Aperture's Blog, page 71

May 19, 2020

Is the Still Life the Form of the Moment?

Six photography curators consider images that have new resonance in the era of social distancing.

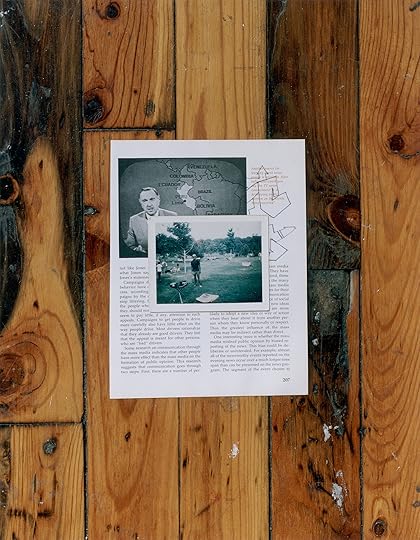

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (3 of 10), from the series Riffs on Real Time, 2008

© the artist and courtesy the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston and Perrotin

Time during shelter-at-home seems to be on perpetual repeat, as days slip into weeks and—can it really be?—into months. Some say photography freezes time, but Leslie Hewitt calls her photographic series Riffs on Real Time, begun in 2002, a durational work, because she combines seemingly unrelated materials from different eras to continually make new meanings. She creates, then photographs, temporary arrangements of books, magazines, snapshots, and other printed materials against a backdrop of colorful shag carpets or well-worn wood floors. Time works in different registers in Hewitt’s series. We peer back in time through printed ephemera (from Ebony, Jet, and other Civil Rights–era publications), but we know that the arrangement itself is fleeting. We bring our own present-day associations to each work, so each reading is, in essence, time-stamped.

In these works, world events and personal events are collapsed, and Hewitt’s juxtapositions speak to dislocation and repetition, feelings all too familiar now. Hewitt’s neatly arranged still life seen here features a seemingly ordinary snapshot of a man in shorts barbecuing in a park (remember BBQs?) atop a magazine page featuring Walter Cronkite reporting the news. I study the JPEG on my screen, its slight pixilation a far cry from the actual work’s crisp description. I scan my visual memory for what it was like to experience this work in person. I wish more than ever that I could see this artwork in the flesh. I think back to when I first showed this series over a decade ago (that seems like a lifetime ago), and if during our many conversations over the years, Hewitt told me about the man in the snapshot. Is it her father, an uncle, a friend, or a stranger? Those shorts are pretty short, so it must be the 1970s or ’80s. But I digress. As I “read” the photograph rather than just look at it, I wonder what kinds of magazines, snapshots, news items, and ephemera will become the mementos of our own distinctive time. I wonder what riffs on tomorrow will look like.

— Eva Respini, Barbara Lee Chief Curator, Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston

Shikanosuke Yagaki, Still Life, 1930–39

© the artist and courtesy Tate

A successful banker, Shikanosuke Yagaki was a self-trained Japanese photographer active in the amateur camera clubs of Osaka and Kyoto throughout the 1930s. In Still Life (1930–39), Yagaki captured an after-dessert moment on a Western-style dining table one afternoon, when the sun cast bright light over glassware, a service bell, and a matchbox. In the left half of the photograph, he let the light choreograph shadows to reveal the objects’ textures and structures. Yagaki was known for his dynamic experiments with light, natural or artificial, and its potential to sculpt space in his pictures of modern life.

Without professional training, Yagaki developed a sophisticated photographic style, which combined the influence of European modernism with everyday subjects he found in Japanese urban settings in the early Shōwa era. In 1931, the Werkbund exhibition Film und Foto—originally staged in Stuttgart in 1929 and featuring the work of artists such as László Moholy-Nagy, El Lissitzky, and Man Ray—traveled to Osaka and had an impact on photographers like Yagaki who embodied the importance of amateur camera clubs as a dominant force in the new photography movement, known as Shinko Shashin, in 1930s Japan. His gaze at modernity, seen in his depiction of chaos, speed, and modern materials and structures, resulted in gelatin-silver prints considered radically avant-garde at that time. Aware of the transformative role of photography in modern visual culture emerged around the world, Yagaki unearthed unexpected beauty in the everyday.

— Yasufumi Nakamori, Senior Curator of International Art (Photography), Tate Modern, London

Bill Owens, Tidy Bowl, Walnut Creek, 1979

© the artist and courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

There is a lot of attention being paid to toilets these days, which can serve as refuges from the clamorous family members or annoying roommates with whom we might currently be sheltering, as well as places to store all that toilet paper we’ve been hoarding. Historically, toilets have also been sources of artistic inspiration. Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) is the ur–example, of course, but there is also Edward Weston’s iconic Excusado (1925), a sensuous study of a porcelain throne. In the best-known version, Weston photographed his commode from below, emphasizing the architectonic shape of the bowl and base. A modernist tour de force, the elegant composition is stripped of any unnecessary detail.

Bill Owens took a different angle in his Tidy Bowl, Walnut Creek (1979), looking right down the tube, so to speak, to capture the vantage he would have had when making use of this particular facility. It is a hilarious riff on Weston, replacing clean lines with jarring suburban clutter. Here, a blood-red seat is offset by claustrophobic 1960s floral wallpaper and an incongruous pair of decorations carefully set out on an olive hand towel. They include a pink silk rose anchored by a rust-colored ribbon next to a small plaster replica of Vincenzo de Rossi’s Hercules and Diomedes from the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, a sculpture known for the unique choice of handhold deployed by one of the wrestlers. People often put their naughty art in the powder room to titillate their guests. That figurine certainly would have made too much of a statement on the coffee table.

—Erin O’Toole, Baker Street Foundation Associate Curator of Photography, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Uta Barth, . . . and of time . (AOT 4), 2000

© the artist and courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In 2000, the J. Paul Getty Museum invited eleven artists, including photographer Uta Barth, to create work in response to objects in the institution’s collection. Finding inspiration in Claude Monet’s Wheatstacks, Snow Effect, Morning (1891)—a painting that demonstrates how light alters the perception and appreciation of a subject—Barth created a series of multipart photographs that examine how daylight streams through her living-room window.

Her not-quite-stereoscopic diptych . . . and of time . (AOT 4) (2000), presents two subtle variations of the same scene: a sparsely appointed interior bathed in warm, soft light. In both images, the outlines of a paned window are cast against a wall, floating over the cushions of a vibrant, yellow sofa like specters. A paper lamp appears suspended in the upper right corner of one image. By relegating these tangible objects to the edges of the frames, Barth emphasizes the negative space in the room, as well as how light can help to reorient our perception of the familiar, transforming the spaces we inhabit into unconventional scenes.

The contents of Barth’s home, from furniture to small ornaments and vessels, have regularly featured in her work for over two decades. But the real pursuit of these visual investigations concerns the act of looking itself. Prolonged observation, especially when applied to one’s immediate surroundings, can encourage reflection and a more nuanced understanding of the mundane. In this moment of collective pause, appreciation of the still life and the careful looking it involves has never felt more relevant.

—Arpad Kovacs, Assistant Curator, Department of Photographs, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Joanne Leonard, Portrait, Plant, and Fishbowl, Corean’s Home, West Oakland, CA, 1970

© the artist and courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Joanne Leonard’s photographs of home interiors from the 1960s and ’70s attend to corners, nooks, shelves, niches, countertops, and note boards by the telephone strewn with to-do lists, messages, and bills to pay: repositories for things that are indispensable, if not immediately alluring. Leonard has said that “feminism is something like a filter” and “a tool for looking at what’s missing”—an outlook that is evident in her approach to still life as a feature of a practice she has called “intimate documentary.”

This photograph is from a series of interiors of the house of her friend Corean, a neighbor in West Oakland, California, where Leonard lived from 1963 to 1972. The woman’s portrait that centers this picture seems to order everything around it. Spanning two walls, the portrait sees the room. So often the place for icons, shrines, and altars, corners are a space for almost-sacred items. Corean’s corner objects all require care. Arranged on a vertical axis, facing Leonard’s camera, they appear stacked, forming an architecture of ascending registers. The houseplant’s foliage ornaments the portrait without obscuring it, separating it from the rest of the room and reinforcing its pride of place.

Often, Leonard’s photographs are also composed to offer a vantage onto a slice of an adjacent space. Here, elements from the margins of the picture—a mirrored shelf, a calendar portrait of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the next room—inform the central arrangement, testifying to the power afforded images and sites of display. Photographic still lifes can communicate the values encoded in objects. Leonard recognized the artful disposition of Corean’s domestic décor, and the camera enabled her to transmit its visual intelligence beyond the private sphere of the home.

—Phil Taylor, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Jimmy DeSana, Baseball, 1985–86

Courtesy the Estate of Jimmy DeSana and Salon 94

In 1985, shortly after having his spleen removed due to complications from AIDS, the New York–based photographer Jimmy DeSana began making still lifes, a genre that for centuries has expressed both the abundance and transitoriness of life and earthly goods. As a central figure in the East Village arts and music scenes during the previous fifteen years, DeSana had made his name creating portraits and vivid tableaux of nude figures in domestic interiors. No longer able to produce such elaborate scenes because of his health, as well as his increasing dissatisfaction with representations of queer bodies in the media, he turned to abstraction, using household objects, colored gels, cutouts, collage techniques, and multiple negatives.

Take, for example, Baseball (1985–86), a chartreuse-hued photograph of an orb perched on a flat-top pyramid. At first glance, the work is a formal study in light, color, and shape that recalls an ancient monument through its unclear scale. Yet those familiar with DeSana’s work might also be reminded of one of his last self-portraits from the same year, in which a long, curved scar on his torso, bathed in red light, evokes the thick stitches on a baseball.

This sort of ambiguity became increasingly important to DeSana. To many, art about AIDS is synonymous with AIDS activism. Relatively shy and taciturn, DeSana performed his own form of activism in the way he knew best: using photography to question representation, taste, and ideology. “If I could do a show that confused people so much, that was so ambiguous that they didn’t know what to think, but they felt sort of sickened by it and also entertained,” DeSana told his friend and fellow artist Laurie Simmons in an interview shortly before he passed away in 1990, “then for me that would capture the moment that we’re going through right now.”

— Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator, Photography, Brooklyn Museum

Subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue.

Los Angeles without Angelenos

Taken during shelter-in-place orders, Pascal Shirley’s aerial pictures of LA are full of poetic foreboding.

By Glen Helfand

Pascal Shirley, 110 South, Los Angeles, 2020

When Los Angeles issued shelter-in-place orders on March 15, due to the coronavirus crisis, something really changed about this car-centric city. The streets were suddenly empty. It had just rained, a situation that created some of the best air quality in decades, the skies crisply clear and the hills and golf courses spring verdant, while the parking-lot trees were lush and blooming. The highway calm was deceptively serene—travel that ordinarily would take time, patience, and the company of a lengthy podcast was navigable in minutes.

Maria Wyeth, the depressive, freeway-addicted antiheroine of Joan Didion’s 1970 novel Play It As It Lays, would have had a field day going nowhere even faster. When you can move freely, the terrain takes on different qualities, our perception of space and time shifts.

There’s even more latitude when you head upwards.

Photographer Pascal Shirley had the inspiration—and the right connection to a pilot, Alex Freidin—to seize the moment and survey the initial dazed shock of catastrophe. In a series of midmorning helicopter flights, Shirley went up with his 100-megapixel medium-format camera in those first days of lockdown. His pictures of sunny abandonment are documents of a deceptively low-impact disaster, and full of poetic foreboding.

Pascal Shirley, Covid Testing, Dodger Stadium, Los Angeles, 2020

Aerial photography, of course, exudes greatness in its sweep. In LA, the helicopter is the vehicle that reports traffic or chases criminals through neighborhoods on sunny afternoons. From the ground, this is all ordinary and perhaps frayed, trash cans on the curb, decently tended yards, but looking down from the heights, those streets look so clean and geometrically contained.

Skimming the sky above downtown provides a full daylight view of empty lanes on the highway headed downtown. The electronic sign offers a message of minimalism: “COVID-19 / LESS IS MORE / AVOID GATHERINGS.” Nearby, there is a curving line of cars arcing through the Dodger Stadium parking lot, as passengers wait for a drive-through coronavirus test. Orange traffic cones, like little pushpin markers, create a flimsy but heeded route. It’s as if the vehicles were getting in formation for a Busby Berkeley car commercial. But this is serious. There are subtle skids from failed doughnut spins and the thin lines that demarcate parking spots.

Culture is on hold, perhaps imperiled. Wilshire Boulevard right in front of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is desolate and cluttered with parallel lines—street markings, palm trees, and Chris Burden’s iconic public sculpture Urban Light (2008), which appears as an orderly cluster of spindles. There are no group selfies in action at this tourist magnet, just one lone man at the corner of the piece; perhaps he’s a security guard dispatched for this unique moment. To the right, you can see a patch of construction fence—old structures would be demolished a few days later to make room for an expensive and controversial new building. Spectators were few.

Pascal Shirley, Urban Light, LACMA, Los Angeles, 2020

Up on the Sunset Strip, the sun still shines on building-size billboards for big movies that won’t be released anytime soon, at least not in theaters. The Hollywood Bowl is empty, as it will remain, for the first time in almost a hundred years, for a full summer season. In less identifiable locations, recently painted parking lots for malls and workplaces are geometric abstractions punctuated by blooming trees.

These places follow architecture critic Reyner Banham’s famous “four ecologies” of the city: the freeway system, Autopia, like an attraction at Disneyland (a site that Shirley and Freidin also zoomed over); the mansion-studded Foothills; the flat, boring neighborhoods dubbed The Plains of Id; and the beaches and beach towns of Surfurbia.

Headed towards the ocean, the beach at Santa Monica is a smooth, blank canvas for the shadows of clouds and the helicopter—its whirling blades register a tiny, soft blur on the sand. And out to sea, four cruise ships sit, socially distanced, like cats lounging on a hazy morning. Only they’re now emblems of mortality, of endangered economics, leisure, and life itself.

The sinister, sublime nature of these photographs is unlike the eco-horror overhead views of Edward Burtynsky’s Nickel Tailings (1996) and strip mines. Neither is it Andreas Gursky or Florian Maier-Aichen digitally removing things in order to amplify the oddness of contemporary life. Shirley described the experience of flying over the city as something akin to “watching a movie.” Though, as Cardi B so succinctly put the pandemic era, this shit is real.

Pascal Shirley, Port of Los Angeles, 2020

Pascal Shirley, Citadel Outlets Mall, Los Angeles, 2020

Pascal Shirley, North Beach, Santa Monica, 2020

Pascal Shirley, School Playground, East Los Angeles, 2020

Pascal Shirley, Public Playground, South Los Angeles, 2020

Pascal Shirley, Cruise Ships, Los Angeles Harbor, 2020

Glen Helfand is an associate professor at California College of the Arts in Oakland, California. All photographs courtesy the artist and Alex Freidin/Hangar 21 Helicopters.

May 15, 2020

Dress for What Job?

As millions file for unemployment, a large-scale exhibition explores the meanings of workwear.

By Sara Knelman

Irving Penn, Les Garçons Bouchers, Paris, 1950

© Condé Nast

Though often designed for function or protection, the uniform is also always symbolic. Each element of its specifics, from cut to color, court assumptions: about class, gender and sexuality, cultural heritage, and other markers of human experience and perspective. Full disclosure: I’ve only worn a uniform for one brief period, when I attended a private Anglican girls school for two years in junior high, a fact I rarely mention and a time I’ve opted largely to forget. The grey box-pleat skirt, tar-flapped white shirt (like a sailor’s) and maroon tie marked me out in ways that made me viscerally conscious of the privileged identity these clothes bestowed, and also of the ways I seemed to betray them. A uniform, after all, can denote the wearer as belonging to something just as much as it can indicate their status as an outsider.

Song Chao, Miners, 2000–02

© the artist

It’s this murky paradox that sparked curator Urs Stahel’s most recent exhibition UNIFORM: INTO THE WORK / OUT OF THE WORK, staged at MAST Foundation in Bologna, Italy. (The exhibition is currently closed to the public, but I was able to watch a video tour with the curator and read the accompanying catalogue.) “The Italian language has two words for this,” Stahel writes in the catalogue, ‘uniforme’ and ‘divisa.’ One word strongly emphasizes the unifying aspect, the other highlights the dividing aspect, the aspect of separation. They show inclusion and exclusion to be two related, connected actions.” UNIFORM brings together imagery made by more than forty photographers across a range of sociohistorical contexts in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, from iconic portraiture and documentary work to more experimental, even fantastical, contemporary projects.

Florian Van Roeke, Chapter Three, V, from the series How Terry likes his Coffee, 2010

© the artist

Yet no one could have imagined, while conceiving of the show, the ways in which this historical moment has sharpened an awareness of the uniform. From the shortage of lifesaving personal protective equipment for doctors and nurses, hospital workers, and first responders, to the new heroism of grocery store employees, to the sudden market for fashionable face masks, the uniform has become a savior and a comfort. It is also a stark reminder of the perils and inequity of a class system that forces service-industry workers to risk their lives while others trade white collars for upscale loungewear in the refuge of the work-from-home world.

Paola Agosti, Forlì, Giovane operaia ferraiola in cantiere (Young iron worker), 1978

© the artist

Photography, like the uniform, can generate a visual order, deploying aesthetic uniformity—of backdrop, lighting, scale—to lend a sense of equality to diverse subjects. The exhibition is grounded by iconic twentieth-century projects that take such an approach. August Sander’s Rigger (1930) and a pair of Irving Penn’s Small Trades works from 1950 betray almost painterly traces of work in regal full-length portraits: blood and knives littering the aprons of a pair of butchers, the bulging eyes of a dead fish hanging limp in the hand of the fishmonger, a loosely gripped wrench. By contrast, Paola Agosti’s documentary project from the 1970s breaks away from the tightly structured image, exploring the rise of women laboring in Italian factories—wearing typically male attire in typically male arenas—such as the striking image Forlì (1978), of a young iron worker donning short hair and a jumpsuit.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Trabajadores del fuego (Fire Workers), 1935

© Archivo Manuel Álvarez Bravo

The functional garb of factory workers and tradespeople seems designed for ease of movement and to keep a layer of clothes beneath clean. Presciently, the exhibition also includes a cluster of work looking at the protective capacity of the uniform. In Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s The Fire Workers, Mexico (1935), two figures walk through a frame that resembles a sci-fi future. In another image, from Sonja Braas’s series An Abundance of Caution (2015), three eerily empty hazmat suits hold their shapes, as though their wearers have vanished, giving way to an unnamable lurking anxiety—the virus as metaphor.

Helga Paris, from the series Women at the Treff-Modelle Clothing Factory, 1984

© the artist

Clothing made to suit a trade, craft, or profession gives way, in the postwar era, to the corporate clerk—en masse, the infantry of consumer culture. Barbara Davatz’s series Beauty lies within. Portraits form a globalised fashion world (2007) is named for a clichéd slogan that used to be printed on H&M shopping bags. Davatz photographed eighty-one H&M employees in her studio, creating a kind of ethnographic study of globalized youth culture and of the aesthetic of mass-produced “fast fashion.” Marianne Mueller, whose work often explores otherwise overlooked everyday environments, captures portraits of the youngest employees of Migros, a Switzerland supermarket chain and that country’s largest employer. Each sitter is set before an orange backdrop—the striking, even overwhelming brand color of the corporation. Presented as large photographic grids, both projects evoke a struggle between homogenization and originality, the same forces at play as our eyes search among the portraits for marks of similarity and difference.

Rineke Dijkstra, Olivier, Camp Rafalli, Calvi, Corsica, June 18, 2001

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Do we choose uniforms as a reflection of belief or value, or do they shape us? Rineke Dijkstra’s series Oliver (2000–03) tracks a young legionnaire, Olivier Silva, through three years of training, his adolescent innocence in the first image giving way to the appearance of hardened authority in the last. Dijkstra, whose work frequently traces moments of transformation, frames Olivier’s shifting identity in ways that appear both melancholy and deceptive. It’s hard not to mourn the boy whose worldview seems to have altered so radically. And yet, what does a sharply pressed uniform and a military haircut tell us about his character? The suit, like the photograph, is only an image.

Walead Beshty, University Museum Preparator, Ann Arbor, Michigan, March 27, 2009

Courtesy the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles

The exhibition has a coda of sorts, a projection of the art world’s more eccentric “uniform.” The voluminous installation includes 364 images of art-world professionals by Los Angeles–based artist Walead Beshty, who’s been amassing an archive of portraits for over a decade of individuals with whom he has worked. As curator, Stahel opted to organize the images according to their primary art-world activity: artist, curator, collector, arts administrator, et cetera (Beshty’s larger archive of 1,400 images and counting is ordered chronologically). Stahel’s catalogue text on them suggests the dream of an art-world counterculture, an “anti-uniform,” albeit an idea which “risks achieving the opposite.” Though moving as a gesture of acknowledgement and collaboration of often unseen labor, I’m not sure what one might glean from such a presentation sociologically, beyond the markers of exclusion and privilege that often inflect cultural work.

Installation view of UNIFORM at MAST Foundation, Bologna, Italy, 2020, with Marianne Mueller’s video Portraits (Guards), 2010–12

Other, spectral museum workers appear in the main exhibition. At various junctions in the show, visitors also encounter Mueller’s series Portraits (Guards) (2010–12), life-size video portraits of uniformed guards, watching over them from strategically placed screens. (All the subjects are real-life museum guards from the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, for which the work was originally made.) As an installation, they force a confrontation and consideration that doesn’t often occur between spectator and custodian. Though the installation itself is difficult to fully appreciate via digital documentation, it’s also one of the most affecting—the vision of these apparitions still guarding the work set against the question of what has happened to them, and others like them, amidst the mass closure of cultural institutions the world over.

Sara Knelman is an educator, curator, and writer living in Toronto.

UNIFORM: INTO THE WORK / OUT OF THE WORK opened at MAST Foundation, Bologna, Italy, on January 25; the museum is currently closed due to the coronavirus crisis. See the museum’s website for updates.

Introducing: Natalie Keyssar

In Venezuela, a photographer finds spontaneous grief and joy in everyday life.

By Laura Cadena

Natalie Keyssar, The inauguration of a new basketball court as part of a violence prevention initiative in Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela, 2019

In the seven years that Natalie Keyssar has spent photographing Venezuela, she has come to understand herself as a student of a culture that produces miracles.

In February 2014, four years into her career as a photojournalist, Keyssar’s first glimpse of Caracas was during a self-appointed assignment to cover the widespread protests that had overtaken Venezuela. Public discontent due to government corruption and deteriorating social and economic conditions soon devolved into violent clashes between protesters and government forces—rattling Nicolás Maduro’s unsteady presidency, whose slim victory the previous April marked a moment of immense fragility for the Bolivarian Revolution. In retrospect, Keyssar describes her first photographs of Venezuela as having “missed the point” and unwittingly contributed to “oversimplified narratives” about the crisis.

“I knew I didn’t understand, and I wanted to understand,” Keyssar recounted during a conversation in late March. “I wanted to communicate the complexities that were causing this unrest, and not just take the unrest out of context.” After wrapping up her assignment, Keyssar traveled home to New York City, only to pack her bags and return to Venezuela—this time compelled by an incipient awareness of the many ways in which Caracas would soon become her classroom.

In the years that followed, Keyssar produced an expansive body of work, which serves as a rare record of contemporary Venezuelan life. Her photographs eschew the photojournalistic tendency to zoom in on crisis, and instead linger on the affective residues and reorganizations of community life that crisis wears into the everyday. In doing so, these images make room for narratives that get written out of patriarchal political representations of Venezuelan life—in particular, the everyday experiences of Venezuelan women.

“So much of documentary photography focuses on the stars of the political show. There’s a circus around the men in power,” Keyssar says. “But if you pull back just a little bit, often in the same spaces, you start to see the roles that women play.”

In her series Make Me A Little Miracle (2014–ongoing), Keyssar proves the radical effects of pulling back by presenting a selection of images where women are no longer portrayed as redundant bodies in masculinized zones of conflict, but are instead acknowledged as fundamental agents in the sculpting and maintenance of Venezuela’s daily realities.

“I often see Venezuelan women as holding the fabric of society together as it tries to fall apart,” Keyssar says. In her photographs, evidence of this holding becomes enfleshed in a variety of iterations: women holding their heads down as an act of protection; holding each other as they climb over a broken fence; a woman holding herself in an empty kitchen. By centralizing these forms of holding, Keyssar’s photographs give stark legibility and protagonism to the ways Venezuelan women support their communities as they mitigate and maneuver the challenges of political violence and economic crisis.

Titled after a stanza in Rubén Blades’s 1978 salsa homage to María Lionza—a national emblem of hope and feminine strength often called upon for miracle work—Make Me A Little Miracle envisions these forms of maneuvering as a type of miracle working. However, miracles should not be understood as spontaneous blessings, but as the direct results of women’s labor and learning. “Despite all the hardship, there’s a space for the miraculous,” Keyssar says. “There’s a culture of overcoming, which has expanded my understanding of what is possible.”

Still, there’s a simultaneous grief and joy to the way Keyssar’s photographs apprehend these miracles while sensing the immanent pressure of hardship. Imbued with both gratitude and cautious admiration, Make Me A Little Miracle functions as the ramo de flores (bouquet of flowers), which Keyssar extends toward María Lionza—and all the women who aid her—in hopes that she might bear witness to one more miracle.

Natalie Keyssar, Anthony Arteago, 20, wounded by a blast of birdshot from Venezuelan forces after clashes on the Colombian border, Caracas, Venezuela, 2019

Natalie Keyssar, Cheerleaders backstage for a performance at a cryptocurrency conference at a luxury hotel, Caracas, Venezuela, 2018

Natalie Keyssar, A rainbow photographed from a helicopter over the Avila mountain range. The helicopter once belonged to Bill Clinton, Caracas, Venezuela, 2015

Natalie Keyssar, Caracas-based neighborhood dance team “Moni Dance” hop a fence on a rooftop, Caracas, Venezuela, 2019

Natalie Keyssar, Protesters clash with the National Guard in Altamira, Caracas, Caracas, Venezuela, 2014

Natalie Keyssar, Exhausted after two days in a row of waking up at 3 a.m. to wait in line for food, Eli rests at home with her daughter Rashelle, Caracas, Venezuela, 2016

Natalie Keyssar, A group of girls from La Vega prepare for a dance performance to celebrate the opening of a soup kitchen for their community, Caracas, Venezuela, 2019

Laura Cadena is a writer based in New York, where she co-facilitates the New York Arts Practicum. All images from the series Make Me A Little Miracle (2014–ongoing) courtesy the artist.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

May 8, 2020

How Should a Mother Be?

Charlie Engman’s portraits of his mother are an intimate—and provocative—exchange of mind, body, and spirit.

By Sheila Heti

Charlie Engman, Mom in the Yellow Suburbs, 2016

Courtesy the artist

What is a grown man supposed to do with his mother? Ignore her. Help her. Visit her dutifully. Keep an emotional and intellectual distance. Bring the grandchildren around to show. Suffer with a plastic smile through Thanksgiving dinners. Keep the thick and invisible wall between grown child and mature parent in its place.

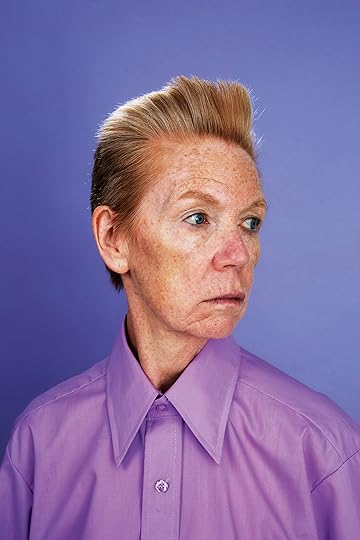

Charlie Engman, Mom in Purple, 2016

Courtesy the artist

To do anything else is a taboo that we do not even talk about. But the heart-stopping fear and wonder and sometimes disgust that Charlie Engman’s portraits of his mother engender in the viewer make this taboo plain. To make art with someone else (as Engman and his mother make these photographs together) is always to engage in an intimate exchange of mind, body, spirit, heart. Why should it be so shocking to see this intimacy happen between a grown man and his mother? If a man sees his mother naked—photographs her naked—the mind reels. It’s not incest, the viewer assures herself, but is it like incest? What sorts of conversations did these two have? It’s not disgust—it’s almost envy. How did this mother-son dyad breach the invisible wall and come to be collaborators? Come to be peers? How did they take on such new (and seemingly free) roles in relation to each other, not the roles prescribed by society—in which the son views his mother with polite forbearance and the mother hides from her child the truth of her aging body (at the very least!)—but something radical they invented in common? The photographs do not answer these questions, but these questions hang in their atmosphere. There is something proud in these photographs—something of the Nietzschean Übermensch. There is also something abject—to abjure the roles that others play is both heroic and abject. That is how these pictures seem. That is how this mother seems.

Charlie Engman, Mom with Brace, 2016

Courtesy the artist

But it is not only that the model is the photographer’s mother that chips away at our conventional sensibilities; it is also that the female model is old. It’s hardly worth saying that the desire of men (and of many women) to look at a woman is most often the desire to look at a young woman. Looking at a young woman is natural, because on some level the (male) looker is looking in order to assess her fertility: there is something wholesome about it. Sure, it is about lust, but that lust is about adding to the human population. Looking at an older woman cannot fit into that equation so snugly. It cannot be as simply explained. If looking at a young woman is natural, looking at an old woman is perverse. No one would argue this. We don’t believe it. And yet that is in these pictures, too.

Charlie Engman, Mom on Rocks, 2014

Courtesy the artist

Also, a mother is supposed to tell her son what to do. A son is not supposed to tell his mother what to do. But even though these two are collaborators in their art, if the viewer doesn’t know this, we credit the photographer with the inevitable power any artist has over their subject, and so, in these pictures, there is a quality of sadism, or at least of revenge: the son orders the mother around now. Finally the child has the upper hand!

Charlie Engman, Mom (detail), 2014

Courtesy the artist

Yet you can’t help but notice, looking at this woman’s face, that she is strong. She is magnetic. She has something deep and compelling inside her. She is not a mere tool of her child’s will. What if she is the artist, and her son is the tool? To dwell on this idea while looking at these pictures is very gratifying.

Charlie Engman, Mom in the Snow, 2012

Courtesy the artist

But that is not where we can end. We must accept that they are both the artist, and that they made these images together, because that is the truth. Which brings us back to their Thanksgiving dinner—achingly, unimaginably unlike our own! Or else, just like our own. Perhaps only in front of and behind the lens, only in the making of art (as is the case with every artist), are this mother and son so free.

Sheila Heti is the author several books, including How Should a Person Be? (2010) and Motherhood (2018).

Read more from Aperture, issue 233, “Family.”

May 7, 2020

5 Depression-Era Photographs That Galvanized Social Change

From Dorothea Lange to Walker Evans, the FSA photographers of the 1930s shaped a vision of the world transformed by economic crisis.

By Eli Cohen

As the United States dives further into what will surely be an economic recession, and as anxiety increases over how the nation will respond, photographs commissioned by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) in the wake of the Great Depression show the potential impact of the arts on an American collective conscience. During the Great Depression, the famed photographers of the FSA, led by director Roy Stryker, dispersed across the once prosperous nation to document the fall. Part of a government-funded relief program, the FSA’s photography division strove to record economic and environmental struggles, propagate the era’s essential photographs, educate Americans on the country’s situation, and inspire social change. “We believed, we knew, we saw,” said Stryker in 1963, “we sensed we were a part of this perception, part of coming in contact, part of seeing a world—a country of ours in turmoil, a country in trouble.”

In the exhibition One Third of a Nation: The Photographs of the Farm Security Administration, viewable online at Howard Greenberg Gallery until May 15, this essential historical record comes rushing back through iconic pictures taken by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, and others. Looking at the FSA photographs today, in an online viewing room presented by necessity rather than comfort or experimentation, we are left to marvel at the lasting strength of these images, as well as their newly relevant meanings, and to wonder how the contemporary moment will be portrayed when we look back in the decades to come.

Dorothea Lange, Greek migratory woman living in a cotton camp near Exeter, California, ca. 1935

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Dorothea Lange

The beginnings of the FSA photography project aligned perfectly with a transition in Dorothea Lange’s early career, when she left San Francisco to focus on photographing agricultural labor and migratory workers throughout the state. Her most powerful work pictured men, women, and children either at work or stranded in the aftermath, like this woman: hands on hips, an understated, worldly experience emanating from her posture. Lange’s monumental photographs from her time in California—Migrant Mother (1936), Filipinos Cutting Lettuce (1935), and White Angel Breadline (1933) are on view in the gallery as well—form the backbone of the FSA’s lasting historical significance. In these photographs, Lange aligned her social documentation with a labor-focused political agenda that remains pointedly relevant today.

Walker Evans, Construction worker, Louisiana, 1936

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Walker Evans

For Evans, the photograph was a site of negotiation, a setting to distill the American experience into a singular moment. His Depression-era portraits, immortalized in his collaborative book with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), portray a commanding stoicism in the face of hardship. When fellow FSA photographer Jack Delano first saw Evans’s photographs, he said he was “stunned by the simplicity, sureness, power, and grace of the images.” This photograph of a construction worker in Louisiana is no different. Shot at an upward angle, Evans’s subject is given nearly mythical status, even as he looks away with a despondent glance.

Russell Lee, Untitled (Floods Kill Hundreds . . .), 1936

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Russell Lee

Feeling limited by his chosen medium of painting, Russell Lee first picked up a camera in 1935; one year later, he was hired by Roy Stryker at the Resettlement Administration—which would later become the Farm Security Administration. Perhaps the most prolific photographer employed by the FSA, Lee is most known for his photo-essays depicting rural Iowa and other locales in his coverage of the Midwest and West Coast. Lee’s photographs presented in One Third of a Nation give new light to the urban scenes he captured over those same years. Here, with a sign overhead proclaiming, “Floods Kill Hundreds in East,” and a man playing violin on the street, the malaise of metropolitan society resonates across America, urban and rural alike.

Marion Post Wolcott, Unemployed coal miner’s daughter carrying home can of kerosene. Company housing, Scotts Run, W. Va., 1938

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Marion Post Wolcott

In 1937, stuck shooting fashion assignments for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Marion Post (later Wolcott) approached her friend and mentor Ralph Steiner for advice. Two weeks later, buoyed by recommendations from Steiner and Paul Strand, she joined Stryker’s team of photographers at the FSA. Post made this photograph on her first assignment, in the coal-mining regions of West Virginia, hard struck by economic depression. A haunting image, the isolation speaks to the contemporary moment in both context and tone. As industries grind to a halt, oil prices implode, and streets empty, Post’s photograph of an unemployed coal miner’s daughter is a loaded reminder of what the next years could look like.

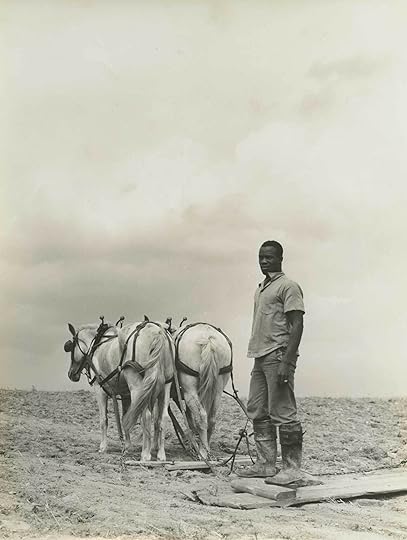

Jack Delano, Greene County, Georgia, 1941

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

Jack Delano

Like Walker Evans’s construction worker, the subjects of Jack Delano’s photographs in Greene County, Georgia, are tall-standing, prophetic figures. A hotbed of FSA and New Deal activity—numerous FSA photographers, including Dorothea Lange, Marion Post Wolcott, and Russell Lee, visited in the late 1930s and early ’40s—Greene County was a Southern center of agriculture, poverty, and racial animosities. In 1941, Delano added his own angle to the county’s photographic record, joining the sociologist Arthur Raper to pair visual documentation with written analysis. There, Delano used his camera to expose Southern poverty and racism alongside surveys of the people he saw, their livelihoods, vernacular architecture, and landscape: timely visual ethnographies set against the backdrop of the Great Depression.

Eli Cohen is the work scholar for Aperture magazine.

One Third of a Nation: The Photographs of the Farm Security Administration is viewable online at Howard Greenberg Gallery through May 15, 2020.

In a World of Loneliness, One Photographer’s Search for Community

Eli Durst speaks about team-building exercises, suburban Americana, and why his photographs resist interpretation.

By Gideon Jacobs

Eli Durst, Gwen in Circle, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Eli Durst’s first monograph, The Community, an examination of “the fundamental search for community in America,” arrives this spring in a moment of unprecedented isolation and alienation. The COVID-19 pandemic has rendered the act of gathering—a behavior coded into our very DNA—unsafe and, in most of the country, illegal. But even before the lockdown, sociological studies have long shown that in-person community is on the decline, and that the practice of building intimacy and identity in a group is migrating, like seemingly everything else, into the digital sphere. I wanted to discuss this—the uncanny relationship between the book and the state of the world it’s entering—but also get a better general understanding of Durst’s photographic approach as he takes on more editorial assignments. We spoke in late April, mediated by our screens, of course, a mode of conversation that felt appropriate for reasons beyond public health mandates.

Eli Durst, Adam, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Gideon Jacobs: To begin, I wanted to ask you about the end of your book, the very direct statement of intent on the final page: “Put simply, these photographs are about the search for purpose and meaning in a world that both demands and resists interpretation.” I was kind of surprised to see you explain what the work is about in such a straightforward way. What made you want to articulate that?

Eli Durst: Well, I wanted to give some context without having to provide titles or details about each image. I felt like a little bit of explanation would give people some more context to interpret the book. However, I put it in the back of the book for a reason—so the viewer can look at the work first. I kept the explanation brief for this same reason. I want the viewer to interpret the work for themselves, but I don’t want to be intentionally opaque.

Eli Durst, Melting Ice Cream, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: It seems like a tricky balance to strike for all photographers, finding a comfortable zone between giving context, explaining, priming, and letting the work speak for itself. Where do you think you fall on that spectrum? Is it something you think about?

Durst: I generally don’t like over-explanatory text, because I want to figure out the work for myself. But at the same time, I think you need to give the viewer a framework through which to interpret the work. I hope the book remains a mysterious object, even with the text in the back.

Eli Durst, Casa Ritual, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: I think it does! Let’s talk about that framework. What is the link between community—the more overt subject of the book—and our search for purpose and meaning—the more subtle subject?

Durst: The book is about pursuing physical community—something that seems even more important now that we have been deprived of it for public-health reasons. The series is not really meant as a documentary project studying the unique qualities of each group or activity. I’m more interested in the commonalities across all these different pursuits. What is everyone after? Why, in the twenty-first century, congregate at a rec center or church basement? What is at stake? What do people gain from being together in physical space? What do people need from each other, from a community?

Eli Durst, Knot Tying with Dante, 2017

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: Something I think a lot about when looking at your pictures is that, for community building activities to be effective, you need an earnest buy-in from the whole group. People can’t be too cool for school. Your photographs are often striking to me in the way they capture earnestness, a rare kind of sincere participation. What is it about that quality in a person or a moment that attracts you?

Durst: That’s true. You have to be vulnerable in some way, open yourself up to other people. With the team-building exercises, people think they’re silly or ridiculous, but that’s the entire point, for your boss to do something that they would never normally do, to make yourself look ridiculous, to give up your ego in some small way. It’s not that trust falls give you some business acumen you lacked before. It’s that you bond with someone by acting outside of yourself.

Eli Durst, Lightbulb, 2016

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: That vulnerability and ridiculousness can make your pictures kind of funny. Do you ever fear that humor? Do you ever worry that these earnest subjects, when viewed by those outside of the team-building activity—especially when viewed by a critical, cynical photo audience—will be laughed at for the wrong reasons?

Durst: Definitely, and it’s something that I really tried to work against in the edit of the book. I cut out some photos that I thought were successful, because they felt too jokey and undermined the project as a whole. But humor is still a part of the work. The statement at the end of the book about “a world that both demands and resists interpretation” alludes to a certain absurdity in our pursuit of meaning. When I started making these photos in graduate school, I gravitated towards funny Americana-type subjects, like bingo for instance, but I quickly realized that I wasn’t satisfied making ironic photos. I also didn’t want the pictures to become overly sappy. The tone of the project changed a lot as I was making it. I tried to learn from the pictures.

Eli Durst, Sam and Ben, 2018

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: What about this body of work feels uniquely American to you? Could this book have been made in another country or culture?

Durst: I don’t think so. The core of my work, regardless of series, has always focused on American identity and suburban iconography. I think the need for a sense of purpose is universal, but the setting in which this pursuit unfolds in The Community is uniquely American. I was an American studies major in undergrad, and I’ve always been drawn to photography for its ability to investigate or think critically about the landscape around me, the landscapes that I feel closest to.

Eli Durst, James with Baby, 2015

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: Did this have anything to do with why you called the book The Community instead of simply Community?

Durst: I liked The Community, because it almost made it feel like this was one fictional community center, in which all these events were unfolding simultaneously.

Jacobs: It seems like one of the possible consequences of the pandemic might be that it has sped up the migration of community from the real world to the digital one. Do you see your book as covering the last vestiges of something? Maybe something that won’t really exist for the next generation?

Durst: I was reading the book Bowling Alone (2000) when I started making the work and thinking about the disappearance of certain aspects of American culture. I wonder if the move online during COVID will be permanent, or if this is actually making people realize how much value they get from interacting with other humans face to face.

Eli Durst, Apple (Meeting), 2016

Jacobs: Over the last several months, you have been shooting a lot of editorial assignments, including a piece about criminal justice in Florida, as well as a profile of Bernie Sanders, for the New York Times Magazine. How do you bring your approach to a more photojournalistic arena? Do you even make a distinction regarding process in your head? Or is it all just one thing: photography?

Durst: It really depends on the assignment. For some, like the story I did about Buc-ee’s for the New York Times, I approach it in the exact same way that I would approach art-making, which makes sense because it’s very much in line with what I’m interested in generally. Other assignments, however, like straightforward portraits, are different. You have to think about the tone and position of the story. I don’t want to just slap a style onto a subject matter or story that doesn’t ask for it. With editorial assignments, you obviously have a lot more restrictions and limitations. I have less directorial control, which is a big part of my art-making—feeling free to change things or move things, or create scenarios in which people have to act or react.

Eli Durst, Brisket Round Up, New Braunfels, Texas, 2019, for the New York Times

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: The photographs in The Community often imply a story, either individually or in sequence, making a viewer consciously or unconsciously extrapolate a narrative that explains how this moment came to be. As your editorial work is usually made to illustrate a written piece, is there room for the abstraction that sometimes flavors the book?

Durst: I hope my images from the Buc-ee’s story have the same, strange, open-ended quality of The Community, but there’s also a photo editor and publication to think of. They have a big say in which photos run, of course.

Eli Durst, Buc-ee the Beaver Statue, Katy, Texas, 2019, for the New York Times

Courtesy the artist

Jacobs: The other clear distinction between your editorial work and your more personal work is that, when working for a magazine, you’re beholden to some orientation around truth, and have to, at least loosely, abide by some photojournalistic codes. Do you find this limiting? Do you ever find it tricky to straddle the line between docu-art and docu-journalism?

Durst: Here’s an example: In the book, there’s a photo of a man named Jerry, who I had put on a wig and act out some basic scenarios. When I photographed Jeff Sessions for an assignment, I would have loved to put a wig on him . . . but that was definitely not allowed. You’re restricted by the story but also the realities of access and journalistic ethics in ways that you’re not when making art. I don’t think changing or manipulating a scene necessarily makes a photo less true. In fact, sometimes you can get at things that wouldn’t otherwise be apparent.

Gideon Jacobs has contributed to the New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, BOMB, Playboy, and VICE.

Eli Durst: The Community was published by Mörel in spring 2020.

April 30, 2020

What Is Street Photography without Street Life?

In the age of pandemic, the romance of the empty street becomes the terror of absence.

By Geoff Dyer

Charles Marville, Rue de Constantine, ca. 1865

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and courtesy Art Resource, NY

So here we are, thrown back to the dawn of street photography! I still remember the thrill I got when I first read that the streets in photographs of nineteenth-century cities weren’t really as empty as they looked—and as ours are now. It was because the slow shutter speeds vaporized or disappeared any people, horses, and carriages moving quickly. London and Paris became cities of the dead, haunted by the faint ghosts of anyone moving slowly or shifting position slightly. Only the rigidly unmoving remained substantial and intact, fully corporeal.

What I find extraordinary now is that I ever took these photographs of empty cities at face value, as it were, since I knew from the densely populated novels of Honoré de Balzac and Charles Dickens how these streets were full of characters bumping into or evading each other according to the needs of the bulky mechanics of theme and plot. In London, even the pollution—the famous fog of Dickens’s Bleak House (1853)—was not just visible, but palpable. It seems that two contradictory versions of the same place—one crowded, the other deserted—were able to coexist in my head. The idyllic quality of the latter, which became more pronounced as pressure was applied by the former, found apocalyptic expression in the opening sequence of an empty Westminster in Danny Boyle’s 2002 zombie movie, 28 Days Later. The nearest one could come to glimpsing this future in the actual life of the present was emerging from a nightclub at six o’clock on a Sunday morning to find the waiting world devoid of life except for a few saucer-eyed and friendly zombies (as corroborated by Richard Renaldi in his 2016 book Manhattan Sunday).

Richard Renaldi, 06:27, from the book Manhattan Sunday (Aperture, 2016)

© the artist

A version of this experience animates Sebastian Schipper’s film Victoria (2015), when the eponymous heroine leaves a club with her new acquaintances to pursue a real-time, single-take adventure in the Berlin dawn. On a smaller scale, Claude Lelouch’s C’etait un rendezvous (1976) features an eight-minute, high-speed journey through Paris, filmed in one take by a camera attached low down, near the front bumper of a car driven by the stunty auteur—at 5:30 am on a Sunday morning in August. It’s not just exciting, it’s terrifying, because although most Parisians are either en vacance or asleep, the city is not empty. The risk is all too real.

Nowadays, even trundling a shopping trolley through Whole Foods feels risky but, as far as I know, photographers have not yet been able to capture the psychic terror of the times. The source of the threat is invisible and its effects, overwhelmingly, are of absence. Its symbol, the mask, hides from view.

Eugène Atget, Café, Avenue de la Grande-Armée, 1924–25

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The camera can only film what is there. So, as John Szarkowski pointed out, while it was possible to construct a memorial to the murdered President Lincoln sitting in a chair, photography was left only with the chair. As a result, empty chairs were themselves altered by the invention of photography. A picture taken by Eugène Atget in 1924–25 of empty chairs outside a Paris café, Szarkowski suggests, is imbued with the thought of soldiers who did not return from the battlefields of the First World War. Published recently in the New Yorker, Philip Montgomery’s photographs of chairs stacked up in cafés attest to what might be termed the consistent contrary of the scene recorded by Atget: the hope of an eventual return of customers and life from the dead time of lockdown.

The last customer at a Jackson Heights restaurant before citywide closures took effect, March 16, 2020. Photograph by Philip Montgomery for the New Yorker

Courtesy the artist

And what of the streets themselves? Garry Winogrand did not like being called a street photographer. Referring to his book The Animals (1968), he said he might as well be called a zoo photographer, but our current predicament shows the limits of his objection. If its cages are empty, a zoo is no longer a zoo, while an empty street remains a street. What’s happened is that street photography has been obliged to become a species of architectural photography. And while it used to be necessary, if you wanted to concentrate on the buildings, to get out of bed as early on a Sunday as Lelouch, there is no longer any need to set your alarm. Time has largely been taken out of the day (just as the days have been taken out of the week), so that the street can be surveyed in its Giorgio de Chirico–like emptiness at all hours. There is no urgent need now to have a Leica loaded with high-speed film, since the fleeting rhymes caught by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Helen Levitt or the collisions jumped on by Winogrand are few and far between. This, instead, is the domain of the large-format view camera. The terror is manifest as its opposite: a ubiquitous visual calm—the opposite of a riot or carnival—which only accentuates the unphotographable wail of ambulances.

Garry Winogrand, New York City, 1968

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

The loss of life from COVID-19 is potentially huge, and the loss of street life necessary to minimize that loss involves the loss of almost everything that makes the life of the street photographer worth living. Winogrand has often been lambasted for leching his way around the streets of New York. He was not shy about admitting that whenever he saw an attractive woman, he wanted to photograph her, and there is ample evidence, to put it mildly, of how doggedly he pursued this ambition. With so much going on, however, an element of this endeavor—and of his work more generally—is easily overlooked: namely, its lyricism. It’s not just that he occasionally conveys that enduring phenomenon, love at first sight. Sometimes in life, this first sight can lead to thirty years of marriage, an outcome that lies beyond the severely limited scope of the picture frame. More usually, on the street, it evaporates—due in no small measure to the necessary observance of decorum and respect—even as it is experienced. The moment it occurs is followed, almost instantly, by its disappearance. And that—unlike the terror—is something that the camera, in sufficiently dexterous hands, has proved itself highly capable of recording: the eternal and transient romance of the street. It is masked and much missed.

Geoff Dyer is the author of numerous books, including The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand (2018) and The Ongoing Moment (2009). See-Saw, a selection of his writing on photography from the last ten years, will be published in May 2021.

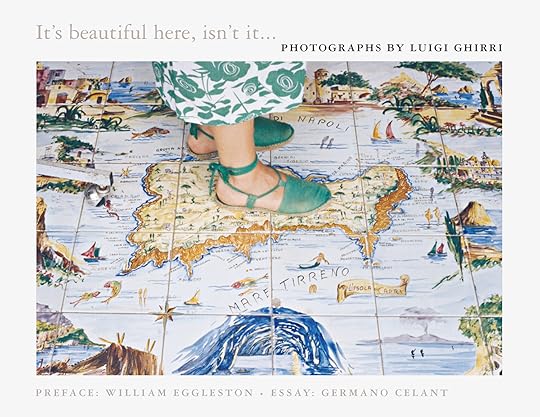

Luigi Ghirri and the Indefinable

Aperture is deeply saddened by the loss of the Italian art historian Germano Celant (1940–2020). Here, we revisit an excerpt from Celant’s introduction to Luigi Ghirri’s 2008 Aperture monograph.

Relating real copies of urban landscapes to real human beings, Ghirri’s photographs always produced an element of surprise.

By Germano Celant

Luigi Ghirri, Lucerne, 1971–72, from Paesaggi di cartone (Cardboard Landscapes)

Courtesy the Estate of Luigi Ghirri

Photography expanded in the 1960s, as photographers sought to imbue it with philosophical meaning, underscoring its connection to the worlds of thought and existential experience. It was to be considered not a secondary, incidental medium, with an almost parasitical relationship to reality, as many still then thought, but an affirmation of interrogative vision and of the principle of bearing visual witness. The camera could record countless phenomena, could produce a potentially infinite flow of images, yet the artist who reflected on the meaning of making photographs could compose them out of elements that might be disparate but were nevertheless ultimately unified. Pleasure or censure, conscious awareness or unconscious impulse, might inform the images that reflected his or her perspective on the world; the realism and naturalism that had come to dominate the understanding of the medium gave way to an interpretation of the photograph as an evaluation or assessment of reality rather than a description of it. The objectification of a perception that moved between the living and the material, the organic and the historical, the animate and the inanimate, the photograph was intellectual in intention, the result of an action that was mental and emotional yet was fused with an appreciation of reality. Even as one was allowed access to something presented as external and objectified, one’s attention was transported elsewhere.

Luigi Ghirri, Rimini, 1985, from Paesaggio Italiano (Italian Landscape)

Courtesy the Estate of Luigi Ghirri

“Artist” photographers from Ugo Mulas to Duane Michals made this transition from work that was documentary, and often took advantage of accident, to an understanding of the photograph as involving an intentional meaning of their own making. Their approaches relied not just on cropping and montage, or on the duration of a sequence of images over time—this is still a simplification—but on the intrinsic, logical value of the experience of seeing. Here was an alternative to the idea of the photographic document as indifferent and neutral; instead it was an act of the imagination, something with an autonomy like that of language, analyzing the continuity of language and contributing to an emerging understanding of the representational surface. From Giulio Paolini to Ed Ruscha, photography was transformed from a practical pursuit into a study of the linguistic devices involved in the construction of the image. It took possession of itself, becoming a vital philosophical elaboration, less an attempt to record reality than the product of a free activity of the mind. Photographic images are “unreal” in that they are “imaginary.” As “unreal” syntheses, they subtend an “elsewhere” that exists only in the eye of the photographer, and of the viewer who observes the photograph, scrutinizes it, analyzes it, interprets it. The experience of making photographs consequently implies a detachment, a suspension, in the confrontation with reality, in favor of an increasing absorption in the photographic process—a subversion of fact in favor of feelings and thoughts that “speak” through the language of images. The photographer moves away from the habits and customs of photographic convention and engages instead in the creation or visualization of a social and cultural communication involving pictorial display. This makes available a concept of space and time, of life and idea, that is interwoven with the persona of the artist/photographer, so that existence and technique enter into an essential relationship.

Luigi Ghirri, Rome, 1979, from Diaframma

Courtesy the Estate of Luigi Ghirri

In the early 1970s, then, photography asserted its autonomy. Surrendering its naturalistic function as a reproducer of facts, insisting on a relationship with reality that was less mimetic than creative, it transformed itself into an “apparition” that put inner aspects of a situation on view, a mirror that “made” details of the world and brought them to attention, that echoed reality yet revealed in it something unknown. Since photography documented preexisting conditions in the world, it could not be wholly new or invented, but it extended the real into the unreal, the true into the false, the original into the simulation. Indeed, photography exists at the threshold between these polarities, for it counterposes perception and “vision”—a vision made up of dreams, impulses, illusions, hallucinations. It brings to the surface events that are personal and therefore unreal, since they are not shared by others, and it makes them real—in fact puts the real and the unreal on the same level, and defines their relationship as the communicative process. Whether printed on light-sensitized paper or projected with a movie or TV screen, it makes visible an inaccessible reality with which we desperately seek to fix some parameters of certainty. But since the camera can produce an infinite flow of images, that certainty wavers, and the distinction between illusion and non-illusion remains undefined; we can only communicate.

Luigi Ghirri, Capri, 1981, from Paesaggio Italiano (Italian Landscape)

Courtesy the Estate of Luigi Ghirri

This is what Luigi Ghirri began to attempt in 1970. He had lived through the “desubjectification” of photography in the era of Process art and Conceptual art—the liberation of the photographic image from its aestheticisms and heroisms—and had seen there a danger of nullification. So he threw himself into affirming the grandeur and power of photographic language as a territory in which extremes—of the conscious and the unconscious, the real and the unreal, the physical and the metaphysical—could be maintained and preserved. Surfaces sensitive equally to lived experience and the linguistic nature of human perception, his pictures both stimulate and question the differences between true and false. A collector of surveys or maps that describe being and nonbeing within a single image, he produced a photography of both action and thought, rooted in history and the past but with its origin in the present, locating something there that occurs only within its frame, while the world flows by.

To continue reading, buy It’s Beautiful Here, Isn’t It… Photographs by Luigi Ghirri, edited by Melissa Harris and Paola Ghirri, and originally published by Aperture in 2008.

April 27, 2020

A Portrait of the Socialites as Bright Young Things

In Cecil Beaton’s glittering world, everyone was dressed up with somewhere to go.

By Lou Stoppard

Cecil Beaton, The Silver Soap Suds (from left, Baba Beaton, the Hon. Mrs Charles Baillie-Hamilton, and Lady Bridget Poulett), 1930

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Everything was so beautiful, until it wasn’t. The parties, the costumes, the faces, the promises.

A visit to the exhibition Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things at London’s National Portrait Gallery (NPG)—before it was closed due to the health crisis—or a read of the accompanying catalogue, provokes a complex kind of tenderness. It’s an imagined nostalgia for the seemingly carefree nature of the interwar years, when the parties were long and the people were unashamedly flamboyant; the days when an elaborate headdress, or the gushing words of so-and-so, could be a ticket to social and artistic success. But there’s an odd kind of revulsion too—at the excess, the navel-gazing, the bickering, the frivolity, the wastefulness, and, of course, the emptiness beneath the glitter.

Yes, Bright Young Things is a diverting riot of stylized portraits, silver hues, polka dots, doodles, and Beaton-style handwritten headings, a festival of high-society titbits and deliciously witty hearsay, located by the exhibition’s curator, the talented Robin Muir, in various biographies and diaries. Even the tone of Beaton’s diary-writing seems to have seeped into Muir’s text, which talks gayly of great beauties, meteoric success, effortless humor, and all manner of people coming up and down to Oxford and Cambridge.

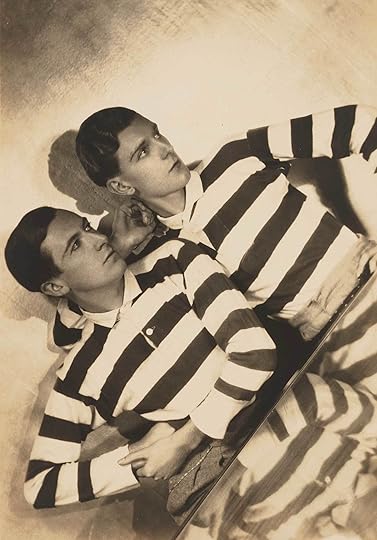

Maurice Beck and Helen Macgregor, Cecil Beaton and Stephen Tennant, 1927

Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

But there’s a probing sense of concern too. In the catalogue’s introduction, Muir writes of the summer of 1927, which solidified the reputation of the Bright Young Things, the monied young people who delighted in endless parties and dress-up opportunities. He quotes from the diary of Evelyn Waugh, who bullied Beaton at school, and whose novels—especially Decline and Fall (1928) and Vile Bodies (1930)—are deliciously bitchy takedowns of the whole Bright Young Things scene. “I went to another party the other night,” wrote Waugh. “Everyone was dressed up and for the most part looking rather ridiculous. Olivia had had her hair died and curled and was dressed to look like Brenda Dean Paul. She seemed so unhappy.”

Dualities are a good way of thinking about Beaton’s work, which is, in some ways, in step with the zeitgeist, when one considers his devotion to artificiality: the performance of identity, a freewheeling approach to gender, the idea that through dress and image, you can become the person you want to be and transcend your lot. Yet these same qualities might strike as jarring, given the conversations around privilege and representation abundant in photography—and society—today. Beaton’s folk were posh folk; the book itself is largely a who’s who, ordered by name and family—the Sitwells, Stephen Tennant, Lady Diana Cooper, the Countess of Oxford and Asquith, the Princesse de Faucigny-Lucinge, the Marquesa de Casa Maury, the Maharani of Cooch Behar.

Cecil Beaton, Paula Gellibrand, Marquesa de Casa Maury, 1928

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

There is talent amongst it all. A web of names spins around every image, every interaction—Virginia Woolf, the actress Anna May Wong, the economist John Maynard Keynes, the author Daphne du Maurier. Everyone seemed to known everyone. And they are all lovely looking, and maybe that in itself is just fine. Beaton, after all, didn’t pretend to care about much more than appearance (recall the title of his lauded book, The Book of Beauty, from 1930, which featured drawings and photographs of some fifty sitters, personally selected by Beaton as a means of cementing his status as an authority on taste, fashion, and the general hierarchy of who was in and who was out). Beaton’s goals, read aloud by Muir at the exhibition’s opening back in March, were, “all the trappings of celebrity.” In 1923, Beaton wrote, “I don’t want people to know me as I really am, but as I am trying and pretending to be.” Has there ever been a more modern sentiment, so fitting for the Instagram age?

As Nicholas Cullinan, the director of the NPG, explains in the catalogue, Beaton’s work offers a nice narrative arc when it comes to the museum’s—and, indeed, Britain’s—display of photography. This is the third Beaton exhibition at the venue. A large retrospective in 1968 was the first of any living photographer to be held in a British museum. The exhibition was extended twice, and its installation saw the gallery change its stance of displaying portraits of living sitters; after the show’s success, the gallery hired its first keeper of photography and film. Another display of Beaton’s portraits was mounted in 2004. It seems fitting that Bright Young Things comes at a time of transition for the gallery, which is scheduled to be closing this year for renovation, and at a point when questions around photography, and, in turn, gender, performance, style, and identity (all Beaton themes) are in a dynamic period of flux.

Cecil Beaton, Anna May Wong, 1929

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Those interested in detail will be well served. Muir, with meticulous research, encourages us to think about the amount Beaton did with so little. At the start, Beaton’s tools were little more than his patient sisters, a folding Kodak A3, and a stash of bedsheets and household objects to be used as backdrops and props. Muir describes Beaton’s photographic style, once fully developed, as “a marriage of Edwardian stage portraiture to nascent European surrealism, filtered through a determinedly English sensibility, one that revered in particular the modes and gestures of the upper classes.” The pictures themselves reveal something elemental about the human condition, about wants, needs, social habits, manners, norms and, that all-important factor in Beaton’s career—maybe the most important factor of all—ambition. We see, through Beaton, his subjects’ relentless search for distraction and, simultaneously, for meaning. We see their quest for a semblance of place, a home, but also, in contradiction, for freedom—for an escape from the humdrum, for that heady, if sometimes startling, sensation of not being trapped, never fully attached, maybe never fully present.

Still, of course, it had to end somewhere. And Bright Young Things smartly chronicles the demise, as well as the rise, of the Bright Young Things—including Beaton’s own fall from grace after he submitted a design with an anti-Semitic slur in the margins to Vogue in 1938. Clearly, from the very fact of this book and exhibition’s existence, and the countless more before it, the downfall was short lived.

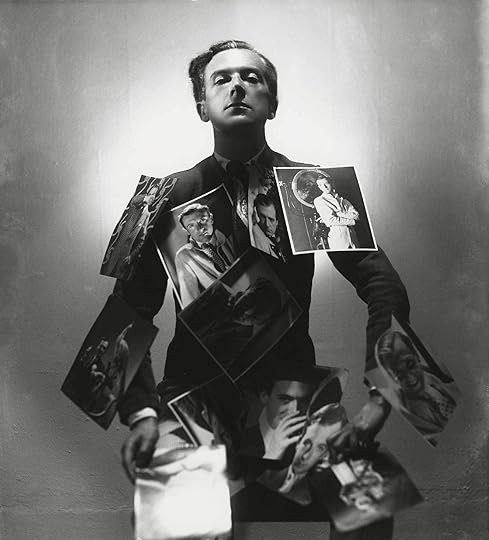

Paul Tanqueray, Cecil Beaton, 1937

© Estate of Paul Tanqueray and courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Elsewhere, we learn of the addictions, the suicides, the time wasted, the unfulfilled potential. I found myself moved by the restlessness of it all—the hedonism, the vaguely nihilistic sense of freedom, but also the guilt. The Bright Young Things were the generation after the war had passed. They were, for a while, the lucky ones. There was, like today, a remarkable split between generations, a chasm between young and old. And if you were young, you were so very young.

Post-lockdown, post-COVID-19, post–all the death and anxiety and the relentlessness of being cooped up and afraid, will the young of today fully take up their place as a “generation after”? Will it be the roaring twenties all over again? Will they break free from worry into parties and make-believe and lightness? Or will they do something more? I’m sure the latter, but who can know. The words of Lord Metroland, in Waugh’s Vile Bodies, have never seemed more poignant: “There was a whole civilization to be saved and remade. And all they seem to do is play the fool.”

Cecil Beaton, Edith Sitwell at Sussex Gardens, 1926

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive

Lou Stoppard is a writer and curator based in London. She is the editor of Fashion Together: Fashion’s Most Extraordinary Duos on the Art of Collaboration (2017), Shirley Baker (2019), and Pools: Lounging, Diving, Floating, Dreaming: Picturing Life at the Swimming Pool (2020).

Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things opened at the National Portrait Gallery, London, on March 12; the museum is currently closed due to the coronavirus crisis. See the museum’s website for updates.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers