Aperture's Blog, page 39

August 24, 2022

8 Summer Reads from Aperture’s Editors

From the very first issue of our magazine, Aperture has explored words and pictures and the relationship between them. As Nancy Newhall mused in that issue, now seventy years ago in the summer of 1952, “Perhaps the new photograph-writing—so new we have no word for it—is [. . .] the form through which we shall speak to each other [. . .] for a thousand years or more.”

Inspired (in part) by Newhall, we’ve asked a few Aperture colleagues to share their current favorite photo-adjacent titles while the Aperture PhotoBook Club pauses for a summer holiday. Below, read an eclectic mix that mirrors the many ways in which we engage with photographs, and the many ways in which they circulate in the world.

—Sarah Meister, Executive Director

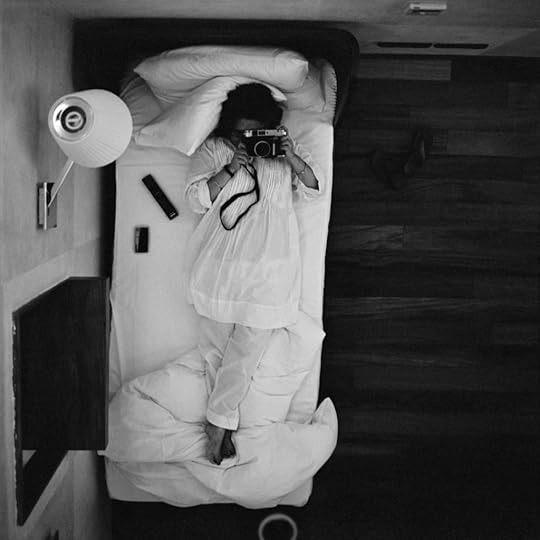

Dayanita Singh from Dancing with my Camera (Hatje Cantz, 2022)

Dayanita Singh from Dancing with my Camera (Hatje Cantz, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Lesley A. Martin, Creative Director

As befits this self-proclaimed “offset artist”—who directly engages with bookmaking as part of her practice—Dayanita Singh produced two catalogues for her survey show at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, which ran from March 18 through August 7. The first is entitled Let’s See. Entirely visual, Singh calls the book a “photo-novel” of her journey as a young photographer. The second book, Dancing with my Camera, however, serves as a primer for those interested in the discourse that surrounds Singh’s expansive practice, and is just right for losing oneself in on a hot summer day. The texts are generous, intriguing. Curator Stephanie Rosenthal highlights the role of the artist’s “gut feeling” during editing, the unique aspects of Singh’s “photo-architecture,” and the way that she sees Singh’s photography as anchored in ideas of choreography. Teju Cole, Thomas Weski, and many others offer equally engaging takes on the work. For those of us who did not have the good fortune of visiting the show itself, there are plenty of installation shots and voices incorporated into the pages of this book—almost enough to imagine oneself there, in the most excellent of company.

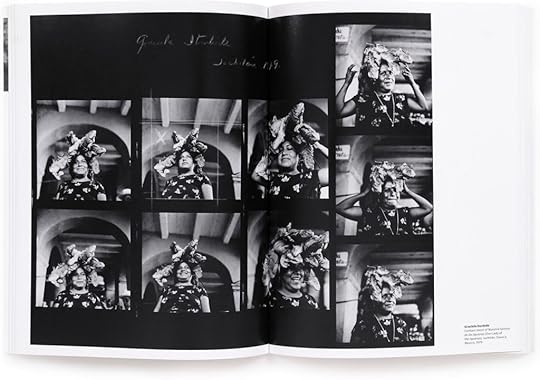

Interior spread from Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Interpretation (Aperture, 2022)

Interior spread from Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Interpretation (Aperture, 2022)In the opening pages of Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Imagination, Iturbide states: “Photography is a pretext to know the world, to know life, to know yourself.” This poetic, lyrical statement is the thread that draws the reader through this book, the most recent offering from Aperture’s Photography Workshop Series (the series as a whole could fuel an entire summer’s worth of reading). In this latest volume, Iturbide guides us through the stories of her most well-known images, as well as images we might not be as familiar with. One of Iturbide’s arguably most iconic photographs, Nuestra Señora de la Iguanas, for example, is accompanied by a contact sheet that shows the precise fraction of a second that “made” this image, alongside fascinating context from the shoot (who knew that the vendor had sewn the iguana’s mouths shut in order to keep them from biting!). In this book, as with Singh’s, you feel as though you’ve been granted access to incredible secrets, legacies, and profound and inspiring conversations about photography.

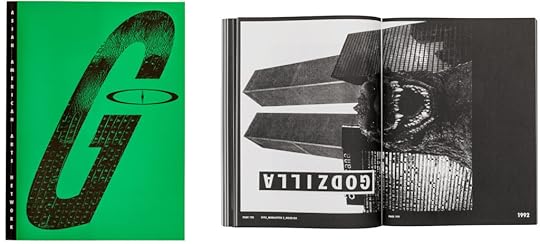

Cover and interior spread of Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001 (Primary Information, 2021)

Cover and interior spread of Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001 (Primary Information, 2021)Noa Lin, Editorial Assistant, Books

Borrowing its name from the popular “anarchistic lizard,” Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network was a vibrant and influential collective, founded in 1990 by artists Ken Chu, Bing Lee, and Margo Machida. The group started as a forum for Asian American artists in New York City to share and develop ideas, but eventually became a nationwide organization that campaigned for the visibility of Asian Americans within the art world. Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network 1990–2001 is a sprawling anthology of the group’s activities and reproduces letters, photographs, publications, and other ephemera from their eleven-year period working. As I encountered the work of Godzilla for the first time through this book, I found it was not only an excellent introduction to their history, but a reminder of the power in community-building for marginalized people, and the necessity of continued political action within an often-exclusionary art world.

Bettina Grossman, From the Xerox portfolios, 1960s, from Bettina (Aperture, 2022)

Bettina Grossman, From the Xerox portfolios, 1960s, from Bettina (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the archive Bettina Grossman

I’ve also enjoyed discovering Bettina, which charts the work of Bettina Grossman, a prolific but widely unsung artist who worked in an incredible range of media. Her photographs, drawings, and sculptures are all striking and hypnotic, and as you see the breadth of her work throughout the book, you can begin to track the way she filtered the world around her into her artistic practice, transmuting the shapes and patterns of the cityscape into wonderful abstractions.

Related Items

Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Imagination

Shop Now[image error]

Philip Montgomery: American Mirror

Shop Now[image error]

Object Lesson: On the Influence of Richard Benson

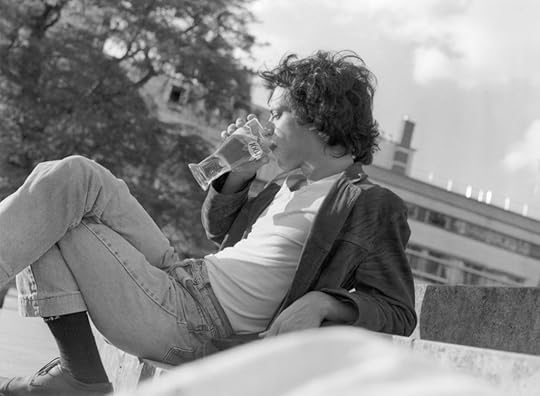

Shop Now[image error] Trent Parke from Cue the Sun (Stanley/Barker, 2022)

Trent Parke from Cue the Sun (Stanley/Barker, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Varun Nayar, Assistant Editor, Aperture

Trent Parke’s new photobook for Stanley/Barker—Cue the Sun—was somewhat accidental. After twenty-five years away, the Magnum photographer returned to India in 2020 to assist the Australian cricketer Steve Waugh with a photobook of his own. Traveling for eight to nine hours a day between shoots, Parke felt he had returned to a different country altogether, one governed increasingly by commerce and faith, and a new book began to take shape. With photographs made from his bus window, Cue the Sun tracks Parke’s journey across the vast north Indian countryside and bears stylistic traces from his previous work in Australia—night photography, dramatic use of flash, and the meandering focus of a road trip. Despite its lack of text, the book is sequenced like a travelog and designed as a fold-out double-printed concertina, splitting the images between night and day. Made just before COVID-19-induced lockdowns across India, I thought Parke’s transient views into pre-pandemic street life feel both striking in their detail and original in their approach.

Philip Montgomery, The Chatman family at home following widespread protests in the wake of the grand jury announcement against the indicment of Darren Wilson, a white police officer charged with the killing of Michael Brown, Ferguson, Missouri, November 2014, from American Mirror (Aperture, 2021)

Philip Montgomery, The Chatman family at home following widespread protests in the wake of the grand jury announcement against the indicment of Darren Wilson, a white police officer charged with the killing of Michael Brown, Ferguson, Missouri, November 2014, from American Mirror (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

Another, very different book I’ve been spending time with is the award-winning photographer Philip Montgomery’s debut monograph from Aperture, American Mirror. Having first discovered him through his work on the front lines of the COVID-19 response, I was delighted to see the book-length treatment, which highlights Montgomery’s natural talent for storytelling and his ability to bear witness in active and attentive ways. While each image tells a distinct story about the country’s recent past, from the opioid addiction crisis to protests in support of Black lives, collectively, as Jelani Cobb writes in an essay reproduced in the book, “these are simply scenes of life seeking to prolong itself.”

Sarah Meister, Executive Director

It was Richard Benson who first revealed the way in which my work might be enhanced by inviting in life (without him, I wouldn’t have dreamed of including my children’s handprints in an exhibition at MoMA!). When I read the fifty-plus contributions to Object Lesson: On the Influence of Richard Benson it’s apparent I’m not the only one. Benson loved photography, catalyzing that love into an exploration of why printed pictures look the way they do, and why we should care. As my colleague (and the book’s editor) Lesley Martin noted, Benson understood that the way photographic images are rendered is an integral part of how we connect with them, and by extension the world they represent. Our appreciation of both is enhanced when we follow his curiosity and careful attention.

Cover of Object Lesson: On the Influence of Richard Benson (Aperture, 2022)

Cover of Object Lesson: On the Influence of Richard Benson (Aperture, 2022)  Cover of Looking at Photographs (Museum of Modern Art, 1973)

Cover of Looking at Photographs (Museum of Modern Art, 1973) Of the many talented artists and creative co-workers featured in Object Lesson, it is John Pilson’s introduction where one finds a reference to John Szarkowski’s 1973 book Looking at Photographs. It was assigned reading in my undergraduate history of photography course, and my admiration for it continues to grow. Both Szarkowski and Benson—friends, fellow photographers, and co-conspirators in probing photography’s peculiar charms—offered their insight in delightfully accessible terms. These books aren’t exactly beach reads, yet they evoke for me a sensation akin to sunshine and sea air.

This text originally appeared in The Aperture PhotoBook Club newsletter. The Aperture PhotoBook Club brings together artists, makers, and photobook lovers. Sign-up for free to become a member.

August 16, 2022

How Irving Penn and Issey Miyake Redefined the Fashion Photograph

The late Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake held a rare appreciation for the role of image-making in design creativity. His longstanding working relationship with the photographer Irving Penn, whom he called Penn-san, is testament to Miyake’s understanding of how he could regard his work anew, by looking at it through the creative eye of another.

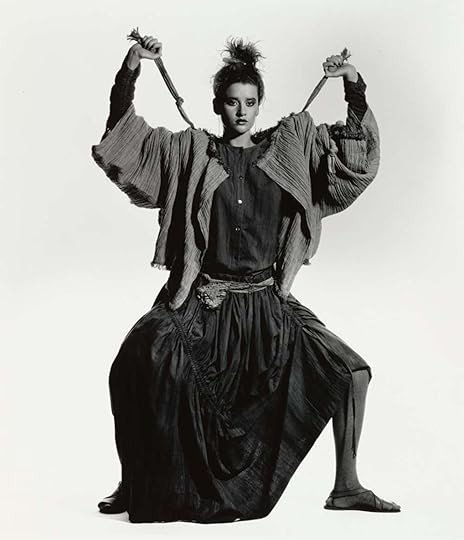

When Miyake saw how Penn had photographed his clothes for an American Vogue editorial in 1983, he exclaimed, “Wow! I never thought of looking at clothes in that way! The clothes have been given a voice of their own!” On one page a model held out the wide-cut legs of a drawstring jumpsuit she wore, drawing attention to the volume of fabric and accentuating the garment’s graphic shape.

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Poncho and Apron Belt, New York, 1987

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Poncho and Apron Belt, New York, 1987 Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Staircase Dress, New York, 1994

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Staircase Dress, New York, 1994The pair met in Tokyo over dinner, after an introduction by a mutual friend, the publisher Nicholas Callaway. In 1986 Penn started to shoot Miyake’s seasonal collections in New York, resulting in advertising campaigns, exhibitions, and publications. But these outputs were not the principal intention; they were the mere fruits of a long-distance creative exchange between the two.

To look at the photographs is to see how Penn essentializes Miyake’s designs, bestowing them with a graphic clarity and a highly dynamic sense of how they can be worn.

Miyake insisted on Penn being unhindered, so he always absented himself from the New York shoots. Instead, Penn was supported by representatives from Miyake’s team, makeup artist and photographer Tyen, and hairstylist John Sahag. Penn would sit at a table with a pencil and paper and sketch as models wearing the designs were directed. Polaroids were then taken in preparation for the main shoot. Following a session, Penn would then send the complete run of transparencies generated to Miyake in Tokyo, who would use them to review his design work and as the springboard for new design directions.

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Design with Black Fan, New York, 1987

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Design with Black Fan, New York, 1987  Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Elephant Crepe (Front View), New York, 1983

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Elephant Crepe (Front View), New York, 1983 A comprehensive set of images from their work together is reproduced in the photobook Irving Penn Regards the Work of Issey Miyake, published in 1999 and edited by Mark Holborn. To look at the photographs is to see how Penn essentializes Miyake’s designs, bestowing them with a graphic clarity and a highly dynamic sense of how they can be worn. The visual directness affirms the precise and calibrated way Miyake’s garments are designed and made, which is magnified by how Penn takes photographs. They possess a visual style that is highly readable, like animation or hieroglyphs. And this clarity arises, according to Holborn, in how “the work of one provides a mirror for the work of the other.”

In an essay for the 1997 exhibition catalogue Irving Penn: A Career in Photography, Miyake reflected, “Through his eyes Penn-san reinterprets the clothes, gives them new breath, and presents them to me from a new vantage point—one that I may not have been aware of, but had been subconsciously trying to capture. Without Penn-san’s guidance, I probably could not have continued to find new themes with which to challenge myself, nor could I have arrived at new solutions.” He ends by crediting Penn’s influence on his invention of permanently pleated garments, known as Pleats Please.

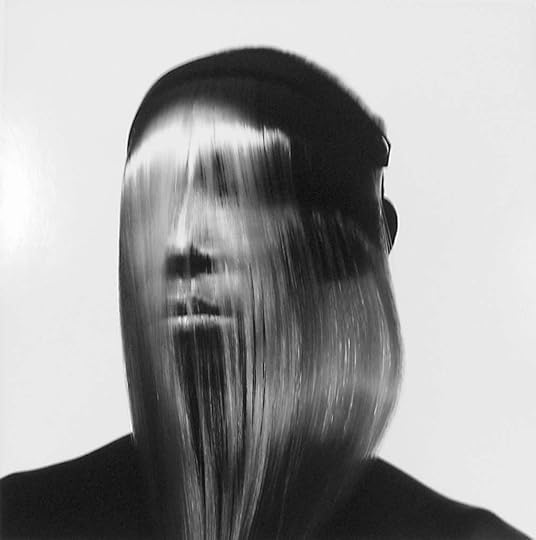

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Fashion: Face Covered with Hair (A), New York, 1991

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Fashion: Face Covered with Hair (A), New York, 1991 Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Onion Flower Bud Coat, New York, 1987

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Onion Flower Bud Coat, New York, 1987All photographs © the artist and courtesy Pace Gallery

In the obituaries published recently in honor of Miyake, many commented on the black mock turtleneck that the fashion designer made for Steve Jobs as his personal uniform. (Jobs ordered over one hundred.) Observers saw this as evidence of the relationship between fashion and technology and the idea of a garment as a kind of machine for living. Penn wore a similar kind of everyday uniform: blue jeans, sneakers, and a shirt with a collar band designed for him by Miyake. It’s an outfit that speaks with great understatement about the relationship between fashion and photography, about the inventiveness and imagination shared between practitioners from adjacent visual fields, and about the need for critical distance and critical friends. It’s an outfit that materializes Miyake’s principle that we all should continue to live by: “One always needs someone who can look over one’s shoulder and evaluate one’s work from a detached and objective point of view—someone who can act as a sounding board.”

August 12, 2022

Thomas Boivin’s Sensitive Exultation of a Parisian Neighborhood

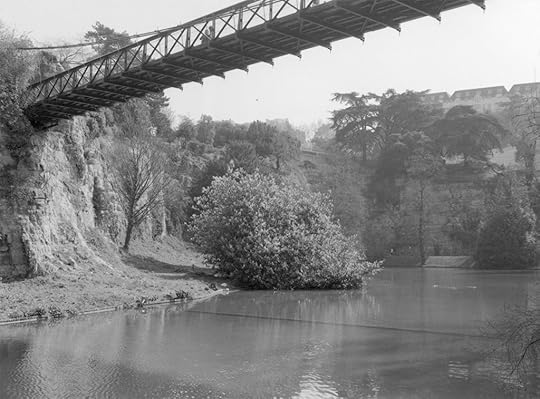

The first time I look through Thomas Boivin’s book Belleville, I try to find the places I know. Belleville is a neighborhood in northeastern Paris, and Boivin made these black-and-white photographs while wandering its streets. I live on rue de Belleville, behind a shop called Bazar de Belleville, which gives the book’s presence on my table a certain Being John Malkovich quality. Immediately I spot the area’s two parks, a certain plumber’s shop front, the hard-to-describe atmosphere of particular points on certain streets. I linger longest on the exterior of the print shop I visited recently for a passport photo, which the employee took in a simple studio in a corner at a cost of €5.50. Boivin’s image centers a side window whose awning guarantees the use of “Kodak-quality paper.”

This text is in both French and Chinese. Belleville is home to one of Paris’s two major Chinatowns, just one community within a patchwork of cultures: Belleville is also more ethnically diverse than almost any other neighborhood in the French capital. To walk down any side street is to pass through several micro-districts that often seem to comprise little more than a shop, café, and bakery, yet feel as though they embody some long-since-settled wave of immigration. The portraits in this book, of strangers Boivin is drawn to, reflect this intricacy but are not essentialized by it. A woman lies on a defunct fountain, reading a novel. A man in a polo shirt and blazer clutches an uprooted plant in Buttes-Chaumont Park.

The second time I look through Belleville I am struck by the stillness, a sort of ghostly silence, that seems to emanate from each photograph, even when people are present. Perhaps this is to do with a certain tonal quietness and Boivin’s aversion to black and white extremes in favor of the middle grays. Or perhaps it stems from his preoccupation with what one could call nonspecific places: a flower bush obscuring a drain, a faded curtain in an anonymous window, tree tendrils on an unplaceable fence. The result has a woozy or hallucinatory quality, as if we are slightly removed from reality. Despite spanning a decade’s work, these fifty-five images, shot on film, feel indifferent to the passing of time. Occasional clues—a bus ad for a 2020 Man Ray exhibition, say—seem merely part of the cyclical flow of a city that both changes and doesn’t.

This is not really a “portrait” of a neighborhood, as some might yearn for. In a statement released with the book, Boivin says: “Although the photographs hardly depict the city, I find they convey the sensation that I had, walking the streets of Belleville.” What is meant by “the city” here, as something that is hardly depicted? Crowds? Belleville is densely populated even by Paris standards, a fact far from evident in this series. Or perhaps Boivin refers to crowd pleasers, such as wider street scenes, emblematic locations, Haussmannian architecture, or other easy tropes of street photography.

Before looking through Belleville for the seventh or eighth time I cycle to the gallery Les Douches by Canal Saint-Martin to see an exhibition of Boivin’s work. While it overlaps somewhat with the book, the show takes a different approach, with almost none of the images featuring people. Where they do appear, they are presented less as subject than as circumstance: a man holds a melon, a woman stands in front of a set of old windows, and each person’s head is cropped out of the shot. Boivin also likes food and drink, and several images nod to the still-life tradition: a half-drunk carafe of water on the table in an empty bar. A lemon squeezer in a shard of light on a kitchen table. Piles of grocery delivery boxes, wrapped in enough cling film to make your recycling efforts seem futile. And the titles always assert a location—either Belleville or somewhere in its immediate vicinity: Melon, Belleville (2019); Serviettes, Les Lilas (2019); Petit Déjeuner, Ménilmontant (2014).

All photographs from Thomas Boivin: Belleville (Stanley/Barker, 2022)

All photographs from Thomas Boivin: Belleville (Stanley/Barker, 2022)A sense of place is more potent when sublimated into something else entirely. Belleville often seems less about questing for the essence of its titular neighborhood than attempting a personal exaltation of the ordinary. It simply makes sense that this occurs where the photographer happens to live. Georges Perec’s term infra-ordinary feels relevant to the preoccupations at play here, as does his famous quote: “What we need to question is bricks, concrete, glass, our table manners, our utensils, our tools, the way we spend our time, our rhythms . . . Describe your street. Describe another. Compare.” Perec, I should add, grew up in Belleville, near the pond that dominates the second image in Boivin’s book. It certainly appears that there is something ordinary in the local water.

Thomas Boivin: Belleville was published by Stanley/Barker in April 2022.

August 11, 2022

The Photographer of Mexican Sex Appeal and Pathos

I was eating a shrimp cocktail by the ocean in Oaxaca one November when I spotted a young man rolling around on the beach, covered in sand and striking cat-like poses for a photographer who was egging him on. “That’s @MexicanoMX!” my friend whispered, lowering her sunglasses to get a better look. Sure enough, when I pulled up his Instagram, the photographer’s stories were full of sun-kissed Oaxacan beauties surfing, fishing, and splashing around in the powerful waves of the Pacific. Watching him work, I was struck by his effortless way of making this young man feel empowered enough to strut his sensuality in front of a crowded beachfront restaurant. “I think it has to do with my honesty,” Dorian Ulises López Macías, the photographer behind the account, tells me two years later over Zoom. “I’ve never been afraid to walk up to a man on the street and say, ‘I want to take your photo because I think you’re handsome.’”

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Toluca, 2018, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Toluca, 2018, from the series MexicanoMacías has refined a genre of street portraiture that skillfully balances pinup sex appeal with soul-gazing pathos. Stylistically, you could say his work hearkens back to the documentary tradition of groups like the Photo League, which set out to produce dignified images of the working class. But where the social realists aspired to eliminate artifice in favor of objectivity, Macías encourages his subjects to pose and preen. He’s particularly drawn to facial features, and not just of men he’s attracted to, but any traits that hint at a person’s rich interiority.

This approach reflects the mindset of his day jobs in fashion—first as art director for magazines like ELLE México, now as director of Casting en el Parque, a Mexican modeling agency—which involve a never-ending hunt for interesting faces. But the faces that interest him aren’t the ones that dominate the Mexican fashion industry, with its overwhelming bias toward white and light-skinned models. Instead, what distinguishes Macías is the way he captures the range and vitality of Mexico’s moreno, or dark-skinned, majority.

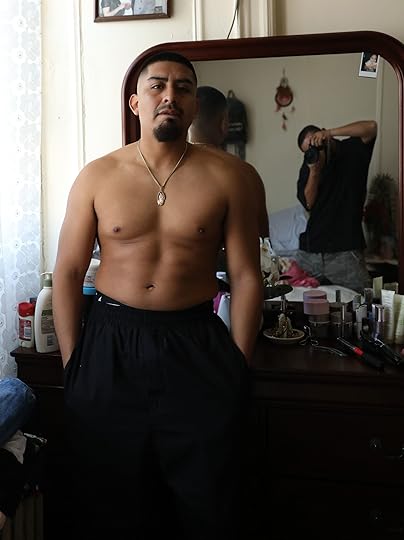

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Mexicano Americano, 2022

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Mexicano Americano, 2022

When Macías connects to our video call, he is silhouetted against a wall jam-packed with photos and paper ephemera: some he took, some were gifts from friends, and others he collected over the years. He’s lived in this Mexico City apartment for seventeen years—it was one of the first rooms he rented when he moved from his rural hometown outside the city of Aguascalientes. Photography has been a hobby for him ever since his father (“a junk collector just like me,” he says) gifted him a camera, and when he got hired for his first job in the capital, he began photographing workers on his commute.

“I grew addicted to going out in the street in search of portraits,” Macías tells me. “I’d bring the camera everywhere, even on the bus, and just wait for interesting people to show up. It was such a thrill.” His approach grew out of a magpie impulse to “conserve moments, to conserve people,” and for years he didn’t share the images with anybody but cherished them like treasures in the privacy of his bedroom. He tried not to overthink his process, allowing his instinct (erotic or otherwise) to take over and guide him on long walks through the city. “It’s like when a dog sees another dog and gets excited,” he says. “Obviously I’m a human so I can control myself, but otherwise I’m just like a dog. I’m driven by the instinct to get up close to other humans.”

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2015, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2015, from the series Mexicano Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2017, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2017, from the series MexicanoFrom his first job as a graphic designer at the now-defunct lifestyle and arts magazine Código, Macías steadily rose through the Mexico City media world, landing at ELLE México in 2012. For years he lived what he calls a “double life.” By night, he was the street photographer who glamorized Mexico’s native features, and by day, the art director of fashion magazines full of gaunt Russian models. “What I was doing as a street photographer was attacking what I was doing in the fashion world,” he says.

Eventually, he started insisting that his clients employ, if not dark-skinned models, at least Mexican ones. Most refused. Several magazines and major fashion brands also stopped working with him, and for a few years he had to borrow rent money from his mother. It wasn’t until Chiara Bardelli-Nonino, the photo editor of Vogue Italia, hired him to direct a fashion editorial with Mexican models that his old clients came crawling back.

“All those producers who had turned their back on me, all of the sudden they were interested in me again,” he says. “Like, Wow, Vogue is paying attention to you, and not just any Vogue—Vogue Italia! Even Vogue Mexico was interested again. That’s how things work in Mexico.”

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Acapulco, 2013, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Acapulco, 2013, from the series Mexicano Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2013, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Mexico City, 2013, from the series MexicanoIn 2016, Macías began uploading portraits to the Instagram account @MexicanoMX. Three months later, the Los Angeles–based performance artist Rafa Esparza invited him to create work to display in his installation at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, a semicircular wall of adobe bricks Esparza had built out of dung, dirt, and water from the Los Angeles River. “It was a shock because I was suddenly entering the art world at this super serious level,” Macías said. “Like, I uploaded the photos, and the next thing I knew I was in the Whitney.” Inside Esparza’s rotunda, Macías hung five closely cropped photos of masculine young men. All make eye contact with the camera but with subtle gestural differences that elude interpretation even as they invite it. In one image, a man in an orange reflector vest and hard hat peers over his right shoulder as if the photographer had just called his name. It’s a psychic glimpse of someone who might otherwise appear as an anonymous construction worker.

“He sees us often times before we even see ourselves. He makes us feel worthy of the space in photography that has historically prioritized white bodies.”

But the Whitney presentation didn’t exactly catapult Macías into art-world fame. He was busy with his day job, building an agency roster and directing surreal, often conceptual, fashion shoots for magazines like Vogue and i-D. Then in early 2020, he received an email from Paulina Lara at LaPau Gallery, an unpretentious new space in the back of a Los Angeles office building. Lara wanted to mount his first solo exhibition in the US, with highlights from his Instagram project. The only issue was that Macías was sitting on, by his estimate, roughly twenty hard drives of photos and videos that had to be pared down. At first, he thought of papering the gallery’s walls with images, like posters in a teenager’s bedroom, but he realized that was too chaotic. “So I decided to give them a sense of what the Mexicano project is like for me,” he says. “I recreated what it’s like for me to come home, put on music, roll a joint, and go through the photos I took that day.”

Installation view of Dorian Ulises López Macías, Hasta Que Te Conocí (Until I met you), LaPau Gallery, Los Angeles, 2022. Photograph by Monica Orozco

Installation view of Dorian Ulises López Macías, Hasta Que Te Conocí (Until I met you), LaPau Gallery, Los Angeles, 2022. Photograph by Monica OrozcoIt took him a year to edit a one-hour slideshow called Hasta Que Te Conocí (Until I met you) (2022), which from last March to May played on a floor-to-ceiling monitor in the dark, diminutive gallery, set to a soundtrack of high-intensity techno—what he listens to while working. The final selection isn’t just a group of lusty photos of butch guys, though there are occasional flashes of homemade pornography. Most of the material is actually quite wholesome, especially his reports from Mexico City Pride parades, which show the seemingly infinite ways of being queer and Mexican. Macías also included dispatches from his travels around Mexico, which document the diversity of its regional customs and characters, from the Afro Mexican surfers of Chacahua to the rodeo cowboys of Aguascalientes. He has a knack for creating family portraits that show what love and care look like outside the Americanized model of middle-class success; his tender shots of men riding with their sons on their bicycle racks or handlebars are an antidote to the media’s tendency to pathologize poverty. “My dream is to take the photo for every Mexican’s ID card,” he says, laughing.

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Agusacalientes, 2015, from the series Mexicano

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Untitled, Agusacalientes, 2015, from the series MexicanoRecently, Macías’s personal and commissioned projects have started to converge. His latest editorial for i-D, Mexicano Americano, uses both Mexican and Mexican American models to illustrate the ties that bind homeland and diaspora. Shot in New York, Los Angeles, and Mexico City, it’s styled with oversized jackets, baggy pants, and other items by designer Willy Chavarria that nod to the sartorial innovations of working-class Chicanos in the US. “Dorian makes us feel beautiful,” Esparza, who modeled for the shoot, wrote in a heartfelt statement on Instagram. “He sees us often times before we even see ourselves. He treats us with integrity, respect and adoration. He values us. He makes us feel worthy of the space in photography that has historically prioritized white bodies.”

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Mexicano Americano, 2022

Dorian Ulises López Macías, Mexicano Americano, 2022All photographs courtesy the artist

As satisfying as a project like this is for Macías, nothing feels as good as flying solo—stepping out the door and chasing his intuition through the city. “At the end of a day,” he tells me, “I love fashion because it’s something I do with my friends. I always enjoy it, even if it’s for a commercial campaign. But there’s never a moment I enjoy as much as when I step off set to take a portrait of a subject I spotted from a distance.”

August 4, 2022

The Monumental Films of Wang Bing

In 2003, the Chinese filmmaker Wang Bing, then an unknown graduate of the Beijing Film Academy, debuted a durational colossus: West of the Tracks, a nine-hour document of industrial decline in the Tiexi factory district of Shenyang Province. Amassed over four years with little more than an amateur video camera and faith in the instructive texture of reality, West of the Tracks found a new form for the chasmic infrastructural changes of post-Socialist China.

Wang Bing, Stills from West of the Tracks, 2003

Wang Bing, Stills from West of the Tracks, 2003

Immense run times and handheld spontaneity have come to define most of Wang’s subsequent films, each teeming with the minutiae of daily subsistence in various pockets of regional China. Although Wang is attuned to the present, his work is always marked by a broader intuition of historical process and state-led economic restructuring. His subjects have spanned the extractive labor of oil-field workers on the Tibetan plateau in Crude Oil (2008), the carceral optics of a psychi- atric institution in Yunnan Province with ’Til Madness Do Us Part (2013), and, in 15 Hours (2017), the conditions of migrant workers at a children’s garment factory in Zhejiang Province.

Wang Bing, Still from 15 Hours, 2017

Wang Bing, Still from 15 Hours, 2017Last fall, these latter two films, along with West of the Tracks; Man with No Name (2010); Father and Sons (2014), which follows the solitary days of a migrant worker’s unsupervised children; and a shorter piece, Traces (2014), were screened as multichannel video installations at Le Bal, a photography space in Paris, in a solo exhibition titled The Walking Eye. For a filmmaker who seems so steadfast in his outward orientation to the world, it’s striking how often he has invoked a vivid subjectivity to describe his output. As Wang recalls about the early days of making West of the Tracks: “I wondered how I could create . . . something singular, something personal.”

Installation view of Wang Bing: The Walking Eye, Le Bal, Paris, 2021. Photograph by Marc Domage

Installation view of Wang Bing: The Walking Eye, Le Bal, Paris, 2021. Photograph by Marc DomageAcross a two-decade oeuvre laden with the heterogeneous rhythms of life in contemporary China, what is “personal” in Wang’s work is not its proximity to his own biography but to a deeply embodied experience of discovery made possible by his filming. Wang seems prone to self- effacement—no on-screen appearance; only the rarest flashes of his voice as interlocutor—but his physical presence is both anchor to and genesis of every film. Even as he enlists a stray assistant here and there, Wang is the very force that walks the camera’s unblinking eye.

Wang Bing, Still from Man with No Name, 2009

Wang Bing, Still from Man with No Name, 2009Against his categorization as a maker of documentaries, Wang has stressed a different impetus: “The most important thing for me is to film people and to understand why and how I film them. Whatever story and whatever kind of cinema that may produce.” Wang’s films exceed the mere accrual of information. We learn, for instance, that the metal- workers in West of the Tracks undergo mandatory hospitalization to treat the lead that has leeched into their bodies. Where another filmmaker might briefly limn this as a sobering medical fact, Wang lingers on the eventless days of he workers’ confinement, as they sing karaoke together in scantly furnished rooms, lounge and rove listlessly through hospital halls awaiting their release.

Installation view of Wang Bing: The Walking Eye, Le Bal, Paris, 2021. Photograph by Marc Domage

Installation view of Wang Bing: The Walking Eye, Le Bal, Paris, 2021. Photograph by Marc DomageIn the usual context of their single-screen display in cinemas, the audience is asked to move through factories and fields, following a figure from behind or stuck to whichever lone purview Wang has framed. But the multiscreen installation of The Walking Eye alters the experience. Of the five films in the exhibition at Le Bal, only Father and Sons was screened in its entirety; the others were presented as curated sequences approved by Wang himself, split across two or more screens. If the theatrical presentation of Wang’s filmmaking invites a kind of temporal immersion into one monumental trajectory, their multiplied projection in the gallery seems to pull apart their layered rhythms, as if to unveil all the dense strata that comprise any given moment in history.

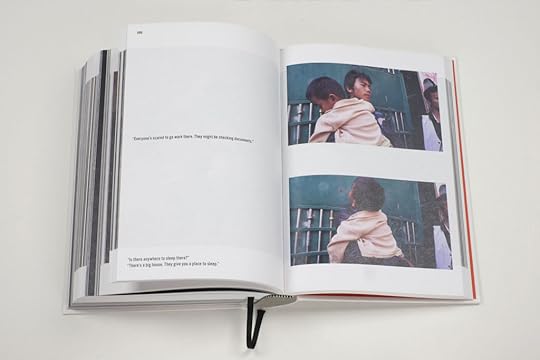

Spread from Wang Bing: The Walking Eye (Roma Publications, 2021)

Spread from Wang Bing: The Walking Eye (Roma Publications, 2021)All works courtesy the artist and Galerie Paris-Beijing and Galerie Chantal Crousel

There is a similar effect in The Walking Eye, the eponymous book published by Roma Publications for the exhibition. Of its over eight hundred pages, more than seven hundred display stills and translated text from eight of Wang’s films. Most of these are single images that bleed across two pages, sandwiched like centerfolds, or vertically stacked, two stills to a page. Some are further miniaturized and arrayed as four—maybe six, maybe eight—frames in quick succession, trained on the unfolding of a specific scene. Any print-based documentation of moving-image work is fated to stasis, but the unusual heft of The Walking Eye is, admittedly, confusing. Why freeze and compile thousands of images from a filmmaker who has said, in an interview closing this very book, “I conceive of the camera as the instrument of movement”?

These arrested frames risk turning real-time discovery into fixed curios of an ethnographic other. Wang knows that the “movement” of a world as it becomes known—as it draws us into its opening— cannot be pinned down and collected. If anything, The Walking Eye in book form shows us the limits of fixing moving-image art on the printed page and, in the end, the power of Wang’s films in motion.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the column “Viewfinder.”

July 28, 2022

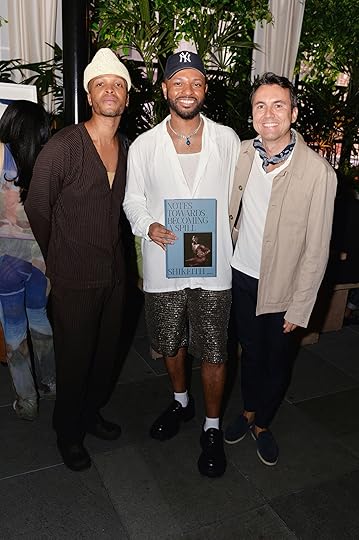

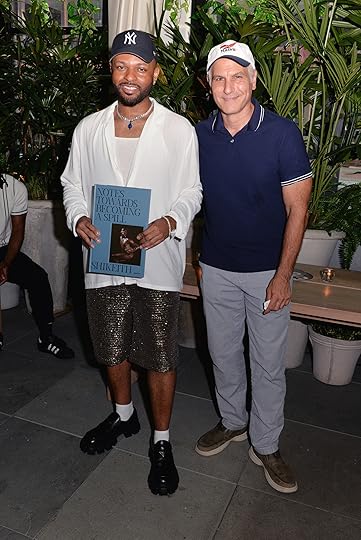

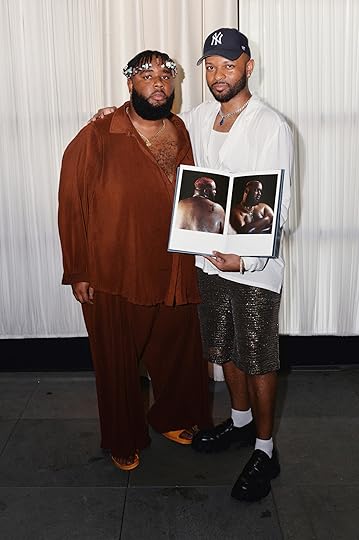

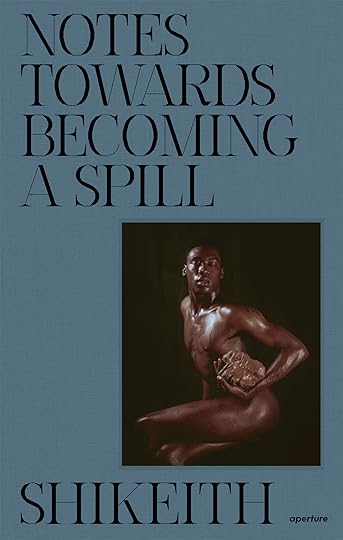

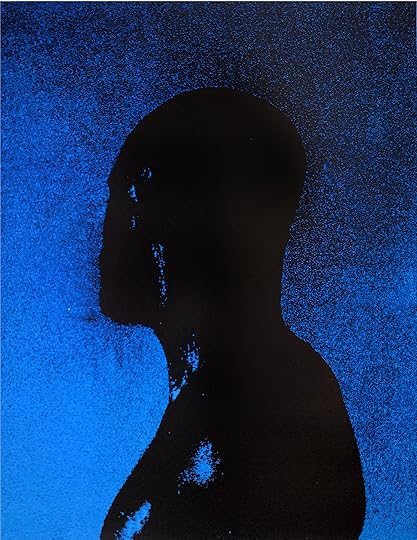

A Look Inside the Launch Party of Shikeith’s Debut Monograph

On July 25 Aperture hosted a special book launch at The Times Square EDITION in partnership with Jack’d to celebrate the launch of Notes towards Becoming a Spill, the first monograph by multimedia artist Shikeith.

The intimate celebration featured an evening of cocktails and hors d’oeuvres alongside a lively DJ set by BMAJR. As part of the event, a newly released limited-edition silkscreen print by Shikeith was installed for viewing, alongside complimentary editions of Aperture magazine.

In attendance to celebrate were curator and critic Antwaun Sargent, Aperture’s executive director Sarah Meister, Aperture Board Trustee Michael Hoeh, designer Rush Jackson, Ian Bradley, Prince Adams, Jahvaris Fulton, Jakeem Powell, Angel Glasby, and many more. Shikeith called the gathering “a truly lovely night.”

Shikeith with guests

Shikeith with guests  Angel Glasby

Angel Glasby  Ty Sherman, Prince Adams, Derrick Sanders

Ty Sherman, Prince Adams, Derrick Sanders  Angel Glasby, Maxi Canion

Angel Glasby, Maxi Canion Antwaun Sargent, Shikeith, Andrea Franchini

Antwaun Sargent, Shikeith, Andrea Franchini Book Launch in partnership wtih Jack’d

Book Launch in partnership wtih Jack’d  Shikeith, Michael Hoeh

Shikeith, Michael Hoeh  Rush Jackson, Kailee Faber

Rush Jackson, Kailee Faber  Shikeith signs editions of his monograph Notes towards Becoming a Spill (Aperture, 2022)

Shikeith signs editions of his monograph Notes towards Becoming a Spill (Aperture, 2022) Miranda Barnes, Shikeith, Rahim Fortune

Miranda Barnes, Shikeith, Rahim Fortune  Ian Bradley, Shikeith

Ian Bradley, Shikeith  Lesley Martin, Michael Hoeh, Sarah Meister

Lesley Martin, Michael Hoeh, Sarah Meister  Isabelle McTwigan, Steven Chaiken, Anna Eisenhour, Kevin Doyle

Isabelle McTwigan, Steven Chaiken, Anna Eisenhour, Kevin Doyle  Shikeith, Bradley Hill

Shikeith, Bradley Hill  DJ BMAJR

DJ BMAJR  Chivas Michael, Jakeem Powell, Shikeith, Israel Erron Ford

Chivas Michael, Jakeem Powell, Shikeith, Israel Erron FordAll photographs by Christos Katsiaouni, July 25, 2022

Related Items

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill

Shop Now[image error]

Hazy Blues, 2022

Shop Now[image error]Book launch made possible by Jack’d and The Times Square EDITION.

For a pro-account on Jack’d use promo code “APFDN2022.”

Shikeith: Notes towards Becoming a Spill was made possible, in part, by leadership support from Arts, Equity, & Education Fund and the 7G Foundation, and by the generosity of Michael Hoeh.

July 26, 2022

Sibylle Bergemann’s Striking Photographs of Postwar Germany

The Sibylle Bergemann retrospective at the Berlinische Galerie—an institution focused on art made in Berlin in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—aligns the late German photographer’s work with a particular haltung. While that word translates directly to “attitude,” the German is more expansive in conveying a way of relating to something, describing a kind of inner compass that guides thoughts and actions. In the myriad photographs that comprise Town and Country and Dogs: Photographs 1966–2010, something in the quality of Bergemann’s observation, whether for a fashion editorial, commissioned reportage, or her own projects, lends the images a palpable coherence. A quiet sensibility, subtler than style, imbues the works on view, and is bolstered by her continuous return to several motifs: women (self-possessed, often in center frame); juxtapositions between remnants of demolished East Berlin and new architectural constructions; and windows, dogs, and people on the move.

Sibylle Bergemann, Unter den Linden, Berlin, 1968

Sibylle Bergemann, Unter den Linden, Berlin, 1968 Sibylle Bergemann, Moscow, 1974

Sibylle Bergemann, Moscow, 1974 Sibylle Bergemann, Caravan Exhibition, Berlin, 1980

Sibylle Bergemann, Caravan Exhibition, Berlin, 1980Bergemann’s mode of documenting—and implicitly addressing—the world around her developed out of the political context of the German Democratic Republic. The native Berliner was just twenty years old when West Berlin was sealed from the East by a wall in 1961 that prevented passage between the regions. While state-sanctioned photography glorified happy workers in vibrant color, Bergemann’s photography stood adjacent to such posturing. Alongside a few other photographers, including her future husband, Arno Fischer, Bergemann formed Gruppe Direkt in 1965, a collective that articulated its members’ principles of free observation. Their preference for black-and-white photography may have been a question of access (color film, like much else, was hard to come by in the GDR), but it also accentuated the contrast between their images and those produced by the state.

Sibylle Bergemann, Marisa and Liane, Sellin, 1981

Sibylle Bergemann, Marisa and Liane, Sellin, 1981The group’s divergence in style and subject matter was largely subtle enough to avoid censorship. However, Bergemann’s Marisa und Liane, Sellin (1981)—a photograph of two women in black racerback dresses beside a row of beach cabanas on the island of Rügen—was edited before it ran in the popular fashion magazine Sibylle: the printer manually retouched the blonde’s scowl to turn her lips up into a smile. The original photo, with the woman’s arresting glare, would become one of Bergemann’s most iconic images and was prescient in tapping into a burgeoning sense of discontent in the GDR.

Another of Bergemann’s most striking images also took on a sense of meaning beyond its original context from February 1986. The image shows a life-size bronze statue of Friedrich Engels, coauthor of The Communist Manifesto, and was made as part of her series Das Denkmal (The Monument) (1975–86), a commission from the East German Ministry of Culture to document the creation of the Karl Marx and Engels monument in Berlin’s Mitte district. Bound in rope, the statue is suspended at a seemingly precarious angle as it is lowered to the ground. The monument bisects the picture plane on a diagonal, while several GDR buildings, including the TV tower that had been built as a symbol of Communist power twenty years prior, hug the corners of the frame.

Sibylle Bergemann, Das Denkmal, Berlin, February 1986

Sibylle Bergemann, Das Denkmal, Berlin, February 1986 Sibylle Bergemann, Birgit, Berlin, 1984

Sibylle Bergemann, Birgit, Berlin, 1984When the wall came down a few years later, Bergemann’s image began to circulate, mistaken as a depiction of the statue’s removal, rather than its installation. (It still stands, beside the seated Marx, in Berlin’s Mitte district.) The mix-up is emblematic of how Bergemann was able to work within, and quietly transcend, the parameters of her commissions. While securing significant opportunities—notions of women’s role in society were relatively progressive in the GDR, particularly compared to West Germany—Bergemann also cultivated a moving visual language. Nine photographs from The Monument series are hung in a grid in the exhibition in Berlin, concluding with the image of the dangling statue. The photographs seem like a study of tones of gray, as Bergemann captures the monument as a work in progress in sequential moments that are anything but grandiose.

Sibylle Bergemann, Nina and Eva Maria Hagen, Berlin, 1976

Sibylle Bergemann, Nina and Eva Maria Hagen, Berlin, 1976 Sibylle Bergemann, Niederlande, 1986

Sibylle Bergemann, Niederlande, 1986 Sibylle Bergemann, Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, 1989

Sibylle Bergemann, Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, 1989Bergemann’s reportage of mounting protests in East Berlin in the weeks before the fall of the wall and the commotion after its toppling are similarly understated. In a small black-and-white photograph titled Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin (1989) she captures a procession of people carrying white candles alongside the elevated railway at Schönhauser Allee. In a another photograph, she lingers on the vacant street after the vigil: the arches beneath the train tracks, spindly winter trees, and several white candles left standing at the edge of the sidewalk. The image appears like a haunting harbinger of the streets that would soon be emptied as scores of East Berliners traversed the breached wall. It is also perhaps an elegy for what the socialist state might have been, in line with writer Christa Wolf’s declaration in her famous speech a few days before the wall toppled: “Revolutions happen from the bottom up . . . Let’s dream with our eyes wide open. Imagine this, it is socialism and no one wants to leave.”

Sibylle Bergemann, Shibam, Yemen, 1999

Sibylle Bergemann, Shibam, Yemen, 1999 Sibylle Bergemann, Bassé, Île de Gorée, Senegal, 2010

Sibylle Bergemann, Bassé, Île de Gorée, Senegal, 2010But leave they did, including Bergemann, who namely went on far-flung international travels to Yemen, Portugal, and Senegal, on assignment for GEO magazine. The photographs taken on these trips until her death in 2010 conclude the exhibition, bringing Bergemann’s perspective into color and turning it toward the world at large. A group of photos from her 1999 trip to the mudbrick town of Shibam in Yemen is particularly stirring, as Bergemann carefully developed the images herself in the darkroom, drawing out numerous tones of beige, white, and pale pink. But Berlin remained her greatest muse, and she always eagerly returned home to document its ever-changing face. As such, this exhibition functions like a window not only into history, but also into the present, underscoring Berlin as a city where the past hangs close to everyday life.

Sibylle Bergemann: Town and Country and Dogs, Photographs 1966–2010 is on view at the Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, through October 10, 2022.

July 20, 2022

How Lee Miller Out-Surrealed the Surrealists

“One could say that Lee’s feel for the incongruities of daily life made her a Surrealist,” writes Lee Miller’s biographer, Carolyn Burke. Although she was never an official member of the group (according to Burke, she couldn’t abide André Breton), her feeling for incongruity and unexpected juxtapositions, for dreamlike imagery and tears in consciousness, her ability to perceive instabilities in apparently ordinary scenes, and her ethical commitments to getting the picture against all odds make her one of the movement’s great photographers.

Miller was surrounded by Surrealist men in both her personal and professional lives. Her mentor turned lover, Man Ray, introduced her to Surrealist art and artistic circles in late 1920s Paris; she starred in Jean Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet (1930); her second husband, Roland Penrose, was an established practitioner of Surrealism in Britain and later a cofounder of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. But while these influences were important to her, Miller had her own decided view of the world. “I think she’s a Surrealist from the beginning to the end,” says Patricia Allmer, author of Lee Miller: Photography, Surrealism, and Beyond (2016).

Lee Miller, Nude bent forward (thought to be Noma Rathner), Paris, ca. 1930

Lee Miller, Nude bent forward (thought to be Noma Rathner), Paris, ca. 1930In The Lives of Lee Miller (1985), recently rereleased in paperback, her son, Antony Penrose, depicts his mother as a woman who bolted from adventure to adventure, who “rode her own temperament through life as if she were clinging to the back of a runaway dragon.” Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907, Miller got started with photography by having her picture taken hundreds of times—often nude—by her father, an amateur photographer with a darkroom tucked under the stairs of the family house. She continued modeling as a young woman in New York City, appearing on the cover of the March 1927 issue of Vogue within months of her meet-cute with Edward Steichen of Condé Nast (she stepped in front of a moving cab; he yanked her out of harm’s way). She became one of his favorite models. In Steichen’s viewfinder, Miller looks modern and eternal at the same time—Baudelaire’s own definition of beauty. However, as Miller herself would later recall, “I looked like an angel, but I was a fiend inside.”

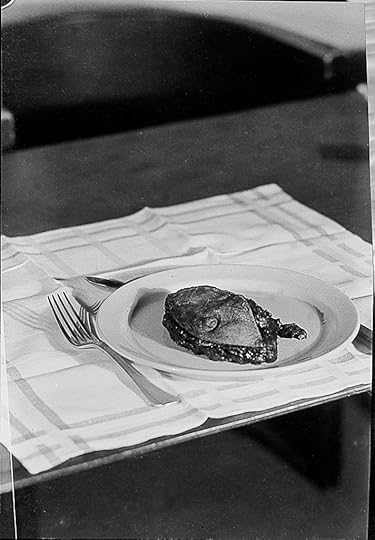

The angel paid the bills, but the fiend wanted to hold the camera herself. In 1929, she got on a boat and tracked down the photographer Man Ray in Paris. “I’m your new student,” she told him. He didn’t take students, but he took her. For three years, they lived and worked together; Miller learned everything she could about making and developing pictures. He would sometimes pass assignments to her; as the story goes, Miller was at the Sorbonne medical school photographing something for Man Ray when she witnessed a mastectomy procedure. She took the severed breast to the offices of Vogue and photographed it on a dinner plate before she and the breast were thrown out.

Lee Miller, Untitled (Severed breast from radical surgery in a place setting 1), Paris, ca. 1929

Lee Miller, Untitled (Severed breast from radical surgery in a place setting 1), Paris, ca. 1929Miller’s Surrealism has to do with her ability to look “awry” at the world, says Allmer. For instance, there is the striking image of a woman’s hand reaching for the doorknob as seen through the scratched shop window at Guerlain, which Miller calls Untitled (Exploding Hand) (ca. 1931). She captures otherwise imperceptible moments like this and, in spite of their ordinariness, finds great drama. There is an element of chance in this picture, but there is also an alertness to the potential readings of the work that is all her own.

By contrast, a studio image such as Nude Bent Forward (ca. 1930) clearly involved planning and forethought to set the camera and the lighting in just the right way so that when the model leaned over, naked, her torso would fill the frame, arms and neck cut off, the lower half of her body seeming to disappear into the shadows below. As Mary Ann Caws, author of Surrealism (2004), writes, the composition creates “the disquieting effect of making the body appear gradually to be dissolving.”

Lee Miller, Untitled (Exploding Hand), Guerlain Parfumerie, Paris, ca. 1931

Lee Miller, Untitled (Exploding Hand), Guerlain Parfumerie, Paris, ca. 1931The female body—so fetishized in Surrealist art—is almost unrecognizable in Nude Bent Forward. That we are looking at a body is clear; the grain of the skin has been beautifully, duskily rendered. But it is also contorted beyond recognition; there is something troubling in its visceral ambiguities.

In 1934, having left Man Ray and resettled in New York to start her own studio two years prior, Miller married the Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey, eventually moving with him to Cairo. The time she spent in Egypt was crucially important to her development as a photographer. In Portrait of Space (1937), her Surrealist gaze could see a whole world of suggestion in the torn and tattered mosquito net, the tent’s window seeming to hang askew like an empty frame. The scholar Katharine Conley writes in Surrealist Ghostliness (2013) that the emptiness of this frame “resembles the ‘unsilvered glass’ of Breton and Soupault’s Magnetic Fields that metaphorically divides a body’s psychic unconscious from consciousness, separating outer from innermost realities.”

Miller’s Surrealism has to do with her ability to look “awry” at the world. She captures otherwise imperceptible moments and, in spite of their ordinariness, finds great drama.

Allmer points out that Miller is present in the form of a shadow in many works from this period—in a photograph of Deir el Soriani Monastery in Egypt about 1936; in one taken from the top of the Great Pyramid of Giza about 1937 (a shadow within a shadow); in the image of Eileen Agar looking pregnant with her camera at Brighton Pavilion in 1937. The shadow is a supremely Surrealist motif, “simply an effect,” Allmer writes, “always in flux.” Or, as the writer Pierre Mac Orlan put it in 1930, with reference to Eugène Atget’s Paris scenes, “Photography makes use of light to study shadow. It is a solar art in the service of night.” Solarization would also be one of Miller’s great contributions to Surrealist photography—it was Miller and Man Ray who discovered what could happen if the lights were suddenly turned on during the development process: the tones reverse, and a ghostly outline forms. Man Ray would create a solarized portrait of Miller in profile, appearing like an electrified angel.

Lee Miller, From the top of the Great Pyramid, Giza, Egypt, ca. 1937

Lee Miller, From the top of the Great Pyramid, Giza, Egypt, ca. 1937All photographs © Lee Miller Archives, England

Allmer considers this interest in the shadow, and a willingness to include herself in the image, an important part of the ethical charge of Miller’s work: “Perhaps, if you’re a photographer, and you are there in these really traumatic situations, you are part of this story and not detached from it.” Miller’s involvement in world events was confirmed during World War II, a time when most of her Surrealist group (Breton and Man Ray among them) fled to the United States to escape the violence. (So much for Surrealism in the service of the revolution.) Miller, on the other hand, stuck it out in London, where she moved after Egypt to be with her second husband, Roland Penrose, surviving the Blitz and the constant threat of annihilation. She even put herself on the front lines of the U.S. invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe in 1944.

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]In Cocteau’s The Blood of a Poet, a title card declares that the poet composes “a realistic documentary of unreal events.” Miller’s work in the war strikes me as a Surrealist corollary to that statement, a surreal documentary of real events. In wartime London, Miller photographed the destruction caused by the Blitz. Her eye was trained to see the uncanny qualities in the fragments of the city she encountered; she out-surrealed the Surrealists.

“She finds the battered typewriter or the mannequin standing in the street corner or the window blown in such a way that the glass makes a pattern. She’s just constantly looking for the concretization of dreams,” Antony Penrose tells me. “That’s what she’s finding.” One such example is of a stone angel, fallen to the ground with her neck severed by a metal bar, a brick smashing her breast. Miller called it Revenge on Culture (1940). “Who is taking the revenge?” asks Caws, the author of Surrealism, when we speak. “She was taking her revenge on us for not knowing whose revenge it was or why . . . and which culture, of course. Everything about that particular image says to me that’s why she’s a Surrealist.” Miller’s wartime photographs would appear in a book called Grim Glory: Pictures of Britain Under Fire (1941), published so that U.S. audiences an ocean away from the conflict could appreciate the terrifying realities of life during the Blitz.

Although her accreditation did not permit her to report from combat zones, Miller found herself in Saint-Malo for the Allied offensive and, staying on with the infantry, was among the first people let into Dachau and Buchenwald after they were liberated. The image of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub is well known (taken in collaboration with David E. Scherman), but the photographs that she made as the concentration camps were liberated are among the most haunting and disturbing documents of the war.

Lee Miller, Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, near Siwa, Egypt, 1937

Lee Miller, Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, near Siwa, Egypt, 1937Suffering from alcoholism and probably post-traumatic stress disorder after her return home, Miller lost the desire to keep taking photographs. Production eventually slowed to such a point that her son didn’t realize the “extent” of what she had made, the “depth and penetration” of her wartime work.

Miller, who in 1966 became Lady Penrose when Roland was knighted for his services to art, threw herself instead into cooking, training at Le Cordon Bleu London and taking great pride in whipping up the most original, surreal dishes she could: Her son remembers being served blue spaghetti and pink breasts made of cauliflower with cherry tomatoes for nipples. Her recipe for chicken was prepared with so many herbs it turned green. Miller’s cooking is often underappreciated as an important continuation of her Surrealist work—it’s domestic, it’s fleeting, and it’s not war photography, after all. But it was just as much about unsettling people’s received ideas about how the world should be. A Surrealist from beginning to end.

July 15, 2022

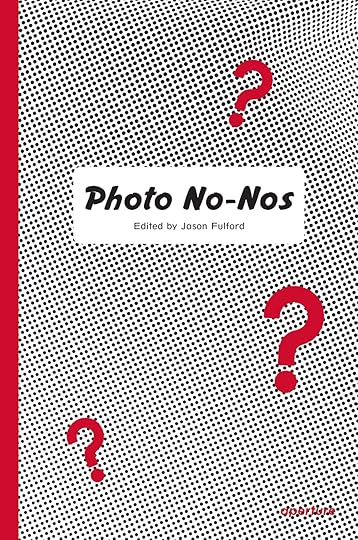

13 Photographers on Their “Photo No-Nos”

What is a “photo no-no”?

Edited by Jason Fulford, Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph (Aperture, 2021) brings together ideas, stories, and anecdotes from over two hundred photographers and photography professionals. Not a strict guide, but a series of meditations on “bad” pictures, it covers a wide range of topics, from sunsets and roses to issues of colonialism, stereotypes, and social responsibility.

At turns humorous and absurd, heartfelt and searching, this encyclopedic volume offers a timely and thoughtful resource on what photographers consider to be off-limits, and how they have contended with their own self-imposed rules without being paralyzed by them.

Below, read excerpts from thirteen artists featured in Photo No-Nos.

Guido Guidi, Passo del Muraglione, 1983

Guido Guidi, Passo del Muraglione, 1983Courtesy the artist

Beautiful Landscapes Seen from Above & from Afar, Guido Guidi

I think most subjects are easily photographable a priori, before observation, and this leads to an annoying proliferation of certain subjects. I would add that the real problem is not the subject, but the way you deal with it. If I had to indicate a subject that I usually avoid, I would say beautiful landscapes seen from above and from afar; perhaps because of the strong myopia that has affected me since childhood. I want to believe that for this very reason, as well as in homage to Eugène Atget, I have become a partisan of the close-up view.

I am wary of categories and subjects constructed from a distance or a priori; they are incompatible with the close-up gaze.

Mimi Plumb, Family by the Side of the Road, 1975

Mimi Plumb, Family by the Side of the Road, 1975Courtesy the artist and Robert Koch Gallery

Car Pictures, Mimi Plumb

I didn’t avoid taking car pictures. My archive is full of them. But I didn’t fully realize the prevalence or richness of those images until I scanned my archive on retiring. The car, in my work, epitomizes the desire for the American dream or symbolizes our degradation of the environment. I try never to stop myself from photographing subjects that are interesting to me. Yet this question of what I avoid photographing, regrettably and sadly, reminded me of a time when I implored my students not to make the car picture. It was likely that cliché picture that I wanted them to avoid, the car as a symbol of status and wealth. Boy or girl standing proudly next to their car in the late afternoon light. Their self-portrait and their desire to be part of the American dream. I think now of the pictures lost in their photographic archive due to my shortsightedness, and my bias. Likely, hopefully, they were smart enough not to listen to me.

Michael Northrup, Tire Fire, 1981

Michael Northrup, Tire Fire, 1981Courtesy the artist

Color as a Subject, Michael Northrup

In 1980, I was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and, like most photo programs at the time, they were opening up to the new color processing kits. I wanted to photograph in color, but after shooting black-and-white for ten formative years, I was way over-self-conscious about it. I started shooting red fire hydrants and yellow curbs. And I was bored to death. A visiting artist recognized this and told me, “Just shoot like you always did in black and white. Don’t think of color.” I think that was the best advice I received in my entire photo-education. Sometimes big problems have simple solutions.

Ricardo Cases, El Blanco, 2016

Ricardo Cases, El Blanco, 2016Courtesy the artist

Distant Cultures, Ricardo Cases

Normally, I don’t even feel that I can legitimately speak about my own neighbor—and this difficulty increases the farther I get from my house, my neighborhood, the suburbs surrounding my city, and, more concretely and by extension, Spain’s Mediterranean coast. I am not attracted to the Iguazú Falls or the peculiar and ancestral diet of the inhabitants of Papua New Guinea. My game is local. My work explores familiar situations, and to do them justice, I need the tools that only someone in everyday contact with that cultural environment can possess. This is why I don’t need to get on an airplane to take pictures. On the contrary, it makes more sense for me to go for a walk or get on my bike with my camera.

“To each their own,” as they say. At this point in my life, I know that my emotions are transformed when I recognize things.

Shane Lavalette, Untitled, 2016, from the series Still (Noon)

Shane Lavalette, Untitled, 2016, from the series Still (Noon)Courtesy the artist and Robert Morat Galerie, Berlin

Hands, Shane Lavalette

In photographs, hands are always alluring. They can be so beautiful in a way that feels timeless, sculptural, even transcendent, though often, all too easily cliché.

At one point, hands became a subject that I felt I may have overphotographed and therefore, should avoid for a while. But after a few years of practicing this arbitrary avoidance, I allowed myself to again appreciate the endless possibilities of a gesture—and, in doing so, I made one of my favorite images.

Whether we photograph them or not, sometimes it’s the very subjects that we tell ourselves to avoid that are worth returning to in order to try and see them differently and, perhaps, more deeply.

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, 1/2 Charity Street, 2014

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, 1/2 Charity Street, 2014Courtesy the artist

Houses, Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

I developed a fascination with looking at American houses when I came to the States for graduate school in 2012. I was dumbstruck by the homogeneity of their design, and read an interesting essay about the propagation of this one ubiquitous style of suburban house in D. W. Meinig’s anthology The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes (1979), which intrigued me. But I was also fascinated by the way that they so often pointed to a particular history of American expansion that (to my untutored eyes) evokes wagon trains and the “open” frontier, and that sublimates settler-colonial violence under an aesthetic of humble domesticity. I gradually realized that photographing houses was not only pleasurable, but also served as a means of deferring having to make other kinds of pictures—a means of keeping people at a certain distance—or as a way of avoiding having to knock on people’s doors, so I forbade myself the freedom to make pictures of houses. Bit by bit, the other pictures began to change and improve as a result of the constraint.

Erica Deeman, Untitled 2 (Self-Portrait During COVID 19 Quarantine), 2020

Erica Deeman, Untitled 2 (Self-Portrait During COVID 19 Quarantine), 2020Courtesy the artist and Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco

Me, Myself, & I, Erica Deeman

Honestly, I never thought I would be the photographer to turn the camera on myself—never, not once. I have found a deep joy in collaboration, making portraits with the people generous enough to give me their time and energy. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the camera and the power it holds, and the care that I’ve taken (and continue to take) in making my work. It never crossed my mind to apply that care and time, holding the camera up to myself. Something switched for me in 2019, almost like a snap of the fingers. I had this desire to see who I was becoming since moving to the United States. So I tentatively began making self-portraits, though

I didn’t intend to share them in a pure photographic form. Then COVID-19 happened, and the ability to work together with another human being became difficult and unsafe. Everything felt (and still feels) compounded. Here I was, in my home, and I knew that the one person I needed to collaborate with, commune with, share, and see, was myself.

Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, Untitled, 2014

Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira, Untitled, 2014Courtesy the artist

Open & Empty Fields, Karen Miranda-Rivadeneira

Empty fields fascinate me: big, open fields; misty fields; green fields. Whenever I’m driving, I feel the urge to stop and photograph them. I wonder about all the lives that have walked through them. I visualize multiple times—deep time, cyclical time, human time—converged and suspended. Giving in to my desire, I get out of the car. Then I remind myself that I have done this hundreds of times and that I never end up using any of these photos. I retrace my steps and continue my driving, until the following day, when the urge arises again.

Jeff Mermelstein, New York City, 1993

Jeff Mermelstein, New York City, 1993Courtesy the artist

Pigeons, Jeff Mermelstein

Quintessential New York creatures, resilient and filthy. Gray feathers with spats of purple and green. Wings flapping sound like rubber or people’s fat shaking. I can’t stop taking pictures of pigeons, really.

Pigeons feed my drive. Overdone, everywhere, again, the same. Avoidance, repeat, question, stop, no more, take another photograph, why not, I don’t know, really I don’t, and when I don’t really know I do know. Worst scenario, I’ll put it in a box.

I don’t think photographers can stop taking pictures of anything; we just may not show some of them. But then twenty-five years later, we might change our minds.

Max Pinckers, Performance #1, Los Angeles, 2018, from the series Margins of Excess

Max Pinckers, Performance #1, Los Angeles, 2018, from the series Margins of ExcessCourtesy the artist

Recycled Icons, Max Pinckers

Documentary photography has always contended with tension between form and content—the subject (and their agency) versus the visual qualities of the photograph itself. Constricted by the frame, photographs cannot escape the fundamental aesthetic conventions that govern it, and the subjects depicted in it cannot become unstuck from the frame. The danger is when visual tropes are arbitrarily applied to whichever subject in whichever situation, simply because of their effective visual rhetoric.

Documentary photography, and especially its cousin photojournalism, is dominated by these recognizable templates, a form of recycled iconography, casting the world in the same mold over and over again. You know them, perhaps unconsciously or by some kind of deeply engrained affinity: pietà figures, toys or shoes among the rubble, bodies emerging from the smoke, wailing women, faces half submerged in water, eyebrows peaking over the bottom of the frame, black silhouettes against brightly lit landscapes, hands displaying objects of interest, kids jumping in the water, feet dangling in the top of the frame, a bomb’s distant smoke-cloud rising above a city, close-ups of emotionally distressed people, photographs made through car windows or other frames within the frame. When applied, conformist aesthetics overpower the subjects depicted. This is when photographic conventions become self-referential instead of self-reflexive.

These types of images are published over and over again with maximum emotional impact, because readers can more comfortably identify with them than with images of the actual transgressive event.

Cristina de Middel, Untitled, 2018, from the series The Body as a Battlefield

Cristina de Middel, Untitled, 2018, from the series The Body as a BattlefieldCourtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Roses, Cristina de Middel

I do not want to be seen as a fragile and romantic person/woman in my work, so I just cannot take pictures of roses. And that’s that. The funny thing is that I absolutely love the smell of roses and wear that perfume a lot, but I try not to take any photos of them. Roses are so loaded with meaning; a picture of a rose is never neutral. They symbolize love and romance, passion and luxury, in cliché ways, and have even come to represent cliché itself. Roses also encapsulate most of the stereotypes for femininity from a masculine point of view: the passive-aggressive energy in the visible beauty versus the hidden spines, that idea of beauty that can hurt you, the trap of sensuality, the metaphor of blooming, the scent of a woman. A photo of a rose taken by a woman has a different meaning.

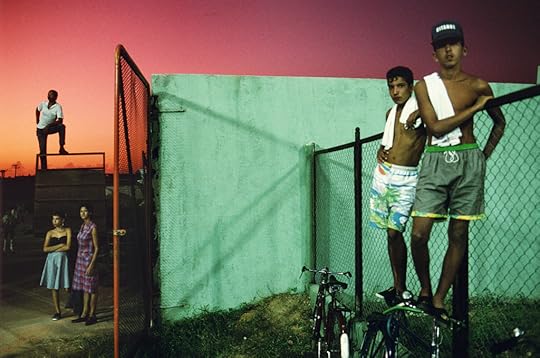

Alex Webb, Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, 1993

Alex Webb, Sancti Spiritus, Cuba, 1993Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

Sunsets, Alex Webb

Ever since I embraced working in intense, vibrant color in the late 1970s, I’ve had a deep ambivalence about photographing sunsets. While their otherworldly glow often seduces the eye, I find that another part of me viscerally resists their clichéd beauty. I remember showing Josef Koudelka an early color photograph of mine from Jamaica of a group of men in trees silhouetted against a brilliant orange sky at a Bob Marley concert. “Too sugar,” he said in his blunt Czech way. And he was right—but it wasn’t just that it was too sweet, it was too easy.

But every once in a while, I discover something that qualifies and complicates the one-note refrain of the setting sun: a mercury vapor lamp casting its greenish hues across baseball spectators in Cuba with a burning red sky behind, or the cold blue tones of a quay in Greece contrasting with the pinkish notes along the horizon. That’s when I leave my anxieties behind, and give myself permission to photograph the complex music of certain sunsets.

Kyoko Hamada, Yakuza, 1999

Kyoko Hamada, Yakuza, 1999Courtesy the artist

Yakuza, Kyoko Hamada

In 1999, while I was going to art school in New York, my father in Japan was diagnosed with terminal cancer. As a result, I’d go back to Japan every three months or so to visit him in the hospital. As a young photographer, I thought a lot about how to approach taking a picture of my fading father. The hospital was near Asakusa, Tokyo, and after these visits, I would roam the streets with my 35 mm camera, usually feeling very sad.

On one of these walks, I happened on a small back road where a group of policemen were hanging out smoking cigarettes. As I walked by, I saw a man lying on the ground in a fetal position. He was passed out with his eyes closed, facing the blue sky, drool dripping out of his mouth. The police weren’t paying him any attention, and a cleaning lady was busy trying to sweep the street around him. It was one of those social-journalism moments. I remember thinking that this was probably not the kind of picture I should take. I knew it wasn’t fair to the man on the street, whose life could be at its lowest point, and who was completely unaware of a girl with a camera observing and contemplating. Against my better judgment, I raised my camera and photographed the cleaning lady and the man on the ground. Then, unable to stop myself, I moved in closer to the fetus shape. His body contrasted with the dark asphalt in the bright daylight, and a water puddle reflected shiny light next to him. He looked like he was floating in a dark universe. As I framed my shot, I fantasized about making a contrasty print in the darkroom to accentuate this. I clicked the shutter and all of the sudden, I heard a deep, heavy voice right next to my ear. It said, “Hey, hey Jo-chan.”

My heart almost stopped. I slowly turned my head and a bald man with a toothpick sticking out of his mouth was staring right into my eyes. He smelled of strong cologne and cigarette smoke, and a colorful flower shirt was sticking out from under his dark pinstriped suit. His eyes were quietly fixated on my face. My brain just repeated the words, Shit, shit, shit. At the same time, I felt that I had to maintain eye contact with him. My heart was pounding, but I was trying not to show it. Then he quietly said, “There’s a photograph to take, and there’s a photograph not to take. Which one do you think this is?” Before I got a chance to respond, he quickly shifted from his threatening yakuza [gangster] character into a silly comedian and said, “Why don’t you take a picture of me? You don’t see too many good-looking gents like me around here!” With that, he struck a pose and waited for me to take a picture. So I did. Click. The yakuza nodded and seemed pleased that my attention had moved from the passed-out man on the street to him.

On the way home that day, I imagined having a drink of cold sake with the yakuza man. I wondered what he would have said about me taking a picture of my dying father in the hospital, plugged into all those tubes and the urinary drainage bag. “There’s a photograph to take, and there’s a photograph not to take. Which one do you think this is?”

Related Items

Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph

Shop Now[image error]

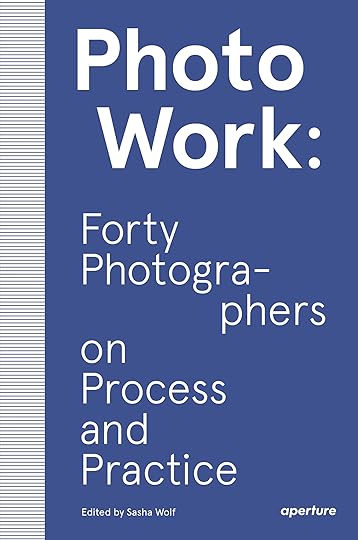

PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice

Shop Now[image error]This text originally appeared in Photo No-Nos: Meditations on What Not to Photograph (Aperture, 2021).

July 13, 2022

Collapsing Time in the Swedish Countryside

Photography is notable both for its ability to objectively witness, and, paradoxically, for its access to the surreal. Something beyond our control can happen after the lens closes. It might be a light leak, movement recorded as blur, some shadow unaccounted for. History is similarly ambivalent, an uneasy conglomerate of fiction and testimony, which often employs photography in staking its claims. It is precisely in the overlap between these two murky territories that Maja Daniels, a Swedish photographer based in London and Gothenburg, begins her work.

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019  Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019 To Daniels, the past is just as fictitious as the future. She leans into the all-too-human penchant for mythmaking and fantasy, our desire for saints and sorcerers and false closures. What becomes apparent is that history is a patchwork of stories and images, a condition that does not make it any less real. She looks for strangeness in what’s already there: “I take that something that must be in the water, and I run with it,” she told me recently.

One weird fish swimming upstream was Tenn Lars Persson, a mystic and photographer, whose early twentieth-century pictures of the Älvdalen region of Daniels’s grandparents have found a place among her own. They appear first, in her book, Elf Dalia (2019), clearly juxtaposed in dialogue, but also in her work as it has developed since. The photographs increasingly form a kind of synthesis; it becomes more and more difficult, and, perhaps, irrelevant, to say which belong to whom. Another example is Gertrud Svensdotter, a twelve-year-old girl, also in Älvdalen, who was thought to have walked on water in 1668, an event that ignited the Swedish witch hunts. Can we see in Daniels’s depictions of knobbly trees and people, shielding their eyes from the sun, some of the same magic and mystery that Persson portrayed a hundred years before? And in other little Älvdalen girls, a similar magnetic pull as Gertrud’s?

Tenn Lars Persson, Älvdalen (1878–1938)

Tenn Lars Persson, Älvdalen (1878–1938)

Courtesy Elfdalens Hembygdsförening (EHF)

Every one of Daniels’s photographs is something of a mystery. Subjects often turn their backs to her lens, or appear without the sort of context that might give us an idea of their purpose or location. An animal in a forest or in a child’s embrace; a collection of feathers held up against the light; a bonfire. About these individual images, we still have to ask what, who, where, why, but we can also expect the answers to refer, more or less, to the world as we know it. The greater mystery is in the space between them; how Daniels arranges her motifs to become part of a story.

Take the picture of a dragonfly on a tree stump, Persson’s one of three women and a child seen from a distance in a pine forest, and that of a green-haired, dog-eared figure, facing away. Look at those pictures all together, spaces included, and ask what the logic of the assemblage is. You’d be hard pressed to answer. Yet in trying to make sense of these fragments of narrative, the possibility of a whole other constructed world, another time opens up. We get the recipe for mythmaking, but without losing the allure of the myth itself.

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2020

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2020 Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019 Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2019 Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2021

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2021 Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2021. All photographs from the series On the Silence of Myth

Maja Daniels, Untitled, Älvdalen, 2021. All photographs from the series On the Silence of MythCourtesy the artist

Related Items

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking,” under the title “On the Silence of Myth.”

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers