Agents of Change on YouTube.

Left to right: Naomi Rosenblum by Paul Strand; Naomi Rosenblum at ICP Infinity Lifetime Achievement Award Ceremony in 1998

Left to right: Naomi Rosenblum by Paul Strand; Naomi Rosenblum at ICP Infinity Lifetime Achievement Award Ceremony in 1998The eminent photography historian, curator, and author Dr. Naomi Rosenblum is being honored for her groundbreaking writings and teachings. These include the books A World History of Photography (1984 first edition, 2019 fifth edition), a canonical and invaluable reference for art historians; and A History of Women Photographers (1994 first edition, 2010 third edition), a definitive, eye-opening chronicle of women’s accomplishments in photography—which went on to inspire one of the first comprehensive traveling exhibitions of women’s achievements in the medium.

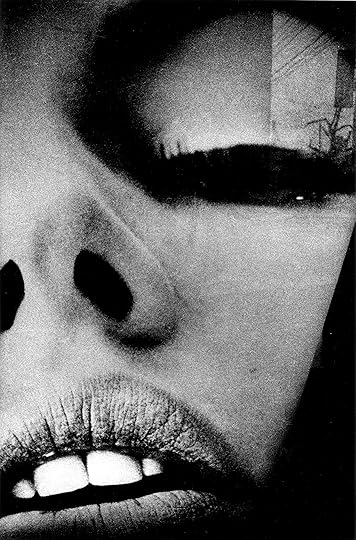

Ming Smith, Self-portrait, ca. 1988

Ming Smith, Self-portrait, ca. 1988Courtesy the artist and Aperture

Aperture honors Ming Smith for her poetic images of twentieth-century African American life on the occasion of her first monograph, Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture/Documentary Arts, 2020). Smith moved to New York in the 1970s, joining the Kamoinge Workshop and publishing her work in the Black Photographers Annual. Known for her lyrical, often experimental meditations on jazz, African American communities, and cultural icons—from Sun Ra and Alvin Ailey, to Gordon Parks and Grace Jones—Smith has established herself as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today.

The 2020 Aperture Virtual Gala: Agents of Change will take place on Tuesday, October 20 at 8:00 p.m. Eastern Time. Click here for full program details and to register to watch the virtual event for free.

October 6, 2020

How Indigenous Filmmakers Are Shaping the Future of Cinema

In the most iconic scene of Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, a 2001 film by the Inuk writer, director, and producer Zacharias Kunuk, the titular character sprints butt naked across the spring ice and toward the camera, bounding through frigid puddles and leaping between floes—his nemesis, the wicked Oki, and Oki’s two followers are in hot pursuit and out for blood.

A close-up shows Atanarjuat panting, but determined, shoulder checking Oki every few strides. The unclothed protagonist has put some distance between himself and his attackers, but as he runs away from land, the puddles become more frequent. The harsh Arctic environment appears to have set another trap. Suddenly, Atanarjuat slips and plunges headfirst into a puddle. He stops and collects himself before continuing on. But then, the ghost of the deceased camp leader, Kumaglak, appears. “This way!” he calls to Atanarjuat. “Over here!” Atanarjuat sprints toward a gap in the ice, leaps across the water, and lands on both feet. In a twist of fortune, Oki slides through a hole in the ice. His henchmen have to call off the chase to pull him from the water. “I won’t sleep till you’re dead!” cries Oki, panting. His revenge against Atanarjuat for marrying Atuat, the woman to whom Oki was promised, has been foiled. The camera cuts to Atanarjuat, still bounding across the ice, his body shrinking to a tiny speck against the Arctic sunset.

When the credits roll, a behind the-scenes clip reveals the labor that went into making this scene: a camera mounted on a sled is dragged by a crew running ahead of Natar Ungalaaq, the actor who plays Atanarjuat. In a 2017 interview for the CBC show The Filmmakers, Ungalaaq said he kept warm while shooting the scene by huddling near a stove inside a tent and making coffee between takes. “In my mind, nobody wanted to get that role—naked in front of camera,” Ungalaaq recalled.

Still from Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, 2001

Still from Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, 2001Courtesy Igloolik Isuma Productions

And that was to shoot just one scene. The entire film was produced with a budget of 1.9 million Canadian dollars. Kunuk started by gathering eight elders’ retellings of the Atanarjuat legend. Then, Kunuk and five writers synthesized these versions of the story into a script in both Inuktitut and English, consulting with Inuit elders to maintain cultural integrity. They trained Inuit locals from the Canadian territory of Nunavut in all the on-set jobs needed to make a feature film: makeup, sound, stunts, special effects. For a community with an unemployment rate around 50 percent when the film was made, Atanarjuat created economic opportunity. All the while, Kunuk endeavored to have the story pull the audience into the emotionally rich and socially complex interior of Inuit life. “The goal of Atanarjuat is to make the viewer feel inside the action, looking out, rather than outside looking in,” reads a post labeled “Filmmaking Inuit Style” on the website for Isuma, the Inuit production company that made the film. “Our objective was not to impose southern filmmaking conventions on our unique story, but to let the story shape the filmmaking process in an Inuit way.”

Based on an ancient Inuit folktale and set in the village of Igloolik, in what is now the Canadian territory of Nunavut, Atanarjuat was the first feature-length film made entirely in the Inuktitut language. It was also the first Canadian motion picture to win the Caméra d’Or at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, and it was ranked the best Canadian film of all time in a 2015 poll conducted by the Toronto International Film Festival.

I first saw Atanarjuat at the San Francisco American Indian Film Festival when I was eight years old. And I was confused for at least half the movie because I was under the impression that it was about another fast runner: the legendary Native American athlete Jim Thorpe. (I recall whispering to my mom during the ice chase, “When are they going to the Olympics?”) Though I was disappointed that Atanarjuat wasn’t a sports movie, the film left an impression on me and on many other Native people. To this day, it is still unusual to make a film where Indigenous people are in front of the camera, much less one where they’re behind it. A generation of Native filmmakers now cites Atanarjuat as a work that inspired them. Kunuk and Isuma have helped other Indigenous communities, directors, and actors tell their own stories on-screen—producing not only Indigenous narratives but also an Indigenous gaze.

Allakariallak as Nanook in Nanook of the North, 1922

Allakariallak as Nanook in Nanook of the North, 1922© Pathé Exchange Inc. and courtesy Pathé/Photofest

Despite the accolades, Kunuk’s and the Inuit’s contributions to the history and future of film remain largely unheralded. To fully appreciate the significance of Atanarjuat, you first have to understand the film it is in conversation with: Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. Released in 1922, Nanook of the North was a pathbreaking film that some consider to be the first documentary ever made. This designation, however, comes with a heavy asterisk.

Flaherty filmed Nanook of the North between 1920 and 1922. His intention was to portray Inuit culture to white audiences before what was left of traditional life was obliterated by Western modernization. The film follows a celebrated hunter, framing scenes of Inuit labor as though they were dioramas in the American Museum of Natural History. There are scenes of Nanook rowing a kayak, traversing ice floes in search of game, trapping Arctic fox, building an igloo, teaching his son to hunt with bow and arrow, eating raw seal meat, glazing the runners of his sled, harpooning a walrus, and fighting a seal, among many other events. There’s even a part early on where Nanook visits a trading post owned by a white merchant who shows the Inuit a gramophone. Nanook, apparently ignorant of the technology, attempts to bite the record, adding a moment of comic relief undoubtedly designed to make white audiences laugh at him.

Like an anthropologist, Flaherty plays the role of informant, homing in on the Inuit mode of production. But like an artist, he pauses to admire the austere beauty of the Arctic and the Inuit’s ingenuity in living amid it. Every so often, the silent film pauses to interject Flaherty’s written narration, which oscillates between these registers. In the final scenes of the film, Flaherty seems to push beyond these self-imposed limits. His camera captures Nanook savoring a bite of raw seal meat as his wife, Nyla, swaddles their child before leaning in to rub noses with the babe: an “Eskimo kiss.” “The shrill piping of the wind, the rasp and hiss of driving snow, the mournful howls of Nanook’s master dog typify the melancholy spirit of the North,” reads Flaherty’s narration as his camera captures nightfall on the windswept landscape outside Nanook’s igloo.

But here’s the thing: it’s all staged. Nanook is actually a guy named Allakariallak, a veteran hunter from the Itivimuit Inuit whom Flaherty had befriended. The seal Nanook fights on-screen is actually already dead. And by the time Flaherty arrived, many Inuit were well adapted to Western technology. Although Flaherty insisted Allakariallak and the cast wear traditional clothing, the Inuit usually wore a hybrid of Western and Inuit attire. While Flaherty’s Nanook hunted with a harpoon, Allakariallak preferred the firepower of a gun. And while Allakariallak played dumb around the gramophone on screen, in real life, he was well aware of the technology and how it worked.

Hand-colored lobby card from Nanook of the North, 1922

Hand-colored lobby card from Nanook of the North, 1922© Pathé Exchange Inc. and courtesy Pathé/Photofest

It’s tempting to call Flaherty a fraud and leave it at that. But on the set of Nanook of the North, the Inuit weren’t just paid actors; they were consultants and production staff. Nyla, Nanook’s young wife, was actually Flaherty’s common-law wife; they had a child together. In Inukjuak and Grise Fiord, in Nunavut, there is still a thriving clan of Inuit with the last name Flaherty. Jay Ruby, an anthropologist, has argued that Flaherty collaborated with the Inuit on set. “The Inuit performed for the camera, reviewed and criticized their performance and were able to offer suggestions for additional scenes in the film—a way of making films that, when tried today, is thought to be ‘innovative and original,’” writes Ruby.

Faye Ginsburg, an anthropology professor at New York University, and Fatimah Tobing Rony, a professor of media studies at the University of California, Irvine, have gone even further, claiming that the Inuit served as camera operators. The Akeley cameras Flaherty used were hefty sixty-pound, hand-cranked devices that required a fifteen-pound tripod—all of which, along with massive quantities of 35mm film, needed to be lugged across snowbanks, ice floes, and Arctic waters. And as the film critic Roger Ebert pointed out in a four-star review for the Chicago Sun-Times: “If you stage a walrus hunt, it still involves hunting a walrus, and the walrus hasn’t seen the script.”

These facts would seem to cast Nanook of the North, and perhaps even the whole early history of documentary and nonfiction film, in a different light. If the Inuit were behind the camera—and not merely prehistoric stock characters in the national imaginary—then we must consider the possibility that the prodigious body of work inspired by Nanook of the North was inspired not just by Flaherty’s artistic talents but also by those of his Inuit collaborators. Indeed, many Inuit have long been proud of the work, perhaps aware of their peoples’ contributions to it. And it is perfectly understandable that Inuit audiences would take some pride in seeing their culture—which, like many Indigenous cultures, has been battered by colonization—celebrated on-screen.

In fact, after watching and researching the film, I started to wonder if the paradigm of salvage anthropology was actually an appropriation of the deeply Indigenous desire to preserve and remember the beauty of Native life before the cataclysm of colonization. “The film excited great pride in the strength and dignity of their ancestors, and they want to share this with their elders and children,” Lyndsay Green, operations manager of the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (now called the Inuit Tapirisat Kanatami), the national governing body representing Inuit in Canada, said of Nanook of the North, which the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation screened into the 1970s. But then, we must also consider the dismissiveness with which Flaherty later addressed his Inuit actors, collaborators, and lovers. “I don’t think you can make a good film of the love affairs of the Eskimo,” he said in a 1949 interview with the BBC, “because they never show much feeling in their faces, but you can make a very good film of Eskimos spearing a walrus.”

Still from SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), 2018

Still from SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), 2018© Igloolik Isuma Productions and courtesy Niijang Xyaalas Productions

The greatest achievements in creative and intellectual pursuits often entail killing the master: to Plato’s ideals, Aristotle responded with empirics; to Richard Wright’s Native Son, James Baldwin responded with a vicious takedown of his friend and mentor’s novel, collected in Notes of a Native Son; to Jay-Z’s “Takeover,” Nas responded with “Ether.” And for Nanook of the North, there’s Kunuk’s Atanarjuat.

A close examination reveals that Kunuk co-opted many of Flaherty’s creative ticks. Atanarjuat was made with a desire to preserve Inuit culture—but Kunuk does it for an Inuit audience, while Flaherty did it for a white one. And Kunuk’s camera moves in a way curiously similar to Flaherty’s. Kunuk shoots his subjects up close, taking time to pause and let the labor and land of the Inuit unfold for the viewer—inviting the audience to move to the rhythm of Inuit life. In one of the first scenes, where the village is cursed by Tungajuaq, a shaman from the north, the polar bear necklace of the shaman is brought right up to the camera, as though the lens is the viewer’s neck. But instead of narration, Kunuk turns to shamanic fortune and fate to explain the twists and turns of his narrative. It’s not a stretch to view Tungajuaq—a strange and evil outsider—as a metaphor for European colonization.

And yet, in this narrative, Europeans are even denied the right to intrude. Kunuk reclaims many of Flaherty’s conventions—perhaps the same ones that could more accurately be attributed to his Inuit collaborators—to produce what I might describe as an Inuit gaze: a visual style and sensibility particular to his Inuk viewpoint. Like the shaman in his story, he playfully wags a finger at Flaherty at every turn. He even does the very thing Flaherty said the Inuit couldn’t do: make a movie about love. Indeed, the central drama of Atanarjuat—the thing that sets Oki at the protagonist’s throat—is the passion between Atuat and Atanarjuat. This is what makes Kunuk’s film a triumph in the fullest sense: like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Kunuk has slain a white giant, for all to see.

Still from SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), 2018

Still from SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), 2018© Igloolik Isuma Productions and courtesy Niijang Xyaalas Productions

Over the past twenty years, Kunuk and his production company, Isuma, have schooled many Indigenous filmmakers, such as the brothers Gwaai and Jaalen Edenshaw, who cowrote the 2018 film SGaawaay K’uuna (Edge of the Knife), the first movie made entirely in the Haida language. And like Kunuk and the Inuit, the Edenshaws and the Haida were drawn to film as a tool to preserve their endangered language and culture. With their cameras, this new generation of filmmakers is capturing Indigenous worlds imperiled but resilient. Like the Inuit who worked with Flaherty a century ago, these filmmakers are asking some of the biggest and most important questions: What is the responsibility of the filmmaker to his or her community? How do we tell stories about worlds collapsing under the weight of colonization, resource extraction, mass extinction, and climate change? And who has the right perspective to tell those stories? This spring’s unseasonably warm weather—the warmest on record since at least 1958—brought an early melt season to the Arctic. The location where Natar Ungalaaq once bounded across the ice as Atanarjuat will soon be unfit to film such a scene, and likely unrecognizable to Kunuk, the Inuit, and all who have come to properly appreciate their films as well as their monumental contributions to art on this shattered earth.

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “The Indigenous Gaze.”

For Alan Michelson, History Is Always Present

“My work is very much grounded in the local, in place, and place can be fraught when you’re Indigenous,” says the New York–based artist Alan Michelson.

Michelson, a Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, has, for more than thirty years, produced evocative, influential works that excavate colonial histories of invasion and eviction. After an early engagement with photography and painting, he gradually shifted to an expanded approach. Video and installation allowed him to abandon a single perspective in favor of unfixed points of view, creating dynamic spaces of visual and auditory immersion. For Alan Michelson: Wolf Nation, his solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2019, he deployed the panoramic form, which he likens to wampum belts—beaded sashes used by Native nations in diplomacy. The show parsed history with references to maps and other archival materials, and to Indigenous geography and philosophy, challenging viewers, via augmented reality, to reconsider the museum’s location, once a Lenape site where tobacco was grown for ceremonial use. For Michelson, history is always present, unfinished business demanding our attention and redress.

This spring, during the city’s shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he spoke with the curator Chrissie Iles about his artistic development, the power of contemporary Indigenous art, and the historical echoes of our public health crisis.

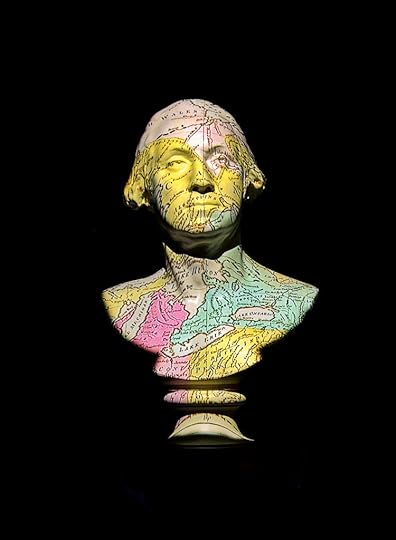

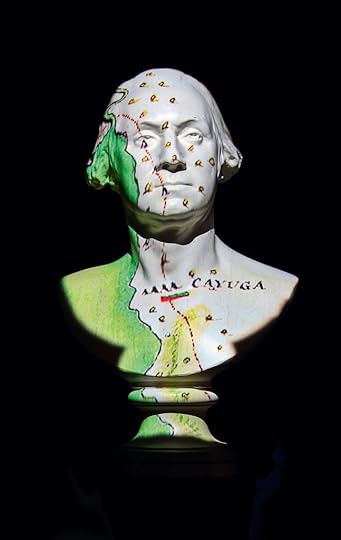

Alan Michelson, Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), 2018. HD video and bondedstone Houdon replica bust, with sound by members of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory

Alan Michelson, Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), 2018. HD video and bondedstone Houdon replica bust, with sound by members of the Six Nations of the Grand River TerritoryChrissie Iles: In all your work, whether in photography or the moving image, you subvert the camera’s history as an instrument of colonialism by transforming the colonial gaze. What is your relationship to the camera?

Alan Michelson: I got a Nikon camera in my early twenties, at that exciting time in the mid 1970s when Susan Sontag’s On Photography (1977) was current. I was always very visual, always drew and painted, and soon became absorbed in that heightened mode of seeing through a viewfinder. I was living in coastal New Hampshire and would go for long walks and take pictures.

The color in the world was really attracting my eye, moody colors and motifs with implicit references to landscape painting and abstract painting. Later, at the Boston Museum School, many of my teachers were from the generation of Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, when artists had turned away from external representation to an internal set of coordinates, where color and gesture were more important.

Iles: How did your work develop after art school?

Michelson: After art school, I gradually moved away from the vertically oriented pictorial space of painting to the receptive, horizontally oriented space that Robert Rauschenberg opened up, Leo Steinberg’s “flatbed picture plane,” where photographic imagery could become palette and two-dimensional imagery could coexist with objects. The kind of space that when applied to a room became installation. And I was fascinated by the possibilities of site specificity, because I’ve always been attracted to history as much as to form. I cycled through all of that to installation, and started really thinking about how history had treated Native people.

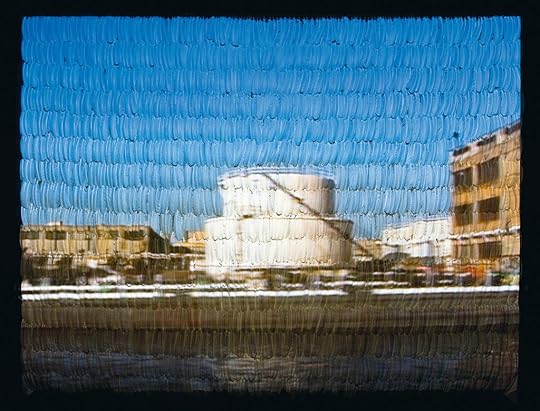

Alan Michelson, Still from Mespat, 2001. Video, turkey feathers, monofilament, and steel, with original soundtrack by Michael J. Schumacher

Alan Michelson, Still from Mespat, 2001. Video, turkey feathers, monofilament, and steel, with original soundtrack by Michael J. SchumacherIles: How did Indigenous knowledge systems, survivance, and a resurfacing of suppressed histories become the substance of your work?

Michelson: I would say that some of my recent work has its roots in my first video, Mespat, which was made in 2001. Valerie Smith invited me to participate in Crossing the Line at the Queens Museum and make work based on the borough of Queens. I was interested in looking at its shoreline from a boat, from the viewpoint of the early explorers, as well as of my ancestors, because waterways were really the highways in those days. It’s not a view that you often see. And I also wanted to reference moving panoramas of the nineteenth century, the ones that simulated marine travel.

So I mounted a camera on a boat and sailed up Newtown Creek, an industrial waterway contaminated by more than a century of oil spills, chemicals, and sewage, a Superfund site. The marine mount enabled a smooth, continuous dolly shot of more than three miles of its shoreline, including scrapyards, bridges, and refineries. I was aware of Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964), and like those films, there was a banal aspect to it. I was just observing what was there. And what was there was a stark catalog of industrial life and death, with the hopeful exception of a white egret.

Iles: You described your engagement with photography in the ’70s, at a moment when photography was an important conceptual medium, especially for Land art and Land artists. What do you think about the ways in which Land art often ignored Native American history and presence?

Michelson: Well, colonists assumed the identity of “Americans.” For Euro-Americans, that meant an entitled legacy, to imagine that the land was American land and no longer Native land with a history. The dearth of historical context in Land art seems to reflect that sense of entitlement, as does its unacknowledged but obvious debt to Native mounds and its sheer grandiosity. However, there’s also a dystopian undercurrent in Land art that can even be seen in the work of Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole. My favorite work of his is The Course of Empire series (1833–36), in which he painted an imagined landscape and charted its evolution from “The Savage State” to its own self-destruction.

Alan Michelson, Still from Mespat, 2001. Video, turkey feathers, monofilament, and steel, with original soundtrack by Michael J. Schumacher

Alan Michelson, Still from Mespat, 2001. Video, turkey feathers, monofilament, and steel, with original soundtrack by Michael J. SchumacherIles: Do you think there’s a relationship between that moment and today?

Michelson: Yes, in this current mess that we’re in with COVID-19, Cole’s allegory has never rung truer. This pandemic is coming from the cross-species migration of a viral infection from animals to humans. Eurasian farming resulted in humans living intimately with animals for thousands of years, during which time those large mammals had viral infections that they passed to human beings, the source of epidemics to which European and Asian people eventually built up immunity.

But conditions here on Turtle Island, our name for North America, were very diff erent, and there were really no domesticated mammals here besides the dog. So, our people had no immunity. To them, the diseases that came over with the colonizers—smallpox, measles, the flu—were deadly, novel viruses. The entire world is now experiencing what our ancestors experienced when European colonizers invaded.

Iles: How does this manifest in Mespat?

Michelson: I was interested in the way that the colonial gaze became an American gaze that didn’t acknowledge itself as colonial; it conceived of itself as entitled. And that colonial sense of entitlement is present not only in landscape painting but in off shoots like panoramas, which offered virtual means of touring “exotic” places minus the expense or risk. Mespat is a counterpanorama, in video pixels and feathers instead of paint, of colonial displacement and destruction.

Iles: Clémence White points out in her essay “Alan Michelson: Site Readings” for the 2019 Whitney exhibition Alan Michelson: Wolf Nation that the horizontality in your work “centers Haudenosaunee culture through its relationship to the wampum belt,” and “Haudenosaunee theology, which proposes that the ‘interconnectedness of all life is sacred and key to human freedom and survival.’” Panoramic photography was very popular in the nineteenth century as part of opening up the world and, at its root, is colonial. You use this perspective as a form of resistance by applying it back to a kind of ethical and social interconnectedness of Native American philosophy and spirituality.

Michelson: Extreme horizontality, extension in space, is always extension in time. Viewing panoramic work entails movement and perspectival shifts, the experience of multiple vantage points rather than a single fixed one, which is consonant with the egalitarianism of Native communities. Also, immersive work becomes interactive, a dynamic environment that activates a dialogue, or a set of relations, reflective of our relational epistemology. My appropriation of colonial formats is informed by those ethics. What do they call it when people restage Civil War battles?

Iles: Reenactments.

Michelson: Yes! Then you could say that my sailing up Newtown Creek, retracing the route taken by the first colonists of what became Queens, was a reenactment. If you can keep 1641 [the year before the colonists displaced the Mespeatches] in mind in 2001, it sets up a dialectic between what you see in 2001 and what was there in 1641.

I’ve also been fascinated with wampum belts, a powerful Haudenosaunee and Eastern Woodlands cultural institution, belts made up of hundreds of shell beads, purple and white, that were used to seal agreements. They were documents, codes, even, but they also embodied the natural world because they were made of the shells of animals. They were also collective works, originating in shellfish gathered by the people as food, recycled as beads, and then woven into patterns that carried messages. I based a four-channel video piece, TwoRow II (2005), on a key wampum belt, the Kaswentha, also known as the Two-Row Wampum. In 1613, we made a trading agreement with the Dutch symbolized in the belt by two rows of purple beads separated by three rows of white. The purple rows represented the parallel courses of two vessels on a river, our canoe and their sailing ship, and the white rows peace, friendship, and mutual respect. In my piece, filmed from a tour boat on the Grand River at Six Nations Reserve, there are two rows of panoramic video moving in opposite directions, one of the non Native townships on the east bank and the other of the reserve on the west, with a soundtrack featuring conflicting narratives about the river—that of a Canadian tour-boat captain and those of Six Nations elders.

Alan Michelson, Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), 2018. HD video and bondedstone Houdon replica bust, with sound by members of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory

Alan Michelson, Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), 2018. HD video and bondedstone Houdon replica bust, with sound by members of the Six Nations of the Grand River TerritoryIles: For your works Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) (2018) and Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World) (2019), which Zuecca Projects showed in Venice last year, you combine the photographic image with maps, drawings, and sound in a form of collage that operates as a resistance to surveillance and a single viewpoint. How do you use the photographic image and the archive to resurface memory and history?

Michelson: Photographic imagery and its documentary aspect are important in my work, both in its moving and still form. I like to use the archive against itself, to challenge the colonial narratives it usually serves. Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) is a projection onto an iconic bust of George Washington by the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. In 2018, the approaching 240th anniversary of Washington’s 1779 destruction of Iroquoia—our extensive homelands in what is now New York State—prompted me to get a life-size replica bust and project archival imagery onto it to tell the story of invasion and forced eviction. The imagery includes historical maps and New York State historic markers, which seem to celebrate genocide, commemorating, for example, “Site of Catherine’s Town, destroyed 1779 by General Sullivan.” My video pans over the map of the campaign, pausing at the places where Washington’s armies destroyed Iroquois villages, all of it playing out over his face. One of my goals is to defeat American amnesia and denial.

Iles: You use three-dimensional surface and form to deepen and trouble the storytelling of the projected image. How did this work in your Venice piece Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World)?

Michelson: Well, the exhibition was about Venice’s role in the early exploration of the Americas.

I had the idea of projecting archival material onto a globe, because that’s essentially what European exploration was—global projections of European power and avidity.

Then I had the idea of doing four of them, referencing the Four Directions and a chart from Andreas Cellarius’s 1660 celestial atlas, Scenographia Systematis Copernicani, depicting four hemispheric globes illuminated by a central sun. I thought, Well, I could do something like that by projecting video onto four spheres.

The first surface I projected onto, in Mespat, was the shallow convex surface of white turkey feathers. The second was the more complex dimensionality and iconography of the bust of Washington. The third was an ideal form, the sphere, but also the form of the world. I’m getting more grandiose as I progress.

Alan Michelson, Still from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), 2019. Four-channel video installation with marine buoys

Alan Michelson, Still from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), 2019. Four-channel video installation with marine buoysIles: This progression is creating what could be described as an Indigenous cinematic. You are rewriting the parameters of the Western history of cinema—a single rectangular screen with a fixed frontal viewpoint and fixed seating—by inscribing Indigenous value systems of horizontal power, shared space, and cyclical time into the projective space. Your use of diff erent material forms as projective surfaces also reframes the cinematographic as something that’s not defined by the West or by American and European—

Michelson: Rectilinearity.

Iles: Yes.

Michelson: Western architecture’s basic program. And of the grid system settlers applied to land, the checkerboards visible from airplanes.

Iles: Last October, during your exhibition at the Whitney, we organized a panel on contemporary Indigenous art in a global context, in which we considered Indigenous communities as the first global communities and discussed their relationships to one another.

Michelson: Both of my fellow speakers at that panel, the Australian Aboriginal artist Richard Bell and the Anishinaabe curator Wanda Nanibush, had previously participated in a 2017 initiative called “Indigenous New York” that I founded and curated with the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, which opened up space for contemporary Indigenous art in New York. The vitality of global Indigenous art was not registering on New York’s radar, and we were trying to save New York from self-fossilizing! Certainly in other places, including Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, Indigenous art was more visible. We hosted some seminal discussions between Indigenous curators, critics, and artists, and their non- Indigenous counterparts. Contemporary Indigenous art is on the rise these days. It has the power not only of aesthetic beauty but of ethics and calling for justice, which are also beautiful.

Alan Michelson, Stills from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), 2019. Four-channel video installation with marine buoys

Alan Michelson, Stills from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World), 2019. Four-channel video installation with marine buoysIles: Those discussions underline the powerful role photography and the moving image can play as forms of witnessing. The use of the camera as a witness obliges you to think about who is behind the camera, and how that operates in an environment in which democratic image making and the circulation of images through social media challenge official versions of whatever the truth might be. The vertical perspective of drones, which takes the camera away from the eye and the body, into a disembodied space of surveillance—

Michelson: Which can also be a military space.

Iles: Exactly. It seems that the ethics of the photographic or cinematographic image are even more compelling than ever.

Do you think the current COVID-19 crisis will change us all forever and the world forever? How do you see it affecting your work and your thinking?

Michelson: I think this crisis is brushing back a lot of the sense of entitlement that people have, maybe making them think more about the planet and our interconnectedness. It’s laying bare gross folly and injustice. I’m agitated by the fact that another raging pandemic is devastating Native people, descendants of the victims of so many previous epidemics of deadly diseases brought to Turtle Island, and that once again the federal government is not delivering on its treaty obligations.

Iles: That shared space can be both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, which seems even more important in relation to what you posted about Indigenous communities not being recognized in government statistics about COVID-19.

Michelson: Yes, even in New York, a liberal city with the highest population of Native people in the country. Right now, in May, the infection rate of the Navajo Nation has surpassed that of New York and New Jersey. Due to the ongoing effects of colonization, Native people are a hugely high-risk group, and they’re not getting direly needed supplies in Indian country.

Alan Michelson, Still from Wolf Nation, 2018. HD video, with sound by Laura Ortman

Iles: Which means that the communities are effectively absent, and therefore don’t exist, and cannot get the support they need to fight the virus. The pandemic is exposing, in stark terms, the economic and political realities of inequity.

Michelson: I’m amazed, Chrissie, how the nineteenth-century trope of the “vanishing Indian” persists, and how government policy continues to reflect that.

Iles: Yes.

Michelson: In times of crisis like this, will doors that have been recently opening close again, and will there just be a reassertion of privilege by those who are most privileged? That can happen on so many levels beyond the art world.

Iles: Yes. This situation is a dress rehearsal for what’s coming in terms of climate change.

Michelson: The signature work in my Wolf Nation exhibition was my 2018 video of that title, which I made for the Indicators: Artists on Climate Change exhibition at Storm King Art Center. People wonder about when and how wolves became dogs. I was thinking about the wolves of Turtle Island, and how we have wolf clans and a profound sense of kinship with animals. Through the cooperative model of the wolf pack, wolves may have taught human beings how to hunt, which is a huge thing, if you think about it. And yet, wolves, like Native people, were themselves hunted and removed. As is clear from converging crises, we urgently need to confront our tortured history and our disastrous leadership, and rethink our current political, economic, social, and environmental models. Indigenous models, including those of survivance, active presence, and resistance, provide an alternative.

Iles: Absolutely. Your work embeds a new social ethics of survivance in the screen, the camera, and the projective space. The old social, political, and cultural models don’t work and are disintegrating. We are entering a new reality, and culture is changing fast. Your work is a map that can help us navigate a different kind of future.

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “History is Present.”

All works courtesy the artist.

September 29, 2020

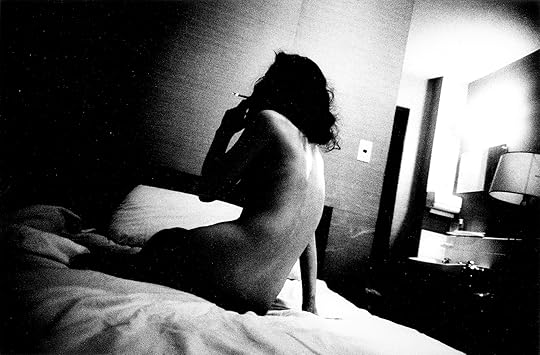

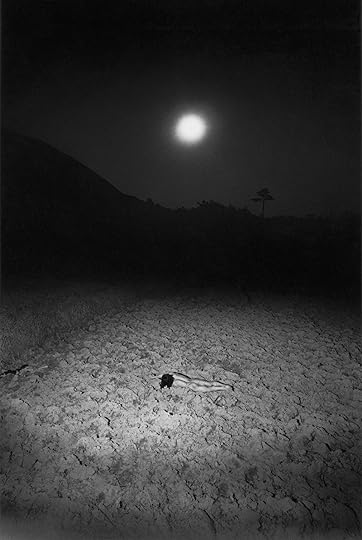

Daido Moriyama on the Unending Newness of Photographs

Japanese photographer Daido Moriyama has been at the forefront of the medium for more than fifty years, first rising to prominence through his contributions to Provoke—a magazine founded by art critic Koji Taki, photographers Takuma Nakahira and Yutaka Takanshi, and poet Takahiko Okada, which published from 1968–69 and fundamentally reshaped postwar Japanese photography. Moriyama has since become one of the world’s most recognized photographers, inspiring generations of image-makers.