Aperture's Blog, page 60

March 4, 2021

Chloe Dewe Mathews’s Sweeping Chronicle of the River Thames

Thames Log is a book that tries both to depict a river and also to encapsulate it, to become it, through stream, drift: a course that feels deliberately uncontrolled, sweeping. Published by Loose Joints earlier this year, the book’s layout is pacey, and there is a refusal to hero key images with pauses or white space. Images fall from one page to the next like tide over a ridge; they lap at each other.

British photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews spent five years—from August 2011 to July 2016—making pictures of the Thames, a river that runs for 215 miles across Southern England. The images were made while Dewe Mathews was simultaneously working on Caspian: The Elements (Aperture, 2018), a project shot along the shores of the Caspian Sea, and in broad terms, the two series do the same things—they show the interactions between people and water, the way human activity can activate or mold a landscape, and how, in turn, a great body of water can shape the communities that live or work around it. The fact that each project feels distinct, and specific, says a lot about the way water can cultivate local differences, shaping cultural practices, honing eccentricities, and influencing everything from the way we mourn, celebrate, and gather, to how we exercise, style ourselves, or decorate.

Spread from Thames Log (Loose Joints, 2021)

Spread from Thames Log (Loose Joints, 2021)Thames Log is a very different project than Dewe Mathews’s earlier, celebrated series Shot at Dawn (Ivorypress, 2014), commemorating British soldiers who were killed by firing squads during the First World War. That was about quiet, memory, reflection. Thames Log is more chaotic, more eclectic, and yet somehow, also peaceful—a duality that reflects water, and the many roles it can play in our lives, from the active to the meditative, the sociable to the reflective.

Photographers have returned again and again to water: the lapping surf on a sandy beach, the perfect blue of a swimming pool, the expanse of sea. Some go for the clean lines, the visual order, others for the magnificence of wild nature. Some go for the light, the sparkling dance of glimmers on the surface. Many go for the characters, the sense of a scene set. Dewe Mathews goes for all of it, seeking to capture the plurality of water, the way it can be anything and everything to anyone. This book is not about a personal love of water (though Dewe Mathews does love it) but instead, about the many ways to love it, and the many figures who display that love. It is about how passion, or commitment, or reverence can make something as wild, as uncompromising, as a great river, briefly, one’s personal ally, one’s own.

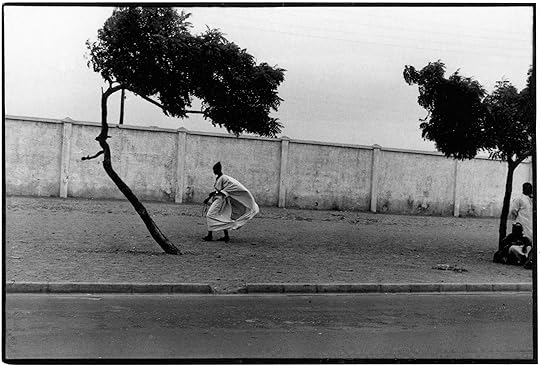

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Maghrib / Evening Prayer, 08/05/2012, 6.30 pm, Southend-on-Sea, 2, daily, 51°31’56.5”N 0°42’51.5”E, fine

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Maghrib / Evening Prayer, 08/05/2012, 6.30 pm, Southend-on-Sea, 2, daily, 51°31’56.5”N 0°42’51.5”E, fineLou Stoppard: You worked on Thames Log for five years. When did it become the project that we see here in the book? Did you set out with specific goals in mind?

Chloe Dewe Mathews: The project came out of doing the Caspian work in Central Asia, Russia, and Iran, where I was taking photographs relating to natural resources, water being one of them. And I was always coming back to Britain, to the Thames, and looking at the landscape, as I’d been doing in Central Asia. I began thinking about trying to make work where I’m from—I grew up just by Hammersmith Bridge in London—along this water body that’s so close to me. I thought I’d just start wandering up and down, exploring and seeing if there might be a project in there. It was always in relation to the Caspian work, which evolved to be about human relationships to landscape and natural resources, but also about how ritual plays a part in that, a kind of repeated activity—sometimes religious, sometimes secular, sometimes in great groups, sometimes very personal and private. It was looking for similar kinds of stories around the Thames. I suppose it became the work as you see it now in the process of thinking about how it would become a book.

For the first years, I was just shooting, not thinking too much about exactly what form the results would take. And although I finished making this series in 2016, I was then working on two other book projects, so it took a couple of years—actually quite a long period of time—until I was able to give my attention to it. A river lends itself to the book as a medium, to that kind of linear form, that constant flow and directionality. I always knew it was a really rich subject for bookmaking. But it was only once I got to the stage of making a book that I knew I wanted to make something quite experimental, in which the form would follow the content.

Stoppard: Thames Log feels like a celebration of the photobook, but it also pushes against clichés of format, or our typical ideas of a photobook, by embracing the idea of flow, of something fast-moving and continuous. Is that what you mean when you say “experimental”?

Dewe Mathews: I often find that when I work on projects, I get very used to my own image-making and used to my own mark. And sometimes, you want to disrupt that a bit. And so in this, there’s the situation of using multiple images, at times, in very quick succession. I suppose that disrupts the idea of a single image, or a kind of decisive moment, a fixed moment.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Ganesh Visarjan, 27/09/2015, 6.15 pm, Richmond, approx. 95, annual, 51°26’55.4”N 0°18’21.9”W, fair

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Ganesh Visarjan, 27/09/2015, 6.15 pm, Richmond, approx. 95, annual, 51°26’55.4”N 0°18’21.9”W, fairStoppard: Which, again, really nods toward this idea of a river, of layers of water moving across each other, of tide, drift.

Dewe Mathews: Yes. I wanted to give that feeling of movement and change happening within space and time as well. That’s partly why I chose to have these sequences of pictures. There are also lots of spreads where the image is flowing over the page. That was actually something that Lewis Chaplin and Sarah Piegay Espenon of Loose Joints suggested. I think they were quite cautious to suggest that to me at first, because they were aware that some photographers can be very precious with their images—and for good reason! But for me, partly because it was a good four years after I’d finished shooting when I started making the book, I felt a real need to disrupt this series of work and do something interesting with it, to reinvigorate the work for me too. So that idea of allowing photographs to flow over the pages, which then creates these really nice pictures within pictures when you get double-page spreads, and new juxtapositions, felt really lovely.

I think having a bit of distance from the shooting allowed me to step back and say the most important thing here for me is to create a book that works as a whole, rather than being too precious about each image. For me, it was always about saying, There’s this wealth of material I’ve collected over five years, what do I want to do with that now? Rather than saying, There’s this specific picture and I desperately want to show it in this way. In a gallery context, there’s more of a traditional way of showing the photographs, printed fairly big, put on the wall, and you can see the whole picture. But I wanted to treat the work quite differently in book form. And I think that’s something that, as the years have gone on, I’ve become more and more interested in—that idea of treating each iteration or each endpoint of my work, whether it’s a book, a show, online thing, differently, rather than trying to do the same thing and squashing it into the different forms. Not every project has to be a book, but when it is a book, it should really make use of the format.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Mudlarking, 10/01/2015 10.00 am Southbank 2 varies 51°30’31.4”N 0°06’26.3”W mostly cloudy

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Mudlarking, 10/01/2015 10.00 am Southbank 2 varies 51°30’31.4”N 0°06’26.3”W mostly cloudyStoppard: In Marina Warner’s essay at the start of the book, there is a quote by Roni Horn about the Thames: “Beneath one water there is always another water.” You can apply that to images as well, this idea that beneath, or behind, every image, there were so many other images that were made, or could have been made—multiple other shots, or setups, or chances that feed into the eventual image.

Dewe Mathews: When I think about how I came to the river, it was on different events, different moments, different weekends, different days. You go to the river and just by chance, you have encountered something or someone. You might have arrived just before something happens. You might have arrived just after—sometimes, it’s just a happy coincidence that you’d seen something. Sometimes, you only see the traces of an event: in the book there’s a photograph of a flour arrow, which is where a running group had been through, and they have left this flour marker on the ground to show which direction to go. Or with a scattering of ashes, flowers that are cast into the water afterwards. I like that idea of, as you say, these events happening in time, but we encounter them at different moments within that timescale. So, rather than always going for the perfect moment, the sort of cover shot of an event, it was about actually trying to echo the human experience of how you encounter these things when you’re wandering along the river.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Girls Drinking, 08/05/2012, 6.15 pm, Southend-on-Sea, varies, 51°31’56.3”N 0°42’52.5”E, fine

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Girls Drinking, 08/05/2012, 6.15 pm, Southend-on-Sea, varies, 51°31’56.3”N 0°42’52.5”E, fineStoppard: In the book, there is a thanks to Martin Parr for his support, so naturally, it made me think of his wife, Susie Parr, who’s a big swimmer and wrote the book The Story of Swimming: A Social History of Bathing in Britain (2011). There’s quote in there: “The four entwining themes that characterize early British swimming are might, method, medicine, and magic.” Those themes apply also to some of the themes that come through in your book. There is this element of looking at spiritual practices, rituals. There’s a sport element. There are elements of the healing ideas that we associate with water. You have everything from teenage girls drinking, through to these very significant, steeped-in-history rituals that take place, such as the cross floating down the Thames.

Dewe Mathews: I was interested in how everyone comes to the same river and sees something different. They project meaning onto it. This whole idea of a river as surrogate; that, as in the Roni Horn quote, you can look at the Thames and you can see the Ganges, you can see the Congo, you can use it as a conduit to travel mentally to other places. That’s why you also get a lot of really interesting, very diverse activity on the water. I spoke to some Hindu elders in a temple in South London who said, “Oh, the Thames now represents the Ganges to us. All rivers flow into one another, and so they are physically connected.” To them, it is as worthwhile to honor your dead, and your gods, at the banks of the Thames, as going all the way back to the Ganges. I love how totally open-ended the river can be. And how that is reflected in the humans and human activity along it.

There’s a lovely quote from Marina’s essay, where she talks about the river as a commons, and this idea that rules that apply on concrete and earth don’t apply to the river, and so, more alternative activity can take place there. That is the kind of activity I was looking for, rather than the things that we’re more aware of—the regattas, genteel rowing clubs, and so on. I saw the river representing something other and something natural, and therefore, undefined; all sorts of things are possible there that aren’t possible elsewhere in the city. When I first started researching, I came across a photograph from 1883—an amazing old picture in black and white, of this pastor dressed in black and a woman dressed in white, being baptized in the Thames at Cricklade. And then there are all these spectators lining the banks, who are dressed in black as well. I remember seeing this moment of activation of the British landscape, this extraordinary spectacle, and just thinking that that doesn’t really happen anymore. And then, of course, the more I worked on the project, the more I found that it did happen; there were lots of echoes of that kind of activity. If you think of land artists or performance artists, people activating the landscape in a certain way—I’m really interested in seeing laypeople or just normal people doing the same.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Morris Dancing on May Day Morning, 01/05/2013, 8.15 am, Oxford, approx. 80, annual, 51°45’21.5”N 1°15’33.0”W, sunny

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Morris Dancing on May Day Morning, 01/05/2013, 8.15 am, Oxford, approx. 80, annual, 51°45’21.5”N 1°15’33.0”W, sunnyStoppard: There is a real spread of different groups, or activities, depicted in the book. Talk to me about the research process of that, and also gaining access to some of these groups or communities—gaining their trust.

Dewe Mathews: With some projects I’ve done, like Shot at Dawn, the research was incredibly fact-based in terms of talking to different historians, curators, battlefield guides—lots of archives and books. Whereas with Thames Log, much of the research took place along the river—in-the-field research—maybe you’d hear something from one person, or you see something which then makes you think, and then you’d come back to a computer and follow up, calling so-and-so. It was quite a patchwork. For example, the baptism in Southend of a Pentecostal group, that probably took at least a year to actually photograph. I remember someone mentioning, “Oh yeah, there’s a big baptism that happens here just outside Adventure Island,” which is one of these amusement parks in Southend. I remember thinking, Seriously, can that really happen here? I asked, “When does it happen?” They said, “Oh, I don’t know, on the weekends in summer.” And so, I was going there every second weekend and just hanging around, as I couldn’t find out more information—no one knew who the people were who were doing the baptism. And some weekends, I’d turn up and someone would say, “Oh, you just missed them, they came last weekend!” So it took a long time. And then finally, it was almost like an apparition, suddenly seeing all of these people dressed in white robes, who had all come in buses from East London with a Pentecostal Evangelical church, pouring onto the beach, totally transforming the landscape of this very busy British beach.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Raft Encampment, 14/10/2012, 12.45 am, Twickenham 15, n/a, 51°26’54.6”N 0°18’34.4”W, sunny

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Raft Encampment, 14/10/2012, 12.45 am, Twickenham 15, n/a, 51°26’54.6”N 0°18’34.4”W, sunnyStoppard: You say this project is about humans’ relationship to the landscape. Do you see it as being a statement on environmentalism?

Dewe Mathews: Yeah, I think it is. It’s so hard to negotiate or to work out how best to explore those subjects without being preachy and without being know-all, when I don’t know all. But I think that to honor or record people’s engagement with landscape is an important thing. I also think there is that responsibility, or a personal interest, an agenda maybe, to recalibrate the mainstream portrayal of who occupies the river and how. There is such a long, almost burdensome history of the Thames—there’s just so much, so many layers, of what’s come before, that sometimes it’s hard to understand what it actually is, or to see what it looks like today. People have so many associations with the past. So for me, it was also about trying to say this is what contemporary Britain looks like, in the context of our landscape.

Stoppard: You also question the way a lot of people associate the Thames with London—partly, I think, just due to pop culture.

Dewe Mathews: Yes. In the book, London pops up halfway through, but it’s certainly not the dominant place. And I think the more you experience the Thames, the more you realize there’s just so much more to it—you get these bucolic natural extravaganzas in the upper reaches of the Thames. It’s achingly beautiful in certain parts of the river. Totally unspoiled, unoccupied. And then, you get into these strange, scrappy semi-industrial bits. And then, of course, the proper wastelands, part-derelict industrial estates, and bleak, seemingly endless car parks. London is this tiny bit of the story—it plays a tiny but crucial part in a much, much wider context. I’ve lived in London most of my life, and I did residencies both in Oxford and in Southend—two important places in the book—which was helpful to understand how the river was viewed, and lived, there.

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Commuting, 09/02/2016, 7.45 am, London Bridge, approx. 15,000, twice daily, 51°30’29.1”N 0°05’15.3”W, overcast

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Commuting, 09/02/2016, 7.45 am, London Bridge, approx. 15,000, twice daily, 51°30’29.1”N 0°05’15.3”W, overcastStoppard: it’s really interesting what you say about the weighty symbolism around the Thames, and trying to battle with it as an emblem of so many things, while also introducing new ideas. There was another quote from Susie Parr’s book, that I thought of when looking at Thames Log, where she talks of access to water, particularly for recreation, as being “a class-based conflict.” And I think themes around class really do come through in your book, sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly. For example, when you see the rowing club in Oxford burning a rowing boat as part of a tradition—this idea of burning something of such value.

Dewe Mathews: I was very keen to represent a wide range of social classes that use the river. And as I said, back to that quote from Marina about rivers as commons—it’s a democratic space. One which isn’t private. That was an important part of the work. And as you said, to try and do these things in a subtle way, which allows for people to look and develop thoughts themselves, rather than me pushing an agenda. That’s also a question for me constantly, this weigh up or balance between documentary photography being quite instructive or specific (saying this is what happens here), but then also trying to allow for a degree of ambiguity, or poetry, or open-endedness. I wanted to convey a quiet potency, something other, or on another level, which I think is part of what people come to the water for. There’s this incredible beauty and lusciousness in the surface of the water that can take you elsewhere. And I offset that with the very factual, data-style information about the tide and weather that sits as text next to the images. It was about trying to involve some of those less tangible qualities of water, alongside very specific marked activities on certain days, for certain reasons, with certain groups of people.

Stoppard: It has always fascinated me the way that water has attracted artists, image-makers, writers. There is this quality that is impossible to pin down. And yet, people continue to try.

Dewe Mathews: Well I suppose, as we were saying, it’s something that is open-ended. You see yourself in it, you see other people in it. It becomes a material that people riff off. It’s characterful because it’s flowing, it’s reflective, or it’s cold; it’s got certain characteristics. And yet, it’s evasive and has none. It trickles through everything and has no body and no form.

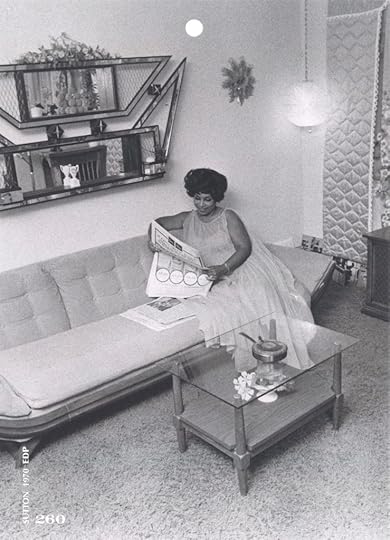

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Reading the Sunday Papers, 21/08/2011, 4.00 pm, Grays, 1, varies, 51°28’11.0”N 0°19’39.0”E, cloudy

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Reading the Sunday Papers, 21/08/2011, 4.00 pm, Grays, 1, varies, 51°28’11.0”N 0°19’39.0”E, cloudyAll images courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

Stoppard: There’s something about water being a thing that is so shared, and so public, yet so highly personal as well, that is intriguing. The idea that something so prominent can also have these very individual, quite secretive things going on around it that you would never encounter elsewhere, even though the water and the river is a part of your daily experience, or a dominant part of your city. I think there’s something in those mysteries.

Dewe Mathews: Yes, there is a publicness in doing anything on the river, and yet the possibility for, as you say, a very private, personal, intimate kind of relationship. And yet, you’re always on view. There is the sense of being taken elsewhere, you’re able to engage in a certain way that makes you forget about that which is happening around you. I think that was also the difficulty of making the work: the knowledge of so many other artists, writers, poets, musicians, every type of artist who has responded to the Thames as a subject, let alone the broader theme of river or water. The Thames has been considered, or photographed, so many times, and yet it still sucks you back in, and there’s still more to be told, and different ways of interpreting it, and questioning it, and documenting it now. I think that’s also why I wanted to make quite a specific kind of artist book, rather than a more catalogue-y type of book. Because there have been so many other photographers and people making work about the Thames over the years, that it had to be something quite specific.

Stoppard: It’s a fascinating project, because it reads as both an attempt to depict the Thames and people’s interactions with it, but also, there is a sense of you trying to encapsulate the Thames in the form of the book—the flow. And even things like the typography, where you used Doves Type, the letter blocks of which were thrown into the Thames in 1917, after a falling-out between the founders of the Doves Press. Today, mudlarkers are always looking for those letters. So to have that font in the book—there was an element that felt like that you could mudlark through the pages. As if the book became the river itself.

Dewe Mathews: That’s a really lovely way of putting it. And I think that’s exactly right. When you’re shooting the work, it’s one thing. And then when you try and translate the pictures into an object, it becomes more about how you can reflect the material itself. A really exciting, stimulating part of the project was that end point of saying, How is it going to become a book? and trying things and going down so many different avenues. The one we went with, as you said, to make the book design take on qualities of the Thames—for it to almost imitate or simulate the river.

Chloe Dewe Mathews’s Thames Log was published by Loose Joints and Martin Parr Foundation in January 2021.

February 25, 2021

Why the Visionary Designer Willi Smith Is More Relevant Than Ever

In 1978, when submitting his biography to the Coty awards, a respected fashion prize, the designer Willi Smith, of WilliWear, wrote, “My mother and grandmother were always ladies of style and still are. I guess they taught me that you didn’t have to be rich to look good. I believe that good clothes don’t have to be expensive.” In appearance, if not price point, WilliWear then was all that fashion is now: sporty, casual, gender-neutral, a mash-up of “high” and “low” (though Smith would never have categorized culture, or life, in those terms), and replete with bold graphic prints and fine-art collaborations. Name your contemporary fashion icon—Kim Jones, Virgil Abloh, Supreme’s James Jebbia—and Smith foreshadowed them. WilliWear was also about more than clothes, as most fashion brands are now; Smith talked of wanting to revolutionize marketing, and he worked across architecture, film, art, and performance, collaborating with the likes of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, SITE, Keith Haring, and Barbara Kruger. He even considered starting a magazine, mocking up a few copies in the mid-1980s, preempting the current role brands have embraced as publishers, speaking to broad audiences of viewers and followers, rather than simply dedicated pools of clients.

WilliWear: so far, so prophetic.

Willi and Toukie-Smith, 1978. Photograph by Anthony Barboza

Willi and Toukie-Smith, 1978. Photograph by Anthony Barboza© the artist

Except, who remembers? Too few followers of fashion know the name Willi Smith, despite the fact that when Smith died at the age of thirty-nine in 1987, of complications related to AIDS, his brand was generating $25 million per year in revenue, and Smith was celebrated as a game-changer, a star, the nucleus of a dynamic group of Black designers who had dominated 1970s fashion. (If he had lived, “for sure Willi would have designed Barack Obama’s inaugural suit,” says Paper magazine founder Kim Hastreiter.) The amnesia is something Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York is keen to rectify with its exhibition and book Willi Smith: Street Couture.

A portrait of Smith featured in the book shot by Anthony Barboza (a member of the Kamoinge Workshop who dated Smith’s sister Toukie in the 1970s), shows the designer standing proud, regal, his face turned toward the camera, with one arm around his sister’s waist. She, clad in heels, red bikini and headwrap, has her back turned and her hip popped. She is the glamour queen; he, the calm support. The image suggests tenderness—Smith is portrayed as an ally, the man shoring up someone else’s confidence, or beauty; a reflection of his mission as a designer. The photographs of Smith’s work featured elsewhere, made by the likes of Steven Meisel and Max Vadukul, show a fresh take on fashion—one that was open, active. Models are seen laughing, being gorgeous, young in New York City. It is an optimistic vision.

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 presentation. Photograph by Peter Gould

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Spring 1986 presentation. Photograph by Peter GouldCourtesy the FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive

And yet, when style critics and curators talk of the game-changers of fashion history, those who pioneered the casual, the free, they mention Yves Saint Laurent or Coco Chanel, or American sportswear pioneers, such as Claire McCardell. Little credit or reverence goes Smith’s way. Naturally, it is easy to say he has been disregarded. But by whom? By the overwhelmingly white fashion establishment? By museums and archives? It is relevant, of course, that this is the very first book in the Smithsonian Institute’s history dedicated to a Black designer, a fact that surely goes some way in answering the question they have made central to their project: how could Smith be overlooked?

In one of the book’s many essays, “Vernaculars of Black and Queer Remembering,” Eric Darnell Pritchard references a lecture given by the poet and writer Melvin Dixon, who was dying of AIDS, at a conference for gay and lesbian writers in 1992. Dixon talked of the role the community—his friends, peers, and rivals—must play in ensuring their histories were not lost, in speaking up, in collecting, in preserving, lest others sweep their stories away. “Remember us,” he said. (He called his address “I’ll Be Somewhere Listening for My Name.”) So, as decades have passed, who has been calling out Smith’s name? It is his clients, his friends, his fans, his collaborators, who are doing the work of remembering. Street Couture makes heavy use of their testimony, relying less on official narratives—though there are quotes from Smith’s interviews with various fashion publications, and some essays from academics and researchers—but instead, on the authority, and memories, of those who worked alongside him, or have been inspired by his legacy, or who wore his clothes, modeled in his shows, those who loved him and were loved by him. “I’ve photographed people for fifty-five years, and very few stand out in my mind as having had that special aura about them,” Barboza writes in a tribute. “Alice Walker, James Baldwin, and Cesar Chavez had it, and so did Willi Smith.”

Installation view of Willi Smith: Street Couture at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2020. Photograph by Ann Sunwoo

Installation view of Willi Smith: Street Couture at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2020. Photograph by Ann Sunwoo© Smithsonian Institution

Street Couture illustrates not only the breadth of Smith’s talents, but also the limits of how fashion has conventionally been archived, chronicled, and discussed, and the way existing hierarchies and habits of thinking hinder change, prevent due credit and celebration, and foster prejudice. Much damage is done by the process of categorization and definitions (a fact central in considering why Smith could be reluctant to being labeled a “Black designer”). The book considers the way Blackness is treated hegemonically, and the way the work of Black designers is often othered, grouped, or ghettoized. Indeed, WilliWear’s popularity led to it being separated away from fashion. It was worn and embraced by editors who simultaneously held it at arm’s length from “their” industry; as Bethann Hardison says in the book, “You used to see WilliWear everywhere. It was a brand that you would see everyone wearing on the street. That’s why editors started referring to it as streetwear.”

Kerby Jean-Raymond, of Pyer Moss, summarized this process in a 2016 interview (quoted in an essay in the book titled “To Be American”), when discussing how the output of Black designers is often automatically referred to as “streetwear”: “I just want to know what’s being called ‘street’—the clothes or me?” Such comments highlight the importance of questioning the limitations of institutional archives, and of challenging the standards laid out by gatekeeps who have, until now, cast themselves as authorities on the histories of design, fashion, and image-making. Whose boundaries should we accept? Whose categories are we working with? Whose acclaim matters?

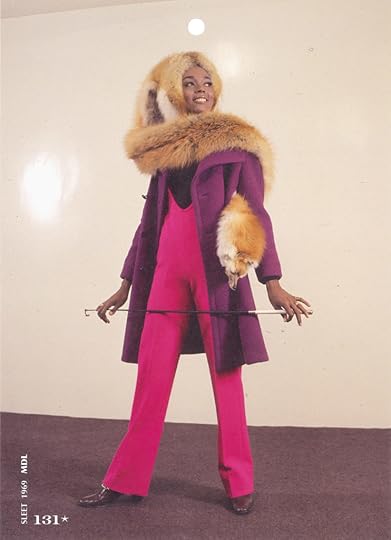

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 presentation. Photograph by Peter Gould

Willi Smith for WilliWear, Fall 1985 presentation. Photograph by Peter GouldCourtesy the FIT Library Special Collections and College Archive

In his commitment to crafting clothes for everyone, Smith was an activist as much as a designer. “I think he participated in politics through how he lived and what he made,” says the dancer Bill T. Jones when reflecting on his collaborations with Smith, including Secret Pastures and Made in New York (both 1984). The recent embracing of politics and social justice issues by numerous mainstream brands vindicates Smith’s approach; contemporary CEOs see now that to succeed in the long run, and in a time when social media has amplified diverse voices, one must be welcoming, one must listen. The fashion mood has shifted toward inclusivity rather than elitism, engagement (albeit often performative) rather than lofty distance. Of course, many brands adopt the language of Smith, while retaining the old business model, the old values. Smith, on the other hand, was all in. He was a savvy businessman, but opportunism or cynicism was not his bag. WilliWear was built with commitment and compassion. As Forest Young argues, “affordability today is not nearly as exquisite, or sincere.” Neither is fashion’s version of openness or diversity.

It’s tempting, because it’s easy, to say that Willi Smith’s work feels more relevant than ever, in part because of the current shifts in how we all get dressed—the supposed sweatpants revolution, the march of the cozy and relaxed—but also because of the widespread desires to spotlight Black makers, Black creatives, to use books and magazine pages and exhibition space to make up for past erasures. It’s tempting to do all this, because it’s obvious. But Willi Smith needs no hook, no justification to be interesting—he has always been relevant, his influence pulses through all that we have worn and consumed across the past five decades. He penetrated culture, infiltrated taste—“tainting the water,” as the artist Lisa Yuskavage puts it in the book. Yuskavage wore clothes made from WilliWear patterns as a youth, and her tribute is an unexpected addition, showing the breadth of Smith’s influences. Read it and then look closely, and you’ll notice that the clothing worn by the curvaceous figures in Yuskavage’s works often recalls WilliWear.

Laceine Owsley Wedderburn and Damon Pooser in Take-Off From a Forced Landing, 1984. Choreographed by Dianne McIntyre. Photograph by Lois Greenfield

Laceine Owsley Wedderburn and Damon Pooser in Take-Off From a Forced Landing, 1984. Choreographed by Dianne McIntyre. Photograph by Lois Greenfield© the artist

“One of Willi Smith’s quotes was ‘style over status,’” Yuskavage writes. “Growing up, I didn’t have status, but through his patterns, I had the ability to make myself look and feel good. Some of my clothes were Willi Smith, but probably some were people copying him, and I’m interested in that too, as a form of influence.” It’s an answer to those who would say that because his name isn’t better known, Willi Smith’s influence must have been, in the end, limited. Instead, his impact is immeasurable. “An exhibition and book like this is trying to reconstruct that,” Yuskavage adds. “It’s like pulling a very complex marionette that’s got twisted strings, up from a lying-down position.”

Willi Smith: Street Couture was presented by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, in 2020. The accompanying catalogue was copublished by Cooper Hewitt and Rizzoli Electa.

February 22, 2021

Seven New Trustees Join Aperture Board

Aperture Foundation is pleased to announce seven new appointments to its board of trustees: Julie Bédard, Kwame Samori Brathwaite, Lyle Ashton Harris, Lindsay McCrum, Colette Veasey-Cullors, Casey Taylor Weyand, and Deborah Willis.

The new trustees, who will join in April, come to Aperture with a breadth of expertise from a variety of fields, and they all share a long-standing commitment to the medium of photography.

Cathy M. Kaplan, chair of the board, welcomes the new roster, saying: “We are honored to have such an amazing group of individuals join the board of trustees of Aperture. They bring a wide range of backgrounds and experiences, including deep knowledge of the history and practice of photography, and of education, to our already terrific board. At this juncture, when we have just announced our new executive director, Sarah Meister (succeeding Chris Boot, after ten years of tenure), our new trustees will add to Aperture’s momentum, and ensure it remains front and center in dialogues about photography.”

Dr. Stephen W. Nicholas and Vasant Nayak also recently joined the Aperture board, in April and July 2020, respectively. Together with the new elected slate, they add to a group of eighteen existing members formed by Peter Barbur, Dawoud Bey, Allan Chapin, Stuart Cooper, Kate Cordsen, Elaine Goldman, Michael Hoeh, Julia Joern, Elizabeth Ann Kahane, Cathy M. Kaplan, Philippe Laumont, Andrew Lewin, Anne Stark Locher, Joel Meyerowitz, Helen Nitkin, Melissa O’Shaughnessy, Lisa Rosenblum, and Thomas Schiff.

Aperture was founded as “common ground for the advancement of photography” in 1952 by photographers, editors, and educators, including Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Barbara Morgan, Beaumont Newhall, Nancy Newhall, and Minor White, among others. A multiplatform publisher and global community, almost seventy years later, Aperture advances photography as vital to society and contemporary culture, connecting audiences to visionary photographers and visual thinkers who shape our perceptions of the world.

Julie Bédard is head of Skadden’s International Litigation and Arbitration Group for the Americas. She is a member of Skadden’s policy committee, the firm’s governing body. Fluent in French, Spanish, and Portuguese, Bédard practices in four languages in complex international litigation and arbitration matters. Trained in both civil and common law, Bédard has a doctorate in conflict of laws, and represents clients in connection with litigation and arbitration proceedings throughout the world, raising disputes on governing law, jurisdiction, the enforcement of arbitration agreements, extraterritoriality, and international judgment enforcement. In 2020, Bédard was named arbitrator for the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s dispute settlement mechanism. She has been repeatedly recognized for her work in leading legal publications, including Chambers, Global Arbitration Review, and the Best Lawyers in America.

Kwame Samori Brathwaite, son of photographer Kwame Brathwaite, is director of the Kwame Brathwaite Archive. Brathwaite authored a chapter in the book Mod New York: Fashion Takes a Trip (2017) and has lectured at numerous institutions, including the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Courtauld Institute of Art, London; and Museum of the City of New York. He cocurated Celebrity and the Everyday at Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles; and curated Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite, a touring exhibition, in partnership with Aperture Foundation. Also a real-estate professional, Brathwaite graduated from Amherst College, Massachusetts, in 1996 with a BA in law, jurisprudence, and social thought; and from the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business in 2018 with an MBA. He lives in San Marino, California, with his wife and three children.

Lyle Ashton Harris has cultivated a diverse artistic practice, ranging from photography and collage to installation and performance art. His work explores intersections between the personal and the political, examining the impact of ethnicity, gender, and desire on the contemporary social and cultural dynamic. Harris is represented in the permanent collections of renowned institutions and has been widely exhibited internationally including, most recently, in Photography’s Last Century at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Basquiat’s “Defacement”: The Untold Story and Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Harris lives and works in New York, serving as professor of art at New York University.

Lindsay McCrum is a California-based fine-art photographer. She received her undergraduate degree from Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, and her MFA from San Francisco Art Institute. Trained as a painter in oils, she switched exclusively to portrait photography in 2003. For close to two decades, she has created work that explores issues of self-image, gender, and popular culture. Her photographs have been exhibited in galleries and museums in the US and Europe. Her work has been reviewed and featured in US publications and media such as Time, the New York Times, NPR, Wired.com, NPR’s All Things Considered, the Los Angeles Times, Juxtapoz, Today.com, W Magazine, and HuffPost, among others.

Colette Veasey-Cullors is founding associate vice president of the Center for Organizing, Representation and Empowerment at Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore. Throughout her career, her photographic work has investigated themes pertaining to socioeconomics, race, class, education, and identity, with a particular focus on social and creative engagement with historically underinvested and underrepresented communities. Veasey-Cullors’s photography is represented in the Photographic History Collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, Washington, DC, and has been widely exhibited. Her work is also included in the publications MFON: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora (2017) and BLACK: A Celebration of a Culture (2004). Veasey-Cullors received her MFA in photography from Maryland Institute College of Art in 1996, and her BFA in photography from the University of Houston in 1992.

Casey Taylor Weyand, CFA, is managing director at Morgan Stanley in New York City. He has worked as an advisor in the investment-management industry since 2005. Prior to joining Morgan Stanley in 2016, he was managing director at J. P. Morgan Private Bank from 2007–16. He sits on the photography acquisitions committee of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, and on the advisory board of RxArt, a New York–based nonprofit organization whose mission is to help children heal through the power of visual art. Weyand was born and raised in Roeland Park, Kansas. He graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, in 2001 with a BFA in photography. In 2012, he earned his CFA designation.

Deborah Willis, PhD, is university professor and chair of the Department of Photography and Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. She is recipient of MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellowships, and is author of The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship (2021) and Posing Beauty: African American Images from the 1890s to the Present (2009), among other books. Willis has curated exhibitions including Let Your Motto Be Resistance: African American Portraits at the International Center of Photography, New York; Out [o] Fashion Photography: Embracing Beauty at the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle; and Reframing Beauty: Intimate Visions at Indiana University Bloomington.

Join Aperture as a member to support all of our nonprofit programs and publications on photography.

February 19, 2021

The Designer Elevating the Present and Future of Photobooks

Discourse around archives as a site of erasure is a persistent part of contemporary design and art practices. Using the book format to establish dominant and authoritative narratives of the historical and cultural record of entire peoples is as old as the book itself. For Zimbabwean-born designer and artist Nontsikelelo Mutiti, this fact—that the book “produces an author”—is a central entry point into publication design. With a conceptual approach informed by her background as a painter, Mutiti’s multidisciplinary design work draws on experimental publishing and archiving practices to elevate Black peoples of the past, present, and future.

Clockwise from top left: Nontsikelelo Mutiti, A-A-A (folded poster; self-published, 2012). Tinashe Mushakavanhu and Nontsikelelo Mutiti, eds., Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (Black Chalk & Co., 2019). Bisi Silva and Stephanie Baptist, eds., Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa (Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, 2017)

Clockwise from top left: Nontsikelelo Mutiti, A-A-A (folded poster; self-published, 2012). Tinashe Mushakavanhu and Nontsikelelo Mutiti, eds., Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (Black Chalk & Co., 2019). Bisi Silva and Stephanie Baptist, eds., Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa (Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, 2017)Interpreting the book as a time-based medium, with bold attention to narrative sequencing that considers images as text, she tasks herself with a grand act of bringing to form that which has been previously omitted. Never is this more evident than in Mutiti’s high-concept design for Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (2019)—the most recent project from Black Chalk & Co., where Mutiti is artistic director—which stitches together anecdotes, aphorisms, and excerpts gathered from interviews with 150 Zimbabwean writers, editors, academics, and publishers. Another book designed by Mutiti, Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa (Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, 2017), documents the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos’s innovative program addressing outdated or nonexistent artistic and curatorial curricula from institutions across Africa, communicating a bold, expansive vision of how to document spaces in art history that have yet to be filled. As a graduate student at the Yale University School of Design, Mutiti developed Sovereign, a typeface based on letterforms found in nineteenth- and twentieth-century colonial bibles. Giving form to that which does not yet exist—and the journey there—is a process rooted in endless probing, through which even the finished project is, for Mutiti, just the beginning of the story.

Kunle Sonuga, Traditional hairstyles for the Blackwoman, 1976, from Nontsikelelo Mutiti, A-A-A (folded poster; self-published, 2012)

Kunle Sonuga, Traditional hairstyles for the Blackwoman, 1976, from Nontsikelelo Mutiti, A-A-A (folded poster; self-published, 2012)Camille Crain Drummond: Is the book an essential format for you?

Nontsikelelo Mutiti: I work in many modes. The book is a possible format, it is an option. A lot of other modes can do similar things, and they also do things that the book can’t. It’s interesting to think about whether something needs to become a book. Could it be a lecture, could it be a film, a series of prints? Why a book, why pages ordered in sequence, bound? I will say that the book is exciting, because it’s a challenge. I’m motivated by things that challenge me, by things that I know the least about. That’s why I came to graphic design. I really believe in learning while doing, and so with every book project, I try to learn something new, try something new, approach it from another angle. Each decision is pushing you forward in terms of wrestling with the book. For me, a book is a fight, and I like a good fight.

The book has become a standard for us, culturally, of authoritative voice. So, I can understand why people would come to me and ask me to make a book. Because they’ve got some content that they want to be framed, they want it to be packaged, and the book has many advantages because of its format, the fact it can be put on shelves, put on a table, put in a bag—it is designed in a way that it can be moved. This cultural marker is key.

The gutter of the book is one of the most important things to me. The spine of the book—it’s what allows for the sequencing—it is also one of the places that you design for the least; it is one of the most neglected parts of the book. Bound books tell us that things happen in a particular sequence, and that for the best reading you have to follow that sequence (though you can jump around in a book if you want to).

Drummond: How does your own cultural background inform your approach to the book?

Mutiti: I’m from Zimbabwe. We were a British colony, then Rhodesians, who created their own system of governance separated from Britain and held onto power until 1980, two years before I was born. The book was such an important thing in my upbringing, and in the biography of my people. The book was used to program and reprogram us. To take away our culture and give us things to stand in for values that were already embedded in our culture. It created a hierarchy between a culture that had been brought to us and what was already sacred to us. It gave us new things to hold sacred. It gave us Christianity. It gave us new names, a new language. Photographs of our ancestors were taken and put in books so other peoples could know about us. Our names were spelled out by other people, and those names and categories were then put into books. So, the book has framed my people. It has been a culprit. And if you want to know about “the culprit,” open a book: that’s the scene of the crime.

Anti-segregation demonstrator repelled by firehose, Birmingham, Alabama, May 1963, from Simone Leigh, ed., The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2019)

Anti-segregation demonstrator repelled by firehose, Birmingham, Alabama, May 1963, from Simone Leigh, ed., The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2019)Courtesy Charles Moore/Getty

Drummond: Can you speak to how you explore patternmaking in your work?

Mutiti: For me, it’s about sequence. And sequence does not necessarily mean things have to be repeated in exactly the same order, or that things need to be ordered and predictable; but there has to be some kind of rationale, even if that rationale is my own. I think about the module. I think about what something can be reduced to and still be potent, and then what to do with that module when we repeat it. I think pattern exists in our lives—culture is a pattern, it’s a set of rules, and again, something that attracts me. My work with patterns is teaching me to think about what structure can do.

A pattern is something that you can be given, as with sewing. So, I also want to acknowledge that there are patterns that were made for me even before I was born—as a woman, as a Black African woman, as a Black woman born in Zimbabwe. There are patterns that have been made for me as someone that is a professor, a designer. I’m interested in those patterns. I want to understand what makes them up: Why do they hold up? What’s so strong about them?

Tinashe Mushakavanhu and Nontsikelelo Mutiti, eds., Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (Black Chalk & Co., 2019)

Tinashe Mushakavanhu and Nontsikelelo Mutiti, eds., Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats (Black Chalk & Co., 2019)Drummond: Your practice is often research-based. The books you have produced with Black Chalk & Co., founded in partnership with the author and scholar Tinashe Mushakavanhu, incorporate many contributors, vernacular images, and references to historical and archival material. Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats, for example, brings together a multitude of writers’ voices on writing—stories, excerpts from interviews, as well as family photos and other images. What role does bringing all of these pieces together (the creation of a new archive) play for you as a designer?

Mutiti: The multimodal, polyvocal nature of the piece is evident in the foundation of this book, in that it is many voices, many voices of different tonalities, many voices speaking to similar themes. It is a portrait of an intergenerational and international community. It is really an extended conversation between people we would like to see in the room together. The work with Black Chalk is about surfacing submerged narratives.

Publishing is a privileged position. It takes a lot to bring a publication out, and SWCGYTH was our first substantial publication. With every publication, you can make it if you have the resources, if you have time— writing takes time, research takes time, being able to be close to the resources that inspire or inform or become the content, having the financial resources to produce the work. I’m in the academy, so that allows me to more easily access archives, to get research funds to travel. We went to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, which has a huge, huge repository of material around African literature. Most of the archives that we are looking at have pieces of ephemera—printed pieces of moments in time—so we’re reading the surface of all of those things.

Clockwise from top left: Mickalene Thomas, Muse (Aperture, 2015). Simone Leigh, ed., Waiting Room Magazine (Creative Time and Tilton Gallery, 2014). Simone Leigh, ed., The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2019)

Clockwise from top left: Mickalene Thomas, Muse (Aperture, 2015). Simone Leigh, ed., Waiting Room Magazine (Creative Time and Tilton Gallery, 2014). Simone Leigh, ed., The Anarchy of Colored Girls Assembled in a Riotous Manner (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2019)All images courtesy Nontsikelelo Mutiti

In the book, we draw on our family photo albums in a way that is not ironic. Biography can be a very powerful tool. We put our family photographs in the book, because we didn’t have access to images of the authors or other leading figures to represent those moments; we didn’t have an image of the person speaking about exile. Our personal biographies mirror those voices, and we went through the same things. So, we also put ourselves in there as subject, as author, as archive, and that is important to us. When I’m looking at the archive, I’m looking at myself.

A lot of my work in graduate school was dealing with this, because there were laws passed in Zimbabwe that you could not photograph outside of your own personal property. You couldn’t just go and snap a building across the road, you couldn’t film as you were driving, you can’t document. I felt lost. When I came to grad school, I really wanted to make work about home but could not access images from the past ten years unless they were images sanctioned by the government—and those were already manipulated, even if it was a real scene. What is documented and not documented creates a manipulation in the archive.

No archive tells the complete story. Those gaps have always inspired me. This is what leads me to create an institution, like Black Chalk, that is really preoccupied with gaps and omissions. I think when you’re doing this kind of work, at times, people make the assumption that you are trying to address those omissions by making sure that everything is made visible. But sometimes, the most powerful thing you can do is point and say, “Look, you left me out.” That is content too.

This piece originally was published in Issue 018 of The PhotoBook Review.

February 11, 2021

A Painter Reconsiders the Photographs of Luigi Ghirri

Before Luigi Ghirri turned to photography, he worked as a land surveyor, an occupation that fostered a way of seeing. Typically taken from a frontal vantage point, his photographs describe the surfaces of what’s before the camera with what at first feels like directness, but upon closer inspection is more akin to a visual puzzle. (He once described his work as a “fresco for our time.”) And with their layers of visual detritus, found image fragments of advertisements and signage, his images speak to their moment while sometimes feeling anachronistic.

Last fall, Matt Connors, a contemporary painter, curated a Ghirri exhibition for Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, titled The Idea of Building. The show argued that Ghirri’s photography grappled with principles of painting. “To me, as a painter,” Connors notes, “the photographs of Luigi Ghirri are built rather than composed, things rather than images.” Connors is now continuing his engagement with the late Italian photographer and, through his own publishing imprint, plans to release a related book this spring.

A relationship between the two artists is visible in how Connors builds layers of color and plays with form on the surface of his vibrant abstract paintings. While there is no obvious illusionistic space in his work, there is a gesture to something outside the painting. “I do feel like I am creating and referencing very real physical and aesthetic presences,” he once remarked. That instinct, perhaps, is what draws him to photography, and to the work of Ghirri, who viewed reality as abstraction, as photomontage, as something to be deciphered in imagistic terms.

Luigi Ghirri, Teatro Valli, Reggio Emilia, 1986, from the series Paesaggio italiano

Luigi Ghirri, Teatro Valli, Reggio Emilia, 1986, from the series Paesaggio italianoMichael Famighetti: The installation for The Idea of Building was quite beautiful and worked so well in the Matthew Marks Gallery space, which has the feel of a modest chapel. How did this project come to be?

Matt Connors: I have been a Ghirri fan for a long time, and a conversation developed with the gallery about me curating a show. The first time they showed Ghirri was in a Thomas Demand–curated show, so I think they were interested in me to see what would happen, because I wasn’t a photographer, but was someone invested in his work.

Famighetti: Did you work closely with the Ghirri estate on the selection?

Connors: I went to Italy to the archive to meet with Adele, his daughter. Before that, I was buying every Ghirri book. I was freaked out because of how admired and loved he is in the photography world, and I felt acutely aware that I was not a photographer. But I kept digging in on my personal research and wrote a minithesis to send to Adele. And then I went in January 2020, one of my last trips before the COVID-19 pandemic. The archive is in what was once Ghirri’s house; it was an absolute fantasy.

Luigi Ghirri, Studio Aldo Rossi, Milano, 1989–90, from the series Studio Aldo Rossi

Luigi Ghirri, Studio Aldo Rossi, Milano, 1989–90, from the series Studio Aldo RossiFamighetti: What vision of Ghirri did you present to the estate?

Connors: The process of choosing a Ghirri photograph is kind of like a psychological intake, because there is so much, many different bodies of work; it involves confessing what you like.

After looking at many images, I started to dig out a vision of him as a painter. It sounds self-serving, but because I’m making paintings all day, putting color together materially, I started to see that parallel so clearly in his work.

In the book Project Prints (2012), which is about how he would make contact prints and cut them out and make little maquettes to play with, you can see that the materiality of his approach was key. He was obsessed with building, actually building things—like making tables, folders, and containers—and that just seemed so present in the work. That became the paradigm. I think his entry into art-making via the drawing that was part of his cartography and surveying work set the stage for him to use photography in a more tactile, painterly, material way.

Famighetti: Ghirri was also a prolific author of concise reflections on photography, and he wrote about how he didn’t take pictures, or compose pictures, but rather saw himself as creating things from images—your building angle seems to naturally emerge from his thinking.

Connors: Yes, and there was a nervousness that the title—The Idea of Building—would read as if the show was about architecture. (I had just seen a show that was all about his photographs connected to architecture.) But I did use a few photos he took of Aldo Rossi’s studio, and there are a few others included that are focused on architectural frameworks. He would go back and then make photographs based on his surveying work. Architecture is embedded in how he sees.

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1970, from the series Fotografie del periodo iniziale

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1970, from the series Fotografie del periodo inizialeFamighetti: You present a wide range of images—fragments of advertising, images that imply sound, mise en abyme, and so on—to communicate this idea of picture-building. And the inclusion of the ephemera and photo-related objects in the vitrines anchored your ideas, especially the wonderful instructional diagrams for making pictures, Prime pitture.

Connors: There was something else that I wanted to bring to New York, but it wasn’t possible. In the hallway to one of his studio rooms, flanking the door, is a children’s instructional poster. On one side, it tells you how to make a painting, and on the other side is this insane poster about making a photograph. They are hung directly opposite each other and are kind of in the style of the Prime pitture book that I included in the vitrine.

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1978, from the series Il paese dei balocchi

Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1978, from the series Il paese dei balocchiFamighetti: The Prime pitture book functions, in a way, as the key to your show, a guide to building a picture. Was that an object that you also discovered in the archive?

Connors: We were just having this playtime in the archive. As an idea would come up, Adele would run into the other room and find something, like the original drawing for the book Kodachrome (1978), made by Ghirri’s widow. We kept finding threads that connected back to each other as we used this idea of building as a prism.

Famighetti: I can understand your anxiety in doing this show, because Ghirri is so beloved. But even though his work has been the focus of some excellent publishing in recent years, he’s strangely still a bit under the radar in the States, at least at the institutional level, which is curious, considering that there’s such a close relationship between his work and the history of photography in the U.S. Walker Evans was critically important to Ghirri, and the connection to American color photographers of the 1970s is self-evident.

Connors: When you get so deep into this, you think everyone is a major fan, but then you take a step back and realize how undervalued he actually is. I was a huge Stephen Shore and Eggleston fan, but I’d never heard of Ghirri until pretty late. The 2012 reissue of Kodachrome, the Matthew Marks show in 2010, and an Artforum cover in 2013—those three things made a critical mass for people discovering him at that point, but that’s pretty late. MoMA just published a book, a facsimile of a handmade book that Ghirri gave to John Szarkowski in 1975. That could have come with a show!

Luigi Ghirri, Studio Aldo Rossi, Milano, 1989–90, from the series Studio Aldo Rossi

Luigi Ghirri, Studio Aldo Rossi, Milano, 1989–90, from the series Studio Aldo RossiFamighetti: I’d also add that Aperture published a monograph and produced an exhibition in 2008, It’s Beautiful Here, Isn’t It…, which included some of the first English-language translations of his writings. In his texts, he speaks of his work in categories, such as the suburban home and other typologies. Did you feel like you needed to honor those, or break away from them?

Connors: I’m a little itchy with how he can be presented as nostalgic. I think that is shortsighted and not true, and just has to do with his use of color as seen today. In doing research, I began to understand how much he was associated with the Conceptual art that was emerging at that time, and I really wanted to bring him away from a strictly melancholy or sentimental view. But I really didn’t pay too much attention to the categories, because in the end, they are really porous. I think one of things he liked about making categories was not respecting them all the time. Maybe the attraction to Conceptual art could have been its efforts to ignore or redefine traditions of art-making and art objects themselves.

Luigi Ghirri, Maranello, Ferrari Automobili, 1985–88

Luigi Ghirri, Maranello, Ferrari Automobili, 1985–88Famighetti: Right, and you even include some of his commercial work, like this image of the Ferrari factory.

Connors: There had just been a photo fair in Bologna, and someone had done a show about Ghirri’s commercial work, which was for Ferrari, Bulgari, and a tile company. Because of that, those pictures were out in the studio when I was there. They had just been returned, and that one so pictorially linked up with what I wanted to do. That just came as a gift. It was just there.

Famighetti: That picture was positioned near this fantastic image of an all-seeing eye, a painted sign. What was your approach to the installation?

Connors: I was working in the way I’d install a painting show. It’s very musical, poetic, associational.

Luigi Ghirri, Lucerna, 1971, from the series Fotografie del periodo iniziale

Luigi Ghirri, Lucerna, 1971, from the series Fotografie del periodo inizialeAll images © the Estate of Luigi Ghirri and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Famighetti: Do you feel a kinship between your paintings and his photographs?

Connors: I’m a painter that looks at nonpainting a lot. For me, the context of painting extends much further than painting, and that’s not often appreciated. I don’t take photos, but I use photo in my work, and I collect photography and photobooks. It’s a big influence on me, but I’d be hard-pressed to explain how exactly, and I like that difficulty.

Famighetti: It’s interesting what you said about the sentimental read of his work. To me, the images are often depictions of these nonspaces, peripheral zones, the kind of landscape you might see in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Red Desert (1964), made a little earlier than Ghirri’s photos.

Connors: Yes, that all lives in the work. If you search the Instagram hashtag for Ghirri, you’ll see that lots of Italians hashtag their own photos “Luigi Ghirri.” It’s a descriptor. It’s really funny. I imagine that, in general, Instagram must be a serious bête noire for photographers, but I also found that interesting in a way.

Maybe the sort of “nonspaces” that Ghirri and Antonioni were finding and even making are not so “non” anymore, as the percentage of people with access to cameras has exponentially increased, and very few corners of the world or human experience are undocumented. Maybe people are actually sentimental for that, when they find what seems to be in-between spaces, or experiences, in their regular lives.

Luigi Ghirri: The Idea of Building was on view at Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, from October 22 – December 19, 2020. An online version of the exhibition is available at matthewmarks.com.

From Christian Marclay, a Primal Scream Inspired by Pop Art and Politics

Christian Marclay’s practice is vast and focused on the huge, expressive themes of sound, music, and media. Yet he works small, on laptops and, in the case of his current show at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, modest collages on paper and stop-motion animation created on a poster-size collage. Most of the material here is gleaned from the pages of comic books, objects you can hold in your hand.

Comic books are filled with words that convey sounds—Wham! Pow! Thwack! Pop!—and deep connections to Pop art. In Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings from the 1960s, such words are enlarged to embody exuberant criticism of a culture on a complicated American upswing. The moderate scale of Marclay’s recent works, however, befits a time of periodic lockdowns, which he spent in London.

He might have been afforded the uninterrupted time to work on something as monumental as his masterpiece The Clock (2010), but the tenor of 2020, when these works here were created, was more internal, personal, and perhaps more emotional. Our anguish in isolation was (and is) something difficult to convey—hence the balcony orchestras in Italy, and the Black Lives Matter demonstrations around the US. These were among the few venues in which we could make our voices heard, to emote in anger, frustration, and, on occasion, joy.

Marclay has mined comic books based on their drawing styles, a mixture of Western and Asian titles, to create collages that convey the expressive voice. The works focus on heads: mouths open, emoting, broadcasting what visually appears to be pain, rage, or simply an audible volume. There’s some iconic art history hovering around here—Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) being the loudest, but also Caravaggio’s Medusa (1597) and some German Expressionism noted for good measure—but it’s difficult not to view these works in the now. How many times did you want to scream, passionately, at someone at the grocery store, or at the inexplicable people in charge? Three layers of antimicrobial fibers have a way of muffling sound and hiding the expressive nature of the mouth. Eyes convey emotion silently. Marclay revels in all forms of the auditory.

Christian Marclay, Face (Ecorché), 2020

Christian Marclay, Face (Ecorché), 2020Face (Ecorché) (all works 2020), a comic-book collage, presents a face-like form created with curving onomatopoeia cutouts: sploosh, slamm, skreeeeeee, rinnggggggg (the latter bringing to mind Marclay’s irresistible 1995 video collage Telephones). The texts extend from this head like the snakes that form Medusa’s enraged coiffure. The clipped strips are glued to board, a pale brown backdrop as dry as the comic-book newsprint. The sentiments and sounds, however, are full of precipitation.

A series of fifteen collages, collectively titled No! (and also presented as a print portfolio), together form a score that will be interpreted and performed by musicians. These convey movement, melody, and gesture. The most traditionally score-like features circular cutouts of mouths sequenced in lines that you can imagine emulating, going from grimace to growl. Another presents a kind of descending audio, as figures are depicted falling in midair alongside a skyscraper.

The emotional temperature of these works is feverish. Raging Fire is another collage composed of flaming red/orange triangular shards, some resembling tiny pizza slices, cut from comic-book pages. It is a field of conflagration, something all too familiar in the Bay Area where, not long ago, the entire sky was a similar shade. A related single-channel silent video, Fire, sets these snippets in motion, so they resemble active flames generating an upward heat—it’s convincing and calmly mesmerizing, like a holiday fireplace video, yet sharper, more angular. Still, compared to Marclay’s previous video works, this one is ultimately ambient and not particularly memorable.

Christian Marclay, Untitled (Pulp), 2020

Christian Marclay, Untitled (Pulp), 2020All works © the artist and courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

There are nine chromogenic prints in this exhibition, photographs that enlarge collages. Most feature a more expansive range of sources—glossy magazine photos of musicians, or perhaps movie stills of men with their mouths open. In Untitled (Shreds), a photo of Elvis Presley’s face is crumpled and black strips, perhaps formed by his leather jumpsuit, create emanating forms that are like a mangled, dimensional version of Alexander Rodchenko’s famous revolutionary poster of the gleeful, female worker shouting in protest, Books (Please)! In All Branches of Knowledge (1924). Elvis’s cry, however, is more opaque, his message disfigured.

Also with the other prints, there is dimension to the original collages formed by crumpling, crinkling, folding, and other physical pressures. Two—Untitled (Burning I) and Untitled (Burning II)—show a face on fire, the flames in their early stages and not immediately visible, though there is a slight haze of developing smoke. The temperature is rising.

Marclay’s show opened the day after President Joe Biden was inaugurated, when screaming was supplanted with a feeling of euphoria (a less vocal emotion), though clearly, there will be rallying cries ahead. There are feelings of dread, anxiety, and anguish that pervade here. It may not be Marclay’s strongest work, but it’s a gently cathartic encapsulation of 2020.

Christian Marclay is on view at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, through March 26.

7 Photobooks That Consider Black Lives and Artistic Visions

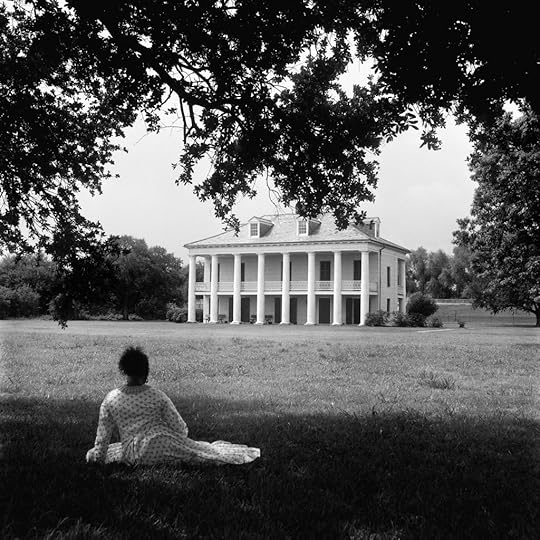

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17

Carrie Mae Weems, While Sitting upon the Ruins of Your Remains, I Pondered the Course of History, 2016–17Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes (September 2020)

Copublished by Aperture and Peabody Museum Press

To Make Their Own Way in the World is a profound consideration of some of the most challenging images in the history of photography: fifteen daguerreotypes of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty—men and women of African descent who were enslaved in South Carolina. Photographed by Joseph T. Zealy for Harvard University professor Louis Agassiz in 1850, the images were rediscovered at Harvard’s Peabody Museum in 1976.

This volume features essays by prominent scholars who explore topics such as the identities and experiences of the seven people depicted in the daguerreotypes, the close relationship between photography and race in the nineteenth century, and visual narratives of slavery and its lasting effects, as well as the ways contemporary artists have used the daguerreotypes to critique institutional racism today. With over two hundred illustrations, including new photography by Carrie Mae Weems, this book frames the Zealy daguerreotypes as works of urgent engagement.

To Make Their Own Way in the World is firmly grounded in the events shaping American lives today. Instead of supporting Agassiz’s pseudoscientific notions about white supremacy and racial hierarchies (as was their original intent), the daguerreotypes provoke wide-ranging interpretations and raise critical questions about representation and identity. “At this moment and in these divided states of America, perhaps more than at any time since their rediscovery in 1976,” Molly Rogers writes, “the daguerreotypes of Jem, Alfred, Delia, Renty, George Fassena, Drana, and Jack command our attention, demanding that we look closely, listen intently, and speak out—however difficult this may be—giving voice to all that we have learned.”

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970

Kwame Brathwaite, Model wearing a natural hairstyle, AJASS, Harlem, ca. 1970Courtesy the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles

Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful (2019)

Kwame Brathwaite’s photographs from the ’50s and ’60s transformed how we define Blackness. Using his photography to popularize the slogan “Black Is Beautiful,” Brathwaite challenged mainstream beauty standards of the time that excluded women of color. Born in Brooklyn and part of the second-wave Harlem Renaissance, Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath founded the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS) and the Grandassa Models. AJASS was a collective of artists, playwrights, designers, and dancers; Grandassa Models was a modeling agency for Black women. Working with these two organizations, Brathwaite organized fashion shows featuring clothing designed by the models themselves, created stunning portraits of jazz luminaries, and captured behind-the-scenes photographs of the Black arts community, including Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Miles Davis.

Until recent years, Brathwaite has been under-recognized. In 2019, Aperture published the first-ever monograph of his work, Black Is Beautiful. “To ‘Think Black’ meant not only being politically conscious and concerned with issues facing the Black community,” writes Tanisha C. Ford, “but also reflecting that awareness of self through dress and self-presentation. They were the woke set of their generation.”

Ming Smith, Oopdeedoo, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney Island

Ming Smith, Oopdeedoo, Brooklyn, 1976, from the series Coney IslandCourtesy the artist and Aperture

Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph (November 2020)

Copublished by Aperture and Documentary Arts

Ming Smith’s poetic and experimental images are icons of twentieth-century African American life. Smith began experimenting with photography as early as kindergarten, when she made pictures of her classmates with her parents’ Brownie camera. She went on to attend Howard University, Washington, DC, where she continued her practice, and eventually moved to New York in the 1970s. Smith supported herself by modeling for agencies like Wilhelmina, and around the same time, joined the Kamoinge Workshop. In 1975, Smith became the first Black woman photographer to have work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Throughout her career, Smith has photographed various forms of Black community and creativity—from mothers and children having an ordinary day in Harlem, to her photographic tribute to playwright August Wilson, to the majestic performance style of Sun Ra. Her trademark lyricism, distinctively blurred silhouettes, and dynamic street scenes established Smith as one of the greatest artist-photographers working today. As Yxta Maya Murray writes in Ming Smith: An Aperture Monograph, “Smith brings her passion and intellect to a remarkable body of photography that belongs in the canon for its wealth of ideas and its preservation of Black women’s lives during an age, much like today, when nothing could be taken for granted.”

Lyle Ashton Harris, M. Lamar, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 1993

Lyle Ashton Harris, M. Lamar, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 1993Courtesy the artist

Lyle Ashton Harris: Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs (2017)

Throughout the late 1980s and ’90s, a radical cultural scene emerged in cities across the globe, finding expression in the galleries, nightclubs, and bedrooms of New York, London, Los Angeles, and Rome. As a young artist experimenting with different artistic mediums at the time, Lyle Ashton Harris began obsessively photographing his friends, lovers, and individuals who were, or would become, figures of influence, including Nan Goldin, Stuart Hall, bell hooks, Catherine Opie, and Marlon Riggs. Harris’s photographs offer a raw, authentic portrait of the cultural and political communities that defined an era and continue to resonate to this day.

In the 2017 volume Today I Shall Judge Nothing That Occurs, the artist’s archive of 35 mm Ektachrome images is presented alongside personal journal entries and recollections from artistic and cultural figures. It offers a unique document of what Harris has described as “ephemeral moments and emblematic figures shot in the ’80s and ’90s, against a backdrop of seismic shifts in the art world, the emergence of multiculturalism, the second wave of AIDS activism, and incipient globalization.” Together, Harris’s photographs and journals not only sketch his personal history and journey as an artist, but also provide an intimate look into this groundbreaking period of art and culture.

Hank Willis Thomas, The Cotton Bowl, 2011, from the series Strange Fruit

Hank Willis Thomas, The Cotton Bowl, 2011, from the series Strange FruitCourtesy the artist

Hank Willis Thomas: All Things Being Equal (2018)

Copublished by Aperture and the Portland Art Museum, Oregon

Throughout his prolific and interdisciplinary career, Hank Willis Thomas’s work has explored issues representation, perception, and American history. At the core of his practice is the ability to parse and critically dissect the flow of images that comprise American culture, with particular attention to race, gender, and cultural identity.

Since his first publication, Pitch Blackness (Aperture, 2008), Thomas has established himself as a significant voice in contemporary art. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge, a transmedia project that uses video to facilitate conversations among Black men, and the artist collective For Freedoms.

In 2018, Aperture and the Portland Art Museum copublished All Things Being Equal, the first in-depth overview of the artist’s extensive career. Featuring over 250 images from his oeuvre, the volume highlights Thomas’s diverse range of visual approaches and mediums—from advertising and branding, Civil Rights and apartheid-era photography, and sculpture, to public art projects and more.

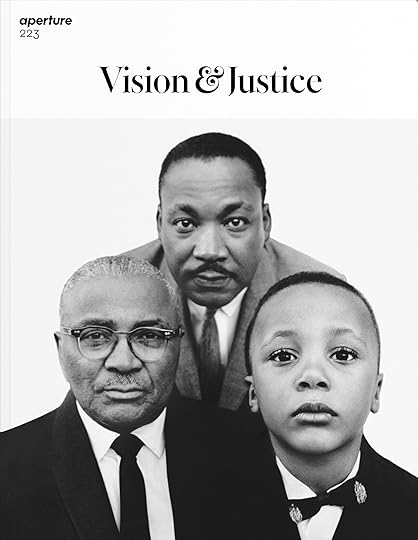

Richard Avedon, Martin Luther King, Jr., civil rights leader, with his father, Martin Luther King, Baptist minister, and his son, Martin Luther King III, Atlanta, Georgia, March 22, 1963