Aperture's Blog, page 67

September 28, 2020

Searching for an Indigenous Fashion Star, Martine Gutierrez Casts Herself

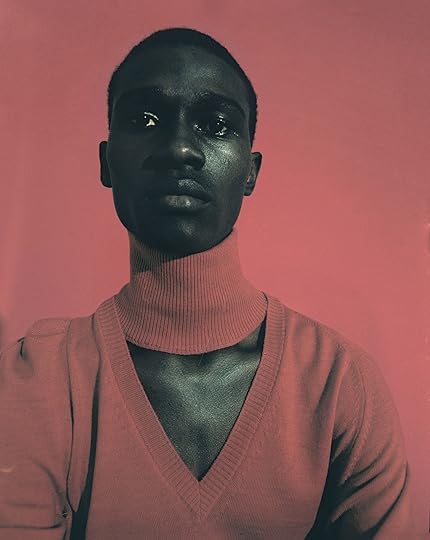

“No one was going to put me on the cover of a Paris fashion magazine, so I thought, I’m gonna make my own,” recounts Martine Gutierrez, speaking about her 2018 project Indigenous Woman, which takes the form of a 124-page magazine. In a series of spreads that encapsulates high-fashion glamour, as well as humor and the absurd, the artist is the project’s featured model, photographer, stylist, creative director, and editor in chief. However, Gutierrez is enacting not simply the “artist as muse” but rather the “artist as media mogul,” staging a guerrilla-style seizure and colonization of space in an image-based world to which she had previously been denied access.

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Legendary Cakchiquel, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Legendary Cakchiquel, 2018The concept of an artist’s book is not new. Since the nineteenth century, following the inception of the photographic medium, artists have engaged the format through the sequencing of images combined with the use of text. In the late twentieth century, the artist’s book took on new meanings. A cultural vehicle associated with the production and dissemination of knowledge was usurped and used to put forth polemical correctives to mainstream ideas about everything ranging from war and immigration to incarceration. But a fashion magazine rests in a decidedly different realm of popular culture. It is less precious, more pedestrian and unassuming. Any linearity dissolves in our casual method of flipping through pages, jumping around between images and spreads. Gutierrez was drawn to this aspect of magazines, and how they offered an opportunity to subvert white, Western standards of beauty: “What better way to do that than in a format we all understand?”

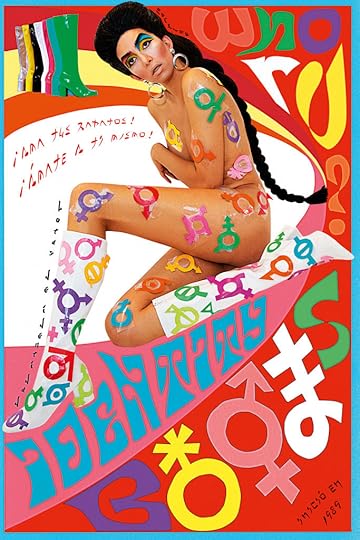

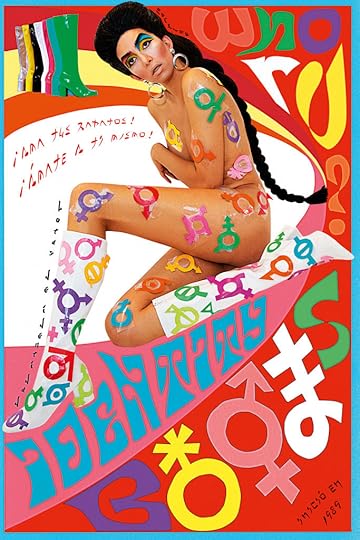

Indeed, appropriation is a thread that runs throughout the entire project. Not only does the artist appropriate the format, but there is a revolving roster of identities that she puts on and takes off as interchangeably as a hairstyle, a mask, or a pair of shoes. In a bilingual, psychedelic advertisement for “Identity Boots,” Gutierrez poses nude in go-go boots, covered in gender symbols that gesture toward glyphs or pictograms. In other images, she appears in Indigenous textiles—some belonging to her Mayan grandmother—against a stark white background, with jewelry, bananas, or the ubiquitous handmade muñecas, a type of doll peddled in markets throughout Mexico and Central America. In each case, makeup, props, and costumes become part of the masquerade that Gutierrez employs as a challenge to stable notions of gender and cultural markers, resulting in a foregrounding of the performative aspects of identity. Within the artist’s critical appropriation of the fashion magazine format, identity itself is put forth as commodity or currency, an item to be formed, expressed, weighed, and exchanged.

Throughout Indigenous Woman, indigeneity becomes a medium to reflect on gender, heritage, and narrative. As a trans artist, Gutierrez mobilizes the concept of indigeneity to question the birth origins of gender—what makes a “Native-born” woman, and what contributes to the stability of this identity? For Gutierrez, who is of Mayan heritage, the title evokes the facets of cultural identity and her family’s Indigenous roots. As a result, the artist deftly avoids being categorized at the same moment that her image is repeated. She is carefully poised within the tension between indigeneity and popular culture. Such sincere investment in both makes the project equal parts impressive and enthralling. Gutierrez states, “Affirming my life is an ongoing project; it’s about identity at large.”

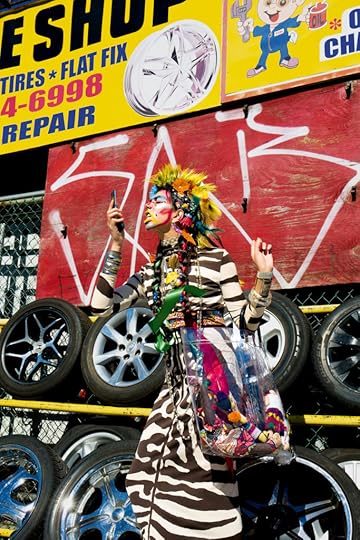

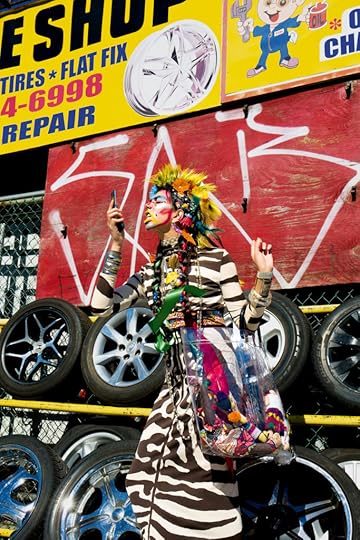

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, That Girl was Me, Now She’s a Somebody, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, That Girl was Me, Now She’s a Somebody, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Ad, Identity Boots, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Ad, Identity Boots, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Kekchí Snatch, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Kekchí Snatch, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, Dear Diary, No Signal During VH1’s Fiercest Divas, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, Dear Diary, No Signal During VH1’s Fiercest Divas, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Mam Going Bananas, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Mam Going Bananas, 2018This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “Indigenous Woman.”

All works from the series Indigenous Woman, 2018. Courtesy the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

Searching for an Indigenous Fashion Star, Martine Gutierrez Cast Herself

“No one was going to put me on the cover of a Paris fashion magazine, so I thought, I’m gonna make my own,” recounts Martine Gutierrez, speaking about her 2018 project Indigenous Woman, which takes the form of a 124-page magazine. In a series of spreads that encapsulates high-fashion glamour, as well as humor and the absurd, the artist is the project’s featured model, photographer, stylist, creative director, and editor in chief. However, Gutierrez is enacting not simply the “artist as muse” but rather the “artist as media mogul,” staging a guerrilla-style seizure and colonization of space in an image-based world to which she had previously been denied access.

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Legendary Cakchiquel, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Legendary Cakchiquel, 2018The concept of an artist’s book is not new. Since the nineteenth century, following the inception of the photographic medium, artists have engaged the format through the sequencing of images combined with the use of text. In the late twentieth century, the artist’s book took on new meanings. A cultural vehicle associated with the production and dissemination of knowledge was usurped and used to put forth polemical correctives to mainstream ideas about everything ranging from war and immigration to incarceration. But a fashion magazine rests in a decidedly different realm of popular culture. It is less precious, more pedestrian and unassuming. Any linearity dissolves in our casual method of flipping through pages, jumping around between images and spreads. Gutierrez was drawn to this aspect of magazines, and how they offered an opportunity to subvert white, Western standards of beauty: “What better way to do that than in a format we all understand?”

Indeed, appropriation is a thread that runs throughout the entire project. Not only does the artist appropriate the format, but there is a revolving roster of identities that she puts on and takes off as interchangeably as a hairstyle, a mask, or a pair of shoes. In a bilingual, psychedelic advertisement for “Identity Boots,” Gutierrez poses nude in go-go boots, covered in gender symbols that gesture toward glyphs or pictograms. In other images, she appears in Indigenous textiles—some belonging to her Mayan grandmother—against a stark white background, with jewelry, bananas, or the ubiquitous handmade muñecas, a type of doll peddled in markets throughout Mexico and Central America. In each case, makeup, props, and costumes become part of the masquerade that Gutierrez employs as a challenge to stable notions of gender and cultural markers, resulting in a foregrounding of the performative aspects of identity. Within the artist’s critical appropriation of the fashion magazine format, identity itself is put forth as commodity or currency, an item to be formed, expressed, weighed, and exchanged.

Throughout Indigenous Woman, indigeneity becomes a medium to reflect on gender, heritage, and narrative. As a trans artist, Gutierrez mobilizes the concept of indigeneity to question the birth origins of gender—what makes a “Native-born” woman, and what contributes to the stability of this identity? For Gutierrez, who is of Mayan heritage, the title evokes the facets of cultural identity and her family’s Indigenous roots. As a result, the artist deftly avoids being categorized at the same moment that her image is repeated. She is carefully poised within the tension between indigeneity and popular culture. Such sincere investment in both makes the project equal parts impressive and enthralling. Gutierrez states, “Affirming my life is an ongoing project; it’s about identity at large.”

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, That Girl was Me, Now She’s a Somebody, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, That Girl was Me, Now She’s a Somebody, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Ad, Identity Boots, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Ad, Identity Boots, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Kekchí Snatch, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Kekchí Snatch, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, Dear Diary, No Signal During VH1’s Fiercest Divas, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Queer Rage, Dear Diary, No Signal During VH1’s Fiercest Divas, 2018 Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Mam Going Bananas, 2018

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Mam Going Bananas, 2018This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “Indigenous Woman.”

All works from the series Indigenous Woman, 2018. Courtesy the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

September 25, 2020

A Photographer’s Personal Account of the Protests in Richmond

Before the COVID-19 lockdown, Christopher “Puma” Smith made landscape and portrait photographs while traveling or touring as lead singer with the band Thievery Corporation. Newly grounded at home in Richmond, Virginia, Smith began to use photography in a different way, engaging with the people and ideas of the former capital of the Confederacy. Under Monument Avenue’s statue of Robert E. Lee, Smith documents the forging of new alliances, which he describes in a recent conversation.

Chris Boot: How did you end up documenting what’s going on in Richmond?

Christopher “Puma” Smith: I moved to Richmond in 2017 from Washington, DC. It was to get away from the noise and have a little bit more peace of mind and space, as opposed to the congestion of DC.

Ever since coming to Richmond, my work changed from documentary and street photography to environmental portraits and landscapes. After the death of Marcus-David Peters in 2018, and especially after the death of George Floyd, I was picking up the camera again to physically be present, as opposed to receiving information and updates from biased news sources and social media. So it was to really motivate myself to be present and to converse and talk with certain individuals who are out there protesting and making demands from our local government.

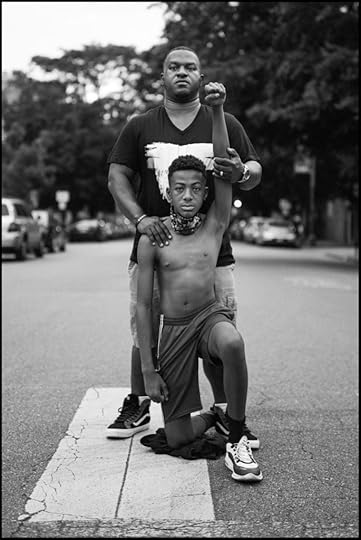

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Vincent and his son Jordon at police headquarters to protest against police brutality, Richmond, Virginia, June 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Vincent and his son Jordon at police headquarters to protest against police brutality, Richmond, Virginia, June 2020Boot: What exactly is going on in Richmond? It’s a place that clearly reflects the issues that America as a whole is facing, but perhaps in a more intense way right now.

Smith: Richmond was formerly known—and to many is still known—as the capital of the Confederacy. We have a very large number of Confederate monuments here, or we did, and of course, the story of African slaves coming over to this country started here, in Virginia.

In 2018, a tension started bubbling to the surface after the killing of Marcus-David Peters. He was a twenty-four-year-old biology teacher that was shot and killed by a Richmond police officer. During, I believe, his first mental episode, leaving his part-time job at a hotel, he stripped his clothing off, ended up in his car, hitting three cars with no major accidents—but he steered off the interstate and got out of his car; he rolled around in the street for a moment after being slightly struck by another passing car. He started approaching the officer with threats. Tasers didn’t stop him. And he ended up being shot and killed by the police officer—an African American police officer at that—and died at midnight.

His family and community organizers started pressuring the local government for transparency and police reform, partially in the form of a “Marcus Alert” that would send members of a mental-health awareness response team for mental-health crisis cases. This was demanded by the community in House Bill 5043 and approved by the Virginia House of Delegates, but currently needs to be approved by the state senate and signed by the governor; that makes us hopeful. The community also was fighting to end qualified immunity with House Bill 5013, but it was voted out. It was a huge letdown knowing that there were Democrats that sided with Republicans to kill the bill.

Christopher “Puma” Smith, A demonstration to convince Governor Ralph Northam to extend the statewide eviction moratorium ends in a physical altercation between protestors and officers and the John Marshall Courthouse, Richmond, Virginia, July 1, 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, A demonstration to convince Governor Ralph Northam to extend the statewide eviction moratorium ends in a physical altercation between protestors and officers and the John Marshall Courthouse, Richmond, Virginia, July 1, 2020Boot: You say “community organizers.” Was that principally Black Lives Matter? Or were many other groups involved?

Smith: With Marcus-David Peters’s case, it was mainly the family. His sister Princess Blanding, is leading that movement, but other independent local organizers have heavily supported it from day one. We don’t have a local chapter of Black Lives Matter. In 757, which is Hampton and Newport News, there is a chapter up there, and it’s called Black Lives Matter 757. They have been in town recently and over the years that I’ve been in Richmond.

Boot: What are the other forces at play? From your pictures, it looks like many different groups, like gun-lobby groups.

Smith: There’s a lot that’s happening besides asking for police reform. There is a huge eviction crisis in Virginia. Richmond is the second city, I believe, in the country with the highest eviction rates. The residents who are at the forefront of these evictions are African Americans, unfortunately. Richmond is predominantly African American. There are organizers who have been fighting for those facing housing issues though. I know of Omari Al-Quadaffi, who works with low-income housing communities and has been on the frontline for these families and individuals. We also have groups like Friends of East End Cemetery and the Evergreen Restoration Foundation, who are working hard to revive two forgotten, heavily overgrown African American cemeteries: East End and Evergreen, where Civil Rights activists like Maggie L. Walker and John Mitchell Jr. are buried. Even veterans from as early as WWI are buried there and were allowed to be completely forgotten, their graves damaged and vandalized.

Also, on July 1 of this year, Richmond passed a lot of new laws, and a big chunk of that had to do with gun restrictions. There was a huge uproar leading up to this, and in January the largest demonstration happened and around 22,000 pro-gun activists and militia groups came through from all over the country into the city to protest around the State Capitol building.

So, it’s kind of melding into this antigovernment movement right now. What has also caught my attention are the African American gun-owners, and your white pro-gun communities—they are both demanding that they still have enough authority to be armed and to protect their own communities. Now, there’s a lot of disagreements around that and between these communities, but what has been obvious to me is that this is what these two communities, or all of the pro-gun communities so far, have in common. They also want police reform. All sides agree to demilitarize the police department. They want more transparency. And they don’t want these Second Amendment–reform laws, because they want to be able to protect their families and communities—both sides do not believe that the police can efficiently police their communities. They don’t trust the police department, basically, in my opinion.

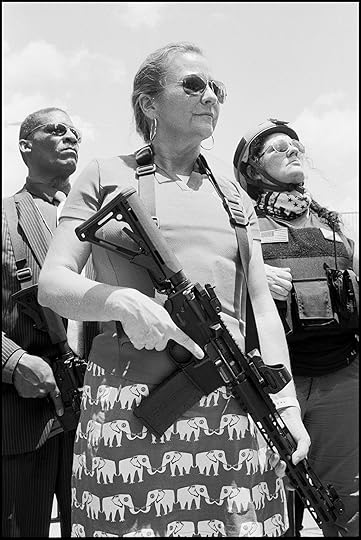

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Virginia State Senator Amanda F. Chase, a candidate for governor who backs replacing all removed Confederate monuments, participates in a Second Amendment rally, Richmond, Virginia, July 4, 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Virginia State Senator Amanda F. Chase, a candidate for governor who backs replacing all removed Confederate monuments, participates in a Second Amendment rally, Richmond, Virginia, July 4, 2020Boot: One gets the sense that it is a place where white supremacists still get to voice their views.

Smith: Yes. What has also bubbled back up to the surface is the talk of the Confederate monuments. I talked to Regina Boone. She is the daughter of the creator of a local newspaper, Richmond Free Press, which mainly reports on the African American community here in Richmond. She expressed to me once that her father has fought for the removal of those statues since the ’60s. The sites of those monuments have melded into the scenery here. But now, as people are pushing for police reform, the degree of anger around that conversation and racism has risen, so that in Richmond, they are on a roll of eliminating any kind of racially divisive symbolism, such as schools named after Confederate soldiers and any Confederate symbolism. A law passed on July 1 was used by Mayor Levar Stoney, a young Black man, to bypass a city council vote to immediately start removing Confederate monuments. There is still a community here that wants to protect this so-called “heritage,” but it’s a predominantly Black city—all the public schools here are predominantly Black, and we have a mayor who is Black, there’s the lieutenant governor who is Black, and our city council consist of members that are Black, white, and people of color. So it’s very strange that they still had these monuments erected down Monument Avenue and around the city today.

You have to remind yourself to follow the dollar though. The statues that are on Monument Avenue provide tourism dollars, and tax incentives for the avenue residents and of course, their property value goes up. The main and largest statue is of Robert E. Lee. He led the Confederate Army and has one of the most infamous reputations in the history of the Confederacy. The property that his statue sits on was donated by a local family, and the city accepted it in 1890. They were the main individuals suing the government based on the deed their family signed in 1887 with the city. Others were suing hoping that the judge, who lives in the area, would side with them so their property value and tax incentives would remain. That judge has since recused himself. The current lawsuit that prevented removal is going to trial in October.

Lee’s is the only state-owned statue, and it was thought by most that state code prevented removing it, but it is becoming clear that wasn’t true. The area has now become this rallying point for the community, for the city. I mean, the statue is covered in graffiti and spray paint, and it’s become this central art piece. Most of the events that are happening, most of the rallies and protests, end up or start at this monument. There have been orchestras out there and local artists. There is a community garden, basketball hoops, and even wellness and voter-registration tents, but those tents were violently removed from the area by police. Even the Floyd family came down and had a hologram art installation and spoke to the community there. So it’s been mainly this powerful space for people to just come together and converse and share their opinions on what’s going on now. The circle has been renamed Marcus-David Peters Circle by locals.

What’s bizarre is that Robert E. Lee was against monuments to the Civil War. He knew it would be divisive, then and now.

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Mike Dunn of the Boogaloo Boys stands guard at Black Guns Matter rally as the Original Black Panthers of Virginia make their way to speak to the crowd, Richmond, Virginia, August 15, 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Mike Dunn of the Boogaloo Boys stands guard at Black Guns Matter rally as the Original Black Panthers of Virginia make their way to speak to the crowd, Richmond, Virginia, August 15, 2020Boot: With so many arms and such strength of feeling, it looks like a war coming. Do you feel this is a sort of continuation of the Civil War?

Smith: Well, there has been a group called the Boogaloo Boys that has come into a lot of people’s attention. Learning about the Boogaloo Boys, we know of 125 groups spread across the country. There’s no local leader. They are known as far right. They are antigovernment, and they believe in inciting a civil war. They, at least the people I have talked to, believe that this government, this dual-party system, is not for the people at the end of the day.

But this group, which is seen as white supremacist, they have been collaborating with the Black Lives Matter 757 chapter. Just the other day, they were invited to a Black Guns Matter rally organized by BLM757. They have shown up for funding schools and for anti-eviction rallies and other protests around the city—though not received and welcomed whole-heartedly, but they have been there. I think their purpose, which they have admitted to, is for some degree of civil war and anarchy to just bring down the system, however that looks.

For me, man, it’s always tricky. There’s definitely a racism problem. There’s also definitely this superiority issue that we have in this country that I think stems from capitalism. But sometimes I don’t know if people are fighting for status, or they are fighting to eliminate or expose racism within the hierarchy here in this country. Because now, there is so much degrees of division, quarreling on social media, and building of brands off of the mistakes from one’s own community members, unfortunately, within African American groups fighting for police reform and equality. Time always tells what people are really fighting for.

Christopher “Puma” Smith, The end to an intense quarrel between Black and white protestors, Richmond, Virginia, July 4, 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, The end to an intense quarrel between Black and white protestors, Richmond, Virginia, July 4, 2020Boot: Are you saying that the extreme right-wing groups are seeking to forge an alliance with Black groups to take on the government together?

Smith: They haven’t explicitly come out and said that. But they have stated their intent—the Boogaloo Boys. This specific group and this specific sect here in Virginia, they have said they are for civil war, and they are antigovernment, and they are for police reform; they want to demilitarize the police department. They want to be able to protect their own community in the way they want, in the way that they see fit. But they have been walking and marching side by side with Black gun activists. On the day Black Lives Matter 757 did a Black gun rally, there was Black Lives Matter 757, there was the Huey P. Newton Gun Club, the Original Black Panthers of Virginia, there were some white militia groups that showed up, and Spike Cohen, the VP nominee for the Libertarian Party was invited to speak and get enough signatures to be on the ballot. It was just this melting pot, but the common ground was the Second Amendment and distrust of the police.

Boot: You see that in your pictures. For the most part, your images don’t show conflict. They show motivated people, activists—maybe they’re angry, but I don’t see venom. I actually see a relatively civil process going on that you could say is a good example of people resolving their issues peacefully.

Smith: Yes. I think I’m more productive when the protests and the rallies are stationary. Marching down the street is good to capture photographically for historical purposes. But the rallies that are stationary, when they start and when they end, is my opportunity to go and record speakers and to interview people one-on-one on their opinions and their perspectives. It hasn’t been as chaotic as Portland. Some of the protests have gotten out of hand. Some cars got set on fire. Buildings are being damaged, protestors being violently handled by police, arrested, and even charged with felonies, unfortunately. But more has been done just pressing our local politicians and policy-makers, and organizing around that, using the internet and our dollars, instead of going out and just bashing windows and setting cars on fire and destroying property. But I cannot deny that the protests and rallies have helped in some way.

I agree with MLK. It’s the voice of the oppressed, and that’s how a certain percentage knows how to get their point across. But at the end of the day, for me, it’s again, follow the dollar and use your dollar to really make a difference. I think people are catching on to that.

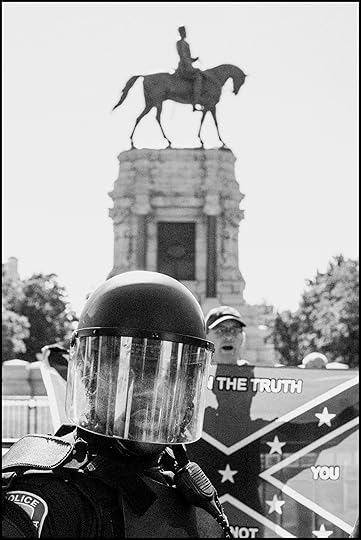

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Neo-Confederates protest the removal of Confederate monuments,

Christopher “Puma” Smith, Neo-Confederates protest the removal of Confederate monuments,Richmond, Virginia, 2020

Boot: Are you trying to make an account of every side of these arguments? Are you talking to white racists?

Smith: Yeah. I’ve talked to some white militia groups and members of the Boogaloo Boys. The community here is still very suspicious of them, and some of them have just flat out not accepted them and basically told them they’re not welcome. They’re anywhere from nineteen to twenty-two years old. They grew up in rural Virginia. They’ve admitted that they’ve had twisted perspectives from early on and still do now. I think because they’re coming out at such a young age and collaborating with the Black community—I think, for the better, their perspectives are changing. Hopefully. I’ve also talked with Senator Amanda Chase, who is running for governor and is pro-gun and believes in replacing statues. In her words, the Confederate flag for her means iced tea and The Dukes of Hazzard. I’ve also briefly talked with Chuck Smith, who is an African American attorney running for attorney general and a veteran who also is pro–Second Amendment and believes in replacing statues.

My reason for talking to people is to find where the common ground is. Ever since I came to Richmond, I listen to right-wing radio more than left-wing radio. I listen to Jeff Katz and John Reid and Rush Limbaugh and Hannity and Glenn Beck. I listen to all these people, and I listen to left-wing radio also. I’m giving up on mainstream media. I want to see how we can actually get something done, and not just, you know, rage and let it pass. What I found is that people want transparency, and they want to have a voice—an opinion on how their communities should be policed.

Christopher “Puma” Smith, The circle around the Robert E. Lee statue, the last remaining Confederate statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond, has been renamed Marcus-David Peters Circle after biology teacher Marcus-David Peters, who was shot and killed by Richmond Police in 2018, Richmond, Virginia, June 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, The circle around the Robert E. Lee statue, the last remaining Confederate statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond, has been renamed Marcus-David Peters Circle after biology teacher Marcus-David Peters, who was shot and killed by Richmond Police in 2018, Richmond, Virginia, June 2020Boot: Are you trying to be objective in the traditions of photojournalism? How do you conceive of your own role as a photographer and a gatherer of documentary evidence and stories?

Smith: I am going out to be an individual, to really learn the community, continue to learn Richmond and the community that has been here fighting for years. It’s really about trying to be an individual, and not going out there with any kind of bias. Again, just trying to find common ground.

But, it’s very tricky, because people want to put you in a group. They want to see: who are you with, who are you defending? And yes, I have my own personal opinions. But again, it’s trying to find: what do we all want, and can we get it accomplished? And maybe, in the midst of that, these prejudices and this degree of racism can be eliminated, once everybody finds a common purpose and a force to communicate and converse and be together for this one purpose. I am going out there really for my own personal education, and to meet people one-on-one, and then to get their perspectives, if they’re willing to share.

Boot: Are you hopeful?

Smith: For the community members, yes. I mean, people who are not elected officials and the people who are starting grassroots movements and have been consistent. I have become hopeful again. I have become hopeful as far as meeting a goal, which is police reform. I am hopeful for that.

Boot: Are you hopeful for America?

Smith: [Laughs] As far as what?

Boot: A better path than the one that we’ve been on, which is division. Hate and division.

Smith: No. Honestly, I’ve tried to be as positive as I can in my short time here. But I see a pattern that we are not breaking, and I am not hopeful. I am not hopeful for America. But I don’t know how we start over. I don’t know how we slow down. Capitalism has been ingrained into everyday life and how we function and how we communicate. It’s hard to answer that, man.

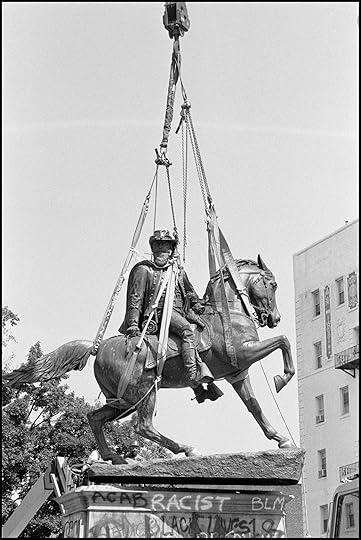

Christopher “Puma” Smith, J. E. B. Stuart Confederate monument being removed, Richmond, Virginia, July 7, 2020

Christopher “Puma” Smith, J. E. B. Stuart Confederate monument being removed, Richmond, Virginia, July 7, 2020Boot: When you say “capitalism” in that context, I presume you mean the way capitalism favors some and discriminates against others.

Smith: There is always going to be a hierarchy. Looking at Richmond, we say we give everybody a fair chance, but we really don’t, because we don’t focus on the basics of humanity when it comes to just living in general and when it comes to surviving in a capitalist economic system. In Richmond, we don’t focus on and invest enough in education, and it’s predominantly Black schools. If we don’t start there, how are we saying, you know, everybody is getting a fair chance—if we don’t start with education first?

Boot: And health second, presumably.

Smith: Yes, it’s very frustrating.

Boot: You have another source of making a living, which is as a singer with a band that tours a lot, so you’ve seen a lot of places. You’ve worked all over the world. You’ve worked in Ethiopia, for example, doing photography assignments. Is it unusual for you to focus on one place and your hometown in this kind of way? Is this the first time you’ve done that, delved into one community as a photographer and a documentarian?

Smith: Yes. I think I’ve finally got the discipline to focus my camera on a story. I’ve shot for papers, taught photography in nonprofits, and I was hired by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to travel to different rural regions in Ethiopia to document pre- and postnatal care in 2019. I’ve also traveled for ten years with Thievery Corporation, mainly as a vocalist, but always with camera in hand documenting the band. Now, I think my previous experiences have given me this discipline. And especially being a person of color in America has allowed me to have the discipline to not be scatterbrained when I’m picking up the camera. It’s allowed me to actually give myself this kind of tunnel vision, in a sense, to focus and form relationships and converse around this one story. The camera motivates me, picks me up and makes me be present. But it is the research and meeting people which is hard to do in this time of social distancing and, you know, “don’t call me, just text me or e-mail me.” People just don’t want to deal with people one-on-one or face-to-face anymore. So it’s harder even to get people to express their perception honestly on audio and on camera. It’s frustrating and depressing at times, but it’s something that I’ve become more passionate about. One day at a time, one person at a time, one conversation at a time.

The Photographer Whose Mother Built Trump Tower

In 1978, when Donald Trump met Barbara Res, he called her a “killer.” Barbara was then one of the few women working as a construction engineer in New York, but after Trump witnessed her berating male workers renovating the Grand Hyatt on 42nd Street (Trump’s first major Manhattan real estate project), he snapped her up. “He said men are better than women, but a good woman is better than ten men,” Barbara recalled in 2016. She would go on to manage the construction of Trump Tower, and pictures of her at the Fifth Avenue construction site in 1980—with her hard hat and wraparound sweater, standing as if on a dais amid scaffolding far above a foundation pit—evince her formidable self-possession. “I was that woman,” Barbara said. She was thirty-one years old.

The photographer Res turned thirty-one on November 8, 2016, the day Trump was elected president. Res was at the Yale School of Art at the time. “The sculpture department threw a party for me and it was the worst party you could imagine,” Res said recently over Zoom from Sweden, where they are currently living. The day after Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, Res and their mother, Barbara Res, joined the Women’s March in Washington, DC. Trump Tower was part of Res’s mythology as a child: Res had pored over profiles of their mother in the magazine Savvy Woman; the mauve Trump Tower marble was as familiar as a household rug. But Barbara had long since left the Trump Organization, and in 2016, she began to speak out against her old boss. Her media appearances provoked a typically offensive tweet from @realDonaldTrump: “I gave a woman named Barbara Res a top N.Y. construction job, when that was unheard of, and now she is nasty. So much for a nice thank you!” For some women, “nasty” is a badge of honor; at the Women’s March, Barbara held aloft a sign that read, “I AM THE WOMAN WHO BUILT TRUMP TOWER.”

Res, Spread from Towers of Thanks (Loose Joints, 2017)

Res grew up in New Jersey and studied photography at Smith College. They started out experimenting with self-portraiture, but “the faculty were just so tired of ‘women’ constantly using themselves as subjects,” Res said. “We were kind of asked not to do self-portraiture.” Later, in 2015, Res—a self-described “jock” who once trained as an amateur boxer—began a project about their father, who had recently lost his job and was spending all his time at home. Res was at Yale, and they would return to New Jersey on weekends, collaborating with their father on what would become the series Thicker Than Water (2015), a speculative family portrait tinged with dramatic shadows and neonoir flair. Res and their father had drifted apart, but the project became a way to relate and mediate feelings about queerness, masculinity, unemployment, and family expectations. Res was motivated to “witness him,” they noted in an interview for MATTE magazine in 2016. “He spends so much time alone and unseen, so it felt special to me that I could put my eyes on him, that I could value him in that way.”

One of the most striking photographs in Thicker Than Water is a self-portrait of Res dressed as Barbara. Res wears Barbara’s wig and an ill-fitting red bra. Barbara did Res’s makeup, pouty lipstick and overapplied rouge. Surrounded by heavy liner, Res’s glowing eyes look searchingly into some faraway distance. As Barbara, Res appears neither behind a mask nor fully embodied; like a Cindy Sherman Hollywood/Hamptons self-portrait or a Duane Hanson sculpture, the uncanny tension between life, image, and pose is unsettling. Res tattooed “Butch” on their chest for the image, which they describe as “one hundred percent” drag: “Drag as my mother. Drag as a woman.” “It is a funny picture,” Corrine Fitzpatrick notes in MATTE, “awkwardly performed and thoughtfully, committedly, composed.”

Res, Me as Mom, 2015

Res, Me as Mom, 2015Elsewhere in Res’s practice, the body and the figure take on similarly sculptural forms. In one image from the series Read You (2013–15), Res captures a subject in a black bra who, as she pulls off a mustard-yellow sweater, obscures her face like a lone René Magritte lover. “I was trying to think about how to describe intimacy outside of the reveal,” Res said. “Sometimes what we don’t show, or what we don’t display, is just as much of a reveal.” Just at the moment when the subject in Stevie (2014) may become known to us by her face, all we can see is outline, as well as a doubling in the form of a shadow on the wall—a totem, a smoky silhouette. The drop of sweat from Stevie’s armpit is the punctum. “And that being kind of what’s out of control,” Res said. “This beautiful gesture of it dripping.”

But sweat, for all of its associations with physical lust, becomes a tragic substance in Res’s series Pulse (2016), made in the aftermath of the mass shooting in 2016 at the eponymous gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Res was driving to Florida for a residency when alerts began to arrive about the massacre. They began to visit the makeshift memorial that had materialized in Pulse’s parking lot but decided against making portraits of survivors or witnesses. Instead, Res was moved by the temporary walls erected of chain link and shrouded in black cloth, into which visitors stuck flowers, signs, and rainbow flags. They were “poetic articulations of public mourning,” Res said, noting that the sweat and the humidity in the parking lot was like the enclosed space of a nightclub. “You think about being in a club, the last breath of these flowers. You’re seeing them die.” Separating life and death, the memorial fences seemed to contain a form of evanescent queer memory: fierce, colorful, and operatic.

In all of their work, Res searches for bonds between people, from the nuclear family in the household to the contingent family of a protest. Res’s self-portrait as Barbara makes a cameo in Towers of Thanks, Res’s 2017 photobook about their mother. Doing overtime as a specific impression and a seemingly universal gesture to the performance of femininity and motherhood, the image fits alongside pages of Res’s photography and collaged vintage images of Trump Tower, news clippings from Barbara’s heyday. At thirty-one, Barbara was atop Trump Tower, a powerful woman working to realize a man’s dreams. At thirty-one, Res was down on the street with Barbara, both their voices shouting together with thousands of others. But history has a way of haunting the present. After the completion of Trump Tower, Barbara was given a Cartier bracelet engraved with the words “Towers of Thanks.” When you turn the bracelet in your hand, another line appears in elegant cursive: “Love, Donald.”

Res, The Woman Who Built Trump Tower, 2017

Res, The Woman Who Built Trump Tower, 2017 Res, Flowers (Blue, Purple, Pink), 2016

Res, Flowers (Blue, Purple, Pink), 2016 Res, Flowers no. 1, 2016

Res, Flowers no. 1, 2016 Res, Stevie, 2014

Res, Stevie, 2014 Res, TV Light, 2015

Res, TV Light, 2015 Res, Mom with Dad’s Shadow, 2015

Res, Mom with Dad’s Shadow, 2015 Res, Like Pearls, 2015

Res, Like Pearls, 2015 Res, Julia’s Back, 2014

Res, Julia’s Back, 2014Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

All photographs courtesy the artist.

September 24, 2020

Kimowan Metchewais’s Search for Visual Sovereignty

For the 2002 installation Without Ground, the Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais transferred dozens of small photographic self-portraits to the white walls of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania. The full length likenesses were posed in the ICA’s Ramp Space as if they were searching the empty expanse for something hidden from both artist and viewer. By cleverly using scale and gently fading some of the photo transfers, Metchewais, who at the time went by his stepfather’s surname, McLain, created the illusion of figures receding into space. Treating the walls of the museum as the “ribcage of a living animal,” he felt that his photographs were like “tattoos etched onto the bones of the beast,” anticipating their burial within the institution’s architectural memory, covered by future layers of accumulated paint.

More than a decade later, in 2014, the Omaskêko Cree artist Duane Linklater meticulously scraped small layers of paint away from the ICA’s walls, creating stratified craters in search of the installation. The effort to uncover these photographic traces was akin to a search for Metchewais himself, an attempt to connect with the artist who had passed away only a few years earlier, in 2011. The search for evidence was forensic, replicating the investigatory nature of Metchewais’s wandering figures. “I think North America is a crime scene,” Metchewais said of Without Ground in 2006. “I hate to say it, but what happened to the land and people here was/is a crime. People today don’t see that. They understand it, they know it, but it doesn’t seem to mean that much to them. To me, it means a lot, in many ways.” The white museum wall became a site on which to consider the theft of Indigenous land evoked by the installation’s title, an example of the ways in which Metchewais’s photography rearticulates colonial memory. His work explores the ground, aesthetic and territorial, on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand, and his images propose a new intellectual space that exceeds the mere subversion of stereotype.

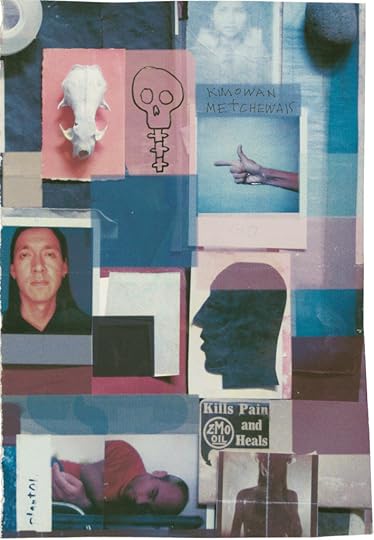

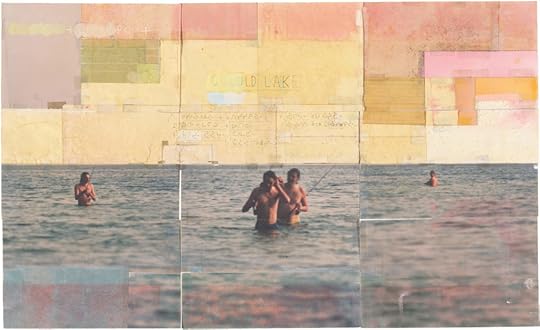

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait collage, undated

Kimowan Metchewais, Self-portrait collage, undatedConsider Metchewais’s most lauded work: the Cold Lake series (2004–6). It consists of photographs of children and other community members from the artist’s homeland of Cold Lake First Nations, Alberta, Canada, shot in the style of straight photography on the street or pictured wading in the namesake Cold Lake. Notes in Metchewais’s sketchbooks offer what he calls “post-Curtis portraits,” works that are empty of ethnographic baggage and instead emote “reclamation” and “a desperate, pathetic attempt to restore” and “to elevate human status.” It is a reference to and an attempt to move beyond the outsize influence of the photographer Edward Curtis, whose staged and romanticized portraits from the twenty-volume anthropological series The North American Indian (1907–30) have permeated the visual imaginary. Cold Lake Venus (2005) features a young girl facing the camera, hip-deep in the water that stretches behind her to meet the sky at the horizon. The photograph is saturated with what Metchewais calls “divine beauty,” emanating from the girl like the ripples in the lake water. “Look at us emerge. We are beautiful, standing in a magical place, just back from the Wal-Mart [sic],” Metchewais writes of the work. He succeeds in building new image worlds to express a fundamental connection to home and place while evoking Indigenous and Greek creation myths.

Born in 1963, in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, Metchewais adopted his mother’s maiden name in the latter part of his life. He began his career creating political cartoons and graphics for Windspeaker, Canada’s most widely distributed Indigenous content newspaper, before receiving a BFA from the University of Alberta in 1996. His early work tackled the legal and cultural frameworks of Indigenous identity and tribal membership, questioning the means by which identity is defined and the demand, still present today, for Indigenous artists to perform a so-called authentic connection to land, language, and community. His 1989 painting A Guide to Doing Contemporary Indian Art pokes fun at the collage aesthetic prevalent in the work of First Nations contemporary artists in the 1980s such as George Longfish, Jane Ash Poitras, and Joane Cardinal-Schubert, the latter of whom was a mentor and purchased the piece. Handwritten penciled text on a red-painted rectangle instructs: “place images below . . . ,” “old photographs,” “some modern stuff for contrast,” “syllabics,” “buffalo(s),” “a few tipis,” and so forth.

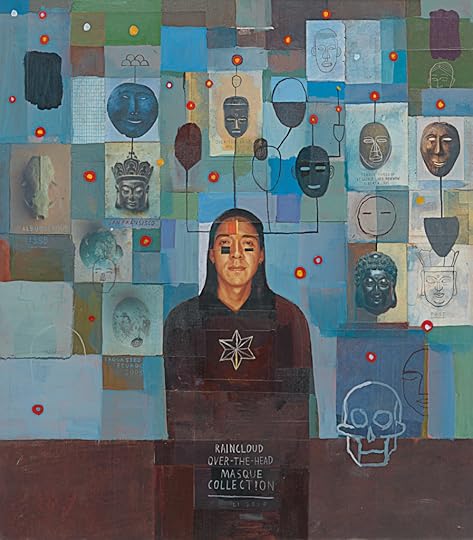

Kimowan Metchewais, Raincloud, 2010

Kimowan Metchewais, Raincloud, 2010Metchewais received his MFA in 1999 from the University of New Mexico (UNM), where he began to rigorously develop the photographic and mixed-media practice he is known for today. He challenged the authority of fixed representation while pursuing answers to the question of authenticity he asked of himself and his work: “What makes Indian people Indian?” His mixed-media compositions and elaborate photo collages incorporate references to Native art history: ledger paper and parfleche designs juxtaposed with images of urban and natural landscapes, or pictures of Plains elders mined from archives and popular culture. His 1999 installation After, first exhibited in his MFA thesis show at UNM’s John Sommers Gallery, included illusionistic photo transfers depicting birds, insects, and bowls on the gallery walls, a process Metchewais called “photographic gallery tattoos.” It was an antecedent to Without Ground and exemplified his pursuit of “elegant solutions to challenges of narrative in space.”

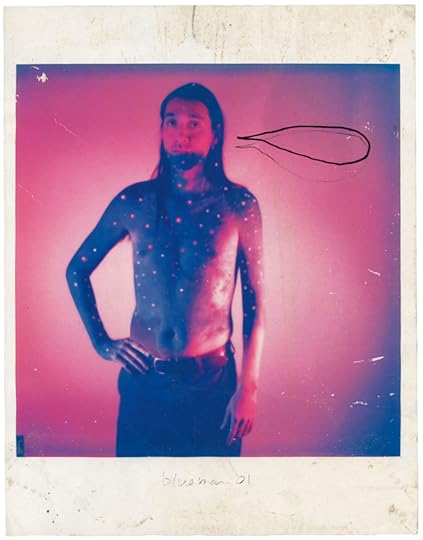

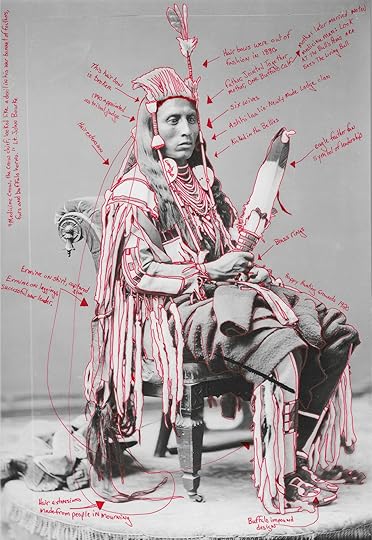

Kimowan Metchewais, Indian Handsign, undated

Kimowan Metchewais, Indian Handsign, undatedThe Polaroid was core to Metchewais’s process, and while at UNM, he began amassing an extensive personal archive, meticulously organized during his lifetime by subject and alphabetized in boxes. He used these photographs as references for his paintings and embedded them in his mixed-media collages and as transfers to large-scale works on paper. He cut up, rearranged, and taped them back together before rephotographing and reentering them into the collection as a shifting and circulating living archive. The tactility of the cut-up photographs, with conspicuous scratches, creases, and Scotch tape fastenings, distinguishes them from digital images, and Metchewais sought to maintain those qualities even when he rephotographed his Polaroids and digitally printed them. Metchewais commented at a 2009 conference on “Visual Sovereignty” at the University of California, Davis, that “few things compare to the silky touch of a newly developed print in the palm of one’s hand.” His Polaroids also freed him from a reliance on archival images. Instead, Metchewais’s use of personal source imagery avoided the need for intervention, interrogation, and reinscription that typically weighs down some work by contemporary Native photographers who explore the archive as a site of privileged access, subjugation, and colonial violence.

Metchewais’s Polaroids contain many series: toy buildings and animals shot in a studio; smokestacks and mountain ranges; flowers, cars, and other quotidian objects. In one undated set, the artist photographed his own hand in a series of gestures, some of which were later modified and digitally printed under the title Indian Handsign. Loosely held poses of an arm and fingers recall anatomical studies, while distinct hand shapes suggest a form of sign language. On these Polaroids, Metchewais penciled labels directly below the images: a trigger-finger pose is labeled “go”; an upward-facing palmis labeled “open.” The hand signs function as study and reference materials while also triangulating a relationship between body, language, and image. The signs do not appear to be based on American Sign Language nor on what is known as Plains Sign Talk, a historical sign language used by Indigenous peoples across central North America in trade and oratory. Purported manuals for Plains Indian Sign Language were published throughout the twentieth century, and the language was widely appropriated by the Boy Scouts and other non-Native societies and summer camps. Eraser smudges on the Polaroids suggest that Metchewais wrote and rewrote the labels, drafting his own language for this series of universal gestures, countering appropriations with a new baseline of bodily signs.

Metchewais circulated language throughout his work. He often signed his name Kimowan in Western Cree syllabics, ᑭᒧᐘᐣ. In several versions of his 2004 photo collage Cold Lake, the Cree name for the lake, atakamew-sakihikan, appears in syllabics underneath the English. These works are examples of what he called his “paper walls,” photographs printed on paper sheets taped together into wall-size constructions. They make clear why Metchewais identified not as a photographer but rather as “a sculptor of flat, rectangular objects of various textures and tone,” and because some of the pieces of tape are in fact photographic images of paper taped together, the simulation of texture blurs reality with representation. The papers were dipped in water colored by rust and tobacco, “baptized,” in the artist’s words, as a ritual act. Because tobacco is a sacred substance among many Indigenous peoples, the material of the work might be considered animate; “Cold Lake is a kind of prayer,” Metchewais said of the work.

Kimowan Metchewais, Spotted Kimowan speaking bubble, undated

Kimowan Metchewais, Spotted Kimowan speaking bubble, undatedThat prayer is to home, family, and memory. Cold Lake depicts multiple iterations of a scene of Metchewais and his brother Conrad wading below the long horizon line of the lake. It combines several snapshots taken by the artist’s mother from the lakeshore. The photographs are “a record of family love,” binding Metchewais, his family members, and the lake and sky in kinship relations. Given its wall-size scale, the close viewer becomes wrapped in the experience and memory of that place. These works are less about the recovery or performance of memory than a living relation to the land. They also situate home and place as terms that escape essentialism. In Goodwill, 118 Avenue, Edmonton (2010), Metchewais captured a scene of dropped-off furniture donations awaiting pickup along a wall in an urban Native neighborhood. The orderly rectangles evoke modernist compositions, and for the artist they stand in as one of many incarnations of home, both territorial and adopted.

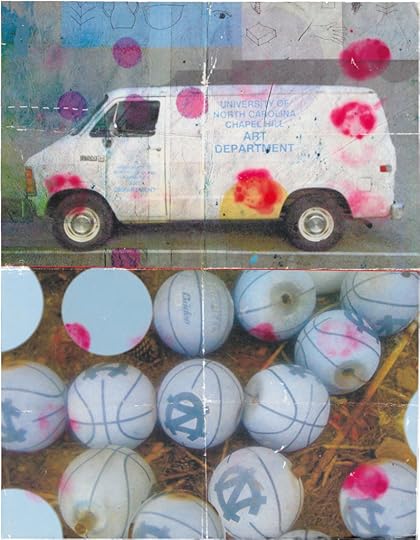

Kimowan Metchewais, UNC Art Department Van, 2010

Kimowan Metchewais, UNC Art Department Van, 2010Metchewais was ever conscious of the pitfalls of representation. He taught in the studio art program at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, from 2000 to 2011, reaching the rank of associate professor, and his course-planning notes include outlines of the histories of depicting Native America, from trope of the “noble savage” to the erroneous notion of the “vanishing race.” His sketchbooks contain drawings based on art historical representations, such as copies of the famous portraits of Native American delegates and visitors to Washington, D.C., drawn by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin from 1804 to 1807. Yet Metchewais’s fully realized works show little of the typically overwhelming concern among Native American photographers of his generation with debunking and overturning such stereotypes. Instead, his self-portraits pursue the kind of “self-made Native imagery” he saw reflected in online culture, as he wrote in a 2009 Facebook note. He fashioned a host of characters, such as the Marlboro Indian smoking a cigarette in a cowboy hat. In a shirtless photograph, his upper body, painted dark blue from the chin down, sparkles with starry points of light like the cosmological images from the late nineteenth-century ledger art of the Itázipcho Lakota artist and visionary Chetán Sápa’ (Black Hawk). A photograph from Metchewais’s graduate-school period depicts a figure wrapped head to toe in a black-and-white striped textile—a body that, while abstracted, evokes the heavily romanticized image of the Plains Indian wrapped in a chief ’s blanket.

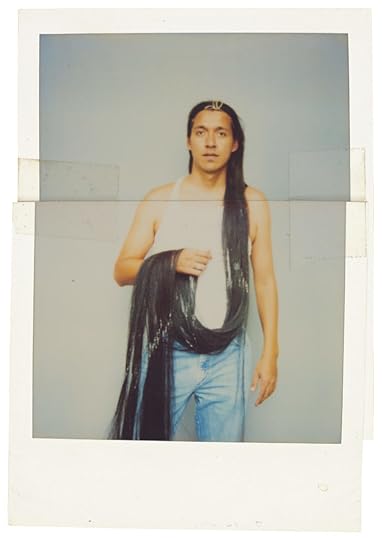

Kimowan Metchewais, Long Hair (detail), ca. 1996–98

Kimowan Metchewais, Long Hair (detail), ca. 1996–98In 1993, Metchewais was diagnosed with a brain tumor that chased him for the rest of his life. Surgery left him with a permanent bald spot on the back of his head. In a series of Polaroid selfportraits, Metchewais, in a white tank top and faded jeans, dons a hairpiece that stretches to the floor. Using two Polaroids to fully capture the length, he drapes the hair over one arm and pictures it dragging along the floor beside his bare feet. Long hair was a sign of Indianness to Metchewais, and he incorporated his own hair into some of his sculptural installations. In a 1984 comic for Windspeaker, a cartoonish Native man with long braided hair, perhaps representing the artist, asks, “Tell me . . . what is the true essence of being an Indian?!” A guru on a mountaintop replies, “That all depends . . . on if your mother married off the reserve before or after 1950 . . . how long yer hair is . . . how much pure blood you have . . .” The exaggerated length of the hairpiece and its visible artificiality make up an ironic take on this sign of Native identity while highlighting a vulnerable feature for the artist, who lost his own hair due to repeated surgeries and treatments.

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake Fishing, undated

Kimowan Metchewais, Cold Lake Fishing, undatedFollowing complications from one such surgery, in 2007, Metchewais lost the movement and feeling in the left side of his body. One notices that his hand-sign Polaroids, which are undated, are almost exclusively of his right hand. Many of the words labeling the Polaroids—“touch,” “flight,” “recall,” “change”—took on a different valence in the wake of his partial paralysis. Metchewais called his studio “a laboratory” where he conducted an “archaeology of the self,” and in the years following his surgery, he seemed to come to terms with his body, identity, and artistic practice. Grow All Over Again (2008), a short film by Christina Wegs, intimately documents Metchewais discussing this process and his return to the studio after his hospital stay and rehabilitation. In the film, he describes a desire to revisit his old works and “to paint white and black rectangles over all the shit that I don’t like, and then go from there.” In an undated self-portrait, the upper right and lower-left sides of his face are split between two cut Polaroids that cast his skin color in different tones, one pink and the other bronze. Amid the Scotch tape is a series of inked black-and-beige rectangles that spread across the artist’s face but don’t mask his features. The original Polaroids were taken prior to his 2007 surgery, but the modifications suggest he continued to explore his body as a site of the etched cultural markers of ethnic and corporeal identity.

Symptoms from his brain tumor returned in 2011, and in July of that year, Metchewais passed away at his mother’s home in Alberta. The artist gifted his personal collection and archive to the National Museum of the American Indian, which finalized the accession in 2015. In addition to that legacy, traces of his presence remain online. In a July 2008 YouTube video diary, “tellytwoface returns from the rez,” Metchewais recounts a recent trip to Cold Lake following his recovery from surgery. He describes in near baptismal terms a full-bodied plunge into its cool waters, dipping his body like a prayer. “To go in the water and come back out, and see that view. That’s good medicine . . . I’m back and I feel full. I’m really full.”

This essay originally was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “A Kind of Prayer.”

All works courtesy the Kimowan Metchewais [McLain] Collection, NMAI. AC.084, National Museum of the American Indian Archives Center, Smithsonian Institution.

September 9, 2020

How Can Native Artists Challenge the Story of North America Today?

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Trade in Your Quiché Skirts, 2018, from the series Indigenous Woman

Courtesy the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

As guest editor of Aperture’s fall 2020 issue, “Native America,” the artist Wendy Red Star aimed to create the publication she wished she’d had to read when setting out to become an artist. “I was thinking about young Native artists, and what would be inspirational and important for them as a road map,” she says. “The people included here have all played an important part in forging pathways, in opening up space in the art world for new ways of seeing and thinking.”

That map spans a diverse array of intergenerational image-making, counting as lodestars the meditative assemblages of Kimowan Metchewais and installation works of Alan Michelson, the stylish self-portraits of Martine Gutierrez, and the speculative mythologies of Karen Miranda Rivadeneira and Guadalupe Maravilla. “Native America” also features essays by distinguished writers and curators, including strikingly personal reflections from acclaimed poets Tommy Pico and Natalie Diaz.

With additional essential contributions from Rebecca Belmore and Julian Brave NoiseCat, as well as a portfolio from Red Star, “Native America” looks into the historic, often fraught relationship between photography and Native representation, while also offering new perspectives by emerging artists who reimagine what it means to be a citizen in North America today.

Join us for a series of free virtual public programs with photographers, historians, and writers that accompany the release of “Native America.”

Inside the “Native America” Issue with Wendy Red Star and Natalie Diaz

Thursday, September 17 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

Guest editor Wendy Red Star and Poet Natalie Diaz will look inside the “Native America” issue, which considers the wide-ranging work of photographers and lens-based artists who pose challenging questions about land rights, identity and heritage, and histories of colonialism. Red Star and Diaz will delve into the various topics, artists, and takeaways in the issue and discuss their own relationships to its contents.

On the Art of Kimowan Metchewais

Thursday, September 24 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais’s multidisciplinary approach rearticulates colonial memory and explores the ground on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand. This panel brings together writer and art historian Christopher Green, filmmaker Christina Wegs, and artist Will Wilson, all of who will discuss Metchewais’s life and continuing influence on the art world.

Martine Gutierrez and Nadiah Rivera Fellah on Indigenous Woman

Thursday, October 1 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

For the 2018 project Indigenous Woman, Martine Gutierrez played the roles of photographer, stylist, creative director, editor in chief, and featured model to create a 124-page art publication. Throughout its pages, Gutierrez transforms herself into a revolving roster of identities—in some spreads, wearing go-go boots; and in others, appearing in Indigenous textiles belonging to her Mayan grandmother. In this discussion, Gutierrez and curator Nadiah Rivera Fellah will take an in-depth look at the project and navigating of contemporary Indigeneity.

This panel is presented in partnership with Parsons School of Design at The New School

Aperture Conversations: Wendy Red Star at Photoville

Saturday, October 3 at 2:00 p.m., online via Photoville

Join Wendy Red Star for an artist talk about her 2017 project Um-basax-bilua (Where They Make the Noise) 1904–2016, a celebration of cultural perseverance, colonial resistance, and ingenuity. A visual record of found and personal photographs and cultural memorabilia, Red Star’s annotated timeline, on view at Photoville 2020, summarizes the century-long history of the Crow Fair, and examines the cultural shift from colonial forced assimilation to cultural reclamation.

History Is Present: A Conversation with Alan Michelson and Chrissie Iles

Thursday, October 8 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

For more than thirty years, New York–based artist Alan Michelson has produced evocative, influential works that excavate colonial histories of invasion and eviction. A Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Michelson uses photography, painting, video, and installation to create dynamic spaces of visual and auditory immersion. In this discussion, Michelson sits down with Chrissie Iles—who cocurated his 2019 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art—to discuss his career and the power of contemporary Indigenous art.

Read more from Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Through September 17, as part of the Aperture Magazine Collectors’ Edition, collect a signed print by Wendy Red Star for $200—with proceeds going to benefit Crow’s Shadow Institute for the Arts and Aperture.

How Can Native Artists Reimagine the Story of North America Today?

Announcing Aperture magazine’s fall 2020 issue and programing around Native artists.

Martine Gutierrez, Neo-Indio, Trade in Your Quiché Skirts, 2018, from the series Indigenous Woman

Courtesy the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

As guest editor of Aperture’s fall 2020 issue, “Native America,” the artist Wendy Red Star aimed to create the publication she wished she’d had to read when setting out to become an artist. “I was thinking about young Native artists, and what would be inspirational and important for them as a road map,” she says. “The people included here have all played an important part in forging pathways, in opening up space in the art world for new ways of seeing and thinking.”

That map spans a diverse array of intergenerational image-making, counting as lodestars the meditative assemblages of Kimowan Metchewais and installation works of Alan Michelson, the stylish self-portraits of Martine Gutierrez, and the speculative mythologies of Karen Miranda Rivadeneira and Guadalupe Maravilla. “Native America” also features essays by distinguished writers and curators, including strikingly personal reflections from acclaimed poets Tommy Pico and Natalie Diaz.

With additional essential contributions from Rebecca Belmore and Julian Brave NoiseCat, as well as a portfolio from Red Star, “Native America” looks into the historic, often fraught relationship between photography and Native representation, while also offering new perspectives by emerging artists who reimagine what it means to be a citizen in North America today.

Join us for a series of free virtual public programs with photographers, historians, and writers that accompany the release of “Native America.”

Inside the “Native America” Issue with Wendy Red Star and Natalie Diaz

Thursday, September 17 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

Guest editor Wendy Red Star and Poet Natalie Diaz will look inside the “Native America” issue, which considers the wide-ranging work of photographers and lens-based artists who pose challenging questions about land rights, identity and heritage, and histories of colonialism. Red Star and Diaz will delve into the various topics, artists, and takeaways in the issue and discuss their own relationships to its contents.

On the Art of Kimowan Metchewais

Thursday, September 24 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

Cree artist Kimowan Metchewais’s multidisciplinary approach rearticulates colonial memory and explores the ground on which contemporary Native art and communities might stand. This panel brings together writer and art historian Christopher Green, filmmaker Christina Wegs, plus additional panelists, all of who will discuss Metchewais’s life and continuing influence on the art world.

Martine Gutierrez and Nadiah Rivera Fellah on Indigenous Woman

Thursday, October 1 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

For the 2018 project Indigenous Woman, Martine Gutierrez played the roles of photographer, stylist, creative director, editor in chief, and featured model to create a 124-page art publication. Throughout its pages, Gutierrez transforms herself into a revolving roster of identities—in some spreads, wearing go-go boots; and in others, appearing in Indigenous textiles belonging to her Mayan grandmother. In this discussion, Gutierrez and curator Nadiah Rivera Fellah will take an in-depth look at the project and navigating of contemporary Indigeneity.

This panel is presented in partnership with Parsons School of Design at The New School

Aperture Conversations: Wendy Red Star at Photoville

Saturday, October 3 at 2:00 p.m., online via Photoville

Join Wendy Red Star for an artist talk about her 2017 project Um-basax-bilua (Where They Make the Noise) 1904–2016, a celebration of cultural perseverance, colonial resistance, and ingenuity. A visual record of found and personal photographs and cultural memorabilia, Red Star’s annotated timeline, on view at Photoville 2020, summarizes the century-long history of the Crow Fair, and examines the cultural shift from colonial forced assimilation to cultural reclamation.

History Is Present: A Conversation with Alan Michelson and Chrissie Iles

Thursday, October 8 at 7:00 p.m., on Zoom

For more than thirty years, New York–based artist Alan Michelson has produced evocative, influential works that excavate colonial histories of invasion and eviction. A Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Michelson uses photography, painting, video, and installation to create dynamic spaces of visual and auditory immersion. In this discussion, Michelson sits down with Chrissie Iles—who cocurated his 2019 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art—to discuss his career and the power of contemporary Indigenous art.

Read more from Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Through September 17, as part of the Aperture Collectors’ Edition series, collect a signed print by Wendy Red Star for $200—with proceeds going to benefit Crow’s Shadow Institute for the Arts and Aperture.

People of the Earth

What can artists, archivists, and communities learn from historic collections of Native photography?

By Wendy Red Star

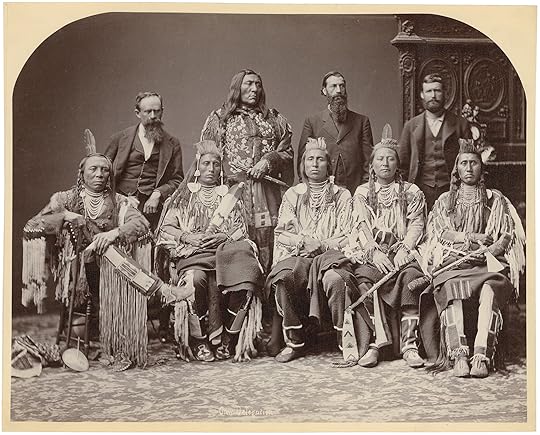

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), 2014, from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation. Original photograph by Charles Milton Bell, 1880, from the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Courtesy the artist

I met Emily Moazami in October of 2018 during my Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship in Washington, D.C. It was my first time in the capital and my first experience working with the Smithsonian museums. My initial goal was to research Apsáalooke (Crow) delegations using the photography archives and material objects at the National Museum of the American Indian, the National Anthropological Archives, and the National Museum of Natural History. Emily, assistant head archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian’s Archive Center, not only produced material pertaining to my research topic but led me to discover a personal connection—a direct link to my ancestors whose images and artifacts are housed in the museum.

In this conversation, Emily and I discuss the photography collections of the National Museum of the American Indian and some of my discoveries from my research, as well as questions about the care of these precious materials. We also talk about the importance of collaboration between communities and institutions in building connections that strengthen the collective knowledge and history of the Archive Center’s holdings.

Fred E. Miller, Red Star, Black Hair, and Small Medicine Tobacco on horseback in front of a tipi. Apsáalooke Reservation, Montana, ca. 1898–1910

Courtesy the National Museum of the American Indian

Wendy Red Star: The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) has a vast collection. But a lot of these images don’t have identification when it comes to Native people. What is your process at the museum for identifying Native people?

Emily Moazami: Unfortunately, a lot of photographers didn’t record the names of Native peoples because they saw them as archetypes of noble savages and a dying race. We are working hard to repersonalize these images and add people’s names to the archival records. Many identifications actually come from descendants of the people depicted. When we have visitors to the archives looking through photographs, we’ll get identifications that way. Or somebody who is not related but from the community recognizes someone.

Red Star: Besides community members, what other resources are used as important measures for identification?

Moazami: Sometimes it will come from an anthropologist’s field notes. An anthropologist goes into a community, and he photographs the people there, he collects objects, and he takes notes. Other times, it might come from a researcher who has worked with a particular community often. As a photo archivist, you tend to recognize people’s faces if you’re researching a particular community a lot. We also get identifications from other institutions’ records.

Red Star: What about professional photographs?

Moazami: Yes, for example, if somebody sat for a delegation photograph taken when Native representatives were meeting with government officials, the image would be clearly documented with the person’s name, so then if you find an amateur photographer’s photograph of that same person, you might be able to match it up that way.

WRS: What happens if different community members have different identifications, or if someone can’t be identified at all? Then what?

Moazami: If someone identifies a person, and later someone else comes along and says, “No, the first identification is wrong,” then what we’ll often do is put both names in the catalog records. We always put the source of that information in an internal note in our database. That way, in the future, if someone shows up at the archives and says, “How do you know it’s this person?” we can trace back to where we got the information in the first place.

But, unfortunately, there are a lot of people in the photographs who may never be identified, and as generations pass on, we lose that opportunity to work with people who have that knowledge. So really, time is of the essence.

Fred E. Miller, Bear Tail standing outside a tipi and holding a sword. He is wearing eyeglasses or goggles. Apsáalooke Reservation, Montana, ca. 1898–1910. (Bear Tail was Wendy Red Star’s great-great grandfather, who gifted objects to the National Museum of the American Indian’s collection.)

Courtesy the National Museum of the American Indian

Red Star: When it came to that supposed image of my great-grandfather Red Star, I tried to figure out if it was him by going through the censuses. But the date of when that photograph was taken indicated that he would have been a middle-aged man and not a child. I thought maybe it could be my grandfather Wallace Red Star Sr. Then I found that same image in the National Anthropological Archives with the child labeled as Sidney Black Hair. How do some images end up in multiple archives across the country, and how can researchers approach tracking down their sources from various collections?

Moazami: It’s the nature of photographs and how they’re shared. Professional photographers made prints and scattered them around. Amateur photographers may have sent some of the photographs to family members or friends. Many of these professional and amateur photographs were then donated to museums, so you get the same image at multiple institutions.

As a researcher, it’s important to think of the context and consider why and where the photographs were shot. Especially the question of why. If it was a professional photographer, or if they were working for a government institution, that could help you track down where the negatives ended up. For example, if it was a delegation portrait, it might end up in the National Anthropological Archives or the National Archives and Records Administration.

Many institutions, such as NMAI, are putting their collections online. Now you can more easily search and find these connections, either the same photograph or a similar photograph that was part of a set.

Red Star: Making the artwork that I make, using historical images, I’ve seen on social media the popularity of historical images of Native people. A lot of them come from Pinterest. What are the effects of sharing these images, and does this influence the work that you’re doing in the archives?

Moazami: I’m torn, because I can imagine, let’s say, there is a Native teenager who happens to stumble across some of these photographs, and they really inspire them, and maybe they didn’t know these photographs existed of their tribe. So in that way, I think it could be really wonderful. I’m assuming a lot of teenagers are not sitting around searching our collections online, so maybe that’s a way to get them interested. But I get frustrated that people don’t always link back to the original source.

Red Star: During my fellowship, I discovered several members of my family who had material objects in NMAI’s collection. It was incredible to also find images of these ancestors in the photography archives. In my excitement in this discovery, I asked if you could help me find as many of the photographers from around the turn of the century who photographed my community in Montana, and, a few months later, you sent me a spreadsheet with fifty-eight photographers.

Moazami: I went through our catalog records to see what photographers we had who were photographing in the region. I also looked at other institutions’ catalog records—for example, the National Anthropological Archives—to find photographs that were taken in the region of the Apsáalooke peoples. There are also some great resources, like biographical dictionaries, that list photographers by state. I looked in the section for Montana, and I saw which photographers were listed as having photographed in the region.

Fred E. Miller, Her Dreams Are True, Apsáalooke Reservation, Montana, ca. 1898–1910. (Also known as Julia Bad Boy-Bear Ground, she was Wendy Red Star’s great-great-grandmother.)

Courtesy the National Museum of the American Indian

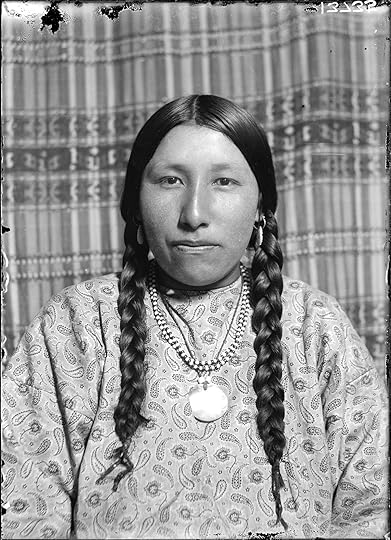

Red Star: When you were showing me photographs that Fred E. Miller took in the early 1900s, one of the images happened to be of my great-great-grandmother Her Dreams Are True, or I’ve also seen her name written as Dreams The Truth—her English name is Julia Bad Boy, which is an excellent name. I was thrilled, because it’s such a beautiful photograph. She’s sitting in front of this striped background—you can tell it’s a weaving of some sort—that really sets off her paisley-style underdress. We found another photograph, of two Crow men with the same background, noting that it was taken at the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, in Crow Agency, Montana. That gave me the location of where my great-great-grandmother’s photograph was taken.

After I finished my research at NMAI, I had a printout of that image of Her Dreams Are True. I decided I should look into another photographer named Richard Throssel, who was also photographing my community around the same time, to see if he took a picture of my great-great grandmother. I researched his archive, and I found a portrait of her. I was so excited. It looks like she’s a few years older in the Throssel photograph. It somehow felt spiritual to find her.

Moazami: That’s incredible to have that connection.

Red Star: Let’s talk about the importance of amateur or noncommercial photographers who contributed to the historical record of Native people—like Miller, who held various governmental positions at the Crow reservation, and Throssel, who also worked for Indian Services.

Moazami: Many of the technological advances in the field of photography coincided with the westward expansion of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was also a period of transition for Native people, who were forced from their traditional homelands and made to live on reservations.

All of a sudden, you had these anthropologists and missionaries and government employees, and even teachers, and they were all grabbing these easy-to-use, handheld cameras with dry plate negatives and, later, film negatives to document their time working with Native communities. Many times, they might have documented it to show their success, for example, at assimilating Native peoples. Though Fred E. Miller, I do believe, was just documenting his life and the people around him. Miller was trained as a photographer; however, he was working with the Crow in the capacity of a government employee rather than that of a commercial photographer. Throssel did some work as a photographer for the Office of Indian Affairs.

Red Star: Yes, Miller and Throssel, who both worked for Indian Services on the Crow reservation, also took personal photographs of regular life on the reservation, gaining the trust of the community to photograph some of their intimate events.

Moazami: Consequently, these photographs give you a glimpse of what everyday life might have been like for various Native communities. You get photographs that document not only chiefs and leaders in the community but also women and men and children, the people who didn’t have the opportunity to go to photography studios.

With studio portraiture, people would always dress up in their best outfits, and they would be posed. Often a photographer would give Native individuals props to make them look like a stereotypical Indian, an archetype. With amateur and candid photographs, you’ve got people wearing their everyday clothing, going about their daily chores, making food for their families. Many amateur photographs were not widely published or circulated; they’re incredibly rare, whereas with Edward Curtis, his photographs are represented in every repository.

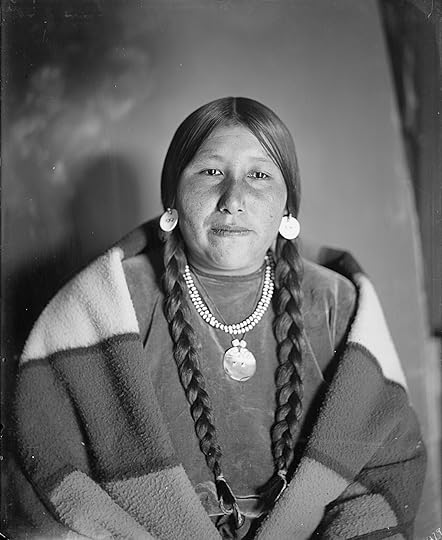

Richard Throssel, Julia, a Crow woman, ca. 1902–33

Courtesy the Richard Throssel Papers, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming

Red Star: Curtis also photographed my community, but I love the Throssel and Miller images more. Maybe because the community really trusted them. Throssel’s portraits of women are extraordinary, so powerful and dignified, really at the forefront of his imagery, whereas I feel like Curtis mainly focused on chiefs and warriors and scouts and things like that. In the Miller and Throssel photographs, it was nice to see some of the camp images of women beading or cooking, or being next to the men or alone.

One of the things that I love in historical images is minutiae like rings or unintentional background details like dogs or chickens. Tracing a small detail can lead to finding out about a trade system with certain shells, for instance. What are some of the things researchers tend to pay attention to?