Aperture's Blog, page 68

August 20, 2020

An Introduction to a New Book about the Zealy Daguerreotypes

Originally made in 1850 and rediscovered by Harvard’s Peabody Museum in 1976, the daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, Fassena, Drana, and Jack ask that we look closely, listen intently, and speak out.

By Molly Rogers

Pictures, like songs, should be left to make their own way in the world. All they can reasonably ask of us is that we place them on the wall, in the best light, and for the rest allow them to speak for themselves.

—Frederick Douglass, “Lecture on Pictures,” 1861

Frederick Douglass understood that a picture could do its work with little fuss, communicating clearly and directly, yet with considerable power. Knowing this, he praised the picture-making arts broadly but particularly welcomed the new medium of photography because it put this tool within everyone’s reach. Young or old, man or woman, Black or white—everyone could experience the power of this new medium by looking at a photograph, yet so, too, could everyone wield it by being photographed. It was, as numerous people have claimed, a truly democratic medium. Even “the humblest servant girl” could now afford to have her picture made, and many did. Douglass himself, a former slave who became a leading abolitionist, was the most photographed American of the nineteenth century, and each time he sat for a portrait, he knew precisely what he was doing. Show the world what I am—what we are—his portraits seem to say; show them that the camera, like nature, cares not one whit about skin color, or any other detail, but instead records everything equally and without prejudice. In this sense, at least, photography was indeed democratic: it could be used by practically anyone to suit their purpose. Douglass, for one, although a great man of words, again and again let the pictures speak for themselves.

But Douglass was not attracted to photography solely on account of its affordability, flexibility, and supposed objectivity. He also found in the practice of photography evidence of human nature. “The power to make and to appreciate pictures belongs to man exclusively,” he told a Boston audience on December 3, 1861, and repeated on more than one occasion. Picture making, he said, was a peculiarly human endeavor. People the world over, regardless of color or culture, were fascinated with pictures—making, sharing, and posing for them in vast numbers. The ability to make pictures, he reasoned, was therefore evidence of one’s humanity. That such a test was necessary, that Douglass had to posit photography in this way—arguing that it was “an important line of distinction between man and all other animals”—reminds us where he lived and when: the slaveholding, segregated states of America.

Douglass specifically aimed his contention “that man is everywhere a picture-making animal” at the men who comprised the “American school” of ethnology in the mid-nineteenth century, including Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon, authors of the popular compendium of racialized science Types of Mankind (1854). “The Notts and Gliddens,” as Douglass called this group, insisted and labored to prove that humans were not of one kind the world over, but belonged to distinct and permanent types: “races.” These men sought in particular to prove that humans of one type, Africans and their descendants, were not only inferior to whites, but formed an altogether different species. Louis Agassiz, the Harvard professor who did much to bring the scientific debate on human diversity into public view, was one of “the Notts and Gliddens”—indeed, he contributed a chapter to Types of Mankind—and Douglass often singled him out in his lectures. When Douglass took to the podium to argue against these men’s ideologies dressed up as natural science, whose theories influence our political discourse even today, nearly two hundred years later, he often did so by celebrating picture making in general and photography in particular.

In 1850, Joseph T. Zealy, a Columbia, South Carolina, photographer, produced a group of daguerreotypes of Africans and African Americans for Agassiz to support his ideas on the origins of human diversity. It is not known if Douglass was familiar with these images, but they surely would have made their mark upon him if he had known them—as they have on so many viewers since their discovery in the attic of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in 1976. The images of Delia and her father, Renty; of Alfred, Fassena, and Jem; and of Drana and her father, Jack, possess all the immediacy and power of which daguerreotypy was capable. But what do they say? Douglass once remarked that pictures should be allowed to “speak for themselves,” yet this is a tricky proposition. Images do not hold a single, unwavering message for all time; pictures can and frequently do change their meaning. The daguerreotypes were created to speak the language of the “Notts and Gliddens,” and they perhaps did fulfill this purpose, or something close to it, particularly for Agassiz and others who shared his views. But the pictures speak other languages as well, telling other stories, some of which refute the efforts of the “American school” of ethnology.

Of course, there is much that the pictures can’t tell us, not of their own accord. They can tell us nothing of the scientific examination each person endured at Agassiz’s hands prior to being photographed; nothing of what Delia thought about the Taylor family, her putative “owners,” or exactly where in Africa her father, Renty, had been born—these are all matters about which the historical record is largely silent and the images altogether mute. A daguerreotype cannot speak with any certainty of a lifetime experienced by a single consciousness, a particular subjectivity. Pictures, like songs, do make their own way in the world, as Douglass said, and they speak to us on their own terms, but they also need interpretation. They speak to us so that we might listen, ask questions, and then turn to others and recount what we have learned.

*

From the outset of the project that led to this volume, it was clear that the daguerreotypes made for Louis Agassiz required an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach in order to responsibly analyze the images and to uncover new information about their history. Two workshops organized by the Peabody Museum and held at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study brought together scholars of documentary photography, memory, slavery, anthropology, American history, African American history, and the history of science to discuss the daguerreotypes and critique one another’s writing on them. This diversity of expertise allowed for a focused yet wide-ranging discussion, and the collaborative approach established at the workshops was carried through the editorial process. Throughout the project, our goal has been to give voice to the many ideas, contexts, and viewpoints that contributed to the making of these fifteen daguerreotypes and the responses that they evoke today. The goal, in short, has been to both listen to and speak of the daguerreotypes without concern for arriving at a definitive, final word on them or any aspect of them.

Owing to this approach, the contributors to this collection address a number of interrelated topics. Following an introduction on how the daguerreotypes came to be made, the authors explore the identities and experiences of the seven people depicted in the daguerreotypes (Gregg Hecimovich); the value of photography to a new nation founded on (but struggling with) principles of democracy (Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Matthew Fox-Amato, John Wood); the close relationship between photography and science, and between photography and memory (Tanya Sheehan, Christoph Irmscher); the overlapping intellectual contexts that made the creation and display of such images possible (Manisha Sinha, Harlan Greene, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis); and responses to those ideas at the time in which the images were made (John Stauffer). More recent responses are also explored, including considerations of the institutional life of the fifteen daguerreotypes and the ways in which artists have used them to extend the critique of scientific and institutional racism into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (Carrie Mae Weems, Deborah Willis with Carrie Mae Weems, Ilisa Barbash, Robin Bernstein, Keziah Clarke, Jonathan Karp, Eliza Blair Mantz, Reggie St. Louis, William Henry Pruitt III, Ian Askew). New photography by Carrie Mae Weems provides a visual counterpoint to many of the issues raised throughout the volume.

The approaches taken by the contributors to this collection vary widely, which is a strength of the enterprise. The nature of these differences may be illustrated with a simple question: What should we call the fifteen daguerreotypes? Are they the Zealy, Agassiz, or Peabody daguerreotypes? Who, ultimately, is responsible for them? To whom do they belong? The artist, the scientist, the institution—or the subjects of the images?

This question of ownership is a deeply uncomfortable one, given that the subjects of the images were enslaved. One way to elide the problem is to refer to the images by the names of their subjects, to use the names of individuals to indicate the group as a whole: Jem, Fassena, Alfred, Delia, Drana, Jack, and Renty. Doing so, however, can make for a long and at times repetitive string of names. It may also render the daguerreotypes—fifteen images of seven individuals as a conglomerate. Using the names of enslaved persons should also be questioned because names were typically assigned by enslavers: “Delia” is what members of the Taylor family called the woman Zealy photographed—we know this from the records they kept—but her family and familiars may have known her by a different name, a name that we will never know. Another thorny question with respect to naming is whether Fassena should be uniformly called Fassena, as he is identified in the label affixed to his daguerreotype or George Fassena, the name he used post-emancipation. These questions of representation and identity cut deep into the histories of the images, the people depicted in them, and the purposes for which they were made and used.

When writing about the daguerreotypes, one must also face the question of whether nineteenth-century ethnology can rightfully be called a science. Science as we understand it today was then just beginning to take shape, to be codified as a profession determined by a specific set of practices. The comparative study of crania and other physical characteristics, which Nott, Gliddon, and others included in their definition of “ethnology,” may have been considered scientific in its day—it was an investigation into the natural world undertaken by men educated in medicine, anatomy, and various strands of natural history, including geology and paleontology. Yet to call their version of nineteenth-century ethnology a “science,” and polygenesis a “scientific theory,” lends these practices twenty-first-century legitimacy. To refer to these ideas as “pseudoscience,” on the other hand, while anachronistic, signals a critical stance. In the essays comprising this collection, each scholar and artist has taken her or his own approach to these and other issues, deciding how best to frame their discussion of the daguerreotypes. The editors have made no attempt to reconcile the different approaches, for this would be tantamount to smoothing over fissures that are very much a part of the daguerreotypes’ difficult history and ongoing legacy.

While the critical approaches in this volume vary greatly, the authors nevertheless shared an important experience: namely, the sense on viewing the fifteen daguerreotypes that a response of some sort was absolutely necessary. “Once seen, the images are hard to forget,” Sarah Elizabeth Lewis writes of encountering Delia and Drana with their clothing pulled down to their waists. Manisha Sinha calls them “Louis Agassiz’s collection of disturbing daguerreotypes.” These images, Harlan Greene notes, hold “as compelling a place in our national imagination as those photos of Black students, in their crisp 1950s outfits, integrating schools, with the hate-contorted faces of whites shaking their fists around them.” Everyone involved in this collection has been moved by the daguerreotypes and feels an obligation to Delia, Renty, Alfred, Fassena, Jack, Drana, and Jem. One cannot simply look at George Fassena—one must also endeavor to see his suffering at the hands of the slaveholder, the scientist, the photographer, and, yes, even the historian. One must, in other words, relate to each of the people in these images, inasmuch as this is possible across time, geography, race, gender, class, and culture. One must seek to understand, and then make something of this experience.

There is another point of intersection among the authors of this volume, and that is the conviction that the images failed utterly in their original purpose. Intended to represent racial types and defend the idea that different groups of humans were and always have been distinct species, thus opening the door to the abuse of one group by another, the daguerreotypes instead present to us seven individuals who endured the manifold terrors of slavery with dignity and humanity. Zealy’s images—which have been used in books and magazine articles, on conference posters, in documentary films, and elsewhere—have become simple visual representations of slavery. They are, in other words, iconic images of the institution they were meant to buttress but which they now pointedly indict by showing us the effects of enslavement on individual bodies and allowing us to look into the eyes of those who suffered. The original evidentiary purpose of the daguerreotypes has been turned completely on its head.

And yet, even as the meaning of the daguerreotypes can be reduced to a single concept slavery—each image also gives us the likeness of a particular man or woman. Alfred is Alfred: he is not a slave, not a victim, not a type, not a lesser being than the men who took his picture or those people, like us, who gaze upon it. He is a man who drew breath and walked the same ground we traverse today. Moreover, while researching and writing about Delia’s humiliation is painful, to say nothing of how it feels to look closely at her photograph, it is remarkable that we are able to see her at all. Millions of women lived and died under slavery, their stories buried together with their bones in unmarked graves, yet we know so much about Delia, including her name, her father’s name, where she lived, and even—perhaps especially—the contours of her face. In this sense, the pictures do indeed speak for themselves.

The inversion or backfiring of the daguerreotypes’ original intent may be due to the nature of photography, a technological means of reproduction given to manifold interpretations, or it may be due to the inherent flaws of the precepts followed by certain nineteenth-century thinkers. Perhaps it is simply poetic justice. Regardless, the failure of the daguerreotypes to perform the ideological purpose for which they were made is one of those twists of fate that history sometimes permits, and it is celebrated throughout the essays and new photography collected in this volume.

*

That the meaning or function of the daguerreotypes has reversed itself over time, that the viewer’s response to the photographs today is often expressed as recognition of the subjects’ shared humanity rather than their difference, undoubtedly has much to do with the passage of time and the clarifying lens of history. The daguerreotypes are no longer the property of a scientist who embraced white supremacy; they are instead curated by an institution devoted to the study and preservation of human cultural history and diversity, steeped in the anthropological method of ethnology, the comparative study of cultures. Now they are not so much the result of scientific inquiry into the origins of human diversity as they are an object lesson in how political expediency can influence intellectual matters that are all too often considered separate from social power and those who wield it. The daguerreotypes have changed with time in a fundamental way. Nevertheless, the motivation behind their creation and acquisition is still very much with us.

Racism persists, and the concepts of racial types and racial hierarchy, while deriving from scientific modes of inquiry, have largely left science behind to take root in various segments of American culture. To deny another human being rights equal to those you enjoy on the basis of skin color is to elevate yourself for no reason other than that it suits you. To dismiss a person’s humanity, whether by word or deed, is to say, I am better than you because I was made that way. Embedded deeply within such acts of discrimination lies the hierarchy so dear to “the Notts and Gliddens” of the nineteenth century. Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, introduced in 1859, may have largely put to rest among the scientific community debates about the mechanism by which organisms change and grow diverse over time, but it did not put an end to ideas fueling those debates. White supremacy has no need for science because it has become integral to the status quo: the same nexus of ideas that moved Agassiz to declare that Africans were of “a distinct origin” from Europeans thrives today within our institutions and our culture.

Since the advent of photography, African Americans have used the medium to combat racism, including stereotypes and other expressions of racial prejudice—as is attested by the success of early Black photographers, Frederick Douglass’s many portraits, W. E. B. Du Bois’s American Negro exhibition for the 1900 Paris Exposition, and many other examples from the history of photography. More recently, however, developments in photographic technology have enabled another order of response, one that is also a kind of reversal—namely, the turning of cameras on oppressors to catch them in the act of harassment, abuse, and murder. Racially motivated violence in this country is not new, but the ability to show the world what is happening as it happens certainly is. Technology is no longer controlled exclusively by those in power. Recordings made by witnesses of violence with their mobile phones have exceptional evidentiary value due to their real-time, documentary nature and also their growing ubiquity. Such images, Douglass might agree, really do speak for themselves. This is not to suggest that mobile phone recordings do not require analysis and contextualization—they, like all images, most certainly do—but to acknowledge that they also communicate meaning clearly, directly, and with considerable force.

This collection of essays and images, a work of historical, cultural, and creative inquiry, is firmly grounded in the events shaping our lives today. At this moment and in these divided states of America, perhaps more than at any time since their rediscovery in 1976, the daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, George Fassena, Drana, and Jack command our attention, demanding that we look closely, listen intently, and speak out—however difficult this may be—giving voice to all that we have learned.

Molly Rogers is associate director of the Center for the Humanities, New York University, and author of Delia’s Tears: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (2010).

This introduction is from To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2020).

To Make Their Own Way in the World: A Note from the Peabody Museum’s Director

How a new interdisciplinary book about the Zealy daguerreotypes can expand critical thinking about photography, museums, and the legacy of slavery.

By Jane Pickering

Museums and archives today are in the throes of profound change as they grapple with the fraught legacies of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery—all of which played fundamental roles in building cultural institutions of the Western world. Exploring and acknowledging the complex histories of their institutions, scholars and museum professionals are scrutinizing with new eyes the objects, documents, and photographs housed and curated in these collections.

Such efforts, at their best, represent a challenge to long-held assumptions, as well as a deep commitment to broad and diverse perspectives on cultural heritage and on what it means to research and interpret museum and archival collections. Museums around the world are recognizing the imperative to open their collections to creative, transformative partnerships and collaborations with members of descendant communities.

The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard exemplifies the type of elite institution that benefitted from American nation building: international and domestic enterprises that both supported exploration and research, and removed from communities of origin a wealth of cultural materials. The daguerreotypes that are the focus of this volume are among those materials: vivid and visceral records of our country’s original sin of slavery.

These fifteen unique photographs of two enslaved women and five enslaved men came to Harvard as records of human difference, acquired in 1850 by Harvard professor of geology and zoology—and founder of the Museum of Comparative Zoology—Louis Agassiz. Agassiz intended to use them as evidence to support his theory that humans were descended from separate creations and that Blacks, in particular, were inferior to whites.

Even at the time, this theory was challenged by other scientists, and it was ultimately refuted by Charles Darwin. When the daguerreotypes were rediscovered at Harvard in 1976, they had not been seen in over one hundred years. Their rediscovery made headlines, and the photographs have been prominent in the awareness of Black Americans, of descendants of slavery, and of scholars and artists ever since. They are evidence of pain, coercion, exploitation, and tragedy—and Harvard played a role in that.

When Harvard President Lawrence S. Bacow announced the university-wide Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery in November 2019, this book was already written. Seven years earlier, the Peabody Museum had convened the first of two seminars hosted by the Radcliffe Institute that brought together a range of thinkers and scholars with the goal of confronting again the significance, and the very existence, of these images. It is impossible to undo the evils of the past, but Harvard and the Peabody take seriously the obligation, articulated by Bacow, “to understand how our traditions and our culture [at Harvard] are shaped by our past and by our surroundings—from the ways the university benefitted from the Atlantic slave trade to the debates and advocacy for abolition on campus” before, during, and long after the Civil War. “It is my hope,” Bacow writes, “that the work of this new initiative will help the university gain important insights about our past and the enduring legacy of slavery— while also providing an ongoing platform for our conversations about our present and our future as a university community committed to having our minds opened and improved by learning.”

The multidisciplinary and collaborative research that went into the creation of this book represents one step in the Peabody Museum’s participation in this larger initiative—an effort to explore the lives and acknowledge the contributions and unimaginable suffering of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty—and millions like them whose names are lost to history. We hope the publication of To Make Their Own Way in the World will stimulate dialogue and critical thinking, expand awareness and sensitivity, and encourage community involvement in ways that help bring the museum to the world—and the world into the museum.

Jane Pickering is the William and Muriel Seabury Howells Director of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

This preface is from To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (Aperture/Peabody Museum Press, 2020).

Endnotes to An Introduction to a New Book about the Zealy Daguerreotypes

1. [democratic medium] See John Wood, “The Curious Art and Science of the Daguerreotype,” chap. 5, this vol.

2. [many did] See Matthew Fox-Amato, “Portraits of Endurance: Enslaved People and Vernacular Photography in the Antebellum South,” chap. 4, this vol.

3. [he knew precisely what he was doing] “Introduction,” Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, eds. (New York and London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015), p. ix.

4. [more than one occasion] Frederick Douglass, “Lecture on Pictures,” in Picturing Frederick Douglass, John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, eds., p. 131.

5. [all important line of distinction] Ibid., p. 132.

6. [American school] Ethnology, originally understood as the comparative study of different cultures, was co-opted by these men to mean the comparative study of different races. The term retains today its original meaning of the comparative study of cultures.

7. [The Notts and Gliddens] Josiah C. Nott and George R. Gliddon, eds., Types of Mankind: or, Ethnological Researches, Based upon the Monuments, Paintings, Sculptures, and Crania of Races, and upon Their Natural, Geographical, Philological, and Biblical History (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co., 1854).

8. [as Douglass called this group] George R. Gliddon spelled his last name with an “o,” but Frederick Douglass repeatedly used an “e,” which may have been intentional and meant to undermine Gliddon’s legitimacy.

9. [speak for themselves] Douglass, “Lecture on Pictures,” p. 130.

10. [the historical record is largely silent] In one publication, Louis Agassiz mentions having “examined closely many native Africans belonging to different tribes” and suggests the examinations were conducted as a kind of guessing game. See Louis Agassiz, “The Diversity of Origin of the Human Races,” Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany 49 (July 1850), p. 125. Such remarks, however, give us no insight into how the examinations were actually conducted or what his subjects thought of the experience. Robert W. Gibbes’s labels, scraps of paper glued to the daguerreotype cases, provide information about the African tribal origins of the men, as well as the name of each person’s enslaver; yet, again, these tell us nothing of the subject’s own experience. The reliability of the biographical information provided by Gibbes is also called into question given Agassiz’s own remarks about having been deceived about the men’s origins during the examinations.

11. [collaborative approach] In keeping with the disciplinary diversity represented by the contributors to this volume, the editors have embraced a certain amount of stylistic diversity, as well; in particular, the use of more than one convention for documentation, footnoting, and capitalization.

12. [a distinct origin] Louis Agassiz quoted by Asa Gray to John Torrey, January 24, 1847, Asa Gray Papers, Gray Herbarium Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

13. [American Negro exhibition] On black photographers, see Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present (New York: W. W. Norton, 2000). Frederick Douglass’s photographs are catalogued in Stauffer, Trodd, and Bernier, eds., Picturing Frederick Douglass; Du Bois’s project is deftly presented by Shawn Michelle Smith in Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2004).

August 13, 2020

Samuel Fosso and the Invention of the Artist as a Young Photographer

In an interview for his new monograph, Fosso spoke with the late curator Okwui Enwezor about his teenage self-portraits from the 1970s and how all his work concerns the question of power.

By Okwui Enwezor

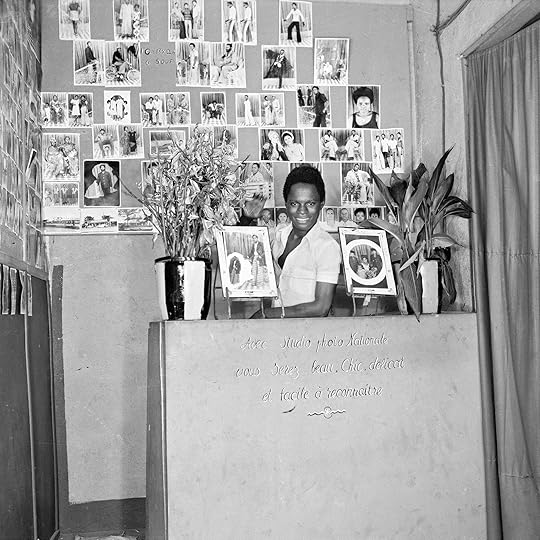

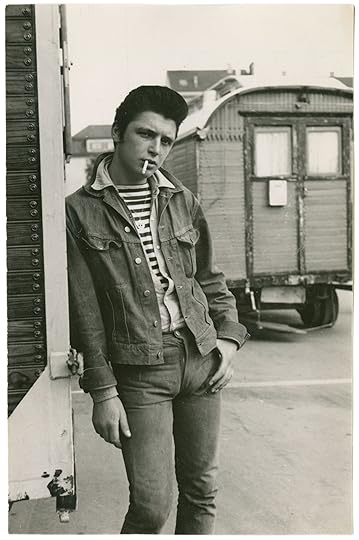

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Okwui Enwezor: Many people know you as a renowned photographer from Nigeria, by way of Cameroon and then the Central African Republic. Each of these countries has played a role in your conception of your identity. So, I would like to start—partly to clear up some misunderstandings about your biography—by asking you where you were born and when.

Samuel Fosso: I was born in Kumba, West Cameroon, in 1962, to Nigerian parents. At the time I was born, I was sick and partly paralyzed—that was why my mother took me back to Nigeria, for a local cure. My grandfather was what was known as a “native doctor.” After the treatments in Nigeria, my mother wanted to bring me back to Cameroon. But this was in 1967, and the Biafran War in Nigeria had started. It was impossible to travel. My mother died during this period, so I stayed with my grandparents in Nigeria until the war ended in 1970. I had an uncle in Cameroon who came back to Nigeria to take me with him. We stayed in Cameroon only for six months, because by this time—it was around 1972—my uncle had relocated to Bangui in the Central African Republic, and I moved with him again. I lived with him in Bangui for several years until I started my photographic career.

Enwezor: What did your uncle do for a living?

Fosso: He was a shoemaker, producing women’s shoes. In fact, when he brought me to Bangui, he had me working with him to make shoes.

Enwezor: You must have been very young.

Fosso: Yes. I was around ten years old when I started working with him. One day, in 1975, on my way to the market to go food shopping for his wife, I saw a photographic studio owned by a Nigerian man from Imo State. Usually, after I finished my housework, I went to rest near where this studio was. It was on one such occasion that I asked the owner of the studio if it would be possible for him to teach me to be a photographer. He agreed, but said that before he could take me in as an apprentice he would need to consult with my uncle. I then asked him what it would cost to learn from him in order to make sure that my uncle agreed. He said the training would cost nothing since the Central African Republic functioned at that time like the French system, where apprentices are paid for their work, unlike the English system in Nigeria, where they don’t pay you.

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: What kind of work did you do in the studio while you were learning?

Fosso: When you are employed as an apprentice, your work involves everything—sweeping the studio, errands, and more. I was very eager to start photographing, but for about one month I did not even touch the camera.

I became impatient and went to the photographer and asked him how long it would take before I could start photographing. He told me it was not a quick process and that I should continue working on the assignments he gave me. Then I found another way, through his assistant, to whom I offered my breakfast money every day for additional instruction. This way, I could learn the job more quickly. It was from then on that I really began to learn to make pictures.

Enwezor: What year did you start this apprenticeship?

Fosso: I worked at the studio for about five months, between October 1974 and March 1975. And in September 1975, I opened my own studio.

Enwezor: You were only thirteen years old. Were there other photographers your age in Bangui at this time?

Fosso: None. There was not a single one. The majority of the photographers were Nigerians and Cameroonians. I was very young, and people sometimes wondered about me when they came to have their pictures taken in the studio.

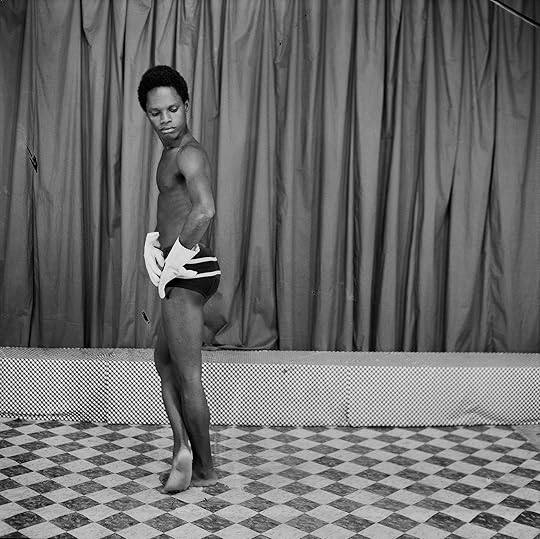

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: Conceptually, the photographs you made were very sophisticated, and would have been even for someone who had been practicing photography for a very long time; for me, this still remains a big point. You were not yet a photographer, but you picked up the techniques very quickly.

Fosso: Before I opened my studio on September 14, 1975, I was already working as a street photographer. So, my training and base of knowledge were ongoing. I was constantly learning.

Enwezor: Do you remember which camera you first worked with?

Fosso: It was a Kodak camera, a small six-by-nine, with only nine images in each roll of film. It was larger than a six-by-six lens. After taking the pictures, I would go to the studio where I had trained to have the film developed.

In early September of that first year, my uncle flew to Douala, Cameroon, and bought a larger camera for me and told me I had to find a studio for myself. There was a Nigerian-owned studio I knew of, which was free because it had been closed. This was where I established my first studio.

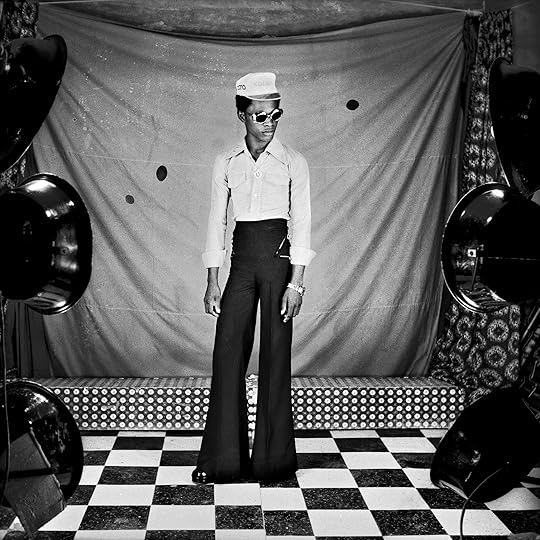

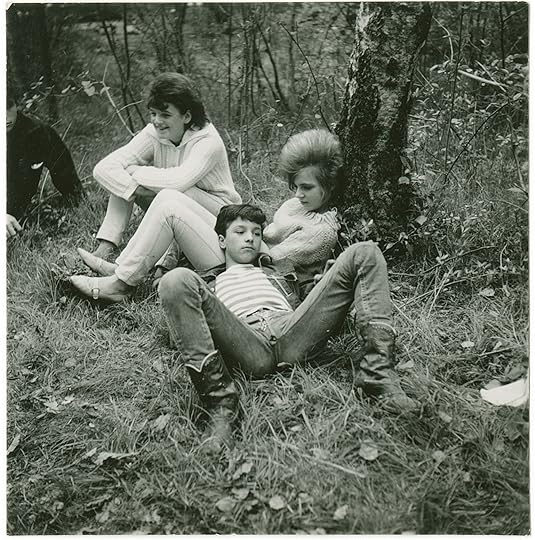

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: I want to discuss the moment when you moved from merely making photographs to becoming an artist. When do you think your work as a photographer shifted from making photographs on commission for your clients to making images for yourself?

Fosso: I first knew that I had become a photographer when I finished my training, while I was pursuing street photography, and started working independently in my studio. In Africa we say to become a real photographer you have to take the picture and then make the print yourself; that’s how you establish your professional credentials. I made pictures for myself only after the studio closed at the end of the day, using whatever unused film was left over in the roll of twelve exposures to make photographs of myself. My primary motivation for these self-portraits was to create images I could send to my grandmother, who was missing me a lot. Sometimes when I made photographs that I was not satisfied with, where I didn’t feel beautiful inside, I would cut up the negatives instead of printing them. But if I felt that the image was beautiful or represented how I felt inside, then I would print the image and keep the negative. I had a box reserved where I would store such important and special negatives.

Samuel Fosso, Vintage Studio Portraits, 1977

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: Your relationship to photography has something much deeper, a more personal motivation. From the start it was autobiographical; it had to do with the conditions of your life and how to document that life as it was being transformed. But what you are very well known for are photographic images in which your studio became a theater, a liberated space where you played with codes of representation of gender, sexuality, masculinity, and fashion. This liberated space that was your studio produced some of the most unique and singular examples of studio practice, and I am here thinking of artists such as John Coplans, Pierre Molinier, Van Leo, Cindy Sherman, Yasumasa Morimura, and others who had also made themselves their own subjects. But in your case, you were not so much making self-portraits as you were invested in working with invented characters, with you as an avatar. This is perhaps why your work has been compared most often with that of Sherman. Can you talk about this aspect of your photographic output?

Fosso: My initial encounter with photographic images outside of the Central African Republic was purely through pictures in magazines, brought by young American Peace Corps volunteers who came to the Central African Republic to visit Pygmies. I was especially excited by the images of African Americans and their sense of style.

I was also very much taken with the style of the popular singer and musician Prince Nico Mbarga, who was very hot around West Africa in 1976 and 1977 with his hit record Sweet Mother. I wanted to replicate these two stylistic approaches in the studio with me posing as a model. To do so, I went to the market and bought different fabrics and commissioned a tailor to make outfits for me, which I then used in the studio. Those are the photographs that I became known for.

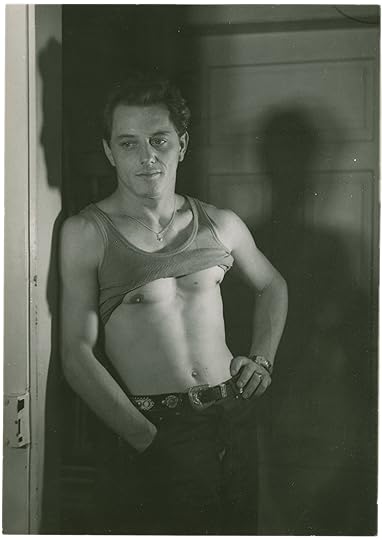

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: How long did you make work in this vein, documenting yourself?

Fosso: From 1975 to 1990.

Enwezor: If initially you saw yourself as only an image-maker, when did it occur to you that you had become an artist?

Fosso: It was at the first Rencontres de Bamako in 1994 that it became clear to me.

Enwezor: Did this realization change your approach and attitude toward photography?

Fosso: Yes.

Samuel Fosso, 70’s Lifestyle, 1975–78

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: What changed?

Fosso: I first realized that I was an artist when I found out that my main task was to create. I then said to myself that if what I had been doing as a job was art, why not continue to create regardless of whether I had clients or not? But I was confronted with a financial problem, of how to reconcile my job and creativity. I did not have the financial means, so the question was how I could continue—because had the talent, and I could do more. Fortunately, I was contacted by Tati, the French department store, for a project with Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. That was a lucky break.

I went to Paris to work on the project. It transpired that Sidibé had already been to Paris, finished his commission, and left for the U.S. for a book signing. However, when I arrived, I learned that the people at Tati had invited us to re-create the African photo-studio environment and make black-and-white pictures. I was not satisfied with this approach, so I asked Tati’s director of photography if it would be possible to work in color. He wondered why, since I had never worked in color, I would want to do so now. That’s how my Tati series (1997) began, because I did not want to go back to the black-and-white style as Keïta and Sidibé had done for their Tati commissions. Since there were three African photographers, I wanted my project to register a different mood of the African imagination, and not the images that were already associated with African photography. My goal was to take a new direction in my work.

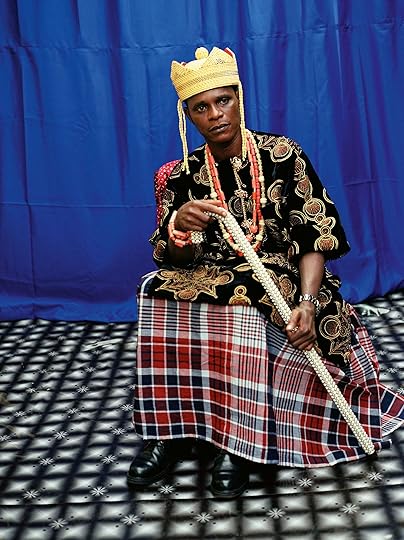

Samuel Fosso, Le rêve de mon grand-père (My Grandfather’s Dream), 2003

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: Although the Tati series was initially a commercial commission, you used it as a springboard into contemporary art.

Fosso: After I finished the Tati project, I returned to Bangui. In 2000, Afrique en Créations financed me to initiate a workshop with two artists from Cameroon, two from the Central African Republic, one from Italy, and one from France. The workshop took place in the eastern part of the country on the border with Cameroon. The project I produced was called Mémoire d’un ami (Memory of a Friend, 2000). In 2004, the Prince Claus Fund financed my next project, Le rêve de mon grandpère (My Grandfather’s Dream, 2003). I went to my village in Nigeria to work on that and presented it in Barcelona the same year.

Enwezor: I want to turn to your process, which, in the work you have presented over the last three decades, has focused on what I could call the “structure of self-representation,” with you playing a role or dramatizing historical, gendered, and autobiographical characters. Over the years, these roles and characters have become more elaborate, more theatrical. Your working method has become more of a big production, with sets, props, makeup, assistants, and lighting technicians, like in a film production. The simplicity of your earlier studio approach, when you worked alone, has largely disappeared from your present mode of making images. In fact, the work is no longer about single self-portraits, but about an ensemble of portraits with diverse psychological and emotional attributes carved into their construction. Can you discuss how you decide on the concept of each series you embark on as you begin planning it?

Fosso: The Tati series was also theatrical and less simple, so my approach was already changing and different from the earlier works of the 1970s.

Samuel Fosso, Le Chef qui a vendu l’Afrique aux colons (The Chief who Sold Africa to the Colonists), 1997, from the series Tati

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: It’s obvious you want to question representations of African masculinity, but also to break certain normative codes of studio photography that are read reductively within the discourse of African modernity. Your work calls all of these assumptions about African representation into doubt. One of the things that has been constant in your practice is your interest in transgression.

Fosso: I recently did an interview, and the interviewer asked me if I have a fear of the politics of Africa. I said I did. However, when it comes to what you call transgression, it was never about responding negatively against someone or against certain ideas. Maybe you are saying that I am not afraid to do what is seemingly not possible to do. But no, that’s not my motivation when I am working. All I will tell you is that my different approach started with my self-portraits, which gave me the opportunity to do whatever I wanted to do.

Enwezor: So, more than merely reflecting yourself—the artist/ego, if you will—the main impetus for your self-portraits was staging a series of ideal selves, situations, and guises in your self-constituted theater of postcolonial identity. There is hardly any kind of sustained photographic focus in contemporary African photography like the one you initiated in 1975. One would have to go back to the 1930s and ʼ40s self-portraits of Van Leo, the Egyptian Armenian photographer in Cairo, for a comparison. It’s quite an achievement for a thirteen-year-old to initiate such a complex study of urban African identity and male desire.

Fosso: I did not know I was making art photography. What I did know was that I was transforming myself into what I wanted to become. I was living out a series of ideas about myself. These images also extend beyond photography. Making them gave me the opportunity to engage in my own biography: going back to when I was a child, when no one thought I was a desirable child to photograph. At the same time, I discovered images of contemporary events in South Africa and the plight of black people in America. All these things contributed to shaping my lens. Art photography was something completely foreign to me until I arrived in Bamako for the first Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie.

Secondly, it became an opportunity for me to profit from the experience and therefore continue doing what I wanted to do. The invitation by Tati in 1997 to develop new work for their fiftieth-anniversary celebration the following year was an extension of what I had been doing in my studio since 1975. When I aspire to create new images, I try to develop the work in such a way that it will be in direct communication with the viewer. My approach is to produce pictures with as little ambiguity as possible, even when they might seem ambiguous. For example, when I adopt the image of a woman in my photographs, I am by no means trying to create a queer picture. What you see is simply an image of a man in women’s clothing. It is not about creating a double meaning.

Samuel Fosso, La femme américaine libérée des années 70 (The Liberated American Woman of the 1970s), 1997, from the series Tati

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: In your work, the studio becomes a sort of theater of fantasy, as well as a space for the mediation of history and social identity. Given the fact that the roles you enact before the camera are multiple, what roles do you see these various guises or personae playing in your overall conception and construction of the image?

Fosso: While all the series I have done can be understood by viewers as discrete and self-contained, and therefore different, to me there is one unifying theme behind all of them—and that is the question of power. I am particularly interested in the role that slavery played in the history of Africa. If I am representing the image of an African chief (in Igbo we call them “Eze” or “Igwe”), I am thinking about power, but also the role of those chiefs in the slave trade. In the case of “African Spirits,” this becomes much more transparent. This, for me, is the red thread, in either an obvious or subliminal way. I want to show the black man’s relationship to the power that oppresses him.

Enwezor: One of the challenges for African artists of your generation today is the state of their archives. Since much of your work was destroyed during the recent conflict in the Central African Republic, have you given any thought to the state of your own archive?

Fosso: This is a very big issue for many photographers and artists in Africa today. My dream is to bring my work and archive back to Nigeria and give it to a museum in Ebonyi State, where my family comes from.

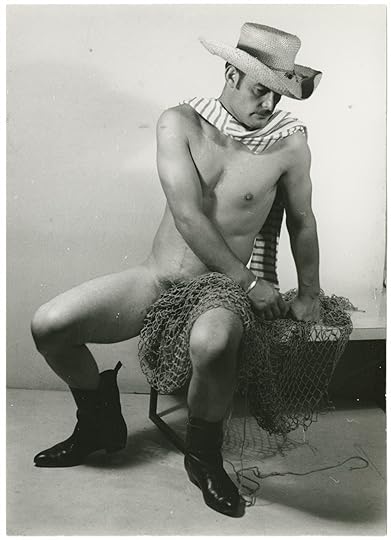

Samuel Fosso, Le marin (The Sailor), 1997, from the series Tati

Courtesy the artist, The Walther Collection, and Jean Marc Patras/Paris

Enwezor: When you look back at your career, having survived a brutal civil war in Nigeria as a young boy, then beginning in 1975 with Studio Photo National, to today, where your photographs are being collected by museums and private collectors, and being exhibited across the world, would it be safe to say that your work has given you a passport to travel the world both physically and imaginatively?

Fosso: All I can say to you is that since starting my career as a young boy in 1975, my choice to become a photographer has been a positive contribution.

Okwui Enwezor (1963–2019) was a curator, scholar, writer, and critic of African photography and global contemporary art. From 2011 and 2018, he was the director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

This conversation is adapted from Samuel Fosso: Autoportrait (Steidl/The Walther Collection, August 2020).

August 6, 2020

How Yurie Nagashima’s Self-Portraits Interrogate the Male Gaze

In her latest photobook, the Japanese photographer discusses self-portraiture as a radical feminist gesture.

By Lesley A. Martin

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

I arrived in Japan in 1992, incredibly anxious about the fact that less than six months earlier I had shaved my head. I felt very butch, much too raw, and totally unprepared to navigate the sophisticated cultural and gender dynamics that I suddenly found myself engulfed by as a young American woman teaching English. Most of my colleagues in the Japanese English Teaching program run by the Ministry of Education had their eyes set on a career in diplomacy or business. Prior to my arrival, I had been tearing down drywall for a housing rehabilitation program, teaching neighborhood kids how to read, and volunteering at a photo gallery. At night, I waitressed at a coffeeshop-slash-bar, dressed in my thrift-store best. As a recent graduate of a liberal arts program with a penchant for semiotics, I was trained to analyze and critique the dominant social and power structures of the American culture wars—when suddenly I was working for a foreign government and tasked with representing my own.

After teaching during the day, I would take respite in Tokyo nightlife, then awash in hip hop, punk, psychobilly, and the emerging Shibuya-kei pop music scene. I went to art galleries perched on the top floors of department stores. And I tried hard to read and understand the cultural signifiers of “lolicon” fashion and cosplay fantasy clubs, used-panty vending machines, and the increasingly inescapable “Hair Nude” trend of soft-core photographs of young women, scratched free of damning pubic hair. Somewhere, somehow, I ran into Yurie Nagashima’s Self-Portraits (1993)—a black-and-white series of herself and her family posing in the nude—a hilariously cutting rebuttal to the usual depiction of women (and families) in Japanese media. They were raw, unabashed, and pointedly critical of the power imbalance saddled upon Japanese women. I didn’t know much about Cindy Sherman then, and as it turns out, neither did she—but in the images Nagashima created in the early to mid-1990s, role playing as the various, absurd sexual fantasies rampant in Japanese pop culture, it was obvious to me that this was someone who had a bead on the skewed gender dynamics of Japanese art and media of the time. This was someone with something to say.

Several decades later, I consider myself lucky and gratified to reconnect with the full scope of Nagashima’s work. In a recent Skype conversation, she and I talked about her self-portraits, the long-standing dismissal of “women’s work,” cable releases, and the changing the nature of aesthetic criteria.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Lesley Martin: I understand that this collection of self-portraits was originally made for your survey exhibition, And a Pinch of Irony with a Hint of Love, which took place at TOP [Tokyo Photographic Art Museum] in 2017. Was that the first time you put all of your self-portraits together?

Yurie Nagashima: Yes. Originally, there were over 600 images, so I showed them as a thirty-minute slideshow, not as prints. When you start working on a subject, you never know how far it will go. But when you look back, you start to find unintentional connections. I began to make self-portraits while I was traveling. Then I chose to use myself for nudes, too, because I just couldn’t ask my friends or anyone else. I felt guilty asking someone to be naked—not in an “arty” way but a controversial way. That’s the primary reason I started making self-portraits. Another good reason is that I had more control. I’m shy, and it’s hard for me to ask a favor without worrying about how the other person feels. Some time later, I realized that self-portraiture is an important genre of photography, especially in the context of feminism.

Martin: When did you come to realize that about self-portraiture? Was there a point in your life as a photographer when you realized that self-portraiture could be a powerful part of your work?

Nagashima: At first, I was angry at the Hair Nude boom, and thought, “Okay, there’s no way men can use and consume a female body for their own agenda.” Then I received the Parco Prize at Urbanart#2 in 1993 for the self-portraits, in which I appear in each image with my real family, I realized that the self-portrait as a technique implies more than just the subversion of the power relationship between men and women. It also says that my body belongs to no one but me. Aside from that, the series of self-portraits with my family was controversial. There were many discussions about it in magazines and papers. People always asked me how I persuaded my family to pose naked, but it just wasn’t a big deal.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Martin: A few years after that prize, in 1995, you were featured in an exhibition alongside Catherine Opie. Is that what made you decide to study at CalArts [California Institute of the Arts, Los Angeles]? And how did that impact your work and your sense of image making in relation to yourself and your body, and also to your family?

Nagashima: She suggested that I should go study there. She had graduated from CalArts but wasn’t actually teaching there, although her friend Kaucyila Brooke was. Brooke is a feminist artist and was my mentor. In Japan, you hardly have female professors in art school, but at CalArts I had her, Jo Ann Callis, Ellen Birrell, and Nathalie Bookchin.

Martin: I’m curious about your experience at an American university at that time, I imagine identity politics were a big topic of discussion.

Nagashima: Yes. Both at school and in my daily life. I was studying with people from different backgrounds and nationalities, young and old with diverse ethnicities and gender, but the majority were Caucasian Americans. For me, it was difficult to make friends who were not Asian or Asian American. I always felt left behind because I couldn’t speak English well enough. I was shocked when my work was severely criticized by some students and a teacher in class because they thought that my work “increased Geisha fantasies.” I wanted to argue back, but I couldn’t accurately explain, not only the concept of the work but also the history of Japanese photography and society, in English. I didn’t understand what the white male’s geisha fantasy even was—because in Japan, such a fetish doesn’t exist. However, it triggered in me for the first time to think about how cultural differences effect the interpretation of artworks.

CalArts kind of broke my belief in art—that art can be understood without language. People can’t always understand what artists are trying to say just by looking at their works. I realized that executing a work and just hoping to be understood is too naïve. Some still say that one talks about her work because the work is not strong enough, but I disagree. Marginalized people always need to speak up about themselves. That I should really try to explain what I am doing, or my work would possibly be misunderstood or even misinterpreted by 180 degrees.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Martin: So is that when you started to write seriously? In Japan, you’ve published an award-winning book of biographical stories from your childhood, Senaka no kioku [A memory of her back], and you’ve just published another book, about the Japanese photo movement in the ’90s and feminism, From Their Onnanoko-Shashin to Our Girly Photo.

Nagashima: I started writing seriously after I became a mother. That experience made me wonder if maybe I didn’t have to get “stuck” being a photographer. Carrying a baby and his diaper bag along with 35mm or 6-x-7 cameras seemed crazy to me. At that time, I was making photographic work dealing with my memory. I was working on that series from 2004 to 2005, but it didn’t turn out well. So I tried to write instead. That’s how I wrote the first book. Besides, I could write at home at night, while my son was sleeping. I wanted to make my own works somehow.

Martin: In an interview, you said that you believe in creating as a way of addressing society. I’m curious how you see self-portraiture as a way of doing so?

Nagashima: About my self-portraits, it’s definitely a way of talking about how the gaze of male society works on the female body. However, the photos were a kind of joke, too. I was serious, but I often laughed alone during the shoots, because of the weird situation I was in. Imagine, a naked girl running back and forth, behind and in front of the camera! It looked pretty silly, and some of the photos are really funny, too. It’s like when you look at the porn magazines, sometimes you just start chuckling because of how unreal the poses or the situations look. Most of them would never happen in a real relationship, unless you are exposed to too many such images and start believing that’s what real women or sex looks like.

My self-portrait is a way of expressing my sarcasm, and I think that many women have had disappointing sex because of the images that the media keeps emitting. After my work started being recognized, I was offered the opportunity to model for some famous male photographers. I was aware that I shouldn’t really take those opportunities, because I knew it would somehow contradict my own work. In art school, for my undergrad degree, I acted and posed for my friends in their movies and photographs, and they made me frustrated with their poor depiction of female characters. It was always awfully stereotypical and boring.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Martin: Do you believe that the self-portrait can be a radical feminist gesture?

Nagashima: Of course. It’s like the best, one of the best. The self-portrait means that you can take on both roles, as a model and as a photographer. When you have a camera on a tripod, you have the space in front of the camera and also the space behind the camera. It’s very symbolic. It’s a way of taking action against the historical roles of the male and female in photography.

Martin: Strangely, I hadn’t really thought about Cindy Sherman in relationship to your work until recently. Do you feel like there’s something in what she is doing or did that you’re interested in?

Nagashima: I wasn’t really into photography when I first started out. I didn’t know about her until somebody wrote a review about my self-portraits and mentioned her work. So I looked her up, and realized that I had this one postcard of hers. She’s standing in a black dress, with long silver hair over her face, sort of like in a horror movie. That was the only image that I knew about her, but later I bought her book, Untitled Film Stills. I love that series.

Martin: There’s certainly a relationship, but I don’t feel like it’s about direct influence; rather it seems as though you were responding to similar issues—namely, how women get portrayed in the media. And how do you redirect that? Redirect it and change it. How do you shift from the male gaze to be able to control the gaze?

Nagashima: I don’t know if I can “redirect” it, because such gender issues are huge and deeply embedded in society. However, I want to change it, or at least do something to try to change it. I am an artist, so the best I can do is keep making my work. I often think that my photos are records of my performance art; I could have ended up as a performance artist. A lot of times, I enjoyed the process more—acting a role and directing the scene at the same time—than what I got as a result. When I executed the early self-portraits, I believed that showing self-portraits as pin-ups in museums could be a great tactic against the Hair Nude boom back in the ’90s. I didn’t know if my work represented feminism or not, but I knew that I was an activist artist in some way.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Martin: There are images in this collection that have been in museums; works that are clearly performative in this way. But as the sequence moves on, it seems to get more personal and diaristic. How do you draw the line between the personal and what you might call “your artwork.” Is there a line?

Nagashima: I see it as a spectrum, and so there is no line. I think when you decide to capture that very moment in a photograph you are already, most likely, outside of “real life.” Because for that moment, you are looking at the world through the finder or on the screen. In that sense, I can say that the more “real” the image looks, the more you are faking it. Back in 1993, when I executed my early self portraits, I never thought that my photographs would ever be looked at by so many people other than my teachers and friends. The first picture in this book is from 1991; I was going on a backpacking trip. It’s in black and white because I was in a black-and-white printing class [laughs].

In this book, I sequenced the images chronologically, so you can see the change. There are often reasons behind my change in camera, lens, or style of shooting. For example, I started using compact-film cameras more, right after I had a child. My subject matter is often changed by my experiences and by the social changes I experienced. I became more aware of feminist issues after having a child, and then the earthquake in 2011 made me face domestic political issues. My personal interests also changed, and aging, too, is just another cause. When I was young, I thought my body was my own property so I could do whatever, but my son changed that idea completely. I think that my photographs—both set-ups and snap shots—are quite personal.

Martin: Right. All of this is part of your work.

Nagashima: It’s a part of my work and also my life. Being an artist is a big part of my life, it’s who I am now. In the beginning of my career, I thought of my life or my body as really simple—just a regular young woman growing up in Japan. When I started my self-portraits, I thought that the fact that I was nobody would work to my advantage. Because it’s very important for my work to be seen by women who have also struggled with the idea that they might be nobody, no matter how talented and capable, or having actually achieved so much. Even if she were a genius, nobody is going to come and do all the housework for this genius. Genius still has to be a domestic servant just because she is a “woman.” I hope that my work empowers those people and makes them understand that they are not alone.

Yurie Nagashima, from Self-Portraits (Dashwood Books, 2020)

Martin: Is there any connection in your work to the watakushi shōsetsu, or shishōsetsu—the “I-novel” or the subjective, autobiographic novel form, which is very much a part of Japanese literature?

Nagashima: In some ways, all my photographs are a form of fiction. Because when you are actually just living your life, you don’t pull out the camera and stop the situation just to take a picture.

Martin: It’s a naturalistic type of fiction. Just as authors use their own experience to write about larger, more universal issues.

Nagashima: It’s also a type of performance. Both my parents belonged to a high school drama club, so sometimes I think I can act because it’s in my blood. Maybe I should state that all of the photos in this book were taken by me. I don’t have a cable release because I thought it wouldn’t fit to my concept of the work.

Martin: Sometimes you see the camera—in mirrors, of course. But otherwise you’re hiding the act of photographing, using tripods and timers. Is this a decision that makes the images feel more like a “real picture”?

Nagashima: I don’t want to say yes to the term “real picture,” but I know what you mean. My early self-portraits were a parody of Hair Nude photos, so I wanted my photographs to look similar to them. I also wanted the concept of those images not to be too obvious, so that the viewer could misunderstand—they could be confused about whether those images were actually a real Hair Nude or not, for example.

Martin: It looks very natural. You really feel in certain photographs that you’re meeting the eyes of someone photographing you. And especially as the work progresses, you realize it’s actually a strange thing to record these very normal, small moments. It’s interesting to me that fiction that deals with the banal, with the domestic, is very much an area that has traditionally been dismissed as “women’s work.” It happens in the 1920s in Japan with what became known as “women’s literature” [joryū bungaku]—a form that was characterized as sentimental, trivial, and beneath the attention of male writers. It’s very similar to how photographic work by women was dismissed in ’90s Japan—“Oh, these women with their small cameras, they’re just shooting their friends, their lives.” Dismissed as inconsequential. It happens again and again.

Nagashima: That’s one of the reasons why I’ve stuck to my methods and the subject matter. It’s not what’s supposed to be the subjects or techniques of “great art.” All of those criteria were created by men. So of course they didn’t care for my work. I feel like I have to build a whole new criteria for women in the art field. When they look at my work, they consider it “female work” based on their own criteria. Because they don’t have the words to understand what I’m doing. And they don’t have a clue about how to look at those works and what I am—they don’t know what we are doing. But I know! [Laughs]

This interview and images appears courtesy Yurie Nagashima and Dashwood Books and was originally published in Self Portraits: Yurie Nagashima (Dashwood Books, 2020).

Introducing: Muge

Since 2004, the Chinese photographer has captured the upheaval and displacement of over a million people caused by the Three Gorges Dam.

By Casey Quackenbush

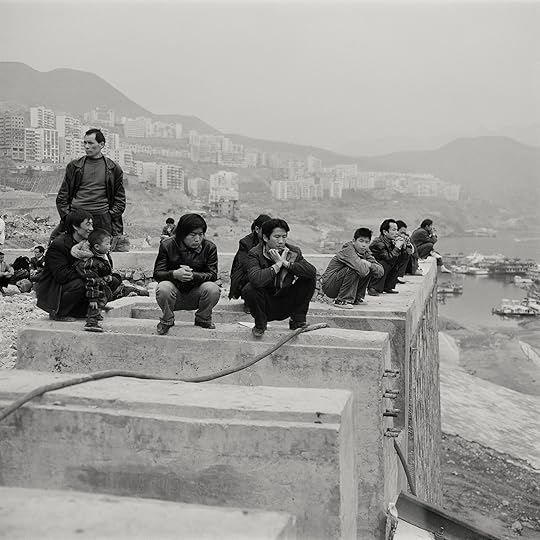

Muge, A man on a motorcycle, 2006, from the series Going Home

Muge’s first memory of the Three Gorges Dam is from 1999, five years after construction began. He and his family were taking a trip to Yunyang, a county along China’s mighty Yangtze River so rich in vistas it’s known as the “Bright Pearl of Chongqing.” They were traveling there to get bulk items for their home in Chongqing’s mountainous Wuxi County, an eighty-nine-mile journey through soaring peaks and lush valleys. It’s a frequent trip Muge took during his childhood; a fond memory turned painful when he arrived in Yunyang that year to find the place demolished.

“I lost my beautiful memories,” Muge said recently, likening the feeling of seeing the past disappear to amnesia. “Although you know there is a past, you can’t witness it for yourself.”

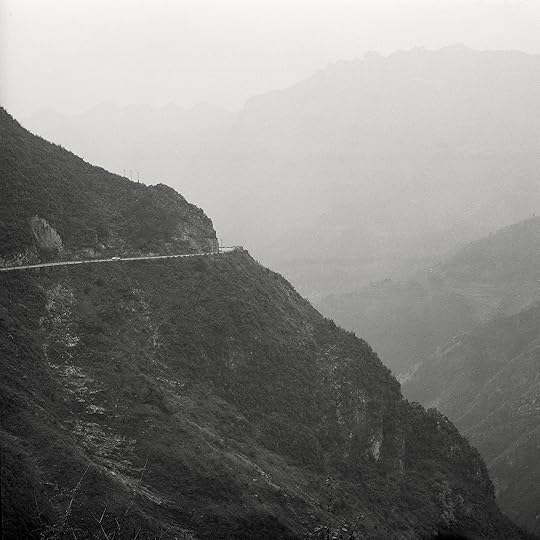

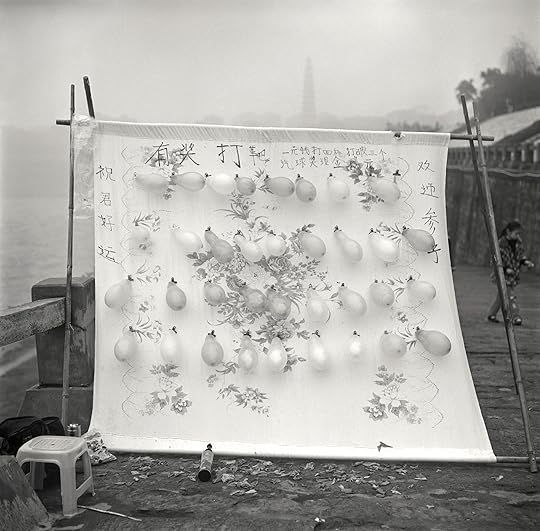

Going Home, begun in 2004, is an ongoing, nearly two-decade-long, endeavor to recover his memory, a monochrome series that captures the yearning of over a million people displaced from their homes along the Yangtze River—including Yunyang—caused by the construction of the six-hundred-foot-tall Three Gorges Dam, completed in the mid-2000s. In the years it took to build, the world’s largest hydroelectric dam wrought ecological and societal devastation. The dam swelled the Yangtze for three hundred miles upstream, creating an inland reservoir that submerged, or prompted the demolition of, hundreds of riverside towns and villages in the area where Muge grew up. Through photographs of dirt roads, rubbled shores, and abandoned cities, Muge chronicles a melancholy, spiritual journey in search of a home that is no longer there.

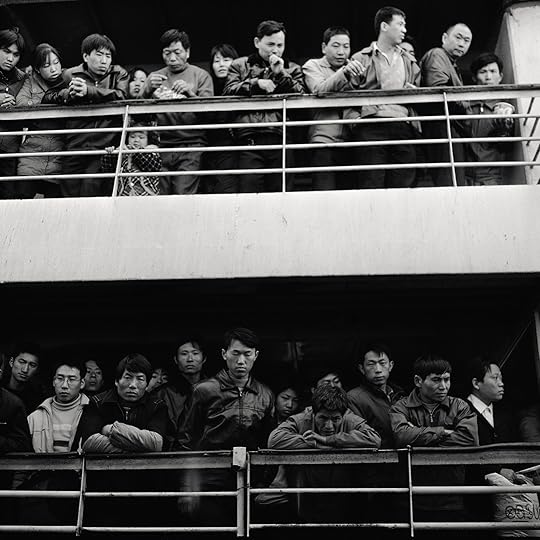

Muge, Passengers queueing to buy tickets, 2007, from the series Going Home

“In the end, you find nothing,” he says. “We wait for better living in desperation.”

Born in 1979 and raised in rural Chongqing, Muge grew up fantasizing about what lay beyond. Travel in those days was slow and crude. Whenever he wanted to do something or go somewhere, it was a journey through the natural world. When his family decided to get a television set when he was seven years old, it was a two-day expedition. “Every trip [was] a new life,” he says. The slowness of travel from Muge’s childhood sets the pace for Going Home. “I am obsessed with the state of being on the road,” he says. Every seemingly trivial detail—from the condition of the road to the majestic landscapes—is a glimpse into his “inner core.”

Because he grew up surrounded by government propaganda, much of Muge’s visual inspiration came later, while he was studying at Sichuan Normal University in Chengdu, where he earned a degree in broadcasting and television directing. There, he was introduced to the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu. He also discovered Peter Henry Emerson, Minor White, and Walker Evans, traces of whom are especially visible in his photogravuresque landscapes: epic, mystic, and lonely. In his later travels, Muge picked up his alias. Born Huang Rong, Muge’s friends coined his nickname after traveling to Tibet, where they learned that muge means “wild man,” which his friends jokingly called him because he moves so fast. (In Mongolian, muge means “rising sun.”)

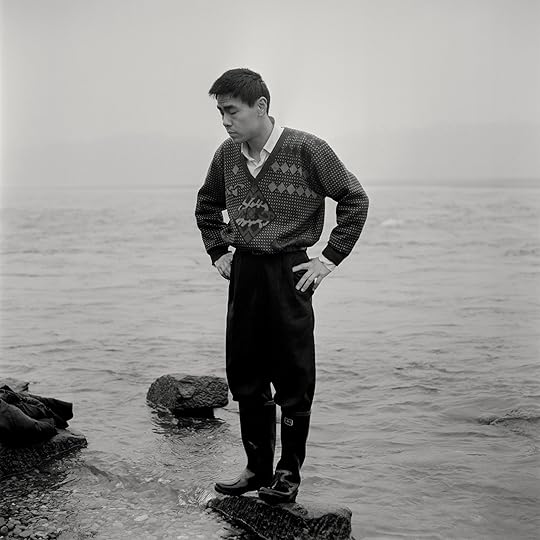

Muge, Lovers, 2007, from the series Going Home

In the wake of the Three Gorges Dam, Going Home becomes more a wandering than a voyage. The expressions of Muge’s subjects—strangers, families, passengers, and migrant workers—are ones of loss and ache, unsure of what the future holds. Some squat along the cement shores of emptied cities waiting for a ferry to arrive. A couple burns a fire in a pile of rubble. Pollution or fog cloaks every sky. Mattresses pile up. A woman naps on an abandoned bunk bed along the river. Construction cranes loom. A policeman crouches in grassland. One man, standing atop a hill of rubble, looks up at a derelict home, looming like a steeple.

“The images are full of collisions between childhood memories and dramatic changes in reality,” says Muge.

Muge, Passengers on a dock, 2006, from the series Going Home

While there is much to be said about China as a rising superpower, Muge’s photography was not created for that arena. To be sure, Muge’s subjects and their experiences are the direct result of China’s rapid economic development. But his intent is neither to comment on China’s macrostate nor to convey his personal feelings. Instead, he aims to “[step] in between,” he says, capturing the spirit of people caught in the nation’s slipstream.

“He’s somebody who’s very curious about people and likes to pay attention to their rhythms, patterns, and personalities,” says Xuan Juliana Wang, a Chinese-born American writer who met Muge in Chengdu, where he is currently based. With Going Home, the aim, above all, is to understand the dirt-level intimacy and complexity of people’s everyday lives. “You can never know about a place or about a people unless you visit it on the ground,” Wang says. “His work is after that.”

Muge, Way home, 2006, from the series Going Home

Muge, The man doing the laundry, 2006, from the series Going Home

Muge, Shooting games, 2005, from the series Going Home

Muge, A ferry on the Yangtze River, from the series Going Home

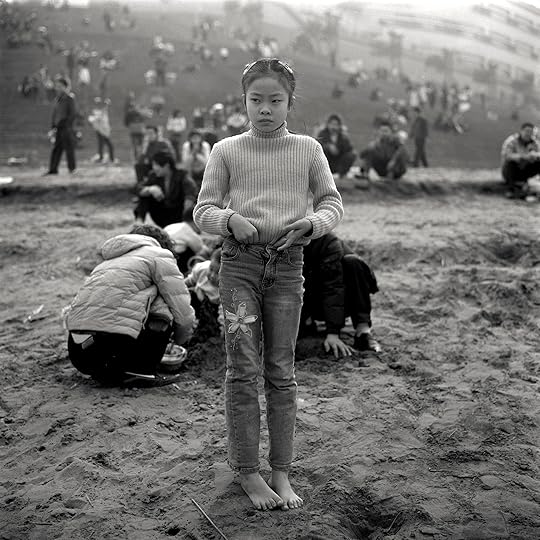

Muge, A girl II, 2006, from the series Going Home

Muge, A boy along the Yangtze River, 2008, from the series Going Home

Casey Quackenbush is a New York/Hong Kong–based journalist who writes about culture and politics. Her writing has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Washington Post, TIME, and Al Jazeera.

All photographs courtesy the artist. Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

July 27, 2020

11 Photographers Reflect on Images of Solidarity

How can photographs represent solidarity? From Bruce Davidson’s iconic images of the Civil Right Movement to Richie Shazam’s coverage of the massive Black Trans Lives Matter march in Brooklyn last month, the act of solidarity can be seen in these demonstrations of unity in the face of adversity and oppression. But solidarity is also captured in moments of community and connection, as seen in the work of Chien-Chi Chang and Denise Stephanie.

We’re excited to share Solidarity: The Magnum Square Print Sale in Collaboration with Vogue, which brings together images from legendary photographers that reflect on the power of togetherness in tumultuous times.

For seven days only, you can acquire these signed and estate-stamped, museum-quality images for $100 each. For the duration of this sale, Magnum and Vogue photographers will donate 50% of their proceeds to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). When you purchase through Aperture’s affiliate link, you directly help support not only the artists, but also Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations.

Selected by Aperture’s editors, here are 11 highlights from the Magnum Square Print Sale.

Chien-Chi Chang, Immigrants sleeping on a fire escape to avoid summer heat, New York City, 1998

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Chien-Chi Chang

“Solidarity is a word that is usually written large. To some, it might mean a great victory by the people. But I have seen it in smaller settings. On the hottest night of a New York summer, in a tenement building by the Manhattan Bridge outside rooms too sweltering to sleep in, these men found—and shared in—a sense of solidarity on a fire escape. The goal was not grand. They just yearned for a breeze.” —Chien-Chi Chang

Miranda Barnes, Lorraine Motel, Memphis, 2018

Courtesy the artist/Vogue

Miranda Barnes

“This photograph was taken for the fiftieth anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination for the New York Times in 2018. It was my first assignment through the newspaper, as well as my first time in Memphis. The experience taught me a great deal on the

importance of research in relation to photography, photographing an assignment alone, and the responsibility you have as the person with the camera. Within the theme of solidarity, this photo resonated, as I believe it is important to reflect on moments of history that have been

whitewashed. Acknowledgment and unlearning are critical to the current movement, and they begin from within.” —Miranda Barnes

Enri Canaj, A small boat with refugees and migrants reached safely the Greek coast, It was hard to get the boat to land because of the bad sea, Lesbos, Greece, October, 2015

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Enri Canaj

“It is always the right time for our strength to be seen. No matter what happens, we should never forget solidarity, which lightly bears our sorrows and joys like a lifeboat, carrying us smoothly and safely towards the next port.” —Enri Canaj

Bruce Davidson, The Selma March, Alabama, 1965

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Bruce Davidson

“This photograph was taken during the 1965 protest marches from Selma to the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery. Martin Luther King Jr. led a group of African American, nonviolent marchers to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression. This was a watershed moment in the Civil Rights Movement. I came across this young demonstrator, wrapped in a flag, protesting racism; behind him is Father Smith of San Antonio, a white Catholic priest who protested against injustice for most of his life.” —Bruce Davidson

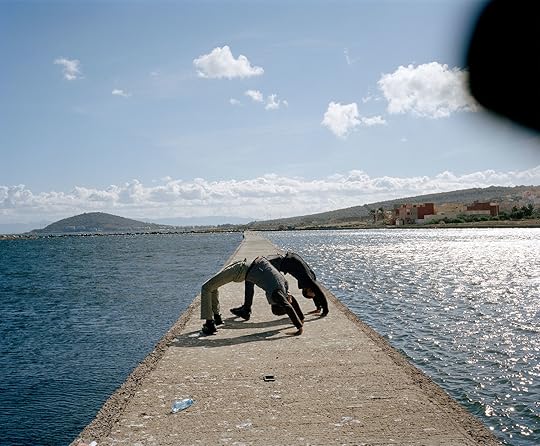

Lua Ribeira, Los Afortunados, Melilla, Spain, 2019

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Lua Ribeira

“This photograph makes me think about bridges, and the extent to which the origins of our issues reside on an illusion that we are separated. Carlos Skliar writes in his essay ‘The Fragile Look’: “to eliminate judgement is no easy task and, despite this, it is exactly what should be done, everything that would have to be done from now onwards so the world could be different and become pure childhood—or pure abnormality. That is: it doesn’t inevitably progress towards self-destruction, but rather, it would lead to the freedom of time and the precious uselessness of the actions undertaken, those actions that lie far from the benefit of profit-making and the trade of bodies and souls.” —Lua Ribeira

Denise Stephanie, In Your Hands, Brooklyn, 2018

Courtesy the artist/Vogue

Denise Stephanie

“The year 2020 has reminded us that human connection is one of life’s greatest treasures. At first, we were forced to be ‘socially distant’ in response to a global pandemic. We substituted FaceTime and Zoom meetings for in-person interaction and discussion. We found ways to cope and attempted to fill the gaps. Virtual communication has been the bridge to strengthen our relationships, show support for one another, and bring light to what haunts us. Then, triggered by tragic and chronic injustice, we covered our faces but joined our hands across the world in solidarity with Black voices, for Black lives. We leveraged digital platforms to turn conversations into action. Through our resilience, we created a new normal but acknowledged that there is no substitute for the human touch. In this double-exposure image, these faceless, melanated women stand together, supporting one another, joined by the same personal touch we have been missing. They remind us that through compassion, our bonds are unbreakable.” —Denise Stephanie

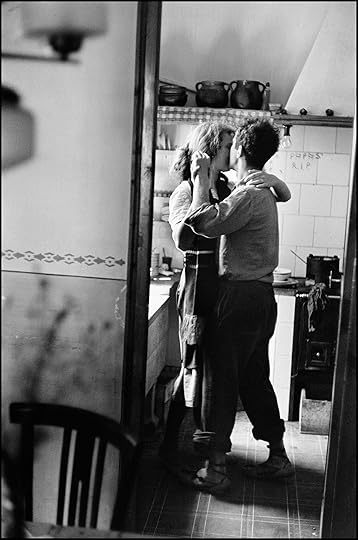

Elliott Erwitt, Valencia, Spain, 1952

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Elliott Erwitt

“The work I care about is terribly simple. I observe, I try to entertain, but above all I want pictures that are emotional. Little else interests me in photography. Today, so much is being done by unemotional people, or at least it looks that way . . . I mean, work that’s fascinating and fun and clever and technically brilliant. But if it’s not personal, then it misses what interesting photography is about.” —Elliott Erwitt, in Personal Exposures, 1988

Sohrab Hura, Pati, India, 2010

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sohrab Hura

“I never quite understood what solidarity meant until I went to Pati for the first time in 2005. Pati is a small village block in Madhya Pradesh in central India. Coming from a bigger metropolitan city like New Delhi, I witnessed and experienced solidarity in a way that felt like a life-changing experience—I guess that is what happens when you have the privilege of not really feeling the immediate need for it yourself, and it only remains a sort of a grand gesture that you might extend on to others. It was here that for the first time, I experienced a collectiveness unlike anything else. It was also here that I learnt that solidarity could even exist in the act of stepping back and listening.” —Sohrab Hura

In addition to the donation to the NAACP, Sohrab Hura’s proceeds from the sale of this print will be used to support Jagrit Adivasi Dalit Sangathan (JADS), a grassroots union formed by people in Pati to fight for basic rights, including the right to work in dignity.

Alex Webb, Erie, Pennsylvania, 2010

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Alex Webb

“I keep returning to these words of James Baldwin, which seem as apt today as when he wrote them nearly sixty years ago: ‘Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.’” —Alex Webb

Richie Shazam, Tell Your Friends to Pull Up, New York City, 2020

Courtesy the artist/Vogue

Richie Shazam

“Through my artistic expression, I’ve learned about myself and was able to learn about others. My photography lets me tell stories, send but also transcend messages. My work connects me to who I am, where I come from, and most of all, those around me. Pride is about celebrating our ability to stand up for ourselves. This year, we are called upon to stand up and against the violence and hate thrust onto so many Black and brown bodies. Attending the Black Trans Lives Matter march in Brooklyn was a moving, historical moment.” —Richie Shazam

Ronan McKenzie, Our Place, Los Angeles, 2019

Courtesy the artist/Vogue

Ronan McKenzie