Aperture's Blog, page 53

July 12, 2021

William Klein Dreams in Black and White

When writer Aaron Schuman first arrived at William Klein’s apartment, five stories above Paris’s rue de Médicis, he was ushered into Klein’s living room by his assistant. Klein, eighty-seven, had been up until four thirty in the morning the night before and was having a rest. After an hour or so of thumbing through this Aladdin’s cave of trophies and treasures, Schuman heard Klein stirring in the rooms at the back of the apartment. “By the tone of his voice, I could tell that he had just woken up, and was reluctant to join me,” Schuman said. “His assistant pleaded, ‘But he’s come all the way from England!’”

Finally, Klein entered the room, eyes wide and shining. This would be the first of two visits with Klein for this interview, which touches on his now-classic books on cities, including his hometown in Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (1956), Rome (1958–59), Tokyo (1964), Moscow (1964), and Paris (2003), all alive with Klein’s signature kineticism; his 1960s fashion work for Alexander Liberman, the celebrated art director at Vogue. This was the era in which Klein turned to moving images, having just made his first film, Broadway by Light, in 1958: he would become known for his fashion-world satire Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966), starring model Dorothy McGowan, and Muhammad Ali: The Greatest (1974), his cinema verité documentary on the fighter, among others. Recently, Klein has been revisiting some of his first experiments with still photography, abstractions from the early 1950s, some of which were exhibited at his London gallery last fall. In the conversation that ensues, he speaks about his remarkable career, now in its seventh decade, with the force and energy that define his photographs and films.

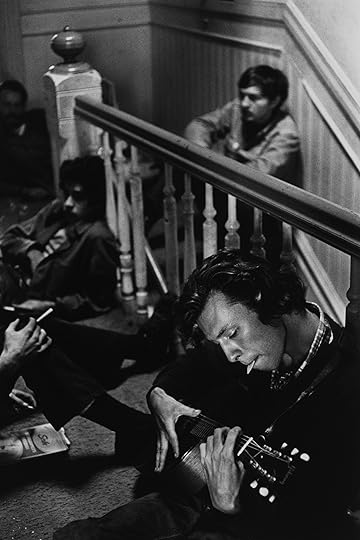

William Klein, Le Petit Magot, Armistice Day, Paris, 1968

William Klein, Le Petit Magot, Armistice Day, Paris, 1968Aaron Schuman: First, how old were you when you knew you wanted to be an artist?

William Klein: I was pretty young—around ten or eleven. I guess I always had this fantasy that I could be an artist. But it was a long time ago; I forget. Do you see the cat? [Points to solar-powered toy cat by the window wagging its tail like a metronome.] You see what it’s doing?

Schuman: It’s wagging its tail.

Klein: Why? Because there’s light. There’s a little solar panel in it. A Japanese editor brought it for me. Every time he comes, he brings another cat. I asked him, “How come you bring all these cats?” and he said, “We love cats.” I said, “Everybody loves cats, but they don’t always bring me cats.”

Schuman: When’s the last time you were in Japan?

Klein: I haven’t been there for twenty-five years. You know my book on Tokyo?

Schuman: Yes.

Klein: Well, there was a group of dancers that became butoh [the dance theater group], and they wanted me to photograph them in the studio, but I said, “No, let’s go out in the street.” So we went out in Ginza, down little streets and everything. There’s one picture I took of this crazy painter—the boxing painter, [Ushio] Shinohara. He lives in Brooklyn now; they did a film on him, Cutie and the Boxer (2013). It was up for an Oscar. Anyway, his wife did most of the talking, and I said “How come you speak such good English, and he can barely say hello?” And she said, “Well, you know—artists are stupid. And he’s stupid” [laughs]. But he’s a great artist.

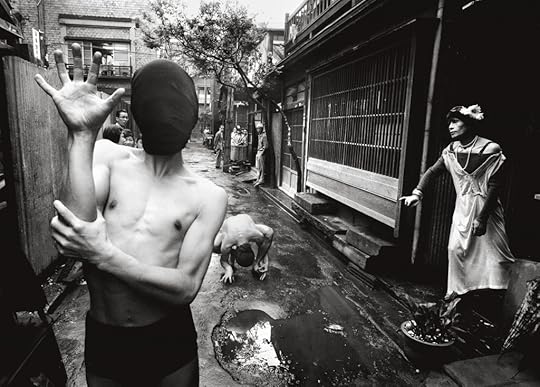

William Klein, Kazuo Ohno, Yoshito Ohno, and Tatsumi Hijikata interpret Genet’s Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs in the “street of small offices,” Tokyo, 1961

William Klein, Kazuo Ohno, Yoshito Ohno, and Tatsumi Hijikata interpret Genet’s Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs in the “street of small offices,” Tokyo, 1961Schuman: Do you think artists are stupid?

Klein: No, I don’t think so. It depends which one [laughs]. Ha, look at the cat. It’s going crazy.

Schuman: What first brought you to Paris?

Klein: The United States Army brought me to Paris. I came to Europe via boat, on the Queen something or other, and was sent to Germany during the occupation. Then I was discharged in Paris. I had gotten into the army at the end of the war, and since I had no knowledge of horses or radio transmissions, I was designated as a radio operator on horseback in Fort Riley, Kansas. After the war, the Americans thought they would be fighting the Japanese in Burma, and so I was trained to be a radio operator on horseback. I got out of college at eighteen and thought that I would have a cushy job in an office, but instead I was doing twenty-five-mile hikes.

Schuman: And why did you stay in Paris?

Klein: I met a French girl and we got married. I thought it was better to live in Paris than in New York. Look at that nice cat I got from the Japanese. I see that fucking cat wagging its tail like a maniac. I asked the Japanese editor, “How long will it continue to wag its tail?” and he said, “Always.” I said, “Perpetual motion doesn’t exist!” My wife became a painter in the last five years before she died, and I really like what went on in her head. She would be painting by the window, and I’d leave in the morning, and in the evening I would come back and there would be a painting [laughs]. But she never went to exhibitions or was worried about exhibiting her work. She was a real primitive.

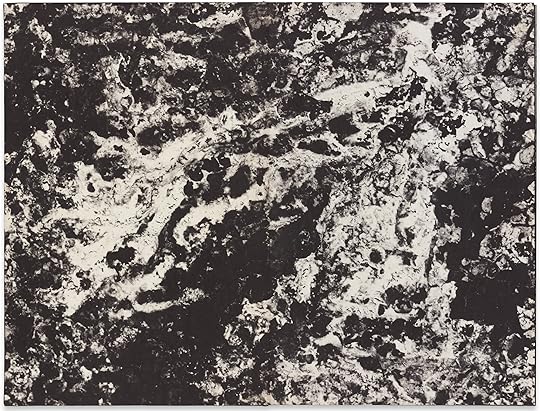

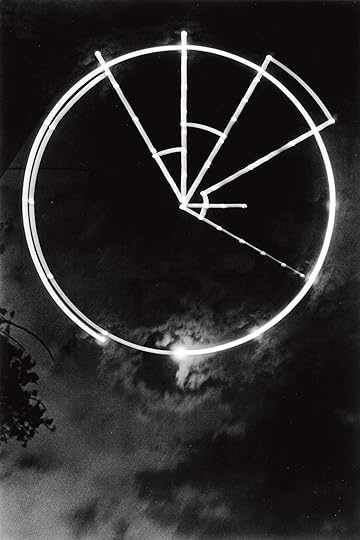

William Klein, Black Barn + White Lines, Island of Walcheren, 1952

William Klein, Black Barn + White Lines, Island of Walcheren, 1952Schuman: You yourself started out as a painter.

Klein: Yeah, as a kid I took courses in high school—Art 201 or whatever—and in college also. When I first came to Paris, I worked in the studio of Fernand Léger. He kept saying to us, “Fuck the galleries. Fuck the collectors. This is not your problem. Your problem is to be part of the city.” At that time, the walls of Paris were covered with these big paintings that the hacks working for the movie industry would paint—scenes from the films. You’d see these big paintings of a scene in a movie, and Léger would say, “These guys are more interesting than the stuff you see in galleries, that you want to imitate and develop in order to seduce collectors. All that’s bullshit. Do what the painters did in the Quattrocento—work with murals and architects.”

Then, in 1952, I had a show in Milan in which I exhibited abstract mural paintings, and an avant-garde architect saw the show. He had developed a space divider in a big apartment in Milan, and he said, “I have these panels that turn and can be moved on rails to cover a wall or divide a space.” He asked me if I would be interested in painting these panels on both sides, so I did. Then I began to photograph them, and since they were on rails, they could turn and move.

While I was photographing the paintings, I had somebody turn them. I was using long exposures because there was little light, and these geometric abstract forms that I had painted began to blur. I thought these hard-edged geometrical forms that I was using became different and more interesting with blur, which was a photographic plus and got me interested in photography. I saw that this was a way in which photography could direct a change in the use of geometrical abstract forms. Then I realized that I didn’t need panels with abstract forms painted on them—I could do it in a darkroom, and so that’s what I did. At that time, I felt that photography was leading the way. By varying the use of graphic forms, and using relatively long exposures to give variation to the forms I photographed, blur became part of my arsenal of graphic techniques.

Schuman: You recently published a new book—which was released in conjunction with a show you had at HackelBury Fine Art in London a few months ago—titled William Klein: Black and Light (2015). It’s based on a maquette for a book that you made of this work in 1952, yes?

Klein: Yeah, it was the first book I ever did—the maquette is over there somewhere. You know Kate Stevens [director of HackelBury Fine Art]? I call her Krazy Kate, like Krazy Kat. Have you seen the old Krazy Kats?

Schuman: Yeah, the comic strip.

Klein: Yeah, the comic strip. But in the old days it was in black and white, and really profound. The cat’s main object in life was to throw a brick at the cop’s head. Anyway, Krazy Kate is what I call her. She’s very determined. Somebody said to me, “Listen, whatever Kate asks you to do, say yes; otherwise she’ll drive you crazy.” So she came to my studio several times, looked in boxes of all sorts, and for some reason she thought that the Black and Light work wasn’t well-known enough, so she decided to make a show out of it. I didn’t really think that was such a good idea. I did these things in a certain manual way, and I have the impression that people with computers do something similar now and wouldn’t be interested in stuff I did sixty years ago. So initially I was against the show, but I remembered that my friend told me to always say yes to Kate. And the show was great. I was kind of surprised by it, and the things that happened leading up to that work I have a kind of nostalgia for.

William Klein, Evelyn + Isabella + Nena + Mirrors, New York (Vogue), 1959

William Klein, Evelyn + Isabella + Nena + Mirrors, New York (Vogue), 1959Schuman: You seem to be nostalgic for things specifically from your early childhood as well—Krazy Kat and so on.

Klein: Well, there were good things in America—Krazy Kat was one of them. In London we had afternoon tea with Kate Stevens, and I told her to look up Krazy Kat on the Internet. She did, and on her iPhone we got a concert of Shirley Temple. [Begins singing] “On the good ship, Lollipop, it’s a sweet trip to a candy shop, where bonbons play, on the road to Mandalay.” I added that Kipling line at the end. My mother decided that my sister would be the new Shirley Temple. In my film Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? the prince fantasizes about Polly, and one of the apparitions is Shirley Temple. So we had to find someone to sing Shirley Temple. Michel Legrand and I did the music, and at the time he was doing a record with Liza Minnelli, so we asked her. But she didn’t know Shirley Temple! She had a voice that could go with Shirley Temple, but she didn’t know Shirley Temple. I thought it was amazing, because Shirley Temple was the biggest star—she did ten or eleven films that were blockbusters. Her films came out, and my mother—who wasn’t a cinephile—would bring me and my sister to Radio City Music Hall to be inspired.

Schuman: Were you inspired?

Klein: Inspired? No, I hated Shirley Temple. We had to move three times because my sister was tap-dancing so much that the downstairs neighbors complained. But it was a nostalgic place to live, and be surrounded by my sister tap-dancing and the neighbors complaining.

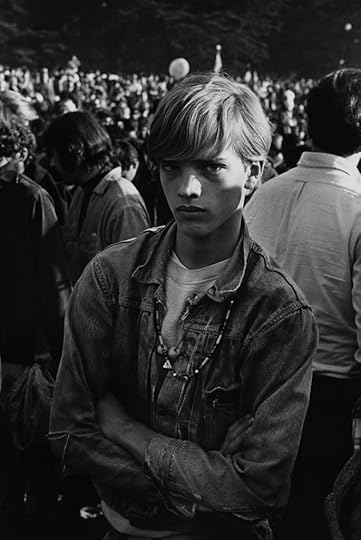

Schuman: Many of the most famous photographs from your first published book—Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels—feature children: kids playing stickball, a boy sitting in front of a checkerboarded candy store, children blurred while mugging for the camera, a kid shoving a toy gun into the lens.

Klein: One time, Life asked well-known photographers to find the people that they had photographed two generations earlier, and they asked me to find the boy with the gun. But actually, when I took that photograph I was just walking down the street, I saw some kids playing cops and robbers, and I asked three of them to look tough, so it was a setup. But the idea of finding them again was crazy. I didn’t go along with it.

William Klein, Dance in Brooklyn, New York, 1954

William Klein, Big face in crowd, St. Patrick’s Day, Fifth Avenue, New York, 1955

Schuman: Did those boys remind you of yourself as a kid?

Klein: I would try to be tough, and also I played cops and robbers. I dream a lot. Last night I was dreaming about a place where we lived, near the river, on 93rd Street. I would play with my sister on the rocks

near the water. That image has kept coming back recently.

Schuman: Do you dream in black and white or color?

Klein: Black and white, of course.

Schuman: What else do you dream about?

Klein: I dream about a million things. It’s incredible. I had a dream recently, and I still don’t know whether it was a dream or not. It was about New York. Jean-Luc Godard was there, it was a Saturday, and there was an art opening. The people there were very friendly, and Godard was so, so nice, and also friendly. He was exhibiting his paintings, and people were saying, “Oh Jean-Luc, you have to come to my studio—I have some nice paintings to show you.” And he would say, “Of course!” which is so little like him. It was so precise, and everybody was the way that they should be. It was Godard being a nice New Yorker. He’s a prick, actually; I know him pretty well.

William Klein, Candy store, Amsterdam Avenue, New York, 1954

William Klein, Candy store, Amsterdam Avenue, New York, 1954Schuman: So how did you go from making abstract black-and-white images in the darkroom to taking photographs on the streets of New York?

Klein: Well, once I had the possibility of enlarging in a darkroom, I realized that the other photographs I’d been taking at the time were not as bad as all that. I was a primitive, and the photographs I was taking for myself were at the level of zero in terms of the evolution of photography. But once I had the opportunity to take the negatives and print them my way, I realized that I could use what I had learned—about graphic art, painting, and charcoal drawings, and so on—in my printing. So when I went back to New York, I had an idea of doing a book. I was twenty-four or twenty-five, something like that, and when you’re twenty-five you can do that sort of thing; if you decide to do it, you just do it. So I turned the bathroom in the hotel I was living in into a darkroom, and had access to a darkroom in my apartment. I washed the prints in the bathtub, and now these prints are considered “vintage prints”—they’re worth a lot of money.

Klein’s wife Janine with painted turning panels, Milan, 1952

Klein’s wife Janine with painted turning panels, Milan, 1952Schuman: I was just looking through some of your old magazines, and saw that the first body of work you published in Vogue was selections from Black and Light.

Klein: Yeah, I was participating in a show called Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in Paris (1953), and Alexander Liberman—who was the art director of Vogue, and then became the art director for all of Condé Nast—left me a note asking me to come and see him. So I did, and he said, “How would you like to work for Vogue?” And I said, “Doing what?” and he said, “Well, we’ll see. You can be assistant art director or something.” We ended up deciding that I would do photographs, but I had no idea what kind of photographs I could do for Vogue.

I looked at the fashion magazines, and I was really convinced that I couldn’t do anything like what the fashion photographers were doing; I mean, I thought their technique was beyond my reach. But when I looked more closely, I thought they weren’t so hot as all that, and the only photographers that impressed me were [Irving] Penn and [Richard] Avedon. The rest were just part of a system, and the more I looked at their photographs, the more I felt that there weren’t any really interesting ideas behind them.

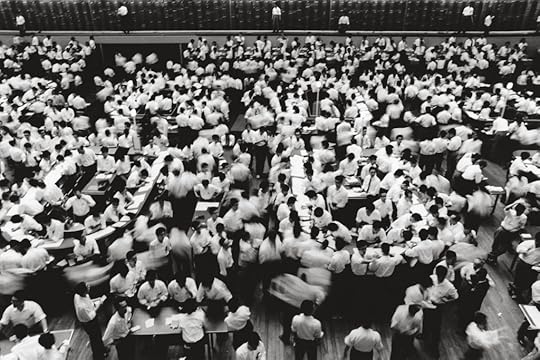

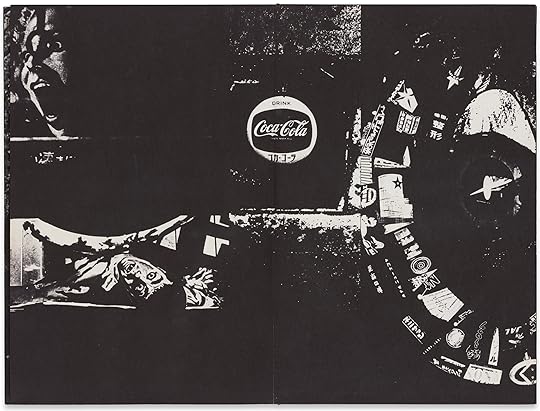

William Klein, Tokyo Stock Market, 1961

William Klein, Tokyo Stock Market, 1961Schuman: Before shooting any fashion photographs for the magazine, you also published a series called “Mondrian Real Life: Zeeland Farms” in Vogue in 1954.

Klein: Yes, my wife inherited a house on the Dutch and Belgian frontier. One day we took our car and drove to the nearby island of Walcheren, and I saw these barns. They reminded me a little bit of the Dutch houses in Pennsylvania, and I learned that Mondrian had lived there during World War I. I thought that there must be some relationship between what he saw there and what he was doing later, so I photographed them. Then, when I met with Liberman again, he asked to see some of the stuff that I was doing, and when he saw those photographs he decided to publish a little portfolio of them in Vogue, which was unusual because it was a fashion magazine. But you know, fashion magazines at that time were the monthly dose of culture that women would get—theater, painting, exhibitions of all kinds—so those photographs fit in with the philosophy of Liberman.

Schuman: Did you enjoy working for such magazines at that time, when they had an important cultural influence as well as being about fashion?

Klein: Why not? It was a way of making a living. The only things that were salable or publishable at the time were fashion photographs.

Schuman: Was that a concern of yours?

Klein: It wasn’t a problem, just an observation I had to make. I thought that the other photographs that I was doing—the abstract photographs, the realistic photographs, the New York photographs, and so on—were more interesting. But nobody else was really interested in them.

Still from Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966) featuring Dorothy McGowan and Donyale Luna in aluminum dresses by the Baschet Brothers and Jeanne Klein

Still from Who Are You, Polly Maggoo? (1966) featuring Dorothy McGowan and Donyale Luna in aluminum dresses by the Baschet Brothers and Jeanne KleinSchuman: Were you frustrated by the fact that people were more interested in your fashion photography than in your art or street photography?

Klein: I thought it was kind of bullshit photographing a dress, because I couldn’t care less. I was interested in photography and in photographic ideas. When I would do a session of fashion photographs my wife would ask, “What was the fashion like?” and I would say, “I have no idea.” I really had no knowledge. It was my fault because there were things going on in fashion photography—people like Yousuf Karsh, Erwin Blumenfeld, and other interesting photographers with a lot of culture. But I had no idea of the progression of fashion in the twentieth century. I did a film later on—Mode en France (1984)—and learned that the progression of the way women dressed, and the attitude of the designers, was also a reflection of what role women played in society. At the beginning of the twentieth century, women were dressed in fortresses; they were not accessible, and the dresses and outfits were stiff and impossible to open up. Then, people like Paul Poiret and especially Coco Chanel liberated the way women put on clothes. Chanel had women wear sweaters, and Poiret took away the stiffness. But I knew nothing about that at the time and didn’t put it into perspective; nobody around me was interested in that. When I took fashion photographs, it was around the time that Dior made his so-called revolution. But when I look back, I realize that it was bullshit, because the real inventors were people like Chanel, who let women wear men’s jackets and sweaters and so on.

Schuman: You mentioned your 1984 film, Mode en France, but you started making films much earlier, in the 1950s—what initially inspired you to start making films?

Klein: Well, you know, once I had done books and told stories with my photographs, movies were an obvious development. In Life Is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels, the layout and turning of the pages was, for me, a movie. Instead of stopping at the level of pseudo-movie, I thought, Why not do a real movie? So photography and variations of graphic work led me to movies as well.

William Klein, Alexandra Yablotchkina, Russian Sarah Bernhardt, Moscow, 1959

William Klein, Red light, Piazzale Flaminio, Rome, 1956

Schuman: Like Black and Light, your first film—Broadway by Light—was quite an abstract, graphic film.

Klein: Yes, the New York photographs were criticized initially because they presented a vision of New York and America that was very harsh, black and white, and grungy. So I thought the next step would be to do a movie; I could do the same thing, but with something as beautiful as Times Square and the incessant ballet of advertising. The first thing that people photograph or digest in New York is Broadway and Times Square—it’s the most beautiful thing in New York, and in America. But what is it, what are people actually seeing? They are seeing the spectacle of advertising; it’s buy this, buy that. It’s beautiful, but it’s made up of sales pitches, and people are fascinated and seduced by advertising. That was American art at the time. And Broadway by Light was a celebration of this whole process of selling—of taking people by the lapels of their suits and saying, “Buy this! Buy that!” and being immersed in the graphic world of advertising. The beginning of Broadway by Light is a big close-up of the bottle cap of the Pepsi-Cola sign, which is like the sun—it comes up, fills the screen, and then you go on to the other advertisements. That was the first film that I did, and people were struck by it.

When I was at Léger’s studio, there were three young American painters working there—Ellsworth Kelly, Jack Youngerman, and me. Ellsworth was very struck by Broadway by Light, and he arranged to have screenings of the film in New York, so all of these people from the art world saw the film and realized that what they were seeing were transpositions of this hard sell, which was Times Square and Broadway. Also, in those days there was a culture of short films, many of which were produced by a guy called Anatole Dauman. He would have filmmakers like Chris Marker, François Reichenbach, and so on making short films, and there was a festival in the city of Tours—the International Festival of Short Films—where everybody would go and see them. Broadway by Light won first prize one year, and later on I also won first prize with Cassius the Great, which was about Cassius Clay preparing for the championship fight against Sonny Liston in 1964, and eventually became the feature film Muhammad Ali: The Greatest.

Schuman: Were you a big fan of boxing?

Klein: Yeah, the sport I took at university was boxing, and then I boxed in the army. I was the middle- weight for my regiment, and we had competitions between regiments. If I boxed on a Friday night, I would have the weekend off, so instead of being AWOL, I would have a pass to spend two days going to the local cities and finding girls. But there were boxers in my regiment who had no idea about boxing as a science. They were farmers or steelworkers, and all they knew was fighting in the streets. I remember that there was a boxer who wasn’t very big, but he was powerful. He would go into the ring and just want to hit the other guy—and when he did, the fight was over.

Still from Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, directed by William Klein, 1966

Still from Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, directed by William Klein, 1966Schuman: What did you see in Cassius Clay that made you want to make a film about him?

Klein: I didn’t understand anything about Cassius Clay when I started making the film. What I knew about Cassius was what I read in the white press. They all thought that he was a clown and that his fights were rigged. He was taken up by a bunch of sportsmen called the Louisville Syndicate. They bought the rights to Cassius Clay as they would a racehorse. They were from Louisville and always dreamt about winning the Kentucky Derby, so they saw a good investment in this young guy who had won the Olympic title. So they got the rights to him, paid for his training, and arranged his first fights. So most people thought that his fights were rigged, and that the career of Cassius Clay was completely manipulated. It was only much later that people realized how good he was, and what a rough fighter he really was, because he demonstrated that he could take a punch. He took too many punches, actually, and said, “I’m the greatest of all time!” before he could prove it. In Miami in 1964 he fought Sonny Liston, who everybody thought would wipe him out. But Sonny Liston had no idea how fast a fighter Ali was; he couldn’t hit him, and after six or seven rounds Liston gave up.

Schuman: Why did you decide to move from making short, abstract films to documentaries, and then to feature-length narrative films?

Klein: Well, most of the filmmakers that became the vanguard of French moviemaking, and eventually became icons, showed their short films at Tours and then went on to make feature films. The short films were all more or less abstract; they told a story, but the story was mostly about movies. So the festival was a place where film ideas were planted, which eventually became French as well as Polish, German, and Italian cinema. And how could you make a feature film without a story?

Schuman: In 1969, you made a satirical superhero film called Mister Freedom, which, like Broadway by Light, was critical of American commercialism, but in a very different way.

Klein: Yes, superheroes are a common language of movies nowadays, but that didn’t exist at that time. You would see all the superheroes in comic strips, but the thing the struck me was that you never knew who Superman, or the Hulk, or Spider-Man was working for. I mean, they were out for the destruction of evil and the promotion of good, but who was financing these guys—who was behind them, and who were they working for? So I had the idea to do a film about a superhero called Mister Freedom, who was pushing American freedom, but treated France like a third-world country. Mister Freedom was like Captain America, but the hero of God knows what—he was selling the American dream, but the American dream in the hands of Mister Freedom was actually a nightmare. At one point in Mister Freedom you see the elevator of the Freedom Building, and each floor is a supernational company—steel, or oil, or Unilever, and so on—and it’s clear that Mister Freedom is working for all the supercompanies of domination and oppression.

William Klein filming Björn Borg for the movie The French, Roland Garros, Paris, 1981

William Klein filming Björn Borg for the movie The French, Roland Garros, Paris, 1981Schuman: You also made a sports documentary in 1981 about the French Open: The French.

Klein: Yes, I used to play a lot of tennis—every day in the summertime, and two times a week all year around. I love to play; I love to hit the ball; I love the idea of geometry, and placement, and everything else that makes tennis great. Also, I was a groupie of heroes like Björn Borg, John McEnroe, and so on, so when I was asked to do a film on Roland Garros I thought that it would be a good opportunity to get to know my tennis heroes, and eventually become friends with some of the people I admired. But it didn’t really work out that way.

I never got to be buddies with Borg or McEnroe, and a lot of these players were pretty stupid—Jimmy Connors’s idea of participating in the movie was to drop his pants and simulate jerking off. There were only two or three guys who I got on with, people like Yannick Noah and a few others, who understood that I was trying to tell the story of what was going on in the world of tennis. But everybody in a tournament is out to make his mark, accumulate points, and progress, so they had no time for philosophizing about tennis and the role that they were playing. But I had fun.

Schuman: Do you see any parallels between great sportsmen and great artists?

Klein: They are superheroes. Borg at one point was unbeatable. I remember there was an advertising poster for JVC with Borg jumping up and hitting a backhand; he was so perfect and beautiful. So these guys—Borg, Muhammad Ali—they knocked me out, and I learned a lot from them.

Schuman: What are you working on now?

Klein: I wrote a film scenario about a year ago that I’m trying to get produced, and I just published a photography book, Brooklyn + Klein (2015). For me, having grown up in Manhattan, Brooklyn was always the pits; nobody used to care about Brooklyn. The only thing I remember is that when I was growing up, every time I met a girl at a dance in college or wherever, she would live in Brooklyn and we would have to take the subway for an hour. But Brooklyn was really a distant suburb. Nowadays, it’s very chic, and everybody wants to live in Brooklyn—even Hillary Clinton has her office in Brooklyn.

William Klein, Candy store, Amsterdam Avenue, New York, 1954

William Klein, Candy store, Amsterdam Avenue, New York, 1954Schuman: Why did you choose to make a book about Brooklyn today?

Klein: I had a contact at Sony—who is now making digital still cameras—and they wanted to commission a project. I was trying to think of a subject that wouldn’t be at the end of the world, so I hit upon Brooklyn. Also, I guess it has something to do with my obsession with New York. But I thought Brooklyn wasn’t what it’s cracked up to be. I still have that Manhattan point of view a little bit, and see it as a second-rate suburb.

Schuman: Did you find it interesting to photograph nevertheless?

Klein: I find everything interesting to photograph. For me it was always Hicksville and still is—even if Hillary Clinton does have her office there—so I wasn’t seduced by Brooklyn. But I loved going to Coney Island when I was a kid, and I still do. And there were things that happened in Brooklyn that I don’t think could happen anywhere else. One night we were watching a [minor league] doubleheader: the Brooklyn Cyclones against the Staten Island Yankees. Staten Island, can you imagine? How can they be Yankees? Anyhow, we were watching the doubleheader and a guy came over. He recognized me and said, “I’m a Czech rabbi. I came over to Brooklyn in 1980, and I remember the 1985 playoffs like it was yesterday. Do you remember that?”

And I said, “No, I don’t” [laughs]. And here’s this Czech rabbi reminiscing about the playoffs in 1985, and he said, “Do you want to see a Hasidic prayer session?” And I said, “Sure.” And this was at, like, midnight. So we went there, and they all had fur hats on; this was in August. And they said, “Okay, you can take photographs, but no faces.” Then after a while they relented and started coming over to me, saying, “Take a picture of that guy—he’s got an incredible face!” That was the weirdest evening I’ve had in a long time.

William Klein, Vertical Diamonds, 1952

William Klein, Vertical Diamonds, 1952All photographs © William Klein and courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York, and HackelBury Fine Art, London

Schuman: What did you do last night?

Klein: David Lynch has a nightclub in Paris called Silencio, and he asks various people to show their work and talk about it. So they invited me to come, and I showed a couple of film excerpts: from Messiah (1999)—a film I made about Handel’s oratorio—and from my film about another messiah called Muhammad Ali, and several other sequences, as well as a mixture of different experiments in photography. I was there until very late last night.

Schuman: What’s it like to be an artist now?

Klein: I think it’s a good way of living and … [pause] I find it difficult to answer that question.

Schuman: What inspires you now?

Klein: The things I’ve done in the past lead to new things … and here I am, a hundred and fifty years old.

Schuman: How does it feel to be eighty-seven? When you look back on your life and reflect on your work, are you proud of what you’ve accomplished?

Klein: How does it feel to be eighty-seven? Not so good. But I’m satisfied with the different things I’ve done. And I want to continue as long as possible.

This article and photographs were originally published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” and in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present (Aperture, 2018).

10 Photographers on Dreams of Escape

Over the past year, due to lockdown measures and travel restrictions, many photographers have seen a drastic shift in their day-to-day creative practices. Some artists took this as an opportunity to reengage with their archives—looking back at previous travels or life before the pandemic. Others turned their cameras inward, focusing on interior environments and new ways of creating photographs.

The latest edition of the Magnum Square Print Sale, Ways for Escape, brings together photographs representing the things we take solace in—and the ways we make our getaway.

Through July 18, 2021, collect these signed and estate-stamped, six-by-six-inch, museum-quality images for $100 each. When you purchase through this link, you directly support Aperture’s programming, publishing, and operations. Below are highlights from Ways for Escape: The Magnum Square Print Sale.

Khalik Allah, Harlem, New York City, 2017, from the series 125th & Lexington

Khalik Allah, Harlem, New York City, 2017, from the series 125th & LexingtonKhalik Allah

“The only way of escaping a problem is by facing it. Averting our gaze is often how problems are deepened. The more you look at fear, the less you see it. Shooting at nighttime in the streets, without a flash, my photography is predicated on available light, proximity, and time; but I’m trying to escape those limits by focusing on what’s eternal in a person. By documenting the light in the eyes of what people in the streets see, the result is emotion written on emulsion. The way the system is built, some of my subjects are locked up on the outside. They’re not contained by barbed wire and prison gates, but by a vicious cycle that’s hard to escape.”

Matt Black, Fort Bragg, California, 2015

Matt Black, Fort Bragg, California, 2015Matt Black

“Photographers are bound by the physical world, but their true region of exploration is the mind. Through pictures, we can find fresh ways of understanding our world, slipping past accepted wisdom and into the new.”

Sabiha Çimen, A shy girl uses a palm leaf to hide her face at a Qur’an school, Istanbul, Turkey, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, A shy girl uses a palm leaf to hide her face at a Qur’an school, Istanbul, Turkey, 2018Sabiha Çimen

“Things can be hidden in plain sight. A face is recognizable even to a newborn, but when that face is hidden, the image can become a mirror, where our selves are reflected back to us. Photography reveals things to the heart even when they cannot be seen with the eyes.”

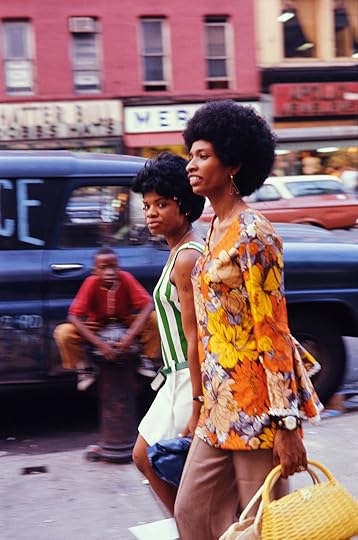

Ernest Cole, New York City, 1971

Ernest Cole, New York City, 1971Ernest Cole

“The extraordinary element of Ernest Cole’s photography is that, rather than ‘choreographing movement’ in the style of film critic André Bazin’s explanation of mise-en-scène, he is ‘stealing momentum’ in real time on the street. Sometimes the best way to escape is by stepping outside. As Bobby Womack sang in 1972: ‘You can find it all in the street, yes you can, oh look around you, look around you, look around you.’” —Estate of Ernest Cole

Cristina De Middel, Mata Atlántica forest, Brazil, 2020, from the series Boa Noite Povo

Cristina De Middel, Mata Atlántica forest, Brazil, 2020, from the series Boa Noite PovoCristina De Middel

“Buy a map, get a car, and run away. Throw away the map after you realize you can use the car navigator. Stop driving after you realize a satellite is sending your coordinates to a database that will predict your need to stop after three hours to fill the tank. Start receiving advertisements about nearby tourist attractions and sodas to calm your thirst. Get out of the car and start walking while you understand that your glorious breakaway is just a performance to fool yourself into believing that you still control your life.

After thousands of years of mythology and philosophy, it turns out that destiny and fate were just a database, and the only real escape is not based on distance (physical or emotional) but in randomness, chaos, and oblivion. Now, start believing that these things actually exist and start trying to control them. Go back to the beginning of this text and start over again.”

Elliott Erwitt, Provence, France, 1955

Elliott Erwitt, Provence, France, 1955Elliott Erwitt

“Photography is really very simple. The only important thing is to keep shooting. Commercial or fine art, it doesn’t matter. Nothing happens when you sit at home.”

Harry Gruyaert, Picnic, Extremadura, Spain, 1998

Harry Gruyaert, Picnic, Extremadura, Spain, 1998Harry Gruyaert

“I was traveling by car in Extremadura, in Spain, when I was attracted by something that sounded like a big party going on. I parked the car and climbed up onto a little hill. From there, I had a perfect vantage point on what was going on: a large gathering of people having a picnic.

The atmosphere, the colors, the mottled light falling on the people sitting around tables: it was like looking at an impressionist painting. I shot a few pictures and drove on. Looking back at this image, I feel it represents everything we have missed during this COVID-19 period: the pleasure of being outside, sharing food, and happy moments with others.”

Ernst Haas, New Mexico, 1952

Ernst Haas, New Mexico, 1952Ernst Haas

“Ernst Haas loved the American desert landscape of the West. When he finally was able to leave Austria after World War II, his dream was to go there and explore all the landscapes he had seen in books and films. This picture symbolizes not only Ernst’s own escape and the journey toward a new beginning; it also shows the loneliness of freedom, where only nature’s light guides the way.

One of Ernst’s favorite places to photograph was among these white sand dunes. The desert embodied not only his, but also humankind’s quiet reflection and search for restored meaning. There, Ernst felt he could heal his life and restore his position within nature. After the chaos of war, the desert offered the reflective purity of nature and an escape from humankind’s disorder.” —Estate of Ernst Haas

Sohrab Hura, from the series Life Is Elsewhere, 2008

Sohrab Hura, from the series Life Is Elsewhere, 2008Sohrab Hura

“I was never interested in photography. In my last year of high school, 1999, my mother fell sick. I’d be locked up in my room and sometimes beaten for reasons I could not understand. Because I was the only other person at home, I could also not leave. At that time, I felt like I had lost everything. My mum was diagnosed with schizophrenia and, after she was hospitalized, an extremely kind photographer took me along with him on his trip to the mountains and taught me the basics of how to use a camera. I’d make photos of sunsets and sunrises and mountains and the large blue sky, photos that I’d feel quite embarrassed to look at today. But it distracted me from everything that had unfolded at home. Later, when I went to collect my prints, the person behind the counter took me aside and told me that he found the photographs very beautiful. For the first time in a long time, at that moment, I felt like I was worth something; not because he had found my photographs beautiful, but because a complete stranger had felt touched by me. For a moment, I felt like I existed.”

Susan Meiselas, Returning home from Manhattan Beach, Little Italy, New York, 1978

Susan Meiselas, Returning home from Manhattan Beach, Little Italy, New York, 1978All images courtesy the artists/Magnum Photos

Susan Meiselas

“In this image, three old friends huddle together, having escaped on a long, hot, summer day at the beach, with no other purpose than to spend time away from home on a small adventure.”

The Magnum Square Print Sale, Ways for Escape, is available through July 18, 2021 at 11:59 p.m. PT. Collect signed and estate-stamped, six-by-six-inch images for $100 each through Aperture’s affiliate link.

July 8, 2021

The Photography Collectives Telling New Stories across South Asia

In South Asia, the visual is deeply connected to history and culture, seeping into the subconscious through storytelling and mythmaking. The photograph and its recent accessibility, in digital and analog forms, mediate questions of identity, creating a space for personal inquiry and experimentation. Many photographers, writers, scholars, and visual anthropologists have chosen to organize themselves collectively to realign their positions with photography. The shared colonial past between India and the subcontinent, including Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, has caused underground histories to be forgotten, buried in the larger narratives of the land. Photographers have come together, over the last decade, to bring alternative histories to the forefront and make sense of the contemporary realities and geographies that seek to define them. New solidarities have emerged that allow for a retelling and a renegotiation of political histories that reference our colonized pasts—a retelling that seeks to upend expected stereotypes of one’s assumed identities.

What has surfaced from this resistance is a larger consortium that pushes the boundaries of what has been considered photographic in both aesthetic and form, incorporating interdisciplinary approaches that look at the relationship between the photograph and its subject in order to place its readings in the hands of the people whose stories are being narrated. For many, this act of coming together has been necessitated through shifts in the social and political landscape of their respective countries. These formations have allowed for multiple intersections of learning and collaboration, forging alliances outside the parameters of geographical and national identities. New alliances give way to creative experiments that can allow for a reimagination of personal histories and, by extension, of the symbolic potential of the image.

Rita Khin, Body and Soul, 2018

Rita Khin, Body and Soul, 2018Members: Khin Kyi Htet, Rita Khin, Shwe Wutt Hmon, Tin Htet Paing, and Yu Yu Myint Than

“Since the coup on the 1st February [2021], we have been under the military junta for exactly one month. Days are tougher one after another. Individually and in collective spirit, we all take part in this revolution every day; some of us document and create work responding to and reflecting on the crisis. When we are traveling alone, we remain in communication to ensure all of us are safe. I feel I am very lucky to be a part of a collective in such a time. I have joined my Thumas in these protests against the coup. A few of us live close to each other and try to support and heal each other. We cook for the group and try to eat together.” Shwe Wutt Hmon sent these words in March, while in the midst of the recent military coup in Myanmar that fractured the short span of quasi democracy the country gained in 2011. This volatile political climate and a search for belonging had created a new space for personal and exploratory voices in lens-based media. Photographers had previously largely worked as documenters of news, keeping the personal away from the public realm. Unsettled by this convention and how women’s voices were negated, five female practitioners were motivated to gather under the name Thuma Collective in 2017. (Thuma translates from Burmese as her.) Their work has created space to explore individual perspectives and self-realizations, touching on subjects ranging from geopolitics to sexuality and identity. Each member brings an awareness of varied forms of photography, from the journalistic to the diaristic, seeking to redefine the cultural identities imposed on them.

Zainab Mufti, Absence, 2019

Zainab Mufti, Absence, 2019Cofounders: Nawal Ali, Ufaq Fatima, and Zainab Mufti

Kashmir has been seen in our visual landscape through the eyes of various authors over time, as a site of either militarized brutality or exoticized beauty. Images that speak of state-supported violence and its physical and psychological manifestations have been imprinted in news archives covering decades of this land under siege. Photography, in that respect, has existed as an economic tool for the region’s largely male-dominated community of image makers. Nawal Ali, Ufaq Fatima, and Zainab Mufti, who live in Kashmir, desired to use the camera to create a counternarrative to this masculine journalistic gaze, and in March 2019, they founded Her Pixel Story. Through their collaboration, they encourage women photographers to find their own voices and tell the stories of other women, which are often forgotten in the larger narratives of political discourse.

A shift of this magnitude requires the creation of support structures for members to question the violence of patriarchy and rethink approaches to photography. Embarking on this journey has also meant a negotiation with state control and India’s Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, where criticism of the state can lead to imprisonment without trial, as happened to the Kashmiri photojournalist Masrat Zahra in 2020. These humsheras (sisters), as the collective’s members call themselves, organize walks with women artists in the city, claiming their public presence as they bear witness to an existence under occupation. Their political concerns are manifested in collaborative projects that allow for diverse bodies of work, with each member developing her own visual language, strengthening an alliance that they hope will grow over time.

Related Items

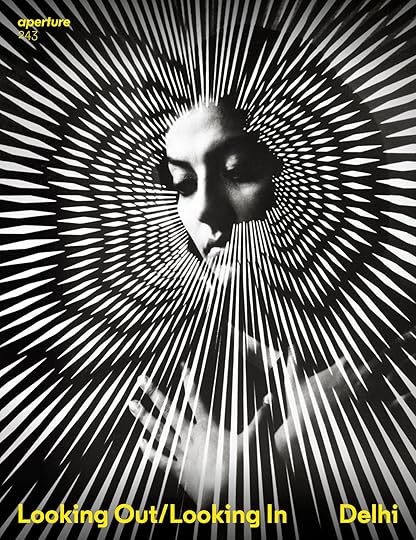

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

How Three Photographers Are Working through India’s COVID-19 Crisis

Learn More[image error] The Packet, Take with you a knife, a camera and a book of myths, 2020

The Packet, Take with you a knife, a camera and a book of myths, 2020Members: Abdul Halik Azeez, Cassie Machado, Ephraim Shadrach, Imaad Majeed, S. P. Pushpakanthan, Sandev Handy, and Venuri Perera

The Packet Collective was formed in Sri Lanka, in 2019, by a community of artists who gathered over extended meals in an apartment in Colombo. As a collective, they wanted to focus on how shared time and slowness can give rise to unique perspectives. This exchange and collaboration among the members, and with other people from the art community, allowed for chance encounters in their personal approaches to the medium. Through informal conversations during walks, community dinners, and travels, they expressed a stand against the privileged and institutionalized mechanisms in the country’s art scene. Their work resulted in a deconstructed, collaborative art book, The Packet, that gave the collective their name. “Instead of ‘speaking at’ or ‘speaking to,’ we’ve been asking what it means to ‘speak from’ and what it looks like to do thinking in public,” the collective states. Through the wide array of approaches and visions of its members, the group emphasizes the local, both in conversation and community building.

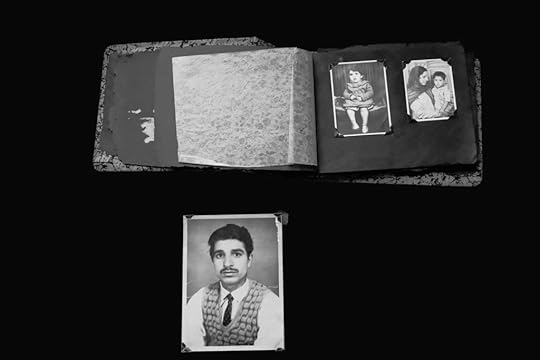

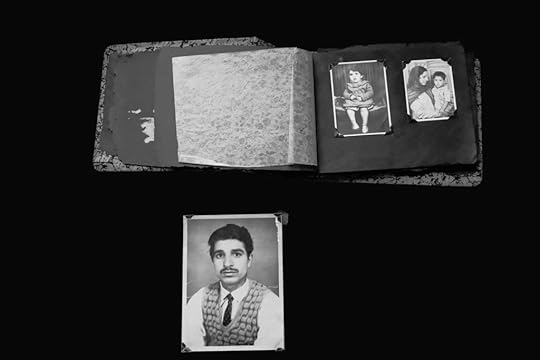

Photo-albums from various collections, 1950–2000

Photo-albums from various collections, 1950–2000Members: Ashwin Sharma, Dipti Tamang, Kunga Tashi Lepcha, Mridu Rai, Praveen Chetri, and Shivam Darnal

In April 2020, during India’s national lockdown, this group of photographers, researchers, curators, and scholars came together to reconsider narratives representing the Darjeeling–Sikkim Himalayan region. The Confluence Collective fosters a deep understanding of regional visual and oral histories by unearthing negated, marginalized knowledge and practices that have been forgotten in entrenched institutional structures. “The collective has allowed us to build our own space and voice where we can practice more freely, engage, share, and collaborate,” Mridu Rai says. “It’s also allowing us to reflect on and confront our own notions about our region and our communities.” The collective has been consolidating local family archives as a counter to exoticized representations of the region. From these encrypted private memories, once invisible histories begin to find a voice and a place. Through their community-engagement programs, organized in different villages and towns across Darjeeling Hills and Sikkim, the collective’s members are deeply invested in taking ownership of their representation, a recognition that was not possible in the past due to the occupation and exploitation of their land by colonial and state powers.

Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, Sealed, 2021. A local politician holds hands with his daughter at a public protest during his campaign for the municipality mayoral election in Noakhali, Bangladesh.

Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, Sealed, 2021. A local politician holds hands with his daughter at a public protest during his campaign for the municipality mayoral election in Noakhali, Bangladesh.Members: Aungmakhai Chak, Farhana Satu, Farzana Hossen, Juthika Dewry Gayatree, Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, and Sadia Marium

The members of Kaali Collective came together in 2018 through a shared desire to find respect and trust in the development of an author’s voice. Having studied photography at the Paathshala South Asian Media Institute in Dhaka, each member was critically looking at what constitutes an art practice, while favoring a decisive movement away from the closed nexus of the art world. The Kaalis, inspired by the mythology of power and destruction embodied by the goddess who is the group’s namesake, draw upon the fierceness of their own individuality while working collaboratively. In their recent exhibition Null and Void, presented in February 2021 at the eleventh edition the Chobi Mela photography festival, they questioned the form of the photobook. The books they exhibited shared authorship, reflecting the many emotional and physical journeys that each of the artists took together to create the work. This negation of individual authorship confronts a long history of territorial claims on the ownership of voices. As the group states, “In a region where there are prolonged histories of torture, domination, injustice, and violence against minorities, women, girls, LGBTQIA people, Kaali rejects the idea of being a mere witness; instead, they believe art and artists can make people vigilant and build a strong network among people who work toward social changes by learning from each other.”

Shashikala Sharma stops by Shanghai during an international tour to the Soviet Union, China, Burma, and East Pakistan, 1963

Shashikala Sharma stops by Shanghai during an international tour to the Soviet Union, China, Burma, and East Pakistan, 1963All photographs courtesy the collectives

Cofounders: Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati and Bhushan Shilpakar

Photo Circle formally established itself in Nepal, in 2006, the year of the Jan Andolan II (People’s Movement) that paved the way for a federal democratic republic, abolishing the country’s 240-year history of monarchy. Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati and Bhushan Shilpakar cofounded the entity to create a platform for photography in Nepal. Since its inception, Photo Circle has grown to encompass the Nepal Picture Library, a digital archive of images of the people’s history of Nepal, and Photo Kathmandu, an international photography festival, to negotiate the growing hunger for photography as an intermediary for conversations on the changing social structures in the country. The photographers today have chosen to take the lens inward, shifting the settled archetypes in the larger visual representation of the region. Through workshops and interdisciplinary engagements, Photo Circle has been an important facilitator in bringing forward fresh perspectives from practitioners and academics. Although organized along institutional lines, the members of Photo Circle and its initiatives retain the hybrid and fluid nature of an artist collective. The Nepal Picture Library, through research engagements with family albums and visual ephemera, has brought to the forefront previously unheard histories, most notably through the Feminist Memory Project and the publication of Dalit: A Quest for Dignity (2018). Photo Kathmandu has placed photographers from Nepal on the global map and reshaped conversations on the medium for audiences in South Asia and beyond.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “Collective Shift: Another South Asia.”

The Photography Collectives Telling New Stories Across South Asia

In South Asia, the visual is deeply connected to history and culture, seeping into the subconscious through storytelling and mythmaking. The photograph and its recent accessibility, in digital and analog forms, mediate questions of identity, creating a space for personal inquiry and experimentation. Many photographers, writers, scholars, and visual anthropologists have chosen to organize themselves collectively to realign their positions with photography. The shared colonial past between India and the subcontinent, including Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, has caused underground histories to be forgotten, buried in the larger narratives of the land. Photographers have come together, over the last decade, to bring alternative histories to the forefront and make sense of the contemporary realities and geographies that seek to define them. New solidarities have emerged that allow for a retelling and a renegotiation of political histories that reference our colonized pasts—a retelling that seeks to upend expected stereotypes of one’s assumed identities.

What has surfaced from this resistance is a larger consortium that pushes the boundaries of what has been considered photographic in both aesthetic and form, incorporating interdisciplinary approaches that look at the relationship between the photograph and its subject in order to place its readings in the hands of the people whose stories are being narrated. For many, this act of coming together has been necessitated through shifts in the social and political landscape of their respective countries. These formations have allowed for multiple intersections of learning and collaboration, forging alliances outside the parameters of geographical and national identities. New alliances give way to creative experiments that can allow for a reimagination of personal histories and, by extension, of the symbolic potential of the image.

Rita Khin, Body and Soul, 2018

Rita Khin, Body and Soul, 2018Members: Khin Kyi Htet, Rita Khin, Shwe Wutt Hmon, Tin Htet Paing, and Yu Yu Myint Than

“Since the coup on the 1st February [2021], we have been under the military junta for exactly one month. Days are tougher one after another. Individually and in collective spirit, we all take part in this revolution every day; some of us document and create work responding to and reflecting on the crisis. When we are traveling alone, we remain in communication to ensure all of us are safe. I feel I am very lucky to be a part of a collective in such a time. I have joined my Thumas in these protests against the coup. A few of us live close to each other and try to support and heal each other. We cook for the group and try to eat together.” Shwe Wutt Hmon sent these words in March, while in the midst of the recent military coup in Myanmar that fractured the short span of quasi democracy the country gained in 2011. This volatile political climate and a search for belonging had created a new space for personal and exploratory voices in lens-based media. Photographers had previously largely worked as documenters of news, keeping the personal away from the public realm. Unsettled by this convention and how women’s voices were negated, five female practitioners were motivated to gather under the name Thuma Collective in 2017. (Thuma translates from Burmese as her.) Their work has created space to explore individual perspectives and self-realizations, touching on subjects ranging from geopolitics to sexuality and identity. Each member brings an awareness of varied forms of photography, from the journalistic to the diaristic, seeking to redefine the cultural identities imposed on them.

Zainab Mufti, Absence, 2019

Zainab Mufti, Absence, 2019Cofounders: Nawal Ali, Ufaq Fatima, and Zainab Mufti

Kashmir has been seen in our visual landscape through the eyes of various authors over time, as a site of either militarized brutality or exoticized beauty. Images that speak of state-supported violence and its physical and psychological manifestations have been imprinted in news archives covering decades of this land under siege. Photography, in that respect, has existed as an economic tool for the region’s largely male-dominated community of image makers. Nawal Ali, Ufaq Fatima, and Zainab Mufti, who live in Kashmir, desired to use the camera to create a counternarrative to this masculine journalistic gaze, and in March 2019, they founded Her Pixel Story. Through their collaboration, they encourage women photographers to find their own voices and tell the stories of other women, which are often forgotten in the larger narratives of political discourse.

A shift of this magnitude requires the creation of support structures for members to question the violence of patriarchy and rethink approaches to photography. Embarking on this journey has also meant a negotiation with state control and India’s Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, where criticism of the state can lead to imprisonment without trial, as happened to the Kashmiri photojournalist Masrat Zahra in 2020. These humsheras (sisters), as the collective’s members call themselves, organize walks with women artists in the city, claiming their public presence as they bear witness to an existence under occupation. Their political concerns are manifested in collaborative projects that allow for diverse bodies of work, with each member developing her own visual language, strengthening an alliance that they hope will grow over time.

Related Items

Aperture 243

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

How Three Photographers Are Working through India’s COVID-19 Crisis

Learn More[image error] The Packet, Take with you a knife, a camera and a book of myths, 2020

The Packet, Take with you a knife, a camera and a book of myths, 2020Members: Abdul Halik Azeez, Cassie Machado, Ephraim Shadrach, Imaad Majeed, S. P. Pushpakanthan, Sandev Handy, and Venuri Perera

The Packet Collective was formed in Sri Lanka, in 2019, by a community of artists who gathered over extended meals in an apartment in Colombo. As a collective, they wanted to focus on how shared time and slowness can give rise to unique perspectives. This exchange and collaboration among the members, and with other people from the art community, allowed for chance encounters in their personal approaches to the medium. Through informal conversations during walks, community dinners, and travels, they expressed a stand against the privileged and institutionalized mechanisms in the country’s art scene. Their work resulted in a deconstructed, collaborative art book, The Packet, that gave the collective their name. “Instead of ‘speaking at’ or ‘speaking to,’ we’ve been asking what it means to ‘speak from’ and what it looks like to do thinking in public,” the collective states. Through the wide array of approaches and visions of its members, the group emphasizes the local, both in conversation and community building.

Photo-albums from various collections, 1950–2000

Photo-albums from various collections, 1950–2000Members: Ashwin Sharma, Dipti Tamang, Kunga Tashi Lepcha, Mridu Rai, Praveen Chetri, and Shivam Darnal

In April 2020, during India’s national lockdown, this group of photographers, researchers, curators, and scholars came together to reconsider narratives representing the Darjeeling–Sikkim Himalayan region. The Confluence Collective fosters a deep understanding of regional visual and oral histories by unearthing negated, marginalized knowledge and practices that have been forgotten in entrenched institutional structures. “The collective has allowed us to build our own space and voice where we can practice more freely, engage, share, and collaborate,” Mridu Rai says. “It’s also allowing us to reflect on and confront our own notions about our region and our communities.” The collective has been consolidating local family archives as a counter to exoticized representations of the region. From these encrypted private memories, once invisible histories begin to find a voice and a place. Through their community-engagement programs, organized in different villages and towns across Darjeeling Hills and Sikkim, the collective’s members are deeply invested in taking ownership of their representation, a recognition that was not possible in the past due to the occupation and exploitation of their land by colonial and state powers.

Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, Sealed, 2021. A local politician holds hands with his daughter at a public protest during his campaign for the municipality mayoral election in Noakhali, Bangladesh.

Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, Sealed, 2021. A local politician holds hands with his daughter at a public protest during his campaign for the municipality mayoral election in Noakhali, Bangladesh.Members: Aungmakhai Chak, Farhana Satu, Farzana Hossen, Juthika Dewry Gayatree, Rajoyana Chowdhury Xenia, and Sadia Marium

The members of Kaali Collective came together in 2018 through a shared desire to find respect and trust in the development of an author’s voice. Having studied photography at the Paathshala South Asian Media Institute in Dhaka, each member was critically looking at what constitutes an art practice, while favoring a decisive movement away from the closed nexus of the art world. The Kaalis, inspired by the mythology of power and destruction embodied by the goddess who is the group’s namesake, draw upon the fierceness of their own individuality while working collaboratively. In their recent exhibition Null and Void, presented in February 2021 at the eleventh edition the Chobi Mela photography festival, they questioned the form of the photobook. The books they exhibited shared authorship, reflecting the many emotional and physical journeys that each of the artists took together to create the work. This negation of individual authorship confronts a long history of territorial claims on the ownership of voices. As the group states, “In a region where there are prolonged histories of torture, domination, injustice, and violence against minorities, women, girls, LGBTQIA people, Kaali rejects the idea of being a mere witness; instead, they believe art and artists can make people vigilant and build a strong network among people who work toward social changes by learning from each other.”

Shashikala Sharma stops by Shanghai during an international tour to the Soviet Union, China, Burma, and East Pakistan, 1963

Shashikala Sharma stops by Shanghai during an international tour to the Soviet Union, China, Burma, and East Pakistan, 1963All photographs courtesy the collectives

Cofounders: Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati and Bhushan Shilpakar

Photo Circle formally established itself in Nepal, in 2006, the year of the Jan Andolan II (People’s Movement) that paved the way for a federal democratic republic, abolishing the country’s 240-year history of monarchy. Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati and Bhushan Shilpakar cofounded the entity to create a platform for photography in Nepal. Since its inception, Photo Circle has grown to encompass the Nepal Picture Library, a digital archive of images of the people’s history of Nepal, and Photo Kathmandu, an international photography festival, to negotiate the growing hunger for photography as an intermediary for conversations on the changing social structures in the country. The photographers today have chosen to take the lens inward, shifting the settled archetypes in the larger visual representation of the region. Through workshops and interdisciplinary engagements, Photo Circle has been an important facilitator in bringing forward fresh perspectives from practitioners and academics. Although organized along institutional lines, the members of Photo Circle and its initiatives retain the hybrid and fluid nature of an artist collective. The Nepal Picture Library, through research engagements with family albums and visual ephemera, has brought to the forefront previously unheard histories, most notably through the Feminist Memory Project and the publication of Dalit: A Quest for Dignity (2018). Photo Kathmandu has placed photographers from Nepal on the global map and reshaped conversations on the medium for audiences in South Asia and beyond.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 243, “Delhi: Looking Out/Looking In,” under the title “Collective Shift: Another South Asia.”

A British Photographer’s Take on Princess Diana and Cinderella

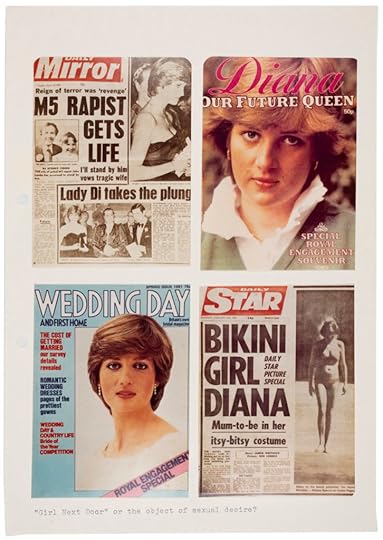

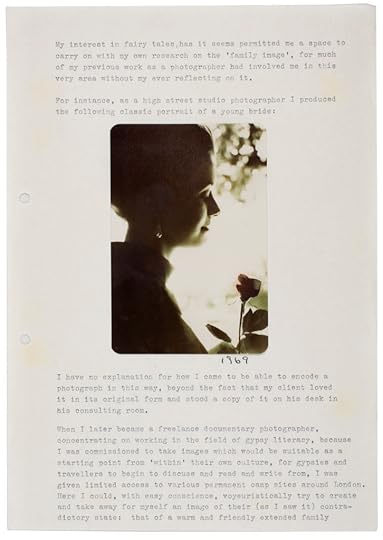

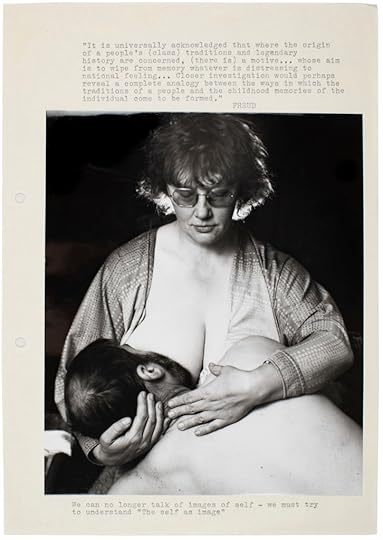

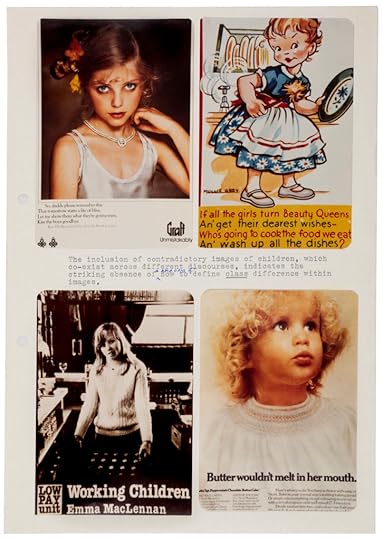

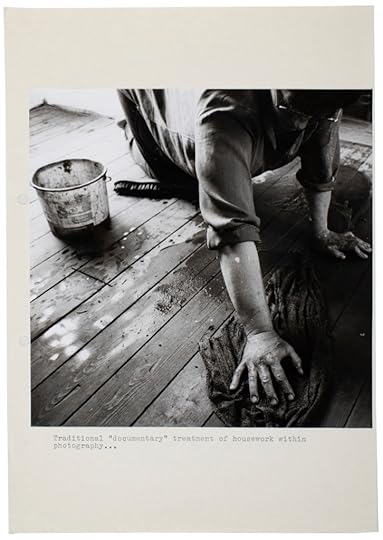

“How do we take a story like Cinderella out of the archives, off the bookshelves, out of the retail stores and attempt to prise out its latent class content? Its political and social uses?” So wrote the late British artist Jo Spence at the beginning of her 1982 university dissertation, “Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella.” In this formative illustrated text—republished last year by RRB Photobooks for the first time in its entirety—Spence traces the roots of the age-old tale across time and media, and she finds the shadow of Cinderella everywhere. By deconstructing the evolution of the story through pantomime and folklore, picture books and literature, children’s toys, Disney, and even in the latent messaging of hundreds of advertising images and newspaper headlines, she maps the endless ways the story has been mobilized throughout the decades.

It becomes clear early on in Fairy Tales and Photography that the context from which it emerged is crucial to its reading. When Spence was completing her thesis, she was living in London, and Margaret Thatcher was prime minister. In circumstances echoing the messages at the heart of “Cinderella,” class warfare was particularly intense, and Thatcherism was rigorously rooted in the idea of aspirational politics. The iconic royal wedding of Prince Charles and Diana had taken place in July 1981, attracting an estimated 750 million viewers in 74 countries, and the public and media reaction was nothing short of overwhelming. Spence was vocally anti-royal; a left-leaning activist in a conservative country, but nevertheless, she found inspiration through fairytales. For her, “Cinderella”—in its historical treatment of gendered labor, family politics, beauty, and love—was the perfect socialist subject. Slowly, she realized she could use it to interrogate the power structures that shape our lives.

In painfully vivid detail, Spence shows how stories like “Cinderella” condition us from childhood to assume our places in society, teaching readers how to behave appropriately and what to expect from one’s station in life. As her own form of visual resistance, she conjures herself into various roles, refusing to be boxed in, and masquerades at turns as the protagonist, the fairy godmother, and the ugly sisters too. It’s hard not to look upon these acts of self-representation in Fairy Tales and Photography with a strange mix of sadness and bemusement. Her work was comedic, but it was also tragic and hauntingly prescient. “I want to be happy. I can transform myself,” she scrawled in red ink around a self-portrait of herself dressed as a fairy, reminding us of the work she made, years later, on female autonomy and mental health. And in another image from 1982, she assembles a still life of household items and a plastic bust, the price tag “65p” written across one breast. This one in particular feels like a pre-echo of her diagnosis with breast cancer later that year and of her final work attacking the monetization of public health-care systems—made before she lost her battle with the illness in 1992.

Princess Diana’s name has reentered the British news cycle recently, when the BBC finally apologized for its manipulative treatment of her in a controversial and infamous 1995 TV interview. I thought of Spence when this happened and about how the scholar Marina Warner—who knew the artist personally and writes an accompanying text for the publication—said Spence was always “acerbic” about the national love of Diana and the media construction of her as “the people’s princess.” Spence died five years before Diana did, and so she never got to see how that fairy tale went awry. There was more than a little of “Cinderella” in Diana’s story, which became one shaped increasingly by the politics of representation and the power of the camera. “How trenchant [Spence’s] response would have been to the paparazzi’s pursuit of Diana,” Warner notes.

“I am not sure what sort of a ‘future’ photographic theory is offering me at the moment,” Spence wrote in the final pages of her chapter on photography. “I am no longer sure who I am talking to; my photography and writing are fragmented, differing from day to day.” As it turns out, and though it was unknown to her at that time, Spence would spend the next two decades grappling with the medium, its social power, and its limitations, while adding a great deal to the canon of photographic thinking by probing its potential as both educational and therapeutic tool.

All works from Jo Spence: Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella, 1982

All works from Jo Spence: Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella, 1982Courtesy RRB Photobooks/The Hyman Collection

Later, in her musings on photography, she riffs on the language of fairy tales to reflect on her work so far. “It is impossible ever after . . . to round off arguments neatly,” she said. When she wrote this text, she was a radical emerging artist, outspoken but unsure, and her metamorphosis was just beginning. Spence’s approach to art making was always one of obsession and excess, and she gathered and gathered research, never truly willing to streamline or minimize what she wanted to say. We can see the seedlings of this clearly in Fairy Tales and Photography, and that’s really the beauty of it. It was, in the end, a way of working she carried with her for the rest of her life.

Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella was published by RRB Photobooks in 2020.

July 3, 2021

Opening Reception: Donavon Smallwood: 2021 Aperture Portfolio Prize Winner

Baxter St Camera Club of New York

126 Baxter St

New York

Online Opening Reception: 2020 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

July 2, 2021

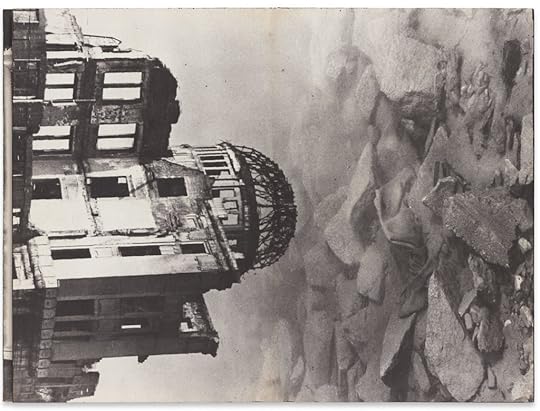

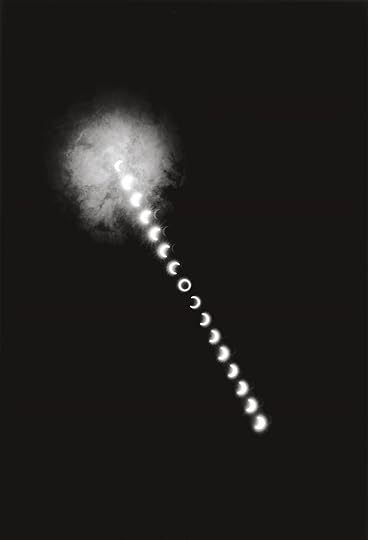

Kikuji Kawada on the Traumas of History and the Skies above Japan

Kikuji Kawada is one of Japan’s most celebrated postwar photographers. In 1959, Kawada—along with Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe, Ikko Narahara, Akira Sato, and Akira Tanno—founded the influential VIVO cooperative, which championed an expressive approach to documentary photography. He is perhaps best known for his now-iconic 1965 book The Map (or Chizu in Japanese), a disquieting exploration of the trauma of World War II. The book, designed by Kohei Sugiura, features images of stains burnt into the walls of Hiroshima’s A-Bomb Dome (now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial), as well as images related to the iconography of the American occupation. Kawada’s subsequent projects continued his interest in connecting the present with historical touchstones and shift between realism and abstraction; some observers have aptly described his work as a form of archaeology. Begun in the late 1960s, his project Los Caprichos (The caprices) was inspired by Goya etchings and features daily life in Tokyo, sometimes with a surrealist twist. Last Cosmology (1969–2000) focuses on the relationship between the terrestrial and the cosmic, capturing astronomical phenomena—solar eclipses, dramatic cloud formations, and the movements of the heavens—often above Tokyo.

Kawada, now eighty-two, continues to attract a wide international audience. His photographs were featured in the 2014 exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography, curated by Simon Baker, for London’s Tate Modern, and MACK books has recently released a volume of The Last Cosmology. For Aperture magazine’s 2015 issue, “Tokyo,” Kawada met with Ryuichi Kaneko, an influential historian and a major collector of Japanese photography books, at Tokyo’s Photo Gallery International. They discussed the arc of Kawada’s six-decade-long engagement with photography.

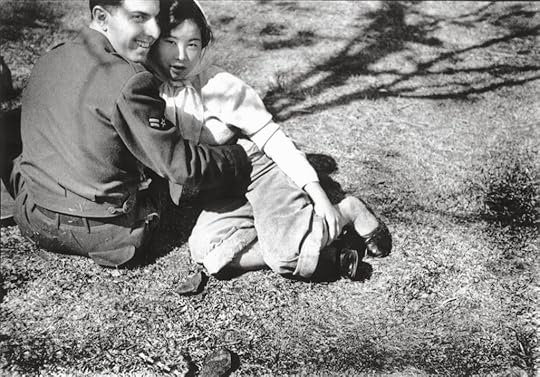

Kikuji Kawada, G.I. and a Woman at Ueno Park, 1953

Kikuji Kawada, G.I. and a Woman at Ueno Park, 1953Ryuichi Kaneko: I’d like to start by asking what made you become a photographer. What inspired your first forays into photography as an art?

Kikuji Kawada: People ask me all the time what made me decide to be a photographer, but I have to say, I’ve always found it hard to put my finger on it. It was more like one thing led to another, really. I got my first camera in high school. The first time I used it, I got on my bike and rode way out into the mountains, out where no one was around, and ended up taking pictures of some dry grass I found out there. Thinking back now, I have no idea why I did that.

I was born in a little town called Tsuchiura—really rural. You could get on your bike and end up in the mountains right away or wander around amid the rice fields.

Kaneko: Most people think of a camera, first and foremost, as a tool for taking pictures of those closest to them. But your first instinct was to go out where there weren’t any people at all.

Kawada: I liked doing things in secret—maybe not the healthiest predilection, now that I think about it [laughs]. I was interested in playing with mechanical things in secret; it felt like I was accessing the heart of the mechanism that way, its essence. Discovering its secrets.

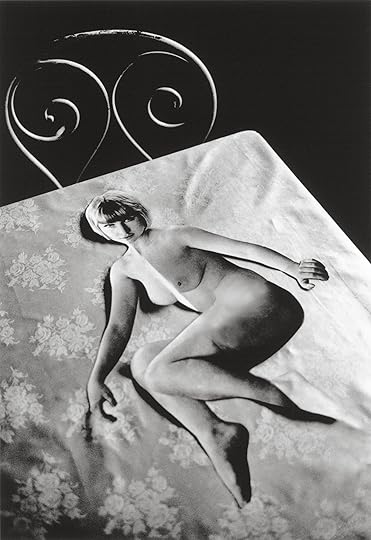

Kikuji Kawada, Nude on Table, 1966, from the series Memoir, 1951–66

Kikuji Kawada, Nude on Table, 1966, from the series Memoir, 1951–66Kaneko: In the 1950s and ’60s you published frequently in photography magazines; Shincho Weekly, Nippon Camera, and Photo Art—those magazines were your mainstay. Looking back at the photographs you published early on— Yaizu and Fishing Port at Yaizu (1957–59), or The Bar Abandoned by the Boom (1957), or even, to a certain extent, the Base photographs (1953)—did these first run in Shincho Weekly?

Kawada: Many photographs were taken for magazines but didn’t end up published. They were too strange. Shincho Weekly wanted less edgy themes for the spreads— though some were things I shot on my own time, when inspiration struck. I would stop to shoot something on the way back from an assignment, for example.

Kaneko: [By the late 1950s] you’d become a member of the postwar generation of photographers, and your work was getting a fair amount of attention. But there’s one series I really must ask you about from this time: when you went to Hiroshima. That was with Domon, right? [Ken Domon, the influential documentary photographer of this period.]

Kawada: It was. I’ve talked about this ad nauseam over the years, but long story short: I proposed a trip to Hiroshima to the editorial board of Shincho Weekly, a documentary shoot, and it was approved. I was excited at the prospect of going, but it was decided that it would have to be a special issue, and in that case it should be Domon who went. That was an order from the top. So, my hopes were dashed in an instant. The people who ended up going were Domon and [freelance journalist] Daizo Kusayanagi. They were charged with gathering evidence under the auspices of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission. It became a huge special issue. And Domon ended up going back and forth to Hiroshima many times during the process of shooting what would become the book Hiroshima (1958). The editor at Shincho was paying for these trips out of his own pocket, and at one point he said to me that he knew I’d been the one to propose the project but that I’d never gotten a chance to go, so he was going to send me along as an assistant. So, it was as Domon’s assistant that I ended up going. That was my first trip to Hiroshima.

Pages from the original maquette Chizu (The Map), 1965

Courtesy the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Kaneko: How many times did you end up going with him?

Kawada: Just once. Domon liked the finer things. He wanted to stay at the very best place in town, so we ended up in a new hotel and would walk to the Peace Park and the A-Bomb Dome, which were nearby. We would go together, but then I’d slip away and walk around on my own. And that’s when I found them: the stains on the walls of the rooms beneath the dome that became the subject of the Stain series. I would just slip away, secretly, without a word to Domon.

Kaneko: So, there were rooms underground, beneath the dome?

Kawada: When the place was destroyed, there were about thirty people—I think it was around eight in the morning or so, but at any rate, in the morning—these people had arrived for work and ended up vaporized. The place had a horrible atmosphere. Just looking at it was overwhelming. And you couldn’t see very well; there were no lights, no electricity. So, I left and gathered up a big camera and some bulbs and headed back.

Kaneko: So, that’s how you first discovered that place?

Kawada: Yes. This was going to be my Hiroshima. I could take so many kinds of pictures there. This was no longer assistant’s work; I was preparing my own project. I wasn’t thinking about anything else.

Kaneko: You said you brought back a big camera. Do you mean a 4 by 5? And lights to illuminate the rooms?

Kawada: It was a 4 by 5, yes. But I didn’t use lights; I shot in natural light. Back then, we could go in and out of the dome as we liked. In the Tate Modern book [Conflict, Time Photography, 2014], there’s that famous photograph of Kiyoshi Kikkawa, who was called genbaku ichi-go [bomb victim number one]. He ran a souvenir stand right next to the dome.

Pages from the original maquette Chizu (The Map), 1965

Pages from the original maquette Chizu (The Map), 1965Courtesy the Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations

Kaneko: I’ve heard you talk before about discovering those “stains” beneath the dome, and when I think about how they may be all that was left of people who were vaporized in an instant, all the hair on my body stands on end. You hear about things like that: people explain what happened as carefully as they can—this happened, that happened, like that. But there’s no comparison to seeing it as one image. It has so much power.

Kawada: The hard part becomes how to organize that kind of material, how to convey its enormity.

Kaneko: You published some of those photographs in Nippon Camera under the title The Map: Stain. That was August 1962. Was that their debut?