Aperture's Blog, page 77

January 30, 2020

Photographing Tupac, Biggie, and Everything in Between

Dana Lixenberg revisits her portraits of pop-culture icons and everyday citizens.

By Stephen Hilger

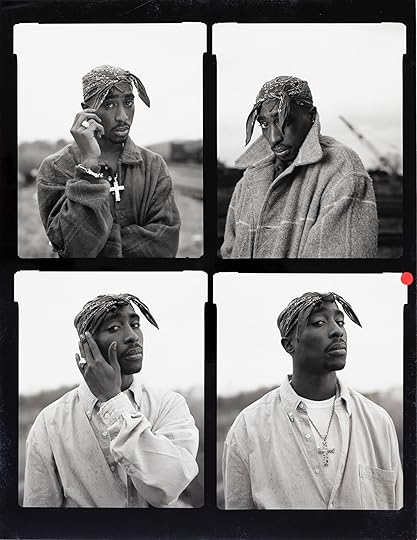

Dana Lixenberg, Wilteysha, 1993, from Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

During the past two decades, Dana Lixenberg has produced an extraordinary collection of portraits of individuals and communities. Whether facing celebrities for editorial shoots or engaging with ordinary citizens, Lixenberg’s lens reflects her subjects with consistently measured sensibility. Throughout a range of subjects and social situations, Lixenberg maintains what late artist, educator, and photo editor George Pitts described as her “unvarnished” photographic style. To date, she has published eight books of photographs, a few of which have considered the culture and place of Lixenberg’s native country, the Netherlands, while the majority of the published material has focused on the United States. Much of this work originates as editorial assignments; and subsequently develops into long-term projects.

In each, Lixenberg’s commitment to her subjects results in an archive where the cultural meanings and narratives of the images continually expand. “I’m trying to make an image that really can tell a story and you can spend time with. An image that can live beyond the context of what it was shot for,” Lixenberg explains in her most recent publication, Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018).

Dana Lixenberg, Contact sheets from photoshoot for VIBE, Christopher Wallace (Biggie), New York, NY, 1996, from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

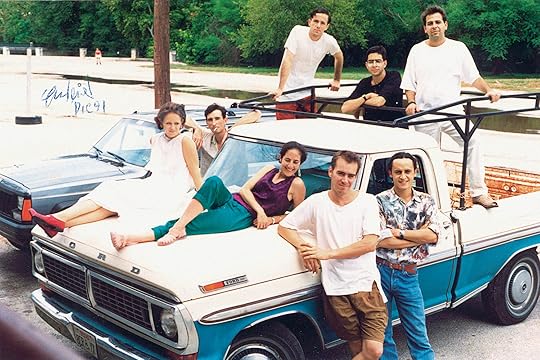

In Tupac Biggie, Lixenberg revisits her photographs of the two pop-culture icons—made for Vibe in 1993 and 1996, during the early years of the influential hip-hop culture magazine. Signaling the magazine as the original vehicle for the images, the book displays Lixenberg’s portraits of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls (aka The Notorious B.I.G.) on glossy pages, saddle-stitched into an oversized format. A progression of Lixenberg’s archival images of the twenty-two-year-old Tupac Shakur runs from the front of the book to the center—beginning with a facsimile of a black-and-white, 4-by-5-inch negative image, and followed by multiple pages of contact sheets from the shoot, an enlarged gelatin-silver print, and tear sheets of the original and subsequent issues of Vibe in which it appeared. In the well-known image, the two knot-ends of

Dana Lixenberg, Contact sheets from photoshoot for VIBE, Tupac Shakur, Atlanta, GA, 1993, from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Tupac’s front-tied bandanna descend down both sides of his face, accentuating his poised look. Small droplets of rain fleck his denim shirt, worn open and displaying his diamond-adorned crucifix. A parallel succession of archival images of Biggie expands from the back of the book toward the center. Lixenberg depicts Biggie in a range of poses: most often defiantly staring down the camera, at times appearing beside producer Sean “Puffy” Combs (currently known as “Diddy”), and—in one of the most memorable images—wearing a flamboyant Coogi sweater and shuffling a large stack of money. The division between Biggie’s right side of the book and Tupac’s left side recalls the East Coast vs. West Coast rivalry perpetuated by the performers, their crews, and the media at the time, while an essay by Vibe editor Rob Kenner recollects the prominence of the hip-hop magazine, as well as its complicity in fanning the flames of the feud between Tupac and Biggie before their fatal shootings, in 1996 and 1997, respectively. The book is dedicated to George Pitts, Lixenberg’s photo director at Vibe, who died in 2017.

Dana Lixenberg, Lisa Kudrow, Los Angeles, CA, 1999, from united states (Artimo, 2001)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg’s ability to create subtly provocative portraits of public figures led to frequent editorial assignments for a variety of magazines, including Interview, Rolling Stone, Details, Elle, Esquire, Out, and many others, in addition to Vibe. United States (Artimo, 2001), a compilation of approximately eighty photographs Lixenberg made on assignment from 1994 to 2000, forms an unexpected, collective portrait of American culture. The book interrelates recognizable cultural figures with noncelebrities, photographed because of particular social circumstances they represented or were associated with—for instance sex work, college sororities, illness, incarceration, and homelessness. In the book’s afterword, George Pitts elucidates, “Virtually all celebrities portrayed by Lixenberg are rendered in a vulnerable way, and perhaps that’s why these images warrant repeated viewings . . . Lixenberg extracts their ordinary (yet richly human) qualities . . . It is almost the reverse of what she does with noncelebrities. With them, Lixenberg reveals their charisma.”

Dana Lixenberg, Snoop, 1993, from Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

The first Lixenberg photographs to appear in Vibe were not of celebrities, but rather portraits of residents of the Imperial Courts housing project in the Watts area of South Central Los Angeles—photographs that Lixenberg had shown to George Pitts. Remembering the context of the day, Pitts reflected on Lixenberg’s “tough non-pandering aesthetic,” in contradiction to “the slicker celebrity and fashion-oriented content,” which helped establish the visual tone of the magazine. Lixenberg continued to photograph the community there for twenty-two years, ultimately producing Imperial Courts 1993–2015 (Roma Publications, 2015), an extensive volume depicting generations of residents photographed on the grounds of the urban housing complex.

Dana Lixenberg, David A. Taylor, 2000, from Jeffersonville, Indiana (Artimo, 2005)

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg had first traveled to South Central to photograph the aftermath of the 1992 Los Angeles riots on assignment for a Dutch weekly, Vrij Nederland. Witnessing the extent of the damage in the city moved Lixenberg to return to the area and establish ties with the community, which lead her to Imperial Courts. Around the same time, Lixenberg embarked on another long-term project— photographing the homeless population in Jeffersonville, Indiana. While a handful of the people photographed in Jeffersonville appear in United States, Lixenberg’s collective portrait of a fragmented community culminates in her subsequent book Jeffersonville, Indiana (Artimo, 2005). The work originated as an assignment to photograph homeless women for Jane, yet it grew into a more extensive undertaking over the course of seven years, from 1997 to 2004. In both Imperial Courts and Jeffersonville, Indiana, Lixenberg approaches complex social realities with an austereness whereby she distills the human subject amid a reductive palette of visual signifiers. The accumulation of time past, and an emphasis on the shared presence of the photographer and subject, activate the singular frames beyond stasis toward a more elastic corpus of images, social exchanges, and meanings.

Centerfold poster from Tupac Biggie (Roma Publications and Patta, 2018), design by Linda van Deursen

Courtesy the artist and GRIMM Amsterdam | New York

Lixenberg’s reexamination of her photographic archive for Tupac Biggie remembers history through the documentary temperament of its images. At the same time, the volume furnishes a mirror in which to glimpse a contemporary image culture in which the proliferation of images and their meanings stretch the imagination. Lixenberg’s material works, commissioned and distributed by Vibe, play out on the pages of the compendium as traces of their subjects (and simultaneously register the images’ usage by Vibe). Nestled within the book’s center, a giant foldout poster shifts the character of the work considerably. On the poster’s verso reads an explosive, free-form poem remembering “Tupac and Biggie,” by writer and activist Kevin Powell. On the front of the poster appears a graphic representation of the trajectory of Lixenberg’s images through their appropriation by a global mass image culture that has refashioned them during the last two decades into memes, taking such forms as murals, paintings, tattoos, and merchandise, such as T-shirts and figurines. Lixenberg’s gesture to include within Tupac Biggie the collectively constructed copies that succeed her original images acknowledges a greater conception of her photographic practice through the medium’s ever evolving social reception. At once, Lixenberg’s work fills the space of the photobook, the magazine, and appropriation by the public. Lixenberg continues to expand the possibilities of photography through a persistent and elongated practice across genres, in which a multiplicity of readings, including mourning and—at the same time—a playful examination of the image, are each evident.

Stephen Hilger is a photographer based in Brooklyn, where he teaches at Pratt Institute.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

American Images is on view at GRIMM, New York, through February 29, 2020.

The post Photographing Tupac, Biggie, and Everything in Between appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 27, 2020

In These Film Collages, Trump’s Washington Looks Just Like “The Shining”

John Pilson’s latest series reveals an uncanny resemblance between the U.S. president and Stanley Kubrick’s failed novelist.

By Sean L. Malin

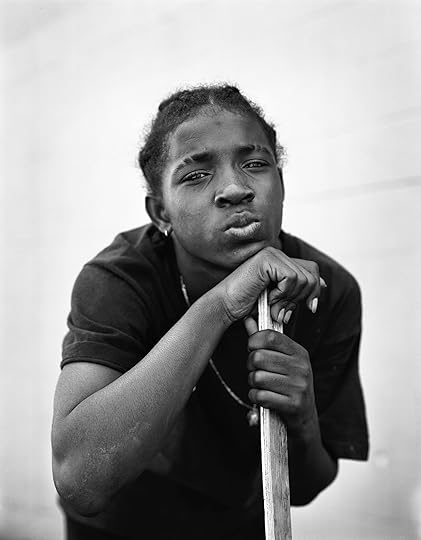

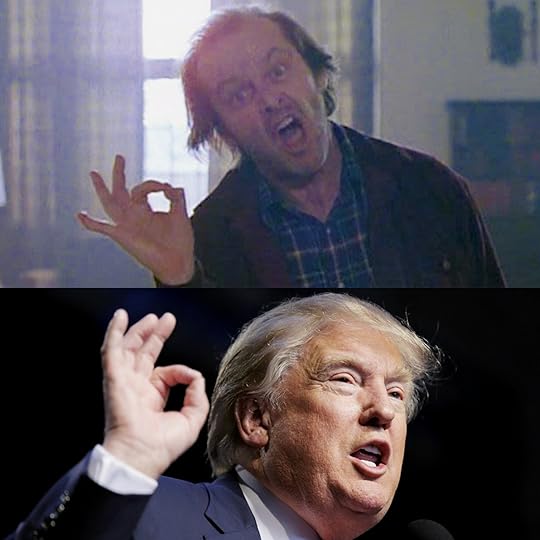

John Pilson, Priority Magic, 2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

For the artist and educator John Pilson, the film director Stanley Kubrick was “the greatest twentieth-century Jewish comedian (and I’m not just talking Dr. Strangelove) and artist as Cold War psychosexual completist.”

It is no surprise that Pilson, whose 1990s photographs from his time working at Merrill Lynch transformed depressed, robotic office drones into clowns of the mundane, is able to laugh with Kubrick, “even at his darkest, especially at his darkest.” The legendary filmmaker was indeed funny, not only in his 1960s comedies—Lolita, Dr. Strangelove—but also at the apex points of his crueler films: the childlike sing-along performed by HAL 9000 as it (he?) deactivates in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the standing ovation Alex DeLarge receives after enduring the Ludovico Technique in A Clockwork Orange, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman traumatically beating his platoon into submission in Full Metal Jacket.

John Pilson, Priority Magic, 2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Kubrick’s 1980 film The Shining, with its blood-flooded elevators and necrotic seductress, may have been his most torturous and grotesque work, and therefore, by default, also his funniest. It stars Jack Nicholson in a bravura performance as Jack Torrance, “a failed novelist” in Pilson’s view, who accepts the position of caretaker at the Overlook Hotel. Eventually, trapped by his failures, he descends into psychosis among the hotel’s ghostly staff, slashing through doors while hunting his own wife, Wendy, and their disturbed son, Danny.

In the winter of 2017, Pilson and his son were snowed in at their home in New York watching The Simpsons. At some point, “we slipped into CNN,” where news about President Donald Trump’s administration “triggered” in Pilson a ferocious anger not unlike what Torrance feels when he reassures Shelley Duvall’s Wendy that he won’t hurt her. Soon, Pilson was “literally yelling—not yelling, but barking, foaming.”

John Pilson, Priority Magic, 2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Pilson was also in that moment inspired. He began noting similarities between Jack Torrance and The Donald: both were “rootless, angry narcissists,” both had young wives and children, and both veered “between suspense and total incoherence.” In a quick Google search, Pilson found “endless analogues” between Kubrick’s masterpiece and the real world political environment. “It’s uncanny on top of uncanny. You realize that more or less with every single plot point in that film, every single theme, there is a pretty stark resemblance.”

From this creative binge emerged what Pilson has titled Priority Magic (2019–ongoing), a series of diptychs pairing scenes from The Shining with imagery from the Orange presidency. The series’ “charmingly ominous” title comes from the Freudian psychologist Fritz Redl’s description of “group behavior made possible when an authority figure, by example or through incitement, sets precedent, gives permission, and conjures a new normal.”

John Pilson, Priority Magic,2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Like Kubrick’s film, these split-screen photographs are amusing and horrifying in equal measure, indicators both of Pilson’s gift for pattern recognition and our collective ability to see evil in cinematic terms. Each diptych contains within itself a transformation narrative: Jack Torrance’s axe becomes Donald Trump’s golf club; Danny Torrance’s telepathic gifts are bestowed on Barron Trump; a concerned Dick Hallorann, the Overlook Hotel’s chef, becomes a weary Barack Obama.

But while comic in tone and bite-size enough for Instagram, these images extend a critical legacy of social-resistance collage stretching from John Heartfield’s 1932 portrait of a gold-eating Hitler, to Lance Letscher’s deceptively quaint collage-covered guns from the early 2000s, to the artist couple known as Stephen and Vanessa’s 2012 headshot of the politician Rick Santorum made entirely of queer pornography.

John Pilson, Priority Magic,2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Like those artists, Pilson forcefully, directly rejects propagandism through the use of montage, explicitly aligning key figures from the contemporary American political elite with their ghastly (Stephen Miller/Lloyd the bartender), rotting (Kellyanne Conway/Mrs. Massey), or outright murderous (Donald Trump/ Jack Torrance) doppelgängers. In so doing, these totems of hypernationalism become horror archetypes within the Overlook Hotel that is America in 2019.

As Priority Magic has found fans in the mocking corners of the Internet, Pilson has further begun to explore connections with other iconic cinematic texts: Barton Fink, Star Wars, James Bond. These collages are available on his private Instagram feed, but as their creator readily admits, none offers the same electric thrill that comes with Trump’s spray frozen mop top imposed on Torrance’s frostbitten jaw. “If there’s anything that is cathartic about it,” notes Pilson, “it’s that violence meets with violent ends. What you’re seeing is so cartoonish, and because it is so cartoonish, you say to yourself, I’ve seen this film before. Then you are certain you’ve seen this film before. And, you know how it ends.”

John Pilson, Priority Magic,2019–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Sean L. Malin is a cultural critic whose writing has been published in LA Weekly, New York Magazine, Filmmaker Magazine, and the Austin Chronicle.

The post In These Film Collages, Trump’s Washington Looks Just Like “The Shining” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 24, 2020

Picturing the American Family, From Frederick Douglass to Jamel Shabazz

In this conversation, Rhea L. Combs and Deborah Willis speak to the power of photographs to envision love and connection for Black American families.

Jamel Shabazz, Twins, 1980

Courtesy the artist

“I have found no standard art history that refers to any Afro-American artist,” Deborah Willis wrote on November 14, 1973, in a statement about her intention to research the contributions of black photographers from 1840 to 1940. After approaching a number of collections and libraries, and drawing up a list that included Roy DeCarava, James VanDerZee, and Gordon Parks, she asked herself: “Could these black photographers receive the same recognition their white colleagues received?” This question has animated Willis’s groundbreaking books, essays, conferences, and curatorial projects concerning the relationship between African American identity and photography, and brought to the foreground the stories of black people as both makers and subjects of images, from Civil War-era portraits to contemporary photo-based art.

For Willis, a distinguished professor of photography at New York University, the image of the family has been central, and deeply personal. Two years after the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., where the story of the American family is told and presented through images, Willis spoke with curator Rhea L. Combs about the enduring legacy—and political resonance—of the African American family in photographs.

Notman Photo Company, Frederick Douglass with his grandson Joseph Douglass, ca. 1890

Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Rhea L. Combs: For decades, you’ve been involved with and dedicated to the life and work of African American image makers. You’ve done groundbreaking research and helped shape and mold some of the brightest minds and thinkers in the field, past and present. What motivated you to do this work, and why photography in particular?

Deborah Willis: I grew up with a father who was the family photographer. As an amateur, he had a Rolleiflex. We had a lot of family events, reunions, and gatherings up until my first year in college, and my dad took most of the photographs. He had a cousin, Alphonso Willis, who had a studio about two or three blocks away from our home, and he took the official portraits with his big 4-by-5-inch camera. Our neighbor was Jack Franklin, who was a photojournalist for the black press in Philadelphia. I also grew up in a beauty shop, as you know, and having that opportunity to look at magazines most of my life, from Ebony to Life, meant that I was always looking at photographs.

Combs: Was there any distinction between what you saw in Ebony and Life and what you were experiencing in the family photographs that your father was taking?

Willis: I always thought that our family stories weren’t visible in the larger magazines, like Life and Look. Ebony definitely had images of black families, but mostly black celebrity families, as well as people who were successful in business or in politics. When I was younger and heading to college, I wanted to make visible some of the stories of the everyday experiences that I enjoyed watching in my neighborhood and within my family, like kids playing jump rope, people seated at a table. And what I found was The Sweet Flypaper of Life (1955), the book by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes. It excited me, even as a younger child, seeing that book. Having family images in the living room, on the mantle, on walls—family photographs were our art form.

Jan Yoors, Four African American women waiting outside a church before a wedding service, ca. 1962–63

© Yoors Family Partnership and courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs, New York, and Gallery Fifty One, Antwerp

Combs: Same for me. Those were the visual cues that let you know you were home.

Willis: Absolutely.

Combs: A lot of your research projects and books expose people to the work of early African American photographers. Once you uncovered these jewels and these photographers, how did they influence your work or help you unpack these ideas around family?

Willis: My family were members of the NAACP, so they had a subscription to its magazine, The Crisis. Growing up with The Crisis in the house and then going to school and learning about W. E. B. Du Bois and his impact on photography was a nice kind of collaboration in my memory. When I started to think about studying photography and the history of photography, I noticed that there were no black photographers in the history books. Even in the 1970s, Gordon Parks was not in my history of photography book, and I had read his book A Choice of Weapons (1966) by then. So I thought, Okay, we need to make a change in this. A professor encouraged me to do a paper on the topic. As a result, I started going through the black press, looking at black newspapers and ads, and finding city directories that had black photographers. I wanted to start at the beginning of photography, because I believed that they were there, that they existed. I knew it. I was lucky enough to find early photographers who were working in the 1840s and 1850s, free men who were also activists and abolitionists. So that was the beginning of a research paper as an undergraduate, when I was looking to fill in the gap in my classroom. That’s how that happened.

Then what I found was that black photographers were photographing black families. At that time, there were a number of stereotyped—troublesome, to me, visually—images of black people in stereographs that circulated in the public, while, at the same time, in the black communities, there were images of successful, proud, happy—not grinning, but happy—black people, happy to be alive, living through a difficult time.

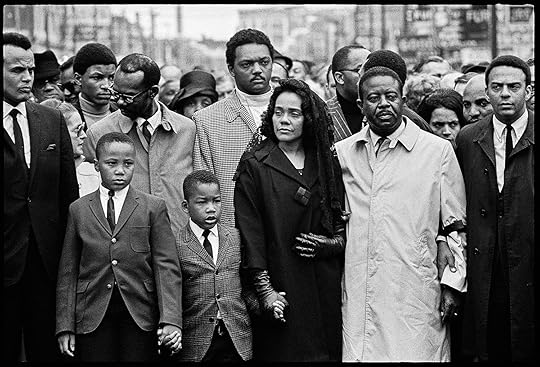

Burk Uzzle, Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral (Coretta Scott King, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Harry Belafonte Jr.), Memphis, Tennessee, 1968

Courtesy the artist

Combs: When you think about photographs of Eva and Alida Stewart, Harriet Tubman’s great-nieces, or the carte de visite of Frederick Douglass and his grandson Joseph Douglass, or photographs of Emmett Till and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, how do you situate these images within the context of your research?

Willis: In the image of Harriet Tubman’s great-nieces—we are familiar with women and adornment, in terms of hats and how they’re seen, and so we are reminded of a past that has been neglected, that has not been discussed in family photography. Women were dressmakers. They created patterns and styles. They looked at magazines. Black women were known as great milliners during this time of the 1890s and early 1900s. In the picture of Tubman’s great-nieces, we can see these prosperous, educated, happy women photographed together, and they’re wearing jewelry, and one has her head cocked to the side, and the other one is looking directly into the camera. Both were sending the message of success and strength—similar to the women in Jan Yoors’s photograph of a wedding in Harlem in the 1960s. The way that they’re wearing their hats—we can connect the fashion of women of that time to the fashion of the women in the 1890s.

I remember seeing the image of Frederick Douglass with his grandson when I was first working at the Schomburg Center, in New York. We know Douglass fought for his family, like the Civil War soldiers fought for their families. In this image, we see him with his grandson, who was a musician, and we see the story. But also, we know it’s in a fancy studio; we can see the furniture in the back. Douglass was using these studios to create a narrative about black life and black experiences.

John Johnson, Talbert Family (Rev. Albert W. Talbert, wife Mildred, son Dakota, and daughter Ruth), Newman Methodist Episcopal Church, Lincoln, Nebraska, ca. 1914

Courtesy the Douglas Keister Collection

Combs: To your point of Frederick Douglass and Joseph Douglass—you see them, as you stated, in this established studio, and there is a sense of prominence. You could juxtapose that with the print of the Talbert family standing in front of a photographic backdrop not in a studio, but outdoors, made around 1914 by the photographer John Johnson. But there’s still a sense of regality and pride and esteem that is established by this family.

Willis: Right. And it’s known to be of Reverend Albert W. Talbert and his family. So we know his station in the community. It’s probably a rural community, and we see that it was important for his family to be photographed, probably for an official church portrait.

Combs: This was in Nebraska.

Willis: One button closed. This is probably not the original one that Johnson, the photographer, selected. We see the scene beyond the backdrop—we see where the photographer could actually crop the image to just show the family as if they were standing in a lighted photographic studio. And the way Reverend Talbert’s son wears his hat—the way that he cuffs the brim—looks as if he is a bit rebellious. He’s wearing the style of the time of the young sporty man.

Combs: Totally.

Willis: The good daughter, with her bow, and the rebellious son, and the supportive wife. Isn’t it wonderful to see the complexity of families, and the stories that are told through photographs?

We see in an early 1950s image of Emmett Till and his mother the pride that his mother had in posing with her son. She is looking away from the camera; he is looking directly into it. He is happy to be with his mother, happy to be photographed. Think about this along with the image of Martin Luther King Jr.’s family at his funeral: here are two images of people who’ve lost family members in a violent manner. We see two mothers with sons. The sense of protection, the sense of having them as witnesses within that frame.

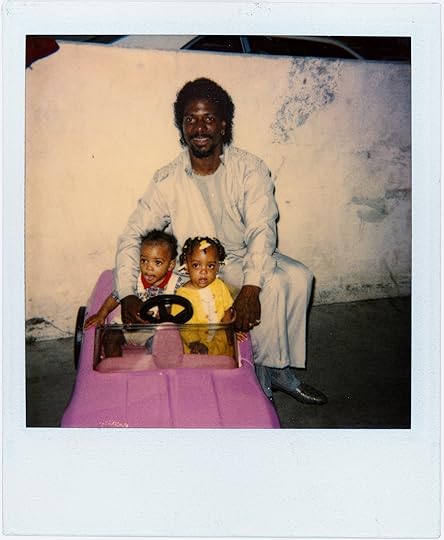

Zun Lee, Found Polaroid images, dates and locations unknown, from the series Fade Resistance, 2012–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Combs: How do you think family photographs have been utilized as a way of understanding the civil rights movement?

Willis: Black photographers like Gordon Parks, Ernest Withers, and Moneta Sleet took their cameras into these communities to look at injustice and asked: How do we educate our children? How do we think about the future of our children? Photographs helped to push the spirit of black people during that time, to think about the act of being photographed as a representative family member, to walk to church, to walk to school, to go to vote, to be activists.

Combs: What you said brings us to the work of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is committed to telling the story of America primarily through the African American lens. In many ways, its physical place becomes a space where families can gather, either literally or metaphorically, through images. I would love to hear from you how this notion of family and family photography, even photo albums, can help tell the American story.

Willis: I think about the images that we know from the movement, and about families who used the Green Book to travel safely, to know where they could rest, stop, and get food. They didn’t have social media then; they had word-of-mouth. And that’s how most families survived during migration and on vacation—it was because one sent a postcard photograph of a family member. The photographs in the museum are essential for showing a contemporary viewer that path. That’s why Du Bois, in the photographs he selected for the Exhibit of American Negroes at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, included Thomas Askew’s photographs taken at homes: they show ownership by blacks. This is right after emancipation, and this was the hope of emancipation—that people could buy homes and perform the duties of family, church, and civic life.

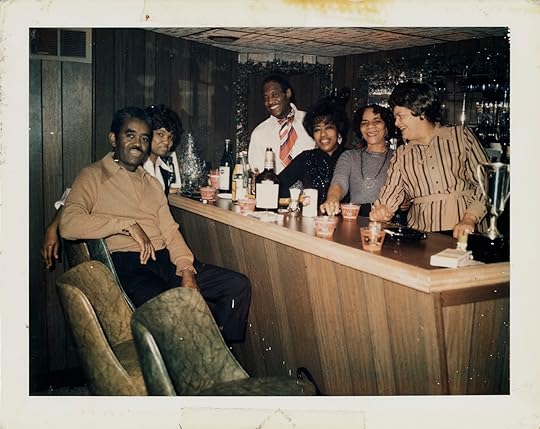

Combs: There’s also an interplay between intimate moments and vernacular photography and interior spaces. I love one particular photograph in the museum’s collection of a young woman with go-go shorts and little heels, posing in the living room. And also another vernacular photograph that was found by photographer and collector, Adreinne Waheed, of this interior space of a family gathering down in, I’d imagine, a basement.

Willis: It reminds me of my house in North Philadelphia. They played cards. They sang and listened to music. They loved dancing. And all this is a memory that’s part of my memory of pure pleasure. Not just family members, but their family friends.

Zun Lee, Found Polaroid images, dates and locations unknown, from the series Fade Resistance, 2012–ongoing

Courtesy the artist

Combs: How do you think an image is affected by who is taking the photograph? Especially as it relates to family photographs.

Willis: Jamel Shabazz is a person who loves photographing groups and people. You can see it in the way he uses that love as a sense of getting to know people through photographing them. Zun Lee’s collection of Polaroids is a way to think about textural memory and visual memory. The first car. The red shoes. Going to church on Easter Sunday. Going to a wedding. Just documenting the sense of joy. We can see what it meant for a black man to buy his child a gift and to pose for it.

Combs: What are the differences between Lee’s image of a man sitting on a toy car with his children and Frederick Douglass posing with his grandson? How do you see the arc shifting across the formal nineteenth-century photographs to the Polaroid photographs, which are so accessible?

Willis: I imagine that the impact is the same. They wanted to document and celebrate a moment and a memory. It’s part of that reflection on why photography of families is so important.

Photographer unknown, Group of people gathered around a bar, ca. 1970

Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Combs: I also wonder what we are not seeing in these photographs. I recognize that families are complex and dynamic, and relationships can run the gamut. So when you see the range of images, intergenerational connections, and the role of family, is there a way in which you could surmise what issues these photographs are not engaging with?

Willis: Well, we think about divorce in families. Family photographs are remembered in certain ways. We think about abuse; who is the abuser in the photograph? When we think about what’s missing in family photographs, we often say that the queer or the trans family members are often not photographed. But sometimes you see that sense of love in those photographs, too. We know that a person is presented a certain way in the photograph. How do we tell that story about a queer family member or a trans family member, and the acceptance of that?

Combs: I was thinking about your recent TED Talk with your son, Hank Willis Thomas, and about how photography is instrumental to your work and his. You articulated so beautifully about love as a verb, and how that infuses and is incorporated in your art. When you think about your body of work and how family has been so critical to your research, I wonder if there’s a way in which your philosophy around love and family and photography filters into the things we’ve discussed.

Willis: The love that I find represented in family photographs—even if there’s abuse and there’s separation—is the initial part that is historicized, the love of family. I just had a death in the family, and we had to collect photographs. My aunt, who was eighty-eight, was a stylishly dressed woman for as long as I remember. All of her photographs show her sense of style, and her love of the camera and of people. We celebrate death with photographs, just as we celebrate life.

Rhea L. Combs is the supervisory museum curator of photography and film and director of the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Picturing the American Family, From Frederick Douglass to Jamel Shabazz appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 16, 2020

A Secret Cache of Polaroids Reveals a Trans Photographer’s Inner World

April Dawn Alison made thousands of pictures focusing on a single subject—herself. But, who was she?

By Glen Helfand

April Dawn Alison, Untitled, n.d.

Courtesy SFMOMA and MACK

“April Dawn Alison was the private feminine persona of a photographer known to family, friends, and neighbors as a man named Alan (Al) Schaefer (1941–2008).” So begins curator Erin O’Toole’s carefully worded introduction to a book and exhibition of Polaroids by Alison. It seems straightforward enough, particularly in an era of gender expansion; and the images, costumed self-portraits, aren’t surprising in themselves. They plumb territory explored by numerous artists who’ve worked with the mutability of identity through disguise, persona, and alter egos. But there’s a slow burn of complex implications to Alison’s work.

Details about Schaefer are scant—he’s described as a commercial photographer who learned the craft in the military, and was reclusive later in life. Boxes containing 9,200 Polaroids were found in his home after his death. They were acquired, through an estate dealer, by artist Andrew Masullo, who donated them to the San Francisco Museum of Art. Alison’s pictures were made over the course of decades focusing on a single subject—herself. But who really made them?

April Dawn Alison, Untitled, n.d.

Courtesy SFMOMA and MACK

As Hilton Als notes in his essay, one of three in the book, “April was a maker, and so was the guy who made April; these pictures are a record of a double consciousness, the he who wants to be a she and the she who is a model and photographer both.” It’s an intersectional double scoop: the range of exploration includes art, gender, fashion, aging, and loneliness. The visual pleasure of performance in utopian solitary space is swirled with a sense of isolation and literal restraints.

The undated Polaroids, which span the 1970s to the 1990s (though Alison’s wardrobe sometimes makes them appear decades older), are presented at actual size, making this a quasi-facsimile of a photo album, punctuated with some full-page enlargements. These are private pictures of Alison in different outfits—she’s a career girl in Qiana, a pearl necklace matron, a vacuuming housewife in green eye shadow, fishnet-stockinged seductress, party girl in vinyl hot pants, and a member of the Starship Enterprise clad in a red minidress. In the continuum of historical views, it’s difficult to know if Alison was trans or, as artist and trans activist Zackary Drucker offers in the book’s most extensive essay, “she seems to exemplify the category of ‘transvestite.’” Alison doesn’t always pass for a woman, but her pictures immediately convey the tropes.

April Dawn Alison, Untitled, n.d.

Courtesy SFMOMA and MACK

Cindy Sherman comes to mind, naturally, as so many of the photos evoke classic female roles, enacted solo; but as much as she fits into various guises, Alison is a consistent, recognizable individual. She transforms situations, but not her face. The pictures were made in Alison’s nondescript apartment, with its pocket doors, burgundy velour couch, and a balcony where Alison poses salaciously with a phallic pink balloon. Often, she’s seen on the floor, legs spread, revealing her panties—thirsty.

For whom were these photographs made? Polaroids resulted in single images, selfies filed away. Did she spend evenings admiring them or share them with others? How would Alison have taken to Instagram—a venue where contemporary queer photographer Christopher Smith, who creates elaborate setups in his bedroom, shares pictures with thousands of people? Alison didn’t seem to need anyone else, including an audience, to “complete” these photographs. Or did she?

April Dawn Alison, Untitled, n.d.

Courtesy SFMOMA and MACK

Alison used different formats of the instant film. Some are rectangular, black and white; others, square SX- 70s, elder cousins to Instagram phone-camera templates. As the formats evolve, so do the sexual overtones—the later pictures are kinkier than the more chaste looks presented earlier in the book. She’s gagged, hung by chains from the ceiling, sometimes upside down. (Was there an assistant or lover there to help? Or was Alison able to fake physics?) These images show wholesome Bettie Page– style BDSM, not the extreme brand of surrealistic erotica of Pierre Molinier’s more contorted, manipulated poses.

It’s only a modest conceptual stretch to connect the crimson cover of the Alison volume to Carl Jung’s The Red Book—a compendium of archetypes published in 2009, long after the psychologist’s death. Alison, like Sherman and Smith, worked alone with iconic selves. Drucker writes how Alison’s “solitude manifests an interior space where art and sexuality coincide.” In that way, the contained page is a fitting format to enter Alison’s intimate bubble. Drucker further amplifies the importance of location: “Many trans people never find spaces to express or manifest their true selves, and they let their authentic interior worlds die with their bodies.”

There is a hint of tragedy to the fact that Alison didn’t live to see the reception of her work, or her identity. But the authenticity, the realness, of these photographs is undeniable. They emerge directly from the source.

Glen Helfand is a writer, curator, and educator based in Oakland, California.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post A Secret Cache of Polaroids Reveals a Trans Photographer’s Inner World appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

January 6, 2020

In Protests from Standing Rock to Hong Kong, the Image of Solidarity

Protest is a form of communion.

By Siddhartha Mitter

Wolfgang Tillmans, Protest, Houston Street, a, 2014

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Maureen Paley, London; and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin

Like all documentation work, protest photography has its habits. One default setting is confrontation. Bare hands linked in a human chain parallel to riot shields. Projectiles. The pregnancy of violence. Another, related, is heroism, frequently individual. The man who stopped the tank in Tiananmen Square. The woman in Baton Rouge, at once steely and angelic, before a row of riot police. In formal terms, there is the appeal of the frame—its necessity, if one is to illustrate the news. A grand boulevard packed with demonstrators as far as the lens can see conveys significance by virtue of the scale and the setting.

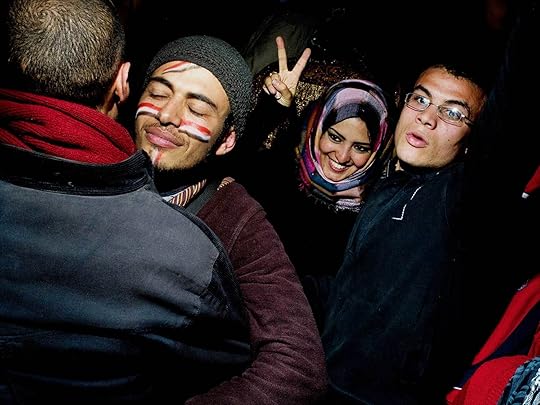

The images in these pages propose another method. The views they offer of protests—across Cairo, Istanbul, New York, Standing Rock, and Hong Kong—are more or less tightly framed or, instead, panoramic. But all center on humans. They confer no exceptionalism, no purpose that surpasses that of being present. These are not fight images; the antagonist is absent; there is no martial undercurrent.

Some, by Carl Court and Anthony Kwan in Hong Kong, are photojournalism, images circulated to news organizations by major photo agencies; they document this year’s protests that began in objection to plans to extradite criminal suspects to mainland China, but soon spread to broad demands for political autonomy. Wolfgang Tillmans’s images, from a Black Lives Matter protest in New York, are an artist’s response to the events and exist outside that professional economy. Larry Towell and Josué Rivas both photographed at Standing Rock. Rivas conducted a slow project, a months-long “offering,” as he put it, “turned … to the latent spirit” of the water protectors encamped against the permitting of a pipeline on native land.

Josué Rivas, North Dakota, 2016

Courtesy the artist

No matter what else it is, protest is communion. The authority and language of religion sometimes mobilize it explicitly, as in the mainstream of the civil rights movement in the United States. But, at root, this sacrament requires no liturgy. It is the work of collective imagination that invests meaning in the banner, the flower, the color, the candle, the cellphone torch beam.

It is resolve in numbers and the comfort of strangers. It is fluid, promiscuous, physical—even in a time of disembodied digital communications.

What binds these humans? Have they met before, traveled together to the meeting point from their campus or office, made a family outing of it, even a date? What small acts of care stitch them together? It matters what happens before and after, of course. People mobilize at cost—deserting schools and jobs, braving tear gas and beatings—in response to moral and material urgencies. But in the instant, there is a transcendence, an energy.

Carl Court, Hong Kong, June 14, 2019

© Getty Images

Care is the ultimate subject of these images, rather than what prompted each protest, what chapter it represented in an ongoing struggle, or what outcome it achieved. Care is the politics. It is what remains, since the advent of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and the ideological unraveling of the idea of the public good and the attacks on the mechanisms of social solidarity throughout the industrial world, a process keenly emulated by predatory elites everywhere else and compounded by depersonalizing technologies.

Care is an antidote to the grotesquerie of unaccountable rule. It is what distinguishes the mass gatherings seen here from others fomented by demagogues, seething with hate. Another world is possible. Human dignity need not be a scarce resource; life is improvable, here and now, and, therefore, it is a duty to improve it. Beyond the news, the specifics, the local histories of outrage and demands for redress, that ethos pervades the images here—and arguably inhabits protest itself, all the more so now, in a time of rising awareness of planet-wide, cataclysmic crisis.

Questions of responsibility follow, not least for photographers, journalists, and all those who make it their craft to document. Dignity is also a practice.

In the meantime, the protests continue.

Larry Towell, Jewish Rabbi praying at Oceti Sakowin Camp, North Dakota, February 22, 2017

Courtesy Magnum Photos

Carolyn Drake, Women’s March, Washington, D.C., January 21, 2017

Courtesy Magnum Photos

Alex Webb, Women’s March, New York City, January 21, 2017

Courtesy Magnum Photos

Alex Majoli, Celebrating Mubarak’s resignation in Tahrir Square, Cairo, February 11, 2011

Courtesy Magnum Photos

Emin Ozmen, Gezi Park, Istanbul, 2013

Courtesy Magnum Photos

Siddhartha Mitter is a writer based in New York and a regular contributor to Artforum and the New York Times.

Read more from Aperture issue 237, “Spirituality,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post In Protests from Standing Rock to Hong Kong, the Image of Solidarity appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

How John Baldessari Threw Three Balls in a Straight Line

The making of a now-famous series of photographs.

By Robin Kelsey

John Baldessari, 2015

Photograph by Molly Berman for Aperture

Ever since the onset of photography, the roles of the hand and the arm in making art have been subject to doubt. Once the definitive means of bringing an idea into form, these human appendages could seem feeble or quaint in an age of science and industry. Allowing gravity to participate in marking became a vital way to give art a deeper or more objective structure. Marcel Duchamp dropped threads to make the lines of his pivotal 1913–14 work 3 Standard Stoppages, and Jackson Pollock later dripped paint to push the limits of his control over line. These tactics called attention to art making as a performative grappling with chance and indifference.

In his 1973 series Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts), John Baldessari brought his impish wit to this modernist turn. He threw three balls in the air in hopes that a snapshot might catch them aloft and aligned. Through the magic of photography, gravity was defeated, and the balls never had to come down. Although he playfully inserted his arm or his finger in other works, in Throwing Three Balls he kept himself out of the frame. Well, not quite: his balls were in the frame, and the playful reference they make both to his surname and to masculine anatomy is crucial. Throwing Three Balls spoofs the swagger of the Pollock myth of a man laying himself bare through his struggle with the elements. Whereas Pollock orbited his canvases on the floor with all the gravitas of a seminal creator, Baldessari sent his tiny planets skyward with a playful toss.

We should remember, however, that Throwing Three Balls was a game for two players. While Baldessari threw, his then-wife Carol Wixom operated the camera. Chance became the intersection of their performances, where the scattershot and the snapshot met. Each resulting image depicted a hanging sculpture made from dime-store materials that invoked, in the deadpan innocence of pop, both the lofty aspirations of the moon-shot era and the absurd randomness of the atomic age. As the catalyst of such images, Baldessari’s arm became one of the most disarming of his generation.

Robin Kelsey is the Burden Professor of Photography at Harvard University. This article was originally published in Aperture issue 221, “Performance.”

The post How John Baldessari Threw Three Balls in a Straight Line appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

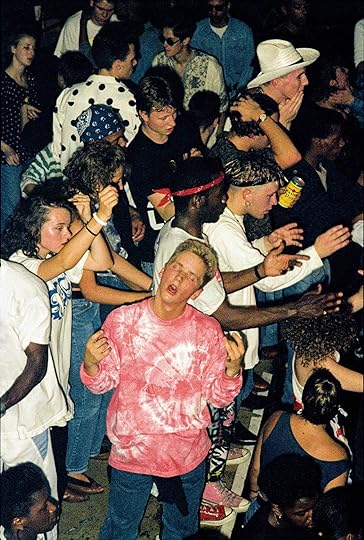

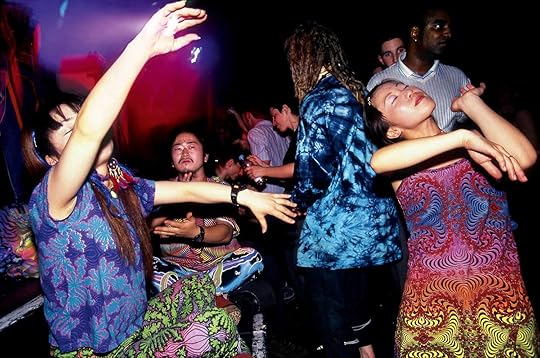

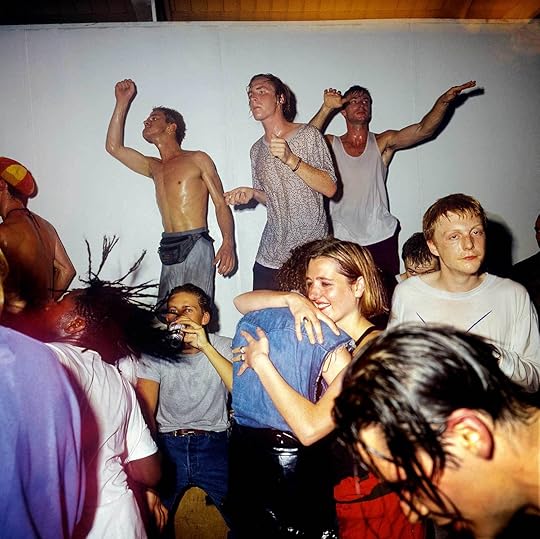

Sweat and Spirit on the British Dance Floor

In Dave Swindells’s photographs, nightclubs become spaces for community and belonging.

By Sheryl Garratt

Dave Swindells, Podium dancers at the Trip, the Astoria, Soho, 1988

Courtesy the artist

This is the British DJ Danny Rampling talking about the atmosphere in the early days of his nightclub Shoom, in 1988 London, at the start of the acid-house explosion that sent shock waves through U.K. youth culture, and eventually worldwide: “It was very spiritual. Some of those moments in the club were unbelievable. People literally went into trance states, including me. Not from the use of drugs, but from that music and the human energy that was going around [the room]. That’s not something that had happened in Britain for centuries. The feeling in that small space was so intense some nights.”

And this is the photographer Dave Swindells talking about that same club: “It was really hot, sweaty and steamy. There was dry ice, strobe lights going off and you’re thinking, ‘I’ve got to wait half an hour for the camera to warm up.’ You can’t use it until it’s at room temperature, because otherwise it’s just going to be fogged the whole time, and you’re not going to see anything. In Shoom, you could barely see the length of your arm sometimes, so it was a challenge! But it was also something you’d not seen before, so you just had to capture it.”

Dave Swindells, Bob’s Full House at Bagley’s Studios, Kings Cross, 1991

Courtesy the artist

At their best, nightclubs have always functioned as what the anarchist writer Hakim Bey calls “temporary autonomous zones”––safe spaces where we can experiment, express ourselves, and explore freedoms we may not be allowed in daily life. In clubs, we can find our tribe, feel a real sense of belonging and community. They are also often at the forefront of social change, encouraging racial integration and asserting gay rights. In the case of acid house, overwhelming numbers of clubgoers defying the police to dance all night at huge, illegal parties eventually led––after new laws failed to contain them––to a gradual loosening of the draconian restrictions on both club opening hours and the sale and consumption of alcohol in the U.K.

These characteristics have also made the nightlife scene hard to record. There are technical issues for photographers in clubs, but also issues of trust. Swindells has been able to take candid pictures in clubs like Shoom because he made himself part of the culture by turning up night after night, year after year, bearing witness without ever being intrusive.

Dave Swindells, Jenni Rampling dancing at Shoom, the Fitness Centre, Southwark, 1988

Courtesy the artist

Swindells started taking photographs while at university in Sheffield, inspired by a 1982 exhibition of Derek Ridgers’s nightclub portraits at the Photographers’ Gallery in London. After graduating, he moved to London and got a bar job in a club––until he was fired for spending too much time taking pictures and not enough time collecting empty glasses. In 1985, he started taking club portraits for the style bible i-D, then became nightlife editor of Time Out. Going out with his camera almost every evening, he remained at the magazine from September 1986 to January 2009, building up an unsurpassed archive on British club culture.

“Taking pictures definitely kept me going, because you had to keep on interacting with the people on the dance floor, and not just the DJ and the promoter, or hang out in the VIP room. You get detached from it all that way. And when electroclash and Nu Rave came along in the noughties, they reinspired me. It was 1980s clubbers re-creating ’80s nightlife, so those things were a lot of fun.”

Dave Swindells, Pendragon at the Fridge, Brixton, 2000

Courtesy the artist

The Internet has given us new ways of finding our tribe, but Swindells says that feeling of togetherness, of being part of something bigger than yourself, can still be found in the clubs on a good night. What is different now is that clubbers are more aware of his presence, often wanting to see the pictures and edit them on the spot. “They’re used to having control of their image, their brand, so they want to be much more involved. Which is fair enough. But what hasn’t changed is the joy on people’s faces when the DJ plays a tune they love, that sense of just pure joy. There’s still a massive buzz that people feel.”

Dave Swindells, The Spectrum Time Out Party in Jubilee Gardens, Waterloo, June 1988

Courtesy the artist

Sheryl Garratt has edited The Face and The Observer Magazine, and documented the rise of rave culture in her book Adventures in Wonderland: A Decade of Club Culture (1998).

Read more from Aperture issue 237, “Spirituality,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Sweat and Spirit on the British Dance Floor appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 29, 2019

Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2019

This year we explored spirituality with Wolfgang Tillmans, revisited Virginia Woolf’s Orlando with Tilda Swinton, considered how Mexican photographers are expanding photography, and started Introducing, a series on exciting new voices in the field. Here are some of the year’s highlights in photography and ideas.

How Can Photography Represent Humanity’s Longing for Spiritual Connection?

Wolfgang Tillmans and philosopher Martin Hägglund grapple with ideas of faith and freedom.

What is a Feminist Photobook?

Carmen Winant on feminism, photobooks, and the radical gestures of world-building.

Tilda Swinton on Virginia Woolf and the Spirit of Limitlessness

Inspired by Woolf’s iconic novel, the artists in Aperture‘s “Orlando” issue explore the territories of identity, history, and consciousness.

When Women Photographers Went to War

From Gerda Taro to Susan Meiselas, a new book examines the ways eight women have expanded the field of war photography.

In the Pacific Northwest, Shifting Landscapes and Mythologies

Against the backdrop of the US presidential election, Garrett Grove documents the region’s growing cultural tensions.

12 Photographers on How They Conceptualize Their Work

What comes first–the idea for a project, or the images themselves?

Santu Mofokeng’s Pensive Visions of Land and Ritual

In a new series of photobooks, the revered photographer conjures the mysteries of faith in South Africa.

The Young Artists Who Transformed Mexico City in the 1990s

How Mexico’s capital became a backdrop for experiments in photography, film, and performance.

A Japanese Photographer’s Encounters with Natural Disasters

Eight years after a devastating tsunami, Lieko Shiga investigates Japan’s haunted landscapes.

Graciela Iturbide’s Dreams and Visions

The life and work of Latin America’s most revered photographer.

Mark McKnight’s Exuberant Tribute to Queer Tenderness

In the male body and the physical world, an unexpected seduction.

In Versailles, Visionary Sculptures and Royal Intrigue

Viviane Sassen’s new photomontages consider the limitless potential of the human condition.

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2019 appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

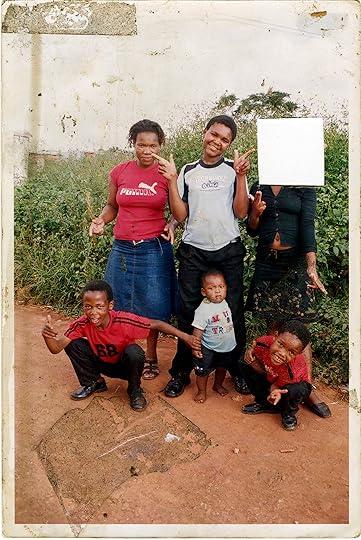

December 22, 2019

Introducing: Lindokuhle Sobekwa

Years after the South African photographer’s sister mysteriously disappeared, his images become a public record of a private myth.

By Nicole Acheampong

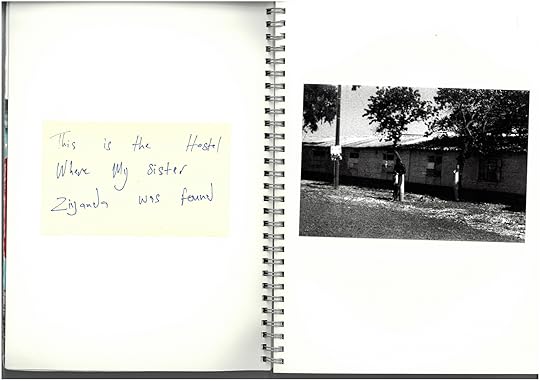

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

The day his older sister Ziyanda disappeared, Lindokuhle Sobekwa was hit by a car. The two were walking together along a road in the Johannesburg suburb of Thokoza when Ziyanda began to chase the seven-year-old Sobekwa. Out of fear, he began to run, and then he was hit. Above him, he recalled before blacking out, was the blurry silhouette of a woman or girl. His sister vanished in the ensuing scramble, with no word as to why. “She was in a period of being a very secretive person,” Sobekwa remembers. She was thirteen years old.

Sobekwa would not see Ziyanda again for a dozen years. Then one day, he returned from school, and Ziyanda was at home. She was reunited with the family for a couple of weeks. At the time, in 2014, Sobekwa was coming into his own as a photographer. He was in his final year of high school and working under the mentorship of Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter and filmmaker Cyprien Clément-Delmas through the Of Soul and Joy project, an artistic initiative based in Thokoza. He remembers walking into Ziyanda’s room one day; in that moment, he saw his favorite would-be portrait of his sister: “She was lying in bed, there was a beautiful light. She said, ‘If you take a photo, I’m going to kill you.’ A few days after that, she passed away.”

Sobekwa did not plan to make a series about his sister. In 2016, he was deep into his first photographic series, Nyaope, which chronicles the cycle of drug abuse that has afflicted Thokoza and takes its name from the heroin-based substance at the center of the crisis. In Nyaope, Sobekwa’s subjects are his peers, many of them childhood friends; he captures their makeshift, communal homes, rituals of abuse, and often frayed, sometimes fearful expressions with a documentarian’s precision, peppered with tenderness.

While photographing the surrogate family structures of nyaope users, Sobekwa came across a portrait of his own family, a photograph he had not seen in years. In it, Sobekwa is a young boy, alongside five family members. Ziyanda is there. She’s wearing a green cardigan and a matching skirt with a delicate floral pattern. The skirt disappears into the green shrubbery that frames the group. Her face has been completely cut out, leaving a sharp white square.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

The photograph prodded at Sobekwa. His sister had become a highly taboo subject in the family, with no one willing to discuss her, neither while she was missing nor after she reappeared. Sobekwa needed a map to trace her disappearance, her passing, and to fill in her missing years. He began to craft a photo diary for himself, gathering snapshots of the places she lingered—like the clothesline in their backyard, where her garments were still hanging.

Disappearances are not rare in South Africa, Sobekwa says. Most Black South African families are familiar with the trauma of disappearances, which date back to the late 1980s and early ’90s, the height of the apartheid crisis. During this time, an ethnopolitical war between two rival parties, the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), suffused the townships with panic, as residents along the factional line were routinely vanished by violence. In Sobekwa’s family, the cycle began with his grandfather, who was the first of the line to come to Johannesburg, in the 1960s. He never returned to the countryside; his fate is still unknown.

In 2017, the Magnum Foundation named Sobekwa a Photography and Social Justice Fellow. Suddenly, he had the resources to expand his search for his sister and develop his personal journal into a full-fledged series, I carry Her photo with Me (2017–ongoing).

“I had my own unanswered questions, maybe guilt of some sort,” says Sobekwa. “I felt the need to go into these spaces and make the camera my excuse. I realized that going alone, it would be difficult.” With his camera in hand, he slipped once more into the role of documentarian.

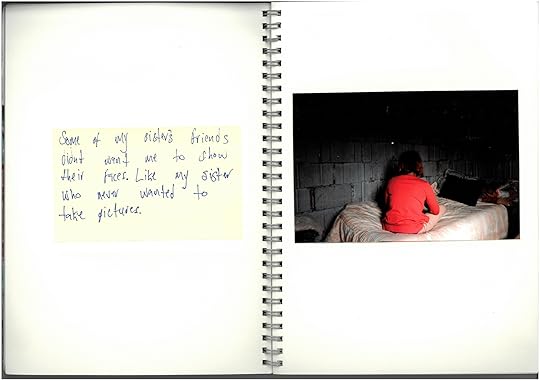

His mother had been the one to find Ziyanda back in 2014, at a men’s-only hostel called Shaye Aze Afe, and so Sobekwa started there. At Shaye Aze Afe, he took photos of the landscape, the shaded exterior of the hostel. He found a cousin who knew someone who knew someone else; they lead him to a second hostel, where tenants had been friends with Ziyanda. He took portraits of these women. He took portraits of strangers, whom he imagined as stand-ins to fill out Ziyanda’s community. In his notebook, he wrote: “Some of my sister’s friends didn’t want me to show their faces. Like my sister who never wanted to take pictures.”

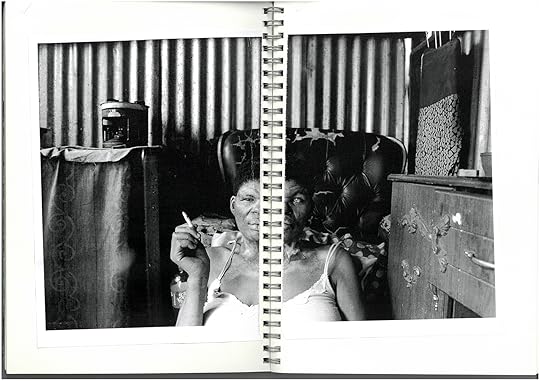

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

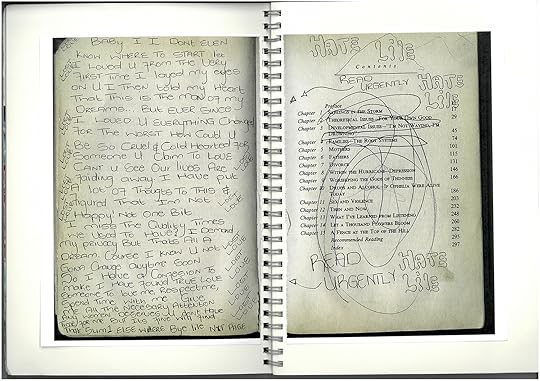

By contrast, other subjects pose on beds and stare straight into the camera with enigmatic expressions—outfitted in a polka dot dress, or a white brassiere-and-briefs set. One tenant scrawled song lyrics over the table of contents of Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls, and these pages rest between Sobekwa’s portraits. Alongside “Chapter 8: Within the Hurricane––Depression” and “Chapter 11: Sex and Violence” are slanted, bubbled words like “HATE” and “READ URGENTLY” and “I Demand My Privacy But That’s All A Dream.”

Cape Town–based writer Sean O’Toole says that Sobekwa shares an “obvious kinship” with Santu Mofokeng, the South African photographer known for his striking black-and-white photo essays on township life. Both artists offer examinations of race, class, and segregation that are as rigorously journalistic as they are rife with the intimacy of lived experience. For Sobekwa, the tactile, scrapbook format is essential to the project, and the photographs are as much a public record as they are the artifacts of a private myth. “Lindo’s practice is, in some ways, discontinuous with the performative leanings of much recent photography I’m seeing made here in South Africa,” O’Toole says.

Photographer Mikhael Subotzky calls Sobekwa—who became a Magnum Photos nominee in 2018—“preternaturally talented,” and he admires in the young artist’s work “a vision and a sensitivity that is already uniquely his.”

Sobekwa and his brother recently journeyed to the countryside, where his grandmother still lives, and where Ziyanda spent her childhood and is now buried. Sobekwa is continuing the series, hoping to unlock the secret of his sister’s disappearance by photographing this other landscape of her life––and afterlife. “If you arrive in the countryside early in the morning, you must visit your ancestors,” he says. “Ziyanda is now my ancestor.”

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, from the series I carry Her photo with Me, 2017–ongoing

Nicole Acheampong is the editorial assistant of Aperture magazine. All images courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

The post Introducing: Lindokuhle Sobekwa appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

December 18, 2019

How One Woman Helped Invent Modern Photography

Through her work with Tina Modotti and Edward Weston, the visionary writer Anita Brenner ushered in the Mexican renaissance.

By María Minera

Tina Modotti, Anita Brenner in profile, 1926

Courtesy Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

“I cannot find a way to live that will produce the two satisfactions that I seem to need,” the polymath Anita Brenner wrote in 1933. One of those satisfactions was primal—food, clothing, shelter, security. The other was intellectual, “the sensation that I am participating in and contributing to some common good.” Judging by her tireless commitment to the latter, one can suspect that for her, this was much more important than safety, and that “common good” was nothing less than the “Mexican renaissance,” a term she coined to refer to the flourishing of culture that made her birth nation “come to herself,” as she wrote in her brilliant 1929 book, Idols Behind Altars.

Brenner was born in Mexico in 1905. Raised in Texas, she returned to Mexico in 1923 at the age of eighteen, drawn by the artistic effervescence of the time. For her, the Mexican renaissance was not only contained in Mexican muralism, but in the blooming of all the arts, including photography, a medium that she saw as the perfect companion to her lifelong endeavor of introducing Mexican art and culture to American audiences. Brenner wrote innumerable articles—for publications such as Harper’s, the Nation, and New York Times Magazine—and several influential books about that moment in Mexican life, when “Revolution was still real in the world,” as she said in 1974.

Edward Weston, Maguey, 1927

Courtesy the Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

The exhibition Anita Brenner. Luz de la modernidad (Light of Modernity)—curated by Karen Cordero and Pablo Ortíz Monasterio, and currently on view at Mexico City’s Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL)—is a precise and beautiful approach to the visual vocabulary developed by a group of photographers that Brenner deployed to tell the story of Mexican art’s rebirth after the Mexican Revolution—a rebirth that was in part defined by the very images Brenner commissioned. In that sense, Brenner’s books are both chronicles of the period and instigators of a new photographic style—she called it “spirit”—that was surging at the same time. In addition to a wide selection of splendidly preserved vintage prints, the exhibition features copies of Brenner’s books and magazines—such as Mexico This Month, which she founded in 1955—a display of original materials she collected for her publications, and even political posters that give an in-depth look into Brenner’s relationship to both Mexico and the art of photography.

Agustín Jiménez, Circus, 1932

Courtesy the Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

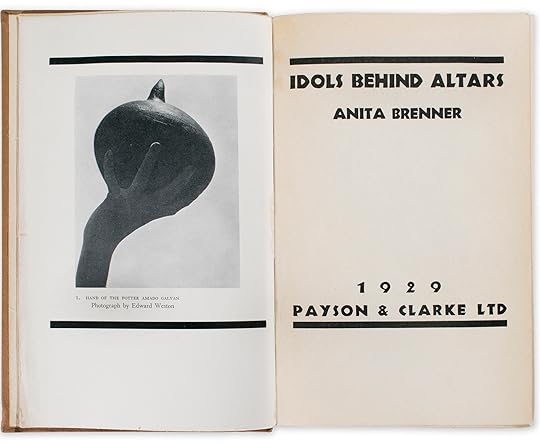

We need only look at the first page of Idols Behind Altars to recognize the relevance of Brenner’s enterprise. When the book was first published in New York by Harcourt, Brace and Company, its first page featured Edward Weston’s famous portrait of the hand of the potter Amado Galván, taken in Tonalá in 1925. The hand, as we know, is holding a huaje—the fruit of the Tecomate tree that artisans let dry and then paint with flower motifs.

For Brenner, it was impossible to approach modern Mexican art—with its unequivocal return to Native values—without going back to its roots, so much of her long essay is devoted to modern crafts, in which she thought traces of the pre-Hispanic world could still be found. The “taste for pure plastic symbol” and “the elegance and intensity that accompanies abstraction in Maya art” were, for her, present in objects like that exquisite huaje. That is why she went to the dean of the National University of Mexico to ask for his support carrying out a project to, basically, “study Mexicans, seriously,” as she put it in a journal entry of December 1925. In order to achieve this, she travelled a lot, and also gave Edward Weston a thousand pesos, so that he and his lover and fellow photographer, Tina Modotti, could roam around the country and provide Brenner with four hundred photographs of their travels—after a year, they delivered “some gorgeous stuff,” Brenner wrote.

Edward Weston, Nude (Anita Brenner), 1925

Courtesy the Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

Brenner chose Weston for this job because his work had “the quality of transmutation. The nude he did of me”—an iconic view of her back, from 1925—“looks like a pear. The hand of Amado Galván […] looks like something growing [and all] without the least alienating objects from their own naturaleza [nature].” She wrote this in her journal in early 1926, when Weston was still at the beginning of his career, so her words were not only prophetic but exact: Weston would soon become famous because of those transmutations. As the curator and photographer Pablo Ortíz Monasterio, explains, “maybe Weston wouldn’t have done that by himself, but it was a commission and he exceeded all expectations.”

Tina Modotti, Portrait of Anita Brenner, 1925

Courtesy the Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

“Brenner is a visionary,” Monasterio adds, “because she understood that photography produced images that are not only nice to be looked at, but more importantly, [they] speak and tell a story.” In Brenner’s books, he says, “photography is always as present as the text itself.” Or even more so, as in the case of The Wind that Swept Mexico, her wonderful account of the Mexican Revolution, where text occupies no more than a third of what ends up being primarily a collection of images of those years (1910–42)—images that George R. Leighton and Walker Evans, on Brenner’s suggestion, selected, carefully oversaw, and printed as magnificent photogravures.

Anita Brenner, Idols Behind Altars [Ídolos tras los altares], 1929

Courtesy the Colección Ricardo B. Salinas Pilego

What Brenner had asked of Weston and Modotti—and later of Agustín Jiménez, for Idols Behind Altars—was to go out and look for objects that overflowed with expression and history. The photographers did exactly that, and more: they simultaneously helped invent modern photography, a new way of looking that pushed things to the verge of abstraction. Monasterio talks about a strategy wherein something is portrayed “devoid of filters and mannerisms of all kinds.” The question was how to make a depiction of objects, crafts, and places that was as objective as it was modern.

Luz de la modernidad shows how Weston, Modotti, and many other photographers found an eloquent and exciting answer to that question, and how Anita Brenner acted as their perfect accomplice. In addition to being a sensible and intelligent writer, Brenner was in tune with the moment, “a time when the world was beginning,” she wrote in her journal. “We believed that you could actually do something.” And clearly, they did.

María Minera is an art writer based in Mexico City.

Anita Brenner. Luz de la modernidad is on view at Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL), Mexico City through February 23, 2020.

The post How One Woman Helped Invent Modern Photography appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers