Aperture's Blog, page 70

June 24, 2020

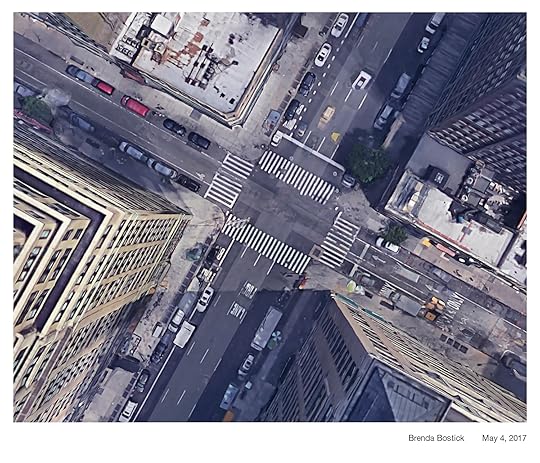

The Fashion Image after Nan Goldin

If fashion photography is defined by artifice, why does the industry crave rawness and reality?

By Lou Stoppard

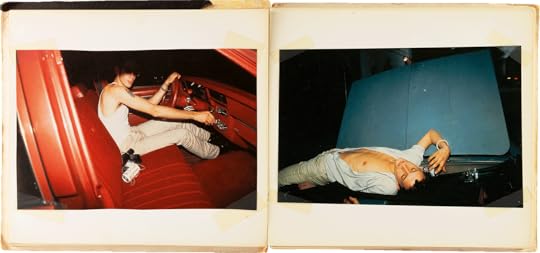

Annie Powers, Vincenzo, Italy, 2018

Courtesy the artist

According to many, fashion is superficial—it is about surface, exaggeration, frivolity. It is, both as a sensibility and a process (the act of getting dressed), about adopting and embracing a disguise, a cover-up. Fashion, at its best and its worst, relies on an acceptance of the fake—the external. Fashion photography is, then, a festival of trickery, a heady, multilayered performance.

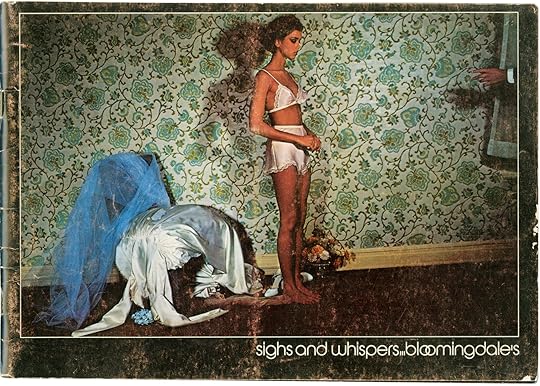

Ironic, then, that Nan Goldin, a photographer whose work is so frequently described as “truthful,” who makes pictures about the internal—pictures that, like jolts to the heart, move us, through the sheer relief of recognition and emotional relatability—is a fan of the fashion image. Goldin discovered fashion photography in the early 1970s through the work of Guy Bourdin. She was particularly enamored with his shoe advertisements for Charles Jourdan and his 1976 lingerie catalog for Bloomingdale’s, Sighs and Whispers (incidentally, the only “book” of Bourdin’s work published during his lifetime).

Cover of Bloomingdales’s Sighs and Whispers catalog, 1976, with photography by Guy Bourdin

Goldin also loved Cecil Beaton and Louise Dahl-Wolfe, who was a pioneer in getting models out of the studio and to locations. Writing in Nan Goldin (2010), Guido Costa says that Goldin’s early works “aspire to a sort of fashion-magazine glamour, and look more towards Vogue than to the classical traditions of photography.” And yet, he says, “There is too much life, too much truth in them—consciously or unconsciously, they reject entirely the language of pretense or illusion. In short, these photographs have the roughness typical of reportage, but their context is different, more intimate and private, more participatory.”

It is the “truth,” to quote Costa, in Goldin’s images that has shaped the significant influence her work has had on young image makers and, in a vaguely appropriate cycle, within the landscape of fashion publishing, where her pictures have been rehashed, referenced, and everything in between.

In the 1990s, one saw the specter of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1983–2008) in the goading grittiness of Corinne Day, whose images pushed for a balance of shock and tenderness toward her waifs and strays. In her personal writings, Day described discovering the book during a 1992 trip to New York, at a time when she was trying to convey her experiences through commercial magazines. “I wanted the ordinary person to see real life in those pages,” she writes. “I found Nan Goldin’s and Larry Clark’s work liberating and their work also validated the way I had started to take photographs myself.”

Corinne Day, Tania colouring her hair, 1995

© Estate of Corinne Day and courtesy Trunk Archive

During the fashion magazine boom of the 1990s, dirt, heartbreak, hedonism, and, on occasion, drug use became something like props, wheeled out to convey rebellion or cool. Such a look is neatly summarized in Fashion: Fashion Photography of the Nineties (1998), in which we see Day’s subjects thrashing around in run-down apartments and hotel rooms. We see Kristen McMenamy, half-dressed, a fine, thin scar on her belly, lipstick scrawled on her skin, in images by Juergen Teller from 1996. We see fraying carpets and chipped paintwork and rumpled bedding and discarded clothes and as-they-are models with charged yet insouciant expressions in work by Jack Pierson, Paolo Roversi, Wolfgang Tillmans, and their peers.

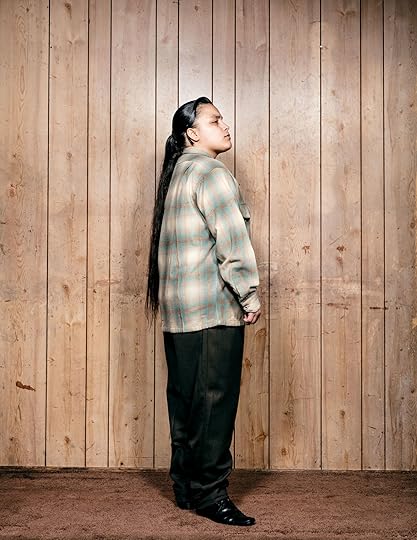

Today, Goldin’s influence can be seen in the vogue for fashion images that seemingly appear raw, real, authentic (a word that litters contemporary culture), or simply unretouched. The desire among young photographers to make such images is sparked, in part, by the success of newer image makers such as Ethan James Green (a Goldin admirer) and Jamie Hawkesworth (a devotee to Nigel Shafran, another champion of understated poignancy and realism), who have attracted commissions for their easy daylight, apparently stumbled-upon locations, and often street-cast subjects.

Ethan James Green, Peter and Stevie, 2019

Courtesy the artist

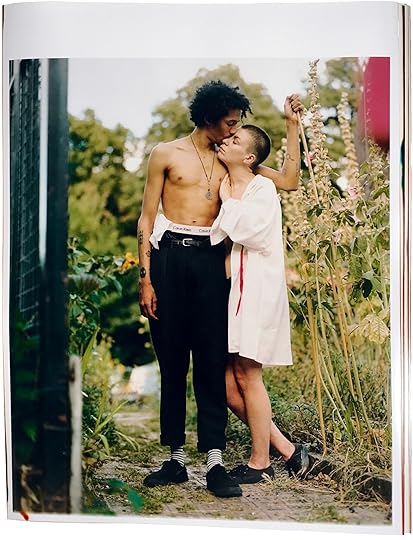

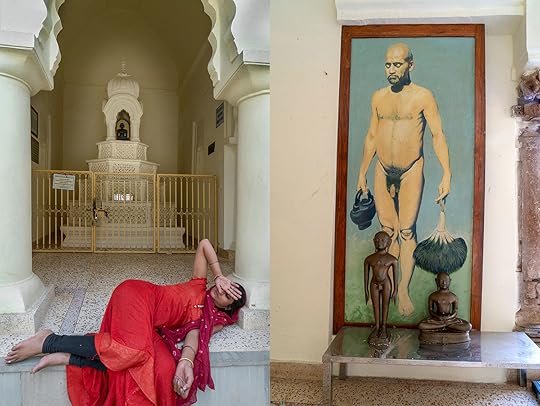

We see Goldin’s shadow on the balance of explicit sensuality and gentleness in Markn Ogue’s Lovers Series (2016–ongoing), which shows young couples entwined. We see it in the calm quietness of Jesse Gouveia’s images. We see it in the liberated, unselfconscious subjects in the work of Annie Powers. We see it in the conviction Guen Fiore has in the importance of showing women’s bodies as they are. Fiore cites Goldin as a key inspiration, pointing to images such as Amanda crying on my bed, Berlin (1992) and Rise and Monty kissing, New York City (1980) as references. “I like to think that I can bring back a hint of honesty in my work, proposing a variety of young women portrayed with simplicity,” she says.

Fashion has flirted with truth pre-Goldin. In the catalog for the Face of Fashion, an exhibition staged at London’s National Portrait Gallery in 2007, Vince Aletti writes, “Fashion magazines have always had a troubled relationship with reality; it’s often in their interest to keep it at bay.” Yet, he continues, they are in tune with cultural shifts. “After the austerity, sacrifice and can-do pluck of the war years, the exuberance of the late 1940s and 1950s was tempered with a new sense of realism . . . the gilt-edged romantic fantasies and neoclassic conceits of an earlier era gave way to a kind of stylized reportage. . . . Authenticity replaced theatricality.”

Markn, Lovers Series – CJ and Kaine, 2016

Courtesy the artist

One doesn’t need to look far to identify sociocultural reasons for the current quest for a semblance of authenticity or truth. Is it a reaction to the explosion of fashion images in other, new, contexts, beyond the magazine—e-commerce images, influencer selfies, Instagram posts—most of which embrace a sort of sanitized, pouty, cartoonish quality, their tweaking done, in many cases, via apps such as Facetune rather than Photoshop? Or is it that in times of climate crisis, when issues of sustainability are more visible, something that promotes high production, or high glamour, simply feels in bad taste? Perhaps, one could simply put it down to cycles; few could argue with the view that nostalgia is rampant in creativity today.

This focus on authenticity has to do with issues of representation. For so long, fashion failed to expand its vision beyond a thin, white body; image by image, it proved itself a censorious critic of anything beyond this narrow fantasy. Today, forums for criticism have expanded; the backlash is loud. “Fashion changes direction every time society is asking for something new and different,” says Fiore. “Nowadays people have a strong voice and are demanding for a more realistic standard of beauty, minorities want to be represented. Beauty as we knew it almost doesn’t exist anymore.”

Jesse Gouveia, Boy’s Room, 2019

Courtesy the artist

“For fashion today, reality often means casting people who don’t look like models,” says Gouveia. “Five years ago, you couldn’t use a kid in a piece of your own personal work and then have a commercial client come along and use that same kid on a billboard. It feels significant. People really want to be a part of movements in image making—they think, I believe in those kinds of pictures so I want to make those kinds of pictures.”

Today, a moral quality is given to fashion images that look like real life—they are presented as a step forward. One must be careful, however, to recall that the agents of construction—the stylist, the glam team, the casting agent, the location scout—are still at work; their contributions have just been better disguised. Clients are usually moneymen—they see that a veneer of realism edifies the product, the brand, the consumption, and makes people feel better. Look, it’s just a girl on the street, just like you. “It’s meant to come across as reality, but really it has so many filtrations happening,” says Gouveia. “A model could have just walked into the studio an hour before, maybe she doesn’t know the photographer, she has her hair and makeup done, but it’s sold as something intimate or private.” To acknowledge that this is not a documentary image, and to do so boldly, is perhaps more honest: “Is it ‘realer’ for a fashion shoot to look like a fashion shoot—to show the glitter?”

Guen Fiore, Samantha and Alyssa, for Jalouse magazine, Paris, 2019

Courtesy the artist

In general, truth is a dangerous word when one is talking of photographs. The relationship between the two has been thrashed out by thinkers since the medium’s inception. In Diving for Pearls, Goldin’s 2016 book, Glenn O’Brien writes, “From its beginning, photography has been the most magical medium and in art, entertainment, and propaganda, it is the greatest liar of all, making the impossible appear palpably true and validating falsehoods.” The title nods to a quote from Goldin’s friend, the photographer David Armstrong, who said that making pictures is like “diving for pearls.” Goldin writes of his observation that “if you took a million pictures you were lucky to come out with one or two gems.” As implied, the editing process moves an image further away from reality—the banal or mediocre, the uneventful (the humble context, perhaps) are removed.

“Most people don’t really understand what photography is,” says Nick Knight, the British fashion image maker. He is drawn to the craft of making pictures—elaborate lighting, experimental postproduction techniques—though his early documentary Skinhead project (1982) has had a great influence on numerous photographers. (He argues that his heavily worked fashion images are no less “truthful” than his Skinhead images, as his intentions—the desire to “show people things they cannot see”—were the same.) Knight prefers the title image maker to photographer. “The sooner that we understand that photography and image making, are not in any way to do with the portrayal of reality, the better,” he says. “Humans experience reality as a progression of emotions and desires and fears and loves, different feelings which are based on what’s just happened, what’s happening next.” A single snippet can never show that. And photographers will always manipulate, however subtly, whether with the lens, the printing, the shadows, the contrast, or the “diving” Nan refers to. According to Knight, “The idea that it’s all down to the moment when the shutter lifts and the light-sensitive material is exposed, and nothing else outside of that is valid or true, is a real misunderstanding of photography.”

The “real” look, Knight reminds, is just “another filter.” “Nan’s pictures are great love poems they speak about the difficulties, and the beauty, of life. You connect with the emotions, not the surface plasticity of the image. Of course, the plasticity can easily be reproduced for scenes that don’t have any depth of emotion.”

Maxwell Granger, Max at Andre’s grandparents’ house, Miami, 2019

Courtesy the artist

Maxwell Granger, a young image maker from the North of England, whose portraits are unfussy and vaguely droll, is similarly wary of the many fashion briefs asking for relatable, so-called authentic images. “No one really knows what that means,” he says. “People seem to think that something that looks candid is authentic, but I don’t believe that. There is this trend for images where people are not posed—but to get someone to stand there and ‘not pose’ is, if course, posing them. Take my mum, if she had a picture taken of her, it wouldn’t be authentic for her to just candidly stand there. It would be authentic for her to pose, because that is who she is.”

The idea that artifice can be somehow truthful is central to understanding Goldin’s work. This is where her understanding of fashion is so interesting—she sees that the surface is central to our sense of self, to the process of being, to happiness, confidence, love, life itself. She takes stylization seriously; it’s obvious from her photographs of great looks, of performers and drag queens, of nights out dressed up, of makeup smeared and newly applied. Look, she seems to say, The surface creation may speak more of reality than the unmarked, untweaked body underneath. Look again: Isn’t all self, all gender, simply a performance? In that case, how can any photograph be truthful if the subject matter, the person in it, is a construction—an act, a cover-up, a dreamed-up fantasy?

Hilton Als put it best in his 2016 profile in The New Yorker, “Nan Goldin’s Life in Progress,” when discussing Goldin’s images of the performer Suzanne Fletcher in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. “The images are a tender evocation of a young woman who shows the camera as much of her real self as she can.” As much of her real self as she can. And, in turn, the camera captures as much as it can, and as much as Goldin intends (and, to an extent, as much as a certain slither of chance allows). Goldin is aware of the camera’s slippery nature, savvy to its limitations, serious about its power. The punch is the pathos—what we read into each image, what we imagine, and how much of ourselves we bring along to each viewing.

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London. She is the editor of Fashion Together: Fashion’s Most Extraordinary Duos on the Art of Collaboration (2017), Shirley Baker (2019), and Pools: Lounging, Diving, Floating Dreaming: Picturing Life at the Swimming Pool (2020).

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

June 18, 2020

Clifford Prince King’s Intimate Photographs of Black Queer Men

Creating tender scenes with friends and lovers, the LA-based artist offers a stirring vision of everyday ritual.

By Marjon Carlos

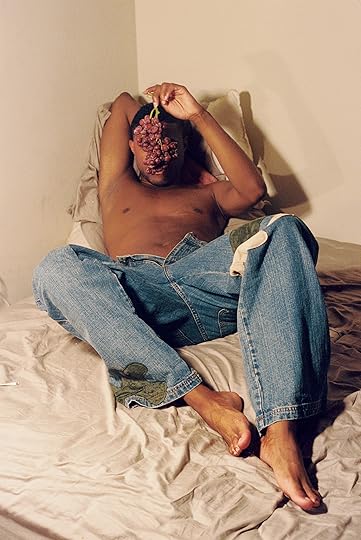

Clifford Prince King, Untitled (Grapes), 2017

Courtesy the artist

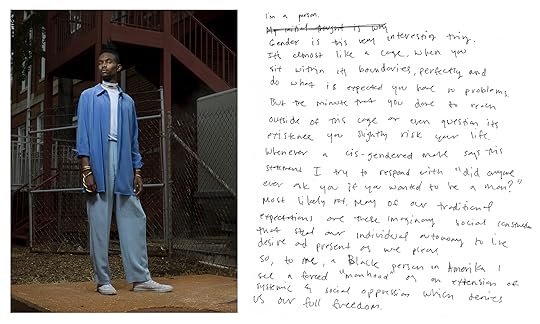

What’s remarkable about Clifford Prince King is his ability to make strangers seem both intimate and removed in his work. There is a sense of perceived recognition with his images. Friends of friends you’ve been meaning to meet are within the frames. The faces of under-the-radar creatives whose work you respect but have never told so in person peer back at you. “Oh, I know him,” you hear yourself say to no one in particular as you gaze on the heartbreakingly youthful subjects that make up King’s world. Queer Black men—friends, lovers, some nebulous place in between—lying languidly across bare apartments, cornrowing each other’s hair, holding blunts to one another’s mouths, or staring meditatively away from the camera, naked. The viewer is able to gain what King describes as a “glimpse into a Black gay world through scenes and rituals of the everyday.”

“A lot of the imagery I try to create is just placing Black men in scenarios or scenes that seem familiar,” King says. “And so the ultimate goal to me is creating imagery where we see these Black men—whether they’re masculine-presenting or effeminate—and give that imagery a space.” Pushing back on myopic gender and racial expectations around Black masculinity, King elevates a certain sensitivity and knowingness among queer Black men’s relationships that we rarely see represented.

Clifford Prince King, Safe Space, 2020

Courtesy the artist

In Safe Space (2020), King almost melds into a single entity with his two friends as they sit on a bed, entwined between one another’s legs, creating a wordless trust, harmony, and a physical closeness. One’s eye can’t avoid the opened canister of Eco Gel that lies at their feet, ready to lay King’s edges. As a true piece of Black ephemera and the expression of our hair traditions, the gesture represents an intersection of Blackness and queerness that is pivotal to King’s vision.

Slightly out of focus and raw, these photographs document ineffable moments of intimacy. It’s why King’s photo sessions are simply dubbed “hanging out.” Inviting his community over to his home in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles, King prepares dinner or pours a glass of wine, creating an environment of quiet repose before lifting the camera to his eye. His photography becomes about communion and belonging, rather than something forced. “Obviously I want people to feel good about themselves if they’re photographed, but the point isn’t body or beauty, it’s more just about the presence of them being their real selves.” Settings aren’t necessarily pristine. Beds that his subjects curl up on go unmade; jeans that they wear appear stained and distressed; rooms they occupy are unadorned.

Clifford Prince King, Run Along Home, 2020

Courtesy the artist

You can’t attach a particular historical moment to Run Along Home (2020), an image of mad abandon, one that evokes not only the Southern adage of getting home before the “streetlights turn on,” but also the joy of escaping to one’s home and being alone with a lover. And that is King’s objective. He is focused on creating work that he hopes can be discussed years from now, and in this way, his photography is in conversation with those artists he counts among his inspirations and friends: Deana Lawson, D’Angelo Lovell Williams, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Black contemporary photographers who are putting Black intimacies at the forefront for a lasting effect. King acknowledges that their work is much more intentional than his. But for now, he’s proving the soft power of the everyday.

Marjon Carlos is a journalist and editor living in New York and a contributor to publications including Essence, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. She is currently working on her first book, a memoir.

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

June 16, 2020

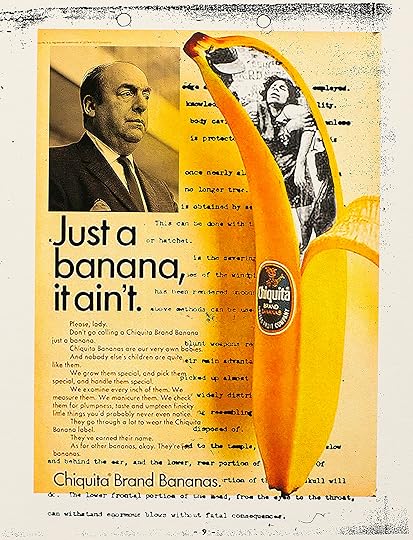

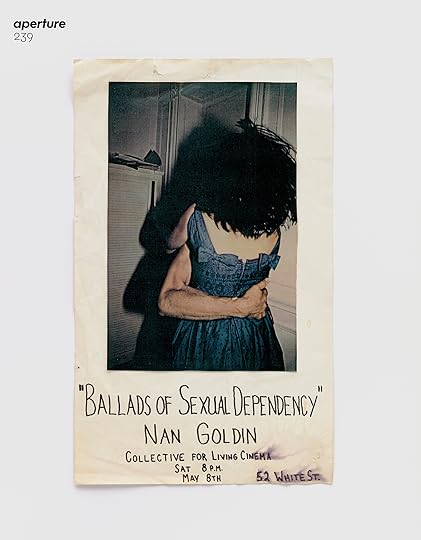

The Original Ballad

How did Nan Goldin’s slideshow with hundreds of images, presented at bars and nightclubs, become an iconic photobook? Elle Pérez speaks with Marvin Heiferman about the making of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

Cover of the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Elle Pérez: I teach The Ballad every semester. And I create this fake slideshow for my students. I’ve scanned the entirety of the book. We put it up on the screen, and we play it in the dark, and I use a playlist for the music.

Marvin Heiferman: Oh, you kind of re-create it. That’s hilarious.

Pérez: It goes from Maria Callas to James Brown, and then—what’s that one song that’s like, “Kiss the girl” … ?

Heiferman: “Miss the Girl.”

Pérez: Yes. So we sit there for forty-five minutes and watch it.

Heiferman: The Ballad as a slideshow is so different from the experience of The Ballad as a book. Part of it is the power of the audio and the sort of trance state you get pulled into when you watch it, and listen to it.

Pérez: The color washes over you in such a different way than when you’re looking at it in the book. When it’s illuminated on a screen, you feel like you’re watching something that has to do with the sequence of the book, which is very romantic.

Heiferman: Romance is not a bad word to use. That’s certainly part of the allure of The Ballad. I don’t look at the book all that often, because I know it all too well. But looking at this new edition, it’s truer to the color and the experience of Nan’s slides in terms of that richness, which has a lot to do with what it takes to move people through The Ballad as a slideshow and as a book.

Pérez: How did you get involved in working with Nan? How did you even meet?

Heiferman: I was working at Castelli Graphics and running the photography program there. On the one hand, I was working with people like Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams, John Gossage, Ralph Gibson, and Mary Ellen Mark. And on the other, I was continually trying to open up the program and look at different ways photography functioned. I worked on Ed Ruscha shows, Andy Warhol shows, and Robert Rauschenberg shows. Marian Goodman’s print publishing business and gallery, Multiples, was around the corner, so I got to meet people like John Baldessari. My boyfriend at the time was in the Whitney Independent Study Program, and through him I met the whole Pictures Generation crowd. I was lucky enough to beat Castelli when multiple image worlds were kind of colliding with one another: modernist photography, the artist-using-photography thing, the Pictures thing, the rise of conceptual photography. Even though the gallery represented a specific group of people, I kept looking at work and kept trying to bridge all those perspectives in many of the projects I did.

One day, I think it was in 1978, I got a phone call from a person who said, “Joel Meyerowitz told me to call you up and show you my work.” It was Nan, and she was still living in Boston. So we made a date, and when the time came, Nan walked up the dramatic red-carpeted spiral staircase in the Upper East Side brownstone where the Castelli Gallery was located with a box of about twenty-five prints under her arm. They were fucked-up prints, with weird and oversaturated color, kind of messy prints, and some were signed “Nancy Goldin” in tiny, tiny handwriting. I looked at them, and I thought they were fantastic. I could tell what she was doing right off the bat, knew nobody else was doing anything like it, and I said, “Bring some more stuff back.”

When she showed up again, it was with a crate full of pictures, scores of them, which we went through. They confirmed to me that what Nan was up to was phenomenal. There was nothing like it. It was clear as day.

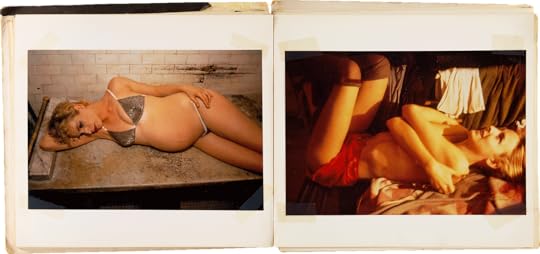

Spread from the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: What did you see?

Heiferman: Pictures about relationships. This was a time when color photography was just starting to gain credibility in some people’s minds—and here were these pictures that looked and felt much more intense than anything that anybody else was doing. Even though Larry Clark’s Tulsa (1971) was already out in the world, Nan’s work looked explosive, too, but different. The pictures were just full of emotion, full of color, full of love. What struck me was what an incredible picture maker she was, which often doesn’t get talked about.

Pérez: I totally agree. I’ve looked at them many, many times. The one of Cookie Mueller sitting at Tin Pan Alley [Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983] is an incredibly well-constructed photograph.

Heiferman: Yes, and while the pictures were individually beautiful in a particular way, it was their cumulative impact that was overwhelming. Nobody was making that kind of work about people in complex, intimate relationships. Nobody was making those pictures about sex who wasn’t glamorizing or pathologizing it.

The work was clearly unique, so I said, “Okay, let’s try to do something with this.”

I wanted to do a show of Nan’s work, but the gallery didn’t want me to do it. Basically, Mrs. Castelli said she thought that Ellsworth Kelly would be horrified by the pictures. (I’m sure Ellsworth would have loved them.) Basically, I think she was afraid of them. And it was that kind of resistance that was a contributing factor to my leaving the gallery.

After I did, I worked with Nan from about 1981 until about 1988 or so, and during that period I helped get the work out into the world. By that time, I had a lot of contacts in the art and photography communities and kept showing people the work and raving about it. Around this time, Nan started to develop the slideshow format, and soon The Ballad began to evolve. It was different every time Nan showed it.

Pérez: You helped produce the slideshows?

Heiferman: Yes, we both worked to line up venues to show it, and I was around when she was editing the slideshow some of the time. That was an extraordinary part of the experience, because while photographers so often work toward distilling a concise body of work, here we were dealing with this expansive, evolving, public, performative, dramatic thing. Some images were always included in the slideshows, but new ones were introduced all the time. Sometimes the chaos of the slideshow coming together—and often in the moments right before we had to throw carousel trays full of slides into bags, get in a cab, and show up someplace and present it—was unbelievable.

Spread from the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: Where were you showing it?

Heiferman: We would show it at clubs and places like OP Screening Room, on Broadway, which no longer exists. There was a notorious showing at the Saint [a gay club in the East Village that was open from 1980 to 1988], which I thought was going to be the end of my life.

Pérez: What made it notorious?

Heiferman: Just keeping things on a schedule and showing up on time was always a challenge, and it almost didn’t happen that night. People don’t realize that before The Ballad got programmed, which was for the Whitney Biennial in 1985, it was different every time we showed up. And when we did, there would be just two projectors, side by side, the music would start, and Nan would clutch the remotes, one in each hand, and the show would begin.

Pérez: So she would run it.

Heiferman: Yes, and there could be glitches. Slides would get stuck. Projector bulbs would burn out. We had to switch out slide trays on cue and as seamlessly as possible. So every time, for me, was a little suspenseful. The Saint was amazing, because it was probably The Ballad’s biggest venue at that point. There were hundreds, a thousand, maybe more—I don’t know how many people were there. I thought we were never going to pull it off, that it was never going to happen. And then it did, and when it was over, the place exploded. What is still vivid in my mind is a bunch of us frantically sorting out slides on Nan’s light boxes in her loft on the Bowery, just blocks away from the club, still traying slides as the show was scheduled to begin. That was a very different experience from working on the book, which we laid out on the floor of my loft in the Garment District in a much calmer process.

Pérez: It went from hundreds of pictures to how many?

Heiferman: The book has 127. That was the big challenge. It was clear that Nan wanted to do a book and wanted it to be an Aperture book, because she had an appreciation for what they did, and she wanted to be part of that history. That kind of ambition was, I thought, terrific, but at that point Aperture had never done anything like The Ballad. For me, what I learned when I was working in the ’80s was that you’ve got to make your own opportunities. The way the photography world was set up at that time, it was stratified, conservative, and dominated largely by straight white guys. If you wanted to make friction or make a break, you had to figure out how to do it yourself.

But I knew I could, pretty easily, take the book project to Aperture because I knew a lot of people working there. I just wasn’t sure they’d bite. I think I showed it to Mark Holborn [an editor there] before I showed it to Michael Hoffman [the former director of Aperture], but when I showed the work to Michael and he said, “We’ll do it,” I thought, Whoa. Whoa, we did that.

Pérez: But then how did you actually do it?

Heiferman: We realized we had to stick to the sequence that the index of songs lays out, which drives the narrative of the piece forward. But first we’d have to edit The Ballad down, get rid of what, six hundred pictures, 550 pictures. If you’re always shooting people in bed, you’re going to have two hundred pictures of people in bed. If you’re always looking in mirrors, there are going to be two hundred pictures of people looking in mirrors. And then, there were always the favorite pictures, the pictures that worked best and, on their own, that created their own worlds, that had their own integrity.

Pictures were spread out on the floor of my loft for a long time. Weeks maybe. Me and Nan, and Mark Holborn, some of the time, and Suzanne Fletcher, some of the time. Sequencing books is very much like making music. The goal is to make things flow, to get somebody both to look and to turn a page. That was the challenge—to get rid of the extraneous stuff, keep the pictures we couldn’t live without, and then keep cutting from there.

Pérez: Were there a few that became the anchor points for the book?

Heiferman: The cover picture. The picture of Nan’s face battered. Some of the sex pictures. The drug pictures. The party pictures. Everybody’s got their own favorites. The Hug (1980) is one of mine.

When I was looking through the book earlier today, something I was struck by, and I’m sure we were conscious of, is the way the book moves from horizontal pictures to vertical pictures, from indoors to outdoors. There’s also the relationship between people looking at the camera versus people looking off to the sides of the frames, which Nan does consistently enough that it becomes an element in sequencing, too. You’re being directed. There’s the narrative. It’s like: Who are these people? What’s happening to them? What’s their relationship to one another? There’s the lush color that runs through the book. There’s the emotional roller coaster that takes you from pictures at parties and of people laughing, to pictures of people crying, and that hooks you. People have called The Ballad “operatic” and for good reason, because its grand scale and expressiveness sweep you along with it.

Spread from the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: Did you know it was going to be an important work?

Heiferman: Yeah. But it took ten years of convincing people. Because photography was still a confusing thing to people.

Pérez: It’s still this confusing thing to many people. It seems a little more accepted now, but I feel like people are still not sure to this day.

Heiferman: We’re still having that conversation, which is ridiculous to us.

Pérez: But we’re in.

Heiferman: Right, we’re in.

When we made the book, one of the challenges was getting model releases from people, which was dicey at times. I remember when Aperture asked, “Do you have model releases for everyone?” and I said, “No.” Something else I remember vividly is going down to the East Village to try to get hold of Brian, Nan’s ex, and get him to sign one and standing on the street, screaming up to his window, trying to cajole him to come down so I could give him a model release to sign—which never happened.

Pérez: And what about the text for the book?

Heiferman: The text that Nan wrote was the only text in the book. It didn’t dawn on us to go get somebody to write an essay for this book, to try to explain this book to the world. The difference between Nan’s text and the kind of postscript text in the back of the recent edition is interesting to see, too. It underscores that Nan always knew what she was doing.

Pérez: She writes, “I don’t ever want to lose the real memory of anyone again.” There is something about that “real memory” that is related to how visceral the book is.

Heiferman: The work’s intensity and authenticity were, and still are, palpable. It’s interesting now, in an Instagram world where everybody is projecting and branding themselves and figuring out how to represent themselves, that what Nan was doing was representing, but with a different set of criteria, a different set of brackets, a different kind of goal in mind.

Pérez: Totally. I think people in general are struggling with the claim that the camera can take control over a person’s own image. But, then, simultaneously, there’s a paradox, where people are very nervous now to use the camera to stake a claim.

Heiferman: You’ve got to take responsibility for yourself, the way you see yourself, and the way you see the world. That’s a tantalizing and scary thing, but that’s what identifies people as artists. Right?

Pérez: That’s a pull quote right there.

Heiferman: You want to see the world through somebody else’s mind or eyes, and Nan lets you do just that. It’s not that she wasn’t influenced by work that came before her. She was, and she knows it, and she has said it—and who wouldn’t be? Nan studied photography enough to know stuff. But what came out was something else.

The process of shooting all the time, which Nan did back then, gave her the option of constantly reediting the work and changing it. The kind of fluidity that the work documents, just on a process level, is also what it represents in terms of people’s lives—the fluidity of those lives. That’s another reason why the slideshow format was kind of perfect. And what makes the book so different is that it freezes The Ballad because people have such respect for and have put so much faith in books, where they experience pictures differently and privately. There was not a lot of opportunity to see The Ballad unless you were in New York, Berlin, Paris, or wherever it played. And there’s still not much opportunity to see it, because it’s such a big deal to mount it and dedicate viewing space to it. Back then, what was extraordinary was the experience of the slideshow, of seeing it in a club where everybody’s drunk and stoned, or at least lots of them are, and a good number of them are also in the pictures and are screaming when they see themselves on-screen.

Spread from the original maquette of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, ca. 1985

Courtesy Nan Goldin

Pérez: That’s amazing.

Heiferman: There’s also the difference of seeing a version of The Ballad when it’s the actual slides that are being projected, when you hear the clunking sound of them advancing in an irregular rhythm against the beats in the music, versus the experience of the digitized, smoother, synched-up versions where everything runs smoothly. No matter what, though, The Ballad works. Every time you see it, it’s different, because there’s so much to process and take in. And, for me, watching it is still a very personal thing, I just tear up. I remember all the stuff that went into it, my closeness to it, and, of course,

I can’t escape the theme of loss—that plays such a big role in it.

Pérez: That’s why I put such an emphasis on actually showing my ghetto version of the slideshow to my students. There’s something about the participation of it, too.

People always have these fantasies of bohemias, art worlds, and these communities of people. In fact, people create their own communities to support the work they’re doing—and here people got to see it celebrated in this kind of glamorous way.

Heiferman: That’s another quality of the work that’s wild. It is, in its own way, glamorous. You get to see this subculture that, for want of a better term, got turned into something cinematic. It’s a word that people tend to use a lot, but in this case the work really is. Nan always said she wanted to be a filmmaker, and I think that was always in her mind; she was always taking so many pictures. It was kind of like [Eadweard] Muybridge. She was both living life and capturing it in stop-motion.

Pérez: The other thing I’m thinking about right now is the relationship of this book to a book like The Americans (1958). That was something like twenty thousand photographs edited down to eighty-three pictures—how do you even reduce that? The Ballad went from some unknown number of photographs to eight hundred pictures. How many pictures do you need to make eight hundred good pictures? And then, to bring that down to 127. They’re both epics, in a way.

Heiferman: Look at Robert Frank and his move to video. Nan has made videos, too. I think there’s this recognition of both the power of individual images or images in a group, and the limitations of them.

Anybody who is making images a lot, and seriously, is going to grapple with that.

Pérez: When I first started making pictures, they were for all the punks up in the Bronx. I would put them up online, and then everybody the next day would look, and I would get immediate feedback. There’s something in the validation of showing things to your community first.

Heiferman: But then to be able to come up with work and narratives that reach beyond that audience is the interesting thing. As you were talking about putting stuff up online, I just kept thinking about Instagram. People’s Instagram feeds are their versions of The Ballad. How many pictures do you tell your story in? It’s an ever-evolving process. There’s a self-consciousness to that and, as The Ballad proved, a good reason to rely on photography to figure out who you’ve been and who you are going to be.

Elle Pérez is an artist based in New York. They are a visiting assistant professor in Harvard University’s Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies and a dean at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

Marvin Heiferman is an editor and writer based in New York and the author, most recently, of Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the Universe (Aperture, 2019).

Read more from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

June 11, 2020

Why Photo Editors Need to Hire Black Photographers Every Day

And not only during a crisis.

By Will Matsuda

Wale Agboola, The Uprising, Minneapolis, 2020

Courtesy the artist

When New York Magazine chose a white conflict photographer’s image for the cover of their June 8, 2020, issue, there was an uproar on Instagram. The magazine’s outspoken (white) art critic Jerry Saltz called the cover “tremendous.” But Lindsay Peoples Wagner, editor in chief at Teen Vogue, commented, “sad that you hardly ever hire black photographers to shoot covers and STILL didn’t this week of all weeks.”

This was not an isolated incident. National Geographic and Vanity Fair both hired prominent white photographers for protest coverage, demonstrating the systemic issue of whiteness throughout the photography industry. When a Google spreadsheet of Black photographers was circulating widely, why would photo editors make this choice?

As Danielle Scruggs, a Chicago-based photo editor at Vox and board member at Authority Collective, told me, “The whole reason why there is so much racism, sexism, ageism, classism in the industry is because all of that exists in society.” Non-profits, media outlets, museums, and photography schools attempt to alleviate this contradiction by elevating “diverse” photographers, giving them grants or putting them on diversity panels. But who actually benefits from those panels? How does a grant or scholarship fix a systemic failure? And who benefits from highlighting Black photographers only during a time of crisis?

I recently spoke with Scruggs and three other Black photo editors and photographers about covering this moment and what needs to change: Lynsey Weatherspoon, a photographer based in Atlanta; Wale Agboola, a photographer based in Minneapolis; and Brent Lewis, photo editor at the New York Times and cofounder of Diversify Photo. They talked about the inherent subjectivity of photojournalism, the racist distribution of power and opportunity in the industry, and their demands for a sustained commitment to make photography more Black, far into the future.

Wale Agboola, State Capital, Minneapolis, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Will Matsuda: Why are you choosing to photograph the protests?

Wale Agboola: As Black people, we have to be able to tell the stories how we want. After I found out about George Floyd’s death, I couldn’t sleep. At 2 a.m., I walked down to Cup Foods [the site of George Floyd’s murder] to see what was happening. When I got there, I broke down. A friend of mine told me that I had to get to the Third Precinct right now. “Everything is on fire,” he said.

So I went and saw Black pain. Fear. People who were angry. They wanted answers. I wanted to do my best and tell the story the way I see it. The way I’m feeling that pain. When I saw the video of George Floyd, I lost a side of me that was peaceful. It turned into anger. I channeled that feeling into my photos.

Lynsey Weatherspoon: I’m originally from Birmingham, Alabama, one of the epicenters of the Civil Rights Movement. I needed to see what was going on, and I needed to walk in solidarity. Photographers have different voices, and I wanted mine to be heard.

Matsuda: What do you think about the current conversation about who should photograph these protests?

Danielle Scruggs: I’m glad we are having these conversations in a really explicit industry-wide way. Sometimes, it feels like I’ve been screaming into the void [laughs]. We need to hire more Black photographers. We need to hire more Black photo editors. Not only to cover things like protests and uprisings, and things that only pertain to Black communities. We need more Black photographers doing food stories. More Black photographers doing culture stories and fashion stories. It shouldn’t be just for hard news; it should be for everything. It should be across the board.

It shouldn’t be a scramble for people to hire Black photographers and photo editors. That should be something ingrained in this industry, and it’s not. There’s especially a problem with how overwhelmingly white leadership positions are in the industry. If you only see predominantly white men crafting visual narratives about everything, that becomes a really big problem. It works right now if you believe in systemic inequality.

Wale Agboola, The Clean Up, Minneapolis, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: It works how it was designed to work.

Scruggs: Yeah, exactly. That’s why I’m over discussions of reform in journalism, but especially in visual journalism. There needs to be a much bigger conversation about who is crafting those images. Why those images are being crafted. Why certain visual tropes come up. Why certain people have been completely shut out of this industry for decades.

Agboola: At George Floyd’s memorial service, every person doing video was white. A bunch of foreign press was in town. This guy came up to me that looked like he was from a very reputable news station and said, “Hey, who is the dude with the family’s lawyer?” The person he was talking about was Reverend Al Sharpton. If you don’t know who that is, you should not be here. It was such an insult.

Looking around and not seeing very many Black photographers felt very disappointing, because the stories weren’t going to come from the right place. It breaks my heart. I see things through the pain I’m feeling. I put that into my work. I have to make sure when I am shooting to not lose myself. I want an imprint of myself in the photo. To make sure that what I am feeling is conveyed. It is a lot of pain. I haven’t been able to take a breath and cope yet.

Wale Agboola, Protest at Minneapolis Third Police Precinct, Minneapolis, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: What would you say to non-Black photographers covering this moment?

Brent Lewis: Well, I do think there should be non-Black photographers out there. Black photographers should lead the way, though. It comes down to understanding. Non-Black photographers should be more empathetic. Have conversations and ask why people are out there. People are protesting to have their voices heard. Don’t just point a camera in someone’s face. I’ve heard some photographers are asking for permission at the protests. If it’s a safe moment, have that conversation. It opens up a dialogue. Even to the Black photographers out there, I would say ask those same questions.

One summer back in Chicago, I was taking pictures of these kids playing in this opened fire hydrant. One of them turned to me and said, “Did somebody die?” The only time they see journalists coming into their neighborhood is when someone gets shot. The media shows up when things are on fire. If people actually cared about the Black experience beforehand, we probably wouldn’t be in this position. It wouldn’t feel so invasive either.

Danielle Scruggs, The Villa at Windsor Park Nursing Home on the South Side of Chicago, 2020

Courtesy the artist for the New York Times

Matsuda: A common refrain I’ve been hearing from non-Black photographers is that they think pictures are objective—they are just photographing what is in front of them. So why does it matter who is taking the picture?

Weatherspoon: Whatever situation I put myself in, I put my full identity in it. That’s being Black. That’s being queer. That’s being a woman. So that all goes into whatever story I’m photographing. If you come to a story from only a gender perspective or a race perspective, it causes mistrust with the people you photograph. Black people are at the center of so much history, but you rarely see Black people, let alone Black women, who are allowed to cover these stories. You have to bring your full identity, your full self, to whatever shoot you’re doing. But you’ll have biases in what you see no matter what.

Scruggs: Objectivity doesn’t exist. You bring all of your lived experiences into whatever you’re doing, whether that’s picking up a pen or a camera. All of your lived experiences affect what you put in a frame and what you keep out of it. What stories you choose to tell and what stories you choose not to tell. The best that we can do is aim to be fair. Tell as complete a story as we can. But objectivity is not a thing. It’s a way for people to hide. It’s a way to avoid having those uncomfortable conversations.

Matsuda: How are you maintaining the energy and strength to keep making these images?

Agboola: I’m not. Today [June 6] is the first day I am taking for myself and not picking up my camera. Today, I want to breathe. Today, I want to acknowledge where I am at emotionally. I haven’t slept this week. I wake up in the middle of the night with sleep paralysis.

In Minneapolis, there have been white supremacists riding around in the middle of the night. Every time I would go outside and hear a loud truck, I ran into the bushes. I couldn’t breathe this week. I was in pain. I couldn’t even feel safe in my home.

Today is the first day where I can assess myself. I need to talk to my therapist. It’s been hard, man, I’m not going to lie. But it’s also been great to see the way Minneapolis has come together in a ridiculous, iconic way. After buildings burnt down, people were out the next morning cleaning it up with shovels and gloves, in the middle of a pandemic. Allowing the anger to go on. They did not even question it. It got me emotional. It was beautiful.

Danielle Scruggs, Travis Johnson, an attendee at the American Descendants of Slavery conference in Louisville, Kentucky, October, 2019

Courtesy the artist for the New York Times

Matsuda: How can photo editors do better?

Weatherspoon: I’m seeing an influx of attention—they want to see more of our work. In a way, it’s a little concerning. Why now? We have been doing this for so long. Why is it now that you want to hear our voices? We have been photographing our joys, our pains, our questions, our everything. You didn’t listen. I question the motive of those who are reaching out to us now.

Matsuda: This interview right now is part of that complex, no doubt.

Weatherspoon: Yeah, let’s be real about that. I hope media outlets, brands, agencies, and galleries understand that we’ve always been out here. People are now starting to catch up on what we’ve been doing. If you decide to hire a Black photographer, make sure you continuously hire them. Don’t give us that line, “We look forward to working with you in the future.” Make it count. None of us are going to be in this for a long time. I can tell you right now. I don’t want to do this for the rest of my life. I do enjoy it, but when it’s my time to sit down, I want to continuously see Black people thriving in this field. Not just now. There’s no excuse for not hiring a Black photographer for any type of story now. Why does it take someone being murdered for us to show our work?

Scruggs: Photo editors need to change who they view as experts. Change who they deem as worthy of getting an assignment to. Just because you aren’t as familiar with someone doesn’t mean that they are not capable of executing an assignment in an accurate and compelling way. There also needs to be a fundamental shift in how photo editors view their jobs. You can’t stop at, “Well this person doesn’t have a lot of experience, so I’m going to go with this white man, because he has twenty years of experience.” Why was that white man given all those opportunities to get twenty years of experience in the first place? You have to be willing to mentor people, and train people, and see that they are getting paid fairly, which is a huge issue in this industry.

I’ve always worked simultaneously between being a photo editor and a freelance photographer. I know firsthand what it is like to front money for travel for an assignment, and then you have to wait three months to get paid back for that expense. If you’re not independently wealthy, how do you make that happen?

What are you doing to make sure freelancers are safe, and paid on time and fairly? Give them the resources and support so they can end up with twenty years of experience.

Lynsey Weatherspoon, A young woman raises her fist in the middle of the street on the first day of the protests, May 29, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Lewis: I understand things are moving quickly, but I need photo editors to understand that people are protesting four hundred years of history. I am happy to see so many people hiring Black. But don’t hire a Black photographer and say, “Alright, I hired my one Black photographer!”

We have been disadvantaged. Many Black photographers didn’t go to all these workshops or legacy photojournalism schools. They’re just damn good photographers. But many of them don’t know the process, because photo editors have never thought to teach them. Or ask them. Things like FTP transfers, captions, or metadata. Take a second and ask if they have questions about what they need to do. Make sure they read through and understand the documents. Ask if there is something they don’t know. When I was coming up, I wouldn’t ask a damn thing.

It takes a little bit longer for photo editors to do that work, but it pays off. Your workflow becomes better. I’ve let myself down by not asking these questions. It has resulted in unnecessary back-and-forth email conversions and texts, or me writing captions when I was on a deadline. All that would have been alleviated if I said, “Hey, you’ve never worked for the New York Times before. Let’s talk everything through while you’re filing. About what you need to do.” That goes so far. These are skills that photographers can take away. Money is cool, but don’t forget about skills that they can take elsewhere. Photo editors need to do that legwork. Especially right now, when so many photographers are getting their first looks. Organizations like Authority Collective and Diversify Photo have been saying this for years. But you can pick it up right now. Teach.

Lynsey Weatherspoon, Sunday morning after two nights of protests in downtown Atlanta. The American flag waves in the window of the Georgia World Congress Center, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: I’ve been spending a lot of time with the work of Angela Davis these past few weeks, and she stresses the importance of critiquing racism and capitalism at the same time. While I agree that we need more Black photographers and photo editors, I am also thinking about how many Black people can’t even afford to get into the industry in the first place because of racial capitalism—to even be part of a shared Google doc of Black photographers. How do we address this structural exclusion?

Scruggs: I’m glad you brought that up, because hiring Black photographers solves only part of the issue. We have to look at this from a systemic level. You can’t redline people and put them in neighborhoods with no resources, no schools, no mental health resources, no grocery stores, no generational wealth, and then compare them to their white counterparts, and tell them to go spend $2,000 on digital camera body, another $2,000 on a laptop, and another $1,300 on lenses. All of that when there is no potable water in the neighborhood either. How do you afford all that to even get started in the industry as a photographer?

The databases [of Black photographers] are great resources, but the problem isn’t just that people didn’t know that there were Black photographers. It’s a good start, but it’s not the full solution. The people in power—people at the leadership level, the publisher level, the corporate level—don’t see us and I don’t think they care. When I say, hire Black photographers, it’s only part of it. Think about how to work in a collaborative way, rather than just an extractive way. Consider the toll that it takes on Black people’s mental health. We need to think about how to really bring people in and make them feel welcome.

Weatherspoon: Economic disparities are certainly a weight on Black photographers since we’re historically denied credit or any funding that would accelerate our business goals. This would make anyone feel defeated, especially when you have White photographers who find you inferior because of what you lack economically. Black creatives are trying to keep up with the world, while trying to find ways to fund our career goals.

As for hiring Black photo editors, it is crucial that we know a job like this exists for us in the first place. Even if you decide to not be a photographer, we have to know that jobs like this exist in newsrooms, publications, and creative spaces.

Lynsey Weatherspoon, Officers stand in front of the Georgia State Capitol, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: I worry that everything that brands and outlets are doing right now is performative. That there’s a lot of attention now, but what about next month? What does the photography industry need to learn from this moment? What does that look like in the long run?

Scruggs: It requires a fundamental shift in society. The whole reason why there is so much racism, sexism, ageism, classism in the industry is because all of that exists in society. White people especially, but also non-Black people of color need to educate themselves in being anti-racist. Really do that work and don’t ask Black people to hold their hands through it. We’ve been doing that and it’s really exhausting. We need that time to ourselves.

It’s been years, decades, centuries. Photography started out as a tool of white supremacy, and people don’t talk about that. One of the main functions of it was to reinforce slavery and colonialism. I wonder how you use a tool originally created for white supremacy to work against white supremacy? That’s a question that all photographers should be asking themselves, not just Black photographers. Specifically, white people need to have these conversations with other white people. Do not turn to your Black friend. They are probably not even your Black friend—they are your coworker. Don’t say, “How can I help? What can I do?” You need to turn to your white friends and say, “What do we do? Why don’t we know these things? Why have we been avoiding these conversations?” Don’t have a diversity panel. Literally, just hire Black people and people of color.

Lewis: Everyone’s hoping they won’t get dragged. That’s a fact. Sorry, not sorry. The goal is to level the playing field, and to do that we need new voices in here. Not just photographers, but editors, and directors of photography. The biggest takeaway for this in the long term is building relationships. Photo editors reply to people they know faster than to people they don’t know. These relationships are important. Build those relationships. A lot of photographers aren’t going to go to workshops or portfolio reviews or legacy photojournalism schools. But they are damn good. Knock down the whole gatekeeping thing. Open up the gates.

Lynsey Weatherspoon, Young man raises his hands during a protest in front of the Georgia State Capitol, 2020

Courtesy the artist

Matsuda: What do you need right now?

Scruggs: Wow, a lot of people don’t really ask that. I would say space. Giving people space to process. There’s a lot going on. Understatement of the year. Give people space to rest, process, be angry, and be sad. I need to have space to feel what I need to feel. I need concrete resources. Mentorships. Money. Fair pay. Historically, Black women are asked to do a lot and shoulder a lot. So I need a real investment. Cash dollars. There was a spreadsheet going around with what people were making in the industry. With only two or three years of experience, people are making three or four times what I’m making. So I need fair pay. Wages. Cash.

Lewis: I need people to care. Don’t do it for likes. Don’t just black out your Instagram. Read. Realize this didn’t start with George Floyd. It goes back four hundred years. Listen to podcasts. Take in everything you can right now. Understand why people are protesting in the middle of a pandemic. That’s how serious it is! People are like, “I’m more likely to die from police violence than I am from a pandemic.” That’s something you need to understand. I need you to look at yourself. You’re stuck in the house. You’re not going anywhere. This is the time to do it!

Weatherspoon: I need sunlight. I need for this bullshit to end. I need people to understand that this issue is not new; it’s always been here. Hopefully we get it right this time. I know we say that every time. We know names like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade, but how many countless names do we not know?

Agboola: Those four officers [responsible for killing George Floyd] need to be charged. There needs to be justice. For me, I need that. All those buildings that burned can be rebuilt; money can be remade. George Floyd is not coming back. As a Black man, I fear for my safety every day. When I get pulled over by police, my body turns into fear and I wonder if this is the end. So as a Black person, that is traumatic. I am dealing with that trauma. You have to listen to Black people. Black lives matter. If there is a protest tomorrow, I will be there. But I want to come home.

Will Matsuda is a photographer and writer based in Portland, Oregon.

Black Is Beautiful

In the 1960s, Kwame Brathwaite’s fashion photographs sent a riveting message about Black culture and freedom.

By Tanisha C. Ford

Kwame Brathwaite, Nomsa Brath wearing earrings by Carolee Prince, ca. 1964

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Everyone knows the phrase “Black is beautiful,” but very few have heard of the man who helped to popularize it. Brooklyn-born black photographer Kwame Brathwaite has lived most of his life behind the camera, devoted to capturing the lives of others on film. Spending much of the 1960s in his tiny darkroom in Harlem, he perfected a processing technique that made black skin pop in a photograph, with a life and energy as complex as that decade. Known by friends and comrades as the “Keeper of the Images,” Brathwaite has logged thousands of hours in the darkroom, dipping his fingers into harsh developing chemicals so often over the decades that the grooves of his fingertips have become worn. His labor reflects his deep commitment to black freedom and radical cultural production. With every dip, measurement of solution, and timing of exposure, Brathwaite styles blackness. His images, carefully calibrated to reflect a moment precisely, made black beautiful for those who lived in the 1960s, and continue to do so for a generation today who might only now be discovering his work.

I first stumbled upon Brathwaite’s photographs in 2009 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. There I found a series of provocative images of black picketers taken at an August 1963 protest of a white-owned beauty supply store in Harlem called Wigs Parisian. The black women and men in the photographs carry placards that boldly declare: “We Don’t Want Any Congo Blondes!” and “He’s Got Straight Hair, but He’s Still an Ape!” Drawings of dark-complexioned women with large lips sporting blonde wigs and an ape with slicked hair dressed in a tuxedo accompany the texts. The photographs are riveting and unlike any that I had previously associated with the protests of the early 1960s, when slogans such as “Freedom now” and “One man, one vote” were rallying cries. They touch a sensitive nerve. They confront our collective feelings of pain and shame. Those feelings about our hair and bodies that we adopted in childhood and still fight to keep at bay. These piercing images, locked away in a small box in Harlem, represent a history that I had never learned in college or graduate school. I wanted to know: Who was this photographer? Who were these protestors? Google searches yielded little; Brathwaite seemed to exist only in the photography of the past and in minor quotes in black nationalist publications such as Muhammad Speaks and the Liberator. My countless email requests for an interview with Brathwaite went unanswered, until I was able to speak with him last winter for this article.

Kwame Brathwaite, Naturally ’68 photo shoot in the Apollo Theater featuring Grandassa models and AJASS founding members (except the photographer). Center from left: Frank Adu, Elombe Brath, and Ernest Baxter, 1968

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Brathwaite found photography through his love of the rollicking rhythms of hard bop jazz. In 1956, he and his teenaged friends, all recent graduates of the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design) in Manhattan, formed the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios (AJASS), a radical collective of playwrights, graphic artists, dancers, and fashion designers. Jazz societies were common at this time, and AJASS modeled itself after the well-established Modern Jazz Society. They opted to use the then much less common word African, which made their group distinct and referenced their political leanings.

Years earlier, Brathwaite and his older brother Elombe Brath, a graphic artist, had heard activist Carlos Cooks espousing the politics of black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey: “Take back our land!” “Go back to Africa!” “Black is beautiful!” His message of black empowerment and economic independence resonated with the brothers, and they joined Cooks’s African Nationalist Pioneer Movement. “We weren’t fond of just being colored folks, being under the yoke of anybody else,” Brathwaite told me when I interviewed him. AJASS members were the “woke” set of their generation, calling themselves African and black when most people were still using the now passé colored or negro. In jazz, they found a similarly rebellious spirit, a music that communicated emotions that could not otherwise be articulated.

Kwame Brathwaite, Sikolo Brathwaite wearing a beaded headpiece by Carolee Prince, ca. 1967

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

AJASS members spent most of their weekends promoting concerts at the legendary Club 845 on Prospect Avenue in the Bronx, the epicenter of the borough’s jazz scene, where they began booking rising stars like John Coltrane, Lee Morgan, and Philly Joe Jones. “We could pick some of the best musicians in the world,” Brathwaite recalls. “We’d have good, packed houses all the time.” One evening in 1956 Brathwaite strolled into the club, greeted customers perched at the bar, then headed toward the back of the venue and into the cavernous performance space, the sound intensifying as he neared the stage. One of his school friends was snapping pictures in the dimly lit club, and Brathwaite was astonished that he was not using a flash or any additional light source. Nothing. Brathwaite, the advertising-arts major who had never really worked with a camera, asked his friend, “How do you do that with no flash?” His friend’s professional camera and Kodak Tri-X film (the film that revolutionized photojournalism because of its speed and versatility) were far superior to the camera Brathwaite had received as a gift at graduation. “I couldn’t do what he was doing with that,” Brathwaite told me as he swatted the air in a dismissive gesture.

And just like that, Brathwaite was hooked. He used his earnings from the jazz shows to buy a professional camera and devoured every photography book he could find. Jazz set the rhythm for his photography, which became central to his artistic approach. “You want to get the feeling, the mood that you’re experiencing when they’re playing,” he explains. “That’s the thing. You want to capture that.” But translating the moody blue notes of jazz onto film is not a skill one can learn from a book; it is sensory knowledge that comes from an understanding of jazz culture—the syncopated rhythms, the elasticity of sound, the spirit of improvisation. The temperament of jazz is the lifeblood of Brathwaite’s work.

Kwame Brathwaite, A school for one of the many modeling groups that had begun to embrace natural hairstyles in the 1960s, ca. 1966

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

The new camera became young Brathwaite’s closest companion, kept within reach so he could take a snap whenever something intriguing crossed his line of sight. Most of his early images were from the Club 845 sets: jazzmen on their horns, spectators enthralled by the music. He also photographed the quiet intimacy of the musicians’ lives. “I’d go to Coltrane’s house at times. He would be playing the soprano sax in his kitchen with his T-shirt on. I got some shots,” Brathwaite told me. As the unofficial photographer of New York’s annual Marcus Garvey Day celebration, he quickly learned that photography required fearlessness. During the parade, Brathwaite would bend and contort his lithe body, often throwing himself into the crowd in order to document the extravagance and pageantry of the lively event.

As Brathwaite perfected his camera skills, taking hundreds of photographs each week in those early years, the movement for black freedom was erupting on the Harlem and Bronx streets around him, as much as it was in the American South. The federal government had overturned “separate but equal,” but black Americans like Brathwaite and his peers still felt the cold fear and unease of stepping too close to the invisible line of Jim Crow segregation. Photography was the insurgent technology through which everyday people and professional photojournalists alike captured the wild violence of police billy clubs and the quiet threat of “Whites only” signs in shop windows from downtown Manhattan to Montgomery, Alabama.

The “Black is beautiful” movement really started to coalesce in and around Harlem in late 1963, after the Wigs Parisian protest. “That’s when we started promoting ‘Black is beautiful’ even more. We had entertainment with fashion shows and concerts and stuff like that, which made us very popular in the community,” Brathwaite said. They began using “Black is beautiful” and other slogans such as “Think black” and “Buy black” on event flyers and other ephemera.

Kwame Brathwaite, AJASS members Robert Gumbs, Frank Adu, Elombe Brath, Kwame Brathwaite, David K. Ward, and Chris Acemendeces Hall, ca. 1961

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Brathwaite wore his “Keeper of the Images” title with great pride and conviction, allowing his brother to take the lead as the public voice of their movement. Yet, the mostly male group realized that beauty and body issues affected black women differently. “We said, ‘We’ve got to do something to make the women feel proud of their hair, proud of their blackness,’” Brathwaite explained to me. In order to truly communicate why black was inherently beautiful, they needed women at the helm. With the help of a well-connected AJASS member, Jimmy Abu, they began recruiting teenage and young adult women to model in a community-based fashion show. They named the group Grandassa, drawing from the word Grandassaland, which Carlos Cooks used to describe the African continent. The original models had deep chocolate skin, full lips and noses, and wore their hair in “natural” styles that highlighted their kinky textures.

The Grandassa models dazzled the crowd of mostly black folks from Harlem and the surrounding neighborhoods who assembled at the Purple Manor on January 28, 1962, for Naturally ’62: The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards. Actor Gus Williams served as host alongside jazz singer and activist Abbey Lincoln, while her husband, jazz drummer Max Roach, led the house band. The models sashayed across the makeshift catwalk in vibrant dresses, skirts, and sophisticated blouses constructed from fabrics with intricate prints. Each woman accessorized her look with large hoop earrings, chunky bracelets, and kitten-heeled mules and sandals.

The event was a smash. AJASS soon produced more shows, eventually making Naturally an annual event. “We started picking up designers, black fashion designers,” Brathwaite said, noting that Carolee Prince, who created headdresses for famed singer Nina Simone, also showcased her original pieces in the Naturally shows.

Kwame Brathwaite, Grandassa models after the Naturally fashion show, Rockland Palace, ca. 1968

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Brathwaite and his crew realized they were now at the center of a brewing national conversation on colorism and race pride within the black community. The Grandassa models were not simply countering the images of pale and frail British models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton who appeared in mainstream U.S. publications. They were also challenging the ubiquitous presence of lighter-complexioned, straight-haired black models in black- owned publications such as Ebony. “There was lots of controversy because we were protesting how, in Ebony magazine, you couldn’t find an ebony girl,” Brathwaite told me.

Spurred on by the cultural zeitgeist of the moment, Brathwaite transformed AJASS from a band of creative teens into a group of businessmen and -women who could “sell” their vision of blackness to an international audience. In 1964, they signed a lease on a studio space next to the Apollo Theater. Brathwaite and Brath produced “Black is beautiful” ephemera—as well as several Blue Note Records album covers—and charged a sitting fee to photograph local women and men. Later, they operated a café-style meeting space called Grandassa Land, on Seventh Avenue between 135th and 136th Streets, where they hosted poetry nights and plays organized by the AJASS Repertory Theatre. Lincoln and Roach introduced them to club owners in the Midwest who invited AJASS to present Naturally shows in Chicago and Detroit. Images of the stylish Grandassa models appeared in black publications in the United States, Britain, Nigeria, and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

The popularity of Grandassa and AJASS made Brathwaite a sought-after photographer for international magazines. His photographs of megastars such as Stevie Wonder, Muhammad Ali, and Sly Stone were published in Britain’s Ad Lib and Blues & Soul magazines, as well as in publications in Japan. With those early paychecks—much larger than the meager sitting fees he charged neighbors in Harlem—Brathwaite upgraded his equipment and traveled the world. He had encounters that a boy from the Bronx, whose only taste of the international had been his mother’s Caribbean coconut bread, could have only dreamed of.

Model inspired by the Grandassa photo shoot at AJASS, ca. 1965

Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Naturally shows became less frequent as the 1960s drew to a close. Brathwaite and Brath delved deeper into pan-Africanist activism, and they traveled extensively across the African continent, working alongside activists in Ghana, Nigeria, Congo, Namibia, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt. Meanwhile, the catchy slogan “Black is beautiful” continued to spread and was used to sell everything from hair-care products and T-shirts to alcohol and cigarettes. The two brothers had helped to usher in this moment, making black nationalism artful and accessible to everyday black folks. But the brothers’ absence from the political, social, and artistic scene in the United States, and the ubiquity of soul music and black power imagery in the early 1970s, meant that most people never came to know them, AJASS, Grandassa, or the vibrant history of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, of which they were at the center. Brathwaite’s photographs, which provide much-needed texture to our understanding of the black freedom movement, never became part of the movement’s visual canon. Instead, his images found a home in the Schomburg Center in Harlem, not far from where the AJASS studio was located, where they lay in wait for an eager researcher to access them and understand their significance. There were no retrospectives, no splashy write-ups.

And Brathwaite was fine with this. He never pursued photography for the accolades. He enjoyed the quiet life outside of the spotlight. Elombe Brath died in 2014, after suffering a series of debilitating strokes. The loss upended Brathwaite’s world. His brother was always the voice, the one who could galvanize the crowd with his booming speeches. With his passing, and that of most others in their collective, Brathwaite realized that he was not only the “Keeper of the Images”; he was now the keeper of the stories, too. If he didn’t share this history, it would be lost to time. At seventy-nine years old, Brathwaite is now telling the tale of how he—the son of West Indian immigrants—and a crew of black teens from the Bronx styled the world.

Tanisha C. Ford is author of Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (2015).

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style,” Fall 2017. See more of Brathwaite’s work in Black Is Beautiful (Aperture, 2019).

June 4, 2020

George Floyd, Gordon Parks, and the Ominous Power of Photographs

From the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter, can images help fight injustice?

By Deborah Willis

Gordon Parks, Malcolm X Gives Speech at Rally, Harlem, New York, New York, 1963, 1963

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

“I find it difficult to look at these photographs without flinching from the memories and from the anger they invoke. But I must look. I must remember, as you must. For this was history in the making. Like it or not, you cannot hide from the camera’s eye.”

—Myrlie Evers-Williams, foreword to The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954–68, 1996

As I reflect on photography and protest, I see it as my life in America from a lived experience to an act of memory. I am troubled by the images I’ve seen over the last two weeks, and I have been asked—by various people—what these images mean to me. Black death has been photographed, broadcasted, painted, recorded, tweeted, and exhibited for the past ninety days. It has been nine days since a teenager posted footage of George Floyd’s murder. It has been nine days of collectively watching George Floyd’s last moments of life, seeing a man struggling and crying, while a white police officer digs his knee deeper into Floyd’s neck, the officer’s left hand slipped casually into his pocket. I watched in horror as the other police officer stood guard, protecting his fellow officer, while the person behind the camera screamed and pleaded with the officers to stop. I heard others begging for his life as George Floyd pleaded “I can’t breathe” over and over again.

The video went viral! Each time I watched the news, my heart cried. It is recorded thanks to cell-phone imaging and surveillance cameras and, because of the camera, we see history repeating itself. Just this past March, Breonna Taylor was killed in Kentucky; in February, Ahmaud Arbery’s death was recorded in Georgia, and not until weeks later did the national news media report his tragic death. COVID-19 killed 100,000 Americans, and their names appeared on the local news and some of their portraits were published in the newspapers. Activists, community members, students, first responders, essential workers, government and city officials, family members, and others have used the images to make change happen because of a history of injustices.

Gordon Parks, Harlem Rally, Harlem, New York, 1963

© and courtesy The Gordon Parks Foundation

I started thinking about Black death well before the global pandemic and global lockdowns and measures of combating and coping that have become our everyday reality. I will never forget the photograph of the brutally beaten and swollen body of the young Emmett Till published in Jet magazine in 1955. Many young people experienced episodes of hostile confrontation with the police that intensified over the years because of social protests. Blacks were being killed, hosed, jailed, and subjected to unjust laws throughout the American landscape. Photographers witnessing both brutal and social assaults created a new visual consciousness for the American public, establishing a visual language of “testifying” about their individual and collective experience. On April 27, 1962, there was a shootout between the Los Angeles police and members of the Nation of Islam (NOI); Ronald Stokes, a member of the Nation of Islam, was killed. Fourteen Muslims were arrested; one was charged with assault with intent to kill and the others with assault and interference with police officers. A year later, Malcolm X investigated the incident and the trial. Noted photographer Gordon Parks remembered his photograph of Malcolm X holding the brutally beaten NOI member in this way:

I recall the night Malcolm spoke after this brother Stokes was killed in Los Angeles, and he was holding up a huge photo showing the autopsy with a bullet hole at [the] back of the head. He was angry then; he was dead angry. It was a huge rally. But he was never out of control. The press tried to project his militancy as wild, unthoughtful, and out of control. But Malcolm was always controlled, always thinking what to do in political arenas.