Aperture's Blog, page 61

February 2, 2021

The Women Artists Who Find Freedom in Collage

In Lorna Simpson’s Earth & Sky #50 (2018), part of a series of collaged portraits of Black women that Simpson has been making for a decade, a constellation glides in streaks and waves from a woman’s head. The subject looks straight out of the frame, one hand poised as if about to relay an important message from the stars. In other images from the series, uncut geological specimens—of asphalt and amber, garnet and malachite—adorn women as magnificent crowns and gowns; in one, a perfect bubble floats, inviolable, above a young, modish face. Galactic, regal, and elemental by turn, Simpson’s subjects appear out of time, their serene expressions foils for exuberant coifs, expansive imaginations, even glints of premonition. What future might they portend?

Simpson propels forward through the past, splicing her subjects out of advertisements from vintage copies of Ebony and Jet, groundbreaking U.S. magazines, begun at midcentury, that focus on Black news, culture, and entertainment. Simpson’s images, neither pedantic nor prescriptive, reference the progressive confidence of the magazines, the illusions of glamour and desire they project, and the fraught history of Black women’s hair (a frequent subject for Simpson across her career). They speak of a once-imagined future and of a present moment grappling with the limits and possibilities of optimism.

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #50, 2018. Collage on paper

Lorna Simpson, Earth & Sky #50, 2018. Collage on paper© the artist and courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Simpson’s artist statement, as Delphic as the works, gathers some of the original ad copy that accompanied the women in the pictures. One line reads:

Star Glow Linda Linda Linda Afrialon Kool-N-Light Lioness

Making poetry out of collisions has long been the purview of collage: to forge from familiar elements something strange, to hide and reveal, deconstruct and reconstruct, eradicate and conjure. Like speculative fiction, collage relies on fragments of experience as a way of teasing out the fantastical. But its mechanisms are deceptively simple: as a visual and literary strategy, it has the capacity to project complex and even contradictory messages, gleaning much from the businesses of propaganda and advertising with which it often intertwines. The great potential of collage is to reveal culture itself as a vulnerable thread of associative ideas, woven together through our assumptions and expectations, and grounded by institutions, law, language—and images that are easily rearranged, so that their meanings shift.

As Simpson’s work reminds us, collage has been central to explorations of feminism, as it has been to many ideologies of resistance. In an era defined by acute threats—different, more dispersed, but no less urgent than those preceding the world wars that shaped much modernist collage—feminism today seeks new models for living as a way of moving forward. The most powerful feminist visions embrace the ideals of “feminism for the 99%,” a philosophy put forward by Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, and Nancy Fraser in their 2019 book of the same name, which repositions the challenges and threats to “womxn” in relation to representation, class division, and environmental devastation. In a moment when even the immediate future seems so obstinately obscure, many artists have returned to the radical material possibilities of collage as a way of contemplating the complexity of these converging issues, utilizing the malleability of the medium to envision feminist futures.

Spread from Hannah Höch: Album, 1933. Facsimile edition published by Hatje Cantz, 2004

Spread from Hannah Höch: Album, 1933. Facsimile edition published by Hatje Cantz, 2004There is a long history of feminist collage. The serial, often performative work of the 1970s and early ’80s is an obvious anchor. Figures such as Martha Rosler, Valie Export, Carrie Mae Weems, and Mary Beth Edelson opened up pathways for connecting historical feminist concerns to issues of race, sexuality, the natural and built environment, class, and commerce. Yet the historical touchstones for much feminist collage today—the driving spirit— reach back further, to the free-form quality and ardent trust in the unconscious of Dada and Surrealist work from the 1920s and ’30s produced by Claude Cahun, Grete Stern, Dora Maar, Meret Oppenheim, Sophie Taeuber-Arp—the list goes on. The breadth and innovation of work by women from this period is formidable and resonant, the full depth of it still coming to light through research and long-overdue monographs and exhibitions.

The most influential collages from this era arguably belong to Hannah Höch, whose now-iconic Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch of Germany (1919–20) and The Beautiful Girl (1919–20) deal unflinchingly (and humorously!) with gender expectations and the Neue Frau—the New Woman. Less known, and more ambiguous, is Höch’s Album, made more than a decade later, in 1933. A thick collage book, Album catalogs images from the worlds of news, fashion, and pop culture, pasting material directly onto the pages of two magazines, frequently using the full-page spread for expansive compositions. Album opens with a collaged page showing a plant, two pumas, and, in the upper right, the high-heeled footsteps of a woman walking through snow, a pair of men’s feet trailing behind her as one Art Deco shoe lifts in the act of leaving. It ends with a single image spread across the fold, an unauthored press photograph showing novelty in all its guises: sleek cars and electric lights, scattered figures traversing the lines of the city, all framed by the quintessentially modernist view from above.

Sara Cwynar, Board Room, 2019

Sara Cwynar, Board Room, 2019Courtesy the artist; Foxy Production, New York; and Cooper Cole, Toronto

No one quite knows how Höch viewed Album, which might have been a kind of creative look book, a way of working out or sketching ideas for more finished pieces, or an artwork in itself. Its ambiguous purpose and immersive form suggest it was, more simply, a way of moving forward into the future. Just how this momentum is galvanized through collage isn’t always clear. Like Höch’s work broadly, Album seems equally born out of superimposition and concealing elements—the balancing of absence and presence, past and present. The pitch and tone of a photomontage often hinge on the subtlety of emphasis.

Sara Cwynar’s Board Room, made in 2019 for a show at the Milwaukee Art Museum, adds bodies originally absent within a historical professional setting, asking us to consider the reverberations of a world emanating from a past fueled by different agents. Still visible beneath Cwynar’s pasted figures, a group of white men in suits sit smiling in a vast room around a large, heavy table. Their patent cheerfulness speaks to a faith in a future they designed—and simultaneously to the crumbling trust in institutions that their homogeneity and exclusion might represent to us today. Cwynar’s diverse array of images from her own Album-like collection includes women of many races and ages, from the contemporary world and from centuries past. In some, youthful figures model clothing, their visibility demarked as transactional and performative, trendy reminders that it may be easier to project an institutional image of inclusion and diversity than to demolish the structures that underlie it.

Mickalene Thomas, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe les Trois Femmes Noires #7, 2017

Mickalene Thomas, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe les Trois Femmes Noires #7, 2017© the artist

Mickalene Thomas announces the presence of her sitters as a wrecking ball, centering and celebrating the Black female body, often posing them defiantly in the vestiges of Western art history. Though sparkling with confidence (and sometimes actual glitter), her work also bears traces of disjuncture and vulnerability. In her photo collage Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe les Trois Femmes Noires #7 (2017), the bodies of Black women replace the white figures of Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting. In this work, Thomas’s women, ripped apart and painstakingly put back together, interrupted by shifts between black-and-white and color pieces, make material the physical and emotional labor of confrontation and the fragmentation of the Black diaspora.

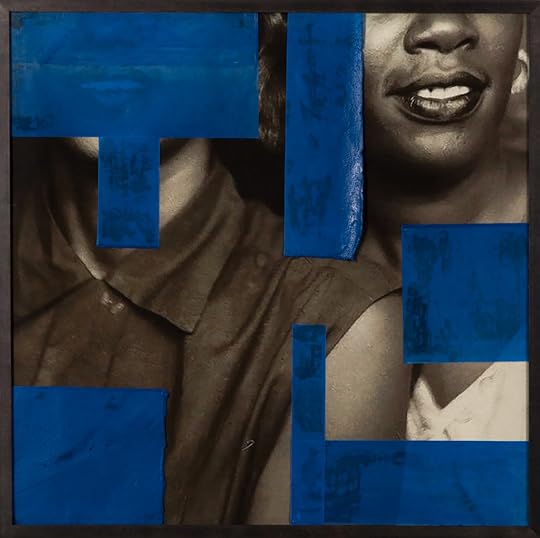

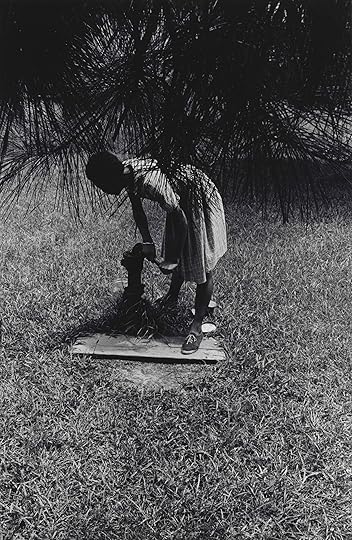

If Thomas and Cwynar counter monumental absences with monumentality, the pared-down collages of Alanna Fields’s series As We Were (2019) instead frame absence and suppression in wax overlays of structured primary colors, locking images of Black queer bodies behind the restraints of their respective historical moments. Noting the dearth of representation of everyday experience of Black queer life in photographic culture before the 1980s, Fields sought vernacular, mostly anonymous images by scouring eBay and regathered a history often hidden in plain sight. Attentive to the body language and gestures of intimacy, Fields built her own archive, eventually scanning and cropping each photograph and using the materiality and varying opacity of wax to highlight or erase moments of transgressive tenderness. Like the experience of trying to read something vitally important in low light, the lines act as frames for and as barriers to visual information, drawing us toward every detail, illuminating the individuality and humanity of the otherwise anonymous sitters, whose stories we can only invent. The quiet stoicism of each work is itself a stand against the systemic suppression of their representation.

Alanna Fields, Untitled (Blue), 2019, from the series As We Were

Alanna Fields, Untitled (Blue), 2019, from the series As We WereCourtesy the artist

The instrumental gestures of collage are to add or subtract to make up a different result—in more or less complicated equations. Yet at the center of collage are always pieces of the world itself, materially and imagistically. In all its innate disjuncture, layers of history and memory are not so easily parsed when we’re unable to take them apart. From the United Arab Emirates and now based in Brooklyn and Dubai, Farah Al Qasimi finds her collage-like compositions readymade or nearly complete. Her subjects, discovered out in the world, light-handedly weave together the complexities of gender roles and the built environment in the U.A.E., and are often revealed or obscured by the omnipresence of mirrors, window reflections, and screens. In one recent photograph, Lady Lady (2020), a woman in a hijab and thick glasses holds up a phone; on its screen a cartoon face is framed by a blue case and, beyond it, by the frame of an image of a vivid bouquet of flowers. The figure sinks further into her surrounds, her gold watch glinting like the gilt frame, the paisley pattern of her clothing echoing the floral view, her diaphanous hijab dissipating in the light tiles that surround it. Al Qasimi’s recent solo exhibition in New York was aptly titled Funhouse, an allusion to the image’s potential to distort, disorient, augment, and distract: to incite ways of seeing that both trouble and avert attendant realities.

Farah Al Qasimi, Lady Lady, 2020

Farah Al Qasimi, Lady Lady, 2020Courtesy Helena Anrather and The Third Line, Dubai

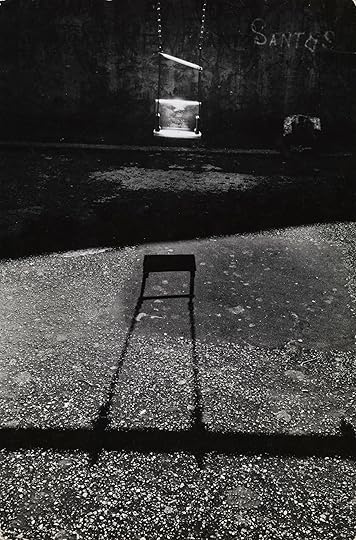

Indeed, on the other side of the world, through the looking glass, is yet another world, and collage can transport us there, too. The long history of photography as theater—the capacity of the medium not only to record but to imagine—underpins Lissa Rivera’s more ominous Dioramas (2013–14). Her painstakingly hand-colored archival images, mounted on cardboard and lit by flashlight, mash up social history, portraiture, and set design. In one image, aristocratic colonists dine in a cave, while an androgynous masked figure reclines in the foreground, a mythical torso emergent at her side, dropping details from a geological survey providing a natural curtain. Rivera’s hallucinatory scenes, deeply recessed in a cavern of psychosexual drama, reach back to the alchemy of early photographic techniques and forward to the possibilities of virtual and augmented reality. Far from an indictment, Rivera reminds us of the past’s spectral presence and its transcendent potential.

The business of real estate capitalizes on such potentials. We now live surrounded by projections of our future environments on seemingly every corner in cities undergoing rapid development. Felicity Hammond draws explicitly on such computer-generated architectural imagery, renderings of realities that have yet to exist. The Contact Photography Festival in Toronto commissioned Hammond to make a site-specific mural, resulting in Post Production (2018), which was ultimately pasted amid the new condos rising up across the city with unrelenting efficiency. Hammond’s amalgam inflects the homogenous sameness of urban gentrification with hints of local heritage, and the presence of green portends the possibility of nature’s resistance, a reminder that today’s visions of grandeur may well be tomorrow’s ruins.

Lissa Rivera, Cave Room, 2013, from the series Dioramas

Lissa Rivera, Cave Room, 2013, from the series DioramasCourtesy the artist and ClampArt, New York

If the past is any kind of indicator, today’s visions of futurity, in any medium, aren’t likely to turn out as blueprints for lived realities. Instead, the contradictions and time-traveling leaps of collage raise vital questions: What is salvageable here? Can we rebuild from these foundations? Or do we need to tear it all down and start again? However different the responses have been and continue to be, collage, like feminism, always brings together the nebulous impossibility of utopian ideals and the materiality of life, the bodily practice of human experience. It reminds us, however gently, to continually renew our perspectives and reorient the way we live and value one another radically, urgently, not only as a way of imagining but as a means of survival.

January 28, 2021

Sarah Meister Named Next Executive Director of Aperture

Aperture Foundation’s Board of Trustees is pleased to announce that Sarah Meister has been selected as its next Executive Director. She will begin her new role in May 2021. As Executive Director, Ms. Meister will serve as the primary creative force and public representative of Aperture, a nonprofit arts organization and preeminent publisher of photography, working closely with the Board and leading the staff of thirty-five to further the organization’s distinguished legacy and set its vision for its future. She will succeed Chris Boot, who will be returning to London after leading Aperture for the past decade.

“Sarah is an accomplished curator and esteemed voice in the photography community and the broader art world,” says Aperture Board Chair Cathy Kaplan. “We are thrilled that she will bring her deep and extensive knowledge and absolute passion for photography to Aperture. Her genuine leadership and scholarly achievements make her an exceptional choice to protect and celebrate Aperture’s history, while entrusting her with its next chapter.”

Ms. Meister will be responsible for directing strategic, operational, and financial planning; overseeing Aperture’s book publishing and flagship magazine, educational and outreach programs, and the Paul Strand archive; cultivating collaborations and partnerships with other institutions, nonprofit organizations, and donors; developing Aperture’s diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives; and continuing to grow its global audience. She will report to the Board of Trustees.

“Photography is inarguably central to our contemporary experience,” says Ms. Meister. “I look forward to working with the brilliant team at Aperture to continue to encourage the medium’s capacity to promote understanding and justice, and to partner with artists in whose hands photography serves as an enduring source of inspiration. For nearly seventy years, Aperture has been a touchstone for all who care about the medium, grappling with its ever-changing nature and embracing its expansive, democratic spirit. I am honored to play a role in furthering its essential position in the field.”

Sarah Meister is currently Curator in the Robert B. Menschel Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, a position she has held since 2009. She has spent over twenty years of an exceptional career at MoMA, organizing a range of critically acclaimed exhibitions, publications, and public programs and securing a wide array of landmark acquisitions for the museum’s collection. She is the lead instructor for the popular online course “Seeing Through Photographs” (offered on Coursera), and is codirector of the August Sander Project, a research initiative hosted by MoMA and Columbia University. The project’s fifth and final gathering will take place in September 2021.

“Aperture . . . has become a platform for redefining the notion of image-making in a more inclusive America, and then placing that alongside a global conversation,” said noted Board member Dawoud Bey, whose work will be the subject of a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art later this year. He adds, “Chris Boot has done an extraordinary job at rebuilding Aperture’s relevance and vitality under his tenure, and Sarah’s appointment will keep the field energized and excited about Aperture in the best possible way.”

Ms. Meister’s appointment follows an international search led by the Board’s Search Committee, which was chaired by Ms. Kaplan and Board members Allan Chapin, Michael Hoeh, and Lisa Rosenblum, together with Pamela Bol Riess, Founder and CEO of PBR Executive Search, which for the past twenty years has focused exclusively on conducting executive leadership searches in the nonprofit sector.

About Aperture

Aperture is a nonprofit arts institution founded in 1952 by a group of photographers, editors, and educators, including Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, Beaumont Newhall, Nancy Newhall, and Minor White. Their vision was to create a quarterly magazine as a common ground for the advancement of photography. Before long, Aperture began publishing books, among them iconic monographs by Diane Arbus, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Nan Goldin, Deana Lawson, Sally Mann, Richard Misrach, Stephen Shore, and many others.

About Sarah Meister

Throughout her career, Sarah Meister has built a reputation anchored in curatorial excellence and distinguished by a generous, collegial spirit. Her highly acclaimed Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures (2020) was recognized as one of the best exhibitions of 2020 by the Washington Post, and in its virtual form as one of the top ten online exhibitions of 2020 by Smithsonian Magazine. Its accompanying catalogue brings a range of contemporary voices into dialogue with Lange’s work, including artists Julie Ault, Sam Contis, Sally Mann, and Wendy Red Star, and critical thinkers Christina Sharpe and Rebecca Solnit, among others. Equally lauded is her Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 (with contributions from Nicole Fleetwood and Bryan Stevenson; published by the Gordon Parks Foundation and Steidl, 2020), inspiring an installation currently on view in the Museum of Modern Art’s Fourth Floor Collection Galleries.

Forthcoming projects that she has led include Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964 opening at MoMA in spring 2021 with an accompanying catalogue, which will introduce the achievements of a São Paulo–based amateur photo club to an international audience. She is contributing essays to the forthcoming publications Fotografia moderna no Brasil? Fragmentos de uma história, 1900–1960 (Instituto Moreira Salles), as well as the catalogue accompanying a major solo exhibition featuring Gertrudes Altschul for MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand). Also this year, another exhibition organized by Meister, Masterworks of Modern Photography 1900–1940: The Thomas Walther Collection at The Museum of Modern Art, will open at MASI (Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana) in Lugano, Switzerland, and travel to Jeu de Paume in Paris and Camera (Centro Italiano per la Fotografia) in Turin, Italy, again with an accompanying catalogue.

Some of Meister’s other notable exhibitions at MoMA include Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction (cocurated with Starr Figura, 2017), From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola (cocurated with Roxana Marcoci, 2015), and Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light (2013). In addition, Meister is an author and editor of numerous publications, most recently Frances Benjamin Johnston: The Hampton Album (2019), Arbus Friedlander Winogrand: New Documents, 1967 (2017), One and One Is Four: The Bauhaus Photocollages of Josef Albers (2016), the three-volume Photography at MoMA (with Quentin Bajac et al., 2015–17), and a series of publications with Maira Kalman and Daniel Handler (2014–16). Other published essays consider the work of Luigi Ghirri (2020), Hank Willis Thomas (2019), Jan Groover (2019), Dorothea Lange (2018), Nicholas Nixon (2015), Walker Evans (2012), Sabine Hornig (2006), Michael Wesely (2004), and Rudy Burckhardt (2002).

Meister’s articles for Aperture magazine have featured Horacio Coppola (2013), Regina Silveira (2014), and the Club Fotográfico de México (2019). She contributed to the Aperture publications The Photographer’s Playbook (2014) and the forthcoming Photo No-Nos (2021). In fall 2020, she served on the shortlist jury for the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards and moderated a conversation around “The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes.”

Meister earned her AB in the Department of Art and Archeology at Princeton University, graduating cum laude with a certificate in American Studies. She has been a fellow at MoMA’s International Curatorial Institute and the Center for Curatorial Leadership.

Zarina Bhimji’s Poetic Confrontation of Postcolonial History

The word that stayed with me the longest after seeing Zarina Bhimji’s exhibition Black Pocket was the one that I couldn’t read. It hovered in the middle of a handwritten letter—an excerpt of which had been photographed, blown up, and hung high above our heads at her recent solo show at the Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates. The phrase “the Abolition of Negro … in his Domain” and the dates “1857, 58 & …” were clear, but in between them, the meaning of a word that resembled “Risirial,” or perhaps “Virinial,” remained just out of reach. It is often the unknown that haunts us the most: the things we cannot decipher, the things we long to learn, and the things we cannot bring ourselves to confront. The elusiveness and ambiguity of this photograph extended to the installation in which it appeared, Lead White (2018)—made up of enlarged images of colonial-era letters, stamps, and maps—rendering it devoid of a singular reading.

What is palpable through the polyphonic nature of Lead White is the power that resides in language: a small signature or seal having had enormous consequences on faraway lands and bodies. Bhimji has spent the last decade forensically looking at such details in documents found at the Zanzibar National Archives, where many of these images were taken, as well as absorbing broader forms of knowledge and rich oral histories from elders in Zanzibar. Based in the U.K., Bhimji ’s fertile research in East Africa and India is largely birthed through photography and film. Bhimji was born in Uganda in 1963, but fled the country at the age of eleven, when General Idi Amin forcibly expelled 80,000 Asians. The artist only returned when she was thirty-five. “We had the experience but missed the meaning,” Bhimji says of this harrowing time, quoting T. S. Eliot, before adding “you can never go back.”

Zarina Bhimji, Installation view of Lead White, 2018. C-prints and embroidery works

Zarina Bhimji, Installation view of Lead White, 2018. C-prints and embroidery worksPhotograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation

According to some sources, Asians in East Africa were always seen as provisional citizens or colonized colonizers, as they were brought in under the aegis of the British Empire, and were middlemen in a three-tiered system, wedged between the British above and the Africans below. Others say that members of these Asian communities became twice migrants or double diaspora once expelled to hostile Britain in the 1970s. Bhimji purposely eschews such categorization, identifying neither as Indian nor African, neither as man nor woman. Bhimji’s work, too, opts for nuance and complexity, poetry and abstraction. This approach seems to fit with scholar Maya Parmar’s suggestion of likening the hybridity of cultures and traditions to multilingualism—as additional lenses or perspectives rather than opposing ones. Bhimji can easily flow between Gujarati, Kutchi, Hindi, Swahili, and English.

When Bhimji initially struggled with English, she says that it was Sarat Maharaj who supported her application to Goldsmiths, University of London. Mentored by figures such as Maharaj and Stuart Hall, and friends with the artists Eddie Chambers, Isaac Julien, and Sonia Boyce, it was in London that Bhimji became part of the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s (in Britain, anyone nonwhite was often called “Black,” and anyone from the Indian subcontinent was simply labeled as “Asian”). This was the heyday of collectives Sankofa, Autograph ABP, and Black Audio Film Collective, all of which challenged the notion of the diaspora as a homogenous entity. Bhimji’s influences were always diverse, from Alfred Stieglitz and Julia Margaret Cameron, to films such as Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeezah (1972) and those by Satyajit Ray. However, it was Iranian cinema, and particularly Samira Makhmalbaf’s Blackboards (2000), a poignant film about teaching children how to write, that spoke to Bhimji the most. She was forever interested in “forms that release love, joy, tenderness, and grief,” she says.

Zarina Bhimji, Installation view of Yellow Patch, 2011. Single-channel 35 mm film, 29 minutes, 43 seconds, color, sound

Zarina Bhimji, Installation view of Yellow Patch, 2011. Single-channel 35 mm film, 29 minutes, 43 seconds, color, soundPhotograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation

Bhimji’s Yellow Patch (2011), one of three elegiac films shown in Black Pocket, similarly privileges affect, texture, painterly visuals, and sonic composition over plot. An empty bureaucrat’s office piled high with forgotten files against the noise of traffic and thunderstorms, a crumbling statue of Queen Victoria layered with sounds of people playing cricket, unfinished boats by the side of a soulless harbor, and decrepit havelis taken over by nature locate us within the vestiges of colony. While audio clips of Lord Louis Mountbatten, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Mahatma Gandhi serve as identifiers of the Partition of India in 1947, sounds of birds and rain evoke atmosphere and sentiment far more strongly. In one moving moment, the camera zooms in on a deeply cracked brick wall—the unnatural zigzag reminiscent of human-made lines drawn in the earth. The image is intensified by an all-engulfing, disturbing, rumbling noise that slowly crescendos.

Sound is paramount to Bhimji. The artist speaks of the microphone as akin to the photographic lens when recording things—always conscious of pursuing translation over truth. Such slippages between cultures and histories could be felt when viewing the photograph Memories Were Trapped inside the Asphalt (1998–2003), depicting an outer room in a Ugandan mosque, in one moment, and hearing the azaan (Islamic call to prayer) from the mosque adjacent to the gallery in another. Sharjah also shares a similar past of occupation, invasion, and British colonialism. Hoor Al Qasimi, the curator of Black Pocket, reveals that scholars have been exploring such linkages and crossovers since the first Arab-Africa relations conference held in Sharjah in 1976. Staging exhibitions such as Bhimji’s in Sharjah can be seen as a way of reclaiming these overlooked narratives, and presenting them with all their contradictions, uncertainties, and gaps—an empowering act of speaking back.

Zarina Bhimji, Memories Were Trapped Inside the Asphalt, 1998–2003

Zarina Bhimji, Memories Were Trapped Inside the Asphalt, 1998–2003Photograph by Shanavas Jamaluddin, Sharjah Art Foundation. All works © the artist/DACS/Artimage

It was only much later that I realized the word in Lead White that I couldn’t read was most likely Vicirial—a word that denotes domination and subjugation, a word that is long gone from daily use, though the impact of empire remains. Underlying the desire to understand the meaning of a word, image, or compilation of objects is the need to fix, locate, and order them into a straightforward and linear story. Instead, the close encounters with fragments of language and landscape in Bhimji’s work force us to contemplate the power, beauty, violence, and trauma that endure in traces and interstices. This, in turn, may reflect the ambiguous and unresolved nature of living with unacknowledged questions, and the impetus of returning to them again and again. What happened on either side of the story? Where does it start? Who else’s story is this? Who didn’t make it in to begin with?

Zarina Bhimji: Black Pocket is on view at the Sharjah Art Foundation, United Arab Emirates, through April 10.

Can Photographs Heal When the Carceral State Fails?

Currently on view at MoMA PS1 in New York, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration is a sweeping exhibition organized by Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood, an accompaniment to her groundbreaking book of the same title. Marking Time takes up the relationship between visual culture and the carceral state, and features work by over thirty-five artists—individuals who are in prison and those who were formerly incarcerated, as well as nonincarcerated artists.

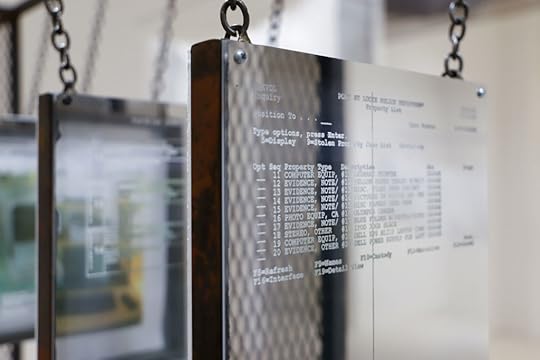

Rowan Renee is one such artist, whose installation, No Spirit for Me (2019), renders publicly visible the records of their father’s criminal case in the state of Florida. Using a variety of techniques that include lithography, metalwork, and weaving as means of translating the state’s documents, Renee creates an environment that troubles the claims of “justice served” so deeply embedded in the mythology of the prison apparatus. In our recent conversation, we discussed this embodied translation further, the conditions of abolition, and the different tasks of the autobiographical.

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1Photograph by Kris Graves. Courtesy MoMA PS1

Jessica Lynne: No Spirit for Me seems to complicate perceptions of truth in photographs. Why is this negotiation of truth and fragility, especially as it exists in the hands of those who are tasked with upholding the carceral state, important to you?

Rowan Renee: The motivation to do this work is personal in the sense that I wanted to know the truth behind family secrets. My father was arrested while I was traveling. I was twenty-one, and I was on the road, and because of the nature of the crimes he committed, it was covered on the TV news. I wasn’t at home living with my mom at the time, and she was trying to keep it from me, because she didn’t want to freak me out or upset me.

I found out about my dad’s arrest from my dad’s oxygen supplier, because he was seventy-eight years old, disabled, and on oxygen. They called me, because I was his next of kin, to say that they were taking his oxygen away. I asked, “Why are you taking his oxygen? What’s wrong with him?” I thought he was in the hospital, or he had died, and no one had told me.

The woman I spoke to hung up, called me back, and said, “So, have you spoken to your father?” I was like, “I haven’t spoken to him in a while.” She responded, “Well, you should, because he’s in jail. You should really talk to your father,” and hung up on me again.

When my dad went through the system, he was arrested, his bond was revoked, and he was put into pretrial detention for about a year and a half before he was convicted and sentenced on a plea deal. I didn’t really have any idea what was happening while it was happening, and I didn’t know the details of his case. I think this is, partially, because of the opaqueness of the criminal-justice system and the shame around it that is felt by the families of those who are accused.

I started to question what happened about seven or eight years after my dad died in prison. That started this process of looking for documentation, stuff that I could find through public court records, and prison medical records and other prison records. This eventually led me to reach out to the lawyers, both my dad’s defense attorney and the prosecuting attorney, who was actually a state attorney, who shared the prosecution’s case file with me, and that was not included in public information.

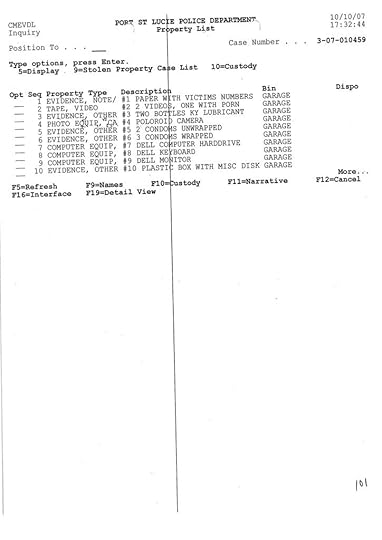

Rowan Renee, Port St. Lucie Police Department Property List, 2019. Xerox on paper

Rowan Renee, Port St. Lucie Police Department Property List, 2019. Xerox on paperLynne: Can you talk about the logistical and technical process of what it means to acquire case files in this manner?

Renee: Because my dad’s case happened in Florida, state laws around public information requests are very open. There’s a lot that you can get online. The court system for criminal cases keeps a searchable database that anyone from the public can log into and see certain details about certain cases.

Then there are also court transcripts, which you have to pay for. I don’t remember the exact amount, but I spent about $400 getting all of the court transcripts from the hearings my dad went to. For example, if you are incarcerated and trying to appeal your case, you will be required to have them for any court appeals, and so there’s this financial barrier to being able to get those transcripts because of the fees associated with it.

The state attorney’s files were surprisingly easy to get once I knew where to go. I think a couple things worked in my favor. I was the next of kin, it was my father’s case, and I had told the state attorney that I was a victim looking for closure. I think that made them sympathetic, and they wanted to help me. They, at their discretion, decided to share everything they could that wasn’t protected by confidentiality laws. Anything related to the victim’s identity—including evidence, photos, or his name—they’re not legally able to share.

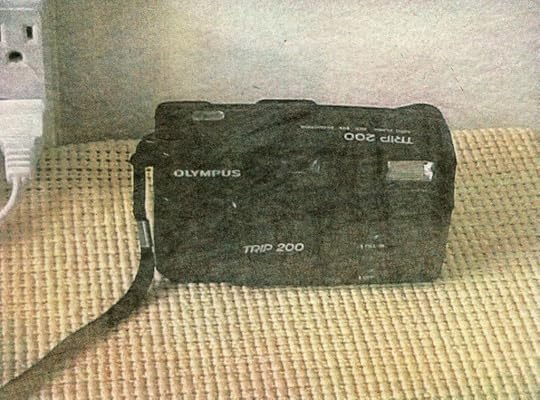

Rowan Renee, Evidence #16: Olympus Camera, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police Department

Rowan Renee, Evidence #16: Olympus Camera, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police DepartmentLynne: I wanted to ask you about the idea of the autobiographical. In a 2009 conversation with Dawoud Bey for BOMB Magazine, Carrie Mae Weems speaks about using herself and her experience as a “vehicle” in her work. But, she says, “It’s never about me; it’s always about something larger.” Does this framework resonate with how you might be grappling with the autobiographical in No Spirit for Me?

Renee: It resonates with me a lot. There has been a trajectory that I can trace between diving deep into a personal story, making that story public, and how I am reading through these documents that are about my father and memories that I have, and connecting those personal stories to a bigger pattern. Why did this other thing not happen? Why was this thing so easy for me, or this other thing so impossible? I am thinking about all those things in the context of these larger dynamics of power, access, privilege, and shame, and how they intersect.

I have a very indirect relationship to photography. I call a lot of things “photography” that aren’t actually photographs, or were not produced with a camera. I feel like I question a lot. Who can tell whose story? Who has the right to represent another? I think, maybe, the deep dive into the personal is a way to tap into what I feel I can adequately represent, and that if I’m vulnerable about the personal, maybe that will speak to and connect with a larger narrative, and to others.

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1Photograph by Kris Graves. Courtesy MoMA PS1

Lynne: There is a nuance here. Your project does not make a mockery of an actual experience that real people ha ve with a system that causes a tremendous amount of harm, and yet it is reminding us of this ongoing harm through the specifics of your father’s case.

Renee: I think I have slivers of didacticism. I basically translated the contents of my father’s case file into just another medium, right? I took it from paper and put it on chiffon. I took the images from digital files—digital images—and printed them as lithographs, and in some way, the transformation was really subtle. I think in doing that, I’m presenting the case to the audience and allowing them to read it and come to their own interpretations and conclusions about justice.

Lynne: Was there ever a moment when you thought against that kind of craft-based element in terms of form? You mentioned that you see, find, and read photography in so many different types of efforts or visualizations. How did lithographs become the container for your ideas?

Renee: I think that embodiment was very much at the center of my material choices and my process of translation. Everything in the installation I made through processes that are very labor-involved. For example, the pages were printed using a lithographic proofing plate through an etching process. Each page was printed by hand, and you spin the wheel on the press and your whole body is involved. In the process of inking, you actually read the text, and that slowness that was built into the translation process gave me time to process not only the material, but also the content of the things I was looking at.

Rowan Renee, Evidence #15, 17: Misc Papers from Desk, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police Department

Rowan Renee, Evidence #15, 17: Misc Papers from Desk, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police DepartmentLynne: How, then, are you defining “transformative justice”? Or, what does it mean to be engaged in such a transformation?

Renee: For me, in the absence of any kind of justice through the criminal-justice system, and also grappling with the trauma caused by the “justice served” of the criminal-justice system, the process of art-making gave me a kind of closure with my father that I don’t think I would have otherwise found. I think it opened up an avenue for understanding the experience and persecution of homosexuality in the South; and my father as a man born in 1929, who went to prison for the first time in 1957, at a time when consensual sodomy was a crime—a felony—with a twenty-year maximum sentence. These structural biases in the law create impossible situations for people to live in. I found a kind of sympathy for my dad through the process of this and also, I think, a sympathy for myself, and maybe a release. Working on this project, for me, affirmed the idea that prison and incarceration does not create accountability, and it does not create justice for violence. It exists in and perpetuates a cycle of violence. Art, I think, and this process of creating this work gave me a way to imagine a kind of justice outside of the carceral logic of punishment.

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1, 2021

Installation view of No Spirit For Me, 2019, in Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration at MoMA PS1, 2021Photograph by Kris Graves. Courtesy MoMA PS1

Lynne: In thinking about how this work refutes the assumption that punishment leads to rehabilitation—which is, again, bound up in carcerality—and as this is part of how the work troubles the perception of truth, do you think that it is a project that will continue to stay with you across time? Or do you feel like there is a certain kind of finiteness to what this project can do as it relates to truth-telling?

Renee: This project has opened a pathway, and it’s the start of something that might take many years to fully work through. I also want to say something about audience, because some people who view this work are moved by it deeply and have reached out to me to say so.

What I’m trying to talk about in the work makes a lot of people uncomfortable and raises very complex issues that are, I think, at the heart of the abolition movement—specifically, how to respond to deep harm that has been done by individual action, or individual acts that have caused deep harm to individuals and communities that sometimes is irreparable.

There’s a lot of discomfort about diving into those issues in a sensitive and compassionate way. There are many different levels of harm that are happening as a result of our criminal-justice system, and there’s a systemic violence that is perpetuated by a system of structural injustice. There’s often harm and trauma in the lives of people who are incarcerated—they have been victims themselves and never experienced justice for the harm they endured. Then there’s the harm of the victims, and the harm caused to the families of those who are incarcerated and seeing their loved ones taken out of their families and communities.

Rowan Renee, Evidence #10: Plastic Box w/Misc Disks, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police Department

Rowan Renee, Evidence #10: Plastic Box w/Misc Disks, 2019. Photolithograph of digital image from the Port St. Lucie Police DepartmentAll works courtesy the artist

Lynne: So, your work might offer a nuanced view without being judgmental.

Renee: The mainstream conversation wants to put these things in a binary and not talk about the complex and messy intersections that exist. What I can do, as my father’s child, is talk about how, in my life, I’ve had to navigate a deep and grievous harm alongside the bond and love I feel for my father, and that perspective illuminates something for me that could be useful to how we could navigate these complex conversations with audiences that might be resistant to the asks of prison abolition.

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration is on view at MoMA PS1, Queens, through April 4.

January 27, 2021

After a Revolution, a Chilean Photographer Mourns the Martyrs

One afternoon a few months ago, an old couple drank a cup of coffee at a dinner table while the setting sun entered through a small window, highlighting their wrinkles. Their eyes, looking down, express more exhaustion than relaxation. Behind the man is a portrait of the couple’s daughter, a beaming woman dressed all in white and sitting on green grass. Her name was Paula Lorca. She was in her mid-forties when her body was found burned in a supermarket on the periphery of Santiago de Chile on the night of October 19, 2019. The market had been looted that night after a series of events her parents are still trying to make sense of. They do not know who was responsible for her death. “What I want most is justice,” her father, Ramón, told the photographer Javier Álvarez. “We are poor, and we might not get it, and that’s what angers me the most.”

Álvarez, born and raised in Chile, and currently based in New York, took a photograph of the couple at their dinner table last fall, after reaching out to the families of men and women killed during the historic nationwide protests that started in October 2019 and continued for months. (According to Chile’s National Institute for Human Rights, law-enforcement officers injured more than four hundred protesters—leaving many partly or completely blind—and more than thirty people died during the unrest.) Álvarez’s research turned into a striking new series, Paisaje Invisible (Invisible Landscape) (2020)—a close-up of the empty corner where a man was shot months before, or the ashes of the supermarket where Paula Lorca’s body was burned. “I wanted to focus on the invisible,” Álvarez says. “On what is left that nobody thinks about.”

Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Paula Lorca’s parents, Ramón and Maria, drink coffee with the family. Just before she died, Paula had dinner at this table with her parents.

Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Paula Lorca’s parents, Ramón and Maria, drink coffee with the family. Just before she died, Paula had dinner at this table with her parents.Álvarez asked the families what he should photograph, or which anecdotes needed foregrounding. “I was looking for a way to expand the limits of documenting,” he explains. “The families chose through which door I could enter [their memories] or leave them, and I had no idea where they would take me.” One man wanted to show him the old soccer shoes he once got for his little brother, who was killed. A father displayed the tattoo he got on his left arm in memory of his son. Most of the people he met, Álvarez says, came from working-class families struggling to make ends meet.

At the time of Paula Lorca’s death, a few months before the global COVID-19 pandemic exposed unconscionable economic disparities in much of the world, Chileans were already engaged in an urgent conversation about inequality. In response to the government raising metro fares, and callously advising students and the working public to wake up earlier to avoid the peak-hour prices, a group of high-school students sparked el estallido social (the social explosion). Civil unrest against the unpopular right-wing government spread far and wide across the country, in protest of not only the subway hike, but also the broader politics of austerity that left more than half the country’s wealth in the hands of the richest 5 percent. Demonstrators set fire to subway stations, toppled statues, and clashed with the police. Chileans united under a single cry, demanding reforms to the private education and pension systems, and an end to the authoritarian constitution that General Augusto Pinochet had put in place in the early eighties. The protesters also renamed Santiago’s main square, Plaza Italia, where they stood vigil day and night for months. They called it “Dignity’s Plaza.”

Related Items

Gus Aronson’s Tokens of New York in the Age of Isolation

Learn More[image error]

A Photographer’s Visual Poem about Solidarity and Protest

Learn More[image error]

The Photographer Who Erased Time

Learn More[image error]A protest or revolution is a golden visual performance: the crowds, the homemade signs, the graffiti. But Álvarez photographs the grief that undergirds the protests. A man by the main statue at Dignity’s Plaza, dressed in all black, waves a flag with the printed photo of his late brother Cristián Valdebenito. “He was a martyr of the people, a martyr of the primera línea,”he told Álvarez, referring to the frontline protesters who risked tear gas or rubber bullets to defend the right to dissent. Valdebenito, a forty-eight-year-old jack-of-all-trades, was killed in confrontation with the police in early March. “When el estallido social began he was, sort of, born again,” Valdebenito’s sister reflected. “He would go to work and, on Fridays, the only thing he cared about was going to the protests, because he said that by doing that, we could all change what was happening.”

Javier Álvarez, Pages from the family scrapbook in honor of Romario Veloz, 2020

Javier Álvarez, Pages from the family scrapbook in honor of Romario Veloz, 2020 Javier Álvarez, Pages from the family scrapbook in honor of Paula Lorca, 2020

Javier Álvarez, Pages from the family scrapbook in honor of Paula Lorca, 2020Álvarez is in his early thirties and, during national demonstrations in 2006 and 2012–13, he was a student protestor. No longer a frontline warrior among the students, he approached the families of those who died the way an archivist would. He photographed scrapbooks that relatives had made to say goodbye to loved ones, including Romario Veloz, a twenty-six-year-old Black Ecuadorian who had migrated to Chile as a child. “You will always be a part of our now-broken family,” Veloz’s partner wrote. Veloz was a hip-hop dancer who’d joined a small protest in the town of La Serena on October 20, 2019, that ended abruptly when the military started shooting at protesters, killing Veloz. Two weeks before Veloz’s murder, his daughter Maite had celebrated her fourth birthday.

A year after el estallido social began, the country voted to change the constitution, and a new process began to elect those who will rewrite it. Following months of lockdown because of the pandemic, hundreds of exhilarated protesters gathered on Dignity’s Plaza to celebrate. Álvarez focused his camera on a lone, shirtless man shouting joyfully to an empty avenue, as if Diego Maradona had just scored a goal against England. As with any revolution, there are not only victories, but martyrs too. With Paisaje Invisible, Álvarez manages to capture revolutionary joy, though he mainly sits with the stillness of bittersweet afternoons, when parents drink coffee while remembering the daughters that el estallido social left behind.

All photographs were created using FUJIFILM X-Pro3 Mirrorless Digital Camera.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. A group of protesters is hit with tear-gas projectiles.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. A group of protesters is hit with tear-gas projectiles. Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. In Chile, a mostly Catholic country, beliefs about life after death are widely accepted. Paula Lorca’s family has felt her presence at their house: footsteps, shadows, sighs, even moving objects. They believe Paula doesn’t know she left.

Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. In Chile, a mostly Catholic country, beliefs about life after death are widely accepted. Paula Lorca’s family has felt her presence at their house: footsteps, shadows, sighs, even moving objects. They believe Paula doesn’t know she left. Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Francesca Escudero, Romario Veloz’s partner and mother of his daughter, demanding justice for his death outside of La Moneda, the presidential palace.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Francesca Escudero, Romario Veloz’s partner and mother of his daughter, demanding justice for his death outside of La Moneda, the presidential palace. Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Marco Valdebenito, Cristián’s brother, was seen as the first protester to climb the monument at Plaza Dignidad.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Marco Valdebenito, Cristián’s brother, was seen as the first protester to climb the monument at Plaza Dignidad.  Javier Álvarez, La Granja, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Alicia González holds her favorite picture of her son Danilo Cárdenas wearing his military uniform.

Javier Álvarez, La Granja, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Alicia González holds her favorite picture of her son Danilo Cárdenas wearing his military uniform. Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. The site of the death of Paula Lorca, who was found inside a looted supermarket on the night of October 19 2019.

Javier Álvarez, San Bernardo, Santiago, Chile, 2020. The site of the death of Paula Lorca, who was found inside a looted supermarket on the night of October 19 2019. Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Protesters gathered at the top of the General Manuel Baquedano monument to celebrate the referendum’s victory to write a new constitution for Chile.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Protesters gathered at the top of the General Manuel Baquedano monument to celebrate the referendum’s victory to write a new constitution for Chile.  Javier Álvarez, La Granja, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Juan Cárdenas’s tattoo in honor of his son Danilo. “I was always against marking your own body,” Juan says. “But I wanted to remember Danilo every day, so I got a tattoo just like him, for him.”

Javier Álvarez, La Granja, Santiago, Chile, 2020. Juan Cárdenas’s tattoo in honor of his son Danilo. “I was always against marking your own body,” Juan says. “But I wanted to remember Danilo every day, so I got a tattoo just like him, for him.” Javier Álvarez, Coquimbo, Chile, 2020. Street corner where Kevin Gómez was killed by military forces. Kevin was shot in the back with his hands in the air. The investigation is still ongoing after a year.

Javier Álvarez, Coquimbo, Chile, 2020. Street corner where Kevin Gómez was killed by military forces. Kevin was shot in the back with his hands in the air. The investigation is still ongoing after a year. Javier Álvarez, Coquimbo, Chile, 2020. Victor Briceño, Kevin Gómez’s adoptive older brother, holds a pair of Kevin’s childhood soccer shoes.

Javier Álvarez, Coquimbo, Chile, 2020. Victor Briceño, Kevin Gómez’s adoptive older brother, holds a pair of Kevin’s childhood soccer shoes.  Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. A man yells alone at Plaza Dignidad after the victory of the referendum to write a new constitution for Chile.

Javier Álvarez, Santiago, Chile, 2020. A man yells alone at Plaza Dignidad after the victory of the referendum to write a new constitution for Chile. All photographs from the series Paisaje Invisible (Invisible Landscape), 2020, for Aperture. Courtesy the artist

Balarama Heller’s Search for Radiant Simplicity

At the center of any spiritual life lie clarity, simplicity, and devotion. We may see and hear the members of, say, the Hare Krishna movement parading through our streets in a jangle of bells and dance, and that seems a vibrant expression of their gratitude, their sense of community, the love they share. But at the heart of every individual life is what happens in silence and solitude, when nobody else is around and one can focus so undistractedly on a single point that the world explodes into color.

Every time I look at Balarama Heller’s work from his 2019 series Sacred Place, I’m pierced by something as haunting as a single plucked note in the dark. It’s as if he’s freed the inner life of all its clutter and discovered the one pure detail that can carry the spirit into a clearer, more elevated world.

I’m also, of course, intrigued by the artist’s name, which I don’t know where to place; it’s as universal in its way as the lamp, the fire, the boat, the joined arms he gives us in these portraits of what I take to be radiant simplicity. Heller, I gather, grew up across the United States in the 1980s, as part of the Hare Krishna movement, a blue-eyed American boy bearing an exotic foreign name and raised among the parallel realities of the counterculture. While his contemporaries were growing fluent in TV and the NFL, he was coming of age in the thick of collective devotion, with all its trials (and its stubborn sense of something better).

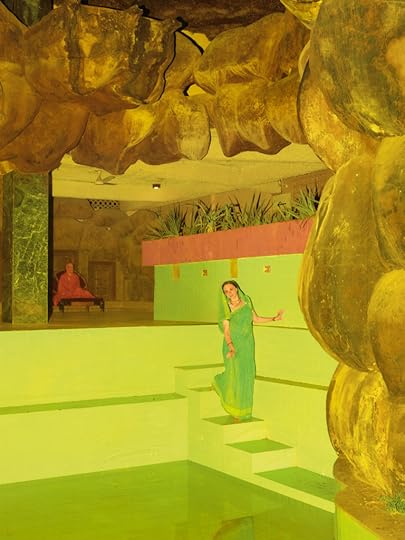

Balarama Heller, Purity and Ego, 2019

Balarama Heller, Purity and Ego, 2019Days before he was born, his young mother fled a commune in a Volkswagen bus, not knowing how to drive. One of his ex-stepfathers served time in prison for robbing seven banks, another as an accomplice to murder. Balarama arrived in elementary school with a shaven head and a determination to change his first name (for a while) to Paul. Yet one result of this itinerant life is that this white-skinned American who was raised within Hinduism can find something in an Indian place of worship that someone like myself, born of two Hindu parents from India, with an Italian first name and little knowledge of the culture and customs of my forebears, might never see.

On Heller’s second trip to Vrndavana, a place of pilgrimage for the Hare Krishna movement southeast of Delhi—by now he’d left the faith himself—what he caught was not the particulars of one tradition but the tonalities, the shadows (the beauty) of them all. This city of temples is a center of worship of the god Krishna, who is said to have grown up there. But what Heller gives us is something much more penetrating and transporting and truer to his own spiritual location now: a portrait of the devotion that lies beyond every name and destination.

Balarama Heller, Reign, 2019

Balarama Heller, Reign, 2019Many of his images were taken between three and six o’clock in the morning, when the devout get up to pray because the boundaries between material and spiritual worlds are said to be especially porous; having been trained to access ecstatic trance states through chant, amid elaborate rituals designed to illuminate the divine within everything, this photographer gives us a tree, a foot that seems to glow with the poetry of something beyond. We all find places—in love, in nature, in sleep—where, as Heller quotes Joseph Campbell, “Eternity shines through time.” This work speaks to me of a soul that has broken free of a single doctrine so as to be responsive to one and all.

In Japan, where I live, and where people likewise gravitate toward an undisturbed attention that allows even the smallest detail to open up a universe, they say that poems, texts, and images of the spirit resemble a finger pointing at the moon. I look again at the ladder, the bell, the flames, even the plastic bag that Heller (who was once embedded with a Sufi order in Istanbul) observes with the exquisite care of a classical miniaturist, and I realize: even everyday objects acquire an almost numinous power when seen clearly and alone in the dark. In the quiet rapture Heller passes on to us, at once mysterious and transparent, I see both the finger and the heavenly bodies to which every soul at its most fortunate returns.

Balarama Heller, All is One, 2019

Balarama Heller, All is One, 2019 Balarama Heller, Empathy Test, 2019

Balarama Heller, Empathy Test, 2019 Balarama Heller, Offer Nothing, 2019

Balarama Heller, Offer Nothing, 2019 Balarama Heller, Wrath of Sorrows, 2019

Balarama Heller, Wrath of Sorrows, 2019 Balarama Heller, Dilation, 2019. All photographs from the series Sacred Place

Balarama Heller, Dilation, 2019. All photographs from the series Sacred Place Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” Winter 2020, under the title “Sacred Place.” Read more or subscribe to Aperture and never miss an issue. An online exhibition of Balarama Heller’s Sacred Place will be on view on Artsy through March 10, 2021.

January 26, 2021

A Three-Volume Book Becomes a Testament to Mary Ellen Mark’s Career

“Mary Ellen would never have made this book,” Martin Bell, Mary Ellen Mark’s husband and collaborator of more than thirty years, writes in an essay accompanying The Book of Everything, the three-volume collection of the photographer’s life’s work recently published by Steidl.

After Mark died at age seventy-five, in 2015, Bell imagined a book that would truly encompass the “everything” of her tremendous output, including her photographs of children in China, Chicago, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, and North Carolina; of circus performers and teenage runaways; of sex workers in Mumbai; and of film sets and drag queens and coal-mining families and twins and celebrities. The result is an affecting testament to the vast scope of Mark’s vision and to the immersive devotion with which she approached the people she photographed.

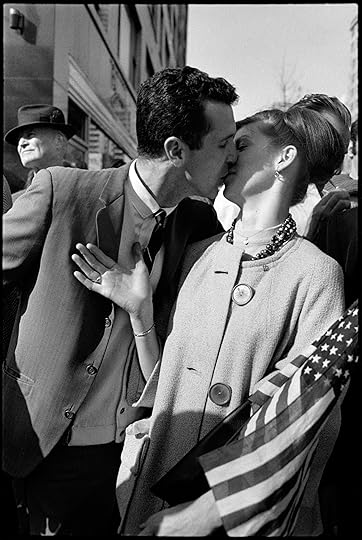

Mary Ellen Mark, Couple kissing at Pro–Vietnam War demonstration, New York, 1968

Mary Ellen Mark, Couple kissing at Pro–Vietnam War demonstration, New York, 1968“It was a mystery to see how unsure she was about her work,” Bell said of the times when Mark would emerge from hours of solo editing and ask for his take on the grease-penciled selects on her contact sheets. “Even when we were working out on the street or in a room, I’d often see her take a great frame and say so. But she would always say, ‘Oh! I don’t know.’ I think she spent her life wondering if she would ever get the elusive iconic frame.”

In 2016, Bell began to pore over more than two million images, a process that turned up resonant and thrilling discoveries, some dating to the early 1960s, when Mark was a student at the University of Pennsylvania and traveled to New York, sleeping at a Bowery hotel where some of the seasonal Santas she photographed also stayed, and others from her 1965 travels to Turkey on a Fulbright scholarship. Bell recognized flashes of her “wicked sense of humor” in pictures of British workers on holiday at Brighton Beach. And how, in frames of a teenage beauty contest in Fort Lee, New Jersey, or of a couple at a Rhode Island diner, Mark’s seemingly simple photographs inevitably produce the epiphanic effect of short fiction—fixed on their protagonists, surrounded by a concise arrangement of minor, yet telling details. Mark was an “angel of truth,” her friend the writer Isabel Allende once observed.

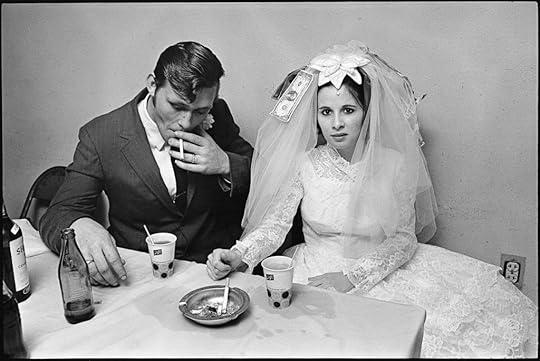

Mary Ellen Mark, Bride and groom, Lafayette, Louisiana, 1972

Mary Ellen Mark, Bride and groom, Lafayette, Louisiana, 1972Bell was struck by two photographs he’d never seen, of a young bride and groom on their wedding day in Louisiana, 1972, the groom appearing suddenly much older in the second image as he takes a deep drag of a cigarette. “The sparse table with paper cups and straws. The electrical outlet on the wall. A dollar bill in her veil. The bride looking directly at Mary Ellen,” he noted, describing an indelible exchange that “is replicated throughout her life’s work. It is a caught moment that tells a story.”

Mark’s ability to instantly establish those relationships is evident in the many fragmented interviews, letters, and journals that are included in The Book of Everything. “When you had Mary Ellen, she was yours,” says Justin Reed Early, one of the teenagers in Mark’s Streetwise photographs of Seattle runaways in the 1980s. “She was your focus, you were her focus, and that was something that was very special about her. When you engaged with her it was real.” Portraits of Mark by Peter Beard, Jack Garofalo, and others, which emphasize her commitment to the exchange between photographer and subject, are also interspersed throughout the volumes.

Even when she was on the other side of the camera, Mark gave genuinely of herself. It was this expressiveness that caught Bell’s eye in 1980. He and Mark met on the set of Miloš Forman’s film Ragtime (1981), where Mark was hired to make photographs. Almost immediately, Mark and Bell became partners in life and work. In 1983, they began a pivotal series of works: Mark’s haunting book Streetwise (Aperture, 1988), a raw and empathetic portrait of the thirteen-year-old Tiny and her fellow teen sex workers and drug addicts on the streets of Seattle; the follow-up, Tiny: Streetwise Revisited (Aperture, 2016); and Bell’s accompanying films.

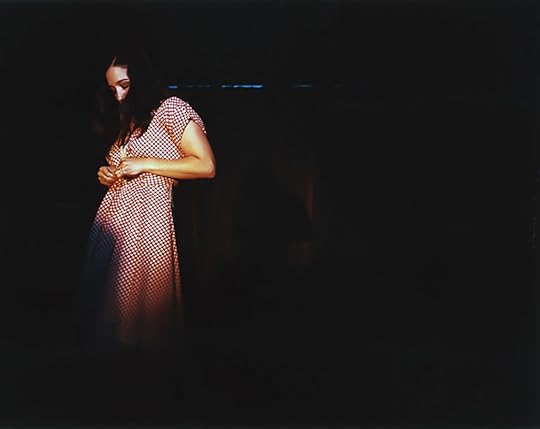

Mary Ellen Mark, Dispensary, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, Kolkata, India, 1981

Mary Ellen Mark, Dispensary, Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity, Kolkata, India, 1981All photographs © Mary Ellen Mark

One of the more unusual discoveries Bell unearthed is the recurring appearance of Mark’s own hand, which Mark photographed again and again, in the foreground of streets and scenes all over the world. Bell initially noticed it in one of a ferry terminal in Turkey in 1965. “At first, I thought it was an accident,” Bell said. “I marked the frame as it was unlike anything I had seen on her contact sheets. “I later came across more frames—some accidental, others I thought intentional. In these it became clear to me this was a deliberate frame to mark this moment in her life.”

Bell and Sonya Dyakova, the book’s designer, used some of these photographs of Mark’s hand throughout the book to illustrate the passage of time, reflecting the chronological sequence. In the opening pages of The Book of Everything, there is a picture from Yugoslavia, made in 1975, in which Mark’s hand, covered in silver rings, reaches toward a black cat that is lazing on a street but visibly drawn to the photographer, as were nearly all the people and animals Mark encountered. In one of the book’s last images, from 2011, Mark’s hand appears in focus against a blurred swimming pool. Her skin is lined and wrinkled with age, and her hand is so thin the stacks of rings are loose on her fingers. Yet here is evidence of the artist considering her own place in the worlds she photographed—the impression they made on her, the deep imprint she left behind.

“Her life’s work is a force to be reckoned with,” Bell said. “Mary Ellen brought to us what she saw along the way.”

Mary Ellen Mark: The Book of Everything was published by Steidl in 2020. This article was originally published in Aperture, issue 241, “Utopia,” under the column “Backstory.”

January 22, 2021

How Alice Rose George Shaped a Pivotal Era in Photography

Perhaps the clearest picture of Alice Rose George, beloved editor, curator, teacher, and poet, who died on December 22, 2020, in Los Angeles at the age of seventy-six, can be seen through her own eye, connecting—as she so innovatively did in the books and magazines where she made her mark—all the seeming and revelatory contrasts of her life.

George’s mother was an accomplished pianist who taught her daughter to play Robert Schumann and Frédéric Chopin; her father, who called her “Sweetie Pie,” liked to sing her the 1919 song “Alice Blue Gown,” about a girl heading to town in her silk dress. After George left rural Mississippi in the 1960s, she whittled her nickname down to “Pi,” got a job in the photo department at Time and, eventually, landed the extremely New York City address of 1 Fifth Avenue—“It was impressive, and so were the drinks, which were stiff,” recalled Jim Goldberg, one of the many photographers she either mentored, taught, edited, or otherwise worked with in her lifetime.

George helped shape a pivotal visual era in publishing. “It was the eighties, a time when magazines were king,” said Catherine Chermayeff, now director of special projects at Magnum Photos, whom George hired when she worked at Fortune. “I didn’t have women as role models who had important jobs. Alice was magical to me; she had a very confident eye, which I respected and copied.”

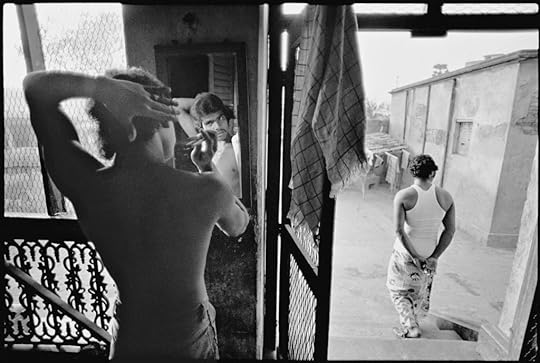

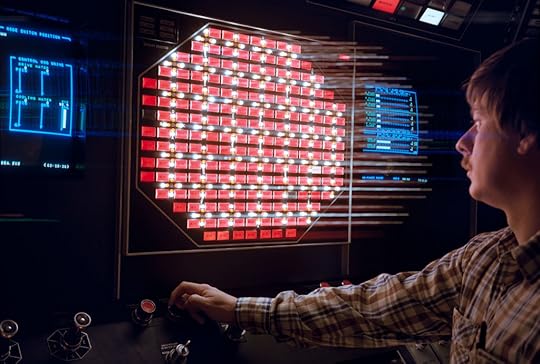

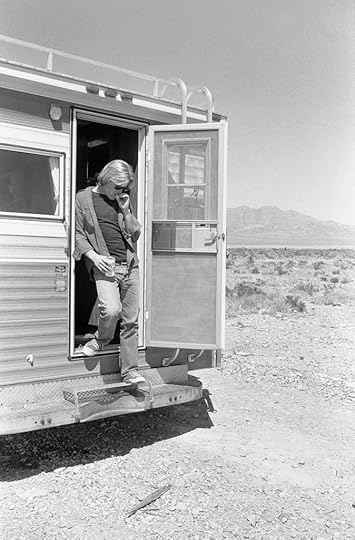

Mitch Epstein was among the unlikely photographers George commissioned to shoot business stories at Fortune—along with Nan Goldin, Peter Hujar, Duane Michals, and Gilles Peress—prioritizing art over technical expertise. George sent Epstein to shoot a story on nuclear power plant control rooms. “It didn’t matter to her that I had no experience shooting industrial environments, and no lighting prowess,” he said. “She was the rare picture editor who appreciated photographers for their idiosyncratic sensibilities.”

Just prior to her job at Fortune, George was photo editor at the short-lived but influential Geo; she would go on to work for Magnum Photos and Details, and as publisher of the literary magazine Granta, and she was an instrumental consultant for other publications, including Aperture magazine. She curated a series of books for Damiani, consulted for private collections, and edited or coedited five books of photography, among them Hope Photographs (1998) and Here Is New York: A Democracy of Photographs (2002), an 864-page celebration of the city which grew out of a grassroots exhibition George organized with Peress after the 9/11 attacks.

I must have met Alice Rose George around 1999. This was at DoubleTake, another short-lived but deeply influential magazine, a literary and photographic quarterly housed at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina. At DoubleTake, words and images were seen as collaborative equals—neither existing to literally depict the other. Even as a young intern, this was exciting to me; and while I was officially working with the fiction editor, I wanted to learn about everything. When Alice came to town, I was allowed to sit in on a couple of her marathon editing sessions—Polaroids of various sequences, prints spread all over the floor of the photo office, lunches ordered in, as Alice, soundtracking these scenes with her infectious laughter, unearthed incongruous, perfect connections in work by both famous and almost totally unknown photographers. In those brief encounters and in the pages that emerged, I witnessed how Alice, the poet, was able to see photographs as texts, words as pictures.

In the last year of George’s life, her partner, Jim Belson, witnessed those same layouts on the table at home in New York and, after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, in Los Angeles. Photographers continued, as they had always done, to send her their work. “She had this uncanny vision about sequences,” Belson told me. He and George had first fallen for each other in 1975 at a reading on the Upper West Side, reconnected in the mid-’90s, but they lived on opposite coasts and lost touch. Eight years ago, on a trip to New York, Belson was sitting in Washington Square Park, when he impulsively looked up George online and sent her an email, unaware that she was still living half a block away. “Now I know why I created that website,” she said when they were finally reunited.

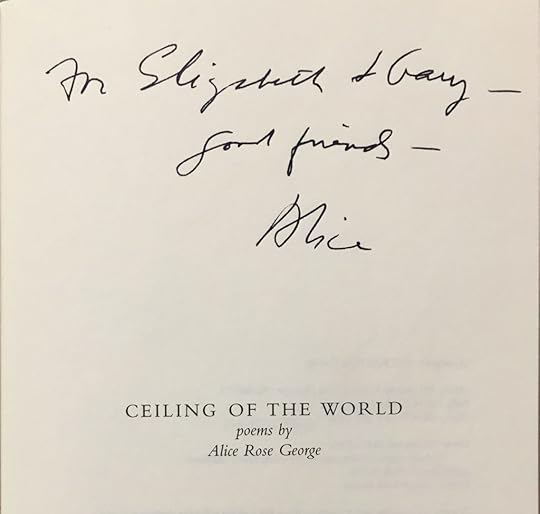

George was a writer first and a raw and visceral poet always, even and especially when it came to photography. George’s poems—collected in Ceiling of the World (1995) and Two Eyes (2015)—appeared in Bomb, the Paris Review, and the Atlantic. In “What Is Beautiful,” the title’s question turns explicitly to the relationship between words and images:

Later, pages turned down, she said,

“It is words.” The most beautiful

thing in the world. “But they aren’t visual.”

“Yes they are.” Without meaning to

he slammed the book shut, started a fire.

They sat face to face.

Here, friends and colleagues, editors and photographers remember Alice Rose George.

Alice Rose George and Jörg Colberg at the Camera Club of New York, December 8, 2011

Alice Rose George and Jörg Colberg at the Camera Club of New York, December 8, 2011Photograph by Daniel Reuter

Melissa Harris, editor-at-large at Aperture Foundation

Alice was remarkably generous. She was generous with young photographers, and she was generous with her colleagues and collaborators.

We met sometime in the 1990s, a few years after I joined Aperture, but it wasn’t until later, when we became neighbors in the Village, that we really got to know each other. Over long dinners at the Knickerbocker, we discussed photography, but also her first love, poetry, as well as music, and her Mississippi roots. There was something charmingly Southern belle-ish about Alice—the grace in her gestures, the lilt in her voice—which became wonderfully apparent to me when I once saw her bantering with William Eggleston. And she had street smarts along with a full-throttle laugh. Occasionally, we ran into each other in Washington Square Park—Alice walking her Shiba Inu, Iko, and me walking my Lhasa Apso, Ella. Sometimes, the two of us would see Mary Ellen Mark on her regular walk around the park with her husband, Martin Bell. Given Mary Ellen’s over-the-moon-ness for dogs, those serendipitous occasions were especially festive.

Alice went out of her way to help emerging photographers, and to advance the medium in which she had invested so much of her heart, mind, and time. Countless photographers went to her for her fine eye, and she helped edit and sequence their projects. Because of her open spirit, how much work she saw and, most importantly, how much I respected her sensibility, when I became Aperture magazine’s editor-in-chief, I invited her to join the editorial advisory board (which later evolved into a stellar group of contributing editors). It was largely because of Alice’s involvement with us, and with Howard Stein’s remarkable organization Joy of Giving Something, that Aperture was able, for the very first time, to commission large-scale photographic stories. We published the first of three commissions—British photographer Jason Florio’s exploration of the “new” Libya—in 2004. Supporting a photographer’s dream project was something we’d always hoped to do, but had never had the means to until then. Without Alice, this unique opportunity would not have been possible. We will always be grateful to her.

Mitch Epstein, Susquehanna Nuclear Power Plant, Pennsylvania, 1983

Mitch Epstein, Susquehanna Nuclear Power Plant, Pennsylvania, 1983Courtesy the artist

Susan Meiselas, photographer and president of Magnum Foundation

Alice had what I called an “authored eye.” She challenged the kind of old magazine photojournalistic framework that meant hiring people to illustrate the ideas of the world as the powers that be wanted to present it. Early on, she understood this shift. You see an expression of it in her work at Geo and Granta, for instance, and in so many books and exhibitions, and her work in supporting collectors.

Fred Ritchin, dean emeritus of the International Center of Photography School, New York

Being a picture editor could be somewhat of a grim business due to the pressure of deadlines and the harrowing photos one often had to look at. Being a picture editor in the 1970s, when I first met Alice, was an extraordinary and impactful position, given the renaissance in photojournalism that occurred in the years after the weekly Life magazine went out of business. Alice was prominent in the field, a major force and a leader, empathetic and open to new ideas.

In 1978, she and I both applied for picture editor positions at Geo and the New York Times Magazine. She got the job with Geo, and I went to the Times. Our paths crossed and we remained friends. She held many positions at major publications, but I remember her especially for her continuing generosity with photographers, helping them to edit their personal projects, often, as I understood it, simply out of friendship. She continued to write poetry, and she began to teach, finding a new equilibrium, even as the industry in which she had played so much a part had constricted. I will miss her laughter, her energy, her warmth, and her discerning eye. She helped to define an era.

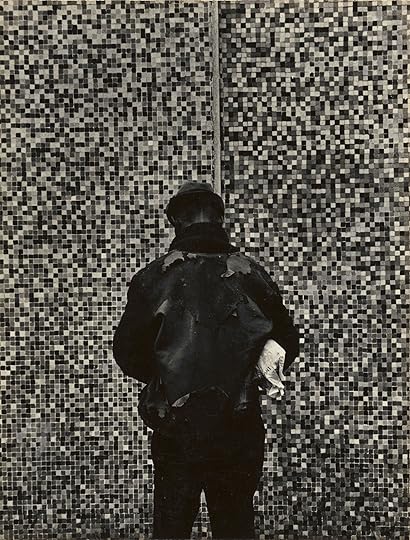

Fortune magazine photography department, 1983. From left: Philip Gefter, Alice Rose George (seated), Janice Pikey, Elizabeth Krist, Catherine Chermayeff, and Maureen Benziger. Photograph by George Lange

Fortune magazine photography department, 1983. From left: Philip Gefter, Alice Rose George (seated), Janice Pikey, Elizabeth Krist, Catherine Chermayeff, and Maureen Benziger. Photograph by George LangePhilip Gefter, author and photography critic

I worked with Alice at Fortune in the 1980s. Fortune had a tradition of using photographers well—including Margaret Bourke-White in the 1930s, and Walker Evans as picture editor in the 1950s. I felt a kinship with Alice, as we shared a similar visual sensibility and a mutual intention to advance that august tradition in photojournalism in a way that would take the history of photography forward.

Alice established a periodic photographic feature called the Fortune Portfolio, a platform for visual documentation and storytelling and an opportunity to allow photographers to do in-depth picture essays. The range was broad and a lot more fun than one would expect from a sober business publication: one, for example, was about the construction of satellites that were being sent into orbit at the beginning of the technological revolution; another chronicled the shoot for the first MTV video with Madonna in Venice. Alice would go to battle with the editors to secure ten pages for the pictures, if necessary. She was a champion of photography. She had imagination, spirit, commitment, and a vision.

Nan Goldin, photographer

I can’t imagine the photo world without Alice. She was one of the pillars. She gave me my first commercial job at Fortune in the ’80s, photographing Paul Newman at the Detroit Grand Prix. She was shocked that I didn’t have a credit card or a driver’s license, but she understood my lifestyle. We always had fun together in and out of bars. She’ll be much missed.

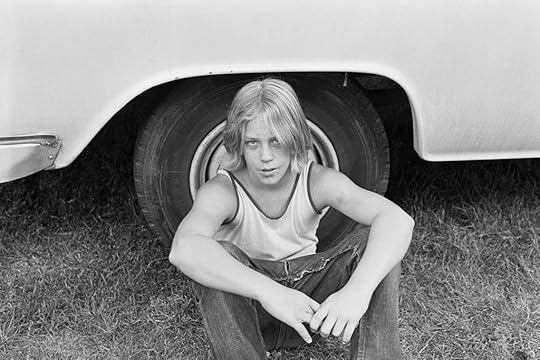

Jim Goldberg, spread from the maquette of Raised By Wolves, 1995

Jim Goldberg, spread from the maquette of Raised By Wolves, 1995Courtesy the artist

Jim Goldberg, photographer

Alice was part of a group of people I would send maquettes to when I was working on what would become the book Raised by Wolves (1995). She would talk about picture relationships and how images could elicit thoughts and memories and stories, and the way I was using text in combination with photographs. I think she felt aligned with that, and also with this idea of playing with truth and playing with documentary. I think that’s what she liked about words—that they could be open and not didactic.

Alec Soth, photographer

Every year, I looked forward to seeing Alice as a fellow faculty member in the University of Hartford MFA program. Alice was worldly and cosmopolitan, but her Mississippi roots ensured she was equally warm and easygoing. She was also funny as hell. She never let me forget the time I managed to get us wildly lost in Connecticut while attempting to bring her back to her hotel in downtown Hartford. Recently, I spent time with Hope Photographs, a book Alice edited in 1998 along with Lee Marks. It feels appropriate to mark Alice’s passing with this book’s spirit of hope and gratitude.

Alex Harris, Camposanto, El Valle, New Mexico, 1986

Alex Harris, Camposanto, El Valle, New Mexico, 1986Courtesy the artist

Alex Harris, photographer

Alice entered our lives at just the right moment in 1995, here in North Carolina, to help us create and launch DoubleTake magazine and to edit books under the DoubleTake imprint. It is one thing to edit a monograph, but another altogether to create a mosaic of disparate voices—this was Alice’s specialty—to delight us and engage our imaginations.

For a magazine devoted equally to the written word and visual image, where writers and photographers had equal weight to wander and wonder, it made sense that DoubleTake would turn to Alice, who brought her poet’s eye to her work as our photography editor. As a poet, Alice believed in the power and necessity of words, but she also knew the world is more complicated than anything you can say about it. That’s where Alice—and photography—came in.

Alexa Dilworth, publishing and awards director and senior editor of CDS Books at the Center for Documentary Studies, Duke University