Aperture's Blog, page 32

March 10, 2023

How Steven Meisel Defined Fashion in 1993

High-end fashion photography toward the end of the 1980s reveled in bravado. Think of the swagger of Herb Ritts and Bruce Weber, or the aristocratic eroticism of Helmut Newton. But by the early 1990s, young British photographers such as Glen Luchford, David Sims, Craig McDean, and Corinne Day arrived to rejuvenate the field, encouraged by a new community of magazines from the United Kingdom, especially iD and The Face. This renaissance disrupted the haute isolation of fashion photography, and cultural themes, street style, pop music, and club life became the fabric of new imagery. Fashion’s aspirational glamour was challenged by a personal narrative of the young.

As always, in this moment, the American photographer Steven Meisel assimilated shifts in both fashion and its photography to push the conversation. The year 1993—which saw the election of a young Bill Clinton, the first bombing of the World Trade Center, and the debut of television series like The X-Files and Beavis and Butt-Head—was also a year of prodigious output by Meisel. The exhibition Steven Meisel 1993: A Year in Photographs gathers images culled from that year alone, featuring twenty-eight international Vogue covers and more than one hundred editorial stories. This is the second exhibition of fashion photography staged at the MOP Foundation (an acronym for Marta Ortega Pérez, daughter of the founder of Zara) in A Coruña, Galicia, on the northwest coast of Spain, a remote location, far from the obvious hubs of international fashion.

Steven Meisel, Michele Hicks, Poppy Lloyd, Marlon Richards, Lucie de la Falaise, Miranda Brooks, and Bill Skinne, New York, for Vogue Italia, April 5, 1993

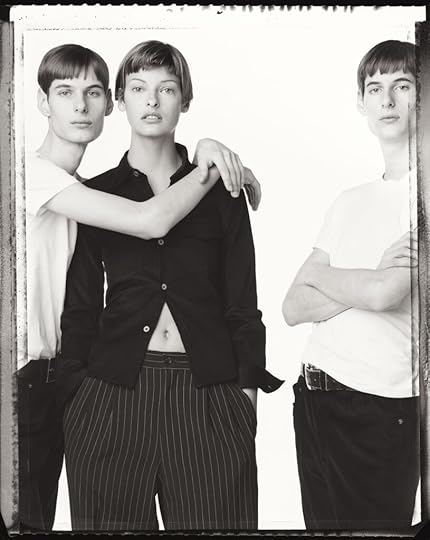

Steven Meisel, Michele Hicks, Poppy Lloyd, Marlon Richards, Lucie de la Falaise, Miranda Brooks, and Bill Skinne, New York, for Vogue Italia, April 5, 1993 Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, Ian Hundley, and Marc Hundley, New York, for Vogue, March 5, 1993

Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, Ian Hundley, and Marc Hundley, New York, for Vogue, March 5, 1993In a career spanning forty years, Meisel has defined the creative potential of fashion photography and has been held in consistent esteem in a traditionally mercurial arena. He moves quickly, and has shuffled through inexhaustible references to performance, nineteenth-century painting, surveillance imagery, pornography, and narrative gesture to make work that is inventive and unpredictable, revitalizing fashion history and anticipating its future. For four decades, the work has been an act of daring and dazzle and shrewd connoisseurship. Together with Guy Bourdin, Tim Walker, Nick Knight, and Steven Klein, Meisel developed fashion photography as a complex narrative in conversation with cultural preoccupations.

Related Items

Aperture 216

Shop Now[image error]

Aperture 228

Shop Now[image error]By isolating one pivotal year, the exhibition extracts a passage from a longer creative arc, and challenges the framework of a conventional career retrospective. Meisel emerges as a portrait photographer of great sensitivity. Fashion photography, like cinema, is a collaborative effort, and Meisel has been credited with cultivating a group of models in the eighties (Naomi! Linda! Christy! Amber!) whose presence and charisma elevated the profession. Although all fashion photography relies on the character and role-playing of those in front of the lens to suggest narrative and mood, Meisel’s work from 1993 goes further in its emphasis on the person as much as on the garments.

Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, New York, for Vogue Italia, February 11, 1993

Steven Meisel, Linda Evangelista, New York, for Vogue Italia, February 11, 1993  Steven Meisel, Stella Tennant, Paris, for Vogue Italia, July 22, 1993

Steven Meisel, Stella Tennant, Paris, for Vogue Italia, July 22, 1993 Here, the totemic Linda Evangelista poses for Vogue Italia in conventional portrait head-and-shoulders format, all the more appropriate to frame her merriment; later that year, we see Stella Tennant (Vogue Italia again) with no noticeable couture, but with an expression of guarded unkindness. Kristen McMenamy perches nude, with the exception of an elaborate headpiece, in the rosy opulence of the Ritz in Paris; a young Marlon Richards appears with a cluster of stylish companions (in a photo somewhat reminiscent of his father’s Rolling Stones Between the Buttons album cover); and a grungy Axel appears in a snapshot for Per Lui.

By isolating one pivotal year, the exhibition extracts a passage from a longer creative arc, and challenges the framework of a conventional career retrospective.

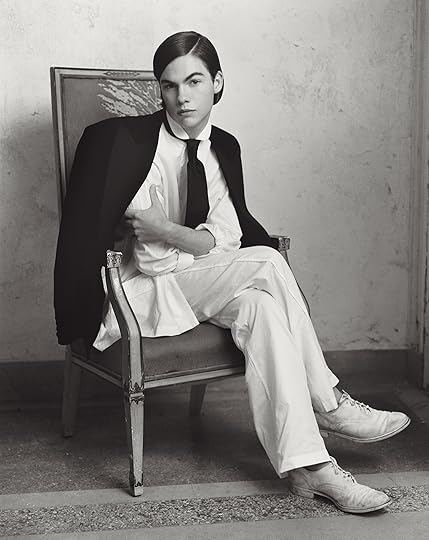

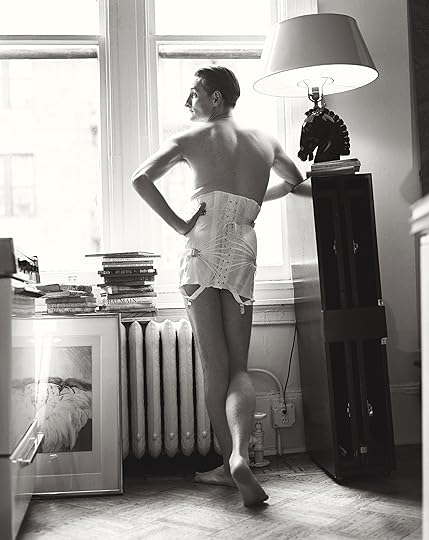

The dominance of black and white supports Meisel’s classicism, and an authenticity—not an idea often associated with fashion—that sidelines artifice. Here, glamour resides in the elegance of individual gesture and body language, the geometry of the frame containing the animation of the figures. Models huddle, stroll, and stride; they drape, their hands flutter unexpectedly, legs akimbo. In a time when men were idealized in fashion as chiseled and aggressive—Mark Wahlberg grabbing his crotch for the camera—the boys here are lithe and gangly, rattling constructions of gender, as in the photographs of Hamish Bowles clinched in lingerie. Much of the work feels improvisational, an impression of play, pleasure, and often mischief, deflating pretension and self-importance.

Steven Meisel, Justin Scott, Brookville, New York, for L’Uomo Vogue, November 11–12, 1993

Steven Meisel, Justin Scott, Brookville, New York, for L’Uomo Vogue, November 11–12, 1993  Steven Meisel, Hamish Bowles, New York, for Per Lui, March 10, 1993

Steven Meisel, Hamish Bowles, New York, for Per Lui, March 10, 1993All photographs courtesy Steven Meisel Studio

Meisel has at times aroused controversy. He has periodically touched upon social questions, racism, addiction, cultural narcissism, and often satirized fashion’s own mannerisms and exhibitionism. “Makeover Madness,” an editorial that occupied eighty pages of Vogue Italia in 2002, casts a narrative of models submitting themselves to all forms of body intervention, gowned in couture but swaddled in gauze. These excursions into social commentary showcased Meisel’s consummate engagement with what might be possible in a fashion photograph.

Meisel maintains the aura of someone who is so private as to be enigmatic. Despite his renown, he rarely gives interviews, and he has never published any of the expected survey books of his work. The news of an exhibition of Steven Meisel is, for the fashion and photography community, an occasion of celebration and curiosity. This selection from 1993 represents how he maintained autonomy from the bandwagon of the moment to reveal how the best fashion photography might honor our collective aspiration for connection and joy.

Steven Meisel 1993: A Year in Photographs is on view at the MOP Foundation in A Coruña, Galicia, Spain, through May 1, 2023.

March 9, 2023

James Welling Recasts the Ancient World

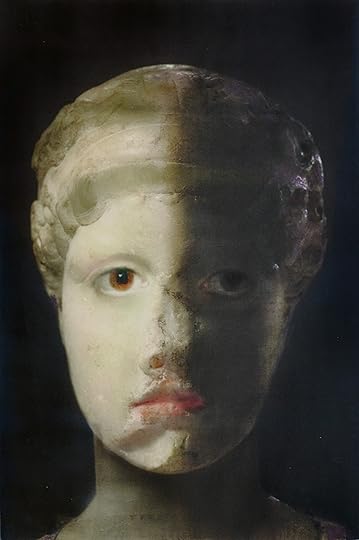

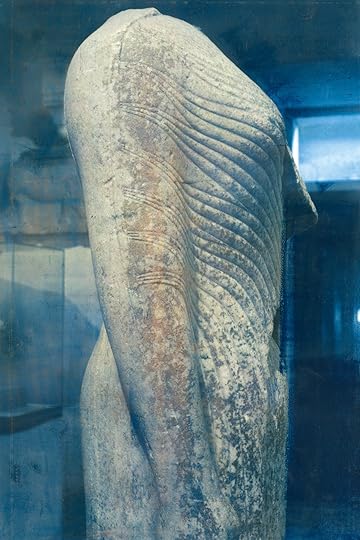

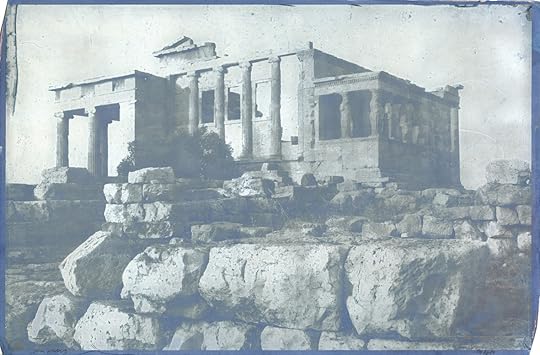

In 2018, the artist James Welling became fascinated with an ancient bust he photographed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that depicted a Roman noblewoman of Syrian origin, Julia Mamaea. The next year, he traveled to Athens and further immersed himself in the architecture, sculpture, and fragmentary remains of the ancient Greek world. Welling photographed extensively, from the facades of temples to small glass game pieces, fragments of tile, and personal adornments. He focused on the gestures and expressiveness of hands carved in stone: a boy holding a luscious bunch of grapes, or Venus demurely covering her nude body.

James Welling, Hands, 2020

James Welling, Hands, 2020  James Welling, Tile Fragment, 2020

James Welling, Tile Fragment, 2020 Much of this work would become the series Cento (2019–21), whose title gestures toward Welling’s method and aims. Typically referring to a work of poetry or music, a cento is made from accumulated fragments of the work of other, earlier artists. Through its form, a cento pulls the past into the present and suggests an inherent curiosity about how those fragments might communicate over time, from one culture and place to another. From Cento, Welling extended his interest in human expressiveness to Personae, works from 2021 to 2022 that begin with sculptural busts of individuals of ancient Roman, Greek, Egyptian, Syrian, and North African origin. Throughout, Welling’s deeply experimental and unique color process incorporates elements of photography, printmaking, digital production, and hand painting.

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture magazine. Sign-up today and your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture magazine. Sign-up today and your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.His most recent portraits of busts further the complexity of the cento: Welling began to add new eyes—eyes previously rendered by Renaissance and modern painters and that Welling photographed at museums—to the busts. To this unlikely pairing, Welling adds skin tone, hair color, jewelry, and other responses to the busts’ original hairstyles and fashions, sometimes updating them with contemporary looks. This depth and range of source material manages—seemingly against the odds—to coalesce into an animated moment of recognition, the sense of seeing another human, from another time, conjured before us.

James Welling, Portrait of Aphrodite, 2022

James Welling, Portrait of Aphrodite, 2022  James Welling, Kore from the Kheramyes Group, 2020

James Welling, Kore from the Kheramyes Group, 2020 In one such portrait, a young woman looks out from behind the partial veil of a dark shadow cast across her face. Her brown eyes, illuminated with light captured by an unknown painter from an unknown time, show her to be lost in thought. A smudge of warm pink enlivens her lip, the edge of her eye, and a blush on her cheek, and a touch of purple at her shoulder, indicating her dress, carries through highlights in her styled hair. Logically, the image is incongruous, built over time by at least three artists (the sculptor of the bust, the painter of the eyes, and now Welling). But intuitively, it is seamless. As a viewer, I know this mood, this transitory and yet timeless feeling of being lost in thought. Aphrodite has never appeared more relatable, even as she is absorbed in her world, unconcerned with ours.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

In the year 2022, there is no shortage of means with which to construct apparently human images, many drawing on the machine learning of artificial intelligence to create unnervingly convincing forms. Faces can be generated endlessly from vast assortments of previously photographed ones, mined from image banks, and scraped from online sources in a feedback loop that easily drains a sense of earlier place, time, and context. Those constructed faces ask something about what it means to be, and to picture, a human. Welling’s images also ask this question, but very differently, with a process that points to their own conclusion about human individuality and its representation. But this conclusion is more of an offer: Welling’s renderings describe not just a world unto themselves but an invitation to connect with those worlds—to recognize them—from the ever-shifting vantage point of this one.

James Welling, Fragment of a Gold Leaf Wreath, 2020

James Welling, Fragment of a Gold Leaf Wreath, 2020  James Welling, Grapes, 2021

James Welling, Grapes, 2021  James Welling, Portrait of Alexander Severus, 2022

James Welling, Portrait of Alexander Severus, 2022  James Welling, Acanthus Stalk, 2021

James Welling, Acanthus Stalk, 2021  James Welling, Glass Astragaloi (Knucklebones), 2020

James Welling, Glass Astragaloi (Knucklebones), 2020  James Welling, Athens. Western Facade of the Erechtheion, 2019

James Welling, Athens. Western Facade of the Erechtheion, 2019  James Welling, Artemision Bronze, 2019

James Welling, Artemision Bronze, 2019All photographs courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Marian Goodman Gallery, and David Zwirner

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 249, “Reference.”

March 8, 2023

9 Inspiring Photobooks by Contemporary Women Photographers

Sam Contis, Overpass (Aperture, 2022)

Sam Contis, Overpass (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Sam Contis: Overpass (2022)

In Overpass, Sam Contis explores what it means to move through the landscape. Walking along a vast network of centuries-old footpaths through the English countryside, Contis focuses on stiles, the simple structures that offer a means of passage over walls and fences and allow public access through privately owned land. In immersive sequences of black-and-white photographs, they become repeating sculptural forms in the landscape, invitations to free movement on one hand and a reminder of the history of enclosure on the other.

In an age of rising nationalism and a renewed insistence on borders, Overpass invites us to reflect on how we cross boundaries, who owns space, and the ways we have shaped the natural environment and how we might shape it in the future.

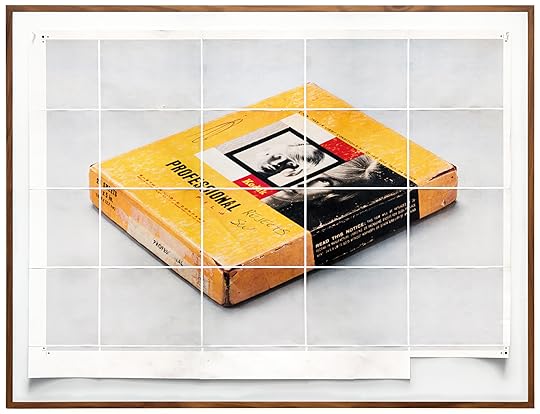

Sara Cwynar, Sahara from SSENSE.com (As Young as You Feel), 2020

Sara Cwynar, Sahara from SSENSE.com (As Young as You Feel), 2020Courtesy the artist

Sara Cwynar: Glass Life (2021)

Sara Cwynar’s multilayered portraits are an investigation of color and image-driven consumer culture. Cwynar’s work circles around a large range of ideas and interests, from the ways subjective notions of beauty form through images, to the fetishization of consumer objects and color, to informal image archives.

Working in her studio, Cwynar collects, arranges, and archives eBay purchases into her visually complex tableaux that examine how images circulate online, as well as how the lives and purposes of both physical objects and their likenesses change over time. This work is brought together in Glass Life, the first comprehensive monograph of this celebrated multidisciplinary artist.

Collect a limited-edition of Sara Cwynar: Glass Life featuring a special case and c-print.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008, from The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2016)

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008, from The Notion of Family (Aperture, 2016)Courtesy the artist

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Notion of Family , 2016 (First published 2014)

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s award-winning first photobook, The Notion of Family, offers an incisive exploration of the legacies of racism and economic decline in America’s small towns, as embodied by her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania. Examining this impact throughout the community and her own family, Frazier intervenes in the histories and narratives of the region. Setting the story across three generations—her grandma Ruby, her mother, and herself—Frazier’s statement becomes both personal and political.

In The Notion of Family, Frazier knowingly acknowledges and expands on the traditions of classic black-and-white documentary photography, enlisting the participation of her family, her mother in particular. In the creation of these collaborative works, Frazier reinforces the idea of art- and image-making as transformative acts, means of resetting traditional power dynamics and narratives—both those of her family and of the community at large.

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)

Rinko Kawauchi, Untitled, from Illuminance (Aperture, 2021)Courtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance , 2021 (First published 2011)

In her images of keenly observed gestures and details, Rinko Kawauchi reveals the mysterious and beautiful realm at the edge of the everyday world. For Kawauchi, the act of photographing is less a way of referring to the appearance of everyday reality than it is evoking the luminous openness that exists when the boundaries between things become blurred. As Kawauchi describes, “I want imagination in the photographs—a photograph is like a prologue. You wonder, ‘What’s going on?’ You feel something is going to happen.”

Ten years after its original publication, Aperture published a new edition of Kawauchi’s beloved photobook, retaining the artist’s original sequence alongside new texts by David Chandler, Masatake Shinohara, and Lesley A. Martin that contribute new context to and perspective on Kawauchi’s influential work.

Collect a limited-edition print from Rinko Kawauchi: Illuminance.

Justine Kurland, Orchard, 1998, from Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020)

Justine Kurland, Orchard, 1998, from Girl Pictures (Aperture, 2020)Courtesy the artist

Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures (2020)

The North American landscape is an enduring symbol of romance, rebellion, escape, and freedom. At the same time, it’s a profoundly masculine myth: cowboys, outlaws, Beat poets. Photographer Justine Kurland, known for her utopian images of American landscapes and their fringe communities, sought to reclaim this space with her now-iconic series Girl Pictures. Taken between 1997 and 2002, Kurland’s photographs stage scenes of teenage girls as imagined runaways, offering a radical vision of community and feminism.

Kurland portrays these girls as fearless and free, tender yet fierce. They hunt and explore, braid each other’s hair, swim in sun-dappled watering holes. Kurland imagines a world at once lawless and utopian, an Eden in the wild. “I wanted to make the communion between girls visible, foregrounding their experiences as primary and irrefutable. I imagined a world in which acts of solidarity between girls would engender even more girls,” writes Kurland. “Behind the camera, I was also somehow in front of it—one of them, a girl made strong by other girls.”

Collect a limited-edition print from Justine Kurland: Girl Pictures.

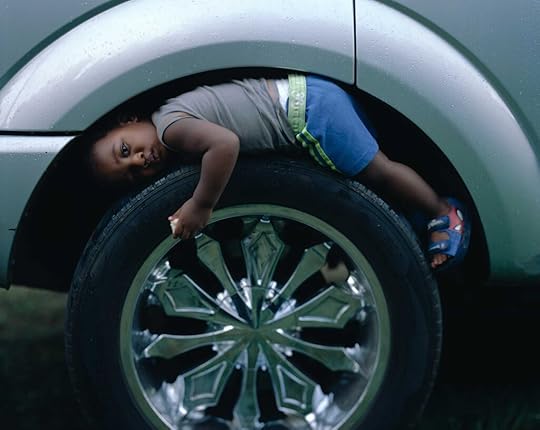

Deana Lawson, Mama Goma, 2014, from Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2018)

Deana Lawson, Mama Goma, 2014, from Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (Aperture, 2018)Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York

Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph (2018)

Over the last decade, Deana Lawson has created a visionary language to describe identities through intimate portraiture and striking accounts of ceremonies and rituals. Using medium- and large-format cameras, Lawson works with models throughout the US, Caribbean, and Africa to construct arresting, highly structured, and deliberately theatrical scenes. Signature to Lawson’s work is an exquisite range of color and attention to detail—from the bedding and furniture in her domestic interiors, to the lush plants and Edenic gardens that serve as dramatic backdrops.

Aperture published the artist’s landmark first publication, Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph, in 2018. In 2020, Lawson became the first photographer to be awarded the Hugo Boss Prize. One of the most compelling photographers of her generation, Lawson portrays the personal and the powerful. “Outside a Deana Lawson portrait you might be working three jobs, just keeping your head above water, struggling,” writes Zadie Smith. “But inside her frame you are beautiful, imperious, unbroken, unfallen.”

Collect a limited-edition of Deana Lawson: An Aperture Monograph featuring a special slipcase and custom tipped-in c-print.

An-My Lê, Night Operations VII, from the series 29 Palms, 2003–4

An-My Lê, Night Operations VII, from the series 29 Palms, 2003–4Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain (2020)

Throughout her thirty-year career, An-My Lê has photographed sites of former battlefields—spaces reserved for training for or reenacting war—and the noncombatant roles of active service members. Lê is part of a lineage of photographers who have adapted the conventions of landscape photography to explore the structures of conflict that have long informed American history and identity. Yet she is one of the few who have experienced the sights and sounds associated with growing up in a war zone, having evacuated her home country of Vietnam as a teenager in 1975.

On Contested Terrain is the first comprehensive survey of Lê’s work, featuring formative early works, as well as her well-known series Small Wars, 29 Palms, and Events Ashore, and Lê’s most recent photographs from the US-Mexico border. “Lê’s photographs are balanced, quiet, and nuanced works of art that offer the viewer an opportunity for contemplation,” Dan Leers writes. “She invites us to examine our own perception of, and involvement in, war as something that is not straightforward or clear-cut.”

Collect a special book and print bundle of An-My Lê: On Contested Terrain.

Diana Markosian, A New Life, 2019, from Santa Barbara (Aperture, 2020)

Diana Markosian, A New Life, 2019, from Santa Barbara (Aperture, 2020)Courtesy the artist

Diana Markosian: Santa Barbara (2020)

In Santa Barbara, Diana Markosian recreates the story of her family’s journey from post-Soviet Russia to the US in the 1990s. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Markosian’s mother, Svetlana, moved to the US with her two young children. The family moved in with a man named Eli in Santa Barbara, California, a city made famous in Russia when the 1980s soap opera of that name became the first American television show broadcast there.

Weaving together reenactments by actors, archival images, and stills from the original Santa Barbara TV show, Markosian reconsiders her family’s story from her mother’s perspective, relating to her mother for the first time as a woman, and coming to terms with the profound sacrifices Svetlana made to become an American. Brought together in Markosian’s debut monograph, the series offers an innovative and compelling hybrid of personal and documentary storytelling.

Collect a limited-edition print portfolio from Diana Markosian: Santa Barbara.

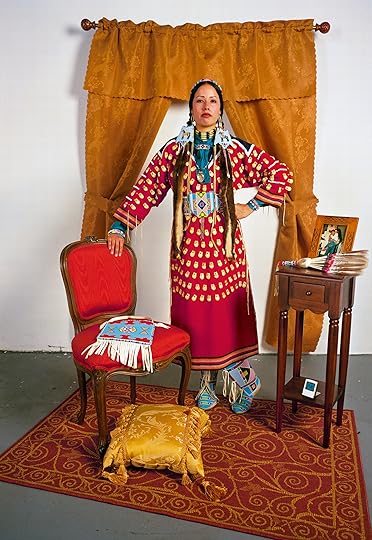

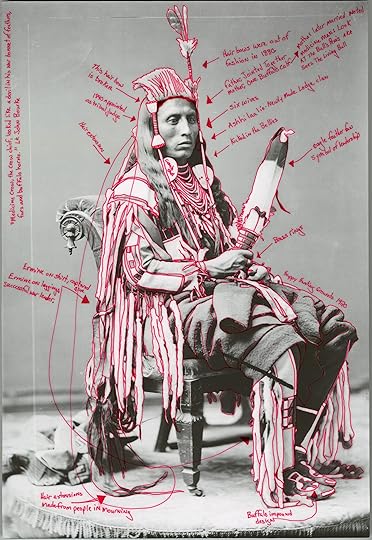

Wendy Red Star, Indian Woman Standing, from the series Indian Woman, 2005, from Wendy Red Star: Delegation (Aperture, 2022)

Wendy Red Star, Indian Woman Standing, from the series Indian Woman, 2005, from Wendy Red Star: Delegation (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014, from Wendy Red Star: Delegation (Aperture, 2022)

Wendy Red Star, Peelatchiwaaxpáash / Medicine Crow (Raven), from the series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation, 2014, from Wendy Red Star: Delegation (Aperture, 2022)Courtesy the artist

Wendy Red Star: Delegation (2022)

In her dynamic photographs, Wendy Red Star recasts historical narratives with wit, candor, and a feminist, Indigenous perspective. Red Star (Apsáalooke/Crow) centers Native American life and material culture through her imaginative self-portraiture, vivid collages, archival interventions, and site-specific installations. Whether referencing nineteenth-century Crow leaders or 1980s pulp fiction, museum collections or family pictures, she constantly questions the role of the photographer in shaping Indigenous representation.

The artists’ first major monograph, Delegation, is a spirited testament to the intricacy of Red Star’s influential practice, gleaning from elements of Native American culture to evoke a vision of today’s world and what the future might bring.

March 3, 2023

A Photographer’s Unsettling Experiments with “Cursed” Images

Picture an ’80s suburban, pastel bedroom with a life-size Elmo beckoning you to join him on the bed. One image shows two toddlers in a playpen lurching toward a medieval sword. In another, a raccoon, adorned in lilac frills, is dancing with its hands in the air while six snails drink milk together from a heart-shaped dog bowl. These are #cursedimages, and in 2016 social media was littered with them.

Defined by their lack of origin and mysterious content, #cursedimages intentionally create confusion. They juxtapose the aura of vernacular photography with uncanny and incongruent elements—in the same potent way nightmares scramble your deepest fears with daily events. The result is a toxic push-pull that leaves you disturbed by their chaos and soothed by their familiarity.

#cursedimages began as a visual shorthand for a bad day and transitioned into a viral phenomenon describing our collective psyche in a year of dramatic social and political upheaval. As they began to shift format—from images to memes, memes to TikToks—they became more feral. Eventually, #cursed took on greater cultural significance, emancipating itself from form and representing a moment in history. In the 2019 New Yorker article “How We Came to Live in ‘Cursed’ Times,” Jia Tolentino writes, “The idea of cursed energy does evoke a feeling that the simulation is breaking and that something terrible is emerging from the breach.”

Patricia Voulgaris, Found Mask, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Found Mask, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Spiderweb, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Spiderweb, 2022 The psychological impact of #cursedimages is a source of much fascination for photographer Patricia Voulgaris, who examines how we put our faith in images and the consequences of this trust. “I’m interested in what makes an image cursed or thinking about myself as being cursed,” she tells me over the phone. “I tried to curse myself for my final, and it did not go over well. Some people don’t believe in the possibility of phenomena.” Voulgaris, an MFA student at the Yale School of Art, is drawn to the fringes of belief and doubt, giving as much credence to the ridiculous as the serious, which, in part, makes her work feel inherently more human.

Photography’s role in cultivating systems of belief is something Voulgaris has been meditating on for years. As a teenager growing up in Levittown, Long Island, she spent Saturday afternoons ghost-hunting with her father. He was an active member of Long Island Paranormal, a Facebook group that met regularly in local cemeteries and haunted houses, hoping to connect with the spirit world. Armed with cameras, sound recorders, and electronic-voice-phenomenon meters, the group would trawl a location, often walking for hours, seeking evidence to confirm their beliefs.

“It felt like a social experiment,” Voulgaris says. “Trying to find proof but profoundly insecure about what would happen if we did. How do you capture an event to debunk a theory? More importantly, how do we create a false narrative that is believable? I am interested in how photography can lead viewers to arrive at a sense of certainty within themselves. It’s ultimately about searching for something concrete in a world that makes no sense.”

Patricia Voulgaris, Lost Bear, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Lost Bear, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Spell, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Spell, 2022 In her latest photographs Voulgaris employs the visual language of the supernatural, taking as her subject the tenuous line between belief and doubt. She collates constructed and caught moments, merging clichés and the mystical to express her ambivalence about both the spirit and the human realm. Voulgaris describes her process as a “response,” enabling her to move “through ideas and move more freely” in a continually iterative practice as opposed to focusing on a resolved body of work. Her intention is to create images as feelings, trading in the world of symbolism and the haptic rather than definitive narratives.

The notion of illusion and perception in a post-truth era has shaped much of Voulgaris’s recent work. In her previous series The Hunter (2020–ongoing), she grapples with the persistent threat of violence to which women are subjected every day, and how it is normalized in our culture. She enlists her partner and parents as protagnosists, crushing and contorting them in bizarre and haunting scenes that resist explanation. Similarly, Voulgaris’s new images fuse constructed moments and improvisation to elicit the same unsettling sensation, this time grounded in unexpected encounters with the natural world.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

While Voulgaris’s photography is rooted in a genuine fascination with the supernatural—nineteenth-century spirit photography, mediums, unexplained events, and projects like Mike Kelley’s Ectoplasm Photographs (1978/2009) are all vital touch points—it also functions as a crutch and a trick. It’s a way to capture the viewer’s attention and draw them into a conversation about something more complex.

At its core, Voulgaris’s work is about the stories we tell ourselves and our tendency to focus on what we want to see rather than what’s in plain sight. Photography has been an accomplice in self-deception, deliberate mistruths, and comforting lies throughout history. In a subversive gesture, Voulgaris illuminates our obsession with certainty while asserting how powerful it is to own the difficult complexities of our existence rather than deny them.

Patricia Voulgaris’s photographs were created using a FUJIFILM GFX50SII camera.

Patricia Voulgaris, Attempting Connection, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Attempting Connection, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Lucky, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Lucky, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Miss Cleo, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Miss Cleo, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Unknown Source, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Unknown Source, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Connected Through You, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Connected Through You, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Silent Stream, 2022

Patricia Voulgaris, Silent Stream, 2022  Patricia Voulgaris, Untitled, 2022. All photographs for Aperture and courtesy the artist

Patricia Voulgaris, Untitled, 2022. All photographs for Aperture and courtesy the artist

February 24, 2023

A Photographer Considers the Vulnerability and Visibility of South Africa’s Shebeens

On June 26, 2022 twenty-one high-school children below the legal drinking age of eighteen died in a tavern in East London, South Africa, after inhaling methanol fumes in the overcrowded, unventilated venue. In a Soweto shebeen two weeks later, fifteen patrons were gunned down with rifles and pistols in what survivors called “an orchestrated hit.” The actual targets had already left. Follow-up reports of other murders dominated the current affairs programming through much of July until the media frenzy cooled off.

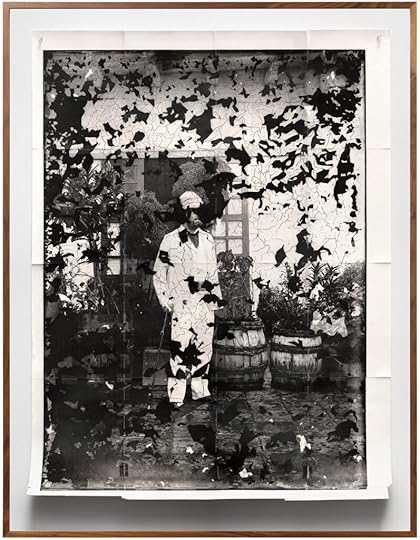

As I mulled over these grisly stories, I thought of the photographer Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo’s work constantly. Last April, the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg presented a solo exhibition by Hlatshwayo, Umnyakazo, which included his compelling tavern-based series Slaghuis I and II. Hlatshwayo, the child of shebeen owners in the township of Lawley, southwest of Johannesburg, doesn’t deny the social impact of the business that fed him. Instead, he seeks catharsis from his inextricable links to it. (Under apartheid, shebeens referred to illegal taverns, as Blacks could not drink or purchase alcohol without restriction.) As a result, there is space and quietude to the images as they explore his invisibility within the shebeen’s confines.

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022  Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 In 2016, Hlatshwayo joined the East Rand–based Of Soul and Joy project based on a tip by his mentor Jabulani Dhlamini, a photographer and project manager of the initiative, which seeks to expose vulnerable youth from Thokoza to photography and art through mentorship. (Alumni include the Magnum photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa.) Through the program, Hlatshwayo was inspired by his contemporary Tshepiso Mazibuko’s use of expired film. The effect was that of “a lot of dirt on the surface,” a kind of spotted, off-color grain. “There was an interruption,” he told me, from his bare home studio in Lawley. “It was not a clean image and I really liked that.”

Hlatshwayo found a permissive environment at Of Soul and Joy and access to photographers who gave interesting workshops. “What I liked about Jabu was that when he didn’t understand the space you were entering, he’d call on someone who could understand it better to give you more feedback,” says Hlatshwayo, referring to Dhlamini. “Some people try to recreate themselves through their students.” Two years later, Hlatshwayo embarked on the series Slaghuis (an Afrikaans word meaning slaughterhouse or butchery) as a way of voicing the violence of his surroundings. In a reflective article he penned for the Mail & Guardian, he describes, at the age of seven, waking up to a dead body and feeling “overwhelmed by the desire to disappear.”

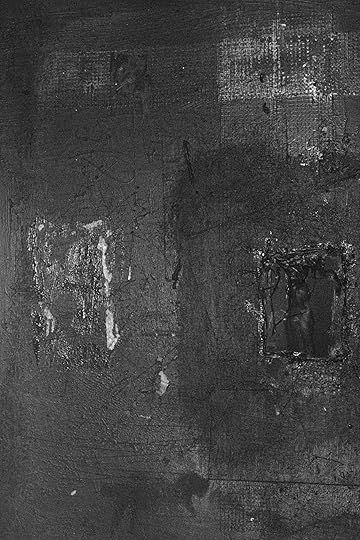

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Repose, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Repose, 2022In Slaghuis I (2018), Hlatshwayo reenacts this desire, layering his images through multiple phases of photography until the subject (often himself) appears distressed, distorted, or dismembered. To add further textures, Hlatshwayo reintroduces prints of the initial photographs into the tavern space, allowing patrons to step on or ash their cigarettes on them, and then rephotographs the paper. In this initial series, Hlatshwayo’s impulse to experiment comes across as feverish and fearless, but also a bit literal.

By the time he has a second go at the topic—Slaghuis II (2019) was first exhibited at the Market Photo Workshop in February 2020—an embodiedness begins to permeate his approach. This time, Hlatshwayo exhibits a flair for the Ballenesque; with less situational context in favor of more conceptual execution. These stylistic changes have been gradual, but the photographer’s openness to collaboration and keenness to explore multiple disciplines has meant that breakthroughs are always around the corner.

As soon as Slaghuis II opened in February 2020, the exhibition had to move online because of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Fatigued, Hlatshwayo retreated and thought about how to create new work. “I was wondering about walls and imposing movement on walls,” he says of a process-driven style through which he began to regard installation as performance. When the photographer and curator Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose was selected to be part of the Goethe-Institut’s Young Curators Incubator 2022 program (in partnership with the History of Art department in the Wits School of the Arts), he opted to collaborate with Hlatshwayo, after they had each exhibited work at the South African Pavilion at the Dubai Expo in 2021.

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022  Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 The resulting exhibition repurposes some of the images contained in Slaghuis I and II and explores interiority through tactility while experimenting with various modes of presentation. “You saw newsprint, you saw wallpaper, you saw video and engraving, which are all super related to his image-making process,” says Nyawose.

Nyawose, who describes their collaboration as “collapsing the line between curator and artist” nudges Hlatshwayo towards the idea of inconclusiveness, where the production process—and the subversion of it—becomes a language in and of itself. The Umnyakazo exhibition became both “format and medium in real time,” says Nyawose, crammed with affective details such as the use of specialist paint that would change hue according to the time of day. He spent time thinking about “the idea of shadows,” which is prominent in Hlatshwayo’s work.

While the shebeen was a site of momentary pleasure and an appendage of the migrant labor system for predecessors like Rose Motau and Santu Mofokeng, for Hlatshwayo the speakeasy of today lays bare the limits of self-determination. What Umnyakazo achieves through a lack of finish, a speculative approach, and a preference for less stable materials, is a sharp dissection of alienation. As we are decreasingly able to physically access the tavern in his newer work, a suggestion that the photographer is no longer preoccupied with his pain as an individual, Hlatshwayo edges towards more systemic concerns. Through the use of scrawls and screens, he ponders the unaltered spatial landscape of apartheid (suggested here by materials that evoke the posterized city), and the overarching violence that still corrals the underclasses to the beer hall.

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Ngingaphakathi, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Ngingaphakathi, 2022 Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022 Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Untitled, 2022All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.

In London, a New Approach to Preserving Britain’s Photographic History and Future

London’s Piccadilly is one of the main arteries of the city. The mile-long stretch of road connects the traffic-choked “circus” to the more genteel surroundings of the Royal Academy of Arts, with Buckingham Palace not far beyond. While slick, commercial art galleries have begun to swallow up the streets to the north, pockets of old Piccadilly remain, not least on Jermyn Street, where traditional purveyors of men’s suits and sundries still dominate.

It is here that British dealer, academic, and photography collector James Hyman has established the Centre for British Photography, which opened on January 26 and celebrates the past and future of photographic practice throughout the United Kingdom. Hyman found the space—an empty Italian tailoring store—only last October, and quickly went about creating a home for the substantial collection of photography that he has built with his wife Claire, chair of the Centre’s board of trustees. Along with housing the roughly three thousand photographs they own, the Centre features three galleries and several research spaces.

Daniel Meadows and Martin Parr, June Street, Salford, 1973

Daniel Meadows and Martin Parr, June Street, Salford, 1973  David Moore, Baby, TV, Earth, 1988

David Moore, Baby, TV, Earth, 1988 This is not the first British institution dedicated to the medium. The Photographers’ Gallery is just up the road, and Autograph has supported underrepresented photographic and filmic practices since the 1980s; the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new photography center is also set to open on May 25, 2023. But Hyman is clear that much more could be done, particularly when it comes to supporting organizations beyond the capital. The Centre functions as a springboard for museums, galleries, and grassroots projects further afield, with its ethos being to shine a light on lesser-known practices while offering a greater degree of autonomy to image makers themselves.

Although it’s privately funded, the Centre will be an open, public-facing institution from the outset, with no entrance fee. “It will not be a private monument, but a public institution,” Hyman says. In an ideal world, he adds, the Centre would eventually be publicly funded, yet, with ever-tightening austerity measures and ferocious cuts to the arts—in 2021, the government announced 50 percent cuts across all arts and design higher education—such a future is far from certain.

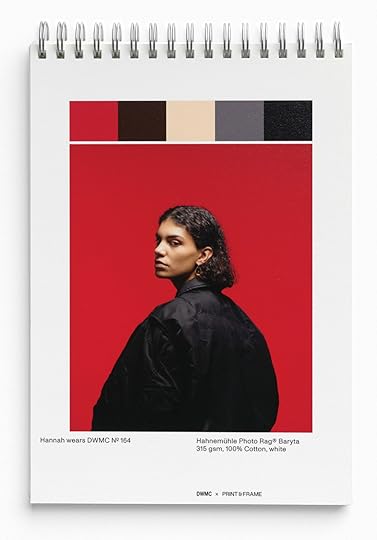

One may have expected an air of nationalistic nostalgia from an institution that focuses on British photographic practices, but the Centre boasts a diverse range of artists and perspectives. “This is not about a passport or nationalism. It is about the subject of Britain, as opposed to the identity of the photographer themselves,” says deputy director Tracy Marshall-Grant, whose previous posts include director of Belfast Exposed, a leading photography gallery in Northern Ireland, and director of development at the Royal Photographic Society.

Vicky Hodgson, Untitled, from the series Beauty Contest, 2022

Vicky Hodgson, Untitled, from the series Beauty Contest, 2022 Maryam Wahid, The orange lehenga, near the Queen Victoria Statue in Birmingham, 2018, from the series Women from the Pakistani Diaspora in England, 2018–ongoing

Maryam Wahid, The orange lehenga, near the Queen Victoria Statue in Birmingham, 2018, from the series Women from the Pakistani Diaspora in England, 2018–ongoingFor the inaugural program, an expansive idea of Britishness is evident, with exhibitions that encompass both Britain as a central subject, but also as a place that has nurtured artists exploring issues ranging from gender roles to systemic racism.

The exhibition that visitors first encounter was curated by the research group Fast Forward: Women in Photography, which focuses on contemporary female self-portraiture. Titled Headstrong: Women and Empowerment, it encompasses artists who are first- and second-generation immigrants, refugees, and women who challenge societal perceptions around aging and visibility.

For example, Vicky Hodgson recreated photographs that she was forced to pose for as a child to enter a beauty contest. The series, titled Beauty Contest (2022), is a poignant investigation of the sexist stereotypes associated with aging. For The Bully Pulpit (2018), Haley Morris-Cafiero created and posed as caricatures of online trolls who have demonized her appearance, while Maryam Wahid’s series Women from the Pakistani Diaspora in England (2018–ongoing) considers the perception of migrant identity. The artist visited places around Birmingham, England, that were significant to her mother when she first moved to the city, and posed for portraits while wearing her mother’s traditional Pakistani clothes. The resulting images forge links between the place Wahid grew up and her ancestral heritage.

Markéta Luskačová, Whitley Bay, 1978

Markéta Luskačová, Whitley Bay, 1978 © the artist

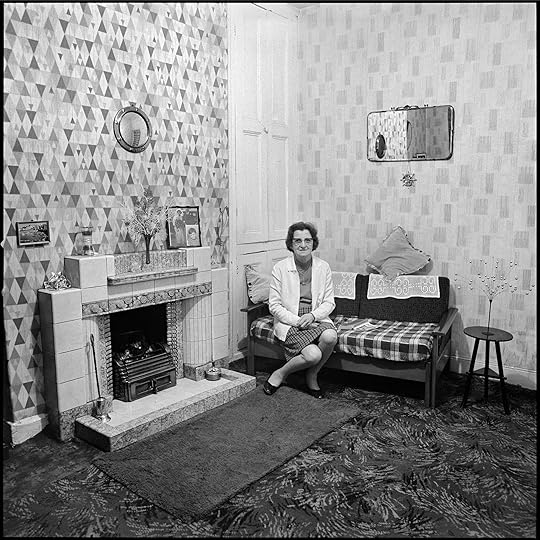

Bill Brandt, West Ham Bedroom (London), 1937

Bill Brandt, West Ham Bedroom (London), 1937© Bill Brandt Estate

Bill Brandt, The Perfect Parlourmaid – English Parlourmaid (Evening), 1935

Bill Brandt, The Perfect Parlourmaid – English Parlourmaid (Evening), 1935© Bill Brandt Estate

Also on display are the outcomes from Fast Forward workshops that took place in different venues around the United Kingdom, including at Impressions Gallery in Bradford and the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh. Photographers and educators worked with people from marginalized groups to help them express themselves creatively through photography, whether that involved making zines or keeping a visual diary. In projects such as Putting Ourselves in the Picture (2021) and I was, I am, I will be (2021), migrant and refugee women visually depict the realities of their lives, from reuniting with loved ones to passing a driving test.

In the Centre’s basement, the allure of more conventional British documentary photography endures in the second major opening exhibition, The English at Home: Photographs from the Hyman Collection. And yet, this selection of some 150 photographs is full of surprises. Alongside well-known accounts of working-class British life by the likes of Bert Hardy and Bill Brandt (who was born in Germany but identified with his English heritage) are images from Karen Knorr’s series Belgravia (1979–81). These see the American photographer peel back the veneer of the English upper crust by including snippets of her sitters’ opinions on politics and identity alongside their portraits. Elsewhere, Czech photographer Markéta Luskacová treats families dedicated to pitching tents on the frigid British seaside with the true curiosity of an outsider.

Back upstairs, three separate displays across the mezzanine focus on individuals who further interrogate representations of women. A presentation of Jo Spence’s Fairy Tales and Photography, or, another look at Cinderella from 1982 (curated by the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive) showcases the photographer’s pivotal work on the performance of gender through annotated photographs that mock “wifely” duties such as cooking and cleaning, and the fantasy of domesticity. Similarly, Natasha Caruana’s series Fairytale for Sale (2011–13), a recent Hyman Foundation acquisition, includes hundreds of images uploaded to e-commerce platforms like eBay, by women hoping to sell their wedding dresses online. The result is an uneasy montage of blurred-out faces and staged portraits, where the dream falls apart.

Natasha Caruana, Fairy Tale for Sale, 2011–2013

Natasha Caruana, Fairy Tale for Sale, 2011–2013Courtesy the artist

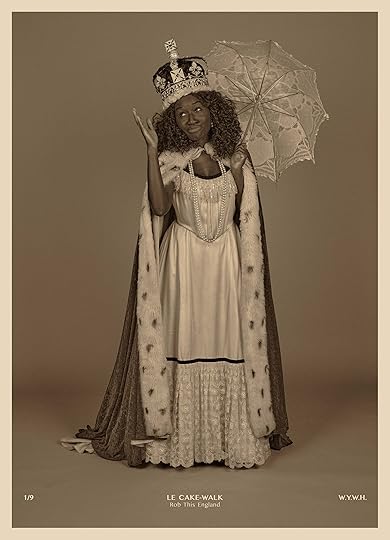

Heather Agyepong, 1. Le Cake-Walk: Rob This England, from the series Wish You Were Here, 2020

Heather Agyepong, 1. Le Cake-Walk: Rob This England, from the series Wish You Were Here, 2020 All photographs courtesy the Centre for British Photography, London

Finally, a display from Heather Agyepong presents the culmination of an original commission from the foundation. The artist was invited to respond to early twentieth-century imagery of the cakewalk, the dance craze dominated by vaudeville sensation Aida Overton Walker that began as a way for enslaved African Americans to mock enslavers, later becoming a popular form of entertainment for white audiences. Agyepong reimagines the postcards used to commemorate Overton Walker’s performances through her own vaudeville scenes, which incorporate historical and contemporary objects to reflect on ideas of self-worth and agency.

With such a variety of works on show, and so much to prove in an inaugural program, there is a risk of attempting to do too much. However, there’s something undeniably cohesive about the Centre. While a “British” remit may at first seem limiting and restrictive, it instead provides a focus for photographic practices that other major institutions may have overlooked. It demonstrates how British identity is fluid, multifaceted, and ever-changing. For the near future, the Centre promises collaborations across the country, sharing resources, and championing upstarts and in-depth research. One can only hope that its work will resonate far beyond British borders.

Headstrong: Women and Empowerment and The English at Home: Photographs from the Hyman Collection are on view at the Centre for British Photography, London, through April 23, 2023.

February 17, 2023

An Uncanny Chronicle of Ukraine, Before and After the War

Olga, a resident of Kyiv, is frightened by sunrises, prefers to be called by her full name, considers the patronymic form a kind of company, loathes the times when the city feels empty, and, when it stays that way too long, begins to “see what nobody sees and hear what nobody hears.” She claims to perform acts of transformation—turning a pot of kasha into a hydrangea, a spoon into a blue ribbon, a postcard commemorating International Women’s Day into a trio of matches. She swears this is all true. Depends, of course, on your definition of truth. This is one of the ideas at the heart of Lucky Breaks (2018), a collection of short fiction by the Kyiv-born photographer Yevgenia Belorusets, who intersperses the thirty-two brief stories, intermittently, subtly, with her documentary pictures.

Since the war broke out in Ukraine—the revolution of 2014, that is—another of Belorusets’s characters has lost all sense of beginnings, and now wakes in the afternoon. This woman and her sister, a dishwasher at the American embassy, wear too-large clothes donated to them by Americans. The sister grows so bored of telling the siblings’ story to the journalists, directors, and actors who come asking to hear that she starts replacing their narrative with the various traumas and misfortunes of their friends and neighbors, or with totally invented stories: “convoluted, complicated tales to force someone to really listen to what she was saying.”

Many of the protagonists in Lucky Breaks may come off as eccentric, probably because they are isolated, which is also because they have been displaced. Most are women. They fled the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, site of the conflicts of 2014, or they have to move away to earn a living, or their husbands are gone for months on end, also for work. The characters in the story “The Stars” finally begin to venture out of their basement shelters by charting the hours in which a newspaper column declares them astrologically safe—all clear for a Pisces to emerge between three and five in the afternoon, while a Scorpio is allowed out into the evening for a walk in a city “both smoky and bright.” Even as long lines of “soiled and sullen” cars exit her city, the title character of the story “My Sister” is determined to stand her ground, no matter that she’s almost all alone, surrounded by broken windowpanes and cords that snake in and out of other apartment windows attempts to steal electricity by others who have refused to leave.

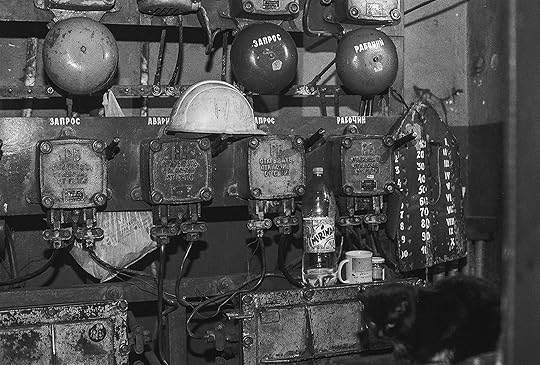

Snaking along, too, below the current of the subjects of the short stories of Lucky Breaks is a fugitive stream of black-and-white pictures made by the author. Belorusets, as translator Eugene Ostashevsky writes in an afterword to the 2022 US edition, came to writing from her life in photography, in which she uses “documentary methods,” and she’d arrived at photography via a life in political and social activism. Her photographic series have focused on animals, brick-factory workers in west Ukraine, queer and trans families throughout the country, the residents of Roma settlements under attack by the far right, and protesters during the revolution of 2014, also known as the Revolution of Dignity. Russian special-ops and troops disguised as locals embedded in the fighting in the Donbas had turned the region into a surreal world in which notions of truth became increasingly murky—a fog of war that in the book Belorusets coats with photography.

Here and there in Lucky Breaks are pictures of abandoned-looking industrial buildings; a grinning, uniformed worker; persons sleeping in the grass. They are pulled, without identifying marks, from two of her documentary series: one, a project depicting people hanging out in parks—the dislocated feeling of leisure during wartime; the other, of the employees of a government-run coal mine who in 2015 and 2016 formed a protest to avert ecological disaster in their homeland, demanding that the mine’s closure adhere to environmental standards.

None of this background is apparent in Lucky Breaks, whose themes already verge on the Gogolian absurd. Dislodged from their original context, thrown into the realm of fiction, her images add a semblance of authenticity—the “presence of the thing,” as Roland Barthes put it, presumably assuring a more skeptical eye—in a place where reality has been upended. At the same time, her inclusion of the photographs plays on the reader’s inherent desire for concrete evidence. At second glance, the picture asks more than it answers.

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }

var container = ''; jQuery('#fl-main-content').find('.fl-row').each(function () { if (jQuery(this).find('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container').length) { container = jQuery(this); } }); if (container.length) { var fullWidthImageContainer = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image-container'); var fullWidthImage = jQuery('.gutenberg-full-width-image img'); var watchFullWidthImage = _.throttle(function() { var containerWidth = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var containerPaddingLeft = Math.abs(jQuery(container).css('padding-left').replace(/\D/g, '')); var bodyWidth = Math.abs(jQuery('body').css('width').replace(/\D/g, '')); var marginLeft = ((bodyWidth - containerWidth) / 2) + containerPaddingLeft; jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('position', 'relative'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('marginLeft', -marginLeft + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImageContainer).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); jQuery(fullWidthImage).css('width', bodyWidth + 'px'); }, 100); jQuery(window).on('load resize', function() { watchFullWidthImage(); }); }Lucky Breaks pushed Belorusets to look further into the unknown. In 2021, she published Modern Animal, her second book of fiction but her first published in English—a short, surreal novel told through diaristic accounts, fairy tales, and a series of lectures, some of which are delivered by animals. As in her photography, Belorusets had used documentary methods before she began to write, sometimes collaborating with her human interview subjects to transform the material of their conversations into fiction—”a kind of contemporary folk literature,” according to one of her editors, Sebastian Clark, of the subscription-based imprint Isolarii. Like Lucky Breaks, Modern Animal includes some of Belorusets’s photographs—the series Zhyvy Kutochok (The Living Corner) (2019–21) of chickens and cows on a farm, dogs, and birds of prey.

Shown in black and white, certain of her images-especially the closely depicted owls and hawks, and the sense of calm that seems to surround her cows and calves-aspire to the sensibility of Peter Hujar’s magnificently secret and intimate photographs of animals. In one sense they are Belorusets’s attempt to redress the hierarchical relationship of humans and animals taught in Soviet-style education—one in which schoolchildren learned to take care of plants and animals that were kept in a dark, small “living corner” of the classroom. “At that time, it was taught that the human being was the pinnacle of creation and animals were just tools,” she said in an interview with Palm, the online magazine from the Paris museum Jeu de Paume.

“Pictures, if you think about it, are a kind of cage for animals,” she continued. “In the book, text and images work in parallel. The photographs are not illustrative of the story, but arise from the same kind of interrogation.” Her desire to photograph animals was grounded in her awareness of the fact that she would never be able to fully know them.

When she photographed and interviewed residents of the Donbas during wartime in 2014, Belorusets often felt like “a guest in a catastrophe.”

The English translation of Lucky Breaks was first published in the United States on March 1, 2022, five days after Russia invaded Ukraine. Belorusets has said that when she photographed and interviewed residents of the Donbas during wartime in 2014, she often felt like “a guest in a catastrophe,” someone who had a home to return to. Photographing and writing short stories had prepared her for the events of February 24, 2022, only in the sense that, when Russia invaded Kyiv, as she wrote in her diary, “my body memory kicked in.” That memory, coupled with shock, soon came to register as grief, and the recognition that the war was a continuation of the work she had already begun, as she also found herself doing things she had imagined for her fictional wartime characters. It gave Lucky Breaks an added layer of eeriness, although most of the eeriness of the book has to do with the cycles of historical time and myth embedded within the tales.

For the first forty-one days of war, Belorusets continued to keep a diary, which was published as a daily online dispatch and eventually collected as In the Face of War (which includes her photographs as well as works by historical artists such as Maria Prymachenko and Tetyana Yablonska, and the contemporary artists Nikita Kadan and Lesia Khomenko), also published by Isolarii. Isolarii titles are designed as tiny volumes, the size of a small cell phone or a pocket hymnal. Each book, even one that amounts to 444 pages, as this one does, fits in the palm of your hand. You are conscious of the sensation of physically holding the first unsettling weeks of the war. In those days, Belorusets compulsively photographed, mostly in color, the things around her—perhaps the most common impulse in photography, to preserve the sense of something before it disappears altogether. She did it, she writes in an afterword, “to somehow interrupt the flow of this particular, unbearable story.” And yet, she was caught in the position of preserving a story she herself had written, with uncanny, disorienting prescience.

All photographs from Yevgenia Belorusets, Lucky Breaks (New Directions, 2018)

All photographs from Yevgenia Belorusets, Lucky Breaks (New Directions, 2018) With Lucky Breaks, Belorusets had been operating in the vein of others before her who have inserted photographs into literary texts, but especially W. G. Sebald, whose melancholic-cosmic novels of time, memory, and the aftermath of war—Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn, and Austerlitz—famously interweave uncaptioned photographs within the twisting narratives that wander alongside their forever rambling protagonist as he falls into digressive encounters with strange fellow travelers, stepping into a great pool of time.

No one likes to be duped, but some people don’t like to have a good time. Some of Sebald’s critics, like all overly literal-minded readers, spend too much energy worrying about what stories and images he may or may not have borrowed or embellished, invented or not, which stories came from familiar photo albums and which came from unknown subjects of photographs sold by antique dealers—which is to miss out on the pleasures and lessons of his books. It is to miss the notes of comedy in his writing, and in the interplay between word and image.

In an essay for the New Yorker praising the too rarely observed humor in Sebald’s work, the writer James Wood locates the comic in the photographs in the books, particularly in the “self-conscious antiquarianism” of Sebald’s unnamed first-person narration: the existence of “an otherworldliness of the present. His very prose functions like an old, unidentified photograph.” The haunting cover image of Austerlitz—an old photograph of a young boy in a field, wearing an outfit as aristocratic as those in a Rembrandt-could not be “of” Jacques Austerlitz, an invented character. But did the picture itself make it seem as if it could be? When Wood, examining the photograph in the author’s archive, flipped it over, he found a junk dealer’s penciled-in price: 30 pence. “Scandalously,” Wood writes, “where documentary witness and fidelity is sacred, Sebald introduces the note of the unreliable.” The greater issue, he proposes, is whether Sebald’s use of that particular photograph implied a more direct connection to the historical events of the book.

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Perhaps we’re meant to question these things, and that’s part of the point—not that Sebald was the sort of writer who had “a” point. For a writer such as Belorusets, whom I would call an indirect descendant of Sebald’s, both photograph and story seem to gain power the more assiduously she calls their veracity into question. “Any document is partly a lie,” Belorusets has said, “and this is especially true of documentary photography, which only ever conveys a small part of reality.”

Like the found photographs of Sebald’s novels, Belorusets’s repurposing of her own pictures allows them to function as enigmas. Rather than illustrate, they suggest the feeling of a world. Rather than dutifully serve the plot, they tend to shift the attention elsewhere. In place of proof, they respond in dreamlike fragments, deliberately casting doubt. Sometimes her photographs misbehave, like punchlines. Reminiscent of the isolated, dream-spinning Silesian narrators of Olga Tokarczuk’s House of Day, House of Night, the protagonist of Belorusets’s “The Seer of Dreams” insists on her fantastic somnambulant visions of ancient Ukraine, of rivers of blood, of elephants wearing embroidered saddles.

The seer’s final divination of the story—of a prophetic, two-headed dog who forecasts images of prosperity and happiness—is instantly undercut by the mortal intrusion of Belorusets’s own photograph, of what appears to be a miners’ locker room, with shelves of rusted tools and hard hats and coffee mugs. Is this a joke on the dreamer or on the reader? Does it matter? Do we even have to ask?

This essay is drawn from Rebecca Bengal’s collection Strange Hours: Photography, Memory, and the Lives of Artists (Aperture, 2023).

The Photographers Who Showed the Whimsy and Eros of Ukraine before the War

A bomb shelter in Kyiv. A mass grave in Mariupol. Bodies of dead civilians strewn on the streets of Bucha. While these pictures of Ukraine have flooded international media and brought the country to the attention of foreign spectators, its struggle for independence and self-determination began long before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. Instead of focusing on these images, might a look back to photographic projects predating the present war reanimate the complex richness of the region and pay tribute to the continued vitality of Ukraine’s people?

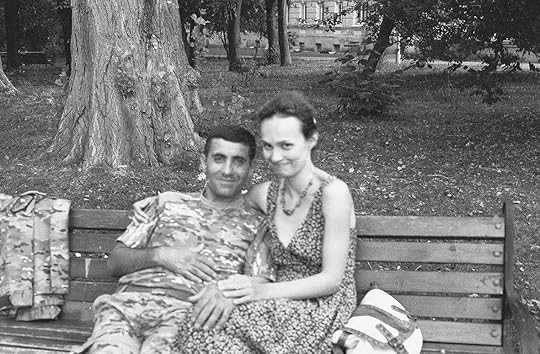

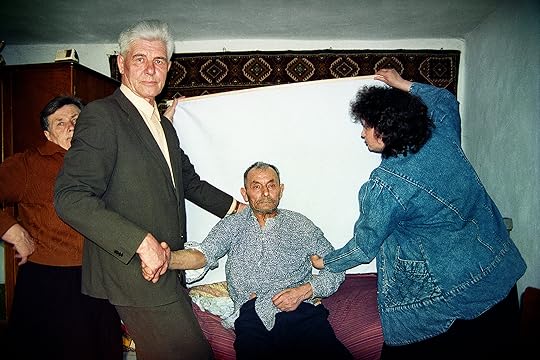

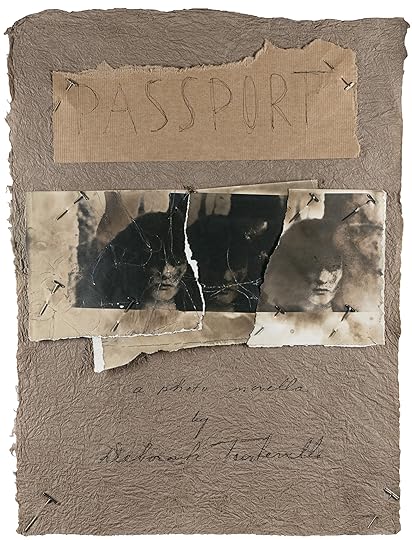

In the mid-1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Alexander Chekmenev took an official assignment on behalf of the newly formed Ukrainian government to make passport photographs of the elderly and disabled in their homes in Luhansk. What he encountered were people in a state of near total impoverishment who had worked for the government all their lives and received nearly nothing in return. Their Soviet-era apartments were not unlike the one Chekmenev himself had lived in with his grandparents, parents, and sister—often with no running water or gas. Chekmenev’s images from these home visits capture a generation largely on the verge of death, untouched by the promise of their burgeoning democratic nation.

Alexander Chekmenev, from the series Passport, Luhansk, Ukraine, 1995

Alexander Chekmenev, from the series Passport, Luhansk, Ukraine, 1995Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

Alexander Chekmenev, from the series Passport, Luhansk, Ukraine, 1995

Alexander Chekmenev, from the series Passport, Luhansk, Ukraine, 1995Courtesy the artist and Dewi Lewis Publishing

Working in black and white with one camera, Chekmenev took the official passport-format headshots of weary visages against a portable white backdrop; while using a wide-angle camera with color film, he captured all that lay beyond in photographs that would eventually form the series Passport (1995). “I saw that the frame needed to be widened,” he told me recently. The photographs represent a people entrenched in an old Soviet system that cared little for, deceived, and effectively abandoned the individual. Depicting a generation trapped in time, the pictures teeter on the precipice of uncertainty.

Even in scenes of war, there is tenderness. Even in a landscape of political strife, there is whimsy and eros.

Chekmenev says he never could have predicted his country’s progressive impoverishment, nor that he would become one of Ukraine’s most renowned documentarians: his reportage of the 2014 invasion in the Donbas region and, over the last year, portraits from the streets of war-torn Kyiv and of President Volodymyr Zelensky have appeared in publications ranging from the New York Times to Time magazine. And could the elderly in his photographs, many of whom had lived through World War II and possibly even Stalin’s 1932 forced famine in Ukraine, have predicted that, thirty years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia would launch a military invasion of their country?

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture magazine. Sign-up today and your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription Get a full year of Aperture magazine. Sign-up today and your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine SubscriptionGet the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

$ 0.00 –1+ View cart Description Get a full year of Aperture—and save 25% off the cover price. Your subscription will begin with the winter 2022 issue, “Reference”. Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18Courtesy the artist and MAPS

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18Courtesy the artist and MAPS

Ukraine Runs Through It (2019), by the Polish documentary photographer Justyna Mielnikiewicz, chronicles mostly the period from 2014 to 2018 and the individuals who took an active part in a major chapter in Ukraine’s fight for sovereignty. The book uses the Dnipro River as its conceptual through line—a body of water marking a divide between eastern and western Ukraine, but also muddying the notion of clearly delineated territories. Mielnikiewicz, like many of the protagonists in her images, believes this independence movement represents a shift from seeing Ukraine as a former Soviet country to seeing it as part of a new Eastern Europe: “When you say the new Eastern Europe, it becomes like East versus West, West versus East. Whereas when you say ex–Soviet Union, Russia is somehow always in the center,” she explains. Mielnikiewicz’s book includes a 2014 photograph of Petro, a young man serving on Ukraine’s eastern front. He had joined the protest movement at Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) in Kyiv earlier that year and wears a teddy bear pinned to his uniform, a gift from a girl he met at the protests.

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Even in scenes of war, there is tenderness. Even in a landscape of political strife, there is whimsy and eros. The artist Julie Poly’s project Ukrzaliznytsia (2020), with photographs that act as a love letter to the Ukrainian national rail company, where Poly was briefly employed, is an homage to a childhood spent traveling the country by train, observing its landscapes and inhabitants. Flamboyant colors attest to the joyful, coquettish aesthetic of a country of sunflowers and watermelon, cherry jam and pickles. Each train car has its own patterned carpet, baby-pink floral drapes, and faded yellow tables—a Technicolor balm against the drab gray of all things Soviet. The young people she photographed may even refuse to define themselves in any relation to the USSR. A lanky man with a red rose in his hair plays cards with two elderly women, but his gaze is outward, staring at the camera. He’s seeing something that they cannot.

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

Still, in the face of war, Poly responds with eros: she is putting together an erotic magazine, inspired by vintage pinups and Marilyn Monroe’s visit to US troops, which will be sent to Ukrainian soldiers on the war front. When Russian air strikes began in 2022, Poly fled Ukraine while eight months pregnant. Now residing in Germany, she continues to be optimistic that life in Kyiv will return to its previous vibrancy. She looks at her photographs from Ukrzaliznytsia with nostalgia and admiration. “Ukrzaliznytsia is still transporting people, but now in the context of evacuating them,” Poly says. “The book itself feels like a testament of the past, but I hope these journeys will start up again. I hope these colors, these patterns, these people, the smiles on their faces will all return.”

Viewed together, the works of Chekmenev, Mielnikiewicz, and Poly generate a kind of “alternative photography,” as the critic John Berger once called for—a photography that instead of freezing images in time returns them to a living context, reintegrating the past into the present for the preservation of socio-political memory. More than mere spectacle, these photographs bear witness to a people immersed, consciously or unconsciously, in emergent history—one in which individual stories play out against the backdrop of a nation’s ongoing becoming and its striving to define its sovereignty.

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20

Julie Poly, from the series Ukrzaliznytsia, 2018–20Courtesy the artist

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18

Justyna Mielnikiewicz, from the series Ukraine Runs Through It, 2014–18Courtesy the artist and MAPS

This article is originally from Aperture, issue 250, spring 2023.

February 16, 2023

William Christenberry, RaMell Ross, and the American Crucible of Hale County, Alabama

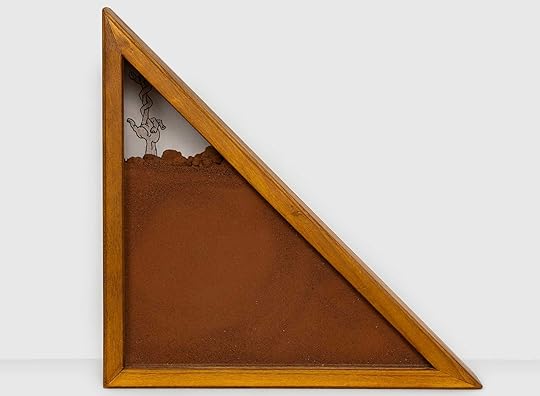

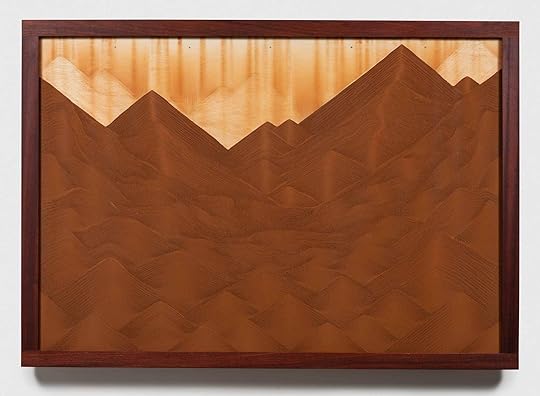

The first landmark you see is red dirt framed in wood, behind museum glass—Alabama red soil, crucially. In Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Altar (2021) by RaMell Ross, red dirt undulates in triangulated peaks, toward a horizon of what appears to be the roof of a house. It’s the opening work in William Christenberry & RaMell Ross: Desire Paths, an exhibition in the form of a dialogue, at Pace Gallery in New York. Desire paths, meaning those trails worn into the ground contrary to roads planned and paved. They are herding animals’ footpaths to water, they are shortcuts sometimes, or they are secret passageways, or they are escape routes, or, particularly when it comes to the impressions left behind by human footprints, they are often driven by some less practical, enigmatic impulse.

Around a corner, that same dirt appears in the base of a sculpture of a barn painted green, by William Christenberry. “You don’t call it dirt, son!” Christenberry recalled in a 2005 Smithsonian lecture, quoting the redressing he’d once received from an Alabama agronomist uncle. “It’s soil! Soil nurtures life!” But soil, he lamented, inevitably came out as soyl in his Tuscaloosa-born accent. He’d eventually adopt the word earth to describe the substance that he’d carry back to his home in Washington, DC. “He would bring home boxes and boxes of red earth, and he had a screen that he made, so he would take it out in the back yard and sift it,” Sandra Deane Christenberry, his wife, told the New York Times in January.

RaMell Ross, Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Superstition, 2021

RaMell Ross, Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Superstition, 2021  RaMell Ross, Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Altar, 2021

RaMell Ross, Earth, Dirt, Soil, Land; Altar, 2021 That red earth rises to meet the countenance and consciousness of a Shel Silverstein drawing—Ross’s appropriation of the cover illustration of A Light in the Attic, featuring a kid with a house sprouting straight from his head, framed under glass surrounded by more Hale County dirt. Ross fills in the space of the line drawing with brown crayon, giving color to the child’s skin; the house and its pointed, triangular roof are left paper-white. Ross, a photographer, artist, writer, and filmmaker whose childhood geography followed the paths of a military family’s relocations, lives both in Rhode Island, where he teaches at Brown University and, since 2009, in Hale County. Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018), his transcendent and acclaimed essay-film, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2019.

Despite being artistically anchored in the same place, Ross and Christenberry, who died in 2016, did not meet in life. But they converse meaningfully, powerfully, in this group of selected works: paths that crisscross, overlap, double up, converge and diverge. It feels less like an exhibition than a spiritual dimension—a Hale County of the mind—and also a real and actual physical place: a forest in which the people of Ross’s photographs move across time, finding their own place among Christenberry’s dream buildings and monuments, barns and slowly transforming buildings, among trees, and among churches. There seem to be as many of those per capita—as those of us who are from these places can attest—in a rural Southern town. Mining, digging, moving through, replanting, Ross and Christenberry are working with the same dirt, that red earth.

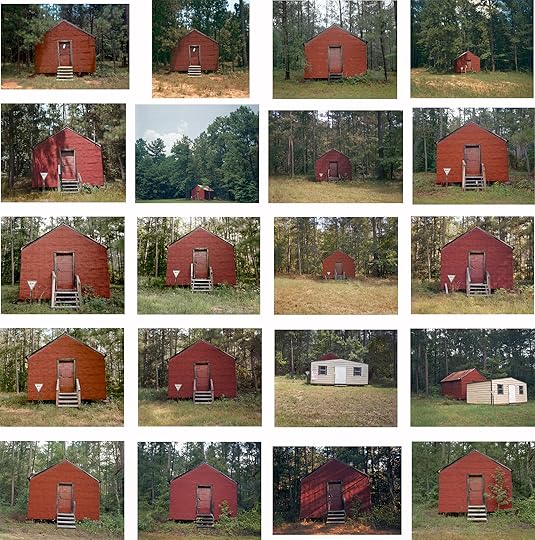

William Christenberry, Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 1974–2004

William Christenberry, Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama, 1974–2004Two more works by Ross hold more red dirt inside containers for memorial flags, but the triangular shape of the frames makes them appear as if they’d been plucked out of a pasture of pyramids. They are signposts along a trail that passes by Red Building in Forest, Hale County, Alabama (1974–2004), twenty 4-by-5-inch pigment prints that Christenberry made over the course of three decades—some of the small, square, serial photographs for which he’s best known and often misunderstood. Even before his good friend William Eggleston turned to color, Christenberry had begun photographing with a Brownie camera he received as a Christmas present in his teens, processing the film at drugstores. A visual artist whose first love was drawing, he initially didn’t think very seriously of the photos.

In 1961, during a year of mostly odd jobs in New York, Christenberry showed his paintings to Walker Evans, whose own Hale County project Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) was known then to Christenberry though it had not yet become the prevailing portrayal of his home region. It was Christenberry’s drugstore photos that Evans, who’d hired the young Alabama artist to file photos at Fortune, was most taken with. “Your camera is like an extension of your eye,” Christenberry later recalled Evans saying. Though he didn’t last long in New York, Evans’s encouragement was enough to propel Christenberry toward Hale County, a place to which he would return annually, from Memphis or Washington, DC, to photograph, over and over, the same places and things. Including this red barn and an old warehouse, with its impossibly verdant, practically fertilized shade of green.

William Christenberry, 5 Cent, Demopolis, Alabama, 1978

William Christenberry, 5 Cent, Demopolis, Alabama, 1978Perhaps you have misread Christenberry before, as simply another photographer of old barns and rural gas stations and general stores and Southern landscapes, subject matter that dares to brush up against sentimentality. And yet his small pictures, approached in a style influenced by Evans (“a severe frontality,” as Christenberry described it), only appear at first to be objective—they demand a closer, longer look to perceive the subjective and conceptual undertones at play. “I don’t want to evoke nostalgia but deep, profound feeling about these little structures,” he once said, meaning both his pictures and the sculptures of them he also made, and the works that would come to him through the subconscious.

Installation view of William Christenberry & RaMell Ross: Desire Paths, Pace Gallery, New York, 2023

Installation view of William Christenberry & RaMell Ross: Desire Paths, Pace Gallery, New York, 2023In truth, Christenberry’s photographs don’t want to show or preserve the little old house as it once was, but to reveal its changes over time, to suggest the impressions of humans without actually depicting any people. The eventual appearance of a prefab gray shed in front of the red barn—tacked with a hand-painted sign reading Vote Here. Christenberry was drawn to the folk expression of a graveside cross made of egg cartons; he loved and collected vernacular signage as object and as omen, whether the benign, the accidentally suggestive (a roadside sign featuring a particularly phallic ear of corn adorned one of his early book covers), and the rural mystic. PALMIST reads the sign of a local reader and fortune teller, its puffy painted hand waving an upside-down hello from a dusty window. (The Underground Club, a similar series not included in this exhibition, witnesses the rise and fall of a country store over decades, eventually resurrected as a nightclub—perhaps following its own desire path.) Returning yearly without wandering inside enhances the buildings’ unknowability: What might have occurred within these places? Who might have met within them? What darker secrets might they hold? “I had a desire, as I say, to come to grips with that landscape in which I grew up, the positive and negative, the dark and the light,” Christenberry said.

RaMell Ross, Man, 2019