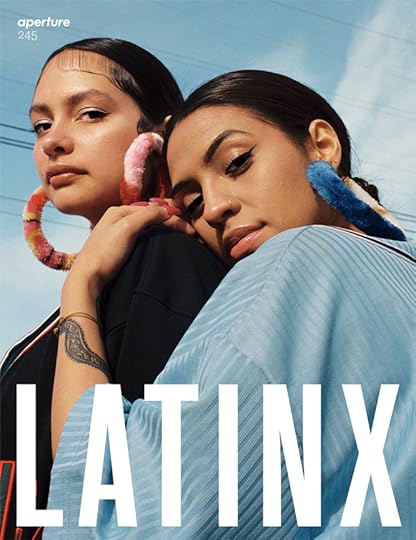

Aperture's Blog, page 38

September 15, 2022

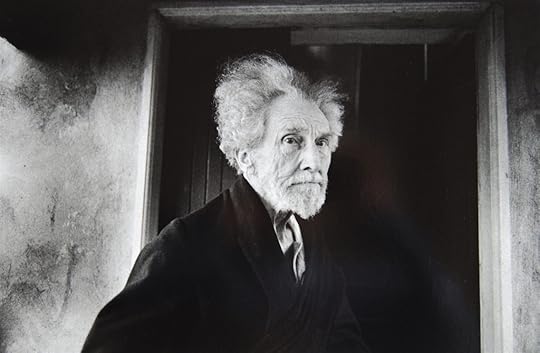

A Long Overdue Look at James O. Mitchell’s Expressive and Evocative Portraits

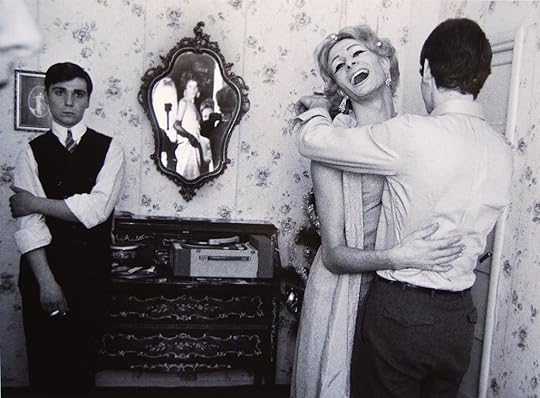

When Diane di Prima, one of the only female poets of the Beat Generation, passed away in October 2020, countless obituaries detailed her distinctive literary voice and her unwavering, often eccentric, view of the world. Remembrances were often illustrated with an introspective and somber portrait of di Prima—the same image that adorned multiple editions of her celebrated book Memoirs of a Beatnik (1969). Similarly, several anthologies on the Beat movement (including the catalogue for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1996 exhibition Beat Culture and the New America: 1950–1965) feature an image of Jack Kerouac smoking in a casually unbuttoned striped shirt on one of his more sober days. These portraits of di Prima and Kerouac appear to successfully capture the personalities of each writer at a pivotal era in their lives. What holds these two images of Beat icons in common? The inimitable person behind the camera: James Oliver Mitchell.

James O. Mitchell, Jack Kerouac, 1963

James O. Mitchell, Jack Kerouac, 1963At times credited as “Jim” or “James O.,” Mitchell was best known as a chronicler of writers in New York and San Francisco. He was obsessive and prolific, working with the photographic medium from age ten to eighty-seven. Yet his name is relatively unknown. The photography world has largely ignored him: a Black photographer with a fairly abrasive personality and an oeuvre that resists easy categorization. Despite his early accolades and impressive resume, he never published a monograph nor had a large-scale exhibition. He died in January 2021 in relative obscurity, only a few months after his friend di Prima.

I first learned of Mitchell’s work in 2019, when Lawrence Rinder, the former director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, mentioned he was considering acquiring Mitchell’s photograph of Diane di Prima. I later visited Mitchell in early 2020 and was welcomed into his Oakland, California apartment, a cramped space that was a splendor of floor-to-ceiling stacks of photography books, magazines, negatives, and prints. It quickly became clear that photography sustained him; his passion for and knowledge of the medium was a marvel, and he told stories of his career and artistry with intense vigor. Through our discussions, I was able to piece together his early years: especially the decades between 1960 and 1980, during which he formally trained in art schools, intersected with various creatives, and experimented with his photographic vision and printing.

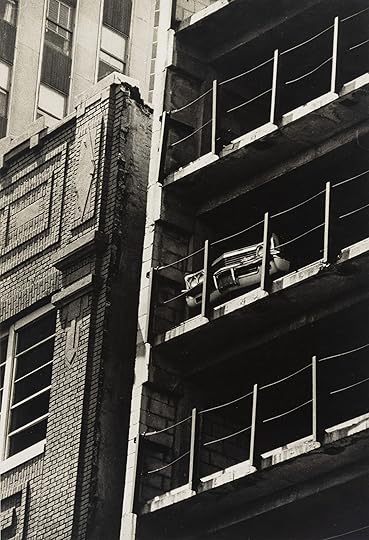

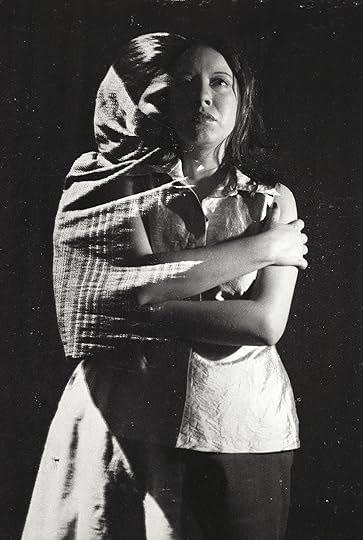

James O. Mitchell, Two Women, San Francisco, ca. 1982

James O. Mitchell, Two Women, San Francisco, ca. 1982 James O. Mitchell, Parking Garage, New York, 1967

James O. Mitchell, Parking Garage, New York, 1967Mitchell was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1933, but his family moved to New York when he was a child. His mother gifted him a camera for his tenth birthday, and he immediately took to photography. Mitchell’s aunt and uncle, who lived in Harlem, were photographed (though not named) by well-known Photo League photographer Aaron Siskind in 1940 for his portfolio Harlem Document. Mitchell later noted this connection with great pride, as a personal link to a momentous series in the history of photography and an informative study for documentary-style imagery of a people and a place.

While enrolled at the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan, Mitchell took a course with Lisette Model at the New School, where she began teaching in 1951. Model encouraged him to apply to the San Francisco Art Institute, but before doing so he left New York to serve in the military. Upon his return in the late 1950s, he mounted a small exhibition at Leica Gallery and was included in a group show at Limelight Gallery. Finally able to take Model’s advice, he applied to and enrolled in SFAI in 1960 on the GI Bill. There, he studied with Brett Weston and Ansel Adams and became close with Ralph Gibson.

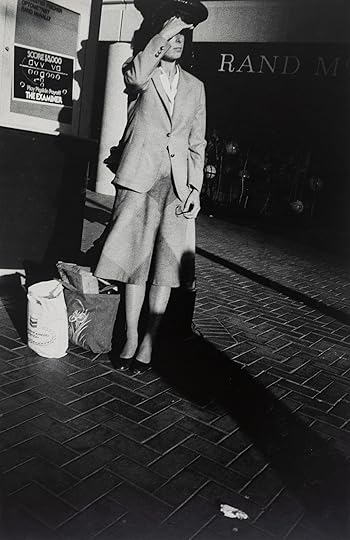

James O. Mitchell, Woman with Bags, San Francisco, 1986

James O. Mitchell, Woman with Bags, San Francisco, 1986 James O. Mitchell, Fish & Chips, Harlem, New York, 1964

James O. Mitchell, Fish & Chips, Harlem, New York, 1964Mitchell’s evolving photographic sensibilities led him to photograph Harlem, a subject he captured from his high-school days into his mid-thirties. His archive is rife with street photography of his former neighborhood, scenes that move between the jubilance of children as they played outdoors, idiosyncrasies of Harlem buildings and signage, and a consistent expression of moments in the minutiae of daily life. Both taken in 1964, the untitled photographs of Sarah’s Beauty Salon and Fish & Chips restaurant are scenes of Harlem captured just after Mitchell graduated from SFAI. Here we see the slow unveiling of lives, suggesting Mitchell’s need to immerse himself in the familiarity of swells of Black folk pouring in and out of local businesses.

Mitchell seems particularly keen to capture the expressions of Black women, a responsive, nonverbal language most legible and cherished among fellow Black folk.

During this time, Mitchell was working for both Magnum Photos and the short-lived Suffolk Sun newspaper, trying to support himself, his wife, and children as a freelance photographer. In one image, the words Beauty Salon hover above a trio of Black women who seem disinterested or unaware of Mitchell. Framing them with the advertisements and signs of the storefronts, Mitchell captures the contrasting patterns of the three women’s dresses—the planes of their skirts fold atop one another linking their distinct styles: pinstripe, plain, and floral print. In this moment Mitchell cites his photographic influences—Siskind, Model, and Dorothea Lange (whom he briefly worked for in the Bay Area), but we can also see the impact of one of his earliest photography commissions as a cameraman for the famed Alvin Ailey dance group.

James O. Mitchell, Sarah’s Beauty Salon, Harlem, New York, 1964

James O. Mitchell, Sarah’s Beauty Salon, Harlem, New York, 1964Connecting Harlem residents to the sinewy bodies of the Black ballerinas, Mitchell is attuned to the silhouettes and shapes of fabric as it falls and accentuates curved Black bodies in motion. The facial expression of the leftmost woman was a carefully chosen moment, as evidenced by his contact sheet for the scene. Such attention to exaggerated faces is perhaps an echo of Model, but Mitchell seems particularly keen to capture the expressions of Black women, a responsive, nonverbal language most legible and cherished among fellow Black folk. (This is also a theme in works by contemporary Black artists including Martine Syms and Rashaad Newsome).

Learning to photograph expressive movement was a pivotal development in Mitchell’s career, but the process was not without disappointments. It was with much vehemence that he shared with me his experiences with photographer Garry Winogrand. In the early 1960s, he and Winogrand frequently shot at the same dance studios; once, Mitchell assisted the famous photographer on assignment. Mitchell described that in each circumstance Winogrand blatantly ignored him, making the young photographer feel painfully invisible. “He was a real racist,” Mitchell told me of his interactions with Winogrand.

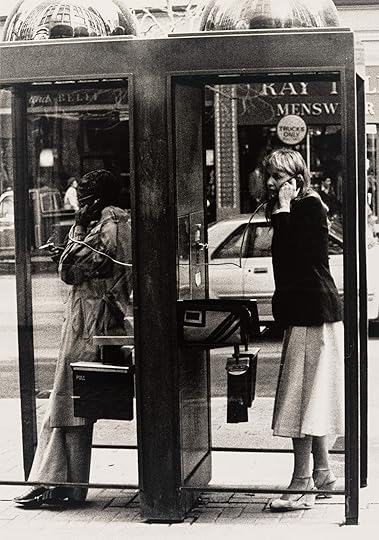

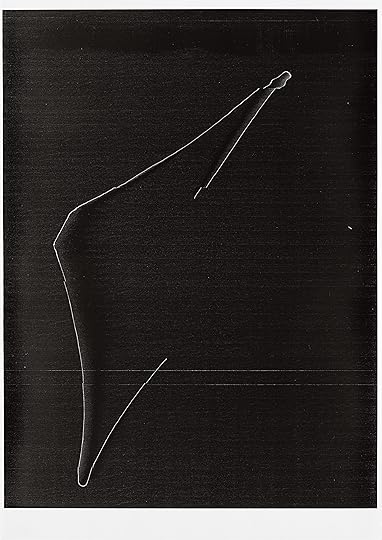

James O. Mitchell, Women in Phone Booths, 1982

James O. Mitchell, Women in Phone Booths, 1982 James O. Mitchell, Untitled, San Francisco, ca. 1980

James O. Mitchell, Untitled, San Francisco, ca. 1980Mitchell permanently moved to the California Bay Area in the 1970s, and it was around this time that his street photography began to shift. While we see in photographs—such as in these two geometric street scenes—an outdated voyeurism of a man photographing women without their consent, we must also recognize the politics of a Black man wielding a camera in public. Mitchell optimized his invisibility while simultaneously making himself vulnerable to the hypervisibility of a loitering. In one image Mitchell offers a visual comment on beauty and race, capturing an incredible moment of separation and comparison created by the structure of a phone booth. In another instance, a shadow enters a brightly lit, angular frame to haunt disembodied, pale legs. Once again, the positionality of the “unseen” photographer holds much weight. Blackness is conceptualized as a mark upon United States history and experience and, as we know, Black men specifically have been articulated by white supremacist systems as a harrowing, shadowy threat that lurks in wait to harm white women.

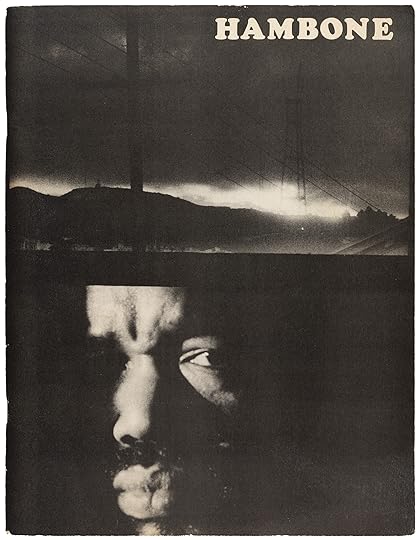

In the early 1970s, Mitchell shifted from photographing Beat writers and aimed to immerse himself among talented Black cultural producers. Referencing Carl Van Vechten’s series Harlem Heroes, he set out to photograph what he identified as another wave of exceptional Black creativity based in the California Bay Area. In 1973 he received a small National Endowment for the Arts grant in support of this project, and he also submitted an unsuccessful application to the Guggenheim Fellowship for photography. The early stages of the series saw him photographing folks like the writer Ernest J. Gaines and the painter Mary Lovelace O’Neal. While the project was never realized, he took more than fifty portraits, some of which were reproduced in a sprinkling of local publications in the 1970s, such as the inaugural edition of Hambone, a literary journal initiated by the Committee on Black Performing Arts at Stanford University. Included in the volume was the portrait of O’Neal as well as a spread of photographs by Mitchell that succinctly spoke to his career as a portraitist and street photographer of both coasts.

Mitchell’s self-portrait on the cover of Hambone, 1974

Mitchell’s self-portrait on the cover of Hambone, 1974  Mitchell’s self-portrait on the cover of J. Oliver Mitchell: An Exhibition of Recent Photographs (Lone Mountain College, 1973)

Mitchell’s self-portrait on the cover of J. Oliver Mitchell: An Exhibition of Recent Photographs (Lone Mountain College, 1973) Hambone’s inception at Stanford—the journal was named and brought to fruition by the poet Nathaniel Mackey—coincided with Mitchell’s own time at the university. In 1973 Stanford hired Mitchell to teach photography, a period in which he believed the university was fulfilling diversity quotas. Unclear to him was why just a year later his contract was not renewed. He was left to contemplate the factors that led to this decision. It seemed to him that the lingering reason was racism, and he shared with me that at this stage in his life he felt depressed.

The cover of the 1974 issue of Hambone features a self-portrait of a dour Mitchell shrouded in enveloping black shadows. Here is the meeting point between black as a color and Blackness as a Black photographer attempted to see himself. Mitchell was a bit of an anomaly among his Black male photographer peers—figures like Kwame Braithwaite, the always appreciated Roy DeCarava, and the men of the Kamoinge Workshop and Black Photographers of California clubs are not particularly known for self-portraits. Mitchell, however, obsessively contemplated his own visage, sitting before his camera throughout his career. He was not a member of a photography collective and we know he was friendly with and photographed the notoriously white Beat circle. He frequented and photographed art events, but such images read as if he were an ignored documenter weaving in and around predominantly white crowds. With this in mind, his self-portraits appear to suggest isolation: a prickly man reaching for a sense of self, grasping to comprehend how he sees himself and how the world sees him.

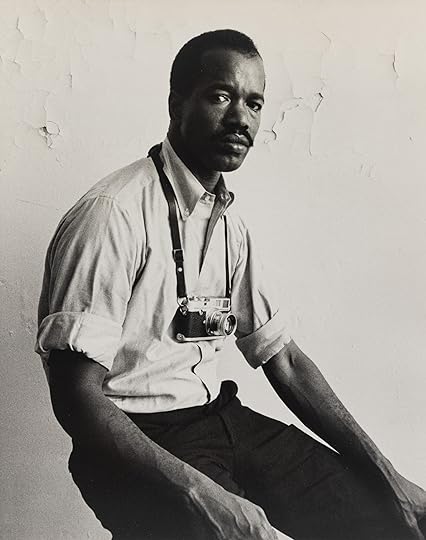

James O. Mitchell, Self-portrait, 1965

James O. Mitchell, Self-portrait, 1965All photographs © the artist and courtesy Estate of James O. Mitchell

In 1965 Harlem, a young Mitchell sits before a cracking wall; he stares with mild intensity as he displays his camera and the rolled-up sleeves of a man who labors. A 1973 self-portrait composed during his MFA program at Lone Mountain College (now University of San Francisco) shows us a stern, sweatered Mitchell outlined by a square of light, his face only partially visible. A tight line up of test prints graces the upper edge of the intimate scene. In both self-portraits, Mitchell gestures to the complex slipperiness of identity, but one theme remains undisturbed: he wanted to be seen as a photographer. When I spoke with Mitchell, I appreciated that he was cantankerous and blunt, and that he refused to cower or bend to his audience. This wasn’t a personality of old age—it’s who he was. He wanted this candor to emanate from his self-portraits. Because Mitchell did not always perform the capitulating and ever-grateful Black person, he often found himself ostracized from the photography world. Though Mitchell is no longer with us, he has left behind a trove of images for us to learn from and critique. His love for the medium was fierce. We should endeavor to research and celebrate his life and photography with the same ferocity.

5 Facts about Diane Arbus, Fifty Years Later

Long before Diane Arbus’s suicide in July 1971, her photographs inspired—incited, even—a visceral response for those who cared to look. Much of this has been recorded in writing. In the intervening half century, her photographs have proved to be immune to the hundreds of thousands of words that surround them, their mystery undiminished. So a few more, offered here, are unlikely to do harm.

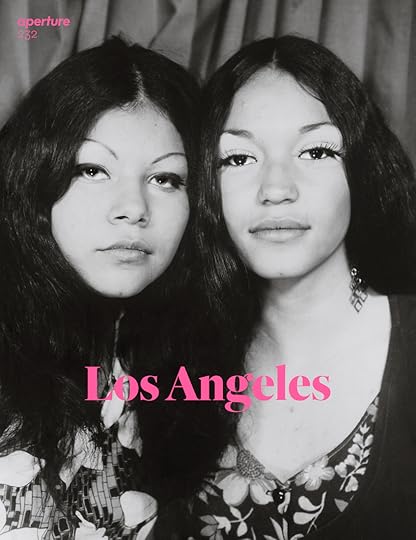

This fall we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Arbus’s posthumous MoMA retrospective, and that of the Aperture monograph published on the occasion. The book almost didn’t happen (see below), although it was an immediate (and lasting) success. For those who missed the similarly iconic 1972 exhibition will be revisited in September at David Zwirner in New York. Aperture also welcomes a new edition of Diane Arbus Revelations to our book list, which you can use to build your own repertoire of Arbus anecdotes. Here are a few of my favorites:

Diane Arbus, Woman with a veil on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C, 1968

Diane Arbus, Woman with a veil on Fifth Avenue, N.Y.C, 1968Shockingly Direct

Arbus was the original research assistant for From the Picture Press, an exhibition that opened at MoMA in January 1973, nine days after the close of her retrospective. As John Szarkowski, director of MoMA’s photography department (and curator of both exhibitions) recognized, these tabloid pictures clearly resonated with Arbus’s photographic sensibility. He could have been speaking of her when he observed this in the press release for From the Picture Press: “As images, the photographs are shockingly direct, and at the same time, mysteriously elliptical and fragmentary, reproducing the texture and flavor of experience without explaining its meaning. They wear the aspect of fact, prove nothing, and ask the best of questions.”

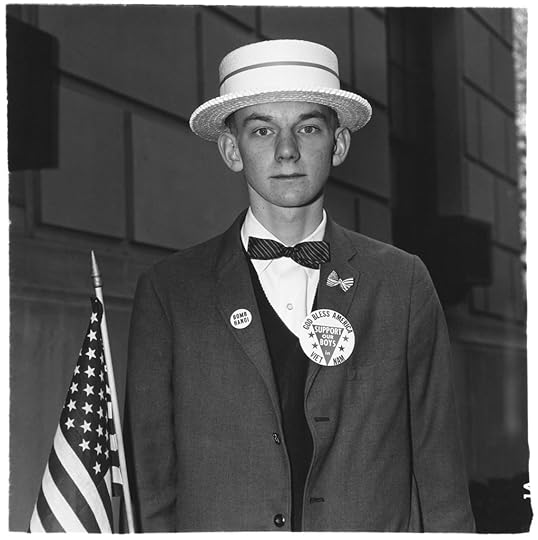

Diane Arbus, Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C, 1967

Diane Arbus, Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C, 1967She Was Always an Artist

The debate surrounding photography’s artistic status can be tiresome—and arguably settled since the late nineteenth century. Regarding Arbus’s photographs, Szarkowski admired that “all the fanciness had been stripped away and all that was left was the marvelous clear airless experience of life, absolutely without […] any concern for art.” Although he went on to clarify, “Of course, that’s not really true. She was always an artist, and she knew she was an artist; her way of being an artist was to conceal that fact as fully as she could from us when we looked at the pictures.” The presence of her Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a pro-war parade, N.Y.C. (1967) on the cover of Artforum in May 1971 (the first time a photograph appeared in the magazine), suggests the editors grasped the significance of her achievement.

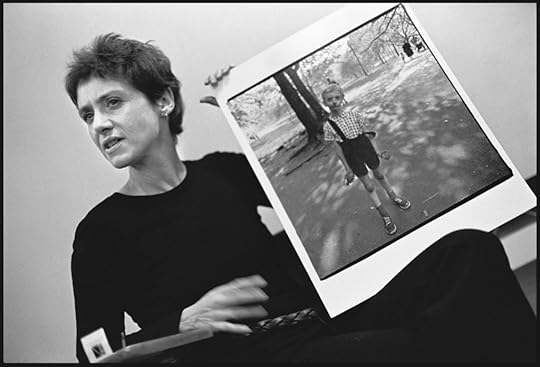

Stephen Frank, Diane Arbus during a class at the Rhode Island School of Design, 1970

The Overwhelming Sensation

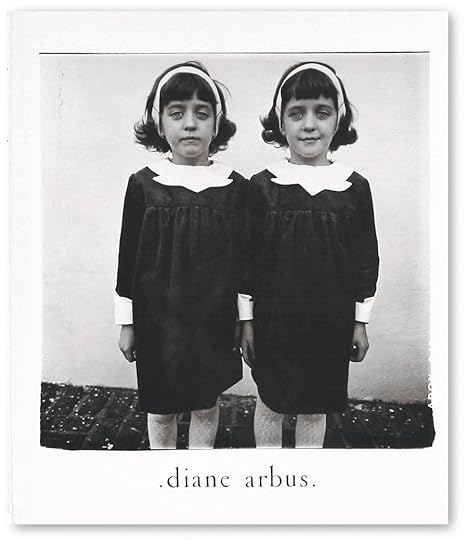

On the subject of art world validation, in July 1972 Diane Arbus was the first photographer to have work exhibited at the Venice Biennale. New York Times critic Hilton Kramer wrote of her display that summer: “… a portfolio of 10 enormous photographs has proved to be the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion. If one’s natural tendency is to be skeptical about legend, it must be said that all suspicion vanishes in the presence of the Arbus work, which is extremely powerful and very strange. It is strange in an unexpected way, however. It is usually said of Miss Arbus that she specialized in freaks, and it is certainly true that her work rejects our customary notions of social normality. It rejects them in two ways—first and foremost, by dwelling on subjects (transvestites, nudists, giants, identical twins) that exist on the margin of the social norm, and then also by dealing with conventional subjects (suburbia, for example) as if they were bizarre.” This and many other key reviews are newly gathered and available in Diane Arbus Documents, which will be published by David Zwirner Books and Fraenkel Gallery this fall.

Cover of Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

Cover of Diane Arbus: An Aperture MonographAn Immediate Success

Aperture did not originally intended to publish the book accompanying MoMA’s exhibition. It was perceived to be a tremendous risk—a quaint perspective in hindsight, with nearly four hundred thousand copies sold—but the relationship was confirmed in August 1972, three months before the opening. The book was an immediate success, and a reprint was underway within weeks of the exhibition opening. Upon receiving his copy, Peter Bunnell (who had recently joined the faculty at Princeton University after working as a curator at MoMA, and before that at Aperture) wrote to Michael Hoffman, Aperture’s executive director: “Just a note to thank you for the Arbus monograph. I know only something of what it took to get it out, but regardless I want you to know how much one reader and friend of Diane’s appreciated having it. It is a superb book…”

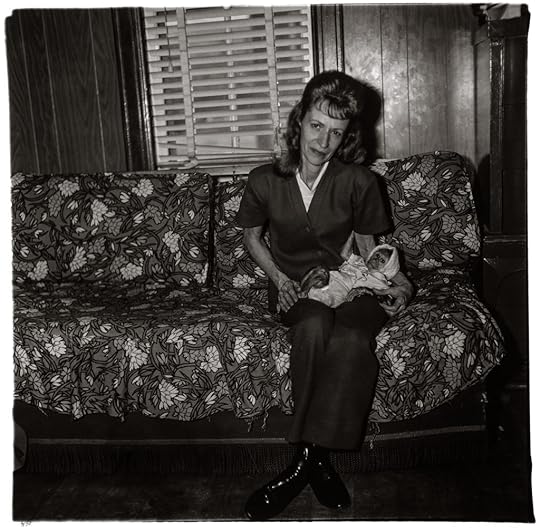

Diane Arbus, Mrs. Gladys ‘Mitzi’ Ulrich with the baby, Sam, a stump-tailed macaque monkey, North Bergen, N.J., 1971; from Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs (Aperture/Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2018)

Diane Arbus, Mrs. Gladys ‘Mitzi’ Ulrich with the baby, Sam, a stump-tailed macaque monkey, North Bergen, N.J., 1971; from Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs (Aperture/Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2018)All photographs © The Estate of Diane Arbus

Another Image

Did you know there used to be another image in Arbus’s Aperture monograph? In the very first printing of the very first edition there was a photograph of two young women wearing matching trench coats in Central Park. Their father objected to their inclusion and the page was subsequently removed, replaced by one of the most recent images in the book, a woman with her baby monkey.

Related Items

Diane Arbus: Revelations

Shop Now[image error]

Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph

Shop Now[image error]

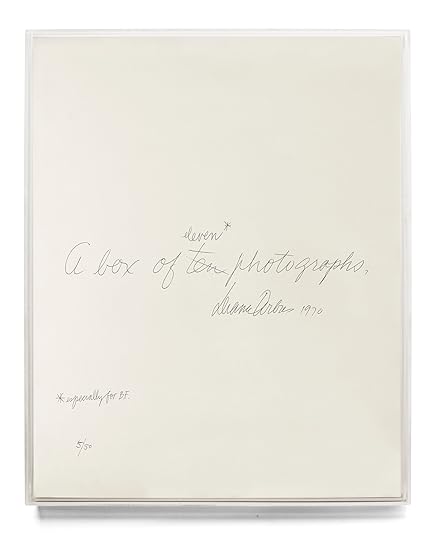

Diane Arbus: A box of ten photographs

Shop Now[image error]September 13, 2022

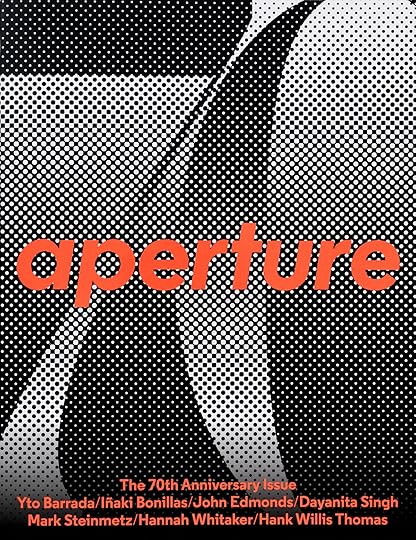

Aperture Celebrates Seventy Years in Print

In Aperture’s first issue, published in 1952, the founding editors mapped out the reasons for bringing the magazine to life. With intelligence—and a hefty dose of earnestness—they sought to create a space for photographers and “creative people everywhere” to communicate and speak to one another. This was a daring endeavor at the time, a labor of love driven by an almost messianic belief that photography mattered. Building a community around the publication was essential to their cause. “Growth,” they wrote, “can be slow and hard when you are groping alone.” Photography was a lonely place back in the early 1950s. The medium wasn’t yet widely appreciated as a serious form of creative expression, and so the founders sought to make the case for the power of a still image that “blazes with significance.” That the magazine has continually remained in print for seven decades amid shifting notions of what photography is—and might become—attests to the strong will of the founders, and of those editors, equally indefatigable, who followed and kept the magazine going, even as print media, in the age of screens, seemed destined for the dustbin. We inhabit a vastly different image world today, but the mission of the magazine, oddly enough, or perhaps likely enough because of the founders’ promising trajectory, remains consistent.

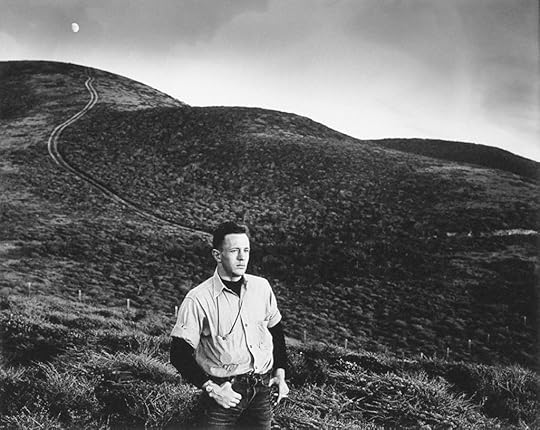

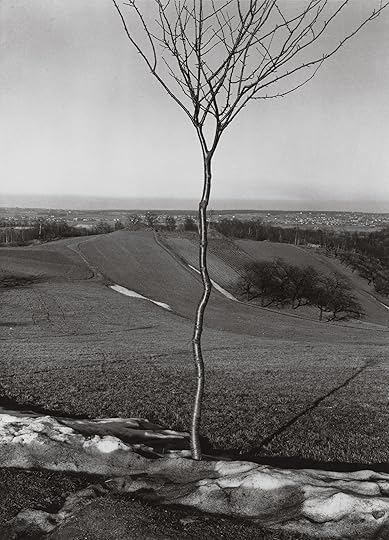

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Mateo County, California, October 24, 1947

Minor White, Tom Murphy, San Mateo County, California, October 24, 1947Courtesy Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum

John Edmonds, Father’s Jewels, 2022, for Aperture

John Edmonds, Father’s Jewels, 2022, for ApertureCourtesy the artist

Hannah Whitaker, Millennium Pictures, 2022, for Aperture

Hannah Whitaker, Millennium Pictures, 2022, for ApertureCourtesy the artist

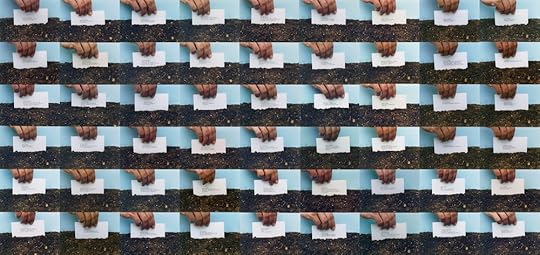

As editors, we are privileged to engage with photographers, artists, writers, and thinkers whose work provokes, challenges, and blazes with significance. We may be searching at times, or finding new footings, but we are never alone. For this seventieth anniversary issue, we drew on our community to assemble a publication that looks at the past with a view to the future. Seven photographers, through original commissions, each explore a decade of the magazine. Each was invited to consider a single issue, an article, an idea, or even an omission, which seeded their portfolios. Iñaki Bonillas, Dayanita Singh, Yto Barrada, Mark Steinmetz, John Edmonds, Hannah Whitaker, and Hank Willis Thomas have all reanimated our past in revelatory ways.

Seven celebrated, incisive writers—Darryl Pinckney, Olivia Laing, Geoff Dyer, Brian Wallis, Susan Stryker, Lynne Tillman, and Salamishah Tillet—were given the same prompt: Tour our archive, see what’s there. What captures your imagination? What questions are emblematic? They reveal that however much photography and this magazine evolved, sometimes radically, Aperture remained committed to thinking about the meanings of pictures, and all that might encompass. The expansive nature of the medium was a strength, and the magazine could surprise, take risks, move against the grain. Aperture might even be, as Pinckney observes, “a home for the most gentle weirdness.”

—The Editors

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, February, 2021, from the series Irina & Amelia, 2017–ongoing, for Aperture

Mark Steinmetz, Amelia, Athens, GA, February, 2021, from the series Irina & Amelia, 2017–ongoing, for ApertureCourtesy the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York

Hank Willis Thomas, Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful, 2022, for Aperture

Hank Willis Thomas, Kwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful, 2022, for Aperture Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photographs by Kwame Brathwaite courtesy Kwame Brathwaite Archive

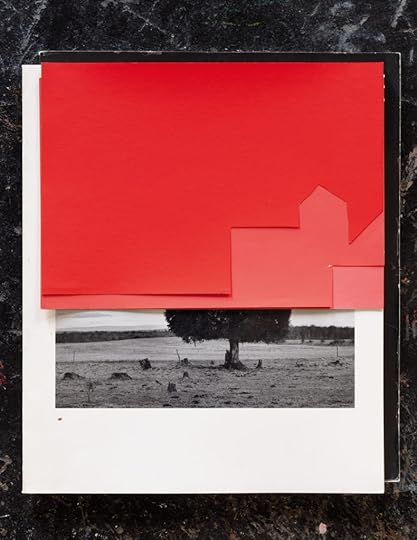

Iñaki Bonillas, from the series Compositions, 2022, for Aperture

Iñaki Bonillas, from the series Compositions, 2022, for ApertureCourtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City/New York

Yto Barrada, Bettina’s Color-aid papers with 1970s Aperture issues, 2022, for Aperture

Courtesy the artist with Charles Benton; Pace Gallery, London; Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut and Hamburg; and Galerie Polaris, Paris

Dayanita Singh, Nony loved to photograph her family (they were also all that she had access to) and posed her sister as Scarlett O’Hara after seeing Gone with the Wind, 1962

Dayanita Singh, Nony loved to photograph her family (they were also all that she had access to) and posed her sister as Scarlett O’Hara after seeing Gone with the Wind, 1962Courtesy the artist

Related Items

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]Read more from Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue.”

September 9, 2022

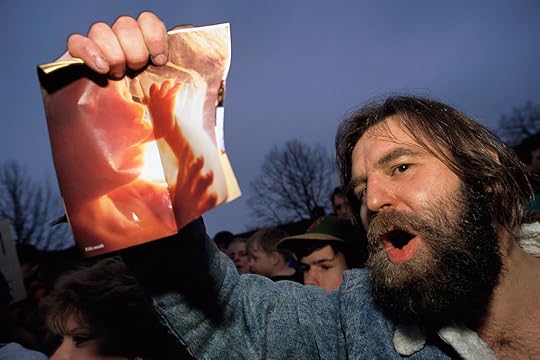

How Conservatives Weaponized Photographs in the Campaign against Abortion

While I’ve been reflecting on the many farces and cruelties that led to the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, thus ending the right to safe abortion in the US, one particularly crass manipulation has been turning in my mind: the successful drive of some anti-abortion campaigners, over the decades leading to the ruling, to ensure that people seeking a termination be pushed to look at ultrasound images of the fetus before moving forward with their abortions. To be forced to look at anything is the stuff of nightmares, an almost cartoonish symbol of extreme control, a torture. By 2013, eight states had passed laws requiring providers to suggest a viewing of images from a mandated ultrasound (in three of these states, the law permits the woman to avert her eyes from the image, though the doctor must still display and describe the image). This was done on the justification of giving patients “information,” and off the back of research from the 1980s conducted with just two women, both of whom actually wanted to give birth, that suggested that seeing grainy photos of the fetus helped with bonding. The push for such requirements shows society’s steadfast belief in images to awaken, to chastise, to shame, to convince. The thrill for anti-abortion campaigners was the motif of baby, of tiny man: the bobbing head, the curved body. Could Roe have fallen without the proliferation of such visuals—the theater of fetuses—brandished outside clinics, in schools, and online?

Pro-Life, anti-abortion protesters block access route outside a Planned Parenthood facility and are later arrested by police and sheriff officers, March 23, 1989, Cypress, California. Photograph by Bob Riha, Jr./Getty Images

Pro-Life, anti-abortion protesters block access route outside a Planned Parenthood facility and are later arrested by police and sheriff officers, March 23, 1989, Cypress, California. Photograph by Bob Riha, Jr./Getty ImagesAs commentators rush to analyze the social, political, and religious shifts and divisions that led to the fall of Roe, the role of photography must also be acknowledged. That means photography in the widest sense, including medical imaging, which, in the context of anti-abortion campaigning, has been subjected to selective editing and visual distortions. See, for example, the infamous anti-abortion propaganda film The Silent Scream—released in 1984 and shown in numerous schools, churches, and at the Reagan White House—in which speed and sound, including doomful music, were used to effectively turn ultrasound recordings of the abortion of a twelve-week fetus into a sensationalized snuff film. The fetus (usually at that moment around the size of a lime and not sufficiently developed to feel pain) was enlarged so as to resemble a grown baby and depicted, via close-ups on key angles of its head and heavy use of slow motion, “screaming” in response to the surgical tools. The visual was intended to back up the narration, by the anti-abortion doctor Bernard Nathanson, that the fetus was “another human being indistinguishable from any of us” and thus acting in ways we would imagine ourselves when in pain: calling out, retreating, writhing.

Images are often taken as evidence of reality, and by default, personhood and existence—all the things anti-abortion advocates are keen to assert. The ability of photographs to supposedly prove, to make things true and lasting, can be a horror and a danger. There was perhaps never a more feverish attempt to harness that power than in the battle to fell Roe, in which the ultrasound has been proffered as an illusion of humanity. In the push for forced pre-abortion fetus-viewing (a drive partly inspired by the sensation caused by The Silent Scream), the hope of anti-abortionists was that women who came face-to-face with the image would be overcome, moved in some way, and change their minds. In fact, researchers have found that the process makes little impact on decisions to go ahead with the procedure. Other impacts of this charade—on women’s time, their patience, their mental health, their peace—are, of course, unknown.

As commentators rush to analyze the social, political, and religious shifts and divisions that led to the fall of Roe, the role of photography must also be acknowledged.

Writing recently on the fall of Roe in the London Review of Books the historian Marina Warner notes of early abortion battles, “it was not only a question of what language to use to express the arguments for women’s authority over their own bodies, but of visual representations too. The antagonists used images quite unscrupulously to spread their arguments about the foetus being a human person, with a soul, images which erased the personhood of the women themselves.” As she implies, the anti-abortion movement owes its success not only to the direct weaponization of images, but also equally to their capacity for misinterpretation, their dangerous veneer of neutrality that smothers questioning, and the impression of progress implicit in the association between photography and technological development.

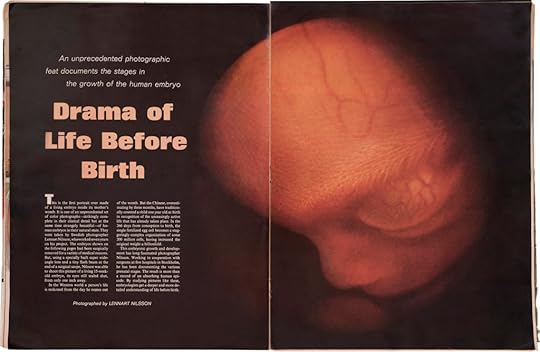

The thrust of the fetus into the public imagination can be traced to the Swedish photographer Lennart Nilsson and his book A Child is Born, first published in 1965 by Bonnier, as well as the corresponding Life magazine cover story “Drama of Life before Birth,” which appeared that same year to promote the book. (Interestingly, 1965 was also the year an obstetrician in Glasgow became the first to experiment with the use of ultrasound imagery for pregnancy.) The story featured color images of supposedly living fetuses at various stages of development—an “unprecedented photographic feat,” according to the magazine’s cover. Through Nilsson’s lens, which purported to offer a direct view inside the human body, the fetus was a tiny floating “spaceman,” a being destined for, and deserving of, the chance to continue its life on Earth—something emphasized equally by the magazine’s chosen headline. The images and their insinuations have, as the historian and gender-studies scholar Barbara Duden writes in her 1993 book Disembodying Women, “since become part of the mental universe of our time.”

Photograph of a spread from Life magazine, April 30, 1965

Photograph of a spread from Life magazine, April 30, 1965Nilsson began making fetal images in 1952, when the Bonnier-owned magazine See commissioned him for a story on the anti-abortion Swedish gynecologist Per Wetterdal and his hospital’s collection of fetal specimens. Wetterdal had hoped that these specimens, if widely seen, could curb enthusiasm for abortion. This story ran with the headline, “Why Must the Foetus be Killed?”. Sensing an opportunity to capitalize on and contribute to moral panic, Bonnier funded Nilsson to continue the project and sent him to tour hospitals; over the subsequent decade it published various anti-abortion articles with his images. But come the mid-1960s, support for abortion in Sweden was growing, and some of these stories received backlash. Also conscious of a wider appetite for improved sex education and information on women’s health, Bonnier abandoned the debate and packaged Nilsson’s A Child Is Born as a pregnancy guide, with additional images guiding couples through conception, fetal development, and birth. It contained no reference to abortion.

Nilsson’s photographs have since had a complex life. Some have, as the publishers supposedly intended, been used in maternity care and education. Others, over the book’s many reprints and international editions, have been proposed as works of art. In 2009, Bonnier repackaged A Child Is Born as a shiny coffee-table book, with commentary from the picture editor Mark Holborn, rather than the gynecologists and doctors of the early editions. The following year, the images went on display at Fotografiska in Stockholm. The breadth of contexts demonstrates how images of the fetus have, through agenda and interest, crossed genres and been liable to repurposing and reformatting. Perhaps the most notable role of Nilsson’s fetus “feat” has been in providing the anti-abortion movement with a readable symbol, a clear logo, and thus the aesthetic punch that is, arguably, essential to any successful protest movement. The images provided content for countless posters and fueled, in the battle over abortion rights, the replacement of medical knowledge with gut reaction and superficial impression.

Ironically—though fittingly, given the anti-abortion movement’s penchant for chicanery—almost all of Nilsson’s images were not, in fact, of babies steadily developing in the womb. Rather, they were of dead fetuses, the remnants of ectopic pregnancies or abortions, which Nilsson had posed in front of a backlight or in dishes of liquid to suggest their position inside the body and the illusion of a prosperous life. “It is presumed that the readers have realized that the pictures show foetuses that are dead,” the doctor Lars Engstrom wrote in 1965, in a critical review of the book in the journal Swedish Medical Associations. He referred to one especially florid caption for an image of a four-month-old fetus: “Infinite calm rests in these faces. They look as if they are waiting for eternity. But it is the short life on earth they are preparing for and it is not sleep that keeps their eyes shut.” Engstrom asked, “Is this embryological poetry or deception? The truth is down to earth and simple: the eyes in the picture will never see.”

Installation views of Lennart Nilsson: A Child is Born, Fotografiska, Stockholm, 2010

Installation views of Lennart Nilsson: A Child is Born, Fotografiska, Stockholm, 2010

Nilsson’s images pay little attention to the bodies that contained the fetuses—it is unlikely the women were even asked for permission before the remnants of their pregnancies were photographed. His work instead turns pregnancy into a story that could be told without or even despite of the pregnant person, or to them, by external observers. As Warner argues in the LRB, this is typical of images popular with the anti-abortion movement, in which the pregnant body is often not even a mere vessel but completely absent. “Treating a fetus as if it were outside a woman’s body, because it can be viewed, is a political act,” Rosalind Pollack Petchesky writes in her important essay “Fetal Images: The Power of Visual Culture in the Politics of Reproduction,” published in Feminist Studies in 1987. Indeed, such visuals helped assert the independence of the fetus, as a separate life and entity, a supposedly soulful being of its own. They helped conjure the utterly inappropriate “pro-life” tag that was, until recently, used widely by anti-abortion campaigners, and create the warped sense of equality between “lives” that allows the rights of the fetus to prevent a ten-year-old rape survivor from pursuing an abortion (as was recently the case in Ohio). The images helped make “real” something that for most people floated tenuously in ambiguities and personal philosophies about the very nature of life—the notion of when personhood begins, of when we become “human.” And, of course, the images are emblematic of the entire concept of photography, the core property of which is to slice, to frame one thing and not the other, to remove context and surroundings. What is out of frame does not matter.

Indeed, there is a bigger link, beyond the fetus, between the fall of Roe and photography. Consider the medium’s entire history as a device for enshrining men’s vision and hopes for the world (natural, given who has typically made and commissioned photography): men as active, driving, moving; women and children as accessories, caring, waiting, fragile. Photography has, for most of its existence, upheld regressive systems. It has been a crucial tool in the lie of the idealized family and the fantasy of serenity. Recall how camera companies, in marketing the technology to the masses, directed new patrons to record their kin and family milestones—weddings, graduations, first days of schools, and births, endless births, and the slippery, ideally pink, forms of babies—and paste them into albums. They directed not only what should be photographed but also what was aspirational, what was normal. In the fight to limit abortion, such motifs have been employed with zeal as a way of reassuring conservatives and disparaging would-be outliers. They appear, for example, in political-campaign videos and images, formats that, tellingly, swelled from the 1984 Reagan presidential campaign onward, and that ushered in a culture of appearances and facades that was crucial to the anti-abortion movement. Such visuals showed domineering fathers, round-cheeked children, and mute wives (the idealized mother). They served to protect an imagined history that was purported, without care for accuracy, to be abortion-free, to be good—better.

A group of Operation Rescue demonstrators protesting outside the home of the mayor of Buffalo, April 21, 1992. Photograph by Mark Peterson/Corbis/Getty Images

A group of Operation Rescue demonstrators protesting outside the home of the mayor of Buffalo, April 21, 1992. Photograph by Mark Peterson/Corbis/Getty ImagesThe lie of abortion as a “new” right—a supposed result of feminism or modernity or spiritual decline—underpins one of the more bizarre moments of interplay between photography and abortion: the strangely avant-garde films of American father-son duo Francis and Frank Schaeffer, which helped radicalize evangelicals, a group previously relatively neutral on abortion. (Though it is near impossible to imagine now, abortion was once accepted by many religious groups, many of whom viewed it as a Catholic issue or a personal matter between woman and doctor, as Jia Tolentino explores in a recent essay in The New Yorker.) The story starts, of course, with male ambition. In the 1960s and ’70s, the aspiring filmmaker Frank Schaeffer, a devotee of Fellini, Bergman, and Vittorio De Sica, was growing up in the Swiss Alps in the evangelical Christian commune L’Abri, led by his father, the theologian Francis Schaeffer. L’Abri hosted a steady stream of high-profile visitors, including Billy Zeoli, who was president of the large Christian film company Gospel Films and, in the mid 1970s, the unofficial “White House chaplain” to President Gerald R. Ford. Zeoli suggested that Schaeffer turn his attention to moving image, proposing, with the guarantee of a multimillion-dollar budget, a series of Christian documentaries. Through rampant nepotism the teenage Frank got to direct. “I was looking at it as film school,” he recently told the writer and podcaster Jon Ronson, noting that he hoped the work could be a springboard to Hollywood, where he could make “real movies.”

Midway through production, Frank had an epiphany, inspired partly by his experience as a teen father: the films should reference abortion, especially the recent Roe case. He convinced his father to target the issue, and the elder Schaeffer appears on camera, saying, “By this ruling, the unborn child is considered not to be a person.” The film series, titled How Should We Then Live?, was a hit with evangelicals. And yet the audience was not totally overcome or inspired by the abortion segments. Frank was undeterred; he recommended doing a new series just about abortion, and the elder Schaeffer agreed. He was keen, Frank told Ronson, to secure “another paycheck for his errant son.”

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018)

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018)The new work, titled Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, was made with similar ambition and a comparable budget. Created in collaboration with C. Everett Koop (later, Surgeon General during the Reagan administration), the five-part documentary includes a scene of an anti-abortion doctor standing on a rock in the Dead Sea, surrounded by a thousand naked baby dolls—a mass of chubby, plastic limbs. Other dolls were filmed rolling down a conveyor belt into an incinerator. In another scene, a toddler is trapped in a cage, crying and rattling the bars. The work is strange and visually experimental, and was, at first, unpopular. Few evangelicals turned up to screenings, and few church leaders cared to give their voice to an issue they considered settled. But when the press picked up on the oddness of the cinematography in the context of the topic of abortion, protestors—including feminist groups—started to picket screenings, which caused Schaeffer fans to turn up in support. With each showing, the group’s size swelled until, eventually, abortion became an issue that reliably attracted evangelical protesters who were inspired by both the film’s rhetoric of baby-killing and the motivational aspect of a clear enemy.

Frank Schaeffer later left the evangelical movement, but he kept images from the films in his show reel and eventually made it to Hollywood. His films include Headhunter, an occult-themed horror film, and the post-apocalyptic Wired to Kill, which features a murderous robot. “[W]ith the abortion issue, the religious right found a catalyst that energized a political movement that then evolved into all sort of other areas, from trying to attack the gay rights movement to getting people to vote for Republican candidates,” Schaeffer told NPR in 2008, “the energy, the catalyst, all of that happened when my father and I went out with these film series and books and basically told Christians you need to apply Christian teaching to all of life.” He recalled the doll scene and how the “surrogates for aborted babies were just this kind of artistic image floating in a turquoise . . . space.” It would be a joke if it weren’t reality. The dreamt-up images of a teen Fellini fan reverberate to this day, shaping policy and ruining freedoms.

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018)

Laia Abril, from the book On Abortion (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2018)Today, the question Warner references—how should pro-abortion campaigners deal with visual representations when it comes to abortion?—remains unsettled, and it will be debated even more as activists unite post-Roe. A small number of photographers have, over the years, offered their own suggestions. In 1972, as part of her bold explorations into women’s limited choices, Abigail Heyman photographed herself having an abortion. The camera points down at her open legs and the light is stark; there is no warmth, no subtlety. More recently, Laia Abril’s exceptional book On Abortion (2018), from her long-term project A History of Misogyny, has been receiving the acclaim it deserves. Abril considers the history of abortion, the damage caused when women lack legal, safe, and free access, and the plight of the forty-seven thousand women, worldwide, who die each year due to botched procedures. The book amalgamates images, text, and ephemera to make its case with clarity and force. It takes on a topic with a thoroughness that exposes how frequently photographers have shied away from addressing it robustly, or from engaging with personal or shared experience.

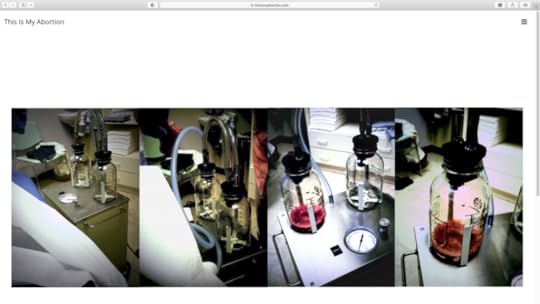

It has become popular to argue that the pro-abortion cause is, in general, unphotogenic. That there is nothing suitable or palatable to pull at heartstrings that isn’t gory or, by contrast, humdrum. Implicit in this idea is the shame that pervades abortion: the notion that to picture the ease of the process would only make the issue seem flippant, the advocate uncaring, or the patient untroubled (one could build a strong argument that this would be a good thing). A rare project that cuts through the expected histrionics is the committedly calm, and brilliantly useful website This Is My Abortion, where an anonymous woman posted photos she took on a concealed camera phone during her abortion. “My hope is this project will help dispel the fear, lies and hysteria around abortion,” she writes on the landing page. In an article for the Guardian, she recalls arriving at the clinic to see protestors: “Viewing, again, the horrific graphic images they displayed, I wasn’t sure if I was more afraid of being harmed by the anti-abortion protesters or if I was more anxious about the procedure itself.”

Screenshot of the website This is My Abortion

Screenshot of the website This is My AbortionA sea of images—what good have they done? To take on Warner’s question, I would propose the answer to the “visual representation” of abortion is not to be found in more photographs. Nor is it to be found in the partisan or the contrivedly wrought. The solution, instead, could come from a push to question what a photograph can be, in the inclination to challenge the truths about images we have accepted in the past. It could also lie in resisting the spray of narratives and sentimental insinuations—of deaths, missed chances, regrets, or could-have-beens—the projections and delusions and imaginatory leaps that have defined the discourse of both photography and abortion. It could be there in the stoicism to confront the tendency to search for meaning or some supposedly lingering emotional truth. Nilsson’s “babies” were not miracles of life but abortions. There was no cry in The Silent Scream. The dolls in the sea were just dolls. The metaphors fall; the reason emerges. A cluster of cells is not a baby. The eyes in the picture will never see.

September 8, 2022

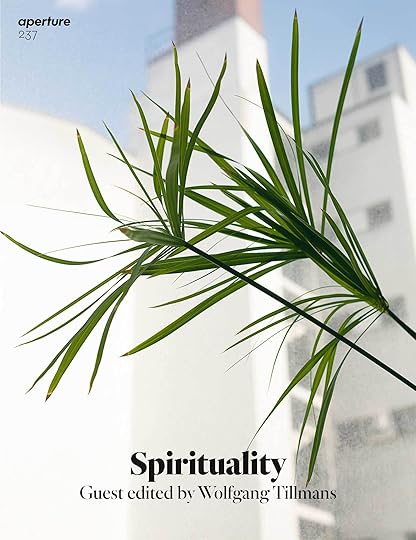

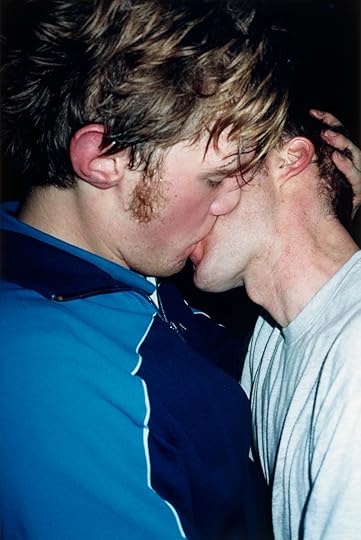

Wolfgang Tillmans’s Democratic Vision of Photography

Wolfgang Tillmans is a convener of intimacy. His static images—from the sweaty, tangled bodies in his photographs of 1990s gay clubs to more recent portraits of friends and lovers in Berlin, London, and Fire Island—invite us to think dynamically about ways to be together. Even his abstract, cameraless photographs involve the sensuous intermingling of chemicals on paper.

This quality was especially poignant for Roxana Marcoci when production on Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, the career survey exhibition she has curated for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, was stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 19, 2020, when museum staff were isolating at home, Marcoci posted a brief essay for MoMA Magazine introducing “On My Own,” a symphonic electro-pop track recorded by Tillmans in 2018. The artist sings a refrain over the sound of rushing New York subway trains, which at the time of lockdown were largely empty: “I’m on my own and not alone.” “The idea of togetherness, which comes up so much in his work, is also at the forefront of how he thinks,” Marcoci told me recently. “At a time when people were secluded and felt completely severed from their friends and family, it was critical.”

Wolfgang Tillmans, still life, New York, 2001

Wolfgang Tillmans, still life, New York, 2001  Wolfgang Tillmans, August self portrait, 2005

Wolfgang Tillmans, August self portrait, 2005  Wolfgang Tillmans, Tukan (Toucan), 2010

Wolfgang Tillmans, Tukan (Toucan), 2010 The pandemic was just one challenge to the organizing of a survey exhibition for an artist with a famously idiosyncratic vision of photographic display. Tillmans is well known for hanging prints of varying sizes clipped and pinned to gallery walls in arrangements that achieve, through startling asymmetries and interruptions, a sense of balance and flow. Since his inaugural 1993 exhibition, at Galerie Buchholz, Cologne, he has exhibited, free of disciplinary hierarchies, conventional photographs alongside notes, drawings, photocopy collages, and magazine pages. This array is partly what makes his work feel so capacious; as Tillmans himself has put it, his roomy installations are “always a world that I want to live in.” The MoMA team spent years studying the strategies he employed in every one of his prior shows. “Wolfgang is someone for whom exhibition and installation making are the very grammar of his practice,” Phil Taylor, a former curatorial assistant at MoMA who helped organize the exhibition, told me. Saying something new about Tillmans’s work required learning his language.

The pandemic was just one challenge to the organizing of an exhibition for an artist with a famously idiosyncratic vision of display.

Unusually for a photographer, that language is very often verbal, and so, in addition to the wide range of literature on display in the galleries, from early zines and journal pages to the collection of news articles and artist texts known as Truth Study Center (2005–ongoing), the exhibition is accompanied by two publications, a catalog and a reader. The latter grew in scope over the pandemic, when the curatorial team was unable to travel or work in the galleries, to encompass brief essays by the artist, interviews, Instagram posts, playlists, and even spam emails.

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022. Photograph by Emile Askey

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2022. Photograph by Emile Askey“It is the installations that I have always understood to be the actual works,” Tillmans writes in the accompanying catalog. At first, visitors to the exhibition may feel overwhelmed by the diversity of materials included. In addition to photographs and text, there are movingimage works from the past twenty years and a room screening the music videos for Tillmans’s 2021 studio album, Moon in Earthlight. Yet this screening room is one of many moments of respite in the sprawling show, which, like all of Tillmans’s installations, aims to be an inviting social space. This approach is a manifestation of what Marcoci calls his “ethics of care”: his steadfast belief that art can prompt us to reflect on lived political and social realities while also making us feel safe and loved. It extends from his tender images to his decades-long commitment to activist causes such as LGBTQIA and immigrant rights. For Tillmans, photographs are no more precious than the world in which they circulate.

Related Items

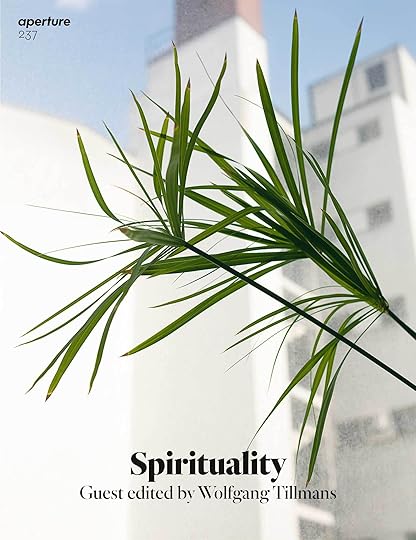

Aperture 237

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]“Wolfgang thinks about the photographic print as akin to a body,” Taylor says, “and focuses on the borders, the edges of photographs, the negative spaces, the intervals between images.” The social dimension of his work exists both in these paper margins and in the dynamic spaces where these photographic bodies come together. Like a body, the show has been subject to changes—“a living entity,” as Marcoci says. If such open-endedness seems anathema to MoMA’s reputation as the gatekeeper of modernism, it’s also reflective of the way the museum has been changing since the rehang of its permanent collection in 2019. It could even be argued that Tillmans partly inspired the erosion of disciplinary hierarchies there. These changes made possible many close relationships, and, like Tillmans’s work, they will create space for new ones.

Wolfgang Tillmans, The Cock (kiss), 2002

Wolfgang Tillmans, The Cock (kiss), 2002All photographs courtesy the artist; David Zwirner; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

“I want to open up an affirmative space,” Tillmans told the curator Neville Wakefield in 1995. MoMA’s survey is proof that in the ensuing decades he has accomplished even more. “To look without fear” perhaps means to look without worrying about what will be reflected back at you. It’s a form of viewership whose root desire is to engage. This democratic vision of photography can be seen equally in the ways Tillmans gathers text and images together and the ways that bodies commune within them. His work has room enough for us all.

Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through January 1, 2023. This piece originally appeared in Aperture, issue 248, “The 70th Anniversary Issue,” under the column “Backstory.”

September 7, 2022

17 Photographers Reflect on Key Images for Aperture’s Seventieth Anniversary

This month, Aperture marks seventy years since its founding in 1952. In celebration of this anniversary, we’re kicking off a special limited-edition print sale bringing together original works by seventy artists, available in editions of seventy each.

“Aperture has always encouraged connection between photographers, and created a space to connect us with the work they do,” observes Sarah Meister, Aperture’s executive director. “It is inspiring to browse through this collection of images that point to our history, and to know that these artists and estates have generously participated to help Aperture create similar opportunities for future generations.”

Throughout September, collect signed or estate-stamped, 8-by-10-inch prints by some of the most revered and influential photographers in the history of the medium, with proceeds directly supporting Aperture and the artists.

See here to browse the complete Seventy x Seventy sale. Below, enjoy a few highlights from the sale.

Tina Barney, Bridesmaids in Pink, 1995, from Aperture, issue 159, Spring 2000

Tina Barney, Bridesmaids in Pink, 1995, from Aperture, issue 159, Spring 2000Courtesy the artist

“This was taken at the wedding of my best friend’s daughter. Two of the girls are my nieces and the other their cousin. Definitely a family affair. My favorite detail is the glove of the brunette on the right. The extended finger almost touching the edge of the frame and its starched, white cotton glove are reason enough to print this picture.

The Jackie O–style pink satin dresses and pillbox hats were definitely chosen with a sense of humor. I sat and watched those hats being made with real roses before I came upon this photo, and knowing the intensive labor involved made me appreciate the scene I witnessed even more. What I can never plan on or even dream of are the perfectly choreographed spaces between this trio: the two girls pushed together on the right and the third girl leaning against the left side of the frame, as if she were the leader of the pack.”

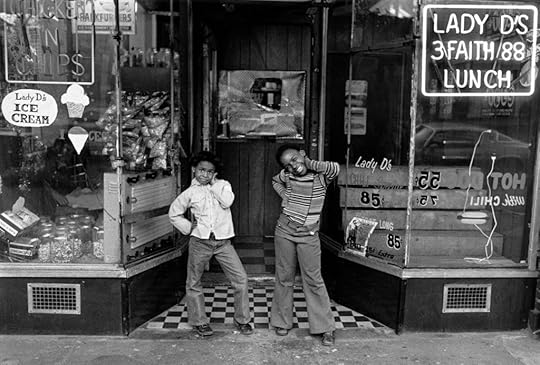

Dawoud Bey, Two Girls at Lady D’s, Harlem, 1976, from Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities (Aperture, 2019)

Dawoud Bey, Two Girls at Lady D’s, Harlem, 1976, from Dawoud Bey on Photographing People and Communities (Aperture, 2019)Courtesy the artist

“I spent five years in the mid-to-late 1970s making photographs in Harlem, New York. It was the first project I undertook at the beginning of my career. I was led back there by my family’s history in the neighborhood: my mother and father had met in a church in Harlem and eventually got married. When I was born several years later, they moved to Queens, to a house with a front yard and backyard, something more spacious than the Harlem apartment they had in Sugar Hill. But we continued to visit the neighborhood, as various friends and family still lived there.

In 1975 I decided to ‘return’ to the community where I had never lived, but had a deep connection to, to make photographs. I encountered these two young girls one afternoon on Seventh Avenue near West 138th Street. When I asked if I could make a picture of them in front of this establishment, they joyfully struck an exuberant pose for me, full of all of the energy and expressiveness of youth.”

Gregory Crewdson, Special Edition Detail from Untitled (2003-2008), from Aperture, issue 190, Spring 2008

Gregory Crewdson, Special Edition Detail from Untitled (2003-2008), from Aperture, issue 190, Spring 2008Courtesy the artist

“In the spring of 2008, Aperture featured Beneath the Roses (2003–2008) in the magazine, a body of work I had just completed over the course of six years and eight large-scale productions. The issue had a double cover using two pictures from the series, and this was one of them. This picture was shot in the summer of 2006.”

Tim Davis, Van, Ocean, Los Angeles, 2021, from I’m Looking Through You (Aperture, 2021)

Tim Davis, Van, Ocean, Los Angeles, 2021, from I’m Looking Through You (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

“All of my pants get holes in the knees. I am constantly kneeling and photographing things down on the ground. I should probably get some steel-kneed pants. Do those exist? This picture was made around the corner from the Oscars ceremonies at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood. I’d gone there to see what catching some of that gaudy glamour would feel like. I made some decent pictures of the setup for the event, but my favorite of the day was this little clamshell of industrial design and the muddy realities of human life. I love images that prod at the flatness of the photographic image and test our sense of its certainty.”

Thalía Gochez, Every Worry Melts Away (Naomi Rodriguez and Grace Sanabria), San Francisco, 2019, from Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx”

Thalía Gochez, Every Worry Melts Away (Naomi Rodriguez and Grace Sanabria), San Francisco, 2019, from Aperture, issue 245, “Latinx”Courtesy the artist

“Every worry melts away when I’m with my community. This photograph was created in hopes of capturing the sense of safety and belonging one may feel when they’re in spaces where their identity and experience are mirrored and honored. A space where you can be yourself and rest your head on another without worry. I was interested in broadening the conversation around BIPOC experiences that isn’t linked to trauma or resiliency but explores tenderness and feels celebratory.”

Ethan James Green, Peter and Stevie, 2018, from Young New York (Aperture, 2019)

Ethan James Green, Peter and Stevie, 2018, from Young New York (Aperture, 2019)Courtesy the artist

“This is a portrait of my friends Peter and Stevie, whom I have always known as a couple. They are the only high-school sweethearts that I have ever encountered in New York. This image was one of the final pictures shot for my book Young New York, and I remember it feeling effortless to capture.”

Graciela Iturbide, La niña del peine, Juchitán, Mexico, 1979, from Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Imagination (Aperture, 2022)

Graciela Iturbide, La niña del peine, Juchitán, Mexico, 1979, from Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols, and Imagination (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

“When I undertake a project, I never start with a preconceived idea. In Juchitán, I began by going out walking with no fixed destination. That is how I came across this girl combing her hair. I titled the portrait La niña del peine because Manuel Álvarez Bravo was very fond of a flamenco singer called La Niña de los Peines. In this way, just walking around, I encountered many of the scenes I portrayed in Oaxaca.”

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2011, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, 2011, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

“What connects the inside to the outside.

What you can see by cutting a rectangle.

Looking out the window helps me to unclench a little bit of what’s been hardening inside of me.”

Tommy Kha, Constellations XVIII, Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (Aperture, 2023)

Tommy Kha, Constellations XVIII, Whitehaven, Memphis, 2019, from Tommy Kha: Half, Full, Quarter (Aperture, 2023)Courtesy the artist

“In my series Facades, ‘cut-up pictures’ take the form of installations, unique photographic prints, puzzles, temporary tattoos, face masks, stickers, lenticulars, as well as my mother’s image. I am a cutout of my mother. I do not use Photoshop in my work—most of my work is done in-camera, using a combination of lo-fi tricks such as inserting fabricated props, using available light, and documenting performances—allowing the artifice of the props and sets to show. Through play and experimentation—NOT foreplay—I create pictures that straddle the lines between still life, portrait, and self-portrait.”

Justine Kurland, Toys R Us, 1998, from Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020)

Justine Kurland, Toys R Us, 1998, from Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020)Courtesy the artist

“I wanted to make the invisible communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experience as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls—they would multiply through the sheer force of togetherness and lay claim to a new territory. Their collective awakening would ignite and spread through suburbs and schoolyards, calling to clusters of girls camped on stoops and the hoods of cars, or aimlessly wandering the neighborhoods where they lived.”

Gillian Laub, Chappaqua backyard, 2000, from Family Matters (Aperture, 2021)

Gillian Laub, Chappaqua backyard, 2000, from Family Matters (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

“Chappaqua backyard is an image from Family Matters, an over two-decade-long project confronting issues of privilege, class, and other fissures in the American dream. Family Matters is an exploration of the conflicted feelings I have about where I come from—which includes people I love and treasure, but with whom, most recently in a divided America, I have also struggled mightily. It is made with the intention to accept as well as to challenge—both them and myself.

When I started making pictures professionally, I would sometimes get editorial fashion assignments. Taking pictures of models never much interested me but creating narratives for them did. Certain editors would let me cast my family and friends, and when they did, my grandparents were always willing participants. They are pictured here in the backyard of the home I grew up in.”

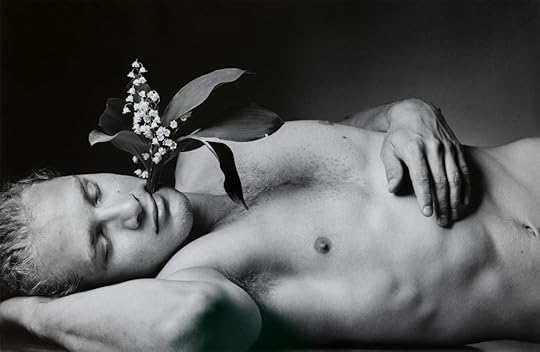

Duane Michals, Young Soldiers Dream in the Garden of the Dead with Flowers Growing from Their Heads, 1995, from Aperture, issue 146, Winter 1997

Duane Michals, Young Soldiers Dream in the Garden of the Dead with Flowers Growing from Their Heads, 1995, from Aperture, issue 146, Winter 1997© Duane Michals and courtesy DC Moore, New York

“During the Korean War I was a second lieutenant in armor. Luckily, I never saw combat. If I had gone to combat, I’m sure I would not have survived. This photograph is about all those innocent young men whose lives were wasted in battle. I see them underground with flowers growing from their heads.”

Tyler Mitchell, Tuesday Afternoon, 2021

Tyler Mitchell, Tuesday Afternoon, 2021 Courtesy the artist

“This image, of my friend Jaycina’s daughter Syx in Atlanta, feels like everything I wanted an afternoon to be as a kid, nearly naked, free, and blowing bubbles. I like that this image can be a potential portal to those sorts of memories and wishes.”

Martin Parr, Mayor of Todmorden’s inaugural banquet, Calderdale, West Yorkshire, England, 1977, from The Non-Conformists (Aperture, 2013)

Martin Parr, Mayor of Todmorden’s inaugural banquet, Calderdale, West Yorkshire, England, 1977, from The Non-Conformists (Aperture, 2013)Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

“Every time I go to an event where there is a buffet, I know there will be a scramble for the food. It’s that slight moment of madness where the greed in us all takes over, and the scrum begins. It is the moment I am waiting for, behind the table, with the action taking place before my lens. However, try as I may, I can never get a better shot than this one taken around 1977. This image just sticks in my mind, with the guy half-cupping a pork pie being the single character I will never forget.”

Alex Prager, Eve, 2008

Alex Prager, Eve, 2008© Alex Prager and courtesy Alex Prager Studio and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul and London

“Eve is part of my Big Valley series that I created very early in my career. At the time I was experimenting a lot with references from artists I admired, and Eve was my homage to Hitchcock. I wanted to be so outward about my love for him that there could be no doubt. The intention of Big Valley was to investigate the human psyche and create images that embody the noir spirit, fabricating moments in time that hint at a much larger story with a disquiet lurking just underneath.”

Stephen Shore, Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts, July 13, 1974, from Uncommon Places

Stephen Shore, Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts, July 13, 1974, from Uncommon PlacesCourtesy the artist

“Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts was the image used on the cover of the first, 1982 edition of Uncommon Places. Not only was Uncommon Places my first book; it was the first monograph in color that Aperture published. That was forty years ago. The book was an early milestone in my career. I cannot begin to express how indebted I am to Aperture for this.”

Silvana Trevale, Mariposa, Corfu, Greece, August 2020

Silvana Trevale, Mariposa, Corfu, Greece, August 2020Courtesy the artist

“This photograph is part of my project Aproximaciones, in which I explore longing for my past through people around me, unfamiliar scenarios, and my relationship with the sea.”

Through September 30, shop the Seventy x Seventy sale to collect signed or estate-stamped, 8-by-10-inch prints available in editions of seventy for $250 each.

September 1, 2022

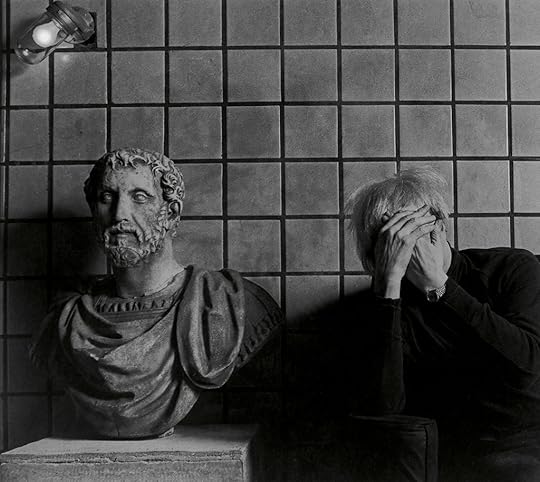

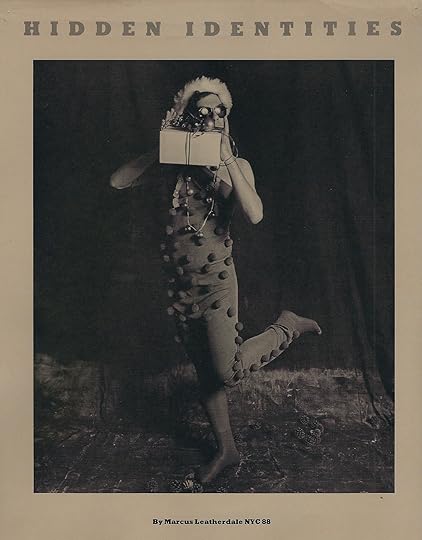

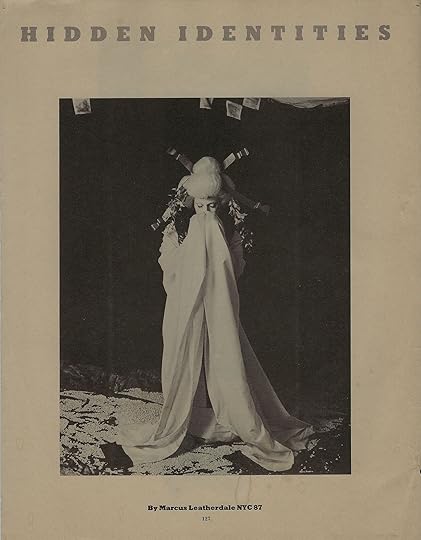

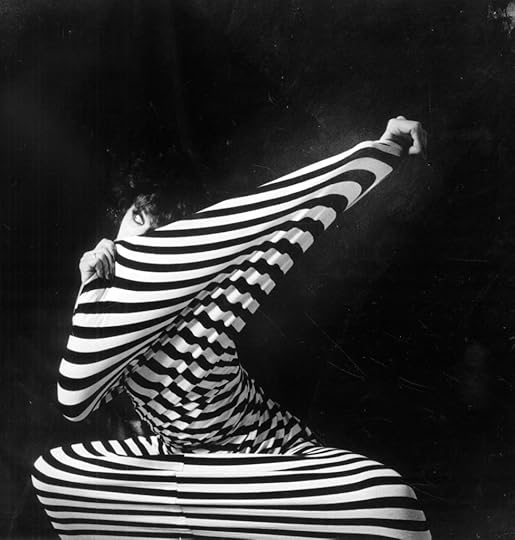

The Punk Portraitist of New York’s Underground

“People thought it was a fake name because I lived in leather. Leather shirts, leather pants, leather jackets,” the photographer Marcus Leatherdale once told me over the phone. Another rumor was that he was the heir to a Canadian logging empire. From the late 1970s until the early 2010s, Leatherdale photographed notable and obscure figures around the world, from New York underground heroes like Cookie Mueller to Bollywood actresses and holy men in India. Looking at photographs of a dashing young Leatherdale, who died last April, one can easily imagine how he elicited a sense of intrigue among admirers, unsettled the stodgy, and inspired rumors among the envious.

Leatherdale was born in 1952 and raised outside of Montreal. He studied fine arts at the École des Beaux-Arts de Montreal, focusing on painting and finding inspiration in formalist beauty and the art of Modigliani, Caravaggio, and Rembrandt. In 1977, he moved to San Francisco to study at the Art Institute. There, he immersed himself in the punk scene and started experimenting with photography. He made his first foray into portraiture outside of the classroom, shooting album covers for his new friends, members of the local cult band The Avengers.

Marcus Leatherdale, Claudia Summers . . . Issey Miyake, 1983

Marcus Leatherdale, Claudia Summers . . . Issey Miyake, 1983San Francisco is also where Leatherdale met Claudia Summers, who would become his roommate, muse, and eventually, wife. Their marriage began as a practical arrangement between dear friends, as it allowed Leatherdale to remain in the US while traveling freely to visit his family in Canada. But the two also found comfort in each other’s presence, as shape-shifters at ease at mosh pits and gay discos alike. “All these years later, I can still see, feel the flash blinding me, bathing me. The low-dull click of the umbrella flash still resonates in my ears,” Summers writes in Out of the Shadows (2019), an anthology of Leatherdale’s work between 1980 and 1992. “Marcus’s contact sheets were sacrosanct. He shared them with no one but me.”

During this time, Leatherdale also met Robert Mapplethorpe, who was visiting from New York for his solo exhibition, Censored, at Simon Lowinsky Gallery. In the spring of 1978, Mapplethorpe sent Leatherdale a postcard, inviting him to stay at his New York apartment while he traveled to Amsterdam. Before the year was over, the young photographer had transferred to the School of Visual Arts in New York, and the two became lovers, starting an intense relationship that lasted for years.

Marcus Leatherdale, Portrait of Robert Mapplethorpe, 1980

Marcus Leatherdale, Portrait of Robert Mapplethorpe, 1980 Marcus Leatherdale, Hidden Identity (Andy Warhol), 1986

Marcus Leatherdale, Hidden Identity (Andy Warhol), 1986New to the city and having run out of scholarship funds, Leatherdale ended up managing both Mapplethorpe’s studio on Bond Street and, later, the studio of photography curator Sam Wagstaff. It was likely a “cash in hand, work off the books” arrangement, as many things were in those days, says the writer Martin Belk, Leatherdale’s longtime friend.

Finding a niche of friends—who also became his subjects—in the downtown nightlife and art scene, Leatherdale evolved as a character-study portraitist, masterfully incorporating myth, melodrama, and identity into his work. He photographed celebrated figures from the art canon, from a young Keith Haring to Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg; fashion luminaries like designer Thierry Mugler and models Tina Chow and Iman; drag queens Divine and Ethyl Eichelberger; nightlife impresarios Susanne Bartsch and Leigh Bowery; and performers Blondie, Lydia Lunch, and International Chrysis.

Marcus Leatherdale, Divine . . . reclining, 1982

Marcus Leatherdale, Divine . . . reclining, 1982Key to Leatherdale’s practice was his conviviality. Often, but not always, he photographed at his home studio, a Lower East Side loft on 281 Grand Street. From 1979 to 1985, he lived there with Summers and his cat ZoZo. At the time, Summers worked as a dominatrix and waited tables. She also sang for the 1984 track “The Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight,” which enjoyed popularity in the club scenes of New York, London, and Paris.

“It was not very glamorous. The outside smelled like rotting Chinese food, with lots of trash and dirty boxes,” says the performance artist Joey Arias, another friend of Leatherdale. “But once you were in the sanctuary, it was great.”

Finding a niche of friends—who also became his subjects—in the downtown nightlife and art scene, Leatherdale evolved as a character-study portraitist.

In 1981, Diego Cortez, co-founder of the legendary Mudd Club, included Leatherdale’s portraits in MoMA PS1’s canonical yet controversial New York/New Wave show. Cortez’s curatorial ethos was to provide a platform for downtown’s emergent post-punk and New Wave artists. A portrait of Summers, topless and in a garter belt (a wedding present from Mapplethorpe), was among the works by Leatherdale on view.

Marcus Leatherdale, Michael Musto in “Hidden Identities,” DETAILS magazine, 1989

Marcus Leatherdale, Michael Musto in “Hidden Identities,” DETAILS magazine, 1989Courtesy Martin Belk

Marcus Leatherdale, Joey Arias in “Hidden Identities,” DETAILS magazine, 1989

Marcus Leatherdale, Joey Arias in “Hidden Identities,” DETAILS magazine, 1989 As a result of his hard work and rising reputation, Leatherdale was commissioned the following year to photograph a monthly series in Annie Flanders’s seminal culture magazine, Details. The page-length feature, titled “Hidden Identities,” focused on the who’s who of New York’s downtown scene as artfully as possible, without revealing their faces. “Marcus loved original people that made a statement—visually, mentally,” says Arias.

Leatherdale honed in on his sitters’ inimitable styles; he had no interest in any obvious fashion branding, even though he was photographing some of the era’s most influential designers and models. A young Dianne Brill stands statuesque, the club maven identifiable by her thick, long hair and a signature latex getup. Designer Stephen Sprouse is masked head to toe, save for his punky black nail polish. Then there’s rock and roll designer Betsey Johnson in one of her own creations, stripes and ambitions outstretched.

“It was so Betsey,” Arias recalls, “to be the Martha Graham of fabrics.”

Marcus Leatherdale, Stretch . . . Betsey Johnson, 1986

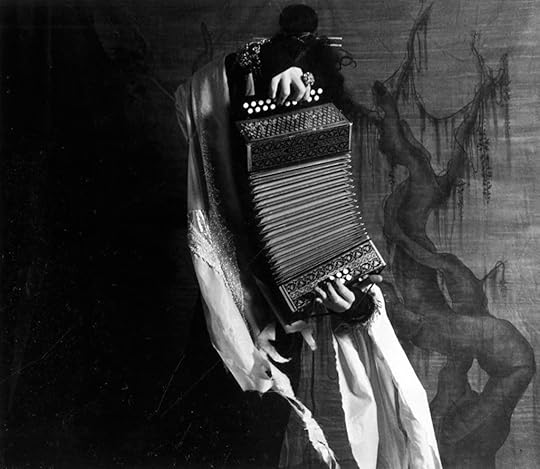

Marcus Leatherdale, Stretch . . . Betsey Johnson, 1986Work continued to go well for Leatherdale. In 1983, as he photographed for Details, he also shot a series of portraits for Issey Miyake’s traveling exhibition and accompanying catalogue, Body Works. Miyake sought out Leatherdale for the “purity of his aesthetic,” says Rande Walsh, Body Works’ production coordinator. The commission led to one of Leatherdale’s most famous photographs, often erroneously attributed to Man Ray.

It was of his dear friend Larissa. Known as the Coco Chanel of rock and roll, Larissa designed fur coats for Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, and Jefferson Airplane, among others. Using dramatic light and shadow, Leatherdale attunes the viewer to Larissa’s enigmatic grin, the texture of her sheer sleeves, and her half-finished cigarette. Like Summers and Mapplethorpe, Larissa left a lasting impression on Leatherdale. His portrait of her resembles another he made for the same series, of Summers, his most photographed subject, wearing a rattan cage around her torso and a hat, an S and M crop in her hand.

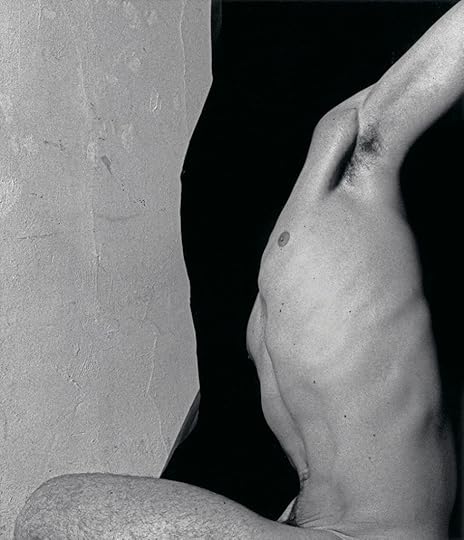

Marcus Leatherdale, Torso, 1984

Marcus Leatherdale, Torso, 1984As the first wave of AIDS ravaged New York in the 1980s, Leatherdale experienced a series of life-altering losses. The death of many of his friends and subjects gave his portraits the anthropological patina of a bygone era: downtown New York as a queer Babylon of upstarts, junkies, starlets, and misfits. Leatherdale made a guest list of every friend he had lost, who he would invite to an imaginary cocktail party. Then he began buying new phone books, which allowed him to omit names as opposed to crossing them out, which he felt was disrespectful.

During the 1990s, Leatherdale met and fell in love with Jorge Serio, a makeup artist from Portugal, who became his partner for the rest of his life; still his tether to New York was loosening. He would often leave for months at a time for India, frequently visiting the northern city of Varanasi. Over the course of nearly three decades, Leatherdale learned Hindi and Sanskrit, studied Hinduism, and photographed rural Adivasi tribes whose customs and languages were on the verge of cultural extinction.

To photograph these Adivasi communities, Leatherdale often went on weeks-long expeditions to remote villages, leading to a lifestyle and practice that was considerably off-grid. Privacy—which included creating a refuge for just Jorge and himself—was critical to his self-expression, sense of security, and happiness.

Another series of tragedies shook his life this past year. In July 2021, Serio died. Then the couple’s dear dog Sascha passed, and a few months later, Leatherdale lost his mother, Grace. When Serio died, Leatherdale left Portugal for New York and Canada, and finally returned to India by the winter of 2022, for what would be the last time. In one of our final phone calls, he also expressed another grief that had been more prolonged: the loss of where he came of age as an artist, the rich bohemian world that no longer exists. “Whenever people ask me if I miss New York, I say, ‘Of course, especially when I’m there,’” he would say.

Marcus Leatherdale, Ethyl Eichelberger, 1985

Marcus Leatherdale, Ethyl Eichelberger, 1985I recently went to 281 Grand with Summers to see what remained. The dirt pits and dope markets on Forsyth, and many of the Jewish linen stores on Grand Street, are gone. And Leatherdale is too. He passed away on April 22, 2022, after hanging himself on the grounds of his estate in Jharkhand, India.

For Summers, the history of 281 Grand, and Leatherdale’s portraits, is something historical as well as deeply personal. It is a place that represents both a generational and an intimate belonging.

“We were all aware of how the work moved against the accepted grain. Not in our community, but outside of it,” she says.

Marcus Leatherdale, Madonna, 1983

Marcus Leatherdale, Madonna, 1983All photographs courtesy Throckmorton Fine Art

Looking back, Summers sees Leatherdale’s gift as this: he could move between the famous and the marginal, photographing both with dignity. “What was so special was that he allowed me the freedom to be who I was—a glamorous but fucked-up individual, sometimes with track marks still on my arms. Marcus photographed the best of who we were.”

I took a photograph of her in front of 281 Grand, and we walked toward what used to be Moishe’s, a diner on Bowery she and Leatherdale frequented for eggs, potatoes, and toast. The rest, she told me, was dangerously bad.

August 25, 2022

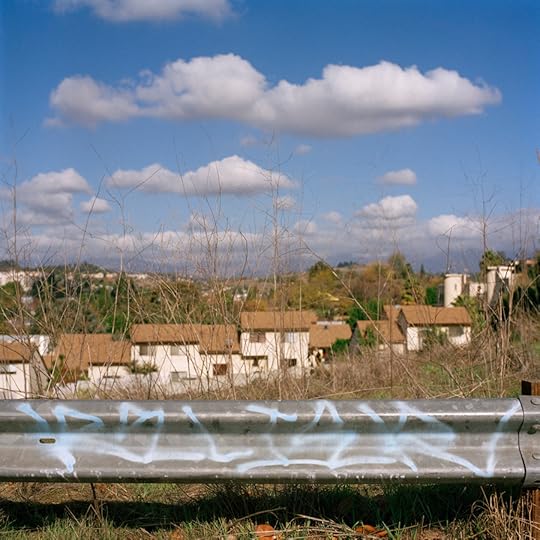

Christina Fernandez’s Multifaceted Visions of Life in California

Christina Fernandez’s eye for images has changed. Recently, while going through contact sheets of her early work, the Los Angeles–based photographer wondered why she chose one image over another—like a writer editing an old draft with a fresh outlook on each sentence or slightly altering how each word leads into the next.

Fernandez’s career spans more than three decades, and this careful looking imbues much of her work. While her images aren’t defined by geography, she is a significant maker of California photography. The series View from Here (2016–18) includes images framed by doorways and windows in artist studios across locations like Desert Hot Springs, Joshua Tree, and Manzanar, the former site of a Japanese internment camp. Sereno (2006–10) captures scenes from El Sereno, the artist’s neighborhood in northeast Los Angeles, particularly those that hint at the parallel existences of nature and urban life. In Lavanderia (2002–3), Fernandez bottles the essence of Los Angeles laundromats, rendering blurry traces of the people who rotate through these spaces. Yet the themes of labor, migration, and capitalism in her work extend the images beyond any borders.

Christina Fernandez, Lavanderia #11, 2003, from the series Lavanderia

Christina Fernandez, Lavanderia #11, 2003, from the series LavanderiaNow, Fernandez is gearing up for the release of her first major monograph, forthcoming in October, as well as three concurrent exhibitions. Her first significant survey exhibition, Christina Fernandez: Multiple Exposures, opens at the California Museum of Photography at UCR Arts on September 10 and runs through February 5, 2023. The exhibition also marks the first time the Lavanderia series will be shown in its entirety. Multiple Exposures will travel to places the artist says she’s never visited before—its future hosts are the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey; San José Museum of Art, California; and DePaul Art Museum, Chicago. (The exhibition was organized by UCR ARTS and is curated by Joanna Szupinska, senior curator at the California Museum of Photography, with curatorial advisor Chon A. Noriega, a distinguished professor of film, television, and digital media at the University of California, Los Angeles.)