Aperture's Blog, page 75

March 19, 2020

These Women Changed the History of Photography

Celebrate Women’s History Month with 14 must-read articles and interviews that chronicle the impact of women artists, from the dawn of photography to today.

The Woman Who Made the World’s First Photobook

Why Anna Atkins deserves her place in the pantheon of great photographers.

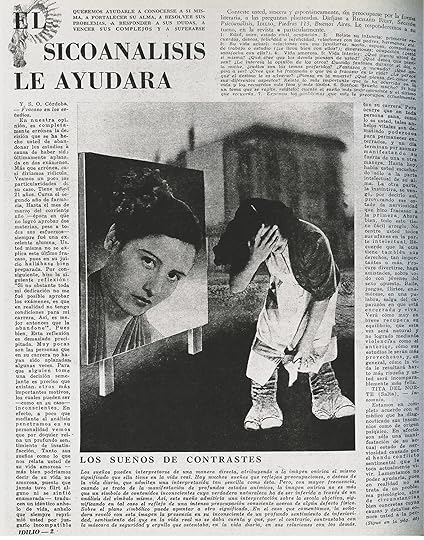

Graciela Iturbide’s Dreams and Visions

The life and work of Latin America’s most revered photographer. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 236, “Mexico City.”

For Annabelle Sellforf, Architecture is Not About Powerful Images

The art world’s favorite architect on her photographic influences, designing sought-after homes, and how buildings can actually “do something.” This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home.”

A Japanese Photographer’s Encounters with Natural Disasters

Eight years after a devastating tsunami, Lieko Shiga investigates Japan’s haunted landscapes. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 234, “Earth.”

When Women Photographers Went to War

From Gerda Taro to Susan Meiselas, a new book examines the ways eight women have expanded the field of war photography. This piece originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review 017.

How Do Portraits Keep Families of Incarcerated Individuals Together?

Drawing from her family’s experience, Nicole R. Fleetwood considers prison photographs as objects of love and belonging. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation.”

What Is A Feminist Photobook?

Carmen Winant on feminism, photobooks, and the radical gestures of world-building. This piece originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review 017.

Tania Franco Klein’s Magic Spells

Inspired by Mexico City’s Sonora Market, the photographer’s cinematic new series depicts an unshakeable belief in enchantment. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 236, “Mexico City.”

The Woman Behind the First Photo Gallery

Helen Gee risked everything to open Limelight in 1954, selling prints by Ansel Adams, Berenice Abbott, and Robert Frank for less than fifty dollars each. This piece was originally published in Helen Gee: Limelight, a Greenwich Village Photography Gallery and Coffeehouse in the Fifties.

Rosalind Fox Solomon’s Confrontational Photographs Transcend Time and Place

In a conversation with Francine Prose, the photographer speaks about the trajectory of her career, as well as her recurring themes of ritual, religion, gender, and travel. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue.”

These Radical Black Women Changed the Art World

Jessica Lynne speaks with the curators behind a landmark exhibition about the revolutionary artists who transformed American culture.

Rosalyne Blumenstein and the Art of Living

In her newest series, artist and activist Zackary Drucker pays homage to a trans icon. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 235, “Orlando.”

12 Inspiring Photobooks by Women Photographers

From seminal first monographs by Diane Arbus and Nan Goldin to modern classics by Deana Lawson, Rinko Kawauchi and more.

Three Women Photographers Reclaim the American Landscape

Susan Lipper, Kristine Potter, and Justine Kurland deconstruct the mythology of the Wild West. This piece originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review 015.

Want to be the first to hear about Aperture’s latest publications? Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss our new releases, latest editorial content, and more.

March 18, 2020

For Annabelle Selldorf, Architecture is Not About Powerful Images

The art world’s favorite architect on her photographic influences, designing sought-after homes, and how buildings can actually “do something.”

By Julian Rose

Annabelle Selldorf, New York, October 2019

Photograph by Balarama Heller for Aperture

Annabelle Selldorf is the art world’s favorite architect. But her work is nothing if not subtle—rather than the splashy icons we have come to expect from the starchitects long chosen to design art galleries and museums, Selldorf prefers to craft what she modestly calls “functional” settings for art. Rooted in an understated modernist aesthetic, with an updated material palate and innovative geometries, Selldorf ’s exhibition spaces have remade the white cube for the twenty-first century. Small wonder, then, that she is frequently sought out to design the homes of high-profile art collectors, or that she has now designed major museums and galleries for over two decades, from the Neue Galerie and the Swiss Institute to David Zwirner and Hauser & Wirth.

Given her sensitivity to art, it’s not surprising that Selldorf ’s practice is also engaged in an ongoing dialogue with artists. She has collaborated directly with contemporary artists such as the photographer Todd Eberle, and she readily acknowledges the influence of a generation of postwar photographers who examine the modern metropolis and industrial landscape—particularly Bernd and Hilla Becher, whose work hangs on the wall of her light-filled New York office just north of Union Square. That’s where the architecture critic Julian Rose visited Selldorf last fall to talk about her relationship to photography, both professional and personal, and the intriguing challenges faced by architects who design homes for art.

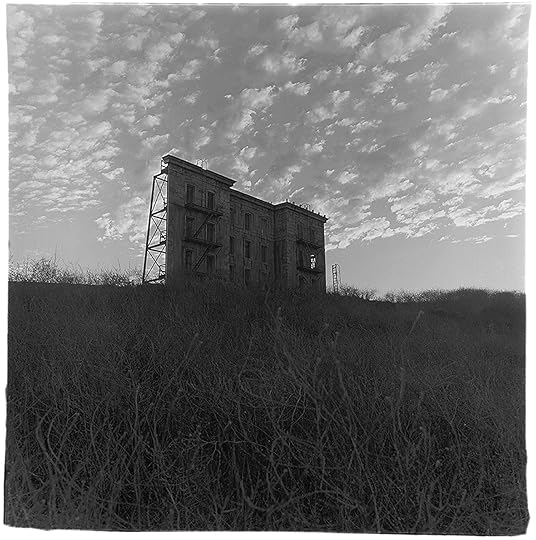

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Wassertürme (Water towers), 1966–86

Courtesy the Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher, and Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur–Bernd and Hilla Archive, Cologne

Julian Rose: Let’s start with the photographs right here in your office. You have works by Bernd and Hilla Becher on the walls. I’d love to hear what they mean to you. Of course their subject is architecture, and they’re gorgeous photographs, no question, but I could argue that they’re critical of architecture too.

Annabelle Selldorf: They are all of that. They have a kind of face value that draws you in. It’s not just what you look at, but how you look at it. The Bechers look without drama, in a way. And the “without drama” is one of the things that I am interested in, because it takes away our need for the sentimental hyperbole that accompanies practically everything people do. We always need to find hyperbole for our architects, for their work: it’s “amazing,” it’s “incredible,” and on and on.

Rose: So what you’re getting from those images is not so much an aesthetic per se, certainly not a style. You’re talking about photography as a mode of looking, an approach to the world— a kind of methodology.

Selldorf: Right. I don’t believe I’ve ever had a conversation with anybody about this, but it is a process of clearing away layers that allows you to look at something straight. Mies van der Rohe once said, “One doesn’t invent a new architecture every Monday morning.” Rather, you develop a methodology.

Rose: What other photographers are important to you?

Selldorf: I love the work of Gabriele Basilico—he has the eye of a humanist, and, at the same time, I think it’s the eye of an architect. He did a series of pictures of war-torn Beirut, and they were riveting.

Gabriele Basilico, Beirut, 1991

Courtesy the artist and Archivio Gabriele Basilico, Milan

Rose: He did study architecture, after all, and there does seem to be a level of sensitivity—an insight into how people and buildings relate—that an architect can bring to photography.

Selldorf: In a funny way, the Bechers don’t have that because to them buildings are objects—they just categorize and anthologize. Whereas with Basilico, I always feel that his photographs are about people and how they interact with architectural environments. Whether it’s images of bombed-out Beirut, or buildings in Milan, or the amazing, very moody photographs he did of the industrial park in Dunkirk, France, his work is unbelievably powerful because it has this human dimension. I’d always hoped that one day I could get him to photograph one of my projects. That’s so naive and silly, but it was a measure of my admiration.

Rose: In general, architectural photography is not often done by the same photographers we think of as artists in their own right. Is that something you think about in relation to your work?

Selldorf: Absolutely. We did a book a couple of years ago, Portfolio and Projects (2016), and I asked my friend the photographer Todd Eberle to do the photography. I think he is one person who negotiates between the two categories. I just asked him to put together a portfolio of images of my work. He went to all these different buildings, and he took pictures.

Rose: With minimal direction from you?

Selldorf: Yes. But we’ve known each other for a long time. And I wanted the portfolio to be as much about his eye as it is about our buildings. In the beginning, I really wanted him to photograph in black and white, because I find that lends a particular focus. But he didn’t want to do that. Early in his career, he photographed a lot in black and white, but now he thinks in color. So I had to make a decision. If I was going to work with an artist, I couldn’t tell him what to do.

Gabriele Basilico, Milano ritratti di fabbriche (Milan factory portraits), 1978–80

Courtesy the artist and Archivio Gabriele Basilico, Milan

Rose: Was it hard to let go?

Selldorf: Not at all.

Rose: What did you learn from seeing your work through his eyes?

Selldorf: He discovers the composition right away. Often the work we do comes from a utilitarian, almost wishful idea about how people will move in a space, and I start to think that this idea is guiding how the spaces should be proportioned, and all of the rest of the design. But, of course, eventually it does return to the question: what does it look like?

Rose: It’s intriguing that you feel his images almost tease out the underlying intention in your designs. I think frequently it’s the reverse—projects are designed for the photograph.

Selldorf: Absolutely. I remember from when I was a young architect people would say, “This is a three-picture job.” It makes you want to weep.

Rose: Does photography play a role in your own process?

Selldorf: It has a lot more than I necessarily intended because of what we were just talking about. Nicholas Venezia, who works in the office in communications, is a photographer, and he has brought his sensibility to our relationship with the outside world. He has learned to understand what we do, and he channels his own talent and his own eye to participate in our process. Sometimes when we’re starting a project, I ask him to document the site, and that is so much better than relying on my own amateurish photographs— I always think that I take such great photographs, and then I look at them and I realize I’m really not very good at it after all.

Rachel Ruysch, A ‘Forest Floor’ Still Life of Flowers, 1679–1750

Courtesy Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Rose: I know you’re also something of a collector. What is the difference between the art you work with and the art you live with?

Selldorf: It’s an interesting question, because it has become so fashionable for people to display their personality through a collection—usually an eclectic collection that portrays them as someone eclectic. But I am not a collector. That’s very important. I have a lot of things, but that’s just because I’m getting old—I’m only half kidding. I have never thought of myself as a collector, but over time, I have discovered things that I respond to. I love drawings, because drawing is something that I can relate to.

Rose: It’s part of your own practice as an architect.

Selldorf: Part of my process, yes. But sometimes I am envious of artists, like when I see a Paul Klee drawing—I can feel his immersion in the drawing process, I marvel at the exploration of color, the detail, the wit. That’s the difference between an artist and an architect. An artist makes a drawing about drawing. I make a drawing because it’s a step toward making something else.

Rose: It’s interesting to me that we haven’t discussed painting yet. Painting was really the preferred medium of modernist architects. Le Corbusier is the most obvious example—he actually fancied himself a painter as much as an architect—but any number of his contemporaries also cited modern painting as an important source of inspiration. Has painting’s importance for architects been usurped by other media, like photography or drawing?

Selldorf: Well, I do have some paintings too. I have two seventeenth- century Dutch still lifes that I like very much. One is a scene in the forest ground. Strictly speaking, it’s not a still life because there is a salamander in it, and a fly, and a butterfly. But the painting takes you into a different world—it’s an almost surrealist setting, but it has been depicted with total realism. There’s something so unfamiliar and unexpected about it; it’s like it opens up a new space in your brain.

Selldorf Architects, Van de Weghe Townhouse, New York, 2012

Photograph by Todd Eberle, 2015

Rose: You’re saying that this kind of image, whether it’s the Klee drawing or the Dutch painting, can transport you into a different world.

Selldorf: That’s exactly right, and actually very different from how I tend to think about photography. Photography, more than anything else, captures a moment in time. I have a photograph that I bought from Fraenkel Gallery a long time ago. It’s of one of those automated photographs from a British bombing mission during the war. The pilots documented the before and after as they flew over. I’ve always found this image fascinating, because it shows the crazy idea that we force change in such a brutal, sudden way, in such a violent and inhuman process.

Rose: I can see how this distinction plays into your own relationship to different kinds of art and affects what you might want to hang in your own home or your own office, but I’m curious to know if it also carries over into the spaces you design in which other people look at art. You’ve done a lot of houses for collectors, for example. Are there certain principles—certain ideas about what it is like to live with art—that add up to a common approach to this kind of project? Or does each one evolve on a case-by- case basis depending on the particular client and the particular collection?

Selldorf: I think that all our work has a kind of specificity that relies on getting to know the client. I also think that many people call themselves collectors when they are not. A lot of people have the money to buy a lot of things they like and to hang them on the wall. A collector is somebody who has a specific mind-set, somebody who pursues art with rigor and a specific intellectual disposition, who systematically fills out a thesis, if you will. Very few people do that. But it’s fun to find someone who is actually putting thought into a collection, because then they think about space differently.

Selldorf Architects, West Village Residence, New York, 2013

Photograph by John Chelsey, 2013

Rose: And I imagine that in these cases, your work can essentially become another formulation of the thesis. You’re shaping the collection, perhaps not in a direct way, but you’re helping to bring a particular vision to life. But this question of having a thesis—or not having one—raises the question of architecture’s neutrality, which I think we should talk about in relation to your gallery architecture. It’s always seemed ironic to me that the term neutrality has become so controversial in this context. Take the white cube, which we all know is a bit of a straw man but is still a dominant typology of exhibition architecture today. On one side, you have artists complaining that their work is always shown in a white cube. They’ll say that the white cube isn’t neutral at all, that it’s ideological and constricting. On the other side, you have architects bristling at the fact that they’re always asked to design white cubes. They’ll ask why architecture needs to stay neutral. You seem to have found a way beyond this binary in your work. I don’t quite know what to call the gallery typology you’ve invented—I wish I could come up with a good neologism.

Selldorf: A good hyperbole?

Rose: Exactly! But what I’m trying to get at is that your gallery spaces aren’t always white, and they’re not cubes either, but they still feel very sensitive, almost respectful to the art that’s displayed in them.

Selldorf: They’re not respectful. They’re functional. I don’t think that neutrality exists. Take the white cube: It’s interesting because it’s a foil, right? I don’t think that’s limiting. It’s not inherently good or bad. Or rather, it’s good only if it’s good architecture, and that has to do with a host of things that have to do with proportions, with light, with the way you place a human being in the middle of it.

Selldorf Architects, Skarstedt Residence, Sagaponack, New York, 2014

Photograph by Nikolas Koenig, 2015

Rose: So would you say that you’re more interested in designing a certain kind of gallery experience than a gallery aesthetic?

Selldorf: I tend to think that distraction is not desirable. I think that noise takes away from focus. In the most primitive way, when we design spaces for art, we facilitate concentration. We give people the opportunity to focus on what they are meant to see. I don’t care whether somebody doesn’t like white, or doesn’t like green, for that matter. What I care about is a kind of calm, or tranquility, that creates a setting. We live in an age where everything is event-driven, and, for me, that’s overwhelming.

Rose: Often this calm seems to be expressed through the details of your architecture. At David Zwirner gallery, I’ve always been struck by the warm wood accenting the concrete.

Selldorf: Zwirner’s gallery is a very good example. It’s about looking at art in the best circumstances, but it doesn’t deny itself a measure of personality or presence. I think it’s in dialogue with the art. It’s not a neutral space.

Rose: It’s not neutral, but also not overpowering.

Selldorf: I want people to feel welcomed by these spaces. That’s not an event-driven sentiment, for me, but more about longevity. These spaces should last. Today, we are questioning how museums function, and everyone agrees that beaux-arts museums are bad and big open spaces are good. But I think exactly how and why we’ve decided this are worth examining.

Selldorf Architects, Chelsea Townhouse, New York, 2015

Photograph by Todd Eberle, 2015

Rose: It’s definitely worth emphasizing that a neoclassical, beaux- arts museum is not inherently any more an expression of power than an ultracontemporary one. But you’re also suggesting, I think, that there are fundamental continuities in the experience of art. Traditionally, museums were designed to be spaces of quiet contemplation, and we still need spaces without distraction. Maybe there is a sense in which going to a great nineteenth- century museum, say [Karl Friedrich] Schinkel’s Altes Museum, is not materially different from going to any museum that has been constructed in the twenty-first century.

Selldorf: Well, it isn’t to you, and it isn’t to me, because we have the confidence that comes from always being afforded that access.

Rose: That’s a good point.

Selldorf: I really think that’s a very, very important thing to understand. We need to ask: How do we create places that are inclusive? And if they are inclusive, they have to be inclusive of everybody, which is by necessity very complicated, because everyone is entering from a different place. How does the architecture of the museum contract or expand in ways that communicate openness?

Rose: So rethinking the institution starts with the architecture, in a very fundamental sense.

Selldorf: I think so. In a way, this gets back to photography. Today, because we are so image-driven, everybody thinks they’re an expert on architecture because they’ve seen photographs of it. But that’s not what architecture is about. Architecture is about being there. Architecture is not about powerful images, it’s about a building actually doing something. When I was in architecture school, we would do field trips to visit buildings, and that was a very different experience from seeing them in photographs. And I think that is no different now.

Selldorf Architects, Neue Galerie, New York, 2001

Photograph by Todd Eberle, 2005

Rose: Architecture has a tortured relationship with images, though. There are so many important buildings that are known almost entirely through photographs. The most extreme example might be Mies’s Barcelona Pavilion, which was built in 1929 and destroyed within a year. It was eventually rebuilt in the 1980s, but its impact on the development of modern architecture—which was enormous—was almost entirely through its circulation in the form of photographic images. Is there a tension between architecture’s reliance on the image and the idea that you just expressed, that a building will always exceed an image somehow? Images can be very powerful tools in the hands of architects, but their work is also supposed to be about specificity, about a relationship to a place—precisely the things that we can’t circulate, that can’t be captured in a photograph.

Selldorf: There is a tension, but today I see it less in photography than in the production of renderings. Everybody wants you to show them, in advance, exactly what they’re going to see when the building is finished. And because it is now possible to make renderings of such high quality that they are truly photo-realistic, that is what everyone expects. I find this incredibly depressing— it’s a fake reality. I know that sometimes we do a rendering that looks exactly like the building, and after it’s built, we don’t have a really good photograph of that particular angle, so we continue to use the rendering because that represents it better. What I really mind about that is a kind of consumer attitude we’re creating. It’s like everyone is telling us, “Give it to me NOW.” We just lost a competition because I didn’t think of providing teaser images. I am heartbroken, because it’s a job I wanted. And I didn’t want this job because I was going to make amazing images; I wanted this job because it was an opportunity to do something with architecture that I haven’t done before.

Rose: What seems so problematic today is that often the image precedes the architecture, and the building is merely catching up. But obviously architects aren’t going to stop making renderings anytime soon. Can you use images in ways that are still surprising?

Selldorf: One interesting thing is that you cannot make a school anymore. Architects like Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown used images to represent a way of thinking.

Rose: And that way of thinking became a broader architectural movement. It’s true that the entire generation of postmodern architects was, on some level, united by a shared interest in certain kinds of images.

Selldorf: There is no longer any interest in that kind of intellectual community. I think architects are valued only as individuals. Sometimes people ask me if I’m a modernist, and I don’t even know what that means. How could I represent something like modernism by myself? The irony is that when I started my office, I was alone, and I was unbelievably intimidated by my colleagues—I really did not seek the company of other architects. Today I do. Because I think, in small ways, I can contribute to changing our conversation.

Julian Rose is an architect and critic based in New York.

Read more from Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Marking Time

When a loved one is incarcerated, how do portrait studios keep families together?

By Nicole R. Fleetwood

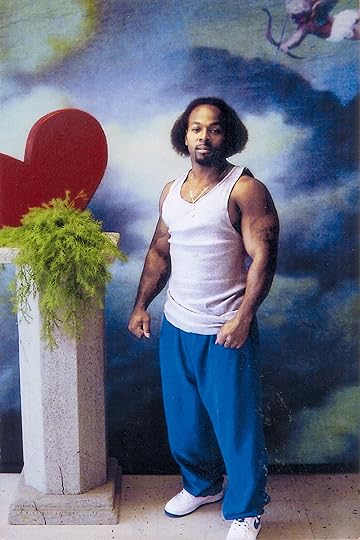

Allen, Valentine’s Day portrait, ca. 2010

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

Since 1994, I have had an exchange of words and images with my cousin Allen, who was sentenced to life in prison at the age of eighteen. We write to each other regularly, often reminiscing about growing up in southwest Ohio. There is such a familiarity in our connection, although our time together is limited to a couple of hours during each of my visits to see him. Allen and I grew up as siblings, along with several other first cousins in our large and close-knit family. His mother is my mother’s older sister, and child-rearing was very much a group effort that was shared among all the female relatives.

Allen ends all his letters to me in the same way: “Niki, send more pictures. Love, your lil cuz Allen.”

His requests for pictures make me think of other populations removed from their loved ones—migrant workers, those in exile or at war, those estranged from their families—who stay connected through letter writing and family photographs. I send him pictures, and he reciprocates. I have a small suitcase of memorabilia from Ohio prisons that includes letters, greeting cards, and prison photographs sent from Allen and other male relatives during their time incarcerated. The photographs are studio portraits taken by incarcerated photographers whose job in prison is to take pictures. Allen poses in them sometimes with props, always in uniform. The backdrops are painted by incarcerated people, and break up the uniformity and repetition of the prison attire and staged poses. There are also photographs from our visits to see Allen. In most of these, he stands in the center, and we huddle around, hugging him tightly.

In the first few years of his imprisonment, I could not look at these photographs that arrived tucked behind his letters. I dreaded opening an envelope from him if I could feel that the contents included something akin to the thickness and flexibility of photo- graphic paper. I would quickly glance and put the photographs back in the envelope, feeling much more comfortable with the letter. With his words, I had space to process and react. With the pictures, I had difficulty controlling my emotions. Gradually, my looks grew longer. I began to fixate on certain details—his hairstyle, a new tattoo, the shape of his arms and his neck. Then, as an experiment, I decided to hang the photographs around my home—secured by magnets on the refrigerator, tacked to a wall, or taped to the back of a door. After a while, they no longer unsettled me; they were just there, along with other images and possessions in my cluttered home.

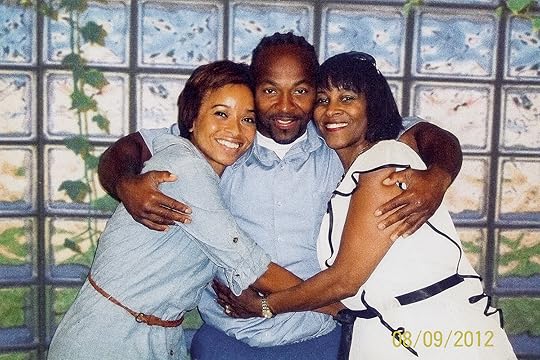

Nicole (the author), Allen, and Sharon (Allen’s mother), August 2012

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

In some ways, I forgot they were on display until a friend, who is an art historian, visited my home and inquired about one of them. Hanging on my refrigerator was a photograph of another cousin, also imprisoned in Ohio. In the portrait, De’Andre, in his late teens, smiles at the camera; he stands in a blue uniform, while hugging his grandmother (my aunt Frances). The backdrop is a painting of a winter scene, with snow-covered trees and rolling hills. A deer’s partial figure animates the landscape. I replied, “That’s my cousin De’Andre in prison during a visit from his grandmother—my aunt.” My friend was shocked: “Wow. That was taken in prison … There’s so much love in that image. They both look so happy.”

My friend had never seen a photograph documenting a family visit to an imprisoned relative and was unaware of how common these images are among groups most affected by mass incarceration—blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, and poor whites. The smiles and hug shared between grandson and grandmother were far from what he associated with prison life and culture. He compared the fantasy backdrops and setting to photographer James VanDerZee’s early twentieth-century portraits of black residents of Harlem. Also notable in VanDerZee’s work is the intentionality of his photographic subjects to use portraiture to document aspirations for upward mobility, equality, and inclusion. VanDerZee’s photographs have a sense of futurity, hopefulness, and often a subtle or explicit claim of the nation (the U.S. flag as prop or black soldiers in uniform); his images document anticipation of a better life for blacks of the time period.

My friend’s comments led me to see these photographs as more than documents of my family’s pain and loss, our separation from De’Andre, Allen, and other loved ones. Millions of them circulate between incarcerated people and their families and friends, given that there are over two million people incarcerated in the United States. In terms of sheer volume, prison photography is one of the largest practices of vernacular photography in the contemporary era. Like most vernacular photography, these images are primarily in private collections, housed in shoeboxes, photo- albums, drawers, and closets. These photographs serve as important visual and haptic objects of love and belonging structured through the U.S. prison regime, and provide an important counterpoint to a long history of visually indexing criminal profiles, such as mug shots and prison ID cards. Alternately, these photographs reveal the quotidian familiarity of penal settings for many millions who must navigate familial and intimate relations through prison bureaucracies and surveillance.

Deana Lawson, Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jasmine & Family, 2013. Installation photograph by Jason Wyche

© the artist

Among the most striking features that set these images apart from more publicly circulated photographs of prisoners are the emotive smiles, the imaginative backdrops, and the familial gazes of the photographic subjects that, one could argue, acknowledge their intended audience. Within portrait photography, backdrops tend to be read as signs of aspiration, futurity, and fantasy. In prison portraiture, the backdrops are more varied than the poses and uniforms of the imprisoned photographic subjects. Carceral backdrops project exterior life—a space outside prison walls—and they fall within landscape-painting traditions. While some backdrops reference iconic landmarks, like New York City’s skyline, the majority do not project a sense of place or specificity of location. Instead, they represent a sense of nonconfinement, a lack of bars, boundaries, borders—an ungoverned, yet manicured, space.

Until recently, vernacular prison portraits have had little visibility outside of their widespread interchange between incarcerated people and their personal networks. However, in the past few years, these images have circulated more broadly in public culture as art, appearing in exhibitions, catalogs, art auctions, and blogs dedicated to prison culture. David Adler’s collection of prison portraits, which has received considerable attention, is one example. Photographer Deana Lawson’s series Mohawk Correctional Facility: Jasmine & Family (2013) is another. The photographs are of Lawson’s cousin Jasmine; Jasmine’s incarcerated partner, Eric; and their young children. The name of the series is taken from the prison where Eric was incarcer- ated—a name that reiterates the dispossession and confinement of indigenous peoples, a carceral facility now primarily occupied by hyperincarcerated young black and Latino men from New York City, and staffed by rural white workers. In the series, we see the power of prison studio portraits to document familial and intimate relations. In some photographs, Jasmine and Eric hold each other affectionately. They kiss and hug. In others, they stand together as a family with their young children. The backdrop is unchanging and more austere than in many prison studios. It is a mural painted on cinder blocks; the lines of the blocks are visible through the paint. Against this backdrop, Jasmine and Eric—and other prisoners with their lovers, families, and friends—make memories shaped by the carceral system.

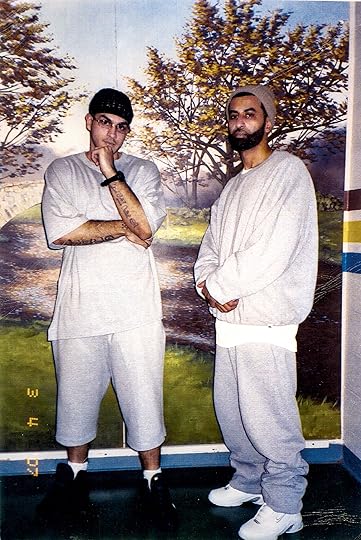

Photographer unknown, Jesus (left) and friend, Bronx, New York, ca. 2009

Courtesy David Adler

In one memorable visit, the emotional weight of this form of memory making comes to the fore. It was September 2012 and I was at Ross Correctional Institution with my cousin Eric. We were visiting De’Andre, his son and my cousin. Then twenty-three years old, De’Andre had been in an adult prison for more than six years and had six years left of his minimum sentencing. Eric was visibly uncomfortable. De’Andre had recently been transferred to Ross from another prison that was closer to home. He had written to both of us, depressed and worried about his safety. He had not had a visitor in over a year.

At Ross, the photography studio is right next to the guard’s desk and close to the visitors’ entrance. The backdrop is of an autumnal setting sun. The sky is a pale shade of pink, and centered at the top of the landscape is a large, warm yellow sun. The outer ring of sun bleeds into the pink and touches the edge of the lone tree on the horizon. The leafless tree stands majestic, peaking up above the sun’s rays. It’s one of the sparest backdrops I have seen, and its color scheme is unusual.

I speak briefly to the photographer while he sets up a shot; communication between the photographer and visitors is not officially allowed, but the guard does not seem to mind. The shift photographer, a middle-aged white man, tells me that he learned to take pictures in prison; he had never given photography much consideration when he was on the outside, he notes. The visiting room experience here feels more casual and less regulated than in most prisons I have visited, and yet this is one of the most restrictive institutions known to house prisoners who have committed serious felonies, or who have had disciplinary records at other penal institutions.

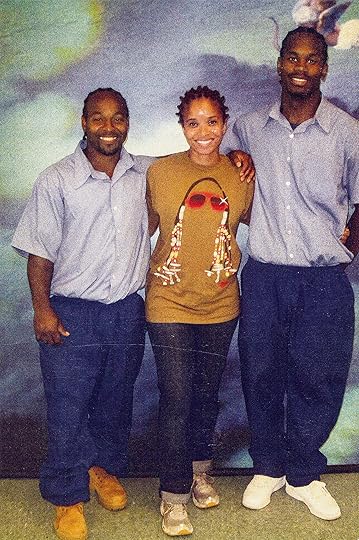

Allen, Nicole and De’Andre, 2011

Courtesy Nicole R. Fleetwood

Photoshoots in prison tend to be quick and cursory. The photographer is careful not to spend much time talking with his subjects for fear of scrutiny by the guards, but today the shoots last longer, and those who are posing linger on the bench and chat with each other. Ahead of us, a young Latino couple spends considerable time, staging several images. The photographer walks to our table and tells us that we are next. De’Andre, Eric, and I take two pictures. In one, De’Andre is in the center, Eric is on his right side, and I am on the left. For the second picture, Eric says that De’Andre and I should take one together. De’Andre likes this idea; he has had very little contact with women in six years. He squeezes me much tighter than I expect when the photographer asks us if we are ready.

I have this photograph collection of Allen and De’Andre aging, maturing, changing in prison. The images of Allen, now almost twenty years into his life sentence, shift from an angry and scared teenager, to a depressed man in his twenties, to a resigned but hopeful man in his late thirties anticipating each time he goes before the parole board that he will be released.

After years of struggling with anger, shame, guilt, and depression about Allen’s life sentence at such a young age—his first time being arrested and convicted of any crime, but the judge having said during sentencing that he was making an example out of Allen so that other boys in our community would stay “in line”—his mother and sister work even harder to incorporate him into their daily lives. Allen is brought up with the frequency of one who shares a home with them. Their 2011 holiday card is evidence of this commitment. The photograph, staged in prison against an idyllic winter backdrop, is thickly layered as it circulates through many locations and emotional registers. Allen is the male central figure customary of family portraiture, as the women—his mother, sister, niece, and daughter—stand at his sides and lean in toward him. The prison portrait has been enfolded into another narrative and way of marking time—the holiday greeting card. The message on the card reads: “Have a blessed & prosperous 2011. Love, Sharon, Cassandra, Allen, Tanasha, & Mariah.”

Eleanor (the author’s mother), Allen, Nicole, and Sharon, 2009

Courtest Nicole R. Fleetwood

There is one image of Allen that unsettles me. He poses with his mother, my mother, and me during a visit in June 2009. My mother and I were in town to celebrate the graduation of four younger cousins from high school, a milestone that Allen did not accomplish. In this shot, we stand close to him. He hugs my mother and me tightly on each side of him. Aunt Sharon leans in, and we wrap our arms around each other. The women, all three of us, smile at the photographer. Our eyes are focused on the moment at hand, documenting our visit, a temporary break in Allen’s routine, a moment of connectedness. Allen’s eyes, his half smile, the creases around his mouth disturb me. His look is painful. It anticipates what will happen after we are finished posing and our visit ends. It will be another year before I see him. He will be here, living in a cell, when we return.

On February 2, 2015, Allen was released from an Ohio prison after serving almost twenty-one years. He walked out of the facility with his mother and sister accompanying him. They walked to the family car and took a group selfie. It was his first photograph outside of prison. In the weeks after his release, Allen used the smartphone that his mother purchased for him and took digital images of many of the photographs that his relatives had sent him over the past two decades. He then sent those photographs to us in text messages and emails with notes of love and playful emoticons. Many of the images that he returned were photographs that we had forgotten about. Allen had archived them. In many respects, he has become the keeper of our family’s photographic record. For the next five years, he will be heavily monitored through parole. Nevertheless, he told me to refer to him in this article’s conclusion as a “free man.”

Nicole R. Fleetwood is Professor of American Studies and Art History at Rutgers University. She is the author of Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (2020) and guest curator of the accompanying exhibition at MoMA PS1, New York.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 230, “Prison Nation,” Spring 2018.

March 12, 2020

Minimal, Messy, or Melancholic?

The many faces of “home” in Japanese photography.

By Lena Fritsch

Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Untitled, 1981–82, from the series Katsura Imperial Villa

Courtesy Kochi Prefecture, Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center and the collection of the Museum of Art, Kochi

The English word home does not have a Japanese equivalent but links to various terms and concepts: ie and katei relate to the house spatially; kazoku (composed of the characters for house and tribe) is the immediate family and household; furusato defines a nostalgic image of one’s home, hometown, or birthplace. Just as the Japanese language is highly situational, the idea of home also depends on the context. It is therefore not surprising that the motif of the home in Japanese photography is diverse, raising compelling questions: How do architectural photographs present the Japanese home? Are Daido Moriyama’s blurry 1970s images of the village of Tono linked to a hometown vision? What kind of family home do younger photographers portray in their work?

Ie : Home as a house

Yoshio Watanabe, best known for his 1953 Ise shrine photographs, and Yasuhiro Ishimoto, who studied at the Institute of Design in Chicago before returning to Japan in 1953, were both concerned with the traditional architecture of Japanese temples, shrines, and villas. Unlike the Western idea of architecture that is durable and permanent, it has been a long custom in Japan to constantly change and re-create space, for example through the use of sliding doors and futon beds that are stored away during the day and taken out at night. In Watanabe’s Japanese architecture photographs and Ishimoto’s meticulously composed Katsura Imperial Villa series (1953–82), sliding paper doors and light tatami flooring contrast with dark wooden pillars; architectural shapes are captured as clear lines and geometric forms reminiscent of the Bauhaus (which in turn was partly inspired by a Japanese “purist” style). No detail is unplanned—forms and materials are in harmonious dialogue. The minimal, almost abstract photographic compositions convey a feeling of balance. The homes that Ishimoto and Watanabe present us with can be viewed as manifestations of the Japanese philosophy of space known as ma, literally “in-between.” The aesthetic of the rooms (and of the photographs) comes into existence through a careful interaction between form and non-form, dark and light. The transient concept of space can be seen as following the tradition of Shinto and Buddhist culture, emphasizing the impermanence of all things.

Ishiuchi Miyako, Apartment #50, 1978

Courtesy the Third Gallery Aya, Osaka

Impermanence is also evident in a small city room in which paint is peeling off a sliding window frame. A pair of gloves, two umbrellas, and a kettle are attached to a laundry line strung across the room. It is the year 1978, and this home in Tokyo is one of manythat Ishiuchi Miyako captured with her handheld camera. The dark gelatin-silver prints show some apartments with and others without their inhabitants. They were published in Ishiuchi’s first photography book, Apartment (1978). In 1979, to her surprise, she received the renowned Kimura Ihei Award for this series. At the time, Japan was characterized by a fast-growing economy, which resulted in the area around Tokyo becoming increasingly urbanized. Residential buildings were erected rapidly and cheaply. Apartment documents people’s simple, provisional living conditions, often in temporary homes. The photographs cannot be separated from the photographer’s personal memories, as she lived in a similar apartment in Yokosuka on Tokyo Bay between the ages of six and nineteen. She has repeatedly told me how she hated growing up there. The apartments symbolize her own childhood home. “I wanted to return to all the places that I associated with bad memories,” she said. She has also described the apartments as being “permeated by a mix of different body smells. I have the feeling that the apartments smell thoroughly like people. These apartments are small, dark, and somewhat dirty, and nobody wants to live in them. But I sense a certain kind of reality in them—they are places that feel very human.” Her Apartment photographs are “human” primarily because they make visible the traces of their countless former inhabitants. Walls are covered in cracks, sweat stains, and fingerprints. Objects suggest stories about their owners. As in Ishiuchi’s later works depicting human bodies, clothes, or objects that people have left behind after their deaths, these poetic images tell of people, their mortality, and bittersweet remembrance.

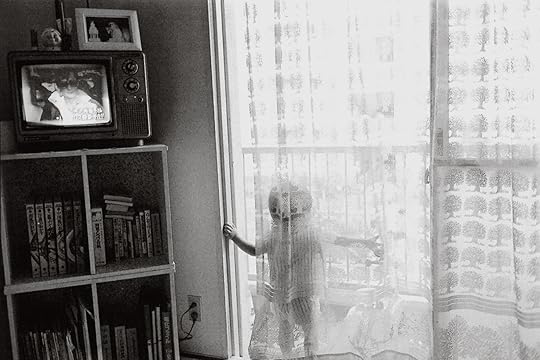

Kyoichi Tsuzuki, Tokyo Style, Tokyo, Japan, 1993, from the series Tokyo Style

Courtesy the artist

In 1993, the photojournalist Kyoichi Tsuzuki published a small-format book, Tokyo Style, that also documented small homes. Compared to Ishiuchi, however, Tsuzuki is less interested in the memories captured in rooms. Rather, his photographs of approximately one hundred apartments are concerned with everyday, real interiors. In one image, an electric guitar and large speakers contrast with traditional tatami flooring. Clothes are provisionally hung on a curtain rail. Using a large-format camera, Tsuzuki carefully constructs his photographs, presenting them with short descriptions about the rooms and their interior design or key furniture pieces, offering the same viewpoint on these inexpensive studio apartments as we might see on stylish apartments designed by famous architects. His now-iconic book was a reaction against the staged photographs of designer apartments found in interior design magazines and coffee-table books. When I spoke with Tsuzuki, he laughed about such fantasies and the “flowers that are usually not there, or fruit that nobody ever eats, and the interior designer who would also be at the photo shoot.” Such magazine photographs, and perhaps also the visual legacies of figures such as Ishimoto or Watanabe, have resulted in a stereotype of Japanese people living in Zen-inspired minimalist homes. “Although the great majority, around nine out of ten people in Tokyo live in tiny apartments, including members of staff that create beautiful architectural magazines, there was not a single book about their rooms,” Tsuzuki said.

Daido Moriyama, Tono Monogatari (The Tales of Tono), 1976

Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Furusato : Longing for home

In 1909, when the writer and ethnologist Kunio Yanagita visited the isolated village of Tono in northeastern Japan, it was mainly inhabited by peasants, and the first railroads were only starting to be constructed. Seeking to record the rural lifestyle and folk beliefs, Yanagita collected oral stories by the folklorist Kizen Sasaki The legends were published in a 1910 book titled Tono Monogatari (The Tales of Tono), revealing a dark world of the fantastic and reflecting a history of severe human existence. In the late 1960s and ’70s, a broad interest in Japanese folklore began to emerge, and Yanagita’s work was rediscovered. With the growth in prosperity, a concern with traditions found its way into people’s leisure life, as evident in the increasing number of cultural centers offering courses in all kinds of “authentic” Japanese arts. Within the contemporary challenges—enormous economic growth and internationalization on the one hand, student revolutions and protests against the 1960 Japan–United States Security Treaty on the other—nostalgic ideas of a “traditional” Japan ensured a familiar national and cultural identity. Moriyama’s photography book Tono Monogatari (1976) and Masatoshi Naito’s Tono Monogatari (published in 1983 but photographed between 1971 and 1982) reflect Japan’s folklore boom. Moriyama’s and Naito’s mostly black-and-white photographs of Tono, with their stark contrasts and dark imagery, convey a sense of the mysterious. Moriyama’s blurry, grainy images taken out of the train window on his journey to Tono or his cropped color photographs of flowers in someone’s garden, as well as Naito’s photographs of Tono at night, shot with a flash, suggest scenes that suddenly appear and then vanish again—just like indeterminate visual recollections unexpectedly surfacing from the dark realms of memory.

Kazuo Kitai, Funabashi Story, Funabashi, Japan, 1984–87

Courtesy the artist and Yumiko Chiba Associates

In Moriyama’s photobook descriptions of his journey, the term furusato plays a major role. The modern notion of furusato (literally “old village”) refers to one’s native place and is associated with nostalgic, warm feelings. Perhaps it is best described by the philosopher Ernst Bloch’s famous words about the home as a place that “shines into the childhood of all and in which no one has yet been.” There is a strong temporal component to furusato: it is linked with an image of the past, constituting a sentimental antithesis to the present. In the 1970s, Tono became regarded as an example of furusato: a warmly pastoral home that functioned as a romantic counterpoint to the prosperous, fast-paced, and Westernized Japan of the present. As the folklore scholar Hermann Bausinger once said, the expansion of the term home tends to coincide with the dissolution of one’s horizon. The loss of the war and the large-scale sociopolitical and economic changes since 1945 had surely dissolved Japan’s former horizon, resulting in a fundamental severance from home. It was this alienation from home that led to Japanese artists’ new concern with the idea. Moriyama writes about his wistful longing for Tono as an embodiment of furusato, which he defines as a “swollen utopia of countless childhood memory fragments.” Both Moriyama and Naito refer to the idea of the hometown as a “primordial image” in our subconscious, using a term coined by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung that defines images from the collective unconscious, shared among all humans. Moriyama confronts his hometown utopia by interacting with the real Tono through his camera. The medium of photography helps him to overcome, at least momentarily, his melancholic search for a home. When Moriyama leaves, he is able to say, “Tono, farewell for now.”

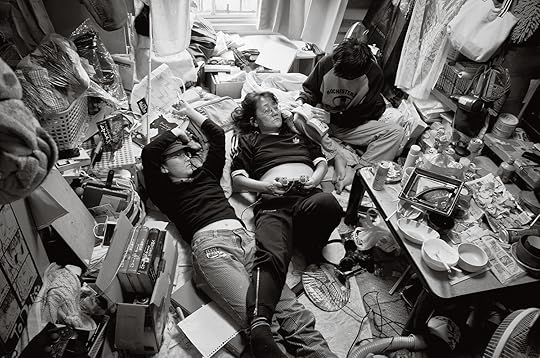

Masaki Yamamoto, GUTS, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, 2014–17

Courtesy the artist and Zen Foto Gallery, Tokyo

Kazoku : Home means family

Sometimes home is neither a particular place nor a distant memory. Funabashi Story, a series of images taken by Kazuo Kitai between 1983 and 1987, beautifully records people’s mundane lives inside apartment complexes in Funabashi, a city on the outskirts of Tokyo that grew rapidly in the 1980s. One of the protagonists is a child behind transparent curtains, curiously looking out a window while the television is on. The photographs have a narrative quality, and when Kitai published them as a photobook in 1989, he added texts that describe the homes and people’s domestic habits. “I decided to take photographs because I wanted to show people’s lives and hear their stories,” he told me, emphasizing that his viewpoint is not neutral but always aligns with the photographic subjects’ position. Kitai’s sincere respect for the residents is evident in his Funabashi Story photographs.

Yurie Nagashima, Takashi Homma, and, most recently, Motoyuki Daifu and Masaki Yamamoto have presented personal stories about their families. Nagashima first received attention in the male-dominated Japanese photography scene in 1993, as a young woman who portrayed herself and her family naked at home. They appear comfortably unclothed when posing for a family photograph or pursuing their daily routines. “I grew up in a free and open family environment, in quite a downtown style,” she said. “My family would walk around half naked with just a towel around their bodies after taking a bath. To me, nakedness is not necessarily something sexual.”

Takashi Homma, Tokyo and My Daughter, ca. 2006

Courtesy the artist

In his photobook Tokyo and My Daughter (2006), Homma portrays the nonglamorous and domestic, interweaving photographs of his studio with a portrait of a small dog and photographs of a young girl who appears to be exposed to the loving eyes of her proud father. We see her grow from a toddler to an elementary-school child. In one photograph, she appears wearing the same shirt as Homma, who is checking the inside of a refrigerator in the back- ground. The girl stares directly into the camera, suggesting that she is aware of the viewer while also looking bored. The sequence of images conveys a diaristic feeling. With this book, Homma has shifted his attention from the formalistic suburban landscape to the closeness of the home space. The fact that the photographic story is fictional (the girl in the series is the photographer’s friend’s daughter) is not visible in the work: the book presents itself convincingly as a personal portrait of a father and a daughter’s life in the city.

Homma’s vision of a middle-class home contrasts with the cluttered, much more modest apartment in Kobe that Yamamoto has captured in a real and movingly intimate family portrait. Their tiny home, explored in his affectionate photobook GUTS (2017), is jam-packed with clothes, plates of food, cans, paper, and countless household objects. In between all this clutter, members of Yamamoto’s family are lying on the floor: sleeping close together, watching television, playing video games, and enjoying each other’s company. The young photographer seems to tell us that home is, above all, where one’s heart is—with one’s family and loved ones.

Lena Fritsch is Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, and the author of Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography since 1945 (2018).

Read more from Aperture, issue 238, “House & Home,” or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

March 6, 2020

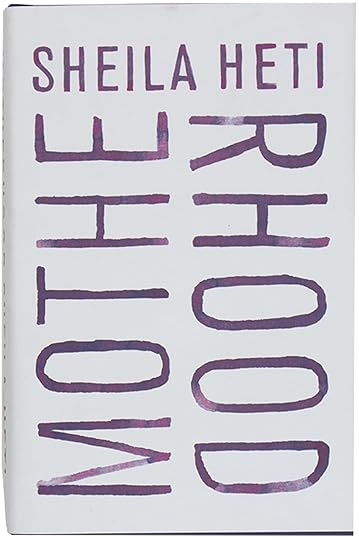

12 Inspiring Photobooks by Women Photographers

Since its founding in 1952, Aperture has elevated the voices of women artists and published important works by female photographers. Our publishing history includes seminal volumes by Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, and Sally Mann, and monographs by today’s leading contemporary artists, including Rinko Kawauchi and Deana Lawson. In celebration of Women’s History Month, we’ve gathered some of Aperture’s most inspiring photobooks by women.

Florence Henri, Composition Portrait, Cora, 1931

Courtesy the artist/Galleria d’arte Martini & Ronchetti

Florence Henri: Mirror of the Avant-Garde, 1927–40, 2015

A central figure at the Bauhaus and an active photographer in the decade before World War II, Florence Henri was a forerunner of photography in the 20th century. Her experimental photographs pushed the medium forward with their highly original use of light, composition, and portraiture. In 1928, supporter and contemporary László Moholy-Nagy wrote: “With Florence Henri’s photos, photographic practice enters a new phase—the scope of which would have been unimaginable before today.” Florence Henri: Mirror of the Avant-Garde, 1927–40 pays homage to her essential, but under-recognized, contributions to photography.

Diane Arbus, A house on a hill, Hollywood, California, 1970–71

Courtesy the Estate of Diane Arbus

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, 2011 (First published 1972)

One of the best-known photographers of her generation, Diane Arbus was already a legend in the photography community when she died in 1971. The following year, Aperture first published Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, featuring eighty of Arbus’s now-iconic portraits, which offered the general public its first encounter with her momentous achievements. The response was unprecedented. Now, nearly fifty years after its original publication, the monograph is universally acknowledged as a timeless masterpiece and remains the foundation of Arbus’s international reputation.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983

Courtesy the artist

Nan Goldin, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 2012 (First published 1986)

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Goldin’s candid, visceral photographs captured a world seething with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis. Over thirty years later, the influence of The Ballad on photography and other aesthetic realms can still be felt, firmly establishing it as a contemporary classic.

Sally Mann, Jessie Bites, 1985

Courtesy the artist

Sally Mann, Immediate Family, 2014 (First published 1992)

When Aperture first published Immediate Family in 1992, it was met with both acclaim and criticism. Mann’s intimate portraits of her children captured the sublime dignity and feral grace of family life—but at the time of publication, the book caused an uproar among religious conservatives who deemed the work pornographic. Today, Mann is firmly established as a preeminent American photographer, and Immediate Family is lauded by critics as one of the great photography books of our time.

Paz Errázuriz, Evelyn IV, Santiago, from the series Adam’s apple, 1987

Courtesy the artist

Paz Errázuriz: Survey, 2016

Chilean photographer Paz Errázuriz is known for her steadfast commitment to her subjects, spending months or years with a community in order to build trust and carefully study social structures. During the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1970s and ’80s, Errázuriz photographed brothels, shelters, psychiatric wards, and boxing clubs—all places where women were not welcome. One of her series, Adam’s apple, documents trans prostitutes working in Santiago and Talca. As Julia Bryan Wilson writes, “Decades before the rise of the phrase trans feminism and the increased mainstreaming of (some) trans bodies, Errázuriz . . . sought to capture Chilean trans women without shame or stigma.”

Susan Meiselas, Sandinistas at the walls of the National Guard Headquarters: “Molotov Man,” Estelí, Nicaragua, July 16, 1979

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline, 2017

One of the earliest women members of Magnum Photos, Susan Meiselas is an immensely influential photographer and an important contributor to the evolution of documentary storytelling. On the Frontline explores the trajectory of Meiselas’s career—from her series Carnival Strippers, to her renowned coverage of the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979, to her six years documenting the Kurdish people—offering key insights into her ideas, processes, and experiences as a photojournalist.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Grandma Ruby and Me, 2005

Courtesy the artist

Latoya Ruby Frazier, The Notion of Family, 2014 (Paperback 2016)

The Notion of Family, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first photobook, offers an exploration of the legacy of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Enlisting the participation of her family, her mother in particular, Frazier reinforces the idea of art and image-making as transformative acts, a means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives—both those of her family and of the community at large. ARTnews named The Notion of Family one of the best art books of the decade.

Justine Kurland, Like a Black Snake, 2008

Courtesy the artist

Justine Kurland: Highway Kind, 2016

Known for her utopian photographs of American landscapes and their fringe communities, Justine Kurland has spent the better part of the last twelve years on the road. Since 2005, Kurland and her son Casper have traveled across the country. Kurland’s deep interest in the road, the Western frontier, escape, and ways of living outside mainstream values pervade Highway Kind, which showcases her vision in equal parts raw and romantic, idyllic and dystopian.

Rinko Kawauchi, from Halo, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi: Halo, 2017

In recent years, Rinko Kawauchi’s photographs of the tender cadences of everyday living have begun to swing further afield from her earlier work. In Halo, Kawauchi expands her inquiry, photographing three main themes—Lunar New Year celebrations in Hebei province in China (where a five-hundred-year-old tradition calls for molten iron hurled in lieu of fireworks), the southern coastal region of Izumo in Japan, and an ongoing fascination with the murmuration of birds along the coast of Brighton, England. The resulting images knit together a mesmerizing exploration of the spirituality of the natural world.

Bieke Depoorter, Al-Mahalla al-Kubra, Al-Gharbiya, November 2015

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bieke Depoorter: As it may be, 2018

Magnum photographer Bieke Depoorter has traveled to Egypt regularly since the beginning of the Egyptian Revolution in 2011, making intimate pictures of families in their homes. In 2017, Depoorter revisited the country with a first draft of her book, returning to the people she photographed and inviting them to write comments directly on its images. The resulting book, As it may be, offers a direct dialogue between photographer and subject rarely found in documentary work, exploring contrasting views on the country, religion, and society between people who may never cross paths in real life.

Deana Lawson, Oath, 2013

Courtesy the artist; Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago; and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, 2018

Over the last ten years, Deana Lawson has portrayed the personal and the powerful in her large-scale, dramatic portraits of people in the US, Caribbean, and Africa. She is one of the most compelling photographers working today, and Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph is the long-awaited first photobook by the visionary artist. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in the book’s essay. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Chloe Dewe Mathews, The “Door to Hell,” Darvaza, Turkmenistan, 2012

Courtesy the artist, Aperture, and Peabody Museum Press

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Caspian: The Elements, 2018

For five years, Chloe Dewe Mathews traveled through the beguiling region surrounding the Caspian Sea, creating a record of the ways materials such as oil, fire, uranium, and water are integral to the mystical, economic, religious, and therapeutic aspects of daily life. Winner of Harvard University’s 2014 Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography, Dewe Mathews’s photographs range from stark and elemental to lush and mysterious—capturing the ways humans are inextricably linked to the enigmatic and much-coveted landscape of the Caspian region.

Want to be the first to hear about Aperture’s latest publications? Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss our new releases, latest editorial content, and more.

March 5, 2020

In Pictures, a Family’s Odyssey from Poland to South Africa

Photographer and writer Terry Kurgan’s recent book considers images, memory, and the reverberations of World War II.

By Oluremi C. Onabanjo

Jasek Kallir, Hotel Jasny Pałac, Zakopane, Poland, August 1939

Courtesy the artist

Sometime in July or August 1939, Karol Joachim (Jasek) Kallir took a candid snapshot in the garden of the grand Jasny Pałac Hotel in Zakopane, a resort town frequented by the Polish intellectual and artistic set in the Tatra Mountains. Portraying his daughter, wife, and an acquaintance of the family, the image is a candid, perhaps even an uninteresting one if found while leafing through the pages of an album. Yet within the context of Everyone Is Present: Essays on Photography, Memory and Family (Fourthwall Books, 2018), a hybrid collection of images and essays by South African photographer and writer Terry Kurgan, it becomes clear that this image “masks a secret. A secret that is too big for [the] page” but also critical to an understanding of the complex tenor of familial relations “at the very outset of what was to become one of the greatest atrocities of the twentieth century.”

Jasek Kallir, Bielsko-Biała, Poland, August 1939

Courtesy the artist

This enigmatic photograph and others like it—battered, worn, and “captioned on the back with [Kallir’s] spidery cursive writing”—serve by turns as the anchor and springboard, a cause of contention or contemplation for Kurgan’s meditations on photography, memory, and family. Kallir is her grandfather, and it is through Kurgan’s compassionate examination of his journal entries and photographs that we are introduced to multiple generations of their family—circumnavigating the spaces, communities, and individuals they encountered, as well as the historical events and geopolitical shifts they endured in the wake of World War II. The book tracks the family’s extensive, winding movements from Poland to South Africa, by way of Turkey, India, Iraq, Syria, and Kenya. In each overture of their journey, we are privy to moments of devastation, repression, and violence, but also intimate instances of joy, comfort, and aspiration.

Passport photographs, detail of a Certificat de Voyage issued in Romania, 1940

Courtesy the artist

Kurgan’s virtual and physical retracing is illuminated by her deft treatment of photography. She divulges her personal relationship to the images featured—the process of viewing them, encountering them, and then searching to ascertain more. A close reading of family photographs yields to leafing through identification documents and scanning social documentary images, then surveying Google Maps cross-sections and YouTube video screenshots. More than the subject of Kurgan’s consideration, photography serves as a generative conceptual node, through which multiple temporalities and materialities are produced by extension.

Bielsko-Biała, Poland, August 2012

Courtesy Google

The sequencing, pacing, and repetition of the book’s images reflect this approach, communicated elegantly through designer Carla Saunders’s graceful hand. Whether staged portraits or candid captures, photographs appear strategically and work in tandem with the text: a full-bleed displays the entirety of an image powerfully; or an iterative appearance of a photograph emerges, strategically cropped and interspersed between passages with a gradual crop. These images display minimal to no retouching; all scratches and surface wear remain present to reflect the materiality of the photographs encountered and their role as both window and witness to the passage of time. Paralleling their multiplicities, Kurgan’s literary voice appears as simultaneously conversational, rigorous, and diaristic throughout.

Anonymous YouTube upload, Screengrab from Bielsko-Biała 39/14

Everyone Is Present is an atmospheric project, wide-ranging in its treatment of prose and image. Following Kurgan’s cues, it is easy to become engulfed in the act of looking, discovering, and deconstructing moments in time. The book reflects core themes in Kurgan’s artistic practice—one deeply concerned with familial intimacy and the historical legacies of sociopolitical fracture.

Everyone Is Present is a welcome arrival from from Fourthwall Books, a nimble publishing house based in Johannesburg, with a penchant for refined, incisive publications. It was founded in 2010 by designer Oliver Barstow and writer and editor Bronwyn Law-Viljoen, and where Kurgan has worked as codirector and coeditor since 2015. Winner of the 2019 Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for Non-Fiction (Johannesburg) and shortlisted for the 2019 Prix du Livre (Arles), Everyone Is Present encompasses many concepts. But most important, it is a book about photography—as medium; as storytelling device; as portal or memento; as marker of capture, fugitivity, or freedom; as site of expression and iterative contemplation; photography as vernacular.

Jasek Kallir, Zakopane, Poland, August 1939

Courtesy the artist

Kurgan deals with photographs that one would consider vernacular representations, but also deploys them to channel a way of speaking, a vernacular form of expression and encounter—ultimately extending the bounds of what we can consider vernacular photography capable of achieving. In the process, she demonstrates how our relation to a photographic object continually shifts and changes, despite the seemingly physical fixity of its surface and the images it renders. With that, there is the implicit refutation of possible resolution in the book. Kurgan’s final account of seeing her reflection elegantly drives home this sentiment. Akin to her own assessment, Everyone Is Present embraces the power of photography to evoke poignant sensation and memory, while highlighting the “complete impossibility of a very particular kind of retrieval.”

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is a curator and scholar of photography and the arts of Africa. A doctoral candidate in the Art History Department at Columbia University, she is the former director of exhibitions and collections at The Walther Collection.

Read more from The PhotoBook Review, Issue 017, or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

The Artist Remixing History, from French Gardens to the Cosmos

Todd Gray’s layered compositions examine legacies of colonialism in Africa and Europe.

By Travis Diehl

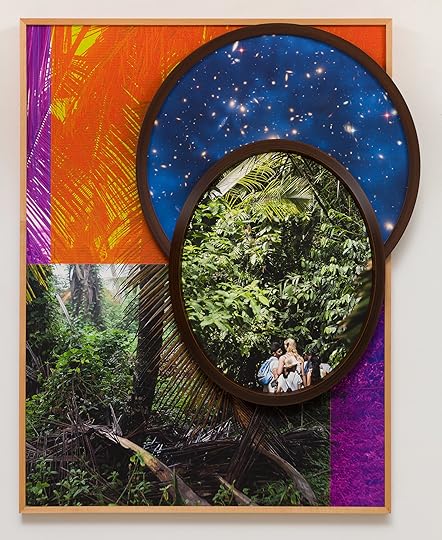

Todd Gray, Euclidean Gris Gris (Love and Happiness), 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Todd Gray knows history. He has made some himself: his current body of work draws on his time as a commercial photographer, shooting album covers, celebrity portraits (famously, he was Michael Jackson’s personal photographer), and live concerts. He also knows the bitter stories of colonial conquest in Africa—how privilege and ideas of landscape and painting feed pernicious narratives, prop them up—and how photography also serves in power’s toolkit. He knows art history too. When we spoke recently on a bench outside the Pomona College Museum of Art—where Euclidean Gris Gris, his shifting, expanding exhibition of new and recent work, is on view—Gray noted that Helene Winer was once director there, before she moved to Artists Space and helped Douglas Crimp mount Pictures in 1977. Gray was a contemporary of the Pictures artists, he tells me, but he was never one of them. The reason? The gris gris of his title.

Todd Gray, Euclidean Gris Gris (Francis), 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Travis Diehl: I want to start with the squiggly, abstract wall drawing, Gris Gris (2019), and how it relates to the photographs.

Todd Gray: Well, let’s see. I envision the whole exhibition almost like kudzu, this organic thing that grows and morphs and surprises me. I usually come here once or twice a month, and I’m just sort of drawing. And then if a student comes, I go, “Hey, you want to pick up a piece of charcoal?” It’s an individual activity that can also incorporate others. The photo works are very specifically mine. That contradiction, to me, is the “Euclidean Gris Gris” of the show’s title. There are pieces that specifically come out of the thought process and determination of the artist. And then there’s this other component that, in its purest form, is pure experimentation.

Diehl: This drawing makes me think about the formal qualities of the photo installations—the degree to which the images are abstract or representational.

Gray: I was in South Africa at Nirox, a World Heritage Site with the oldest forensic evidence of mankind. And I thought, you know, I’m of African descent. How can I connect to this place? How can I go past my Western European–American education and culturalization, and create form, and express? And that’s when I said, Okay, cave drawing. Really simple marking. I got into photography because I couldn’t draw. Photography gave me pictures. So the only thing I felt comfortable drawing was a circle. Over a couple years, these circles have morphed into a practice, but it’s not a practice that I control. It’s something that I let occur, spontaneous and improvisational, in the moment. I surrender to that.

Todd Gray, Parisian Hoods in Bamboo Village, 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: Is that how you think about the collage or superimposition of the images in the photo-based works too?

Gray: Not at all. The photo-based works come out of a thinking process. The drawings, if they come out of a thinking process, they fail.

Diehl: Your frames look like frames for paintings. How does painting relate to the photographs that you put in them?

Gray: Painting is privilege, right? That goes back to my investigation of imperial gardens and their relationship to monarchy, or—for lack of a better term—the historical one percent. I was using those big, gold rococo frames to point to ideas of privilege, wealth, class.

Diehl: Yes, those things overlap in your photo-based works. The French garden is also a rectangle, and you contrast these perpendicular systems of control to jungles or mangroves, or oval frames. Just to harp on the formal qualities a little bit more—photography is also a European invention. It’s a rectangular format. Its rectangular logic comes out of the same moment as these kinds of angular gardens, and constructed ideas about nature. I wonder how you think the medium of photography relates to these systems of knowledge that you’re using it to depict and explore.

Gray: Well, I’m a student of Allan Sekula. It’s funny—Allan affected my humanity more than he affected my art. It was only after studying with Allan that I saw photography as an instrument of control. Photography is a way for power to have a direct line into subjects, into us, into the masses; to formulate narratives that we don’t question, because we think these narratives are something called reality. But Stuart Hall thinks that we cannot overcome this immense hegemonic power, and our only power as individuals is to be in a constant state of resistance. I use this thing called beauty in the work to attract a viewer, and then the semiotics start taking place in contrast to the seductiveness of the picture.

Todd Gray, Euclidean Gris Gris (Ship of Fools), 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: The way you superimpose images resists that seduction too. You have a lush landscape, and then you have this kind of interruption—a superimposed, partial portrait in an oval frame. Or vice versa. It’s pretty jarring.

Gray: The way I use space and perspective, your mind is getting mixed messages as to how to interpret the picture field, and then you become conscious that you have to make a decision. I’m not offering up a pictorial solution; I’m offering up a pictorial problem. I’m hoping that I can reveal the plasticity of photography and the necessity of a viewer to actually create meaning. Like Allan said, you need a caption to anchor a picture. I’m trying to really blow that up. My work is super captionless. I use one photograph to destabilize another photograph to hopefully make you more aware of how unstable photography is.

Diehl: In your work, it’s not simply an abstract idea of jungle versus an abstract idea of garden, or nature versus culture; your images are more specific than that. How important is it to locate those photos in a particular place?

Gray: I want to have macro-conversations, larger-view conversations. Which is why I use pictures of the cosmos. We’re fooling ourselves when we think we can control nature, control humans, control everything. It’s absurd. That’s why we’re facing global warming and the possibility of self-extinction. There’s one installation where a picture of a fire in Cape Town is covering a statue—like I placed it on a plinth, like a trophy. That’s a highly cynical image for me.

Todd Gray, Euclidean Gris Gris (The Young Shall Inherit the Earth), 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: A moment of iconoclasm.

Gray: We can make a rationale for any action, and we can use logic to solve any problem. Even an atomic bomb—we can rationalize why we should use that. And we can rationalize slavery. Years ago, I just thought, Wow, this system of thought is highly corruptible and highly plastic and can do anything, and so I gotta look at other ways of thinking. I gotta think with my body, not with my head. Which is odd because that’s this modernist idea of the noble savage. I was taught to be cautious of these modernist notions. But now I’m saying, It’s more complicated, there are more parts to this machine.

Diehl: To your title—Euclidean geometry is an idealistic, geometric way of ordering the universe, and a gris gris is a talisman, something more shamanic and intuitive. It seems like art fits into both sides. It’s that combination.

Gray: Art is the clearest way for me to express my thinking and my being. Yes, I have protested in the street, but that’s not my vocation. My vocation is visual. So, I want to use my vocation to express my thinking and express my point of view and my relationship to culture and my relationship to community.

Todd Gray, Patterns (2), 2018

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: Patterns (2), from 2018, is the only piece in your exhibition that incorporates a Michael Jackson photo, which is actually the only human face you show here. It feels different in so many ways from the other work, and it’s set off to the side.

Gray: That comes out of the series Exquisite Terribleness, which was where I dove into my MJ archive and intersected it with photos from my African archive. I wanted to see how that piece worked with the other works, and I set it aside. The drawing is a hallway. Since that Michael Jackson documentary came out [Leaving Neverland, 2019], the whole cultural relationship with MJ has changed, and I wanted to see how that affected that piece.

Diehl: There are several layered figures in that one—three, or four if you count Michael Jackson. They’re all covering each other up, so that his is the only face you see. It feels like a statement about portraiture. Like a way you can have a portrait without having a face.

Gray: Right. I did a show called Portraits (2018) at Meliksetian Briggs, and only a couple times you see a face. You can’t see the face, but you get a sense of the person, you get a sense of the narrative. In the Exquisite Terribleness series, I rarely showed Michael’s whole likeness. I didn’t want that read to hijack the whole work, because then it’s about celebrity. No, I want it to be about culture and Blackness and this representation of a Black person who is loved and hated, globally—the most famous Black person on the planet, if not the most famous person on the planet. He was a signifier that I wanted to wrestle away from Hollywood celebrity and entertainment and place him in an area where we can speak about the African diaspora. Because now you have to deal with history, you have to deal with slavery, you have to deal with economic exploitation; we have to talk India, East Asia, the Philippines, all of these colonial “destinations” exploited by Europe. He made himself a product. You know, the Faustian bargain. He went all in.

Todd Gray, Euclidean Gris Gris (Paris/Cape Town), 2019

Courtesy of the artist, David Lewis, New York, and Meliksetian | Briggs

Diehl: So that’s why Michael Jackson, among the hundreds of celebrities that you have in your archive, is the only one that comes into the work. You wouldn’t say you’re interested in celebrity in general.

Gray: No. But, for me, commercial work and artwork were church and state. Now I’m really looking back and I’m saying, No, commerce is part of culture. One thing that John Baldessari taught me is context is everything. Context changes meaning. And so now, I’m trying to see the work that I did as a commercial photographer as part of mass media. I mean, pop culture pushes us forward more than high culture.

Diehl: Artists often feel self-conscious about not being part of pop culture, but they’re also really drawn to it, as another version of what they do.