Aperture's Blog, page 42

May 13, 2022

2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Juan Brenner

After ten years working in fashion photography in New York, Juan Brenner, originally from Guatemala, decided to return to his country and turn his lens on his community, specifically the people who inhabit the Western Highlands.

Brenner’s approach, inspired by his decade of fashion experience and borrowing from traditional documentary techniques, is first and foremost driven by a thorough research that aims at depicting the ever-changing character of the country, its people, and ultimately the artist’s own identity.

After tracing Guatemala’s historical path in Tonatiuh, his first monograph published by Editorial RM, where he observed the ways in which history has shaped the current Guatemalan society, Brenner detaches himself from a mere observer’s attitude and embraces a more engaging way of documenting the current fractures of the territory.

It’s in the project Genesis, featured in Aperture magazine’s “Cosmologies” issue, that Brenner starts researching, as he points out, “the ‘process of becoming,’ the shift and changes of the social structure in the highlands.” And then it’s with the project B’oko’, City of Walls that the artist consolidates his vision and begins communicating, or even denouncing, in a clear and enticing manner, how the territory, afflicted for more than five hundred years, now continues to suffer due to the current circumstances and criminal organizations.

In B’oko’, City of Walls, the series submitted to this year’s Portfolio Prize open call, Brenner shows us his streetwise knowledge gained in fashion photography used to picture the impact of a prison experiment in the Chimaltenango community. As the government decided to transfer more than five hundred members of one of the most prevalent gangs in the country to an unfinished prison in the area, the photographer started to analyze the recent repercussions of this decision.

Commissioned by ASU Art Museum in 2019 for “Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration”—a group show at the museum in Tempe, Arizona—the project features striking portraits of domestic life and details of the changing landscape. Brenner worked on this series for over two years, facing several challenges, like the pandemic and various security issues.

Describing the prison as a “really gray place, with lots of rusty metal and cinder block,” the photographer focused his lens on the ecosystem around it, the history of the town, and how its citizens were affected by this intervention. Brenner brings us a unique vision of contemporary Guatemalan society, one that mingles the tradition of documentary work with vibrant color palettes and striking portraits, typical of a fashion-photography approach.

All photographs Juan Brenner, Untitled , 2021, from the series B’OKO’, City of Walls

All photographs Juan Brenner, Untitled , 2021, from the series B’OKO’, City of WallsCourtesy the artist

Juan Brenner is a runner-up for the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Margo Ovcharenko

In the series Overtime, a composite portrait of a local soccer team from the Moscow suburbs, Margo Ovcharenko emphasizes the fierceness and strength of a community of women who feel entirely at home with themselves and with each other. Her subject—a women’s sports team, its individual players, and the industrial suburban landscape of their home—is rendered via cool, quasi-constructivist angles in black and white. In the way that she frequently hones in on abruptly cropped but telling details, the images resonate with the dynamic work of Russian avant-garde artists such as Varvara Stepanova and Maria Bri-Bein. In many ways, Ovcharenko’s depiction of powerful, independent women feels rooted in the radical, visual language of early Soviet photography—as does her use of sport as a metaphor for community, strength, and self-determination. However, she both draws on and diverges from these histories in crucial ways having to do with how the image aligns with or subverts official state narratives.

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2020

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2020Last year, Russian-born Ovcharenko made the choice to move permanently to Ukraine, having found the censorship of her work and pressures of Russia’s increasing cultural isolation too much to bear. “Love, femininity, and desire are carefully controlled concepts in countries like Russia,” she writes, from Kyiv, where she is now based, teaching online and spending time with colleagues and friends. She also writes of her work as grounded in a belief in the power of the image to shape a counternarrative against state propaganda, especially in relation to gender and the role of women in contemporary society. Today, the image of women athletes has become highly politicized—a lightning rod for discussions around the power dynamics of gender, consent, and individual autonomy. Ovcharenko deftly taps into these currents with this series, as with her previous work, to fashion her own radical manifesto.

In her previous series, Country of Women, she created a powerful collection of portraits of queer Eastern European women, and in an earlier series about young women gymnasts, she explored the pressures on body image and on a performative enactment of femininity. Overtime extends these explorations to focus on the importance of a chosen community as a framework for the definition of self. In doing so, she makes a concerted effort to turn the narratives wielded by the state apparatus back on itself. “A documentary approach to portraiture is a powerful tool,” Ovcharenko confirms, “especially when it is applied to athletes whose public image is historically created by the state as a stand-in for its power.”

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2018

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2018 Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021 Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2020

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2020 Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021 Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2019

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2019 Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021

Margo Ovcharenko, Untitled, 2021All photographs from the series Overtime and courtesy the artist

Margo Ovcharenko is a runner-up for the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2022 Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Adrien Selbert

Between 1992 and 1995, the Bosnian War saw the death of over one hundred thousand people and displaced more than 2.2 million. The war was led by Bosnian Serb forces following the dissolution of Yugoslavia, and is widely seen as leading to the rise of the term “ethnic cleansing.” Thirty years later, the citizens of Bosnia still grapple with the aftereffect of the war, even more so in light of Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine—leading to the question: Is there really an end at the end of war?

Photographer and filmmaker Adrien Selbert has been making work in, and about, Bosnia since 2005. Selbert has been interested in examining the long-lasting traumas and aftereffect of conflict on a place and its people. His previous works include the film Nino’s Place (2010), which follows a mother’s struggle to find the body of her son who disappeared during the war in 1995, and the series Srebrenica, From Night to Night (2015), which documents the lives of young adults living in the shadows of Srebrenica’s war atrocities.

In 2016, Selbert began his series The Real Edges, a portrait of contemporary Bosnia as it exists in the aftermath of its war trauma. Over the course of four years, Selbert returned to Bosnia more than thirty times, traveling throughout the country, creating photographs of its people and landscapes. “The idea of this in-between time that we call ‘post-war’ always fascinated me,” Selbert states. “In Bosnia, war is no more, but it is not yet peace. It is the time comprised of the dash between those two words.”

Adrien Selbert, Krstovdan, 2020

Adrien Selbert, Krstovdan, 2020  Adrien Selbert, The Veteran, 2020

Adrien Selbert, The Veteran, 2020 This concept of “in-between” threads throughout each of Selbert’s moody vignettes. Working with both color and black-and-white, the people and locations Selbert documents are cast in a hazy veil of dark greens, blues, and grays. The scenes depicted in The Real Edges offer an ambiguous look at life in Bosnia, which Selbert has described as “a strange and turbulent coma.” A man walks along a railroad track, his figure clouded; two lovers lay in the forest hugged by dark foliage; a pair of young men rest in a set of ruins in the countryside. Though Selbert’s series functions within the documentary genre, the photographer is more interested in the impression of realness than its actuality, stating, “It’s about transcribing a sensation of this country, rather than describing it.”

The Real Edges does not aim to provide answers or solutions, instead it offers an unwavering, intimate study of a country still trying to resolve its past—and perhaps, a warning of the ways war extends beyond its battles. As Selbert states, “This project is like the never-ending dash between the war and its aftermath.”

Adrien Selbert, The Boys II, 2020

Adrien Selbert, The Boys II, 2020 Adrien Selbert, The Hole II, 2020

Adrien Selbert, The Hole II, 2020 Adrien Selbert, Family Men, 2020

Adrien Selbert, Family Men, 2020 Adrien Selbert, The Lovers, 2020

Adrien Selbert, The Lovers, 2020 Adrien Selbert, The Abandoned House, 2020

Adrien Selbert, The Abandoned House, 2020All photographs from the series The Real Edges and courtesy the artist

Adrien Selbert is a runner-up for the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize Runner-Up: Allie Tsubota

We know relatively little about Necessary Evil, one of the seven aircraft deployed in the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Being the only camera plane in the squadron, its primary objective was to observe and record, then produce a scientific, strategic, and visually consistent picture of the attack—which repeated three days later in Nagasaki. As an instrument of administering and archiving war, the camera plane held particular significance in the wanning years of World War II, when aerial bombings were increasingly central to military strategy. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, for instance, employed over a thousand people to assess the efficacy of Allied aerial attacks, first in Europe and then in the Pacific. Published a year after the atomic bombings, the USSBS collated some 330 individual reports, including nearly 10,000 images in the Japan segment alone.

“I’m interested in the idea that volume actually incites a type of withdrawal,” says photographer Allie Tsubota, whose ongoing project, The Magician’s Bombardier, contends with the limits and possibilities of photographic archives to confront the aftermath of nuclear warfare, both in the Pacific Theatre and the US. “Images of war have generalized meanings that many spectators are already primed to project on the photographs,” she says. Interpolating visual material from collections, such as the USSBS, with a series of essays and original photographs of carceral ruins from Japanese American internment in the US, Tsubota explores how historical memory is constituted, framed, and often effaced in service of archival designs. The acts of making images and making war are intimately connected; the title of her project references this connection, suggesting “that acts of war (like acts of photography) are invested in a type of fatal and ghostly magic.”

Allie Tsubota, Unidentified Bunker from USSBS General Photographic File, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives

Allie Tsubota, Unidentified Bunker from USSBS General Photographic File, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National ArchivesExhuming images from a military archive is not without its complications, and Tsubota is aware of the dangers of extracting archival materials in a way that might reproduce the state’s indexical relationship to the image. In her own re-aggregation of original and archived images, she suggests more subtle and expansive connections, paying close attention to where the camera is located across this trans-Pacific history. A recent image of shattered porcelain strewn across the Tule Lake Segregation Center—one of ten internment camps constructed by the US to forcibly detain Japanese Americans in the 1940s—mirrors a US Air Force photograph of bomb ruins in Otake, Hiroshima; another archival image from an unidentified bunker made by the USSBS Photo Intelligence Division in Japan bears a striking resemblance to images of abandoned American theatres made by photographer and architect Hiroshi Sugimoto in the 1970s.

Against the disciplinarian logic of the military survey—and the function of tools such as Necessary Evil—Tsubota is committed to the imaginative and civil political potential of archives. “History keeps haunting us,” she says, “and any attempt to foreclose on the haunting is to foreclose on the history itself, an attempt to contain it as a catastrophe of the past.”

Allie Tsubota, Strike Attack, Himeji, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives

Allie Tsubota, Strike Attack, Himeji, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives Allie Tsubota, Aerial Photographer Poses for Ground Photographer, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives

Allie Tsubota, Aerial Photographer Poses for Ground Photographer, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives Allie Tsubota, Shattered Porcelain, 2021

Allie Tsubota, Shattered Porcelain, 2021 Allie Tsubota, Lineup of Japanese Aircrafts, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives

Allie Tsubota, Lineup of Japanese Aircrafts, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives Allie Tsubota, Persimmons Tree, 2021

Allie Tsubota, Persimmons Tree, 2021 Allie Tsubota, Bomb Ruins at Otake, Hiroshima, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives

Allie Tsubota, Bomb Ruins at Otake, Hiroshima, 2021. Reproduced courtesy the National Archives Allie Tsubota, Big Sur, 2021. All photographs from the series The Magician’s Bombardier

Allie Tsubota, Big Sur, 2021. All photographs from the series The Magician’s BombardierCourtesy the artist

Allie Tsubota is a runner-up for the 2022 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.

May 12, 2022

Why Daido Moriyama’s Radical Vision Is Misunderstood

Daido Moriyama is, to a great extent, an artist both incomprehensible and misunderstood. Incomprehensible because the question he poses, What is a photograph?—besides being too far-reaching and allowing for infinite answers, all probably inconclusive—seems lost in a world ever thirstier for easily applicable definitions. Misunderstood because the labels proposed for him, such as that of a photographer who portrayed Japan in the post–World War II period, do no more than scratch the surface. Although it is seductive to view Moriyama’s dark and grainy pictures as a mirror of the American occupation of his country, his true interest lies in dissecting images down to their essence, far from social-documentary work that attempts to offer a totalizing vision of history.

Daido Moriyama, Shibuya, Tokyo, 1969

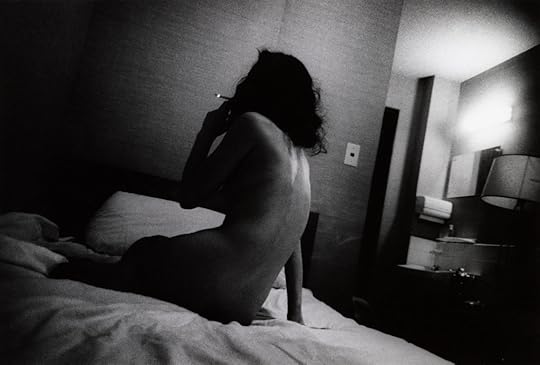

Daido Moriyama, Shibuya, Tokyo, 1969Likewise, some observers have tended to focus on the idea that his work is defined by the strong sexual component found in some of his images. This limited lens, through which many other Japanese artists are also understood, may give Western observers an easy excuse for classifying something they do not understand very well. These sexual elements are present, of course, evidenced by the photographs that have come to be seen as quintessential Moriyama, from the mesmerizing graphics of a woman’s legs in fishnet stockings to the urban scenes that crumble into the grains of a silver print. But they offer a glimpse of the artist’s vision without revealing all.

Daido Moriyama, Kanagawa, 1967, from the series A Hunter

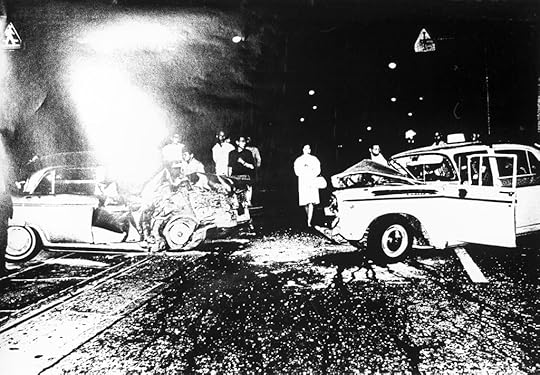

Daido Moriyama, Kanagawa, 1967, from the series A Hunter Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1969, from the series Accident, premeditated or not

Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1969, from the series Accident, premeditated or notA retrospective of Moriyama’s work currently on view at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, highlights the Japanese photographer’s conceptual thinking and reveals the seeds that led to his radical works. A centerpiece is Farewell Photography, a photobook that brings together photographs, cropped negatives, and even works of other artists. The 1972 work epitomizes the process through which Moriyama sought to totally negate authorial work and style—which, ironically, he ended up reaffirming. Images from this now iconic book cover one exhibition wall from top to bottom. Before arriving there, viewers pass works that served as Moriyama’s research for essays (he also wrote about the medium) that sought to understand how photographs are produced.

In a society already overloaded with mass media, Moriyama defied the conventions of photojournalism, publishing his radical, experimental works in a number of Japanese photography magazines of the era. He was greatly moved by images of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination and responded by creating his own reproductions. He rephotographed images found in newspapers, magazines, and on television, publishing them in 1969 in Asahi Camera. In another series, Accident, from that year, he accompanied police to crime scenes, so he could shoot the immediate aftermath of incidents, avoiding the tendency of the press to relay something from secondary sources or outside witnesses. In both cases, he questions the role of the photographer as someone who has the power to present a summary or prepackaged view of a situation.

Daido Moriyama from Provoke magazine, Tokyo, 1969

Daido Moriyama from Provoke magazine, Tokyo, 1969 Daido Moriyama, Misawa, 1971, from the series A Hunter

Daido Moriyama, Misawa, 1971, from the series A HunterMoriyama’s reproduction of a Tokyo transit agency’s poster featuring a photograph of a car accident is a clear allusion to the images Warhol derived from newspaper cuttings. In this case, however, in place of the many-colored versions made by the Pop artist, Moriyama opted for heavy black and white, the result evoking a rough photocopy with the texture of a Warhol silkscreen. If photography imitates the world, a photocopy is the most radical and transgressive form of the image. The show highlights another link between the two artists with a series of images of tin cans. The fact that Moriyama shot these products on a supermarket shelf, and not isolated against the white background of a photography studio, as Warhol did, is only one of the striking differences. Again, using black and white, without the advertising approach or the stark lines of a Warhol, Moriyama traces a subtle critique of American influence in Japan in the postwar era. It is one of his rare works that openly expresses social and political critique.

Although it is seductive to view Moriyama’s dark and grainy pictures as a mirror of the American occupation of his country, his true interest lies in dissecting images down to their essence.

The exhibition’s curator, Thyago Nogueira, featured Farewell Photography on the venue’s first two floors by hanging framed pictures over wallpapered reproductions of spreads from the entire photobook. The display follows the wishes of Moriyama, who believed his photographs were made for books and magazines, not for museums. The exhibition also presents his many photobooks to be browsed through, and includes other important moments of the artist’s journey, such as the work he published in the short-lived Provoke magazine, now a landmark of Japanese photography.

Daido Moriyama, Yokosuka, 1970

Daido Moriyama, Yokosuka, 1970With his determination to strip photography of any pretense of explaining the world, Moriyama provokes political debate around engagement versus alienation, or what is special or banal. Farewell Photography is a radical photobook that might have been made by anyone, since at the core of the work is the elimination of the figure of the author—but, of course, that wouldn’t have been possible without Moriyama as author. The more Moriyama attempted to erase himself from the image’s interpretation, the more he strengthened the presence of an artistic thought process. Today, the aesthetic of black-and-white images, with a high level of contrast and frequently out of focus, have become synonymous with Moriyama. This black-and-white work is so forceful that a rare series of color photos included in the show appears to have been created, with a few exceptions, by some other, more conventional photographer. However, one of Moriyama’s most well-known images, of a prostitute in an alley seen from a crooked perspective, is famous as a monochromatic portrait, although it was originally produced in color.

Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1971

Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1971 Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1970, from the series Farewell Photography

Daido Moriyama, Tokyo, 1970, from the series Farewell PhotographyAll photographs courtesy the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

The second part of the retrospective features works created from the 1980s onwards, after Moriyama overcame depression and resumed wandering the streets after a long hiatus, documenting everything that caught his attention. His approaches are varied, as are the objects he captures, as though he was reacting instinctively and using the camera as a notepad. This process is evident at the end of the exhibition, in a room containing three large projections that show a long, immersive sequence of more than one thousand photos made by the artist for Record magazine from 1972 to today. As in his photobooks, the accumulation of images here has power, making clear that spending hours surrounded by images left behind by Moriyama may be the best way to experience his often misunderstood vision.

Translated from the Portuguese by Clara Allain.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is on view at the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, through August 14, 2022.

May 5, 2022

The Sicilian Photographer Who Fought the Mafia

“You seem like such a nice girl,” Letizia kept faxing back to me—always evasive and never, ever answering my usually welcome question: “Are you interested in working with me on a book for Aperture?”

Letizia Battaglia died on April 13, 2022, in Cefalù, near Palermo, Italy. She was eighty-seven. I first saw Letizia’s work exposing the Mafia’s oppressive, unrelentingly brutal grip on her native Sicily while working at Aperture Foundation, editing various issues of their quarterly publication, as well as books. At this time, the early to mid-1990s, Letizia was little known in the United States outside photojournalistic circles. In 1985, she had won the coveted W. Eugene Smith Fund Grant for humanistic photography, sharing it with Donna Ferrato—the first time two winners had been named. Then, in May 1986, the New York Times Magazine, in an article titled “Sicily and the Mafia,” published a selection of Letizia’s and Franco Zecchin’s images. Some of the most iconic became forever embedded in the mind’s eye of many—although both photographers were still relatively unknown.

Letizia Battaglia, Trial of Mafiosi, 1980

Letizia Battaglia, Trial of Mafiosi, 1980When I decided to devote an issue of Aperture to Italian photography, Immagini Italiane (1993), we included Letizia’s work, accompanied by an interview with the wonderful Italian editor and writer Giovanna Calvenzi, who in 2010 would author Letizia Battaglia: Sulle ferite dei suoi sogni (On the wounds of her dreams). I thought Letizia was pleased, and I was fairly certain she had gone to see and liked the traveling exhibition we did in conjunction with the issue in Venice, where it opened at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, or in Naples, where it was presented at Museo Diego Aragona Pignatelli Cortes. So why wasn’t she responding “yes” to my book entreaty, or at least acknowledging the question? This was her M.O., I would come to learn, but at the time I was flummoxed—it had become personal.

So, in 1994, I took the long way to Naples, where I had a project, and stopped in Palermo. Letizia saw me for maybe an hour. She showed me not one photograph. We sat in her home, in Palermo’s wonderful old center (I would soon learn that she and others helped to save it from Mafia-plotted destruction), and we shared an espresso together. Still, when I left, I was frustrated and bewildered, not to mention empty-handed. She had promised to send me a package. Yeah, sure: the check was in the mail.

Letizia Battaglia, Young girl with soccer ball in La Cala neighborhood where drugs are sold, Palermo, Sicily, 1980

Letizia Battaglia, Young girl with soccer ball in La Cala neighborhood where drugs are sold, Palermo, Sicily, 1980But, wow—I was nonetheless blown away by her. Her fierce intensity felt almost feral. The proverbial force of nature and then some. And not only as a photographer but also as a publisher, Green Party member with the Palermo city council, ecological activist, and defender of women’s and of human rights. We spoke about women, we spoke about justice, she asked me personal questions—not my forte, as I’m so private, but she was like truth serum. I soon understood I was being tested. That she was naturally suspicious. But our conversation was somehow instantly intimate. From that moment on, there was this extraordinary, powerful woman in my life who declared herself my sister, who could get annoyed with me, and who demanded a kind of complicity.

That package bursting with prints, most with handwritten Italian captions scribbled on the backs, arrived two weeks later. Her work took my breath away, as it did for Aperture’s director and publisher at the time, Michael Hoffman. It wasn’t just the photographs’ visual power, or Letizia’s clear commitment to bearing witness to the horrific violence plaguing her city, especially as it affected women and children. It was her all-in engagement, her toughness, her advocacy, her profound sense of justice. Her passion.

Letizia Battaglia, Young mafiosi, 1977

Letizia Battaglia, Young mafiosi, 1977And so our story began, as she would only agree to collaborate on the book if I would write the accompanying essay about her that I had asserted was crucial. In this way, I would be invested not just as the book’s editor, but also as the person to whom she would tell her story in words. Of course, I accepted her challenge. Letizia Battaglia: Passion, Justice, Freedom—Photographs of Sicily was published by Aperture in 1999. I have chosen to quote many of her words from the book here, adding context when useful, as Letizia spoke so ardently and persuasively about what mattered to her.

Letizia was born in Palermo on March 5, 1935. Her father was in the navy and they moved around Italy. She spent much of her childhood in Trieste, in the north, and was ten when her family moved back to Palermo. At first she sought freedom by marrying an older man, and with him she had three daughters: Cinzia, Shobha (also a photographer), and Patrizia. But she became desperately unhappy and claustrophobic. She credited the Freudian psychoanalyst Francesco Corrao with helping her to understand that she was strong, telling her, “You can make your own peace, your own equilibrium. You can rebuild your life and save yourself.”

It wasn’t just the photographs’ visual power. It was Battaglia’s all-in engagement, her toughness, her advocacy, her profound sense of justice. Her passion.

This gave her the strength to leave her husband in 1971, at age thirty-six. She went to Milan and began writing for a newspaper there, while also continuing to write for the left-wing Sicilian daily newspaper L’Ora, as she had done for the previous two years. She had always wanted to be a writer, to tell stories. She soon realized that she’d have more success selling her articles if they were accompanied by images, and so she began making photographs. Very quickly, she just wanted to take pictures. After she had done a small photographic job for L’Ora, the paper asked her to return to Palermo as its director of photography, and she became a full-time photographer. “I think that my life truly began with my camera,” she told me. “I mean my freedom as a person, my voice.” Diane Arbus, Josef Koudelka, Mary Ellen Mark, and Eugene Richards were the photographers whose work she especially admired.

Letizia Battaglia, Brother and Sister of an Aristocratic Family, 1983

Letizia Battaglia, Brother and Sister of an Aristocratic Family, 1983In 1975, she traveled to Venice to see Jerzy Grotowski’s Apocalypsis cum Figuris and met members of his Theatre of Participation. Eventually she ended up working with them, and that’s where she met the twenty-two-year-old Franco Zecchin, who would become her partner in work and life over the next two decades. During our conversations, which took place between 1996 and 1998, she described how their “beautiful story” began:

We spent our first . . . what would you call it . . . encounter on a floor full of dry leaves, because Grotowski was pushing to create things with nature. . . . Bit by bit, we got down in the leaves and began to know each other. After that, I returned to Palermo, and Franco returned to Milan—but then he came to Palermo and stayed for nineteen years. We experienced some very dramatic things together, and accomplished many positive things as well, including our work against the Mafia. Franco was not Sicilian, so it was different for him. He completely understood, but it was more of an intellectual fight for him, whereas for me it was my home, my people, who were so threatened. Besides, I am incapable of elaborating on an intellectual idea with the camera. I live life with the camera. The camera is like a piece of my heart, an extension of my intuition, my sensitivity. . . .

I was bare-handed, except for my camera, against them with all of their weapons. I took pictures of everything. Suddenly I had an archive of blood. An archive of pain, of desperation, of terror, of young people on drugs, of young widows, of trials and arrests. There in my house, Franco Zecchin and I were surrounded by the dead, the murdered. It was like being in the middle of a revolution. I was so afraid.

One of Letizia’s and Zecchin’s most provocative and risky actions was displaying large-scale prints of their images of Mafia victims in Corleone’s main piazza. Letizia was desperate for her fellow Sicilians to truly understand the Mafia’s barbarity, and to speak up and out against them, despite her understandable fear. The acute brilliance of her reportage was always intertwined heart and soul with her activism.

Letizia Battaglia, Michele Reina, Secretary of the Sicilian Christian Democratic Party, killed by the Mafia, 1979

Letizia Battaglia, Michele Reina, Secretary of the Sicilian Christian Democratic Party, killed by the Mafia, 1979Letizia’s own performative nature and instinct to take it to the streets eventually led her to enter politics. She met Mayor Leoluca Orlando when she was first elected to Palermo’s Municipal Council in 1985; although they were not predisposed toward working together, they soon completely accepted, trusted, and respected each other—especially once Letizia understood that he was “ferociously anti-Mafia, and also much more progressive than I was at the time on issues of the environment, for example.” They ultimately became close collaborators and friends, and Orlando poetically expressed his appreciation for Letizia’s heart, mind, and willfulness in a letter to her, written for our book.

About her work in politics, Letizia told me:

When I stopped taking pictures and entered politics—first as municipal councilwoman, then as regional deputy, and lastly as municipal councilwoman again—I was afraid I had betrayed photography, and maybe even the struggle, since I had felt that taking pictures was my only weapon. But then I realized that the same motivation lies behind my photography and my politics, the same will to combat, to stay on the front line. Working in a different way, I could accomplish different things. So, despite many difficult times, we continued into the eighties with our politics, photography, publishing, meetings, and anti-Mafia demonstrations. And then came those wonderful men who gave us such hope—Judge Giovanni Falcone, Judge Paolo Borsellino—prosecutors who were good and brave; and who then, in 1992, were murdered.

Another contributor to the book Passion, Justice, Freedom was Magistrate Roberto Scarpinato, who at the time was prosecuting Italy’s ex–prime minister Giulio Andreotti for collusion with the Mafia—and using one of Letizia’s photographs as evidence. Also writing for our book and discussing this image, along with her work in general, was journalist Alexander Stille, author of Excellent Cadavers (1995), which insightfully chronicles the violence and workings of the Sicilian Mafia in light of the assassinations of Falcone and Borsellino. In 2005, when Marco Turco turned Excellent Cadavers into a film, Letizia’s commanding presence throughout was electrifying.

Letizia’s approach was one of advocacy and empowerment, especially of women, on the most human and humane level. In Palermo she started a women’s theater project, and when she began her publishing house the initial idea was to give women (although not exclusively women) a place to be heard, a platform. The principal motivation for these books was desperation after the murders of Falcone and Borsellino, but Edizioni della battaglia soon embraced talented voices and addressed the struggle for human rights worldwide. In time, Mayor Orlando assigned her a counseling position to work with prisoners in Palermo: “It’s necessary,” she told me, “to work for justice but also to help those who have made mistakes to transform their lives.” She and Zecchin also set up a photography school and volunteered in the psychiatric hospital in Palermo, working with the patients. Around 2013, Letizia told me about the photography center she had conceived for Palermo: Il Centro Internazionale di Fotografia—Cantieri culturali alla Zisa. She asked if I’d curate one of the first exhibitions; she wanted a show of American women photographers. And, would I please include Mary Ellen Mark? Mary Ellen, who died in 2015, consented without hesitation. “For Letizia.”

Letizia Battaglia, Joyless dance, New Year’s Day, 1984

Letizia Battaglia, Joyless dance, New Year’s Day, 1984All photographs © Letizia Battaglia

In the summer of 2015, I received an email from Letizia further describing the center. Mayor Orlando had provided funding to restore the building, “but there will be no money for anything else. . . . I need the help of many,” she wrote. “I need photographers who will give me photographs to exhibit at no cost. Everyone must know that I have much respect for the photographs and photographers. This is a heroic operation, because it was born in Palermo, still the powerful city of the Mafia. Whoever helps me has to do it by faith.”

I sent a rough translation to Nina Berman, Lynsey Addario, Donna Ferrato, Graciela Iturbide, Mary Ellen Mark’s studio, Susan Meiselas, Sylvia Plachy, and Stephanie Sinclair. These remarkable photographers joined forces with me (as did designer Yolanda Cuomo and translator Meg Shore). The 2018 show, Donne Fotografano Donne (Women Photograph Women), was born. Letizia was profoundly moved by their generosity of spirit and the support of her community. She understood that this exhibition came about because of the woman and photographer we all understood her to be. This spring, Mayor Orlando announced that the Palermo photography center would be renamed in her honor.

April 29, 2022

A Photographer Envisions the Lives and Dreams of Turkish Girls

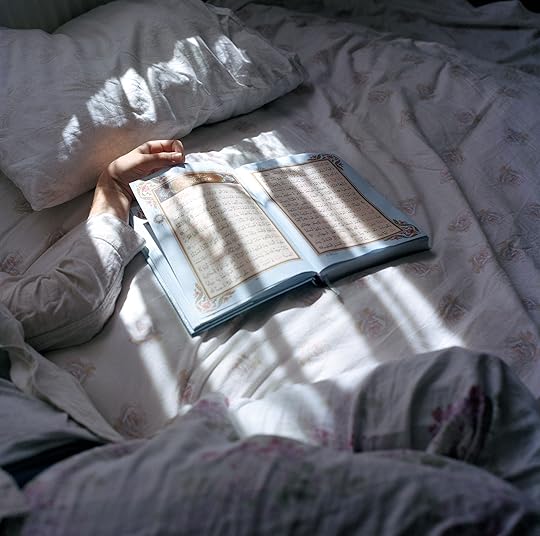

Sabiha Çimen was twelve when, in 1998, she enrolled at a hafiz okulu (guardian school) in Istanbul. Since 1970 more than 160,000 girls in Turkey, aged eight to nineteen, have studied in these single-sex schools, memorizing the Koran’s 6,236 verses, which takes around three years, and becoming protectors of Islam’s sacred book. Çimen’s upbringing made such a deep impression on her that, a quarter of a century later, these schools became the subject of Hafiz (2021), her first photobook. Intensely intimate, Çimen’s portraits, made between 2017 and 2021, surveil the double lives religious students lead in contemporary Turkey, where it is legal for parents to send children even as young as two years old to study at Koran courses.

Sabiha Çimen, Hatice, nine, tries to recite Quran passages from memory to her classmate, Istanbul, 2021

Sabiha Çimen, Sisters Gülnur (left) and Havvanur (right) graduate from Quran school, Kars, 2018

Çimen belongs to an ethnically Kurdish Persian family. Her older sisters had gone through the same education, which was a rigid and traumatizing process; Çimen attended the Koran course with her twin sister. “I used to imagine these schools like prisons as a kid, but once inside, I saw I was mistaken,” Çimen, who was named a Magnum nominee in 2020 and has published her photography in The New York Times Magazine, Le Monde, and Vogue, told me last fall in an Istanbul coffee shop. “It was a vibrant environment. You couldn’t find such wise and bold women together anywhere else in the world.”

Sabiha Çimen, The youngest students at the Quran school, Istanbul, 2017

Sabiha Çimen, The youngest students at the Quran school, Istanbul, 2017Studying there alongside six hundred other girls for three years formed a large part of Çimen’s DNA. But on graduation in 2001, Turkey’s headscarf ban postponed her plans to attend college. In those listless years, she became infatuated with photography. During an umrah pilgrimage in 2002 to Mecca, Islam’s holiest city, Çimen saw a Canon camera in a Saudi Arabian shop window. Over the next two years, she used it to keep a diary, making portraits of her mother and one of her sisters, and finessing her craft as a self-taught photographer. At college Çimen studied international trade and business, a field she had no interest in. She pursued a master’s in cultural studies, savoring Homi K. Bhabha and Giorgio Agamben’s texts, and wondering whether she should be a scholar. For her graduate thesis, she worked in Fatih, the Istanbul neighborhood where she resided, photographing Syrians who had once been dermatologists, engineers, and architects, but who now worked at kebab and barber shops.

In 2015, Çimen bought a secondhand, medium-format Hasselblad. Once assured of her technical competency, she searched to find a subject for an extensive project. “These memories from my religious- education days haunted me,” she recalls. One day, Çimen summoned up her courage, visited the school she had attended, and gave a presentation to the current group of girls proclaiming: “Like you, I was a student here, in 1998. Now, I have this project about which I don’t know precisely what to do. We’ll discover it together! Would you like to spend time with me?”

Sabiha Çimen, Kevser, who is shy, uses a palm leaf to hide her face at a Quran school, Istanbul, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, Kevser, who is shy, uses a palm leaf to hide her face at a Quran school, Istanbul, 2018Girls reluctantly agreed. On the first day, Çimen placed her camera on a desk to acquaint the students with its features. She spent a fortnight with them, living in their quarters, eating lunch, hearing their stories, and mostly avoiding the teachers. She went on to photograph Koran schools across Turkey: in Kars, Hatay, Malatya, and Rize. “Those girls are bashful, and I struggled to earn their trust,” she says. “Those I photographed in Istanbul were more outward looking but harder to work with.”

Hanging out with the girls, Çimen witnessed their strict discipline. Reading novels was banned. Smartphones were out of the question. Girls went to sleep at nine at night and woke up at five with the morning call to prayer. “They were like recording devices, memorizing the Koran around the clock,” she says. Getting permits to portray their world proved a challenge. One mufti (religious administrator) bluntly murmured: “You can’t photograph Muslim women. It’s forbidden in Islam.” Undeterred, Çimen realized her dream.

Sabiha Çimen, Asya plays with pet birds in the teachers’ room, Rize, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, Havva lies in the sickroom at a Quran school while listening to music with earbuds under her headscarf, Istanbul, 2017

Hafiz’s world is Dickensian, with gangs of girls abounding in its corridors. There are fragile girls, tough girls, playful and traumatized girls. They hide behind a locker, a curtain, or a palm leaf. They Rollerblade, tend roses, play hopscotch, hold dead fish, look at caged birds, pore over a loaf of bread, eat ice cream, perform at a religious play. They’re primarily daydreaming—something Çimen did often in her student years. She explains that Koran-school graduates retain “organic ties” to each other throughout their lives. When some of these girls showed an interest in photography, Çimen mentored them, giving tips on which cameras to buy and how to look for interesting subjects. “Incredible talents will emerge among them. It was fate that placed me here, and the same can happen to them,” she says. During the photoshoots, Çimen resisted lifting her camera and remained on the same level as her subjects. She gave girls the time and space to slowly open themselves up to her. While Çimen was photographing a wall at a Koran school one day, a girl asked: “Why don’t you photograph me instead?” This question became a turning point in what Çimen calls their “invisible agreement.” Afterward, on an outing, students spotted an exploded watermelon on the pavement—“I said: ‘Stop, girls! I want to photograph you around this watermelon.’ Having internalized my style, they soon began to gravitate toward things I like to put in my compositions.”

Sabiha Çimen, A plane flies low over students at an amusement park, Istanbul, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, A plane flies low over students at an amusement park, Istanbul, 2018All photographs courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

I wonder who the audience will be for Hafiz, a poetic book that took Çimen three years to compile from three hundred images. Turkish photographers? Pious young girls? What will her book tell foreigners about their lives of religious devotion? “I wish that these kids and their families would be my audience,” muses Çimen, “but sadly, it won’t be them.” Out of Hafiz’s print run of two thousand, only one hundred books are in Turkish. “As for those Islamist men who have always been against me, never looked at my art and instead tried to ban it—they won’t be my audience either.” Yet Çimen seems fated to be a guardian for the young students whose experiences she shared and captured, serving as their hafiza—the Turkish word for memory.

This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the column “Viewfinder.”

April 21, 2022

Myriam Boulos’s Visceral Images of Lebanon at a Time of Revolution

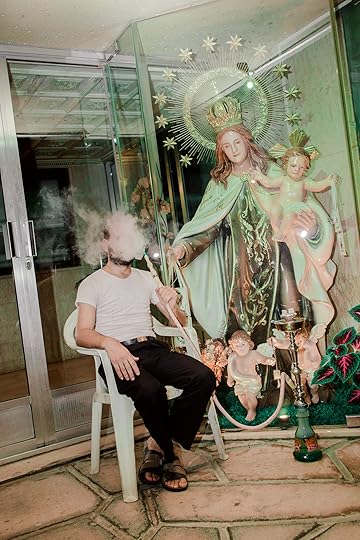

“Reach out and touch faith,” Depeche Mode implored in “Personal Jesus.” In Myriam Boulos’s photographs, I could’ve sworn I heard her subjects whisper, “Reach out and touch me.”

Faith is touch; touch is sacred. And the body is its own god.

Against a purple sky, two naked men tenderly embrace; one is, indeed, whispering, not to us the welcome voyeurs—but into the ear of his beloved. Juxtapose the delicacy of that moment—men stripped of the confines that patriarchy makes of masculinity—with the altogether more robust, and much more tightly cropped, image of two women kissing. Swallowing each other whole, more like. It is difficult to ascertain where one begins and the other ends. There is power in their desire.

And that is what the revolution renders: powerful women and tender men.

In a global pandemic that has starved us of touch, who would not genuflect before the heady carnality captured by Boulos’s gaze? In almost every photograph in her series What’s Ours (2019–ongoing), hands knead into flesh, skin lies on top of skin, body hair on disjointed limbs serves like rivers on a map, luring us closer toward sustenance, enticing us with intimacy, destination freedom.

Boulos was born in 1992, in Lebanon, two years after the official end of the seventeen-year civil war. Her fluency for turning her country inside out with her gaze has landed her work in Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Time. She is based in Beirut, but she was in Paris on a two-month fellowship when we spoke last year.

Reflecting on What’s Ours, Boulous has written that when the revolution began in Lebanon in October 2019, with protests against corruption and austerity measures, “It all felt as if we were coming out of an abusive relationship to finally say: No, this is not normal.”

Those who truly want to be free know that is how the revolution succeeds. The revolution against the political tyrant alone is the minor one. Taking a leader down does little to topple the personal tyrants who live on street corners, in our bedrooms, in our minds. Their overthrow is the stuff of major revolution.

Who does the revolution belong to? What do we own if not our bodies? What is ours?

“My friends and I used to take pictures naked in the streets of Beirut,” Boulos writes. “It was our own way of reclaiming our streets and our bodies. Everything that is supposed to be ours.”

The inhabitants of Boulos’s Beirut clearly trust her. Obsessed as she tells me she is with “the body and the present moment,” it is as if she has stepped inside the embrace that she captures, presenting it to us with awe and reverence; as if she sliced through the thin veil that separates the “us” from the “them” and entered the embrace on another, ethereal level that does not disturb or distract the divine creatures she captures.

Her eyes, heart, and camera are the holy trinity.

“A revolution was happening in my country, a revolution was happening in me. It made me question everything,” Boulos writes. Revolutions—I know as an Egyptian marking ten years since my country’s revolution—inspire you to say no to more, to everyone. One “no” leads to another like a stairway to liberation. When that staircase is yanked, you take a vulnerable punch to the gut. In Lebanon, a financial crisis, the pandemic, and the Beirut port explosion of August 2020 did not just yank at the staircase to liberation but seemed to fray it to bits.

“Since the explosion, I feel like a glass of water that overflows constantly,” Boulos writes.

In a Zoom chat—she in Paris, I in Montreal—we talk about the leitmotif of compounded trauma and unresolved grief that connects our parts of the Middle East. And we talk about the body’s need to fuck to mark its survival. She tells me of post-Beirut port explosion sex with an ex. I am reminded of how, soon after Egyptian riot police broke both my arms and sexually assaulted me in 2011, I began an on-again, off-again entanglement with a survivor of a postrevolution massacre in Egypt.

“An acute awareness of our mortality makes the physical especially important,” I tell her. “This is your body saying to you, You are alive, and you have to do what you’re meant to do, and that is fuck. Do it now!”

I am delighted that her new project is on women’s sexual fantasies.

Faith is touch; touch is sacred. And the body is its own god. We are each other’s personal saviors because, as the poet and activist June Jordan wrote in her 1978 Poem for South African Women, “We are the ones we have been waiting for.”

All photographs by Myriam Boulos, Untitled, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017–August 2020

All photographs by Myriam Boulos, Untitled, Beirut, Lebanon, November 2017–August 2020Courtesy the artist

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the title “What’s Ours.”

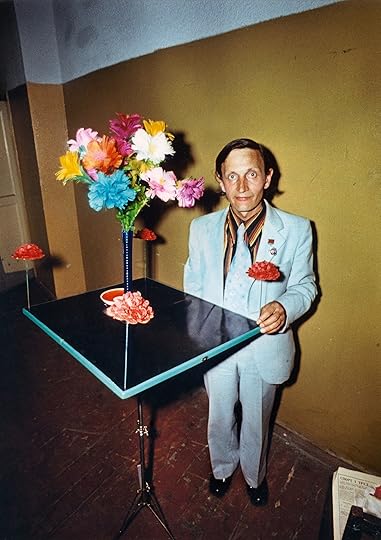

Boris Mikhailov on Liberation, Vulgarity, and Chance in Photography

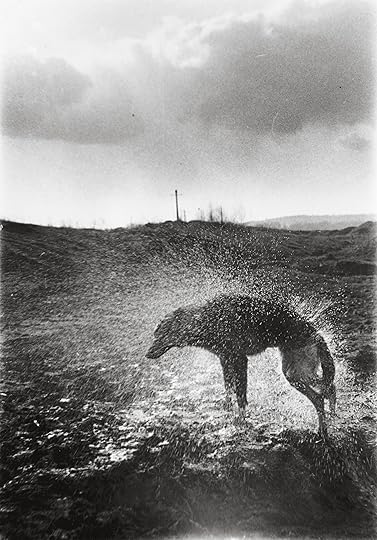

Prankster, performer, and self-taught photographer Boris Mikhailov might be said to embody the archetype of the holy fool—that idea originating in the Russian Orthodox Church and carrying into literature in which someone pretends to be mad in order to offer spiritual guidance. Since he began making photographs in 1965, Mikhailov has continually broken the rules, both formal and ideological, to convey larger truths. He was born in 1938 in Kharkov, Ukraine; years later, in a now-famous story, Mikhailov was fired from his job as an engineer when he was caught using the factory’s darkroom to develop nude photographs of his wife. The body—whether his own or his subjects’—remains a constant presence in his work, including images from the 1970s and ’80s that played with and subverted Soviet-era visual codes. This play was often sexualized, leading one observer to describe Mikhailov as a “surrealist eroticist.”

Throughout his career, his irreverent work has flirted with both conceptual and documentary traditions, employing a range of photographic techniques. Much of this prolific and diverse output was not shown in public until the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Shortly thereafter, in 1997, Mikhailov began his controversial series Case History (1997–98), which documented post-Soviet Kharkov’s growing homeless population.

Mikhailov now makes his home in Berlin, where he lives with his wife, Vita, his longtime creative collaborator. In May 2015, in Venice, during the opening of the Venice Biennale, curator Viktor Misiano, an old acquaintance of Mikhailov’s, met the photographer in an apartment near the Campo Santo Stefano. Vita Mikhailov was also present and joins in this conversation that touches on Mikhailov’s work then and now, the Soviet dissident poet Eduard Limonov, and Ukraine’s recent political upheaval.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Case History, 1997–98

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Case History, 1997–98Viktor Misiano: The last time we saw one another was last year in Kharkov, at the Yermilov Centre for Contemporary Art at the opening of an exhibition in honor of your seventy-fifth birthday. I happened to be moderating a lengthy, heated panel discussion on your work. It was impossible to ignore how proud the city is of you, how much you mean to it. And for you Kharkov means so much! It’s your city, after all. And so much of your artwork is tied to this place.

Boris Mikhailov: At one point I spent a lot of time developing this theme and came to the conclusion that Kharkov and I are one and the same. Not only because I was born there, but mostly because, having lived there for many years—though I now live in Berlin—I’ve deeply felt all of its good and bad sides. Maybe I’m wrong—after all, I don’t have a formal artistic education, I came to art from the outside, as an amateur—but it seems to me that there isn’t a serious artistic tradition in this city. There’s just a small museum and an arts institute that hasn’t produced anybody of significance. In spite of all that, Kharkov is a city with lots of energy, a city with enormous factories and scientific centers (as a matter of fact, this was the first place in the USSR to split the atom). This is the first capital of Ukraine. In other words, this is a highly tense place with a disproportionately limited cultural tradition. As a result, there was nothing here to influence me. Living here, I found myself in a sort of zero state— a state of total openness. If there was anything of importance here for me it was the local literature and song. This is where the singer [Klavdiya] Shulzhenko was from; she was an idol for the entire country. Though we have to admit she was rather vulgar, very much so in fact. Just like the poet [Eduard] Limonov—a bright writer, but even he is vulgar. So I think vulgarity is one of the particular characteristics of this place, since it doesn’t have a cultural tradition, but it does have energy and ambition. In some sense this vulgarity can even be considered revolutionary.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Berdjansk Beach, Sunday, from 12.00 till 13.00, 1981

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Berdjansk Beach, Sunday, from 12.00 till 13.00, 1981Misiano: It’s good that you mention Limonov; I always thought you two had a lot in common. In fact, he has a story, “East Side, West Side,” in which over the course of thirty pages he describes walking through New York’s Harlem at night. Nothing of note happens—he just re-creates his visual impressions—but it’s impossible to tear oneself away from these unbelievably vivid descriptions. The way he builds these descriptions is like a film reel, they develop before us like a literary photographic sequence.

Mikhailov: As soon as I got to New York, in the late ’80s, I went to Harlem. Everybody told me not to go, and if I went, not to take pictures. Of course I went, and I went with a camera. I photographed from the hip, without looking through the lens. That was a special camera, a Horizon—prolonged exposure, panoramic views. I was incredibly curious; I’d never seen anything like it.

It seemed important to me at that time to break out of the traditional role of the photographer who is removed from life. I wanted to raise the question: Why do you have the right to photograph other people?

Many years ago in Kharkov, I was at a party where there was a student from Africa. Then, at my job as a factory engineer, I was warned that if I was ever found in the company of foreigners again, I would be fired. Because of that, I was extremely interested to find myself surrounded by African Americans, to understand how they live—what’s the atmosphere of this neighborhood? All of a sudden, as I was crossing the street, right in the middle of it, some tall person suddenly hit me in the mouth unexpectedly with his huge fist. My ears were ringing. I was stunned and started yelling; he grumbled something at me and walked off. Then, I hadn’t walked more than fifty meters before some other guy, squatting by a wall, shook his finger at me and also grumbled something. I had a feeling like he already knew what had just happened to me. So that punch in the face was what I remembered more than anything, for a long time, about my first trip to America. And the most amazing thing was that nothing even hurt from that punch. It was a kind of warning: “Careful, buddy, we have our own way of life here.”

Misiano: It’s a very telling story. It seems that the life you were interested in exploring entered into dialogue with you, answered your call. I was also in Harlem during that same time, in the late ’80s, but no one laid a finger on me. That’s precisely what, in my understanding, you men of Kharkov—you and Limonov—have in common, this unbelievable ability to unmask the vital pulse hidden beneath reality’s shell.

Mikhailov: Worse—we bring real life upon ourselves! In one of his poems, Limonov has this line: “You smelled like Iranian piss.” At the time, this frank and urinary image, completely unheard of then, won me over. Then, when I met the woman to whom these lines were dedicated, I tried to photograph her, but nothing turned out. Yes, there’s definitely a connection between me and Limonov: We’re both concerned with letting go of aesthetics and outward beauty. What’s most important for us aren’t outward appearances but the innermost depths of life and humanity.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series City, 1973

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series City, 1973Misiano: There’s also another thing you have in common. Limonov has a tendency to turn life into a performance, presenting himself as an artistic persona. You can’t deny that elements of this are also very much part of your being. For both of you life is a performance, it’s a stage on which to perform.

Mikhailov: I can’t say that the performative was initially embedded in my work. Early on in my career I made a few self-portraits, and in some of them I even depicted myself as historical or literary characters, but I stopped making that kind of work. But then came 1991—the time when the Soviet Union fell. That’s when I made a series called I am not I, in which I once again began photographing myself. But why did I create that work? Probably because with the country changing, I felt it was necessary to uncover a new protagonist. But this was a protagonist who was sort of trying on the icons of the superheroes of Western mass culture—like Rambo, etc., and he was an antihero at the same time. It seemed important to me at that time to break out of the traditional role of the photographer who is removed from life, which he photographs as if from the outside. I wanted to raise the question: Why do you have the right to photograph other people? And who are you? That’s when I started featuring myself, suggesting in these images an answer to my own question: the part I play, that is who I really am.

Misiano: Do you mean to say that the fall of the foundations of Soviet life also broke the foundations of photography, broke the traditional subject-object interrelation between the photograph and reality? Very interesting idea!

Mikhailov: Yes, what was happening in the country at that time had a huge impact on me. It forced me to position myself differently in life and in photography.

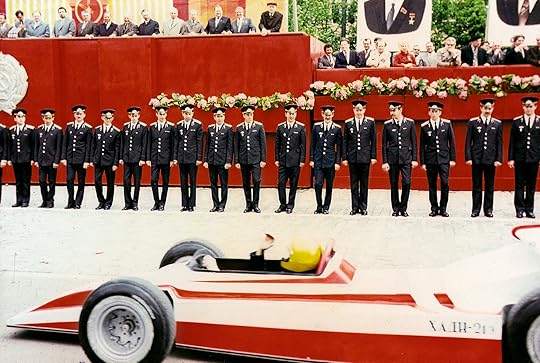

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from The Red Series, 1968–75

Misiano: And yet, when I was talking about the performative, I was referring not only to your appearing as a character in the photographs but also to various forms of artistic intervention that you have employed in the developing process. For example, in The Red Series (1968–75), you began painting over photographs of Soviet demonstrations. Ilya Kabakov [the Soviet-born American Conceptual artist] was very enthusiastic about this series. It was, he said, as if the artist-protagonist is expressing himself through this method. That he, i.e., you, imagines himself as some superloyal Soviet citizen who not only docilely attends official parades, but also innocently colors the photographs of those parades to make them more joyful and festive.

Mikhailov: I actually adopted that technique because it harks back to an earlier epoch in the history of photography when it was still black and white and customary to color photographs in. I was doing that sort of work by commission and receiving lots of orders. Of course, when I started using this method on my own photographs, there arose this element of playful liberation of which you speak. But there’s another important point here: Oddly enough, this doctoring of the photograph, this supposedly awkward coloration, brought the image closer to reality. It made it a bit vulgar or unrespectable (as a matter of fact, that same anniversary exhibition in Kharkov was called just that—Unrespectable). And that’s how life really is—it’s vulgar and unrespectable.

Vita Mikhailov [Boris’s wife]: Viktor’s question had a point that you overlooked. It’s not just that you perform in your own photographs but that you look at life itself as a performance. For me, for example, a person on the street is just walking, but to you, he’s performing.

Misiano: That reminds me of a book by the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More (2005). It describes how, in the later Soviet period, people who observed regime-imposed social rituals, such as May Day demonstrations or trade-union and party meetings, rather than interpreting them as roles to be performed, were actually changing the meaning of the social order. That’s precisely why, though it seemed to everyone that the USSR would last forever, no one was surprised when it ended.

Mikhailov: I’m not sure the word performance pertains to me. I’ll put it differently. After the Khrushchev reforms of the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was clear to me that everything had to change. And though on the surface everything was becoming frozen, I was still constantly looking for signs of actual change. That’s why all of life—built as it was on contrasting rituals and changes—seemed so unreal, at times almost carnival-like. Life was kind of struggling to break out of narrow forms that were being imposed on it externally. That’s precisely what I was trying to show in my work.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Look at me I look at water, 1998–2000

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Look at me I look at water, 1998–2000Misiano: That’s probably why your Soviet-period work is free from the photojournalistic clichés that aimed to expose the repressiveness of the Soviet regime. For you that life is still vital, playful, and comical, at times even to the point of idiocy.

Mikhailov: Still, life then was clouded by a sort of tension. After all, the beginning of my photographic career brought me face-to-face with the KGB. I wasn’t jailed, but I was fired from my job and the visit by the KGB to check on me disturbed my inner peace. I felt their watchful gaze all the time. Especially when I traveled to Lithuania to attend photo-festivals.

Vita Mikhailov: Moreover, at that time not only the regime but all of society exercised control over what he photographed. If Borya would be photographing sunsets, there would have been no objection. But when he photographed something out of the ordinary, then anyone could come up to him and ask: What are you photographing here? That sort of random monitor passerby was always looking over our shoulder.

Mikhailov: Every time I take a picture of unusual things—some kind of rusty pipe on the street—I feel a certain degree of tension, I feel a certain degree of fear. Society continues to control you—controlling behavior for which it can’t find a reasonable explanation.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Suzi et cetera, early ’80s

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Suzi et cetera, early ’80sMisiano: Society controls your gaze—where and how you should be looking.

Mikhailov: It raises the constant question—to photograph or not to photograph? Will you dare or won’t you? And we’re not just talking about political or social conduct, we’re talking about photographs, about conduct in photography. You know you can’t photograph in a certain way, but you feel that the photograph is demanding that you do. You have to do it! To photograph precisely in this way!

Vita Mikhailov: In the 1950s in Kharkov there was a sadly famous event. A group of young people dreamed of a different and freer life; they listened to Western music, engaged in creative projects, and so on. They were arrested and some of them were imprisoned. We later saw their case file, which contained a lot of photographs: these young folks had taken pictures of themselves on the beach in bathing suits. As a result, according to what was written in their official case file, they were charged with taking “Western poses,” and were sent to prison on pornography charges. That was the atmosphere at the time when Borya took up photography.

Misiano: And then there was your series Suzi etcetera, from the early 1980s, for which you could easily have been charged with making pornography. And your Crimean Snobbism series from 1982, in which you and your friends are depicted on a carefree vacation messing around and acting out the most idiotic mise-en-scènes; couldn’t you say that in this series, you’re taking on “Western poses”?

Mikhailov: I would say these were exercises in liberation.

Misiano: But the series was created during the Soviet period?!

Mikhailov: Yes, it was even before perestroika. But I showed that people had already prepared themselves for another way of life; they had already begun living it.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Case History, 1997–98

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Case History, 1997–98Misiano: Now, it seems, is the right time to talk about Case History. In these dramatic images, once again you challenged yourself to show the new post-Soviet life. I remember after you first exhibited this series that you were very concerned with how ethical it was to make this work and exhibit it. But I think that it makes no sense to come back to this topic at this point. What I would like to draw attention to, given this line of our conversation, is the fact that in Case History, you, in your constant quest to dive into life, reached, perhaps, the maximum depth. But again you not only show images of reality but also enter into a kind of relationship, implicating your protagonists—the homeless of Kharkov—in some sort of action.

Mikhailov: When Vita and I were shooting that series, it made me think of the American Depression, when the American government actively recruited photographers and commissioned them to photograph what was happening, to capture these experiences for history’s sake. I was motivated by this precedent: I felt that it was important to photograph what was happening. And then yes, of course, in the new poverty, I saw a new protagonist. Of course there had been drunks on the street before, and homeless people, but they were less noticeable, there wasn’t as large a concentration of them. Yet it was difficult to approach them because Society, with a capital S, tracked your every move, as we mentioned earlier. The reason I was engaging with them was because it wasn’t possible to photograph them stealthily—that would have been impolite and unethical. Communication was necessary. There arose a need to overcome some inner resistance—if you can communicate with them, then it means you can cross some sort of boundary.

Related Items

Aperture 220

Shop Now[image error]

The Dissident Photographers of Ukraine

Learn More[image error]

Aperture Conversations

Shop Now[image error]Misiano: Although your motivation was photography, you arrived at a particular code of ethics, a new way of living. You felt that the new protagonists required a new approach to the work, and this in turn assumed a new kind of human relations.

Mikhailov: Yes, that’s true. Also, in those years, anybody could suddenly find themselves in such a situation. Vita and I were lucky, but it might have been otherwise. Hence the social barriers between us and them were very relative. For that reason photographing these people required a tremendous amount of empathy and respect on our part.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Tea Coffee Cappuccino, 2000–2010

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Tea Coffee Cappuccino, 2000–2010Misiano: You’ve spent many years living in Europe. Have you been able to feel life here as deeply and profoundly as you were able to in your home country? And are you able to interfere with life here, to play with it as much?

Mikhailov: There’s no question here: the difficulty of photographing in the West is my lack of knowing the language.

Vita Mikhailov: It’s not just a matter of language. It’s a matter of context. Your place is there: you know it and understand it. Borya takes fantastic photographs of Berlin and it will probably become clear later on that no one else has captured such a Berlin.

Mikhailov: Yes, of course at home I have a better sense for the changing times, the rise of something new—and this has always been important to me. Although not too long ago, a year ago, it was easier for me to photograph in Berlin since I felt a glut of information back home. I wasn’t feeling anything new. But when all of the political events began in Ukraine everything changed again. We’ll travel back there soon and perhaps will encounter something new there.

Vita Mikhailov: As a matter of fact, after making Case History, between 2000 and 2010 we completed a very good series called Tea Coffee Cappuccino, which we then compiled into a book (2011). It reflected that new situation, which replaced the transitional 1990s.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Suzi et cetera, ca. early 1980s

Misiano: I remember that series: it showed the streets of Kharkov, its markets and flea markets. And while it was clear from the photographs that a prosperous life was still far away, they projected a tremendous amount of great positive energy. It was a bright contrast with Case History, and it definitely represented a new period of post-Soviet life. Although you did show what that epoch ended with in your 2013 series dedicated to the protesters in Maidan [Square, Kiev], which was exhibited at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg in 2014 as part of Manifesta 10. Once again, you showed these two themes that we’ve been discussing today: an organic element of life that reveals itself from behind the shell of reality, and how that inner life takes on the veneer of a social performance. In this work, the Maidan protest movement appears in a sort of dark spectacle, almost gothic, controlled by irrational forces. These photographs show the fragility of the norms and conventions ruling the social order, how easily they give rise to something dark and frightening.

Mikhailov: Yes, I tried to accentuate all of this through the exhibition. But I have to say, the people at Maidan sensed all of this and worried about it. It was clear that they were preparing themselves for something; they remained in tense anticipation. And of course in large part this was the foreboding sense of war. People were very worried about it and I worried alongside them.

Vita Mikhailov: Don’t forget, these photographs were taken in December, before the bloody culmination of events. [The protests eventually led to the Ukrainian revolution in February 2014.] Even then there was a fire burning in the square, and smoke was rising, but people were simply warming themselves around it. There were a lot of strange things there. That’s where Borya photographed a person who ended up being one of the first victims. He was the first person to die at Maidan.

Mikhailov: And there were thousands of people there! Ultimately, the photographer needs to get lucky; what’s important is the moment of photographic luck, though of course with reference to this situation it sounds somewhat sacrilegious. I’m not talking about mysticism, but some kind of inevitable event. When you’re open to life, it responds to you. That is what an intuitive possibility of photography is—to crawl deeper into the depths of life than what you see on its surface. I can’t say what this is and how it occurs, but that’s how it is.

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Yesterday’s Sandwich, ca. late 1960s–early ’70s

Boris Mikhailov, Untitled, from the series Yesterday’s Sandwich, ca. late 1960s–early ’70sAll photographs courtesy the artist

Misiano: But isn’t the camera always an extension of your gaze, which is diving deeply into life?

Mikhailov: Yes, but it’s important to keep in mind that without the camera this diving would be impossible.

Misiano: On the other hand, you always trusted chance. Let’s recall your series from the late ’60s and early ’70s, Yesterday’s Sandwich—your early experimental series—to which, insofar as I understand, you’ve been returning conceptually of late. In those works you randomly placed one image onto another, not knowing in advance how it would turn out. And it ended up being extremely evocative.

Mikhailov: I can’t explain it in theoretical terms but this has always interested me. Photographic accident may be more interesting than a consciously constructed collage. I was recently thinking about this. You photograph one subject, then another, you place them between one another and this unintentional connection turns into a story about life in its entirety. And this is all borne from chance, and this chance is photography.

Translated from the Russian by Elianna Kan. This interview was first published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue,” fall 2015.

April 20, 2022

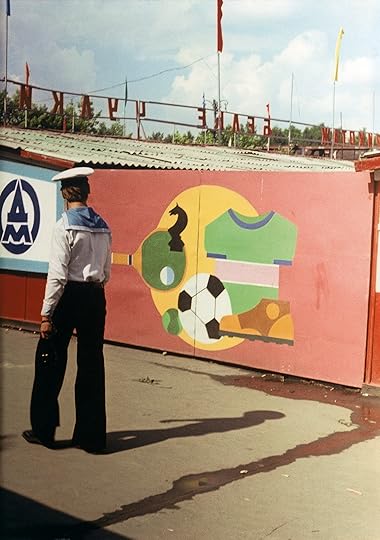

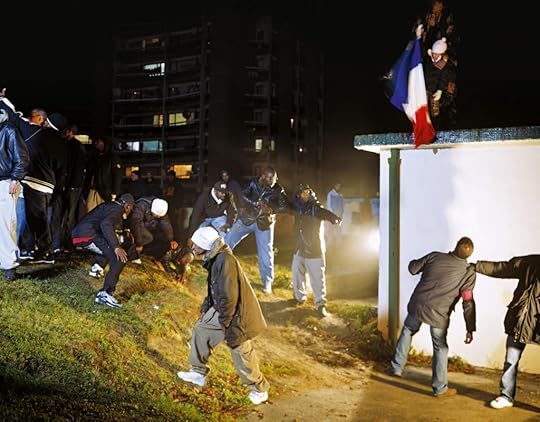

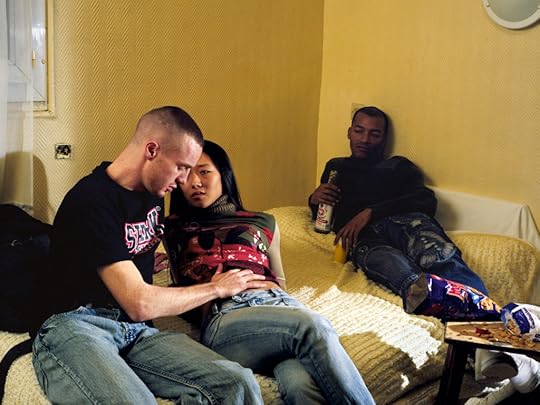

Mohamed Bourouissa’s Staged Portraits of Youth on the Peripheries of Paris

Mohamed Bourouissa was still an art student in 2004 when he took his first photographs of young people, mostly his male friends from the banlieues, or suburbs, of Paris. He had wanted to represent their particular sartorial aesthetic. At the time, the Parisian transportation system was laid out such that the easiest way for kids living in different banlieues to meet was to take the direct train to Châtelet–Les Halles in the center of the city. On arrival, their dynamic style a lot of brightly colored athletic wear—stood out among the drab but formal uniform of most Parisian kids, clearly marking them as residents of the peripheries. They were obviously issus de l’immigration—second- or third-generation French youth whose families were from the former colonies—though no one really articulated these distinct identities at the time.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Le téléphone, 2006

Mohamed Bourouissa, Le téléphone, 2006Not long afterward, in the fall of 2005, widespread demonstrations broke out in the banlieues following the deaths of two young men from one of the neighborhoods who were running to escape police. Bourouissa realized he’d been on to something and spent the next three years working on a modified concept of the project. He relocated it out to the banlieues, to the spaces of the périphérique, as the series, made from 2005 to 2008, came to be called, these urban areas that border the city but are clearly not of it. And, pivoting from what had begun as a documentary project, Bourouissa decided to stage the photographs. Bourouissa’s background was in painting, and he wanted to incorporate the formal compositions and attributes he had come to love from classical French painters—the tensions expressed through the gestures of the hands, the suggestiveness of the gaze.

“All these things that are really part of European culture,” Bourouissa told me recently, “I wanted to reinterpret with this new French youth, with its own history, its own codes.” For example, in La main (2006), from Périphérique, a young woman reclines on a bed like a figure of erotic romanticism, gazing at a man who is leaning over her with a hand placed on her abdomen, which is illuminated by a strip of light from a window. A third figure, another man, looks on ambivalently from a darkened corner behind them. Another from the series, La république (2006), shows a scene of collectivity; whether the group is engaged in some kind of combat, or rebellion, or something else, we don’t know. A French flag is planted provocatively in the upper corner as the men signal to each other in a kind of sacral drama. Still, the staging is subtle, not necessarily immediately obvious enough to draw a stark distinction from documentary photography.

Mohamed Bourouissa, La république, 2006

Mohamed Bourouissa, La république, 2006Périphérique, which in fall 2021 was collected in a monograph published by Loose Joints, is heavily male: its subjects are mostly young men, and masculinity itself is a clear topic of study. Some of these men were Bourouissa’s friends, the people he saw most often and knew best. But the choice was also, in part, pragmatic—the public spaces of the banlieues were then, and still are, male spaces, where young men hang out together and where complicated notions of masculinity are worked out. “How do you affirm yourself when your parents are devalued by society?” Bourouissa asks. Social standards, he observed, demand that everyone be powerful, strong, and rich. How does one construct a sense of one’s own power in relation to others if it cannot be inherited? Amid the poverty that surrounded him and his friends, the answer was through the body. “It’s almost like a reproduction of the mechanisms of power in the body,” Bourouissa says. “There is a physical experience of what we live through. And we incorporate that experience into our bodies as a kind of memory.”

When he looks at these photographs now, Bourouissa sees very clear differences: “Race” was a word that no one spoke at the time.

Périphérique brought Bourouissa widespread recognition before the age of thirty. Photographs from the series were included in New York at the New Museum’s inaugural Triennial, in 2009, an international exhibition of young artists titled Younger Than Jesus; are in the permanent collection of the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration, in Paris; and were recently displayed at a solo exhibition in Copenhagen, at the Kunsthal Charlottenborg. Many of Bourouissa’s admirers suggested that he continue focusing on the topic, but he decided to diversify and moved on to other projects, including Shoplifters (2014), for which he repurposed a collection of disarming Polaroids of shoplifters in New York, and Brutal Family Roots (2020), an immersive installation that used acacia trees to reflect on migration and dispersion. Still, he considers the fact that Périphérique is being published in book form now, for the first time, more than a decade after the work was created, an indicator that it has stood the test of time.

Mohamed Bourouissa, La main, 2006

Mohamed Bourouissa, La main, 2006All photographs courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

It is tempting to look at Périphérique, from the mid-aughts, and ask what, if anything, has changed. Clearly, with regard to poverty, stigmatization, and the myriad issues affecting identity and history in the banlieues, with France’s ongoing cultural battles playing out in the background, one might take a pessimistic view. But Bourouissa insists that when he looks at those photographs now, he sees certain, very clear, differences: Race was a word that no one spoke at the time. “No one dared to name it,” he says, but that has changed. Now, people, especially young people, talk about matters of race, and the French are starting to “untie” what that word means, its implications in historical understanding, and the afterlife of history in France today.

Mohamed Bourouissa’s Périphérique was published by Loose Joints in November 2021. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations,” under the column “Backstory.”

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers