Aperture's Blog, page 64

November 24, 2020

Arrivals and Departures Along the Trans-Siberian Railway

Fierce eyed in their filmy black dresses and off-the-shoulder numbers, the girls of Ulaanbaatar were strutting down the corridors of the gleaming new Shangri-La Hotel last August as if in Bangkok or Shanghai. Some were carrying bags from the shiny Vuitton outlet down the street; others had no doubt been pastoralists on the grasslands just years before. Every time the branch train of the Trans-Siberian Railway stops in the Mongolian capital, fresh faces—new thoughts of faraway worlds—flood out to transform a world of horses and heart-stopping emptiness. “You know,” a Mongolian friend said to me just before heading to the bar Naadam, “Genghis Khan was the WTO of the thirteenth century.” What he didn’t need to say was that what used to be a trade of spices and tea is now very often one of promises and dreams.

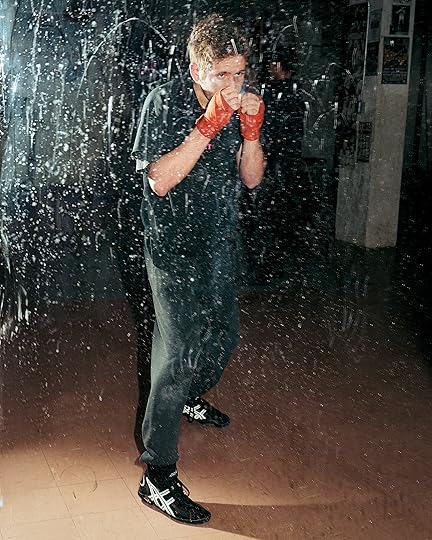

As I sauntered among the Thai massage joints and “Vegas” nightclubs of Ulaanbaatar last summer, I might have been in the stark and sometimes unsettling world that Jacob Aue Sobol has made his own. Since 2012, on one month-long trip after another, the Danish wanderer has been opening up a boldly contemporary Asia, as he rides the Trans-Siberian and its branch lines, taking us into Chinese, Russian, and Mongolian lives. At every stage, we feel not just the textures of societies in transition, but something inward and very private on the far side of the tracks. The mixed feelings of a traveler slipping out after a quickie, the unease of arriving in a place that is itself on the move (or even, in Mongolia, on the hunt). The view not through the window of the celebrated train, but from within a shuttered room, looking back.

It’s easy—perhaps too easy—to say that the tourist wants to go somewhere while the traveler likes to linger. The tourist hopes to catch something through his lens, while the traveler seeks to surrender, even to be claimed by a surprise in very real life. Yet Sobol’s work goes even deeper than most travelers, by seeing what is left behind when the train pulls out, and by seeking out the shadows, the unintended consequences, of a journey that leads not just to discovery but confrontation. Though the title of his ongoing series is Arrivals and Departures, he clearly has little interest in the names and times listed on railway-station announcement boards. Destinations are less important to him than those feelings—of guilt, of disquiet, of wanderlust—that arise whenever a wayfarer draws close enough to a local to feel (or impart) real hurt. I think of Jackson Browne’s haunting line about running for a morning flight “through the whispered promises and the changing light / Of the bed where we both lie.” With the emphasis on “lie.”

As a traveler through the alleyways of contemporary urban Asia for the past thirty-two years, I’ve always sought out those scenes that can’t be caught on any screen. I’ve been interested in why, a few miles from the wind-whipped silences of Mongolia, a “Luxury Nail Spa” is opening amid crowds of Dubai-worthy glass towers, and why Mongolian Airlines is showing Two Night Stand, of all Hollywood comedies, as we fly into the land of Genghis Khan. But looking at Sobol’s work, I’m reminded of how we writers will always lag behind: it’s not so much that a picture is worth a thousand words as that it can grasp a thousand silences. The unspoken moment; the impenitent stare; every murmur or grunt or tremor that no words can begin to transcribe. In the age of the selfie, Sobol’s camera looks out—and finds a brazenness that conceals at least as much as reticence does.

In China, bullet trains are being built to travel over 300 miles per hour; coming in from the airport in Shanghai, I rode a Maglev train that whisks passengers past avenues of skyscrapers at 268 miles per hour. In Russia, the ghostly gray monuments of Leninism have given way, almost overnight, to over-the-top dance clubs and, in Moscow alone, eight separate Rolex outlets. Even in Mongolia, I found last summer, the memory of the worldly conquerors known as the Golden Horde is being trumped by the prospect of hoarded gold. Yes, Sobol’s inky black-and-whites take us past the glitter of the twenty-first-century Silk Road into more uncertain moments that recall the elemental, even predatory street poetry of Daido Moriyama or Jack Kerouac. This comes from having the patience to step off the train and walk slowly into the lives and bewildering landscapes all around.

These images stay with me in part because they give back so little, and what they do give back is not consoling. They’re antisnapshots of a kind about the displacing truth of travel—that places are often resistant to our gaze, and the deeper we enter them, the more we lose all sense of where we are. In this context, the stress on Trans-Siberian Railway falls emphatically on “Trans”—the sense of movement, of crossing frontiers, of stepping toward a human contact that will always remain out of reach. Less transcendence, you might say, than transgression. And—as in the most memorable trips—no answers, but questions that keep on turning inside of you, forever.

This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 222, “Odyssey,” Spring 2016.

November 19, 2020

Aperture’s 2020 Holiday Gift Guide

From the best-selling Aperture photobooks The New Black Vanguard and PhotoWork; to new monographs by Ming Smith, Josef Koudelka, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya; to essay and activity books to inspire readers, we’ve rounded up titles for everyone on your list.

Must-Haves for Photography Lovers

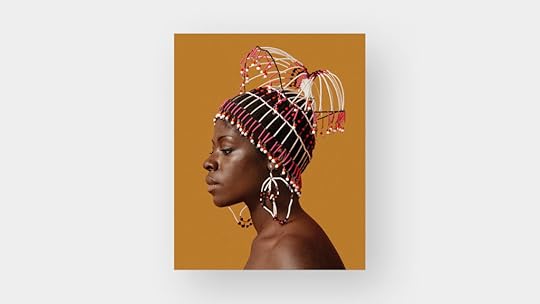

The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion

In The New Black Vanguard, curator and critic Antwaun Sargent addresses a radical transformation taking place in art and fashion today, highlighting the work of fifteen contemporary Black photographers rethinking the possibilities of representation.

Josef Koudelka: Ruins

For more than twenty years, Josef Koudelka has traveled throughout the Mediterranean, photographing over two hundred archaeological sites. With its stark and mesmerizing panoramic images, Ruins is a monument to architectural and cultural history, as well as to civilizations long past.

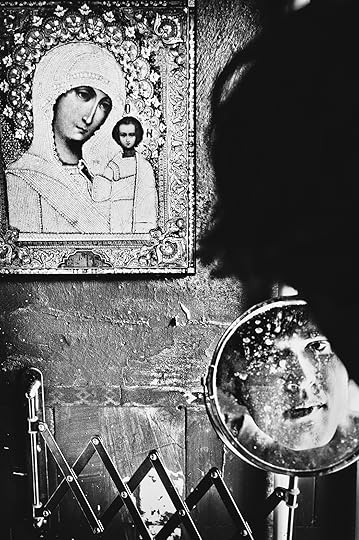

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Nan Goldin’s iconic visual diary chronicles the struggle for intimacy and understanding between her friends, family, and lovers in the 1970s and ’80s. Goldin’s candid, visceral photographs captured a world seething with life—and challenged censorship, disrupted gender stereotypes, and brought crucial visibility and awareness to the AIDS crisis. Over thirty years after it was first published, the influence of The Ballad on photography and other aesthetic realms can still be felt, firmly establishing it as a contemporary classic.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Leading the conversation on contemporary photography with thought-provoking commentary and visually immersive portfolios, Aperture is required reading for everyone seriously interested in photography. With thematic issues ranging from “Vision & Justice” to “Future Gender,” “Native America,” and more, Aperture has been the essential guide to photography since 1952. This year, gift a subscription and receive four issues of Aperture and a copy of The PhotoBook Review.

Give the Gift of Inspiration

PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice

How does a photographic project or series evolve? How important are “style” and “genre”? What comes first—the photographs or a concept? PhotoWork is a collection of interviews by forty photographers about their approaches to making photographs and a sustained a body of work. Structured as a Proust-like questionnaire, editor Sasha Wolf’s interviews provide essential insights and advice from both emerging and established photographers—including LaToya Ruby Frazier, Todd Hido, Alec Soth, Rinko Kawauchi, and more—while also revealing that there is no single path in photography.

Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present

What led Stephen Shore to work with color? Why was Sophie Calle accused of stealing Johannes Vermeer’s The Concert? Aperture Conversations presents a selection of interviews pulled from Aperture’s publishing history, highlighting critical dialogue between esteemed photographers and artists, critics, curators, and editors since 1985.

Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities

In the latest from our Photography Workshop Series, Dawoud Bey offers insights into portrait photography. Through images and words, he shares his own creative process and discusses a wide range of issues—from how he approaches strangers and establishes relationships, to how he sensitively represents communities.

The Photographer’s Playbook: 307 Assignments and Ideas

The best way to learn is by doing. The Photographer’s Playbook features photography assignments, ideas, stories, and anecdotes from many of the world’s most talented photographers and photography professionals. Whether you’re looking for exercises to improve your craft, or just interested in learning more about the medium, this playful collection will inspire fresh ways of engaging with photographic processes.

Photobooks Celebrating Black Artists

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the ’50s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color. Born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite and his brother Elombe were responsible for creating the African Jazz Arts Society and Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. Until now, Brathwaite has been under-recognized, and Black Is Beautiful is the first-ever monograph dedicated to his remarkable career.

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph

Over the last ten years, Deana Lawson has portrayed the personal and the powerful in her large-scale, dramatic portraits of people in the US, Caribbean, and Africa. One of the most compelling photographers working today, Lawson’s An Aperture Monograph is the long-awaited first photobook by the visionary artist. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith in the book’s essay. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Paul Mpagi Sepuya is the first widely released publication of one of the most celebrated up-and-coming photographers working today. Sepuya’s photographs challenge and deconstruct traditional portraiture by way of collage, layering, fragmentation, and mirror imagery, all through the perspective of a Black, queer gaze.

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph

One of the greatest artist-photographers working today, Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. This long-awaited monograph brings together four decades of Smith’s work, celebrating her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes, alongside a range of illuminating essays and interviews.

For the True New Yorker

Danny Lyon: The Destruction of Lower Manhattan

First published in 1969, The Destruction of Lower Manhattan is a lasting document of nearly sixty acres of downtown New York architecture before its destruction in a wave of urban development. In 1966, Danny Lyon settled into a downtown loft, becoming one of the few artists to document the dramatic changes taking place. More than fifty years later, his striking photographs still appeal to our emotions, capturing this singular period of time.

Perfect Strangers: New York City Street Photographs by Melissa O’Shaughnessy

Over the last seven years, Melissa O’Shaughnessy has photographed daily on the streets of New York, capturing the fleeting moments when light, people, and the chaos of the city collide in surprising, poignant, and humorous ways. Brought together in her first book, featuring an introduction by Joel Meyerowitz, Perfect Strangers offers a refreshing addition to the tradition of street photography.

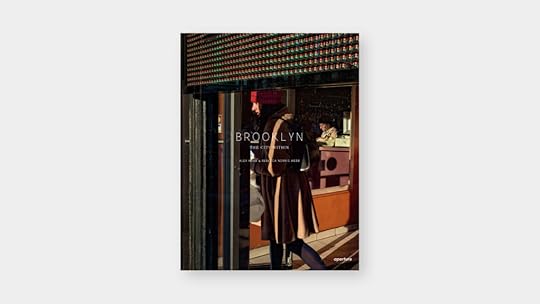

Brooklyn: The City Within by Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb

Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb have been photographing this New York City borough for the past five years, creating a profound and vibrant portrait. The two artists took individual approaches to capturing the borough: Alex photographed across the various neighborhoods; and Rebecca focused on three major green spaces in the heart of Brooklyn—the “green city within the city”—in both images and words. Together, their photographs of Brooklyn tell a larger American story, one that touches on immigration, identity, and home.

Ethan James Green: Young New York

Ethan James Green’s first monograph presents a selection of striking portraits of New York’s Millennial scene-makers, a gloriously diverse cast of models, artists, nightlife icons, queer youth, and gender binary–flouting muses of the fashion world and beyond. Young New York showcases a bright young talent who is redefining beauty and identity for a new generation.

Photobooks for the Armchair Traveler

Gail Albert Halaban: Italian Views

Through Gail Albert Halaban’s lens, the viewer is welcomed into the private lives of ordinary Italians. Her photographs explore the conventions and tensions of urban lifestyles, feelings of isolation in the city, and the intimacies of home and daily life. Francine Prose’s wonderful essay discusses the curious thrill of being a viewer. This invitation to imagine the lives of neighbors across windows renders the characters and settings personal and mysterious.

Throughout the late 1970s and early ’80s, Joel Meyerowitz spent his summers in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a safe haven for the queer community and a getaway for artists. Provincetown collects one hundred exquisite, sharply observed portraits—most never before published—of families, couples, children, artists, and other denizens of the progressive community.

In recent years, Rinko Kawauchi’s photographs of the tender cadences of everyday living have begun to swing further afield from her earlier work. In Halo, Kawauchi expands her inquiry, photographing three main themes—Lunar New Year celebrations in Hebei province in China (where a five-hundred-year-old tradition calls for molten iron hurled in lieu of fireworks), the southern coastal region of Izumo in Japan, and an ongoing fascination with the murmuration of birds along the coast of Brighton, England. The resulting images knit together a mesmerizing exploration of the spirituality of the natural world.

Uncommon Places: The Complete Works by Stephen Shore

Originally published in 1982, Stephen Shore’s legendary Uncommon Places has influenced a generation of photographers. Shore was among the first artists to take color beyond the domain of advertising and fashion photography, and his large-format color work on the American vernacular landscape stands at the root of what has become a vital photographic tradition over the past forty years.

Children’s Activity and Educational Books

This Equals That by Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin

This clever and surprising picture book by artists Jason Fulford and Tamara Shopsin takes young viewers on a whimsical journey while teaching them associative thinking and visual language, as well as colors, shapes, and numbers. Through a simple narrative and a rhythmic sequence of photographs, the book generates multiple meanings, making the experience of reading it interactive—with everyday scenes transformed into a game of pairs, enjoyable for adults and children alike.

Seeing Things by Joel Meyerowitz

Seeing Things is a wonderful introduction to photography that asks how photographers transform ordinary things into meaningful moments. Joel Meyerowitz introduces young readers to the power and magic of photography, exploring key concepts in photography—from light, gesture, and composition, through the work of master photographers such as William Eggleston, Mary Ellen Mark, Helen Levitt, Martin Parr, and more.

Go Photo! An Activity Book for Kids

Go Photo! features twenty-five hands-on and creative activities inspired by photography. Aimed at children between eight and twelve years old, this playful and fun collection of projects encourages young readers to experiment with their imaginations and build their own visual language. Indoors or outdoors, from a half-hour to a whole day, there is a photo activity for all occasions—and some don’t even require a camera!

For the Collector

This highly collectible, limited-edition pop-up book is a work of art in itself, rendering Daniel Gordon’s sculptural forms into a new layer of materiality and animating them in a pop-up performance. The book consists of six works in pop-up form, some featuring simple plants, others unfolding more elaborate tableaux.

Vik Muniz: Postcards from Nowhere

Vik Muniz’s two-volume Postcards from Nowhere grapples with how, through photographs, we have come to “see” and understand distant yet iconic sites we may never actually view with our own eyes, while also serving as an homage to the quasi-obsolete artifact of the picture postcard. Volume I includes thirty-two single postcards displaying each of the images in the series; while Volume II presents a series of thirty-six postcards that, when assembled, can be viewed as a single, large-scale work of thirty-by-forty inches.

Gregory Halpern: Let the Sun Beheaded Be (Limited Edition)

In Let the Sun Beheaded Be, Gregory Halpern presents a thoughtful and visually striking depiction of the Caribbean archipelago of Guadeloupe, a French overseas region with a complicated and violent colonial history. Featuring texts by Clément Chéroux and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, the book offers a poetic examination of Guadeloupe’s natural beauty and troubling history side by side. This limited-edition box set features a signed print and special version of the book, with artist proceeds donated to Locust Street Art (Buffalo, New York) and the Pan American Health Organization.

Gregory Crewdson: An Eclipse of Moths

This limited-edition, slipcased volume expands on Gregory Crewdson’s obsessive exploration of the small-town, postindustrial American landscape. Featuring sixteen never-before-published photographs, An Eclipse of Moths is luxuriously produced at a scale that offers an immersive experience of each of Crewdson’s carefully crafted scenes.

Shop Aperture’s Holiday Sale and save up to 35% off books, magazines, and prints, as well as newly released signed books by Antwaun Sargent, Justine Kurland, Ming Smith, and more.

November 17, 2020

Dannielle Bowman Finds History in the Shadows

If ever a sentence begins with the colloquialism “What had happened was . . . ,” know that a rich story is to follow. It’s a clearing-of-the-throat kind of expression that sets up a fantastical plot twist in a gripping narrative, leaving listeners begging for more. If you’re not totally familiar with the phrase, I suppose that’s the point. For Black Americans, it’s a benchmark expression of our parlance, AAVE, or African American Vernacular English, a sociolinguistic continuum that tracks our inhabitance of the United States from slavery to the Great Migration to the post–civil rights era and the present. Black folks of any generation are fluent in its varieties.

When the photographer Dannielle Bowman named her 2020 exhibition, held at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, What Had Happened, the gesture was telling: something most certainly did happen, and it was decidedly Black. Adrift in the shadows that only the Los Angeles sun can create, Bowman captures in black-and-white images the African American, middle-class families of her native community—Baldwin Hills, Inglewood, and Crenshaw—by nestling her lens deep within the interior of their homes and inner emotional lives.

Zooming in on the plush, yet worn, carpeted stairs of her aunt and uncle’s Hollywood Hills home, Bowman underscores a signifier of suburban decor, but suggests a childlike wonder through her eye-level perspective. She transports us to a well-appointed living room, where we see two family portraits of young Black men, perched on the mantel of a fireplace. Sons, brothers, or cousins—there is a line of familial resemblance that runs straight through them. Their high-top fades age the photographs—these were not taken recently. She clocks other details, from a woman’s elegant hand fixing the slats of her vertical blinds, to the throwback bump-and-curl coiffure of a mysterious woman in her garden, festooned in a grass sweeping gown, whose back is turned to the camera. She could be anyone’s auntie tending to her plants.

Dannielle Bowman, Vision (Bump’N’Curl), 2019

Dannielle Bowman, Vision (Bump’N’Curl), 2019 Dannielle Bowman, Faces, 2019

Dannielle Bowman, Faces, 2019What Had Happened is about the subtext that lies within the objects, events, and locations that make up the worlds of Black folks. It’s like “a Black noir,” Bowman told me earlier this year. “Something did happen, and we have to get to the bottom of it.” That thing being the Great Migration, which Bowman explores throughout her work. Maya Deren’s experimental film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) was also an influence: Deren’s use of repetition, shadows, and the home as a site of emotional and domestic interiority moved Bowman to infuse images with shadows and mystery.

But Bowman is also digging, unearthing a personal history that she had previously distanced from her work. “I think for years I have resisted any kind of urge to make explicitly Black art,” she explains. Growing up, Bowman had never been situated within predominantly Black environments, having attended a tony all-girls high school in Brentwood, California; the Cooper Union for undergraduate; and later Yale University, where she earned her MFA in photography in 2018. She worked hard to fit in with her mostly white classmates.

Dannielle Bowman, Vision (Garage), 2019

Dannielle Bowman, Vision (Garage), 2019 Dannielle Bowman, Upkeep, 2018

Dannielle Bowman, Upkeep, 2018What Had Happened is a corrective, Bowman says, allowing her to embrace her personal narrative publicly for the first time. “It is important that I acknowledge who I am. And it is important that the faces and the hands and hints of people in the images are brown, because that’s the world I’m coming from. I don’t have to try hard to photograph Black homes, because I grew up in them. And I don’t think that I understood the wealth that was right in front of me.” Bowman is not alone in this internal battle—Black artists have long wrestled with the significance of identity politics within their work but overcoming that conflict ultimately proved freeing for the photographer. She landed upon the “pleasure principle,” a guiding force that pushes her work forward.

As Bowman was working on What Had Happened, she was tapped by the journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones and the director of photography for The New York Times Magazine, Kathy Ryan, for the 1619 Project, an ambitious initiative that seeks to survey the legacy of transatlantic slavery. For the assignment, Bowman set off to photograph landmarks of slave auctions across the country. Her haunting and reverential imagery unearths sites of racial violence that were hiding in plain sight, from her iconic cover image of rippling waves near Hampton, Virginia, the first recorded point of entry for ships carrying enslaved Africans to colonial America, to abandoned train tracks outside Savannah, cast in an early morning haze, that were once the site of the United States’ largest slave auction in 1859. It’s a placid scene that belies the atrocities committed there.

Dannielle Bowman, Weeping Time Landscape, Savannah, Georgia, 2019, for The New York Times Magazine

Dannielle Bowman, Weeping Time Landscape, Savannah, Georgia, 2019, for The New York Times Magazine“I was not allowing myself to be overcome with emotion because I really felt like I had a sacred job to do. And all of this history was kind of on my shoulders, Bowman says. “While working, I just had to work.” Bowman was a Black woman traveling in the South, alone. Following brushes with danger, she was left feeling vulnerable and worried for her safety, but also concerned about doing the story justice: the 1619 Project was, for her, an “act of service, a memorial, a sacrifice.” And perhaps that fraught emotional experience can be felt within Bowman’s images. Hannah-Jones earned a Pulitzer Prize for her essay in the 1619 Project issue, and Bowman finished What Had Happened with a newfound selflessness, that “pleasure principle.” “It allowed me to really prioritize my desires.”

Dannielle Bowman is the winner of the 2020 Aperture Portfolio Prize. Her solo exhibition will be copresented by Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York from January 6 to February 4, 2021.

This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the column “Spotlight.”

November 16, 2020

How a Chinese Photographer Navigates Queer Identity and Resilience

Mengwen Cao doesn’t want to drift. When the Chinese-born, New York–based photographer speaks about their life, they like to place themselves in metaphors of natural forces. “Some people swim far into the ocean. Others try to ride the waves,” Cao says. “But I realize my favorite is to see the wave, and right before it comes, I jump in.”

Cao’s work tackles the forces that have, at times, unmoored their life. Their first project to receive wide recognition, Here We Are (2016), includes a recording of the FaceTime conversation in which Cao looked on as their parents viewed a video-letter they had made to come out as queer. “Twenty-two to twenty-five seems to be my belated adolescence, yet I try to follow my heart in everything I do,” Cao recites in the video, as their mother leans her head onto her husband’s shoulder, glancing at Cao, who is nervously covering their face on the other side of the screen.

Using the website design and UX skills they had acquired while studying education technology at the University of Texas at Austin, Cao created a digital portal where their video could be shared alongside the stories of other Chinese LGBTQ people in New York City. Here We Are was widely circulated and landed two features in the New York Times.

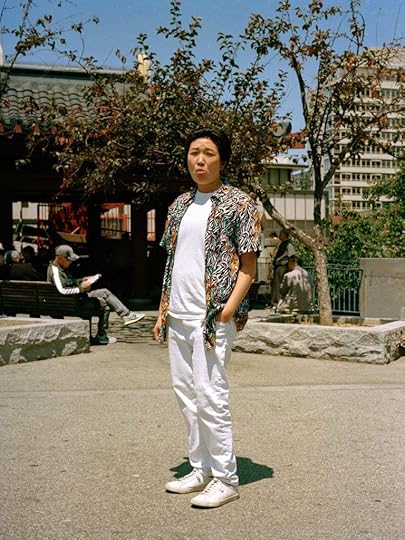

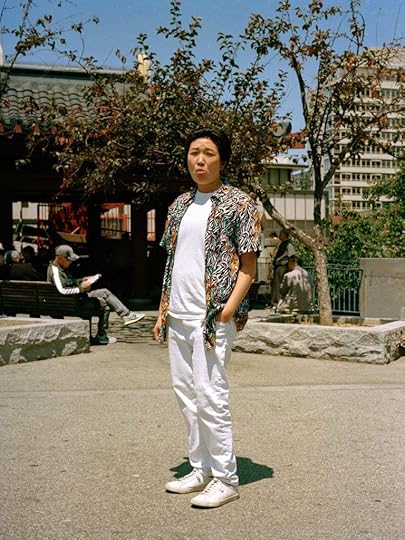

Mengwen Cao, Yellow Jackets Collective, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Yellow Jackets Collective, 2019After several years in the United States, Cao’s experience of their shifting identity as a Chinese person inspired a second digital project, I Stand Between (2017–18). Turning their attention to the ambiguities and tensions of diasporic identity, Cao combined photography and audio interviews to build a digital platform about the experiences of transracial and transnational Asian American adoptees.

“I was trying to research alternative family structures, and wanted to talk about more nuanced forms of racism. Everyone I interviewed had very different experiences within loving families, but that doesn’t mean that they didn’t have problems,” Cao says. “So, how do you navigate the situation where someone who loves you still hurts you in ways that they might not even recognize? And how do you heal from that?”

In the interviews, Cao makes sure to include the touching pauses and reiterations in the voices of the people they spoke with—carefully tending to the gentle ambivalence of their subjects’ accounts as they make sense of the discrimination and imperfect modes of caring wound into their upbringings.

The questions of how to navigate family, acknowledge pain, and seek healing are persistently probed by Cao’s work. But with time, these are questions that Cao has learned to explore in collective settings, as they have become part of a community of queer, New York–based artists/activists enmeshed through the rhizomatic networks of Yellow Jackets Collective, Authority Collective, and BUFU.

Mengwen Cao, Sueann, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Sueann, 2019Cao’s newest photographic series, Liminal Space (2017–ongoing), documents the queer friends/chosen family in their life that have been part of this process. Made over the course of the past three years, the series emerged from Cao’s disidentification from the world of images that gamify queer life into spectacularized visions of violence and/or glamour. Instead, the photographs in this series linger on the privacies and agencies that are perhaps too soft and silent to draw the eye of anyone other than a devoted friend—scenes that Cao refers to as “quiet moments.”

Reflecting on what “quiet moments” might mean, Cao describes a meditation technique that they’ve recently learned: listening “for the three layers of a song” and finding “the silence in between.” There is a kinship between this exercise and the way Cao has opted to capture queer life in Liminal Space. By documenting friends relaxing, cooking, or seeking out moments of privacy, Liminal Space enshrines the reprieves where queer people rest and make room for ecologies that better support their needs: the silence that structures queer noise/music/life. Choosing to work with natural light, Cao is skilled in capturing the glimmers, streaks, and shades that illuminate the rich inner landscapes tucked behind the quotidian intimacy of their portraits.

By anchoring queer life in everyday spaces, Cao’s work refuses to see exploitation as the driving force of queer survival, and instead acknowledges the interior and exterior worlds that queer people have continually built to protect themselves and each other: “When I say I am marginalized, I don’t actually believe it anymore. For me, this is my world. I’m gradually cultivating this community that I call family and friends. And we are the majority.”

Mengwen Cao, Grace, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Grace, 2019 Mengwen Cao, Sonia, 2017

Mengwen Cao, Sonia, 2017 Mengwen Cao, Luke, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Luke, 2018 Mengwen Cao, Sandy, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Sandy, 2018 Mengwen Cao, Jazmin and Yeelen, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Jazmin and Yeelen, 2018All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

A previous version of this article misstated the title and scope of Mengwen Cao’s project Here We Are (2016). The original headline misidentified Cao as Chinese American; they are Chinese, not American. We apologize for the errors.

[image error]

How a Chinese American Photographer Navigates Queer Identity and Resilience

Mengwen Cao doesn’t want to drift. When the Chinese-born, New York–based photographer speaks about their life, they like to place themselves in metaphors of natural forces. “Some people swim far into the ocean. Others try to ride the waves,” Cao says. “But I realize my favorite is to see the wave, and right before it comes, I jump in.”

Cao’s work tackles the forces that have, at times, unmoored their life. Their first project to receive wide recognition, Here We Are (2016), is a recording of the FaceTime conversation in which Cao looked on as their parents viewed a video-letter they had made to come out as queer. “Twenty-two to twenty-five seems to be my belated adolescence, yet I try to follow my heart in everything I do,” Cao recites in the video, as their mother leans her head onto her husband’s shoulder, glancing at Cao, who is nervously covering their face on the other side of the screen.

Using the website design and UX skills they had acquired while studying education technology at the University of Texas at Austin, Cao later expanded the project by creating a digital portal where their video could be shared alongside the stories of other Chinese LGBTQ people in New York City. This larger project, We Are Here (2017) was widely circulated, and Here I Am landed two features in the New York Times.

Mengwen Cao, Yellow Jackets Collective, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Yellow Jackets Collective, 2019After several years in the United States, Cao’s experience of their shifting identity as a Chinese person inspired a second digital project, I Stand Between (2017–18). Turning their attention to the ambiguities and tensions of diasporic identity, Cao combined photography and audio interviews to build a digital platform about the experiences of transracial and transnational Asian American adoptees.

“I was trying to research alternative family structures, and wanted to talk about more nuanced forms of racism. Everyone I interviewed had very different experiences within loving families, but that doesn’t mean that they didn’t have problems,” Cao says. “So, how do you navigate the situation where someone who loves you still hurts you in ways that they might not even recognize? And how do you heal from that?”

In the interviews, Cao makes sure to include the touching pauses and reiterations in the voices of the people they spoke with—carefully tending to the gentle ambivalence of their subjects’ accounts as they make sense of the discrimination and imperfect modes of caring wound into their upbringings.

The questions of how to navigate family, acknowledge pain, and seek healing are persistently probed by Cao’s work. But with time, these are questions that Cao has learned to explore in collective settings, as they have become part of a community of queer, New York–based artists/activists enmeshed through the rhizomatic networks of Yellow Jackets Collective, Authority Collective, and BUFU.

Mengwen Cao, Sueann, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Sueann, 2019Cao’s newest photographic series, Liminal Space (2017–ongoing), documents the queer friends/chosen family in their life that have been part of this process. Made over the course of the past three years, the series emerged from Cao’s disidentification from the world of images that gamify queer life into spectacularized visions of violence and/or glamour. Instead, the photographs in this series linger on the privacies and agencies that are perhaps too soft and silent to draw the eye of anyone other than a devoted friend—scenes that Cao refers to as “quiet moments.”

Reflecting on what “quiet moments” might mean, Cao describes a meditation technique that they’ve recently learned: listening “for the three layers of a song” and finding “the silence in between.” There is a kinship between this exercise and the way Cao has opted to capture queer life in Liminal Space. By documenting friends relaxing, cooking, or seeking out moments of privacy, Liminal Space enshrines the reprieves where queer people rest and make room for ecologies that better support their needs: the silence that structures queer noise/music/life. Choosing to work with natural light, Cao is skilled in capturing the glimmers, streaks, and shades that illuminate the rich inner landscapes tucked behind the quotidian intimacy of their portraits.

By anchoring queer life in everyday spaces, Cao’s work refuses to see exploitation as the driving force of queer survival, and instead acknowledges the interior and exterior worlds that queer people have continually built to protect themselves and each other: “When I say I am marginalized, I don’t actually believe it anymore. For me, this is my world. I’m gradually cultivating this community that I call family and friends. And we are the majority.”

Mengwen Cao, Grace, 2019

Mengwen Cao, Grace, 2019 Mengwen Cao, Sonia, 2017

Mengwen Cao, Sonia, 2017 Mengwen Cao, Luke, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Luke, 2018 Mengwen Cao, Sandy, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Sandy, 2018 Mengwen Cao, Jazmin and Yeelen, 2018

Mengwen Cao, Jazmin and Yeelen, 2018All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

[image error]

November 4, 2020

Gregory Halpern’s Lyrical Chronicle of a Rust Belt City

“I’ve never been able to make a successful picture of Manhattan,” photographer Gregory Halpern says. “It feels like every inch of that island has been claimed.” By contrast, Buffalo, New York, where Halpern has photographed often since 2003, has less than half its peak population. “There’s an emptiness in the landscape that was compelling and intriguing.”

He knows whereof he speaks: Halpern was raised in the city. After the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825, Buffalo grew rapidly as it helped connect the East with an expanding American West. By century’s end itwas one of America’s ten largest cities, and played host to the Pan-American Exposition in 1901. (A major celebration of progress and industry in the Americas, the event is remembered today as the site of President McKinley’s assassination.) The city’s grain and steel industries kept Buffalo’s economy afloat through much of the twentieth century. But its recent history mirrors that of other American Rust Belt cities and is marked by deindustrialization, suburbanization, and population shifts to the American South and West. The opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959, which took shipping elsewhere, caused further difficulties.

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16Halpern grew up in the city confronting these developments. As a child in the 1980s, he explored Buffalo’s abandoned buildings and vacant lots with his brother. They delighted in the imaginative possibilities of its rich history and unclaimed spaces. Halpern concedes this aspect of Buffalo may have helped him learn, as a young photographer, to leave room for interpretation. His photographs of the city create atmospheres rather than arguments. Overcast skies are prevalent and even interior scenes feature pallid light. There is little action, and often a sense of isolation: a solitary red bowling ball rolls down a lane; a solitary man pauses during a meal at a cheap café; a solitary building rises in the middle distance, beyond snowdrifts.

These are not showy pictures. Halpern frequently places his subjects at dead center. Nearly as often, his photographs also feature arresting, seemingly unrelated details that add surprising depth. A beaten-down passenger van, its door ajar and its interior piled high with beer cans, might be a story of lower-class despair. But the single balloon tied to the van’s side-view mirror makes literal a contrasting sense of buoyancy.

Buffalo’s economic slump defines the city in the popular imagination. That understanding is rooted in fact: Buffalo is one of the poorest large cities in America. And you can find that story in Halpern’s photographs, which feature unkempt places and people with ragged edges. In March 1964, Walker Evans, another photographer who captured American poverty, delivered a lecture at Yale University titled “Lyric Documentary.” In this talk Evans spoke at length about his collection of early twentieth-century postcards depicting cities like Buffalo in their era of rude health. He understood that from small moments comes profound understanding. “Those honest, direct little pictures have a quality today that is more than that of mere social history.” So, too, Halpern recognizes through these pictures that, amid Buffalo’s difficulties, “babies are born there. People fall in love there. Certain people would say the city is dying, but it’s also continually being born.”

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16 Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

Gregory Halpern, Untitled, 2003–16

All images courtesy the artist

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 226, “American Destiny,” Spring 2017.

In the West, Carolyn Drake Seeks New Expressions of American Identity

Sometimes you need the eyes of an outsider to see your world afresh. The sustained focus of the newcomer; the quizzical glances of the passerby; the curiosity-filled wanderings of the traveler—they refresh our ideas of ourselves and help us rediscover the familiar. Indeed, they even render the invisible visible. Seeing alongside outsiders expands our scope—and, at its best, deepens our understanding and appreciation—by returning us to a childlike inquisitiveness. As the Polish poet Wisława Szymborska wrote, “there are no questions more urgent / than the naïve ones.”

Carolyn Drake, Kyle in Target parking lot, Twin Falls, Idaho, 2016

Carolyn Drake, Kyle in Target parking lot, Twin Falls, Idaho, 2016Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Carolyn Drake, who has photographed across the world (notably in western China and the Ukraine), where she benefited from the outsider’s remove, returned in 2013, after seven years away, to her native United States and chose to pursue the naïve questions by adopting the stance of a stranger. In fact, she had become a stranger of sorts—much of her country felt foreign, as she had been “thinking about other places for a long time.” But she was also too close to her country, and it too much a part of her, for her to see people and their environments as clearly as she desired. She needed to revisit her homeland with a new way of looking.

She decided to counter her disadvantage by traveling westward, using the nineteenth-century diary of an ancestor who, during a time of national expansion, went from Iowa to California. The diary is both guide and point of departure; Drake wanted to undertake a journey with a personal connection, and connect with those she encountered, not, as she said recently, “re-enact the journey or reaffirm our national mythologies. Rather, I’m seeking out stories that subvert and confound the boilerplate Western narrative.” She not only traversed the landscape, but also circled it, paying patient attention to those who sprung up from the soil and those new to it.

Abandoning the romantic myths of the frontier for the stories that animate those in pursuit of or left behind by—or even unconcerned with—the American Dream, Drake captures the worlds she encounters with warmth and lyricism. A family of African refugees traveling from Boise, Idaho, makes a pit stop at a gas station in Baker City, Oregon, to pray and refuel. We’ve seen this gas station before—a staple of American realist photography—but this scene feels fresh, different: friendly banter with a stranger illuminates the life often found in the societal interstices between those from here and those from elsewhere. The encounter resembles a delightful community gathering; perhaps we haven’t seen this gas station before, after all.

Carolyn Drake, Lacy in Safeway parking lot, Pendleton, Oregon, 2015

Carolyn Drake, Lacy in Safeway parking lot, Pendleton, Oregon, 2015Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Drake gives us people inscribing themselves on the landscape—which might mean inscribing the place on one’s very self (a tattoo of the state of Idaho adorns a man’s back, its vibrant colors at once badge and beauty), or asserting one’s agency in a place where daily life threatens to be a rote cycle of quiet desperation. Her interplay between the roles of insider and outsider suffuses her photographs, and we meet people who are as beguiling as they are mysterious: her subjects (students, refugees, workers, the unemployed, to name a few from a very broad range) draw you in with arresting gazes, but a moody atmosphere—those warm colors—holds you at bay, searching. It’s as if Drake invites us to see people’s agency, then insists it not be denied them—the African refugees’ smiles, expanding the photograph’s frame, intermingle with their veils. In their mystery is their magic.

Carolyn Drake, Road trip rest stop, Baker City, Oregon, 2015

Carolyn Drake, Road trip rest stop, Baker City, Oregon, 2015Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Drake is rediscovering—discovering, really—the United States as a native-made-newcomer, and as one tracing a path behind those whose footsteps reveal the wild, varying textures of a nation too often reduced to myths, stereotypes, and clichés. “What is America to me?” her work asks, pointing to the outsiders, the recent transplants, the strangers among us. Will they be strangers forever? Or will they eventually be welcomed as Americans, too? Carolyn Drake reminds us, to borrow Robert Frost’s words, that “America is hard to see.” We ought not to forget, then, that the meaning of America is bound up in the treatment and fate of those who see the way we don’t.

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 226, “American Destiny,” Spring 2017.

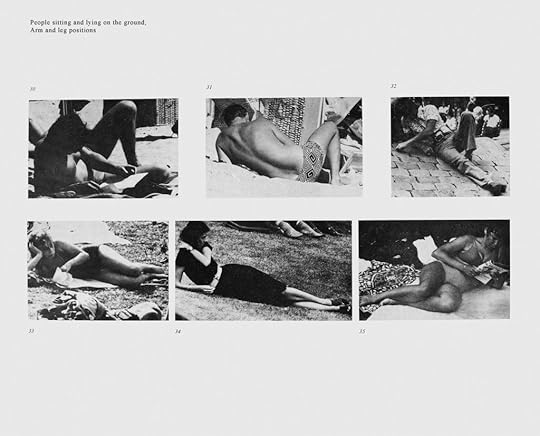

Marianne Wex’s Study of Gender and Power in Images

German artist Marianne Wex started out as a painter before producing her photographic project Let’s Take Back Our Space, one of the great unsung works of 1970s feminist history and cultural analysis. Born in Hamburg in 1937, Wex studied at the city’s University of Fine Arts, where she later taught for seventeen years. In 1979, she published Let’s Take Back Our Space as a book, with the subtitle “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures. It is a visual survey comprised of hundreds of photographs assembled into dozens of thematic grids: seated persons—leg and feet; arm and hand positions; standing persons—leg and feet; arm and hand positions; people sitting and laying on the ground; arm and leg positions; Egyptian, Greek, and Roman statuary; how the men of Christianity took over an old goddess gesture; the stultifying effect of the patriarchal socialization of men. And so on. The images were culled from a huge range of sources—advertisements, reportage, fashion magazines, studio portraits, the history of art—and many were taken on the streets of Hamburg by Wex, who proposes that our smallest, most unconscious gestures speak volumes about the power relations of gender in daily life.

It is an argument made with images, and, as such, it is highly dubious as science. We all know photographs can be chosen and sequenced to make an argument, that their evidential quality can be bent to serve almost any view. But Wex goes beyond the scientific. Her project is an intervention, and its claims to authority come less from the presentation of facts than from the flashes of recognition we may have in response to what she presents. Thirty-four years later, it’s impossible not to see aspects of ourselves and of present society in these images.

Moreover, there is space in the project for plenty of experiments and anomalies. Women do sometimes stand with their feet turned outward, but only if they are working class and not in the company of men, Wex notes. When shown stereotypical photos of men asserting themselves, women can easily and comfortably imitate them. But when men are shown images of women in “feminine” poses, they either can’t or won’t imitate them, even for the sake of an experiment. The few images of children and young adolescents are very telling: we can sense how the gender and sexuality-neutral body language of early youth is soon conventionalized into familiar patterns. Not always, but most of the time. Wex is careful not to make the argument seem totalizing, or the situation hopeless, and she seems to retain a revolutionary zeal for change. Yes, her approach uses heterosexuality as a kind of default, and there is little space for questions of ethnicity, subculture, or the ironic adoption of the body language of the powerful.

Such complexities would make updating the project almost impossible, if Wex were still a working artist today. Let’s Take Back Our Space was first exhibited as photo panels at NGBK (Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst) in West Berlin in 1977, but a serious illness turned Wex away from art and toward the study of alternative medicine. This remarkable project wasn’t shown again until Mike Sperlinger curated a show, in 2009, for London’s Focal Point Gallery, allowing us to reconsider Let’s Take Back Our Space both as a remarkable record of its time and a still-troubling reflection of our own.

All images from Marianne Wex, Let’s Take Back Our Space: “Female” and “Male” Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (Berlin: Frauenliteraturverlag Hermine Fees, 1979)

This piece was originally published in Aperture, issue 213, “Photography as you don’t know it,” Winter 2013.

October 31, 2020

What It’s Like to See Photographs Again

Earlier, the air had turned against us. This was a year of interrogating the we and decentering the I. Removing one’s body from the public, yet putting it on the line to fight for the safety of others. A loneliness so physical it could be mistaken for an illness amid a virus so codependent, it could only thrive in groups.

This was also a year of endless images. In the spring, the shuttered art-institutional complex tried out online viewing galleries, but interest in those murky spaces burned off in the summer’s incandescent rage at institutions—art and otherwise—and their complicity and passivity in the face of injustice. The galleries, and their patrons, soon decamped to greener pastures in Miami and the Hamptons.

Instagram took over. Which of your friends were secretly rich? Which of your protest photos might be used by cops to geolocate, to track and imprison (or worse) Black Lives Matter organizers? Did you notice how many men who once posed by themselves on the piers of the Scruff grid had paired up? Had everyone moved Upstate?

I mostly yearned. I longed to pay too much for a coffee and take it to Chelsea, Bushwick, Tribeca, the Met. I missed art in the flesh. On screen, photos I admired paled—no, just seemed to vanish—if scrolled next to, say, Erin Schaff’s photo for the New York Times of ghoulish Christianists laying hands on the door of the U.S. Supreme Court as the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg lay in state, a single mourner writhing on the marble before the prayer warriors in a pitiless pietà. It was impossible to look away.

Jenna Westra, Park Picture (Les Fleurs), 2020

Jenna Westra, Park Picture (Les Fleurs), 2020Courtesy the artist and Lubov, New York

But one bright morning this fall, I packed a tote with masks, rubber gloves, and hand sanitizer, and then risk-managed a subway ride. I made a deal with my body to shut down, so as not to risk “toilet plumes,” and with my heart to not forget—whether I ran into friends (straining to feel carefree as I was), or whether I might cruise (in this climate, sure), or indulge in a drink at a queer bar—that I was on my own, outside, six feet and in every other way distant from the world. Where’s the frisson for a flaneur?

I began at Lubov, Francisco Correa Cordero’s small white box in Chinatown. Cordero greeted me warmly, then sat masked at a laptop; I had not been in a room with a stranger in months, and I found myself distracting. The photographs by Jenna Westra—a mix of gelatin-silver and color-pigment prints of mostly women’s bodies draped around each other, tenderly cropped—seemed performatively intimate. And more so as Cordero explained these subjects were strangers to Westra, solicited on Craigslist and given ambiguous texts to express. They met her as I had met Cordero, by appointment. I had forgotten that sometimes productive, but often irritating aspect of viewing actual objects: you see yourself reflected in them. A bit melancholy, I fell hard for Park Picture (Les Fleurs) (2020), a photo Westra took from a distance of strangers embracing in the park. The 800 ISO film is enlarged into grains so thick you could chew them; the woman wears a scrunchie around her wrist with a sentimentality that got stuck in my throat. Imagine embracing your lover on a warm day, leaving your hair untied, a stranger capturing and mounting the image elsewhere later.

Christopher Makos, Keith Haring and Juan Dubose at the Piers, 1980s

Christopher Makos, Keith Haring and Juan Dubose at the Piers, 1980sCourtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art

At Daniel Cooney Fine Art, in Chelsea, two very good dogs growled curiously at me from behind their little gate, as I walked around the Christopher Makos show Dirty. Talk about caged animals: Makos’s early ’80s portraits of Debbie Harry barely contain her charisma, not to mention the contents of Kevin Kendall in Red Bikini (1986). I could have stared at Keith Haring and Juan Dubose at the Piers (1980s) for hours; the lovers’ affection and ambition seem to spurt from the Hudson River like waterworks. (On the other hand, I sort of feel like I could use a full decade free of Warhol and his aspirational blankness.) Makos’s collages, in the flesh, were surprisingly bittersweet. Four prints of the bodybuilder Johnny Germain were stitched together in squares like the back pockets of the 501s he decidedly was not wearing. Several later images, of pearl necklaces and pistols, amused me with their allusions to sex and violence, until I thought of how they were quilts, of a kind, and of loss. I petted the dogs and left.

Ruminating on mortality is a reasonable pastime these days, but if I was out in the city, I wanted a bit of spectacle—and the FLAG Art Foundation delivered. After a welcome bit of COVID theater—the temperature gun to the head, the waiver questionnaire—Awol Erizku’s Mystic Parallax offered a riot. Incense burned, and had burned paper into drawings; and Christian Scott’s soundtrack bumped through speakers, while a disco ball busted into the form of Nefertiti spun and flared. Erizku’s photos appeared variously as vivid chromatic prints and ghostly light boxes. (I wouldn’t swear that an ivory horse in one didn’t move.) Hollywood prop guns kept popping up—offered like the fabled Big Black Cock or a piece of camera equipment in one diptych, and like a flashlight or the weapon it pretends to be in another. The lifestyle magazines that commissioned some work stood like patron plaques in a nook. It all felt immediate and temporal, hilarious and furious, heavy as the symbolism in an Old Master painting and the bass of an 808.

Awol Erizku, Head Hunters, 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Head Hunters, 2018–20Courtesy the artist and FLAG Art Foundation

Awol Erizku, Love is bond (Young Queens), 2018–20

Awol Erizku, Love is bond (Young Queens), 2018–20Courtesy the artist and FLAG Art Foundation

The beleaguered Whitney Museum had enough theatrics for Broadway: branded signs everywhere of what to do with your body (“Wash hands frequently. Cover your cough.”), as many staff members sanitizing surfaces as timed guests in the galleries, a reconfigured circulation route that dumped you before an unmarked door at the end of your trip. Getting lost in a museum rarely felt so potentially terminal. But the diminutive Tina Modotti photographs included in the show Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945 felt as enormous as the murals. Their elegant form and impassioned antifascism felt more in keeping with recent Instagram trends than a selfie in front of the Diego Rivera. Elsewhere, a grid of William Winter’s moody, almost elegiac Camera Studies of the Whitney Museum of American Art (ca. 1933) offered looks into the Whitney’s previous life. After the Met refused Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s art collection, she built a museum of her own, “with brightly colored walls and domestic furniture,” per the wall text, though the photos are mostly light and shadow. It’s a long way from $40 branded face masks and former board members profiteering from tear gas.

Tina Modotti, Campesinos Reading “El Machete,” 1929

Tina Modotti, Campesinos Reading “El Machete,” 1929Courtesy Throckmorton Fine Art, New York

Carmen Winant, Togethering 9 (detail), 2020

Carmen Winant, Togethering 9 (detail), 2020Courtesy the artist and Fortnight Institute

From Gansevoort Street, I wandered over to Julius’ where, in a bit of queer magic, a friend who lives down the road from me deep in Brooklyn was seeing off another friend. But even at Julius’, one needs a reservation, so I went home, cut the elastics off my paper mask, and took a long shower. The next morning, I walked for hours through Brooklyn, until I located Fortnight Institute’s current home in an enviable Columbia Heights apartment. There, Carmen Winant’s show Togethering offered one of the most profound experiences I’ve had in the pandemic.

Winant’s photo collages depicted instances of intimacy, funny and generous and kitschy and strange. People held each other in birth and rebirth, in ecstatic communion. They altered themselves to become themselves. The otherwise mostly-empty room of the home gallery was bedecked with strands of feminist history, alternative spirituality, politics; the personally erotic and the politically nostalgic weaving in my head and heart like a Senga Nengudi sculpture. Their frames—some with ridges and some with trompe l’oeil painted borders—must be seen, off-screen, to be believed. I thought of those old multiphoto wall displays of many shapes my parents filled of images of me and my grandparents. When would I see them again? I thought of an Instagram scroll molten, discarded. I wanted to meet every person Winant introduced with such kindness to me. I felt, for a vanishing moment, unalone.

October 30, 2020

Announcing Zora J Murff as Recipient of the Inaugural Next Step Award

Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York have joined forces, with the generous support of 7|G Foundation, to launch the inaugural Next Step Award and announce photographer Zora J Murff as its winner. As a recipient of the award, Murff will receive a $10,000 grant, the publication of a photobook with Aperture, and an accompanying exhibition at Baxter St at CCNY.

At a pivotal time in reconsidering equity across the country and in arts institutions, the Next Step Award aims to identify strong emerging or evolving voices whose work deserves greater recognition. The annual award will support underrepresented US-based artists at a critical juncture in their artistic development. It will also support the presentation of diverse opinions, as well as timely lens-based work that’s relevant to today’s visual culture and society, across a wide array of genres or approaches.

“The Next Step Award was created with the specific focus on fostering inclusivity in the industry and taking action steps to creating greater equity within it,” says Michi Jigarjian, president of Baxter St. “We are thrilled to partner with Aperture to present the work of Zora Murff to the cultural landscape and also invest in its scholarship.”

Zora J Murff, Self Portrait as a Dreamed Man (after Bayard), 2020, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, Self Portrait as a Dreamed Man (after Bayard), 2020, from the series American Mother, American FatherSelected for the work he began with the published series At No Point In Between and has continued in American Mother, American Father, Zora Murff describes his project as “a discursive narrative on the evolution and perpetuation of anti-Black violence.” Lesley A. Martin, creative director at Aperture, notes that “Zora Murff’s work distinguished itself for his rigorous approach to photographic storytelling, one that challenges how images can simultaneously support or subvert the spectacle of violence against Black individuals, while also using photography to explore memory and identity on a personal level.”

Murff was named the winner out of an extremely competitive list of artists, nominated by an intensely knowledgeable and diverse group of artists and curators who brought expertise and artistic experience to the selection process. The nomination committee included Dawoud Bey, Nayland Blake, Isolde Brielmaier, Zoe Buckman, Howie Chen, Carmen Hermo, Justine Kurland, An-My Lê, Christopher Lew, Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, Aspen Mays, Sarah Hermanson Meister, José Parlá, Seph Rodney, Antwaun Sargent, Drew Sawyer, Lisa Sutcliffe, Mickalene Thomas, Ka-Man Tse, Jasmine Wahi, Deborah Willis, and Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa.

The roster of nominated artists who submitted to the prize included Arielle Bobb-Willis, Kierra Branker, Tommy Bruce, Widline Cadet, William Camargo, Shikeith Cathey, Kevin Claiborne, Robin Crookall, Delphine Diallo, Jason Elizondo, Nona Faustine, Delphine Fawundu, Christina Fernandez, Oto Gillen, Allison Janae Hamilton, Jon Henry, Pao Houa Her, María José, Dionne Lee, Nate Lewis, Qiana Mestrich, Star Montana, Cheryl Mukherji, Zora J Murff, Matthew Placek, Clifford Prince King, Daniel Ramos, Carter Seddon, Dana Scruggs, A. L. Steiner, and Chanell Stone.

Zora J Murff, American Mother, 2019, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, American Mother, 2019, from the series American Mother, American Father Zora J Murff, Two in the hand (Affirmation #2), 2019, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, Two in the hand (Affirmation #2), 2019, from the series American Mother, American Father Zora J Murff, Primp and prosper (Slide 705), 2020, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, Primp and prosper (Slide 705), 2020, from the series American Mother, American Father Zora J Murff, Rondell (talking about love), 2018, from the series At No Point In Between

Zora J Murff, Rondell (talking about love), 2018, from the series At No Point In Between Zora J Murff, The reflection of most visible wavelengths of light, 2018, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, The reflection of most visible wavelengths of light, 2018, from the series American Mother, American Father Zora J Murff, American Father, 2019, from the series American Mother, American Father

Zora J Murff, American Father, 2019, from the series American Mother, American FatherAll images courtesy Webber Gallery and the artist

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers