Aperture's Blog, page 76

February 20, 2020

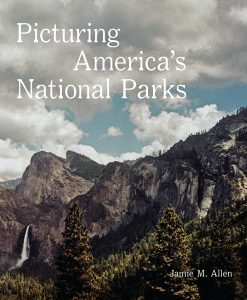

A History of Photography in America’s National Parks

From Ansel Adams to Rebecca Norris Webb, we trace the symbiotic relationship that the parks and photography have developed over 150 years.

Carleton Watkins, The Yo Semite Valley from the Mariposa Trail, ca. 1876. Boudoir card

Courtesy the George Eastman Museum, museum accession

When the United States Congress first voted to protect California’s Yosemite Valley in 1864, most people living in the country had never set foot in the American West, let alone experienced the sublimity of Half Dome and El Capitan first hand. Instead, photographs were crucial to conservation efforts, with Carleton Watkins’s mammoth-plate images of Yosemite Valley sealing the decision to grant the land to the State of California and later establish it as a national park.

By the time Ansel Adams was at his height of exploring and photographing the Yosemite Valley in the 1930s and ’40s, more and more tourists were flocking to the parks. The urgency to carefully preserve park ecosystems became a primary focus for land and wildlife conservation groups like the Sierra Club. Adams’s iconic photographs, along with his work for the Sierra Club, established the parks as globally recognized icons and fostered a sense of national pride for their conservation.

Over the course of their history, the national parks have faced numerous threats, both political and environmental. Along the way, over six generations of photographers, including Adams, have been drawn to the parks, bearing witness to their changing landscapes, examining the implications of public land use, and capturing their grandeur.

When Aperture and George Eastman Museum first published Picturing America’s National Parks in 2016, we sought to tell the story of how photography has shaped the parks over their hundred-year history. The book brings together some of the finest landscape photography from America’s most magnificent and sacred environments, examining how photographs have defined the way we see both the parks and America itself.

Since then, threats to America’s national parks have increased, from the reduction of public land protections to prioritizing mining and other industries. In a climate of heightened environmental and political tension, the work explored in Picturing America’s National Parks is relevant now more than ever. Now, on the occasion of Ansel Adams’s birthday, we look back on photographers whose work helped to shape the history of the parks and ensure their survival.

For a limited time, purchase Picturing America’s National Parks at a discount, and $5 from each sale will be donated to the Sierra Club Foundation.

Ansel Adams, Noon Clouds, Glacier Park, Montana, 1942

© The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust, courtesy George Eastman Museum and The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams’s lifelong passion for the national parks began in 1916 when, at the age of fourteen, he convinced his parents to take him on vacation to the Yosemite Valley. Equipped with a No. 1 Brownie camera that his parents had given him, Adams took his first images of Yosemite that year. Soon after, he became involved with the Sierra Club, leading tours and participating in trips to the Yosemite High Country. He was eventually elected to the board of directors and lobbied for additional areas to be set aside as national parks and monuments. His images of the parks have come to represent the grandeur of the American landscape, conjuring a sense of pride for American viewers in both the land itself and the preservation of these spaces through the National Park Service. Adams’s photographs have also had broad international appeal, establishing the national parks as globally recognizable icons.

Marion Belanger, Alligator in Swamp, 2002; from the series Everglades

© the artist

Marion Belanger

In 2004, Marion Belanger served as artist in residence at Everglades National Park in Florida, an area with a complicated history. Considered potential farmland by early settlers, it was drained for development in the early 1900s, impacting the delicate ecosystem of plants and animals that live along the waterways; advocates lobbied for the area to be made into a national park, which it became in 1947. Belanger’s body of work draws on this unsettled history, documenting sites within the park, as well as those just beyond its borders. Ultimately, her work calls into question the ways that we divide land, making invisible borders that establish what is “important” to preserve and subdividing the fragile ecosystems that have survived for thousands of years.

Mitch Epstein, Exit Glacier, Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska, 2007

© Black River Productions, Ltd./Mitch Epstein, courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Mitch Epstein

Mitch Epstein began his series American Power in 2003. Like the photographs of Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, Epstein’s work confronts the viewer with issues of land preservation, now incorporating elements of our twenty-first-century debates on climate change. The photographs comment on America’s energy-driven lifestyle and reliance on fossil fuels. The series includes an image of Exit Glacier at Kenai Fjords National Park in Alaska, the only landmark in the park accessible by car; Epstein’s photograph freezes the glacier in time, an effort to preserve the changing landscape—which, despite its status as a protected national park, is not immune to climate change—prompting us to pause and consider our own impact on the world.

Roger Minick, Family at Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1980; from the series Sightseers

© the artist

Roger Minick

While teaching an Ansel Adams workshop at Yosemite National Park in 1976, Roger Minick was inspired to begin a series on sightseers. He was particularly interested in how people experienced the parks, the infrastructure that guided their visits, and the sense of awe that struck them at each vista, as if they were on a religious pilgrimage. While Minick’s work serves as a time capsule of 1980s American culture, it also pokes fun at our obsession with these spaces and the ways the parks are both contained and consumed.

Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, Pommes Frites, 2005

© the artists and courtesy RaebervonStenglin, Sies, + Höke, Peter Lav Gallery

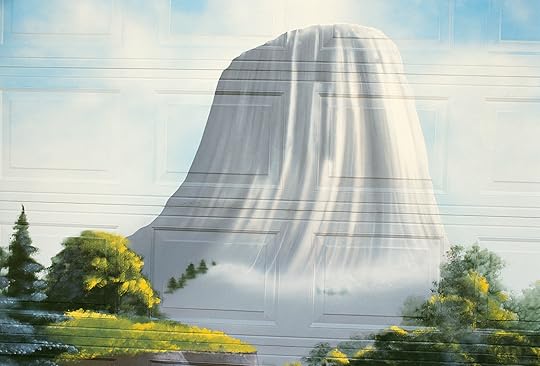

Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs

Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs approach nature as a place of creation, both through natural acts and what we impose on the landscape. The views in their images are disrupted by a commodity culture that is constantly seeking more from the environment. Pommes Frites (2005) depicts an attentive audience of french fries enjoying the view at the edge of the Grand Canyon. These fried potato strips are no different than the thousands of visitors who stand at the rim and perform the typical reaction of awe. With humor and play, Onorato and Krebs portray a culture where the divided highway and fast food are as iconic as the grand vista of any national park.

John Pfahl, 2 Balanced Rock Drive, Springdale, Utah, June 1980; from the series Picture Windows

© the artist, courtesy George Eastman Museum

John Pfahl

While most people experience the national parks during day trips or vacation excursions, a select few own homes or businesses that overlook the preserved landscapes. In his series Picture Windows, John Pfahl sought out these destinations, framing his photographs behind glass. His images depict beautiful landscapes as if already framed pictures on a wall, highlighting the fact that these spaces have risen to the status of art and represent symbols of national identity. Yet they also draw attention to the man-made aspects that disrupt the views. With the same careful balance of preservation and access that the park system navigates, Pfahl’s images demonstrate how we can simultaneously enjoy nature and alter it with our presence.

David Benjamin Sherry, Sunrise on Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley, California, 2013

© the artist, courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York

David Benjamin Sherry

David Benjamin Sherry’s photograph Sunrise on Mesquite Flat Dunes, Death Valley, California (2013) seems all too familiar. It brings to mind Edward Weston’s photographs of Death Valley, and Minor White’s ability to abstract landscapes into pure form and emotion. This feeling of déjà vu is purposeful on Sherry’s part, as he reimages classic black-and-white views with a wash of monochromatic color. By rephotographing vistas that have become emblems of American national identity and applying a dizzying hue, Sherry sends our sense of reality into a tailspin. For him, this experience parallels that of coming out as a gay man, as he establishes his own queer gaze in a world full of expectations, conventions, and standards that do not always align with his own.

Rebecca Norris Webb, Ghost Mountain, 2009

© the artist/Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco

Rebecca Norris Webb

In her series My Dakota, Rebecca Norris Webb explores her home state of South Dakota, including Badlands National Park and the surrounding area. Attempting to capture what the open space of the West felt like to someone who grew up there, Norris Webb was dealt an unexpected blow when her brother passed away. As she wandered, her photographic journey paralleled her emotional one. Norris Webb’s meandering paths of travel and grief resulted in photographs that serve as meditations on life, death, home, and family.

Michael Matthew Woodlee, Chris, Campground Ranger, Tuolumne Meadows Campground, 2014; from the series Yos-E-Mite

© the artist

Michael Matthew Woodlee

Michael Matthew Woodlee’s images reveal a side of Yosemite that is exceedingly ordinary, as if it is just another common campground. National parks require caretakers, which is in reality a twofold job. While employees and volunteers are responsible for providing services for guests, they are also charged with preserving the spaces for generations to come. The everyday lives of these workers include tasks such as cleaning buildings, fixing trails, taking tolls at the front gate, and staffing gift shops and restaurants. Yet these workers have the unique experience of inhabiting the places that others visit only on vacation. In Woodley’s photos, one might even forget that a sweeping natural vista is perhaps just outside the frame, prompting the viewer to wonder if the workers experience the same phenomenon, inattentive to the beauty that surrounds them as they go about their day-to-day tasks to preserve it.

Click here to purchase Picturing America’s National Parks at a discount.

February 18, 2020

On the Cover: Aperture’s “House & Home” Issue

Mauro Restiffe, from the series Santo Sospir, 2018

Courtesy the artist

They called it the “tattooed villa.” In 1950, Jean Cocteau began to draw mythological frescoes on the walls of Villa Santo Sospir, a home on the French Riviera, where he was visiting the socialite Francine Weisweiller. For twelve years, he “tattooed” the house with charismatic images of unicorns, a sleeping Dionysus, and Pan, the god of fields and shepherds. “Matisse told me that if you decorate one wall, you should do the others as well,” Cocteau said. But by 2018, when the Brazilian photographer Mauro Restiffe was invited to document the house, the frescoes were deteriorating.

“These aren’t the glossy, presentational kind of photographs of the house you’ll find in home-and-garden magazines; they ask us to see the drawings as more than home décor,” Lauren Elkin notes of Restiffe’s series Santo Sospir (2018) in Aperture magazine’s “House & Home” issue. Restiffe stayed in the house alone for a week, finding unexpected angles and surprising details. “My approach is to get into the textures of places,” he says. “I want to give more warmth to architecture, to offer traces of human life.”

Just as photographers have trained their lenses on the built environment, architects have equally been drawn to photography. In this issue, four visionary architects—David Adjaye, Denise Scott Brown, Frida Escobedo, and Annabelle Selldorf—discuss how they conceive of homes, civic spaces, and the fabric of our cities. “Photography is not just images of places,” says Adjaye, whose own Instagram “sketchbook” is a lesson in looking at buildings and thinking through urbanism. It is “a whole set of information that really captures the narrative about a time, or a place, or a form . . . or even just a sensation.”

From Seher Shah and Randhir Singh’s abstracted cyanotypes of the brutalist geometries of London’s Barbican Estate, to Ezra Stoller’s luminous images of mid-century modern designs and Robert Adams’s austere suburban interiors, “House & Home” considers how artists are more interested in interpreting than rendering buildings: They go beyond converting three-dimensional form into two-dimensional surface. They also tell us something about the nature of change. Restiffe’s photographs “capture our moment,” Elkin adds. “They record not only Cocteau’s work, but the work of time.”

Read more from Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

February 12, 2020

The Biennale Embracing Fear and Ambiguity in Photography

Ahead of an ambitious exhibition in Germany, curator David Campany speaks about the lives of images.

By Diane Smyth

Antonia Pérez Rio, Portrait of James Stuart, 2017, from the series Masterpieces

Courtesy the artist

“Photography has come to symbolize the extremes of contemporary society,” writes author, curator, and artist David Campany in the introduction to The Lives and Loves of Images, a series of exhibitions he has organized for the 2020 Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie in Germany, on view across museums in the cities of Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Heidelberg. “It is deeply personal, and yet thoroughly public. Freeing at times, yet also limited and limiting. Expressive, yet culturally dominant. Pleasurable, but worrying. There is affection for photography, and it is a source of great fascination but we are, or ought to be, suspicious of its power and manipulations.”

The biennale features more than fifty image-makers—including Stephen Shore, Vanessa Winship, Max Pinckers, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, and Sohrab Hura—whose work is included throughout six exhibitions concerning the reinterpretation of classic photographs. In Reconsidering Icons, artists take on classic images; in All Art Is Photography, they consider art institutions and mediums; and in Walker Evans Revisited, they work in the spirit of the great photographer, or riff on his images. When Images Collide includes work using more than one shot, and Yesterday’s News Today looks at rescued news photographs, while Between Art and Commerce explores the boundaries between commercial, editorial, and fine-art photography. Ahead of the opening on February 29, writer Diane Smyth met with Campany to discuss the many themes of his ambitious biennale.

George Georgiou, Charro Days Parade, Brownsville, Texas, 2016, from the series Americans Parade

Courtesy the artist

Diane Smyth: I just had a look through the catalogue for the biennale, and I realized how big it is.

David Campany: It is big! It just so happened that when the organizers asked me to do it, I had half a dozen ideas for shows rattling around in my head. I think if I’d had nothing in my head, I would have said no, because it would have been terrifying. But the first thing to do was go and see all the venues and think about how the exhibitions might work in them.

Smyth: I can see why you had the Walker Evans show, Walker Evans Revisited, rattling around in your head, as you’ve done a lot of work with him.

Campany: That’s true, but what interested me about him was two-pronged. One thing was, why him out of all of those twentieth-century figures? Why is he still so influential? Then, he was quite prescient in a kind of thinking that concerns so many photographers today, which is that it’s not enough to just make the images. You’ve got to take care of how they get into the world.

Smyth: Was that the exhibition you had most clear in your mind to start with?

Campany: No, that was When Images Collide, because I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about image editing. I’m always swinging between thinking of photographs as rather individual, isolated things, and as bodies of work. So I thought it would be interesting to do a show that took the diptych as a starting point, because you can argue that that’s the start of image editing.

Daniel Stier, ways of knowing, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: Did you have lots of artists in mind already?

Campany: Yes, my projects always come out of artists or particular works that have lodged themselves in my mind. I’m led by the works. Suddenly, I get a constellation of things in my mind, and I start to wonder: Why have these things stayed in my head? What’s the hidden logic that has allowed them to circle around each other?

Smyth: That’s interesting, because some of the works fit into one show in the biennale but could have been argued into another.

Campany: It’s true, and there are also a number of artists who are in more than one show. That was quite deliberate, because I think there’s a terrible problem with the way photographers get pigeonholed now. The contemporary approach you’re supposed to take is to do something very distinctive, but I think the richest period in photography was the 1920s and ’30s, when so many photographers could do anything. The field was wide open. Why can’t you be a great photojournalist as well as a very interested architectural photographer and still-life photographer and fashion photographer? Why can’t you appear in the avant-garde journals and the mainstream press? That seems in the nature of the medium.

Smyth: That makes me think about the willingness to keep experimenting. You write in the catalogue essay about Walker Evans using the new wide-angle lens on his Contax to take the subway pictures.

Campany: Totally, he used every camera and format going; he never really fixed his attitude toward the medium or his understanding of it. I’m interested most in photographers who are interested in renewal, in the idea that you could start again somewhere else.

Hein Gorny, Untitled (Cellophane), 1931

Courtesy Hein Gorny—Collection Regard, Berlin

Smyth: Like Broomberg and Chanarin? They’ve used virtual reality for the piece they’re showing, Woe From Wit (2018), which takes as its starting point a controversial, World Press Photo–winning image by Burhan Ozbilici, showing the murdered Russian ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, and his assassin, Mevlüt Mert Altıntaş. The work is part of Reconsidering Icons.

Campany: Yes, they embody something in the heart of the biennale, which has to do with this balance of feeling a certain kind of fascination and affection for photography, and also feeling very suspicious of and dubious about it.

People are deeply frightened of photographs, I think, because of their ambiguity. People want to know that an image is coming from a good place—when it’s disturbing to them, they want to know that the photographer was well intentioned. But sometimes, the most significant images don’t come from a good place. Art doesn’t necessarily come from a good place. It might be contradictory, or an artist might not necessarily have a clear view of things.

When I was writing the catalogue, I was trying to take out as much writing as possible. If these images are well chosen and well sequenced, they’ll do most of the work, and they’ll leave that ambiguity open.

Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger, Making of “Milk Drop Coronet” (by Harold Edgerton, 1957), from the series Icons

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: And likewise, the exhibitions will be shown with even less information?

Campany: There will be a brief introduction and sometimes, there will be a little bit of information, enough to be a key to open something. But there’s a fine line between writing that’s a key to opening something and writing that slams the door in the face of ambiguity.

Photographs have a way of covering their traces—when you look at a photograph, it’s often hard to know how it was made or why it was made, and that produces an anxiety. So people often want to know that and think that that’s the meaning. I am deeply suspicious of that. John Cage had a nice expression; he called it “response ability,” the freedom to respond, but also a kind of obligation to bring what you can to it.

Smyth: So it’s a bit lazy to want to be told what to think?

Campany: Well, it’s debilitating. I like it when people have radically different opinions about images; there’s something utopian about that. It’s like, OK great, we’re away from the tyranny.

Smyth: This makes me think of something else you’ve written in the catalogue, about images that were first used one way but which artists have reused in another way, the idea that there’s no definitive understanding of the image.

Campany: That’s partly why the biennale title has the word lives in it, because once one accepts that images don’t have meanings, they have potential to mean, and once one accepts that there’s no home for photography that is not legitimate somehow, you then have to accept that an image is going to have a life. It might have a short one; it might have a very long one. And if it’s long, it’s going to be unpredictable. It’s not going to mean the same thing through history and across contexts.

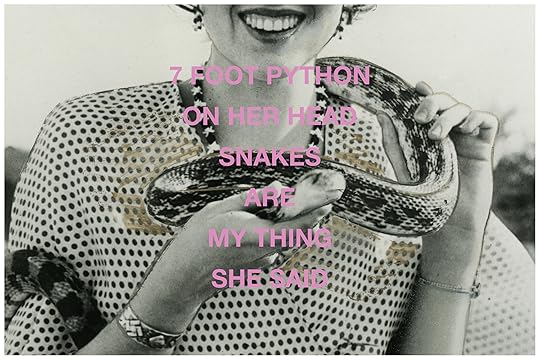

Clare Strand, from the series Snake, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: Do you see the exhibitions as very separate from each other, or interrelated—in that they’re all relating to the form or context of photography?

Campany: They are [interrelated], and yet they’re all very visually distinct, and they will all have their own logic. There’s a show called Between Art and Commerce, for example, which looks at that 1920s, 1930s legacy, in which the most interesting avant-garde photographers were also the most highly paid commercial photographers. That show is quite playful; it’s trying to keep the audience on its toes. One of the photographers, Daniel Stier, works commercially, editorially, and for fun, and he will be presenting his pictures without telling the audience which is which. They’ll just have to think for themselves.

I guess with a biennale, it should add up, but you do want each show to be its own thing. I talked to the organizers and they said, “Some people will see everything. Some people may see one show or two shows or five shows or six shows.” You can’t overprescribe that. You don’t know how something is going to be remembered—you don’t know what’s going to stick in someone’s mind and why. After it’s done, you hand it over to the audience, and they make of it what they will.

Andrea Diefenbach, Natascha, 2006, from the series AIDS in Odessa

Courtesy the artist

Smyth: But do you think that an interest in form can be disparaged? That people might say there are more important things to worry about at the moment?

Campany: I’m much more interested in how people think than what they think, because, in a way, the what will follow from the how. We live in an era of propaganda and counterpropaganda; it’s very difficult for any of the voices of sanity to make themselves heard. But given that an exhibition is by nature a slow space, I think you’re obliged to set up a space where response ability is more important than what that response is. In the end, you get a better society out of granting and encouraging people to think, not telling them what to think.

Diane Smyth is a freelance journalist who writes for publications such as the Guardian, Observer, FT Weekend Magazine, Creative Review, British Journal of Photography, and Foam Magazine.

The 2020 Biennale für aktuelle Fotografie, The Lives and Loves of Images, is on view February 29–April 26, 2020, in Mannheim, Ludwigshafen, and Heidelberg, Germany.

A Photographer’s Chronicle of Indigenous Life in Brazil

Throughout her career, Claudia Andujar has always experimented with visual language to portray her country’s most pressing cultural questions.

By Thyago Nogueira

Claudia Andujar, Rua Direita (Direita Street), São Paolo, ca. 1970

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

On one of the hottest days of the Brazilian summer last February, I sat with Claudia Andujar in her apartment to talk about her remarkable life and career in photography. Claudia, now eighty-three, has lived in São Paulo since the mid-1950s, but the story of how she came to live in Brazil parallels some of the tragedies of the twentieth century. Born in Switzerland, Claudia spent her early years in Hungary, before fleeing during World War II. She lived in New York, where she finished high school, attended Hunter College, and embarked on a career as a painter. After a brief marriage, Claudia rejoined her mother who was living in São Paulo, in 1955, and left painting for photography. During the 1960s, Claudia returned regularly to New York, maintaining ties to the city’s artistic community, including figures like Edward Steichen and documentarian W. Eugene Smith, who would profoundly influence her humanist vision. Her photographs were published in Life magazine and in Aperture, in 1971, then edited by Minor White. In 1960, her work was included in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.

In Brazil, Claudia worked as a photo-journalist for magazines such as Realidade, until the early seventies, when she quit everything to focus on a personal project about the struggles of an indigenous group in the Amazon region called the Yanomami. This would become her life’s work. She photographed the Yanomami extensively, in hopes of preserving and understanding their culture, and fought politically for the respect of their traditions and land. today, Claudia has not slowed down. In September, Inhotim, a contemporary art museum in the state of Minas Gerais, north of São Paulo, will inaugurate a permanent pavilion dedicated to her work on the Yanomami. I am currently organizing an exhibition, opening at the Instituto Moreira Salles in Rio de Janeiro in 2015, focused on Claudia’s career, which includes her years in photojournalism and her experiments with color and infrared film.

Claudia Andujar, Rua Direita (Direita Street), São Paolo, ca. 1970

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Thyago Nogueira: How did someone who was born in Switzerland and grew up in Hungary end up living in São Paulo?

Claudia Andujar: It’s a long story. My mother was Swiss and my father was Hungarian. They lived in Transylvania, a place that was sometimes Romania and sometimes Hungary. For some reason—I should have asked why—she wanted me to be born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and so she went there for my birth.

We then came back to our city, which is called Oradea in Romanian (in Hungarian it’s called Nagyvárad). We lived there until World War II. In 1944, all the Jews were deported. My father was Jewish. He and his whole family were deported; they died in a concentration camp. I was living with my mother, who was divorced from my father. After he was deported, the Russians began closing in, so my mother decided to go to Switzerland. The rail trip took weeks because of all the broken bridges on the way. We also had to stop in Vienna, because my mother became ill. In the city, which was under German rule, my mother stayed at a hospital and I was interrogated daily. They wanted to know why we had fled. I had to hide the fact that my father was Jewish or they would have taken me. They never discovered my story. I stayed in Switzerland for two years, until one of my father’s brothers found out that I was there and asked me if I wanted to come to the United States. I went as a refugee to New York in 1947 to live with my aunt and uncle.

Nogueira: How was your time in New York? Why did you leave for Brazil?

Andujar: I didn’t really get along with my aunt and uncle. They accused my mother of leaving my father. It’s a complicated story …. I decided to rent a room and go to work. I worked at the United Nations and I painted. At night I studied at the university. After a while I felt abandoned and married a Spanish refugee; that’s why I have the name Andujar. But he became a soldier in the Army and had to go to Korea. I was really unhappy. At that time my mother was living in Brazil, where she had gone to marry a Romanian who ran away from the Russian occupation. After two years, my husband returned from Korea and we separated. I then decided to visit my mother. That’s how I came to Brazil, in 1955.

Claudia Andujar, Sem titulo—Sonhos Yanomami (Untitled–Yanomami Dreams), 1974

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: When did you take up photography?

Andujar: I abandoned my painting career when I arrived in Brazil. But I needed a language to communicate—for me, this was photographing people I met. I wanted to get to know Brazil because I felt at home there. So I picked up a camera, and when I could, I photographed. I’m self-taught. I would go to the north coast of São Paulo a lot, and I began to travel to the islands of the fishermen and became friends with the families. What interested me were the origins of Brazil, the native population. I wasn’t interested in the middle or upper classes.

Nogueira: Did you ever feel unsafe as a European woman traveling alone?

Andujar: No, traveling was easy. In the crowd I was mixing with, this wasn’t a problem at all. I was adopted by the families of these people. I think that the connection through photography, showing the work to the people I was photographing, helped me identify with people and learn Portuguese. At that time, I met the famous anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro, and he suggested that I go visit an indigenous village. I embraced the suggestion and went to meet the Karajá Indians. Later, I tried to show my work to the Brazilian magazines O Cruzeiro and Manchete. But they weren’t interested.

Claudia Andujar, Sem titulo—Sonhos Yanomami (Untitled–Yanomami Dreams), 1974

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: Why?

Andujar: I was a foreigner, a woman who was messing with things she shouldn’t. I stayed with the Karajá twice, two months each time. Then I decided to go back to the States to show my photography and was well-received. I went to Life magazine, to the museums. I had tried in Brazil, but nothing had panned out. In New York, I knew the world of photography. But I didn’t want to stay in the States; I wanted to go back to Brazil.

Nogueira: When you came back, you worked for the magazine Realidade (1966–1976), which was critical to the history of Brazilian photojournalism. the majority of their photographers were immigrants like you. What was it like there?

Andujar: The story of Realidade is special. The magazine’s journalists were against the military government that took power in 1964; they looked for stories that spoke of the difficulties in Brazil. I did well there because the places I went were always places with people who were in some way oppressed by the political situation.

Cover and inside views of Realidade magazine, featuring Andujar’s photographs

Nogueira: You photographed stories on the erotic theaters in downtown São Paulo, childbirths, prostitutes in the countryside. What moved you?

Andujar: I was the person the magazine could always send to shoot in difficult places. I always sought out people on the margins. I wanted to get into people’s souls. Later I got interested in the spiritualist medium Chico Xavier. There are things that to this day I don’t understand. I would almost say that he had a connection with shamanism. But it isn’t shamanism. He had a very strong spiritual life. The way he managed to do certain things—I can’t explain it. Once I photographed someone being cured of cataracts. He hypnotized the person, gained some power over her, and stuck a knife into her eye. A knife! A regular knife, to cure her. And he cured her, but I don’t know how this person kept quiet, leaning against the wall, and letting him do that. If I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it.

Nogueira: You were also exploring the city.

Andujar: Yes, my photos of Direita Street and those made with infrared film are from that time, but those weren’t for Realidade. I did those for myself. Before Realidade, I didn’t photograph in color.

Nogueira: You squatted on the ground to make the Direita Street photos. Did people find that strange?

Andujar: Well, they didn’t find it very common; they thought it was a little curious, but nobody messed with me. They got a kick out of my attitude, that’s for sure.

Claudia Andujar, Untitled from Kayapó series, 1970

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: Your 1970s work has a visual freedom that’s rare for someone who worked for the press—the infrared film, the dislocated point of view, or even when you rephotographed slides, like in the photos of Sônia. Where did that experimentation come from?

Andujar: I would say that it was my contact with George Love, my second husband. He was interested in new angles, new ways of photographing. But even with these new techniques, I still maintained a humanist vision, don’t you think?

Nogueira: You once took a model and magazine crew to do a fashion shoot in an indigenous village. How did that come about?

Andujar: In the 1970s there was a fashion magazine called Setenta, for which I did various jobs. I suggested a fashion piece with the Xicrin Indians, which Setenta published.

Nogueira: You were criticized severely for this piece, weren’t you?

Andujar: I was—an anthropologist said I had gone to the Xicrin to show that they were inferior. For me it was nothing like that. I wanted to show that the Xicrin had their own style, their own inventiveness, that they were creative. But everyone has their own interpretation.

Claudia Andujar, Urihi-a, 1974

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: In 1971, Realidade did a special edition on the Amazon. Why were they interested in the region?

Andujar: The Trans-Amazonian Highway was being built; an American had bought all this land there. When I went to photograph, there was so much deforestation going on. It was a disaster, but the Brazilian government allowed it to happen. They said that the Amazon was an empty space that had to be developed. The magazine was interested in showing what the Amazon was like at that time.

Nogueira: Was it then that you made your first contact with the Yanomami?

Andujar: Yes. When I went to photograph in the Amazon, they asked me not to photograph the indigenous people because the Brazilian government was mistreating them. It was a type of government repression. But after I had been there for some time, I found out that a priest had died suddenly, and nobody knew how. I asked the magazine if they would be interested in this story. They said yes. So I went to the Yanomami. I never found out why the priest died, but I photographed the Yanomami. I liked them a lot, and in the end the magazine published many pages and put one Yanomami on the cover. The Yanomami hadn’t received any Western influences yet; they were first-contact people. The magazine accepted the story … and we all forgot about the priest.

Nogueira: Realidade had a short life span, did it not?

Andujar: After the special edition on the Amazon, they started letting people go. The whole office was fired for political reasons, because all of us were leftists. I decided to leave and no longer work in photojournalism. I decided to go deeper into the question of the Yanomami.

Claudia Andujar, Metrópole (Metropolis), 1974

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: So you went on to photograph them regularly, as an ongoing project?

Andujar: I tried to penetrate the Yanomami culture. I wanted to understand their beliefs, social practices, shamanism. I began this work in 1971. Later, in 1974, the government began the construction of the Northern Perimeter Highway, the second longest roadway in the Amazon. I was there when it began. And it changed me profoundly. I saw hundreds and hundreds of people dying. These people had no immunity to the diseases that were suddenly brought there. And, because of that, I decided to dedicate my life to their lives and culture.

I tried to show the shamanism, which is essential to their culture. And I explored the contact and the harm this brought to these people, which was sickness and death. I used color a lot, and double exposures. I thought that I had found a kind of visual expression that referred to the culture.

Nogueira: Therein lies the beauty of the work. You are always experimenting with visual language to deal with cultural questions.

Andujar: That’s right.

Claudia Andujar, Exercises with Sônia, early 1970s

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: What was your routine in the village like? Did you take special precautions?

Andujar: In the beginning, they didn’t know what photography was. When they first saw it, they didn’t recognize themselves. With time I believe they will refer to the images I took of them as a reference to their past, their cultural heritage. But I think that to this day, it still isn’t totally clear to them. I never photographed anything they didn’t want me to. The death rituals, for example. They thought that through photography something of the person was stolen. In their funeral rites, they destroyed and burned everything that linked the person to his life, to free his soul so he could live for eternity. That included burning the photographs.

Nogueira: You received many grants to continue the work, including two from the Guggenheim, but in 1977, together with foreign anthropologists and researchers, you were taken by force from Yanomami lands. What happened there?

Andujar: I was ousted by the Brazilian government. They didn’t understand what I was doing there. They thought I was trying to show how the government was mistreating the Indians. That I did this to show to people abroad, that I was some sort of spy.

Claudia Andujar, View of São Paulo, 1974

Courtesy the artist and Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo

Nogueira: You’ve said you are not convinced your work in photography has been the most important thing you’ve done to date. What do you mean?

Andujar: Photography is an eternal search for myself—a language. But the work of trying to understand the life and the culture of a people is much more than photography. Photography is part of that, but not everything. One day we asked the Indians what art was for them. And they said we make our categories, and one of them is art, but for them it is not the same. Photography has brought me many things, but the survival of the world, of humanity, is something we struggle for constantly.

Nogueira: Do you see a parallel between your story and that of the Yanomami?

Andujar: Yes, I do, of course. I lost my whole family and I always think my relatives were marked to die. I’ve learned so much from the Yanomami. We are destroying nature, destroying life. The Indians consider themselves part of this totality of nature, the human being as part of the whole. If you destroy any part of the whole, you destroy the world. That’s why I did the photo of the end of the world in the series Sonhos Yanomami (Yanomami Dreams).

Thyago Nogueira is editor of Revista ZUM, a Brazilian photography magazine, and the head of the contemporary photography department at Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 215, Summer 2014.

In Harry Gruyaert’s Radical Street Photography, Color is the Defining Element

No matter where he turns his eye, the Belgian photographer constantly explores of the potential of color in a seemingly colorless urban world.

By Wilco Versteeg

Harry Gruyaert, Rue Royale, Brussels, Belgium, 1981, from Roots (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2012/2018)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Harry Gruyaert’s intuitive and candid color work was not always understood in a world that looked skeptically at anything smacking of “street photography” and equated black-and-white photography with serious artistry well into the 1980s. His work is under renewed consideration as one of Europe’s most important photographers. This retrospective moment in his career sees the reissue of Roots (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2012 and 2018), a large exhibition at Fotomuseum Antwerp, and the publication of several other volumes of his work. Among them is East/West (Éditions Textuel, 2017), featuring his photographs from the United States and the Soviet Union, and his fifth book to date with the publisher. No matter where he turns his eye, his work attests to a constant exploration of the potentialities of color in seemingly colorless urban environments.

Harry Gruyaert, In the first class carriage, between the towns of Ostende and Brussels, Belgium, 1975, from Roots (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2012/2018)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Roots offers a large selection of black-and-white photographs alongside Gruyaert’s groundbreaking work in color portraying life in Belgium, his country of origin, in the 1970s and 1980s. Gruyaert has asserted that it wasn’t until he had shot color during his circumnavigations around the globe, that he became able to see the hues of Belgium for the first time. Viewing the earlier works in the book, one cannot help but feel a crucial element is missing that would take those earlier images beyond traditional documentary: color. In Gruyaert’s best images, such as a photo radically cut in half by a brightly colored lamppost, color becomes the structuring element. The same shot in black and white would merely have been a failed composition; this colorful rupture is instead artistic as much as it is psychological. To the untrained eye, Belgian public life can seem hopeless and dilapidated, best captured in black and white. But its Felliniesque Catholicism, local bars, carnivals, cycling races (and propensity to enjoy a drink or two) are well-matched with Gruyaert’s color treatment. The absurdity and true grit of a country that is fragmented along political, cultural, and linguistic fault lines is best portrayed in high-key color—a medium that Gruyaert helped come of age just as much as the acknowledged American heroes of the so-called New Color of the 1970s. His is an active, relentless exploration of color—one that allows Gruyaert to create a new hierarchy based on chromatic tones rather than a supposed politics of representation. Gruyaert, although intimately connected with Belgium, fortunately eschews anthropological pretensions. Mirroring surfaces and windows are abundant: the man and woman sitting in a café, or the prostitute whose leg is visible through a window in the multicolored facade of an Antwerp brothel, attest to Gruyaert’s self-chosen distance, while nonetheless situating the photographer as observer and frame-giver—the quintessential flâneur. Rather than explicating large political or societal issues through his work, he prefers to speak about the contradictions of reality through the quality of light, color, and contrasts.

Harry Gruyaert, “Place de la Bourse” square, Coffee, Brussels, Belgium, 1981, from Roots (Éditions Xavier Barral, 2012/2018)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Looking through Harry Gruyaert’s lens at Belgium, a country I deeply love and whose language is also my mother tongue, I experience what Ralph Waldo Emerson called “alienated majesty”: I recognize it—but it is made strange, if deeply compelling. Belgium’s neighboring countries used to smirk about its rise of right-wing politics, gang violence, and political murder, thinking them remnants of a history that had already disappeared in other European countries. Today we see that Belgium never was an anomaly in the upward progress toward the End of History, but rather an example of where Europe is collectively headed.

Harry Gruyaert, Moscow, Russia, 1989, from East/West (Éditions Textuel, 2017)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

In Roots, Gruyaert brings his Belgium to the world; in East/West, his inalienable vision is brought to Moscow and in the United States, Las Vegas and Los Angeles. In the 1980s, as the U.S. seemed to be ascendant and the USSR in decline, their visual cultures might have seemed to be miles apart. Thanks to Gruyaert’s astute intervention, we are invited to consider the dialogue between them. His work from Moscow in 1989 is especially important. Seeing Moscow in cinema-like color is an aesthetic revelation: a distinct Soviet visual culture, lacking the smoothness and commercialism of the United States, is shown in a humane light that seems to contest our perceived ideas on the grayness of the region with pops of brilliant color. Take, for instance, the photograph showing decorated scaffolding contrasting with the dark figures of two Soviet officials, or the collection of images showing vibrant public playgrounds.

Harry Gruyaert, Freemont Street, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1982, from East/West (Éditions Textuel, 2017)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

His photographs from Las Vegas and LA show a world that is awe-inspiring and spectacular but that seems to have lost its need for humans. (The cars appear to inhabit the landscape more vibrantly than the people). For a photographer searching for the marvels of color, places that naturally look better in black and white turn out to be more interesting: the West Coast is brilliantly pigmented; it does not need Gruyaert to discover its own nature. While the images from the United States sparkle, it seems that Gruyaert is tempted and challenged more effectively by the Soviet Union and Belgium.

Harry Gruyaert, 1st of May celebrations, Moscow, Russia, 1989, from East/West (Éditions Textuel, 2017)

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Looking at Roots and East/West side by side, we get a clear view of the singular vision of a true auteur. Whether Gruyaert roams the streets of Antwerp, Las Vegas, Moscow, or Paris, it is not the need to document that drives him, but his appetite for interpretation. He directs us toward the unsung joys and tragedies of realities that upon first observation seem barren and empty, but in fact are structured through colored planes and details. It takes a hungry eye to artistically reinvest in these places and reestablish their contorted majesty.

Wilco Versteeg is a writer, photographer, and PhD candidate in contemporary war photography at Université Paris Diderot.

This piece was originally published in The PhotoBook Review 014, spring 2018.

February 6, 2020

Picturing Utopia, From Shakers to Hippie Communes

A visual record of American longing and discontent.

By Chris Jennings

Justine Kurland, Waterfall Lesson, Drawing a Stick Figure, 2007

Courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

And I John saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her bridegroom. —Revelation 21:2

And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the Garden. —Joni Mitchell, “Woodstock”

Utopia is invisible. Only the utopian can see it. Take, for instance, Nathan Meeker. In 1844, soon after graduating from Oberlin, Meeker joined the Trumbull Phalanx, a community of two hundred fifty men and women in the wilds of eastern Ohio that was modeled on the ideas of the French visionary Charles Fourier. Fourier believed that if women were emancipated, labor was organized according to his elaborate specifications, and everyone gathered into cooperative communities of precisely 1,620 (called phalanxes), then the world would be briskly transformed into a paradise he called Harmony. In Harmony, he prophesied, every human impulse, even the most taboo sexual predilection, would be satisfied and rendered productive; abundance would prevail; friendly whales would tow our ships; and the oceans, tinctured by “boreal fluid” from the melting Arctic icecap, would taste like lemonade. Fourier’s ideas—pasteurized of their erotic digressions by his American translators—became so popular in the United States that twenty-nine American phalanxes were established during the 1840s and ’50s. New Jersey’s North American Phalanx, the ruins of which are pictured here, lasted the longest, from 1843 to 1855.

Charles François Daubigny, View of a French Phalanstery (lithograph), 1800s

Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris/Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library

One spring afternoon at the Trumbull Phalanx, young Meeker sat down with his notebook and took stock of his new home:

Seating myself in the venerable orchard, with the temporary dwellings on the opposite side, the joiners at their benches in their open shops under the green boughs, and hearing on every side the sound of industry, the roll of wheels in the mills, and merry voices, I could not help exclaiming mentally: Indeed my eyes see men making haste to free the slave of all names, nations and tongues, and my ears hear them driving, thick and fast, nails into the coffin of despotism. I can but look on the establishment of this phalanx as a step of as much importance as any which secured our political independence; and much greater than that which gained the Magna Carta, the foundation of English liberty.

Looking upon the most mundane tableau of rural life, Meeker saw the transformation of the world. If he had been carrying a camera rather than a pen, the picture he would have taken would be indistinguishable from one taken in any other American village: a dusty orchard, a gristmill, men and women hard at work. The gulf separating what the believer sees and what a camera can record haunts every photograph of utopian living. Some images deliberately try to bridge this gulf by approximating on film what the utopian sees. An image of the theosophist community at Point Loma—shot from below and at a distance like the dream of a shining hilltop city—is a perfect example. Other photographs make the gulf itself their subject.

North American Phalanx, Country Route 537, Monmouth County, New Jersey (photographer unknown)

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Utopia, as its most ardent citizens see it, may be camera-shy, but images have always been the lifeblood of utopianism. In the past those images have usually existed in the form of fiction, that meters-long shelf of novels describing life in the perfect society. These books typically recount the adventures of a wide-eyed, sunburnt explorer as he stumbles upon a delightful yet unknown nation. As he drifts about, chatting up the locals and taking in the sights (often falling for some winsome utopian lass), the explorer narrates in detail what life in utopia looks like. How do the utopians get to work? What color are their costumes? Are their streets clean? If the novel is any good, the shape and texture of life in utopia slowly forms in the reader’s imagination. The whole point of writing a utopian novel—instead of, say, a political tract on the virtues of universal education and collectivized agriculture—is that fiction can render ideas visible, allowing us to evaluate the author’s particular notion of the ideal society by the most intimate criterion: can I picture myself living there?

Rachel Barret, Zoe, 2009

Courtesy the artist

There are as many utopias as there are utopians, but two general visions of paradise tend to dominate the communitarian mind. These two visions are probably as old as human imagination, but their most influential formulations, at least in the West, come from scripture, where they form the bookends of biblical history. In the beginning, it is written, God planted a garden eastward in Eden. And with it was planted the half-remembered dream of a bountiful, property-free existence in the venerable orchards of Paradise, a life uncorrupted by capitalism, technology, or pants.

History, as the Bible tells it, might begin in a garden, but it ends in a metropolis: the gleaming, prefab city of New Jerusalem that God will lower down to earth at the time of the millennium (the thousand-year reign of heaven on earth). For those utopians who do not take the Book of Revelation literally, the prophecy of New Jerusalem has been swapped for (or merged with) the Enlightenment’s promise of ceaseless human progress, the belief that science and reason will someday usher humanity into an orderly, air-conditioned paradise of comfort and fraternity.

Photographer unknown, Raja Yoga Academy and Aryan Memorial Temple at the International Theosophical Headquarters, Point Loma, California, 1919

Over the last few centuries no place on the globe has been more crowded with utopian longing than North America. Since its “discovery” by Europeans, “the fresh, green breast of the New World,” as F. Scott Fitzgerald described it, has stirred dreams of abandoning the crumbling edifice of the Old World to build the perfect society from scratch. At the outset most of this thinking was theological. Many early visitors to the New World (including Captain Columbus himself) believed that they had arrived at, or at least near, the “historical” location of Eden. Many others, including the Shakers and Oneida Perfectionists (whose communal home is pictured here) believed that the young American republic would be ground zero for a new dispensation of social perfection. They believed that this was where the millennium was slated to commence (or had already commenced) and that it was up to them to begin building the perfect society, their own New Jerusalem.

A group of Oneida Community Perfectionists posed in front of their communal home, the Mansion House, ca. 1875

Courtesy Oneida Community Mansion House

The first major wave of communal utopianism in the United States peaked just before the widespread availability of pho-tography (roughly 1820–50, with a lull in the 1830s). During this era, utopians such as the textile magnate Robert Owen and the apostles of Fourier broadcast their visions of a secular, cooperative New Jerusalem using paintings and lithographs. These technical-looking images of the ideal city were printed in utopian newsletters and Whig broadsheets like the New York Tribune and hung on the walls of “associationist” clubs and workingmen’s halls. Owen, who came to the United States from Scotland in 1824 to found Indiana’s New Harmony community, was the canniest of the utopian propagandists. He commissioned a British architect to build an elaborate, six-foot-square model of the “parallelogram” that he intended to build on the Western frontier. Owen’s parallelogram, like Fourier’s “phalanstery,” was essentially an entire city contained in a single building, a sprawling, high-tech palace for the people. John Quincy Adams was so captivated by Owen’s model that he displayed it in the White House during the winter of 1825.

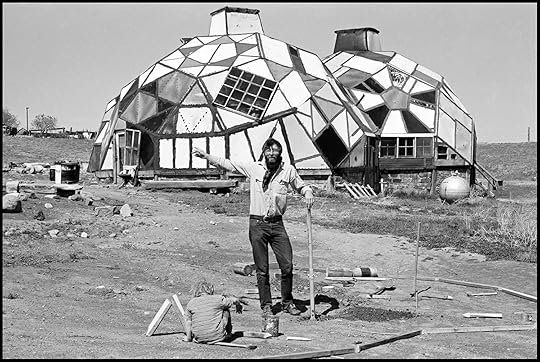

Dennis Stock, Drop City Artists’ Commune, Colorado, 1969

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

These pre-photographic images, projected straight from the imagination onto the page, helped inspire thousands of Americans to pursue the dream of building a New World utopia. The immense scale of the structures dreamed up by Owen and Fourier mirrored the grandiosity of their aspirations. As Meeker’s letter makes plain, the utopians of the mid-nineteenth century aimed for nothing less than a peaceful, worldwide revolution. Their logic was simple: if they could build one working model of the perfect society—a society founded on cooperation rather than competition—its shining example would inspire rapid and endless duplication, or, as one Fourierist optimistically put it, “thousands of analogous organizations will rapidly arise without obstacle and as if by enchantment around the first specimens.” This was how they planned to trigger a secular millennium. “The only practical difficulty,” Owen wrote with typical breeziness, “will be to restrain men from rushing too precipitously” into the new utopia.

A century later communitarian fever once again swept the United States. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, after the scene went sour in the East Village and the Haight, longhaired youths flocked to the remote counties of New York, California, Colorado, and New Mexico to build their own small utopias. Although they tried and often succeeded to build strongholds of consciousness and fraternity amidst the competitive bustle of American life, they rarely spoke, as their utopian forebears had, of global transformation. The dream of an American New Jerusalem was, for the most part, replaced by the search for a new Eden, a paradise walled-off from the fallen world.

Lucas Foglia, Victoria Bringing in the Goats, Tennessee, 2008

Courtesy the artist

The buildings tell the story. The “unitary dwellings” of the nineteenth-century utopians—the fanatically symmetrical Shaker dormitories, the ornate Oneida “Mansion House,” and Fourier’s (unrealized) Versailles-like phalanstery—were replaced, in the 1960s and ‘70s, by Drop City’s improvised Fuller Domes (called zomes), the scattered teepees of the New Buffalo Commune, and the assorted yurts, lean-tos, and chicken coops of countless backwoods communes. Like the nineteenth-century utopians, the hippie communards built homes intended to expand the meaning of the word “family,” but their ambitions were more modest, more spontaneous, and more realistic. They did not attempt to supplant the dominant institutions of America or “free the slave of all names.” They simply aspired to take leave of what they regarded as a repressed, faltering culture. (The lysergic cheerleaders at the vanguard of the psychedelic revolution are an interesting exception. Their rhetoric of instantaneous global awakening occasionally echoed the high-flown prophecies of utopians like Owen and Fourier.) Even those communes that were expressly organized around political activism did not regard cooperative living as the chief lever of social change. For them, communalism was a means—an inexpensive place to crash between marches—not an end.

On its face utopianism is a way of thinking about the future, of picturing, in H. G. Wells’s elegant phrase, “the shape of things to come.” For this reason, photographs of old utopias may seem quaint in the way that all antique visions of the future can. And yet, building or imagining a utopia is not only a way of thinking about the future, it is also a way to organize our grievances with the here and now, to nail our complaints to the wall. Nobody tries to build a new society if they like the one they live in. Seen in this light, the utopian experiments of the past offer up a surprisingly accurate psychological history, a chronicle of each era’s most acute frustrations. While these images may not reveal utopia as it was seen by fervid dreamers like Nathan Meeker, they present us with something just as valuable: a visual record of American longing and American discontent.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 209, Winter 2012.

Dreamlike Photographs of Life Among the Trees

Clare Richardson and David Spero document communities embedded in nature—and search for the promised land.

By Jason Oddy

Clare Richardson, from the series Harlemville, 2000

Courtesy the artist

From its inception, photography has been a bearer of conscience. Long before the traditions of reportage or “concerned” photography emerged, the medium’s capacity to produce an afterimage of reality meant that the past could persist into the present. Instantly invoking nostalgia, these fragments of the has-been reproach the complacency of the here and now. As early beholders of daguerreotypes intuited, there is an uncanny relation of past to present through photography. Photographer Karl Dauthendey commented: “We didn’t trust ourselves at first to look at the first pictures he [Daguerre] developed. We were abashed by the distinctness of these human images, and believed that the little tiny faces in the picture could see us, so powerfully was everyone affected by the unaccustomed clarity and the unaccustomed truth to nature of the first daguerreotypes.”

Yet if a century and a half on we have outgrown (or at least suppressed) that instinctive reaction, photographs still remind us of the contingency of our present. Forwarded across space and time, these emanations create a ripple in our consciousness. And since in front of the intractable stillness of a photograph it is we who undergo change, it is perhaps no exaggeration to say that photographs behold us, at least to the same degree that we behold them.

Clare Richardson, from the series Harlemville, 2000

Courtesy the artist

Over the years, photographers have harnessed this principle of mutual regard in various ways. The genres of photojournalism and socially engaged photography customarily depict a fractured world in order to prod the viewer’s conscience. But this is not the only way the medium can steer our emotional and moral outlook in new directions. Recently, as disenchantment with contemporary ways of living and anxieties about impending environmental catastrophes continue to grow, a handful of photographers have discovered a new brand of romanticism, turning their attention–and by extension ours–to various arcadias, in particular those that would lead us back toward a promised land.

For her series “Harlemville” (2000), the young British photographer Clare Richardson spent several months over a period of two years with a Rudolf Steiner community in upstate New York. Founded by refugees from late twentieth-century capitalism, Harlemville is a town where every attempt is made to live in harmony with nature. As part of the Steiner educational philosophy, children are sent into the woods in order to experience and understand the continuum that must exist between the environment and the self. Their immersion in the natural world is the focus of Richardson’s series.

Clare Richardson, from the series Harlemville, 2000

Courtesy the artist

Unlike many other recent bodies of work that have taken adolescence as their theme, these photographs portray this purportedly troubled period of life as a time of wonder, growth, and serenity. Richardson ‘s approach is observational, as though her subjects are unaware of her presence. She manages to achieve an intimacy with her subjects that surpasses simple candor. Looking at the images of Harlemville, the viewer is linked in a chain of empathy that seems to invite us to become part of the picture.

In one photograph, a group of boys stand in a river, bathed in Edenic sunshine. Their fishing spears are at the ready, their faces a picture of concentration. In another image, we see a boy in the water by a riverbank, his eyes closed and head framed by the roots of a tree. He seems almost to be dreaming nature into existence. In these, as in many of the other images, the audience is privy to more than just the secret world of childhood: Richardson’s sensibility allows us to enter into the youths’ rapt absorption and apparent oneness with their surroundings.

Laughter features little in “Harlemville,” but if the pictures are full of seriousness it is because they are above all works of feeling. Joel Sternfeld’s recently published project Sweet Earth looks at various instances of utopian communities in America with an ironic, distancing eye; Richardson, by contrast, is not in the least bit interested either in setting things into a historical perspective or in creating a conceptual framework for her work. Rather, her photographs are charged with the same idealistic sentiments that they describe.

David Spero, Mary and Joe’s, Tinker’s Bubble, Somerset, June 2004

Courtesy the artist

At the heart of “Harlemville” lies the notion of sustainability, not just in today’s common ecological understanding of the term, but in a deeper holistic way as well. This is a body of work that, in both content and form, would offer us moral and emotional sustenance. It provides a glimpse into a different way of life, one that exhorts us to pay humble attention to nature instead of being locked into a system that constantly obliges us to conquer and destroy it––and thus ultimately ourselves, too.

Many of the same ideas underlie “Settlements,” a project by British photographer David Spem, who has spent nearly three years taking pictures of environmentally “low-impact” communities in the forests of England and Wales. Although shot in an objective, almost Becheresque manner, Spero’s photographs are as much an expression of sentiment as is “Harlemville.” As its name implies, “Settlements” is a document of the dwellings that comprise these outposts of idealism. Their inhabitants hardly feature: the photographer feels that it is the structures themselves that best portray the back-to-the-land ideology that led to their creation.

David Spero, Cheryl’s, Steward Community Woodland, November 2004

Courtesy the artist

Looking at pictures such as Emma and John’s, Tir Ysbrydol (Spiritual Land), Brithdir Mawr, Pembrokeshire (2004), you can only wonder at how this human habitation with its turf roof and mud walls melds so perfectly with its surroundings. In another picture, The Longhouse, Steward Community Woodland, Devon (2004), we see how that building has almost disappeared into the adjacent trees. This seeming harmony between the natural and the man-made is one of the central themes that Spero tackles in this body of work. “I was particularly interested in the lightness of these structures and in how the world you build around you affects your relationship to the environment,” he explains. “It’s quite amazing how close to the environment these people actually are.”

Spero’s frontal approach and preference for flat, undramatic lighting lend his pictures a decidedly factual air. Yet even the everyday clutter––dirty dishes or log piles or pots heaped up beside the homes––does not disturb the apparent deeper unity depicted here. Instead, these mundane details seem to belong in the landscape, as though they are necessary preconditions for a realizable arcadia.

David Spero, Tony and June’s, Brithdir Mawr, Pembrokeshire, July 2005

Courtesy the artist

While such a tack is somewhat grittier than Richardson’s visual reveries, both “Settlements” and “Harlemville” envision a mythic wholeness that opposes what many of us understand to be humanity’s current fractured condition.The search for a lost Eden, or for a promised land, is as old as civilization. Here it is updated using the magic of photography, whose close contact with reality tends to brand the myths it depicts with the stamp of veracity. When treated in other media–in painting, say–the theme of arcadia is likely to remain an idle if agreeable daydream. When represented in photographs, it becomes a vision of something possible. And so, however partial and to varying degrees romantic Richardson’s and Spero’s portrayals of their rustic idylls may be, they contain an incontrovertible dimension of actuality that seems to indicate that they are something more than just useful fictions.

Traditionally, photographs have either berated or tantalized us with the unalterable, unrepeatable past. By picturing communities that have broken step with the mainstream march toward global doom, these two British artists have instead chosen to put potential futures on view, to similar effect. The numbers of people involved in Harlemville and in the forest communes of Britain may be few, and their attempts to establish tangible ecotopias may be fraught with problems. But the fact that these places exist at all is of no small symbolic importance. For like every utopia, they refute the inevitability of history. As we look around for models to keep us going now, and into the uncertain future, we could do worse than to follow the gaze of photographers such as Richardson and Spero. Their focus on the realized fantasies that these experimental communities represent might just prick us into turning away from our engineered existences, to seek a new life among the trees.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 186, Spring 2007.

February 4, 2020

A Photographer’s Intimate Portraits of East Village Art Stars

In the early 1980s, Tim Greathouse photographed David Wojnarowicz, Greer Lankton, and Jimmy DeSana—and captured New York’s downtown scene before the destruction of AIDS.

By Jesse Dorris

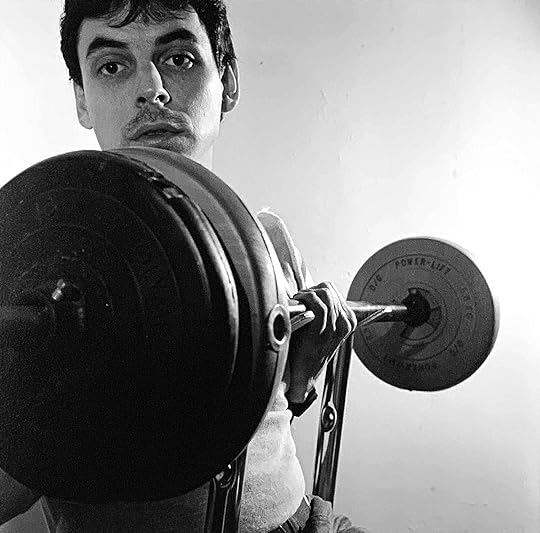

Tim Greathouse, Self-Portrait, 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

At most parties, the really good stuff happens in the bathroom. And so it was at a gathering in a tenement on East 9th Street in New York’s East Village one evening in March 1982. Gracie Mansion, a downtown fixture who had appropriated the mayor’s residence for her name, made a gallery out of her water closet, called it the Loo Division, and filled it with prints by her friend, photographer and artist Tim Greathouse. Everybody seemed to visit, including Melik Kaylan, who reviewed the show for the Village Voice and thereby anointed the gallery. It must have felt like any number of futures were beginning.

Tim Greathouse, Gracie Mansion, Gallerist, 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Sixteen years later, Greathouse would be dead of AIDS, along with countless others who had seen their world reflected in the photos on Gracie’s walls—in Work Prints (1982) and, later, another show in the Gracie’s permanent space on St. Mark’s. Or who had seen early work from Jimmy DeSana and Zoe Leonard at Greathouse’s own gallery, Oggi Domani, the first in the East Village devoted entirely to photography. Or who had taken in the visual identity Greathouse as a designer developed for Marlborough Gallery and other clients. Those who survived the plague, however, wouldn’t see much more of Greathouse’s own work. He tended to champion other artists over himself, and when he died at the age of forty-eight without a proper estate, his high-contrast black-and-white portraits and graphic works on paper (and the odd sculpture) were returned to the apartments of his devoted friends, unremembered by the downtown art world Greathouse intensely, if only briefly, did so much to encourage.

Tim Greathouse, Jimmy DeSana, Artist, 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Until now. Albeit, currently on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, offers a new view of Greathouse that centers his own electric body of work. Gathered with crucial assistance by Mansion and Greathouse’s longtime friend and roommate Sur Rodney (Sur), Albeit includes a few fine late paintings which now look like relics of activism, in which stenciled letters hector “AIDS” à la Gran Fury’s bittersweet swipe of Robert Indiana; or the lyrics to “We Shall Overcome” breaking apart like a Christopher Wool, fighting to be seen in fields of jaundiced yellow, or perhaps submerged under blood-red blurred boxes. “Ecce Homo,” says a dark piece from 1988, and it’s tough not to see faces of the dead in the blank spaces around the command.

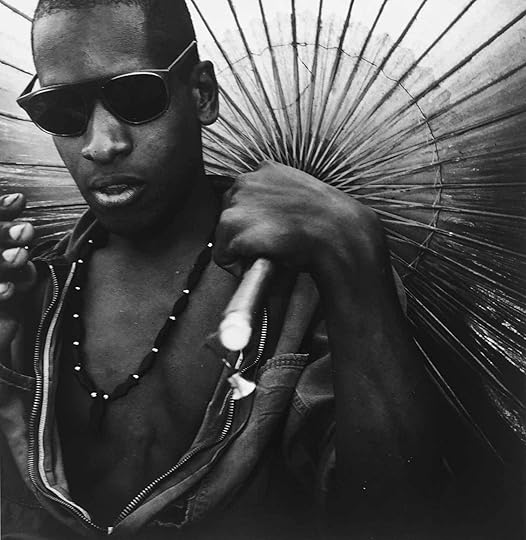

Tim Greathouse, Sur Rodney Sur, Archivist, Gallerist, Gracie Mansion Gallery, 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Indeed, faces form the heart of this show, vibrating so strongly in Greathouse’s gelatin-silver prints that the photographs almost become holograms. Two barely contain Sur Rodney (Sur); both taken at Gracie Mansion Gallery in 1983, they show him either boldly wearing big sunglasses and carrying a paper umbrella, or just staring down the lens at the center of it all. “It never felt like I was posing,” Sur told me recently. “We were living in the midst of drug trade and guns on Avenue C.” Greathouse had moved into a storefront his friend Larry Loffredo rented, but because it was a commercial space, he had to open a business. “So why not a photo gallery? He could live illegally in the back, something easy for him because all his belongings could fit into a file drawer,” Sur says. “He was a minimalist monk.”

Tim Greathouse, Rhonda Zwillinger, Artist, 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

A monk with a keen eye for cropping: Greathouse’s portrait of Larry Loffrado is equal parts chest and head, with a stiff shadow parallel to his jawline. The image is coolly formal, like the bust on a coin you’d spend on a dime bag. In one portrait, artist Rhonda Zwillinger emerges from the shadows like a Hollywood star getting her first break; in another, she goes full Farrah Fawcett, in a black swimsuit so dark it creates one triangle for her chest and another for her arm—akimbo, as if the glamor of her body were a mathematical fact.

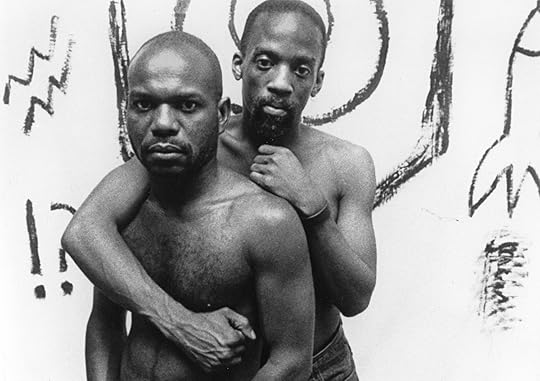

Tim Greathouse, David Wojnarowicz, Artist, ca. 1983

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Gracie Mansion herself shows up in two photographs, taken at her show of Stephen Lack’s paintings, either peeking from behind her chic fringe of hair or topless and charismatically flexing her bicep. “Tim was my best friend,” she told me. “So it felt like a collaboration.” Lack himself shows up in another work, eyes ablaze and hands holding his head as buildings twist behind him. In a pair of landscapes of the infamous gay Valhalla, Pier 47, buildings collapse as if felled by the force of a vibrant Keith Haring piece poking through a corner, or another by David Wojnarowicz—who glares at the viewer in perhaps the show’s most astonishing photograph, sitting in a T-shirt in two-thirds of the frame and taking up the viewer’s entire field of vision.

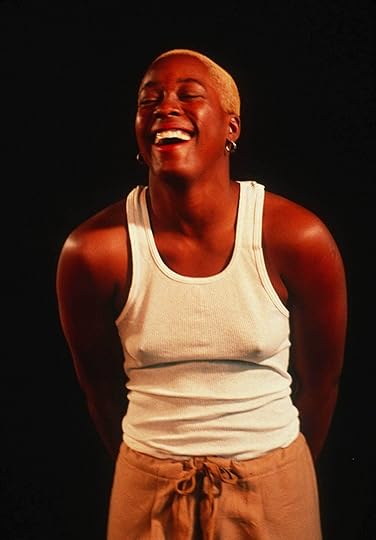

Tim Greathouse, Greer Lankton, Artist, 1984

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

A couple of self-portraits capture Greathouse’s evident charm, whether serving the “clone” look—white tank top, mustache, stern bedroom eyes—in a 1978 shot or hovering in a blur of his own paintings a few years later. In 1983, he peeked through the hole of a wooden spoon and gave a little smile: I’ve never seen a photograph I’d more like to hug. Albeit, a first draft for a much-needed history of Greathouse and his warmhearted work, will hopefully nudge others who gathered in bathroom parties back then to go through their own file cabinets and see what else might remain.

Tim Greathouse, Self-Portrait, ca. 1980s

Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

Jesse Dorris is a writer based in New York.

Tim Greathouse: Albeit is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, through February 29, 2020.

January 30, 2020

Laia Abril: Research, Narratives, and Platforms

Join artist Laia Abril for a two-day workshop to learn the best strategies and practices to use when developing a long-term project. Abril, whose research-based work revolves around the conceptualization and interpretation of facts, will teach participants how to enhance the investigation and construction of a photographic narrative.

Trained as a journalist, and through her experience as a photographer, bookmaker, and art director, Abril has developed a collaborative creative method to construct, analyze, and refine narratives across a number of different platforms. Examples of her work methodology will encourage participants to think laterally about their own projects.

This workshop will also look at how a combination of different media—such as photography, design, text, film, and illustration—can transform an idea into a wider artistic project. Participants will think about how a body of work can take shape in various forms, whether as a photobook, editorial piece, or exhibition. Participants are encouraged to bring an existing body of work, book mock-up, or installation proposal that they would like to evolve beyond the scope of photography. Participants that have projects or ideas at an earlier stage will focus on developing a research plan for the work.

Laia Abril (born in Barcelona, 1986) is a multidisciplinary artist working in photography, text, video, and sound. Abril focuses on photography that raises uneasy and hidden realities related to sexuality, eating disorders, and gender equality. Her projects are produced across various media, such as installations, books, web docs, and films. Her work has been shown widely and published internationally. She has published several monographs—the highly acclaimed The Epilogue (2014) was shortlisted for the Paris Photo–Aperture First PhotoBook Award, Kassel Photobook Award, and PHotoE SPAÑA Best Photography Book of the Year Award. After completing her five-year project On Eating Disorders in 2015, Abril embarked on a new long-term project, A History of Misogyny. Its first chapter, “On Abortion,” was first exhibited at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2016, and was the first recipient of the Prix de la Photo Madame Figaro. Her book On Abortion: And the Repercussions of Lack of Access (2018) won the 2018 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year Award, and was a finalist in the 2019 Deutsche Borse Photography Foundation Prize. Abril is currently developing the next chapters. She lives and works in Barcelona.

div.important {

background-color: #eeeff3;

color: black;

margin: 20px 0 20px 0;

padding: 20px;

}

Objectives:

Build a set of goals that will help further advance your project(s)

Strategize how to build out your narrative project

Plan a photobook project for your students

Materials To Bring:

A body of work, either in progress or finished. You can bring the work as prints, digital files, in book form, as an exhibition proposal, etc.

Tuition:

Tuition for this workshop is $500 and includes lunch and light refreshments.

Currently enrolled students and Aperture Members at the $250 level and above receive a 10% discount on workshop tuition. Please contact education@aperture.org for a discount code. Students will need to provide proper documentation of enrollment.

REGISTER HERE

Registration ends on Friday, March 20, 2020

Contact education@aperture.org with any questions.

GENERAL TERMS AND CONDITIONS

Please refer to all information provided regarding individual workshop details and requirements. Registration in any workshop will constitute your agreement to the terms and conditions outlined.

Aperture workshops are intended for adults 18 years or older.

If the workshop includes lunch, attendees are asked to notify Aperture at the time of registration regarding any special dietary requirements. Please contact us at education@aperture.org.