Aperture's Blog, page 69

July 17, 2020

Remembering Paul Fusco’s Legendary RFK Funeral Train

Fusco’s photographs remain an incomparable document of gestures of public grief, capturing a moment of cultural shift unlike almost any other.

By Vicki Goldberg

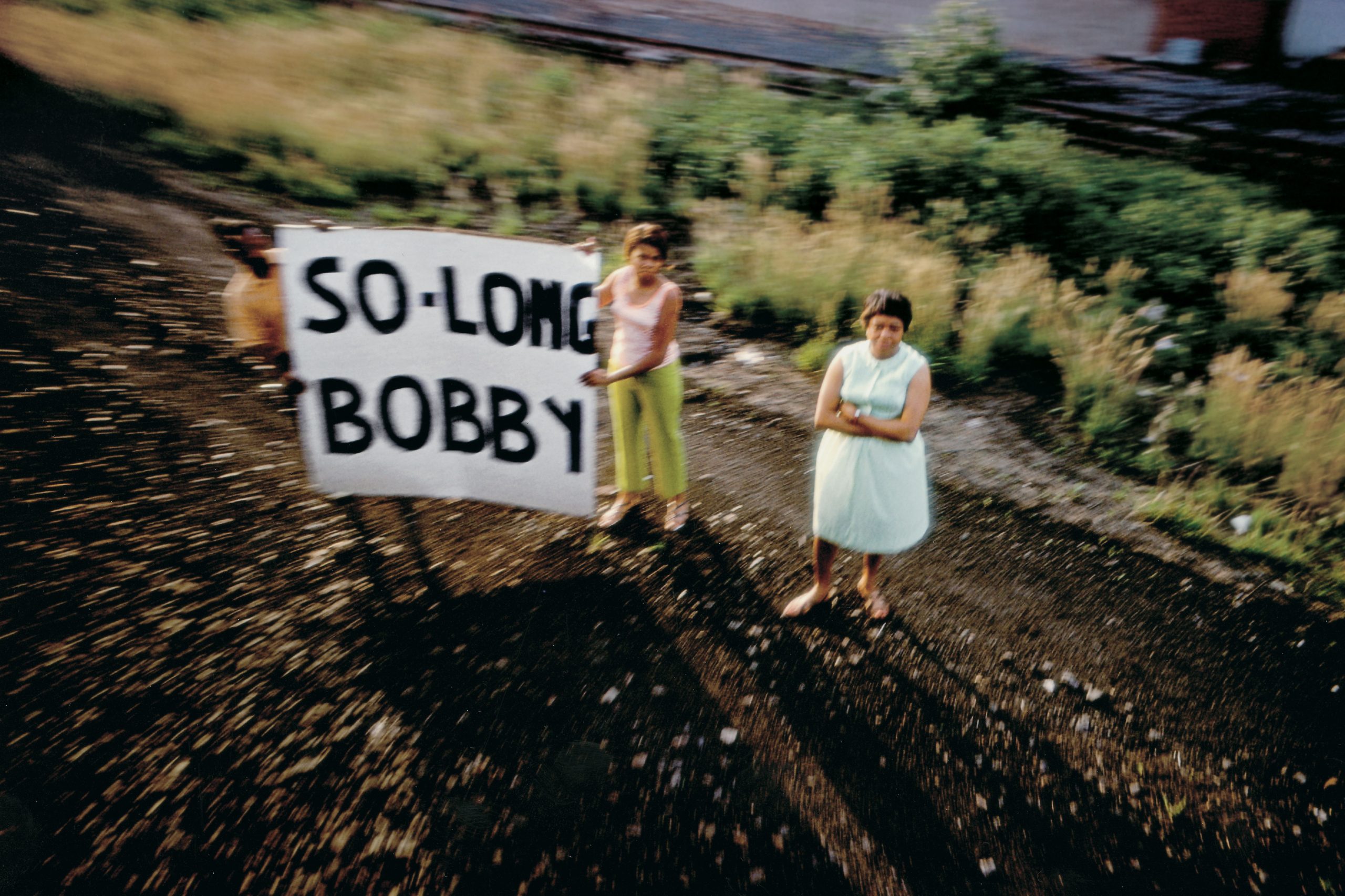

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

On June 5, 1968, New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated while campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president. His death, which occurred only two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., came as a terrible shock to the already grieving nation.

Three days later, a funeral train carried his coffin from New York to its final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery. Hundreds of thousands of people stood patiently in the searing heat as the train traveled slowly en route to Washington, DC. Paul Fusco, then a staff photographer for LOOK magazine, accompanied the train on its journey. The images he made reveal the respect that the American people—both rich and poor, Black and white—held for RFK, a man who had come to symbolize social justice and hope for a better tomorrow.

Fusco went on to become a member of Magnum Photos in 1974 and held a career that spanned from documenting Cesar Chavez to life in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, remaining committed to the principles of civil rights and a more equitable, just society as espoused by RFK and MLK.

Yet for many, Fusco’s RFK Funeral Train remains a touchstone body of work. An incomparable document of gestures of public grief, Fusco’s incredible collection of photographs captures a moment of cultural shift unlike almost any other.

On the occasion of the artist’s passing at the age of ninety, we revisit an essay by Vicki Goldberg from the monograph Paul Fusco: RFK (Aperture, 2008). —The Editors

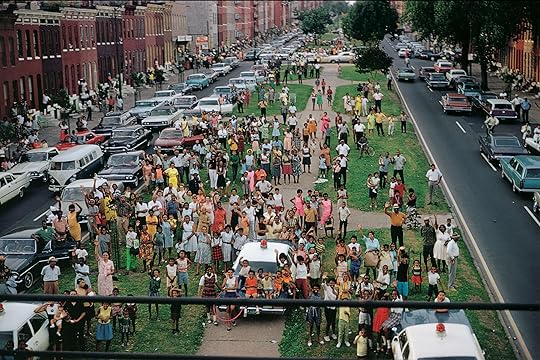

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

Late on June 4, 1968, after winning the California primary, RFK delivered a victory speech in the Ambassador Hotel ballroom in Los Angeles. Shortly after midnight, he left through a service area, and as he stopped to shake hands with supporters and the kitchen staff, an unemployed drifter named Sirhan Sirhan shot him three times at close range. Kennedy’s last words as he lay mortally wounded were “Is everybody all right?”

He died not long after. The body was flown to New York, where the casket remained in St. Patrick’s for two nights and a day. The line of people waiting outside the cathedral to pay their respects stretched for twenty-five blocks in wilting heat. After the funeral on June 8, a train carried Bobby’s coffin to Washington. Paul Fusco, then a photographer for LOOK magazine and now a Magnum photographer, photographed the mourners outside and inside the cathedral, rode that train, and photographed the grieving crowds—some estimates say as many as a million people lined the route—who stood for hours to pay their last respects to a man who had reached the hearts of a vast public as few politicians had before and none so widely since.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

The journey through this book, which now includes St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Arlington National Cemetery, is accompanied by more echoes and meanings than most photographs can support. The most obvious one is the enormous loss of a man of intelligence and compassion who had the power to inspire others—a man who might have been president. (Much has been written about how this country might have been different had RFK lived.) The horror of a second young Kennedy cut down by gunfire ran through the event, a sense that the curse of the House of Atreus had been revived in America. Martin Luther King Jr. had been murdered a mere sixty-three days earlier; the accumulated assassinations of three outstanding leaders had plunged the nation’s mind yet again into the morbid record of the country’s violent history. Bobby’s death created one more nationwide display of fierce tragedy and bloodshed to add to the copious stream of such news. Less than a year later, President Richard Nixon organized an attack on the media and the news itself, that bearer of bad tidings—an attack that hit a responsive chord in the populace and still resonates today.

In Fusco’s photographs, sorrow broods over St. Patrick’s Cathedral as people soberly and patiently wait in aisles marked out by police tape. Some women cannot keep themselves from crying. Then there are the people along the way, so representative of the citizenry, so intent on honoring the dead in the traditional way by coming into his presence to pay respects, and so silently. Their numbers and races, their assorted classes and unanimous allegiance to the ritual remind us that we are one nation and that we share a sense that we must personally honor those we cared about with our presence. Some women came in curlers, some in hats and heels, nuns in their habits. Men wore shorts, T-shirts, undershirts, or ties. A few even wore suits. Uniformed men stood in line and presented rifles or saluted smartly. Some men in casual clothes saluted too, and some women placed a hand over the heart as if pledging allegiance. Young boys came bare-chested; girls wore bathing suits, shorts, or school uniforms. Women carried babies. Many people raised an arm with the palm toward the train, a combined greeting and civilian salute. One woman knelt on the ground to pray.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

They gathered anywhere they could get a view of the train: station platforms, tracks, back steps of tenements, rooftops, bridges, baseball fields, small boats in the sea, cemeteries. They peered from passing trains. They stood atop cars, atop boats hitched to cars, on the back of pickup trucks, on fence posts. They stood on distant ridges or clambered to the roof of a parked train car, where the sunlight ate away at heads and bodies until they looked like sculptures by Giacometti. Most touching of all were single figures, one holding a baby, standing alone in a wide green field to watch. Some held up flags, or pictures of Bobby, or signs that said “God Bless the Kennedys,” “God Bless Bobby,” “We Will Miss You,” “Who Will Be the Next One?” “Pray For Us Bobby,” and “We Have Lost Our Last Hope.”

Fusco’s simple, direct, snapshot-like pictures make the book all the more heartrending and all the more convincing: this is the way it was, a tale too powerful to need embellishment or flourish. The immediacy and casualness, the blur of some figures and the indistinctness of others in the distance or darkness presage the ever rougher, caught-on-the-fly images to which we are rapidly becoming accustomed now that cameras in ubiquitous cell phones report news events.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

Ineluctably tied to the progress of time, the images of the train’s passage coalesce into a literally moving hybrid that lies halfway between still and motion pictures. The journey rolls along the tracks as the reader turns the pages, almost as if it were recorded in frames cut from a video and pasted into an album. Trains changed the visual experience of travel long ago, abruptly snatching away the passing scene, glimpses of people and places sliding past the window so quickly they are either tantalizing or forgettable, at least until the train pulls into a station. The RFK train moved slowly; it took eight hours rather than the usual four to go from New York to Washington, partly because two people had been killed on the tracks in New Jersey when they failed to notice that an express train was coming around a curve in the opposite direction. The funeral train moved on, and a number of Fusco’s pictures are so blurred that the sense of motion stays at the forefront of consciousness.

Because the train took so long, the interment took place at night; what was a metaphorical time of darkness merged with reality, groups of mourners dressed in black—the family, President Lyndon B. and Mrs. Johnson—moving through the darkness to the grave.

Numerous bystanders along the railroad route had brought their own cameras to record the train; at least once, a man turned his camera on the people lined up beside him. Cameras were, of course, the way to memorialize and keep the event, but as Fusco’s camera watches the people watching, there runs beneath the grief and ritual farewell a quiet reminder of those intertwined phenomena of spectator culture and image culture.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

Kennedy’s killing itself was not televised, but the subsequent events associated with his funeral and interment were. The mind, however, can only preserve bits and pieces and impressions from television, an essentially disposable medium. No one who watched the televised days of President John F. Kennedy’s funeral will ever forget it, yet the singular images—the dignified widow, the little boy saluting his father, Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald—have been most indelibly imprinted on memory by still photographs, which also create memories for those too young to have been there. Fusco’s photographs bring us back to a tragedy that left many thousands as stricken as if a parent had been murdered. His images put us next to the mourner and the mourning and quietly detail how people deep in shock and sorrow took refuge in the rituals that have been devised to reassert community and continuity after a leader’s death.

In the Renaissance and after, a king’s (and often a noble’s) death was memorialized with great pomp: an elaborate procession with ornate decorations and the participation of great numbers of soldiers and courtiers, panoply that could only be observed by an audience on the scene, and later at one remove in engravings. Such funerals followed conventional and prescribed rituals that emphasized not merely the greatness of the dead but also the permanence of leadership: it was loudly proclaimed that “the king is dead, long live the king.”

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

This impulse continues, though the trappings have changed somewhat over time (and in democracies). The coffins of leaders and celebrities, lying in state or simply in a church or a funeral home, are the focus of communal grief and the need to honor someone great and beloved. (When Rudolph Valentino died in 1926, more than one hundred thousand fans filed past his coffin in the funeral home.) The invention of the railroad made such attendance possible across great distances: Lincoln’s funeral train, which took him from Washington to Springfield, Illinois, 103 years before RFK’s body made its briefer journey, attracted crowds at every stop. (When Bobby Kennedy’s train arrived in Baltimore, the waiting throng joined hands and sang “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” just as the waiting mourners had for Lincoln.) President William McKinley’s funeral train drew crowds, too, after he was assassinated in 1901 and his body taken home to Ohio; so did the train that took Franklin Roosevelt home to New York after he died of natural causes in 1945.

Photography, like the railroad, extended the reach of funeral observances. Television took this around the globe; millions in twenty-three countries watched President Kennedy’s funeral when international broadcasts were only a few years old. In America, that weekend-long ceremony was watched by at least 166 million citizens. People who lived on opposite coasts were seeing and thus, in a way, present at the funeral at the same time, apart but together, sharing feelings of shock and grief in an electronic unification of the country.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

Martin Luther King Jr.’s death and funeral were similarly widely televised, but for many whites, the riots and fires that broke out almost immediately in Black communities stirred such fear that they took up a comparable, perhaps a greater, place in memory than the obsequies. Bobby Kennedy’s funeral was also fully covered by the media. Once again, the still images are more accessible and more likely to imprint on the mind than those in the transient flow of television, certainly on the minds of those too young to have witnessed the coverage. The impact was not quite like the impact of his brother’s funeral. A fallen president has an immediate successor, so the nation goes on; a fallen presidential candidate does not—another candidate steps in, but this fact means little to the continuity of anything but a campaign. If JFK’s death and funeral united the country even momentarily (at least before the conspiracy theories got loose), MLK’s and RFK’s assassinations ruptured the national fabric.

An idea of America seemed to die with them. Though many new liberties, rights, and valuable social changes came out of the tumult of the sixties, those years were marked by protest and horror. The Vietnam War underlay it all. There were massive protest marches in the streets, and citizens were gassed by the police and jailed. The war’s wounded had begun to turn up in American hospitals and on some streets, making visible the mounting statistics of the dead and injured. At the end of January 1968, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet invasion, entering Saigon, the supposedly secure capital of South Korea, and even occupying the American embassy there for a short while. Just months before, the administration and the military had repeatedly told Americans that we were winning the war. The Tet Offensive was a double blow: we were not only losing but had also been lied to by the people we ought to trust most. Opinion swung to the side of the antiwar movement and against President Johnson.

Paul Fusco, Untitled, from the series RFK Funeral Train, 1968

While the war raged, other national disasters played out on American streets. Civil rights volunteers in the South were brutally murdered; the National Guard kept Black students from entering schools in several states and eventually were required to protect those doing so; dogs and fire hoses were turned on Black adults and children; riots broke out in cities in the North; a president was assassinated; and an apostle of nonviolence was murdered, unleashing the fury of African Americans who saw nothing but oppression and death in their future. For millions, Bobby Kennedy’s murder was, in effect, the final blow; few could believe any more that ideals could be turned into reality. Some say it spelled the end of liberalism as a potent force. Jack Newfield, who knew RFK well, later wrote about his anguish at the funeral:

Now I realized what makes our generation unique, what defines us apart from those who came before the hopeful winter of 1961, and those who came after the murderous spring of 1968. We are the first generation that learned from experience, in our innocent twenties, that things were not really getting better, that we shall not overcome. We felt, by the time we reached thirty, that we had already glimpsed the most compassionate leaders our nation could produce, and they had all been assassinated. And from this time forward, things would get worse: our best political leaders were part of memory now, not hope.

Newfield thought the disillusion was thorough and lasting, noting that fewer and fewer Americans have voted in presidential elections since 1968.

The murder of Bobby Kennedy killed more than the man alone; it extinguished a spark, a promise, and a sense of hope that America has been struggling to recover ever since. Forty years later, the manifold echoes of that assassination seem to sound through Fusco’s photographs, which once were news—and stirring evidence of an incalculable sorrow.

This essay was first published in Paul Fusco: RFK (Aperture, 2008). All images courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos.

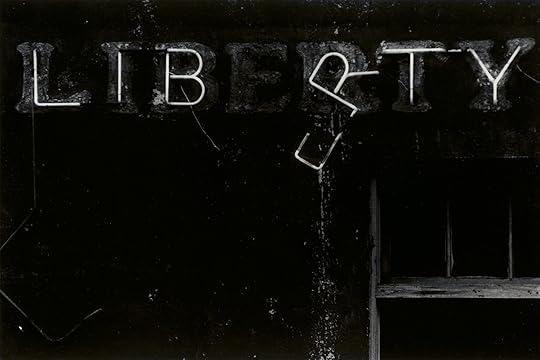

July 16, 2020

Joel Meyerowitz Tells the Story Behind Three Photographs from His Archive

An early advocate of color photography, Joel Meyerowitz has impacted and influenced generations of artists. For fifty-eight years, the master photographer has documented the US’s ever-changing social landscape. Now, Aperture and Meyerowitz launch a special ten-day print sale, featuring three 5-by-7-inch prints signed by the artist.

This also marks the launch of a new undertaking by Meyerowitz and his studio to scan his archive of over 140,000 previously unseen Kodachrome slides. At the age of eighty-two, Meyerowitz feels the necessity of bringing his nearly six decades of work into a searchable and comprehensive archive and study center.

“In the early years of the ’60s and ’70s, photography wasn’t taken as seriously as it is now, nor were there many places showing photographs,” Meyerowitz explains. “So, there were lots of images that went into the files after a first look and remained there, waiting to see daylight someday. That time is here, and at my age, I want to act on scanning all this work while I can still feel the excitement.”

Proceeds from the print sale not only help support Aperture and fund Meyerowitz’s archiving project, but a portion will also be donated to the Equal Justice Initiative.

“Aperture and I have a long and supportive relationship, and any way I can help further their not-for-profit programs is a step toward keeping the medium, and Aperture’s efforts, alive,” Meyerowitz says. “At the same time, the Equal Justice Initiative needs our support to do their work, which is absolutely necessary if we want to evolve as a just society.”

Below are insights from Meyerowitz on his three selected prints, available exclusively through Aperture through July 26.

Madison Avenue, New York, 1974

The corner, back in the ’70s, was where I most often liked to work because of the chaotic mix that traversed it. There was always such good nonstop energy up and down the avenue, while the cross streets poured their abundance continuously across the frame. So when a sudden gust of hot, New York summer air made the woman clamp her hat to her head she became, in that split second, like a ship’s figurehead to me, and I reacted immediately.

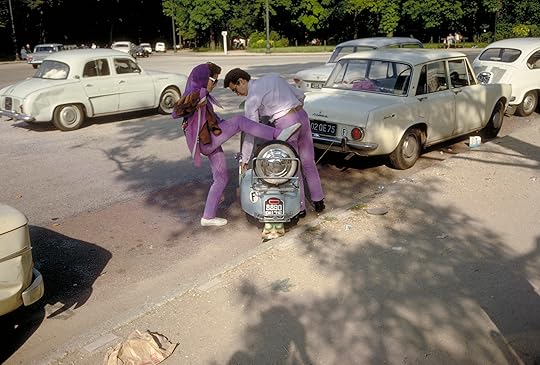

Paris, France, 1967

I remember being in Paris for the first time in 1966—67, and for the six weeks that I was there, I often saw this purple couple scooting around the city, always dressed in some version of this color. But then, to be walking through the Bois de Boulogne and to see them there mounting their scooter, while their color appeared both in the car window and under their feet, was a kind of eye candy I couldn’t resist. Not to mention that all the cars played a perfect background color for me.

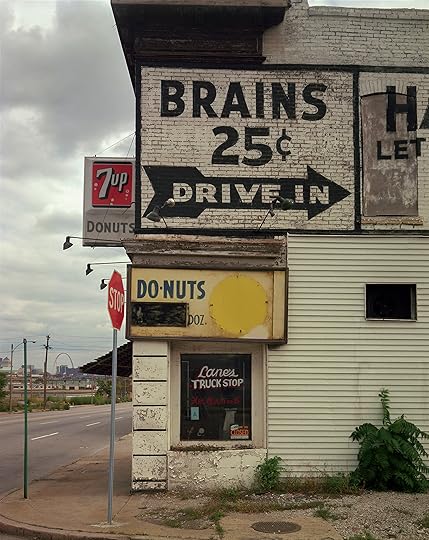

St. Louis, Missouri, 1978

How could I pass this up? It’s many things all at once: a great collection of signage and graphics probably from before the Great Depression; the visual joke of BRAINS 25¢ and the idea of driving in to get some, which still pleases me; and then there is the aching, bittersweet loneliness of finding myself at the edges of a failing middle American city and discovering this kind of original beauty.

For ten days only, collect three signed 5-by-7-inch prints by Joel Meyerowitz for just $120.20 each during our special print sale. Proceeds support Aperture and Meyerowitz’s archive project, with an additional percentage of sales being donated to Equal Justice Initiative. Sale ends Saturday, July 26 at midnight EDT.

July 14, 2020

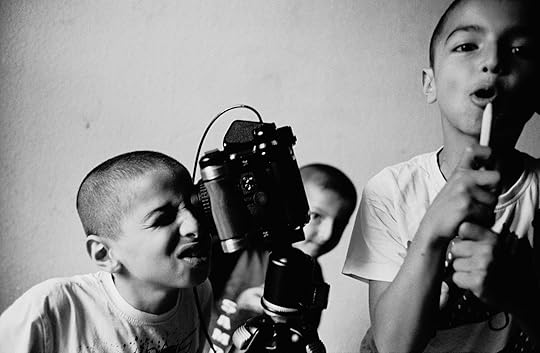

In London, an Exhibition Provokes Questions about Masculinity

For some men, masculinity is a habit or an addiction—a promise of power. But in the #MeToo era, can “liberation” be found through photography?

By Lou Stoppard

Catherine Opie, Rusty, 2008

© the artist and courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London

In January, when invitations went out for the opening of the exhibition Masculinities: Liberation through Photography at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, one invitee emailed the show’s curator, Alona Pardo, to ask, “Do men really need liberating?” It’s a question that has, in recent weeks, become all the more compelling. “In one way, no, of course they don’t, because they hold the power,” Pardo told me recently. “But on the other hand, they do, because that power is incredibly constricting.”

There have been many exhibitions about men. And as the Guerrilla Girls have succinctly argued, the history of museums and their collections is, by and large, the history of men. But such exhibitions were usually not about “men as men”—they were about their brushstrokes, their visions, their camera work, the magnificence of their talent. The Masculinities exhibition, which reopened to the public on July 13, and accompanying catalogue are about “men as men.” The project, which includes fifty-five artists and work dating from the 1960s onward, considers, to quote Pardo and Jane Allison (the Barbican’s head of visual arts) in the catalogue’s foreword, “the ways in which masculinity is variously experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed.”

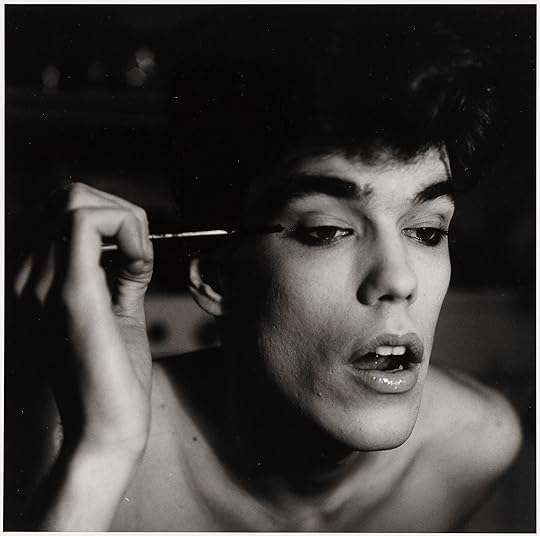

Peter Hujar, David Brintzenhofe Applying Makeup (II), 1982

© The Peter Hujar Archive LLC, and courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

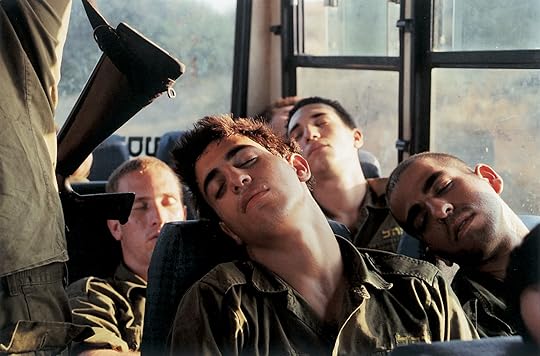

Masculinities brings together names one would predict given such a topic—Wolfgang Tillmans, Hal Fischer, Adi Nes, Robert Mapplethorpe—alongside less expected (and thus often more rousing) works by the likes of Liz Johnson Artur, Kalen Na’il Roach, and Aneta Bartos. There is a significant amount of conceptually driven photography—“performative work” as Pardo puts it—which makes sense given that this is an exhibition of the Judith Butler school of thinking: gender is socially constructed and, by default, masculinity and femininity are learned, and performed, behaviors.

The notion of “men as men” is borrowed from the sociologist Michael Kimmel, who observed that there are thousands of books about adventures, travels, and battles, “but books about men are not books about men as men.” Chris Haywood, reader in critical masculinity studies at Newcastle University, UK, cites Kimmel in his catalogue essay looking at popular discourse around masculinity. Haywood argues that the very act of looking at men undermines notions of masculinity because, conventionally, it is “dependent on its being natural, effortless and normal.” Indeed, it seems that to be a man is to try at everything—building one’s body, excelling at work, earning more money—without ever admitting one is actually trying to become more of a man, in an attempt to bolster some shared sense of self-importance, a standard to keep up. To browse the photography in Masculinities and regard that effort, to see men as objects, flawed, constructed, fragile—in other words, to regard them in the way we often regard women—can feel pleasurable, or elicit an odd sense of vindication. One can revel in repulsion at the almost lazy bravado of some frat boy captured by Richard Mosse, or a high-school football player by Catherine Opie. Or one can feel more tender, if so inclined, when encountering a young dreamer in the self-portraits of Samuel Fosso.

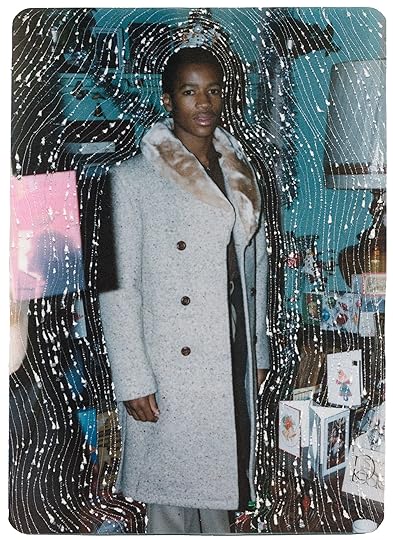

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Untitled, 1985

© the artist and courtesy Autograph, London

Masculinity has long been omnipresent yet strangely invisible. In 1997, Sally Johnson observed that “it is precisely men’s status as ‘ungendered representatives of humanity’ that is the key to patriarchy.” And yet, right now, it is widely advocated that “good” masculinity is rooted in self-awareness which, of course, means that some men (though not nearly enough) are reflecting on gender in relation to themselves, rather than seeing it as some exterior, foreign thing that affects women or queer people.

“It is a newfound phenomenon that men are looking at themselves, and men, for the first time, properly. Really examining forensically,” Pardo said. She also does some of the work for these men by considering the influence of campus traditions, the military, and sports on masculinity (although a broader analysis of the influence of capitalism would have been useful). Some photographers have done this for a long time—Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, Herb Ritz, Rotimi Fani-Kayode—but such work was seen as a fringe endeavor, or some kind of homoerotic play: “not noble, not masculine,” as Pardo puts it. In photography, gender is primarily treated—and, in turn, viewed—superficially, as a matter of appearance. Masculinities is frequently concerned with style, fashion, uniform, facial hair, and fitness. Mapplethorpe’s 1980 images of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon—toned, muscular, and thus clearly included because she looks somehow “like a man”—highlight the way that the exhibition’s agenda returns intuitively to the archetype, to the clichés of hegemonic masculinity (strength, fitness, control) as a starting point, all while trying to push against them.

Hal Fischer, Street Fashion: Jock, 1977/2016, from the series Gay Semiotics

Courtesy the artist and Project Native Informant, London

Pardo takes as a given that masculinity is in “crisis,” although the extent to which that crisis is recognized, beyond certain “bubbles,” as she calls them, is up for debate. Look at President Trump and the attendees at his campaign rallies, clapping along at brutishness and bullying. Or the rise of “incel” groups. Or the boom in revenge porn. Or the spread of domestic violence during COVID-19 lockdowns. Or the frequency of male suicide. Or so much more. The bubbles Pardo mentions are not utopias, but instead sites of hypocrisy and self-delusion, as much as progress.

One can be aware of a problem while also unable to feel it, to turn empathy into personal action. A “woke” millennial man tweets about feminism but then ghosts his Tinder dates. Almost any woman you speak to will say that she, or one of her friends, has been sexually assaulted or harassed, and yet no man will admit that their social circle is full of creeps and rapists. “I really didn’t want the show to be men-bashing,” Pardo said. Why not? For some men, masculinity is a habit, performed with a mindless rhythm; for others, it’s an addiction, damaging but alluring, the promise of access to some higher place, some new sensation of power and control and possibility.

Adi Nes, Untitled, 1999, from the series Soldiers

Courtesy the artist and Praz-Delavallade Paris, Los Angeles

The book is organized into sections which consider, first, Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space; followed by Too Close to Home: Family and Fatherhood. Next come Queering Masculinity, Reclaiming the Black Body, and Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze—an order that neatly seems to parody our broader, problematic social hierarchy, headed, as this book observes, by the cis white male. “And while it is safe to say that numerous masculinities exist within every culture and that they often vary according to class, race, ethnicity, sexuality and religion,” Pardo writes in the book’s opening essay, “it should be noted here that hegemonic masculinity sits atop this gendered social hierarchy by embodying the culturally idealised definition of masculinity, constructed as both oppositional and superior to femininity.”

And yet, it seems that the intentions of the ordering are sincere rather than goading. It is something of a shame to see these latter areas othered away from the earlier chapters on power, space, and family—notions relevant to understanding queer culture and its representation, or Black life, and, of course, women’s art. Still, the study of gender is full of divisions, generalizations, conceptual confusions, and, increasingly, angst. It is easy to dismiss any attempt to contribute to the conversation as having missed the mark, given the way the topic intersects the public and private; the obvious and obscure; the legal, bureaucratic, and structural with the all-important individual lived experience. Masculinities grapples with all this as earnestly as any institution can, especially when dealing with a medium (photography) that has its own baggage of patriarchy, exclusion, cliché, and erasure—themes that run through the work of some of the artists featured, from the exquisite portraits of Deana Lawson to the layered work of Sam Contis. The latter’s Deep Springs series (2017), an exploration of the American West and the relationship between its enduring motifs and masculinity, is a highlight of the book.

Perhaps because the US is currently in the run-up to a presidential election, I found myself especially entranced by Richard Avedon’s project The Family, originally made for Rolling Stone in the bicentennial election year of 1976 and featuring, among other influential figures, Ronald Reagan, who had just lost his bid for the Republican nomination to incumbent President Gerald Ford. Reagan looms large in the exhibition as a whole, an emblem for a Hollywood-cowboy kind of masculinity that presents itself as the embodiment of dignity, strength, and righteousness, an identity Reagan manipulated—as others do today. Reagan is cited by Larry Sultan, in the context of his adored series Pictures from Home (1992): “These were the Reagan years, when the image and the institution of the family were being used as an inspirational symbol by resurgent conservatives. I wanted to puncture this mythology of the family and to show what happens when we are driven by images of success.”

Karen Knorr, Newspapers are no longer ironed, Coins no longer boiled So far have Standards fallen, 1981–83, from the series Gentlemen

© the artist

In Avedon’s series, we see bankers, executives, publishers—the network that, through a well-oiled cycle of backstabbing and propping up, shapes America’s highest office. It is one of the most convincing attempts in the book at capturing not the surface nature of masculinity, but its goals, the insidious way it pulls individuals into its cause. Such themes preempt the ideas explored in Karen Knorr’s series Gentlemen (1981–83), a study of the British political class, and Andrew Moisey’s book The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual (2018) which, to Pardo, show the “structures and scaffolding” that prop up patriarchy and “the way it is handed like a baton, from one generation to the next.” Avedon’s photographs are formal, still portraits, but you imagine the way the subjects made their way to the session, and the way they left. The cufflinks jangling as a hand is extended to shake. The woody smell of cologne. The straightening of the tie. The agreement, over lunch at the club, that the son of a friend will be given a coveted position. The box of cigars in the study. The wives in the other room while the men talk. The firmness of a hand on a woman’s lower back as it ushers her through the door. The discreet call to a lawyer to “make this whole thing go away.”

Much has changed since Avedon’s and Knorr’s pictures were made. A turning point, of course, was #MeToo, which is cited repeatedly throughout the book. Pardo said that while she had been thinking about the exhibition for years, the events of 2017 certainly “galvanized it.” This is just as I see it, but to me, the greatest shift post-#MeToo is that men now see what it is to spend each day afraid—something women have always known. We spend our time hyperaware of what others may read into our movements, our actions. What they may take from us, whether or not we want to give it. We women, through habit and pressure, turn ourselves into malleable vessels, ready to expand or retract or streamline depending on how we are treated. We are told to worry about being hurt or raped or killed with the kind of pragmatism of someone giving road directions: “Don’t walk that way at night.” Men, who once thought their actions, their dominance would never be challenged, now know that daily fear. It’s not identical—they are not afraid of being injured, but they are afraid of being shamed, accused, outed. Such fear stings.

Sam Contis, Untitled (Neck), 2015

© the artist

So maybe that’s why, when reading the book, I found myself returning to the fearful gazes. I found them poignant in the images purportedly partly about strength—could the subjects sense that their power was crumbling around them? The vulnerability in the eyes of Rineke Dijkstra’s bullfighters. The pathetic bile of Anna Fox’s father’s words, screamed at her mother, and perfectly, awfully, transcribed by the artist alongside photographs of mundane props of domesticity in her series My Mother’s Cupboards and My Father’s Words (1999). The tight way a frail father grips his son, the photographer Masahisa Fukase, in the series Memories of Father (1971–90). There are various projects in the book in which a male image-maker captures his father. Aren’t all of these largely centered on fear? An exercise in grappling with, and pre-empting, the particulars of one’s own forthcoming demise?

In another essay in the book, on the subject of order, Edwin Coomasaru, associate lecturer at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art, interprets the same fear, a lingering nervousness, beneath the bravado on show in Knorr’s Gentlemen which, alongside images, includes quotes and phrases from her subjects. Coomasaru writes that “anxiety creeps into the proclamations of custodianship. The breakup of the British empire haunts such bravado; it is as though the speakers are struggling to adjust to the UK’s loss of influence on the world stage.”

“When the Rule of law Breaks / down, the World takes a further step towards Chaos,” reads one of Knorr’s captions, the words of a man in a suit photographed near St James’s Palace, London. Today, a text like this could be read as defending a man accused of sexual assault on social media but never prosecuted. Or criticizing the current protests against racism and police brutality, the couple of days of looting, the overall urgency. Another step towards chaos? Or a step towards his own irrelevance?

Kalen Na’il Roach, My Father Posing, 2013, from the series My Dad Without Everybody Else

© the artist

It is strange to think of the conversations happening when this show was first conceived and those occurring when it reopens. George Floyd murdered. Black Lives Matter activists marching. The US president even more tyrannical. The police again exposed for their racism and violence. And man proven powerless against a virus. The enormity of it all.

In his 1985 essay “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood,” cited repeatedly in the Masculinities book, James Baldwin writes that the American ideal of masculinity “has created cowboys and Indians, good guys and bad guys, punks and studs, tough guys and softies, butch and faggot, black and white.” He also writes: “Violence has been the American daily bread since we have heard of America. This violence, furthermore, is not merely literal and actual but appears to be admired and lusted after, and the key to the American imagination.” The recent, unbearable visibility of that lust—the sense of self that a police officer seemed to draw from placing his knee on the neck of an already restrained Floyd—should make us see all the pictures in Masculinities, and the power balances and struggles they purportedly show, afresh. If Masculinities is a battle cry against the tyranny of hegemonic masculinity, then mere liberation is one solution. But in recent weeks, there have been many others, more radical and more compelling in their urgency.

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London and a regular contributor to the Financial Times, New York Times, and Aperture.

Masculinities: Liberation through Photography is on view at Barbican Art Gallery, London, through August 23, 2020.

Justine Kurland Reflects on Her Photographs of Teenage Girl Runaways

Between 1997 and 2002, the photographer portrayed teenage girls as imagined rebels, offering a radical vision of community and feminism against the masculine myth of the American landscape.

By Justine Kurland

Justine Kurland, Orchard, 1998

The Runaways are everything that’s great about teenage girls. The tough ones who never came to school because they were out too late the night before. It’s true, there have always been as many girl punks as boys. The Runaways are as real as getting beat up after school.

—Lisa Fancher, album liner notes to The Runaways, 1976

I channeled the raw, angry energy of girl bands into my photographs of teenagers. It was as if I took Cherie Currie—The Runaways’ lead singer—on a picnic somewhere out in the country. I would show her my favorite tree to climb, braid her hair by a gently flowing river, and read aloud to her, my gaze occasionally drifting toward the horizon while she lazily plucked a blade of grass and tasted its sweet greenness. All the power chords we would ever need lay within reach, latent, coiled in wait. The intensity of our becoming funneled up vertically from where we sat.

Justine Kurland, Pink Tree, 1999

Alyssum was the first girl I photographed. At age fifteen, she had been sent to live with her father—a punitive measure for skipping school and smoking pot. I happened to be dating her father at the time, but I vastly preferred her company to his. After he left for work, we spent long conspiratorial mornings stretched under the air conditioner in his Midtown Manhattan condominium. Together we conceived a plan to shoot film stills starring Alyssum as a teenage runaway. I outfitted her in my own ratty clothes and brought her to the Port Authority Bus Terminal. The only surviving picture from the time shows her in a cherry tree by the West Side Highway. The branches seem too thin to support even her small weight; their cloud of petals offers little camouflage. She hovers pinkly between the river and the highway, two modes of travel that share a single vanishing point.

Justine Kurland, Toys R Us, 1998

I expanded the cast to include some college freshmen and eventually started trolling the streets around various high schools, cruising for genuine teenage collaborators. Looking back, it seems miraculous that so many of them were prepared to get into a stranger’s car and be driven off to an out-of-the-way location. But then, being a teenage girl is nothing without the willingness and ability to posture as the teenage girl.

My original inspiration was the after-school TV special—those cautionary tales of teenage delinquency that unintentionally glamorize the transgression they’re meant to condemn. The usually male protagonist doesn’t belong to the world as he has inherited it. He fights alienation by striking out to find a world of his own. I think first of Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye, but I trace the teenage runaway story further back to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which in turn rubs against tales of early immigrants pushing violently westward. Like a game of telephone, each reiteration alters and distorts a fundamentally American myth of rebellion and conquest, emphasizing or erasing certain details as new social and historical contexts demand. At least my narratives were honest about what they were: fantasies of attachment and belonging that sharply diverged from the hardships experienced by so many actual teenage runaways.

Justine Kurland, Golden Field, 1998

My runaways built forts in idyllic forests and lived communally in a perpetual state of youthful bliss. I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls—they would multiply through the sheer force of togetherness and lay claim to a new territory. Their collective awakening would ignite and spread through suburbs and schoolyards, calling to clusters of girls camped on stoops and the hoods of cars, or aimlessly wandering the neighborhoods where they lived. Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it—one of them, a girl made strong by other girls.

Justine Kurland, Kung Fu Fighters, 1999

Lily was my dream of a teenage runaway; it was as if she walked out of a picture I had yet to make. She lived in Tribeca but dated boys only from Brooklyn, the kind that say “Waz good?” when they answer the phone. She would climb into my car slightly stoned, her legs weighed down by Rollerblades, making it difficult for her to pull them inside. Lily died some years later. At her memorial, her father told a story about pulling the car over to the side of the road and lecturing his kids not to fight while he drove. “As long as you live in my house and wear the clothes I buy you,” he recalled saying, “you will live by my rules.” Lily pulled her sundress off over her head, got out of the car, and walked naked down the country road.

Justine Kurland, Puppy Love, 1999

The first condition of freedom is the ability to move at will, and sometimes that means getting into a car rather than getting out of one. It’s difficult to describe the joy of a carload of girls, going somewhere with the radio turned up and the windows rolled down. They sing along with the music, tell stories in rushed spurts, lounge across each other, swap shirts, scatter clothes all over the back seat, lick melted chocolate off their fingers, and stick their heads out the windows, hair whipping back and mouths expanding with air. At last we arrive at a view, a place where the landscape opens up—a place to plant a garden, build a home, picture a world. They spill out of the car along with candy wrappers and crushed soda cans, bounding into the frame, already becoming a photograph.

Justine Kurland, Ship Wrecked, 2000

The car itself was the invisible collaborator in these pictures. I spent more and more time in it, over greater and greater distances. I could find girls wherever I stopped, but they went home after we made photographs, while I kept driving. My road trips underscored the pictures I staged—the adventure of driving west a performance in itself. I cross the Mississippi and when I reach Kansas, the land starts buckling up through the waving grass. Colorado crests, jagged and crystalline. The valley rolls between the Sierra Nevada and the Coastal Ranges, velvet green in the spring and scratchy yellow the rest of the year. Finally, the Pacific. The waves change to blue and flatten against the horizon. I pull into a turnout on Highway 1 and get out of my car with the radio still blaring and the surf pounding ahead of me. I dance in the beams of my headlights, because I’ve traveled as far away from far away as the highways will take me. Hello world! I’m your wild girl. I’m your ch- ch-ch-ch-ch-ch-cherry bomb!

That was then. Revisiting these photographs now, twenty years later, I am confronted by a standing army of teenage runaway girls, deployed across the American landscape, at a time when they need each other more than ever. “So what,” they say, “we’re never coming back.”

Essay and photographs originally published in Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020). All images courtesy the artist.

July 9, 2020

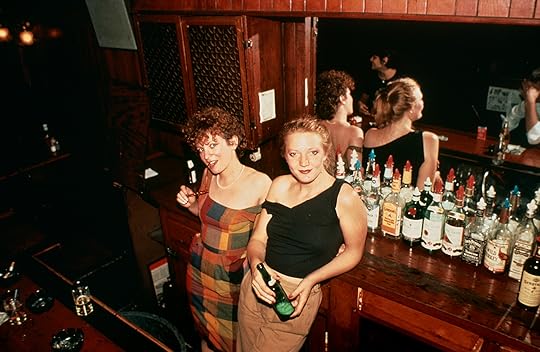

Nan Goldin’s Profound Influence on Film and Television

With its vivid color, indelible characters, and documentation of a pre-gentrified New York City, Goldin’s photography is a readymade mood board.

By Rebecca Bengal

Nan Goldin, Nan and Julie working, Tin Pan Alley, NYC, 1983

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

The year is 1977 tucked into 2018, and Times Square is playing its grittier, garish, four-decades younger self. Cigarette smoke floats above the gloam of the Hi-Hat bar, dark and loud and disco, the setting of an exhibition opening for Viv (played by Adelind Horan). She darts around the room snapping pictures of her friends dancing and flirts dangerously with the bartender as patrons inspect her photographs, pinned to the red-painted brick walls. Not everyone is a fan. A red-haired woman peers at an image of a red-haired woman who looks a lot like she does, sitting in a bar that looks a lot like this one.

“I coulda done that,” she scoffs to the guy next to her, whose good-natured smirk shows behind his mustache. “Eh, I kinda like it,” he says, taking a drag. This is Vincent, played by James Franco in The Deuce, David Simon and George Pelecanos’s HBO series about the 1970s and 1980s porn industry in New York. The actress is Nan Goldin, the woman in the photograph is Nan Goldin, the photograph (Buzz and Nan at the Afterhours, New York City [1980]) was made by Nan Goldin, and all of this, really, is Nan Goldin, regarding yet another reflection of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1983–2008) and its enduring, flexible influence on film and television. Claire Denis dedicated her 2002 film Vendredi soir (Friday Night), a largely wordless film about two strangers who meet at night amid a Paris transit workers’ strike, to Goldin. The saturated color of The Ballad is soaked into the palettes of the films of Wong Kar-wai and of Alejandro González Iñárritu in his 2000 crime and comic film Amores Perros, set in Mexico. In an effort to duplicate the hypervivid tones of Goldin’s pictures, Iñárritu opted for a processing method that risks ruining the film itself; the film critic Karen Redrobe writes that, at times, his interiors feel so close to The Ballad, they produce an “uncanny effect, as though Goldin’s photographs had been strangely transformed into tableaux vivants.” The subcultural worlds of Iñárritu’s film and Goldin’s project, however, remain vastly distinct.

James Franco and Nan Goldin in The Deuce, 2018

© HBO

The Deuce is another story. When Simon was casting about for the second season of the series, he phoned Goldin. His homage was sincere and immersive—after her episode aired, he wrote online that he’d “injected the raw DNA” of The Ballad into the sets, wardrobes, and also “the story and themes” of the series. “The character Viv is a composite of a Nan Goldin,” the executive producer Pelecanos has said (the emerald tone of the character’s tank top echoes the shade of Goldin’s Vivienne in the green dress [1980]). On the day Goldin visited the set and filmed her cameo, she also made several stills—morning-after, tangled bodies in a barely furnished bedroom; a red blur of a dress in a pale-pink tiled bathroom; the actress Maggie Gyllenhaal in a plunging neckline. Again, essentially images of images of her own images.

“This is my form of making movies,” Goldin told me in 2015 when I asked her about those days, when The Ballad was constantly evolving. She recalled how, in the early ’80s, the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch told her the slideshow reminded him of Chris Marker’s 1962 film La Jetée, which is also composed of stills. There were distinct differences, Goldin noted, such as Marker’s use of recurring images. “I mean, I would love to make something like La Jetée, but it’s a lot more complex in the way that it uses the still.”

Film, she said, was her life’s dream—fed by a teenage habit of going to the movies three times a week with David Armstrong, who would remain her beloved, longtime friend as they both became photographers. By age fifteen, she had constructed a foundation that included Bernardo Bertolucci, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Jacques Rivette; she had seen all the heroines her future drag-queen subjects would emulate—Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Barbara Stanwyck—and the drag queens themselves in John Waters’s films. She had seen the classic photographers’ films, “all of Antonioni,” a crucial influence. Andy Warhol’s 1966 Chelsea Girls, she once remarked, was the kind of film she wanted to make, and one that unconsciously prepared her for the cinematic feel of The Ballad.

Still from The Deuce, 2018

© HBO

By the early ’80s, Goldin was screening soundtracked slideshows of The Ballad at such venues as the former screening room Rafik and the Mudd Club and tending bar at Tin Pan Alley in Times Square. “That bar really toughened me up,” Goldin recalled. (She eventually quit the day a drunk urinated on her camera: “I screamed like an opera diva—you could hear me all over Manhattan.”) It became one of the central locations for Bette Gordon’s 1983 film noir influenced Variety, named for a former vaudeville house transformed into a porn theater, and spun straight out of the world of The Ballad and the seedy atmosphere of Times Square before its Rudy Giuliani–era Disneyfication. The film’s spirit of downtown artistic collaboration was itself like a mirror of the people Goldin photographed in The Ballad, her family. “They were all bartenders, friends, strippers, workers from the neighborhood. At the time, Kiki Smith was cooking in the kitchen, John Ahearn’s sculptures of people from the Bronx were on the wall,” Gordon once recalled. “They were a mixed group of artists, local sex workers, pimps, street people from Times Square, and film industry people. The woman who owned the bar helped facilitate the shoot, and the location was perfect.” Gordon worked on her treatment with Spalding Gray; his then partner Renée Shafransky was a producer; Kathy Acker wrote the script; and John Lurie created the score. Goldin photographed stills for the film, as she did for Sleepwalk, Sara Driver’s downtown-set film of the same era. In Variety, alongside her good friend Cookie Mueller, Goldin also had an acting role, playing a character who shares her own first name.

In one of the first scenes, Goldin’s character and Christine, an out-of-work writer played by Sandy McLeod, are seen in the mirrors of a swimming pool locker room, which reflects images of them as they get dressed, put on lipstick, commiserate about predatory would-be employers and sad-sack bar clientele. Goldin’s character has been working in the same bar for three years. “I mean I’m not selling my photographs,” she says. “At this rate I’m going to be a fifty-year-old barmaid.”

Nan Goldin, “Variety” booth, New York City, 1983

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

But she knows of a ticket-taker job at the Variety peep show down the street from her bar in Times Square, if Christine is willing to give it a shot. As the film unfolds, the lurid reds and the neon glow of the New York City theaters, and the bars, and the grimy cabs, and the clubs, and the motel rooms, and the cheap apartments littered with friends’ art and rumpled bedsheets—and even the Asbury Park boardwalk—all echo The Ballad settings. It’s the locker-room and barroom encounters though—the intimate, impromptu gatherings of the women of the film—that evoke the feeling of The Ballad most, its sense of sexual liberation and camaraderie, as its mood swings between desire and violence and tenderness and solidarity. Artists and service-industry workers and nightclub dancers cluster at Nan’s bar—drinks on the house—sharing hard-luck stories of loser men and worse. Cookie Mueller’s character refuses to chase after a man. A topless dancer recounts a night spent in jail after undercover cops framed her as a prostitute. Nan lights their cigarettes, and counsels Christine, who has hinted at a strange encounter at the Variety.

At work, Christine is caged in a street-facing ticket booth where she is as much on display as the porn stars of the Variety’s screenings. But she takes her breaks inside the theater: Christine wants to watch too. She’s the lone woman among men at the newsstand, flipping through the skin mags alongside them, refusing their advances. Eventually her desire and voyeurism become a kind of spying. In the tradition of voyeuristic cinema (Blow-Up, Rear Window), Gordon makes her the artist-writer figure obsessed with a mystery unfolding in her midst—but a woman, not a man. In the tradition of The Ballad, Christine is at her core an artist obsessed with gazing into all the lurid corners of her world.

For other films, Goldin’s influence plays out explicitly. In the 1998 film High Art, Ally Sheedy plays Lucy Berliner, an elusive, renowned photographer living with a heroin-addicted girlfriend and a druggy cast of hangers-on; her pictures, photographed for the film by JoJo Whilden, are based on Goldin’s. In some films that share a commonality with The Ballad, there exists an inherent swapping of influence. In the 1970s, Larry Clark’s transgressive, diaristic Tulsa images had a deep impact on Goldin, and Clark’s 1995 Kids, though a narrative film scripted by Harmony Korine and set in a downtown New York 1990s teenage skater milieu, felt kindred to The Ballad. Like The Ballad, Kids bears the illusion of verité and the sensation of insiderness, of being a voyeur on the fringes of a forbidden world. John Waters’s Pecker (1998) is in essence a joyous, playful take on The Ballad. The incessantly photographing central character, Pecker, gets famous by taking pictures of his friends, but shucks off the Whitney Museum and New York accolades. Instead, the elite, buttoned-up art world comes by the busload to Baltimore, for a raucous opening with drag queens and local eccentrics, a place where the family of The Ballad would have felt equally at home.

In its earliest slideshow iterations, The Ballad was never static, never the same—it grew shorter or longer, pictures were added and subtracted, the music was changed, true to the nature of the form. Traditionally, ballads are passed down orally, adapted over time, reinterpreted by later generations, but sung to the same melody. As much as they owe to Goldin, the cinematic and television heirs affirm the spirit of The Ballad as a living, changing piece, existing on a continuum. The films unspool in its wake like a series of reflections, charged with Goldin-esque electric color, as artists after attempt to find their own ways into the secret worlds of her bedrooms and bars and streets. The lines begin to beautifully blur.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York. Her story “The Jeremys” is included in Justine Kurland’s book Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020).

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

In “Pleasant Street,” Thirty Years of a Family’s Life

Judith Black’s new photobook traces her home life in New England from 1968 to 2000—and builds upon an American documentary tradition.

By Laura Guy

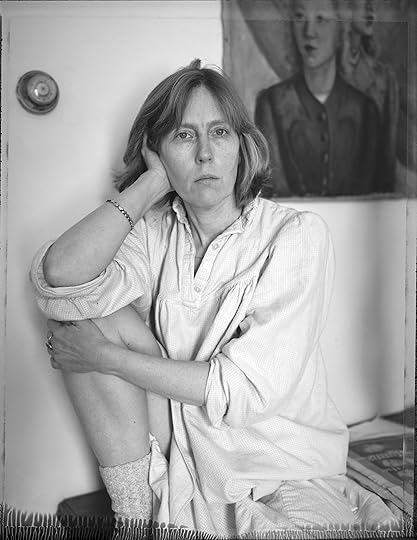

Judith Black, Self, February 1993

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Judith Black’s photographs of her family, made over a period of thirty years, insist on the home as a site of concerted documentary inquiry. Published together for the first time in her new photobook Pleasant Street (Stanley/Barker, 2020), they are a study of domestic life during a period in which many established American documentarians turned away from their favored subject of the street, and toward the home.

Judith Black, Laura and Johanna, May 2, 1982

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

In 1991, Black was included alongside many such photographers—William Eggleston and Larry Sultan, among others—in Pleasures and Terrors of Domestic Comfort, the first exhibition that Peter Galassi organized at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in his new role as chief curator of photography. Pleasures and Terrors is often cited alongside “Mothers and Daughters,” Aperture magazine’s Summer 1987 issue (and its accompanying traveling exhibition), in which Black’s work was also featured. Both projects engaged in documentary as a public form refocused on the private sphere, charting a new vernacular language in American photography to emerge from the 1970s onward. Galassi’s take on all this was that many artists “began to photograph at home not because it was important, in the sense that political issues are important, but because it was there—the one place that is easier to get to than the street.”

Judith Black, Family Group, June 19, 1983

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

For a photographer like Sultan, his suburban upbringing was one among many subjects that featured throughout a lifetime in pictures. For Black, it seems home is all there is. Most of the photographs that appear in her new book were made inside or, occasionally, in the immediate vicinity of a house on Pleasant Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The clapboard-sided building—a trope that pervades American photography as much as it does the American psyche—provides a frame for this family album produced between 1968 and 2000.

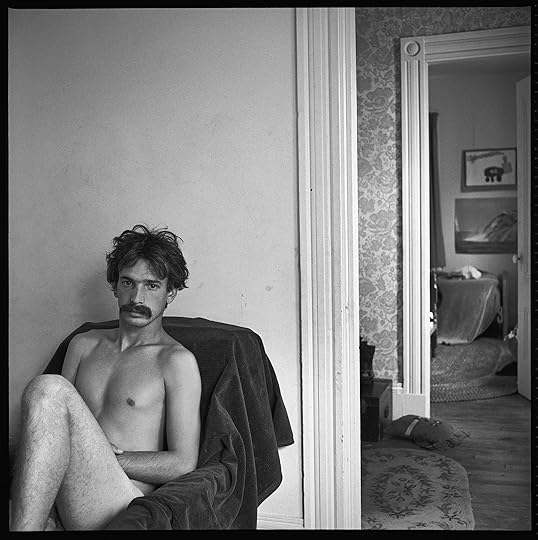

Judith Black, Rob, Just returned after six-month trip, March 29, 1980

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Black’s work is formally considered and technically precise. Her subject is narrow in focus. Thirty-two years accommodate a handful of tousled-haired toddlers, plenty of scowls, and eventually, shaved heads and nose piercings. It also shares quarters with a mustached partner. The period begins with one of a number of self-portraits that punctuate the book. Black is shown reflected in a mirror, her pregnant belly cupped by tendril-like stretch marks, as her arms cradle a camera awkwardly in order to take in the scene. The period concludes with Black’s dungareed daughter, now fully grown, carrying her own children. The chronological arrangement of images folds back on itself to become a cycle—if only a cycle still determined by a pattern of family life that is often mapped in the linear terms of procreation and generation.

Judith Black, Dylan and Laura, October 1984

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

Pleasant Street sounds like an idyllic place to raise—and photograph—a family. In reality, the street, a fifteen-or-so-minute walk from the Creative Photography Lab at MIT—founded in 1965 by Minor White, a cofounder and longtime editor of Aperture—was the ideal location to stage a family album as a documentary practice. In 1979, Black, a single parent, moved her four children to Cambridge and enrolled at the Creative Photography Lab, where she both studied and worked as a technician. Rather than reflecting White’s emphasis on experimentation and individual expression, however, Pleasant Street belongs to a broader tradition of documentary practice connected to New England—from Paul Strand and Edward Weston, to the fine-grained black-and-white images of Black’s contemporaries Mark Steinmetz and Sage Sohier. (Both Steinmetz and Sohier share Black’s connections to Massachusetts and to publisher Stanley/Barker.) Here is a lineage of photography enmeshed with American national identity, typically white and largely conventional.

Judith Black, Erik, Almost 18, November 6, 1988

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

The photographs in Pleasant Street are all black and white, either made using medium format or, beginning around the mid-1990s, Polaroid Type 55 film. Neither process is a particularly speedy one, especially the large-format polaroid film that produces both a positive image and a negative. These are photographs that are made over time (reflecting a kind of persistent looking) and with time. They are carefully staged, their figures colluding, if sometimes wearily, in the act of making a photograph rather than posing for a snap.

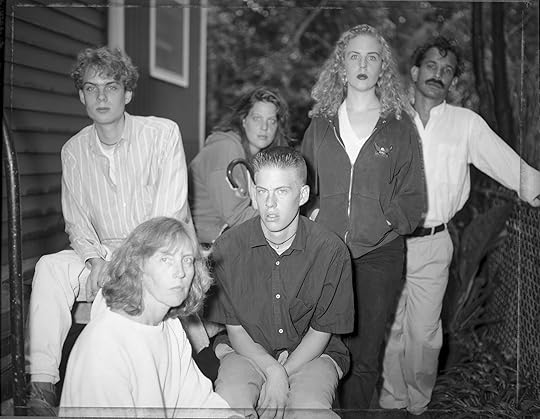

Judith Black, Family Group, August 9, 1992

© the artist and courtesy Stanley/Barker

There are few smiles in this family album. Black’s self-portraits are particularly haunting for the fixed stare she holds with the camera or, on occasion, with which she observes her subjects. The effect is distancing, and the safety of the home as subject produces unease. The certainty with which Galassi declared home “there” is not necessarily here. “Needless to say, our life was chaotic and often difficult,” Black notes in the book’s only text, referring to the contingent conditions through which homes, and photographs, are often made. “Sometimes I thought we wouldn’t make it.” Elsewhere, in a hand-annotated index, one self-portrait is labeled, simply, “HARD TIMES.” This is documentary photography in the middle ranges. Between the urgent commitments of paid employment and family life, Pleasant Street performs a kind of erratic housework, gathers up the traces of the home and shows image making for the reproductive labor it often is.

Laura Guy is an early career academic fellow in art history at Newcastle University, UK.

Judith Black: Pleasant Street was published by Stanley/Barker in April 2020.

July 2, 2020

A Visual Record of Queer Experience in China

Lin Zhipeng, the photographer known as 223, looks for beauty, connection, and the impulse of friendship.

By Xuan Juliana Wang

223, JinJing on the Couch, 2016

Courtesy the artist

If you let him, 223 will come over to your place, open your fridge, rummage through your closet, and inspect your bedroom on a search for props he can use for an impromptu photo shoot. His friends have grown accustomed to his ever-present camera. Taking photographs has become second nature. “Some people, when I meet them, I immediately want to take their photograph,” he says. “Others, I’ll know for years, yet it never occurs to me to do that. I really can’t explain why. It’s just a feeling, a connection between us.”

Lin Zhipeng, the photographer known as 223, named himself after the lovelorn Hong Kong police officer in Wong Kar-wai’s 1994 film Chungking Express. Born in Shantou, China, in 1979, 223 spent his childhood on an army base in Fujian, eventually going to college and working in Guangzhou before drifting to Beijing, where he still lives today. He tells me has had no formal training in photography or obvious early influences in the arts. He’s never been someone who makes plans: “I make impulsive decisions. I take trips without preparation. I do that in my life, and I do that in my work.”

223, Leaves Alienation, 2010

Courtesy the artist

223’s images act as memory, a cadenced record of a life searching for things that intrigue him. “When I open any photograph I’ve taken, I am reawakened to everything happening at that very moment,” he says. He likes to be surprised, to find the numerous frequencies of existence no matter how mundane. A portrait might appear as a romantic overture, but then there is a turn. His point of view is set to the beautiful as well as to the grotesque, the ordinary, and the obscene.

223 captures friends kissing their lovers, running into the darkness, and eating noodles side by side with their heads cocked. An ex-boyfriend appears on a secondhand sofa, with the fallen leaves of their houseplant thrown at him. All easy gestures, aching with seemingly interminable youth. Then there is a black-and-white portrait of his friend, a young gay man. The photograph was taken in 2009. The following year, the friend committed suicide, and 223 wouldn’t find out for quite some time. “What I have is his photograph. I don’t tell his story often, only if people ask,” he says.

223, Peng Fei, 2009

Courtesy the artist

These days, 223 wants to live a quiet life and do as he pleases. “I am looking at the world with a sense of peace and serenity,” he says. “As I get older, I can feel my heart growing bigger and bigger. I am not trying to become emotional about every little thing.” If you follow his work, you will find that the same people reappear over fifteen years. He photographs some friends every time he sees them. One woman is first depicted as a teenager, but in a later series she is nearing middle age. People move, from Beijing to Shanghai or to the United States, and appear anew with gray hair and wrinkles around their eyes. “When I look at photographs from five, ten years ago, I can trace the small changes,” he says. “Some lovers have broken up, others have stayed together, and that will make me feel this immense sadness or joy for them. That is what I cherish most.”

223, I LOVE WE, Vol2, 2011

Courtesy the artist

223, New Pants, 2008

Courtesy the artist

223, Run Uki Run, 2006

Courtesy the artist

223, Fog City, 2010

Courtesy the artist

223, Flower Bed, 2011

Courtesy the artist

223, Kissers in the WHITE PARTY, 2010

Courtesy the artist

Xuan Juliana Wang is the author of the story collection Home Remedies (2019).

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

July 1, 2020

What the Photo Critic Vince Aletti Found at Home during Quarantine

What does an insatiable collector do when all of New York’s bookstores and markets are closed?

Vince Aletti at home in New York, June 2020

Photograph by Balarama Heller for Aperture

Like many of you, I’ve been using much of these past few months at home to sort through and (attempt to) organize every drawer and box in my apartment. But after more than forty years in the same seven rooms, I think there’s a good chance I have more stuff than you do. I still haven’t come to grips with all the layers of ephemera, memorabilia, printed matter, and collections within collections here, but in the process of sifting through everything, I found a ton of things I’d squirreled away and forgotten. I pulled a few of them out to show you. —Vince Aletti

Distinctive Physique

Mid-1950s mail-order catalogue for the Denver-based Western Photography Guild, offering “Distinctive Physique Photographs” by Don Whitman—uncredited until the late 1960s, when the laws regulating the distribution of images of male (semi)nudity were relaxed. The models are described inside: “Possessor of a Grecian profile and body to match, Johnny Rotolante appears in a beautiful array of poses to inspire the imagination of artist, sculptor, and student.” Twelve 4-by-5 “Premium Finish” photographs from his series cost $2.

Jimmy De Sana

A photo by Jimmy De Sana that appears to be a change-of-address announcement. The tiny type on the letterhead under the umbrella says “De Sana Uptown,” followed by an address on East 70th Street.

Smashing

An invitation to “Smashing,” a regular party at Club USA in Times Square, which I never attended. Apparently, I didn’t miss much: Club USA ranks first on Michael Musto’s list of “The 10 Worst NYC Nightclubs in History.” It closed in 1995, but the folded invitation cards that illustrator Jeffrey Fulvimari designed live on. Fulvimari’s Warhol-meets-Deee-Lite aesthetic had a real moment in the mid-’90s, and this was among his most sustained projects, before Madonna tapped him to illustrate her series of English Roses children’s books.

Futura 2000

A real photo-postcard portrait of the great post-graffiti artist Futura 2000 (aka Leonard Hilton McGurr, and now simply, “Futura”) made in 1983 by a photographer whose name I cannot decipher.

Hard Day’s Night

Ringo and John, my favorite Beatles, on bubblegum cards. John’s is #33 from the Hard Day’s Night series.

Rear View

One of ten pages from a spiral-bound Polaroid scrapbook bought from a seller with a blanket of junk on St. Marks Place sometime in the early 1970s. Photographer unknown; the only dated images are from 1967 and ’70, all apparently made in the same New York apartment. Pages vary between frontal and rear views, carefully trimmed and arranged in grids of twelve.

Greetings from America!

A postcard by and from Michael Gomes, whose gossipy Mixmaster zine chronicled the New York disco scene from its earliest days. “Greetings From America! NYC 1975,” it says on the reverse, above a handwritten message from Gomes: “His name is Gregory and I photographed him at the Gallery the morning of the night we were there.” The Gallery was DJ Nicky Siano’s club, located at the time around the corner from David Mancuso’s 99 Prince Street iteration of The Loft. Both legendary.

Vintage 14th Street

A survey photograph of a stretch of West 14th Street sometime in the last century—possibly the 1930s. One of four, all stamped “RESTRICTED MASTER PROOF Not to be loaned out or removed from photographic department.” Do any of these buildings remain?

Musclebound

Two drawings, graphite on notebook paper, from a group of nearly thirty by an unknown artist who took his inspiration from muscle magazines of the 1940s, but added his own anatomical details. Found at Physique Memorabilia, a store specializing in vintage gay erotica and run like a private club out of a live-in loft on East 12th Street, complete with noisy parrot; it closed in the mid-’90s.

Fab and Fun

The color Xerox announcement for an exhibition by the artist better known as Fab Five Freddy at Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery, one of the first to define the East Village scene.

Poetry Reading

A flyer advertising “Poem Visuals” by Andy Warhol and his assistant, poet Gerard Malanga, at the Leo Castelli Gallery, circa 1964. Pin holes and tape residue on every corner; it was nearly always pinned to the wall of whatever dorm room or apartment I was living in for at least a decade. I have others on white and pink papers. I had a crush on Malanga, one of Warhol’s original “Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys,” at the height of his beauty here.

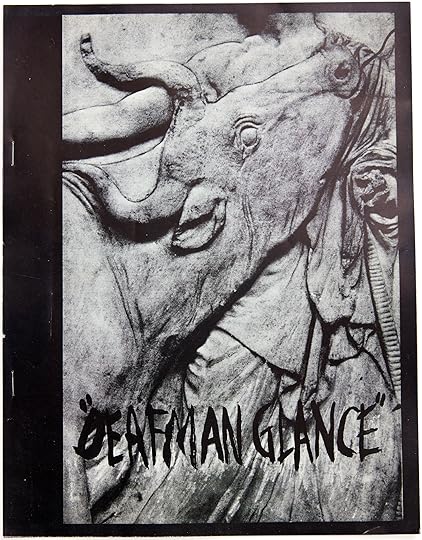

Deafman Glance

Program booklet for the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s premiere of Robert Wilson’s “Deafman Glance,” February 25, 1973. Following a three-page list of the cast, headed by Jack Smith in the role of Sharkbait Starflesh, there are nine pages of rambling, diary-like entries signed by Wilson avatar Byrd Hoffman and prefaced with this text: “These notes are from my notebook. They offer no explanation to explain what I am doing although some might think they explain the work. They do not have to be read to further understand the theater.” An excerpt: “The house sinks. The dog howls into the night. The old man’s eye becomes bright. The frog jumps as the ox swallows the Sun, the moon, the stars, the Son.”

Talk of the Town

A clipping from the New York Times, showing Rudolf Nureyev dancing at Arthur with the club’s co-owner and figurehead Sybil Burton in 1965. Having written a column on disco for the music trade magazine Record World for four years in the late ’70s, I tend to clip anything about dance clubs, especially an early, notorious one like Arthur, but I was surprised to turn this over the other day and see the unsettlingly contemporary image on the other side.

Vince Aletti is a critic, curator, and collector who lives in the East Village. Photographs by Balarama Heller for Aperture.

June 26, 2020

Months After Being Closed, Three Museums Reconsider Their Photography Exhibitions

In the wake of the pandemic and worldwide protests, exhibitions that address climate change, civil rights, and Black photographers take on new resonance.

By Eli Cohen

Marion Palfi, Chicago School Boycott, 1963–64

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

At the Armory Show in early March, the mood among visitors and exhibitors was ominous. At New York’s Piers 90 and 94, ordinarily packed with visitors, the scene this year was much quieter. Due to rising concern over COVID-19, exhibitors exchanged elbow bumps instead of handshakes, although few wore any sort of mask. Outside, a cruise liner blocked the horizon. It was unclear whether the ship was empty or locked down in quarantine, as was a similar ship off the coast of California. One exhibitor, looking at the ship, mused that they would rather be on board than at the empty art fair.

Within a week, the city’s major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art, announced temporary closures due to the pandemic—at first, only until the end of the month. Exhibitions that had opened were put on hold, and upcoming exhibitions were pushed back.

Months later, many of these shows are still in limbo.

With museums around the country facing decisions about reopening, where does this leave the near future of exhibitions, many the result of years of research and planning? I recently checked in with a few curators, in the US and abroad, to discuss how museums have evolved during this unpredictable moment.

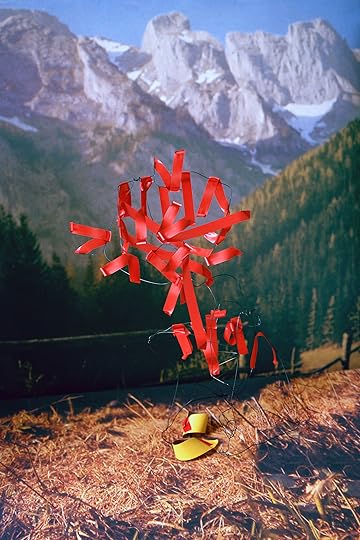

Thomas Albdorf, Typical Alpine Flora at the Hochschwab Area, 2014

© the artist

On Earth and Vivian Maier

On March 14, when institutional closures reached Foam, the photography museum and magazine in Amsterdam, curators were forced into action. Of immediate concern was the exhibition On Earth—Imaging, Technology, and the Natural World, which contends with the twenty-first-century relationship between image-making practices and the environment, and features photographers including Drew Nikonowicz and Adam Jeppesen. On Earth was scheduled to open just five days after the museum shut down, and the team at Foam quickly pivoted to digital programming. Curators Hinde Haest and Marcel Feil organized a live video tour of the exhibition on Instagram. “We are informed by means of images,” says Feil in the video. “Photographs, videos, all kinds of imagery made by all kinds of technological tools.” Viewing this video on Instagram, one click away from the global imagery of the coronavirus pandemic as it circulates on magazine covers and digital platforms, the curatorial statement behind On Earth strikes a prescient note.

Vivian Maier, Location unknown, 1956

© Estate of Vivian Maier and courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

In accordance with guidelines in Amsterdam, Foam reopened its doors on June 1. While the curatorial staff remains working from home, curators say that the presence of visitors creates a hopeful atmosphere and a vision of life beyond the pandemic. Alongside On Earth, the exhibition Vivian Maier—Works in Color also opened, a month and a half after its scheduled launch. Claartje van Dijk, Foam’s head of exhibitions and curator of Vivian Maier, is hopeful that the exhibition will comfort people returning to public life. Unknown until after her death, Maier mostly photographed street scenes in black and white, and the Foam exhibition showcases the success of her less-published color photographs. “In her color photography,” notes van Dijk, Maier “focuses more on composition and texture, rather than on activities.” The attention to detail in the bright images seems to resonate with visitors who have been stuck at home during the lockdown. “I think it’s almost refreshing,” says van Dijk.

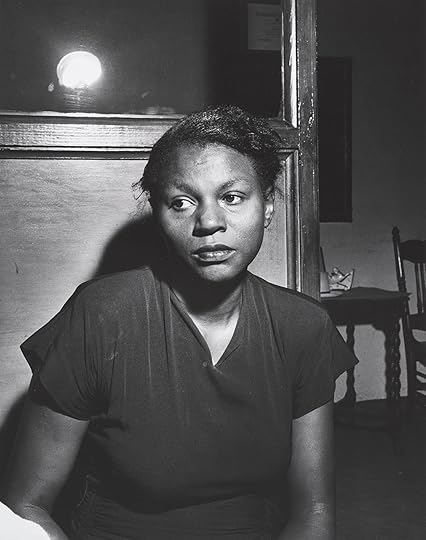

Marion Palfi, Wife of a Lynch Victim, Irwinton, Georgia, 1949

© Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

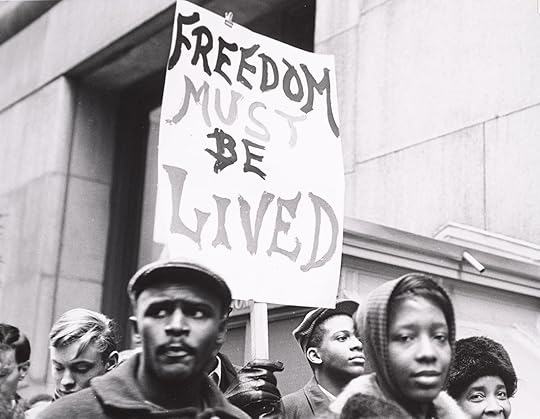

Freedom Must Be Lived

Elsewhere, reopening remains a distant goal, and museums are attempting to keep work on track. Audrey Sands, the Norton Family Assistant Curator of Photography at the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona and the Phoenix Art Museum, was in Houston at the Fotofest Biennial 2020 when things began to close in Arizona, and she was unable to return to the university before the shutdown. For her upcoming exhibition Freedom Must Be Lived: Marion Palfi’s America, 1940–1978, Sands requires access to CCP’s extensive Palfi archive, both for research related to the exhibition and to coordinate with museum conservators and preparators regarding the conditions of the photographs. With the archive closed, research has halted. Of the last set of photographs she has left to examine—about fifteen percent of the Palfi archive—“none of that material has been digitized,” Sands says. “That has been really hard, just being frozen.”

By the time Freedom Must Be Lived opens, most likely not until the spring of 2021, the curatorial vision of the exhibition will have shifted. The last month of protests across America following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis has disrupted how art institutions approach their collections, and the resonance of Palfi’s Civil Rights–era photographs invites new conversations about the work. Yet while the series presented in Freedom Must Be Lived—which also includes photographs of the forced relocation of Native Americans and depictions of aging communities in New York—are especially relevant given the demographics hit hardest by COVID-19, Sands hopes not to “flatten” the protests today with historical moments of the past. “There is so much resonance to be found in so much of our visual culture from the Civil Rights era,” says Sands, “and yet I think it’s really important to look at the 1960s in their historical specificity.”

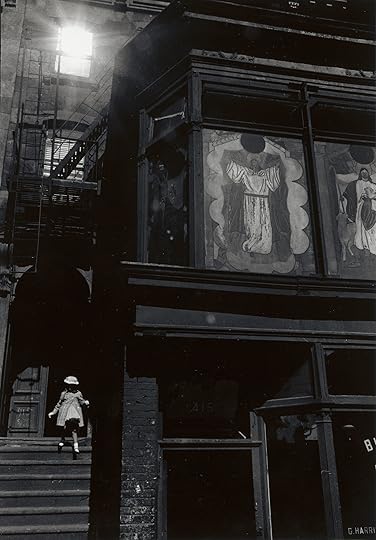

Herbert Randall, Untitled, Bed-Stuy, New York, ca. 1960s

© the artist

Working Together

Questioning how to respond to layers of history within the pandemic is not unique to the Arizona museums. Curators at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA), in Richmond, are dealing with narratives both in the museum and in the local community, where just down the street stand the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. On Richmond’s streets, recent protests enact a nationwide reckoning with the history of Confederate monuments. A recent Los Angeles Times article notes that as protestors focus on removing statues of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and J. E. B. Stuart, they protect VMFA and its monumental Kehinde Wiley sculpture, Rumors of War (2019), installed outside the museum last December.

Inside VMFA, Working Together: Louis Draper and the Kamoinge Workshop—an exhibition of the early circulation of images by Black photographers in New York who banded together under the umbrella of the Kamoinge Workshop—opened at the beginning of February. Featuring iconic names including Roy DeCarava, Ming Smith, and Louis Draper (a Richmond local whose archive is in VMFA’s collection), the Kamoinge Workshop shows the potential for artists responding to a historical moment within their communities. “A lot of the photographs that the Kamoinge members made about the Civil Rights Movement were less about documenting the movement itself,” says the show’s curator, Sarah Eckhardt. Instead, the images “were photographic statements they were making about liberty.”

Anthony Barboza, Pensacola, Florida, 1966

© the artist

VMFA plans to reopen July 4 to limited visitors, but Working Together faces uncertain conditions. The show was meant to travel to New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art later this summer; for now, the exhibition will stay in Richmond through mid-October. A symposium of Kamoinge photographers, curators, and scholars had been scheduled to convene at VMFA in late March, just after the museum closed—the program, Eckhardt hopes, will become a digital event if the museum’s in-person gatherings are restricted for much longer. After the first few weeks of the shutdown, the curators at VMFA created an online exhibition of Working Together, and the successes of digital accessibility have prompted discussions about how to utilize wide-reaching platforms online, even as museums prepare to reopen. “When you can only be digital,” Eckhardt says, “then it’s a moment to reassess and to think about how you can do both in the future.”