Aperture's Blog, page 46

January 28, 2022

How Claudia Gordillo Documented the Realities of Life in Nicaragua

In the aftermath of the Sandinista revolution’s triumph in 1979, the Nicaraguan photographer Claudia Gordillo Castellón began documenting her country’s urban and rural landscape. She observed rapidly transforming social and political realities during the 1980s and 1990s, producing an important body of documentary work while remaining committed to aesthetic experimentation. As a correspondent for the Sandinista daily Barricada from 1982 to 1984, she was assigned to the war photographers’ division and charged with documenting the controversial US-funded Contra war.

Even on the frontlines, Gordillo sought to document the context around the armed conflict, focusing on the lives of civilians caught in the cross fire. This interest in capturing the minutiae of everyday life, in the midst of dramatic and difficult historical events, characterizes her entire body of work through and through; this is ultimately what sets it apart. Whether in the barrios of Managua or the most remote regions of Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast, Gordillo sought to privilege the photographic subject, observing Nicaraguan society, habits, and daily rituals from a close yet critical distance. A persistent defender of freedom of expression, she argued that a certain degree of autonomy was necessary and that, ultimately, documentary work should not be made to serve an ideological agenda. This autonomous position nonetheless proved difficult to sustain within a context of heated ideological debate; her work still draws toward the unexpected, accidental, and even uncanny, revealing the absurdity of life, regardless of outside demands.

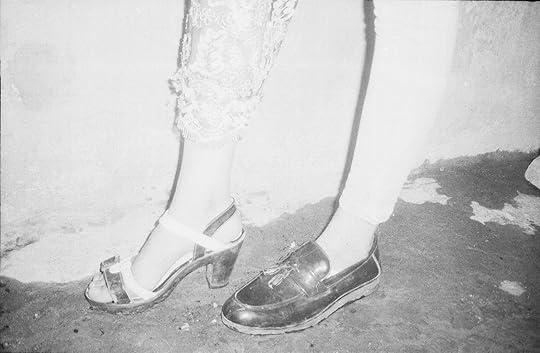

Claudia Gordillo, Quinceañera celebration on the slopes of the Mombacho volcano, 1995

Claudia Gordillo, Quinceañera celebration on the slopes of the Mombacho volcano, 1995The Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua was one of the most photographed political movements of the late twentieth century. Photographers from around the world, including across Latin America, converged upon the small Central American nation to witness and document what was seen as an ideological conflict between post–Cuban revolutionary movements and an emerging global neoliberal regime. Gordillo documented encounters and social realities that often took place alongside the most celebrated, decisive, or so-called iconic moments of that struggle. This is a crucial distinction that has to do with decolonizing the very notion of what constitutes a political, or revolutionary, act. Inherited notions about Latin American photography maintain that a “local” documentary tradition emerged in direct response to political circumstances, which demanded taking a position. As Gordillo’s practice demonstrates, notwithstanding the photographer’s commitment to social justice, her stance was nonetheless informed by an awareness of contemporary photographic practices in conversation with Euro-American and Latin American counterparts.

I met Claudia Gordillo in 2011 in Managua, while conducting research on photography in Nicaragua. In this interview, which took place online in January 2022, we discuss the span of her career from the early 1980s to the late 1990s, and address her approach to documentary photography. Gordillo speaks about how her work responded to the pressing issues of the time, and foregrounded aesthetics while seeking to avoid cliché and ideological bias. She also reflects on her archives and how the transition from analog to digital has impacted her current perception of her body of work.

Claudia Gordillo, Francisco Sambola, garifuna leader from Orinoco, and sailors, Pearl Lagoon, 1990

Claudia Gordillo, Francisco Sambola, garifuna leader from Orinoco, and sailors, Pearl Lagoon, 1990Ileana L. Selejan: At the beginning of your career, you had returned from Italy in the immediate aftermath of the triumph of the Sandinista revolution in July 1979. What was that experience like? And how did you perceive your work within that context?

Claudia Gordillo: I left Nicaragua for Europe and Italy in 1977 without a clear plan, searching for a design school. After about a year, I visited the Istituto Europeo di Design in Rome. However, as this was the best school in the field, there were no places available, except for two in the photography course. I decided to enroll immediately, so as not to lose this opportunity.

When I returned to Nicaragua after more or less two years, having completed my course, I got disappointed and began watching the outside reality through TV. I closed myself indoors, not having a sense of purpose, without a direction for my work, until I started driving around Managua in my father’s car. I was observing the changes left by the war and the earthquake that had destroyed our city. I repeated these outings many times and discovered thus the [ruins of the old] cathedral where I made a series of photographs, which later ended up stirring an entire debate about the role of the arts in the revolution.

Claudia Gordillo, Old Cathedral, Managua, 1981

Claudia Gordillo, Old Cathedral, Managua, 1981Selejan: Could you talk about the controversy surrounding your first exhibition in Managua, where you showed that series from the old cathedral? I know it was a very difficult moment in your career.

Gordillo: The exhibition of the cathedral series created a debate against freedom of expression. Because, according to one of the nine Sandinista commanders [from the National Directorate] who gave an interview at the time, the arts were to serve the revolution, nothing else.

Selejan: At the start of the 1980s, you worked for the newspaper Barricada, which was the official publication of the FSLN [Sandinista National Liberation Front]. How would you describe the work environment at the newspaper? Was there great interest in photographic reportage?

Gordillo: Yes, there was interest in reportage, however, only if favorable to the party. This was, after all, the official outlet for the FSLN.

Back then, there was hope that the revolution could be defended against attacks from the Contra, and the type of photography Barricada commissioned reflected this triumphalist stance with regard to the war. When I got to the San Juan River [in the south of Nicaragua] on an assignment, volunteer battalions were still present in the barracks at San Carlos. We’re talking about 1983, a high point in the Contra war. I felt very good there, away from directives and with more freedom of movement. I ended up staying for around three months, and every now and then, they would send me [collaborating] journalists, film, and money. Since they were most interested in photographs of the war, I decided to move to the headquarters in the area, with permission from the regional army chief. This was my best assignment as a correspondent, and Barricada liked it.

Claudia Gordillo, Relocation of rural communities from the war zone to Los Chiles, Río San Juan, 1983

Claudia Gordillo, Relocation of rural communities from the war zone to Los Chiles, Río San Juan, 1983Selejan: Several of your trips to the war zone led to you witnessing dramatic events, such as the relocation of local communities. Were those images controversial at the time? I see them as contradicting the official narrative of the revolution.

Gordillo: I only witnessed relocations in the area around the San Juan River, precisely where previous errors in such campaigns were taken into account. That is to say, they allowed the transfer of animals and crops with the help of Sandinista militias. It was different, even if mandatory, because they helped people to evacuate. I was myself part of the well-seasoned brigade of militiamen, peasants, and militants that carried out the operation. This was a unique experience, since I was living at the San Carlos headquarters, sleeping in a hammock in front of the San Juan River. My story was published, with Barricada selecting the photographs.

Claudia Gordillo, Rainforest in Río Grande de Matagalpa, 1987

Claudia Gordillo, Rainforest in Río Grande de Matagalpa, 1987Selejan: Some of the work from this period you returned to later, reconsidered as the series Fragmentos de una revolución [Fragments of a revolution]. What does a retrospective view add to your reading of the work? And how has that changed throughout the almost four decades since?

Gordillo: Learning to scan negatives was what changed my perspective. I was always looking at my contact sheets, marking the shots to be printed. Because I was working, I never really had enough time to do proper lab work. For instance, the San Juan River story took up many film rolls and contained many frames that I had actually never seen. It was only when I started to scan them that I could properly appreciate many of the negatives that were stored away for over thirty years. My work focused on the people, rather than on politics and leaders.

Even with Barricada, I went on several assignments where, say, one of the commanders would give the main speech, but even then, it wasn’t the most interesting part for me. I wasn’t that inspired, beyond my duty toward the newspaper and managing to get the images they requested. Neither did I have any sentimental attachment to anyone, because I thought that would negatively impact my observation. I needed to have freedom of thought—I was always very clear about that. It was always very present in my mind. As the years passed, I realized this was the most adequate stance, given my status as a reporter or photographer. And I was dedicated to searching for images that somewhat questioned the system.

Claudia Gordillo, Presidential elections in San Carlos de Río Coco, North Carribean, 1990

Claudia Gordillo, Presidential elections in San Carlos de Río Coco, North Carribean, 1990Selejan: The 1980s were a tumultuous decade in the history of Nicaragua, to say the least. You documented the sociocultural changes taking place with great interest, yet chose to focus on everyday life instead of heroic deeds and history with a capital H, always with an eye for the extraordinary in the ordinary. This strikes me as greatly contrasting to the work of other photographers who were working in the country at the time, including those coming from abroad. Is this the case?

Gordillo: What happened was that I was living here, and so the political discourses sounded hollow to me. The Sandinistas talked a lot about the “achievements of the revolution,” while we were living right in the middle of this tremendous poverty, with shortages of all kinds. Many of those coming from abroad believed this discourse. Not all, it must be said. But I wasn’t paying much attention to this. I wanted to get to know, and to understand, Nicaragua from the perspective of the [popular] markets, how people lived here. I wanted to understand how traditions functioned, their logic and origins, things that were not [necessarily] related to contemporary politics. My intention was to continue discovering those elements I identified with.

Claudia Gordillo, Jovita Knight, from the Ulwa community of Karawala, Río Grande de Matagalpa, 1990

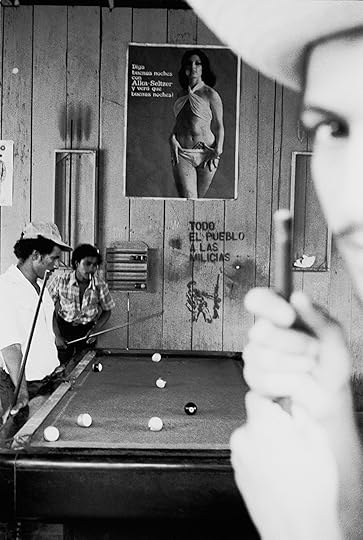

Claudia Gordillo, Billiards in La Libertad, Chontales, 1982

Selejan: After leaving Barricada, quite early on you started working with CIDCA [Center for Research and Documentation of the Atlantic Coast] on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. At the time, the FSLN government was seeking to expand its influence in that region, while being quite ignorant of local dynamics among the primarily Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. A significant body of work ensued from that experience. How do you perceive it now, several decades later?

Gordillo: The outcome of my work on the Caribbean coast is quite anthropological, without a doubt due to the influence of [anthropologist] Galio Gurdián, who was then director of CIDCA, and who set out to research local cultures, ethnic groups, and their traditions. I thought it was interesting to photograph life in the Caribbean, approaching significant details, although you couldn’t speak about other subjects—it was already a challenge to do so without falling into the usual clichés. Also, there was not enough information about the political issues between the Pacific and the Caribbean. That was a confidential topic. Still, at CIDCA we had a lot of freedom in pursuing our work, even if within certain limits.

Claudia Gordillo, Easter vigil in La Concha, 1998

Claudia Gordillo, Easter vigil in La Concha, 1998Selejan: In the early 2000s, you published the book Estampas del Caribe nicaragüense: Portraits of the Nicaraguan Caribbean with filmmaker and photographer María José Alvarez. It brought together documentary work that you produced over a significant time frame while traveling across vast Indigenous territories. The Caribbean coast is often stereotyped, perceived as exotic and extremely remote, peripheral to most of what goes on in the rest of Nicaragua. By contrast, your work portrays a highly relatable, albeit singular world, one that lives according to its own rules and logic. What was it like to make that work, and how do you perceive it now?

Gordillo: Some exoticism pervades in at least some of the photographs from the Caribbean. It was hard to avoid, given the monumental beauty of the region. Galio Gurdián always gave me a lot of license in my work to document the coast, despite his ties to the FSLN. CIDCA’s commissions were always concerned with the different ethnic groups, their ways of life, fishing, and all that concerned the organization of the various communities. A bit of politics slipped in there, although discreetly.

I can see now that I stuck to the rules, an outcome that is visible in some of the photographs. You needed a special permit to go into the Caribbean region, a type of passport, nationals and foreigners alike, which was why I always thought there were serious long-term issues that were deliberately hidden. CIDCA’s task was to generate historical documentation of the region. A lot of things were achieved, such as the publication of the first grammar of the Rama language, something that had never been done before.

Claudia Gordillo, Fiesta of Torovenado in Masaya, 1996

Claudia Gordillo, Fiesta of Torovenado in Masaya, 1996Selejan: Here, I’d like to return to a project that you started even earlier in your career, after returning to Nicaragua, Memoria Oculta de Mestizajes [The hidden memory of mestizajes]. I feel like you approached this subject from an anthropological angle, something that ultimately characterizes the majority of your work. Yet I would say that your analytical perspective shines forth powerfully. I remember many years ago, you mentioned how your photography was a means to learn about Nicaraguan identities, what made the country tick. Is that part of what’s happening?

Gordillo: Yes, it’s part of the same. Identities are important, especially in a multiethnic and pluricultural country.

Claudia Gordillo, Fisherwoman, Rama Cay island, 1990

Claudia Gordillo, Fisherwoman, Rama Cay island, 1990All photographs courtesy the artist

Selejan: You have spent over twenty years working as a curator, conservator, and archivist caring for the photography collection at the IHNCA [Institute of History of Nicaragua and Central America] in Managua. We are both tragically aware of the extent to which neglect and lack of funding has led to the destruction of a lot of the photographic heritage in the country. You have been looking at those fascinating materials while going through your own archive. How has this process of revision impacted the way you look at your own work?

Gordillo: Archives are always a fascinating resource for books, documents, and historical images. With time, I learned a lot about the conservation and proper handling of such materials. Digital technology taught me to look at my work in ways I never considered before. In the analog era, you had to first print out a contact sheet, and then print a [selected] frame as a small or medium-sized print, before finally choosing a negative. Learning to scan film was a great discovery for me, seeing my photographs on the screen, many of which I had never printed before and, therefore, wasn’t familiar with. I was very curious to see certain photographs, and the digital allowed me to get to know my own archive better.

January 21, 2022

How Have Photography Curators Responded to Demands for Diversity?

In summer 2020, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, along with many museums in between, were rightly criticized for their responses to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and others at the hands of police and to the protests sparked by those tragedies. Several institutions searched their collections and used artworks by Black artists, without permission, in social media posts. Some paired images with statements that did not directly condemn the killings or adequately acknowledge the pain in their communities

As Kimberly Drew, a writer and formerly the social media manager for the Metropolitan Museum, put it on Twitter, “I understand firsthand that finding something to say can be hard work. I am also saying that I would like to see you do that work.”

For decades, museums have embraced some artists whose work reveals and criticizes the inequities and violence that characterize North American societies. One lesson of 2020, however, was that too often the dialogue surrounding their work, especially conversations about race, had only haltingly led to meaningful institutional change. Major museums appeared ill prepared for the scale and the force of demands to decolonize their practices. How could museums create programming to welcome all audiences and, at the same time, increase diversity, equity, and inclusion among their staffs? More than a year later, what has been the result in the arts of a national reckoning? What steps have museums taken to catch up to a vastly changed social landscape?

Jo Ractliffe, Raising the flag, Riemvasmaak, 2013, from the series The Borderlands

Jo Ractliffe, Raising the flag, Riemvasmaak, 2013, from the series The Borderlands© the artist and courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

The Art Institute of Chicago seems to have been among those better poised to respond. In 1994, the museum created a Leadership Advisory Committee composed of African American community members. The museum’s current director, James Rondeau, has accelerated similar efforts. When Matthew Witkovsky, head of the museum’s photography and media department, arrived in Chicago in 2009, he spent three-and-a-half years surveying the department’s photographic holdings and found them overwhelmingly composed of works from Western Europe and the United States, mostly by white men from about 1910 to 1960. Looking to expand that perspective, in 2012, he mounted Dawoud Bey: Harlem U.S.A. and arranged for twenty supporters, led by Leadership Advisory Committee members, to acquire for the museum vintage prints of the full series. Since then, Witkovsky and his colleagues have acquired more works from the artists they exhibit, including Deana Lawson and David Hartt; shown permanent collection pieces by lesser-known African American artists in exhibitions such as Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980 (2018); presented exhibitions on African artists, including Jo Ractliffe and Mimi Cherono Ng’ok; and hired specialists in African and Black photography.

Witkovsky makes a distinction between working with the collection, which proceeds from the art, and rethinking how the institution functions, which “is absolutely about redressing wrongs and thinking categorically.” These two “different sets of concerns can converge, and it’s best when they do converge so that all the audiences you want to reach, not least your own staff, see things that excite them.”

Photographer unknown, Martinique Woman, ca. 1890

Photographer unknown, Martinique Woman, ca. 1890Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs, Art Gallery of Ontario

Julie Crooks, who last fall was appointed to lead the department of arts of global Africa and the diaspora at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), had been a curator in the photography department since 2017. Accepting the museum’s job offer partly stemmed, she says, from a conversation with the AGO photography curator Sophie Hackett about “the importance of building a more diverse collection that reflects the character of Toronto.” Hackett had made major acquisitions of queer photography, along with a huge archive of Diane Arbus prints. Crooks’s most significant acquisition was of the Montgomery Collection of Caribbean Photographs, more than 3,500 historical images from thirty-four countries, which is billed as perhaps the largest compendium of Caribbean photography in a museum outside that region.

How could museums create programming to welcome all audiences? More than a year later, what has been the result in the arts of a national reckoning?

How Crooks and her colleagues acquired the Montgomery Collection is remarkable; it chimes with the Bey acquisition in Chicago and suggests a path forward. Rather than find one wealthy supporter to cover the cost, the AGO built a coalition of twenty-seven donors who contributed to the effort. Many are from Toronto’s Black and Caribbean communities; many are first-time donors to the museum. “It was important for us that there were feelings of ownership and legacy attached to this acquisition,” Crooks says. “Many of the supporters are adamant that these photographs won’t sit in a vault; they’re advocates for the collection being accessible.” The AGO’s 2021 exhibition Fragments of Epic Memory features selections from the Montgomery Collection.

Ishimoto Yasuhiro, Untitled, 1959–61

Ishimoto Yasuhiro, Untitled, 1959–61Courtesy the New Orleans Museum of Art

At the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), the photography curator Russell Lord performed his own collection audit on his arrival in 2011 and found that the overwhelming bulk of the holdings, as in Chicago, was “canonical: white, American and European, male.” Lord knew he wanted to fill in the gaps. The department has recently acquired historical works from Japan and contemporary works by Chinese artists. It is building a Latin American collection. But Lord is also trying to find ways to suggest “diverse perspectives within the United States,” as with a 2021 collection-based exhibition of images by Ishimoto Yasuhiro, the American-born Japanese photographer whose feeling of being an outsider led him to immigrate to Tokyo in 1961.

In 2020, NOMA devoted all its available acquisition funds to buying art by BIPOC artists, more than half of whom call New Orleans home. Lord’s department acquired works by local artists Eric Waters and Akasha Rabut, among others. “It was important for the museum to make a visible commitment to the local community and to the diversity of its collection,” he says. “That was one result of a practice we’ve been moving toward over the past decade.”

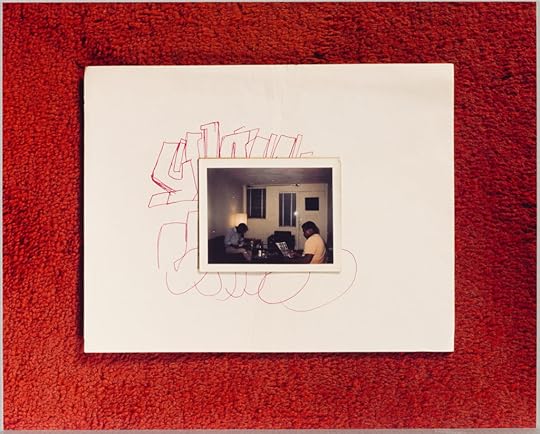

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (6 of 10), 2006–9

Leslie Hewitt, Riffs on Real Time (6 of 10), 2006–9Courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion have been particularly prominent around the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in New York, since 2019, when Chaédria LaBouvier, a Black independent curator, accused the museum of racism in how it handled her exhibition on Jean-Michel Basquiat. After identifying omissions in the collection while organizing a major collection exhibition in 2010, Jennifer Blessing, senior curator of photography, has worked deliberately to make the museum more global, “especially in terms of African and African diaspora artists.” Blessing notes that while the 1996 exhibition In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, organized for the Guggenheim primarily by guest curators, including Okwui Enwezor, was a significant moment, that effort was “not fully recognized as part of our institutional history.”

It took a 2001 gift from the Bohen Foundation of over two hundred works to bring photography by African artists, such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, into the Guggenheim’s collection. Blessing and her colleagues have supplemented this representation with purchases of photography by the South African artist Zanele Muholi, along with those of African American peers including Lorna Simpson, Hank Willis Thomas, and Leslie Hewitt. “When people talk about diversity and how we measure it, there is a tendency to focus on the number of artists or the number of objects,” Blessing says. “I think we should also consider how much money is being spent on artworks by artists of color.”

Installation view of Off the Record, with works by Tomashi Jackson and Sara Cwynar, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021. Photograph by David Heald

Installation view of Off the Record, with works by Tomashi Jackson and Sara Cwynar, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2021. Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Ashley James joined the Guggenheim as an associate curator in 2019 and immediately organized Off the Record (2021), an exhibition—with works by Simpson, Thomas, Hewitt, and others—about what’s left out of mainstream narratives. Like Crooks’s acquisition in Toronto, Off the Record created a gravitational force—the museum acquired the one piece in the show that was not previously in the collection: Tomashi Jackson’s Ecology of Fear (Gillum for Governor of Florida) (Freedom Riders bus bombed by KKK) (2020). According to James, “Off the Record has offered a bridge to people who can see their own visions reflected in the Guggenheim’s holdings.”

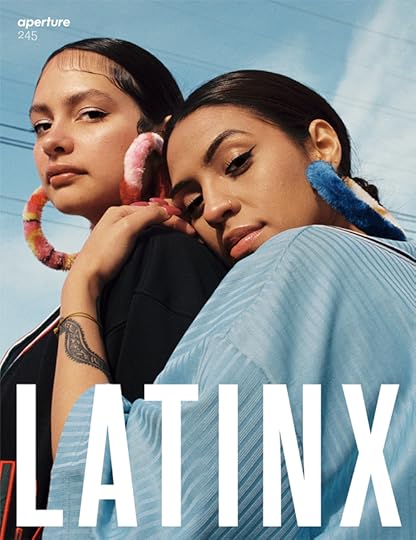

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the column “Backstory.”

January 15, 2022

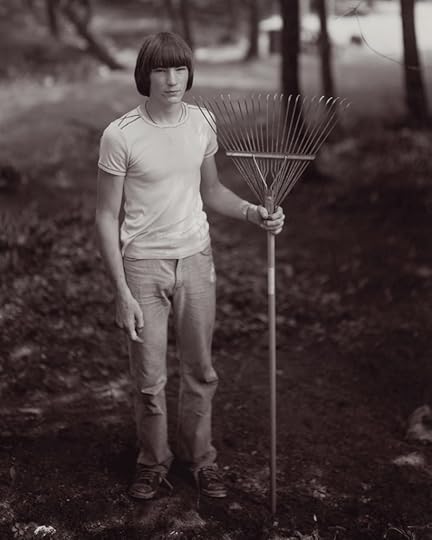

The Radiant Intimacy of Jarod Lew’s Family Portraits

All those clichés that steer the movement of light tend toward revelation: the light bathes, washes, or pools—but rarely does it obscure. In photographer Jarod Lew’s latest body of work, In Between You and Your Shadow (2021), light is both a literal and figurative source of occlusion. A woman in a floral shirt side-eyes the camera, while the gauzy rounds of a lens flare blot out her face; elsewhere, her arms are crossed in repose on a couch, head clouded by a pale blur, as if overexposed into anonymity. This figure is Lew’s mother, both the series’s inspiration and, along with his family, its reluctant subject. She does not like being seen, Lew tells me, which was the project’s core obstacle: “How do you photograph your mother without photographing your mother?”

In the stray refractions of a blazing sun and other such tricks of light, Lew has found a way into his project’s central paradox of visibility: In 2012, he discovered that his mother had been engaged to Vincent Chin, the Chinese American draftsman murdered in 1982 by two Detroit autoworkers days before his wedding to Lew’s mother, a turning point in the history of Asian American civil rights. “I kept coming back to this thought about who my mother evolved into after the killing,” Lew says. “What part of her died when she had to be thrown into the spotlight of the national news?”

Four years elapsed before Lew could confront the weight of this personal and juridical trauma, which led to Please Take Off Your Shoes (2016–20), a project made in the homes of various Asian American strangers in Metro Detroit. For In Between You and Your Shadow, Lew turned to his parents’ home, also in the Detroit area, at first stifled by the etiolated blandness of suburbia, but soon attentive to the narrative possibilities in its banal geometry—a bathroom mirror turned nested frame for his mother’s half-hidden face, or a frosted glass door smudging her familiar features. These corners of the home are vectors as much as props for partial obscuration, as if making a display of her withholding.

At other times, white walls become backdrops for a different form of spectacle. One picture shows arcing lamplight as it pierces the silhouette of Lew’s bearded father, luminous yellow pouring into his shadow. Another contains a glossy Buddha figurine, once owned by Lew’s late grandmother, sitting in a dim corner and dwarfed by its own strangely doubled shadow. I’m struck by the thematic precision of this particular image and its making. Before a happy accident with LED stickers cast these dark and voluptuous shapes, Lew had used a full-on flash but found the image uninteresting. Excess light had stolen its depth.

Many of the photographs in this series bear the stark, flattening clarity of flash for a different reason. “The momentum of this project really started with specific memories I had as a child,” Lew says, “so I recreated them to get my family comfortable with the camera, but also to lead into newer pictures of them that were maybe less staged.” His process began as a kind of conjuring, the studio setup lighting a way into the unspoken densities of his familial past. Some of the earliest shots were images gleaned from the vivid archive of Lew’s childhood: his gym-going father flexing in the mirror; his red-manicured mother’s hand shaving his father’s head. Any other start would’ve made the project impossible, Lew explains. It’s a neat workaround, invoking these unstable fantasias of personal memory, pocked by elisions and revisions, like so much immigrant history. Between a taciturn parent and a cultural identity long patchworked from state-authored illusions, traveling through fiction might be the best way to chance on something like truth.

Lew’s routine dramatizations, in which his brother and Lew himself also make appearances, were enough to coax a certain ease from his parents, their slow-blooming candor opening up a more spontaneous practice. “There are moments when I see light, see how it cuts through things,” Lew says. “I’ve lived in this house my whole life, so I know where to wait.” Most of these impromptu images are marked by honeyed slants of daylight, the sun sneaking through half-shut blinds onto a tiny snapshot of Lew’s mother as a teen, or striating a tender close-up on his parents at dusk. But these radiant intimacies belie one of the project’s thornier realizations.

“Making these photographs revealed this disconnect I have with my parents,” Lew says. “Though we are becoming closer, because we’re playing with one another, there’s still this performance that’s happening, this constant guard between us that I don’t think they’ll ever drop.” Across these staged and mutable frames, Lew has built a way of seeing that centers contradiction, moving past the hypervisibility of racial injury to ask: what does this ubiquity obscure? Necessary mysteries, maybe, or something like gratitude for shadows.

Jarod Lew’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX100S with a FUJINON GF 80mm F1.7 R WR lens.

All photographs by Jarod Lew from the series In Between You and Your Shadow, 2021, for Aperture

All photographs by Jarod Lew from the series In Between You and Your Shadow, 2021, for ApertureCourtesy the artist

January 14, 2022

A Syrian Documentary Photographer Teaches Children to Capture Their Lives

Since 2012, in the village of Mardin, Turkey, close to the Syrian border, a community center called Her Yerde Sanat-Sirkhane has been organizing workshops in the circus arts and photography for local children affected by war. “Children have the opportunity to collaborate and form friendships with one another, beyond gender, social and cultural differences,” reads Sirhkane’s mission statement. “In doing so, they manifest peace, harmony, open mindedness and cheerfulness in their local and global communities.” Syrian documentary photographer Serbest Salih leads the photography workshops, encouraging local kids—many of them fellow refugees—to capture their surroundings, developing the black-and-white film and printing the photos themselves in a mobile darkroom. Yet the photographs the kids make are seldom as grim as the ongoing war that has surrounded them for most of their young lives; instead, they capture their friends playing outside, their families at home, and the local goats wandering the village. A new book, I Saw the Air Fly, collects more than one hundred of these images, all made and chosen by the kids themselves—with some help and guidance from Salih.

Photograph by Bilal, 13 years old, from Alhaske, Syria

Photograph by Bilal, 13 years old, from Alhaske, SyriaElena Goukassian: Tell me about the Sirkhane Darkroom. How did it start, how did you get involved, and where did the idea for a mobile darkroom come from?

Serbest Salih: I’m originally from Kobanî, a Syrian city on the Turkish border. In 2014, when ISIS attacked my city, I fled to Turkey and started working with some NGOs as a photographer. When I moved to Mardin, I started working as a volunteer with Sirkhane, a social circus group for vulnerable children and children who are affected by war. One day, me and my friend went to an area where we saw people who are Syrian, Turkish, Arab, Syrian Kurdish, Syrian Arabs—they are in the same neighborhood, but there’s never been good communication with each other, they don’t know each other. So, we got the idea to use photography as the language to let their children express themselves. After ten months, the project got support from a German NGO called Welthungerhilfe.

In 2019, we were talking about transportation issues. We take children from the area where they live to Sirkhane, which is very hard sometimes, especially for parents, because they don’t know us and they usually tell children to never trust anyone. So, I thought we could use a mobile program. We had a container belonging to Sirkhane, and I changed it into a darkroom, and every two months, I change my location.

When COVID-19 started, I changed my program into mobile, online workshops. It was hard, because most of the children cannot access the internet, or they don’t have a smartphone. Luckily, we started face-to-face workshops again, as the situation in terms of coronavirus is getting better here in Turkey. It’s been four months since we started face-to-face workshops again. And now we are using a caravan, which we got with money from our fundraising. I turned the caravan into a darkroom, and we are traveling from village to village and doing workshops with the children.

Photograph by Ilava, 10 years old, from Kobanî, Syria

Photograph by Ilava, 10 years old, from Kobanî, SyriaGoukassian: How involved are the parents in these workshops? How do you make sure they trust you enough to send their kids there?

Salih: In the beginning of the workshops, we invite the families to see the stuff we are doing. They might think it’s just sending their children to spend a little bit of time outside, but we invite them to Sirkhane, and they see our communication with the children and how we take children seriously. In terms of communication with their child, they also start taking children very seriously. So, yeah. They trust us.

Goukassian: What does a typical workshop look like?

Salih: We do an orientation week first. In the beginning, most of the children are very shy, so we make a circle to let them introduce themselves. In the circle, they are all equals. I explain to them why I chose analog photography—because if you want to learn photography, you should start from zero. And after that, I show them all different types of cameras—some of them are pinhole, analog, digital cameras. After that, I show them compositional photography, and explain that compositional photography doesn’t have rules, and I add with compositional photography awareness of subjects such as child brides, child marriage, gender, and bullying. Then we go outside in the yard, shooting without film, just to practice how to use a camera, and after that, we come back and I show them pictures by the best female and male photographers, to show them that gender is not a basis for anything. After that, I give them cameras with film. I’m not telling them what to shoot; I tell them they can select whatever they want; it’s just that you have to feel it when you shoot a photo. After two or three weeks, I show them how to develop film inside the darkroom, and after that, we print all the negatives inside the darkroom. After they’ve done all these courses, I let them do it themselves. I’m just watching them after that. We scan negatives together, and we discuss their photos.

In the beginning of the workshop, the children are very shy, but then they are participating, speaking about their life, and when we develop their film, they start speaking about their photos when they shoot them. The results are mostly the children sharing moments inside the house, outside, with their families, eating breakfast or lunch or playing with their friends. In the beginning of the project, we used to get more reactions from adults and parents, who always thought the pictures would be about sadness, because these are children who are affected by war and vulnerable children. But mostly, in the workshops we talk about happiness.

Photograph by Zeynao, 13 years old, from Nusaybin, Turkey

Photograph by Sultan, 14 years old, from Nusaybin, Turkey

Goukassian: What kinds of cameras do you have the kids use?

Salih: They’re very simple compact cameras. Mostly, I get second-hand cameras. Kodak, Fujifilm, Canon. Many different brands. All auto-focus.

Goukassian: What languages do you teach in?

Salih: Turkish, Arabic, and Kurdish, mostly.

Goukassian: Do you teach in all three languages at once, because the kids come from different backgrounds? Or do you have, for example, a Turkish-language class and then a separate Kurdish-language class?

Salih: My goal is to integrate the community, so I’m trying to not do any separate groups according to language. Sometimes, our common language is Turkish, sometimes it’s Kurdish, sometimes it’s Arabic. Most of the time, it’s Turkish. The main aim of this project is to integrate the children. Most of the children grew up here, in Turkey, so now they are speaking Turkish.

Goukassian: Where are you now? Do you currently have a class? How many kids are in it?

Salih: Three weeks ago, I finished a workshop. Next week, I’m planning to start workshops in a village called Karakuyu. Five days of the week, I’m planning to do workshops every day with two groups, with eight to ten children in each group. Every day it’s two groups: one from 10 a.m., and the second group starts at 2 or 3 p.m.

Photograph by Muhammed, 17 years old, from Raqqa, Syria

Photograph by Muhammed, 17 years old, from Raqqa, SyriaAll photographs from the book I Saw the Air Fly (MACK, 2021)

Goukassian: What are your plans for the future? How can the larger photography community support your workshops?

Salih: I’ll continue doing workshops with the caravan. Right now, we are in need of photography materials, especially black-and-white film and compact cameras. We have a donation page, where people can support us or send us second-hand cameras.

Goukassian: Have you shown the book I Saw the Air Fly to any of the kids whose pictures are featured in it? What were their reactions?

Salih: I showed photos and the photobook to some of the children. Their reaction was amazing. They were very happy, because in the beginning, when we decided we would create a photobook, I gathered up all the children and I put the photos on the table so they could select photos for the book themselves, and when they saw the result in the photobook, they were very happy. They still don’t believe that it’s published worldwide.

Goukassian: What about your own reaction to the book?

Salih: I see this photobook as a celebration of childhood.

I Saw the Air Fly was published by MACK in August 2021.

January 13, 2022

Does “Greater New York” Look Ahead by Looking Back?

My first encounter at the latest edition of Greater New York—the survey of artists living and working in New York City that MoMA PS1 has put on every five years since 2000—was with Diane Burns’s “Alphabet City Serenade.” In a video on loop, the artist, whose parents were Chemehuevi and Anishinabe, recites her poem about Indigenous alienation and downtown displacement, connecting Manifest Destiny to the gentrification of the late-’80s Lower Manhattan she wanders: “I’m American royalty / walking around with a hole in my knee / I’m a hopeful Aborigine / trying to find a place to be / oh East Village, ay yay yay yay yay yay yay.”

Diane Burns, Poetry Spots: Diane Burns reads “Alphabet City Serenade,” 1989. Video, color, sound

Diane Burns, Poetry Spots: Diane Burns reads “Alphabet City Serenade,” 1989. Video, color, soundCourtesy Bob Holman

This time, Greater New York features forty-seven artists and collectives, the “greater” extending to include the Haudenosaunee, the confederacy of Indigenous nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) referred to as Iroquois by colonizers, and artists’ ethnicities are listed in wall texts to emphasize the global scope of what “New York” art might mean today. PS1 curator Ruba Katrib, along with director of the museum Kate Fowle, MoMA curator Inés Katzenstein, and independent curator Serubiri Moses, introduce the show by invoking science-fiction writer Samuel R. Delany on a gentrifying Times Square at the end of the twentieth century.

Manhattan-born Delany argued that integral to a city’s “vibrant life” is “contact,” which the wall text paraphrases as the “encounters, liaisons, bonds, and casual exchanges made possible in spaces that bridge social worlds and cut through hierarchies established by commercial interests.” The lamented loss of these sorts of spontaneous, often anonymous meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic has become a familiar refrain, especially in New York, where such “contact” is meaningful, magical, and a part of the mythos. At the same time, the expansion of mutual-aid networks and the uprisings in support of Black life have reemphasized the importance of community-based care and communal refusal of racial capitalism. With the pandemic of 2020 continuing into 2021 and now 2022, many may wonder what’s next. Seventy-nine-year-old Delany recently told an interviewer, “One of the things that I know as a science-fiction writer is if there’s one thing you cannot predict, it’s the future.”

Installation view of Greater New York 2021, MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Noel Woodford

Installation view of Greater New York 2021, MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Noel WoodfordCourtesy MoMA PS1

Both documentary and surrealism are prevalent in the show—not, the wall text explains, in opposition but “integrated and entangled as they represent and reimagine the world.” And yet, I left Greater New York with a strange sensation, perhaps as tiresomely simple as the fact that, because this show (like so many others) was delayed by the pandemic, it felt uncannily out of time. That most of the documentary photographs on view recall the past—the violence, protests, and joys of previous eras—made the last two pivotal years in New York feel like a fever dream, haunting but only half-remembered. As I moved through the gallery, I could still hear Burns’s flat singsong—part nursery rhyme, part dirge—and I left with her melody stuck in my head.

The loss of spontaneous, often anonymous meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic has become a familiar refrain, especially in New York, where such “contact” is meaningful, magical, and a part of the mythos.

Gentrification, migration, and belonging are taken up by works made both thirty years ago and this past year alike. Iranian artist Hadi Fallahpisheh’s Young and Clueless (2021) explores immigration—dislocation and cat-and-mouse competition—with cartoonish drawings of the aforesaid plus dog, created in the darkroom with a flashlight on photosensitive paper. Seneca artist G. Peter Jemison takes on the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794 acknowledging Haudenosaunee sovereignty, which—despite violations and subsequent treaties—to this day stipulates annual supply by the US Army to the tribes of yardage cloth, which Jemison incorporates into a map-like work, along with old family photographs, sketched roads, and scraps of language.

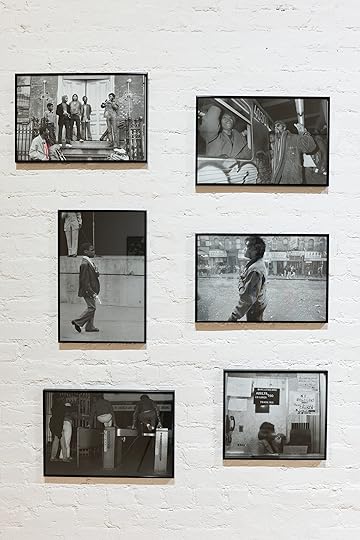

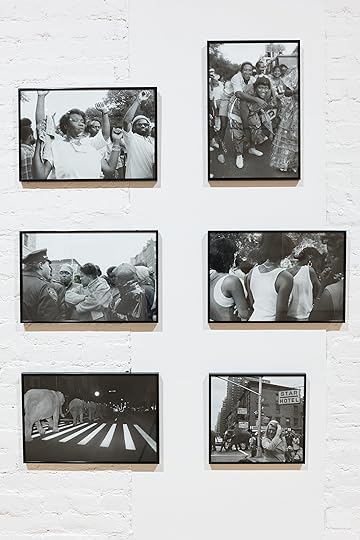

Installation views of work by Marilyn Nance in Greater New York 2021, MoMA PS1, 2021. Photographs by Steven Paneccasio

Courtesy MoMA PS1

Striking documentary photography from the 1960s–80s makes this period loom large. The images of Puerto Rican American artist Hiram Maristany fill one wall, where freedom and play exist amid violence and confinement in East Harlem of the 1960s–70s. Maristany was the official photographer of the Young Lords; and these stylish images, rightly recognized today, likely faced a different reception by institutions at the time the Young Lords sought civil rights and self-determination in the decades pictured.

On another wall, Marilyn Nance’s carefully chosen moments—like those of revelers on Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway at the 1986 West Indian Day Parade, or people jumping the subway turnstiles in 1975—create a potent portrait of the era. Girls Listening to Rap Music (1986), their poised attention beautifully captured from behind, hangs beside the front-facing young women of Police and Demonstrators, MLK Day March. Little Black Book. Carol Taylor (1/18/1998), cross-armed and staunch. One might imagine these women are the same girls a decade later, and wonder where they are today.

Marie Karlberg, Still from The Good Terrorist, 2021. Video, color, sound

Marie Karlberg, Still from The Good Terrorist, 2021. Video, color, soundCourtesy the artist

Perhaps, I began to feel, the photo-based works of Greater New York tell a more complicated story about the tenor of time.

The Swedish artist Marie Karlberg’s film The Good Terrorist (2021) isbased on Doris Lessing’s 1985 novel of the same name, about a squat of Communists who debate housekeeping, the Irish Republican Army, and their own plot to blow up a fancy London hotel to further the group’s political cause. The film, made during the pandemic in an empty Upper East Side apartment, follows comrades played by artists like Nicole Eisenman and Jacolby Satterwhite—whose own work is displayed downstairs in the exhibition (Never) As I Was: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2020–21—as they disagree about how best to oppose capitalism and fascism with bourgeois finger-pointing and leftist racism and sexism (“You don’t seem to understand the value of property,” Karlberg’s character’s boyfriend tells her. “You haven’t even read Marx’s The Law of Value”). A transcendent dance sequence to “Ave Maria” deftly signifies the violent climax.

Greater New York has been criticized for its “pitch-perfect politics” rather than more boldly “seeking disapproval.” I bristled at these responses. (Instead of work addressing Indigenous land sovereignty that one critic deemed safely politically correct, would they have preferred an art that more radically embodies the kind of Land Back activism that has recently implicated institutions like MoMA itself? Seems unlikely.) But I also couldn’t help but wonder if the critiques came from the same root as my strange sensation—perhaps stemming from some similar source, if leading to different conclusions.

Robin Graubard, Selection from Peripheral Vision, 1979–2021

Robin Graubard, Selection from Peripheral Vision, 1979–2021Courtesy the artist and Office Baroque, Antwerp

Visiting a second time, I felt that what has been mistaken for nostalgia by critics is, in fact, the employment of time—the true subject of the show’s photographic works—as a looking glass. What I additionally craved, fairly or not, was a more palpable sense of how the last two years have changed the reflection. The curators were interested, they’ve said, in conveying the city’s international and intergenerational art world, and in complicating the linearity of time and exchange of influence between artists of different generations. The works of both young and long-gone artists never recognized in their lifetimes hang side by side.

As do the years in Robin Graubard’s series Peripheral Vision, with documentary images taken between 1979 and 2021 displayed on mostly unframed paper, punks, mafia thugs, Times Square pregentrification, and more, together in a scrapbook patchwork. Bettina Grossman’s Phenomenology Project (1979–80) is a collection of dreamlike cityscapes seen through the warped reflections of storefront windows. It’s an easy but nevertheless effective gag, the funhouse grotesquerie of wavering American flags not at all up for the task. A room over, in the surrealist tableaux of Indian artist Avijit Halder, friends drape, throw, and wrap themselves in a brighter fabric: with Halder’s late mother’s saris they express fluidity—of gender, but also of time and place as colored by movement and memory, and by grief.

Two images by British Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode—whose work explores Black queer desire, transgression, mortality, and alienation—feel both of the past and for the present. Half Opened Eyes Twins, made in 1989, the year Fani-Kayode’s life was cut short by AIDS-related complications, shows the mirrored pair sitting, nude and illuminated in darkness, each covering one eye, the other open to meet the viewer with a question unique, I imagine, to all who come upon this indelible photograph.

Installation view of work by Diane Severin Nguyen in Greater New York 2021, MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Steven Paneccasio

Installation view of work by Diane Severin Nguyen in Greater New York 2021, MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Steven PaneccasioCourtesy MoMA PS1

More abstractly, Vietnamese American artist Diane Severin Nguyen’s ephemeral sculptures made from found materials are like exquisite biological specimens, captured at close range before they decompose. She specifies that the gallery wall opposite be slit open for light to stream through—a reminder of the natural world, the machinery of the camera, and the artificiality of the museum itself. Nearby, Japanese artist Yuji Agematsu conveys the experience of quarantine in New York with a collection of detritus found on the street during his daily walks. Displayed in cellophane cigarette-wrapper assemblages on plexiglass shelves, they form a grid of 366 captivating curiosities in miniature.

Shelley Niro’s (member of the Six Nations Reserve, Bay of Quinte Mohawk, Turtle Clan) Resting Place of Our Ancestors 1–4 are large-scale photographs of ancient fossils on Lake Erie rock faces. British and Ugandan artist Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa intersperses archival images with his own, along with a simple brick-and-wood sculpture, threatening and mundane. In both these artists’ works, time and provenance are in play to consider the ways in which history remains with us, obscured.

Installation view of work by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa in Greater New York 2021 at MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Martin Seck

Installation view of work by Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa in Greater New York 2021 at MoMA PS1, 2021. Photograph by Martin SeckCourtesy MoMA PS1

“Have we been looking, these many years, at the combustible surfaces of our historical present? Have we been paying attention?” Wolukau-Wanambwa asks in Dark Mirrors, his recently published collection of essays on (primarily US-based) fine arts photo and video work. With an eye attentive especially to the photographic book form, his criticism is itself “a sustained examination of what it is that hides in plain sight as its presence is unveiled or intimated by the image,” he writes.

At Greater New York, Wolukau-Wanambwa’s Separation(s) (2021) is a triptych of the same anonymous man wearing glasses and a suit and tie: the subject is white, with white hair, maybe seventy-something. Foggy plexiglass hovers a few inches over the prints, where the figure is traced lightly in ink, giving the multiply exposed man a ghostly stutter. What historically might have been the image of a trustee or CEO hanging unquestioned on the walls of some hallowed hall or corporation here becomes a monument to seeing itself—foregrounding the lens through which we understand the past, the sketchy mirror by which we strain to see the uncertain future.

Greater New York 2021 is on view at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, through April 18, 2022.

January 6, 2022

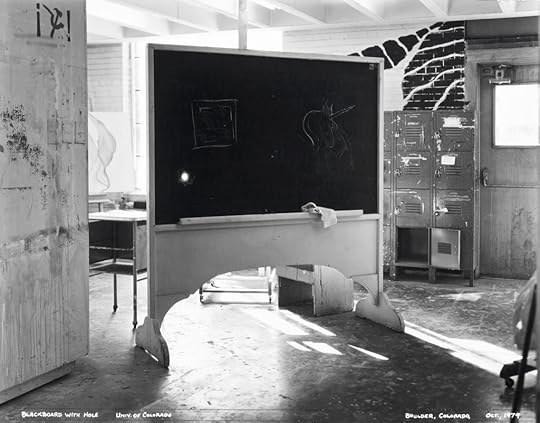

How Robert Cumming Pushed the Boundaries of Photography and Narrative

In 2016, Aperture published The Difficulties of Nonsense, the first comprehensive publication to survey Robert Cumming’s significant series of conceptual black-and-white and color photographs from the 1970s, now a touchstone for contemporary artists, and focus on the artist’s fascination with illusion and trickery. From his base in Los Angeles, Cumming made functional-looking but ultimately useless constructions, created primarily to be photographed with his 8 x 10 camera. Playing with props, proportions, unusual angles, light and mirrors, Cumming invited viewers to look in—and then to look again, second-guessing what they saw. On the occasion of Cumming’s death in December 2021, we revisit David Campany’s interview with the photographer, who playfully pushed the boundaries of image and narrative.

Robert Cumming, Chair Trick, 1973

Robert Cumming, Chair Trick, 1973David Campany: Robert, you made your photographic work pretty intensively for a decade or so, and then moved on to other things, but the ground you covered was very rich. Are you the same person now who made that work? Do you relate to it as yours?

Robert Cumming: Yeah, it does feel like mine.

Campany: There’s a lot of energy in the work. So many of the pictures are very labor-intensive.

Cumming: To start off an idea, I would do a drawing, like a little pencil sketch. And I had made a promise to myself never to act on these ideas until I’d waited at least a month. I think about one drawing in five was actually made into a photograph. It was a good discipline for me because, you know, the newest idea was always fantastic, and I’d launch into this complicated prop and then realize in the middle, “This really sucks—what was I thinking?” So there was a pact to let each one simmer first as a drawing.

Campany: But do you think that something that works as a drawing might not work as a photograph, or the other way around?

Cumming: Yeah, that would happen. But this waiting helped me understand which path to take.

Campany: There are so many translations going on: idea into drawing, then drawing into objects or situations, and then into a photograph. And you need to be keeping an eye on all of those translations to get somewhere worthwhile. I wouldn’t have been able to say so at the time, but I remember when I first saw your work there was something about the visual qualities of the pictures: they seemed so unlikely with the subject matter and the working process. I know it’s overstated that conceptual artists weren’t interested in craft, but your photographs had such a fascination and affection for the finest qualities of the photographic print.

Cumming: It’s true. But I had by that time really studied photography and its history, and I got more and more taken in by it.

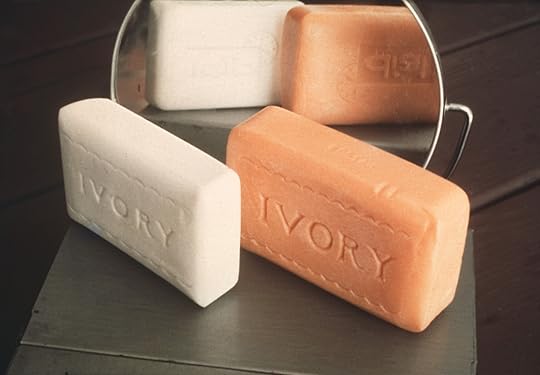

Robert Cumming, Depleted Ivory/Dial, 1971

Robert Cumming, Ivory/Dial Switch, 1971

Campany: You were a real bridge back then between what they used to call “photographers” and “artists using photography.”

Cumming: I’m sort of in the middle there. And my exhibitions were like that, too. I did some sculpture shows, some conceptual art shows, and some photographic exhibitions as well.

Campany: Did you go straight to the 8-by-10 camera?

Cumming: Well, I started with a little Instamatic in undergraduate school. I was taking reference pictures mainly as, I don’t know, studies for drawings I was doing.

Campany: Notations.

Cumming: Notations. Notations for these big industrial landscapes—what locomotive roundhouses looked like, that sort of thing. In undergraduate school from 1961 to 1965, in our photography class, we were learning how to use 4-by-5 cameras. Then in graduate school, although it was a supposed elective, it was strongly pressed on us that it would be a good thing for us to do large-format work. I really didn’t like it, but later, when I was out of school, I thought, Jeez, I kind of miss this. I bought a 5-by-7 because I couldn’t see lugging an enormous 8-by-10 around. But it was stolen from my car, which was great because there were no supplies. Getting film for 5-by-7 was almost impossible; I had taken maybe thirty, forty pictures on it. I then bought an 8-by-10 Burke & James, which was the main recording device through about 1980.

Campany: Did you do all your own darkroom work?

Cumming: Oh, yes.

Campany: And you were exhibiting 8-by-10 contact prints?

Cumming: Usually, yes.

Campany: I was talking to Stephen Shore recently about the necessary discipline of using an 8-by-10. He felt it was kind of cosmic because there’s more information than you could ever possibly want.

Cumming: Sure, that’s sort of why I use it.

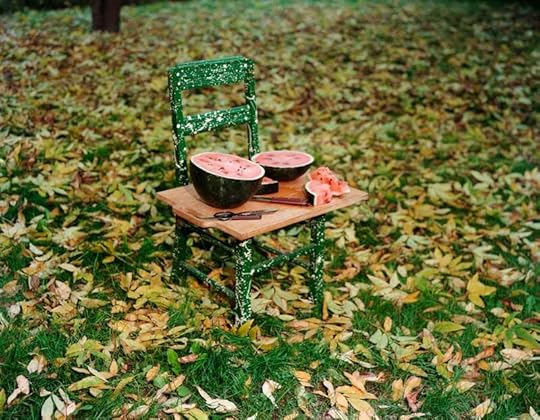

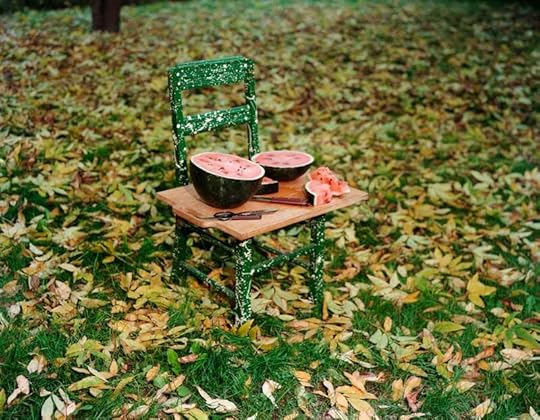

Robert Cumming, Watermelon and Chair, 1982

Robert Cumming, Watermelon and Chair, 1982Campany: On the one hand, the pictures have this very demonstrative, playful, pedagogical dimension. But when you use an 8-by-10, you have a great surfeit of visual information that exceeds those meanings. It’s just this huge richness that’s . . . there, surplus to any obvious requirement.

Cumming: There were very few exhibitions, catalogues, or books on photography when I started. Art Sinsabaugh was our instructor [in graduate school], a purist whose aesthetic I had no use for; at that point I wanted to do 35 mm collages that I’d make into silkscreens à la Rauschenberg. We had a bumpy two years together. But I’d slowly gotten sucked into this big negative thing. To backtrack just a little, it was sculpture that first prompted me to make the photographs back in Milwaukee in the late 1960s.

Campany: You were documenting your sculpture?

Cumming: If you did sculpture and entered sculpture competitions or juried shows, you had to send photos. Sculpture is just too big and heavy. I always thought I had an unfair advantage because I could take a picture that could often be better than the actual piece. And in some cases other artists who did much better sculptures weren’t juried into the shows—on the basis of their skills as photographers. I shot everything with the new 8-by-10.

Campany: Well, that problem has only got worse. We live in an art culture that’s just full of reproductions. Sometimes I think all art culture has ended up being photographic, whether it was photographic originally or not. We see so much in magazines and on websites.

Cumming: At some point, I was just happier with the photograph than the sculpture. And I could photograph them in different positions and in different locations, not just in the studio, and embellish the lighting.

Campany: You were making very photogenic sculptures somehow.

Cumming: Well, the sculpture and the photography certainly fed off each other.

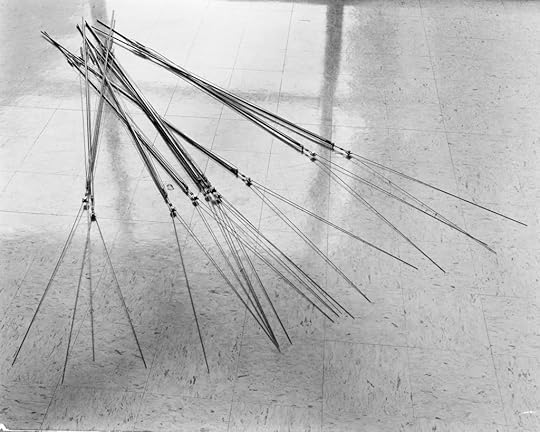

Campany: Sculptures, Milwaukee [1968] reminds me of some of the pictures that Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel ended up with in their book Evidence, which was published almost a decade later, I think. The photograph as factual enigma.

Cumming: I used to know them, though not very closely. All the artists from LA would wind up at the same shows eventually, at the same openings.

Robert Cumming, Sculptures, Milwaukee, 1968

Robert Cumming, Sculptures, Milwaukee, 1968Campany: I was reading somewhere that you kept your distance from the art world. Was that just a temperamental thing?

Cumming: That also describes my current situation.

Campany: There’s something so individual about your work and the pursuit of the making of it. It’s isolated but it’s informed. You’re not completely in a world of your own, but you want a freedom and space that’s yours.

Cumming: That’s how it’s been, definitely.

Campany: Although you went to art school, I sense the heart of your learning is more self-taught, more autodidactic. I don’t know what I would base that on, but just looking at the work it seems that way.

Cumming: Pretty much. None of our classes taught assembled, “additive” sculpture; everyone was chipping away at wood or stone, molding clay—“reductive” sculpture. I wanted to put things together with screws and nails, maybe weld. Even out of graduate school, I couldn’t screw wood together properly; I had very few tools. But I wanted my objects to look like things from the real world, stuff you’d find in hardware stores: rakes, springs, brush cutters, prosthetic devices, etc. Very soon my sculptures took on that language. I liked learning how to do practical things, from the manual. Every year I’d learn a new trade: how to sew, type, weld . . .

Campany: It’s interesting that the sculptures, kind of like the photography, begin with something utilitarian and then end up being useless. Or contemplating utility without being useful!

Cumming: Yeah, exactly.

Campany: In some ways your photography is very pure and seems to be an investigation of the properties or qualities of a distinct medium. Against that notion, you arrived at photography because it’s where all of your interests can come together—the writing, painting, sculpture, performance, handiwork, and the problem-solving. There’s something about the way photography can be a kind of container for all of those things.

Cumming: In the beginning, many of my pictures were like one-liners. Easy. Once you saw them, you thought, OK, very amusing. But at a certain point, very early on, I realized I wanted to make more complicated pieces that would read more slowly. In other words, you’d get the main point, but then in time, on closer inspection, this other stuff would creep in from the margins, changing contexts and meanings, making the story more complex.

Robert Cumming, Black & White/White & Black Rope Trick, 1973

Campany: If you had been a die-hard conceptualist, I suppose you’d have been making all of your set-ups in a kind of blank white studio—

Cumming: Right, right.

Campany: But the world comes into your pictures. The backyards, the bits of interiors, or gardens at the margins.

Cumming: Yes. Often there’s a staging, as if these are little theater pieces. In Chair Trick [1973], the tiny “stage” is framed by my tiny backyard, only about four feet wide. It’s typical California-suburban.

Campany: But you want all of that extra stuff in the frame. It’s titled Chair Trick and there’s a trick going on with the chair, but what you end up with is a picture about diffused lighting, about fauna, about backyards. There’s a whole world, rather than the mere execution of an idea.

Cumming: That’s right. It’s all in there deliberately. Actually, Chair Trick was one of the very first I made experimenting with the parameters of my backyard at night. Only a few feet away, a couple nights later, I made Black &White/White & Black Rope Trick [1973]. I had found this copper wire, fine as a spider’s web, that took three pieces to hold up just the one foot-long length of clothesline rope. I wanted to see if the wire would show in an 8-by-10 contact print, which it did.

Campany: That’s amazing. Do you like magic? Close-up magic? Looking at these kinds of photographs is a little bit like watching somebody very consummate perform a magic trick in front of your eyes.

Cumming: Yes, the pictures would give away the trick, I think.

Campany: There’s often a tension between something that the title tells you to look at and something less specific to be thought about.

Cumming: And sometimes my titles are intentionally misleading.

Robert Cumming, 120 Alternatives, 1970

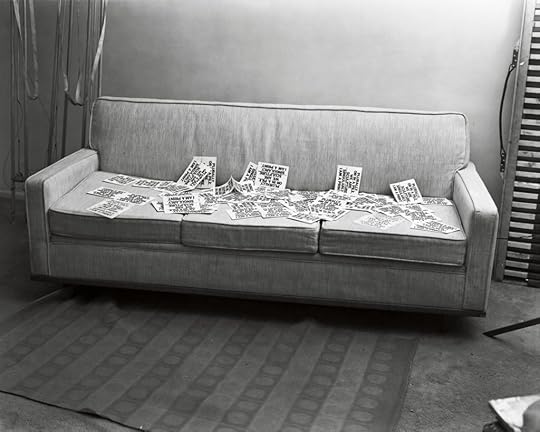

Robert Cumming, 120 Alternatives, 1970Campany: You made a piece called 120 Alternatives [1970], which shows a sofa on which you scattered 120 identical pieces of paper.

Cumming: Yes, the text on the paper reads: “Plurally or in a Pile We Are Sculpture / Singularly, I Am a Print.”

Campany: I really like it as an image. It’s so much more than idea. The photographic print is very fine, with all those shades of gray. The angle is strange. You have to strain a little to read the text. Why is it that sofa? Is that the leg of a light stand?

Cumming: A light stand left in on purpose. William Wegman and I were close for about ten years—as undergrads at Mass Art, roommates at Illinois, teaching in Wisconsin, and sharing a studio in Milwaukee for a couple years, before winding up in Southern California around 1970. His take on it was something like, “Cumming, you shouldn’t be giving away all your tricks. You should stash all your sets and props in a big warehouse, then after you die they’ll be found and it’ll be revealed what a big hoax your pictures were.” But for me, the whole point was the slow discovery of how the illusions worked.

Campany: The pictures are not about the riddle of how it was done. They are much more about the fact that it was done.

Cumming: Exactly. The funny thing is, for all the information, all the detail and complexity, me talking about them—you can describe them to death and you’re ultimately just not closer to what they’re really about.

Campany: It’s an incredibly rich period, Californian photography of the 1970s. Quite rightly there’s still a lot of interest in what went on back then. I discovered it as a student in London in the early 1990s, looking for catalogues of long-gone West Coast group shows.

Cumming: [Laughs]

Campany: There was something about European conceptualism that always seemed a little too dry for its own good. Maybe there was something about sunshine that kept people humorous!

Cumming: The sunshine is supposed to melt your brains [laughs].

Related Items

Robert Cumming: The Difficulties of Nonsense

Shop Now[image error]

Watermelon and Chair, W. Suffield, Connecticut, 1982

Shop Now[image error]Campany: Well, there’s more irony in West Coast work of that time. Or there’s a kind of understanding that humor is a profound and intellectual thing. It’s not the enemy of seriousness; it’s another path toward it. In hindsight, what do you think about that period, making those 8-by-10s?

Cumming: It’s hard to encapsulate. I was working like a maniac—sort of burning the candle at both ends.

Campany: Where did that energy come from? Did you feel you were searching for something?

Cumming: Well, part of it was practical. It was a difficult period. California art departments weren’t putting on any new full-time faculty, which was my main source of income. I had to work more jobs to support the artwork, and because I was doing more shows, needed more paying work, etc., etc. I was working all the time; eight art schools in eight years, janitor, sign painter, visiting artist gigs, lectures, etc. It peaked in 1980 with thirty exhibitions, fourteen lectures, a couple portfolios, and a government jury for the National Endowment for the Arts.

Campany: Were you selling any work?

Cumming: Basically, no. The work all went out to shows and all came back. Making matters worse, my first New York dealer, John Gibson, seldom paid us for work he sold. He was also the one who insisted I make editions of two or three, which I’ve been saddled with to this day.

Campany: Do you know which museums or collectors have your work?

Cumming: Around 1982, a Chicago collector bought one version of everything—230 prints—and donated them to four museums. So I know exactly where they are.

Campany: I’ve hardly seen any of your work in exhibition. I think I only know it through publications. I know the prints themselves will always be far richer than any reproduction.

Cumming: Someone came up to me after a slide lecture and said, “You know that’s just a trick to get people to come to your shows, telling them all the stuff you can only see in the contact print.” [Laughs]

Campany: I teach students at the moment, and I show them your work and they’re shocked when I tell them the dates of your pictures. It feels very contemporary to them.

Cumming: Maybe it’s because the work looks deconstructive.

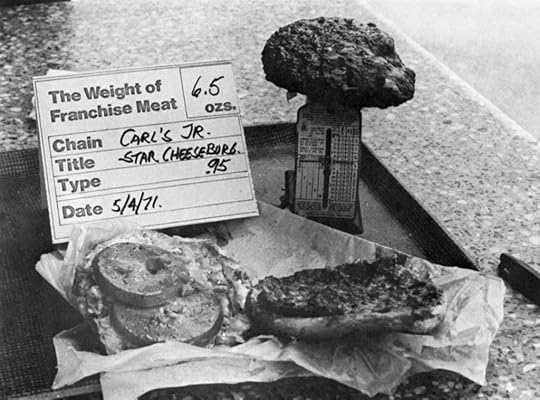

Robert Cumming, Carl’s Jr., Star Cheeseburger, 6.5 oz, 1971, from The Weight of Franchise Meat (Self-published, 1971)

Robert Cumming, Carl’s Jr., Star Cheeseburger, 6.5 oz, 1971, from The Weight of Franchise Meat (Self-published, 1971)Campany: It might be that. I think in the last five or so years there’s been an opening up again between photography and other media. At the same time, there’s a real interest in the craft of making pictures. So again your work is that kind of bridge we were talking about at the beginning. I think students today probably see something of that—relating to the photographs pictorially, and as explorations of ideas. There’s real synergy between those two aspects. There’s also a spirit that mixes the very logical and the slightly mad. Your photographs are analytical studies that are also arcane and ritualized and obsessive.

Cumming: Oh, good! [Laughs]

Campany: Let’s talk a little about your making books. The books were the place where you put your different investigations together—the photographs and the writing—and in books they became more than the sum of their parts.

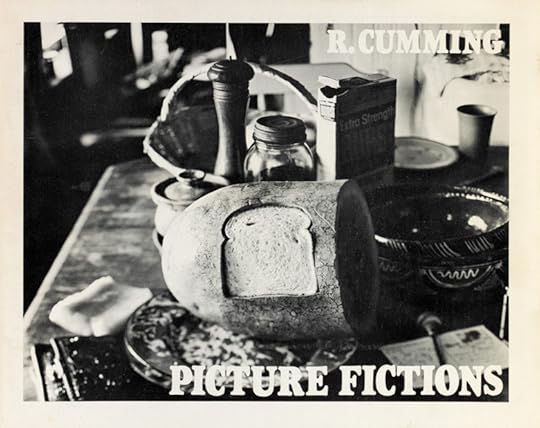

Cumming: Maybe the self-publishing was just ego. My first book, Picture Fictions [1971], was a compilation of work through 1971. The second, The Weight of Franchise Meat [1971], I really hate. I just ran too quickly with a bad idea.

Campany: Did you approach the making of books as another discipline to learn, or did you know anything about the process before?

Cumming: No—I got the idea, of course, from Ed Ruscha. He was very early on in the scene, if not the first, with Twentysix Gasoline Stations, and later with Royal Road Test, Thirtyfour Parking Lots in Los Angeles, and of course, Every Building on the Sunset Strip. The work is brilliant.

Robert Cumming, Picture Fictions (Self-Published, 1971)

Robert Cumming, Picture Fictions (Self-Published, 1971)Campany: Did you know Ruscha at the time?

Cumming: I’d meet these people at openings every once in a while, but you know, not an awful lot more than a handshake. I knew his books were published by Heavy Industry Press, so on a lark, I sent some pictures with a note [that said], “Hey, would you like to print these, make them into a book?” I got a nice letter from a woman who said, “Well, basically Heavy Industry Press is Ed Ruscha’s printing company and does only his work. But good luck with your career.” So I thought I’d do the same thing: publish my own stuff, starting with one thousand copies, sell lots, send them out, and it would be wonderful. Then arrived the new boxes from the printer with that fresh smell of printer’s ink. Sitting there in the middle of the studio, I thought, “What now?”

Campany: Distribution is the thing.

Cumming: Distribution. I hadn’t even thought of distribution. Now I had to start being my own distributor. I started by charging $2.50 per copy. I’d drive halfway across the LA basin to one bookstore. The manager wouldn’t be in so I’d return home and come back on Thursday. He didn’t come in—he’d called in sick—so you’d have to come back a third time. By that time, after five hundred miles on the odometer through notorious LA freeway traffic, he’d buy three copies for $7 (asking for a special discount—$5.75). It was totally, totally hopeless.

In 1973 I did a book called A Training in the Arts with Coach House Press in Toronto, and they had a proper catalogue of titles and distribution. It actually went into reprint

in 1975.

Campany: You ended up doing three books with Coach House: A Training in the Arts, A Discourse on Domestic Disorder (1975), and Interruptions in Landscape and Logic (1977). Those books were very “writerly,” too.

Cumming: Well, they’re literary experiments in a way. The normal way an illustrated story operates is as a triad: illustration assists the text, assisted by the caption. All are connected. But I wondered what it would be like if one of the three connectors was clipped—if caption assisted illustration, but illustration didn’t connect with the story.

Robert Cumming, When She Was Alone, Miss Quinn Liked to Think of Herself as Karin, 1972, from A Training in the Arts (Couch House Press, 1972/77)

Campany: I can’t think of anyone else who would write in that kind of tone. It’s very consistent with your visual work.

Cumming: That’s perhaps true. Training in the Arts was a parody of Harlequin romance novels—the text is so . . . flat. I don’t know how else to describe [Harlequin books]; they’re just dead. Thousands of words lying there on a page . . . which seem to make millions of readers happy. Additionally, it parodied a couple I knew, art-education majors for whom every damned thing was a “tasting experience” or a “learning experience.” They had a way of leeching life out of everything that passed before them.

Campany: Your writing is a bit like your pictures. Flat-footed, informational prose can be very open for the reader—it gives them a lot of space. You don’t feel hectored or overly guided. It’s like the writing and theories of Alain Robbe-Grillet. Deadpan, uninflected writing can be a very generous writing. It doesn’t force emotions on the reader.

Cumming: I was very influenced by Robbe-Grillet.

Campany: You were? I sense there are many photographers who like his work. There are deep affinities. All those facts with no clear explanation!

Cumming: Yes, it takes us back to the idea that you can describe things endlessly and it’s still a mystery. Robbe- Grillet describes positions, topography—describe, describe, describe. But ultimately it lacks some sort of glue, doesn’t adhere, just kind of disintegrates. But that’s the point; it’s his kind of magic.

Campany: When it’s done really well, it’s extremely memorable. And even though the work is kind of anti- narrative, you can’t help but put it into your own narrative because humans are narrative beings.

Cumming: I love In the Labyrinth, Robbe-Grillet’s book with the soldier wandering around in a vacant city. It starts to snow. And the snow comes down and down and he walks into a tavern and there’s dust falling, and on the wall a print of a landscape, way in the background—a city? And the dust and the snow keep falling, glass rings in the dust…

Campany: In the short piece “The Dressmaker’s Dummy,” from the book Snapshots, he describes one room in great detail—objects, positions, angles of view—but eventually you realize that the room doesn’t add up. The description is illogical. I had to draw the room to figure that out.

Cumming: That’s a nice way to respond to writing—draw a picture!

Robert Cumming, Rotary Disc on Crest Waterfall, 1978, from Equilibrium and the Rotary Disc (Diana’s Bimonthly Press, 1980)

Robert Cumming, Rotary Disc on Crest Waterfall, 1978, from Equilibrium and the Rotary Disc (Diana’s Bimonthly Press, 1980)Campany: A question I’ve always thought about in relation to your work, which never seems to come up anywhere in any of the writings—maybe we can talk about it in relation to your book Equilibrium and the Rotary Disc—is your relation to the art of Marcel Duchamp. The technical know-how, the strange allegories, the jokes, the balance between mystery and revelation.

Cumming: My work has been in a couple of shows that have tried to pair my work with Duchamp, but I really don’t feel a strong affinity for him, for some reason.

Campany: No?

Cumming: The last Cumming–Duchamp show I was in, a kind of Duchamp colloquium in Philadelphia, I finally figured out why . . . but I’ve forgotten [laughs]. It was complicated. If there’s been an artist I’ve had a lasting affection for, it’s probably Piranesi. There’s a lot of him in my stuff from back in the 1960s. His prisons and architectural studies of Rome—all that description, like intense needlework. He also pulls a lot of funny strings, reducing his figures to make their settings mightier than they really are.

Campany: Your rotary disc on a waterfall does remind me of Duchamp’s last work Étant donnés, but it also looks like a Max Ernst—a very lucid but unlikely vision from the nineteenth century. The viewer knows there’s a central thing going on in the presentation, but again it can’t be reduced to an idea.

Cumming: When I was working on Equilibrium and the Rotary Disc, between 1977 to 1978, I was thinking of moving out of California and going back East. Part of it was the growing dissatisfaction with illusion in the work. Growing up in New England, there was a nostalgia for its history: New England mill towns, the Industrial Revolution, and the smaller scale of the mill valleys. Enthusiasm for Hollywood was starting to wane. Also, I was tired of being poor, feeling that I was never going to make a decent living. The only chance in LA seemed to be something like starting up a studio for shooting celebrities, doing commercial work like Annie Leibovitz. But it was obvious I had to get closer to New York and connect with a New York gallery, and get closer to Europe, where there was a growing enthusiasm for American artists.

Campany: It’s hard to feel one’s own historical consciousness in a place like Los Angeles, where you’re surrounded by the present.

Cumming: Exactly. So this interest in the Industrial Revolution sparked a general renewal in history. I made drawings to show how mill towns evolved. The waterfall—the central source of energy—turned the water wheel, and the shafts and machinery inside. The workshops grew into factories, workers lived in row houses, and by the 1890s or 1900, the cities were pretty large. It was the evolution of the kind of towns I’d grown up in. I didn’t understand them until I’d been away from them ten or more years and had seen them from the very different perspectives of the Midwest and the West.