Aperture's Blog, page 40

July 7, 2022

A Photographer’s Search for Acceptance in the Landscapes of Ohio

In 2002, when he was living in rural Ohio, Blake Jacobsen convinced his hairdresser mom to give him highlights. He had been watching the first season of the new singing competition show American Idol and found himself captivated by Kelly Clarkson. Kelly had highlights, so Jacobsen wanted them as well. His mom dutifully helped him actualize his vision, much like she would help color and style his hair for other looks he became fascinated with—there was a period during fourth grade when he became the living embodiment of Ash Ketchum.

“She really would bleach my hair or dye it crazy colors, which was super taboo for boys my age where I’m from,” Jacobsen said recently of those early years. “But then, when I got older, she started to impose her own sort of rigid expectations.”

The title of the twenty-nine-year-old’s latest body of work is built, in part, around that ritualistic experience: taking care of roots. The name at once refers to the process of tending to undyed hair roots, or treating them with other harsh chemicals, as well as to the roots from which you came: your family and home. “The duality between love and care and harm and violence is really rich territory for me,” Jacobsen says.

Blake Jacobsen, Taking care of Mimi’s roots, 2021

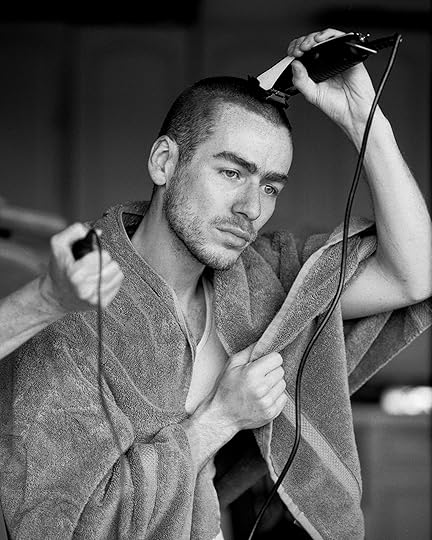

Blake Jacobsen, Taking care of Mimi’s roots, 2021Shown as the thesis project for his masters of fine arts in photography at the University of California, Los Angeles, taking care of roots includes a chapter titled buzzcuts, baptisms, and bleach: notes on gender and beauty in the bible belt. This subseries features photographs of Jacobsen’s mother doing his hair as well as the hair of various family members like his grandmother. The images swirl with the themes Jacobsen often engages with: working-class labor, gender expression, sexuality, religion, family, and community.

Here, his mother is both a conduit and gatekeeper of Jacobsen’s gender presentation while cutting his hair. There, she baptizes his grandmother Mimi in the kitchen sink, the depiction of a routine hair washing charged with tension: Mimi seems to brace herself as her daughter cradles her head. Elsewhere, Jacobsen and his mother swap tools of their respective trades, with him poised to cut his hair while she operates the camera’s cable release.

“When I first started this project that involved my mother, it was very intimidating,” he recalls. He points to the work of LaToya Ruby Frazier that features her mother, like the series The Notion of Family (2001–14), as inspiration. He was “forcing this dialogue to happen, and there was an awareness that certain truths may be revealed that I had been avoiding, and that was also why I wanted to do it. But it was hard.” Those truths included Jacobsen’s own sexuality.

Buzzcuts, baptisms, and bleach also includes landscapes that document the Ohio countryside. Jacobsen’s intent was to imbue the genre of landscape photography with a queer subjectivity. This materialized in work like Out of the closet and into the barn (2019), a black-and-white scene of a barn and farmland, which Jacobsen has imagined as a possible locale for cruising—a site of potential discreet homoerotic activity. In other lush, full-bleed color images, Jacobsen puts his own queer body into these same, often unforgiving, environments.

Blake Jacobsen, Out of the closet and into the barn, 2019

Blake Jacobsen, Out of the closet and into the barn, 2019“Those two parallels have been there since the start,” he says of the inclusion of self-portraiture alongside landscape photography. “The awareness that photography could be used as a tool to represent myself or create a visibility for myself, along with photography’s ability to document a place or landscape.”

In 2009, at the age of sixteen, that meant shooting portraits of the landscape by day on a cross-country trip from Florida to Alaska and running off to secretly shoot self-portraits in area parks during the evening. Jacobsen published many of those self-portraits on platforms such as a fashion blog that he ran called The Style Manual and his Lookbook.nu profile, where he racked up more than thirteen thousand fans over several years. But now, those parallels have crystalized into this body of work that tackles specific questions: How do you belong somewhere that doesn’t accept you? How do you appreciate a landscape that doesn’t welcome you? These are questions that Jacobsen ultimately finds himself confronting as he wrestles with his hometown and family being at the center of a gravitational pull, despite the ongoing pain emanating from those very sources.

Throughout taking care of roots, Jacobsen also digs deeper into his family and the fraught relationships battered by migration, trauma, and tropes of masculinity. In Learning to carry weight (2020), his nephew Hudson attempts to pick up a jug of water. The photograph becomes a portrayal of “how masculinity and, specifically, toxic masculinity is being projected onto him through the way he’s fashioned, through the way that he carries himself, and through the weight that he’s decided to carry,” Jacobsen says. In another image, a version of that masculinity is represented as an American-made pickup truck, left rusted and decaying, having been taken over by nature.

In what Jacobsen calls one of the more powerful images of the series, Hudson crawls through a hole in a door that’s been kicked in by his father, Jacobsen’s brother. The family dog had chewed away at the jagged edges of the splintered wood. “It becomes, in a way, a portrait of my brother.”

Blake Jacobsen, Learning to carry weight, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Learning to carry weight, 2020 Blake Jacobsen, In your image, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, In your image, 2020  Blake Jacobsen, Wombs and Wounds, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Wombs and Wounds, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Migrant Son, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Migrant Son, 2020  Blake Jacobsen, Relics of Adolescence, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Relics of Adolescence, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Crucifix, 2020

Blake Jacobsen, Crucifix, 2020All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.’s Uncanny Inner Worlds

The photographer Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. makes imagery that is weird, obscure, ambiguous, and freaky, packed with impossible, hard-to-decipher elements that never betray any simple or obvious meaning. His titles are cryptic, often splitting the difference between punchy non sequiturs and deeply felt but emotionally abstract poetry—information that only gets more puzzling when you learn that Brown writes them in reference to part of the overall picture. His subjects, who are without exception Black men and women, are often out of frame, subtly distorted, or caught in the cross fire of competing optical illusions. In the rare instances when they face Brown’s camera directly, their features are lit up with campfire-story menace or bolts of neon light, their expressions halfway between a belly laugh and a masklike grimace.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Slowly, surely (after Jill), 2020

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Slowly, surely (after Jill), 2020  Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., A well commanded army tucked at the corners of his lips, 2019

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., A well commanded army tucked at the corners of his lips, 2019 Inspired by Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, and Deana Lawson, Brown’s early work riffed on the idea of the domestic realm as a private theater of unguarded Black humanity, posing his friends and family in casual scenes heavy on themes of desire and intimacy. In subsequent years, Brown internalized his heroines’ ambiguity (Simpson), drama (Weems), and boldness (Lawson), while veering away from literal living spaces into much odder kinds of interiority, ditching straightforward representation or easily nameable emotions in the process.

His recent work is more intuitive, informed by the contrived-casual body language on Instagram, notes and sketches on his iPhone, and the practicalities of photographing. Brown occasionally finds inspiration closer to home. Holes in the plastic lattice weave of his kitchen chair led to the unusual shot-from-below composition of I want to impress leaves on paper with colors they could only know there, where cherries blossom in jacaranda blue (2020). The portrait depicts two men embracing at a table. In the foreground, a hazy fist is either clutching or punching the viewer while what looks like a child’s homework assignment and sixth-birthday candle are taped to the wall beside it. On closer observation, you realize that the “wall” is the underside of the table, the punch is actually holding them steady, and the embrace is both sweeter and stickier than at first appearance.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Brown’s subjects’ inner worlds are as elliptical and compelling as an M. C. Escher staircase, with an internal logic built up more from fiction than depiction. In breaking from the familiar, the artist has front-loaded his images with uncanny details that are striking and confounding: skin crawling textures, poisonously bright colors. In the tradition of Hitchcock, much of the suspense found in Brown’s photography comes from what he withholds from the frame. We seek the answers to the riddles: Why does he photograph from those angles? What are the reactions on his models’ faces? Where in the flurry of impressions should we direct our focus?

In a 2020 interview with W, Brown explained, “Working with the margins at first grew out of a political positioning, recognizing that the margin is an important way to read the center. And what’s held at the margin—there’s a lot of power there . . . tucking things into the margins of the photograph allows me to indicate that there is something beyond the focus, or the purported focus.” By keeping his viewer looking on from the furthest ends of the margins, Brown creates a vision of Black subjectivity that is infinitely definable, drawing the viewer’s attention past more obvious emotional and political dimensions to the most fraught and unresolvable states of what it means to be human.

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.,

Dish soap in the jacuzzi

, 2020

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr.,

Dish soap in the jacuzzi

, 2020  Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., 2021

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., 2021  Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Slow want, 2020

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Slow want, 2020  Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Fallen out of responsibility with myself, she was born into something that could receive her, 2020

Elliott Jerome Brown Jr., Fallen out of responsibility with myself, she was born into something that could receive her, 2020All photographs courtesy the artist and Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the title “Where Cherries Blossom.”

July 1, 2022

A Photographer’s Unseen Archive of the Hawaiian Renaissance

What to do with a photographic archive that can’t be viewed? This sounds like the premise of a Jorge Luis Borges short story, but the question haunts the half-century of photography taken by Franco Salmoiraghi, the Illinois-born photographer who has documented life and art in Hawaii since he moved to the islands in 1968. Because the Hawaiian Renaissance from the 1960s to the 2000s saw a flourishing of Native Hawaiian, or Kanaka Maoli, art and cultural practices, his black-and-white images—usually taken with a medium-format camera, or one of several Leicas—document the rebirth of interest in music, dance, navigation, food, and other traditional ways of life termed aloha ʻāina. Next year, his image of Hawaiian kuma hula (hula master) Edith Kanakaʻole will circulate widely, having been chosen to appear on a new US quarter.

Franco Salmoiraghi, Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole chanting in the koa forest of Kipuka Puaulu in Volcano National Park, Hawai‘i, 1976

Franco Salmoiraghi, Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole chanting in the koa forest of Kipuka Puaulu in Volcano National Park, Hawai‘i, 1976Some of what Salmoiraghi has been invited to document by the Native Hawaiian community has been sacred: burial sites, makahiki (annual religious celebrations), and cultural practices conducted both at protests and in private. For this reason, some of his best-known work can be seen, at his request, only through collaboration with Hawaii’s community of Kanaka Maoli activists, scholars, and curators. A recent exhibitionat the Honolulu bookstore Arts & Letters Nu‘uanu, titled I Ola Kanaloa! I Ola Kākou! Photographs of Kaho‘olawe, 1976–1987, documents trips Salmoiraghi made to the island of Kaho’olawe during the peak of the Hawaiian Renaissance in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It featured eleven archival photographs and a dozen contemporary reprints selected in collaboration with Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana, the grassroots group of Native Hawaiian aloha ʻāina activists that cares for the island.

Franco Salmoiraghi, Hiking 1,800 feet above Hi‘ilawe Falls in Waipi‘o Valley, Hawai‘i Island, 1976

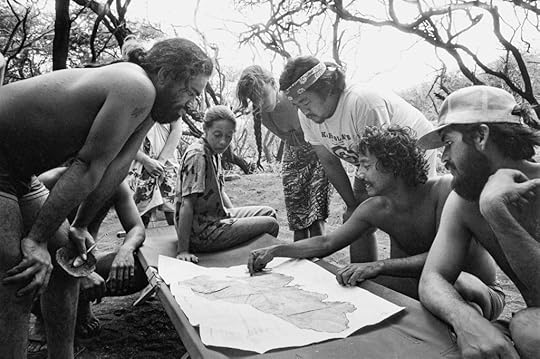

Franco Salmoiraghi, Hiking 1,800 feet above Hi‘ilawe Falls in Waipi‘o Valley, Hawai‘i Island, 1976 Franco Salmoiraghi, Planning an exploration of the island of Kaho‘olawe on foot, 1979

Franco Salmoiraghi, Planning an exploration of the island of Kaho‘olawe on foot, 1979Salmoiraghi moved to Hawaii on an invitation from the University of Hawaii to teach darkroom photography in 1968, after studying photojournalism at Southern Illinois University and earning an MFA in photography in Athens, Ohio. His aunt and uncle had once sent his family a postcard from Waikiki, and he remembers having seen The Don Ho Show, but he’d never previously visited the state. Immediately upon his arrival over winter break, the state’s archaeology department asked him to photograph sites along a long road being constructed from Waimea to Kailua-Kona. Officials air-dropped him in a remote lava field, amid ancient stone houses that were later destroyed.

In an archive of half a million negatives, Salmoiraghi eschews easy romanticism for a look at the cultural contradictions of life and landscapes in America’s newest state.

Throughout the 1970s, a period of extensive commercial development in Hawaii, the Hawaiian state hired Salmoiraghi to document historic sites on the islands. Later, the Native Hawaiian community invited him to photograph land-back protests (starting with Waipiʻo Valley in 1974) and religious ceremonies. Over coffee at Fendu café in his neighborhood of Manoa, he recently described to me his subjects as places “you cannot buy your way in. There is no price. Like fate dropping me off in that helicopter for a week on that lava field.” His gelatin-silver prints of Hawaiian people and landscapes evoke aspects of the lucid magic of the photographer Peter Henry Emerson; Salmoiraghi himself references Cartier-Bresson. “I like to print full frame, no cropping, some spotting,” he says.

Franco Salmoiraghi, US Navy Marine helicopters landing to remove a group of PKO members visiting Kaho‘olawe, 1976

Franco Salmoiraghi, US Navy Marine helicopters landing to remove a group of PKO members visiting Kaho‘olawe, 1976 Franco Salmoiraghi, Entering Diamond Head crater tunnel for the Sunshine Music Festival, 1970

Franco Salmoiraghi, Entering Diamond Head crater tunnel for the Sunshine Music Festival, 1970 Franco Salmoiraghi, Laupae kalo loi in Waipi‘o Valley on Hawai‘i Island, 1974

Franco Salmoiraghi, Laupae kalo loi in Waipi‘o Valley on Hawai‘i Island, 1974In an archive of half a million negatives, he eschews easy romanticism for a look at the cultural contradictions of life and landscapes in America’s newest state. One sees derelict industrial sugar mills and historic sites, vast fields of taro and native flowers that feel lit from within with metaphoric meaning, and portraits of families who have lived on the land behind them forever. Others photographing and filming the Hawaiian Renaissance include Phil Spalding, Ed Greevy, and Francis Haar. Of this group, Salmoiraghi’s prints have perhaps the most deft and uncanny touch.

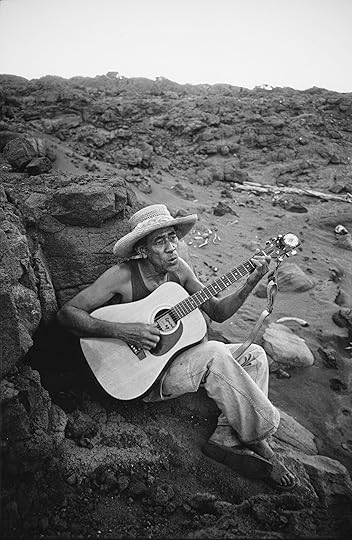

His Kaho‘olawe images, for instance, tell the story of the struggle for land and self-determination. The island was repeatedly bombed by the US military, and its use as target practice rendered it inaccessible and dotted with unexploded mines. Letters on display at Arts & Letters Nu‘uanu, between the activist George Helm, Salmoiraghi, and the Navy, document the process of the group of activists obtaining permission from the US military to conduct cultural ceremonies on the island. The group of Native Hawaiian aloha ‘aina leaders, including Noa Emmett Aluli, Walter Ritte, and Aunty Emma DeFries, was eventually able to do them in the presence of the Navy’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal personnel. In the photographs, the activists look ragtag with their shag haircuts, guitars, cutoff shorts, and kalo cookouts. The prints, on warm Agfa paper, render cultural protest both quotidian and glowing. As a result of these interventions, the Navy stopped the bombings in 1990; in 2003, the US military returned the island to the state of Hawaii. Today, as the Navy’s pollution of urban Honolulu’s major aquifer from ongoing leakage of the once-secret Red Hill military fuel-storage facility is under scrutiny, the exhibition of the PKO protests at Kaho’olawe was a timely reminder of a recent past when protest changed the fate of the land.

Franco Salmoiraghi, Wao Kele o Puna protest on Hawai‘i Island, 1989

Franco Salmoiraghi, Wao Kele o Puna protest on Hawai‘i Island, 1989 Franco Salmoiraghi, Uncle Harry Kunihi Mitchell, mentor to the PKO, sings “Mele o Kaho’olawe,” a song he wrote for the island, 1979

Franco Salmoiraghi, Uncle Harry Kunihi Mitchell, mentor to the PKO, sings “Mele o Kaho’olawe,” a song he wrote for the island, 1979What viewers cannot see are images that the Native community deems sacred. One, which Salmoiraghi described to me, shows a man “chanting [another man] into invisibility,” as the photographer put it. In another set of photographs deemed kapu, or taboo, women beat kapa, or mulberry paper. The collaborative discussion initiated by Salmoiraghi with members of PKO about what may and may not be shown adds to the contemporary interest of exhibitions of his historical work. Salmoiraghi cites several “five-hour meetings” leading to the selection of the images. “There is a tremendous amount of protocol in the Hawaiian culture,” he says. The Kanaka Maoli curator Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick, who helped organize the exhibition, adds, “Some of the moments Franco witnessed and recorded are appropriate for public display and some are not. Knowing the difference is how we demonstrate our understanding and sense of responsibility.”

Franco Salmoiraghi, Orange Heliconia flower with leaves, 1991

Franco Salmoiraghi, Orange Heliconia flower with leaves, 1991All photographs courtesy the artist

Franco Salmoiraghi, Art and his apprentice, 1991

Franco Salmoiraghi, Art and his apprentice, 1991 Salmoiraghi’s negatives are contact printed, and in his vast archive, images of the sacred mix with ones that might reasonably be shown, complicating the very act of preserving his life’s work. What can and can’t be shown also changes over time, with photographs that were once carried or widely shown on the sides of trucks at protests in the 1970s retroactively considered kapu by the community today. The dangers are not only in showing what was never meant to be seen, or seen only by certain groups. “My grandsons are part Hawaiian. I have a lot of feeling for them,” says Salmoiraghi. He would like to preserve the archive, he adds, decades into the future for Hawaiians to see what happened during the 1970s and ’80s, in part because he fears the commercial exploitation of sacred images on merchandise that target tourists. His archive is in constant conversation with contemporary notions of the sacred and the unseeable—and its preservation is essential.

“Photography is about stories,” Salmoiraghi says. “Even if you come home without a photograph, you lose your film, for example, you still have that experience. This is what my whole life in photography has been about.”

June 30, 2022

In Iran, Death Has a Face

During the heady days of the Arab Spring in early 2011, we were celebrating a low-key Persian New Year in Tehran, transfixed by scenes on television of the protests across Muslim countries. A year earlier, out of fear of violence, we had abandoned our own protests in Iran, which were triggered by the disputed presidential elections that brought Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to his second term in 2009. So we watched in wonder as people in Arab-speaking nations, from Tunisia to Syria, took to the streets, and when they seemed so close to their goal of achieving democracy—which we have been regularly trying for in the past hundred years—a sense of jealousy set in. Yet, all the time, the number of dead increased in Egypt, and especially in Syria, where the uprising would soon be followed by outright war.

I asked a Colombian friend and journalist who has covered Iraq and Syria why we Iranians retreated after some two hundred people died in our protests, but Syrians would still go out despite reports of thousands of deaths. What makes them go on? She had an interesting take: “Every time a protester is killed, Iranians immediately circulate their photograph. They very quickly turn a number into a face, a person.”

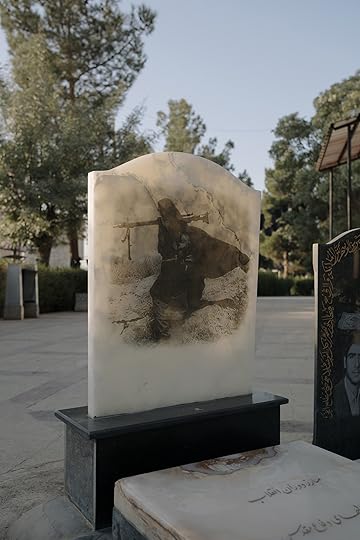

Amin Yousefi, Martyrs Admiral Mahmoud Reza Koosha and Amir Mohammad Reza Safaei, Sayad Shirzi Highway, Tehran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Martyrs Admiral Mahmoud Reza Koosha and Amir Mohammad Reza Safaei, Sayad Shirzi Highway, Tehran, 2021In Iran, death has a face. Our mourning rituals are now influenced by photography and the digital technology that can transmit images in all sorts of media, including setting the dead person’s photo in stone. When you step outside in Iran, you literally walk on the memory of the dead: almost every street and highway is named after martyrs of the Iran-Iraq War or the lost heroes of the Islamic Republic, an ideological system that thrives on memorialization of martyrdom through huge murals, posters, billboards, stamps. Any flat surface that can be seen.

Death is a big event for Iranians, marked with obligatory rituals that last for an intense seven days, peaking on the third, and later repeating at day forty and the one-year anniversary. The rituals are accompanied by printed notices that are posted around the deceased’s neighborhood and placed in the rear windscreen of relatives’ cars. A picture of the deceased is set in the center of the notice amid decorative margins, with a brief eulogizing text and details about the time and place of mourning.

Amin Yousefi, Death notice, Mohammad Shahr, Karaj, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Death notice, Mohammad Shahr, Karaj, Iran, 2021The rules of modesty imposed in Islam are upheld beyond this earthly life, so no photographs of dead women can be displayed on their death notices. Instead, they are generically represented by a block print–style representation of a flower in black or recently with a color photograph of an actual flower. Once traveling through Qom, a desert city of seminaries where the guardians of faith and fortune in the country congregate, I saw a death notice for a woman that was adorned rather eerily with the shape of a magna’e, the wimple-style hijab women are required to wear to access universities and government offices. The flat, white void in the middle of a rigid, black bell shape was a genius of contradiction, effacement rendered in eye-catching graphics. Sometimes the families of a departed woman don’t bother with the visual metaphors that are meant to soften this last blow of censorship and instead dive straight into the text. While the portraits of men gazing at the living—fixed, suspended in a different time, visually present for the duration of the funeral—help remind mourners of what they looked like when they lived, the women disappear as soon as they die.

Amin Yousefi, Laserprint headstones, Emamzadeh Taher, Karaj, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Laserprint headstones, Emamzadeh Taher, Karaj, Iran, 2021 Amin Yousefi, Headstone, Bagh-e Rezvan Cemetery, Isfahan, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Headstone, Bagh-e Rezvan Cemetery, Isfahan, Iran, 2021Until a few years ago, headstones were embellished with poetry in fine calligraphy. These days, walk into any cemetery in Iran and you are likely to stand among rows and rows of faces, etched in white onto black marble, creating a collage like a giant monochrome yearbook. Many of these images are of women, some lifted from photographs of them in private moments when they were not observing the enforced rules of hijab. This new fashion in memorializing the dead so violently contradicts the decree on the representation of women that some local authorities are covering the images with white paint or trying to ban the practice altogether. But on the dusty road outside Tehran’s main cemetery, rows of stone masons’ shops display these eye-catching new forms of art to draw new customers in. How did this trend take hold in a country that likes to hide its women from view?

Amin Yousefi, Behesht-e Zahra Cemetery, Tehran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Behesht-e Zahra Cemetery, Tehran, 2021  Amin Yousefi, Martyr, Behesht-e Zahra Cemetery, Tehran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Martyr, Behesht-e Zahra Cemetery, Tehran, 2021 The answer may lie in the cemetery itself. A large section of Behesht-e Zahra, or Zahra’s Paradise, the sprawling cemetery south of Tehran and the country’s largest, is dedicated to the dead of the Iran-Iraq War, the eight-year conflict that began in 1980 soon after Iran convulsed into a revolution that put an end to secular rule. The official count of the dead varies from hundreds of thousands to a million. This section of the cemetery is packed with graves. Almost all are decorated with some kind of photograph. Some have a glass box that contains personal and military paraphernalia and resemble small shrines; some of their photographs show the soldier dead. In keeping with the main cemetery in the capital, every small cemetery across Iran has a martyrs’ plot, where regimented rows of graves feature enlarged headshots set in metal vitrines. These figures all have that vacant look common to passport photography.

Visuals of death became a staple of life in Iran. People became used to seeing banners and posters of those who died in the war.

Iranian news photography was invigorated by the revolution, but it was the war with Iraq that birthed the genre of war photography in the country. The Islamic Republic has never shied from depicting death in its full gory detail. Unlike the depiction in the West of soldiers as untiring warriors, Iran’s memorialization of the war relied heavily on the demise of the soldiers. Their martyrdom, echoing the martyrdom of Imam Hossein who is beloved by Shia Muslims, is a badge of honor that secures entry to heaven. Such idolatry of death brought the Iranian public face to face with disturbing and graphic scenes that would be censored in other cultures. Visuals of death became a staple of life in Iran. People became used to seeing banners and posters of those who died in the war. State television produced documentaries of the front, beaming images of the war into Iranian homes at peak hours. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s burial was a widely televised affair, as one would expect, but his death, on his hospital bed, complete with a ticking clock and the flatline on the cardiogram, was also recorded for posterity.

Amin Yousefi, Laserprint headstone, Emamzadeh Taher, Karaj, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Laserprint headstone, Emamzadeh Taher, Karaj, Iran, 2021 Amin Yousefi, Child’s headstone, Bagh-e Rezvan Cemetery, Isfahan, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Child’s headstone, Bagh-e Rezvan Cemetery, Isfahan, Iran, 2021The printing press brought us paper death notices. The new technology of laser-engraving digital images onto stone would seem a natural evolution and may be the reason for this new enthusiasm for picturing the dead on headstones. The practice exists in Russia, as seen in the works of Denis Tarasov, who has collected a series of similar engravings. Marina Abramović’s Seven Deaths (2021) also uses the same technique to transfer imaginary death portraits of herself onto alabaster, referencing this headstone art. Depicting dead people, of course, is not a new phenomenon. As Egypt’s mummy portraits, the full-scale statues that wealthy medieval Europeans commissioned to rest on top of their tombs, and Victorian-era postmortem photography demonstrate, the impulse to preserve an image of the dead is an enduring one. There is a difference, however, in this new Iranian trend. The photos engraved on these headstones capture a moment of life and set them literally in stone: a young man is shown with his boxing gloves, a business man with his briefcase, an elderly couple stands close to each other. We endlessly record every moment of our living lives on our phones, so this last grand photographic gesture for our dead seems like a fitting substitute for the complex and costly mourning rituals that had to be cancelled as COVID-19 swept mercilessly across Iran.

Amin Yousefi, Death notice, Mohammad Shahr, Karaj, Iran, 2021

Amin Yousefi, Death notice, Mohammad Shahr, Karaj, Iran, 2021All photographs for Aperture. Courtesy the artist

Beyond the cemetery, new death rituals are emerging with the help of photography. Iranians have an established tradition to publicly express their condolences by hanging cloth banners, with messages of respect made by professional calligraphers, on the walls of a house, alerting the neighborhood that the household was in mourning. The minimal handwritten banners have now transformed into digital banners with extra color and decorations. But we have gone one step further. Nowadays mourning families order advertising banners, with an enlarged photograph of their dead relative, which they affix to lampposts on the main street, replicating the posters and banners with images of the war dead that proliferate the country’s public spaces. Instead of the lofty poetry of the gravestones, or the propaganda of the war, these banners have short everyday messages for passersby, like one I recently saw of a young man who had turned to wave back at the camera as he was walking away. The banner read, “Goodbye friends, bless my soul.”

June 28, 2022

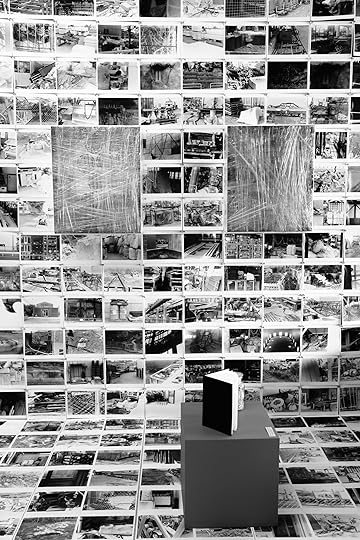

The Japanese Photographers Who Build Experimental Artist Books

In October 2021, Hiroko Komatsu and Osamu Kanemura held a parallel set of exhibitions at the newly reopened gallery space of dieFirma, New York—Komatsu’s Sincerity Department Loyal Division and Kanemura’s Looper Syndicate. In Komatsu’s installation, upstairs, visitors were welcomed by a subtle and moving smell, a combination of photographic paper and printing chemicals, that enveloped them as they walked through photographs, and on photographs, in a multisensorial experience. Amidst the prints, Komatsu also presented a selection of her new artist books. Downstairs, in Kanemura’s exhibition, visitors encountered a monumental collage made of twenty thousand color photographs, mainly of the artist’s hometown, Tokyo, and a few of New York, complemented by a (loud) film on a loop as well as a myriad of books on pedestals that all were invited to browse. Pauline Vermare recently spoke with Komatsu and Kanemura about these experimental installations.

Hiroko Komatsu and Osamu Kanemura, 2021

Hiroko Komatsu and Osamu Kanemura, 2021Pauline Vermare: What struck me first as I visited both of your installations is their incredible physicality: the utter joy of being surrounded by unframed prints and handmade books, of being in such direct contact with your art in an intimate and nonprecious way. It seems like a visceral reaction to our world, a desire to re-materialize, which feels so good in the midst of this COVID crisis. How did this work come to life?

Osamu Kanemura: While many people have been staying home for the past year, I’ve been out taking photographs of Tokyo using the Ricoh GR. I’ve been thinking that a digital camera should be completely different from a film camera and wondering how I could exhibit digital photography that is more than an imitation of film photography. That’s why I decided to present a large number of photographs, not in a conventional way where enlarged, framed photographs are exhibited in a white-cube gallery but as an installation and as handmade books.

Hiroko Komatsu: Same as Osamu, I was busy going outside to take pictures. Actually, I found it very easy to do so because there were few people outside amid the pandemic. In Tokyo, there had been a building rush linked to the Olympic Games, but much of the construction had been halted as part of lockdown. I enjoyed taking photographs of those empty construction sites, which gave me an impression of shiny ruins. When people look at those pictures, they can’t tell whether the scenery shows the process of building or of demolishing something. Those who work in these sites are so-called blue workers, and I believe those sites are where you can see the people who make up the lower part of our society and our infrastructure most clearly. As a photographer, I think it is very important to visit such places to take pictures.

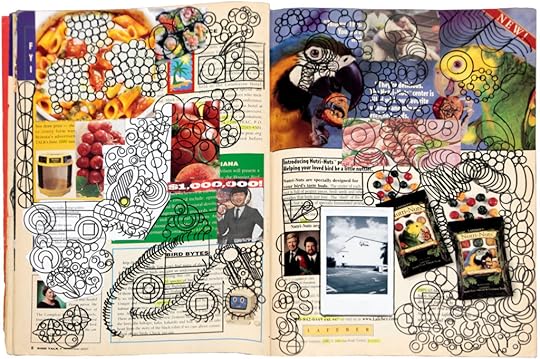

Spread from Osamu Kanemura, Bird Study (Artist book, 2021)

Spread from Osamu Kanemura, Bird Study (Artist book, 2021)Vermare: Osamu, would you tell us about your other camera of choice, the Plaubel Makina? In your excellent 2019 book, Beta Exercise: The Theory and Practice of Osamu Kanemura, a collection of your interviews and writings, you explain: “The Plaubel Makina, which creates an element of unintentional noise, taught me the importance of unintended effects. . . . This adds street snap-like motion to static, urban landscape photos.”Why did you choose that camera?

Kanemura: Well, Daido Moriyama was already photographing Tokyo with a 35mm camera, and I didn’t want to do the same thing as him. So I decided to use a camera with better image quality, which was a 6-by-7 camera. I chose Plaubel Makina because it was lighter, which is an important factor for someone like me who shoots all day long. One of the features of the camera is that its viewfinder coverage is 80 percent. With such a wide coverage, when I try to take a picture of something, the object in the foreground enters the picture. Now, I consciously include things in the foreground in my photographs, but I used to think such a photograph would be a failure. Eventually, I realized that it would be more interesting if things I hadn’t imagined or things I had thought of as obstacles were in the images. This kind of “noise” in photography should be appreciated, I thought.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Vermare: Both of you have incorporated the creation of objects into your recent practice, which we are surrounded with tonight as they feature prominently in the exhibition. I’d love for you both, maybe starting with Hiroko, to talk about those incredible objects—they’re something more than books, really. Black Book #1 (2021) actually is a bottle, filled with little cut-out pieces of paper that are the words from Greta Thunberg’s book No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference. Another one is filled with Theodore Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and Its Future: The Unabomber Manifesto. Hiroko, can you tell us about those books, those objects, and how you started making them?

Komatsu: In making my first artist book, Book #1 (2016), I wasn’t interested in selecting photographs from the approximately one thousand photographs to be shown in my exhibition and arranging them. Nor did I want to make a catalog from the photographs. I felt such a book would not represent what I was doing. I’ve been photographing my exhibition sites with the same camera I use in making the work outside. One time, I put those photographs of my installation side by side with the ones I took outside, and there was something consistent about them, and that inspired me to put them together for Book #1. Digital technology is also an important tool for me, and I digitally scan images made with an 8mm camera. The idea behind my artist book Black Book #1 is that text and photographs are very similar. A single photograph is not enough to make sense. A single word doesn’t make sense by itself, either. And when you put together multiple photographs or words, a meaning emerges. Also, when you take a picture, you frame a part of reality, and then you move the image to another place, such as an exhibition venue or bookstore. I thought the process was very similar to cutting out texts from a book and putting them in an object—in this installation, a bottle.

Installation view of Hiroko Komatsu: Sincerity Department Loyal Division, dieFirma, New York, 2021. Photograph by Hiroko Komatsu

Installation view of Hiroko Komatsu: Sincerity Department Loyal Division, dieFirma, New York, 2021. Photograph by Hiroko KomatsuAll photographs courtesy dieFirma, New York

Vermare: In your case, and in Osamu’s work with books as well as with photographs, there’s this idea of accumulation. Osamu, you have recently been making two kinds of books: the ones that are collages of images and elements that you cut out and assemble in colorful, unique albums and those made from existing books that you intervene on, by drawing in them, cutting them. When did you start this process?

Kanemura: Before, I had a strong idea of what a photobook should be like. The reason I’m interested in handmade books is because it’s very interesting to see the preconceived notions of books that I’ve been trapped in until now breaking down. I couldn’t treat photobooks violently because I was thinking about distribution and preservation. But once I got rid of those things, many ideas came to me. For example, I cut or fold the pages of a book with a cutter or use tape that will not be well preserved. I made my first artist book two years ago. I was beginning to feel uncomfortable about my black-and-white photographs because they were like tableaux. It was also then that I visited New York and bookdummypress (bdp). I was shocked to see the handmade books of Victor Sira, the director of bdp. I thought, This is more like a drawing. I also found it very interesting that he didn’t aim to complete his works but presented them unfinished. I decided to do what he was doing, with collage as a start.

A single photograph is not enough to make sense. A single word doesn’t make sense by itself, either. And when you put together multiple photographs or words, a meaning emerges.

In making collages, I use such materials as digital photographs and clippings from magazines and newspapers. I also realized that I could do things with digital photography that are difficult to do with film photography: taking photographs of my life, of what I see on a daily basis, and displaying my politics. I’m Zainichi—a Korean living in Japan—and because of my origins, I’ve encountered situations that have forced me to feel uncomfortable with the Japanese system since I was a child. In Japan, for example, you can see ads of racist magazines in major national newspapers. They say, “Zainichi Koreans should leave Japan.” This is also my daily life, and I’m clipping those words, too, in my collages. I like to make something out of something that exists, rather than creating something from scratch.

When I make my artist books, I use other people’s photographs, texts, and printed matters, and by doing so, I try to deconstruct the meaning and context of others’ materials and create another context. In this respect, photography is the same. It’s about framing the part of reality that exists in front of us. You may have noticed that I have repeatedly drawn circles in my artist books, using a special ruler. In other words, I drew the shape of an object with a tool, which made me realize that what I do with a camera is photograph the shape of an object. My every action serves to expand my concept of photography.

This piece originally appeared in The PhotoBook Review in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking.” Interview translation by Yuri Mano.

June 24, 2022

Aperture, For Freedoms, and FREE THE WORK Partner to Launch Google’s Image Equity Fellowship

Today, in partnership with Google, For Freedoms, and FREE THE WORK, Aperture is announcing a six-month, application-based program that will award $20,000 in unrestricted funds to 20 selected creators in the US.

Applications are open to early-career artists who self-identify as a person of color, are based in the US, and are at least 18 years old. The awardees will develop visual bodies of work that present urgent, untold stories of their communities. In addition to a $20,000 award, each fellow will receive support exhibiting their completed projects in-person and online as well as mentorship and dedicated workshops with industry experts.

Led by Google as part of their Real Tone initiative, the fellowship is a continuation of the company’s efforts to more accurately and beautifully represent communities of color on Pixel 6 and in Google Photos. A key part of their work on Real Tone was made possible by partnering with image experts—renowned photographers, cinematographers, colorists, and directors—whose work has uplifted and expanded our collective understanding of whose stories need to be told. This emphasis on community-driven storytelling is the foundation of the inaugural Image Equity Fellowship.

“We are thrilled to partner with Google on the Image Equity Fellowship,” says Aperture’s executive director, Sarah Meister. “This is an extraordinary opportunity to further Aperture’s support of the photography community by collaborating with a group of talented artists alongside renowned mentors. Together, they will be showing us how linking technology with cultural partnerships can create a path toward a more expansive future for photography.”

In addition to Google, Aperture is proud to partner with For Freedoms, an artist collective that centers art and creativity as a catalyst for transformative connection and collective liberation. And FREE THE WORK, a non-profit organization committed to addressing the lack of diversity in media and to creating opportunities for a global workforce of underrepresented creators behind the lens in TV, film, and marketing. Together, we have selected five mentors to guide the twenty awardees: Lebanese filmmaker and photographer Ahmed Klink; American artist and 2016 Guggenheim Fellow Lyle Ashton Harris; photographer and documentarian Bee Walker; multi-hyphenate creative Mahaneela; and Rujeko Hockley, Assistant Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Submit now to the Image Equity Fellowship, open until July 18, 2022.

June 21, 2022

Lora Webb Nichols’s Mysterious Images of the American West

A blurry bird in a cage against a bright window, like a shadow cast, an omen. A child, ears askew in a kangaroo costume, lit up by the camera’s flash. A sapling flanked by two women, prophets or apparitions, in a far-reaching field. The American West of the photographer Lora Webb Nichols appears as visions from a dream, her breathtaking and improbable archive inspiring a disorienting reverie.

Lora Webb Nichols, Wendy Peryam, 1948

Lora Webb Nichols, Wendy Peryam, 1948Born in 1883, Nichols was given her first camera in 1899, at age sixteen, and would spend the next sixty-some years taking photographs, many of them in Encampment, Wyoming, the frontier town where her homesteading family had settled. She would watch Encampment boom and bust with copper mining, documenting—in some cases for pay—the industry, ranch life, and the coming railroad. From early on Nichols photographed people with an artist’s intuition. She was attuned to moments not often memorialized then, and her access to quiet, private moments among women allowed her to capture, unusual for photography of the time, images of women brushing out their long hair or outstretched across a settee.

Lora Webb Nichols, “Tabernickle” and team, 1925

Lora Webb Nichols, “Tabernickle” and team, 1925The distance between the last gasp of the Old West and the present can seem a chasm too wide to mentally and emotionally cross, even with visual aid. As the photographer Nicole Jean Hill observes in her essay for Encampment, Wyoming: Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive 1899–1948 (2021), which Hill edited, archival images tend to feel remote, in part, because early film’s lack of sensitivity to light often required staging and rigidity. Despite these limitations, Nichols’s inclination toward intimate and idiosyncratic subjects and composition is pioneering. But what brings the eye to widen, then squint with recognition, is the bearing of the people Nichols photographed—how they hold themselves so openly, so honestly in her presence.

Lora Webb Nichols, Clella Brown (left) and unknown (right), 1899

Lora Webb Nichols, Clella Brown (left) and unknown (right), 1899Nichols was among the influx of women who in the early twentieth-century—with the period’s newfound freedoms for women, along with the proliferation of news photographs and portrait studios—made a career in commercial photography. Nichols’s Rocky Mountain Studio, operational from 1925 to 1935, was a Kodak franchise photo-finishing business where Nichols developed film for other photographers in the area, buying negatives she liked and selling the images as postcards. She also briefly ran a local newspaper, The Encampment Echo, as well as a soda fountain where she photographed anyone who’d allow it, including the young men who came through from the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Women, in pairs and alone, recur in Nichols’s work, sharing a laugh or food, or with their animals, and a sense of Nichols’s own conviviality is often apparent in her subjects. There can be a haunting quality, too, to Nichols’s photographs that’s difficult to characterize—a glimpse of the violence and hardship of westward expansion maybe? The landscape, sublime, and our knowledge of how we’ve transformed it? That dreamlike disorientation, again. Nichols’s work is best viewed in miscellany; her portraits of people, place, and industry are inextricable.

Lora Webb Nichols, Frank Nichols, 1942

Lora Webb Nichols, Frank Nichols, 1942  Lora Webb Nichols, Name unknown, 1938

Lora Webb Nichols, Name unknown, 1938 Nichols died in 1962, leaving behind a vast archive of twenty-four thousand images that are in the public domain and viewable at the University of Wyoming’s American Heritage Center website. A natural record-keeper, Nichols kept extensive diaries that tell, beyond chipper daily details, of financial and marital struggles (she was married twice) and the difficulties of balancing business with the domestic (she had six children, four of them within six years). Nancy F. Anderson, a close friend of Nichols who’s helped to preserve her work, says she continued to take pictures and write in her diary up to her death in 1962.

Lora Webb Nichols, Guy Nichols recovering from flu, 1919

Lora Webb Nichols, Guy Nichols recovering from flu, 1919All photographs courtesy the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming

In a photograph of unflinching intimacy, her second husband, Guy Nichols, is pictured recovering from the flu during the 1918 to 1919 epidemic. Here, Nichols conjures a state somewhere between sleeping and waking, a dappled fever dream. Her husband’s vulnerable body, streaked in sunlight, is eclipsed only by the look on his face. Is it resignation or relief?

Dreaming, our minds walk while we sleep. Most vividly remembered when we wake is the lingering feeling left by our nocturnal wanderings, sometimes carried by a memorable image but not often explained by it. What Lora Webb Nichols made are astonishing and mysterious images of pure feeling, at once familiar and faraway.

This article is published coinciding with Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” guest edited by Alec Soth.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]June 16, 2022

The Subversive Dream Logic of Emila Medková’s Photographs

Dream logic is essentially sideways logic: similarities or kinships that work not by means of sense but along other avenues of relationship. Puns, for example, exhibit dream logic. What kind of socks do bears wear? None. They usually have bare feet.

Visual puns likewise find resemblances between objects not otherwise the same. Since human eyes are self-interested, the similarities they tend to discover are to human faces, from the composite vegetative figures of the sixteenth-century painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo to those comic staples of today’s social media, the carrot that seems to smirk or the leering face in a tree.

Emila Medková, Konec obrazu (The end of the painting), 1948

Emila Medková, Konec obrazu (The end of the painting), 1948Back up eighty years, and here’s the Czech Surrealist photographer Emila Medková, carrying out an austere version of the same absurdist project. Her work spans four decades, from the end of World War II to her death in 1985. With the exception of the brief liberalization in 1968 around the Prague Spring, Medková operated in the dark of totalitarian rule. Her work was rarely exhibited. Censorship was rife and resistance necessarily coded and covert. Her photographs were made as an act of subversion and bitter humor for a close circle of Czech Surrealists.

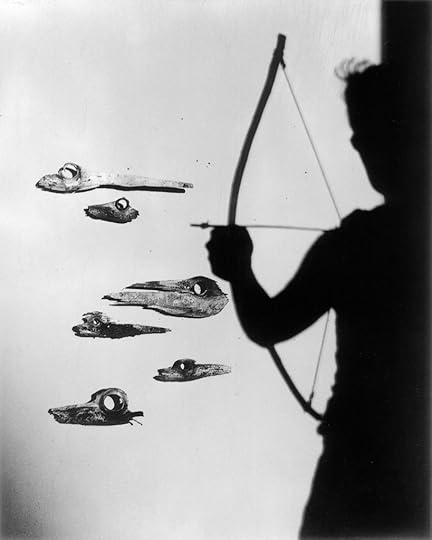

She started out in a fairly conventional, if virtuosic Surrealist mode. In the Shadowplay series of the 1940s, real objects are twinned with their shadow selves, the exception being a female figure in Lukostřelec (Archer) (1949), who exists solely in the domain of shadow. With an arrow, she pursues what looks like a flotilla of fish, made perhaps from knots in wood. In another scene, she gazes at a mysterious assemblage, which includes a tap gushing hair and an eggcup that appears to be capped with an eyeball, cheery as the cherry on an ice cream sundae.

Emila Medková, Křik (The scream), 1971

Emila Medková, Křik (The scream), 1971  Emila Medková, Zavřená hlava (Closed head), from the series Zavřeno (Closed), 1960–61

Emila Medková, Zavřená hlava (Closed head), from the series Zavřeno (Closed), 1960–61 These images have a definite power, but are in some ways reliant on a readymade Surrealist language, which centers on the objectification and estrangement of the female body. In her later work, Medková excised the human form altogether, finding far stranger and more potent bodily resonances by way of objects.

I’ve got four of her found forms in front of me. The first, Zavřená hlava (Closed head), from her long-running series Closed (1960–61), shows the middle region of two wooden doors, their surfaces riven and pockmarked. Each has a square black aperture near the top. Underneath, there’s a metal hasp, yoking the two doors together, which has been padlocked shut. It’s irresistible to read this image as a cartoon face, with doleful eyes and flat mouth. In fact, it looks exactly like the emoji for shhh or zip it, the ideal affective icon for the Stalinist government under which Medková worked.

Emila Medková, Lukostřelec (Archer), from the series Stínohry (Shadowplays), 1949

Emila Medková, Lukostřelec (Archer), from the series Stínohry (Shadowplays), 1949The face is above all a conveyer of expression, while the object is intrinsically speechless and inert. That’s the weird bathos, the lol of the face-in-object. In Medková’s faces, this tension is heightened by the way they’re so often further encumbered by having their mouths locked, filled, choked, or otherwise impeded. Everywhere, these faces that can’t speak are having their capacity for speech emphatically denied.

In Křik (The scream, 1971), we’re seeing another virtuosic surface, every crater and crevice crisply rendered. Is it a road in close-up? Much of the photograph appears dark, surrounding a pale region shaped like a cartoon face in profile—like the “Kilroy was here” face ubiquitous in 1940s graffiti. Kilroy’s hair is grass and his mouth is enormously wide. It looks as if he’s vomiting the darker matter, or, on the other hand, as if it’s being forced down his open gullet, choking the apparatus from which language is produced.

Emila Medková, Untitled, from the series Inkvizitoři (Inquisitors), 1951

Emila Medková, Untitled, from the series Inkvizitoři (Inquisitors), 1951There’s more uncanniness afoot in an untitled 1951 photograph from the series Inkvizitoři (Inquisitors). The face is made of bark, with a hank of hair, and another single eyeball, maybe a marble, though it looks a lot like what my godson calls “googly eyes” (a natural-born Surrealist, he often sticks them on unsuspecting fruit and eggs). But this face is lying on a table, as food tends to do. It has a fork shoved in its mouth, which pushes it toward the status of face, and a knife skewered through its cheek, which converts it back into food. Object or subject? Who’s doing the eating, and who is being consumed?

One more, this time not a face at all. This image, wittily titled Arcimboldo (1978), shows a crumple of machinery, with intestinal spokes and ribs and teeth. It looks like a torso, the damaged interior of a body. The French Surrealists, well-fed, enjoyed imagining women’s bodies emerging from inanimate objects in ways that were alternately nightmarish and exposing. Medková’s take is more skeptical and scathing.

Emila Medková, Arcimboldo, 1978

Emila Medková, Arcimboldo, 1978All photographs © Eva Kosáková Medková

Perhaps this is all a person is, she seems to say, a bundle of disarticulated parts, functional until it’s not. But what could seem like a dutiful totalitarian statement is undermined by the cool, displacing irony of Medková’s gaze. The oddness of the composition makes it impossible not to sense the presence behind the camera. The shadow is no longer necessary. What she’s actually managed to document is a person in the forbidden act of looking, thinking, dreaming freely. Maybe this particular rebellious object wasn’t so silent after all.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the title “Sideways Logic.”

June 15, 2022

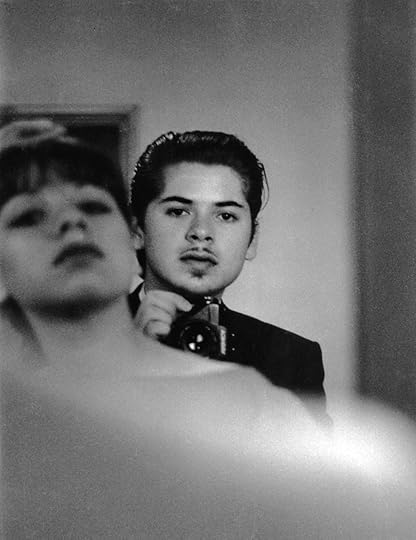

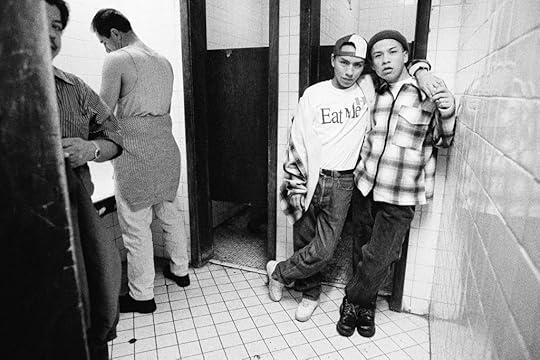

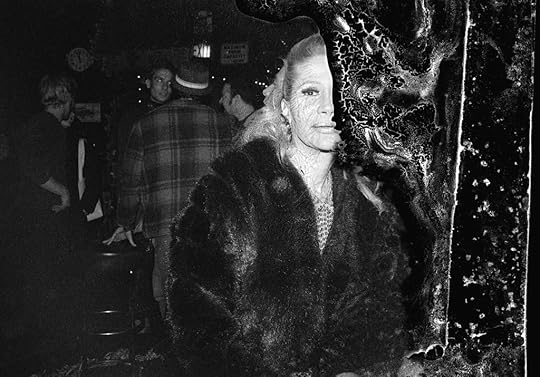

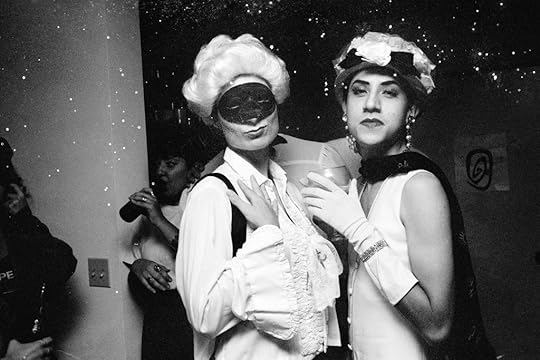

Reynaldo Rivera’s Delirious Chronicle of Los Angeles Nightlife

In Reynaldo Rivera’s life there are three fires, two of which nearly wiped out his life’s work.

Rivera has been taking photographs for the majority of his life: of friends, lovers, strangers, performers, and those who watch them, mostly in and around Los Angeles. Some document the sun-cracked landscapes and ladies who cleaned the SRO hotel rooms he stayed at in Stockton, California, where, as a teen, he worked seasonally in a Campbell’s soup cannery to support his picture taking and glam thrift habit. Later, as his world grew, he would take pictures in Mexico, Europe, Central and South America, but it’s mainly his photographs of LA scenes in the 1980s and 1990s that are driving an unprecedented institutional interest in his work. These images interpolate every facet of the word scene. Scene as in the East LA scene, the drag scene, the queer scene, the punk scene, the art scene, impressions of a greater scene created by the mix of genders, classes, and orientations milling about the house parties, drag bars, music shows, and bathrooms captured by Rivera’s camera. It’s hard not to cry. Mexican kids growing up under the shadow of the Hollywood sign are haunted by a glamour we’re constantly told is not ours.

The scenic quality of Rivera’s lens was pressed into him by an early love of silent movies and glamorous Mexican singers such as Lucha Reyes and Toña la Negra. “When I was working in Stockton, there was this big used bookstore. The Filipino lady that worked there really liked me. She would let me take boxes of books for like three dollars. I would devour old photo magazines and old movie star magazines because I had nothing else to do. That was my education.” At fifteen, Rivera was rifling through a box of stolen stuff outside the St. Leo Hotel, where he stayed with his father during cannery season. He spied a camera and asked about it. “My dad was like, ‘You want it? Give me 150 bucks.’ I was making a lot of money at this point—well, for that time. And I bought this fucking, broken-down-ass camera. I didn’t even know I could have bought a new camera for a hundred bucks. Some poor tourist probably got whacked over the head for it.” If the bookstore was his aesthetic education, the local Fotomat was his technical education. “I didn’t even know the light meter wasn’t working. I figured out how to load the film, and I would look through this thing, and I couldn’t figure out what anything was. None of my images came out. I started asking the girl at the store, ‘What do you think is going on?’ She taught me how to get an image. She explained that if it was darker I needed to go slower. Basic things.”

Reynaldo Rivera, Gaby, Reynaldo, and Angela, La Plaza, 1993

Reynaldo Rivera, Gaby, Reynaldo, and Angela, La Plaza, 1993We’re sitting at an iron bistro table in the front yard of the large, two-story Victorian Rivera shares with his husband, Christopher Arellano (Bianco to friends), in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. There are fruit trees all around—persimmons, limes, pomegranates, lemons, and oranges, some hanging on to their branches, some smooshed and bleeding on the ground, all lightly powdered in smog dust from the mechanic shop next door. In the backyard—weed, herbs, little red-pepper plants, and a wounded dove in a wooden cage. The sun is setting. We’re having doughnuts and coffee. I want to talk about the fires, I say, because I know there are two of them.

“Well, two big ones,” he explains. “There was one before, but let’s just say the first real one was with my ex-boyfriend Steven, after he poked my eye out. Sliced it in half with a piece of glass.” According to Rivera, he ran into Steven at the Dresden Room in Los Feliz. They both got drunk, were removed from the premises, and went back to Rivera’s Echo Park apartment on Laguna Avenue, site of many of the louche gatherings in the background of his party photographs. Steven asked if Rivera was sleeping with his ex-girlfriend. “He always said to me, ‘Whatever you do, tell me the truth!’” Rivera answered yes, and Steven proceeded to trash the apartment, at one point breaking a window with his head. Rivera lunged toward him, and Steven spun around, slashing at his face with a shard of glass. Afterward, Rivera went out to meet some other friends, one of whom happened to be a doctor. She convinced Rivera to go to a hospital, where he underwent emergency surgery, and he finally returned to his apartment two days later. “I walked in, and there’s this little fogata, a pile of burned shit in my living room”—Steven had tried to set fire to Rivera’s life’s work. “He must have been holding the negs and trying to burn them one by one.”

Reynaldo Rivera, Herminia and Reynaldo Rivera, 1981

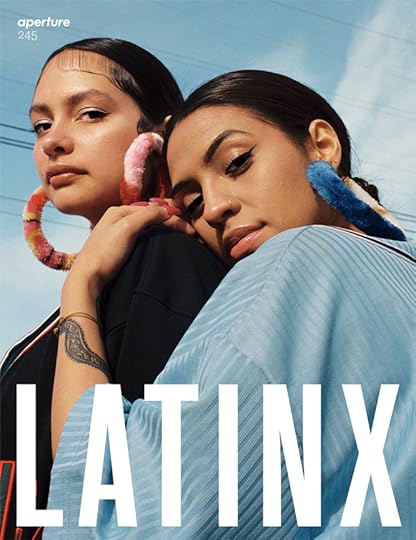

Reynaldo Rivera, Herminia and Reynaldo Rivera, 1981Rivera was born in Mexicali, in 1964, and pinballed between cities on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border throughout his childhood, sometimes escorted back and forth by his father, who worked as a fence for stolen goods, which sometimes included Rivera and his sister. “My dad kidnapped us and took us to Mexico in 1969. We came back to the U.S. in 1975. It was a different world. You didn’t have to be told that everything Mexican was inferior, you could just feel it.” That feeling permeates much of what gets stamped as “Latino culture” in a city whose most influential export is movies that portray Latinos in a limited number of caricatured roles or presents Latino culture disingenuously filtered through a folkloric lens. As an actor, I, too, have been guilty of ethnic pose, of attempts to make the word Mexican broadly legible to the wider culture, to say nothing of the semantic welter that is Latinx—all due respect to this publication—a word we are both ambivalent about. “I’m Mexican,” Rivera says. “In English, Mexican doesn’t have a gender. It’s already gender neutral. I don’t need to get that complicated.”

Reynaldo Rivera, La Plaza, 1997

Reynaldo Rivera, La Plaza, 1997Rivera switches seamlessly between pronouns, often using several to describe the same person. He was versed in fluidity before there was a lexicon to describe it—the girls were the girls, whether they had dicks or not. Everyone is a cunt sometimes. Men are mostly motherfuckers. For someone who has spent most of his life evading capture—by the poverty of his youth, the gang violence of his adolescence, sexual prejudice, AIDS, house fires, the housing market, you name it—the overdue interest in his work has much to do with a refusal to be caught under certain labels. Labels make it easier to categorize, and, more importantly, fund certain forms of art making. Who gets invited to the Latino group show? “We’ve always been here,” Rivera says. “We’ve been part of everything that’s happened—not just in the city—but art in general. But somehow, we get put into our own little category. We say we want to sit at the table. We never said the table was ‘How to be Latino!’”

“I took people that were ordinarily considered freaky and made them look amazing, or cool, or normal. My gig was to have people look the way they wanted to look.”

Rivera’s work isn’t at the Latino table. It’s not even in the same restaurant. It’s down the street taking a smoke break in a piss-stained alley behind Mugy’s, where inside the owner, Yoshi, is stomping the stage in a flamenco dress while singing in Japanese. Rivera was included in the Hammer Museum’s biennial Made in L.A. 2020: a version. Last summer, he began preparing for a solo exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, in New York, and working with an editor to expand the video he created for the Hammer Museum into a longer film “to submit to festivals and shit.” The exposure of Rivera’s work dovetails with interest in photographers such as Sunil Gupta and Alvin Baltrop, who documented ways of life that complicate the aesthetic and historical narratives set by the canon of white street photographers including Diane Arbus and Garry Winogrand. The people in Rivera’s photographs are complicated, glamorous, louche. And while Rivera is quite deliberate about the cinematic qualities of his images, they contain the layered ambiguity of a Manet painting. Tolerance of ambiguity in our cultural products is the necessary precursor to appreciate his work. Loving ambiguity is how to see yourself in these pictures, however unfabulous you may be in life.

Reynaldo Rivera, Tatiana Volty, Silverlake Lounge, 1986

Reynaldo Rivera, Tatiana Volty, Silverlake Lounge, 1986And yet, his story already has the signs of apocrypha, the constellation of anecdotes that settles into shape around an artist as they become part of art history: a history laid out lovingly and neatly (as much as is possible) by the writer Chris Kraus in a monograph published by Semiotext(e) in 2020. The book, named after her essay, is titled Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City. In addition to Kraus’s introduction, there’s a dizzying stream-of-consciousness text by Rivera himself, set apart by pastel peach matte paper inserted in the middle of the book, like how in the Bible the words thought to come directly from Jesus are printed in red. There’s a biography of Tatiana Volty, one of the drag queens in the book, written by the writer Luis Bauz, and a protracted email exchange between Rivera and Vaginal Davis, another artist who exploded genres and labels, mainly through her punk performances and bands and writing. Rivera captured portraits of her before she moved to Berlin in 2006, and their volley of anecdotes is rhetorical sport of the highest, most shit- talking order.

Many of the drag performers and club goers in Los Angeles chronicled by Rivera are no longer around, succumbing either to drugs or AIDS or violence, but some aspects of his city still concatenate into the present. Rita Gonzalez, currently head of contemporary art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is caught looking cute and puckish at a house party in the 1990s. Miss Alex, the drag performer who helped Rivera get backstage access to many of the drag bars around LA, where he captured some of his most intimate scenes, died of a stroke at the same county hospital where I had often sat on the floor, waiting six, eight hours to see a doctor when I didn’t have insurance. When I lived in Echo Park in the early 2000s, it was on the same block on Laveta Terrace that Rivera lived on nearly twenty years earlier. Little Joy was still a bit of a shithole then, allowing seventeen- year-old me to drink, and where I’ve known a friend or two to be stabbed. Rivera shows me a picture of a drag queen in a butterfly mask crawling on the pool table there, serving equal parts Mardi Gras and Moulin Rouge in the dingy bar at the foot of Dodger Stadium.

Related Items

Aperture 245

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]He shows me more ruined prints: “These were from the other fire.” The one that happened in 2012 and nearly took out his current home. The origins of that fire are less theatrical, more apropos to the life Rivera lives now with his husband and their dog, Coco, surrounded by his work and the books and records that inspire it. Roofers accidentally set the entire attic—where Rivera’s negatives are stored—aflame while sealing roofing tar with a torch. The pressure from the blast of the fire department’s hoses caused more damage than the fire itself, resulting in a strange body of compromised negatives that Rivera has been printing nonetheless. They look otherworldly.

“This was unpublished until I posted it on Instagram, then Hedi saw it, and he’s going to use it for a book cover,” Rivera says, referring to Semiotext(e)’s editor Hedi El Kholti. All that’s legible from what appears to be a house-party scene is the plaid-clad boy on the right, casually leaning against the cabinetry in what might be a kitchen. To the left, a T-shirt and an arm extend downward from the central bloom of damage that makes up the majority of the frame. It spills out like rot, like lungs, like a coral reef, like lava or dried mushrooms, the kind that get you high. These “ruined” photographs feel oddly fitting—to Rivera, to the intensity of the times he lived in, to the fragile and ever-shifting nature of what he documented. “These are definitely more creative,” he laughs. “The water and the heat did something very specific to them. It took a mélange of misfortunes to create these.”

Reynaldo Rivera, Elyse Regehr and Javier Orosco, Downtown LA, 1989

Reynaldo Rivera, Elyse Regehr and Javier Orosco, Downtown LA, 1989All photographs courtesy the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles

It’s hard to square the sensitive aspects of Rivera, who refers to his camera as a “saving grace” from a chaotic and violent childhood, with the lucid confidence with which he talks about his work. “I used to always be compared to what’s-her-name”— Nan Goldin—“or Diane Arbus. We’re completely different. When you look at her shit, I don’t know . . .” He spreads his arms out wide, reifying the spiritual and emotional distance Arbus kept from her subjects, “. . . it felt like you were excluded. Like you’re not invited to that party. My work is not like that at all. She took people that were normal and made them look freaky. I took people that were ordinarily considered freaky and made them look amazing, or cool, or normal. My gig was to have people look the way they wanted to look.”

Some histories do not spool out in a straight line, they explode like confetti left on the ground after a party. A book is one way to do it, so is an exhibition, or a film, all enterprises Rivera has in the works. But words and pictures can’t hold everything that has happened. “Originally the book was more of an homage to these girls than anything else. That’s why I thought it was important to have these texts in here, to give meaning to all this stuff, to connect the dots.” Often what is recovered can only point toward what is lost. “I’m such a cunt,” he says, anytime he struggles to recall a detail. Names and stories fall out of his mouth like glitter, and some are beginning to escape him. To wrangle them is like stuffing a kaleidoscope. The pieces are all there, no one is missing, it’s just that the image never sits still. It will always change depending on how you hold it and from where you look. It’s the aftermath of a party that may be over, but you’re still invited. That has always been the subtext of these images, lit up and brought to life by the third and final fire, Rivera himself.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx,” under the title “Reynaldo Rivera: Glitter for the Fire.”

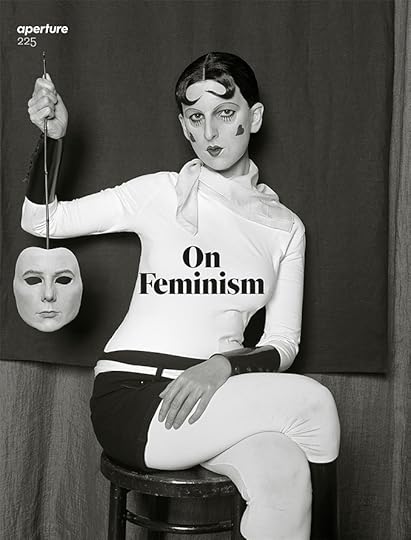

How a Generation of Women Artists Broke New Ground in Abstract Photography

In 1971, Linda Nochlin famously asked in the title of an essential essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Lamenting the meager representation of women in art, she declared: “There are no women equivalents for Michelangelo or Rembrandt, Delacroix or Cézanne, Picasso or Matisse, or even, in very recent times, for de Kooning or Warhol.” In the heated debates of second-wave feminism, these dialogues were crucial and vital, and were essential to creating a more pluralistic narrative of art in the twentieth century. But those conversations rarely included photography—or film, or architecture, or design, for that matter—art forms that were other.

Photography is now our lingua franca—it is the dominant medium of our image-saturated era. Over the last half century photography has joined the ranks of painting and sculpture in the art market and the museum (this May, for instance, the newly expanded San Francisco Museum of Modern Art dedicated an unprecedented 15,500 square feet to photography). Recent years have also seen a spate of women-only exhibitions, including the Centre Pompidou’s 2010 elles@centrepompidou featuring works from their collection, the Musée d’Orsay’s Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? 1839–1945 (2015–16), and Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947–2016 (2016) at Hauser Wirth & Schimmel in Los Angeles.

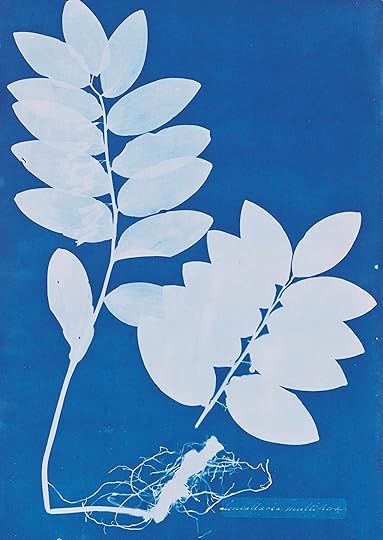

Anna Atkins, Convalaria Multiflora, 1854

Anna Atkins, Convalaria Multiflora, 1854Courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program

Despite exhibitions to further the visibility of women artists, many museums have fallen short of presenting balanced and diverse programs. In 2007, the Museum of Modern Art came under fire for its lack of female representation in its permanent galleries, with critic Jerry Saltz tallying a pitiful 3.5 percent of the art on view from their collection as being by women. But his numbers reflected displays from the collections of painting and sculpture only, not the collections of architecture and design, drawings and prints, and photography, where there were more works by women on view (although still not 50 percent). As a curator working at MoMA at the time, I was acutely aware of the imbalance, but dismayed by Saltz’s limited (and retrograde) view of art. In fact, MoMA was in the midst of organizing Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography (2010–11), an exhibition (of which I was a cocurator) that surveyed the history of photography with some two hundred works by women. This is all to say that even in the early twenty-first century, photography is still other.

This century has witnessed a boom of women artists investigating the possibilities of the photographic medium in new and exciting ways. Artists such as Liz Deschenes, Sara VanDerBeek, Eileen Quinlan, Miranda Lichtenstein, Erin Shirreff, Anne Collier, Mariah Robertson, and Leslie Hewitt all defy the dominant idea of a photograph as an observation of life, a window onto the world. While each artist possesses her own aesthetic language and artistic concerns, as a whole, their practices represent a look inward—to the studio, still life, rephotography, material experimentation, abstraction, and nonrepresentation. Driven by a profound engagement with the medium, these artists have created a dynamic domain for experimentation that has taken contemporary photography by storm.

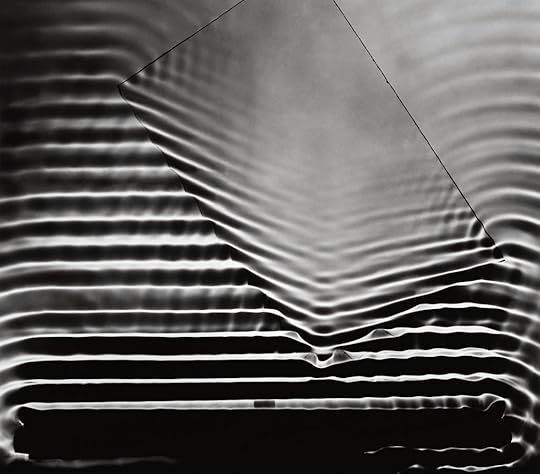

Berenice Abbott, Water waves change direction, 1958–61

Berenice Abbott, Water waves change direction, 1958–61

© Berenice Abbott/Getty Images

It’s certainly risky to create a binary of “traditional” photography, which claims an indexical relationship to the world, versus the avant-garde tradition that considers the properties of photography itself: its circulation, production, and reproduction. As curator Matthew S. Witkovsky notes, “Abstraction … is not photography’s secret common denominator, nor is it the antidote to ‘traditional’ photography.” Recent scholarship has gone a long way to recuperate, and problematize, the status of experimental photography within photographic discourse. Nevertheless, throughout photography’s history, the avant-garde tradition has been considered an “alternate” to the dominant understanding of photography.

Can an argument be made that women have found fertile ground in the underchampioned arena of nonconventional image making? Have the historic marginalizations (of photography, avant-garde experimentation, and women artists) contributed to the vitality we see today? Can working against photographic convention, in a medium that is still sometimes considered other, be viewed as an act of defiance? It’s also challenging to make an argument based on gender (or race, sexuality, geography), since men have undoubtedly made accomplished work in the avant-garde tradition. Do we still need to discuss gender? Do we need exhibitions of women artists to shine the spotlight on underrecognized practices?

Miranda Lichtenstein, Last Exit, 2013

Miranda Lichtenstein, Last Exit, 2013Courtesy the artist

I think so. At the time of this writing, Hillary Clinton has clinched the Democratic nomination for president, but the threat to reproductive rights and women’s scant representation in boardrooms and in government confirm that there is still much work to do. In the arts, there is marked gender inequality. Last year ARTnews cited the paucity of solo exhibitions dedicated to women in major New York museums (and for women of color, it’s even more dismal), and a 2014 study, “The Gender Gap in Art Museum Directorships,” by the Association of Art Museum Directors, reports that female art museum directors earn substantially less than their male counterparts. While there has been some progress since Nochlin’s rallying cry, the artists of this generation are more aware than ever of their roles in an imbalanced art world.

Photography has always been hospitable to women, and women have made some of the most radical accomplishments in nonconventional image making. It’s a relatively new medium, free from the crushing millennia-long history of painting and sculpture. In its infancy, photography was practiced by scientists and alchemists, not artists. A photographer didn’t have to be enrolled in the hallowed halls of the academy; she could cook it up in the kitchen. Victorian England saw the early botany experiments of Anna Atkins, narrative allegories by Lady Clementina Hawarden (featuring her daughters as sitters), and Julia Margaret Cameron’s purposeful “misuse” of the wet collodion process to create her signature portraits. The proliferation of mass media and new camera and printing technologies in the early twentieth century ushered in radical collages by Hannah Höch, Bauhaus experiments by Lucia Moholy and Florence Henri, and the modernist compositions of Tina Modotti. Some women worked in isolation, like Lotte Jacobi, who created her light drawings in seclusion in New Hampshire; others had patronage, such as Berenice Abbott, who was commissioned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to make pictures of scientific phenomena. The postwar movements of pop art, land art, conceptual art, and performance art significantly incorporated photography—Hannah Wilke, Ana Mendieta, and Adrian Piper leaned heavily on photography, in all its uses. Their work is unfathomable without it.

Recent years have witnessed a generation of women exploring new ground in the photographic medium.

The experimentation, manipulation, and disruption of photographic conventions of the early twentieth century reached a crescendo in the century’s last decades. Art of the past forty years has set the stage for the dominance of contemporary experiments by women today. Since the 1970s there has been a plethora of women working in photography (some asserting they are artists “using photography,” not photographers), including Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, Barbara Kasten, Lorna Simpson, Barbara Kruger, and Carrie Mae Weems. These artists share an interest in the status, power, and representation of both images and women within cultural production. They collectively challenge the chief tenets of traditional photography—originality, faithful reproduction, and indexicality. While we now refer to many of the women of this time period as Pictures Generation artists, Sherman recalls, in a 2003 issue of Artforum, the unprecedented prevalence of female practitioners:

In the later ’80s, when it seemed like everywhere you looked people were talking about appropriation—then it seemed like a thing, a real presence. But I wasn’t really aware of any group feeling…. What probably did increase the feeling of community was when more women began to get recognized for their work, most of them in photography…. I felt there was more of a support system then among the women artists. It could also have been that many of us were doing this other kind of work—we were using photography—but people like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer were in there too. There was a female solidarity.

These women embraced the expansiveness of photography’s parameters and have deeply informed, animated, and ultimately liberated the work of the artists who came after.

Liz Deschenes, Gallery 4.1.1, installation at MASS MoCA, 2015. Photograph by David Dashiell