Aperture's Blog, page 56

May 28, 2021

Aperture Patron and Trustee Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla Passes Away

Aperture is deeply saddened to learn of the death of Sondra Gilman Gonzalez-Falla, who served as a dedicated, generous patron and trustee of Aperture Foundation for many decades. Her husband and partner, Celso Gonzalez-Falla, served on the Aperture board as longtime chair and ongoing patron. Sondra also created and chaired the influential Photography Acquisition Committee at the Whitney Museum. Together, Sondra and Celso worked tirelessly to support the photo community and to build an unparalleled collection around the photographs they loved. In Shared Vision: The Sondra Gilman and Celso Gonzalez-Falla Collection of Photography (2011), Sondra described their mutual commitment as follows: “We are custodians, and we feel an obligation to the photographer—to the artist who created the work—to allow it to be seen and exposed as much as it can. We don’t own it. Nobody owns art. It’s passing through us, and we have to take care of it.”

We celebrate Sondra’s life and her passion; the work she and Celso gathered with such care lives on.

In a Bracing Exhibition at the Guggenheim, Artists Challenge the Way History Is Told

When Sadie Barnette was a kid growing up in Oakland, California, her father didn’t talk much about his time in the Black Panther Party. It’s possible he simply had other things to say. Rodney Barnette, who is now in his late seventies, has lived an uncommonly fascinating life. Born and raised in one of the oldest Black communities in the Boston area, he got involved in community organizing early on, followed the teachings of Malcolm X, was drafted into the army, earned a Purple Heart in Vietnam, took a job with the US Postal Service, joined the anti-war movement, took some time off to read W. E. B. DuBois and Karl Marx, helped the national campaign to free Angela Davis, and opened the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco, which for three crucial years in the 1990s offered a sanctuary and a site of resistance for the city’s queer communities of color. In the late 1960s, he also cofounded the ninth chapter of the Black Panthers, in downtown Compton.

Sadie Barnette, My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation, 2017

Sadie Barnette, My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation, 2017Rodney may have been reluctant to discuss the experience with his daughter when she was little because of his lingering uneasiness about how the party had broken up and drifted away from popular community service initiatives like a free breakfast program for schoolchildren. He felt paranoid at times, but he was sure the movement had been infiltrated by informers who, through various disciplinary stratagems, damaged the party’s work from within. In 2011, Barnette sat down with his daughter and her mother to fill out a request for his FBI file through the Freedom of Information Act. It took more than four years for the file to arrive, not in the form of a dusty old box of papers but as redacted scans on CD-ROMS. Still, filled as it was with the blacked-out names of agents who were omnipresent and lied through their teeth, the file confirmed his suspicions, and so much more.

For several years now, Sadie Barnette has been transforming pages from her father’s 500-plus page FBI file into a series of ruminative artworks, embellished with surprising irruptions of pink spray paint, sparkly stickers, and glitter. On documents revealing patterns of harassment and intimidation that cost Rodney Barnette his job, among other things, the explosions of color read like expressions of love from a little girl to a daddy she adores. Three years ago, five prints from My Father’s FBI File; Government Employees Installation (2017) entered the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

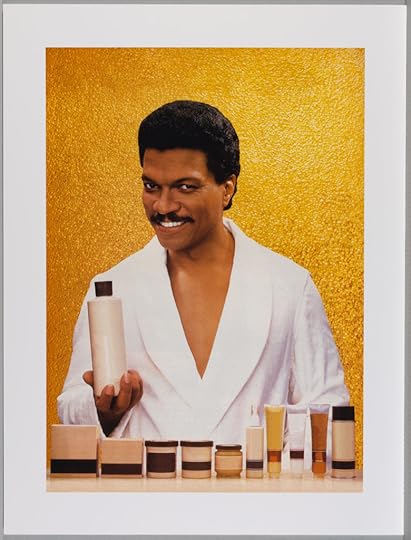

Hank Willis Thomas, Something to Believe In, 1984/2007

Hank Willis Thomas, Something to Believe In, 1984/2007Thanks to the curator Ashley James’s ambitious, far-reaching, and decidedly self-critical approach to a collection survey highlighting recent acquisitions, an otherwise often dutiful form of exhibition-making, Barnette’s series is now on view throughout the summer. It holds its own hanging adjacent to a searing and powerful suite of prints by Adrian Piper as part of Off the Record, a bracing show of thirteen bodies of work, each of them challenging the role of documents (including official government records, newspaper pages, images from mainstream magazines, pedagogical tools, and scholarly photographic archives) in shaping, obscuring, or suppressing the histories they purport to tell. The exhibition fills a handful of side galleries with predominantly photo-based images that all but one of the artists (Lorna Simpson) used but did not themselves produce. The burst of pink on Barnette’s black-and-white pages signal the exhibition’s interest in interruptions and interventions, in the ways in which the featured artists have not only located and appropriated these records but more importantly acted upon them.

The archival impulse runs deep in contemporary art. Generations of artists have developed a veritable subgenre of documentary projects turning historical records into an artistic medium, from Hans Haacke, Martha Rosler, and Alfredo Jaar to Walid Raad, the Otolith Group, Mariam Ghani, Eric Baudelaire, Julia Meltzer and David Thorne’s Speculative Archive, Yto Barrada, and the Pad.ma project initiated in 2007 by three collectives from Mumbai, Berlin, and Bangalore. Obsessions with archival material tend to trace out some of the most intractable political conflicts on Earth, cohering them into a map of colonial and neocolonial cruelties. Off the Record moves in a similar way, cleaving to the core horrors of racism and power in America. But it also does something different.

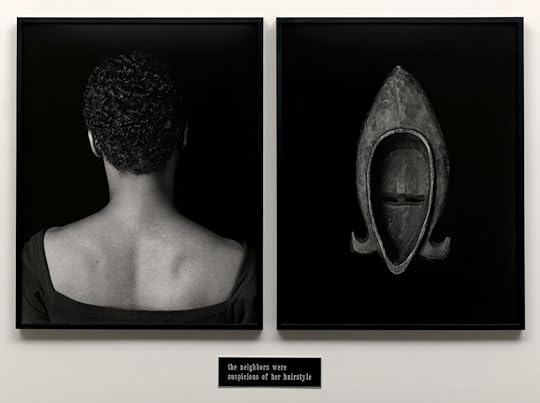

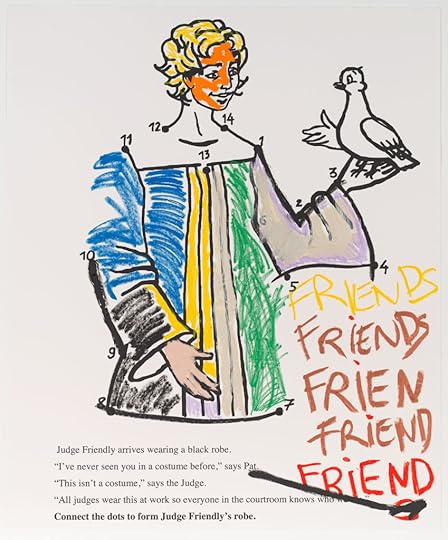

Lorna Simpson, Flipside, 1991

Lorna Simpson, Flipside, 1991The title plays on the notion of going “off the record” in interactions with the media, when a source says something to a journalist that must, by convention, remain unprinted. According to James, the title here can also be understood as a verb, “killing” the record as a means of redress. All of this suggests not so much the melancholy engagements of a scholarly artist as archivist, working through old dusty photographs as forms of evidence, storytelling prompts, or mnemonic devices. The artists in Off the Record are more actively engaged, more playful and pugilistic. Through acts of repetition (Glenn Ligon), deletion (Hank Willis Thomas), subtraction (Sarah Charlesworth), juxtaposition (Lorna Simpson), collage (Leslie Hewitt), brutal captioning (Carrie Mae Weems), they actually seem to tussle with their materials and win. In Coloring Book 9 and Coloring Book 18 (both from 2018), Sable Elyse Smith willfully colors outside the lines on the enlarged pages of children’s activity books introducing the justice system and the carceral state; in Ecology of Fear (Gillum for Governor)(Freedom Riders Bus Bombed by KKK), from 2020—and the only work on loan in the show—Tomashi Jackson creates wells of tension and emotion by layering lines and colors into an accumulation of found images printed on clear vinyl, including an enlarged photograph of Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act into law, the face of Martin Luther King Jr. just visible in the background.

Like many museums in New York and around the world, the Guggenheim has struggled—and sometimes stumbled—in its efforts to address the wider systemic racism of the art world and the urgent need to diversify its exhibitions, collections, leadership, and staffing decisions. Off the Record presents a strong example of how curators with fresh eyes, real vision, and deep art historical knowledge might begin to reform institutions from within, rifling through their own collections, materials, and records to find the pieces of vital new arguments to be made. (James, who previously worked on blockbuster exhibitions such as Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, as well as solo shows devoted to Adrian Piper, Charles White, Eric N. Mack, and John Edmonds, joined the Guggenheim in 2019.)

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 18, 2018

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 18, 2018All works courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

In an interview with her father that Sadie Barnette recorded a few years ago for the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she was once an artist-in-residence, she asked him where his political convictions began. He told her the story of finding a photograph of a lynching in The Pittsburgh Courier, a leading Black newspaper in the first half of the twentieth century. He was horrified by the cheering crowd in the picture. In another interview made for the current show, Barnette reflected on how their father-daughter story is bigger than them; it is a family story that speaks to universal experience. But she also admitted, about her pink adornments on her father’s FBI file: “How powerful it does feel to know that just me and my small self with my spray paint in my studio can interject.”

Off the Record is on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, through September 27, 2021.

May 24, 2021

How a Collective of Photographers Aims to Affirm Black Life

At the height of the racial justice protests in the wake of George Floyd’s, Breonna Taylor’s, and Tony McDade’s deaths by law enforcement in 2020, a group of six young Black photographers organized themselves into the collective See In Black. Spearheaded by the New York–based image makers Micaiah Carter and Joshua Kissi, the mission was simple: use art to affirm that Black life, disproportionately affected by the coronavirus and state-sanctioned violence, matters beyond moments of crisis.

“See In Black formed as a collective of Black photographers to dismantle white supremacy and systemic oppression,” the coalition’s statement of solidarity reads. “Our intention is to replenish those we’ve been nourished by.” Their first action was to establish a print sale titled Vol. 001 Black In America, which included snapshots, street scenes, self-portraits, still lifes, and editorial images of Blackness by nearly eighty photographers. Collectively, these intimate portrayals present community as an act of hope. Image by image, you see Black America honestly gazed at from within the circle of lived experience. At a time of deep despair, their photographs were a testament that Black narratives will not be devalued. The print sale raised over $500,000, which they donated to five homelessness, youth, queer, political, and legal organizations.

A number of the photographers call New York home. The city, battered badly over the past year, has allowed these artists to establish themselves creatively and to attune their eyes to construct counternarratives that squarely capture what the collective calls “Black prosperity.” Here, I speak with seven of the photographers about how art meets activism in New York.

Joshua Kissi, Nike, BHM Campaign, 2019

Joshua Kissi, Nike, BHM Campaign, 2019Courtesy the arist

Joshua Kissi

Antwaun Sargent: How does New York inform your practice as an image maker?

Joshua Kissi: Being of West African descent, in a place in the Bronx that has a lot of West Africans, people from Ghana and Nigeria and Guinea and Senegal, made me think about what this vibrancy looked like within my work. I always thought, What do color and tone look like? How do I make this photo feel like you’re really in Little Senegal, or on the west side of the Bronx?

Sargent: You see the multiplicity in Blackness in your images. There are differences in the way that skin color needs to be shot from neighborhood to neighborhood to make sure that you capture the richness and the specificity of that identity.

Kissi: Yeah, absolutely.

Sargent: Our city experienced this pandemic like no other at the beginning, and then we went into racial protest. You and Micaiah decided to launch See In Black.

Kissi: We were just thinking, like, Will we be able to live the same type of lives that we were living before? We knew that we weren’t the type of photographers to necessarily go out and photograph protests. That’s really an emotional thing. We love and support the people who do. But, what else can we do that isn’t necessarily on the front lines but is on the front lines? It isn’t necessarily just about a trend. It’s about, How do we solidify our perspective when it comes to image makers who are Black?

Everybody put their head down and just got to work. Getting the photographers together. Trying to organize, getting logos and websites and photos. We were really in it. But we didn’t feel like it was work because we knew the work needed to be done. And we were like, Man, we need to do something. We need to say something.

Sargent: How did you select the photographers?

Kissi: We know a lot of photographers in New York and LA, but there are so many multitudes and layers of Blackness. So it was important to have as much representation as possible within the Black community. We wanted other photographers to be like, “My personal work may not be in there. But I see my lens, I see my understanding, I see my practice.” The main point was if you see your work within this selection, the job is done. You could continue to add on to that narrative. You can continue to shape that story.

Joshua Kissi is a Ghanaian American photographer and creative director based in New York.

Micaiah Carter, Highsnobiety, 2019

Micaiah Carter, Highsnobiety, 2019Courtesy the artist

Micaiah Carter

Sargent: Why did you and Joshua start See In Black?

Micaiah Carter: We wanted to have a response. As Black photographers, how can we give back to our own communities, not only based in New York but across the country? We wanted to have a plethora of people that we could reach out to for the first round of what See In Black was, and to raise money and help people in need.

Sargent: One of the first actions was a print sale—and they weren’t necessarily all images of activism. It really was about a real deep look at Black life. Why was that important to you?

Carter: Black trauma is something that is expected. There always has to be some type of struggle. We wanted to show that’s not always the case. There are moments of happiness. There are moments of mundaneness.

Sargent: Your photography often takes moments from our rich past as Black people and remixes them in these contemporary images.

Carter: I think that’s consistent from when I first started. Even now, when I’m home, I look back at my dad’s photographs. That’s still a big inspiration for how I view photography, the family album as a whole.

Sargent: How did you develop that style?

Carter: I think it’s just my perspective on how I am as a person reflecting on other people. I am inspired by certain people. So, for example, like with Megan Thee Stallion, when I shot her, I wanted her to be in her style element. I wanted this softness that you don’t really see with her.

Sargent: What do you want the future of See In Black to be?

Carter: Almost like a boys and girls club—to have, from different pockets of America and the world, accessibility to Black photography, Black tools. Like, say there’s a Black photographer who really wants to start. They can go into See In Black, know just how they want to network, and from there build to where they want to go. It’s not an agency; it’s more like a mecca for knowledge and a mecca for community.

Sargent: And history. Right?

Carter: Yeah, and history.

Micaiah Carter is a photographer based in Brooklyn and Los Angeles.

Florian Koenigsberger, Carley Adonis, from the series Coloureds, Cape Town, South Africa, 2019

Florian Koenigsberger, Carley Adonis, from the series Coloureds, Cape Town, South Africa, 2019Courtesy the artist

Florian Koenigsberger

Sargent: You grew up in the city, right?

Florian Koenigsberger: Born and raised here.

Sargent: How has being a native New Yorker informed the development of your photo practice?

Koenigsberger: Growing up here makes you unafraid of approaching strangers. I remember when I got my first camera in late middle school, early high school days, the big story for me was having a chance to walk around New York and ask questions to people that I didn’t know, and to make their pictures.

Sargent: Why did you want to use your images in service of the mission of See In Black?

Koenigsberger: Many of us were fearful that what was happening in the aftermath of Mr. Floyd’s death was going to be a moment and not a movement. How do you carry this forward? For us, it was: If you can live with this representation of Blackness in your space, and this becomes something that you interact with daily, it really fundamentally challenges the racism and bias that many people are operating with daily. The other side was we wanted the community to have work. It shouldn’t just be people who are used to buying this work that can have their ideas challenged in their space.

Sargent: This is not a traditional sort of activism. What led you to have an active role beyond sharing your image and actually organizing?

Koenigsberger: My role is operations. I work as a product marketing manager at Google in my full-time job, and my work is focused on making cameras more equitable, particularly for people with darker skin tones. I got the call from Joshua, and he was talking to me about help with finance and legal for this thing that they were going to try to put together.

It was this rare alignment, like, Oh, every skill set that I have been trained to direct toward this multibillion-dollar corporation can now be repurposed to directly serve the community. No frills. No middleman. To me, that was the greatest honor. To spend all of this time learning all of these skills and to finally be able to bring them back into the community in a way that really directly and immediately serves its needs was incredible. And there was never a question for me that that wasn’t the thing to immediately dive all the way into.

Florian Koenigsberger is a photographer and storyteller living and working in New York.

Texas Isaiah, Riley, 2016

Texas Isaiah, Riley, 2016Courtesy the artist

Texas Isaiah

Sargent: How did New York help you develop as an image maker?

Texas Isaiah: My first experience of community was being involved in nightlife. It taught me so much about the different ways we can take care of each other within the work that we want to do. When we were curating parties, like Alien or like Roxy Cottontail or like Good Peoples with Katie Longmyer, at least the crew that I was with, we’d come together and just ask, like, “Who are the folk that need support right now? Maybe we can hire them for the door.”

Sargent: One of the things that emerges in your work is this mosaic of young creative New York. Why was this communal portrait making important?

Texas Isaiah: Everyone contributes to a space in some way. You have the door person. You have the host. The DJ. The bartender. The person who cleans up at the end of the night. I took that idea and extended that to the everyday. I want to photograph everybody that will allow me to photograph them. And that felt important to how I was establishing an archive. Everyone is valuable. Everyone deserves a visual space.

Sargent: Why was it important for you to show up in the way that you did by joining See In Black and offering to the community your images?

Texas Isaiah: It was a way to give back. I’m not a big protester. Not everyone can be a part of a protest for five hours. So, it was just a way to remind people that they do have access to artwork during this time. I’ve known Joshua for a while now, and I trusted that Joshua would hold this space, along with Micaiah. It really felt important to also be a part of something that was established by Black people and for Black people.

Sargent: Have your ideas about activism changed?

Texas Isaiah: Activism for me is an everyday thing. It’s how I show up for my partner and how I treat my friends. I think See In Black is part of that, showing up for community and showing up for each other, even if not all of us are familiar with one another. We’re coming together and just trying to figure out how we can make our work more accessible to the community, and then also how we can raise funds and donate them to a plethora of Black organizations and collectives.

Sargent: Do you think of your archive making as a form of activism?

Texas Isaiah: I do. I’m just trying to turn away from these traditional structures of how people believe photography should be valued, and what it means to be photographed, and what it means to step into that space, and how it can be a space for everyone, every single person. It doesn’t matter if you are a janitor or if you are a gardener. You are still contributing to this world, and you deserve that space.

Texas Isaiah is a visual narrator based in New York, Los Angeles, and Oakland, California.

Kreshonna Keane, Project Princess, Bronx, 2019

Kreshonna Keane, Project Princess, Bronx, 2019Courtesy the artist

Kreshonna Keane

Sargent: How has New York informed your work?

Kreshonna Keane: A lot of people strive to move to New York because it seems like the greatest place on earth. I think, being from here, I started to hate it and resent it. Then, moving to Atlanta and coming back, I grew a larger appreciation for New York and, more specifically, for the Bronx, which is where I was born and raised.

Sargent: What are you trying to capture about the Bronx in your images?

Keane: Originally, it started out as the life and culture. I was shooting our local restaurants, my friends in front of them, and things like that. Then I kind of wanted to start a deeper meaning, maybe by shooting the people who own these places and things like that. The part of the Bronx that I live in, the culture there, a lot of the things that we focus on are, like, food and the mom and-pop shops that are owned there. It’s heavily Caribbean-based and Caribbean-owned.

But then it kind of grew into something larger for me. I took these overlooked places, like New York City public housing. We see these project buildings every day when we walk past, and they have these negative connotations attached to them. I tried to turn it into something more beautiful by giving it an editorial spin and putting a model that you wouldn’t see there.

Sargent: When you joined See In Black, why did you feel like your photography could be used in a way to help the city?

Keane: I was actually shocked that I was asked to join it. Looking at the list, I was like, Wow, I don’t really see my work as comparable to all the other artists up there. But I realized that I should be a part of this, that maybe my work could be something for people. It felt good to be part of a larger collective and to make a difference, and I knew the impact that we could make.

Sargent: The brilliant thing about what you did with See In Black was to share images of the breadth and depth of Black life. Why is it important to you that the Bronx is a character in your images?

Keane: Because it’s so overlooked. There’s always this talk about boroughs. Everybody always says, “Oh, my borough is the best—the Bronx is the best,” or “Brooklyn is the best,” or “Queens is the best.” Ever since I was younger, I always used to hate it. I would hate being from the Bronx. I would hate what I saw when I walked around the Bronx. I was experiencing things walking around the Bronx. It’s always been a place to be feared, and a place to be looked down on, and a place to be frowned upon when you tell people you’re from there. So it’s always been important to me to show that there’s beauty here; regardless of the struggle or not, there’s beauty in it.

Sargent: And with your camera, you’re showing it.

Keane: Exactly.

Kreshonna Keane is a photographer, creative director, and visual artist based in New York.

Flo Ngala, Untitled, Brooklyn Bridge, NY, 2020

Flo Ngala, Untitled, Brooklyn Bridge, NY, 2020Courtesy the artist

Flo Ngala

Sargent: How has New York shaped you as an artist?

Flo Ngala: It’s pretty much the whole reason why I think I’m able to approach the world of photography the way I do. From a young age, I’ve always been outgoing and talkative and excited about life. It’s a vigor that I acquired growing up. I think it would be very different if I was raised in the country or another city.

Sargent: Early on, your practice was largely self-portraits at home in Harlem, of you on the roof. How did you frame those images in relationship to the city’s landscape?

Ngala: People call New York a concrete jungle. The city itself builds up more than we build across. So just even being on a roof was something I was used to, being on a fire escape was something I was used to in the homes that my parents and my family lived in.

Sargent: When See In Black was formed, what did it mean to you to use your images in a way that gave back to the community?

Ngala: I remember being in high school and being a fan of what Josh was doing with Street Etiquette. I loved that so much because it was this awesome representation of the city and fashion photography and Black men. So, I was honored to be included. To be able to show an image that a lot of people felt was powerful, that a lot of people felt moved to purchase, something that was taken in my home literally a couple of blocks from my house, to me, that’s a representation of the community at a very important moment in time.

Sargent: Unlike a lot of other photographers who did See In Black, you actually went out there and documented the protests. And we saw each other a couple of times.

Ngala: Well, at my core, I am a street photographer. And I’m grateful that even though I’ve done other work as the years have gone on, that muscle is very sixth-sense, it’s very muscle-memory, it’s very natural to pop back into the action of it and just be in the moment. You communicate with people. And I love that I can hop back into that kind of work very naturally. It’s really a blessing.

To be able to see my work, not just on my social media or on my website, but to see it in people’s homes and to have people hit me up, and say, “I want to buy that print”—I’m like, Wow, that’s so cool. That moment spoke to you enough that you wanted to bring it home with you and have it forever.

Flo Ngala is a New York–based portrait photographer and photojournalist from Harlem.

Mahaneela, Stay Tru, 2019

Mahaneela, Stay Tru, 2019Courtesy the artist

Mahaneela

Sargent: How does New York inform your way of seeing?

Mahaneela: I should start with how much identity informs my work and my practice, being someone of multiethnic backgrounds. I’m from Jamaica; I’m from West Africa; I’m from India, born and raised in London. My parents are from East Africa, even though they’re Indian. I am used to the mix and blend of cultures. So, for me, that’s always been a really big part of how I see things, and being in New York is a gold mine of cultural richness.

Sargent: Has your portrait practice changed from England to New York?

Mahaneela: Yes, it has, actually. In England a lot of my photography was of people I knew, people within my community; in New York it’s shifted. I’m creating a new home for myself—and so I have to go outside of myself, to kind of reach out to people and start these conversations and connections, rather than them already being there.

I’ve been coming back and forth to New York for years, like since 2014. That’s actually when I met Josh. He showed me around New York. We’d never met before; we just knew each other on Instagram. He was the one who took me around and gave me my first insight into the city.

The subject that I shot for See In Black, she is somebody I met in New York. I met her randomly, at a party. Which I felt was such a New York experience. That was the reason I feel I did that image. Because really, that image reminds me of how things come full circle, and how I just met this girl at a random party, I didn’t know anyone, we started talking, and then maintained that relationship, and ended up doing this shoot, which was very spontaneous. New York gives me that confidence.

Sargent: Why was it important to use your images in a social justice movement?

Mahaneela: I was able to feel like I was actually being an agent for change in a way that was acceptable to me. That period of time between March and June was an extremely scary and unstable time for New Yorkers, especially being that there was such a high concentration of COVID-19. It felt like a moment of powerlessness, coupled with the murder of George Floyd. And it also felt like a time in which we could kind of take matters into our own hands.

See In Black was a way of making a change in a positive way. We are raising money for the Black Youth Empowerment Project, the National Black Justice Coalition, the Black Futures Lab, and also the Bail Project. And we are giving a broad look into what Black photography and what the canon of photography are now. Even just seeing all of our prints there, seeing the diversity of composition and people and characters and subjects that exist within the work, was eye opening. We are not one homogeneous thing, and yet we still come together for these causes that affect all of us and all our families and all of the communities that we belong to.

We saw close to half a million in sales for See In Black. The demand and the value are there. It goes to show the value of this work and our contributions to the world.

Mahaneela is a multidisciplinary artist and DJ from London.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 242, “New York,” under the title “Seeing In Black.”

May 19, 2021

May 17, 2021

Self-Taught Photographers in Pursuit of Revelation

Joseph Yoakum, the self-taught landscape artist who worked most of his life in Chicago, described his immanent, imagined panoramas as a “spiritual enfoldment.”

“What I don’t get,” he told a newspaper reporter in 1967, “God didn’t intend me to have.”

The list of artists who operated by much the same mechanism is long and extraordinary, many of them arrayed outside the confines of the art world proper: William Blake, Hilma af Klint, Madge Gill, Howard Finster, Frank Jones, Minnie Evans, probably Martín Ramírez (though we’ll never know because he stopped speaking upon his involuntary commitment to a California mental hospital in 1931).

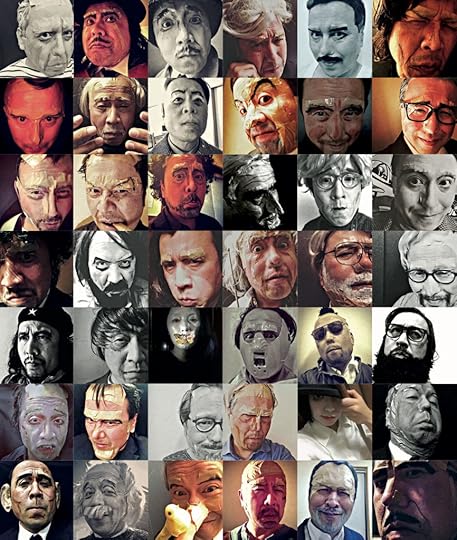

Tomasz Machciński, Untitled, 1988

Tomasz Machciński, Untitled, 1988© Tomasz Machciński/Collection Bruno Decharme

The widespread availability of the camera to the middle classes by the end of the nineteenth century effected a kind of short circuit in the celestial wiring of this visionary production and even in the work of so-called outsider artists without such religious impetus. It was as if the combination of emulsion and shutter provided an accidental portal for the gods—or simply the hidden contours of the world—to slip unawares into the visible, bypassing mediation of mind and hand. Something no one saw manifests itself in the developer bath. Some kind of message is on offer. Or more commonly, a simple snapshot click yields an image of an ordinary thing unintentionally transformed into a marvel that a band of surrealists couldn’t have dreamed up on a bushel of opium.

The spirit-photography charlatan William H. Mumler—sued in 1869 for duping the bereaved with fabricated images of loved ones’ ghosts—got at the public feeling for this possibility when he hailed himself as a pioneer of “new truths” and described the camera as “a medium,” in the metaphysical sense of the word.

Ichiwo Sugino, Untitled, 2015

Ichiwo Sugino, Untitled, 2015© the artist

Photo | Brut: Collection Bruno Decharme & Compagnie, the sprawling, messy, deeply engrossing exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum in New York, is by far the most comprehensive look yet by an American institution at how the camera’s entry into the domain of art-making materials gave outsider artists a fantastically pliable new means of expression, alluring especially because of its subversive ability “to imbue fantasy with the stamp of realism,” as the art historian Michel Thévoz writes in the show’s catalogue.

The Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý, a foundational figure in the world the exhibition explores, trained as a painter, but the pallid requirements of socialist realism drove him from an establishment career. His intentionally primitive homemade cameras, with their toothpaste-polished lenses, rendered the figural (and erotic) fabric of his eccentric mind in a way that paint likely never could have anyway, accomplishing for a twentieth-century European what André Breton, in reference to Oceanic art, described as a “triumph over the dualism of perception and representation.”

With the camera, Tichý said: “I saw everything in a new light. It was a new world.”

Like Tichý, many of the artists in the show, in pursuit of revelation or titillation or self-transformation, cannot bear to leave the photographic image alone. Modernist formalism might present itself as an influence or element, but stopping at it would be like leaving the cake half-baked; far too much life needs squeezing in for such narrowness.

Steve Ashby, Untitled, n.d. Wood, magazine clippings, lace, and metal

Steve Ashby, Untitled, n.d. Wood, magazine clippings, lace, and metalCollection of Robert A. Roth. Photograph by John Faier

Long before Robert Frank or Jim Goldberg began to marry handwriting and image, Lee Godie was layering language and drawing atop her photo-booth portraits. Steve Ashby migrated photos onto wooden sculpture and lamps (he called them “fixing-ups”). Eugene Von Bruenchenhein dyed and double-exposed images. Karel Forman used them to ornament every square inch of his tiny, drab Moravian apartment. Elke Tangeten embroiders them with wandering stitches, bequeathing objects that feel both lovingly handcrafted and pockmarked with contagion.

Throughout the show runs a fever-pulse feeling of film as a miraculous gift especially to artists with emotional and developmental disabilities, offering a way that no other medium can to gobble up, make sense of, and rearrange the world, reminding me of my favorite observation about the camera’s stupendous capacity, from Lee Friedlander: “I only wanted Uncle Vernon standing by his own car (a Hudson) on a clear day, I got him and the car. I also got a bit of Aunt Mary’s laundry and Beau Jack, the dog, peeing on the fence, and a row of potted tuberous begonias on the porch and 78 trees and a million pebbles in the driveway and more. It’s a generous medium, photography.”

The artist I kept returning to in the show, time and again, is its most spartan and tranquil, an outlier in an assembly of often cacophonous outliers. Elisabeth Van Vyve, a woman with autism and hearing problems who now lives in a retirement home in Antwerp, has used disposable color-film cameras for decades to catalogue her circumscribed visual environment in obsessive detail, creating albums of thousands of snapshots that inevitably evoke the postmodern banal-sublime of William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and early Fischli & Weiss.

Elisabeth Van Vyve, Untitled, 1993–2013

Elisabeth Van Vyve, Untitled, 1993–2013© Clément Van Vyve/Collection Bruno Decharme

Except that in Van Vyve’s case, the achingly precise arrangements of color, object, and light—a pair of striped gloves lying side by side on a plaid bedspread, a white dress shirt hanging in a white corner, a yellow custard on a cane chair, clear water swirling in a bathtub, twilight cloud banks seen through a window—feel like images born not of scopophilic necessity, as Eggleston’s can, but of absolute necessity, as imperative to Van Vyve’s daily survival as eating and breathing. This is the vocation of a person documenting her world while also building its exalted counterpart in physical art objects.

In an interview for the exhibition, the French filmmaker Bruno Decharme, whose collection constitutes the majority of the works, aptly describes the sense in which these wildly varied artists share a language spoken beyond the conventional art world, bringing its own into vivid utterance: “Their works are like music scores playing on a parallel stage in another time; they could be called mythological.”

PHOTO | BRUT: Collection Bruno Decharme & Compagnie is on view at the American Folk Art Museum, New York, through June 6, 2021.

May 14, 2021

Donavon Smallwood’s Photographs Envision Black Tranquility in Central Park

There has been increased foot traffic in public spaces over the past year. As the pandemic set in, with lockdown restrictions put in place, loosened, and then put in place again, people turned to their parks as an easy salve: a place to work out, take a socially distanced walk with friends, and even cruise. For some, the pandemic marks the beginning of their relationship with the outdoor spaces in their vicinity—providing an opportunity to get out and get fresh air beyond the four walls that have boxed in their Zoom calls. For others, the connection goes back much further.

For much of his life, Donavon Smallwood found respite in New York’s Central Park. It has been his stomping grounds, of sorts, a short walk from where he lives in East Harlem. “Growing up, basically whenever we weren’t inside playing video games, we would go to the park and hang out,” he says. Friends, girlfriends, classmates, all came along. Smallwood had favorite spots by the Ravine, an area featuring small waterfalls and hiking trails. But when Smallwood watched The Lost Neighborhood Under New York’s Central Park, an eight-minute documentary released on Vox in 2020, that relationship changed.

The short video tells the story of Seneca Village, a community, started in the 1800s, of mostly Black folks who lived on some of the land now occupied by Central Park. In the mid-nineteenth century, when their land was being claimed for Central Park’s creation, the Seneca Village community was belittled, mischaracterized, and bulldozed in favor of breaking ground for a public space. “It was so interesting that this place that I’d been coming to, that had been like a second home for me, was a literal home that was stripped from people and turned into this nature space that I was enamored with,” Smallwood says.

In his series Languor (2020), Smallwood, who studied documentary film and English literature at Hunter College, contends with ideas, he says, about “what it means to be Black and losing your home to nature” as well as the idea of Black tranquility. In essence, it’s a project depicting Black folks at rest, just being.

History is rife with Black people and communities that have had their mere existence questioned, attacked, or negated, as was the case of Seneca Village. Often clips on Instagram and YouTube of Black folks doing nothing more than sharing their lives, laughing, and joking go viral. But on the other side of that coin, just as many viral videos depict Black folks having the authorities called on them, or in some other way being made victims of harassment for shopping, bird-watching, and many other unremarkable activities. Within this duality, Smallwood began a photographic investigation, attempting to divorce his sitters from either narrative.

“When you see Black people just being themselves, that’s what the art is,” Smallwood says of his project, which he hopes to turn into a book in the future. “Just existing in the park. Or on TikTok, if you go through the viral sounds, it’s all Black people in their daily lives. It’s a sound that has a million people using it, and it’s some guy walking into a room with his daughter and saying, ‘Surprise, shorty. Look what I got you.’” So within his second home with its dark history, the self-taught photographer, who has long nursed an interest in anthropology and archaeology, made a series of portraits devoid of pretension.

Those featured in the photographs were mostly cast either in the park, where Smallwood photographed daily, or from online sites, from Craigslist to Facebook and Instagram. “Part of this project was about just being, about not having to put on anything fake, or being too enthusiastic, or being too happy, or being too sad,” Smallwood says. To preempt participants’ urges to don their Sunday best or put on appearances, and to bring authenticity into the frame, Smallwood often asked them to wear looks he had previously seen them wearing in candid snapshots taken by their friends. There are no toothy, full-faced grins, no “Black boy joy” or “Black girl magic,” no vibrantly colored backdrops to signal exuberance. Instead, Smallwood used a medium-format film camera set on a tripod to create a more placid pace when making the images in Languor.

From YouTube and various online forums, Smallwood learned how to develop his own film—he’s only taken one high school class on photography in his life—and printed these images typically the night after shooting. Though he initially chose to make black-and-white photographs, since they were more economical, the limited palette became a way to focus on, he explains, the “mood of the images,” as opposed to potentially distracting backgrounds or clothing. The photographs in Languor are serene, awash in shades of gray, and invite the viewer to take a meditative moment, gazing into a leafy respite. Staring endlessly. Being.

All photographs Untitled, 2020, from the series Languor

All photographs Untitled, 2020, from the series LanguorCourtesy the artist

Donavon Smallwood (born in New York, 1994) is a self-trained photographer who grew up in a household that emphasized literature and deep engagement with the tradition of art. For him, photography—like all art and creation—is a communion with the divine; and he uses the medium as a means of exploring humankind, imagination, essence, and nature. Smallwood holds a BA from Hunter College, New York. His first monograph, Languor, is forthcoming in June 2021.

This article will appear in Aperture, issue 243, summer 2021.

Donavon Smallwood is the winner of the 2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize. His solo exhibition will be on view at Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, July 21—August 25, 2021.

2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: William Camargo

In his project Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, Histories & Possibilities, photographer and educator William Camargo addresses issues of gentrification, Chicanx and Latinx histories, and the systemic erasure of the stories of Brown people in his hometown of Anaheim, California—located southeast of Los Angeles, and Orange County’s largest city by population. A lot of people associate Anaheim with Disneyland, the Anaheim Ducks, the Los Angeles Angels, and the manicured resort district, but in the early 1900s, Anaheim was a rural agricultural community with acres of citrus orchards and an ugly history of systemic racism and violence. This included large gatherings of KKK members, who were also involved in city government; school segregation in the Mexican American community; and police violence against Black and Brown people, which continues to this day. Anaheim is more than fifty percent Latinx, and home to a large, diverse immigrant community. After spending a brief time away from Anaheim, Camargo returned with the intention of discovering the erased origins of his hometown.

William Camargo, Anaheim Landscape, 2020

William Camargo, Lavinia, 2019

While sifting through the local public library’s archive, Camargo discovered a history that he didn’t know, one that wasn’t taught to residents and youth in his community—which included photographs of Latinx life in Anaheim. Through the use of photography and performance, Camargo uses his own body and handwritten signs to address the stories repeatedly erased from historical documents, photographs, and news archives. In the photograph Y’all Forgot Who Worked Here?, Camargo stands in front of the Anaheim Packing House, a renovated 1919 Sunkist citrus packing house that is now a gourmet food hall, with a sign that reads “Brown Women Used to Pack Oranges Here.” The image is striking, not only because of the tension that exists between the message on the sign and the space being occupied, but also Camargo’s presence in the frame. His face is hidden—something he does in all of his performative images—and his body becomes a stand-in for other people. These images force viewers to consider the spaces we occupy and question the systems and people that shape our understanding of a place. “I want viewers to reflect on where they live, and the history that is not really centered,” Camargo explains. “Even if it’s a history that’s not so bright.”

Camargo’s work addresses the continued systemic racism that exists in Anaheim—whether by inserting himself into the photograph, documenting contemporary landscapes, or creating intimate portraits of people in their homes. As a community archivist, Camargo approaches his subjects with respect and collaboration. “A lot of my work is a mutual agreement. I am trying to focus on cooperation with community, instead of going in there, photographing, and then leaving,” says Camargo. “It’s an exchange. There’s a power structure in photography, and I’m aware of that.” There is an inherent intimacy and mutual understanding between him and his community; his subjects look relaxed and seem to know that these photographs are important and will go on to tell their stories. While Camargo is working to contextualize and repackage historical texts and contemporary narratives through photography, he is also creating a body of work that will live on as its own archive.

William Camargo, After Stephen Shore but in Penquin City and Paisa, 2019

William Camargo, After Stephen Shore but in Penquin City and Paisa, 2019 William Camargo,

Y’all Forgot Who Worked Here?

, 2020

William Camargo,

Y’all Forgot Who Worked Here?

, 2020 William Camargo,

Esperanza

, 2020

William Camargo,

Esperanza

, 2020 William Camargo,

That Paisa Haircut

, 2020

William Camargo,

That Paisa Haircut

, 2020 William Camargo, Chicanx Still Life #5, 2019. All photographs from the series Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, History, and Possibilities

William Camargo, Chicanx Still Life #5, 2019. All photographs from the series Origins & Displacements: Making Sense of Place, History, and PossibilitiesCourtesy the artist

William Camargo (born in Anaheim, California, 1989) is an arts educator, photo-based artist, and arts advocate. He is currently commissioner of heritage and culture for the City of Anaheim, and working toward an MFA at Claremont Graduate University, California. He is founder and curator of Latinx Diaspora Archives, an Instagram page that elevates communities of color through family photos. He attained a BFA from California State University, Fullerton, and an AA in photography from Fullerton College. Camargo has held residencies at ProjectArt, Chicago; Chicago Artists Coalition; Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions, Steuben, Wisconsin; LA Summer at Otis School of Art and Design; and the Latinx Project at New York University. He attended the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures’s Leadership (2018) and Advocacy (2020) Institutes, and is a current member of Diversify Photo. Camargo was awarded a Friedman Grant from Claremont Graduate University, and has given lectures at the University of Wisconsin–Parkside; Gallery 400, Chicago; University of San Diego; California State University, Long Beach; Claremont Colleges; and University of Southern California’s Roski School of Art and Design, among others. His work has been shown at the Chicago Cultural Center; Loisaida Center, New York; University of Indianapolis; Mexican Center for Culture and Cinematic Arts, Los Angeles; Stevenson University, Maryland; Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Irvine Fine Arts Center, California; and upcoming at the Phoenix Art Museum.

The Aperture Portfolio Prize is an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Chance DeVille

Today, one in four women and one in ten men in the US experience intimate partner violence in their lifetime, and growing evidence shows COVID-19 lockdown measures have led to a drastic increase in cases. What’s missing in these numbers are violence against nonbinary individuals (who are statistically most at risk) and the unreported cases—in reality, the numbers are far higher.

Chance DeVille is intimately aware of these numbers and the impact behind them. When DeVille was a child, their mother, Tammy, suffered physical and mental abuse by her ex-husband, David, leading to a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia and severe PTSD. As Tammy went on to reject psychiatric treatment and struggled with substance abuse, her relationship with DeVille and their power dynamic as mother and child took a drastic turn. Now, years later, DeVille has set out to create a photographic examination of their mother and the long-lasting effects of David’s abuse on their family. “I started making this work with a frustration that a story like my mom’s was not out there,” DeVille recounts. “When I started studying photography, I found that this conversation wasn’t being held in that space either.”

Through careful photographs and ritual observation, DeVille weaves together collaborative images of their mother, self-portraits, and archival imagery. The resulting series, David’s Mark, speaks to the complex relationships between abuse, trauma, sexual desire, and mental health, while also acting as a vital space for reclamation and healing. DeVille describes the experience of photographing their mother as building a new relationship through the act of documenting: “The camera has given us a foundation to a relationship that would not have been there otherwise.”

Chance DeVille, Fingering David, Self Portrait, 2020

Chance DeVille, Fingering David II, Self Portrait, 2020

DeVille’s black-and-white and color photographs navigate between an almost painful, performative energy and moments of contemplative observation. In one image, leaves reflect in a car window, a haze of smoke swirling from the interior, covering Tammy in a physical manifestation of a dreamlike state. Throughout domestic interiors, a foreboding presence of clutter fills the frame, from a tangle of wires to overwhelming piles of clothes. One haunting image, an earlier self-portrait of DeVille referencing the sexual abuse they faced from David as a child, takes on new meaning when paired with an archival image found a year later, directly tying bodily trauma and repressed memories. DeVille, who is queer and nonbinary, sees an irrefutable connection between David’s acts and their own understanding of desire and attraction, and seeks self-portraiture as a way to “regain agency of [their] body, sexuality, and perception.”

Ultimately, DeVille wants their work to make an impact, but also to give light to the deep repercussions abuse has beyond its immediate action. “Trying to understand what makes a ‘good’ photograph is really difficult whenever it comes to displaying trauma. Studying and understanding the ethics, and my ethics, of photography through this work has been challenging,” DeVille reflects. “I hope my work shows that trauma is complicated and these complications are normal. Domestic abuse weaves its way into every aspect of someone’s life and creates ripple effects.”

Chance DeVille, Sometimes We Scream in Unison, 2020

Chance DeVille, Sometimes We Scream in Unison, 2020 Chance DeVille, Mom in a Dream, 2020

Chance DeVille, Mom in a Dream, 2020

Chance DeVille, Mom’s Room, Labyrinth III, 2020

Chance DeVille, Labyrinth, 2020

Chance DeVille, The Offering, 2020

Chance DeVille, The Offering, 2020 Chance DeVille, Suspension, Self Portrait, 2020. All photographs from the series David’s Mark

Chance DeVille, Suspension, Self Portrait, 2020. All photographs from the series David’s MarkCourtesy the artist

Chance DeVille (born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, 1994) is a nonbinary Southern-born and -raised artist, currently based in Providence, Rhode Island, where they attend the photography MFA program at the Rhode Island School of Design. Deville was named a Henry Wolf Scholar in spring 2020. They earned their BA at McNeese State University, Lake Charles, Louisiana, as a first-generation student. DeVille has exhibited all over the country, as well as internationally, and was recently a winner of the Magenta Foundation’s Flash Forward competition and VSA Emerging Young Artists competition, as well as an honorable mention in Lenscratch’s Student Prize.

The Aperture Portfolio Prize is an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Jarod Lew

In 2012, Jarod Lew unearthed a piece of his personal family history that set the groundwork for an exploration of what it means to be Asian American: his mother was the fiancé of Vincent Chin—a Chinese American draftsman whose murder in 1982, just days before their wedding, would respark the Asian American Civil Rights movement. Lew’s series Please Take Off Your Shoes, set in his hometown of Detroit—the geographical backdrop to Chin’s life and murder—takes an intimate but emboldened look at what remains in Chin’s legacy and the long history of survival and erasure in displacement.

Enveloped in the American suburban interior, Lew’s photographs capture a particular cross section of “Asian” and “American” visual artifacts. Ornate golden lovebirds hover above silken living-room pillows featuring the Chinese character for prosperity. A turtle shell stuffed with American dollars appears beside a framed five-yuan bill featuring Mao Zedong. A Korean adoptee adorns a white Korean face mask and a Japanese T-shirt of Homer Simpson. Through a paradoxical landscape of assimilation, a singular aesthetic begins to register.

Jarod Lew, Winson, 2019

Jarod Lew, The Guilty Pleasure of a Ladies Home, 2018

Often emerging in stark contrast against the blank backdrops of their bedrooms, the young Asian American individuals in Lew’s solitary portraits inhabit the same nebulous space. Lew’s gravitation toward photographing people in the safest and most private areas of their homes reveals the shared alienation and complex tensions of a younger generation and their experiences with identity and belonging. Their own safe spaces are visually absent of Asian ornaments and objects; we are left unable to access them through the spectacle of any “Asian” aesthetic. “You can leave a room being the most Asian thing in the room and go into a public space of the house and be the least Asian thing in the room,” Lew explains. “I used underrepresentation as a freedom to play, and I think the people I photographed had that same feeling of wanting to play with our experience.” Vincent Chin may have been the access point into how Lew wanted to understand his Asian American experience in the aftermath of a hate crime, but the resulting body of work in Please Take Off Your Shoes moves far beyond the racial violence Chin endured. In the subverted visual language of the hyper-visible (and invisible), the resilient reflection of a community comes into focus.

Jarod Lew, The Tethers of Love (Eugene, Miyi, and Qun), 2020

Jarod Lew, The Tethers of Love (Eugene, Miyi, and Qun), 2020 Jarod Lew, Uncle Danny, 2018

Jarod Lew, Uncle Danny, 2018 Jarod Lew, Miyi and Qun, 2020

Jarod Lew, Miyi and Qun, 2020 Jarod Lew, The Endurance of Love, 2018

Jarod Lew, The Endurance of Love, 2018 Jarod Lew, Tommy, 2019. All photographs from the series Please Take Off Your Shoes

Jarod Lew, Tommy, 2019. All photographs from the series Please Take Off Your ShoesCourtesy the artist

Jarod Lew (born in Detroit, 1987) is a Chinese American photographer based in Detroit. His photographs explore themes of identity, place, community, and displacement. In 2012, Lew discovered that his mother was the fiancé of Vincent Chin, who was murdered by two autoworkers in Highland Park, Michigan, in 1982, resparking the Asian American Civil Rights movement. Since this discovery, Lew has focused his attention on his own identity as a Chinese American, trying to visually understand “Asian-ness” in the American landscape. His photographs have been exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC; Center for Photography at Woodstock, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts; Design Museum, London; and Philharmonie de Paris. His clients include the New Yorker, New York Times, Financial Times Weekend, GQ, and NPR.

The Aperture Portfolio Prize is an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Anouchka Renaud-Eck

Anouchka Renaud-Eck was newly brokenhearted and starting to question perfect unions. The French photographer, who lives and works between Paris and Kerala, India, began her vibrant series Ardhanarishvara: In Search of Union in 2020 as a means of parsing through not only her own recent breakup, but also that of a close friend who, pressured by his parents, had just ended a six-year romantic relationship. Renaud-Eck’s conversations with her friend opened up a trapdoor into the complexities of Indian matchmaking—the cultural, educational and, in some cases, astral compatibilities that must be taken into account by the families involved—and laid the groundwork for flash portraits that situate centuries of honed courtship practices alongside millennial, tech-savvy tactics.

Starting with her friend’s social circle, Renaud-Eck’s subjects soon expanded to include strangers, schoolchildren, and newfound friends that the artist met during her frequent travels through the Indian states of Kerala, Karnataka, and Maharashtra. The people she photographs—wide-ranging in terms of age, gender, and religious backgrounds—are posed in portraits that often look like freeze-frames. A hand just lifted, a head still swiveled away from the camera. Renaud-Eck maintains details of unsettled action across Ardhanarishvara, echoing the swift movements and constant seeking of what she calls the “wedding race.” The series title is the name for a composite form of two Hindu deities, the masculine Shiva and the feminine Parvati. One of Renaud-Eck’s portraits recreates the unified being’s likeness and, at a glance, the reclining subject might seem to offer a rare moment of serene stillness, a reprieve from the race. Look closer—this god holds a cellphone. They, too, must prepare for the next caller.

Anouchka Renaud-Eck,

Girls Surrounded by Boys

, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck,

Girls Surrounded by Boys

, 2020 Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Ardhanarishvara on Bed, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Ardhanarishvara on Bed, 2020 Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Triplet’s Fate, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Triplet’s Fate, 2020 Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Chosen One, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Chosen One, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, Mudras of Union, Love, and Affection, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Kite of Life, 2020

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Immersion, 2020. All photographs from the series

Ardhanarishvara

Anouchka Renaud-Eck, The Immersion, 2020. All photographs from the series

Ardhanarishvara

Courtesy the artist

Anouchka Renaud-Eck (born in Briançon, France, 1990) lives and works between Paris and India. Her photographic work questions and focuses on the construction of identity echoing with the “other.” Renaud-Eck mainly concentrates on themes of twinship, as well as the sense of belonging in a group or family, in order to question the construction of the fundamental characteristics of an individual and their uniqueness within a group. Since January 2020, Renaud-Eck has been working on a long-term project about arranged marriages and love in India. She works primarily in portraiture and photographing youth.

The Aperture Portfolio Prize is an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers