Aperture's Blog, page 34

January 13, 2023

The Cutting Cleverness of Martha Rosler’s Collages

When I was a teenager, I would create collages from women’s magazines like Vogue and Elle by cutting out the images I was drawn to and gluing them into new formations on computer paper. Strange and, to me, beautiful scenes came of this practice, this instinct to disassemble and reassemble visual aspects of the modern world—particularly women’s bodies, objectified and disaggregated in order to sell things. I particularly remember a collage made only from eyes—a hundred different irises, pupils, and lashes arranged in a kind of altarpiece to seeing, staring back at me.

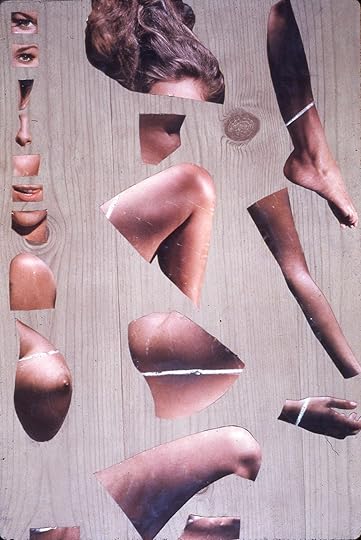

Martha Rosler, Transparent Box or Vanity Fair, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72

Martha Rosler, Transparent Box or Vanity Fair, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72  Martha Rosler, Bowl of Fruit, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72

Martha Rosler, Bowl of Fruit, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72 The photomontages on view at Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash in New York through January 21, are at once striking and deeply familiar, whether you’ve seen them before or not. Made between 1966 and 1972, the works from Rosler’s series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, convey a radical and playful feminist analysis of advertising that has by now become conventional wisdom. In Cold Meat I and II, refrigerators hold red buttocks and breasts in addition to the usual suburban provisions; in Transparent Box, or Vanity Fair and Isn’t it Nice…, or Baby Dolls models advertising lingerie are overlaid with breasts, lips, and pubis—the real products. Pop Art, or Wallpaper takes this critique to its natural conclusion with a medley of disembodied women’s body parts organized almost like butterflies, sorted by genus and pinned to wood, limbs lined up to the point of abstraction. The show’s inclusion of preparatory constructions and drafts of some of the works that hang on the walls suggests the humble tactility of Rosler’s project: one can imagine her sifting through the magazines of the day, scissors glinting.

Martha Rosler, Bathroom Surveillance, or Vanity Eye, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72

Martha Rosler, Bathroom Surveillance, or Vanity Eye, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72 Martha Rosler, Pop Art, or Wallpaper, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, 1966–72

Martha Rosler, Pop Art, or Wallpaper, from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, 1966–72There’s a cutting cleverness to Rosler’s collages, a dark wit that might as easily veer into horror, like laughing hysterics tipping over to tears. While the models, with their orange tans and full bosoms rendered in the washed-out vibrancy of film at the time, insist on their 1960s provenance, they also advertise a story out of time. Like Christian saint martyrs depicted holding their own body parts as proof of their purity (Saint Lucy holding her eyes, Saint Agatha her breasts), these women are dismembered and rearranged by Rosler in order to expose the primacy of this mandate: that to be good is to be disembodied. What if wholeness could be achieved not through the purchase of a bra or dishwasher, but some other way?

Martha Rosler, Nature Girls (Jumping Janes), from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72

Martha Rosler, Nature Girls (Jumping Janes), from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain, ca. 1966–72In House Beautiful: The Colonies (1969–72), Rosler critiques Cold War–era competition with the Soviet Union. These works are reminiscent of her series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72), in which House & Garden–style magazine spreads showcasing lavish homes are infiltrated by images from the Vietnam War, scenes of violence and horror wrought by America’s fear of Communism, of having our things taken from us. “I saw the clear reference to the home itself as being central to our ideology of why we were fighting people abroad,” Rosler has said, pointing also to all the ways in which imperialism and colonialism might be understood in tandem with patriarchy.

Installation view of Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2022–23

Installation view of Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2022–23 Installation view of Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2022–23

Installation view of Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others, Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, 2022–23There are a few comics and conceptual works on view as well. Selected works of sculpture and installation include Diaper Pattern (1973–75), where cloth diapers are scrawled with xenophobic and anti-Vietnam sentiments. A grassy airplane’s outline on the ground called B-52 in Baby’s Tears (1972) is a bit ineffectually overt. In Objects With No Titles (1971–73), lingerie and children’s clothing are stuffed and hanging, ghostly comical disruptions of the idealized female form found in advertisements across the gallery. Nearby, atop a mini mattress, a slip is outfitted with a mechanism and audio to simulate the rise and fall of breath.

Later installations and videos, like A Gourmet Experience (1974) and Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975)—in which Rosler, humorously deadpan, demonstrates the uses of various kitchen items to ridiculous and even violent ends—critique the domestic space. But here, the power of Rosler’s vision is best conveyed in her photomontages: a cutting apart and putting back together to analyze the patriarchal uncanny—exposing the violence and vanity, the unfreedom and absurdity of the way things are. Like Saint Lucy both holding her gouged out eyes while seeing through those planted firmly in her head, this rearranging—the reclamation that is collage—creates the perspective of a sight regained after it’s been taken.

Martha Rosler, Still from Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Black and white video, sound, 6 minutes, 35 seconds

Martha Rosler, Still from Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Black and white video, sound, 6 minutes, 35 secondsAll works courtesy the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

“It points to the compartmentalization that people are used to producing in how we live our lives,” Rosler has said of her work on American wars fought abroad. But her words could as easily point to a range of disassociations and divisions—almost three years into a global pandemic it’s never been clearer how inextricable are our fates, how fundamental our collective reliance, how we resist it at our own peril. This habit of disassembly “prevents us from being a whole society and from being whole individuals,” Rosler says. “We are not a here and a there. We are all one, and this is crucial.”

Martha Rosler: Changing the Subject… in the Company of Others is on view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, through January 21, 2023.

January 11, 2023

An Artist’s Clever Reuse of the Fashion Image

In 2017, the Vienna-based multidisciplinary artist Jojo Gronostay founded Dead White Men’s Clothes (DWMC), an art project styled similarly to a fashion brand, featuring upcycled garments from the Kantamanto Market in Accra, Ghana—one of the biggest collection points for used clothing worldwide. In those early days, he was strict about the categorization: “I always told everyone, ‘It’s an art project.’”

When Gronostay first exhibited the work, he built a shop of sorts inside a Vienna art gallery. Even today, despite the project having won a 2021 Austrian Fashion Award, he resists the idea of being labeled a designer. Although his work often involves restyling clothes, he does so to ask questions about recycling, economic structures, neocolonialism, and visual representation. “If you show something in an art context, people tend to look at it longer, and you have this aura of the space,” he told me recently. “In fashion, it’s something different. You have a shorter attention span.”

This pseudo-brand features pieces that are always one of a kind, given the nature of their creation, and are released outside of the typical collection schedule. All of this stems from Gronostay’s first visit, early in his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, to the packed market in Accra, a trip he took because of his interest in and research into replica clothing, which is also available in Kantamanto. “It was very quick. I thought, ‘I have to do a brand with all of this clothing.’”

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.His recent photographic series The Repros (2022), a collaboration with the artist Maximilian Anelli-Monti, plays on systems of fashion as well, and began with a custom-made sample book displaying different papers available at a photography print shop. The samples are meant to give customers a sense of the establishment’s capabilities in terms of paper and how colors will appear in a final print. Anelli-Monti made the studio photographs of the models, the book was designed by Christian Konrad, and Gronostay decided the project could also serve as a lookbook of sorts for DWMC, showing the scope of his pieces.

Related Stories Interviews Grace Wales Bonner on the Photographers That Inspire Her Visionary Fashion Design

Interviews Grace Wales Bonner on the Photographers That Inspire Her Visionary Fashion Design

“We thought about the Shirley card,” Gronostay says, referring to an old photography-industry standard that based the correct skin tones in the printing process on a white model named Shirley. The casting of Anelli-Monti’s portraits, which feature agency-represented models, can be viewed as a response to a photography and fashion canon that established white skin as the default. The project now exists in various iterations: a sample book for the print shop, a lookbook for the label, and an art object, available for purchase through Gronostay’s gallery.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Gronostay then took it all a step further by rephotographing the lookbook himself, adopting a direct, straightforward style inspired by the New Objectivity movement of 1920s Germany, shifting the context of the original work yet again. “I think it’s also about ownership,” he says. “If I rephotograph, it becomes, maybe, more my project.” The resulting eight images make up The Repros. By wringing every last drop from its original reference, each reinterpretation adds value in layers of accrued meaning. The method falls in line with the work done at DWMC. “It’s a good thing to reuse everything and use it until the end,” Gronostay says. “But you could also see it as the ultimate form of capitalism.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

January 6, 2023

The Double Life of a French Armenian Photographer

There are two Rebeccas. One Rebecca has two more days of rain a year. The second Rebecca lives in a place eighteen times smaller than the other’s. The first sleeps soundly in the cream-colored Haussmannian morning of France’s Paname. The second has long showered and eaten, and is out in the Pink City of Yerevan, Armenia’s capital with rose-stone Soviet-era buildings that radiate in the sunlight. The day advances with a three-hour air bubble between the two women. Parisian Rebecca walks on the living-room floorboards of an apartment built on land that has been independent since 843 CE. Yerevantsi Rebecca crosses a cobblestoned street of a recently independent Armenian nation. Nearly one thousand years of freedom between their feet.

A midday yawn starts in one mouth and finishes in the jaw of the other. Every now and then, their fingers move in unison, wrapping themselves around a coffee cup, as the women take a sip, swallowing with the same throat. Western Rebecca has run out into the chilled autumn day without her scarf. Eastern Rebecca’s neck prickles. Bisous are given on the cheeks of an old friend, two café crèmes on the round table in the eleventh arrondissement. Arms around the neck of a new friend who has been called to war on the Nagorno-Karabakh border of Armenia.

Topakian as her average Parisian self, 2022

Topakian as her average Parisian self, 2022  Topakian as Yerevan chic, 2022

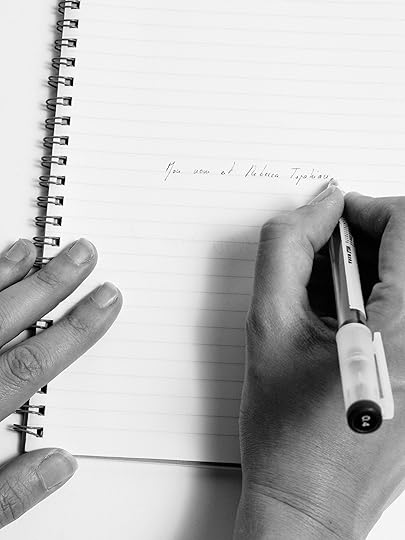

Topakian as Yerevan chic, 2022 In her newest series, Dual Nationality (2022), the photographer Rebecca Topakian reconstructs her own double identity from object-clues. Topakian, who was born and raised in France with Armenian roots, was inspired by the French Hungarian novelist Nina Yargekov’s 2016 book Double Nationalité (Dual Nationality), which follows a woman struck by amnesia. She finds herself at the airport with two sets of passports, keys, and mobile phones, and must piece together her identity. In late September 2020, the Nagorno-Karabakh war at the tensely disputed border between Armenia and Azerbaijan began. Unlike the First Nagorno-Karabakh War of the eighties that lasted six years, this armed conflicted didn’t make it to two months, with Armenia underarmed and overpowered by Azerbaijan’s abundant foreign military aid. Bayraktars, Turkish drones. A tree in flames. Zoom calls. No word. There are two Rebeccas. One on each line of a dead tone. Armenia’s defeat results in the return of those borderland territories inhabited since the mid-’90s. Soon after, Topakian decides to look for her Armenian dopplegänger. She learns the language, makes friends, applies for citizenship, and buys an apartment in Yerevan.

Related Stories Featured Ashish Shah’s Languorous Portrait of the Indian Countryside

Featured Ashish Shah’s Languorous Portrait of the Indian Countryside

Featured The Elusive Gaze in Chanell Stone’s Self-Portraits

Featured The Elusive Gaze in Chanell Stone’s Self-Portraits  Left: The keys to xx rue Dxxx, Maisons-Alfort, France, 2022; right: The keys to Saryan poghots xx, Kentron, Yerevan, Armenia, 2022

Left: The keys to xx rue Dxxx, Maisons-Alfort, France, 2022; right: The keys to Saryan poghots xx, Kentron, Yerevan, Armenia, 2022  Left: French Topakian’s ID card, 2022; right: Armenian Topakian cannot have an ID card because her name and patronym contain middles names, as French names do, which doesn’t fit the sixteen-character limit of the Armenian ID chip, 2022

Left: French Topakian’s ID card, 2022; right: Armenian Topakian cannot have an ID card because her name and patronym contain middles names, as French names do, which doesn’t fit the sixteen-character limit of the Armenian ID chip, 2022 In this series, we enter a Kieślowskian world of the double self: French Rebecca Topakian and Armenian Rebbeca Topakian are joined at the hand and through the Instagram handle @rebitopi. At Charles de Gaulle Airport, she receives spam proposing a deal for the purchase of a driver’s license or legal aid for French paperwork. At Zvartnots International Airport, threats pop up with photos of mutilated Armenian civilians, ads to join the army. Topakian collects these traces of herself in the virtual and physical geographies. Side-by-side portraits of two women are staged against the backdrop of a white light—an administrative absolute. An identity card, books, cigarettes, two sets of outfits rest against the blank wall like stark souvenirs. The seemingly flat visual hides a third dimension, a glaring airport walkway from one Rebecca to the other.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Dual Identity stems from another, more tactile approach to the same subject. Working with the Paris-based Armenian Spanish transdisciplinary artist and translator Araks Sahakyan, a carpet mapper, and two weavers, Topakian created a traditional Armenian rug bearing a glitched image of slaughtered Armenians she was harassed with on Instagram. She and Sahakyan cataloged their process in a new book, titled Rouge Insecte (Editions Sometimes, 2022), which involved retracing the decline of vordan karmir, a red insect indigenous to the Ararat valley used for its carmine tint—a native species facing extinction, a haunting echo of the Armenian people.

A sign for the Armenian Church on Komitas Street in Alfortville, France, known as Little Armenia, 2022. Komitas (1869–1935) was an Armenian theologist and musicologist who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after surviving the Armenian Genocide. He later died at a hospital in Paris.

A sign for the Armenian Church on Komitas Street in Alfortville, France, known as Little Armenia, 2022. Komitas (1869–1935) was an Armenian theologist and musicologist who suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after surviving the Armenian Genocide. He later died at a hospital in Paris.In both works, Topakian overlaps the historically displaced with the daily misplaced. Yargekov writes in her novel, “To be born in France is always an accident.” Nationality as chance or choice. The citizen as identity or identification. This is the morphology of the Rebeccas, eyes that peer out with a double gaze, at times one affirming the other, at others, putting her into question. When authorities stopped Topakian at the Georgia-Armenia border, they scrutinized her Armenian passport. The face doesn’t match the age. The height doesn’t fit the name. “He thinks I have a fake passport,” Topakian thought, panicking. “I need to prove that I am me.”

It is not proof, however, that Topakian assembles. It is doubt, intimate and unresolved, that allows the twin strangers to finally meet.

Rebecca Topakian’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera.

Topakian as “qyartu,” 2022

Topakian as “qyartu,” 2022  Topakian as patriot, 2022

Topakian as patriot, 2022  A bus stop named after the Armenian town of Ashtarak in Alfortville, France, 2022

A bus stop named after the Armenian town of Ashtarak in Alfortville, France, 2022  A memorial to the Armenian Genocide, Rue Etienne Dolet, Alfortville, France, 2022. The site was attacked by bombings in 1984 and 2002.

A memorial to the Armenian Genocide, Rue Etienne Dolet, Alfortville, France, 2022. The site was attacked by bombings in 1984 and 2002.  French Topakian uses a French SIM card and the Latin alphabet, 2022

French Topakian uses a French SIM card and the Latin alphabet, 2022  Armenian Topakian uses an Armenian SIM card and the Armenian alphabet, 2022

Armenian Topakian uses an Armenian SIM card and the Armenian alphabet, 2022  Topakian as parisian chic, 2022

Topakian as parisian chic, 2022 In the case of holding several citizenships, one should present the passport of the country they’re entering or leaving, 2022

In the case of holding several citizenships, one should present the passport of the country they’re entering or leaving, 2022  Mon nom est Rebecca Topakian (My name is Rebecca Topakian), 2022

Mon nom est Rebecca Topakian (My name is Rebecca Topakian), 2022  Իմ անունը Ռեբեկա Թոփաքյան է: (My name is Rebecca Topakian), 2022

Իմ անունը Ռեբեկա Թոփաքյան է: (My name is Rebecca Topakian), 2022

An Exhibition Revives the Legacy of “Life” Magazine

Had Life magazine still existed the second week of March 2020, one could easily imagine its editors scrambling to pull together a large feature that contextualized the rapidly unfolding COVID-19 pandemic. Global in scope, with scientific, personal-interest, and economic angles, it was precisely the kind of story that the magazine, in its mid-twentieth-century heyday, helped millions of readers understand. What made Life unique, and what helps make it an object of enduring historical fascination, is that the stories it told were primarily visual.

Life magazine, November 23, 1936, with cover photograph by Margaret Bourke-White

Life magazine, November 23, 1936, with cover photograph by Margaret Bourke-White© LIFE Picture Collection

Yet in recent decades, the curators Katherine A. Bussard and Kristen Gresh argue, that historical fascination has not led to much scholarship on the “complexities and collaborations behind its famed photo-essays.” Their book, which features twenty contributors, and the related exhibition, LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography, curated with the assistance of Alissa Schapiro, proposes a “material history” that outlines the process by which photographs were transformed into stories on the page. That undertaking involved “layout artists, a story-building team, caption writers, researchers, negatives editors,” according to Gresh. “Life is often thought of as a monolith, whether because of Henry Luce or particularly famous individual photographers. So it was exciting to uncover this collective effort.”

Carl Mydans, Young man playing guitar in the stockade, Tule Lake Internment Camp, Newell, California, 1944

Carl Mydans, Young man playing guitar in the stockade, Tule Lake Internment Camp, Newell, California, 1944© LIFE Picture Collection

The Life exhibition opened at the Princeton University Art Museum in February 2020, less than three weeks before the pandemic brought much of the world to a halt. “We lived in a virtual world for those first months of the pandemic, which reminded us of the importance of physical objects and underscored one of the show’s most important themes,” Gresh says. The show remained open in Princeton until September, but continuing pandemic-related challenges meant it didn’t open at its second location, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, until last October.

Fritz Goro, Red laser light focused through a lens blasts a pin‑point hole through a razor blade in a thousandth of a second, 1962

Fritz Goro, Red laser light focused through a lens blasts a pin‑point hole through a razor blade in a thousandth of a second, 1962© LIFE Picture Collection

The two-year delay offered Gresh the opportunity to rethink its presentation. She and her colleagues not only developed a polyvocal audio guide but also adapted the exhibition’s three-part structure by adding “contemporary moments” that feature artworks by Alfredo Jaar, recent work by Alexandra Bell, and a new commission by Julia Wachtel in the galleries between its main sections. These artists’ practices, Gresh notes, “really interrogate the media; they have long been thinking about the significant issues we address in the historical sections of the exhibition.”

Alfredo Jaar, The Silence of Nduwayezu, 1997. One million slides, light table, magnifiers, illuminated text on wall. Installation view of LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2022

Alfredo Jaar, The Silence of Nduwayezu, 1997. One million slides, light table, magnifiers, illuminated text on wall. Installation view of LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2022 Julia Wachtel, Untitled Commission, 2022. Two freestanding walls with vinyl wallpaper, one silkscreen painting, two hand-painted canvases. Installation view of LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2022

Julia Wachtel, Untitled Commission, 2022. Two freestanding walls with vinyl wallpaper, one silkscreen painting, two hand-painted canvases. Installation view of LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2022Gresh has chosen several works by Jaar that provoke reflection on the first section, which explores how the magazine’s photographs came into being. Among them are two pieces from his Rwanda Project: The Silence of Nduwayezu (1997), which is composed of one million slides piled onto a light table, and Real Pictures (1995), in which graphic photographs are hidden inside archival boxes bearing descriptive labels. They suggest, respectively, what can and cannot be conveyed in photographs and which kinds of pictures make it into mass-media settings.

Related Items

Aperture 249

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error] Alfredo Jaar, Life Magazine, April 19, 1968, 1995

Alfredo Jaar, Life Magazine, April 19, 1968, 1995The MFA has acquired a third work by Jaar that bears more directly on the exhibition’s subject: Life Magazine, April 19, 1968 (1995), which is composed of three poster-size photographic prints. The leftmost image is an enlargement of the iconic photograph of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral procession that was printed in the magazine; the other two offer the same image, only faded and desaturated. In the middle print, Jaar has placed black circles over the faces of Black mourners and, in the rightmost print, red circles over the faces of white mourners. The difference in the number of circles is striking. It’s a simple device, and “using words would not be as powerful,” Gresh says. “The second and third images are basically whitewashed, which could reference the whitewashing of our own history of racism, or more specifically the whitewashing of Life magazine’s narratives. The triptych format could also reference traditional Christian altarpieces.”

Alexandra Bell’s artworks offer an emotional yet critical view of American print media.

In 2017, Alexandra Bell became widely known for her series Counternarratives, which alters the front page of the New York Times with revisions to headlines and photographs marked in red pen that reveal the paper’s racial biases. She presented the work as large wheat-pasted posters around Brooklyn and, subsequently, in—and on—museums. The Boston show includes four of those works, which, Gresh says, “play a crucial role in framing a larger conversation for our visitors about implicit biases and systemic racism in photojournalism.”

Alexandra Bell, Gang Leader, 2022

Alexandra Bell, Gang Leader, 2022All works courtesy the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“I see news as an art object,” Bell told the New Yorker critic Doreen St. Félix after she began the series. In this way, her contributions to the Life show, including Gang Leader (2022), about the disconcerting white-nationalist activities of Vice Media co-founder Gavin McInnes, offer an emotional yet critical view of American print media that resonates with Jarr’s work and provokes new ways of reading the history of Life. As Gresh notes, “We want to do justice to all different types of photography.”

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

What Is the Environmental Cost of Photography?

Over the past twenty years, the rhetoric of corporate-driven globalization has spun a fantasy about the digitalization of images, as if we have entered the epoch of dematerialized photography. Undoubtedly, we print photographs less frequently than we used to, yet the ubiquity of the smartphone means that today far more photographic images are being produced, as well as exchanged via networks and stored as data files. Today’s glut of digital images may seem divorced from the previous era of the negative-based print, yet excess characterizes both eras at the levels of circulation and production. Analog photography was tremendously resource-intensive, just as digital photography relies on the proliferation of mobile devices that employ approximately seventy-five elements from the periodic chart to function.

Anaïs Tondeur, Carbon Black, 2017

Anaïs Tondeur, Carbon Black, 2017Courtesy the artist

How can we account for the continuities between analog and digital photography, and their shared problem of overabundance? The exhibition Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production, recently presented by the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Hamburg, Germany, addresses various topics such as these about the supply chains of the medium. It contains archival photography and the work of nearly two dozen modern and contemporary artists and collectives, including Mary Mattingly, the Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio, Madame d’Ora, Robert Smithson, Simon Starling, and Anaïs Tondeur. Emerging from the exhibition, which will travel over two years from Hamburg to Vienna and Winterthur, Switzerland, the accompanying catalog features a half-dozen highly engaging and informative commissioned essays and a series of conversations between historians, curators, and creative practitioners.

Unknown photographer, Silver bars in the Kodak vault, 1945. Gelatin-silver paper, Kodak Historical Collection #003, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, University of Rochester

Unknown photographer, Silver bars in the Kodak vault, 1945. Gelatin-silver paper, Kodak Historical Collection #003, Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, University of RochesterEastman Kodak Company

Unknown photographer, Raw paper storage, Agfa AG, Leverkusen, 1956

Unknown photographer, Raw paper storage, Agfa AG, Leverkusen, 1956Agfa Collection, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

The book is a superb primer on how to understand the material substrata that make photography possible: the copper, bitumen, silver, albumen, gelatin, cotton rag, and celluloid of the analog, and the lithium, cobalt, and other so-called rare earth elements used in today’s magnet-based digital devices. As Nadia Bozak points out in one of the volume’s essays, there are hidden and invisible forces and histories behind how a photograph presents what is before the lens. One chronic suppression is how the image came to be created at all: for example, how the camera and recording technologies were assembled and produced.

Fossil fuel is always among the primary unseens of photography. The invention of the medium coincided with that of the steam engine and large-scale factory production, which relied on coal, peat, and later petroleum power. For how else other than with steam-powered mining equipment and transatlantic steamboats do you import all that silver from mines in Bolivia to Berlin, Antwerp, or Rochester, New York, to coat paper with photosensitive silver salts? How else, without logging operations fueled by coal- or gas-powered vehicles, do you gather all the hewn logs to be pulped and boiled in sulfuric acid to make cellulose paper?

F&D Cartier, Wait and See, 1998–ongoing. Exposure tests, untreated gelatin silver photographic papers from Leonar, Illingworth & Co., Hans Mahn & Co., Wephota

F&D Cartier, Wait and See, 1998–ongoing. Exposure tests, untreated gelatin silver photographic papers from Leonar, Illingworth & Co., Hans Mahn & Co., Wephota© the artists

As the nineteenth-century marched on, machinery to transport and process these materials needed to be assembled and deployed, originating in yet more fossil fuel–powered factories. Sometimes, as with photogravures that coated paper with asphalt or bitumen to print using soot dust, the image became an artifact of pollution and energy consumption. Mining Photography also points to other fascinating circularities, such as how the mercury used in gold-washed, copper-plate daguerreotypes continues to contaminate streams in the Western United States where itinerant photographers set up studios to cash in on boom-time gold miners’ portraits.

The outsized appreciation given to individual photographers in the story of photography’s origins neglects the key role of trade networks, resource depletion, and labor struggles.

What if we were also to examine, as Katherine Mintie does in her insightful conversation with Mining Photography’s editor Boaz Levin, “the material networks and the production of photographic goods . . . to recognize the labor of those who are often marginalized in photographic histories—women, the enslaved, the working class, and even animals”? The outsized appreciation given to individual photographers, many of them white and male, as Mintie points out, in the story of photography’s origins neglects the key role of trade networks, resource depletion, and labor struggles in supporting the physical and discursive apparatuses of image creation and circulation.

Robert Smithson, Asphalt Rundown, 1969. Cava dei Selce, Rome, Italy

Robert Smithson, Asphalt Rundown, 1969. Cava dei Selce, Rome, Italy© Holt/Smithson Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Installation view of Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, 2022

Installation view of Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, 2022Take, for example, those animals Mintie refers to—chickens, pigs, cows, and horses. Mining Photography directs readers to consider the material reality of photography, like the billions of eggs required to produce albumen papers. Levin also points out that “as late as 1999 Kodak was still processing over thirty million kilos of cow skeletons every year,” their skins and bones rendered into gelatin, the main fixative of photosensitive paper.

And consider the enslaved workers who mined the copper, gold, and silver for daguerreotypes, and later, the tons of silver needed to embed in that gelatin-coated paper. Or the enslaved who grew and picked the cotton, later woven into textiles by women and children in mills, fabric that eventually found its way into trash collected and sorted by largely female, underaged, or elderly ragpickers, and that was eventually bleached and boiled by women who worked in factories to produce rag paper. How manual labor became divorced from the labor of authorship—anonymized as merely “raw” production against “refined” artistic creativity—is the cornerstone of this story.

John Cooper, Woman miner, 1860s. Carte de visite

John Cooper, Woman miner, 1860s. Carte de visiteTrinity College Library, Cambridge

Tobias Zielony, Dunkelraum, 2022. Slide installation

Tobias Zielony, Dunkelraum, 2022. Slide installation© the artist

Mining Photography presents a fascinating case study of a trove of 1860s cartes-de-visite of so-called pit brow women of Britain’s coal mines, collected by the poet Arthur J. Munby, who also commissioned several examples. The images are a striking departure from Victorian-era stereotypes of femininity, as the miners stand in sometimes fancy-looking studios wearing dirty, rolled-up jeans and holding the pans and shovels of their trade, or sit, legs spread wide, on wheelbarrows. In their work clothes, staring frankly out to viewers with nonplussed gazes, they make visible the labor of production behind modernity’s comforts.

The book’s pages are interspersed with unsigned archival images, such as those of the “pit brow” women, and with contemporary works that explicitly share authorship with nature. One could say that photography, as an indexical medium capturing subjects external to the camera, and doing so by relying mostly on sunlight, has always “collaborated” with nature. In the case of Tondeur’s work, the artist creates a printing medium using soot caught in respirators that she wears in highly polluted areas. Her process references the photogravure method of using coal or bitumen to produce a carbon medium for the image. Her images of the sites, which are shown with the respirators and vials of particulate matter, labeled to identify the areas where she sampled, are utterly dependent on invisible aspects of the landscape in a way that most photographs are not.

Tobias Zielony, Dunkelraum, 2022. Slide installation

Tobias Zielony, Dunkelraum, 2022. Slide installation© the artist

Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke und Richard Nielsen), Lake Bed Developing Process, 2013

Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio (Lauren Bon, Tristan Duke und Richard Nielsen), Lake Bed Developing Process, 2013© Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio

Projects that take up digital photography are likewise concerned with the materiality of the image-capture process. They focus on how technology companies that produce lithium-battery-powered devices with high screen luminosity aspire to literally outshine their ethically suspect and largely hidden back-end supply chains. Mary Mattingly’s work on cobalt mining in the United States and the Democratic Republic of the Congo represents the mundane realities of the material. It appears in one photograph as a rather unassuming silver-gray metal; flow charts depict its byzantine interpenetration of nearly every aspect of contemporary existence: the rechargeable batteries in tablets, phones, cameras, laptops, and electric cars, as well as cobalt’s presence in industrial chemicals and dental and surgical equipment.

Mary Mattingly, Eagle Mine, 2016

Mary Mattingly, Eagle Mine, 2016© the artist

Supply chains are rooted in trade networks that rely on the rapid and reliable circulation of goods, often without explicitly marking that complex process as part of the consumer’s purchase. Beyond the standard back matter credits, however, the book initiates no conversation about the materials and supply chains that contributed to the production and distribution of the physical volume itself, which would have presented an interesting moment of self-reflection about the often-globalized reality of contemporary publishing. This oversight notwithstanding, in its timeliness and historical depth, Mining Photography provides a much-needed corrective to many blind spots of production in the consumer economy.

Mining Photography: The Ecological Footprint of Image Production was published by Spector Books in 2022.

January 4, 2023

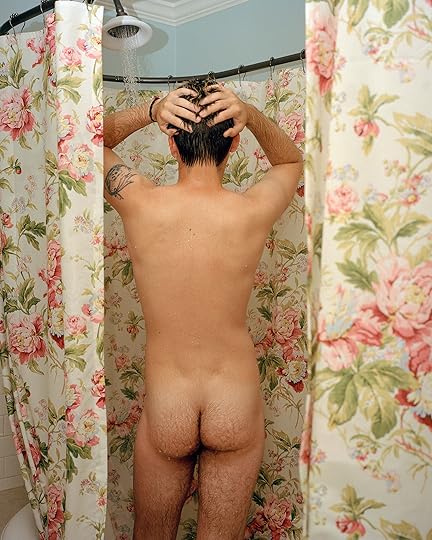

Caroline Tompkins Explores the Territory between Fear and Desire

It’s intoxicating to be desired and cared for, even when that care is ruinous. In the introduction to her new book, Bedfellow, the photographer Caroline Tompkins describes a disquieting dream that came to her while in bed with an abusive former partner. “While we were together,” she writes, “I’d dream that I was covered in leeches.” In her vision, wet-looking, wiggling worms blanketed her smooth skin and sucked at her body. While Tompkins was involved with this man, he would break into her apartment when she was out of town and send her photos of its interior. He stalked her friends and threatened to kill himself if she ever left.

Pondering their relationship, Tompkins writes unflinchingly about her response to this controlling behavior. “I became comfortable being violated,” she says in the book’s introduction, recalling how she would text him back and sleep with him despite the abuse, “and I was always so, so sorry.” The leeches started appearing in her dreams near the end of their relationship. In Bedfellow, she reflects on the motif: “To dream of leeches is to understand that something is taking the vigor out of you.”

Years later, Tompkins decided to yank that dream out of her mind and turn it into a photograph. She researched leech therapy—a bloodletting practice in which therapists strategically place leeches on a client’s body—and ordered six medium medicinal leeches on leech.com. A friend offered up his body for the photograph, and she arranged him on her own bed in Queens before carefully setting the leeches on his skin.

The resulting photograph is one of the most striking and disturbing images in Tompkins’s new book. In the picture, an anonymous young man (we see only his torso) reclines on wrinkled blue sheets while three fat leeches sit, curled in a pool of blood, on his stomach. One of the worms rears up, its body gorged, slimy, and alarmingly animate. Only after we’ve noted the leeches do we realize that the man has his hand down the front of his pants.

In Bedfellow (Palm Studios, 2022), Tompkins explores the shadowy territory where fear and desire overlap. As in her leech photograph, where she pairs eroticism with horror, Tompkins bluntly foregrounds the psychic agitation that many people have learned to associate with arousal. In a conversation with the photographer this past fall, I asked about the image and her decision to have her subject touch himself. “That’s the last picture I made for the book,” she said slowly, “and I was after a confusing image.” She knew instinctively that the photograph needed a sexual component to feel complete. “It felt like it would end the circle,” she explained. She wanted to symbolically close the loop on a man who had manipulated her and scared her—but whom she desired nonetheless.

What happens to your understanding of sex when your early experiences of love and lust are tied to unease and anxiety?

For many young people, especially women, our earliest dialogues about sex are nested in conversations about danger. Is it any surprise, then, that we learn to associate one with the other? Bedfellow approaches an uncomfortable question: What happens to your understanding of sex when your early experiences of love and lust are tied to unease and anxiety? How do these experiences define identity? At what point do we begin to associate panic with anticipation? Fear and excitement feel deceptively similar in the body: your brain is shaking every tree and lighting fire to the ground.

Cultural reckonings like #MeToo made it clear that women tiptoe through minefields when they meet men at bars, through friends, at work. Approximately eight out of ten acts of sexual violence are committed by an acquaintance. More than a third are committed by a current or former partner.

As subjects, fear and sex have been present in Tompkins’s photography since art school. After moving to New York from Ohio in 2011, Tompkins was catcalled on a daily basis—a new experience. Rather than shouting back, she chose to respond through her photography. In the resulting series, Hey Baby (2011–14), she photographed the men who made her uncomfortable. Some of the catcallers shied away from the camera; others posed defiantly. That series, with its themes of transgression, aggression, and the male gaze, was a clear precursor to Bedfellow.

Most pages in Bedfellow pluck at the viewer uncomfortably, and though the source of the discomfort isn’t immediately clear, its generator is the body. Although it inspires endless fantasies, the naked body is often an awkward thing, with its jutting bones, tangled chest hair, and dry, scaly skin. Tompkins’s photography pokes at the male body in particular. Her interest lies in examining contemporary presentations of masculinity, both gentle and antagonistic. One image, a portrait of a man with a thick, curling beard and a small child, takes male tenderness as its focus. The adult in that image is imposing—he has a heavy chain tattooed around his neck and thick black wraps around one wrist—but he gently curls his lips as he kisses the kid’s cheek. Other images present a menacing vision of masculinity, as in the photograph of a bright blue, veiny scrotum dangling from a truck’s trailer hitch, or the image featuring a thin, naked man with serious eyes who licks his upper lip, his erect penis on full display.

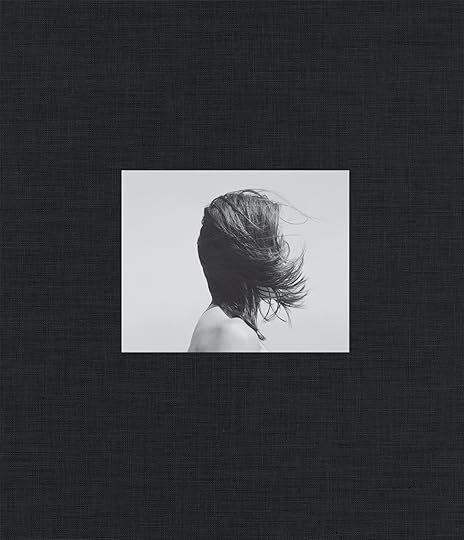

All photographs by Caroline Tompkins from the book Bedfellow (Palm Editions, 2022)

All photographs by Caroline Tompkins from the book Bedfellow (Palm Editions, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Many of the photographs in Bedfellow would seem innocuous were it not for the perplexing discomfort that wiggles at the back of the viewer’s brain, and Tompkins’s best images are often her most subtle. A deeply sensitive photographer, she has the impressive ability to assess her surroundings and pinpoint the moment her contentment falters, like spotting a snarl in the weft. Bedfellow is at its strongest when it scratches at the porous boundary between arousal and discomfort. Years ago, Tompkins attended a nudist festival and was surprised by the level of anxiety she felt in that space. She was surrounded by nakedness and sensuality, but she couldn’t quell the alarm bells in her mind. “I became really interested in how those reactions are two sides of the same coin,” she told me. “They’re two experiences that we hold at the same time, and to me, that felt like a truer picture of desire.”

Caroline Tompkins’s Bedfellow was published by Palm Studios in 2022.

December 26, 2022

Aperture’s Best Photography Features of 2022

Aperture turned seventy this year. And to celebrate this milestone, we revisited our past and were reminded of why our founding editors believed so strongly that photographs mattered. Global and local events this year also underscored photography’s unique power to shape our view of the world, to make sense of what unfolds around us.

Below, we assemble some of this year’s highlights in photography and ideas. In them, we see photography as a form of witness and resistance, as a means of celebrating the everyday, and as a powerful mode of connection. —The Editors

Nan Goldin, Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983

Nan Goldin, Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, London, and Paris

Nan Goldin Reflects on Art, Addiction, and Activism

A conversation with Darryl Pinckney, from Aperture, issue 239, “Ballads”

Throughout her career, Goldin photographed her friends, her lovers, and the family she made for herself. Her work constitutes an autobiography in several volumes, her life as an episodic tale. In this extensive and inspiring interview from Aperture’s 2020 issue “Ballads,” the photographer speaks with Darryl Pinckney, an acclaimed novelist and longtime friend.

Wolfgang Tillmans, still life, New York, 2001

Wolfgang Tillmans, still life, New York, 2001Courtesy the artist; David Zwirner; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

Wolfgang Tillmans’s Democratic Vision of Photography

by Evan Moffitt

Wolfgang Tillmans is a convener of intimacy. For the artist, whose work is the subject of a major new retrospective, images prompt us to reflect on political and social realities while also making us feel safe and loved. “This democratic vision of photography can be seen equally in the ways Tillmans gathers text and images together and the ways that bodies commune within them,” writes Evan Moffitt. “His work has room enough for us all.”

Natalie Keyssar, Soldiers say emotional goodbyes to their partners at the Lviv train station before heading to the front lines, March 8, 2022, for Time

Natalie Keyssar, Soldiers say emotional goodbyes to their partners at the Lviv train station before heading to the front lines, March 8, 2022, for TimeCourtesy the artist

A Photographer’s Account of Covering the War in Ukraine

A conversation with Cassidy Paul

This year, documentary photographer and photojournalist Natalie Keyssar traveled throughout Ukraine creating powerful, yet devastating records of those affected by Russia’s invasion. Here, she speaks about her experiences in Ukraine, the uncomfortable line between aesthetics and storytelling, and the essential need for photography in a moment of crisis.

Oleg Maliovany, Fresco, 1973–74

Oleg Maliovany, Fresco, 1973–74Courtesy the Collection of the Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography, Kharkiv, Ukraine

The Dissident Photographers of Ukraine

by Luca Fiore

Now under siege, the city of Kharkiv has a long history of artistic experimentation—one embodied by inventive, avant-garde photographers. “Today,” writes Luca Fiore, “the artists of the three generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography share the uncertain fate of the Ukrainian people.”

Dorothea Lange, Bad Trouble over the Weekend, 1965, from Aperture, Fall 1969

Dorothea Lange, Bad Trouble over the Weekend, 1965, from Aperture, Fall 1969© The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and courtesy Art Resource, NY

The Midcentury Photographers Who Balanced Reportage with Artistry

by Olivia Laing, from Aperture, issue 248, “70th Anniversary issue”

From W. Eugene Smith to Dorothea Lange, photography in the 1950s and ’60s was alive with the tensions between record and metaphor. “But is pure form any more attainable than pure reportage?” writes Olivia Laing. “Even the most fantastical image betrays something about the world, not to mention about the person making it.”

Alec Soth, Two Towels, 2004, from Niagara (Steidl, 2008)

Alec Soth, Two Towels, 2004, from Niagara (Steidl, 2008)Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

How to Produce a Photobook

by Diane Smyth

Making a photobook is like playing a puzzle or a game, one with plenty of room for creativity within certain rules or parameters. “There’s no one right way or recipe or formula,” says designer Hans Gremmen. “A book should always listen to its own rules.” Here, four bookmaking experts speak about each step of the production process—from making an image sequence to finding the perfect paper, size, and design.

Jamie Hawkesworth, Untitled, 2011–21

Jamie Hawkesworth, Untitled, 2011–21Courtesy the artist

How Jamie Hawkesworth Creates a Dreamscape of Everyday Encounters

by Alistair O’Neill, from Aperture, issue 246 “Celebrations”

In his newest work, the British photographer embarked on a worldwide journey, seeking connection in scenes from Detroit to Mongolia. Alistair O’Neill writes: “Hawkesworth is not interested in a grand tour. Instead, we see an accumulated, and fragmented, picture of the world as it appears in the twenty-first century.”

David E. Scherman, Lee Miller (Mirror Series), Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London, 1946

David E. Scherman, Lee Miller (Mirror Series), Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London, 1946© Lee Miller Archives, England

The Woman Photographer Who Out-Surrealed the Surrealists

by Lauren Elkin, from Aperture, issue 247, “Sleepwalking”

An artist, muse, fearless war correspondent, and professional chef, Miller looked at the world with a flair for drama—and an eye for the unexpected. “Miller’s Surrealism has to do with her ability to look ‘awry’ at the world,” writes Lauren Elkin. “She captures otherwise imperceptible moments and, in spite of their ordinariness, finds great drama.”

Related Items

Aperture 246

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 247

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 248

Shop Now[image error] Ashley Markle, Picnic, June 2020, from the series Weekends with My Mother and Her Lover

Ashley Markle, Picnic, June 2020, from the series Weekends with My Mother and Her LoverCourtesy the artist

A Photographer Casts Her Parents in a Story about Intimacy

by Coralie Kraft

Ashley Markle’s compelling images of her mother and stepfather reveal the intricate dynamics of family relationships. Taken over the course of ten-months, Markle’s series Weekends with My Mother and Her Lover is intensely personal, exploring themes of intimacy, communication, and the ways individual experiences shape our relationships.

John Goto, Lovers’ Rock 02, Lewisham, London, 1977

John Goto, Lovers’ Rock 02, Lewisham, London, 1977Courtesy the artist

Grace Wales Bonner on the Photographers That Inspire Her Visionary Fashion Design

A conversation with Ekow Eshun, from Aperture, issue 249, “Reference”

In an exclusive interview, the influential designer speaks about her artistic collaborations with Liz Johnson Artur, Tyler Mitchell, and Paul Mpagi Sepuya—and how she uses images to salute the past and imagine the future. “The way I think about references is that they’re a library,” says Wales Bonner. “Everything that’s in there is important.”

Sabiha Çimen, A student who has left the school mid-term waits for her father to pick her up, Istanbul, 2018

Sabiha Çimen, A student who has left the school mid-term waits for her father to pick her up, Istanbul, 2018Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

A Photographer Envisions the Lives and Dreams of Turkish Girls

by Kaya Genç, from Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations”

Sabiha Çimen’s photobook Hafiz portrays the world of Turkey’s single-sex Koran schools, where girls are tough, disciplined, and playful. “Çimen seems fated to be a guardian for the young students whose experiences she shared and captured,” writes Kaya Genç, “serving as their hafiza—the Turkish word for memory.”

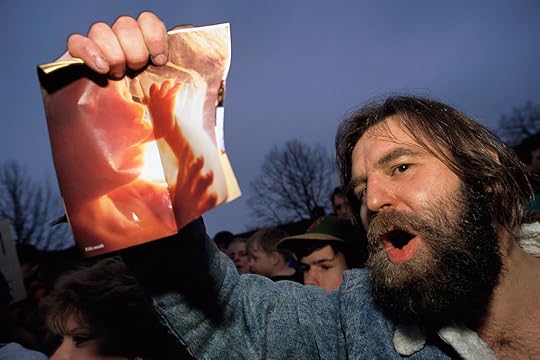

A group of Operation Rescue demonstrators protesting outside the home of the mayor of Buffalo, April 21, 1992. Photograph by Mark Peterson/Corbis/Getty Images

A group of Operation Rescue demonstrators protesting outside the home of the mayor of Buffalo, April 21, 1992. Photograph by Mark Peterson/Corbis/Getty ImagesHow Conservatives Weaponized Photographs in the Campaign against Abortion

by Lou Stoppard

For decades, medical images have been subjected to selective editing to create disturbing visions about the perils of abortion. But in the post-Roe era, how should pro-choice advocates handle visual representations? As Lou Stoppard writes: “As commentators rush to analyze the social, political, and religious shifts and divisions that led to the fall of Roe, the role of photography must also be acknowledged.”

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007

Tom Sandberg, Untitled, 2007Courtesy Tom Sandberg Foundation

Tom Sandberg’s Elusive Photographs Show Mysteries in Plain Sight

by Pico Iyer, from Tom Sandberg: Photographs (Aperture, 2022)

The Norwegian who pioneered photography in Scandinavia was always training his lens on the objects that we overlook, offering black-and-white scenes scorched of excess. “Nothing comes between us and what we’re seeing,” writes Pico Iyer. “We’re getting reality—or mystery—unmediated. Or so, at least, he makes me feel.”

Mohamed Bourouissa, Le téléphone, 2006

Mohamed Bourouissa, Le téléphone, 2006Mohamed Bourouissa’s Staged Portraits of Youth on the Peripheries of Paris

by Elisabeth Zerofsky, from Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations”

In a new photobook, Bourouissa returns to his signature series Périphérique, a critique of French culture and the politics of representation. As Elisabeth Zerofsky writes: “When he looks at these photographs now, Bourouissa sees very clear differences: ‘Race’ was a word that no one spoke at the time.”

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Fashion, White and Black, New York, 1990

Irving Penn, Issey Miyake Fashion, White and Black, New York, 1990© the artist and courtesy Pace Gallery

How Irving Penn and Issey Miyake Redefined the Fashion Photograph

by Alistair O’Neill

In their long-standing creative exchange, the two titans created some of the most memorable images in the history of fashion. Miyake, who died earlier this month, once commented that Penn gave his clothing a voice of its own. As Alistair O’Neill writes: “To look at the photographs is to see how Penn essentializes Miyake’s designs, bestowing them with a graphic clarity and a highly dynamic sense of how they can be worn.”

Marilyn Nance, Mid-festival, the first contingent of FESTAC ’77 U.S. participants greets the second U.S. contingent at the Lagos airport, 1977

Marilyn Nance, Mid-festival, the first contingent of FESTAC ’77 U.S. participants greets the second U.S. contingent at the Lagos airport, 1977© the artist and courtesy Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marilyn Nance’s Euphoric Chronicle of a Legendary African Arts Festival

by Anakwa Dwamena, from Aperture, issue 246, “Celebrations”

In 1977, when the photographer Marilyn Nance traveled to Nigeria for FESTAC, she discovered a thrilling reunion of the African Diaspora. As Anakwa Dwamena writes: “Nance’s archive remains one of the largest visual records of this monumental occasion, where the poet Audre Lorde ‘felt the earth move.’”

Related Items

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 249

Shop Now[image error]

Tom Sandberg: Photographs

Shop Now[image error]December 19, 2022

Announcing Pao Houa Her as the Recipient of the 2023–24 Next Step Award

Aperture and Baxter St at the Camera Club of New York, in partnership with the 7|G Foundation, are excited to announce Pao Houa Her as recipient of the 2023–24 Next Step Award. As the winning recipient, Her will receive a $10,000 artist’s grant and publish a photobook with Aperture, accompanied by an exhibition at Baxter St at CCNY in spring of 2024.

Initiated in 2020, The Next Step Award supports US-based artists at critical junctures in their artistic development. Reconsidering equity across the country and in arts institutions, the award also supports the presentation of diverse opinions, as well as timely lens-based work that is relevant to today’s visual culture and society across a wide array of genres or approaches. Previous recipients include Zora J Murff and Tommy Kha, whose forthcoming publication and exhibition will be presented in February 2023.

“Baxter St’s is thrilled to present Pao Houa Her with the 2023–24 Next Step Award,” says Jil Weinstock, executive director of Baxter St. “As an incubator to support and amplify dynamic and emerging voices, Baxter St is proud to support Her’s work, which highlights the shared experience of the Hmong community both abroad and as immigrants in the US. Aligning with an ethos of uplifting voices deserving greater recognition, Baxter St is honored to support Her’s practice and ongoing artistic growth.”

Pao Houa Her, Three bachelors at the Elder Center, 2016

Pao Houa Her, Three bachelors at the Elder Center, 2016Her has been granted this award for her various series exploring how the international Hmong community makes and remakes their collective memory. “My work attempts to break down the larger story of what it means to be a Hmong American into discrete moments in time. I see each small moment, each new portrait, as a kind of poetic note in a broader, diffuse narrative,” says Her. “My most recent work moves into even more conceptual space, using constructed/staged elements to play with themes of geography and longing.”

“For the many who were inspired by Pao Houa Her’s installation at the Whitney Biennial earlier this year, this exhibition at Baxter St and the accompanying Aperture publication provide a welcome opportunity to experience her work on its own terms,” observes Sarah Meister, Aperture’s executive director. “We are grateful for the opportunity to partner with Baxter St and 7|G to support emerging voices in the field.”

Her was chosen out of a competitive list of artists, nominated by a diverse group of artists and curators who brought expertise and artistic experience to the selection process. The nomination committee included Shantell Martin, Greg Harris, Wendy Red Star, and Akili Tommasino.

The roster of nominated artists who submitted to the prize included Nydia Blas, Rose Marie Cromwell, Jill Frank, Lizzie Gill, Genevieve Gaignard, Kyoko Hamaguchi, Tarrah Krajnak, Qiana Mestrich, Flo Ngala, Chanell Stone, and Patssi Valdez.

Pao Houa Her, Guy Cousin in Thailand, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Guy Cousin in Thailand, 2017  Pao Houa Her, Flower Penis, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Flower Penis, 2017  Pao Houa Her, Handcrafted Jungle Tiger, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Handcrafted Jungle Tiger, 2017  Pao Houa Her, After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw (Como Park conservatory), 2017

Pao Houa Her, After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw (Como Park conservatory), 2017  Pao Houa Her, Vince crying, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Vince crying, 2017  Pao Houa Her, Two Red Chair inside Western Union, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Two Red Chair inside Western Union, 2017  Pao Houa Her, After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw (portrait), 2017

Pao Houa Her, After the Fall of Hmong Tebchaw (portrait), 2017All photographs from the series My grandfather turned into a tiger (2016–2018) and courtesy the artist

Pao Houa Her, Maroon Backdrop, 2017

Pao Houa Her, Maroon Backdrop, 2017

December 16, 2022

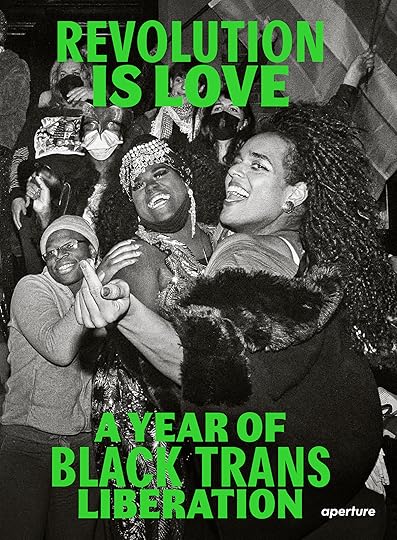

The Photographers Who Built an “Army of Lovers” through Protest and Celebration

In June 2020, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Over the following year, protests in the form of marches, voguing balls, or vigils brought together thousands of people across communities and social movements to gather in solidarity, resistance, and communion.

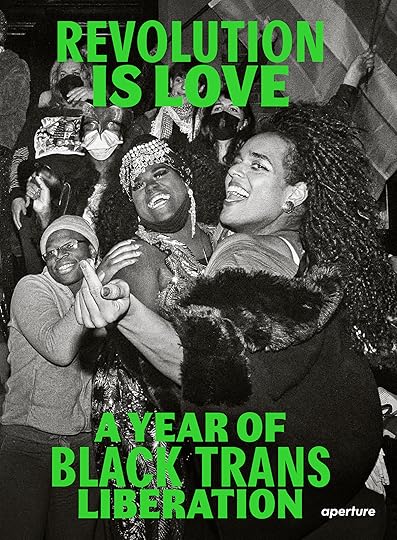

Bringing together works from twenty-four photographers, Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation (Aperture, 2022) is a powerful and celebratory visual record of New York City’s contemporary activist movement. Below, read a conversation from the volume between Raquel Willis and Qween Jean.

Ryan McGinley, Black Trans History Ball, February 2021

Ryan McGinley, Black Trans History Ball, February 2021Courtesy the artist

Snake Garcia, Icons Liberation Ball, October 2020

Snake Garcia, Icons Liberation Ball, October 2020Courtesy the artist

Raquel Willis: Could you place us in the environment of young Qween Jean, and the journey that laid the foundation for you to become so invested in Black Trans Liberation?

Qween Jean: To set the world for young Qween is difficult. She faced a lot of issues with self-worth, value, and wanting to be- long, a lot of which was tied to faith and spirituality. My household was rooted in faith and discipline, and focused on preservation and appearance. How are we viewed as a family? Will we make our parents proud? But in the end, those ideals and visions didn’t really include me, all of me, the full parts of myself. I thought, If this is family, I don’t want it. Because I can’t be myself here, I can’t dress the way that I want here. I have to constantly conform myself and shift, code-switch into this being, into this boy.

Willis: I resonate so much with that feeling of not belonging and not having a space of salvation. Church is often a safe haven for Black families and communities, but I wasn’t in a “Black church,” I was in a Catholic church. So as a Black family in the South, there were multiple layers of feeling we’re not where we’re supposed to be. And I’m not who I’m supposed to be. As a kid, I felt all these questions of, What is the rulebook? What is this script that seemingly works for everyone else that I just cannot get the lines and blocking down for? I think the points that hurt the most were when I knew that I was queer or that I was gender nonconforming, and I really wanted to own it, but I didn’t because I wanted to save face for my family and for all the people that I was supposed to represent. But I was never going to stay silent. I was silent for too long. It just got to a point in high school where I knew, this is the point of no return, honey.

Jean: High school was a big turning point for me as well. It is when I started my physical journey into femininity, into womanness, into Qween. And honestly, if I didn’t do something, it would have been a thorn in my side. The point of no return: I’m ooout! And I’m proud!

Ruvan Wijesooriya, Say Their Names, December 2020

Ruvan Wijesooriya, Say Their Names, December 2020Courtesy the artist

Ryan McGinley, Illumination Ball, October 2020

Ryan McGinley, Illumination Ball, October 2020Courtesy the artist

Willis: Exactly. I’m out. So what are we gonna do about it now? Because I’ve had to navigate and strategize for my own survival up until this point, so you figure out the rest, because I’m not going to live with this secret anymore.

Jean: Before I started reading stories of Black queerness, seeing Black queer elders, seeing other young trans women, I spent a lot of years in turmoil, angry and conflicted. The first time I saw a Black trans woman, I was in a flea market with my mother. There was definitely a disdain for her presence from the other Southern Black women. But for me, there was complete eruption of joy to see myself, essentially. Moments like this have inspired me to ensure that young people don’t feel ostracized or less than because they’re different, because they’re heavyset, because they’re dark-skinned, because they’re disabled, because they love Sailor Moon, for any reason.

Willis: Well, you are the evangelist, honey. Every time I see you, I hear you speak, I hear you sing, there is a testimony. What is that testimony that led you to activism and to the Stonewall Protests?

Jean: Wow, yes! It is a testimony. Personally, I believe that God doesn’t give me the spirit of fear, so why should I be afraid? There have been so many things in my life that I have navigated, dealt with, am still struggling with, that didn’t kill me. And so why should I not sing? Why should I not fight? I always come back to the phrase “come as you are.” There’s such power in that idea: to come with your experience, your struggles, your burdens, all the trespasses that have been made against you, to show up and still have faith and to still know, without a shadow of a doubt, that you will win, that you will persevere. I, and all queer people, experience moments where we feel we are alone or will no longer be accepted, that we won’t be loved, that we won’t make it. And I’m here to say we are. And we will.

Willis: And we have!

Jean: And we have. Because the reality is, we’ve always been here. We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social justice movement. We’ve existed.

Ryan McGinley, Liberation Not Deportation, October 2020

Ryan McGinley, Liberation Not Deportation, October 2020Courtesy the artist

Willis: I think about how depleted so many of us were in June 2020 after the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and then of course the overlooked Black trans murders: our brother Tony McDade in Tallahassee by police, Nina Pop and Monika Diamond, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells and Riah Milton. We were depleted but still managed to organize and to show up for the first Brooklyn Liberation march on June 14, 2020, which became one of the largest marches for Black trans lives in history.

Jean: The Brooklyn Liberation march in 2020 has been one of the most powerful moments in my entire life. I think that people are going to talk about that day for the rest of eternity, truly. Because we saw so many people come out who were depleted, who felt like, Is this ever going to end? The violence is just not stopping. But there was so much love and joy in that space. It truly was an alternate reality. And that was liberation. It was a space of liberation, where people felt seen, held, celebrated. We were with our living deities. What a gift.

We have been at every moment of history, we’ve been at every fight, at every social justice movement. We’ve existed.

Willis: Liberation is so speculative and can feel impossible. You’re literally writing fiction in your head when you’re thinking about liberation. But that day when upwards of twenty thousand folks came out—a whole congregation of folks who weren’t necessarily Black, who weren’t necessarily trans—it felt possible.

Jean: I will never forget being able to turn any direction and see so many beautiful kinsmen, kin sisters, kin siblings who had also come out to receive that blessing. So many people that I admire and look up to testified that day about love, about community, about taking pride in the self, about standing up to your enemy, to your oppressor, and saying to them, “You will not win.” It was a benediction for me. It gave me marching orders and gave me direction. I recited the benediction every chance I could, because it was a way for me to connect back to that moment of liberation.

Erica Lansner, Trans Day of Remembrance, November 2020

Erica Lansner, Trans Day of Remembrance, November 2020Courtesy the artist

Phoenix Robles, Justice for Breonna Taylor, March 2021

Phoenix Robles, Justice for Breonna Taylor, March 2021Courtesy the artist

Willis: It’s divine inspiration. Whenever it feels impossible for us to reach liberation, I have that moment, that day, to look back on. With the Stonewall Protests, you have so many moments to look back on from that year because you gathered every week after Brooklyn Liberation. What is that like for you, to be living with those glimpses? And what does that make you hungry for now?

Jean: At the Stonewall Protests, we came out to seek truth: emotional truth, the overwhelming political truth that exists within our world, and personal truth. And we needed space. Week after week in 2020, more of our Black trans siblings were being killed, and we needed a way to heal, to escape and gather, to scream it out, to march it out, to rejoice, to join in fellowship and to dance. And to truly be connected and fortified. It was like church in so many ways.

Willis: And a ball. It was everything at one time.

Jean: The community was so powerful. We were ultimately coined an army of lovers. People from all walks of life, from all backgrounds, all ages, all intersections of race and culture and religion. We held space, and we gave reverence, and we all understood the role that we had to play in that moment. We had to combat and to speak out against injustice, the ongoing racism, transphobic violence, transphobia, homophobia that exists in all of the subcultures that we know, that we come from, and all the communities that we shy away from, where we don’t feel safe, where we don’t feel accepted. This was a space where we could belong. And I want that to be a permanent space. I want to create a place of worship for queer people, for trans and nonbinary-identified folks. We deserve a trans choir! So many of our people have an anointed gift. Young queer people, we need a space to just have, to hold, to call our own. That is something that I know in my destiny has to happen. In so many ways, the Stonewall Protests was the church experience that I wish I could have had as a child. I prayed that I could have met up with community once a week in my Sunday best and come with a spirit and a fervor for truth.

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation is the powerful and celebratory visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City, and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community.

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation is the powerful and celebratory visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City, and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community.In June 2020, after a Black trans woman in Missouri and a Black trans man in Florida were killed just weeks apart, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Brought together by the urgent need to center Black trans and queer lives within the Black Lives Matter movement, a vibrant and radical community emerged.

Over the following year, the Stonewall Protests brought together thousands of people across communities and social movements to gather in solidarity, resistance, and communion. Each Thursday was an invitation for protests, healing, and celebration—whether through marches, voguing balls, or vigil—and a living testament to love in revolution. This book gathers twenty-four photographers who participated in these actions to share images and words on the demonstrations and their community at large, preserving this legacy as it unfolded. Through photographs, interviews, and text, Revolution Is Love celebrates the power of shared joy and struggle in trans community and liberation.

Featuring images and text by Ramie Ahmed, Lucy Baptiste, Budi, Brandon English, Deb Fong, Snake Garcia, Stas Ginzburg, Katie Godowski, Robert Hamada, Chae Kihn, Zak Krevitt, Erica Lansner, Daniel Lehrhaupt, Caroline Mardok, Ryan McGinley, Josh Pacheco, Jarrett Robertson, Phoenix Robles, Souls of a Movement, Madison Swart, Cindy Trinh, Sean Waltrous, Ruvan Wijesooriya, and David Zung

$45.00Add to cart

[image error] [image error]

In stock

Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans LiberationText by Qween Jean, Joela Rivera, and Mikelle Street. Interviewer Raquel Willis. Interviewee Qween Jean.

$ 45.00 –1+$45.00Add to cart

View cart Description Revolution Is Love: A Year of Black Trans Liberation is the powerful and celebratory visual record of a contemporary activist movement in New York City, and a moving testament to the enduring power of photography in activism, advocacy, and community.In June 2020, after a Black trans woman in Missouri and a Black trans man in Florida were killed just weeks apart, activists Qween Jean and Joela Rivera returned to the historic Stonewall Inn—site of the 1969 riots that launched the modern gay rights movement—where they initiated weekly actions known thereafter as the Stonewall Protests. Brought together by the urgent need to center Black trans and queer lives within the Black Lives Matter movement, a vibrant and radical community emerged.

Over the following year, the Stonewall Protests brought together thousands of people across communities and social movements to gather in solidarity, resistance, and communion. Each Thursday was an invitation for protests, healing, and celebration—whether through marches, voguing balls, or vigil—and a living testament to love in revolution. This book gathers twenty-four photographers who participated in these actions to share images and words on the demonstrations and their community at large, preserving this legacy as it unfolded. Through photographs, interviews, and text, Revolution Is Love celebrates the power of shared joy and struggle in trans community and liberation.

Featuring images and text by Ramie Ahmed, Lucy Baptiste, Budi, Brandon English, Deb Fong, Snake Garcia, Stas Ginzburg, Katie Godowski, Robert Hamada, Chae Kihn, Zak Krevitt, Erica Lansner, Daniel Lehrhaupt, Caroline Mardok, Ryan McGinley, Josh Pacheco, Jarrett Robertson, Phoenix Robles, Souls of a Movement, Madison Swart, Cindy Trinh, Sean Waltrous, Ruvan Wijesooriya, and David Zung Details

Format: Paperback / softback

Number of pages: 224

Number of images: 147

Publication date: 2022-10-25

Measurements: 6.75 x 9.25 x 0.81 inches

ISBN: 9781597115308

Willis: I love that you have documentation of what was happening from week to week, that the photographers were present and part of the community.

Jean: At the Stonewall Protests, we had such dedicated and passionate community members who are storytellers, photojournalists, archivists, muralists, who would show up. No one’s getting paid for this. No one is earning a salary to fight for Black lives. We are doing this so that we don’t have to in the future. We’re doing this so that we can have liberation now. To feel it, to exist in it. The documentarians who showed up for us have made such an impact. For me, it’s an offering. For our movement to not only have been recorded but to be shared and amplified, for other queer people to bear witness or to be able to hear it, who don’t necessarily have the access to community, to a weekly protest. That truly has been a huge gift and, I hope, something to mark our fight, to show it wasn’t just a onetime thing, that it’s still happening.

Robert Hamada, Justice for Daniel Prude, September 2020

Robert Hamada, Justice for Daniel Prude, September 2020Courtesy the artist

Souls of a Movement, An Honoring of the African Diaspora, February 2021

Souls of a Movement, An Honoring of the African Diaspora, February 2021Courtesy Souls of a Movement (Carlos von der Heyde).

Willis: When we think about the Civil Rights movement, we think about images and film from the [1963] March on Washington, from Selma and the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And the grueling moments, like [the murder of] Emmett Till and other victims of lynching. We have the benefit of looking at past generations and understanding how important visual documentation is for the next ones coming up. But, something we grapple with as Black trans and queer people is that we often weren’t in the frame, both physically and metaphorically, and so we continuously are excavating ourselves and our direct ancestors in these stories and histories. What are your thoughts on the importance of documenting what’s happening in real time?

Jean: I think it is so important and necessary to document, period. If we don’t know where we’ve come from, we won’t have the full knowledge to take us to where we need to go. But I completely agree that it often feels like excavation work. We are literally trying to find the fossils of our Black trans history. Trying to find any recollection, any relic that connects us to our past. I often think about the photographs and video footage of Black people being hosed or beaten by batons, things that are now archetypes of Black American experience and culture, unfortunately. So what does it mean to see Black trans people celebrating, having joy, being in community with one another, being able to rejoice, to not only mourn another sibling’s life but to celebrate it in the way that Black people do? That is part of our culture, to have a repass that does not just exist in a home, that truly carries out onto the street, that alerts and informs the entire neighborhood that Black trans lives are valuable, that so many of our siblings deserved better. They deserve to be alive, quite frankly. So I’m grateful that this visual documentation allows for this message to continue, to keep these names, faces, and lives in print, in vogue, in conversation as part of our culture.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});