Aperture's Blog, page 73

April 18, 2020

2020 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Jessica Chou

Photographing in Monterey Park, Jessica Chou evaluates how immigrant communities fit into today’s suburban landscape.

By Emily Stewart

Jessica Chou, Superco, 2013, from the series Suburban Chinatown

A short distance east of Los Angeles sits the San Gabriel Valley, a cluster of majority Asian suburbs that is home to a large immigrant community. Monterey Park, located in the San Gabriel Valley, was the first city in the United States to reach a majority Asian-descent population, and it is where photographer Jessica Chou grew up.

In her series Suburban Chinatown, Chou tackles the notion of the suburban landscape and how immigrant communities fit into that narrative. Inspired by the work of Stephen Shore and Larry Sultan, Chou approaches Monterey Park with an urgency to document a space she’s called home for most of her life. Chou describes growing up in Monterey Park as living in a bubble, aware that her childhood experiences were drastically different from what she read in novels or watched on TV, which was often an idealized white suburbia.

Chou explores the importance of recontextualizing suburban ideals and the American dream in today’s social landscape. Her title, Suburban Chinatown, is a nod to how society typically thinks about Asian immigrant communities in America: what often comes to mind is a space like Chinatown. “Chinatown has this timeless, exotic foreignness and otherness that often mimics what people want to see,” notes Chou. The San Gabriel Valley, and specifically Monterey Park, offers a different entry point into American life for Asian immigrants.

Chou’s photographs capture subtle moments of intertwined Asian and American identities in Monterey Park. They often showcase the subtlety of Asian culture in Southern California in small details, like Chinese characters on the side of the building or hymns sung in Chinese during a church service. A photograph of a cactus—a symbol of the desert and the Southern California landscape—graffitied with both English and Chinese writing, symbolizes an immigrant community carving its mark on American identity. Chou’s work is a gentle reminder that not all suburban spaces look the same, nor are they occupied by the same type of people. “There are many interpretations of the American dream,” she says. “And I hope this work updates both the immigrant and suburban story.”

Jessica Chou, Daydream, 2018, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou, RHCCC Chinese Speaking Service, 2019, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou, Monterey Park City Council Election, 2015, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou, Marine Corps SSgt Chen, Recruiter, 2019, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou, Woman in Abercrombie, 2013, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou, China, Monterey Park, Los Angeles, 2016, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Jessica Chou was born in Taipei, Taiwan, and raised in the San Gabriel Valley, in the suburbs of Los Angeles. She graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with a degree in history with an emphasis on the Middle East. In her photographic work, Chou is interested in chronicling contemporary events that are shaping conversations around how we understand ourselves. She regularly contributes to publications such as the New York Times, California Sunday Magazine, and Bloomberg Businessweek, among others. Chou’s work can also be found in the permanent collection of the Tweed Museum of Art, Duluth, Minnesota. She currently lives and works between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Emily Stewart is manager of education and engagement programs at Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

2020 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Daniel Jack Lyons

Daniel Jack Lyons explores environmental peril and Indigenous youth culture in the Amazon.

By Michael Famighetti

Daniel Jack Lyons, Leo, 2019, from the series Amazônica

The Earth’s lungs are in peril. With Brazil under the control of Jair Bolsonaro and his right-wing regime, illegal mining and agricultural expansion in the Amazon have recently contributed to catastrophic fires. While some image-makers captured dramatic aerial views of the spectacle of smoke and fire, Daniel Jack Lyons, a Los Angeles–based photographer who has spent much of his career focusing on the lives of youth subcultures—often in marginalized communities—was drawn to the largely unseen lives of young Indigenous people in the region.

A Portuguese speaker who had previously worked in Brazil, Lyons teamed up with a local community organizer based in a remote location in the Amazon and set out on a series of intimate portraits, realized in his characteristic soft, earthy palette. His photographs offer an individualized take on Indigenous communities in the region: his subjects are skateboarders, drag queens, heavy-metal fans, and farmers. “I wanted to document the banality of everyday life and the rebellious creativity it inspires,” Lyons says. “This universal impulse to express and affirm one’s individuality is resilient but at risk from a toxic mix of environmental degradation, violence, and discrimination. As another generation passes through the quotidian rites and rituals of adolescence, what sort of world will they inhabit and how much autonomy will they have over it?”

Daniel Jack Lyons, Milton, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons, Rio Tupana, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons, Stefani and Fabricio, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons, Alvaro’s Crocodile, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons, Lucas, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons, Diana and Alejandra, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Daniel Jack Lyons’s background as a social anthropologist is very much at the heart of his practice as a photographer. His work, both personal and commissioned, focuses largely on marginalized youth, whether occupying spaces on the periphery of society or in the face of conflict. He employs collaborative methods that grant his subjects a greater sense of autonomy in guiding each project’s message, infusing Lyons’s work with a deeper creative spirit that often illuminates universal experiences. Creating this kind of work has taken him to Mozambique, Ukraine, New York, the Amazon, and Los Angeles. In each case, Lyons documents the particular expressions of joy, optimism, and concern that tap into the general insouciance and naiveté of “coming of age.” He is a regular contributor to the New York Times, More or Less, and Vogue Italia, and his body of work Hotel Luso was included in the exhibition Labs New Artists II at Red Hook Labs, Brooklyn, in 2018.

Michael Famighetti is editor of Aperture magazine. All images courtesy the artist.

2020 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Lindley Warren Mickunas

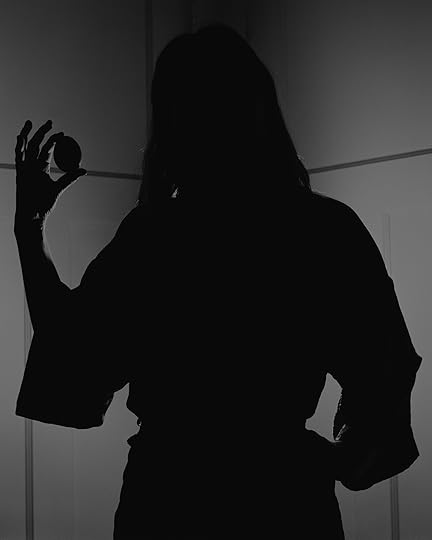

In haunting black-and-white photographs, Lindley Warren Mickunas investigates the complexities of the maternal bond.

By Cassidy Paul

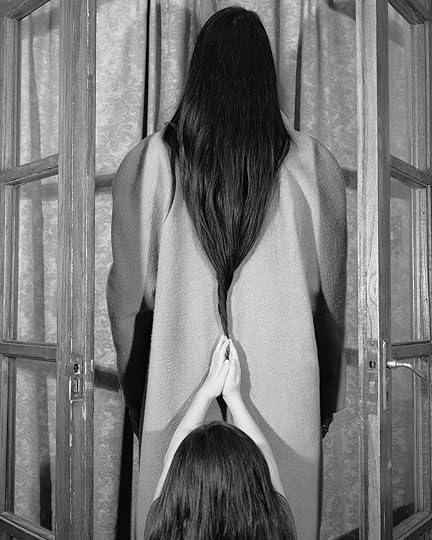

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Mother and Daughter, 2017, from the series Maternal Sheet

We are all born of our mothers. This symbiotic relationship is fraught with complexities, yet it is instrumental to our very being. But what happens when the mother and child separate? Or when their relationship extends beyond what is healthy? For the past three years, Chicago-based artist Lindley Warren Mickunas has created a haunting investigation of the maternal bond—examining codependency, the violence placed on female bodies, and generational trauma in families.

Drawing from her childhood experiences, Warren Mickunas mixes together staged reenactments performed by nonrelatives alongside documentation of her family. The resulting series, Maternal Sheet, speaks to the complicated dynamics found within families, juxtaposing the ways comfort, trauma, and coldness all coexist. There is no single perspective, shifting between mother, child, parent, and the ominous, removed, viewer. For Warren Mickunas, addressing these complexities is vital. “I approach this series both as a woman who intends to someday be a mother, and as a daughter,” she explains. “I’m not only thinking about the way that motherhood and the maternal shape life, but also how these concepts are imbedded into my practice as a female artist. Every creative act that springs forth from me I view as an act of mothering.”

Intentionally blending the line between real and fabricated, Warren Mickunas’s images live in different states between past, dream, concept, and memory. Utilizing black and white alongside a harsh flash, the artist trades the intimacy often associated with family and motherhood for cold detachment. A child plays with her mother’s hair. Gloves filled with milk resemble an udder, squeezed harshly by a child that remains unseen. Figures of parents and children are clouded by shadows and haze. A single rocking chair sits poised in a corner, as if pulled from a horror film. Two opposing adult arms battle for a helpless child. Each frame has an almost atmospheric sense of tension, hinting at a darker presence lurking beyond that single moment.

Though Maternal Sheet started with Warren Mickunas’s personal history, she sees it as addressing a much larger experience. “I hope that the work can communicate the complexities within the home and the pressures placed on the traumatized family,” Warren Mickunas reflects, “but also the truth that we as humans, especially as children, possess an incredible resiliency and ability to adapt and cope with very challenging circumstances.”

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Milk, 2020, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Mouth, 2019, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Three Hands, 2019, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Rocking Chair, 2017, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Feeding, 2019, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Egg, 2018, from the series Maternal Sheet

Lindley Warren Mickunas is a Chicago-based photographer, editor, and curator. She is the founder of various publications, including The Ones We Love andThe Reservoir, a collective editorial project on the politics of image-making. Warren Mickunas is an MFA candidate in photography at Columbia College Chicago, and curatorial assistant at the Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago. Most recently, she was published in FotoFilmic’s JRNL 2 (guest edited by Rachel and Gregory Barker of STANLEY/BARKER) and exhibited by Der Greif at Berlin Photo Week.

Cassidy Paul is the digital editor at Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

2020 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Gloria Oyarzabal

Mixing archival images with contemporary snapshots, Gloria Oyarzabal examines the effects of colonialism and the follies of white feminism in West Africa.

By Nicole Acheampong

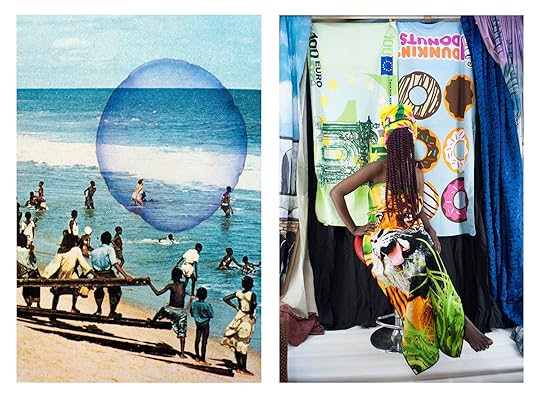

Gloria Oyarzabal, Ambiguity, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal’s entry point for her Lagos–based series WOMAN GO NO’GREE (2017–ongoing) was principally academic: the Spanish artist began by creating for herself a curriculum of Nigerian feminist theory, zeroing in on canonical gender scholarship, like Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí’s The Invention of Women: Making an African Sense of Western Gender Discourses (1997) and Ifi Amadiume’s Male Daughters, Female Husbands: Gender and Sex in an African Society (1987). These texts, which radically displace the binary, Western framework for understanding gender difference, catalyzed Oyarzabal’s interest in imaging the effects of colonialism and the follies of white feminism in West Africa.

Oyarzabal crafts provocative juxtapositions of Lagosians in motion with archival images and her own contemporary snapshots: a woman with sparkly, purple eyelids, holding a manicured index finger to her puckered lips, for example, converges with an explosion careening above water and a masked figure arched from heel to head. Oyarzabal liberally manipulates the archival extracts throughout the series, flipping figures upside down or applying unreal washes of color that beget a fable-like aesthetic. These enigmatic images enter an open dialogue with Oyarzabal’s own photographs of Nigeria, which feature a range of cosmopolitan subjects that Oyarzabal encountered on the street, at bars, through friends, or in the clamor of art openings for the Lagos Biennial in 2017.

In some portraits, Oyarzabal stages her subjects in a studio setting, dressed in pointedly eclectic ensembles. She uses patterned fabrics and exaggerated silhouettes to explore how the gaze of the colonizer refracts the image of the African woman. In one instance, this performance is paired with a found image from a colonial-era Nigerian magazine, in which a lone white woman at a bustling beach is enclosed in a blue bubble. For Oyarzabal, the bubble, an incidental photo discoloration, serves as an apt metaphor for the white privilege she seeks to reckon with. The blue borders also hint at other limits: the failures of white feminist discourse to properly account for a cultural context outside of its own bubble.

Oyarzabal doesn’t claim to speak for Nigerians or to make a statement about feminism in broad strokes. Instead, she considers the project and the research from which it sprung to be an exercise in decolonizing her own gaze, and for that reason, she welcomes debate that her work might prompt. “The feedback is what nourishes me,” she says. The title WOMAN GO NO’GREE, borrowed from Fela Kuti’s famous and widely debated song “Lady” (1972), encapsulates Oyarzabal’s challenging relationship with the material. “Women don’t have to agree,” she says of the diverging theories about how women might attain empowerment. “And that’s the point.”

Gloria Oyarzabal, Sorority, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal, White Privilege – Wild (on exotization, Hipersexualation, Victimization and other – zations), 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal, Pim Pam Pum, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal, Phantom Riot, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal, Empowerment, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal, La Dimension Féminine, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Gloria Oyarzabal is a Spanish artist who works between photography, cinema, and teaching. She has a BFA from the Complutense University Madrid and a master’s degree from the Blank Paper School of Photography, Madrid. Oyarzabal is cofounder of the Independent Cinema “La Enana Marrón” (The Brown Dwarf) Madrid (1999–2009), which was dedicated to the diffusion of films d’auteur and experimental and alternative cinema. From 2009–12, she lived in Bamako, Mali, developing her interests in the construction of the “idea of Africa,” histories of colonization and decolonization, new tactics of colonialism, and African feminisms. Her work has been shown at festivals and venues including FORMAT, Derby, UK; LagosPhoto, Nigeria; PHotoEspaña, Madrid; and the Thessaloniki Museum of Photography, Greece; among others. In 2017, Oyarzabal won the Landskrona Foto Dummy Award, which allowed her to publish her first photobook, Picnos Tshombé. In 2018, she won the Encontros da Imagem Discovery Award. In 2019, her work was selected for the Images Vevey Dummy Award, PHOTO IS:RAEL Meitar Award for Excellence in Photography, and the Grand Prix Fotofestiwal.

Nicole Acheampong is the editorial assistant of Aperture magazine. All images courtesy the artist.

April 16, 2020

Are Virtual Viewing Rooms the Future of Photography?

With museums and galleries closed, the touch-screen world is the only one we have.

By Jesse Dorris

Ray K. Metzker, 59 R-5, Chicago, 1959

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

They say it’s spring. I should be dreaming and adrift. Instead, I am moored to my Womb chair, which is covered in cat hair. This is the chair in which I used to read, but lately I’ve been watching drone footage of men in white hazmat suits fill a crumbling trench with coffins. I’ve been thinking about Hart Island and anonymous graves, for victims of AIDS in the 1980s, for victims of the coronavirus today. I’ve been thinking of Helène Aylon, who, in 1982, unloaded a truck full of pillowcases, filthy with uranium mine dust, onto stretchers and buried them near the UN headquarters in Manhattan. Aylon called the action Earth Ambulance; she died of COVID-19-related causes earlier this month, on April 6.

Helène Aylon, The Earth Ambulance, 1982

© Estate of Helène Aylon and Courtesy Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

The internet was supposed to be everything at once, unfurled on a series of scrolls. Lately, it just feels like peepholes. I watch that drone footage on a browser next to a tab with a long scroll of photos of Aylon’s action; and another of footage from an “Anti-COVID-19 Volunteer Drone Task Force” demanding social distancing above Manhattan’s East River Park; and some porn; and my endless fucking email; and the initial iteration of David Zwirner’s Platform: New York digital viewing room, which gathers artists like Troy Michie and Nathaniel Robinson from a dozen New York galleries and presents a piece of theirs for sale. “Brandon Ndife’s work envisions a post-disaster horizon where vegetal and fungal forms take over our built environments,” reads one sales pitch, “a prescient mirror to our current reality.” It’s preceded by a glamorous headshot of the artist, something you would never see in a gallery IRL, and a new practice that probably doesn’t bode well for artists who are less attractive than their art.

Nathaniel Robinson, Untitled, 2020. Oil on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Magenta Plains, New York

Enough.

The repetitive black boxes on the Zwirner platform make me think of Zoom, and then of Zoe Leonard. I once went cruising and took the train home, blotto, looking at Leonard’s photographs of empty MTA stations that Douglas Crimp reproduced in his memoir Before Pictures, which means it was 2016. I was coming home alone and thinking, Doesn’t Leonard make NYC look lonely? Not ruins, not tombs, just a place built for gathering where nobody does. And now no one can.

Zoe Leonard, from the series Downtown (for Douglas), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Buchholz, New York

On the Whitney’s website, details of Leonard’s The Fae Richards Photo Archive (1993–96) are part tackboard, part ungridded social-media platform, too small on my screen but still larger than life. Leonard just won a Guggenheim fellowship to carry on work like what she’s offering in The ties that bind, a new Hauser & Wirth online show that—opened? launched? went live? on April 11. One of her works, Untitled Aerial (1988/2008), is a gelatin silver print of something traveling through somewhere. It might be a river winding in the sun, gathering silt. (An electronics wipe clears up nothing on my computer screen as it heightens the contrast of some central flares.) However, there’s no doubt about Chastity Belt (1990–93)—that puts the current lack of sexual congress, for the single or otherwise unbothered, in context.

Zoe Leonard, Chastity Belt, 1990/1993

© the artist and courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Thirty-seven days since a man has touched me in any way, I put my finger on the screen of my phone and push toward a photo my friend has sent me of his two cats. Each furls inside a rather nice MCM wooden bowl. He texts to tell me the cats have already somehow broken other bowls (they’re valuable!) and these might be next. I’m in the viewing room for Wide Open Spaces, a show at Howard Greenberg (which was supposed to close on April 7): a row of Joel Meyerowitz photos taken in a pre-AIDS Provincetown, Massachusetts, where the ocean rumples like sheets and sheets flap like sails; then a Mark Citret image, where light comes through a grate and turns the air into grains of Xerox.

Joel Meyerowitz, Laundry, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1977

© the artist and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Further down, I see Vivian Maier’s Self-portrait, Chicago, early 1960s, a mystery in ice blue and concrete. I am grateful that the website allows me to poke and prod at the photo, to draw it open until I can sort the snow from the grit, the lake from the sky. My fingers are the focus. I go wash my hands.

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, Chicago, early 1960s

© Estate of Vivian Maier, and courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Later, drinking two fingers of whiskey bathed in cubes of frozen ginger pulp (I’ve gone through the lemons), I’m in Paul Graham’s The Seasons digital viewing gallery at Pace, a series of single exposures of Park Avenue bank headquarters. There’s one called SPRING (missing), J.P Morgan Chase, 270 Park Avenue (2018), in which the horizontal stripes of an American flag intersect the vertical steel-and-glass façade, and there are pink trees, like the one outside my window. The 1961 modernist building was designed by Natalie Griffin de Blois—though her bosses at the firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill took the credit—and was the tallest building designed by a woman for almost fifty years; JP Morgan Chase was set to demolish it as of January, though now, who knows? Anyway, Graham’s photograph looks good and flat on my screen; it really works. Pace has helpfully labeled it “Available” and listed the price. Maybe a banker will click that pill-shaped Inquire button and buy it for his corner office. If he still has one.

Paul Graham, SPRING (missing), J.P. Morgan Chase, 270 Park Avenue, 2018

© the artist and courtesy Pace Gallery

I hope TV Eye in Ridgewood, Queens, still has its new Zone 6 Art Gallery, so I can someday check out Ebru Yildiz’s high-contrast snaps of women in the music industry. There’s a quick slideshow on Yildiz’s Instagram, but that’s it—and everything on Instagram looks better because we’ve all decided that’s how things look. (Every picture of someone on Instagram makes them look like somebody you might want to drink an iced coffee and walk through the park with. Well, I’m lonely.) I bet Yildiz’s images are beguiling in person. So, too, probably is Naima Green’s Pur·suit, an update of Catherine Opie’s Dyke Deck (1995), playing cards with portraits of people Green’s gallery describes as “queer womxn, trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming.” Green’s pack poses people solo and in groups in front of mauve drapery; their existence is sui generis and the evidence thrills. Her idea is to accompany the deck with open studio hours for further portraiture. The world will be a better place when that resumes.

Naima Green, Kenya+Alexandra, from the series Pur·suit, 2020

Courtesy the artist and Recess, New York

For now, though, we’re all living in the world of the moods, myths, and illusionary schemes Blossom Dearie sang of.

I’m dreaming of throwing my arm around someone as we walk down John Boskovich’s Millennial Hallway, and examine, let’s say, the conversation pieces in his Psycho Salon. When Boskovich’s partner, Stephen Earabino, died in 1995, Boskostudio was born as an LA studio and residence, in which every last inch out of grief had been aestheticized and activated. A lá Joris-Karl Huysmans’s fictional recluse Jean des Esseintes in the novel À Rebours (1884), Boskovitch conceived a retreat to push the limits of his own imagination and—reversing the rarified des Esseints—of a trash aesthetic. Before whenever this now is, only Toshi Yoshimi’s photographs—and the tales of those who claim to have visited—could vouch for the pentagram area rug; chain-link menorah emblazoned with a quote from Jean Genet; black-and-white tiger-stripe, peace-sign bong; and chandelier with leather bondage mask diffusers. David Lewis recently pulled off the infernal task of recreating, on the Lower East Side, four Bokostudio rooms. Who knows when we can enter them again?

Installation view of John Boskovich’s Psycho Salon. Photograph by Phoebe D’Heurle, 2020

Courtesy the artist and David Lewis, New York

There’s some occult perversity in looking at photographs of a space recreated from photographs of a space. It’s alchemical, like a smudge on your thumb from a gold-leaf wrapping of a gold-plated piece of fool’s gold.

The toddler upstairs has been running in circles for thirty-two days now. On Twitter, in the air above quarantined Manhattan, a lightning rod bisects a pink supermoon.

I want to go where I cannot get to.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York and a frequent contributor to Aperture, Metropolis, and Pitchfork.

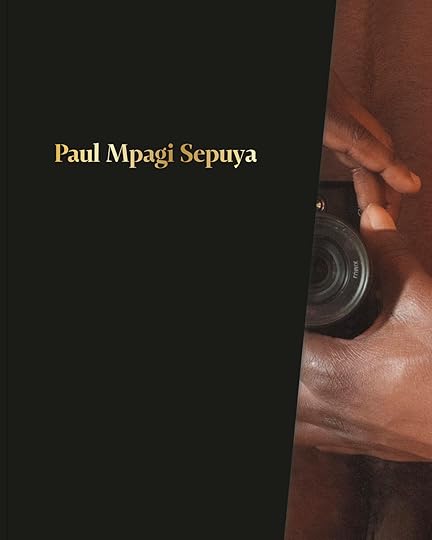

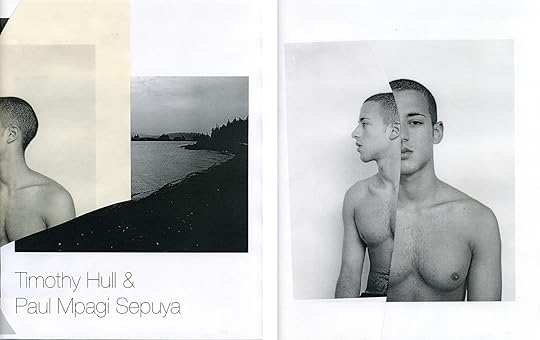

For Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Books Are a Way to Think About Time

The LA-based artist speaks about the process of editing—and re-editing—and the role that bookmaking has played in the evolution of his work.

By Lesley A. Martin

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Self-portraits (Studio Practice), 2011

Courtesy the artist

In recent years, Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s work has been widely introduced to viewers in galleries and museums worldwide, including a star turn at the 2019 Whitney Biennial and a traveling solo exhibition organized by the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. His rise to the main stage of the art world, however, was preceded by fifteen years of creating zines and small-run publications—Sepuya would often have his own table at the NY Art Book Fair—and his practice is rooted in the printed page, both of photobooks and literature. On the occasion of his newest publication, I spoke with Sepuya about the process of editing—and re-editing—and the role that bookmaking has played in the evolution of his work.

Lesley A. Martin: Your work is most often associated with the studio as a formal site in which work is made and reinterpreted. I’m curious, though, to what degree it is also indebted to the book form, and how does that manifest itself?

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Before the studio, it was definitely zine-making that served as a framework for my art-making. I had a traditional “film to darkroom to portfolio” relationship to photography—all the good training I had from my undergraduate studies. But my desire to connect to a community—to form channels for conversation and make opportunities, rather than wait for validation—led me to zines. Zines let me think about sequencing, created a channel for me to begin revisiting negatives, contact sheets, and outtakes, and to explore how meaning shifted from when I took images versus what happened when they were printed and when they went out into the world. All of those images were portraits, mostly of young gay subjects, in an expanding economy of social media exchange. That all happened within zine culture. The studio and book-making emerged alongside each other during my residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem (SMH), which culminated in a zine catalogue and self-published book, Paul Mpagi Sepuya: Studio Work (2012). The book was a way to begin to think about time—time in making, social time, and studio time—and its effects on myself, the space I was inhabiting, and the subjects in my social world.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, STUDIO WORK (Franklin Artworks, 2011) (cover and interior)

Courtesy the artist

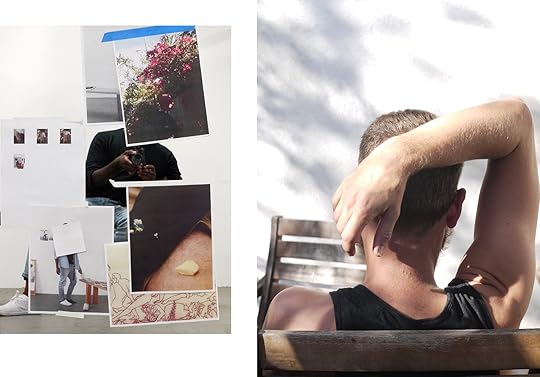

Martin: Your table installations (such as the one that appeared in the exhibition Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon at the New Museum, New York, and at Franklin Art Works in Minneapolis) draw from books, magazines, printouts in manila envelopes—they are studio tables, but are they also the scenes of books in process?

Sepuya: Yes, they all incorporate some kind of in-process material. That strategy comes from the first installations of an archive of materials from my exhibition Studio Work (at SMH)—test prints, outtakes, ephemera, notes, books, scraps—that served as the repository of sources that would later get incorporated into discrete, formalized photographs and artworks. Franklin Art Works in 2011 was the first time the SMH project was shown in full, with all the material spread out across the table tops.

In the few years between my residency at SMH and my return to California, I didn’t have a studio, and so I made these provisional books: binder clip–bound arrangements of laser printouts, which became the way of organizing my non-studio, studio practice. That was 2011–14. I returned to this book-zine form in the absence of being able to afford a stable studio. Those provisional bundles continue to be generated, and in time, I’m binding and indexing them all as hardcover volumes. They’re a sort of indexing of all the material you continue to see as fragments in the current works. What has been shown in installations, like in Trigger, are arrangements of material currently in my studio, along with bound and yet-to-be-finished and bound, bundles of the laser printouts.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, STUDIO WORK, 2013, Artspeak, Vancouver (installation view)

Courtesy the artist

Martin: The interpretive nature of your work within the picture frame, in which images and pieces of images are recirculated and reinvented across different series, seems to also be present within the publications you have made. Images accumulate and are paired and re-paired to create different networks of ideas from an essential set of ingredients. Can you describe how this iterative process draws from and can be seen in your books? Elements of various series also initially appear in the sketchbooks, or “bundles,” as you call them, that record the works as they evolve. How does one thing lead to another, from zine to book, to the next book?

Sepuya: It’s a cumulative process, one that I don’t set out to find answers to in the form of a grand thesis. I can’t plan what will happen. Each of those projects has attempted to answer a question that the project before, or perhaps an outtake or afterthought that continued to bother me, left behind.

I began portraits believing that photographs affixed meaning. And then I realized they only opened up more questions, with the possibility of ongoing selection, editing, and time. Enter the zines, to make use of that problem. The SMH residency was something I had no idea would become a book, but I realized, as material accumulated, that it had to be a book and that’s where meaning would be made. Simply, one thing leads to another by necessity and constant questioning.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Abi, April 29, 2011

Courtesy the artist

Martin: You seem to be pretty open to the rough and ready reproduction of your images—from laser copies and zines like SHOOT, to more fully and lushly rendered books, and of course, the prints themselves. How does that spectrum work for your process, and what do the various stations along that arc, from bundles of xeroxes to something “exquisitely realized,” mean to you and your process?

Sepuya: Each is a different way of handling material, either for ease or for formal exhibition, and everywhere in between. I really love reworking all materials that remains in my grasp. They don’t have meaning in themselves, but help meaning take form.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, SHOOT no. 5 (Self-published, 2006) (interior)

Courtesy the artist

Martin: Critic Tricia Rose has cited Arthur Jafa as identifying three stylistic continuities, or shared approaches, found in cultural contributions that come via the African diaspora: “flow, layering, and ruptures in line.” She further states: “Let us imagine these . . . principles as a blueprint for social resistance and affirmation: create sustaining narratives, accumulate them, layer, embellish and transform them. But also be prepared for rupture, find pleasure in it, in fact, plan on social rupture. When these ruptures occur, use them in creative ways which will prepare you for a future in which survival will demand a sudden shift in ground tactics.”

The narrative of queer spaces and communities has been central to the interpretation of your work—including the radical statement of Black, queer desire within the formal, academic, often biased world of studio practice. I wonder if these statements and principles that she identifies as emerging from contemporary Black visual and musical contributions (Rose was using these to interpret graffiti art and early hip-hop music) resonate for you in any meaningful way.

Sepuya: My first encounter (that I can recall) with Arthur Jafa’s work was at the Made in L.A. biennial in 2016. His notebooks of edits and his sampling from visual culture in a totally democratic and distinctly Black way just blew my mind. I instantly related it to my formative attraction to and use of photographs, to my adolescent taking and queering of subject matter simply by using it queerly. Layering for the strategy of plausible deniability, but instant recognition when it mattered to make oneself recognizable. Embellishment, transformation. All of that. It’s always a gift to find an artist who’s so successfully articulated a feeling that you don’t fully realize you had, and struggled to name.

Martin: I want to also make sure to talk about the book The Accidental Egyptian and Occidental Arrangements (2010), which you made in collaboration with Timothy Hull. In a video you made for Self Publish, Be Happy, you talk about your fascination with “Egypt as a vessel that gets filled and interpreted and reinterpreted”; the book itself is a collage that gets remade again and again from a set of source images, and the book and the photographs of each stage of the collage are the final record. The collages themselves do not exist, nor were they intended as permanent, fixed records; rather, they are a record of an exchange between two people. Is this something of a metaphor for your artistic process as a whole?

Sepuya: Oh, I am so glad you brought up that project. It’s the point at which collage entered into my toolbox, all thanks to Tim! I had been making arrangements of contact sheets, zine material, and test prints, but I had not, until then, considered the cut and combination of materials into a new, different work. I didn’t follow up on it, but I can say I wouldn’t have considered collage-like strategies five years later without the possibilities uncovered in AEOA. We also made another, similar collage project with TM Davy for the Ferro-Grumley literary award in 2011. But, yes. It’s important to note that those collages, composed from fragments of both of our works combined, were made to be images, not collages in a physical sense: material arranged for the scanner bed, for the purpose of making a book.

Until I was about fourteen years old, I believed I’d grow up to be an Egyptologist.

Timothy Hull and Paul Mpagi Sepuya, The Accidental Egyptian and Occidental Arrangements (Self-published, 2010) (cover and interior)

Courtesy the artist

Martin: In the interview with David Velasco and Dean Sameshima that appears in your book Beloved Object & Amorous Subject (2007), you talk about editing and re-editing. You mention that you “love the idea that you can return to an image, reprint a photograph as its meaning changes over time,” and how photography is an ideal medium for re-editing—from contact sheets to image sequences. The idea of re-editing is really deeply embedded in your work. What attracts you to that idea, and how has it continued to play through in your work?

Sepuya: What attracted me was that editing revealed itself as a fundamental aspect of making photographic prints. Returning. Facilitating that return is that truth that photographic reproduction presupposes a chain of desire yet to be formed. Desire and return. Revisiting, and then continuing to work.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Some Recent Pictures (Self-published, 2015) (interior)

Courtesy the artist

Martin: Over the course of this conversation, a totally new reality has been forged in the wake of the global pandemic. I’ve come to realize that we’re not going to be going back to “normal” anytime soon. Have you been able to process yet what this new reality of social distancing is going to mean for your work moving forward? Does it put the intimacy of your work until now into a new perspective? Is it a good time for processing—maybe for more books?

Sepuya: This question has been coming up, along with a level of inquiry that’s overwhelming. It sounds strange, or uncomfortable to complain about it, to be honest. A rush of media has asked artists to respond, and all I can say is, “No.” I have not thought about it with regard to my work, or moving forward, or anything else. It’s simply too soon. I’m scrambling, trying to figure out how to teach students online, how to keep basic studio infrastructure going, worrying about what galleries and institutions will do, how bills are going to get paid. I miss seeing friends in groups, but I don’t feel distance. Before, I barely made it to one or two non-work things a week—a gallery or a dinner. And now, there’s a burden to participate in what seems like dozens of virtual social gatherings and talks, and it’s overwhelming. I actually desperately want some time off to think about all of this.

Lesley A. Martin is the creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya: A conversation about around pictures opened on March 25, 2020 at Vielmetter, Los Angeles, and is viewable online.

See more in Paul Mpagi Sepuya (Aperture/Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, 2020)

April 9, 2020

How to Be a Photographer Right Now

Three artists confront how COVID-19 has changed their lives and work—and how they see the world.

By Aaron Schuman

Gus Powell, NY Subway Etiquette – Wrapped Reflection, March 11, 2020

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

One morning at the end of February, I was sitting in Eisenberg’s Sandwich Shop, a grease-stained diner directly across from the Flatiron Building in New York. (Monas Eisenberg opened the shop in 1929, in hopes that it might get him and his family through the Great Depression.) I’d just arrived in New York for a flying visit, and I was feeling hazy and jet-lagged. Knowing that I’d be up early, I’d arranged to have breakfast with the photographer Gus Powell.

When Powell arrived, he wrapped his bag and bright red coat around the back of his chair and apologized for being a few minutes late. He’d just dropped off “the VIPs”—his children—at school in Brooklyn. Over our pastrami and eggs, we talked shop—mostly photobooks, new projects, his commercial portfolio, and parenting. We were both scheduled to have exhibitions and workshops at Micamera in Milan in the coming months, but because there were four hundred reported cases of coronavirus in Italy, it looked likely that our shows might get postponed for a few weeks. Powell was on his way downtown for a meeting with an advertising agency, and I was headed uptown to the Met, so as we hurried out into midmorning rush hour, we shook hands, hugged, and went opposite ways on a frenetic Fifth Avenue.

That was then.

Gus Powell, NY Subway Etiquette – Fingers Only, March 6, 2020

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

I often have anxiety-driven dreams, in which I’m endlessly racing through a crowded, anonymous, Gotham-like metropolis, trying in vain to catch a subway, train, or plane that I’m desperately late for. I’ve been having a lot of those dreams lately. Now, in self-isolation in my attic-cum-home-office in the southwest of England for the past nineteen days, I’ve started to wonder if I’ve gone stir-crazy. Had my breakfast with Gus, in fact, just been the opening scene to another one of these strangely pedestrian nightmares?

On March 13, Bloomberg published a series of photographs by Powell titled What Social Distancing Looks Like in Public Spaces. “The editors of Bloomberg Businessweek reached out to me on March 4 and asked if I’d make a portfolio of images that showed signs of current ‘social distancing’ in New York,” Powell wrote to me recently in an email. “I’d already made a few images on the subway of hands avoiding poles, and had been thinking a lot about how to photograph public space in the city at this specific moment in time.” Powell shot the assignment throughout the following week. “I went to the busy places that I always frequent when I’m making my own work—the Financial District, Herald Square, Fifth Avenue—as well as areas that I knew would be farther along in terms of practicing social distancing, like Main Street in Flushing, Queens.”

Gus Powell, A Social Distance – Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn, NY, March 20, 2020

Courtesy the artist and Lee Marks Fine Art

As Powell sees it, the pictures published by Bloomberg were those that represented the clearest manifestations of change, specifically hand etiquette on the subway. “But the ones that I’m most interested in,” he added, “are those where there is still little sign of change at all—pictures that may be a last look at public life in New York before COVID-19.” When I first saw his Bloomberg story, I was slightly worried about Powell’s safety, but he told me he hadn’t left Brooklyn since Friday, March 13. “I walked two-thirds of the way across the Brooklyn Bridge, and then turned back.”

Newsha Tavakolian, The view from my balcony on a foggy day, March 2020

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

Since the onset of the pandemic, many photographers have been seeking ways to capture this moment in time in a safe yet productive way. On March 20, National Geographic published a story online by the Tehran-based photographer Newsha Tavakolian about the “hard pause” the coronavirus has caused in Iran. (Its subtitle referred to the “suspended state of life in the country.”) “I was already two weeks into self-isolation when Nat Geo’s editors contacted me,” Tavakolian, who has covered social issues in Iran, Syria, and Russia, said by email. “I had to think about it carefully. Naturally, I was worried about the virus and about potentially infecting others, so I decided to try to make an intimate report. For the most part I stayed close to my own surroundings—although I did also go along on several disinfection patrols.”

Newsha Tavakolian, One year after my father’s death, my sister went out to buy flowers for his grave and we yelled at her because she wasn’t wearing any gloves, March 2020

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

Iran was among the first countries outside of China to be hit by the epidemic. By accepting the National Geographic assignment, Tavakolian explained that she “was trying to show the readers what sort of life was coming for them. Of course, citizen-journalists are capturing many things on social media, but I think that there will be a need for professional reporting now more than ever, as in the aftermath of all of this there will be plenty of debates about truths and facts. I hope that this massive crisis will lead to a renewed appreciation of our profession,” she added, “and a realization that independent reporting is key, especially in difficult times.”

Newsha Tavakolian, Sometimes my mother stands in front of her bedroom window to gaze at the tree blossoming in the garden, which makes her happy, at least for a moment, March 2020

Courtesy the artist/Magnum for National Geographic

The crisis is not only affecting photographers engaged in documentary and reportage, but also practitioners who work in a wide array of genres. “Art always feels somewhat inconsequential in times of real crisis,” lens-based artist Hannah Whitaker, who lives in New York and is well known for her experimental, multilayered and semiabstracted studio-based photographic approach, noted in an email. “But I know it’s important. It might not be able to get us out of this crisis, but it can help us out of our holes—like Ariana Reines’ recent new moon report, ‘Our Crown,’ in Artforum, which gave words to that strange combination of death and mundanity that characterizes this moment.”

Hannah Whitaker, Speak, 2019

Courtesy the artist

For many studio-based artists and photographers, like Whitaker, social distancing and self-isolation are not entirely unfamiliar territory when it comes to being both productive and creative. “In some ways, my life is ideally suited for this crisis,” Whitaker explained. “Solitude and volatility are baked into being an artist, and usually I thrive in those conditions. I like being alone and normally embrace these kinds of structural limitations: What can I do with one sheet of 4×5 film? What photograph can I make with just the lighting and props I have on hand?” Whitaker acknowledges that she can walk to her studio, where she has all the equipment she needs, and can work alone—that is, when she isn’t looking after her three-year-old son. “But today is my day to stay at home with my son, who hasn’t played with another child in over three weeks,” she said, “so to be honest, I’m having a hard time.”

Hannah Whitaker, We Us And That, 2020

Courtesy the artist

The potential long-term effects of all of this are also starting to weigh on the minds of many photographers and artists. “I can deal with the normal ups and downs of my income and so on,” Whitaker noted, “but what’s new now is that I’m aware of the fact that this down may not be followed by an up for a long time, and may go deeper than any I’ve known. I know how lucky I am to be an artist, but I’ve worked my whole life to build this life as an artist—a life that is central to my selfhood—and that’s what I worry could be lost.”

From studio practice to commercial and editorial work, all photographers are aware that we are entering a new landscape. “Everything feels different now,” Powell told me, “and I’m uncertain about how to push my practice forward right now. There’s a different sense of time, which is simultaneously both intimate and global; sometimes the clock seems to be ticking very loudly, and other times not at all.” To keep himself busy and inspired, Powell explained that he’s reading a lot, looking at photobooks—“They still work, and will keep on working,” he stressed—and trying to make pictures of his life: his home, his children climbing trees, or the streets of Brooklyn from the driver’s seat of his car on a run for groceries.

Hannnah Whitaker, Raise, 2020

Courtesy the artist

“I’m not thinking about maintaining what I’ve already done,” Powell said, “but instead about how something new can be made, and about the kind of artist I want to be. I’m asking myself, How I can contribute to humanity with creativity and honesty?”

For Tavakolian, who has had her press credentials revoked several times in Iran, including just this past year, periods of being unable to work freely are nothing new. Like Powell, she sees the “pause” as an opportunity to broaden her vision. She suggests reading, slowing down, and revisiting unfinished projects. “I believe that this is a time to take in what is happening, and let everything sink in,” she said. “There will be a life after coronavirus, and we will be able to work and be creative. If there is any silver lining to this hard pause that we all face now as photographers—and as humans—it’s that disruption can lead to creativity. You can end up doing things that you never dreamed you’d do.”

Aaron Schuman is a photographer, writer, and curator based in Bristol, England.

In Mexico City, a Visual Archive of AIDS Activism

What does an exhibition about Mexico’s response to the HIV epidemic reveal about the connections between art and public health?

By María Minera

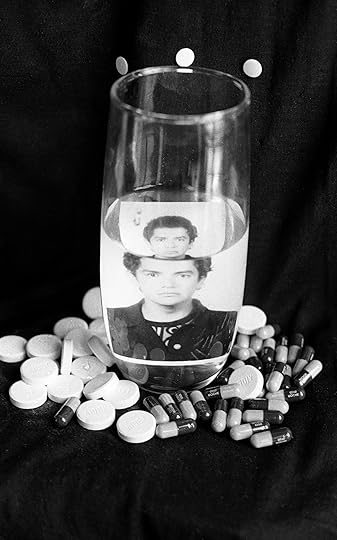

Óscar Sánchez Gómez, Untitled, from the series Adherencia (Adherence), 2001–3

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

At the beginning of the exhibition The Seropositive Files, recently presented at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City, is a provocative statement: “We are all seropositive.” As the curators Sol Henaro and Luis Matus note, “Having the virus in one’s blood or not does not determine one’s level of political commitment with the issue.” Today, even amid the COVID-19 crisis, the HIV/AIDS epidemic remains one of the world’s most serious public health challenges—and, as Henaro and Matus put it, “the construction of a collective memory” is as relevant as ever.

With all this in mind, Henaro and Matus have built an archive composed of materials of many sorts—photography, video, magazines, prevention campaign ads, and even a codex painted with blood—with the purpose of revisiting the recent past so that younger generations can access documentation of the emergence of HIV/AIDS, a time when AIDS was seen as an inevitably fatal disease, and artists and activists, seropositive or not, confronted both the fear of the virus and the vacuum of knowledge and medical treatment in extremely diverse and original ways.

“Few diseases in the history of humanity have stirred the imaginations of individuals and societies to the extent of AIDS,” the gay activist Alejandro Brito points out. Photography, in particular, plays an important role: by being blunt, as in the image of Antonio Salazar embracing his dying partner; or playful, as in the Óscar Sánchez Gómez series where he portrays himself engulfed by all kinds of pills.

Earlier this year, Sol Henaro patiently walked me through the exhibition, explaining, in detail, every piece and every accompanying story.

Richard Moszka, Un año de pastillas (One year of pills), 2001–2

Arkheia Documentatoin Center, MUAC, Mexico City

María Minera: Could you start by telling us how the Visualidades y VIH collection came about in Mexico, and what its purpose was?

Sol Henaro: When I first came to the Arkheia Documentation Center [at MUAC], I requested authorization to create an active documentation center. This meant we would not only search through the existing archives, but develop brand new documentary repositories. My initial interest was the creation of a collection on visuality and social mobilization in Mexico. Back then, I was mainly thinking of working on Ayotzinapa [the forty-three students forcibly abducted and disappeared in the Mexican state of Guerrero in 2014] and trying to bring together the visual remains of the movement that resulted from that event.

Along the way, the possibility of also creating a collection on HIV came up. This was partially due to a personal situation, as one of my closest friends, who is older than me, turned out to be HIV positive right in that moment; and he went through that situation as he would have in the 1980s—thinking that he would die, isolating himself from the world. This forced me to try to understand what HIV was and how I could support him by becoming informed about it. Then I realized that I had more acquaintances living with HIV than I had before.

Today, eight of my friends between the ages of 25 and 30 are living with HIV, and they faced the diagnosis in a very different way than my older friend, without the ghost of stigma and catastrophe. The situation has changed a lot since the development of antiretrovirals, PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, a medical treatment taken on a daily basis by people who are at a high risk of HIV infection as a prevention measure], and other medical and pharmaceutical improvements that have allowed us to understand HIV as a chronic condition rather than as a death sentence.

I started to recall what was happening in the ’90s, the events we participated in back in the day, such as evenings for those who died from AIDS, concerts where condoms were given away, and prevention campaigns. Where did the visual dimension of all those events go? I thought we had to bring it back. And this is how the specific repository on HIV in Mexico was born, in the intent to rescue the visuals I remembered being made decades ago. At first, it was meant to be a documentary collection that would support research and memory, but in time, we added pieces with a rather artistic character.

Óscar Sánchez Gómez, Untitled, from the series Adherencia (Adherence), 2001–3

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

Minera: AIDS representations from the 1980s and ’90s walk a thin line between art and social action. They function both as documents and images that shape the experience of living with the virus, making the condition visible. While the art and social functions are often indivisible, could you say more about how production worked back then as a way of keeping records or producing evidence of what Alejandro Brito defines in his catalogue text as the need to “politicize AIDS in order to achieve the scientific and technological advances that gave patients their dignity back”?

Henaro: Indeed. All these exercises of cultural activism are the ones that prompted the development of antiretrovirals, for instance. In Mexico, it is very clear that prevention campaigns have decreased, but also that the cultural community has stopped following the status of HIV, because the emergency has passed, at least for the media. Nowadays, it is rare to develop AIDS. You live with HIV, and that’s about it.

On the other hand—without this being a moral judgment whatsoever—emotional and sexual relationships have evolved to become extremely permeable, and the fear of AIDS that had been there for decades is gone. Many people have stopped using condoms, whereas twenty or thirty years ago, it was mandatory; also, hardly anyone gets tested anymore. Thus, we tend to forget that the virus is not gone yet.

Statistics are growing considerably. This is why we deemed it important to create this collection, to socialize this first research stage through an exhibition, a publication, and the development of public programs to bring the question of HIV to the public at a university museum, where most visitors are young. It also made sense to set visuality at the core of the project rather than focusing only on the artistic realm.

Oscar Gámez, The Dark Book, 2004

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Diseases and epidemics—plagues, such as cholera or smallpox—have always come accompanied by visuals and representations, but the appearance of AIDS introduced a variant: they were no longer just things made from the outside, with a sociological viewpoint, but much more intimate ones, situated in the body living with HIV. What kinds materials did you gather for the exhibition?

Henaro: We were interested in escaping the equation that our work would end up reinforcing stigma of a certain community. We had to find a way to escape male genital fixation, for example. We focused on looking for “accompaniment productions” [artistic works made by people not necessarily ill, but concerned], because you don’t have to be either homosexual or HIV positive to be able to make comments or declarations, or to develop affectionate, solidarity-based work. There are several works of this sort. But there are also others from people living with HIV, who turned the condition into their own production material. We can mention Óscar Sánchez Gómez, whose work has focused precisely on that: asserting his position in public and accepting his own condition at a time when he was still very stigmatized.

Armando Cristeto, El Condón (The condom), 1978–79

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Where do the materials come from?

Henaro: The exhibition is a review of everything we managed to gather during our research. Many materials are part of the documentary collection, whereas others come from the museum’s art collection, university collections, or other museums and galleries. Others are very specific loans from a variety of artists. And many of the things we managed to locate have now been donated to the museum.

For example, the codex, Icnocuicatl Sidaids (Songs of Anguish to AIDS), from 1996, which was lent by Rolando de la Rosa. The first case of HIV in the world was reported in 1981, but the oldest material in the exhibition is the series El condón (The Condom) by Armando Cristeto, dating from 1978–79. We included this work because of how it managed to anticipate the issue of the asepsis of bodies, latex being the new interface. And although the first AIDS case in Mexico was registered in 1983, the emergence of cultural production was much greater in the ’90s. It seems like it took some time to understand the crisis, the fear; only then did most of the initiatives emerge.

Rolando de la Rosa was one of the most active artists at that time. He is neither homosexual nor HIV positive, but he did a series of works to disseminate the role of the condom through art, such as Un condón para México (A Condom for Mexico), the 1995 event that consisted of a series of choreographies and the installation of a ten-meter inflatable condom in the esplanade of the Palacio de Bellas Artes, as well as of a giant red ribbon, a gesture of solidarity with AIDS victims. This happened at a time when Provida [an antiabortion organization] was saying that the condom was a threat to life.

We went to see Rolando because of that event at Bellas Artes. He showed us the codex, which consists of thirteen parchment sheets, drawn with the artist’s own blood, addressing the movement of the virus between Mexico and the United States carried by migrants. It became something very interesting at that time. It combined elements of pop culture with pre-Hispanic iconography, which triggered discussions about all the genital possibilities of transmission, sharp objects, syringes.

Oscar Gámez, The Dark Book, 2004

MUAC Collection, UNAM, Mexico City

Minera: Is it possible to identify the period specificities and types of practices in terms of artistic proposals?

Henaro: Definitely. There are, for instance, many records of actions that were carried out at museums and festivals, and that were typical forms of expression in the ’90s. We can talk about the action of collective 19 Concreto [formed by Roberto de la Torre, Fernando de Alba, Lorena Orozco, Víctor Martínez, Ulises Mora, Luis Barbosa and Alejandro Sánchez], CD4, from 1995, in which two chess players carried a counter on their backs, showing global HIV transmission figures. We can also mention Richard Moszka, who stuck on a wall 4,800 pills that a person living with HIV has to take every year—Un año de pastillas (A Year in Pills), from 2001–2. What de la Rosa did at the Palace of Fine Arts was also an action, just like Roberto de la Torre’s 1996 Cinética moderna (Modern Kinetics), where he extracted blood from several volunteers and deposited it in test tubes that were placed on moving and crashing electric cars, aiming to show the random movement of bodies.

There are also examples of art objects, like the work of Hilda Campillo. Her Del buró de Blanca Nieves (From Snow White’s Bedside Table), from 1995, is a work that allows us to broaden our scope and talk about other perspectives on HIV. Using a drawer full of little condoms, Campillo suggests the infection risk Snow White would be exposed to in her relationships with the seven dwarfs—one we would nowadays classify as polyamorous.

Taller Documentación Visual (Antonio Salazar, coordinator), Jesús y el diablo (Jesus and the devil), 1994

Courtesy Salvador Irys

Minera: Do you think photography became these artists’ favorite tool due to the need to literally epitomize HIV in the body itself?

Henaro: We used Antonio Salazar’s photograph Jesús y el diablo (Jesus and the Devil, 1994), where he appears holding his partner, for whom he decides to engage in HIV/AIDS activism. Yet, this was the only image we decided to use showing these types of visibly ill bodies. While these bodies are those my generation remembers, we wanted to take a new direction and chose a different symbolic order, an affectionate and strong one which was not about—once again—pointing at stigma. We wanted our work to have a different visual dimension.

We include Omar Gámez’s series The Dark Book, from 2004, made out of images he took inside a dark room where he introduced a camera. We thought it was important not to focus only on these types of atmospheres; however, it was relevant to show a glimpse of them. This becomes especially relevant in the present, as we talk about “bugchasing” and “chemsex,” and these spaces—dark rooms, saunas—can be linked, although not exclusively, to HIV transmission. That’s why it was important to address them.

Gabriel Figueroa Flores’s photographs were important to include, as he was the photographic eye of many AIDS-prevention campaigns undertaken by the Mexican government. There is also a selection of Óscar Sánchez Gómez’s work, with pieces from his series Adherencia (Adherence, 2001–3), as well as Ajustada cárcel que me cubre (This cramped prison that covers me, 1997), that we deemed representative, and that are linked to medication and side effects.

Óscar Sánchez Gómez, Ajustada Cárcel Que Me Cubre (This cramped prison that covers me), 1997

Visualities and HIV in Mexico Collection, MUAC, Mexico City

Minera: By a strange coincidence of timing, The Seropositive Files happens to be presented as the world confronts the COVID-19 crisis. Once again, we are facing a pandemic. In this context, we are witnessing new forms of representing health issues, especially on social media. Do you see a resonance between the exhibition and what is happening today?

Henaro: The fact that we are living through this new global epidemiological crisis raises new questions and revives ghosts from the past. How does the response of government institutions, the economic warfare of pharmaceutical companies, the civil society response, and the possible emergence of new stigmas relating to COVID-19 compare to those related to HIV back in the early 1980s? I remember an urban legend back in the ’90s of having to be careful when sitting on cinema seats, because there might be pins with HIV+ blood. Today, an aseptic paranoia around objects and contact is emerging again. How long does a virus survive on a surface? Are we temporarily condemned to fear any contact or approach? In our exhibition, we include a piece by Hugo Corripio that reads, “AIDS is transmitted by fear”—a sentence that makes sense again amidst the current pandemic.

In “Chronicles of the Psycho-deflation,” a text that began to circulate recently on social media, the Italian thinker Franco “Bifo” Berardi alludes to the fact that “the effect of the virus lies in the relational palsy that the virus is spreading around.” The question that will concern us in the future is how will we restore and reconfigure our relationships to break through the relational paralysis that afflicts us today. It is indeed up to us—as it was during the HIV crisis—to imagine new ways of being and existing while we try to understand what we are going through.

María Minera is an art writer based in Mexico City. Translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles.

The Seropositive Files: Visualizing HIV in Mexico opened on February 1, 2020, at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Mexico City. Please see the museum’s website for updates during the coronavirus crisis. The bilingual exhibition catalogue is available for free download here.

April 6, 2020

13 Photographers on Turning Points in Their Work

Turning points in the lives and works of photographers often span the extremes—from global and national events to the most personal moments. Photographers such as Alec Soth and Zun Lee are able to not only bear witness to events that shape our collective history, but also to map more intimate transitions within their craft and their everyday lives.

We’re excited to share the Spring 2020 Square Print Sale from Magnum Photos and The Everyday Projects, which brings together images from their archives that relate to or capture events that changed the course of history, society, a life, or a practice.

When you purchase through Aperture’s affiliate link, you directly help support not only the artists but also Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations. For seven days only, you can acquire these signed and estate-stamped, museum-quality images for $100 each, with a percentage of sales donated to Doctors Without Borders’s COVID-19 emergency response. In this critical time, we all need your support, now more than ever.

Selected by Aperture’s editors, here are 13 highlights from the Magnum Square Print Sale.

Peter van Agtmael, Somewhere between Mazar-e-Sharif and Kabul, Afghanistan, 2008

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Peter van Agtmael

“I had just woken up on a flight in Afghanistan, when I looked out the window and saw this scene. I scrambled for my camera and took a few frames before the cloud began to break apart and pass from view. Looking back, this photograph marked the point I understood war was deeper and more complex than the brutality I’d chased over the previous two years. Now, twelve years later, I see war in the totality of the human experience: a cyclical and cynical exercise in power, violence, ignorance and fear, but paradoxically one that also embodies humanity, courage and moments of transcendent beauty. These seem like irreconcilable forces, yet nonetheless hold true in defining our perplexing species.” —Peter van Agtmael

Tasneem Alsultan, A group of relatives busy on their social media phone apps at Al-Jenadriyah, a cultural festival in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Courtesy the artist

Tasneem Alsultan

“I was walking through the crowds at a cultural festival in Riyadh when I noticed this group of girls, all wearing flower crowns and discussing their next booth to visit. In an era full of digital screens and filters, it took me a few seconds to realize that the scene I was looking at was real. As a Saudi woman, I realize women are subjected to many stereotypes and misrepresentations across the world. This is even more true for women wearing niqab, despite the many recent changes for women’s rights in Saudi Arabia. Here we get to see a striking moment, which for these girls was mundane, everyday.” —Tasneem Alsultan

Jonas Bendiksen, Altai Territory, Russia, 2000

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Jonas Bendiksen

“I took this image almost exactly twenty years ago. Without knowing it, just seconds before, I had taken the image that would become my most published. That magic scene of thousands of butterflies, a stormy sky, a crashed Russian Soyuz space rocket, and a pair of local scrap-metal collectors gave my career wind in its sails, and gave me confidence in my vision. It also landed me in a lot of trouble—I was deported from Russia soon after I had published this story, about the fallout from the Russian space launches. Being banned from Russia led me into my first book project, Satellites (2006), which traced the borderlands of the former USSR—and the butterflies naturally became the cover. There are only a couple of images of this exact scene: the one that has been shown all over the world, and this one, which is the next frame in the roll.” —Jonas Bendiksen

Matt Black, A farmer checks his sprinklers, Sylvester, Georgia, 2017

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Matt Black

“To me, the turning point in photography comes when you stop looking and start seeing. Your work takes its own direction, rather than being directed, and unremarkable moments become clear.” —Matt Black

Rory Doyle, Big Mac Dancing — Tyrese Evans, Jeremy Melvin, and Gee McGee dance atop their horses in a McDonald’s parking lot in Cleveland, Mississippi, August, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Rory Doyle

“This image is part of my ongoing project documenting the subculture of African American cowboys and cowgirls in the rural Mississippi Delta. Just after the Civil War, one in four cowboys was African American, yet this population was drastically underrepresented in popular accounts. And it is still. But the ‘cowboy’ identity retains a strong presence in many contemporary black communities. The story is timely with the current political environment, and it’s one that provides a renewed focus on rural America. With the hit release of ‘Old Town Road’ by Lil Nas X, the topic of black cowboy history has become a mainstream topic of discussion. The project is a counter-narrative to the often negative portrayal of African Americans. Instead, I have captured a community showing love for their horses and fellow riders, while also passing down traditions and historical perspectives from one generation to the next. Ultimately, the project aims to press against old archetypes — who could and could not be a cowboy, and what it means to be black in Mississippi — while uplifting the subjects’ voices.” —Rory Doyle

Yagazie Emezi, A child’s direct stare during the parade for International Day of the Girl Child in Monrovia, Liberia

Courtesy the artist

Yagazie Emezi

“Realizing the power of photography: It speaks multiple languages and so can spur a range of emotions. Knowing that it is art, and can be and has been a weapon. And like all things powerful, with the ability to do good and bad comes responsibility. It’s a dangerous and beautiful tool, depending on who is holding it.” —Yagazie Emezi

Elliott Erwitt, California, 1956

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“In life’s saddest winter moments, when you’ve been under a cloud for weeks, suddenly a glimpse of something wonderful can change the whole complexion of things, your entire feeling.” —Elliott Erwitt

Bruce Gilden, Fellini, Coney Island, New York City, 1969

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bruce Gilden

“It was 1969. I had picked up my first camera (a Miranda) two years before. That year, I had started shooting my first long-term personal essay on Coney Island. I had been looking at as many photos as I could to see what interested me visually and what direction I should go with my photography. This was the first photo I had taken that I thought at the time had artistic credibility. I was so happy to have achieved something that I felt I could be proud of. Even if all my photos are untitled, I affectionately call this image ‘Fellini’.” —Bruce Gilden

Nanna Heitmann, Yenisei River, Kyzyl, Russia, 2018

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Nanna Heitmann

“For less than a second, two athletes stand close to one another. Their eyes are closed, their heads lean on each other’s shoulders, as if they are embracing each other peacefully. I tried to capture this scene in the moment before the fight—with all its tearing and throwing each other back and forth—started.

This photograph shows two figures training in khuresh, a type of wrestling and the national sport of the Tuva Republic, a partially recognized state in southern Siberia. The people of Tuva create sagas and legends about their favorite athletes, ascribing supernatural qualities to them.” —Nanna Heitmann

Zun Lee, Jerell Willis and son Fidel enjoy the sunset over downtown New York, November 2012, from the series Father Figure

Courtesy the artist

Zun Lee

“Coming from street photography, I often privilege the single-frame narrative through random, found, or decisive moments. But even in those early days, none of my images were really random; my desire to photograph was mainly driven by a need to make sense out of my experiential knowledge. Growing into long-form storytelling marked a key turning point, as I settled into the realization of what my photographic practice was about—not so much ‘making work,’ but a practice of living and being. As such, my ‘projects’ never end. They all inform each other as complementary facets of the same body of work, an investigation of the societal forces that regulate Black life, seen through the lens of the workaday realities of Black domestic spaces.” —Zun Lee

Herbert List, View From a Window: Dance of the Dresses, Trastevere, Rome, 1953

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Herbert List

“Herbert List injured his foot in 1953, while visiting friend and fellow photographer Max Scheler in Rome. He could not leave the apartment for some time, so Scheler left him his Leica with telephoto lens to play around with, while Scheler himself was away on an assignment. It was equipment which List had not used previously. The series View From a Window, including the image Dance of the Dresses, was born of the first two rolls of 35 mm film List shot in his life. This encounter with 35 mm was a turning point toward a more spontaneous style, and revitalized List’s love for street photography late in his career.” —Peer-Olaf Richter, Herbert List Estate

Lua Ribeira, Settat, Morocco, 2019

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Lua Ribeira

“This image is from an ongoing project working with Moroccan youth who are trying to cross the border into Europe. They attempt—through various means—to jump onto the ferries or lorries that move from Melilla (a Spanish territory situated in Morocco) and Nador to the south of Spain. The majority of these kids begin their journey by train or bus from their hometowns toward the border. I made a journey with someone who was expelled from Melilla and returned to his hometown, close to Casablanca. This photograph is of one of his friends, who has not yet made the decision to travel to the border—something currently considered by many youths in Morocco.” —Lua Ribeira

Alec Soth, Sydney, Tallahassee, Florida, 2004

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alec Soth

“In 2004, I shot one of my first traveling editorial assignments in Tallahassee, Florida. I photographed a second-rate celebrity for an equally unimpressive magazine. My photographs were terrible. After the shoot, I went to a local diner to drown my sorrows in fried chicken. When I walked in the door, I saw a beautiful young girl falling asleep at her table. This was the moment I learned that the ability to choose my own subject was essential to my creative success. The picture I made that day became one of my all-time favorites.” —Alec Soth

Magnum’s Square Print Sale, Turning Points, is now online through April 12, 2020 at 6:00 p.m. EDT. For seven days only, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch square prints are exceptionally priced at $100. By using this link to make your purchase, you directly help support not only the artists but also Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations.

April 3, 2020

Announcing the 2020 Aperture Portfolio Prize Shortlist

Aperture’s support of emerging photographers and artists is an important part of our mission—especially in this current moment. This year, Aperture’s editors reviewed over 900 submissions to our annual Portfolio Prize competition. We are thrilled to announce the finalists for the 2020 Aperture Portfolio Prize.

Dannielle Bowman

Jessica Chou

Daniel Jack Lyons

Gloria Oyarzabal

Lindley Warren Mickunas

We are delighted to welcome these five finalists to our ranks of illustrious past selected artists, joining such artists as Mark McKnight, Ka-Man Tse, Jack Latham, Zora J Murff, Fabiola Cedillo, Natalie Krick, Eli Durst, Drew Nikonowicz, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Sarah Palmer, Bryan Schutmaat, and many others.

Our challenge now is to select one winner from this impressive group of finalists. The winning artist, to be announced on Friday, April 17, will be published in Aperture magazine, receive a $3,000 cash prize, and present an exhibition in New York. Finalists’ portfolios and statements will be featured on Aperture Online.

Dannielle Bowman, Faces, 2019, from the series What Had Happened

Jessica Chou, Daydream, 2018, from the series Suburban Chinatown

Daniel Jack Lyons, Milton, 2019, from the series Amazônica

Gloria Oyarzabal, Sorority, 2019, from the series Woman Go No’Gree

Lindley Warren Mickunas, Milk, 2020, from the series Maternal Sheet

Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss our news announcements, publications, latest editorial content, and more.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers