Aperture's Blog, page 79

November 20, 2019

The Strange and Hidden Worlds of Mexico City

Because of luck, serendipity, or absurd connection, Miguel Calderón’s photographs unlock the power of things in daily life. (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

By María Virginia Jaua

Miguel Calderón, Color Scheme Grey, 2012

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

I remember a few days after the earthquake of September 19, 2017, I went to see Miguel Calderón at a space a friend had lent him. We tried to watch a few fragments of the video he had been working on about the life of Camaleón, its main character, a strange man who works by night as the bouncer at a bar and, by day, as a falconer. But I struggled to concentrate. I had arrived from Spain to Mexico just a few days prior and found myself in a state of shock on seeing the damage Mexico City had suffered. I remember photographing the cracks in the walls of the house Calderón was using as a studio in the neighborhood of Condesa.

Calderón was born in 1971, in Mexico City, and produces work—antiformal, and a bit anarchic—that is distinctive within the Mexican art world of the last few decades. He often displays tremendous freedom when it comes to his choice of medium, working across installation, video, photography, painting, music, and writing. At first glance, Calderón seems to be an artist who avoids dealing with major themes such as politics, the economy, ecology, or colonialism. But upon close viewing, larger concerns emerge: one’s search for meaning in life, the relationships between power and work, the energy of living beings, and also the underlying power of things.

Miguel Calderón, Cibeles 2, 2018

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

In a recent video and photographic project titled El placer después (Pleasure afterward), Calderón uncovers the well-kept secret of a man—somewhere between watchman and indigent—who has lived for many years, without anyone noticing, in a space underneath the Fountain of Cibeles in the neighborhood of Roma, which, along with Condesa, was among the most damaged in the earthquake. The fountain, a replica of one in Madrid, was a gift to Mexico City by exiled Spanish Republicans to thank their hosts for their hospitality during the Spanish Civil War. In one image, the man’s face peeks out, his arm propping up his head in the position of The Thinker. (Other pictures reveal the subterranean space beneath the public monument.) Calderón struck up a friendship with this person who, until the recent earthquake, tended to the maintenance of the fountain dedicated to the goddess Cybele, cleaning her and ensuring her upkeep. He also re-created a scene he had witnessed in which two drunk tourists from the United States crashed their car and went swimming in the fountain.

Whether because of luck, or serendipity, or connection, or empathy, Calderón unlocks and discovers hidden worlds, strange beings, and unusual situations throughout the city. Policemen on motorcycles attempt and fail at complex balancing exercises in their effort to create a perfect human triangle. A man swallows a young woman’s hand, reminding us of François Rabelais’s Pantagruel or Francisco Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring His Son. A body falls through a hole in the asphalt. A finger is disguised as a Swiss Army knife. All are examples of the aplomb, accident, and sense of humor with which the artist constructs certain images. Sometimes his work borders on writing, not only because of its characters and situations but also because of the method he uses to re-create images he saw, or thought he saw.

Miguel Calderón, Perfect Triangle 5, 2010

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Calderón’s knack for penetrating obscure worlds and rituals is also evident in his series of photographs depicting birds. In these images, we enter a universe of people who dedicate themselves to breeding and taking care of falcons, eagles, hawks, and other birds of prey. This age-old practice comes from the East, likely China. Calderón’s interest in birds goes back to his childhood when, by chance, he saw a falcon for the first time in a pet shop. He was so seduced and obsessed by the sight of this animal that, in order to obtain it, he bet his first creation—a one-of-a-kind bicycle he had built. Calderón managed to win the falcon and keep the bicycle. The intense relationship he forged with the animal proved essential in his period of adolescent discovery.

Miguel Calderón, Untitled, 2012

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

In contrast to the artist’s more absurdist images that might make us laugh, the photographs with birds feel more serious. Birds are believed to be the closest relatives of the dinosaurs, and yet humankind has managed to train them. This symbiotic process, in some ways, means reining in and appropriating their animal strength. The animal becomes so merged with the human that the mutual submission arising between them is a kind of devotion to a freedom that, deep down, is known to be unobtainable. For Calderón, this existential concern manifests itself in a triangle of experiences and free associations—bird, bicycle, art—all representative, in their own way, of the aspiration to break free and transcend.

Miguel Calderón, Falconer’s Code #3, 2017

Courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

María Virginia Jaua is a writer and editor based between Mexico City and Madrid. Translated from the Spanish by Elianna Kan.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post The Strange and Hidden Worlds of Mexico City appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

When Women Photographers Went to War

From Gerda Taro to Susan Meiselas, a new book examines the ways eight women have expanded the field of war photography.

By Haleh Anvari

Françoise Demulder, Lebanese Civil War. Quarantine camp. Palestinians. Christian militia. Beirut. January 19, 1976

© Françoise Demulder/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works

It may seem surprising in 2019 that there is still a need for a gendered exhibition to acknowledge the work of women in the field of war photography. But as the director general of Düsseldorf’s Kunstpalast, Felix Krämer, writes in the forward to this book: “Even though female photographers have been present at the front lines since the First World War [. . .] our understanding of war still has a masculine connotation.”

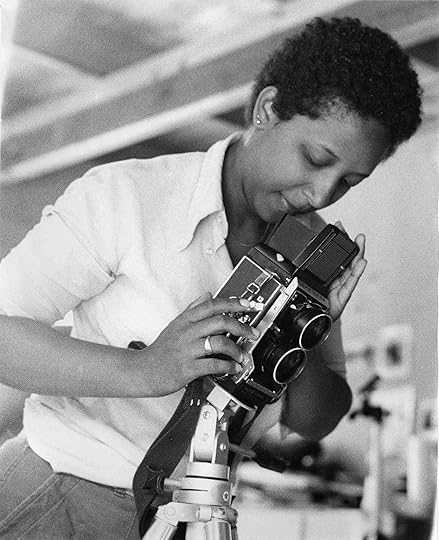

Women War Photographers: From Lee Miller to Anja Niedringhaus (Kunstpalast and Prestel, 2019) is the companion photobook to the exhibition of the same name that opened at Kunstpalast in March 2019 and will travel to Switzerland’s Fotomuseum Winterthur in February 2020. Showcasing the work of eight photographers, the exhibition was inspired by the museum’s acquisition of seventy-four photographs by the Pulitzer Prize-winning German photographer Anja Niedringhaus, killed on assignment in Afghanistan in 2014. The curators, Anne-Marie Beckmann and Felicity Korn, go a little further than Krämer. They believe that women photographers need special attention because their work is “still quite invisible in the history of not only war photography, but photography in general.”

Anja Niedringhaus, Afghan men on a motorcycle overtake Canadian soldiers with the Royal Canadian Regiment during a patrol in the Panjwaii district, southwest of Kandahar, Salavat, Afghanistan, September 2010

© picture alliance/AP Images

In a 224-page hardback survey, which includes 163 plates, Beckmann and Korn have succeeded in providing an overview of the work of women photographers covering wars from the Spanish Civil War and World War II, to Vietnam and Nicaragua, to the conflicts that have dogged the Middle East in the past six decades. These photographers include Gerda Taro, Lee Miller, Catherine Leroy, Françoise Demulder, Christine Spengler, Susan Meiselas, Carolyn Cole, and, of course, Anja Niedringhaus.

Christine Spengler, Nouenna, fighter of the Polisario Front, Western Sahara, 1976

© Christine Spengler, Paris

The book begins and ends with two photographers who died while covering a war, emphasizing that women are not spared the dangers that beset photographers in areas of conflict. The first of these, Gerda Taro, is regarded as the first woman war photographer. A committed antifascist, she covered the Spanish Civil War, accompanied by her lover and professional partner, Endre Friedmann, whose alias, Robert Capa, they initially shared to sell their photos. Taro died at the age of twenty-six, during the retreat from the Battle at Brunete in 1937, crushed by a tank. Her contribution to the original Capa brand was largely forgotten until the 1990s. The book’s last chapter is dedicated to Anja Niedringhaus, who was shot dead by a policeman while waiting in a car with her Associated Press colleague Kathy Gannon in Afghanistan. She was the only woman on a team of eleven Associated Press photographers who won the Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2005 for their coverage of combat in Iraq.

Gerda Taro, Republican militiawoman training on the beach outside Barcelona, Spain, August 1936

© International Center of Photography, New York

Women have always played a part in wars, often as victims of the aggression and violence that it brings. They have also joined the ranks of combatants. One of Taro’s iconic photographs of the Spanish Civil War is an evocative black-and-white picture of a woman on one knee, aiming her pistol to shoot. Christine Spengler also photographed women combatants—in Lebanon and the Western Sahara.

It’s telling, however, that it took more than twenty years for the Overseas Press Club of America, which honored Robert Capa with a Gold Medal Award named after him—for the “best published photographic reporting from abroad requiring exceptional courage and enterprise”—to award the prize to a woman. That woman was Catherine Leroy, a French photographer, who won it in 1976 for her coverage of street fighting in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War. She was also the first woman photographer to parachute into an area near the Cambodian border with the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, having covered the Vietnam War from the tender age of twenty-one.

Susan Meiselas, Searching everyone traveling by car, truck, bus or foot, Ciudad Sandino, Nicaragua, 1978

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Korn and Beckmann feel there is no difference between the male and female gaze in photography, but there is certainly a difference in the access that is afforded women. Susan Meiselas, best known for covering Nicaragua and El Salvador, describes the advantages of being a woman in a zone of conflict: “in Central America, I could approach people because they weren’t afraid of women as they were fearful of men. In these highly militarized environments, a woman was perceived as less threatening.”

In patriarchal societies, women photographers can access the female spaces that are guarded from male intrusion. This access inevitably provides women photographers with a different angle, seeing a conflict from the point of view of women and children, an angle that was not always valued. For example, Françoise Demulder’s photograph Massacre at Quarantaine, taken in Beirut in 1976, focuses on the helplessness of a Palestinian woman after a Phalangist attack. Unfortunately, the photograph was archived for eight months by her agency because it “wasn’t commercial enough.” Once published, it went on to win the World Press Photo Foundation’s Photo of the Year prize in 1977, the first time it was awarded to a woman. Patriarchal attitudes exist regardless of the destination. Niedringhaus had to write to her editor every day for six weeks before she was finally sent to cover the war in the Balkans.

Catherine Leroy, Corpsman in Anguish, 1967

© Dotation Catherine Leroy

Maybe this book should have been called Eight Women War Photographers, since there are obvious gaps in it. Names like Margaret Bourke-White, Dickie Chapelle, and Lynsey Addario come to mind immediately. The curators explain that they could only show the work of selected photographers in enough depth by limiting their number, but there is room for further books on this subject. In Women War Photographers, we are given a starting point to discover the range of subjects these eight women photographed in their various styles over nearly a century of covering war throughout the world.

As Susan Sontag once said, “There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture.” Yet there is a poetic sense of justice in the increasing number of women who choose to cast a woman’s shadow as witness to war through this predatory act.

Carolyn Cole, An image of Saddam Hussein, riddled with bullet holes, is painted over by Salem Yuel. Symbols of the leader disappeared quickly throughout Baghdad soon after US troops arrived in the city and took control. Baghdad, Iraq, April 2003

© Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times

Haleh Anvari is an artist and writer based in Tehran. She has written for Aperture, the Guardian, the New York Times, and The New Yorker.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post When Women Photographers Went to War appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 14, 2019

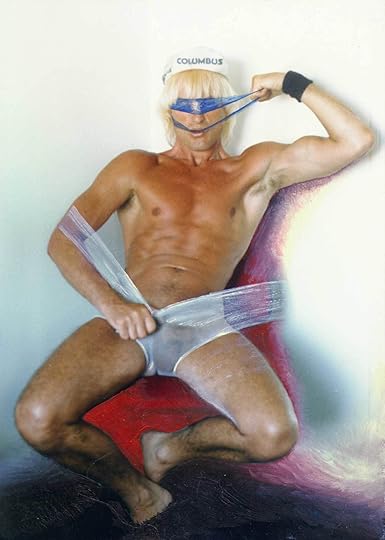

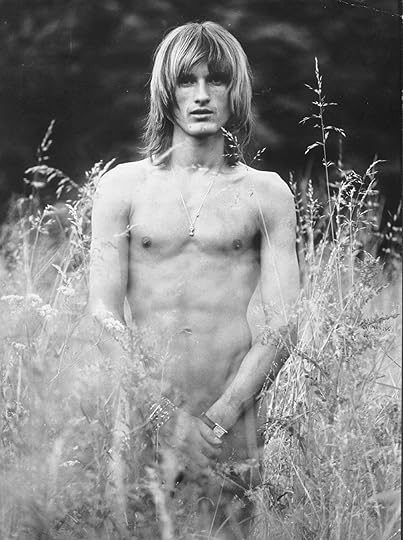

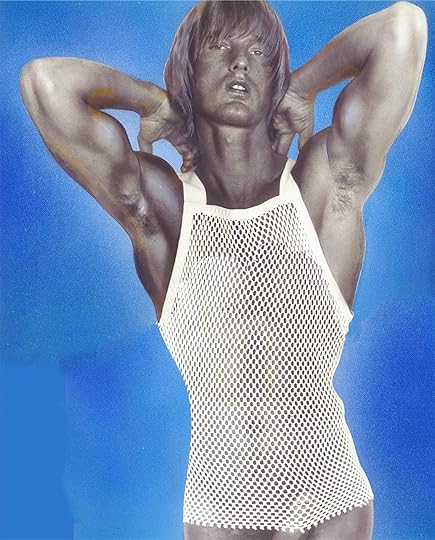

Peter Berlin was the First “Photosexual”

Decades before Grindr, Instagram, and erotic selfies, the photographer was famous for his extreme sexual-artistic practice.

By Michael Bullock

If Narcissus—the famous character from Greek mythology—had been mentored by Peter Berlin, his story might not have ended in tragedy. After falling in love with his own reflection and then realizing that it actually wasn’t another person, Narcissus was so devastated by the prospect of never being able to experience true romantic love that he took his own life. But had he come of age in the early ’70s, when the tools of photographic reproduction were available to the general public, Peter Berlin’s example would have taught him that focusing entirely on your own image can be quite a satisfying substitute for traditional romantic love.

Berlin’s cultural contributions were so many decades ahead of his time and so unique—not fitting cleanly into either the world of art or the world of pornography—that understanding their relevance and impact requires the invention of a new terminology. I propose the word photosexuality and aim to make the case that Berlin was the first acclaimed male photosexual and the leading pioneer of its practice. As I see it, photosexuality is a contemporary mainstream sexuality in which erotic self-portraiture—the documentation of one’s own sex acts and the private and public distribution of those images—is intertwined so completely with one’s sex life that it becomes as important as the sex acts themselves and, in some cases, even more important.

In our all-encompassing social-media culture where, increasingly, no experience can be personally validated until it is publicly validated via online sharing, photosexuality has thrived. It has shifted the camera’s role from a tool used to document sexuality to that of becoming a sexual partner in and of itself. The mainstreaming of photosexuality is a fairly recent phenomenon, enabled and accelerated by four technological developments: online video streaming (from the mid ’90s until the mid 2000s); the iPhone camera (starting in 2007); GPS dating apps (Grindr, beginning in 2009); and Instagram (2010). For better or worse, these tools have enabled people all over the world to take their erotic representation and self-objectification into their own hands. The activity has particularly resonated with gay men and is now pervasive.

If you’ve sent a risqué picture of yourself to the cell phone of a current or potential sex partner, or shared a picture of a recent sex partner with a close friend’s cell phone to brag about your experience, or have uploaded a video of your sexual activity to Pornhub, or posted a sensual self-portrait on a beach in a thong, showcasing a perfect tan, feeling confident and beautiful, full of life, desire, and sexual pride and have then been satisfied by the pleasure of sharing this version of yourself with the audience you’ve cultivated, then you have engaged in photosexuality. And almost fifty years before these technologies made this commonplace at the dawn of the decriminalization of homosexual imagery, one determined man arrived there before all others. Peter Berlin’s unusual and extreme sexual-artistic practice made him the world’s first internationally famous photosexual.

Berlin’s two feature-length films took audiences with him on his personal evolution from sexual to photosexual. Nights in Black Leather (1972) is a cinema-vérité style self-portrait of an erotically vibrant young German immigrant experiencing his first tastes of the hedonistic sexual paradise of pre-AIDS, early 1970s San Francisco. In themes and structure, the film is an unexpected but direct predecessor to HBO’s megahit Sex and the City (1998–2004). In both the show and its two films, Sex and the City’s main character writes about her exploits after each encounter. Similarly, in Berlin’s film, he sits alone with his journal in a park, reporting on each experience. Like Carrie Bradshaw, a voiceover of Berlin reading his entries can be heard as he writes, sharing his self-examination.

After a period of cruising bars, streets and house parties, Berlin comes to the realization that “normal sex”—meaning sex in a bedroom with one partner—barely interests him. Throughout the course of the film he discovers the key elements he needs to get turned on: leather, public spaces, role-play, and exhibitionism. The film concludes with him journaling as his voiceover explains, “By now, normal sex seems so boring to me. I like much more to get into perverse trips . . . but as far as normal sex is concerned, one of the best experiences I have ever had was last week, when these two boys approached me at the gym. They asked me to come with them, because they enjoyed nothing more then having sex on a couch with spotlights aimed at them and an audience watching.” For Berlin’s rapidly advancing taste, “normal” has come to mean engaging with multiple partners for spectators. By the film’s end, he is finished with traditional sexuality.

When Nights in Black Leather was released, it was embraced by an international audience of gay men desperately needing a role model to help them shed stifling patriarchal standards of masculine representation; and for Peter Berlin, the act of making the film was just as much of a guide as it was for his audience, helping him to sharpen his own uncompromised libidinous impulses. That project was the result of a collaboration with his friend and filmmaker Richard Abel. It leveraged the local celebrity Berlin had developed in San Francisco by creating a highly specific, incredibly confident hyper-homo persona, which he’d been performing and refining on the city streets for years. In conjunction with this public display, Peter had already been engaged in an elaborate and disciplined practice of erotic self-portraiture. His goal was not art, politics, or commerce. As he describes it, it was, simply, “chronicling the moments in my life when I felt the best.”

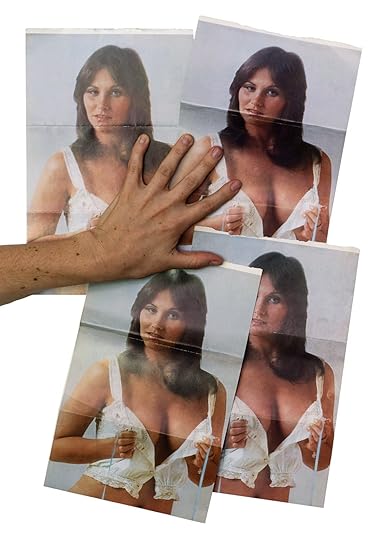

The success of Nights in Black Leather created more demand for Berlin’s image, so he monetized his private self-portraiture and developed a lucrative mail-order business. Through advertisements in gay publications, customers purchased photographs of Berlin for their own private pleasure. These new commercial endeavors allowed him to streamline his work further and enabled him to dedicate his time entirely to the few activities that enhanced his sexual pleasure: clothing design, photography, filmmaking, and cruising. On his own terms, he successfully turned his lifestyle into his primary revenue stream, which allowed his favorite practices to thrive. These unusual circumstances lead to the formation of a sexuality that established a profound and irreversible entanglement of dressing up, photography, and sexual fulfillment.

Of course, even then, the relationship between sex and the camera was far from new. Since its inception, the camera had been used to document the beauty and wonderment of the naked human form. What was new about Peter’s approach was that it was an independent enterprise. He wasn’t a muse for another artist or a model for a pornographer; nor was he a sex symbol produced by a film studio, like Garbo, Brando, or Monroe. He didn’t wait for an adoring and powerful benefactor to hand him the capitalist machinery of star production. As an out gay man, such tools were only available to his counterparts who had agreed to remain closeted for the purpose of becoming cultural icons. Berlin, on the other hand, valued himself and his sexuality with such militant pride that he took his identity into his own hands and became his own muse. “I wanted to turn myself into the type of man I wished I would see on the streets,” he has said as a way of explaining his style.

By the time Berlin’s second film came out two years later, the experience of making Nights in Black Leather and the response to it had given him a refined understanding of what he wanted from his sex life and the cinematic representation of it. For his next film, That Boy (1974), he stripped his filmmaking crew down even more sparsely, becoming his own director, producer, writer, and star. That Boy begins with Berlin cruising the daytime streets of 1974 San Francisco in a look that most hustlers would be embarrassed to wear at night: a leather biker cap that covered his signature golden pageboy locks, a tight black leather jacket that exposed his chest, a red bandana rolled up and knotted around his neck, dark aviator glasses, and custom self-tailored white sailor pants designed to showcase his crotch and elegantly cascade into thin bell-bottoms. In the film, a throng of Cockettes, the members of a queer theater collective who were known for their retro Hollywood or gypsy-like styles, parts for him, studying his look as he takes in theirs. Berlin struts through streets with determination until he encounters a handsome blind boy, the love interest of the film, who is dressed like a rocker and holding a cane. As he courts his new target, a paparazzi-style photographer appears out of nowhere to capture the young men flirting.

The photographer escorts Berlin (whose character is called Helmut) back to his studio. In a scene that is both sexy and hilarious, Berlin strips for the camera, taking off one layer after another and surprising the audience: no matter how skimpy the garment, there is always another skimpier piece beneath it. In this sequence and throughout all the sex scenes in the film, there are slideshow montages interspersed with the live action, a device that mimics the camera capturing an image. In this moment, desire is showcased traditionally through the presentation of firm young bodies intertwining; but mixed in between close-ups of stomachs, asses, and cocks are images of the camera flashing. And the camera flash becomes as important and as fetishized as the naked bodies. Finally, the room is covered with prints of Berlin. The shoot continues with him surrounded by hundreds of images of himself.

More naked young men join the photo shoot; they adore Berlin as he stands on a podium like a statue while the camera continues to flash. “I want to take pictures of them watching you,” the cameraman exclaims. “I want my camera to hold you all. To capture every one of you in its fine lens.” The climax of the scene has no penetrative sex or ejaculation. It ends with a slideshow of imagery hitting a rapid-fire pace. The erotic thrust of the scene is not traditional, not solely based on men’s enjoyment of each other’s bodies. It favors the camera’s actions and outcomes over penetrative sex or climax. Much more than just a simple pornographic film, through the lens of history, That Boy can now be understood as a photosexual manifesto.

Forty-four years after the release of That Boy, Peter Berlin is still a committed photosexual. What had grown out of instinct, desire, and circumstance had turned into its own distinct, long-lasting variant of sexuality. As the first photosexual, Peter Berlin gave a world starved of blatantly gay visual role models a new conception of the beautiful, empowered, self-loving, sensual, shameless gay man. Now that technology has allowed the mainstream to catch up with his project, thousands of gay men on Instagram are working toward achieving what Berlin already accomplished in the ’70s using only analog tools—his camera and the postal service. However, while social-media sharing of self-created erotic imagery might be a means to an end for today’s photosexual, Berlin’s work was always an equal companion to the live act of cruising. “Real for me,” he explains, “is when I walk the streets and you pass me, I look at you, you look at me, we pass each other, and then I look back, and you look back, and you stop. That’s real! That will never happen inside a computer.”

Michael Bullock is the associate publisher of PIN–UP and a contributing editor to Apartamento magazine. This essay is adapted from his new book, Peter Berlin: Artist, Icon, Photosexual, published by Damiani in November 2019. All photographs by Peter Berlin courtesy the artist and Damiani.

The post Peter Berlin was the First “Photosexual” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

Aperture Releases New Edition of Josef Koudelka’s Seminal Photobook, “Gypsies”

Koudelka’s foundational body of work offers an intimate glimpse into Europe’s Roma communities.

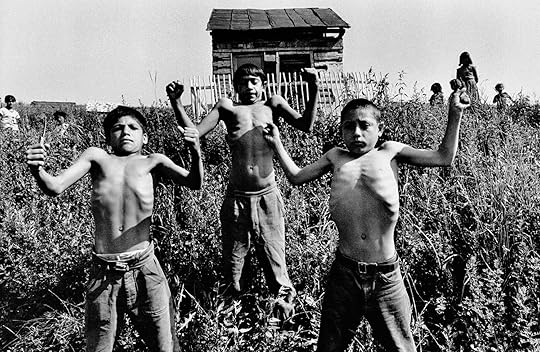

Josef Koudelka, Slovakia, 1967

© Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

In 1962, Czech French photographer Josef Koudelka began documenting the everyday lives of Europe’s Roma communities. Carrying only his equipment and a rucksack, Koudelka would spend the next decade moving between different Roma settlements and villages in then-Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, France, and Spain. His resulting images offered an intimate glimpse into these largely marginalized communities, exploring themes of alienation and displacement.

Josef Koudelka, Romania, 1968

© Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

In 1975, Aperture and Josef Koudekla collaborated with French publisher Robert Delpire to publish Gitans, la fin du voyage (Gypsies in the English-language edition), a tightly edited sequence of sixty black-and-white photographs made between 1962–71 in various Roma settlements. In the book, curator John Szarkowski wrote, “Koudelka’s pictures seem to concern themselves with prototypical rituals, and a theater of ancient and unchangeable fables. Their motive is perhaps not psychological but religious. Perhaps they describe not the small and cherished differences that distinguish each of us from all others, but the prevailing circumstance that encloses us.”

Josef Koudelka, Slovakia, 1966

© Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos

In 2011, Aperture released a new extended version of Gypsies. This revised and enlarged edition included 109 images from Koudelka’s series Cik´ni, lavishly printed in a unique quadratone mix by Gerhard Steidl. Unlike the traditional horizontal format of Delpire’s book, with only one photograph per right-hand page, the extended edition’s layout is much closer to Koudelka’s original maquette from 1968, prepared with graphic designer Milan Kopriva, and includes full-height vertical pictures and horizontals spread across two pages.

From left: Gypsies, 1975; Gypsies expanded edition, 2011; Gypsies mini paperback edition, 2019

Today, Gypsies remains a seminal photobook of the twentieth century. This fall, Aperture once again revisits this series in a new mini paperback edition, making the foundational body of work newly accessible to the larger public. Roma scholar and sociologist Will Guy, who wrote for both the 1975 and 2011 editions, updates his analysis of the condition of the Roma today, including recent upheavals in Europe. Stuart Alexander, photo historian and newly appointed editor in chief of Delpire Éditeur, contributes a brief historiography of the evolution of the body of work in book form. In his introduction, Alexander writes of the importance of Koudelka’s continued examination of this work: “Unlike most photographers, Koudelka has refined the presentation of an early body of work over a fifty-year period. In widely varying formats, he has modified the sequence and presentation to achieve the greatest impact of his intentions. As with any work of art, it is up to the viewer to complete the interpretation.”

Click here to purchase Gypsies.

The post Aperture Releases New Edition of Josef Koudelka’s Seminal Photobook, “Gypsies” appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 13, 2019

Gabriel Orozco Isn’t Interested in the Decisive Moment

For the Mexican artist, it’s all about the sculptural form—sweat, shadows, futons, and tortillas. (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

By María Minera

Gabriel Orozco, Buddha and Lemon, 2013

Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Walter Benjamin described Eugène Atget as a photographer who “always passed by the ‘great sights and so-called landmarks’” but instead was attentive to “a long row of boot lasts … or tables after people have finished eating and left, the dishes not yet cleared away.” We could go on: nor would he overlook a flowery carpet hanging from a window to dry under the sun, or a bakery display with piled-up bread forming peculiar geometric patterns. That is, Atget was the rare kind of photographer who was interested not in human beings, but rather in the traces they left in the world.

An artist like Gabriel Orozco fits comfortably into this category. Instead of following in the steps of Mexican photographers dedicated, above all, to trying to penetrate “the country’s soul”—as French Surrealist André Breton would say—by means of its people, Orozco focuses on the footprints of those people, or of others abroad, as he is a tireless traveler. Manuel Álvarez Bravo, in Los agachados (The crouched ones, 1934), portrays a group of laborers wearing ragged and dusty clothes, sitting on benches chained to the bar of an old diner. The men have their backs to the camera and the shadow produced by the metal curtain of the place cuts off their faces, making them appear crouched (with the double meaning of agachado because it refers also to people who allow themselves to be subdued).

Gabriel Orozco, Nubes de espuma, 2014

Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Orozco, in turn, creates an image, Sillas de espera (Waiting chairs, 1998), that could almost be the same image, except in his work everyone is gone. On a visit to India, he captured a row of four empty plastic chairs, each one positioned under a dark circle on the wall—marks left by the sweaty heads of individuals who have waited sitting on those chairs throughout the years, now almost replaced by their own ghosts who sit patiently in that deserted space. In his approach, Orozco resembles Atget, preferring to show an unpopulated world, where there are only vestiges of human life.

The significant difference is that, for Orozco, all these traces function, above all, as sculptural matter. The photographic image is secondary. What primarily interests him is what is happening not as a photographic instant, but as a form. To him, that shot of a waiting room in India is only indirectly photographic. One could call it collateral, in that it accompanies a sculptural event.

Gabriel Orozco, Pollo pescuezo, 2016

Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Since the beginning of his career, back in the 1980s, Orozco saw himself as an artist whose working materials were not inside an atelier but rather out on the street. The type of sculpture that seemed possible to him was not made with a chisel, but discovered in the configurations taking place randomly in the world, without the artist’s intervention—or, at most, subtle intervention. Like that mattress left on a sidewalk (Futon Homeless, 1992), which the artist perceives as a sculpture not because of its being a mass—which it is—but rather for the way it is rolled up on itself to the point of completely challenging the idea of a mattress as an object used to sleep on, and turning it into some sort of involuntary Henry Moore sculpture left to its fate on a New York street. Yet, Orozco does not take the mattress into an exhibition space—first of all, because he would need a moving truck. Rather, he takes a photograph that, while being a sign of something we can perceive happening in the real world, is also a signaling: literally, a way of pointing out that peculiar organization of matter in space, which is nothing but sculptural.

And, as a matter of fact, he sometimes decides to alter what is happening in order to precisely highlight the condition of an object. Another example, Tortillas y ladrillos (Tortillas and bricks, 1990): next to a gas cylinder, the artist finds a series of piled-up bricks. This composition could have been enough to him; these volumes of clay have sculptural traits on their own but, at the same time, lack specificity: they are nothing but towers of ordinary bricks, like the ones you would see anywhere. The artist then proceeds to place a tortilla on top of each pile. A minimal gesture, but one that gives the scene that strangeness, bringing together, at the same time—as Benjamin would say—the absence of intention and the most absolute intentionality.

Gabriel Orozco, Knife on Glass, 2000

Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

But is photography then not the work itself but a mere record? “It is the work indeed,” says Orozco. “As, in some cases, it is the only way I have to present something, an idea, an experience. I do not use an image as a ‘patronizing’ document intending to show something important to the others. . . . That doesn’t interest me. My intention is that the image presents itself as a chair, a tree, a fact: it is there.” The thing is: that which “is there” is indeed there, but in an unsustainable present outside the photographic image. That is to say, it does not operate in the same way as does a statue in the park, which will be there every time you return. Orozco’s statues are only there when he sees them. Afterward, they disappear, like that egg (Sunny Side Up, 2015) that has just been poured on a plate, which most probably ended up fried and in someone’s stomach. However, for a few seconds, that sunny-side up could boast of being a colorful, viscous planet. Here we are seeing an image act as a transportable doppelgänger of a momentary sculpture.

It is the photographic image that allows us to put ourselves in the sculptor’s place and see what he saw, from where he saw it. The gravity-defying knife in Knife on Glass (2000) is there, floating in the air, but only if one looks at it from a very precise angle. Look a few centimeters beyond, and the trick of the glass that holds it is revealed. In that sense, photography can be seen as a second act that, while closely participating in the creation of the form, does not stop being an ulterior reflection that adds, through its unique point of view, a new condition of possibility to the work. To Orozco, not only does photography capture, but it also sculpts.

Gabriel Orozco, Piñanona en el muro, 2013

Courtesy the artist; Marian Goodman Gallery, New York; and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Orozco’s work is about identifying the sculptural quality of certain spontaneous formations in space, and also about creating structures that express their sculptural value only when being captured. Nowhere does this become clearer than in Piñanona en el muro (Piñanona in the wall, 2013), an image in which the sculpture is made half of leaves, half of shadow, something that could by no means translate into sculptural volumes due to the elusive nature of the shadow. One begins to understand what Orozco has said about photography: that rather than a window, it is “like a ‘space’ that tries to capture situations.” This is how his images are to be seen: as receptacles of transient and fragile, nonetheless forceful, material incidents.

María Minera is an art writer based in Mexico City. Translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Gabriel Orozco Isn’t Interested in the Decisive Moment appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 12, 2019

Laura Aguilar Was a Proud Latina Lesbian, and She Flaunted It

What do the late artist’s emotional photo-text letters reveal about the craft of self-expression?

By Yxta Maya Murray

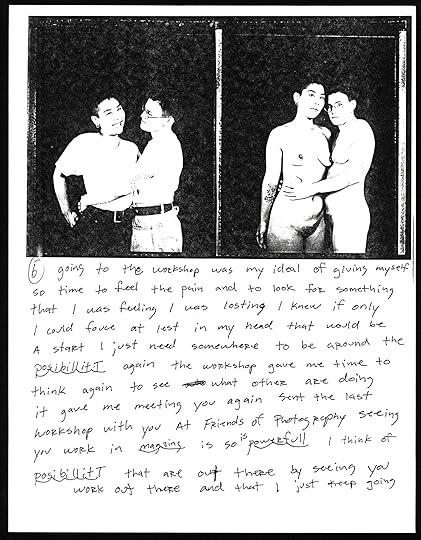

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Pat Martel, October 5, 1992

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

In September 1982, then-twenty-three-year-old photographer Laura Aguilar wrote a letter to her teacher and mentor Suda House. “Im not sure do you feel or do you learn how to feel?” she wondered,

And went you learn how to feel is that really how you feel or is it what you learn? Went your not sure about your feelings or how you feel about people and things. How do you know what you feel and what you think you feel is how you feel? How do you learn to understand things you don’t understand?

This letter, along with a large cache of others, is stored today in Stanford University’s Special Collections, which houses many of Aguilar’s papers and ephemera. In these and other documents, Aguilar expresses her anguish over her perceived inability to understand herself and other people, and over whether others could understand her. They form a key part of Aguilar’s oeuvre, as they document emotions and practices that would help shape a critical phase in her artistic development. From roughly 1988 to 1993, Aguilar became one of the most radical innovators of “photo-text,” a style that she embraced in order to confront her anxieties about being overlooked and misconstrued. Aguilar experienced auditory dyslexia, which caused her to write in a unique style; she also wrestled with fears of misunderstanding and being misunderstood as a consequence of her Mexicanness, her lesbianism, her large physical size, and her poverty. Together, the letters constitute a feminist photobook, detailing Aguilar’s interior life and marking her as a photo-text pioneer.

Laura Aguilar was born in 1959 to Mexican American and Irish Mexican American parents; she was raised with her older brother Johnny in the Los Angeles County neighborhood of South San Gabriel. As art historian Sybil Venegas has documented in an oral history, Aguilar formed one of her closest relationships with her grandmother, Mary Salgado Grisham, who often brought her to a local river where they would collect rocks and study the natural landscape. A young girl with a learning disability and a queer identity, Aguilar grew up in a hostile environment, and her parents did not always support her artistic leanings. (The first major study of dyslexia would not be published until the 1960s, and California would not begin to dismantle its anti-sodomy laws until 1976—in 1986, the United States Supreme Court upheld such statutes’ constitutionality, a ruling that lasted until 2003.)

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Joyce Tenneson, September 7, 1991

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Aguilar attended East Los Angeles College. There, a teacher told her that she was wasting her time trying to be an artist when she could not even read. Aguilar transferred to Pasadena City College, which had a better program for people with learning difficulties, but she was already experiencing intense feelings about her fraught relationships with language and people. In a 1983 paper that she wrote for a Pasadena composition class, Aguilar confessed: “I don’t know why I even deny the fact that I have a learning disability. I know better than anyone else that I do . . . . All I ever saw was that I am inadequate it hurts to much to admit to anyone.”

People with auditory dyslexia have difficulty processing the basic sounds of language, and the syndrome can result in a strained reading process. In a 2009 study, psychologists concluded that dyslexic people who have issues with self-esteem are more likely to experience emotional and behavioral problems—a perhaps unsurprising finding that Aguilar herself, in an undated videotape titled Work In Progress, commented on in blunter terms: “No matter how hard I try I can’t prove I that understand things in a way that you need to in this society. . . . when you’re at a function and people have nametags on and I’ve met them before and the nametag’s right there and I can’t read it, and I hate myself . . . I want to die.”

What is surprising is that a person with this fractured rapport with writing would choose to incorporate text so prominently into her artwork. In 1987, Aguilar embarked on her Latina Lesbians series, a suite of black-and-white portraits of queer Latinas framed by large white margins that contain notes written by the subjects. Carla Barboza (1987), for example, portrays a fit woman sitting in a wing chair while smoking a cigarette and wearing stylish black boots. Beneath the image, Barboza wrote in clean, black-inked cursive: “I used to worry about being different. Now I realize my differences are my strengths.” Similarly, in Cookie (1987), we see a dramatic, curly haired woman clutching her chest. In exclamation point-inflected script, Cookie inscribed: “I am a proud Latina Lesbiana and I do flaunt it.”

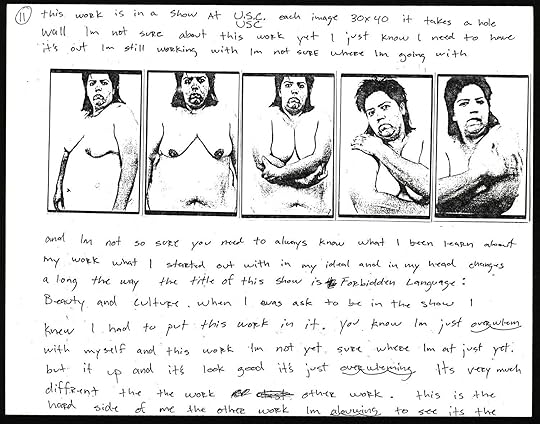

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Joyce Tenneson, September 7, 1991

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Aguilar incorporated writing into her art even as her reading problems made her feel “inadequate” and suicidal; this choice creates tension and even mystery in her work. In May 1987, Aguilar offered some insight into her methods in a letter to photographer Jim Goldberg, who created the landmark series Rich and Poor (1977–85), black-and-white images of San Franciscans living on either side of the economic divide, with notes written by the subjects. Aguilar’s association with Goldberg indicates his influence on her, but she reflected on her independent motivation for combining words and images in this beguiling passage:

The series is called Latina Lesbian . . . [It shows] a positive image of Latina Lesbian . . . its hard when I have had a lot of years of thinking of myself as being mexican as being negative as being inferior I do feel poud of my culture and who I am but the past and the past thinking and feeling is still around it take time for the hart heart and the bring brain to get together and belive at the same time and truly belive. So the only to say something about being Latina and a Lesbian through photos was to add language.

What was the “something” that Aguilar was trying to say? When Aguilar embarked on her photo-text work, she became part of an artistic heritage radiant with luminaries who joined words and images, such as Goldberg, André Breton, W.G. Sebald, Carrie Mae Weems, Martha Rosler, and Lorna Simpson, to name a few. Goldberg used words and images to humanize economic inequality, Breton did so as part of his Surrealist project (Nadja, 1928), Sebald to confound his readers about the nature of reality (Emigrants, 1992; Austerlitz, 2001), Weems to punctuate atrocities committed against Black people (From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995; Colored People, 1989–90), Rosler to reflect on photography’s inadequacies (The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1974–75), and Simpson to narrate her complex studies of the Black female experience (Necklines, 1989). Aguilar’s letters underscore that she pursued the marriage of script and photo to fulfill social projects akin to those of Goldberg, Rosler, Weems, and Simpson—she engaged photo-text to bring the heart and the brain together to generate positive images of her sisters.

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Joyce Tenneson, September 7, 1991

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Still, Aguilar’s letters unveil such a thrashed relationship with written texts that they offer proof that in making this work, she tried to smash public stereotypes but simultaneously strove to cope with very private harms. In connecting her beloved photography with the threats of written script, she hurtled toward the very thing that she feared would destroy her.

In 1990, Aguilar wrote a letter to her close friend Pat Martel, in which she described how she felt: “lest then [less than]. . . knowing that to pick up a book and to be ably to read it and . . . knowing that I have this Lim A ta tion that stop me that eat at me and that at time turn into hate.” In January 1992, Aguilar sent Martel another letter, written on glossy photo paper and illustrated with ghostly images of stone angels from her ongoing Cemeteries series (1990–96): “I felt like killing myself again Im anger cause what made me get out of this place was cause I had to fight again deg deep? [dig deep] my feet down and fight Im anger for always having to fight for myself.”

Aguilar’s torment certainly did not come solely from reading problems, but also from her poverty and health. In 1991, she was diagnosed with diabetes—which would kill her in 2018. She suffered intensely as a result of the deaths of her mother and brother, and, as her later work would show, of her feelings of invisibility in the art world. (Her doctor prescribed helpful antidepressants that she feared would be taken from her when her insurance ran out.) Aguilar used letters as a laboratory to express her rages in the language that she both loved and feared, and to see how her writings paired with her images. As her friend and estate administrator, photographer Christopher Velasco, remembers: “Laura told me that her Letters were her way to express herself because it was so hard to explain to people in person, because she was so shy to say it in person. It was another way to showcase her work to her friends and artists she admired.”

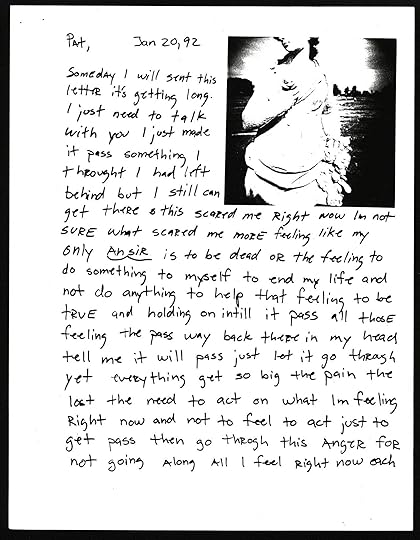

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Pat Martel, January 20, 1992

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Aguilar’s most famous photo-text work may be her incendiary four-photo series Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt (1993), which shows Aguilar brandishing a gun; as the pictures progress, she removes her clothing and sticks the barrel into her mouth and closes her eyes. At the bottom of the photos, she wrote a narrative about being shut out of the art world: “The believing can pull at one’s soul. So much that one wants to give up.”

But these photos had an earlier airing—as illustrations in an October 1992 letter to Martel. Here, Aguilar told the story of how, at the opening of her group show at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, a rich white woman insultingly ignored her. These feelings of inaudibility developed into a more generalized anxiety that motivated her to pantomime her own suicide: “I feel a lot of pain Im scared of losting my grip.” Her handwriting sprawls all around the pictures. The letters engage a propulsive use of text to underscore both Aguilar’s feelings of fragility as well as her talent for leveraging her supposed weaknesses into unforgettable representations.

The letters and essays that Aguilar wrote from the early 1980s until the mid-1990s show her contending with intense mental suffering, both caused and expressed by language. In Latina Lesbians and Don’t Tell Her, and in the letters where she practiced photo-text, Aguilar dealt with her fears and her disability at the same time. They are acts of survival, experimentation, and courage. But at some point, Aguilar had a breakthrough.

Laura Aguilar, Personal letter to Joyce Tenneson, February 22, 1993

Courtesy the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

In a November 1993 letter to photographer and teacher Joyce Tenneson—which Aguilar illustrated with more images from her Cemeteries series—Aguilar wrote about her burgeoning work with nude self-portraiture, which began around 1990. During this process, Aguilar began to feel differently about herself:

I think a lot about why I photography myself nude I know it started at a place of shame . . . before I don’t think I really every look at myself no one else look at me notice me so I just pick up that I don’t exist. . . . Now somedays I find myself just standing there looking at myself naked in front of the mirror thinking, looking to find something new to photography and there come this big smile on my face and I think yes you are crazy and its ok.

It would be too much to say that Aguilar’s work with nude self-portraiture created an immediate transformation that allowed her to freely read herself. Nevertheless, the feelings of self-acceptance and happiness that she first began to experience during these sessions later blossomed into her series Clothed/Unclothed (1991–94), which shows lovers and families in states of dress and undress.

These later branched into masterpieces, which depict Aguilar nude in the natural landscapes that harken back to her riverside musings with her grandmother—Nature Self-Portrait (1996), Stillness (1999), and Motion (1999). The photographs reveal Aguilar and her friends wandering loose and exultant through the deserts and woods; they are very beautiful. These images contain no text at all.

Yxta Maya Murray is a professor at Loyola Law School, Los Angeles, and author of the forthcoming novel Art Is Everything.

The post Laura Aguilar Was a Proud Latina Lesbian, and She Flaunted It appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 11, 2019

Introducing: Garrett Grove

Against the backdrop of the US presidential election, a photographer documents growing cultural tensions in the Pacific Northwest’s rural communities.

By Cassidy Paul

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Jack’s Cowboy Hat), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

On a snowy night, against a midnight-blue sky, a single cowboy hat flies above a landscape of trees. The camera’s flash freezes a dizzying array of snowflakes dancing around it, resembling confetti bursting from a magician’s hat thrown up during a magic trick. It was the first photograph I saw from Garrett Grove’s series Errors of Possession—and I was hooked.

As a native to the Pacific Northwest, I was drawn to Grove’s portrayal of the region’s rural towns and communities. Though the area is widely seen as liberal and strictly blue, a larger cultural and political divide exists between the eastern and western sides. Growing up, we called this the “Cascade curtain,” referring to the dividing line through Washington, Oregon, and Northern California made by the Cascade Mountains.

Born in California, Grove’s family moved to the Pacific Northwest at an early age, settling north of Seattle. He went on to receive his MFA in photography from the University of Hartford in Connecticut, before moving back West and settling in Skagit Valley, Washington. “I have always been more drawn to rural communities, even though I wasn’t raised in one,” he says. “I am much more at ease in a natural environment with more wide-open spaces.”

In the years leading up to and following the 2016 US presidential election, Grove began photographing in and around small coastal, farming, and logging towns in Oregon and Washington. Despite being made against that backdrop, Errors of Possession (2015–17) features no direct political imagery of the controversial event, instead offering a more poetic look at the growing cultural tensions alongside an economic and agricultural depression. “With the election gaining momentum, it was apparent that the polarization of our country was making this divide bigger, and I wanted to travel between these two psychological realities,” Grove says.

Initially inspired by early black-and-white archival photographs of agriculture and industry workers during the cultivation of the American West, Grove intentionally plays within the documentary genre. By setting classical, black-and-white images alongside color photographs often taken with a harsh flash, he assembles images that are anxious, humorous, strange, and deeply ambiguous. Tracks in a field create extraterrestrial-like symbols, a man slides down a mountain of potatoes, halos of light outline a mother and daughter, and lines of men and women walk through abandoned fields. Although the world Grove captures features familiar scenes of the American West, each frame gives the sensation that something is not quite right. “I am interested in taking the viewer into a psychological state filled with unknowns and non-answers,” he says.

Bryan Schutmaat, photographer and publisher of Trespasser Books, which recently released a photobook of this series, was drawn to the sublime yet perplexing quality of Grove’s images. “In the grandeur of the American West, [Grove] points out little oddities that are often poignant or humorous. His look into the Northwest relays disappearing wilderness, transformed agricultural land, and people among it who are rugged and peculiar,” Schutmaat says. “It does what work in this American genre does best—tells us in a unique voice what we’ve done to the landscape and to each other.”

Errors of Possession captures a moment of unrest and shifting landscapes and mythologies. “I don’t think it provides any answers, but it does take the confusion that I was—and am—feeling and infuses it into the work,” Grove says. “I’d hope that this work offers a new way of looking at and thinking about the American dream.”

Garrett Grove, Untitled (José & Potatoes), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Farmers & Scientists), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Spinning Brodies), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Honeycrisp), 2015, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Man & Combine), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Okanogan Complex), 2015, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Crystal & Daughter), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Garrett Grove, Untitled (Man & Lumber), 2016, from the series Errors of Possession

Cassidy Paul is the social media editor of Aperture Foundation. All images courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

The post Introducing: Garrett Grove appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 8, 2019

Announcing the Winners of the 2019 PhotoBook Awards

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation are pleased to announce the winners of the 2019 edition of the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards, celebrating the photobook’s contribution to the evolving narrative of photography. “At Paris Photo, the photobook is thriving, and in the eight years that we have partnered with Aperture Foundation, we have seen a tremendous evolution in the field with a multiplicity of new forms and diverse content,” said Paris Photo director Florence Bourgeois and artistic director Christoph Wiesner. “We are proud to play a role in the recognition of these authors and publishers, and to bring together the photography community in celebration of this art form.”

Winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year

Enghelab Street, A Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983

Hannah Darabi

Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, and LE BAL, Paris

Iranian artist Hannah Darabi’s catalogue Enghelab Street, a Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983 (Spector Books, Leipzig, Germany, and LE BAL, Paris), winner of Photography Catalogue of the Year, is a comprehensive and smartly designed book about books, pinpointing the burst of photobook production in Iran between the fall of the Shah’s regime in 1979 and the postrevolutionary introduction of the Islamic State in 1983. Irene Attinger described the book as an important addition to the narrative of the photobook with its focus on underground protest and propaganda books in Iran. “It’s a critical work by a female artist and scholar; it brings together specialized research and an artist perspective with a very strong design.”

Winner of PhotoBook of the Year

Sohrab Hura

The Coast

UGLY DOG (self-published), New Delhi, India

The Coast (UGLY DOG [self-published], New Delhi, India), winner of PhotoBook of the Year, is Indian photographer Sohrab Hura’s fourth photobook. The unsettling and graphic nature of the images alludes to rampant violence—religious, caste, sexual, or otherwise—and the increasing normalization of it. The images follow a propulsive, if elusive, narrative that guides the book using the structure of repetition. Nina Strand spoke highly of The Coast for its presentation “almost as a novel or a thriller in its format, cover, and design; it’s a photobook that works on the same level as a challenging work of fiction.” The jury was also impressed with the adept use of repetition in the sequence and structure of the book; Emma Bowkett praised it as “a lyrical, political narrative with a strong, determined voice.”

Winner of First PhotoBook ($10,000 prize)

Gao Shan

The Eighth Day

Imageless, Wuxi, China

Gao Shan is a Chinese photographer who was adopted eight days after he was born. The Eighth Day (Imageless, Wuxi, China), winner of the First PhotoBook Award, was born out of his desire to connect with his adoptive mother, who he shares a roughly-seventy-square-meter apartment with. Shan was praised for the simple yet thoughtful and emotionally potent design and sequence. Takashi Homma observed that while the work appears on one hand to be straightforward documentary, it also employs “performative and conceptual approaches in a sophisticated way.” As Homma noted, “This is someone who seems to know their history of photography and photobooks. I would like to see his next book!”

Juror’s Special Mention

Drew Nikonowicz

This World and Others Like It

Fw:Books, Amsterdam, and Yoffy Press, Atlanta

This World and Others Like It (Fw:Books, Amsterdam, and Yoffy Press, Atlanta), the Jurors’ Special Mention, showcases Drew Nikonowicz’s ongoing exploration of the divide between traditional and emerging modes of photography. Osei Bonsu described it as “a strong example of an artist working at the interstices of art and science, asking pertinent questions about photography in the contemporary world.”

A final jury at Paris Photo selected this year’s winners. The jury included: Irene Attinger, curator; Osei Bonsu, curator of international art at Tate Modern; Emma Bowkett, director of photography at FT Weekend Magazine; Takashi Homma, artist; and Nina Strand, editor and founder, Objektiv Press.

This year’s shortlist selection was made by Amanda Maddox, associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Joanna Milter, director of photography at the New Yorker, Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum, Lesley A. Martin, creative director of Aperture Foundation and publisher of The PhotoBook Review, and Christoph Wiesner, artistic director of Paris Photo.

The shortlist was first announced on Aperture Online and at the New York Art Book Fair. The thirty-five selected photobooks are profiled in issue 017 of The PhotoBook Review, Aperture Foundation’s biannual publication dedicated to the consideration of the photobook. Copies will be available at Aperture Gallery and Bookstore. Subscribers to Aperture magazine receive free copies of The PhotoBook Review with their summer and winter issues.

The post Announcing the Winners of the 2019 PhotoBook Awards appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

November 7, 2019

Tania Franco Klein’s Magic Spells

Inspired by Mexico City’s Sonora Market, the photographer’s cinematic new series depicts an unshakeable belief in enchantment. (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

By Chloe Aridjis

Tania Franco Klein, Mercado de Sonora, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Many of Tania Franco Klein’s photographs depict female figures who seem lost in the vastness of an inhospitable landscape or in a moment of contemplation, the edges of the self contained within those of a geometrical interior. Her images are bathed in a warm cinematic light, boudoir red, and suffused with a Lynchian sense of menace—they resemble film stills taken midnarrative, though it’s unclear whether the climactic moment has yet taken place.

For her newest series, Mercado de Sonora (2019), Franco Klein focuses her gaze for the first time, after many photographic projects abroad, on her native Mexico. In the past, she has often donned a wig and turned the camera on herself; in this body of work, her mother and grandmother become the models in an extended form of self-portraiture that captures the ways in which beliefs are passed from generation to generation.

The Mercado de Sonora, a vast traditional market in southeast Mexico City, is a space, Franco Klein explains, where class boundaries dissolve: a cross-section of society, from the house servant to the industrialist’s wife, comes here to find esoteric cures. The politics of the marketplace are evident in its gender distribution: women sell spells, men sell animals. For alongside the stalls of abracadabra and Santa Muerte figurines is a squirming menagerie of trafficked wildlife, a vast array of fauna crammed into cages, heaped on one another, struggling for air and space. Around 70 percent of creatures transported to the market die en route, and those that survive often meet their end in a gruesome Santeria ritual or, in the case of the more exotic species, as pets to narco juniors. For decades, authorities have turned a blind eye toward this lucrative hub of illegal trafficking.

Tania Franco Klein, Mercado de Sonora, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Because of the rampant criminal activity, photography at the market is strictly forbidden. Franco Klein decided to shift the context and bring the spells, the promises being sold, into a more private realm, in order to explore what happens once these products are taken home. In doing so, she has created spaces of longing and atmospheric ambiguity, where every detail is freighted with forensic significance. Over and over, the viewer is invited to imagine the psychodrama unfolding within.

In one disquieting photograph, a hand appears to hold down the shoulder of a woman in a silky dress and black wig, while the other hand runs an egg over her head as part of a limpia, or spiritual cleansing, the negative energy extracted condensing into shadow. Elsewhere, the components of an abandoned magic spell are strewn across a carpeted floor in a palette of dusky reds and greens—a small voodoo doll, a lock of hair, a burnt candle. Nearby, the feet of a woman soak in a green bowl; it’s unclear whether this is part of the ritual. Another photograph shows three perfume bottles, one resting on a two-hundred-peso note, on a linoleum floor; meeting them head-on is the white shoe of a woman. Both images suggest a schism between the magical product and the human subject, an abyss between expectation and fulfillment.

Tania Franco Klein, Mercado de Sonora, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Animals, the most troubling “items” for sale at the Mercado de Sonora, feature in the two darkest photographs. A piglet perches on a table covered by a red cloth; it stares at the camera, accompanied only by its shadow, like a stage prop missing its magician. In the other, a green velvet sofa is juxtaposed with the curled tail of a (presumably dead) crocodile. Torn from their habitats, these animals, decontextualized in the marketplace, appear now even further estranged from nature.

The most hopeful composition—should faith be correlative to levels of brightness—shows a green soap and its box, which bears the words Ven a mi (Come to me), resting on a bathroom shelf alongside a plastic green comb and a bright red dustpan. The playful primary color scheme, set against a blue-tiled wall, evokes an optimism absent from the murky incertitude elsewhere.

Throughout this series of lyrical and unsettling mise-en-scènes, Franco Klein deconstructs the human subject and the magic charm. Female figures—defamiliarized by wigs or disembodied—interact with spells that have also, in some way, become fragmented. In our Mexico, a country beset by violence, poverty, and environmental crisis, these images depict an unshakable belief in enchantment, however tenuous its promise.

Tania Franco Klein, Mercado de Sonora, 2019, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist

Chloe Aridjis is a Mexican writer based in London and the author, most recently, of the novel Sea Monsters (2019).

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Tania Franco Klein’s Magic Spells appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

What is a Feminist Photobook?

Carmen Winant on feminism, photobooks, and the radical gestures of world-building.

Centerfold by Carmen Winant for The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, 2019

Carmen Winant, the guest editor of the latest issue of The PhotoBook Review, is an alchemist when it comes to books—her practice as an artist is one of creation and transformation, an Ouroborus in which printed material is both created and destroyed. In the following conversation, I am joined by my colleague and contributing editor Brendan Embser, who has worked closely with Winant on other projects for Aperture. We spoke to her by phone as this particular issue developed, to talk about how her thoughts about bookmaking have been informed by her deeply held commitment to feminism and a critical approach to the depiction of women via the photographic image.—Lesley A. Martin

Brendan Embser: Carmen, two years ago, you and I were at a symposium on feminism and image making at the FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, and we were discussing this idea of “emergency feminism”—basically the idea that we all have to be feminists now. I wanted to start there, and ask you how you’re feeling about feminism right now, especially in relation to art, photography, and books.

Carmen Winant: That’s not a small question! I am of many minds about where I see feminism now. On one hand, I feel, as I did then, really energized by the cross-generational commitment of people, not just women—but of all people, and ranging in age—to this thing that we call feminism. I understand feminism to have, in some sense, risen from the dead; it’s no longer seen as pass. to call yourself a feminist. And that is what we need: bodies in the room working toward coalition. On the other hand, there is a certain radicality that has, in my opinion, become rather dilute. We no longer have an agenda of “liberation.” We no longer understand world-building to be a part of the picture. That was once the feminist imperative, to believe that another world was possible.

Lesley A. Martin: I’m interested in your use of the word world-building. I’m curious, especially, about its application to art, photography, even to bookmaking.

Winant: One thing that my current project, Notes on Fundamental Joy [Printed Matter, 2019], has taught me is that imagination belongs to organizers and policy-makers as much as to artists: the act of world-building is nuanced, messy, and to collaborative. As an artist and art educator, I am intent on pushing my students to access channels of their own imagination. And that means not only to imagine superficially—a shape or a color—but to be sensitive to their world, imagining whole new systems that don’t exist, or could exist in parallel. Working on this book, which is comprised of photographs made by lesbian separatist artists in the early 1980s, enabled me to witness a kind of imagination I’d never seen, a literal world-building. These projects—the aesthetic work of imagining, and the political work of imagining—are indelibly connected. It’s no coincidence that the women/womyn in this book were artists and feminists, were world-builders and separatists. All of those things remain connected in a functional sense.

Carol Newhouse, Untitled, from Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression though the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us (Printed Matter, 2019)

© Carol Newhouse; Courtesy the artist

Embser: Lesley and I were excited to work with you on this issue, in part because of your attention to the history of women in photography, and pictures of women in your own artworks. But we also wanted to ask how you make photobooks, and how you have been thinking about making “feminist” photobooks.

Winant: In her book Living a Feminist Life, the writer Sara Ahmed qualifies the feminist movement as both a philosophical and an embodied movement; something that can move between people and something that physically moves people. What occupies that potential more than books? They can be shared, packed up and moved between countries, sent cheaply in the mail. Feminists have long been inclined to making books, leaflets, and pamphlets; this way of working runs hand in hand with, as Ahmed said, an agenda of the movement.

In terms of my own work, I make feminist books about women’s lives, largely in relationship to what we might call sexual politics. I’ve been particularly interested lately in the potential of women’s imaginations. I am perpetually thinking about how photobooks function to transmute, or fail to transmute, our agendas and our insides.

Our work in this issue orbits these ideas, probing this question: what is a feminist photobook? What do we do with a feminist photobook?

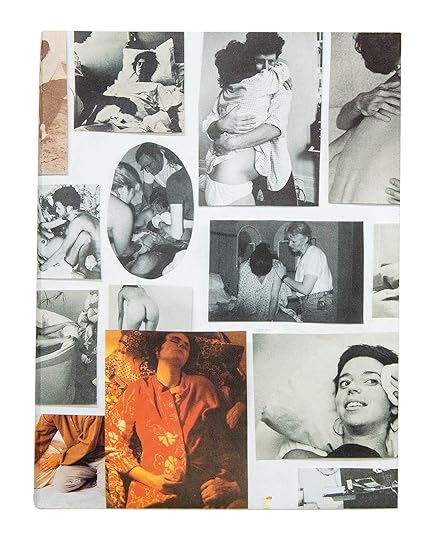

Carmen Winant, My Birth (Image Text Ithaca Press and SPBH Editions, 2018)

Martin: In your own work, you’re also using books as source material. There’s a tension between the physical and the symbolic that plays itself out in the book form. Is this important and where do you find this imagery?

Winant: People often assume that either I’m printing images out myself, finding them on the internet or in magazines. But for My Birth [Image Text Ithaca Press and SPBH Editions, 2018] and this new book, it is important to me that they originate as bound, physical objects—which I’m undoing in order to make a new physical thing. The books are truly destroyed by the time that I’m done with them. In that sense, there’s a strange cycle of destruction and regeneration. It’s a private thing that occurs in the studio, from book to book to book. It’s not without some sadness that I destroy some of the books, if I’m being perfectly honest.

That physicality is important, because that’s how I read books, especially books of images. They have a feel, a texture. They have patina. When I was working with Bruno Ceschel of Self Publish, Be Happy, he finally said to me, “Just make something in the studio. Put together a book the way you would produce something with your hands, in the way that your cuts would be uneven, your placement would be off-center, and we’ll reproduce that as the book without interference.” That was really liberating, and frankly, opened up some possibilities for me in what bookmaking could be.

Honey Lee Cottrell, Untitled, from Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression though the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us (Printed Matter, 2019)

© Honey Lee Cottrell; Courtesy the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Martin: I do think that trace of the human hand is something that comes up a lot in feminist work, and I’m wondering how you see that as a feminist gesture as well as a practical matter—that you end up seeing the tape on the page or the jagged edges of the appropriated images. It makes me think of Abigail Heyman’s Growing Up Female [Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974], in which the handwritten text performs as such a concrete and specific gesture of feminine identity.

Winant: I have always worked in an explosive way, but I used to “clean up” the work before it left the studio. I would smooth out the edges, take off the tape, disguise the hand. It took me a long time to understand that impulse as reflecting my own inculcated sexism about what might be considered “serious” artwork. I was worried that my work would be read as “crafty,” which for me meant feminized.

I had to understand that impulse; I had to figure out why I was embarrassed in the first place. I’ve come to realize that it had to do with my own expectations of wanting my work to look more—be perceived as what I understood to be—masculine.

Martin: More polished.

Winant: Yes. People work in all sorts of ways, of course. But I will say, there is an echo between lives. Many artist mothers I know have described similar shifts across their working methods after having children; their art became smaller, looser, or quicker along with the limited time. I’ve certainly felt that to be the case—I work at home when my kids are asleep—and now I recognize it as a kind of critical evolution. There are certain tendencies or gestures like this that we fail to acknowledge, that are superimposed by our gendered positions in the world.

Carol Newhouse, Untitled, from Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression though the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us (Printed Matter, 2019)

© Carol Newhouse; Courtesy the artist

Embser: In one of the features in this issue, you’ve posed the question to various writers and curators: what gesture or spread or moment in a book strikes a reader as feminist? How would you answer that yourself?

Winant: When I was in college, one night I discovered, in the UCLA Library, a book about Valie Export. I hadn’t learned about her in any of my classes. The book was full of photographs, because she makes photographic objects and photographic collages, and uses photo-documentation as an element of work. And I was stunned by it. I felt like it was a new way to be an artist and a new way to be a feminist. It was so fearless.

Jo Spence is another person whose books appear as part of this feature. I was surprised that I didn’t know about Spence sooner. I learned about her books The Final Project [Ridinghouse, 2013] and Putting Myself in the Picture [Real Comet Press, 1988] through Drew Sawyer, who writes about Spence in this issue. Her work felt unfamiliar to me, and wildly brave. There is something about her vulnerability, her testimony in photographs and text—an understanding of those things as a way to research our interior lives. And to recognize that our interior states are valid to mine as subject matter, and to take seriously.

Honey Lee Cottrell, Untitled, from Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression though the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us (Printed Matter, 2019)

© Honey Lee Cottrell; Courtesy the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Martin: Carmen, I want to talk more about your newest project, Notes on Fundamental Joy, which is constructed in response to images created by and for queer women. What does it mean for a cisgender woman, partnered with the father of your children, to work with this material? And how do you deal with the essentialist critique that these are not “your” images to work with?

Winant: I address this in the essay in the book. For me, these images form a map to a world that I didn’t know existed. Here were women who sidestepped the patriarchy altogether. This was the actualized work of world-building. I was really attracted to the joyousness of that, to its possibility beyond the metaphorical.

I had to ask myself, “Why do I feel that I belong here? Is this a kind of imposition? Am I trespassing?” I really wanted to take these questions seriously, without letting them overwhelm the photographs themselves, or the power of this history. I was in touch with every single photographer whose work was used in the book. Everyone was credited. Everyone was paid. Same goes for the photographs that were in institutions, institutional archives, the estates of women who passed away. One by one by one, every permission was granted. It was important that people have the credit that they deserve, but also in a larger sense, that those conversations were had with the women who were still alive and working, and that they felt like they could be collaborators on the project, and that they felt as though their own authority was not being stripped away. Those conversations—which are ongoing—were sometimes affirming, sometimes difficult or uneasy. The stakes are very real. Taken together, they form the foundation for this project.

Embser: By the same logic, how do you want people coming to this issue of The PhotoBook Review—who may not consider feminism “for them” and don’t normally read about feminism—to feel that this topic is their topic as well?

Winant: Basically, I never stop talking about feminism. I’m sort of relentless about it. I believe this is how we elevate consciousness, by lacing it through our everyday lives: through the way we talk about art and art history, parenting, heath care, and so on. You can’t just talk about feminism when it’s convenient, or when the moment strikes. And my students are receptive! Slowly, we build a coalition. That’s how, eventually, we’re moved.

Embser: Finally, could you tell us about your Linda Lovelace centerfold?