Aperture's Blog, page 44

March 30, 2022

A Photographer’s Canny Investigation of American Privilege

For Buck Ellison, a California-based photographer who stages deadpan, meticulously stylized pictures of people in elite, banal-seeming scenarios, privilege is defined in minute details and practically unseen movements. Elise Silver, a model cast in Oh (2015), a study of innocuous teenage expression, will be recognizable to those who have seen her as a glamorous figure in luxury car advertisements. In Untitled (Cars) (2008), when Ellison ventures into the world of automobiles, two Land Rovers are parked at ridiculously steep angles. It captures a dealership’s demonstration of the vehicles’ rugged capabilities—cartoonishly tough, masculine, expensive. At closer glance, one of the cars bears a vanity license plate reading MARIN, the name of the Northern California county where Ellison was raised, one of the most affluent in the country.

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Cars), 2008

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Cars), 2008Growing up, Ellison says, “I felt guilty that I was attracted to symbols of wealth, because they are often facilitated by things I find reprehensible.” When he was fifteen, Ellison saw an editorial campaign for the brand Kate Spade that he later learned had been photographed by Larry Sultan. It depicts, in staged scenes, an upper-middle-class family’s tourist trip to New York to visit their daughter, with their accompanying forays into consumerism. A photographer himself since 2008, Ellison sets about re-creating deliberately artificial depictions of the kind of life he was born into, crafted with the precision of commercial shoots.

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017

Buck Ellison, Untitled (Family Portrait), 2017For a commission by Arena Homme +, Ellison cast agency models to portray members of his own family, approximating the idea of a traditional, seated portrait. (“It was always my dream to do a portrait of my family,” he says, “but they didn’t share my enthusiasm.”) Working with the stylist Charlotte Collet, Ellison shot nearly four thousand frames, purposefully exhausting his subjects until they stopped acting. Embedded are subtle codes and imperfections: the stiffened smiles, the wrinkles and rumples in the carefully dressed-down clothing, the silver tray of cocktail tumblers, the child with his face in a phone.

Ellison’s stage-managed casualness brings to mind Tina Barney’s complex, intimate photographs of her family; they share Barney’s rarefied milieu and immersive feeling without being documentary. “It’s not about capturing a moment before it disappears, but finding something that’s almost invisible or illegible to the rest of us,” he says. His pictures are an investigation of small gestures—a frank, off-kilter conversation between advertised and unspoken wealth, somewhere between aspiration, imagination, and projected reality.

Buck Ellison, Hilda, 2014

Buck Ellison, Anxious Avoidant, 2016

The similarity between the minimalism of Hilda (2014) and the cool detachment of Thomas Ruff and the photographers of the Düsseldorf School—in particular the painterly, late 1980s and early ’90s family portraits of Thomas Struth—isn’t a coincidence. Ellison studied German literature at college in New York before relocating to Germany for graduate school, a move that added another dimension of distance from which to view the visual projections of privilege in the United States. At the Städelschule Frankfurt, Ellison collected advertisements for Deutsche Bank and luxury watches—“images of prudent investment,” he says a little wryly. He looked at early U.S. colonial portraits, particularly those by less technically skilled painters: “There was so much insecurity about who we were as a country.” In his studio, he pinned Bruce Weber’s photographs from Ralph Lauren campaigns to his wall: contemporary, idealized renderings of the American West as envisioned by the Bronx-born fashion designer who changed his name from the Belarusian Ralph Lifshitz to create a global brand.

Buck Ellison, Oh, 2015

Buck Ellison, Oh, 2015In their own way, Ellison’s photographs lift the taboo that still protects the upper echelons of American life. “It’s like, ‘don’t talk about money,’” Ellison says from Los Angeles, where he lives and works now. Instead, he borrows that attitude of reserve to provoke dialogue, allowing complicated social dynamics to play out beneath the exterior of clean, formal arrangements. Using the inner vocabulary of privilege, Ellison shows the fissures that seep through its idealized surfaces.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 228, “Elements of Style.”

Lucy Raven’s Sonic Journeys Near and Far

Lucy Raven wanted to get wired. Searching for the networks of power that hold up global communications and commerce, she traveled from a pit mine in Nevada to a smelter in China to trace the transformation of raw ore into copper wire, the conduit for transmitting energy. China Town (2009), the resulting photographic animation, combines thousands of still images with on-location ambient sounds, locked together by wild sync—sounds that correspond to an image, but are not actually synchronized. For Raven, a New York–based artist whose practice incorporates photography, video, installation, and performance, the research becomes the work itself. Following China Town, Raven used test patterns for film and sound as both raw material and subject matter, turning the spotlight on standards for picture and audio quality developed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. Her experiments in 3D filmmaking yielded video installations that place stereoscopic photographs within immersive surround-sound environments. Connecting all of these disparate strands is the artist’s continuing exploration into the effects of technology and labor in the production of movies, as well as the poetic relationship between sound and image. In advance of the New York debut of her major installation Tales of Love and Fear (2015) at the Park Avenue Armory, in September 2016, Raven spoke with curator Drew Sawyer about sonic journeys near and far.

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015

Lucy Raven, Tales of Love and Fear, 2015Stereoscopic photograph, custom-built projection rig, and sound, Installation view, Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York

Drew Sawyer: Thinking about sound and its relationship to images, let’s start with your work China Town, which consists of thousands of still photographs and a sound track, and explores the production of copper from a pit in Nevada to a smelter in China. It’s not a typical film. I’m curious about your choice to use still images with a separate sound track rather than working in a more traditional video format.

Lucy Raven: The choice to use stills came first. I’d been working on stop-action animations and exploring ideas of work and exhaustion. When I had the initial ideas that led to China Town, I was still thinking about those questions. I had a residency with the Center for Land Use Interpretation at their site in Wendover, Utah, in the middle of the Great Basin. I became interested in a copper mine called Bingham Pit, where Robert Smithson had proposed, but never completed, a reclamation project.

The other impetus comes from Paul Valéry, who suggested that just as we receive water and gas and electricity into the home from far off with a very minimal effort, one day we’ll be receiving images and sounds into the home, appearing and disappearing with barely a signal of the hand, hardly more than a sign. Now that Valéry’s idea has become commonplace, and wireless technology has made images and sounds coming into the home ubiquitous, the part of his construction that I found more abstract was how water, gas, and, in this case, electricity get into the home.

So I had an idea from the beginning that the images and sounds would “appear and disappear” using some form of animation. As I began to work on the edit, with my editor Mike Olenick, it started to become clear that the sound would need to be continuous alongside the disjunctive imagery. It becomes a means of orientation. Each recording was made at the same location where I took the images.

Lucy Raven, 29Hz, 2012. Randomized audio samples from optical and magnetic film sound track test material

Lucy Raven, 29Hz, 2012. Randomized audio samples from optical and magnetic film sound track test materialSawyer: How did you go about recording? Obviously, when you were going to these different locations, you were taking the still photographs. Were you simultaneously recording sound?

Raven: I couldn’t do both at the same time, because my camera made an audible shutter sound, so I had to switch between the two modes. Luckily, most every process I recorded in the film happens twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, so even though it sometimes required revisiting a site I hadn’t intended to return to, I was able to rerecord when necessary. I became very interested in experimenting with wild sync, which is when the sound corresponds to the image, but is not actually synchronized.

Since I was taking still photographs and animating them later, the process precluded the possibility of recording synchronous sound. So sound, at the beginning, was unhinged completely from the images. It could maintain a sort of loose association with what you were watching, or could be attached more precisely to actions depicted in images so the two correspond, or seem to. When you see a sequence of photographs of a truck dumping copper ore, you hear the sound of ore being dumped, but it might be from a trip I made months later to the same location. Of course, some places were more difficult to access, like the wire factory in Shenzhen, or the furnace in Tongling, both in China. At those times I was just trying my best to do both in quick succession.

Lucy Raven, RP31, 2012. 35mm film (Installation view), Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Lucy Raven, RP31, 2012. 35mm film (Installation view), Hammer Museum, Los AngelesSawyer: In the tradition of documentary film, sound or text usually provides some sort of narrative that frames what one is seeing. It seems your use of sound doesn’t do that in a typical way.

Raven: My process involves figuring out how to strip down both the visuals and the sounds to what’s essential. You bring up the documentary tradition. As I assembled all the parts that eventually became China Town, I came to think of both the images and the sounds as records, or documents, of particular places and processes. That’s one reason I decided to record sound on location rather than use industrial sounds recorded elsewhere, or archival recordings. It was important to me to document the very particular production line I was following, and that neither the process nor the sites come to operate on the level of metaphor. Rather than explaining, or even understanding, this global commodity flow, I was more interested in how the form of the movie could relate to the gaps, inequalities, and intervals inherent in such a system. Nothing really comes together in the movie—the many parts of the production remain disjointed, as do the images. The sound becomes a through line.

Related Items

Aperture 224

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Sawyer: Which is why your term animation makes so much sense, because in a way the sound is animating the images. That film makes me think of this idea of the “disassembled movie,” which Allan Sekula used to describe his piece Aerospace Folktales, from 1973. The work consisted of 142 photographs installed in a gallery like a filmstrip, and then four audio tracks played separately. This idea of the disassembled movie also relates to your work in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, RP47 (2012), and projects you’ve done at the Hammer Museum, like RP31 (2012), using test patterns, as well as purely audio works that are related, like 29Hz (2012). What led you in the direction of looking into cinema?

Raven: Working on China Town prompted a number of questions having to do with the relationship between still and moving images, and, more basically, how movies are made today.

The works you’re referring to started with an interest in motion capture that I saw as related to—in some ways the inverse of—how I’d shot China Town. I had a research residency at the Hammer, and I visited one of the motion capture studios used for big Hollywood films. The day I showed up, everyone had just found out that a huge amount of the work they were doing would be outsourced to India, specifically the backdrops and landscapes for the figures developed through motion capture. They would also be sending over films shot in 2D to be converted into 3D through a very elaborate process that involves the digital creation of a synthetic second-eye view for every frame in the film. I found myself confronted with what seemed like a twenty-first-century version of China Town. Here, though, the raw materials being exported from the American West to overseas were images— literally raw files, one for every frame of film. In the case of 3D conversion, what was being outsourced was actually the labor to produce the illusion of spatial depth.

I began trying to understand how 3D film works, and how it has developed technologically since its quite early invention. I found myself looking at 3D calibration charts, used to align dual 35mm projectors for 3D projection. The images were beautiful—the first ones I saw were clearly photographed from handmade paper maquettes that read “See with Left Eye” and “See with Right Eye.” I searched out more of these charts, and soon realized that there were charts used to calibrate and test most every type and gauge of film projector. This then led me to their sonic equivalent—test tones meant to play in an empty theater before showtime to calibrate the theater’s sound.

While I was researching and beginning production on the works having to do with Hollywood’s outsourcing of its images— the pieces that later became Curtains (2014) and then Tales of Love and Fear (2015)—I became interested in these charts as logging a history of the standardization of perception that was developed for optimal viewing and listening standards, yet born of economic, cultural, and technological conditions as much as for some notion of pristine image or sound.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009Sawyer: So 29Hz is the audio for test sounds.

Raven: Yes. I used twenty-nine different test tones in the work, and Hz is the abbreviation for hertz, which is the unit of frequency for sound. The RP in the filmic work titles is borrowed from the most common test pattern for 35mm film, RP40, where RP stands for recommended practices. In RP47, I included forty-seven different test patterns, and in RP31 there are thirty-one.

Sawyer: Does RP31 also have a sound track?

Raven: For RP31, you hear the sound of the 35mm projector that is running constantly, in tandem with a film looper, in the room. The presence and the sound of the projector is an important part of the installation. For RP47, I asked two genius friends, Jesse Stiles and Rob Ray, to design a software program for the work that would also enable me to add more images and sounds as I continued to find and archive them. The pairing of images and sounds in that piece is randomized, and the image stays up for as long as the duration of the sound file.

Sawyer: But they wouldn’t be related otherwise?

Raven: No, they are two different types of tests—one for sound, one for images.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009Sawyer: So those projects led to Curtains, and then Tales of Love and Fear the following year, which both involve 3D images and surround sound.

Raven: Curtains consists of ten different scenes, each of which animates a stereoscopic photograph that I took in one of ten different postproduction facilities around the globe—from cities in Asia with very low labor costs to some of the most expensive cities in the world, such as London and Vancouver, where local governments offer studios massive tax breaks and incentives— that convert Hollywood films from 2D to 3D. In the piece, the stereoscopic image is split into left- and right-eye images using old-school anaglyph red-cyan separations. The two images come together from offscreen, briefly converge, then diverge again, passing through some strange intermediate zones of overlap that the eyes struggle, nearly involuntarily, to resolve. I recorded the sound in much the same way I approached it in China Town. The sound for each section is based on field recordings from each facility. They’re all office spaces, but the subtle differences between them register substantial differences in location, culture, and activity.

Tales of Love and Fear is a piece I worked on through a residency at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute up in Troy, New York. The idea was to make a cinema for a stereoscopic photograph. In collaboration with EMPAC’s amazing production team, we built a rig that enables 360-degree rotation of two projectors over the forty-minute duration of the work. The rig acts as both 3D film projection apparatus and as a kinetic sculpture performing the architecture of the space.

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009

Lucy Raven, Still from China Town, 2009All works courtesy the artist

Sawyer: How are the image and sound related?

Raven: The image comes from a stereo photograph I took of bas- relief carvings at a site in India. One of the first sounds you hear in the piece is from a field recording I’d made while seeing a Bollywood horror film with a few friends. One of them, an actress, was translating to me in real time from Hindi to English—the film’s sound was pulpy and totally overblown.

So my friend is doing different voices while whispering the translations, people are screaming, and we’re eating popcorn and laughing. Paul Corley, a composer and sound engineer, worked with me to shape a score, a sonic journey from the Mumbai movie theater, into the film itself, and out the other side into a very different, nearly meditative drone state.

Sawyer: Your most recent project, Fatal Act (2016), involves, in part, the history of one sound in particular.

Raven: Yes, sound is an important aspect of Fatal Act, a new moving- image work I’m currently at work on with my research and production collective Thirteen Black Cats. The eventual film centers on the difficulty of imaging and recording the atomic. One scene includes the description of a CBS sound engineer tasked with providing sound for a nuclear-bomb test detonation in Frenchman Flat, Nevada, in 1951. Camera crews had been invited to film the explosion for television broadcast, but to escape fallout, they were necessarily positioned too far away to record sound. Given three turntables, twenty minutes, and the CBS sound library, the engineer improvised, using the slowed-down roar of an African waterfall to make the now iconic sound of an atomic chemical fireball.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 224, “Sounds,” under the title “Wild Sync.”

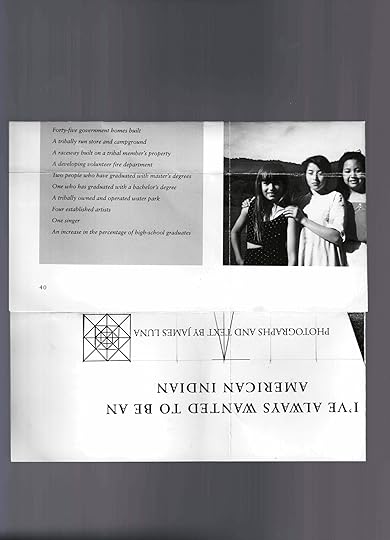

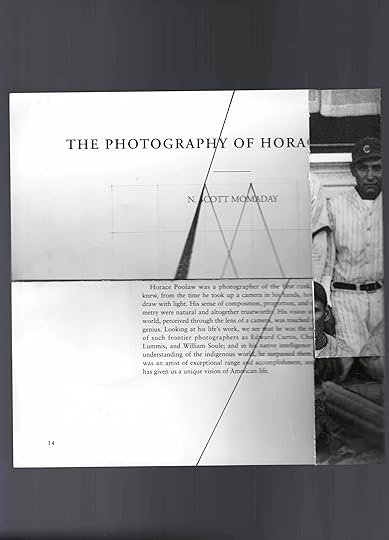

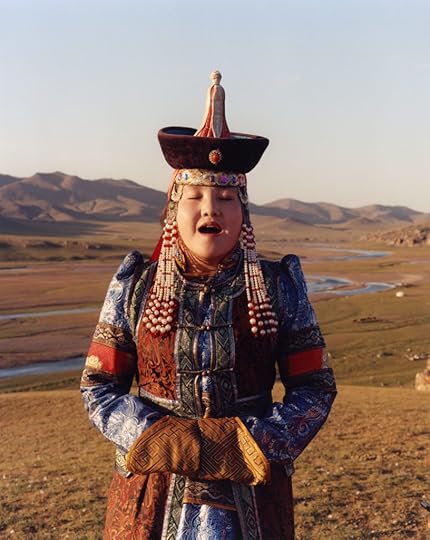

Duane Linklater Redraws the Recent History of Indigenous Representation

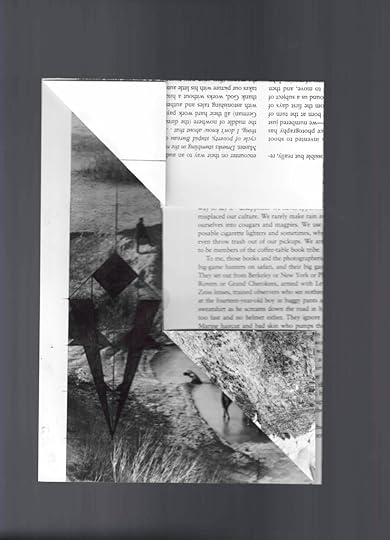

When Wendy Red Star asked Duane Linklater to contribute to this issue, he remembered Aperture 139, “Strong Hearts: Native American Visions and Voices,” from 1995. He cannot recollect how he acquired that issue, but it was among his first exposures to contemporary art by Indigenous people and has remained in his mind these many years. When Linklater received a copy of that same edition earlier this year, he was happy to recall his original interaction with the magazine and consider the continued relevance of the works represented within. He reread Paul Chaat Smith’s sagacious essay with new understanding, lingered on the sensitivity of James Luna’s photo-text work about his community, and was reinvigorated by Zig Jackson’s stunning self-portraiture in San Francisco.

Taking cues from the conceptual work of Sol LeWitt and Charles Gaines, who explored the grid as a system to develop ideas and test boundaries, Linklater began his own line work atop scanned pages from that earlier Aperture issue to establish a space of experimentation and improvisation. Ruminating on several pages of particular resonance, he began to draw, write, fold, and scan, his lines a continuation of the formal ways of working long used by Indigenous artisans to map out beadwork and quillwork while delimiting the scale and pace of his own practice.

Linklater’s contribution to this issue, Other Workers Will Follow (2020), reminds me of conversations we have had over the past several years about how art and artists are read by others. I was specifically reminded of what poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant called our “right to opacity”—to retain parts of ourselves away from others and maintain our complexity, ritual, and sanity. That people should be able to live in peace and respect what they cannot understand and know about one another. Linklater spent the majority of the last year developing can the circle be unbroken (2019), which was included in SOFT POWER, an exhibition I organized at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In this series, painter’s linen is cut, printed, sewn, dyed, and marked to create five soft sculptures in the form of tipi covers, nearly seven meters long. There were many ideas, struggles, memories, and knowledges put into these objects before they arrived in the galleries, but it was within the museum that Linklater enacted his most physical and lasting impact on the works as he gave them their final forms: draping one vertically, rubbing another with sumac pollen, scrawling on others with chunks of homemade charcoal. But it was the most modest gesture—folding one of these enormous vessels into a portable size—that is echoed on the following pages. The works’ potential mobility emphasizes the Indigenous technology of the tipi, while the folds of this flat sculpture refuse to reveal its elaborate surface; it obscures part of itself from view to demand autonomy while maintaining potential.

Coming across Horace Poolaw’s image Carnegie Indians Baseball Team (ca. 1933) again in the “Strong Hearts” issue, Linklater remembered that one of those players always reminded him of his father. But even as he was drawn to address this image, he acknowledged a tension in the appropriation and rephotography of images in his art. While the original works remain significant in their own articulation, Linklater sought a way for these gestures of the past to live among us again. As he marked the pages, he folded, collapsed, and covered much of his own drawing to hide his decisions and leave us only with possibility. Other Workers Will Follow revisits works published a quarter century ago, to feed us forward. They are a way for Linklater to point at other Indigenous people with recognition and intent in a way that representations by others do not afford—to look, greet, and think about each other.

All photographs by Duane Linklater from the series Other Workers Will Follow, 2020, for Aperture

All photographs by Duane Linklater from the series Other Workers Will Follow, 2020, for ApertureCourtesy the artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “Other Workers Will Follow.”

March 26, 2022

“Please Tell the World What Is Happening to Us”: A Photographer’s Account of Covering the War in Ukraine

For the past month, the documentary photographer and photojournalist Natalie Keyssar has been traveling throughout Poland and Ukraine. She has produced powerful, yet devastating records of those affected by Russia’s invasion, many taken on assignment for Time magazine. The war, which escalated on February 24 following Russia’s attack, has left disastrous effects on Ukraine and its citizens, with no end in sight. Russian forces continue their attacks as they face resistance from Ukrainian troops and civilians fighting for their country. This week, the United Nations reported that more than 3.7 million people have fled Ukraine so far.

Regularly working for Time, the New York Times, National Geographic, and other publications, Keyssar has developed a practice that is notable for her commitment to going beyond the surface of the stories she’s assigned—with series that range from the long-term effects of the 2014 Venezuelan protests to the female equestrians keeping Mexican traditions alive in California. Here, Cassidy Paul speaks with Keyssar about her experiences in Ukraine, the uncomfortable line between aesthetics and storytelling, and the essential need for photography in a moment of crisis.

Natalie Keyssar, Alisa Kosheleva (far left) on the phone during the train ride from Poland to Lviv with other mothers on their own journeys towards their children, March 6, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Alisa Kosheleva (far left) on the phone during the train ride from Poland to Lviv with other mothers on their own journeys towards their children, March 6, 2022, for TimeCassidy Paul: How did you decide to travel to the border between Poland and Ukraine? Were you sent on assignment, or did you go by personal motivation?

Natalie Keyssar: Most of my great-grandparents were from Ukraine, and I’d always wanted to come and see where they were from—I just never ever thought it would be under these circumstances. When the news of the war broke out, I was reading the reports about all of these civilians taking up arms to defend their home, and all of these families running for safety, and it was one of those situations where I got this really powerful compulsion to go.

Which, to be honest, I’m not sure how I feel about. I think this feeling is something that governed a lot of my life and that of other journalists—something between inspiration and anxiety and obsession. I’m not at all sure it’s wholly altruistic; in fact, I’m sure it’s not. But there was something about this moment that was so moving, and I wanted to be here, and so I started contacting editors and letting them know I was coming. When I spoke with my editors at Time, we started planning to work together with the wonderful journalist Amie Ferris Rotman.

Natalie Keyssar, Fatima Ezzahra shows a message to Time using Google Translate at the Medyka border in Poland, March 1, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Refugees sleep on the cold ground on the Polish side of the Medyka crossing, March 1, 2022, for Time

Paul: What are the stories you’ve been working on while there?

Keyssar: The first story we did was about the horrific racism that people of color living in Ukraine faced as they tried to flee the cities under attack. Report after report was coming out, mostly via social media at first, about African, Asian, and Middle Eastern people being left for days in long lines out in the cold at the border, being beaten by police, or refused entry to trains, in the midst of this desperate wartime dash for safety. Amie and I started by photographing and interviewing many of these people as they finally arrived in Poland. That story felt very urgent—one of those rare cases where you feel as a journalist that if you can highlight a terrible human-rights violation, maybe you can apply some pressure to improve the situation a little bit. It was very painful hearing these people’s stories of abuse in the midst of such an already awful situation, but I was so inspired by their courage and dignity as I spoke with them.

Natalie Keyssar, Refugees wake after sleeping on blankets and cardboard on the ground on the Polish side of the Medyka crossing, March 1, 2022, Medyka, Poland, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Refugees wake after sleeping on blankets and cardboard on the ground on the Polish side of the Medyka crossing, March 1, 2022, Medyka, Poland, for TimeThe second story I worked on for Time with Amie Ferris Rotman is about mothers returning to Ukraine from abroad to be with their families or to help evacuate them. We were speaking with women at the train station in Przemyśl, Poland, where so many thousands of refugees were crossing through, and we realized that there were a lot of women in line for the trains entering Ukraine, among the majority of men returning to fight. Amie and I looked at each other like, This is really important.

There is this simplified narrative that the women are all fleeing with children while the men run to the front line to fight, and here were all these steadfast mothers, with their jaws set and their eyes steely, who were going home to get their kids, or care for their parents, or sign up and fight. We believe it is really important to report on the courage and strength of these Ukrainian women. A lot of people refer to them as the “rear front line,” and I think that’s a very good term for a lot of what they do, although there are also so many women on the actual front lines. So, we realized we had to follow them back into Ukraine to do this story, and that’s what we did with the support of our editors at Time.

Natalie Keyssar, Women cut strips for camp nets at a Library in Lviv, March 7, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Women cut strips for camp nets at a Library in Lviv, March 7, 2022, for TimePaul: From the work you’ve made, what has stuck out to you the most in the moment? Was there anything you experienced that was different from what you expected?

Keyssar: Definitely what’s stuck out to me most are the moments I’ve shared with these people and how moving and inspiring and unfathomably strong everyone I’ve met has been. What I will remember is their courage and grace. I’ll remember Fatima staring back through the fence at the Medyka crossing, weeping because her brother had been stopped and beaten and was in the hospital, and she couldn’t help him, but I’ll also remember how she found the strength to comfort his wife, who was even more upset about it than she was. I’ll remember Varun, an Indian student and entrepreneur, who hadn’t slept in days during his escape from Ukraine and had no idea where he would go, and still managed to crack hilarious jokes all morning as we chatted and apologized for his dirty clothing as though he had any control over that.

The way people take care of each other. The volunteers working tirelessly to help in any way they can. The determination of artists and DJs and cooks and IT techs to defend their country at any cost. Maybe more than anything, I’ll remember a young woman named Anna, who I was hanging out and chatting with when she got the call that her mother, a military medic, had been killed. That is war to me. The faces of people when the worst thing imaginable happens. The helplessness when there is absolutely nothing you can do. Anna is on her way back to the front lines right now, as I write this. And the sheer volume of the horror and the suffering. That so many millions of people are experiencing the worst moments of their lives in unison, all at the hands of fellow human beings who are choosing to do this. It’s been a lesson in cruelty too.

Natalie Keyssar, At the train station in Lviv, a night train departs for Kyiv, March 9, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Alisa Kosheleva, photographed in Lviv, was abroad in Barcelona when the war began. Her son was with his father in Mariupol, March 8, 2022, for Time

Paul: What have been some of the differences or similarities of shooting this experience, compared to past series or assignments you’ve worked on?

Keyssar: A lot of my work has to do with violence and crisis, but I personally have never witnessed something of this scale before, where so many millions of people have suddenly had their lives shattered in the same moment. For the past several years, I’ve increasingly believed that the actual photography I make is by far the least important part of my work. It’s the moments I share with people and what I learn from them. But my work is to find a way to express these moments in imagery, to make them seen and felt.

I’ve been trying to reconcile this sense of, “What does a picture even mean here?” with the need and desire to make images that stop people and make them listen to the people I photograph and their stories. It’s a mess in my head between deprioritizing aesthetics in favor of photographing gently and slowly and collaboratively, and wanting the aesthetics to grab people and make them pay attention. Of course, the two things are not mutually exclusive—in fact, often the opposite—but I’m constantly reviewing and obsessing about the ethics and best practices of making pictures during crisis. With such an overwhelming amount of need and trauma here, sometimes it’s a real battle to lift the camera. It feels like such a stupid thing to do sometimes, at a funeral for fallen soldiers, at a train station where every inch of the floor is lined with weary refugees. Around a barrel fire in a field near the border, where students from Nigeria who slept on the ground, nursing bruises from racist beatings, and have just lost everything and have no idea where they will go, are warming their frostbitten fingers.

Honestly, the more experience I have, sometimes the harder it gets for me to squeak out the words, “Hello, can I make your portrait?” But it’s the people that inspire me—who want people to know what they have been through, who want people to know what is happening in their home—that remind me to keep going. Alisa, one of the mothers I photographed in Mariupol, ran up to us and said: “Please tell the world what is happening to us.” Moments like that are when I feel my work has the most value.

Natalie Keyssar, In a room upstairs in the Lviv train station, designated as a shelter for women and children, many take a moment to rest, March 8, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, In a room upstairs in the Lviv train station, designated as a shelter for women and children, many take a moment to rest, March 8, 2022, for TimePaul: Has there been one specific photograph you’ve made so far that has stuck with you?

Keyssar: I think it’s going to be a while until I can really look at and understand the pictures I’ve made here and what they mean to me. To be honest, as usual, a lot of the most important moments have been things I couldn’t photograph out of respect or for safety reasons—instead, I’m trying to write about them.

I made some pictures of young women saying goodbye to their boyfriends and husbands at the train station in Lviv a couple of weeks back. There’s one of a young couple holding each other before he heads off on one of the trains to the front, and she’s holding onto him like she can’t will her hands to let go, and there’s a tear running down her cheek. It hurts to look at, but it captures a lot of what I feel about this amazing country and this awful war. I think of picture making often as the process of creating totems and symbols—universal touchstones that are both literal and universal. This moment at the train station evokes a sense of history, but most importantly I think it shows the hope and heartbreak of war. Ukrainians are being forced to sacrifice everything to protect themselves from Russia’s attacks right now—and in this moment I felt I could see it.

Natalie Keyssar, The Lviv train station was packed with lines stretching in wide circles around the nearby plaza with people trying to get out of Ukraine, March 8, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, The Lviv train station was packed with lines stretching in wide circles around the nearby plaza with people trying to get out of Ukraine, March 8, 2022, for TimePaul: What do you think is most important for photographers working in Ukraine or on stories related to the war right now?

Keyssar: I think what’s important is commitment and empathy. There are so many amazing, brave photographers and journalists on the ground right now, and I’m so grateful to all of them for telling these stories. Just to name a few: Julia Kochetova, who is Ukrainian and creating some of the most powerful work I’ve seen from here in her home of Kyiv; Anastasia Taylor Lind, who has been working in Ukraine for a decade and producing powerful, committed, thoughtful work from the region; Erin Trieb and Lynsey Addario, who have been on the front lines for weeks now; Evgeniy Maloletka, a Ukrainian photographer who has been documenting places like Mariupol, which are under such heavy bombardment and vicious atrocities of civilian populations that it is nearly impossible to work there, and yet he has been one of the only people telling their stories from the ground, creating a document of war crimes and massacres that would otherwise remain hidden because the area is completely cut off from the outside world right now.

Natalie Keyssar, Sofia, 13, of Luhansk, poses for a portrait at the Women’s shelter, March 10 2022, for Time

All photographs courtesy the artist

Natalie Keyssar, Volunteer efforts across Lviv including packing food boxes, sewing flak jackets, and weaving camouflage nets, March 8 2022, for Time

Paul: How do you think photography plays a role in the telling of stories or information during a moment of crisis like this?

Keyssar: I think images really humanize and individualize situations like wars, which sometimes might seem too big and awful and abstract to understand on an intimate level, maybe especially if you’ve never experienced something similar. In the longer term, making photographs of these situations and these people is really creating the historical record of these terrible events. So in that way, it is incredibly important, especially in a time when the realities of what’s happening are often distorted or even erased by propaganda and disinformation.

There is a particular value in photography being a universal language. We see ourselves in the eyes of the people in the photographs. We don’t need a translation to read the feelings and feel them in our own bodies. I have admiration for every single person I’ve photographed—and my heart breaks at what humans are capable of doing to each other.

March 25, 2022

The Dissident Photographers of Ukraine

“From an artistic standpoint, Ukraine has fought the system inherited from the Soviet past, and the battle has been won,” the photographer Evgeniy Pavlov says recently over Zoom. “Censorship no longer exists and artists can do what they wish, including criticizing politics without being persecuted. But today, Russia seems to want to turn back the clock, and Ukrainians are well aware of what they are fighting against, because they have been there before. And they don’t want to turn back.” Pavlov, who is seventy-seven years old, now lives in Graz, Austria, where he has sought refuge. He left Kharkiv in February on the third day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when he saw a missile fall several yards from his car. He was able to bring a few personal effects with him and a handful of vintage prints from his archive.

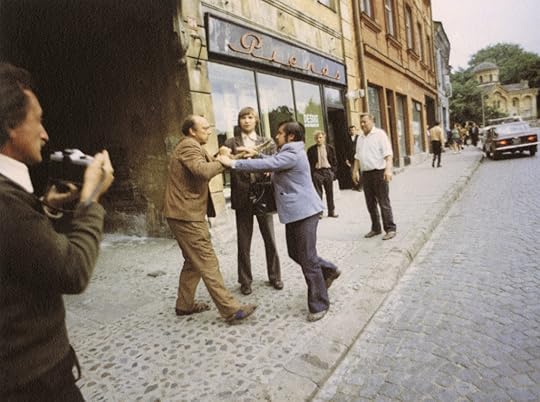

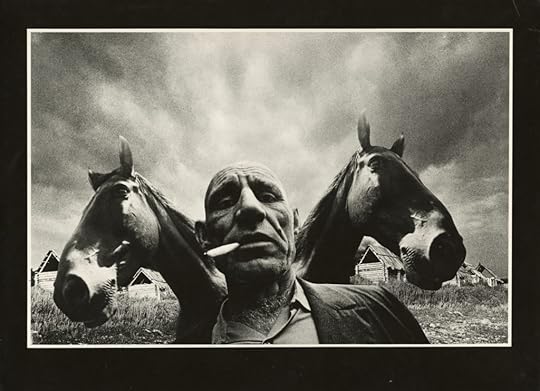

Jury Rupin, from The Fight shooting, 1976

Jury Rupin, from The Fight shooting, 1976In the early 1970s, Pavlov and Jury Rupin founded the Vremia Group in Kharkiv, the second-largest Ukrainian city, now besieged by Russian troops. A collective of nonconformist photographers that included the acclaimed photographer Boris Mikhailov, the Vremia group is considered the original core of the Kharkiv School of Photography (KSOP), and it is now well known throughout the world. (Other members include Anatoliy Makiyenko, Oleg Maliovany, Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Oleksandr Suprun, and the late Gennadiy Tubalev.) Apart from Rupin, who died in Vilnius, Lithuania in 2008, these artists are still alive. In 2019, they had a large retrospective at the PinchukArtCentre in Kyiv. The following year, their works entered the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, when the institution acquired one hundred and thirty images from private Ukrainian collectors.

Evgeniy Pavlov, from the series Total Photography, 1992

Evgeniy Pavlov, from the series Total Photography, 1992Courtesy the artist

The origins of the Vremia Group go back to a photography club in Kharkiv, where the members got to know each other and realized they had a shared artistic calling, one contrary to the direction imposed by the Soviet regime. “I never thought of myself as an anti-Soviet dissident. I only felt the need to express myself in a sincere and honest way,” Pavlov explains. “But this was enough to make me an underground artist. When they asked me why I was creating images so far removed from the official aesthetic, which was tied to Socialist Realism, I responded that the regime imposed a saccharine view of man, but man is not just sugar. I wanted to show something different—aspects of life that everyone had before their eyes, but which were being ignored by official art.”

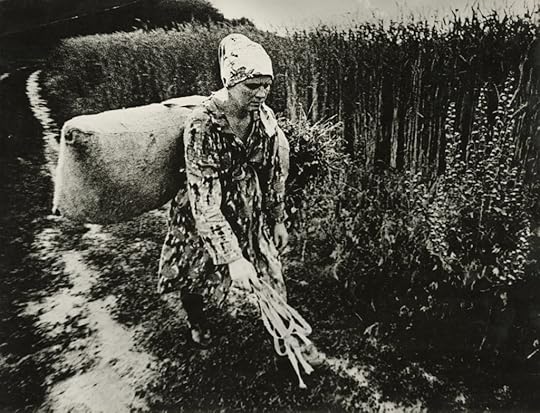

Anatoliy Makiyenko, Hard Day (In the Field), 1974

Anatoliy Makiyenko, Hard Day (In the Field), 1974In Russian, vremia, or vremya, means “time.” It is an innocuous term, but one that was interpreted within the underground context as contemporary, a dangerous word at that time. “As our symbol, we adopted the owl, a nocturnal animal, opposed to the winged Pegasus used by Soviet propaganda,” Pavlov says. In Diary of a Photographer, Rupin’s autobiographical novel published in the 2000s, he writes: “During our discussions, we devised our concept of photography as an art form and developed certain theories about the way in which images had to interact with those who view them. One of these was the ‘theory of stroke.’ The work had to act on the viewer instantly, like an unexpected blow.”

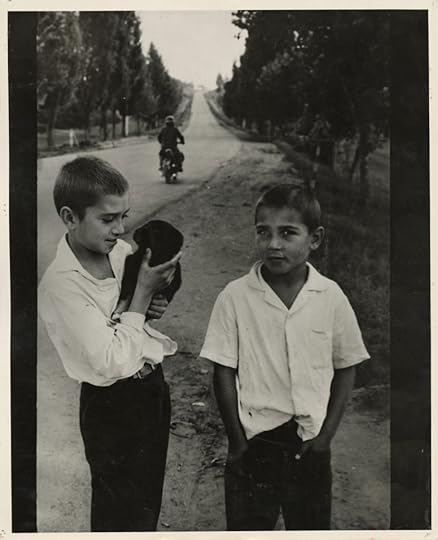

Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Untitled, 1976

Oleksandr Sitnichenko, Untitled, 1976In 1972, Pavlov participated in a clandestine countercultural gathering that was part of a hippie movement inspired by contemporaneous Western trends, and he suggested that it would be interesting to create an image of a naked man in water, playing an accordion. The young people instead found a violin. This marked the genesis of a series that went down in history as The Violin, in which the instrument appears in almost all the shots. The images might be considered documentation of the first “happening” in Soviet history. The vitality of the naked body immersed in nature resembles something that Ryan McGinley might have made, but forty years earlier, and in a radically different context. The effect of the work was explosive. In the Soviet Union, pornography was a criminal offense, and the legal definition was so vague that any photographer who shot nude photos could be accused of obscenity. The series of photographs was smuggled out of the country and published in the Polish magazine Fotografia in 1973.

Evgeniy Pavlov, from the series The Violin, 1972

Evgeniy Pavlov, from the series The Violin, 1972Courtesy the artist

The Vremia Group was able to organize a single exhibition in 1983 that remained open for only two hours. “We were at the Kharkiv House of Scientists,” Pavlov tells me. “The KGB headquarters were across the street. When the manager saw the works, she ran into her office to denounce us, and we immediately took down the show.” When I ask why it was worth it to oppose the regime with art, Pavlov responds, “Political life was toxic and was poisoning us. I felt a need from within, to contribute to what truth could demonstrate: we were slaves, but we wanted to be able to communicate the fullness of life, the fullness of our being.” Observing his country being bombed by Vladimir Putin’s army in recent weeks, Pavlov made a melancholic remark. “Today, in Russia, the propaganda machine has gotten going again. Imperialist rhetoric has reappeared, nearby countries are considered colonies, and the human has gone back to being irrelevant.”

Today, the artists of the three generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography share the uncertain fate of the Ukrainian people.

Taking refuge with Pavlov in Austria is his wife, Tatjana Pavlova, a photography historian who oversees the Contemporary Art Department at the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts. She is considered the theorist of the Kharkiv School of Photography and wrote the entry on Ukraine for the monumental six-volume encyclopedia The History of European Photography, published published between 2010 and 2016 by the Central European House of Photography in Bratislava, Slovakia. The city of Kharkiv has a long history of experimentation in the arts, and its school of photography can be considered the apex of this tradition. It was in Kharkiv that the first Soviet skyscraper was built, in 1928: the Derzhprom, a masterpiece of Constructivism. Before the Stalinist purges, the city was a center of avant-garde debate, and the magazine Nova Generatsiya (New Generation), published by the Futurist poet Mykhail Semenko, printed Kazimir Malevich’s principle theoretical texts when the Kyiv-born painter had already fallen into disgrace with the regime.

Jury Rupin, We, 1971

Jury Rupin, We, 1971For Pavlova, when people in the West speak of the “Russian avant-garde,” they don’t consider that many of the protagonists of that movement were Ukrainians. “In addition to Malevich, Aleksandra Ėkster, David and Volodymyr Burljuk are also from our country,” Pavlova explains. “Vasyl Yermylov and Boris Kosarev were born in Kharkiv and worked there, teaching at the Academy of Design and Fine Arts.” One of their students was Volodymyr Grygorov, who, years later, taught some of the leading figures in the Vremia Group. “The lesson of the avant-garde at the beginning of the [twentieth] century was imbibed by these photographers,” Pavlova says. Another characteristic of the Kharkiv School of Photography derives from the city’s geographic location, a few minutes by car from the border with Russia, which also corresponds to a cultural position of straddling two different sensibilities in artistic expression. “In Russia we see a more conceptual approach, well expressed in the performing arts and in installations,” Pavlova continues. “The Ukrainian approach, instead, tends more to achieve an expressionist visual richness, with strong contrasts and saturated colors. In the images of photographers from various generations of the KSOP, both these tensions coexist.”

Oleksandr Suprun, The Three, 1979

Oleksandr Suprun, The Three, 1979The Kharkiv School could be described in three generations. The first is the Vremia Group, which worked from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. The second generation falls into the years before perestroika, up to the 1990s. The third generation emerges in the 2000s with the Shilo Group (shilo means “awl”), formed in 2010, and the Boba Group, which came together in 2012 (Boba references Boris Mikhailov’s nickname). According to Oleksandra Osadcha, the curator of the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography, the school’s main characteristic is a focus on the idea of community. “The daily association among artists, who sometimes are friends who vacation together with their families, is a constant in the three generations. It is a phenomenon that, in other parts of the Soviet Union, in Moscow, Leningrad, or Kyiv, did not occur in this manner.” There are stylistic and aesthetic constants as well, like “the use of solarization, ‘photo-sandwiches,’ collages,” Osadcha notes. “These are techniques that come from the past, but which were discussed in interminable small talk, over coffee, when they would show each other cardboard displays, kartonchiki, with each of their works.”

Oleg Maliovany, Act Trio, 1973

Oleg Maliovany, Act Trio, 1973Photographs courtesy the Collection of the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography, Kharkiv, Ukraine

The Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography was founded in 2018, through the initiative of Sergiy Lebedynskyy, a member of the Shilo Group, and is sponsored by the engineering firm Manometer Factory. “Part of our collection was already safe in Germany before the beginning of the war, but most of it has been evacuated recently,” Osadcha, who has been displaced to Ivano-Frankivsk in western Ukraine, explains. “But at the moment we are busy helping photographers who have remained in Kharkiv, salvaging the archives of artists from various generations.” She tells me of the work of Veronika Skliarova, director of the Kharkiv cultural event Parade Fest, who is working out of Poland to coordinate the evacuation of archives of artists from the city, and of Rodion Prokhorenko, the owner of Kharkiv’s last remaining analog photography lab, who, among others, has remained in the city, moving from studio to studio to secure archives and move them west to Lviv. Today, the artists of the three generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography share the uncertain fate of the Ukrainian people. They do not know if they will ever be able to return to their homes, and they do not know if there will be space for their art in the Ukraine of the future.

Translated from Italian by Marguerite Shore. Read more about how the photography community is responding to the war in Ukraine.

In Los Angeles, a Photography Project Shows the Power of Mentorship for Latinx Youth

In photographs, Los Angeles can take on many forms based on the city’s mythos. But one vantage point often under-highlighted is that of the city’s youth. In capturing photographs of their homes, neighborhoods, and friends, the students of nonprofit organization Las Fotos Project are framing the city through their own unique lens.

Founded in 2010 by Eric V. Ibarra, the organization fosters creativity in young folks ages thirteen to eighteen, primarily across Central, South, and East Los Angeles. Beyond teaching teens the technical basics of photography, Las Fotos Project focuses on the power of storytelling. The workshops function to spark ideas—and to encourage values like self-confidence and leadership.

Las Fotos Project teaching artist Gemma Jimenez supports student Jocelyn Pena during their community photojournalism class. Photograph by Carolina Ferreira

Las Fotos Project teaching artist Gemma Jimenez supports student Jocelyn Pena during their community photojournalism class. Photograph by Carolina FerreiraCourtesy Las Fotos

The programs range in their themes: Esta Soy Yo focuses on the personal and explores the therapeutic nature of photography, while Creative Entrepreneurship Opportunities gives teens career insights and on-the-job training through gigs with brands and local organizations. Las Fotos Project has also hosted multiple exhibitions, previously staging them at well-known spaces throughout Los Angeles like Plaza de la Raza, Casa 0101 Theater, and Self-Help Graphics & Art.

During pre-COVID times, the annual Viva La Muxer event included food, vendors, live performances, and art—all of which encourages Angelenos to support the organization. The 2020 event was cancelled; in 2021, it went virtual and included programming such as Instagram Live conversations with the podcast producer Mukta Mohan and artist Gabriella Sanchez. In addition, the Foto Awards honor youth and established photographers and pays homage to female and gender-expansive creators. The environment supports young creators and also gives Angelenos (and people everywhere) the chance to see their work.

Thalía Gochez, Genai, 2020, for Foot Locker x Nike

Thalía Gochez, Genai, 2020, for Foot Locker x NikeCourtesy the artist

Thalía Gochez, a Los Angeles–based photographer, has previously worked with the organization. Gochez, whose work was featured on the cover of Aperture’s “Latinx” issue, is known for her focus on Latinx women and for combining her photographic eye with a love of fashion; her portraits celebrate the full complexity of the subject’s identity. She photographs people she rarely saw in magazine pages or photography classes when she was in school figuring out what she wanted to do.

As part of a brand partnership with Forever 21, youth photographers with Las Fotos Project shadowed Gochez during a photo shoot and took some behind-the-scenes shots. A Las Fotos student who had shadowed Gochez three years ago for another project recently joined Gochez on a shoot for Converse for Women’s History Month. “I’m like, Oh, my gosh, we’ve kind of grown together in this way,” Gochez says. “It’s just so beautiful to see the evolution of this young creative.” Gochez says that access to on-set experiences was something she didn’t have as a young, self-taught photographer trying to find her footing.

Photography lends itself to quick connections; photos, Torres says, can help teens get their message across without having to write or say anything.

Mentorship, Gochez says, ended up being extremely important as she pursued a career in photography. Early on, she received a direct message on Instagram from a creative director who ended up guiding Gochez through all the complexities of working with brands and making sure she got paid. This mentorship was invaluable during her first professional photography job with Nike.

“We still are in contact, and I still ask her questions because I don’t know everything,” Gochez says. “But I remember thinking, Wow, that was really needed. And I hope to be as amazing as she was to me, to someone else . . . it left an impression on me and a beautiful message of the power of mentorship with folks that already can relate to your story.”

Las Fotos Project teaching artist Kenzie Floyd supports student Rocio Hernandez during their creative career class. Photograph by Carolina Ferreira

Las Fotos Project teaching artist Kenzie Floyd supports student Rocio Hernandez during their creative career class. Photograph by Carolina FerreiraCourtesy Las Fotos

In her portrait photography, Gochez prefers to have a connection with her subject. She asks questions about where they want the photo shoot to happen and considers details like what they’re wearing. She says she “always felt a strong desire to capture stories and to capture real people and really honor their story and identity.”

Lucia Torres, executive director of Las Fotos Project, says that the organization strives to include teaching artists and mentors who come from backgrounds similar to those of their students. Formerly a board member, she says that Ibarra made the decision to step down in 2019 to allow the organization to be woman-led. Torres remembers first seeing the artwork of Las Fotos Project students in an alleyway in Boyle Heights; the public space was transformed into a DIY gallery that highlighted the work of the youth.

Las Fotos Project students Eunice Shin and Lucy Hwang participate in a Foto Walk around Boyle Heights near the Las Fotos Project gallery. Photograph by Carolina Ferreira

Las Fotos Project students Eunice Shin and Lucy Hwang participate in a Foto Walk around Boyle Heights near the Las Fotos Project gallery. Photograph by Carolina FerreiraCourtesy Las Fotos

She especially appreciated the organization’s mission to give teens a chance to share their stories “in a way that’s authentically them.” Photography lends itself to quick connections; photos, Torres says, can help teens get their message across without having to write or say anything. She recalls how teens have been so proud to see their work on display, whether in a show or at a bus stop. One student from Arizona joined Las Fotos Project when it went virtual—and when she found out her work would be on view, her family planned a trip to LA.

“I saw myself in a lot of the students who were coming through and participating in the program,” Torres says. “When I was 13 years old . . . I couldn’t really put myself out there because there was a lot of pressure for me to just be very charismatic and very vocal. As a very awkward and introverted teenager, I just did not want to do that. So I felt shut out. Photography offers you the opportunity to be able to do that—to be very loud and vocal with your story while at the same time being quiet.”

Photograph by Michelle Montenegro for Las Fotos Project, Fall 2021

Photograph by Michelle Montenegro for Las Fotos Project, Fall 2021Courtesy Las Fotos

Michelle Montenegro, a current student at Las Fotos Project, can attest to this experience. She says that her love of photography started getting serious in high school. “Photography has always been something I’ve been able to go to when I’m feeling really stressed out,” Montenegro, who is eighteen, says. “And to share my voice without actually having to say anything.”

Montenegro found out about Las Fotos Project through a friend and has enrolled in classes like Esta Soy Yo, which she appreciates for its inclusion of self-care. A current student at the University of Southern California (USC), she often finds it difficult to find moments for herself in a hectic schedule. Showing up to class at Las Fotos Project once a week helps with that.

Montenegro says the environment has been supportive from the start, and seeing the work of her peers expands her understanding of the medium, since everyone tells their story their own way. “I love documentary photography as well as combining photography with journalism,” she says. “I love to capture my mom, my parents, my community around me—and finding beauty in unconventional spaces that aren’t really highlighted.”

Thalía Gochez, Michelle, 2020, for Bella Doña

Thalía Gochez, Michelle, 2020, for Bella DoñaCourtesy the artist

Things are evolving at the organization. Its new space in Boyle Heights was designed to offer teens the tools they need for creative expression, including a studio space with professional equipment like backdrops and lighting. Torres says her team also plans to create a darkroom, since several students have expressed interest in print photography. Las Fotos Project will invite local creatives to rent out the space at affordable rates for their own projects.

“Hopefully, we become this creative hub for young creatives in East LA,” Torres says. These resources are meant to help teens bring their own creative visions to life. Gochez emphasizes that in her own mentorship, she wants to foster a space for artistic freedom. “Ultimately, I can teach them a lot of technical aspects, but I think the most valuable lesson that I feel like I teach them is just how to be a photographer with integrity and respect,” Gochez says. “To me, taking someone’s photo is a very beautiful, sacred act. If there’s any way that I can show that to them, then I win.”

Watch a conversation with Thalía Gochez about Las Fotos Project on Aperture’s YouTube channel.

March 24, 2022

A Photographer’s Pensive Vision of Life on a Yemeni Island

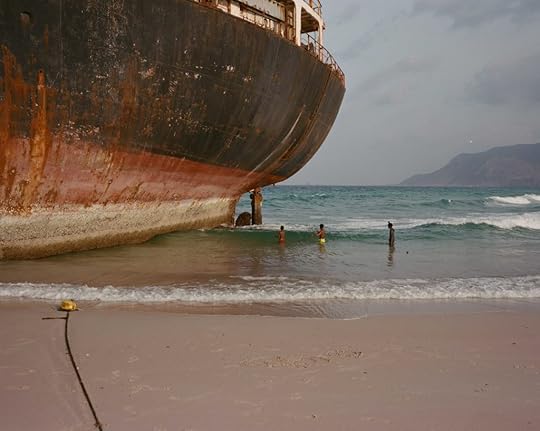

In Charles Thiefaine’s photographs of the Yemeni island of Socotra, the sea is a persistent presence, a leading character. It encloses, laps, borders. The sea is at the heart of Socotra’s prospects—a key factor in its striking natural splendor and wildlife—and, in turn, its many problems: conflict, constant uncertainty, the international meddling from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and others, driven by struggles for power, water access, and trade (from the beaches of Socotra one can gaze to the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, a busy choke point between the Horn of Africa and the Middle East). “The water, it is their way to survive, to get money, and to eat,” Thiefaine, who is French and lives in Paris, notes of the people he met and photographed on Socotra. “But it is also their borders. They are stuck in this island, most of the people there, they cannot move, or they can only move to the mainland, where there is a war.”

Charles Thiefaine, A stranded ship in Delisha Beach, near Hadibo, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, A stranded ship in Delisha Beach, near Hadibo, Socotra, 2021Socotra lies in the Indian Ocean, tugged by competing hopes, identities, and ideals. It is 155 miles from Somalia and 210 miles from Yemen. Politically it is part of the latter, which sits on the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia, even if, geographically, Socotra seems to be a fragment of Africa. In the 1970s and early ’80s, Socotra was a Soviet navy base—one of Thiefaine’s photos shows an abandoned Soviet tank on the beach—and a part of South Yemen. Since the 1990 unification, it has been part of Yemen, which has in turn, since 2014, been in a lengthy, tangled conflict, the frustrations and oddities and duplicities of which are plainly revealed by Socotra’s current situation.

Today, Socotra is controlled by the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC), following a long struggle between the Council and troops loyal to Yemen’s President Hadi. The STC, a separatist movement, seeks an independent South Yemen, which contradicts the agenda of Hadi’s government. And yet, across the sea on the mainland, the UAE supports the government, and both the STC and pro-Hadi forces are fighting against the Houthis. As the circle of violence beats on, the tide comes in and out, the coral fish swim, and, in Thiefaine’s photos, the surface of the water glitters and teases in turquoise. So much trouble, so much beauty.

Charles Thiefaine, A diodon fish in the hand of Abdullah, a fisherman from Qalansiyah, Socotra, 2021

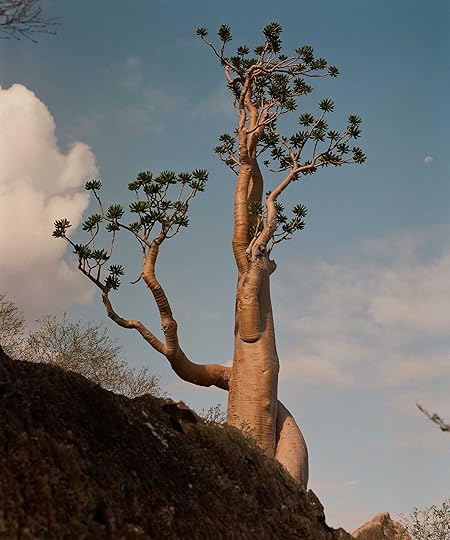

Charles Thiefaine, Socotran Desert Rose, an extraordinary-looking plant sometimes called “the bottle tree” due to its odd shape, Socotra, 2021

Thiefaine, who is thirty, explains that the nature on Socotra offers inhabitants a counterbalance to the oppressive turmoil. “Almost all of the people in the island go fishing,” he says. “They sell their fish, or they eat their fish. Almost everyone knows how to fish. They fished when it was USSR, now it is STC, before it was the Yemeni government—they keep doing it.”

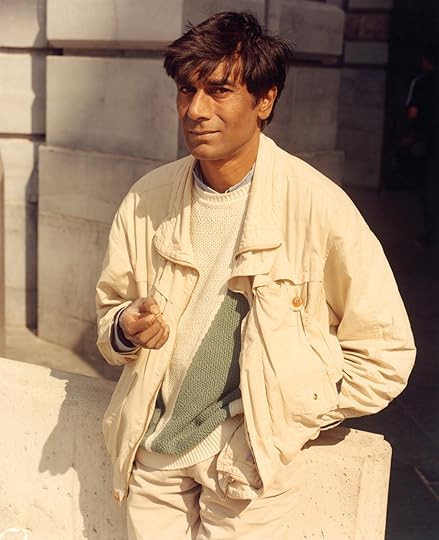

The notion of consistency and routine in the face of upheaval has shaped Thiefaine’s current work as a photographer, and his recent shift from classic photojournalism. He has a background shooting in areas of conflict and first visited Iraq in 2015, when still a student. Just as he was graduating, the battle of Mosul broke out, and he returned, forming friendships and bonds with locals. He has since returned some fifteen times on assignments for publications such as Vice, and yet recently, he has rethought the focus of his images, believing that seeing inhabitants solely within the context of distress—conflict, invasion, death—only serves to other them. “These are countries that are stuck with a certain kind of imagery, which is most of the time linked with violence, or images that show them as victims,” he says.

Thiefaine’s approach has been fueled, in part, by the ongoing refugee crisis shaming Europe’s governments.

As if in direct contrast, he now deliberately seeks out the quiet, the simple: day-to-day habits and seemingly mundane occurrences, rather than the epic or shocking. His decision to go to Socotra was partly inspired by this shift; he wanted to go somewhere where he had no experience, where he could see things afresh. When making work, Thiefaine will often follow certain people for weeks, integrating himself in their pastimes and commutes to show their “adaptability, their way of acting, their routines and gestures.” He shoots with film on a medium-format camera—the bulkiness of which sometimes amuses his subjects. He likes natural pictures, though he occasionally directs his subjects, often ironically, in the pursuit of ease, to avoid them making signals at the camera or posing.

Charles Thiefaine, Ibrahim, originally from Taez, a city in south Yemen where Yemeni troops and Houthi militias fought at the beginning of the civil war in 2015, came to Socotra in September 2021, and works in a restaurant with his friend Mohamed, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Fishing is the main activity on Socotra, 2021

Thiefaine arrived in Socotra on November 14, 2021, without a fixer or translator; he had no plan of whom he would photograph or how he would get access. He did not have a journalist’s visa—which is tricky to acquire—and instead attained the right to travel by taking a job teaching English in a school in Hadiboh. He spent one month living in a small room above Shabwa, a restaurant named after the owner’s home city in Yemen: “I went to the restaurant every day, and they started to recognize me and to talk with me, and I got to know one of the people who worked there, and then eventually all the staff.”

His new friends invited him to come hitchhiking on their days off, join them on the beaches for swims, play football, hang out in their homes, and visit Firmhin forest, where one can find dragon’s blood trees, which, in Thiefaine’s photos, look like rolls of soft, squidgy flesh or the folds of a tightly clenched fist. Most of the men Thiefaine captured were in their late twenties or thirties. “We really, really had fun together,” he says. “The violence they are facing, it’s real, it exists, so it’s important for me to acknowledge it, but it’s important also for me to show how people are dealing with this violence, and how they manage to have a good life.” The images show “la bonne vie,” as Thiefaine calls it.

Thiefaine’s approach has been fueled, in part, by the ongoing refugee crisis shaming Europe’s governments. In recent years, thousands of migrants have drowned at sea, attempting to reach the EU. Public support for settling many of those displaced by war is muted (a sentiment made more blatant by the contrasting enthusiasm among Europeans for housing and supporting recently displaced Ukrainians). Xenophobia and racism thrive, fostered and fanned by various right-wing political figures across the continent. Thiefaine says that many people in Europe see those in the Middle East “as foreigners, people who live another life, who don’t have the same routines.” In his pictures, he tries to draw connections, to reveal shared points or experiences. We see the reach of technology, branding, and commerce: Gucci T-shirts, iPhones. His subjects photograph each other. They pass around clips from YouTube. One man attaches his device to his cap to go hands-free while fishing. “I am trying to show their contemporaneity,” Thiefaine says.

Charles Thiefaine, Mohamed, Khalifa, and others watch the match between Qalansiyah and Hadibo, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Mohamed, Khalifa, and others watch the match between Qalansiyah and Hadibo, Socotra, 2021Thiefaine’s photographs capture the bizarre contrasts of Socotra—not only between the seeming bliss of the landscape and the backdrop of violence, but also between the sense of history and heritage embodied by those trees, the creatures, the rocks, and the arrival of the new, the glossy, the plastic, the man-made, and with it, so many questionable priorities and warped customs. His portraits provoke intrigue, comparison, identification. And yet, the quest to highlight his subjects’ modernity—to relate them to Western norms and standards in the hope of sparking a kinship, a kindness among viewers—bolsters some of the habits of thinking the project seeks to question, by inferring loaded ideas of who the images will be consumed by and whose norms they are catering to.

Thiefaine acknowledges that he cannot ever untangle his work from what he calls “the personal approach of me, a European, white photographer from France, from somewhere where there is no violence, no war.” Still, he says, these are images without manifesto or political argument, without great claim, other than a desire to know how another man spends time, how he passes his day, how he looks when happy, when living well. “I don’t pretend to show the reality,” he says. “I prefer to assume that it’s not the reality, but a personal approach, a personal way to photograph them. It is only some things I discovered, with the people I decided to spend time with.”

Charles Thiefaine, A fisherman gets on his motorbike to sell fish in Hadibo’s restaurants, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, A fisherman gets on his motorbike to sell fish in Hadibo’s restaurants, Socotra, 2021 Charles Thiefaine, Ibrahim, a young man from Taez, Yemen, came to Socotra in 2021, and works in a restaurant in Hadibo, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Ibrahim, a young man from Taez, Yemen, came to Socotra in 2021, and works in a restaurant in Hadibo, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Khalifa, a young painter from Hadibo, spends time with his brothers, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Mohamed, a young man from Hadibo, goes to fish with his friends, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Socotra dragon trees (or dragon blood trees) on the mountain of Firmhin, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Socotra dragon trees (or dragon blood trees) on the mountain of Firmhin, Socotra, 2021 Charles Thiefaine, Mohamed fishes with his friends, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Mohamed fishes with his friends, Socotra, 2021 Charles Thiefaine, Young Socotri supporters watch a football match in Hadibo, Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Young Socotri supporters watch a football match in Hadibo, Socotra, 2021 Charles Thiefaine, “Allah Foq” (God is above us) carved in the trunk of a bottle tree, an endemic species of Socotra, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, “Allah Foq” (God is above us) carved in the trunk of a bottle tree, an endemic species of Socotra, 2021 Charles Thiefaine, Owad, a fisherman from Qalansiyah, fishes every day with his father, Socotra, 2021. All photographs from the series Walking with Dragons, Socotra, Yemen, 2021

Charles Thiefaine, Owad, a fisherman from Qalansiyah, fishes every day with his father, Socotra, 2021. All photographs from the series Walking with Dragons, Socotra, Yemen, 2021Courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

March 23, 2022

The Inventive French Magazine That Published Legendary Photographers

“There was just one delicate catch,” Robert Delpire once remarked. “I had no competence.” Then twenty-four years old and studying to become a doctor, he had been asked by faculty to create a periodical aimed at medical professionals with an interest in art and culture as well as medicine. “No experience in publishing. Nothing even related,” Delpire continued. “I came from a milieu in which the word ‘culture’ didn’t exist. . . . So, in the unconsciousness of youth, I asked for texts from Claude Roy, Jacques Prévert, André Breton; photographs by Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Brassaï; drawings from André François, Saul Steinberg. And I was astonished to be so warmly welcomed.” Delpire was destined to be a publisher, not a surgeon.

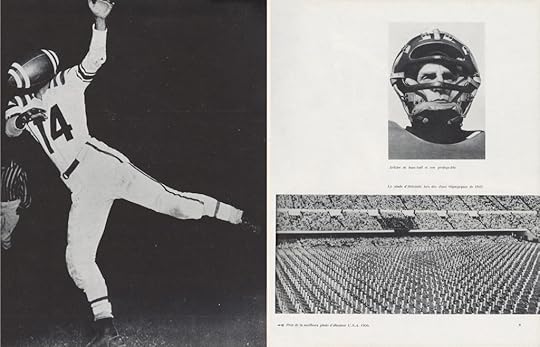

Spread from NEUF, no. 4, devoted to the theme of sports, October 1951

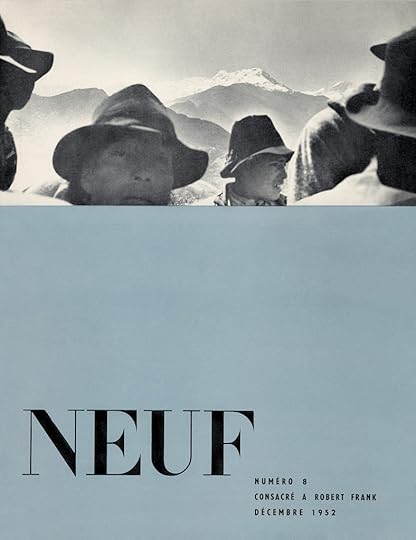

Spread from NEUF, no. 4, devoted to the theme of sports, October 1951For his new periodical, he chose the name NEUF. Perhaps this was because nine was the number on his basketball jersey, and he was an avid player. Or simply because neuf in French means “nine” but also “new.” NEUF would run for nine issues before ceasing publication in 1953 (it did not have enough subscriptions to sustain itself). But seventy years after publication, no complete collection of NEUF, public or private, exists; even the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s set is incomplete. To make the periodical accessible to photography enthusiasts and a larger public, delpire & co recently decided to reissue a facsimile of the original nine issues in a slipcase. The box set also contains a special supplement by art critic Michel Ragon titled Expression and Non-Figuration (1951), as well as another pamphlet with an essay by photography historian Michel Frizot.

Cover of NEUF, no. 8, with photography by Robert Frank, December 1952

Cover of NEUF, no. 8, with photography by Robert Frank, December 1952To produce his magazine, Delpire was helped by his friends: Ragon and Pierre Faucheux, an innovative graphic designer. With their guidance and the support of the medical board dedicated to the arts, the cultural periodical was diverted to increasingly reflect Delpire’s eclectic interests. He learned day by day on the job, and NEUF evolved from issue to issue, giving greater room to photography until entire issues were dedicated to photographs of a selected theme (such as the heart, games, sport, the circus) or to an individual artist (such as Brassaï, Robert Frank, or, in the last issue, illustrator André François). To finance high-quality printing, Delpire obtained money from pharmaceutical companies who wanted their products shown in full-page ads, often in color, and he also persuaded them to assign his photographer friends to create visually striking advertisements. Paul Facchetti’s ad for a protein pill, for instance, features a surreal wicker mannequin projecting ominous shadows onto the background; for an ad for Mitosyl skin cream, a photographer who went by the name Casini made a compelling image of a tricolor snake emerging from its transparent molted skin.

The early issues reflect Delpire’s eclectic, whimsical taste, with its mix of illustrations, documentary photography, drawings, poetry, ethnography, and literature.

Delpire excelled as a photo researcher. He culled stock photographs from agencies or archives and often gave them the same full-page billing as photographs by recognized authors. He likened their unpolished charm to “a kind of raw state of photography.” For instance, in one image in the circus-themed issue, a trumpet-playing bear in the foreground looms over the circus master in a braided military tunic. In an issue dedicated to sports, the curved body of a diver is crowned with a cloud of bubbles, and the body of another swimmer, whose arms and legs we see from above, parallels an octopus’ twisted limbs. Their compositions and focuses may be imperfect, yet these photographs have the spur-of-the moment charm of amateur photographs found in family albums.

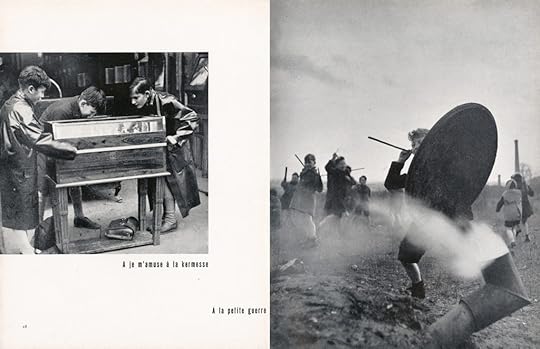

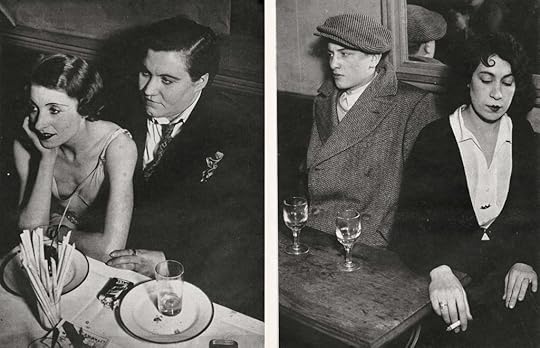

Spread from NEUF, no. 3, with photography by Robert Doisneau, May 1951

Spread from NEUF, no. 3, with photography by Robert Doisneau, May 1951Still, NEUF relied on major photographers of the era, especially on humanists such as the Dutch photographer Carel Blazer, Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Izis, and George Rodger. Izis and Brassaï are featured with studio portraits of painters such as Raoul Dufy, Henri Matisse, and Marc Chagall. Other photographs by Izis show a melancholic street florist on a cold day, sitting in a tiny stand with hands warming in her muffs, and an extraordinary, surreal image of two socks suspended, like a hanged man’s legs, in front of an attic window with views of Paris roofs. Some of Doisneau’s strongest images—first published in his 1949 book, La Banlieue de Paris, with text by Blaise Cendrars—appear in a thematic issue about games: children, armed with sticks and a garbage-can lid as a giant shield, wage war in a desolate wasteland of smoke and fog.

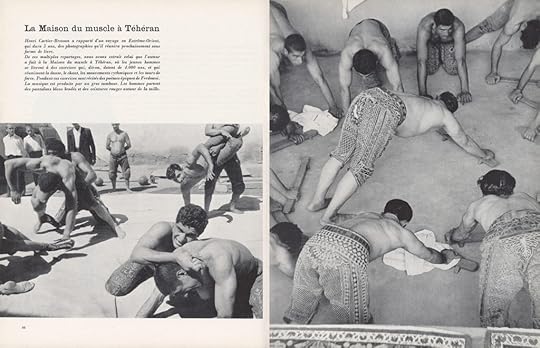

Spread from NEUF, no. 4, with photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson, October 1951

Spread from NEUF, no. 4, with photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson, October 1951Delpire’s visit to Magnum Photos, the agency that had been recently established, yielded two important portfolios: George Rodger’s on the Nuba people of Sudan and their rituals, in which warriors, their limbs rubbed with ash, fight in a desolate landscape; and Cartier-Bresson’s “La Maison du muscle à Téheran (Muscle House in Tehran),” a competent but somewhat undistinguished and short reportage shot during a brief trip to Iran in 1950. The portfolio ends with a surprising pairing of an image of an Iranian man in training with a calligraphic ink drawing of dynamic silhouettes by Henri Michaux.

The early issues of NEUF reflect Delpire’s eclectic, whimsical taste, with its mix of illustrations, documentary photography, drawings, poetry, ethnography, and literature, but an abrupt change in editorial direction took place with issue number five. Dated December 1951, it focuses firmly on one artist, Brassaï, and his photography, drawings, and sculptures. The photographs are printed as full pages, with minimal captions grouped near the beginning; the only texts are passages from Brassaï’s memoir about his childhood, and articles by Henry Miller (“L’Oeil de Paris” is titled after his nickname for Brassaï, following the photographer’s 1932 publication Paris de nuit). On the red cover, two hoodlums appear as if emerging from behind a velvet theater curtain. Delpire deliberately mixed images from different series and periods of Brassaï’s work to create unusual visual connections. The reader’s gaze travels from image to image. When two images shot inside cafés are aligned, their characters seem to join to form a triangle. Two night photographs of a sex worker are shot from the back, then from the front, as if we were following the photographer as he circles his subject. Two little-known, surreal photos close the sequence: a still life of ivy cascading down a broken plaster statue, and a group of cornette-wearing nuns walking away under a vault of gigantic, lush saguaro.

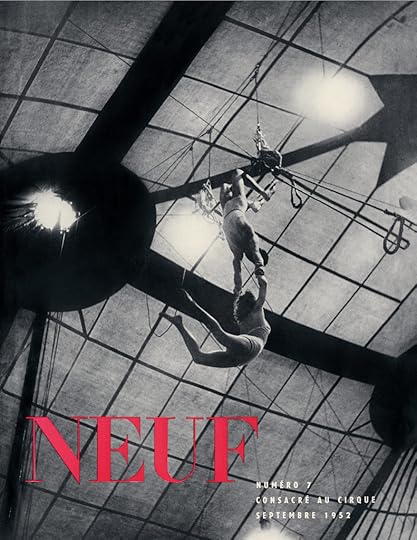

Cover of Revue NEUF, no. 7, with photography by Carel Blazer, September 1952

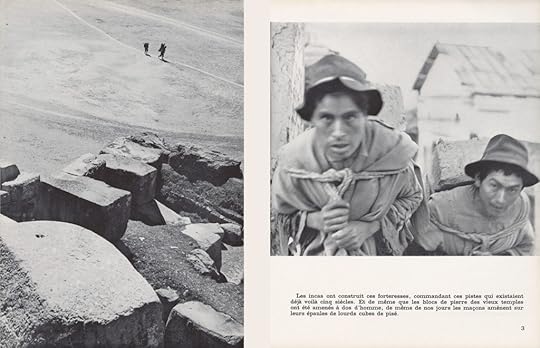

Cover of Revue NEUF, no. 7, with photography by Carel Blazer, September 1952Issue number seven is dedicated to the theme of the circus, with a beautiful photographic cover of acrobats by Blazer, and photos by Doisneau, Cartier-Bresson, and, for the first time, Robert Frank, who was almost unknown at the time and contributed images of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus at Madison Square Garden. The most striking is perhaps a portrait of the famous clown Emmett Kelly: He faces us, holding a cigar in his outsized glove, and wears a wistful expression. His white face in full makeup is framed by the back of a black overcoat, worn by a man in a top hat. Frank’s diaristic-like vision, with offbeat, uncentered views, strongly differed from the style of photography usually championed by Delpire. Even so, the following issue would be dedicated solely to Frank’s study of Indigenous people in Peru. His images are empathetic and melancholy, not a classic reportage with a narrative but a loose wandering, where his drifting eye follows his subjects’ exiles and displacements. The accompanying text, however, by Georges Arnaud is shocking for its stark and racist view of these Native people.

Spread from NEUF, no. 8, with photography by Robert Frank, December 1952