Aperture's Blog, page 80

November 6, 2019

On the Cover: Wolfgang Tillmans Guest Edits Aperture’s “Spirituality” Issue

Wolfgang Tillmans, Flatsedge, 2019

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong; Maureen Paley, London; and Galerie Buchholz, Cologne/Berlin

“At this time I feel a strong need for the affirmation of spirit in photography in published form,” Minor White wrote to a colleague in 1966. “Aperture is the only place it can possibly be published at this time. Too bad for photography but that is the way it is.” A photographer and influential educator, White also cofounded this magazine and served as its editor from 1952 to 1976. His approach to seeing and making images was deeply informed by a belief in the possibilities of transcendence, by a longing for the metaphysical. More than four decades on, when we asked Wolfgang Tillmans to guest edit an issue, he proposed a theme resonant with this history. “I immediately knew that it should be spirituality,” he says, “because I strongly sense that the political shifts in Western society in the last ten years stem from a lack of meaning in the capitalist world.”

Throughout his work, Tillmans has examined the modes and messages of photography. His vision is capacious. He has trained his endlessly curious and often-loving gaze on everything from blue jeans splayed over a railing and fruit arranged on a light-splashed windowsill to friends and lovers, a Shaker community in Maine, the Concorde gliding across the sky, and astronomical phenomena. His large-scale abstractions delight in color, pattern, and the chemical foundations of the medium. This inclusive way of seeing unfolds in dynamic constellations of pictures in his self-described “multi-vectored” gallery and museum installations. Small, framed images hang beside large, bull-clipped prints. His varied processes encompass inkjet prints, photocopies, and tear sheets from magazines—a reminder that Tillmans often worked with influential music and style publications, like i-D, in the 1990s. “There is no definite or permanent answer in photography,” he has said. “I like the way it’s constantly in flux.” But what is never in flux is the discipline, precision, and ethic of care Tillmans brings to his art.

Recently, that care has extended to activist work around political crises unfolding in Europe: migration, Brexit, the uncertain future of the European Union. As guest editor, rather than consider spiritual awareness as an inward-looking exercise of self-betterment, or as a feature of organized, hierarchical religion, Tillmans poses the questions: How is human connection a form of spiritual engagement? And what is the relationship between spirituality and solidarity? The answers take many forms—protests in Hong Kong, dance floors in London, or spiritual healing in Johannesburg. In the hours following the release of the first-ever image of a black hole, a billion people shared the astounding picture that reminds us of the staggering scale of the universe, and of our own fragility, our finitude, our need to make meaning through experience. “Solidarity,” Olivia Laing writes in this issue, “is founded on the notion that what connects us is more powerful than what keeps us apart.”

Pre-order Aperture, issue 237, “Spirituality,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post On the Cover: Wolfgang Tillmans Guest Edits Aperture’s “Spirituality” Issue appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 31, 2019

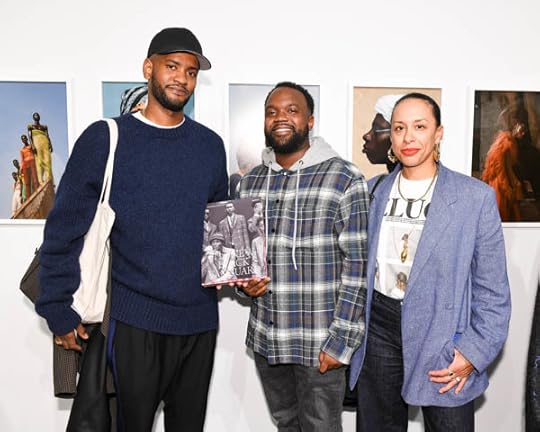

A Look Inside the Opening of The New Black Vanguard Exhibition

Last week, in partnership with Airbnb Magazine, Aperture celebrated the opening of The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion curated by Antwaun Sargent.

Antwaun Sargent

Zach Hilty/BFA

Micaiah Carter, Justin French, Antwaun Sargent, Quil Lemons, Arielle Bobb-Willis, Adrienne Raquel, Daveed Baptiste, Jamal Nxedlana

Zach Hilty/BFA

Veuve Clicquot

Steven Davis/Aperture

Jermaine Daley, Micaiah Carter, Shibon Kennedy

Zach Hilty/BFA

Sarah McNear, WM Hunt, Catherine Evans

Zach Hilty/BFA

Quil Lemons

Zach Hilty/BFA

Arielle Bobb-Willis, Adrienne Raquel, Daveed Baptiste

Zach Hilty/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana

Zach Hilty/BFA

Kerby Jean-Raymond, Antwaun Sargent, Kennedy Yanko

Zach Hilty/BFA

Lesley Martin, Antwaun Sargent, Isabelle McTwigan

Zach Hilty/BFA

Ben Kasman, Brooke Williams, Natasha Lunn, Lesley Martin, Jamal Nxedlana

Zach Hilty/BFA

Cathy Kaplan, Mfon Usoro, Eno Usoro

Zach Hilty/BFA

Flo Ngala

Zach Hilty/BFA

Matthew So, Kristen Joy Watts

Zach Hilty/BFA

Quil Lemons

Zach Hilty/BFA

Roze Traore, Corey Stokes

Zach Hilty/BFA

Arielle Bobb-Willis

Zach Hilty/BFA

Lazarus Lynch, JiaJia Fei

Zach Hilty/BFA

Lesley Martin, Campbell Adu

Zach Hilty/BFA

Jari Jones

Zach Hilty/BFA

Jordan Robson, Amina Ibrahim, Campbell Adu

Zach Hilty/BFA

Vincent Rutherford, Michael Umesi

Zach Hilty/BFA

Daniel Levi, Mark Hsu

Zach Hilty/BFA

Zach Hilty/BFA

Christine Hollingsworth

Zach Hilty/BFA

Trevor James, Xya Rachel, Tyler Artiss

Zach Hilty/BFA

Arnold Beretta, Katie Booth

Zach Hilty/BFA

Becky Akinyode, Quil Lemons, Jade Lee

Zach Hilty/BFA

Henny Garfunkel

Zach Hilty/BFA

Isabelle McTwigan, Ben Kasman, Sally Carmichael, Mike Steele

Zach Hilty/BFA

Joshua Kissi

Zach Hilty/BFA

Tyler Mitchell

Zach Hilty/BFA

Miriam Sall, Justin French, Amy Sall

Zach Hilty/BFA

Anastasia Simpson

Zach Hilty/BFA

Chi Vengia, Yannis Davy, Marie-Ange Zibi

Zach Hilty/BFA

Boram Lee, Frances Nguyen, Stephanie Johansen

Zach Hilty/BFA

Javone Armada, Micaiah Carter, Bella Barnes

Zach Hilty/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Tyler Mitchell

Zach Hilty/BFA

Akeem Rasul, Gabriella Karefa-Johnson

Zach Hilty/BFA

Brandon St. Regis, Desmond Sam

Zach Hilty/BFA

Hannah Gottlieb-Graham, Antwaun Sargent

Zach Hilty/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Mickalene Thomas

Zach Hilty/BFA

Valerie Blaze, Andrew Grace, Zachary Tye Richardson, Cassandra Angelique

Zach Hilty/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Miles Greenberg

Zach Hilty/BFA

Calvin Reedy, Katie Booth

Zach Hilty/BFA

Erica Olson, Jamal Nxedlana

Zach Hilty/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Oscar Nñ

Zach Hilty/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Tyler Mitchell

Zach Hilty/BFA

Addis Boyd, Bella Barnes, DeRay Mckesson

Zach Hilty/BFA

Monique Long, Maria Carrasquillo

Zach Hilty/BFA

Mickalene Thomas

Zach Hilty/BFA

Zach Hilty/BFA

Catherine Matteo, Valen Brana, Adrienne Raquel, Chas Chevonne

Zach Hilty/BFA

Miles Greenberg, JiaJIa Fei

Zach Hilty/BFA

Noreen Ahmad, Mike Brisa

Zach Hilty/BFA

Myla Williams, Ashia Williams, Ash Felder

Zach Hilty/BFA

Tyler Mitchell, Jeremy O. Harris

Zach Hilty/BFA

Jeremy O. Harris

Zach Hilty/BFA

Anzie Dasabe, Al Green, Nico Kartel, Imani Shante

Zach Hilty/BFA

Trevor Begnal, Jonathan Samedy, Joshua Edwards, Ali Williams

Zach Hilty/BFA

Al Green, Nico Kartel, Imani Shante

Zach Hilty/BFA

Zach Hilty/BFA

Faith Couch

Zach Hilty/BFA

On Thursday, October 24, guests gathered at Aperture Gallery to celebrate the opening of The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, curated by Antwaun Sargent. The exhibition presents an expanded view of the book, featuring works by forty groundbreaking contemporary photographers.

Framed photographs are presented alongside vitrines of publications, past and present, that contextualize the images and chart the history of inclusion, and exclusion, in the creation of the commercial Black image, while simultaneously proposing a brilliantly reenvisioned future.

Guests included Mickalene Thomas, Miles Greenberg, Natasha Lunn, JiaJia Fei, Zachary Tye Richardson, Dig Ferreira, and New Black Vanguard artists Tyler Mitchell, Arielle Bobb-Willis, Jamal Nxedlana, Micaiah Carter, Campbell Addy, and Adrienne Raquel. Attendees enjoyed champagne by Veuve Clicquot.

Welcoming the crowd, Chris Boot, Aperture’s executive director, thanked Antwaun Sargent and project editor Lesley A. Martin; he also extended thanks to Aperture’s board of trustees, members, patrons, and staff, as well as Airbnb Magazine, Veuve Clicquot, and BFA, which photographed the event.

Lesley A. Martin, Aperture’s creative director, reflected on the inception of the project. “I do think it’s an editor’s job (and something we do here at Aperture) to try to assess where things are changing related to the image and power, and to find the key people who have their finger on that pulse,” she said. “It’s really clear that the right person to tell this story was Antwaun Sargent—and that we should build a platform and get out of the way.”

Sargent thanked all the artists included in the book and exhibition. He told the audience, “I hope you all continue to engage with these artists. If you’re an editor, hire these artists. If you’re a collector, buy their work. If you’re a writer, write about them. The New Black Vanguard is really, for me, a spotlight that hopefully creates more opportunities.”

Following the exhibition opening at Aperture Gallery, guests made their way to The Top of The Standard for an intimate celebration, where they danced to a DJ set by Oscar Nunez.

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion is on view at Aperture Gallery through January 18, 2020.

The evening was photographed by BFA.

Supporters

The New Black Vanguard is presented in partnership with Airbnb Magazine.

Aperture also thanks The Standard and Veuve Clicquot for their support.

Click here to view the launch of The New Black Vanguard at NeueHouse on October 21, 2019.

The post A Look Inside the Opening of The New Black Vanguard Exhibition appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

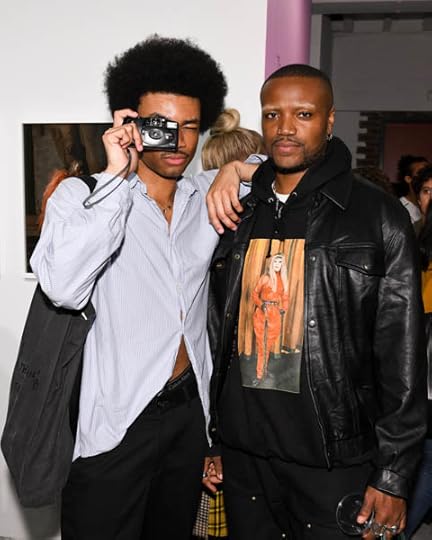

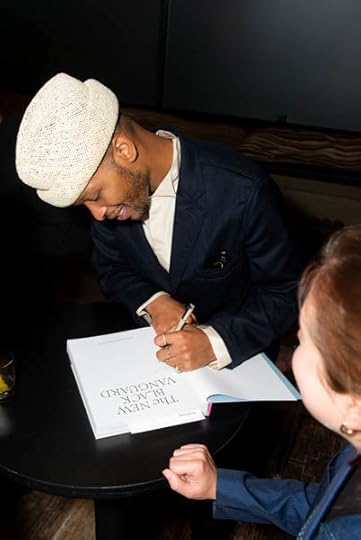

Aperture Launches The New Black Vanguard with Antwaun Sargent at NeueHouse

Last week, in partnership with Airbnb Magazine, Aperture celebrated the launch of The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion by Antwaun Sargent.

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Tyler Mitchell, Chris Boot

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Deborah Willis, Antwaun Sargent, Tyler Mitchell

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent, Natasha Lunn, Lesley Martin, Chris Boot, Isabelle Mctwigan

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Chris Boot, Philip Gefter, Lesley Martin

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Deborah Willis, Chris Boot

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Brendan Embser, Michael Famighetti, Nicole Acheampong

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Michael Hoeh, Chris Boot, Philip Gefter

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Tanzania James, Jade Stuckey, Ian Coma, Megan Harris

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Deborah Willis, Antwaun Sargent, Tyler Mitchell, Jamal Nxedlana

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Julie Solovyeva

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Lesley Martin

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Travis Hackett, Zachary Richardson, Cerrie Bamford

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Betsy Goldberg, Sola Biu, Ben Kasman

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Andrea Minarcek, Annette Farrell, Lisa Lok, Danji McCrory

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Antwaun Sargent, Miles Greenberg

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Tyler Mitchell

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Airbnb Magazine

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Maureen Chevalier, Laurent Chevalier

Madison Voelkel/BFA

JiaJia Fei, Antwaun Sargent, Julie Solovyeva, Miles Greenberg

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Jamal Nxedlana, Tyler Mitchell, Antwaun Sargent

Madison Voelkel/BFA

Books with Friends: The New Black Vanguard with Antwaun Sargent at NeueHouse

On Monday, October 21, guests gathered at NeueHouse in New York City for a book launch, cocktail, and conversation featuring New Black Vanguard author Antwaun Sargent and artist contributors Tyler Mitchell and Jamal Nxedlana. Sargent, Mitchell, and Nxedlana spoke about their work and the international scope of Black artists working today, and signed copies of the newly released book. Guests enjoyed whiskey and specialty cocktails by Glenfiddich.

Curator and critic Antwaun Sargent kicked off the discussion. “As someone who has been devoted to Black artistic production, particularly emerging voices, the only choice was to look at the ways in which young Black photographers were redefining space in photography,” he remarked. “I wanted to create a book that held that space. That not only looked at the moment, but also looked at the past, and possibly a future.”

In The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in fashion and art today. The publication opens up conversations around the role of the Black body and Black lives as subject matter. Collectively, the fifteen artists featured celebrate Black creativity and the cross-pollination between art, fashion, and culture in constructing an image.

“You have to be so radically committed to highlighting people who look like you. Highlighting friends, people who are unknown, who are not models, who aren’t traditional models, who live in the middle of nowhere, who you found on Instagram,” said Tyler Mitchell of his approach to casting in his work.

Johannesburg-based Nxedlana is similarly unorthodox in sourcing his material: “Joburg is a subject for me, not just a backdrop,” he remarked. “I try to showcase its subcultures in the work that I create.” Nxedlana, a cultural entrepreneur and visual artist, is cofounder of Bubblegum Club, a platform for alternative narratives on South African art and society. “We’re living in a place with a colonial history, and a history of oppression. So, my work tries to contest that,” he shared. “It’s about creating your own spaces,” added Mitchell. “To take control of the image, which is to say, to take control of Blackness.”

The evening was photographed by BFA.

Supporters

The New Black Vanguard is presented in partnership with Airbnb Magazine.

Aperture also thanks NeueHouse and Glenfiddich for their support.

Click here for a look inside the opening of The New Black Vanguard, Curated by Antwaun Sargent on October 24, 2019.

The post Aperture Launches The New Black Vanguard with Antwaun Sargent at NeueHouse appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 30, 2019

An Index of Mexico City’s Skin

Pablo López Luz traces volcanic rock from the days of the Aztecs to the rise of modernist architecture. (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

By Álvaro Enrigue

Pablo López Luz, Jardines del Pedregal XXVI, Ciudad de México, 2018

Courtesy the artist

The first time I saw an image by Pablo López Luz, I thought that his work dealt with the problem of abstraction in photography. To register the mineral-infused waves of the volcanic-rock walls of Mexico City, in his series Piedra Volcánica (2018–19), seemed, at first impression, like a meditation on layers of texture and tone. It was not until I saw his pictures with fragments of the city’s detritus—the bumper of a parked car, bird shit, a piece of a lamppost, regular trash that I understood the artist’s approach to be exactly the opposite: to make an index of Mexico City’s skin.

Skin is the most obvious and most mysterious of our organs: it’s a liminal fortress, our concrete connection to the world, the moving map that defines a self, the codex in which whatever beauty we may have interacts with marks of past pains. The Mexican author Margo Glantz has written that the fundamental document with which the generation of the conquistadors claimed the land of the Americas as property was their skin: the scars of past combats were the only inscriptions left of a confusing moment of which nobody else could give testimony.

Pablo López Luz, Teotihuacán II, Estado de México, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Piedra Volcánica gives an organizing principle to López Luz’s work and is characterized by the presence of walls rising from the original chaos of untamed volcanic basalt rock. The flow of the stone locked between the sidewalk’s cement and the wall provides a means for a meditation on the ancient origins of Mexico City and its amazing persistence: an almost-seven-hundred-year-old town that has gone through innumerable invasions, earthquakes, bombings, and floods, yet always returns as a stronger and more brilliant version of itself. The unpolished basalt functions as the register of a past whose grammar we stopped processing long ago, but which keeps boiling in the collective unconscious, as our cultural peculiarity, as an open question about how the world would look if the Aztecs had won the war.

After years of working throughout Latin America, in 2018, López Luz returned to Mexico City his hometown, and mine—where, the same year, Museo Experimental El Eco commissioned him to make a series of pictures loosely related to the museum’s building, designed by the neo-Mexicanist architect Mathias Goeritz. López Luz started the project by documenting the volcanic-stone surfaces of pre-Hispanic and colonial temples, but soon the material of those constructions became the true subject of his research. Expanding on that formalist quest, he began to photograph the lava valleys left by the Paricutín and Xitle volcanoes, as well as the basaltic modernist architecture of neighborhoods such as El Pedregal or Ciudad Universitaria.

Pablo López Luz, Colonia Anáhuac I, Ciudad de México, 2019

Courtesy the artist

There is something uncanny about the photographer rediscovering an intimacy with Mexico City after a long absence by studying the persistence of basalt as a construction material in the metropolis’s skin. I grew up on top of the same lava mantle: knees and elbows endlessly scratched by stone walls so treacherous that a soccer ball can be ripped if bounced in the wrong place. The danger of those rocks is not limited to their rough edges: in Mexico City you always have to roll over a stone with your shoe before picking it up because scorpions tend to nest there. But that volcanic skin, like the city itself, is tough and hospitable at the same time: there is that chill in the shadow cast by a basalt wall, its smell when it rains, the beautiful ways in which the bravest of seeds extend their roots and embrace the rock to flourish, letting us remember that no matter how hard the stone waves are, our skin is still the mark of our persistent individuality.

Álvaro Enrigue is a Mexican writer based in New York and a professor at Hofstra University. His latest novel, Now I surrender and that’s all, is forthcoming.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post An Index of Mexico City’s Skin appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 28, 2019

15 Photographers Reveal What’s Hidden in Their Work

What does a photographer see that is otherwise hidden?

Since its beginnings, photography has functioned in part as a vehicle for showing what is neither accessible nor visible to most of us. It also has the power to shed light on the things around us that are otherwise overlooked—from remote societies to elite fraternities, isolated places to objects so common we don’t even stop to look at them. From Daidō Moriyama to Susan Meiselas, Aperture and Magnum photographers have long demonstrated how photographs can reveal hidden things, places, and lives.

This week, for five days only, collect signed or estate-stamped, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by over 120 acclaimed Aperture and Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase, and a percentage of each sale will support Aperture Foundation.

Jacob Aue Sobol, Sabine, Eastern Greenland, 2000

© Jacob Aue Sobol/Magnum Photos

Jacob Aue Sobol

“I’m in love with Sabine but I can’t talk to her about it. The locals don’t want us to be together. When I said I couldn’t visit her she became sad. It rained that night—unusual for March. I was lying on my mattress in the attic when I heard footsteps in the snow outside the window. I looked out without switching the light on. Sabine was down there looking up at my window. Had she seen me? I crawled back under the duvet and waited. Half an hour passed. Maybe I hadn’t heard her leave? I looked out of the window again. Sabine, drenched, was still standing there looking up at my window. I switched on the light and waved. That night we spent hours walking around in the rain together.” —Jacob aue Sobol, Sabine (self-published 2004)

Gregory Crewdson, Untitled production still from “An Eclipse of Moths,” 2018

© Gregory Crewdson

Gregory Crewdson

“Two boys are framed by the open door of a mechanic’s garage. They are hidden among cinematic lights and haze, awaiting their moment on set.” —Gregory Crewdson

Elliott Erwitt, Paris, France, 1989

© Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“Why is our mysterious jumper jumping? Well…Because I asked him to!” —Elliott Erwitt

Leonard Freed, New York City, New York, USA, 1963

© Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

Leonard Freed

“Basically there are informational photographs and emotional photographs. I don’t take informational photographs. I am not a journalist. I am an author. I am not interested in facts. I want a photograph you can take out of context and put on your wall to read like a poem.” —Leonard Freed (Worldview, Steidl 2007)

Nan Goldin, Sunny at the spa, distortion, L’Hotel, Paris, 2010

© Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin

“The intimacy between [Sunny and I] allowed the camera the freedom to access the magic. My favorite photos of mine are the mistakes.” —Nan Goldin

Bob Gruen, Joe Strummer & Gaby, New York City, USA, 1981

© Bob Gruen

Bob Gruen

“Sometimes people create their own private place with each other and let the world go by. We see them, but they only see each other.” —Bob Gruen

Todd Hido, #7851, 2008

© Todd Hido

Todd Hido

“I drive, I drive a lot.

People ask me how I find my pictures. I tell them I drive around. I drive and drive and I mostly don’t find anything that is interesting to me. But then, something calls out. Something that looks sort of off, or maybe an empty space. Sometimes it’s a sad scene. I like that kind of stuff. I remember this foggy night, wondering about the hidden world behind the frosted glass of the garage door. Did somebody just leave the light on? Or is there a whole world of activity going on in the middle of the night out in the garage under the veil of the fog? And so I keep driving and looking and taking pictures.” —Todd Hido

Justine Kurland, Dairy Queen, 2000

© Justine Kurland

Justine Kurland

“I wanted to make the invisible communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experience as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls—they would multiply through the sheer force of togetherness and lay claim to a new territory. Their collective awakening would ignite and spread through suburbs and schoolyards, calling to clusters of girls camped on stoops and the hoods of cars, or aimlessly wandering the neighborhoods where they lived.” —Justine Kurland

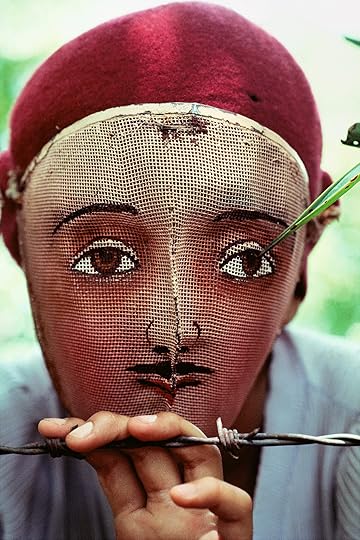

Susan Meiselas, Traditional Indian dance mask from the town of Monimbó, adopted by the rebels during the fight against Somoza to conceal identity, Nicaragua, 1978

© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

The Mask

“A mask, not to hide but to disguise

to draw on a past

to create a future.

Traditionally for folkloric dance, reclaimed by rebels—once

to bring down a dictatorship, now used to face a new fight.”

—Susan Meiselas

Joel Meyerowitz, Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1976

© Joel Meyerowitz, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery

Joel Meyerowitz

“This photograph could be the opening line of a joke: ‘So, a girl rides up to a bar on a horse …’ But really what happened was that I was there getting some ice cream for my kids when this girl rode up to the window on her horse and ordered two lobster rolls and some fries; as soon as I saw the girl, the horse, and the ice cream sign, I saw the photograph. My 8×10 was always with me then, and in less time than it took to get the lobster rolls, I made the photograph.” —Joel Meyerowitz

Daidō Moriyama, Farewell Photography, 1972

© Daidō Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daidō Moriyama

“This self-portrait is from my photobook from 1972, Farewell Photography. I wouldn’t be able to take this kind of photo nowadays, because it is a photo that represents the feelings I had at that time.” —Daidō Moriyama

W. Eugene Smith, Dream Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, 1955

© W. Eugene Smith/Magnum Photos

W. Eugene Smith

“Like many other symbols of a bygone era, the actual Dream Street has vanished over time and is no longer recognizable in Pittsburgh. Yet the image remains more relevant than ever. As Smith himself wrote, ‘The one full freedom is man’s right to dream. No government of whatever nature, no tyranny, no circumstance can remove possession of this right.’”—Kevin Smith, W. Eugene Smith Estate

Alec Soth, New Orleans, 2018

© Alec Soth/Magnum Photos

Alec Soth

“When I was a boy, I used to pretend my little bed was a one-man spaceship. It was a place to simultaneously explore my dreams and hide from the world. In some ways that’s how I now think of my camera.” —Alec Soth

Dustin Thierry, Thaynah Vineyard at the “We Are The Future—And The Future Is Fluid” ball organized by Legendary Marina 007 and Mother Amber Vineyard, Body painting by visual artist Airich, Amsterdam, 2018

© Dustin Thierry

Dustin Thierry

“My current project Opulence is an ode to my late brother, and all people of Afro-Caribbean descent who still are not free to live and express their sexuality to its fullest. To this day, homosexuality is strongly stigmatized and condemned within the Caribbean community. In addition, Black people from the former colonies and the Caribbean islands in the Netherlands are increasingly racialized and objectified. This project seeks to break out of this dichotomy by portraying subjects in unadorned, raw yet graceful portraits.” —Dustin Thierry

William Wegman, False Eyes, 2019

© William Wegman

William Wegman

“If there are aliens, what might they look like? To address that question, I collected a selection of props and my dog, Flo. Among the props was a package of false eyelashes, and after several failed attempts to stick them on, I gave up. Fortunately, the packaging was even more arresting than the actual product, so I cut off the part with the eyes and stuck them on Flo. Hiding behind these paper eyes, Flo could still keep one eye on me, and so I had three eyes watching me. Maybe that is what an alien looks like.” —William Wegman

For five days only, collect signed or estate-stamped, museum-quality, 6-by-6-inch prints by over 120 acclaimed Aperture and Magnum photographers for $100 each. Use this link to make your purchase, and a percentage of each sale will support Aperture Foundation. Sale ends Friday, November 1, midnight EST.

The post 15 Photographers Reveal What’s Hidden in Their Work appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 24, 2019

Down and Out on the West Side Piers

Alvin Baltrop made an indelible record of gay life in New York before AIDS. But why is a queer, Black artist’s work only valuable after his death?

By Jesse Dorris

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (sunbathing platform with Tava mural), n.d. (1975–86)

Courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust; Third Streaming, New York; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

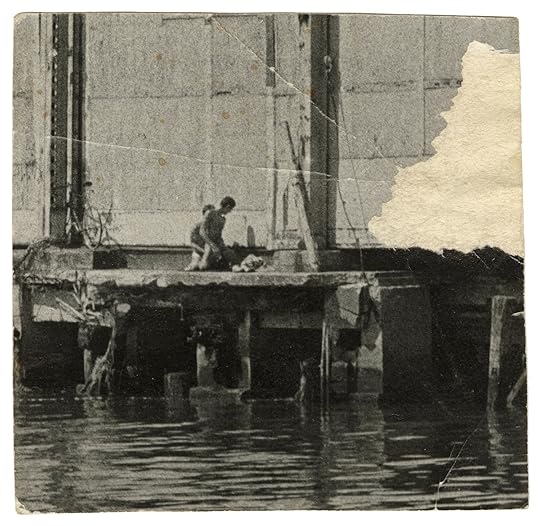

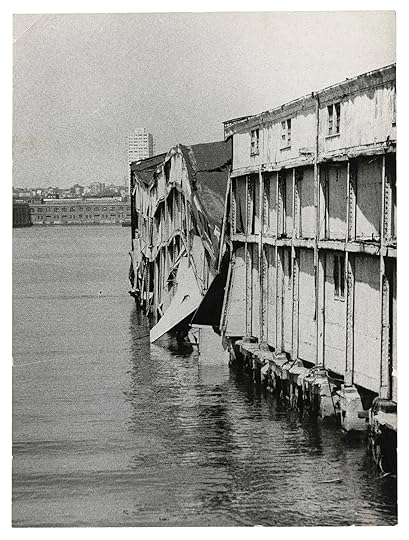

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, men disenfranchised and terrorized by their country built sexual and social playgrounds in the abandoned piers along the West Side of Manhattan. It was a dangerous world, where floors could collapse below you and assignations could turn to predations—but then, America in general was a dangerous world for queer people. Edmund White describes the irresistible allure in his 2009 memoir, City Boy: “Once I was in the backs of trucks or in the ruined piers along the Hudson, I simply couldn’t make myself go home. Even after a satisfying encounter with one man or ten I still wanted to hang around to see what the next ten minutes would bring.”

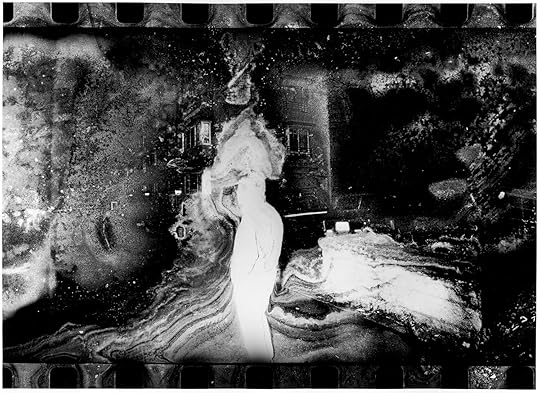

Those minutes brought orgasms, friendships, crime, the clap. Bleakly holy architectural interventions by Gordon Matta-Clark and street artist Tava’s perhaps half-camp butch murals. Fodder for recountings by David Wojnarowicz and John Rechy. Love, heartbreak, crabs, death. And now, to all that, we must add the photography of Alvin Baltrop, an African American war vet who hung around those piers in a harness stories off the ground, who horsed around with the horny, played mirror to the vain, and caught it all—images that somehow achieve the formal clarity of Julius Shulman, the spellbound sensationalism of Weegee, the lust and light of David Armstrong, and the empathetic curiosity of Catherine Opie. In curator Antonio Sergio Bessa’s The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop—on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through February 9, 2020—Baltrop’s photographs remind us what can be lost and found.

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (man wearing jockstrap), n.d. (1975–86)

Courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust; Third Streaming, New York; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

Baltrop was born in the Bronx in 1948. At thirteen, his uncle gave him a camera. When Baltrop was a teenager, his mother, a devout Jehovah’s Witness, is said to have discovered and destroyed a box of her son’s photographs of naked young men—yet a lovely shot of a sun-filled Cloisters nook, taken when he was seventeen, still remains. In 1969, Baltrop enlisted in the Navy, bringing his camera on a warship captained by a polygamous Mormon who kept his crew in the Mediterranean. (An exhibition wall at the Bronx Museum includes formations of warplanes, weaponry, smoke, raindrops, and frayed patches on shoulders.)

“Some of them are like Robert Capa—heroic,” Bessa told me as we examined Baltrop’s photographs from that time. Baltrop’s portraits are even more powerful: developed in medical trays at a makeshift warship lab, they make amiable idols of his friends. In one, a naked man leans into built-in storage across a cabin wall, positioned both casually and perhaps passively, light bathing his back and setting his front into detailed relief. The admiration and lust are palpable. In another, an armpit glows like an oracle. Photos of men sleeping, whether in close-up or from above, detailing their faces or feet or backs, all somehow manage not to implicate a leering eye. “There’s camaraderie,” Bessa says. “Maybe also just a little voyeurism.”

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (exterior with couple having sex), n.d. (1975–86)

Courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust; Third Streaming, New York; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

In 1972, Baltrop was discharged from the Navy after swallowing a dozen tabs of Doriden in order, according to a psychiatric report, to “show another man in the ship who was allegedly contemplating suicide what it might be like.” Baltrop said he did it to save the man’s life; his doctor called it schizoid personality disorder. It’s difficult to know the truth—if there is only one—of this action in a military context of brutal institutional racism, and where homosexuality was officially a mental disorder.

Baltrop’s engagement with people in crises would carry through the rest of his life, beginning with his civilian arrival to New York, where his home borough of the Bronx was burning and the flaming creatures of the Village were ascending. He went to the School of Visual Arts on the GI Bill and supported himself by driving a cab, eventually winding his way down to the piers, where hundreds (if not thousands) of men gathered to fuck and sun and moon on the warehouses’ salt-bitten planks. And to be themselves. Like White and all the rest—and particularly like the queer African American community mostly unwelcome at the neighboring bars and sex clubs—Baltrop made a kind of home for himself on those piers.

Soon, he’d sold the cab and was working as a street vendor and jewelry designer and then, finally, as a mover—with a van he lived in and could park nearby. This all might have been due to his fascination with the piers, or a result of the lack of opportunities New York afforded a queer African American artist in the 1970s. Either way, it meant he no longer had access to the ersatz darkroom he’d set up in his apartment. (He made tens of thousands of negatives he never developed.) The art world didn’t seem to take notice: Baltrop showed only twice before his death, once at a gay nonprofit called the Glines, and later, in 1992, in a small show at the Bar—where Baltrop sometimes worked as a bouncer—a mostly forgotten dive that was the Plague Years’ equivalent to Max’s Kansas City.

Alvin Baltrop, Marsha P. Johnson, n.d. (1975–86)

Courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust; Third Streaming, New York; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

Meanwhile, Baltrop found others in need: horny strangers, yes, but also men who reveled in showing themselves off for his lens. One of his photographs from the piers sets a pair of young Black guys before windows blazing like Klieg lights. One man stares down Baltrop, with spread legs and bold eyes, beside another, who’s dressed to work with a business jacket draped around his crotch. Other photographs valorize nude men perched on a log, their heads stretched toward the sun or at a wrecked window, showing off their jockstraps (and what’s inside them) or the greased patina of their leathers. They’re handsome and available. All around them are dizzying geometries of architectural collapse.

Baltrop sometimes climbed down from the harness he used to get an overhead view and took his subjects to a health clinic for STI testing, or bandaged kids who’d been beaten up. Of course, something much worse was soon to come. Baltrop moved to the East Village and became known as “an official AIDS educator and Gay Daddy” as the plague decimated the community he knew and documented so intimately. Life and Times ends with a wall of photos Baltrop took of body bags, each almost bursting with tragic loss. Baltrop himself died of cancer in 2004, broke and mostly homeless. Four years later, Douglas Crimp wrote an appreciation in Artforum that sparked interest in his work. But as Osa Atoe asks in a crucial essay on Baltrop in Colorlines, “Why is a Black, poor, queer artist’s work only valuable after he is dead?”

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (collapsed architecture), n.d. (1975–86)

Courtesy the Alvin Baltrop Trust; Third Streaming, New York; and Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York

Near the end of Life and Times, an incandescent portrait of activist and drag queen Marsha P. Johnson serves as a reminder that each of the subjects here were actors in their own lives. The image belongs inextricably to Baltrop, who found splendor in the way plaster flutters around a tube-socked calf, the way pockmarked fiberglass does and doesn’t look like the naked leg kneeling beside it, how glass can shatter in the shape of a fan or an akimbo trophy. Most of all, how from a distance—the literal distance from Baltrop to the sources of his admiration, and also the distances enforced by racism, mental illness, the PTSD of being queer in a bigoted world, an interest in looking that supersedes a desire to participate—a world falling apart forms an order for itself. Broken structures become visions of bisecting shadows. Brackets take shape as bedside tables.

You have to look long and hard at this world. And once you do, you see, in the distance, men making love to each other. You see pleasure and kinship and loss. Baltrop’s landscapes of men fucking in ruins, without him, could be Boschian hellscapes or an X-rated Where’s Waldo? His genius was to offer his photographs as evidence of how difficult it is to find what you need, and how beautiful need can be when you see it.

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop is on view at the Bronx Museum of the Arts through February 9, 2020.

The post Down and Out on the West Side Piers appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 23, 2019

A History of Violence

How can women photographers represent Mexico’s disappeared? (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

Maya Goded and Mayra Martell in Conversation with Marcela Turati

Maya Goded, Marcela and Paty, two sex workers, at the motel where Marcela’s children live, 1999, from the series Plaza de la Soledad

Courtesy the artist

Maya Goded and Mayra Martell are two Mexico City–based photographers who chronicle the stories of families whose daughters have been murdered or disappeared in Ciudad Juárez. Martell has worked her whole life—first in Juárez, her hometown, and then across Latin America—on the identities and vestiges of young women who are absent, yet present in the places they used to inhabit. She has also documented those affected by other forms of violence, such as the mothers of people murdered by the Colombian Army or the everyday nature of drug culture in Sinaloa.

In turn, Goded’s work has been, as she describes it herself, “exploring the subjects of female sexuality, prostitution, and gender violence in a society in which the role of women is narrowly defined and femininity is shrouded in myths of chastity, fragility, and motherhood.” Goded has done so by photographing sex workers in Mexico City and on the U.S.-Mexico border, Afro Mexican communities, and traditional Indigenous healers defending their territory.

In this conversation, Goded and Martell speak with Mexican journalist Marcela Turati about their work portraying the violence suffered by women, how they deal with the pain they photograph, their hesitations and lessons learned, and the conflicts surrounding their lives in Mexico, a country where people continue to disappear—more than forty thousand in the past twelve years.

Maya Goded, Mother looking for her missing daughter, Chihuahua, 2004, from the series Missing

Courtesy the artist

Marcela Turati: Maya, how did you discover and decide to explore violence against women? And Mayra, how did you decide to go deeper and explore the same issue in your hometown, having grown up in Ciudad Juárez?

Mayra Martell: I am the daughter of a single mother of two, who juggled two jobs. It was very hard to see how the rest of the family and our environment treated her. I noticed violence right then. In Ciudad Juárez, I learned how to treat people very lovingly because you never know what others might be going through.

Maya Goded: When you are out there taking photographs, you are also carrying around your own story. That defines what you are going to look at and what your eyes will prioritize. I grew up with women who also broke through that structure: a grandmother who had to flee her own country, at the age of nineteen, during the Spanish Civil War, never to see her parents again. She reinvented herself and fought on her own.

My mother also left home at the age of nineteen, running away from domestic violence. From the United States, she migrated to Mexico, to study anthropology. Both of them decided to act against the violence they were going through. They moved on. They sought healing. Every time I am out there photographing women, I think of them.

Within excluded communities, women suffered from further exclusion. I started to photograph this normalization of violence. I was interested in women who fought to break patterns and reject whatever society expected from them.

Turati: Maya, in a previous interview you mentioned that you were scared of being a mother yourself. What were you scared of? And what were you looking for when you went to Mexico City’s La Merced neighborhood?

Goded: I refused to be part of this classification of being a good or a bad woman, that Christian moral judgment implying women must sacrifice themselves for the sake of children and their household, not being allowed to live with unrestrained sexuality. With motherhood, I was terrified of losing the freedom that I had fought for all my life. I carried those narratives of guilt. I gravitated toward La Merced. When I arrived in Plaza Loreto, that square seemed like a microcosm. It condensed the different types of violence experienced by women and the solidarity established among them. I saw how men divide women and how violence unites them.

Mayra Martell, Yanira Fraire, 15 years old. On June 10, 2010 she went to pay her tuition at a bank located downtown and never returned. She was a junior in high school. In January 2012, her remains were found in the city’s outskirts. She was one of the twenty-six victims of the human trafficking organization that operated at the Hotel Verde in the downtown of Ciudad Juárez, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, how did you make it into the homes of disappeared women? How did you present yourself, and how did you start portraying their absence?

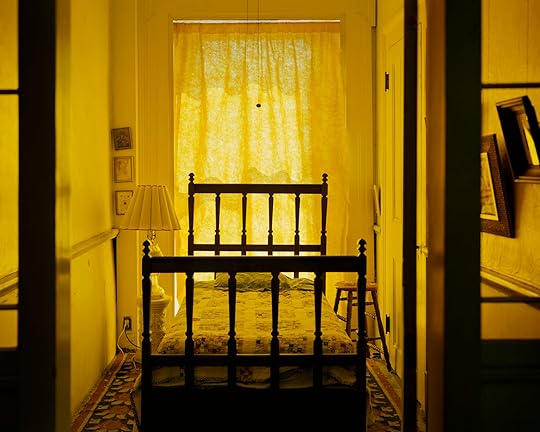

Martell: One day, I dialed one of the numbers written on the missing-women posters that covered the city center. I knew that that poster had been put up by the missing girl’s mother. The first call led me to Hortensia, the mother of Erika Carrillo. I told her I was a photographer, and that I wanted to interview her. It was obvious that I had no idea of what I would do, and she immediately noticed my clumsiness. She reacted lovingly, invited me to her home, and that’s where it all began. I guess she felt nostalgic when looking at me. I was as old as her daughter back then, and she would ask about what I had done in the past years, where I had been, what I had studied. It was a very weird relationship. Two strangers establishing a close bond where the only meeting point was a person who was not there. I tried to solve the problem of her absence with her presence. I photographed everything that proved that girl’s existence: her room, her letters, her clothes, her photographs.

Turati: Mayra, did the fact of experiencing the intimacy of the victims, those rooms that seem to be memorials, make you feel any sort of commitment?

Martell: It was a situation full of sensations. In some rooms, I could still perceive the smell of the person. At times, I even felt observed by them. I have always known that everything is energy, and that, one way or another, in death or in life, we all share this space. On other occasions, I did not feel anything, as if her spiritual energy was also gone. Of all the cases I have documented, no one has ever returned home.

The only thing I know how to do is to record the situation family members are going through as a way to embrace them and accompany them through the hardships they are living, from which they will never recover.

Turati: Maya, you went from La Merced to Juárez in order to accompany other women, mothers of victims of femicide. Why did you think it was important to bring a camera with you?

Goded: One day, a young, Indigenous, unknown girl was killed at the busiest hotel around La Merced in broad daylight, strangled with her own pantyhose. I followed the case during that whole day. The girl was going to the mass grave. A man said he knew her. Afterward, rumors spread that he was her pimp. I was shocked to see how many girls have their papers, their identities, their names, their birth certificates changed. As we learned about the disappearance of women in Ciudad Juárez, I was sent there to do a report for a magazine.

Ciudad Juárez was the place where I had fallen in love with my husband. Back then, I had traveled with him to that border town in order to attend a film festival, and we did not stop dancing for three or four days. It was a place full of life. But this time, everything had changed. I discovered women were being kidnapped, victims of human trafficking. Then I began to investigate who those girls were: young, poor, most of them without children. The government said they deserved it because they ran around wearing miniskirts and went out at night, and condemned them for breaking the rules. It was very frustrating to talk about women who are no longer there, about the violence that you do not see but that manifests itself in many other ways.

I am not quite sure whether I like this series. It was a hard one. I’ve always fallen short when addressing Juárez. Even though I’ve returned, I always feel powerless. I went back several times in order to work on it by means of different formats—photography, video installations of the children and sisters of disappeared women, and a video of one of the sisters of a disappeared girl, which was subsequently used as part of an experiential theater production.

Mayra Martell, Main Avenue, from the book Ciudad Juárez, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, how did your portrayal of the absences in Juárez mutate into your subsequent work on the types of violence suffered by women? For instance, the case of women in Sinaloa, violence experienced by ficheras [ballroom escorts who are paid to dance, often to live music, with their partners] in Mexico City, or by the mothers of individuals murdered by the Colombian Army?

Martell: Every project is new to me. I put aside every prejudice, start from scratch, and decide what to do in the course of the project. Ciudad Juárez was a real emotional challenge. I came in contact with situations I was not used to dealing with: funerals, interviews with alleged murderers, the monitoring of the nota roja [local newspapers that exclusively publish cases of murder, rape, and other violent crimes]. I would attend trials, accompany mothers to identify bodies that might belong to their daughters. Very painful situations in which I often had to hold back my tears. Now I know that if I had not gone through all those experiences, I would have never emotionally stood the projects that came afterward.

Turati: Maya, when you introduce yourself to a sex worker from La Merced or to a mother who has lost a daughter or a migrant whose newborn son has been taken away, how do you explain that you want to photograph them? What do you do to be accepted?

Goded: You have to be as honest as possible with your intentions, otherwise you will generate false expectations or come across as something you are not. It is hard. You keep on questioning what is ethical. When I started taking photographs, it was very frustrating to realize that you are not going to change anything, that you are a witness, and how uncomfortable it is to be nothing but a witness. Then, over time, you can become involved in activism as a consequence.

Turati: Could you say more about this inner struggle between being a photographer-witness against the impulse to do something in the face of difficult realities. Is this something you have solved, or something you are still trying to solve?

Goded: The inner struggle of being a photographer-witness has changed what I am. In pursuit of topics for my projects, I intend to explore and record all those stories of resilience and self-reconstruction, which often originate in the personal and collective realms, away from the political sphere. My current quest relates to healing, not only on the legal level—which is very important—but also spiritually and bodily, in our connection to the earth, the water. After having captured such hard realities, I want to dedicate my work and energy to documenting small drivers of change, such as the alleviation of pain, which have become a tool of resistance. This fight energizes me.

Turati: What are your ethical conflicts as a photographer, Mayra?

Martell: I have been in conflict with a number of things. The first was having to interview alleged murderers. I struggled not to judge and to carry out the interviews as objectively and humanely as possible.

Turati: How did you manage to stay calm?

Martell: I think what caused me the greatest distress was when I had to leave Ciudad Juárez, because I lived surrounded by mothers who protected me and listened to me, and suddenly I had to turn my life around in a matter of days. From that moment on, I haven’t stopped feeling lonely. It was like a big wave that swept away my whole life and took everything I had. I work through it by doing my job, which is the only way I have to feel present.

Turati: What happened to you? Is this something you can talk about?

Martell: I left Ciudad Juárez at the end of 2009 because I was kidnapped. In those situations, the government appoints security guards to protect you for four days so that you can pack your stuff and leave.

In the end, I left after two days because they tried to kidnap me again, and the people who were in charge of protecting me had to take me directly to the airport. My partner at that time met me there, brought along a piece of luggage, and the rest of my things were shipped afterward.

Turati: That is horrifying. Was it because of your work?

Martell: Things got pretty heavy when [President Felipe] Calderón declared a war on drugs. The city became a mess, so it also became easier to disappear people.

Maya Goded, Red Zone, also called Tolerance Zone, near the U.S.-Mexico border, where sex workers live in isolation in enclosed spaces and which have their origins in a Mexican regulatory system from the mid-nineteenth century, 2009, from the series Welcome to Lipstick

Courtesy the artist

Turati: What types of violence have you suffered as women photographers? Do you have to take care of yourselves in a different way than a man would in a certain kind of place? Are you more vulnerable in this country where it is dangerous to be a woman?

Martell: I am not aware of having suffered violence in my projects for being a woman. As I grew up in Ciudad Juárez, where being a woman, a girl, a boy, a teenager is dangerous, I learned to move around and act discretely when I am being stared at. I am some sort of spy who knows how to respond to each situation: I change my way of dressing, of speaking, and that has always kept me safe wherever I work. I am very much aware of what it could mean to be a woman in these kinds of environments.

Goded: I imagine that all women photographers have gone through situations of violence and normalized them as if they were part of being a woman photographer and traveling alone. This is why I love #MeToo and that the new generation’s questioning it all. The way I take care of myself is by being close to other women. They warn me about any problems or threats. I increasingly look for that solidarity that has protected me so that I can do my work. This is a country riddled with violence and, based on the topics you address, you might become a threat to the state—even without realizing. It is dangerous to both women and men, but danger is always gender differentiated and particularly latent for women in this country. There is always fear in the air.

Turati: What do you do with violence that permeates your skin, that stays in your body when you see it so close and live around these realities for so long?

Martell: I have never actually recovered from all this because, at the end of the day, things keep on happening. Therefore, I believe I will never stop working on denouncing. I have seen horrible things. People who were close to me have been murdered; mothers of disappeared or murdered women are dying; I’ve lost my own personal life so many times that I can’t even remember who I used to be. I don’t quite know where my life ends or starts since I had to flee Ciudad Juárez. I haven’t been able to become emotionally grounded because whatever is happening in that city is beyond my understanding. However, what helps me when I am feeling really bad is to think that, while I might be feeling sad, the mothers of those women and girls must be feeling a thousand times worse, and that pushes me to get up and get down to work. It is necessary to accompany those who are suffering such situations.

Goded: When I was working with cases of disappeared women and then went to Chiapas to do a report, I was very scared by some things that happened to me while photographing. Sadness and horror invaded my body. I couldn’t sleep. One day, when my daughter was thirteen, I did not want to let her go out because I was scared; and she, wise as she’s always been, said, “Mom, those are your ghosts, not mine. Work them through.” I realized I was not allowing myself to say: I am scared, I am feeling sadness, I am disappointed. I stopped taking photographs. I was not traveling on my own as I used to. I did not see the point of photography anymore. I got into psychoanalysis and explored other ways of healing and understanding pain, focusing on the kinds of pain that remain in the body.

I started photographing women who do witchcraft, in the north of Mexico, as well as doing research on Spanish and Indigenous women from the 1700s who healed with plants, were accused of witchcraft, and burned at the stake. I started to heal that pain by learning about them. My current quest began there.

I also went deeper into sacred plants, around which this country has a great tradition, and started working with healers to understand that, even though justice heals, you also have to heal at the energy level, honoring both your ancestors and future generations. Coming from a rather rational family, this has made me question my views and forced me to try to see things from another perspective.

Mayra Martell, Shop of artistic drawings on Av. Benito Juárez, next to the International Bridge from El Paso, Texas, Ciudad Juárez, 2007, from the book Ciudad Juárez, 2013

Courtesy the artist

Turati: Mayra, what thought or sensation overtakes you when you realize this is not only about Ciudad Juárez, but that we live in a country where mothers with missing sons and daughters march every May 10, or that the very places you photographed continue seeing the disappearance of young women?

Martell: There is a book, Juárez: The Laboratory of Our Future (1998) by Charles Bowden, with texts by Noam Chomsky and Eduardo Galeano, as well as images by press photographers from Ciudad Juárez, that explains very well the situation of Juárez and Mexico. It elaborates on the social decomposition none of us can escape. In Juárez, there were many warning signs around us, which nobody paid attention to because it was always about the neighbor, the poor fellow, the girl from the maquiladora [foreign-owned factory]. Nobody understood that if things were happening to people across the street, it would someday reach their homes too. Violence is expandable.

Turati: Maya, what advice would you give, if you could meet your younger self—that photographer who was only starting to capture the violence in La Merced or in Juárez?

Goded: That she should study philosophy, read about culture in general, because technique is learned quickly, but, in the end, photography is enriched by life and knowledge.

Turati: Mayra, what would you advise a younger Mayra who was just starting?

Martell: I’d hug myself so tight that I’d cast a spell of protection to last for years. I haven’t changed that much—it’s just that the little flame in my heart has been extinguished several times. But it always lights up again. And I would say to myself, I love you. That would have helped me in a lot of personal situations.

Marcela Turati is an investigative journalist based in Mexico. She is the author of Fuego Cruzado: Las víctimas atrapadas en la guerra del narco (Crossfire: Victims trapped in the war on drugs, 2011). Translated from the Spanish by Enrique Pérez Rosiles.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post A History of Violence appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 21, 2019

Three Artists Lend Fresh Perspectives to Burberry’s Latest Collection

Working with Aperture and Antwaun Sargent, New Black Vanguard photographers were commissioned to create images celebrating Burberry’s Monogram puffer collection.

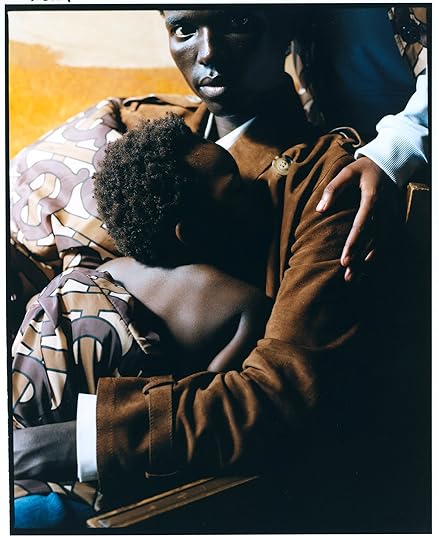

© Renell Medrano for Burberry

To celebrate the launch of Aperture’s The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion and Burberry’s newly released Monogram puffer collection, three New Black Vanguard photographers— Arielle Bobb-Willis, Micaiah Carter, and Renell Medrano—were commissioned to make images for a social-media campaign. In their alluring images, the artists’ unique photographic styles mix with Burberry’s new aesthetic to provide a modern look at identity and fashion. The images reveal how each photographer has used their cameras to celebrate community and rethink notions of beauty and dress in our culture. Central to the power of these images are the conversations they open up about diversity and representation in fashion, art, and society. Carter’s studio portraits of youth, Medrano’s pictures of family, and Bobb-Willis’s street scenes draw on such genres as portraiture and documentary, conceptual and still-life photography, to bring a whole new set of references and possibilities to the fashion photograph. These artists are part of a global movement of Black artists who are working alongside fashion houses, like Burberry, to construct vibrant portraits that present fresh perspectives on the medium of photography, youth culture, and the notions of power and belonging.

© Arielle Bobb-Willis for Burberry

© Arielle Bobb-Willis for Burberry

© Arielle Bobb-Willis for Burberry

Arielle Bobb-Willis

Born in New York, 1994

“I love the idea of seeing Black people represented in an abstract way. It’s important to me to continue to reject the notion that Black expression is limited—or limiting.”

New York–based photographer Arielle Bobb-Willis was thirteen years old and living in South Carolina when a teacher gifted her an old Nikon N80 film camera, and with it the image maker captured her own body in the privacy of her childhood bedroom. There were pictures of her hands and feet all rendered in color, which were a metaphor for identity in free fall and a feeling of fragmentation caused by depression. “I became a photographer to step out of my depression in a way that felt the most fulfilling,” says the artist, whose images have been published in the New Yorker, British Journal of Photography, and L’Uomo Vogue. As her work has evolved, Bobb-Willis has maintained an interest in exploring what it means to claim joy through periods of sadness. She considers her work “anti-selfies,” containing visual complexity with a serene sense of movement and empowerment through a search for self, inspired by vivid painters such as the modernists Jacob Lawrence and Benny Andrews.

© Micaiah Carter for Burberry

© Micaiah Carter for Burberry

© Micaiah Carter for Burberry

Micaiah Carter

Born in Apple Valley, California, 1995

“Blackness can get pigeon-holed into a one-dimensional viewpoint, but in reality, it is as diverse as the galaxies in the universe.”

A central inspiration for fashion photographer Micaiah Carter comes from his father, Andrew Carter, a retired Air Force Sergeant who came of age in the 1970s, a period defined by the “Black Is Beautiful” movement and disco. “I’m using the past as a compass,” Carter explains, “while at the same time shooting new trajectories.” His growing oeuvre of impeccably lit, positive pictures of Black celebrities and youth, often in repose, have appeared on the covers of TIME, King Kong, Wonderland, Adweek, and Cultured magazines. Carter makes symbol-laden photographs, and his way of seeing the Black figure is influenced by his father’s scrapbooks, which in turn led him to the documentary images of John H. White. The Chicago photojournalist’s ability to capture his subjects with dignity—no matter their station in life—left an impression on Carter’s image making. Another influence on the Brooklyn-based photographer is artist Carrie Mae Weems. Of Weems, he says, “I am in awe of her use of intent, and her initiative to create a love language about the culture and Black experience.”

© Renell Medrano for Burberry

© Renell Medrano for Burberry

© Renell Medrano for Burberry

Renell Medrano

Born in New York, 1992

“I never try and make a perfect picture. I just try to photograph what I see around me.”

In 2014, New York–based, Dominican American photographer Renell Medrano shot Untitled Youth, an intimate look at the lives of four teenage girls growing up in the Bronx. The series, which mirrors her own uptown upbringing, was her undergraduate thesis project at Parsons/The New School, where she earned her BFA in 2014. The series established Medrano as an image maker interested in the beauty and patina of real-life circumstance. The evocative rawness and psychological intensity of Medrano’s documentary photographs, which won her a New York Times Lens Blog Award in 2014, have become trademarks, as have stylistic choices, such as imperfection as a marker of authenticity. “I don’t really give that much direction when I’m on set,” says Medrano. “I honestly try and just capture moments within the time that I have with my subject, and that mean something to me.” She has developed a fashion-photography practice in which she often depicts young, glamorous subjects against gritty, urban landscapes. “I carry this very scenic backstory—growing up in the Bronx,” she explains. “I try to portray that in my images.”

Learn more aboutThe New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion here.

The post Three Artists Lend Fresh Perspectives to Burberry’s Latest Collection appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 16, 2019

Spiral City

In the 1990s, a group of inventive young artists remade Mexico’s capital as a backdrop for experiments in photography, film, and performance. (Visita gatopardo.com para leer este artículo en español.)

By Kit Hammonds

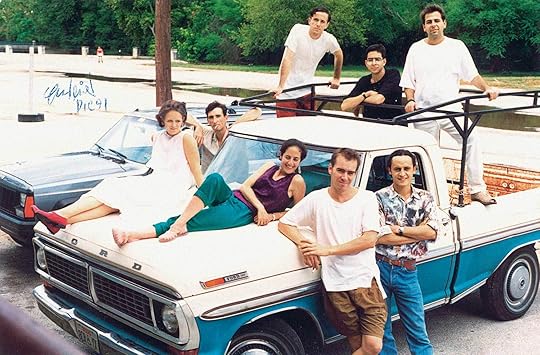

Photographer unknown, Artists from the exhibition D.F., curated by Alejandro Díaz, at BlueStar Contemporary Space, San Antonio, Texas, 1991. Bottom row, left to right: Melanie Smith, Francis Alÿs, Silvia Gruner, Thomas Glassford, Gabriel Orozco

Courtesy David Zwirner, New York

While Mexico City has been intermittently a progressive and modern city with a cosmopolitan culture, it has been equally notorious for state-, military-, and narcotic-related violence and corruption, along with sharp class distinctions. On September 19, 1985, one of the country’s most devastating earthquakes occurred in the city. Hundreds of buildings fell, and thousands of lives were lost. Whole neighborhoods in the center lay abandoned, and distrust in the government was rampant, a condition that was exacerbated in the years that followed, as in 1994, when Mexico entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement with the United States and Canada, widely considered at the time to be serving only the elite. Against this backdrop, however, something of a renaissance took place in the 1990s, with sudden attention being paid to the city by contemporary artists. In the wake of another devastating earthquake in 2017, occurring thirty-two years to the day after the 1985 tragedy, it’s instructive to look back at a formative period of Mexico City’s role in today’s globalized art market and at the work of artists who impacted the continuing image of the metropolis as precarious and creative in equal measure.

Among the markers of this shift was the arrival of European artists—including Francis Alÿs, Santiago Sierra, and Melanie Smith—who chose Mexico as a place where they could work outside the confines of the established art circuit. Alongside a number of Mexican artists—Miguel Calderón, Silvia Gruner, Yoshua Okón, and Gabriel Orozco, to name but a few—these contemporaries frequently used the social milieu as a studio in which to enact performances, interventions, and works of assemblage from and amidst the prolific detritus that could be found in the streets and markets. Hostile bureaucracy butting up against the anarchic informality of street life became the physical backdrop and sounding board for their practices. For many, the Zócalo, Mexico City’s edgy and dilapidated historic center, particularly around the Calle Licenciado Verdad, provided both constant stimulus and affordable rent and, in turn, became a place where artist-run galleries emerged, as documented in Daniel Montero’s 2014 exploration of a pivotal moment in contemporary art—and the emergence of a critical debate on Mexico’s increasingly significant position in a global market—El cubo de Rubik, arte mexicano en los años 90 (The Rubik’s Cube: Mexican art in the ’90s). Others colonized the Condesa area, opening exhibition spaces such as La Panaderia in the then run-down neighborhood that has since been gentrified.

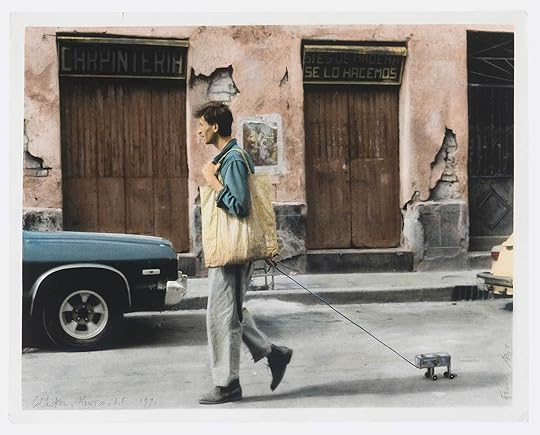

Francis Alÿs, Collector, Mexico, D.F., 1991

© the artist and courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York

Mexico City street life displays both petty freedoms and ad hoc systems. For these transplanted artists, one might consider it a mise-en-scène, but something of a partial one, alongside the stereotyped images of the megalopolis. Trained as an architect, Belgian artist Francis Alÿs arrived as part of a humanitarian project to aid reconstruction following the 1985 earthquake. In his earlier artwork, Alÿs had developed distinctive, poetic, and personal investigations of a city’s flows and ambiences more than its physical environments. This approach lent itself to an artistic practice that coalesced in Mexico, where he chose to remain. Alÿs’s walking excursions through the dilapidated city center saw him tapping into its own sometimes languid, sometimes staccato rhythms. Activities such as pushing a block of ice through the streets until it melted into nothingness or wearing a magnetic pair of shoes that attracted nails, bottle tops, and other discarded shrapnel of the comings and goings of the city’s inhabitants were among his strategies. Often derived from observation of everyday activities, they presented an appropriation of psychogeographical methods in a “third-world” context. In his meanderings, Alÿs was especially drawn to the contrast of modern and premodern found in the urban fabric, which he described as paradoxically existing in the Zócalo, around which many of these works were made. As he has described it: “Does it matter even if or up to which point this modernity has really been lived here . . . ? What matters today is just the memory of it, fictitious or real. . . . All the ingredients of modernity may be there, but the city often continues to function on the basis of a pre-modern parallel economy.”

Whether Alÿs was reenacting and reframing the overlooked quotidian aspects of people’s routines and labors or commissioning premodern laborers to copy his own paintings, his images and actions accrued their potency from the city itself. Alÿs’s works also avoided a singular definition: photographic documentation of his performances was presented in the gallery, alongside video and drawings, while reproduced images on postcards, with short didactic texts adopting the style of Conceptual art, were intended to be distributed beyond its confines. As philosopher Jacques Rancière writes, the aesthetic revolution of modern times “shifts the focus from great names and events to the life of the anonymous; it finds symptoms of an epoch, a society, or a civilization in the minute details of ordinary life.” Alÿs and his contemporaries created their own exceptional moments that circulated within the ordinary.

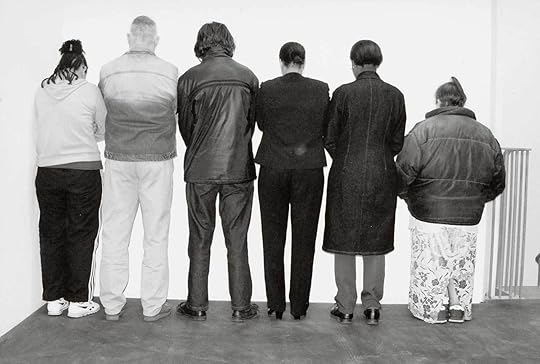

Santiago Sierra, Group of people facing a wall and person facing into a corner, Lisson Gallery, London, October 2002 (detail)

© the artist and courtesy Lisson Gallery, London

The Spanish artist Santiago Sierra took a more antagonistic approach to the city’s movements of traffic and people. Simply documented in black-and-white photographs and video, his piece Obstruction of a Freeway with a Truck’s Trailer, Anillo Perférico Sur, Mexico City, Mexico. November 1998 (1998) appears to depict an unusual, quasi-criminal action. Sierra refers to the work in terms that blur sociopolitical and Minimalist aesthetics, stating that it “consisted of positioning a white prism perpendicular to the road, generating a traffic jam.’’ As the artist also noted, “the driver didn’t mind’’ being asked to perform a five-minute rupture on the at times dystopic Fordian roadways that are more often than not at a standstill anyway. The work reenacts a significant experience of the city many would recognize; delivery trailers reversing to jam the traffic on a Mexico City freeway exit are not, in fact, uncommon. Nor is its location arbitrary. The work is observed from a footbridge loaded with its own history of violence and protest, while toward the rear stands Gonzalo Fonseca’s 1968 Torre de los vientos (Tower of the winds), a sculpture that forms part of the Ruta de la Amistad (Route of friendship), a seventeen-kilometer-long sculpture park designed to be viewed by drivers on their way to the Olympic stadiums for the 1968 games.

Manuel Gutiérrez Paredes, Mexican students detained during the Tlatelolco massacre, Mexico City, October 2, 1968

Courtesy Archivo Historico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City

More broadly, Sierra’s actions emphasized capitalist imbalances and dehumanizations as part of a broader question of institutional power versus the individual. In a series of works realized both in Mexico and elsewhere, Sierra imposed his art directly on people’s bodies, replicating the conditions of exploitation for remuneration that are often found in Latin America. The lines of bodies that appear in his photographic documents—whether of addicts being paid the price of a heroin fix to be tattooed or of the unemployed to simply stand against a wall—echo photographs of the student oppression by police during the protests at the time of the 1968 Olympics. In particular, one piece of reportage stands out as an antecedent: Manuel Gutiérrez Paredes’s photograph of the police searching detained protesters. Cemented in the Mexican cultural imagination, this lineup of subjugated students arrested at the Tlatelolco demonstrations, where forty-four people were killed, lingers more than the constructed media images that the games were meant to project. As the president of the Organizing Committee of the games stated: “Of least importance was the Olympic competition; the records fade away, but the image of a country does not.’’ Undoubtedly, such brutal authoritarianism would be the lasting image, even if it was a distinctly modern one, compared with the rural depictions that persisted prior to the 1960s. It is not merely the physical but also the psychic resonance that is embedded in reportage of events like this, or of the subsequent traumas, captured by photographers such as Enrique Metinides, of violent robberies, plane crashes, and disasters. While veracious in many respects, these pictures amplified imagery of violence and “low’’ culture over other more positive aspects of life in Mexico City.

Sierra’s and Alÿs’s photographic works are often deliberate snapshots not intended to be part of the photographic canon per se, but rather a use of the camera as an apparatus of vérité and documentation. Sierra’s images, perhaps more than others, are consciously engaged in creating a particular idiom. The choice of black and white at a time when color film was already the norm lent a deliberately staged air to the records of his actions. Both Sierra’s and Alÿs’s form of photography sits between journalism, documentary, and the street photography of Weegee and his ilk. Certainly it is informed by these traditions in its framing and intention, just as it is informed by post-Minimalist and Conceptual art imported from the United States and Europe.

Melanie Smith, Untitled II, 2002, from the series Spiral City

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

In 2002, Melanie Smith, a British-born artist (who contributed to the 1990s art scene in Mexico City with the weekly Mel’s Café she ran in her studio then), created Spiral City, a project including a movie and still photography of Mexico City that pay homage to Spiral Jetty (1970), Robert Smithson’s landmark earthwork tucked behind a remote promontory of Utah’s Great Salt Lake and his film of the same name. Smithson’s film is not only an image of Spiral Jetty and its landscape; it also explores cultural ideas and phenomena that are just as influential in constructing the mythology of a place, such as science fiction and natural-history museums. These intercut references add a modern mythical dimension to his documentation. Smith applied Smithson’s methodology to Mexico City, itself constructed on a drying lake bed. In Spiral City, the seemingly boundless grid of Mexico City’s housing, all low-rise and barren, whether in low-income or middle-class neighborhoods, has the same sense of accretion as Smith’s inspiration. Her film moves at a biological rather than geological speed as it pans over mainly informal and unplanned dwellings. Seen in this way, the city resembles Mike Davis’s description of it, in his book Planet of Slums (2005): “The giant amoeba of Mexico City, already having consumed Toluca, is extending pseudopods that will eventually incorporate much of central Mexico, including the cities of Cuernavaca, Puebla, Cuautla, Pachuca, and Queretaro, into a single megalopolis.’’

This is not to suggest that these practices were the only approaches of relevance in the 1990s and into the early 2000s. Gabriel Orozco was producing sculptural interventions in dilapidated interiors, vacated lots, and other liminal urban sites in both Mexico and New York, where he was simultaneously based. Many of these assemblages of discarded materials appear animate, suggestive of mythical figures as much as of playful forms, drawing on two distinct histories of modern and premodern to forge his own hybrid aesthetics. Silvia Gruner was using her own body as a tool to explore relations with traditions and identities, which also reflect the dualistic time frame in which Mexico seemed to exist.

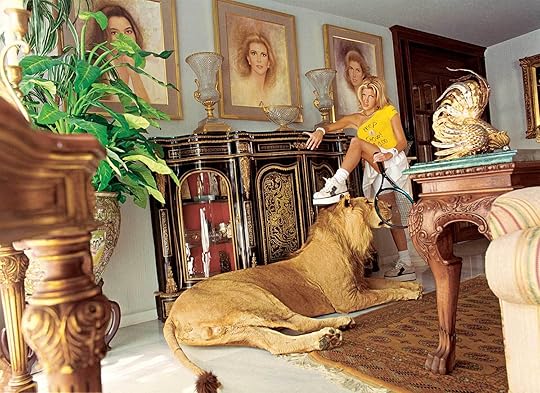

Daniela Rossell, Untitled, 1999, from the series Ricas y famosas

Courtesy Estate of Candy Jernigan and Greene Naftali, New York

Mexico City has always been full of extreme contrasts. Another facet, one that few artists have engaged, is that of the enclosures of the wealthy industrial classes, the thirty-eight families who control the majority of economic and political power in the country. Daniela Rossell’s portraits of society women in their homes, grouped together under the series Ricas y famosas (Rich and famous, 1994–2001) and Third World Blondes (2000–2002), are the exception, although they also play with certain stereotypes. How these images were produced and circulated are as significant as what they portray, revealing the codes of viewing embedded in both local and international contexts even more acutely than artists who work in Mexico City’s public spaces. Rossell’s portraits are remarkable on many levels. Among the first thing one notices about their main subjects is their propensity to be blond, a social marker among Mexican wealthy classes that differentiates them from their housekeepers and maids, many of whom appear in the photographs in subservience to their employers. The homes of these women have been referred to as gilded cages, and the overadornment of their interiors is akin to those of the bodies that inhabit them, often with fantastical implications—for instance, one woman is seen dressed as a mermaid with Medusa-like hair, with the bed as her sea, and a Native American doll lying beside her.

Daniela Rossell, Untitled, 1999, from the series Ricas y famosas

Courtesy Estate of Candy Jernigan and Greene Naftali, New York

Rossell’s work was produced in full cooperation with her subjects; Rossell, who is from the same class herself, was able to gain access to these extravagant homes through family and social ties. We can see these photographs as representations of people as they choose to present themselves. In this light, perhaps it is too easy to judge the excessive taste and apply the same criteria to the person within the image. Somewhat inevitably, once unveiled to the world at large, these isolated creatures and their exotic artificial universes were critically addressed in the media and by art-world cognoscenti for the brash way in which they displayed and performed wealth. Once it became clear that they had become the subject of ridicule, many of those pictured withdrew their consent. Given the nature of family businesses and the nature of business itself in Mexico, often intertwining legitimate and not-so legitimate practices, Rossell found it impossible to continue with the project, and found herself under genuine threat.

The images in Ricas y famosas are, in fact, neither celebratory nor parodic, but rather a means of addressing attitudes toward women, particularly in the media. It should not be overlooked that the series’ title is itself taken from a long-running telenovela and suggestive of the vacuous stereotypes it portrays. Arguably, Rossell’s lens reveals not just the absurdities of wealth but also the public mores and judgments of the upper class—demonstrating a self-awareness that is noticeably lacking in the art of her European colleagues working in Mexico during the same era, who often placed acts within a deprived social sphere without truly being part of it.

Kit Hammonds is a curator at Museo Jumex in Mexico City.

Read more from Aperture issue 236, “Mexico City,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The post Spiral City appeared first on Aperture Foundation NY.

October 15, 2019

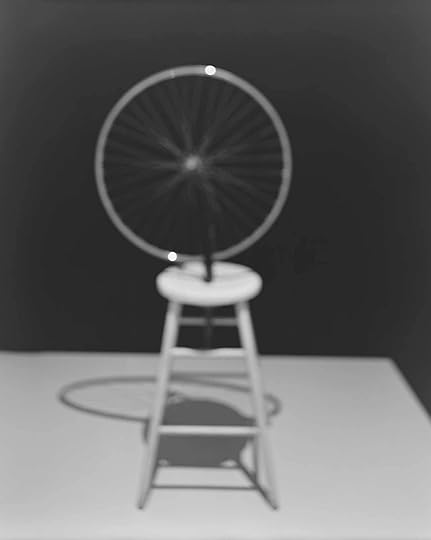

A Lesson in Art History from Hiroshi Sugimoto

What do modern masterworks look like in black and white?