Aperture's Blog, page 50

October 4, 2021

Announcing the 2021 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist

Initiated in 2012, the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards celebrate the photobook’s contributions to the evolving narrative of photography. Each year, thirty-five selected books are shortlisted in three major categories: First PhotoBook, PhotoBook of the Year, and Photography Catalogue of the Year.

This year’s shortlist selection took place over the course of three days at Aperture’s offices in New York, and involved the review of more than eight hundred submissions. The jury for the shortlist included Emilie Boone (art historian), Sonel Breslav (director of fairs and editions, Printed Matter), Darius Himes (international head of photographs, Christie’s), Lesley A. Martin (creative director, Aperture Foundation), and Jody Quon (director of photography, New York Magazine).

“This year’s submissions faced more than eighteen months of unprecedented production challenges in scheduling and labor, access to material, and the uncertainty of another important element in bookmaking—the ability of artists, publishers, and their collaborators to come together,” observed Breslav. “It’s inspiring to witness the resilience of these artists, subjects, and communities. We’ve all had to learn to adapt in order to continue our work, finding new directions along the way.”

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact made itself known in more than one way, as Martin describes, through “the notable number of very strong, introspective projects that brought forth material grounded in the studio, as well as those drawn from archives and older bodies of work.” This year’s shortlist jury also selected three books as a Jurors’ Special Mention, acknowledging the prevalence of catalogues that responded to canceled shows or reduced audience access with publications that can also serve as DIY exhibitions.

A final jury will gather at Paris Photo this November to select the winners for all three categories. From there, the shortlisted and winning titles will be profiled in The PhotoBook Review (a newsprint publication that will accompany the Winter 2021 issue of Aperture magazine) and exhibited in Paris, New York, and tour internationally thereafter.

Below, see the thirty-five selected titles for the 2021 PhotoBook Awards shortlist.

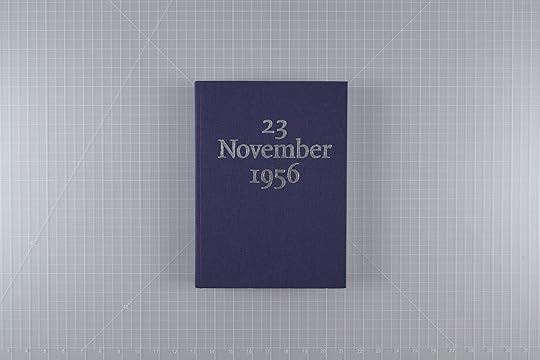

First PhotoBook

Andrea Alessandrini, Piccola Russia, Witty Books, Turin, Italy

Indu Antony, Why can’t bras have buttons?, Mazhi Books (self-published), Bangalore, India

Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina and Verónica Fieiras, eds., Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina, CHACO, Buenos Aires

Melba Arellano, Carretera Nacional, Los Sumergidos, Hudson, New York

Wiosna van Bon, Family Stranger, Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Deanna Dikeman, Leaving and Waving, Chose Commune, Marseille, France

Jeano Edwards, EverWonderful, Self-published, Brooklyn

Nancy Floyd, Weathering Time, GOST Books, London

Will Harris, You Can Call Me Nana, Overlapse, London

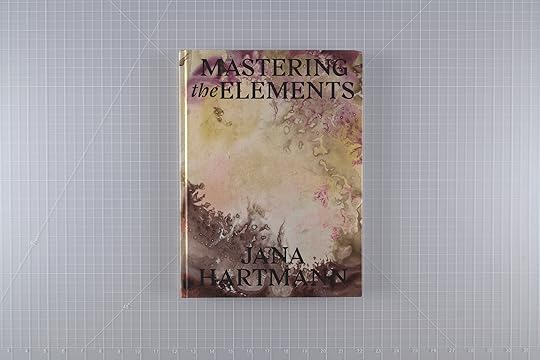

Jana Hartmann, Mastering the Elements, Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

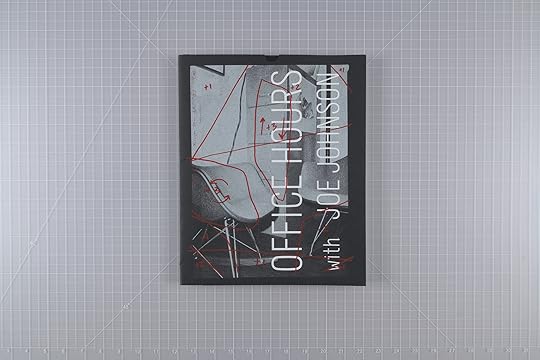

Joe Johnson, Office Hours, There There Now, Columbia, Missouri

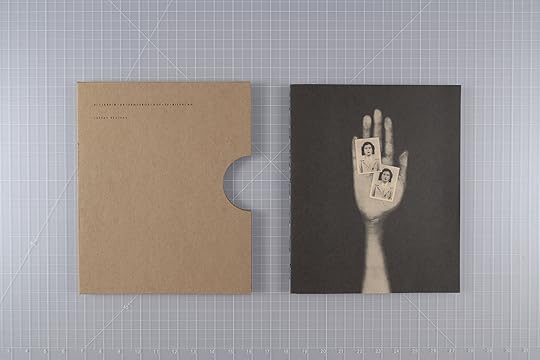

Tarrah Krajnak, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan, Dais Books, Casper, Wyoming

Luke Le, What are you looking for?, Perimeter Editions, Melbourne, Australia

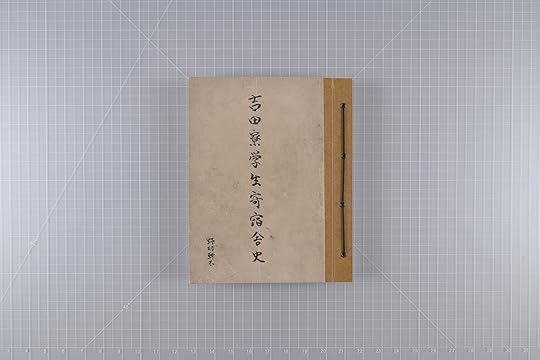

Kanta Nomura, The Yoshida Dormitory Students’ History, Reminders Photography Stronghold, Tokyo

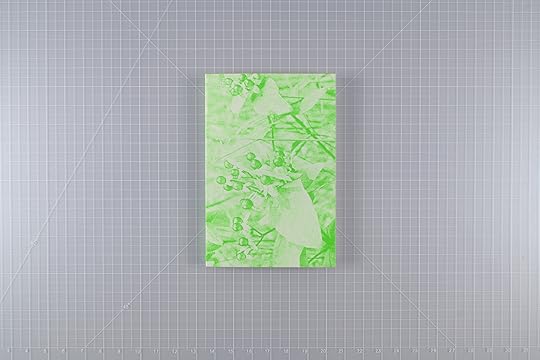

Sasha Phyars-Burgess, Untitled, Capricious Publishing, New York

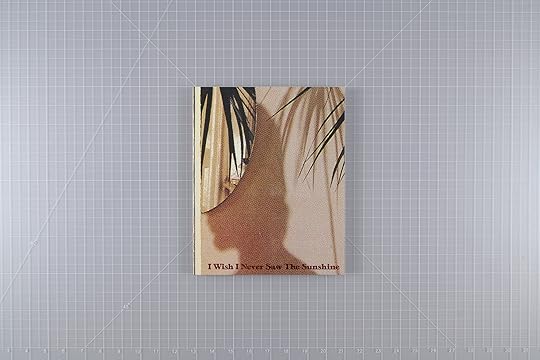

Pacifico Silano, I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine, Loose Joints, Marseille, France

Sebastian Stadler, A Close Up of a Large Rock, I Think, Kodoji Press, Baden, Switzerland

Al J Thompson, Remnants of an Exodus, Gnomic Book, Portland, Oregon

Eva Veldhoen, Play, Self-published, Utrecht, Netherlands

Elliott Verdier, Reaching for Dawn, Dunes, Paris

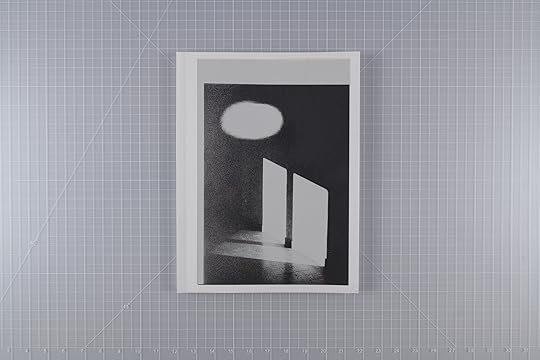

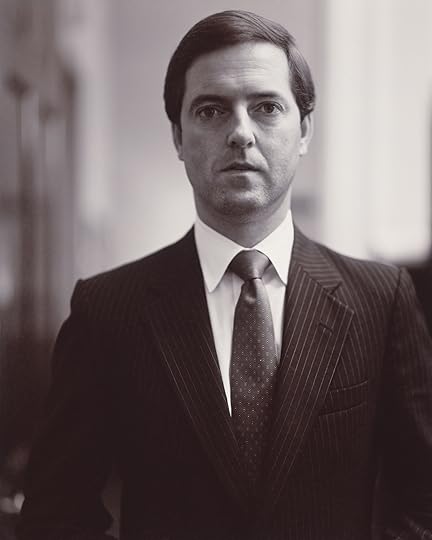

Previous NextAndrea Alessandrini

Piccola Russia

Witty Books, Turin, Italy

Indu Antony

Why can’t bras have buttons?

Mazhi Books (self-published), Bangalore, India

Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina and Verónica Fieiras, eds.

Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina

CHACO, Buenos Aires

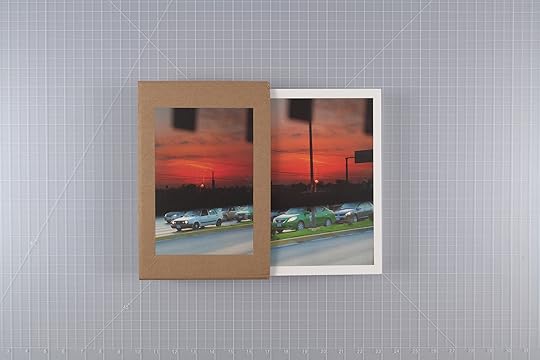

Melba Arellano

Carretera Nacional

Los Sumergidos, Hudson, New York

Wiosna van Bon

Family Stranger

Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Deanna Dikeman

Leaving and Waving

Chose Commune, Marseille, France

Jeano Edwards

EverWonderful

Self-published, Brooklyn

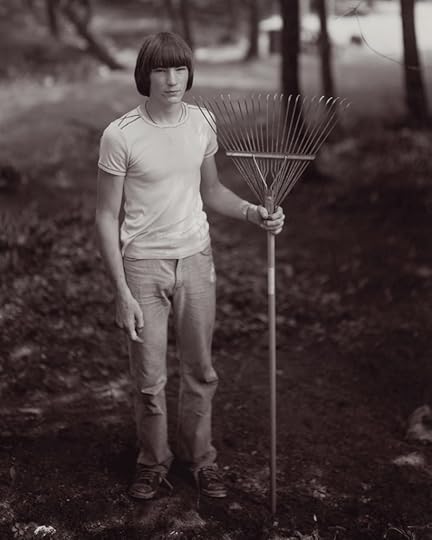

Nancy Floyd

Weathering Time

GOST Books, London

Will Harris

You Can Call Me Nana

Overlapse, London

Jana Hartmann

Mastering the Elements

Eriskay Connection, Breda, Netherlands

Joe Johnson

Office Hours

There There Now, Columbia, Missouri

Tarrah Krajnak

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan

Dais Books, Casper, Wyoming

Luke Le

What are you looking for?

Perimeter Editions, Melbourne, Australia

Kanta Nomura

The Yoshida Dormitory Students’ History

Reminders Photography Stronghold, Tokyo

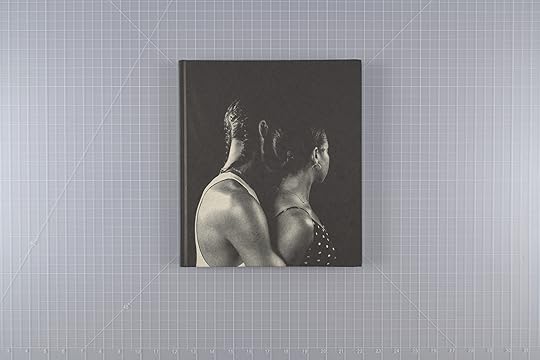

Sasha Phyars-Burgess

Untitled

Capricious Publishing, New York

Pacifico Silano

I Wish I Never Saw the Sunshine

Loose Joints, Marseille, France

Sebastian Stadler

A Close Up of a Large Rock, I Think

Kodoji Press, Baden, Switzerland

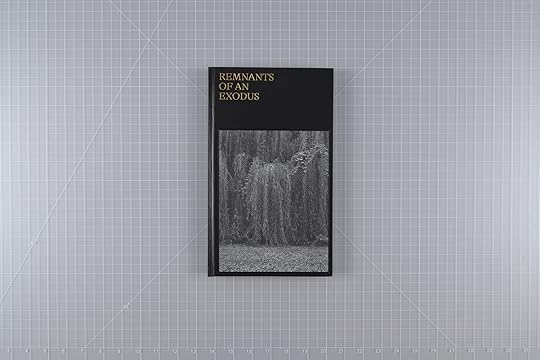

Al J Thompson

Remnants of an Exodus

Gnomic Book, Portland, Oregon

Eva Veldhoen

Play

Self-published, Utrecht, Netherlands

Elliott Verdier

Reaching for Dawn

Dunes, Paris

PhotoBook of the Year

Farah Al Qasimi, Hello Future, Capricious Publishing, New York

Jessica Backhaus, Cut Outs, Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany

Alejandro Cartagena, Suburban Bus, The Velvet Cell, Berlin

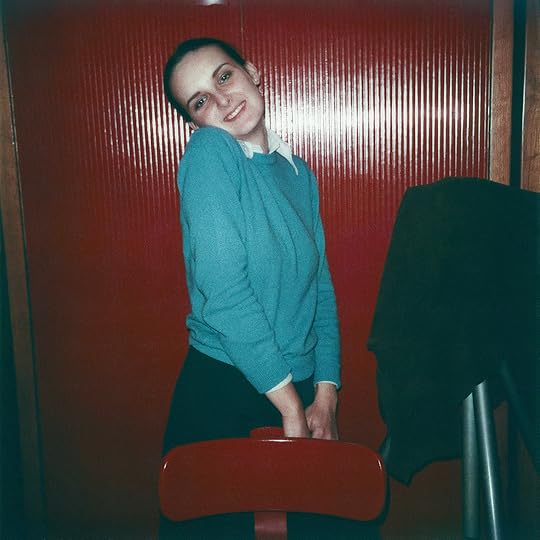

Bieke Depoorter, Agata, Des Palais (self-published), Ghent, Belgium

Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel, Electronic Landscapes: Music, Space and Resistance in Detroit, +KGP, Queens, New York

Muhammad Fadli and Fatris MF, The Banda Journal, Jordan, jordan Édition, Jakarta, Indonesia

Rahim Fortune, I Can’t Stand to See You Cry, Loose Joints, Marseille, France

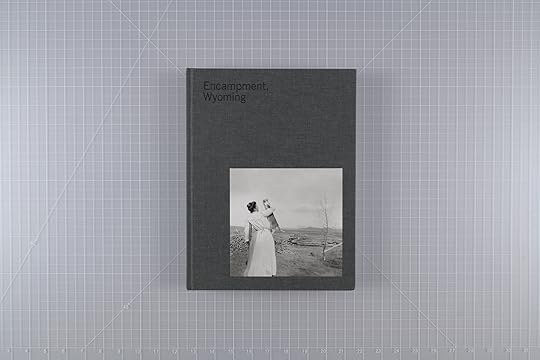

Lora Webb Nichols, Encampment, Wyoming, Fw:Books, Amsterdam

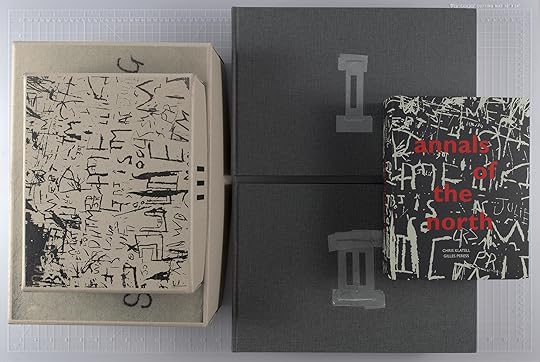

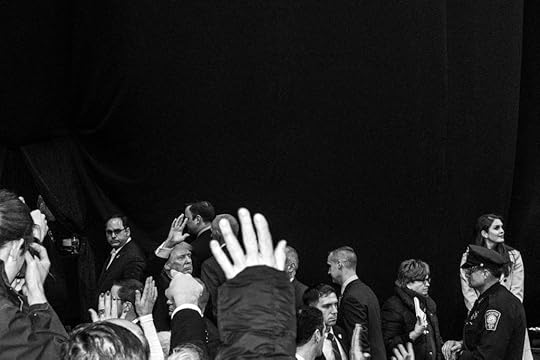

Gilles Peress, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing, Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Vasantha Yogananthan, Amma, Chose Commune, Marseille, France

Previous NextFarah Al Qasimi

Hello Future

Capricious Publishing, New York

Jessica Backhaus

Cut Outs

Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany

Alejandro Cartagena

Suburban Bus

The Velvet Cell, Berlin

Bieke Depoorter

Agata

Des Palais (self-published), Ghent, Belgium

Isaac Diggs and Edward Hillel

Electronic Landscapes: Music, Space and Resistance in Detroit

+KGP, Queens, New York

Muhammad Fadli and Fatris MF

The Banda Journal

Jordan, jordan Édition, Jakarta, Indonesia

Rahim Fortune

I Can’t Stand to See You Cry

Loose Joints, Marseille, France

Lora Webb Nichols

Encampment, Wyoming

Fw:Books, Amsterdam

Gilles Peress

Whatever You Say, Say Nothing

Steidl, Göttingen, Germany

Vasantha Yogananthan

Amma

Chose Commune, Marseille, France

Photography Catalogue of the Year

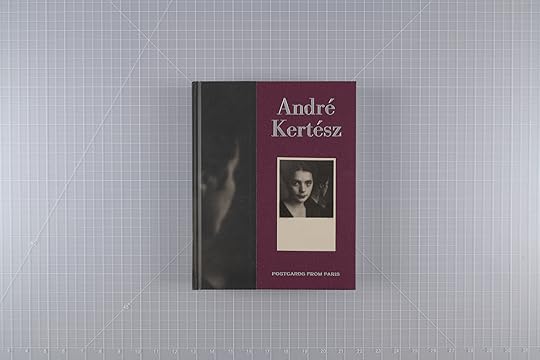

André Kertész: Postcards from Paris, Elizabeth Siegel, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Bad Ass and Beauty—One Love, Mao Ishikawa, T&M Projects, Tokyo

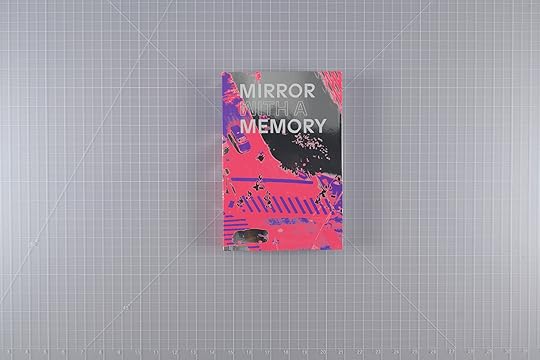

Mirror with a Memory, Dan Leers and Taylor Fisch, eds., Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

The New Woman Behind the Camera, Andrea Nelson, ed., National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999, Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, eds., 10×10 Photobooks, New York

Previous NextAndré Kertész: Postcards from Paris

Elizabeth Siegel

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Bad Ass and Beauty—One Love

Mao Ishikawa

T&M Projects, Tokyo

Mirror with a Memory

Dan Leers and Taylor Fisch, eds.

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

The New Woman Behind the Camera

Andrea Nelson, ed.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999

Russet Lederman and Olga Yatskevich, eds.

10×10 Photobooks, New York

Jurors’ Special Mention: Catalogue as DIY Exhibition

Pass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories, Daria Tuminas, ed., Fotodok, Utrecht, Netherlands, and Meteoro Editions, Amsterdam

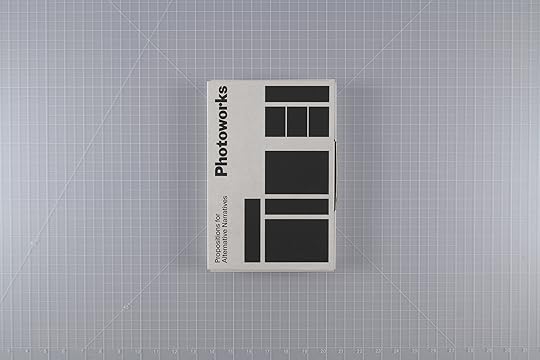

Propositions for Alternative Narratives, Photoworks, ed., Brighton, United Kingdom

Take It from Here, Zora J Murff and Rana Young, eds., There There Now, Columbia, Missouri

Previous NextPass It On. Private Stories, Public Histories

Daria Tuminas, ed.

Fotodok, Utrecht, Netherlands, and Meteoro Editions, Amsterdam

Propositions for Alternative Narratives

Photoworks, ed.

Brighton, United Kingdom

Take It from Here

Zora J Murff and Rana Young, eds.

There There Now, Columbia, Missouri

The 2021 PhotoBook Award winners will be announced during Paris Photo on Friday, November 12, 2021.

September 30, 2021

Announcing the Winning Artists of the Creator Labs Photo Fund

This summer, Aperture and Google’s Creator Labs teamed up to launch a new initiative, the Creator Labs Photo Fund, aimed at providing financial support to photographers in the wake of COVID-19. Selected by Aperture’s editors, the twenty winning artists are recognized for their exceptional vision as well as the strength and originality of their portfolios, and will be awarded a prize of $5,000 each to sustain their work and practice.

The winners of the Creator Labs Photo Fund are:

Daveed Baptiste, Adraint Bereal, Shawn Bush, Jasmine Clarke, Matt Eich, Arielle Gray, Naomieh Jovin, Priya Suresh Kambli, Tommy Kha, Sydney Mieko King, Miguel Limon, Sophie Lopez, Giancarlo Montes Santangelo, Alana Perino, Jade Thiraswas, Bryan Thomas, Maximilian Thuemler, Allie Tsubota, Aaron Turner, and Jasmine Veronica.

Aperture serves as an essential platform for artists, fostering critical dialogue in the photographic community—in print, in person, and online. “We are honored to partner with Google on the Creator Labs Photo Fund,” says Aperture’s creative director, Lesley A. Martin. “Aperture’s team of editors has selected a dynamic and diverse group of photographers, whose talent, vision, and promise are truly inspiring. We all communicate with images today—and we encourage all photographers to continue their practices ensuring a more rigorous, more expansive range of expressions to the field. Together, Aperture and Google are proud to offer these twenty photographers our support, which we hope will be meaningful for their work and careers.”

Daveed Baptise, from the series Haiti To Hood, 2018–ongoing

Daveed Baptise, from the series Haiti To Hood, 2018–ongoingDaveed Baptiste

In a series of built environments, photographer and fashion designer Daveed Baptiste examines social dynamics in Haitian American life. Drawing from his experience immigrating to and growing up in the US, Baptiste collects and rearranges materials into domestic scenes. “The common home is composed of a series of objects and surfaces within their own state of being, at times symbolizing financial status, choice, and personality,” says Baptiste. Brought together in his series Haiti to Hood, Baptiste’s layered tableaux showcase his subjects as individuals, while speaking to the evolution of their Haitian American identity.

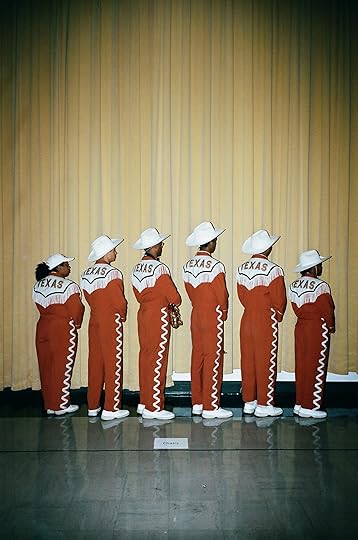

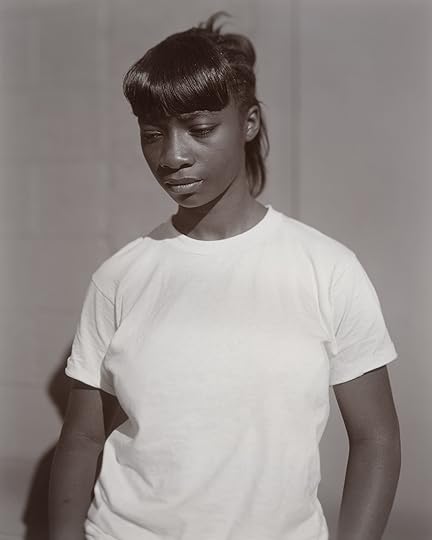

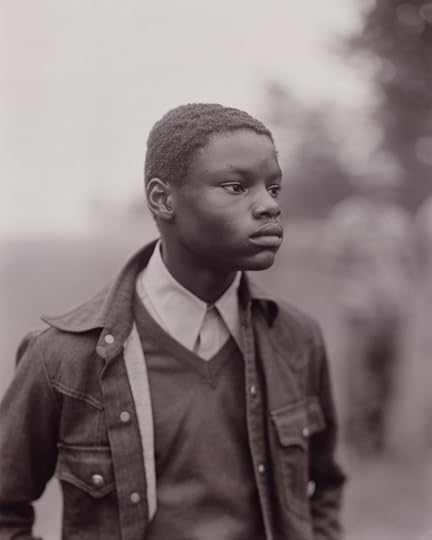

Adraint Bereal, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Black Yearbook

Adraint Bereal, Untitled, 2020, from the series The Black YearbookAdraint Bereal

Adraint Bereal’s The Black Yearbook combines images and interviews in an effort to share the experiences of Black students at the University of Texas at Austin—where only 5 percent of students identify as Black on a campus of 52,000. Since 2017, Bereal has carried his camera around, photographing moments of communal gatherings and making portraits of his peers. In one image, band members stand in formation with their backs turned to the camera, a choice Bereal explains as an act of “affirming we could hold that space and choose not to face anyone. I like to think of it as giving yourself grace.” For Bereal, this series aims to examine not only the adversity faced, but “the joy of existing in such a place that has historically gone out of their way to keep Black students outside the institution.”

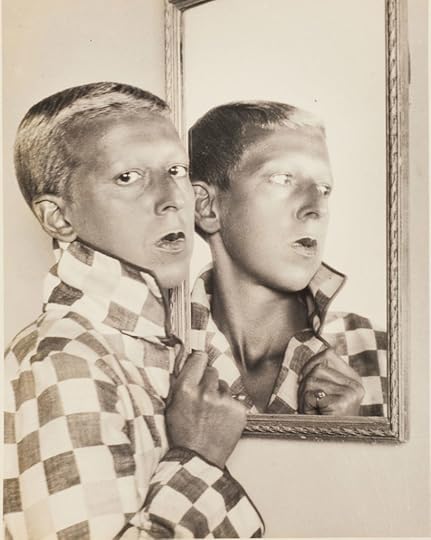

Shawn Bush, Sublimated Notation, 2020, from the series Angle of Draw

Shawn Bush, Sublimated Notation, 2020, from the series Angle of DrawShawn Bush

Through the lenses of the natural landscape and propaganda imagery, Shawn Bush examines the intersections of power, sustainability, and whiteness in the US. Working in his studio, Bush draws from propaganda imagery from the 1900s, 1960s, and 1970s to create his starkly lit, almost surreal black-and-white photographs. Throughout his process, Bush has considered the impact of the fossil-fuel industry on the natural environment, local economy, and future prospects of those left behind by corporations. The resulting series, Angle of Draw, considers the ways framing imagery impacts the national imagination—upholding systems of social, political, and economic control. “I was thinking about the photographic frame and the ability to crop as a form that censors and advertises,” Bush says.

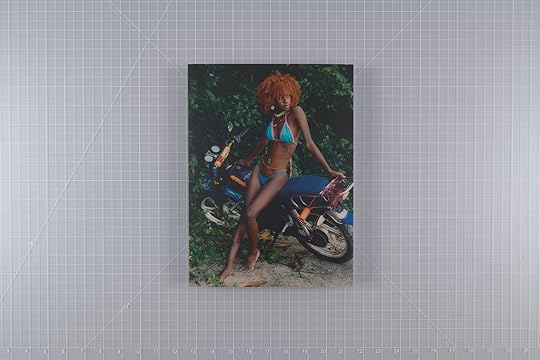

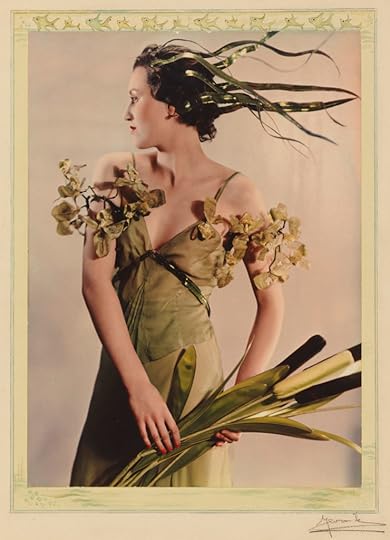

Jasmine Clarke, Marissa, 2018, from the series Shadow of the Palm

Jasmine Clarke, Marissa, 2018, from the series Shadow of the Palm Jasmine Clarke

“Myths, like photographs, exist somewhere between truth and fabrication, exactly where I want to stand as an artist,” states Jasmine Clarke. Inspired by a wide range of artists, from novelist Haruki Murakami to filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty, each of Clarke’s photographic vignettes transports the viewer into a dreamscape. A shadowed figure stands ominously behind patterned curtains, smoke rises against a fence, an obscured Ludi board’s “Home” is alit with a harsh flash, a single eye peers through shuttered doors. Walking the line between dreams and reality, Clarke’s lushly colored, uncanny images bring together her own disparate strands of familial identity and history. “I see memory and family history as fragmented, pieced together through images, telling multiple overarching narratives of cultural identity,” says Clarke. “Family is also mythology, passed down through generations.”

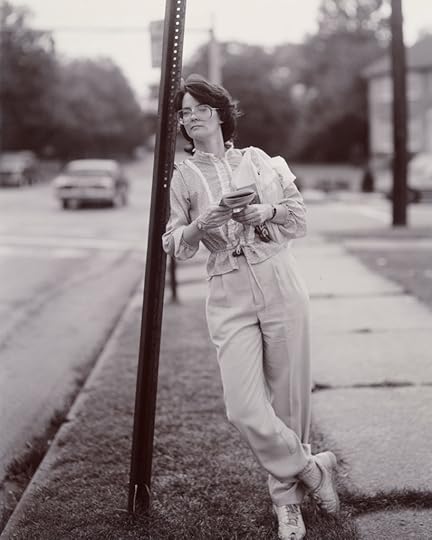

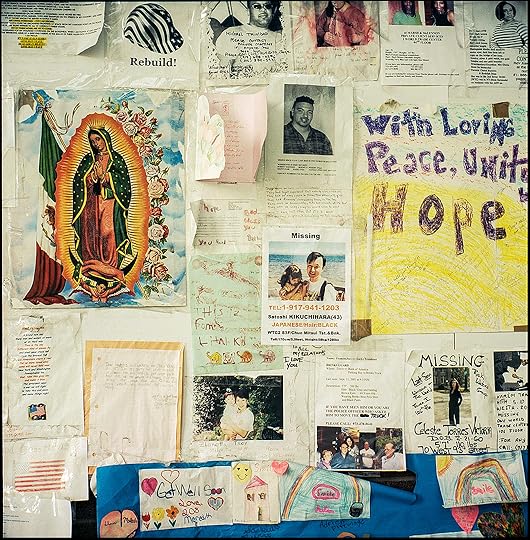

Matt Eich, Untitled, Charlottesville, Virginia, 2020, from the series Bird Song Over Black Water

Matt Eich, Untitled, Charlottesville, Virginia, 2020, from the series Bird Song Over Black WaterMatt Eich

Since 2015, Matt Eich has photographed his home state of Virginia in the ongoing series Bird Song over Black Water. Working with medium- and large-format cameras, Eich documents the natural beauty and brokenness of the landscape, exploring the ways humans have left their mark on the environment. Describing his process as largely intuitive, Eich’s black-and-white photographs simultaneously hold a quality of intimacy and detachment. Informed by the state’s colonial history, the resulting body of work presents a disarming portrait of life in Virginia. As Eich states, “I’m interested in pictures that elicit questions rather than pretend to hold answers.”

Arielle Gray, Otis’ Room, 2020, from the series Exodus 3:14

Arielle Gray, Otis’ Room, 2020, from the series Exodus 3:14Arielle Gray

Arielle Gray’s photographs beckon to a near mythical surrounding. Her series Exodus 3:14 takes its name from the scripture in which God tells Moses, “I am that I am,” followed by the instruction to state: “I am has sent me to you.” For Gray, this passage is particularly meaningful, as it nods “to a situation in which a group of people are struggling to find peace and salvation.” Photographing her close friends and family as they sifted through ideas of mortality and guilt—from her grandmother burning a catheter, to her uncle Otis’s bedroom and serene portraits of her loved ones—Gray’s work gives us a glimpse into how a group finds everyday deliverance in each other. After all, as Gray notes, “This is a story of many.”

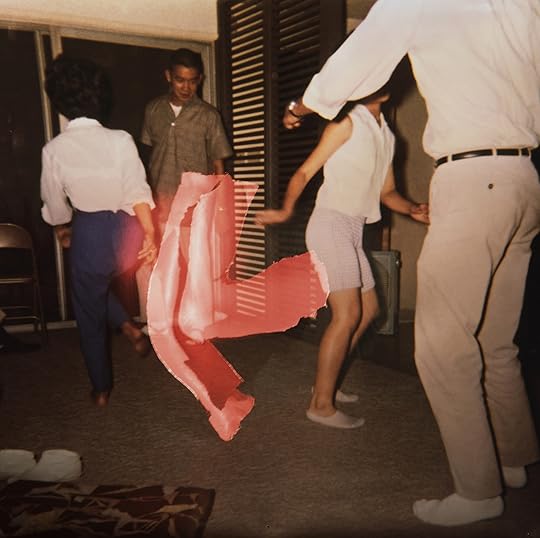

[image error]Naomieh Jovin, The Gathering, 2021, from the series Gwo FanmNaomieh Jovin

The title of Naomieh Jovin’s series Gwo Fanm translates to “Big Woman” in Haitian Creole, alluding to women whose impact on those around them radiates outward. After the passing of her parents, Jovin found herself coming back to this phrase as she explored her family’s origin story. She combines found and original images, audio interviews, and installations into richly multilayered photographs—often featuring the artist’s own direct intervention through colored paper, cutouts, or writing. “I kept in the parts that still complete the narrative and give context to what is taking place in the image while accounting for loss,” she notes. “I’ve always been able to recognize whose body part belongs to who and create this fuller perspective. It impresses me each time, because the picture becomes richer, more vibrant—almost to the point of me being able to imagine the sounds and voices.”

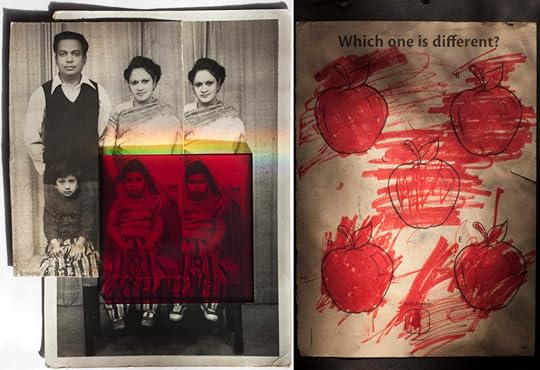

Priya Suresh Kambli, Kambli Family (Studio Portrait) & Which one is different, 2019, from the series Buttons for Eyes

Priya Suresh Kambli, Kambli Family (Studio Portrait) & Which one is different, 2019, from the series Buttons for EyesPriya Suresh Kambli

Pulling from her family’s photographic archive, Priya Suresh Kambli’s series Buttons for Eyes explores cultural hybridization, identity, and migration. Working intuitively, Kambli combines photographs and family heirlooms—such as a letter she and her sister wrote to their father—before concealing elements of the images or drawing out certain features. Through the inclusion of natural light and rainbows created through the use of a prism, Kambli infuses playful experimentation throughout the series. She had asked her husband for the prism for her fortieth birthday, but she initially had difficulty using it. “I literally couldn’t make it work,” she says. “It sat in my studio for two years, and when I picked it up again, it worked, like magic.”

Tommy Kha, May (A Costume Drama), 2020, from the series Facades

Tommy Kha, May (A Costume Drama), 2020, from the series FacadesTommy Kha

For Tommy Kha, picture-making is tied directly to fragmentation. His series Facades incorporates this concept of fragments in an exploration of Asian American identity and otherness in today’s social landscape. Kha’s playfully experimental images incorporate cardboard cutouts, jigsaw puzzles, paper masks, temporary tattoos, and more, straddling the line between still life, portrait, and self-portrait. Without the use of Photoshop, Kha builds all of his scenes in-camera using a combination of fabricated props, available light, and performance. Leaning into moments of awkwardness, Kha views his work as an aesthetic device to decode, confirm, and validate Asian American identity, stating, “at the moment, there’s quite a bit of space to visualize Asian American narratives and archives, and what that can look like. There’s excitement to see what those pictures can look like.”

Sydney Mieko King, Redcliff St., 2020, from the series Entanglement

Sydney Mieko King, Redcliff St., 2020, from the series Entanglement Sydney Mieko King

Sydney Mieko King fuses the two- and three-dimensional in her abstracted images layering family archival photographs against plaster molds of her body. Through this intersection, King’s body acts as a container of personal and ancestral memory, as well as a means of exploring her own identity as a mixed-race woman. The plaster molds she creates are attempts at evoking movement and breath, such as a “bend in the stomach, legs wrapped around each other, the overlapping parts of the body.” Ironically, the task of molding herself is an exercise in stillness, in order to prevent the plaster from falling off of her body. “Photography allows me to invent overlaps between my own body and experiences and those of my family. The medium flattens and resolves space,” says King. “The camera’s way of equalizing presence and nonpresence allows me to capture a shifting space in which present and past moments are suspended in time and thus able to interact.”

Miguel Limon, Al Principio, 2019, from the series Hogares Perdidos

Miguel Limon, Al Principio, 2019, from the series Hogares PerdidosMiguel Limon

When Miguel Limon visited the steel mill where their grandfather worked on the South Side of Chicago, they recalled feeling overwhelmed: “Having known the impact the steel industry has had locally and nationally, it’s a lot to consider how many different histories are tied to the space.” Limon’s series Hogares Perdidos highlights the impact of Latinx and Chicanx immigrants in the Midwest, reconnecting members of the community to their work and grappling with familial memory. Citing LaToya Ruby Frazier and Laura Aguilar as influences, Limon utilizes self-portraiture to insert himself into scenes of family life and labor. Limon reflects, “As a whole, I believe being both in front of and behind the camera allows for an assertion of identity outwardly but also inwardly, providing the liminal space to define my histories and their worldly contexts.”

Sophie Lopez, At times I forget my mother has existed in the minds of others, 2021, from the series Productions of Chimera

Sophie Lopez, At times I forget my mother has existed in the minds of others, 2021, from the series Productions of ChimeraSophie Lopez

Inspired by I Spy books, Sophie Lopez combines family photos, household objects, and other ephemera into richly layered tableaux. Certain recurring motifs appear throughout her images, from fruit peeled or cut open, to the artist’s hand intervening into the frame, to washi tape—which Lopez uses to represent nonlinear thinking and history-making. Grounded in postcolonial theory, Lopez’s work explores concepts of belonging, power in agency, and the vernacular photo as evidence. “I named this series Productions of Chimera because it felt as though I was rewriting as I saw fit,” says Lopez. “Chimera is defined as an object that is aspirationally longed for but is ultimately illusionary or impossible to achieve.”

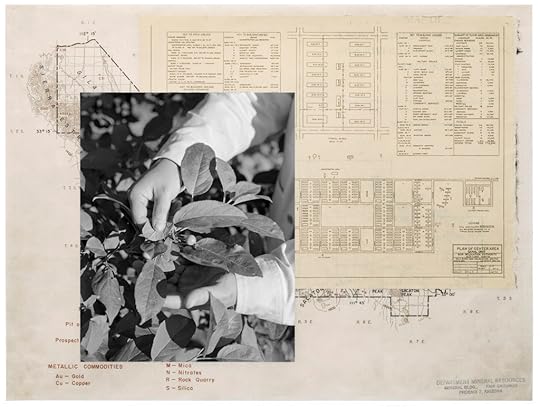

Giancarlo Montes Santangelo, “Young banana plants, growing prospects of a country,” 2021

Giancarlo Montes Santangelo, “Young banana plants, growing prospects of a country,” 2021Giancarlo Montes Santangelo

In an ongoing series, Giancarlo Montes Santangelo traces the effects of colonization in Puerto Rico and Argentina, mapping the relationships between memory, the body, race, and history. Montes Santangelo’s collaged photographs bring together the artist’s own body and staged scenes against archival images from the two countries. “These two archives offer an index of divergent histories that cemented the ways in which many—my family and I included—have had to negotiate with the past, present, and future,” says Montes Santangelo. “Collaging offers me a way to recontextualize archival images and position queer world-making as a method of renegotiating with colonial pasts.”

Alana Perino, Dad, 2020, from the series Pictures of Birds

Alana Perino, Dad, 2020, from the series Pictures of BirdsAlana Perino

Alana Perino’s family has often expressed a concern around the “strangeness” of their work. Their stepmother, Letty, was known to ask, “Why don’t you take pictures of birds?” and eventually, Perino accepted her suggestion. “Everything became a bird to me,” they say. “The plants were birds of paradise; my father is a snowbird.” Depicting otherworldly Floridian scenes that confront disparate ideas, Perino’s photographs possess an uncanny quality that collapses the boundaries between the naturally occurring and the staged. Nativity figures shrouded in plastic stand abandoned on the sidewalk, shells gather in memorial around a bathtub, their father floats in a pool with only his face breaking above the surface. Perino finds their images feel most successful when conceptions of “abundance and scarcity, vitality and despair, acceptance and critique become porous or indistinguishable.” Ultimately, Pictures of Birds serves as a remarkable and bitterly affectionate attempt to find strength in the insecurities of heritage.

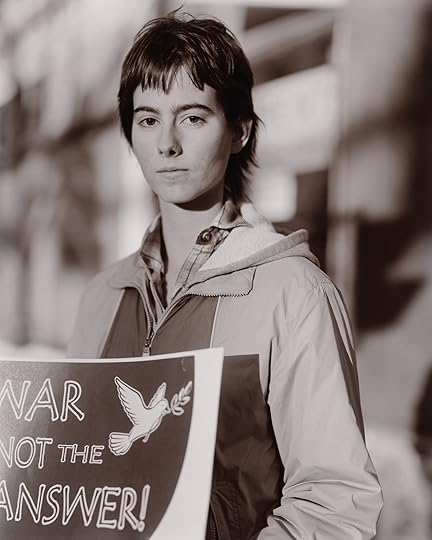

Jade Thiraswas, Portrait of Eh Sun at 14 years old, Rochester, New York, 2018, from the series Young Cash Karen

Jade Thiraswas, Portrait of Eh Sun at 14 years old, Rochester, New York, 2018, from the series Young Cash Karen Jade Thiraswas

Since 2017, Jade Thiraswas has documented a tight-knit community of refugee youth from Myanmar who have resettled in Rochester, New York. The men in Thiraswas’s series are Karen, an Indigenous ethnic minority from Southeast Asia. Thiraswas photographs her subjects in their homes, in the backyard, in traditional clothing and soccer uniforms, offering an intimate look into systems of care and belonging. Yet for Thiraswas, these everyday moments balance against the subtle and apparent effects of globalization, assimilation to American society, and the preservation of an endangered Southeast Asian culture. The series title, Young Cash Karen, refers to the self-chosen name the men formed together. “They proudly use the name to express a sense of belonging and solidarity amongst each other and with the global Karen refugee diaspora,” says Thiraswas. “They retain a sense of unapologetic pride of their identity and history.”

Bryan Thomas, Mexico Beach, 2019, from the series The Sea in the Darkness Calls

Bryan Thomas, Mexico Beach, 2019, from the series The Sea in the Darkness Calls Bryan Thomas

Each day seems to bring a new alarming statistic about the impact of climate change. Bryan Thomas’s ongoing series The Sea in the Darkness Calls documents the Florida coastline, depicting rising sea levels against present and future changes to its landscape. Rather than exclusively focusing on foreboding research findings, Thomas describes his work as speaking “to the more elemental ways in which our lives—and our physical and spiritual relationship to nature—are being permanently and detrimentally affected.” Photographing the land and sea, and people whose livelihoods depend on them, Thomas searches for the somber truths about the inevitability of loss and the shame of inaction in the face of climate change, asking us to consider how we will respond, not so much in the distant future, but in our present moment.

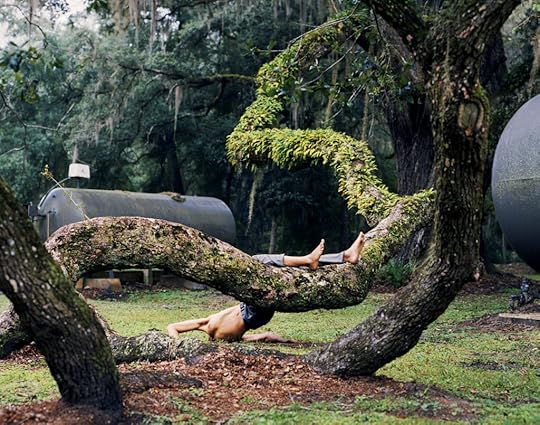

Maximilian Thuemler, Self-Portrait Toppled Over Out Back, Glynn County, Georgia, 2020, from the series Born From the Limb

Maximilian Thuemler, Self-Portrait Toppled Over Out Back, Glynn County, Georgia, 2020, from the series Born From the LimbMaximilian Thuemler

Maximilian Thuemler’s Born from the Limb uses the landscape of the US South as a means of exploring relationships between labor, land, and migration. Working in the natural world, Thuemler finds “physical traces of the past . . . in the form of ruins, marks, imprints, vacancies.” Approaching his photographs with a balanced mix of directness and obscurity, these traces materialize as the backdrop for his performances. Throughout his images, Thuemler droops over a tree, wrestles with mud, or repeatedly moves around in circles. These movements highlight a cyclical exhaustion that Thuemler views as analogous to the relationship between the US and its history, stating, “The topic of Blackness and its representation is exhausting, because it is in part infinite.”

Allie Tsubota, Untitled (Gila River), 2021, from the series This Brilliant Flash of Light

Allie Tsubota, Untitled (Gila River), 2021, from the series This Brilliant Flash of LightAllie Tsubota

Weaving together archival imagery of maps detailing sites of Japanese American incarceration during World War II with black-and-white portraits and seascapes, Allie Tsubota examines how the camera can recall and recover historical relics and psychic refuse embedded in both the landscape and the body. Deploying ideas of migration, racialization, and assimilation, Tsubota’s series This Brilliant Flash of Light traces racial melancholia through the past and present. “How do we resist closure in a society that fetishizes resolution? How do we advocate for reparations while refusing to forget the injustices that warrant them?” Tsubota asks. “To stand in an open wound is to resist the neatening of history—to honor the oceans that continue to live in our bodies, and to adopt a temporality through which our pasts, presents, and futures remain intimately entwined.”

Aaron Turner, Untitled (self, extended), 2020, from the series Black Alchemy Vol. 3

Aaron Turner, Untitled (self, extended), 2020, from the series Black Alchemy Vol. 3 Aaron Turner

Aaron Turner asks: what is the role of the color black and what is considered Black art? Working in the studio, his constructed scenes consider how the past, present, and future interact in issues of abstraction, race, and history. Influenced by the work of Frank Bowling, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Adrienne Edwards, among others, Turner’s series Black Alchemy explores what “Black art” is and the representation of the Black experience. In discussing the color black, Turner notes “There are different tones, hues, values of black, just like blue or red. Why treat it as secondary?” Seeing it as both material and metaphor, Turner identifies a duality (or double consciousness) that Blackness can inhabit.

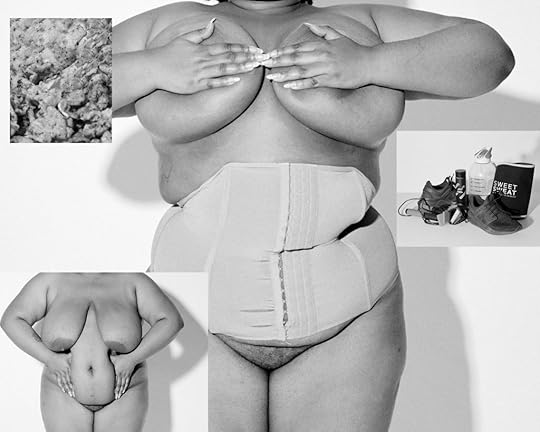

Jasmine Veronica, Snatched Waist, 2021, from the series Guide to a Healthy Body

Jasmine Veronica, Snatched Waist, 2021, from the series Guide to a Healthy BodyAll photographs courtesy the artists

Jasmine Veronica

Jasmine Veronica’s Guide to a Healthy Body critiques societal assumptions around health and wellness. Layering imagery of the body, nature, food, and movement, Veronica’s compositions bring into conversation the ways our health is often blindly defined by outward appearance. In one image, Veronica contrasts two photos—one of herself wearing a waist trainer; and in the second, holding the stomach the trainer is meant to hide—interlaying them against images of food and workout gear. Presented in a uniform black and white, each image has an almost rhythmic quality, reflecting the ways body positivity, diet, and workout culture continuously consume our day-to-day lives. Veronica’s series wonders aloud what it means to be seen as healthy, while reflecting on her own journey through body positivity. “This is something that I’m still trying to find the answer to,” Veronica says. “I would say that I resonate more with body neutrality or anything that allows someone to love themselves without fear of critique and harassment.”

The Creator Labs Photo Fund is presented by Aperture and Google’s Creator Labs. Artist statements by Allie Monck.

September 28, 2021

Visions of Nightlife from Johannesburg to Ibiza

To be in a nightclub. Bodies moving in rhythm. The smells—sweat, cigarettes, that sweet tang of a smoke machine. And the beat. The beat, which rewires your movements, your mind. The sway, the ecstasy of release. In that moment, you are saved.

Such memories have been the stuff of lockdown pipe dreams. It is, therefore, both diverting and bittersweet to browse two recently published books on clubbing—one expansive in its broad geography and history, the other contrastingly specific. Ten Cities: Clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Berlin, Naples, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol, Lisbon 1960–March 2020 (2020) is an ambitious record of these select music scenes. Dave Swindells’s Ibiza ’89 (2020) brings together images Swindells made on a short magazine assignment in the summer of 1989, sparked by the influence of the island on the U.K.’s then thriving acid house and rave scenes, known as the Second Summer of Love.

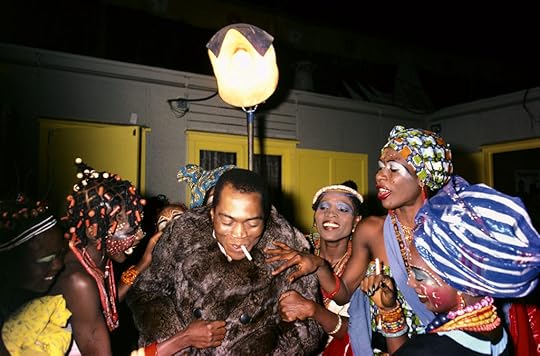

Bernard Matussiere, Fela Kuti with the queens, Stratford, London, 1983

Bernard Matussiere, Fela Kuti with the queens, Stratford, London, 1983Courtesy the artist

The books take distinct, even opposing, views. Ten Cities tries to push against the idea that clubbing is a frivolous or universal experience, citing, through exhaustive essays from various international figures, the political, economic, geographic, and local particularities of various nightlife scenes. Clubs, the book’s editors Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo, and Florian Sievers explain, are “prisms and laboratories of society and the city.” Ten Cities centers Africa’s music and culture, and makes 1960 the narrative starting point because that was when independence swept the continent. “As a general rule, the history of club culture is told without the African musical metropoles,” Hossfeld Etyang writes. The authors position Nairobi as their project’s home—a vivid picture is painted of the Starlight nightclub where Barack Obama Sr. danced in the 1960s—before veering off to other cities, chosen in an attempt to disrupt established ideas of certain cities as clubbing meccas and others as backwaters or slums.

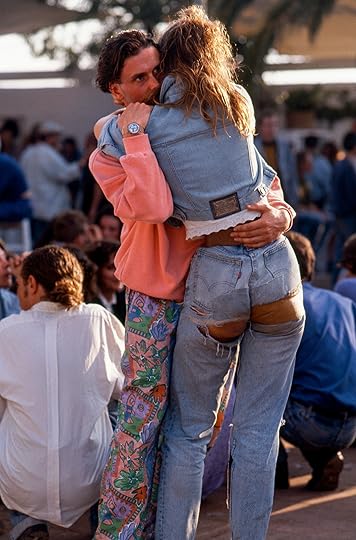

Dave Swindells, Go-go dancing superstars at Ku, 1989, from Ibiza ’89

Dave Swindells, Hug club: celebrating making it through the night

(just about) at Amnesia, 1989, from Ibiza ’89

Amusingly, Ibiza ’89 does everything Ten Cities tries to avoid; it is Eurocentric and fawning (Ibiza, we learn, is “Europe’s best party island,” according to the music producer Terry Farley), and it paints clubbing as hedonistic and vaguely manic, focusing on the young, the beautiful. Still, the photographs are lovely to look at.

In the 1930s, the South African musician and author Todd Matshikiza, then a young boy, attended a party thrown by the musician Boet Gashe, an event he recalled in 1957, in Drum magazine: “You saw the delirious effect of perpetual motion. . . . Perpetual motion in a musty hold where man makes friends without restraint.” The line, which captures the heady feel of clubbing, the existential epiphanies found in ephemeral places, could be a description of any one of the photographs of gyrating revelers in Ibiza ’89, but it is quoted in Ten Cities. Its inclusion there highlights the challenge of analyzing, or indeed photographing, club culture. How does one balance a focus on the shared and at the same time on the specific, the local, the “scene”?

Jürgen Schadeberg, The Jazzolomos: Jacob “Mzala” Lepers (bass), Sol “Beegeepee” Klaaste (piano), and Benni “Gwigwi” Mrwebi (alto sax), Johannesburg, 1953

Jürgen Schadeberg, The Jazzolomos: Jacob “Mzala” Lepers (bass), Sol “Beegeepee” Klaaste (piano), and Benni “Gwigwi” Mrwebi (alto sax), Johannesburg, 1953© the artist

Mosa’ab Elshamy, Mahraganat, Cairo, 2013

Mosa’ab Elshamy, Mahraganat, Cairo, 2013Courtesy the artist

Frágil birthday party at Convento do Beato, Lisbon, 1996

Frágil birthday party at Convento do Beato, Lisbon, 1996Courtesy LuxFrágil

It is notable that so many astounding clubbing photography projects exist—for example, Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 or Tom Wood’s Looking for Love. Yet nearly all work around familiar themes: beauty, sex, and glamour, peppered with moments of sexual rejection and flashes of exhaustion. Ten Cities is smart in not scrupling to celebrate these familiar elements, while simultaneously homing in on the unexplored, the theoretical, the minutiae. We are reminded that clubs are shaped not just by dancing bodies and good DJs but also by transport links, alcohol taxes, parking spaces, coups, elections, and governments. Yet gems by Jürgen Schadeberg and Tobias Zielony lend a “God, to have been there” air and offset some of the more intensive academic positing.

Margarida Martins and Mário Marques, Absolut Citron Party, Frágil, Lisbon, ca. late 1980s

Tobias Zielony, Shine, from the series Maskirovka, Kyiv, 2017

Courtesy the artist and KOW, Berlin

For those convinced that COVID-19 has decimated nightclubs, it will be uplifting to remember that they have survived big trouble in the past, be it a monthlong, dusk-to-dawn curfew in Nairobi in 1982, regulations that banned amateur bands in Kyiv in the early 1970s, or ad hoc surveillance, such as that of Fela Kuti, whose growing popularity with Lagos crowds briefly irked the Nigerian government, which, ironically, raided him right ahead of FESTAC ’77, a landmark international festival celebrating African culture.

If Ten Cities encourages reflection, Ibiza ’89 thrills to escapism, embracing the cliché of sun, sea, sand, and sex—the gaze on a thong-clad bottom, the close crops on beautiful youths, the sweat on an entangled couple. It is a fascinating lesson in how myths are made, how rose-tinted glasses are applied. In the book’s introduction, Swindells recalls how clubbers on the island would tell him that 1989 was too late, he should have come earlier: “You’d have loved it here in 1987!”

Dave Swindells, The bold and the beautiful: great pattern clashing from Boy George and the gang at Amnesia, 1989, from Ibiza ’89

Dave Swindells, The bold and the beautiful: great pattern clashing from Boy George and the gang at Amnesia, 1989, from Ibiza ’89All photographs by Dave Swindells courtesy the artist

And yet, despite Swindells’s mocking tone, his book is driven by the same nostalgia, proffering the idea that those were the glory years, that later, in Farley’s estimation, the scene “lost its character.” The beauty of the pictures and the hazy memories tussle with the reality briefly alluded to in Alix Sharkey’s 1989 essay, produced on the same commission as the images, with its smattered references to burnout, addiction, and local distress. But today’s zeitgeist is nostalgic too. Just weeks after its publication, Ibiza ’89 sold out, trading for triple the price on fashion resale sites—evidence of the current thirst for the retro in fashion, photography, and, most visibly, on Instagram. Still, how appropriate. As both Ten Cities and Ibiza ’89 show us, great clubs cannot exist without some nostalgia, without the sense of time slipping away, without FOMO, without the intoxicating promise of unrepeatable experiences, all bolstered by fables and hearsay.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 244, “Cosmologies,” under the column “Viewfinder.”

September 22, 2021

A Japanese Photographer’s Bittersweet Archive of His Late Wife

Seiichi Furuya, based in Graz, Austria, for almost fifty years, is an established member of the European photo community and cofounder of the esteemed journal Camera Austria International. But his departure from his native Japan to his adopted country of Austria is not widely known. At the end of September 1973, Furuya left from Yokohama on a Soviet cargo ship, arriving in Vienna in early October. Furuya had been a student of photography at Tokyo Polytechnic University during an increasingly turbulent time in postwar Japan. Between the university riots, the anti–Vietnam War movement, and the anti–Japan-US Security Treaty movement, Tokyo was like a battlefield. Furuya frequently participated in the demonstrations with his camera. But as the movement cooled off, realizing that there was no longer a place for him in Japan, he burned his negatives and left.

Furuya moved to Graz two years after his arrival in Vienna and soon connected with other photographers. He became a founding and active member of Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, an artist cooperative organizing exhibitions and occasionally planning workshops with photographers, including Mary Ellen Mark and Ralph Gibson. In 1979, the group started the inaugural Symposion über Fotografie (Symposium on Photography), which occurred annually until 1997. The inaugural three-day symposium included participants such as Lee Friedlander, Robert Heinecken, Joseph Kosuth, and John Szarkowski. Furuya also served as liaison to many key Japanese photographers working at that time, including Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Masahisa Fukase, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Nobuyoshi Araki, helping many of them set up their first exhibitions in Europe. Around the same time as the launch of the symposium, Furuya collaborated with Manfred Willmann and Christine Frisinghelli to launch a new magazine, Camera Austria, the first issue of which was published in 1980.

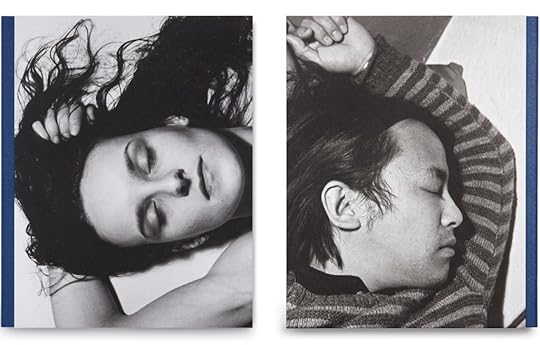

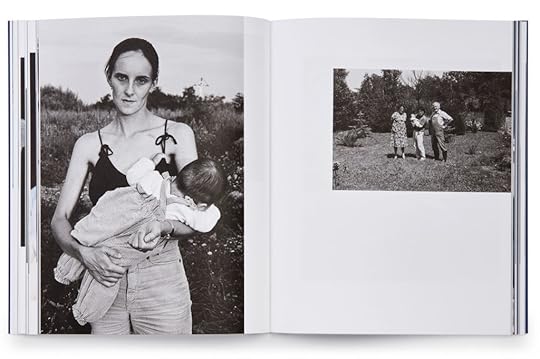

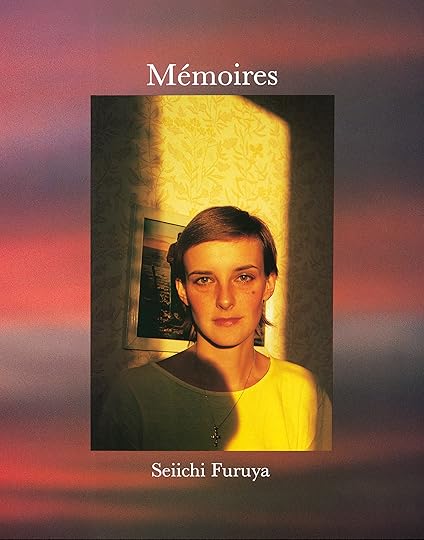

Face to Face is the sixth volume of work Seiichi Furuya has published under a variation of the title Mémoires (1989, 1995, 1997, 2006, 2010). Unlike with the other five books, Furuya shares equal authorship in this edition: Christine Gössler’s gaze at Furuya, and his gaze at Gössler, intersect through photographs that each made of the other. While Furuya continues to work with the materials created during Gössler’s life—like an ongoing body of work that resulted from a trip they took to Bologna, among other images from their life together—he has stated that this is the last of the Mémoires variations. In these works, Furuya challenges us to think about what it means for an artist to go so deep into a single, emotionally charged body of work, made so long ago and revisited time and time again.

Cover and back of Seiichi Furuya and Christine Gössler, Face to Face (Chose Commune, 2020)

Cover and back of Seiichi Furuya and Christine Gössler, Face to Face (Chose Commune, 2020)Yasufumi Nakamori: Face to Face [Chose Commune, 2020], published last year, is the first entry to the Mémoires series in ten years. Before diving into Face to Face, please tell us how you left Japan for Austria in the early 1970s and what you were doing before that in Japan.

Seiichi Furuya: At the end of September 1973, I left Japan from the Port of Yokohama on a Soviet cargo ship called Khabarousk and arrived in Austria’s capital Vienna in early October, along the way passing Nakhodka, Khabarovsk, and Moscow. Around 1970, I was a student photographer in Tokyo during what was known as a turbulent time in postwar Japan. Between university riots, the anti–Vietnam War movement, and the anti–Japan-US Security Treaty movement, Tokyo was like a battlefield. I was around twenty years old at the time. Although I didn’t belong to any particular group, I was one of those people who frequently participated in the demonstrations. For me, bringing my camera and taking photos did not preclude me from participating in the demonstrations. The highly charged atmosphere of the society gradually cooled off as the Japan-US Security Treaty was set up to renew automatically. When the turbulence ended, I started realizing that there was no longer a place for me in Japan, and that thought grew stronger over time. I had a friend who had left Japan earlier and was living in Vienna at the time. Eventually I left Japan under the pretext of visiting this friend. After spending two nights on the ship, we docked at Nakhodka. The moment I stepped onto the land, I thought to myself that I was probably never going to return to Japan. Right before leaving Japan, I burned all the photographic records of my bustling life in Tokyo.

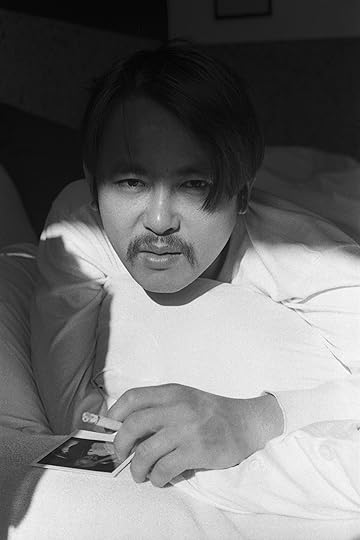

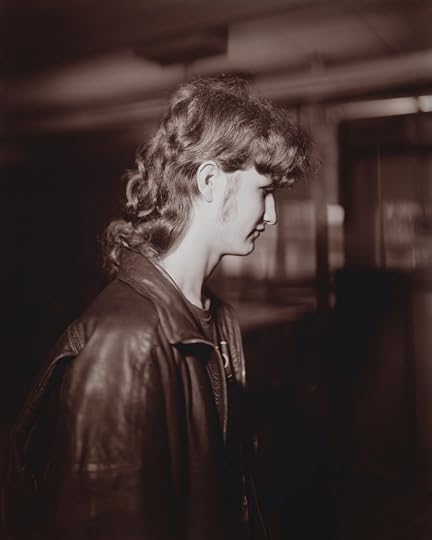

Christine Gössler, Graz, 1979

Christine Gössler, Graz, 1979Nakamori: Graz has been the base of your creative activities for forty-five years, during which you cofounded Camera Austria. When and for what reason did you move to Graz? Please talk about how you arrived at co-founding Camera Austria, especially your involvement with Symposion on Photography.

Furuya: After staying in Vienna for two years, I moved to Graz, which is the second largest city in Austria, and I have been here since. The biggest reason for the move was that I got a job at a camera store in Graz through an acquaintance whom I came to know through photography. While working at the store, I came to know others who shared interest in photography and eventually became a founding and active member of Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, an artist-based voluntary organization. In the beginning, we organized about ten photo exhibitions a year and planned workshops of famous photographers from time to time. Some notable workshops that I attended include ones for Mary Ellen Mark and Ralph Gibson. Three years ago, I found in the attic some black-and-white Super 8 film, which had detailed footages of Mark’s workshop from 1979. In the fall of 1979, we started the inaugural Symposion über Fotografie [Symposion on Photography]. We invited a dozen or so guests from around the world who were active in photography and hosted a three-day symposium.

Americans including Lee Friedlander, Robert Heinecken, Joseph Kosuth, Allan Porter, and John Szarkowski also attended the symposium. As part of the brain behind the whole operation, Christine Frisinghelli was involved with the founding of both the organization as well as Camera Austria International. She was in charge of all the negotiations and translated the inadequate words of those of us who were self-claimed photographers into something beautiful. I remember it as if everything happened only a few days ago… driving to the airport to pick up Friedlander and Szarkowski, working on a draft version of what was going to be published about the symposium, Friedlander used a handmade lightbox which was stored in the darkroom up in the attic to copy slides he brought for the lecture. At the time, for Europeans and Japanese, the mecca of photography was America. Instead of us going over to America, we invited folks who were active on the frontline of photography in America to come over and it was a huge success. For the inaugural symposium, we also invited Shoji Yamagishi from Japan. Unfortunately, he passed away while still corresponding with me to finalize his lecture. Szarkowski paid tribute in front of his portrait at the symposium.

We hosted the Symposion on Photography every fall for seventeen years until 1997. In charge of Japanese affairs, I worked with Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Masahisa Fukase, Tsuneo Enari, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Nobuyoshi Araki, and probably helped many of them set up their first show or solo exhibition in Europe. While working on the symposium, we started planning for the publication of a photography magazine. Manfred Willmann of the organization and I worked on initial drafts of the new magazine while referencing the latest Japanese camera magazines that were getting delivered to my place every month. In 1980, the first issue of Camera Austria was published. At first, we thought about using our own photos and publishing the magazine under issue 0 as a pilot. Before we knew it, the magazine was published as the inaugural issue. I think it’s worth mentioning the origin of the name of the magazine: When contents of the first issue were mostly decided, we held a meeting in the basement of Forum Stadtpark to decide on its name. Six or seven members put forward their proposed names, but none of them got a decisive yes from the group. At the time, an acquaintance of mine who also left Japan, and was in the middle of his own wandering journey, shouted out the name “Camera Austria.” No one objected. I think that over the years Symposion on Photography has provided a platform to discuss and demonstrate the evolving definition and meaning of photographic expression through real-life examples. Meanwhile, Camera Austria continued to grow while keeping pace with changes that were happening at the symposium.

Spread from Seiichi Furuya and Christine Gössler, Face to Face (Chose Commune, 2020)

Spread from Seiichi Furuya and Christine Gössler, Face to Face (Chose Commune, 2020)Nakamori: Please tell us how you met Christine Gössler, your life partner and a coauthor of Face to Face, who tragically took her own life in 1985.

Furuya: In February 1978, at Forum Stadtpark, I met Christine for the first time at the opening of a solo exhibition by Gwenn Thomas called Color Photographs. Christine came with another woman who was a mutual acquaintance of both Manfred Willmann and mine. Ten days later, I mustered up the courage to call her and asked her to watch a movie together. We saw the Japanese movie Harakiri. From that day on, our lives became inseparable. Looking back, I realize that our relationship started with a movie about suicide, and ended with her own suicide. In mid-March of that year, we went to Bologna for a week. According to her notebook, I made up my mind to marry her while we were in Bologna. One week after returning from Bologna, I went back to Japan for the first time since 1973 and Christine came with me. During our two-month stay in Japan, we took part in a Shinto-style wedding ceremony at my home in Izu, and with that our relationship quickly moved on to the next level. Thinking back, it may have been the happiest time for us, although she seemed a bit caught off guard by the sudden change in environment. Shortly after returning from Japan, I quit my job at the camera store and started a new phase of life without a regular job. Christine was aiming to complete her thesis at university, but she eventually gave up and started working for the Austrian National Broadcasting Corporation.

There is an old passage that I wrote that describes, in simple terms, our encounter and how I felt about her. The passage was included alongside a portrait of Christine in the first issue of Camera Austria in 1980. It implied a deep connection between the human encounter and the characteristics and essence of photography as an expressive medium. So much so that it wouldn’t be strange to say that the passage could also have been written for Face to Face, published in 2020.

From the first day I began taking photographs of her regularly. I have seen in her a woman who passes me by, sometimes a model, sometimes the woman I love, sometimes the woman who belongs to me. I feel it is my duty to continue to photograph the woman who holds so many meanings for me.

When I consider that taking photographs means fixing time and space, then this work—the documenting of the life of one human being—is exceptionally thrilling for me. In facing her, in photographing her, and looking at her in photographs, I also see and discover “myself.”

Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1978–1988 (Edition Camera Austria, 1989)

Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1995 (Scalo/Fotomuseum Winterthur, 1995)

Nakamori: After Christine passed away, you edited and published several different editions of Mémoires featuring photographs from her life. I was wondering if all of that might have helped you get to know her better.

Furuya: In 1981, our son was born. Around the summer of 1982, the three of us left Graz and moved to Vienna. By that time, Christine had already started producing her own radio program at the Austrian National Broadcasting Station. One day, out of the blue, she said to me, “I want to be an actor. I want to be on the stage. It’s a dream I’ve had since I was a kid.” I was against it. After having lived together for four years by then, I honestly didn’t think she had what it takes to get through all the hardship that’s necessary in order to become an actor. I thought I knew her sensitive and compassionate personality. I thought I knew how, despite her modesty and tendency to not show her true feelings and thoughts, she was the type of person who would devote herself completely to something. However, as someone who didn’t have a job with steady pay and was at the mercy of Camera Austria, I strongly felt responsible for the impoverished life my family was going through, and thus I couldn’t convince her otherwise. When she started taking private lessons in order to matriculate at a theater college, Christine became like a shell with a closed lid and stopped talking to me about not just theater, but also things in her daily life. This lasted until her final day in Berlin in October 1985. It wasn’t until 2005 that I became fully aware that she was dealing with theater and other problems in her life alone.

Nakamori: Please tell us how Face to Face came about. You published five photobooks from 1989 to 2010 under the title Mémoires (all with Christine as subject). What’s the relationship between those five books and Face to Face?

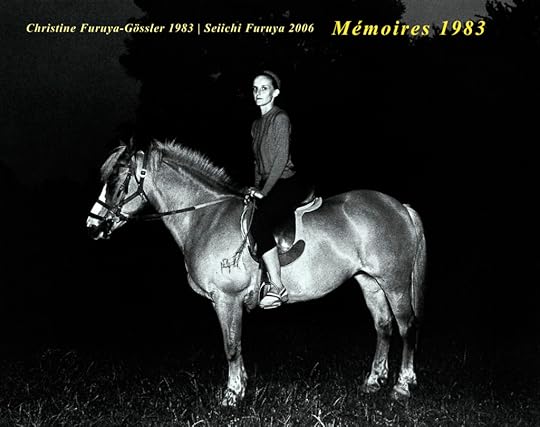

Furuya: In the summer of 1987, I went back to Graz from East Berlin. It was when I started organizing her belongings that I discovered her notes. But I didn’t have the courage to read them right away. I was afraid that it was something that I either couldn’t bear to know or didn’t need to know. The notes were handwritten in German, so it wasn’t like I could easily read and understand them anyway. If they were written in Japanese, I’m sure things would have been different. It wasn’t until almost twenty years after her death, around Christmas 2005, that I finally decided to find out what the notes were about. I asked a girl who was a total stranger working part-time at the Graz Art Museum to reproduce a clean copy of the notes. I read and reread that clean copy carefully during a two-month stay in Paris. I hadn’t hid any secrets from Christine and always thought that I was living a straightforward life. However, Christine’s notes revealed that she’d become obsessed with theater and was increasingly struggling with her own limits while dealing with her mother and our child. I was shocked to read that at some point, she thought her theater instructor had become the only person who could forgive her, like a true mother. I didn’t know any of this, and it was as if I was reading about a different person. For me, the expressive power of her notes was beyond what photography could achieve. There were quite a few parts of her notes that even the female student who reproduced the clean copy couldn’t fully understand. In 2006, I published the fourth edition of Mémoires [titled Mémoires 1983] using portions of her notes along with photos.

After Christine killed herself in East Berlin in 1985, I worked there for two more years, finishing my job as an interpreter. In the summer of 1987, I returned to Graz to reunite with my son. On June 12, 1987, President Reagan delivered his “Tear Down This Wall” speech to Gorbachev on the west side of the Brandenburg Gate, which was also a symbol of the division between East and West Berlin. I listened to the speech along with many Stasi, National Secret Police of East Germany, on the east side of the gate. Of course, for someone who always carried a camera, I took photos of this historic occasion. Although at the time, no one, including probably President Reagan himself, foresaw that just two years later the Berlin Wall would come down along with the collapse of East Germany. In 2010, the fifth and final volume of Mémoires was published, which documented our lives moving from Dresden to East Berlin in 1984 and up until my return to Graz in 1987.

In 1989, my solo exhibition was held at the Neue Galerie Graz [the state museum of modern art in Graz]. The first edition of Mémoires was published at the same time. Meeting the museum director to discuss the name of the exhibition, I suggested a few names, such as Travelogue. But it took a while for us to agree. Eventually, the director said that what I was thinking about and trying to do would fit well with the French word mémoires. Thus, the name of the exhibition and my photobook was born. The exhibition was supposed to be important for both commemorating Christine and for sorting through my own feelings. It toured Vienna and Tokyo, and in the midst of changing venues, I felt that something new was stirring inside me. This feeling first came about when the 1995 edition of Mémoires was published, and lingered over the course of publishing the 1997 and 2006 editions, and even when I published what was meant to be the final iteration of Mémoires in 2010.

I publicly announced, at my solo exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography [formerly the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum] in 2010, that this would be the final publication in the Mémoires series. I felt that no matter how many times I tried with the publications of these photobooks, I didn’t really understand anything new. At the same time, I wanted to work on a book of my works that were not directly related to Christine. However, I had a stroke just before the exhibition in Tokyo, and it took me at least five years to recover. Since the announcement in 2010, I avoided works related to Christine and spent my days away from photography to focus on recovering my health.

Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1983 (Akaaka Art Publishing, 2006)

Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1983 (Akaaka Art Publishing, 2006)Nakamori: What brought you back to photography and back to the world of Mémoires?

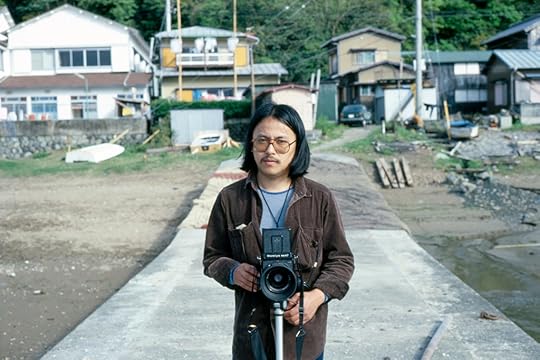

Furuya: Something came along out of the blue. At the end of 2017, the director of a photography museum in Japan reached out to me about doing a solo exhibition. While on the phone, I had this sudden feeling that I was being pulled back into the world of Mémoires. I was surprised, as I had been avoiding it until then, but the feelings just rushed in as if bursting through a dam. But this time, there was a definitive difference from the previous books, as I thought about presenting mainly works done by Christine herself for the exhibition. With only a few exceptions, the different editions of Mémoires had mainly presented photos that I took of Christine. Over the years, I was consumed with my own works, and I didn’t realize that Christine was a creator in her own right, with works expressing herself, until some thirty years after she passed away. To prepare for the exhibition, I started organizing her belongings, which had been stored in the attic for decades. I found her writings, Super 8 footage, cassette tapes, 110 film—things that I had forgotten about or saw for the first time. There was a reversal film of me standing behind a tripod with a 6 by 7 camera, which was taken on the coast of my hometown of West Izu in 1978. Christine must have taken that picture while I was taking a portrait of her standing on the edge of the cliff, with a Leica camera strapped around her neck, wearing tall, black rubber boots and carrying a bamboo stick. I was excited to have discovered this and found myself uttering the words “face to face.”

I arrived at Face to Face after going through five volumes of Mémoires. In a sense, my photos in each of those books are the starting point to make sense of the tragedy and mystery of the woman that is Christine. It was difficult for me to dismiss her death simply as a result of schizophrenia, which is a standard response given by society these days. Some friends tried to comfort me by using this standardized response. But after going through trial and error for over twenty years, the sad truth remains that I still don’t fully understand why it happened. Finally, with Face to Face, at least Christine can be recognized as a creator herself. It’s another volume of Mémoires, with her being credited as the author of her own works.

Christine Gössler, Izu, 1978

Christine Gössler, Izu, 1978Nakamori: A key difference between Face to Face and your other works is the alternation between photos you took of Christine and photos that she took of you. Please tell us about the challenges of making and editing a photobook that focuses on the intersection of two creators.

Furuya: I was hoping to find more photos that Christine took. As if answering my prayer, I found 110 film negatives that I didn’t know existed, as well as color negatives from a 35 mm camera from when she started taking photos again in 1985. Eventually, it became clear that Christine was often taking pictures of me, and that we were taking pictures of each other at almost the same time. The act of taking photos and having our own photos taken continued, with varying frequency, until the day before she took her own life. On top of that, the hardest part was finding myself in my own photographs. I carefully checked the photos that I took from the time I first met her until I lost her, because sometimes she took photos of me with cameras that I was using. I made prints from selected films, arranged them in chronological order, and started to look at them carefully. The exhibition hall for Camera Austria was an ideal place for doing so. When viewed side by side, the prints were about twenty meters long. Just when the prints were completed such that they would fit nicely with the layout of the venue in Japan, we heard the news that the exhibition had been canceled. At the beginning of 2019, I immediately switched from planning an exhibition to planning a photobook, and carried on working. At that time, after having finished the selection of photos and arranging the material in chronological order, I selected the Marseille-based Chose Commune to be the publisher. I was told that Cécile Sayuri Poimboeuf-Koizumi was the editor in charge, and I entrusted the production of the book to her. If the editor wasn’t a woman, I’m not sure that I could have entrusted the whole process to someone else. Instead, I was completely hands-off.

I was shocked when I viewed the printed photobook for the first time in December 2020. After opening the cover and going through the pages, I almost felt that the two people in the book were talking to each other. It was like traveling back in time and space. I didn’t realize this when I was still preparing for an exhibition. I’m sure it has a lot to do with the binding of the photobook and the layout of each page. When the book is closed, the two people are still and facing each other, just like the title, face to face. But when you turn the pages, it’s as if a switch has been flipped, and the two people start to move and talk to each other. I reread the book and it felt the same every time. Maybe it’s something only I can experience, since I know the background of the photos. I also thought that might be what it means to have a book of moving pictures for adults. Some might simply think that what’s happening here is two people staring at each other and trying to read into the meaning of each other’s facial expressions, but one should be mindful that such reproduction of the act of staring is only made possible by the incredible invention of photography. Capturing a momentary image is one of the most salient characteristics of, and the original purpose of, photography. In that sense, what you see in terms of two people’s facial expressions satisfies that aspect of photography very well. But I can’t help but feel that those photos also express something beyond that. This is something that one becomes aware of only after a photo, which captures a past reality, is taken, and it’s something that is almost impossible to experience in real life. Even on the occasions when we take photos of each other, everything is a series of moments that keep changing. The moments when we stare at each other are so fleeting amid the passing flow of time that it is impossible to consciously read into and interact with each other mentally there and then. Photography is the only expressive medium through which we can relive and reconfirm a moment from the past. In that sense, I think Face to Face is a perfect embodiment of the magic of photography.

Seiichi Furuya, Graz, 1978

Christine Gössler, Graz, 1978

Nakamori: What does the act of taking photos mean to you? What does making and publishing photobooks mean to you?

Furuya: While thinking about how to respond to this question, I realized that I had never thought about the meaning of taking photos. I just always took photos before thinking about meaning or purpose. But for the last ten years, I haven’t taken many pictures. The reason is simple—things are less visible to me now, and my inner desire and need to take photos are not what they used to be. I think one of the reasons is that I have had almost no chance to expose myself to the vicissitudes of today’s world, and the lifestyle or habit of always carrying a camera with me wherever I go has largely gone away. For a while, I was taking pictures with a digital camera for blogging. Starting about a year ago, I’ve been taking photos of my grandkids and the change of seasons in my garden with my mobile phone. But at the end of the day, for me, a photo is a copy of reality printed on film that can be touched by hand. I have no interest in creating “artworks” using the medium of photography. For me, photography is the act of quickly capturing an image that approximates a premonition we feel when encountering moments of anxiety or interest in daily life. In my case, it can also be said that the act of taking photos, instead of, say, writing, is a way for me to record my impression and experience of encountering things that I can’t comprehend even through imagination, but is somehow connected to my existence. I’ve been called a “boundary” photographer by some. In fact, one of my works is called Boundary and I took photos of the Berlin Wall, but many portraits of Christine also portray the boundaries between people. It doesn’t matter if the quality of a photo is good or bad; it is no longer my concern in the moment it’s taken. Then, when it revives with the passage of time, it becomes the first time for me to face a photo that I once took.

I think that making a photobook is like assembling chaotic and complex images toward one big theme in your head. As the work progresses, the outline of the theme becomes clearer. I think it might be similar to how a composer writes a symphony by combining individual notes. For me, with the exception of my first photobook, AMS [Edition Camera Austria, 1981], I keep making photobooks so that I can bring them along with me when I eventually meet Christine again. Maybe they can also be called reports. There is another important reason why I keep making these photobooks—it is to tell our son and our grandchildren what kind of a person she was in ways that I could never do with words. The day after Face to Face arrived from Chose Commune, I brought it with me to the front door of my son’s house. There were strict rules in place related to the novel coronavirus. My son was fearful that I might contract the virus from my grandchildren, so we didn’t see each other. It seems that my son was more worried than I was about older folks getting infected. In Face to Face, my son showed up on many of the pages. Since this was his first time seeing these photos, I wasn’t sure how he would react. I was told that later that night, he read the photobook with his eldest daughter, who was six years old at the time. They seem to have enjoyed the book, and he was asked a lot of questions. My granddaughter was a little confused at first since her grandmother, Christine, looked youthful in those photos.

Now that I’m over seventy years old, I feel that I don’t need to hide anything anymore. There are a few reasons why I’ve published photobooks and portraits of Christine again and again over the years, but there’s one key reason that I’ve never publicly stated. That is, I want to help accomplish her childhood dream of standing on the stage—a dream that tormented her and may have forced her to kill herself. For example, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and MoMA in New York have collected several photos of her, and her portrait on the coast of Izu in 1978 was just exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Seeing her smile at me with that same bamboo stick, this time in New York, I couldn’t help but go up to the photo and talk to her. I never thought I could meet her again in such a place. I will continue to publish works of her and works by her, all of which always contain my unwavering desire to give my deceased wife an eternal life.

Seiichi Furuya, Graz, 1979

Seiichi Furuya, Graz, 1979All images courtesy the artist and Chose Commune

Nakamori: What do you think about COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown of cities and nations from last year to the present day? Also, please tell us what you are currently working on or would like to work on in a situation like this.

Furuya: It has been exactly one year since measures to battle COVID-19 were issued here in Austria [as of March 2021]. It actually has been a very fulfilling year for me. Thanks to the lockdown, I was able to focus on work that required a lot of patience and concentration. From the non-stop and inescapable news cycle about the virus, the idea that has related to me the most is death. From the moment of birth, a person begins their journey toward death. Yet, for a period of time, there is no need to think about the idea or meaning of death, so one is not aware of death and thinks that death has nothing to do with them. One might even think that they can live forever. After the age of seventy, death creeps into our life on many more occasions, while the eventuality of our own death remains ever more present. In my case, death is neither unpleasant nor frightening, and recently I’m even starting to feel that confronting death can make one feel refreshed. There is a tall gingko tree in my garden. I used to totally ignore its existence. These days, I watch the tree change throughout the seasons and think about the fateful encounters in life. Some of us live to be thirty-two years old, others to seventy-something years old, and yet others to a thousand years old (since I was a child, I’ve heard that gingko trees can live to be a thousand years old). I spend my days meditating on the trajectory and stories of my life, while being amazed at the small miracle that I got through all the trials and tribulations in my life since leaving Japan, and that I’m still around. Since we are still required to refrain from social activities to fight the virus, this is not a bad way to spend my otherwise solitary life.

At the moment, I’m getting started on the production of a new photobook called First Trip to Bologna. The book consists of materials from our trip to Bologna shortly after I met Christine in 1978. I plan on using only frames from videos taken with a Super 8 camera instead of the still photos that appear in this book. I also found this film in the attic and was very surprised when I watched the digitized film on a screen. No matter how many times I watched the video, I couldn’t recollect memories from the trip. It got to the point where I doubted if I was even there with her. It’s as if days that I didn’t know existed were brought back and recreated in front of me. Since I don’t remember anything, I thought about creating a brand-new story of the Bologna trip for us. In addition, I would like to publish a collection of photos taken solely by Christine. I wonder which project would come first, but I hope to bring this photobook with me as a souvenir when I see her again. I want to leave behind records of Christine’s works for our son and his kids. For me, the days of taking photos are mostly over. From this point on, I think my job will be to work with the newly discovered materials belonging to Christine and bring them to the public as her own works as much as possible. Other than that, I would probably continue to take family photos of my son and grandchildren with a 6 by 7 camera from time to time.

Nakamori: Thank you very much.

This piece originally was published in Issue 019 of The PhotoBook Review. Translated from Japanese to English by Shiwei Yin.

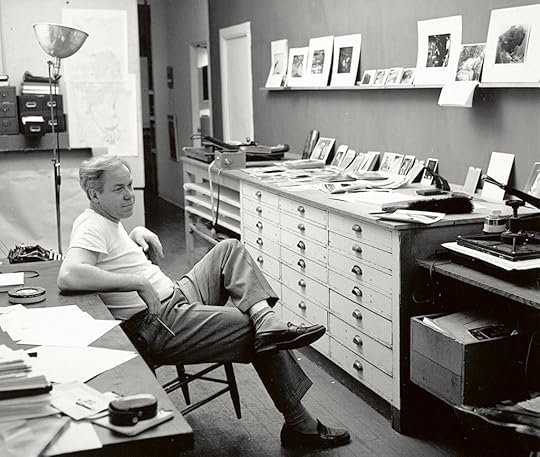

How Peter C. Bunnell Shaped the Photography World

It is with deep sadness that Aperture learned of Peter C. Bunnell’s passing on September 20, 2021. An eminent photography historian and curator, Bunnell (born in 1937) was also a mentor and friend to scores of individuals engaged with the medium of photography today, including me. Curiously, our professional paths have followed inverse trajectories—his from Aperture to New York’s Museum of Modern Art to Princeton University; mine from Princeton to MoMA to Aperture—but at each step, his example served as a guiding light.

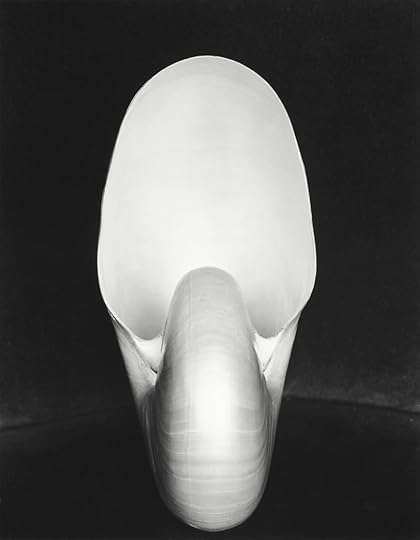

I met Professor Bunnell in 1992, when I took his history of photography course as an undergraduate at Princeton. He animated the full sweep of this history with insight and anecdote. Edward Weston wasn’t simply a legendary name from the past; he was someone with whom Bunnell had corresponded in 1956. As I recall the story, my esteemed professor was a sophomore at the Rochester Institute of Technology, studying with Minor White, and he wrote a letter to Weston requesting two prints and enclosing a check for $30. Weston wrote back, enclosing two prints! I also vividly remember encountering a work by Uta Barth in a seminar my senior year, which Bunnell had just acquired for the university’s collection. Bunnell’s attentiveness to new achievements and his passion for Barth’s distinctive approach—removing the ostensible subject of her photograph to draw attention to the surrounding (often blurred) background—was an inspiration to all of us fortunate enough to be in his orbit.

In 1972, Bunnell had been named the inaugural David Hunter McAlpin Professor of the History of Photography and Modern Art at Princeton, the nation’s first endowed professorship of the history of photography. Previously, he was a curator in the Department of Photography at MoMA, and it was there that I headed (as an intern) after graduation. Eventually I, too, became a MoMA photography curator, ever-conscious of several landmark exhibitions Bunnell had organized during his tenure there. The most radical of these, still today, is Photography into Sculpture (1970), but he also brought a fresh perspective to historical figures such as Barbara Morgan (a founder of Aperture) and Clarence H. White, whom he described as being “interested in revealing how things are, rather than showing things as they are.” To my mind, Pictorialism was so unfashionable that this embrace of one of its leading figures was itself a radical gesture.

Before MoMA, Bunnell had spent a decade working closely with Minor White at Aperture, nurturing the magazine through uncertain times. The interview that follows, with Diana C. Stoll, was originally published in Aperture Magazine Anthology: The Minor White Years, 1952–1976 (Aperture, 2012), a treasured resource for anyone interested in the field and full of Bunnellian flair. Peter C. Bunnell’s achievements as a scholar and writer will continue to instruct and inspire—he will be missed.

— Sarah Meister, Executive Director, Aperture Foundation

Robert C. Bishop, Bar in the Hotel Jerome, Aspen Conference, 1951

Robert C. Bishop, Bar in the Hotel Jerome, Aspen Conference, 1951Seated left to right: unidentified woman, Victor Babin (musician), Aline Porter, Will Connell, Wayne Miller, Ferenc Berko, Vitya Vronsky (musician), Eliot Porter, Nancy Newhall, unidentified man, Beaumont Newhall, Minor White

Image courtesy Norma and Laura Bishop, and The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

Diana C. Stoll: From today’s perspective, the world of photography in 1952 seems so appealingly finite and manageable. Who was reading Aperture in the beginning? For whom was it intended?

Peter C. Bunnell: In a way, Aperture was for a small niche. It was intended for those who were committed to serious photography.

After World War II, photography as an art was confronted with the new status of photojournalism—the residue of 1930s documentary work—as well as the rise of advertising and magazine photography. Aperture was essentially driven by the idea that there must be some way to reposition a kind of serious photography, and that notion drew together the group of people who founded the magazine.

Aperture grew out of a 1951 conference on photography that was held at the Aspen Institute. A number of people had been invited to the conference who could address the reality of the field. If you look at the seminar titles, you get an idea of what some of the concerns were: “Evolution of a New Photographic Vision,” “Photography and Civilization,” “Picture Language and the Magazine,” “Photography in Advertising and Promotion,” “Photography and Painting,” “Objectives for Photography,” “Creative Directions in Color Photography.”

There was a subgroup at the gathering, which included Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, Minor White, Frederick Sommer, Ansel Adams, and Dorothea Lange. Aperture literally started with attendees of that Aspen conference, who after the meeting received letters saying: “This magazine has now been born. Here we go.”

To get it moving, Ansel reached out to people he knew, people like photography patron David McAlpin, for instance, and writer and editor Dorothy Norman, who had been Stieglitz’s sponsor. And there were other bits of help along the way. Jacob Deschin announced the first issue of the magazine in the New York Times [March 16, 1952] and gave the address for subscriptions. So progressively, mostly by word of mouth, it began to reach people. Including faculty and students of universities—like me.

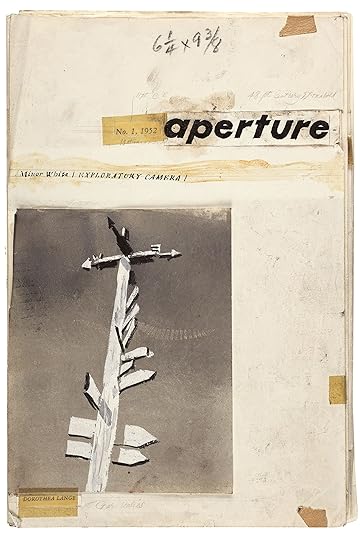

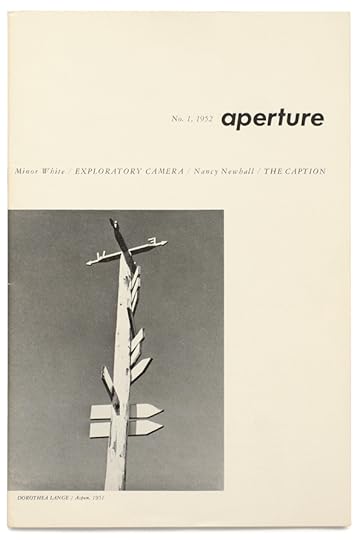

Maquette and final edition of Aperture issue 1, 1952, featuring an untitled photograph by Dorothea Lange

Stoll: What led you to photography?

Bunnell: When I was young, my initial idea was to be a fashion or magazine-illustration photographer. I thought that’s where the glamour was. My father, who was a mechanical engineer, wanted me to be an engineer, but I didn’t want to do that. As a teenager, I bought my first camera, an Argus C3 (which I later learned was the first camera Minor bought, in 1937). I learned how to develop and print, and I realized that I could make money photographing couples at dances and things like that. So I set up a little makeshift studio, and started selling 8-by-10 prints—and it kept getting me further and further from having to be an engineer.

I went to the Rochester Institute of Technology—R.I.T.—to study. R.I.T. was one of the few places to go for photography in 1954 or 1955; it had just begun a four-year program for photography. Minor had been brought in as added faculty when they expanded from a two-year program. He was first hired to teach photojournalism.

Stoll: But he wasn’t a photojournalist.

Bunnell: Right, he was not a photojournalist, but the idea was: if you know anything about photography, you can do it. You just put it in Life magazine! R.I.T.’s photography program was run like a trade school. For the first two years you studied physics, sensitometry, photochemistry; then maybe you could take a few pictures, but not many, because you were always busy in a lab someplace.

Then, all of a sudden, there was Minor. He taught a sophomore course (which derived from his curriculum at the California School of Fine Arts [C.S.F.A.], where he had taught previously) called “Visual Communication.” It was a whole new approach. We cut out pictures and glued them together to make multiple images. We did everything in that class—including learning how to “read” photographs. It was very eye opening.